User login

Short-course therapy for recurrent genital herpes and herpes labialis

- Consider giving patients an oral antiviral (OAV) medication to self-administer when HSV prodromal symptoms occur.

- Patient-initiated, short-course, high-dose OAV treatment of recurrent HSV outbreaks may be as effective as the traditional, longer-course regimens.

Hit early, hit hard. That expression arose during the evolution of treatment for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).1 While this approach has not lived up to expectations for HIV treatment, it may have found its place in the treatment of recurrent herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections.

Our review focuses on episodic treatment of acute recurrent HSV outbreaks for immunocompetent persons. We do not discuss suppressive therapy, which may be indicated for frequent or severe recurrences (6 or more per year) in immunocompetent persons, for immunocompromised patients, or as an adjunctive measure to reduce genital herpes transmission.2

As we will describe in detail, the efficacy of the new short-course therapy is, at minimum, comparable to that seen with the older, longer-course trials of topical and oral antiviral therapy. In one head-to-head comparison, Leone et al compared a short-course regimen (3 days) of valacyclovir with 5 days of treatment; they found no difference in results.3 If the efficacy of short-course treatment is the same as that of longer courses, the increased convenience and expected improvement in patient adherence with these new regimens argue strongly in their favor. (See Scope of the problem.)

The strategy: Take advantage of a brief therapeutic window

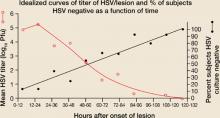

The innate and acquired immune responses of chronically infected, immunocompetent persons rapidly limit cutaneous viral replication, thereby truncating the duration of recurrent HSV outbreaks.13,14 In both recurrent herpes labialis and genital herpes, HSV viral titers peak in the first 24 hours following lesion onset (FIGURE 1A).13-15

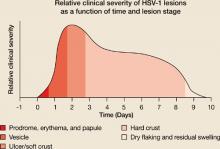

Herpes labialis lesion size and pain are also greatest in the first 24 hours.13,16 Most herpes labialis lesions progress from the vesicle stage to the ulcer/soft crust stage within 48 hours, with a hard crust forming by day 2 or 3 (FIGURE 1B).17

With genital lesions, crust formation depends on whether the skin area is dry (3–4 days) or moist (8–9 days).14

The likely events are a burst of virus replication in the first 24 hours of outbreak that lyses basal keratinocytes in a discreet area of epidermis innervated by the infected neuron(s), followed by a vigorous immune response that curtails the infection and creates, in part, the clinical disease (erythema, swelling, vesiculation, and ulceration). The subsequent elements of the illness, which are the majority of the lesion course, are related to wound healing

Recognizing the window. Given the brief period of viral replication and the rapid evolution of lesions, the therapeutic window for treating HSV outbreaks with antiviral drugs is both early and short, making it problematic to effectively treat HSV recurrences. Patients often have mature lesions by the time they consult a physician, rendering subsequent anti-viral treatment less effective.18 However, before lesions appear, many patients experience prodromal symptoms such as pain, burning, or itching.13,18 These symptoms can be a prompt to start treatment early, thereby taking advantage of the transient therapeutic window.

If a patient is able to self-administer therapy when prodromal symptoms occur, there may be a greater benefit to treatment. Giving patients drugs for self-administration is therefore an important strategy in managing HSV recurrences.

Traditionally, patient-initiated episodic therapy for recurrent genital herpes and herpes labialis has involved multiple daily doses of topical or oral antiviral agents for 4 to 5 days.19-26 Studies of the pathogenesis of HSV recurrences, however, indicate—as said earlier—that the period of virus replication is early and brief, such that a shorter duration of treatment might be more appropriate and equally effective. Other recent clinical studies have indicated that patient-initiated, short-course, high-dose OAV treatment of recurrent HSV infections may be as effective as the traditional therapies.3,27-30 In the section that follows, we examine and compare the results of these trials. (See The agents and how they work.)

FIGURE 1A

Lesion HSV-1 titer peaks within 24 hours of onset of herpes labialis lesions

Source: Krueger et al, J Clin Epidemiol Derm 1978.15 Reproduced with permission from GG Krueger.

FIGURE 1B

Hard crust formation occurs by 48 to 72 hours of onset of herpes labialis lesions

Source: Spruance, Sem Dermatol 1992.17 With permission from Elsevier.

