User login

Democracy - best, but only if....

A stated goal of the United States is to support and promote democracy throughout the world. This seems reasonable, because democracy has often worked well in our own and other Western countries, and because no other form of government has consistently been better. So is democracy the best form of government? I submit that it is the best only if certain conditions are met.

For democracy to work, the public must be well informed and willing to consider, at least to some extent, the country’s interests in addition to their own self-interests. If a major fraction of the public does not care about or know what is good for the country or is totally motivated by self-interest, the government and the country will fail. Sadly this appears to be the case in the U.S. today as evidenced by Jay Leno’s "JayWalking Segments" in which most young people interviewed – even college graduates – have no idea about issues important to our country. They appear to be more interested in sports and their social life and more knowledgeable about TV sitcoms and reality shows.

How can such individuals be relied upon to pick government leaders who will take care of our country’s interests in the trying times it faces politically and economically? An ill-informed and non-caring public is more likely to pick leaders who are the slickest talkers and who promise the most despite the impossibility or negative effects of keeping these promises. This know-nothing or self-interested nature of our electorate contributes importantly to the ever expanding entitlement culture in the U.S. and the resulting dangerous expansion of our national debt.

Another related requirement for democracy to be an effective form of government is the need for an honest and objective media and press. A controlled or biased source of information contributes hugely to an ill-informed public. Whoever controls the media and the press controls the minds of the voters. For democracy to work effectively, the public must not only want to be informed, they must also be given the necessary objective facts to make valid judgments. The press has a vital responsibility to provide such facts with minimal bias. There is considerable doubt about whether or not this is occurring today in the U.S.

Of even greater importance to a successful democracy is the ethical stature of its leaders and their motivation – once elected – to act in the best interests of the country. Many forces act upon our leaders and are counter to these interests. These include obligations to those who helped elect them, ideology, personal gain, a desire to be re-elected, and most importantly the corrupting requirement to solicit campaign financing. In the U.S. currently, the need to finance expensive campaigns is a major flaw in our democracy, and is really a veiled form of bribery.

For a democratic leader to be successful in terms of doing a good job of leading the country, all these forces must be overridden by the desire to do what is right and best for the whole country. This means the leader must not serve solely special or self-interests, and must have the courage and inner strength to do what may at the moment be unpopular with his or her electoral base. He or she must unite the country rather than divide it for short-term political or parochial gain. Unfortunately many of our recently elected U.S. leaders have not met any of these requirements. If this trend continues, our democracy will serve the country’s interests poorly, and the U.S. will decline rather than gain in stature and strength.

Efforts at democracy in the Middle East and elsewhere have failed because some or all of the requirements discussed here have not been met. A similar decline awaits our U.S. democracy if the current flaws in the underlying system cannot be corrected.

So far this discussion has largely been related to the U.S. federal government. However, the same considerations apply to effective governments at the county, state, and city levels, and to governing bodies of other entities which purport to be managed in a democratic fashion. This even applies to our vascular societies. The ethics and character of the leaders and those choosing them are important to effective governance and the success of the organization. If special interests, financial conflicts, and self-interest prevail over the needs of the organization, the latter will fail and decline.

Dr. Veith is Professor of Surgery at New York University Medical Center and the Cleveland Clinic. He is an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

The ideas and opinions expressed in Vascular Specialist do not necessarily reflect those of the Society or Publisher.

A stated goal of the United States is to support and promote democracy throughout the world. This seems reasonable, because democracy has often worked well in our own and other Western countries, and because no other form of government has consistently been better. So is democracy the best form of government? I submit that it is the best only if certain conditions are met.

For democracy to work, the public must be well informed and willing to consider, at least to some extent, the country’s interests in addition to their own self-interests. If a major fraction of the public does not care about or know what is good for the country or is totally motivated by self-interest, the government and the country will fail. Sadly this appears to be the case in the U.S. today as evidenced by Jay Leno’s "JayWalking Segments" in which most young people interviewed – even college graduates – have no idea about issues important to our country. They appear to be more interested in sports and their social life and more knowledgeable about TV sitcoms and reality shows.

How can such individuals be relied upon to pick government leaders who will take care of our country’s interests in the trying times it faces politically and economically? An ill-informed and non-caring public is more likely to pick leaders who are the slickest talkers and who promise the most despite the impossibility or negative effects of keeping these promises. This know-nothing or self-interested nature of our electorate contributes importantly to the ever expanding entitlement culture in the U.S. and the resulting dangerous expansion of our national debt.

Another related requirement for democracy to be an effective form of government is the need for an honest and objective media and press. A controlled or biased source of information contributes hugely to an ill-informed public. Whoever controls the media and the press controls the minds of the voters. For democracy to work effectively, the public must not only want to be informed, they must also be given the necessary objective facts to make valid judgments. The press has a vital responsibility to provide such facts with minimal bias. There is considerable doubt about whether or not this is occurring today in the U.S.

Of even greater importance to a successful democracy is the ethical stature of its leaders and their motivation – once elected – to act in the best interests of the country. Many forces act upon our leaders and are counter to these interests. These include obligations to those who helped elect them, ideology, personal gain, a desire to be re-elected, and most importantly the corrupting requirement to solicit campaign financing. In the U.S. currently, the need to finance expensive campaigns is a major flaw in our democracy, and is really a veiled form of bribery.

For a democratic leader to be successful in terms of doing a good job of leading the country, all these forces must be overridden by the desire to do what is right and best for the whole country. This means the leader must not serve solely special or self-interests, and must have the courage and inner strength to do what may at the moment be unpopular with his or her electoral base. He or she must unite the country rather than divide it for short-term political or parochial gain. Unfortunately many of our recently elected U.S. leaders have not met any of these requirements. If this trend continues, our democracy will serve the country’s interests poorly, and the U.S. will decline rather than gain in stature and strength.

Efforts at democracy in the Middle East and elsewhere have failed because some or all of the requirements discussed here have not been met. A similar decline awaits our U.S. democracy if the current flaws in the underlying system cannot be corrected.

So far this discussion has largely been related to the U.S. federal government. However, the same considerations apply to effective governments at the county, state, and city levels, and to governing bodies of other entities which purport to be managed in a democratic fashion. This even applies to our vascular societies. The ethics and character of the leaders and those choosing them are important to effective governance and the success of the organization. If special interests, financial conflicts, and self-interest prevail over the needs of the organization, the latter will fail and decline.

Dr. Veith is Professor of Surgery at New York University Medical Center and the Cleveland Clinic. He is an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

The ideas and opinions expressed in Vascular Specialist do not necessarily reflect those of the Society or Publisher.

A stated goal of the United States is to support and promote democracy throughout the world. This seems reasonable, because democracy has often worked well in our own and other Western countries, and because no other form of government has consistently been better. So is democracy the best form of government? I submit that it is the best only if certain conditions are met.

For democracy to work, the public must be well informed and willing to consider, at least to some extent, the country’s interests in addition to their own self-interests. If a major fraction of the public does not care about or know what is good for the country or is totally motivated by self-interest, the government and the country will fail. Sadly this appears to be the case in the U.S. today as evidenced by Jay Leno’s "JayWalking Segments" in which most young people interviewed – even college graduates – have no idea about issues important to our country. They appear to be more interested in sports and their social life and more knowledgeable about TV sitcoms and reality shows.

How can such individuals be relied upon to pick government leaders who will take care of our country’s interests in the trying times it faces politically and economically? An ill-informed and non-caring public is more likely to pick leaders who are the slickest talkers and who promise the most despite the impossibility or negative effects of keeping these promises. This know-nothing or self-interested nature of our electorate contributes importantly to the ever expanding entitlement culture in the U.S. and the resulting dangerous expansion of our national debt.

