User login

No laughing matter: Laughter is good psychiatric medicine

CASE REPORT: Laughter as therapy

Mrs. A is a 56-year-old married woman who has bipolar disorder. She has survived several suicide attempts. Her family history is positive for bipolar disorder and completed suicides.

After her most recent suicide attempt and a course of electroconvulsive therapy, Mrs. A recovered sufficiently to begin a spiritual journey that led her to practice a technique known as Laughter Yoga (Box) and, eventually, to become a Laughter Yoga instructor.

Mrs. A begins Laughter Yoga sessions by talking openly with students about her illness and the beneficial effects that laughter therapy has had on its course: She once had at least two major bipolar episodes a year, she explains, but has been in full remission for several years despite severe psychosocial stressors. In addition to practicing Laughter Yoga, Mrs. A is now maintained on a mood stabilizer that failed in the past to control her mood cycles.

Does laughter have a place in your practice?

It is said that laughter is good medicine—but is it good psychiatric medicine? Where might humor and laughter fit in the psychiatrist’s armamentarium? Is laughter physiologically beneficial to psychiatric patients? And are there adverse effects or contraindications to laughter in psychiatry? This article:

• reviews studies that have examined the anatomy, physiology, and psychology of humor and laughtera

• offers answers to the questions posed above (Table).

“Gelotology,” from the Greek “gelos,” laughter, is the science of laughter. The three components of humor and laughter are:

• the emotional component, which triggers emotions produced by a humorous situation

• the cognitive component, in which a person “gets it”

• the movement of facial, respiratory, and abdominal muscles.

Furthermore, tension and surprise are needed for laughter.

Theories about humor are varied

Philosophers since Plato have proposed theories of humor; modern theories of humor can be traced to Freud’s work.1 The psychoanalytic literature on humor focuses on the role of humor in sublimation of feelings of anger and hostility, while releasing affect in an economical way.

Erikson also wrote about the role of humor in a child’s developing superego, which helps resolve the conflict with maternal authority.2

In a comprehensive review of theories of humor, Krichtafovitch explains that cognitive theories address the role of incongruity and contrast in the induction of laughter, whereas social theories explore the roles of aggression, hostility, superiority, triumph, derision, and disparagement in humor and laughter. The effect of humor, Krichtafovitch explains, is to elevate the social status of the joker while the listener’s social status is lifted through his (her) ability to “get it.” Thus, humor plays a meaningful role in creating a bond between speaker and listener.3

The neuroanatomy of laughter

Here is some of what we have learned about mapping the brain to the basis of laughter:

• Consider a 16-year-old girl who underwent neurosurgery for intractable seizures. During surgery, various parts of the brain were stimulated to test for the focus of the seizures. She laughed every time the left frontal superior gyrus was stimulated. According to the report, she apparently laughed first, then made up a story that was funny to her.4

• Pseudobulbar affect—excessive, usually incongruent laughter, secondary to neurologic disease or traumatic brain injury—is an example of the biologic basis of laughter.

• Many functional brain imaging studies of laughter have been published.5 These studies show involvement of various regions of the brain in laughter, including the amygdala, hypothalamus, and temporal and cerebellar regions.

• Sex differences also have been noted in the neuroanatomy of laughter. Females activate the left prefrontal cortex more than males do, suggesting a greater degree of executive processing and language-based decoding. Females also exhibit greater activation of mesolimbic regions, including the nucleus accumbens, implying a greater reward network response.6

• Wild et al7 reported that separate cortical regions are responsible for the production of facial expressions that are emotionally driven (through laughter) and voluntary.

The physiology of laughter

Humans begin to laugh at approximately 4 months of age. Children laugh, on average, 400 times a day; adults do so an average of only 5 times a day.8 In addition:

• Tickling a baby induces her (him) to laugh, which, in turn, makes the parent laugh; a social bond develops during this playful exercise. This response is probably mediated by 5-HT1A receptors, which, when stimulated, induces the release of oxytocin, which facilitates social bonding.9

• Potent stimulation of 5-HT1A receptors through ingestion of 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine (Ecstasy) leads to uncontrollable laughter and mirth.10

• Lower species are also known to enjoy humor. Mice emit a chirping sound when tickled, and laughter is contagious among monkeys.11

• Berk et al12,13 reported that, when 52 healthy men watched a funny video for 30 minutes, they had significantly higher activity of natural killer (NK) cells and higher levels of IgG, IgA, and IgM compared with men who watched an emotionally neutral documentary.

• Bennett et al14 showed that, in 33 healthy women, the harder the laughter, the higher the NK activity.

• Sugawara et al15 showed improved cardiovascular function in 17 healthy persons (age 23 to 42) who watched a 30-minute comedy video, compared with their cardiovascular function when they watched a documentary video of equal length.

• Svebak et al16 examined the effect of humor as measured by the Sense of Humor Survey on the survival rate of more then 53,000 adults in one county in Norway. They concluded that the higher the sense of humor score, the higher the odds ratio of surviving 7 years, compared with subjects who had a lower sense of humor.

Clinical studies of laughter

The Coping Humor Scale (CHS) and the Humor Response Scale (HRS) are the two most widely used tools to measure a person’s innate sense of humor (the CHS) and the ability to respond to a humorous situation (the HRS).17 Several studies about the effects of laughter on illness are notable:

• Laughter increased NK cell activity, lowered prorenin gene expression, and lowered the postprandial glucose level in 34 patients with diabetes, compared with 16 matched controls.18-21

• Clark et al studied the sense of humor of 150 patients with cardiac disease compared with 150 controls. They found that “people with heart disease responded less humorously to everyday life situations.” They generally laughed less, even in positive situations, and displayed more anger and hostility.22

• In his work on the salutatory effect of laughter on the experience of pain, Cousins described how he dealt with his painful arthritis by watching Marx Brothers movies23:

I made the joyous discovery that 10 minutes of genuine belly laughter had an anesthetic effect and would give me at least two hours of pain-free sleep… When the pain-killing effect of the laughter wore off, we would switch on the motion picture projector again and not infrequently, it would lead to another pain-free interval.

• Hearty laughter leads to pain relief, probably through the release of endorphins. Dunbar et al24 tested this hypothesis in a series of six experimental studies in the laboratory (watching videos) and in a naturalistic context (watching stage performances), using a change in pain threshold as an indirect measure of endorphin release. The results show that the pain threshold is significantly higher after laughter than in the control condition. This pain-tolerance effect is caused by the laughter itself, not simply because of a change in positive affect.

Laughter therapy for depression

Three studies have demonstrated the benefit of laughter therapy in depression:

• When Ko and Youn25 studied 48 geriatric depressed patients and 61 age-matched controls, they found a significantly lower Geriatric Depression Scale score and a better Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index score in patients who had been exposed to four weekly laughter groups, compared with persons who had been exposed to a control group.

• Shahidi et al26 randomly assigned 60 community-dwelling female, geriatric, depressed patients to a laughter yoga group, an exercise group, and a control group. Laughter yoga and exercise were equally effective, and both were significantly superior to the control condition. The laughter yoga group scored significantly better than the other two groups on the Life Satisfaction Scale. The researchers concluded that, in addition to improved mood, patients who laugh experience increased life satisfaction.

• Fonzi et al27 summarized data on the neurophysiology of laughter and the effect of laughter on the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis. They noted that depression reduces the frequency of laughter and, inversely, laughter reduces the severity of depression. Laughter, they reported, also increases the connectivity of patients with people in their life, which further alleviates symptoms of depression.

Other therapeutic uses of laughter

Humor can strengthen the bond of the therapeutic relationship. Patients who laugh with their physicians are more likely to feel connected with them, follow their advice, and feel more satisfied with their encounter. One study found that primary care physicians who gave positive statements, spent more time with patients, and included humor or laughter during their visits lowered their risk of being sued for malpractice.28

Consider also the use of laughter in altering family dynamics in a therapeutic setting: Mr. and Mrs. B attend therapy in my practice to address a difficult situation with their adult children. One of them enables their children socially and financially; the other continually complains about this enabling. When the tension was high and the couple had reached an impasse during a visit, the therapist offered an anecdote from the 2006 motion picture Failure to Launch (in which a man lives in the security of his parents’ home even though he is in his 30s), that dissipated the hostility they had shown toward each other and toward their children. The couple was then able to proceed to conflict resolution.