Clinical trials: Short-course, high-dose, patient-initiated episodic OAV therapy for recurrent genital herpes

Three-day vs 5-day valacyclovir therapy. The efficacy of 3-day treatment with oral valacyclovir was compared with that of 5-day treatment in immunocompetent adults with a history of ≥4 episodes of recurrent genital herpes and confirmed HSV infection.3 Eight hundred participants were randomized to receive 500 mg twice daily valacyclovir for 3 days (and placebo for the remaining 2 days) or 500 mg twice daily for 5 days, and were required to self-administer therapy no later than 24 hours after the onset of symptoms.

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 (HSV-1) or type 2 (HSV-2) results in periodic, recurrent outbreaks of skin lesions after first infection. Herpes labialis (fever blisters or cold sores) is usually caused by HSV-1, while genital herpes is usually caused by HSV-2.4 HSV-2 lesions of the lips have been reported, and the incidence of genital herpes caused by HSV-1 is on the rise in the developed world, likely because of increased oral-genital sexual behavior.5,6 Patients with HSV-1 genital herpes typically have fewer recurrences than those with HSV-2 genital infection.7

The prevalence of HSV-1 and HSV-2 infection varies according to age, geography, gender, and population subgroup, such as people who exhibit high-risk sexual behavior.8 approximately 45% of americans are infected with HSV-1 by adolescence,8 and approximately 22% of all american adults are infected with HSV-2.9 The global prevalence of HSV is even greater: as many as 60% to 90% of older adults worldwide are seropositive for HSV-1, and as many as 30% are seropositive for HSV-2. HSV-2 seropositivity is more prevalent among women than men.8 overall, the burden of recurrent genital herpes outbreaks can have a profound, negative impact on patient quality of life.10,11 The psychological impact of recurrent herpes labialis has not been thoroughly investigated, but an undefined burden is thought to exist, particularly in young patients with frequent or severe recurrences.12

The primary endpoint was time to lesion healing (defined as the number of days from initiation of therapy to lesion reepithelialization). Secondary endpoints were pain duration, episode duration (defined as time from initiation of therapy to resolution of all symptoms) and percentage of patients with aborted lesions.

The 3-day valacyclovir treatment exhibited similar time to lesion healing, length of episode, and percentage of patients with aborted lesions as the 5-day treatment (TABLE 1), suggesting equal efficacy. Duration of pain was also similar (data not shown). Adverse events were similar for both treatment groups, with the most common being headache (10%), nausea (4%), and diarrhea (4%, 5-day treatment vs 2%, 3-day treatment).

Placebo-controlled trial of 2-day acyclovir therapy. Wald and coworkers examined the effect of a shorter treatment regimen of acyclovir (2 days) on recurrent genital herpes.28 Eighty-four immunocompetent HSV-2–infected patients with a history of ≥3 recurrences in the previous 12 months were randomized to receive either 2 days of 800 mg 3 times daily acyclovir or matching placebo. Patients were asked to take their medication no later than 12 hours after the first sign or symptom of an episode.

Efficacy endpoints were time to lesion healing, episode duration, and percentage of patients with aborted lesions. Short-course acyclovir therapy was shown to decrease time to healing (P=.001) and episode duration (P<.001) by 2 days compared with placebo (TABLE 1). Short-course acyclovir therapy also increased the percentage of patients with aborted lesions compared with placebo (27% vs 11%; P=.029 (TABLE 1). Adverse events were not recorded in this analysis.

Placebo-controlled trial of single-day famciclovir therapy. Aoki and colleagues29 performed a randomized, double-blind, patient-initiated, placebo-controlled trial to assess the efficacy and safety of patient-initiated, single-day famciclovir 1000 mg twice daily in immunocompetent adults with recurrent genital herpes. The 329 patients in the study were instructed to self-initiate therapy within 6 hours of the onset of prodromal symptoms or genital herpes lesions, and were asked to return to the clinic no later than 24 hours after initiation of therapy. Patients were followed until their lesions healed or for up to 14 days.

The primary endpoint was time to lesion healing of nonaborted lesions. Secondary endpoints were time to healing of all lesions (aborted and nonaborted), time to resolution of pain and other symptoms, and the percentage of patients who did not progress to a full outbreak.