Another related requirement for democracy to be an effective form of government is the need for an honest and objective media and press. A controlled or biased source of information contributes hugely to an ill-informed public. Whoever controls the media and the press controls the minds of the voters. For democracy to work effectively, the public must not only want to be informed, they must also be given the necessary objective facts to make valid judgments. The press has a vital responsibility to provide such facts with minimal bias. There is considerable doubt about whether or not this is occurring today in the U.S.

Of even greater importance to a successful democracy is the ethical stature of its leaders and their motivation – once elected – to act in the best interests of the country. Many forces act upon our leaders and are counter to these interests. These include obligations to those who helped elect them, ideology, personal gain, a desire to be re-elected, and most importantly the corrupting requirement to solicit campaign financing. In the U.S. currently, the need to finance expensive campaigns is a major flaw in our democracy, and is really a veiled form of bribery.

For a democratic leader to be successful in terms of doing a good job of leading the country, all these forces must be overridden by the desire to do what is right and best for the whole country. This means the leader must not serve solely special or self-interests, and must have the courage and inner strength to do what may at the moment be unpopular with his or her electoral base. He or she must unite the country rather than divide it for short-term political or parochial gain. Unfortunately many of our recently elected U.S. leaders have not met any of these requirements. If this trend continues, our democracy will serve the country’s interests poorly, and the U.S. will decline rather than gain in stature and strength.

Efforts at democracy in the Middle East and elsewhere have failed because some or all of the requirements discussed here have not been met. A similar decline awaits our U.S. democracy if the current flaws in the underlying system cannot be corrected.

So far this discussion has largely been related to the U.S. federal government. However, the same considerations apply to effective governments at the county, state, and city levels, and to governing bodies of other entities which purport to be managed in a democratic fashion. This even applies to our vascular societies. The ethics and character of the leaders and those choosing them are important to effective governance and the success of the organization. If special interests, financial conflicts, and self-interest prevail over the needs of the organization, the latter will fail and decline.

Dr. Veith is Professor of Surgery at New York University Medical Center and the Cleveland Clinic. He is an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

The ideas and opinions expressed in Vascular Specialist do not necessarily reflect those of the Society or Publisher.

Online tool calculates Medicare incentives, penalties

Not sure if you’re going to be getting a bonus or paying a penalty to Medicare this year? You’re not alone.

Between the Medicare e-prescribing program, the "meaningful use" incentives for implementing electronic health records (EHRs), and the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) – all with different incentive and penalty schedules – it’s hard to keep track of whether payments are going up or down and by how much.

Apparently, officials at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) agree. They have launched an online tool that allows physicians to click through a few questions and figure out what their payment adjustments will look like based on 2013 participation in the eRx Incentive Program, the Medicare EHR Incentive Program, and the PQRS.

For instance, if a physician attested to meaningful use of certified EHR technology in 2013 and plans on demonstrating that use, then he will avoid the 2015 payment adjustment and be eligible for incentive payments of between $8,000 and $12,000, depending on the year that he first demonstrated meaningful use.

The tool can also help physicians figure out how the three programs interact. If a physician reported the eRx measure’s numerator code at least 25 times in 2012, he will avoid the 2014 eRx penalty. But if he also successfully attested to meaningful use in 2012, then he can’t "double dip" and pick up the 1% eRx bonus, according to the CMS.

–By Mary Ellen Schneider

Dr. Stuart M. Garay, FCCP, comments:

Meeting CMS requirements for Medicare reimbursement is becoming increasingly complicated. During the past few years e-prescribing, EHR meaningful use, and PQRS have been rolled out to physicians with different incentive and penalty schedules. Physicians have been presented a confusing mess! Finally CMS has provided an online tool to sort this out. Take advantage; don't miss out!

Dr. Stuart M. Garay, FCCP, comments:

Meeting CMS requirements for Medicare reimbursement is becoming increasingly complicated. During the past few years e-prescribing, EHR meaningful use, and PQRS have been rolled out to physicians with different incentive and penalty schedules. Physicians have been presented a confusing mess! Finally CMS has provided an online tool to sort this out. Take advantage; don't miss out!

Dr. Stuart M. Garay, FCCP, comments:

Meeting CMS requirements for Medicare reimbursement is becoming increasingly complicated. During the past few years e-prescribing, EHR meaningful use, and PQRS have been rolled out to physicians with different incentive and penalty schedules. Physicians have been presented a confusing mess! Finally CMS has provided an online tool to sort this out. Take advantage; don't miss out!

Not sure if you’re going to be getting a bonus or paying a penalty to Medicare this year? You’re not alone.

Between the Medicare e-prescribing program, the "meaningful use" incentives for implementing electronic health records (EHRs), and the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) – all with different incentive and penalty schedules – it’s hard to keep track of whether payments are going up or down and by how much.

Apparently, officials at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) agree. They have launched an online tool that allows physicians to click through a few questions and figure out what their payment adjustments will look like based on 2013 participation in the eRx Incentive Program, the Medicare EHR Incentive Program, and the PQRS.

For instance, if a physician attested to meaningful use of certified EHR technology in 2013 and plans on demonstrating that use, then he will avoid the 2015 payment adjustment and be eligible for incentive payments of between $8,000 and $12,000, depending on the year that he first demonstrated meaningful use.

The tool can also help physicians figure out how the three programs interact. If a physician reported the eRx measure’s numerator code at least 25 times in 2012, he will avoid the 2014 eRx penalty. But if he also successfully attested to meaningful use in 2012, then he can’t "double dip" and pick up the 1% eRx bonus, according to the CMS.

–By Mary Ellen Schneider

Not sure if you’re going to be getting a bonus or paying a penalty to Medicare this year? You’re not alone.

Between the Medicare e-prescribing program, the "meaningful use" incentives for implementing electronic health records (EHRs), and the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) – all with different incentive and penalty schedules – it’s hard to keep track of whether payments are going up or down and by how much.

Apparently, officials at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) agree. They have launched an online tool that allows physicians to click through a few questions and figure out what their payment adjustments will look like based on 2013 participation in the eRx Incentive Program, the Medicare EHR Incentive Program, and the PQRS.

For instance, if a physician attested to meaningful use of certified EHR technology in 2013 and plans on demonstrating that use, then he will avoid the 2015 payment adjustment and be eligible for incentive payments of between $8,000 and $12,000, depending on the year that he first demonstrated meaningful use.

The tool can also help physicians figure out how the three programs interact. If a physician reported the eRx measure’s numerator code at least 25 times in 2012, he will avoid the 2014 eRx penalty. But if he also successfully attested to meaningful use in 2012, then he can’t "double dip" and pick up the 1% eRx bonus, according to the CMS.

–By Mary Ellen Schneider

Elevated troponin but no CVD: What’s the prognosis?

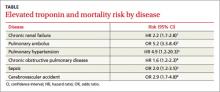

Patients with elevated troponin levels and chronic renal disease, pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary embolism, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, sepsis, or acute ischemic stroke have a 2- to 5-fold increased risk of death, even in the absence of known cardiovascular disease (TABLE)1-6 (strength of recommendation: B, meta-analysis, multiple prospective and retrospective observational studies.)

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

To investigate the prognostic value of troponin on overall mortality, a multicenter prospective study followed 847 patients 18 years and older (mean age 59 years) with end-stage renal disease whose troponin T levels were measured 3 months from the start of peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis until transplantation or death.1 At enrollment, 566 patients had a troponin level of ≤0.04 ng/dL, 188 had a value between 0.05 and 0.10 ng/dL, and 93 had a level of more than 0.10 ng/dL.

