User login

A nondrug approach to dementia

› Attempt nonpharmacologic treatment for dementia behavioral problems before moving on to medications, which are of questionable efficacy for symptoms other than aggression and psychosis. A

› Obtain informed consent from patients and/or their caregivers if you plan to use antipsychotic medications because their use increases morbidity and mortality in the elderly. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE Ms. M, 86 years old, lives with her daughter, son-in-law, and granddaughter. For several years she has been forgetful, but she has never had a formal work-up for dementia. Her daughter finally brings her to their primary care physician because she was refusing to take showers, was increasingly irritable, and had tried to hit her daughter’s husband.

In the office, however, Ms. M is calm and pleasant. The family says that most nights Ms. M gets up and wanders around the house. She denies feeling depressed or anxious, but her Folstein Mini-Mental State Exam score is 22/30, indicating moderate dementia. (For more on assessment, see “Tools for assessing patients with dementia—and their caregivers” on page 552.)

The physician offers a trial of risperidone 0.25 mg at bedtime to assist with sleep and behavior.

Was this prescription a wise decision? What other questions should this physician have asked?

Understanding the behavioral symptoms

Noncognitive symptoms of dementia, sometimes referred to as behavioral and psychological symptoms, are common, affecting almost 90% of patients with dementia,1-3 which itself can be classified as early, intermediate, and late.

In early dementia, sociability is usually not affected, but patients may repeat questions, misplace items, use poor judgment, and begin to have difficulty with more complex daily tasks like finances and driving.

In intermediate dementia, basic activities of daily living become impaired and normal social and environmental cues may not register.

In late dementia, patients become entirely dependent on others; they may lose the ability to speak, walk, and eventually, eat. Long- and short-term memory is lost.

Behavioral symptoms most often occur when the condition enters the intermediate phase, but they may occur at any time during the course of the disease.4 Behaviors may include refusal of care, yelling, aggressive behavior, agitation, restlessness, reversal of the normal sleep-wake cycle, wandering, hoarding, sexual disinhibition, culturally inappropriate behaviors, hallucinations, delusions, anxiety, depression, apathy, and psychosis.2,5

Behavioral disturbances often overwhelm families, and lack of treatment increases patient morbidity, may result in physical harm, and almost always precipitates institutionalization.2 Dementia-related behavioral disturbances also increase the risk of caregiver burnout and depression.2

These symptoms are difficult to treat with medications or nonpharmacologic therapy and strong evidence for most therapies is lacking. Physicians have historically prescribed either typical or atypical antipsychotics in an attempt to control these behaviors. In fact, medication is often still considered first-line therapy.6,7

CASE Ms. M’s daughter calls the clinic 2 weeks after the initial visit to tell the physician that her mother has been sleeping much better, but had a fall and was admitted to the hospital for a hip fracture. That’s not surprising; typical and atypical antipsychotics increase the risk of falls in the elderly.8

The risks associated with the use of antipsychotics

In 2005, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a black box warning for atypical antipsychotics because they were found to increase mortality in the elderly. The increased mortality is due to cardiac events or infection.9,10 In 2008, the FDA warning was added to typical antipsychotics, as well.11,12 Both typical and atypical antipsychotics have been found to increase the risk of falls and strokes in the elderly,8,13 and their efficacy in treating the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia has recently been questioned.13-16

Trazodone and medications approved for the specific treatment of cognitive decline, such as donepezil or memantine, are also prescribed for behavioral disturbances, but evidence to support their efficacy is limited.14,17-20 More recently, a meta-analysis of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) suggests that they may be effective for treating agitation associated with dementia.21 However, SSRIs may also contribute to falls and to hyponatremia in the elderly.22,23

Pharmacologic Tx is not your only option

Considering the questionable safety and efficacy of pharmacologic treatment, physicians should consider nondrug therapies first, or at least concurrently with medication.2,15,16,24

But before you get started, be sure to look for and treat medical conditions that cause or contribute to behavioral disturbances, including infection, pain, and adverse effects of medication.6,7,25 Similarly, it is essential that unmet needs, such as hunger, thirst, or desire for attention or socialization, be addressed.6,7,26 Also, discuss disturbing environmental factors, including loud noises, poorly lit quarters, and strong smells, with patients and their caregivers.5-7 In complex situations, you may need to seek assistance from a geriatrician, neurologist, geropsychiatrist, or psychologist, although their availability may be limited.6

CASE Ms. M becomes markedly delirious while in the hospital after hip surgery, and a geriatrics consultation is requested. This is not surprising, given that underlying dementia increases a patient’s risk of delirium in the hospital.27 The geriatrician recommends several measures to reduce the likelihood of delirium—providing good pain control, minimizing night time wake-ups, minimizing Foley catheter use, Hep-locking the IV to encourage mobility, and having staff reorient her frequently by referring to a large print clock and calendar on the wall.

Specific interventions

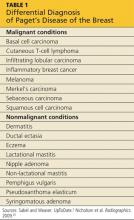

Most specific nonpharmacologic therapies have not been robustly studied in randomized controlled trials. But a series of smaller studies have been evaluated in systematic reviews. The level of evidence for each intervention is summarized in TABLE 1.28-40

As you review the options that follow, keep 2 things in mind: (1) It is important to set realistic expectations when considering these approaches (as well as pharmacologic ones). Reducing the frequency or severity of problematic behaviors may be more reasonable than their total elimination.6,25 (2) Consider targeting specific symptoms when treating behavioral Behavioral symptoms most often occur when dementia enters the intermediate phase, but they may occur at any time during the course of the disease. disturbances.2,24,41 Such targeting allows physicians and families to better evaluate the effectiveness of interventions because it helps to focus the discussion of the patient’s progress at follow-up visits.

Massage/touch therapy. A 2006 Cochrane review concluded that improvement in nutritional intake and hand massage, when combined with positive encouragement during a meal, may produce a short-term positive effect on agitation.29 Similarly, a meta-analysis of randomized controlled and randomized crossover studies found a statistically significant improvement in agitation with hand massage, although this finding was based on the same single study referenced in the 2006 review.30 Opinions differ among 5 high-quality guidelines included in the systematic review by Azermai et al regarding the value of massage, with 2 of the 5 practice guidelines recommending its use.28

Aromatherapy. Several trials suggest that aroma therapy may reduce agitated behaviors. Lemon balm and lavender oils have been the most commonly studied agents. Two systematic reviews cite the same 2002 randomized controlled trial, which found a reduction in behavioral problems in people who received arm massage with lemon balm compared with those who received arm massage with an odorless cream.30,31 A systematic review by Holt et al also cites a study that found lavender oil placed in a sachet on each side of the pillow for at least one hour during sleep seemed to reduce problem behaviors.31 Several evidence-based guidelines have concluded that aromatherapy may be helpful, and 2 of the 5 practice guidelines reviewed by Azermai et al recommend it.28

Exercise has been shown to benefit patients of all ages, even those with terminal diseases.42 Some studies have indicated a positive effect of physical activities on behaviors ranging from wandering to aggression and agitation. Activities have included group gentle stretches, indoor exercises, and a volunteer-led walking program that encouraged hand holding and singing.34 However, a 2008 Cochrane review concluded that the effect of exercise on behavioral disturbances in dementia has not been adequately studied.35

Music therapy. Numerous types of music therapy have been studied, including listening to music picked out by a patient’s family based on known patient preference, classical music, pleasant sounds such as ocean waves, and even stories and comforting prayer recorded by family members. While most of these smaller studies yielded positive results,34 a 2003 Cochrane review concluded there is not enough evidence to recommend for or against music therapy.43 A more recent meta-analysis suggests that music may be effective for agitation.30 A systematic review of quality guidelines also indicates that most of these guidelines rate the evidence as moderate to high in favor of music and 3 of 5 practice guidelines recommend it.28

