User login

Predicting Recurrence Risk

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) is a serious and costly condition whose volume in US hospitals has doubled over the last decade.[1, 2, 3] Along with this rise in incidence, its severity has also increased. Although in the United States there has been a doubling in age‐adjusted case fatality, in the same time period Canadian studies reported a high and increasing CDI‐associated case fatality in the setting of an outbreak of a novel epidemic hypervirulent strain BI/NAP1/027.[2, 4, 5, 6] The costs of CDI range widely ($2500 to $13,000 per hospitalization), with cumulative annual cost to the US healthcare system estimated at nearly $5 billion.[7, 8, 9]

One of the drivers of these clinical and economic outcomes is CDI recurrence (rCDI). In 2 recent randomized controlled trials, up to 25% of patients with an initial CDI (iCDI) episode developed rCDI.[10, 11] There are few data that quantify the impact of rCDI on quality of life and survival. However, patients often are readmitted to the hospital with rCDI, and physicians who treat patients with multiple episodes of rCDI can attest to the devastating toll it takes on the lives of the patients and their families (personal communications from numerous patients to E.R.D.).[12] Reducing the incidence of rCDI may significantly improve the course of this disease.

The advent of such new treatments as fidaxomicin aimed at rCDI is promising.[10, 11] However, evidence for its efficacy so far is limited to treatment‐naive iCDI patients, thus challenging clinicians to identify patients at high risk for rCDI at iCDI onset. To address this challenge, we set out to develop a bedside prediction model for rCDI based on the factors present and routinely available at the onset of iCDI.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Source

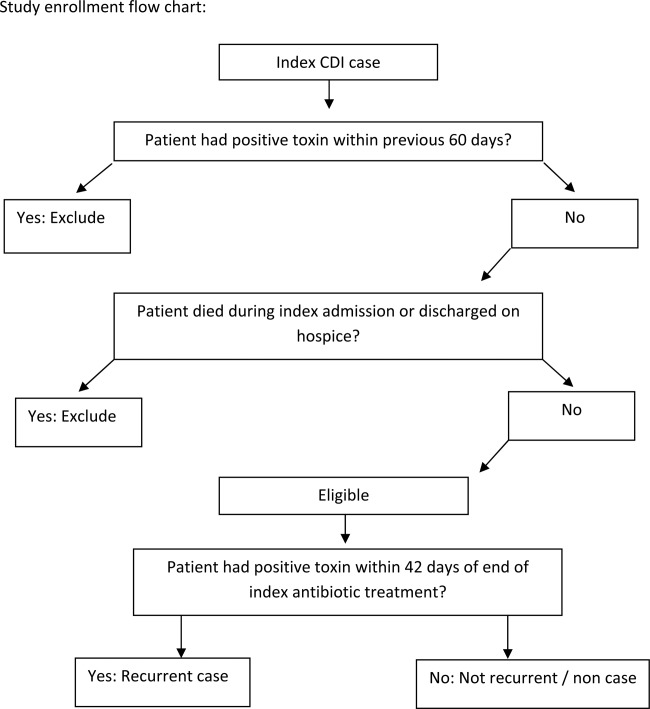

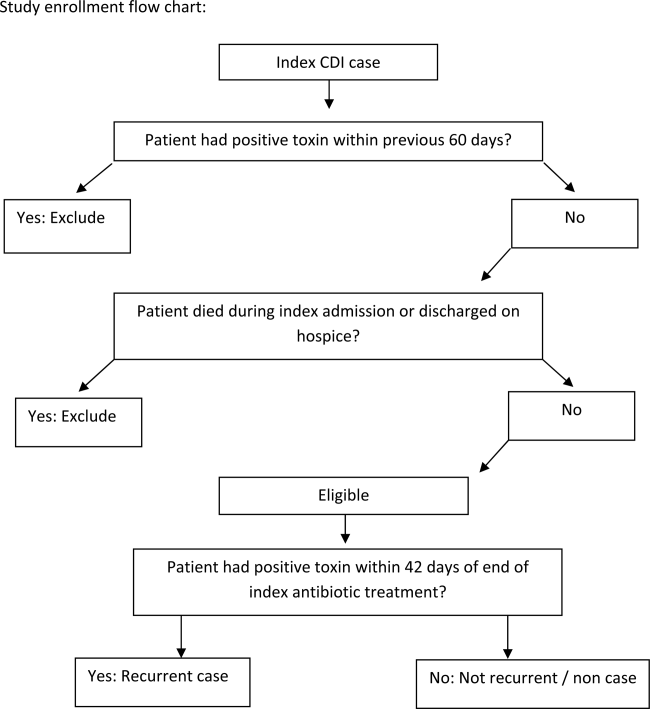

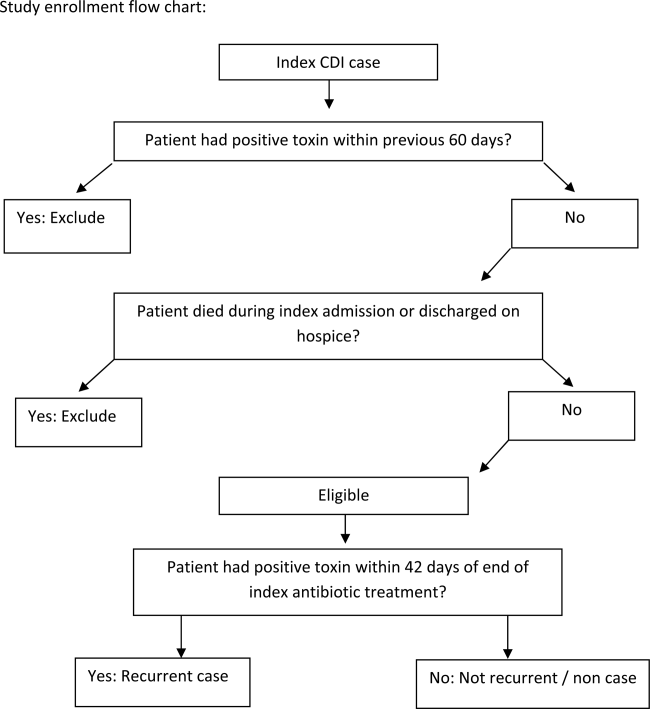

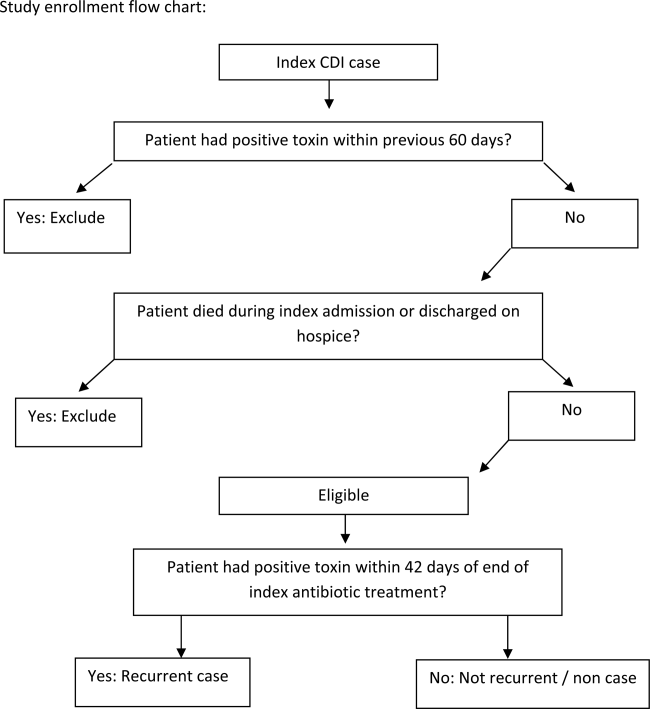

We conducted a retrospective single‐center cohort study to examine the factors present at the onset of iCDI that impact the incidence of rCDI among hospitalized patients. Patients were included in the study if they were adults (18 years) hospitalized at Barnes‐Jewish Hospital (BJH), St. Louis, Missouri, between January 1, 2003 and December 31, 2009, and who had a positive toxin assay for C difficile in the setting of unformed stools and no history of CDI in the previous 60 days (as defined by positive toxin assay). Patients were excluded if they either died during or were discharged to hospice from the iCDI hospitalization. Cases of iCDI were categorized according to published surveillance definitions as community onset‐healthcare facility associated (CO‐HCFA), healthcare facility onset, and community associated.[13] Notably, the CO‐HCFA category included surveillance definitions for both CO‐HCFA and indeterminate cases. We defined rCDI as a repeat positive toxin within 42 days following the end of iCDI treatment. This period of risk for rCDI was chosen because the current surveillance definition for rCDI is a new episode of CDI occurring within 8 weeks from the last episode of CDI, with the assumption the patient would receive 10 to 14 days of CDI treatment at the beginning of the 8‐week period.[14] Medical charts were reviewed for all readmissions during the recurrence risk period to identify patients diagnosed with rCDI by methods other than toxin assay. A study enrollment flow chart is shown in Figure 1.

Demographic and clinical data were derived from the BJH medical informatics databases and the BJH electronic medical records (see Supporting Appendix Table 1 in the online version of this article). Comorbidities were grouped using the Charlson‐Deyo categories.[15] All variables were limited to data that are consistent throughout a hospitalization (eg, race or age) or were present within 48 hours of iCDI (eg, medications).

Model Development and Validation

First, we examined risk factors for rCDI present at the time of the iCDI diagnosis and initiation of iCDI therapy. We used principal‐component analyses, corresponding analyses, and cluster analyses to reduce the data dimensions by combining variables reflecting the same underlying construct.[16] Several antibiotic categories were created. The high‐risk category included cephalosporins, clindamycin, and aminopenicillins.[17] Other categories examined separately were fluoroquinolones, intravenous vancomycin, and antibiotics considered low risk (all other drugs not encompassed in the prior categories). Proton pump inhibitor and histamine 2 receptor‐blockers were combined into a single variable of gastric acid suppressors.

