User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

Armchair epidemiology

Real epidemiologists are out knocking on doors, chasing down contacts, or hunched over their computers trying to make sense out of screens full of data and maps. A few are trying valiantly to talk some sense into our elected officials.

This leaves the rest of us with time on our hands to fabricate our own less-than-scientific explanations for the behavior of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. So I have decided to put on hold my current mental challenge of choosing which pasta shape to pair with the sauce I’ve prepared from an online recipe. Here is my educated guess based on what I can glean from media sources that may have been filtered through a variety politically biased lenses. Remember, I did go to medical school; however, when I was in college the DNA helix was still just theoretical.

From those halcyon days of mid-February when our attention was focused on the Diamond Princess quarantined in Yokohama Harbor, it didn’t take a board-certified epidemiologist to suspect that the virus was spreading through the ventilating system in the ship’s tight quarters. Subsequent outbreaks on U.S. and French military ships suggests a similar explanation.

While still not proven, it sounds like SARS-CoV-2 jumped to humans from bats. It should not surprise us that having evolved in a dense population of mammals it would thrive in other high-density populations such as New York and nursing homes. Because we have lacked a robust testing capability, it has been less obvious until recently that, while it is easily transmitted, the virus has infected many who are asymptomatic (“Antibody surveys suggesting vast undercount of coronavirus infections may be unreliable,” Gretchen Vogel, Science, April 21, 2020). Subsequent surveys seem to confirm this higher level carrier state; it suggests that the virus is far less deadly than was previously suggested. However, it seems to be a crafty little bug attacking just about any organ system it lands on.

I don’t think any of us are surprised that the elderly population with weakened immune systems, particularly those in congregate housing, has been much more vulnerable. However, many of the deaths among younger apparently healthy people have defied explanation. The anecdotal observations that physicians, particularly those who practice in-your-face medicine (e.g., ophthalmologists and otolaryngologists) may be more vulnerable raises the issue of viral load. It may be that, although it can be extremely contagious, the virus is not terribly dangerous for most people until the inoculum dose of the virus reaches a certain level. To my knowledge this dose is unknown.

A published survey of more than 300 outbreaks from 120 Chinese cities also may support my suspicion that viral load is of critical importance. The researchers found that all the “identified outbreaks of three or more cases occurred in an indoor environment, which confirms that sharing indoor space is a major SARS-CoV-2 infection risk” (Huan Qian et al. “Indoor transmission of SARS-CoV-2,” MedRxiv. 2020 Apr 7. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.04.20053058). Again, this data shouldn’t surprise us when we look back at what little we know about the outbreaks in the confined spaces on cruise ships and in nursing homes.

I’m not sure that we have any data that helps us determine whether wearing a mask in an outdoor space has any more than symbolic value when we are talking about this particular virus. We may read that the virus in a droplet can survive on the surface it lands on for 8 minutes, and we can see those slow motion videos of the impressive plume of snot spray released by a sneeze. It would seem obvious that even outside someone within 10 feet of the sneeze has a good chance of being infected. However, how much of a threat is the asymptomatic carrier who passes within three feet of you while you are out on lovely summer day stroll? This armchair epidemiologist suspects that, when we are talking about an outside space, the 6-foot guideline for small groups of a dozen or less is overly restrictive. But until we know, I’m staying put in my armchair ... outside on the porch overlooking Casco Bay.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” He has no disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

Real epidemiologists are out knocking on doors, chasing down contacts, or hunched over their computers trying to make sense out of screens full of data and maps. A few are trying valiantly to talk some sense into our elected officials.

This leaves the rest of us with time on our hands to fabricate our own less-than-scientific explanations for the behavior of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. So I have decided to put on hold my current mental challenge of choosing which pasta shape to pair with the sauce I’ve prepared from an online recipe. Here is my educated guess based on what I can glean from media sources that may have been filtered through a variety politically biased lenses. Remember, I did go to medical school; however, when I was in college the DNA helix was still just theoretical.

From those halcyon days of mid-February when our attention was focused on the Diamond Princess quarantined in Yokohama Harbor, it didn’t take a board-certified epidemiologist to suspect that the virus was spreading through the ventilating system in the ship’s tight quarters. Subsequent outbreaks on U.S. and French military ships suggests a similar explanation.

While still not proven, it sounds like SARS-CoV-2 jumped to humans from bats. It should not surprise us that having evolved in a dense population of mammals it would thrive in other high-density populations such as New York and nursing homes. Because we have lacked a robust testing capability, it has been less obvious until recently that, while it is easily transmitted, the virus has infected many who are asymptomatic (“Antibody surveys suggesting vast undercount of coronavirus infections may be unreliable,” Gretchen Vogel, Science, April 21, 2020). Subsequent surveys seem to confirm this higher level carrier state; it suggests that the virus is far less deadly than was previously suggested. However, it seems to be a crafty little bug attacking just about any organ system it lands on.

I don’t think any of us are surprised that the elderly population with weakened immune systems, particularly those in congregate housing, has been much more vulnerable. However, many of the deaths among younger apparently healthy people have defied explanation. The anecdotal observations that physicians, particularly those who practice in-your-face medicine (e.g., ophthalmologists and otolaryngologists) may be more vulnerable raises the issue of viral load. It may be that, although it can be extremely contagious, the virus is not terribly dangerous for most people until the inoculum dose of the virus reaches a certain level. To my knowledge this dose is unknown.

A published survey of more than 300 outbreaks from 120 Chinese cities also may support my suspicion that viral load is of critical importance. The researchers found that all the “identified outbreaks of three or more cases occurred in an indoor environment, which confirms that sharing indoor space is a major SARS-CoV-2 infection risk” (Huan Qian et al. “Indoor transmission of SARS-CoV-2,” MedRxiv. 2020 Apr 7. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.04.20053058). Again, this data shouldn’t surprise us when we look back at what little we know about the outbreaks in the confined spaces on cruise ships and in nursing homes.

I’m not sure that we have any data that helps us determine whether wearing a mask in an outdoor space has any more than symbolic value when we are talking about this particular virus. We may read that the virus in a droplet can survive on the surface it lands on for 8 minutes, and we can see those slow motion videos of the impressive plume of snot spray released by a sneeze. It would seem obvious that even outside someone within 10 feet of the sneeze has a good chance of being infected. However, how much of a threat is the asymptomatic carrier who passes within three feet of you while you are out on lovely summer day stroll? This armchair epidemiologist suspects that, when we are talking about an outside space, the 6-foot guideline for small groups of a dozen or less is overly restrictive. But until we know, I’m staying put in my armchair ... outside on the porch overlooking Casco Bay.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” He has no disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

Real epidemiologists are out knocking on doors, chasing down contacts, or hunched over their computers trying to make sense out of screens full of data and maps. A few are trying valiantly to talk some sense into our elected officials.

This leaves the rest of us with time on our hands to fabricate our own less-than-scientific explanations for the behavior of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. So I have decided to put on hold my current mental challenge of choosing which pasta shape to pair with the sauce I’ve prepared from an online recipe. Here is my educated guess based on what I can glean from media sources that may have been filtered through a variety politically biased lenses. Remember, I did go to medical school; however, when I was in college the DNA helix was still just theoretical.

From those halcyon days of mid-February when our attention was focused on the Diamond Princess quarantined in Yokohama Harbor, it didn’t take a board-certified epidemiologist to suspect that the virus was spreading through the ventilating system in the ship’s tight quarters. Subsequent outbreaks on U.S. and French military ships suggests a similar explanation.

While still not proven, it sounds like SARS-CoV-2 jumped to humans from bats. It should not surprise us that having evolved in a dense population of mammals it would thrive in other high-density populations such as New York and nursing homes. Because we have lacked a robust testing capability, it has been less obvious until recently that, while it is easily transmitted, the virus has infected many who are asymptomatic (“Antibody surveys suggesting vast undercount of coronavirus infections may be unreliable,” Gretchen Vogel, Science, April 21, 2020). Subsequent surveys seem to confirm this higher level carrier state; it suggests that the virus is far less deadly than was previously suggested. However, it seems to be a crafty little bug attacking just about any organ system it lands on.

I don’t think any of us are surprised that the elderly population with weakened immune systems, particularly those in congregate housing, has been much more vulnerable. However, many of the deaths among younger apparently healthy people have defied explanation. The anecdotal observations that physicians, particularly those who practice in-your-face medicine (e.g., ophthalmologists and otolaryngologists) may be more vulnerable raises the issue of viral load. It may be that, although it can be extremely contagious, the virus is not terribly dangerous for most people until the inoculum dose of the virus reaches a certain level. To my knowledge this dose is unknown.

A published survey of more than 300 outbreaks from 120 Chinese cities also may support my suspicion that viral load is of critical importance. The researchers found that all the “identified outbreaks of three or more cases occurred in an indoor environment, which confirms that sharing indoor space is a major SARS-CoV-2 infection risk” (Huan Qian et al. “Indoor transmission of SARS-CoV-2,” MedRxiv. 2020 Apr 7. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.04.20053058). Again, this data shouldn’t surprise us when we look back at what little we know about the outbreaks in the confined spaces on cruise ships and in nursing homes.

I’m not sure that we have any data that helps us determine whether wearing a mask in an outdoor space has any more than symbolic value when we are talking about this particular virus. We may read that the virus in a droplet can survive on the surface it lands on for 8 minutes, and we can see those slow motion videos of the impressive plume of snot spray released by a sneeze. It would seem obvious that even outside someone within 10 feet of the sneeze has a good chance of being infected. However, how much of a threat is the asymptomatic carrier who passes within three feet of you while you are out on lovely summer day stroll? This armchair epidemiologist suspects that, when we are talking about an outside space, the 6-foot guideline for small groups of a dozen or less is overly restrictive. But until we know, I’m staying put in my armchair ... outside on the porch overlooking Casco Bay.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” He has no disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

Time series analysis of poison control data

The US Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS) publishes annual reports describing exposures to various substances among the general population.1 Table 22B of each NPDS report shows the number of outcomes from exposures to different pharmacologic treatments in the United States, including psychotropic medications.2 In this Table, the relative morbidity (RM) of a medication is calculated as the ratio of serious outcomes (SO) to single exposures (SE), where SO = moderate + major + death. In this article, I use the NPDS data to demonstrate how time series analysis of the RM ratios for hypertension and psychiatric medications can help predict SO associated with these agents, which may help guide clinicians’ prescribing decisions.2,3

