User login

Repair of Lumbar Dural Tears With a Suture Patch: Retrospective Single-Surgeon Case Series

A new perspective on immunotherapy

Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells represent a new approach to immune therapy in the treatment of hematologic malignancies. The clinical activity of chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) has been published in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).1 The results have been remarkable, although only a very small number of patients have been treated. We are anticipating further clinical trials and further development of this technology for more wide spread treatment opportunities for patients. The CARs that have been the most successful clinically have a similar basic make-up. They are genetically modified T cells. The T cells are collected from the patients through leukapheresis, then they are genetically

modified to express an extracellular recognition domain that is connected in the intracellular signaling domains of the T cells. Various extracellular recognition domains have been engineered, but the target of CD19 has proven most successful in patients with B cell malignancies, and CD19 is widely expressed on CLL and B-cell ALL. The cells are infused back into the patient, sometimes after undergoing chemotherapy to lymphodeplete the patient (which may improve the recovery and persistence of the cells after treatment). The infusion responses have been

dramatic in some patients, with severe cytokine storm described in reports, usually several days after treatment.2 This is thought to reflect the very rapid identification of the target protein and response of the T cells to the target. Those patients with acute leukemia who have responded also appear to respond rapidly, with disappearance of blasts from the peripheral blood within a month. The cells have been detectable in some patients for months after treatment.

Please click here to view the PDF.

Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells represent a new approach to immune therapy in the treatment of hematologic malignancies. The clinical activity of chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) has been published in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).1 The results have been remarkable, although only a very small number of patients have been treated. We are anticipating further clinical trials and further development of this technology for more wide spread treatment opportunities for patients. The CARs that have been the most successful clinically have a similar basic make-up. They are genetically modified T cells. The T cells are collected from the patients through leukapheresis, then they are genetically

modified to express an extracellular recognition domain that is connected in the intracellular signaling domains of the T cells. Various extracellular recognition domains have been engineered, but the target of CD19 has proven most successful in patients with B cell malignancies, and CD19 is widely expressed on CLL and B-cell ALL. The cells are infused back into the patient, sometimes after undergoing chemotherapy to lymphodeplete the patient (which may improve the recovery and persistence of the cells after treatment). The infusion responses have been

dramatic in some patients, with severe cytokine storm described in reports, usually several days after treatment.2 This is thought to reflect the very rapid identification of the target protein and response of the T cells to the target. Those patients with acute leukemia who have responded also appear to respond rapidly, with disappearance of blasts from the peripheral blood within a month. The cells have been detectable in some patients for months after treatment.

Please click here to view the PDF.

Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells represent a new approach to immune therapy in the treatment of hematologic malignancies. The clinical activity of chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) has been published in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).1 The results have been remarkable, although only a very small number of patients have been treated. We are anticipating further clinical trials and further development of this technology for more wide spread treatment opportunities for patients. The CARs that have been the most successful clinically have a similar basic make-up. They are genetically modified T cells. The T cells are collected from the patients through leukapheresis, then they are genetically

modified to express an extracellular recognition domain that is connected in the intracellular signaling domains of the T cells. Various extracellular recognition domains have been engineered, but the target of CD19 has proven most successful in patients with B cell malignancies, and CD19 is widely expressed on CLL and B-cell ALL. The cells are infused back into the patient, sometimes after undergoing chemotherapy to lymphodeplete the patient (which may improve the recovery and persistence of the cells after treatment). The infusion responses have been

dramatic in some patients, with severe cytokine storm described in reports, usually several days after treatment.2 This is thought to reflect the very rapid identification of the target protein and response of the T cells to the target. Those patients with acute leukemia who have responded also appear to respond rapidly, with disappearance of blasts from the peripheral blood within a month. The cells have been detectable in some patients for months after treatment.

Please click here to view the PDF.

Information Exchange Among Hospitals, Healthcare Providers Spikes

A new report that shows double-digit gains in hospitals’ electronic health information exchanges with other providers is a boon to healthcare, says one of SHM’s leading health information technology experts.

Published last month at HealthAffairs.org, “Hospital Electronic Health Information Exchange Grew Substantially in 2008-2012,” found that nearly 6 in 10 hospitals actively exchanged electronic health information with providers and hospitals outside of their own organization in 2012, a 41% jump since 2008.

Kendall Rogers, MD, FACP, SFHM, chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center in Albuquerque, says in an email to The Hospitalist that the growth is a good thing.

“Obviously, flow of information is never a bad thing for hospital medicine,” writes Dr. Rogers, chair of SHM’s Information Technology Executive Committee. “I think we have made more progress getting information back out to providers in the community, [and] helping with a safer transition (though we still have a long way to go), but we still lack significantly [in] getting info from providers or other hospitals on admission.”

The report notes that while more information has flowed among hospitals and providers, exchanges of clinical-care summaries and medication lists remain limited. The authors suggest that “new and ongoing policy initiatives and payment reforms may accelerate” the process.

Dr. Rogers adds that making systems more user-friendly may also encourage meaningful participation. “We have a health information exchange here in New Mexico that includes most hospitals”; however, he writes, “it is cumbersome and not routinely used, but definitely a step in the right direction.”

Visit our website for more information on health information technology.

A new report that shows double-digit gains in hospitals’ electronic health information exchanges with other providers is a boon to healthcare, says one of SHM’s leading health information technology experts.

Published last month at HealthAffairs.org, “Hospital Electronic Health Information Exchange Grew Substantially in 2008-2012,” found that nearly 6 in 10 hospitals actively exchanged electronic health information with providers and hospitals outside of their own organization in 2012, a 41% jump since 2008.

Kendall Rogers, MD, FACP, SFHM, chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center in Albuquerque, says in an email to The Hospitalist that the growth is a good thing.

“Obviously, flow of information is never a bad thing for hospital medicine,” writes Dr. Rogers, chair of SHM’s Information Technology Executive Committee. “I think we have made more progress getting information back out to providers in the community, [and] helping with a safer transition (though we still have a long way to go), but we still lack significantly [in] getting info from providers or other hospitals on admission.”

The report notes that while more information has flowed among hospitals and providers, exchanges of clinical-care summaries and medication lists remain limited. The authors suggest that “new and ongoing policy initiatives and payment reforms may accelerate” the process.

Dr. Rogers adds that making systems more user-friendly may also encourage meaningful participation. “We have a health information exchange here in New Mexico that includes most hospitals”; however, he writes, “it is cumbersome and not routinely used, but definitely a step in the right direction.”

Visit our website for more information on health information technology.

A new report that shows double-digit gains in hospitals’ electronic health information exchanges with other providers is a boon to healthcare, says one of SHM’s leading health information technology experts.

Published last month at HealthAffairs.org, “Hospital Electronic Health Information Exchange Grew Substantially in 2008-2012,” found that nearly 6 in 10 hospitals actively exchanged electronic health information with providers and hospitals outside of their own organization in 2012, a 41% jump since 2008.

Kendall Rogers, MD, FACP, SFHM, chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center in Albuquerque, says in an email to The Hospitalist that the growth is a good thing.

“Obviously, flow of information is never a bad thing for hospital medicine,” writes Dr. Rogers, chair of SHM’s Information Technology Executive Committee. “I think we have made more progress getting information back out to providers in the community, [and] helping with a safer transition (though we still have a long way to go), but we still lack significantly [in] getting info from providers or other hospitals on admission.”

The report notes that while more information has flowed among hospitals and providers, exchanges of clinical-care summaries and medication lists remain limited. The authors suggest that “new and ongoing policy initiatives and payment reforms may accelerate” the process.

Dr. Rogers adds that making systems more user-friendly may also encourage meaningful participation. “We have a health information exchange here in New Mexico that includes most hospitals”; however, he writes, “it is cumbersome and not routinely used, but definitely a step in the right direction.”

Visit our website for more information on health information technology.

Healthcare Cost Containment Not High Priority for Most Physicians

When it comes to controlling healthcare costs, only 36% of physicians agree that practicing physicians have a “major responsibility” to participate in cost containment, according to a recently published Journal of the American Medical Association study, "Views of U.S. Physicians About Controlling Health Care Costs.”

More than half of the 2,556 physicians who responded to a survey said trial lawyers, health insurance companies, hospitals and health systems, pharmaceutical and device manufacturers, and patients have a major responsibility for controlling healthcare costs.

In an accompanying editorial, Ezekiel Emanuel, MD, PhD, and Andrew Steinmetz, BA, of the department of medical ethics and health policy at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, labeled the responses as “somewhat discouraging” and “a denial of responsibility” by physicians about their role in bringing costs under control.

Christopher Moriates, MD, a hospitalist at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) who developed a cost-awareness curriculum for physicians and serves as co-chair of UCSF’s High Value Care Committee, calls the survey a snapshot of changing attitudes in medicine because it does not include medical students or residents who, he says, are more engaged in fighting wasteful spending.

“Younger physicians are growing up in a medical world that has stressed systems-thinking and teamwork,” Dr. Moriates says. “They are ready to take that major responsibility for our healthcare system. We just need to make sure that we are teaching them how.”

Visit our website for more information on controlling healthcare costs.

