User login

Robotic vesicovaginal fistula repair: A systematic, endoscopic approach

In modern times in the United States, the vesicovaginal fistula (VVF) arises chiefly as a sequela of gynecologic surgery, usually hysterectomy. The injury most likely occurs at the time of dissection of the bladder flap off of the lower uterine segment and upper vagina.1 With increasing use of endoscopy and electrosurgery at the time of hysterectomy,2 the occurrence of VVF is likely to increase. Because of this, fistulas stemming from benign gynecologic surgical activity tend to occur above the trigone near the vaginal cuff.

Current technique of fistula repair involves either a vaginal approach, with the Latsko procedure,3 or an abdominal approach, involving a laparotomy; laparoscopy also is used with increasing frequency.4

Vaginal versus endoscopic approach. The vaginal approach can be straightforward, such as in cases of vault prolapse or a distally located fistula, or more difficult if the fistula is apical in location, especially if the apex is well suspended and the vagina is of normal length. I have found the abdominal approach to be optimal if the fistula is near the cuff and the vagina is of normal length and well suspended.

Classical teaching tells us that the first repair of the VVF is likely to be the most successful, with successively lower cure rates as the number of repair attempts increases. For this reason, I advocate the abdominal approach in most cases of apically placed VVFs.

Surgical approach

Why endoscopic, why robotic? Often, repair of the VVF is complicated by:

-

the challenge of locating the defect in the bladder

-

the technical difficulty in oversewing the bladder, which often must be done on the underside of the bladder, between the vaginal and bladder walls.

To tackle these challenges, an endoscopic approach promises improved visualization, and the robotic approach allows for surgical closure with improved visibility characteristic of endoscopy, while preserving the manual dexterity characteristic of open surgery.

Timing. It is believed that, in order to improve chances of successful surgical repair, the fistula should be approached either immediately (ie, within 1 to 2 weeks of the insult) or delayed by 8 to 12 or more weeks after the causative surgery.5

Preparation. Vesicovaginal fistulas can rarely involve the ureters, and this ureteric involvement needs to be ruled out. Accordingly, the workup of the VVF should begin with a thorough cystoscopic evaluation of the bladder, with retrograde pyelography to evaluate the integrity of the ureters bilaterally.

During this procedure, the location of the fistulous tract should be meticulously mapped. Care should be taken to document the location and extent of the fistula, as well as to identify the presence of multiple or separate tracts. If these tracts are present, they also need also to be catalogued. In my practice, the cystoscopy/retrograde pyelogram is performed as a separate surgical encounter.

Surgical technique

After the fistula is mapped and ureteric integrity is confirmed, the definitive surgical repair is performed. The steps to the surgical approach are straightforward.

1. Insert stents into the fistula and bilaterally into the ureters

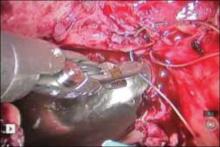

Stenting the fistula permits rapid identification of the fistula tract without the need to enter the bladder separately. The ureteric stents you use should be one color, and the fistula stent should be a second color. I use 5 French yellow stents to cannulate the ureters and a 6 French blue stent for the fistula itself. Insert the fistula stent from the bladder side of the fistula. It should exit through the vagina (FIGURES 1A and 1B). In addition, place a 3-way Foley catheter for drainage and irrigate the bladder when indicated.

Figure 1. Stent insertion

Cystoscopically place a 6 French blue stent into the bladder side of the fistula. (A) The stent as seen from inside the bladder. (B) The stent as seen from the vaginal side.

2. Place the ports for optimal access

A 0° camera is adequate for visualization. Port placement is similar to that used for robotic sacral colpopexy; I use a supraumbilically placed camera port and three 8-mm robot ports (two on the left and one on the right of the umbilicus). Each port should be separated by about 10 cm. An assistant port is placed to the far right, for passing and retrieving sutures (FIGURE 2). An atraumatic grasper, monopolar scissors, and bipolar Maryland-type forceps are placed within the ports to begin the surgical procedure.

Figure 2. Ideal port placement

Place the camera port supraunbilically, with two 8-mm robot ports

3. Place a vaginal stent to aid dissection

The stent should be a sterile cylinder and have a diameter of 2 cm to 5 cm (to match the vaginal caliber). The tip should be rounded and flattened, with an extended handle available for manipulating the stent. The handle can be held by an assistant or attached to an external uterine positioning system (FIGURE 3); I use the Uterine Positioning SystemTM (Cooper Surgical, Trumbull, Connecticut).

4. Incise the vaginal cuff

Transversely incise the vaginal cuff with the monopolar scissors (VIDEO 1).

This allows entry into the vagina at the apex. The blue stent in the fistula should be visible at the anterior vaginal wall, as demonstrated in FIGURE 4.

5. Dissect the vaginal wall

Dissect the anterior vaginal wall down to the fistula, and dissect the bladder off of the vaginal wall for about 1.5 cm to 2 cm around the fistula tract (FIGURE 5 and VIDEO 2).

6. Cut the stent

Cut the stent passing thru the fistula, to move it out of the way.

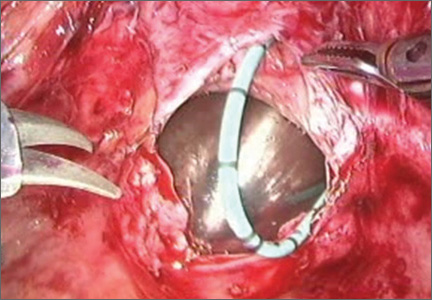

7. Close the bladder

Stitch the bladder in a running fashion using three layers of 3-0 rapid absorbable synthetic suture (FIGURE 6 and Video 3 . I prefer polyglactin 910 (Vicryl; Ethicon, Somerville, New Jersey) because it is easier to handle.

FIGURE 6: Close the bladderStitch the bladder in a running fashion using three layers of 3-0 rapid absorbable synthetic suture. Keep the closure line free of tension.

8. Close the vaginal side of the fistula

Stitch the vaginal side of the fistula in a running fashion with 2-0 absorbable synthetic suture.

9. Verify closure

Check for watertight closure by retrofilling the bladder with 100 mL of sterile milk (obtained from the labor/delivery suite). Observe the suture line for any evidence of milk leakage. (Sterile milk does not stain the tissues, and this preserves tissue visibility. For this reason, milk is preferable to indigo carmine or methylene blue.)

10. Remove the stents from the bladder

Cystoscopically remove all stents.

11. Close the laparoscopic ports

12. Follow up to ensure surgical success

Leave the indwelling Foley catheter in place for 2 to 3 weeks. After such time, remove the catheter and perform voiding cystourethrogram to document bladder wall integrity.

Discussion

I have described a systematic approach to robotic VVF repair. The robotic portion of the procedure should require about 60 to 90 minutes in the absence of significant adhesions. The technique is amenable to a laparoscopic approach, when performed by an appropriately skilled operator.

Final takeaways. Important takeaways to this repair include:

- Stent the fistula to make it easy to find intraoperatively.

- Enter the vagina from above to rapidly locate the fistula tract.

- Use sterile milk to fill the bladder to look for leaks. This works without staining the tissues.

- Minimize tension on the bladder suture line.

In modern times in the United States, the vesicovaginal fistula (VVF) arises chiefly as a sequela of gynecologic surgery, usually hysterectomy. The injury most likely occurs at the time of dissection of the bladder flap off of the lower uterine segment and upper vagina.1 With increasing use of endoscopy and electrosurgery at the time of hysterectomy,2 the occurrence of VVF is likely to increase. Because of this, fistulas stemming from benign gynecologic surgical activity tend to occur above the trigone near the vaginal cuff.

Current technique of fistula repair involves either a vaginal approach, with the Latsko procedure,3 or an abdominal approach, involving a laparotomy; laparoscopy also is used with increasing frequency.4

Vaginal versus endoscopic approach. The vaginal approach can be straightforward, such as in cases of vault prolapse or a distally located fistula, or more difficult if the fistula is apical in location, especially if the apex is well suspended and the vagina is of normal length. I have found the abdominal approach to be optimal if the fistula is near the cuff and the vagina is of normal length and well suspended.

Classical teaching tells us that the first repair of the VVF is likely to be the most successful, with successively lower cure rates as the number of repair attempts increases. For this reason, I advocate the abdominal approach in most cases of apically placed VVFs.

Surgical approach

Why endoscopic, why robotic? Often, repair of the VVF is complicated by:

-

the challenge of locating the defect in the bladder

-

the technical difficulty in oversewing the bladder, which often must be done on the underside of the bladder, between the vaginal and bladder walls.

To tackle these challenges, an endoscopic approach promises improved visualization, and the robotic approach allows for surgical closure with improved visibility characteristic of endoscopy, while preserving the manual dexterity characteristic of open surgery.

Timing. It is believed that, in order to improve chances of successful surgical repair, the fistula should be approached either immediately (ie, within 1 to 2 weeks of the insult) or delayed by 8 to 12 or more weeks after the causative surgery.5

Preparation. Vesicovaginal fistulas can rarely involve the ureters, and this ureteric involvement needs to be ruled out. Accordingly, the workup of the VVF should begin with a thorough cystoscopic evaluation of the bladder, with retrograde pyelography to evaluate the integrity of the ureters bilaterally.

During this procedure, the location of the fistulous tract should be meticulously mapped. Care should be taken to document the location and extent of the fistula, as well as to identify the presence of multiple or separate tracts. If these tracts are present, they also need also to be catalogued. In my practice, the cystoscopy/retrograde pyelogram is performed as a separate surgical encounter.

Surgical technique

After the fistula is mapped and ureteric integrity is confirmed, the definitive surgical repair is performed. The steps to the surgical approach are straightforward.

1. Insert stents into the fistula and bilaterally into the ureters

Stenting the fistula permits rapid identification of the fistula tract without the need to enter the bladder separately. The ureteric stents you use should be one color, and the fistula stent should be a second color. I use 5 French yellow stents to cannulate the ureters and a 6 French blue stent for the fistula itself. Insert the fistula stent from the bladder side of the fistula. It should exit through the vagina (FIGURES 1A and 1B). In addition, place a 3-way Foley catheter for drainage and irrigate the bladder when indicated.

Figure 1. Stent insertion

Cystoscopically place a 6 French blue stent into the bladder side of the fistula. (A) The stent as seen from inside the bladder. (B) The stent as seen from the vaginal side.

2. Place the ports for optimal access

A 0° camera is adequate for visualization. Port placement is similar to that used for robotic sacral colpopexy; I use a supraumbilically placed camera port and three 8-mm robot ports (two on the left and one on the right of the umbilicus). Each port should be separated by about 10 cm. An assistant port is placed to the far right, for passing and retrieving sutures (FIGURE 2). An atraumatic grasper, monopolar scissors, and bipolar Maryland-type forceps are placed within the ports to begin the surgical procedure.

Figure 2. Ideal port placement

Place the camera port supraunbilically, with two 8-mm robot ports

3. Place a vaginal stent to aid dissection

The stent should be a sterile cylinder and have a diameter of 2 cm to 5 cm (to match the vaginal caliber). The tip should be rounded and flattened, with an extended handle available for manipulating the stent. The handle can be held by an assistant or attached to an external uterine positioning system (FIGURE 3); I use the Uterine Positioning SystemTM (Cooper Surgical, Trumbull, Connecticut).

4. Incise the vaginal cuff

Transversely incise the vaginal cuff with the monopolar scissors (VIDEO 1).

This allows entry into the vagina at the apex. The blue stent in the fistula should be visible at the anterior vaginal wall, as demonstrated in FIGURE 4.

5. Dissect the vaginal wall

Dissect the anterior vaginal wall down to the fistula, and dissect the bladder off of the vaginal wall for about 1.5 cm to 2 cm around the fistula tract (FIGURE 5 and VIDEO 2).

6. Cut the stent

Cut the stent passing thru the fistula, to move it out of the way.

7. Close the bladder

Stitch the bladder in a running fashion using three layers of 3-0 rapid absorbable synthetic suture (FIGURE 6 and Video 3 . I prefer polyglactin 910 (Vicryl; Ethicon, Somerville, New Jersey) because it is easier to handle.

FIGURE 6: Close the bladderStitch the bladder in a running fashion using three layers of 3-0 rapid absorbable synthetic suture. Keep the closure line free of tension.

8. Close the vaginal side of the fistula

Stitch the vaginal side of the fistula in a running fashion with 2-0 absorbable synthetic suture.

9. Verify closure

Check for watertight closure by retrofilling the bladder with 100 mL of sterile milk (obtained from the labor/delivery suite). Observe the suture line for any evidence of milk leakage. (Sterile milk does not stain the tissues, and this preserves tissue visibility. For this reason, milk is preferable to indigo carmine or methylene blue.)

10. Remove the stents from the bladder

Cystoscopically remove all stents.