Time series analysis of hypertension medications

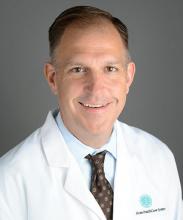

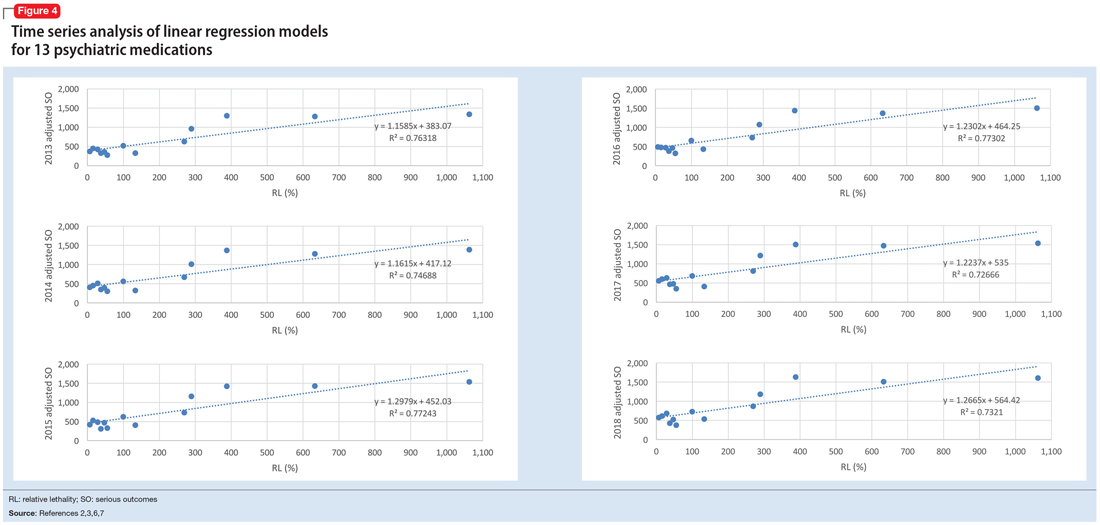

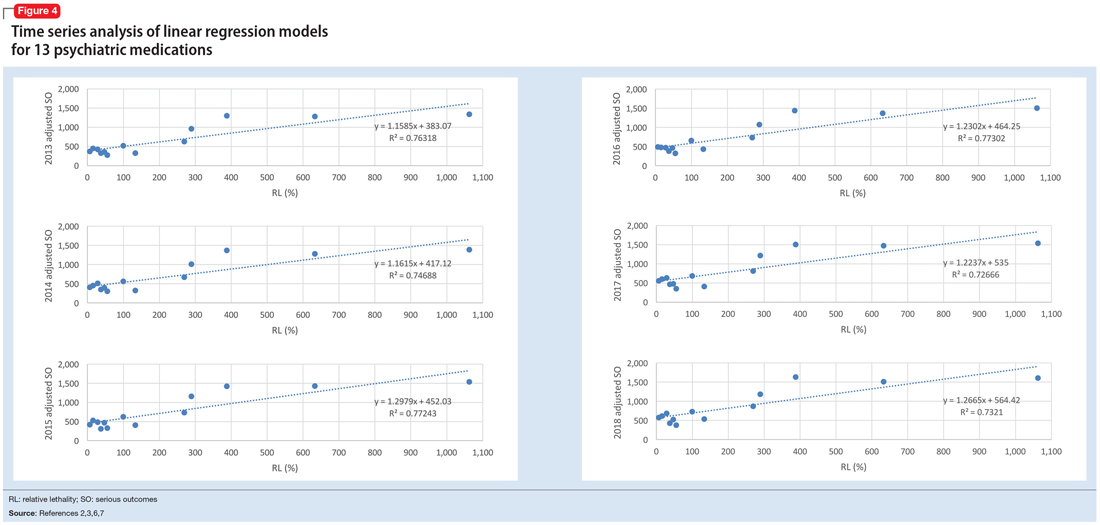

Due to the high prevalence of hypertension, it is not surprising that more suicide deaths occur each year from calcium channel blockers (CCB) than from lithium (37 vs 2, according to 2017 NPDS data).3 I used time series analysis to compare SO during 2006-2017 for 5 classes of hypertension medications: CCB, beta blockers (BB), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), and diuretics (Figure 1).

Time series analysis of 2006-2017 data predicted the following number of deaths for 2018: CCB ≥33, BB ≥17, ACEI ≤2, ARB 0, and diuretics ≤1. The observed deaths in 2018 were 41, 23, 0, 0, and 1, respectively.2 The 2018 predicted RM were CCB 10.66%, BB 11.10%, ACEI 3.51%, ARB 2.04%, and diuretics 3.38%. The 2018 observed RM for these medications were 11.01%, 11.37%, 3.02%, 2.40%, and 2.88%, respectively.2

