User login

News and Views that Matter to Pediatricians

The leading independent newspaper covering news and commentary in pediatrics.

The Mysterious Latch

While there may be some lactation consultants who disagree, in my experience counseling women attempting to breastfeed is more art than science. Well before the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) began to offer mini courses on breastfeeding for practitioners I was left to help new mothers based on watching my wife nurse our three children and what scraps of common sense I could sweep up off the floor.

Using my own benchmarks of success I would say I did a decent job with dyads who sought my help. I began by accepting that even under optimal conditions, not every woman and/or child can successfully breastfeed. None of the infants died or was hospitalized with dehydration. A few may have required some additional phototherapy, but they all completed infancy in good shape. On the maternal side I am sure there were a few mothers who had lingering feelings of inadequacy because they had “failed” at breastfeeding. But, for the most part, I think I succeeded in helping new mothers remain as mentally healthy as they could be given the rigors of motherhood. At least I gave it my best shot.

If I had a strategy, it was a focus on maintaining a routine (schedule can have an ugly aura about it) that allowed mothers to achieve spells of restorative rest. Helping mothers with the difficult task of deciding whether their infant was hungry, or tired, or uncomfortable was always a struggle, but well worth the effort when we succeeded. Finally, I tried to help mothers step back off the ledge and look at the bigger picture — breastfeeding was not the only way to feed their baby while we were working to overcome the bumps in the road.

Where I failed was in my inability to effectively counsel when it came to the mysteries of the latch. In large part it was because I was a man and helping the dyad succeed at latching on to the breast can require a hands-on approach with which I felt a bit uncomfortable. I could certainly test a baby’s suck and oral architecture with my pinky but otherwise I had to rely on women to help if latching was a problem. I think even trained lactation consultants have difficulty with this mysterious process, which is completely hidden from view inside the baby’s mouth.

Fortunately for me and the dyads I was working with, we rarely considered ankyloglossia as a problem. My training had been that tongue-tie seldom, if ever, contributed to speech problems and even less commonly hindered latch. I think I recall snipping a couple of lingual frenulums early in my career in a bloodless and seemingly painless procedure. But, for the life of me I can’t recall the motivation. It may have been that the ankyloglossia was so obvious that I couldn’t convince the parents it would resolve or it was at the request of a lactation consultant.

But, obviously after I stopped seeing newborns a decade and a half ago the lingual frenulum became a target of surgical assault with, at times, unfortunate results that made breastfeeding painful and more difficult. It’s hard for me to imagine why anyone would consider using a laser for such a simple procedure. But, then I haven’t invested in a laser that allowed me to charge $800 for the procedure. I doubt I even charged for it. It wouldn’t have been worth the time and effort to look up the code. But, then, technology and money can be powerful motivators.

The good news is the AAP has been watching and recently issued a clinical report in which they state what many of us have known from personal observation — They further note that “the symptoms of ankyloglossia overlap those of other breastfeeding difficulties.”

So there you have it. Another fad has been squashed and we’ve come full circle. The latch still remains mystery hidden from view. I think we have to suspect that there exists a small number of dyads in which tongue-tie creates a problem with nursing. And, there may be some safe imaging technique coming along that gives us a glimpse of what happens in the dark recesses of a nursing baby’s mouth. Until then we must rely on masters of the art of lactation consulting, the “Latch Whisperers.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

While there may be some lactation consultants who disagree, in my experience counseling women attempting to breastfeed is more art than science. Well before the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) began to offer mini courses on breastfeeding for practitioners I was left to help new mothers based on watching my wife nurse our three children and what scraps of common sense I could sweep up off the floor.

Using my own benchmarks of success I would say I did a decent job with dyads who sought my help. I began by accepting that even under optimal conditions, not every woman and/or child can successfully breastfeed. None of the infants died or was hospitalized with dehydration. A few may have required some additional phototherapy, but they all completed infancy in good shape. On the maternal side I am sure there were a few mothers who had lingering feelings of inadequacy because they had “failed” at breastfeeding. But, for the most part, I think I succeeded in helping new mothers remain as mentally healthy as they could be given the rigors of motherhood. At least I gave it my best shot.

If I had a strategy, it was a focus on maintaining a routine (schedule can have an ugly aura about it) that allowed mothers to achieve spells of restorative rest. Helping mothers with the difficult task of deciding whether their infant was hungry, or tired, or uncomfortable was always a struggle, but well worth the effort when we succeeded. Finally, I tried to help mothers step back off the ledge and look at the bigger picture — breastfeeding was not the only way to feed their baby while we were working to overcome the bumps in the road.

Where I failed was in my inability to effectively counsel when it came to the mysteries of the latch. In large part it was because I was a man and helping the dyad succeed at latching on to the breast can require a hands-on approach with which I felt a bit uncomfortable. I could certainly test a baby’s suck and oral architecture with my pinky but otherwise I had to rely on women to help if latching was a problem. I think even trained lactation consultants have difficulty with this mysterious process, which is completely hidden from view inside the baby’s mouth.

Fortunately for me and the dyads I was working with, we rarely considered ankyloglossia as a problem. My training had been that tongue-tie seldom, if ever, contributed to speech problems and even less commonly hindered latch. I think I recall snipping a couple of lingual frenulums early in my career in a bloodless and seemingly painless procedure. But, for the life of me I can’t recall the motivation. It may have been that the ankyloglossia was so obvious that I couldn’t convince the parents it would resolve or it was at the request of a lactation consultant.

But, obviously after I stopped seeing newborns a decade and a half ago the lingual frenulum became a target of surgical assault with, at times, unfortunate results that made breastfeeding painful and more difficult. It’s hard for me to imagine why anyone would consider using a laser for such a simple procedure. But, then I haven’t invested in a laser that allowed me to charge $800 for the procedure. I doubt I even charged for it. It wouldn’t have been worth the time and effort to look up the code. But, then, technology and money can be powerful motivators.

The good news is the AAP has been watching and recently issued a clinical report in which they state what many of us have known from personal observation — They further note that “the symptoms of ankyloglossia overlap those of other breastfeeding difficulties.”

So there you have it. Another fad has been squashed and we’ve come full circle. The latch still remains mystery hidden from view. I think we have to suspect that there exists a small number of dyads in which tongue-tie creates a problem with nursing. And, there may be some safe imaging technique coming along that gives us a glimpse of what happens in the dark recesses of a nursing baby’s mouth. Until then we must rely on masters of the art of lactation consulting, the “Latch Whisperers.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

While there may be some lactation consultants who disagree, in my experience counseling women attempting to breastfeed is more art than science. Well before the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) began to offer mini courses on breastfeeding for practitioners I was left to help new mothers based on watching my wife nurse our three children and what scraps of common sense I could sweep up off the floor.

Using my own benchmarks of success I would say I did a decent job with dyads who sought my help. I began by accepting that even under optimal conditions, not every woman and/or child can successfully breastfeed. None of the infants died or was hospitalized with dehydration. A few may have required some additional phototherapy, but they all completed infancy in good shape. On the maternal side I am sure there were a few mothers who had lingering feelings of inadequacy because they had “failed” at breastfeeding. But, for the most part, I think I succeeded in helping new mothers remain as mentally healthy as they could be given the rigors of motherhood. At least I gave it my best shot.

If I had a strategy, it was a focus on maintaining a routine (schedule can have an ugly aura about it) that allowed mothers to achieve spells of restorative rest. Helping mothers with the difficult task of deciding whether their infant was hungry, or tired, or uncomfortable was always a struggle, but well worth the effort when we succeeded. Finally, I tried to help mothers step back off the ledge and look at the bigger picture — breastfeeding was not the only way to feed their baby while we were working to overcome the bumps in the road.