When it comes to controlling healthcare costs, only 36% of physicians agree that practicing physicians have a “major responsibility” to participate in cost containment, according to a recently published Journal of the American Medical Association study, "Views of U.S. Physicians About Controlling Health Care Costs.”

More than half of the 2,556 physicians who responded to a survey said trial lawyers, health insurance companies, hospitals and health systems, pharmaceutical and device manufacturers, and patients have a major responsibility for controlling healthcare costs.

In an accompanying editorial, Ezekiel Emanuel, MD, PhD, and Andrew Steinmetz, BA, of the department of medical ethics and health policy at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, labeled the responses as “somewhat discouraging” and “a denial of responsibility” by physicians about their role in bringing costs under control.

Christopher Moriates, MD, a hospitalist at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) who developed a cost-awareness curriculum for physicians and serves as co-chair of UCSF’s High Value Care Committee, calls the survey a snapshot of changing attitudes in medicine because it does not include medical students or residents who, he says, are more engaged in fighting wasteful spending.

“Younger physicians are growing up in a medical world that has stressed systems-thinking and teamwork,” Dr. Moriates says. “They are ready to take that major responsibility for our healthcare system. We just need to make sure that we are teaching them how.”

Visit our website for more information on controlling healthcare costs.

When it comes to controlling healthcare costs, only 36% of physicians agree that practicing physicians have a “major responsibility” to participate in cost containment, according to a recently published Journal of the American Medical Association study, "Views of U.S. Physicians About Controlling Health Care Costs.”

More than half of the 2,556 physicians who responded to a survey said trial lawyers, health insurance companies, hospitals and health systems, pharmaceutical and device manufacturers, and patients have a major responsibility for controlling healthcare costs.

In an accompanying editorial, Ezekiel Emanuel, MD, PhD, and Andrew Steinmetz, BA, of the department of medical ethics and health policy at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, labeled the responses as “somewhat discouraging” and “a denial of responsibility” by physicians about their role in bringing costs under control.

Christopher Moriates, MD, a hospitalist at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) who developed a cost-awareness curriculum for physicians and serves as co-chair of UCSF’s High Value Care Committee, calls the survey a snapshot of changing attitudes in medicine because it does not include medical students or residents who, he says, are more engaged in fighting wasteful spending.

“Younger physicians are growing up in a medical world that has stressed systems-thinking and teamwork,” Dr. Moriates says. “They are ready to take that major responsibility for our healthcare system. We just need to make sure that we are teaching them how.”

Visit our website for more information on controlling healthcare costs.

Hospitalists and PCPs, a potentially formidable force

We as hospitalists have been missing a huge piece of the puzzle when it comes to readmissions. With such a huge push to reduce the readmission rate at our hospitals and avoid the resultant penalties, have we been too internally focused?

In a recent article in, titled, "A primary care physician’s ideal transitions of care – where’s the evidence?" Dr. Ning Tang gives a PCP’s perspective on how outpatient providers can greatly facilitate our common goal of optimizing patients’ transition from hospital to home (J. Hosp. Med. 2013;8:472-7). After all, most of our patients do have a PCP, who has known them for a long time and who will have much more insight into their values and support systems, their idiosyncrasies, what they will and won’t follow through on, and even their pet peeves. When we who may interact with them for only a couple of hours try to use a cookie-cutter approach to care, it simply may not be received well, if at all.

Dr. Tang suggests that PCP communication begins at the point of admission. While some ERs and admissions offices have automated systems in place to contact PCPs when their patients are admitted, for most of us, this communication comes by way of a phone call or as an electronic or faxed copy of the admission note. While I do not think anyone would argue that early involvement by the PCP has a tremendous potential to improve both the patient’s transition from home into the hospital and vice versa, in real life doctors are frequently too busy and stressed to meet this basic expectation. Hopefully that will change in the future.

Some PCPs have no desire to talk with a hospitalist each time a patient is admitted because it takes them away from seeing patients in their office. Yet others would welcome the opportunity for early involvement. It is an individual preference, one we should strive to understand in order to optimize our patients’ experience – and the experience of the physician who has entrusted patients to us.

Medication reconciliation is but the tip of the iceberg of issues the PCP could assist with, and the realization that their patient may not actually be taking all the medications they prescribed (or taking medications they didn’t) can help improve the level of care patients receive once discharged.

In the midst of brutal day, we have all had medication nightmares that make us cringe, as we slowly count to three while practicing deep-breathing exercises. You know, the patient who pulls out a crumpled list of medications. Some have been crossed out and others are too illegible to read. Then, the spouse pulls out another "updated" list, and the physician and pharmacist each have their own list, and no two lists are exactly alike.

But these nightmares could soon end. I was surprised to find out that in January of this year, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services introduced new codes to reimburse primary care providers for care coordination after hospital discharge. These codes, 99495 and 99496 reimburse a substantial fee, carrying weights of 3.96 and 5.81 RVUs (relative value units), respectively, a lot more than we typically make for even an extended history and physical.

So, I have to agree with Dr. Tang. We, PCPs and hospitalists alike, are missing a huge potential to optimize care transitions, decrease our readmission rate, and lower medical costs. Dialogue needs to take place between hospitalist and the PCPs they serve to bridge some of these gaps.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

We as hospitalists have been missing a huge piece of the puzzle when it comes to readmissions. With such a huge push to reduce the readmission rate at our hospitals and avoid the resultant penalties, have we been too internally focused?

In a recent article in, titled, "A primary care physician’s ideal transitions of care – where’s the evidence?" Dr. Ning Tang gives a PCP’s perspective on how outpatient providers can greatly facilitate our common goal of optimizing patients’ transition from hospital to home (J. Hosp. Med. 2013;8:472-7). After all, most of our patients do have a PCP, who has known them for a long time and who will have much more insight into their values and support systems, their idiosyncrasies, what they will and won’t follow through on, and even their pet peeves. When we who may interact with them for only a couple of hours try to use a cookie-cutter approach to care, it simply may not be received well, if at all.

Dr. Tang suggests that PCP communication begins at the point of admission. While some ERs and admissions offices have automated systems in place to contact PCPs when their patients are admitted, for most of us, this communication comes by way of a phone call or as an electronic or faxed copy of the admission note. While I do not think anyone would argue that early involvement by the PCP has a tremendous potential to improve both the patient’s transition from home into the hospital and vice versa, in real life doctors are frequently too busy and stressed to meet this basic expectation. Hopefully that will change in the future.

Some PCPs have no desire to talk with a hospitalist each time a patient is admitted because it takes them away from seeing patients in their office. Yet others would welcome the opportunity for early involvement. It is an individual preference, one we should strive to understand in order to optimize our patients’ experience – and the experience of the physician who has entrusted patients to us.

Medication reconciliation is but the tip of the iceberg of issues the PCP could assist with, and the realization that their patient may not actually be taking all the medications they prescribed (or taking medications they didn’t) can help improve the level of care patients receive once discharged.

In the midst of brutal day, we have all had medication nightmares that make us cringe, as we slowly count to three while practicing deep-breathing exercises. You know, the patient who pulls out a crumpled list of medications. Some have been crossed out and others are too illegible to read. Then, the spouse pulls out another "updated" list, and the physician and pharmacist each have their own list, and no two lists are exactly alike.

But these nightmares could soon end. I was surprised to find out that in January of this year, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services introduced new codes to reimburse primary care providers for care coordination after hospital discharge. These codes, 99495 and 99496 reimburse a substantial fee, carrying weights of 3.96 and 5.81 RVUs (relative value units), respectively, a lot more than we typically make for even an extended history and physical.

So, I have to agree with Dr. Tang. We, PCPs and hospitalists alike, are missing a huge potential to optimize care transitions, decrease our readmission rate, and lower medical costs. Dialogue needs to take place between hospitalist and the PCPs they serve to bridge some of these gaps.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

We as hospitalists have been missing a huge piece of the puzzle when it comes to readmissions. With such a huge push to reduce the readmission rate at our hospitals and avoid the resultant penalties, have we been too internally focused?

In a recent article in, titled, "A primary care physician’s ideal transitions of care – where’s the evidence?" Dr. Ning Tang gives a PCP’s perspective on how outpatient providers can greatly facilitate our common goal of optimizing patients’ transition from hospital to home (J. Hosp. Med. 2013;8:472-7). After all, most of our patients do have a PCP, who has known them for a long time and who will have much more insight into their values and support systems, their idiosyncrasies, what they will and won’t follow through on, and even their pet peeves. When we who may interact with them for only a couple of hours try to use a cookie-cutter approach to care, it simply may not be received well, if at all.

Dr. Tang suggests that PCP communication begins at the point of admission. While some ERs and admissions offices have automated systems in place to contact PCPs when their patients are admitted, for most of us, this communication comes by way of a phone call or as an electronic or faxed copy of the admission note. While I do not think anyone would argue that early involvement by the PCP has a tremendous potential to improve both the patient’s transition from home into the hospital and vice versa, in real life doctors are frequently too busy and stressed to meet this basic expectation. Hopefully that will change in the future.

Some PCPs have no desire to talk with a hospitalist each time a patient is admitted because it takes them away from seeing patients in their office. Yet others would welcome the opportunity for early involvement. It is an individual preference, one we should strive to understand in order to optimize our patients’ experience – and the experience of the physician who has entrusted patients to us.

