User login

FDA study suggests dabigatran’s pros outweigh cons

Credit: Darren Baker

After reviewing data from more than 134,000 patients, researchers at the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have concluded that dabigatran has a favorable risk-benefit profile.

Their research showed that, compared to warfarin, dabigatran decreased the risk of stroke, death, and intracranial hemorrhage in patients with atrial fibrillation.

On the other hand, dabigatran increased the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, and the risk of myocardial infarction was similar for the 2 drugs.

This study was part of the FDA’s ongoing review of dabigatran. The agency has been investigating the safety of dabigatran since 2011, following reports of serious bleeding events associated with the drug.

A previous FDA study, announced in 2012, suggested dabigatran does not pose an increased risk of serious bleeding when compared to warfarin. But other studies have provided conflicting results, so the FDA decided to conduct additional research.

This study included information from more than 134,000 Medicare patients, aged 65 years or older. The researchers compared dabigatran and warfarin, evaluating the risk of ischemic stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, major gastrointestinal bleeding, myocardial infarction, and death.

The FDA said this study is based on a much larger and older patient population than those used in the agency’s earlier review of post-market data, and researchers employed a more sophisticated analytical method to capture and analyze the events of concern.

The data showed that, among new users of anticoagulants, dabigatran was associated with a lower risk of ischemic stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, and death, when compared to warfarin.

The incidence rate of ischemic stroke per 1000 person-years was 11.3 among dabigatran users and 13.9 among warfarin users (hazard ratio [HR]=0.80).

The incidence of intracranial hemorrhage was 3.3 and 9.6, respectively (HR=0.34). And the incidence of death was 32.6 and 37.8, respectively (HR=0.86).

The study also showed an increased risk of major gastrointestinal bleeding with the use of dabigatran compared to warfarin. The incidence rate per 1000 person-years was 34.2 and 26.5, respectively (HR=1.28).

The risk of myocardial infarction was similar for the 2 drugs. The incidence rate per 1000 person-years was 15.7 for dabigatran users and 16.9 for warfarin users (HR=0.92).

These results, except with regard to myocardial infarction, are consistent with the clinical trial results that provided the basis for dabigatran’s approval.

The FDA said these findings suggest dabigatran has a favorable risk-benefit profile, so the agency has made no changes to the drug’s current label or recommendations for use.

The FDA is planning to publish detailed data from this study. Until then, some information is available on the agency’s website.

The FDA said it will continue to investigate the reasons for differences in major gastrointestinal bleeding rates for dabigatran and warfarin. And it will continue reviewing anticoagulant use and the risk of bleeding. ![]()

Credit: Darren Baker

After reviewing data from more than 134,000 patients, researchers at the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have concluded that dabigatran has a favorable risk-benefit profile.

Their research showed that, compared to warfarin, dabigatran decreased the risk of stroke, death, and intracranial hemorrhage in patients with atrial fibrillation.

On the other hand, dabigatran increased the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, and the risk of myocardial infarction was similar for the 2 drugs.

This study was part of the FDA’s ongoing review of dabigatran. The agency has been investigating the safety of dabigatran since 2011, following reports of serious bleeding events associated with the drug.

A previous FDA study, announced in 2012, suggested dabigatran does not pose an increased risk of serious bleeding when compared to warfarin. But other studies have provided conflicting results, so the FDA decided to conduct additional research.

This study included information from more than 134,000 Medicare patients, aged 65 years or older. The researchers compared dabigatran and warfarin, evaluating the risk of ischemic stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, major gastrointestinal bleeding, myocardial infarction, and death.

The FDA said this study is based on a much larger and older patient population than those used in the agency’s earlier review of post-market data, and researchers employed a more sophisticated analytical method to capture and analyze the events of concern.

The data showed that, among new users of anticoagulants, dabigatran was associated with a lower risk of ischemic stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, and death, when compared to warfarin.

The incidence rate of ischemic stroke per 1000 person-years was 11.3 among dabigatran users and 13.9 among warfarin users (hazard ratio [HR]=0.80).

The incidence of intracranial hemorrhage was 3.3 and 9.6, respectively (HR=0.34). And the incidence of death was 32.6 and 37.8, respectively (HR=0.86).

The study also showed an increased risk of major gastrointestinal bleeding with the use of dabigatran compared to warfarin. The incidence rate per 1000 person-years was 34.2 and 26.5, respectively (HR=1.28).

The risk of myocardial infarction was similar for the 2 drugs. The incidence rate per 1000 person-years was 15.7 for dabigatran users and 16.9 for warfarin users (HR=0.92).

These results, except with regard to myocardial infarction, are consistent with the clinical trial results that provided the basis for dabigatran’s approval.

The FDA said these findings suggest dabigatran has a favorable risk-benefit profile, so the agency has made no changes to the drug’s current label or recommendations for use.

The FDA is planning to publish detailed data from this study. Until then, some information is available on the agency’s website.

The FDA said it will continue to investigate the reasons for differences in major gastrointestinal bleeding rates for dabigatran and warfarin. And it will continue reviewing anticoagulant use and the risk of bleeding. ![]()

Credit: Darren Baker

After reviewing data from more than 134,000 patients, researchers at the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have concluded that dabigatran has a favorable risk-benefit profile.

Their research showed that, compared to warfarin, dabigatran decreased the risk of stroke, death, and intracranial hemorrhage in patients with atrial fibrillation.

On the other hand, dabigatran increased the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, and the risk of myocardial infarction was similar for the 2 drugs.

This study was part of the FDA’s ongoing review of dabigatran. The agency has been investigating the safety of dabigatran since 2011, following reports of serious bleeding events associated with the drug.

A previous FDA study, announced in 2012, suggested dabigatran does not pose an increased risk of serious bleeding when compared to warfarin. But other studies have provided conflicting results, so the FDA decided to conduct additional research.

This study included information from more than 134,000 Medicare patients, aged 65 years or older. The researchers compared dabigatran and warfarin, evaluating the risk of ischemic stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, major gastrointestinal bleeding, myocardial infarction, and death.

The FDA said this study is based on a much larger and older patient population than those used in the agency’s earlier review of post-market data, and researchers employed a more sophisticated analytical method to capture and analyze the events of concern.

The data showed that, among new users of anticoagulants, dabigatran was associated with a lower risk of ischemic stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, and death, when compared to warfarin.

The incidence rate of ischemic stroke per 1000 person-years was 11.3 among dabigatran users and 13.9 among warfarin users (hazard ratio [HR]=0.80).

The incidence of intracranial hemorrhage was 3.3 and 9.6, respectively (HR=0.34). And the incidence of death was 32.6 and 37.8, respectively (HR=0.86).

The study also showed an increased risk of major gastrointestinal bleeding with the use of dabigatran compared to warfarin. The incidence rate per 1000 person-years was 34.2 and 26.5, respectively (HR=1.28).

The risk of myocardial infarction was similar for the 2 drugs. The incidence rate per 1000 person-years was 15.7 for dabigatran users and 16.9 for warfarin users (HR=0.92).

These results, except with regard to myocardial infarction, are consistent with the clinical trial results that provided the basis for dabigatran’s approval.

The FDA said these findings suggest dabigatran has a favorable risk-benefit profile, so the agency has made no changes to the drug’s current label or recommendations for use.

The FDA is planning to publish detailed data from this study. Until then, some information is available on the agency’s website.

The FDA said it will continue to investigate the reasons for differences in major gastrointestinal bleeding rates for dabigatran and warfarin. And it will continue reviewing anticoagulant use and the risk of bleeding. ![]()

Study links warfarin dosing and dementia

SAN FRANSICO—New research suggests bleeds and thrombosis are not the only adverse effects of improper warfarin dosing.

The study showed an increased risk of dementia among patients with atrial fibrillation whose warfarin doses were outside the therapeutic range for an extended period of time.

Jared Bunch, MD, of the Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute in Murray, Utah, and his colleagues presented this finding at the 2014 Annual Heart Rhythm Society Scientific Session (PO05-169).

Previous research suggested that patients with atrial fibrillation had an increased risk of developing dementia. But the cause of that association

was unknown.

“[W]e now know that if warfarin doses are consistently too high or too low, one of the long-term consequences can be brain damage,” Dr Bunch said. “This points to the possibility that dementia in atrial fibrillation patients is partly due to small, repetitive clots and/or bleeds in the brain.”

To make this connection, the researchers analyzed data from 2693 atrial fibrillation patients receiving warfarin. The team evaluated the relationship between dementia and the percentage of time that patients’ warfarin doses were within the therapeutic range (international normalized ratio of 2 to 3).

In all, 4.1% of patients (n=111) were diagnosed with dementia. This included senile dementia (n=37, 1.4%), vascular dementia (n=8, 0.3%), and Alzheimer’s dementia (n=66, 2.4%).

The researchers’ analysis (adjusted for the risk of stroke and bleeding) revealed that the more time a patient’s warfarin dosages were outside the therapeutic range, the greater his risk of developing dementia.

Specifically, patients within the therapeutic range less than 25% of the time were 4.6 times more likely to develop dementia than patients within range more than 75% of the time.

Patients within the therapeutic range 25% to 50% of the time were 4.1 times more likely to develop dementia. And patients within the therapeutic range 51% to 75% of the time were 2.5 times more likely to develop dementia.

“Our results from the study tell us 2 things,” Dr Bunch said. “With careful use of anticoagulation medications, the dementia risk can be reduced.

Patients on warfarin need very close follow-up in specialized anticoagulation centers, if possible, to ensure their blood levels are within the recommended levels more often.”

“Second, these results also point to a potential new long-term consequence of dependency on long-term anticoagulation medications. In this regard, stroke prevention therapies do not require long-term anticoagulation medications, and reducing the use of these drugs will hopefully lower

dementia risk.” ![]()

SAN FRANSICO—New research suggests bleeds and thrombosis are not the only adverse effects of improper warfarin dosing.

The study showed an increased risk of dementia among patients with atrial fibrillation whose warfarin doses were outside the therapeutic range for an extended period of time.

Jared Bunch, MD, of the Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute in Murray, Utah, and his colleagues presented this finding at the 2014 Annual Heart Rhythm Society Scientific Session (PO05-169).

Previous research suggested that patients with atrial fibrillation had an increased risk of developing dementia. But the cause of that association

was unknown.

“[W]e now know that if warfarin doses are consistently too high or too low, one of the long-term consequences can be brain damage,” Dr Bunch said. “This points to the possibility that dementia in atrial fibrillation patients is partly due to small, repetitive clots and/or bleeds in the brain.”

To make this connection, the researchers analyzed data from 2693 atrial fibrillation patients receiving warfarin. The team evaluated the relationship between dementia and the percentage of time that patients’ warfarin doses were within the therapeutic range (international normalized ratio of 2 to 3).

In all, 4.1% of patients (n=111) were diagnosed with dementia. This included senile dementia (n=37, 1.4%), vascular dementia (n=8, 0.3%), and Alzheimer’s dementia (n=66, 2.4%).

The researchers’ analysis (adjusted for the risk of stroke and bleeding) revealed that the more time a patient’s warfarin dosages were outside the therapeutic range, the greater his risk of developing dementia.

Specifically, patients within the therapeutic range less than 25% of the time were 4.6 times more likely to develop dementia than patients within range more than 75% of the time.

Patients within the therapeutic range 25% to 50% of the time were 4.1 times more likely to develop dementia. And patients within the therapeutic range 51% to 75% of the time were 2.5 times more likely to develop dementia.

“Our results from the study tell us 2 things,” Dr Bunch said. “With careful use of anticoagulation medications, the dementia risk can be reduced.

Patients on warfarin need very close follow-up in specialized anticoagulation centers, if possible, to ensure their blood levels are within the recommended levels more often.”

“Second, these results also point to a potential new long-term consequence of dependency on long-term anticoagulation medications. In this regard, stroke prevention therapies do not require long-term anticoagulation medications, and reducing the use of these drugs will hopefully lower

dementia risk.” ![]()

SAN FRANSICO—New research suggests bleeds and thrombosis are not the only adverse effects of improper warfarin dosing.