Single-day treatment with famciclovir shortened the time to healing of nonaborted genital herpes lesions by approximately 2 days (P<.001), and the time to healing of all lesions by 1.5 days (P<.001) compared with placebo, and increased the percentage of patients who did not progress to a full outbreak (23% vs 13%;P=.003) (TABLE 1). Famciclovir also reduced the time to resolution of all symptoms by approximately 2 days (P<.001) (data not shown).

Adverse events were mild to moderate; the most common in the famciclovir and placebo groups, respectively, were headache (13.5% vs 5.4%), nausea (2.5% vs 3.6%), and diarrhea (4.9% vs 1.2%).

TABLE 1

Short-course, patient-initiated OAV therapy is effective for treating episodic genital herpes

| DRUG | TREATMENT DURATION | TREATMENT DOSE | CONTROL | MEDIAN TIME (DAYS) TO LESION HEALING (TREATMENT VS CONTROL) | MEDIAN EP ISODE DURATION (DAYS) (TREATMENT VS CONTROL) | PATIENTS WITH ABORTED EPISODES (%) (TREATMENT VS CONTROL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valacyclovir3 | 3 days | 500 mg 2×daily | valacyclovir 500 mg 2×/day for 5 days | 4.4 vs 4.7 (P=NS) | 4.3 vs 4.4 (P=NS) | 25 vs 27 (P=NS) |

| Acyclovir28 | 2 days | 800 mg 3×daily | Placebo | 4.0 vs 6.0 (P=.001) | 4.0 vs 6.0 (P=.001) | 27 vs 11 (P=.029) |

| Famciclovir29 | 1 day | 1000 mg 2×daily | Placebo | 4.3 vs 6.1 (P<.001) | 3.5 vs 5.0 (P<.001) | 23 vs 13 (P=.003) |

| Lesion healing time measures the duration of a subset of severe or classical herpetic outbreaks, characterized by the formation of vesicles, ulcers, or crusts (also papules in some studies28,29). The endpoint is lesion reepithelialization/loss of crust. Episodes where there were only prodromal symptoms, erythema, and/or papule formation (or only symptoms and/or erythema in some studies28,29) were considered “aborted” or prevented lesions. The occurrence of these favorable episode outcomes is described as a percentage of all episodes. Episode duration, sometimes called healing time of all lesions or time to return to normal skin, is the time to resolution of all episodes, regardless of lesion severity. The definition of normal skin varies among the different studies. | ||||||

| NS=not significant. | ||||||

Short-course, high-dose, patient-initiated episodic OAV therapy for recurrent herpes labialis

Placebo-controlled trial of single-day and 2-day valacyclovir therapy. Spruance and coworkers studied the efficacy of single-day and 2-day valacyclovir treatments in comparison with placebo for an episode of herpes labialis.27 Two identical studies were performed on individuals who were at least 12 years old, had a clinical history of recurrent cold sores, and had experienced ≥3 episodes in the preceding year. Participants in both studies (study 1, N=1524; study 2, N=1627) were required to self-administer 2 g valacyclovir twice daily for 1 day (valacyclovir 1 day), 2 g valacyclovir twice daily for 1 day followed by 1 g twice daily for 1 day (valacyclovir 2 days), or matching placebo at the earliest onset of prodromal symptoms and before the appearance of lesions. Patients were asked to return to the clinic within 24 hours of initiation of therapy.

The primary endpoint in study 1 was clinician-observed duration of all herpes labialis lesions and the secondary endpoint was the percentage of subjects who had herpes labialis lesions that did not progress beyond the papule stage. In study 2, the endpoints were reversed: the primary endpoint was the percentage of patients with lesions that did not progress and the secondary endpoint was the duration of lesions. Other efficacy endpoints were time to healing of vesicular (classical) lesions and duration of pain and discomfort.

Both studies demonstrated that single-day valacyclovir treatment significantly decreased lesion healing time and the duration of herpes labialis episodes by 0.5 to 1.0 days compared with placebo (TABLE 2). A statistically significant decrease in the duration of pain and other symptoms was also seen with single-day valacyclovir compared with placebo (data not shown). In both studies, a higher percentage of patients in the valacyclovir group did not progress to full outbreak compared with placebo, but these differences were not statistically significant. The results with 2 days of valacyclovir treatment were similar. Adverse events were similar between the treatment groups and the placebo group.