Where I failed was in my inability to effectively counsel when it came to the mysteries of the latch. In large part it was because I was a man and helping the dyad succeed at latching on to the breast can require a hands-on approach with which I felt a bit uncomfortable. I could certainly test a baby’s suck and oral architecture with my pinky but otherwise I had to rely on women to help if latching was a problem. I think even trained lactation consultants have difficulty with this mysterious process, which is completely hidden from view inside the baby’s mouth.

Fortunately for me and the dyads I was working with, we rarely considered ankyloglossia as a problem. My training had been that tongue-tie seldom, if ever, contributed to speech problems and even less commonly hindered latch. I think I recall snipping a couple of lingual frenulums early in my career in a bloodless and seemingly painless procedure. But, for the life of me I can’t recall the motivation. It may have been that the ankyloglossia was so obvious that I couldn’t convince the parents it would resolve or it was at the request of a lactation consultant.

But, obviously after I stopped seeing newborns a decade and a half ago the lingual frenulum became a target of surgical assault with, at times, unfortunate results that made breastfeeding painful and more difficult. It’s hard for me to imagine why anyone would consider using a laser for such a simple procedure. But, then I haven’t invested in a laser that allowed me to charge $800 for the procedure. I doubt I even charged for it. It wouldn’t have been worth the time and effort to look up the code. But, then, technology and money can be powerful motivators.

The good news is the AAP has been watching and recently issued a clinical report in which they state what many of us have known from personal observation — They further note that “the symptoms of ankyloglossia overlap those of other breastfeeding difficulties.”

So there you have it. Another fad has been squashed and we’ve come full circle. The latch still remains mystery hidden from view. I think we have to suspect that there exists a small number of dyads in which tongue-tie creates a problem with nursing. And, there may be some safe imaging technique coming along that gives us a glimpse of what happens in the dark recesses of a nursing baby’s mouth. Until then we must rely on masters of the art of lactation consulting, the “Latch Whisperers.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Case Series: Upadacitinib Effective for Granulomatous Cheilitis

TOPLINE:

in a small retrospective case series.

METHODOLOGY:

- Granulomatous cheilitis is a rare, nonnecrotizing granulomatous inflammatory disorder characterized by intermittent or persistent swelling of the lips.

- In a retrospective case series of five patients (median age, 30 years; four women) with granulomatous cheilitis resistant to systemic treatments at a Belgian hospital between June 2023 and March 2024, all five were treated with a high dose of upadacitinib (30 mg daily).

- The primary endpoint was objective clinical improvement in lip swelling and infiltration over a median follow-up of 7.2 months.

- Three patients had concomitant dormant Crohn’s disease (CD); a secondary outcome was disease activity in these patients.

TAKEAWAY:

- Upadacitinib treatment resulted in a complete response in four patients (80%) within a median of 3.8 months and a partial response in one patient.

- CD remained dormant in the three patients with CD.

- The safety profile of upadacitinib was favorable, and no serious adverse events were reported. Two patients experienced headaches, acne, mild changes in lipids, and/or transaminitis.

IN PRACTICE:

“Upadacitinib was effective in treating patients with recalcitrant and long-lasting granulomatous cheilitis, even in cases of concomitant CD, which could substantially improve the quality of life of affected patients,” the authors wrote. More studies are needed to confirm these results in larger groups of patients over longer periods of time, “and with other JAK inhibitors.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Axel De Greef, MD, Department of Dermatology, Cliniques universitaires Saint-Luc, Université catholique de Louvain (UCLouvain), Brussels, Belgium. It was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The small sample size and short follow-up may limit the generalizability of the findings to a larger population of patients with granulomatous cheilitis.

DISCLOSURES:

The study did not report any funding sources. Some authors reported receiving nonfinancial support and personal fees from various pharmaceutical companies outside the submitted work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

in a small retrospective case series.

METHODOLOGY:

- Granulomatous cheilitis is a rare, nonnecrotizing granulomatous inflammatory disorder characterized by intermittent or persistent swelling of the lips.

- In a retrospective case series of five patients (median age, 30 years; four women) with granulomatous cheilitis resistant to systemic treatments at a Belgian hospital between June 2023 and March 2024, all five were treated with a high dose of upadacitinib (30 mg daily).

- The primary endpoint was objective clinical improvement in lip swelling and infiltration over a median follow-up of 7.2 months.

- Three patients had concomitant dormant Crohn’s disease (CD); a secondary outcome was disease activity in these patients.

TAKEAWAY:

- Upadacitinib treatment resulted in a complete response in four patients (80%) within a median of 3.8 months and a partial response in one patient.

- CD remained dormant in the three patients with CD.

- The safety profile of upadacitinib was favorable, and no serious adverse events were reported. Two patients experienced headaches, acne, mild changes in lipids, and/or transaminitis.

IN PRACTICE:

“Upadacitinib was effective in treating patients with recalcitrant and long-lasting granulomatous cheilitis, even in cases of concomitant CD, which could substantially improve the quality of life of affected patients,” the authors wrote. More studies are needed to confirm these results in larger groups of patients over longer periods of time, “and with other JAK inhibitors.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Axel De Greef, MD, Department of Dermatology, Cliniques universitaires Saint-Luc, Université catholique de Louvain (UCLouvain), Brussels, Belgium. It was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The small sample size and short follow-up may limit the generalizability of the findings to a larger population of patients with granulomatous cheilitis.

DISCLOSURES:

The study did not report any funding sources. Some authors reported receiving nonfinancial support and personal fees from various pharmaceutical companies outside the submitted work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

in a small retrospective case series.

METHODOLOGY:

- Granulomatous cheilitis is a rare, nonnecrotizing granulomatous inflammatory disorder characterized by intermittent or persistent swelling of the lips.

- In a retrospective case series of five patients (median age, 30 years; four women) with granulomatous cheilitis resistant to systemic treatments at a Belgian hospital between June 2023 and March 2024, all five were treated with a high dose of upadacitinib (30 mg daily).

- The primary endpoint was objective clinical improvement in lip swelling and infiltration over a median follow-up of 7.2 months.

- Three patients had concomitant dormant Crohn’s disease (CD); a secondary outcome was disease activity in these patients.

TAKEAWAY:

- Upadacitinib treatment resulted in a complete response in four patients (80%) within a median of 3.8 months and a partial response in one patient.

- CD remained dormant in the three patients with CD.

- The safety profile of upadacitinib was favorable, and no serious adverse events were reported. Two patients experienced headaches, acne, mild changes in lipids, and/or transaminitis.

IN PRACTICE:

“Upadacitinib was effective in treating patients with recalcitrant and long-lasting granulomatous cheilitis, even in cases of concomitant CD, which could substantially improve the quality of life of affected patients,” the authors wrote. More studies are needed to confirm these results in larger groups of patients over longer periods of time, “and with other JAK inhibitors.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Axel De Greef, MD, Department of Dermatology, Cliniques universitaires Saint-Luc, Université catholique de Louvain (UCLouvain), Brussels, Belgium. It was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The small sample size and short follow-up may limit the generalizability of the findings to a larger population of patients with granulomatous cheilitis.

DISCLOSURES:

The study did not report any funding sources. Some authors reported receiving nonfinancial support and personal fees from various pharmaceutical companies outside the submitted work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Psychiatric, Autoimmune Comorbidities Increased in Patients with Alopecia Areata

TOPLINE:

and were at greater risk of developing those comorbidities after diagnosis.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers evaluated 63,384 patients with AA and 3,309,107 individuals without AA (aged 12-64 years) from the Merative MarketScan Research Databases.

- The matched cohorts included 16,512 patients with AA and 66,048 control individuals.

- Outcomes were the prevalence of psychiatric and autoimmune diseases at baseline and the incidence of new-onset psychiatric and autoimmune diseases during the year after diagnosis.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, patients with AA showed a greater prevalence of any psychiatric disease (30.9% vs 26.8%; P < .001) and any immune-mediated or autoimmune disease (16.1% vs 8.9%; P < .0001) than those with controls.