Nonphysical barriers have long been used as a creative nonrestraining method of preventing wandering. They include such tricks as camouflaging exits by painting them to look like bookcases, painting a black square in front of an elevator to make it look like a hole, and placing a thin Velcro strip across doorways. Although it would appear from a limited number of small studies and anecdotal evidence that nonphysical barriers work, a Cochrane review concluded that they have not been studied enough to perform a meta-analysis.36

Cognitive stimulation typically consists of activities such as reviewing current events, promoting sensory awareness, drawing, associating words, discussion of hobbies, and planning daily activities. This type of therapy has been shown to improve cognition in patients with dementia, as well as well-being and quality of life. It does not improve behavioral problems, per se.37

Reminiscence therapy is a popular modality that involves stimulating memories of the past by looking at personal photos and newspaper clippings and discussing the past. It is well received by patients and caregivers. It has been shown to improve mood in elderly patients without dementia, but studies of reminiscence therapy have been too dissimilar to draw conclusions regarding its effect on behavioral disturbances in patients with dementia.38

Other therapies that are common in dementia care, such as respite care and specialized dementia units, have simply not been studied well enough to provide any conclusions as to their effectiveness.39,40

CASE When Ms. M is discharged from the hospital, her family enrolls her in an adult day care program, where Ms. M will be able to participate in social activities, exercise, and communal meals. Her daughter asks the family physician what other steps they can take in the home to make things easier on her mother. And as an aside, the daughter admits that while she is glad that she and her family can “be there” for her mother, there have been times when she has simply not felt up to the task.

Help family members care for the patient—and themselves

A recent meta-analysis suggests that caregiver interventions have a positive effect on behavioral problems in patients with dementia.32 Successful programs are tailored to the individual needs of the patient and caregiver and delivered over multiple sessions. Unfortunately, the aforementioned meta-analysis did not provide evidenced-based interventions for specific problems.32 With this in mind, the following are some practical caregiver “do’s and don’ts” that are based on reviews and consensus guidelines.

Don’t take it personally. It is extremely important to help caregivers understand that the disturbing behaviors of patients with dementia lack intentionality and are part of the normal progression of the disorder.25 Caregivers also need to appreciate that hallucinations are normal in these patients and do not require medications if they don’t disturb the patient or place the patient or anyone else at risk.

Don’t try to reason with the patient; redirect him or her instead. Clinicians should offer caregivers suggestions for reassuring, redirecting, or distracting agitated patients rather than trying to reason with them. Encourage caregivers to develop and maintain routines and consistency.6,25 Using a calm, low tone of voice, giving very simple instructions, and leaving and then reattempting care that is refused the first time may also be effective.5 Some experts have suggested techniques such as giving positive rewards for desired behaviors and not rewarding negative behaviors.6,26

Do create a safe environment. Recommend that caregivers create a safe environment. Make sure that they lock up all guns. Also, encourage them to use locks, alarms, or ID bracelets when patients are prone to wandering.25

Do consider a caregiver support program. Caregivers can make a big difference in the lives of patients with dementia, Help caregivers understand that the disturbing behaviors of patients with dementia lack intentionality and are part of the normal progression of the disorder. but only if they have support, as well.

A recent meta-analysis concluded that active involvement of caregivers in making choices about treatments distinguishes effective from ineffective support programs, decreases the odds of institutionalization, and may lengthen time to institutionalization.33 To ease caregiver strain and depression, encourage them to make use of resources such as nursing home respite care and community agencies that include the Alzheimer’s Association (http://www.alz.org).6,44,45

CASE Ms. M’s daughter joins a local support group for families of patients with dementia, where she learns redirection techniques to try when her mother refuses care. The exercise and daytime social stimulation that Ms. M receives through the adult day care program helps her to sleep at night. When Ms. M refuses to take a shower—a challenge the family had before her hospitalization—the daughter does not argue with her. Instead, she returns 10 to 20 minutes later and asks again, or tries a bedside sponge bath with a lavender soap that Ms. M seems to like.

Ms. M’s nighttime wandering is markedly reduced and the family no longer uses any antipsychotic medications. The family physician counsels them, however, about the progressive nature of the disease and encourages them to set up periodic follow-up visits, so that he can see how everyone—patient and caregivers alike—are doing.

Welcoming the reprieves, recognizing the realities

The behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia are the most challenging aspect of dementia care. Unacceptable behaviors sometimes persist even when aggressively addressing modifiable factors and attempting behavioral interventions (TABLE 2).2,5-7,15,16,24-26,32,41,44-46 Patients with behavioral disturbances frequently require a pharmacologic agent or transfer to a different care setting.

But clinicians need to use psychotropic medications with informed patient and/or caregiver consent.7 On a case-by-case basis, a trial of antipsychotics is often justified, despite the black box warning. A family may choose to try an antipsychotic despite the risk to help manage the patient at home in the hope of delaying or preventing institutionalization.

However, even with good home support, in conjunction with nonpharmacologic and/or pharmacologic therapies, most patients with dementia will eventually require institutionalization.47 Because patients and families often rely on family physicians to guide them through these difficult challenges and decisions, you’ll need to remain well versed on the available On a case-by- case basis, a trial of antipsychotics is often justified, despite the black box warning. treatments for the psychological and behavioral symptoms of dementia, as well as the resources available in your community.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jaqueline Raetz, MD, 331 NE Thornton Place, Seattle, WA 98125; [email protected]

1. Mega MS, Cummings JL, Fiorello T, et al. The spectrum of behavioral changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1996;46:130-135.

2. Feil DG, MacLean C, Sultzer D. Quality indicators for the care of dementia in vulnerable elders. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(suppl 2):S293-S301.

3. Hort J, O’Brien JT, Gainotti G, et al. EFNS guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17:1236-1248.

4. Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, et al. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: results from the cardiovascular health study. JAMA. 2002;288:1475-1483.

5. Omelan C. Approach to managing behavioural disturbances in dementia. Can Fam Physician. 2006;52:191-199.

6. Sadowsky CH, Galvin JE. Guidelines for the management of cognitive and behavioral problems in dementia. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25:350-366.

7. Salzman C, Jeste DV, Meyer RE, et al. Elderly patients with dementia-related symptoms of severe agitation and aggression: consensus statement on treatment options, clinical trials methodology, and policy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:889-898.

8. Hill KD, Wee R. Psychotropic drug-induced falls in older people: a review of interventions aimed at reducing the problem. Drugs Aging. 2012;29:15-30.

9. US Food and Drug Administration. Public health advisory: deaths with antipsychotics in elderly patients with behavioral disturbances. April 11, 2005. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/DrugSafetyInformationforHeathcareProfessionals/PublicHealthAdvisories/ucm053171.htm. Accessed September 16, 2013.

10. Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA. 2005;294:1934-1943.

11. US Food and Drug Administration. Antipsychotics, conventional and atypical. June 16, 2008. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm110212.htm. Accessed September 16, 2013.

12. Wang PS, Schneeweiss S, Avorn J, et al. Risk of death in elderly users of conventional vs. atypical antipsychotic medications. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2335-2341.

13. Ballard C, Waite J. The effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of aggression and psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD003476.

14. Sink KM, Holden KF, Yaffe K. Pharmacological treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: a review of the evidence. JAMA. 2005;293:596-608.

15. Lonergan E, Luxenberg J, Colford JM. Haloperidol for agitation in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(2):CD002852.

16. Schneider LS, Tariot PN, Dagerman KS, et al; CATIE-AD Study Group. Effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic drugs in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1525-1538.

17. Martinón-Torres G, Fioravanti M, Grimley EJ. Trazodone for agitation in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(4):CD004990.