Placebo-controlled trial of single-dose and single-day famciclovir therapy. Spruance and coworkers assessed patient-initiated famciclovir 1500 mg (single-dose) and 750 mg twice daily (single-day) in immunocompetent adults with recurrent cold sores.30 Subjects (N=1376) were at least 18 years of age and had experienced ≥3 episodes of cold sores over the previous 12 months. Subjects were instructed to administer 1500 mg (single-dose), 750 mg twice daily (single-day), or matching placebo within 1 hour of the onset of prodromal symptoms and before the onset of lesions, and were asked to return to the clinic within 24 hours of initiating medication.

Topical antiviral drug formulations were the first treatments approved for recurrent HSV-1 and HSV-2 outbreaks, but these were only marginally efficacious.19-21,31 orally-administered antiviral agents appear to be more effective, possibly because of better delivery of the drug to the site of infection. Three oral antiviral agents (OAVs) are currently approved for the treatment of recurrent genital herpes: acyclovir, an acyclic nucleoside analog; valacyclovir, the prodrug of acyclovir; and famciclovir, the prodrug of penciclovir, another acyclic nucleoside analog. one OAV (valacyclovir) is currently approved for the treatment of herpes labialis in immunocompetent patients.27 The prodrugs of acyclovir and penciclovir, valacyclovir and famciclovir, respectively, were synthesized to provide high oral bioavailability and thus permit less frequent administration and potentially greater efficacy compared to the parent compounds.

Following oral administration, valacyclovir and famciclovir undergo first-pass metabolism to acyclovir and penciclovir, respectively.4,32 acyclovir and penciclovir are selectively phosphorylated by the viral thymidine kinase of infected cells and then converted to the active triphosphate by cellular enzymes. The triphosphate forms (which have different half-lives depending upon the compound)33 inhibit viral DNA polymerase and interfere with DNA chain extension,34 thereby halting viral DNA synthesis. The drugs cannot prevent the death of a cell once it is infected, but they can reduce, in a dose-dependent manner, the quantity of virions produced by an infected cell. The mechanism of action of HSV-selective antiviral drugs suggests that the most logical strategy for episodic treatment is to maximally inhibit HSV replication using high doses.18,35

The primary endpoint was time to healing of primary vesicular lesions. Secondary endpoints included time to healing of all vesicular lesions (primary and secondary [secondary lesions are defined as lesions that developed in addition to and on 1 or more days after primary lesions and that were located at least 1 cm from primary lesions]), time to return to normal skin for all lesions (defined as loss of crust, swelling, and dry flaking), duration of lesion tenderness and pain, and proportion of patients with aborted lesions.

There was a statistically significant decrease in time to healing of primary vesicular lesions by approximately 2 days with both single-dose and single-day famciclovir compared with placebo, with no significant difference between the 2 famciclovir regimens in time to healing of primary vesicular lesions (TABLE 2). There was also a statistically significant decrease in the time to healing of all lesions (primary and secondary) by approximately 2 days with both famciclovir treatments compared with placebo, with no significant differences seen in healing between the famciclovir arms (data not shown).

However, only single-dose famciclovir had a statistically significant decrease in the duration of lesion tenderness and pain and the time to return to normal skin compared with placebo (data not shown). No difference was noted between the famciclovir arms in the percentage of patients with aborted lesions compared with placebo. Adverse events in both famciclovir groups were similar to those in the placebo group.

TABLE 2

Short-course, patient-initiated OAV therapy is effective against recurrent herpes labialis

| DRUG | TREATMENT DURATION | TREATMENT DOSE | COMPARATOR REGIMEN | CONTROL | MEDIAN TIME (DAYS) TO LESION HEALING (TREATMENT VS COMPARATOR VS CONTROL)* | MEDIAN EP ISODE DURATION (DAYS) (TREATMENT VS COMPARATOR VS CONTROL)* | PATIENTS WITH ABORTED LESIONS (%)(TREATMENT VS COMPARATOR VS CONTROL)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valacyclovir27 | 1 day | 2000 mg 2×daily | valacyclovir 2000 mg 2×daily×1 day 1000 mg 2×daily for a 2nd day | Placebo | study 1 4.3 vs 4.3 vs 5.1 study 2 4.8 vs 4.6 vs 5.4 | study 1 4.0 vs 4.5 vs 5.0 study 2 2 5.0 vs 5.0 vs 5.5 | study 1 44 vs 46 vs 38 study 2 43 vs 43 vs 35 |