The study showed an increased risk of dementia among patients with atrial fibrillation whose warfarin doses were outside the therapeutic range for an extended period of time.

Jared Bunch, MD, of the Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute in Murray, Utah, and his colleagues presented this finding at the 2014 Annual Heart Rhythm Society Scientific Session (PO05-169).

Previous research suggested that patients with atrial fibrillation had an increased risk of developing dementia. But the cause of that association

was unknown.

“[W]e now know that if warfarin doses are consistently too high or too low, one of the long-term consequences can be brain damage,” Dr Bunch said. “This points to the possibility that dementia in atrial fibrillation patients is partly due to small, repetitive clots and/or bleeds in the brain.”

To make this connection, the researchers analyzed data from 2693 atrial fibrillation patients receiving warfarin. The team evaluated the relationship between dementia and the percentage of time that patients’ warfarin doses were within the therapeutic range (international normalized ratio of 2 to 3).

In all, 4.1% of patients (n=111) were diagnosed with dementia. This included senile dementia (n=37, 1.4%), vascular dementia (n=8, 0.3%), and Alzheimer’s dementia (n=66, 2.4%).

The researchers’ analysis (adjusted for the risk of stroke and bleeding) revealed that the more time a patient’s warfarin dosages were outside the therapeutic range, the greater his risk of developing dementia.

Specifically, patients within the therapeutic range less than 25% of the time were 4.6 times more likely to develop dementia than patients within range more than 75% of the time.

Patients within the therapeutic range 25% to 50% of the time were 4.1 times more likely to develop dementia. And patients within the therapeutic range 51% to 75% of the time were 2.5 times more likely to develop dementia.

“Our results from the study tell us 2 things,” Dr Bunch said. “With careful use of anticoagulation medications, the dementia risk can be reduced.

Patients on warfarin need very close follow-up in specialized anticoagulation centers, if possible, to ensure their blood levels are within the recommended levels more often.”

“Second, these results also point to a potential new long-term consequence of dependency on long-term anticoagulation medications. In this regard, stroke prevention therapies do not require long-term anticoagulation medications, and reducing the use of these drugs will hopefully lower

dementia risk.” ![]()

Discharge Planning Tool in the EHR

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics clinical report on physicians' roles in coordinating care of hospitalized children, there are several important components of hospital discharge planning.[1] Foremost is that discharge planning should begin, and discharge criteria should be set, at the time of hospital admission. This allows for optimal engagement of parents and providers in the effort to adequately prepare patients for the transition to home.

As pediatric inpatients become increasingly complex,[2] adequately preparing families for the transition to home becomes more challenging.[3] There are a myriad of issues to address and the burden of this preparation effort falls on multiple individuals other than the bedside nurse and physician. Large multidisciplinary teams often play a significant role in the discharge of medically complex children.[4] Several challenges may hinder the team's ability to effectively navigate the discharge process such as financial or insurance‐related issues, language differences, or geographic barriers. Patient and family anxieties may also complicate the transition to home.[5]

The challenges of a multidisciplinary approach to discharge planning are further magnified by the limitations of the electronic health record (EHR). The EHR is well designed to record individual encounters, but poorly designed to coordinate longitudinal care across settings.[6] Although multidisciplinary providers may spend significant and well‐intentioned energy to facilitate hospital discharge, their efforts may go unseen or be duplicative.

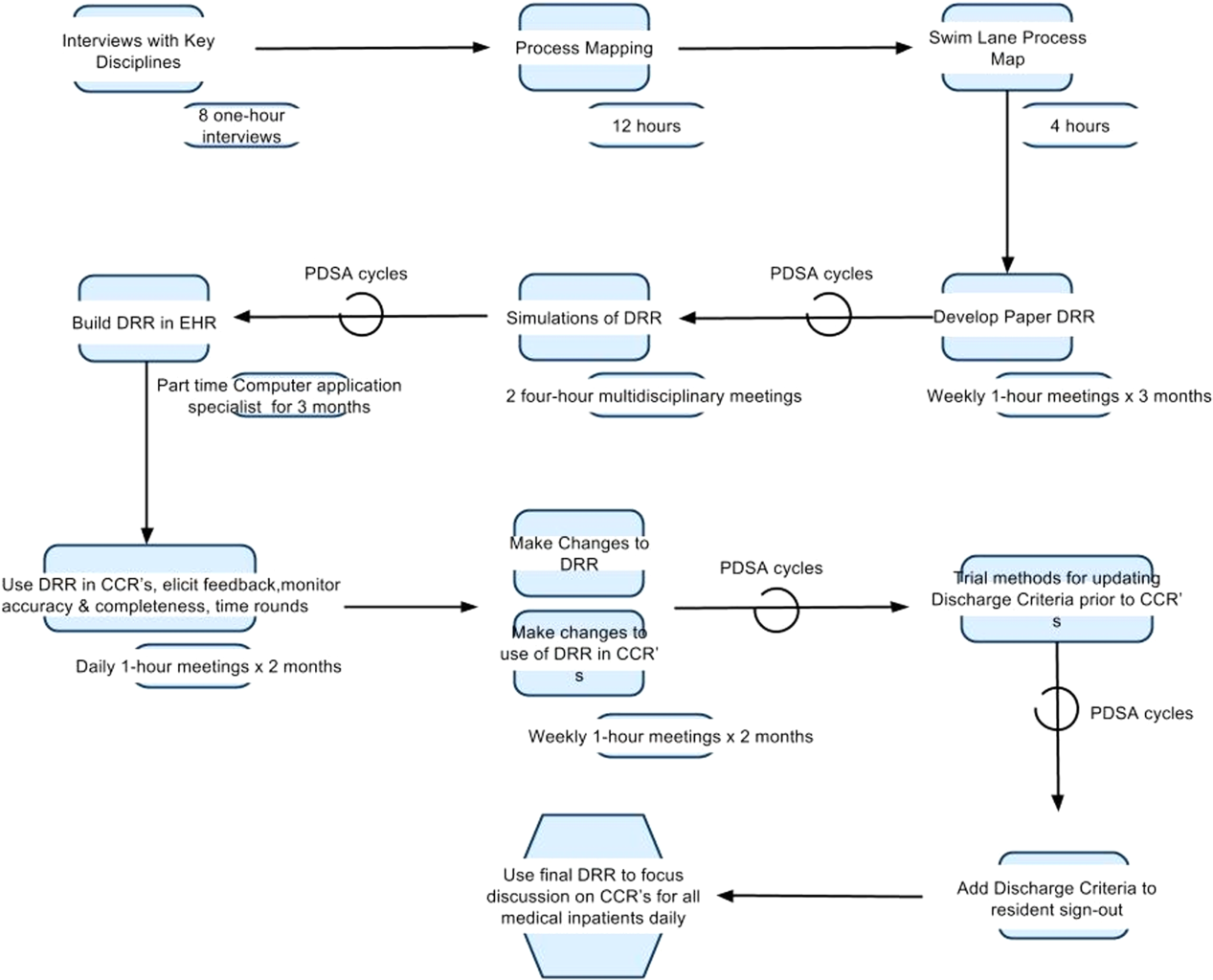

We developed a discharge readiness report (DRR) for the EHR, an integrated summary of discharge‐related issues, organized into a highly visible and easily accessible report. The development of the discharge planning tool was the first step in a larger quality improvement (QI) initiative aimed at improving the efficiency, effectiveness, and safety of hospital discharge. Our team recognized that improving the flow and visibility of information between disciplines was the first step toward accomplishing this larger aim. Health information technology offers an important opportunity for the improvement of patient safety and care transitions7; therefore, we leveraged the EHR to create an integrated discharge report. We used QI methods to understand our hospital's discharge processes, examined potential pitfalls in interdisciplinary communication, determined relevant information to include in the report, and optimized ways to display the data. To our knowledge, this use of the EHR is novel. The objectives of this article were to describe our team's development and implementation strategies, as well as challenges encountered, in the design of this electronic discharge planning tool.

METHODS

Setting

Children's Hospital Colorado is a 413‐bed freestanding tertiary care teaching hospital with over 13,000 inpatient admissions annually and an average patient length of stay of 5.7 days. We were the first children's hospital to fully implement a single EHR (Epic Systems, Madison, WI) in 2006. This discharge improvement initiative emerged from our hospital's involvement in the Children's Hospital Association Discharge Collaborative between October 2011 and October 2012. We were 1 of 12 participating hospitals and developed several different projects within the framework of the initiative.

Improvement Team

Our multidisciplinary project team included hospitalist physicians, case managers, social workers, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, medical interpreters, process improvement specialists, clinical application specialists whose daily role is management of our hospital's EHR software, and resident liaisons whose daily role is working with residents to facilitate care coordination.

Ethics

The project was determined to be QI work by the Children's Hospital Colorado Organizational Research Risk and Quality Improvement Review Panel.