Recommendations, caveats

If you are considering incorporating laughter into therapy, keep in mind that:

• you should ensure that the patient does not perceive humor as minimizing the seriousness of their problems

• humor can be a minefield if not used judiciously, or if used at all, around certain sensitive topics, such as race, ethnicity, religion, political affiliation, and sexual orientation

• the timing of humor is particularly essential for it to succeed in the context of a therapeutic relationship

• from a medical perspective, laughter in patients who are recovering from abdominal or other major surgery might compromise wound healing because of increased intra-abdominal pressure associated with laughing

• patients who have asthma, especially exercise-induced asthma, might be at risk of developing an acute asthmatic attack when they laugh very hard. Lebowitz et al29 demonstrated that laughter can have a negative effect on patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

It is advisable in some situations to avoid humor in psychotherapy, such as when the patient or family is hostile—because, as noted, they might perceive laughter and humor as an attempt to minimize the seriousness of their discontent.

Bottom Line

Humor and laughter are underutilized and underreported in therapy, in part because it is a nascent field of research. Laughter has social and physiologic benefits that can be used in the context of a therapeutic relationship to help patients with a variety of ailments, including depression, anxiety, and pain.

Related Resources

- Association for Applied and Therapeutic Humor. www.aath.org.

- Mora-Ripoll R. The therapeutic value of laughter in medicine. Altern Ther Health Med. 2010;16:56-64.

- Strean WB. Laughter prescription. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:965-967.

Disclosure

Dr. Nasr reports no financial relationship with manufacturers of any products mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the assistance of Francois E. Alouf, MD, for suggestions on topics to include in the article; John W. Crayton, MD, for reviewing the manuscript; and Burdette Wendt for assistance with the references.

1. Freud S, Strachey J, trans., ed. Jokes and their relation to the unconscious. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company; 1990.

2. Capps D. Mother, melancholia, and humor in Erik H. Erikson’s earliest writings. J Relig Health. 2008;47:415-432.

3. Krichtafovitch I. Humor theory. Parker, CO: Outskirts Press; 2006.

4. Fried I, Wilson CL, MacDonald KA, et al. Electric current stimulates laughter. Nature. 1998;12;391:650.

5. Bartolo A, Benuzzi F, Nocetti L, et al. Humor comprehension and appreciation: an FMRI study. J Cogn Neurosci. 2006;18:1789-1798.

6. Azim E, Mobbs D, Jo B, et al. Sex differences in brain activation elicited by humor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16496-16501.

7. Wild B, Rodden FA, Rapp A, et al. Humor and smiling: cortical regions selective for cognitive, affective, and volitional components. Neurology. 2006;66:887-893.

8. Freedman LW. Mosby’s complementary and alternative medicine. A research-based approach. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2004:24.

9. Lukas M, Toth I, Reber SO, et al. The neuropeptide oxytocin facilitates pro-social behavior and prevents social avoidance in rats and mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:

2159-2168.

10. Thompson MR, Callaghan PD, Hunt GE, et al. A role for oxytocin and 5-HT(1A) receptors in the prosocial effects of 3,4 methylenedioxymethamphetamine (“ecstasy”). Neuroscience. 2007;146:509-514.

11. Ross MD, Owren MJ, Zimmermann E. The evolution of laughter in great apes and humans. Commun Integr Biol. 2010;3(2):191-194.

12. Berk LS, Tan SA, Fry WF, et al. Neuroendocrine and stress hormone changes during mirthful laughter. Am J Med Sci. 1989;298:390-396.

13. Berk LS, Felten DL, Tan SA, et al. Modulation of neuroimmune parameters during the eustress of humor-associated mirthful laughter. Altern Ther Health Med. 2001; 7:62-72,74-76.

14. Bennett MP, Zeller JM, Rosenberg L, et al. The effect of mirthful laughter on stress and natural killer cell activity. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9:38-45.

15. Sugawara J, Tarumi T, Tanaka H. Effect of mirthful laughter on vascular function. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:856-859.

16. Svebak S, Romundstad S, Holmen J. A 7-year prospective study of sense of humor and mortality in an adult county population: the HUNT-2 study. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2010;40:125-146.

17. Martin RA. The Situational Humor Response Questionnaire (SHRQ) and Coping Humor Scale (CHS): a decade of research findings. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research. 1996;9(3-4):251-272.

18. Hayashi T, Urayama O, Hori M, et al. Laughter modulates prorenin receptor gene expression in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Psychosom Res. 2007;62:703-706.

19. Hayashi T, Murakami K. The effects of laughter on post-prandial glucose levels and gene expression in type 2 diabetic patients. Life Sci. 2009;85:185-187.

20. Takahashi K, Iwase M, Yamashita K, et al. The elevation of natural killer cell activity induced by laughter in a crossover designed study. Int J Mol Med. 2001;8:645-650.

21. Nasir UM, Iwanaga S, Nabi AH, et al. Laughter therapy modulates the parameters of renin-angiotensin system in patients with type 2 diabetes. Int J Mol Med. 2005;16:1077-1081.

22. Clark A, Seidler A, Miller M. Inverse association between sense of humor and coronary heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 2001;80:87-88.

23. Cousins N. The anatomy of an illness as perceived by the patient: reflections on healing and regeneration. New York, NY: Norton; 1979:39.

24. Dunbar RI, Baron R, Frangou A, et al. Social laughter is correlated with an elevated pain threshold. Proc Biol Sci. 2012;279(1731):1161-1167.

25. Ko HJ, Youn CH. Effects of laughter therapy on depression, cognition and sleep among the community-dwelling elderly. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2011;11:267-274.

26. Shahidi M, Mojtahed A, Modabbernia A, et al. Laughter yoga versus group exercise program in elderly depressed women: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:322-327.

27. Fonzi L, Matteucci G, Bersani G. Laughter and depression: hypothesis of pathogenic and therapeutic correlation. Riv Psichiatr. 2010;45:1-6.

28. Levinson W, Roter DL, Mullooly JP, et al. Physician-patient communication: the relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA. 1997;277:553-559.

29. Lebowitz KR, Suh S, Diaz PT, et al. Effects of humor and laughter on psychological functioning, quality of life, health status, and pulmonary functioning among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a preliminary investigation. Heart Lung. 2011;40:310-319.

CASE REPORT: Laughter as therapy

Mrs. A is a 56-year-old married woman who has bipolar disorder. She has survived several suicide attempts. Her family history is positive for bipolar disorder and completed suicides.

After her most recent suicide attempt and a course of electroconvulsive therapy, Mrs. A recovered sufficiently to begin a spiritual journey that led her to practice a technique known as Laughter Yoga (Box) and, eventually, to become a Laughter Yoga instructor.

Mrs. A begins Laughter Yoga sessions by talking openly with students about her illness and the beneficial effects that laughter therapy has had on its course: She once had at least two major bipolar episodes a year, she explains, but has been in full remission for several years despite severe psychosocial stressors. In addition to practicing Laughter Yoga, Mrs. A is now maintained on a mood stabilizer that failed in the past to control her mood cycles.

Does laughter have a place in your practice?

It is said that laughter is good medicine—but is it good psychiatric medicine? Where might humor and laughter fit in the psychiatrist’s armamentarium? Is laughter physiologically beneficial to psychiatric patients? And are there adverse effects or contraindications to laughter in psychiatry? This article:

• reviews studies that have examined the anatomy, physiology, and psychology of humor and laughtera

• offers answers to the questions posed above (Table).

“Gelotology,” from the Greek “gelos,” laughter, is the science of laughter. The three components of humor and laughter are:

• the emotional component, which triggers emotions produced by a humorous situation

• the cognitive component, in which a person “gets it”

• the movement of facial, respiratory, and abdominal muscles.

Furthermore, tension and surprise are needed for laughter.

Theories about humor are varied

Philosophers since Plato have proposed theories of humor; modern theories of humor can be traced to Freud’s work.1 The psychoanalytic literature on humor focuses on the role of humor in sublimation of feelings of anger and hostility, while releasing affect in an economical way.