We developed a logistic regression model to identify a set of variables that best predicted the risk of rCDI. Variables with P 0.20 on univariate analyses were included in multivariable models. Backward elimination was used to determine the final model (P 0.1 for removal). The model's discrimination was examined via the C statistic and calibration through Brier score.[16] A C statistic value of 0.5 implies that the model is no better than chance, whereas the value of 1.0 means that the model is perfect in differentiating cases from noncases. A Brier score closer to zero indicates better model calibration, or how closely the predicted probabilities for rCDI match the actual observed probabilities. We validated the model using the bootstrap method with 500 iterations. To explore its properties as a decision tool to help make the decision to initiate an intervention to prevent rCDI, we tested the model's sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values at various thresholds of prior probability of rCDI.

RESULTS

Among the 4196 patients with iCDI enrolled in the study, 425 (10.1%) developed at least 1 recurrence within 42 days of the end of iCDI treatment (Table 1). Compared to patients without a recurrence, in univariate analysis those with an rCDI episode were older and had a greater comorbidity burden. In particular, diabetes mellitus (odds ratio 1.34; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.08‐1.66) and cerebrovascular disease (odds ratio 1.47; 95% CI, 1.04‐2.08) were significantly more prevalent in the rCDI group. The index CDI episode for patients with rCDI was approximately twice as likely to fit the surveillance definition for CO‐HCFA than the index episode for those without a recurrence (odds ratio 2.24; 95% CI, 1.80‐2.79). Commensurately, patients with rCDI also had greater odds for experiencing multiple recent hospitalizations than those without rCDI. Neither type of CDI treatment (oral metronidazole vs oral vancomycin vs both), nor duration, was significantly associated with recurrence.

| Patient Characteristics | Patients Who Developed rCDI, N = 425 | Patients Who Did Not Develop rCDI, n = 3771) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, y, median (range)a | 64.8(18.398.2) | 61.6(18.0102.4) | 1.10 (1.041.16) | <0.001 |

| Female | 210 (49) | 1822 (48) | 1.05 (0.861.28) | 0.67 |

| Nonwhite race | 149 (35) | 1149 (31) | 1.23 (1.001.52) | 0.05 |

| Comorbiditiesb | ||||

| Myocardial infarction | 40 (9) | 328 (9) | 1.10 (0.771.54) | 0.62 |

| Congestive heart failure | 108 (25) | 854 (23) | 1.17 (0.931.47) | 0.19 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 34 (8) | 269 (7) | 1.13 (0.781.64) | 0.51 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 41 (10) | 256 (7) | 1.47 (1.042.08) | 0.03 |

| Chronic renal failure | 21 (5) | 190 (5) | 0.98 (0.621.56) | 0.94 |

| Dementia | 5 (1) | 23 (1) | 1.94 (0.735.14) | 0.18 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 116 (27) | 911 (24) | 1.18 (0.941.48) | 0.15 |

| Rheumatologic disease | 18 (4) | 146 (4) | 1.10 (0.671.81) | 0.71 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 20 (5) | 154 (4) | 1.16 (0.721.87) | 0.54 |

| Mild liver disease | 17 (4) | 201 (5) | 0.74 (0.451.23) | 0.25 |

| Moderate‐to‐severe liver disease | 12 (3) | 134 (4) | 0.79 (0.431.44) | 0.44 |

| Diabetes, any | 135 (32) | 974 (26) | 1.34 (1.081.66) | 0.009 |

| Paraplegia or hemiplegia | 12 (3) | 77 (2) | 1.38 (0.742.55) | 0.31 |

| Any malignancy (excluding leukemia/lymphoma) | 83 (20) | 770 (20) | 0.95 (0.741.22) | 0.67 |

| Leukemia or lymphoma | 78 (18) | 660 (18) | 1.06 (0.821.38) | 0.66 |

| Metastatic solid tumor | 56 (13) | 449 (12) | 1.12 (0.841.51) | 0.44 |

| HIV/AIDS | 10 (2) | 66 (2) | 1.36 (0.692.67) | 0.38 |

| Charlson composite score | ||||

| 02 | 223 (53) | 2179 (58) | Ref | |

| 35 | 117 (28) | 921 (24) | 1.24 (0.981.57) | 0.07 |

| 6 | 85(20) | 671 (18) | 1.24 (0.951.61) | 0.11 |

| Case statusc | ||||

| HCFO/HCFA | 203 (48) | 2331 (62) | Ref | |

| CA or unknown | 57 (13) | 595 (16) | 1.10 (0.811.50) | 0.54 |

| CO/HCFA, indeterminate, or non‐ BJHHCFA | 165 (39) | 845 (22) | 2.24 (1.802.79) | <0.001 |

| Prior hospitalizations | ||||

| Admitted from another healthcare facility | 109 (26) | 1018 (27) | 0.93 (0.741.17) | 0.55 |

| No. of inpatient admissions in previous 60 days | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 200 (47) | 2310 (61) | Ref | |

| 1 | 150 (35) | 1020 (27) | 1.70 (1.362.13) | <0.001 |

| 2+ | 75 (18) | 441 (12) | 1.96 (1.482.61) | <0.001 |

| Baseline laboratory datad | ||||

| Low albumin at iCDI | 50 (12) | 548 (15) | 0.78 (0.581.07) | 0.312 |

| Low WBC at iCDI | 64 (15) | 635 (17) | 0.88 (0.661.16) | 0.36 |

| High WBC at iCDI | 247 (58) | 2027 (54) | 1.20 (0.981.46) | 0.08 |

| Low hemoglobin at iCDI | 218 (51) | 1985 (53) | 0.95 (0.781.16) | 0.61 |

| High creatinine at iCDI | 99 (23) | 862 (23) | 1.02 (0.811.30) | 0.83 |

| Low creatinine clearance at iCDI | 218 (51) | 1635 (43) | 1.38 (1.131.68) | 0.002 |

| ICU admission at iCDI | 32 (8) | 562 (15) | 0.47 (0.320.68) | <0.001 |

| Medications | ||||

| New gastric acid suppressor at iCDI | 54 (13) | 255 (7) | 2.01 (1.472.74) | <0.001 |

| Any antibiotic at iCDI | 314 (74) | 2727 (72) | 1.08 (0.861.36) | 0.49 |

| High‐risk antibiotics at iCDIe | 174 (41) | 1489 (40) | 1.06 (0.871.30) | 0.56 |

| Fluoroquinolone at iCDI | 120 (28) | 860 (23) | 1.33 (1.061.67) | 0.01 |

| Low‐risk antibiotics at iCDI | 95 (22) | 1058 (28) | 0.74 (0.580.94) | 0.01 |

| IV vancomycin at iCDI | 130 (31) | 1321 (35) | 0.82 (0.671.02) | 0.07 |

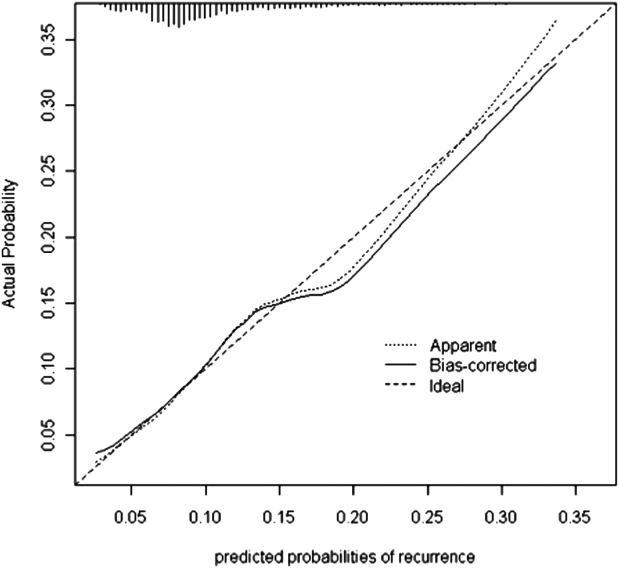

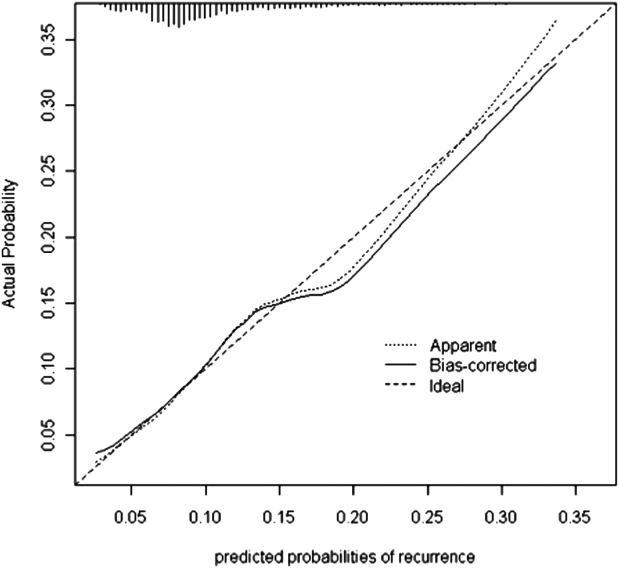

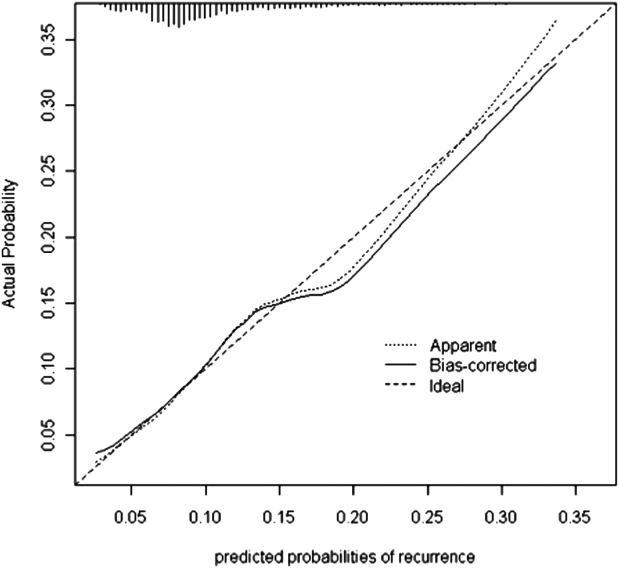

Seven factors present at the onset of iCDI were found to predict a recurrence in multivariable analysis (Table 2). Older age, CO‐HCFA status of iCDI, and 2 or more hospitalizations in the prior 60 days increased the risk of rCDI. Concomitant exposures to gastric acid suppressors, fluoroquinolone antibiotics, and high‐risk antibiotics were also significantly associated with a recurrence. Being in the intensive care unit (ICU) at the onset of iCDI was protective against rCDI in the multivariable model. This model had a C statistic of 0.642 and a Brier score of 0.089. After cross‐validation with 500 bootstrapping iterations, the model exhibited a moderately good fit (Figure 2). The prediction was particularly accurate in the lower risk ranges, with slight divergence in the risk strata over 20%. The validated model had a C statistic of 0.630 and Brier score of 0.089.