11. Close the laparoscopic ports

12. Follow up to ensure surgical success

Leave the indwelling Foley catheter in place for 2 to 3 weeks. After such time, remove the catheter and perform voiding cystourethrogram to document bladder wall integrity.

Discussion

I have described a systematic approach to robotic VVF repair. The robotic portion of the procedure should require about 60 to 90 minutes in the absence of significant adhesions. The technique is amenable to a laparoscopic approach, when performed by an appropriately skilled operator.

Final takeaways. Important takeaways to this repair include:

- Stent the fistula to make it easy to find intraoperatively.

- Enter the vagina from above to rapidly locate the fistula tract.

- Use sterile milk to fill the bladder to look for leaks. This works without staining the tissues.

- Minimize tension on the bladder suture line.

In modern times in the United States, the vesicovaginal fistula (VVF) arises chiefly as a sequela of gynecologic surgery, usually hysterectomy. The injury most likely occurs at the time of dissection of the bladder flap off of the lower uterine segment and upper vagina.1 With increasing use of endoscopy and electrosurgery at the time of hysterectomy,2 the occurrence of VVF is likely to increase. Because of this, fistulas stemming from benign gynecologic surgical activity tend to occur above the trigone near the vaginal cuff.

Current technique of fistula repair involves either a vaginal approach, with the Latsko procedure,3 or an abdominal approach, involving a laparotomy; laparoscopy also is used with increasing frequency.4

Vaginal versus endoscopic approach. The vaginal approach can be straightforward, such as in cases of vault prolapse or a distally located fistula, or more difficult if the fistula is apical in location, especially if the apex is well suspended and the vagina is of normal length. I have found the abdominal approach to be optimal if the fistula is near the cuff and the vagina is of normal length and well suspended.

Classical teaching tells us that the first repair of the VVF is likely to be the most successful, with successively lower cure rates as the number of repair attempts increases. For this reason, I advocate the abdominal approach in most cases of apically placed VVFs.

Surgical approach

Why endoscopic, why robotic? Often, repair of the VVF is complicated by:

-

the challenge of locating the defect in the bladder

-

the technical difficulty in oversewing the bladder, which often must be done on the underside of the bladder, between the vaginal and bladder walls.

To tackle these challenges, an endoscopic approach promises improved visualization, and the robotic approach allows for surgical closure with improved visibility characteristic of endoscopy, while preserving the manual dexterity characteristic of open surgery.

Timing. It is believed that, in order to improve chances of successful surgical repair, the fistula should be approached either immediately (ie, within 1 to 2 weeks of the insult) or delayed by 8 to 12 or more weeks after the causative surgery.5

Preparation. Vesicovaginal fistulas can rarely involve the ureters, and this ureteric involvement needs to be ruled out. Accordingly, the workup of the VVF should begin with a thorough cystoscopic evaluation of the bladder, with retrograde pyelography to evaluate the integrity of the ureters bilaterally.

During this procedure, the location of the fistulous tract should be meticulously mapped. Care should be taken to document the location and extent of the fistula, as well as to identify the presence of multiple or separate tracts. If these tracts are present, they also need also to be catalogued. In my practice, the cystoscopy/retrograde pyelogram is performed as a separate surgical encounter.

Surgical technique

After the fistula is mapped and ureteric integrity is confirmed, the definitive surgical repair is performed. The steps to the surgical approach are straightforward.

1. Insert stents into the fistula and bilaterally into the ureters

Stenting the fistula permits rapid identification of the fistula tract without the need to enter the bladder separately. The ureteric stents you use should be one color, and the fistula stent should be a second color. I use 5 French yellow stents to cannulate the ureters and a 6 French blue stent for the fistula itself. Insert the fistula stent from the bladder side of the fistula. It should exit through the vagina (FIGURES 1A and 1B). In addition, place a 3-way Foley catheter for drainage and irrigate the bladder when indicated.

Figure 1. Stent insertion

Cystoscopically place a 6 French blue stent into the bladder side of the fistula. (A) The stent as seen from inside the bladder. (B) The stent as seen from the vaginal side.

2. Place the ports for optimal access

A 0° camera is adequate for visualization. Port placement is similar to that used for robotic sacral colpopexy; I use a supraumbilically placed camera port and three 8-mm robot ports (two on the left and one on the right of the umbilicus). Each port should be separated by about 10 cm. An assistant port is placed to the far right, for passing and retrieving sutures (FIGURE 2). An atraumatic grasper, monopolar scissors, and bipolar Maryland-type forceps are placed within the ports to begin the surgical procedure.

Figure 2. Ideal port placement

Place the camera port supraunbilically, with two 8-mm robot ports

3. Place a vaginal stent to aid dissection

The stent should be a sterile cylinder and have a diameter of 2 cm to 5 cm (to match the vaginal caliber). The tip should be rounded and flattened, with an extended handle available for manipulating the stent. The handle can be held by an assistant or attached to an external uterine positioning system (FIGURE 3); I use the Uterine Positioning SystemTM (Cooper Surgical, Trumbull, Connecticut).

4. Incise the vaginal cuff

Transversely incise the vaginal cuff with the monopolar scissors (VIDEO 1).

This allows entry into the vagina at the apex. The blue stent in the fistula should be visible at the anterior vaginal wall, as demonstrated in FIGURE 4.

5. Dissect the vaginal wall

Dissect the anterior vaginal wall down to the fistula, and dissect the bladder off of the vaginal wall for about 1.5 cm to 2 cm around the fistula tract (FIGURE 5 and VIDEO 2).

6. Cut the stent

Cut the stent passing thru the fistula, to move it out of the way.

7. Close the bladder

Stitch the bladder in a running fashion using three layers of 3-0 rapid absorbable synthetic suture (FIGURE 6 and Video 3 . I prefer polyglactin 910 (Vicryl; Ethicon, Somerville, New Jersey) because it is easier to handle.

FIGURE 6: Close the bladderStitch the bladder in a running fashion using three layers of 3-0 rapid absorbable synthetic suture. Keep the closure line free of tension.

8. Close the vaginal side of the fistula

Stitch the vaginal side of the fistula in a running fashion with 2-0 absorbable synthetic suture.

9. Verify closure

Check for watertight closure by retrofilling the bladder with 100 mL of sterile milk (obtained from the labor/delivery suite). Observe the suture line for any evidence of milk leakage. (Sterile milk does not stain the tissues, and this preserves tissue visibility. For this reason, milk is preferable to indigo carmine or methylene blue.)

10. Remove the stents from the bladder

Cystoscopically remove all stents.

11. Close the laparoscopic ports

12. Follow up to ensure surgical success

Leave the indwelling Foley catheter in place for 2 to 3 weeks. After such time, remove the catheter and perform voiding cystourethrogram to document bladder wall integrity.

Discussion

I have described a systematic approach to robotic VVF repair. The robotic portion of the procedure should require about 60 to 90 minutes in the absence of significant adhesions. The technique is amenable to a laparoscopic approach, when performed by an appropriately skilled operator.

Final takeaways. Important takeaways to this repair include:

- Stent the fistula to make it easy to find intraoperatively.

- Enter the vagina from above to rapidly locate the fistula tract.

- Use sterile milk to fill the bladder to look for leaks. This works without staining the tissues.

- Minimize tension on the bladder suture line.

Patient privacy

Do no harm. There are few words that mean more to physicians, which is why many are reluctant to engage with patients online. They see social media as a minefield of potential privacy violations.

Avoiding social media entirely for fear of committing a privacy violation is not the answer in today’s increasingly social world. Instead, you should educate yourself about how to use social media safely and effectively.

Numerous medical centers and governing bodies are trying to establish social media guidelines for physicians and health care workers, but since social media is continually evolving, so will the guidelines for using it. Some existing guidelines include the following:

• American College of Physicians: new recommendations offer guidance for preserving trust when using social media.

• The Federation of State Medical Boards Model Policy Guidelines.

• Cleveland Clinic Social Media Policy.

• Mayo Clinic Social Media Policy for Employees.

• Centers for Disease Controls Social Media Guidelines and Best Practices.

It’s true that engaging with patients online poses risks to us as providers. It’s also true that we take on risk every day that we see patients. And just as a physician who violates a patient’s privacy in person could face legal ramifications, so too could he face them from committing a privacy breach online.

I encourage everyone to do their own research before engaging in social media, but here are the guidelines I adhere to for using it safely:

• Include a disclaimer on your social networks that states content is not medical advice, but rather educational information. For example, on my @Dermdoc Twitter account, my bio includes "Views here are my own, and are not medical advice."

• Maintain separate personal and professional online accounts, and direct patients to your professional accounts only.

• E-mail and other electronic modes of communication should be used only within a secure system with an established patient/physician relationship and with patient consent.

• Never respond to specific clinical questions from nonpatients online. Encourage the individual to contact his or her medical provider, or in the case of an emergency, to go to the nearest emergency department.

• Text messaging should be used only with established patients and with their consent.

• Never post information or photos online that could re-identify a patient, unless you have his or her written consent.

• If a patient identifies himself online of his own accord, you are not responsible. However, you should explain to him that you’d rather not discuss his specific case in public and redirect him to a secure means of communication with you.

• Never argue, demean, or accuse patients online. Your online behavior should reflect your professionalism and respect of others.

• Never post content or photos of yourself that are unprofessional or incriminating, such as a photo of you and your buddies partying.

In my next column, I’ll present specific examples of safe and appropriate responses to patients online.

Dr. Benabio is Physician Director of Innovation at Kaiser Permanente in San Diego. Visit his consumer health blog at thedermblog.com and his health care blog at benabio.com. Connect with him on Twitter @Dermdoc and on Facebook (DermDoc).

Do no harm. There are few words that mean more to physicians, which is why many are reluctant to engage with patients online. They see social media as a minefield of potential privacy violations.

Avoiding social media entirely for fear of committing a privacy violation is not the answer in today’s increasingly social world. Instead, you should educate yourself about how to use social media safely and effectively.

Numerous medical centers and governing bodies are trying to establish social media guidelines for physicians and health care workers, but since social media is continually evolving, so will the guidelines for using it. Some existing guidelines include the following:

• American College of Physicians: new recommendations offer guidance for preserving trust when using social media.

• The Federation of State Medical Boards Model Policy Guidelines.

• Cleveland Clinic Social Media Policy.

• Mayo Clinic Social Media Policy for Employees.

• Centers for Disease Controls Social Media Guidelines and Best Practices.

It’s true that engaging with patients online poses risks to us as providers. It’s also true that we take on risk every day that we see patients. And just as a physician who violates a patient’s privacy in person could face legal ramifications, so too could he face them from committing a privacy breach online.

I encourage everyone to do their own research before engaging in social media, but here are the guidelines I adhere to for using it safely:

• Include a disclaimer on your social networks that states content is not medical advice, but rather educational information. For example, on my @Dermdoc Twitter account, my bio includes "Views here are my own, and are not medical advice."

• Maintain separate personal and professional online accounts, and direct patients to your professional accounts only.

• E-mail and other electronic modes of communication should be used only within a secure system with an established patient/physician relationship and with patient consent.

• Never respond to specific clinical questions from nonpatients online. Encourage the individual to contact his or her medical provider, or in the case of an emergency, to go to the nearest emergency department.

• Text messaging should be used only with established patients and with their consent.

• Never post information or photos online that could re-identify a patient, unless you have his or her written consent.

• If a patient identifies himself online of his own accord, you are not responsible. However, you should explain to him that you’d rather not discuss his specific case in public and redirect him to a secure means of communication with you.

• Never argue, demean, or accuse patients online. Your online behavior should reflect your professionalism and respect of others.

• Never post content or photos of yourself that are unprofessional or incriminating, such as a photo of you and your buddies partying.

In my next column, I’ll present specific examples of safe and appropriate responses to patients online.

Dr. Benabio is Physician Director of Innovation at Kaiser Permanente in San Diego. Visit his consumer health blog at thedermblog.com and his health care blog at benabio.com. Connect with him on Twitter @Dermdoc and on Facebook (DermDoc).

Do no harm. There are few words that mean more to physicians, which is why many are reluctant to engage with patients online. They see social media as a minefield of potential privacy violations.

Avoiding social media entirely for fear of committing a privacy violation is not the answer in today’s increasingly social world. Instead, you should educate yourself about how to use social media safely and effectively.

Numerous medical centers and governing bodies are trying to establish social media guidelines for physicians and health care workers, but since social media is continually evolving, so will the guidelines for using it. Some existing guidelines include the following:

• American College of Physicians: new recommendations offer guidance for preserving trust when using social media.

• The Federation of State Medical Boards Model Policy Guidelines.

• Cleveland Clinic Social Media Policy.

• Mayo Clinic Social Media Policy for Employees.

• Centers for Disease Controls Social Media Guidelines and Best Practices.

It’s true that engaging with patients online poses risks to us as providers. It’s also true that we take on risk every day that we see patients. And just as a physician who violates a patient’s privacy in person could face legal ramifications, so too could he face them from committing a privacy breach online.