Erikson also wrote about the role of humor in a child’s developing superego, which helps resolve the conflict with maternal authority.2

In a comprehensive review of theories of humor, Krichtafovitch explains that cognitive theories address the role of incongruity and contrast in the induction of laughter, whereas social theories explore the roles of aggression, hostility, superiority, triumph, derision, and disparagement in humor and laughter. The effect of humor, Krichtafovitch explains, is to elevate the social status of the joker while the listener’s social status is lifted through his (her) ability to “get it.” Thus, humor plays a meaningful role in creating a bond between speaker and listener.3

The neuroanatomy of laughter

Here is some of what we have learned about mapping the brain to the basis of laughter:

• Consider a 16-year-old girl who underwent neurosurgery for intractable seizures. During surgery, various parts of the brain were stimulated to test for the focus of the seizures. She laughed every time the left frontal superior gyrus was stimulated. According to the report, she apparently laughed first, then made up a story that was funny to her.4

• Pseudobulbar affect—excessive, usually incongruent laughter, secondary to neurologic disease or traumatic brain injury—is an example of the biologic basis of laughter.

• Many functional brain imaging studies of laughter have been published.5 These studies show involvement of various regions of the brain in laughter, including the amygdala, hypothalamus, and temporal and cerebellar regions.

• Sex differences also have been noted in the neuroanatomy of laughter. Females activate the left prefrontal cortex more than males do, suggesting a greater degree of executive processing and language-based decoding. Females also exhibit greater activation of mesolimbic regions, including the nucleus accumbens, implying a greater reward network response.6

• Wild et al7 reported that separate cortical regions are responsible for the production of facial expressions that are emotionally driven (through laughter) and voluntary.

The physiology of laughter

Humans begin to laugh at approximately 4 months of age. Children laugh, on average, 400 times a day; adults do so an average of only 5 times a day.8 In addition:

• Tickling a baby induces her (him) to laugh, which, in turn, makes the parent laugh; a social bond develops during this playful exercise. This response is probably mediated by 5-HT1A receptors, which, when stimulated, induces the release of oxytocin, which facilitates social bonding.9

• Potent stimulation of 5-HT1A receptors through ingestion of 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine (Ecstasy) leads to uncontrollable laughter and mirth.10

• Lower species are also known to enjoy humor. Mice emit a chirping sound when tickled, and laughter is contagious among monkeys.11

• Berk et al12,13 reported that, when 52 healthy men watched a funny video for 30 minutes, they had significantly higher activity of natural killer (NK) cells and higher levels of IgG, IgA, and IgM compared with men who watched an emotionally neutral documentary.

• Bennett et al14 showed that, in 33 healthy women, the harder the laughter, the higher the NK activity.

• Sugawara et al15 showed improved cardiovascular function in 17 healthy persons (age 23 to 42) who watched a 30-minute comedy video, compared with their cardiovascular function when they watched a documentary video of equal length.

• Svebak et al16 examined the effect of humor as measured by the Sense of Humor Survey on the survival rate of more then 53,000 adults in one county in Norway. They concluded that the higher the sense of humor score, the higher the odds ratio of surviving 7 years, compared with subjects who had a lower sense of humor.

Clinical studies of laughter

The Coping Humor Scale (CHS) and the Humor Response Scale (HRS) are the two most widely used tools to measure a person’s innate sense of humor (the CHS) and the ability to respond to a humorous situation (the HRS).17 Several studies about the effects of laughter on illness are notable:

• Laughter increased NK cell activity, lowered prorenin gene expression, and lowered the postprandial glucose level in 34 patients with diabetes, compared with 16 matched controls.18-21

• Clark et al studied the sense of humor of 150 patients with cardiac disease compared with 150 controls. They found that “people with heart disease responded less humorously to everyday life situations.” They generally laughed less, even in positive situations, and displayed more anger and hostility.22

• In his work on the salutatory effect of laughter on the experience of pain, Cousins described how he dealt with his painful arthritis by watching Marx Brothers movies23:

I made the joyous discovery that 10 minutes of genuine belly laughter had an anesthetic effect and would give me at least two hours of pain-free sleep… When the pain-killing effect of the laughter wore off, we would switch on the motion picture projector again and not infrequently, it would lead to another pain-free interval.

• Hearty laughter leads to pain relief, probably through the release of endorphins. Dunbar et al24 tested this hypothesis in a series of six experimental studies in the laboratory (watching videos) and in a naturalistic context (watching stage performances), using a change in pain threshold as an indirect measure of endorphin release. The results show that the pain threshold is significantly higher after laughter than in the control condition. This pain-tolerance effect is caused by the laughter itself, not simply because of a change in positive affect.

Laughter therapy for depression

Three studies have demonstrated the benefit of laughter therapy in depression:

• When Ko and Youn25 studied 48 geriatric depressed patients and 61 age-matched controls, they found a significantly lower Geriatric Depression Scale score and a better Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index score in patients who had been exposed to four weekly laughter groups, compared with persons who had been exposed to a control group.

• Shahidi et al26 randomly assigned 60 community-dwelling female, geriatric, depressed patients to a laughter yoga group, an exercise group, and a control group. Laughter yoga and exercise were equally effective, and both were significantly superior to the control condition. The laughter yoga group scored significantly better than the other two groups on the Life Satisfaction Scale. The researchers concluded that, in addition to improved mood, patients who laugh experience increased life satisfaction.

• Fonzi et al27 summarized data on the neurophysiology of laughter and the effect of laughter on the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis. They noted that depression reduces the frequency of laughter and, inversely, laughter reduces the severity of depression. Laughter, they reported, also increases the connectivity of patients with people in their life, which further alleviates symptoms of depression.

Other therapeutic uses of laughter

Humor can strengthen the bond of the therapeutic relationship. Patients who laugh with their physicians are more likely to feel connected with them, follow their advice, and feel more satisfied with their encounter. One study found that primary care physicians who gave positive statements, spent more time with patients, and included humor or laughter during their visits lowered their risk of being sued for malpractice.28

Consider also the use of laughter in altering family dynamics in a therapeutic setting: Mr. and Mrs. B attend therapy in my practice to address a difficult situation with their adult children. One of them enables their children socially and financially; the other continually complains about this enabling. When the tension was high and the couple had reached an impasse during a visit, the therapist offered an anecdote from the 2006 motion picture Failure to Launch (in which a man lives in the security of his parents’ home even though he is in his 30s), that dissipated the hostility they had shown toward each other and toward their children. The couple was then able to proceed to conflict resolution.

Recommendations, caveats

If you are considering incorporating laughter into therapy, keep in mind that:

• you should ensure that the patient does not perceive humor as minimizing the seriousness of their problems

• humor can be a minefield if not used judiciously, or if used at all, around certain sensitive topics, such as race, ethnicity, religion, political affiliation, and sexual orientation

• the timing of humor is particularly essential for it to succeed in the context of a therapeutic relationship

• from a medical perspective, laughter in patients who are recovering from abdominal or other major surgery might compromise wound healing because of increased intra-abdominal pressure associated with laughing

• patients who have asthma, especially exercise-induced asthma, might be at risk of developing an acute asthmatic attack when they laugh very hard. Lebowitz et al29 demonstrated that laughter can have a negative effect on patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

It is advisable in some situations to avoid humor in psychotherapy, such as when the patient or family is hostile—because, as noted, they might perceive laughter and humor as an attempt to minimize the seriousness of their discontent.

Bottom Line

Humor and laughter are underutilized and underreported in therapy, in part because it is a nascent field of research. Laughter has social and physiologic benefits that can be used in the context of a therapeutic relationship to help patients with a variety of ailments, including depression, anxiety, and pain.

Related Resources

- Association for Applied and Therapeutic Humor. www.aath.org.

- Mora-Ripoll R. The therapeutic value of laughter in medicine. Altern Ther Health Med. 2010;16:56-64.

- Strean WB. Laughter prescription. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:965-967.

Disclosure

Dr. Nasr reports no financial relationship with manufacturers of any products mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the assistance of Francois E. Alouf, MD, for suggestions on topics to include in the article; John W. Crayton, MD, for reviewing the manuscript; and Burdette Wendt for assistance with the references.

CASE REPORT: Laughter as therapy

Mrs. A is a 56-year-old married woman who has bipolar disorder. She has survived several suicide attempts. Her family history is positive for bipolar disorder and completed suicides.

After her most recent suicide attempt and a course of electroconvulsive therapy, Mrs. A recovered sufficiently to begin a spiritual journey that led her to practice a technique known as Laughter Yoga (Box) and, eventually, to become a Laughter Yoga instructor.