Understanding the Problem

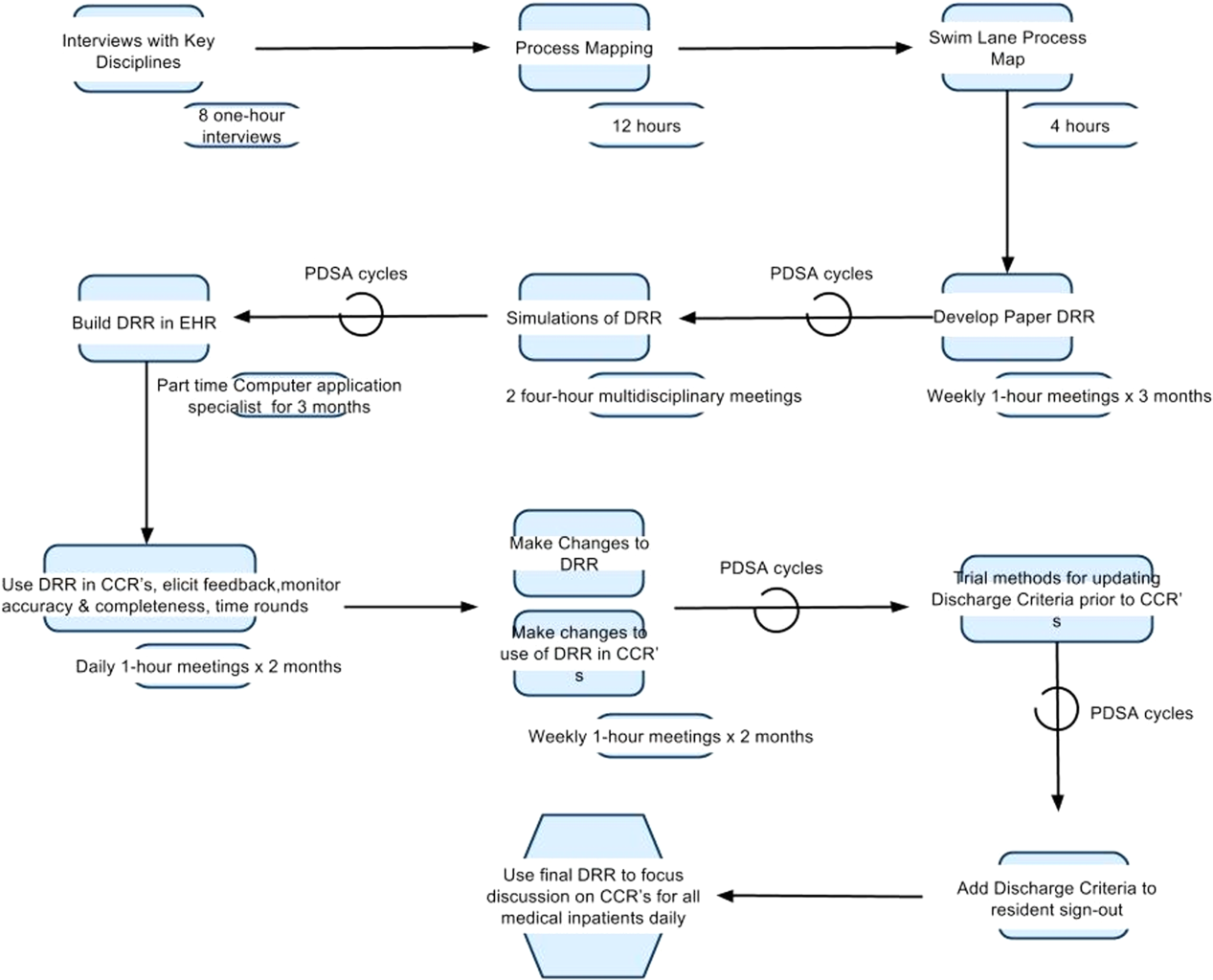

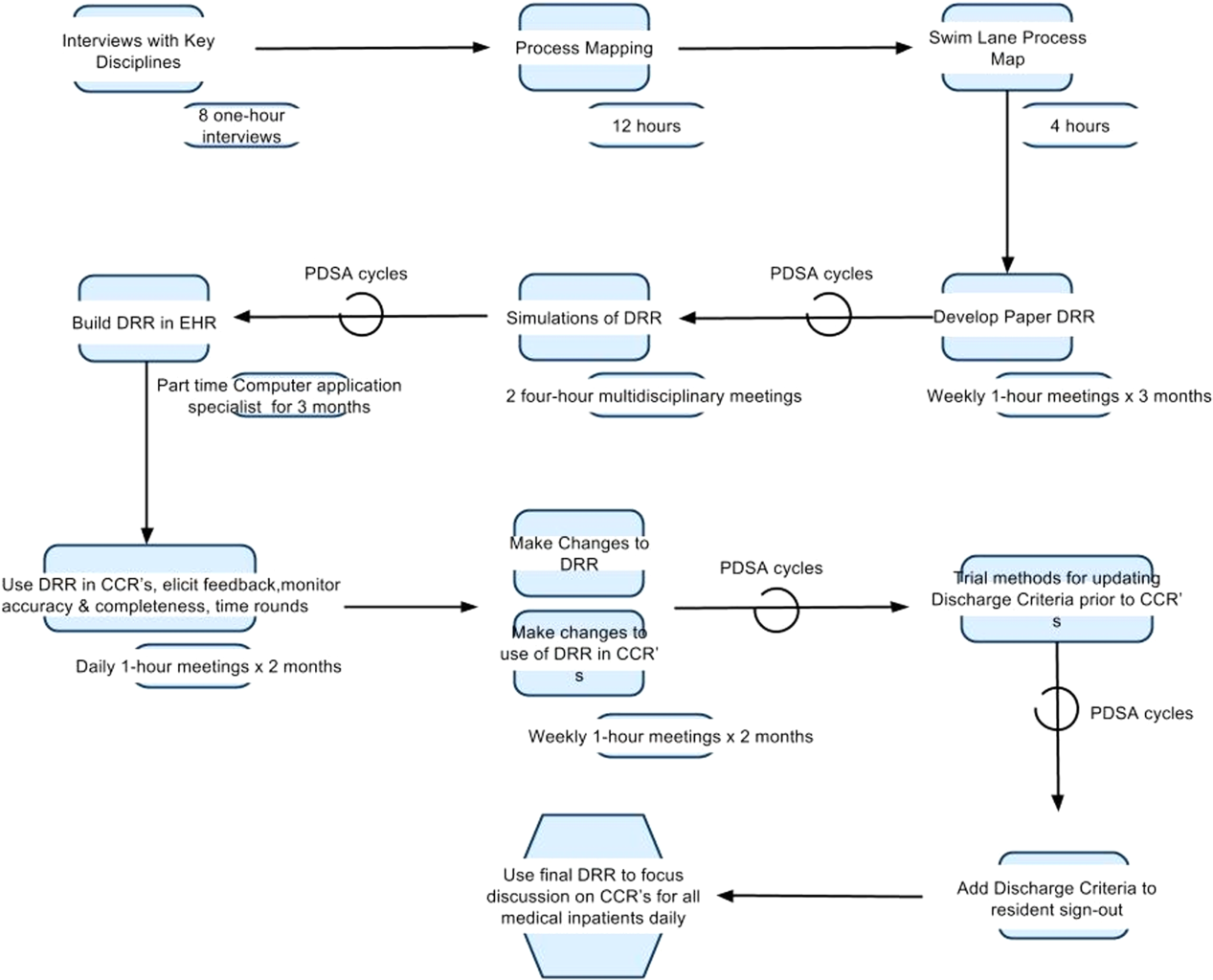

To understand the perspectives of each discipline involved in discharge planning, the lead hospitalist physician and a process improvement specialist interviewed key representatives from each group. Key informant interviews were conducted with hospitalist physicians, case managers, nurses, social workers, resident liaisons, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, medical interpreters, and residents. We inquired about their informational needs, their methods for obtaining relevant information, and whether the information was currently documented in the EHR. We then used process mapping to learn each disciplines' workflow related to discharge planning. Finally, we gathered key stakeholders together for a group session where discharge planning was mapped using the example of a patient admitted with asthma. From this session, we created a detailed multidisciplinary swim lane process map, a flowchart displaying the sequence of events in the overall discharge process grouped visually by placing the events in lanes. Each lane represented a discipline involved in patient discharge, and the arrows between lanes showed how information is passed between the various disciplines. Using this diagram, the team was able to fully understand provider interdependence in discharge planning and longitudinal timing of discharge‐related tasks during the patient's hospitalization.

We learned that: (1) discharge planning is complex, and there were often multiple provider types involved in the discharge of a single patient; (2) communication and coordination between the multitude of providers was often suboptimal; and (3) many of the tasks related to discharge were left to the last minute, resulting in unnecessary delays. Underlying these problems was a clear lack of organized and visible discharge planning information within the EHR.

There were many examples of obscure and siloed discharge processes. Physicians were aware of discharge criteria, but did not document these criteria for others to see. Case management assessments of home health needs were conveyed verbally to other team members, creating the potential for omissions, mistakes, or delays in appropriate home health planning. Social workers helped families to navigate financial hurdles (eg, assistance with payments for prescription medications). However, the presence of financial or insurance problems was not readily apparent to front‐line clinicians making discharge decisions. Other factors with potential significance for discharge planning, such as English‐language proficiency or a family's geographic distance from the hospital, were buried in disparate flow sheets or reports and not available or apparent to all health team members. There were also clear examples of discharge‐related tasks occurring at the end of hospitalization that could easily have been completed earlier in the admission such as identifying a primary care provider (PCP), scheduling follow‐up appointments, and completing work/subhool excuses because of lack of care team awareness that these items were needed.

Planning the Intervention

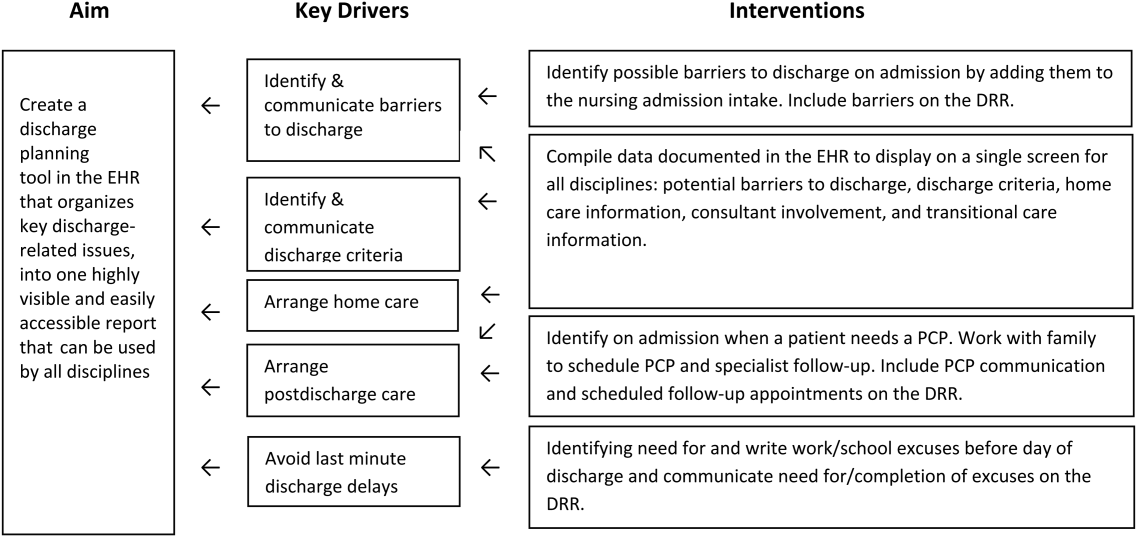

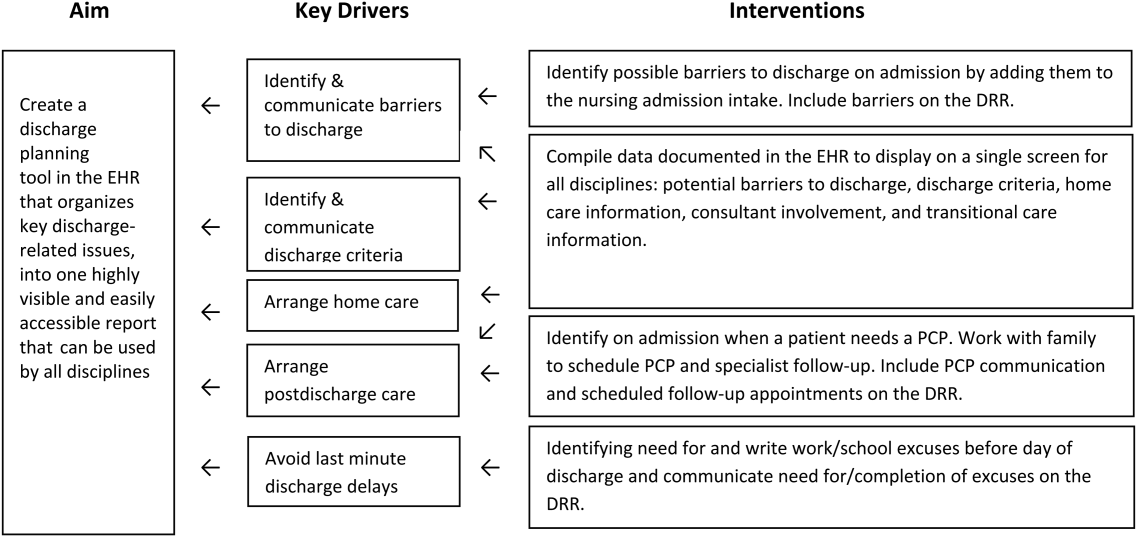

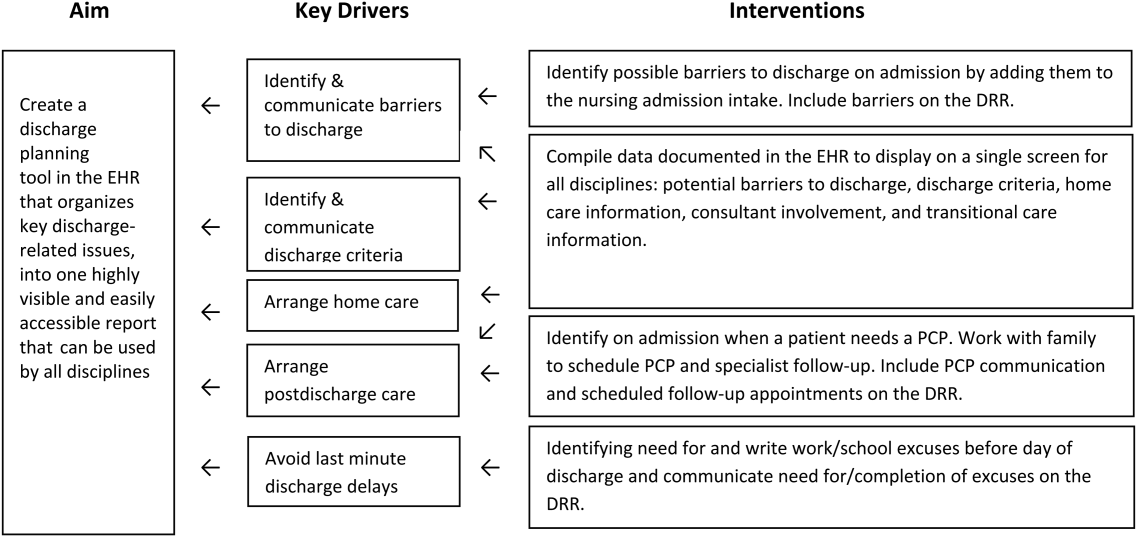

Based on our learning, we developed a key driver diagram (Figure 1). Our aim was to create a DRR that organized important discharge‐related information into 1 easily accessible report. Key drivers that were identified as relevant to the content of the DRR included: barriers to discharge, discharge criteria, home care, postdischarge care, and last minute delays. We also identified secondary drivers related to the design of the DRR. We hypothesized that addressing the secondary drivers would be essential to end user adoption of the tool. The secondary drivers included: accessibility, relevance, ease of updating, automation, and readability.