Medication reconciliation is but the tip of the iceberg of issues the PCP could assist with, and the realization that their patient may not actually be taking all the medications they prescribed (or taking medications they didn’t) can help improve the level of care patients receive once discharged.

In the midst of brutal day, we have all had medication nightmares that make us cringe, as we slowly count to three while practicing deep-breathing exercises. You know, the patient who pulls out a crumpled list of medications. Some have been crossed out and others are too illegible to read. Then, the spouse pulls out another "updated" list, and the physician and pharmacist each have their own list, and no two lists are exactly alike.

But these nightmares could soon end. I was surprised to find out that in January of this year, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services introduced new codes to reimburse primary care providers for care coordination after hospital discharge. These codes, 99495 and 99496 reimburse a substantial fee, carrying weights of 3.96 and 5.81 RVUs (relative value units), respectively, a lot more than we typically make for even an extended history and physical.

So, I have to agree with Dr. Tang. We, PCPs and hospitalists alike, are missing a huge potential to optimize care transitions, decrease our readmission rate, and lower medical costs. Dialogue needs to take place between hospitalist and the PCPs they serve to bridge some of these gaps.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

Ethnic Differences in Hospice Enrollment

Studies have documented the persisting lower rates of hospice enrollment among ethnic minority groups.[1, 2] Given the positive outcomes related to hospice enrollment,[3] investigating interventions that may reduce these disparities is critical.

Inpatient palliative care (IPC) programs were developed to improve pain and symptom management, provide patients with holistic and comprehensive prognosis and treatment options, and help patient and families clarify goals of care.[4] Although significant evidence of IPC program effectiveness in improving patient outcomes exists,[5] studies have not examined the ability of IPC programs to diminish ethnic disparities in access to hospice. We conducted a retrospective cohort study to determine if ethnic differences in hospice enrollment are experienced among patients following receipt of IPC consultation.

METHODS

A retrospective study was conducted in a nonprofit health maintenance organization medical center. The sample included seriously ill patients aged 65 years and over who received an IPC consultation and survived to hospital discharge. Data were collected from IPC databases, IPC consultation checklist (which included recording of code status discussion), and electronic medical records. The IPC team recorded discharge disposition including discharge to hospice care, home‐based palliative care (a standard program similar to hospice but offered for patients with an estimated prognosis of 1 year or less and without the caveat of foregoing curative care),[6] home with home healthcare, nursing facility, and home with standard outpatient care. Ethnicity was collected via patient report.

2 and t tests were conducted to compare those admitted to hospice with those who were not. We used logistic regression to determine the effects of ethnicity on enrollment in hospice, adjusting for demographics and clinical factors. We conducted analysis using IBM SPSS 19 (IBM, Armonk, NY).

FINDINGS

From 2007 to 2009, 408 patients received IPC consults and were subsequently discharged from the hospital. Forty‐four had missing data on ethnicity or discharge disposition, leaving 364 in the analytic sample. The mean age was 80.1 years (standard deviation [SD]=8.2), and 48.9% were female. The sample was diverse; 42.6% were white, 25.5% Latino, 23.1% black, and 8.8% of other ethnic background. Primary diagnosis included cancer (33.8%), congestive heart failure (CHF) (17.4%), coronary artery disease (12.6%), dementia (12.4%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (6%), cerebral vascular accident (CVA) (5.2%), and other conditions (13.6%). More than half (57.7%) were discharged to hospice, 15.4% to home‐based palliative care,[6] 14.6% to a nursing facility, 8.2% to home with usual outpatient care, and 4.1% to home with home healthcare. Code status was discussed by the IPC team among 81% of the patients, with no difference between ethnic groups.

Those discharged to hospice were older (80.8, SD=8.4 vs 79.1, SD=7.8), more likely to have cancer (71.5%) or CVA (79.5%) and less likely to have end stage renal disease (28.6%) or CHF (39%), and more likely to have had a code discussion (85.8%). There were no differences between hospice users and nonusers in gender, marital status, ethnicity, and number of chronic conditions (Table 1).

| Variable | All, N=364 | Hospice Users, n=210 | Nonhospice Users, n=154 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 80.1 (8.2) | 80.8 (8.4) | 79.1 (7.8) | 0.049 |

| Gender (female), % | 48.9 | 56.2 | 43.8 | 0.568 |

| Ethnicity, % | 0.702 | |||

| White | 42.6 | 43.3 | 41.6 | |

| Latino | 25.5 | 27.1 | 23.4 | |

| African American | 23.1 | 21.4 | 25.3 | |

| Other | 8.8 | 8.1 | 9.7 | |

| Marital status, % | 0.809 | |||

| Married | 45.6 | 43.8 | 48.1 | |

| Widowed | 36.0 | 38.1 | 33.1 | |

| Divorced | 7.7 | 7.6 | 7.8 | |

| Other | 7.7 | 7.6 | 7.8 | |

| Missing | 3.0 | 2.9 | 3.2 | |

| Diagnosis, % | 0.001 | |||

| Cancer | 33.8 | 42.1 | 22.9 | |

| CHF | 16.2 | 11.0 | 23.5 | |

| CAD | 12.6 | 12.4 | 13.1 | |

| Dementia | 12.4 | 12.4 | 12.4 | |

| COPD | 6.0 | 5.3 | 7.2 | |

| CVA | 5.2 | 7.2 | 2.6 | |

| Other | 13.6 | 9.6 | 18.3 | |

| Number of chronic conditions, mean (SD) | 1.0 | 1.7 (0.8) | 1.7 (0.9) | 0.949 |

| Code status discussed, % | 81.1 | 87.0 | 72.8 | 0.001 |

Significant differences between hospice users and nonusers were controlled in a regression adjusting for age, gender, marital status, and number of chronic conditions. Compared to whites, no significant differences in hospice use were found for blacks (odds ratio [OR]: 0.67; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.37‐1.21), Latinos (OR: 1.24; 95% CI: 0.68‐2.25), or other ethnic groups (OR: 0.78; 95% CI: 0.34‐1.56). Compared with other diagnoses, those with cancer (OR: 3.66; 95% CI: 1.77‐7.59) and older patients (OR: 1.05; 95% CI: 1.01‐1.08) were significantly more likely to receive hospice care following IPC consult. Those discussing code status were twice as likely to be discharged to hospice (OR: 2.14; 95% CI: 1.20‐3.79).

DISCUSSION

This study found similar rates of hospice enrollment following IPC consult among Latinos, blacks, and other ethnic groups as compared with whites. Others found comparable rates of advance directive completion between whites and African Americans following IPC consultation,[7]and that IPC intensity resulting in a plan of care was highly associated with receipt of hospice care.[8] Likewise, our study found that discussion of code status, another marker of intensity, was positively associated with hospice use.

Our findings among patients receiving IPC consultation contrast with previous studies examining ethnic variation in hospice use among general samples of decedents. A study of California dual eligibles found that blacks were 26% and Asians 34% less likely than whites to use hospice. Others have found similar results among patients with CHF and lung cancer.[9, 10]

Misconceptions and lack of awareness, knowledge, and trust in healthcare providers serve as barriers to hospice care for minorities.[11, 12] IPC consultations may overcome these barriers by discussing goals of care including discussing the condition, eliciting patient/family understanding of the condition, and presenting options for code status.

This study employed a single‐cohort design without a comparison group. It was conducted within a health maintenance organization with strong hospice and palliative care programs and may not represent other settings. Nevertheless, this study provides promise for IPC consultation to increase equitable access to hospice care among minority groups. Further studies are needed to confirm the preliminary findings reported here.

Disclosures: Supported in part by a career development award from the National Palliative Care Research Center and by a grant from the Archstone Foundation. Evie Vesper and Dr. Rebecca Goldstein were employees of the healthcare organization at the time of the study. Susan Enguidanos received compensation for project evaluation during the original study. The sponsors had no role in the design, implementation, or analysis of the study. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , . Ethnic variation in site of death among Medicaid/Medicare dually eligible older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(8):1411–1416.

- . Racial/ethnic disparities in hospice care: a systematic review. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(5):763–768.

- . The Medicare hospice benefit: 15 years of success. J Palliat Med. 1998;1(2):139–146.

- . Palliative care in hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(1):21–28.

- , , , et al. Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: a randomized control trial. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(2):180–190.

- , , , et al. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: results of a randomized trial of in‐home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(7):993–1000.

- , , , et al. Ethnicity, race, and advance directives in an inpatient palliative care consultation service. Palliat Support Care. 2012;6(1):1–7.

- , , . Hospice referrals and code status: outcomes of inpatient palliative care consultations among Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42(4):557–564.

- , , , , . Racial differences in hospice use and patterns of care after enrollment in hospice among Medicare beneficiaries with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2012;163(6):987–993.

- , , , et al. Racial disparities in length of stay in hospice care by tumor stage in a large elderly cohort with non‐small cell lung cancer. Palliat Med. 2012;26(1):61–71.

- , , , , . Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about end‐of‐life care among inner‐city African Americans and Latino/Hispanic Americans. J Palliat Med. 2004;7(2):247–256.

- , , . Does caregiver knowledge matter for hospice enrollment and beyond? Pilot study of minority hospice patients. Am J Hospice Palliat Med. 2009;26(3):165–171.

