User login

FDA expands use of dapagliflozin to broader range of HF

– including HF with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF) and with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

The sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor was previously approved in the United States for adults with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).

The expanded indication is based on data from the phase 3 DELIVER trial, which showed clear clinical benefits of the SGLT2 inhibitor for patients with HF regardless of left ventricular function.

In the trial, which included more than 6,200 patients, dapagliflozin led to a statistically significant and clinically meaningful early reduction in the primary composite endpoint of cardiovascular (CV) death or worsening HF for patients with HFmrEF or HFpEFF.

In addition, results of a pooled analysis of the DAPA-HF and DELIVER phase 3 trials showed a consistent benefit from dapagliflozin treatment in significantly reducing the combined endpoint of CV death or HF hospitalization across the range of LVEF.

The European Commission expanded the indication for dapagliflozin (Forxiga) to include HF across the full spectrum of LVEF in February.

The SGLT2 inhibitor is also approved for use by patients with chronic kidney disease. It was first approved in 2014 to improve glycemic control for patients with diabetes mellitus.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

– including HF with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF) and with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

The sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor was previously approved in the United States for adults with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).

The expanded indication is based on data from the phase 3 DELIVER trial, which showed clear clinical benefits of the SGLT2 inhibitor for patients with HF regardless of left ventricular function.

In the trial, which included more than 6,200 patients, dapagliflozin led to a statistically significant and clinically meaningful early reduction in the primary composite endpoint of cardiovascular (CV) death or worsening HF for patients with HFmrEF or HFpEFF.

In addition, results of a pooled analysis of the DAPA-HF and DELIVER phase 3 trials showed a consistent benefit from dapagliflozin treatment in significantly reducing the combined endpoint of CV death or HF hospitalization across the range of LVEF.

The European Commission expanded the indication for dapagliflozin (Forxiga) to include HF across the full spectrum of LVEF in February.

The SGLT2 inhibitor is also approved for use by patients with chronic kidney disease. It was first approved in 2014 to improve glycemic control for patients with diabetes mellitus.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

– including HF with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF) and with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

The sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor was previously approved in the United States for adults with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).

The expanded indication is based on data from the phase 3 DELIVER trial, which showed clear clinical benefits of the SGLT2 inhibitor for patients with HF regardless of left ventricular function.

In the trial, which included more than 6,200 patients, dapagliflozin led to a statistically significant and clinically meaningful early reduction in the primary composite endpoint of cardiovascular (CV) death or worsening HF for patients with HFmrEF or HFpEFF.

In addition, results of a pooled analysis of the DAPA-HF and DELIVER phase 3 trials showed a consistent benefit from dapagliflozin treatment in significantly reducing the combined endpoint of CV death or HF hospitalization across the range of LVEF.

The European Commission expanded the indication for dapagliflozin (Forxiga) to include HF across the full spectrum of LVEF in February.

The SGLT2 inhibitor is also approved for use by patients with chronic kidney disease. It was first approved in 2014 to improve glycemic control for patients with diabetes mellitus.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Nurses: The unsung heroes

Try practicing inpatient medicine without nurses.

You can’t.

We blow in and out of the rooms, write notes, check results and vitals, then move on to the next person.

But the nurses are the ones who actually make this all happen. And, amazingly, can do all that work with a smile.

But in our current postpandemic world, we’re facing a serious shortage. A recent survey of registered nurses found that only 15% of hospital nurses were planning on being there in 1 year. Thirty percent said they were planning on changing careers entirely in the aftermath of the pandemic. Their job satisfaction scores have dropped 15% from 2019 to 2023. Their stress scores, and concerns that the job is affecting their health, have increased 15%-20%.

The problem reflects a combination of things intersecting at a bad time: Staffing shortages resulting in more patients per nurse, hospital administrators cutting corners on staffing and pay, and the ongoing state of incivility.

The last one is a particularly new issue. Difficult patients and their families are nothing new. We all encounter them, and learn to deal with them in our own way. It’s part of the territory.

But since 2020 it’s climbed to a new-level of in-your-face confrontation, rudeness, and aggression, sometimes leading to violence. Physical attacks on people in all jobs have increased, but health care workers are five times more likely to encounter workplace violence than any other field.

Underpaid, overworked, and a sitting duck for violence. Can you blame people for looking elsewhere?

All of this is coming at a time when a whole generation of nurses is retiring, another generation is starting to reach an age of needing more health care, and nursing schools are short on teaching staff, limiting the number of new people that can be trained. Nursing education, like medical school, isn’t a place to cut corners (neither is care, obviously).

These days we toss the word “burnout” around to the point that it’s become almost meaningless, but to those affected by it, the consequences are quite real. And when it causes a loss of staff and impairs the ability of all to provide quality medical care, it quickly becomes everyone’s problem.

Finding solutions for such things isn’t a can you just kick down the road, as governmental agencies have always been so good at doing. These are things that have real-world consequences for all involved, and solutions need to involve private, public, and educational sectors working together.

I don’t have any ideas, but I hope the people who can change this will sit down and work some out.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Try practicing inpatient medicine without nurses.

You can’t.

We blow in and out of the rooms, write notes, check results and vitals, then move on to the next person.

But the nurses are the ones who actually make this all happen. And, amazingly, can do all that work with a smile.

But in our current postpandemic world, we’re facing a serious shortage. A recent survey of registered nurses found that only 15% of hospital nurses were planning on being there in 1 year. Thirty percent said they were planning on changing careers entirely in the aftermath of the pandemic. Their job satisfaction scores have dropped 15% from 2019 to 2023. Their stress scores, and concerns that the job is affecting their health, have increased 15%-20%.

The problem reflects a combination of things intersecting at a bad time: Staffing shortages resulting in more patients per nurse, hospital administrators cutting corners on staffing and pay, and the ongoing state of incivility.

The last one is a particularly new issue. Difficult patients and their families are nothing new. We all encounter them, and learn to deal with them in our own way. It’s part of the territory.

But since 2020 it’s climbed to a new-level of in-your-face confrontation, rudeness, and aggression, sometimes leading to violence. Physical attacks on people in all jobs have increased, but health care workers are five times more likely to encounter workplace violence than any other field.

Underpaid, overworked, and a sitting duck for violence. Can you blame people for looking elsewhere?

All of this is coming at a time when a whole generation of nurses is retiring, another generation is starting to reach an age of needing more health care, and nursing schools are short on teaching staff, limiting the number of new people that can be trained. Nursing education, like medical school, isn’t a place to cut corners (neither is care, obviously).

These days we toss the word “burnout” around to the point that it’s become almost meaningless, but to those affected by it, the consequences are quite real. And when it causes a loss of staff and impairs the ability of all to provide quality medical care, it quickly becomes everyone’s problem.

Finding solutions for such things isn’t a can you just kick down the road, as governmental agencies have always been so good at doing. These are things that have real-world consequences for all involved, and solutions need to involve private, public, and educational sectors working together.

I don’t have any ideas, but I hope the people who can change this will sit down and work some out.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Try practicing inpatient medicine without nurses.

You can’t.

We blow in and out of the rooms, write notes, check results and vitals, then move on to the next person.

But the nurses are the ones who actually make this all happen. And, amazingly, can do all that work with a smile.

But in our current postpandemic world, we’re facing a serious shortage. A recent survey of registered nurses found that only 15% of hospital nurses were planning on being there in 1 year. Thirty percent said they were planning on changing careers entirely in the aftermath of the pandemic. Their job satisfaction scores have dropped 15% from 2019 to 2023. Their stress scores, and concerns that the job is affecting their health, have increased 15%-20%.

The problem reflects a combination of things intersecting at a bad time: Staffing shortages resulting in more patients per nurse, hospital administrators cutting corners on staffing and pay, and the ongoing state of incivility.

The last one is a particularly new issue. Difficult patients and their families are nothing new. We all encounter them, and learn to deal with them in our own way. It’s part of the territory.

But since 2020 it’s climbed to a new-level of in-your-face confrontation, rudeness, and aggression, sometimes leading to violence. Physical attacks on people in all jobs have increased, but health care workers are five times more likely to encounter workplace violence than any other field.

Underpaid, overworked, and a sitting duck for violence. Can you blame people for looking elsewhere?