| Famciclovir30 1 dose | 1 Does | 1500 mg | famciclovir 750 mg 2x daily for 1 day | Placebo | 4.4 vs 4.0 vs 6.2 | 4.5 vs 5.7 vs 7.0 | 33 vs 29 vs 34 |

| Lesion healing time measures the duration of a subset of severe or classical herpetic outbreaks, characterized by the formation of vesicles, ulcers, or crusts (also papules in some studies28,29). The endpoint is lesion reepithelialization/loss of crust. Episodes where there were only prodromal symptoms, erythema, and/or papule formation (or only symptoms and/or erythema in some studies28,29) were considered “aborted” or prevented lesions. The occurrence of these favorable episode outcomes is described as a percentage of all episodes. Episode duration, sometimes called healing time of all lesions or time to return to normal skin, is the time to resolution of all episodes, regardless of lesion severity. The definition of normal skin varies among the different studies. | |||||||

| *All of the healing time and episode duration values for the active treatment arms in both studies differed statistically significantly from placebo, except for famciclovir 750 mg twice daily for 1 day. | |||||||

| †None of the frequencies of aborted lesions in the active treatment arms in either study differed statistically significantly from placebo. | |||||||

CORRESPONDENCE

Spotswood Spruance MD Professor of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Utah School of Medicine, Room 4B319, 30 North 1900 East, Salt Lake City, UT 84132-2405. E-mail:[email protected]

1. Ho D. Time to hit HIV, early and hard. N Engl J Med 1995;333:450-451.

2. Corey L, Wald A, Patel R, et al. Once-daily valacyclovir to reduce the risk of transmission of genital herpes. N Engl J Med 2004;350:11-20.

3. Leone PA, Trottier S, Miller JM. Valacyclovir for episodic treatment of genital herpes: a shorter 3-day treatment course compared with 5-day treatment. Clin Infect Dis 2002;34:958-962.

4. Whitley RJ, Kimberlin DW, Roizman B. Herpes simplex viruses. Clin Infect Dis 1998;26:541-555.

5. Wald A, Ericsson M, Krantz E, Selkes S, Corey L. Oral shedding of herpes simplex virus type 2. Sex Transm Infect 2004;80:272-276.

6. Mertz GJ, Rosenthal Sl, Stanberry LR. Editorial response: Is herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) now more common than HSV-2 in first episodes of genital herpes? Sex Transm Dis 2003;30:801-802.

7. Lafferty WE, Coombs RW, Benedetti J, Critchlow C, Corey L. Recurrences after oral and genital herpes simplex virus infection. N Engl J Med 1987;316:1444-1449.

8. Smith JS, Robinson RJ. Age-specific prevalence of infection with herpes simplex virus types 2 and 1: a global review. J Infect Dis 2002;186(suppl 1):S3-S28.

9. Fleming DT, McQuillan GM, Johnson RE, et al. Herpes simplex virus type 2 in the united States, 1976 to 1994. N Engl J Med 1997;337:1105-1111.

10. Bierman SM. A retrospective study of 375 patients with genital herpes simplex infections seen between 1973 and 1980. Cutis 1983;31:548-565.

11. Drob S, Loemer M, Lifshutz H. Genital herpes: the psychological consequences. Br J Med Psychol 1985;58:307-315.

12. Spruance SL, Kriesel JD. Treatment of herpes simplex labialis. Herpes 2002;9:64-69.

13. Spruance SL, overall JC, Jr, Kern ER, Krueger GG, Pliam V, Miller W. The natural history of recurrent herpes simplex labialis. N Engl J Med 1977;297:69-75.

14. Brown ZA, Kern ER, Spruance SL, Overall JC, Jr. Clinical and virologic course of herpes simplex genitalis. West J Med 1979;130:414-421.

15. Krueger GG, Spruance SL, Overall JC, Jr. Herpes simplex labialis: a review of pathogenesis and therapy. J Clin Epidemiol Derm 1978;1:19-37.

16. Spruance SL, Wenerstrom G. Pathogenesis of herpes simplex labialis: IV. Maturation of lesions during within 8 hours after onset and implications for antiviral treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Path 1984;58:667-671.