- In matched cohorts, patients with AA also showed a higher incidence of any new-onset psychiatric diseases (10.2% vs 6.8%; P < .001) or immune-mediated or autoimmune disease (6.2% vs 1.5%; P <.001) within the first 12 months of AA diagnosis than those with controls.

- Among patients with AA, the risk of developing a psychiatric comorbidity was higher (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.3; 95% CI, 1.3-1.4). The highest risks were seen for adjustment disorder (aHR, 1.5), panic disorder (aHR, 1.4), and sexual dysfunction (aHR, 1.4).

- Compared with controls, patients with AA were also at an increased risk of developing immune-mediated or autoimmune comorbidities (aHR, 2.7; 95% CI, 2.5-2.8), with the highest for systemic lupus (aHR, 5.7), atopic dermatitis (aHR, 4.3), and vitiligo (aHR, 3.8).

IN PRACTICE:

“Routine monitoring of patients with AA, especially those at risk of developing comorbidities, may permit earlier and more effective intervention,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Arash Mostaghimi, MD, MPA, MPH, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard University, Boston. It was published online on July 31, 2024, in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Causality could not be inferred because of the retrospective nature of the study. Comorbidities were solely diagnosed on the basis of diagnostic codes, and researchers did not have access to characteristics such as lab values that could have indicated any underlying comorbidity before the AA diagnosis. This study also did not account for the varying levels of severity of the disease, which may have led to an underestimation of disease burden and the risk for comorbidities.

DISCLOSURES:

AbbVie provided funding for this study. Mostaghimi disclosed receiving personal fees from Abbvie and several other companies outside of this work. The other four authors were current or former employees of Abbvie and have or may have stock and/or stock options in AbbVie.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

and were at greater risk of developing those comorbidities after diagnosis.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers evaluated 63,384 patients with AA and 3,309,107 individuals without AA (aged 12-64 years) from the Merative MarketScan Research Databases.

- The matched cohorts included 16,512 patients with AA and 66,048 control individuals.

- Outcomes were the prevalence of psychiatric and autoimmune diseases at baseline and the incidence of new-onset psychiatric and autoimmune diseases during the year after diagnosis.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, patients with AA showed a greater prevalence of any psychiatric disease (30.9% vs 26.8%; P < .001) and any immune-mediated or autoimmune disease (16.1% vs 8.9%; P < .0001) than those with controls.

- In matched cohorts, patients with AA also showed a higher incidence of any new-onset psychiatric diseases (10.2% vs 6.8%; P < .001) or immune-mediated or autoimmune disease (6.2% vs 1.5%; P <.001) within the first 12 months of AA diagnosis than those with controls.

- Among patients with AA, the risk of developing a psychiatric comorbidity was higher (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.3; 95% CI, 1.3-1.4). The highest risks were seen for adjustment disorder (aHR, 1.5), panic disorder (aHR, 1.4), and sexual dysfunction (aHR, 1.4).

- Compared with controls, patients with AA were also at an increased risk of developing immune-mediated or autoimmune comorbidities (aHR, 2.7; 95% CI, 2.5-2.8), with the highest for systemic lupus (aHR, 5.7), atopic dermatitis (aHR, 4.3), and vitiligo (aHR, 3.8).

IN PRACTICE:

“Routine monitoring of patients with AA, especially those at risk of developing comorbidities, may permit earlier and more effective intervention,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Arash Mostaghimi, MD, MPA, MPH, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard University, Boston. It was published online on July 31, 2024, in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Causality could not be inferred because of the retrospective nature of the study. Comorbidities were solely diagnosed on the basis of diagnostic codes, and researchers did not have access to characteristics such as lab values that could have indicated any underlying comorbidity before the AA diagnosis. This study also did not account for the varying levels of severity of the disease, which may have led to an underestimation of disease burden and the risk for comorbidities.

DISCLOSURES:

AbbVie provided funding for this study. Mostaghimi disclosed receiving personal fees from Abbvie and several other companies outside of this work. The other four authors were current or former employees of Abbvie and have or may have stock and/or stock options in AbbVie.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

and were at greater risk of developing those comorbidities after diagnosis.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers evaluated 63,384 patients with AA and 3,309,107 individuals without AA (aged 12-64 years) from the Merative MarketScan Research Databases.

- The matched cohorts included 16,512 patients with AA and 66,048 control individuals.

- Outcomes were the prevalence of psychiatric and autoimmune diseases at baseline and the incidence of new-onset psychiatric and autoimmune diseases during the year after diagnosis.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, patients with AA showed a greater prevalence of any psychiatric disease (30.9% vs 26.8%; P < .001) and any immune-mediated or autoimmune disease (16.1% vs 8.9%; P < .0001) than those with controls.

- In matched cohorts, patients with AA also showed a higher incidence of any new-onset psychiatric diseases (10.2% vs 6.8%; P < .001) or immune-mediated or autoimmune disease (6.2% vs 1.5%; P <.001) within the first 12 months of AA diagnosis than those with controls.

- Among patients with AA, the risk of developing a psychiatric comorbidity was higher (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.3; 95% CI, 1.3-1.4). The highest risks were seen for adjustment disorder (aHR, 1.5), panic disorder (aHR, 1.4), and sexual dysfunction (aHR, 1.4).

- Compared with controls, patients with AA were also at an increased risk of developing immune-mediated or autoimmune comorbidities (aHR, 2.7; 95% CI, 2.5-2.8), with the highest for systemic lupus (aHR, 5.7), atopic dermatitis (aHR, 4.3), and vitiligo (aHR, 3.8).

IN PRACTICE:

“Routine monitoring of patients with AA, especially those at risk of developing comorbidities, may permit earlier and more effective intervention,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Arash Mostaghimi, MD, MPA, MPH, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard University, Boston. It was published online on July 31, 2024, in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Causality could not be inferred because of the retrospective nature of the study. Comorbidities were solely diagnosed on the basis of diagnostic codes, and researchers did not have access to characteristics such as lab values that could have indicated any underlying comorbidity before the AA diagnosis. This study also did not account for the varying levels of severity of the disease, which may have led to an underestimation of disease burden and the risk for comorbidities.

DISCLOSURES:

AbbVie provided funding for this study. Mostaghimi disclosed receiving personal fees from Abbvie and several other companies outside of this work. The other four authors were current or former employees of Abbvie and have or may have stock and/or stock options in AbbVie.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