Mrs. A begins Laughter Yoga sessions by talking openly with students about her illness and the beneficial effects that laughter therapy has had on its course: She once had at least two major bipolar episodes a year, she explains, but has been in full remission for several years despite severe psychosocial stressors. In addition to practicing Laughter Yoga, Mrs. A is now maintained on a mood stabilizer that failed in the past to control her mood cycles.

Does laughter have a place in your practice?

It is said that laughter is good medicine—but is it good psychiatric medicine? Where might humor and laughter fit in the psychiatrist’s armamentarium? Is laughter physiologically beneficial to psychiatric patients? And are there adverse effects or contraindications to laughter in psychiatry? This article:

• reviews studies that have examined the anatomy, physiology, and psychology of humor and laughtera

• offers answers to the questions posed above (Table).

“Gelotology,” from the Greek “gelos,” laughter, is the science of laughter. The three components of humor and laughter are:

• the emotional component, which triggers emotions produced by a humorous situation

• the cognitive component, in which a person “gets it”

• the movement of facial, respiratory, and abdominal muscles.

Furthermore, tension and surprise are needed for laughter.

Theories about humor are varied

Philosophers since Plato have proposed theories of humor; modern theories of humor can be traced to Freud’s work.1 The psychoanalytic literature on humor focuses on the role of humor in sublimation of feelings of anger and hostility, while releasing affect in an economical way.

Erikson also wrote about the role of humor in a child’s developing superego, which helps resolve the conflict with maternal authority.2

In a comprehensive review of theories of humor, Krichtafovitch explains that cognitive theories address the role of incongruity and contrast in the induction of laughter, whereas social theories explore the roles of aggression, hostility, superiority, triumph, derision, and disparagement in humor and laughter. The effect of humor, Krichtafovitch explains, is to elevate the social status of the joker while the listener’s social status is lifted through his (her) ability to “get it.” Thus, humor plays a meaningful role in creating a bond between speaker and listener.3

The neuroanatomy of laughter

Here is some of what we have learned about mapping the brain to the basis of laughter:

• Consider a 16-year-old girl who underwent neurosurgery for intractable seizures. During surgery, various parts of the brain were stimulated to test for the focus of the seizures. She laughed every time the left frontal superior gyrus was stimulated. According to the report, she apparently laughed first, then made up a story that was funny to her.4

• Pseudobulbar affect—excessive, usually incongruent laughter, secondary to neurologic disease or traumatic brain injury—is an example of the biologic basis of laughter.

• Many functional brain imaging studies of laughter have been published.5 These studies show involvement of various regions of the brain in laughter, including the amygdala, hypothalamus, and temporal and cerebellar regions.

• Sex differences also have been noted in the neuroanatomy of laughter. Females activate the left prefrontal cortex more than males do, suggesting a greater degree of executive processing and language-based decoding. Females also exhibit greater activation of mesolimbic regions, including the nucleus accumbens, implying a greater reward network response.6

• Wild et al7 reported that separate cortical regions are responsible for the production of facial expressions that are emotionally driven (through laughter) and voluntary.

The physiology of laughter

Humans begin to laugh at approximately 4 months of age. Children laugh, on average, 400 times a day; adults do so an average of only 5 times a day.8 In addition:

• Tickling a baby induces her (him) to laugh, which, in turn, makes the parent laugh; a social bond develops during this playful exercise. This response is probably mediated by 5-HT1A receptors, which, when stimulated, induces the release of oxytocin, which facilitates social bonding.9

• Potent stimulation of 5-HT1A receptors through ingestion of 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine (Ecstasy) leads to uncontrollable laughter and mirth.10

• Lower species are also known to enjoy humor. Mice emit a chirping sound when tickled, and laughter is contagious among monkeys.11

• Berk et al12,13 reported that, when 52 healthy men watched a funny video for 30 minutes, they had significantly higher activity of natural killer (NK) cells and higher levels of IgG, IgA, and IgM compared with men who watched an emotionally neutral documentary.

• Bennett et al14 showed that, in 33 healthy women, the harder the laughter, the higher the NK activity.

• Sugawara et al15 showed improved cardiovascular function in 17 healthy persons (age 23 to 42) who watched a 30-minute comedy video, compared with their cardiovascular function when they watched a documentary video of equal length.

• Svebak et al16 examined the effect of humor as measured by the Sense of Humor Survey on the survival rate of more then 53,000 adults in one county in Norway. They concluded that the higher the sense of humor score, the higher the odds ratio of surviving 7 years, compared with subjects who had a lower sense of humor.

Clinical studies of laughter

The Coping Humor Scale (CHS) and the Humor Response Scale (HRS) are the two most widely used tools to measure a person’s innate sense of humor (the CHS) and the ability to respond to a humorous situation (the HRS).17 Several studies about the effects of laughter on illness are notable:

• Laughter increased NK cell activity, lowered prorenin gene expression, and lowered the postprandial glucose level in 34 patients with diabetes, compared with 16 matched controls.18-21

• Clark et al studied the sense of humor of 150 patients with cardiac disease compared with 150 controls. They found that “people with heart disease responded less humorously to everyday life situations.” They generally laughed less, even in positive situations, and displayed more anger and hostility.22

• In his work on the salutatory effect of laughter on the experience of pain, Cousins described how he dealt with his painful arthritis by watching Marx Brothers movies23:

I made the joyous discovery that 10 minutes of genuine belly laughter had an anesthetic effect and would give me at least two hours of pain-free sleep… When the pain-killing effect of the laughter wore off, we would switch on the motion picture projector again and not infrequently, it would lead to another pain-free interval.

• Hearty laughter leads to pain relief, probably through the release of endorphins. Dunbar et al24 tested this hypothesis in a series of six experimental studies in the laboratory (watching videos) and in a naturalistic context (watching stage performances), using a change in pain threshold as an indirect measure of endorphin release. The results show that the pain threshold is significantly higher after laughter than in the control condition. This pain-tolerance effect is caused by the laughter itself, not simply because of a change in positive affect.

Laughter therapy for depression

Three studies have demonstrated the benefit of laughter therapy in depression:

• When Ko and Youn25 studied 48 geriatric depressed patients and 61 age-matched controls, they found a significantly lower Geriatric Depression Scale score and a better Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index score in patients who had been exposed to four weekly laughter groups, compared with persons who had been exposed to a control group.

• Shahidi et al26 randomly assigned 60 community-dwelling female, geriatric, depressed patients to a laughter yoga group, an exercise group, and a control group. Laughter yoga and exercise were equally effective, and both were significantly superior to the control condition. The laughter yoga group scored significantly better than the other two groups on the Life Satisfaction Scale. The researchers concluded that, in addition to improved mood, patients who laugh experience increased life satisfaction.

• Fonzi et al27 summarized data on the neurophysiology of laughter and the effect of laughter on the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis. They noted that depression reduces the frequency of laughter and, inversely, laughter reduces the severity of depression. Laughter, they reported, also increases the connectivity of patients with people in their life, which further alleviates symptoms of depression.

Other therapeutic uses of laughter

Humor can strengthen the bond of the therapeutic relationship. Patients who laugh with their physicians are more likely to feel connected with them, follow their advice, and feel more satisfied with their encounter. One study found that primary care physicians who gave positive statements, spent more time with patients, and included humor or laughter during their visits lowered their risk of being sued for malpractice.28

Consider also the use of laughter in altering family dynamics in a therapeutic setting: Mr. and Mrs. B attend therapy in my practice to address a difficult situation with their adult children. One of them enables their children socially and financially; the other continually complains about this enabling. When the tension was high and the couple had reached an impasse during a visit, the therapist offered an anecdote from the 2006 motion picture Failure to Launch (in which a man lives in the security of his parents’ home even though he is in his 30s), that dissipated the hostility they had shown toward each other and toward their children. The couple was then able to proceed to conflict resolution.

Recommendations, caveats

If you are considering incorporating laughter into therapy, keep in mind that:

• you should ensure that the patient does not perceive humor as minimizing the seriousness of their problems

• humor can be a minefield if not used judiciously, or if used at all, around certain sensitive topics, such as race, ethnicity, religion, political affiliation, and sexual orientation

• the timing of humor is particularly essential for it to succeed in the context of a therapeutic relationship

• from a medical perspective, laughter in patients who are recovering from abdominal or other major surgery might compromise wound healing because of increased intra-abdominal pressure associated with laughing

• patients who have asthma, especially exercise-induced asthma, might be at risk of developing an acute asthmatic attack when they laugh very hard. Lebowitz et al29 demonstrated that laughter can have a negative effect on patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

It is advisable in some situations to avoid humor in psychotherapy, such as when the patient or family is hostile—because, as noted, they might perceive laughter and humor as an attempt to minimize the seriousness of their discontent.

