User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

Burnout among surgeons: Lessons for psychiatrists

Burnout is an occupational phenomenon and a syndrome resulting from unsuccessfully managed chronic workplace stress. The characteristic features of burnout include feelings of exhaustion, cynicism, and reduced professional efficacy.1 A career in surgery is associated with demanding and unpredictable work hours in a high-stress environment.2-8 Research indicates that surgeons are at an elevated risk for developing burnout and mental health problems that can compromise patient care. A survey of the fellows of the American College of Surgeons found that 40% of surgeons experience burnout, 30% experience symptoms of depression, and 28% have a mental quality of life (QOL) score greater than one-half an SD below the population norm.9,10 Surgeon burnout was also found to compromise the delivery of medical care.9,10

To prevent serious harm to surgeons and patients, it is critical to understand the causative factors of burnout among surgeons and how they can be addressed. We conducted this systematic review to identify factors linked to burnout across surgical specialties and to suggest ways to mitigate these risk factors.

Methods

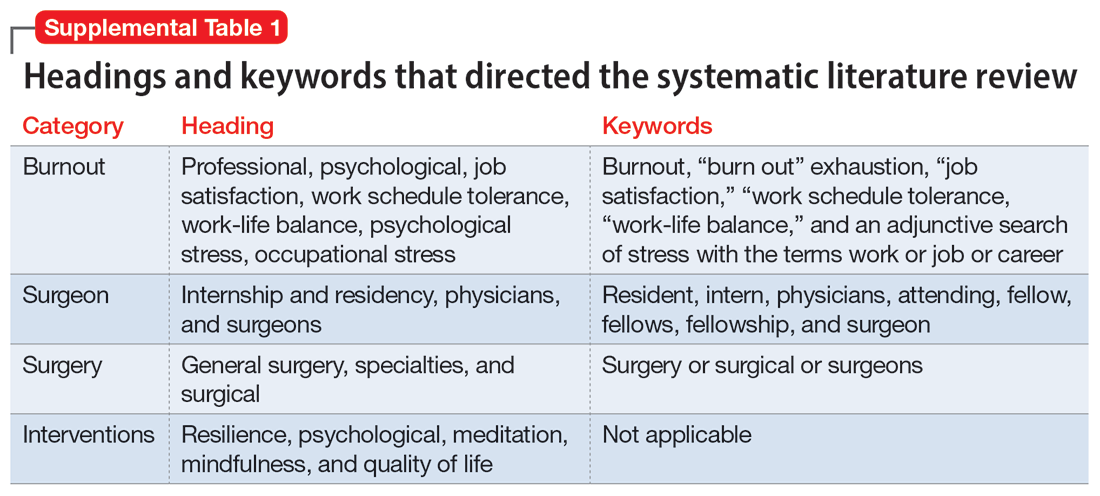

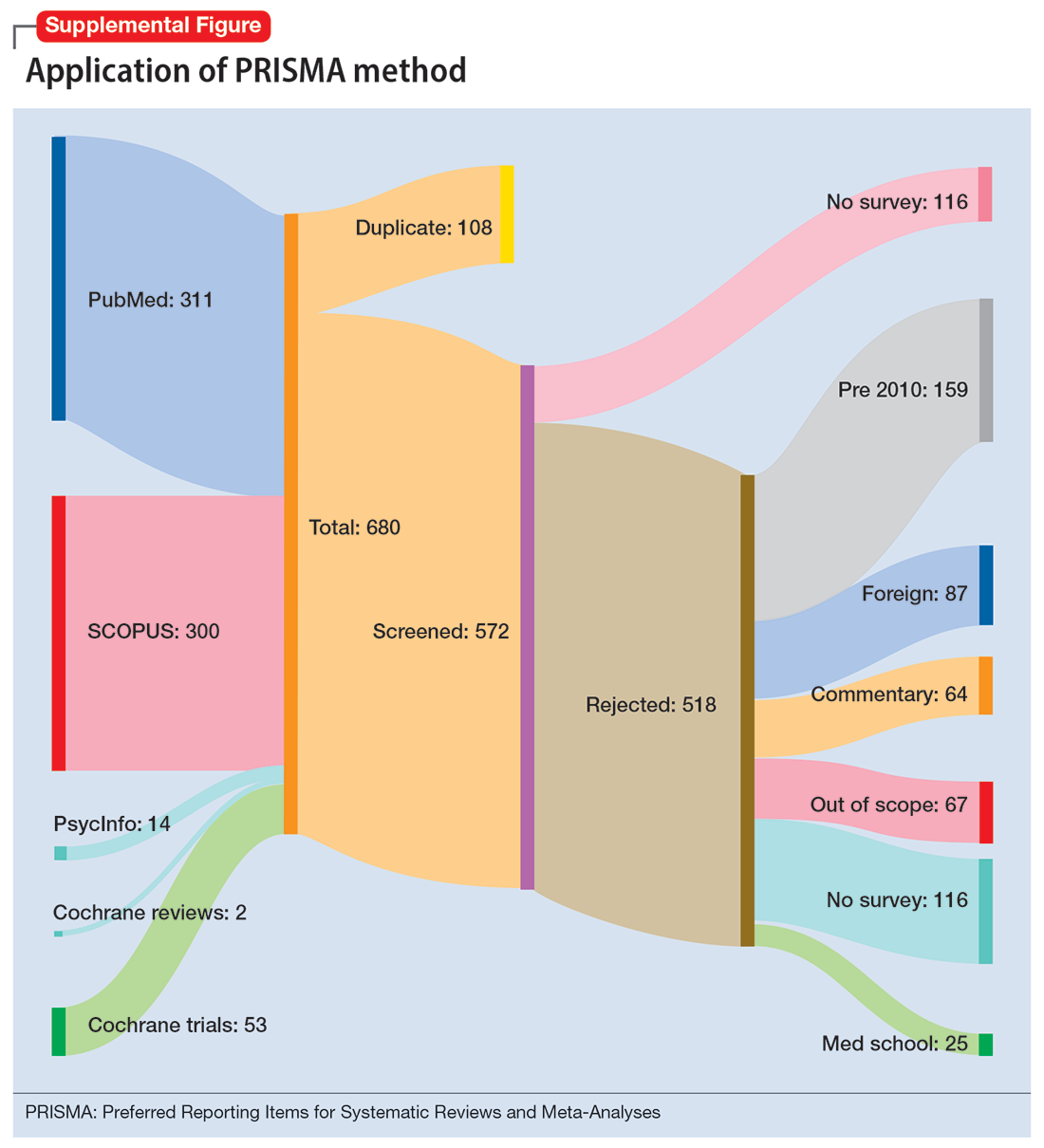

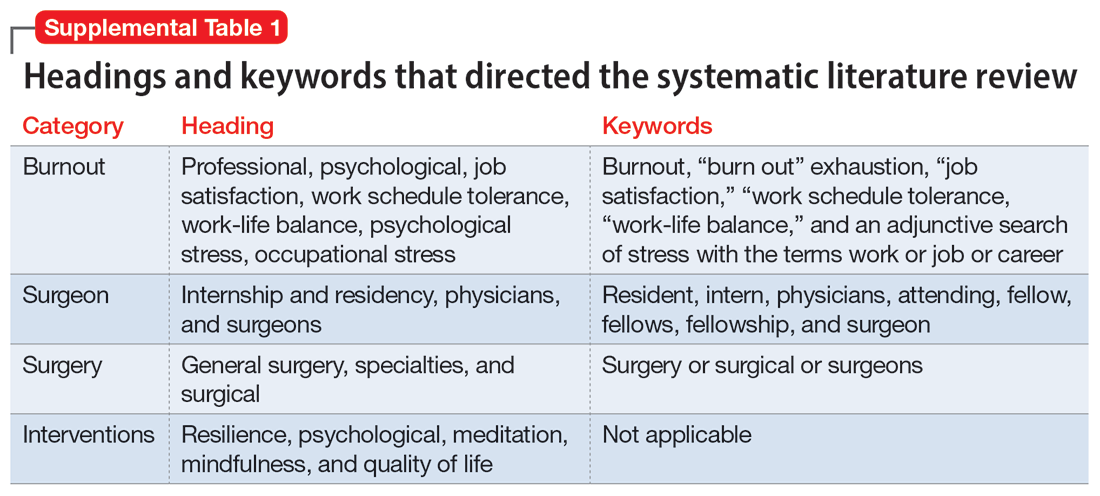

