User login

Potpourri of travel medicine tips and updates

School’s out for the summer soon! Many of your patients may have plans to travel to areas where they may be exposed to infectious diseases and other health risks not routinely encountered in the United States. They will join the 29 million Americans, including almost 3 million children, who traveled to overseas destinations in 2013. The potential for exposures to these risks is dependent on several factors, including the traveler’s age, health and immunization status, destination, accommodations, and duration of travel. Leisure travel, including visiting friends and relatives, accounts for approximately 90% of overseas travel. Some adolescents are traveling to resource-limited areas for adventure travel, educational experiences, and volunteerism. Many times they will reside with host families as part of this experience. There are also children who will have prolonged stays as a result of parental job relocation.

Unfortunately, health precautions often are not considered as many make their travel arrangements. International trips on average are planned at least 105 days in advance; however, many patients wait until the last minute to seek medical advice, if at all. Of 10,032 ill persons who sought post-travel evaluations at participating surveillance facilities (U.S. GeoSentinel sites) between 1997 and 2011, less than half (44%) reported seeking pretravel advice (MMWR 2013;62(SS03):1-15).

Here are some tips that should be useful and easy to implement in your practice for your internationally traveling patients.

• Make sure routine immunizations are up-to-date for age. The exception to this rule is for measles. All children at least 12 months age should receive two doses of MMR prior to departure regardless of their international destination. The second dose of MMR can be administered as early as 4 weeks after the first. Children between 6 and 11 months of age should receive a single dose of MMR prior to departure. If the initial dose is administered at less than 12 months of age, two additional doses will need to be administered to complete the series beginning at 12 months of age.

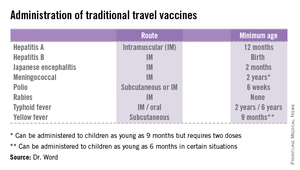

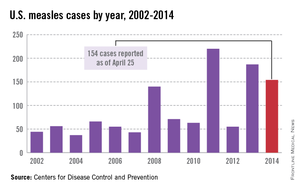

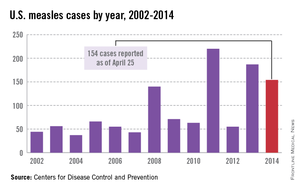

While measles is no longer endemic in the United States, as of April 25, 2014, there have been 154 cases reported from 14 states. (See measles graphic.) The majority of cases were imported by unvaccinated travelers who became ill after returning home and exposed susceptible individuals. In the last few years, most of the U.S. cases were imported from Western Europe. Currently, there are several countries experiencing record numbers of cases, including Vietnam (3,700) and the Philippines (26,000). This is not to imply that ongoing international outbreaks are limited to these two countries. For additional information, go to cdc.gov/measles.

• Identify someone in your area as a local resource for travel-related information and referrals. Make sure they are willing to see children. Develop a system to send out reminders to families to seek pretravel advice, ideally at least 1 month prior to departure. For children with chronic diseases or compromised immune systems, destination selection may need to be adjusted depending on their medical needs, availability of comparable health care at the overseas destination, and ability to receive pretravel vaccine interventions. Involvement prior to booking the trip would be advisable. Many offices successfully send out reminders for well visits and influenza vaccine. Consider incorporating one for overseas travel.

• The timing of initiation of antimalarial prophylaxis is dependent on the medication. Weekly medications such as chloroquine and mefloquine should begin at least 2 weeks prior to exposure. Atovaquone/proguanil and doxycycline are two drugs that are administered daily, and travelers can begin as late as 2 days prior to entry into a malaria-endemic area. This is a great option for the last-minute traveler.

However, there are contraindications for the use of each drug. Some are age dependent, while others are directly related to the presence of a specific medical condition. Areas where chloroquine-sensitive malaria is present are limited. It is always important to prescribe a prophylactic antimalarial agent, but even more prudent to prescribe the appropriate drug and dosage.

Not sure which drug is most appropriate for your patient? Refer to your local travel medicine expert, or visit cdc.gov/malaria.

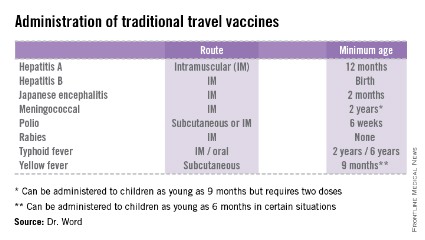

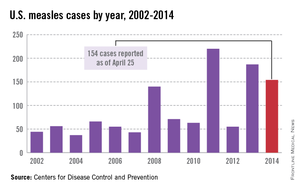

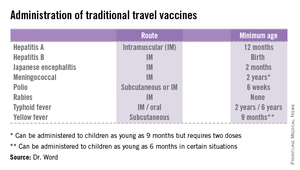

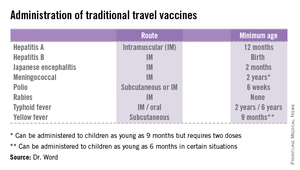

• The accompanying table lists vaccines that are traditionally considered to be travel vaccines, but pediatricians and family physicians might not consider all to belong in that group. Most are not required for entry into a specific country, but are recommended based on the risk for potential exposure and disease acquisition. In contrast, yellow fever and meningococcal vaccines are required for entry into certain countries. Yellow fever vaccine can be administered only at authorized sites and should be received at least 10 days prior to arrival at the destination. As with routinely administered vaccines, occasionally there are shortages of travel-related vaccines. Most recently, a shortage of yellow fever vaccine has been resolved.

The majority of vaccines should be administered at least 2 weeks prior to departure, while others, such as rabies and Japanese encephalitis, take at least 28 days to complete the series. These are a few additional reasons it behooves your patients to seek advice early.

Travel updates

Chikungunya virus (CHIK V). Local transmission in the Americas was first reported from St. Martin in December 2013. As of May 5, 2014, a total of 12 Caribbean countries have reported locally acquired cases. The disease is transmitted by Aedes species, which are the same species that transmit dengue fever. Disease is characterized by sudden onset of high fever with severe polyarthralgia. Additional symptoms can include headache, myalgias, rash, nausea, and vomiting. Epidemics have historically occurred in Africa, Asia, and islands in the Indian Ocean. Outbreaks also have occurred in Italy and France.

There is no preventive vaccine or drug available. Treatment is symptomatic care. The disease is best prevented by taking adequate mosquito precautions, especially during the daytime. Application of DEET (N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide) and picaridin-containing agents to the skin or treating clothes with a permethrin-containing agent are just two ways to avoid sustaining a mosquito bite.

While no cases Chikungunya virus have been acquired in the United States, there is a potential risk that the virus will be introduced by an infected traveler or mosquito. The Aedes species that transmits the virus is present in several areas of the United States. For additional information, go to cdc.gov/chikungunya.

Polio. While polio has been eliminated in the United States since 1979, it has never been eradicated in Afghanistan, Nigeria, and Pakistan. For a country to be certified as polio free, there cannot be evidence of circulation of wild polio virus for 3 consecutive years. In spite of a massive global initiative to eliminate this disease, in the last 3 months there have been cases confirmed in the following countries: Cameroon, Ethiopia, Equatorial Guinea, Iraq, Kenya, Somalia, and Syria. While no cases of flaccid paralysis have been confirmed in Israel, wild polio virus has been detected in sewage and isolated from stool of asymptomatic individuals.

Completion of the polio series is recommended for those persons inadequately immunized, and a one-time booster dose is recommended for all adults with travel plans to these countries. This should not be an issue for most pediatric patients, except those who may have deferred immunizations. Booster doses are no longer recommended for travel to countries that border countries with active circulation

African tick bite fever. Frequently overshadowed by the appropriate concern for prevention and acquisition of malaria is a rickettsial disease caused by Rickettsia africae, one of the spotted fever group of rickettsial infections. Its geographic distribution is limited to sub-Saharan Africa, and as its name implies, it is transmitted by a tick. It is the most commonly diagnosed rickettsial disease acquired by travelers (Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009;15:1791-8). Of 280 individuals diagnosed with rickettsiosis, 231 (82.5%) had spotted fever; almost 87% of the spotted fever rickettsiosis cases were acquired in sub-Saharan Africa, and 69% of these patients reported leisure travel to South Africa. In another review, it was the second-leading cause of systemic febrile illnesses acquired in travelers to sub-Saharan Africa. It was surpassed only by malaria (N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:119-30). All age groups are at risk.

