User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

Psychological/neuropsychological testing: When to refer for reexamination

The evolution of illness prevention, diagnosis, and treatment has involved an increased appreciation for the clinical utility of longitudinal assessment. This has included the implementation of screening evaluations for high base rate medical conditions, such as cancer, that involve considerable morbidity and mortality.

Unfortunately, the mental health professions have been slow to embrace this approach. Baseline assessment with psychological/neuropsychological screening tests and more comprehensive test batteries to clarify diagnostic status and facilitate treatment planning is far more the exception than the rule in mental health care. This seems to be the case despite the strong evidence supporting this practice as well as multiple surveys indicating that psychiatrists and other physicians report a high level of satisfaction with the findings and recommendations of psychological/neuropsychological test reports.1-3

There is a substantial literature that reviews the relative indications and contraindications for initial psychological/neuropsychological test evaluations.4-7 However, there is a paucity of clinical and evidence-based information regarding criteria for follow-up assessment. Moreover, there are no consensus guidelines to inform decision-making regarding this issue.

In general, good clinical practice for baseline assessment and reexamination should include administration of both psychological and neuropsychological tests. Based on clinical experience, this article addresses the relative indications and contraindications for psychological/neuropsychological test reassessment of adults seen in psychiatric care. It also outlines suggested time frames for such reevaluations, based on the patient’s clinical status and circumstances.

Why are patients not referred for reassessment more often?

There are several reasons patients are not referred for follow-up testing, beginning with the failure, at times, of the psychologist to state in the recommendations section of the test report whether a reassessment is indicated, under what circumstances, and within what time frame. Empirical data is lacking, but predicated on clinical experience, even when a strong and unequivocal recommendation is made for reassessment, only a very small percentage of patients are seen for follow-up evaluation.

There are numerous reasons why this occurs. The patient and/or the psychiatrist may overlook or forget about the recommendation for reassessment, particularly if it was embedded in a lengthy list of recommendations and the suggested time frame for the reassessment was several years away. The patient and the psychiatrist may decide against going forward with a reexamination, for a variety of substantive reasons. The patient might decline, against medical advice, to be retested. The patient may fail to make or keep an appointment for the follow-up reexamination. The patient might leave treatment and become lost to follow-up. The patient might not be able to find an appropriate psychologist. The insurance company may decline to authorize follow-up testing.8

Indications for reevaluation

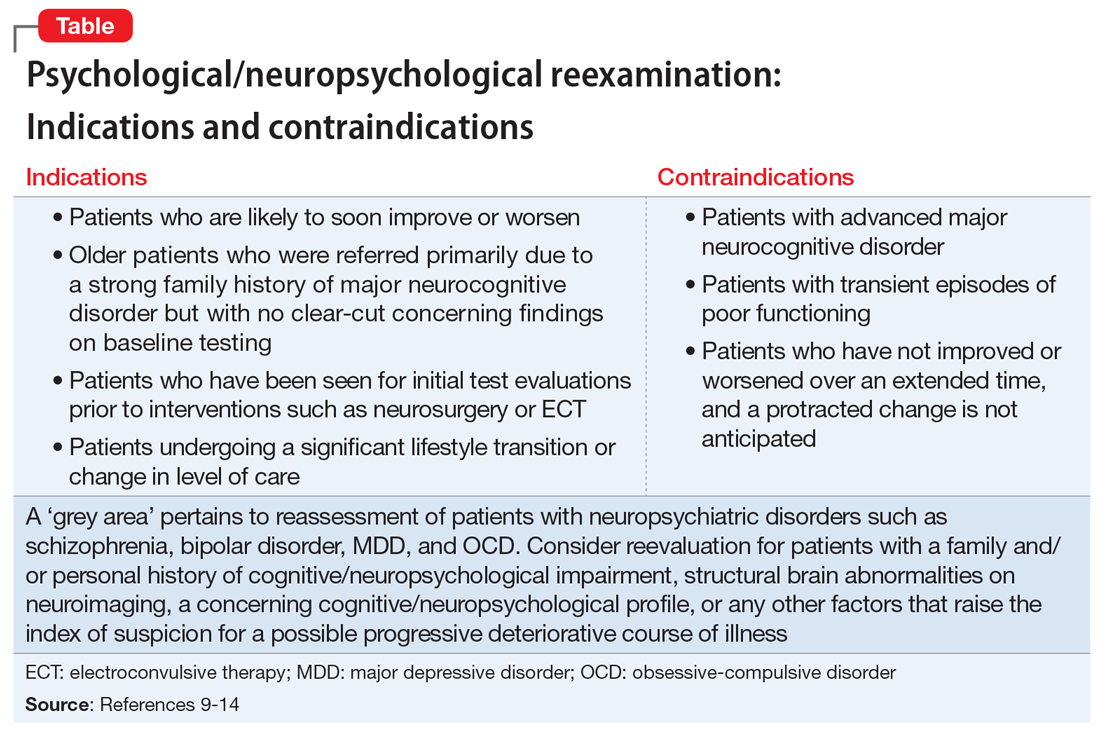

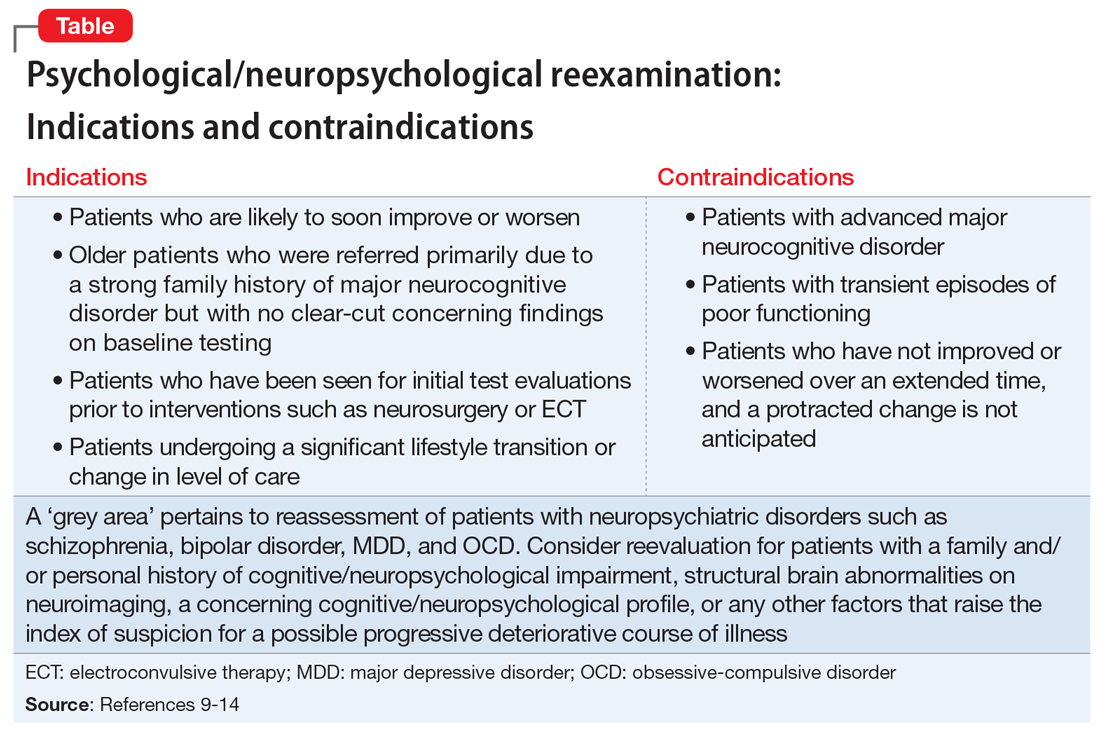

Follow-up testing generally is indicated in the following circumstances:

Patients who are likely to soon improve or worsen. Reassessment is indicated when, based on the initial evaluation, the patient has been identified as having a neuropsychiatric disorder that is likely to improve or worsen over the next year or 2 due to the natural trajectory of the condition and the degree to which it may respond to treatment.

Continue to: Patients who are likely...

Patients who are likely to improve include those with mental status changes referable to ≥1 medical and/or neuropsychiatric factors that are considered at least partially treatable and reversible. Patients who fall within this category include those who have mild to moderately severe head trauma or stroke, have a suspected or known medication- or substance-induced altered mental status, appear to have depression-related cognitive difficulties, or have an initial or recurrent episode of idiopathic psychosis.

Patients whose conditions can be expected to worsen over time include those with a mild neurocognitive disorder or major neurocognitive disorder of mild severity that is considered referable to a progressive neurodegenerative illness such as Alzheimer’s disease based on family and personal history, their psychometric test profile, and other factors, including findings from positron emission tomography scanning.

