User login

Widespread prescribing of stimulants with other CNS-active meds

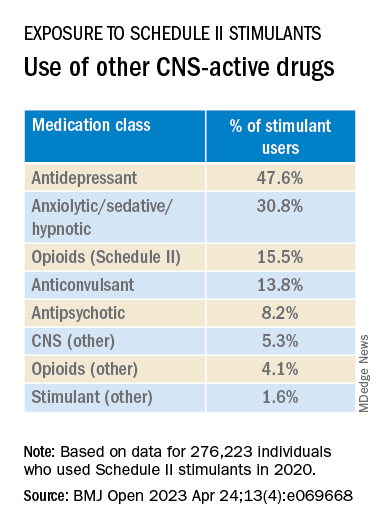

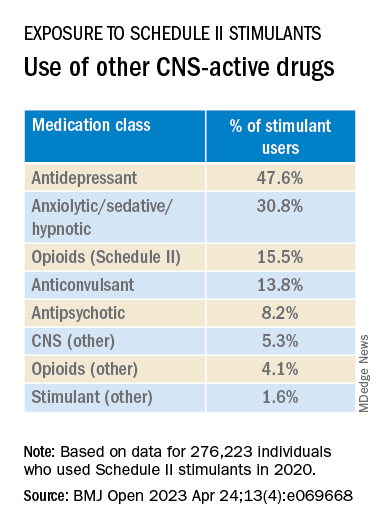

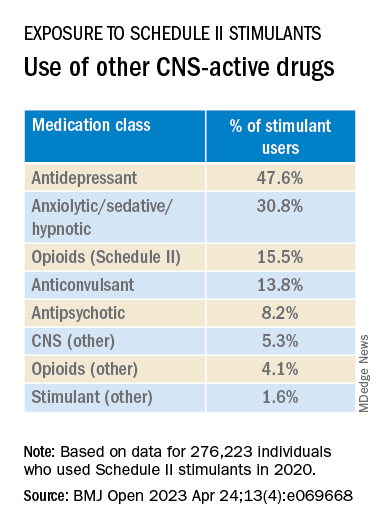

Investigators analyzed prescription drug claims for over 9.1 million U.S. adults over a 1-year period and found that 276,223 (3%) had used a schedule II stimulant, such as methylphenidate and amphetamines, during that time. Of these 276,223 patients, 45% combined these agents with one or more additional CNS-active drugs and almost 25% were simultaneously using two or more additional CNS-active drugs.

Close to half of the stimulant users were taking an antidepressant, while close to one-third filled prescriptions for anxiolytic/sedative/hypnotic meditations, and one-fifth received opioid prescriptions.

The widespread, often off-label use of these stimulants in combination therapy with antidepressants, anxiolytics, opioids, and other psychoactive drugs, “reveals new patterns of utilization beyond the approved use of stimulants as monotherapy for ADHD, but because there are so few studies of these kinds of combination therapy, both the advantages and additional risks [of this type of prescribing] remain unknown,” study investigator Thomas J. Moore, AB, faculty associate in epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, told this news organization.

The study was published online in BMJ Open.

‘Dangerous’ substances

Amphetamines and methylphenidate are CNS stimulants that have been in use for almost a century. Like opioids and barbiturates, they’re considered “dangerous” and classified as schedule II Controlled Substances because of their high potential for abuse.

Over many years, these stimulants have been used for multiple purposes, including nasal congestion, narcolepsy, appetite suppression, binge eating, depression, senile behavior, lethargy, and ADHD, the researchers note.

Observational studies suggest medical use of these agents has been increasing in the United States. The investigators conducted previous research that revealed a 79% increase from 2013 to 2018 in the number of adults who self-report their use. The current study, said Mr. Moore, explores how these stimulants are being used.

For the study, data was extracted from the MarketScan 2019 and 2020 Commercial Claims and Encounters Databases, focusing on 9.1 million adults aged 19-64 years who were continuously enrolled in an included commercial benefit plan from Oct. 1, 2019 to Dec. 31, 2020.

The primary outcome consisted of an outpatient prescription claim, service date, and days’ supply for the CNS-active drugs.

The researchers defined “combination-2” therapy as 60 or more days of combination treatment with a schedule II stimulant and at least one additional CNS-active drug. “Combination-3” therapy was defined as the addition of at least two additional CNS-active drugs.

The researchers used service date and days’ supply to examine the number of stimulant and other CNS-active drugs for each of the days of 2020.

CNS-active drug classes included antidepressants, anxiolytics/sedatives/hypnotics, antipsychotics, opioids, anticonvulsants, and other CNS-active drugs.

Prescribing cascade

Of the total number of adults enrolled, 3% (n = 276,223) were taking schedule II stimulants during 2020, with a median of 8 (interquartile range, 4-11) prescriptions. These drugs provided 227 (IQR, 110-322) treatment days of exposure.

Among those taking stimulants 45.5% combined the use of at least one additional CNS-active drug for a median of 213 (IQR, 126-301) treatment days; and 24.3% used at least two additional CNS-active drugs for a median of 182 (IQR, 108-276) days.

“Clinicians should beware of the prescribing cascade. Sometimes it begins with an antidepressant that causes too much sedation, so a stimulant gets added, which leads to insomnia, so alprazolam gets added to the mix,” Mr. Moore said.

He cautioned that this “leaves a patient with multiple drugs, all with discontinuation effects of different kinds and clashing effects.”

These new findings, the investigators note, “add new public health concerns to those raised by our previous study. ... this more-detailed profile reveals several new patterns.”

Most patients become “long-term users” once treatment has started, with 75% continuing for a 1-year period.

“This underscores the possible risks of nonmedical use and dependence that have warranted the classification of these drugs as having high potential for psychological or physical dependence and their prominent appearance in toxicology drug rankings of fatal overdose cases,” they write.

They note that the data “do not indicate which intervention may have come first – a stimulant added to compensate for excess sedation from the benzodiazepine, or the alprazolam added to calm excessive CNS stimulation and/or insomnia from the stimulants or other drugs.”

Several limitations cited by the authors include the fact that, although the population encompassed 9.1 million people, it “may not represent all commercially insured adults,” and it doesn’t include people who aren’t covered by commercial insurance.

Moreover, the MarketScan dataset included up to four diagnosis codes for each outpatient and emergency department encounter; therefore, it was not possible to directly link the diagnoses to specific prescription drug claims, and thus the diagnoses were not evaluated.

“Since many providers will not accept a drug claim for a schedule II stimulant without an on-label diagnosis of ADHD,” the authors suspect that “large numbers of this diagnosis were present.”

Complex prescribing regimens

Mark Olfson, MD, MPH, professor of psychiatry, medicine, and law and professor of epidemiology, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, said the report “highlights the pharmacological complexity of adults who are treated with stimulants.”

Dr. Olfson, who is a research psychiatrist at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, and was not involved with the study, observed there is “evidence to support stimulants as an adjunctive therapy for treatment-resistant unipolar depression in older adults.”

However, he added, “this indication is unlikely to fully explain the high proportion of nonelderly, stimulant-treated adults who also receive antidepressants.”

These new findings “call for research to increase our understanding of the clinical contexts that motivate these complex prescribing regimens as well as their effectiveness and safety,” said Dr. Olfson.

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Mr. Moore declares no relevant financial relationships. Coauthor G. Caleb Alexander, MD, is past chair and a current member of the Food and Drug Administration’s Peripheral and Central Nervous System Advisory Committee; is a cofounding principal and equity holder in Monument Analytics, a health care consultancy whose clients include the life sciences industry as well as plaintiffs in opioid litigation, for whom he has served as a paid expert witness; and is a past member of OptumRx’s National P&T Committee. Dr. Olfson declares no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators analyzed prescription drug claims for over 9.1 million U.S. adults over a 1-year period and found that 276,223 (3%) had used a schedule II stimulant, such as methylphenidate and amphetamines, during that time. Of these 276,223 patients, 45% combined these agents with one or more additional CNS-active drugs and almost 25% were simultaneously using two or more additional CNS-active drugs.