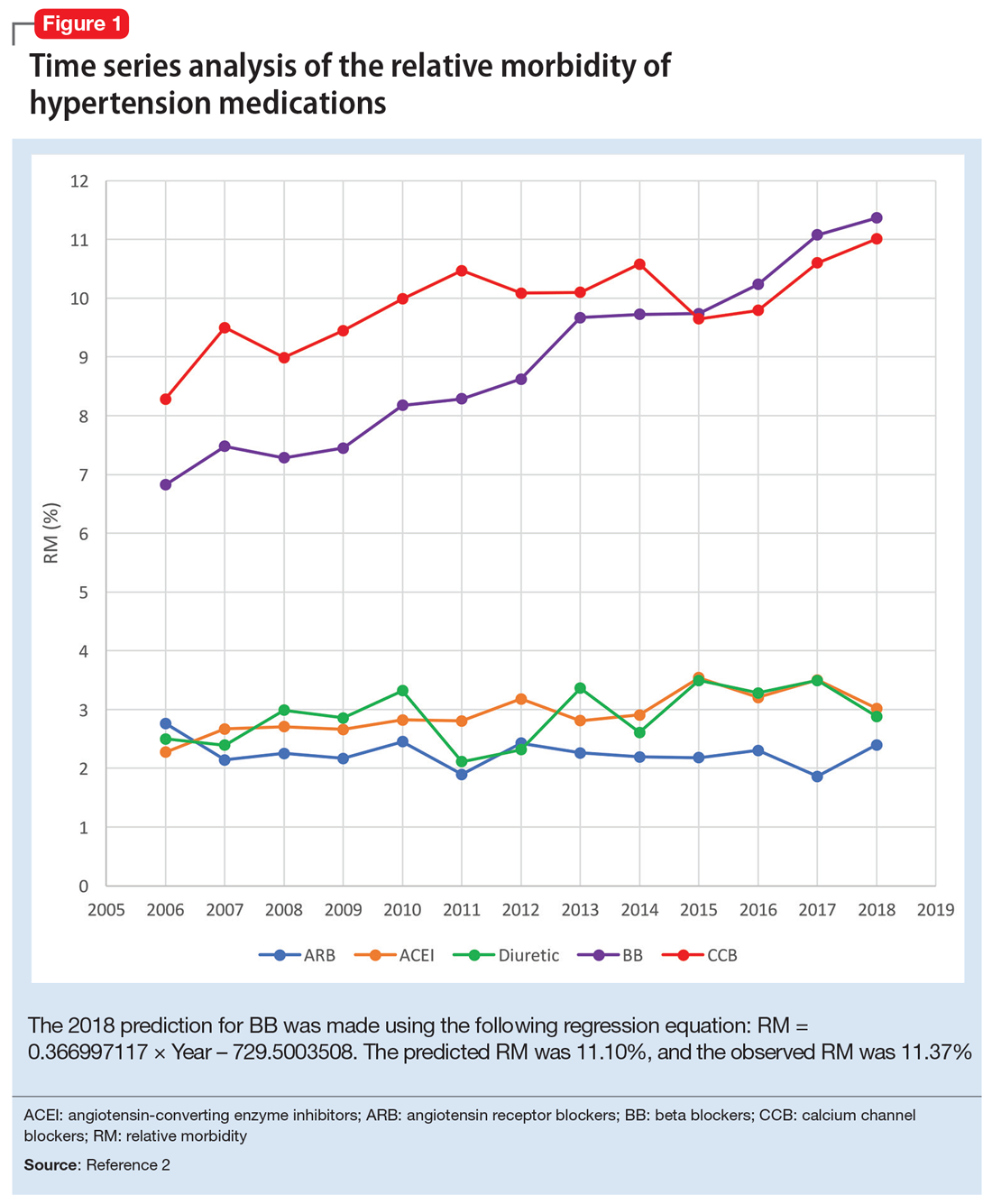

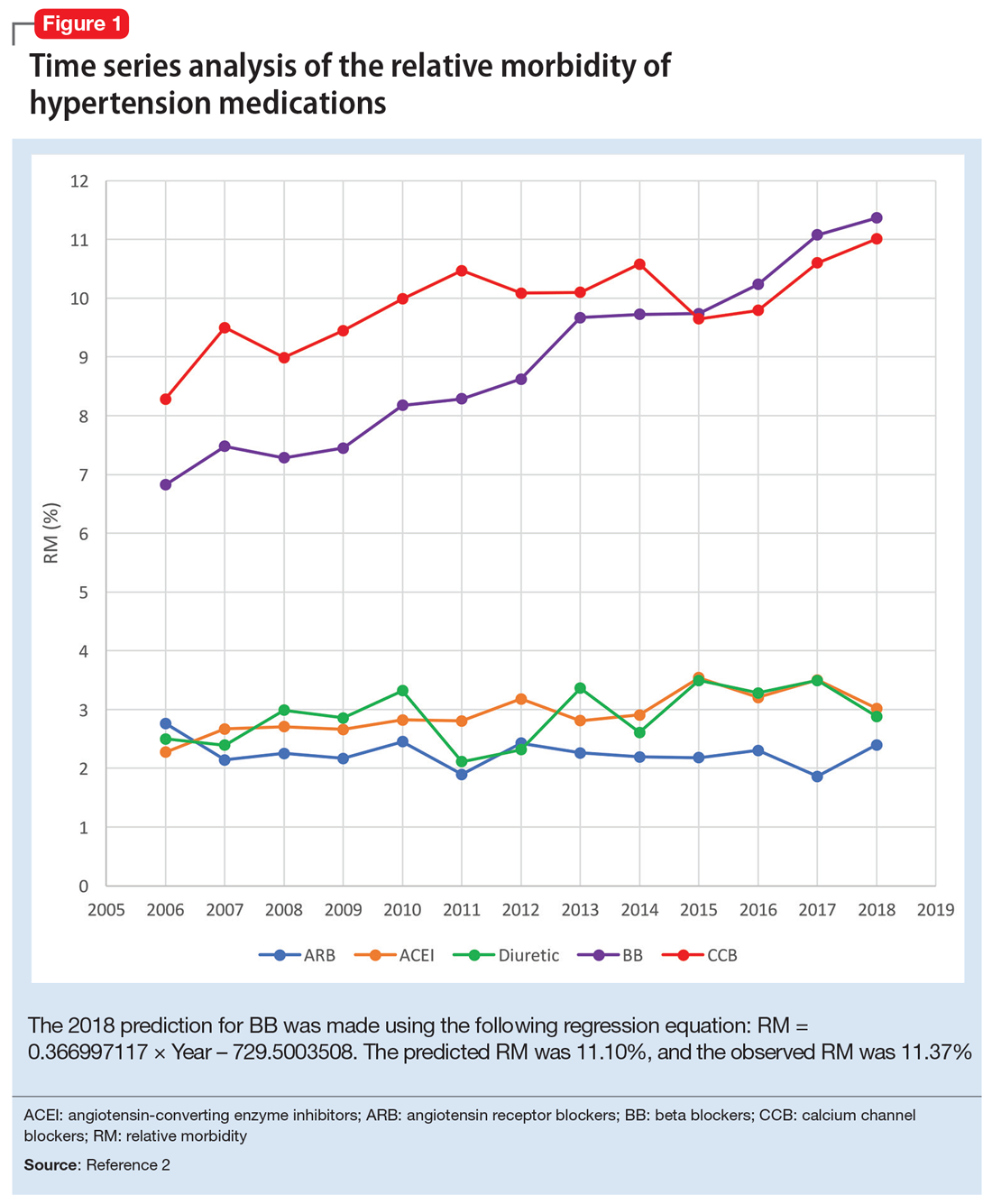

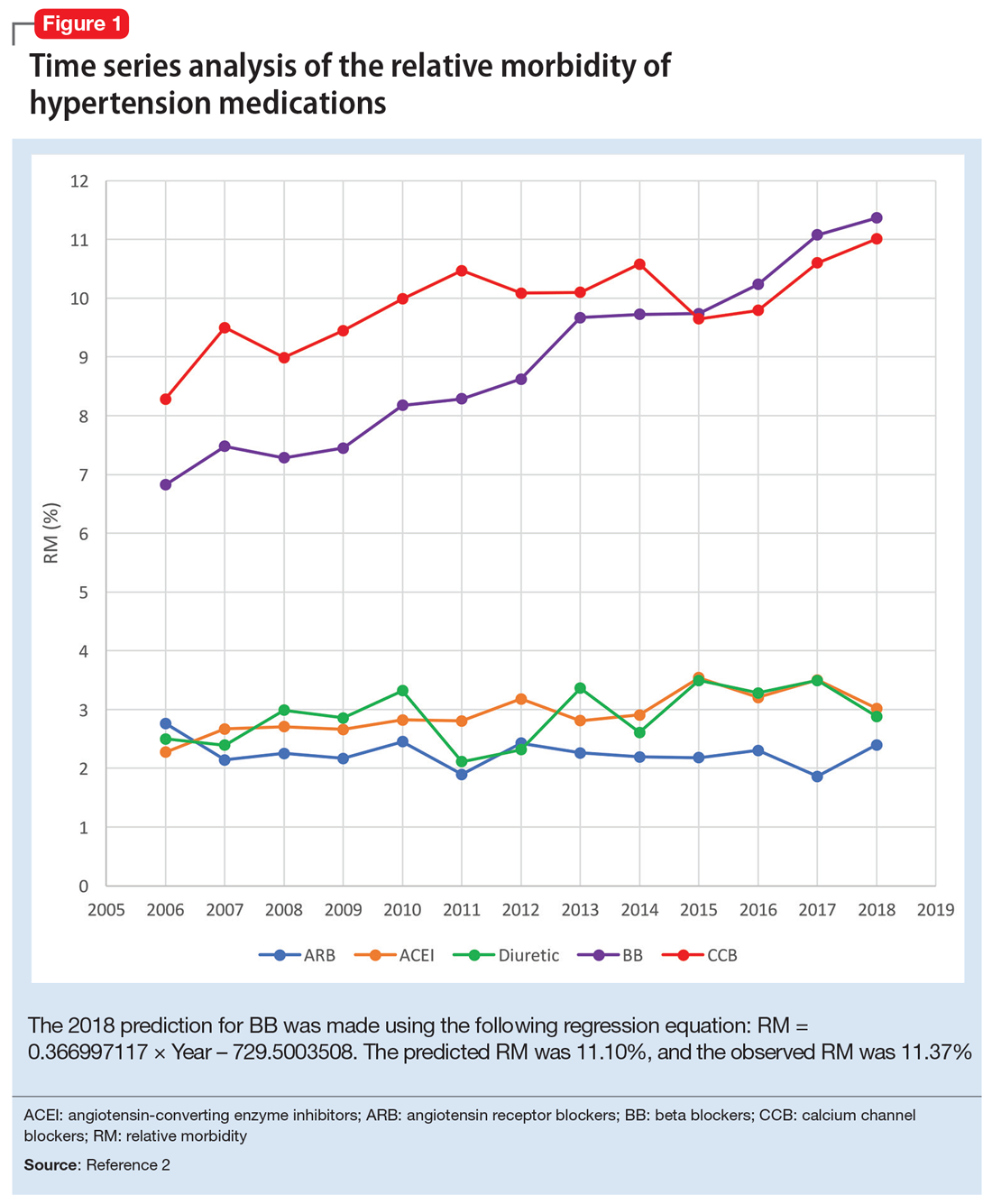

Because the NPDS data for hypertension medications was only provided by class, in order to detect differences within each class, I used the relative lethality (RL) equation: RL = 310x / LD50, where x is the maximum daily dose of a medication prescribed for 30 days, and LD50 is the rat oral lethal dose 50. The RL equation represents the ratio of a 30-day supply of medication to the human equivalent LD50 for a 60-kg person.4 The RL equation is useful for comparing the safety of various medications, and can help clinicians avoid prescribing a lethal amount of a given medication (Figure 2). For example, the equation shows that among CCB, felodipine is 466 times safer than verapamil and 101 times safer than diltiazem. Not surprisingly, 2006-2018 data shows many deaths via intentional verapamil or diltiazem overdose vs only 1 reference to felodipine. A regression model shows significant correlation and causality between RL and SO over time.5 Integrating all 3 mathematical models suggests that the higher RM of CCB and BB may be caused by the high RL of verapamil, diltiazem, nicardipine, propranolol, and labetalol.

These mathematical models can help physicians consider whether to switch the patient’s current medication to another class with a lower RM. For patients who need a BB or CCB, prescribing a medication with a lower RL within the same class may be another option. The data suggest that avoiding hypertension medications with RL >100% may significantly decrease morbidity and mortality.