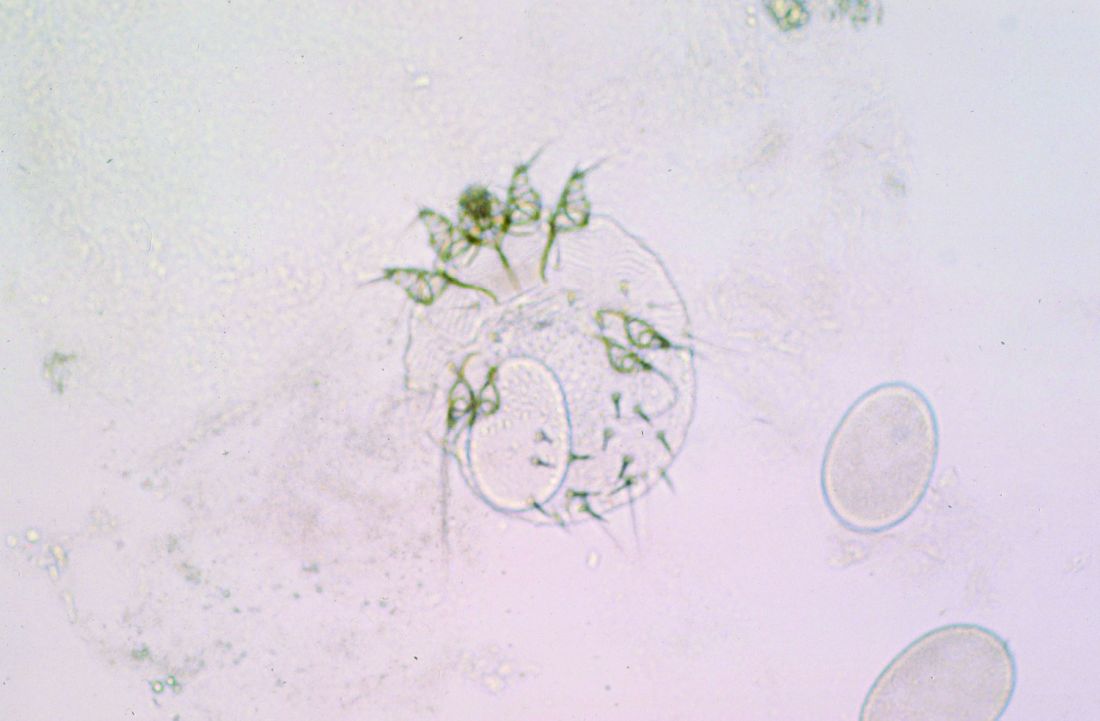

Skin Dxs in Children in Refugee Camps Include Fungal Infections, Leishmaniasis

on the topic, a literature review showed. However, likely culprits include infectious diseases with cutaneous manifestations, such as pediculosis, tinea capitis, and scabies.

“Current data indicates that one in two refugees are children,” one of the study investigators, Mehar Maju, MPH, a fourth-year student at of the University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, said in an interview following the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, where the results were presented during a poster session.

“The number of refugees continues to rise to unprecedented levels every year,” and climate change continues to drive increases in migration, “impacting those residing in camps,” she said. “As we continue to think about what this means for best supporting those residing in camps, I think it’s also important to consider how to best support refugees, specifically children, when they arrive in the United States. Part of this is to know what conditions are most prevalent and what type of social support this vulnerable population needs.”

To identify the common dermatologic conditions among children living in refugee camps, Ms. Maju and fellow fourth-year University of Washington medical student Nadia Siddiqui searched PubMed and Google Scholar for studies that were published in English and reported on the skin disease prevalence and management for refugees who are children. Key search terms used included “refugees,” “children,” “dermatology,” and “skin disease.” Of approximately 105 potential studies identified, 19 underwent analysis. Of these, only five were included in the final review.

One of the five studies was conducted in rural Nyala, Sudan. The study found that 88.8% of those living in orphanages and refugee camps were reported to have a skin disorder, commonly fungal or bacterial infections and dermatitis. In a separate case series, researchers found that cutaneous leishmaniasis was rising among Syrian refugee children.

A study that looked at morbidity and disease burden in mainland Greece refugee camps found that the skin was the second-most common site of communicable diseases among children, behind those of the respiratory tract. In another study that investigated the health of children in Australian immigration detention centers, complaints related to skin conditions were significantly elevated among children who were detained offshore, compared with those who were detained onshore.

Finally, in a study of 125 children between the ages of 1 and 15 years at a Sierra Leone–based displacement camp, the prevalence of scabies was 77% among those aged < 5 years and peaked to 86% among those aged 5-9 years.

“It was surprising to see the limited information about dermatologic diseases impacting children in refugee camps,” Ms. Maju said. “I expected that there would be more information on the specific proportion of diseases beyond those of infectious etiology. For example, I had believed that we would have more information on the prevalence of atopic dermatitis, vitiligo, and other more chronic skin diseases.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, mainly the lack of published information on the skin health of pediatric refugees. “A study that evaluates the health status and dermatologic prevalence of disease among children residing in camps and those newly arrived in the United States from camps would provide unprecedented insight into this topic,” Ms. Maju said. “The results could guide public health efforts in improving care delivery and preparedness in camps and clinicians serving this particular population when they arrive in the United States.”

She and Ms. Siddiqui reported having no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

on the topic, a literature review showed. However, likely culprits include infectious diseases with cutaneous manifestations, such as pediculosis, tinea capitis, and scabies.

“Current data indicates that one in two refugees are children,” one of the study investigators, Mehar Maju, MPH, a fourth-year student at of the University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, said in an interview following the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, where the results were presented during a poster session.

“The number of refugees continues to rise to unprecedented levels every year,” and climate change continues to drive increases in migration, “impacting those residing in camps,” she said. “As we continue to think about what this means for best supporting those residing in camps, I think it’s also important to consider how to best support refugees, specifically children, when they arrive in the United States. Part of this is to know what conditions are most prevalent and what type of social support this vulnerable population needs.”

To identify the common dermatologic conditions among children living in refugee camps, Ms. Maju and fellow fourth-year University of Washington medical student Nadia Siddiqui searched PubMed and Google Scholar for studies that were published in English and reported on the skin disease prevalence and management for refugees who are children. Key search terms used included “refugees,” “children,” “dermatology,” and “skin disease.” Of approximately 105 potential studies identified, 19 underwent analysis. Of these, only five were included in the final review.

One of the five studies was conducted in rural Nyala, Sudan. The study found that 88.8% of those living in orphanages and refugee camps were reported to have a skin disorder, commonly fungal or bacterial infections and dermatitis. In a separate case series, researchers found that cutaneous leishmaniasis was rising among Syrian refugee children.

A study that looked at morbidity and disease burden in mainland Greece refugee camps found that the skin was the second-most common site of communicable diseases among children, behind those of the respiratory tract. In another study that investigated the health of children in Australian immigration detention centers, complaints related to skin conditions were significantly elevated among children who were detained offshore, compared with those who were detained onshore.

Finally, in a study of 125 children between the ages of 1 and 15 years at a Sierra Leone–based displacement camp, the prevalence of scabies was 77% among those aged < 5 years and peaked to 86% among those aged 5-9 years.

“It was surprising to see the limited information about dermatologic diseases impacting children in refugee camps,” Ms. Maju said. “I expected that there would be more information on the specific proportion of diseases beyond those of infectious etiology. For example, I had believed that we would have more information on the prevalence of atopic dermatitis, vitiligo, and other more chronic skin diseases.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, mainly the lack of published information on the skin health of pediatric refugees. “A study that evaluates the health status and dermatologic prevalence of disease among children residing in camps and those newly arrived in the United States from camps would provide unprecedented insight into this topic,” Ms. Maju said. “The results could guide public health efforts in improving care delivery and preparedness in camps and clinicians serving this particular population when they arrive in the United States.”

She and Ms. Siddiqui reported having no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

on the topic, a literature review showed. However, likely culprits include infectious diseases with cutaneous manifestations, such as pediculosis, tinea capitis, and scabies.

“Current data indicates that one in two refugees are children,” one of the study investigators, Mehar Maju, MPH, a fourth-year student at of the University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, said in an interview following the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, where the results were presented during a poster session.

“The number of refugees continues to rise to unprecedented levels every year,” and climate change continues to drive increases in migration, “impacting those residing in camps,” she said. “As we continue to think about what this means for best supporting those residing in camps, I think it’s also important to consider how to best support refugees, specifically children, when they arrive in the United States. Part of this is to know what conditions are most prevalent and what type of social support this vulnerable population needs.”

To identify the common dermatologic conditions among children living in refugee camps, Ms. Maju and fellow fourth-year University of Washington medical student Nadia Siddiqui searched PubMed and Google Scholar for studies that were published in English and reported on the skin disease prevalence and management for refugees who are children. Key search terms used included “refugees,” “children,” “dermatology,” and “skin disease.” Of approximately 105 potential studies identified, 19 underwent analysis. Of these, only five were included in the final review.