Studies have documented the persisting lower rates of hospice enrollment among ethnic minority groups.[1, 2] Given the positive outcomes related to hospice enrollment,[3] investigating interventions that may reduce these disparities is critical.

Inpatient palliative care (IPC) programs were developed to improve pain and symptom management, provide patients with holistic and comprehensive prognosis and treatment options, and help patient and families clarify goals of care.[4] Although significant evidence of IPC program effectiveness in improving patient outcomes exists,[5] studies have not examined the ability of IPC programs to diminish ethnic disparities in access to hospice. We conducted a retrospective cohort study to determine if ethnic differences in hospice enrollment are experienced among patients following receipt of IPC consultation.

METHODS

A retrospective study was conducted in a nonprofit health maintenance organization medical center. The sample included seriously ill patients aged 65 years and over who received an IPC consultation and survived to hospital discharge. Data were collected from IPC databases, IPC consultation checklist (which included recording of code status discussion), and electronic medical records. The IPC team recorded discharge disposition including discharge to hospice care, home‐based palliative care (a standard program similar to hospice but offered for patients with an estimated prognosis of 1 year or less and without the caveat of foregoing curative care),[6] home with home healthcare, nursing facility, and home with standard outpatient care. Ethnicity was collected via patient report.

2 and t tests were conducted to compare those admitted to hospice with those who were not. We used logistic regression to determine the effects of ethnicity on enrollment in hospice, adjusting for demographics and clinical factors. We conducted analysis using IBM SPSS 19 (IBM, Armonk, NY).

FINDINGS

From 2007 to 2009, 408 patients received IPC consults and were subsequently discharged from the hospital. Forty‐four had missing data on ethnicity or discharge disposition, leaving 364 in the analytic sample. The mean age was 80.1 years (standard deviation [SD]=8.2), and 48.9% were female. The sample was diverse; 42.6% were white, 25.5% Latino, 23.1% black, and 8.8% of other ethnic background. Primary diagnosis included cancer (33.8%), congestive heart failure (CHF) (17.4%), coronary artery disease (12.6%), dementia (12.4%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (6%), cerebral vascular accident (CVA) (5.2%), and other conditions (13.6%). More than half (57.7%) were discharged to hospice, 15.4% to home‐based palliative care,[6] 14.6% to a nursing facility, 8.2% to home with usual outpatient care, and 4.1% to home with home healthcare. Code status was discussed by the IPC team among 81% of the patients, with no difference between ethnic groups.

Those discharged to hospice were older (80.8, SD=8.4 vs 79.1, SD=7.8), more likely to have cancer (71.5%) or CVA (79.5%) and less likely to have end stage renal disease (28.6%) or CHF (39%), and more likely to have had a code discussion (85.8%). There were no differences between hospice users and nonusers in gender, marital status, ethnicity, and number of chronic conditions (Table 1).

| Variable | All, N=364 | Hospice Users, n=210 | Nonhospice Users, n=154 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 80.1 (8.2) | 80.8 (8.4) | 79.1 (7.8) | 0.049 |

| Gender (female), % | 48.9 | 56.2 | 43.8 | 0.568 |

| Ethnicity, % | 0.702 | |||

| White | 42.6 | 43.3 | 41.6 | |

| Latino | 25.5 | 27.1 | 23.4 | |

| African American | 23.1 | 21.4 | 25.3 | |

| Other | 8.8 | 8.1 | 9.7 | |

| Marital status, % | 0.809 | |||

| Married | 45.6 | 43.8 | 48.1 | |

| Widowed | 36.0 | 38.1 | 33.1 | |

| Divorced | 7.7 | 7.6 | 7.8 | |

| Other | 7.7 | 7.6 | 7.8 | |

| Missing | 3.0 | 2.9 | 3.2 | |

| Diagnosis, % | 0.001 | |||

| Cancer | 33.8 | 42.1 | 22.9 | |

| CHF | 16.2 | 11.0 | 23.5 | |

| CAD | 12.6 | 12.4 | 13.1 | |

| Dementia | 12.4 | 12.4 | 12.4 | |

| COPD | 6.0 | 5.3 | 7.2 | |

| CVA | 5.2 | 7.2 | 2.6 | |

| Other | 13.6 | 9.6 | 18.3 | |

| Number of chronic conditions, mean (SD) | 1.0 | 1.7 (0.8) | 1.7 (0.9) | 0.949 |

| Code status discussed, % | 81.1 | 87.0 | 72.8 | 0.001 |

Significant differences between hospice users and nonusers were controlled in a regression adjusting for age, gender, marital status, and number of chronic conditions. Compared to whites, no significant differences in hospice use were found for blacks (odds ratio [OR]: 0.67; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.37‐1.21), Latinos (OR: 1.24; 95% CI: 0.68‐2.25), or other ethnic groups (OR: 0.78; 95% CI: 0.34‐1.56). Compared with other diagnoses, those with cancer (OR: 3.66; 95% CI: 1.77‐7.59) and older patients (OR: 1.05; 95% CI: 1.01‐1.08) were significantly more likely to receive hospice care following IPC consult. Those discussing code status were twice as likely to be discharged to hospice (OR: 2.14; 95% CI: 1.20‐3.79).

DISCUSSION

This study found similar rates of hospice enrollment following IPC consult among Latinos, blacks, and other ethnic groups as compared with whites. Others found comparable rates of advance directive completion between whites and African Americans following IPC consultation,[7]and that IPC intensity resulting in a plan of care was highly associated with receipt of hospice care.[8] Likewise, our study found that discussion of code status, another marker of intensity, was positively associated with hospice use.

Our findings among patients receiving IPC consultation contrast with previous studies examining ethnic variation in hospice use among general samples of decedents. A study of California dual eligibles found that blacks were 26% and Asians 34% less likely than whites to use hospice. Others have found similar results among patients with CHF and lung cancer.[9, 10]

Misconceptions and lack of awareness, knowledge, and trust in healthcare providers serve as barriers to hospice care for minorities.[11, 12] IPC consultations may overcome these barriers by discussing goals of care including discussing the condition, eliciting patient/family understanding of the condition, and presenting options for code status.

This study employed a single‐cohort design without a comparison group. It was conducted within a health maintenance organization with strong hospice and palliative care programs and may not represent other settings. Nevertheless, this study provides promise for IPC consultation to increase equitable access to hospice care among minority groups. Further studies are needed to confirm the preliminary findings reported here.

Disclosures: Supported in part by a career development award from the National Palliative Care Research Center and by a grant from the Archstone Foundation. Evie Vesper and Dr. Rebecca Goldstein were employees of the healthcare organization at the time of the study. Susan Enguidanos received compensation for project evaluation during the original study. The sponsors had no role in the design, implementation, or analysis of the study. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Studies have documented the persisting lower rates of hospice enrollment among ethnic minority groups.[1, 2] Given the positive outcomes related to hospice enrollment,[3] investigating interventions that may reduce these disparities is critical.

Inpatient palliative care (IPC) programs were developed to improve pain and symptom management, provide patients with holistic and comprehensive prognosis and treatment options, and help patient and families clarify goals of care.[4] Although significant evidence of IPC program effectiveness in improving patient outcomes exists,[5] studies have not examined the ability of IPC programs to diminish ethnic disparities in access to hospice. We conducted a retrospective cohort study to determine if ethnic differences in hospice enrollment are experienced among patients following receipt of IPC consultation.

METHODS

A retrospective study was conducted in a nonprofit health maintenance organization medical center. The sample included seriously ill patients aged 65 years and over who received an IPC consultation and survived to hospital discharge. Data were collected from IPC databases, IPC consultation checklist (which included recording of code status discussion), and electronic medical records. The IPC team recorded discharge disposition including discharge to hospice care, home‐based palliative care (a standard program similar to hospice but offered for patients with an estimated prognosis of 1 year or less and without the caveat of foregoing curative care),[6] home with home healthcare, nursing facility, and home with standard outpatient care. Ethnicity was collected via patient report.

2 and t tests were conducted to compare those admitted to hospice with those who were not. We used logistic regression to determine the effects of ethnicity on enrollment in hospice, adjusting for demographics and clinical factors. We conducted analysis using IBM SPSS 19 (IBM, Armonk, NY).

FINDINGS

From 2007 to 2009, 408 patients received IPC consults and were subsequently discharged from the hospital. Forty‐four had missing data on ethnicity or discharge disposition, leaving 364 in the analytic sample. The mean age was 80.1 years (standard deviation [SD]=8.2), and 48.9% were female. The sample was diverse; 42.6% were white, 25.5% Latino, 23.1% black, and 8.8% of other ethnic background. Primary diagnosis included cancer (33.8%), congestive heart failure (CHF) (17.4%), coronary artery disease (12.6%), dementia (12.4%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (6%), cerebral vascular accident (CVA) (5.2%), and other conditions (13.6%). More than half (57.7%) were discharged to hospice, 15.4% to home‐based palliative care,[6] 14.6% to a nursing facility, 8.2% to home with usual outpatient care, and 4.1% to home with home healthcare. Code status was discussed by the IPC team among 81% of the patients, with no difference between ethnic groups.