All of this is coming at a time when a whole generation of nurses is retiring, another generation is starting to reach an age of needing more health care, and nursing schools are short on teaching staff, limiting the number of new people that can be trained. Nursing education, like medical school, isn’t a place to cut corners (neither is care, obviously).

These days we toss the word “burnout” around to the point that it’s become almost meaningless, but to those affected by it, the consequences are quite real. And when it causes a loss of staff and impairs the ability of all to provide quality medical care, it quickly becomes everyone’s problem.

Finding solutions for such things isn’t a can you just kick down the road, as governmental agencies have always been so good at doing. These are things that have real-world consequences for all involved, and solutions need to involve private, public, and educational sectors working together.

I don’t have any ideas, but I hope the people who can change this will sit down and work some out.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

A nod to the future of AGA

CHICAGO – It’s been 125 years since the founding of the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA). It’s gone from a small organization in which gastroenterology wasn’t even a known medical specialty, to an organization that grants millions of dollars in research funding each year.

He spoke with optimism about gastroenterology’s future during his presidential address on May 8 at the annual Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) meeting in Chicago.

“I congratulate the AGA on its quasquicentennial, or 125th anniversary,” said Dr. Carethers, who is distinguished professor of medicine and vice chancellor for health sciences at the University of California, San Diego.

The AGA was founded in 1897 by Detroit-based physician Charles Aaron, MD. His passion was gastroenterology, but at that point, it wasn’t an established medical discipline. Dr. Aaron, Max Einhorn, MD, and 8 other colleagues formed the American Gastroenterological Association. Today, with nearly 16,000 members, the organization has become a driving force in improving the care of patients with gastrointestinal conditions.

Among AGA’s accomplishments since its founding: In 1940, the American Board of Internal Medicine certified gastroenterology as a subspecialty. Three years later, the first issue of Gastroenterology, the AGA’s flagship journal, was published. And, in 1971, the very first Digestive Disease Week® meeting took place.

In terms of medical advances that have been made since those early years, the list is vast: From the description of ileitis in 1932 by Burril B. Crohn, MD, in 1932 to the discovery of the hepatitis B surface antigen in 1965 and the more recent discovery of germline mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes as a cause of Lynch syndrome.

Dr. Carethers outlined goals for the future, including building a leadership team that is “reflective of our practice here in the United States,” Dr. Carethers said. Creating a culturally and gender diverse leadership team will only strengthen the organization and the practice of gastroenterology. The AGA’s first female president, Sarah Jordan, MD, was named in 1942, and since then, the AGA has been led by women and men from different ethnic backgrounds, including himself, who is AGA’s first president of African American heritage.

The AGA has committed to a number of diversity and equity objectives, including the AGA Equity Project, an initiative launched in 2020 whose goal is to achieve equity and eradicate disparities in digestive diseases with a focus on justice and equity, research and funding, workforce and leadership, recognition of the achievements of people of color, unconscious bias, and engagement with early career members.

“I am not only excited about the diversity and equity objectives within our specialty ... but also the innovation and things to come for our specialty,” Dr. Carethers said.

Securing funding for early-stage innovations in medicine can be difficult across medical disciplines, including gastroenterology. So, last year, the AGA, with Varia Ventures, launched the GI Opportunity Fund 1 to support early-stage GI-based companies. The goal is to raise $25 million for the initial fund. Through the AGA’s Center for GI Innovation and Technology and the AGA Tech Summit, early-stage companies may have new funding opportunities.

And, through the AGA Research Foundation, the organization will continue to support clinical research. Last year, $2.6 million in grants were awarded to investigators.

Dr. Carethers is a board director at Avantor, a life sciences supply company.

The meeting is sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract.

CHICAGO – It’s been 125 years since the founding of the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA). It’s gone from a small organization in which gastroenterology wasn’t even a known medical specialty, to an organization that grants millions of dollars in research funding each year.

He spoke with optimism about gastroenterology’s future during his presidential address on May 8 at the annual Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) meeting in Chicago.

“I congratulate the AGA on its quasquicentennial, or 125th anniversary,” said Dr. Carethers, who is distinguished professor of medicine and vice chancellor for health sciences at the University of California, San Diego.

The AGA was founded in 1897 by Detroit-based physician Charles Aaron, MD. His passion was gastroenterology, but at that point, it wasn’t an established medical discipline. Dr. Aaron, Max Einhorn, MD, and 8 other colleagues formed the American Gastroenterological Association. Today, with nearly 16,000 members, the organization has become a driving force in improving the care of patients with gastrointestinal conditions.

Among AGA’s accomplishments since its founding: In 1940, the American Board of Internal Medicine certified gastroenterology as a subspecialty. Three years later, the first issue of Gastroenterology, the AGA’s flagship journal, was published. And, in 1971, the very first Digestive Disease Week® meeting took place.

In terms of medical advances that have been made since those early years, the list is vast: From the description of ileitis in 1932 by Burril B. Crohn, MD, in 1932 to the discovery of the hepatitis B surface antigen in 1965 and the more recent discovery of germline mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes as a cause of Lynch syndrome.

Dr. Carethers outlined goals for the future, including building a leadership team that is “reflective of our practice here in the United States,” Dr. Carethers said. Creating a culturally and gender diverse leadership team will only strengthen the organization and the practice of gastroenterology. The AGA’s first female president, Sarah Jordan, MD, was named in 1942, and since then, the AGA has been led by women and men from different ethnic backgrounds, including himself, who is AGA’s first president of African American heritage.

The AGA has committed to a number of diversity and equity objectives, including the AGA Equity Project, an initiative launched in 2020 whose goal is to achieve equity and eradicate disparities in digestive diseases with a focus on justice and equity, research and funding, workforce and leadership, recognition of the achievements of people of color, unconscious bias, and engagement with early career members.

“I am not only excited about the diversity and equity objectives within our specialty ... but also the innovation and things to come for our specialty,” Dr. Carethers said.

Securing funding for early-stage innovations in medicine can be difficult across medical disciplines, including gastroenterology. So, last year, the AGA, with Varia Ventures, launched the GI Opportunity Fund 1 to support early-stage GI-based companies. The goal is to raise $25 million for the initial fund. Through the AGA’s Center for GI Innovation and Technology and the AGA Tech Summit, early-stage companies may have new funding opportunities.

And, through the AGA Research Foundation, the organization will continue to support clinical research. Last year, $2.6 million in grants were awarded to investigators.

Dr. Carethers is a board director at Avantor, a life sciences supply company.

The meeting is sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract.

CHICAGO – It’s been 125 years since the founding of the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA). It’s gone from a small organization in which gastroenterology wasn’t even a known medical specialty, to an organization that grants millions of dollars in research funding each year.

He spoke with optimism about gastroenterology’s future during his presidential address on May 8 at the annual Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) meeting in Chicago.

“I congratulate the AGA on its quasquicentennial, or 125th anniversary,” said Dr. Carethers, who is distinguished professor of medicine and vice chancellor for health sciences at the University of California, San Diego.

The AGA was founded in 1897 by Detroit-based physician Charles Aaron, MD. His passion was gastroenterology, but at that point, it wasn’t an established medical discipline. Dr. Aaron, Max Einhorn, MD, and 8 other colleagues formed the American Gastroenterological Association. Today, with nearly 16,000 members, the organization has become a driving force in improving the care of patients with gastrointestinal conditions.

Among AGA’s accomplishments since its founding: In 1940, the American Board of Internal Medicine certified gastroenterology as a subspecialty. Three years later, the first issue of Gastroenterology, the AGA’s flagship journal, was published. And, in 1971, the very first Digestive Disease Week® meeting took place.

In terms of medical advances that have been made since those early years, the list is vast: From the description of ileitis in 1932 by Burril B. Crohn, MD, in 1932 to the discovery of the hepatitis B surface antigen in 1965 and the more recent discovery of germline mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes as a cause of Lynch syndrome.

Dr. Carethers outlined goals for the future, including building a leadership team that is “reflective of our practice here in the United States,” Dr. Carethers said. Creating a culturally and gender diverse leadership team will only strengthen the organization and the practice of gastroenterology. The AGA’s first female president, Sarah Jordan, MD, was named in 1942, and since then, the AGA has been led by women and men from different ethnic backgrounds, including himself, who is AGA’s first president of African American heritage.