17. Spruance SL. The natural history of recurrent oral-facial herpes simplex virus infection. Sem Dermatol 1992;11:200-206.

18. Spruance SL. Herpes simplex labialis. In: Clinical Management of Herpes Viruses. Sacks SL, Straus SE, Whitley RJ, Griffiths PD, eds. amsterdam, Netherlands: IOS Press; 1995.

19. Spruance SL, Nett R, Marbury T, Wolff R, Johnson J, Spaulding T. Acyclovir cream for treatment of herpes simplex labialis: results of two randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, multicenter clinical trials. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002;46:2238-2243.

20. Spruance SL, Rea TL, Thoming C, Tucker R, Saltzman R, Boon R. Penciclovir cream for the treatment of herpes simplex labialis. JAMA 1997;277:1374-1379.

21. Raborn GW, Martel AY, lassonde M, et al. Worldwide Topical Penciclovir Collaborative Study Group. Effective treatment of herpes simplex labialis with penciclovir cream: combined results of two trials. J Am Dent Assoc 2002;133:303-309.

22. Reichman RC, Badger GJ, Mertz GJ, et al. Treatment of recurrent genital herpes simplex infections with oral acyclovir: a controlled trial. JAMA 1984;251:2103-2107.

23. Sacks SL, Aoki FY, Diaz-Mitoma F, Sellors J, Shafran SD. Canadian Famciclovir Study Group. Patient-initiated, twice-daily oral famciclovir for early recurrent genital herpes: a randomized, double-blind multicenter trial. JAMA 1996;276:44-49.

24. Tyring SK, Douglas JM, Jr, Corey L, Spruance SL, Esmann J. The valaciclovir International Study Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled comparison of oral valcyclovir and acyclovir in immunocompetent patients with recurrent genital herpes infections. Arch Dermatol 1998;134:185-191.

25. Spruance S, Stewart JCB, Rowe NH, McKeough MB, Wenerstrom G, Freeman DJ. Treatment of herpes simplex labialis with oral acyclovir. J Infect Dis 1990;161:185-190.

26. Spruance SL, Tyring SK, DeGregorio B, Miller C, Beutner K; valaciclovir HSV Study Group. A large-scale, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trial of peroral valaciclovir for episodic treatment of recurrent herpes genitalis. Arch Intern Med 1996;156:1729-1735.

27. Spruance SL, Jones TM, Blatter MM, et al. High-dose, short-duration, early valacyclovir therapy for episodic treatment of cold sores: results of two randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter studies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2003;47:1072-1080.

28. Wald A, Carrell D, Remington M, Kexel E, Zeh J, Corey L. Two-day regimen of acyclovir for treatment of recurrent genital herpes simplex virus type 2 infection. Clin Infect Dis 2002;34:944-948.

29. Aoki FY, Tyring S, Dias-Mitoma F, Gross G, Gao J, Hamed K. Single-day patient initiated famciclovir therapy for recurrent genital herpes: a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 2006;42:8-13.

30. Spruance S, Bodsworth N, Resnick H, et al. Single-dose, patient-initiated famciclovir: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial for episodic treatment of herpes labialis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;55:47-53.

31. Reichman RC, Badger GJ, Guinan ME, et al. Topically administered acyclovir in the treatment of recurrent herpes simplex genitalis: a controlled trial. J Infect Dis 1983;147:336-340.

32. Gill KS, Wood MJ. The clinical pharmacokinetics of famciclovir. Clin Pharmacokinet 1996;31:1-8.

33. Earnshaw DL, Bacon TH, Darlison SJ, Edmonds K, Perkins RM, Vere Hodge RA. Mode of antiviral action of penciclovir in MRC-5 cells infected with herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), HSV-2, and varicella-zoster virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1992;36:2747-2757.

34. Vere Hodge RA, Perkins RM. Mode of action of 9-(4-hydroxy-3-hydroxymethylbut-1-yl)guanine (Brl 39123) against herpes simplex virus in MrC-5 cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1989;33:223-229.

35. Spruance SL, Freeman DJ. Topical treatment of cutaneous herpes simplex virus infections. Antivir Res 1990;14:305-321.

- Consider giving patients an oral antiviral (OAV) medication to self-administer when HSV prodromal symptoms occur.