Bottom Line

Humor and laughter are underutilized and underreported in therapy, in part because it is a nascent field of research. Laughter has social and physiologic benefits that can be used in the context of a therapeutic relationship to help patients with a variety of ailments, including depression, anxiety, and pain.

Related Resources

- Association for Applied and Therapeutic Humor. www.aath.org.

- Mora-Ripoll R. The therapeutic value of laughter in medicine. Altern Ther Health Med. 2010;16:56-64.

- Strean WB. Laughter prescription. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:965-967.

Disclosure

Dr. Nasr reports no financial relationship with manufacturers of any products mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the assistance of Francois E. Alouf, MD, for suggestions on topics to include in the article; John W. Crayton, MD, for reviewing the manuscript; and Burdette Wendt for assistance with the references.

1. Freud S, Strachey J, trans., ed. Jokes and their relation to the unconscious. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company; 1990.

2. Capps D. Mother, melancholia, and humor in Erik H. Erikson’s earliest writings. J Relig Health. 2008;47:415-432.

3. Krichtafovitch I. Humor theory. Parker, CO: Outskirts Press; 2006.

4. Fried I, Wilson CL, MacDonald KA, et al. Electric current stimulates laughter. Nature. 1998;12;391:650.

5. Bartolo A, Benuzzi F, Nocetti L, et al. Humor comprehension and appreciation: an FMRI study. J Cogn Neurosci. 2006;18:1789-1798.

6. Azim E, Mobbs D, Jo B, et al. Sex differences in brain activation elicited by humor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16496-16501.

7. Wild B, Rodden FA, Rapp A, et al. Humor and smiling: cortical regions selective for cognitive, affective, and volitional components. Neurology. 2006;66:887-893.

8. Freedman LW. Mosby’s complementary and alternative medicine. A research-based approach. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2004:24.

9. Lukas M, Toth I, Reber SO, et al. The neuropeptide oxytocin facilitates pro-social behavior and prevents social avoidance in rats and mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:

2159-2168.

10. Thompson MR, Callaghan PD, Hunt GE, et al. A role for oxytocin and 5-HT(1A) receptors in the prosocial effects of 3,4 methylenedioxymethamphetamine (“ecstasy”). Neuroscience. 2007;146:509-514.

11. Ross MD, Owren MJ, Zimmermann E. The evolution of laughter in great apes and humans. Commun Integr Biol. 2010;3(2):191-194.

12. Berk LS, Tan SA, Fry WF, et al. Neuroendocrine and stress hormone changes during mirthful laughter. Am J Med Sci. 1989;298:390-396.

13. Berk LS, Felten DL, Tan SA, et al. Modulation of neuroimmune parameters during the eustress of humor-associated mirthful laughter. Altern Ther Health Med. 2001; 7:62-72,74-76.

14. Bennett MP, Zeller JM, Rosenberg L, et al. The effect of mirthful laughter on stress and natural killer cell activity. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9:38-45.

15. Sugawara J, Tarumi T, Tanaka H. Effect of mirthful laughter on vascular function. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:856-859.

16. Svebak S, Romundstad S, Holmen J. A 7-year prospective study of sense of humor and mortality in an adult county population: the HUNT-2 study. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2010;40:125-146.

17. Martin RA. The Situational Humor Response Questionnaire (SHRQ) and Coping Humor Scale (CHS): a decade of research findings. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research. 1996;9(3-4):251-272.

18. Hayashi T, Urayama O, Hori M, et al. Laughter modulates prorenin receptor gene expression in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Psychosom Res. 2007;62:703-706.

19. Hayashi T, Murakami K. The effects of laughter on post-prandial glucose levels and gene expression in type 2 diabetic patients. Life Sci. 2009;85:185-187.

20. Takahashi K, Iwase M, Yamashita K, et al. The elevation of natural killer cell activity induced by laughter in a crossover designed study. Int J Mol Med. 2001;8:645-650.

21. Nasir UM, Iwanaga S, Nabi AH, et al. Laughter therapy modulates the parameters of renin-angiotensin system in patients with type 2 diabetes. Int J Mol Med. 2005;16:1077-1081.

22. Clark A, Seidler A, Miller M. Inverse association between sense of humor and coronary heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 2001;80:87-88.

23. Cousins N. The anatomy of an illness as perceived by the patient: reflections on healing and regeneration. New York, NY: Norton; 1979:39.

24. Dunbar RI, Baron R, Frangou A, et al. Social laughter is correlated with an elevated pain threshold. Proc Biol Sci. 2012;279(1731):1161-1167.

25. Ko HJ, Youn CH. Effects of laughter therapy on depression, cognition and sleep among the community-dwelling elderly. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2011;11:267-274.

26. Shahidi M, Mojtahed A, Modabbernia A, et al. Laughter yoga versus group exercise program in elderly depressed women: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:322-327.

27. Fonzi L, Matteucci G, Bersani G. Laughter and depression: hypothesis of pathogenic and therapeutic correlation. Riv Psichiatr. 2010;45:1-6.

28. Levinson W, Roter DL, Mullooly JP, et al. Physician-patient communication: the relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA. 1997;277:553-559.

29. Lebowitz KR, Suh S, Diaz PT, et al. Effects of humor and laughter on psychological functioning, quality of life, health status, and pulmonary functioning among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a preliminary investigation. Heart Lung. 2011;40:310-319.

1. Freud S, Strachey J, trans., ed. Jokes and their relation to the unconscious. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company; 1990.

2. Capps D. Mother, melancholia, and humor in Erik H. Erikson’s earliest writings. J Relig Health. 2008;47:415-432.

3. Krichtafovitch I. Humor theory. Parker, CO: Outskirts Press; 2006.

4. Fried I, Wilson CL, MacDonald KA, et al. Electric current stimulates laughter. Nature. 1998;12;391:650.

5. Bartolo A, Benuzzi F, Nocetti L, et al. Humor comprehension and appreciation: an FMRI study. J Cogn Neurosci. 2006;18:1789-1798.

6. Azim E, Mobbs D, Jo B, et al. Sex differences in brain activation elicited by humor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16496-16501.

7. Wild B, Rodden FA, Rapp A, et al. Humor and smiling: cortical regions selective for cognitive, affective, and volitional components. Neurology. 2006;66:887-893.

8. Freedman LW. Mosby’s complementary and alternative medicine. A research-based approach. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2004:24.

9. Lukas M, Toth I, Reber SO, et al. The neuropeptide oxytocin facilitates pro-social behavior and prevents social avoidance in rats and mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:

2159-2168.

10. Thompson MR, Callaghan PD, Hunt GE, et al. A role for oxytocin and 5-HT(1A) receptors in the prosocial effects of 3,4 methylenedioxymethamphetamine (“ecstasy”). Neuroscience. 2007;146:509-514.

11. Ross MD, Owren MJ, Zimmermann E. The evolution of laughter in great apes and humans. Commun Integr Biol. 2010;3(2):191-194.

12. Berk LS, Tan SA, Fry WF, et al. Neuroendocrine and stress hormone changes during mirthful laughter. Am J Med Sci. 1989;298:390-396.

13. Berk LS, Felten DL, Tan SA, et al. Modulation of neuroimmune parameters during the eustress of humor-associated mirthful laughter. Altern Ther Health Med. 2001; 7:62-72,74-76.

14. Bennett MP, Zeller JM, Rosenberg L, et al. The effect of mirthful laughter on stress and natural killer cell activity. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9:38-45.

15. Sugawara J, Tarumi T, Tanaka H. Effect of mirthful laughter on vascular function. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:856-859.

16. Svebak S, Romundstad S, Holmen J. A 7-year prospective study of sense of humor and mortality in an adult county population: the HUNT-2 study. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2010;40:125-146.

17. Martin RA. The Situational Humor Response Questionnaire (SHRQ) and Coping Humor Scale (CHS): a decade of research findings. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research. 1996;9(3-4):251-272.

