User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Few Women Know Uterine Fibroid Risk, Treatment Options

Most women (72%) are not aware they are at risk for developing uterine fibroids, though up to 77% of women will develop them in their lifetime, results of a new survey indicate.

Data from The Harris Poll, conducted on behalf of the Society of Interventional Radiology, also found that 17% of women mistakenly think a hysterectomy is the only treatment option, including more than one in four women (27%) who are between the ages of 18 and 34. Results were shared in a press release. The survey included 1,122 US women, some who have been diagnosed with uterine fibroids.

Fibroids may not cause symptoms for some, but some women may have heavy, prolonged, debilitating bleeding. Some women experience pelvic pain, a diminished sex life, and declining energy. However, the growths do not spread to other body regions and typically are not dangerous.

Hysterectomy Is Only One Option

Among the women in the survey who had been diagnosed with fibroids, 53% were presented the option of hysterectomy and 20% were told about other, less-invasive options, including over-the-counter NSAIDs (19%); uterine fibroid embolization (UFE) (17%); oral contraceptives (17%); and endometrial ablation (17%).

“Women need to be informed about the complete range of options available for treating their uterine fibroids, not just the surgical options as is most commonly done by gynecologists,” John C. Lipman, MD, founder and medical director of the Atlanta Fibroid Center in Smyrna, Georgia, said in the press release.

The survey also found that:

- More than half of women ages 18-34 (56%) and women ages 35-44 (51%) were either not familiar with uterine fibroids or never heard of them.

- Awareness was particularly low among Hispanic women, as 50% of Hispanic women say they’ve never heard of or aren’t familiar with the condition, compared with 37% of Black women who answered that way.

- More than one third (36%) of Black women and 22% of Hispanic women mistakenly think they are not at risk for developing fibroids, yet research has shown that uterine fibroids are three times more common in Black women and two times more common in Hispanic women than in White women.

For this study, the full sample data is accurate to within +/– 3.2 percentage points using a 95% confidence level. The data are part of the report “The Fibroid Fix: What Women Need to Know,” published on July 9 by the Society of Interventional Radiology.

Linda Fan, MD, chief of gynecology at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, said she is not surprised by those numbers. She says many patients are referred to her department who have not been given the full array of medical options for their fibroids or have not had thorough discussions with their providers, such as whether they want to preserve their fertility, or how they feel about an incision, undergoing anesthesia, or having their uterus removed.

Sometimes the hysterectomy choice is clear, she said — for instance, if there are indications of the rare cancer leiomyosarcoma, or if a postmenopausal woman has rapid growth of fibroids or heavy bleeding. Fibroids should not start growing after menopause, she said.

Additional options include radiofrequency ablation, performed while a patient is under anesthesia, by laparoscopy or hysteroscopy. The procedure uses ultrasound to watch a probe as it shrinks the fibroids with heat.

Currently, if a woman wants large fibroids removed and wants to keep her fertility options open, Dr. Fan says, myomectomy or medication are best “because we have the most information or data on (those options).”

When treating patients who don’t prioritize fertility, she said, UFE is a good option that doesn’t need incisions or anesthesia. But patients sometimes require a lot of pain medication afterward, Dr. Fan said. With radiofrequency ablation, specifically the Acessa and Sonata procedures, she said, “patients don’t experience a lot of pain after the procedure because the shrinking happens when they’re asleep under anesthesia.”

Uterine Fibroid Embolization a Nonsurgical Option

The report describes how UFE works but the Harris Poll showed that 60% of women who have heard of UFE did not hear about it first from a healthcare provider.

“UFE is a nonsurgical treatment, performed by interventional radiologists, that has been proven to significantly reduce heavy menstrual bleeding, relieve uterine pain, and improve energy levels,” the authors write. “Through a tiny incision in the wrist or thigh, a catheter is guided via imaging to the vessels leading to the fibroids. Through this catheter, small clear particles are injected to block the blood flow leading to the fibroids causing them to shrink and disappear.”

After UFE, most women leave the hospital the day of or the day after treatment, according to the report authors, who add that many patients also report they can resume normal activity in about 2 weeks, more quickly than with surgical treatments.

In some cases, watchful waiting will be the best option, the report notes, and that may require repeated checkups and scans.

Dr. Lipman is an adviser on The Fibroid Fix report.

Most women (72%) are not aware they are at risk for developing uterine fibroids, though up to 77% of women will develop them in their lifetime, results of a new survey indicate.

Data from The Harris Poll, conducted on behalf of the Society of Interventional Radiology, also found that 17% of women mistakenly think a hysterectomy is the only treatment option, including more than one in four women (27%) who are between the ages of 18 and 34. Results were shared in a press release. The survey included 1,122 US women, some who have been diagnosed with uterine fibroids.

Fibroids may not cause symptoms for some, but some women may have heavy, prolonged, debilitating bleeding. Some women experience pelvic pain, a diminished sex life, and declining energy. However, the growths do not spread to other body regions and typically are not dangerous.

Hysterectomy Is Only One Option

Among the women in the survey who had been diagnosed with fibroids, 53% were presented the option of hysterectomy and 20% were told about other, less-invasive options, including over-the-counter NSAIDs (19%); uterine fibroid embolization (UFE) (17%); oral contraceptives (17%); and endometrial ablation (17%).

“Women need to be informed about the complete range of options available for treating their uterine fibroids, not just the surgical options as is most commonly done by gynecologists,” John C. Lipman, MD, founder and medical director of the Atlanta Fibroid Center in Smyrna, Georgia, said in the press release.

The survey also found that:

- More than half of women ages 18-34 (56%) and women ages 35-44 (51%) were either not familiar with uterine fibroids or never heard of them.

- Awareness was particularly low among Hispanic women, as 50% of Hispanic women say they’ve never heard of or aren’t familiar with the condition, compared with 37% of Black women who answered that way.

- More than one third (36%) of Black women and 22% of Hispanic women mistakenly think they are not at risk for developing fibroids, yet research has shown that uterine fibroids are three times more common in Black women and two times more common in Hispanic women than in White women.

For this study, the full sample data is accurate to within +/– 3.2 percentage points using a 95% confidence level. The data are part of the report “The Fibroid Fix: What Women Need to Know,” published on July 9 by the Society of Interventional Radiology.

Linda Fan, MD, chief of gynecology at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, said she is not surprised by those numbers. She says many patients are referred to her department who have not been given the full array of medical options for their fibroids or have not had thorough discussions with their providers, such as whether they want to preserve their fertility, or how they feel about an incision, undergoing anesthesia, or having their uterus removed.

Sometimes the hysterectomy choice is clear, she said — for instance, if there are indications of the rare cancer leiomyosarcoma, or if a postmenopausal woman has rapid growth of fibroids or heavy bleeding. Fibroids should not start growing after menopause, she said.

Additional options include radiofrequency ablation, performed while a patient is under anesthesia, by laparoscopy or hysteroscopy. The procedure uses ultrasound to watch a probe as it shrinks the fibroids with heat.

Currently, if a woman wants large fibroids removed and wants to keep her fertility options open, Dr. Fan says, myomectomy or medication are best “because we have the most information or data on (those options).”

When treating patients who don’t prioritize fertility, she said, UFE is a good option that doesn’t need incisions or anesthesia. But patients sometimes require a lot of pain medication afterward, Dr. Fan said. With radiofrequency ablation, specifically the Acessa and Sonata procedures, she said, “patients don’t experience a lot of pain after the procedure because the shrinking happens when they’re asleep under anesthesia.”

Uterine Fibroid Embolization a Nonsurgical Option

The report describes how UFE works but the Harris Poll showed that 60% of women who have heard of UFE did not hear about it first from a healthcare provider.

“UFE is a nonsurgical treatment, performed by interventional radiologists, that has been proven to significantly reduce heavy menstrual bleeding, relieve uterine pain, and improve energy levels,” the authors write. “Through a tiny incision in the wrist or thigh, a catheter is guided via imaging to the vessels leading to the fibroids. Through this catheter, small clear particles are injected to block the blood flow leading to the fibroids causing them to shrink and disappear.”

After UFE, most women leave the hospital the day of or the day after treatment, according to the report authors, who add that many patients also report they can resume normal activity in about 2 weeks, more quickly than with surgical treatments.

In some cases, watchful waiting will be the best option, the report notes, and that may require repeated checkups and scans.

Dr. Lipman is an adviser on The Fibroid Fix report.

Most women (72%) are not aware they are at risk for developing uterine fibroids, though up to 77% of women will develop them in their lifetime, results of a new survey indicate.

Data from The Harris Poll, conducted on behalf of the Society of Interventional Radiology, also found that 17% of women mistakenly think a hysterectomy is the only treatment option, including more than one in four women (27%) who are between the ages of 18 and 34. Results were shared in a press release. The survey included 1,122 US women, some who have been diagnosed with uterine fibroids.

Fibroids may not cause symptoms for some, but some women may have heavy, prolonged, debilitating bleeding. Some women experience pelvic pain, a diminished sex life, and declining energy. However, the growths do not spread to other body regions and typically are not dangerous.

Hysterectomy Is Only One Option

Among the women in the survey who had been diagnosed with fibroids, 53% were presented the option of hysterectomy and 20% were told about other, less-invasive options, including over-the-counter NSAIDs (19%); uterine fibroid embolization (UFE) (17%); oral contraceptives (17%); and endometrial ablation (17%).

“Women need to be informed about the complete range of options available for treating their uterine fibroids, not just the surgical options as is most commonly done by gynecologists,” John C. Lipman, MD, founder and medical director of the Atlanta Fibroid Center in Smyrna, Georgia, said in the press release.

The survey also found that:

- More than half of women ages 18-34 (56%) and women ages 35-44 (51%) were either not familiar with uterine fibroids or never heard of them.

- Awareness was particularly low among Hispanic women, as 50% of Hispanic women say they’ve never heard of or aren’t familiar with the condition, compared with 37% of Black women who answered that way.

- More than one third (36%) of Black women and 22% of Hispanic women mistakenly think they are not at risk for developing fibroids, yet research has shown that uterine fibroids are three times more common in Black women and two times more common in Hispanic women than in White women.

For this study, the full sample data is accurate to within +/– 3.2 percentage points using a 95% confidence level. The data are part of the report “The Fibroid Fix: What Women Need to Know,” published on July 9 by the Society of Interventional Radiology.