The AGA has committed to a number of diversity and equity objectives, including the AGA Equity Project, an initiative launched in 2020 whose goal is to achieve equity and eradicate disparities in digestive diseases with a focus on justice and equity, research and funding, workforce and leadership, recognition of the achievements of people of color, unconscious bias, and engagement with early career members.

“I am not only excited about the diversity and equity objectives within our specialty ... but also the innovation and things to come for our specialty,” Dr. Carethers said.

Securing funding for early-stage innovations in medicine can be difficult across medical disciplines, including gastroenterology. So, last year, the AGA, with Varia Ventures, launched the GI Opportunity Fund 1 to support early-stage GI-based companies. The goal is to raise $25 million for the initial fund. Through the AGA’s Center for GI Innovation and Technology and the AGA Tech Summit, early-stage companies may have new funding opportunities.

And, through the AGA Research Foundation, the organization will continue to support clinical research. Last year, $2.6 million in grants were awarded to investigators.

Dr. Carethers is a board director at Avantor, a life sciences supply company.

The meeting is sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract.

AT DDW 2023

Replacing the Lung Allocation Score

Diffuse Lung Disease and Lung Transplant Network

Lung Transplant Section

In March 2023, the Composite Allocation Score (CAS) will replace the Lung Allocation Score (LAS) for matching donor lungs to transplant candidates in the United States. The LAS was implemented in 2005 to improve lung organ utilization. Its score was determined by two main factors: (1) risk of 1-year waitlist mortality and (2) likelihood of 1-year post-transplant survival, with the first factor having twice the weight. However, LAS did not account for candidate biology attributes, such as pediatric age, blood type, allosensitization, or height. Long-term survival outcomes under LAS may be reduced, given the greater emphasis on waitlist mortality. Candidates were also subjected to strict geographical distributions within a 250-nautical-mile radius, which frequently resulted in those with lower LAS obtaining a transplant. CAS differs from the LAS in that it assigns an allocation score in a continuous distribution based on the following factors: medical urgency, expected survival benefit following transplant, pediatric age, blood type, HLA antibody sensitization, candidate height, and geographical proximity to the donor organ. Each factor has a specific weight, and because donor factors contribute to CAS, a candidate’s score changes with each donor-recipient match run. Continuous distribution removes hard geographical boundaries and aims for more equitable organ allocation. To understand how allocation might change with CAS, Valapour and colleagues created various CAS scenarios using data from individuals on the national transplant waiting list (Am J Transplant. 2022;22[12]:2971).

They found that waitlist deaths decreased by 36%-47%. This effect was greatest in scenarios where there was less weight on placement efficiency (ie, geography) and more weight on post-transplant outcomes. Transplant system equity also improved in their simulation models. It will be exciting to see how candidate and recipient outcomes are affected once CAS is implemented.

Gloria Li, MD

Member-at-Large

Reference

1. United Network for Organ Sharing. www.unos.org.

Diffuse Lung Disease and Lung Transplant Network

Lung Transplant Section

In March 2023, the Composite Allocation Score (CAS) will replace the Lung Allocation Score (LAS) for matching donor lungs to transplant candidates in the United States. The LAS was implemented in 2005 to improve lung organ utilization. Its score was determined by two main factors: (1) risk of 1-year waitlist mortality and (2) likelihood of 1-year post-transplant survival, with the first factor having twice the weight. However, LAS did not account for candidate biology attributes, such as pediatric age, blood type, allosensitization, or height. Long-term survival outcomes under LAS may be reduced, given the greater emphasis on waitlist mortality. Candidates were also subjected to strict geographical distributions within a 250-nautical-mile radius, which frequently resulted in those with lower LAS obtaining a transplant. CAS differs from the LAS in that it assigns an allocation score in a continuous distribution based on the following factors: medical urgency, expected survival benefit following transplant, pediatric age, blood type, HLA antibody sensitization, candidate height, and geographical proximity to the donor organ. Each factor has a specific weight, and because donor factors contribute to CAS, a candidate’s score changes with each donor-recipient match run. Continuous distribution removes hard geographical boundaries and aims for more equitable organ allocation. To understand how allocation might change with CAS, Valapour and colleagues created various CAS scenarios using data from individuals on the national transplant waiting list (Am J Transplant. 2022;22[12]:2971).

They found that waitlist deaths decreased by 36%-47%. This effect was greatest in scenarios where there was less weight on placement efficiency (ie, geography) and more weight on post-transplant outcomes. Transplant system equity also improved in their simulation models. It will be exciting to see how candidate and recipient outcomes are affected once CAS is implemented.

Gloria Li, MD

Member-at-Large

Reference

1. United Network for Organ Sharing. www.unos.org.

Diffuse Lung Disease and Lung Transplant Network

Lung Transplant Section

In March 2023, the Composite Allocation Score (CAS) will replace the Lung Allocation Score (LAS) for matching donor lungs to transplant candidates in the United States. The LAS was implemented in 2005 to improve lung organ utilization. Its score was determined by two main factors: (1) risk of 1-year waitlist mortality and (2) likelihood of 1-year post-transplant survival, with the first factor having twice the weight. However, LAS did not account for candidate biology attributes, such as pediatric age, blood type, allosensitization, or height. Long-term survival outcomes under LAS may be reduced, given the greater emphasis on waitlist mortality. Candidates were also subjected to strict geographical distributions within a 250-nautical-mile radius, which frequently resulted in those with lower LAS obtaining a transplant. CAS differs from the LAS in that it assigns an allocation score in a continuous distribution based on the following factors: medical urgency, expected survival benefit following transplant, pediatric age, blood type, HLA antibody sensitization, candidate height, and geographical proximity to the donor organ. Each factor has a specific weight, and because donor factors contribute to CAS, a candidate’s score changes with each donor-recipient match run. Continuous distribution removes hard geographical boundaries and aims for more equitable organ allocation. To understand how allocation might change with CAS, Valapour and colleagues created various CAS scenarios using data from individuals on the national transplant waiting list (Am J Transplant. 2022;22[12]:2971).

They found that waitlist deaths decreased by 36%-47%. This effect was greatest in scenarios where there was less weight on placement efficiency (ie, geography) and more weight on post-transplant outcomes. Transplant system equity also improved in their simulation models. It will be exciting to see how candidate and recipient outcomes are affected once CAS is implemented.

Gloria Li, MD

Member-at-Large

Reference

1. United Network for Organ Sharing. www.unos.org.

We need more efforts to prevent sepsis readmissions

Critical Care Network

Sepsis/Shock Section

(https://datatools.ahrq.gov/hcup-fast-stats; Kim H, et al. Front Public Health. 2022;10:882715; Torio C, Moore B. 2016. HCUP Statistical Brief #204).

Since 2013, the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) adopted pneumonia as a readmission measure, and in 2016, this measure included sepsis patients with pneumonia and aspiration pneumonia. For 2023, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) suppressed pneumonia as a readmission measure due to COVID-19’s significant impact (www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program). Though sepsis is not a direct readmission measure, it could be one in the future. Studies found higher long-term mortality for patients with sepsis readmitted for recurrent sepsis (Pandolfi F, et al. Crit Care. 2022;26[1]:371; McNamara JF, et al. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;114:34).

A systematic review showed independent risk factors predictive of sepsis readmission: older age, male gender, African American and Asian ethnicities, higher baseline comorbidities, and discharge to a facility. In contrast, sepsis-specific risk factors were extended-spectrum beta-lactamase gram-negative bacterial infections, increased hospital length of stay during initial admission, and increased illness severity (Shankar-Hari M, et al. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46[4]:619; Amrollahi F, et al. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2022;29[7]:1263; Gadre SK, et al. Chest. 2019;155[3]:483).

McNamara and colleagues found that patients with gram-negative bloodstream infections had higher readmission rates for sepsis during a 4-year follow-up and had a lower 5-year survival rates Int J Infect Dis. 2022;114:34). Hospitals can prevent readmissions by strengthening antimicrobial stewardship programs to ensure appropriate and adequate treatment of initial infections. Other predictive risk factors for readmission are lower socioeconomic status (Shankar-Hari M, et al. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46[4]:619), lack of health insurance, and delays seeking medical care due to lack of transportation (Amrollahi F, et al. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2022;29[7]:1263).

Sepsis readmissions can be mitigated by predictive analytics, better access to health care, establishing post-discharge clinic follow-ups, transportation arrangements, and telemedicine. More research is needed to evaluate sepsis readmission prevention.

Shu Xian Lee, MD

Fellow-in-Training

Deepa Gotur, MD, FCCP

Member-at-Large

Critical Care Network

Sepsis/Shock Section

(https://datatools.ahrq.gov/hcup-fast-stats; Kim H, et al. Front Public Health. 2022;10:882715; Torio C, Moore B. 2016. HCUP Statistical Brief #204).

Since 2013, the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) adopted pneumonia as a readmission measure, and in 2016, this measure included sepsis patients with pneumonia and aspiration pneumonia. For 2023, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) suppressed pneumonia as a readmission measure due to COVID-19’s significant impact (www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program). Though sepsis is not a direct readmission measure, it could be one in the future. Studies found higher long-term mortality for patients with sepsis readmitted for recurrent sepsis (Pandolfi F, et al. Crit Care. 2022;26[1]:371; McNamara JF, et al. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;114:34).

A systematic review showed independent risk factors predictive of sepsis readmission: older age, male gender, African American and Asian ethnicities, higher baseline comorbidities, and discharge to a facility. In contrast, sepsis-specific risk factors were extended-spectrum beta-lactamase gram-negative bacterial infections, increased hospital length of stay during initial admission, and increased illness severity (Shankar-Hari M, et al. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46[4]:619; Amrollahi F, et al. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2022;29[7]:1263; Gadre SK, et al. Chest. 2019;155[3]:483).

McNamara and colleagues found that patients with gram-negative bloodstream infections had higher readmission rates for sepsis during a 4-year follow-up and had a lower 5-year survival rates Int J Infect Dis. 2022;114:34). Hospitals can prevent readmissions by strengthening antimicrobial stewardship programs to ensure appropriate and adequate treatment of initial infections. Other predictive risk factors for readmission are lower socioeconomic status (Shankar-Hari M, et al. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46[4]:619), lack of health insurance, and delays seeking medical care due to lack of transportation (Amrollahi F, et al. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2022;29[7]:1263).

Sepsis readmissions can be mitigated by predictive analytics, better access to health care, establishing post-discharge clinic follow-ups, transportation arrangements, and telemedicine. More research is needed to evaluate sepsis readmission prevention.

Shu Xian Lee, MD

Fellow-in-Training

Deepa Gotur, MD, FCCP

Member-at-Large

Critical Care Network

Sepsis/Shock Section

(https://datatools.ahrq.gov/hcup-fast-stats; Kim H, et al. Front Public Health. 2022;10:882715; Torio C, Moore B. 2016. HCUP Statistical Brief #204).

Since 2013, the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) adopted pneumonia as a readmission measure, and in 2016, this measure included sepsis patients with pneumonia and aspiration pneumonia. For 2023, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) suppressed pneumonia as a readmission measure due to COVID-19’s significant impact (www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program). Though sepsis is not a direct readmission measure, it could be one in the future. Studies found higher long-term mortality for patients with sepsis readmitted for recurrent sepsis (Pandolfi F, et al. Crit Care. 2022;26[1]:371; McNamara JF, et al. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;114:34).

A systematic review showed independent risk factors predictive of sepsis readmission: older age, male gender, African American and Asian ethnicities, higher baseline comorbidities, and discharge to a facility. In contrast, sepsis-specific risk factors were extended-spectrum beta-lactamase gram-negative bacterial infections, increased hospital length of stay during initial admission, and increased illness severity (Shankar-Hari M, et al. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46[4]:619; Amrollahi F, et al. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2022;29[7]:1263; Gadre SK, et al. Chest. 2019;155[3]:483).

McNamara and colleagues found that patients with gram-negative bloodstream infections had higher readmission rates for sepsis during a 4-year follow-up and had a lower 5-year survival rates Int J Infect Dis. 2022;114:34). Hospitals can prevent readmissions by strengthening antimicrobial stewardship programs to ensure appropriate and adequate treatment of initial infections. Other predictive risk factors for readmission are lower socioeconomic status (Shankar-Hari M, et al. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46[4]:619), lack of health insurance, and delays seeking medical care due to lack of transportation (Amrollahi F, et al. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2022;29[7]:1263).

Sepsis readmissions can be mitigated by predictive analytics, better access to health care, establishing post-discharge clinic follow-ups, transportation arrangements, and telemedicine. More research is needed to evaluate sepsis readmission prevention.

Shu Xian Lee, MD

Fellow-in-Training

Deepa Gotur, MD, FCCP

Member-at-Large

Joint symposium addresses exocrine pancreatic insufficiency

Based on discussions during PancreasFest 2021, , according to a recent report in Gastro Hep Advances

Due to its complex and individualized nature, EPI requires multidisciplinary approaches to therapy, as well as better pancreas function tests and biomarkers for diagnosis and treatment, wrote researchers who were led by David C. Whitcomb, MD, PhD, AGAF, emeritus professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition at the University of Pittsburgh.

“This condition remains challenging even to define, and serious limitations in diagnostic testing and therapeutic options lead to clinical confusion and frequently less than optimal patient management,” the authors wrote.

EPI is clinically defined as inadequate delivery of pancreatic digestive enzymes to meet nutritional needs, which is typically based on a physician’s assessment of a patient’s maldigestion. However, there’s not a universally accepted definition or a precise threshold of reduced pancreatic digestive enzymes that indicates “pancreatic insufficiency” in an individual patient.

Current guidelines also don’t clearly outline the role of pancreatic function tests, the effects of different metabolic needs and nutrition intake, the timing of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT), or the best practices for monitoring or titrating multiple therapies.

In response, Dr. Whitcomb and colleagues proposed a new mechanistic definition of EPI, including the disorder’s physiologic effects and impact on health. First, they said, EPI is a disorder caused by failure of the pancreas to deliver a minimum or threshold level of specific pancreatic digestive enzymes to the intestine in concert with ingested nutrients, followed by enzymatic digestion of individual meals over time to meet certain nutritional and metabolic needs. In addition, the disorder is characterized by variable deficiencies in micronutrients and macronutrients, especially essential fats and fat-soluble vitamins, as well as gastrointestinal symptoms of nutrient maldigestion.

The threshold for EPI should consider the nutritional needs of the patient, dietary intake, residual exocrine pancreas function, and the absorptive capacity of the intestine based on anatomy, mucosal function, motility, inflammation, the microbiome, and physiological adaptation, the authors wrote.

Due to challenges in diagnosing EPI and its common chronic symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating, and diarrhea, several conditions may mimic EPI, be present concomitantly with EPI, or hinder PERT response. These include celiac disease, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, disaccharidase deficiencies, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), bile acid diarrhea, giardiasis, diabetes mellitus, and functional conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome. These conditions should be considered to address underlying pathology and PERT diagnostic challenges.

Although there is consensus that exocrine pancreatic function testing (PFT) is important to diagnosis EPI, no optimal test exists, and pancreatic function is only one aspect of digestion and absorption that should be considered. PFT may be needed to make an objective EPI diagnosis related to acute pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer, pancreatic resection, gastric resection, cystic fibrosis, or IBD. Direct or indirect PFTs may be used, which typically differs by center.

“The medical community still awaits a clinically useful pancreas function test that is easy to perform, well tolerated by patients, and allows personalized dosing of PERT,” the authors wrote.

After diagnosis, a general assessment should include information about symptoms, nutritional status, medications, diet, and lifestyle. This information can be used for a multifaceted treatment approach, with a focus on lifestyle changes, concomitant disease treatment, optimized diet, dietary supplements, and PERT administration.

PERT remains a mainstay of EPI treatment and has shown improvements in steatorrhea, postprandial bloating and pain, nutrition, and unexplained weight loss. The Food and Drug Administration has approved several formulations in different strengths. The typical starting dose is based on age and weight, which is derived from guidelines for EPI treatment in patients with cystic fibrosis. However, the recommendations don’t consider many of the variables discussed above and simply provide an estimate for the average subject with severe EPI, so the dose should be titrated as needed based on age, weight, symptoms, and the holistic management plan.

For optimal results, regular follow-up is necessary to monitor compliance and treatment response. A reduction in symptoms can serve as a reliable indicator of effective EPI management, particularly weight stabilization, improved steatorrhea and diarrhea, and reduced postprandial bloating, pain, and flatulence. Physicians may provide patients with tracking tools to record their PERT compliance, symptom frequency, and lifestyle changes.

For patients with persistent concerns, PERT can be increased as needed. Although many PERT formulations are enteric coated, a proton pump inhibitor or H2 receptor agonist may improve their effectiveness. If EPI symptoms persist despite increased doses, other causes of malabsorption should be considered, such as the concomitant conditions mentioned above.

“As EPI escalates, a lower fat diet may become necessary to alleviate distressing gastrointestinal symptoms,” the authors wrote. “A close working relationship between the treating provider and the [registered dietician] is crucial so that barriers to optimum nutrient assimilation can be identified, communicated, and overcome. Frequent monitoring of the nutritional state with therapy is also imperative.”

PancreasFest 2021 received no specific funding for this event. The authors declared grant support, adviser roles, and speaking honoraria from several pharmaceutical and medical device companies and health care foundations, including the National Pancreas Foundation.

Recognition of recent advances and unaddressed gaps can clarify key issues around exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI).

The loss of pancreatic digestive enzymes and bicarbonate is caused by exocrine pancreatic and proximal small intestine disease. EPI’s clinical impact has been expanded by reports that 30% of subjects can develop EPI after a bout of acute pancreatitis. Diagnosing and treating EPI challenges clinicians and investigators.

The contribution on EPI by Whitcomb and colleagues provides state-of-the-art content relating to diagnosing EPI, assessing its metabolic impact, enzyme replacement, nutritional considerations, and how to assess the effectiveness of therapy.

Though the diagnosis and treatment of EPI have been examined for over 50 years, a consensus for either is still needed. Assessment of EPI with luminal tube tests and endoscopic collections of pancreatic secretion are the most accurate, but they are invasive, limited in availability, and time-consuming. Indirect assays of intestinal activities of pancreatic enzymes by the hydrolysis of substrates or stool excretion are frequently used to diagnose EPI. However, they need to be more insensitive and specific to meet clinical and investigative needs.

Indeed, all tests of exocrine secretion are surrogates of unclear value for the critical endpoint of EPI, its nutritional impact. An unmet need is the development of nutritional standards for assessing EPI and measures for the adequacy of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy. In this context, a patient’s diet, and other factors, such as the intestinal microbiome, can affect pancreatic digestive enzyme activity and must be considered in designing the best EPI treatments. The summary concludes with a thoughtful and valuable road map for moving forward.

Fred Sanford Gorelick, MD, is the Henry J. and Joan W. Binder Professor of Medicine (Digestive Diseases) and of Cell Biology for Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn. He also serves as director of the Yale School of Medicine NIH T32-funded research track in gastroenterology; and as deputy director of Yale School of Medicine MD-PhD program.

Potential conflicts: Dr. Gorelick serves as chair of NIH NIDDK DSMB for Stent vs. Indomethacin for Preventing Post-ERCP Pancreatitis (SVI) study. He also holds grants for research on mechanisms of acute pancreatitis from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense.

Recognition of recent advances and unaddressed gaps can clarify key issues around exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI).

The loss of pancreatic digestive enzymes and bicarbonate is caused by exocrine pancreatic and proximal small intestine disease. EPI’s clinical impact has been expanded by reports that 30% of subjects can develop EPI after a bout of acute pancreatitis. Diagnosing and treating EPI challenges clinicians and investigators.

The contribution on EPI by Whitcomb and colleagues provides state-of-the-art content relating to diagnosing EPI, assessing its metabolic impact, enzyme replacement, nutritional considerations, and how to assess the effectiveness of therapy.

Though the diagnosis and treatment of EPI have been examined for over 50 years, a consensus for either is still needed. Assessment of EPI with luminal tube tests and endoscopic collections of pancreatic secretion are the most accurate, but they are invasive, limited in availability, and time-consuming. Indirect assays of intestinal activities of pancreatic enzymes by the hydrolysis of substrates or stool excretion are frequently used to diagnose EPI. However, they need to be more insensitive and specific to meet clinical and investigative needs.

Indeed, all tests of exocrine secretion are surrogates of unclear value for the critical endpoint of EPI, its nutritional impact. An unmet need is the development of nutritional standards for assessing EPI and measures for the adequacy of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy. In this context, a patient’s diet, and other factors, such as the intestinal microbiome, can affect pancreatic digestive enzyme activity and must be considered in designing the best EPI treatments. The summary concludes with a thoughtful and valuable road map for moving forward.

Fred Sanford Gorelick, MD, is the Henry J. and Joan W. Binder Professor of Medicine (Digestive Diseases) and of Cell Biology for Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn. He also serves as director of the Yale School of Medicine NIH T32-funded research track in gastroenterology; and as deputy director of Yale School of Medicine MD-PhD program.

Potential conflicts: Dr. Gorelick serves as chair of NIH NIDDK DSMB for Stent vs. Indomethacin for Preventing Post-ERCP Pancreatitis (SVI) study. He also holds grants for research on mechanisms of acute pancreatitis from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense.

Recognition of recent advances and unaddressed gaps can clarify key issues around exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI).

The loss of pancreatic digestive enzymes and bicarbonate is caused by exocrine pancreatic and proximal small intestine disease. EPI’s clinical impact has been expanded by reports that 30% of subjects can develop EPI after a bout of acute pancreatitis. Diagnosing and treating EPI challenges clinicians and investigators.

The contribution on EPI by Whitcomb and colleagues provides state-of-the-art content relating to diagnosing EPI, assessing its metabolic impact, enzyme replacement, nutritional considerations, and how to assess the effectiveness of therapy.

Though the diagnosis and treatment of EPI have been examined for over 50 years, a consensus for either is still needed. Assessment of EPI with luminal tube tests and endoscopic collections of pancreatic secretion are the most accurate, but they are invasive, limited in availability, and time-consuming. Indirect assays of intestinal activities of pancreatic enzymes by the hydrolysis of substrates or stool excretion are frequently used to diagnose EPI. However, they need to be more insensitive and specific to meet clinical and investigative needs.

Indeed, all tests of exocrine secretion are surrogates of unclear value for the critical endpoint of EPI, its nutritional impact. An unmet need is the development of nutritional standards for assessing EPI and measures for the adequacy of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy. In this context, a patient’s diet, and other factors, such as the intestinal microbiome, can affect pancreatic digestive enzyme activity and must be considered in designing the best EPI treatments. The summary concludes with a thoughtful and valuable road map for moving forward.

Fred Sanford Gorelick, MD, is the Henry J. and Joan W. Binder Professor of Medicine (Digestive Diseases) and of Cell Biology for Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn. He also serves as director of the Yale School of Medicine NIH T32-funded research track in gastroenterology; and as deputy director of Yale School of Medicine MD-PhD program.

Potential conflicts: Dr. Gorelick serves as chair of NIH NIDDK DSMB for Stent vs. Indomethacin for Preventing Post-ERCP Pancreatitis (SVI) study. He also holds grants for research on mechanisms of acute pancreatitis from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense.

Based on discussions during PancreasFest 2021, , according to a recent report in Gastro Hep Advances

Due to its complex and individualized nature, EPI requires multidisciplinary approaches to therapy, as well as better pancreas function tests and biomarkers for diagnosis and treatment, wrote researchers who were led by David C. Whitcomb, MD, PhD, AGAF, emeritus professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition at the University of Pittsburgh.

“This condition remains challenging even to define, and serious limitations in diagnostic testing and therapeutic options lead to clinical confusion and frequently less than optimal patient management,” the authors wrote.

EPI is clinically defined as inadequate delivery of pancreatic digestive enzymes to meet nutritional needs, which is typically based on a physician’s assessment of a patient’s maldigestion. However, there’s not a universally accepted definition or a precise threshold of reduced pancreatic digestive enzymes that indicates “pancreatic insufficiency” in an individual patient.

Current guidelines also don’t clearly outline the role of pancreatic function tests, the effects of different metabolic needs and nutrition intake, the timing of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT), or the best practices for monitoring or titrating multiple therapies.

In response, Dr. Whitcomb and colleagues proposed a new mechanistic definition of EPI, including the disorder’s physiologic effects and impact on health. First, they said, EPI is a disorder caused by failure of the pancreas to deliver a minimum or threshold level of specific pancreatic digestive enzymes to the intestine in concert with ingested nutrients, followed by enzymatic digestion of individual meals over time to meet certain nutritional and metabolic needs. In addition, the disorder is characterized by variable deficiencies in micronutrients and macronutrients, especially essential fats and fat-soluble vitamins, as well as gastrointestinal symptoms of nutrient maldigestion.

The threshold for EPI should consider the nutritional needs of the patient, dietary intake, residual exocrine pancreas function, and the absorptive capacity of the intestine based on anatomy, mucosal function, motility, inflammation, the microbiome, and physiological adaptation, the authors wrote.

Due to challenges in diagnosing EPI and its common chronic symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating, and diarrhea, several conditions may mimic EPI, be present concomitantly with EPI, or hinder PERT response. These include celiac disease, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, disaccharidase deficiencies, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), bile acid diarrhea, giardiasis, diabetes mellitus, and functional conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome. These conditions should be considered to address underlying pathology and PERT diagnostic challenges.

Although there is consensus that exocrine pancreatic function testing (PFT) is important to diagnosis EPI, no optimal test exists, and pancreatic function is only one aspect of digestion and absorption that should be considered. PFT may be needed to make an objective EPI diagnosis related to acute pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer, pancreatic resection, gastric resection, cystic fibrosis, or IBD. Direct or indirect PFTs may be used, which typically differs by center.

“The medical community still awaits a clinically useful pancreas function test that is easy to perform, well tolerated by patients, and allows personalized dosing of PERT,” the authors wrote.

After diagnosis, a general assessment should include information about symptoms, nutritional status, medications, diet, and lifestyle. This information can be used for a multifaceted treatment approach, with a focus on lifestyle changes, concomitant disease treatment, optimized diet, dietary supplements, and PERT administration.

PERT remains a mainstay of EPI treatment and has shown improvements in steatorrhea, postprandial bloating and pain, nutrition, and unexplained weight loss. The Food and Drug Administration has approved several formulations in different strengths. The typical starting dose is based on age and weight, which is derived from guidelines for EPI treatment in patients with cystic fibrosis. However, the recommendations don’t consider many of the variables discussed above and simply provide an estimate for the average subject with severe EPI, so the dose should be titrated as needed based on age, weight, symptoms, and the holistic management plan.

For optimal results, regular follow-up is necessary to monitor compliance and treatment response. A reduction in symptoms can serve as a reliable indicator of effective EPI management, particularly weight stabilization, improved steatorrhea and diarrhea, and reduced postprandial bloating, pain, and flatulence. Physicians may provide patients with tracking tools to record their PERT compliance, symptom frequency, and lifestyle changes.

For patients with persistent concerns, PERT can be increased as needed. Although many PERT formulations are enteric coated, a proton pump inhibitor or H2 receptor agonist may improve their effectiveness. If EPI symptoms persist despite increased doses, other causes of malabsorption should be considered, such as the concomitant conditions mentioned above.

“As EPI escalates, a lower fat diet may become necessary to alleviate distressing gastrointestinal symptoms,” the authors wrote. “A close working relationship between the treating provider and the [registered dietician] is crucial so that barriers to optimum nutrient assimilation can be identified, communicated, and overcome. Frequent monitoring of the nutritional state with therapy is also imperative.”

PancreasFest 2021 received no specific funding for this event. The authors declared grant support, adviser roles, and speaking honoraria from several pharmaceutical and medical device companies and health care foundations, including the National Pancreas Foundation.

Based on discussions during PancreasFest 2021, , according to a recent report in Gastro Hep Advances

Due to its complex and individualized nature, EPI requires multidisciplinary approaches to therapy, as well as better pancreas function tests and biomarkers for diagnosis and treatment, wrote researchers who were led by David C. Whitcomb, MD, PhD, AGAF, emeritus professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition at the University of Pittsburgh.

“This condition remains challenging even to define, and serious limitations in diagnostic testing and therapeutic options lead to clinical confusion and frequently less than optimal patient management,” the authors wrote.

EPI is clinically defined as inadequate delivery of pancreatic digestive enzymes to meet nutritional needs, which is typically based on a physician’s assessment of a patient’s maldigestion. However, there’s not a universally accepted definition or a precise threshold of reduced pancreatic digestive enzymes that indicates “pancreatic insufficiency” in an individual patient.

Current guidelines also don’t clearly outline the role of pancreatic function tests, the effects of different metabolic needs and nutrition intake, the timing of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT), or the best practices for monitoring or titrating multiple therapies.

In response, Dr. Whitcomb and colleagues proposed a new mechanistic definition of EPI, including the disorder’s physiologic effects and impact on health. First, they said, EPI is a disorder caused by failure of the pancreas to deliver a minimum or threshold level of specific pancreatic digestive enzymes to the intestine in concert with ingested nutrients, followed by enzymatic digestion of individual meals over time to meet certain nutritional and metabolic needs. In addition, the disorder is characterized by variable deficiencies in micronutrients and macronutrients, especially essential fats and fat-soluble vitamins, as well as gastrointestinal symptoms of nutrient maldigestion.

The threshold for EPI should consider the nutritional needs of the patient, dietary intake, residual exocrine pancreas function, and the absorptive capacity of the intestine based on anatomy, mucosal function, motility, inflammation, the microbiome, and physiological adaptation, the authors wrote.

Due to challenges in diagnosing EPI and its common chronic symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating, and diarrhea, several conditions may mimic EPI, be present concomitantly with EPI, or hinder PERT response. These include celiac disease, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, disaccharidase deficiencies, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), bile acid diarrhea, giardiasis, diabetes mellitus, and functional conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome. These conditions should be considered to address underlying pathology and PERT diagnostic challenges.

Although there is consensus that exocrine pancreatic function testing (PFT) is important to diagnosis EPI, no optimal test exists, and pancreatic function is only one aspect of digestion and absorption that should be considered. PFT may be needed to make an objective EPI diagnosis related to acute pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer, pancreatic resection, gastric resection, cystic fibrosis, or IBD. Direct or indirect PFTs may be used, which typically differs by center.

“The medical community still awaits a clinically useful pancreas function test that is easy to perform, well tolerated by patients, and allows personalized dosing of PERT,” the authors wrote.

After diagnosis, a general assessment should include information about symptoms, nutritional status, medications, diet, and lifestyle. This information can be used for a multifaceted treatment approach, with a focus on lifestyle changes, concomitant disease treatment, optimized diet, dietary supplements, and PERT administration.

PERT remains a mainstay of EPI treatment and has shown improvements in steatorrhea, postprandial bloating and pain, nutrition, and unexplained weight loss. The Food and Drug Administration has approved several formulations in different strengths. The typical starting dose is based on age and weight, which is derived from guidelines for EPI treatment in patients with cystic fibrosis. However, the recommendations don’t consider many of the variables discussed above and simply provide an estimate for the average subject with severe EPI, so the dose should be titrated as needed based on age, weight, symptoms, and the holistic management plan.

For optimal results, regular follow-up is necessary to monitor compliance and treatment response. A reduction in symptoms can serve as a reliable indicator of effective EPI management, particularly weight stabilization, improved steatorrhea and diarrhea, and reduced postprandial bloating, pain, and flatulence. Physicians may provide patients with tracking tools to record their PERT compliance, symptom frequency, and lifestyle changes.

For patients with persistent concerns, PERT can be increased as needed. Although many PERT formulations are enteric coated, a proton pump inhibitor or H2 receptor agonist may improve their effectiveness. If EPI symptoms persist despite increased doses, other causes of malabsorption should be considered, such as the concomitant conditions mentioned above.

“As EPI escalates, a lower fat diet may become necessary to alleviate distressing gastrointestinal symptoms,” the authors wrote. “A close working relationship between the treating provider and the [registered dietician] is crucial so that barriers to optimum nutrient assimilation can be identified, communicated, and overcome. Frequent monitoring of the nutritional state with therapy is also imperative.”

PancreasFest 2021 received no specific funding for this event. The authors declared grant support, adviser roles, and speaking honoraria from several pharmaceutical and medical device companies and health care foundations, including the National Pancreas Foundation.

FROM GASTRO HEP ADVANCES

Study of environmental impact of GI endoscopy finds room for improvement

CHICAGO – according to Madhav Desai, MD, MPH, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. About 20% of the waste, most of which went to landfills, was potentially recyclable, he said in a presentation given at the annual Digestive Disease Week® meeting.

