User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

Training more doctors should be our first priority, says ethicist

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Recently, the Supreme Court of the United States struck down the use of affirmative action in admissions to colleges, universities, medical schools, and nursing schools. This has led to an enormous amount of worry and concern, particularly in medical school admissions in the world I’m in, where people start to say that diversity matters. Diversity is important.

I know many deans of medical schools immediately sent out messages of reassurance to their students, saying New York University or Stanford or Harvard or Minnesota or Case Western is still deeply concerned about diversity, and we’re going to do what we can to preserve attention to diversity.

I’ve served on admissions at a number of schools over the years for med school. I understand – and have been told – that diversity is important, and according to the Supreme Court, not explicitly by race. There are obviously many variables to take into account when trying to keep diversity at the forefront of admissions.

At the schools I’ve been at, including Columbia, NYU, University of Pittsburgh, University of Minnesota, and University of Pennsylvania, there are plenty of qualified students. Happily, we’ve always been engaged in some effort to try and whittle down the class to the size that we can manage and accept, and many qualified students don’t get admitted.

The first order of business for me is not to worry about how to maintain diversity. It’s to recognize that we need more doctors, nurses, and mental health care providers. I will, in a second, say a few words about diversity and where it fits into admissions, but I want to make the point clearly that what we should be doing is trying to expand the pool of students who are going to become doctors, nurses, mental health care providers, and social workers.

There are too many early retirements. We don’t have the person power we need to manage the health care challenges of an aging population. Let’s not get lost in arguing about what characteristics ought to get you into the finest medical schools. Let’s realize that we have to expand the number of schools we have.

We better be working pretty hard to expand our physician assistant programs, to make sure that we give full authority to qualified dentists and nurses who can help deliver some clinical care. We need more folks. That’s really where the battle ought to be: How do we get that done and how do we get it done quickly, not arguing about who’s in, who’s out, and why.

That said, diversity to me has never meant just race. I’m always interested in gender orientation, disability, and geographic input. Sometimes in decisions that you’re looking at, when I have students in front of me, they tell me they play a musical instrument or about the obstacles they had to overcome to get to medical school. Some of them will say they were involved in 4-H and did rodeo in high school or junior high school, which makes them a diverse potential student with characteristics that maybe some others don’t bring.

I’m not against diversity. I think having a rich set of experiences in any class – medicine, nursing, whatever it’s going to be – is beneficial to the students. They learn from each other. It is sometimes said that it’s also good for patients. I’m a little less excited about that, because I think our training goal should be to make every medical student and nursing student qualified to treat anybody.

I don’t think that, just because you’re Latinx or gay, that’s going to make a gay patient feel better. I think we should teach our students how to give care to everybody that they encounter. They shouldn’t have to match up characteristics to feel like they’re going to get quality care. That isn’t the right reason.

When you have a diverse set of providers, they can call that out and be on the alert for it, and that’s very important.

I also believe that we should think widely and broadly about diversity. Maybe race is out, but certainly other experiences related to income, background, struggle that got you to the point where you’re applying to medical school, motivation, the kinds of experiences you might have had caring for an elderly person, dealing with a disability or learning disability, and trying to overcome, let’s say, going to school in a poor area with not such a wonderful school, really help in terms of forming professionalism, empathy, and a caring point of view.

To me, the main goal is to expand our workforce. The secondary goal is to stay diverse, because we get better providers when we do so.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Recently, the Supreme Court of the United States struck down the use of affirmative action in admissions to colleges, universities, medical schools, and nursing schools. This has led to an enormous amount of worry and concern, particularly in medical school admissions in the world I’m in, where people start to say that diversity matters. Diversity is important.

I know many deans of medical schools immediately sent out messages of reassurance to their students, saying New York University or Stanford or Harvard or Minnesota or Case Western is still deeply concerned about diversity, and we’re going to do what we can to preserve attention to diversity.

I’ve served on admissions at a number of schools over the years for med school. I understand – and have been told – that diversity is important, and according to the Supreme Court, not explicitly by race. There are obviously many variables to take into account when trying to keep diversity at the forefront of admissions.

At the schools I’ve been at, including Columbia, NYU, University of Pittsburgh, University of Minnesota, and University of Pennsylvania, there are plenty of qualified students. Happily, we’ve always been engaged in some effort to try and whittle down the class to the size that we can manage and accept, and many qualified students don’t get admitted.

The first order of business for me is not to worry about how to maintain diversity. It’s to recognize that we need more doctors, nurses, and mental health care providers. I will, in a second, say a few words about diversity and where it fits into admissions, but I want to make the point clearly that what we should be doing is trying to expand the pool of students who are going to become doctors, nurses, mental health care providers, and social workers.

There are too many early retirements. We don’t have the person power we need to manage the health care challenges of an aging population. Let’s not get lost in arguing about what characteristics ought to get you into the finest medical schools. Let’s realize that we have to expand the number of schools we have.

We better be working pretty hard to expand our physician assistant programs, to make sure that we give full authority to qualified dentists and nurses who can help deliver some clinical care. We need more folks. That’s really where the battle ought to be: How do we get that done and how do we get it done quickly, not arguing about who’s in, who’s out, and why.

That said, diversity to me has never meant just race. I’m always interested in gender orientation, disability, and geographic input. Sometimes in decisions that you’re looking at, when I have students in front of me, they tell me they play a musical instrument or about the obstacles they had to overcome to get to medical school. Some of them will say they were involved in 4-H and did rodeo in high school or junior high school, which makes them a diverse potential student with characteristics that maybe some others don’t bring.

I’m not against diversity. I think having a rich set of experiences in any class – medicine, nursing, whatever it’s going to be – is beneficial to the students. They learn from each other. It is sometimes said that it’s also good for patients. I’m a little less excited about that, because I think our training goal should be to make every medical student and nursing student qualified to treat anybody.

I don’t think that, just because you’re Latinx or gay, that’s going to make a gay patient feel better. I think we should teach our students how to give care to everybody that they encounter. They shouldn’t have to match up characteristics to feel like they’re going to get quality care. That isn’t the right reason.

When you have a diverse set of providers, they can call that out and be on the alert for it, and that’s very important.

I also believe that we should think widely and broadly about diversity. Maybe race is out, but certainly other experiences related to income, background, struggle that got you to the point where you’re applying to medical school, motivation, the kinds of experiences you might have had caring for an elderly person, dealing with a disability or learning disability, and trying to overcome, let’s say, going to school in a poor area with not such a wonderful school, really help in terms of forming professionalism, empathy, and a caring point of view.

To me, the main goal is to expand our workforce. The secondary goal is to stay diverse, because we get better providers when we do so.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Recently, the Supreme Court of the United States struck down the use of affirmative action in admissions to colleges, universities, medical schools, and nursing schools. This has led to an enormous amount of worry and concern, particularly in medical school admissions in the world I’m in, where people start to say that diversity matters. Diversity is important.

I know many deans of medical schools immediately sent out messages of reassurance to their students, saying New York University or Stanford or Harvard or Minnesota or Case Western is still deeply concerned about diversity, and we’re going to do what we can to preserve attention to diversity.

I’ve served on admissions at a number of schools over the years for med school. I understand – and have been told – that diversity is important, and according to the Supreme Court, not explicitly by race. There are obviously many variables to take into account when trying to keep diversity at the forefront of admissions.

At the schools I’ve been at, including Columbia, NYU, University of Pittsburgh, University of Minnesota, and University of Pennsylvania, there are plenty of qualified students. Happily, we’ve always been engaged in some effort to try and whittle down the class to the size that we can manage and accept, and many qualified students don’t get admitted.

The first order of business for me is not to worry about how to maintain diversity. It’s to recognize that we need more doctors, nurses, and mental health care providers. I will, in a second, say a few words about diversity and where it fits into admissions, but I want to make the point clearly that what we should be doing is trying to expand the pool of students who are going to become doctors, nurses, mental health care providers, and social workers.