Linda Fan, MD, chief of gynecology at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, said she is not surprised by those numbers. She says many patients are referred to her department who have not been given the full array of medical options for their fibroids or have not had thorough discussions with their providers, such as whether they want to preserve their fertility, or how they feel about an incision, undergoing anesthesia, or having their uterus removed.

Sometimes the hysterectomy choice is clear, she said — for instance, if there are indications of the rare cancer leiomyosarcoma, or if a postmenopausal woman has rapid growth of fibroids or heavy bleeding. Fibroids should not start growing after menopause, she said.

Additional options include radiofrequency ablation, performed while a patient is under anesthesia, by laparoscopy or hysteroscopy. The procedure uses ultrasound to watch a probe as it shrinks the fibroids with heat.

Currently, if a woman wants large fibroids removed and wants to keep her fertility options open, Dr. Fan says, myomectomy or medication are best “because we have the most information or data on (those options).”

When treating patients who don’t prioritize fertility, she said, UFE is a good option that doesn’t need incisions or anesthesia. But patients sometimes require a lot of pain medication afterward, Dr. Fan said. With radiofrequency ablation, specifically the Acessa and Sonata procedures, she said, “patients don’t experience a lot of pain after the procedure because the shrinking happens when they’re asleep under anesthesia.”

Uterine Fibroid Embolization a Nonsurgical Option

The report describes how UFE works but the Harris Poll showed that 60% of women who have heard of UFE did not hear about it first from a healthcare provider.

“UFE is a nonsurgical treatment, performed by interventional radiologists, that has been proven to significantly reduce heavy menstrual bleeding, relieve uterine pain, and improve energy levels,” the authors write. “Through a tiny incision in the wrist or thigh, a catheter is guided via imaging to the vessels leading to the fibroids. Through this catheter, small clear particles are injected to block the blood flow leading to the fibroids causing them to shrink and disappear.”

After UFE, most women leave the hospital the day of or the day after treatment, according to the report authors, who add that many patients also report they can resume normal activity in about 2 weeks, more quickly than with surgical treatments.

In some cases, watchful waiting will be the best option, the report notes, and that may require repeated checkups and scans.

Dr. Lipman is an adviser on The Fibroid Fix report.

Managing Cancer in Pregnancy: Improvements and Considerations

Introduction: Tremendous Progress on Cancer Extends to Cancer in Pregnancy

The biomedical research enterprise that took shape in the United States after World War II has had numerous positive effects, including significant progress made during the past 75-plus years in the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of cancer.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1944 request of Dr. Vannevar Bush, director of the then Office of Scientific Research and Development, to organize a program that would advance and apply scientific knowledge for times of peace — just as it been advanced and applied in times of war — culminated in a historic report, Science – The Endless Frontier. Presented in 1945 to President Harry S. Truman, this report helped fuel decades of broad, bold, and coordinated government-sponsored biomedical research aimed at addressing disease and improving the health of the American people (National Science Foundation, 1945).

Discoveries made from research in basic and translational sciences deepened our knowledge of the cellular and molecular underpinnings of cancer, leading to advances in chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and other treatment approaches as well as continual refinements in their application. Similarly, our diagnostic armamentarium has significantly improved.

As a result, we have reduced both the incidence and mortality of cancer. Today, some cancers can be prevented. Others can be reversed or put in remission. Granted, progress has been variable, with some cancers such as ovarian cancer still having relatively low survival rates. Much more needs to be done. Overall, however, the positive effects of the U.S. biomedical research enterprise on cancer are evident. According to the National Cancer Institute’s most recent report on the status of cancer, death rates from cancer fell 1.9% per year on average in females from 2015 to 2019 (Cancer. 2022 Oct 22. doi: 10.1002/cncr.34479).

It is not only patients whose cancer occurs outside of pregnancy who have benefited. When treatment is appropriately selected and timing considerations are made, patients whose cancer is diagnosed during pregnancy — and their children — can have good outcomes.

To explain how the management of cancer in pregnancy has improved, we have invited Gautam G. Rao, MD, gynecologic oncologist and associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, to write this installment of the Master Class in Obstetrics. As Dr. Rao explains, radiation is not as dangerous to the fetus as once thought, and the safety of many chemotherapeutic regimens in pregnancy has been documented. Obstetricians can and should counsel patients, he explains, about the likelihood of good maternal and fetal outcomes.

E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist, is dean emeritus of the University of Maryland School of Medicine, former university executive vice president; currently the endowed professor and director of the Center for Advanced Research Training and Innovation (CARTI), and senior scientist in the Center for Birth Defects Research. Dr. Reece reported no relevant disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

Managing Cancer in Pregnancy

Cancer can cause fear and distress for any patient, but when cancer is diagnosed during pregnancy, an expectant mother fears not only for her own health but for the health of her unborn child. Fortunately, ob.gyn.s and multidisciplinary teams have good reason to reassure patients about the likelihood of good outcomes.

Cancer treatment in pregnancy has improved with advancements in imaging and chemotherapy, and while maternal and fetal outcomes of prenatal cancer treatment are not well reported, evidence acquired in recent years from case series and retrospective studies shows that most imaging studies and procedural diagnostic tests – and many treatments – can be performed safely in pregnancy.

Decades ago, we avoided CT scans during pregnancy because of concerns about radiation exposure to the fetus, leaving some patients without an accurate staging of their cancer. Today, we have evidence that a CT scan is generally safe in pregnancy. Similarly, the safety of many chemotherapeutic regimens in pregnancy has been documented in recent decades,and the use of chemotherapy during pregnancy has increased progressively. Radiation is also commonly utilized in the management of cancers that may occur during pregnancy, such as breast cancer.1

Considerations of timing are often central to decision-making; chemotherapy and radiotherapy are generally avoided in the first trimester to prevent structural fetal anomalies, for instance, and delaying cancer treatment is often warranted when the patient is a few weeks away from delivery. On occasion, iatrogenic preterm birth is considered when the risks to the mother of delaying a necessary cancer treatment outweigh the risks to the fetus of prematurity.1

Pregnancy termination is rarely indicated, however, and information gathered over the past 2 decades suggests that fetal and placental metastases are rare.1 There is broad agreement that prenatal treatment of cancer in pregnancy should adhere as much as possible to protocols and guidelines for nonpregnant patients and that treatment delays driven by fear of fetal anomalies and miscarriage are unnecessary.