Gastrointestinal endoscopies are critical for the screening, diagnosis, and treatment of a variety of gastrointestinal conditions. But like other medical procedures, endoscopies are a source of environmental waste, including plastic, sharps, personal protective equipment (PPE), and cleaning supplies, and also energy waste.

“This all goes back to the damage that mankind is inflicting on the environment in general, with the health care sector as one of the top contributors to plastic waste generation, landfills and water wastage,” Dr. Desai said. “Endoscopies, with their numerous benefits, substantially increase waste generation through landfill waste and liquid consumption and waste through the cleaning of endoscopes. We have a responsibility to look into this topic.”

To prospectively assess total waste generation from their institution, Dr. Desai, who was with the Kansas City (Mo.) Veterans Administration Medical Center, when the research was conducted, collected data on the items used in 450 consecutive procedures from May to June 2022. The data included procedure type, accessory use, intravenous tubing, numbers of biopsy jars, linens, PPE, and more, beginning at the point of patient entry to the endoscopy unit until discharge. They also collected data on waste generation related to reprocessing after each procedure and daily energy use (including endoscopy equipment, lights, and computers). With an eye toward finding opportunities to improve and maximize waste recycling, they stratified waste into the three categories of biohazardous, nonbiohazardous, or potentially recyclable.

“We found that the total waste generated during the time period was 1,398.6 kg, with more than half of it, 61.6%, going directly to landfill,” Dr. Desai said in an interview. “That’s an amount that an average family in the U.S. would use for 2 months. That’s a huge amount.”

Most waste consists of sharps

Exactly one-third was biohazard waste and 5.1% was sharps, they found. A single procedure, on average, sent 2.19 kg of waste to landfill. Extrapolated to 1 year, the waste total amounts to 9,189 kg (equivalent to just over 10 U.S. tons) and per 100 procedures to 219 kg (about 483 pounds).

They estimated 20% of the landfill waste was potentially recyclable (such as plastic CO2 tubing, O2 connector, syringes, etc.), which could reduce the total landfill burden by 8.6 kg per day or 2,580 kg per year (or 61 kg per 100 procedures). Reprocessing endoscopes generated 194 gallons of liquid waste (735.26 kg) per day or 1,385 gallons per 100 procedures.

Turning to energy consumption, Dr. Desai reported that daily use in the endoscopy unit was 277.1 kW-hours (equivalent to 8.2 gallons of gasoline), adding up to about 1,980 kW per 100 procedures. “That 100-procedure amount is the equivalent of the energy used for an average fuel efficiency car to travel 1,200 miles, the distance from Seattle to San Diego,” he said.

“One next step,” Dr. Desai said, “is getting help from GI societies to come together and have endoscopy units track their own performance. You need benchmarks so that you can determine how good an endoscopist you are with respect to waste.”

He commented further:“We all owe it to the environment. And, we have all witnessed what Mother Nature can do to you.”

Working on the potentially recyclable materials that account for 20% of the total waste would be a simple initial step to reduce waste going to landfills, Dr. Desai and colleagues concluded in the meeting abstract. “These data could serve as an actionable model for health systems to reduce total waste generation and move toward environmentally sustainable endoscopy units,” they wrote.

The authors reported no disclosures.

DDW is sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, the American Gastroenterological Association, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and The Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract.

CHICAGO – according to Madhav Desai, MD, MPH, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. About 20% of the waste, most of which went to landfills, was potentially recyclable, he said in a presentation given at the annual Digestive Disease Week® meeting.

Gastrointestinal endoscopies are critical for the screening, diagnosis, and treatment of a variety of gastrointestinal conditions. But like other medical procedures, endoscopies are a source of environmental waste, including plastic, sharps, personal protective equipment (PPE), and cleaning supplies, and also energy waste.

“This all goes back to the damage that mankind is inflicting on the environment in general, with the health care sector as one of the top contributors to plastic waste generation, landfills and water wastage,” Dr. Desai said. “Endoscopies, with their numerous benefits, substantially increase waste generation through landfill waste and liquid consumption and waste through the cleaning of endoscopes. We have a responsibility to look into this topic.”

To prospectively assess total waste generation from their institution, Dr. Desai, who was with the Kansas City (Mo.) Veterans Administration Medical Center, when the research was conducted, collected data on the items used in 450 consecutive procedures from May to June 2022. The data included procedure type, accessory use, intravenous tubing, numbers of biopsy jars, linens, PPE, and more, beginning at the point of patient entry to the endoscopy unit until discharge. They also collected data on waste generation related to reprocessing after each procedure and daily energy use (including endoscopy equipment, lights, and computers). With an eye toward finding opportunities to improve and maximize waste recycling, they stratified waste into the three categories of biohazardous, nonbiohazardous, or potentially recyclable.

“We found that the total waste generated during the time period was 1,398.6 kg, with more than half of it, 61.6%, going directly to landfill,” Dr. Desai said in an interview. “That’s an amount that an average family in the U.S. would use for 2 months. That’s a huge amount.”

Most waste consists of sharps

Exactly one-third was biohazard waste and 5.1% was sharps, they found. A single procedure, on average, sent 2.19 kg of waste to landfill. Extrapolated to 1 year, the waste total amounts to 9,189 kg (equivalent to just over 10 U.S. tons) and per 100 procedures to 219 kg (about 483 pounds).

They estimated 20% of the landfill waste was potentially recyclable (such as plastic CO2 tubing, O2 connector, syringes, etc.), which could reduce the total landfill burden by 8.6 kg per day or 2,580 kg per year (or 61 kg per 100 procedures). Reprocessing endoscopes generated 194 gallons of liquid waste (735.26 kg) per day or 1,385 gallons per 100 procedures.

Turning to energy consumption, Dr. Desai reported that daily use in the endoscopy unit was 277.1 kW-hours (equivalent to 8.2 gallons of gasoline), adding up to about 1,980 kW per 100 procedures. “That 100-procedure amount is the equivalent of the energy used for an average fuel efficiency car to travel 1,200 miles, the distance from Seattle to San Diego,” he said.

“One next step,” Dr. Desai said, “is getting help from GI societies to come together and have endoscopy units track their own performance. You need benchmarks so that you can determine how good an endoscopist you are with respect to waste.”

He commented further:“We all owe it to the environment. And, we have all witnessed what Mother Nature can do to you.”

Working on the potentially recyclable materials that account for 20% of the total waste would be a simple initial step to reduce waste going to landfills, Dr. Desai and colleagues concluded in the meeting abstract. “These data could serve as an actionable model for health systems to reduce total waste generation and move toward environmentally sustainable endoscopy units,” they wrote.

The authors reported no disclosures.

DDW is sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, the American Gastroenterological Association, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and The Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract.

CHICAGO – according to Madhav Desai, MD, MPH, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. About 20% of the waste, most of which went to landfills, was potentially recyclable, he said in a presentation given at the annual Digestive Disease Week® meeting.

Gastrointestinal endoscopies are critical for the screening, diagnosis, and treatment of a variety of gastrointestinal conditions. But like other medical procedures, endoscopies are a source of environmental waste, including plastic, sharps, personal protective equipment (PPE), and cleaning supplies, and also energy waste.

“This all goes back to the damage that mankind is inflicting on the environment in general, with the health care sector as one of the top contributors to plastic waste generation, landfills and water wastage,” Dr. Desai said. “Endoscopies, with their numerous benefits, substantially increase waste generation through landfill waste and liquid consumption and waste through the cleaning of endoscopes. We have a responsibility to look into this topic.”

To prospectively assess total waste generation from their institution, Dr. Desai, who was with the Kansas City (Mo.) Veterans Administration Medical Center, when the research was conducted, collected data on the items used in 450 consecutive procedures from May to June 2022. The data included procedure type, accessory use, intravenous tubing, numbers of biopsy jars, linens, PPE, and more, beginning at the point of patient entry to the endoscopy unit until discharge. They also collected data on waste generation related to reprocessing after each procedure and daily energy use (including endoscopy equipment, lights, and computers). With an eye toward finding opportunities to improve and maximize waste recycling, they stratified waste into the three categories of biohazardous, nonbiohazardous, or potentially recyclable.

“We found that the total waste generated during the time period was 1,398.6 kg, with more than half of it, 61.6%, going directly to landfill,” Dr. Desai said in an interview. “That’s an amount that an average family in the U.S. would use for 2 months. That’s a huge amount.”