Predicting serious outcomes of psychiatric medications

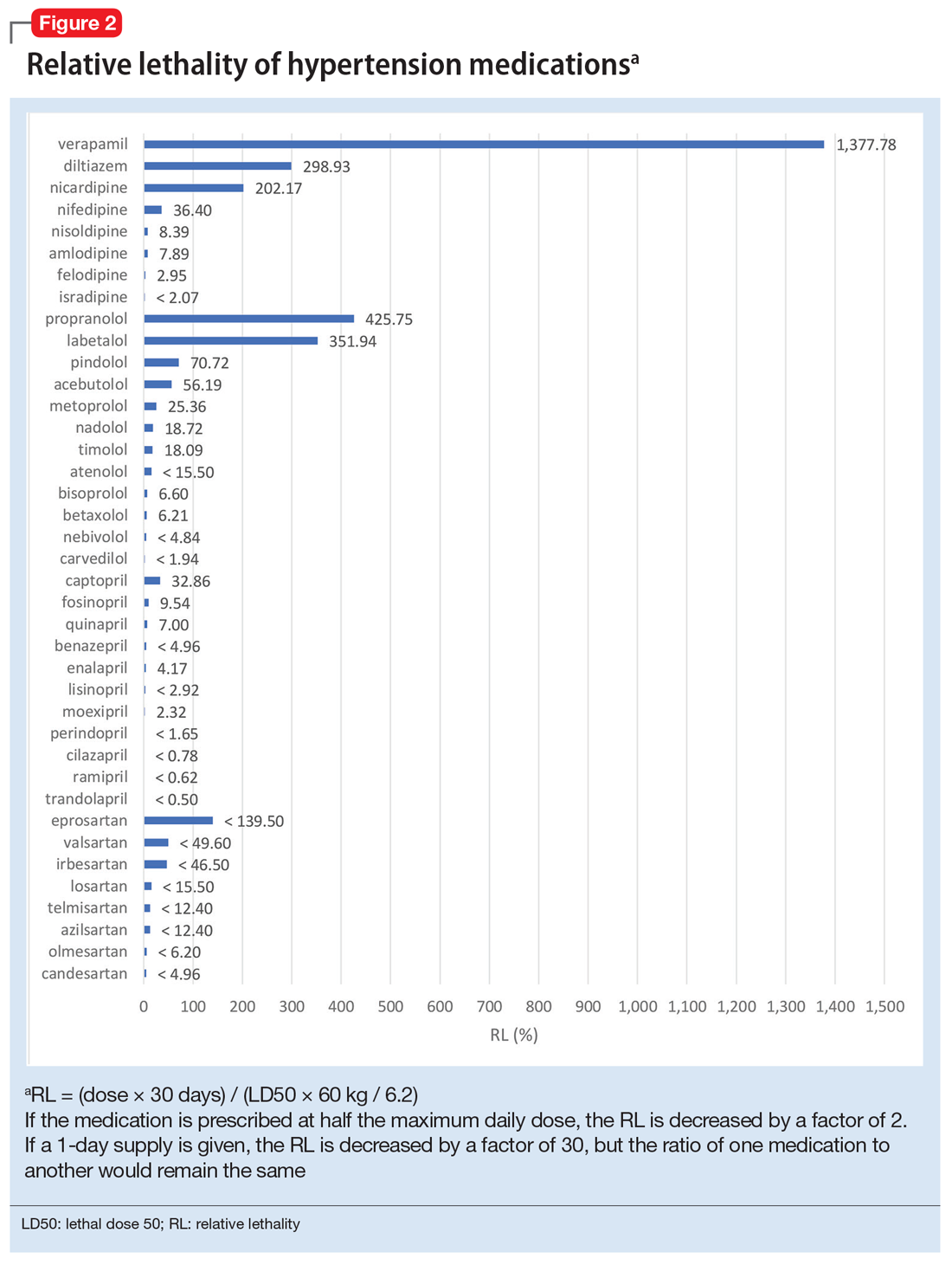

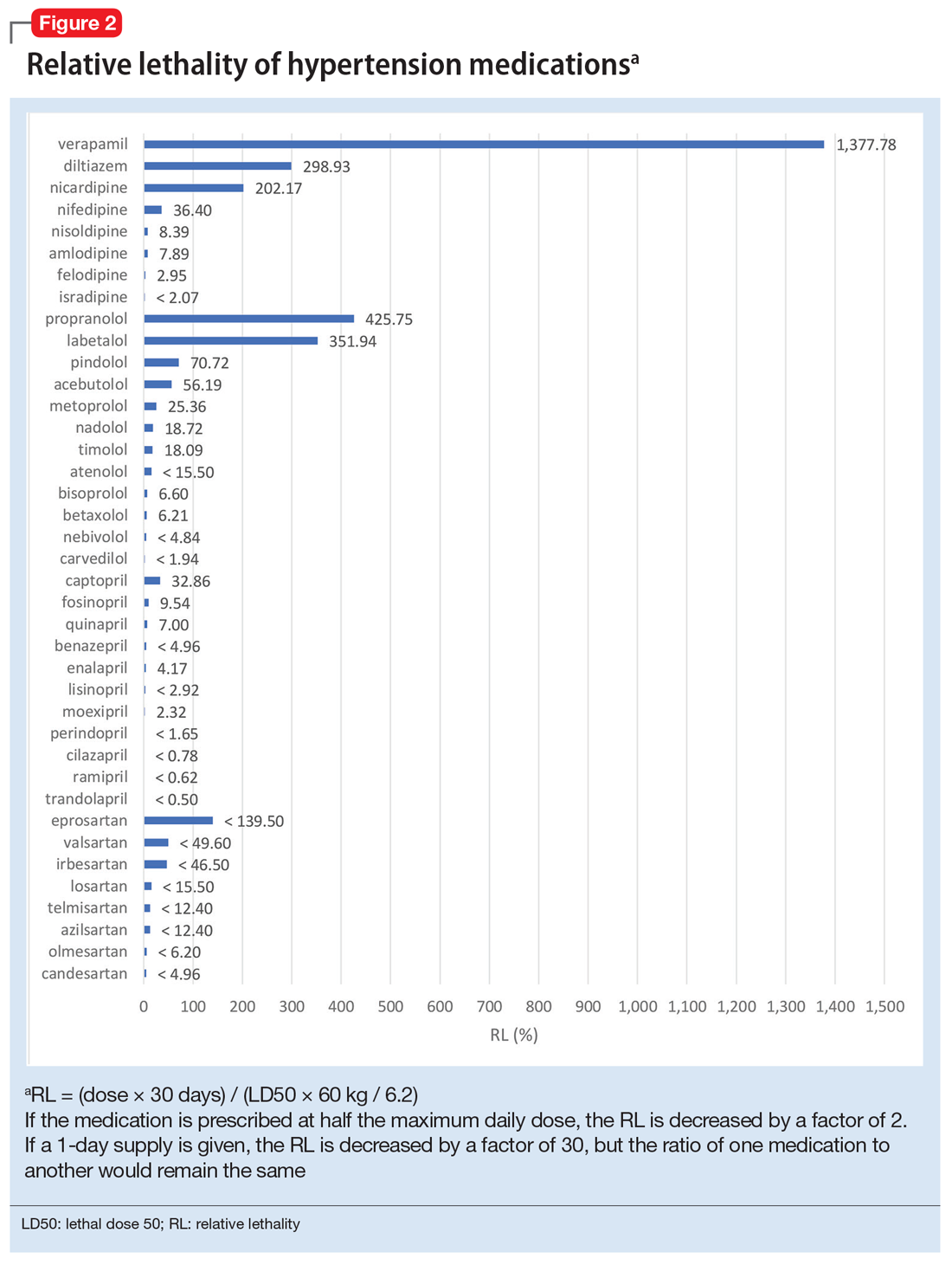

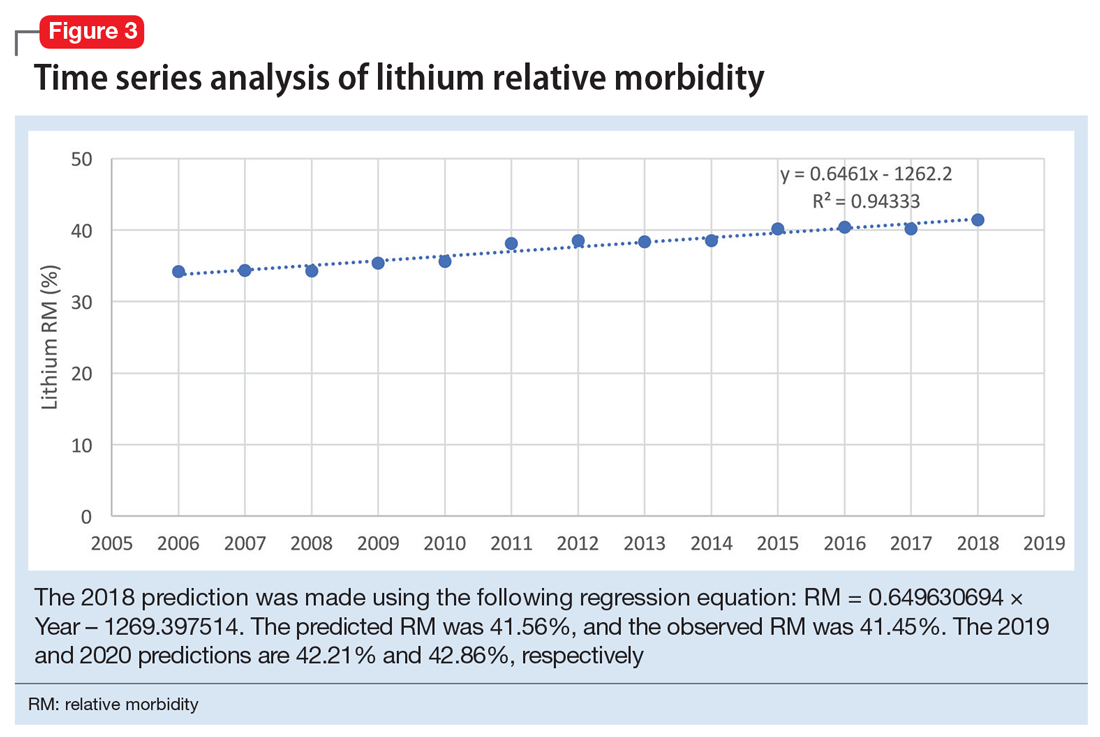

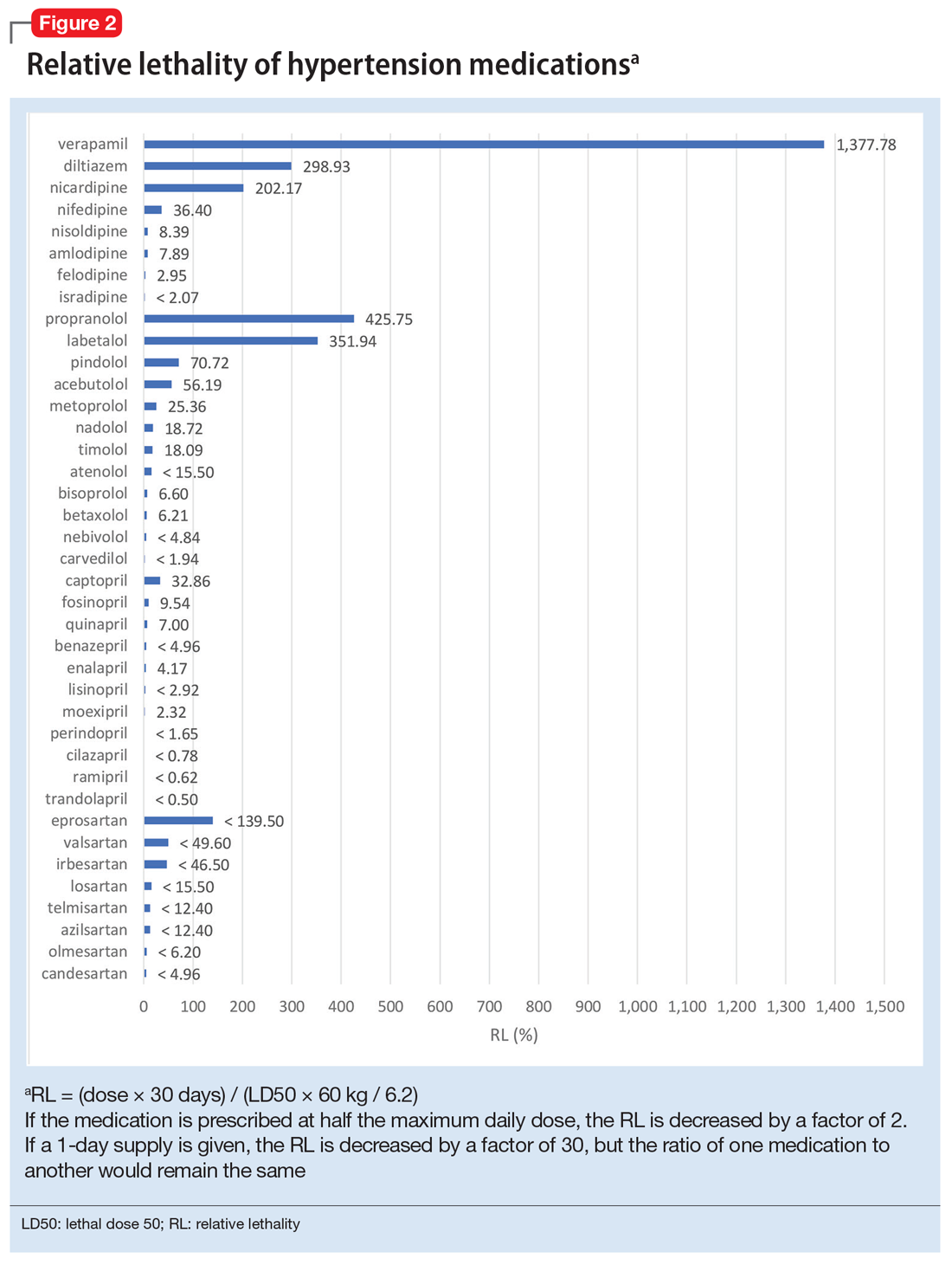

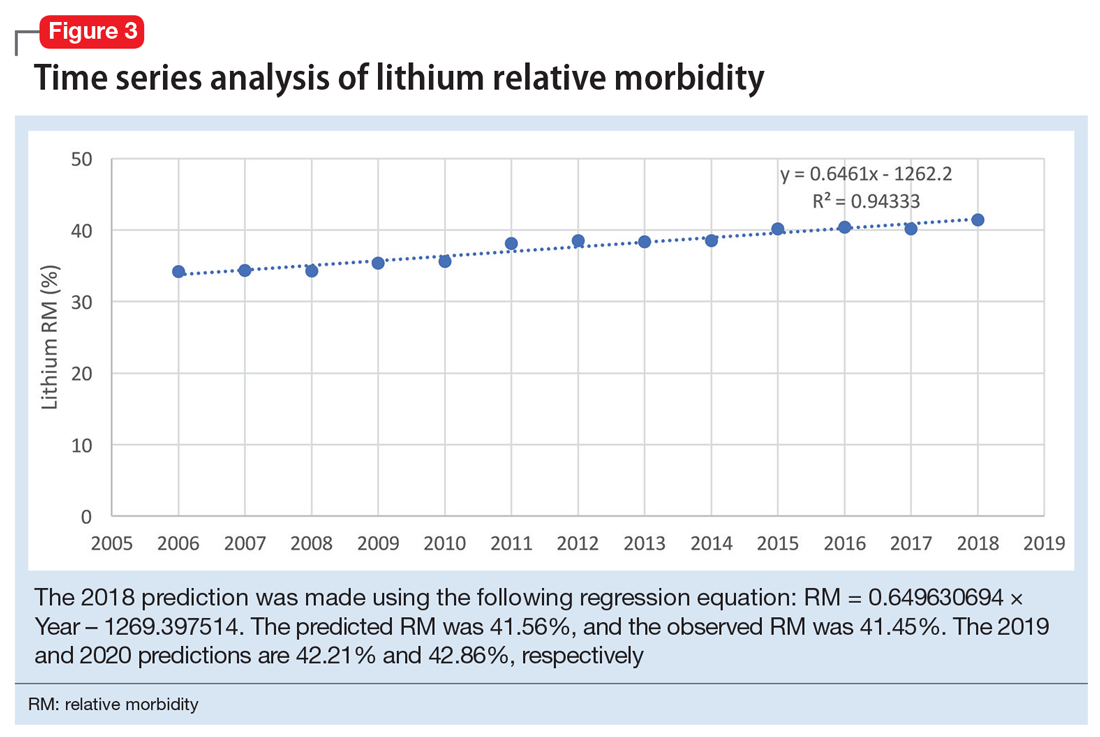

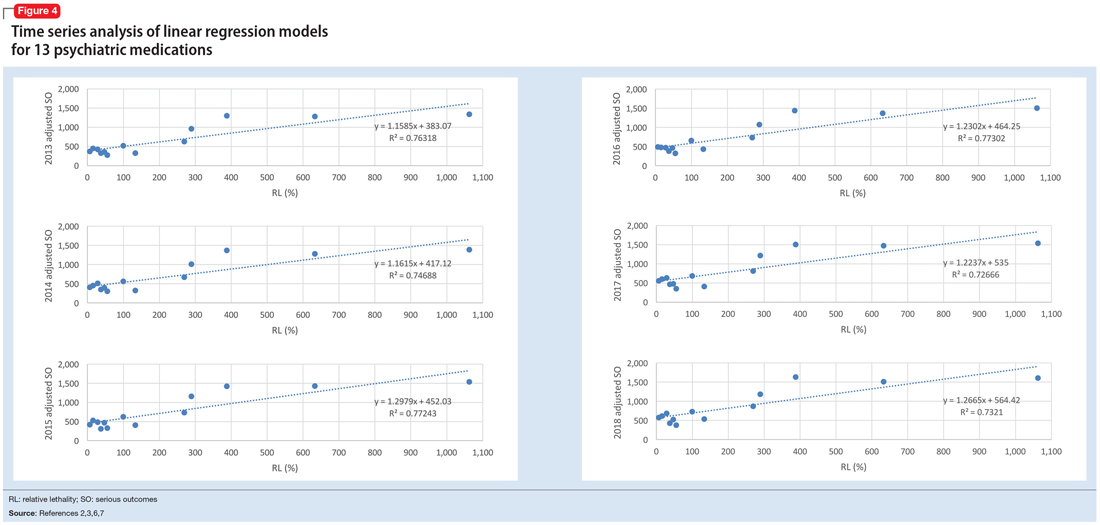

The 2018 NPDS data for psychiatric medications show similarly important results.2 For example, the lithium RM is predictable over time (Figure 3) and has been consistently the highest among psychiatric medications. Using 2006-2017 NPDS data,3 I predicted that the 2018 lithium RM would be 41.56%. The 2018 observed lithium RM was 41.45%.2 I created a linear regression model for each NPDS report from 2013 to 2018 to illustrate the correlation between RL and adjusted SO for 13 psychiatric medications.2,3,6,7 To account for different sample sizes among medications, the lithium SE for each respective year was used for all medications (adjusted SO = SE × RM). A time series analysis of these regression models shows that SO data points hover in the same y-axis region from year to year, with a corresponding RL on the x-axis: escitalopram 6.33%, citalopram 15.50%, mirtazapine 28.47%, paroxetine 37.35%, sertraline 46.72%, fluoxetine 54.87%, venlafaxine 99.64%, duloxetine 133.33%, trazodone 269.57%, bupropion 289.42%, amitriptyline 387.50%, doxepin 632.65%, and lithium 1062.86% (Figure 4). Every year, the scatter plot shape remains approximately the same, which suggests that both SO and RM can be predicted over time. Medications with RL >300% have SO ≈ 1500 (RM ≈ 40%), and those with RL <100% have SO ≈ 500 (RM ≈ 13%).