There are too many early retirements. We don’t have the person power we need to manage the health care challenges of an aging population. Let’s not get lost in arguing about what characteristics ought to get you into the finest medical schools. Let’s realize that we have to expand the number of schools we have.

We better be working pretty hard to expand our physician assistant programs, to make sure that we give full authority to qualified dentists and nurses who can help deliver some clinical care. We need more folks. That’s really where the battle ought to be: How do we get that done and how do we get it done quickly, not arguing about who’s in, who’s out, and why.

That said, diversity to me has never meant just race. I’m always interested in gender orientation, disability, and geographic input. Sometimes in decisions that you’re looking at, when I have students in front of me, they tell me they play a musical instrument or about the obstacles they had to overcome to get to medical school. Some of them will say they were involved in 4-H and did rodeo in high school or junior high school, which makes them a diverse potential student with characteristics that maybe some others don’t bring.

I’m not against diversity. I think having a rich set of experiences in any class – medicine, nursing, whatever it’s going to be – is beneficial to the students. They learn from each other. It is sometimes said that it’s also good for patients. I’m a little less excited about that, because I think our training goal should be to make every medical student and nursing student qualified to treat anybody.

I don’t think that, just because you’re Latinx or gay, that’s going to make a gay patient feel better. I think we should teach our students how to give care to everybody that they encounter. They shouldn’t have to match up characteristics to feel like they’re going to get quality care. That isn’t the right reason.

When you have a diverse set of providers, they can call that out and be on the alert for it, and that’s very important.

I also believe that we should think widely and broadly about diversity. Maybe race is out, but certainly other experiences related to income, background, struggle that got you to the point where you’re applying to medical school, motivation, the kinds of experiences you might have had caring for an elderly person, dealing with a disability or learning disability, and trying to overcome, let’s say, going to school in a poor area with not such a wonderful school, really help in terms of forming professionalism, empathy, and a caring point of view.

To me, the main goal is to expand our workforce. The secondary goal is to stay diverse, because we get better providers when we do so.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Loneliness tied to increased risk for Parkinson’s disease

TOPLINE:

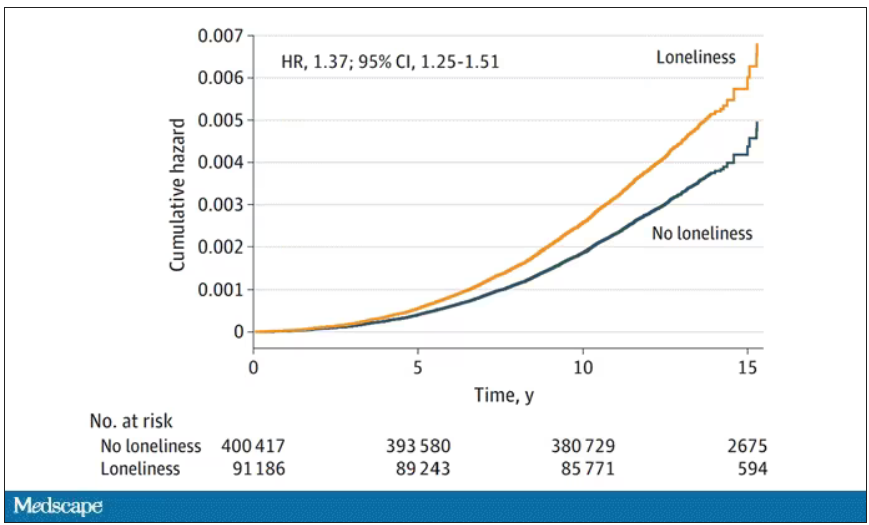

Loneliness is associated with a higher risk of developing Parkinson’s disease (PD) across demographic groups and independent of other risk factors, data from nearly 500,000 U.K. adults suggest.

METHODOLOGY:

- Loneliness is associated with illness and death, including higher risk of neurodegenerative diseases, but no study has examined whether the association between loneliness and detrimental outcomes extends to PD.

- The current analysis included 491,603 U.K. Biobank participants (mean age, 56; 54% women) without a diagnosis of PD at baseline.

- Loneliness was assessed by a single question at baseline and incident PD was ascertained via health records over 15 years.

- Researchers assessed whether the association between loneliness and PD was moderated by age, sex, or genetic risk and whether the association was accounted for by sociodemographic factors; behavioral, mental, physical, or social factors; or genetic risk.

TAKEAWAY:

- Roughly 19% of the cohort reported being lonely. Compared with those who were not lonely, those who did report being lonely were slightly younger and were more likely to be women. They also had fewer resources, more health risk behaviors (current smoker and physically inactive), and worse physical and mental health.

- Over 15+ years of follow-up, 2,822 participants developed PD (incidence rate: 47 per 100,000 person-years). Compared with those who did not develop PD, those who did were older and more likely to be male, former smokers, have higher BMI and PD polygenetic risk score, and to have diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction or stroke, anxiety, or depression.

- In the primary analysis, individuals who reported being lonely had a higher risk for PD (hazard ratio, 1.37) – an association that remained after accounting for demographic and socioeconomic status, social isolation, PD polygenetic risk score, smoking, physical activity, BMI, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction, depression, and having ever seen a psychiatrist (fully adjusted HR, 1.25).

- The association between loneliness and incident PD was not moderated by sex, age, or polygenetic risk score.

- Contrary to expectations for a prodromal syndrome, loneliness was not associated with incident PD in the first 5 years after baseline but was associated with PD risk in the subsequent 10 years of follow-up (HR, 1.32).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings complement other evidence that loneliness is a psychosocial determinant of health associated with increased risk of morbidity and mortality [and] supports recent calls for the protective and healing effects of personally meaningful social connection,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Antonio Terracciano, PhD, of Florida State University College of Medicine, Tallahassee, was published online in JAMA Neurology.

LIMITATIONS:

This observational study could not determine causality or whether reverse causality could explain the association. Loneliness was assessed by a single yes/no question. PD diagnosis relied on hospital admission and death records and may have missed early PD diagnoses.

DISCLOSURES:

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institutes of Health and National Institute on Aging. The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

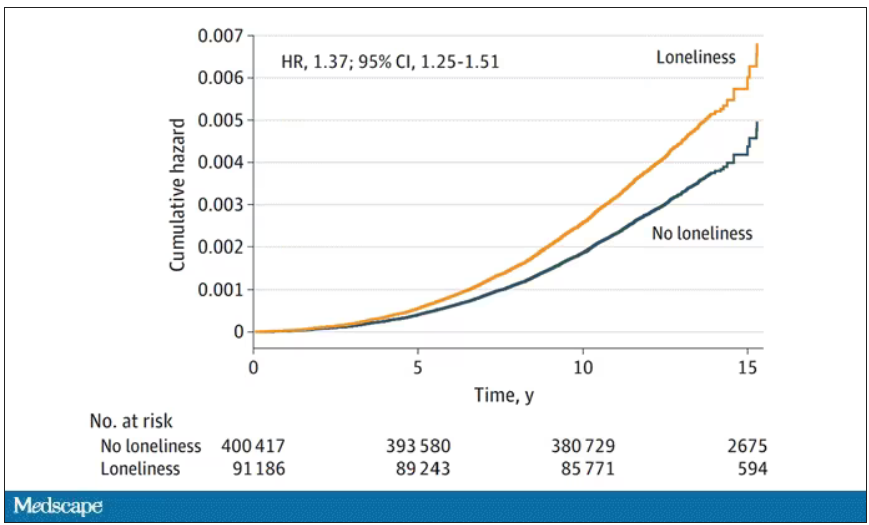

Loneliness is associated with a higher risk of developing Parkinson’s disease (PD) across demographic groups and independent of other risk factors, data from nearly 500,000 U.K. adults suggest.

METHODOLOGY:

- Loneliness is associated with illness and death, including higher risk of neurodegenerative diseases, but no study has examined whether the association between loneliness and detrimental outcomes extends to PD.

- The current analysis included 491,603 U.K. Biobank participants (mean age, 56; 54% women) without a diagnosis of PD at baseline.