Using Cox regression, patients whose troponin levels were more than 0.10 ng/dL had an increased hazard ratio (HR) for all-cause mortality of 2.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.7-2.8) compared with patients who had levels ≤0.04 ng/dL. Cardiovascular mortality also was higher (HR=1.9; 95% CI, 0.9-3.7) with troponin elevations, but didn’t reach statistical significance. Investigators found no significant differences in mortality risk between patients on peritoneal or hemodialysis, patients with or without a history of acute myocardial infarction, or patients who suffered cerebrovascular accidents.

Elevated troponin raises risk of death 5-fold in pulmonary embolism patients

A meta-analysis of 20 trials with a total of 1985 patients assessed the prognostic value of troponin for short-term mortality in patients admitted with acute pulmonary embolism.2 Sixteen studies (1527 patients) were prospective trials and the remainder (458 patients) were retrospective trials. Investigators obtained troponin levels for all patients at admission. They used several different troponin assays (both I and T), but most of the studies used the assay manufacturers’ cutoff points (exceeding the 99th percentile).

High troponin levels were associated with a 5-fold increased risk of short-term death, defined as in-hospital death up to 30 days after discharge (19.7% with elevated troponin vs 3.7% with normal troponin; odds ratio [OR]=5.24; 95% CI, 3.3-8.4).

Increased risk of death among those with pulmonary hypertension, COPD A prospective single-center study of 56 patients with chronic pulmonary hypertension found that the 14% of those whose troponin T was elevated (≥0.01 ng/mL) had a lower survival rate than the other patients. Patients who either had a positive troponin on initial assessment or developed troponin elevation within the 2-year follow-up period had a cumulative 24-month survival rate of 29%, compared with 81% for their troponin T-negative counterparts (P=.001).3

Patients with elevated troponin levels and certain conditions have a 2- to 5-fold increased risk of death, even without known cardiovascular disease.

Elevated troponin I is an independent predictor of mortality in severe sepsis

A double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial evaluated the effect of drotrecogin alfa (activated)—withdrawn from the market in 2011—on survival of patients with severe sepsis.5 Investigators used positive troponin I levels (≥0.06 ng/mL) as a prognostic indicator of mortality. Patients who were troponin-positive had a 28-day mortality rate of 32%, compared with 14% in the troponin-negative group (P<.0001).

A bias of this study is that the patients with positive troponin levels tended to be older and more critically ill. However, in a multivariate model, troponin I still remained an independent predictor of mortality.

Elevated troponin predicts increased death risk in up to 20% of stroke patients

A systematic review of 15 trials with a total of 2901 patients evaluated the relationship between troponin levels and stroke.6 Investigators assessed the prevalence of elevated troponin in acute stroke patients, the association of elevated troponin levels with electrocardiographic changes, and the overall morbidity and mortality associated with troponin levels. Thirteen of the 15 studies used a troponin T or I level obtained within 72 hours of admission and a cut-off level of 0.1 ng/mL. The remaining 2 studies used troponin I cut-off levels >0.2 and 0.4 ng/mL.

Overall, 18% of acute stroke patients had elevated troponin levels. Studies that excluded patients with known cardiac disease had a lower prevalence of elevated levels (10% vs 22%). Patients with elevated troponin levels had an associated overall increased risk of death (OR=2.9; 95% CI, 1.7-4.8) and were 3 times more likely to have ischemic changes on electrocardiogram (OR=3.0; 95% CI, 1.5-6.2). Investigators concluded that elevated troponin levels occur in as many as one in 5 patients and are associated with an increased risk of death.

Troponin elevations may be observed in congestive heart failure, chest wall trauma, cardioversion/defibrillator shocks, rhabdomyolysis, and ultra-endurance activities.7 However, this analysis didn’t address prognostic implications of elevated troponins.

RECOMMENDATIONS

No recommendation exists for biochemical testing of troponins in various medical conditions except in the presence of signs and symptoms consistent with acute coronary syndrome. The American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association recommend routine testing of cardiac troponins in patients hospitalized for worsening congestive heart failure symptoms.8

The European Society of Cardiology recommends measuring troponin levels to further stratify risk in non-high-risk patients with confirmed pulmonary embolus.9

The National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry recommends using cardiac troponins to help define mortality risk in end-stage renal disease and critically ill patients.10

1. Havekes B, van Manen J, Krediet R, et al. Serum troponin T concentration as a predictor of mortality in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;47:823-829.

2. Becattini C, Vedovati MC, Agnelli G. Prognostic value of tropo- nins in acute pulmonary embolism. Circulation. 2007;116:427- 433.

3. Torbicki A, Kurzyna M, Kuca P, et al. Detectable serum cardiac troponin T as a marker of poor prognosis among patients with chronic precapillary pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2003;108:844-848.

4. Brekke PH, Omland T, Holmedal SH, et al. Troponin T eleva- tion and long-term mortality after chronic obstructive pulmo- nary disease exacerbation. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:563-570.

5. John J, Woodward DB, Wang Y, et al. Troponin I as a prog- nosticator of mortality in severe sepsis patients. J Crit Care. 2010;25:270-275.

6. Kerr G, Ray G, Wu O, et al. Elevated troponin after stroke: a sys- tematic review. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;28:220-226.

7. Korff S, Katus HA, Giannitsis E. Differential diagnosis of el- evated troponins. Heart. 2006;92:987-993.

8. Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. 2009 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the diag- nosis and management of heart failure in adults. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines devel- oped in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:e1-e90.

9. Torbicki A, Perrier A, Konstantinides S, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2276-2315.

10. Wu AH, Jaffe AS, Apple FS, et al. National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry laboratory medicine practice guidelines: use of cardiac troponin and B-type natriuretic peptide or N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide for etiologies other than acute coronary syndromes and heart failure. Clin Chem. 2007;53:2086-2096.

Patients with elevated troponin levels and chronic renal disease, pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary embolism, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, sepsis, or acute ischemic stroke have a 2- to 5-fold increased risk of death, even in the absence of known cardiovascular disease (TABLE)1-6 (strength of recommendation: B, meta-analysis, multiple prospective and retrospective observational studies.)

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

To investigate the prognostic value of troponin on overall mortality, a multicenter prospective study followed 847 patients 18 years and older (mean age 59 years) with end-stage renal disease whose troponin T levels were measured 3 months from the start of peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis until transplantation or death.1 At enrollment, 566 patients had a troponin level of ≤0.04 ng/dL, 188 had a value between 0.05 and 0.10 ng/dL, and 93 had a level of more than 0.10 ng/dL.

Using Cox regression, patients whose troponin levels were more than 0.10 ng/dL had an increased hazard ratio (HR) for all-cause mortality of 2.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.7-2.8) compared with patients who had levels ≤0.04 ng/dL. Cardiovascular mortality also was higher (HR=1.9; 95% CI, 0.9-3.7) with troponin elevations, but didn’t reach statistical significance. Investigators found no significant differences in mortality risk between patients on peritoneal or hemodialysis, patients with or without a history of acute myocardial infarction, or patients who suffered cerebrovascular accidents.

Elevated troponin raises risk of death 5-fold in pulmonary embolism patients

A meta-analysis of 20 trials with a total of 1985 patients assessed the prognostic value of troponin for short-term mortality in patients admitted with acute pulmonary embolism.2 Sixteen studies (1527 patients) were prospective trials and the remainder (458 patients) were retrospective trials. Investigators obtained troponin levels for all patients at admission. They used several different troponin assays (both I and T), but most of the studies used the assay manufacturers’ cutoff points (exceeding the 99th percentile).