Transmission occurs most frequently during the spring and summer months, coinciding with increased tick activity and greater outdoor activities. It is commonly acquired by tourists between November and April in South Africa during a safari or game hunting vacation. Because the incubation period is 5 to 14 days, most travelers may not become symptomatic until after their return. This disease should be suspected in any traveler who presents with fever, headache, and myalgias; has an eschar; and indicates they have recently returned from South Africa. Diagnosis is based on clinical history and serology. Therapy with doxycycline is initiated pending laboratory results.

Disease is controlled by prevention of transmission of the organism by the vector to humans. Use of repellents that contain 20%-30% DEET on exposed skin and wearing clothes treated with permethrin are recommended. Pretreated clothing is also available. Travelers should be encouraged to always check their body after exposure and remove ticks if discovered. Many advocate a bath or shower after coming indoors to facilitate finding any ticks.

Parents should check their children thoroughly for ticks under the arms, in and around the ears, inside the belly button, behind the knees, between the legs, around the waist, and especially in their hair.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She had no relevant financial disclosures. Write to Dr. Word at [email protected].

School’s out for the summer soon! Many of your patients may have plans to travel to areas where they may be exposed to infectious diseases and other health risks not routinely encountered in the United States. They will join the 29 million Americans, including almost 3 million children, who traveled to overseas destinations in 2013. The potential for exposures to these risks is dependent on several factors, including the traveler’s age, health and immunization status, destination, accommodations, and duration of travel. Leisure travel, including visiting friends and relatives, accounts for approximately 90% of overseas travel. Some adolescents are traveling to resource-limited areas for adventure travel, educational experiences, and volunteerism. Many times they will reside with host families as part of this experience. There are also children who will have prolonged stays as a result of parental job relocation.

Unfortunately, health precautions often are not considered as many make their travel arrangements. International trips on average are planned at least 105 days in advance; however, many patients wait until the last minute to seek medical advice, if at all. Of 10,032 ill persons who sought post-travel evaluations at participating surveillance facilities (U.S. GeoSentinel sites) between 1997 and 2011, less than half (44%) reported seeking pretravel advice (MMWR 2013;62(SS03):1-15).

Here are some tips that should be useful and easy to implement in your practice for your internationally traveling patients.

• Make sure routine immunizations are up-to-date for age. The exception to this rule is for measles. All children at least 12 months age should receive two doses of MMR prior to departure regardless of their international destination. The second dose of MMR can be administered as early as 4 weeks after the first. Children between 6 and 11 months of age should receive a single dose of MMR prior to departure. If the initial dose is administered at less than 12 months of age, two additional doses will need to be administered to complete the series beginning at 12 months of age.

While measles is no longer endemic in the United States, as of April 25, 2014, there have been 154 cases reported from 14 states. (See measles graphic.) The majority of cases were imported by unvaccinated travelers who became ill after returning home and exposed susceptible individuals. In the last few years, most of the U.S. cases were imported from Western Europe. Currently, there are several countries experiencing record numbers of cases, including Vietnam (3,700) and the Philippines (26,000). This is not to imply that ongoing international outbreaks are limited to these two countries. For additional information, go to cdc.gov/measles.

• Identify someone in your area as a local resource for travel-related information and referrals. Make sure they are willing to see children. Develop a system to send out reminders to families to seek pretravel advice, ideally at least 1 month prior to departure. For children with chronic diseases or compromised immune systems, destination selection may need to be adjusted depending on their medical needs, availability of comparable health care at the overseas destination, and ability to receive pretravel vaccine interventions. Involvement prior to booking the trip would be advisable. Many offices successfully send out reminders for well visits and influenza vaccine. Consider incorporating one for overseas travel.

• The timing of initiation of antimalarial prophylaxis is dependent on the medication. Weekly medications such as chloroquine and mefloquine should begin at least 2 weeks prior to exposure. Atovaquone/proguanil and doxycycline are two drugs that are administered daily, and travelers can begin as late as 2 days prior to entry into a malaria-endemic area. This is a great option for the last-minute traveler.

However, there are contraindications for the use of each drug. Some are age dependent, while others are directly related to the presence of a specific medical condition. Areas where chloroquine-sensitive malaria is present are limited. It is always important to prescribe a prophylactic antimalarial agent, but even more prudent to prescribe the appropriate drug and dosage.

Not sure which drug is most appropriate for your patient? Refer to your local travel medicine expert, or visit cdc.gov/malaria.

• The accompanying table lists vaccines that are traditionally considered to be travel vaccines, but pediatricians and family physicians might not consider all to belong in that group. Most are not required for entry into a specific country, but are recommended based on the risk for potential exposure and disease acquisition. In contrast, yellow fever and meningococcal vaccines are required for entry into certain countries. Yellow fever vaccine can be administered only at authorized sites and should be received at least 10 days prior to arrival at the destination. As with routinely administered vaccines, occasionally there are shortages of travel-related vaccines. Most recently, a shortage of yellow fever vaccine has been resolved.

The majority of vaccines should be administered at least 2 weeks prior to departure, while others, such as rabies and Japanese encephalitis, take at least 28 days to complete the series. These are a few additional reasons it behooves your patients to seek advice early.

Travel updates

Chikungunya virus (CHIK V). Local transmission in the Americas was first reported from St. Martin in December 2013. As of May 5, 2014, a total of 12 Caribbean countries have reported locally acquired cases. The disease is transmitted by Aedes species, which are the same species that transmit dengue fever. Disease is characterized by sudden onset of high fever with severe polyarthralgia. Additional symptoms can include headache, myalgias, rash, nausea, and vomiting. Epidemics have historically occurred in Africa, Asia, and islands in the Indian Ocean. Outbreaks also have occurred in Italy and France.

There is no preventive vaccine or drug available. Treatment is symptomatic care. The disease is best prevented by taking adequate mosquito precautions, especially during the daytime. Application of DEET (N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide) and picaridin-containing agents to the skin or treating clothes with a permethrin-containing agent are just two ways to avoid sustaining a mosquito bite.

While no cases Chikungunya virus have been acquired in the United States, there is a potential risk that the virus will be introduced by an infected traveler or mosquito. The Aedes species that transmits the virus is present in several areas of the United States. For additional information, go to cdc.gov/chikungunya.

Polio. While polio has been eliminated in the United States since 1979, it has never been eradicated in Afghanistan, Nigeria, and Pakistan. For a country to be certified as polio free, there cannot be evidence of circulation of wild polio virus for 3 consecutive years. In spite of a massive global initiative to eliminate this disease, in the last 3 months there have been cases confirmed in the following countries: Cameroon, Ethiopia, Equatorial Guinea, Iraq, Kenya, Somalia, and Syria. While no cases of flaccid paralysis have been confirmed in Israel, wild polio virus has been detected in sewage and isolated from stool of asymptomatic individuals.

Completion of the polio series is recommended for those persons inadequately immunized, and a one-time booster dose is recommended for all adults with travel plans to these countries. This should not be an issue for most pediatric patients, except those who may have deferred immunizations. Booster doses are no longer recommended for travel to countries that border countries with active circulation

African tick bite fever. Frequently overshadowed by the appropriate concern for prevention and acquisition of malaria is a rickettsial disease caused by Rickettsia africae, one of the spotted fever group of rickettsial infections. Its geographic distribution is limited to sub-Saharan Africa, and as its name implies, it is transmitted by a tick. It is the most commonly diagnosed rickettsial disease acquired by travelers (Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009;15:1791-8). Of 280 individuals diagnosed with rickettsiosis, 231 (82.5%) had spotted fever; almost 87% of the spotted fever rickettsiosis cases were acquired in sub-Saharan Africa, and 69% of these patients reported leisure travel to South Africa. In another review, it was the second-leading cause of systemic febrile illnesses acquired in travelers to sub-Saharan Africa. It was surpassed only by malaria (N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:119-30). All age groups are at risk.