- Patient-initiated, short-course, high-dose OAV treatment of recurrent HSV outbreaks may be as effective as the traditional, longer-course regimens.

Hit early, hit hard. That expression arose during the evolution of treatment for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).1 While this approach has not lived up to expectations for HIV treatment, it may have found its place in the treatment of recurrent herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections.

Our review focuses on episodic treatment of acute recurrent HSV outbreaks for immunocompetent persons. We do not discuss suppressive therapy, which may be indicated for frequent or severe recurrences (6 or more per year) in immunocompetent persons, for immunocompromised patients, or as an adjunctive measure to reduce genital herpes transmission.2

As we will describe in detail, the efficacy of the new short-course therapy is, at minimum, comparable to that seen with the older, longer-course trials of topical and oral antiviral therapy. In one head-to-head comparison, Leone et al compared a short-course regimen (3 days) of valacyclovir with 5 days of treatment; they found no difference in results.3 If the efficacy of short-course treatment is the same as that of longer courses, the increased convenience and expected improvement in patient adherence with these new regimens argue strongly in their favor. (See Scope of the problem.)

The strategy: Take advantage of a brief therapeutic window

The innate and acquired immune responses of chronically infected, immunocompetent persons rapidly limit cutaneous viral replication, thereby truncating the duration of recurrent HSV outbreaks.13,14 In both recurrent herpes labialis and genital herpes, HSV viral titers peak in the first 24 hours following lesion onset (FIGURE 1A).13-15

Herpes labialis lesion size and pain are also greatest in the first 24 hours.13,16 Most herpes labialis lesions progress from the vesicle stage to the ulcer/soft crust stage within 48 hours, with a hard crust forming by day 2 or 3 (FIGURE 1B).17

With genital lesions, crust formation depends on whether the skin area is dry (3–4 days) or moist (8–9 days).14

The likely events are a burst of virus replication in the first 24 hours of outbreak that lyses basal keratinocytes in a discreet area of epidermis innervated by the infected neuron(s), followed by a vigorous immune response that curtails the infection and creates, in part, the clinical disease (erythema, swelling, vesiculation, and ulceration). The subsequent elements of the illness, which are the majority of the lesion course, are related to wound healing

Recognizing the window. Given the brief period of viral replication and the rapid evolution of lesions, the therapeutic window for treating HSV outbreaks with antiviral drugs is both early and short, making it problematic to effectively treat HSV recurrences. Patients often have mature lesions by the time they consult a physician, rendering subsequent anti-viral treatment less effective.18 However, before lesions appear, many patients experience prodromal symptoms such as pain, burning, or itching.13,18 These symptoms can be a prompt to start treatment early, thereby taking advantage of the transient therapeutic window.

If a patient is able to self-administer therapy when prodromal symptoms occur, there may be a greater benefit to treatment. Giving patients drugs for self-administration is therefore an important strategy in managing HSV recurrences.

Traditionally, patient-initiated episodic therapy for recurrent genital herpes and herpes labialis has involved multiple daily doses of topical or oral antiviral agents for 4 to 5 days.19-26 Studies of the pathogenesis of HSV recurrences, however, indicate—as said earlier—that the period of virus replication is early and brief, such that a shorter duration of treatment might be more appropriate and equally effective. Other recent clinical studies have indicated that patient-initiated, short-course, high-dose OAV treatment of recurrent HSV infections may be as effective as the traditional therapies.3,27-30 In the section that follows, we examine and compare the results of these trials. (See The agents and how they work.)

FIGURE 1A

Lesion HSV-1 titer peaks within 24 hours of onset of herpes labialis lesions

Source: Krueger et al, J Clin Epidemiol Derm 1978.15 Reproduced with permission from GG Krueger.

FIGURE 1B

Hard crust formation occurs by 48 to 72 hours of onset of herpes labialis lesions

Source: Spruance, Sem Dermatol 1992.17 With permission from Elsevier.

Clinical trials: Short-course, high-dose, patient-initiated episodic OAV therapy for recurrent genital herpes

Three-day vs 5-day valacyclovir therapy. The efficacy of 3-day treatment with oral valacyclovir was compared with that of 5-day treatment in immunocompetent adults with a history of ≥4 episodes of recurrent genital herpes and confirmed HSV infection.3 Eight hundred participants were randomized to receive 500 mg twice daily valacyclovir for 3 days (and placebo for the remaining 2 days) or 500 mg twice daily for 5 days, and were required to self-administer therapy no later than 24 hours after the onset of symptoms.