High troponin levels were associated with a 5-fold increased risk of short-term death, defined as in-hospital death up to 30 days after discharge (19.7% with elevated troponin vs 3.7% with normal troponin; odds ratio [OR]=5.24; 95% CI, 3.3-8.4).

Increased risk of death among those with pulmonary hypertension, COPD A prospective single-center study of 56 patients with chronic pulmonary hypertension found that the 14% of those whose troponin T was elevated (≥0.01 ng/mL) had a lower survival rate than the other patients. Patients who either had a positive troponin on initial assessment or developed troponin elevation within the 2-year follow-up period had a cumulative 24-month survival rate of 29%, compared with 81% for their troponin T-negative counterparts (P=.001).3

Patients with elevated troponin levels and certain conditions have a 2- to 5-fold increased risk of death, even without known cardiovascular disease.

Elevated troponin I is an independent predictor of mortality in severe sepsis

A double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial evaluated the effect of drotrecogin alfa (activated)—withdrawn from the market in 2011—on survival of patients with severe sepsis.5 Investigators used positive troponin I levels (≥0.06 ng/mL) as a prognostic indicator of mortality. Patients who were troponin-positive had a 28-day mortality rate of 32%, compared with 14% in the troponin-negative group (P<.0001).

A bias of this study is that the patients with positive troponin levels tended to be older and more critically ill. However, in a multivariate model, troponin I still remained an independent predictor of mortality.

Elevated troponin predicts increased death risk in up to 20% of stroke patients

A systematic review of 15 trials with a total of 2901 patients evaluated the relationship between troponin levels and stroke.6 Investigators assessed the prevalence of elevated troponin in acute stroke patients, the association of elevated troponin levels with electrocardiographic changes, and the overall morbidity and mortality associated with troponin levels. Thirteen of the 15 studies used a troponin T or I level obtained within 72 hours of admission and a cut-off level of 0.1 ng/mL. The remaining 2 studies used troponin I cut-off levels >0.2 and 0.4 ng/mL.

Overall, 18% of acute stroke patients had elevated troponin levels. Studies that excluded patients with known cardiac disease had a lower prevalence of elevated levels (10% vs 22%). Patients with elevated troponin levels had an associated overall increased risk of death (OR=2.9; 95% CI, 1.7-4.8) and were 3 times more likely to have ischemic changes on electrocardiogram (OR=3.0; 95% CI, 1.5-6.2). Investigators concluded that elevated troponin levels occur in as many as one in 5 patients and are associated with an increased risk of death.

Troponin elevations may be observed in congestive heart failure, chest wall trauma, cardioversion/defibrillator shocks, rhabdomyolysis, and ultra-endurance activities.7 However, this analysis didn’t address prognostic implications of elevated troponins.

RECOMMENDATIONS

No recommendation exists for biochemical testing of troponins in various medical conditions except in the presence of signs and symptoms consistent with acute coronary syndrome. The American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association recommend routine testing of cardiac troponins in patients hospitalized for worsening congestive heart failure symptoms.8

The European Society of Cardiology recommends measuring troponin levels to further stratify risk in non-high-risk patients with confirmed pulmonary embolus.9

The National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry recommends using cardiac troponins to help define mortality risk in end-stage renal disease and critically ill patients.10

Patients with elevated troponin levels and chronic renal disease, pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary embolism, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, sepsis, or acute ischemic stroke have a 2- to 5-fold increased risk of death, even in the absence of known cardiovascular disease (TABLE)1-6 (strength of recommendation: B, meta-analysis, multiple prospective and retrospective observational studies.)

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

To investigate the prognostic value of troponin on overall mortality, a multicenter prospective study followed 847 patients 18 years and older (mean age 59 years) with end-stage renal disease whose troponin T levels were measured 3 months from the start of peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis until transplantation or death.1 At enrollment, 566 patients had a troponin level of ≤0.04 ng/dL, 188 had a value between 0.05 and 0.10 ng/dL, and 93 had a level of more than 0.10 ng/dL.

Using Cox regression, patients whose troponin levels were more than 0.10 ng/dL had an increased hazard ratio (HR) for all-cause mortality of 2.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.7-2.8) compared with patients who had levels ≤0.04 ng/dL. Cardiovascular mortality also was higher (HR=1.9; 95% CI, 0.9-3.7) with troponin elevations, but didn’t reach statistical significance. Investigators found no significant differences in mortality risk between patients on peritoneal or hemodialysis, patients with or without a history of acute myocardial infarction, or patients who suffered cerebrovascular accidents.

Elevated troponin raises risk of death 5-fold in pulmonary embolism patients

A meta-analysis of 20 trials with a total of 1985 patients assessed the prognostic value of troponin for short-term mortality in patients admitted with acute pulmonary embolism.2 Sixteen studies (1527 patients) were prospective trials and the remainder (458 patients) were retrospective trials. Investigators obtained troponin levels for all patients at admission. They used several different troponin assays (both I and T), but most of the studies used the assay manufacturers’ cutoff points (exceeding the 99th percentile).

High troponin levels were associated with a 5-fold increased risk of short-term death, defined as in-hospital death up to 30 days after discharge (19.7% with elevated troponin vs 3.7% with normal troponin; odds ratio [OR]=5.24; 95% CI, 3.3-8.4).

Increased risk of death among those with pulmonary hypertension, COPD A prospective single-center study of 56 patients with chronic pulmonary hypertension found that the 14% of those whose troponin T was elevated (≥0.01 ng/mL) had a lower survival rate than the other patients. Patients who either had a positive troponin on initial assessment or developed troponin elevation within the 2-year follow-up period had a cumulative 24-month survival rate of 29%, compared with 81% for their troponin T-negative counterparts (P=.001).3

Patients with elevated troponin levels and certain conditions have a 2- to 5-fold increased risk of death, even without known cardiovascular disease.

Elevated troponin I is an independent predictor of mortality in severe sepsis

A double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial evaluated the effect of drotrecogin alfa (activated)—withdrawn from the market in 2011—on survival of patients with severe sepsis.5 Investigators used positive troponin I levels (≥0.06 ng/mL) as a prognostic indicator of mortality. Patients who were troponin-positive had a 28-day mortality rate of 32%, compared with 14% in the troponin-negative group (P<.0001).

A bias of this study is that the patients with positive troponin levels tended to be older and more critically ill. However, in a multivariate model, troponin I still remained an independent predictor of mortality.

Elevated troponin predicts increased death risk in up to 20% of stroke patients

A systematic review of 15 trials with a total of 2901 patients evaluated the relationship between troponin levels and stroke.6 Investigators assessed the prevalence of elevated troponin in acute stroke patients, the association of elevated troponin levels with electrocardiographic changes, and the overall morbidity and mortality associated with troponin levels. Thirteen of the 15 studies used a troponin T or I level obtained within 72 hours of admission and a cut-off level of 0.1 ng/mL. The remaining 2 studies used troponin I cut-off levels >0.2 and 0.4 ng/mL.

Overall, 18% of acute stroke patients had elevated troponin levels. Studies that excluded patients with known cardiac disease had a lower prevalence of elevated levels (10% vs 22%). Patients with elevated troponin levels had an associated overall increased risk of death (OR=2.9; 95% CI, 1.7-4.8) and were 3 times more likely to have ischemic changes on electrocardiogram (OR=3.0; 95% CI, 1.5-6.2). Investigators concluded that elevated troponin levels occur in as many as one in 5 patients and are associated with an increased risk of death.

Troponin elevations may be observed in congestive heart failure, chest wall trauma, cardioversion/defibrillator shocks, rhabdomyolysis, and ultra-endurance activities.7 However, this analysis didn’t address prognostic implications of elevated troponins.