With the swim lane diagram as well as our primary and secondary drivers in mind, we created a mock DRR on paper. We conducted multiple patient discharge simulations with representatives from all disciplines, walking through each step of a patient hospitalization from registration to discharge. This allowed us to map out how preexisting, yet disparate, EHR data could be channeled into 1 report. A few changes were made to processes involving data collection and documentation to facilitate timely transfer of information to the report. For example, questions addressing potential barriers to discharge and whether a school/work excuse was needed were added to the admission nursing assessment.

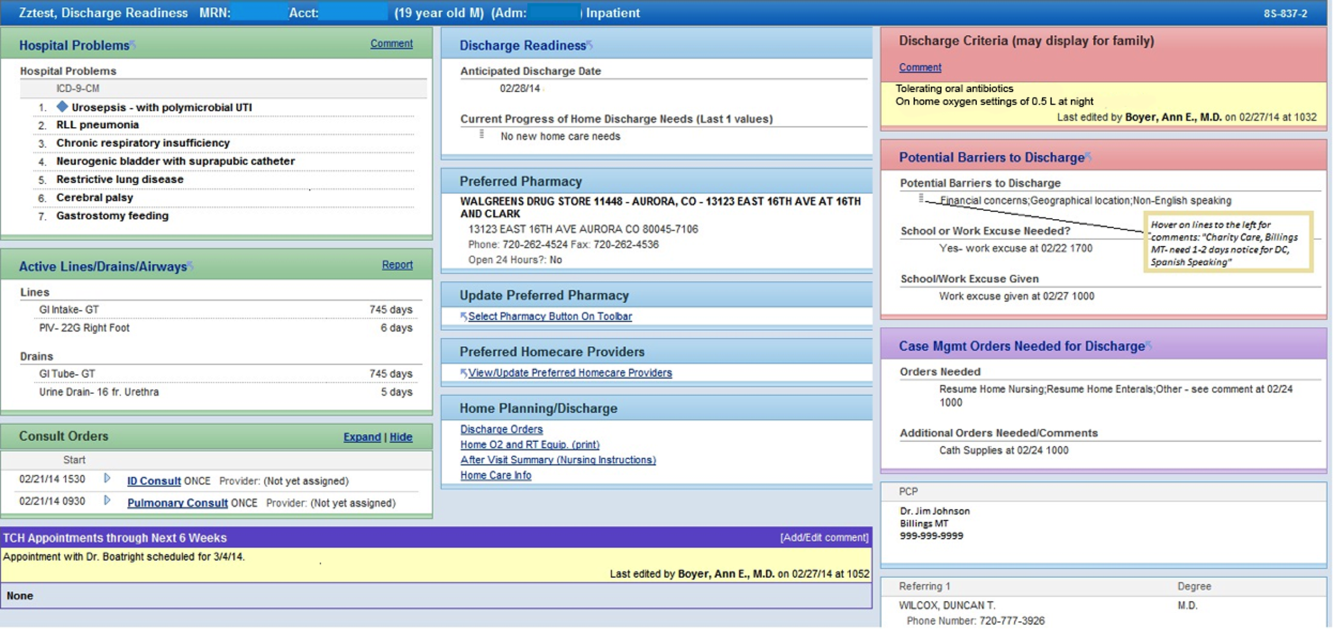

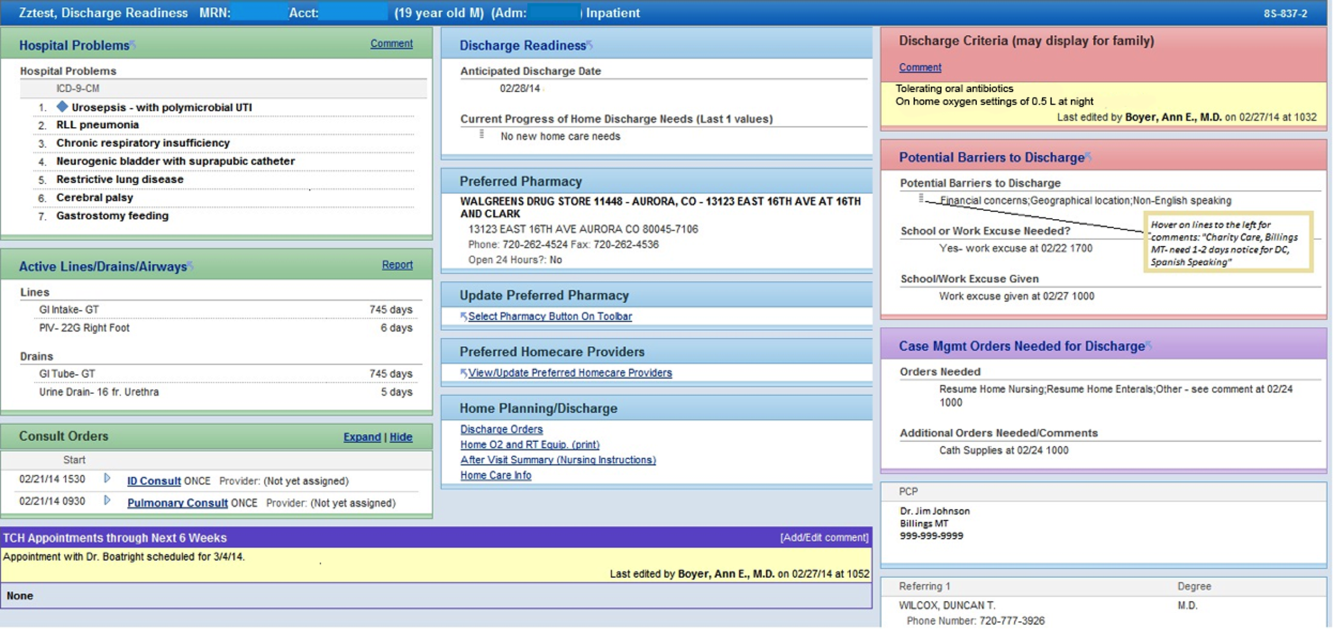

We then moved the paper DRR to the electronic environment. Data elements that were pulled automatically into the report included: potential barriers to discharge collected during nursing intake, case management information on home care needs, discharge criteria entered by resident and attending physicians, PCP, home pharmacy, follow‐up appointments, school/work excuse information gathered by resident liaisons, and active patient problems drawn from the problem list section. These data were organized into 4 distinct domains within the final DRR: potential barriers, transitional care, home care, and discharge criteria (Table 1).

| Discharge Readiness Report Domain | Example Content |

|---|---|

| |

| Potential barriers to discharge | Geographic location of the family, whether patient lives in more than 1 household, primary spoken language, financial or insurance concern, and need for work/subhool excuses |

| Transitional care | PCP and home pharmacy information, follow‐up ambulatory and imaging appointments, and care team communications with the PCP |

| Home care | Planned discharge date/time and home care needs assessments such as needs for special equipment or skilled home nursing |

| Discharge criteria | Clinical, social, or other care coordination conditions for discharge |

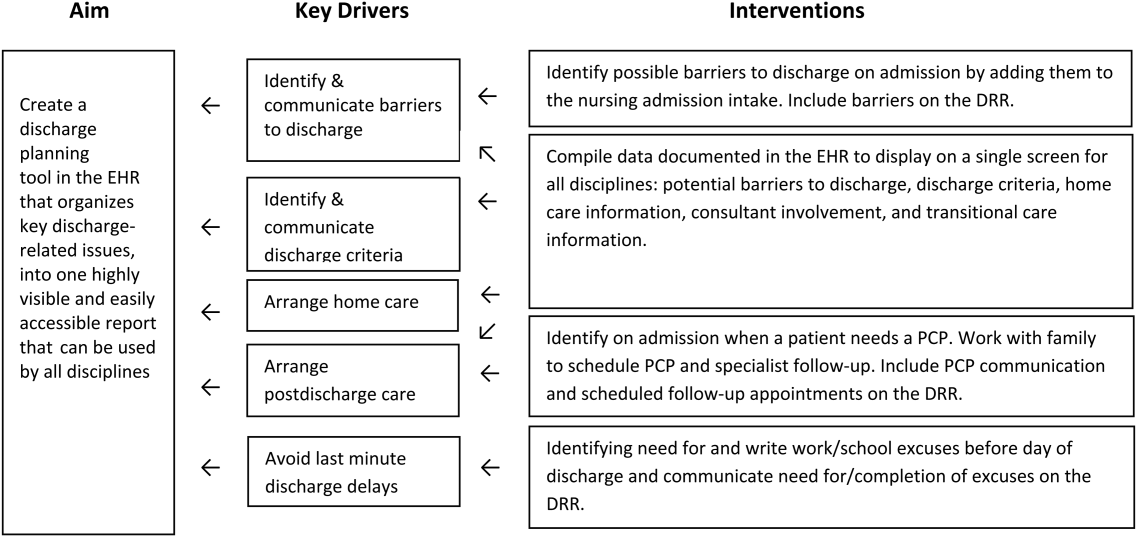

Additional features potentially important to discharge planning were also incorporated into the report based on end user feedback. These included hyperlinks to discharge orders, home oxygen prescriptions, and the after‐visit summary for families, and the patient's home care company (if present). To facilitate discharge and transitional care related communication between the primary team and subspecialty teams, consults involved during the hospitalization were included on the report. As home care arrangements often involve care for active lines and drains, they were added to the report (Figure 2).

Implementation

The report was activated within the EHR in June 2012. The team focused initial promotion and education efforts on medical floors. Education was widely disseminated via email and in‐person presentations.

The DRR was incorporated into daily CCRs for medical patients in July 2012. These multidisciplinary rounds occurred after medical‐team bedside rounds, focusing on care coordination and discharge planning. For each patient discussed, the DRR was projected onto a large screen, allowing all team members to view and discuss relevant discharge information. A process improvement (PI) specialist attended CCRs daily for several months, educating participants and monitoring use of the DRR. The PI specialist solicited feedback on ways to improve the DRR, and timed rounds to measure whether use of the DRR prolonged CCRs.

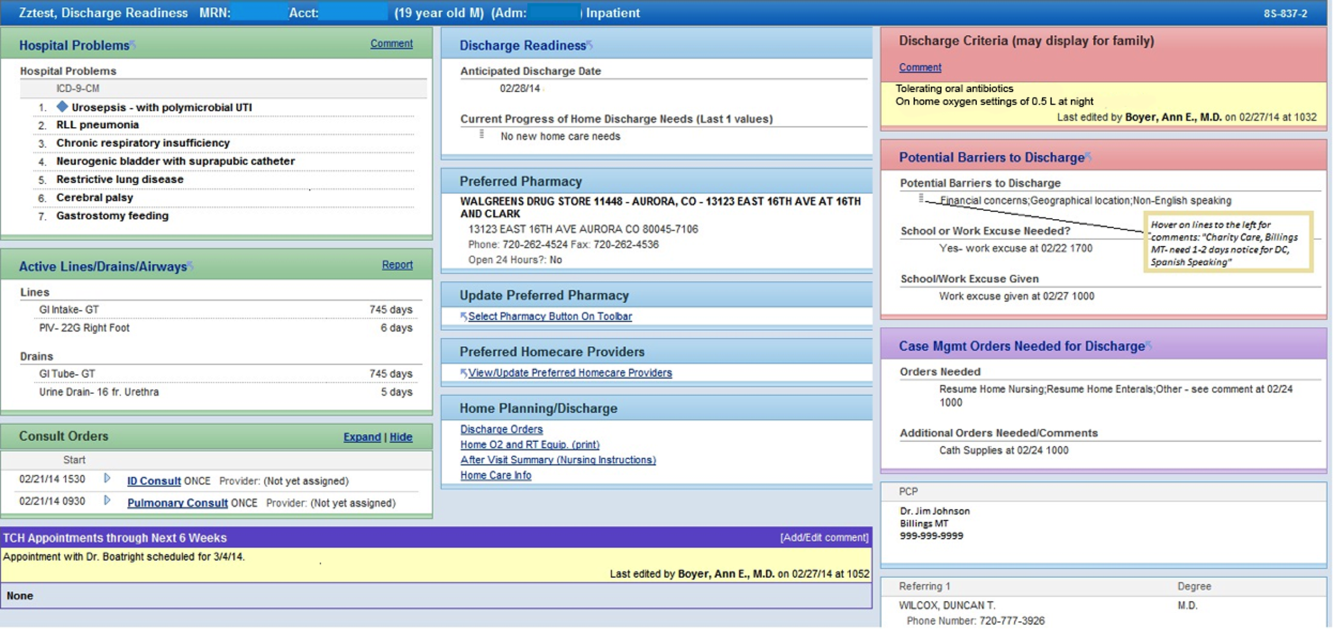

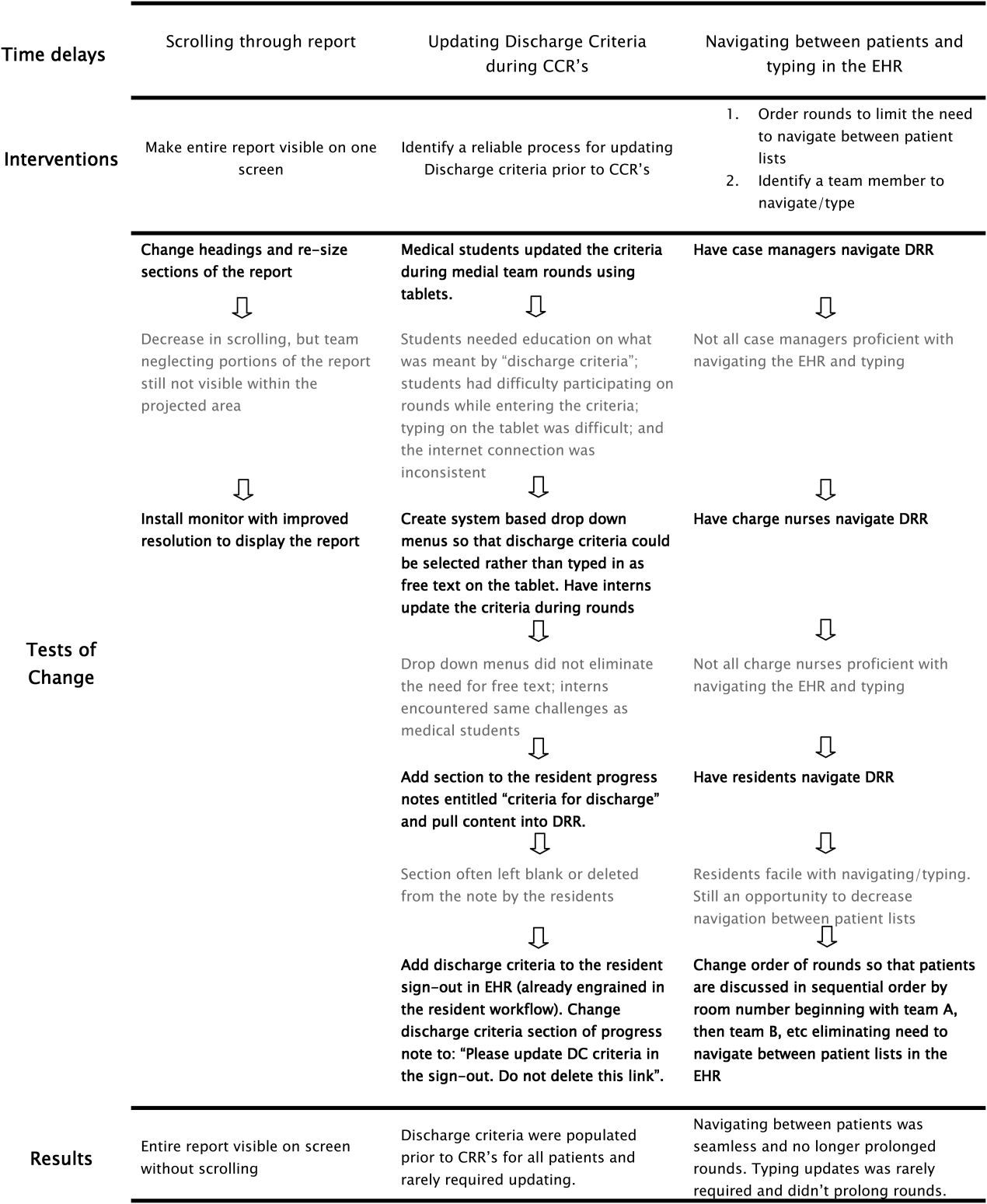

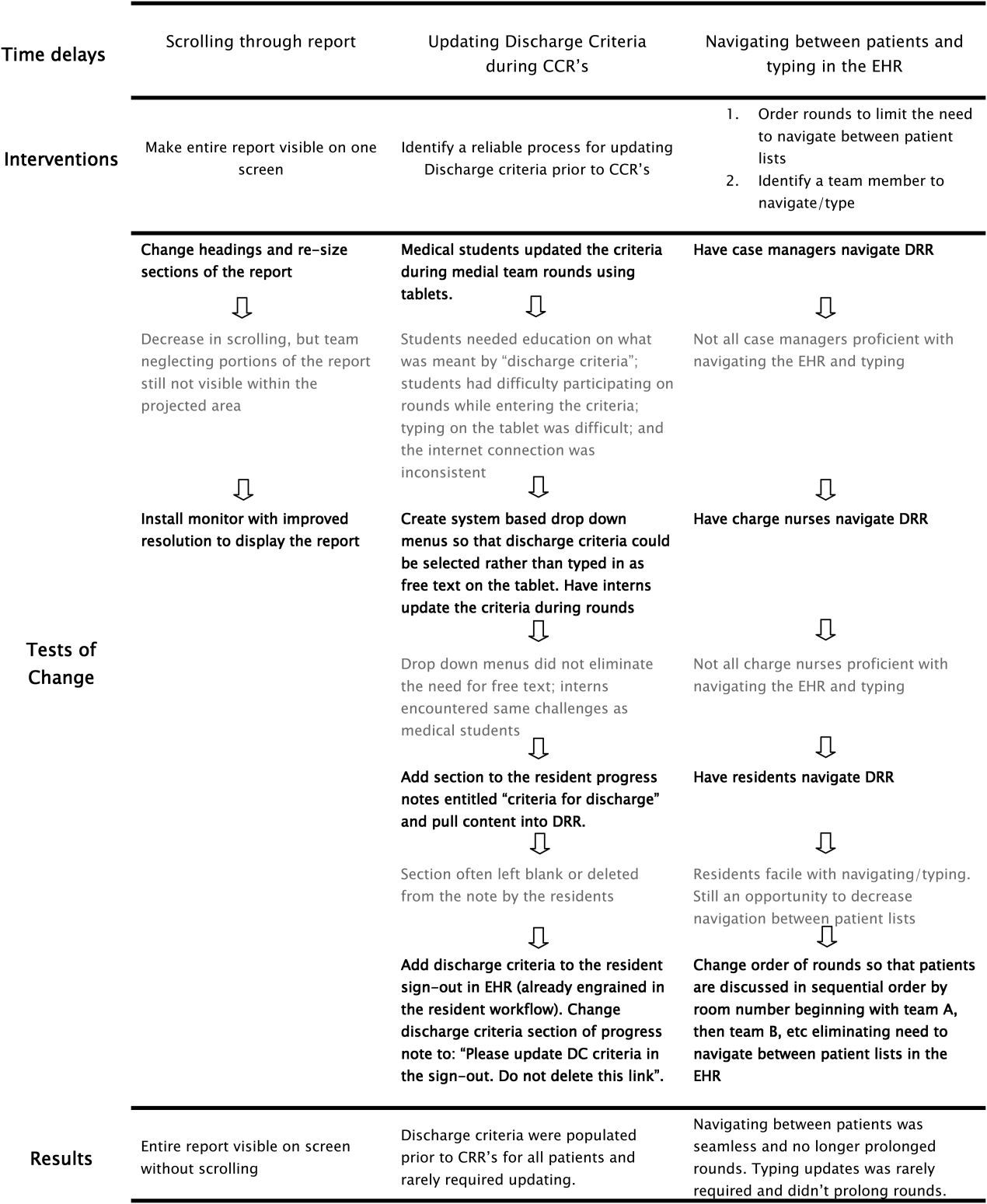

In the first weeks postimplementation, the use of the DRR prolonged rounds by as much as 1 minute per patient. Based on direct observation, the team focused interventions on barriers to the efficient use of the report during CCRs including: the need to scroll through the report, which was not visible on 1 screen; the need to navigate between patients; the need to quickly update the report based on discussion; and the need to update discharge criteria (Figure 3).

RESULTS

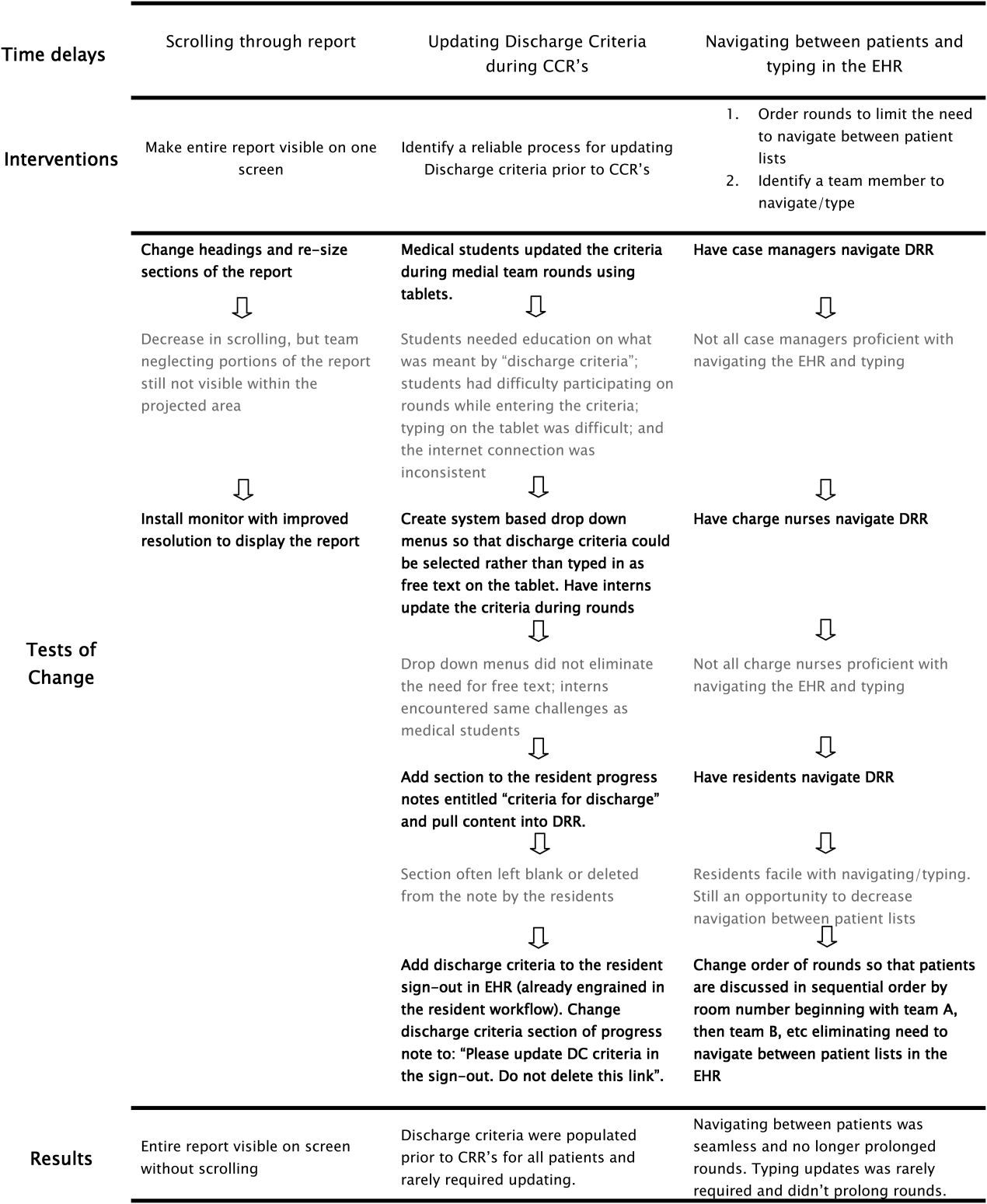

Creation of the final DRR required significant time and effort and was the culmination of a uniquely collaborative effort between clinicians, ancillary staff, and information technology specialists (Figure 4). The report is used consistently for all general medical and medical subspecialty patients during CCRs. After interventions were implemented to improve the efficiency of using the DRR during CCRs, the use of the DRR did not prolong CCRs. Members of the care team acknowledge that all sections of the report are populated and accurate. Though end users have commented on their use of the report outside of CCRs, we have not been able to formally measure this.

We have noticed a shift in the focus of discussion since implementation of the DRR. Prior to this initiative, care teams at our institution did not regularly discuss discharge criteria during bedside or CCRs. The phrase discharge criteria has now become part of our shared language.

Informally, the DRR appears to have reduced inefficiency and the potential for communication error. The practice of writing notes on printed patient lists to be used to sign‐out or communicate to other team members not in attendance at CCRs has largely disappeared.

The DRR has proven to be adaptable across patient units, and can be tailored to the specific transitional care needs of a given patient population. At discharge institution, the DRR has been modified for, and has taken on a prominent role in, the discharge planning of highly complex populations such as rehabilitation and ventilated patients.

DISCUSSION

Discharge planning is a multifaceted, multidisciplinary process that should begin at the time of hospital admission. Safe patient transition depends on efficient discharge processes and effective communication across settings.[8] Although not well studied in the inpatient setting, care process variability can result in inefficient patient flow and increased stress among staff.[9] Patients and families may experience confusion, coping difficulties, and increased readmission due to ineffective discharge planning.[10] These potential pitfalls highlight the need for healthcare providers to develop patient‐centered, systematic approaches to improving the discharge process.[11]

To our knowledge, this is the first description of a discharge planning tool for the EHR in the pediatric setting. Our discharge report is centralized, easily accessible by all members of the care team, and includes important patient‐specific discharge‐related information that be used to focus discussion and streamline multidisciplinary discharge planning rounds.

We anticipate that the report will allow the entire healthcare team to function more efficiently, decrease discharge‐related delays and failures based on communication roadblocks, and improve family and caregiver satisfaction with the discharge process. We are currently testing these hypotheses and evaluating several implementation strategies in an ongoing research study. Assuming positive impact, we plan to spread the use of the DRR to all inpatient care areas at our hospital, and potentially to other hospitals.

The limitations of this QI project are consistent with other initiatives to improve care. The challenges we encounter at our freestanding tertiary care teaching hospital with regard to effective discharge planning and multidisciplinary communication may not be generalizable to other nonteaching or community hospitals, and the DRR may not be useful in other settings. Though the report is now a part of our EHR, the most impactful implementation strategies remain to be determined. The report and related changes represent significant diversion from years of deeply ingrained workflows for some providers, and we encountered some resistance from staff during the early stages of implementation. The most important of which was that some team members are uncomfortable with technology and prefer to use paper. Most of this initial resistance was overcome by implementing changes to improve the ease of use of the report (Figure 3). Though input from end users and key stakeholders has been incorporated throughout this initiative, more work is needed to measure end user adoption and satisfaction with the report.

CONCLUSION

High‐quality hospital discharge planning requires an increasingly multidisciplinary approach. The EHR can be leveraged to improve transparency and interdisciplinary communication around the discharge process. An integrated summary of discharge‐related issues, organized into 1 highly visible and easily accessible report in the EHR has the potential to improve care transitions.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- . Clinical report—physicians' roles in coordinating care of hospitalized children. Pediatrics. 2010;126:829–832.

- , , , , , . Increasing prevalence of medically complex children in US hospitals. Pediatrics. 2010;126:638–646.

- , , . Hospitalist care of the medically complex child. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005;52:1165–1187, x.

- , . Discharge planning and home care of the technology‐dependent infant. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1995;24:77–83.

- , , , . Pediatric discharge planning: complications, efficiency, and adequacy. Soc Work Health Care. 1995;22:1–18.

- , , , et al. The current capabilities of health information technology to support care transitions. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2013;2013:1231.

- , , , et al. Provider‐to‐provider electronic communication in the era of meaningful use: a review of the evidence. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:589–597.

- , , , . Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2:314–323.

- , , , , . A 5‐year time study analysis of emergency department patient care efficiency. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34:326–335.

- , , , et al. Quality of discharge practices and patient understanding at an academic medical center. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(18):1715–1722.

- , . Addressing postdischarge adverse events: a neglected area. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:85–97.

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics clinical report on physicians' roles in coordinating care of hospitalized children, there are several important components of hospital discharge planning.[1] Foremost is that discharge planning should begin, and discharge criteria should be set, at the time of hospital admission. This allows for optimal engagement of parents and providers in the effort to adequately prepare patients for the transition to home.

As pediatric inpatients become increasingly complex,[2] adequately preparing families for the transition to home becomes more challenging.[3] There are a myriad of issues to address and the burden of this preparation effort falls on multiple individuals other than the bedside nurse and physician. Large multidisciplinary teams often play a significant role in the discharge of medically complex children.[4] Several challenges may hinder the team's ability to effectively navigate the discharge process such as financial or insurance‐related issues, language differences, or geographic barriers. Patient and family anxieties may also complicate the transition to home.[5]

The challenges of a multidisciplinary approach to discharge planning are further magnified by the limitations of the electronic health record (EHR). The EHR is well designed to record individual encounters, but poorly designed to coordinate longitudinal care across settings.[6] Although multidisciplinary providers may spend significant and well‐intentioned energy to facilitate hospital discharge, their efforts may go unseen or be duplicative.

We developed a discharge readiness report (DRR) for the EHR, an integrated summary of discharge‐related issues, organized into a highly visible and easily accessible report. The development of the discharge planning tool was the first step in a larger quality improvement (QI) initiative aimed at improving the efficiency, effectiveness, and safety of hospital discharge. Our team recognized that improving the flow and visibility of information between disciplines was the first step toward accomplishing this larger aim. Health information technology offers an important opportunity for the improvement of patient safety and care transitions7; therefore, we leveraged the EHR to create an integrated discharge report. We used QI methods to understand our hospital's discharge processes, examined potential pitfalls in interdisciplinary communication, determined relevant information to include in the report, and optimized ways to display the data. To our knowledge, this use of the EHR is novel. The objectives of this article were to describe our team's development and implementation strategies, as well as challenges encountered, in the design of this electronic discharge planning tool.

METHODS

Setting

Children's Hospital Colorado is a 413‐bed freestanding tertiary care teaching hospital with over 13,000 inpatient admissions annually and an average patient length of stay of 5.7 days. We were the first children's hospital to fully implement a single EHR (Epic Systems, Madison, WI) in 2006. This discharge improvement initiative emerged from our hospital's involvement in the Children's Hospital Association Discharge Collaborative between October 2011 and October 2012. We were 1 of 12 participating hospitals and developed several different projects within the framework of the initiative.

Improvement Team

Our multidisciplinary project team included hospitalist physicians, case managers, social workers, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, medical interpreters, process improvement specialists, clinical application specialists whose daily role is management of our hospital's EHR software, and resident liaisons whose daily role is working with residents to facilitate care coordination.

Ethics

The project was determined to be QI work by the Children's Hospital Colorado Organizational Research Risk and Quality Improvement Review Panel.

Understanding the Problem

To understand the perspectives of each discipline involved in discharge planning, the lead hospitalist physician and a process improvement specialist interviewed key representatives from each group. Key informant interviews were conducted with hospitalist physicians, case managers, nurses, social workers, resident liaisons, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, medical interpreters, and residents. We inquired about their informational needs, their methods for obtaining relevant information, and whether the information was currently documented in the EHR. We then used process mapping to learn each disciplines' workflow related to discharge planning. Finally, we gathered key stakeholders together for a group session where discharge planning was mapped using the example of a patient admitted with asthma. From this session, we created a detailed multidisciplinary swim lane process map, a flowchart displaying the sequence of events in the overall discharge process grouped visually by placing the events in lanes. Each lane represented a discipline involved in patient discharge, and the arrows between lanes showed how information is passed between the various disciplines. Using this diagram, the team was able to fully understand provider interdependence in discharge planning and longitudinal timing of discharge‐related tasks during the patient's hospitalization.

We learned that: (1) discharge planning is complex, and there were often multiple provider types involved in the discharge of a single patient; (2) communication and coordination between the multitude of providers was often suboptimal; and (3) many of the tasks related to discharge were left to the last minute, resulting in unnecessary delays. Underlying these problems was a clear lack of organized and visible discharge planning information within the EHR.

There were many examples of obscure and siloed discharge processes. Physicians were aware of discharge criteria, but did not document these criteria for others to see. Case management assessments of home health needs were conveyed verbally to other team members, creating the potential for omissions, mistakes, or delays in appropriate home health planning. Social workers helped families to navigate financial hurdles (eg, assistance with payments for prescription medications). However, the presence of financial or insurance problems was not readily apparent to front‐line clinicians making discharge decisions. Other factors with potential significance for discharge planning, such as English‐language proficiency or a family's geographic distance from the hospital, were buried in disparate flow sheets or reports and not available or apparent to all health team members. There were also clear examples of discharge‐related tasks occurring at the end of hospitalization that could easily have been completed earlier in the admission such as identifying a primary care provider (PCP), scheduling follow‐up appointments, and completing work/subhool excuses because of lack of care team awareness that these items were needed.

Planning the Intervention

Based on our learning, we developed a key driver diagram (Figure 1). Our aim was to create a DRR that organized important discharge‐related information into 1 easily accessible report. Key drivers that were identified as relevant to the content of the DRR included: barriers to discharge, discharge criteria, home care, postdischarge care, and last minute delays. We also identified secondary drivers related to the design of the DRR. We hypothesized that addressing the secondary drivers would be essential to end user adoption of the tool. The secondary drivers included: accessibility, relevance, ease of updating, automation, and readability.

With the swim lane diagram as well as our primary and secondary drivers in mind, we created a mock DRR on paper. We conducted multiple patient discharge simulations with representatives from all disciplines, walking through each step of a patient hospitalization from registration to discharge. This allowed us to map out how preexisting, yet disparate, EHR data could be channeled into 1 report. A few changes were made to processes involving data collection and documentation to facilitate timely transfer of information to the report. For example, questions addressing potential barriers to discharge and whether a school/work excuse was needed were added to the admission nursing assessment.

We then moved the paper DRR to the electronic environment. Data elements that were pulled automatically into the report included: potential barriers to discharge collected during nursing intake, case management information on home care needs, discharge criteria entered by resident and attending physicians, PCP, home pharmacy, follow‐up appointments, school/work excuse information gathered by resident liaisons, and active patient problems drawn from the problem list section. These data were organized into 4 distinct domains within the final DRR: potential barriers, transitional care, home care, and discharge criteria (Table 1).

| Discharge Readiness Report Domain | Example Content |

|---|---|

| |

| Potential barriers to discharge | Geographic location of the family, whether patient lives in more than 1 household, primary spoken language, financial or insurance concern, and need for work/subhool excuses |

| Transitional care | PCP and home pharmacy information, follow‐up ambulatory and imaging appointments, and care team communications with the PCP |

| Home care | Planned discharge date/time and home care needs assessments such as needs for special equipment or skilled home nursing |

| Discharge criteria | Clinical, social, or other care coordination conditions for discharge |

Additional features potentially important to discharge planning were also incorporated into the report based on end user feedback. These included hyperlinks to discharge orders, home oxygen prescriptions, and the after‐visit summary for families, and the patient's home care company (if present). To facilitate discharge and transitional care related communication between the primary team and subspecialty teams, consults involved during the hospitalization were included on the report. As home care arrangements often involve care for active lines and drains, they were added to the report (Figure 2).

Implementation

The report was activated within the EHR in June 2012. The team focused initial promotion and education efforts on medical floors. Education was widely disseminated via email and in‐person presentations.

The DRR was incorporated into daily CCRs for medical patients in July 2012. These multidisciplinary rounds occurred after medical‐team bedside rounds, focusing on care coordination and discharge planning. For each patient discussed, the DRR was projected onto a large screen, allowing all team members to view and discuss relevant discharge information. A process improvement (PI) specialist attended CCRs daily for several months, educating participants and monitoring use of the DRR. The PI specialist solicited feedback on ways to improve the DRR, and timed rounds to measure whether use of the DRR prolonged CCRs.

In the first weeks postimplementation, the use of the DRR prolonged rounds by as much as 1 minute per patient. Based on direct observation, the team focused interventions on barriers to the efficient use of the report during CCRs including: the need to scroll through the report, which was not visible on 1 screen; the need to navigate between patients; the need to quickly update the report based on discussion; and the need to update discharge criteria (Figure 3).

RESULTS

Creation of the final DRR required significant time and effort and was the culmination of a uniquely collaborative effort between clinicians, ancillary staff, and information technology specialists (Figure 4). The report is used consistently for all general medical and medical subspecialty patients during CCRs. After interventions were implemented to improve the efficiency of using the DRR during CCRs, the use of the DRR did not prolong CCRs. Members of the care team acknowledge that all sections of the report are populated and accurate. Though end users have commented on their use of the report outside of CCRs, we have not been able to formally measure this.

We have noticed a shift in the focus of discussion since implementation of the DRR. Prior to this initiative, care teams at our institution did not regularly discuss discharge criteria during bedside or CCRs. The phrase discharge criteria has now become part of our shared language.

Informally, the DRR appears to have reduced inefficiency and the potential for communication error. The practice of writing notes on printed patient lists to be used to sign‐out or communicate to other team members not in attendance at CCRs has largely disappeared.

The DRR has proven to be adaptable across patient units, and can be tailored to the specific transitional care needs of a given patient population. At discharge institution, the DRR has been modified for, and has taken on a prominent role in, the discharge planning of highly complex populations such as rehabilitation and ventilated patients.

DISCUSSION

Discharge planning is a multifaceted, multidisciplinary process that should begin at the time of hospital admission. Safe patient transition depends on efficient discharge processes and effective communication across settings.[8] Although not well studied in the inpatient setting, care process variability can result in inefficient patient flow and increased stress among staff.[9] Patients and families may experience confusion, coping difficulties, and increased readmission due to ineffective discharge planning.[10] These potential pitfalls highlight the need for healthcare providers to develop patient‐centered, systematic approaches to improving the discharge process.[11]

To our knowledge, this is the first description of a discharge planning tool for the EHR in the pediatric setting. Our discharge report is centralized, easily accessible by all members of the care team, and includes important patient‐specific discharge‐related information that be used to focus discussion and streamline multidisciplinary discharge planning rounds.

We anticipate that the report will allow the entire healthcare team to function more efficiently, decrease discharge‐related delays and failures based on communication roadblocks, and improve family and caregiver satisfaction with the discharge process. We are currently testing these hypotheses and evaluating several implementation strategies in an ongoing research study. Assuming positive impact, we plan to spread the use of the DRR to all inpatient care areas at our hospital, and potentially to other hospitals.

The limitations of this QI project are consistent with other initiatives to improve care. The challenges we encounter at our freestanding tertiary care teaching hospital with regard to effective discharge planning and multidisciplinary communication may not be generalizable to other nonteaching or community hospitals, and the DRR may not be useful in other settings. Though the report is now a part of our EHR, the most impactful implementation strategies remain to be determined. The report and related changes represent significant diversion from years of deeply ingrained workflows for some providers, and we encountered some resistance from staff during the early stages of implementation. The most important of which was that some team members are uncomfortable with technology and prefer to use paper. Most of this initial resistance was overcome by implementing changes to improve the ease of use of the report (Figure 3). Though input from end users and key stakeholders has been incorporated throughout this initiative, more work is needed to measure end user adoption and satisfaction with the report.

CONCLUSION

High‐quality hospital discharge planning requires an increasingly multidisciplinary approach. The EHR can be leveraged to improve transparency and interdisciplinary communication around the discharge process. An integrated summary of discharge‐related issues, organized into 1 highly visible and easily accessible report in the EHR has the potential to improve care transitions.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics clinical report on physicians' roles in coordinating care of hospitalized children, there are several important components of hospital discharge planning.[1] Foremost is that discharge planning should begin, and discharge criteria should be set, at the time of hospital admission. This allows for optimal engagement of parents and providers in the effort to adequately prepare patients for the transition to home.

As pediatric inpatients become increasingly complex,[2] adequately preparing families for the transition to home becomes more challenging.[3] There are a myriad of issues to address and the burden of this preparation effort falls on multiple individuals other than the bedside nurse and physician. Large multidisciplinary teams often play a significant role in the discharge of medically complex children.[4] Several challenges may hinder the team's ability to effectively navigate the discharge process such as financial or insurance‐related issues, language differences, or geographic barriers. Patient and family anxieties may also complicate the transition to home.[5]

The challenges of a multidisciplinary approach to discharge planning are further magnified by the limitations of the electronic health record (EHR). The EHR is well designed to record individual encounters, but poorly designed to coordinate longitudinal care across settings.[6] Although multidisciplinary providers may spend significant and well‐intentioned energy to facilitate hospital discharge, their efforts may go unseen or be duplicative.

We developed a discharge readiness report (DRR) for the EHR, an integrated summary of discharge‐related issues, organized into a highly visible and easily accessible report. The development of the discharge planning tool was the first step in a larger quality improvement (QI) initiative aimed at improving the efficiency, effectiveness, and safety of hospital discharge. Our team recognized that improving the flow and visibility of information between disciplines was the first step toward accomplishing this larger aim. Health information technology offers an important opportunity for the improvement of patient safety and care transitions7; therefore, we leveraged the EHR to create an integrated discharge report. We used QI methods to understand our hospital's discharge processes, examined potential pitfalls in interdisciplinary communication, determined relevant information to include in the report, and optimized ways to display the data. To our knowledge, this use of the EHR is novel. The objectives of this article were to describe our team's development and implementation strategies, as well as challenges encountered, in the design of this electronic discharge planning tool.

METHODS

Setting

Children's Hospital Colorado is a 413‐bed freestanding tertiary care teaching hospital with over 13,000 inpatient admissions annually and an average patient length of stay of 5.7 days. We were the first children's hospital to fully implement a single EHR (Epic Systems, Madison, WI) in 2006. This discharge improvement initiative emerged from our hospital's involvement in the Children's Hospital Association Discharge Collaborative between October 2011 and October 2012. We were 1 of 12 participating hospitals and developed several different projects within the framework of the initiative.

Improvement Team

Our multidisciplinary project team included hospitalist physicians, case managers, social workers, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, medical interpreters, process improvement specialists, clinical application specialists whose daily role is management of our hospital's EHR software, and resident liaisons whose daily role is working with residents to facilitate care coordination.

Ethics

The project was determined to be QI work by the Children's Hospital Colorado Organizational Research Risk and Quality Improvement Review Panel.

Understanding the Problem

To understand the perspectives of each discipline involved in discharge planning, the lead hospitalist physician and a process improvement specialist interviewed key representatives from each group. Key informant interviews were conducted with hospitalist physicians, case managers, nurses, social workers, resident liaisons, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, medical interpreters, and residents. We inquired about their informational needs, their methods for obtaining relevant information, and whether the information was currently documented in the EHR. We then used process mapping to learn each disciplines' workflow related to discharge planning. Finally, we gathered key stakeholders together for a group session where discharge planning was mapped using the example of a patient admitted with asthma. From this session, we created a detailed multidisciplinary swim lane process map, a flowchart displaying the sequence of events in the overall discharge process grouped visually by placing the events in lanes. Each lane represented a discipline involved in patient discharge, and the arrows between lanes showed how information is passed between the various disciplines. Using this diagram, the team was able to fully understand provider interdependence in discharge planning and longitudinal timing of discharge‐related tasks during the patient's hospitalization.

We learned that: (1) discharge planning is complex, and there were often multiple provider types involved in the discharge of a single patient; (2) communication and coordination between the multitude of providers was often suboptimal; and (3) many of the tasks related to discharge were left to the last minute, resulting in unnecessary delays. Underlying these problems was a clear lack of organized and visible discharge planning information within the EHR.

There were many examples of obscure and siloed discharge processes. Physicians were aware of discharge criteria, but did not document these criteria for others to see. Case management assessments of home health needs were conveyed verbally to other team members, creating the potential for omissions, mistakes, or delays in appropriate home health planning. Social workers helped families to navigate financial hurdles (eg, assistance with payments for prescription medications). However, the presence of financial or insurance problems was not readily apparent to front‐line clinicians making discharge decisions. Other factors with potential significance for discharge planning, such as English‐language proficiency or a family's geographic distance from the hospital, were buried in disparate flow sheets or reports and not available or apparent to all health team members. There were also clear examples of discharge‐related tasks occurring at the end of hospitalization that could easily have been completed earlier in the admission such as identifying a primary care provider (PCP), scheduling follow‐up appointments, and completing work/subhool excuses because of lack of care team awareness that these items were needed.

Planning the Intervention

Based on our learning, we developed a key driver diagram (Figure 1). Our aim was to create a DRR that organized important discharge‐related information into 1 easily accessible report. Key drivers that were identified as relevant to the content of the DRR included: barriers to discharge, discharge criteria, home care, postdischarge care, and last minute delays. We also identified secondary drivers related to the design of the DRR. We hypothesized that addressing the secondary drivers would be essential to end user adoption of the tool. The secondary drivers included: accessibility, relevance, ease of updating, automation, and readability.

With the swim lane diagram as well as our primary and secondary drivers in mind, we created a mock DRR on paper. We conducted multiple patient discharge simulations with representatives from all disciplines, walking through each step of a patient hospitalization from registration to discharge. This allowed us to map out how preexisting, yet disparate, EHR data could be channeled into 1 report. A few changes were made to processes involving data collection and documentation to facilitate timely transfer of information to the report. For example, questions addressing potential barriers to discharge and whether a school/work excuse was needed were added to the admission nursing assessment.

We then moved the paper DRR to the electronic environment. Data elements that were pulled automatically into the report included: potential barriers to discharge collected during nursing intake, case management information on home care needs, discharge criteria entered by resident and attending physicians, PCP, home pharmacy, follow‐up appointments, school/work excuse information gathered by resident liaisons, and active patient problems drawn from the problem list section. These data were organized into 4 distinct domains within the final DRR: potential barriers, transitional care, home care, and discharge criteria (Table 1).

| Discharge Readiness Report Domain | Example Content |

|---|---|

| |

| Potential barriers to discharge | Geographic location of the family, whether patient lives in more than 1 household, primary spoken language, financial or insurance concern, and need for work/subhool excuses |

| Transitional care | PCP and home pharmacy information, follow‐up ambulatory and imaging appointments, and care team communications with the PCP |

| Home care | Planned discharge date/time and home care needs assessments such as needs for special equipment or skilled home nursing |

| Discharge criteria | Clinical, social, or other care coordination conditions for discharge |

Additional features potentially important to discharge planning were also incorporated into the report based on end user feedback. These included hyperlinks to discharge orders, home oxygen prescriptions, and the after‐visit summary for families, and the patient's home care company (if present). To facilitate discharge and transitional care related communication between the primary team and subspecialty teams, consults involved during the hospitalization were included on the report. As home care arrangements often involve care for active lines and drains, they were added to the report (Figure 2).

Implementation

The report was activated within the EHR in June 2012. The team focused initial promotion and education efforts on medical floors. Education was widely disseminated via email and in‐person presentations.

The DRR was incorporated into daily CCRs for medical patients in July 2012. These multidisciplinary rounds occurred after medical‐team bedside rounds, focusing on care coordination and discharge planning. For each patient discussed, the DRR was projected onto a large screen, allowing all team members to view and discuss relevant discharge information. A process improvement (PI) specialist attended CCRs daily for several months, educating participants and monitoring use of the DRR. The PI specialist solicited feedback on ways to improve the DRR, and timed rounds to measure whether use of the DRR prolonged CCRs.

In the first weeks postimplementation, the use of the DRR prolonged rounds by as much as 1 minute per patient. Based on direct observation, the team focused interventions on barriers to the efficient use of the report during CCRs including: the need to scroll through the report, which was not visible on 1 screen; the need to navigate between patients; the need to quickly update the report based on discussion; and the need to update discharge criteria (Figure 3).

RESULTS

Creation of the final DRR required significant time and effort and was the culmination of a uniquely collaborative effort between clinicians, ancillary staff, and information technology specialists (Figure 4). The report is used consistently for all general medical and medical subspecialty patients during CCRs. After interventions were implemented to improve the efficiency of using the DRR during CCRs, the use of the DRR did not prolong CCRs. Members of the care team acknowledge that all sections of the report are populated and accurate. Though end users have commented on their use of the report outside of CCRs, we have not been able to formally measure this.

We have noticed a shift in the focus of discussion since implementation of the DRR. Prior to this initiative, care teams at our institution did not regularly discuss discharge criteria during bedside or CCRs. The phrase discharge criteria has now become part of our shared language.

Informally, the DRR appears to have reduced inefficiency and the potential for communication error. The practice of writing notes on printed patient lists to be used to sign‐out or communicate to other team members not in attendance at CCRs has largely disappeared.

The DRR has proven to be adaptable across patient units, and can be tailored to the specific transitional care needs of a given patient population. At discharge institution, the DRR has been modified for, and has taken on a prominent role in, the discharge planning of highly complex populations such as rehabilitation and ventilated patients.

DISCUSSION

Discharge planning is a multifaceted, multidisciplinary process that should begin at the time of hospital admission. Safe patient transition depends on efficient discharge processes and effective communication across settings.[8] Although not well studied in the inpatient setting, care process variability can result in inefficient patient flow and increased stress among staff.[9] Patients and families may experience confusion, coping difficulties, and increased readmission due to ineffective discharge planning.[10] These potential pitfalls highlight the need for healthcare providers to develop patient‐centered, systematic approaches to improving the discharge process.[11]

To our knowledge, this is the first description of a discharge planning tool for the EHR in the pediatric setting. Our discharge report is centralized, easily accessible by all members of the care team, and includes important patient‐specific discharge‐related information that be used to focus discussion and streamline multidisciplinary discharge planning rounds.

We anticipate that the report will allow the entire healthcare team to function more efficiently, decrease discharge‐related delays and failures based on communication roadblocks, and improve family and caregiver satisfaction with the discharge process. We are currently testing these hypotheses and evaluating several implementation strategies in an ongoing research study. Assuming positive impact, we plan to spread the use of the DRR to all inpatient care areas at our hospital, and potentially to other hospitals.

The limitations of this QI project are consistent with other initiatives to improve care. The challenges we encounter at our freestanding tertiary care teaching hospital with regard to effective discharge planning and multidisciplinary communication may not be generalizable to other nonteaching or community hospitals, and the DRR may not be useful in other settings. Though the report is now a part of our EHR, the most impactful implementation strategies remain to be determined. The report and related changes represent significant diversion from years of deeply ingrained workflows for some providers, and we encountered some resistance from staff during the early stages of implementation. The most important of which was that some team members are uncomfortable with technology and prefer to use paper. Most of this initial resistance was overcome by implementing changes to improve the ease of use of the report (Figure 3). Though input from end users and key stakeholders has been incorporated throughout this initiative, more work is needed to measure end user adoption and satisfaction with the report.

CONCLUSION

High‐quality hospital discharge planning requires an increasingly multidisciplinary approach. The EHR can be leveraged to improve transparency and interdisciplinary communication around the discharge process. An integrated summary of discharge‐related issues, organized into 1 highly visible and easily accessible report in the EHR has the potential to improve care transitions.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- . Clinical report—physicians' roles in coordinating care of hospitalized children. Pediatrics. 2010;126:829–832.

- , , , , , . Increasing prevalence of medically complex children in US hospitals. Pediatrics. 2010;126:638–646.

- , , . Hospitalist care of the medically complex child. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005;52:1165–1187, x.

- , . Discharge planning and home care of the technology‐dependent infant. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1995;24:77–83.

- , , , . Pediatric discharge planning: complications, efficiency, and adequacy. Soc Work Health Care. 1995;22:1–18.

- , , , et al. The current capabilities of health information technology to support care transitions. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2013;2013:1231.

- , , , et al. Provider‐to‐provider electronic communication in the era of meaningful use: a review of the evidence. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:589–597.

- , , , . Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2:314–323.

- , , , , . A 5‐year time study analysis of emergency department patient care efficiency. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34:326–335.

- , , , et al. Quality of discharge practices and patient understanding at an academic medical center. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(18):1715–1722.

- , . Addressing postdischarge adverse events: a neglected area. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:85–97.

- . Clinical report—physicians' roles in coordinating care of hospitalized children. Pediatrics. 2010;126:829–832.

- , , , , , . Increasing prevalence of medically complex children in US hospitals. Pediatrics. 2010;126:638–646.

- , , . Hospitalist care of the medically complex child. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005;52:1165–1187, x.

- , . Discharge planning and home care of the technology‐dependent infant. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1995;24:77–83.

- , , , . Pediatric discharge planning: complications, efficiency, and adequacy. Soc Work Health Care. 1995;22:1–18.

- , , , et al. The current capabilities of health information technology to support care transitions. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2013;2013:1231.

- , , , et al. Provider‐to‐provider electronic communication in the era of meaningful use: a review of the evidence. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:589–597.

- , , , . Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2:314–323.

- , , , , . A 5‐year time study analysis of emergency department patient care efficiency. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34:326–335.

- , , , et al. Quality of discharge practices and patient understanding at an academic medical center. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(18):1715–1722.

- , . Addressing postdischarge adverse events: a neglected area. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:85–97.

Outcomes in CVC Occlusions

Long‐term central venous catheters (CVCs) facilitate care for patients with chronic illness by providing easy venous access for laboratory tests, administration of medication, and parenteral nutrition. However, several complications resulting from the use of CVCs, including sepsis, extravasation of infusions, and venous thrombosis, can increase associated morbidity and mortality. These complications can also interrupt and delay treatment for the underlying disease and thereby affect outcomes. One of the most common CVC complications is catheter occlusion.[1]

Catheter occlusion occurs in 14% to 36% of patients within 1 to 2 years of catheter placement.[2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8] A catheter occlusion can be partial or complete, and can occur secondary to a variety of mechanical problems, including an uncommon, but potentially life‐threatening, pinch‐off syndrome. Medication or parenteral nutrition can also cause occlusion, which can be acute or gradual, with increasingly sluggish flow through the catheter. Inappropriate concentrations or incompatible mixtures can cause medications to precipitate within the catheter lumen.

Occlusions are either thrombotic or nonthrombotic. One autopsy study of patients with a long‐term CVC found that a fibrin sheath encased the catheter tip in every case.[9] An occluded catheter may compromise patient care[9, 10]; it may cause cancellation or delay of procedures, it potentially interrupts administration of critical therapies including vesicants, it may result in risk of infection, and it potentially leads to catheter replacement. This can further complicate care, leading to increased length of stay (LOS) and hospital costs.

To better understand resource utilization, LOS, and cost implications of alteplase compared with catheter replacement, we conducted a preplanned, retrospective analysis of hospitalized patients captured between January 2006 and December 2011 in the database maintained by Premier. The Premier database is a large, US hospital‐based, service‐level, all‐payer, comparative database, with information collected primarily from nearly 600 geographically diverse, nonprofit, nongovernment community and teaching hospitals.

METHODS

Data Sources

The Premier database contains information on over 42 million hospital discharges (mean 5.5 million discharges/year)one‐fifth of all US hospitalizationsfrom the year 2000 to the present. The database contains data from standard hospital discharge files, including patient demographic information and disease state. Patients can be tracked, with a unique identifier, across the inpatient and hospital‐based outpatient settings, as well as across visits. In addition to the data elements available in most of the standard hospital discharge files, the Premier database also contains a date‐stamped log of billed items, including procedures, medications, and laboratory, diagnostic, and therapeutic services at the individual patient level. Drug utilization information is available by day of stay and includes quantity, dosing, strength used, and cost.

The Premier database has been used extensively to benchmark hospital clinical and financial performance as well as by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for drug surveillance and by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to evaluate next‐generation payment models. Preliminary comparisons between patient and hospital characteristics for hospitals that submit data to Premier and those of the probability sample of hospitals and patients selected for the National Hospital Discharge Survey suggest that the patient populations are similar with regard to patient age, gender, LOS, mortality, primary discharge diagnosis, and primary procedure groups.

Patient Population

In this retrospective observational database analysis, inpatients of all ages were initially identified who were discharged from a hospital between January 1, 2006 and December 31, 2011 and whose records contained 1 or more International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD‐9) procedural codes or Current Procedural Terminology (CPT‐4) codes signifying CVC placement. The catheter replacement group comprised patients having a catheter replacement during the hospitalization. The alteplase treatment group was identified through patient billing records and by computing the dose administered (2 mg) during the index hospitalization period. Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System J‐codes (J2996, alteplase recombinant injection 10 mg; J2997, alteplase recombinant 1 mg) were also evaluated during the analysis to supplement the search string identification. To account for and eliminate catheter replacement due to mechanical failure rather than occlusion, patients with ICD‐9 diagnosis code 996.1 for mechanical failure were excluded. Patients with an ICD‐9 diagnosis code for infection or who received antibiotics on the day of replacement were excluded as an additional way to narrow the study to patients with occlusion as the reason for catheter replacement. In addition, patients receiving kidney dialysis, a chronic condition prone to greater‐than‐usual risk of catheter occlusion, were excluded. When a patient had multiple hospital stays with CVC insertions or placement during the study period, the first hospitalization with insertions or placement was used in our analyses.

Of the CVC patient population (N=574,252), 36,680 patient discharges resulted in the need for CVC replacement, alteplase therapy, or both. Patients receiving both replacement and alteplase (N=144) were excluded from analysis, resulting in 33,551 patient discharges with alteplase and 1028 patient discharges with CVC replacement.

Outcome Measures

The main outcomes of interest were LOS and hospital costs after occlusion, and readmissions at 30 and 90 days. Secondary measures, as they were thought to play a role in influencing outcomes, included LOS and costs before occlusion, as well as departmental costs such as pharmacy, radiology, and days in the intensive care unit (ICU).

Statistical Analysis

Univariate descriptive statistics were used to characterize the patient population by patient, clinical, and hospital attributes. In addition, subgroup analyses were performed among patients with any cardiology diagnosis (using ICD‐9 diagnosis or procedure codes), heart failure, myocardial infarction, and cancer, which were potentially overlapping categories chosen prior to initiating the analyses. Data measured on a continuous scale were expressed as mean, standard deviation, range, and median. Categorical data were expressed as count/percentages in the categories. In addition, categorical costs were also examined before and after occlusion. Tables of results included P values comparing patients who received CVC replacement with those who received alteplase across all measures. The [2] tests were used to test for differences in categorical variables, and t tests were utilized for differences in continuous variables.