Most waste consists of sharps

Exactly one-third was biohazard waste and 5.1% was sharps, they found. A single procedure, on average, sent 2.19 kg of waste to landfill. Extrapolated to 1 year, the waste total amounts to 9,189 kg (equivalent to just over 10 U.S. tons) and per 100 procedures to 219 kg (about 483 pounds).

They estimated 20% of the landfill waste was potentially recyclable (such as plastic CO2 tubing, O2 connector, syringes, etc.), which could reduce the total landfill burden by 8.6 kg per day or 2,580 kg per year (or 61 kg per 100 procedures). Reprocessing endoscopes generated 194 gallons of liquid waste (735.26 kg) per day or 1,385 gallons per 100 procedures.

Turning to energy consumption, Dr. Desai reported that daily use in the endoscopy unit was 277.1 kW-hours (equivalent to 8.2 gallons of gasoline), adding up to about 1,980 kW per 100 procedures. “That 100-procedure amount is the equivalent of the energy used for an average fuel efficiency car to travel 1,200 miles, the distance from Seattle to San Diego,” he said.

“One next step,” Dr. Desai said, “is getting help from GI societies to come together and have endoscopy units track their own performance. You need benchmarks so that you can determine how good an endoscopist you are with respect to waste.”

He commented further:“We all owe it to the environment. And, we have all witnessed what Mother Nature can do to you.”

Working on the potentially recyclable materials that account for 20% of the total waste would be a simple initial step to reduce waste going to landfills, Dr. Desai and colleagues concluded in the meeting abstract. “These data could serve as an actionable model for health systems to reduce total waste generation and move toward environmentally sustainable endoscopy units,” they wrote.

The authors reported no disclosures.

DDW is sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, the American Gastroenterological Association, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and The Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract.

AT DDW 2023

The 30th-birthday gift that could save a life

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

Milestone birthdays are always memorable – those ages when your life seems to fundamentally change somehow. Age 16: A license to drive. Age 18: You can vote to determine your own future and serve in the military. At 21, 3 years after adulthood, you are finally allowed to drink alcohol, for some reason. And then ... nothing much happens. At least until you turn 65 and become eligible for Medicare.

But imagine a future when turning 30 might be the biggest milestone birthday of all. Imagine a future when, at 30, you get your genome sequenced and doctors tell you what needs to be done to save your life.

That future may not be far off, as a new study shows us that

Getting your genome sequenced is a double-edged sword. Of course, there is the potential for substantial benefit; finding certain mutations allows for definitive therapy before it’s too late. That said, there are genetic diseases without a cure and without a treatment. Knowing about that destiny may do more harm than good.

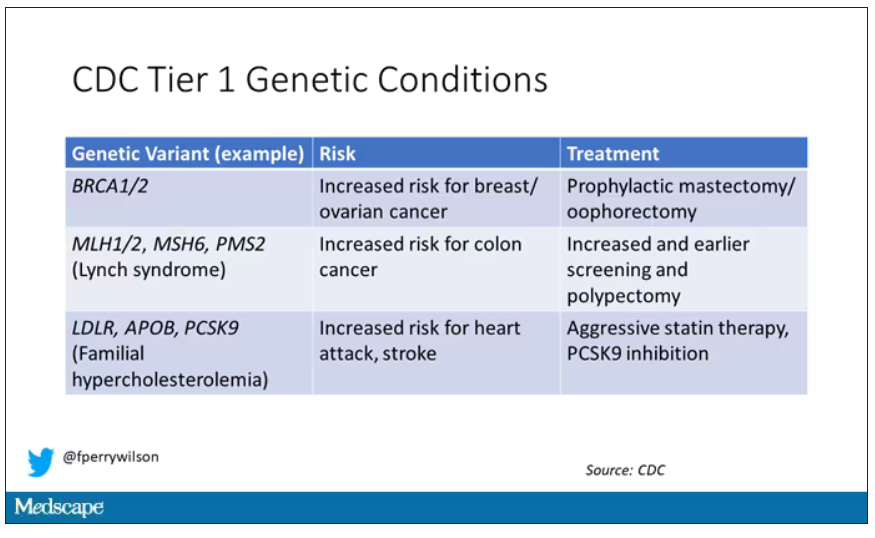

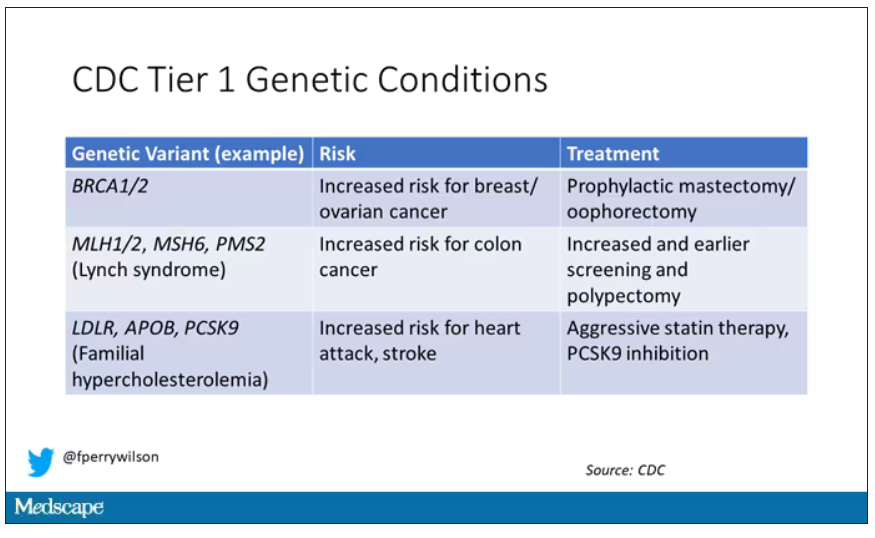

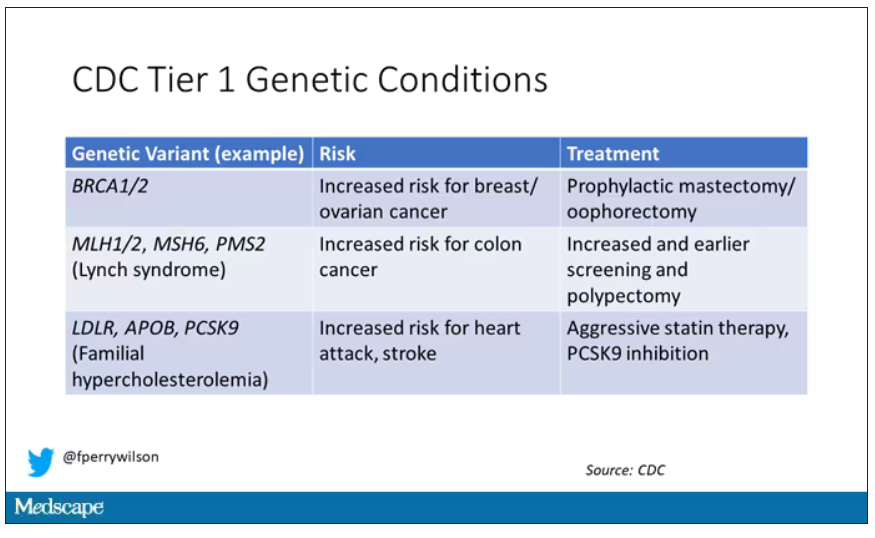

Three conditions are described by the CDC as “Tier 1” conditions, genetic syndromes with a significant impact on life expectancy that also have definitive, effective therapies.

These include mutations like BRCA1/2, associated with a high risk for breast and ovarian cancer; mutations associated with Lynch syndrome, which confer an elevated risk for colon cancer; and mutations associated with familial hypercholesterolemia, which confer elevated risk for cardiovascular events.

In each of these cases, there is clear evidence that early intervention can save lives. Individuals at high risk for breast and ovarian cancer can get prophylactic mastectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy. Those with Lynch syndrome can get more frequent screening for colon cancer and polypectomy, and those with familial hypercholesterolemia can get aggressive lipid-lowering therapy.

I think most of us would probably want to know if we had one of these conditions. Most of us would use that information to take concrete steps to decrease our risk. But just because a rational person would choose to do something doesn’t mean it’s feasible. After all, we’re talking about tests and treatments that have significant costs.