RECOMMENDATIONS

No recommendation exists for biochemical testing of troponins in various medical conditions except in the presence of signs and symptoms consistent with acute coronary syndrome. The American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association recommend routine testing of cardiac troponins in patients hospitalized for worsening congestive heart failure symptoms.8

The European Society of Cardiology recommends measuring troponin levels to further stratify risk in non-high-risk patients with confirmed pulmonary embolus.9

The National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry recommends using cardiac troponins to help define mortality risk in end-stage renal disease and critically ill patients.10

1. Havekes B, van Manen J, Krediet R, et al. Serum troponin T concentration as a predictor of mortality in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;47:823-829.

2. Becattini C, Vedovati MC, Agnelli G. Prognostic value of tropo- nins in acute pulmonary embolism. Circulation. 2007;116:427- 433.

3. Torbicki A, Kurzyna M, Kuca P, et al. Detectable serum cardiac troponin T as a marker of poor prognosis among patients with chronic precapillary pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2003;108:844-848.

4. Brekke PH, Omland T, Holmedal SH, et al. Troponin T eleva- tion and long-term mortality after chronic obstructive pulmo- nary disease exacerbation. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:563-570.

5. John J, Woodward DB, Wang Y, et al. Troponin I as a prog- nosticator of mortality in severe sepsis patients. J Crit Care. 2010;25:270-275.

6. Kerr G, Ray G, Wu O, et al. Elevated troponin after stroke: a sys- tematic review. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;28:220-226.

7. Korff S, Katus HA, Giannitsis E. Differential diagnosis of el- evated troponins. Heart. 2006;92:987-993.

8. Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. 2009 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the diag- nosis and management of heart failure in adults. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines devel- oped in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:e1-e90.

9. Torbicki A, Perrier A, Konstantinides S, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2276-2315.

10. Wu AH, Jaffe AS, Apple FS, et al. National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry laboratory medicine practice guidelines: use of cardiac troponin and B-type natriuretic peptide or N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide for etiologies other than acute coronary syndromes and heart failure. Clin Chem. 2007;53:2086-2096.

1. Havekes B, van Manen J, Krediet R, et al. Serum troponin T concentration as a predictor of mortality in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;47:823-829.

2. Becattini C, Vedovati MC, Agnelli G. Prognostic value of tropo- nins in acute pulmonary embolism. Circulation. 2007;116:427- 433.

3. Torbicki A, Kurzyna M, Kuca P, et al. Detectable serum cardiac troponin T as a marker of poor prognosis among patients with chronic precapillary pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2003;108:844-848.

4. Brekke PH, Omland T, Holmedal SH, et al. Troponin T eleva- tion and long-term mortality after chronic obstructive pulmo- nary disease exacerbation. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:563-570.

5. John J, Woodward DB, Wang Y, et al. Troponin I as a prog- nosticator of mortality in severe sepsis patients. J Crit Care. 2010;25:270-275.

6. Kerr G, Ray G, Wu O, et al. Elevated troponin after stroke: a sys- tematic review. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;28:220-226.

7. Korff S, Katus HA, Giannitsis E. Differential diagnosis of el- evated troponins. Heart. 2006;92:987-993.

8. Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. 2009 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the diag- nosis and management of heart failure in adults. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines devel- oped in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:e1-e90.

9. Torbicki A, Perrier A, Konstantinides S, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2276-2315.

10. Wu AH, Jaffe AS, Apple FS, et al. National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry laboratory medicine practice guidelines: use of cardiac troponin and B-type natriuretic peptide or N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide for etiologies other than acute coronary syndromes and heart failure. Clin Chem. 2007;53:2086-2096.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Fruits, but not vegetables, shown to lower AAA risk

The consumption of fruits, but not vegetables, was associated with a decreased risk of abdominal aortic aneurysm, especially the risk of rupture, according to results of a large database study of two prospective cohorts of Swedish men and women.

"The risk of AAA decreased with increasing consumption of fruit (P =.003), whereas no significant association was observed for vegetable consumption," wrote Dr. Otto Stackelberg and his colleagues at Uppsala (Sweden) University (Circulation 2013;128:795-802).

The study population in the final analysis of the two cohorts consisted of 36,109 women from the Swedish Mammography Cohort (established between 1987 and 1990) and 44,317 men from the Cohort of Swedish Men (established in 1997).

Both cohorts responded in 1997 to extensive questionnaires – identical except for sex-specific questions – that included 96 food-item questions accompanied by other lifestyle factors. Results were linked to the Swedish Inpatient Register and the Swedish National Cause of Death Register to follow outcomes of these patients.

National health coverage in Sweden has been nearly 100% since 1987. All cases of AAA were identified by clinical events, not by general screening. AAA repair was identified via the Nordic Classification of Surgical Procedures. To classify aneurysmal localization and rupture status of AAA repairs, the researchers linked the cohorts to the Swedish Registry for Vascular Surgery (founded in 1987, which accounted for 93.1% of all AAA repairs in Sweden).

Fruit and vegetable consumption was summed from results of the 96 food item questionnaire and converted to daily consumption categories ranging from never to greater than or equal to 3 times daily.

Covariates assessed included education, alcohol consumption, diet, physical activity, waist circumference, and smoking duration and amount. The study population was ethnically homogenous. History of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia was obtained from the Swedish Inpatient Register, the Swedish National Diabetes Register, and the self-reported data from the questionnaire.

During 13 years of follow-up (1998-2010), the researchers found that there were 1,086 primary cases (899 in men; 83%) and 222 cases of ruptured AAA (181 in men; 82%). The mean age for nonruptured AAA was 74 years in men and 76 years in women. For ruptured AAA it was 76 and 78.5 years in men and women, respectively. Cox proportional hazard analysis was used to estimate hazard ratios.

Individuals in the highest quartile of fruit consumption (greater than 2 servings per day) had a 25% lower risk of AAA and a 43% lower risk of ruptured AAA, compared with those in the lowest quartiles of fruit consumption (less than 0.7 servings per day). No association was observed between vegetable consumption and AAA risk. There was no impact of smoking or sex of the individual on the fruit consumption–related AAA risk for both ruptured and nonruptured AAA.

Men and women with a high consumption of fruit and vegetables were more educated; consumed more fish, meat, and whole grains; and were more likely to be leaner and physically active, and less likely to be smokers, according to the researchers. In addition, high consumers of fruit consumed less alcohol, whereas the reverse was true of high consumers of vegetables.

"A diet high in fruits may help to prevent many vascular diseases, and this study provides evidence that a lower risk of AAA will be among the benefits," the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by grants from the Swedish Research Council and the Karolinska Institute. The authors reported they had no disclosures.

So I guess the old adage is correct ... "An apple a day keeps the doctor away," or should I say "An Apple A day keeps the AAA Away?"

Dr. Russell Samson is the Medical Editor of Vascular Specialist.

So I guess the old adage is correct ... "An apple a day keeps the doctor away," or should I say "An Apple A day keeps the AAA Away?"

Dr. Russell Samson is the Medical Editor of Vascular Specialist.

So I guess the old adage is correct ... "An apple a day keeps the doctor away," or should I say "An Apple A day keeps the AAA Away?"

Dr. Russell Samson is the Medical Editor of Vascular Specialist.

The consumption of fruits, but not vegetables, was associated with a decreased risk of abdominal aortic aneurysm, especially the risk of rupture, according to results of a large database study of two prospective cohorts of Swedish men and women.

"The risk of AAA decreased with increasing consumption of fruit (P =.003), whereas no significant association was observed for vegetable consumption," wrote Dr. Otto Stackelberg and his colleagues at Uppsala (Sweden) University (Circulation 2013;128:795-802).

The study population in the final analysis of the two cohorts consisted of 36,109 women from the Swedish Mammography Cohort (established between 1987 and 1990) and 44,317 men from the Cohort of Swedish Men (established in 1997).

Both cohorts responded in 1997 to extensive questionnaires – identical except for sex-specific questions – that included 96 food-item questions accompanied by other lifestyle factors. Results were linked to the Swedish Inpatient Register and the Swedish National Cause of Death Register to follow outcomes of these patients.

National health coverage in Sweden has been nearly 100% since 1987. All cases of AAA were identified by clinical events, not by general screening. AAA repair was identified via the Nordic Classification of Surgical Procedures. To classify aneurysmal localization and rupture status of AAA repairs, the researchers linked the cohorts to the Swedish Registry for Vascular Surgery (founded in 1987, which accounted for 93.1% of all AAA repairs in Sweden).

Fruit and vegetable consumption was summed from results of the 96 food item questionnaire and converted to daily consumption categories ranging from never to greater than or equal to 3 times daily.

Covariates assessed included education, alcohol consumption, diet, physical activity, waist circumference, and smoking duration and amount. The study population was ethnically homogenous. History of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia was obtained from the Swedish Inpatient Register, the Swedish National Diabetes Register, and the self-reported data from the questionnaire.

During 13 years of follow-up (1998-2010), the researchers found that there were 1,086 primary cases (899 in men; 83%) and 222 cases of ruptured AAA (181 in men; 82%). The mean age for nonruptured AAA was 74 years in men and 76 years in women. For ruptured AAA it was 76 and 78.5 years in men and women, respectively. Cox proportional hazard analysis was used to estimate hazard ratios.

Individuals in the highest quartile of fruit consumption (greater than 2 servings per day) had a 25% lower risk of AAA and a 43% lower risk of ruptured AAA, compared with those in the lowest quartiles of fruit consumption (less than 0.7 servings per day). No association was observed between vegetable consumption and AAA risk. There was no impact of smoking or sex of the individual on the fruit consumption–related AAA risk for both ruptured and nonruptured AAA.

Men and women with a high consumption of fruit and vegetables were more educated; consumed more fish, meat, and whole grains; and were more likely to be leaner and physically active, and less likely to be smokers, according to the researchers. In addition, high consumers of fruit consumed less alcohol, whereas the reverse was true of high consumers of vegetables.

"A diet high in fruits may help to prevent many vascular diseases, and this study provides evidence that a lower risk of AAA will be among the benefits," the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by grants from the Swedish Research Council and the Karolinska Institute. The authors reported they had no disclosures.

The consumption of fruits, but not vegetables, was associated with a decreased risk of abdominal aortic aneurysm, especially the risk of rupture, according to results of a large database study of two prospective cohorts of Swedish men and women.

"The risk of AAA decreased with increasing consumption of fruit (P =.003), whereas no significant association was observed for vegetable consumption," wrote Dr. Otto Stackelberg and his colleagues at Uppsala (Sweden) University (Circulation 2013;128:795-802).

The study population in the final analysis of the two cohorts consisted of 36,109 women from the Swedish Mammography Cohort (established between 1987 and 1990) and 44,317 men from the Cohort of Swedish Men (established in 1997).

Both cohorts responded in 1997 to extensive questionnaires – identical except for sex-specific questions – that included 96 food-item questions accompanied by other lifestyle factors. Results were linked to the Swedish Inpatient Register and the Swedish National Cause of Death Register to follow outcomes of these patients.

National health coverage in Sweden has been nearly 100% since 1987. All cases of AAA were identified by clinical events, not by general screening. AAA repair was identified via the Nordic Classification of Surgical Procedures. To classify aneurysmal localization and rupture status of AAA repairs, the researchers linked the cohorts to the Swedish Registry for Vascular Surgery (founded in 1987, which accounted for 93.1% of all AAA repairs in Sweden).

Fruit and vegetable consumption was summed from results of the 96 food item questionnaire and converted to daily consumption categories ranging from never to greater than or equal to 3 times daily.

Covariates assessed included education, alcohol consumption, diet, physical activity, waist circumference, and smoking duration and amount. The study population was ethnically homogenous. History of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia was obtained from the Swedish Inpatient Register, the Swedish National Diabetes Register, and the self-reported data from the questionnaire.

During 13 years of follow-up (1998-2010), the researchers found that there were 1,086 primary cases (899 in men; 83%) and 222 cases of ruptured AAA (181 in men; 82%). The mean age for nonruptured AAA was 74 years in men and 76 years in women. For ruptured AAA it was 76 and 78.5 years in men and women, respectively. Cox proportional hazard analysis was used to estimate hazard ratios.

Individuals in the highest quartile of fruit consumption (greater than 2 servings per day) had a 25% lower risk of AAA and a 43% lower risk of ruptured AAA, compared with those in the lowest quartiles of fruit consumption (less than 0.7 servings per day). No association was observed between vegetable consumption and AAA risk. There was no impact of smoking or sex of the individual on the fruit consumption–related AAA risk for both ruptured and nonruptured AAA.

Men and women with a high consumption of fruit and vegetables were more educated; consumed more fish, meat, and whole grains; and were more likely to be leaner and physically active, and less likely to be smokers, according to the researchers. In addition, high consumers of fruit consumed less alcohol, whereas the reverse was true of high consumers of vegetables.

"A diet high in fruits may help to prevent many vascular diseases, and this study provides evidence that a lower risk of AAA will be among the benefits," the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by grants from the Swedish Research Council and the Karolinska Institute. The authors reported they had no disclosures.

Postoperative Gum Chewing; The Importance of Prostate Screening Discussions

EHR Report: One step at a time

The response to our request for readers to comment on their experiences with electronic health records continues to astonish us, with the quantity, depth, and intensity of responses. The majority of e-mails discuss concerns about the way EHRs have affected both patient care and office workflow, and we have made an effort to make sure that these voices are heard.

This month, we thought that we would emphasize a response from Dr. Don Weinshenker, a general internist in Denver who has worked in the VA system since 1992 and who describes himself as a "champion" of the EHR for over a decade. What we like about Dr. Weinshenker’s comments is that while he acknowledges the challenges inherent in adopting electronic records, he also offers some solutions based on a decade of experience. Some of his suggestions remind us of columns we published about a year ago on Humanism and EHRs, two words seldom used together, but which present what we feel is an important concept – discerning how to use our new tools to carry out, not distract us from, our core goals of connecting with other human beings to help safely alleviate suffering and improve health using an empathic manner that communicates caring and understanding. Dr. Weinshenker shares his thoughts as follows:

I feel it is quite possible and relatively easy to integrate the computer into an exam room while maintaining the excellent clinician/patient experience for which we all strive.

The first thing I do when I walk into a room is greet the patient and look the patient in the eye. I don’t look at the computer at first. I then acknowledge the "elephant in the room." I usually say something to the effect of, "As you likely know, we do almost everything on the computer. I will be using the computer today during this visit." I have not had a single patient object.

Next I do bring the patient’s chart up on the computer, if I hadn’t already preloaded it, and open a progress note with my simple template. I then turn to the patient, away from the computer, and start to take a history. At an appropriate pause I say, "Let me get that into your chart." I do turn to the computer at that time and start to type. I repeat what the patient told me as I type. By doing this, patients know what I am typing as well as experiencing a version of "reflective listening" so that they know that I truly did hear them. Also, I always clarify as I type. "The left foot pain has been going on for 2 weeks, or was it 3 weeks?" I write my primary care note in real time while talking with the patient. The majority of the content of my notes is in natural language, as opposed to clicking on little phrases.

Then, I talk about what I am doing in terms of ordering on the computer. "I am going to go ahead and order that podiatry consult now. You said that you would prefer to be seen after the 15th, right? I’ll order that x-ray we talked about as well."

I am sitting at a desk with the patient next to me facing me. It only takes a small turn of my head to face the patient. It is common for me to turn the computer screen a little so it faces the patient. I involve the patients with the computer. Very frequently, they can actually see what I am typing into the computer. In addition, for many of the computerized clinical reminders that we use, I will have the patient read the questions off the screen, e.g., for depression screening, so that they can answer the questions directly.

It appears that some of your readers have misconceptions about the role of computers. At least one mentioned that the computers are essentially going to replace doctors. Ideally, the use of computers is synergistic. The whole is more than the sum of the parts. Using cars as an analogy, no one complains about having power steering or brakes in a car. They make the car easier to drive. It is more common to have a lane change warning if there is a car in the next lane. Some of the fanciest cars, such as the top-end Mercedes, monitor what is in front of the car and will automatically put on the brakes if a pedestrian is present. I can’t afford that car but would be grateful if I had it and it saved the life of a pedestrian who stepped in front of me.

This brings up the questions of alerts and alert fatigue. One wouldn’t want a beep and/or a warning light every time a car passes you in the next lane. Clearly, there has to be more work on alerts making them smarter and more configurable, as otherwise they just become noise. EHRs are far from perfect, but with good design and with thoughtful implementation, I am completely convinced that they are an aid rather than a hindrance.

We like Dr. Weinshenker’s thoughts – he has figured out and shared ways to incorporate and communicate his care for and attention to patients into his workflow with the EHR. We are still at the beginning of our transformation from paper to electronic records, and this change is not easy. It has been said, beginnings are always hard. It is through shared suggestions like those provided by Dr. Weinshenker that we will together develop a patient-oriented electronic approach. Keep those comments coming.

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia. He is editor-in-chief of Redi-Reference, a company that creates mobile apps. Dr. Notte practices family medicine and health care informatics at Abington Memorial. They are partners in EHR Practice Consultants. Contact them at [email protected].

The response to our request for readers to comment on their experiences with electronic health records continues to astonish us, with the quantity, depth, and intensity of responses. The majority of e-mails discuss concerns about the way EHRs have affected both patient care and office workflow, and we have made an effort to make sure that these voices are heard.

This month, we thought that we would emphasize a response from Dr. Don Weinshenker, a general internist in Denver who has worked in the VA system since 1992 and who describes himself as a "champion" of the EHR for over a decade. What we like about Dr. Weinshenker’s comments is that while he acknowledges the challenges inherent in adopting electronic records, he also offers some solutions based on a decade of experience. Some of his suggestions remind us of columns we published about a year ago on Humanism and EHRs, two words seldom used together, but which present what we feel is an important concept – discerning how to use our new tools to carry out, not distract us from, our core goals of connecting with other human beings to help safely alleviate suffering and improve health using an empathic manner that communicates caring and understanding. Dr. Weinshenker shares his thoughts as follows:

I feel it is quite possible and relatively easy to integrate the computer into an exam room while maintaining the excellent clinician/patient experience for which we all strive.

The first thing I do when I walk into a room is greet the patient and look the patient in the eye. I don’t look at the computer at first. I then acknowledge the "elephant in the room." I usually say something to the effect of, "As you likely know, we do almost everything on the computer. I will be using the computer today during this visit." I have not had a single patient object.

Next I do bring the patient’s chart up on the computer, if I hadn’t already preloaded it, and open a progress note with my simple template. I then turn to the patient, away from the computer, and start to take a history. At an appropriate pause I say, "Let me get that into your chart." I do turn to the computer at that time and start to type. I repeat what the patient told me as I type. By doing this, patients know what I am typing as well as experiencing a version of "reflective listening" so that they know that I truly did hear them. Also, I always clarify as I type. "The left foot pain has been going on for 2 weeks, or was it 3 weeks?" I write my primary care note in real time while talking with the patient. The majority of the content of my notes is in natural language, as opposed to clicking on little phrases.

Then, I talk about what I am doing in terms of ordering on the computer. "I am going to go ahead and order that podiatry consult now. You said that you would prefer to be seen after the 15th, right? I’ll order that x-ray we talked about as well."

I am sitting at a desk with the patient next to me facing me. It only takes a small turn of my head to face the patient. It is common for me to turn the computer screen a little so it faces the patient. I involve the patients with the computer. Very frequently, they can actually see what I am typing into the computer. In addition, for many of the computerized clinical reminders that we use, I will have the patient read the questions off the screen, e.g., for depression screening, so that they can answer the questions directly.

It appears that some of your readers have misconceptions about the role of computers. At least one mentioned that the computers are essentially going to replace doctors. Ideally, the use of computers is synergistic. The whole is more than the sum of the parts. Using cars as an analogy, no one complains about having power steering or brakes in a car. They make the car easier to drive. It is more common to have a lane change warning if there is a car in the next lane. Some of the fanciest cars, such as the top-end Mercedes, monitor what is in front of the car and will automatically put on the brakes if a pedestrian is present. I can’t afford that car but would be grateful if I had it and it saved the life of a pedestrian who stepped in front of me.

This brings up the questions of alerts and alert fatigue. One wouldn’t want a beep and/or a warning light every time a car passes you in the next lane. Clearly, there has to be more work on alerts making them smarter and more configurable, as otherwise they just become noise. EHRs are far from perfect, but with good design and with thoughtful implementation, I am completely convinced that they are an aid rather than a hindrance.

We like Dr. Weinshenker’s thoughts – he has figured out and shared ways to incorporate and communicate his care for and attention to patients into his workflow with the EHR. We are still at the beginning of our transformation from paper to electronic records, and this change is not easy. It has been said, beginnings are always hard. It is through shared suggestions like those provided by Dr. Weinshenker that we will together develop a patient-oriented electronic approach. Keep those comments coming.

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia. He is editor-in-chief of Redi-Reference, a company that creates mobile apps. Dr. Notte practices family medicine and health care informatics at Abington Memorial. They are partners in EHR Practice Consultants. Contact them at [email protected].

The response to our request for readers to comment on their experiences with electronic health records continues to astonish us, with the quantity, depth, and intensity of responses. The majority of e-mails discuss concerns about the way EHRs have affected both patient care and office workflow, and we have made an effort to make sure that these voices are heard.

This month, we thought that we would emphasize a response from Dr. Don Weinshenker, a general internist in Denver who has worked in the VA system since 1992 and who describes himself as a "champion" of the EHR for over a decade. What we like about Dr. Weinshenker’s comments is that while he acknowledges the challenges inherent in adopting electronic records, he also offers some solutions based on a decade of experience. Some of his suggestions remind us of columns we published about a year ago on Humanism and EHRs, two words seldom used together, but which present what we feel is an important concept – discerning how to use our new tools to carry out, not distract us from, our core goals of connecting with other human beings to help safely alleviate suffering and improve health using an empathic manner that communicates caring and understanding. Dr. Weinshenker shares his thoughts as follows:

I feel it is quite possible and relatively easy to integrate the computer into an exam room while maintaining the excellent clinician/patient experience for which we all strive.

The first thing I do when I walk into a room is greet the patient and look the patient in the eye. I don’t look at the computer at first. I then acknowledge the "elephant in the room." I usually say something to the effect of, "As you likely know, we do almost everything on the computer. I will be using the computer today during this visit." I have not had a single patient object.

Next I do bring the patient’s chart up on the computer, if I hadn’t already preloaded it, and open a progress note with my simple template. I then turn to the patient, away from the computer, and start to take a history. At an appropriate pause I say, "Let me get that into your chart." I do turn to the computer at that time and start to type. I repeat what the patient told me as I type. By doing this, patients know what I am typing as well as experiencing a version of "reflective listening" so that they know that I truly did hear them. Also, I always clarify as I type. "The left foot pain has been going on for 2 weeks, or was it 3 weeks?" I write my primary care note in real time while talking with the patient. The majority of the content of my notes is in natural language, as opposed to clicking on little phrases.

Then, I talk about what I am doing in terms of ordering on the computer. "I am going to go ahead and order that podiatry consult now. You said that you would prefer to be seen after the 15th, right? I’ll order that x-ray we talked about as well."

I am sitting at a desk with the patient next to me facing me. It only takes a small turn of my head to face the patient. It is common for me to turn the computer screen a little so it faces the patient. I involve the patients with the computer. Very frequently, they can actually see what I am typing into the computer. In addition, for many of the computerized clinical reminders that we use, I will have the patient read the questions off the screen, e.g., for depression screening, so that they can answer the questions directly.

It appears that some of your readers have misconceptions about the role of computers. At least one mentioned that the computers are essentially going to replace doctors. Ideally, the use of computers is synergistic. The whole is more than the sum of the parts. Using cars as an analogy, no one complains about having power steering or brakes in a car. They make the car easier to drive. It is more common to have a lane change warning if there is a car in the next lane. Some of the fanciest cars, such as the top-end Mercedes, monitor what is in front of the car and will automatically put on the brakes if a pedestrian is present. I can’t afford that car but would be grateful if I had it and it saved the life of a pedestrian who stepped in front of me.

This brings up the questions of alerts and alert fatigue. One wouldn’t want a beep and/or a warning light every time a car passes you in the next lane. Clearly, there has to be more work on alerts making them smarter and more configurable, as otherwise they just become noise. EHRs are far from perfect, but with good design and with thoughtful implementation, I am completely convinced that they are an aid rather than a hindrance.

We like Dr. Weinshenker’s thoughts – he has figured out and shared ways to incorporate and communicate his care for and attention to patients into his workflow with the EHR. We are still at the beginning of our transformation from paper to electronic records, and this change is not easy. It has been said, beginnings are always hard. It is through shared suggestions like those provided by Dr. Weinshenker that we will together develop a patient-oriented electronic approach. Keep those comments coming.

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia. He is editor-in-chief of Redi-Reference, a company that creates mobile apps. Dr. Notte practices family medicine and health care informatics at Abington Memorial. They are partners in EHR Practice Consultants. Contact them at [email protected].

Know Your Prostate

Start sleep apnea therapy with CPAP, not surgery

First-line treatment for adults with obstructive sleep apnea should be continuous positive airway pressure therapy or a mandibular advancement device, according to the American College of Physicians’ clinical practice guideline published online Sept. 24 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

In contrast, no surgical procedures or pharmacologic agents should be considered as first-line treatment, because there is insufficient evidence supporting those approaches, said Dr. Amir Qaseem, director of clinical policy at the ACP, Philadelphia, and his associates on the clinical guidelines committee.

Overweight and obese patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) should be encouraged to lose weight, because that has been shown to improve symptoms and reduce scores on the Apnea-Hypopnea Index. Weight loss also confers many other health benefits, they added, while carrying minimal risk of adverse effects.

Those are the chief recommendations of the clinical practice guideline, which was compiled "to present information on both the benefits and harms of interventions" to all clinicians who treat adults with OSA. The guideline is based on a rigorous review of the evidence regarding OSA published in the literature from 1966 through 2012.

Overall, the evidence concerning hard clinical outcomes for any intervention for OSA was extremely limited.

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) was the most extensively studied intervention for OSA, but the evidence from most studies was considered to be only of moderate quality. Studies assessed only the treatment’s effect on immediate outcomes and did not evaluate longer term outcomes such as cardiovascular illness or mortality. In addition, studies that examined CPAP’s effect on quality of life "were inconsistent and therefore inconclusive."

Nevertheless, the balance of evidence does show that CPAP is more effective than are control conditions or sham CPAP at improving scores on the apnea-hypopnea index, which measures the number of apneic and hypopneic episodes per hour of monitored sleep. CPAP also improved scores on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, a self-administered questionnaire in which patients rate their likelihood of dozing off during various situations.

CPAP also is effective at improving oxygen saturation and reducing scores on the arousal index, which measures the frequency of arousals per hour of sleep using electroencephalography. However, there were insufficient data to compare the different types of CPAP, such as fixed CPAP, auto-CPAP, flexible bilevel CPAP, or CPAP with humidification.

There also was insufficient evidence to directly compare CPAP against other interventions, Dr. Qaseem and his colleagues said (Ann. Intern. Med. 2013;159:471-83).

The guideline recommends that mandibular or dental advancement devices to position the patient’s jaw while sleeping are a useful alternative for those who prefer this intervention to CPAP or for those who cannot tolerate or adhere to CPAP. Moderate-quality evidence showed that mandibular advancement devices improve scores on the apnea-hypopnea index and the arousal index.

However, that recommendation is considered "weak," because the overall data supporting the use of mandibular advancement devices are of low quality.

The data also were insufficient to recommend the use of any pharmacologic agents as a first-line therapy for OSA, or indeed as any therapy for the condition. Those include mirtazapine, xylometazoline, fluticasone, paroxetine, pantoprazole, steroids, acetazolamide, and protriptyline.

Only seven studies assessed surgical interventions for OSA. They were of varied quality, and their outcomes were inconsistent, so, the evidence is insufficient to support any surgery as first-line treatment. The procedures assessed in the studies included uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP); laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty; radiofrequency ablation; and various combinations of pharyngoplasty, tonsillectomy, adenoidectomy, genioglossal advancement septoplasty, ablation of the nasal turbinates, and other nasal surgeries.

However, there was some evidence to suggest that UPPP and tracheostomy reduced mortality in patients with OSA.

The guideline strongly recommends that all OSA patients who are overweight or obese should be encouraged to lose weight. The evidence, albeit of low quality, shows that any intensive weight-loss intervention helps improve OSA symptoms and scores on the apnea-hypopnea index.

Finally, the evidence was insufficient to assess the potential benefits of positional therapy, oropharyngeal exercise, palatal implants, or atrial overdrive pacing for patients who already have dual-chamber pacemakers, Dr. Qaseem and his associates said.

The guideline was supported entirely by the American College of Physicians. The investigators had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Obesity is

epidemic in the United States

and “recommending to patients that they lose weight” is not a particularly

effective intervention. The real take-home message from this study is that

there is poor evidence for all treatments, but that the only studies showing a decreased

mortality were those involving surgery. Noninvasive remedies should generally

be preferred when deemed effective. Many patients find CPAP and oral appliances

uncomfortable and compliance rates with these treatments are poor. Obstructive

sleep apnea presents with a wide spectrum of symptoms, and occasionally, an

emergency tracheotomy may be lifesaving for a moribund patient. Patients with

severe OSA have a three- to sixfold increase in all-cause mortality. Motor

vehicle accidents are a major cause of death in patients with severe OSA. It

should also be emphasized that patients with OSA are best evaluated with a formal

sleep study to quantitate the degree of sleep apnea. OSA is a serious health

problem for which a variety of treatments are available. Although surgery is

rarely the first-line therapy, it plays an important role for patients with

particularly severe OSA, some of whom will require a tracheotomy, and in patients

for whom medical therapy is intolerable, not complied with, or ineffective.

Dr. Mark