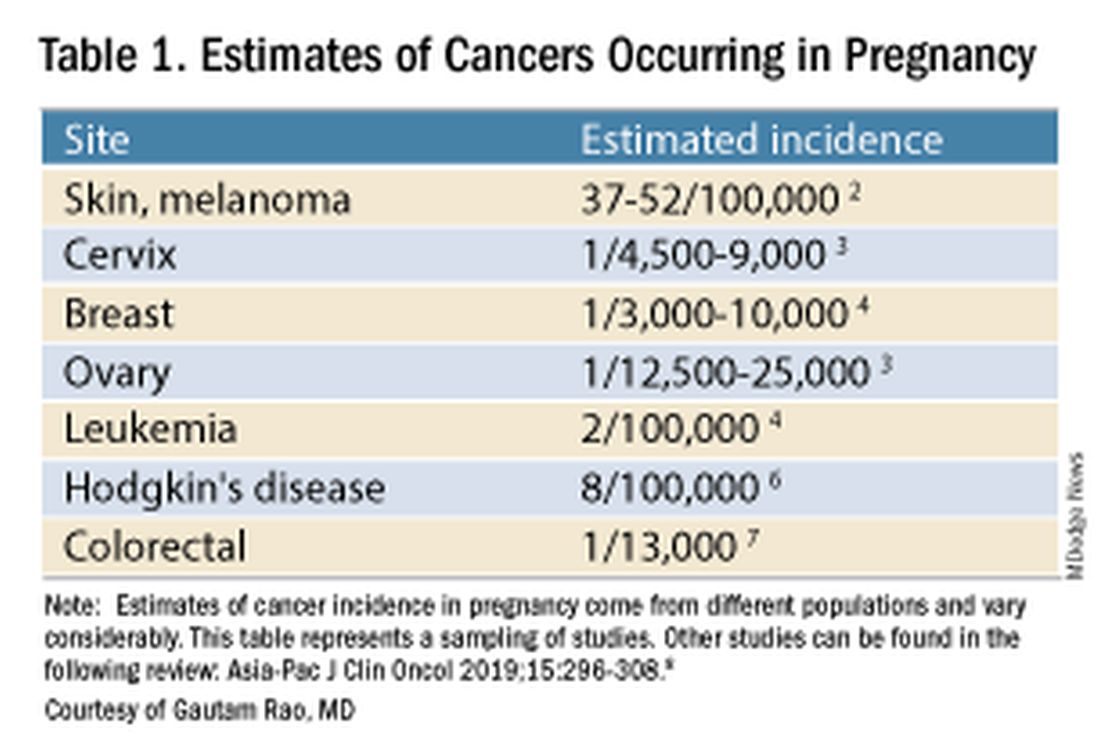

Cancer Incidence, Use of Diagnostic Imaging

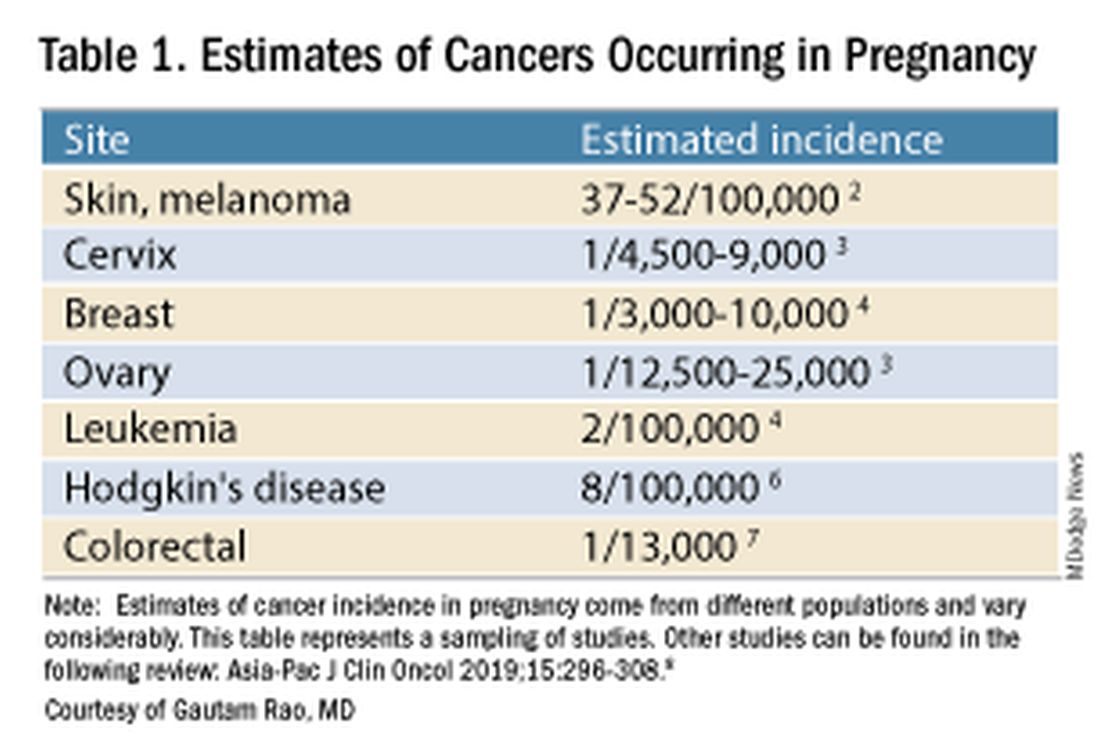

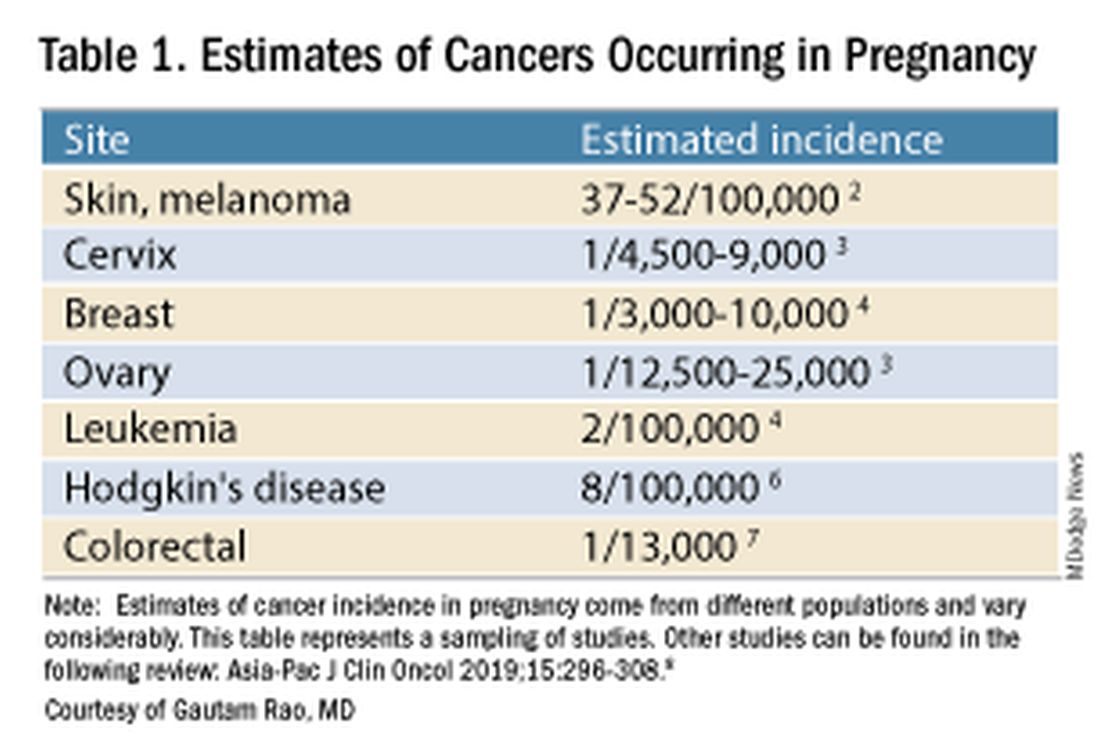

Data on the incidence of cancer in pregnancy comes from population-based cancer registries, and unfortunately, these data are not standardized and are often incomplete. Many studies include cancer diagnosed up to 1 year after pregnancy, and some include preinvasive disease. Estimates therefore vary considerably (see Table 1 for a sampling of estimates incidences.)

It has been reported, and often cited in the literature, that invasive malignancy complicates one in 1,000 pregnancies and that the incidence of cancer in pregnancy (invasive and noninvasive malignancies) has been rising over time.8 Increasing maternal age is believed to be playing a role in this rise; as women delay childbearing, they enter the age range in which some cancers become more common. Additionally, improvements in screening and diagnostics have led to earlier cancer detection. The incidence of ovarian neoplasms found during pregnancy has increased, for instance, with the routine use of diagnostic ultrasound in pregnancy.1

Among the studies showing an increased incidence of pregnancy-associated cancer is a population-based study in Australia, which found that from 1994 to 2007 the crude incidence of pregnancy-associated cancer increased from 112.3 to 191.5 per 100,000 pregnancies (P < .001).9 A cohort study in the United States documented an increase in incidence from 75.0 per 100,000 pregnancies in 2002 to 138.5 per 100,000 pregnancies in 2012.10

Overall, the literature shows us that the skin, cervix, and breast are also common sites for malignancy during pregnancy.1 According to a 2022 review, breast cancer during pregnancy is less often hormone receptor–positive and more frequently triple negative compared with age-matched controls.11 The frequencies of other pregnancy-associated cancers appear overall to be similar to that of cancer occurring in all women across their reproductive years.1

Too often, diagnosis is delayed because cancer symptoms can be masked by or can mimic normal physiological changes in pregnancy. For instance, breast cancer can be difficult to diagnose during pregnancy and lactation due to anatomic changes in the breast parenchyma. Several studies published in the 1990s showed that breast cancer presents at a more advanced stage in pregnant patients than in nonpregnant patients because of this delay.1 Skin changes suggestive of melanoma can be attributed to hyperpigmentation of pregnancy, for instance. Several observational studies have suggested that thicker melanomas found in pregnancy may be because of delayed diagnosis.8

It is important that we thoroughly investigate signs and symptoms suggestive of a malignancy and not automatically attribute these symptoms to the pregnancy itself. Cervical biopsy of a mass or lesion suspicious for cervical cancer can be done safely during pregnancy and should not be delayed or deferred.