Transmission occurs most frequently during the spring and summer months, coinciding with increased tick activity and greater outdoor activities. It is commonly acquired by tourists between November and April in South Africa during a safari or game hunting vacation. Because the incubation period is 5 to 14 days, most travelers may not become symptomatic until after their return. This disease should be suspected in any traveler who presents with fever, headache, and myalgias; has an eschar; and indicates they have recently returned from South Africa. Diagnosis is based on clinical history and serology. Therapy with doxycycline is initiated pending laboratory results.

Disease is controlled by prevention of transmission of the organism by the vector to humans. Use of repellents that contain 20%-30% DEET on exposed skin and wearing clothes treated with permethrin are recommended. Pretreated clothing is also available. Travelers should be encouraged to always check their body after exposure and remove ticks if discovered. Many advocate a bath or shower after coming indoors to facilitate finding any ticks.

Parents should check their children thoroughly for ticks under the arms, in and around the ears, inside the belly button, behind the knees, between the legs, around the waist, and especially in their hair.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She had no relevant financial disclosures. Write to Dr. Word at [email protected].

School’s out for the summer soon! Many of your patients may have plans to travel to areas where they may be exposed to infectious diseases and other health risks not routinely encountered in the United States. They will join the 29 million Americans, including almost 3 million children, who traveled to overseas destinations in 2013. The potential for exposures to these risks is dependent on several factors, including the traveler’s age, health and immunization status, destination, accommodations, and duration of travel. Leisure travel, including visiting friends and relatives, accounts for approximately 90% of overseas travel. Some adolescents are traveling to resource-limited areas for adventure travel, educational experiences, and volunteerism. Many times they will reside with host families as part of this experience. There are also children who will have prolonged stays as a result of parental job relocation.

Unfortunately, health precautions often are not considered as many make their travel arrangements. International trips on average are planned at least 105 days in advance; however, many patients wait until the last minute to seek medical advice, if at all. Of 10,032 ill persons who sought post-travel evaluations at participating surveillance facilities (U.S. GeoSentinel sites) between 1997 and 2011, less than half (44%) reported seeking pretravel advice (MMWR 2013;62(SS03):1-15).

Here are some tips that should be useful and easy to implement in your practice for your internationally traveling patients.

• Make sure routine immunizations are up-to-date for age. The exception to this rule is for measles. All children at least 12 months age should receive two doses of MMR prior to departure regardless of their international destination. The second dose of MMR can be administered as early as 4 weeks after the first. Children between 6 and 11 months of age should receive a single dose of MMR prior to departure. If the initial dose is administered at less than 12 months of age, two additional doses will need to be administered to complete the series beginning at 12 months of age.

While measles is no longer endemic in the United States, as of April 25, 2014, there have been 154 cases reported from 14 states. (See measles graphic.) The majority of cases were imported by unvaccinated travelers who became ill after returning home and exposed susceptible individuals. In the last few years, most of the U.S. cases were imported from Western Europe. Currently, there are several countries experiencing record numbers of cases, including Vietnam (3,700) and the Philippines (26,000). This is not to imply that ongoing international outbreaks are limited to these two countries. For additional information, go to cdc.gov/measles.

• Identify someone in your area as a local resource for travel-related information and referrals. Make sure they are willing to see children. Develop a system to send out reminders to families to seek pretravel advice, ideally at least 1 month prior to departure. For children with chronic diseases or compromised immune systems, destination selection may need to be adjusted depending on their medical needs, availability of comparable health care at the overseas destination, and ability to receive pretravel vaccine interventions. Involvement prior to booking the trip would be advisable. Many offices successfully send out reminders for well visits and influenza vaccine. Consider incorporating one for overseas travel.

• The timing of initiation of antimalarial prophylaxis is dependent on the medication. Weekly medications such as chloroquine and mefloquine should begin at least 2 weeks prior to exposure. Atovaquone/proguanil and doxycycline are two drugs that are administered daily, and travelers can begin as late as 2 days prior to entry into a malaria-endemic area. This is a great option for the last-minute traveler.

However, there are contraindications for the use of each drug. Some are age dependent, while others are directly related to the presence of a specific medical condition. Areas where chloroquine-sensitive malaria is present are limited. It is always important to prescribe a prophylactic antimalarial agent, but even more prudent to prescribe the appropriate drug and dosage.

Not sure which drug is most appropriate for your patient? Refer to your local travel medicine expert, or visit cdc.gov/malaria.

• The accompanying table lists vaccines that are traditionally considered to be travel vaccines, but pediatricians and family physicians might not consider all to belong in that group. Most are not required for entry into a specific country, but are recommended based on the risk for potential exposure and disease acquisition. In contrast, yellow fever and meningococcal vaccines are required for entry into certain countries. Yellow fever vaccine can be administered only at authorized sites and should be received at least 10 days prior to arrival at the destination. As with routinely administered vaccines, occasionally there are shortages of travel-related vaccines. Most recently, a shortage of yellow fever vaccine has been resolved.

The majority of vaccines should be administered at least 2 weeks prior to departure, while others, such as rabies and Japanese encephalitis, take at least 28 days to complete the series. These are a few additional reasons it behooves your patients to seek advice early.

Travel updates

Chikungunya virus (CHIK V). Local transmission in the Americas was first reported from St. Martin in December 2013. As of May 5, 2014, a total of 12 Caribbean countries have reported locally acquired cases. The disease is transmitted by Aedes species, which are the same species that transmit dengue fever. Disease is characterized by sudden onset of high fever with severe polyarthralgia. Additional symptoms can include headache, myalgias, rash, nausea, and vomiting. Epidemics have historically occurred in Africa, Asia, and islands in the Indian Ocean. Outbreaks also have occurred in Italy and France.

There is no preventive vaccine or drug available. Treatment is symptomatic care. The disease is best prevented by taking adequate mosquito precautions, especially during the daytime. Application of DEET (N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide) and picaridin-containing agents to the skin or treating clothes with a permethrin-containing agent are just two ways to avoid sustaining a mosquito bite.

While no cases Chikungunya virus have been acquired in the United States, there is a potential risk that the virus will be introduced by an infected traveler or mosquito. The Aedes species that transmits the virus is present in several areas of the United States. For additional information, go to cdc.gov/chikungunya.

Polio. While polio has been eliminated in the United States since 1979, it has never been eradicated in Afghanistan, Nigeria, and Pakistan. For a country to be certified as polio free, there cannot be evidence of circulation of wild polio virus for 3 consecutive years. In spite of a massive global initiative to eliminate this disease, in the last 3 months there have been cases confirmed in the following countries: Cameroon, Ethiopia, Equatorial Guinea, Iraq, Kenya, Somalia, and Syria. While no cases of flaccid paralysis have been confirmed in Israel, wild polio virus has been detected in sewage and isolated from stool of asymptomatic individuals.

Completion of the polio series is recommended for those persons inadequately immunized, and a one-time booster dose is recommended for all adults with travel plans to these countries. This should not be an issue for most pediatric patients, except those who may have deferred immunizations. Booster doses are no longer recommended for travel to countries that border countries with active circulation

African tick bite fever. Frequently overshadowed by the appropriate concern for prevention and acquisition of malaria is a rickettsial disease caused by Rickettsia africae, one of the spotted fever group of rickettsial infections. Its geographic distribution is limited to sub-Saharan Africa, and as its name implies, it is transmitted by a tick. It is the most commonly diagnosed rickettsial disease acquired by travelers (Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009;15:1791-8). Of 280 individuals diagnosed with rickettsiosis, 231 (82.5%) had spotted fever; almost 87% of the spotted fever rickettsiosis cases were acquired in sub-Saharan Africa, and 69% of these patients reported leisure travel to South Africa. In another review, it was the second-leading cause of systemic febrile illnesses acquired in travelers to sub-Saharan Africa. It was surpassed only by malaria (N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:119-30). All age groups are at risk.

Transmission occurs most frequently during the spring and summer months, coinciding with increased tick activity and greater outdoor activities. It is commonly acquired by tourists between November and April in South Africa during a safari or game hunting vacation. Because the incubation period is 5 to 14 days, most travelers may not become symptomatic until after their return. This disease should be suspected in any traveler who presents with fever, headache, and myalgias; has an eschar; and indicates they have recently returned from South Africa. Diagnosis is based on clinical history and serology. Therapy with doxycycline is initiated pending laboratory results.