- Loneliness was assessed by a single question at baseline and incident PD was ascertained via health records over 15 years.

- Researchers assessed whether the association between loneliness and PD was moderated by age, sex, or genetic risk and whether the association was accounted for by sociodemographic factors; behavioral, mental, physical, or social factors; or genetic risk.

TAKEAWAY:

- Roughly 19% of the cohort reported being lonely. Compared with those who were not lonely, those who did report being lonely were slightly younger and were more likely to be women. They also had fewer resources, more health risk behaviors (current smoker and physically inactive), and worse physical and mental health.

- Over 15+ years of follow-up, 2,822 participants developed PD (incidence rate: 47 per 100,000 person-years). Compared with those who did not develop PD, those who did were older and more likely to be male, former smokers, have higher BMI and PD polygenetic risk score, and to have diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction or stroke, anxiety, or depression.

- In the primary analysis, individuals who reported being lonely had a higher risk for PD (hazard ratio, 1.37) – an association that remained after accounting for demographic and socioeconomic status, social isolation, PD polygenetic risk score, smoking, physical activity, BMI, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction, depression, and having ever seen a psychiatrist (fully adjusted HR, 1.25).

- The association between loneliness and incident PD was not moderated by sex, age, or polygenetic risk score.

- Contrary to expectations for a prodromal syndrome, loneliness was not associated with incident PD in the first 5 years after baseline but was associated with PD risk in the subsequent 10 years of follow-up (HR, 1.32).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings complement other evidence that loneliness is a psychosocial determinant of health associated with increased risk of morbidity and mortality [and] supports recent calls for the protective and healing effects of personally meaningful social connection,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Antonio Terracciano, PhD, of Florida State University College of Medicine, Tallahassee, was published online in JAMA Neurology.

LIMITATIONS:

This observational study could not determine causality or whether reverse causality could explain the association. Loneliness was assessed by a single yes/no question. PD diagnosis relied on hospital admission and death records and may have missed early PD diagnoses.

DISCLOSURES:

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institutes of Health and National Institute on Aging. The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

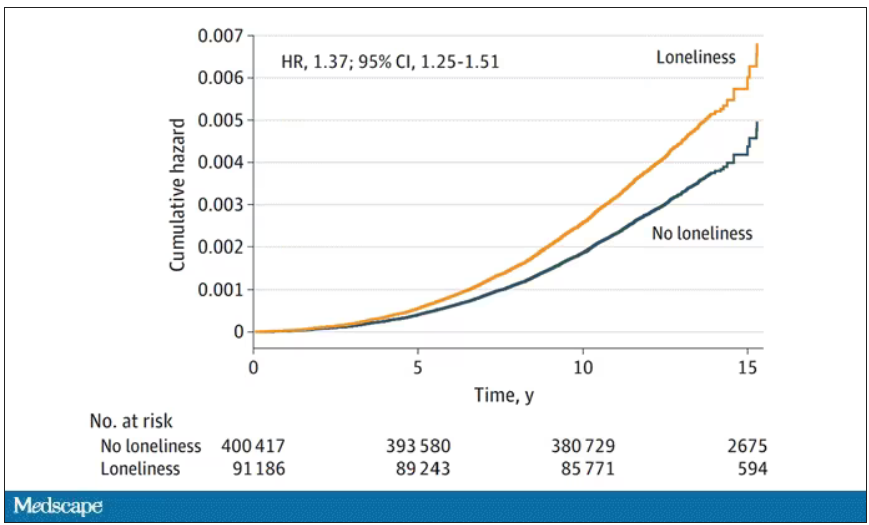

Loneliness is associated with a higher risk of developing Parkinson’s disease (PD) across demographic groups and independent of other risk factors, data from nearly 500,000 U.K. adults suggest.

METHODOLOGY:

- Loneliness is associated with illness and death, including higher risk of neurodegenerative diseases, but no study has examined whether the association between loneliness and detrimental outcomes extends to PD.

- The current analysis included 491,603 U.K. Biobank participants (mean age, 56; 54% women) without a diagnosis of PD at baseline.

- Loneliness was assessed by a single question at baseline and incident PD was ascertained via health records over 15 years.

- Researchers assessed whether the association between loneliness and PD was moderated by age, sex, or genetic risk and whether the association was accounted for by sociodemographic factors; behavioral, mental, physical, or social factors; or genetic risk.

TAKEAWAY:

- Roughly 19% of the cohort reported being lonely. Compared with those who were not lonely, those who did report being lonely were slightly younger and were more likely to be women. They also had fewer resources, more health risk behaviors (current smoker and physically inactive), and worse physical and mental health.

- Over 15+ years of follow-up, 2,822 participants developed PD (incidence rate: 47 per 100,000 person-years). Compared with those who did not develop PD, those who did were older and more likely to be male, former smokers, have higher BMI and PD polygenetic risk score, and to have diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction or stroke, anxiety, or depression.

- In the primary analysis, individuals who reported being lonely had a higher risk for PD (hazard ratio, 1.37) – an association that remained after accounting for demographic and socioeconomic status, social isolation, PD polygenetic risk score, smoking, physical activity, BMI, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction, depression, and having ever seen a psychiatrist (fully adjusted HR, 1.25).

- The association between loneliness and incident PD was not moderated by sex, age, or polygenetic risk score.

- Contrary to expectations for a prodromal syndrome, loneliness was not associated with incident PD in the first 5 years after baseline but was associated with PD risk in the subsequent 10 years of follow-up (HR, 1.32).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings complement other evidence that loneliness is a psychosocial determinant of health associated with increased risk of morbidity and mortality [and] supports recent calls for the protective and healing effects of personally meaningful social connection,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Antonio Terracciano, PhD, of Florida State University College of Medicine, Tallahassee, was published online in JAMA Neurology.

LIMITATIONS:

This observational study could not determine causality or whether reverse causality could explain the association. Loneliness was assessed by a single yes/no question. PD diagnosis relied on hospital admission and death records and may have missed early PD diagnoses.

DISCLOSURES:

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institutes of Health and National Institute on Aging. The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The surprising link between loneliness and Parkinson’s disease

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

On May 3, 2023, Surgeon General Vivek Murthy issued an advisory raising an alarm about what he called an “epidemic of loneliness” in the United States.

Now, I am not saying that Vivek Murthy read my book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t” – released in January and available in bookstores now – where, in chapter 11, I call attention to the problem of loneliness and its relationship to the exponential rise in deaths of despair. But Vivek, if you did, let me know. I could use the publicity.

No, of course the idea that loneliness is a public health issue is not new, but I’m glad to see it finally getting attention. At this point, studies have linked loneliness to heart disease, stroke, dementia, and premature death.

The UK Biobank is really a treasure trove of data for epidemiologists. I must see three to four studies a week coming out of this mega-dataset. This one, appearing in JAMA Neurology, caught my eye for its focus specifically on loneliness as a risk factor – something I’m hoping to see more of in the future.

The study examines data from just under 500,000 individuals in the United Kingdom who answered a survey including the question “Do you often feel lonely?” between 2006 and 2010; 18.4% of people answered yes. Individuals’ electronic health record data were then monitored over time to see who would get a new diagnosis code consistent with Parkinson’s disease. Through 2021, 2822 people did – that’s just over half a percent.

So, now we do the statistics thing. Of the nonlonely folks, 2,273 went on to develop Parkinson’s disease. Of those who said they often feel lonely, 549 people did. The raw numbers here, to be honest, aren’t that compelling. Lonely people had an absolute risk for Parkinson’s disease about 0.03% higher than that of nonlonely people. Put another way, you’d need to take over 3,000 lonely souls and make them not lonely to prevent 1 case of Parkinson’s disease.

Still, the costs of loneliness are not measured exclusively in Parkinson’s disease, and I would argue that the real risks here come from other sources: alcohol abuse, drug abuse, and suicide. Nevertheless, the weak but significant association with Parkinson’s disease reminds us that loneliness is a neurologic phenomenon. There is something about social connection that affects our brain in a way that is not just spiritual; it is actually biological.