Older patients who were referred primarily due to a strong family history of major neurocognitive disorder but with no clear-cut concerning findings on baseline testing warrant reevaluation in the event of the emergence of significant cognitive and/or psychiatric symptoms and/or a functional decline since the baseline examination.

Patients who have been seen for initial test evaluations prior to interventions such as neurosurgery (including psychosurgery), electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), transcranial magnetic stimulation, cognitive rehabilitation, etc.

Patients undergoing a substantial transition. Reevaluation is appropriate for a broad range of patients experiencing difficulties when undergoing a significant lifestyle transition or change in level of care. This includes patients considering a return to school or work after a prolonged absence due to neuropsychiatric illness, or for whom there are questions regarding the need for a change in their level of everyday care. The latter includes patients who are returning to home care from assisted living, or transferring from home-based services to assisted living or a skilled nursing facility.

Continue to: What about patients with psychiatric disorders?

What about patients with psychiatric disorders? A “grey area” pertains to reassessment of patients with neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Patients with these conditions often have high rates of cognitive/neuropsychological impairment on baseline testing, even when they appear to be improving from a psychiatric perspective, are reasonably stable, and may even be in remission.9-12

These deficits are frequently a mix of pre-illness, prodromal, and early-stage illness– related neurocognitive difficulties that, for the most part, remain stable over time. That said, there is emerging evidence of worsening cognitive change over time following a first episode of psychosis for some patients with schizophrenia.13

In general, reevaluation should be considered for patients with a family and/or personal history of cognitive/neuropsychological impairment, structural brain abnormalities on neuroimaging, a concerning cognitive/neuropsychological profile, or any other factors that raise the index of suspicion for a possible progressive deteriorative course of illness.13,14

Patients with personality disorders who have had a baseline psychometric evaluation do not clearly warrant reassessment unless they develop medical and/or psychosocial difficulties that are often linked to problematic personality traits/patterns and that result in significant and persistent mental status changes. For example, reassessment might be indicated for a patient with borderline personality disorder who has new-onset or worsening cognitive and/or psychiatric complaints/symptoms after sustaining a head injury while intoxicated and embroiled in a domestic conflict triggered by anger and fears related to abandonment and separation.

Reevaluation also should be considered when a patient with a personality disorder has had a baseline assessment and subsequently completes an intensive, long-term treatment program that is likely to improve their clinical status. In this context, retesting may help document these gains. Examples of such programs/services include residential psychiatric and/or substance abuse care, object relational/psychodynamically-based psychotherapy, an extended course of dialectical behavioral therapy, or a related coping skills/distress tolerance psychotherapy.

Continue to: Contraindications for reassessment

Contraindications for reassessment

Retesting generally is not indicated in the following circumstances:

Patients with advanced major neurocognitive disorder. Reassessment is not indicated for such patients when there are no new questions regarding diagnosis, prognosis, level of care, and/or related disposition issues.

Patients with transient episodes of poor functioning. For the most part, reassessment is not helpful for patients with well-established diagnoses and treatment plans who, based on their history, experience time-limited, recurrent episodes of poor functioning and then reliably return to their baseline with ongoing psychiatric care. This includes patients with borderline personality disorder and other personality difficulties with histories of transient decompensation in response to psychosocial and psychodynamic triggers.

Patients who do not improve or worsen over time. Reassessment is not indicated when there has been no clear, sustained improvement or worsening of a patient’s clinical status over an extended time, and a protracted change is not anticipated. In this situation, reassessment is unlikely to yield clinically useful information beyond what is already known or meaningfully impact case formulation and treatment planning.

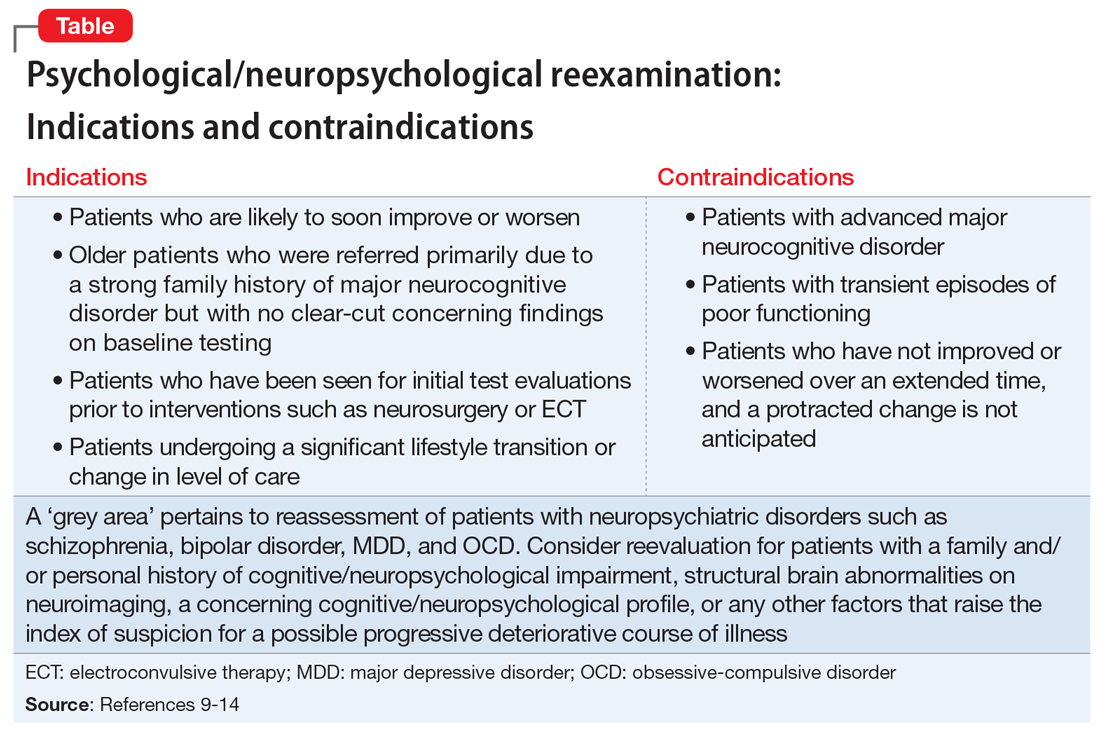

The Table9-14 summarizes the relative indications and contraindications for psychological/neuropsychological reexamination.

Continue to: Time frames for reassessment

Time frames for reassessment

Time frames for retesting vary considerably depending on factors such as diagnostic status, longitudinal course, treatment parameters, and recent/current life circumstances.

While empirical data is lacking regarding this matter, based on clinical experience, reevaluation in 18 to 24 months is generally appropriate for patients with neuropsychiatric conditions who are likely to gradually improve or slowly worsen over this time. Still, reexamination can be sooner (within 12 to 18 months) for patients who have experienced a more rapid and steep negative change in clinical status than initially anticipated.

For most patients with major mental illness, reexamination in 3 to 5 years is probably a reasonable time interval, barring a poorly understood and clinically significant negative change in functioning that warrants a shorter time frame. This suggested time frame would allow for sufficient time to better gauge improvement, stability, or deterioration in functioning and whether the reason(s) for referral have evolved. On the other hand, this time interval is somewhat arbitrary given the lack of empirical data. Therefore, on a case-by-case basis, it would be helpful for psychiatrists to consult with their patients and preferably with the psychologist who completed the baseline evaluation to determine a reasonable interval between assessments.

For patients who have undergone long-term/intensive treatment, reassessment in 3 or 6 months to as long as 1 year after the patient completes the program should be considered. Patients who undergo medical interventions such as neurosurgery or ECT—which can be associated with short-term, at least partially reversible negative effects on mental status—reassessment usually is most helpful when initiated as one or more screening level examinations for several weeks, followed by a comprehensive psychometric reassessment at the 3- to 6-month mark.

Suggestions for future research

Additional research is needed to ascertain the attitudes and opinions of psychiatrists and other physicians who use psychometric test data regarding how psychologists can most effectively communicate a recommendation for reassessment in their reports and clarify the ways psychiatrists can productively address this issue with their patients. Survey research of this kind should include questions about the frequency with which psychiatrists formally refer patients for retesting, and estimates of the rate of follow-through.

Continue to: It also would be desirable...

It also would be desirable to investigate factors that may facilitate follow-through with recommendations for reassessment, or, conversely, identify reasons that psychiatrists and their patients may decide to forgo reassessment. It would be important to try to obtain information regarding the optimum time frames for such reevaluation, depending on the patient’s circumstances and other variables. Evidence-based data pertaining to these issues would contribute to the development of consensus guidelines and a standard of care for psychological/neuropsychological test reevaluation.