Close to half of the stimulant users were taking an antidepressant, while close to one-third filled prescriptions for anxiolytic/sedative/hypnotic meditations, and one-fifth received opioid prescriptions.

The widespread, often off-label use of these stimulants in combination therapy with antidepressants, anxiolytics, opioids, and other psychoactive drugs, “reveals new patterns of utilization beyond the approved use of stimulants as monotherapy for ADHD, but because there are so few studies of these kinds of combination therapy, both the advantages and additional risks [of this type of prescribing] remain unknown,” study investigator Thomas J. Moore, AB, faculty associate in epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, told this news organization.

The study was published online in BMJ Open.

‘Dangerous’ substances

Amphetamines and methylphenidate are CNS stimulants that have been in use for almost a century. Like opioids and barbiturates, they’re considered “dangerous” and classified as schedule II Controlled Substances because of their high potential for abuse.

Over many years, these stimulants have been used for multiple purposes, including nasal congestion, narcolepsy, appetite suppression, binge eating, depression, senile behavior, lethargy, and ADHD, the researchers note.

Observational studies suggest medical use of these agents has been increasing in the United States. The investigators conducted previous research that revealed a 79% increase from 2013 to 2018 in the number of adults who self-report their use. The current study, said Mr. Moore, explores how these stimulants are being used.

For the study, data was extracted from the MarketScan 2019 and 2020 Commercial Claims and Encounters Databases, focusing on 9.1 million adults aged 19-64 years who were continuously enrolled in an included commercial benefit plan from Oct. 1, 2019 to Dec. 31, 2020.

The primary outcome consisted of an outpatient prescription claim, service date, and days’ supply for the CNS-active drugs.

The researchers defined “combination-2” therapy as 60 or more days of combination treatment with a schedule II stimulant and at least one additional CNS-active drug. “Combination-3” therapy was defined as the addition of at least two additional CNS-active drugs.

The researchers used service date and days’ supply to examine the number of stimulant and other CNS-active drugs for each of the days of 2020.

CNS-active drug classes included antidepressants, anxiolytics/sedatives/hypnotics, antipsychotics, opioids, anticonvulsants, and other CNS-active drugs.

Prescribing cascade

Of the total number of adults enrolled, 3% (n = 276,223) were taking schedule II stimulants during 2020, with a median of 8 (interquartile range, 4-11) prescriptions. These drugs provided 227 (IQR, 110-322) treatment days of exposure.

Among those taking stimulants 45.5% combined the use of at least one additional CNS-active drug for a median of 213 (IQR, 126-301) treatment days; and 24.3% used at least two additional CNS-active drugs for a median of 182 (IQR, 108-276) days.

“Clinicians should beware of the prescribing cascade. Sometimes it begins with an antidepressant that causes too much sedation, so a stimulant gets added, which leads to insomnia, so alprazolam gets added to the mix,” Mr. Moore said.

He cautioned that this “leaves a patient with multiple drugs, all with discontinuation effects of different kinds and clashing effects.”

These new findings, the investigators note, “add new public health concerns to those raised by our previous study. ... this more-detailed profile reveals several new patterns.”

Most patients become “long-term users” once treatment has started, with 75% continuing for a 1-year period.

“This underscores the possible risks of nonmedical use and dependence that have warranted the classification of these drugs as having high potential for psychological or physical dependence and their prominent appearance in toxicology drug rankings of fatal overdose cases,” they write.

They note that the data “do not indicate which intervention may have come first – a stimulant added to compensate for excess sedation from the benzodiazepine, or the alprazolam added to calm excessive CNS stimulation and/or insomnia from the stimulants or other drugs.”

Several limitations cited by the authors include the fact that, although the population encompassed 9.1 million people, it “may not represent all commercially insured adults,” and it doesn’t include people who aren’t covered by commercial insurance.

Moreover, the MarketScan dataset included up to four diagnosis codes for each outpatient and emergency department encounter; therefore, it was not possible to directly link the diagnoses to specific prescription drug claims, and thus the diagnoses were not evaluated.

“Since many providers will not accept a drug claim for a schedule II stimulant without an on-label diagnosis of ADHD,” the authors suspect that “large numbers of this diagnosis were present.”

Complex prescribing regimens

Mark Olfson, MD, MPH, professor of psychiatry, medicine, and law and professor of epidemiology, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, said the report “highlights the pharmacological complexity of adults who are treated with stimulants.”

Dr. Olfson, who is a research psychiatrist at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, and was not involved with the study, observed there is “evidence to support stimulants as an adjunctive therapy for treatment-resistant unipolar depression in older adults.”

However, he added, “this indication is unlikely to fully explain the high proportion of nonelderly, stimulant-treated adults who also receive antidepressants.”

These new findings “call for research to increase our understanding of the clinical contexts that motivate these complex prescribing regimens as well as their effectiveness and safety,” said Dr. Olfson.

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Mr. Moore declares no relevant financial relationships. Coauthor G. Caleb Alexander, MD, is past chair and a current member of the Food and Drug Administration’s Peripheral and Central Nervous System Advisory Committee; is a cofounding principal and equity holder in Monument Analytics, a health care consultancy whose clients include the life sciences industry as well as plaintiffs in opioid litigation, for whom he has served as a paid expert witness; and is a past member of OptumRx’s National P&T Committee. Dr. Olfson declares no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators analyzed prescription drug claims for over 9.1 million U.S. adults over a 1-year period and found that 276,223 (3%) had used a schedule II stimulant, such as methylphenidate and amphetamines, during that time. Of these 276,223 patients, 45% combined these agents with one or more additional CNS-active drugs and almost 25% were simultaneously using two or more additional CNS-active drugs.

Close to half of the stimulant users were taking an antidepressant, while close to one-third filled prescriptions for anxiolytic/sedative/hypnotic meditations, and one-fifth received opioid prescriptions.

The widespread, often off-label use of these stimulants in combination therapy with antidepressants, anxiolytics, opioids, and other psychoactive drugs, “reveals new patterns of utilization beyond the approved use of stimulants as monotherapy for ADHD, but because there are so few studies of these kinds of combination therapy, both the advantages and additional risks [of this type of prescribing] remain unknown,” study investigator Thomas J. Moore, AB, faculty associate in epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, told this news organization.

The study was published online in BMJ Open.

‘Dangerous’ substances

Amphetamines and methylphenidate are CNS stimulants that have been in use for almost a century. Like opioids and barbiturates, they’re considered “dangerous” and classified as schedule II Controlled Substances because of their high potential for abuse.

Over many years, these stimulants have been used for multiple purposes, including nasal congestion, narcolepsy, appetite suppression, binge eating, depression, senile behavior, lethargy, and ADHD, the researchers note.

Observational studies suggest medical use of these agents has been increasing in the United States. The investigators conducted previous research that revealed a 79% increase from 2013 to 2018 in the number of adults who self-report their use. The current study, said Mr. Moore, explores how these stimulants are being used.

For the study, data was extracted from the MarketScan 2019 and 2020 Commercial Claims and Encounters Databases, focusing on 9.1 million adults aged 19-64 years who were continuously enrolled in an included commercial benefit plan from Oct. 1, 2019 to Dec. 31, 2020.

The primary outcome consisted of an outpatient prescription claim, service date, and days’ supply for the CNS-active drugs.

The researchers defined “combination-2” therapy as 60 or more days of combination treatment with a schedule II stimulant and at least one additional CNS-active drug. “Combination-3” therapy was defined as the addition of at least two additional CNS-active drugs.

The researchers used service date and days’ supply to examine the number of stimulant and other CNS-active drugs for each of the days of 2020.

CNS-active drug classes included antidepressants, anxiolytics/sedatives/hypnotics, antipsychotics, opioids, anticonvulsants, and other CNS-active drugs.

Prescribing cascade

Of the total number of adults enrolled, 3% (n = 276,223) were taking schedule II stimulants during 2020, with a median of 8 (interquartile range, 4-11) prescriptions. These drugs provided 227 (IQR, 110-322) treatment days of exposure.

Among those taking stimulants 45.5% combined the use of at least one additional CNS-active drug for a median of 213 (IQR, 126-301) treatment days; and 24.3% used at least two additional CNS-active drugs for a median of 182 (IQR, 108-276) days.

“Clinicians should beware of the prescribing cascade. Sometimes it begins with an antidepressant that causes too much sedation, so a stimulant gets added, which leads to insomnia, so alprazolam gets added to the mix,” Mr. Moore said.

He cautioned that this “leaves a patient with multiple drugs, all with discontinuation effects of different kinds and clashing effects.”

These new findings, the investigators note, “add new public health concerns to those raised by our previous study. ... this more-detailed profile reveals several new patterns.”

Most patients become “long-term users” once treatment has started, with 75% continuing for a 1-year period.

“This underscores the possible risks of nonmedical use and dependence that have warranted the classification of these drugs as having high potential for psychological or physical dependence and their prominent appearance in toxicology drug rankings of fatal overdose cases,” they write.

They note that the data “do not indicate which intervention may have come first – a stimulant added to compensate for excess sedation from the benzodiazepine, or the alprazolam added to calm excessive CNS stimulation and/or insomnia from the stimulants or other drugs.”

Several limitations cited by the authors include the fact that, although the population encompassed 9.1 million people, it “may not represent all commercially insured adults,” and it doesn’t include people who aren’t covered by commercial insurance.

Moreover, the MarketScan dataset included up to four diagnosis codes for each outpatient and emergency department encounter; therefore, it was not possible to directly link the diagnoses to specific prescription drug claims, and thus the diagnoses were not evaluated.

“Since many providers will not accept a drug claim for a schedule II stimulant without an on-label diagnosis of ADHD,” the authors suspect that “large numbers of this diagnosis were present.”

Complex prescribing regimens

Mark Olfson, MD, MPH, professor of psychiatry, medicine, and law and professor of epidemiology, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, said the report “highlights the pharmacological complexity of adults who are treated with stimulants.”

Dr. Olfson, who is a research psychiatrist at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, and was not involved with the study, observed there is “evidence to support stimulants as an adjunctive therapy for treatment-resistant unipolar depression in older adults.”

However, he added, “this indication is unlikely to fully explain the high proportion of nonelderly, stimulant-treated adults who also receive antidepressants.”

These new findings “call for research to increase our understanding of the clinical contexts that motivate these complex prescribing regimens as well as their effectiveness and safety,” said Dr. Olfson.

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Mr. Moore declares no relevant financial relationships. Coauthor G. Caleb Alexander, MD, is past chair and a current member of the Food and Drug Administration’s Peripheral and Central Nervous System Advisory Committee; is a cofounding principal and equity holder in Monument Analytics, a health care consultancy whose clients include the life sciences industry as well as plaintiffs in opioid litigation, for whom he has served as a paid expert witness; and is a past member of OptumRx’s National P&T Committee. Dr. Olfson declares no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM BMJ OPEN

Asthma tied to increased risk for multiple cancers

People with asthma have an elevated risk for a variety of cancers other than lung cancer, including melanoma as well as blood, kidney, and ovarian cancers, new research suggests.

But, the authors found, treatment with an inhaled steroid may lower that risk, perhaps by keeping inflammation in check.

“Using real-world data, our study is the first to provide evidence of a positive association between asthma and cancer risk in United States patients,” Yi Guo, PhD, with the University of Florida, Gainesville, said in a news release.

The study was published online in Cancer Medicine.

The relationship between chronic inflammation and cancer remains a key area of exploration in cancer etiology. Data show that the risk for developing cancer is higher in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases, and patients with asthma have complex and chronic inflammation. However, prior studies exploring a possible link between asthma and cancer have yielded mixed results.

To investigate further, Dr. Guo and colleagues analyzed electronic health records and claims data in the OneFlorida+ clinical research network for roughly 90,000 adults with asthma and a matched cohort of about 270,000 adults without asthma.

Multivariable analysis revealed that adults with asthma were more likely to develop cancer, compared with peers without asthma (hazard ratio, 1.36), the investigators found.

Adults with asthma had an elevated cancer risk for five of the 13 cancers assessed, including melanoma (HR, 1.98), ovarian cancer (HR, 1.88), lung cancer (HR, 1.56), kidney cancer (HR, 1.48), and blood cancer (HR, 1.26).

Compared with adults without asthma, those with asthma who did not treat it with an inhaled steroid had a more pronounced overall cancer risk, compared with those who were on an inhaled steroid (HR, 1.60 vs. 1.11).

For specific cancer types, the risk was elevated for nine of 13 cancers in patients with asthma not taking an inhaled steroid: prostate (HR, 1.50), lung (HR, 1.74), colorectal (HR, 1.51), blood (HR, 1.44), melanoma (HR, 2.05), corpus uteri (HR, 1.76), kidney (HR, 1.52), ovarian (HR, 2.31), and cervical (HR, 1.46).

In contrast, in patients with asthma who did use an inhaled steroid, an elevated cancer risk was observed for only two cancers, lung cancer (HR, 1.39) and melanoma (HR, 1.92), suggesting a potential protective effect of inhaled steroid use on cancer, the researchers said.

Although prior studies have shown a protective effect of inhaled steroid use on some cancers, potentially by reducing inflammation, the “speculative nature of chronic inflammation (asthma as a common example) as a driver for pan-cancer development requires more investigation,” Dr. Guo and colleagues cautioned.

And because of the observational nature of the current study, Dr. Guo’s team stressed that these findings do not prove a causal relationship between asthma and cancer.

“More in-depth studies using real-word data are needed to further explore the causal mechanisms of asthma on cancer risk,” the researchers concluded.

Funding for the study was provided in part by grants to the researchers from the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, National Institute on Aging, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This project was supported by the Cancer Informatics Shared Resource in the University of Florida Health Cancer Center. The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People with asthma have an elevated risk for a variety of cancers other than lung cancer, including melanoma as well as blood, kidney, and ovarian cancers, new research suggests.

But, the authors found, treatment with an inhaled steroid may lower that risk, perhaps by keeping inflammation in check.

“Using real-world data, our study is the first to provide evidence of a positive association between asthma and cancer risk in United States patients,” Yi Guo, PhD, with the University of Florida, Gainesville, said in a news release.

The study was published online in Cancer Medicine.

The relationship between chronic inflammation and cancer remains a key area of exploration in cancer etiology. Data show that the risk for developing cancer is higher in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases, and patients with asthma have complex and chronic inflammation. However, prior studies exploring a possible link between asthma and cancer have yielded mixed results.

To investigate further, Dr. Guo and colleagues analyzed electronic health records and claims data in the OneFlorida+ clinical research network for roughly 90,000 adults with asthma and a matched cohort of about 270,000 adults without asthma.

Multivariable analysis revealed that adults with asthma were more likely to develop cancer, compared with peers without asthma (hazard ratio, 1.36), the investigators found.

Adults with asthma had an elevated cancer risk for five of the 13 cancers assessed, including melanoma (HR, 1.98), ovarian cancer (HR, 1.88), lung cancer (HR, 1.56), kidney cancer (HR, 1.48), and blood cancer (HR, 1.26).

Compared with adults without asthma, those with asthma who did not treat it with an inhaled steroid had a more pronounced overall cancer risk, compared with those who were on an inhaled steroid (HR, 1.60 vs. 1.11).

For specific cancer types, the risk was elevated for nine of 13 cancers in patients with asthma not taking an inhaled steroid: prostate (HR, 1.50), lung (HR, 1.74), colorectal (HR, 1.51), blood (HR, 1.44), melanoma (HR, 2.05), corpus uteri (HR, 1.76), kidney (HR, 1.52), ovarian (HR, 2.31), and cervical (HR, 1.46).

In contrast, in patients with asthma who did use an inhaled steroid, an elevated cancer risk was observed for only two cancers, lung cancer (HR, 1.39) and melanoma (HR, 1.92), suggesting a potential protective effect of inhaled steroid use on cancer, the researchers said.

Although prior studies have shown a protective effect of inhaled steroid use on some cancers, potentially by reducing inflammation, the “speculative nature of chronic inflammation (asthma as a common example) as a driver for pan-cancer development requires more investigation,” Dr. Guo and colleagues cautioned.

And because of the observational nature of the current study, Dr. Guo’s team stressed that these findings do not prove a causal relationship between asthma and cancer.

“More in-depth studies using real-word data are needed to further explore the causal mechanisms of asthma on cancer risk,” the researchers concluded.

Funding for the study was provided in part by grants to the researchers from the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, National Institute on Aging, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This project was supported by the Cancer Informatics Shared Resource in the University of Florida Health Cancer Center. The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People with asthma have an elevated risk for a variety of cancers other than lung cancer, including melanoma as well as blood, kidney, and ovarian cancers, new research suggests.

But, the authors found, treatment with an inhaled steroid may lower that risk, perhaps by keeping inflammation in check.

“Using real-world data, our study is the first to provide evidence of a positive association between asthma and cancer risk in United States patients,” Yi Guo, PhD, with the University of Florida, Gainesville, said in a news release.

The study was published online in Cancer Medicine.

The relationship between chronic inflammation and cancer remains a key area of exploration in cancer etiology. Data show that the risk for developing cancer is higher in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases, and patients with asthma have complex and chronic inflammation. However, prior studies exploring a possible link between asthma and cancer have yielded mixed results.

To investigate further, Dr. Guo and colleagues analyzed electronic health records and claims data in the OneFlorida+ clinical research network for roughly 90,000 adults with asthma and a matched cohort of about 270,000 adults without asthma.

Multivariable analysis revealed that adults with asthma were more likely to develop cancer, compared with peers without asthma (hazard ratio, 1.36), the investigators found.

Adults with asthma had an elevated cancer risk for five of the 13 cancers assessed, including melanoma (HR, 1.98), ovarian cancer (HR, 1.88), lung cancer (HR, 1.56), kidney cancer (HR, 1.48), and blood cancer (HR, 1.26).

Compared with adults without asthma, those with asthma who did not treat it with an inhaled steroid had a more pronounced overall cancer risk, compared with those who were on an inhaled steroid (HR, 1.60 vs. 1.11).

For specific cancer types, the risk was elevated for nine of 13 cancers in patients with asthma not taking an inhaled steroid: prostate (HR, 1.50), lung (HR, 1.74), colorectal (HR, 1.51), blood (HR, 1.44), melanoma (HR, 2.05), corpus uteri (HR, 1.76), kidney (HR, 1.52), ovarian (HR, 2.31), and cervical (HR, 1.46).

In contrast, in patients with asthma who did use an inhaled steroid, an elevated cancer risk was observed for only two cancers, lung cancer (HR, 1.39) and melanoma (HR, 1.92), suggesting a potential protective effect of inhaled steroid use on cancer, the researchers said.

Although prior studies have shown a protective effect of inhaled steroid use on some cancers, potentially by reducing inflammation, the “speculative nature of chronic inflammation (asthma as a common example) as a driver for pan-cancer development requires more investigation,” Dr. Guo and colleagues cautioned.

And because of the observational nature of the current study, Dr. Guo’s team stressed that these findings do not prove a causal relationship between asthma and cancer.

“More in-depth studies using real-word data are needed to further explore the causal mechanisms of asthma on cancer risk,” the researchers concluded.

Funding for the study was provided in part by grants to the researchers from the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, National Institute on Aging, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This project was supported by the Cancer Informatics Shared Resource in the University of Florida Health Cancer Center. The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pausing endocrine therapy to attempt pregnancy is safe

The results provide the “strongest evidence to date on the short-term safety of this choice,” Sharon Giordano, MD, MPH, with University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, wrote in an editorial accompanying the study.

“Physicians should now incorporate these positive data into their shared decision-making process with patients,” Dr. Giordano said.

The POSITIVE trial findings were published online in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Before the analysis, the risks associated with taking a break from endocrine therapy among young women with hormone receptor (HR)–positive breast cancer remained unclear.

In the current trial, Ann Partridge, MD, MPH, and colleagues sought prospective data on the safety associated with taking a temporary break from therapy to attempt pregnancy.

The single-group trial enrolled more than 500 premenopausal women who had received 18-30 months of endocrine therapy for mostly stage I or II HR-positive breast cancer. After a 3-month washout, the women were given 2 years to conceive, deliver, and breastfeed, if desired, before resuming treatment. Breast cancer events – the primary outcome – were defined as local, regional, or distant recurrence of invasive breast cancer or new contralateral invasive breast cancer.

The results, initially reported at San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS) 2022, showed that a temporary interruption of therapy to attempt pregnancy did not appear to lead to worse breast cancer outcomes.

Among 497 women who were followed for pregnancy status, 368 (74%) had at least one pregnancy, and 317 (64%) had at least one live birth.

After a median follow-up of 3.4 years, 44 women had had a breast cancer event – a result that was close to, but did not exceed, the safety threshold of 46 breast cancer events.

The 3-year incidence of breast cancer events was 8.9% (95% confidence interval [CI], 6.3-11.6) in the treatment-interruption group compared with 9.2% (95% CI, 7.6-10.8) among historical controls, which included women who would have met the entry criteria for the trial.

“These results suggest that although endocrine therapy for a period of 5-10 years substantially improves disease outcomes in patients with hormone receptor–positive early breast cancer, a temporary interruption of therapy to attempt pregnancy does not appear to have an appreciable negative short-term effect,” wrote Dr. Partridge, vice chair of medical oncology at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues.

The authors cautioned, however, that the median follow-up was only 3.4 years and that 10-year follow-up data will be “critical” to confirm the safety of interruption of adjuvant endocrine therapy.

Dr. Giordano agreed, noting that “recurrences of breast cancer are reported to occur at a steady rate for up to 20 years after diagnosis among patients with hormone receptor–positive disease; the protocol-specified 10-year follow-up data will be essential to establish longer-term safety.”

The study was supported by the International Breast Cancer Study Group and by the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology in North America in collaboration with the Breast International Group (BIG). Disclosures for authors and editorial writer are available at NEJM.org.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The results provide the “strongest evidence to date on the short-term safety of this choice,” Sharon Giordano, MD, MPH, with University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, wrote in an editorial accompanying the study.

“Physicians should now incorporate these positive data into their shared decision-making process with patients,” Dr. Giordano said.

The POSITIVE trial findings were published online in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Before the analysis, the risks associated with taking a break from endocrine therapy among young women with hormone receptor (HR)–positive breast cancer remained unclear.

In the current trial, Ann Partridge, MD, MPH, and colleagues sought prospective data on the safety associated with taking a temporary break from therapy to attempt pregnancy.

The single-group trial enrolled more than 500 premenopausal women who had received 18-30 months of endocrine therapy for mostly stage I or II HR-positive breast cancer. After a 3-month washout, the women were given 2 years to conceive, deliver, and breastfeed, if desired, before resuming treatment. Breast cancer events – the primary outcome – were defined as local, regional, or distant recurrence of invasive breast cancer or new contralateral invasive breast cancer.

The results, initially reported at San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS) 2022, showed that a temporary interruption of therapy to attempt pregnancy did not appear to lead to worse breast cancer outcomes.

Among 497 women who were followed for pregnancy status, 368 (74%) had at least one pregnancy, and 317 (64%) had at least one live birth.

After a median follow-up of 3.4 years, 44 women had had a breast cancer event – a result that was close to, but did not exceed, the safety threshold of 46 breast cancer events.

The 3-year incidence of breast cancer events was 8.9% (95% confidence interval [CI], 6.3-11.6) in the treatment-interruption group compared with 9.2% (95% CI, 7.6-10.8) among historical controls, which included women who would have met the entry criteria for the trial.

“These results suggest that although endocrine therapy for a period of 5-10 years substantially improves disease outcomes in patients with hormone receptor–positive early breast cancer, a temporary interruption of therapy to attempt pregnancy does not appear to have an appreciable negative short-term effect,” wrote Dr. Partridge, vice chair of medical oncology at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues.

The authors cautioned, however, that the median follow-up was only 3.4 years and that 10-year follow-up data will be “critical” to confirm the safety of interruption of adjuvant endocrine therapy.

Dr. Giordano agreed, noting that “recurrences of breast cancer are reported to occur at a steady rate for up to 20 years after diagnosis among patients with hormone receptor–positive disease; the protocol-specified 10-year follow-up data will be essential to establish longer-term safety.”

The study was supported by the International Breast Cancer Study Group and by the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology in North America in collaboration with the Breast International Group (BIG). Disclosures for authors and editorial writer are available at NEJM.org.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The results provide the “strongest evidence to date on the short-term safety of this choice,” Sharon Giordano, MD, MPH, with University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, wrote in an editorial accompanying the study.

“Physicians should now incorporate these positive data into their shared decision-making process with patients,” Dr. Giordano said.

The POSITIVE trial findings were published online in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Before the analysis, the risks associated with taking a break from endocrine therapy among young women with hormone receptor (HR)–positive breast cancer remained unclear.

In the current trial, Ann Partridge, MD, MPH, and colleagues sought prospective data on the safety associated with taking a temporary break from therapy to attempt pregnancy.

The single-group trial enrolled more than 500 premenopausal women who had received 18-30 months of endocrine therapy for mostly stage I or II HR-positive breast cancer. After a 3-month washout, the women were given 2 years to conceive, deliver, and breastfeed, if desired, before resuming treatment. Breast cancer events – the primary outcome – were defined as local, regional, or distant recurrence of invasive breast cancer or new contralateral invasive breast cancer.

The results, initially reported at San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS) 2022, showed that a temporary interruption of therapy to attempt pregnancy did not appear to lead to worse breast cancer outcomes.

Among 497 women who were followed for pregnancy status, 368 (74%) had at least one pregnancy, and 317 (64%) had at least one live birth.

After a median follow-up of 3.4 years, 44 women had had a breast cancer event – a result that was close to, but did not exceed, the safety threshold of 46 breast cancer events.

The 3-year incidence of breast cancer events was 8.9% (95% confidence interval [CI], 6.3-11.6) in the treatment-interruption group compared with 9.2% (95% CI, 7.6-10.8) among historical controls, which included women who would have met the entry criteria for the trial.

“These results suggest that although endocrine therapy for a period of 5-10 years substantially improves disease outcomes in patients with hormone receptor–positive early breast cancer, a temporary interruption of therapy to attempt pregnancy does not appear to have an appreciable negative short-term effect,” wrote Dr. Partridge, vice chair of medical oncology at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues.

The authors cautioned, however, that the median follow-up was only 3.4 years and that 10-year follow-up data will be “critical” to confirm the safety of interruption of adjuvant endocrine therapy.

Dr. Giordano agreed, noting that “recurrences of breast cancer are reported to occur at a steady rate for up to 20 years after diagnosis among patients with hormone receptor–positive disease; the protocol-specified 10-year follow-up data will be essential to establish longer-term safety.”

The study was supported by the International Breast Cancer Study Group and by the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology in North America in collaboration with the Breast International Group (BIG). Disclosures for authors and editorial writer are available at NEJM.org.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NEJM

New AACE type 2 diabetes algorithm individualizes care

SEATTLE – The latest American Association of Clinical Endocrinology type 2 diabetes management algorithm uses graphics to focus on individualized care while adding newly compiled information about medication access and affordability, vaccinations, and weight loss drugs.

The clinical guidance document was presented at the annual scientific & clinical congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology and simultaneously published in Endocrine Practice.

Using text and colorful graphics, the document summarizes information from last year’s update and other recent AACE documents, including those addressing dyslipidemia and use of diabetes technology.

lead author Susan L. Samson, MD, PhD, chair of endocrinology, diabetes & metabolism at the Mayo Clinic Florida, Jacksonville, said in an interview.

Asked to comment, Anne L. Peters, MD, professor of clinical medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said: “I like their simple graphics. For the Department of Health Services in Los Angeles County, we have been painstakingly trying to create our own flow diagrams. ... These will help.”

Eleven separate algorithms with text and graphics

Included are 11 visual management algorithms, with accompanying text for each one. The first lists 10 overall management principles, including “lifestyle modification underlies all therapy,” “maintain or achieve optimal weight,” “choice of therapy includes ease of use and access,” “individualize all glucose targets,” “avoid hypoglycemia,” and “comorbidities must be managed for comprehensive care.”

Three more algorithms cover the diabetes-adjacent topics of adiposity-based chronic disease, prediabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension.

Four separate graphics address glucose-lowering. Two are “complications-centric” and “glucose-centric” algorithms, another covers insulin initiation and titration, and a table summarizes the benefits and risks of currently available glucose-lowering medications, as well as cost.

Splitting the glucose-lowering algorithms into “complications-centric” and “glucose-centric” graphics is new, Dr. Samson said. “The complications one comes first, deliberately. You need to think about: Does my patient have a history of or high risk for cardiovascular disease, heart failure, stroke, or diabetic kidney disease? And, you want to prioritize those medications that have evidence to improve outcomes with those different diabetes complications versus a one-size-fits-all approach.”

And for patients without those complications, the glucose-centric algorithm considers obesity, hypoglycemia risk, and access/cost issues. “So, overall the diabetes medication algorithm has been split in order to emphasize that personalized approach to decision-making,” Dr. Samson explained.

Also new is a table listing the benefits and risks of weight-loss medications, and another covering immunization guidance for people with diabetes based on recommendations from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Coming out of the pandemic, we’re thinking about how can we protect our patients from infectious disease and all the comorbidities. In some cases, people with diabetes can have a much higher risk for adverse events,” Dr. Samson noted.

Regarding the weight-loss medications table, she pointed out that the task force couldn’t include the blockbuster twincretin tirzepatide because it’s not yet approved for weight loss by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. However, it is included in the glucose-lowering drug table with weight loss listed among its benefits.

“We want this to be a living document that should be updated in a timely fashion, and so, as these new indications are approved and we see more evidence supporting their different uses, this should be updated in a really timely fashion to reflect that,” Dr. Samson said.

The end of the document includes a full page of each graphic, meant for wall posting.

Dr. Peters noted that for the most part, the AACE guidelines and algorithm align with joint guidance by the American Diabetes Association and European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

“For many years there seemed to be big differences between the AACE and ADA guidelines for the management of type 2 diabetes. Although small differences still exist ... the ADA and AACE guidelines have become quite similar,” she said.

Dr. Peters also praised the AACE algorithm for providing “a pathway for people who have issues with access and cost.”

“I am incredibly proud that in the County of Los Angeles you can get a [glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist] and/or a [sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor] even with the most restricted MediCal insurance if indications are met. But there remain many people in many places where access and cost limit options, and I am grateful that AACE includes this in their algorithms,” she said.

Dr. Samson has reported receiving research support to the Mayo Clinic from Corcept, serving on a steering committee and being a national or overall principal investigator for Chiasma and Novartis, and being a committee chair for the American Board of Internal Medicine. Dr. Peters has reported relationships with Blue Circle Health, Vertex, and Abbott Diabetes Care, receiving research grants from Abbott Diabetes Care and Insulet, and holding stock options in Teladoc and Omada Health.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

SEATTLE – The latest American Association of Clinical Endocrinology type 2 diabetes management algorithm uses graphics to focus on individualized care while adding newly compiled information about medication access and affordability, vaccinations, and weight loss drugs.

The clinical guidance document was presented at the annual scientific & clinical congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology and simultaneously published in Endocrine Practice.

Using text and colorful graphics, the document summarizes information from last year’s update and other recent AACE documents, including those addressing dyslipidemia and use of diabetes technology.

lead author Susan L. Samson, MD, PhD, chair of endocrinology, diabetes & metabolism at the Mayo Clinic Florida, Jacksonville, said in an interview.

Asked to comment, Anne L. Peters, MD, professor of clinical medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said: “I like their simple graphics. For the Department of Health Services in Los Angeles County, we have been painstakingly trying to create our own flow diagrams. ... These will help.”

Eleven separate algorithms with text and graphics

Included are 11 visual management algorithms, with accompanying text for each one. The first lists 10 overall management principles, including “lifestyle modification underlies all therapy,” “maintain or achieve optimal weight,” “choice of therapy includes ease of use and access,” “individualize all glucose targets,” “avoid hypoglycemia,” and “comorbidities must be managed for comprehensive care.”

Three more algorithms cover the diabetes-adjacent topics of adiposity-based chronic disease, prediabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension.

Four separate graphics address glucose-lowering. Two are “complications-centric” and “glucose-centric” algorithms, another covers insulin initiation and titration, and a table summarizes the benefits and risks of currently available glucose-lowering medications, as well as cost.

Splitting the glucose-lowering algorithms into “complications-centric” and “glucose-centric” graphics is new, Dr. Samson said. “The complications one comes first, deliberately. You need to think about: Does my patient have a history of or high risk for cardiovascular disease, heart failure, stroke, or diabetic kidney disease? And, you want to prioritize those medications that have evidence to improve outcomes with those different diabetes complications versus a one-size-fits-all approach.”

And for patients without those complications, the glucose-centric algorithm considers obesity, hypoglycemia risk, and access/cost issues. “So, overall the diabetes medication algorithm has been split in order to emphasize that personalized approach to decision-making,” Dr. Samson explained.

Also new is a table listing the benefits and risks of weight-loss medications, and another covering immunization guidance for people with diabetes based on recommendations from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Coming out of the pandemic, we’re thinking about how can we protect our patients from infectious disease and all the comorbidities. In some cases, people with diabetes can have a much higher risk for adverse events,” Dr. Samson noted.

Regarding the weight-loss medications table, she pointed out that the task force couldn’t include the blockbuster twincretin tirzepatide because it’s not yet approved for weight loss by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. However, it is included in the glucose-lowering drug table with weight loss listed among its benefits.

“We want this to be a living document that should be updated in a timely fashion, and so, as these new indications are approved and we see more evidence supporting their different uses, this should be updated in a really timely fashion to reflect that,” Dr. Samson said.

The end of the document includes a full page of each graphic, meant for wall posting.

Dr. Peters noted that for the most part, the AACE guidelines and algorithm align with joint guidance by the American Diabetes Association and European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

“For many years there seemed to be big differences between the AACE and ADA guidelines for the management of type 2 diabetes. Although small differences still exist ... the ADA and AACE guidelines have become quite similar,” she said.

Dr. Peters also praised the AACE algorithm for providing “a pathway for people who have issues with access and cost.”

“I am incredibly proud that in the County of Los Angeles you can get a [glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist] and/or a [sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor] even with the most restricted MediCal insurance if indications are met. But there remain many people in many places where access and cost limit options, and I am grateful that AACE includes this in their algorithms,” she said.

Dr. Samson has reported receiving research support to the Mayo Clinic from Corcept, serving on a steering committee and being a national or overall principal investigator for Chiasma and Novartis, and being a committee chair for the American Board of Internal Medicine. Dr. Peters has reported relationships with Blue Circle Health, Vertex, and Abbott Diabetes Care, receiving research grants from Abbott Diabetes Care and Insulet, and holding stock options in Teladoc and Omada Health.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

SEATTLE – The latest American Association of Clinical Endocrinology type 2 diabetes management algorithm uses graphics to focus on individualized care while adding newly compiled information about medication access and affordability, vaccinations, and weight loss drugs.

The clinical guidance document was presented at the annual scientific & clinical congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology and simultaneously published in Endocrine Practice.

Using text and colorful graphics, the document summarizes information from last year’s update and other recent AACE documents, including those addressing dyslipidemia and use of diabetes technology.

lead author Susan L. Samson, MD, PhD, chair of endocrinology, diabetes & metabolism at the Mayo Clinic Florida, Jacksonville, said in an interview.

Asked to comment, Anne L. Peters, MD, professor of clinical medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said: “I like their simple graphics. For the Department of Health Services in Los Angeles County, we have been painstakingly trying to create our own flow diagrams. ... These will help.”

Eleven separate algorithms with text and graphics

Included are 11 visual management algorithms, with accompanying text for each one. The first lists 10 overall management principles, including “lifestyle modification underlies all therapy,” “maintain or achieve optimal weight,” “choice of therapy includes ease of use and access,” “individualize all glucose targets,” “avoid hypoglycemia,” and “comorbidities must be managed for comprehensive care.”

Three more algorithms cover the diabetes-adjacent topics of adiposity-based chronic disease, prediabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension.

Four separate graphics address glucose-lowering. Two are “complications-centric” and “glucose-centric” algorithms, another covers insulin initiation and titration, and a table summarizes the benefits and risks of currently available glucose-lowering medications, as well as cost.

Splitting the glucose-lowering algorithms into “complications-centric” and “glucose-centric” graphics is new, Dr. Samson said. “The complications one comes first, deliberately. You need to think about: Does my patient have a history of or high risk for cardiovascular disease, heart failure, stroke, or diabetic kidney disease? And, you want to prioritize those medications that have evidence to improve outcomes with those different diabetes complications versus a one-size-fits-all approach.”

And for patients without those complications, the glucose-centric algorithm considers obesity, hypoglycemia risk, and access/cost issues. “So, overall the diabetes medication algorithm has been split in order to emphasize that personalized approach to decision-making,” Dr. Samson explained.

Also new is a table listing the benefits and risks of weight-loss medications, and another covering immunization guidance for people with diabetes based on recommendations from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Coming out of the pandemic, we’re thinking about how can we protect our patients from infectious disease and all the comorbidities. In some cases, people with diabetes can have a much higher risk for adverse events,” Dr. Samson noted.

Regarding the weight-loss medications table, she pointed out that the task force couldn’t include the blockbuster twincretin tirzepatide because it’s not yet approved for weight loss by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. However, it is included in the glucose-lowering drug table with weight loss listed among its benefits.

“We want this to be a living document that should be updated in a timely fashion, and so, as these new indications are approved and we see more evidence supporting their different uses, this should be updated in a really timely fashion to reflect that,” Dr. Samson said.

The end of the document includes a full page of each graphic, meant for wall posting.

Dr. Peters noted that for the most part, the AACE guidelines and algorithm align with joint guidance by the American Diabetes Association and European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

“For many years there seemed to be big differences between the AACE and ADA guidelines for the management of type 2 diabetes. Although small differences still exist ... the ADA and AACE guidelines have become quite similar,” she said.

Dr. Peters also praised the AACE algorithm for providing “a pathway for people who have issues with access and cost.”

“I am incredibly proud that in the County of Los Angeles you can get a [glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist] and/or a [sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor] even with the most restricted MediCal insurance if indications are met. But there remain many people in many places where access and cost limit options, and I am grateful that AACE includes this in their algorithms,” she said.

Dr. Samson has reported receiving research support to the Mayo Clinic from Corcept, serving on a steering committee and being a national or overall principal investigator for Chiasma and Novartis, and being a committee chair for the American Board of Internal Medicine. Dr. Peters has reported relationships with Blue Circle Health, Vertex, and Abbott Diabetes Care, receiving research grants from Abbott Diabetes Care and Insulet, and holding stock options in Teladoc and Omada Health.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

AT AACE 2023

Clinic responsible for misdiagnosing newborn’s meningitis, must pay millions

according to a report in the Star Tribune, among other news outlets.

The story of the jury verdict begins in 2013, when the boy, Johnny Galligan, was just 8 days old.

Alarmed by the newborn’s crying, lack of appetite, and fever, his parents, Alina and Steve Galligan, brought him to Essentia-Health-Ashland Clinic, located in Memorial Medical Center, Ashland, Wisc. There, the baby was seen by Andrew D. Snider, MD, a family physician. Dr. Snider noted the baby’s extreme fussiness and irritability and was concerned that he was being overfed. Without ordering additional tests, the family physician sent the baby home but arranged for the Galligans to be visited by a county nurse the following day.

Her visit raised concerns, as court documents make clear. She contacted Dr. Snider’s office and explained that the baby needed to be seen immediately. After writing a script for reflux and constipation, Dr. Snider arranged for the baby to be taken to his office later that day.

Events proceeded rapidly from this point.

Following an x-ray, Johnny appeared lethargic and in respiratory distress. He was then taken down the hall to Memorial’s emergency department, where doctors suspected a critical bowel obstruction. Arrangements were made for him to be transported by helicopter to Essentia Health, Duluth, Minn. There, doctors saw that Johnny was acidotic and in respiratory failure. Once again, he was rerouted, this time to Children’s Hospital, Minneapolis, where physicians finally arrived at a definitive diagnosis: meningitis.

In 2020, the Galligans filed a medical malpractice claim against several parties, including Dr. Snider, Duluth Clinic (doing business as Essentia Health and Essentia Health–Ashland Clinic), and Memorial Hospital. In their suit, Johnny’s parents alleged that the collective failure to diagnose their son’s severe infection led directly to his permanent brain damage.

But a Bayfield County, Wisconsin, jury didn’t quite see things that way. After deliberating, it dismissed the claim against Dr. Snider and the other named defendants and found the staff of Duluth Clinic to be solely responsible for injuries to Johnny Galligan.

Duluth must pay $19 million to the Galligan family, of which the largest amount ($7,500,00) is to be directed to Johnny’s “future medical expenses and care needs.”

These expenses and costs are likely to be significant. Currently, at 10 years of age, Johnny can’t walk and is confined to a wheelchair. He has serious neurologic problems and is almost completely deaf and blind.

“He’s doing fairly well, which I attribute to his family providing care for him,” says the attorney who represented the Galligans. “They care for him 24/7. They take him swimming and on four-wheeler rides. He’s not bedridden. He has the best possible quality of life he could have, in my opinion.”

In a statement following the verdict, Essentia Health said that, while it felt “compassion for the family,” it stood by the care it had provided in 2013: “We are exploring our options regarding next steps and remain committed to delivering high-quality care to the patients and communities we are privileged to serve.”

ED physician found not liable for embolism, jury finds

A Missouri doctor accused of incorrectly treating a woman’s embolism has been found not liable for her death, reports a story in Missouri Lawyers Media.

The woman went to her local hospital’s ED complaining of pain and swelling in her leg. At the ED, an emergency physician examined her and discovered an extensive, visible thrombosis. No other symptoms were noted.

In the past, such a finding would have prompted immediate hospital admission. But the standard of care has evolved. Now, many doctors first prescribe enoxaparin sodium (Lovenox), an anticoagulant used to treat deep-vein thrombosis. This was the option chosen by the Missouri emergency physician to treat his patient. After administering a first dose of the drug, he wrote a script for additional doses; consulted with his patient’s primary care physician; and arranged for the patient to be seen by him, the ED physician, the following day.

At the drugstore, though, the woman became ill, and an emergency medical services crew was alerted. Despite its quick response, the woman died en route to the hospital. No autopsy was later performed, and it was generally presumed that she had died of a pulmonary embolism.

Following the woman’s death, her family sued the emergency physician, alleging that his failure to admit the woman to the hospital most likely delayed treatment that could have saved her life.

The defense pushed back, arguing that the ED physician had followed the standard of care. “Even if she [had] come into the ER with full-blown [pulmonary embolism],” says the attorney representing the emergency physician, “the first thing you do is give Lovenox. It is just one of those rare circumstances where you can do everything right, but the patient can still die.”

The trial jury agreed. After deliberating for more than an hour, it found that the emergency physician was not responsible for the patient’s death.

At press time, there was no word on whether the plaintiffs planned to appeal.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to a report in the Star Tribune, among other news outlets.

The story of the jury verdict begins in 2013, when the boy, Johnny Galligan, was just 8 days old.

Alarmed by the newborn’s crying, lack of appetite, and fever, his parents, Alina and Steve Galligan, brought him to Essentia-Health-Ashland Clinic, located in Memorial Medical Center, Ashland, Wisc. There, the baby was seen by Andrew D. Snider, MD, a family physician. Dr. Snider noted the baby’s extreme fussiness and irritability and was concerned that he was being overfed. Without ordering additional tests, the family physician sent the baby home but arranged for the Galligans to be visited by a county nurse the following day.

Her visit raised concerns, as court documents make clear. She contacted Dr. Snider’s office and explained that the baby needed to be seen immediately. After writing a script for reflux and constipation, Dr. Snider arranged for the baby to be taken to his office later that day.

Events proceeded rapidly from this point.

Following an x-ray, Johnny appeared lethargic and in respiratory distress. He was then taken down the hall to Memorial’s emergency department, where doctors suspected a critical bowel obstruction. Arrangements were made for him to be transported by helicopter to Essentia Health, Duluth, Minn. There, doctors saw that Johnny was acidotic and in respiratory failure. Once again, he was rerouted, this time to Children’s Hospital, Minneapolis, where physicians finally arrived at a definitive diagnosis: meningitis.

In 2020, the Galligans filed a medical malpractice claim against several parties, including Dr. Snider, Duluth Clinic (doing business as Essentia Health and Essentia Health–Ashland Clinic), and Memorial Hospital. In their suit, Johnny’s parents alleged that the collective failure to diagnose their son’s severe infection led directly to his permanent brain damage.

But a Bayfield County, Wisconsin, jury didn’t quite see things that way. After deliberating, it dismissed the claim against Dr. Snider and the other named defendants and found the staff of Duluth Clinic to be solely responsible for injuries to Johnny Galligan.

Duluth must pay $19 million to the Galligan family, of which the largest amount ($7,500,00) is to be directed to Johnny’s “future medical expenses and care needs.”

These expenses and costs are likely to be significant. Currently, at 10 years of age, Johnny can’t walk and is confined to a wheelchair. He has serious neurologic problems and is almost completely deaf and blind.

“He’s doing fairly well, which I attribute to his family providing care for him,” says the attorney who represented the Galligans. “They care for him 24/7. They take him swimming and on four-wheeler rides. He’s not bedridden. He has the best possible quality of life he could have, in my opinion.”

In a statement following the verdict, Essentia Health said that, while it felt “compassion for the family,” it stood by the care it had provided in 2013: “We are exploring our options regarding next steps and remain committed to delivering high-quality care to the patients and communities we are privileged to serve.”

ED physician found not liable for embolism, jury finds

A Missouri doctor accused of incorrectly treating a woman’s embolism has been found not liable for her death, reports a story in Missouri Lawyers Media.

The woman went to her local hospital’s ED complaining of pain and swelling in her leg. At the ED, an emergency physician examined her and discovered an extensive, visible thrombosis. No other symptoms were noted.

In the past, such a finding would have prompted immediate hospital admission. But the standard of care has evolved. Now, many doctors first prescribe enoxaparin sodium (Lovenox), an anticoagulant used to treat deep-vein thrombosis. This was the option chosen by the Missouri emergency physician to treat his patient. After administering a first dose of the drug, he wrote a script for additional doses; consulted with his patient’s primary care physician; and arranged for the patient to be seen by him, the ED physician, the following day.

At the drugstore, though, the woman became ill, and an emergency medical services crew was alerted. Despite its quick response, the woman died en route to the hospital. No autopsy was later performed, and it was generally presumed that she had died of a pulmonary embolism.

Following the woman’s death, her family sued the emergency physician, alleging that his failure to admit the woman to the hospital most likely delayed treatment that could have saved her life.

The defense pushed back, arguing that the ED physician had followed the standard of care. “Even if she [had] come into the ER with full-blown [pulmonary embolism],” says the attorney representing the emergency physician, “the first thing you do is give Lovenox. It is just one of those rare circumstances where you can do everything right, but the patient can still die.”

The trial jury agreed. After deliberating for more than an hour, it found that the emergency physician was not responsible for the patient’s death.

At press time, there was no word on whether the plaintiffs planned to appeal.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to a report in the Star Tribune, among other news outlets.

The story of the jury verdict begins in 2013, when the boy, Johnny Galligan, was just 8 days old.

Alarmed by the newborn’s crying, lack of appetite, and fever, his parents, Alina and Steve Galligan, brought him to Essentia-Health-Ashland Clinic, located in Memorial Medical Center, Ashland, Wisc. There, the baby was seen by Andrew D. Snider, MD, a family physician. Dr. Snider noted the baby’s extreme fussiness and irritability and was concerned that he was being overfed. Without ordering additional tests, the family physician sent the baby home but arranged for the Galligans to be visited by a county nurse the following day.

Her visit raised concerns, as court documents make clear. She contacted Dr. Snider’s office and explained that the baby needed to be seen immediately. After writing a script for reflux and constipation, Dr. Snider arranged for the baby to be taken to his office later that day.

Events proceeded rapidly from this point.

Following an x-ray, Johnny appeared lethargic and in respiratory distress. He was then taken down the hall to Memorial’s emergency department, where doctors suspected a critical bowel obstruction. Arrangements were made for him to be transported by helicopter to Essentia Health, Duluth, Minn. There, doctors saw that Johnny was acidotic and in respiratory failure. Once again, he was rerouted, this time to Children’s Hospital, Minneapolis, where physicians finally arrived at a definitive diagnosis: meningitis.

In 2020, the Galligans filed a medical malpractice claim against several parties, including Dr. Snider, Duluth Clinic (doing business as Essentia Health and Essentia Health–Ashland Clinic), and Memorial Hospital. In their suit, Johnny’s parents alleged that the collective failure to diagnose their son’s severe infection led directly to his permanent brain damage.

But a Bayfield County, Wisconsin, jury didn’t quite see things that way. After deliberating, it dismissed the claim against Dr. Snider and the other named defendants and found the staff of Duluth Clinic to be solely responsible for injuries to Johnny Galligan.

Duluth must pay $19 million to the Galligan family, of which the largest amount ($7,500,00) is to be directed to Johnny’s “future medical expenses and care needs.”

These expenses and costs are likely to be significant. Currently, at 10 years of age, Johnny can’t walk and is confined to a wheelchair. He has serious neurologic problems and is almost completely deaf and blind.

“He’s doing fairly well, which I attribute to his family providing care for him,” says the attorney who represented the Galligans. “They care for him 24/7. They take him swimming and on four-wheeler rides. He’s not bedridden. He has the best possible quality of life he could have, in my opinion.”

In a statement following the verdict, Essentia Health said that, while it felt “compassion for the family,” it stood by the care it had provided in 2013: “We are exploring our options regarding next steps and remain committed to delivering high-quality care to the patients and communities we are privileged to serve.”

ED physician found not liable for embolism, jury finds

A Missouri doctor accused of incorrectly treating a woman’s embolism has been found not liable for her death, reports a story in Missouri Lawyers Media.

The woman went to her local hospital’s ED complaining of pain and swelling in her leg. At the ED, an emergency physician examined her and discovered an extensive, visible thrombosis. No other symptoms were noted.

In the past, such a finding would have prompted immediate hospital admission. But the standard of care has evolved. Now, many doctors first prescribe enoxaparin sodium (Lovenox), an anticoagulant used to treat deep-vein thrombosis. This was the option chosen by the Missouri emergency physician to treat his patient. After administering a first dose of the drug, he wrote a script for additional doses; consulted with his patient’s primary care physician; and arranged for the patient to be seen by him, the ED physician, the following day.

At the drugstore, though, the woman became ill, and an emergency medical services crew was alerted. Despite its quick response, the woman died en route to the hospital. No autopsy was later performed, and it was generally presumed that she had died of a pulmonary embolism.

Following the woman’s death, her family sued the emergency physician, alleging that his failure to admit the woman to the hospital most likely delayed treatment that could have saved her life.

The defense pushed back, arguing that the ED physician had followed the standard of care. “Even if she [had] come into the ER with full-blown [pulmonary embolism],” says the attorney representing the emergency physician, “the first thing you do is give Lovenox. It is just one of those rare circumstances where you can do everything right, but the patient can still die.”

The trial jury agreed. After deliberating for more than an hour, it found that the emergency physician was not responsible for the patient’s death.

At press time, there was no word on whether the plaintiffs planned to appeal.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

H. pylori eradication therapy curbs risk for stomach cancer

People with H. pylori who were treated had about a 63% lower risk of developing noncardia gastric adenocarcinoma (NCGA) after 8 years of follow-up, compared with peers with H. pylori who were not treated.

The U.S. data align with previous studies, conducted mostly in Asia, that found that treating the infection can reduce stomach cancer incidence.

The KPNC study shows the “potential for stomach cancer prevention in U.S. populations through H. pylori screening and treatment,” study investigator Dan Li, MD, gastroenterologist with the Kaiser Permanente Medical Group and Kaiser Permanente Division of Research in Oakland, Calif., said in an interview.

Judith Kim, MD, a gastroenterologist at NYU Langone Health in New York, who wasn’t involved in the research, said that the study is significant because “it is the first to show this effect in a large, diverse population in the U.S., where gastric cancer incidence is lower.”

The study was published online in Gastroenterology.

Top risk factor

About 30% of people in the United States are infected with H. pylori, which is the No. 1 known risk factor for stomach cancer, Dr. Li said.

The study cohort included 716,567 KPNC members who underwent H. pylori testing and/or treatment between 1997 and 2015.

Among H. pylori–infected individuals (based on positive nonserology test results), the subdistribution hazard ratio was 6.07 for untreated individuals and 2.68 for treated individuals, compared with H. pylori–negative individuals.

It’s not surprising that people who were treated for the infection still had a higher risk of NCGA than people who had never had the infection, Dr. Li said.

“This is likely because many people with chronic H. pylori infection had already developed some precancerous changes in their stomach before they were treated. This finding suggests that H. pylori ideally should be treated before precancerous changes develop,” he said.

When compared directly with H. pylori–positive/untreated individuals, the risk for NCGA in H. pylori–positive/treated individuals was somewhat lower at less than 8 years follow-up (sHR, 0.95) and significantly lower at 8+ years of follow-up (sHR, 0.37).

“After 7-10 years of follow-up, people with H. pylori who received treatment had nearly half the risk of developing stomach cancer as the general population,” Dr. Li said. “This is likely because most people infected with H. pylori in the general population are not screened nor treated. This highlights the impact screening and treatment can have.”

The data also show that cumulative incidence curves for H. pylori–positive/untreated and H. pylori–positive/treated largely overlapped during the first 7 years of follow-up and started to separate after 8 years.

At 10 years, cumulative NCGA incidence rates for H. pylori–positive/untreated, H. pylori–positive/treated, and H. pylori negative were 31.0, 19.7, and 3.5 per 10,000 persons, respectively (P < .0001).

This study shows that treating H. pylori reduces stomach cancer incidence in the United States, thus “filling an important research and knowledge gap,” Dr. Li said.

In the United States, Asian, Black, and Hispanic adults are much more likely to be infected with H. pylori, and they have a two- to threefold higher risk of developing stomach cancer, he noted.

“This suggests it may be reasonable to consider targeted screening and treatment in these high-risk groups. However, the optimal strategy for population-based H. pylori screening has not been established, and more research is needed to determine who should be screened for H. pylori and at what age screening should begin,” Dr. Li said.

Strong data, jury out on universal screening