I encourage everyone to do their own research before engaging in social media, but here are the guidelines I adhere to for using it safely:

• Include a disclaimer on your social networks that states content is not medical advice, but rather educational information. For example, on my @Dermdoc Twitter account, my bio includes "Views here are my own, and are not medical advice."

• Maintain separate personal and professional online accounts, and direct patients to your professional accounts only.

• E-mail and other electronic modes of communication should be used only within a secure system with an established patient/physician relationship and with patient consent.

• Never respond to specific clinical questions from nonpatients online. Encourage the individual to contact his or her medical provider, or in the case of an emergency, to go to the nearest emergency department.

• Text messaging should be used only with established patients and with their consent.

• Never post information or photos online that could re-identify a patient, unless you have his or her written consent.

• If a patient identifies himself online of his own accord, you are not responsible. However, you should explain to him that you’d rather not discuss his specific case in public and redirect him to a secure means of communication with you.

• Never argue, demean, or accuse patients online. Your online behavior should reflect your professionalism and respect of others.

• Never post content or photos of yourself that are unprofessional or incriminating, such as a photo of you and your buddies partying.

In my next column, I’ll present specific examples of safe and appropriate responses to patients online.

Dr. Benabio is Physician Director of Innovation at Kaiser Permanente in San Diego. Visit his consumer health blog at thedermblog.com and his health care blog at benabio.com. Connect with him on Twitter @Dermdoc and on Facebook (DermDoc).

Implications of Hospital‐Acquired Anemia

Anemia is associated with poor quality of life and increased risk for death and hospitalization in population‐based and cohort investigations.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7] Evidence suggests that patients with normal hemoglobin (Hgb) values on hospital admission who subsequently develop hospital‐acquired anemia (HAA) have increased morbidity and mortality compared with those who do not.[8, 9] HAA is multifaceted and may occur as a result of processes of care during hospitalization, such as hemodilution from intravenous fluid administration, procedural blood loss and phlebotomy, and impaired erythropoiesis associated with critical illness.[8, 9] Moreover, correcting anemia by red blood cell transfusion also carries risk.[10, 11, 12, 13]

Our primary objective was to examine the prevalence of HAA in a population of medical and surgical patients admitted to a large quaternary referral health system. Our secondary objectives were to examine whether HAA is associated with increased mortality, length of stay (LOS), and total hospital charges compared to patients without HAA.

METHODS

Patient Population and Data Sources

The patient population consisted of 417,301 hospitalizations in adult patients (18 years of age) who were admitted to the Cleveland Clinic Health System from January 2009 to September 2011. Data for these hospitalizations came from 2 sources. Patient demographics, baseline comorbidities, and outcomes were extracted from the University HealthSystem Consortium's (UHC) clinical database/resource manager. UHC is an alliance of 116 US academic medical centers and their 272 affiliated hospitals, representing more than 90% of the nation's nonprofit academic medical centers. These data had originally been retrieved from our hospitals' administrative data systems, normalized according to UHC standardized data specifications, and submitted for inclusion in the UHC repository. Data quality was assessed using standardized error checking and data completeness algorithms and was required to meet established minimum thresholds to be included in the UHC repository.