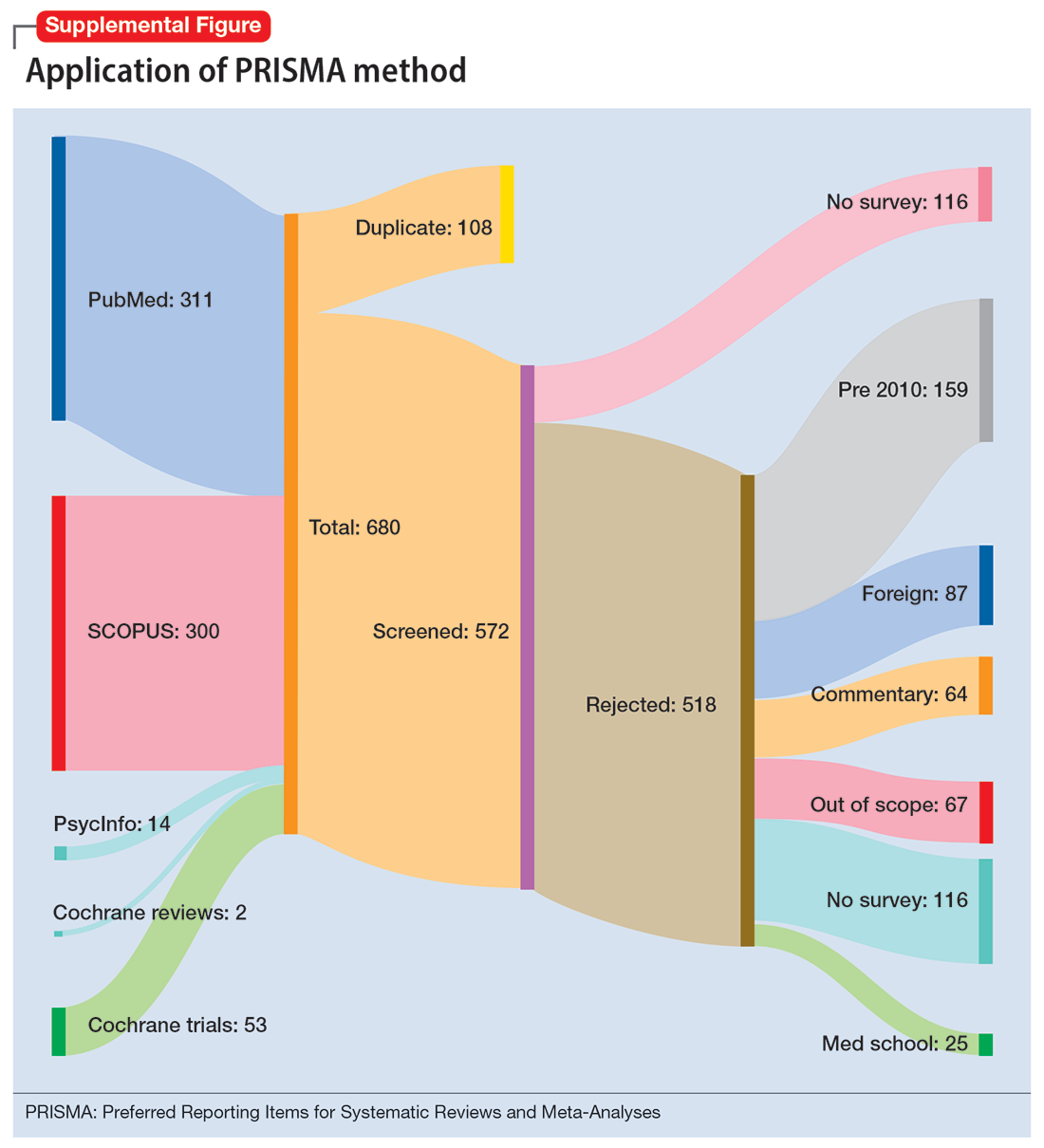

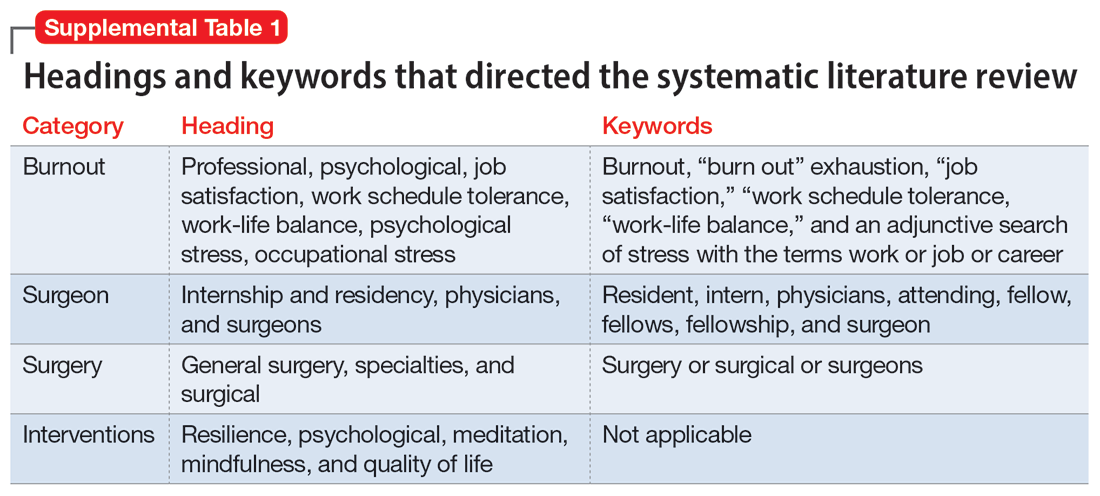

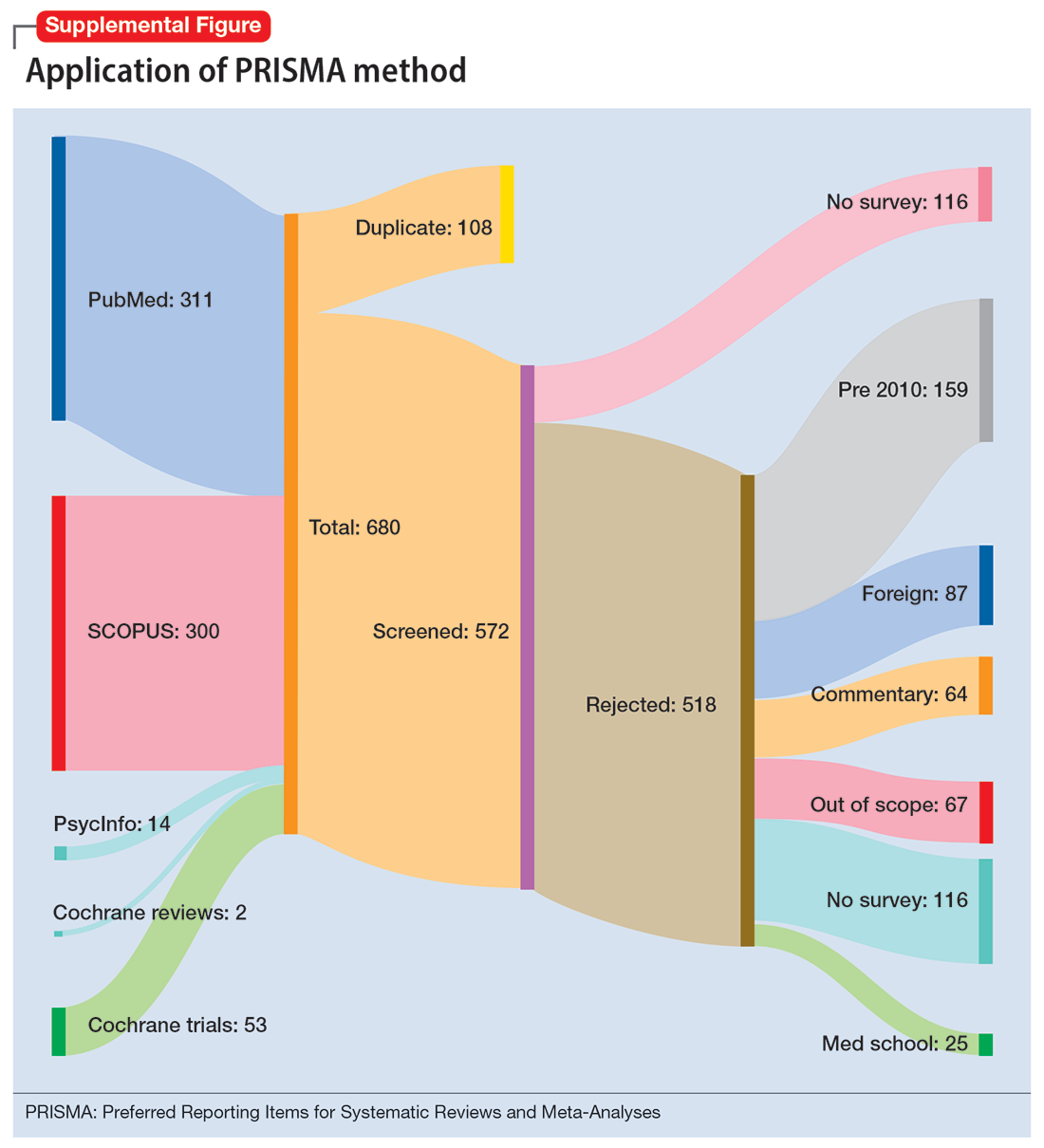

To identify studies of burnout among surgeons, we conducted an electronic search of Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid PsycInfo, SCOPUS, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. The headings and keywords used are listed in Supplemental Table 1. Studies met the inclusion criteria if they evaluated residents or attendings, used a tool to measure burnout, and examined any surgical specialty. Studies were excluded if they were published before 2010; were conducted outside the United States; were review articles, commentaries, or abstracts without full text articles; evaluated medical school students; were published in a language other than English; did not use a tool to measure burnout; or examined a nonsurgical specialty. Our analysis was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)11 and is outlined in the Supplemental Figure.

Results

Surgical specialties and burnout

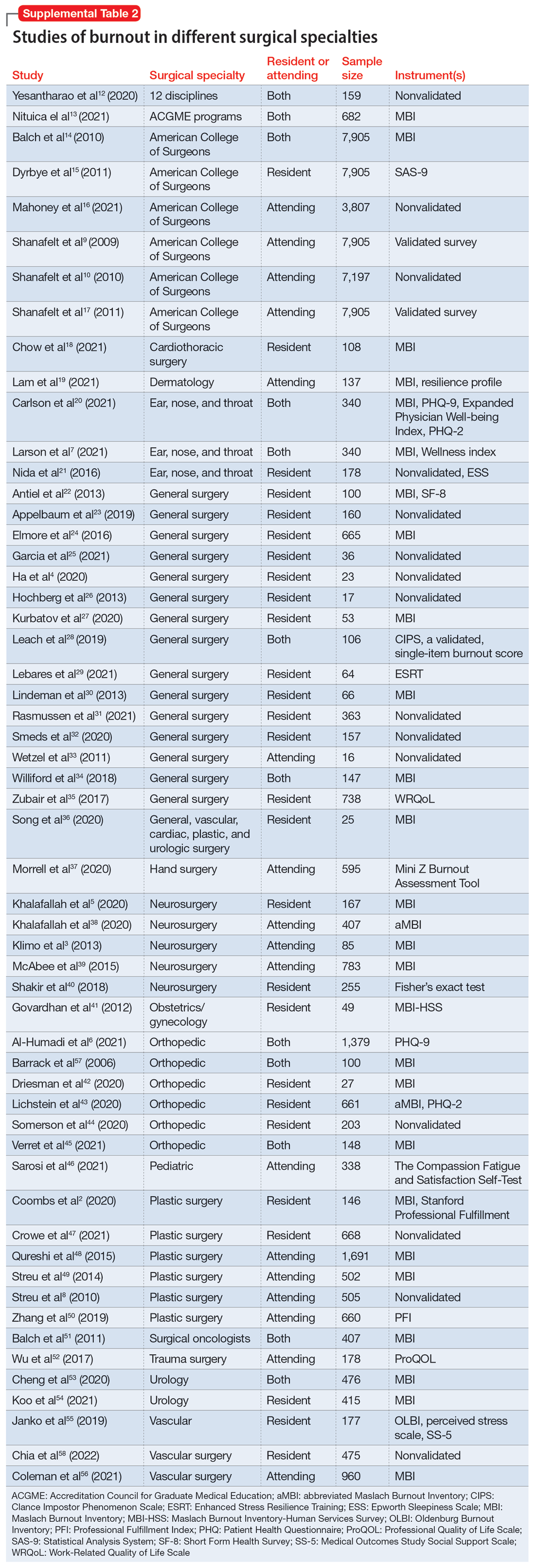

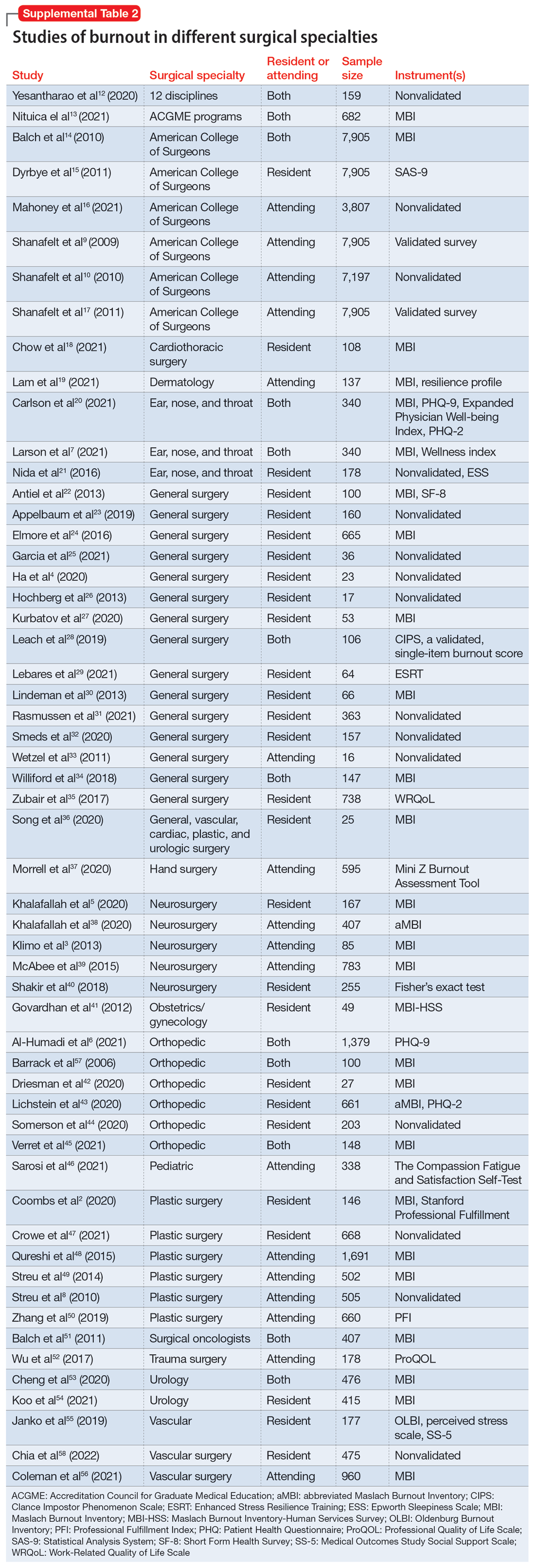

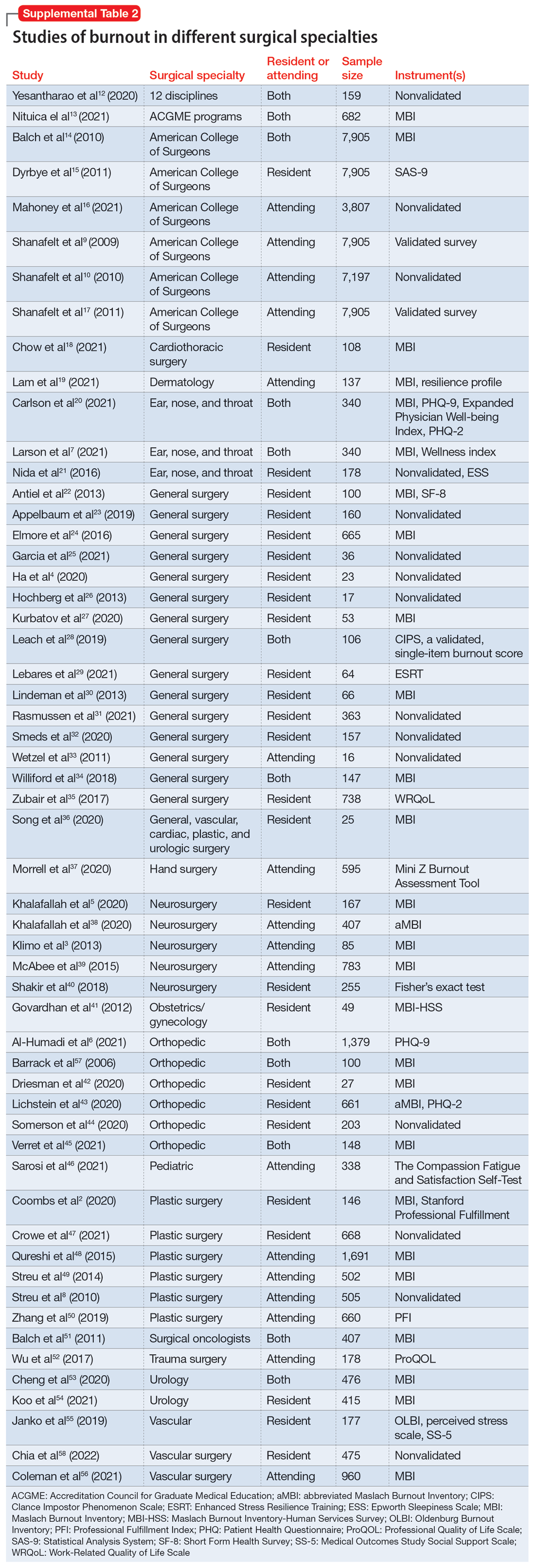

We identified 56 studies2-10,12-58 that focused on specific surgical specialties in relation to burnout. Supplemental Table 22-10,12-58 lists these studies and the surgical specialties they evaluated.

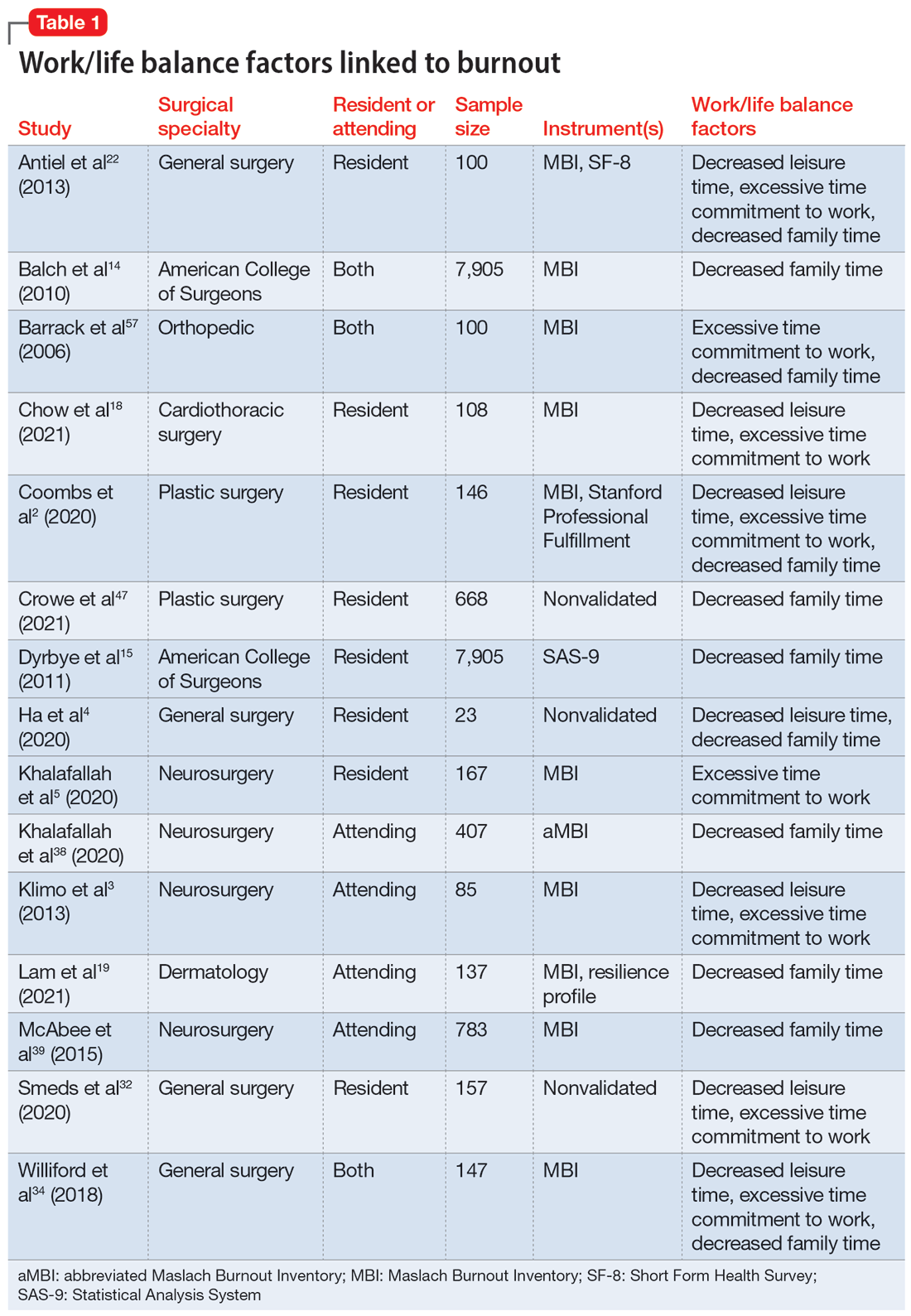

Work/life balance factors

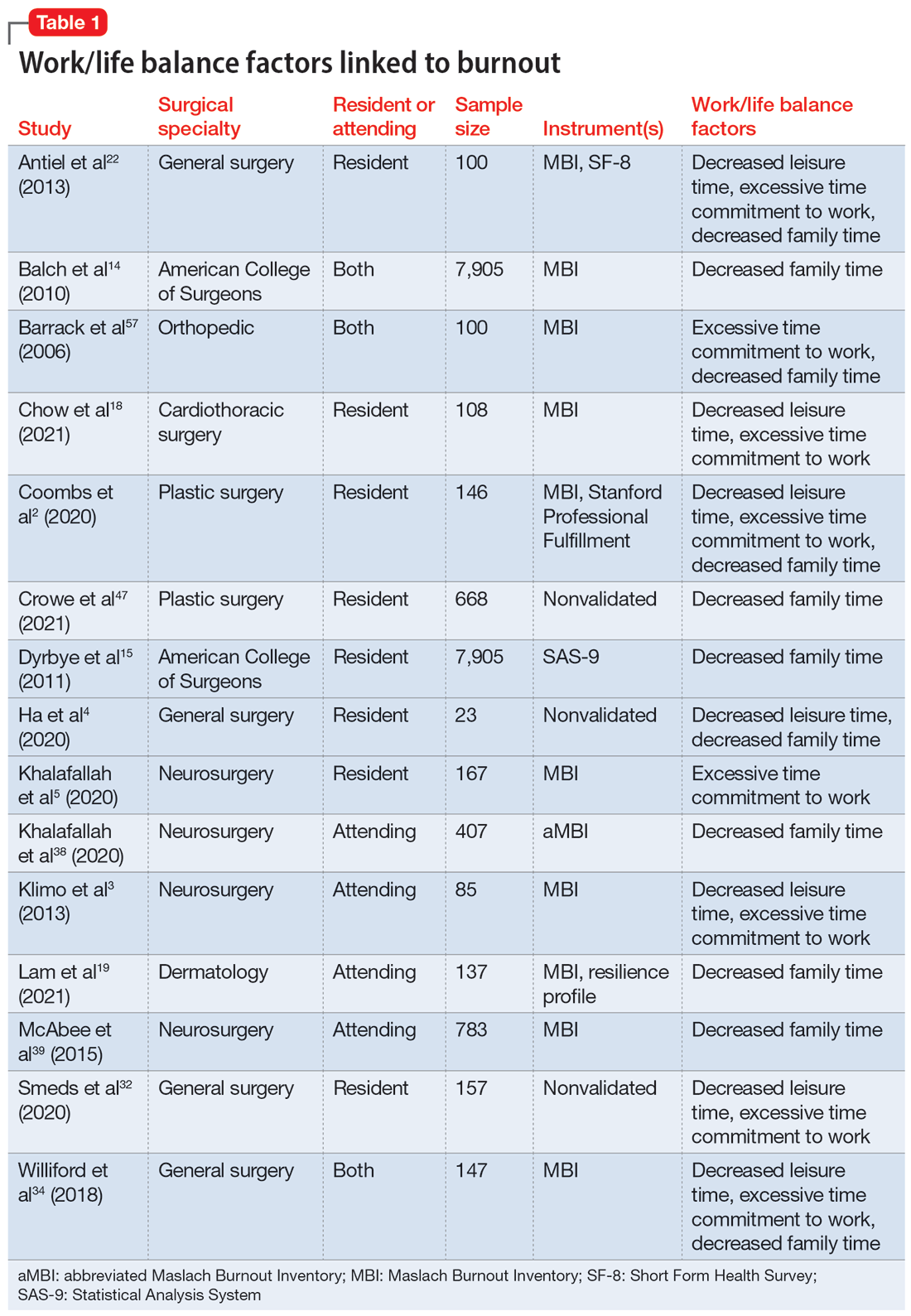

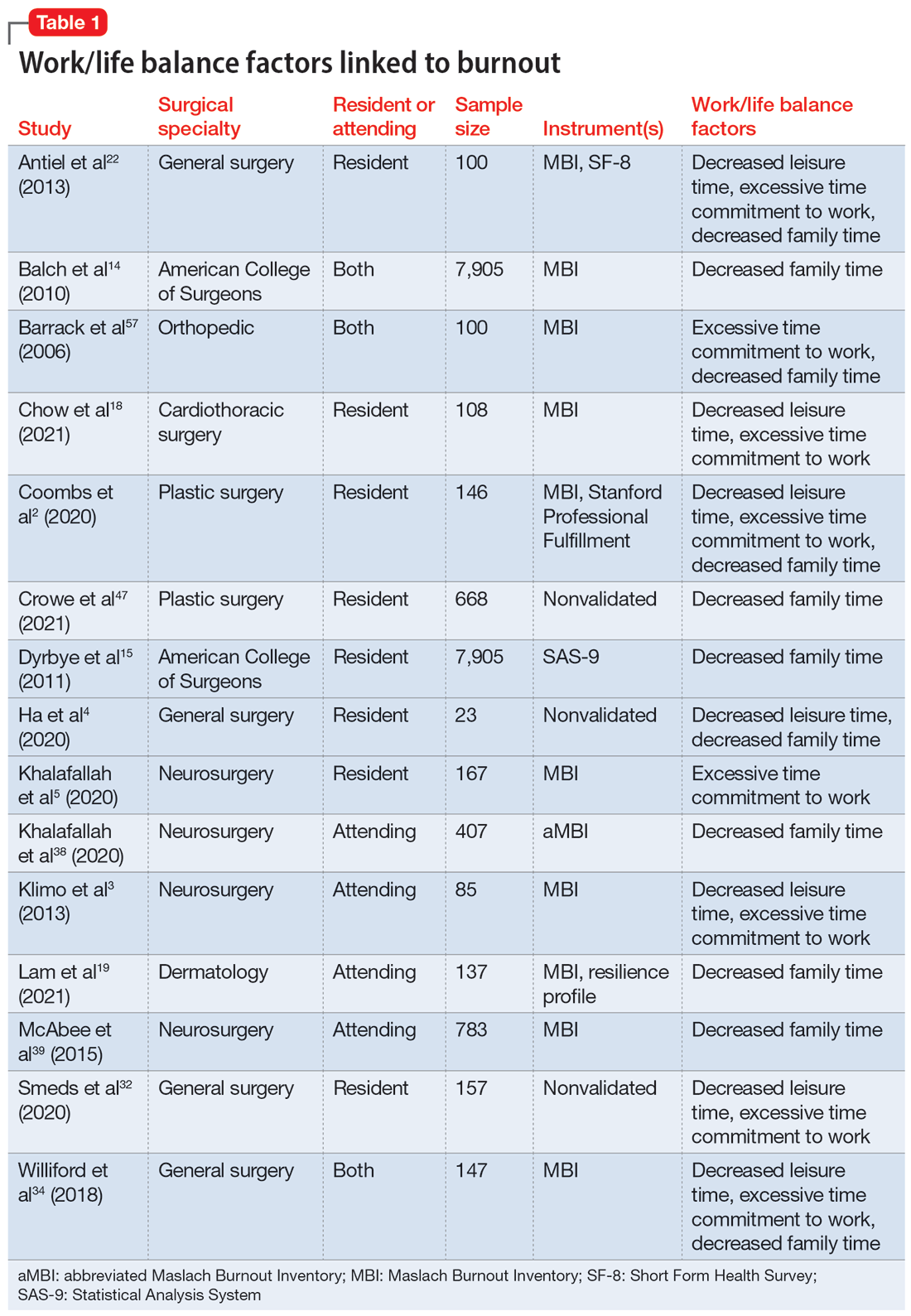

Fifteen studies

Work hours

Fifteen studies2,7,14,20,21,30,34,41,42,44-46,50,52,56 examined work hours and burnout. Of these, 142,7,14,20,21,30,34,42,44-46,50,52,56 found a correlation between increased work hours and burnout, while only 1 study41 found no correlation between these factors.

Medical errors

Six studies2,14,18,43,49,52 discussed the role of burnout in medical errors. Of these, 52,14,43,49,52 reported a correlation between burnout and medical errors, while 1 study18 found no link between burnout and medical errors. The medical errors were self-reported.14,49 They included actions that resulted in patient harm, sample collection error, and errors in medication orders and laboratory test orders.2

Continue to: Institutional and organizational factors

Institutional and organizational factors

Eighteen studies3,13,14,18,20,22,23,29,30,36-38,44,45,47,54,56,57 examined how different organizational factors play a role in burnout. Four studies3,13,20,37 discussed administrative/bureaucratic work, 420,45,54,57 mentioned electronic medical documentation, 222,30 covered duty hour regulations, 318,45,57 discussed mistreatment of physicians, and 613,18,23,44,47,56 described the importance of workplace support in addressing burnout.

Physical and mental health factors

Eighteen studies6,7,14,15,17,20,26,27,29,34,43,44,48,52,54,57-59 discussed aspects of physical and mental health linked to burnout. Among these, 334,43,59 discussed the importance of physical health and focused on how improving physical health can reduce stress and burnout. Three studies6,17,58 noted the prevalence of suicidal ideation in both residents and attendings experiencing prolonged burnout. Five studies26,29,43,44,48 described the systematic barriers that inhibit physicians from getting professional help. Two studies7,27 reported marital status as a factor for burnout; participants who were single reported higher levels of depression and suicidal ideation. Five studies6,14,15,54,57 outlined how depression is associated with burnout.

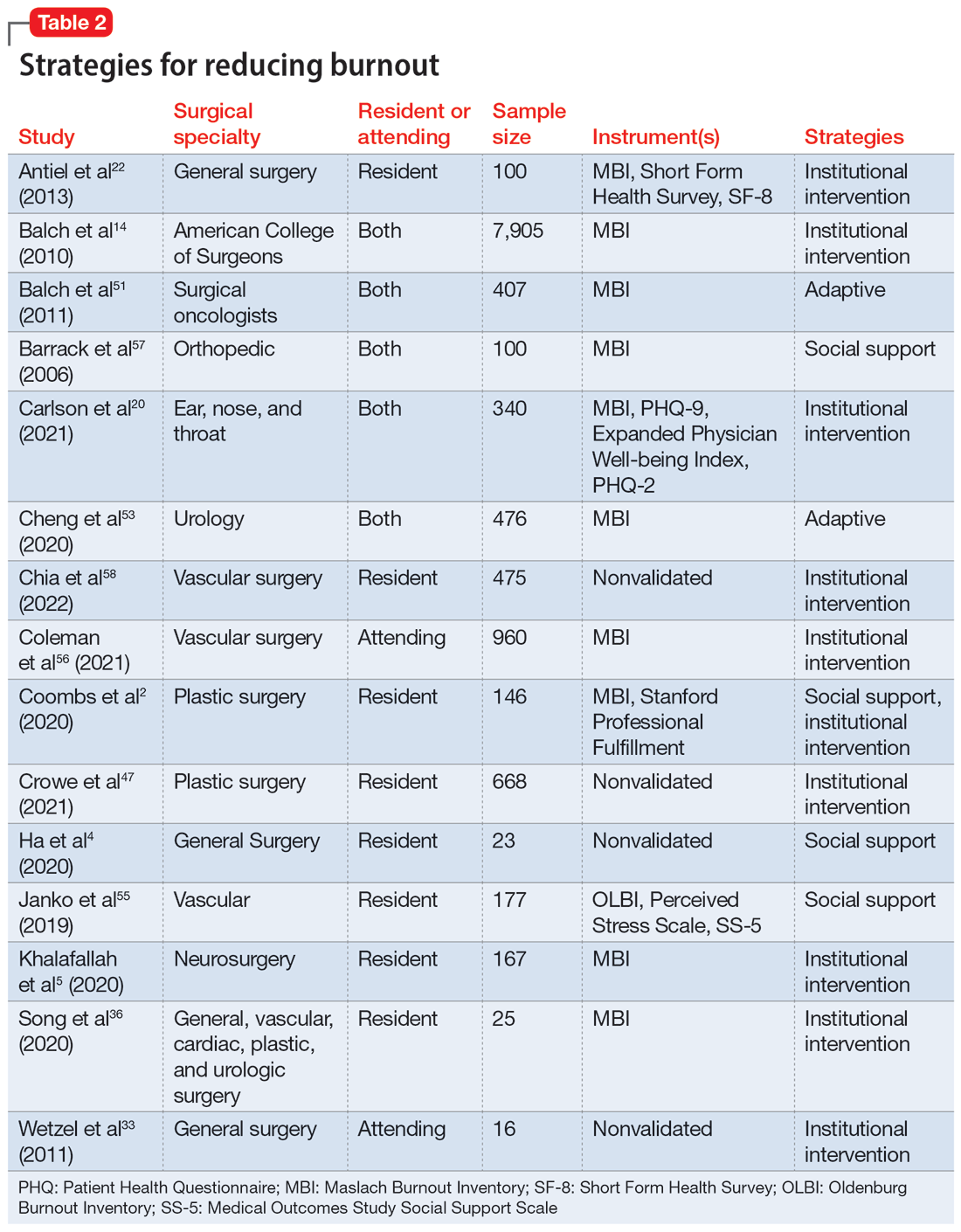

Strategies to mitigate burnout

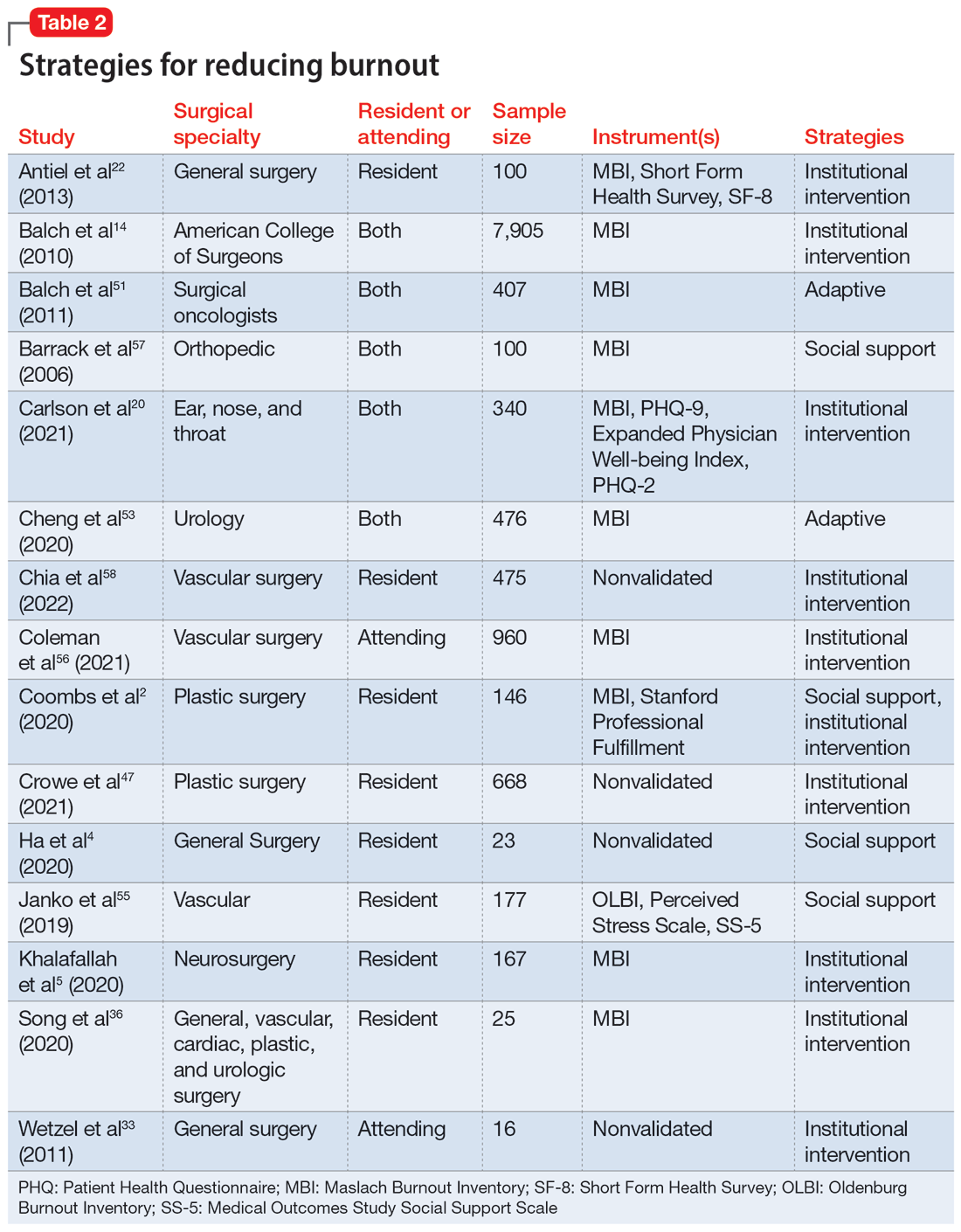

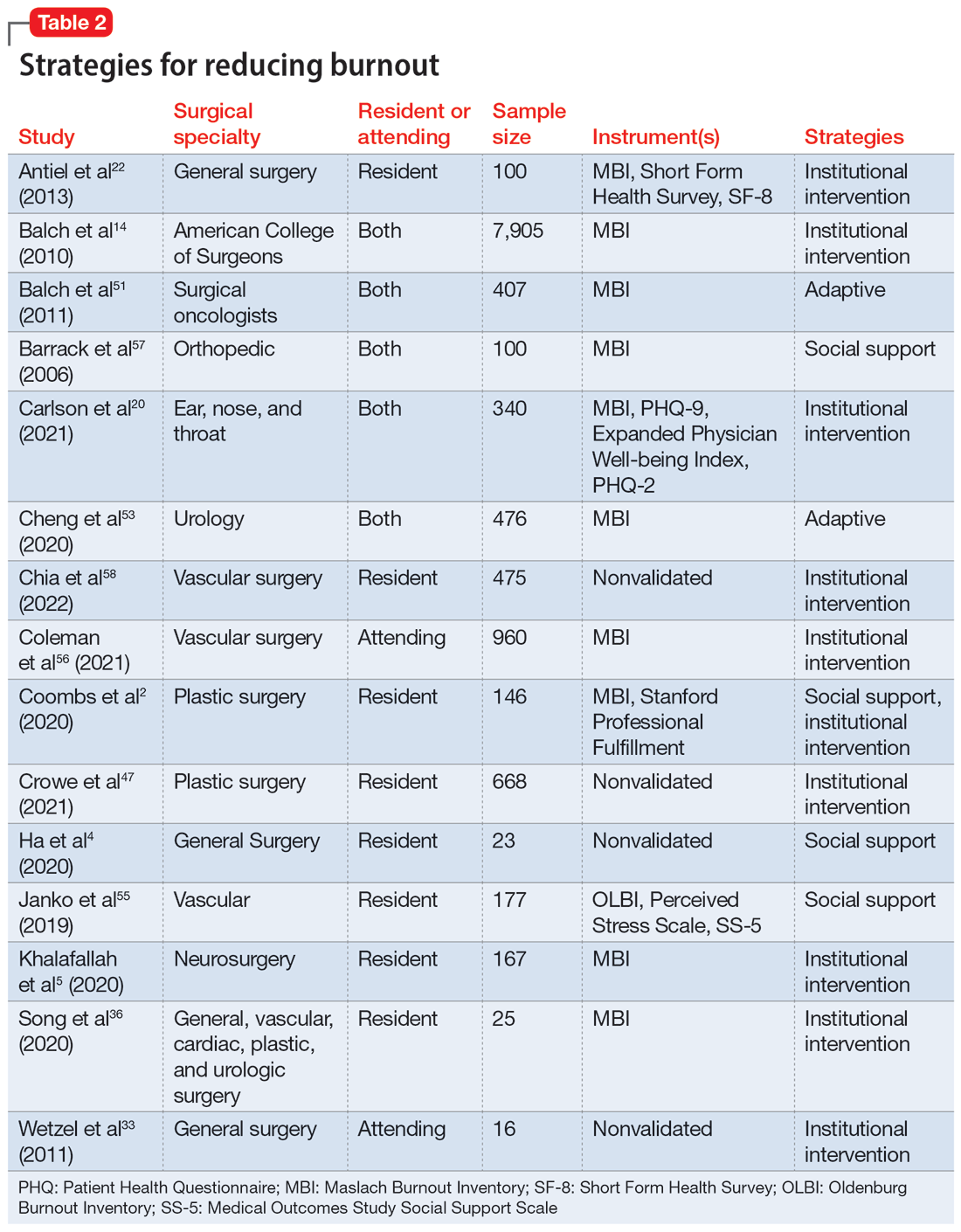

Fifteen studies

Take-home points

Research that focused on work/life balance and burnout found excessive time commitment to work is a major factor associated with poor work/life balance. Residents who worked >80 hours a week had a significantly higher burnout rate.56 One study found that 70% of residents reported not getting enough sleep, 30% reported not having enough energy for relationships, and 39% reported that they were not eating or exercising due to time constraints.4 A high correlation was found between the number of hours worked per week and rates of burnout, emotional exhaustion, and depersonalization. Emotional exhaustion and depersonalization are aspects of burnout measured by the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI).24 The excessive time commitment to work not only contributes to burnout but also prevents physicians from getting professional help. In 1 study, both residents (56%) and attendings (24%) reported that 1 of the biggest barriers to getting help for their burnout symptoms was the inability to take time off.34 Research indicates that the hours worked per week and work/home conflicts were independently associated with burnout and career satisfaction.15 A decrease of weekly work hours may give physicians time to meet their responsibilities at work and home, allowing for a decrease in burnout and an increase in career satisfaction.

Increased work hours have also been found to be correlated with medical errors. One study found that those who worked 60 hours per week were significantly less likely to report any major medical errors in the previous 3 months compared with those who worked 80 hours per week.9 The risk for the number of medical errors has been reported as being 2-fold if surgeons are unable to combat the burnout.49 On the other hand, a positive and supportive environment with easy access to resources to combat burnout and burnout prevention programs can reduce the frequency of medical errors, which also can reduce the risk of malpractice, thus further reducing stress and burnout.43

Continue to: In response to resident complaints...

In response to resident complaints about long duty hours, a new rule has been implemented that states residents cannot work >16 hours per shift.30 This rule has been found to increase quality of life and prevent burnout.30

The amount of time spent on electronic medical records and documentation has been a major complaint from doctors and was identified as a factor contributing to burnout.45 It can act as a time drain that impedes the physician from providing optimal patient care and cause additional stress. This suggests the need for organizations to find solutions to minimize this strain.

A concerning issue reported as an institutional factor and associated with burnout is mistreatment through discrimination, harassment, and physical or verbal abuse. A recent study found 45% of general and vascular surgeons reported being mistreated in some fashion.57 The strategies reported as helpful for institutions to combat mistreatment include resilience training, improved mentorship, and implicit bias training.57

Burnout has been positively correlated with anxiety and depression.6 A recent study reported that 13% of orthopedic surgery residents screened positive for depression.44 Higher levels of burnout and depersonalization have been found to be closely associated with increased rates of suicidal ideation.17 In a study of vascular surgeons, 8% were found to report suicidal ideation, and this increased to 15% among vascular surgeons who had higher levels of depersonalization and emotional exhaustion,58 both of which are associated with burnout. In another study, surgery residents and fellows were found to have lower levels of personal achievement and higher levels of depersonalization, depressive symptoms, alcohol abuse, and suicidal ideation compared to attending physicians and the general population.54 These findings spell out the association between burnout and depressive symptoms among surgeons and emphasize the need for institutions to create a culture that supports the mental health needs of their physicians. Without access to supportive resources, residents resort to alternative methods that may be detrimental in the long run. In a recent study, 17% of residents admitted to using alcohol, including binge drinking, to cope with their stress.4

Burnout and depression are linked to physical health risks such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, substance abuse, and male infertility.6 Exercise has been shown to be beneficial for stress reduction, which can lead to changes in metabolism, inflammation, coagulation, and autonomic function.6 One study of surgeons found aerobic exercise and strength training were associated with lower rates of burnout and a higher quality of life.59

Continue to: The amount of burnout physicians...

The amount of burnout physicians experience can be determined by how they respond to adversities. Adaptive behaviors such as socializing, mindfulness, volunteering, and exercising have been found to be protective against burnout.6,37,54 Resilience training and maintaining low stress at work can decrease burnout.37 These findings highlight the need for physicians to be trained in the appropriate ways to combat their burnout symptoms.

Unfortunately, seeking help by health care professionals to improve mental health has been stigmatized, causing physicians to not seek help and instead resort to other ways to cope with their distress.26,34 While some of these coping methods may be positive, others—such as substance abuse or stress eating—can be maladaptive, leading to a poor quality of life, and in some cases, suicide.54 It is vital that effective mental health services become more accessible and for health care professionals to become aware of their maladaptive behaviors.34

Institutions finding ways to ease the path for their physicians to seek professional help to combat burnout may mitigate its negative impact. One strategy is to embed access to mental health services within regular wellness checks. Institutions can use wellness checks to provide resources to physicians who need it. These interventions have been found to be effective because they give physicians a safe space to seek help and become aware of any factors that could lead to burnout.18 Apart from these direct attempts to combat burnout, program-sponsored social events would also promote social connectedness with colleagues and contribute to a sense of well-being that could help decrease levels of burnout and depression.13 Mentorship has been shown to play a crucial role in decreasing burnout among residents. One study that examined the role of mentorship reported that 55% of residents felt supported, and of these, 96% felt mentorship was critical to their success.18 The role of institutions in helping to improve the well-being of surgeons is highlighted by the finding that increasing workplace support results in psychological resilience that can mitigate burnout at its roots.29

Bottom Line

Surgeons are at risk for burnout, which can impact their mental health and reduce their professional efficacy. Both institutions and surgeons themselves can take action to prevent burnout and treat burnout early when it occurs.

Related Resources

- Pahal P, Lippmann S. Building a better work/life balance. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(8):e1-e2. doi:10.12788/cp.0158

- Gibson R, Hategan A. Physician burnout vs depression: recognize the signs. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(10):41-42.

1. World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD). 11th ed. World Health Organization; 2019.

2. Coombs DM, Lanni MA, Fosnot J, et al. Professional burnout in United States plastic surgery residents: is it a legitimate concern? Aesthet Surg J. 2020;40(7):802-810.

3. Klimo P Jr, DeCuypere M, Ragel BT, et al. Career satisfaction and burnout among U.S. neurosurgeons: a feasibility and pilot study. World Neurosurg. 2013;80(5):e59-e68.

4. Ha GQ, Go JT, Murayama KM, et al. Identifying sources of stress across years of general surgery residency. Hawaii J Health Soc Welf. 2020;79(3):75-81.

5. Khalafallah AM, Lam S, Gami A, et al. A national survey on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic upon burnout and career satisfaction among neurosurgery residents. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;80:137-142.

6. Al-Humadi SM, Cáceda R, Bronson B, et al. Orthopaedic surgeon mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Geriatric Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2021;12:21514593211035230.

7. Larson DP, Carlson ML, Lohse CM, et al. Prevalence of and associations with distress and professional burnout among otolaryngologists: part I, trainees. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;164(5):1019-1029.

8. Streu R, Hawley S, Gay A, et al. Satisfaction with career choice among U.S. plastic surgeons: results from a national survey. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(2):636-642.

9. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps GJ, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2009;250(3):463-471.

10. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995-1000.

11. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336-341.

12. Yesantharao P, Lee E, Kraenzlin F, et al. Surgical block time satisfaction: a multi-institutional experience across twelve surgical disciplines. Perioperative Care Operating Room Manage. 2020;21:100128.

13. Nituica C, Bota OA, Blebea J. Specialty differences in resident resilience and burnout - a national survey. Am J Surg. 2021;222(2):319-328.

14. Balch CM, Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye L, et al. Surgeon distress as calibrated by hours worked and nights on call. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211(5):609-619.

15. Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Satele D, Sloan J, Freischlag J. Relationship between work-home conflicts and burnout among American surgeons: a comparison by sex. Arch Surg. 2011;146(2):211-217.

16. Mahoney ST, Irish W, Strassle PD, et al. Practice characteristics and job satisfaction of private practice and academic surgeons. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(3):247-254.

17. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Dyrbye L, et al. Special report: suicidal ideation among American surgeons. Arch Surg. 2011;146(1):54-62.

18. Chow OS, Sudarshan M, Maxfield MW, et al. National survey of burnout and distress among cardiothoracic surgery trainees. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021;111(6):2066-2071.

19. Lam C, Kim Y, Cruz M, et al. Burnout and resiliency in Mohs surgeons: a survey study. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7(3):319-322.

20. Carlson ML, Larson DP, O’Brien EK, et al. Prevalence of and associations with distress and professional burnout among otolaryngologists: part II, attending physicians. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;164(5):1030-1039.

21. Nida AM, Googe BJ, Lewis AF, et al. Resident fatigue in otolaryngology residents: a Web based survey. Am J Otolaryngol. 2016;37(3):210-216.

22. Antiel RM, Reed DA, Van Arendonk KJ, et al. Effects of duty hour restrictions on core competencies, education, quality of life, and burnout among general surgery interns. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(5):448-455.

23. Appelbaum NP, Lee N, Amendola M, et al. Surgical resident burnout and job satisfaction: the role of workplace climate and perceived support. J Surg Res. 2019;234:20-25.

24. Elmore LC, Jeffe DB, Jin L, et al. National survey of burnout among US general surgery residents. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;223(3):440-451.

25. Garcia DI, Pannuccio A, Gallegos J, et al. Resident-driven wellness initiatives improve resident wellness and perception of work environment. J Surg Res. 2021;258:8-16.

26. Hochberg MS, Berman RS, Kalet AL, et al. The stress of residency: recognizing the signs of depression and suicide in you and your fellow residents. Am J Surg. 2013;205(2):141-146.

27. Kurbatov V, Shaughnessy M, Baratta V, et al. Application of advanced bioinformatics to understand and predict burnout among surgical trainees. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(3):499-507.

28. Leach PK, Nygaard RM, Chipman JG, et al. Impostor phenomenon and burnout in general surgeons and general surgery residents. J Surg Educ. 2019;76(1):99-106.

29. Lebares CC, Greenberg AL, Ascher NL, et al. Exploration of individual and system-level well-being initiatives at an academic surgical residency program: a mixed-methods study. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2032676.

30. Lindeman BM, Sacks BC, Hirose K, et al. Multifaceted longitudinal study of surgical resident education, quality of life, and patient care before and after July 2011. J Surg Educ. 2013;70(6):769-776.

31. Rasmussen JM, Najarian MM, Ties JS, et al. Career satisfaction, gender bias, and work-life balance: a contemporary assessment of general surgeons. J Surg Educ. 2021;78(1):119-125.

32. Smeds MR, Janko MR, Allen S, et al. Burnout and its relationship with perceived stress, self-efficacy, depression, social support, and programmatic factors in general surgery residents. Am J Surg. 2020;219(6):907-912.

33. Wetzel CM, George A, Hanna GB, et al. Stress management training for surgeons--a randomized, controlled, intervention study. Ann Surg. 2011;253(3):488-494.

34. Williford ML, Scarlet S, Meyers MO, et al. Multiple-institution comparison of resident and faculty perceptions of burnout and depression during surgical training. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(8):705-711.

35. Zubair MH, Hussain LR, Williams KN, et al. Work-related quality of life of US general surgery residents: is it really so bad? J Surg Educ. 2017;74(6):e138-e146.

36. Song Y, Swendiman RA, Shannon AB, et al. Can we coach resilience? An evaluation of professional resilience coaching as a well-being initiative for surgical interns. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(6):1481-1489.

37. Morrell NT, Sears ED, Desai MJ, et al. A survey of burnout among members of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand. J Hand Surg Am. 2020;45(7):573-581.e516.

38. Khalafallah AM, Lam S, Gami A, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among attending neurosurgeons during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020;198:106193.

39. McAbee JH, Ragel BT, McCartney S, et al. Factors associated with career satisfaction and burnout among US neurosurgeons: results of a nationwide survey. J Neurosurg. 2015;123(1):161-173.

40. Shakir HJ, McPheeters MJ, Shallwani H, et al. The prevalence of burnout among US neurosurgery residents. Neurosurgery. 2018;83(3):582-590.

41. Govardhan LM, Pinelli V, Schnatz PF. Burnout, depression and job satisfaction in obstetrics and gynecology residents. Conn Med. 2012;76(7):389-395.

42. Driesman AS, Strauss EJ, Konda SR, et al. Factors associated with orthopaedic resident burnout: a pilot study. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28(21):900-906.

43. Lichstein PM, He JK, Estok D, et al. What is the prevalence of burnout, depression, and substance use among orthopaedic surgery residents and what are the risk factors? A collaborative orthopaedic educational research group survey study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020;478(8):1709-1718.

44. Somerson JS, Patton A, Ahmed AA, et al. Burnout among United States orthopaedic surgery residents. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(4):961-968.

45. Verret CI, Nguyen J, Verret C, et al. How do areas of work life drive burnout in orthopaedic attending surgeons, fellows, and residents? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2021;479(2):251-262.

46. Sarosi A, Coakley BA, Berman L, et al. A cross-sectional analysis of compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction in pediatric surgeons in the U.S. J Pediatr Surg. 2021;56(8):1276-1284.

47. Crowe CS, Lopez J, Morrison SD, et al. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on resident education and wellness: a national survey of plastic surgery residents. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;148(3):462e-474e.

48. Qureshi HA, Rawlani R, Mioton LM, et al. Burnout phenomenon in U.S. plastic surgeons: risk factors and impact on quality of life. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(2):619-626.

49. Streu R, Hansen J, Abrahamse P, et al. Professional burnout among US plastic surgeons: results of a national survey. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;72(3):346-350.

50. Zhang JQ, Riba L, Magrini L, ET AL. Assessing burnout and professional fulfillment in breast surgery: results from a national survey of the American Society of Breast Surgeons. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(10):3089-3098.

51. Balch CM, Shanafelt TD, Sloan J, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among surgical oncologists compared with other surgical specialties. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(1):16-25.

52. Wu D, Gross B, Rittenhouse K, et al. A preliminary analysis of compassion fatigue in a surgeon population: are female surgeons at heightened risk? Am Surg. 2017;83(11):1302-1307.

53. Cheng JW, Wagner H, Hernandez BC, et al. Stressors and coping mechanisms related to burnout within urology. Urology. 2020;139:27-36.

54. Koo K, Javier-DesLoges JF, Fang R, ET AL. Professional burnout, career choice regret, and unmet needs for well-being among urology residents. Urology. 2021;157:57-63.

55. Janko MR, Smeds MR. Burnout, depression, perceived stress, and self-efficacy in vascular surgery trainees. J Vasc Surg. 2019;69(4):1233-1242.

56. Coleman DM, Money SR, Meltzer AJ, et al. Vascular surgeon wellness and burnout: a report from the Society for Vascular Surgery Wellness Task Force. J Vasc Surg. 2021;73(6):1841-1850.e3.

57. Barrack RL, Miller LS, Sotile WM, et al. Effect of duty hour standards on burnout among orthopaedic surgery residents. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;449:134-137.

58. Chia MC, Hu YY, Li RD, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for burnout in U.S. vascular surgery trainees. J Vasc Surg. 2022;75(1):308-315.e4.

59. Shanafelt TD, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, et al. Avoiding burnout: the personal health habits and wellness practices of US surgeons. Ann Surg. 2012;255(4):625-633.

Burnout is an occupational phenomenon and a syndrome resulting from unsuccessfully managed chronic workplace stress. The characteristic features of burnout include feelings of exhaustion, cynicism, and reduced professional efficacy.1 A career in surgery is associated with demanding and unpredictable work hours in a high-stress environment.2-8 Research indicates that surgeons are at an elevated risk for developing burnout and mental health problems that can compromise patient care. A survey of the fellows of the American College of Surgeons found that 40% of surgeons experience burnout, 30% experience symptoms of depression, and 28% have a mental quality of life (QOL) score greater than one-half an SD below the population norm.9,10 Surgeon burnout was also found to compromise the delivery of medical care.9,10

To prevent serious harm to surgeons and patients, it is critical to understand the causative factors of burnout among surgeons and how they can be addressed. We conducted this systematic review to identify factors linked to burnout across surgical specialties and to suggest ways to mitigate these risk factors.

Methods

To identify studies of burnout among surgeons, we conducted an electronic search of Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid PsycInfo, SCOPUS, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. The headings and keywords used are listed in Supplemental Table 1. Studies met the inclusion criteria if they evaluated residents or attendings, used a tool to measure burnout, and examined any surgical specialty. Studies were excluded if they were published before 2010; were conducted outside the United States; were review articles, commentaries, or abstracts without full text articles; evaluated medical school students; were published in a language other than English; did not use a tool to measure burnout; or examined a nonsurgical specialty. Our analysis was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)11 and is outlined in the Supplemental Figure.

Results

Surgical specialties and burnout

We identified 56 studies2-10,12-58 that focused on specific surgical specialties in relation to burnout. Supplemental Table 22-10,12-58 lists these studies and the surgical specialties they evaluated.

Work/life balance factors

Fifteen studies

Work hours

Fifteen studies2,7,14,20,21,30,34,41,42,44-46,50,52,56 examined work hours and burnout. Of these, 142,7,14,20,21,30,34,42,44-46,50,52,56 found a correlation between increased work hours and burnout, while only 1 study41 found no correlation between these factors.

Medical errors

Six studies2,14,18,43,49,52 discussed the role of burnout in medical errors. Of these, 52,14,43,49,52 reported a correlation between burnout and medical errors, while 1 study18 found no link between burnout and medical errors. The medical errors were self-reported.14,49 They included actions that resulted in patient harm, sample collection error, and errors in medication orders and laboratory test orders.2

Continue to: Institutional and organizational factors

Institutional and organizational factors

Eighteen studies3,13,14,18,20,22,23,29,30,36-38,44,45,47,54,56,57 examined how different organizational factors play a role in burnout. Four studies3,13,20,37 discussed administrative/bureaucratic work, 420,45,54,57 mentioned electronic medical documentation, 222,30 covered duty hour regulations, 318,45,57 discussed mistreatment of physicians, and 613,18,23,44,47,56 described the importance of workplace support in addressing burnout.

Physical and mental health factors

Eighteen studies6,7,14,15,17,20,26,27,29,34,43,44,48,52,54,57-59 discussed aspects of physical and mental health linked to burnout. Among these, 334,43,59 discussed the importance of physical health and focused on how improving physical health can reduce stress and burnout. Three studies6,17,58 noted the prevalence of suicidal ideation in both residents and attendings experiencing prolonged burnout. Five studies26,29,43,44,48 described the systematic barriers that inhibit physicians from getting professional help. Two studies7,27 reported marital status as a factor for burnout; participants who were single reported higher levels of depression and suicidal ideation. Five studies6,14,15,54,57 outlined how depression is associated with burnout.

Strategies to mitigate burnout

Fifteen studies

Take-home points

Research that focused on work/life balance and burnout found excessive time commitment to work is a major factor associated with poor work/life balance. Residents who worked >80 hours a week had a significantly higher burnout rate.56 One study found that 70% of residents reported not getting enough sleep, 30% reported not having enough energy for relationships, and 39% reported that they were not eating or exercising due to time constraints.4 A high correlation was found between the number of hours worked per week and rates of burnout, emotional exhaustion, and depersonalization. Emotional exhaustion and depersonalization are aspects of burnout measured by the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI).24 The excessive time commitment to work not only contributes to burnout but also prevents physicians from getting professional help. In 1 study, both residents (56%) and attendings (24%) reported that 1 of the biggest barriers to getting help for their burnout symptoms was the inability to take time off.34 Research indicates that the hours worked per week and work/home conflicts were independently associated with burnout and career satisfaction.15 A decrease of weekly work hours may give physicians time to meet their responsibilities at work and home, allowing for a decrease in burnout and an increase in career satisfaction.

Increased work hours have also been found to be correlated with medical errors. One study found that those who worked 60 hours per week were significantly less likely to report any major medical errors in the previous 3 months compared with those who worked 80 hours per week.9 The risk for the number of medical errors has been reported as being 2-fold if surgeons are unable to combat the burnout.49 On the other hand, a positive and supportive environment with easy access to resources to combat burnout and burnout prevention programs can reduce the frequency of medical errors, which also can reduce the risk of malpractice, thus further reducing stress and burnout.43

Continue to: In response to resident complaints...

In response to resident complaints about long duty hours, a new rule has been implemented that states residents cannot work >16 hours per shift.30 This rule has been found to increase quality of life and prevent burnout.30

The amount of time spent on electronic medical records and documentation has been a major complaint from doctors and was identified as a factor contributing to burnout.45 It can act as a time drain that impedes the physician from providing optimal patient care and cause additional stress. This suggests the need for organizations to find solutions to minimize this strain.

A concerning issue reported as an institutional factor and associated with burnout is mistreatment through discrimination, harassment, and physical or verbal abuse. A recent study found 45% of general and vascular surgeons reported being mistreated in some fashion.57 The strategies reported as helpful for institutions to combat mistreatment include resilience training, improved mentorship, and implicit bias training.57

Burnout has been positively correlated with anxiety and depression.6 A recent study reported that 13% of orthopedic surgery residents screened positive for depression.44 Higher levels of burnout and depersonalization have been found to be closely associated with increased rates of suicidal ideation.17 In a study of vascular surgeons, 8% were found to report suicidal ideation, and this increased to 15% among vascular surgeons who had higher levels of depersonalization and emotional exhaustion,58 both of which are associated with burnout. In another study, surgery residents and fellows were found to have lower levels of personal achievement and higher levels of depersonalization, depressive symptoms, alcohol abuse, and suicidal ideation compared to attending physicians and the general population.54 These findings spell out the association between burnout and depressive symptoms among surgeons and emphasize the need for institutions to create a culture that supports the mental health needs of their physicians. Without access to supportive resources, residents resort to alternative methods that may be detrimental in the long run. In a recent study, 17% of residents admitted to using alcohol, including binge drinking, to cope with their stress.4

Burnout and depression are linked to physical health risks such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, substance abuse, and male infertility.6 Exercise has been shown to be beneficial for stress reduction, which can lead to changes in metabolism, inflammation, coagulation, and autonomic function.6 One study of surgeons found aerobic exercise and strength training were associated with lower rates of burnout and a higher quality of life.59

Continue to: The amount of burnout physicians...

The amount of burnout physicians experience can be determined by how they respond to adversities. Adaptive behaviors such as socializing, mindfulness, volunteering, and exercising have been found to be protective against burnout.6,37,54 Resilience training and maintaining low stress at work can decrease burnout.37 These findings highlight the need for physicians to be trained in the appropriate ways to combat their burnout symptoms.

Unfortunately, seeking help by health care professionals to improve mental health has been stigmatized, causing physicians to not seek help and instead resort to other ways to cope with their distress.26,34 While some of these coping methods may be positive, others—such as substance abuse or stress eating—can be maladaptive, leading to a poor quality of life, and in some cases, suicide.54 It is vital that effective mental health services become more accessible and for health care professionals to become aware of their maladaptive behaviors.34

Institutions finding ways to ease the path for their physicians to seek professional help to combat burnout may mitigate its negative impact. One strategy is to embed access to mental health services within regular wellness checks. Institutions can use wellness checks to provide resources to physicians who need it. These interventions have been found to be effective because they give physicians a safe space to seek help and become aware of any factors that could lead to burnout.18 Apart from these direct attempts to combat burnout, program-sponsored social events would also promote social connectedness with colleagues and contribute to a sense of well-being that could help decrease levels of burnout and depression.13 Mentorship has been shown to play a crucial role in decreasing burnout among residents. One study that examined the role of mentorship reported that 55% of residents felt supported, and of these, 96% felt mentorship was critical to their success.18 The role of institutions in helping to improve the well-being of surgeons is highlighted by the finding that increasing workplace support results in psychological resilience that can mitigate burnout at its roots.29

Bottom Line

Surgeons are at risk for burnout, which can impact their mental health and reduce their professional efficacy. Both institutions and surgeons themselves can take action to prevent burnout and treat burnout early when it occurs.

Related Resources

- Pahal P, Lippmann S. Building a better work/life balance. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(8):e1-e2. doi:10.12788/cp.0158

- Gibson R, Hategan A. Physician burnout vs depression: recognize the signs. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(10):41-42.

Burnout is an occupational phenomenon and a syndrome resulting from unsuccessfully managed chronic workplace stress. The characteristic features of burnout include feelings of exhaustion, cynicism, and reduced professional efficacy.1 A career in surgery is associated with demanding and unpredictable work hours in a high-stress environment.2-8 Research indicates that surgeons are at an elevated risk for developing burnout and mental health problems that can compromise patient care. A survey of the fellows of the American College of Surgeons found that 40% of surgeons experience burnout, 30% experience symptoms of depression, and 28% have a mental quality of life (QOL) score greater than one-half an SD below the population norm.9,10 Surgeon burnout was also found to compromise the delivery of medical care.9,10

To prevent serious harm to surgeons and patients, it is critical to understand the causative factors of burnout among surgeons and how they can be addressed. We conducted this systematic review to identify factors linked to burnout across surgical specialties and to suggest ways to mitigate these risk factors.

Methods

To identify studies of burnout among surgeons, we conducted an electronic search of Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid PsycInfo, SCOPUS, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. The headings and keywords used are listed in Supplemental Table 1. Studies met the inclusion criteria if they evaluated residents or attendings, used a tool to measure burnout, and examined any surgical specialty. Studies were excluded if they were published before 2010; were conducted outside the United States; were review articles, commentaries, or abstracts without full text articles; evaluated medical school students; were published in a language other than English; did not use a tool to measure burnout; or examined a nonsurgical specialty. Our analysis was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)11 and is outlined in the Supplemental Figure.

Results

Surgical specialties and burnout

We identified 56 studies2-10,12-58 that focused on specific surgical specialties in relation to burnout. Supplemental Table 22-10,12-58 lists these studies and the surgical specialties they evaluated.

Work/life balance factors

Fifteen studies

Work hours

Fifteen studies2,7,14,20,21,30,34,41,42,44-46,50,52,56 examined work hours and burnout. Of these, 142,7,14,20,21,30,34,42,44-46,50,52,56 found a correlation between increased work hours and burnout, while only 1 study41 found no correlation between these factors.

Medical errors

Six studies2,14,18,43,49,52 discussed the role of burnout in medical errors. Of these, 52,14,43,49,52 reported a correlation between burnout and medical errors, while 1 study18 found no link between burnout and medical errors. The medical errors were self-reported.14,49 They included actions that resulted in patient harm, sample collection error, and errors in medication orders and laboratory test orders.2

Continue to: Institutional and organizational factors

Institutional and organizational factors

Eighteen studies3,13,14,18,20,22,23,29,30,36-38,44,45,47,54,56,57 examined how different organizational factors play a role in burnout. Four studies3,13,20,37 discussed administrative/bureaucratic work, 420,45,54,57 mentioned electronic medical documentation, 222,30 covered duty hour regulations, 318,45,57 discussed mistreatment of physicians, and 613,18,23,44,47,56 described the importance of workplace support in addressing burnout.

Physical and mental health factors

Eighteen studies6,7,14,15,17,20,26,27,29,34,43,44,48,52,54,57-59 discussed aspects of physical and mental health linked to burnout. Among these, 334,43,59 discussed the importance of physical health and focused on how improving physical health can reduce stress and burnout. Three studies6,17,58 noted the prevalence of suicidal ideation in both residents and attendings experiencing prolonged burnout. Five studies26,29,43,44,48 described the systematic barriers that inhibit physicians from getting professional help. Two studies7,27 reported marital status as a factor for burnout; participants who were single reported higher levels of depression and suicidal ideation. Five studies6,14,15,54,57 outlined how depression is associated with burnout.

Strategies to mitigate burnout

Fifteen studies

Take-home points

Research that focused on work/life balance and burnout found excessive time commitment to work is a major factor associated with poor work/life balance. Residents who worked >80 hours a week had a significantly higher burnout rate.56 One study found that 70% of residents reported not getting enough sleep, 30% reported not having enough energy for relationships, and 39% reported that they were not eating or exercising due to time constraints.4 A high correlation was found between the number of hours worked per week and rates of burnout, emotional exhaustion, and depersonalization. Emotional exhaustion and depersonalization are aspects of burnout measured by the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI).24 The excessive time commitment to work not only contributes to burnout but also prevents physicians from getting professional help. In 1 study, both residents (56%) and attendings (24%) reported that 1 of the biggest barriers to getting help for their burnout symptoms was the inability to take time off.34 Research indicates that the hours worked per week and work/home conflicts were independently associated with burnout and career satisfaction.15 A decrease of weekly work hours may give physicians time to meet their responsibilities at work and home, allowing for a decrease in burnout and an increase in career satisfaction.

Increased work hours have also been found to be correlated with medical errors. One study found that those who worked 60 hours per week were significantly less likely to report any major medical errors in the previous 3 months compared with those who worked 80 hours per week.9 The risk for the number of medical errors has been reported as being 2-fold if surgeons are unable to combat the burnout.49 On the other hand, a positive and supportive environment with easy access to resources to combat burnout and burnout prevention programs can reduce the frequency of medical errors, which also can reduce the risk of malpractice, thus further reducing stress and burnout.43

Continue to: In response to resident complaints...

In response to resident complaints about long duty hours, a new rule has been implemented that states residents cannot work >16 hours per shift.30 This rule has been found to increase quality of life and prevent burnout.30

The amount of time spent on electronic medical records and documentation has been a major complaint from doctors and was identified as a factor contributing to burnout.45 It can act as a time drain that impedes the physician from providing optimal patient care and cause additional stress. This suggests the need for organizations to find solutions to minimize this strain.

A concerning issue reported as an institutional factor and associated with burnout is mistreatment through discrimination, harassment, and physical or verbal abuse. A recent study found 45% of general and vascular surgeons reported being mistreated in some fashion.57 The strategies reported as helpful for institutions to combat mistreatment include resilience training, improved mentorship, and implicit bias training.57

Burnout has been positively correlated with anxiety and depression.6 A recent study reported that 13% of orthopedic surgery residents screened positive for depression.44 Higher levels of burnout and depersonalization have been found to be closely associated with increased rates of suicidal ideation.17 In a study of vascular surgeons, 8% were found to report suicidal ideation, and this increased to 15% among vascular surgeons who had higher levels of depersonalization and emotional exhaustion,58 both of which are associated with burnout. In another study, surgery residents and fellows were found to have lower levels of personal achievement and higher levels of depersonalization, depressive symptoms, alcohol abuse, and suicidal ideation compared to attending physicians and the general population.54 These findings spell out the association between burnout and depressive symptoms among surgeons and emphasize the need for institutions to create a culture that supports the mental health needs of their physicians. Without access to supportive resources, residents resort to alternative methods that may be detrimental in the long run. In a recent study, 17% of residents admitted to using alcohol, including binge drinking, to cope with their stress.4

Burnout and depression are linked to physical health risks such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, substance abuse, and male infertility.6 Exercise has been shown to be beneficial for stress reduction, which can lead to changes in metabolism, inflammation, coagulation, and autonomic function.6 One study of surgeons found aerobic exercise and strength training were associated with lower rates of burnout and a higher quality of life.59

Continue to: The amount of burnout physicians...

The amount of burnout physicians experience can be determined by how they respond to adversities. Adaptive behaviors such as socializing, mindfulness, volunteering, and exercising have been found to be protective against burnout.6,37,54 Resilience training and maintaining low stress at work can decrease burnout.37 These findings highlight the need for physicians to be trained in the appropriate ways to combat their burnout symptoms.

Unfortunately, seeking help by health care professionals to improve mental health has been stigmatized, causing physicians to not seek help and instead resort to other ways to cope with their distress.26,34 While some of these coping methods may be positive, others—such as substance abuse or stress eating—can be maladaptive, leading to a poor quality of life, and in some cases, suicide.54 It is vital that effective mental health services become more accessible and for health care professionals to become aware of their maladaptive behaviors.34

Institutions finding ways to ease the path for their physicians to seek professional help to combat burnout may mitigate its negative impact. One strategy is to embed access to mental health services within regular wellness checks. Institutions can use wellness checks to provide resources to physicians who need it. These interventions have been found to be effective because they give physicians a safe space to seek help and become aware of any factors that could lead to burnout.18 Apart from these direct attempts to combat burnout, program-sponsored social events would also promote social connectedness with colleagues and contribute to a sense of well-being that could help decrease levels of burnout and depression.13 Mentorship has been shown to play a crucial role in decreasing burnout among residents. One study that examined the role of mentorship reported that 55% of residents felt supported, and of these, 96% felt mentorship was critical to their success.18 The role of institutions in helping to improve the well-being of surgeons is highlighted by the finding that increasing workplace support results in psychological resilience that can mitigate burnout at its roots.29

Bottom Line

Surgeons are at risk for burnout, which can impact their mental health and reduce their professional efficacy. Both institutions and surgeons themselves can take action to prevent burnout and treat burnout early when it occurs.

Related Resources

- Pahal P, Lippmann S. Building a better work/life balance. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(8):e1-e2. doi:10.12788/cp.0158

- Gibson R, Hategan A. Physician burnout vs depression: recognize the signs. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(10):41-42.

1. World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD). 11th ed. World Health Organization; 2019.

2. Coombs DM, Lanni MA, Fosnot J, et al. Professional burnout in United States plastic surgery residents: is it a legitimate concern? Aesthet Surg J. 2020;40(7):802-810.

3. Klimo P Jr, DeCuypere M, Ragel BT, et al. Career satisfaction and burnout among U.S. neurosurgeons: a feasibility and pilot study. World Neurosurg. 2013;80(5):e59-e68.

4. Ha GQ, Go JT, Murayama KM, et al. Identifying sources of stress across years of general surgery residency. Hawaii J Health Soc Welf. 2020;79(3):75-81.

5. Khalafallah AM, Lam S, Gami A, et al. A national survey on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic upon burnout and career satisfaction among neurosurgery residents. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;80:137-142.

6. Al-Humadi SM, Cáceda R, Bronson B, et al. Orthopaedic surgeon mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Geriatric Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2021;12:21514593211035230.

7. Larson DP, Carlson ML, Lohse CM, et al. Prevalence of and associations with distress and professional burnout among otolaryngologists: part I, trainees. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;164(5):1019-1029.

8. Streu R, Hawley S, Gay A, et al. Satisfaction with career choice among U.S. plastic surgeons: results from a national survey. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(2):636-642.

9. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps GJ, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2009;250(3):463-471.

10. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995-1000.

11. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336-341.

12. Yesantharao P, Lee E, Kraenzlin F, et al. Surgical block time satisfaction: a multi-institutional experience across twelve surgical disciplines. Perioperative Care Operating Room Manage. 2020;21:100128.

13. Nituica C, Bota OA, Blebea J. Specialty differences in resident resilience and burnout - a national survey. Am J Surg. 2021;222(2):319-328.

14. Balch CM, Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye L, et al. Surgeon distress as calibrated by hours worked and nights on call. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211(5):609-619.

15. Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Satele D, Sloan J, Freischlag J. Relationship between work-home conflicts and burnout among American surgeons: a comparison by sex. Arch Surg. 2011;146(2):211-217.

16. Mahoney ST, Irish W, Strassle PD, et al. Practice characteristics and job satisfaction of private practice and academic surgeons. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(3):247-254.

17. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Dyrbye L, et al. Special report: suicidal ideation among American surgeons. Arch Surg. 2011;146(1):54-62.

18. Chow OS, Sudarshan M, Maxfield MW, et al. National survey of burnout and distress among cardiothoracic surgery trainees. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021;111(6):2066-2071.

19. Lam C, Kim Y, Cruz M, et al. Burnout and resiliency in Mohs surgeons: a survey study. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7(3):319-322.

20. Carlson ML, Larson DP, O’Brien EK, et al. Prevalence of and associations with distress and professional burnout among otolaryngologists: part II, attending physicians. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;164(5):1030-1039.

21. Nida AM, Googe BJ, Lewis AF, et al. Resident fatigue in otolaryngology residents: a Web based survey. Am J Otolaryngol. 2016;37(3):210-216.

22. Antiel RM, Reed DA, Van Arendonk KJ, et al. Effects of duty hour restrictions on core competencies, education, quality of life, and burnout among general surgery interns. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(5):448-455.

23. Appelbaum NP, Lee N, Amendola M, et al. Surgical resident burnout and job satisfaction: the role of workplace climate and perceived support. J Surg Res. 2019;234:20-25.

24. Elmore LC, Jeffe DB, Jin L, et al. National survey of burnout among US general surgery residents. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;223(3):440-451.

25. Garcia DI, Pannuccio A, Gallegos J, et al. Resident-driven wellness initiatives improve resident wellness and perception of work environment. J Surg Res. 2021;258:8-16.

26. Hochberg MS, Berman RS, Kalet AL, et al. The stress of residency: recognizing the signs of depression and suicide in you and your fellow residents. Am J Surg. 2013;205(2):141-146.

27. Kurbatov V, Shaughnessy M, Baratta V, et al. Application of advanced bioinformatics to understand and predict burnout among surgical trainees. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(3):499-507.

28. Leach PK, Nygaard RM, Chipman JG, et al. Impostor phenomenon and burnout in general surgeons and general surgery residents. J Surg Educ. 2019;76(1):99-106.

29. Lebares CC, Greenberg AL, Ascher NL, et al. Exploration of individual and system-level well-being initiatives at an academic surgical residency program: a mixed-methods study. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2032676.

30. Lindeman BM, Sacks BC, Hirose K, et al. Multifaceted longitudinal study of surgical resident education, quality of life, and patient care before and after July 2011. J Surg Educ. 2013;70(6):769-776.

31. Rasmussen JM, Najarian MM, Ties JS, et al. Career satisfaction, gender bias, and work-life balance: a contemporary assessment of general surgeons. J Surg Educ. 2021;78(1):119-125.

32. Smeds MR, Janko MR, Allen S, et al. Burnout and its relationship with perceived stress, self-efficacy, depression, social support, and programmatic factors in general surgery residents. Am J Surg. 2020;219(6):907-912.

33. Wetzel CM, George A, Hanna GB, et al. Stress management training for surgeons--a randomized, controlled, intervention study. Ann Surg. 2011;253(3):488-494.

34. Williford ML, Scarlet S, Meyers MO, et al. Multiple-institution comparison of resident and faculty perceptions of burnout and depression during surgical training. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(8):705-711.

35. Zubair MH, Hussain LR, Williams KN, et al. Work-related quality of life of US general surgery residents: is it really so bad? J Surg Educ. 2017;74(6):e138-e146.

36. Song Y, Swendiman RA, Shannon AB, et al. Can we coach resilience? An evaluation of professional resilience coaching as a well-being initiative for surgical interns. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(6):1481-1489.

37. Morrell NT, Sears ED, Desai MJ, et al. A survey of burnout among members of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand. J Hand Surg Am. 2020;45(7):573-581.e516.

38. Khalafallah AM, Lam S, Gami A, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among attending neurosurgeons during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020;198:106193.

39. McAbee JH, Ragel BT, McCartney S, et al. Factors associated with career satisfaction and burnout among US neurosurgeons: results of a nationwide survey. J Neurosurg. 2015;123(1):161-173.

40. Shakir HJ, McPheeters MJ, Shallwani H, et al. The prevalence of burnout among US neurosurgery residents. Neurosurgery. 2018;83(3):582-590.

41. Govardhan LM, Pinelli V, Schnatz PF. Burnout, depression and job satisfaction in obstetrics and gynecology residents. Conn Med. 2012;76(7):389-395.

42. Driesman AS, Strauss EJ, Konda SR, et al. Factors associated with orthopaedic resident burnout: a pilot study. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28(21):900-906.

43. Lichstein PM, He JK, Estok D, et al. What is the prevalence of burnout, depression, and substance use among orthopaedic surgery residents and what are the risk factors? A collaborative orthopaedic educational research group survey study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020;478(8):1709-1718.

44. Somerson JS, Patton A, Ahmed AA, et al. Burnout among United States orthopaedic surgery residents. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(4):961-968.

45. Verret CI, Nguyen J, Verret C, et al. How do areas of work life drive burnout in orthopaedic attending surgeons, fellows, and residents? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2021;479(2):251-262.

46. Sarosi A, Coakley BA, Berman L, et al. A cross-sectional analysis of compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction in pediatric surgeons in the U.S. J Pediatr Surg. 2021;56(8):1276-1284.

47. Crowe CS, Lopez J, Morrison SD, et al. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on resident education and wellness: a national survey of plastic surgery residents. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;148(3):462e-474e.

48. Qureshi HA, Rawlani R, Mioton LM, et al. Burnout phenomenon in U.S. plastic surgeons: risk factors and impact on quality of life. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(2):619-626.

49. Streu R, Hansen J, Abrahamse P, et al. Professional burnout among US plastic surgeons: results of a national survey. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;72(3):346-350.

50. Zhang JQ, Riba L, Magrini L, ET AL. Assessing burnout and professional fulfillment in breast surgery: results from a national survey of the American Society of Breast Surgeons. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(10):3089-3098.

51. Balch CM, Shanafelt TD, Sloan J, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among surgical oncologists compared with other surgical specialties. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(1):16-25.

52. Wu D, Gross B, Rittenhouse K, et al. A preliminary analysis of compassion fatigue in a surgeon population: are female surgeons at heightened risk? Am Surg. 2017;83(11):1302-1307.

53. Cheng JW, Wagner H, Hernandez BC, et al. Stressors and coping mechanisms related to burnout within urology. Urology. 2020;139:27-36.

54. Koo K, Javier-DesLoges JF, Fang R, ET AL. Professional burnout, career choice regret, and unmet needs for well-being among urology residents. Urology. 2021;157:57-63.

55. Janko MR, Smeds MR. Burnout, depression, perceived stress, and self-efficacy in vascular surgery trainees. J Vasc Surg. 2019;69(4):1233-1242.

56. Coleman DM, Money SR, Meltzer AJ, et al. Vascular surgeon wellness and burnout: a report from the Society for Vascular Surgery Wellness Task Force. J Vasc Surg. 2021;73(6):1841-1850.e3.

57. Barrack RL, Miller LS, Sotile WM, et al. Effect of duty hour standards on burnout among orthopaedic surgery residents. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;449:134-137.

58. Chia MC, Hu YY, Li RD, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for burnout in U.S. vascular surgery trainees. J Vasc Surg. 2022;75(1):308-315.e4.

59. Shanafelt TD, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, et al. Avoiding burnout: the personal health habits and wellness practices of US surgeons. Ann Surg. 2012;255(4):625-633.

1. World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD). 11th ed. World Health Organization; 2019.

2. Coombs DM, Lanni MA, Fosnot J, et al. Professional burnout in United States plastic surgery residents: is it a legitimate concern? Aesthet Surg J. 2020;40(7):802-810.

3. Klimo P Jr, DeCuypere M, Ragel BT, et al. Career satisfaction and burnout among U.S. neurosurgeons: a feasibility and pilot study. World Neurosurg. 2013;80(5):e59-e68.

4. Ha GQ, Go JT, Murayama KM, et al. Identifying sources of stress across years of general surgery residency. Hawaii J Health Soc Welf. 2020;79(3):75-81.

5. Khalafallah AM, Lam S, Gami A, et al. A national survey on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic upon burnout and career satisfaction among neurosurgery residents. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;80:137-142.

6. Al-Humadi SM, Cáceda R, Bronson B, et al. Orthopaedic surgeon mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Geriatric Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2021;12:21514593211035230.

7. Larson DP, Carlson ML, Lohse CM, et al. Prevalence of and associations with distress and professional burnout among otolaryngologists: part I, trainees. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;164(5):1019-1029.

8. Streu R, Hawley S, Gay A, et al. Satisfaction with career choice among U.S. plastic surgeons: results from a national survey. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(2):636-642.

9. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps GJ, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2009;250(3):463-471.

10. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995-1000.

11. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336-341.

12. Yesantharao P, Lee E, Kraenzlin F, et al. Surgical block time satisfaction: a multi-institutional experience across twelve surgical disciplines. Perioperative Care Operating Room Manage. 2020;21:100128.

13. Nituica C, Bota OA, Blebea J. Specialty differences in resident resilience and burnout - a national survey. Am J Surg. 2021;222(2):319-328.

14. Balch CM, Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye L, et al. Surgeon distress as calibrated by hours worked and nights on call. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211(5):609-619.

15. Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Satele D, Sloan J, Freischlag J. Relationship between work-home conflicts and burnout among American surgeons: a comparison by sex. Arch Surg. 2011;146(2):211-217.

16. Mahoney ST, Irish W, Strassle PD, et al. Practice characteristics and job satisfaction of private practice and academic surgeons. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(3):247-254.

17. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Dyrbye L, et al. Special report: suicidal ideation among American surgeons. Arch Surg. 2011;146(1):54-62.

18. Chow OS, Sudarshan M, Maxfield MW, et al. National survey of burnout and distress among cardiothoracic surgery trainees. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021;111(6):2066-2071.

19. Lam C, Kim Y, Cruz M, et al. Burnout and resiliency in Mohs surgeons: a survey study. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7(3):319-322.

20. Carlson ML, Larson DP, O’Brien EK, et al. Prevalence of and associations with distress and professional burnout among otolaryngologists: part II, attending physicians. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;164(5):1030-1039.

21. Nida AM, Googe BJ, Lewis AF, et al. Resident fatigue in otolaryngology residents: a Web based survey. Am J Otolaryngol. 2016;37(3):210-216.

22. Antiel RM, Reed DA, Van Arendonk KJ, et al. Effects of duty hour restrictions on core competencies, education, quality of life, and burnout among general surgery interns. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(5):448-455.

23. Appelbaum NP, Lee N, Amendola M, et al. Surgical resident burnout and job satisfaction: the role of workplace climate and perceived support. J Surg Res. 2019;234:20-25.

24. Elmore LC, Jeffe DB, Jin L, et al. National survey of burnout among US general surgery residents. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;223(3):440-451.

25. Garcia DI, Pannuccio A, Gallegos J, et al. Resident-driven wellness initiatives improve resident wellness and perception of work environment. J Surg Res. 2021;258:8-16.

26. Hochberg MS, Berman RS, Kalet AL, et al. The stress of residency: recognizing the signs of depression and suicide in you and your fellow residents. Am J Surg. 2013;205(2):141-146.

27. Kurbatov V, Shaughnessy M, Baratta V, et al. Application of advanced bioinformatics to understand and predict burnout among surgical trainees. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(3):499-507.

28. Leach PK, Nygaard RM, Chipman JG, et al. Impostor phenomenon and burnout in general surgeons and general surgery residents. J Surg Educ. 2019;76(1):99-106.

29. Lebares CC, Greenberg AL, Ascher NL, et al. Exploration of individual and system-level well-being initiatives at an academic surgical residency program: a mixed-methods study. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2032676.

30. Lindeman BM, Sacks BC, Hirose K, et al. Multifaceted longitudinal study of surgical resident education, quality of life, and patient care before and after July 2011. J Surg Educ. 2013;70(6):769-776.

31. Rasmussen JM, Najarian MM, Ties JS, et al. Career satisfaction, gender bias, and work-life balance: a contemporary assessment of general surgeons. J Surg Educ. 2021;78(1):119-125.

32. Smeds MR, Janko MR, Allen S, et al. Burnout and its relationship with perceived stress, self-efficacy, depression, social support, and programmatic factors in general surgery residents. Am J Surg. 2020;219(6):907-912.

33. Wetzel CM, George A, Hanna GB, et al. Stress management training for surgeons--a randomized, controlled, intervention study. Ann Surg. 2011;253(3):488-494.

34. Williford ML, Scarlet S, Meyers MO, et al. Multiple-institution comparison of resident and faculty perceptions of burnout and depression during surgical training. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(8):705-711.

35. Zubair MH, Hussain LR, Williams KN, et al. Work-related quality of life of US general surgery residents: is it really so bad? J Surg Educ. 2017;74(6):e138-e146.

36. Song Y, Swendiman RA, Shannon AB, et al. Can we coach resilience? An evaluation of professional resilience coaching as a well-being initiative for surgical interns. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(6):1481-1489.

37. Morrell NT, Sears ED, Desai MJ, et al. A survey of burnout among members of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand. J Hand Surg Am. 2020;45(7):573-581.e516.

38. Khalafallah AM, Lam S, Gami A, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among attending neurosurgeons during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020;198:106193.

39. McAbee JH, Ragel BT, McCartney S, et al. Factors associated with career satisfaction and burnout among US neurosurgeons: results of a nationwide survey. J Neurosurg. 2015;123(1):161-173.

40. Shakir HJ, McPheeters MJ, Shallwani H, et al. The prevalence of burnout among US neurosurgery residents. Neurosurgery. 2018;83(3):582-590.

41. Govardhan LM, Pinelli V, Schnatz PF. Burnout, depression and job satisfaction in obstetrics and gynecology residents. Conn Med. 2012;76(7):389-395.

42. Driesman AS, Strauss EJ, Konda SR, et al. Factors associated with orthopaedic resident burnout: a pilot study. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28(21):900-906.

43. Lichstein PM, He JK, Estok D, et al. What is the prevalence of burnout, depression, and substance use among orthopaedic surgery residents and what are the risk factors? A collaborative orthopaedic educational research group survey study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020;478(8):1709-1718.

44. Somerson JS, Patton A, Ahmed AA, et al. Burnout among United States orthopaedic surgery residents. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(4):961-968.

45. Verret CI, Nguyen J, Verret C, et al. How do areas of work life drive burnout in orthopaedic attending surgeons, fellows, and residents? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2021;479(2):251-262.

46. Sarosi A, Coakley BA, Berman L, et al. A cross-sectional analysis of compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction in pediatric surgeons in the U.S. J Pediatr Surg. 2021;56(8):1276-1284.

47. Crowe CS, Lopez J, Morrison SD, et al. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on resident education and wellness: a national survey of plastic surgery residents. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;148(3):462e-474e.

48. Qureshi HA, Rawlani R, Mioton LM, et al. Burnout phenomenon in U.S. plastic surgeons: risk factors and impact on quality of life. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(2):619-626.

49. Streu R, Hansen J, Abrahamse P, et al. Professional burnout among US plastic surgeons: results of a national survey. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;72(3):346-350.

50. Zhang JQ, Riba L, Magrini L, ET AL. Assessing burnout and professional fulfillment in breast surgery: results from a national survey of the American Society of Breast Surgeons. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(10):3089-3098.

51. Balch CM, Shanafelt TD, Sloan J, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among surgical oncologists compared with other surgical specialties. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(1):16-25.

52. Wu D, Gross B, Rittenhouse K, et al. A preliminary analysis of compassion fatigue in a surgeon population: are female surgeons at heightened risk? Am Surg. 2017;83(11):1302-1307.

53. Cheng JW, Wagner H, Hernandez BC, et al. Stressors and coping mechanisms related to burnout within urology. Urology. 2020;139:27-36.

54. Koo K, Javier-DesLoges JF, Fang R, ET AL. Professional burnout, career choice regret, and unmet needs for well-being among urology residents. Urology. 2021;157:57-63.

55. Janko MR, Smeds MR. Burnout, depression, perceived stress, and self-efficacy in vascular surgery trainees. J Vasc Surg. 2019;69(4):1233-1242.

56. Coleman DM, Money SR, Meltzer AJ, et al. Vascular surgeon wellness and burnout: a report from the Society for Vascular Surgery Wellness Task Force. J Vasc Surg. 2021;73(6):1841-1850.e3.

57. Barrack RL, Miller LS, Sotile WM, et al. Effect of duty hour standards on burnout among orthopaedic surgery residents. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;449:134-137.

58. Chia MC, Hu YY, Li RD, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for burnout in U.S. vascular surgery trainees. J Vasc Surg. 2022;75(1):308-315.e4.

59. Shanafelt TD, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, et al. Avoiding burnout: the personal health habits and wellness practices of US surgeons. Ann Surg. 2012;255(4):625-633.

Brain damage from recurrent relapses of bipolar mania: A call for early LAI use

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a psychotic mood disorder. Like schizophrenia, it has been shown to be associated with significant degeneration and structural brain abnormalities with multiple relapses.1,2

Just as I have always advocated preventing recurrences in schizophrenia by using long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotic formulations immediately after the first episode to prevent psychotic relapses and progressive brain damage,3 I strongly recommend using LAIs right after hospital discharge from the first manic episode. It is the most rational management approach for bipolar mania given the grave consequences of multiple episodes, which are so common in this psychotic mood disorder due to poor medication adherence.

In contrast to the depressive episodes of BD I, where patients have insight into their depression and seek psychiatric treatment, during a manic episode patients often have no insight (anosognosia) that they suffer from a serious brain disorder, and refuse treatment.4 In addition, young patients with BD I frequently discontinue their oral mood stabilizer or second-generation antipsychotic (which are approved for mania) because they miss the blissful euphoria and the buoyant physical and mental energy of their manic episodes. They are completely oblivious to (and uninformed about) the grave neurobiological damage of further manic episodes, which can condemn them to clinical, functional, and cognitive deterioration. These patients are also likely to become treatment-resistant, which has been labeled as “the malignant transformation of bipolar disorder.”5

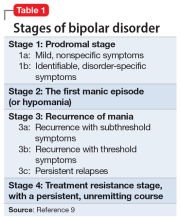

The evidence for progressive brain tissue loss, clinical deterioration, functional decline, and treatment resistance is abundant.6 I was the lead investigator of the first study to report ventricular dilatation (which is a proxy for cortical atrophy) in bipolar mania,7 a discovery that was subsequently replicated by 2 dozen researchers. This was followed by numerous neuroimaging studies reporting a loss of volume across multiple brain regions, including the frontal lobe, temporal lobe, cerebellum, thalamus, hippocampus, and basal ganglia. BD is heterogeneous8 with 4 stages (Table 19), and patients experience progressively worse brain structure and function with each stage.

Many patients with bipolar mania end up with poor clinical and functional outcomes, even when they respond well to initial treatment with lithium, anticonvulsant mood stabilizers, or second-generation antipsychotics. With their intentional nonadherence to oral medications leading to multiple recurrent relapses, these patients are at serious risk for neuroprogression and brain atrophic changes driven by multiple factors: inflammatory cytokines, increased cortical steroids, decreased neurotrophins, deceased neurogenesis, increased oxidative stress, and mitochondrial energy dysfunction. The consequences include progressive shortening of the interval between episodes with every relapse and loss of responsiveness to pharmacotherapy as the illness progresses.6,10 Predictors of a downhill progression include genetic vulnerability, perinatal complication during fetal life, childhood trauma (physical, sexual, emotional, or neglect), substance use, stress, psychiatric/medial comorbidities, and especially the number of episodes.9,11

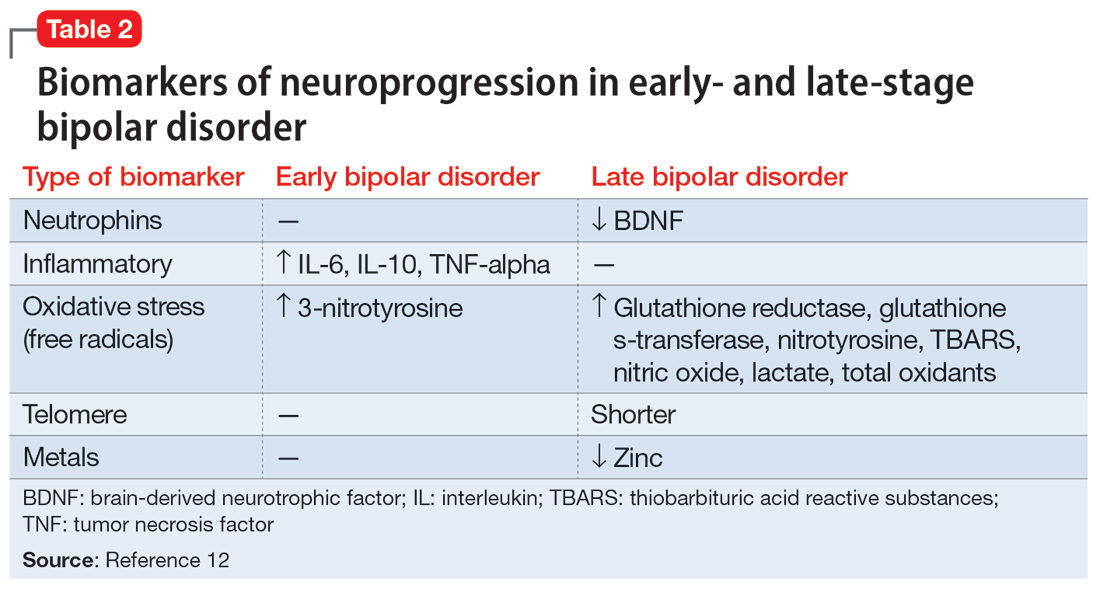

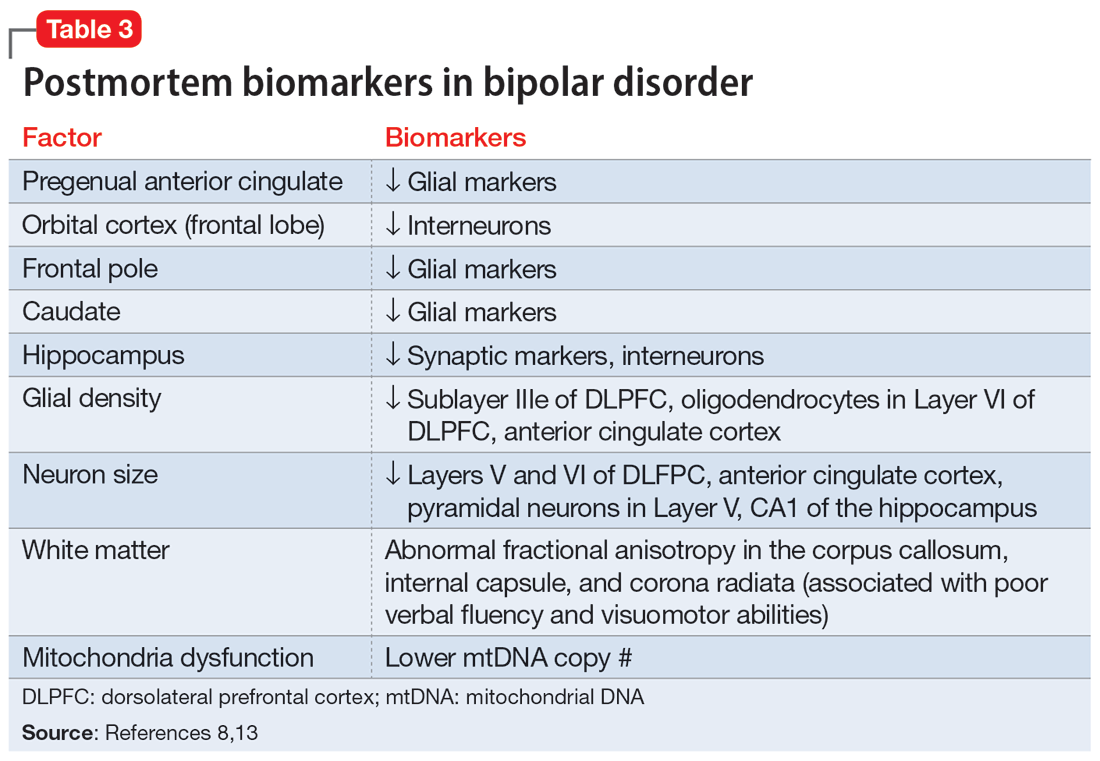

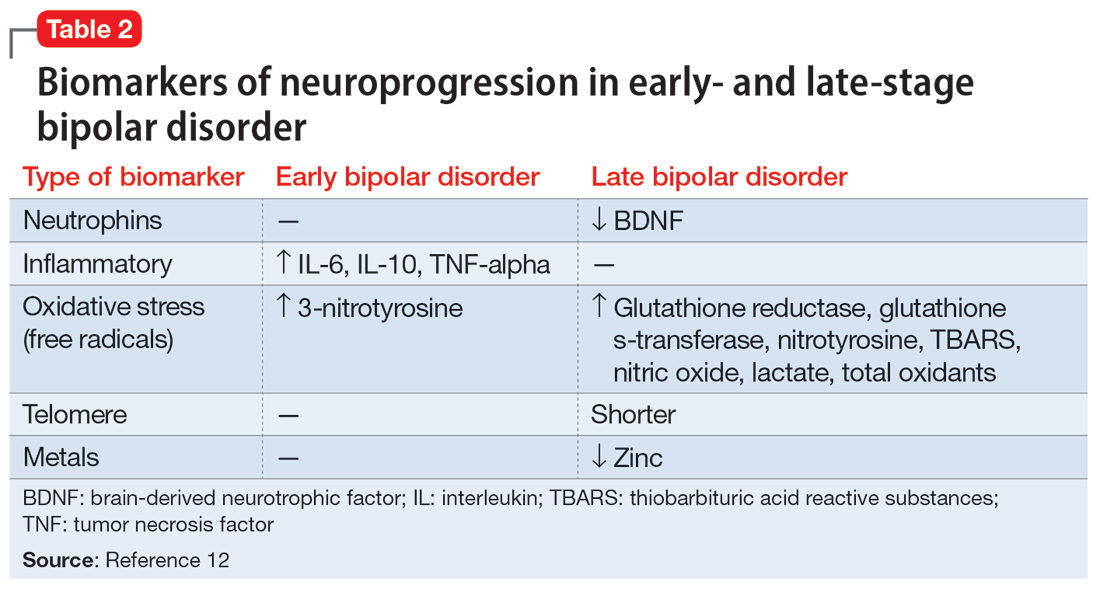

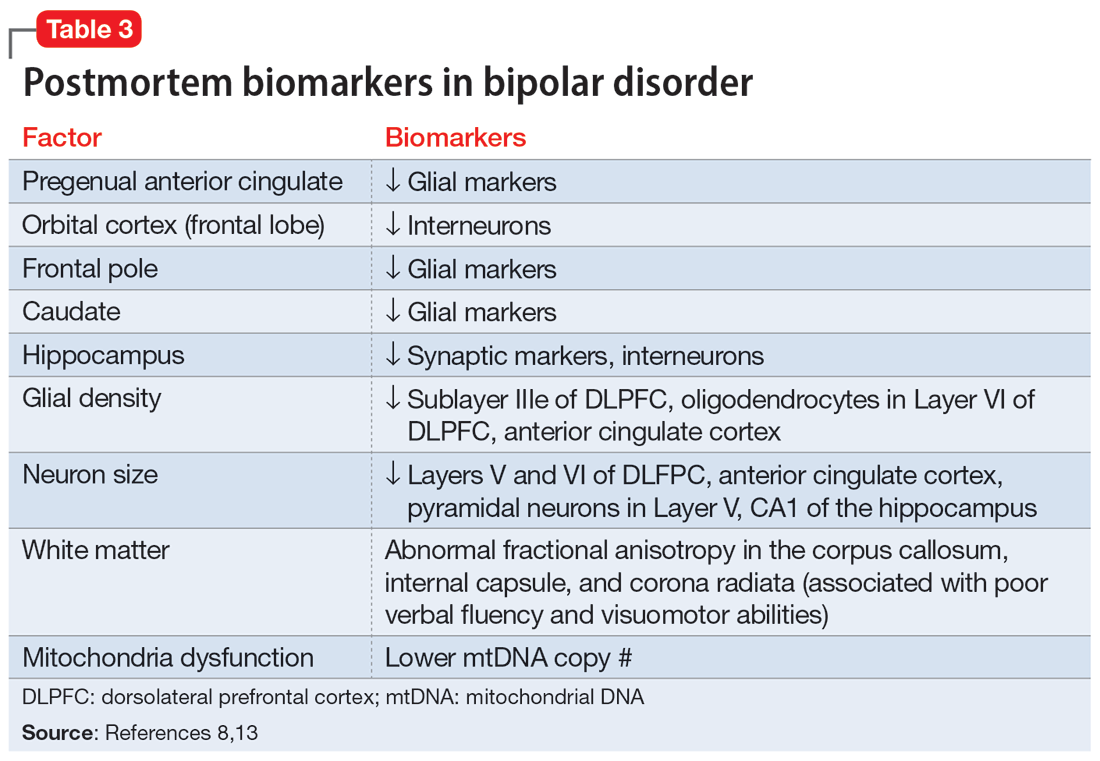

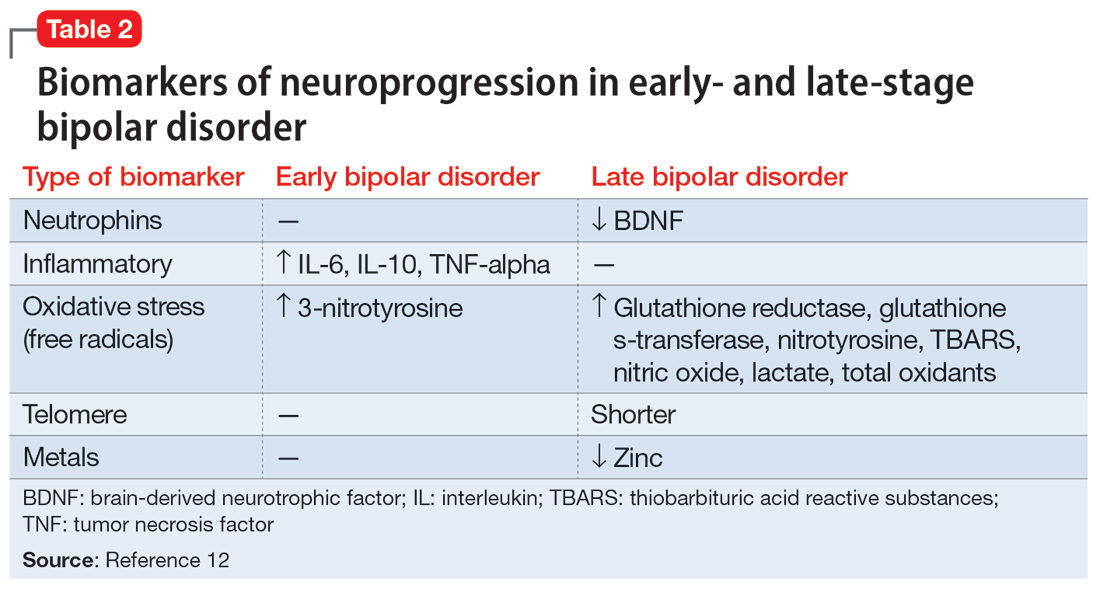

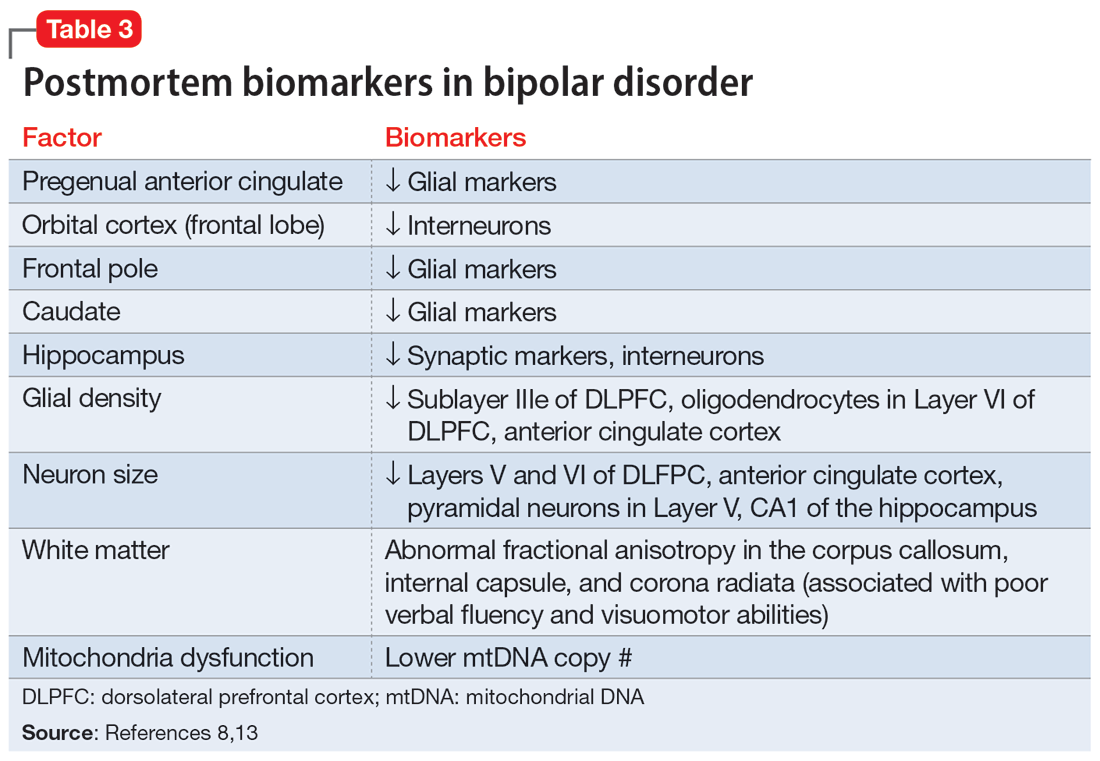

Biomarkers have been reported in both the early and late stages of BD (Table 212) as well as in postmortem studies (Table 38,13). They reflect the progressive neurodegenerative nature of recurrent BD I episodes as the disorder moves to the advanced stages. I summarize these stages in Table 19 and Table 212 for the benefit of psychiatric clinicians who do not have access to the neuroscience journals where such findings are usually published.

BD I is also believed to be associated with accelerated aging14,15 and an increased risk for dementia16 or cognitive deterioration.17 There is also an emerging hypothesis that neuroprogression and treatment resistance in BD is frequently associated with insulin resistance,18 peripheral inflammation,19 and blood-brain barrier permeability dysfunction.20

The bottom line is that like patients with schizophrenia, where relapses lead to devastating consequences,21 those with BD are at a similar high risk for neuroprogression, which includes atrophy in several brain regions, treatment resistance, and functional disability. This underscores the urgency for implementing LAI therapy early in the illness, when the first manic episode (Stage 2) emerges after the prodrome (Stage 1). This is the best strategy to preserve brain health in persons with BD22 and to allow them to remain functional with their many intellectual gifts, such as eloquence, poetry, artistic talents, humor, and social skills. It is unfortunate that the combination of patients’ and clinicians’ reluctance to use an LAI early in the illness dooms many patients with BD to a potentially avoidable malignant outcome.

1. Strakowski SM, DelBello MP, Adler CM. The functional neuroanatomy of bipolar disorder: a review of neuroimaging findings. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10(1):105-106.

2. Kapezinski NS, Mwangi B, Cassidy RM, et al. Neuroprogression and illness trajectories in bipolar disorder. Expert Rev Neurother. 2017;17(3):277-285.

3. Nasrallah HA. Errors of omission and commission in psychiatric practice. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(11):4,6,8.

4. Nasrallah HA. Is anosognosia a delusion, a negative symptom, or a cognitive deficit? Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(1):6-8,14.

5. Post RM. Preventing the malignant transformation of bipolar disorder. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1197-1198.

6. Berk M, Kapczinski F, Andreazza AC, et al. Pathways underlying neuroprogression in bipolar disorder: focus on inflammation, oxidative stress and neurotrophic factors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35(3):804-817.

7. Nasrallah HA, McCalley-Whitters M, Jacoby CG. Cerebral ventricular enlargement in young manic males. A controlled CT study. J Affective Dis. 1982;4(1):15-19.

8. Maletic V, Raison C. Integrated neurobiology of bipolar disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:98.

9. Berk M. Neuroprogression: pathways to progressive brain changes in bipolar disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12(4):441-445.

10. Berk M, Conus P, Kapczinski F, et al. From neuroprogression to neuroprotection: implications for clinical care. Med J Aust. 2010;193(S4):S36-S40.

11. Passos IC, Mwangi B, Vieta E, et al. Areas of controversy in neuroprogression in bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;134(2):91-103.

12. Fries GR, Pfaffenseller B, Stertz L, et al. Staging and neuroprogression in bipolar disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14(6):667-675.

13. Manji HK, Drevets WC, Charney DS. The cellular neurobiology of depression. Nat Med. 2001;7(5):541-547.

14. Fries GR, Zamzow MJ, Andrews T, et al. Accelerated aging in bipolar disorder: a comprehensive review of molecular findings and their clinical implications. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;112:107-116.

15. Fries GR, Bauer IE, Scaini G, et al. Accelerated hippocampal biological aging in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Dis. 2020;22(5):498-507.

16. Diniz BS, Teixeira AL, Cao F, et al. History of bipolar disorder and the risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25(4):357-362.

17. Bauer IE, Ouyang A, Mwangi B, et al. Reduced white matter integrity and verbal fluency impairment in young adults with bipolar disorder: a diffusion tensor imaging study. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;62:115-122.

18. Calkin CV. Insulin resistance takes center stage: a new paradigm in the progression of bipolar disorder. Ann Med. 2019;51(5-6):281-293.

19. Grewal S, McKinlay S, Kapczinski F, et al. Biomarkers of neuroprogression and late staging in bipolar disorder: a systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2023;57(3):328-343.

20. Calkin C, McClelland C, Cairns K, et al. Insulin resistance and blood-brain barrier dysfunction underlie neuroprogression in bipolar disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:636174.

21. Nasrallah HA. 10 devastating consequences of psychotic relapses. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(5):9-12.

22. Berk M, Hallam K, Malhi GS, et al. Evidence and implications for early intervention in bipolar disorder. J Ment Health. 2010;19(2):113-126.

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a psychotic mood disorder. Like schizophrenia, it has been shown to be associated with significant degeneration and structural brain abnormalities with multiple relapses.1,2

Just as I have always advocated preventing recurrences in schizophrenia by using long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotic formulations immediately after the first episode to prevent psychotic relapses and progressive brain damage,3 I strongly recommend using LAIs right after hospital discharge from the first manic episode. It is the most rational management approach for bipolar mania given the grave consequences of multiple episodes, which are so common in this psychotic mood disorder due to poor medication adherence.

In contrast to the depressive episodes of BD I, where patients have insight into their depression and seek psychiatric treatment, during a manic episode patients often have no insight (anosognosia) that they suffer from a serious brain disorder, and refuse treatment.4 In addition, young patients with BD I frequently discontinue their oral mood stabilizer or second-generation antipsychotic (which are approved for mania) because they miss the blissful euphoria and the buoyant physical and mental energy of their manic episodes. They are completely oblivious to (and uninformed about) the grave neurobiological damage of further manic episodes, which can condemn them to clinical, functional, and cognitive deterioration. These patients are also likely to become treatment-resistant, which has been labeled as “the malignant transformation of bipolar disorder.”5

The evidence for progressive brain tissue loss, clinical deterioration, functional decline, and treatment resistance is abundant.6 I was the lead investigator of the first study to report ventricular dilatation (which is a proxy for cortical atrophy) in bipolar mania,7 a discovery that was subsequently replicated by 2 dozen researchers. This was followed by numerous neuroimaging studies reporting a loss of volume across multiple brain regions, including the frontal lobe, temporal lobe, cerebellum, thalamus, hippocampus, and basal ganglia. BD is heterogeneous8 with 4 stages (Table 19), and patients experience progressively worse brain structure and function with each stage.