Time series analysis of NPDS data sheds light on hidden patterns. It may help clinicians discern patterns of potential SO associated with various hypertension and psychiatric medications. RL based on rat experimental data is highly correlated to RM based on human observational data, and the causality is self-evident. On a global scale, data-driven prescribing of medications with RL <100% could potentially help prevent millions of SO every year.

1. National Poison Data System Annual Reports. American Association of Poison Control Centers. https://www.aapcc.org/annual-reports. Updated November 2019. Accessed May 5, 2020.

2. Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, et al. 2018 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 36th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2019;57(12):1220-1413.

3. Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, et al. 2017 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 35th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2018;56(12):1213-1415.

4. Giurca D. Decreasing suicide risk with math. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(2):57-59,A,B.

5. Giurca D. Data-driven prescribing. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(10):e6-e8.

6. Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Brooks DE, et al. 2015 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 33rd Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2016;54(10):924-1109.

7. Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, et al. 2016 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 34th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2017;55(10):1072-1252.

The US Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS) publishes annual reports describing exposures to various substances among the general population.1 Table 22B of each NPDS report shows the number of outcomes from exposures to different pharmacologic treatments in the United States, including psychotropic medications.2 In this Table, the relative morbidity (RM) of a medication is calculated as the ratio of serious outcomes (SO) to single exposures (SE), where SO = moderate + major + death. In this article, I use the NPDS data to demonstrate how time series analysis of the RM ratios for hypertension and psychiatric medications can help predict SO associated with these agents, which may help guide clinicians’ prescribing decisions.2,3

Time series analysis of hypertension medications

Due to the high prevalence of hypertension, it is not surprising that more suicide deaths occur each year from calcium channel blockers (CCB) than from lithium (37 vs 2, according to 2017 NPDS data).3 I used time series analysis to compare SO during 2006-2017 for 5 classes of hypertension medications: CCB, beta blockers (BB), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), and diuretics (Figure 1).

Time series analysis of 2006-2017 data predicted the following number of deaths for 2018: CCB ≥33, BB ≥17, ACEI ≤2, ARB 0, and diuretics ≤1. The observed deaths in 2018 were 41, 23, 0, 0, and 1, respectively.2 The 2018 predicted RM were CCB 10.66%, BB 11.10%, ACEI 3.51%, ARB 2.04%, and diuretics 3.38%. The 2018 observed RM for these medications were 11.01%, 11.37%, 3.02%, 2.40%, and 2.88%, respectively.2

Because the NPDS data for hypertension medications was only provided by class, in order to detect differences within each class, I used the relative lethality (RL) equation: RL = 310x / LD50, where x is the maximum daily dose of a medication prescribed for 30 days, and LD50 is the rat oral lethal dose 50. The RL equation represents the ratio of a 30-day supply of medication to the human equivalent LD50 for a 60-kg person.4 The RL equation is useful for comparing the safety of various medications, and can help clinicians avoid prescribing a lethal amount of a given medication (Figure 2). For example, the equation shows that among CCB, felodipine is 466 times safer than verapamil and 101 times safer than diltiazem. Not surprisingly, 2006-2018 data shows many deaths via intentional verapamil or diltiazem overdose vs only 1 reference to felodipine. A regression model shows significant correlation and causality between RL and SO over time.5 Integrating all 3 mathematical models suggests that the higher RM of CCB and BB may be caused by the high RL of verapamil, diltiazem, nicardipine, propranolol, and labetalol.

These mathematical models can help physicians consider whether to switch the patient’s current medication to another class with a lower RM. For patients who need a BB or CCB, prescribing a medication with a lower RL within the same class may be another option. The data suggest that avoiding hypertension medications with RL >100% may significantly decrease morbidity and mortality.

Predicting serious outcomes of psychiatric medications

The 2018 NPDS data for psychiatric medications show similarly important results.2 For example, the lithium RM is predictable over time (Figure 3) and has been consistently the highest among psychiatric medications. Using 2006-2017 NPDS data,3 I predicted that the 2018 lithium RM would be 41.56%. The 2018 observed lithium RM was 41.45%.2 I created a linear regression model for each NPDS report from 2013 to 2018 to illustrate the correlation between RL and adjusted SO for 13 psychiatric medications.2,3,6,7 To account for different sample sizes among medications, the lithium SE for each respective year was used for all medications (adjusted SO = SE × RM). A time series analysis of these regression models shows that SO data points hover in the same y-axis region from year to year, with a corresponding RL on the x-axis: escitalopram 6.33%, citalopram 15.50%, mirtazapine 28.47%, paroxetine 37.35%, sertraline 46.72%, fluoxetine 54.87%, venlafaxine 99.64%, duloxetine 133.33%, trazodone 269.57%, bupropion 289.42%, amitriptyline 387.50%, doxepin 632.65%, and lithium 1062.86% (Figure 4). Every year, the scatter plot shape remains approximately the same, which suggests that both SO and RM can be predicted over time. Medications with RL >300% have SO ≈ 1500 (RM ≈ 40%), and those with RL <100% have SO ≈ 500 (RM ≈ 13%).

Time series analysis of NPDS data sheds light on hidden patterns. It may help clinicians discern patterns of potential SO associated with various hypertension and psychiatric medications. RL based on rat experimental data is highly correlated to RM based on human observational data, and the causality is self-evident. On a global scale, data-driven prescribing of medications with RL <100% could potentially help prevent millions of SO every year.

The US Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS) publishes annual reports describing exposures to various substances among the general population.1 Table 22B of each NPDS report shows the number of outcomes from exposures to different pharmacologic treatments in the United States, including psychotropic medications.2 In this Table, the relative morbidity (RM) of a medication is calculated as the ratio of serious outcomes (SO) to single exposures (SE), where SO = moderate + major + death. In this article, I use the NPDS data to demonstrate how time series analysis of the RM ratios for hypertension and psychiatric medications can help predict SO associated with these agents, which may help guide clinicians’ prescribing decisions.2,3

Time series analysis of hypertension medications

Due to the high prevalence of hypertension, it is not surprising that more suicide deaths occur each year from calcium channel blockers (CCB) than from lithium (37 vs 2, according to 2017 NPDS data).3 I used time series analysis to compare SO during 2006-2017 for 5 classes of hypertension medications: CCB, beta blockers (BB), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), and diuretics (Figure 1).

Time series analysis of 2006-2017 data predicted the following number of deaths for 2018: CCB ≥33, BB ≥17, ACEI ≤2, ARB 0, and diuretics ≤1. The observed deaths in 2018 were 41, 23, 0, 0, and 1, respectively.2 The 2018 predicted RM were CCB 10.66%, BB 11.10%, ACEI 3.51%, ARB 2.04%, and diuretics 3.38%. The 2018 observed RM for these medications were 11.01%, 11.37%, 3.02%, 2.40%, and 2.88%, respectively.2

Because the NPDS data for hypertension medications was only provided by class, in order to detect differences within each class, I used the relative lethality (RL) equation: RL = 310x / LD50, where x is the maximum daily dose of a medication prescribed for 30 days, and LD50 is the rat oral lethal dose 50. The RL equation represents the ratio of a 30-day supply of medication to the human equivalent LD50 for a 60-kg person.4 The RL equation is useful for comparing the safety of various medications, and can help clinicians avoid prescribing a lethal amount of a given medication (Figure 2). For example, the equation shows that among CCB, felodipine is 466 times safer than verapamil and 101 times safer than diltiazem. Not surprisingly, 2006-2018 data shows many deaths via intentional verapamil or diltiazem overdose vs only 1 reference to felodipine. A regression model shows significant correlation and causality between RL and SO over time.5 Integrating all 3 mathematical models suggests that the higher RM of CCB and BB may be caused by the high RL of verapamil, diltiazem, nicardipine, propranolol, and labetalol.

These mathematical models can help physicians consider whether to switch the patient’s current medication to another class with a lower RM. For patients who need a BB or CCB, prescribing a medication with a lower RL within the same class may be another option. The data suggest that avoiding hypertension medications with RL >100% may significantly decrease morbidity and mortality.

Predicting serious outcomes of psychiatric medications

The 2018 NPDS data for psychiatric medications show similarly important results.2 For example, the lithium RM is predictable over time (Figure 3) and has been consistently the highest among psychiatric medications. Using 2006-2017 NPDS data,3 I predicted that the 2018 lithium RM would be 41.56%. The 2018 observed lithium RM was 41.45%.2 I created a linear regression model for each NPDS report from 2013 to 2018 to illustrate the correlation between RL and adjusted SO for 13 psychiatric medications.2,3,6,7 To account for different sample sizes among medications, the lithium SE for each respective year was used for all medications (adjusted SO = SE × RM). A time series analysis of these regression models shows that SO data points hover in the same y-axis region from year to year, with a corresponding RL on the x-axis: escitalopram 6.33%, citalopram 15.50%, mirtazapine 28.47%, paroxetine 37.35%, sertraline 46.72%, fluoxetine 54.87%, venlafaxine 99.64%, duloxetine 133.33%, trazodone 269.57%, bupropion 289.42%, amitriptyline 387.50%, doxepin 632.65%, and lithium 1062.86% (Figure 4). Every year, the scatter plot shape remains approximately the same, which suggests that both SO and RM can be predicted over time. Medications with RL >300% have SO ≈ 1500 (RM ≈ 40%), and those with RL <100% have SO ≈ 500 (RM ≈ 13%).

Time series analysis of NPDS data sheds light on hidden patterns. It may help clinicians discern patterns of potential SO associated with various hypertension and psychiatric medications. RL based on rat experimental data is highly correlated to RM based on human observational data, and the causality is self-evident. On a global scale, data-driven prescribing of medications with RL <100% could potentially help prevent millions of SO every year.

1. National Poison Data System Annual Reports. American Association of Poison Control Centers. https://www.aapcc.org/annual-reports. Updated November 2019. Accessed May 5, 2020.

2. Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, et al. 2018 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 36th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2019;57(12):1220-1413.

3. Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, et al. 2017 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 35th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2018;56(12):1213-1415.

4. Giurca D. Decreasing suicide risk with math. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(2):57-59,A,B.

5. Giurca D. Data-driven prescribing. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(10):e6-e8.

6. Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Brooks DE, et al. 2015 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 33rd Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2016;54(10):924-1109.

7. Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, et al. 2016 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 34th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2017;55(10):1072-1252.

1. National Poison Data System Annual Reports. American Association of Poison Control Centers. https://www.aapcc.org/annual-reports. Updated November 2019. Accessed May 5, 2020.

2. Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, et al. 2018 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 36th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2019;57(12):1220-1413.

3. Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, et al. 2017 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 35th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2018;56(12):1213-1415.

4. Giurca D. Decreasing suicide risk with math. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(2):57-59,A,B.

5. Giurca D. Data-driven prescribing. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(10):e6-e8.

6. Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Brooks DE, et al. 2015 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 33rd Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2016;54(10):924-1109.

7. Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, et al. 2016 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 34th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2017;55(10):1072-1252.

Telepsychiatry during COVID-19: Understanding the rules

In addition to affecting our personal lives, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has altered the way we practice psychiatry. Telepsychiatry—the delivery of mental health services via remote communication—is being used to replace face-to-face outpatient encounters. Several rules and regulations governing the provision of care and prescribing have been temporarily modified or suspended to allow clinicians to more easily use telepsychiatry to care for their patients. Although these requirements are continually changing, here I review some of the telepsychiatry rules and regulations clinicians need to understand to minimize their risk for liability.

Changes in light of COVID-19

In March 2020, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released guidance that allows Medicare beneficiaries to receive various services at home through telehealth without having to travel to a doctor’s office or hospital.1 Many commercial insurers also are allowing patients to receive telehealth services in their home. The US Department of Health & Human Services Office for Civil Rights, which enforces the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), reported in March 2020 that it will not impose penalties for not complying with HIPAA requirements on clinicians who provide good-faith telepsychiatry during the COVID-19 crisis.2

Clinicians who want to use audio or video remote communication to provide any type of telehealth services (not just those related to COVID-19) should use “non-public facing” products.2 Non-public facing products (eg, Skype, WhatsApp video call, Zoom) allow only the intended parties to participate in the communication.3 Usually, these products employ end-to-end encryption, which allows only those engaging in communication to see and hear what is transmitted.3 To limit access and verify the participants, these products also support individual user accounts, login names, and passwords.3 In addition, these products usually allow participants and/or “the host” to exert some degree of control over particular features, such as choosing to record the communication, mute, or turn off the video or audio signal.3 When using these products, clinicians should enable all available encryption and privacy modes.2

“Public-facing” products (eg, Facebook Live, TikTok, Twitch) should not be used to provide telepsychiatry services because they are designed to be open to the public or allow for wide or indiscriminate access to the communication.2,3 Clinicians who desire additional privacy protections (and a more permanent solution) should choose a HIPAA-compliant telehealth vendor (eg, Doxy.me, VSee, Zoom for Healthcare) and obtain a Business Associate Agreement with the vendor to ensure data protection and security.2,4

Regardless of the product, obtain informed consent from your patients that authorizes the use of remote communication.4 Inform your patients of any potential privacy or security breaches, the need for interactions to be conducted in a location that provides privacy, and whether the specific technology used is HIPAA-compliant.4 Document that your patients understand these issues before using remote communication.4

How licensing requirements have changed

As of March 31, 2020, the CMS temporarily waived the requirement that out-of-state clinicians be licensed in the state where they are providing services to Medicare beneficiaries.5 The CMS waived this requirement for clinicians who meet the following 4 conditions5,6:

- must be enrolled in Medicare

- must possess a valid license to practice in the state that relates to his/her Medicare enrollment

- are furnishing services—whether in person or via telepsychiatry—in a state where the emergency is occurring to contribute to relief efforts in his/her professional capacity

- are not excluded from practicing in any state that is part of the nationally declared emergency area.

Note that individual state licensure requirements continue to apply unless waived by the state.6 Therefore, in order for clinicians to see Medicare patients via remote communication under the 4 conditions described above, the state also would have to waive its licensure requirements for the type of practice for which the clinicians are licensed in their own state.6 Regarding commercial payers, in general, clinicians providing telepsychiatry services need a license to practice in the state where the patient is located at the time services are provided.6 During the COVID-19 pandemic, many governors issued executive orders waiving licensure requirements, and many have accelerated granting temporary licenses to out-of-state clinicians who wish to provide telepsychiatry services to the residents of their state.4

Continue to: Prescribing via telepsychiatry

Prescribing via telepsychiatry

Effective March 31, 2020 and lasting for the duration of COVID-19 emergency declaration, the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) suspended the Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act of 2008, which requires clinicians to conduct initial, in-person examinations of patients before they can prescribe controlled substances electronically.6,7 The DEA suspension allows clinicians to prescribe controlled substances after conducting an initial evaluation via remote communication. In addition, the DEA waived the requirement that a clinician needs to hold a DEA license in the state where the patient is located to be able to prescribe a controlled substance electronically.4,6 However, you still must comply with all other state laws and regulations for prescribing controlled substances.4

Staying informed

Although several telepsychiatry rules and regulations have been modified or suspended during the COVID-19 pandemic, the standard of care for services rendered via telepsychiatry remains the same as services provided via face-to-face encounters, including patient evaluation and assessment, treatment plans, medication, and documentation.4 Clinicians can keep up-to-date on how practicing telepsychiatry may evolve during these times by using the following resources from the American Psychiatric Association:

- Telepsychiatry Toolkit: www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry

- Practice Guidance for COVID-19: www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/covid-19-coronavirus/practice-guidance-for-covid-19.

1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. COVID-19: President Trump expands telehealth benefits for Medicare beneficiaries during COVID-19 outbreak. https://www.cms.gov/outreach-and-educationoutreachffsprovpartprogprovider-partnership-email-archive/2020-03-17. Published March 17, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

2. US Department of Health & Human Services. Notification of enforcement discretion for telehealth remote communications during the COVID-19 nationwide public health emergency. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/emergency-preparedness/notification-enforcement-discretion-telehealth/index.html. Updated March 30, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

3. US Department of Health & Human Services. What is a “non-public facing” remote communication product? https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/faq/3024/what-is-a-non-public-facing-remote-communication-product/index.html. Updated April 10, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

4. Huben-Kearney A. Risk management amid a global pandemic. Psychiatric News. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2020.5a38. Published April 28, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

5. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. COVID-19 emergency declaration blanket waivers for health care providers. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/summary-covid-19-emergency-declaration-waivers.pdf. Published April 29, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

6. American Psychiatric Association. Update on telehealth restrictions in response to COVID-19. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry/blog/apa-resources-on-telepsychiatry-and-covid-19. Updated May 1, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

7. US Drug Enforcement Agency. How to prescribe controlled substances to patients during the COVID-19 public health emergency. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/GDP/(DEA-DC-023)(DEA075)Decision_Tree_(Final)_33120_2007.pdf. Published March 31, 2020. Accessed on May 6, 2020.

In addition to affecting our personal lives, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has altered the way we practice psychiatry. Telepsychiatry—the delivery of mental health services via remote communication—is being used to replace face-to-face outpatient encounters. Several rules and regulations governing the provision of care and prescribing have been temporarily modified or suspended to allow clinicians to more easily use telepsychiatry to care for their patients. Although these requirements are continually changing, here I review some of the telepsychiatry rules and regulations clinicians need to understand to minimize their risk for liability.

Changes in light of COVID-19

In March 2020, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released guidance that allows Medicare beneficiaries to receive various services at home through telehealth without having to travel to a doctor’s office or hospital.1 Many commercial insurers also are allowing patients to receive telehealth services in their home. The US Department of Health & Human Services Office for Civil Rights, which enforces the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), reported in March 2020 that it will not impose penalties for not complying with HIPAA requirements on clinicians who provide good-faith telepsychiatry during the COVID-19 crisis.2

Clinicians who want to use audio or video remote communication to provide any type of telehealth services (not just those related to COVID-19) should use “non-public facing” products.2 Non-public facing products (eg, Skype, WhatsApp video call, Zoom) allow only the intended parties to participate in the communication.3 Usually, these products employ end-to-end encryption, which allows only those engaging in communication to see and hear what is transmitted.3 To limit access and verify the participants, these products also support individual user accounts, login names, and passwords.3 In addition, these products usually allow participants and/or “the host” to exert some degree of control over particular features, such as choosing to record the communication, mute, or turn off the video or audio signal.3 When using these products, clinicians should enable all available encryption and privacy modes.2

“Public-facing” products (eg, Facebook Live, TikTok, Twitch) should not be used to provide telepsychiatry services because they are designed to be open to the public or allow for wide or indiscriminate access to the communication.2,3 Clinicians who desire additional privacy protections (and a more permanent solution) should choose a HIPAA-compliant telehealth vendor (eg, Doxy.me, VSee, Zoom for Healthcare) and obtain a Business Associate Agreement with the vendor to ensure data protection and security.2,4

Regardless of the product, obtain informed consent from your patients that authorizes the use of remote communication.4 Inform your patients of any potential privacy or security breaches, the need for interactions to be conducted in a location that provides privacy, and whether the specific technology used is HIPAA-compliant.4 Document that your patients understand these issues before using remote communication.4

How licensing requirements have changed

As of March 31, 2020, the CMS temporarily waived the requirement that out-of-state clinicians be licensed in the state where they are providing services to Medicare beneficiaries.5 The CMS waived this requirement for clinicians who meet the following 4 conditions5,6:

- must be enrolled in Medicare

- must possess a valid license to practice in the state that relates to his/her Medicare enrollment

- are furnishing services—whether in person or via telepsychiatry—in a state where the emergency is occurring to contribute to relief efforts in his/her professional capacity

- are not excluded from practicing in any state that is part of the nationally declared emergency area.

Note that individual state licensure requirements continue to apply unless waived by the state.6 Therefore, in order for clinicians to see Medicare patients via remote communication under the 4 conditions described above, the state also would have to waive its licensure requirements for the type of practice for which the clinicians are licensed in their own state.6 Regarding commercial payers, in general, clinicians providing telepsychiatry services need a license to practice in the state where the patient is located at the time services are provided.6 During the COVID-19 pandemic, many governors issued executive orders waiving licensure requirements, and many have accelerated granting temporary licenses to out-of-state clinicians who wish to provide telepsychiatry services to the residents of their state.4

Continue to: Prescribing via telepsychiatry

Prescribing via telepsychiatry

Effective March 31, 2020 and lasting for the duration of COVID-19 emergency declaration, the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) suspended the Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act of 2008, which requires clinicians to conduct initial, in-person examinations of patients before they can prescribe controlled substances electronically.6,7 The DEA suspension allows clinicians to prescribe controlled substances after conducting an initial evaluation via remote communication. In addition, the DEA waived the requirement that a clinician needs to hold a DEA license in the state where the patient is located to be able to prescribe a controlled substance electronically.4,6 However, you still must comply with all other state laws and regulations for prescribing controlled substances.4

Staying informed

Although several telepsychiatry rules and regulations have been modified or suspended during the COVID-19 pandemic, the standard of care for services rendered via telepsychiatry remains the same as services provided via face-to-face encounters, including patient evaluation and assessment, treatment plans, medication, and documentation.4 Clinicians can keep up-to-date on how practicing telepsychiatry may evolve during these times by using the following resources from the American Psychiatric Association:

- Telepsychiatry Toolkit: www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry

- Practice Guidance for COVID-19: www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/covid-19-coronavirus/practice-guidance-for-covid-19.