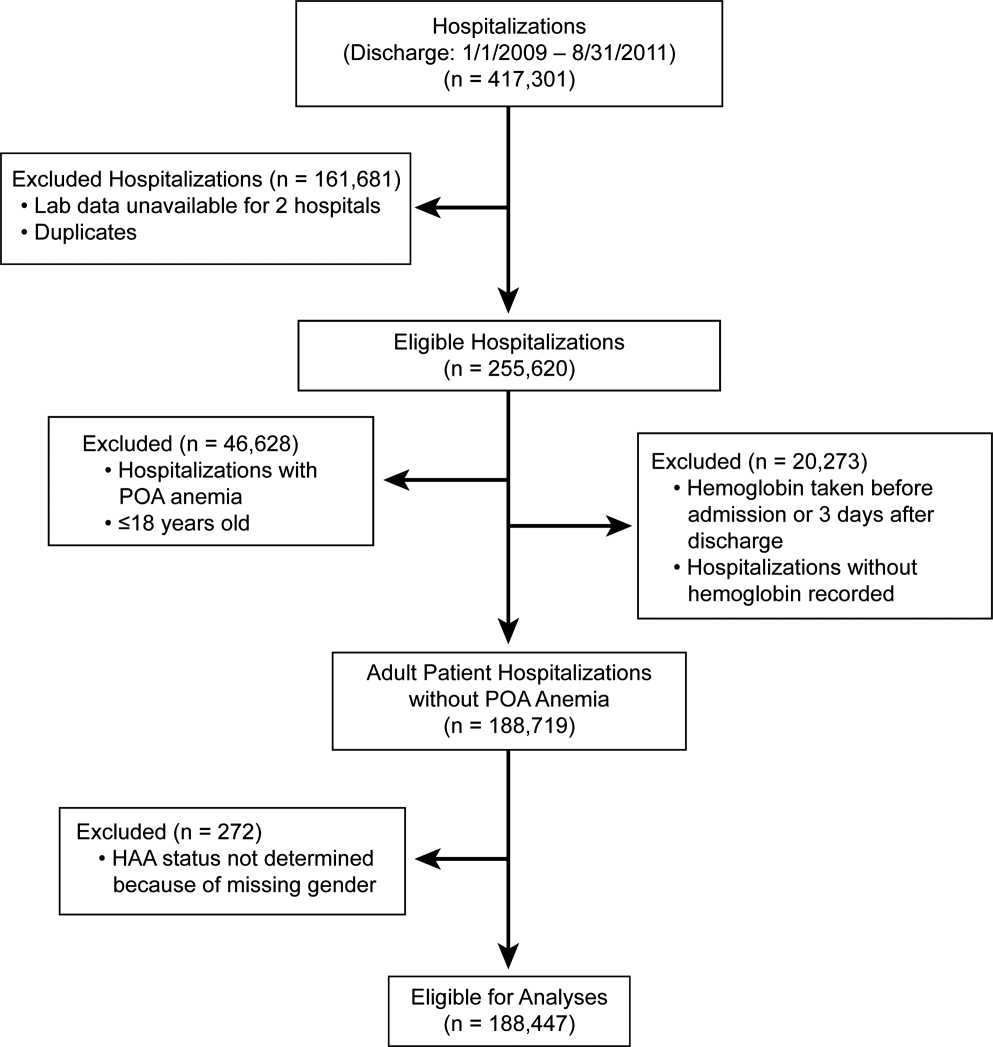

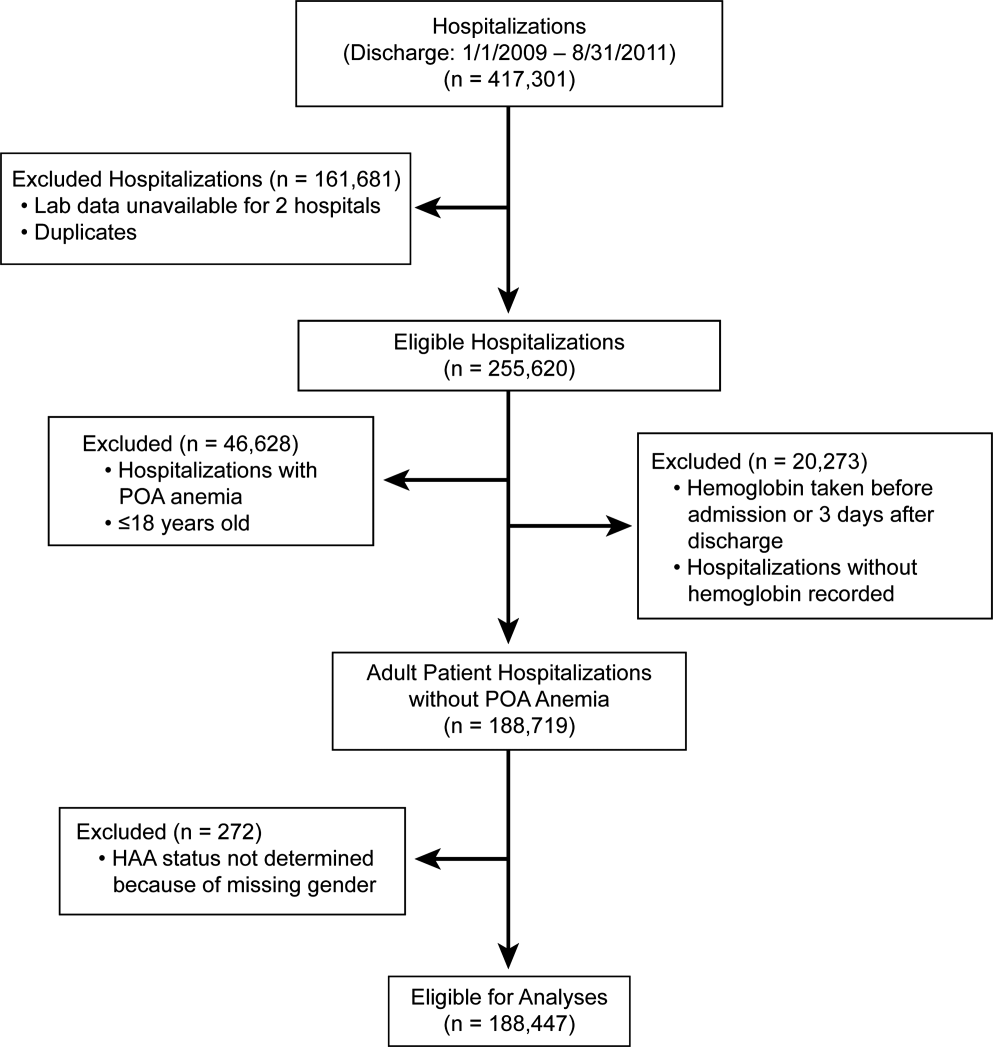

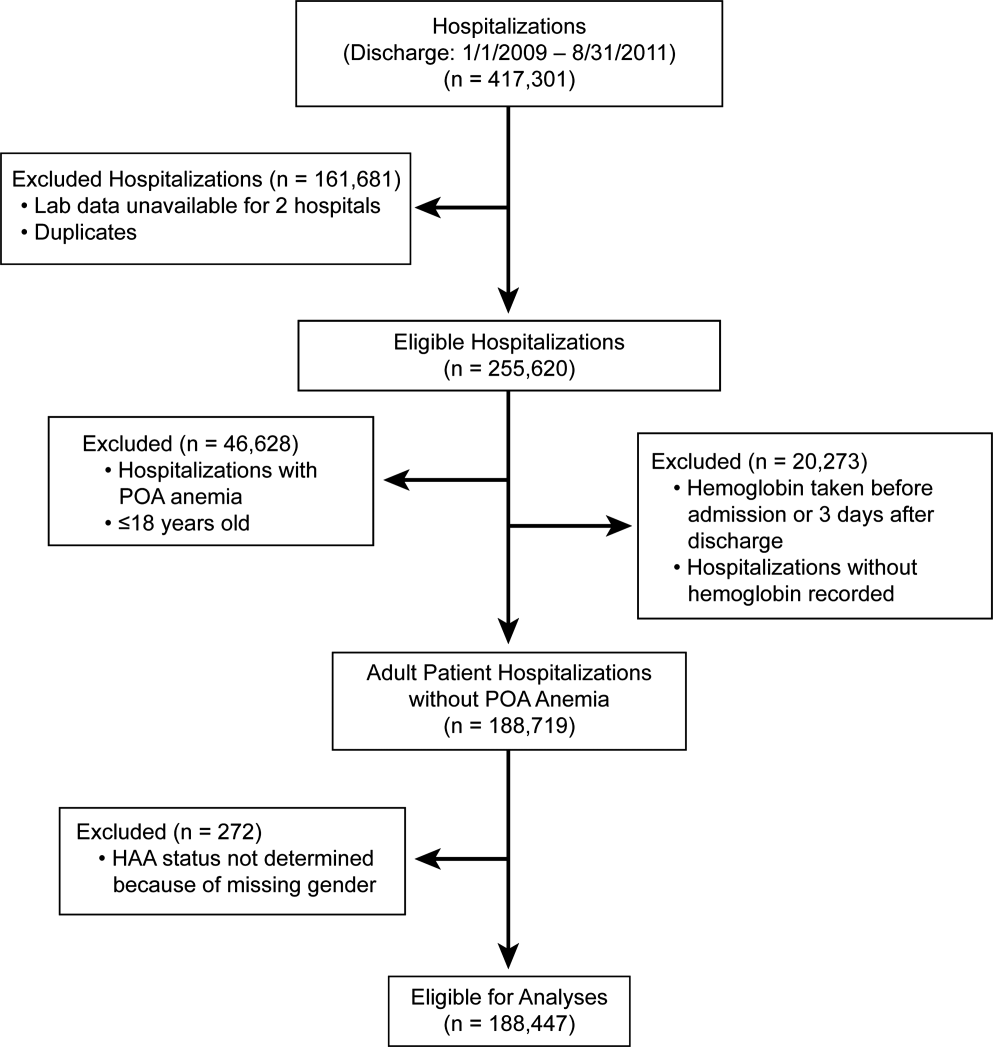

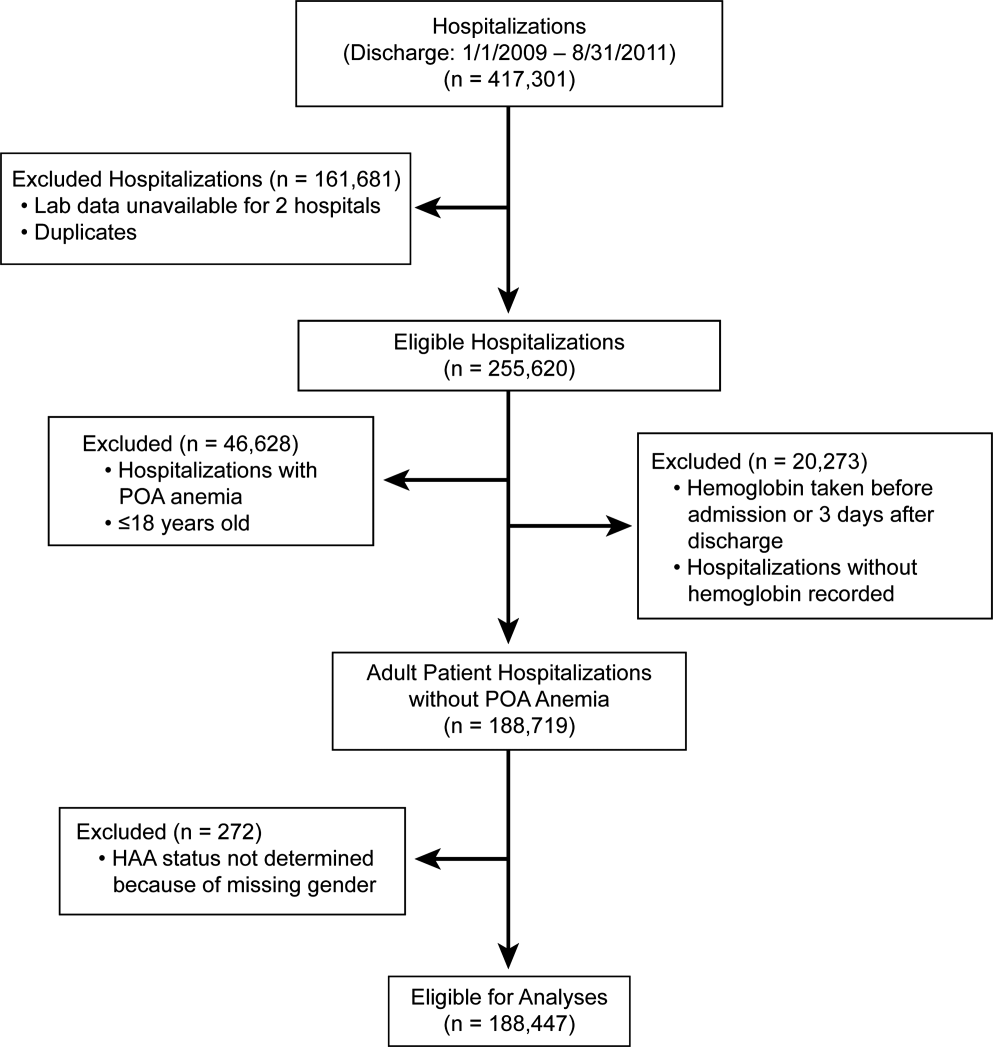

The second source of data was measured Hgb values retrieved from the hospitals' electronic medical record from complete blood count testing. Present‐on‐admission (POA) anemia was defined by an International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification diagnosis code of anemia with a positive POA indicator; these patients were excluded from the analysis (Figure 1). Patients without available Hgb values and those with Hgb data dated 3 days or more after discharge date were also excluded. In addition, 2 hospitals within the health system did not have electronically available laboratory data and therefore were excluded from the analysis as well. The final dataset consisted of 188,447 patient hospitalizations. The institutional review board approved this investigation, with individual patient consent waived.

Anemia

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines anemia as a Hgb value l<12 g/dL in women and <13 g/dL in men. HAA was defined as a nadir Hgb value during the course of hospitalization meeting WHO criteria. We further grouped Hgb by degree into no anemia, mild anemia (Hgb >11 and <12 g/dL in women, >11 and <13 g/dL in men), moderate anemia (Hgb >9 and 11 g/dL), and severe anemia (Hgb 9 g/dL).

Outcomes

Outcomes were all‐cause in‐hospital mortality, total hospital LOS, and total hospital charges.

Data Analysis

For risk adjustment, we used methods developed by Elixhauser and colleagues[14] for use with in‐patient administrative databases. These included a comprehensive set of comorbidity indicators, used to control for patients' underlying conditions in models of outcomes. Among the 30 variables defined by Elixhauser and colleagues, we excluded the 2 administrative anemia codes because this was our variable of interest (Table 1). For all models, demographics, medical conditions, and hospitalization type (medical vs surgical) were included as covariables in addition to the anemia groupings (no HAA and mild, moderate, and severe HAA).

| Characteristic | Hospital‐Acquired Anemia Group | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Anemia, n=48,640 | Mild, n=40,828 | Moderate, n=57,184 | Severe, n=41,795 | ||

| |||||

| Age at admission, y | 5518 | 5818 | 5819 | 6117 | <0.0001 |

| Female | 25,123 (52) | 17,938 (44) | 35,858 (63) | 23,533 (56) | <0.0001 |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.0001 | ||||

| White | 39,100 (80) | 32,610 (80) | 45,977 (80) | 33,810 (81) | |

| Black | 7580 (16) | 6607 (16) | 8946 (16) | 6204 (15) | |

| Other | 1960 (4.0) | 1611 (3.9) | 2261 (4.0) | 1781 (4.3) | |

| Hospitalization type | <0.0001 | ||||

| Surgery | 9681 (20) | 14,076 (34) | 26,100 (46) | 27,865 (67) | |

| Medicine | 38,958 (80) | 26,750 (66) | 31,081 (54) | 13,922 (33) | |

| Hypertension | 25,591 (53) | 22,218 (54) | 29,963 (52) | 24,257 (58) | <0.0001 |

| Heart failure | 2811 (5.8) | 3182 (7.8) | 5086 (8.9) | 4278 (10) | <0.0001 |

| Valvular disease | 1201 (2.5) | 1259 (3.1) | 2126 (3.7) | 1890 (4.5) | <0.0001 |

| Pulmonary circulation disease | 667 (1.4) | 730 (1.8) | 1221 (2.1) | 1484 (3.6) | <0.0001 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 2417 (5.0) | 2728 (6.7) | 4187 (7.3) | 4508 (11) | <0.0001 |

| Paralysis | 1216 (2.5) | 1175 (2.9) | 1568 (2.7) | 1305 (3.1) | <0.0001 |

| Other neurologic disorders | 3013 (6.2) | 2780 (6.8) | 3599 (6.3) | 2829 (6.8) | <0.0001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 9225 (19) | 7885 (19) | 10,960 (19) | 8057 (19) | 0.5 |

| Diabetes without chronic complications | 8306 (17) | 7733 (19) | 10,417 (18) | 7911 (19) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes with chronic complications | 1547 (3.2) | 1922 (4.7) | 2989 (5.2) | 2779 (6.6) | <0.0001 |

| Hypothyroidism | 5008 (10) | 4258 (10) | 6938 (12) | 5567 (13) | <0.0001 |

| Renal failure | 2006 (4.1) | 3278 (8.0) | 5787 (10) | 5954 (14) | <0.0001 |

| Liver disease | 1394 (2.9) | 1341 (3.3) | 1788 (3.1) | 2013 (4.8) | <0.0001 |

| Peptic ulcer disease, excluding bleeding | 5 (0.01) | 9 (0.022) | 15 (0.026) | 30 (0.072) | <0.0001 |

| Acquired immune deficiency syndrome | 49 (0.10) | 74 (0.18) | 79 (0.14) | 56 (0.13) | 0.01 |

| Lymphoma | 182 (0.37) | 310 (0.76) | 624 (1.1) | 718 (1.7) | <0.0001 |

| Metastatic cancer | 489 (1.0) | 789 (1.9) | 1889 (3.3) | 1993 (4.8) | <0.0001 |

| Solid tumor without metastasis | 499 (1.0) | 760 (1.9) | 1297 (2.3) | 1123 (2.7) | <0.0001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis/collagen vascular disease | 1250 (2.6) | 1260 (3.1) | 2214 (3.9) | 1729 (4.1) | <0.0001 |

| Coagulopathy | 1096 (2.3) | 1402 (3.4) | 2517 (4.4) | 6214 (15) | <0.0001 |

| Obesity | 7404 (15) | 5177 (13) | 7112 (12) | 5279 (13) | <0.0001 |

| Weight loss | 972 (2.0) | 1240 (3.0) | 2746 (4.8) | 5841 (14) | <0.0001 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 7262 (15) | 7501 (18) | 12,828 (22) | 17,201 (41) | <0.0001 |

| Alcohol abuse | 3312 (6.8) | 1977 (4.8) | 1699 (3.0) | 1319 (3.2) | <0.0001 |

| Drug abuse | 3357 (6.9) | 1554 (3.8) | 1197 (2.1) | 657 (1.6) | <0.0001 |

| Psychoses | 3479 (7.2) | 2345 (5.7) | 2544 (4.4) | 1727 (4.1) | <0.0001 |

| Depression | 5999 (12) | 4662 (11) | 6605 (12) | 4895 (12) | <0.0001 |

Logistic regression was used to assess the association of HAA with in‐hospital mortality, and linear regression to assess the association of HAA with hospital LOS and total hospital charges. LOS and total charges were logarithmically transformed because of right‐skewed distributions. The exponential of the resulting regression coefficients quantifies the relative change in LOS or total charges compared to patients without HAA. Unless otherwise specified, a P value of0.05 was considered statistically significant. The Bonferroni method was used to adjust for multiple comparisons.

Our primary analysis excluded patients with anemia at the time of hospitalization based on administratively determined POA anemia positive indicator coding. We also performed a sensitivity analysis to exclude patients with anemia based on the first Hgb values determined by laboratory testing.