18. Hayashi T, Urayama O, Hori M, et al. Laughter modulates prorenin receptor gene expression in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Psychosom Res. 2007;62:703-706.

19. Hayashi T, Murakami K. The effects of laughter on post-prandial glucose levels and gene expression in type 2 diabetic patients. Life Sci. 2009;85:185-187.

20. Takahashi K, Iwase M, Yamashita K, et al. The elevation of natural killer cell activity induced by laughter in a crossover designed study. Int J Mol Med. 2001;8:645-650.

21. Nasir UM, Iwanaga S, Nabi AH, et al. Laughter therapy modulates the parameters of renin-angiotensin system in patients with type 2 diabetes. Int J Mol Med. 2005;16:1077-1081.

22. Clark A, Seidler A, Miller M. Inverse association between sense of humor and coronary heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 2001;80:87-88.

23. Cousins N. The anatomy of an illness as perceived by the patient: reflections on healing and regeneration. New York, NY: Norton; 1979:39.

24. Dunbar RI, Baron R, Frangou A, et al. Social laughter is correlated with an elevated pain threshold. Proc Biol Sci. 2012;279(1731):1161-1167.

25. Ko HJ, Youn CH. Effects of laughter therapy on depression, cognition and sleep among the community-dwelling elderly. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2011;11:267-274.

26. Shahidi M, Mojtahed A, Modabbernia A, et al. Laughter yoga versus group exercise program in elderly depressed women: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:322-327.

27. Fonzi L, Matteucci G, Bersani G. Laughter and depression: hypothesis of pathogenic and therapeutic correlation. Riv Psichiatr. 2010;45:1-6.

28. Levinson W, Roter DL, Mullooly JP, et al. Physician-patient communication: the relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA. 1997;277:553-559.

29. Lebowitz KR, Suh S, Diaz PT, et al. Effects of humor and laughter on psychological functioning, quality of life, health status, and pulmonary functioning among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a preliminary investigation. Heart Lung. 2011;40:310-319.

Incidental ovarian cysts: When to reassure, when to reassess, when to refer

Ovarian cysts, sometimes reported as ovarian masses or adnexal masses, are frequently found incidentally in women who have no symptoms. These cysts can be physiologic (having to do with ovulation) or neoplastic—either benign, borderline (having low malignant potential), or frankly malignant. Thus, these incidental lesions pose many diagnostic challenges to the clinician.

The vast majority of cysts are benign, but a few are malignant, and ovarian malignancies have a notoriously poor survival rate. The diagnosis can only be obtained surgically, as aspiration and biopsy are not definitive and may be harmful. Therefore, the clinician must try to balance the risks of surgery for what may be a benign lesion with the risk of delaying diagnosis of a malignancy.

In this article we provide an approach to evaluating these cysts, with guidance on when the patient can be reassured and when referral is needed.

THE DILEMMA OF OVARIAN CYSTS

Ovarian cysts are common

Premenopausal women can be expected to make at least a small cyst or follicle almost every month. The point prevalence for significant cysts has been reported to be almost 8% in premenopausal women.1

Surprisingly, the prevalence in postmenopausal women is as high as 14% to 18%, with a yearly incidence of 8%. From 30% to 54% of postmenopausal ovarian cysts persist for years.2,3

Little is known about the cause of most cysts

Little is known about the cause of most ovarian cysts. Functional or physiologic cysts are thought to be variations in the ovulatory process. They do not seem to be precursors to ovarian cancer.

Most benign neoplastic cysts are also not thought to be precancerous, with the possible exception of the mucinous kind.4 Ovarian cysts do not increase the risk of ovarian cancer later in life,3,9 and removing benign cysts has not been shown to decrease the risk of death from ovarian cancer.10

Most ovarian cysts and masses are benign

Simple ovarian cysts are much more likely to be benign than malignant. Complex and solid ovarian masses are also more likely to be benign, regardless of menopausal status, but more malignancies are found in this group.

With any kind of mass, the chances of malignancy increase with age. Children and adolescents are not discussed in this article; they should be referred to a specialist.

Ovarian cancer often has a poor prognosis

This “silent” cancer is most often discovered and treated when it has already spread, contributing to a reported 5-year survival rate of only 33% to 46%.11–13 Ideally, ovarian cancer would be found and removed while still confined to the ovary, when the 5-year survival rate is greater than 90%.

Unfortunately, there does not seem to be a precursor lesion for most ovarian cancers, and there is no good way of finding it in the stage 1 phase, so detecting this cancer before it spreads remains an elusive goal.11,14

Surgery is required to diagnose difficult cases

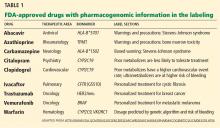

There is no perfect test for the preoperative assessment of a cystic ovarian mass. Every method has drawbacks (Table 1).15–18 Therefore, the National Institutes of Health estimates that 5% to 10% of women in the United States will undergo surgical exploration for an ovarian cyst in their lifetime. Only 13% to 21% of these cysts will be malignant.5

ASSESSING AN INCIDENTALLY DISCOVERED OVARIAN MASS

Certain factors in the history, physical examination, and blood work may suggest the cyst is either benign or malignant and may influence the subsequent assessment. However, in most cases, the best next step is to perform transvaginal ultrasonography, which we will discuss later in this paper.

History

Age is a major risk factor for ovarian cancer; the median age at diagnosis is 63 years.9 In the reproductive-age group, ovarian cysts are much more likely to be functional than neoplastic. Epithelial cancers are rare before the age of 40, but other cancer types such as borderline, germ cell, and sex cord stromal tumors may occur.19

In every age group a cyst is more likely to be benign than malignant, although, as noted above, the probability of malignancy increases with age.

Symptoms. Most ovarian cysts, benign or malignant, are asymptomatic and are found only incidentally.

The most commonly reported symptoms are pelvic or lower-abdominal pressure or pain. Acutely painful conditions include ovarian torsion, hemorrhage into the cyst, cyst rupture with or without intra-abdominal hemorrhage, ectopic pregnancy, and pelvic inflammatory disease with tubo-ovarian abscess.

Some patients who have ovarian cancer report vague symptoms such as urinary urgency or frequency, abdominal distention or bloating, and difficulty eating or early satiety.20 Although the positive predictive value of this symptom constellation is only about 1%, its usefulness increases if these symptoms arose recently (within the past year) and occur than 12 days a month.21

Family history of ovarian, breast, endometrial, or colon cancer is of particular interest. The greater the number of affected relatives and the closer the degree of relation, the greater the risk; in some cases the relative risk is 40 times greater.22 Breast-ovarian cancer syndromes, hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome, and family cancer syndrome, as well as extremely high-risk pedigrees such as BRCA1, BRCA2, and Lynch syndrome, all place women at significantly higher risk. Daughters tend to develop cancer at a younger age than their affected mothers.

However, only 10% of ovarian cancers occur in patients who have a family history of it, leaving 90% as sporadic occurrences.

Other history. Factors protective against ovarian cancer include use of oral contraceptives at any time, tubal ligation, hysterectomy, having had children, breastfeeding, a low-fat diet, and possibly use of aspirin and acetaminophen.23,24

Risk factors for malignancy include advanced age; nulliparity; family history of ovarian or breast cancer; personal history of breast cancer; talc use; asbestos exposure; white ethnicity; pelvic irradiation; smoking; alcohol use; possibly the previous use of fertility drugs, estrogen, or androgen; history of mumps; urban location; early menarche; and late menopause.24

Physical examination

Vital signs. Fever can indicate an infectious process or torsion of the ovary. A sudden onset of low blood pressure or rapid pulse can indicate a hemorrhagic condition such as ectopic pregnancy or ruptured hemorrhagic cyst.

Bimanual pelvic examination is notoriously inaccurate for detecting and characterizing ovarian cysts. In one prospective study, examiners blinded to the reason for surgery evaluated women under anesthesia. The authors concluded that bimanual examination was of limited value even under the best circumstances.15 Pelvic examination can be even more difficult in patients who are obese, are virginal, have vaginal atrophy, or are in pain.

Useful information that can be obtained through the bimanual examination includes the exact location of pelvic tenderness, the relative firmness of an identified mass, and the existence of nodularity in the posterior cul-de-sac, suggesting advanced ovarian cancer.