Those discharged to hospice were older (80.8, SD=8.4 vs 79.1, SD=7.8), more likely to have cancer (71.5%) or CVA (79.5%) and less likely to have end stage renal disease (28.6%) or CHF (39%), and more likely to have had a code discussion (85.8%). There were no differences between hospice users and nonusers in gender, marital status, ethnicity, and number of chronic conditions (Table 1).

| Variable | All, N=364 | Hospice Users, n=210 | Nonhospice Users, n=154 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 80.1 (8.2) | 80.8 (8.4) | 79.1 (7.8) | 0.049 |

| Gender (female), % | 48.9 | 56.2 | 43.8 | 0.568 |

| Ethnicity, % | 0.702 | |||

| White | 42.6 | 43.3 | 41.6 | |

| Latino | 25.5 | 27.1 | 23.4 | |

| African American | 23.1 | 21.4 | 25.3 | |

| Other | 8.8 | 8.1 | 9.7 | |

| Marital status, % | 0.809 | |||

| Married | 45.6 | 43.8 | 48.1 | |

| Widowed | 36.0 | 38.1 | 33.1 | |

| Divorced | 7.7 | 7.6 | 7.8 | |

| Other | 7.7 | 7.6 | 7.8 | |

| Missing | 3.0 | 2.9 | 3.2 | |

| Diagnosis, % | 0.001 | |||

| Cancer | 33.8 | 42.1 | 22.9 | |

| CHF | 16.2 | 11.0 | 23.5 | |

| CAD | 12.6 | 12.4 | 13.1 | |

| Dementia | 12.4 | 12.4 | 12.4 | |

| COPD | 6.0 | 5.3 | 7.2 | |

| CVA | 5.2 | 7.2 | 2.6 | |

| Other | 13.6 | 9.6 | 18.3 | |

| Number of chronic conditions, mean (SD) | 1.0 | 1.7 (0.8) | 1.7 (0.9) | 0.949 |

| Code status discussed, % | 81.1 | 87.0 | 72.8 | 0.001 |

Significant differences between hospice users and nonusers were controlled in a regression adjusting for age, gender, marital status, and number of chronic conditions. Compared to whites, no significant differences in hospice use were found for blacks (odds ratio [OR]: 0.67; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.37‐1.21), Latinos (OR: 1.24; 95% CI: 0.68‐2.25), or other ethnic groups (OR: 0.78; 95% CI: 0.34‐1.56). Compared with other diagnoses, those with cancer (OR: 3.66; 95% CI: 1.77‐7.59) and older patients (OR: 1.05; 95% CI: 1.01‐1.08) were significantly more likely to receive hospice care following IPC consult. Those discussing code status were twice as likely to be discharged to hospice (OR: 2.14; 95% CI: 1.20‐3.79).

DISCUSSION

This study found similar rates of hospice enrollment following IPC consult among Latinos, blacks, and other ethnic groups as compared with whites. Others found comparable rates of advance directive completion between whites and African Americans following IPC consultation,[7]and that IPC intensity resulting in a plan of care was highly associated with receipt of hospice care.[8] Likewise, our study found that discussion of code status, another marker of intensity, was positively associated with hospice use.

Our findings among patients receiving IPC consultation contrast with previous studies examining ethnic variation in hospice use among general samples of decedents. A study of California dual eligibles found that blacks were 26% and Asians 34% less likely than whites to use hospice. Others have found similar results among patients with CHF and lung cancer.[9, 10]

Misconceptions and lack of awareness, knowledge, and trust in healthcare providers serve as barriers to hospice care for minorities.[11, 12] IPC consultations may overcome these barriers by discussing goals of care including discussing the condition, eliciting patient/family understanding of the condition, and presenting options for code status.

This study employed a single‐cohort design without a comparison group. It was conducted within a health maintenance organization with strong hospice and palliative care programs and may not represent other settings. Nevertheless, this study provides promise for IPC consultation to increase equitable access to hospice care among minority groups. Further studies are needed to confirm the preliminary findings reported here.

Disclosures: Supported in part by a career development award from the National Palliative Care Research Center and by a grant from the Archstone Foundation. Evie Vesper and Dr. Rebecca Goldstein were employees of the healthcare organization at the time of the study. Susan Enguidanos received compensation for project evaluation during the original study. The sponsors had no role in the design, implementation, or analysis of the study. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , . Ethnic variation in site of death among Medicaid/Medicare dually eligible older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(8):1411–1416.

- . Racial/ethnic disparities in hospice care: a systematic review. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(5):763–768.

- . The Medicare hospice benefit: 15 years of success. J Palliat Med. 1998;1(2):139–146.

- . Palliative care in hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(1):21–28.

- , , , et al. Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: a randomized control trial. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(2):180–190.

- , , , et al. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: results of a randomized trial of in‐home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(7):993–1000.

- , , , et al. Ethnicity, race, and advance directives in an inpatient palliative care consultation service. Palliat Support Care. 2012;6(1):1–7.

- , , . Hospice referrals and code status: outcomes of inpatient palliative care consultations among Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42(4):557–564.

- , , , , . Racial differences in hospice use and patterns of care after enrollment in hospice among Medicare beneficiaries with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2012;163(6):987–993.

- , , , et al. Racial disparities in length of stay in hospice care by tumor stage in a large elderly cohort with non‐small cell lung cancer. Palliat Med. 2012;26(1):61–71.

- , , , , . Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about end‐of‐life care among inner‐city African Americans and Latino/Hispanic Americans. J Palliat Med. 2004;7(2):247–256.

- , , . Does caregiver knowledge matter for hospice enrollment and beyond? Pilot study of minority hospice patients. Am J Hospice Palliat Med. 2009;26(3):165–171.

- , , . Ethnic variation in site of death among Medicaid/Medicare dually eligible older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(8):1411–1416.

- . Racial/ethnic disparities in hospice care: a systematic review. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(5):763–768.

- . The Medicare hospice benefit: 15 years of success. J Palliat Med. 1998;1(2):139–146.

- . Palliative care in hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(1):21–28.

- , , , et al. Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: a randomized control trial. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(2):180–190.

- , , , et al. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: results of a randomized trial of in‐home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(7):993–1000.

- , , , et al. Ethnicity, race, and advance directives in an inpatient palliative care consultation service. Palliat Support Care. 2012;6(1):1–7.

- , , . Hospice referrals and code status: outcomes of inpatient palliative care consultations among Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42(4):557–564.

- , , , , . Racial differences in hospice use and patterns of care after enrollment in hospice among Medicare beneficiaries with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2012;163(6):987–993.

- , , , et al. Racial disparities in length of stay in hospice care by tumor stage in a large elderly cohort with non‐small cell lung cancer. Palliat Med. 2012;26(1):61–71.

- , , , , . Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about end‐of‐life care among inner‐city African Americans and Latino/Hispanic Americans. J Palliat Med. 2004;7(2):247–256.

- , , . Does caregiver knowledge matter for hospice enrollment and beyond? Pilot study of minority hospice patients. Am J Hospice Palliat Med. 2009;26(3):165–171.

Drug Resistance in Pneumonia and BSI

Administration of initially appropriate antimicrobial therapy represents a key determinant of outcome in patients with severe infection.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9] The variable patterns of antimicrobial resistance seen between and within healthcare institutions complicate the process of antibiotic selection. Although much attention has historically focused on Staphylococcus aureus, resistance among Gram‐negative pathogens has emerged as a major challenge in the care of hospitalized, and particularly critically ill, patients.[2, 10, 11] Multidrug, and more specifically carbapenem resistance, among such common organisms as Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) and Enterobacteriaceae represents a major treatment challenge.[2] A recent US‐based surveillance study reported that a quarter of device‐related infections in hospitalized patients were caused by carbapenem‐resistant PA.[10]

In addition to changes in resistance patterns seen among PA isolates, increasing rates of nonsusceptibility have been described among Enterobacteriaceae. Resistance rates to third‐generation cephalosporins in these pathogens have risen steadily since 1988, reaching 20% among Klebsiella pneumoniae and 5% among Escherichia coli isolates by 2004.[11] In response to this, clinicians have increasingly utilized carbapenems to treat patients with serious Gram‐negative infections. However, the development of several types of carbapenemases by Enterobacteriaceae has led to a greater prevalence of carbapenem‐resistant Enterobacteriaceae species (CRE).[12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18] In fact, a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) documents a rapid rise in both the prevalence and extent of CRE in the United States.[19]

These Gram‐negative multidrug‐resistant (MDR) organisms frequently cause serious infections including pneumonia and bloodstream infections (BSI). The fact that these conditions, if not addressed in a timely and appropriate manner, lead to high morbidity, mortality, and costs, makes understanding the patterns of resistance that much more critical. To gain a better understanding of the prevalence and characteristics of MDR rates among PA and carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae in patients hospitalized in the United States with pneumonia and BSI, we conducted a multicenter survey of microbiology data.