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC) and R version 2.13 (

RESULTS

Prevalence of HAA

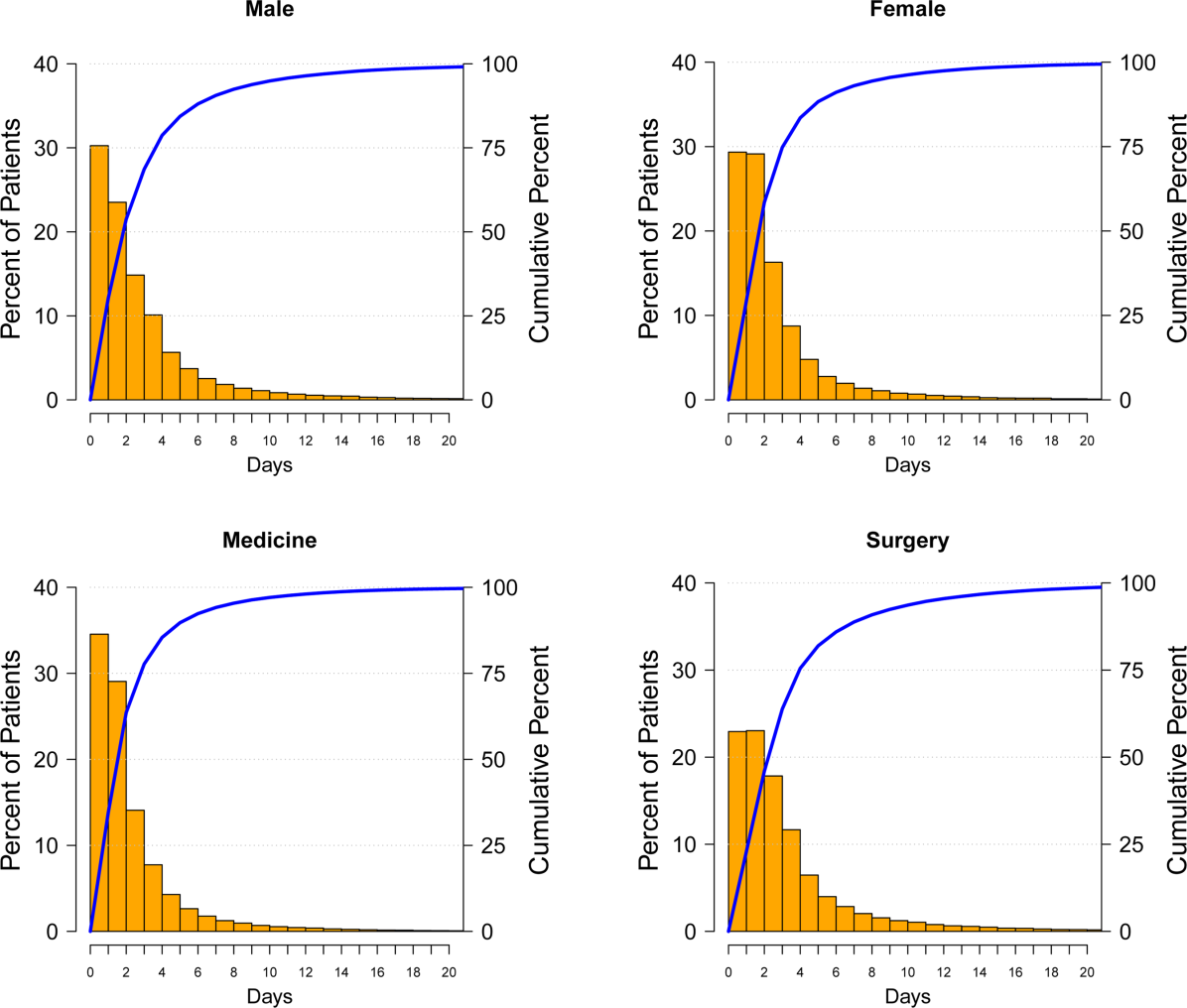

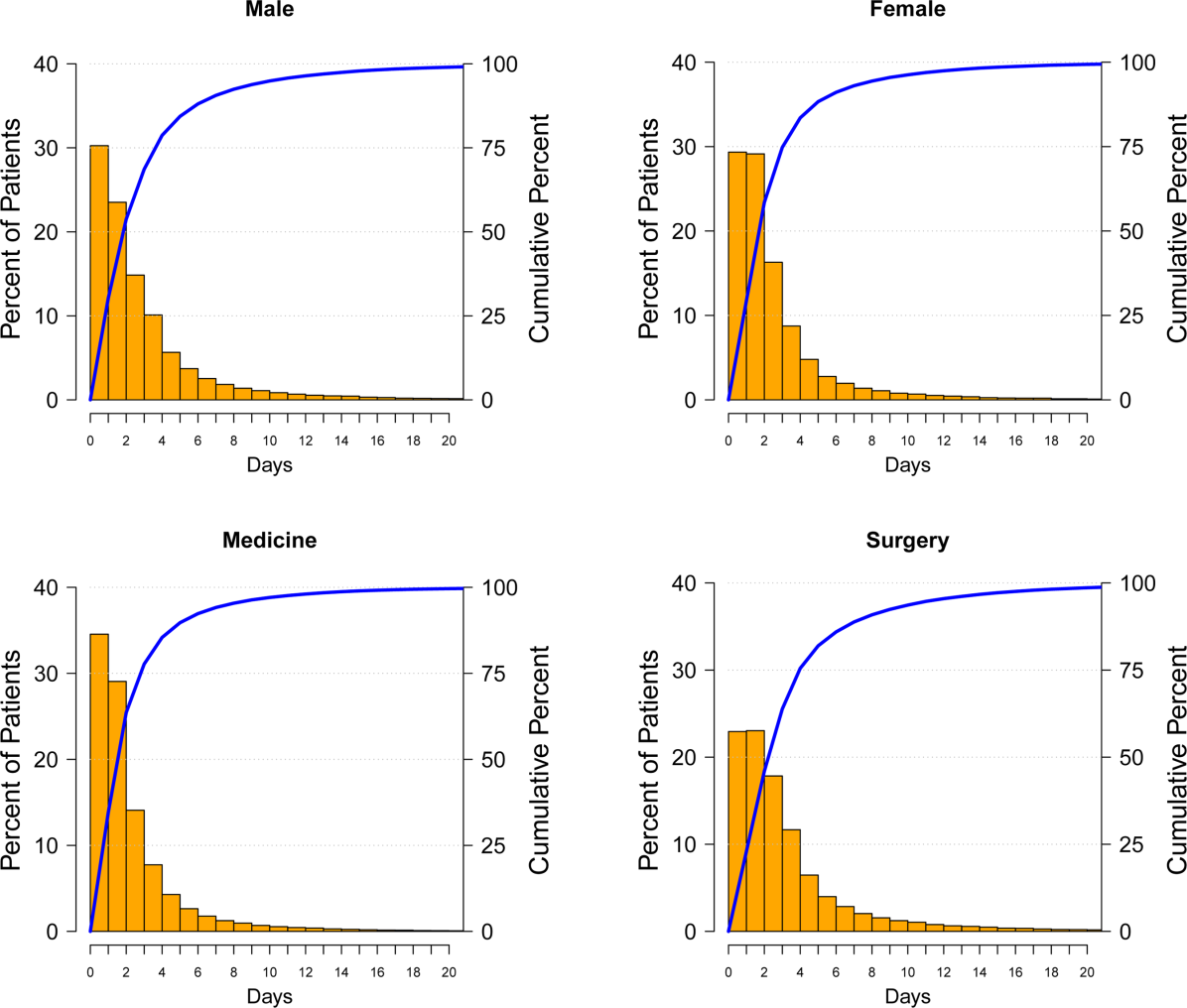

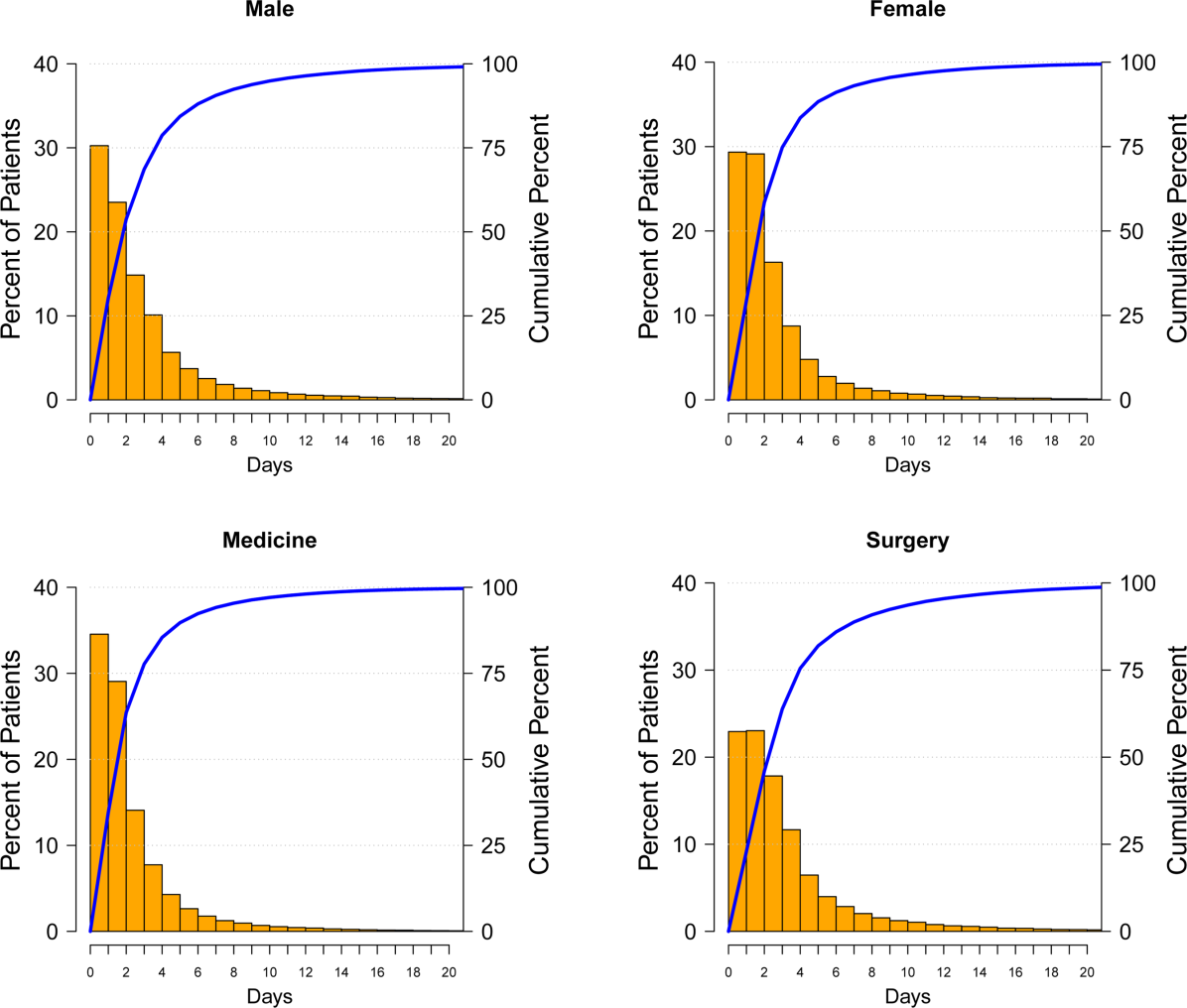

Among the 188,447 hospitalizations, 139,807 patients (74%) developed HAA and 48,640 (26%) did not. Of the 74%, 40,828 developed mild, 57,184 moderate, and 41,795 severe HAA (Figure 2). Patients who developed HAA were older than those who did not and had more comorbidities, including hypertension, heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, and renal and liver disease. They were hospitalized more commonly for surgical intervention than were those who did not develop HAA (Table 1). Time‐related patterns for developing HAA, however, showed that it developed earlier in men and more frequently with medical versus surgical hospitalization (Figure 3).

