User login

Advance care planning codes not being used

Starting in 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services began paying physicians for advance care planning discussions with the approval of two new codes: 99497 and 99498. The codes pay about $86 for the first 30 minutes of a face-to-face conversation with a patient, family member, and/or surrogate and about $75 for additional sessions. Services can be furnished in both inpatient and ambulatory settings, and payment is not limited to particular physician specialties.

In 2016, health care professionals in New England (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont) billed Medicare 26,522 times for the advance care planning (ACP) codes for a total of 24,536 patients, which represented less than 1% of Medicare beneficiaries in New England at the time, according to Kimberly Pelland, MPH, of Healthcentric Advisors, Providence, R.I., and her colleagues. Most claims were billed in the office, followed by in nursing homes, and in hospitals; 40% of conversations occurred during an annual wellness visit (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 March 11. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8107).

Internists billed Medicare the most for ACP claims (65%), followed by family physicians (22%) gerontologists (5%), and oncologist/hematologists (0.3%), according to the analysis based on 2016 Medicare claims data and Census Bureau data. A greater proportion of patients with ACP claims were female, aged 85 years or older, enrolled in hospice, and died in the study year. Patients had higher odds of having an ACP claim if they were older and had lower income, and if they had cancer, heart failure, stroke, chronic kidney disease, or dementia. Male patients who were Asian, black, and Hispanic had lower chances of having an ACP claim.

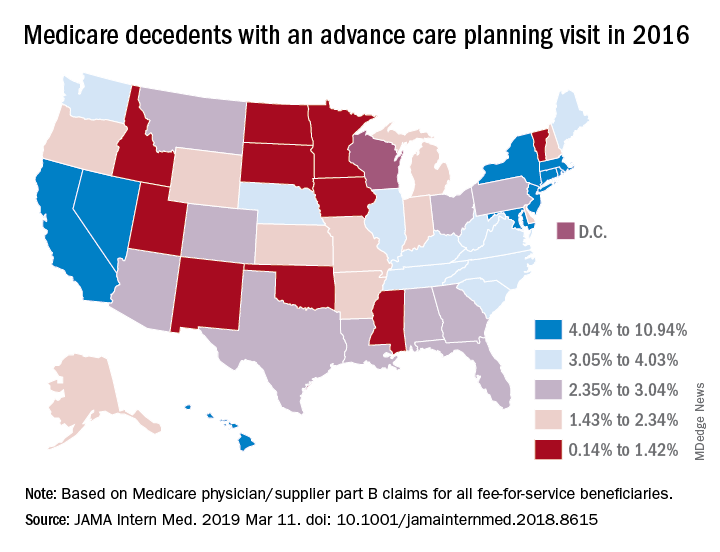

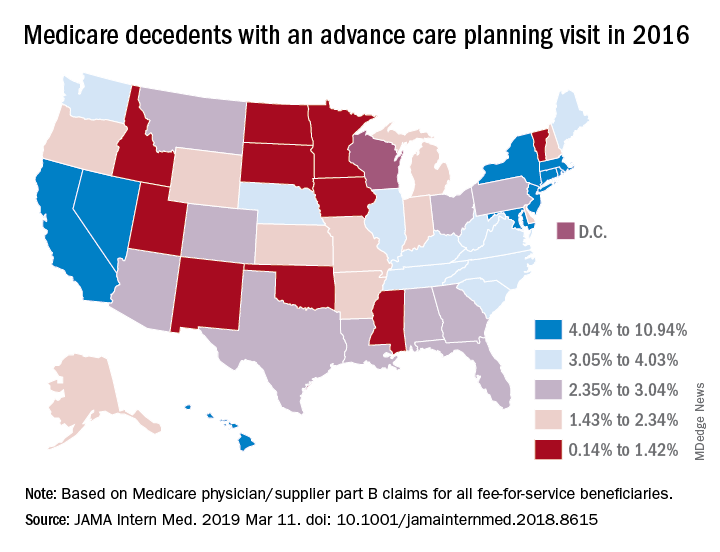

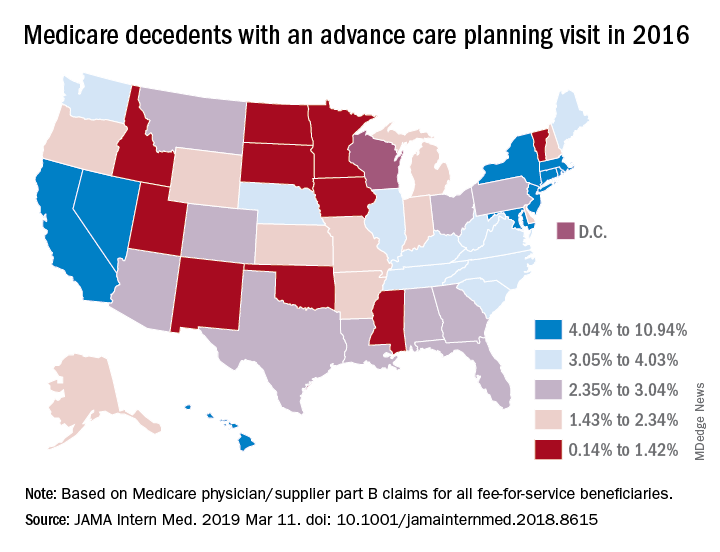

In a related study, Emmanuelle Belanger, PhD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and her colleagues examined national Medicare data from 2016 to the third quarter of 2017. Across the United States, 2% of Medicare patients aged 65 years and older received advance care planning services that were billed under the ACP codes (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 March 11. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8615). Visits billed under the ACP codes increased from 538,275 to 633,214 during the same time period. Claim rates were higher among patients who died within the study period, reaching 3% in 2016 and 6% in 2017. The percentage of decedents with an ACP billed visit varied strongly across states, with states such as North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming having the fewest ACP visits billed and states such as California and Nevada having the most. ACP billed visits increased in all settings in 2017, but primarily in hospitals and nursing homes. Nationally, internists billed the codes most (48%), followed by family physicians (28%).

While the two studies indicate low usage of the ACP codes, many physicians are discussing advance care planning with their patients, said Mary M. Newman, MD, an internist based in Lutherville, Md., and former American College of Physicians adviser to the American Medical Association Relative Scale Value Update Committee (RUC).

“What cannot be captured by tracking under Medicare claims data are those shorter conversations that we have frequently,” Dr. Newman said in an interview. “If we have a short conversation about advance care planning, it gets folded into our evaluation and management visit. It’s not going to be separately billed.”

At the same time, some patients are not ready to discuss end-of-life options and decline the discussions when asked, Dr. Newman said. Particularly for healthier patients, end of life care is not a primary focus, she noted.

“Not everybody’s ready to have an advance care planning [discussion] that lasts 16-45 minutes,” she said. “Many people over age 65 are not ready to deal with advance care planning in their day-to-day lives, and it may not be what they wish to discuss. I offer the option to patients and some say, ‘Yes, I’d love to,’ and others decline or postpone.”

Low usage of the ACP codes may be associated with lack of awareness, uncertainty about appropriate code use, or associated billing that is not part of the standard workflow, Ankita Mehta, MD, of Mount Sinai in New York wrote an editorial accompanying the studies (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 March 11. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8105).

“Regardless, the low rates of utilization of ACP codes is alarming and highlights the need to create strategies to integrate ACP discussions into standard practice and build ACP documentation and billing in clinical workflow,” Dr. Mehta said.

Dr. Newman agreed that more education among physicians is needed.

“The amount of education clinicians have received varies tremendously across the geography of the country,” she said. “I think the codes are going to be slowly adopted. The challenge to us is to make sure we’re all better educated on palliative care as people age and get sick and that we are sensitive to our patients explicit and implicit needs for these discussions.”

Starting in 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services began paying physicians for advance care planning discussions with the approval of two new codes: 99497 and 99498. The codes pay about $86 for the first 30 minutes of a face-to-face conversation with a patient, family member, and/or surrogate and about $75 for additional sessions. Services can be furnished in both inpatient and ambulatory settings, and payment is not limited to particular physician specialties.

In 2016, health care professionals in New England (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont) billed Medicare 26,522 times for the advance care planning (ACP) codes for a total of 24,536 patients, which represented less than 1% of Medicare beneficiaries in New England at the time, according to Kimberly Pelland, MPH, of Healthcentric Advisors, Providence, R.I., and her colleagues. Most claims were billed in the office, followed by in nursing homes, and in hospitals; 40% of conversations occurred during an annual wellness visit (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 March 11. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8107).

Internists billed Medicare the most for ACP claims (65%), followed by family physicians (22%) gerontologists (5%), and oncologist/hematologists (0.3%), according to the analysis based on 2016 Medicare claims data and Census Bureau data. A greater proportion of patients with ACP claims were female, aged 85 years or older, enrolled in hospice, and died in the study year. Patients had higher odds of having an ACP claim if they were older and had lower income, and if they had cancer, heart failure, stroke, chronic kidney disease, or dementia. Male patients who were Asian, black, and Hispanic had lower chances of having an ACP claim.

In a related study, Emmanuelle Belanger, PhD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and her colleagues examined national Medicare data from 2016 to the third quarter of 2017. Across the United States, 2% of Medicare patients aged 65 years and older received advance care planning services that were billed under the ACP codes (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 March 11. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8615). Visits billed under the ACP codes increased from 538,275 to 633,214 during the same time period. Claim rates were higher among patients who died within the study period, reaching 3% in 2016 and 6% in 2017. The percentage of decedents with an ACP billed visit varied strongly across states, with states such as North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming having the fewest ACP visits billed and states such as California and Nevada having the most. ACP billed visits increased in all settings in 2017, but primarily in hospitals and nursing homes. Nationally, internists billed the codes most (48%), followed by family physicians (28%).

While the two studies indicate low usage of the ACP codes, many physicians are discussing advance care planning with their patients, said Mary M. Newman, MD, an internist based in Lutherville, Md., and former American College of Physicians adviser to the American Medical Association Relative Scale Value Update Committee (RUC).

“What cannot be captured by tracking under Medicare claims data are those shorter conversations that we have frequently,” Dr. Newman said in an interview. “If we have a short conversation about advance care planning, it gets folded into our evaluation and management visit. It’s not going to be separately billed.”

At the same time, some patients are not ready to discuss end-of-life options and decline the discussions when asked, Dr. Newman said. Particularly for healthier patients, end of life care is not a primary focus, she noted.

“Not everybody’s ready to have an advance care planning [discussion] that lasts 16-45 minutes,” she said. “Many people over age 65 are not ready to deal with advance care planning in their day-to-day lives, and it may not be what they wish to discuss. I offer the option to patients and some say, ‘Yes, I’d love to,’ and others decline or postpone.”

Low usage of the ACP codes may be associated with lack of awareness, uncertainty about appropriate code use, or associated billing that is not part of the standard workflow, Ankita Mehta, MD, of Mount Sinai in New York wrote an editorial accompanying the studies (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 March 11. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8105).

“Regardless, the low rates of utilization of ACP codes is alarming and highlights the need to create strategies to integrate ACP discussions into standard practice and build ACP documentation and billing in clinical workflow,” Dr. Mehta said.

Dr. Newman agreed that more education among physicians is needed.

“The amount of education clinicians have received varies tremendously across the geography of the country,” she said. “I think the codes are going to be slowly adopted. The challenge to us is to make sure we’re all better educated on palliative care as people age and get sick and that we are sensitive to our patients explicit and implicit needs for these discussions.”

Starting in 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services began paying physicians for advance care planning discussions with the approval of two new codes: 99497 and 99498. The codes pay about $86 for the first 30 minutes of a face-to-face conversation with a patient, family member, and/or surrogate and about $75 for additional sessions. Services can be furnished in both inpatient and ambulatory settings, and payment is not limited to particular physician specialties.

In 2016, health care professionals in New England (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont) billed Medicare 26,522 times for the advance care planning (ACP) codes for a total of 24,536 patients, which represented less than 1% of Medicare beneficiaries in New England at the time, according to Kimberly Pelland, MPH, of Healthcentric Advisors, Providence, R.I., and her colleagues. Most claims were billed in the office, followed by in nursing homes, and in hospitals; 40% of conversations occurred during an annual wellness visit (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 March 11. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8107).

Internists billed Medicare the most for ACP claims (65%), followed by family physicians (22%) gerontologists (5%), and oncologist/hematologists (0.3%), according to the analysis based on 2016 Medicare claims data and Census Bureau data. A greater proportion of patients with ACP claims were female, aged 85 years or older, enrolled in hospice, and died in the study year. Patients had higher odds of having an ACP claim if they were older and had lower income, and if they had cancer, heart failure, stroke, chronic kidney disease, or dementia. Male patients who were Asian, black, and Hispanic had lower chances of having an ACP claim.

In a related study, Emmanuelle Belanger, PhD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and her colleagues examined national Medicare data from 2016 to the third quarter of 2017. Across the United States, 2% of Medicare patients aged 65 years and older received advance care planning services that were billed under the ACP codes (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 March 11. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8615). Visits billed under the ACP codes increased from 538,275 to 633,214 during the same time period. Claim rates were higher among patients who died within the study period, reaching 3% in 2016 and 6% in 2017. The percentage of decedents with an ACP billed visit varied strongly across states, with states such as North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming having the fewest ACP visits billed and states such as California and Nevada having the most. ACP billed visits increased in all settings in 2017, but primarily in hospitals and nursing homes. Nationally, internists billed the codes most (48%), followed by family physicians (28%).

While the two studies indicate low usage of the ACP codes, many physicians are discussing advance care planning with their patients, said Mary M. Newman, MD, an internist based in Lutherville, Md., and former American College of Physicians adviser to the American Medical Association Relative Scale Value Update Committee (RUC).

“What cannot be captured by tracking under Medicare claims data are those shorter conversations that we have frequently,” Dr. Newman said in an interview. “If we have a short conversation about advance care planning, it gets folded into our evaluation and management visit. It’s not going to be separately billed.”

At the same time, some patients are not ready to discuss end-of-life options and decline the discussions when asked, Dr. Newman said. Particularly for healthier patients, end of life care is not a primary focus, she noted.

“Not everybody’s ready to have an advance care planning [discussion] that lasts 16-45 minutes,” she said. “Many people over age 65 are not ready to deal with advance care planning in their day-to-day lives, and it may not be what they wish to discuss. I offer the option to patients and some say, ‘Yes, I’d love to,’ and others decline or postpone.”

Low usage of the ACP codes may be associated with lack of awareness, uncertainty about appropriate code use, or associated billing that is not part of the standard workflow, Ankita Mehta, MD, of Mount Sinai in New York wrote an editorial accompanying the studies (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 March 11. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8105).

“Regardless, the low rates of utilization of ACP codes is alarming and highlights the need to create strategies to integrate ACP discussions into standard practice and build ACP documentation and billing in clinical workflow,” Dr. Mehta said.

Dr. Newman agreed that more education among physicians is needed.

“The amount of education clinicians have received varies tremendously across the geography of the country,” she said. “I think the codes are going to be slowly adopted. The challenge to us is to make sure we’re all better educated on palliative care as people age and get sick and that we are sensitive to our patients explicit and implicit needs for these discussions.”

Hospital-onset sepsis twice as lethal as community-onset disease

SAN DIEGO – Patients who develop sepsis in the hospital appear to be in greater risk for mortality than those who bring it with them, a new study suggests. Patients with hospital-onset sepsis were twice as likely to die as those infected in the outside world.

“There could be some differences in quality of care that explains the difference in mortality,” said study lead author Chanu Rhee, MD, assistant professor of population medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, in a presentation about the findings at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

In an interview, Dr. Rhee said researchers launched the study to gain a greater understanding of the epidemiology of sepsis in the hospital. They relied on a new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definition of sepsis that is “enhancing the consistency of surveillance across hospitals and allowing more precise differentiation between hospital-onset versus community-onset sepsis.”

The study authors retrospectively tracked more than 2.2 million patients who were treated at 136 U.S. hospitals from 2009 to 2015. In general, hospital-onset sepsis was defined as patients who had a blood culture, initial antibiotic therapy, and organ dysfunction on their third day in the hospital or later.*

Of the patients, 83,600 had community-onset sepsis and 11,500 had hospital-onset sepsis. Those with sepsis were more likely to be men and have comorbidities such as cancer, congestive heart failure, diabetes, and renal disease.

Patients with hospital-onset sepsis had longer median lengths of stay (19 days) than the community-onset group (8 days) and the no-sepsis group (4 days). The hospital-onset group also had a greater likelihood of ICU admission (61%) than the community-onset (44%) and no-sepsis (9%) groups.

About 34% of those with hospital-onset sepsis died, compared with 17% of the community-onset group and 2% of the patients who didn’t have sepsis. After adjustment, those with hospital-onset sepsis were still more likely to have died (odds ratio, 2.1; 95% confidence interval, 2.0-2.2).

“Other studies have suggested that there may be delays in the recognition and care of patients who develop sepsis in the hospital as opposed to presenting to the hospital with sepsis,” Dr. Rhee said. “It is also possible that hospital-onset sepsis tends to be caused by organisms that are more virulent and resistant to antibiotics.”

Overall, he said, “our findings underscore the importance of targeting hospital-onset sepsis with surveillance, prevention, and quality improvement efforts.”

The study was funded by the CDC and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Rhee C et al. CCC48, Abstract 29.

*Correction, 3/19/19: An earlier version of this article misstated the definition of sepsis.

SAN DIEGO – Patients who develop sepsis in the hospital appear to be in greater risk for mortality than those who bring it with them, a new study suggests. Patients with hospital-onset sepsis were twice as likely to die as those infected in the outside world.

“There could be some differences in quality of care that explains the difference in mortality,” said study lead author Chanu Rhee, MD, assistant professor of population medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, in a presentation about the findings at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

In an interview, Dr. Rhee said researchers launched the study to gain a greater understanding of the epidemiology of sepsis in the hospital. They relied on a new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definition of sepsis that is “enhancing the consistency of surveillance across hospitals and allowing more precise differentiation between hospital-onset versus community-onset sepsis.”

The study authors retrospectively tracked more than 2.2 million patients who were treated at 136 U.S. hospitals from 2009 to 2015. In general, hospital-onset sepsis was defined as patients who had a blood culture, initial antibiotic therapy, and organ dysfunction on their third day in the hospital or later.*

Of the patients, 83,600 had community-onset sepsis and 11,500 had hospital-onset sepsis. Those with sepsis were more likely to be men and have comorbidities such as cancer, congestive heart failure, diabetes, and renal disease.

Patients with hospital-onset sepsis had longer median lengths of stay (19 days) than the community-onset group (8 days) and the no-sepsis group (4 days). The hospital-onset group also had a greater likelihood of ICU admission (61%) than the community-onset (44%) and no-sepsis (9%) groups.

About 34% of those with hospital-onset sepsis died, compared with 17% of the community-onset group and 2% of the patients who didn’t have sepsis. After adjustment, those with hospital-onset sepsis were still more likely to have died (odds ratio, 2.1; 95% confidence interval, 2.0-2.2).

“Other studies have suggested that there may be delays in the recognition and care of patients who develop sepsis in the hospital as opposed to presenting to the hospital with sepsis,” Dr. Rhee said. “It is also possible that hospital-onset sepsis tends to be caused by organisms that are more virulent and resistant to antibiotics.”

Overall, he said, “our findings underscore the importance of targeting hospital-onset sepsis with surveillance, prevention, and quality improvement efforts.”

The study was funded by the CDC and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Rhee C et al. CCC48, Abstract 29.

*Correction, 3/19/19: An earlier version of this article misstated the definition of sepsis.

SAN DIEGO – Patients who develop sepsis in the hospital appear to be in greater risk for mortality than those who bring it with them, a new study suggests. Patients with hospital-onset sepsis were twice as likely to die as those infected in the outside world.

“There could be some differences in quality of care that explains the difference in mortality,” said study lead author Chanu Rhee, MD, assistant professor of population medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, in a presentation about the findings at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

In an interview, Dr. Rhee said researchers launched the study to gain a greater understanding of the epidemiology of sepsis in the hospital. They relied on a new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definition of sepsis that is “enhancing the consistency of surveillance across hospitals and allowing more precise differentiation between hospital-onset versus community-onset sepsis.”

The study authors retrospectively tracked more than 2.2 million patients who were treated at 136 U.S. hospitals from 2009 to 2015. In general, hospital-onset sepsis was defined as patients who had a blood culture, initial antibiotic therapy, and organ dysfunction on their third day in the hospital or later.*

Of the patients, 83,600 had community-onset sepsis and 11,500 had hospital-onset sepsis. Those with sepsis were more likely to be men and have comorbidities such as cancer, congestive heart failure, diabetes, and renal disease.

Patients with hospital-onset sepsis had longer median lengths of stay (19 days) than the community-onset group (8 days) and the no-sepsis group (4 days). The hospital-onset group also had a greater likelihood of ICU admission (61%) than the community-onset (44%) and no-sepsis (9%) groups.

About 34% of those with hospital-onset sepsis died, compared with 17% of the community-onset group and 2% of the patients who didn’t have sepsis. After adjustment, those with hospital-onset sepsis were still more likely to have died (odds ratio, 2.1; 95% confidence interval, 2.0-2.2).

“Other studies have suggested that there may be delays in the recognition and care of patients who develop sepsis in the hospital as opposed to presenting to the hospital with sepsis,” Dr. Rhee said. “It is also possible that hospital-onset sepsis tends to be caused by organisms that are more virulent and resistant to antibiotics.”

Overall, he said, “our findings underscore the importance of targeting hospital-onset sepsis with surveillance, prevention, and quality improvement efforts.”

The study was funded by the CDC and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Rhee C et al. CCC48, Abstract 29.

*Correction, 3/19/19: An earlier version of this article misstated the definition of sepsis.

REPORTING FROM CCC48

Developing clinical mastery at HM19

Boosting your bedside diagnostic skills

A new three-session minitrack devoted to the clinical mastery of diagnostic and treatment skills at the hospitalized patient’s bedside should be a highlight of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s 2019 annual conference.

The “Clinical Mastery” track is designed to help hospitalists enhance their skills in making expert diagnoses at the bedside, said Dustin T. Smith, MD, SFHM, course director for HM19, and associate professor of medicine at Emory University, Atlanta. “We feel that all of the didactic sessions offered at HM19 are highly useful for hospitalists, but there is growing interest in having sessions devoted to learning clinical pearls that can aid in practicing medicine and acquiring the skill set of a master clinician.”

The three clinical mastery sessions at HM19 will address neurologic symptoms, ECG interpretation, and the role of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS), currently a hot topic in hospital medicine. Recent advances in ultrasound technology have resulted in probes that can cost as little as $2,000, fit inside a lab coat pocket, and be read from a smartphone – making ultrasound far easier to bring to the bedside of hospitalized patients, said Ria Dancel, MD, FHM, associate professor of internal medicine and pediatrics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Dr. Dancel will copresent the POCUS clinical mastery track at HM19. “Our focus will be on how POCUS and the physical exam relate to each other. These are not competing technologies but complementary, reflecting the evolution in bedside medicine. Because these new devices will soon be in the pockets of your colleagues, residents, physician assistants, and others, you should at least have the knowledge and vocabulary to communicate with them,” she said.

POCUS is a new technology that is not yet in wide use at the hospital bedside, but clearly a wave is building, said Dr. Dancel’s copresenter, Michael Janjigian, MD, associate professor in the department of medicine at NYU Langone Health in New York City.

“We’re at the inflection point where the cost of the machine and the availability of training means that hospitals need to decide if it’s time to embrace it,” he said. Hospitalists may also consider petitioning their hospital’s leadership to offer the machines and training.

“Hospitalists’ competencies and strengths lie primarily in making diagnoses,” Dr. Janjigian said. “We like to think of ourselves as master diagnosticians. Our session at HM19 will explore the strengths and weaknesses of both the physical exam and POCUS, presenting clinical scenarios common to hospital medicine. This course is designed for those who have never picked up an ultrasound probe and want to better understand why they should, and for those who want a better sense of how they might integrate it into their practice.”

While radiology and cardiology have been using ultrasound for decades, internists are finding uses at the bedside to speed diagnosis or focus their next diagnostic steps, Dr. Dancel noted. For certain diagnoses, the physical exam is still the tool of choice. But when looking for fluid around the heart or ascites buildup in the abdomen or when looking at the heart itself, she said, there is no better tool at the bedside than ultrasound.

In January 2019, the SHM issued a position statement on POCUS1, which is intended to inform hospitalists about the technology and its uses, encourage them to be more integrally involved in decision making processes surrounding POCUS program management for their hospitals, and promote development of standards for hospitalists in POCUS training and assessment. The SHM has also developed a pathway to teach the use of ultrasound, the Point-of-Care Ultrasound Certificate of Completion.

In order to qualify, clinicians complete online training modules, attend two live learning courses, compile a portfolio of ultrasound video clips on the job that are reviewed by a panel of experts, and then pass a final exam. The exam will be offered at HM19 for clinicians who have completed preliminary work for this new certificate – as well as precourses devoted to ultrasound and other procedures – and another workshop on POCUS.

Earning the POCUS certificate of completion requires a lot of effort, Dr. Dancel acknowledged. “It is a big commitment, and we don’t want hospitalists thinking that just because they have completed the certificate that they have fully mastered ultrasound. We encourage hospitalists to find a proctor in their own hospitals and to work with them to continue to refine their skills.”

Dr. Dancel and Dr. Janjigian reported no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Soni NJ et al. Point-of-care ultrasound for hospitalists: A position statement of the Society of Hospital Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019 Jan 2. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3079.

Boosting your bedside diagnostic skills

Boosting your bedside diagnostic skills

A new three-session minitrack devoted to the clinical mastery of diagnostic and treatment skills at the hospitalized patient’s bedside should be a highlight of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s 2019 annual conference.

The “Clinical Mastery” track is designed to help hospitalists enhance their skills in making expert diagnoses at the bedside, said Dustin T. Smith, MD, SFHM, course director for HM19, and associate professor of medicine at Emory University, Atlanta. “We feel that all of the didactic sessions offered at HM19 are highly useful for hospitalists, but there is growing interest in having sessions devoted to learning clinical pearls that can aid in practicing medicine and acquiring the skill set of a master clinician.”

The three clinical mastery sessions at HM19 will address neurologic symptoms, ECG interpretation, and the role of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS), currently a hot topic in hospital medicine. Recent advances in ultrasound technology have resulted in probes that can cost as little as $2,000, fit inside a lab coat pocket, and be read from a smartphone – making ultrasound far easier to bring to the bedside of hospitalized patients, said Ria Dancel, MD, FHM, associate professor of internal medicine and pediatrics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Dr. Dancel will copresent the POCUS clinical mastery track at HM19. “Our focus will be on how POCUS and the physical exam relate to each other. These are not competing technologies but complementary, reflecting the evolution in bedside medicine. Because these new devices will soon be in the pockets of your colleagues, residents, physician assistants, and others, you should at least have the knowledge and vocabulary to communicate with them,” she said.

POCUS is a new technology that is not yet in wide use at the hospital bedside, but clearly a wave is building, said Dr. Dancel’s copresenter, Michael Janjigian, MD, associate professor in the department of medicine at NYU Langone Health in New York City.

“We’re at the inflection point where the cost of the machine and the availability of training means that hospitals need to decide if it’s time to embrace it,” he said. Hospitalists may also consider petitioning their hospital’s leadership to offer the machines and training.

“Hospitalists’ competencies and strengths lie primarily in making diagnoses,” Dr. Janjigian said. “We like to think of ourselves as master diagnosticians. Our session at HM19 will explore the strengths and weaknesses of both the physical exam and POCUS, presenting clinical scenarios common to hospital medicine. This course is designed for those who have never picked up an ultrasound probe and want to better understand why they should, and for those who want a better sense of how they might integrate it into their practice.”

While radiology and cardiology have been using ultrasound for decades, internists are finding uses at the bedside to speed diagnosis or focus their next diagnostic steps, Dr. Dancel noted. For certain diagnoses, the physical exam is still the tool of choice. But when looking for fluid around the heart or ascites buildup in the abdomen or when looking at the heart itself, she said, there is no better tool at the bedside than ultrasound.

In January 2019, the SHM issued a position statement on POCUS1, which is intended to inform hospitalists about the technology and its uses, encourage them to be more integrally involved in decision making processes surrounding POCUS program management for their hospitals, and promote development of standards for hospitalists in POCUS training and assessment. The SHM has also developed a pathway to teach the use of ultrasound, the Point-of-Care Ultrasound Certificate of Completion.

In order to qualify, clinicians complete online training modules, attend two live learning courses, compile a portfolio of ultrasound video clips on the job that are reviewed by a panel of experts, and then pass a final exam. The exam will be offered at HM19 for clinicians who have completed preliminary work for this new certificate – as well as precourses devoted to ultrasound and other procedures – and another workshop on POCUS.

Earning the POCUS certificate of completion requires a lot of effort, Dr. Dancel acknowledged. “It is a big commitment, and we don’t want hospitalists thinking that just because they have completed the certificate that they have fully mastered ultrasound. We encourage hospitalists to find a proctor in their own hospitals and to work with them to continue to refine their skills.”

Dr. Dancel and Dr. Janjigian reported no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Soni NJ et al. Point-of-care ultrasound for hospitalists: A position statement of the Society of Hospital Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019 Jan 2. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3079.

A new three-session minitrack devoted to the clinical mastery of diagnostic and treatment skills at the hospitalized patient’s bedside should be a highlight of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s 2019 annual conference.

The “Clinical Mastery” track is designed to help hospitalists enhance their skills in making expert diagnoses at the bedside, said Dustin T. Smith, MD, SFHM, course director for HM19, and associate professor of medicine at Emory University, Atlanta. “We feel that all of the didactic sessions offered at HM19 are highly useful for hospitalists, but there is growing interest in having sessions devoted to learning clinical pearls that can aid in practicing medicine and acquiring the skill set of a master clinician.”

The three clinical mastery sessions at HM19 will address neurologic symptoms, ECG interpretation, and the role of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS), currently a hot topic in hospital medicine. Recent advances in ultrasound technology have resulted in probes that can cost as little as $2,000, fit inside a lab coat pocket, and be read from a smartphone – making ultrasound far easier to bring to the bedside of hospitalized patients, said Ria Dancel, MD, FHM, associate professor of internal medicine and pediatrics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Dr. Dancel will copresent the POCUS clinical mastery track at HM19. “Our focus will be on how POCUS and the physical exam relate to each other. These are not competing technologies but complementary, reflecting the evolution in bedside medicine. Because these new devices will soon be in the pockets of your colleagues, residents, physician assistants, and others, you should at least have the knowledge and vocabulary to communicate with them,” she said.

POCUS is a new technology that is not yet in wide use at the hospital bedside, but clearly a wave is building, said Dr. Dancel’s copresenter, Michael Janjigian, MD, associate professor in the department of medicine at NYU Langone Health in New York City.

“We’re at the inflection point where the cost of the machine and the availability of training means that hospitals need to decide if it’s time to embrace it,” he said. Hospitalists may also consider petitioning their hospital’s leadership to offer the machines and training.

“Hospitalists’ competencies and strengths lie primarily in making diagnoses,” Dr. Janjigian said. “We like to think of ourselves as master diagnosticians. Our session at HM19 will explore the strengths and weaknesses of both the physical exam and POCUS, presenting clinical scenarios common to hospital medicine. This course is designed for those who have never picked up an ultrasound probe and want to better understand why they should, and for those who want a better sense of how they might integrate it into their practice.”

While radiology and cardiology have been using ultrasound for decades, internists are finding uses at the bedside to speed diagnosis or focus their next diagnostic steps, Dr. Dancel noted. For certain diagnoses, the physical exam is still the tool of choice. But when looking for fluid around the heart or ascites buildup in the abdomen or when looking at the heart itself, she said, there is no better tool at the bedside than ultrasound.

In January 2019, the SHM issued a position statement on POCUS1, which is intended to inform hospitalists about the technology and its uses, encourage them to be more integrally involved in decision making processes surrounding POCUS program management for their hospitals, and promote development of standards for hospitalists in POCUS training and assessment. The SHM has also developed a pathway to teach the use of ultrasound, the Point-of-Care Ultrasound Certificate of Completion.

In order to qualify, clinicians complete online training modules, attend two live learning courses, compile a portfolio of ultrasound video clips on the job that are reviewed by a panel of experts, and then pass a final exam. The exam will be offered at HM19 for clinicians who have completed preliminary work for this new certificate – as well as precourses devoted to ultrasound and other procedures – and another workshop on POCUS.

Earning the POCUS certificate of completion requires a lot of effort, Dr. Dancel acknowledged. “It is a big commitment, and we don’t want hospitalists thinking that just because they have completed the certificate that they have fully mastered ultrasound. We encourage hospitalists to find a proctor in their own hospitals and to work with them to continue to refine their skills.”

Dr. Dancel and Dr. Janjigian reported no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Soni NJ et al. Point-of-care ultrasound for hospitalists: A position statement of the Society of Hospital Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019 Jan 2. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3079.

Prior authorization an increasing burden

The use of prior authorization for prescriptions and medical services has continued to increase in recent years, despite the consequences to continuity of care, according to a survey by the American Medical Association.

and 41% said that PA for medical services has done the same. The corresponding numbers for 5-year decreases in PAs were 2% and 1%, the AMA reported March 12.

Results of the survey, conducted in December 2018, also show that 85% of physicians believe that prior authorization sometimes, often, or always has a negative effect on the continuity of patients’ care. Almost 70% of respondents said that it is somewhat or extremely difficult to determine when PA is required for a prescription or medical service, and only 8% reported contracting with a health plan that offers programs to exempt physicians from the PA process, the AMA said.

“Physicians follow insurance protocols for prior authorization that require faxing recurring paperwork, multiple phone calls, and hours spent on hold. At the same time, patients’ lives can hang in the balance until health plans decide if needed care will qualify for insurance coverage,” AMA President Barbara L. McAneny, MD, said in a statement.

In January 2018, two organizations representing insurers – America’s Health Insurance Plans and the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association – signed onto a joint consensus statement with the AMA and other health care groups that provided five areas for improvement of the PA process. The current survey results show that “most health plans are not making meaningful progress on reforming the cumbersome prior authorization process,” the AMA said.

The use of prior authorization for prescriptions and medical services has continued to increase in recent years, despite the consequences to continuity of care, according to a survey by the American Medical Association.

and 41% said that PA for medical services has done the same. The corresponding numbers for 5-year decreases in PAs were 2% and 1%, the AMA reported March 12.

Results of the survey, conducted in December 2018, also show that 85% of physicians believe that prior authorization sometimes, often, or always has a negative effect on the continuity of patients’ care. Almost 70% of respondents said that it is somewhat or extremely difficult to determine when PA is required for a prescription or medical service, and only 8% reported contracting with a health plan that offers programs to exempt physicians from the PA process, the AMA said.

“Physicians follow insurance protocols for prior authorization that require faxing recurring paperwork, multiple phone calls, and hours spent on hold. At the same time, patients’ lives can hang in the balance until health plans decide if needed care will qualify for insurance coverage,” AMA President Barbara L. McAneny, MD, said in a statement.

In January 2018, two organizations representing insurers – America’s Health Insurance Plans and the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association – signed onto a joint consensus statement with the AMA and other health care groups that provided five areas for improvement of the PA process. The current survey results show that “most health plans are not making meaningful progress on reforming the cumbersome prior authorization process,” the AMA said.

The use of prior authorization for prescriptions and medical services has continued to increase in recent years, despite the consequences to continuity of care, according to a survey by the American Medical Association.

and 41% said that PA for medical services has done the same. The corresponding numbers for 5-year decreases in PAs were 2% and 1%, the AMA reported March 12.

Results of the survey, conducted in December 2018, also show that 85% of physicians believe that prior authorization sometimes, often, or always has a negative effect on the continuity of patients’ care. Almost 70% of respondents said that it is somewhat or extremely difficult to determine when PA is required for a prescription or medical service, and only 8% reported contracting with a health plan that offers programs to exempt physicians from the PA process, the AMA said.

“Physicians follow insurance protocols for prior authorization that require faxing recurring paperwork, multiple phone calls, and hours spent on hold. At the same time, patients’ lives can hang in the balance until health plans decide if needed care will qualify for insurance coverage,” AMA President Barbara L. McAneny, MD, said in a statement.

In January 2018, two organizations representing insurers – America’s Health Insurance Plans and the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association – signed onto a joint consensus statement with the AMA and other health care groups that provided five areas for improvement of the PA process. The current survey results show that “most health plans are not making meaningful progress on reforming the cumbersome prior authorization process,” the AMA said.

Crafting a “well-rounded” program

New tracks, interactive programs highlight HM19

As course director for the Society of Hospital Medicine’s 2019 annual conference – Hospital Medicine 2019 (HM19) – to be held March 24-27 in National Harbor, Md., Dustin T. Smith, MD, SFHM, hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at Emory University, Atlanta, tried his best to apply democratic processes to the work of the annual conference committee.

“We created numerous email surveys to go out to the 20 committee members for their vote. So many great topics were proposed for HM19, with so many great faculty, that we had to make hard choices – although we see that as a good problem. It was my job to make sure that we had a process that works,” Dr. Smith explained. “We have planned what we believe will be another well-attended and well-received hospital medicine conference. Every year it’s been great, but every year we try something to make it a little better.”

The SHM annual conference committee meets in person at the conference to kick off planning for the following year’s conference, then holds weekly conference calls for the next 4-5 months, Dr. Smith said. “These are all highly creative leaders in hospital medicine, with voices to be heard and taken under consideration.”

Committee members wear badges at the annual meeting to encourage attendees to offer them feedback and suggestions. “We have our ears to the ground. We look at the session ratings from prior years, speaker ratings, and all of the feedback we have received, and we take all of that into account to come up with new ideas for educational tracks,” Dr. Smith said. New for 2019 are “Between the Guidelines” and “Clinical Mastery”. “We went around the table at our meeting and asked everybody for their ideas for new tracks, and then we voted in the most popular ones.”

One change for 2019 was to “completely open” the call for submission of proposals – and for nominations of content to be covered and who should present it – for all sessions at HM19, not just for the workshop tracks. Dr. Smith said all submissions were peer reviewed by committee members and scored with objective ratings.

“For example, there was a lot of interest in emergency and disaster preparedness for hospitalists in a number of the submissions. Whether we’re talking about wildfires or mass shootings, it affects hospitals, and we are among the frontline practitioners for whatever happens in those hospitals. So we may need to be able to respond to large-scale emergencies,” he said. “But most of us haven’t been trained for that.”

A love of teaching

Dr. Smith’s preparation for being the HM19 course director includes his work teaching medical students, residents, and physicians at Emory University where he also attended medical school. He chairs the Emory division of hospital medicine’s education council, directs hospital medicine grand rounds at Emory, and serves as associate program director for the J. Willis Hurst Internal Medicine Residency Program at Emory as well as a section chief for education in medical specialty at the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Dr. Smith has also codirected, since 2012, the annual Southern Hospital Medicine regional conference.

“I have long had an interest in medical education for medical students, trainees, and faculty and I wanted to do more of it – with a number of mentors encouraging me along the way,” he said. “I have planned and coordinated teaching sessions needed for maintenance of board certification, which is similar to what we will present at HM19. Based on that experience, I applied to be on SHM’s annual conference committee, starting in 2012 for the planning of Hospital Medicine 2013. I believe I have been preparing myself all along to take on this role.”

A well-rounded program

The HM19 educational program will be well rounded, Dr. Smith said, offering clinical updates on topics such as sepsis, heart failure, and new clinical practice guidelines.

“You will see a big focus on wellness and how to avoid burnout, as well as other sessions on how to develop and sustain a career in hospital medicine,” he said. Another important HM19 theme will be the delivery of new models of population health and accountable care and their impact on both patients and hospital operations.

The 2019 agenda emphasizes other interactive formats, such as the “Great Debates,” where experts in the field are paired to debate clinical conundrums in hospital medicine. The number of Great Debates has grown from one on perioperative medicine at the 2017 annual conference, to three in 2018, and now to seven planned for 2019. “This format is very popular. We’re also planning ‘Medical Jeopardy,’ with three brilliant master clinicians in a quiz show format, and two ‘Stump the Professor’ sessions with expert diagnosticians,” Dr. Smith said.

It’s important to make every session at the conference interactive to engage attendees in learning from, and talking to, experts in the field, he said. “But it’s also important for some of them to be more entertaining in approach as a way to encourage learning. We know that this actually increases retention of information.”

The annual conference course director typically is selected several years in advance, in order to plan for the time commitment that will be required, and spends the year before this term as assistant course director. “It is a big honor to serve as course director. It’s fun and exciting to work with such a talented and diverse committee, but it’s also a lot of work,” Dr. Smith acknowledged. “I reviewed all 450 session proposals from this year’s open call for course content. The volume of emails is pretty outstanding, and I was extremely busy with conference planning for a season.”

Dr. Smith has continued to pursue his full-time commitments at Emory, without getting dedicated time off for planning the SHM conference. “But as a parent of three young children, I already feel busy all the time,” he said. “I put in a lot of late nights, but I found a way to make it work.”

New tracks, interactive programs highlight HM19

New tracks, interactive programs highlight HM19

As course director for the Society of Hospital Medicine’s 2019 annual conference – Hospital Medicine 2019 (HM19) – to be held March 24-27 in National Harbor, Md., Dustin T. Smith, MD, SFHM, hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at Emory University, Atlanta, tried his best to apply democratic processes to the work of the annual conference committee.

“We created numerous email surveys to go out to the 20 committee members for their vote. So many great topics were proposed for HM19, with so many great faculty, that we had to make hard choices – although we see that as a good problem. It was my job to make sure that we had a process that works,” Dr. Smith explained. “We have planned what we believe will be another well-attended and well-received hospital medicine conference. Every year it’s been great, but every year we try something to make it a little better.”

The SHM annual conference committee meets in person at the conference to kick off planning for the following year’s conference, then holds weekly conference calls for the next 4-5 months, Dr. Smith said. “These are all highly creative leaders in hospital medicine, with voices to be heard and taken under consideration.”

Committee members wear badges at the annual meeting to encourage attendees to offer them feedback and suggestions. “We have our ears to the ground. We look at the session ratings from prior years, speaker ratings, and all of the feedback we have received, and we take all of that into account to come up with new ideas for educational tracks,” Dr. Smith said. New for 2019 are “Between the Guidelines” and “Clinical Mastery”. “We went around the table at our meeting and asked everybody for their ideas for new tracks, and then we voted in the most popular ones.”

One change for 2019 was to “completely open” the call for submission of proposals – and for nominations of content to be covered and who should present it – for all sessions at HM19, not just for the workshop tracks. Dr. Smith said all submissions were peer reviewed by committee members and scored with objective ratings.

“For example, there was a lot of interest in emergency and disaster preparedness for hospitalists in a number of the submissions. Whether we’re talking about wildfires or mass shootings, it affects hospitals, and we are among the frontline practitioners for whatever happens in those hospitals. So we may need to be able to respond to large-scale emergencies,” he said. “But most of us haven’t been trained for that.”

A love of teaching

Dr. Smith’s preparation for being the HM19 course director includes his work teaching medical students, residents, and physicians at Emory University where he also attended medical school. He chairs the Emory division of hospital medicine’s education council, directs hospital medicine grand rounds at Emory, and serves as associate program director for the J. Willis Hurst Internal Medicine Residency Program at Emory as well as a section chief for education in medical specialty at the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Dr. Smith has also codirected, since 2012, the annual Southern Hospital Medicine regional conference.

“I have long had an interest in medical education for medical students, trainees, and faculty and I wanted to do more of it – with a number of mentors encouraging me along the way,” he said. “I have planned and coordinated teaching sessions needed for maintenance of board certification, which is similar to what we will present at HM19. Based on that experience, I applied to be on SHM’s annual conference committee, starting in 2012 for the planning of Hospital Medicine 2013. I believe I have been preparing myself all along to take on this role.”

A well-rounded program

The HM19 educational program will be well rounded, Dr. Smith said, offering clinical updates on topics such as sepsis, heart failure, and new clinical practice guidelines.

“You will see a big focus on wellness and how to avoid burnout, as well as other sessions on how to develop and sustain a career in hospital medicine,” he said. Another important HM19 theme will be the delivery of new models of population health and accountable care and their impact on both patients and hospital operations.

The 2019 agenda emphasizes other interactive formats, such as the “Great Debates,” where experts in the field are paired to debate clinical conundrums in hospital medicine. The number of Great Debates has grown from one on perioperative medicine at the 2017 annual conference, to three in 2018, and now to seven planned for 2019. “This format is very popular. We’re also planning ‘Medical Jeopardy,’ with three brilliant master clinicians in a quiz show format, and two ‘Stump the Professor’ sessions with expert diagnosticians,” Dr. Smith said.

It’s important to make every session at the conference interactive to engage attendees in learning from, and talking to, experts in the field, he said. “But it’s also important for some of them to be more entertaining in approach as a way to encourage learning. We know that this actually increases retention of information.”

The annual conference course director typically is selected several years in advance, in order to plan for the time commitment that will be required, and spends the year before this term as assistant course director. “It is a big honor to serve as course director. It’s fun and exciting to work with such a talented and diverse committee, but it’s also a lot of work,” Dr. Smith acknowledged. “I reviewed all 450 session proposals from this year’s open call for course content. The volume of emails is pretty outstanding, and I was extremely busy with conference planning for a season.”

Dr. Smith has continued to pursue his full-time commitments at Emory, without getting dedicated time off for planning the SHM conference. “But as a parent of three young children, I already feel busy all the time,” he said. “I put in a lot of late nights, but I found a way to make it work.”

As course director for the Society of Hospital Medicine’s 2019 annual conference – Hospital Medicine 2019 (HM19) – to be held March 24-27 in National Harbor, Md., Dustin T. Smith, MD, SFHM, hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at Emory University, Atlanta, tried his best to apply democratic processes to the work of the annual conference committee.

“We created numerous email surveys to go out to the 20 committee members for their vote. So many great topics were proposed for HM19, with so many great faculty, that we had to make hard choices – although we see that as a good problem. It was my job to make sure that we had a process that works,” Dr. Smith explained. “We have planned what we believe will be another well-attended and well-received hospital medicine conference. Every year it’s been great, but every year we try something to make it a little better.”

The SHM annual conference committee meets in person at the conference to kick off planning for the following year’s conference, then holds weekly conference calls for the next 4-5 months, Dr. Smith said. “These are all highly creative leaders in hospital medicine, with voices to be heard and taken under consideration.”

Committee members wear badges at the annual meeting to encourage attendees to offer them feedback and suggestions. “We have our ears to the ground. We look at the session ratings from prior years, speaker ratings, and all of the feedback we have received, and we take all of that into account to come up with new ideas for educational tracks,” Dr. Smith said. New for 2019 are “Between the Guidelines” and “Clinical Mastery”. “We went around the table at our meeting and asked everybody for their ideas for new tracks, and then we voted in the most popular ones.”

One change for 2019 was to “completely open” the call for submission of proposals – and for nominations of content to be covered and who should present it – for all sessions at HM19, not just for the workshop tracks. Dr. Smith said all submissions were peer reviewed by committee members and scored with objective ratings.

“For example, there was a lot of interest in emergency and disaster preparedness for hospitalists in a number of the submissions. Whether we’re talking about wildfires or mass shootings, it affects hospitals, and we are among the frontline practitioners for whatever happens in those hospitals. So we may need to be able to respond to large-scale emergencies,” he said. “But most of us haven’t been trained for that.”

A love of teaching

Dr. Smith’s preparation for being the HM19 course director includes his work teaching medical students, residents, and physicians at Emory University where he also attended medical school. He chairs the Emory division of hospital medicine’s education council, directs hospital medicine grand rounds at Emory, and serves as associate program director for the J. Willis Hurst Internal Medicine Residency Program at Emory as well as a section chief for education in medical specialty at the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Dr. Smith has also codirected, since 2012, the annual Southern Hospital Medicine regional conference.

“I have long had an interest in medical education for medical students, trainees, and faculty and I wanted to do more of it – with a number of mentors encouraging me along the way,” he said. “I have planned and coordinated teaching sessions needed for maintenance of board certification, which is similar to what we will present at HM19. Based on that experience, I applied to be on SHM’s annual conference committee, starting in 2012 for the planning of Hospital Medicine 2013. I believe I have been preparing myself all along to take on this role.”

A well-rounded program

The HM19 educational program will be well rounded, Dr. Smith said, offering clinical updates on topics such as sepsis, heart failure, and new clinical practice guidelines.

“You will see a big focus on wellness and how to avoid burnout, as well as other sessions on how to develop and sustain a career in hospital medicine,” he said. Another important HM19 theme will be the delivery of new models of population health and accountable care and their impact on both patients and hospital operations.

The 2019 agenda emphasizes other interactive formats, such as the “Great Debates,” where experts in the field are paired to debate clinical conundrums in hospital medicine. The number of Great Debates has grown from one on perioperative medicine at the 2017 annual conference, to three in 2018, and now to seven planned for 2019. “This format is very popular. We’re also planning ‘Medical Jeopardy,’ with three brilliant master clinicians in a quiz show format, and two ‘Stump the Professor’ sessions with expert diagnosticians,” Dr. Smith said.

It’s important to make every session at the conference interactive to engage attendees in learning from, and talking to, experts in the field, he said. “But it’s also important for some of them to be more entertaining in approach as a way to encourage learning. We know that this actually increases retention of information.”

The annual conference course director typically is selected several years in advance, in order to plan for the time commitment that will be required, and spends the year before this term as assistant course director. “It is a big honor to serve as course director. It’s fun and exciting to work with such a talented and diverse committee, but it’s also a lot of work,” Dr. Smith acknowledged. “I reviewed all 450 session proposals from this year’s open call for course content. The volume of emails is pretty outstanding, and I was extremely busy with conference planning for a season.”

Dr. Smith has continued to pursue his full-time commitments at Emory, without getting dedicated time off for planning the SHM conference. “But as a parent of three young children, I already feel busy all the time,” he said. “I put in a lot of late nights, but I found a way to make it work.”

Experts offer HM19 ‘must-see’ tips

There are about as many sessions at HM19 as there are cherry blossoms on the springtime trees in the nation’s capital. Attendees are bound to find something they love – probably too many somethings, in fact.

Fear not. Seasoned experts are here to ease your struggle with suggestions for sessions they consider the best of the best and tips on getting the most out of the conference.

“Download the HM19 At Hand app to plan your conference schedule, rate speakers and sessions, and participate in audience-response systems,” said Dustin Smith, MD, SFHM, the HM19 course director and associate professor of medicine at Emory University, Atlanta. “Read the track descriptions first before reviewing the individual sessions to determine which educational tracks initially pique your interest. Don’t be wedded to one track; pick and choose sessions from the different tracks to curate a schedule that best fits your educational needs.”

SHM staff and Annual Conference committee members will be easily identifiable and eager to help on site, Dr. Smith added.

HM19 was the first Annual Conference for which SHM issued a call for content to members and nonmembers alike. The contributions yielded a few new offerings. A new Clinical Mastery track includes sessions for hospitalists wanting to enhance or refine their skills in an effort to achieve a master clinician designation, Dr. Smith said, while the new Between the Guidelines track explores clinical conundrums and lessons from history that may not be covered in clinical practice guidelines.

There also is a new Palliative Care and Pain Management pre-course and a new course on emergent airway management, Dr. Smith noted. His suggestions for sessions that are new, have a new format, or are particularly timely, are too numerous to list in full but include a fun “Medical Jeopardy” session (Wednesday, 9:10 – 9:50 a.m., Maryland C), sessions on discharge dilemmas (Monday, 11:25 a.m. to 12:05 p.m., Maryland BD/4-6) and LGBTQ health (Wednesday, 10:50 to 11:30 a.m., Maryland BD/4-6) and the workshop “Being Fe(male) in Hospital Medicine Part 2: Diversifying the Discussion” (Tuesday, 2:10 to 3:40 p.m., Potomac 1-3).

The Hospitalist polled its editorial advisory board members for each of their top two suggestions for “must-see” sessions:

Raman Palabindala, MD, SFHM, hospital medicine division chief at the University of Mississippi Medical Center

“A Battle Plan Against Career Inertia: A Blueprint for an Education Series to Retain Hospitalists, Reduce Burnout and Advance Careers” (Monday, 10:35 a.m. – 12:05 p.m., Potomac 1-3)

“I strongly recommend this to all hospitalist leaders – in big or small programs – given the importance of burnout in recent years. [Speaker] Dan Hunt is one of the best,” Dr. Palabindala said.

Special Interest Forums (Monday, 4:30 – 5:25 p.m., Tuesday, 5:30 – 6:25 p.m., multiple rooms)

Dr. Palabindala said these are valuable, small sessions when you have a focused interest in a certain topic – whether IT, academics, policy, or others.

“This is the best place to make contacts with national leaders,” he said. “Be proactive in confirming your spot.”

James Kim, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Emory University

“Delirium and Dementia in the Inpatient Setting” (Tuesday, 11:50 a.m. – 12:30 p.m., Maryland BD/4-6)

“This session is a repeat from previous years, but it is an engaging lecture with a lot of great material,” Dr. Kim said. “It has changed my approach to my practice of inpatients.”

“The Role of Primary Palliative Care in Complex, Chronic Disease Management” (Tuesday, 3:50 – 4:50 p.m., National Harbor 12-13)

“As the population grows older, palliative care’s role in disease management is going to become more important,” he said. “I watched one of Dr. [Aziz] Ansari’s lectures in a previous SHM meeting, and he delivers a dynamic presentation that is both informative and entertaining.”

Hyung (Harry) Cho, MD, SFHM, chief value officer at NYC Health + Hospitals

“Tweet your Way to the Top? Social Media as a Career Development Tool in Hospital Medicine” (Monday, 12:45 – 2:15 p.m., Potomac 1-3)

This includes a team of presenters who are experienced in the use of Twitter in conjunction with the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Dr. Cho said.

“Research Shark Tank” (Monday, 1:35 – 2:35 p.m., Baltimore 3-5)

This session involves judging and critiquing the latest research proposals with “contestants” in a Shark Tank format. Among the judges is Andrew Auerbach, MD, SFHM, past editor of the JHM. It “looks very engaging,” Dr. Cho said.

Lonika Sood, MD, FHM, clinical education director of internal medicine at Washington State University

“Making Your Educational Activities Count Twice: What it Takes These Days to Publish in Medical Education Journals” (Wednesday, 8:40 – 9:40 a.m., Baltimore 3-5)

“This is an important topic for clinician educators who are interested in taking a scholarly approach to their teaching,” Dr. Sood said. “Having some form of a framework to guide us in the direction of publishing our hard work will be very helpful.”“Managing the Hidden Curriculum: Do

You Know What You’re Teaching?” (Monday, 10:35 – 11:35 a.m., Baltimore 3-5)

“This is also an important, yet ‘hidden’ topic for the clinician educator when they are in the clinical environment with learners. Having hospitalists be aware of what is actually being ‘learned’ as opposed to what they think is being ‘taught’ on the wards is a critical part of the teaching process.”

Raj Sehgal, MD, FHM, clinical associate professor at South Texas Veterans Health Care System and UT Health San Antonio

“Call Night: Common Scenarios Encountered and Strategies to Make It Through the Night” (Monday, 10:35 – 11:15 a.m., Annapolis) and “Nocturnal Admissions: Cases That Keep Me Up at Night” (Monday, 2 – 2:40 p.m., Maryland A/1-3)

“I’m glad to see several different sessions about issues hospitalists face when working nights,” Dr. Sehgal said. “After all, most hours of the week are actually ‘off-hours’ (nights and weekends), so it’s important to focus on how care is delivered during these times. Even though we see the same diagnoses regardless of the time of day, our management is often very different because of external forces, such as the availability of tests and consultants.”

Marina Farah, MD, MHA, a national expert on improving clinical quality, cost, and efficiency

"Delivering Population Health as a Hospitalist in a Value-Based Healthcare Era” (Monday, 3:45 – 4:25 p.m., Maryland A/1-3)

“Hospital care is responsible for a third of the U.S. health care spending,” Dr. Farah said. “Hospitalists serve 75% of total hospital patients and have a unique perspective and power to drive national health care outcomes. This session will offer guidance on what hospitalists can do to improve population health, decrease total cost of care, and succeed under value-based reimbursement models.”

“Things We Do for No Reason: The 2019 Clinical Update for Hospitalists” (Tuesday, 11:50 a.m. – 12:30 p.m., Woodrow Wilson)

“Every hospitalist needs to know clinical practices that aren’t evidence-based, costly, and do not improve patient outcomes,” she said.

Amith Skandhan, MD, SFHM, assistant professor and medical director/clinical liaison for clinical documentation improvement at Southeast Health Medical Center

“How To Be a Great Teaching Attending” (Wednesday, 10 – 10:40 a.m., Maryland C)

“Being an academic hospitalist, I look up to great inpatient teachers,” Dr. Skandhan said. “Dr. [Jeffrey] Wiese has an amazing presence when he talks. His book on bedside teaching has been quite a guide for me as I embarked on my journey as a teacher.”

“Amplify Your Impact: Leverage Data to Accelerate Your Efforts in Quality Improvement” (Tuesday, 3:50 – 5:20 p.m., Potomac 1-3)

“Hospital medicine is a fairly new branch of medicine, and we are now the leaders of inpatient quality improvement,” he said. “To understand data and to convert it to useful information that can be utilized in quality improvement strategies would be great.”

Danielle Scheurer, MD, SFHM, physician editor of The Hospitalist and chief quality officer, Medical University of South Carolina

“Top New Guidelines Every Hospitalist Needs to Know in Clinical Practice” (Monday, 10:35 - 11:15 a.m., Woodrow Wilson)

“It’s important to remain up to date on all the new guideline releases.”“

Your Hospital, Your Group and Yourself: Opportunities for Promoting Well Being and Reducing Burnout” (Monday, 1:35 - 2:35 p.m., National Harbor 12-13)

“This session will help you and your teams to garner ideas and tactics for reducing the prevalence of burnout,” she said.

For more information on the HM19 education sessions, check the latest version of the conference schedule at https://shmannualconference.org/interactive-schedule/ .

There are about as many sessions at HM19 as there are cherry blossoms on the springtime trees in the nation’s capital. Attendees are bound to find something they love – probably too many somethings, in fact.

Fear not. Seasoned experts are here to ease your struggle with suggestions for sessions they consider the best of the best and tips on getting the most out of the conference.

“Download the HM19 At Hand app to plan your conference schedule, rate speakers and sessions, and participate in audience-response systems,” said Dustin Smith, MD, SFHM, the HM19 course director and associate professor of medicine at Emory University, Atlanta. “Read the track descriptions first before reviewing the individual sessions to determine which educational tracks initially pique your interest. Don’t be wedded to one track; pick and choose sessions from the different tracks to curate a schedule that best fits your educational needs.”

SHM staff and Annual Conference committee members will be easily identifiable and eager to help on site, Dr. Smith added.

HM19 was the first Annual Conference for which SHM issued a call for content to members and nonmembers alike. The contributions yielded a few new offerings. A new Clinical Mastery track includes sessions for hospitalists wanting to enhance or refine their skills in an effort to achieve a master clinician designation, Dr. Smith said, while the new Between the Guidelines track explores clinical conundrums and lessons from history that may not be covered in clinical practice guidelines.

There also is a new Palliative Care and Pain Management pre-course and a new course on emergent airway management, Dr. Smith noted. His suggestions for sessions that are new, have a new format, or are particularly timely, are too numerous to list in full but include a fun “Medical Jeopardy” session (Wednesday, 9:10 – 9:50 a.m., Maryland C), sessions on discharge dilemmas (Monday, 11:25 a.m. to 12:05 p.m., Maryland BD/4-6) and LGBTQ health (Wednesday, 10:50 to 11:30 a.m., Maryland BD/4-6) and the workshop “Being Fe(male) in Hospital Medicine Part 2: Diversifying the Discussion” (Tuesday, 2:10 to 3:40 p.m., Potomac 1-3).

The Hospitalist polled its editorial advisory board members for each of their top two suggestions for “must-see” sessions:

Raman Palabindala, MD, SFHM, hospital medicine division chief at the University of Mississippi Medical Center

“A Battle Plan Against Career Inertia: A Blueprint for an Education Series to Retain Hospitalists, Reduce Burnout and Advance Careers” (Monday, 10:35 a.m. – 12:05 p.m., Potomac 1-3)

“I strongly recommend this to all hospitalist leaders – in big or small programs – given the importance of burnout in recent years. [Speaker] Dan Hunt is one of the best,” Dr. Palabindala said.

Special Interest Forums (Monday, 4:30 – 5:25 p.m., Tuesday, 5:30 – 6:25 p.m., multiple rooms)

Dr. Palabindala said these are valuable, small sessions when you have a focused interest in a certain topic – whether IT, academics, policy, or others.

“This is the best place to make contacts with national leaders,” he said. “Be proactive in confirming your spot.”

James Kim, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Emory University

“Delirium and Dementia in the Inpatient Setting” (Tuesday, 11:50 a.m. – 12:30 p.m., Maryland BD/4-6)

“This session is a repeat from previous years, but it is an engaging lecture with a lot of great material,” Dr. Kim said. “It has changed my approach to my practice of inpatients.”

“The Role of Primary Palliative Care in Complex, Chronic Disease Management” (Tuesday, 3:50 – 4:50 p.m., National Harbor 12-13)

“As the population grows older, palliative care’s role in disease management is going to become more important,” he said. “I watched one of Dr. [Aziz] Ansari’s lectures in a previous SHM meeting, and he delivers a dynamic presentation that is both informative and entertaining.”

Hyung (Harry) Cho, MD, SFHM, chief value officer at NYC Health + Hospitals

“Tweet your Way to the Top? Social Media as a Career Development Tool in Hospital Medicine” (Monday, 12:45 – 2:15 p.m., Potomac 1-3)

This includes a team of presenters who are experienced in the use of Twitter in conjunction with the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Dr. Cho said.

“Research Shark Tank” (Monday, 1:35 – 2:35 p.m., Baltimore 3-5)

This session involves judging and critiquing the latest research proposals with “contestants” in a Shark Tank format. Among the judges is Andrew Auerbach, MD, SFHM, past editor of the JHM. It “looks very engaging,” Dr. Cho said.

Lonika Sood, MD, FHM, clinical education director of internal medicine at Washington State University

“Making Your Educational Activities Count Twice: What it Takes These Days to Publish in Medical Education Journals” (Wednesday, 8:40 – 9:40 a.m., Baltimore 3-5)

“This is an important topic for clinician educators who are interested in taking a scholarly approach to their teaching,” Dr. Sood said. “Having some form of a framework to guide us in the direction of publishing our hard work will be very helpful.”“Managing the Hidden Curriculum: Do

You Know What You’re Teaching?” (Monday, 10:35 – 11:35 a.m., Baltimore 3-5)

“This is also an important, yet ‘hidden’ topic for the clinician educator when they are in the clinical environment with learners. Having hospitalists be aware of what is actually being ‘learned’ as opposed to what they think is being ‘taught’ on the wards is a critical part of the teaching process.”

Raj Sehgal, MD, FHM, clinical associate professor at South Texas Veterans Health Care System and UT Health San Antonio

“Call Night: Common Scenarios Encountered and Strategies to Make It Through the Night” (Monday, 10:35 – 11:15 a.m., Annapolis) and “Nocturnal Admissions: Cases That Keep Me Up at Night” (Monday, 2 – 2:40 p.m., Maryland A/1-3)

“I’m glad to see several different sessions about issues hospitalists face when working nights,” Dr. Sehgal said. “After all, most hours of the week are actually ‘off-hours’ (nights and weekends), so it’s important to focus on how care is delivered during these times. Even though we see the same diagnoses regardless of the time of day, our management is often very different because of external forces, such as the availability of tests and consultants.”

Marina Farah, MD, MHA, a national expert on improving clinical quality, cost, and efficiency

"Delivering Population Health as a Hospitalist in a Value-Based Healthcare Era” (Monday, 3:45 – 4:25 p.m., Maryland A/1-3)

“Hospital care is responsible for a third of the U.S. health care spending,” Dr. Farah said. “Hospitalists serve 75% of total hospital patients and have a unique perspective and power to drive national health care outcomes. This session will offer guidance on what hospitalists can do to improve population health, decrease total cost of care, and succeed under value-based reimbursement models.”

“Things We Do for No Reason: The 2019 Clinical Update for Hospitalists” (Tuesday, 11:50 a.m. – 12:30 p.m., Woodrow Wilson)

“Every hospitalist needs to know clinical practices that aren’t evidence-based, costly, and do not improve patient outcomes,” she said.

Amith Skandhan, MD, SFHM, assistant professor and medical director/clinical liaison for clinical documentation improvement at Southeast Health Medical Center

“How To Be a Great Teaching Attending” (Wednesday, 10 – 10:40 a.m., Maryland C)

“Being an academic hospitalist, I look up to great inpatient teachers,” Dr. Skandhan said. “Dr. [Jeffrey] Wiese has an amazing presence when he talks. His book on bedside teaching has been quite a guide for me as I embarked on my journey as a teacher.”

“Amplify Your Impact: Leverage Data to Accelerate Your Efforts in Quality Improvement” (Tuesday, 3:50 – 5:20 p.m., Potomac 1-3)

“Hospital medicine is a fairly new branch of medicine, and we are now the leaders of inpatient quality improvement,” he said. “To understand data and to convert it to useful information that can be utilized in quality improvement strategies would be great.”

Danielle Scheurer, MD, SFHM, physician editor of The Hospitalist and chief quality officer, Medical University of South Carolina