Of course, people who say they are often lonely are different in other ways from people who report not being lonely. Lonely people, in this dataset, were younger, more likely to be female, less likely to have a college degree, in worse physical health, and engaged in more high-risk health behaviors like smoking.

The authors adjusted for all of these factors and found that, on the relative scale, lonely people were still about 20%-30% more likely to develop Parkinson’s disease.

So, what do we do about this? There is no pill for loneliness, and God help us if there ever is. Recognizing the problem is a good start. But there are some policy things we can do to reduce loneliness. We can invest in public spaces that bring people together – parks, museums, libraries – and public transportation. We can deal with tech companies that are so optimized at capturing our attention that we cease to engage with other humans. And, individually, we can just reach out a bit more. We’ve spent the past few pandemic years with our attention focused sharply inward. It’s time to look out again.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

On May 3, 2023, Surgeon General Vivek Murthy issued an advisory raising an alarm about what he called an “epidemic of loneliness” in the United States.

Now, I am not saying that Vivek Murthy read my book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t” – released in January and available in bookstores now – where, in chapter 11, I call attention to the problem of loneliness and its relationship to the exponential rise in deaths of despair. But Vivek, if you did, let me know. I could use the publicity.

No, of course the idea that loneliness is a public health issue is not new, but I’m glad to see it finally getting attention. At this point, studies have linked loneliness to heart disease, stroke, dementia, and premature death.

The UK Biobank is really a treasure trove of data for epidemiologists. I must see three to four studies a week coming out of this mega-dataset. This one, appearing in JAMA Neurology, caught my eye for its focus specifically on loneliness as a risk factor – something I’m hoping to see more of in the future.

The study examines data from just under 500,000 individuals in the United Kingdom who answered a survey including the question “Do you often feel lonely?” between 2006 and 2010; 18.4% of people answered yes. Individuals’ electronic health record data were then monitored over time to see who would get a new diagnosis code consistent with Parkinson’s disease. Through 2021, 2822 people did – that’s just over half a percent.

So, now we do the statistics thing. Of the nonlonely folks, 2,273 went on to develop Parkinson’s disease. Of those who said they often feel lonely, 549 people did. The raw numbers here, to be honest, aren’t that compelling. Lonely people had an absolute risk for Parkinson’s disease about 0.03% higher than that of nonlonely people. Put another way, you’d need to take over 3,000 lonely souls and make them not lonely to prevent 1 case of Parkinson’s disease.

Still, the costs of loneliness are not measured exclusively in Parkinson’s disease, and I would argue that the real risks here come from other sources: alcohol abuse, drug abuse, and suicide. Nevertheless, the weak but significant association with Parkinson’s disease reminds us that loneliness is a neurologic phenomenon. There is something about social connection that affects our brain in a way that is not just spiritual; it is actually biological.

Of course, people who say they are often lonely are different in other ways from people who report not being lonely. Lonely people, in this dataset, were younger, more likely to be female, less likely to have a college degree, in worse physical health, and engaged in more high-risk health behaviors like smoking.

The authors adjusted for all of these factors and found that, on the relative scale, lonely people were still about 20%-30% more likely to develop Parkinson’s disease.

So, what do we do about this? There is no pill for loneliness, and God help us if there ever is. Recognizing the problem is a good start. But there are some policy things we can do to reduce loneliness. We can invest in public spaces that bring people together – parks, museums, libraries – and public transportation. We can deal with tech companies that are so optimized at capturing our attention that we cease to engage with other humans. And, individually, we can just reach out a bit more. We’ve spent the past few pandemic years with our attention focused sharply inward. It’s time to look out again.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

On May 3, 2023, Surgeon General Vivek Murthy issued an advisory raising an alarm about what he called an “epidemic of loneliness” in the United States.

Now, I am not saying that Vivek Murthy read my book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t” – released in January and available in bookstores now – where, in chapter 11, I call attention to the problem of loneliness and its relationship to the exponential rise in deaths of despair. But Vivek, if you did, let me know. I could use the publicity.

No, of course the idea that loneliness is a public health issue is not new, but I’m glad to see it finally getting attention. At this point, studies have linked loneliness to heart disease, stroke, dementia, and premature death.

The UK Biobank is really a treasure trove of data for epidemiologists. I must see three to four studies a week coming out of this mega-dataset. This one, appearing in JAMA Neurology, caught my eye for its focus specifically on loneliness as a risk factor – something I’m hoping to see more of in the future.

The study examines data from just under 500,000 individuals in the United Kingdom who answered a survey including the question “Do you often feel lonely?” between 2006 and 2010; 18.4% of people answered yes. Individuals’ electronic health record data were then monitored over time to see who would get a new diagnosis code consistent with Parkinson’s disease. Through 2021, 2822 people did – that’s just over half a percent.

So, now we do the statistics thing. Of the nonlonely folks, 2,273 went on to develop Parkinson’s disease. Of those who said they often feel lonely, 549 people did. The raw numbers here, to be honest, aren’t that compelling. Lonely people had an absolute risk for Parkinson’s disease about 0.03% higher than that of nonlonely people. Put another way, you’d need to take over 3,000 lonely souls and make them not lonely to prevent 1 case of Parkinson’s disease.

Still, the costs of loneliness are not measured exclusively in Parkinson’s disease, and I would argue that the real risks here come from other sources: alcohol abuse, drug abuse, and suicide. Nevertheless, the weak but significant association with Parkinson’s disease reminds us that loneliness is a neurologic phenomenon. There is something about social connection that affects our brain in a way that is not just spiritual; it is actually biological.

Of course, people who say they are often lonely are different in other ways from people who report not being lonely. Lonely people, in this dataset, were younger, more likely to be female, less likely to have a college degree, in worse physical health, and engaged in more high-risk health behaviors like smoking.

The authors adjusted for all of these factors and found that, on the relative scale, lonely people were still about 20%-30% more likely to develop Parkinson’s disease.

So, what do we do about this? There is no pill for loneliness, and God help us if there ever is. Recognizing the problem is a good start. But there are some policy things we can do to reduce loneliness. We can invest in public spaces that bring people together – parks, museums, libraries – and public transportation. We can deal with tech companies that are so optimized at capturing our attention that we cease to engage with other humans. And, individually, we can just reach out a bit more. We’ve spent the past few pandemic years with our attention focused sharply inward. It’s time to look out again.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

From scrubs to screens: Growing your patient base with social media

With physicians under increasing pressure to see more patients in shorter office visits, developing a social media presence may offer valuable opportunities to connect with patients, explain procedures, combat misinformation, talk through a published article, and even share a joke or meme.

But there are caveats for doctors posting on social media platforms. This news organization spoke to four doctors who successfully use social media.

Use social media for the right reasons

While you’re under no obligation to build a social media presence, if you’re going to do it, be sure your intentions are solid, said Don S. Dizon, MD, professor of medicine and professor of surgery at Brown University, Providence, R.I. Dr. Dizon, as @DoctorDon, has 44,700 TikTok followers and uses the platform to answer cancer-related questions.

“It should be your altruism that motivates you to post,” said Dr. Dizon, who is also associate director of community outreach and engagement at the Legorreta Cancer Center in Providence, R.I., and director of medical oncology at Rhode Island Hospital. “What we can do for society at large is to provide our input into issues, add informed opinions where there’s controversy, and address misinformation.”

If you don’t know where to start, consider seeking a digital mentor to talk through your options.

“You may never meet this person, but you should choose them if you like their style, their content, their delivery, and their perspective,” Dr. Dizon said. “Find another doctor out there on social media whom you feel you can emulate. Take your time, too. Soon enough, you’ll develop your own style and your own online persona.”

Post clear, accurate information

If you want to be lighthearted on social media, that’s your choice. But Jennifer Trachtenberg, a pediatrician with nearly 7,000 Instagram followers in New York who posts as @askdrjen, prefers to offer vaccine scheduling tips, alert parents about COVID-19 rates, and offer advice on cold and flu prevention.