Bottom Line

Only a very small percentage of patients referred for follow-up psychological/ neuropsychological test reevaluation actually undergo reexamination. Such retesting may be most helpful for certain patient populations, such as those who are likely to soon improve or worsen, were referred based on a family history of major cognitive disorder but have no concerning findings on baseline testing, or are undergoing a substantial life transition.

Related Resources

- Thom R, Farrell HM. Neuroimaging in psychiatry: potentials and pitfalls. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(12):27-28;33-34.

- Papakostas GI. Cognitive symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder and their implications for clinical practice. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(1):8-14.

- American Board of Professional Neuropsychology. https://abn-board.com

1. Schroeder RW, Martin PK, Walling A. Neuropsychological evaluations in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(2):101-198.

2. Bucher MA, Suzuki T, Samuel DB. A meta-analytic review of personality traits and their associations with mental health treatment outcomes. Clin Psychol Rev. 2019;70:51-63.

3. Pollak J. Feedback to the psychodiagnostician: a challenge for assessment psychologists in independent practice. Independent Practitioner: The community of psychologists in independent practice. 2020;40,6-9.

4. Pollak J. To test or not to test: considerations before going forward with psychometric testing. The Clinical Practitioner. 2011;6:5-10.

5. Schwarz L, Roskos PT, Grossberg GT. Answers to 7 questions about using neuropsychological testing in your practice. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):33-39.

6. Zucchella C, Federico A, Martini A, et al. Neuropsychological testing. Pract Neurol. 2018;18(3):227-237.

7. Moller MD, Parmenter BA, Lane DW. Neuropsychological testing: a useful but underutilized resource. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(11):40-46,51.

8. Pollak J. Psychodiagnostic testing services: the elusive quest for clinicians. Clinical Psychiatry News. Published October 18, 2019. Accessed July 8, 2021. https://www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/210439/schizophrenia-other-psychotic-disorders/psychodiagnostic-testing-services

9. Mesholam-Gately RI, Giuliano AJ, Goff KP, et al. Neurocognition in first episode schizophrenia: a meta- analytic review. Neuropsychology. 2009;23(3):315-336.

10. Lam RW, Kennedy SH, McIntyre RS et al. Cognitive dysfunction in major depressive disorder: effects on psychosocial functioning and implications for treatment. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(12):649-654.

11. Szmulewicz AG, Samamé C, Martino DJ, et al. An updated review on the neuropsychological profile of subjects with bipolar disorder. Arch Clin Psychiatry. 2015;42(5):139-146.

12. Shin NY, Lee TY, Kim, E, et al. Cognitive functioning in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2013;44(6):1121-1130.

13. Zanelli J, Mollon J, Sandin S, et al. Cognitive change in schizophrenia and other psychoses in the decade following the first episode. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(10):811-819.

14. Mitleman SA, Buchsbaum MS. Very poor outcome schizophrenia: clinical and neuroimaging aspects. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19(4):345-357.

The evolution of illness prevention, diagnosis, and treatment has involved an increased appreciation for the clinical utility of longitudinal assessment. This has included the implementation of screening evaluations for high base rate medical conditions, such as cancer, that involve considerable morbidity and mortality.

Unfortunately, the mental health professions have been slow to embrace this approach. Baseline assessment with psychological/neuropsychological screening tests and more comprehensive test batteries to clarify diagnostic status and facilitate treatment planning is far more the exception than the rule in mental health care. This seems to be the case despite the strong evidence supporting this practice as well as multiple surveys indicating that psychiatrists and other physicians report a high level of satisfaction with the findings and recommendations of psychological/neuropsychological test reports.1-3

There is a substantial literature that reviews the relative indications and contraindications for initial psychological/neuropsychological test evaluations.4-7 However, there is a paucity of clinical and evidence-based information regarding criteria for follow-up assessment. Moreover, there are no consensus guidelines to inform decision-making regarding this issue.

In general, good clinical practice for baseline assessment and reexamination should include administration of both psychological and neuropsychological tests. Based on clinical experience, this article addresses the relative indications and contraindications for psychological/neuropsychological test reassessment of adults seen in psychiatric care. It also outlines suggested time frames for such reevaluations, based on the patient’s clinical status and circumstances.

Why are patients not referred for reassessment more often?

There are several reasons patients are not referred for follow-up testing, beginning with the failure, at times, of the psychologist to state in the recommendations section of the test report whether a reassessment is indicated, under what circumstances, and within what time frame. Empirical data is lacking, but predicated on clinical experience, even when a strong and unequivocal recommendation is made for reassessment, only a very small percentage of patients are seen for follow-up evaluation.

There are numerous reasons why this occurs. The patient and/or the psychiatrist may overlook or forget about the recommendation for reassessment, particularly if it was embedded in a lengthy list of recommendations and the suggested time frame for the reassessment was several years away. The patient and the psychiatrist may decide against going forward with a reexamination, for a variety of substantive reasons. The patient might decline, against medical advice, to be retested. The patient may fail to make or keep an appointment for the follow-up reexamination. The patient might leave treatment and become lost to follow-up. The patient might not be able to find an appropriate psychologist. The insurance company may decline to authorize follow-up testing.8

Indications for reevaluation

Follow-up testing generally is indicated in the following circumstances:

Patients who are likely to soon improve or worsen. Reassessment is indicated when, based on the initial evaluation, the patient has been identified as having a neuropsychiatric disorder that is likely to improve or worsen over the next year or 2 due to the natural trajectory of the condition and the degree to which it may respond to treatment.

Continue to: Patients who are likely...

Patients who are likely to improve include those with mental status changes referable to ≥1 medical and/or neuropsychiatric factors that are considered at least partially treatable and reversible. Patients who fall within this category include those who have mild to moderately severe head trauma or stroke, have a suspected or known medication- or substance-induced altered mental status, appear to have depression-related cognitive difficulties, or have an initial or recurrent episode of idiopathic psychosis.

Patients whose conditions can be expected to worsen over time include those with a mild neurocognitive disorder or major neurocognitive disorder of mild severity that is considered referable to a progressive neurodegenerative illness such as Alzheimer’s disease based on family and personal history, their psychometric test profile, and other factors, including findings from positron emission tomography scanning.

Older patients who were referred primarily due to a strong family history of major neurocognitive disorder but with no clear-cut concerning findings on baseline testing warrant reevaluation in the event of the emergence of significant cognitive and/or psychiatric symptoms and/or a functional decline since the baseline examination.

Patients who have been seen for initial test evaluations prior to interventions such as neurosurgery (including psychosurgery), electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), transcranial magnetic stimulation, cognitive rehabilitation, etc.

Patients undergoing a substantial transition. Reevaluation is appropriate for a broad range of patients experiencing difficulties when undergoing a significant lifestyle transition or change in level of care. This includes patients considering a return to school or work after a prolonged absence due to neuropsychiatric illness, or for whom there are questions regarding the need for a change in their level of everyday care. The latter includes patients who are returning to home care from assisted living, or transferring from home-based services to assisted living or a skilled nursing facility.

Continue to: What about patients with psychiatric disorders?

What about patients with psychiatric disorders? A “grey area” pertains to reassessment of patients with neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Patients with these conditions often have high rates of cognitive/neuropsychological impairment on baseline testing, even when they appear to be improving from a psychiatric perspective, are reasonably stable, and may even be in remission.9-12

These deficits are frequently a mix of pre-illness, prodromal, and early-stage illness– related neurocognitive difficulties that, for the most part, remain stable over time. That said, there is emerging evidence of worsening cognitive change over time following a first episode of psychosis for some patients with schizophrenia.13

In general, reevaluation should be considered for patients with a family and/or personal history of cognitive/neuropsychological impairment, structural brain abnormalities on neuroimaging, a concerning cognitive/neuropsychological profile, or any other factors that raise the index of suspicion for a possible progressive deteriorative course of illness.13,14

Patients with personality disorders who have had a baseline psychometric evaluation do not clearly warrant reassessment unless they develop medical and/or psychosocial difficulties that are often linked to problematic personality traits/patterns and that result in significant and persistent mental status changes. For example, reassessment might be indicated for a patient with borderline personality disorder who has new-onset or worsening cognitive and/or psychiatric complaints/symptoms after sustaining a head injury while intoxicated and embroiled in a domestic conflict triggered by anger and fears related to abandonment and separation.

Reevaluation also should be considered when a patient with a personality disorder has had a baseline assessment and subsequently completes an intensive, long-term treatment program that is likely to improve their clinical status. In this context, retesting may help document these gains. Examples of such programs/services include residential psychiatric and/or substance abuse care, object relational/psychodynamically-based psychotherapy, an extended course of dialectical behavioral therapy, or a related coping skills/distress tolerance psychotherapy.