In addition to affecting our personal lives, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has altered the way we practice psychiatry. Telepsychiatry—the delivery of mental health services via remote communication—is being used to replace face-to-face outpatient encounters. Several rules and regulations governing the provision of care and prescribing have been temporarily modified or suspended to allow clinicians to more easily use telepsychiatry to care for their patients. Although these requirements are continually changing, here I review some of the telepsychiatry rules and regulations clinicians need to understand to minimize their risk for liability.

Changes in light of COVID-19

In March 2020, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released guidance that allows Medicare beneficiaries to receive various services at home through telehealth without having to travel to a doctor’s office or hospital.1 Many commercial insurers also are allowing patients to receive telehealth services in their home. The US Department of Health & Human Services Office for Civil Rights, which enforces the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), reported in March 2020 that it will not impose penalties for not complying with HIPAA requirements on clinicians who provide good-faith telepsychiatry during the COVID-19 crisis.2

Clinicians who want to use audio or video remote communication to provide any type of telehealth services (not just those related to COVID-19) should use “non-public facing” products.2 Non-public facing products (eg, Skype, WhatsApp video call, Zoom) allow only the intended parties to participate in the communication.3 Usually, these products employ end-to-end encryption, which allows only those engaging in communication to see and hear what is transmitted.3 To limit access and verify the participants, these products also support individual user accounts, login names, and passwords.3 In addition, these products usually allow participants and/or “the host” to exert some degree of control over particular features, such as choosing to record the communication, mute, or turn off the video or audio signal.3 When using these products, clinicians should enable all available encryption and privacy modes.2

“Public-facing” products (eg, Facebook Live, TikTok, Twitch) should not be used to provide telepsychiatry services because they are designed to be open to the public or allow for wide or indiscriminate access to the communication.2,3 Clinicians who desire additional privacy protections (and a more permanent solution) should choose a HIPAA-compliant telehealth vendor (eg, Doxy.me, VSee, Zoom for Healthcare) and obtain a Business Associate Agreement with the vendor to ensure data protection and security.2,4

Regardless of the product, obtain informed consent from your patients that authorizes the use of remote communication.4 Inform your patients of any potential privacy or security breaches, the need for interactions to be conducted in a location that provides privacy, and whether the specific technology used is HIPAA-compliant.4 Document that your patients understand these issues before using remote communication.4

How licensing requirements have changed

As of March 31, 2020, the CMS temporarily waived the requirement that out-of-state clinicians be licensed in the state where they are providing services to Medicare beneficiaries.5 The CMS waived this requirement for clinicians who meet the following 4 conditions5,6:

- must be enrolled in Medicare

- must possess a valid license to practice in the state that relates to his/her Medicare enrollment

- are furnishing services—whether in person or via telepsychiatry—in a state where the emergency is occurring to contribute to relief efforts in his/her professional capacity

- are not excluded from practicing in any state that is part of the nationally declared emergency area.

Note that individual state licensure requirements continue to apply unless waived by the state.6 Therefore, in order for clinicians to see Medicare patients via remote communication under the 4 conditions described above, the state also would have to waive its licensure requirements for the type of practice for which the clinicians are licensed in their own state.6 Regarding commercial payers, in general, clinicians providing telepsychiatry services need a license to practice in the state where the patient is located at the time services are provided.6 During the COVID-19 pandemic, many governors issued executive orders waiving licensure requirements, and many have accelerated granting temporary licenses to out-of-state clinicians who wish to provide telepsychiatry services to the residents of their state.4

Continue to: Prescribing via telepsychiatry

Prescribing via telepsychiatry

Effective March 31, 2020 and lasting for the duration of COVID-19 emergency declaration, the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) suspended the Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act of 2008, which requires clinicians to conduct initial, in-person examinations of patients before they can prescribe controlled substances electronically.6,7 The DEA suspension allows clinicians to prescribe controlled substances after conducting an initial evaluation via remote communication. In addition, the DEA waived the requirement that a clinician needs to hold a DEA license in the state where the patient is located to be able to prescribe a controlled substance electronically.4,6 However, you still must comply with all other state laws and regulations for prescribing controlled substances.4

Staying informed

Although several telepsychiatry rules and regulations have been modified or suspended during the COVID-19 pandemic, the standard of care for services rendered via telepsychiatry remains the same as services provided via face-to-face encounters, including patient evaluation and assessment, treatment plans, medication, and documentation.4 Clinicians can keep up-to-date on how practicing telepsychiatry may evolve during these times by using the following resources from the American Psychiatric Association:

- Telepsychiatry Toolkit: www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry

- Practice Guidance for COVID-19: www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/covid-19-coronavirus/practice-guidance-for-covid-19.

1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. COVID-19: President Trump expands telehealth benefits for Medicare beneficiaries during COVID-19 outbreak. https://www.cms.gov/outreach-and-educationoutreachffsprovpartprogprovider-partnership-email-archive/2020-03-17. Published March 17, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

2. US Department of Health & Human Services. Notification of enforcement discretion for telehealth remote communications during the COVID-19 nationwide public health emergency. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/emergency-preparedness/notification-enforcement-discretion-telehealth/index.html. Updated March 30, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

3. US Department of Health & Human Services. What is a “non-public facing” remote communication product? https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/faq/3024/what-is-a-non-public-facing-remote-communication-product/index.html. Updated April 10, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

4. Huben-Kearney A. Risk management amid a global pandemic. Psychiatric News. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2020.5a38. Published April 28, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

5. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. COVID-19 emergency declaration blanket waivers for health care providers. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/summary-covid-19-emergency-declaration-waivers.pdf. Published April 29, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

6. American Psychiatric Association. Update on telehealth restrictions in response to COVID-19. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry/blog/apa-resources-on-telepsychiatry-and-covid-19. Updated May 1, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

7. US Drug Enforcement Agency. How to prescribe controlled substances to patients during the COVID-19 public health emergency. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/GDP/(DEA-DC-023)(DEA075)Decision_Tree_(Final)_33120_2007.pdf. Published March 31, 2020. Accessed on May 6, 2020.

1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. COVID-19: President Trump expands telehealth benefits for Medicare beneficiaries during COVID-19 outbreak. https://www.cms.gov/outreach-and-educationoutreachffsprovpartprogprovider-partnership-email-archive/2020-03-17. Published March 17, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

2. US Department of Health & Human Services. Notification of enforcement discretion for telehealth remote communications during the COVID-19 nationwide public health emergency. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/emergency-preparedness/notification-enforcement-discretion-telehealth/index.html. Updated March 30, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

3. US Department of Health & Human Services. What is a “non-public facing” remote communication product? https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/faq/3024/what-is-a-non-public-facing-remote-communication-product/index.html. Updated April 10, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

4. Huben-Kearney A. Risk management amid a global pandemic. Psychiatric News. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2020.5a38. Published April 28, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

5. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. COVID-19 emergency declaration blanket waivers for health care providers. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/summary-covid-19-emergency-declaration-waivers.pdf. Published April 29, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

6. American Psychiatric Association. Update on telehealth restrictions in response to COVID-19. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry/blog/apa-resources-on-telepsychiatry-and-covid-19. Updated May 1, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

7. US Drug Enforcement Agency. How to prescribe controlled substances to patients during the COVID-19 public health emergency. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/GDP/(DEA-DC-023)(DEA075)Decision_Tree_(Final)_33120_2007.pdf. Published March 31, 2020. Accessed on May 6, 2020.

The resident’s role in combating burnout among medical students

Burnout among health care professionals has been increasingly recognized by the medical community over the past several years. The concern for burnout among medical students is equally serious. In this article, I review the prevalence of burnout among medical students, and the personal and clinical effects they experience. I also discuss how as psychiatry residents we can be more effective in preventing and identifying medical student burnout.

An underappreciated problem

Burnout has been defined as long-term unresolvable job stress that leads to exhaustion and feeling overwhelmed, cynical, and detached from work, and lacking a sense of personal accomplishment. It can lead to depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation—one survey found that 5.8% of medical students had experienced suicidal ideation at some point in the previous 12 months.1 Burnout affects not only the individual, but also his/her team and patients. One study found that compared to medical students who didn’t report burnout, medical students who did had lower scores on measures of empathy and professionalism.2

While burnout among physicians and residents has received increasing attention, it often may go unrecognized and unreported in medical students. A literature review that included 51 studies found 28% to 45% of medical students report burnout.3 In a survey at one institution, 60% of medical students reported burnout.4 It is evident that medical schools have an important role in helping to minimize burnout rates in their students, and many schools are working toward this goal. However, what happens when students leave the classroom setting for clinical rotations?

A recent study found burnout among medical students peaks during the third year of medical school.5 This is when students are on their clinical rotations, new to the hospital environment, and without the inherent structure and support of being at school.

How residents can help

Like most medical students, while on my clinical rotations, I spent most of my day with residents, and I believe residents can help to both recognize burnout in medical students and prevent it.

The first step in addressing this problem is to understand why it occurs. A survey of medical students showed that inadequate sleep and decreased exercise play a significant role in burnout rates.6 Another study found a correlation between burnout and feeling emotionally exhausted and a decreased perceived quality of life.7 A medical student I recently worked with stated, “How can you not feel burnt out? Juggling work hours, studying, debt, health, and trying to have a life… something always gets dropped.”

So as residents, what can we do to identify and assist medical students who are experiencing burnout, or are at risk of getting there? When needed, we can utilize our psychiatry training to assess our students for depression and substance use disorders, and connect them with appropriate resources. When identifying a medical student with burnout, I believe it can become necessary to notify the attending, the site director responsible for the student, and often the school, so that the student has access to all available resources.

Continue to: It's as important to be proactive...

It’s as important to be proactive as it is to be reactive. Engaging in regular check-ins with our students about self-care and workload, as well as asking about how they are feeling, can offer them opportunities to talk about issues that they might not be getting anywhere else. One medical student I worked with told me, “It’s easy to fade into the background as the student, or to feel like I can’t complain because this is just how medical school is supposed to be.” We have the ability to change this notion with each student we work with.

It is likely that as residents we have worked with a student struggling with burnout without even realizing it. I believe we can play an important role in helping to prevent burnout by identifying at-risk students, offering assistance, and encouraging them to seek professional help. Someone’s life may depend on it.

1. Dyrbye L, Thomas M, Massie F, et al. Burnout and suicidal ideation among U.S. medical students. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(5):334-341.

2. Brazeau C, Schroeder R, Rovi S. Relationships between medical student burnout, empathy, and professionalism climate. Acad Med. 2010;85(suppl 10):S33-S36. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ed4c47.

3. IsHak WW, Lederer S, Mandili C, et al. Burnout during residency training: a literature review. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;1(2):236-242.

4. Chang E, Eddins-Folensbee F, Coverdale J. Survey of the prevalence of burnout, stress, depression, and the use of supports by medical students at one school. Acad Psychiatry. 2012;36(3):177-182.

5. Hansell MW, Ungerleider RM, Brooks CA, et al. Temporal trends in medical student burnout. Fam Med. 2019;51(5):399-404.

6. Wolf M, Rosenstock J. Inadequate sleep and exercise associated with burnout and depression among medical students. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(2):174-179.

7. Colby L, Mareka M, Pillay S, et al. The association between the levels of burnout and quality of life among fourth-year medical students at the University of the Free State. S Afr J Psychiatr. 2018;24:1101.

Burnout among health care professionals has been increasingly recognized by the medical community over the past several years. The concern for burnout among medical students is equally serious. In this article, I review the prevalence of burnout among medical students, and the personal and clinical effects they experience. I also discuss how as psychiatry residents we can be more effective in preventing and identifying medical student burnout.

An underappreciated problem

Burnout has been defined as long-term unresolvable job stress that leads to exhaustion and feeling overwhelmed, cynical, and detached from work, and lacking a sense of personal accomplishment. It can lead to depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation—one survey found that 5.8% of medical students had experienced suicidal ideation at some point in the previous 12 months.1 Burnout affects not only the individual, but also his/her team and patients. One study found that compared to medical students who didn’t report burnout, medical students who did had lower scores on measures of empathy and professionalism.2

While burnout among physicians and residents has received increasing attention, it often may go unrecognized and unreported in medical students. A literature review that included 51 studies found 28% to 45% of medical students report burnout.3 In a survey at one institution, 60% of medical students reported burnout.4 It is evident that medical schools have an important role in helping to minimize burnout rates in their students, and many schools are working toward this goal. However, what happens when students leave the classroom setting for clinical rotations?

A recent study found burnout among medical students peaks during the third year of medical school.5 This is when students are on their clinical rotations, new to the hospital environment, and without the inherent structure and support of being at school.

How residents can help

Like most medical students, while on my clinical rotations, I spent most of my day with residents, and I believe residents can help to both recognize burnout in medical students and prevent it.

The first step in addressing this problem is to understand why it occurs. A survey of medical students showed that inadequate sleep and decreased exercise play a significant role in burnout rates.6 Another study found a correlation between burnout and feeling emotionally exhausted and a decreased perceived quality of life.7 A medical student I recently worked with stated, “How can you not feel burnt out? Juggling work hours, studying, debt, health, and trying to have a life… something always gets dropped.”

So as residents, what can we do to identify and assist medical students who are experiencing burnout, or are at risk of getting there? When needed, we can utilize our psychiatry training to assess our students for depression and substance use disorders, and connect them with appropriate resources. When identifying a medical student with burnout, I believe it can become necessary to notify the attending, the site director responsible for the student, and often the school, so that the student has access to all available resources.

Continue to: It's as important to be proactive...

It’s as important to be proactive as it is to be reactive. Engaging in regular check-ins with our students about self-care and workload, as well as asking about how they are feeling, can offer them opportunities to talk about issues that they might not be getting anywhere else. One medical student I worked with told me, “It’s easy to fade into the background as the student, or to feel like I can’t complain because this is just how medical school is supposed to be.” We have the ability to change this notion with each student we work with.

It is likely that as residents we have worked with a student struggling with burnout without even realizing it. I believe we can play an important role in helping to prevent burnout by identifying at-risk students, offering assistance, and encouraging them to seek professional help. Someone’s life may depend on it.

Burnout among health care professionals has been increasingly recognized by the medical community over the past several years. The concern for burnout among medical students is equally serious. In this article, I review the prevalence of burnout among medical students, and the personal and clinical effects they experience. I also discuss how as psychiatry residents we can be more effective in preventing and identifying medical student burnout.

An underappreciated problem

Burnout has been defined as long-term unresolvable job stress that leads to exhaustion and feeling overwhelmed, cynical, and detached from work, and lacking a sense of personal accomplishment. It can lead to depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation—one survey found that 5.8% of medical students had experienced suicidal ideation at some point in the previous 12 months.1 Burnout affects not only the individual, but also his/her team and patients. One study found that compared to medical students who didn’t report burnout, medical students who did had lower scores on measures of empathy and professionalism.2

While burnout among physicians and residents has received increasing attention, it often may go unrecognized and unreported in medical students. A literature review that included 51 studies found 28% to 45% of medical students report burnout.3 In a survey at one institution, 60% of medical students reported burnout.4 It is evident that medical schools have an important role in helping to minimize burnout rates in their students, and many schools are working toward this goal. However, what happens when students leave the classroom setting for clinical rotations?

A recent study found burnout among medical students peaks during the third year of medical school.5 This is when students are on their clinical rotations, new to the hospital environment, and without the inherent structure and support of being at school.

How residents can help

Like most medical students, while on my clinical rotations, I spent most of my day with residents, and I believe residents can help to both recognize burnout in medical students and prevent it.

The first step in addressing this problem is to understand why it occurs. A survey of medical students showed that inadequate sleep and decreased exercise play a significant role in burnout rates.6 Another study found a correlation between burnout and feeling emotionally exhausted and a decreased perceived quality of life.7 A medical student I recently worked with stated, “How can you not feel burnt out? Juggling work hours, studying, debt, health, and trying to have a life… something always gets dropped.”

So as residents, what can we do to identify and assist medical students who are experiencing burnout, or are at risk of getting there? When needed, we can utilize our psychiatry training to assess our students for depression and substance use disorders, and connect them with appropriate resources. When identifying a medical student with burnout, I believe it can become necessary to notify the attending, the site director responsible for the student, and often the school, so that the student has access to all available resources.

Continue to: It's as important to be proactive...

It’s as important to be proactive as it is to be reactive. Engaging in regular check-ins with our students about self-care and workload, as well as asking about how they are feeling, can offer them opportunities to talk about issues that they might not be getting anywhere else. One medical student I worked with told me, “It’s easy to fade into the background as the student, or to feel like I can’t complain because this is just how medical school is supposed to be.” We have the ability to change this notion with each student we work with.

It is likely that as residents we have worked with a student struggling with burnout without even realizing it. I believe we can play an important role in helping to prevent burnout by identifying at-risk students, offering assistance, and encouraging them to seek professional help. Someone’s life may depend on it.

1. Dyrbye L, Thomas M, Massie F, et al. Burnout and suicidal ideation among U.S. medical students. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(5):334-341.

2. Brazeau C, Schroeder R, Rovi S. Relationships between medical student burnout, empathy, and professionalism climate. Acad Med. 2010;85(suppl 10):S33-S36. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ed4c47.

3. IsHak WW, Lederer S, Mandili C, et al. Burnout during residency training: a literature review. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;1(2):236-242.

4. Chang E, Eddins-Folensbee F, Coverdale J. Survey of the prevalence of burnout, stress, depression, and the use of supports by medical students at one school. Acad Psychiatry. 2012;36(3):177-182.

5. Hansell MW, Ungerleider RM, Brooks CA, et al. Temporal trends in medical student burnout. Fam Med. 2019;51(5):399-404.

6. Wolf M, Rosenstock J. Inadequate sleep and exercise associated with burnout and depression among medical students. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(2):174-179.

7. Colby L, Mareka M, Pillay S, et al. The association between the levels of burnout and quality of life among fourth-year medical students at the University of the Free State. S Afr J Psychiatr. 2018;24:1101.

1. Dyrbye L, Thomas M, Massie F, et al. Burnout and suicidal ideation among U.S. medical students. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(5):334-341.

2. Brazeau C, Schroeder R, Rovi S. Relationships between medical student burnout, empathy, and professionalism climate. Acad Med. 2010;85(suppl 10):S33-S36. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ed4c47.

3. IsHak WW, Lederer S, Mandili C, et al. Burnout during residency training: a literature review. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;1(2):236-242.

4. Chang E, Eddins-Folensbee F, Coverdale J. Survey of the prevalence of burnout, stress, depression, and the use of supports by medical students at one school. Acad Psychiatry. 2012;36(3):177-182.

5. Hansell MW, Ungerleider RM, Brooks CA, et al. Temporal trends in medical student burnout. Fam Med. 2019;51(5):399-404.

6. Wolf M, Rosenstock J. Inadequate sleep and exercise associated with burnout and depression among medical students. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(2):174-179.

7. Colby L, Mareka M, Pillay S, et al. The association between the levels of burnout and quality of life among fourth-year medical students at the University of the Free State. S Afr J Psychiatr. 2018;24:1101.

Life during COVID-19: A pandemic of silence

Our world has radically changed during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) crisis, and this impact has quickly transformed many lives. Whether you’re on the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic or waiting in eager anticipation to return to practice, there is no denying that a few months ago we could never have imagined the health care and humanitarian crisis that is now before us. While we are united in our longing for a better time, we couldn’t be further apart socially and emotionally … and I’m not just talking about 6 feet.

One thing that has been truly striking to me is the silence. While experts have suggested there is a “silent pandemic” of mental illness on the horizon,1 I’ve been struck by the actual silence that exists as we walk through our stores and neighborhoods. We’re not speaking to each other anymore; it’s almost as if we’re afraid to make eye contact with one another.

Humans are social creatures, and the isolation that many people are experiencing during this pandemic could have detrimental and lasting effects if we don’t take action. While I highly encourage and support efforts to employ social distancing and mitigate the spread of this illness, I’m increasingly concerned about another kind of truly silent pandemic brewing beneath the surface of the COVID-19 crisis. Even under the best conditions, many individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and other psychiatric disorders may lack adequate social interaction and experience feelings of isolation. These individuals need connection—not silence.

What happens to people who already felt intense isolation before COVID-19 and may have had invaluable lifelines cut off during this time of social distancing? What about individuals with alcohol or substance use disorders, or families who are sheltered in place in unsafe or violent home conditions? How can they reach out in silence? How can we help?

Fostering human connection

To address this, we must actively work to engage our patients and communities. One simple way to help is to acknowledge the people you encounter. Yes, stay 6 feet apart, and wear appropriate personal protective equipment. However, it is still OK to smile and greet someone with a nod, a smile, or a “hello.” A genuine smile can still be seen in someone’s eyes. We need these types of human connection, perhaps now more than ever before. We need each other.

Most importantly, during this time, we need to be aware of individuals who are most at risk in this silent pandemic. We can offer our patients appointments via video conferencing. We can use texting, e-mail, social media, phone calls, and video conferencing to check in with our families, friends, and neighbors. We’re at war with a terrible foe, but let’s not let the human connection become collateral damage.

1. Galea S, Merchant RM, Lurie N, et al. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: the need for prevention and early intervention [published online April 10, 2020]. JAMA Intern Med. 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562.

Our world has radically changed during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) crisis, and this impact has quickly transformed many lives. Whether you’re on the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic or waiting in eager anticipation to return to practice, there is no denying that a few months ago we could never have imagined the health care and humanitarian crisis that is now before us. While we are united in our longing for a better time, we couldn’t be further apart socially and emotionally … and I’m not just talking about 6 feet.

One thing that has been truly striking to me is the silence. While experts have suggested there is a “silent pandemic” of mental illness on the horizon,1 I’ve been struck by the actual silence that exists as we walk through our stores and neighborhoods. We’re not speaking to each other anymore; it’s almost as if we’re afraid to make eye contact with one another.

Humans are social creatures, and the isolation that many people are experiencing during this pandemic could have detrimental and lasting effects if we don’t take action. While I highly encourage and support efforts to employ social distancing and mitigate the spread of this illness, I’m increasingly concerned about another kind of truly silent pandemic brewing beneath the surface of the COVID-19 crisis. Even under the best conditions, many individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and other psychiatric disorders may lack adequate social interaction and experience feelings of isolation. These individuals need connection—not silence.

What happens to people who already felt intense isolation before COVID-19 and may have had invaluable lifelines cut off during this time of social distancing? What about individuals with alcohol or substance use disorders, or families who are sheltered in place in unsafe or violent home conditions? How can they reach out in silence? How can we help?

Fostering human connection

To address this, we must actively work to engage our patients and communities. One simple way to help is to acknowledge the people you encounter. Yes, stay 6 feet apart, and wear appropriate personal protective equipment. However, it is still OK to smile and greet someone with a nod, a smile, or a “hello.” A genuine smile can still be seen in someone’s eyes. We need these types of human connection, perhaps now more than ever before. We need each other.