One of the five studies was conducted in rural Nyala, Sudan. The study found that 88.8% of those living in orphanages and refugee camps were reported to have a skin disorder, commonly fungal or bacterial infections and dermatitis. In a separate case series, researchers found that cutaneous leishmaniasis was rising among Syrian refugee children.

A study that looked at morbidity and disease burden in mainland Greece refugee camps found that the skin was the second-most common site of communicable diseases among children, behind those of the respiratory tract. In another study that investigated the health of children in Australian immigration detention centers, complaints related to skin conditions were significantly elevated among children who were detained offshore, compared with those who were detained onshore.

Finally, in a study of 125 children between the ages of 1 and 15 years at a Sierra Leone–based displacement camp, the prevalence of scabies was 77% among those aged < 5 years and peaked to 86% among those aged 5-9 years.

“It was surprising to see the limited information about dermatologic diseases impacting children in refugee camps,” Ms. Maju said. “I expected that there would be more information on the specific proportion of diseases beyond those of infectious etiology. For example, I had believed that we would have more information on the prevalence of atopic dermatitis, vitiligo, and other more chronic skin diseases.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, mainly the lack of published information on the skin health of pediatric refugees. “A study that evaluates the health status and dermatologic prevalence of disease among children residing in camps and those newly arrived in the United States from camps would provide unprecedented insight into this topic,” Ms. Maju said. “The results could guide public health efforts in improving care delivery and preparedness in camps and clinicians serving this particular population when they arrive in the United States.”

She and Ms. Siddiqui reported having no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM SPD 2024

Government Accuses Health System of Paying Docs Outrageous Salaries for Patient Referrals

Strapped for cash and searching for new profits, Tennessee-based Erlanger Health System illegally paid excessive salaries to physicians in exchange for patient referrals, the US government alleged in a federal lawsuit.

Erlanger changed its compensation model to entice revenue-generating doctors, paying some two to three times the median salary for their specialty, according to the complaint.

The physicians in turn referred numerous patients to Erlanger, and the health system submitted claims to Medicare for the referred services in violation of the Stark Law, according to the suit, filed in US District Court for the Western District of North Carolina.

The government’s complaint “serves as a warning” to healthcare providers who try to boost profits through improper financial arrangements with referring physicians, said Tamala E. Miles, Special Agent in Charge for the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG).

In a statement provided to this news organization, Erlanger denied the allegations and said it would “vigorously” defend the lawsuit.

“Erlanger paid physicians based on amounts that outside experts advised was fair market value,” Erlanger officials said in the statement. “Erlanger did not pay for referrals. A complete picture of the facts will demonstrate that the allegations lack merit and tell a very different story than what the government now claims.”

The Erlanger case is a reminder to physicians to consult their own knowledgeable advisors when considering financial arrangements with hospitals, said William Sarraille, JD, adjunct professor for the University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law in Baltimore and a regulatory consultant.

“There is a tendency by physicians when contracting ... to rely on [hospitals’] perceived compliance and legal expertise,” Mr. Sarraille told this news organization. “This case illustrates the risks in doing so. Sometimes bigger doesn’t translate into more sophisticated or more effective from a compliance perspective.”

Stark Law Prohibits Kickbacks

The Stark Law prohibits hospitals from billing the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) for services referred by a physician with whom the hospital has an improper financial relationship.

CMS paid Erlanger about $27.8 million for claims stemming from the improper financial arrangements, the government contends.

“HHS-OIG will continue to investigate such deals to prevent financial arrangements that could compromise impartial medical judgment, increase healthcare costs, and erode public trust in the healthcare system,” Ms. Miles said in a statement.

Suit: Health System’s Money Woes Led to Illegal Arrangements

Erlanger’s financial troubles allegedly started after a previous run-in with the US government over false claims.

In 2005, Erlanger Health System agreed to pay the government $40 million to resolve allegations that it knowingly submitted false claims to Medicare, according to the government’s complaint. At the time, Erlanger entered into a Corporate Integrity Agreement (CIA) with the OIG that required Erlanger to put controls in place to ensure its financial relationships did not violate the Stark Law.

Erlanger’s agreement with OIG ended in 2010. Over the next 3 years, the health system lost nearly $32 million and in fiscal year 2013, had only 65 days of cash on hand, according to the government’s lawsuit.

Beginning in 2013, Erlanger allegedly implemented a strategy to increase profits by employing more physicians, particularly specialists from competing hospitals whose patients would need costly hospital stays, according to the complaint.

Once hired, Erlanger’s physicians were expected to treat patients at Erlanger’s hospitals and refer them to other providers within the health system, the suit claims. Erlanger also relaxed or eliminated the oversight and controls on physician compensation put in place under the CIA. For example, Erlanger’s CEO signed some compensation contracts before its chief compliance officer could review them and no longer allowed the compliance officer to vote on whether to approve compensation arrangements, according to the complaint.

Erlanger also changed its compensation model to include large salaries for medical director and academic positions and allegedly paid such salaries to physicians without ensuring the required work was performed. As a result, Erlanger physicians with profitable referrals were among the highest paid in the nation for their specialties, the government claims. For example, according to the complaint:

- Erlanger paid an electrophysiologist an annual clinical salary of $816,701, a medical director salary of $101,080, an academic salary of $59,322, and a productivity incentive based on work relative value units (wRVUs). The medical director and academic salaries paid were near the 90th percentile of comparable salaries in the specialty.

- The health system paid a neurosurgeon a base salary of $654,735, a productivity incentive based on wRVUs, and payments for excess call coverage ranging from $400 to $1000 per 24-hour shift. In 2016, the neurosurgeon made $500,000 in excess call payments.

- Erlanger paid a cardiothoracic surgeon a base clinical salary of $1,070,000, a sign-on bonus of $150,000, a retention bonus of $100,000 (payable in the 4th year of the contract), and a program incentive of up to $150,000 per year.

In addition, Erlanger ignored patient safety concerns about some of its high revenue-generating physicians, the government claims.

For instance, Erlanger received multiple complaints that a cardiothoracic surgeon was misusing an expensive form of life support in which pumps and oxygenators take over heart and lung function. Overuse of the equipment prolonged patients’ hospital stays and increased the hospital fees generated by the surgeon, according to the complaint. Staff also raised concerns about the cardiothoracic surgeon’s patient outcomes.

But Erlanger disregarded the concerns and in 2018, increased the cardiothoracic surgeon’s retention bonus from $100,000 to $250,000, the suit alleges. A year later, the health system increased his base salary from $1,070,000 to $1,195,000.

Health care compensation and billing consultants alerted Erlanger that it was overpaying salaries and handing out bonuses based on measures that overstated the work physicians were performing, but Erlanger ignored the warnings, according to the complaint.

Administrators allegedly resisted efforts by the chief compliance officer to hire an outside consultant to review its compensation models. Erlanger fired the compliance officer in 2019.

The former chief compliance officer and another administrator filed a whistleblower lawsuit against Erlanger in 2021. The two administrators are relators in the government’s July 2024 lawsuit.

How to Protect Yourself From Illegal Hospital Deals

The Erlanger case is the latest in a series of recent complaints by the federal government involving financial arrangements between hospitals and physicians.

In December 2023, Indianapolis-based Community Health Network Inc. agreed to pay the government $345 million to resolve claims that it paid physicians above fair market value and awarded bonuses tied to referrals in violation of the Stark Law.

Also in 2023, Saginaw, Michigan–based Covenant HealthCare and two physicians paid the government $69 million to settle allegations that administrators engaged in improper financial arrangements with referring physicians and a physician-owned investment group. In another 2023 case, Massachusetts Eye and Ear in Boston agreed to pay $5.7 million to resolve claims that some of its physician compensation plans violated the Stark Law.