| Prediction Factors | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Agea | 1.08 | 1.021.14 |

| CO‐HCFA CDI (ref: HO‐CDI) | 1.71 | 1.322.22 |

| 2+ hospitalizations in prior 60 days (ref: 0 hospitalizations) | 1.49 | 1.082.06 |

| New gastric acid suppression at the onset of iCDI | 1.59 | 1.132.23 |

| High‐risk antibiotic at the onset of iCDIbb | 1.25 | 1.011.55 |

| Fluoroquinolone at the onset of iCDI | 1.31 | 1.041.65 |

| ICU at the onset of iCDI | 0.49 | 0.340.72 |

The sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of the model at various probability thresholds of rCDI are presented in Table 3. Thus, when the probability of rCDI was low, the model exhibited high sensitivity and low specificity. The situation was reversed as the probability of rCDI approached 30% (very low sensitivity and high specificity). The model's performance was optimal when the rCDI risk matched that in the current cohort, or 10.1%, with a sensitivity of 56% and specificity of 65%. However, when the rCDI risk dropped to 5%, the specificity dropped to below 30%. The sensitivity dropped to below 30% when rCDI risk rose to 15% (Table 3). Across the entire range of the probabilities tested, the negative predictive value of the model was persistently 90% or higher.

| Model Predicted Probability Cutpoint | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Positive Likelihood Ratio | Negative Likelihood Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| 0.025 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 1.00 | 1.0 | Undef |

| 0.050 | 0.96 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.95 | 1.05 | 0.44 |

| 0.101a | 0.56 | 0.65 | 0.15 | 0.93 | 1.60 | 0.68 |

| 0.151 | 0.27 | 0.86 | 0.18 | 0.91 | 1.93 | 0.85 |

| 0.303 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.40 | 0.90 | Undef | 0.99 |

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that in a cohort of hospitalized patients with iCDI, 10% developed at least 1 episode of rCDI within 42 days of the end of iCDI treatment. The factors present at iCDI onset that predicted recurrence were age, CO‐HCFA CDI, prior hospitalization, high‐risk antibiotic and fluoroquinolone use, and gastric acid suppression. Although the model's performance was only moderate, its negative predictive value was 90% or higher across the entire range of rCDI probabilities tested. This means that the absence of this combination of risk factors in a patient with iCDI diminishes the probability of a rCDI episode to 10% or below, depending on the prior population risk for rCDI.

Prior investigators have developed prediction rules for rCDI. Hebert et al., using methodology similar to ours, constructed a model to predict the risk of rCDI among patients hospitalized with iCDI.[17] For example, the recurrence rate in their study was 23% compared to our 10%. This is likely due to the differing definitions of both iCDI and rCDI between the 2 studies. Although our definitions of hospital‐associated C difficile‐associated diarrhea (CDAD) conformed to the recommended surveillance definitions,[13] Hebert and colleagues used different definitions.[18] If this is so, the higher rate of rCDI in their study may have reflected these differences in surveillance definition, rather than the true prevalence of recurrent CDAD.

Several other studies have relied on either specialized laboratory tests alone or in combination with clinical factors. Stewart et al., in a small single‐center cohort study, reported the presence of the binary toxin to be the only independent predictor of rCDI.[19] Others have found lower antitoxin immunoglobulin levels at various times following the onset of iCDI to be predictive of a recurrence.[20, 21] A disadvantage of using these specialized tests as tools for clinical prediction is that they are not widely available in clinical practice. Even if these tests are available, their results are likely to return only after iCDI treatment has commenced. To make risk stratification more generalizable, we specifically focused on common data available in all clinical settings at the onset of iCDI.

We chose to restrict our risk stratification to factors present at the onset of iCDI for several reasons. First, earlier identification of patients at increased risk for rCDI may encourage clinicians to minimize subsequent exposures to non‐CDI antimicrobials and gastric acid suppressors. Second, newer anticlostridial therapies in development appear to target specifically CDI recurrence. The first anti‐CDI drug to be approved in 2 decades, fidaxomicin, has been shown to reduce the risk of a recurrence by nearly one‐half compared to vancomycin.[10, 11] Although in practice it is tempting to reserve this treatment for those patients who have multiple recurrences, there is no convincing evidence to date that the drug is similarly effective at reducing further recurrences in this population.[22, 23] Currently, the only population in which fidaxomicin treatment has been shown to reduce the risk of rCDI contains patients with at most 1 prior episode, whose first anti‐CDI exposure was to fidaxomicin.[10, 11] Thus, the intent of our model was to insure appropriate use of these new technologies from the perspective of both under‐ and overtreatment.

In general, most of the factors included in our model are neither novel nor surprising, including concurrent antibiotics and gastric acid suppression.[24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30] What is interesting about these exposures, however, is the fact that we measured them only at the onset of the iCDI episode. This implies that it is not merely the continuation of these medications after onset, but even exposure to them prior to the initial bout of CDI, that may promote a recurrence. This finding should give pause to the widespread practice of routinely prescribing gastric acid suppression to many hospitalized patients. It should also prompt a reexamination of antimicrobial choices for patients admitted for the treatment of infectious diseases in favor of those deemed at low risk for CDI whenever possible.

A relatively novel risk factor emerging from our model is the designation of the iCDI episode as CO‐HCFA.[30] A likely explanation for this relationship is that CO‐HCFA identifies a population of patients who are more ill, as evidenced by their prior hospitalization history. However, because recent hospitalizations themselves emerged as an independent predictor of rCDI in our model, CO‐HCFA designation clearly incorporates other factors important to this outcome.

Our data on illness severity are divergent from prior results. Previous work has found that increasing severity of illness is positively associated with the risk of a recurrence.[21, 31] In contrast, we found that the need for the ICU at the onset of iCDI appeared protective from rCDI. There are several explanations for this finding, the most likely being the competing mortality risk. Although we excluded from the study those patients who did not survive their iCDI hospitalizations, patients who received care in an ICU were more likely to die in the rCDI risk period than patients who did not receive care in an ICU (data not shown). Another potential explanation for this observation is that patients who develop iCDI while in the ICU may generally get more aggressive care than those contracting it on other wards, resulting in a lower risk for recurrence.

The recurrence rate in the current study is at the lower limit of what has been reported previously either in the meta‐analysis by Garey (13%50%) or in recent randomized controlled trials (25%).[10, 11, 25] This is likely due to our case identification pathway, and ascertainment bias is a potential limitation of our study. Patients with mild recurrent CDI diagnosed and treated as outpatients were not captured in our study unless their toxin assay was performed by the BJH laboratory (approximately 15% of specimens submitted to the BJH microbiology laboratory come from outpatients or affiliated outpatient or skilled nursing facilities). Similarly, recurrences diagnosed at other inpatient facilities were not captured in our study unless they were transferred to BJH for care. On the other hand, rCDI in randomized trials may be subject to a detection bias, because enrolled patients are prospectively monitored for and instructed to seek testing for recurrent diarrhea.

Our study also has limitations inherent to observational data such as confounding. We adjusted for all the available relevant potential confounders in the regression model. However, the possibility of residual confounding remains. Because our cohort was too small for a split‐cohort model validation, we employed a bootstrap method to cross‐validate our results. However, the model requires further validation in a prospective cohort in the future. The biggest limitation of our model, however, is its generalizability, because the data reflect patients and treatment patterns at an urban academic medical center, and may not mirror those of institutions with different characteristics or patients with iCDI diagnosed and managed completely in the outpatient setting.

In summary, we have developed a model to predict iCDI patients' risk of recurrence. The advantage of our model is the availability of all the factors at the onset of iCDI, when treatment decisions need to be made. Although far from perfect in its ability to discriminate those who will from those who will not develop a recurrence, it should serve as a beginning step in the direction of appropriately aggressive care that may result not only in diminishing the pool of this infection, but also in containing its spiraling costs. The cost‐benefit balance of these decisions needs to be examined explicitly, not only in terms of the financial cost of over‐ or undertreatment, but with respect to the implications of such overtreatment on development of resistance to newer anticlostridial agents.

Disclosures

This study was funded by Cubist Pharmaceuticals, Jersey City, New Jersey. The data in the article were presented in part as a poster presentation at IDWeek 2012, San Diego, California, October 1721, 2012. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , . Clostridium difficile infection in patients discharged from US short‐stay hospitals, 1996–2003. Emerge Infect Dis. 2006;12:409–415.

- , , . Increase in adult Clostridium difficile‐related hospitalizations and case‐fatality rate, United States, 2000–2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:929–931.

- , , . Clostridium difficile infections (CDI) in hospital stays, 2009. HCUP statistical brief #124. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012. Available at: http://www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb124.pdf. Accessed July 19, 2013.

- , , , et al. A predominantly clonal multi‐institutional outbreak of Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhea with high morbidity and mortality. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2442–2449.

- , , , et al. Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhea in a region of Quebec from 1991 to 2003: a changing pattern of disease severity. CMAJ. 2004;171:466–472.

- , , , et al. An epidemic, toxin gene‐variant strain of Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(23):2433–2441.

- , , , , . Short‐ and long‐term attributable costs of Clostridium difficile‐associated disease in nonsurgical inpatients. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(4):497–504.

- , , , . The emerging infectious challenge of Clostridium difficile‐associated disease in Massachusetts hospitals: clinical and economic consequences. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:1219–1227.

- , . Burden of Clostridium difficile on the healthcare system. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(suppl 2):S88–S92.

- , , , et al. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for infection with Clostridium difficile in Europe, Canada, and the USA: a double‐blind, non‐inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(4):281–289.

- , , , et al. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:422–431.

- , , , , , . Recurrent Clostridium difficile disease: epidemiology and clinical characteristics. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20:43–50.

- , , , et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:431–455.

- , , , , , ; Ad Hoc Clostridium difficile Surveillance Working Group. Recommendations for surveillance of Clostridium difficile‐associated disease. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:140–145.

- , , . Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD‐9‐CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619.

- , , , . Measures for evaluating model performance. Proceedings of the Biometrics Section. Alexandria, VA: American Statistical Association, Biometrics Section; 1997:253–258.

- , , , et al. Development and validation of a Clostridium difficile infection risk prediction model. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32:360–366.

- , , , . Electronic health record‐based detection of risk factors for Clostridium difficile infection relapse. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34:407–414.

- , , . Predicting recurrence of C. difficile colitis using bacterial virulence factors: binary toxin is the key. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:118–125.

- , , , . Association between antibody response to toxin A and protection against recurrent Clostridium difficile diarrhoea. Lancet. 2001;357:189–193.

- , , , et al. Prospective derivation and validation of a clinical prediction rule for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1206–1214.

- . Fidaxomicin failures in recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a problem of timing. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:613–614.

- , . Fidaxomicin “chaser” regimen following vancomycin for patients with multiple Clostridium difficile recurrences. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:309–310.

- , , , et al. Predictors of first recurrence of Clostridium difficile infection: implications for initial management. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(suppl 2):S77–S87.

- , , , . Meta‐analysis to assess risk factors for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. J Hosp Infect. 2008;70:298–304.

- , , , , , . Recurrent Clostridium difficile diarrhea: characteristics of and risk factors for patients enrolled in a prospective, randomized, double‐blinded trial. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:324–333.

- , , , , . Association of proton‐pump inhibitors with outcomes in Clostridium difficile colitis. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64:2359–2363.

- , , , et al. Proton pump inhibitors as a risk factor for recurrence of Clostridium‐difficile‐associated diarrhea. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3573–3577.

- , , . Proton pump inhibitor use and recurrent Clostridium difficile‐associated disease: a case‐control analysis matched by propensity score. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:397–400.

- , , , , , . Risk of Clostridium difficile infection with acid suppressing drugs and antibiotics: meta‐analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(7):1011–1019.

- , , , et al. Risk factors for early recurrent Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:954–959.

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) is a serious and costly condition whose volume in US hospitals has doubled over the last decade.[1, 2, 3] Along with this rise in incidence, its severity has also increased. Although in the United States there has been a doubling in age‐adjusted case fatality, in the same time period Canadian studies reported a high and increasing CDI‐associated case fatality in the setting of an outbreak of a novel epidemic hypervirulent strain BI/NAP1/027.[2, 4, 5, 6] The costs of CDI range widely ($2500 to $13,000 per hospitalization), with cumulative annual cost to the US healthcare system estimated at nearly $5 billion.[7, 8, 9]

One of the drivers of these clinical and economic outcomes is CDI recurrence (rCDI). In 2 recent randomized controlled trials, up to 25% of patients with an initial CDI (iCDI) episode developed rCDI.[10, 11] There are few data that quantify the impact of rCDI on quality of life and survival. However, patients often are readmitted to the hospital with rCDI, and physicians who treat patients with multiple episodes of rCDI can attest to the devastating toll it takes on the lives of the patients and their families (personal communications from numerous patients to E.R.D.).[12] Reducing the incidence of rCDI may significantly improve the course of this disease.

The advent of such new treatments as fidaxomicin aimed at rCDI is promising.[10, 11] However, evidence for its efficacy so far is limited to treatment‐naive iCDI patients, thus challenging clinicians to identify patients at high risk for rCDI at iCDI onset. To address this challenge, we set out to develop a bedside prediction model for rCDI based on the factors present and routinely available at the onset of iCDI.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Source

We conducted a retrospective single‐center cohort study to examine the factors present at the onset of iCDI that impact the incidence of rCDI among hospitalized patients. Patients were included in the study if they were adults (18 years) hospitalized at Barnes‐Jewish Hospital (BJH), St. Louis, Missouri, between January 1, 2003 and December 31, 2009, and who had a positive toxin assay for C difficile in the setting of unformed stools and no history of CDI in the previous 60 days (as defined by positive toxin assay). Patients were excluded if they either died during or were discharged to hospice from the iCDI hospitalization. Cases of iCDI were categorized according to published surveillance definitions as community onset‐healthcare facility associated (CO‐HCFA), healthcare facility onset, and community associated.[13] Notably, the CO‐HCFA category included surveillance definitions for both CO‐HCFA and indeterminate cases. We defined rCDI as a repeat positive toxin within 42 days following the end of iCDI treatment. This period of risk for rCDI was chosen because the current surveillance definition for rCDI is a new episode of CDI occurring within 8 weeks from the last episode of CDI, with the assumption the patient would receive 10 to 14 days of CDI treatment at the beginning of the 8‐week period.[14] Medical charts were reviewed for all readmissions during the recurrence risk period to identify patients diagnosed with rCDI by methods other than toxin assay. A study enrollment flow chart is shown in Figure 1.

Demographic and clinical data were derived from the BJH medical informatics databases and the BJH electronic medical records (see Supporting Appendix Table 1 in the online version of this article). Comorbidities were grouped using the Charlson‐Deyo categories.[15] All variables were limited to data that are consistent throughout a hospitalization (eg, race or age) or were present within 48 hours of iCDI (eg, medications).

Model Development and Validation

First, we examined risk factors for rCDI present at the time of the iCDI diagnosis and initiation of iCDI therapy. We used principal‐component analyses, corresponding analyses, and cluster analyses to reduce the data dimensions by combining variables reflecting the same underlying construct.[16] Several antibiotic categories were created. The high‐risk category included cephalosporins, clindamycin, and aminopenicillins.[17] Other categories examined separately were fluoroquinolones, intravenous vancomycin, and antibiotics considered low risk (all other drugs not encompassed in the prior categories). Proton pump inhibitor and histamine 2 receptor‐blockers were combined into a single variable of gastric acid suppressors.

We developed a logistic regression model to identify a set of variables that best predicted the risk of rCDI. Variables with P 0.20 on univariate analyses were included in multivariable models. Backward elimination was used to determine the final model (P 0.1 for removal). The model's discrimination was examined via the C statistic and calibration through Brier score.[16] A C statistic value of 0.5 implies that the model is no better than chance, whereas the value of 1.0 means that the model is perfect in differentiating cases from noncases. A Brier score closer to zero indicates better model calibration, or how closely the predicted probabilities for rCDI match the actual observed probabilities. We validated the model using the bootstrap method with 500 iterations. To explore its properties as a decision tool to help make the decision to initiate an intervention to prevent rCDI, we tested the model's sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values at various thresholds of prior probability of rCDI.

RESULTS

Among the 4196 patients with iCDI enrolled in the study, 425 (10.1%) developed at least 1 recurrence within 42 days of the end of iCDI treatment (Table 1). Compared to patients without a recurrence, in univariate analysis those with an rCDI episode were older and had a greater comorbidity burden. In particular, diabetes mellitus (odds ratio 1.34; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.08‐1.66) and cerebrovascular disease (odds ratio 1.47; 95% CI, 1.04‐2.08) were significantly more prevalent in the rCDI group. The index CDI episode for patients with rCDI was approximately twice as likely to fit the surveillance definition for CO‐HCFA than the index episode for those without a recurrence (odds ratio 2.24; 95% CI, 1.80‐2.79). Commensurately, patients with rCDI also had greater odds for experiencing multiple recent hospitalizations than those without rCDI. Neither type of CDI treatment (oral metronidazole vs oral vancomycin vs both), nor duration, was significantly associated with recurrence.

| Patient Characteristics | Patients Who Developed rCDI, N = 425 | Patients Who Did Not Develop rCDI, n = 3771) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, y, median (range)a | 64.8(18.398.2) | 61.6(18.0102.4) | 1.10 (1.041.16) | <0.001 |

| Female | 210 (49) | 1822 (48) | 1.05 (0.861.28) | 0.67 |

| Nonwhite race | 149 (35) | 1149 (31) | 1.23 (1.001.52) | 0.05 |

| Comorbiditiesb | ||||

| Myocardial infarction | 40 (9) | 328 (9) | 1.10 (0.771.54) | 0.62 |

| Congestive heart failure | 108 (25) | 854 (23) | 1.17 (0.931.47) | 0.19 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 34 (8) | 269 (7) | 1.13 (0.781.64) | 0.51 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 41 (10) | 256 (7) | 1.47 (1.042.08) | 0.03 |

| Chronic renal failure | 21 (5) | 190 (5) | 0.98 (0.621.56) | 0.94 |

| Dementia | 5 (1) | 23 (1) | 1.94 (0.735.14) | 0.18 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 116 (27) | 911 (24) | 1.18 (0.941.48) | 0.15 |

| Rheumatologic disease | 18 (4) | 146 (4) | 1.10 (0.671.81) | 0.71 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 20 (5) | 154 (4) | 1.16 (0.721.87) | 0.54 |

| Mild liver disease | 17 (4) | 201 (5) | 0.74 (0.451.23) | 0.25 |

| Moderate‐to‐severe liver disease | 12 (3) | 134 (4) | 0.79 (0.431.44) | 0.44 |

| Diabetes, any | 135 (32) | 974 (26) | 1.34 (1.081.66) | 0.009 |

| Paraplegia or hemiplegia | 12 (3) | 77 (2) | 1.38 (0.742.55) | 0.31 |

| Any malignancy (excluding leukemia/lymphoma) | 83 (20) | 770 (20) | 0.95 (0.741.22) | 0.67 |

| Leukemia or lymphoma | 78 (18) | 660 (18) | 1.06 (0.821.38) | 0.66 |

| Metastatic solid tumor | 56 (13) | 449 (12) | 1.12 (0.841.51) | 0.44 |

| HIV/AIDS | 10 (2) | 66 (2) | 1.36 (0.692.67) | 0.38 |

| Charlson composite score | ||||

| 02 | 223 (53) | 2179 (58) | Ref | |

| 35 | 117 (28) | 921 (24) | 1.24 (0.981.57) | 0.07 |

| 6 | 85(20) | 671 (18) | 1.24 (0.951.61) | 0.11 |

| Case statusc | ||||

| HCFO/HCFA | 203 (48) | 2331 (62) | Ref | |

| CA or unknown | 57 (13) | 595 (16) | 1.10 (0.811.50) | 0.54 |

| CO/HCFA, indeterminate, or non‐ BJHHCFA | 165 (39) | 845 (22) | 2.24 (1.802.79) | <0.001 |

| Prior hospitalizations | ||||

| Admitted from another healthcare facility | 109 (26) | 1018 (27) | 0.93 (0.741.17) | 0.55 |

| No. of inpatient admissions in previous 60 days | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 200 (47) | 2310 (61) | Ref | |

| 1 | 150 (35) | 1020 (27) | 1.70 (1.362.13) | <0.001 |

| 2+ | 75 (18) | 441 (12) | 1.96 (1.482.61) | <0.001 |

| Baseline laboratory datad | ||||

| Low albumin at iCDI | 50 (12) | 548 (15) | 0.78 (0.581.07) | 0.312 |

| Low WBC at iCDI | 64 (15) | 635 (17) | 0.88 (0.661.16) | 0.36 |

| High WBC at iCDI | 247 (58) | 2027 (54) | 1.20 (0.981.46) | 0.08 |

| Low hemoglobin at iCDI | 218 (51) | 1985 (53) | 0.95 (0.781.16) | 0.61 |

| High creatinine at iCDI | 99 (23) | 862 (23) | 1.02 (0.811.30) | 0.83 |

| Low creatinine clearance at iCDI | 218 (51) | 1635 (43) | 1.38 (1.131.68) | 0.002 |

| ICU admission at iCDI | 32 (8) | 562 (15) | 0.47 (0.320.68) | <0.001 |

| Medications | ||||

| New gastric acid suppressor at iCDI | 54 (13) | 255 (7) | 2.01 (1.472.74) | <0.001 |

| Any antibiotic at iCDI | 314 (74) | 2727 (72) | 1.08 (0.861.36) | 0.49 |

| High‐risk antibiotics at iCDIe | 174 (41) | 1489 (40) | 1.06 (0.871.30) | 0.56 |

| Fluoroquinolone at iCDI | 120 (28) | 860 (23) | 1.33 (1.061.67) | 0.01 |

| Low‐risk antibiotics at iCDI | 95 (22) | 1058 (28) | 0.74 (0.580.94) | 0.01 |

| IV vancomycin at iCDI | 130 (31) | 1321 (35) | 0.82 (0.671.02) | 0.07 |

Seven factors present at the onset of iCDI were found to predict a recurrence in multivariable analysis (Table 2). Older age, CO‐HCFA status of iCDI, and 2 or more hospitalizations in the prior 60 days increased the risk of rCDI. Concomitant exposures to gastric acid suppressors, fluoroquinolone antibiotics, and high‐risk antibiotics were also significantly associated with a recurrence. Being in the intensive care unit (ICU) at the onset of iCDI was protective against rCDI in the multivariable model. This model had a C statistic of 0.642 and a Brier score of 0.089. After cross‐validation with 500 bootstrapping iterations, the model exhibited a moderately good fit (Figure 2). The prediction was particularly accurate in the lower risk ranges, with slight divergence in the risk strata over 20%. The validated model had a C statistic of 0.630 and Brier score of 0.089.

| Prediction Factors | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Agea | 1.08 | 1.021.14 |

| CO‐HCFA CDI (ref: HO‐CDI) | 1.71 | 1.322.22 |

| 2+ hospitalizations in prior 60 days (ref: 0 hospitalizations) | 1.49 | 1.082.06 |

| New gastric acid suppression at the onset of iCDI | 1.59 | 1.132.23 |

| High‐risk antibiotic at the onset of iCDIbb | 1.25 | 1.011.55 |

| Fluoroquinolone at the onset of iCDI | 1.31 | 1.041.65 |

| ICU at the onset of iCDI | 0.49 | 0.340.72 |

The sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of the model at various probability thresholds of rCDI are presented in Table 3. Thus, when the probability of rCDI was low, the model exhibited high sensitivity and low specificity. The situation was reversed as the probability of rCDI approached 30% (very low sensitivity and high specificity). The model's performance was optimal when the rCDI risk matched that in the current cohort, or 10.1%, with a sensitivity of 56% and specificity of 65%. However, when the rCDI risk dropped to 5%, the specificity dropped to below 30%. The sensitivity dropped to below 30% when rCDI risk rose to 15% (Table 3). Across the entire range of the probabilities tested, the negative predictive value of the model was persistently 90% or higher.

| Model Predicted Probability Cutpoint | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Positive Likelihood Ratio | Negative Likelihood Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| 0.025 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 1.00 | 1.0 | Undef |

| 0.050 | 0.96 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.95 | 1.05 | 0.44 |

| 0.101a | 0.56 | 0.65 | 0.15 | 0.93 | 1.60 | 0.68 |

| 0.151 | 0.27 | 0.86 | 0.18 | 0.91 | 1.93 | 0.85 |

| 0.303 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.40 | 0.90 | Undef | 0.99 |

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that in a cohort of hospitalized patients with iCDI, 10% developed at least 1 episode of rCDI within 42 days of the end of iCDI treatment. The factors present at iCDI onset that predicted recurrence were age, CO‐HCFA CDI, prior hospitalization, high‐risk antibiotic and fluoroquinolone use, and gastric acid suppression. Although the model's performance was only moderate, its negative predictive value was 90% or higher across the entire range of rCDI probabilities tested. This means that the absence of this combination of risk factors in a patient with iCDI diminishes the probability of a rCDI episode to 10% or below, depending on the prior population risk for rCDI.

Prior investigators have developed prediction rules for rCDI. Hebert et al., using methodology similar to ours, constructed a model to predict the risk of rCDI among patients hospitalized with iCDI.[17] For example, the recurrence rate in their study was 23% compared to our 10%. This is likely due to the differing definitions of both iCDI and rCDI between the 2 studies. Although our definitions of hospital‐associated C difficile‐associated diarrhea (CDAD) conformed to the recommended surveillance definitions,[13] Hebert and colleagues used different definitions.[18] If this is so, the higher rate of rCDI in their study may have reflected these differences in surveillance definition, rather than the true prevalence of recurrent CDAD.

Several other studies have relied on either specialized laboratory tests alone or in combination with clinical factors. Stewart et al., in a small single‐center cohort study, reported the presence of the binary toxin to be the only independent predictor of rCDI.[19] Others have found lower antitoxin immunoglobulin levels at various times following the onset of iCDI to be predictive of a recurrence.[20, 21] A disadvantage of using these specialized tests as tools for clinical prediction is that they are not widely available in clinical practice. Even if these tests are available, their results are likely to return only after iCDI treatment has commenced. To make risk stratification more generalizable, we specifically focused on common data available in all clinical settings at the onset of iCDI.

We chose to restrict our risk stratification to factors present at the onset of iCDI for several reasons. First, earlier identification of patients at increased risk for rCDI may encourage clinicians to minimize subsequent exposures to non‐CDI antimicrobials and gastric acid suppressors. Second, newer anticlostridial therapies in development appear to target specifically CDI recurrence. The first anti‐CDI drug to be approved in 2 decades, fidaxomicin, has been shown to reduce the risk of a recurrence by nearly one‐half compared to vancomycin.[10, 11] Although in practice it is tempting to reserve this treatment for those patients who have multiple recurrences, there is no convincing evidence to date that the drug is similarly effective at reducing further recurrences in this population.[22, 23] Currently, the only population in which fidaxomicin treatment has been shown to reduce the risk of rCDI contains patients with at most 1 prior episode, whose first anti‐CDI exposure was to fidaxomicin.[10, 11] Thus, the intent of our model was to insure appropriate use of these new technologies from the perspective of both under‐ and overtreatment.

In general, most of the factors included in our model are neither novel nor surprising, including concurrent antibiotics and gastric acid suppression.[24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30] What is interesting about these exposures, however, is the fact that we measured them only at the onset of the iCDI episode. This implies that it is not merely the continuation of these medications after onset, but even exposure to them prior to the initial bout of CDI, that may promote a recurrence. This finding should give pause to the widespread practice of routinely prescribing gastric acid suppression to many hospitalized patients. It should also prompt a reexamination of antimicrobial choices for patients admitted for the treatment of infectious diseases in favor of those deemed at low risk for CDI whenever possible.

A relatively novel risk factor emerging from our model is the designation of the iCDI episode as CO‐HCFA.[30] A likely explanation for this relationship is that CO‐HCFA identifies a population of patients who are more ill, as evidenced by their prior hospitalization history. However, because recent hospitalizations themselves emerged as an independent predictor of rCDI in our model, CO‐HCFA designation clearly incorporates other factors important to this outcome.

Our data on illness severity are divergent from prior results. Previous work has found that increasing severity of illness is positively associated with the risk of a recurrence.[21, 31] In contrast, we found that the need for the ICU at the onset of iCDI appeared protective from rCDI. There are several explanations for this finding, the most likely being the competing mortality risk. Although we excluded from the study those patients who did not survive their iCDI hospitalizations, patients who received care in an ICU were more likely to die in the rCDI risk period than patients who did not receive care in an ICU (data not shown). Another potential explanation for this observation is that patients who develop iCDI while in the ICU may generally get more aggressive care than those contracting it on other wards, resulting in a lower risk for recurrence.

The recurrence rate in the current study is at the lower limit of what has been reported previously either in the meta‐analysis by Garey (13%50%) or in recent randomized controlled trials (25%).[10, 11, 25] This is likely due to our case identification pathway, and ascertainment bias is a potential limitation of our study. Patients with mild recurrent CDI diagnosed and treated as outpatients were not captured in our study unless their toxin assay was performed by the BJH laboratory (approximately 15% of specimens submitted to the BJH microbiology laboratory come from outpatients or affiliated outpatient or skilled nursing facilities). Similarly, recurrences diagnosed at other inpatient facilities were not captured in our study unless they were transferred to BJH for care. On the other hand, rCDI in randomized trials may be subject to a detection bias, because enrolled patients are prospectively monitored for and instructed to seek testing for recurrent diarrhea.

Our study also has limitations inherent to observational data such as confounding. We adjusted for all the available relevant potential confounders in the regression model. However, the possibility of residual confounding remains. Because our cohort was too small for a split‐cohort model validation, we employed a bootstrap method to cross‐validate our results. However, the model requires further validation in a prospective cohort in the future. The biggest limitation of our model, however, is its generalizability, because the data reflect patients and treatment patterns at an urban academic medical center, and may not mirror those of institutions with different characteristics or patients with iCDI diagnosed and managed completely in the outpatient setting.

In summary, we have developed a model to predict iCDI patients' risk of recurrence. The advantage of our model is the availability of all the factors at the onset of iCDI, when treatment decisions need to be made. Although far from perfect in its ability to discriminate those who will from those who will not develop a recurrence, it should serve as a beginning step in the direction of appropriately aggressive care that may result not only in diminishing the pool of this infection, but also in containing its spiraling costs. The cost‐benefit balance of these decisions needs to be examined explicitly, not only in terms of the financial cost of over‐ or undertreatment, but with respect to the implications of such overtreatment on development of resistance to newer anticlostridial agents.

Disclosures

This study was funded by Cubist Pharmaceuticals, Jersey City, New Jersey. The data in the article were presented in part as a poster presentation at IDWeek 2012, San Diego, California, October 1721, 2012. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) is a serious and costly condition whose volume in US hospitals has doubled over the last decade.[1, 2, 3] Along with this rise in incidence, its severity has also increased. Although in the United States there has been a doubling in age‐adjusted case fatality, in the same time period Canadian studies reported a high and increasing CDI‐associated case fatality in the setting of an outbreak of a novel epidemic hypervirulent strain BI/NAP1/027.[2, 4, 5, 6] The costs of CDI range widely ($2500 to $13,000 per hospitalization), with cumulative annual cost to the US healthcare system estimated at nearly $5 billion.[7, 8, 9]

One of the drivers of these clinical and economic outcomes is CDI recurrence (rCDI). In 2 recent randomized controlled trials, up to 25% of patients with an initial CDI (iCDI) episode developed rCDI.[10, 11] There are few data that quantify the impact of rCDI on quality of life and survival. However, patients often are readmitted to the hospital with rCDI, and physicians who treat patients with multiple episodes of rCDI can attest to the devastating toll it takes on the lives of the patients and their families (personal communications from numerous patients to E.R.D.).[12] Reducing the incidence of rCDI may significantly improve the course of this disease.

The advent of such new treatments as fidaxomicin aimed at rCDI is promising.[10, 11] However, evidence for its efficacy so far is limited to treatment‐naive iCDI patients, thus challenging clinicians to identify patients at high risk for rCDI at iCDI onset. To address this challenge, we set out to develop a bedside prediction model for rCDI based on the factors present and routinely available at the onset of iCDI.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Source

We conducted a retrospective single‐center cohort study to examine the factors present at the onset of iCDI that impact the incidence of rCDI among hospitalized patients. Patients were included in the study if they were adults (18 years) hospitalized at Barnes‐Jewish Hospital (BJH), St. Louis, Missouri, between January 1, 2003 and December 31, 2009, and who had a positive toxin assay for C difficile in the setting of unformed stools and no history of CDI in the previous 60 days (as defined by positive toxin assay). Patients were excluded if they either died during or were discharged to hospice from the iCDI hospitalization. Cases of iCDI were categorized according to published surveillance definitions as community onset‐healthcare facility associated (CO‐HCFA), healthcare facility onset, and community associated.[13] Notably, the CO‐HCFA category included surveillance definitions for both CO‐HCFA and indeterminate cases. We defined rCDI as a repeat positive toxin within 42 days following the end of iCDI treatment. This period of risk for rCDI was chosen because the current surveillance definition for rCDI is a new episode of CDI occurring within 8 weeks from the last episode of CDI, with the assumption the patient would receive 10 to 14 days of CDI treatment at the beginning of the 8‐week period.[14] Medical charts were reviewed for all readmissions during the recurrence risk period to identify patients diagnosed with rCDI by methods other than toxin assay. A study enrollment flow chart is shown in Figure 1.

Demographic and clinical data were derived from the BJH medical informatics databases and the BJH electronic medical records (see Supporting Appendix Table 1 in the online version of this article). Comorbidities were grouped using the Charlson‐Deyo categories.[15] All variables were limited to data that are consistent throughout a hospitalization (eg, race or age) or were present within 48 hours of iCDI (eg, medications).

Model Development and Validation

First, we examined risk factors for rCDI present at the time of the iCDI diagnosis and initiation of iCDI therapy. We used principal‐component analyses, corresponding analyses, and cluster analyses to reduce the data dimensions by combining variables reflecting the same underlying construct.[16] Several antibiotic categories were created. The high‐risk category included cephalosporins, clindamycin, and aminopenicillins.[17] Other categories examined separately were fluoroquinolones, intravenous vancomycin, and antibiotics considered low risk (all other drugs not encompassed in the prior categories). Proton pump inhibitor and histamine 2 receptor‐blockers were combined into a single variable of gastric acid suppressors.

We developed a logistic regression model to identify a set of variables that best predicted the risk of rCDI. Variables with P 0.20 on univariate analyses were included in multivariable models. Backward elimination was used to determine the final model (P 0.1 for removal). The model's discrimination was examined via the C statistic and calibration through Brier score.[16] A C statistic value of 0.5 implies that the model is no better than chance, whereas the value of 1.0 means that the model is perfect in differentiating cases from noncases. A Brier score closer to zero indicates better model calibration, or how closely the predicted probabilities for rCDI match the actual observed probabilities. We validated the model using the bootstrap method with 500 iterations. To explore its properties as a decision tool to help make the decision to initiate an intervention to prevent rCDI, we tested the model's sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values at various thresholds of prior probability of rCDI.

RESULTS

Among the 4196 patients with iCDI enrolled in the study, 425 (10.1%) developed at least 1 recurrence within 42 days of the end of iCDI treatment (Table 1). Compared to patients without a recurrence, in univariate analysis those with an rCDI episode were older and had a greater comorbidity burden. In particular, diabetes mellitus (odds ratio 1.34; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.08‐1.66) and cerebrovascular disease (odds ratio 1.47; 95% CI, 1.04‐2.08) were significantly more prevalent in the rCDI group. The index CDI episode for patients with rCDI was approximately twice as likely to fit the surveillance definition for CO‐HCFA than the index episode for those without a recurrence (odds ratio 2.24; 95% CI, 1.80‐2.79). Commensurately, patients with rCDI also had greater odds for experiencing multiple recent hospitalizations than those without rCDI. Neither type of CDI treatment (oral metronidazole vs oral vancomycin vs both), nor duration, was significantly associated with recurrence.

| Patient Characteristics | Patients Who Developed rCDI, N = 425 | Patients Who Did Not Develop rCDI, n = 3771) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, y, median (range)a | 64.8(18.398.2) | 61.6(18.0102.4) | 1.10 (1.041.16) | <0.001 |

| Female | 210 (49) | 1822 (48) | 1.05 (0.861.28) | 0.67 |

| Nonwhite race | 149 (35) | 1149 (31) | 1.23 (1.001.52) | 0.05 |

| Comorbiditiesb | ||||

| Myocardial infarction | 40 (9) | 328 (9) | 1.10 (0.771.54) | 0.62 |

| Congestive heart failure | 108 (25) | 854 (23) | 1.17 (0.931.47) | 0.19 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 34 (8) | 269 (7) | 1.13 (0.781.64) | 0.51 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 41 (10) | 256 (7) | 1.47 (1.042.08) | 0.03 |

| Chronic renal failure | 21 (5) | 190 (5) | 0.98 (0.621.56) | 0.94 |

| Dementia | 5 (1) | 23 (1) | 1.94 (0.735.14) | 0.18 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 116 (27) | 911 (24) | 1.18 (0.941.48) | 0.15 |

| Rheumatologic disease | 18 (4) | 146 (4) | 1.10 (0.671.81) | 0.71 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 20 (5) | 154 (4) | 1.16 (0.721.87) | 0.54 |

| Mild liver disease | 17 (4) | 201 (5) | 0.74 (0.451.23) | 0.25 |

| Moderate‐to‐severe liver disease | 12 (3) | 134 (4) | 0.79 (0.431.44) | 0.44 |

| Diabetes, any | 135 (32) | 974 (26) | 1.34 (1.081.66) | 0.009 |

| Paraplegia or hemiplegia | 12 (3) | 77 (2) | 1.38 (0.742.55) | 0.31 |

| Any malignancy (excluding leukemia/lymphoma) | 83 (20) | 770 (20) | 0.95 (0.741.22) | 0.67 |

| Leukemia or lymphoma | 78 (18) | 660 (18) | 1.06 (0.821.38) | 0.66 |

| Metastatic solid tumor | 56 (13) | 449 (12) | 1.12 (0.841.51) | 0.44 |

| HIV/AIDS | 10 (2) | 66 (2) | 1.36 (0.692.67) | 0.38 |

| Charlson composite score | ||||

| 02 | 223 (53) | 2179 (58) | Ref | |

| 35 | 117 (28) | 921 (24) | 1.24 (0.981.57) | 0.07 |

| 6 | 85(20) | 671 (18) | 1.24 (0.951.61) | 0.11 |

| Case statusc | ||||

| HCFO/HCFA | 203 (48) | 2331 (62) | Ref | |

| CA or unknown | 57 (13) | 595 (16) | 1.10 (0.811.50) | 0.54 |

| CO/HCFA, indeterminate, or non‐ BJHHCFA | 165 (39) | 845 (22) | 2.24 (1.802.79) | <0.001 |

| Prior hospitalizations | ||||

| Admitted from another healthcare facility | 109 (26) | 1018 (27) | 0.93 (0.741.17) | 0.55 |

| No. of inpatient admissions in previous 60 days | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 200 (47) | 2310 (61) | Ref | |

| 1 | 150 (35) | 1020 (27) | 1.70 (1.362.13) | <0.001 |

| 2+ | 75 (18) | 441 (12) | 1.96 (1.482.61) | <0.001 |

| Baseline laboratory datad | ||||

| Low albumin at iCDI | 50 (12) | 548 (15) | 0.78 (0.581.07) | 0.312 |

| Low WBC at iCDI | 64 (15) | 635 (17) | 0.88 (0.661.16) | 0.36 |

| High WBC at iCDI | 247 (58) | 2027 (54) | 1.20 (0.981.46) | 0.08 |

| Low hemoglobin at iCDI | 218 (51) | 1985 (53) | 0.95 (0.781.16) | 0.61 |

| High creatinine at iCDI | 99 (23) | 862 (23) | 1.02 (0.811.30) | 0.83 |

| Low creatinine clearance at iCDI | 218 (51) | 1635 (43) | 1.38 (1.131.68) | 0.002 |

| ICU admission at iCDI | 32 (8) | 562 (15) | 0.47 (0.320.68) | <0.001 |

| Medications | ||||

| New gastric acid suppressor at iCDI | 54 (13) | 255 (7) | 2.01 (1.472.74) | <0.001 |

| Any antibiotic at iCDI | 314 (74) | 2727 (72) | 1.08 (0.861.36) | 0.49 |

| High‐risk antibiotics at iCDIe | 174 (41) | 1489 (40) | 1.06 (0.871.30) | 0.56 |

| Fluoroquinolone at iCDI | 120 (28) | 860 (23) | 1.33 (1.061.67) | 0.01 |

| Low‐risk antibiotics at iCDI | 95 (22) | 1058 (28) | 0.74 (0.580.94) | 0.01 |

| IV vancomycin at iCDI | 130 (31) | 1321 (35) | 0.82 (0.671.02) | 0.07 |

Seven factors present at the onset of iCDI were found to predict a recurrence in multivariable analysis (Table 2). Older age, CO‐HCFA status of iCDI, and 2 or more hospitalizations in the prior 60 days increased the risk of rCDI. Concomitant exposures to gastric acid suppressors, fluoroquinolone antibiotics, and high‐risk antibiotics were also significantly associated with a recurrence. Being in the intensive care unit (ICU) at the onset of iCDI was protective against rCDI in the multivariable model. This model had a C statistic of 0.642 and a Brier score of 0.089. After cross‐validation with 500 bootstrapping iterations, the model exhibited a moderately good fit (Figure 2). The prediction was particularly accurate in the lower risk ranges, with slight divergence in the risk strata over 20%. The validated model had a C statistic of 0.630 and Brier score of 0.089.

| Prediction Factors | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Agea | 1.08 | 1.021.14 |

| CO‐HCFA CDI (ref: HO‐CDI) | 1.71 | 1.322.22 |

| 2+ hospitalizations in prior 60 days (ref: 0 hospitalizations) | 1.49 | 1.082.06 |

| New gastric acid suppression at the onset of iCDI | 1.59 | 1.132.23 |

| High‐risk antibiotic at the onset of iCDIbb | 1.25 | 1.011.55 |

| Fluoroquinolone at the onset of iCDI | 1.31 | 1.041.65 |

| ICU at the onset of iCDI | 0.49 | 0.340.72 |

The sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of the model at various probability thresholds of rCDI are presented in Table 3. Thus, when the probability of rCDI was low, the model exhibited high sensitivity and low specificity. The situation was reversed as the probability of rCDI approached 30% (very low sensitivity and high specificity). The model's performance was optimal when the rCDI risk matched that in the current cohort, or 10.1%, with a sensitivity of 56% and specificity of 65%. However, when the rCDI risk dropped to 5%, the specificity dropped to below 30%. The sensitivity dropped to below 30% when rCDI risk rose to 15% (Table 3). Across the entire range of the probabilities tested, the negative predictive value of the model was persistently 90% or higher.

| Model Predicted Probability Cutpoint | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Positive Likelihood Ratio | Negative Likelihood Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| 0.025 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 1.00 | 1.0 | Undef |

| 0.050 | 0.96 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.95 | 1.05 | 0.44 |

| 0.101a | 0.56 | 0.65 | 0.15 | 0.93 | 1.60 | 0.68 |

| 0.151 | 0.27 | 0.86 | 0.18 | 0.91 | 1.93 | 0.85 |

| 0.303 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.40 | 0.90 | Undef | 0.99 |

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that in a cohort of hospitalized patients with iCDI, 10% developed at least 1 episode of rCDI within 42 days of the end of iCDI treatment. The factors present at iCDI onset that predicted recurrence were age, CO‐HCFA CDI, prior hospitalization, high‐risk antibiotic and fluoroquinolone use, and gastric acid suppression. Although the model's performance was only moderate, its negative predictive value was 90% or higher across the entire range of rCDI probabilities tested. This means that the absence of this combination of risk factors in a patient with iCDI diminishes the probability of a rCDI episode to 10% or below, depending on the prior population risk for rCDI.

Prior investigators have developed prediction rules for rCDI. Hebert et al., using methodology similar to ours, constructed a model to predict the risk of rCDI among patients hospitalized with iCDI.[17] For example, the recurrence rate in their study was 23% compared to our 10%. This is likely due to the differing definitions of both iCDI and rCDI between the 2 studies. Although our definitions of hospital‐associated C difficile‐associated diarrhea (CDAD) conformed to the recommended surveillance definitions,[13] Hebert and colleagues used different definitions.[18] If this is so, the higher rate of rCDI in their study may have reflected these differences in surveillance definition, rather than the true prevalence of recurrent CDAD.

Several other studies have relied on either specialized laboratory tests alone or in combination with clinical factors. Stewart et al., in a small single‐center cohort study, reported the presence of the binary toxin to be the only independent predictor of rCDI.[19] Others have found lower antitoxin immunoglobulin levels at various times following the onset of iCDI to be predictive of a recurrence.[20, 21] A disadvantage of using these specialized tests as tools for clinical prediction is that they are not widely available in clinical practice. Even if these tests are available, their results are likely to return only after iCDI treatment has commenced. To make risk stratification more generalizable, we specifically focused on common data available in all clinical settings at the onset of iCDI.

We chose to restrict our risk stratification to factors present at the onset of iCDI for several reasons. First, earlier identification of patients at increased risk for rCDI may encourage clinicians to minimize subsequent exposures to non‐CDI antimicrobials and gastric acid suppressors. Second, newer anticlostridial therapies in development appear to target specifically CDI recurrence. The first anti‐CDI drug to be approved in 2 decades, fidaxomicin, has been shown to reduce the risk of a recurrence by nearly one‐half compared to vancomycin.[10, 11] Although in practice it is tempting to reserve this treatment for those patients who have multiple recurrences, there is no convincing evidence to date that the drug is similarly effective at reducing further recurrences in this population.[22, 23] Currently, the only population in which fidaxomicin treatment has been shown to reduce the risk of rCDI contains patients with at most 1 prior episode, whose first anti‐CDI exposure was to fidaxomicin.[10, 11] Thus, the intent of our model was to insure appropriate use of these new technologies from the perspective of both under‐ and overtreatment.

In general, most of the factors included in our model are neither novel nor surprising, including concurrent antibiotics and gastric acid suppression.[24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30] What is interesting about these exposures, however, is the fact that we measured them only at the onset of the iCDI episode. This implies that it is not merely the continuation of these medications after onset, but even exposure to them prior to the initial bout of CDI, that may promote a recurrence. This finding should give pause to the widespread practice of routinely prescribing gastric acid suppression to many hospitalized patients. It should also prompt a reexamination of antimicrobial choices for patients admitted for the treatment of infectious diseases in favor of those deemed at low risk for CDI whenever possible.

A relatively novel risk factor emerging from our model is the designation of the iCDI episode as CO‐HCFA.[30] A likely explanation for this relationship is that CO‐HCFA identifies a population of patients who are more ill, as evidenced by their prior hospitalization history. However, because recent hospitalizations themselves emerged as an independent predictor of rCDI in our model, CO‐HCFA designation clearly incorporates other factors important to this outcome.

Our data on illness severity are divergent from prior results. Previous work has found that increasing severity of illness is positively associated with the risk of a recurrence.[21, 31] In contrast, we found that the need for the ICU at the onset of iCDI appeared protective from rCDI. There are several explanations for this finding, the most likely being the competing mortality risk. Although we excluded from the study those patients who did not survive their iCDI hospitalizations, patients who received care in an ICU were more likely to die in the rCDI risk period than patients who did not receive care in an ICU (data not shown). Another potential explanation for this observation is that patients who develop iCDI while in the ICU may generally get more aggressive care than those contracting it on other wards, resulting in a lower risk for recurrence.

The recurrence rate in the current study is at the lower limit of what has been reported previously either in the meta‐analysis by Garey (13%50%) or in recent randomized controlled trials (25%).[10, 11, 25] This is likely due to our case identification pathway, and ascertainment bias is a potential limitation of our study. Patients with mild recurrent CDI diagnosed and treated as outpatients were not captured in our study unless their toxin assay was performed by the BJH laboratory (approximately 15% of specimens submitted to the BJH microbiology laboratory come from outpatients or affiliated outpatient or skilled nursing facilities). Similarly, recurrences diagnosed at other inpatient facilities were not captured in our study unless they were transferred to BJH for care. On the other hand, rCDI in randomized trials may be subject to a detection bias, because enrolled patients are prospectively monitored for and instructed to seek testing for recurrent diarrhea.

Our study also has limitations inherent to observational data such as confounding. We adjusted for all the available relevant potential confounders in the regression model. However, the possibility of residual confounding remains. Because our cohort was too small for a split‐cohort model validation, we employed a bootstrap method to cross‐validate our results. However, the model requires further validation in a prospective cohort in the future. The biggest limitation of our model, however, is its generalizability, because the data reflect patients and treatment patterns at an urban academic medical center, and may not mirror those of institutions with different characteristics or patients with iCDI diagnosed and managed completely in the outpatient setting.

In summary, we have developed a model to predict iCDI patients' risk of recurrence. The advantage of our model is the availability of all the factors at the onset of iCDI, when treatment decisions need to be made. Although far from perfect in its ability to discriminate those who will from those who will not develop a recurrence, it should serve as a beginning step in the direction of appropriately aggressive care that may result not only in diminishing the pool of this infection, but also in containing its spiraling costs. The cost‐benefit balance of these decisions needs to be examined explicitly, not only in terms of the financial cost of over‐ or undertreatment, but with respect to the implications of such overtreatment on development of resistance to newer anticlostridial agents.

Disclosures

This study was funded by Cubist Pharmaceuticals, Jersey City, New Jersey. The data in the article were presented in part as a poster presentation at IDWeek 2012, San Diego, California, October 1721, 2012. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , . Clostridium difficile infection in patients discharged from US short‐stay hospitals, 1996–2003. Emerge Infect Dis. 2006;12:409–415.

- , , . Increase in adult Clostridium difficile‐related hospitalizations and case‐fatality rate, United States, 2000–2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:929–931.

- , , . Clostridium difficile infections (CDI) in hospital stays, 2009. HCUP statistical brief #124. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012. Available at: http://www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb124.pdf. Accessed July 19, 2013.

- , , , et al. A predominantly clonal multi‐institutional outbreak of Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhea with high morbidity and mortality. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2442–2449.

- , , , et al. Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhea in a region of Quebec from 1991 to 2003: a changing pattern of disease severity. CMAJ. 2004;171:466–472.

- , , , et al. An epidemic, toxin gene‐variant strain of Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(23):2433–2441.

- , , , , . Short‐ and long‐term attributable costs of Clostridium difficile‐associated disease in nonsurgical inpatients. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(4):497–504.

- , , , . The emerging infectious challenge of Clostridium difficile‐associated disease in Massachusetts hospitals: clinical and economic consequences. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:1219–1227.

- , . Burden of Clostridium difficile on the healthcare system. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(suppl 2):S88–S92.

- , , , et al. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for infection with Clostridium difficile in Europe, Canada, and the USA: a double‐blind, non‐inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(4):281–289.

- , , , et al. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:422–431.

- , , , , , . Recurrent Clostridium difficile disease: epidemiology and clinical characteristics. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20:43–50.

- , , , et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:431–455.

- , , , , , ; Ad Hoc Clostridium difficile Surveillance Working Group. Recommendations for surveillance of Clostridium difficile‐associated disease. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:140–145.

- , , . Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD‐9‐CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619.

- , , , . Measures for evaluating model performance. Proceedings of the Biometrics Section. Alexandria, VA: American Statistical Association, Biometrics Section; 1997:253–258.

- , , , et al. Development and validation of a Clostridium difficile infection risk prediction model. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32:360–366.

- , , , . Electronic health record‐based detection of risk factors for Clostridium difficile infection relapse. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34:407–414.

- , , . Predicting recurrence of C. difficile colitis using bacterial virulence factors: binary toxin is the key. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:118–125.

- , , , . Association between antibody response to toxin A and protection against recurrent Clostridium difficile diarrhoea. Lancet. 2001;357:189–193.

- , , , et al. Prospective derivation and validation of a clinical prediction rule for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1206–1214.

- . Fidaxomicin failures in recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a problem of timing. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:613–614.

- , . Fidaxomicin “chaser” regimen following vancomycin for patients with multiple Clostridium difficile recurrences. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:309–310.

- , , , et al. Predictors of first recurrence of Clostridium difficile infection: implications for initial management. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(suppl 2):S77–S87.

- , , , . Meta‐analysis to assess risk factors for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. J Hosp Infect. 2008;70:298–304.

- , , , , , . Recurrent Clostridium difficile diarrhea: characteristics of and risk factors for patients enrolled in a prospective, randomized, double‐blinded trial. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:324–333.

- , , , , . Association of proton‐pump inhibitors with outcomes in Clostridium difficile colitis. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64:2359–2363.

- , , , et al. Proton pump inhibitors as a risk factor for recurrence of Clostridium‐difficile‐associated diarrhea. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3573–3577.

- , , . Proton pump inhibitor use and recurrent Clostridium difficile‐associated disease: a case‐control analysis matched by propensity score. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:397–400.

- , , , , , . Risk of Clostridium difficile infection with acid suppressing drugs and antibiotics: meta‐analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(7):1011–1019.

- , , , et al. Risk factors for early recurrent Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:954–959.

- , , . Clostridium difficile infection in patients discharged from US short‐stay hospitals, 1996–2003. Emerge Infect Dis. 2006;12:409–415.

- , , . Increase in adult Clostridium difficile‐related hospitalizations and case‐fatality rate, United States, 2000–2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:929–931.

- , , . Clostridium difficile infections (CDI) in hospital stays, 2009. HCUP statistical brief #124. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012. Available at: http://www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb124.pdf. Accessed July 19, 2013.

- , , , et al. A predominantly clonal multi‐institutional outbreak of Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhea with high morbidity and mortality. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2442–2449.

- , , , et al. Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhea in a region of Quebec from 1991 to 2003: a changing pattern of disease severity. CMAJ. 2004;171:466–472.

- , , , et al. An epidemic, toxin gene‐variant strain of Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(23):2433–2441.

- , , , , . Short‐ and long‐term attributable costs of Clostridium difficile‐associated disease in nonsurgical inpatients. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(4):497–504.

- , , , . The emerging infectious challenge of Clostridium difficile‐associated disease in Massachusetts hospitals: clinical and economic consequences. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:1219–1227.

- , . Burden of Clostridium difficile on the healthcare system. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(suppl 2):S88–S92.

- , , , et al. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for infection with Clostridium difficile in Europe, Canada, and the USA: a double‐blind, non‐inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(4):281–289.

- , , , et al. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:422–431.

- , , , , , . Recurrent Clostridium difficile disease: epidemiology and clinical characteristics. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20:43–50.

- , , , et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:431–455.

- , , , , , ; Ad Hoc Clostridium difficile Surveillance Working Group. Recommendations for surveillance of Clostridium difficile‐associated disease. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:140–145.

- , , . Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD‐9‐CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619.

- , , , . Measures for evaluating model performance. Proceedings of the Biometrics Section. Alexandria, VA: American Statistical Association, Biometrics Section; 1997:253–258.

- , , , et al. Development and validation of a Clostridium difficile infection risk prediction model. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32:360–366.

- , , , . Electronic health record‐based detection of risk factors for Clostridium difficile infection relapse. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34:407–414.

- , , . Predicting recurrence of C. difficile colitis using bacterial virulence factors: binary toxin is the key. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:118–125.

- , , , . Association between antibody response to toxin A and protection against recurrent Clostridium difficile diarrhoea. Lancet. 2001;357:189–193.

- , , , et al. Prospective derivation and validation of a clinical prediction rule for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1206–1214.

- . Fidaxomicin failures in recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a problem of timing. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:613–614.

- , . Fidaxomicin “chaser” regimen following vancomycin for patients with multiple Clostridium difficile recurrences. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:309–310.

- , , , et al. Predictors of first recurrence of Clostridium difficile infection: implications for initial management. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(suppl 2):S77–S87.

- , , , . Meta‐analysis to assess risk factors for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. J Hosp Infect. 2008;70:298–304.

- , , , , , . Recurrent Clostridium difficile diarrhea: characteristics of and risk factors for patients enrolled in a prospective, randomized, double‐blinded trial. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:324–333.

- , , , , . Association of proton‐pump inhibitors with outcomes in Clostridium difficile colitis. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64:2359–2363.

- , , , et al. Proton pump inhibitors as a risk factor for recurrence of Clostridium‐difficile‐associated diarrhea. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3573–3577.

- , , . Proton pump inhibitor use and recurrent Clostridium difficile‐associated disease: a case‐control analysis matched by propensity score. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:397–400.