Disease is controlled by prevention of transmission of the organism by the vector to humans. Use of repellents that contain 20%-30% DEET on exposed skin and wearing clothes treated with permethrin are recommended. Pretreated clothing is also available. Travelers should be encouraged to always check their body after exposure and remove ticks if discovered. Many advocate a bath or shower after coming indoors to facilitate finding any ticks.

Parents should check their children thoroughly for ticks under the arms, in and around the ears, inside the belly button, behind the knees, between the legs, around the waist, and especially in their hair.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She had no relevant financial disclosures. Write to Dr. Word at [email protected].

A more precise method of delivering gene therapy

Jeff Fitlow/Rice University

Researchers have developed an adeno-associated virus (AAV) that releases its payload only in the presence of 2 selected proteases.

Because certain proteases are elevated at tumor sites, the virus can be designed to target and destroy cancer cells.

Junghae Suh, PhD, of Rice University in Houston, Texas, and her colleagues engineered the virus and described their work in ACS Nano.

AAVs have become the object of study as delivery vehicles for gene therapy.

Researchers often try to target AAVs to cellular receptors that may be slightly overexpressed on diseased cells, but Dr Suh’s team took a different approach.

“We were looking for other types of biomarkers beyond cellular receptors present at disease sites,” she said. “In breast cancer, for example, it’s known the tumor cells oversecrete extracellular proteases, but perhaps more important are the infiltrating immune cells that migrate into the tumor microenvironment and start dumping out a whole bunch of proteases as well.”

“So that’s what we’re going after to do targeted delivery. Our basic idea is to create viruses that, in the locked configuration, can’t do anything.”

But when the programmed AAVs encounter the right proteases at sites of disease, they unlock and bind to the cells. The AAVs then deliver payloads that will either kill the cells, in the case of cancer therapy, or deliver genes that can repair the cells.

Dr Suh and her colleagues genetically insert peptides into the self-assembling AAVs to lock the capsids, the hard shells that protect genes contained within. The target proteases recognize the peptides and “chew off the locks,” effectively unlocking the virus and allowing it to bind to the diseased cells.

“If we were just looking for 1 protease, it might be at the cancer site, but it could also be somewhere else in your body where you have inflammation,” Dr Suh said. “This could lead to undesirable side effects.”

“By requiring 2 different proteases—let’s say protease A and protease B—to open the locked virus, we may achieve higher delivery specificity since the chance of having both proteases elevated at a site becomes smaller.”

The ultimate vision of this technology is to design viruses that can carry out a combination of steps for targeting.

“To increase the specificity of virus unlocking, you can imagine creating viruses that require many more keys to open,” Dr Suh said. “For example, you may need both proteases A and B, as well as a cellular receptor, to unlock the virus. The work reported here is a good first step toward this goal.” ![]()

Jeff Fitlow/Rice University

Researchers have developed an adeno-associated virus (AAV) that releases its payload only in the presence of 2 selected proteases.

Because certain proteases are elevated at tumor sites, the virus can be designed to target and destroy cancer cells.

Junghae Suh, PhD, of Rice University in Houston, Texas, and her colleagues engineered the virus and described their work in ACS Nano.

AAVs have become the object of study as delivery vehicles for gene therapy.

Researchers often try to target AAVs to cellular receptors that may be slightly overexpressed on diseased cells, but Dr Suh’s team took a different approach.

“We were looking for other types of biomarkers beyond cellular receptors present at disease sites,” she said. “In breast cancer, for example, it’s known the tumor cells oversecrete extracellular proteases, but perhaps more important are the infiltrating immune cells that migrate into the tumor microenvironment and start dumping out a whole bunch of proteases as well.”

“So that’s what we’re going after to do targeted delivery. Our basic idea is to create viruses that, in the locked configuration, can’t do anything.”

But when the programmed AAVs encounter the right proteases at sites of disease, they unlock and bind to the cells. The AAVs then deliver payloads that will either kill the cells, in the case of cancer therapy, or deliver genes that can repair the cells.

Dr Suh and her colleagues genetically insert peptides into the self-assembling AAVs to lock the capsids, the hard shells that protect genes contained within. The target proteases recognize the peptides and “chew off the locks,” effectively unlocking the virus and allowing it to bind to the diseased cells.

“If we were just looking for 1 protease, it might be at the cancer site, but it could also be somewhere else in your body where you have inflammation,” Dr Suh said. “This could lead to undesirable side effects.”

“By requiring 2 different proteases—let’s say protease A and protease B—to open the locked virus, we may achieve higher delivery specificity since the chance of having both proteases elevated at a site becomes smaller.”

The ultimate vision of this technology is to design viruses that can carry out a combination of steps for targeting.

“To increase the specificity of virus unlocking, you can imagine creating viruses that require many more keys to open,” Dr Suh said. “For example, you may need both proteases A and B, as well as a cellular receptor, to unlock the virus. The work reported here is a good first step toward this goal.” ![]()

Jeff Fitlow/Rice University

Researchers have developed an adeno-associated virus (AAV) that releases its payload only in the presence of 2 selected proteases.

Because certain proteases are elevated at tumor sites, the virus can be designed to target and destroy cancer cells.

Junghae Suh, PhD, of Rice University in Houston, Texas, and her colleagues engineered the virus and described their work in ACS Nano.

AAVs have become the object of study as delivery vehicles for gene therapy.

Researchers often try to target AAVs to cellular receptors that may be slightly overexpressed on diseased cells, but Dr Suh’s team took a different approach.

“We were looking for other types of biomarkers beyond cellular receptors present at disease sites,” she said. “In breast cancer, for example, it’s known the tumor cells oversecrete extracellular proteases, but perhaps more important are the infiltrating immune cells that migrate into the tumor microenvironment and start dumping out a whole bunch of proteases as well.”

“So that’s what we’re going after to do targeted delivery. Our basic idea is to create viruses that, in the locked configuration, can’t do anything.”

But when the programmed AAVs encounter the right proteases at sites of disease, they unlock and bind to the cells. The AAVs then deliver payloads that will either kill the cells, in the case of cancer therapy, or deliver genes that can repair the cells.

Dr Suh and her colleagues genetically insert peptides into the self-assembling AAVs to lock the capsids, the hard shells that protect genes contained within. The target proteases recognize the peptides and “chew off the locks,” effectively unlocking the virus and allowing it to bind to the diseased cells.

“If we were just looking for 1 protease, it might be at the cancer site, but it could also be somewhere else in your body where you have inflammation,” Dr Suh said. “This could lead to undesirable side effects.”

“By requiring 2 different proteases—let’s say protease A and protease B—to open the locked virus, we may achieve higher delivery specificity since the chance of having both proteases elevated at a site becomes smaller.”

The ultimate vision of this technology is to design viruses that can carry out a combination of steps for targeting.

“To increase the specificity of virus unlocking, you can imagine creating viruses that require many more keys to open,” Dr Suh said. “For example, you may need both proteases A and B, as well as a cellular receptor, to unlock the virus. The work reported here is a good first step toward this goal.” ![]()

Agricultural chemicals and the risk of NHL

EPA/John Messina

After reviewing nearly 30 years’ worth of data, investigators have compiled a list of agricultural chemicals that appear to increase a person’s risk of developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).

Meta-analyses suggested that occupational exposure to phenoxy herbicides, carbamate insecticides, organochlorine insecticides, and organophosphorus insecticides/herbicides can increase the risk of NHL.

The research also revealed associations between certain chemicals and specific NHL subtypes.

Leah Schinasi, PhD, and Maria E. Leon, PhD, of the International Agency for Research on Cancer in Lyon, France, described the analysis and its results in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.

The investigators reviewed epidemiological research spanning nearly 30 years and identified 44 relevant papers. The papers recounted studies conducted in the US, Canada, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand.

Drs Schinasi and Leon used these data to assess occupational exposure to 80 active ingredients and 21 chemical groups and clarify their role in the development of NHL. Most, but not all, of the studies looked at lifetime exposure to the chemicals in question.