METHODS

To determine the prevalence of predefined resistance patterns among PA and Enterobacteriaceae in pneumonia and BSI specimens, we examined The Surveillance Network (TSN) database from Eurofins between years 2000 and 2009. The database has been used extensively for surveillance purposes since 1994 and has previously been described in detail.[17, 20, 21, 22, 23] Briefly, TSN is a warehouse of routine clinical microbiology data collected from a nationally representative sample of microbiology laboratories in 217 hospitals in the United States. To minimize selection bias, laboratories are included based on their geography and the demographics of the populations they serve.[20] Only clinically significant samples are reported. No personal identifying information for source patients is available in this database. Only source laboratories that perform antimicrobial susceptibility testing according standard US Food and Drug Administration‐approved testing methods and interpret susceptibility in accordance with the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute breakpoints are included.[24] All enrolled laboratories undergo a pre‐enrollment site visit. Logical filters are used for routine quality control to detect unusual susceptibility profiles and to ensure appropriate testing methods. Repeat testing and reporting are done as necessary.[20]

Laboratory samples are reported as susceptible, intermediate, or resistant.[24] We required that samples have susceptibility data for each of the antimicrobials needed to determine their resistance phenotype. These susceptibility patterns served as phenotypic surrogates for resistance. We grouped intermediate samples together with the resistant ones for the purposes of the current analysis. Duplicate isolates were excluded. Only samples representing 1 of the 2 infections of interest, pneumonia and BSI, were included.

We defined MDR‐PA as any isolate resistant to 3 of the following drug classes: aminoglycoside (gentamicin), antipseudomonal penicillin (piperacillin‐tazobactam), antipseudomonal cephalosporin (ceftazidime), carbapenems (imipenem, meropenem), and fluoroquinolone (ciprofloxacin). Enterobacteriaceae were considered CRE if resistant to both a third‐generation cephalosporin and a carbapenem. We examined the data by infection type, year, the 9 US Census geographical divisions, and intensive care unit (ICU) origin.

We did not pursue hypothesis testing due to a high risk of type I error in this large dataset. Therefore, only clinically important trends are highlighted.

RESULTS

Source specimen characteristics for the 205,526 PA (187,343 pneumonia and 18,183 BSI) and 95,566 Enterobacteriaceae specimens (58,810 pneumonia and 36,756 BSI) identified are presented in Table 1. The median age of the patients from which the isolates derive was similar among the PA pneumonia, Enterobacteriaceae pneumonia, and Enterobacteriaceae BSI groups, but higher in the PA BSI group. Similarly, there were differences in the gender distribution of source patients between the organisms and infections. Namely, although females represented a stable 42% of each of the infections with PA, the proportions of females with Enterobacteriaceae pneumonia (36.2%) differed from that in the BSI group (48.6%). Pneumonia specimens (34.0% PA and 39.0% Enterobacteriaceae) were more likely to originate in the ICU than those from BSI (28.4% PA and 21.1% Enterobacteriaceae).

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa, N=205,526 | Enterobacteriaceae, N=95,566 | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Pneumonia, n | 187,343 | 58,810 |

| Age, y, median (IQR 25, 75) | 54 (23, 71) | 55 (21, 71) |

| Gender, female, n (%) | 78,418 (41.9) | 21,305 (36.2) |

| ICU origin, n (%) | 63,755 (34.0) | 22,942 (39.0) |

| Meeting definitions of resistance, n (%) | 41,180 (22.0) | 930 (1.6) |

| BSI, n | 18,183 | 36,756 |

| Age, y, median (IQR 25, 75) | 59 (31, 75) | 55 (24, 71) |

| Gender, female, n (%) | 7,448 (41.8) | 17,871 (48.6) |

| ICU origin, n (%) | 5,170 (28.4) | 7,751 (21.1) |

| Meeting definitions of resistance, n (%) | 2,668 (14.7) | 394 (1.1) |

The prevalence of resistance among PA isolates was approximately 15‐fold higher than among Enterobacteriaceae specimens in both infection types (Table 1). This pattern persisted when stratified by infection type (pneumonia: 22.0% MDR‐PA vs 1.6% CRE; BSI: 14.7% MDR‐PA vs 1.1% CRE).

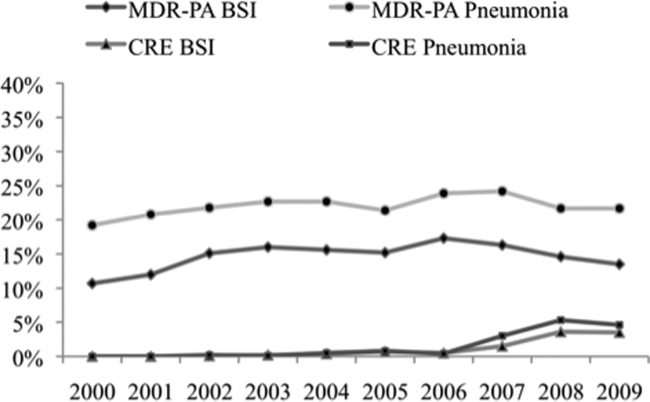

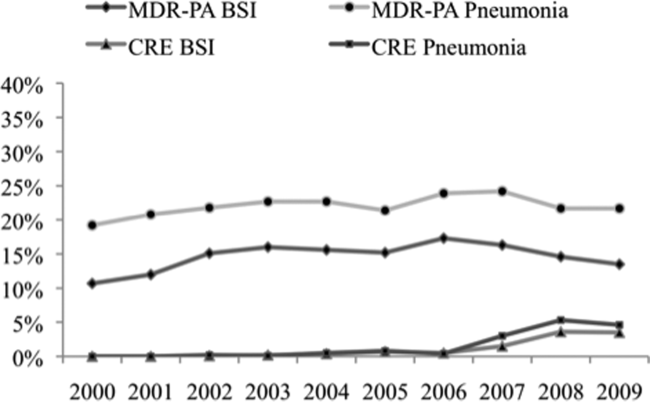

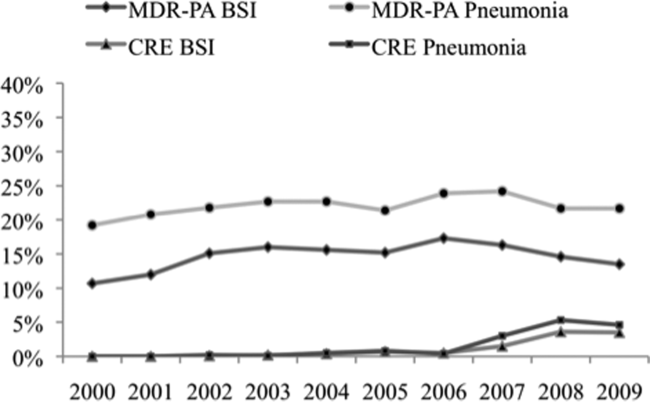

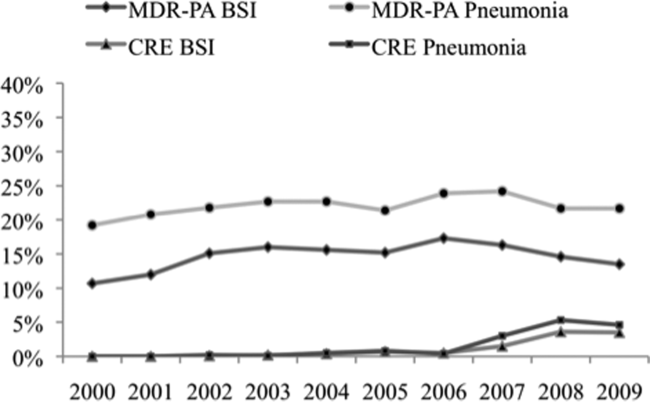

Over the time frame of the study, we detected variable patterns of resistance in the 2 groups of organisms (Figure 1). Namely, among PA in both pneumonia and BSI there was an initial rise in the proportion of MDR specimens between 2000 and 2003, followed by a stabilization until 2005, an additional rise in 2006, and a gradual decline and stabilization through 2009. These fluctuations notwithstanding, there was a net rise in MDR‐PA as a proportion of all PA from 10.7% in 2000 to 13.5% in 2009 among BSI, and from 19.2% in 2000 to 21.7% in 2009 among pneumonia specimens. Among Enterobacteriaceae, the CRE phenotype emerged in 2002 in both infection types and peaked in 2008 at 3.6% in BSI and 5.3% in pneumonia. This peak was followed by a stabilization in 2009 in BSI (3.5%) and a further decline, albeit minor, to 4.6% in pneumonia.

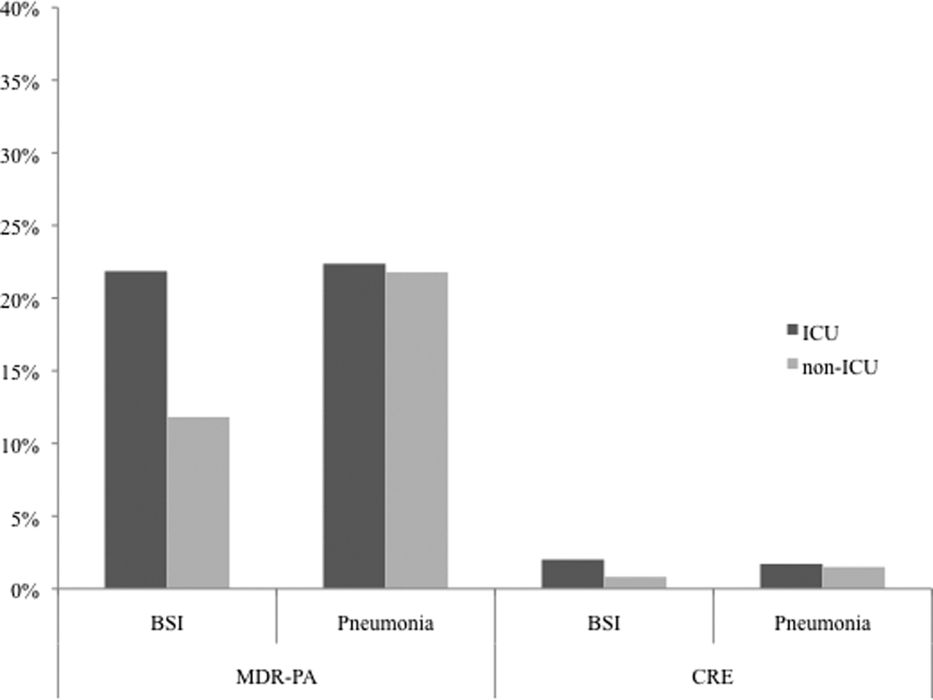

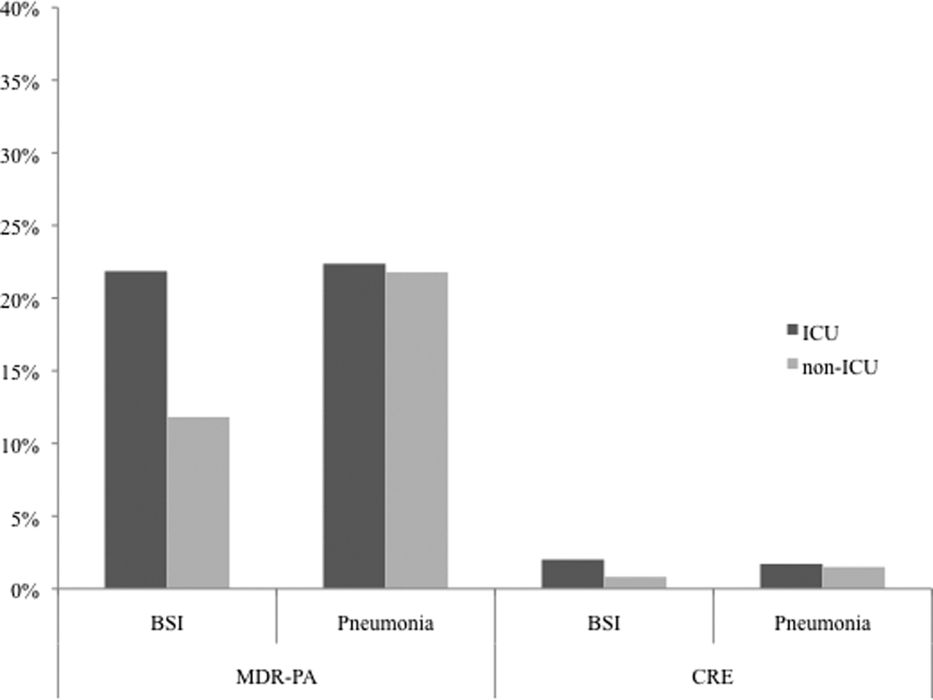

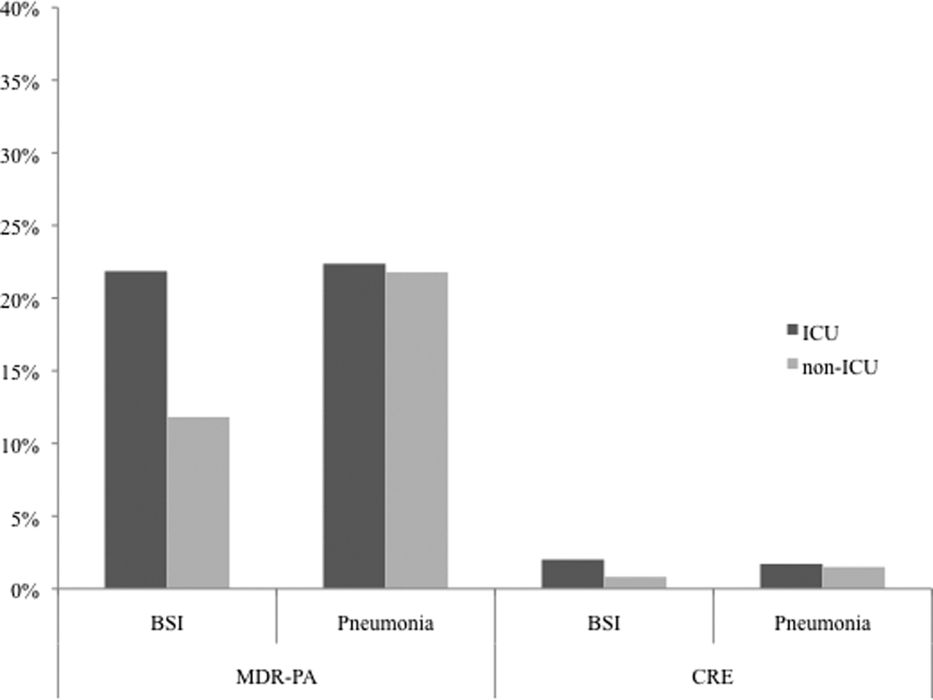

We noted geographic differences in the distribution of resistance (Table 2). Although MDR‐PA was more likely to originate from the East and West North Central divisions, and least likely from the New England and Mountain states, most CRE was detected in the specimens from the latter 2 regions. When stratified by ICU as the location of specimen origin, there were differences in the prevalence of resistant organisms of both types, but these differences were observed only in BSI specimens and not in pneumonia (Figure 2). That is, in BSI, the likelihood of a resistant organism originating from the ICU was approximately double that from a non‐ICU location for both MDR‐PA (21.9% vs 11.8%) and CRE (2.0% vs 0.8%).

| Census Division | MDR‐PA | CRE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSI | Pneumonia | BSI | Pneumonia | |

| ||||

| East North Central | 20.8% | 26.9% | 2.0% | 1.9% |

| West North Central | 18.0% | 22.1% | 0.8% | 0.7% |

| East South Central | 15.8% | 20.5% | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| West South Central | 13.5% | 21.7% | 0.3% | 0.5% |

| Pacific | 13.1% | 20.3% | 0.3% | 0.3% |

| Mid‐Atlantic | 12.6% | 20.5% | 2.5% | 3.8% |

| South Atlantic | 12.6% | 21.6% | 0.9% | 1.5% |

| New England | 10.7% | 19.7% | 1.3% | 2.9% |

| Mountain | 8.5% | 19.4% | 0.4% | 1.1% |

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that among both pneumonia and BSI specimens, PA and Enterobacteriaceae have a high prevalence of multidrug resistance. When examined cross‐sectionally, in both pneumonia and BSI, the prevalence of MDR‐PA was approximately 15‐fold higher than the prevalence of CRE among Enterobacteriaceae. Over the time frame of the study, MDR‐PA rose and then fell and stabilized to levels only slightly higher than those observed at the beginning of the observation period. In contrast, CRE emerged and rose precipitously between 2006 and 2008, and appeared to stabilize in 2009 in both infection types. Interestingly, we observed geographic variability among resistant isolates. Specifically, the prevalence of CRE was highest in the region with a relatively low prevalence of MDR‐PA. Despite this heterogeneity geographically, resistance for both isolate types in BSI but not in pneumonia was substantially higher in the ICU than outside the ICU.

Our data enhance the current understanding of distribution of Gram‐negative resistance in the United States. A recent study by Braykov and colleagues examined time trends in the development of CRE phenotype among Klebsiella pneumoniae in the United States.[17] By focusing on this single pathogen in various infections within Eurofin's TSN database between 1999 and 2010, they pinpointed its initial emergence to year 2002, with a notably steep rise between 2006 and 2009, with some reduction in the pace of growth in 2010. We have documented an analogous rise in the CRE phenotype among all Enterobacteriaceae, particularly in pneumonia and BSI within a similar time period. Thus, our data on the 1 hand broaden the concern about this pathogen beyond just a single organism within Enterobacteraceae and a single antimicrobial class, and on the other hand serve to focus attention on 2 clinically burdensome infection types, pneumonia and BSI.

Another recent investigation reported a rise in carbapenem‐resistant Enterobacteriaceae in US hospitals over the past decade.[19] Drawing on data from multiple sources, including the dataset used for the current analysis, this study examined the patterns of single‐class resistance to carbapenems among central line‐associated BSI (CLABSI) and catheter‐associated urinary tract infection specimens. Consistent with our findings, these authors noted that the highest percentage of hospitals reporting such single‐class carbapenem‐resistant specimens were located in the Northeastern United States. They also described that the proportion of Enterobacteriaceae with single‐class carbapenem resistance rose from 0% in 2001 to 1.4% in 2010. An additional CDC analysis reported that single‐class carbapenem resistance now exists in 4.2% of Enterobacteraciae as compared to 1.2% of isolates in 2001. We confirm that this rise in single‐class resistance is echoed by a rise in the prevalence of the CRE phenotype, and provides further granularity to this problem, specifically in the setting of pneumonia and BSI.

Although CRE has become an important concern in the treatment of patients with pneumonia and BSI, MDR‐PA remains a far larger challenge in these infections. CREs appear to occur more frequently than in the past but remain relatively dwarfed by the prevalence of MDR‐PA. Our data are generally in agreement with the 2009 to 2010 data from the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) maintained by the CDC, which focuses on CLABSI and ventilator‐associated pneumonia (VAP) rather than general BSI and pneumonia in US hospitals.[25] In this report, the proportion of PA that were classified as MDR according to a definition similar to ours was 15.4% in CLABSI and 17.7% in VAP. In contrast, we document that 13.5% of PA causing BSI and 21.7% causing pneumonia were due to MDR‐PA organisms. This mild divergence likely reflects the slightly different antimicrobials utilized to define MDR‐PA in the 2 studies, as well as variance in the populations examined. An additional data point reported in the NHSN study is the proportion of MDR‐PA CLABSI originating in the ICU (16.8%) versus non‐ICU hospital locations (13.3%). Although the difference we found in the prevalence of BSI by the location in the hospital was greater, we confirm that ICU specimens carry a higher risk of harboring MDR‐PA.

Our study has a number of strengths and limitations. Because we used a nationally representative database to derive our estimates, our results are highly generalizable.

The TSN database consists of microbiology samples from hospital laboratories. Although we attempted to reduce the risk of duplication, because of how samples are numbered in the database, repeat sampling remains a possibility. The definitions of resistance were based on phenotypic patterns of resistance to various antimicrobial classes. This makes our resistant organisms subject to misclassification.

In summary, although carbapenem resistance among Enterobacteriaceae has emerged as an important phenomenon, multidrug resistance among PA remains relatively more prevalent in the United States. Furthermore, over the decade examined, MDR‐PA has remained an important pathogen in pneumonia and BSI that persists across all geographic regions of the United States. Although CRE is rightfully receiving a disproportionate share of attention from public health officials, it would be shortsighted to ignore the importance of MDR‐PA as a target, not only for transmission prevention and antimicrobial stewardship, but also for new therapeutic development. Because the patterns of resistance are rapidly evolving, it is incumbent upon our public health enterprise to perform more granular real‐time surveillance to allow changes in epidemiology to inform policy and treatment decisions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Disclosures: This study was supported by a grant from Cubist Pharmaceuticals. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System Report. Am J Infect Control. 2004;32:470.

- , , , . National surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates obtained from intensive care unit patients from 1993 to 2002. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:4606–4610.

- , , , et al. Health care‐associated pneumonia and community‐acquired pneumonia: a single‐center experience. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:3568–3573.

- , , , et al. Clinical importance of delays in the initiation of appropriate antibiotic treatment for ventilator‐associated pneumonia. Chest. 2002;122:262–268.

- . Modification of empiric antibiotic treatment in patients with pneumonia acquired in the intensive care unit. ICU‐Acquired Pneumonia Study Group. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:387–394.

- , , , , . Antimicrobial therapy escalation and hospital mortality among patients with HCAP: a single center experience. Chest. 2008:134:963–968.

- , , , et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:296–327.

- , , , , , . Inappropriate antibiotic therapy in Gram‐negative sepsis increases hospital length of stay. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:46–51.

- , , , . Inadequate antimicrobial treatment of infections: a risk factor for hospital mortality among critically ill patients. Chest. 1999;115:462–474.

- , , , et al. Antimicrobial‐resistant pathogens associated with healthcare‐associated infections: annual summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006–2007. Infect Control Hospital Epidemiol. 2008;29:996–1011.

- , ; National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System. Overview of nosocomial infections caused by Gram‐negative bacilli. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:848–854.

- , , . The real threat of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase‐producing bacteria. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:228–236.

- , , , . Household transmission of carbapenemase‐producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:859–860.

- , , , . Isolation of imipenem‐resistant Enterobacter species: emergence of KPC‐2 carbapenemase, molecular characterization, epidemiology, and outcomes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:1413–1418.

- , , , , . Outcomes of carbapenem‐resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infection and the impact of antimicrobial and adjunctive therapies. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29:1099–1106.

- , , , , , ; for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Epicenter Program. Emergence and rapid regional spread of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase‐producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:532–540.

- , , , , . Trends in resistance to carbapenems and third‐generation cephalosporins among clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae in the United States, 1999–2010. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34:259–268.

- , , , . Population‐based incidence of carbapenem‐resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae along the continuum of care, Los Angeles County. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34:144–150.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: carbapenem‐resistant enterobacteriaceae. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:165–170.

- , , . Antimicrobial resistance in key bloodstream bacterial isolates: electronic surveillance with the Surveillance Network Database–USA. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:259–263.

- , , . Community‐associated methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus in outpatients, United States, 1999–2006. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1925–1930.

- , , . Increasing resistance of Acinetobacter species to imipenem in United States hospitals, 1999–2006. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:196–197.

- , , , , . Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria isolated from central nervous system specimens as reported by U.S. hospital laboratories from 2000 to 2002. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2004;3:3.

- Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute. Available at: http://www.clsi.org. Accessed July 8, 2013.

- , , , et al. Antimicrobial‐resistant pathogens associates with healthcare‐associated infections: Summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009–2010. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34:1–14.

Administration of initially appropriate antimicrobial therapy represents a key determinant of outcome in patients with severe infection.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9] The variable patterns of antimicrobial resistance seen between and within healthcare institutions complicate the process of antibiotic selection. Although much attention has historically focused on Staphylococcus aureus, resistance among Gram‐negative pathogens has emerged as a major challenge in the care of hospitalized, and particularly critically ill, patients.[2, 10, 11] Multidrug, and more specifically carbapenem resistance, among such common organisms as Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) and Enterobacteriaceae represents a major treatment challenge.[2] A recent US‐based surveillance study reported that a quarter of device‐related infections in hospitalized patients were caused by carbapenem‐resistant PA.[10]

In addition to changes in resistance patterns seen among PA isolates, increasing rates of nonsusceptibility have been described among Enterobacteriaceae. Resistance rates to third‐generation cephalosporins in these pathogens have risen steadily since 1988, reaching 20% among Klebsiella pneumoniae and 5% among Escherichia coli isolates by 2004.[11] In response to this, clinicians have increasingly utilized carbapenems to treat patients with serious Gram‐negative infections. However, the development of several types of carbapenemases by Enterobacteriaceae has led to a greater prevalence of carbapenem‐resistant Enterobacteriaceae species (CRE).[12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18] In fact, a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) documents a rapid rise in both the prevalence and extent of CRE in the United States.[19]

These Gram‐negative multidrug‐resistant (MDR) organisms frequently cause serious infections including pneumonia and bloodstream infections (BSI). The fact that these conditions, if not addressed in a timely and appropriate manner, lead to high morbidity, mortality, and costs, makes understanding the patterns of resistance that much more critical. To gain a better understanding of the prevalence and characteristics of MDR rates among PA and carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae in patients hospitalized in the United States with pneumonia and BSI, we conducted a multicenter survey of microbiology data.

METHODS

To determine the prevalence of predefined resistance patterns among PA and Enterobacteriaceae in pneumonia and BSI specimens, we examined The Surveillance Network (TSN) database from Eurofins between years 2000 and 2009. The database has been used extensively for surveillance purposes since 1994 and has previously been described in detail.[17, 20, 21, 22, 23] Briefly, TSN is a warehouse of routine clinical microbiology data collected from a nationally representative sample of microbiology laboratories in 217 hospitals in the United States. To minimize selection bias, laboratories are included based on their geography and the demographics of the populations they serve.[20] Only clinically significant samples are reported. No personal identifying information for source patients is available in this database. Only source laboratories that perform antimicrobial susceptibility testing according standard US Food and Drug Administration‐approved testing methods and interpret susceptibility in accordance with the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute breakpoints are included.[24] All enrolled laboratories undergo a pre‐enrollment site visit. Logical filters are used for routine quality control to detect unusual susceptibility profiles and to ensure appropriate testing methods. Repeat testing and reporting are done as necessary.[20]

Laboratory samples are reported as susceptible, intermediate, or resistant.[24] We required that samples have susceptibility data for each of the antimicrobials needed to determine their resistance phenotype. These susceptibility patterns served as phenotypic surrogates for resistance. We grouped intermediate samples together with the resistant ones for the purposes of the current analysis. Duplicate isolates were excluded. Only samples representing 1 of the 2 infections of interest, pneumonia and BSI, were included.

We defined MDR‐PA as any isolate resistant to 3 of the following drug classes: aminoglycoside (gentamicin), antipseudomonal penicillin (piperacillin‐tazobactam), antipseudomonal cephalosporin (ceftazidime), carbapenems (imipenem, meropenem), and fluoroquinolone (ciprofloxacin). Enterobacteriaceae were considered CRE if resistant to both a third‐generation cephalosporin and a carbapenem. We examined the data by infection type, year, the 9 US Census geographical divisions, and intensive care unit (ICU) origin.

We did not pursue hypothesis testing due to a high risk of type I error in this large dataset. Therefore, only clinically important trends are highlighted.

RESULTS