Tumor markers

Cancer antigen 125 (CA125) is the most studied and widely used of the ovarian cancer tumor markers. When advanced epithelial ovarian cancer is associated with a markedly elevated level, the value correlates with tumor burden.25

Unfortunately, only about half of early-stage ovarian cancers and 75% to 80% of advanced ovarian cancers express this marker.26 Especially in premenopausal women, there are many pelvic conditions that can falsely elevate CA125. Therefore, its sensitivity and specificity for predicting ovarian cancer are suboptimal. Nevertheless, CA125 is often used to help stratify risk when assessing known ovarian cysts and masses.

The value considered abnormal in postmenopausal women is 35 U/mL or greater, while in premenopausal women the cutoff is less well defined. The lower the cutoff level is set, the more sensitive the test. Recent recommendations advise 50 U/mL or 67 U/mL, rather than the 200 U/mL recommended in the 2002 joint guidelines of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Gynecologic Oncology.27,28

However, specificity is likely to be lower with these lower cutoff values. Conditions that can elevate CA125 levels include almost anything that irritates the peritoneum, including pregnancy, menstruation, fibroids, endometriosis, infection, and ovarian hyperstimulation, as well as medical conditions such as liver or renal disease, colitis, diverticulitis, congestive heart failure, diabetes, autoimmune diseases, and ascites.

Following serial CA125 levels may be more sensitive than trying to establish a single cutoff value.29 CA125 should not be used as a screening tool in average-risk women.26

OVA1. Several biomarker panels have been developed and evaluated for risk assessment in women with pelvic masses. OVA1, a proprietary panel of tests (Vermillion; Austin, TX) received US Food and Drug Administration approval in 2009. It includes CA125 and four other proteins, from which it calculates a probability score (high or low) using a proprietary formula.

In prospective studies, OVA1 was more sensitive than clinical assessment or CA125 alone.30 The higher sensitivity and negative predictive value were counterbalanced by a lower specificity and positive predictive value.31 Its cost ($650) is not always covered by insurance. OVA1 is not a screening tool.

EVALUATION WITH ULTRASONOGRAPHY

Ultrasonography is the imaging test of choice in assessing adnexal cysts and masses, and therefore it is the best next step after taking a history, performing a physical examination, and obtaining blood work.32 In cases in which an incidental ovarian mass is discovered on computed tomography (CT), further characterization by ultrasonography will likely yield helpful information.

Pelvic ultrasonography can be performed transabdominally or transvaginally. Vaginal ultrasonography gives the clearest images in most patients. Abdominal scanning is indicated for large masses, when vaginal access is difficult (as in virginal patients or those with vaginal atrophy) or when the mass is out of the focal length of the vaginal probe. A full bladder is usually required for the best transabdominal images.

The value of the images obtained depends on the experience of the ultrasonographer and reader and on the equipment. Also, there is currently no widely used standard for reporting the findings33—descriptions are individualized, leading some authors to recommend that the clinician personally review the films to get the most accurate picture.19

Size

Size alone cannot be used to distinguish between benign and malignant lesions. Simple cysts up to 10 cm are most likely benign regardless of menopausal status.2,34 However, in a complex or solid mass, size correlates somewhat with the chance of malignancy, with notable exceptions, such as the famously large sizes of some solid fibromas or mucinous cystadenomas. Also, size may correlate with risk of other complications such as torsion or symptomatic rupture.

Complexity

Simple cysts have clear fluid, thin smooth walls, no loculations or septae, and enhanced through-transmission of echo waves.32,33

Complexity is described in terms of septations, wall thickness, internal echoes, and solid nodules. Increasing complexity does correlate with increased risk of malignancy.

Worrisome findings

The most worrisome findings are:

- Solid areas that are not hyperechoic, especially when there is blood flow to them

- Thick septations, more than 2 or 3 mm wide, especially if there is blood flow within them

- Excrescences on the inner or outer aspect of a cystic area

- Ascites

- Other pelvic or omental masses.

Benign conditions

Several benign conditions have characteristic complex findings on ultrasonography (Table 2), whereas other findings can be indeterminate (Table 3) or worrisome for malignancy (Table 4).

Hemorrhagic corpus luteum cysts can be complex with an internal reticular pattern due to organizing clot and fibrin strands. A “ring of fire” vascular pattern is often seen around the cyst bed.

Dermoids (mature cystic teratomas) may have hyperechoic elements with acoustic shadowing and no internal Doppler flow. They can have a complex appearance due to fat, hair, and sebum within the cyst. Dermoid cysts have a pathognomonic appearance on CT with a clear fat-fluid level.

Endometriomas classically have a homogeneous “ground-glass” appearance or low-level echoes, without internal color Doppler flow, wall nodules, or other malignant features.

Fibroids may be pedunculated and may appear to be complex or solid adnexal masses.

Hydrosalpinges may present as tortuous tubular-shaped cystic masses. There may be incomplete septations or indentations seen on opposite sides (the “waist” sign).

Paratubal and paraovarian cysts are usually simple round cysts that can be demonstrated as separate from the ovary. Sometimes these appear complex as well.

Peritoneal inclusion cysts, also known as pseudocysts, are seen in patients with intra-abdominal adhesions. Often multiple septations are seen through clear fluid, with the cyst conforming to the shape of other pelvic structures.

Torsion of the ovary may occur with either benign or malignant masses. Torsion can be diagnosed when venous flow is absent on Doppler. The presence of flow, however, doesn’t rule out torsion, as torsion is often intermittent. The twisted ovary is most often enlarged and can have an edematous appearance. Although typically benign, these should be referred for urgent surgical treatment.

Vascularity

Doppler imaging is being extensively studied. The general principle is that malignant masses will be more vascular, with a high-volume, low-resistance pattern of flow. This can result in a pulsatility index of less than 1 or a resistive index of less than 0.4. In practice, however, there is significant overlap between high and low pulsatility indices and resistive indices in benign and malignant cysts. Low resistance can also be found in endometriomas, corpus luteum cysts, inflammatory masses, and vascular benign neoplasms. A normal (high) resistive index does not rule out malignancy.32,33

One Doppler finding that does seem to correlate with malignancy is the presence of any flow within a solid nodule or wall excrescence.

3D ultrasonography

As the use of 3D ultrasonography increases, studies are yielding different results as to its utility in describing ovarian masses. 3D ultrasonography may be useful in finding centrally located vessels so that Doppler can be applied.32

OTHER IMAGING

Although ultrasonography is the initial imaging study of choice in the evaluation of adnexal masses owing to its high sensitivity, availability, and low cost, studies have shown that up to 20% of adnexal masses can be reported as indeterminate by ultrasonography (Table 1).

Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is emerging as a very valuable tool when ultrasonography is inconclusive or limited.35 Although MRI is very accurate (Table 1), it is not considered a first-line imaging test because it is more expensive, less available, and more inconvenient for the patient than ultrasonography.

MRI provides additional information on the composition of soft-tissue tumors. Usually, MRI is ordered with contrast, unless there are contraindications to it. The radiologist will evaluate morphologic features, signal intensity, and enhancement of solid areas. Techniques such as dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (following the distribution of contrast material over time), in- and out-of-phase T1 imaging (looking for fat, such as in dermoids), and the newer diffusion-weighted imaging may further improve characterization.

In one study of MRI as second-line imaging, contrast-enhanced MRI contributed to a greater change in the probability of ovarian cancer than did CT, Doppler ultrasonography, or MRI without contrast.36 This may result in a reduction in unnecessary surgeries and in an increase in proper referrals in cases of suspected malignancy.

Computed tomography

Disadvantages of CT include radiation exposure and poor discrimination of soft tissue. It can, however, differentiate fat or calcifications that may be found in dermoids. While CT is not often used to describe an ovarian lesion, it may be used preoperatively to stage an ovarian cancer or to look for a primary intra-abdominal cancer when an ovarian mass may represent metastasis.32

MANAGING AN INCIDENTAL OVARIAN CYST OR CYSTIC MASS

Combining information from the history, physical examination, imaging, and blood work to assign a level of risk of malignancy is not straightforward. The clinician must weigh several imperfect tests, each with its own sensitivity and specificity, against the background of the individual patient’s likelihood of malignancy. Whereas a 4-cm simple cyst in a premenopausal woman can be assigned to a low-risk category and a complex mass with flow to a solid component in a postmenopausal woman can be assigned to a high-risk category, many lesions are more difficult to assess.