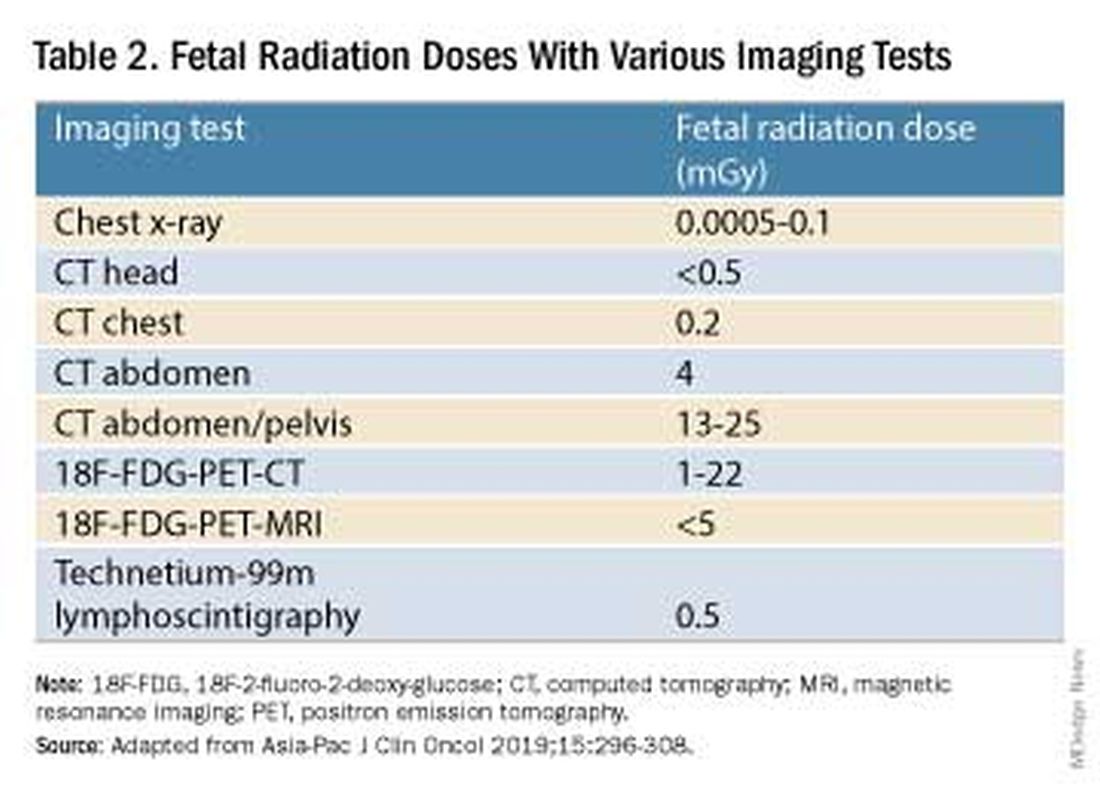

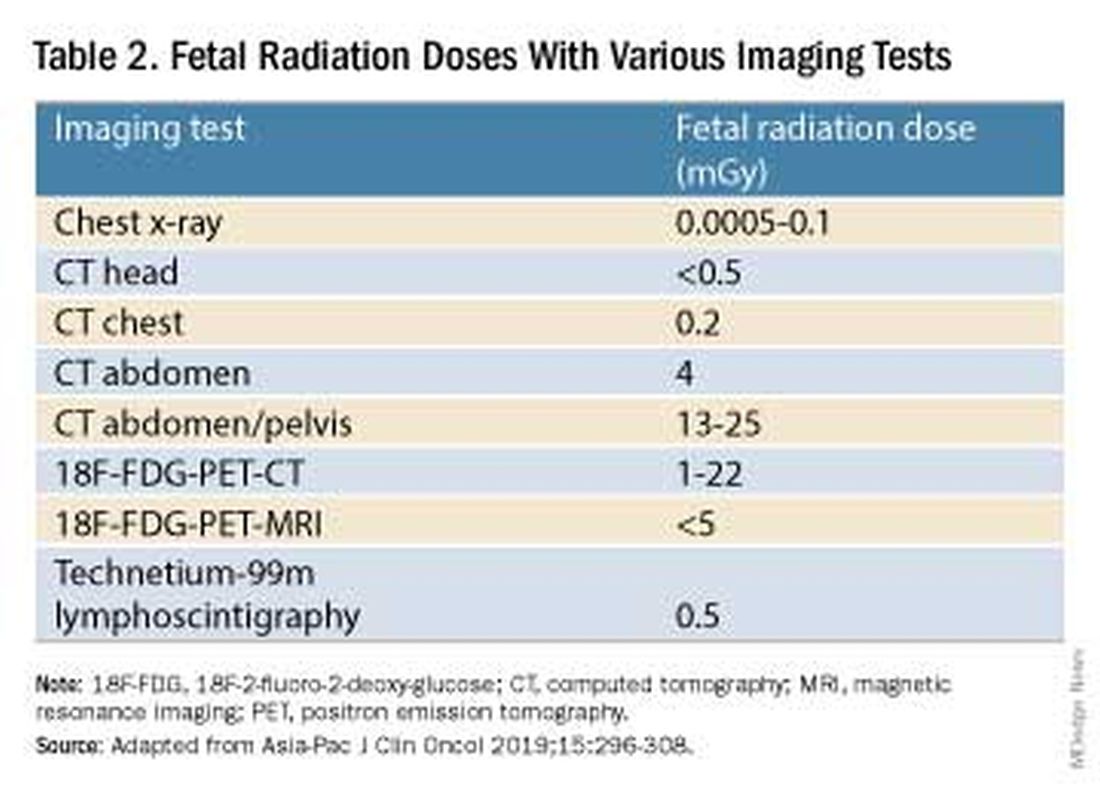

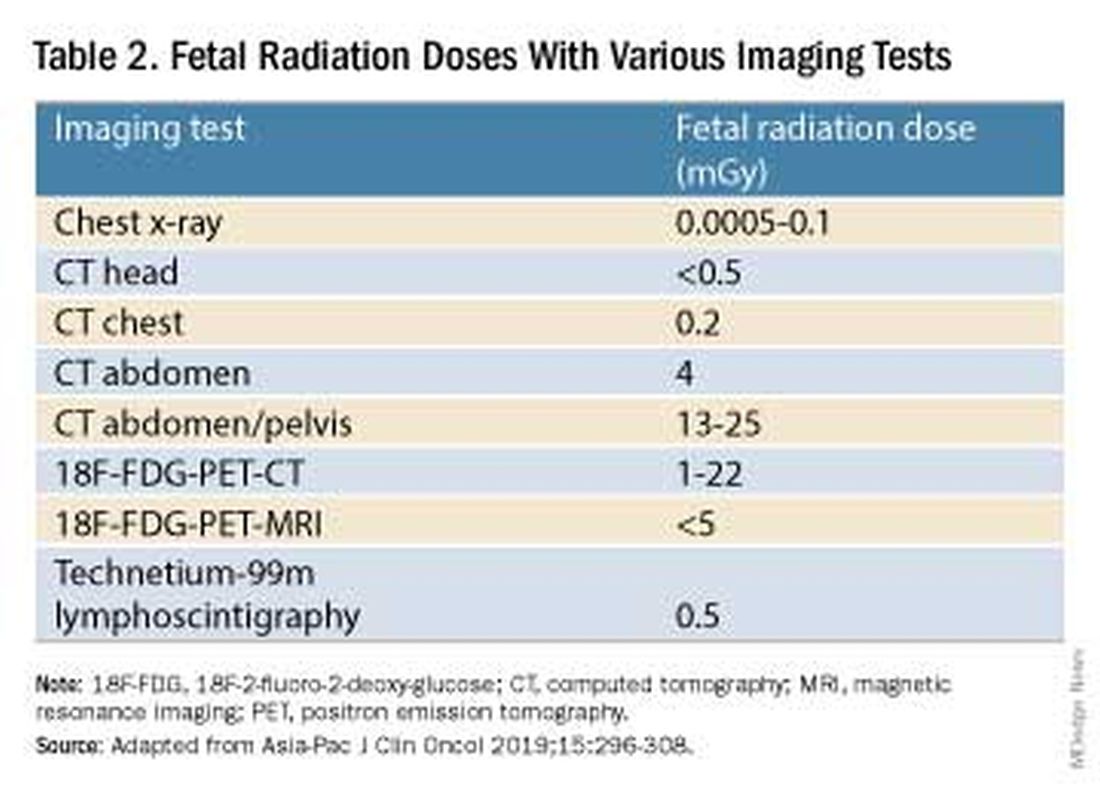

Fetal radiation exposure from radiologic examinations has long been a concern, but we know today that while the imaging modality should be chosen to minimize fetal radiation exposure, CT scans and even PET scans should be performed if these exams are deemed best for evaluation. Embryonic exposure to a dose of less than 50 mGy is rarely if at all associated with fetal malformations or miscarriage and a radiation dose of 100 mGy may be considered a floor for consideration of therapeutic termination of pregnancy.1,8

CT exams are associated with a fetal dose far less than 50 mGy (see Table 2 for radiation doses).

Magnetic resonance imaging with a magnet strength of 3 Tesla or less in any trimester is not associated with an increased risk of harm to the fetus or in early childhood, but the contrast agent gadolinium should be avoided in pregnancy as it has been associated with an increased risk of stillbirth, neonatal death, and childhood inflammatory, rheumatologic, and infiltrative skin lesions.1,8,12

Chemotherapy, Surgery, and Radiation in Pregnancy

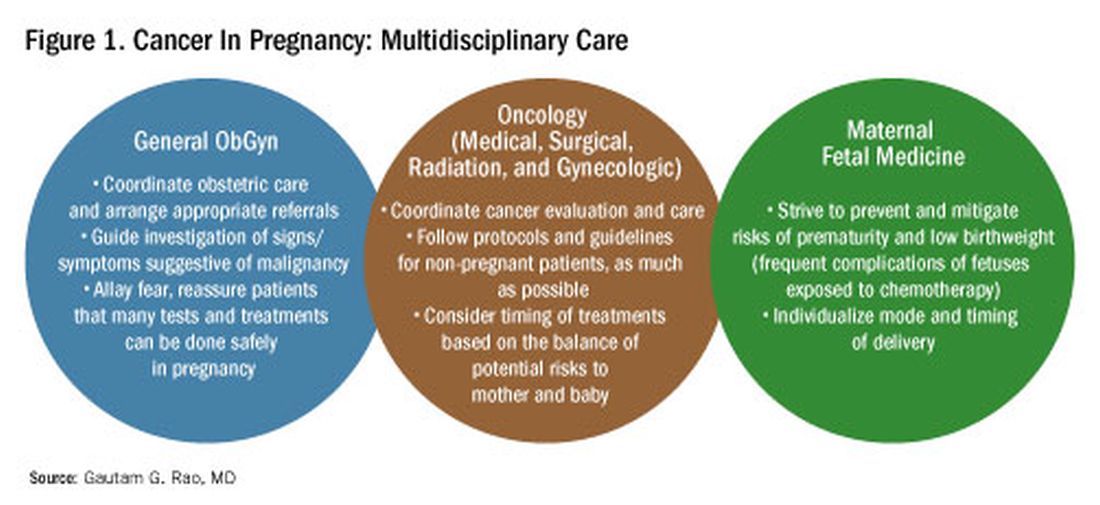

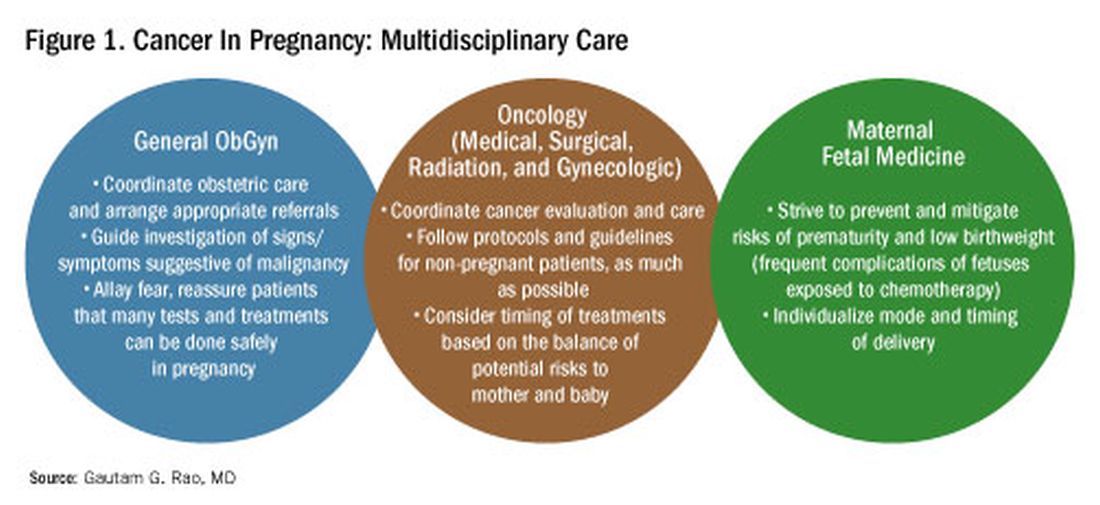

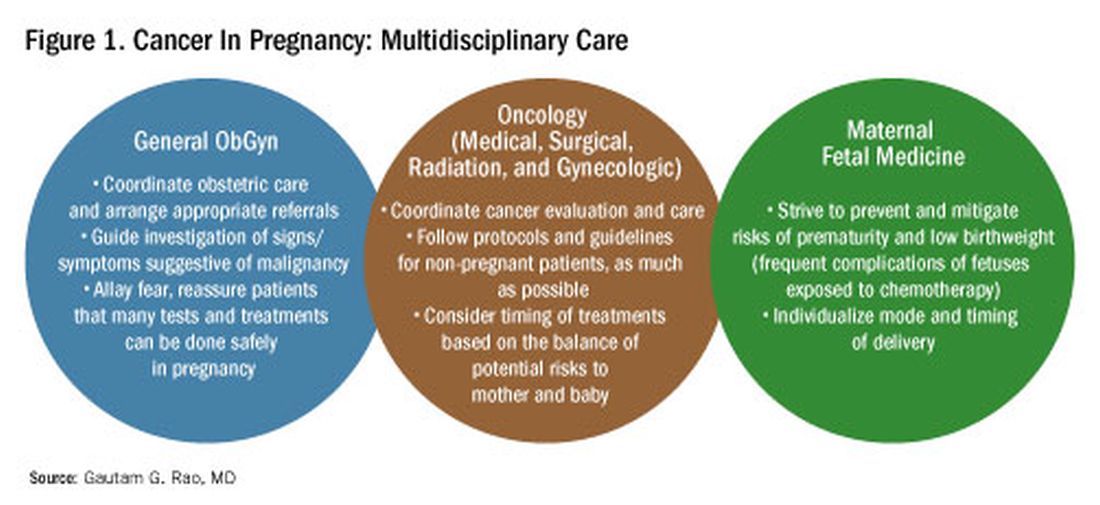

The management of cancer during pregnancy requires a multidisciplinary team including medical, gynecologic, or radiation oncologists, and maternal-fetal medicine specialists (Figure 1). Prematurity and low birth weight are frequent complications for fetuses exposed to chemotherapy, although there is some uncertainty as to whether the treatment is causative. However, congenital anomalies no longer are a major concern, provided that drugs are appropriately selected and that fetal exposure occurs during the second or third trimester.