“Right now, I’m mainly doing this to educate patients and make them aware of topics that I think are important and that I see my patients needing more information on,” she said. “We have to be clear: People take what we say seriously. So, while it’s important to be relatable, it’s even more important to share evidence-based information.”

Many patients get their information on social media

While patients once came to the doctor armed with information sourced via “Doctor Google,” today, just as many patients use social media to learn about their condition or the medications they’re taking.

Unfortunately, a recent Ohio State University, Columbus, study found that the majority of gynecologic cancer advice on TikTok, for example, was either misleading or inaccurate.

“This misinformation should be a motivator for physicians to explore the social media space,” Dr. Dizon said. “Our voices need to be on there.”

Break down barriers – and make connections

Mike Natter, MD, an endocrinologist in New York, has type 1 diabetes. This informs his work – and his life – and he’s passionate about sharing it with his 117,000 followers as @mike.natter on Instagram.

“A lot of type 1s follow me, so there’s an advocacy component to what I do,” he said. “I enjoy being able to raise awareness and keep people up to date on the newest research and treatment.”

But that’s not all: Dr. Natter is also an artist who went to art school before he went to medical school, and his account is rife with his cartoons and illustrations about everything from valvular disease to diabetic ketoacidosis.

“I found that I was drawing a lot of my notes in medical school,” he said. “When I drew my notes, I did quite well, and I think that using art and illustration is a great tool. It breaks down barriers and makes health information all the more accessible to everyone.”

Share your expertise as a doctor – and a person

As a mom and pediatrician, Krupa Playforth, MD, who practices in Vienna, Va., knows that what she posts carries weight. So, whether she’s writing about backpack safety tips, choking hazards, or separation anxiety, her followers can rest assured that she’s posting responsibly.

“Pediatricians often underestimate how smart parents are,” said Dr. Playforth, who has three kids, ages 8, 5, and 2, and has 137,000 followers on @thepediatricianmom, her Instagram account. “Their anxiety comes from an understandable place, which is why I see my role as that of a parent and pediatrician who can translate the knowledge pediatricians have into something parents can understand.”

Dr. Playforth, who jumped on social media during COVID-19 and experienced a positive response in her local community, said being on social media is imperative if you’re a pediatrician.

“This is the future of pediatric medicine in particular,” she said. “A lot of pediatricians don’t want to embrace social media, but I think that’s a mistake. After all, while parents think pediatricians have all the answers, when we think of our own children, most doctors are like other parents – we can’t think objectively about our kids. It’s helpful for me to share that and to help parents feel less alone.”

If you’re not yet using social media to the best of your physician abilities, you might take a shot at becoming widely recognizable. Pick a preferred platform, answer common patient questions, dispel medical myths, provide pertinent information, and let your personality shine.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With physicians under increasing pressure to see more patients in shorter office visits, developing a social media presence may offer valuable opportunities to connect with patients, explain procedures, combat misinformation, talk through a published article, and even share a joke or meme.

But there are caveats for doctors posting on social media platforms. This news organization spoke to four doctors who successfully use social media.

Use social media for the right reasons

While you’re under no obligation to build a social media presence, if you’re going to do it, be sure your intentions are solid, said Don S. Dizon, MD, professor of medicine and professor of surgery at Brown University, Providence, R.I. Dr. Dizon, as @DoctorDon, has 44,700 TikTok followers and uses the platform to answer cancer-related questions.

“It should be your altruism that motivates you to post,” said Dr. Dizon, who is also associate director of community outreach and engagement at the Legorreta Cancer Center in Providence, R.I., and director of medical oncology at Rhode Island Hospital. “What we can do for society at large is to provide our input into issues, add informed opinions where there’s controversy, and address misinformation.”

If you don’t know where to start, consider seeking a digital mentor to talk through your options.

“You may never meet this person, but you should choose them if you like their style, their content, their delivery, and their perspective,” Dr. Dizon said. “Find another doctor out there on social media whom you feel you can emulate. Take your time, too. Soon enough, you’ll develop your own style and your own online persona.”

Post clear, accurate information

If you want to be lighthearted on social media, that’s your choice. But Jennifer Trachtenberg, a pediatrician with nearly 7,000 Instagram followers in New York who posts as @askdrjen, prefers to offer vaccine scheduling tips, alert parents about COVID-19 rates, and offer advice on cold and flu prevention.

“Right now, I’m mainly doing this to educate patients and make them aware of topics that I think are important and that I see my patients needing more information on,” she said. “We have to be clear: People take what we say seriously. So, while it’s important to be relatable, it’s even more important to share evidence-based information.”

Many patients get their information on social media

While patients once came to the doctor armed with information sourced via “Doctor Google,” today, just as many patients use social media to learn about their condition or the medications they’re taking.

Unfortunately, a recent Ohio State University, Columbus, study found that the majority of gynecologic cancer advice on TikTok, for example, was either misleading or inaccurate.

“This misinformation should be a motivator for physicians to explore the social media space,” Dr. Dizon said. “Our voices need to be on there.”

Break down barriers – and make connections

Mike Natter, MD, an endocrinologist in New York, has type 1 diabetes. This informs his work – and his life – and he’s passionate about sharing it with his 117,000 followers as @mike.natter on Instagram.

“A lot of type 1s follow me, so there’s an advocacy component to what I do,” he said. “I enjoy being able to raise awareness and keep people up to date on the newest research and treatment.”

But that’s not all: Dr. Natter is also an artist who went to art school before he went to medical school, and his account is rife with his cartoons and illustrations about everything from valvular disease to diabetic ketoacidosis.

“I found that I was drawing a lot of my notes in medical school,” he said. “When I drew my notes, I did quite well, and I think that using art and illustration is a great tool. It breaks down barriers and makes health information all the more accessible to everyone.”

Share your expertise as a doctor – and a person

As a mom and pediatrician, Krupa Playforth, MD, who practices in Vienna, Va., knows that what she posts carries weight. So, whether she’s writing about backpack safety tips, choking hazards, or separation anxiety, her followers can rest assured that she’s posting responsibly.

“Pediatricians often underestimate how smart parents are,” said Dr. Playforth, who has three kids, ages 8, 5, and 2, and has 137,000 followers on @thepediatricianmom, her Instagram account. “Their anxiety comes from an understandable place, which is why I see my role as that of a parent and pediatrician who can translate the knowledge pediatricians have into something parents can understand.”

Dr. Playforth, who jumped on social media during COVID-19 and experienced a positive response in her local community, said being on social media is imperative if you’re a pediatrician.

“This is the future of pediatric medicine in particular,” she said. “A lot of pediatricians don’t want to embrace social media, but I think that’s a mistake. After all, while parents think pediatricians have all the answers, when we think of our own children, most doctors are like other parents – we can’t think objectively about our kids. It’s helpful for me to share that and to help parents feel less alone.”

If you’re not yet using social media to the best of your physician abilities, you might take a shot at becoming widely recognizable. Pick a preferred platform, answer common patient questions, dispel medical myths, provide pertinent information, and let your personality shine.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With physicians under increasing pressure to see more patients in shorter office visits, developing a social media presence may offer valuable opportunities to connect with patients, explain procedures, combat misinformation, talk through a published article, and even share a joke or meme.

But there are caveats for doctors posting on social media platforms. This news organization spoke to four doctors who successfully use social media.

Use social media for the right reasons

While you’re under no obligation to build a social media presence, if you’re going to do it, be sure your intentions are solid, said Don S. Dizon, MD, professor of medicine and professor of surgery at Brown University, Providence, R.I. Dr. Dizon, as @DoctorDon, has 44,700 TikTok followers and uses the platform to answer cancer-related questions.

“It should be your altruism that motivates you to post,” said Dr. Dizon, who is also associate director of community outreach and engagement at the Legorreta Cancer Center in Providence, R.I., and director of medical oncology at Rhode Island Hospital. “What we can do for society at large is to provide our input into issues, add informed opinions where there’s controversy, and address misinformation.”

If you don’t know where to start, consider seeking a digital mentor to talk through your options.