Several systems have been proposed for analyzing data and standardizing risk assessment. There are a number of scoring systems based on ultrasonographic morphology and several mathematical regression models that include menopausal status and tumor markers. But each has drawbacks, and none is definitively superior to expert opinion.16,17,37,38

A 2012 systematic review and meta-analysis39 calculated sensitivity and specificity for several imaging tests, scoring systems, and blood tumor markers. Some results are presented in Table 1.

The management of an ovarian cyst depends on symptoms, likelihood of torsion or rupture, and the level of concern for malignancy. At the lower-risk end of the spectrum, reassurance or observation over time may be appropriate. A general gynecologist can evaluate indeterminate or symptomatic ovarian cysts. Patients with masses frankly suspicious for malignancy are best referred to a gynecologic oncologist.

Expectant management for low-risk lesions

Low-risk lesions such as simple cysts, endometriomas, and dermoids have a less than 1% chance of malignancy. Most patients who have them require only reassurance or follow-up with serial ultrasonography. Oral contraceptives may prevent new cysts from forming. Aspiration is not recommended.

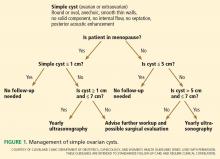

In 2010, the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound issued a consensus statement regarding re-imaging of simple ovarian cysts.33

In premenopausal women, they recommend no further testing for cysts 5 cm or smaller, yearly follow-up for cysts larger than 5 cm and up to and including 7 cm, and MRI or surgical evaluation for cysts larger than 7 cm, as it is difficult to completely image a large cyst with ultrasonography.

In postmenopausal women, if the cyst is 1 cm in diameter or smaller, no further studies need to be done. For simple cysts larger than 1 cm and up to and including 7 cm, yearly re-imaging is recommended. And for cysts larger than 7 cm, MRI or surgery is indicated. The American College of Radiology recommends repeat ultrasonography and CA125 testing for cysts 3 cm and larger but doesn’t specify an interval.32

A cyst that is otherwise simple but has a single thin septation (< 3 mm) or a small calcification in the wall is almost always benign. Such a cyst should be followed as if it were a simple cyst, as indicated by patient age and cyst size.

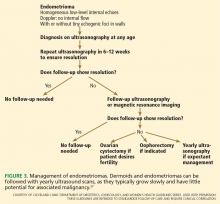

There are no official guidelines as to when to stop serial imaging,22,32 but a recent paper suggested one or two ultrasonographic examinations to confirm size and morphologic stability.19 Once a lesion has resolved, there is no need for further imaging (Figures 1–3).

Birth control pills for suppression of new cysts. Oral contraceptives do not hasten the resolution of ovarian cysts, according to a 2011 Cochrane review.40 Some practitioners will, nevertheless, prescribe them in an attempt to prevent new cysts from confusing the picture.

Aspiration is not recommended for either diagnosis or treatment. It can only be considered in patients at high risk who are not surgical candidates. Results of cytologic study of specimens obtained by fine-needle aspiration cannot reliably determine the presence or absence of malignancy.41 There is also a theoretical risk of spreading cancer from an early-stage lesion. A retrospective study has suggested that spillage of cyst contents during surgery in early ovarian cancer is associated with a worse prognosis.42

From a therapeutic point of view, studies have shown the same resolution rate at 6 months for aspirated cysts vs those followed expectantly.43 Another study found a recurrence rate of 25% within 1 year of aspiration.44

Referral for medium-risk or indeterminant-risk ovarian masses

Patients who have medium- or indeterminaterisk ovarian masses (Table 3) should be referred to a gynecologist. Further testing will help stratify the risk of malignancy. This can include tumor marker blood tests, MRI, or CT, the addition of Doppler or 3D ultrasonography, serial ultrasonography, or surgical exploration.

If repeat ultrasonography is chosen, the interval will likely be 6 to 12 weeks. Surgery may consist of removing only the cyst itself, or the whole ovary with or without the tube, or sometimes both ovaries. Purely diagnostic laparoscopy is rarely performed, as direct visualization of a lesion is rarely helpful. Frozen section should be employed, and the operating gynecologist should have oncologic backup, since the surgery is performed to rule out malignancy.

In the case of a benign-appearing cyst larger than 6 cm, thought must be given as to whether it is likely to rupture or twist. Rupture of a large cyst can lead to pain and in some cases to hemorrhage. Contents of a ruptured dermoid cyst can cause chemical peritonitis. Torsion of an ovary can result in loss of the ovary through compromised perfusion. A general gynecologist can decide with the patient whether preemptive surgery is indicated.

Operative evaluation for high-risk masses

Patients with high-risk ovarian masses (Table 4) are best referred to a gynecologic oncologist for operative evaluation. If features are seen that indicate malignancy, such as thick septations, solid areas with blood flow, ascites, or other pelvic masses, surgery is indicated. The surgical approach may be through laparoscopy or laparotomy.45 It should be noted that even in the face of worrisome features on ultrasonography, many masses turn out to be benign.

In 2011, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Gynecologic Oncology issued new guidelines recommending oncologic referral of patients with high-risk masses. Elevated CA125, ascites, a nodular or fixed pelvic mass, or evidence of metastasis in postmenopausal women requires oncologic evaluation.26 For premenopausal women, a very elevated CA125, ascites, or metastasis requires referral (Table 4).26

Direct referral to a gynecologic oncologist is underutilized. A recent study found that fewer than half of primary care physicians said that they would refer a classic suspicious case directly to a subspecialist.46 It is estimated that only 33% of ovarian cancers are first operated on by a gynecologic oncologist.47

A 2011 Cochrane review confirmed a survival benefit for women with cancer who are operated on by gynecologic oncologists primarily, rather than by a general gynecologist and then referred.48 A gynecologic oncologist is most likely to perform proper staging and debulking at the time of initial diagnosis.49

Special situations require consultation

Ovarian cysts in pregnancy are most often benign,50 but malignancy is always a possibility. Functional cysts and dermoids are the most common. These may remain asymptomatic or may rupture or twist or cause difficulty with delivering the baby. Surgical intervention, if needed, should be performed in the second trimester if possible. A multidisciplinary approach and referral to a perinatologist and gynecologic oncologist are advised.

Symptomatic ovarian cysts that may need surgical intervention are the purview of the general gynecologist. If the risk of a surgical emergency is judged to be low, a symptomatic patient may be supported with pain medication and may be managed on an outpatient basis. Immediate surgical consultation is appropriate if the patient appears toxic or in shock. Depending on the clinical picture, there may be a ruptured tubo-ovarian abscess, ruptured ectopic pregnancy, ruptured hemorrhagic cyst, or ovarian torsion, any of which may need immediate surgical intervention.

If a symptomatic mass is highly suspicious for cancer, a gynecologic oncologist should be consulted directly.

WHEN TO REASSURE, REASSESS, REFER

Ovarian masses often pose diagnostic and management dilemmas. Reassurance can be offered to women with small simple cysts. Interval follow-up with ultrasonography is appropriate for cysts that are most likely to be benign. If malignancy is suspected based on ultrasonography, other imaging, blood testing, or expert opinion, referral to a surgical gynecologist or gynecologic oncologist is recommended. If malignancy is strongly suspected, direct referral to a gynecologic oncologist offers the best chance of survival if cancer is actually present.

Reassure

- When simple cysts are less than 1 cm in postmenopausal women

- When simple cysts are less than 5 cm in premenopausal patients.

Reassess

- With yearly ultrasonography in cases of very low risk

- With repeat ultrasonography in 6 to 12 weeks when the diagnosis is not clear but the cyst is likely benign.

Refer

- To a gynecologist for symptomatic cysts, cysts larger than 6 cm, and cysts that require ancillary testing

- To a gynecologic oncologist for findings worrisome for cancer, such as thick septations, solid areas with flow, ascites, evidence of metastasis, or high cancer antigen 125 levels.

- Borgfeldt C, Andolf E. Transvaginal sonographic ovarian findings in a random sample of women 25–40 years old. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1999; 13:345–350.

- Modesitt SC, Pavlik EJ, Ueland FR, DePriest PD, Kryscio RJ, van Nagell JR. Risk of malignancy in unilocular ovarian cystic tumors less than 10 centimeters in diameter. Obstet Gynecol 2003; 102:594–599.