Hospital Mortality and HAA

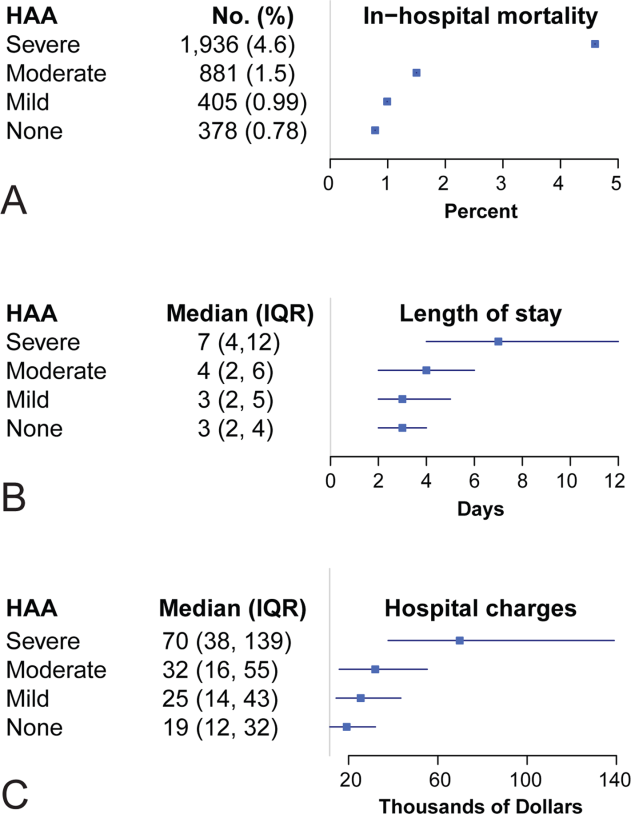

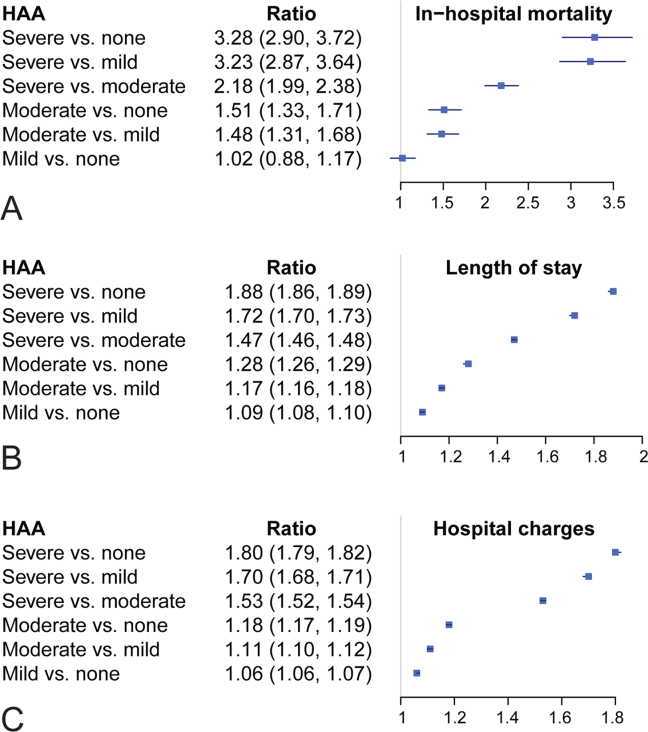

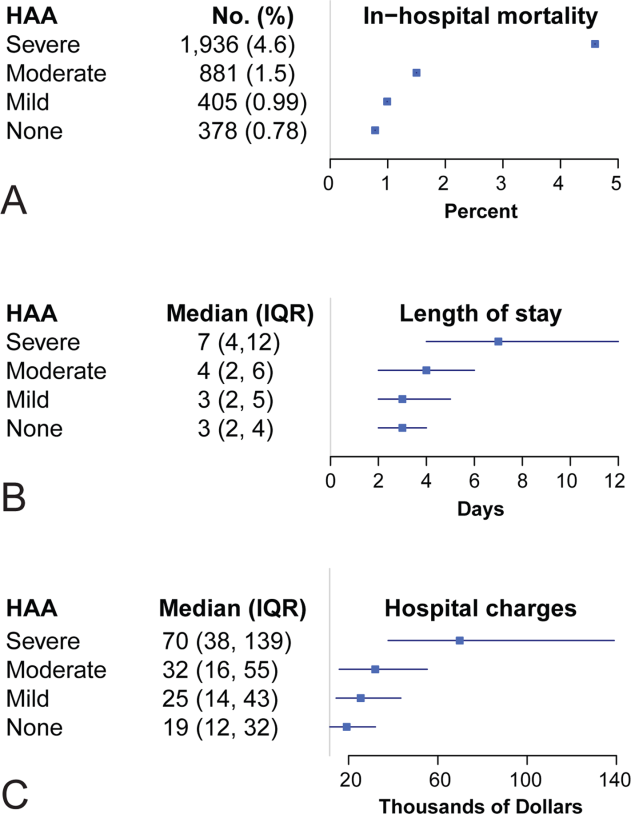

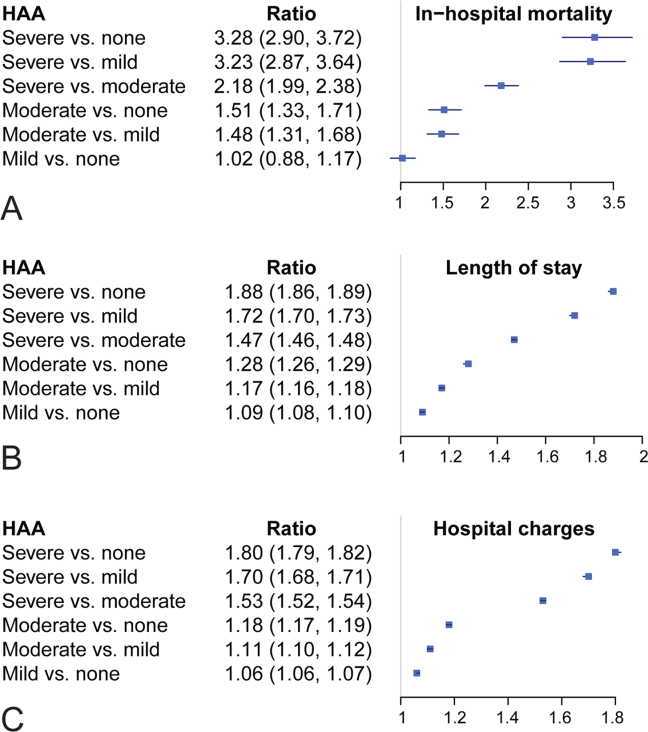

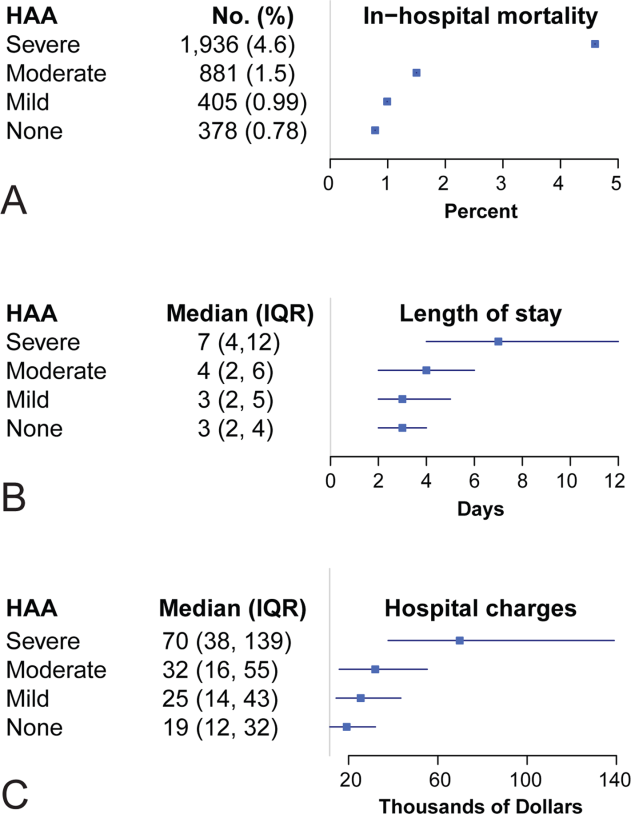

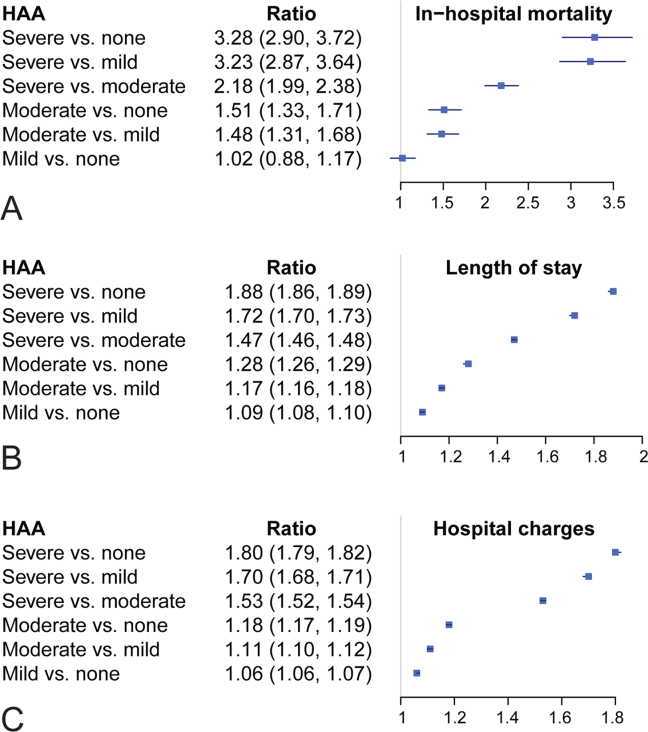

Unadjusted mortality progressively increased with increasing degree of HAA: no HAA, 0.78% (n=378); mild HAA, 0.99% (n=405); moderate HAA, 1.5% (n=881); and severe HAA, 4.6% (n=1936) (P<0.001) (Figure 4A). Patients with mild HAA did not have higher risk‐adjusted mortality than those not having HAA (odds ratio: 1.02, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.88‐1.17). However, as HAA increased to moderate and severe, risk of hospital mortality increased in a dose‐dependent manner compared with patients not developing HAA: moderate HAA, 1.51 (95% CI: 1.33‐1.71, P<0.001) and severe HAA, 3.28 (95% CI: 2.90‐3.72, P<0.001) (Figure 5A) (see Supporting Information, Supplement A, in the online version of this article).

Resource Utilization and HAA

Length of Hospital Stay

Unadjusted median (25th, 75th percentiles) LOS was progressively higher in patients who developed HAA: no HAA, 3 days (2, 4); mild HAA, 3 days (2, 5); moderate HAA, 4 days (2, 6); and severe HAA, 7 days (4, 12) (P<0.001) (Figure 4B). Mild HAA was associated with a mean relative increase of 1.09 (95% CI: 1.08‐1.10, P<0.001); moderate HAA, 1.28 (95% CI: 1.26‐1.29, P<0.001); and severe HAA, 1.88 (95% CI: 1.86‐1.89, P<0.001). For example, if expected LOS was 4 days for a patient with no HAA, then for a patient with severe anemia, it would be 7.52 (a 1.88‐fold increase) when all comorbidities were the same (Figure 5B) (see Supporting Information, Supplement A, in the online version of this article).

Total Hospital Charges

Unadjusted hospital charges became progressively higher as degree of HAA increased (P<0.001) (Figure 4C). The mean relative increase was 1.06 (95% CI: 1.06‐1.07, P<0.001) for mild HAA compared with no HAA, 1.18 (95% CI: 1.17‐1.19, P<0.001) for moderate HAA, and 1.80 (95% CI: 1.79‐1.82, P<0.001) for severe HAA. For example, if the expected total charge was $30,000 for a patient with no HAA, then for a patient with severe anemia, it would be $54,000 (a 1.80‐fold increase) when all comorbidities were the same (Figure 5C) (see Supporting Information, Supplement A, in the online version of this article).

Sensitivity Analysis

Among patients without anemia based on the first available Hgb value (n=96,975), 50% of patients developed HAA: mild HAA, 24% (n=23,063); moderate HAA, 19% (n=18,134); and severe HAA, 8% (n=7373). There was a similar relationship between increasing magnitude of HAA and an increase in mortality, LOS, and total charges in the unadjusted and adjusted analyses (see Supporting Information, Supplement C, in the online version of this article).

DISCUSSION

A substantial number of patients entering our health system became anemic during the course of their hospitalization. Among those who developed HAA, in‐hospital mortality was higher, LOS longer, and total hospital charges greater in a dose‐dependent manner. A recent editorial noted that HAA might be a hazard of hospitalization similar to other complications, such as infections and deep vein thrombosis.[15] Our findings have significance in terms of demonstrating increased mortality and resource utilization associated with a potentially modifiable hospital‐acquired condition. Even mild HAA was associated with increased resource utilization, although not increased hospital mortality.

Others have noted negative consequences of HAA in subpopulations of hospital patients. Salisbury and colleagues examined 17,676 patients with acute myocardial infarction who had normal Hgb on admission.[16] They defined HAA as development of new anemia during hospitalization based on nadir Hgb. HAA developed in 57.5% of patients and was associated with increased mortality in a progressive manner. Risk‐adjusted odds ratios for in‐hospital death were greater in patients with moderate and severe HAA, 1.38 (95% CI: 1.10‐1.73) and 3.39 (95% CI: 2.59‐4.44), respectively.[16] A separate investigation of 2902 patients from a multicenter registry of patients admitted to the hospital with acute myocardial infarction reported that nearly half of those with normal Hgb values on admission developed HAA.[17] Most of these patients did not have documented bleeding; therefore, the authors suggested that HAA was not a surrogate for bleeding during hospitalization. Moreover, HAA was associated with higher mortality and worse health status 1 year after myocardial infarction.[17] Others have reported that development of HAA is not uncommon in the setting of acute myocardial infarction and is associated with increased long‐term mortality.[18]

Development of anemia during hospitalization is multifactorial and may result from procedural bleeding, phlebotomy, occult bleeding, hemodilution from intravenous fluid administration, and blunted erythropoietin production associated with critical illness.[8, 9] An investigation of general internal medicine patients reported phlebotomy was highly associated with changes in Hgb levels and contributed to anemia during hospitalization.[19] The authors reported that for every 1 mL of blood drawn, mean decreases in Hgb and hematocrit were 0.070.011 g/L1 and 0.0190.003%, respectively. They suggested reporting cumulative phlebotomy volumes to physicians and use of pediatric‐sized tubes for collection.[19] Salisbury and colleagues reported that mean phlebotomy volume was higher in patients who developed HAA; for every 50 mL of blood drawn, the risk of moderate to severe HAA increased by 18%.[20] In an intensive care population, Chant and colleagues reported small decreases in phlebotomy volume were associated with reduced transfusion requirements in patients with prolonged stay.[21]

Attempts to ameliorate HAA should focus on modifiable processes‐of‐care factors. Patients with chronic illness have blunted erythropoiesis[8] and therefore cannot mount an adequate response to blood loss from procedures or phlebotomy. Whether use of erythropoietin, iron, or both would be effective in this population requires further investigation. One of the most studied risk factors for HAA is blood loss from hospital laboratory testing.[20] Sanchez‐Giron and Alvarez‐Mora found that all laboratory tests could be performed with smaller‐volume collection tubes without need for additional samples.[22] Others have proposed batching laboratory requests, recording cumulative daily blood loss due to phlebotomy for individual patients,[23] and use of blood conservation devices in intensive care units.

Figure 3 suggests that surgical patients develop anemia slightly later than medical patients. Features specific to surgery, such as perioperative intravenous fluid loading, third spacing, and subsequent plasma volume expansion when reabsorption occurs days later, likely contribute to differences in trends for development of HAA.[24, 25, 26] In addition, specific surgical cases with highly anticipated red blood cell loss should make use of antifibrinolytic agents to reduce blood loss and red cell salvage devices to reprocess and infuse shed blood.

Limitations

A recent commentary explored the question of benchmarks for anemia diagnosis, and in particular, what defines the lower limit of normal.[27] Although we used WHO criteria, others have used criteria establishing lower benchmarks according to race and gender.[27] Our results would have been similar if we had used these lower benchmarks, because our moderate and severe anemia Hgb cutoff values were beneath alternative benchmarks for diagnosing anemia. For example, Beutler and Waalen provide a definition of anemia that includes an Hgb cutoff of 12.2 g/dL for white women aged 20 to 49 years, 11.5 g/dL for black women of similar age, 13.7 g/dL for white men, and 12.9 g/dL for black men.[27]

Our study is limited by the nature of administrative data. However, use of demographic data, hospitalization type, and use of a large number of comorbidities for risk adjustment improved our findings. Adding nonadministrative clinical laboratory data from the electronic record for patient Hgb values provided us with a more accurate diagnosis of HAA and an ability to further subdivide anemia into mild, moderate, and severe categories that have prognostic implications. We are aware of the inherent limitations associated with use of administrative data. However, coded data are currently readily available and are the source of information on which many healthcare policies are made.[28, 29]

The POA anemia administrative code was used to identify patients with preexisting anemia. We did not use the first Hgb value upon admission because it is often made following interventions (eg, surgical patients have preoperative laboratory testing prior to admission, and the first Hgb value available following hospitalization is commonly obtained following surgical interventions). However, we performed a sensitivity analysis that defined preexisting anemia based on the first available Hgb value. The results from the sensitivity analysis were consistent with our primary findings with the use of administrative data coding. Of note, use of administrative codes for determining POA indicators is consistent with methods employed for all current publically reported quality and patient safety initiatives. Specifically, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patient Safety Indicators used by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to assess hospital quality of care and to modify reimbursement for services.

Our focus was on development of HAA; treatment of HAA with red blood cell transfusion and standardized blood draw orders were not investigated. Finally, our results are reflective of a single health system; further work with multicenter data would help clarify our findings.

CONCLUSION

Development of HAA is common and has important healthcare implications, including higher in‐hospital mortality and increased resource utilization. Treating HAA by transfusion has attendant morbidity risks and increased costs.[11, 12, 30] Hospitals must continue to focus on improving patient safety and raising awareness of HAA and other modifiable hospital‐acquired conditions. Closer prospective investigation for both medical and surgical patients of cumulative blood loss from laboratory testing, procedural blood loss, and a risk‐benefit analysis of treatment options is necessary.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , , , , . A population‐based study of hemoglobin, race, and mortality in elderly persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(8):873–878.

- , , , . Anemia in the elderly: a public health crisis in hematology. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2005:528–532.

- , , . The definition of anemia in older persons. JAMA. 1999;281(18):1714–1717.

- , . Anemia in the elderly: how should we define it, when does it matter, and what can be done? Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82(8):958–966.

- , , , et al. A prospective study of anemia status, hemoglobin concentration, and mortality in an elderly cohort: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(19):2214–2220.

- , , , et al. Association of mild anemia with hospitalization and mortality in the elderly: the Health and Anemia population‐based study. Haematologica. 2009;94(1):22–28.

- , , , et al. Association of mild anemia with cognitive, functional, mood and quality of life outcomes in the elderly: the “Health and Anemia” study. PLoS One. 2008;3(4):e1920.

- . Anemia in the critically ill. Crit Care Clin. 2004;20(2):159–178.

- . Scope of the problem: epidemiology of anemia and use of blood transfusions in critical care. Crit Care. 2004;8(suppl 2):S1–S8.

- , , , , , . Transfusion and pulmonary morbidity after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88(5):1410–1418.

- , , , et al. Morbidity and mortality risk associated with red blood cell and blood‐component transfusion in isolated coronary artery bypass grafting. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(6):1608–1616.

- , , , et al. Duration of red‐cell storage and complications after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(12):1229–1239.

- , , , et al. Transfusion in coronary artery bypass grafting is associated with reduced long‐term survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81(5):1650–1657.

- , , , . Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27.

- , . Hazards of hospitalization: more than just “never events”. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(18):1653–1654.

- , , , et al. Hospital‐acquired anemia and in‐hospital mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2011;162(2):300–309.e3.

- , , , et al. Incidence, correlates, and outcomes of acute, hospital‐acquired anemia in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(4):337–346.

- , , , et al. Changes in haemoglobin levels during hospital course and long‐term outcome after acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(11):1289–1296.

- , , , , . Do blood tests cause anemia in hospitalized patients? The effect of diagnostic phlebotomy on hemoglobin and hematocrit levels. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(6):520–524.

- , , , et al. Diagnostic blood loss from phlebotomy and hospital‐acquired anemia during acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(18):1646–1653.

- , , . Anemia, transfusion, and phlebotomy practices in critically ill patients with prolonged ICU length of stay: a cohort study. Crit Care. 2006;10(5):R140.

- , . Reduction of blood loss from laboratory testing in hospitalized adult patients using small‐volume (pediatric) tubes. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132(12):1916–1919.

- , . Phlebotomy for diagnostic laboratory tests in adults. Pattern of use and effect on transfusion requirements. N Engl J Med. 1986;314(19):1233–1235.

- , , , , . Perioperative monitoring of circulating and central blood volume in cardiac surgery by pulse dye densitometry. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(11):2053–2059.

- , , , , . Perioperative red cell, plasma, and blood volume change in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Transfusion. 2006;46(3):392–397.

- , , , . Changes in circulating blood volume after cardiac surgery measured by a novel method using hydroxyethyl starch. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(2):336–341.

- , . The definition of anemia: what is the lower limit of normal of the blood hemoglobin concentration? Blood. 2006;107(5):1747–1750.

- , , , , , . What are the real rates of postoperative complications: elucidating inconsistencies between administrative and clinical data sources. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214(5):798–805.

- . Medicare program: hospital inpatient value‐based purchasing program, final rule. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality‐Initiatives‐Patient‐Assessment‐Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/index.html. Accessed May 6, 2011.

- , , , , , . Increased mortality, postoperative morbidity, and cost after red blood cell transfusion in patients having cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2007;116(22):2544–2552.

Anemia is associated with poor quality of life and increased risk for death and hospitalization in population‐based and cohort investigations.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7] Evidence suggests that patients with normal hemoglobin (Hgb) values on hospital admission who subsequently develop hospital‐acquired anemia (HAA) have increased morbidity and mortality compared with those who do not.[8, 9] HAA is multifaceted and may occur as a result of processes of care during hospitalization, such as hemodilution from intravenous fluid administration, procedural blood loss and phlebotomy, and impaired erythropoiesis associated with critical illness.[8, 9] Moreover, correcting anemia by red blood cell transfusion also carries risk.[10, 11, 12, 13]

Our primary objective was to examine the prevalence of HAA in a population of medical and surgical patients admitted to a large quaternary referral health system. Our secondary objectives were to examine whether HAA is associated with increased mortality, length of stay (LOS), and total hospital charges compared to patients without HAA.

METHODS

Patient Population and Data Sources

The patient population consisted of 417,301 hospitalizations in adult patients (18 years of age) who were admitted to the Cleveland Clinic Health System from January 2009 to September 2011. Data for these hospitalizations came from 2 sources. Patient demographics, baseline comorbidities, and outcomes were extracted from the University HealthSystem Consortium's (UHC) clinical database/resource manager. UHC is an alliance of 116 US academic medical centers and their 272 affiliated hospitals, representing more than 90% of the nation's nonprofit academic medical centers. These data had originally been retrieved from our hospitals' administrative data systems, normalized according to UHC standardized data specifications, and submitted for inclusion in the UHC repository. Data quality was assessed using standardized error checking and data completeness algorithms and was required to meet established minimum thresholds to be included in the UHC repository.

The second source of data was measured Hgb values retrieved from the hospitals' electronic medical record from complete blood count testing. Present‐on‐admission (POA) anemia was defined by an International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification diagnosis code of anemia with a positive POA indicator; these patients were excluded from the analysis (Figure 1). Patients without available Hgb values and those with Hgb data dated 3 days or more after discharge date were also excluded. In addition, 2 hospitals within the health system did not have electronically available laboratory data and therefore were excluded from the analysis as well. The final dataset consisted of 188,447 patient hospitalizations. The institutional review board approved this investigation, with individual patient consent waived.

Anemia

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines anemia as a Hgb value l<12 g/dL in women and <13 g/dL in men. HAA was defined as a nadir Hgb value during the course of hospitalization meeting WHO criteria. We further grouped Hgb by degree into no anemia, mild anemia (Hgb >11 and <12 g/dL in women, >11 and <13 g/dL in men), moderate anemia (Hgb >9 and 11 g/dL), and severe anemia (Hgb 9 g/dL).

Outcomes

Outcomes were all‐cause in‐hospital mortality, total hospital LOS, and total hospital charges.

Data Analysis

For risk adjustment, we used methods developed by Elixhauser and colleagues[14] for use with in‐patient administrative databases. These included a comprehensive set of comorbidity indicators, used to control for patients' underlying conditions in models of outcomes. Among the 30 variables defined by Elixhauser and colleagues, we excluded the 2 administrative anemia codes because this was our variable of interest (Table 1). For all models, demographics, medical conditions, and hospitalization type (medical vs surgical) were included as covariables in addition to the anemia groupings (no HAA and mild, moderate, and severe HAA).

| Characteristic | Hospital‐Acquired Anemia Group | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Anemia, n=48,640 | Mild, n=40,828 | Moderate, n=57,184 | Severe, n=41,795 | ||

| |||||

| Age at admission, y | 5518 | 5818 | 5819 | 6117 | <0.0001 |

| Female | 25,123 (52) | 17,938 (44) | 35,858 (63) | 23,533 (56) | <0.0001 |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.0001 | ||||

| White | 39,100 (80) | 32,610 (80) | 45,977 (80) | 33,810 (81) | |

| Black | 7580 (16) | 6607 (16) | 8946 (16) | 6204 (15) | |

| Other | 1960 (4.0) | 1611 (3.9) | 2261 (4.0) | 1781 (4.3) | |

| Hospitalization type | <0.0001 | ||||

| Surgery | 9681 (20) | 14,076 (34) | 26,100 (46) | 27,865 (67) | |

| Medicine | 38,958 (80) | 26,750 (66) | 31,081 (54) | 13,922 (33) | |

| Hypertension | 25,591 (53) | 22,218 (54) | 29,963 (52) | 24,257 (58) | <0.0001 |

| Heart failure | 2811 (5.8) | 3182 (7.8) | 5086 (8.9) | 4278 (10) | <0.0001 |

| Valvular disease | 1201 (2.5) | 1259 (3.1) | 2126 (3.7) | 1890 (4.5) | <0.0001 |

| Pulmonary circulation disease | 667 (1.4) | 730 (1.8) | 1221 (2.1) | 1484 (3.6) | <0.0001 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 2417 (5.0) | 2728 (6.7) | 4187 (7.3) | 4508 (11) | <0.0001 |

| Paralysis | 1216 (2.5) | 1175 (2.9) | 1568 (2.7) | 1305 (3.1) | <0.0001 |

| Other neurologic disorders | 3013 (6.2) | 2780 (6.8) | 3599 (6.3) | 2829 (6.8) | <0.0001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 9225 (19) | 7885 (19) | 10,960 (19) | 8057 (19) | 0.5 |

| Diabetes without chronic complications | 8306 (17) | 7733 (19) | 10,417 (18) | 7911 (19) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes with chronic complications | 1547 (3.2) | 1922 (4.7) | 2989 (5.2) | 2779 (6.6) | <0.0001 |

| Hypothyroidism | 5008 (10) | 4258 (10) | 6938 (12) | 5567 (13) | <0.0001 |

| Renal failure | 2006 (4.1) | 3278 (8.0) | 5787 (10) | 5954 (14) | <0.0001 |

| Liver disease | 1394 (2.9) | 1341 (3.3) | 1788 (3.1) | 2013 (4.8) | <0.0001 |

| Peptic ulcer disease, excluding bleeding | 5 (0.01) | 9 (0.022) | 15 (0.026) | 30 (0.072) | <0.0001 |

| Acquired immune deficiency syndrome | 49 (0.10) | 74 (0.18) | 79 (0.14) | 56 (0.13) | 0.01 |

| Lymphoma | 182 (0.37) | 310 (0.76) | 624 (1.1) | 718 (1.7) | <0.0001 |

| Metastatic cancer | 489 (1.0) | 789 (1.9) | 1889 (3.3) | 1993 (4.8) | <0.0001 |

| Solid tumor without metastasis | 499 (1.0) | 760 (1.9) | 1297 (2.3) | 1123 (2.7) | <0.0001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis/collagen vascular disease | 1250 (2.6) | 1260 (3.1) | 2214 (3.9) | 1729 (4.1) | <0.0001 |

| Coagulopathy | 1096 (2.3) | 1402 (3.4) | 2517 (4.4) | 6214 (15) | <0.0001 |

| Obesity | 7404 (15) | 5177 (13) | 7112 (12) | 5279 (13) | <0.0001 |

| Weight loss | 972 (2.0) | 1240 (3.0) | 2746 (4.8) | 5841 (14) | <0.0001 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 7262 (15) | 7501 (18) | 12,828 (22) | 17,201 (41) | <0.0001 |

| Alcohol abuse | 3312 (6.8) | 1977 (4.8) | 1699 (3.0) | 1319 (3.2) | <0.0001 |

| Drug abuse | 3357 (6.9) | 1554 (3.8) | 1197 (2.1) | 657 (1.6) | <0.0001 |

| Psychoses | 3479 (7.2) | 2345 (5.7) | 2544 (4.4) | 1727 (4.1) | <0.0001 |

| Depression | 5999 (12) | 4662 (11) | 6605 (12) | 4895 (12) | <0.0001 |

Logistic regression was used to assess the association of HAA with in‐hospital mortality, and linear regression to assess the association of HAA with hospital LOS and total hospital charges. LOS and total charges were logarithmically transformed because of right‐skewed distributions. The exponential of the resulting regression coefficients quantifies the relative change in LOS or total charges compared to patients without HAA. Unless otherwise specified, a P value of0.05 was considered statistically significant. The Bonferroni method was used to adjust for multiple comparisons.

Our primary analysis excluded patients with anemia at the time of hospitalization based on administratively determined POA anemia positive indicator coding. We also performed a sensitivity analysis to exclude patients with anemia based on the first Hgb values determined by laboratory testing.

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC) and R version 2.13 (

RESULTS

Prevalence of HAA

Among the 188,447 hospitalizations, 139,807 patients (74%) developed HAA and 48,640 (26%) did not. Of the 74%, 40,828 developed mild, 57,184 moderate, and 41,795 severe HAA (Figure 2). Patients who developed HAA were older than those who did not and had more comorbidities, including hypertension, heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, and renal and liver disease. They were hospitalized more commonly for surgical intervention than were those who did not develop HAA (Table 1). Time‐related patterns for developing HAA, however, showed that it developed earlier in men and more frequently with medical versus surgical hospitalization (Figure 3).

Hospital Mortality and HAA

Unadjusted mortality progressively increased with increasing degree of HAA: no HAA, 0.78% (n=378); mild HAA, 0.99% (n=405); moderate HAA, 1.5% (n=881); and severe HAA, 4.6% (n=1936) (P<0.001) (Figure 4A). Patients with mild HAA did not have higher risk‐adjusted mortality than those not having HAA (odds ratio: 1.02, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.88‐1.17). However, as HAA increased to moderate and severe, risk of hospital mortality increased in a dose‐dependent manner compared with patients not developing HAA: moderate HAA, 1.51 (95% CI: 1.33‐1.71, P<0.001) and severe HAA, 3.28 (95% CI: 2.90‐3.72, P<0.001) (Figure 5A) (see Supporting Information, Supplement A, in the online version of this article).

Resource Utilization and HAA

Length of Hospital Stay

Unadjusted median (25th, 75th percentiles) LOS was progressively higher in patients who developed HAA: no HAA, 3 days (2, 4); mild HAA, 3 days (2, 5); moderate HAA, 4 days (2, 6); and severe HAA, 7 days (4, 12) (P<0.001) (Figure 4B). Mild HAA was associated with a mean relative increase of 1.09 (95% CI: 1.08‐1.10, P<0.001); moderate HAA, 1.28 (95% CI: 1.26‐1.29, P<0.001); and severe HAA, 1.88 (95% CI: 1.86‐1.89, P<0.001). For example, if expected LOS was 4 days for a patient with no HAA, then for a patient with severe anemia, it would be 7.52 (a 1.88‐fold increase) when all comorbidities were the same (Figure 5B) (see Supporting Information, Supplement A, in the online version of this article).

Total Hospital Charges

Unadjusted hospital charges became progressively higher as degree of HAA increased (P<0.001) (Figure 4C). The mean relative increase was 1.06 (95% CI: 1.06‐1.07, P<0.001) for mild HAA compared with no HAA, 1.18 (95% CI: 1.17‐1.19, P<0.001) for moderate HAA, and 1.80 (95% CI: 1.79‐1.82, P<0.001) for severe HAA. For example, if the expected total charge was $30,000 for a patient with no HAA, then for a patient with severe anemia, it would be $54,000 (a 1.80‐fold increase) when all comorbidities were the same (Figure 5C) (see Supporting Information, Supplement A, in the online version of this article).

Sensitivity Analysis

Among patients without anemia based on the first available Hgb value (n=96,975), 50% of patients developed HAA: mild HAA, 24% (n=23,063); moderate HAA, 19% (n=18,134); and severe HAA, 8% (n=7373). There was a similar relationship between increasing magnitude of HAA and an increase in mortality, LOS, and total charges in the unadjusted and adjusted analyses (see Supporting Information, Supplement C, in the online version of this article).

DISCUSSION

A substantial number of patients entering our health system became anemic during the course of their hospitalization. Among those who developed HAA, in‐hospital mortality was higher, LOS longer, and total hospital charges greater in a dose‐dependent manner. A recent editorial noted that HAA might be a hazard of hospitalization similar to other complications, such as infections and deep vein thrombosis.[15] Our findings have significance in terms of demonstrating increased mortality and resource utilization associated with a potentially modifiable hospital‐acquired condition. Even mild HAA was associated with increased resource utilization, although not increased hospital mortality.

Others have noted negative consequences of HAA in subpopulations of hospital patients. Salisbury and colleagues examined 17,676 patients with acute myocardial infarction who had normal Hgb on admission.[16] They defined HAA as development of new anemia during hospitalization based on nadir Hgb. HAA developed in 57.5% of patients and was associated with increased mortality in a progressive manner. Risk‐adjusted odds ratios for in‐hospital death were greater in patients with moderate and severe HAA, 1.38 (95% CI: 1.10‐1.73) and 3.39 (95% CI: 2.59‐4.44), respectively.[16] A separate investigation of 2902 patients from a multicenter registry of patients admitted to the hospital with acute myocardial infarction reported that nearly half of those with normal Hgb values on admission developed HAA.[17] Most of these patients did not have documented bleeding; therefore, the authors suggested that HAA was not a surrogate for bleeding during hospitalization. Moreover, HAA was associated with higher mortality and worse health status 1 year after myocardial infarction.[17] Others have reported that development of HAA is not uncommon in the setting of acute myocardial infarction and is associated with increased long‐term mortality.[18]

Development of anemia during hospitalization is multifactorial and may result from procedural bleeding, phlebotomy, occult bleeding, hemodilution from intravenous fluid administration, and blunted erythropoietin production associated with critical illness.[8, 9] An investigation of general internal medicine patients reported phlebotomy was highly associated with changes in Hgb levels and contributed to anemia during hospitalization.[19] The authors reported that for every 1 mL of blood drawn, mean decreases in Hgb and hematocrit were 0.070.011 g/L1 and 0.0190.003%, respectively. They suggested reporting cumulative phlebotomy volumes to physicians and use of pediatric‐sized tubes for collection.[19] Salisbury and colleagues reported that mean phlebotomy volume was higher in patients who developed HAA; for every 50 mL of blood drawn, the risk of moderate to severe HAA increased by 18%.[20] In an intensive care population, Chant and colleagues reported small decreases in phlebotomy volume were associated with reduced transfusion requirements in patients with prolonged stay.[21]

Attempts to ameliorate HAA should focus on modifiable processes‐of‐care factors. Patients with chronic illness have blunted erythropoiesis[8] and therefore cannot mount an adequate response to blood loss from procedures or phlebotomy. Whether use of erythropoietin, iron, or both would be effective in this population requires further investigation. One of the most studied risk factors for HAA is blood loss from hospital laboratory testing.[20] Sanchez‐Giron and Alvarez‐Mora found that all laboratory tests could be performed with smaller‐volume collection tubes without need for additional samples.[22] Others have proposed batching laboratory requests, recording cumulative daily blood loss due to phlebotomy for individual patients,[23] and use of blood conservation devices in intensive care units.

Figure 3 suggests that surgical patients develop anemia slightly later than medical patients. Features specific to surgery, such as perioperative intravenous fluid loading, third spacing, and subsequent plasma volume expansion when reabsorption occurs days later, likely contribute to differences in trends for development of HAA.[24, 25, 26] In addition, specific surgical cases with highly anticipated red blood cell loss should make use of antifibrinolytic agents to reduce blood loss and red cell salvage devices to reprocess and infuse shed blood.

Limitations

A recent commentary explored the question of benchmarks for anemia diagnosis, and in particular, what defines the lower limit of normal.[27] Although we used WHO criteria, others have used criteria establishing lower benchmarks according to race and gender.[27] Our results would have been similar if we had used these lower benchmarks, because our moderate and severe anemia Hgb cutoff values were beneath alternative benchmarks for diagnosing anemia. For example, Beutler and Waalen provide a definition of anemia that includes an Hgb cutoff of 12.2 g/dL for white women aged 20 to 49 years, 11.5 g/dL for black women of similar age, 13.7 g/dL for white men, and 12.9 g/dL for black men.[27]

Our study is limited by the nature of administrative data. However, use of demographic data, hospitalization type, and use of a large number of comorbidities for risk adjustment improved our findings. Adding nonadministrative clinical laboratory data from the electronic record for patient Hgb values provided us with a more accurate diagnosis of HAA and an ability to further subdivide anemia into mild, moderate, and severe categories that have prognostic implications. We are aware of the inherent limitations associated with use of administrative data. However, coded data are currently readily available and are the source of information on which many healthcare policies are made.[28, 29]

The POA anemia administrative code was used to identify patients with preexisting anemia. We did not use the first Hgb value upon admission because it is often made following interventions (eg, surgical patients have preoperative laboratory testing prior to admission, and the first Hgb value available following hospitalization is commonly obtained following surgical interventions). However, we performed a sensitivity analysis that defined preexisting anemia based on the first available Hgb value. The results from the sensitivity analysis were consistent with our primary findings with the use of administrative data coding. Of note, use of administrative codes for determining POA indicators is consistent with methods employed for all current publically reported quality and patient safety initiatives. Specifically, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patient Safety Indicators used by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to assess hospital quality of care and to modify reimbursement for services.

Our focus was on development of HAA; treatment of HAA with red blood cell transfusion and standardized blood draw orders were not investigated. Finally, our results are reflective of a single health system; further work with multicenter data would help clarify our findings.

CONCLUSION

Development of HAA is common and has important healthcare implications, including higher in‐hospital mortality and increased resource utilization. Treating HAA by transfusion has attendant morbidity risks and increased costs.[11, 12, 30] Hospitals must continue to focus on improving patient safety and raising awareness of HAA and other modifiable hospital‐acquired conditions. Closer prospective investigation for both medical and surgical patients of cumulative blood loss from laboratory testing, procedural blood loss, and a risk‐benefit analysis of treatment options is necessary.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Anemia is associated with poor quality of life and increased risk for death and hospitalization in population‐based and cohort investigations.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7] Evidence suggests that patients with normal hemoglobin (Hgb) values on hospital admission who subsequently develop hospital‐acquired anemia (HAA) have increased morbidity and mortality compared with those who do not.[8, 9] HAA is multifaceted and may occur as a result of processes of care during hospitalization, such as hemodilution from intravenous fluid administration, procedural blood loss and phlebotomy, and impaired erythropoiesis associated with critical illness.[8, 9] Moreover, correcting anemia by red blood cell transfusion also carries risk.[10, 11, 12, 13]

Our primary objective was to examine the prevalence of HAA in a population of medical and surgical patients admitted to a large quaternary referral health system. Our secondary objectives were to examine whether HAA is associated with increased mortality, length of stay (LOS), and total hospital charges compared to patients without HAA.

METHODS

Patient Population and Data Sources

The patient population consisted of 417,301 hospitalizations in adult patients (18 years of age) who were admitted to the Cleveland Clinic Health System from January 2009 to September 2011. Data for these hospitalizations came from 2 sources. Patient demographics, baseline comorbidities, and outcomes were extracted from the University HealthSystem Consortium's (UHC) clinical database/resource manager. UHC is an alliance of 116 US academic medical centers and their 272 affiliated hospitals, representing more than 90% of the nation's nonprofit academic medical centers. These data had originally been retrieved from our hospitals' administrative data systems, normalized according to UHC standardized data specifications, and submitted for inclusion in the UHC repository. Data quality was assessed using standardized error checking and data completeness algorithms and was required to meet established minimum thresholds to be included in the UHC repository.