For instance, alkylating agents including cisplatin (an important drug in the management of gynecologic malignancies) have been associated with congenital anomalies in the first trimester but not in the second and third trimesters, and a variety of antimetabolites — excluding methotrexate and aminopterin — similarly have been shown to be relatively safe when used after the first trimester.1

Small studies have shown no long-term effects of chemotherapy exposure on postnatal growth and long-term neurologic/neurocognitive function,1 but this is an area that needs more research.

Also in need of investigation is the safety of newer agents in pregnancy. Data are limited on the use of new targeted treatments, monoclonal antibodies, and immunotherapies in pregnancy and their effects on the fetus, with current knowledge coming mainly from single case reports.13

Until more is learned — a challenge given that pregnant women are generally excluded from clinical trials — management teams are generally postponing use of these therapies until after delivery. Considering the pace of new developments revolutionizing cancer treatment, this topic will likely get more complex and confusing before we begin acquiring sufficient knowledge.

The timing of surgery for malignancy in pregnancy is similarly based on the balance of maternal and fetal risks, including the risk of maternal disease progression, the risk of preterm delivery, and the prevention of fetal metastases. In general, the safest time is the second trimester.

Maternal surgery in the third trimester may be associated with a risk of premature labor and altered uteroplacental perfusion. A 2005 systematic review of 12,452 women who underwent nonobstetric surgery during pregnancy provides some reassurance, however; compared with the general obstetric population, there was no increase in the rate of miscarriage or major birth defects.14

Radiotherapy used to be contraindicated in pregnancy but many experts today believe it can be safely utilized provided the uterus is out of field and is protected from scattered radiation. The head, neck, and breast, for instance, can be treated with newer radiotherapies, including stereotactic ablative radiation therapy.8 Patients with advanced cervical cancer often receive chemotherapy during pregnancy to slow metastatic growth followed by definitive treatment with postpartum radiation or surgery.

More research is needed, but available data on maternal outcomes are encouraging. For instance, there appear to be no significant differences in short- and long-term complications or survival between women who are pregnant and nonpregnant when treated for invasive cervical cancer.8 Similarly, while earlier studies of breast cancer diagnosed during pregnancy suggested a poor prognosis, data now show similar prognoses for pregnant and nonpregnant patients when controlled for stage.1

Dr. Rao is a gynecologic oncologist and associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore. He reported no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Rao GG. Chapter 42. Clinical Obstetrics: The Fetus & Mother, 4th ed. Reece EA et al. (eds): 2021.

2. Bannister-Tyrrell M et al. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;55:116-122.

3. Oehler MK et al. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;43(6):414-420.

4. Ruiz R et al. Breast. 2017;35:136-141. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2017.07.008.

5. Nolan S et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(1):S480. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.11.752.

6. El-Messidi A et al. J Perinat Med. 2015;43(6):683-688. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2014-0133.

7. Pellino G et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29(7):743-753. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000863.

8. Eastwood-Wilshere N et al. Asia-Pac J Clin Oncol. 2019;15:296-308.

9. Lee YY et al. BJOG. 2012;119(13):1572-1582.

10. Cottreau CM et al. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019 Feb;28(2):250-257.

11. Boere I et al. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;82:46-59.

12. Ray JG et al. JAMA 2016;316(9):952-961.

13. Schwab R et al. Cancers. (Basel) 2021;13(12):3048.

14. Cohen-Kerem et al. Am J Surg. 2005;190(3):467-473.

Introduction: Tremendous Progress on Cancer Extends to Cancer in Pregnancy

The biomedical research enterprise that took shape in the United States after World War II has had numerous positive effects, including significant progress made during the past 75-plus years in the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of cancer.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1944 request of Dr. Vannevar Bush, director of the then Office of Scientific Research and Development, to organize a program that would advance and apply scientific knowledge for times of peace — just as it been advanced and applied in times of war — culminated in a historic report, Science – The Endless Frontier. Presented in 1945 to President Harry S. Truman, this report helped fuel decades of broad, bold, and coordinated government-sponsored biomedical research aimed at addressing disease and improving the health of the American people (National Science Foundation, 1945).

Discoveries made from research in basic and translational sciences deepened our knowledge of the cellular and molecular underpinnings of cancer, leading to advances in chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and other treatment approaches as well as continual refinements in their application. Similarly, our diagnostic armamentarium has significantly improved.

As a result, we have reduced both the incidence and mortality of cancer. Today, some cancers can be prevented. Others can be reversed or put in remission. Granted, progress has been variable, with some cancers such as ovarian cancer still having relatively low survival rates. Much more needs to be done. Overall, however, the positive effects of the U.S. biomedical research enterprise on cancer are evident. According to the National Cancer Institute’s most recent report on the status of cancer, death rates from cancer fell 1.9% per year on average in females from 2015 to 2019 (Cancer. 2022 Oct 22. doi: 10.1002/cncr.34479).

It is not only patients whose cancer occurs outside of pregnancy who have benefited. When treatment is appropriately selected and timing considerations are made, patients whose cancer is diagnosed during pregnancy — and their children — can have good outcomes.

To explain how the management of cancer in pregnancy has improved, we have invited Gautam G. Rao, MD, gynecologic oncologist and associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, to write this installment of the Master Class in Obstetrics. As Dr. Rao explains, radiation is not as dangerous to the fetus as once thought, and the safety of many chemotherapeutic regimens in pregnancy has been documented. Obstetricians can and should counsel patients, he explains, about the likelihood of good maternal and fetal outcomes.

E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist, is dean emeritus of the University of Maryland School of Medicine, former university executive vice president; currently the endowed professor and director of the Center for Advanced Research Training and Innovation (CARTI), and senior scientist in the Center for Birth Defects Research. Dr. Reece reported no relevant disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

Managing Cancer in Pregnancy

Cancer can cause fear and distress for any patient, but when cancer is diagnosed during pregnancy, an expectant mother fears not only for her own health but for the health of her unborn child. Fortunately, ob.gyn.s and multidisciplinary teams have good reason to reassure patients about the likelihood of good outcomes.

Cancer treatment in pregnancy has improved with advancements in imaging and chemotherapy, and while maternal and fetal outcomes of prenatal cancer treatment are not well reported, evidence acquired in recent years from case series and retrospective studies shows that most imaging studies and procedural diagnostic tests – and many treatments – can be performed safely in pregnancy.

Decades ago, we avoided CT scans during pregnancy because of concerns about radiation exposure to the fetus, leaving some patients without an accurate staging of their cancer. Today, we have evidence that a CT scan is generally safe in pregnancy. Similarly, the safety of many chemotherapeutic regimens in pregnancy has been documented in recent decades,and the use of chemotherapy during pregnancy has increased progressively. Radiation is also commonly utilized in the management of cancers that may occur during pregnancy, such as breast cancer.1

Considerations of timing are often central to decision-making; chemotherapy and radiotherapy are generally avoided in the first trimester to prevent structural fetal anomalies, for instance, and delaying cancer treatment is often warranted when the patient is a few weeks away from delivery. On occasion, iatrogenic preterm birth is considered when the risks to the mother of delaying a necessary cancer treatment outweigh the risks to the fetus of prematurity.1

Pregnancy termination is rarely indicated, however, and information gathered over the past 2 decades suggests that fetal and placental metastases are rare.1 There is broad agreement that prenatal treatment of cancer in pregnancy should adhere as much as possible to protocols and guidelines for nonpregnant patients and that treatment delays driven by fear of fetal anomalies and miscarriage are unnecessary.

Cancer Incidence, Use of Diagnostic Imaging

Data on the incidence of cancer in pregnancy comes from population-based cancer registries, and unfortunately, these data are not standardized and are often incomplete. Many studies include cancer diagnosed up to 1 year after pregnancy, and some include preinvasive disease. Estimates therefore vary considerably (see Table 1 for a sampling of estimates incidences.)

It has been reported, and often cited in the literature, that invasive malignancy complicates one in 1,000 pregnancies and that the incidence of cancer in pregnancy (invasive and noninvasive malignancies) has been rising over time.8 Increasing maternal age is believed to be playing a role in this rise; as women delay childbearing, they enter the age range in which some cancers become more common. Additionally, improvements in screening and diagnostics have led to earlier cancer detection. The incidence of ovarian neoplasms found during pregnancy has increased, for instance, with the routine use of diagnostic ultrasound in pregnancy.1

Among the studies showing an increased incidence of pregnancy-associated cancer is a population-based study in Australia, which found that from 1994 to 2007 the crude incidence of pregnancy-associated cancer increased from 112.3 to 191.5 per 100,000 pregnancies (P < .001).9 A cohort study in the United States documented an increase in incidence from 75.0 per 100,000 pregnancies in 2002 to 138.5 per 100,000 pregnancies in 2012.10

Overall, the literature shows us that the skin, cervix, and breast are also common sites for malignancy during pregnancy.1 According to a 2022 review, breast cancer during pregnancy is less often hormone receptor–positive and more frequently triple negative compared with age-matched controls.11 The frequencies of other pregnancy-associated cancers appear overall to be similar to that of cancer occurring in all women across their reproductive years.1

Too often, diagnosis is delayed because cancer symptoms can be masked by or can mimic normal physiological changes in pregnancy. For instance, breast cancer can be difficult to diagnose during pregnancy and lactation due to anatomic changes in the breast parenchyma. Several studies published in the 1990s showed that breast cancer presents at a more advanced stage in pregnant patients than in nonpregnant patients because of this delay.1 Skin changes suggestive of melanoma can be attributed to hyperpigmentation of pregnancy, for instance. Several observational studies have suggested that thicker melanomas found in pregnancy may be because of delayed diagnosis.8

It is important that we thoroughly investigate signs and symptoms suggestive of a malignancy and not automatically attribute these symptoms to the pregnancy itself. Cervical biopsy of a mass or lesion suspicious for cervical cancer can be done safely during pregnancy and should not be delayed or deferred.

Fetal radiation exposure from radiologic examinations has long been a concern, but we know today that while the imaging modality should be chosen to minimize fetal radiation exposure, CT scans and even PET scans should be performed if these exams are deemed best for evaluation. Embryonic exposure to a dose of less than 50 mGy is rarely if at all associated with fetal malformations or miscarriage and a radiation dose of 100 mGy may be considered a floor for consideration of therapeutic termination of pregnancy.1,8

CT exams are associated with a fetal dose far less than 50 mGy (see Table 2 for radiation doses).

Magnetic resonance imaging with a magnet strength of 3 Tesla or less in any trimester is not associated with an increased risk of harm to the fetus or in early childhood, but the contrast agent gadolinium should be avoided in pregnancy as it has been associated with an increased risk of stillbirth, neonatal death, and childhood inflammatory, rheumatologic, and infiltrative skin lesions.1,8,12

Chemotherapy, Surgery, and Radiation in Pregnancy

The management of cancer during pregnancy requires a multidisciplinary team including medical, gynecologic, or radiation oncologists, and maternal-fetal medicine specialists (Figure 1). Prematurity and low birth weight are frequent complications for fetuses exposed to chemotherapy, although there is some uncertainty as to whether the treatment is causative. However, congenital anomalies no longer are a major concern, provided that drugs are appropriately selected and that fetal exposure occurs during the second or third trimester.

For instance, alkylating agents including cisplatin (an important drug in the management of gynecologic malignancies) have been associated with congenital anomalies in the first trimester but not in the second and third trimesters, and a variety of antimetabolites — excluding methotrexate and aminopterin — similarly have been shown to be relatively safe when used after the first trimester.1

Small studies have shown no long-term effects of chemotherapy exposure on postnatal growth and long-term neurologic/neurocognitive function,1 but this is an area that needs more research.

Also in need of investigation is the safety of newer agents in pregnancy. Data are limited on the use of new targeted treatments, monoclonal antibodies, and immunotherapies in pregnancy and their effects on the fetus, with current knowledge coming mainly from single case reports.13

Until more is learned — a challenge given that pregnant women are generally excluded from clinical trials — management teams are generally postponing use of these therapies until after delivery. Considering the pace of new developments revolutionizing cancer treatment, this topic will likely get more complex and confusing before we begin acquiring sufficient knowledge.

The timing of surgery for malignancy in pregnancy is similarly based on the balance of maternal and fetal risks, including the risk of maternal disease progression, the risk of preterm delivery, and the prevention of fetal metastases. In general, the safest time is the second trimester.

Maternal surgery in the third trimester may be associated with a risk of premature labor and altered uteroplacental perfusion. A 2005 systematic review of 12,452 women who underwent nonobstetric surgery during pregnancy provides some reassurance, however; compared with the general obstetric population, there was no increase in the rate of miscarriage or major birth defects.14

Radiotherapy used to be contraindicated in pregnancy but many experts today believe it can be safely utilized provided the uterus is out of field and is protected from scattered radiation. The head, neck, and breast, for instance, can be treated with newer radiotherapies, including stereotactic ablative radiation therapy.8 Patients with advanced cervical cancer often receive chemotherapy during pregnancy to slow metastatic growth followed by definitive treatment with postpartum radiation or surgery.

More research is needed, but available data on maternal outcomes are encouraging. For instance, there appear to be no significant differences in short- and long-term complications or survival between women who are pregnant and nonpregnant when treated for invasive cervical cancer.8 Similarly, while earlier studies of breast cancer diagnosed during pregnancy suggested a poor prognosis, data now show similar prognoses for pregnant and nonpregnant patients when controlled for stage.1

Dr. Rao is a gynecologic oncologist and associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore. He reported no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Rao GG. Chapter 42. Clinical Obstetrics: The Fetus & Mother, 4th ed. Reece EA et al. (eds): 2021.

2. Bannister-Tyrrell M et al. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;55:116-122.

3. Oehler MK et al. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;43(6):414-420.

4. Ruiz R et al. Breast. 2017;35:136-141. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2017.07.008.

5. Nolan S et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(1):S480. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.11.752.

6. El-Messidi A et al. J Perinat Med. 2015;43(6):683-688. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2014-0133.

7. Pellino G et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29(7):743-753. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000863.

8. Eastwood-Wilshere N et al. Asia-Pac J Clin Oncol. 2019;15:296-308.

9. Lee YY et al. BJOG. 2012;119(13):1572-1582.

10. Cottreau CM et al. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019 Feb;28(2):250-257.

11. Boere I et al. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;82:46-59.

12. Ray JG et al. JAMA 2016;316(9):952-961.

13. Schwab R et al. Cancers. (Basel) 2021;13(12):3048.

14. Cohen-Kerem et al. Am J Surg. 2005;190(3):467-473.

Introduction: Tremendous Progress on Cancer Extends to Cancer in Pregnancy

The biomedical research enterprise that took shape in the United States after World War II has had numerous positive effects, including significant progress made during the past 75-plus years in the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of cancer.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1944 request of Dr. Vannevar Bush, director of the then Office of Scientific Research and Development, to organize a program that would advance and apply scientific knowledge for times of peace — just as it been advanced and applied in times of war — culminated in a historic report, Science – The Endless Frontier. Presented in 1945 to President Harry S. Truman, this report helped fuel decades of broad, bold, and coordinated government-sponsored biomedical research aimed at addressing disease and improving the health of the American people (National Science Foundation, 1945).

Discoveries made from research in basic and translational sciences deepened our knowledge of the cellular and molecular underpinnings of cancer, leading to advances in chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and other treatment approaches as well as continual refinements in their application. Similarly, our diagnostic armamentarium has significantly improved.

As a result, we have reduced both the incidence and mortality of cancer. Today, some cancers can be prevented. Others can be reversed or put in remission. Granted, progress has been variable, with some cancers such as ovarian cancer still having relatively low survival rates. Much more needs to be done. Overall, however, the positive effects of the U.S. biomedical research enterprise on cancer are evident. According to the National Cancer Institute’s most recent report on the status of cancer, death rates from cancer fell 1.9% per year on average in females from 2015 to 2019 (Cancer. 2022 Oct 22. doi: 10.1002/cncr.34479).

It is not only patients whose cancer occurs outside of pregnancy who have benefited. When treatment is appropriately selected and timing considerations are made, patients whose cancer is diagnosed during pregnancy — and their children — can have good outcomes.

To explain how the management of cancer in pregnancy has improved, we have invited Gautam G. Rao, MD, gynecologic oncologist and associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, to write this installment of the Master Class in Obstetrics. As Dr. Rao explains, radiation is not as dangerous to the fetus as once thought, and the safety of many chemotherapeutic regimens in pregnancy has been documented. Obstetricians can and should counsel patients, he explains, about the likelihood of good maternal and fetal outcomes.

E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist, is dean emeritus of the University of Maryland School of Medicine, former university executive vice president; currently the endowed professor and director of the Center for Advanced Research Training and Innovation (CARTI), and senior scientist in the Center for Birth Defects Research. Dr. Reece reported no relevant disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

Managing Cancer in Pregnancy

Cancer can cause fear and distress for any patient, but when cancer is diagnosed during pregnancy, an expectant mother fears not only for her own health but for the health of her unborn child. Fortunately, ob.gyn.s and multidisciplinary teams have good reason to reassure patients about the likelihood of good outcomes.

Cancer treatment in pregnancy has improved with advancements in imaging and chemotherapy, and while maternal and fetal outcomes of prenatal cancer treatment are not well reported, evidence acquired in recent years from case series and retrospective studies shows that most imaging studies and procedural diagnostic tests – and many treatments – can be performed safely in pregnancy.

Decades ago, we avoided CT scans during pregnancy because of concerns about radiation exposure to the fetus, leaving some patients without an accurate staging of their cancer. Today, we have evidence that a CT scan is generally safe in pregnancy. Similarly, the safety of many chemotherapeutic regimens in pregnancy has been documented in recent decades,and the use of chemotherapy during pregnancy has increased progressively. Radiation is also commonly utilized in the management of cancers that may occur during pregnancy, such as breast cancer.1

Considerations of timing are often central to decision-making; chemotherapy and radiotherapy are generally avoided in the first trimester to prevent structural fetal anomalies, for instance, and delaying cancer treatment is often warranted when the patient is a few weeks away from delivery. On occasion, iatrogenic preterm birth is considered when the risks to the mother of delaying a necessary cancer treatment outweigh the risks to the fetus of prematurity.1

Pregnancy termination is rarely indicated, however, and information gathered over the past 2 decades suggests that fetal and placental metastases are rare.1 There is broad agreement that prenatal treatment of cancer in pregnancy should adhere as much as possible to protocols and guidelines for nonpregnant patients and that treatment delays driven by fear of fetal anomalies and miscarriage are unnecessary.

Cancer Incidence, Use of Diagnostic Imaging

Data on the incidence of cancer in pregnancy comes from population-based cancer registries, and unfortunately, these data are not standardized and are often incomplete. Many studies include cancer diagnosed up to 1 year after pregnancy, and some include preinvasive disease. Estimates therefore vary considerably (see Table 1 for a sampling of estimates incidences.)

It has been reported, and often cited in the literature, that invasive malignancy complicates one in 1,000 pregnancies and that the incidence of cancer in pregnancy (invasive and noninvasive malignancies) has been rising over time.8 Increasing maternal age is believed to be playing a role in this rise; as women delay childbearing, they enter the age range in which some cancers become more common. Additionally, improvements in screening and diagnostics have led to earlier cancer detection. The incidence of ovarian neoplasms found during pregnancy has increased, for instance, with the routine use of diagnostic ultrasound in pregnancy.1

Among the studies showing an increased incidence of pregnancy-associated cancer is a population-based study in Australia, which found that from 1994 to 2007 the crude incidence of pregnancy-associated cancer increased from 112.3 to 191.5 per 100,000 pregnancies (P < .001).9 A cohort study in the United States documented an increase in incidence from 75.0 per 100,000 pregnancies in 2002 to 138.5 per 100,000 pregnancies in 2012.10

Overall, the literature shows us that the skin, cervix, and breast are also common sites for malignancy during pregnancy.1 According to a 2022 review, breast cancer during pregnancy is less often hormone receptor–positive and more frequently triple negative compared with age-matched controls.11 The frequencies of other pregnancy-associated cancers appear overall to be similar to that of cancer occurring in all women across their reproductive years.1

Too often, diagnosis is delayed because cancer symptoms can be masked by or can mimic normal physiological changes in pregnancy. For instance, breast cancer can be difficult to diagnose during pregnancy and lactation due to anatomic changes in the breast parenchyma. Several studies published in the 1990s showed that breast cancer presents at a more advanced stage in pregnant patients than in nonpregnant patients because of this delay.1 Skin changes suggestive of melanoma can be attributed to hyperpigmentation of pregnancy, for instance. Several observational studies have suggested that thicker melanomas found in pregnancy may be because of delayed diagnosis.8

It is important that we thoroughly investigate signs and symptoms suggestive of a malignancy and not automatically attribute these symptoms to the pregnancy itself. Cervical biopsy of a mass or lesion suspicious for cervical cancer can be done safely during pregnancy and should not be delayed or deferred.

Fetal radiation exposure from radiologic examinations has long been a concern, but we know today that while the imaging modality should be chosen to minimize fetal radiation exposure, CT scans and even PET scans should be performed if these exams are deemed best for evaluation. Embryonic exposure to a dose of less than 50 mGy is rarely if at all associated with fetal malformations or miscarriage and a radiation dose of 100 mGy may be considered a floor for consideration of therapeutic termination of pregnancy.1,8

CT exams are associated with a fetal dose far less than 50 mGy (see Table 2 for radiation doses).

Magnetic resonance imaging with a magnet strength of 3 Tesla or less in any trimester is not associated with an increased risk of harm to the fetus or in early childhood, but the contrast agent gadolinium should be avoided in pregnancy as it has been associated with an increased risk of stillbirth, neonatal death, and childhood inflammatory, rheumatologic, and infiltrative skin lesions.1,8,12

Chemotherapy, Surgery, and Radiation in Pregnancy

The management of cancer during pregnancy requires a multidisciplinary team including medical, gynecologic, or radiation oncologists, and maternal-fetal medicine specialists (Figure 1). Prematurity and low birth weight are frequent complications for fetuses exposed to chemotherapy, although there is some uncertainty as to whether the treatment is causative. However, congenital anomalies no longer are a major concern, provided that drugs are appropriately selected and that fetal exposure occurs during the second or third trimester.

For instance, alkylating agents including cisplatin (an important drug in the management of gynecologic malignancies) have been associated with congenital anomalies in the first trimester but not in the second and third trimesters, and a variety of antimetabolites — excluding methotrexate and aminopterin — similarly have been shown to be relatively safe when used after the first trimester.1

Small studies have shown no long-term effects of chemotherapy exposure on postnatal growth and long-term neurologic/neurocognitive function,1 but this is an area that needs more research.

Also in need of investigation is the safety of newer agents in pregnancy. Data are limited on the use of new targeted treatments, monoclonal antibodies, and immunotherapies in pregnancy and their effects on the fetus, with current knowledge coming mainly from single case reports.13

Until more is learned — a challenge given that pregnant women are generally excluded from clinical trials — management teams are generally postponing use of these therapies until after delivery. Considering the pace of new developments revolutionizing cancer treatment, this topic will likely get more complex and confusing before we begin acquiring sufficient knowledge.

The timing of surgery for malignancy in pregnancy is similarly based on the balance of maternal and fetal risks, including the risk of maternal disease progression, the risk of preterm delivery, and the prevention of fetal metastases. In general, the safest time is the second trimester.

Maternal surgery in the third trimester may be associated with a risk of premature labor and altered uteroplacental perfusion. A 2005 systematic review of 12,452 women who underwent nonobstetric surgery during pregnancy provides some reassurance, however; compared with the general obstetric population, there was no increase in the rate of miscarriage or major birth defects.14

Radiotherapy used to be contraindicated in pregnancy but many experts today believe it can be safely utilized provided the uterus is out of field and is protected from scattered radiation. The head, neck, and breast, for instance, can be treated with newer radiotherapies, including stereotactic ablative radiation therapy.8 Patients with advanced cervical cancer often receive chemotherapy during pregnancy to slow metastatic growth followed by definitive treatment with postpartum radiation or surgery.

More research is needed, but available data on maternal outcomes are encouraging. For instance, there appear to be no significant differences in short- and long-term complications or survival between women who are pregnant and nonpregnant when treated for invasive cervical cancer.8 Similarly, while earlier studies of breast cancer diagnosed during pregnancy suggested a poor prognosis, data now show similar prognoses for pregnant and nonpregnant patients when controlled for stage.1

Dr. Rao is a gynecologic oncologist and associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore. He reported no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Rao GG. Chapter 42. Clinical Obstetrics: The Fetus & Mother, 4th ed. Reece EA et al. (eds): 2021.

2. Bannister-Tyrrell M et al. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;55:116-122.

3. Oehler MK et al. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;43(6):414-420.

4. Ruiz R et al. Breast. 2017;35:136-141. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2017.07.008.

5. Nolan S et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(1):S480. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.11.752.

6. El-Messidi A et al. J Perinat Med. 2015;43(6):683-688. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2014-0133.

7. Pellino G et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29(7):743-753. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000863.

8. Eastwood-Wilshere N et al. Asia-Pac J Clin Oncol. 2019;15:296-308.

9. Lee YY et al. BJOG. 2012;119(13):1572-1582.

10. Cottreau CM et al. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019 Feb;28(2):250-257.

11. Boere I et al. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;82:46-59.

12. Ray JG et al. JAMA 2016;316(9):952-961.

13. Schwab R et al. Cancers. (Basel) 2021;13(12):3048.

14. Cohen-Kerem et al. Am J Surg. 2005;190(3):467-473.

Benefit of Massage Therapy for Pain Unclear

The effectiveness of massage therapy for a range of painful adult health conditions remains uncertain. Despite hundreds of randomized clinical trials and dozens of systematic reviews, few studies have offered conclusions based on more than low-certainty evidence, a systematic review in JAMA Network Open has shown (doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.22259).

Some moderate-certainty evidence, however, suggested massage therapy may alleviate pain related to such conditions as low-back problems, labor, and breast cancer surgery, concluded a group led by Selene Mak, PhD, MPH, program manager in the Evidence Synthesis Program at the Veterans Health Administration Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System in Los Angeles, California.

“More high-quality randomized clinical trials are needed to provide a stronger evidence base to assess the effect of massage therapy on pain,” Dr. Mak and colleagues wrote.

The review updates a previous Veterans Affairs evidence map covering reviews of massage therapy for pain published through 2018.

To categorize the evidence base for decision-making by policymakers and practitioners, the VA requested an updated evidence map of reviews to answer the question: “What is the certainty of evidence in systematic reviews of massage therapy for pain?”

The Analysis

The current review included studies published from 2018 to 2023 with formal ratings of evidence quality or certainty, excluding other nonpharmacologic techniques such as sports massage therapy, osteopathy, dry cupping, dry needling, and internal massage therapy, and self-administered techniques such as foam rolling.

Of 129 systematic reviews, only 41 formally rated evidence quality, and 17 were evidence-mapped for pain across 13 health states: cancer, back, neck and mechanical neck issues, fibromyalgia, labor, myofascial, palliative care need, plantar fasciitis, postoperative, post breast cancer surgery, and post cesarean/postpartum.

The investigators found no conclusions based on a high certainty of evidence, while seven based conclusions on moderate-certainty evidence. All remaining conclusions were rated as having low- or very-low-certainty evidence.

The priority, they added, should be studies comparing massage therapy with other recommended, accepted, and active therapies for pain and should have sufficiently long follow-up to allow any nonspecific outcomes to dissipate, At least 6 months’ follow-up has been suggested for studies of chronic pain.

While massage therapy is considered safe, in patients with central sensitizations more aggressive treatments may cause a flare of myofascial pain.

This study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development. The authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The effectiveness of massage therapy for a range of painful adult health conditions remains uncertain. Despite hundreds of randomized clinical trials and dozens of systematic reviews, few studies have offered conclusions based on more than low-certainty evidence, a systematic review in JAMA Network Open has shown (doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.22259).

Some moderate-certainty evidence, however, suggested massage therapy may alleviate pain related to such conditions as low-back problems, labor, and breast cancer surgery, concluded a group led by Selene Mak, PhD, MPH, program manager in the Evidence Synthesis Program at the Veterans Health Administration Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System in Los Angeles, California.

“More high-quality randomized clinical trials are needed to provide a stronger evidence base to assess the effect of massage therapy on pain,” Dr. Mak and colleagues wrote.

The review updates a previous Veterans Affairs evidence map covering reviews of massage therapy for pain published through 2018.

To categorize the evidence base for decision-making by policymakers and practitioners, the VA requested an updated evidence map of reviews to answer the question: “What is the certainty of evidence in systematic reviews of massage therapy for pain?”

The Analysis

The current review included studies published from 2018 to 2023 with formal ratings of evidence quality or certainty, excluding other nonpharmacologic techniques such as sports massage therapy, osteopathy, dry cupping, dry needling, and internal massage therapy, and self-administered techniques such as foam rolling.

Of 129 systematic reviews, only 41 formally rated evidence quality, and 17 were evidence-mapped for pain across 13 health states: cancer, back, neck and mechanical neck issues, fibromyalgia, labor, myofascial, palliative care need, plantar fasciitis, postoperative, post breast cancer surgery, and post cesarean/postpartum.

The investigators found no conclusions based on a high certainty of evidence, while seven based conclusions on moderate-certainty evidence. All remaining conclusions were rated as having low- or very-low-certainty evidence.

The priority, they added, should be studies comparing massage therapy with other recommended, accepted, and active therapies for pain and should have sufficiently long follow-up to allow any nonspecific outcomes to dissipate, At least 6 months’ follow-up has been suggested for studies of chronic pain.

While massage therapy is considered safe, in patients with central sensitizations more aggressive treatments may cause a flare of myofascial pain.

This study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development. The authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The effectiveness of massage therapy for a range of painful adult health conditions remains uncertain. Despite hundreds of randomized clinical trials and dozens of systematic reviews, few studies have offered conclusions based on more than low-certainty evidence, a systematic review in JAMA Network Open has shown (doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.22259).

Some moderate-certainty evidence, however, suggested massage therapy may alleviate pain related to such conditions as low-back problems, labor, and breast cancer surgery, concluded a group led by Selene Mak, PhD, MPH, program manager in the Evidence Synthesis Program at the Veterans Health Administration Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System in Los Angeles, California.

“More high-quality randomized clinical trials are needed to provide a stronger evidence base to assess the effect of massage therapy on pain,” Dr. Mak and colleagues wrote.

The review updates a previous Veterans Affairs evidence map covering reviews of massage therapy for pain published through 2018.

To categorize the evidence base for decision-making by policymakers and practitioners, the VA requested an updated evidence map of reviews to answer the question: “What is the certainty of evidence in systematic reviews of massage therapy for pain?”

The Analysis

The current review included studies published from 2018 to 2023 with formal ratings of evidence quality or certainty, excluding other nonpharmacologic techniques such as sports massage therapy, osteopathy, dry cupping, dry needling, and internal massage therapy, and self-administered techniques such as foam rolling.

Of 129 systematic reviews, only 41 formally rated evidence quality, and 17 were evidence-mapped for pain across 13 health states: cancer, back, neck and mechanical neck issues, fibromyalgia, labor, myofascial, palliative care need, plantar fasciitis, postoperative, post breast cancer surgery, and post cesarean/postpartum.

The investigators found no conclusions based on a high certainty of evidence, while seven based conclusions on moderate-certainty evidence. All remaining conclusions were rated as having low- or very-low-certainty evidence.

The priority, they added, should be studies comparing massage therapy with other recommended, accepted, and active therapies for pain and should have sufficiently long follow-up to allow any nonspecific outcomes to dissipate, At least 6 months’ follow-up has been suggested for studies of chronic pain.

While massage therapy is considered safe, in patients with central sensitizations more aggressive treatments may cause a flare of myofascial pain.

This study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development. The authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Medicare Rates in 2025 Would Cut Pay For Docs by 3%

Federal officials on July 11 proposed Medicare rates that effectively would cut physician pay by about 3% in 2025, touching off a fresh round of protests from medical associations.

, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said.

The American Medical Association (AMA), the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and other groups on July 10 reiterated calls on Congress to revise the law on Medicare payment for physicians and move away from short-term tweaks.

This proposed cut is mostly due to the 5-year freeze in the physician schedule base rate mandated by the 2015 Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA). Congress designed MACRA with an aim of shifting clinicians toward programs that would peg pay increases to quality measures.

Lawmakers have since had to soften the blow of that freeze, acknowledging flaws in MACRA and inflation’s significant toll on medical practices. Yet lawmakers have made temporary fixes, such as a 2.93% increase in current payment that’s set to expire.

“Previous quick fixes have been insufficient — this situation requires a bold, substantial approach,” Bruce A. Scott, MD, the AMA president, said in a statement. “A Band-Aid goes only so far when the patient is in dire need.”

Dr. Scott noted that the Medicare Economic Index — a measure of practice cost inflation — is expected to rise by 3.6% in 2025.

“As a first step, Congress must enact an annual inflationary update to help physician payment rates keep pace with rising practice costs,” Steven P. Furr, MD, AAFP’s president, said in a statement released July 10. “Any payment reductions will threaten practices and exacerbate workforce shortages, preventing patients from accessing the primary care, behavioral health care, and other critical preventive services they need.”

Many medical groups, including the AMA, AAFP, and the Medical Group Management Association, are pressing Congress to pass a law that would tie the conversion factor of the physician fee schedule to inflation.

Influential advisory groups also have backed the idea of increasing the conversion factor. For example, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission in March recommended to Congress that it increase the 2025 conversion factor, suggesting a bump of half of the projected increase in the Medicare Economic Index.

Congress seems unlikely to revamp the physician fee schedule this year, with members spending significant time away from Washington ahead of the November election.

That could make it likely that Congress’ next action on Medicare payment rates would be another short-term tweak — instead of long-lasting change.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Federal officials on July 11 proposed Medicare rates that effectively would cut physician pay by about 3% in 2025, touching off a fresh round of protests from medical associations.

, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said.

The American Medical Association (AMA), the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and other groups on July 10 reiterated calls on Congress to revise the law on Medicare payment for physicians and move away from short-term tweaks.

This proposed cut is mostly due to the 5-year freeze in the physician schedule base rate mandated by the 2015 Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA). Congress designed MACRA with an aim of shifting clinicians toward programs that would peg pay increases to quality measures.

Lawmakers have since had to soften the blow of that freeze, acknowledging flaws in MACRA and inflation’s significant toll on medical practices. Yet lawmakers have made temporary fixes, such as a 2.93% increase in current payment that’s set to expire.

“Previous quick fixes have been insufficient — this situation requires a bold, substantial approach,” Bruce A. Scott, MD, the AMA president, said in a statement. “A Band-Aid goes only so far when the patient is in dire need.”

Dr. Scott noted that the Medicare Economic Index — a measure of practice cost inflation — is expected to rise by 3.6% in 2025.

“As a first step, Congress must enact an annual inflationary update to help physician payment rates keep pace with rising practice costs,” Steven P. Furr, MD, AAFP’s president, said in a statement released July 10. “Any payment reductions will threaten practices and exacerbate workforce shortages, preventing patients from accessing the primary care, behavioral health care, and other critical preventive services they need.”

Many medical groups, including the AMA, AAFP, and the Medical Group Management Association, are pressing Congress to pass a law that would tie the conversion factor of the physician fee schedule to inflation.

Influential advisory groups also have backed the idea of increasing the conversion factor. For example, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission in March recommended to Congress that it increase the 2025 conversion factor, suggesting a bump of half of the projected increase in the Medicare Economic Index.

Congress seems unlikely to revamp the physician fee schedule this year, with members spending significant time away from Washington ahead of the November election.

That could make it likely that Congress’ next action on Medicare payment rates would be another short-term tweak — instead of long-lasting change.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Federal officials on July 11 proposed Medicare rates that effectively would cut physician pay by about 3% in 2025, touching off a fresh round of protests from medical associations.

, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said.

The American Medical Association (AMA), the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and other groups on July 10 reiterated calls on Congress to revise the law on Medicare payment for physicians and move away from short-term tweaks.

This proposed cut is mostly due to the 5-year freeze in the physician schedule base rate mandated by the 2015 Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA). Congress designed MACRA with an aim of shifting clinicians toward programs that would peg pay increases to quality measures.

Lawmakers have since had to soften the blow of that freeze, acknowledging flaws in MACRA and inflation’s significant toll on medical practices. Yet lawmakers have made temporary fixes, such as a 2.93% increase in current payment that’s set to expire.

“Previous quick fixes have been insufficient — this situation requires a bold, substantial approach,” Bruce A. Scott, MD, the AMA president, said in a statement. “A Band-Aid goes only so far when the patient is in dire need.”

Dr. Scott noted that the Medicare Economic Index — a measure of practice cost inflation — is expected to rise by 3.6% in 2025.

“As a first step, Congress must enact an annual inflationary update to help physician payment rates keep pace with rising practice costs,” Steven P. Furr, MD, AAFP’s president, said in a statement released July 10. “Any payment reductions will threaten practices and exacerbate workforce shortages, preventing patients from accessing the primary care, behavioral health care, and other critical preventive services they need.”

Many medical groups, including the AMA, AAFP, and the Medical Group Management Association, are pressing Congress to pass a law that would tie the conversion factor of the physician fee schedule to inflation.

Influential advisory groups also have backed the idea of increasing the conversion factor. For example, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission in March recommended to Congress that it increase the 2025 conversion factor, suggesting a bump of half of the projected increase in the Medicare Economic Index.

Congress seems unlikely to revamp the physician fee schedule this year, with members spending significant time away from Washington ahead of the November election.

That could make it likely that Congress’ next action on Medicare payment rates would be another short-term tweak — instead of long-lasting change.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Eribulin Similar to Taxane When Paired With Dual HER2 Blockade in BC

The results of this multicenter, randomized, open-label, parallel-group, phase 3 Japanese trial suggest that patients who cannot tolerate the standard taxane-based regimen have a new option for treatment.

“Our study is the first to show the non-inferiority of eribulin to a taxane, when used in combination with dual HER2 blockade as first-line treatment for this population,” lead author Toshinari Yamashita, MD, PhD, from the Kanagawa Cancer Center, in Kanagawa, Japan, said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

“To our knowledge, noninferiority of eribulin to a taxane when used in combination with dual HER2 blockade has not been investigated,” Dr. Yamashita said.

“The combination of trastuzumab, pertuzumab, and taxane is a current standard first-line therapy for recurrent or metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer,” explained Dr. Yamashita. “However, because of taxane-induced toxicity, the development of less toxic but equally effective alternatives are needed.

“Because its efficacy is comparable to that of the current standard regimen, the combination of eribulin, trastuzumab, and pertuzumab is one of the options for first-line treatment of how to fight locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer,” he continued.

Study Results and Methods

The trial enrolled 446 patients, mean age 56 years, all of whom had locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer and no prior use of chemotherapy, excluding T-DM1. Patients who had received hormonal or HER2 therapy alone or the combination, as treatment for recurrence, were also eligible.

They were randomized 1:1 to receive a 21-day chemotherapy cycle of either (i) eribulin (1.4 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8), or (ii) a taxane (docetaxel 75 mg/m2 on day 1 or paclitaxel 80 mg/m2 on days 1, 8 and 15), each being administered in combination with a dual HER2 blockade of trastuzumab plus pertuzumab.

Baseline characteristics of both groups were well balanced, with 257 (57.6%) having ER-positive disease, 292 (65.5%) visceral metastasis, and 263 (59%) with de novo stage 4 disease, explained Dr. Yamashita.

For the primary endpoint, the median progression-free survival (PFS) was 14 versus 12.9 months in the eribulin and taxane group, respectively (hazard ratio [HR] 0.95, P = .6817), confirming non-inferiority of the study regimen, he reported.

The clinical benefit rate was similar between the two groups, with an objective response rate of 76.8% in the eribulin group and 75.2% in the taxane group.

Median OS was 65.3 months in the taxane group, but has not been reached in the study group (HR 1.09).

In terms of side-effects, the incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events was similar between the eribulin and taxane groups (58.9% vs 59.2%, respectively, for grade 3 or higher).

“Skin-related adverse events (62.4% vs 40.6%), diarrhea (54.1% vs 36.6%), and edema (42.2% vs 8.5%) tend to be more common with taxane, whereas neutropenia (61.6% vs 30.7%) and peripheral neuropathy (61.2% vs 52.8%) tend to be more common with eribulin use,” he said.