Before you enter into a financial arrangement with a hospital, it’s also important to examine what percentile the aggregate compensation would reflect, law professor Mr. Sarraille said. The Erlanger case highlights federal officials’ suspicion of compensation, in aggregate, that exceeds the 90th percentile and increased attention to compensation that exceeds the 75th percentile, he said.

To research compensation levels, doctors can review the Medical Group Management Association’s annual compensation report or search its compensation data.

Before signing any contracts, Mr. Sarraille suggests, physicians should also consider whether the hospital shares the same values. Ask physicians at the hospital what they have to say about the hospital’s culture, vision, and values. Have physicians left the hospital after their practices were acquired? Consider speaking with them to learn why.

Keep in mind that a doctor’s reputation could be impacted by a compliance complaint, regardless of whether it’s directed at the hospital and not the employed physician, Mr. Sarraille said.

“The [Erlanger] complaint focuses on the compensation of specific, named physicians saying they were wildly overcompensated,” he said. “The implication is that they sold their referral power in exchange for a pay day. It’s a bad look, no matter how the case evolves from here.”

Physicians could also face their own liability risk under the Stark Law and False Claims Act, depending on the circumstances. In the event of related quality-of-care issues, medical liability could come into play, Mr. Sarraille noted. In such cases, plaintiffs’ attorneys may see an opportunity to boost their claims with allegations that the patient harm was a function of “chasing compensation dollars,” Mr. Sarraille said.

“Where that happens, plaintiff lawyers see the potential for crippling punitive damages, which might not be covered by an insurer,” he said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Strapped for cash and searching for new profits, Tennessee-based Erlanger Health System illegally paid excessive salaries to physicians in exchange for patient referrals, the US government alleged in a federal lawsuit.

Erlanger changed its compensation model to entice revenue-generating doctors, paying some two to three times the median salary for their specialty, according to the complaint.

The physicians in turn referred numerous patients to Erlanger, and the health system submitted claims to Medicare for the referred services in violation of the Stark Law, according to the suit, filed in US District Court for the Western District of North Carolina.

The government’s complaint “serves as a warning” to healthcare providers who try to boost profits through improper financial arrangements with referring physicians, said Tamala E. Miles, Special Agent in Charge for the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG).

In a statement provided to this news organization, Erlanger denied the allegations and said it would “vigorously” defend the lawsuit.

“Erlanger paid physicians based on amounts that outside experts advised was fair market value,” Erlanger officials said in the statement. “Erlanger did not pay for referrals. A complete picture of the facts will demonstrate that the allegations lack merit and tell a very different story than what the government now claims.”

The Erlanger case is a reminder to physicians to consult their own knowledgeable advisors when considering financial arrangements with hospitals, said William Sarraille, JD, adjunct professor for the University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law in Baltimore and a regulatory consultant.

“There is a tendency by physicians when contracting ... to rely on [hospitals’] perceived compliance and legal expertise,” Mr. Sarraille told this news organization. “This case illustrates the risks in doing so. Sometimes bigger doesn’t translate into more sophisticated or more effective from a compliance perspective.”

Stark Law Prohibits Kickbacks

The Stark Law prohibits hospitals from billing the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) for services referred by a physician with whom the hospital has an improper financial relationship.

CMS paid Erlanger about $27.8 million for claims stemming from the improper financial arrangements, the government contends.

“HHS-OIG will continue to investigate such deals to prevent financial arrangements that could compromise impartial medical judgment, increase healthcare costs, and erode public trust in the healthcare system,” Ms. Miles said in a statement.

Suit: Health System’s Money Woes Led to Illegal Arrangements

Erlanger’s financial troubles allegedly started after a previous run-in with the US government over false claims.

In 2005, Erlanger Health System agreed to pay the government $40 million to resolve allegations that it knowingly submitted false claims to Medicare, according to the government’s complaint. At the time, Erlanger entered into a Corporate Integrity Agreement (CIA) with the OIG that required Erlanger to put controls in place to ensure its financial relationships did not violate the Stark Law.

Erlanger’s agreement with OIG ended in 2010. Over the next 3 years, the health system lost nearly $32 million and in fiscal year 2013, had only 65 days of cash on hand, according to the government’s lawsuit.

Beginning in 2013, Erlanger allegedly implemented a strategy to increase profits by employing more physicians, particularly specialists from competing hospitals whose patients would need costly hospital stays, according to the complaint.

Once hired, Erlanger’s physicians were expected to treat patients at Erlanger’s hospitals and refer them to other providers within the health system, the suit claims. Erlanger also relaxed or eliminated the oversight and controls on physician compensation put in place under the CIA. For example, Erlanger’s CEO signed some compensation contracts before its chief compliance officer could review them and no longer allowed the compliance officer to vote on whether to approve compensation arrangements, according to the complaint.

Erlanger also changed its compensation model to include large salaries for medical director and academic positions and allegedly paid such salaries to physicians without ensuring the required work was performed. As a result, Erlanger physicians with profitable referrals were among the highest paid in the nation for their specialties, the government claims. For example, according to the complaint:

- Erlanger paid an electrophysiologist an annual clinical salary of $816,701, a medical director salary of $101,080, an academic salary of $59,322, and a productivity incentive based on work relative value units (wRVUs). The medical director and academic salaries paid were near the 90th percentile of comparable salaries in the specialty.

- The health system paid a neurosurgeon a base salary of $654,735, a productivity incentive based on wRVUs, and payments for excess call coverage ranging from $400 to $1000 per 24-hour shift. In 2016, the neurosurgeon made $500,000 in excess call payments.

- Erlanger paid a cardiothoracic surgeon a base clinical salary of $1,070,000, a sign-on bonus of $150,000, a retention bonus of $100,000 (payable in the 4th year of the contract), and a program incentive of up to $150,000 per year.

In addition, Erlanger ignored patient safety concerns about some of its high revenue-generating physicians, the government claims.

For instance, Erlanger received multiple complaints that a cardiothoracic surgeon was misusing an expensive form of life support in which pumps and oxygenators take over heart and lung function. Overuse of the equipment prolonged patients’ hospital stays and increased the hospital fees generated by the surgeon, according to the complaint. Staff also raised concerns about the cardiothoracic surgeon’s patient outcomes.

But Erlanger disregarded the concerns and in 2018, increased the cardiothoracic surgeon’s retention bonus from $100,000 to $250,000, the suit alleges. A year later, the health system increased his base salary from $1,070,000 to $1,195,000.

Health care compensation and billing consultants alerted Erlanger that it was overpaying salaries and handing out bonuses based on measures that overstated the work physicians were performing, but Erlanger ignored the warnings, according to the complaint.

Administrators allegedly resisted efforts by the chief compliance officer to hire an outside consultant to review its compensation models. Erlanger fired the compliance officer in 2019.

The former chief compliance officer and another administrator filed a whistleblower lawsuit against Erlanger in 2021. The two administrators are relators in the government’s July 2024 lawsuit.

How to Protect Yourself From Illegal Hospital Deals

The Erlanger case is the latest in a series of recent complaints by the federal government involving financial arrangements between hospitals and physicians.

In December 2023, Indianapolis-based Community Health Network Inc. agreed to pay the government $345 million to resolve claims that it paid physicians above fair market value and awarded bonuses tied to referrals in violation of the Stark Law.

Also in 2023, Saginaw, Michigan–based Covenant HealthCare and two physicians paid the government $69 million to settle allegations that administrators engaged in improper financial arrangements with referring physicians and a physician-owned investment group. In another 2023 case, Massachusetts Eye and Ear in Boston agreed to pay $5.7 million to resolve claims that some of its physician compensation plans violated the Stark Law.

Before you enter into a financial arrangement with a hospital, it’s also important to examine what percentile the aggregate compensation would reflect, law professor Mr. Sarraille said. The Erlanger case highlights federal officials’ suspicion of compensation, in aggregate, that exceeds the 90th percentile and increased attention to compensation that exceeds the 75th percentile, he said.

To research compensation levels, doctors can review the Medical Group Management Association’s annual compensation report or search its compensation data.

Before signing any contracts, Mr. Sarraille suggests, physicians should also consider whether the hospital shares the same values. Ask physicians at the hospital what they have to say about the hospital’s culture, vision, and values. Have physicians left the hospital after their practices were acquired? Consider speaking with them to learn why.

Keep in mind that a doctor’s reputation could be impacted by a compliance complaint, regardless of whether it’s directed at the hospital and not the employed physician, Mr. Sarraille said.

“The [Erlanger] complaint focuses on the compensation of specific, named physicians saying they were wildly overcompensated,” he said. “The implication is that they sold their referral power in exchange for a pay day. It’s a bad look, no matter how the case evolves from here.”

Physicians could also face their own liability risk under the Stark Law and False Claims Act, depending on the circumstances. In the event of related quality-of-care issues, medical liability could come into play, Mr. Sarraille noted. In such cases, plaintiffs’ attorneys may see an opportunity to boost their claims with allegations that the patient harm was a function of “chasing compensation dollars,” Mr. Sarraille said.

“Where that happens, plaintiff lawyers see the potential for crippling punitive damages, which might not be covered by an insurer,” he said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Strapped for cash and searching for new profits, Tennessee-based Erlanger Health System illegally paid excessive salaries to physicians in exchange for patient referrals, the US government alleged in a federal lawsuit.

Erlanger changed its compensation model to entice revenue-generating doctors, paying some two to three times the median salary for their specialty, according to the complaint.

The physicians in turn referred numerous patients to Erlanger, and the health system submitted claims to Medicare for the referred services in violation of the Stark Law, according to the suit, filed in US District Court for the Western District of North Carolina.

The government’s complaint “serves as a warning” to healthcare providers who try to boost profits through improper financial arrangements with referring physicians, said Tamala E. Miles, Special Agent in Charge for the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG).

In a statement provided to this news organization, Erlanger denied the allegations and said it would “vigorously” defend the lawsuit.

“Erlanger paid physicians based on amounts that outside experts advised was fair market value,” Erlanger officials said in the statement. “Erlanger did not pay for referrals. A complete picture of the facts will demonstrate that the allegations lack merit and tell a very different story than what the government now claims.”

The Erlanger case is a reminder to physicians to consult their own knowledgeable advisors when considering financial arrangements with hospitals, said William Sarraille, JD, adjunct professor for the University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law in Baltimore and a regulatory consultant.

“There is a tendency by physicians when contracting ... to rely on [hospitals’] perceived compliance and legal expertise,” Mr. Sarraille told this news organization. “This case illustrates the risks in doing so. Sometimes bigger doesn’t translate into more sophisticated or more effective from a compliance perspective.”

Stark Law Prohibits Kickbacks

The Stark Law prohibits hospitals from billing the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) for services referred by a physician with whom the hospital has an improper financial relationship.

CMS paid Erlanger about $27.8 million for claims stemming from the improper financial arrangements, the government contends.

“HHS-OIG will continue to investigate such deals to prevent financial arrangements that could compromise impartial medical judgment, increase healthcare costs, and erode public trust in the healthcare system,” Ms. Miles said in a statement.

Suit: Health System’s Money Woes Led to Illegal Arrangements

Erlanger’s financial troubles allegedly started after a previous run-in with the US government over false claims.

In 2005, Erlanger Health System agreed to pay the government $40 million to resolve allegations that it knowingly submitted false claims to Medicare, according to the government’s complaint. At the time, Erlanger entered into a Corporate Integrity Agreement (CIA) with the OIG that required Erlanger to put controls in place to ensure its financial relationships did not violate the Stark Law.

Erlanger’s agreement with OIG ended in 2010. Over the next 3 years, the health system lost nearly $32 million and in fiscal year 2013, had only 65 days of cash on hand, according to the government’s lawsuit.

Beginning in 2013, Erlanger allegedly implemented a strategy to increase profits by employing more physicians, particularly specialists from competing hospitals whose patients would need costly hospital stays, according to the complaint.

Once hired, Erlanger’s physicians were expected to treat patients at Erlanger’s hospitals and refer them to other providers within the health system, the suit claims. Erlanger also relaxed or eliminated the oversight and controls on physician compensation put in place under the CIA. For example, Erlanger’s CEO signed some compensation contracts before its chief compliance officer could review them and no longer allowed the compliance officer to vote on whether to approve compensation arrangements, according to the complaint.

Erlanger also changed its compensation model to include large salaries for medical director and academic positions and allegedly paid such salaries to physicians without ensuring the required work was performed. As a result, Erlanger physicians with profitable referrals were among the highest paid in the nation for their specialties, the government claims. For example, according to the complaint:

- Erlanger paid an electrophysiologist an annual clinical salary of $816,701, a medical director salary of $101,080, an academic salary of $59,322, and a productivity incentive based on work relative value units (wRVUs). The medical director and academic salaries paid were near the 90th percentile of comparable salaries in the specialty.

- The health system paid a neurosurgeon a base salary of $654,735, a productivity incentive based on wRVUs, and payments for excess call coverage ranging from $400 to $1000 per 24-hour shift. In 2016, the neurosurgeon made $500,000 in excess call payments.

- Erlanger paid a cardiothoracic surgeon a base clinical salary of $1,070,000, a sign-on bonus of $150,000, a retention bonus of $100,000 (payable in the 4th year of the contract), and a program incentive of up to $150,000 per year.

In addition, Erlanger ignored patient safety concerns about some of its high revenue-generating physicians, the government claims.

For instance, Erlanger received multiple complaints that a cardiothoracic surgeon was misusing an expensive form of life support in which pumps and oxygenators take over heart and lung function. Overuse of the equipment prolonged patients’ hospital stays and increased the hospital fees generated by the surgeon, according to the complaint. Staff also raised concerns about the cardiothoracic surgeon’s patient outcomes.

But Erlanger disregarded the concerns and in 2018, increased the cardiothoracic surgeon’s retention bonus from $100,000 to $250,000, the suit alleges. A year later, the health system increased his base salary from $1,070,000 to $1,195,000.

Health care compensation and billing consultants alerted Erlanger that it was overpaying salaries and handing out bonuses based on measures that overstated the work physicians were performing, but Erlanger ignored the warnings, according to the complaint.

Administrators allegedly resisted efforts by the chief compliance officer to hire an outside consultant to review its compensation models. Erlanger fired the compliance officer in 2019.

The former chief compliance officer and another administrator filed a whistleblower lawsuit against Erlanger in 2021. The two administrators are relators in the government’s July 2024 lawsuit.

How to Protect Yourself From Illegal Hospital Deals

The Erlanger case is the latest in a series of recent complaints by the federal government involving financial arrangements between hospitals and physicians.

In December 2023, Indianapolis-based Community Health Network Inc. agreed to pay the government $345 million to resolve claims that it paid physicians above fair market value and awarded bonuses tied to referrals in violation of the Stark Law.

Also in 2023, Saginaw, Michigan–based Covenant HealthCare and two physicians paid the government $69 million to settle allegations that administrators engaged in improper financial arrangements with referring physicians and a physician-owned investment group. In another 2023 case, Massachusetts Eye and Ear in Boston agreed to pay $5.7 million to resolve claims that some of its physician compensation plans violated the Stark Law.

Before you enter into a financial arrangement with a hospital, it’s also important to examine what percentile the aggregate compensation would reflect, law professor Mr. Sarraille said. The Erlanger case highlights federal officials’ suspicion of compensation, in aggregate, that exceeds the 90th percentile and increased attention to compensation that exceeds the 75th percentile, he said.

To research compensation levels, doctors can review the Medical Group Management Association’s annual compensation report or search its compensation data.