“You may never meet this person, but you should choose them if you like their style, their content, their delivery, and their perspective,” Dr. Dizon said. “Find another doctor out there on social media whom you feel you can emulate. Take your time, too. Soon enough, you’ll develop your own style and your own online persona.”

Post clear, accurate information

If you want to be lighthearted on social media, that’s your choice. But Jennifer Trachtenberg, a pediatrician with nearly 7,000 Instagram followers in New York who posts as @askdrjen, prefers to offer vaccine scheduling tips, alert parents about COVID-19 rates, and offer advice on cold and flu prevention.

“Right now, I’m mainly doing this to educate patients and make them aware of topics that I think are important and that I see my patients needing more information on,” she said. “We have to be clear: People take what we say seriously. So, while it’s important to be relatable, it’s even more important to share evidence-based information.”

Many patients get their information on social media

While patients once came to the doctor armed with information sourced via “Doctor Google,” today, just as many patients use social media to learn about their condition or the medications they’re taking.

Unfortunately, a recent Ohio State University, Columbus, study found that the majority of gynecologic cancer advice on TikTok, for example, was either misleading or inaccurate.

“This misinformation should be a motivator for physicians to explore the social media space,” Dr. Dizon said. “Our voices need to be on there.”

Break down barriers – and make connections

Mike Natter, MD, an endocrinologist in New York, has type 1 diabetes. This informs his work – and his life – and he’s passionate about sharing it with his 117,000 followers as @mike.natter on Instagram.

“A lot of type 1s follow me, so there’s an advocacy component to what I do,” he said. “I enjoy being able to raise awareness and keep people up to date on the newest research and treatment.”

But that’s not all: Dr. Natter is also an artist who went to art school before he went to medical school, and his account is rife with his cartoons and illustrations about everything from valvular disease to diabetic ketoacidosis.

“I found that I was drawing a lot of my notes in medical school,” he said. “When I drew my notes, I did quite well, and I think that using art and illustration is a great tool. It breaks down barriers and makes health information all the more accessible to everyone.”

Share your expertise as a doctor – and a person

As a mom and pediatrician, Krupa Playforth, MD, who practices in Vienna, Va., knows that what she posts carries weight. So, whether she’s writing about backpack safety tips, choking hazards, or separation anxiety, her followers can rest assured that she’s posting responsibly.

“Pediatricians often underestimate how smart parents are,” said Dr. Playforth, who has three kids, ages 8, 5, and 2, and has 137,000 followers on @thepediatricianmom, her Instagram account. “Their anxiety comes from an understandable place, which is why I see my role as that of a parent and pediatrician who can translate the knowledge pediatricians have into something parents can understand.”

Dr. Playforth, who jumped on social media during COVID-19 and experienced a positive response in her local community, said being on social media is imperative if you’re a pediatrician.

“This is the future of pediatric medicine in particular,” she said. “A lot of pediatricians don’t want to embrace social media, but I think that’s a mistake. After all, while parents think pediatricians have all the answers, when we think of our own children, most doctors are like other parents – we can’t think objectively about our kids. It’s helpful for me to share that and to help parents feel less alone.”

If you’re not yet using social media to the best of your physician abilities, you might take a shot at becoming widely recognizable. Pick a preferred platform, answer common patient questions, dispel medical myths, provide pertinent information, and let your personality shine.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CBT effectively treats sexual concerns in menopausal women

PHILADELPHIA – . Four CBT sessions specifically focused on sexual concerns resulted in decreased sexual distress and concern, reduced depressive and menopausal symptoms, and increased sexual desire and functioning, as well as improved body image and relationship satisfaction.

An estimated 68%-87% of perimenopausal and postmenopausal women report sexual concerns, Sheryl Green, PhD, CPsych, an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral neurosciences at McMaster University and a psychologist at St. Joseph’s Healthcare’s Women’s Health Concerns Clinic, both in Hamilton, Ont., told attendees at the meeting.

“Sexual concerns over the menopausal transition are not just physical, but they’re also psychological and emotional,” Dr. Green said. “Three common challenges include decreased sexual desire, a reduction in physical arousal and ability to achieve an orgasm, and sexual pain and discomfort during intercourse.”

The reasons for these concerns are multifactorial, she said. Decreased sexual desire can stem from stress, medical problems, their relationship with their partner, or other causes. A woman’s difficulty with reduced physical arousal or ability to have an orgasm can result from changes in hormone levels and vaginal changes, such as vaginal atrophy, which can also contribute to the sexual pain or discomfort reported by 17%-45% of postmenopausal women.

Two pharmacologic treatments exist for sexual concerns: oral flibanserin (Addyi) and injectable bremelanotide (Vyleesi). But many women may be unable or unwilling to take medication for their concerns. Previous research from Lori Brotto has found cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness interventions to effectively improve sexual functioning in women treated for gynecologic cancer and in women without a history of cancer.

“Sexual function needs to be understood from a bio-psychosocial model, looking at the biologic factors, the psychological factors, the sociocultural factors, and the interpersonal factors,” Sheryl Kingsberg, PhD, a professor of psychiatry and reproductive biology at Case Western Reserve University and a psychologist at University Hospitals in Cleveland, said in an interview.

“They can all overlap, and the clinician can ask a few pointed questions that help identify what the source of the problem is,” said Dr. Kingsberg, who was not involved in this study. She noted that the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health has an algorithm that can help in determining the source of the problems.

“Sometimes it’s going to be a biologic condition for which pharmacologic options are nice, but even if it is primarily pharmacologic, psychotherapy is always useful,” Dr. Kingsberg said. “Once the problem is there, even if it’s biologically based, then you have all the things in terms of the cognitive distortion, anxiety,” and other issues that a cognitive behavioral approach can help address. “And access is now much wider because of telehealth,” she added.

‘Psychology of menopause’

The study led by Dr. Green focused on peri- and postmenopausal women, with an average age of 50, who were experiencing primary sexual concerns based on a score of at least 26 on the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI). Among the 20 women recruited for the study, 6 had already been prescribed hormone therapy for sexual concerns.

All reported decreased sexual desire, 17 reported decreased sexual arousal, 14 had body image dissatisfaction related to sexual concerns, and 6 reported urogenital problems. Nine of the women were in full remission from major depressive disorder, one had post-traumatic stress syndrome, and one had subclinical generalized anxiety disorder.

After spending 4 weeks on a wait list as self-control group for the study, the 15 women who completed the trial underwent four individual CBT sessions focusing on sexual concerns. The first session focused on psychoeducation and thought monitoring, and the second focused on cognitive distortions, cognitive strategies, and unhelpful beliefs or expectations related to sexual concerns. The third session looked at the role of problematic behaviors and behavioral experiments, and the fourth focused on continuation of strategies, long-term goals, and maintaining gains.

The participants completed eight measures at baseline, after the 4 weeks on the wait list, and after the four CBT sessions to assess the following:

- Sexual satisfaction, distress, and desire, using the FSFI, the Female Sexual Distress Scale-Revised (FSDS-R), and the Female Sexual Desire Questionnaire (FSDQ).

- Menopause symptoms, using the Greene Climacteric Scale (GCS).

- Body image, using the Dresden Body Image Questionnaire (DBIQ).

- Relationship satisfaction, using the Couples Satisfaction Index (CSI).

- Depression, using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II).

- Anxiety, using the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A).

The women did not experience any significant changes while on the wait list except a slight decrease on the FSDQ concern subscale. Following the CBT sessions, however, the women experienced a significant decrease in sexual distress and concern as well as an increase in sexual dyadic desire and sexual functioning (P = .003 for FSFI, P = .002 for FSDS-R, and P = .003 for FSDQ).

Participants also experienced a decrease in depression (P < .0001) and menopausal symptoms (P = .001) and an increase in body-image satisfaction (P = .018) and relationship satisfaction (P = .0011) after the CBT sessions. The researchers assessed participants’ satisfaction with the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire after the CBT sessions and reported some of the qualitative findings.