The investigators performed a meta-analysis of the data and found associations between NHL and a range of insecticides and herbicides. But the strongest risk ratios (RRs) were for subtypes of NHL.

There was a positive association between exposure to the organophosphorus herbicide glyphosate and any NHL (RR=1.5), but the link was stronger for B-cell lymphoma in particular (RR=2.0).

Phenoxy herbicide exposure was associated with an increased risk of NHL in general (RR=1.4), B-cell lymphoma (RR=1.8), lymphocytic lymphoma (RR=1.8), and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (RR=2.0). As for specific phenoxy herbicides, both MCPA (RR=1.5) and 2,4-D (RR=1.4) were associated with NHL.

Carbamate insecticides, as a group, appeared to confer an increased risk of NHL (RR=1.7). The individual insecticides carbaryl and carbofuran showed positive associations with NHL as well (RRs of 1.7 and 1.6, respectively).

There was a positive association with NHL for organophosphorus insecticides as a group (RR=1.6), as well as the individual insecticides chlorpyrifos (RR=1.6), diazinon (RR=1.6), dimethoate (RR=1.4), and malathion (RR=1.8).

Lastly, organochlorine insecticides appeared to confer an increased risk of NHL (RR=1.3). DDT was associated with NHL (RR=1.3), B-cell lymphoma (RR=1.4), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (RR=1.2), and follicular lymphoma (RR=1.5). And lindane was associated with NHL in general (RR=1.6).

The investigators said this analysis represents one of the most comprehensive reviews on the topic of occupational exposure to agricultural chemicals in the scientific literature.

But it also suggests a need to study a wider variety of chemicals in more geographic areas, especially in low- and middle-income countries, as they were missing from the literature. ![]()

EPA/John Messina

After reviewing nearly 30 years’ worth of data, investigators have compiled a list of agricultural chemicals that appear to increase a person’s risk of developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).

Meta-analyses suggested that occupational exposure to phenoxy herbicides, carbamate insecticides, organochlorine insecticides, and organophosphorus insecticides/herbicides can increase the risk of NHL.

The research also revealed associations between certain chemicals and specific NHL subtypes.

Leah Schinasi, PhD, and Maria E. Leon, PhD, of the International Agency for Research on Cancer in Lyon, France, described the analysis and its results in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.

The investigators reviewed epidemiological research spanning nearly 30 years and identified 44 relevant papers. The papers recounted studies conducted in the US, Canada, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand.

Drs Schinasi and Leon used these data to assess occupational exposure to 80 active ingredients and 21 chemical groups and clarify their role in the development of NHL. Most, but not all, of the studies looked at lifetime exposure to the chemicals in question.

The investigators performed a meta-analysis of the data and found associations between NHL and a range of insecticides and herbicides. But the strongest risk ratios (RRs) were for subtypes of NHL.

There was a positive association between exposure to the organophosphorus herbicide glyphosate and any NHL (RR=1.5), but the link was stronger for B-cell lymphoma in particular (RR=2.0).

Phenoxy herbicide exposure was associated with an increased risk of NHL in general (RR=1.4), B-cell lymphoma (RR=1.8), lymphocytic lymphoma (RR=1.8), and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (RR=2.0). As for specific phenoxy herbicides, both MCPA (RR=1.5) and 2,4-D (RR=1.4) were associated with NHL.

Carbamate insecticides, as a group, appeared to confer an increased risk of NHL (RR=1.7). The individual insecticides carbaryl and carbofuran showed positive associations with NHL as well (RRs of 1.7 and 1.6, respectively).

There was a positive association with NHL for organophosphorus insecticides as a group (RR=1.6), as well as the individual insecticides chlorpyrifos (RR=1.6), diazinon (RR=1.6), dimethoate (RR=1.4), and malathion (RR=1.8).

Lastly, organochlorine insecticides appeared to confer an increased risk of NHL (RR=1.3). DDT was associated with NHL (RR=1.3), B-cell lymphoma (RR=1.4), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (RR=1.2), and follicular lymphoma (RR=1.5). And lindane was associated with NHL in general (RR=1.6).

The investigators said this analysis represents one of the most comprehensive reviews on the topic of occupational exposure to agricultural chemicals in the scientific literature.

But it also suggests a need to study a wider variety of chemicals in more geographic areas, especially in low- and middle-income countries, as they were missing from the literature. ![]()

EPA/John Messina

After reviewing nearly 30 years’ worth of data, investigators have compiled a list of agricultural chemicals that appear to increase a person’s risk of developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).

Meta-analyses suggested that occupational exposure to phenoxy herbicides, carbamate insecticides, organochlorine insecticides, and organophosphorus insecticides/herbicides can increase the risk of NHL.

The research also revealed associations between certain chemicals and specific NHL subtypes.

Leah Schinasi, PhD, and Maria E. Leon, PhD, of the International Agency for Research on Cancer in Lyon, France, described the analysis and its results in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.

The investigators reviewed epidemiological research spanning nearly 30 years and identified 44 relevant papers. The papers recounted studies conducted in the US, Canada, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand.

Drs Schinasi and Leon used these data to assess occupational exposure to 80 active ingredients and 21 chemical groups and clarify their role in the development of NHL. Most, but not all, of the studies looked at lifetime exposure to the chemicals in question.

The investigators performed a meta-analysis of the data and found associations between NHL and a range of insecticides and herbicides. But the strongest risk ratios (RRs) were for subtypes of NHL.

There was a positive association between exposure to the organophosphorus herbicide glyphosate and any NHL (RR=1.5), but the link was stronger for B-cell lymphoma in particular (RR=2.0).

Phenoxy herbicide exposure was associated with an increased risk of NHL in general (RR=1.4), B-cell lymphoma (RR=1.8), lymphocytic lymphoma (RR=1.8), and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (RR=2.0). As for specific phenoxy herbicides, both MCPA (RR=1.5) and 2,4-D (RR=1.4) were associated with NHL.

Carbamate insecticides, as a group, appeared to confer an increased risk of NHL (RR=1.7). The individual insecticides carbaryl and carbofuran showed positive associations with NHL as well (RRs of 1.7 and 1.6, respectively).

There was a positive association with NHL for organophosphorus insecticides as a group (RR=1.6), as well as the individual insecticides chlorpyrifos (RR=1.6), diazinon (RR=1.6), dimethoate (RR=1.4), and malathion (RR=1.8).

Lastly, organochlorine insecticides appeared to confer an increased risk of NHL (RR=1.3). DDT was associated with NHL (RR=1.3), B-cell lymphoma (RR=1.4), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (RR=1.2), and follicular lymphoma (RR=1.5). And lindane was associated with NHL in general (RR=1.6).

The investigators said this analysis represents one of the most comprehensive reviews on the topic of occupational exposure to agricultural chemicals in the scientific literature.

But it also suggests a need to study a wider variety of chemicals in more geographic areas, especially in low- and middle-income countries, as they were missing from the literature. ![]()

Protein interaction may be therapeutic target for AML

University of Queensland

Inhibiting the interaction of 2 proteins can prevent the development of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to a study published in Blood.

Researchers found evidence to suggest the “docking” of one protein, Myb, with another, p300, is essential for AML development.

“Our data identifies the critical role of this Myb-p300 interaction and shows that the disruption of this interaction could lead to a potential therapeutic strategy,” said Tom Gonda, PhD, of the University of Queensland’s School of Pharmacy in Woolloongabba, Queensland, Australia.

“This finding could lead to our team developing a drug to block this interaction and stop the growth of not only acute myeloid leukemia cells but probably the cells of other types of leukemia as well.”

Dr Gonda and his colleagues conducted this research using cells from Booreana mice, which carry a mutant allele of Myb, as well as cells from wild-type mice.

Experiments showed that the Myb-p300 interaction was necessary for in vitro transformation by the oncogenes AML1-ETO, AML1-ETO9a, MLL-ENL, and MLL-AF9.

The researchers also transduced cells from Booreana mice and wild-type mice with either AML1-ETO9a or MLL-AF9 retroviruses and transplanted the cells into irradiated mice. The cells from wild-type mice generated leukemia in the recipients, but the Booreana cells did not.

Lastly, the team performed gene expression analyses to gain more insight into the Myb-p300 relationship. They found that several genes already implicated in myeloid leukemogenesis and hematopoietic stem cell function are regulated in an Myb-p300-dependent manner.

The researchers therefore concluded that the Myb-p300 interaction is important to myeloid leukemogenesis. And disrupting this interaction could prove useful in the fight against AML.

Dr Gonda pointed out, however, that the Myb protein is produced by the MYB oncogene. And although this oncogene is required for the continued growth of leukemia cells, it is also essential for normal blood cell formation.

“[S]o we need an approach for targeting it that won’t completely disrupt normal blood cell production,” he said. “Our research shows that normal blood cells can continue to form even when the Myb-p300 interaction is unable to occur, suggesting that a drug that blocks the interaction could be safe for use in patients.”

Dr Gonda and his colleagues are also planning to examine the possibility of targeting genes and proteins that work downstream of MYB. ![]()

University of Queensland

Inhibiting the interaction of 2 proteins can prevent the development of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to a study published in Blood.

Researchers found evidence to suggest the “docking” of one protein, Myb, with another, p300, is essential for AML development.

“Our data identifies the critical role of this Myb-p300 interaction and shows that the disruption of this interaction could lead to a potential therapeutic strategy,” said Tom Gonda, PhD, of the University of Queensland’s School of Pharmacy in Woolloongabba, Queensland, Australia.

“This finding could lead to our team developing a drug to block this interaction and stop the growth of not only acute myeloid leukemia cells but probably the cells of other types of leukemia as well.”

Dr Gonda and his colleagues conducted this research using cells from Booreana mice, which carry a mutant allele of Myb, as well as cells from wild-type mice.

Experiments showed that the Myb-p300 interaction was necessary for in vitro transformation by the oncogenes AML1-ETO, AML1-ETO9a, MLL-ENL, and MLL-AF9.

The researchers also transduced cells from Booreana mice and wild-type mice with either AML1-ETO9a or MLL-AF9 retroviruses and transplanted the cells into irradiated mice. The cells from wild-type mice generated leukemia in the recipients, but the Booreana cells did not.

Lastly, the team performed gene expression analyses to gain more insight into the Myb-p300 relationship. They found that several genes already implicated in myeloid leukemogenesis and hematopoietic stem cell function are regulated in an Myb-p300-dependent manner.

The researchers therefore concluded that the Myb-p300 interaction is important to myeloid leukemogenesis. And disrupting this interaction could prove useful in the fight against AML.

Dr Gonda pointed out, however, that the Myb protein is produced by the MYB oncogene. And although this oncogene is required for the continued growth of leukemia cells, it is also essential for normal blood cell formation.

“[S]o we need an approach for targeting it that won’t completely disrupt normal blood cell production,” he said. “Our research shows that normal blood cells can continue to form even when the Myb-p300 interaction is unable to occur, suggesting that a drug that blocks the interaction could be safe for use in patients.”

Dr Gonda and his colleagues are also planning to examine the possibility of targeting genes and proteins that work downstream of MYB. ![]()

University of Queensland

Inhibiting the interaction of 2 proteins can prevent the development of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to a study published in Blood.

Researchers found evidence to suggest the “docking” of one protein, Myb, with another, p300, is essential for AML development.

“Our data identifies the critical role of this Myb-p300 interaction and shows that the disruption of this interaction could lead to a potential therapeutic strategy,” said Tom Gonda, PhD, of the University of Queensland’s School of Pharmacy in Woolloongabba, Queensland, Australia.

“This finding could lead to our team developing a drug to block this interaction and stop the growth of not only acute myeloid leukemia cells but probably the cells of other types of leukemia as well.”

Dr Gonda and his colleagues conducted this research using cells from Booreana mice, which carry a mutant allele of Myb, as well as cells from wild-type mice.

Experiments showed that the Myb-p300 interaction was necessary for in vitro transformation by the oncogenes AML1-ETO, AML1-ETO9a, MLL-ENL, and MLL-AF9.

The researchers also transduced cells from Booreana mice and wild-type mice with either AML1-ETO9a or MLL-AF9 retroviruses and transplanted the cells into irradiated mice. The cells from wild-type mice generated leukemia in the recipients, but the Booreana cells did not.

Lastly, the team performed gene expression analyses to gain more insight into the Myb-p300 relationship. They found that several genes already implicated in myeloid leukemogenesis and hematopoietic stem cell function are regulated in an Myb-p300-dependent manner.

The researchers therefore concluded that the Myb-p300 interaction is important to myeloid leukemogenesis. And disrupting this interaction could prove useful in the fight against AML.

Dr Gonda pointed out, however, that the Myb protein is produced by the MYB oncogene. And although this oncogene is required for the continued growth of leukemia cells, it is also essential for normal blood cell formation.

“[S]o we need an approach for targeting it that won’t completely disrupt normal blood cell production,” he said. “Our research shows that normal blood cells can continue to form even when the Myb-p300 interaction is unable to occur, suggesting that a drug that blocks the interaction could be safe for use in patients.”

Dr Gonda and his colleagues are also planning to examine the possibility of targeting genes and proteins that work downstream of MYB. ![]()

Wnt pathway appears key to cell reprogramming

Salk Institute

The Wnt signaling pathway plays a key role in the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), according to a study published in Stem Cell Reports.

Researchers found they could increase the efficiency of the cell reprogramming process by inhibiting the Wnt pathway.

“[U]ntil now, this was a very inefficient process,” said study author Ilda Theka, a PhD student at the Centre for Genomic Regulation in Barcelona, Spain.

“There are many groups trying to understand the mechanism by which adult cells become pluripotent and what blocks that process and makes only a small percentage of cells end up being reprogrammed. We are providing information on why it happens.”

The researchers studied how the Wnt pathway behaves throughout the process of transforming mature cells into iPSCs, which usually lasts 2 weeks. It’s a dynamic process that produces oscillations from the pathway, which is not active all the time.

“We have seen that there are two phases and that, in each one of them, Wnt fulfils a different function,” Theka said. “And we have shown that, by inhibiting it at the beginning of the process and activating it at the end, we can increase the efficiency of reprogramming and obtain a larger number of pluripotent cells.”

The team also discovered that the exact moment when the Wnt pathway is activated is crucial. Activating the pathway too early makes the cells begin to differentiate, and they are not reprogrammed.

To artificially control the pathway, the researchers used a molecule called Iwp2, a Wnt-secretion inhibitor that does not permanently alter the cells. ![]()

Salk Institute

The Wnt signaling pathway plays a key role in the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), according to a study published in Stem Cell Reports.

Researchers found they could increase the efficiency of the cell reprogramming process by inhibiting the Wnt pathway.

“[U]ntil now, this was a very inefficient process,” said study author Ilda Theka, a PhD student at the Centre for Genomic Regulation in Barcelona, Spain.

“There are many groups trying to understand the mechanism by which adult cells become pluripotent and what blocks that process and makes only a small percentage of cells end up being reprogrammed. We are providing information on why it happens.”

The researchers studied how the Wnt pathway behaves throughout the process of transforming mature cells into iPSCs, which usually lasts 2 weeks. It’s a dynamic process that produces oscillations from the pathway, which is not active all the time.

“We have seen that there are two phases and that, in each one of them, Wnt fulfils a different function,” Theka said. “And we have shown that, by inhibiting it at the beginning of the process and activating it at the end, we can increase the efficiency of reprogramming and obtain a larger number of pluripotent cells.”

The team also discovered that the exact moment when the Wnt pathway is activated is crucial. Activating the pathway too early makes the cells begin to differentiate, and they are not reprogrammed.

To artificially control the pathway, the researchers used a molecule called Iwp2, a Wnt-secretion inhibitor that does not permanently alter the cells. ![]()

Salk Institute

The Wnt signaling pathway plays a key role in the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), according to a study published in Stem Cell Reports.

Researchers found they could increase the efficiency of the cell reprogramming process by inhibiting the Wnt pathway.

“[U]ntil now, this was a very inefficient process,” said study author Ilda Theka, a PhD student at the Centre for Genomic Regulation in Barcelona, Spain.

“There are many groups trying to understand the mechanism by which adult cells become pluripotent and what blocks that process and makes only a small percentage of cells end up being reprogrammed. We are providing information on why it happens.”

The researchers studied how the Wnt pathway behaves throughout the process of transforming mature cells into iPSCs, which usually lasts 2 weeks. It’s a dynamic process that produces oscillations from the pathway, which is not active all the time.

“We have seen that there are two phases and that, in each one of them, Wnt fulfils a different function,” Theka said. “And we have shown that, by inhibiting it at the beginning of the process and activating it at the end, we can increase the efficiency of reprogramming and obtain a larger number of pluripotent cells.”

The team also discovered that the exact moment when the Wnt pathway is activated is crucial. Activating the pathway too early makes the cells begin to differentiate, and they are not reprogrammed.

To artificially control the pathway, the researchers used a molecule called Iwp2, a Wnt-secretion inhibitor that does not permanently alter the cells. ![]()

The official dermatologist [YOUR NAME HERE]

Who do you call when your windshield’s busted?

Call Giant Glass!

There isn’t a Boston Red Sox fan on the planet who can’t sing that annoying jingle in his or her sleep. This is because, as they never tire of reminding us, Giant Glass is the Official Windshield Replacer of the Boston Red Sox.

Why does a baseball team need an Official Windshield Replacer? The announcers like to say, "Hey, Joe, that homer went over the Green Monster right onto Yawkey Way – somebody’s gonna have to fix their windshield!"

If that answer satisfies you, you might ponder why EMC is the Official Data Storage company for the team. Or why Benjamin Moore is the Official Paint. Or why Poland Spring is the Official Water.

Or why Beth Israel Deaconess is the Red Sox Official Hospital.

You can see where I’m going with this, can’t you?

In our increasingly complex and competitive environment (EHRs! ACOs!), your columnist is always on the lookout for ways to help you to get a leg up on the competition. (Branding! Online reviews!)

I have therefore embarked on an ambitious effort to become Official Dermatologist to the Official Sponsors of the Boston Red Sox. Follow my example, Colleagues.

*******************

Marriott Hotels

Dear Mr. or Ms. Marriott:

I salute you as Official Hotel of the Red Sox!

But suppose one of your guests uses a hotel Jacuzzi and comes down with nasty Pseudomonas folliculitis. It happens. Who ya gonna call?

Call Rockoff Dermatology! We’ll do the job right, fix up your guests fast, and explain why even state-of-the-art hot tub disinfection sometimes fails. Once the pustules go away, your guests will happily come back to you.

Our rates are reasonable. Give us a call!

*******************

Dunkin’ Donuts

Dear Donuts:

It has come to our notice that you are the Official Coffee of the Boston Red Sox. Good for you!

I should mention that I really like your coffee, especially the Pumpkin Blend you make around Thanksgiving. You might wonder why you need an Official Dermatologist. Well, most of your fine coffee beverages come with milk – and dairy products have been implicated in acne. Of course, the evidence is a little thin, but if one of your customers has a latte and breaks out in major zits, don’t you want to send them to a skin doctor who cares not just about the pimples, but about your corporate image?

That would be me! Let’s get together over a cup of Seattle’s Best. (Just kidding!)

*******************

John Hancock Insurance

Dear Mr. Hancock,

Congratulations on being the Official Insurance of the Boston Red Sox.

I just love your building, a real Boston landmark.

Here’s why you need an Official Dermatologist: You sell insurance – and we dermatologists know insurance. Between updating coverage, scanning insurance cards, and checking online eligibility, our patients spend way more time registering than they do being examined. (Hey, we’re skin doctors – How long do you think that takes?)

While patients are filling out all our forms, we can show them a list of all your fine insurance products. Synergy! Win-win! For faster service, you could even put an agent in our waiting room.

Let’s do lunch. Do you like Dunkin’ Donuts?

*******************

You get the idea. Just pick a popular institution in your area – opera company, sports team, bowling alley – whatever image you have in mind. Then contact them about sponsorship opportunities. Be the first one to do it, and have your agent nail down an exclusive.

Here’s a sample letter:

Toledo Mud Hens

Toledo, Ohio

Dear Mud Hens,

I am writing to suggest you consider having us [INSERT NAME] as Official Dermatology and Aesthetic Rejuvenation Center of the Toledo Mud Hens Baseball Club. We already have a close affiliation with Downtown Latte on South St. Clair Street, and are the exclusive providers of skin care to their clients who get breakouts from dairy products added to their fine coffees.

Let’s all get together and triangulate.

Go Mud Hens!

*******************

OK, colleagues, I’ve given you direction. Now get out there and make it happen!

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass. He is on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. Dr. Rockoff has contributed to the Under My Skin column in Skin & Allergy News since 1997.

Who do you call when your windshield’s busted?

Call Giant Glass!

There isn’t a Boston Red Sox fan on the planet who can’t sing that annoying jingle in his or her sleep. This is because, as they never tire of reminding us, Giant Glass is the Official Windshield Replacer of the Boston Red Sox.

Why does a baseball team need an Official Windshield Replacer? The announcers like to say, "Hey, Joe, that homer went over the Green Monster right onto Yawkey Way – somebody’s gonna have to fix their windshield!"

If that answer satisfies you, you might ponder why EMC is the Official Data Storage company for the team. Or why Benjamin Moore is the Official Paint. Or why Poland Spring is the Official Water.

Or why Beth Israel Deaconess is the Red Sox Official Hospital.

You can see where I’m going with this, can’t you?

In our increasingly complex and competitive environment (EHRs! ACOs!), your columnist is always on the lookout for ways to help you to get a leg up on the competition. (Branding! Online reviews!)

I have therefore embarked on an ambitious effort to become Official Dermatologist to the Official Sponsors of the Boston Red Sox. Follow my example, Colleagues.

*******************

Marriott Hotels

Dear Mr. or Ms. Marriott:

I salute you as Official Hotel of the Red Sox!

But suppose one of your guests uses a hotel Jacuzzi and comes down with nasty Pseudomonas folliculitis. It happens. Who ya gonna call?

Call Rockoff Dermatology! We’ll do the job right, fix up your guests fast, and explain why even state-of-the-art hot tub disinfection sometimes fails. Once the pustules go away, your guests will happily come back to you.

Our rates are reasonable. Give us a call!

*******************

Dunkin’ Donuts

Dear Donuts:

It has come to our notice that you are the Official Coffee of the Boston Red Sox. Good for you!

I should mention that I really like your coffee, especially the Pumpkin Blend you make around Thanksgiving. You might wonder why you need an Official Dermatologist. Well, most of your fine coffee beverages come with milk – and dairy products have been implicated in acne. Of course, the evidence is a little thin, but if one of your customers has a latte and breaks out in major zits, don’t you want to send them to a skin doctor who cares not just about the pimples, but about your corporate image?

That would be me! Let’s get together over a cup of Seattle’s Best. (Just kidding!)

*******************

John Hancock Insurance

Dear Mr. Hancock,

Congratulations on being the Official Insurance of the Boston Red Sox.

I just love your building, a real Boston landmark.

Here’s why you need an Official Dermatologist: You sell insurance – and we dermatologists know insurance. Between updating coverage, scanning insurance cards, and checking online eligibility, our patients spend way more time registering than they do being examined. (Hey, we’re skin doctors – How long do you think that takes?)

While patients are filling out all our forms, we can show them a list of all your fine insurance products. Synergy! Win-win! For faster service, you could even put an agent in our waiting room.

Let’s do lunch. Do you like Dunkin’ Donuts?

*******************

You get the idea. Just pick a popular institution in your area – opera company, sports team, bowling alley – whatever image you have in mind. Then contact them about sponsorship opportunities. Be the first one to do it, and have your agent nail down an exclusive.

Here’s a sample letter:

Toledo Mud Hens

Toledo, Ohio

Dear Mud Hens,

I am writing to suggest you consider having us [INSERT NAME] as Official Dermatology and Aesthetic Rejuvenation Center of the Toledo Mud Hens Baseball Club. We already have a close affiliation with Downtown Latte on South St. Clair Street, and are the exclusive providers of skin care to their clients who get breakouts from dairy products added to their fine coffees.

Let’s all get together and triangulate.

Go Mud Hens!

*******************

OK, colleagues, I’ve given you direction. Now get out there and make it happen!

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass. He is on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. Dr. Rockoff has contributed to the Under My Skin column in Skin & Allergy News since 1997.

Who do you call when your windshield’s busted?

Call Giant Glass!

There isn’t a Boston Red Sox fan on the planet who can’t sing that annoying jingle in his or her sleep. This is because, as they never tire of reminding us, Giant Glass is the Official Windshield Replacer of the Boston Red Sox.

Why does a baseball team need an Official Windshield Replacer? The announcers like to say, "Hey, Joe, that homer went over the Green Monster right onto Yawkey Way – somebody’s gonna have to fix their windshield!"

If that answer satisfies you, you might ponder why EMC is the Official Data Storage company for the team. Or why Benjamin Moore is the Official Paint. Or why Poland Spring is the Official Water.

Or why Beth Israel Deaconess is the Red Sox Official Hospital.

You can see where I’m going with this, can’t you?

In our increasingly complex and competitive environment (EHRs! ACOs!), your columnist is always on the lookout for ways to help you to get a leg up on the competition. (Branding! Online reviews!)

I have therefore embarked on an ambitious effort to become Official Dermatologist to the Official Sponsors of the Boston Red Sox. Follow my example, Colleagues.

*******************

Marriott Hotels

Dear Mr. or Ms. Marriott:

I salute you as Official Hotel of the Red Sox!

But suppose one of your guests uses a hotel Jacuzzi and comes down with nasty Pseudomonas folliculitis. It happens. Who ya gonna call?

Call Rockoff Dermatology! We’ll do the job right, fix up your guests fast, and explain why even state-of-the-art hot tub disinfection sometimes fails. Once the pustules go away, your guests will happily come back to you.

Our rates are reasonable. Give us a call!

*******************

Dunkin’ Donuts

Dear Donuts:

It has come to our notice that you are the Official Coffee of the Boston Red Sox. Good for you!

I should mention that I really like your coffee, especially the Pumpkin Blend you make around Thanksgiving. You might wonder why you need an Official Dermatologist. Well, most of your fine coffee beverages come with milk – and dairy products have been implicated in acne. Of course, the evidence is a little thin, but if one of your customers has a latte and breaks out in major zits, don’t you want to send them to a skin doctor who cares not just about the pimples, but about your corporate image?

That would be me! Let’s get together over a cup of Seattle’s Best. (Just kidding!)

*******************

John Hancock Insurance

Dear Mr. Hancock,

Congratulations on being the Official Insurance of the Boston Red Sox.

I just love your building, a real Boston landmark.

Here’s why you need an Official Dermatologist: You sell insurance – and we dermatologists know insurance. Between updating coverage, scanning insurance cards, and checking online eligibility, our patients spend way more time registering than they do being examined. (Hey, we’re skin doctors – How long do you think that takes?)

While patients are filling out all our forms, we can show them a list of all your fine insurance products. Synergy! Win-win! For faster service, you could even put an agent in our waiting room.

Let’s do lunch. Do you like Dunkin’ Donuts?

*******************

You get the idea. Just pick a popular institution in your area – opera company, sports team, bowling alley – whatever image you have in mind. Then contact them about sponsorship opportunities. Be the first one to do it, and have your agent nail down an exclusive.

Here’s a sample letter:

Toledo Mud Hens

Toledo, Ohio

Dear Mud Hens,

I am writing to suggest you consider having us [INSERT NAME] as Official Dermatology and Aesthetic Rejuvenation Center of the Toledo Mud Hens Baseball Club. We already have a close affiliation with Downtown Latte on South St. Clair Street, and are the exclusive providers of skin care to their clients who get breakouts from dairy products added to their fine coffees.

Let’s all get together and triangulate.

Go Mud Hens!

*******************

OK, colleagues, I’ve given you direction. Now get out there and make it happen!

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass. He is on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. Dr. Rockoff has contributed to the Under My Skin column in Skin & Allergy News since 1997.

Rise in VKDB cases prompts call for a tracking system

Credit: Petr Kratochvil

Physicians at a Tennessee hospital have seen a rise in late-onset vitamin K deficiency bleeding (VKDB) in young infants, due to parents declining a vitamin K shot at birth.

Over a period of 8 months, 7 infants were diagnosed with vitamin K deficiency, and 5 of them had VKDB.

Four of the infants experienced intracranial hemorrhaging, and 2 required urgent neurosurgical intervention.

These cases were diagnosed at Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt in Nashville.

And they were described in Pediatric Neurology.

Now, the authors are calling for a state and national tracking system to help them determine how many infants are not receiving a vitamin K shot at birth.

“There is no national tracking of this in the US, unfortunately, and cases are rarely reported,” said Robert Sidonio Jr, MD, of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

“We are probably just seeing the tip of the iceberg, and I worry that people are missing these cases often and not considering this diagnosis when presented with a sick infant.”

He and his colleagues are also calling for better education on this issue for healthcare providers and families. The group believes misinformation—that the shot causes leukemia, is a toxin, or is unnecessary in uncomplicated births—may be leading some families to decline the shot.

The American Academy of Pediatrics has recommended the single-dose shot of vitamin K at birth since 1961. Most cases of VKDB seen today occur in infants in the first 6 months of life who did not get the shot and are exclusively breastfed or who have an undiagnosed liver disorder.

Following a recent rise in cases in Tennessee, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention discovered that 28% (61/218) of parents of children born at private birthing centers in the state declined the shot.

Mark and Melissa Knotowicz declined the shot for their twins, Silas and Abel, following their birth last July at a Nashville hospital.

“From the information we had, we heard the main side effect was a preservative in the shot that could lead to childhood leukemia,” said Mark Knotowicz. “We thought, ‘We don’t want our kids to have childhood leukemia,’ so we declined it without really hearing any of the benefits.”

At about 6 weeks old, Silas was noticeably fussy. He vomited overnight, woke up extremely pale, and wouldn’t nurse.

The twins had a checkup scheduled that day. The pediatrician suspected sepsis and told the Knotowiczes to take Silas to the Emergency Department at Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital.

Because of a rash of VKBD cases, the staff there had received additional education. After Silas’s parents confirmed that he had not received the vitamin K shot, CT scans and blood work revealed he had suffered multiple brain bleeds.

Silas received a double dose of vitamin K to get the bleeding under control. His twin, Abel, was diagnosed with asymptomatic vitamin K deficiency and received the shot.

Silas spent a week in the hospital. Today, he undergoes physical therapy for neuromuscular development issues. Any effects on cognitive development aren’t yet known.

“The twins’ cases highlight our inability to determine which infants will go on to develop vitamin K deficiency bleeding, as they both had prolonged bleeding times at presentation,” Dr Sidonio said.

Mark Knotowicz wishes medical staff at the birthing hospital had more clearly defined the risks of declining the shot.

“Why didn’t they say, ‘There have been 4 other cases in Nashville, and we’re trying to prevent a lethal brain hemorrhage in your child?’”

Anna Morad, MD, of the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, has worked to raise awareness about the vitamin K shot and the risk of VKDB, with some success.

“After our educational outreach, we have seen a decrease in our refusal rates [with about 3.4% of parents declining vitamin K],” she said. “Our goal is to fully educate parents on the risk of declining so they can make an informed choice for their baby.” ![]()

Credit: Petr Kratochvil

Physicians at a Tennessee hospital have seen a rise in late-onset vitamin K deficiency bleeding (VKDB) in young infants, due to parents declining a vitamin K shot at birth.

Over a period of 8 months, 7 infants were diagnosed with vitamin K deficiency, and 5 of them had VKDB.

Four of the infants experienced intracranial hemorrhaging, and 2 required urgent neurosurgical intervention.

These cases were diagnosed at Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt in Nashville.

And they were described in Pediatric Neurology.

Now, the authors are calling for a state and national tracking system to help them determine how many infants are not receiving a vitamin K shot at birth.

“There is no national tracking of this in the US, unfortunately, and cases are rarely reported,” said Robert Sidonio Jr, MD, of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.