Before signing any contracts, Mr. Sarraille suggests, physicians should also consider whether the hospital shares the same values. Ask physicians at the hospital what they have to say about the hospital’s culture, vision, and values. Have physicians left the hospital after their practices were acquired? Consider speaking with them to learn why.

Keep in mind that a doctor’s reputation could be impacted by a compliance complaint, regardless of whether it’s directed at the hospital and not the employed physician, Mr. Sarraille said.

“The [Erlanger] complaint focuses on the compensation of specific, named physicians saying they were wildly overcompensated,” he said. “The implication is that they sold their referral power in exchange for a pay day. It’s a bad look, no matter how the case evolves from here.”

Physicians could also face their own liability risk under the Stark Law and False Claims Act, depending on the circumstances. In the event of related quality-of-care issues, medical liability could come into play, Mr. Sarraille noted. In such cases, plaintiffs’ attorneys may see an opportunity to boost their claims with allegations that the patient harm was a function of “chasing compensation dollars,” Mr. Sarraille said.

“Where that happens, plaintiff lawyers see the potential for crippling punitive damages, which might not be covered by an insurer,” he said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SUNY Downstate Emergency Medicine Doc Charged With $1.5M Fraud

In a case that spotlights the importance of comprehensive financial controls in medical offices,

Michael Lucchesi, MD, who had served as chairman of Emergency Medicine at SUNY Downstate Medical Center in New York City, was arraigned on July 9 and pleaded not guilty. Dr. Lucchesi’s attorney, Earl Ward, did not respond to messages from this news organization, but he told the New York Post that “the funds he used were not stolen funds.”

Dr. Lucchesi, who’s in his late 60s, faces nine counts of first- and second-degree grand larceny, first-degree falsifying business records, and third-degree criminal tax fraud. According to a press statement from the district attorney of Kings County, which encompasses the borough of Brooklyn, Dr. Lucchesi is accused of using his clinical practice’s business card for cash advances (about $115,000), high-end pet care ($176,000), personal travel ($348,000), gym membership and personal training ($109,000), catering ($52,000), tuition payments for his children ($46,000), and other expenses such as online shopping, flowers, liquor, and electronics.

Most of the alleged pet care spending — $120,000 — went to the Green Leaf Pet Resort, which has two locations in New Jersey, including one with “56 acres of nature and lots of tail wagging.” Some of the alleged spending on gym membership was at the New York Sports Clubs chain, where monthly membership tops out at $139.99.

The alleged spending occurred between 2016 and 2023 and was discovered by SUNY Downstate during an audit. Dr. Lucchesi reportedly left his position at the hospital, where he made $399,712 in 2022 as a professor, according to public records.

“As a high-ranking doctor at this vital healthcare institution, this defendant was entrusted with access to significant funds, which he allegedly exploited, stealing more than 1 million dollars to pay for a lavish lifestyle,” District Attorney Eric Gonzalez said in a statement.

SUNY Downstate is in a fight for its life amid efforts by New York Governor Kathy Hochul to shut it down. According to The New York Times, it is the only state-run hospital in New York City.

Dr. Lucchesi, who had previously served as the hospital’s chief medical officer and acting head, was released without bail. His next court date is September 25, 2024.

Size of Alleged Theft Is ‘Very Unusual’

David P. Weber, JD, DBA, a professor and fraud specialist at Salisbury University, Salisbury, Maryland, told this news organization that the fraudulent use of a business or purchase credit card is a form of embezzlement and “one of the most frequently seen types of frauds against organizations.”

William J. Kresse, JD, MSA, CPA/CFF, who studies fraud at Governors State University in University Park, Illinois, noted in an interview with this news organization that the high amount of alleged fraud in this case is “very unusual,” as is the period it is said to have occurred (over 6 years).

Mr. Kresse highlighted a 2024 report by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, which found that the median fraud loss in healthcare, on the basis of 117 cases, is $100,000. The most common form of fraud in the industry is corruption (47%), followed by billing (38%), noncash theft such as inventory (22%), and expense reimbursement (21%).

The details of the current case suggest that “SUNY Downstate had weak or insufficient internal controls to prevent this type of fraud,” Salisbury University’s Mr. Weber said. “However, research also makes clear that the tenure and position of the perpetrator play a significant role in the size of the fraud. Internal controls are supposed to apply to all employees, but the higher in the organization the perpetrator is, the easier it can be to engage in fraud.”

Even Small Medical Offices Can Act to Prevent Fraud

What can be done to prevent this kind of fraud? “Each employee should be required to submit actual receipts or scanned copies, and the reimbursement requests should be reviewed and inputted by a separate department or office of the organization to ensure that the expenses are legitimate,” Mr. Weber said. “In addition, all credit card statements should be available for review by the organization either simultaneously with the bill going to the employee or available for audit or review at any time without notification to the employee. Expenses that are in certain categories should be prohibited automatically and coded to the card so such a charge is rejected by the credit card bank.”

Smaller businesses — like many medical practices — may not have the manpower to handle these roles. In that case, Mr. Weber said, “The key is segregation or separation of duties. The bookkeeper cannot be the person receiving the bank statements, the payments from patients, and the invoices from vendors. There needs to be at least one other person in the loop to have some level of control.”

One strategy, he said, “is that the practice should institute a policy that only the doctor or owner of the practice can receive the mail, not the bookkeeper. Even if the practice leader does not actually review the bank statements, simply opening them before handing them off to the bookkeeper can provide a level of deterrence [since] the employee may get caught if someone else is reviewing the bank statements.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a case that spotlights the importance of comprehensive financial controls in medical offices,

Michael Lucchesi, MD, who had served as chairman of Emergency Medicine at SUNY Downstate Medical Center in New York City, was arraigned on July 9 and pleaded not guilty. Dr. Lucchesi’s attorney, Earl Ward, did not respond to messages from this news organization, but he told the New York Post that “the funds he used were not stolen funds.”

Dr. Lucchesi, who’s in his late 60s, faces nine counts of first- and second-degree grand larceny, first-degree falsifying business records, and third-degree criminal tax fraud. According to a press statement from the district attorney of Kings County, which encompasses the borough of Brooklyn, Dr. Lucchesi is accused of using his clinical practice’s business card for cash advances (about $115,000), high-end pet care ($176,000), personal travel ($348,000), gym membership and personal training ($109,000), catering ($52,000), tuition payments for his children ($46,000), and other expenses such as online shopping, flowers, liquor, and electronics.

Most of the alleged pet care spending — $120,000 — went to the Green Leaf Pet Resort, which has two locations in New Jersey, including one with “56 acres of nature and lots of tail wagging.” Some of the alleged spending on gym membership was at the New York Sports Clubs chain, where monthly membership tops out at $139.99.

The alleged spending occurred between 2016 and 2023 and was discovered by SUNY Downstate during an audit. Dr. Lucchesi reportedly left his position at the hospital, where he made $399,712 in 2022 as a professor, according to public records.

“As a high-ranking doctor at this vital healthcare institution, this defendant was entrusted with access to significant funds, which he allegedly exploited, stealing more than 1 million dollars to pay for a lavish lifestyle,” District Attorney Eric Gonzalez said in a statement.

SUNY Downstate is in a fight for its life amid efforts by New York Governor Kathy Hochul to shut it down. According to The New York Times, it is the only state-run hospital in New York City.

Dr. Lucchesi, who had previously served as the hospital’s chief medical officer and acting head, was released without bail. His next court date is September 25, 2024.

Size of Alleged Theft Is ‘Very Unusual’

David P. Weber, JD, DBA, a professor and fraud specialist at Salisbury University, Salisbury, Maryland, told this news organization that the fraudulent use of a business or purchase credit card is a form of embezzlement and “one of the most frequently seen types of frauds against organizations.”