“The treatment program was able to assist me with recognizing that some of my sexual concerns were normal, emotional as well as physical and hormonal, and provided me the ability to delve more deeply into the psychology of menopause and how to work through symptoms and concerns in more manageable pieces,” one participant wrote. Another found helpful the “homework exercises of recognizing a thought/feeling/emotion surrounding how I feel about myself/body and working through. More positive thought pattern/restructuring a response the most helpful.”

The main complaint about the program was that it was too short, with women wanting more sessions to help continue their progress.

Not an ‘either-or’ approach

Dr. Kingsberg said ISSWSH has a variety of sexual medicine practitioners, including providers who can provide CBT for sexual concerns, and the American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors and Therapists has a referral directory.

“Keeping in mind the bio-psychosocial model, sometimes psychotherapy is going to be a really effective treatment for sexual concerns,” Dr. Kingsberg said. “Sometimes the pharmacologic option is going to be a really effective treatment for some concerns, and sometimes the combination is going to have a really nice treatment effect. So it’s not a one-size-fits-all, and it doesn’t have to be an either-or.”

The sexual concerns of women still do not get adequately addressed in medical schools and residencies, Dr. Kingsberg said, which is distinctly different from how male sexual concerns are addressed in health care.

“Erectile dysfunction is kind of in the norm, and women are still a little hesitant to bring up their sexual concerns,” Dr. Kingsberg said. “They don’t know if it’s appropriate and they’re hoping that their clinician will ask.”

One way clinicians can do that is with a global question for all their patients: “Most of my patients have sexual questions or concerns; what concerns do you have?”

“They don’t have to go through a checklist of 10 things,” Dr. Kingsberg said. If the patient does not bring anything up, providers can then ask a single follow up question: “Do you have any concerns with desire, arousal, orgasm, or pain?” That question, Dr. Kingsberg said, covers the four main areas of concern.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institute of Health Research. Dr. Green reported no disclosures. Dr. Kingsberg has consulted for or served on the advisory board for Alloy, Astellas, Bayer, Dare Bioscience, Freya, Reunion Neuroscience, Materna Medical, Madorra, Palatin, Pfizer, ReJoy, Sprout, Strategic Science Technologies, and MsMedicine.

PHILADELPHIA – . Four CBT sessions specifically focused on sexual concerns resulted in decreased sexual distress and concern, reduced depressive and menopausal symptoms, and increased sexual desire and functioning, as well as improved body image and relationship satisfaction.

An estimated 68%-87% of perimenopausal and postmenopausal women report sexual concerns, Sheryl Green, PhD, CPsych, an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral neurosciences at McMaster University and a psychologist at St. Joseph’s Healthcare’s Women’s Health Concerns Clinic, both in Hamilton, Ont., told attendees at the meeting.

“Sexual concerns over the menopausal transition are not just physical, but they’re also psychological and emotional,” Dr. Green said. “Three common challenges include decreased sexual desire, a reduction in physical arousal and ability to achieve an orgasm, and sexual pain and discomfort during intercourse.”

The reasons for these concerns are multifactorial, she said. Decreased sexual desire can stem from stress, medical problems, their relationship with their partner, or other causes. A woman’s difficulty with reduced physical arousal or ability to have an orgasm can result from changes in hormone levels and vaginal changes, such as vaginal atrophy, which can also contribute to the sexual pain or discomfort reported by 17%-45% of postmenopausal women.

Two pharmacologic treatments exist for sexual concerns: oral flibanserin (Addyi) and injectable bremelanotide (Vyleesi). But many women may be unable or unwilling to take medication for their concerns. Previous research from Lori Brotto has found cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness interventions to effectively improve sexual functioning in women treated for gynecologic cancer and in women without a history of cancer.

“Sexual function needs to be understood from a bio-psychosocial model, looking at the biologic factors, the psychological factors, the sociocultural factors, and the interpersonal factors,” Sheryl Kingsberg, PhD, a professor of psychiatry and reproductive biology at Case Western Reserve University and a psychologist at University Hospitals in Cleveland, said in an interview.

“They can all overlap, and the clinician can ask a few pointed questions that help identify what the source of the problem is,” said Dr. Kingsberg, who was not involved in this study. She noted that the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health has an algorithm that can help in determining the source of the problems.

“Sometimes it’s going to be a biologic condition for which pharmacologic options are nice, but even if it is primarily pharmacologic, psychotherapy is always useful,” Dr. Kingsberg said. “Once the problem is there, even if it’s biologically based, then you have all the things in terms of the cognitive distortion, anxiety,” and other issues that a cognitive behavioral approach can help address. “And access is now much wider because of telehealth,” she added.

‘Psychology of menopause’

The study led by Dr. Green focused on peri- and postmenopausal women, with an average age of 50, who were experiencing primary sexual concerns based on a score of at least 26 on the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI). Among the 20 women recruited for the study, 6 had already been prescribed hormone therapy for sexual concerns.

All reported decreased sexual desire, 17 reported decreased sexual arousal, 14 had body image dissatisfaction related to sexual concerns, and 6 reported urogenital problems. Nine of the women were in full remission from major depressive disorder, one had post-traumatic stress syndrome, and one had subclinical generalized anxiety disorder.

After spending 4 weeks on a wait list as self-control group for the study, the 15 women who completed the trial underwent four individual CBT sessions focusing on sexual concerns. The first session focused on psychoeducation and thought monitoring, and the second focused on cognitive distortions, cognitive strategies, and unhelpful beliefs or expectations related to sexual concerns. The third session looked at the role of problematic behaviors and behavioral experiments, and the fourth focused on continuation of strategies, long-term goals, and maintaining gains.

The participants completed eight measures at baseline, after the 4 weeks on the wait list, and after the four CBT sessions to assess the following:

- Sexual satisfaction, distress, and desire, using the FSFI, the Female Sexual Distress Scale-Revised (FSDS-R), and the Female Sexual Desire Questionnaire (FSDQ).

- Menopause symptoms, using the Greene Climacteric Scale (GCS).

- Body image, using the Dresden Body Image Questionnaire (DBIQ).

- Relationship satisfaction, using the Couples Satisfaction Index (CSI).

- Depression, using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II).

- Anxiety, using the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A).

The women did not experience any significant changes while on the wait list except a slight decrease on the FSDQ concern subscale. Following the CBT sessions, however, the women experienced a significant decrease in sexual distress and concern as well as an increase in sexual dyadic desire and sexual functioning (P = .003 for FSFI, P = .002 for FSDS-R, and P = .003 for FSDQ).

Participants also experienced a decrease in depression (P < .0001) and menopausal symptoms (P = .001) and an increase in body-image satisfaction (P = .018) and relationship satisfaction (P = .0011) after the CBT sessions. The researchers assessed participants’ satisfaction with the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire after the CBT sessions and reported some of the qualitative findings.

“The treatment program was able to assist me with recognizing that some of my sexual concerns were normal, emotional as well as physical and hormonal, and provided me the ability to delve more deeply into the psychology of menopause and how to work through symptoms and concerns in more manageable pieces,” one participant wrote. Another found helpful the “homework exercises of recognizing a thought/feeling/emotion surrounding how I feel about myself/body and working through. More positive thought pattern/restructuring a response the most helpful.”

The main complaint about the program was that it was too short, with women wanting more sessions to help continue their progress.

Not an ‘either-or’ approach

Dr. Kingsberg said ISSWSH has a variety of sexual medicine practitioners, including providers who can provide CBT for sexual concerns, and the American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors and Therapists has a referral directory.

“Keeping in mind the bio-psychosocial model, sometimes psychotherapy is going to be a really effective treatment for sexual concerns,” Dr. Kingsberg said. “Sometimes the pharmacologic option is going to be a really effective treatment for some concerns, and sometimes the combination is going to have a really nice treatment effect. So it’s not a one-size-fits-all, and it doesn’t have to be an either-or.”

The sexual concerns of women still do not get adequately addressed in medical schools and residencies, Dr. Kingsberg said, which is distinctly different from how male sexual concerns are addressed in health care.