Continue to: Contraindications for reassessment

Contraindications for reassessment

Retesting generally is not indicated in the following circumstances:

Patients with advanced major neurocognitive disorder. Reassessment is not indicated for such patients when there are no new questions regarding diagnosis, prognosis, level of care, and/or related disposition issues.

Patients with transient episodes of poor functioning. For the most part, reassessment is not helpful for patients with well-established diagnoses and treatment plans who, based on their history, experience time-limited, recurrent episodes of poor functioning and then reliably return to their baseline with ongoing psychiatric care. This includes patients with borderline personality disorder and other personality difficulties with histories of transient decompensation in response to psychosocial and psychodynamic triggers.

Patients who do not improve or worsen over time. Reassessment is not indicated when there has been no clear, sustained improvement or worsening of a patient’s clinical status over an extended time, and a protracted change is not anticipated. In this situation, reassessment is unlikely to yield clinically useful information beyond what is already known or meaningfully impact case formulation and treatment planning.

The Table9-14 summarizes the relative indications and contraindications for psychological/neuropsychological reexamination.

Continue to: Time frames for reassessment

Time frames for reassessment

Time frames for retesting vary considerably depending on factors such as diagnostic status, longitudinal course, treatment parameters, and recent/current life circumstances.

While empirical data is lacking regarding this matter, based on clinical experience, reevaluation in 18 to 24 months is generally appropriate for patients with neuropsychiatric conditions who are likely to gradually improve or slowly worsen over this time. Still, reexamination can be sooner (within 12 to 18 months) for patients who have experienced a more rapid and steep negative change in clinical status than initially anticipated.

For most patients with major mental illness, reexamination in 3 to 5 years is probably a reasonable time interval, barring a poorly understood and clinically significant negative change in functioning that warrants a shorter time frame. This suggested time frame would allow for sufficient time to better gauge improvement, stability, or deterioration in functioning and whether the reason(s) for referral have evolved. On the other hand, this time interval is somewhat arbitrary given the lack of empirical data. Therefore, on a case-by-case basis, it would be helpful for psychiatrists to consult with their patients and preferably with the psychologist who completed the baseline evaluation to determine a reasonable interval between assessments.

For patients who have undergone long-term/intensive treatment, reassessment in 3 or 6 months to as long as 1 year after the patient completes the program should be considered. Patients who undergo medical interventions such as neurosurgery or ECT—which can be associated with short-term, at least partially reversible negative effects on mental status—reassessment usually is most helpful when initiated as one or more screening level examinations for several weeks, followed by a comprehensive psychometric reassessment at the 3- to 6-month mark.

Suggestions for future research

Additional research is needed to ascertain the attitudes and opinions of psychiatrists and other physicians who use psychometric test data regarding how psychologists can most effectively communicate a recommendation for reassessment in their reports and clarify the ways psychiatrists can productively address this issue with their patients. Survey research of this kind should include questions about the frequency with which psychiatrists formally refer patients for retesting, and estimates of the rate of follow-through.

Continue to: It also would be desirable...

It also would be desirable to investigate factors that may facilitate follow-through with recommendations for reassessment, or, conversely, identify reasons that psychiatrists and their patients may decide to forgo reassessment. It would be important to try to obtain information regarding the optimum time frames for such reevaluation, depending on the patient’s circumstances and other variables. Evidence-based data pertaining to these issues would contribute to the development of consensus guidelines and a standard of care for psychological/neuropsychological test reevaluation.

Bottom Line

Only a very small percentage of patients referred for follow-up psychological/ neuropsychological test reevaluation actually undergo reexamination. Such retesting may be most helpful for certain patient populations, such as those who are likely to soon improve or worsen, were referred based on a family history of major cognitive disorder but have no concerning findings on baseline testing, or are undergoing a substantial life transition.

Related Resources

- Thom R, Farrell HM. Neuroimaging in psychiatry: potentials and pitfalls. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(12):27-28;33-34.

- Papakostas GI. Cognitive symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder and their implications for clinical practice. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(1):8-14.

- American Board of Professional Neuropsychology. https://abn-board.com

The evolution of illness prevention, diagnosis, and treatment has involved an increased appreciation for the clinical utility of longitudinal assessment. This has included the implementation of screening evaluations for high base rate medical conditions, such as cancer, that involve considerable morbidity and mortality.

Unfortunately, the mental health professions have been slow to embrace this approach. Baseline assessment with psychological/neuropsychological screening tests and more comprehensive test batteries to clarify diagnostic status and facilitate treatment planning is far more the exception than the rule in mental health care. This seems to be the case despite the strong evidence supporting this practice as well as multiple surveys indicating that psychiatrists and other physicians report a high level of satisfaction with the findings and recommendations of psychological/neuropsychological test reports.1-3

There is a substantial literature that reviews the relative indications and contraindications for initial psychological/neuropsychological test evaluations.4-7 However, there is a paucity of clinical and evidence-based information regarding criteria for follow-up assessment. Moreover, there are no consensus guidelines to inform decision-making regarding this issue.

In general, good clinical practice for baseline assessment and reexamination should include administration of both psychological and neuropsychological tests. Based on clinical experience, this article addresses the relative indications and contraindications for psychological/neuropsychological test reassessment of adults seen in psychiatric care. It also outlines suggested time frames for such reevaluations, based on the patient’s clinical status and circumstances.

Why are patients not referred for reassessment more often?

There are several reasons patients are not referred for follow-up testing, beginning with the failure, at times, of the psychologist to state in the recommendations section of the test report whether a reassessment is indicated, under what circumstances, and within what time frame. Empirical data is lacking, but predicated on clinical experience, even when a strong and unequivocal recommendation is made for reassessment, only a very small percentage of patients are seen for follow-up evaluation.

There are numerous reasons why this occurs. The patient and/or the psychiatrist may overlook or forget about the recommendation for reassessment, particularly if it was embedded in a lengthy list of recommendations and the suggested time frame for the reassessment was several years away. The patient and the psychiatrist may decide against going forward with a reexamination, for a variety of substantive reasons. The patient might decline, against medical advice, to be retested. The patient may fail to make or keep an appointment for the follow-up reexamination. The patient might leave treatment and become lost to follow-up. The patient might not be able to find an appropriate psychologist. The insurance company may decline to authorize follow-up testing.8

Indications for reevaluation

Follow-up testing generally is indicated in the following circumstances:

Patients who are likely to soon improve or worsen. Reassessment is indicated when, based on the initial evaluation, the patient has been identified as having a neuropsychiatric disorder that is likely to improve or worsen over the next year or 2 due to the natural trajectory of the condition and the degree to which it may respond to treatment.

Continue to: Patients who are likely...

Patients who are likely to improve include those with mental status changes referable to ≥1 medical and/or neuropsychiatric factors that are considered at least partially treatable and reversible. Patients who fall within this category include those who have mild to moderately severe head trauma or stroke, have a suspected or known medication- or substance-induced altered mental status, appear to have depression-related cognitive difficulties, or have an initial or recurrent episode of idiopathic psychosis.

Patients whose conditions can be expected to worsen over time include those with a mild neurocognitive disorder or major neurocognitive disorder of mild severity that is considered referable to a progressive neurodegenerative illness such as Alzheimer’s disease based on family and personal history, their psychometric test profile, and other factors, including findings from positron emission tomography scanning.

Older patients who were referred primarily due to a strong family history of major neurocognitive disorder but with no clear-cut concerning findings on baseline testing warrant reevaluation in the event of the emergence of significant cognitive and/or psychiatric symptoms and/or a functional decline since the baseline examination.

Patients who have been seen for initial test evaluations prior to interventions such as neurosurgery (including psychosurgery), electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), transcranial magnetic stimulation, cognitive rehabilitation, etc.

Patients undergoing a substantial transition. Reevaluation is appropriate for a broad range of patients experiencing difficulties when undergoing a significant lifestyle transition or change in level of care. This includes patients considering a return to school or work after a prolonged absence due to neuropsychiatric illness, or for whom there are questions regarding the need for a change in their level of everyday care. The latter includes patients who are returning to home care from assisted living, or transferring from home-based services to assisted living or a skilled nursing facility.

Continue to: What about patients with psychiatric disorders?

What about patients with psychiatric disorders? A “grey area” pertains to reassessment of patients with neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Patients with these conditions often have high rates of cognitive/neuropsychological impairment on baseline testing, even when they appear to be improving from a psychiatric perspective, are reasonably stable, and may even be in remission.9-12

These deficits are frequently a mix of pre-illness, prodromal, and early-stage illness– related neurocognitive difficulties that, for the most part, remain stable over time. That said, there is emerging evidence of worsening cognitive change over time following a first episode of psychosis for some patients with schizophrenia.13

In general, reevaluation should be considered for patients with a family and/or personal history of cognitive/neuropsychological impairment, structural brain abnormalities on neuroimaging, a concerning cognitive/neuropsychological profile, or any other factors that raise the index of suspicion for a possible progressive deteriorative course of illness.13,14

Patients with personality disorders who have had a baseline psychometric evaluation do not clearly warrant reassessment unless they develop medical and/or psychosocial difficulties that are often linked to problematic personality traits/patterns and that result in significant and persistent mental status changes. For example, reassessment might be indicated for a patient with borderline personality disorder who has new-onset or worsening cognitive and/or psychiatric complaints/symptoms after sustaining a head injury while intoxicated and embroiled in a domestic conflict triggered by anger and fears related to abandonment and separation.

Reevaluation also should be considered when a patient with a personality disorder has had a baseline assessment and subsequently completes an intensive, long-term treatment program that is likely to improve their clinical status. In this context, retesting may help document these gains. Examples of such programs/services include residential psychiatric and/or substance abuse care, object relational/psychodynamically-based psychotherapy, an extended course of dialectical behavioral therapy, or a related coping skills/distress tolerance psychotherapy.

Continue to: Contraindications for reassessment

Contraindications for reassessment

Retesting generally is not indicated in the following circumstances:

Patients with advanced major neurocognitive disorder. Reassessment is not indicated for such patients when there are no new questions regarding diagnosis, prognosis, level of care, and/or related disposition issues.

Patients with transient episodes of poor functioning. For the most part, reassessment is not helpful for patients with well-established diagnoses and treatment plans who, based on their history, experience time-limited, recurrent episodes of poor functioning and then reliably return to their baseline with ongoing psychiatric care. This includes patients with borderline personality disorder and other personality difficulties with histories of transient decompensation in response to psychosocial and psychodynamic triggers.

Patients who do not improve or worsen over time. Reassessment is not indicated when there has been no clear, sustained improvement or worsening of a patient’s clinical status over an extended time, and a protracted change is not anticipated. In this situation, reassessment is unlikely to yield clinically useful information beyond what is already known or meaningfully impact case formulation and treatment planning.

The Table9-14 summarizes the relative indications and contraindications for psychological/neuropsychological reexamination.

Continue to: Time frames for reassessment

Time frames for reassessment

Time frames for retesting vary considerably depending on factors such as diagnostic status, longitudinal course, treatment parameters, and recent/current life circumstances.

While empirical data is lacking regarding this matter, based on clinical experience, reevaluation in 18 to 24 months is generally appropriate for patients with neuropsychiatric conditions who are likely to gradually improve or slowly worsen over this time. Still, reexamination can be sooner (within 12 to 18 months) for patients who have experienced a more rapid and steep negative change in clinical status than initially anticipated.

For most patients with major mental illness, reexamination in 3 to 5 years is probably a reasonable time interval, barring a poorly understood and clinically significant negative change in functioning that warrants a shorter time frame. This suggested time frame would allow for sufficient time to better gauge improvement, stability, or deterioration in functioning and whether the reason(s) for referral have evolved. On the other hand, this time interval is somewhat arbitrary given the lack of empirical data. Therefore, on a case-by-case basis, it would be helpful for psychiatrists to consult with their patients and preferably with the psychologist who completed the baseline evaluation to determine a reasonable interval between assessments.

For patients who have undergone long-term/intensive treatment, reassessment in 3 or 6 months to as long as 1 year after the patient completes the program should be considered. Patients who undergo medical interventions such as neurosurgery or ECT—which can be associated with short-term, at least partially reversible negative effects on mental status—reassessment usually is most helpful when initiated as one or more screening level examinations for several weeks, followed by a comprehensive psychometric reassessment at the 3- to 6-month mark.

Suggestions for future research

Additional research is needed to ascertain the attitudes and opinions of psychiatrists and other physicians who use psychometric test data regarding how psychologists can most effectively communicate a recommendation for reassessment in their reports and clarify the ways psychiatrists can productively address this issue with their patients. Survey research of this kind should include questions about the frequency with which psychiatrists formally refer patients for retesting, and estimates of the rate of follow-through.

Continue to: It also would be desirable...

It also would be desirable to investigate factors that may facilitate follow-through with recommendations for reassessment, or, conversely, identify reasons that psychiatrists and their patients may decide to forgo reassessment. It would be important to try to obtain information regarding the optimum time frames for such reevaluation, depending on the patient’s circumstances and other variables. Evidence-based data pertaining to these issues would contribute to the development of consensus guidelines and a standard of care for psychological/neuropsychological test reevaluation.

Bottom Line

Only a very small percentage of patients referred for follow-up psychological/ neuropsychological test reevaluation actually undergo reexamination. Such retesting may be most helpful for certain patient populations, such as those who are likely to soon improve or worsen, were referred based on a family history of major cognitive disorder but have no concerning findings on baseline testing, or are undergoing a substantial life transition.

Related Resources

- Thom R, Farrell HM. Neuroimaging in psychiatry: potentials and pitfalls. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(12):27-28;33-34.

- Papakostas GI. Cognitive symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder and their implications for clinical practice. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(1):8-14.

- American Board of Professional Neuropsychology. https://abn-board.com

1. Schroeder RW, Martin PK, Walling A. Neuropsychological evaluations in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(2):101-198.

2. Bucher MA, Suzuki T, Samuel DB. A meta-analytic review of personality traits and their associations with mental health treatment outcomes. Clin Psychol Rev. 2019;70:51-63.

3. Pollak J. Feedback to the psychodiagnostician: a challenge for assessment psychologists in independent practice. Independent Practitioner: The community of psychologists in independent practice. 2020;40,6-9.

4. Pollak J. To test or not to test: considerations before going forward with psychometric testing. The Clinical Practitioner. 2011;6:5-10.

5. Schwarz L, Roskos PT, Grossberg GT. Answers to 7 questions about using neuropsychological testing in your practice. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):33-39.

6. Zucchella C, Federico A, Martini A, et al. Neuropsychological testing. Pract Neurol. 2018;18(3):227-237.

7. Moller MD, Parmenter BA, Lane DW. Neuropsychological testing: a useful but underutilized resource. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(11):40-46,51.

8. Pollak J. Psychodiagnostic testing services: the elusive quest for clinicians. Clinical Psychiatry News. Published October 18, 2019. Accessed July 8, 2021. https://www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/210439/schizophrenia-other-psychotic-disorders/psychodiagnostic-testing-services

9. Mesholam-Gately RI, Giuliano AJ, Goff KP, et al. Neurocognition in first episode schizophrenia: a meta- analytic review. Neuropsychology. 2009;23(3):315-336.

10. Lam RW, Kennedy SH, McIntyre RS et al. Cognitive dysfunction in major depressive disorder: effects on psychosocial functioning and implications for treatment. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(12):649-654.

11. Szmulewicz AG, Samamé C, Martino DJ, et al. An updated review on the neuropsychological profile of subjects with bipolar disorder. Arch Clin Psychiatry. 2015;42(5):139-146.

12. Shin NY, Lee TY, Kim, E, et al. Cognitive functioning in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2013;44(6):1121-1130.

13. Zanelli J, Mollon J, Sandin S, et al. Cognitive change in schizophrenia and other psychoses in the decade following the first episode. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(10):811-819.

14. Mitleman SA, Buchsbaum MS. Very poor outcome schizophrenia: clinical and neuroimaging aspects. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19(4):345-357.

1. Schroeder RW, Martin PK, Walling A. Neuropsychological evaluations in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(2):101-198.

2. Bucher MA, Suzuki T, Samuel DB. A meta-analytic review of personality traits and their associations with mental health treatment outcomes. Clin Psychol Rev. 2019;70:51-63.

3. Pollak J. Feedback to the psychodiagnostician: a challenge for assessment psychologists in independent practice. Independent Practitioner: The community of psychologists in independent practice. 2020;40,6-9.

4. Pollak J. To test or not to test: considerations before going forward with psychometric testing. The Clinical Practitioner. 2011;6:5-10.

5. Schwarz L, Roskos PT, Grossberg GT. Answers to 7 questions about using neuropsychological testing in your practice. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):33-39.

6. Zucchella C, Federico A, Martini A, et al. Neuropsychological testing. Pract Neurol. 2018;18(3):227-237.

7. Moller MD, Parmenter BA, Lane DW. Neuropsychological testing: a useful but underutilized resource. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(11):40-46,51.

8. Pollak J. Psychodiagnostic testing services: the elusive quest for clinicians. Clinical Psychiatry News. Published October 18, 2019. Accessed July 8, 2021. https://www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/210439/schizophrenia-other-psychotic-disorders/psychodiagnostic-testing-services

9. Mesholam-Gately RI, Giuliano AJ, Goff KP, et al. Neurocognition in first episode schizophrenia: a meta- analytic review. Neuropsychology. 2009;23(3):315-336.

10. Lam RW, Kennedy SH, McIntyre RS et al. Cognitive dysfunction in major depressive disorder: effects on psychosocial functioning and implications for treatment. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(12):649-654.

11. Szmulewicz AG, Samamé C, Martino DJ, et al. An updated review on the neuropsychological profile of subjects with bipolar disorder. Arch Clin Psychiatry. 2015;42(5):139-146.

12. Shin NY, Lee TY, Kim, E, et al. Cognitive functioning in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2013;44(6):1121-1130.

13. Zanelli J, Mollon J, Sandin S, et al. Cognitive change in schizophrenia and other psychoses in the decade following the first episode. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(10):811-819.

14. Mitleman SA, Buchsbaum MS. Very poor outcome schizophrenia: clinical and neuroimaging aspects. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19(4):345-357.

Beyond DSM symptoms: Behavioral clues to diagnosing bipolar II disorder

The diagnosis of bipolar II disorder is one of the most common challenges in psychiatric practice. Bipolar II disorder is frequently misdiagnosed as major depressive disorder (MDD) because symptoms of transient hypomanic episodes are either insufficiently probed or are rather vague. However, there are many valuable biographical clues that can expedite the diagnosis of bipolar II disorder.

The late Hagop S. Akiskal, MD, who passed away in January 2021, was an internationally recognized expert in mood disorders, and a dear friend for decades. He was a keen observer of human behavior who delved into the “life stories” of patients seeking help for depression. By thinking “outside the DSM box,” Dr. Akiskal was the first to recognize and codify a variety of behavioral and biographical clues for the bipolar spectrum (of which he was a pioneer) in patients presenting with a chief complaint of depression. He proposed a colorful set of behavioral stigmata in most patients with bipolar II disorder by carefully canvassing the life experiences of the patients he treated in the mood disorder clinic he established in the 1970s, which is believed to have been the first mood specialty clinic in the country.

Based on a review of >1,000 patients in his clinic who presented with depressive symptoms and were ultimately diagnosed as bipolar II disorder, Dr. Akiskal highlighted what he labeled as “behavioral activation, flamboyance and extravagance” among those patients. He referred to the cluster of those behaviors as “the soft spectrum” of bipolar disorder, which manifests in a set of distinctive behaviors in addition to depressive symptoms. He found that research tools such as the DSM-based Structured Clinical Interview often fail and frequently lead to a misdiagnosis of bipolar II disorder as MDD. This often condemns the patient to multiple failed trials of antidepressant monotherapy, and a delay in improvement, thus increasing the risk of job loss, disrupted relationships, and even suicide.

Over 3 decades, Dr. Akiskal developed the Mood Clinic Data Questionnaire (MCDQ) to systematize unstructured observations of patients presenting with a chief complaint of depression. His tool expedites the diagnosis of bipolar II disorder by understanding the patient as an individual, revealing personal and behavioral features consistent with what he labeled as episodic “hyperthymia” within the context of recurrent depression. This “social and behavioral phenotype,” as Dr. Akiskal called it, is rarely observed among patients with MDD.

By examining many patients with bipolar II disorder, Dr. Akiskal identified several “triads” of behavioral traits in the patients’ biographical history and in some of their close blood relatives as well. He also noticed that temperamentally, patients with bipolar II disorder thrive on “activity” and lovingly referred to themselves as “activity junkies.” Some of them may qualify as workaholics.

Biographical features that suggest bipolar II disorder

Here is a summary of the unique biographical features of patients with bipolar II disorder that Dr. Akiskal described:

Multilingual. Speaking ≥3 languages is unusual among individuals born in the United States, but often encountered among those with bipolar II disorder.

Continue to: Eminence

Eminence. Patients with bipolar II disorder, as well as their family members, tend to have leadership roles and prominence in journalism, media, and entertainment, fields that require interpersonal charm and eloquence. Those are common features of the “hyperthymic” temperament.

Creativity. Artists, poets, painters, and musicians who experience depression are more likely to have bipolar II disorder than MDD.

Biographical instability and/or excess. This is exemplified by going to 3 colleges and not necessarily obtaining a degree, or by frequently changing one’s line of work or city of residence. A classic example is a professor of medicine who also practices law and regularly sings in the opera, or a physician who is board-certified in 3 distinct specialties.

Activity junkies. Examples include a person with boundless energy, such as a novelist who writes 3 books a year or a professional who regularly works 12 hours a day without getting exhausted but seeks treatment for depressive episodes.

Multiple substances of abuse, such as nicotine, alcohol, stimulants, and opiates.

Continue to: Multiple psychiatric comorbidities

Multiple psychiatric comorbidities, such as having 3 types of anxiety (panic attacks, social phobia, and obsessive-compulsive disorder) or bulimia, seasonal depression, and anxiety.

Multiple pleasure-seeking or “outrageous” behaviors, such as compulsive gambling, sexual addiction, car racing, or skydiving. Another example is having a history of shoplifting, paraphilia, or arrest for participating in a riot, all of which are suggestive of antisocial traits in a patient seeking help for depression.

Sexual excesses, such as dating or having sex with ≥3 individuals concurrently, sometimes on the same day, or demanding sexual intercourse from a partner several times a day. Dr. Akiskal suggested that “sexual prowess” may represent an evolutionary advantage for the perpetuation of bipolar II disorder.

Marital history, such as a history of ≥3 marriages, or maintaining ≥2 families in different cities without being married.

Flamboyance and/or ornamentation. Examples might include wearing loud, colorful clothing (especially red), wearing ≥3 rings, or having piercings in ≥3 different body parts (tongue, nipples, navel, genitalia). Having elaborate tattoos across the body is no longer unique to “hyperthymic” persons with bipolar II disorder because tattoos have become far more common in the general population than they were in the 1970s. However, some take their tattoos to extremes.

Continue to: The above behaviors...

The above behaviors are condensed in a list that Dr. Akiskal called “the rule of 3” in patients with depression (Table1). Not all patients with bipolar II disorder will meet all the criteria of the rule of 3, but the first item in the mental status exam (appearance) alone may reflect the “soft bipolar spectrum,” such as garish clothing, red sneakers, multiple rings, bizarre hair coloring, and multiple piercings. This might prompt the clinician to ask further questions about hypomanic episodes as well as other personal behaviors related to the rule of 3.

Dr. Akiskal’s contributions to psychiatry are legendary in their originality, creativity, and clinical relevance. The rule of 3 is but one of his clinical concepts that may help identify many individuals with bipolar II disorder who are misdiagnosed as having MDD and prescribed a treatment that does not help or may exacerbate their illness course and worsen their outcome.

Based on the referrals of patients who are “treatment-resistant” to our Resident Mood Clinic, there are numerous persons in the country with bipolar II disorder (possibly millions) who are mislabeled with MDD and receiving the wrong treatments, to which they failed to respond. Their lifestyles and behaviors can provide valuable clinical insights into their true psychopathology, and that will lead to developing the right treatment plan.

1. Akiskal HS. Searching for behavioral indicators of bipolar II in patients presenting with major depressive episodes: the “red sign,” the “rule of three” and other biographic signs of temperamental extravagance, activation and hypomania. J Affect Disord. 2005;84(2-3):279-290.

The diagnosis of bipolar II disorder is one of the most common challenges in psychiatric practice. Bipolar II disorder is frequently misdiagnosed as major depressive disorder (MDD) because symptoms of transient hypomanic episodes are either insufficiently probed or are rather vague. However, there are many valuable biographical clues that can expedite the diagnosis of bipolar II disorder.

The late Hagop S. Akiskal, MD, who passed away in January 2021, was an internationally recognized expert in mood disorders, and a dear friend for decades. He was a keen observer of human behavior who delved into the “life stories” of patients seeking help for depression. By thinking “outside the DSM box,” Dr. Akiskal was the first to recognize and codify a variety of behavioral and biographical clues for the bipolar spectrum (of which he was a pioneer) in patients presenting with a chief complaint of depression. He proposed a colorful set of behavioral stigmata in most patients with bipolar II disorder by carefully canvassing the life experiences of the patients he treated in the mood disorder clinic he established in the 1970s, which is believed to have been the first mood specialty clinic in the country.

Based on a review of >1,000 patients in his clinic who presented with depressive symptoms and were ultimately diagnosed as bipolar II disorder, Dr. Akiskal highlighted what he labeled as “behavioral activation, flamboyance and extravagance” among those patients. He referred to the cluster of those behaviors as “the soft spectrum” of bipolar disorder, which manifests in a set of distinctive behaviors in addition to depressive symptoms. He found that research tools such as the DSM-based Structured Clinical Interview often fail and frequently lead to a misdiagnosis of bipolar II disorder as MDD. This often condemns the patient to multiple failed trials of antidepressant monotherapy, and a delay in improvement, thus increasing the risk of job loss, disrupted relationships, and even suicide.

Over 3 decades, Dr. Akiskal developed the Mood Clinic Data Questionnaire (MCDQ) to systematize unstructured observations of patients presenting with a chief complaint of depression. His tool expedites the diagnosis of bipolar II disorder by understanding the patient as an individual, revealing personal and behavioral features consistent with what he labeled as episodic “hyperthymia” within the context of recurrent depression. This “social and behavioral phenotype,” as Dr. Akiskal called it, is rarely observed among patients with MDD.

By examining many patients with bipolar II disorder, Dr. Akiskal identified several “triads” of behavioral traits in the patients’ biographical history and in some of their close blood relatives as well. He also noticed that temperamentally, patients with bipolar II disorder thrive on “activity” and lovingly referred to themselves as “activity junkies.” Some of them may qualify as workaholics.

Biographical features that suggest bipolar II disorder

Here is a summary of the unique biographical features of patients with bipolar II disorder that Dr. Akiskal described:

Multilingual. Speaking ≥3 languages is unusual among individuals born in the United States, but often encountered among those with bipolar II disorder.

Continue to: Eminence

Eminence. Patients with bipolar II disorder, as well as their family members, tend to have leadership roles and prominence in journalism, media, and entertainment, fields that require interpersonal charm and eloquence. Those are common features of the “hyperthymic” temperament.

Creativity. Artists, poets, painters, and musicians who experience depression are more likely to have bipolar II disorder than MDD.

Biographical instability and/or excess. This is exemplified by going to 3 colleges and not necessarily obtaining a degree, or by frequently changing one’s line of work or city of residence. A classic example is a professor of medicine who also practices law and regularly sings in the opera, or a physician who is board-certified in 3 distinct specialties.

Activity junkies. Examples include a person with boundless energy, such as a novelist who writes 3 books a year or a professional who regularly works 12 hours a day without getting exhausted but seeks treatment for depressive episodes.

Multiple substances of abuse, such as nicotine, alcohol, stimulants, and opiates.

Continue to: Multiple psychiatric comorbidities

Multiple psychiatric comorbidities, such as having 3 types of anxiety (panic attacks, social phobia, and obsessive-compulsive disorder) or bulimia, seasonal depression, and anxiety.

Multiple pleasure-seeking or “outrageous” behaviors, such as compulsive gambling, sexual addiction, car racing, or skydiving. Another example is having a history of shoplifting, paraphilia, or arrest for participating in a riot, all of which are suggestive of antisocial traits in a patient seeking help for depression.

Sexual excesses, such as dating or having sex with ≥3 individuals concurrently, sometimes on the same day, or demanding sexual intercourse from a partner several times a day. Dr. Akiskal suggested that “sexual prowess” may represent an evolutionary advantage for the perpetuation of bipolar II disorder.

Marital history, such as a history of ≥3 marriages, or maintaining ≥2 families in different cities without being married.

Flamboyance and/or ornamentation. Examples might include wearing loud, colorful clothing (especially red), wearing ≥3 rings, or having piercings in ≥3 different body parts (tongue, nipples, navel, genitalia). Having elaborate tattoos across the body is no longer unique to “hyperthymic” persons with bipolar II disorder because tattoos have become far more common in the general population than they were in the 1970s. However, some take their tattoos to extremes.

Continue to: The above behaviors...

The above behaviors are condensed in a list that Dr. Akiskal called “the rule of 3” in patients with depression (Table1). Not all patients with bipolar II disorder will meet all the criteria of the rule of 3, but the first item in the mental status exam (appearance) alone may reflect the “soft bipolar spectrum,” such as garish clothing, red sneakers, multiple rings, bizarre hair coloring, and multiple piercings. This might prompt the clinician to ask further questions about hypomanic episodes as well as other personal behaviors related to the rule of 3.

Dr. Akiskal’s contributions to psychiatry are legendary in their originality, creativity, and clinical relevance. The rule of 3 is but one of his clinical concepts that may help identify many individuals with bipolar II disorder who are misdiagnosed as having MDD and prescribed a treatment that does not help or may exacerbate their illness course and worsen their outcome.

Based on the referrals of patients who are “treatment-resistant” to our Resident Mood Clinic, there are numerous persons in the country with bipolar II disorder (possibly millions) who are mislabeled with MDD and receiving the wrong treatments, to which they failed to respond. Their lifestyles and behaviors can provide valuable clinical insights into their true psychopathology, and that will lead to developing the right treatment plan.

The diagnosis of bipolar II disorder is one of the most common challenges in psychiatric practice. Bipolar II disorder is frequently misdiagnosed as major depressive disorder (MDD) because symptoms of transient hypomanic episodes are either insufficiently probed or are rather vague. However, there are many valuable biographical clues that can expedite the diagnosis of bipolar II disorder.

The late Hagop S. Akiskal, MD, who passed away in January 2021, was an internationally recognized expert in mood disorders, and a dear friend for decades. He was a keen observer of human behavior who delved into the “life stories” of patients seeking help for depression. By thinking “outside the DSM box,” Dr. Akiskal was the first to recognize and codify a variety of behavioral and biographical clues for the bipolar spectrum (of which he was a pioneer) in patients presenting with a chief complaint of depression. He proposed a colorful set of behavioral stigmata in most patients with bipolar II disorder by carefully canvassing the life experiences of the patients he treated in the mood disorder clinic he established in the 1970s, which is believed to have been the first mood specialty clinic in the country.

Based on a review of >1,000 patients in his clinic who presented with depressive symptoms and were ultimately diagnosed as bipolar II disorder, Dr. Akiskal highlighted what he labeled as “behavioral activation, flamboyance and extravagance” among those patients. He referred to the cluster of those behaviors as “the soft spectrum” of bipolar disorder, which manifests in a set of distinctive behaviors in addition to depressive symptoms. He found that research tools such as the DSM-based Structured Clinical Interview often fail and frequently lead to a misdiagnosis of bipolar II disorder as MDD. This often condemns the patient to multiple failed trials of antidepressant monotherapy, and a delay in improvement, thus increasing the risk of job loss, disrupted relationships, and even suicide.

Over 3 decades, Dr. Akiskal developed the Mood Clinic Data Questionnaire (MCDQ) to systematize unstructured observations of patients presenting with a chief complaint of depression. His tool expedites the diagnosis of bipolar II disorder by understanding the patient as an individual, revealing personal and behavioral features consistent with what he labeled as episodic “hyperthymia” within the context of recurrent depression. This “social and behavioral phenotype,” as Dr. Akiskal called it, is rarely observed among patients with MDD.

By examining many patients with bipolar II disorder, Dr. Akiskal identified several “triads” of behavioral traits in the patients’ biographical history and in some of their close blood relatives as well. He also noticed that temperamentally, patients with bipolar II disorder thrive on “activity” and lovingly referred to themselves as “activity junkies.” Some of them may qualify as workaholics.

Biographical features that suggest bipolar II disorder

Here is a summary of the unique biographical features of patients with bipolar II disorder that Dr. Akiskal described:

Multilingual. Speaking ≥3 languages is unusual among individuals born in the United States, but often encountered among those with bipolar II disorder.

Continue to: Eminence

Eminence. Patients with bipolar II disorder, as well as their family members, tend to have leadership roles and prominence in journalism, media, and entertainment, fields that require interpersonal charm and eloquence. Those are common features of the “hyperthymic” temperament.

Creativity. Artists, poets, painters, and musicians who experience depression are more likely to have bipolar II disorder than MDD.

Biographical instability and/or excess. This is exemplified by going to 3 colleges and not necessarily obtaining a degree, or by frequently changing one’s line of work or city of residence. A classic example is a professor of medicine who also practices law and regularly sings in the opera, or a physician who is board-certified in 3 distinct specialties.

Activity junkies. Examples include a person with boundless energy, such as a novelist who writes 3 books a year or a professional who regularly works 12 hours a day without getting exhausted but seeks treatment for depressive episodes.

Multiple substances of abuse, such as nicotine, alcohol, stimulants, and opiates.

Continue to: Multiple psychiatric comorbidities

Multiple psychiatric comorbidities, such as having 3 types of anxiety (panic attacks, social phobia, and obsessive-compulsive disorder) or bulimia, seasonal depression, and anxiety.

Multiple pleasure-seeking or “outrageous” behaviors, such as compulsive gambling, sexual addiction, car racing, or skydiving. Another example is having a history of shoplifting, paraphilia, or arrest for participating in a riot, all of which are suggestive of antisocial traits in a patient seeking help for depression.

Sexual excesses, such as dating or having sex with ≥3 individuals concurrently, sometimes on the same day, or demanding sexual intercourse from a partner several times a day. Dr. Akiskal suggested that “sexual prowess” may represent an evolutionary advantage for the perpetuation of bipolar II disorder.

Marital history, such as a history of ≥3 marriages, or maintaining ≥2 families in different cities without being married.

Flamboyance and/or ornamentation. Examples might include wearing loud, colorful clothing (especially red), wearing ≥3 rings, or having piercings in ≥3 different body parts (tongue, nipples, navel, genitalia). Having elaborate tattoos across the body is no longer unique to “hyperthymic” persons with bipolar II disorder because tattoos have become far more common in the general population than they were in the 1970s. However, some take their tattoos to extremes.

Continue to: The above behaviors...

The above behaviors are condensed in a list that Dr. Akiskal called “the rule of 3” in patients with depression (Table1). Not all patients with bipolar II disorder will meet all the criteria of the rule of 3, but the first item in the mental status exam (appearance) alone may reflect the “soft bipolar spectrum,” such as garish clothing, red sneakers, multiple rings, bizarre hair coloring, and multiple piercings. This might prompt the clinician to ask further questions about hypomanic episodes as well as other personal behaviors related to the rule of 3.

Dr. Akiskal’s contributions to psychiatry are legendary in their originality, creativity, and clinical relevance. The rule of 3 is but one of his clinical concepts that may help identify many individuals with bipolar II disorder who are misdiagnosed as having MDD and prescribed a treatment that does not help or may exacerbate their illness course and worsen their outcome.

Based on the referrals of patients who are “treatment-resistant” to our Resident Mood Clinic, there are numerous persons in the country with bipolar II disorder (possibly millions) who are mislabeled with MDD and receiving the wrong treatments, to which they failed to respond. Their lifestyles and behaviors can provide valuable clinical insights into their true psychopathology, and that will lead to developing the right treatment plan.

1. Akiskal HS. Searching for behavioral indicators of bipolar II in patients presenting with major depressive episodes: the “red sign,” the “rule of three” and other biographic signs of temperamental extravagance, activation and hypomania. J Affect Disord. 2005;84(2-3):279-290.

1. Akiskal HS. Searching for behavioral indicators of bipolar II in patients presenting with major depressive episodes: the “red sign,” the “rule of three” and other biographic signs of temperamental extravagance, activation and hypomania. J Affect Disord. 2005;84(2-3):279-290.

Conspiracy theory or delusion? 3 questions to tell them apart

Many psychiatrists conceptualize mental illnesses, including psychotic disorders, across a continuum where their borders can be ambiguous.1 The same can be said of individual symptoms such as delusions, where the line separating clear-cut pathology from nonpathological or subclinical “delusion-like beliefs” is often blurred.2,3 However, the categorical distinction between mental illness and normality is fundamental to diagnostic reliability and crucial to clinical decisions about whether and how to intervene.

Conspiracy theory beliefs are delusion-like beliefs that are commonly encountered within today’s political landscape. Surveys have consistently revealed that approximately one-half of the population believes in at least 1 conspiracy theory, highlighting the normality of such beliefs despite their potential outlandishness.4 Here are 3 questions you can ask to help differentiate conspiracy theory beliefs from delusions.

1. What is the evidence for the belief?

Drawing from Karl Jaspers’ conceptualization of delusions as “impossible” and “unshareable,” the DSM-5 distinguishes delusions from culturally-sanctioned shared beliefs such as religious creeds.3 Whereas delusions often arise out of anomalous subjective experiences, individuals who come to believe in conspiracytheories have typically sought explanations and found them from secondary sources, often on the internet.5 Despite the familiar term “conspiracy theorist,” most who believe in conspiracy theories aren’t so much theorizing as they are adopting counter-narratives based on assimilated information. Unlike delusions, conspiracy theory beliefs are learned, with the “evidence” to support them easily located online.

2. Is the belief self-referential?

The stereotypical unshareability of delusions often hinges upon their self-referential content. For example, while it is easy to find others who believe in the Second Coming, it would be much harder to convince others that you are the Second Coming. Unlike delusions, conspiracy theories are beliefs about the world and explanations of real-life events; their content is rarely, if ever, directly related to the believer.

Conspiracy theory beliefs involve a negation of authoritative accounts that is rooted in “epistemic mistrust” of authoritative sources of information.5 While conspiratorial mistrust has been compared with paranoia, with paranoia found to be associated with belief in conspiracy theories,6 epistemic mistrust encompasses a range of justified cultural mistrust, unwarranted mistrust based on racial prejudice, and subclinical paranoia typical of schizotypy. The more self-referential the underlying paranoia, the more likely an associated belief is to cross the boundary from conspiracy theory to delusion.7

3. Is there overlap?

Conspiracy theory beliefs and delusions are not mutually exclusive. “Gang stalking” offers a vexing example of paranoia that is part shared conspiracy theory, part idiosyncratic delusion.8 Reliably disentangling these components requires identifying the conspiracy theory component as a widely-shared belief about government surveillance, while carefully analyzing the self-referential component to determine credibility and potential delusionality.

1. Pierre JM. The borders of mental disorder in psychiatry and the DSM: past, present, and future. J Psychiatric Practice. 2010;16(6):375-386.

2. Pierre JM. Faith or delusion? At the crossroads of religion and psychosis. J Psychiatr Practice. 2001;7(3):163-172.

3. Pierre JM. Forensic psychiatry versus the varieties of delusion-like belief. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2020;48(3):327-334.

4. Oliver JE, Wood, TJ. Conspiracy theories and the paranoid style(s) of mass opinion. Am J Pol Sci. 2014;58(5);952-966.

5. Pierre JM. Mistrust and misinformation: a two-component, socio-epistemic model of belief in conspiracy theories. J Soc Polit Psychol. 2020;8(2):617-641.

6. Dagnall N, Drinkwater K, Parker A, et al. Conspiracy theory and cognitive style: a worldview. Front Psychol. 2015;6:206.

7. Imhoff R, Lamberty P. How paranoid are conspiracy believers? Toward a more fine-grained understanding of the connect and disconnect between paranoia and belief in conspiracy theories. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2018;48(7):909-926.

8. Sheridan LP, James DV. Complaints of group-stalking (‘gang-stalking’): an exploratory study of their natures and impact on complainants. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol. 2015;26(5):601-623.

Many psychiatrists conceptualize mental illnesses, including psychotic disorders, across a continuum where their borders can be ambiguous.1 The same can be said of individual symptoms such as delusions, where the line separating clear-cut pathology from nonpathological or subclinical “delusion-like beliefs” is often blurred.2,3 However, the categorical distinction between mental illness and normality is fundamental to diagnostic reliability and crucial to clinical decisions about whether and how to intervene.

Conspiracy theory beliefs are delusion-like beliefs that are commonly encountered within today’s political landscape. Surveys have consistently revealed that approximately one-half of the population believes in at least 1 conspiracy theory, highlighting the normality of such beliefs despite their potential outlandishness.4 Here are 3 questions you can ask to help differentiate conspiracy theory beliefs from delusions.

1. What is the evidence for the belief?

Drawing from Karl Jaspers’ conceptualization of delusions as “impossible” and “unshareable,” the DSM-5 distinguishes delusions from culturally-sanctioned shared beliefs such as religious creeds.3 Whereas delusions often arise out of anomalous subjective experiences, individuals who come to believe in conspiracytheories have typically sought explanations and found them from secondary sources, often on the internet.5 Despite the familiar term “conspiracy theorist,” most who believe in conspiracy theories aren’t so much theorizing as they are adopting counter-narratives based on assimilated information. Unlike delusions, conspiracy theory beliefs are learned, with the “evidence” to support them easily located online.

2. Is the belief self-referential?

The stereotypical unshareability of delusions often hinges upon their self-referential content. For example, while it is easy to find others who believe in the Second Coming, it would be much harder to convince others that you are the Second Coming. Unlike delusions, conspiracy theories are beliefs about the world and explanations of real-life events; their content is rarely, if ever, directly related to the believer.

Conspiracy theory beliefs involve a negation of authoritative accounts that is rooted in “epistemic mistrust” of authoritative sources of information.5 While conspiratorial mistrust has been compared with paranoia, with paranoia found to be associated with belief in conspiracy theories,6 epistemic mistrust encompasses a range of justified cultural mistrust, unwarranted mistrust based on racial prejudice, and subclinical paranoia typical of schizotypy. The more self-referential the underlying paranoia, the more likely an associated belief is to cross the boundary from conspiracy theory to delusion.7

3. Is there overlap?