18. Birks J, Harvey RJ. Donepezil for dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD001190.

19. McShane R, Areosa Sastre A, Minakaran N. Memantine for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD003154.

20. Raina P, Santaguida P, Ismaila A, et al. Effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for treating dementia: evidence review for a clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:379-397.

21. Seitz DP, Adunuri N, Gill SS, et al. Antidepressants for agitation and psychosis in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(2): CD008191.

22. Sterke CS, Ziere G, van Beeck EF, et al. Dose-response relationship between selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors and injurious falls: a study in nursing home residents with dementia. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73:812-820.

23. Jacob S, Spinler SA. Hyponatremia associated with selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in older adults. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:1618-1622.

24. Segal-Gidan F, Cherry D, Jones R, et al. Alzheimer’s disease management guideline: update 2008. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:e51-e59.

25. Rayner A, O’Brien J, Shoenbachler B. Behavior disorders of dementia: recognition and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2006;73:647-652.

26. Ayalon L, Gum AM, Feliciano L, et al. Effectiveness of nonpharmacological interventions for the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2182-2188.

27. Elie M, Cole MG, Primeau FJ, et al. Delirium risk factors in elderly hospitalized patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:204-212.

28. Azermai M, Petrovic M, Elseviers MM, et al. Systematic appraisal of dementia guidelines for the management of behavioural and psychological symptoms. Aging Res Rev. 2012;11:78-86.

29. Viggo Hansen N, Jørgensen T, Ørtenblad L. Massage and touch for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD004989.

30. Kong EH, Evans LK, Guevara JP. Nonpharmacological intervention for agitation in dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13:512-520.

31. Thorgrimsen LM, Spector A, Wiles A, et al. Aroma therapy for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(3):CD003150.

32. Brodaty H, Arasaratnam C. Review of meta-analysis of nonpharmacological interventions for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Am J Psychiatry 2012;169:946-953.

33. Spijker A, Vernooij-Dassen M, Vasse E, et al. Effectiveness of nonpharmacological interventions in delaying the institutionalization of patients with dementia: A meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1116-1128.

34. Opie J, Rosewarne R, O’Connor DW. The efficacy of psychosocial approaches to behaviour disorders in dementia: a systematic literature review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1999;33:789-799.

35. Forbes D, Forbes S, Morgan DG, et al. Physical activity programs for persons with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(3):CD006489.

36. Price JD, Hermans DG, Grimley Evans J. Subjective barriers to prevent wandering of cognitively impaired people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(4):CD001932.

37. Woods B, Aguirre E, Spector AE, et al. Cognitive stimulation to improve cognitive functioning in people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(2):CD005562.

38. Woods B, Spector A, Jones C, et al. Reminiscence therapy for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2):CD001120.

39. Lee H, Cameron M. Respite care for people with dementia and their carers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(2):CD004396.

40. Lai CK, Yeung JH, Mok V, et al. Special care units for dementia individuals with behavioural problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4):CD006470.

41. Waldemar G, Dubois B, Emre M, et al. Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders associated with dementia: EFNS guideline. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14:e1-e26.

42. Oldervoll LM, Loge JH, Paltiel H, et al. The effect of a physical exercise program in palliative care: a phase II study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31:421-430.

43. Vink AC, Birks JS, Bruinsma MS, et al. Music therapy for people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD003477.

44. Gitlin LN, Kales HC, Lyketsos CG. Nonpharmacologic management of behavioral symptoms in dementia. JAMA. 2012;308:2020-2029.

45. Bass DM, Clark PA, Looman WJ, et al. The Cleveland Alzheimer’s managed care demonstration: outcomes after 12 months of implementation. Gerontologist. 2003;43:73-85.

46. Gitlin LN, Winter L, Dennis MP, et al.. A biobehavioral home-based intervention and the well-being of patients with dementia and their caregivers: the COPE randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304:983-991.

47. Smith GE, Kokmen E, O’Brien PC. Risk factors for nursing home placement in a population-based dementia cohort. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:519-525.

› Attempt nonpharmacologic treatment for dementia behavioral problems before moving on to medications, which are of questionable efficacy for symptoms other than aggression and psychosis. A

› Obtain informed consent from patients and/or their caregivers if you plan to use antipsychotic medications because their use increases morbidity and mortality in the elderly. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE Ms. M, 86 years old, lives with her daughter, son-in-law, and granddaughter. For several years she has been forgetful, but she has never had a formal work-up for dementia. Her daughter finally brings her to their primary care physician because she was refusing to take showers, was increasingly irritable, and had tried to hit her daughter’s husband.

In the office, however, Ms. M is calm and pleasant. The family says that most nights Ms. M gets up and wanders around the house. She denies feeling depressed or anxious, but her Folstein Mini-Mental State Exam score is 22/30, indicating moderate dementia. (For more on assessment, see “Tools for assessing patients with dementia—and their caregivers” on page 552.)

The physician offers a trial of risperidone 0.25 mg at bedtime to assist with sleep and behavior.

Was this prescription a wise decision? What other questions should this physician have asked?

Understanding the behavioral symptoms

Noncognitive symptoms of dementia, sometimes referred to as behavioral and psychological symptoms, are common, affecting almost 90% of patients with dementia,1-3 which itself can be classified as early, intermediate, and late.

In early dementia, sociability is usually not affected, but patients may repeat questions, misplace items, use poor judgment, and begin to have difficulty with more complex daily tasks like finances and driving.

In intermediate dementia, basic activities of daily living become impaired and normal social and environmental cues may not register.

In late dementia, patients become entirely dependent on others; they may lose the ability to speak, walk, and eventually, eat. Long- and short-term memory is lost.

Behavioral symptoms most often occur when the condition enters the intermediate phase, but they may occur at any time during the course of the disease.4 Behaviors may include refusal of care, yelling, aggressive behavior, agitation, restlessness, reversal of the normal sleep-wake cycle, wandering, hoarding, sexual disinhibition, culturally inappropriate behaviors, hallucinations, delusions, anxiety, depression, apathy, and psychosis.2,5

Behavioral disturbances often overwhelm families, and lack of treatment increases patient morbidity, may result in physical harm, and almost always precipitates institutionalization.2 Dementia-related behavioral disturbances also increase the risk of caregiver burnout and depression.2

These symptoms are difficult to treat with medications or nonpharmacologic therapy and strong evidence for most therapies is lacking. Physicians have historically prescribed either typical or atypical antipsychotics in an attempt to control these behaviors. In fact, medication is often still considered first-line therapy.6,7

CASE Ms. M’s daughter calls the clinic 2 weeks after the initial visit to tell the physician that her mother has been sleeping much better, but had a fall and was admitted to the hospital for a hip fracture. That’s not surprising; typical and atypical antipsychotics increase the risk of falls in the elderly.8

The risks associated with the use of antipsychotics

In 2005, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a black box warning for atypical antipsychotics because they were found to increase mortality in the elderly. The increased mortality is due to cardiac events or infection.9,10 In 2008, the FDA warning was added to typical antipsychotics, as well.11,12 Both typical and atypical antipsychotics have been found to increase the risk of falls and strokes in the elderly,8,13 and their efficacy in treating the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia has recently been questioned.13-16

Trazodone and medications approved for the specific treatment of cognitive decline, such as donepezil or memantine, are also prescribed for behavioral disturbances, but evidence to support their efficacy is limited.14,17-20 More recently, a meta-analysis of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) suggests that they may be effective for treating agitation associated with dementia.21 However, SSRIs may also contribute to falls and to hyponatremia in the elderly.22,23

Pharmacologic Tx is not your only option

Considering the questionable safety and efficacy of pharmacologic treatment, physicians should consider nondrug therapies first, or at least concurrently with medication.2,15,16,24

But before you get started, be sure to look for and treat medical conditions that cause or contribute to behavioral disturbances, including infection, pain, and adverse effects of medication.6,7,25 Similarly, it is essential that unmet needs, such as hunger, thirst, or desire for attention or socialization, be addressed.6,7,26 Also, discuss disturbing environmental factors, including loud noises, poorly lit quarters, and strong smells, with patients and their caregivers.5-7 In complex situations, you may need to seek assistance from a geriatrician, neurologist, geropsychiatrist, or psychologist, although their availability may be limited.6

CASE Ms. M becomes markedly delirious while in the hospital after hip surgery, and a geriatrics consultation is requested. This is not surprising, given that underlying dementia increases a patient’s risk of delirium in the hospital.27 The geriatrician recommends several measures to reduce the likelihood of delirium—providing good pain control, minimizing night time wake-ups, minimizing Foley catheter use, Hep-locking the IV to encourage mobility, and having staff reorient her frequently by referring to a large print clock and calendar on the wall.

Specific interventions

Most specific nonpharmacologic therapies have not been robustly studied in randomized controlled trials. But a series of smaller studies have been evaluated in systematic reviews. The level of evidence for each intervention is summarized in TABLE 1.28-40

As you review the options that follow, keep 2 things in mind: (1) It is important to set realistic expectations when considering these approaches (as well as pharmacologic ones). Reducing the frequency or severity of problematic behaviors may be more reasonable than their total elimination.6,25 (2) Consider targeting specific symptoms when treating behavioral Behavioral symptoms most often occur when dementia enters the intermediate phase, but they may occur at any time during the course of the disease. disturbances.2,24,41 Such targeting allows physicians and families to better evaluate the effectiveness of interventions because it helps to focus the discussion of the patient’s progress at follow-up visits.

Massage/touch therapy. A 2006 Cochrane review concluded that improvement in nutritional intake and hand massage, when combined with positive encouragement during a meal, may produce a short-term positive effect on agitation.29 Similarly, a meta-analysis of randomized controlled and randomized crossover studies found a statistically significant improvement in agitation with hand massage, although this finding was based on the same single study referenced in the 2006 review.30 Opinions differ among 5 high-quality guidelines included in the systematic review by Azermai et al regarding the value of massage, with 2 of the 5 practice guidelines recommending its use.28

Aromatherapy. Several trials suggest that aroma therapy may reduce agitated behaviors. Lemon balm and lavender oils have been the most commonly studied agents. Two systematic reviews cite the same 2002 randomized controlled trial, which found a reduction in behavioral problems in people who received arm massage with lemon balm compared with those who received arm massage with an odorless cream.30,31 A systematic review by Holt et al also cites a study that found lavender oil placed in a sachet on each side of the pillow for at least one hour during sleep seemed to reduce problem behaviors.31 Several evidence-based guidelines have concluded that aromatherapy may be helpful, and 2 of the 5 practice guidelines reviewed by Azermai et al recommend it.28

Exercise has been shown to benefit patients of all ages, even those with terminal diseases.42 Some studies have indicated a positive effect of physical activities on behaviors ranging from wandering to aggression and agitation. Activities have included group gentle stretches, indoor exercises, and a volunteer-led walking program that encouraged hand holding and singing.34 However, a 2008 Cochrane review concluded that the effect of exercise on behavioral disturbances in dementia has not been adequately studied.35

Music therapy. Numerous types of music therapy have been studied, including listening to music picked out by a patient’s family based on known patient preference, classical music, pleasant sounds such as ocean waves, and even stories and comforting prayer recorded by family members. While most of these smaller studies yielded positive results,34 a 2003 Cochrane review concluded there is not enough evidence to recommend for or against music therapy.43 A more recent meta-analysis suggests that music may be effective for agitation.30 A systematic review of quality guidelines also indicates that most of these guidelines rate the evidence as moderate to high in favor of music and 3 of 5 practice guidelines recommend it.28

Nonphysical barriers have long been used as a creative nonrestraining method of preventing wandering. They include such tricks as camouflaging exits by painting them to look like bookcases, painting a black square in front of an elevator to make it look like a hole, and placing a thin Velcro strip across doorways. Although it would appear from a limited number of small studies and anecdotal evidence that nonphysical barriers work, a Cochrane review concluded that they have not been studied enough to perform a meta-analysis.36

Cognitive stimulation typically consists of activities such as reviewing current events, promoting sensory awareness, drawing, associating words, discussion of hobbies, and planning daily activities. This type of therapy has been shown to improve cognition in patients with dementia, as well as well-being and quality of life. It does not improve behavioral problems, per se.37

Reminiscence therapy is a popular modality that involves stimulating memories of the past by looking at personal photos and newspaper clippings and discussing the past. It is well received by patients and caregivers. It has been shown to improve mood in elderly patients without dementia, but studies of reminiscence therapy have been too dissimilar to draw conclusions regarding its effect on behavioral disturbances in patients with dementia.38

Other therapies that are common in dementia care, such as respite care and specialized dementia units, have simply not been studied well enough to provide any conclusions as to their effectiveness.39,40

CASE When Ms. M is discharged from the hospital, her family enrolls her in an adult day care program, where Ms. M will be able to participate in social activities, exercise, and communal meals. Her daughter asks the family physician what other steps they can take in the home to make things easier on her mother. And as an aside, the daughter admits that while she is glad that she and her family can “be there” for her mother, there have been times when she has simply not felt up to the task.

Help family members care for the patient—and themselves

A recent meta-analysis suggests that caregiver interventions have a positive effect on behavioral problems in patients with dementia.32 Successful programs are tailored to the individual needs of the patient and caregiver and delivered over multiple sessions. Unfortunately, the aforementioned meta-analysis did not provide evidenced-based interventions for specific problems.32 With this in mind, the following are some practical caregiver “do’s and don’ts” that are based on reviews and consensus guidelines.

Don’t take it personally. It is extremely important to help caregivers understand that the disturbing behaviors of patients with dementia lack intentionality and are part of the normal progression of the disorder.25 Caregivers also need to appreciate that hallucinations are normal in these patients and do not require medications if they don’t disturb the patient or place the patient or anyone else at risk.

Don’t try to reason with the patient; redirect him or her instead. Clinicians should offer caregivers suggestions for reassuring, redirecting, or distracting agitated patients rather than trying to reason with them. Encourage caregivers to develop and maintain routines and consistency.6,25 Using a calm, low tone of voice, giving very simple instructions, and leaving and then reattempting care that is refused the first time may also be effective.5 Some experts have suggested techniques such as giving positive rewards for desired behaviors and not rewarding negative behaviors.6,26

Do create a safe environment. Recommend that caregivers create a safe environment. Make sure that they lock up all guns. Also, encourage them to use locks, alarms, or ID bracelets when patients are prone to wandering.25

Do consider a caregiver support program. Caregivers can make a big difference in the lives of patients with dementia, Help caregivers understand that the disturbing behaviors of patients with dementia lack intentionality and are part of the normal progression of the disorder. but only if they have support, as well.

A recent meta-analysis concluded that active involvement of caregivers in making choices about treatments distinguishes effective from ineffective support programs, decreases the odds of institutionalization, and may lengthen time to institutionalization.33 To ease caregiver strain and depression, encourage them to make use of resources such as nursing home respite care and community agencies that include the Alzheimer’s Association (http://www.alz.org).6,44,45

CASE Ms. M’s daughter joins a local support group for families of patients with dementia, where she learns redirection techniques to try when her mother refuses care. The exercise and daytime social stimulation that Ms. M receives through the adult day care program helps her to sleep at night. When Ms. M refuses to take a shower—a challenge the family had before her hospitalization—the daughter does not argue with her. Instead, she returns 10 to 20 minutes later and asks again, or tries a bedside sponge bath with a lavender soap that Ms. M seems to like.

Ms. M’s nighttime wandering is markedly reduced and the family no longer uses any antipsychotic medications. The family physician counsels them, however, about the progressive nature of the disease and encourages them to set up periodic follow-up visits, so that he can see how everyone—patient and caregivers alike—are doing.

Welcoming the reprieves, recognizing the realities

The behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia are the most challenging aspect of dementia care. Unacceptable behaviors sometimes persist even when aggressively addressing modifiable factors and attempting behavioral interventions (TABLE 2).2,5-7,15,16,24-26,32,41,44-46 Patients with behavioral disturbances frequently require a pharmacologic agent or transfer to a different care setting.

But clinicians need to use psychotropic medications with informed patient and/or caregiver consent.7 On a case-by-case basis, a trial of antipsychotics is often justified, despite the black box warning. A family may choose to try an antipsychotic despite the risk to help manage the patient at home in the hope of delaying or preventing institutionalization.

However, even with good home support, in conjunction with nonpharmacologic and/or pharmacologic therapies, most patients with dementia will eventually require institutionalization.47 Because patients and families often rely on family physicians to guide them through these difficult challenges and decisions, you’ll need to remain well versed on the available On a case-by- case basis, a trial of antipsychotics is often justified, despite the black box warning. treatments for the psychological and behavioral symptoms of dementia, as well as the resources available in your community.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jaqueline Raetz, MD, 331 NE Thornton Place, Seattle, WA 98125; [email protected]

› Attempt nonpharmacologic treatment for dementia behavioral problems before moving on to medications, which are of questionable efficacy for symptoms other than aggression and psychosis. A

› Obtain informed consent from patients and/or their caregivers if you plan to use antipsychotic medications because their use increases morbidity and mortality in the elderly. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE Ms. M, 86 years old, lives with her daughter, son-in-law, and granddaughter. For several years she has been forgetful, but she has never had a formal work-up for dementia. Her daughter finally brings her to their primary care physician because she was refusing to take showers, was increasingly irritable, and had tried to hit her daughter’s husband.

In the office, however, Ms. M is calm and pleasant. The family says that most nights Ms. M gets up and wanders around the house. She denies feeling depressed or anxious, but her Folstein Mini-Mental State Exam score is 22/30, indicating moderate dementia. (For more on assessment, see “Tools for assessing patients with dementia—and their caregivers” on page 552.)

The physician offers a trial of risperidone 0.25 mg at bedtime to assist with sleep and behavior.

Was this prescription a wise decision? What other questions should this physician have asked?

Understanding the behavioral symptoms

Noncognitive symptoms of dementia, sometimes referred to as behavioral and psychological symptoms, are common, affecting almost 90% of patients with dementia,1-3 which itself can be classified as early, intermediate, and late.

In early dementia, sociability is usually not affected, but patients may repeat questions, misplace items, use poor judgment, and begin to have difficulty with more complex daily tasks like finances and driving.

In intermediate dementia, basic activities of daily living become impaired and normal social and environmental cues may not register.

In late dementia, patients become entirely dependent on others; they may lose the ability to speak, walk, and eventually, eat. Long- and short-term memory is lost.

Behavioral symptoms most often occur when the condition enters the intermediate phase, but they may occur at any time during the course of the disease.4 Behaviors may include refusal of care, yelling, aggressive behavior, agitation, restlessness, reversal of the normal sleep-wake cycle, wandering, hoarding, sexual disinhibition, culturally inappropriate behaviors, hallucinations, delusions, anxiety, depression, apathy, and psychosis.2,5

Behavioral disturbances often overwhelm families, and lack of treatment increases patient morbidity, may result in physical harm, and almost always precipitates institutionalization.2 Dementia-related behavioral disturbances also increase the risk of caregiver burnout and depression.2

These symptoms are difficult to treat with medications or nonpharmacologic therapy and strong evidence for most therapies is lacking. Physicians have historically prescribed either typical or atypical antipsychotics in an attempt to control these behaviors. In fact, medication is often still considered first-line therapy.6,7

CASE Ms. M’s daughter calls the clinic 2 weeks after the initial visit to tell the physician that her mother has been sleeping much better, but had a fall and was admitted to the hospital for a hip fracture. That’s not surprising; typical and atypical antipsychotics increase the risk of falls in the elderly.8

The risks associated with the use of antipsychotics

In 2005, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a black box warning for atypical antipsychotics because they were found to increase mortality in the elderly. The increased mortality is due to cardiac events or infection.9,10 In 2008, the FDA warning was added to typical antipsychotics, as well.11,12 Both typical and atypical antipsychotics have been found to increase the risk of falls and strokes in the elderly,8,13 and their efficacy in treating the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia has recently been questioned.13-16

Trazodone and medications approved for the specific treatment of cognitive decline, such as donepezil or memantine, are also prescribed for behavioral disturbances, but evidence to support their efficacy is limited.14,17-20 More recently, a meta-analysis of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) suggests that they may be effective for treating agitation associated with dementia.21 However, SSRIs may also contribute to falls and to hyponatremia in the elderly.22,23

Pharmacologic Tx is not your only option

Considering the questionable safety and efficacy of pharmacologic treatment, physicians should consider nondrug therapies first, or at least concurrently with medication.2,15,16,24

But before you get started, be sure to look for and treat medical conditions that cause or contribute to behavioral disturbances, including infection, pain, and adverse effects of medication.6,7,25 Similarly, it is essential that unmet needs, such as hunger, thirst, or desire for attention or socialization, be addressed.6,7,26 Also, discuss disturbing environmental factors, including loud noises, poorly lit quarters, and strong smells, with patients and their caregivers.5-7 In complex situations, you may need to seek assistance from a geriatrician, neurologist, geropsychiatrist, or psychologist, although their availability may be limited.6

CASE Ms. M becomes markedly delirious while in the hospital after hip surgery, and a geriatrics consultation is requested. This is not surprising, given that underlying dementia increases a patient’s risk of delirium in the hospital.27 The geriatrician recommends several measures to reduce the likelihood of delirium—providing good pain control, minimizing night time wake-ups, minimizing Foley catheter use, Hep-locking the IV to encourage mobility, and having staff reorient her frequently by referring to a large print clock and calendar on the wall.

Specific interventions

Most specific nonpharmacologic therapies have not been robustly studied in randomized controlled trials. But a series of smaller studies have been evaluated in systematic reviews. The level of evidence for each intervention is summarized in TABLE 1.28-40

As you review the options that follow, keep 2 things in mind: (1) It is important to set realistic expectations when considering these approaches (as well as pharmacologic ones). Reducing the frequency or severity of problematic behaviors may be more reasonable than their total elimination.6,25 (2) Consider targeting specific symptoms when treating behavioral Behavioral symptoms most often occur when dementia enters the intermediate phase, but they may occur at any time during the course of the disease. disturbances.2,24,41 Such targeting allows physicians and families to better evaluate the effectiveness of interventions because it helps to focus the discussion of the patient’s progress at follow-up visits.

Massage/touch therapy. A 2006 Cochrane review concluded that improvement in nutritional intake and hand massage, when combined with positive encouragement during a meal, may produce a short-term positive effect on agitation.29 Similarly, a meta-analysis of randomized controlled and randomized crossover studies found a statistically significant improvement in agitation with hand massage, although this finding was based on the same single study referenced in the 2006 review.30 Opinions differ among 5 high-quality guidelines included in the systematic review by Azermai et al regarding the value of massage, with 2 of the 5 practice guidelines recommending its use.28

Aromatherapy. Several trials suggest that aroma therapy may reduce agitated behaviors. Lemon balm and lavender oils have been the most commonly studied agents. Two systematic reviews cite the same 2002 randomized controlled trial, which found a reduction in behavioral problems in people who received arm massage with lemon balm compared with those who received arm massage with an odorless cream.30,31 A systematic review by Holt et al also cites a study that found lavender oil placed in a sachet on each side of the pillow for at least one hour during sleep seemed to reduce problem behaviors.31 Several evidence-based guidelines have concluded that aromatherapy may be helpful, and 2 of the 5 practice guidelines reviewed by Azermai et al recommend it.28

Exercise has been shown to benefit patients of all ages, even those with terminal diseases.42 Some studies have indicated a positive effect of physical activities on behaviors ranging from wandering to aggression and agitation. Activities have included group gentle stretches, indoor exercises, and a volunteer-led walking program that encouraged hand holding and singing.34 However, a 2008 Cochrane review concluded that the effect of exercise on behavioral disturbances in dementia has not been adequately studied.35

Music therapy. Numerous types of music therapy have been studied, including listening to music picked out by a patient’s family based on known patient preference, classical music, pleasant sounds such as ocean waves, and even stories and comforting prayer recorded by family members. While most of these smaller studies yielded positive results,34 a 2003 Cochrane review concluded there is not enough evidence to recommend for or against music therapy.43 A more recent meta-analysis suggests that music may be effective for agitation.30 A systematic review of quality guidelines also indicates that most of these guidelines rate the evidence as moderate to high in favor of music and 3 of 5 practice guidelines recommend it.28

Nonphysical barriers have long been used as a creative nonrestraining method of preventing wandering. They include such tricks as camouflaging exits by painting them to look like bookcases, painting a black square in front of an elevator to make it look like a hole, and placing a thin Velcro strip across doorways. Although it would appear from a limited number of small studies and anecdotal evidence that nonphysical barriers work, a Cochrane review concluded that they have not been studied enough to perform a meta-analysis.36

Cognitive stimulation typically consists of activities such as reviewing current events, promoting sensory awareness, drawing, associating words, discussion of hobbies, and planning daily activities. This type of therapy has been shown to improve cognition in patients with dementia, as well as well-being and quality of life. It does not improve behavioral problems, per se.37

Reminiscence therapy is a popular modality that involves stimulating memories of the past by looking at personal photos and newspaper clippings and discussing the past. It is well received by patients and caregivers. It has been shown to improve mood in elderly patients without dementia, but studies of reminiscence therapy have been too dissimilar to draw conclusions regarding its effect on behavioral disturbances in patients with dementia.38

Other therapies that are common in dementia care, such as respite care and specialized dementia units, have simply not been studied well enough to provide any conclusions as to their effectiveness.39,40

CASE When Ms. M is discharged from the hospital, her family enrolls her in an adult day care program, where Ms. M will be able to participate in social activities, exercise, and communal meals. Her daughter asks the family physician what other steps they can take in the home to make things easier on her mother. And as an aside, the daughter admits that while she is glad that she and her family can “be there” for her mother, there have been times when she has simply not felt up to the task.

Help family members care for the patient—and themselves

A recent meta-analysis suggests that caregiver interventions have a positive effect on behavioral problems in patients with dementia.32 Successful programs are tailored to the individual needs of the patient and caregiver and delivered over multiple sessions. Unfortunately, the aforementioned meta-analysis did not provide evidenced-based interventions for specific problems.32 With this in mind, the following are some practical caregiver “do’s and don’ts” that are based on reviews and consensus guidelines.

Don’t take it personally. It is extremely important to help caregivers understand that the disturbing behaviors of patients with dementia lack intentionality and are part of the normal progression of the disorder.25 Caregivers also need to appreciate that hallucinations are normal in these patients and do not require medications if they don’t disturb the patient or place the patient or anyone else at risk.

Don’t try to reason with the patient; redirect him or her instead. Clinicians should offer caregivers suggestions for reassuring, redirecting, or distracting agitated patients rather than trying to reason with them. Encourage caregivers to develop and maintain routines and consistency.6,25 Using a calm, low tone of voice, giving very simple instructions, and leaving and then reattempting care that is refused the first time may also be effective.5 Some experts have suggested techniques such as giving positive rewards for desired behaviors and not rewarding negative behaviors.6,26

Do create a safe environment. Recommend that caregivers create a safe environment. Make sure that they lock up all guns. Also, encourage them to use locks, alarms, or ID bracelets when patients are prone to wandering.25

Do consider a caregiver support program. Caregivers can make a big difference in the lives of patients with dementia, Help caregivers understand that the disturbing behaviors of patients with dementia lack intentionality and are part of the normal progression of the disorder. but only if they have support, as well.

A recent meta-analysis concluded that active involvement of caregivers in making choices about treatments distinguishes effective from ineffective support programs, decreases the odds of institutionalization, and may lengthen time to institutionalization.33 To ease caregiver strain and depression, encourage them to make use of resources such as nursing home respite care and community agencies that include the Alzheimer’s Association (http://www.alz.org).6,44,45

CASE Ms. M’s daughter joins a local support group for families of patients with dementia, where she learns redirection techniques to try when her mother refuses care. The exercise and daytime social stimulation that Ms. M receives through the adult day care program helps her to sleep at night. When Ms. M refuses to take a shower—a challenge the family had before her hospitalization—the daughter does not argue with her. Instead, she returns 10 to 20 minutes later and asks again, or tries a bedside sponge bath with a lavender soap that Ms. M seems to like.

Ms. M’s nighttime wandering is markedly reduced and the family no longer uses any antipsychotic medications. The family physician counsels them, however, about the progressive nature of the disease and encourages them to set up periodic follow-up visits, so that he can see how everyone—patient and caregivers alike—are doing.

Welcoming the reprieves, recognizing the realities

The behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia are the most challenging aspect of dementia care. Unacceptable behaviors sometimes persist even when aggressively addressing modifiable factors and attempting behavioral interventions (TABLE 2).2,5-7,15,16,24-26,32,41,44-46 Patients with behavioral disturbances frequently require a pharmacologic agent or transfer to a different care setting.

But clinicians need to use psychotropic medications with informed patient and/or caregiver consent.7 On a case-by-case basis, a trial of antipsychotics is often justified, despite the black box warning. A family may choose to try an antipsychotic despite the risk to help manage the patient at home in the hope of delaying or preventing institutionalization.

However, even with good home support, in conjunction with nonpharmacologic and/or pharmacologic therapies, most patients with dementia will eventually require institutionalization.47 Because patients and families often rely on family physicians to guide them through these difficult challenges and decisions, you’ll need to remain well versed on the available On a case-by- case basis, a trial of antipsychotics is often justified, despite the black box warning. treatments for the psychological and behavioral symptoms of dementia, as well as the resources available in your community.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jaqueline Raetz, MD, 331 NE Thornton Place, Seattle, WA 98125; [email protected]

1. Mega MS, Cummings JL, Fiorello T, et al. The spectrum of behavioral changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1996;46:130-135.

2. Feil DG, MacLean C, Sultzer D. Quality indicators for the care of dementia in vulnerable elders. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(suppl 2):S293-S301.

3. Hort J, O’Brien JT, Gainotti G, et al. EFNS guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17:1236-1248.

4. Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, et al. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: results from the cardiovascular health study. JAMA. 2002;288:1475-1483.

5. Omelan C. Approach to managing behavioural disturbances in dementia. Can Fam Physician. 2006;52:191-199.

6. Sadowsky CH, Galvin JE. Guidelines for the management of cognitive and behavioral problems in dementia. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25:350-366.

7. Salzman C, Jeste DV, Meyer RE, et al. Elderly patients with dementia-related symptoms of severe agitation and aggression: consensus statement on treatment options, clinical trials methodology, and policy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:889-898.

8. Hill KD, Wee R. Psychotropic drug-induced falls in older people: a review of interventions aimed at reducing the problem. Drugs Aging. 2012;29:15-30.

9. US Food and Drug Administration. Public health advisory: deaths with antipsychotics in elderly patients with behavioral disturbances. April 11, 2005. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/DrugSafetyInformationforHeathcareProfessionals/PublicHealthAdvisories/ucm053171.htm. Accessed September 16, 2013.

10. Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA. 2005;294:1934-1943.

11. US Food and Drug Administration. Antipsychotics, conventional and atypical. June 16, 2008. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm110212.htm. Accessed September 16, 2013.

12. Wang PS, Schneeweiss S, Avorn J, et al. Risk of death in elderly users of conventional vs. atypical antipsychotic medications. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2335-2341.

13. Ballard C, Waite J. The effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of aggression and psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD003476.

14. Sink KM, Holden KF, Yaffe K. Pharmacological treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: a review of the evidence. JAMA. 2005;293:596-608.

15. Lonergan E, Luxenberg J, Colford JM. Haloperidol for agitation in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(2):CD002852.

16. Schneider LS, Tariot PN, Dagerman KS, et al; CATIE-AD Study Group. Effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic drugs in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1525-1538.

17. Martinón-Torres G, Fioravanti M, Grimley EJ. Trazodone for agitation in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(4):CD004990.

18. Birks J, Harvey RJ. Donepezil for dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD001190.

19. McShane R, Areosa Sastre A, Minakaran N. Memantine for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD003154.

20. Raina P, Santaguida P, Ismaila A, et al. Effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for treating dementia: evidence review for a clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:379-397.

21. Seitz DP, Adunuri N, Gill SS, et al. Antidepressants for agitation and psychosis in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(2): CD008191.

22. Sterke CS, Ziere G, van Beeck EF, et al. Dose-response relationship between selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors and injurious falls: a study in nursing home residents with dementia. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73:812-820.

23. Jacob S, Spinler SA. Hyponatremia associated with selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in older adults. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:1618-1622.

24. Segal-Gidan F, Cherry D, Jones R, et al. Alzheimer’s disease management guideline: update 2008. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:e51-e59.

25. Rayner A, O’Brien J, Shoenbachler B. Behavior disorders of dementia: recognition and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2006;73:647-652.

26. Ayalon L, Gum AM, Feliciano L, et al. Effectiveness of nonpharmacological interventions for the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2182-2188.

27. Elie M, Cole MG, Primeau FJ, et al. Delirium risk factors in elderly hospitalized patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:204-212.

28. Azermai M, Petrovic M, Elseviers MM, et al. Systematic appraisal of dementia guidelines for the management of behavioural and psychological symptoms. Aging Res Rev. 2012;11:78-86.

29. Viggo Hansen N, Jørgensen T, Ørtenblad L. Massage and touch for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD004989.

30. Kong EH, Evans LK, Guevara JP. Nonpharmacological intervention for agitation in dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13:512-520.

31. Thorgrimsen LM, Spector A, Wiles A, et al. Aroma therapy for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(3):CD003150.

32. Brodaty H, Arasaratnam C. Review of meta-analysis of nonpharmacological interventions for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Am J Psychiatry 2012;169:946-953.

33. Spijker A, Vernooij-Dassen M, Vasse E, et al. Effectiveness of nonpharmacological interventions in delaying the institutionalization of patients with dementia: A meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1116-1128.

34. Opie J, Rosewarne R, O’Connor DW. The efficacy of psychosocial approaches to behaviour disorders in dementia: a systematic literature review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1999;33:789-799.

35. Forbes D, Forbes S, Morgan DG, et al. Physical activity programs for persons with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(3):CD006489.

36. Price JD, Hermans DG, Grimley Evans J. Subjective barriers to prevent wandering of cognitively impaired people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(4):CD001932.

37. Woods B, Aguirre E, Spector AE, et al. Cognitive stimulation to improve cognitive functioning in people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(2):CD005562.

38. Woods B, Spector A, Jones C, et al. Reminiscence therapy for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2):CD001120.

39. Lee H, Cameron M. Respite care for people with dementia and their carers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(2):CD004396.

40. Lai CK, Yeung JH, Mok V, et al. Special care units for dementia individuals with behavioural problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4):CD006470.

41. Waldemar G, Dubois B, Emre M, et al. Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders associated with dementia: EFNS guideline. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14:e1-e26.

42. Oldervoll LM, Loge JH, Paltiel H, et al. The effect of a physical exercise program in palliative care: a phase II study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31:421-430.

43. Vink AC, Birks JS, Bruinsma MS, et al. Music therapy for people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD003477.

44. Gitlin LN, Kales HC, Lyketsos CG. Nonpharmacologic management of behavioral symptoms in dementia. JAMA. 2012;308:2020-2029.

45. Bass DM, Clark PA, Looman WJ, et al. The Cleveland Alzheimer’s managed care demonstration: outcomes after 12 months of implementation. Gerontologist. 2003;43:73-85.

46. Gitlin LN, Winter L, Dennis MP, et al.. A biobehavioral home-based intervention and the well-being of patients with dementia and their caregivers: the COPE randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304:983-991.

47. Smith GE, Kokmen E, O’Brien PC. Risk factors for nursing home placement in a population-based dementia cohort. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:519-525.

1. Mega MS, Cummings JL, Fiorello T, et al. The spectrum of behavioral changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1996;46:130-135.

2. Feil DG, MacLean C, Sultzer D. Quality indicators for the care of dementia in vulnerable elders. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(suppl 2):S293-S301.

3. Hort J, O’Brien JT, Gainotti G, et al. EFNS guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17:1236-1248.

4. Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, et al. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: results from the cardiovascular health study. JAMA. 2002;288:1475-1483.

5. Omelan C. Approach to managing behavioural disturbances in dementia. Can Fam Physician. 2006;52:191-199.

6. Sadowsky CH, Galvin JE. Guidelines for the management of cognitive and behavioral problems in dementia. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25:350-366.

7. Salzman C, Jeste DV, Meyer RE, et al. Elderly patients with dementia-related symptoms of severe agitation and aggression: consensus statement on treatment options, clinical trials methodology, and policy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:889-898.

8. Hill KD, Wee R. Psychotropic drug-induced falls in older people: a review of interventions aimed at reducing the problem. Drugs Aging. 2012;29:15-30.

9. US Food and Drug Administration. Public health advisory: deaths with antipsychotics in elderly patients with behavioral disturbances. April 11, 2005. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/DrugSafetyInformationforHeathcareProfessionals/PublicHealthAdvisories/ucm053171.htm. Accessed September 16, 2013.

10. Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA. 2005;294:1934-1943.

11. US Food and Drug Administration. Antipsychotics, conventional and atypical. June 16, 2008. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm110212.htm. Accessed September 16, 2013.

12. Wang PS, Schneeweiss S, Avorn J, et al. Risk of death in elderly users of conventional vs. atypical antipsychotic medications. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2335-2341.

13. Ballard C, Waite J. The effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of aggression and psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD003476.

14. Sink KM, Holden KF, Yaffe K. Pharmacological treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: a review of the evidence. JAMA. 2005;293:596-608.

15. Lonergan E, Luxenberg J, Colford JM. Haloperidol for agitation in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(2):CD002852.

16. Schneider LS, Tariot PN, Dagerman KS, et al; CATIE-AD Study Group. Effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic drugs in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1525-1538.

17. Martinón-Torres G, Fioravanti M, Grimley EJ. Trazodone for agitation in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(4):CD004990.

18. Birks J, Harvey RJ. Donepezil for dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD001190.

19. McShane R, Areosa Sastre A, Minakaran N. Memantine for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD003154.

20. Raina P, Santaguida P, Ismaila A, et al. Effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for treating dementia: evidence review for a clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:379-397.

21. Seitz DP, Adunuri N, Gill SS, et al. Antidepressants for agitation and psychosis in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(2): CD008191.

22. Sterke CS, Ziere G, van Beeck EF, et al. Dose-response relationship between selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors and injurious falls: a study in nursing home residents with dementia. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73:812-820.

23. Jacob S, Spinler SA. Hyponatremia associated with selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in older adults. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:1618-1622.

24. Segal-Gidan F, Cherry D, Jones R, et al. Alzheimer’s disease management guideline: update 2008. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:e51-e59.

25. Rayner A, O’Brien J, Shoenbachler B. Behavior disorders of dementia: recognition and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2006;73:647-652.

26. Ayalon L, Gum AM, Feliciano L, et al. Effectiveness of nonpharmacological interventions for the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2182-2188.

27. Elie M, Cole MG, Primeau FJ, et al. Delirium risk factors in elderly hospitalized patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:204-212.

28. Azermai M, Petrovic M, Elseviers MM, et al. Systematic appraisal of dementia guidelines for the management of behavioural and psychological symptoms. Aging Res Rev. 2012;11:78-86.

29. Viggo Hansen N, Jørgensen T, Ørtenblad L. Massage and touch for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD004989.

30. Kong EH, Evans LK, Guevara JP. Nonpharmacological intervention for agitation in dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13:512-520.

31. Thorgrimsen LM, Spector A, Wiles A, et al. Aroma therapy for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(3):CD003150.

32. Brodaty H, Arasaratnam C. Review of meta-analysis of nonpharmacological interventions for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Am J Psychiatry 2012;169:946-953.

33. Spijker A, Vernooij-Dassen M, Vasse E, et al. Effectiveness of nonpharmacological interventions in delaying the institutionalization of patients with dementia: A meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1116-1128.

34. Opie J, Rosewarne R, O’Connor DW. The efficacy of psychosocial approaches to behaviour disorders in dementia: a systematic literature review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1999;33:789-799.

35. Forbes D, Forbes S, Morgan DG, et al. Physical activity programs for persons with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(3):CD006489.

36. Price JD, Hermans DG, Grimley Evans J. Subjective barriers to prevent wandering of cognitively impaired people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(4):CD001932.

37. Woods B, Aguirre E, Spector AE, et al. Cognitive stimulation to improve cognitive functioning in people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(2):CD005562.

38. Woods B, Spector A, Jones C, et al. Reminiscence therapy for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2):CD001120.

39. Lee H, Cameron M. Respite care for people with dementia and their carers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(2):CD004396.

40. Lai CK, Yeung JH, Mok V, et al. Special care units for dementia individuals with behavioural problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4):CD006470.

41. Waldemar G, Dubois B, Emre M, et al. Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders associated with dementia: EFNS guideline. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14:e1-e26.

42. Oldervoll LM, Loge JH, Paltiel H, et al. The effect of a physical exercise program in palliative care: a phase II study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31:421-430.

43. Vink AC, Birks JS, Bruinsma MS, et al. Music therapy for people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD003477.

44. Gitlin LN, Kales HC, Lyketsos CG. Nonpharmacologic management of behavioral symptoms in dementia. JAMA. 2012;308:2020-2029.

45. Bass DM, Clark PA, Looman WJ, et al. The Cleveland Alzheimer’s managed care demonstration: outcomes after 12 months of implementation. Gerontologist. 2003;43:73-85.

46. Gitlin LN, Winter L, Dennis MP, et al.. A biobehavioral home-based intervention and the well-being of patients with dementia and their caregivers: the COPE randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304:983-991.

47. Smith GE, Kokmen E, O’Brien PC. Risk factors for nursing home placement in a population-based dementia cohort. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:519-525.

Woman, 45, With Red, Scaly Nipple

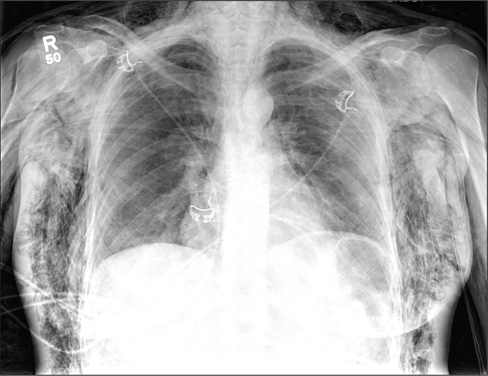

A 45-year-old woman noticed some redness and scaling around her right nipple. She applied peroxide and OTC antibiotic ointment for approximately seven months with mixed results. She sought medical attention when pain developed in the breast, along with some bloody discharge from the nipple (see Figure 1). Around that time, she also noticed three small nodules in the upper outer portion of the breast.

A mammogram and ultrasound revealed a 1.7 × 2.0–cm spiculated mass in the axillary tail, as well as two smaller breast lesions. A PET/CT scan ordered subsequently revealed intense uptake in the periareolar region and a suspicious axillary node. By then, the biopsy results had confirmed invasive ductal carcinoma, later determined to be Paget’s disease of the breast (PDB).

The patient’s previous medical history was significant for cystic breasts (never biopsied), chronic back pain, anxiety, and obesity. She was perimenopausal with irregular periods, the last one about 10 months ago. Her obstetric history included two pregnancies resulting in live births and no history of abortion; her menarche occurred at age 14 and her first pregnancy at 27. Family history was significant for leukemia in her maternal grandmother and niece. She did not use tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs. She lived at home with her husband and two daughters, who were all very supportive.

The patient elected to undergo a right modified radical mastectomy (MRM) and prophylactic left total mastectomy. MRM was performed on the right breast because sentinel lymph node identification was unsuccessful. This may have been due to involvement of the right subareolar plexus. Five of eight lymph nodes later tested positive for malignancy. The surgery was completed by placement of bilateral tissue expanders for eventual breast reconstruction.

Chemotherapy was started six weeks after surgery and included 15 weeks (five cycles) of docetaxel, carboplatin, and trastuzumab (a combination known as TCH), followed by 51 weeks (17 cycles) of trastuzumab, along with daily tamoxifen. The TCH regimen was followed by four weekly cycles of external beam radiation therapy (EBRT). Adverse effects of treatment have included chest wall dermatitis, right upper extremity lymphedema, nausea/vomiting, dyspnea, peripheral neuropathy, alopecia, and fatigue.

Discussion

Nearly 150 years ago, James Paget recognized a connection between skin changes around the nipple and deeper lesions in the breast.1 The disease that Paget identified is defined as the presence of intraepithelial adenocarcinoma cells (ie, Paget’s cells) within the epidermis of the nipple, with or without an underlying carcinoma.

An underlying breast cancer is present 85% to 95% of the time but is palpable in only approximately 50% of cases (see Figure 2). However, 25% of the time there is neither a palpable mass nor a mammographic abnormality. In these cases particularly, timely diagnosis depends on recognition of suspicious nipple changes, followed by a prompt and thorough diagnostic workup. Unfortunately, the accurate diagnosis of Paget’s disease still takes an average of several months.2

Paget’s disease is rare; it represents only 1% to 3% of new cases of female breast cancer, or about 2,250 cases a year.2-4 (The number of Paget’s disease cases per year was calculated by the author, based on the reported incidence of all breast cancers.) It is even more rare among men. For both genders, the peak age for this disease is between 50 and 60.2

Paget’s disease is an important entity for primary care PAs and NPs because it presents an opportunity to make a timely and life-changing diagnosis, and because it provides an elegant model for understanding current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to breast cancer.

Clinical Presentation and Pathophysiology