“Erectile dysfunction is kind of in the norm, and women are still a little hesitant to bring up their sexual concerns,” Dr. Kingsberg said. “They don’t know if it’s appropriate and they’re hoping that their clinician will ask.”

One way clinicians can do that is with a global question for all their patients: “Most of my patients have sexual questions or concerns; what concerns do you have?”

“They don’t have to go through a checklist of 10 things,” Dr. Kingsberg said. If the patient does not bring anything up, providers can then ask a single follow up question: “Do you have any concerns with desire, arousal, orgasm, or pain?” That question, Dr. Kingsberg said, covers the four main areas of concern.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institute of Health Research. Dr. Green reported no disclosures. Dr. Kingsberg has consulted for or served on the advisory board for Alloy, Astellas, Bayer, Dare Bioscience, Freya, Reunion Neuroscience, Materna Medical, Madorra, Palatin, Pfizer, ReJoy, Sprout, Strategic Science Technologies, and MsMedicine.

PHILADELPHIA – . Four CBT sessions specifically focused on sexual concerns resulted in decreased sexual distress and concern, reduced depressive and menopausal symptoms, and increased sexual desire and functioning, as well as improved body image and relationship satisfaction.

An estimated 68%-87% of perimenopausal and postmenopausal women report sexual concerns, Sheryl Green, PhD, CPsych, an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral neurosciences at McMaster University and a psychologist at St. Joseph’s Healthcare’s Women’s Health Concerns Clinic, both in Hamilton, Ont., told attendees at the meeting.

“Sexual concerns over the menopausal transition are not just physical, but they’re also psychological and emotional,” Dr. Green said. “Three common challenges include decreased sexual desire, a reduction in physical arousal and ability to achieve an orgasm, and sexual pain and discomfort during intercourse.”

The reasons for these concerns are multifactorial, she said. Decreased sexual desire can stem from stress, medical problems, their relationship with their partner, or other causes. A woman’s difficulty with reduced physical arousal or ability to have an orgasm can result from changes in hormone levels and vaginal changes, such as vaginal atrophy, which can also contribute to the sexual pain or discomfort reported by 17%-45% of postmenopausal women.

Two pharmacologic treatments exist for sexual concerns: oral flibanserin (Addyi) and injectable bremelanotide (Vyleesi). But many women may be unable or unwilling to take medication for their concerns. Previous research from Lori Brotto has found cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness interventions to effectively improve sexual functioning in women treated for gynecologic cancer and in women without a history of cancer.

“Sexual function needs to be understood from a bio-psychosocial model, looking at the biologic factors, the psychological factors, the sociocultural factors, and the interpersonal factors,” Sheryl Kingsberg, PhD, a professor of psychiatry and reproductive biology at Case Western Reserve University and a psychologist at University Hospitals in Cleveland, said in an interview.

“They can all overlap, and the clinician can ask a few pointed questions that help identify what the source of the problem is,” said Dr. Kingsberg, who was not involved in this study. She noted that the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health has an algorithm that can help in determining the source of the problems.

“Sometimes it’s going to be a biologic condition for which pharmacologic options are nice, but even if it is primarily pharmacologic, psychotherapy is always useful,” Dr. Kingsberg said. “Once the problem is there, even if it’s biologically based, then you have all the things in terms of the cognitive distortion, anxiety,” and other issues that a cognitive behavioral approach can help address. “And access is now much wider because of telehealth,” she added.

‘Psychology of menopause’

The study led by Dr. Green focused on peri- and postmenopausal women, with an average age of 50, who were experiencing primary sexual concerns based on a score of at least 26 on the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI). Among the 20 women recruited for the study, 6 had already been prescribed hormone therapy for sexual concerns.

All reported decreased sexual desire, 17 reported decreased sexual arousal, 14 had body image dissatisfaction related to sexual concerns, and 6 reported urogenital problems. Nine of the women were in full remission from major depressive disorder, one had post-traumatic stress syndrome, and one had subclinical generalized anxiety disorder.

After spending 4 weeks on a wait list as self-control group for the study, the 15 women who completed the trial underwent four individual CBT sessions focusing on sexual concerns. The first session focused on psychoeducation and thought monitoring, and the second focused on cognitive distortions, cognitive strategies, and unhelpful beliefs or expectations related to sexual concerns. The third session looked at the role of problematic behaviors and behavioral experiments, and the fourth focused on continuation of strategies, long-term goals, and maintaining gains.

The participants completed eight measures at baseline, after the 4 weeks on the wait list, and after the four CBT sessions to assess the following:

- Sexual satisfaction, distress, and desire, using the FSFI, the Female Sexual Distress Scale-Revised (FSDS-R), and the Female Sexual Desire Questionnaire (FSDQ).

- Menopause symptoms, using the Greene Climacteric Scale (GCS).

- Body image, using the Dresden Body Image Questionnaire (DBIQ).

- Relationship satisfaction, using the Couples Satisfaction Index (CSI).

- Depression, using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II).

- Anxiety, using the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A).

The women did not experience any significant changes while on the wait list except a slight decrease on the FSDQ concern subscale. Following the CBT sessions, however, the women experienced a significant decrease in sexual distress and concern as well as an increase in sexual dyadic desire and sexual functioning (P = .003 for FSFI, P = .002 for FSDS-R, and P = .003 for FSDQ).

Participants also experienced a decrease in depression (P < .0001) and menopausal symptoms (P = .001) and an increase in body-image satisfaction (P = .018) and relationship satisfaction (P = .0011) after the CBT sessions. The researchers assessed participants’ satisfaction with the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire after the CBT sessions and reported some of the qualitative findings.

“The treatment program was able to assist me with recognizing that some of my sexual concerns were normal, emotional as well as physical and hormonal, and provided me the ability to delve more deeply into the psychology of menopause and how to work through symptoms and concerns in more manageable pieces,” one participant wrote. Another found helpful the “homework exercises of recognizing a thought/feeling/emotion surrounding how I feel about myself/body and working through. More positive thought pattern/restructuring a response the most helpful.”

The main complaint about the program was that it was too short, with women wanting more sessions to help continue their progress.

Not an ‘either-or’ approach

Dr. Kingsberg said ISSWSH has a variety of sexual medicine practitioners, including providers who can provide CBT for sexual concerns, and the American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors and Therapists has a referral directory.

“Keeping in mind the bio-psychosocial model, sometimes psychotherapy is going to be a really effective treatment for sexual concerns,” Dr. Kingsberg said. “Sometimes the pharmacologic option is going to be a really effective treatment for some concerns, and sometimes the combination is going to have a really nice treatment effect. So it’s not a one-size-fits-all, and it doesn’t have to be an either-or.”

The sexual concerns of women still do not get adequately addressed in medical schools and residencies, Dr. Kingsberg said, which is distinctly different from how male sexual concerns are addressed in health care.

“Erectile dysfunction is kind of in the norm, and women are still a little hesitant to bring up their sexual concerns,” Dr. Kingsberg said. “They don’t know if it’s appropriate and they’re hoping that their clinician will ask.”

One way clinicians can do that is with a global question for all their patients: “Most of my patients have sexual questions or concerns; what concerns do you have?”

“They don’t have to go through a checklist of 10 things,” Dr. Kingsberg said. If the patient does not bring anything up, providers can then ask a single follow up question: “Do you have any concerns with desire, arousal, orgasm, or pain?” That question, Dr. Kingsberg said, covers the four main areas of concern.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institute of Health Research. Dr. Green reported no disclosures. Dr. Kingsberg has consulted for or served on the advisory board for Alloy, Astellas, Bayer, Dare Bioscience, Freya, Reunion Neuroscience, Materna Medical, Madorra, Palatin, Pfizer, ReJoy, Sprout, Strategic Science Technologies, and MsMedicine.

AT NAMS 2023

CBT linked to reduced pain, less catastrophizing in fibromyalgia

TOPLINE:

In patients with fibromyalgia, cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) can reduce pain through its effect on pain-related catastrophizing, which involves intensified cognitive and emotional responses to things like intrusive thoughts, a new study suggests.

METHODOLOGY: