User login

How do hydrochlorothiazide and chlorthalidone compare for treating hypertension?

Both medications reduce theincidence of cardiovascular events in patients with hypertension, but chlorthalidone may confer additional cardiovascular risk reduction (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, conflicting network meta-analysis and cohort studies). (No head-to-head studies of hydrochlorothiazide [HCTZ] and chlorthalidone have been done.)

Serious hypokalemia and hyponatremia can occur with either medication; it is unclear if the rates of these adverse effects are the same at equivalent doses. Patients taking chlorthalidone are less likely to need a second antihypertensive medication but more likely to be nonadherent than patients taking HCTZ (SOR: B, cohort studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A network meta-analysis—designed to compare 2 interventions that haven’t been studied head-to-head—examined 9 trials that evaluated cardiovascular outcomes in 18,000 patients taking HCTZ and 60,000 patients taking chlorthalidone against outcomes for placebo or other antihypertensive agents.1 Daily doses ranged from 12.5 to 25 mg for HCTZ and 12.5 to 100 mg for chlorthalidone (although most patients taking chlorthalidone were on 12.5-25 mg).

In a drug-adjusted analysis using shared comparator medications, chlorthalidone proved superior to HCTZ in reducing the risk of both heart failure (relative risk [RR]=0.77; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.61-0.98) and combined cardiovascular events—myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, a new diagnosis of coronary artery disease, and new-onset congestive heart failure (RR=0.79; 95% CI, 0.72-0.88).

After adjusting for achieved blood pressure, chlorthalidone was still associated with lower rates of cardiovascular events than HCTZ (RR=0.82; 95% CI, 0.70-0.97). Relative to HCTZ, the number needed to treat with chlorthalidone to prevent 1 additional cardiovascular event over 5 years was 27. Because network meta-analyses draw from a wider body of research than standard meta-analyses, they may be weakened by increased variability in study design and patient demographics.

But another study shows no significant difference in cardiovascular outcomes

A subsequent retrospective cohort study didn’t find a significant difference in cardiovascular outcomes between HCTZ and chlorthalidone. The study compared pooled cardiovascular outcomes (MI, heart failure, and stroke) in 10,400 patients recently started on chlorthalidone and 19,500 started on HCTZ.2 Initial doses were typically either 25 mg chlorthalidone (70% of patients on chlorthalidone) or 12.5 mg HCTZ (67% of patients on HCTZ). The median follow-up was about a year, but lasted as long as 5 years in some cases.

The 2 groups showed no significant difference in cardiovascular events (3.2 events per 100 person-years for chlorthalidone compared with 3.4 for HCTZ; adjusted hazard ratio [aHR]=0.93; 95% CI, 0.81-1.06).

Serious hypokalemia and hyponatremia are risks

Patients taking chlorthalidone were more likely to be hospitalized for hypokalemia (0.69 per 100 person-years vs 0.27 for HCTZ; aHR=3.1; 95% CI, 2.0-4.6; number needed to harm [NNH]=238 in 1 year) or hyponatremia (0.69 per 100 person-years vs 0.49 for HCTZ; aHR=1.7; 95% CI, 1.2-2.3; NNH=434 in 1 year).2 However, the all-cause hospitalization rates for the 2 drugs were the same (aHR=1.0; 95% CI, 0.93-1.07).

Lower systolic BP and serum potassium found with chlorthalidone

A smaller retrospective cohort analysis (6441 participants who received either chlorthalidone or HCTZ starting at 50 mg and stepped once to 100 mg) also assessed the difference in cardiovascular events between patients taking the 2 drugs.3 (Cardiovascular events were defined as pooled MIs, onset of angina or peripheral artery occlusive disease, or need for coronary artery bypass.) Although significant reductions in pooled events occurred in both groups over the 7-year study, these reductions were significantly lower in the chlorthalidone group than in the HCTZ group (aHR=0.79; 95% CI, 0.68-0.92).

Systolic blood pressures were statistically lower in the chlorthalidone group during Years 1 through 5 but not in Years 6 and 7 (difference 2-4 mm Hg). Serum potassium was also lower in patients taking chlorthalidone (3.8 mEq/L on chlorthalidone vs 4.0 mEq/L on HCTZ after 7 years; P<.05).

Chlorthalidone users more responsive, but less adherent than HCTZ users

A retrospective cohort study investigated medication tolerance in veterans who had recently started either HCTZ (120,000 patients) or chlorthalidone (2200 patients) and were followed for a year.4 Most received doses between 12.5 and 25 mg of active drug.

One primary outcome was “nonpersistence,” defined as failure to refill the medication after double the number of days as the initial prescription. The other was “insufficient response,” defined as the need to start another antihypertensive medication. Chlorthalidone users were less likely than HCTZ users to have an insufficient response (odds ratio [OR]=0.71; 95% CI, 0.63-0.80) but more likely to exhibit nonpersistence (OR=1.6; 95% CI, 1.5-1.8).

RECOMMENDATIONS

For primary hypertension, the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends diuretic monotherapy in patients older than 55 years who are poor candidates for calcium channel blockers.5 If a diuretic is to be initiated or changed, NICE recommends chlorthalidone (12.5-25 mg daily) or indapamide (1.5-2.5 mg daily) in preference to HCTZ. The guideline set forth in the eighth annual report of the United States Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure makes no distinction between chlorthalidone and HCTZ; it refers only to “thiazidetype diuretics.” Thiazide-type diuretics are listed as one option (along with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and calcium channel blockers) for initial monotherapy in nonblack patients.6

1. Roush GC, Holford TR, Guddati AK. Chlorthalidone compared with hydrochlorothiazide in reducing cardiovascular events: systematic review and network meta-analyses. Hypertension. 2012;59:1110–1117.

2. Dhalla IA, Gomes T, Yao Z, et al. Chlorthalidone versus hydrochlorothiazide for the treatment of hypertension in older adults: a population-based cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:447–455.

3. Dorsh MP, Gillespie BW, Erickson SR, et al. Chlorthalidone reduces cardiovascular events compared with hydrochlorothiazide: a retrospective cohort analysis. Hypertension. 2011;57:689–694.

4. Lund BC, Ernst ME. The comparative effectiveness of hydrochlorothiazide and chlorthalidone in an observational cohort of veterans. J Clin Hypertension. 2012;14:623–629.

5. Hypertension: clinical management of primary hypertension in adults. (NICE Clinical Guideline 127). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Web site. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2011. Available at: www.nice.org.UK/guidance/CG127. Accessed December 16, 2013.

6. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC8). JAMA. 2014;311:507-520.

Both medications reduce theincidence of cardiovascular events in patients with hypertension, but chlorthalidone may confer additional cardiovascular risk reduction (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, conflicting network meta-analysis and cohort studies). (No head-to-head studies of hydrochlorothiazide [HCTZ] and chlorthalidone have been done.)

Serious hypokalemia and hyponatremia can occur with either medication; it is unclear if the rates of these adverse effects are the same at equivalent doses. Patients taking chlorthalidone are less likely to need a second antihypertensive medication but more likely to be nonadherent than patients taking HCTZ (SOR: B, cohort studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A network meta-analysis—designed to compare 2 interventions that haven’t been studied head-to-head—examined 9 trials that evaluated cardiovascular outcomes in 18,000 patients taking HCTZ and 60,000 patients taking chlorthalidone against outcomes for placebo or other antihypertensive agents.1 Daily doses ranged from 12.5 to 25 mg for HCTZ and 12.5 to 100 mg for chlorthalidone (although most patients taking chlorthalidone were on 12.5-25 mg).

In a drug-adjusted analysis using shared comparator medications, chlorthalidone proved superior to HCTZ in reducing the risk of both heart failure (relative risk [RR]=0.77; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.61-0.98) and combined cardiovascular events—myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, a new diagnosis of coronary artery disease, and new-onset congestive heart failure (RR=0.79; 95% CI, 0.72-0.88).

After adjusting for achieved blood pressure, chlorthalidone was still associated with lower rates of cardiovascular events than HCTZ (RR=0.82; 95% CI, 0.70-0.97). Relative to HCTZ, the number needed to treat with chlorthalidone to prevent 1 additional cardiovascular event over 5 years was 27. Because network meta-analyses draw from a wider body of research than standard meta-analyses, they may be weakened by increased variability in study design and patient demographics.

But another study shows no significant difference in cardiovascular outcomes

A subsequent retrospective cohort study didn’t find a significant difference in cardiovascular outcomes between HCTZ and chlorthalidone. The study compared pooled cardiovascular outcomes (MI, heart failure, and stroke) in 10,400 patients recently started on chlorthalidone and 19,500 started on HCTZ.2 Initial doses were typically either 25 mg chlorthalidone (70% of patients on chlorthalidone) or 12.5 mg HCTZ (67% of patients on HCTZ). The median follow-up was about a year, but lasted as long as 5 years in some cases.

The 2 groups showed no significant difference in cardiovascular events (3.2 events per 100 person-years for chlorthalidone compared with 3.4 for HCTZ; adjusted hazard ratio [aHR]=0.93; 95% CI, 0.81-1.06).

Serious hypokalemia and hyponatremia are risks

Patients taking chlorthalidone were more likely to be hospitalized for hypokalemia (0.69 per 100 person-years vs 0.27 for HCTZ; aHR=3.1; 95% CI, 2.0-4.6; number needed to harm [NNH]=238 in 1 year) or hyponatremia (0.69 per 100 person-years vs 0.49 for HCTZ; aHR=1.7; 95% CI, 1.2-2.3; NNH=434 in 1 year).2 However, the all-cause hospitalization rates for the 2 drugs were the same (aHR=1.0; 95% CI, 0.93-1.07).

Lower systolic BP and serum potassium found with chlorthalidone

A smaller retrospective cohort analysis (6441 participants who received either chlorthalidone or HCTZ starting at 50 mg and stepped once to 100 mg) also assessed the difference in cardiovascular events between patients taking the 2 drugs.3 (Cardiovascular events were defined as pooled MIs, onset of angina or peripheral artery occlusive disease, or need for coronary artery bypass.) Although significant reductions in pooled events occurred in both groups over the 7-year study, these reductions were significantly lower in the chlorthalidone group than in the HCTZ group (aHR=0.79; 95% CI, 0.68-0.92).

Systolic blood pressures were statistically lower in the chlorthalidone group during Years 1 through 5 but not in Years 6 and 7 (difference 2-4 mm Hg). Serum potassium was also lower in patients taking chlorthalidone (3.8 mEq/L on chlorthalidone vs 4.0 mEq/L on HCTZ after 7 years; P<.05).

Chlorthalidone users more responsive, but less adherent than HCTZ users

A retrospective cohort study investigated medication tolerance in veterans who had recently started either HCTZ (120,000 patients) or chlorthalidone (2200 patients) and were followed for a year.4 Most received doses between 12.5 and 25 mg of active drug.

One primary outcome was “nonpersistence,” defined as failure to refill the medication after double the number of days as the initial prescription. The other was “insufficient response,” defined as the need to start another antihypertensive medication. Chlorthalidone users were less likely than HCTZ users to have an insufficient response (odds ratio [OR]=0.71; 95% CI, 0.63-0.80) but more likely to exhibit nonpersistence (OR=1.6; 95% CI, 1.5-1.8).

RECOMMENDATIONS

For primary hypertension, the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends diuretic monotherapy in patients older than 55 years who are poor candidates for calcium channel blockers.5 If a diuretic is to be initiated or changed, NICE recommends chlorthalidone (12.5-25 mg daily) or indapamide (1.5-2.5 mg daily) in preference to HCTZ. The guideline set forth in the eighth annual report of the United States Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure makes no distinction between chlorthalidone and HCTZ; it refers only to “thiazidetype diuretics.” Thiazide-type diuretics are listed as one option (along with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and calcium channel blockers) for initial monotherapy in nonblack patients.6

Both medications reduce theincidence of cardiovascular events in patients with hypertension, but chlorthalidone may confer additional cardiovascular risk reduction (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, conflicting network meta-analysis and cohort studies). (No head-to-head studies of hydrochlorothiazide [HCTZ] and chlorthalidone have been done.)

Serious hypokalemia and hyponatremia can occur with either medication; it is unclear if the rates of these adverse effects are the same at equivalent doses. Patients taking chlorthalidone are less likely to need a second antihypertensive medication but more likely to be nonadherent than patients taking HCTZ (SOR: B, cohort studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A network meta-analysis—designed to compare 2 interventions that haven’t been studied head-to-head—examined 9 trials that evaluated cardiovascular outcomes in 18,000 patients taking HCTZ and 60,000 patients taking chlorthalidone against outcomes for placebo or other antihypertensive agents.1 Daily doses ranged from 12.5 to 25 mg for HCTZ and 12.5 to 100 mg for chlorthalidone (although most patients taking chlorthalidone were on 12.5-25 mg).

In a drug-adjusted analysis using shared comparator medications, chlorthalidone proved superior to HCTZ in reducing the risk of both heart failure (relative risk [RR]=0.77; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.61-0.98) and combined cardiovascular events—myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, a new diagnosis of coronary artery disease, and new-onset congestive heart failure (RR=0.79; 95% CI, 0.72-0.88).

After adjusting for achieved blood pressure, chlorthalidone was still associated with lower rates of cardiovascular events than HCTZ (RR=0.82; 95% CI, 0.70-0.97). Relative to HCTZ, the number needed to treat with chlorthalidone to prevent 1 additional cardiovascular event over 5 years was 27. Because network meta-analyses draw from a wider body of research than standard meta-analyses, they may be weakened by increased variability in study design and patient demographics.

But another study shows no significant difference in cardiovascular outcomes

A subsequent retrospective cohort study didn’t find a significant difference in cardiovascular outcomes between HCTZ and chlorthalidone. The study compared pooled cardiovascular outcomes (MI, heart failure, and stroke) in 10,400 patients recently started on chlorthalidone and 19,500 started on HCTZ.2 Initial doses were typically either 25 mg chlorthalidone (70% of patients on chlorthalidone) or 12.5 mg HCTZ (67% of patients on HCTZ). The median follow-up was about a year, but lasted as long as 5 years in some cases.

The 2 groups showed no significant difference in cardiovascular events (3.2 events per 100 person-years for chlorthalidone compared with 3.4 for HCTZ; adjusted hazard ratio [aHR]=0.93; 95% CI, 0.81-1.06).

Serious hypokalemia and hyponatremia are risks

Patients taking chlorthalidone were more likely to be hospitalized for hypokalemia (0.69 per 100 person-years vs 0.27 for HCTZ; aHR=3.1; 95% CI, 2.0-4.6; number needed to harm [NNH]=238 in 1 year) or hyponatremia (0.69 per 100 person-years vs 0.49 for HCTZ; aHR=1.7; 95% CI, 1.2-2.3; NNH=434 in 1 year).2 However, the all-cause hospitalization rates for the 2 drugs were the same (aHR=1.0; 95% CI, 0.93-1.07).

Lower systolic BP and serum potassium found with chlorthalidone

A smaller retrospective cohort analysis (6441 participants who received either chlorthalidone or HCTZ starting at 50 mg and stepped once to 100 mg) also assessed the difference in cardiovascular events between patients taking the 2 drugs.3 (Cardiovascular events were defined as pooled MIs, onset of angina or peripheral artery occlusive disease, or need for coronary artery bypass.) Although significant reductions in pooled events occurred in both groups over the 7-year study, these reductions were significantly lower in the chlorthalidone group than in the HCTZ group (aHR=0.79; 95% CI, 0.68-0.92).

Systolic blood pressures were statistically lower in the chlorthalidone group during Years 1 through 5 but not in Years 6 and 7 (difference 2-4 mm Hg). Serum potassium was also lower in patients taking chlorthalidone (3.8 mEq/L on chlorthalidone vs 4.0 mEq/L on HCTZ after 7 years; P<.05).

Chlorthalidone users more responsive, but less adherent than HCTZ users

A retrospective cohort study investigated medication tolerance in veterans who had recently started either HCTZ (120,000 patients) or chlorthalidone (2200 patients) and were followed for a year.4 Most received doses between 12.5 and 25 mg of active drug.

One primary outcome was “nonpersistence,” defined as failure to refill the medication after double the number of days as the initial prescription. The other was “insufficient response,” defined as the need to start another antihypertensive medication. Chlorthalidone users were less likely than HCTZ users to have an insufficient response (odds ratio [OR]=0.71; 95% CI, 0.63-0.80) but more likely to exhibit nonpersistence (OR=1.6; 95% CI, 1.5-1.8).

RECOMMENDATIONS

For primary hypertension, the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends diuretic monotherapy in patients older than 55 years who are poor candidates for calcium channel blockers.5 If a diuretic is to be initiated or changed, NICE recommends chlorthalidone (12.5-25 mg daily) or indapamide (1.5-2.5 mg daily) in preference to HCTZ. The guideline set forth in the eighth annual report of the United States Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure makes no distinction between chlorthalidone and HCTZ; it refers only to “thiazidetype diuretics.” Thiazide-type diuretics are listed as one option (along with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and calcium channel blockers) for initial monotherapy in nonblack patients.6

1. Roush GC, Holford TR, Guddati AK. Chlorthalidone compared with hydrochlorothiazide in reducing cardiovascular events: systematic review and network meta-analyses. Hypertension. 2012;59:1110–1117.

2. Dhalla IA, Gomes T, Yao Z, et al. Chlorthalidone versus hydrochlorothiazide for the treatment of hypertension in older adults: a population-based cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:447–455.

3. Dorsh MP, Gillespie BW, Erickson SR, et al. Chlorthalidone reduces cardiovascular events compared with hydrochlorothiazide: a retrospective cohort analysis. Hypertension. 2011;57:689–694.

4. Lund BC, Ernst ME. The comparative effectiveness of hydrochlorothiazide and chlorthalidone in an observational cohort of veterans. J Clin Hypertension. 2012;14:623–629.

5. Hypertension: clinical management of primary hypertension in adults. (NICE Clinical Guideline 127). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Web site. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2011. Available at: www.nice.org.UK/guidance/CG127. Accessed December 16, 2013.

6. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC8). JAMA. 2014;311:507-520.

1. Roush GC, Holford TR, Guddati AK. Chlorthalidone compared with hydrochlorothiazide in reducing cardiovascular events: systematic review and network meta-analyses. Hypertension. 2012;59:1110–1117.

2. Dhalla IA, Gomes T, Yao Z, et al. Chlorthalidone versus hydrochlorothiazide for the treatment of hypertension in older adults: a population-based cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:447–455.

3. Dorsh MP, Gillespie BW, Erickson SR, et al. Chlorthalidone reduces cardiovascular events compared with hydrochlorothiazide: a retrospective cohort analysis. Hypertension. 2011;57:689–694.

4. Lund BC, Ernst ME. The comparative effectiveness of hydrochlorothiazide and chlorthalidone in an observational cohort of veterans. J Clin Hypertension. 2012;14:623–629.

5. Hypertension: clinical management of primary hypertension in adults. (NICE Clinical Guideline 127). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Web site. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2011. Available at: www.nice.org.UK/guidance/CG127. Accessed December 16, 2013.

6. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC8). JAMA. 2014;311:507-520.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Which prophylactic therapies best prevent gout attacks?

Allopurinol and febuxostat reduce the frequency of gout attacks equally after 8 weeks of treatment (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, multiple randomized control trials [RCTs] with limitations).

Intravenous pegloticase decreases serum uric acid and gout attacks and improves quality of life (QOL) (SOR: A, 2 RCTs).

Colchicine reduces gout attacks when combined with probenecid or allopurinol at the start of urate-lowering therapy (SOR: B, 1 high-quality and 1 low-quality RCT).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 28-week RCT compared the effects of placebo, allopurinol (300 mg/d), and febuxostat (80 mg, 120 mg, and 240 mg) on serum uric acid levels (sUA) and gout attacks in 1067 patients with gout and hyperuricemia (94% male, 78% white, 18 to 85 years of age with mean age ranging from 51 to 54 years ± 12 years in each group).1 Patients also received prophylaxis with either colchicine or naproxen during the first 8 weeks of the study.

During Weeks 1 through 8, investigators found no statistically significant differences in the percentage of patients requiring treatment for gout attacks between the febuxostat 80 mg, allopurinol, and placebo groups (28%, 23%, and 20%, respectively). During Weeks 8 through 28, no statistically significant differences in gout attack rates occurred between the allopurinol and febuxostat groups, although the study didn’t report specific attack rates for this period.

Both allopurinol and all doses of febuxostat reduced sUA to <6 mg/dL more effectively than placebo; more patients treated with febuxostat than allopurinol achieved a uric acid level of less than <6 mg/dL.

Another RCT of 762 mostly white, male patients (mean age 52 years) with gout and sUA >8 mg/dL—35% of whom had renal impairment, defined as creatinine clearance <80 mL/min/1.73m2—also concluded that febuxostat and allopurinol are equally effective in reducing gout attacks (incidence of gout flares during Weeks 9 to 52 was 64% with both febuxostat 80 mg and allopurinol 300 mg).2 The percentage of patients with sUA <6 mg/dL at the last 3 monthly visits was 53% in the febuxostat 80 mg group compared with 21% in the allopurinol 300 mg group (P<.001; number needed to treat [NNT]=4]).

One significant limitation of both RCTs was the fixed dose of allopurinol (300 mg/d). US Food and Drug Administration-approved dosing for allopurinol allows for titration to a maximum of 800 mg/d to achieve serum uric acid <6 mg/dL.

IV pegloticase decreases gout attacks after 3 months, improves quality of life

Pegloticase is an intravenously administered, recombinant form of uricase, the natural enzyme that converts uric acid to more soluble allantoin. Two RCTs compared pegloticase with placebo in a total of 212 patients with gout (mean age 54 to 59 years; 70% to 90% male) intolerant or refractory to allopurinol (defined as baseline sUA of ≥8 mg/dL and at least one of the following: ≥3 self-reported gout flares during the previous 18 months, ≥1 tophi, or gouty arthropathy.

These trials found that treatment with 8 mg of pegloticase every 2 weeks for 6 months initially increased gout flares during Months 1 to 3 (75% with pegloticase, 53% with placebo; P=.02; number needed to harm [NNH]=5) but then decreased the incidence of acute gout attacks during Months 4 to 6 (41% with pegloticase, 67% with placebo; P=.007; NNT=4).3 In addition, pegloticase resulted in statistically significant improvements in QOL measured at the final visit using the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) pain scale, the HAQ-Disability Index, and the 36-item Short Form Health Survey.

Colchicine plus probenecid or allopurinol reduces gout attacks

One small, low-quality RCT (N=38) found that colchicine 0.5 mg administered 3 times daily effectively prevented gout attacks when administered concomitantly with probenecid initiated to lower urate (gout attacks per month in colchicine and placebo-treated patients, respectively, were 0.19±0.05 and 0.48±0.12; P<.05).4

Another RCT that compared allopurinol with and without colchicine showed that coadministration of colchicine 0.6 mg twice daily reduced gout attacks: 33% of patients treated with colchicine experienced a gout flare compared with 77% of placebo-treated patients (P=.008; NNT=3 over 6 months).5

We identified no RCTs that evaluated the uricosuric agent probenecid and no studies that assessed the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to prevent recurrent gout attacks.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidelines on managing gout recommend allopurinol or febuxostat as first-line pharmacologic urate-lowering therapy, with a goal of reducing sUA to <6 mg/dL. They recommend probenecid as an alternative if contraindications exist or the patient is intolerant to allopurinol and febuxostat.6 The guidelines note that allopurinol doses may exceed 300 mg/d, even in patients with chronic kidney disease.

The ACR recommends anti-inflammatory prophylaxis with colchicine or NSAIDs upon initiation of urate-lowering therapy. Anti-inflammatory prophylaxis should be continued as long as clinical evidence of continuing gout disease exists and until the sUA target has been acheived.7

1. Schumacher HR Jr, Becker MA, Wortmann RL, et al. Effects of febuxostat versus allopurinol and placebo in reducing serum urate in subjects with hyperuricemia and gout: a 28-week, phase III, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1540-1548.

2. Becker MA, Schumacher HR Jr, Wortmann RL, et al. Febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with hyperuricemia and gout. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2450-2461.

3. Sundy JS, Baraf HSB, Yood RA, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of pegloticase for the treatment of chronic gout in patients refractory to conventional treatment: two randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2011;306:711-720.

4. Paulus HE, Schlosstein LH, Godfrey RG, et al. Prophylactic colchicine therapy of intercritical gout: a placebo-controlled study of probenecid-treated patients. Arthritis Rheum. 1974;17:609-614.

5. Borstad GC, Bryant LR, Abel MP, et al. Colchicine for prophylaxis of acute flares when initiating allopurinol for chronic gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:2429-2432.

6. Khanna D, Fitzgerald JD, Khanna PP, et al; American College of Rheumatology. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:1431-1446.

7. Khanna D, Khanna PP, Fitzgerald JD, et al; American College of Rheumatology. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 2: therapy and anti-inflammatory prophylaxis of acute gouty arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:1447-1461.

Allopurinol and febuxostat reduce the frequency of gout attacks equally after 8 weeks of treatment (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, multiple randomized control trials [RCTs] with limitations).

Intravenous pegloticase decreases serum uric acid and gout attacks and improves quality of life (QOL) (SOR: A, 2 RCTs).

Colchicine reduces gout attacks when combined with probenecid or allopurinol at the start of urate-lowering therapy (SOR: B, 1 high-quality and 1 low-quality RCT).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 28-week RCT compared the effects of placebo, allopurinol (300 mg/d), and febuxostat (80 mg, 120 mg, and 240 mg) on serum uric acid levels (sUA) and gout attacks in 1067 patients with gout and hyperuricemia (94% male, 78% white, 18 to 85 years of age with mean age ranging from 51 to 54 years ± 12 years in each group).1 Patients also received prophylaxis with either colchicine or naproxen during the first 8 weeks of the study.

During Weeks 1 through 8, investigators found no statistically significant differences in the percentage of patients requiring treatment for gout attacks between the febuxostat 80 mg, allopurinol, and placebo groups (28%, 23%, and 20%, respectively). During Weeks 8 through 28, no statistically significant differences in gout attack rates occurred between the allopurinol and febuxostat groups, although the study didn’t report specific attack rates for this period.

Both allopurinol and all doses of febuxostat reduced sUA to <6 mg/dL more effectively than placebo; more patients treated with febuxostat than allopurinol achieved a uric acid level of less than <6 mg/dL.

Another RCT of 762 mostly white, male patients (mean age 52 years) with gout and sUA >8 mg/dL—35% of whom had renal impairment, defined as creatinine clearance <80 mL/min/1.73m2—also concluded that febuxostat and allopurinol are equally effective in reducing gout attacks (incidence of gout flares during Weeks 9 to 52 was 64% with both febuxostat 80 mg and allopurinol 300 mg).2 The percentage of patients with sUA <6 mg/dL at the last 3 monthly visits was 53% in the febuxostat 80 mg group compared with 21% in the allopurinol 300 mg group (P<.001; number needed to treat [NNT]=4]).

One significant limitation of both RCTs was the fixed dose of allopurinol (300 mg/d). US Food and Drug Administration-approved dosing for allopurinol allows for titration to a maximum of 800 mg/d to achieve serum uric acid <6 mg/dL.

IV pegloticase decreases gout attacks after 3 months, improves quality of life

Pegloticase is an intravenously administered, recombinant form of uricase, the natural enzyme that converts uric acid to more soluble allantoin. Two RCTs compared pegloticase with placebo in a total of 212 patients with gout (mean age 54 to 59 years; 70% to 90% male) intolerant or refractory to allopurinol (defined as baseline sUA of ≥8 mg/dL and at least one of the following: ≥3 self-reported gout flares during the previous 18 months, ≥1 tophi, or gouty arthropathy.

These trials found that treatment with 8 mg of pegloticase every 2 weeks for 6 months initially increased gout flares during Months 1 to 3 (75% with pegloticase, 53% with placebo; P=.02; number needed to harm [NNH]=5) but then decreased the incidence of acute gout attacks during Months 4 to 6 (41% with pegloticase, 67% with placebo; P=.007; NNT=4).3 In addition, pegloticase resulted in statistically significant improvements in QOL measured at the final visit using the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) pain scale, the HAQ-Disability Index, and the 36-item Short Form Health Survey.

Colchicine plus probenecid or allopurinol reduces gout attacks

One small, low-quality RCT (N=38) found that colchicine 0.5 mg administered 3 times daily effectively prevented gout attacks when administered concomitantly with probenecid initiated to lower urate (gout attacks per month in colchicine and placebo-treated patients, respectively, were 0.19±0.05 and 0.48±0.12; P<.05).4

Another RCT that compared allopurinol with and without colchicine showed that coadministration of colchicine 0.6 mg twice daily reduced gout attacks: 33% of patients treated with colchicine experienced a gout flare compared with 77% of placebo-treated patients (P=.008; NNT=3 over 6 months).5

We identified no RCTs that evaluated the uricosuric agent probenecid and no studies that assessed the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to prevent recurrent gout attacks.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidelines on managing gout recommend allopurinol or febuxostat as first-line pharmacologic urate-lowering therapy, with a goal of reducing sUA to <6 mg/dL. They recommend probenecid as an alternative if contraindications exist or the patient is intolerant to allopurinol and febuxostat.6 The guidelines note that allopurinol doses may exceed 300 mg/d, even in patients with chronic kidney disease.

The ACR recommends anti-inflammatory prophylaxis with colchicine or NSAIDs upon initiation of urate-lowering therapy. Anti-inflammatory prophylaxis should be continued as long as clinical evidence of continuing gout disease exists and until the sUA target has been acheived.7

Allopurinol and febuxostat reduce the frequency of gout attacks equally after 8 weeks of treatment (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, multiple randomized control trials [RCTs] with limitations).

Intravenous pegloticase decreases serum uric acid and gout attacks and improves quality of life (QOL) (SOR: A, 2 RCTs).

Colchicine reduces gout attacks when combined with probenecid or allopurinol at the start of urate-lowering therapy (SOR: B, 1 high-quality and 1 low-quality RCT).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 28-week RCT compared the effects of placebo, allopurinol (300 mg/d), and febuxostat (80 mg, 120 mg, and 240 mg) on serum uric acid levels (sUA) and gout attacks in 1067 patients with gout and hyperuricemia (94% male, 78% white, 18 to 85 years of age with mean age ranging from 51 to 54 years ± 12 years in each group).1 Patients also received prophylaxis with either colchicine or naproxen during the first 8 weeks of the study.

During Weeks 1 through 8, investigators found no statistically significant differences in the percentage of patients requiring treatment for gout attacks between the febuxostat 80 mg, allopurinol, and placebo groups (28%, 23%, and 20%, respectively). During Weeks 8 through 28, no statistically significant differences in gout attack rates occurred between the allopurinol and febuxostat groups, although the study didn’t report specific attack rates for this period.

Both allopurinol and all doses of febuxostat reduced sUA to <6 mg/dL more effectively than placebo; more patients treated with febuxostat than allopurinol achieved a uric acid level of less than <6 mg/dL.

Another RCT of 762 mostly white, male patients (mean age 52 years) with gout and sUA >8 mg/dL—35% of whom had renal impairment, defined as creatinine clearance <80 mL/min/1.73m2—also concluded that febuxostat and allopurinol are equally effective in reducing gout attacks (incidence of gout flares during Weeks 9 to 52 was 64% with both febuxostat 80 mg and allopurinol 300 mg).2 The percentage of patients with sUA <6 mg/dL at the last 3 monthly visits was 53% in the febuxostat 80 mg group compared with 21% in the allopurinol 300 mg group (P<.001; number needed to treat [NNT]=4]).

One significant limitation of both RCTs was the fixed dose of allopurinol (300 mg/d). US Food and Drug Administration-approved dosing for allopurinol allows for titration to a maximum of 800 mg/d to achieve serum uric acid <6 mg/dL.

IV pegloticase decreases gout attacks after 3 months, improves quality of life

Pegloticase is an intravenously administered, recombinant form of uricase, the natural enzyme that converts uric acid to more soluble allantoin. Two RCTs compared pegloticase with placebo in a total of 212 patients with gout (mean age 54 to 59 years; 70% to 90% male) intolerant or refractory to allopurinol (defined as baseline sUA of ≥8 mg/dL and at least one of the following: ≥3 self-reported gout flares during the previous 18 months, ≥1 tophi, or gouty arthropathy.

These trials found that treatment with 8 mg of pegloticase every 2 weeks for 6 months initially increased gout flares during Months 1 to 3 (75% with pegloticase, 53% with placebo; P=.02; number needed to harm [NNH]=5) but then decreased the incidence of acute gout attacks during Months 4 to 6 (41% with pegloticase, 67% with placebo; P=.007; NNT=4).3 In addition, pegloticase resulted in statistically significant improvements in QOL measured at the final visit using the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) pain scale, the HAQ-Disability Index, and the 36-item Short Form Health Survey.

Colchicine plus probenecid or allopurinol reduces gout attacks

One small, low-quality RCT (N=38) found that colchicine 0.5 mg administered 3 times daily effectively prevented gout attacks when administered concomitantly with probenecid initiated to lower urate (gout attacks per month in colchicine and placebo-treated patients, respectively, were 0.19±0.05 and 0.48±0.12; P<.05).4

Another RCT that compared allopurinol with and without colchicine showed that coadministration of colchicine 0.6 mg twice daily reduced gout attacks: 33% of patients treated with colchicine experienced a gout flare compared with 77% of placebo-treated patients (P=.008; NNT=3 over 6 months).5

We identified no RCTs that evaluated the uricosuric agent probenecid and no studies that assessed the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to prevent recurrent gout attacks.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidelines on managing gout recommend allopurinol or febuxostat as first-line pharmacologic urate-lowering therapy, with a goal of reducing sUA to <6 mg/dL. They recommend probenecid as an alternative if contraindications exist or the patient is intolerant to allopurinol and febuxostat.6 The guidelines note that allopurinol doses may exceed 300 mg/d, even in patients with chronic kidney disease.

The ACR recommends anti-inflammatory prophylaxis with colchicine or NSAIDs upon initiation of urate-lowering therapy. Anti-inflammatory prophylaxis should be continued as long as clinical evidence of continuing gout disease exists and until the sUA target has been acheived.7

1. Schumacher HR Jr, Becker MA, Wortmann RL, et al. Effects of febuxostat versus allopurinol and placebo in reducing serum urate in subjects with hyperuricemia and gout: a 28-week, phase III, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1540-1548.

2. Becker MA, Schumacher HR Jr, Wortmann RL, et al. Febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with hyperuricemia and gout. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2450-2461.

3. Sundy JS, Baraf HSB, Yood RA, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of pegloticase for the treatment of chronic gout in patients refractory to conventional treatment: two randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2011;306:711-720.

4. Paulus HE, Schlosstein LH, Godfrey RG, et al. Prophylactic colchicine therapy of intercritical gout: a placebo-controlled study of probenecid-treated patients. Arthritis Rheum. 1974;17:609-614.

5. Borstad GC, Bryant LR, Abel MP, et al. Colchicine for prophylaxis of acute flares when initiating allopurinol for chronic gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:2429-2432.

6. Khanna D, Fitzgerald JD, Khanna PP, et al; American College of Rheumatology. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:1431-1446.

7. Khanna D, Khanna PP, Fitzgerald JD, et al; American College of Rheumatology. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 2: therapy and anti-inflammatory prophylaxis of acute gouty arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:1447-1461.

1. Schumacher HR Jr, Becker MA, Wortmann RL, et al. Effects of febuxostat versus allopurinol and placebo in reducing serum urate in subjects with hyperuricemia and gout: a 28-week, phase III, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1540-1548.

2. Becker MA, Schumacher HR Jr, Wortmann RL, et al. Febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with hyperuricemia and gout. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2450-2461.

3. Sundy JS, Baraf HSB, Yood RA, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of pegloticase for the treatment of chronic gout in patients refractory to conventional treatment: two randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2011;306:711-720.

4. Paulus HE, Schlosstein LH, Godfrey RG, et al. Prophylactic colchicine therapy of intercritical gout: a placebo-controlled study of probenecid-treated patients. Arthritis Rheum. 1974;17:609-614.

5. Borstad GC, Bryant LR, Abel MP, et al. Colchicine for prophylaxis of acute flares when initiating allopurinol for chronic gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:2429-2432.

6. Khanna D, Fitzgerald JD, Khanna PP, et al; American College of Rheumatology. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:1431-1446.

7. Khanna D, Khanna PP, Fitzgerald JD, et al; American College of Rheumatology. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 2: therapy and anti-inflammatory prophylaxis of acute gouty arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:1447-1461.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

ADHD medication is not working

Welcome to a new column designed to provide practical advice regarding issues related to child mental health. It will be a joint effort, featuring contributions from several child psychiatrists working at the University of Vermont and the Vermont Center for Children, Youth, and Families. While psychopharmacology will certainly be a part of many of the columns, all of us here feel strongly that medications should be only one part of a comprehensive family-oriented plan. We encourage you to submit questions that you would like us address in future issues to [email protected].

Case summary

A 10-year-old boy presents for a follow-up appointment. He was diagnosed by another pediatrician in the practice 2 months ago with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and now returns to the office with continued symptoms and a complaint from the mother that medication "isn’t working." The boy was started on an extended-release preparation of methylphenidate at 18 mg to take each morning. The child is in the fifth grade and weighs 80 lb (36 kg). He lives with his mother and 8-year-old brother. The father is no longer involved in the patient’s life, which puts added stress on the mother. The diagnosis of ADHD was made by the pediatrician based upon the history, the child’s hyperactive and intrusive behavior in the office, and the results of a standardized rating scale that was completed by the mother, who now requests that the pediatrician "try something different."

Discussion

Many children and adolescents respond extremely well to ADHD medications. Some, however, do not, and the parental complaint that the "medication isn’t working" is a frequent expression heard in pediatrician offices across the country. It is also one of the primary reasons a family is referred to a child psychiatrist. In the course of performing hundreds of these consultations, I have found that there are several possibilities to consider before assuming the medication simply isn’t effective.

We will start with simpler problems and work our way toward more challenging reasons.

• The dose is too low. Methylphenidate often needs to be dosed over 1 mg/kg/day to be effective. If the patient reports minimal response to the medication while experiencing no side effects, an increase may certainly be reasonable.

• The medication is working but wearing off. Despite the advertisements of long-acting stimulants continuing their therapeutic effect for 10-12 hours, many children seem to lose the benefit of the medication much faster. Gathering some data from the school or asking the mother about weekend mornings compared with evenings can be useful. If indeed such a wear-off is found, adding a dose of an immediate-release stimulant in the early afternoon may help.

• Symptoms are being caused by something other than ADHD. Hyperactivity due to exposures such as lead may not change your management of the symptoms, but certainly could necessitate other types of intervention. Chronic sleep problems and inadequate nutrition, especially when it comes to breakfast, also should be queried and can lead to problems with concentration.

• There is psychiatric comorbidity. Unlike many differentials in other specialties, psychiatric differential diagnosis is often a matter of "and" rather than "or." Anxiety disorders, for example, can frequently masquerade as ADHD or be present in addition to ADHD. Oppositional behavior is also very commonly present with ADHD and suggests additional types of treatment.

• There is noncompliance. This problem can surface frequently in two ways. Older children may be responsible at home for taking their medications and forget or refuse to do so. I often ask, "Are you taking the medication every single day?" Diversion is also a potential problem from the parents or for an adolescent. Checking if the refills are occurring on time can provide a clue here, and some states have systems to check for duplicate prescriptions from multiple clinicians.

• Side effects are appearing as untreated ADHD. Sometimes medications are the problem, not the solution, and a failure to recognize this phenomenon can lead to unnecessary and sometimes harmful polypharmacy. Stimulants in some children can lead to increased agitation, anger outbursts, and impulsivity. Trying a medication holiday for several days can sometimes reveal the need to back off rather than add medications.

• Family is expecting improvement for non-ADHD symptoms. Asking what particular behaviors the family is hoping to improve can sometimes expose a situation in which parents expect change in non-ADHD domains. Unfortunately, there is no pill to make kids respect their parents more or want to do their homework. Being clear from the outset about what behaviors are and are not medication responsive can sometimes prevent this problem.

• There is substance abuse. In addition to the potential problem of abuse of the stimulants described previously, other substances such as cannabis can sabotage the benefits of medications.

• There is over-reliance on medications as the sole modality of treatment. ADHD is best treated using a wide range of strategies. Nonpharmacological interventions such as exercise, good nutrition and sleep, parent behavioral training, organizational help, regular reading, screen time reduction, and school supports are critical components of a comprehensive treatment approach.

• There is parental psychopathology. In our opinion, this area is one of the most frequently neglected aspects of child mental health treatment and can have huge implications. ADHD in particular is known to have very high heritability (similar to height). If a mother or father shares the condition, their struggles can frequently contribute to an environment that can exacerbate the child’s symptoms. A pattern in which the ADHD symptoms are more prominent at home compared with school is one clue to look in this direction. When addressing parental psychopathology, it can be important not to come off as blaming the parents for their child’s problems, but rather to convey how challenging dealing with ADHD can be as a parent and how they need to be functioning at their highest mental level as well.

Of course, sometimes the medication truly is not working, and it is time to try something else.

Dr. David C. Rettew is associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics, director of the child and adolescent psychiatry fellowship, and director of the pediatric psychiatry clinic at the University of Vermont, Burlington.

Welcome to a new column designed to provide practical advice regarding issues related to child mental health. It will be a joint effort, featuring contributions from several child psychiatrists working at the University of Vermont and the Vermont Center for Children, Youth, and Families. While psychopharmacology will certainly be a part of many of the columns, all of us here feel strongly that medications should be only one part of a comprehensive family-oriented plan. We encourage you to submit questions that you would like us address in future issues to [email protected].

Case summary

A 10-year-old boy presents for a follow-up appointment. He was diagnosed by another pediatrician in the practice 2 months ago with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and now returns to the office with continued symptoms and a complaint from the mother that medication "isn’t working." The boy was started on an extended-release preparation of methylphenidate at 18 mg to take each morning. The child is in the fifth grade and weighs 80 lb (36 kg). He lives with his mother and 8-year-old brother. The father is no longer involved in the patient’s life, which puts added stress on the mother. The diagnosis of ADHD was made by the pediatrician based upon the history, the child’s hyperactive and intrusive behavior in the office, and the results of a standardized rating scale that was completed by the mother, who now requests that the pediatrician "try something different."

Discussion

Many children and adolescents respond extremely well to ADHD medications. Some, however, do not, and the parental complaint that the "medication isn’t working" is a frequent expression heard in pediatrician offices across the country. It is also one of the primary reasons a family is referred to a child psychiatrist. In the course of performing hundreds of these consultations, I have found that there are several possibilities to consider before assuming the medication simply isn’t effective.

We will start with simpler problems and work our way toward more challenging reasons.

• The dose is too low. Methylphenidate often needs to be dosed over 1 mg/kg/day to be effective. If the patient reports minimal response to the medication while experiencing no side effects, an increase may certainly be reasonable.

• The medication is working but wearing off. Despite the advertisements of long-acting stimulants continuing their therapeutic effect for 10-12 hours, many children seem to lose the benefit of the medication much faster. Gathering some data from the school or asking the mother about weekend mornings compared with evenings can be useful. If indeed such a wear-off is found, adding a dose of an immediate-release stimulant in the early afternoon may help.

• Symptoms are being caused by something other than ADHD. Hyperactivity due to exposures such as lead may not change your management of the symptoms, but certainly could necessitate other types of intervention. Chronic sleep problems and inadequate nutrition, especially when it comes to breakfast, also should be queried and can lead to problems with concentration.

• There is psychiatric comorbidity. Unlike many differentials in other specialties, psychiatric differential diagnosis is often a matter of "and" rather than "or." Anxiety disorders, for example, can frequently masquerade as ADHD or be present in addition to ADHD. Oppositional behavior is also very commonly present with ADHD and suggests additional types of treatment.

• There is noncompliance. This problem can surface frequently in two ways. Older children may be responsible at home for taking their medications and forget or refuse to do so. I often ask, "Are you taking the medication every single day?" Diversion is also a potential problem from the parents or for an adolescent. Checking if the refills are occurring on time can provide a clue here, and some states have systems to check for duplicate prescriptions from multiple clinicians.

• Side effects are appearing as untreated ADHD. Sometimes medications are the problem, not the solution, and a failure to recognize this phenomenon can lead to unnecessary and sometimes harmful polypharmacy. Stimulants in some children can lead to increased agitation, anger outbursts, and impulsivity. Trying a medication holiday for several days can sometimes reveal the need to back off rather than add medications.

• Family is expecting improvement for non-ADHD symptoms. Asking what particular behaviors the family is hoping to improve can sometimes expose a situation in which parents expect change in non-ADHD domains. Unfortunately, there is no pill to make kids respect their parents more or want to do their homework. Being clear from the outset about what behaviors are and are not medication responsive can sometimes prevent this problem.

• There is substance abuse. In addition to the potential problem of abuse of the stimulants described previously, other substances such as cannabis can sabotage the benefits of medications.

• There is over-reliance on medications as the sole modality of treatment. ADHD is best treated using a wide range of strategies. Nonpharmacological interventions such as exercise, good nutrition and sleep, parent behavioral training, organizational help, regular reading, screen time reduction, and school supports are critical components of a comprehensive treatment approach.

• There is parental psychopathology. In our opinion, this area is one of the most frequently neglected aspects of child mental health treatment and can have huge implications. ADHD in particular is known to have very high heritability (similar to height). If a mother or father shares the condition, their struggles can frequently contribute to an environment that can exacerbate the child’s symptoms. A pattern in which the ADHD symptoms are more prominent at home compared with school is one clue to look in this direction. When addressing parental psychopathology, it can be important not to come off as blaming the parents for their child’s problems, but rather to convey how challenging dealing with ADHD can be as a parent and how they need to be functioning at their highest mental level as well.

Of course, sometimes the medication truly is not working, and it is time to try something else.

Dr. David C. Rettew is associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics, director of the child and adolescent psychiatry fellowship, and director of the pediatric psychiatry clinic at the University of Vermont, Burlington.

Welcome to a new column designed to provide practical advice regarding issues related to child mental health. It will be a joint effort, featuring contributions from several child psychiatrists working at the University of Vermont and the Vermont Center for Children, Youth, and Families. While psychopharmacology will certainly be a part of many of the columns, all of us here feel strongly that medications should be only one part of a comprehensive family-oriented plan. We encourage you to submit questions that you would like us address in future issues to [email protected].

Case summary

A 10-year-old boy presents for a follow-up appointment. He was diagnosed by another pediatrician in the practice 2 months ago with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and now returns to the office with continued symptoms and a complaint from the mother that medication "isn’t working." The boy was started on an extended-release preparation of methylphenidate at 18 mg to take each morning. The child is in the fifth grade and weighs 80 lb (36 kg). He lives with his mother and 8-year-old brother. The father is no longer involved in the patient’s life, which puts added stress on the mother. The diagnosis of ADHD was made by the pediatrician based upon the history, the child’s hyperactive and intrusive behavior in the office, and the results of a standardized rating scale that was completed by the mother, who now requests that the pediatrician "try something different."

Discussion

Many children and adolescents respond extremely well to ADHD medications. Some, however, do not, and the parental complaint that the "medication isn’t working" is a frequent expression heard in pediatrician offices across the country. It is also one of the primary reasons a family is referred to a child psychiatrist. In the course of performing hundreds of these consultations, I have found that there are several possibilities to consider before assuming the medication simply isn’t effective.

We will start with simpler problems and work our way toward more challenging reasons.

• The dose is too low. Methylphenidate often needs to be dosed over 1 mg/kg/day to be effective. If the patient reports minimal response to the medication while experiencing no side effects, an increase may certainly be reasonable.

• The medication is working but wearing off. Despite the advertisements of long-acting stimulants continuing their therapeutic effect for 10-12 hours, many children seem to lose the benefit of the medication much faster. Gathering some data from the school or asking the mother about weekend mornings compared with evenings can be useful. If indeed such a wear-off is found, adding a dose of an immediate-release stimulant in the early afternoon may help.

• Symptoms are being caused by something other than ADHD. Hyperactivity due to exposures such as lead may not change your management of the symptoms, but certainly could necessitate other types of intervention. Chronic sleep problems and inadequate nutrition, especially when it comes to breakfast, also should be queried and can lead to problems with concentration.

• There is psychiatric comorbidity. Unlike many differentials in other specialties, psychiatric differential diagnosis is often a matter of "and" rather than "or." Anxiety disorders, for example, can frequently masquerade as ADHD or be present in addition to ADHD. Oppositional behavior is also very commonly present with ADHD and suggests additional types of treatment.

• There is noncompliance. This problem can surface frequently in two ways. Older children may be responsible at home for taking their medications and forget or refuse to do so. I often ask, "Are you taking the medication every single day?" Diversion is also a potential problem from the parents or for an adolescent. Checking if the refills are occurring on time can provide a clue here, and some states have systems to check for duplicate prescriptions from multiple clinicians.

• Side effects are appearing as untreated ADHD. Sometimes medications are the problem, not the solution, and a failure to recognize this phenomenon can lead to unnecessary and sometimes harmful polypharmacy. Stimulants in some children can lead to increased agitation, anger outbursts, and impulsivity. Trying a medication holiday for several days can sometimes reveal the need to back off rather than add medications.

• Family is expecting improvement for non-ADHD symptoms. Asking what particular behaviors the family is hoping to improve can sometimes expose a situation in which parents expect change in non-ADHD domains. Unfortunately, there is no pill to make kids respect their parents more or want to do their homework. Being clear from the outset about what behaviors are and are not medication responsive can sometimes prevent this problem.

• There is substance abuse. In addition to the potential problem of abuse of the stimulants described previously, other substances such as cannabis can sabotage the benefits of medications.

• There is over-reliance on medications as the sole modality of treatment. ADHD is best treated using a wide range of strategies. Nonpharmacological interventions such as exercise, good nutrition and sleep, parent behavioral training, organizational help, regular reading, screen time reduction, and school supports are critical components of a comprehensive treatment approach.

• There is parental psychopathology. In our opinion, this area is one of the most frequently neglected aspects of child mental health treatment and can have huge implications. ADHD in particular is known to have very high heritability (similar to height). If a mother or father shares the condition, their struggles can frequently contribute to an environment that can exacerbate the child’s symptoms. A pattern in which the ADHD symptoms are more prominent at home compared with school is one clue to look in this direction. When addressing parental psychopathology, it can be important not to come off as blaming the parents for their child’s problems, but rather to convey how challenging dealing with ADHD can be as a parent and how they need to be functioning at their highest mental level as well.

Of course, sometimes the medication truly is not working, and it is time to try something else.

Dr. David C. Rettew is associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics, director of the child and adolescent psychiatry fellowship, and director of the pediatric psychiatry clinic at the University of Vermont, Burlington.

How can we effectively treat stress urinary incontinence without drugs or surgery?

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) and intravaginal electrical stimulation seem to be the best bets. PFMT increases urinary continence and improves symptoms of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review or randomized, controlled trials [RCTs]). PFMT also improves quality of life (QOL) (activity and psychological impact) (SOR: B, 1 RCT).

Intravaginal electrical stimulation increases urinary continence and improves SUI symptoms; percutaneous electrical stimulation also improves SUI symptoms and likely improves QOL measures (SOR: A, systematic review).

Magnetic stimulation doesn’t increase continence, has mixed effects on SUI symptoms, and produces no clinically meaningful improvement in QOL (SOR: B, heterogeneous RCTs with conflicting results). Vaginal cones don’t increase continence or QOL (SOR: B, 2 RCTs with methodologic flaws).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

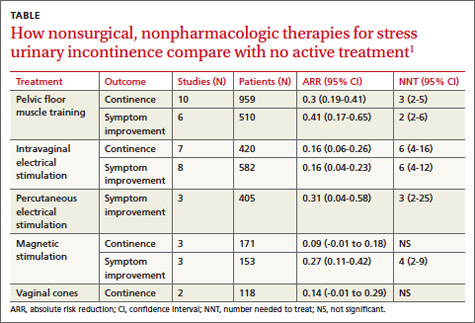

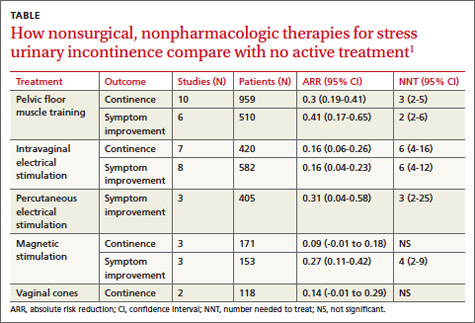

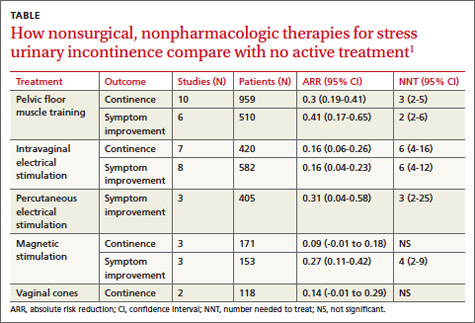

A systematic review by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality of adult female outpatients with SUI examined the effectiveness of PFMT, electrical stimulation, magnetic stimulation, and vaginal cones compared with no active treatment or sham treatment to produce continence (90% to 100% symptom reduction) or improve symptoms (at least 50% patient-reported symptom reduction).1 The TABLE summarizes the results.1 Investigators also assessed improvement in patient-reported QOL.

Pelvic floor muscle training improves continence, quality of life

A meta-analysis of 10 RCTs demonstrated that PFMT produced continence more often than placebo, and a meta-analysis of 6 RCTs found that PFMT improved SUI symptoms.1 PFMT regimens ranged in duration from 8 weeks to 6 months, including unsupervised treatment (8 to 12 repetitions, 3 to 10 times a day) and supervised treatment (as long as an hour, as often as 3 times a week).1

Both unsupervised and supervised PFMT produced similar results. One RCT evaluating QOL measures found that PFMT improved activity and reduced psychological impact (number needed to treat [NNT]=1; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1-2).1

Intravaginal electrical stimulation improves continence and symptoms

A meta-analysis of 7 RCTs found that intravaginal electrical stimulation increased continence compared with sham treatment.1 A meta-analysis of 8 RCTs found that intravaginal electrical stimulation also improved SUI symptoms.1 All of the trials used electrical stimulation at frequencies between 4 and 50 Hz for 15 to 20 minutes, 1 to 3 times daily for 4 to 15 weeks.

Percutaneous electrical stimulation improves symptoms

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs found that percutaneous electrical stimulation improved SUI symptoms compared with no active treatment. Four RCTs found that electrical stimulation improved QOL, although a meta-analysis couldn’t be performed because of clinical heterogeneity.1

Magnetic stimulation produces conflicting results

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs found that magnetic stimulation at frequencies of 10 to 18.5 Hz given over 1 to 8 weeks didn’t increase continence. A meta-analysis of an additional 3 RCTs concluded that magnetic stimulation improved continence, but the individual studies reported conflicting results and were heterogenous.1

Two RCTs evaluating QOL scores found conflicting results. One study found a mean difference of 3.9 points on the 100-point Incontinence Quality of Life Questionnaire (95% CI, 2.08-5.72; minimal clinically important difference rated 2-5 points).1

Vaginal cones are ineffective and not well-tolerated

Two RCTs found that vaginal cones didn’t improve continence or QOL compared with no treatment. Investigators reported high discontinuation rates and adverse effects with the cones, which weighed 20 to 70 g and were worn for 20 minutes a day for as long as 24 weeks.1

RECOMMENDATIONS

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends PFMT comprising at least 8 contractions 3 times daily for at least 3 months as first-line therapy for women with SUI.2 They don’t recommend electrical stimulation or intravaginal devices for women who can actively contract their pelvic floor muscles. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends PFMT as first-line therapy for women with SUI and states that PFMT is more effective than electrical stimulation or vaginal cones.3

1. Nonsurgical treatments for urinary incontinence in adult women: Diagnosis and comparative effectiveness. Executive summary. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Web site. Available at: http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/169/1021/CER36_Urinary-Incontinence_execsumm.pdf. Accessed March 19, 2014.

2. Urinary Incontinence: The management of urinary incontinence in women. NICE Clinical Guideline 171. London: NICE; 2006. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Web site. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/CG171. Accessed March 19, 2014.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Urinary incontinence in women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1533-1545.

AHIP; stress urinary incontinence; SUI; pelvic floor muscle training; PFMT; intravaginal electrical stimulation

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) and intravaginal electrical stimulation seem to be the best bets. PFMT increases urinary continence and improves symptoms of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review or randomized, controlled trials [RCTs]). PFMT also improves quality of life (QOL) (activity and psychological impact) (SOR: B, 1 RCT).

Intravaginal electrical stimulation increases urinary continence and improves SUI symptoms; percutaneous electrical stimulation also improves SUI symptoms and likely improves QOL measures (SOR: A, systematic review).

Magnetic stimulation doesn’t increase continence, has mixed effects on SUI symptoms, and produces no clinically meaningful improvement in QOL (SOR: B, heterogeneous RCTs with conflicting results). Vaginal cones don’t increase continence or QOL (SOR: B, 2 RCTs with methodologic flaws).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality of adult female outpatients with SUI examined the effectiveness of PFMT, electrical stimulation, magnetic stimulation, and vaginal cones compared with no active treatment or sham treatment to produce continence (90% to 100% symptom reduction) or improve symptoms (at least 50% patient-reported symptom reduction).1 The TABLE summarizes the results.1 Investigators also assessed improvement in patient-reported QOL.

Pelvic floor muscle training improves continence, quality of life

A meta-analysis of 10 RCTs demonstrated that PFMT produced continence more often than placebo, and a meta-analysis of 6 RCTs found that PFMT improved SUI symptoms.1 PFMT regimens ranged in duration from 8 weeks to 6 months, including unsupervised treatment (8 to 12 repetitions, 3 to 10 times a day) and supervised treatment (as long as an hour, as often as 3 times a week).1

Both unsupervised and supervised PFMT produced similar results. One RCT evaluating QOL measures found that PFMT improved activity and reduced psychological impact (number needed to treat [NNT]=1; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1-2).1

Intravaginal electrical stimulation improves continence and symptoms

A meta-analysis of 7 RCTs found that intravaginal electrical stimulation increased continence compared with sham treatment.1 A meta-analysis of 8 RCTs found that intravaginal electrical stimulation also improved SUI symptoms.1 All of the trials used electrical stimulation at frequencies between 4 and 50 Hz for 15 to 20 minutes, 1 to 3 times daily for 4 to 15 weeks.

Percutaneous electrical stimulation improves symptoms

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs found that percutaneous electrical stimulation improved SUI symptoms compared with no active treatment. Four RCTs found that electrical stimulation improved QOL, although a meta-analysis couldn’t be performed because of clinical heterogeneity.1

Magnetic stimulation produces conflicting results

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs found that magnetic stimulation at frequencies of 10 to 18.5 Hz given over 1 to 8 weeks didn’t increase continence. A meta-analysis of an additional 3 RCTs concluded that magnetic stimulation improved continence, but the individual studies reported conflicting results and were heterogenous.1

Two RCTs evaluating QOL scores found conflicting results. One study found a mean difference of 3.9 points on the 100-point Incontinence Quality of Life Questionnaire (95% CI, 2.08-5.72; minimal clinically important difference rated 2-5 points).1

Vaginal cones are ineffective and not well-tolerated

Two RCTs found that vaginal cones didn’t improve continence or QOL compared with no treatment. Investigators reported high discontinuation rates and adverse effects with the cones, which weighed 20 to 70 g and were worn for 20 minutes a day for as long as 24 weeks.1

RECOMMENDATIONS

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends PFMT comprising at least 8 contractions 3 times daily for at least 3 months as first-line therapy for women with SUI.2 They don’t recommend electrical stimulation or intravaginal devices for women who can actively contract their pelvic floor muscles. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends PFMT as first-line therapy for women with SUI and states that PFMT is more effective than electrical stimulation or vaginal cones.3

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) and intravaginal electrical stimulation seem to be the best bets. PFMT increases urinary continence and improves symptoms of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review or randomized, controlled trials [RCTs]). PFMT also improves quality of life (QOL) (activity and psychological impact) (SOR: B, 1 RCT).

Intravaginal electrical stimulation increases urinary continence and improves SUI symptoms; percutaneous electrical stimulation also improves SUI symptoms and likely improves QOL measures (SOR: A, systematic review).

Magnetic stimulation doesn’t increase continence, has mixed effects on SUI symptoms, and produces no clinically meaningful improvement in QOL (SOR: B, heterogeneous RCTs with conflicting results). Vaginal cones don’t increase continence or QOL (SOR: B, 2 RCTs with methodologic flaws).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality of adult female outpatients with SUI examined the effectiveness of PFMT, electrical stimulation, magnetic stimulation, and vaginal cones compared with no active treatment or sham treatment to produce continence (90% to 100% symptom reduction) or improve symptoms (at least 50% patient-reported symptom reduction).1 The TABLE summarizes the results.1 Investigators also assessed improvement in patient-reported QOL.

Pelvic floor muscle training improves continence, quality of life

A meta-analysis of 10 RCTs demonstrated that PFMT produced continence more often than placebo, and a meta-analysis of 6 RCTs found that PFMT improved SUI symptoms.1 PFMT regimens ranged in duration from 8 weeks to 6 months, including unsupervised treatment (8 to 12 repetitions, 3 to 10 times a day) and supervised treatment (as long as an hour, as often as 3 times a week).1

Both unsupervised and supervised PFMT produced similar results. One RCT evaluating QOL measures found that PFMT improved activity and reduced psychological impact (number needed to treat [NNT]=1; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1-2).1

Intravaginal electrical stimulation improves continence and symptoms

A meta-analysis of 7 RCTs found that intravaginal electrical stimulation increased continence compared with sham treatment.1 A meta-analysis of 8 RCTs found that intravaginal electrical stimulation also improved SUI symptoms.1 All of the trials used electrical stimulation at frequencies between 4 and 50 Hz for 15 to 20 minutes, 1 to 3 times daily for 4 to 15 weeks.

Percutaneous electrical stimulation improves symptoms

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs found that percutaneous electrical stimulation improved SUI symptoms compared with no active treatment. Four RCTs found that electrical stimulation improved QOL, although a meta-analysis couldn’t be performed because of clinical heterogeneity.1

Magnetic stimulation produces conflicting results

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs found that magnetic stimulation at frequencies of 10 to 18.5 Hz given over 1 to 8 weeks didn’t increase continence. A meta-analysis of an additional 3 RCTs concluded that magnetic stimulation improved continence, but the individual studies reported conflicting results and were heterogenous.1

Two RCTs evaluating QOL scores found conflicting results. One study found a mean difference of 3.9 points on the 100-point Incontinence Quality of Life Questionnaire (95% CI, 2.08-5.72; minimal clinically important difference rated 2-5 points).1

Vaginal cones are ineffective and not well-tolerated

Two RCTs found that vaginal cones didn’t improve continence or QOL compared with no treatment. Investigators reported high discontinuation rates and adverse effects with the cones, which weighed 20 to 70 g and were worn for 20 minutes a day for as long as 24 weeks.1

RECOMMENDATIONS

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends PFMT comprising at least 8 contractions 3 times daily for at least 3 months as first-line therapy for women with SUI.2 They don’t recommend electrical stimulation or intravaginal devices for women who can actively contract their pelvic floor muscles. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends PFMT as first-line therapy for women with SUI and states that PFMT is more effective than electrical stimulation or vaginal cones.3

1. Nonsurgical treatments for urinary incontinence in adult women: Diagnosis and comparative effectiveness. Executive summary. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Web site. Available at: http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/169/1021/CER36_Urinary-Incontinence_execsumm.pdf. Accessed March 19, 2014.

2. Urinary Incontinence: The management of urinary incontinence in women. NICE Clinical Guideline 171. London: NICE; 2006. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Web site. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/CG171. Accessed March 19, 2014.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Urinary incontinence in women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1533-1545.

1. Nonsurgical treatments for urinary incontinence in adult women: Diagnosis and comparative effectiveness. Executive summary. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Web site. Available at: http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/169/1021/CER36_Urinary-Incontinence_execsumm.pdf. Accessed March 19, 2014.

2. Urinary Incontinence: The management of urinary incontinence in women. NICE Clinical Guideline 171. London: NICE; 2006. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Web site. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/CG171. Accessed March 19, 2014.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Urinary incontinence in women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1533-1545.

AHIP; stress urinary incontinence; SUI; pelvic floor muscle training; PFMT; intravaginal electrical stimulation

AHIP; stress urinary incontinence; SUI; pelvic floor muscle training; PFMT; intravaginal electrical stimulation

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Pitfalls & pearls for 8 common lab tests

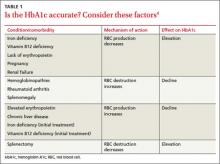

› When interpreting hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels, assess for anemia and other comorbidities that can significantly affect the lifespan of red blood cells and skew HbA1c test results. B

› Order nonfasting lipid panels for patients for whom fasting laboratory tests are difficult to obtain, as they have good clinical utility in screening and initial treatment. A

› Avoid routine thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) testing in asymptomatic adults; when testing is indicated, start with TSH. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Laboratory mistakes are not defined as diagnostic errors, but they contribute significantly to the thousands of medical errors that occur every year.1 Part of the problem: While accurate interpretation of lab tests often depends on the use of statistical concepts we all learned in medical training, it is difficult to find the time to incorporate these principles into a busy practice.