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 (HSV-1) or type 2 (HSV-2) results in periodic, recurrent outbreaks of skin lesions after first infection. Herpes labialis (fever blisters or cold sores) is usually caused by HSV-1, while genital herpes is usually caused by HSV-2.4 HSV-2 lesions of the lips have been reported, and the incidence of genital herpes caused by HSV-1 is on the rise in the developed world, likely because of increased oral-genital sexual behavior.5,6 Patients with HSV-1 genital herpes typically have fewer recurrences than those with HSV-2 genital infection.7

The prevalence of HSV-1 and HSV-2 infection varies according to age, geography, gender, and population subgroup, such as people who exhibit high-risk sexual behavior.8 approximately 45% of americans are infected with HSV-1 by adolescence,8 and approximately 22% of all american adults are infected with HSV-2.9 The global prevalence of HSV is even greater: as many as 60% to 90% of older adults worldwide are seropositive for HSV-1, and as many as 30% are seropositive for HSV-2. HSV-2 seropositivity is more prevalent among women than men.8 overall, the burden of recurrent genital herpes outbreaks can have a profound, negative impact on patient quality of life.10,11 The psychological impact of recurrent herpes labialis has not been thoroughly investigated, but an undefined burden is thought to exist, particularly in young patients with frequent or severe recurrences.12

The primary endpoint was time to lesion healing (defined as the number of days from initiation of therapy to lesion reepithelialization). Secondary endpoints were pain duration, episode duration (defined as time from initiation of therapy to resolution of all symptoms) and percentage of patients with aborted lesions.

The 3-day valacyclovir treatment exhibited similar time to lesion healing, length of episode, and percentage of patients with aborted lesions as the 5-day treatment (TABLE 1), suggesting equal efficacy. Duration of pain was also similar (data not shown). Adverse events were similar for both treatment groups, with the most common being headache (10%), nausea (4%), and diarrhea (4%, 5-day treatment vs 2%, 3-day treatment).

Placebo-controlled trial of 2-day acyclovir therapy. Wald and coworkers examined the effect of a shorter treatment regimen of acyclovir (2 days) on recurrent genital herpes.28 Eighty-four immunocompetent HSV-2–infected patients with a history of ≥3 recurrences in the previous 12 months were randomized to receive either 2 days of 800 mg 3 times daily acyclovir or matching placebo. Patients were asked to take their medication no later than 12 hours after the first sign or symptom of an episode.

Efficacy endpoints were time to lesion healing, episode duration, and percentage of patients with aborted lesions. Short-course acyclovir therapy was shown to decrease time to healing (P=.001) and episode duration (P<.001) by 2 days compared with placebo (TABLE 1). Short-course acyclovir therapy also increased the percentage of patients with aborted lesions compared with placebo (27% vs 11%; P=.029 (TABLE 1). Adverse events were not recorded in this analysis.

Placebo-controlled trial of single-day famciclovir therapy. Aoki and colleagues29 performed a randomized, double-blind, patient-initiated, placebo-controlled trial to assess the efficacy and safety of patient-initiated, single-day famciclovir 1000 mg twice daily in immunocompetent adults with recurrent genital herpes. The 329 patients in the study were instructed to self-initiate therapy within 6 hours of the onset of prodromal symptoms or genital herpes lesions, and were asked to return to the clinic no later than 24 hours after initiation of therapy. Patients were followed until their lesions healed or for up to 14 days.

The primary endpoint was time to lesion healing of nonaborted lesions. Secondary endpoints were time to healing of all lesions (aborted and nonaborted), time to resolution of pain and other symptoms, and the percentage of patients who did not progress to a full outbreak.

Single-day treatment with famciclovir shortened the time to healing of nonaborted genital herpes lesions by approximately 2 days (P<.001), and the time to healing of all lesions by 1.5 days (P<.001) compared with placebo, and increased the percentage of patients who did not progress to a full outbreak (23% vs 13%;P=.003) (TABLE 1). Famciclovir also reduced the time to resolution of all symptoms by approximately 2 days (P<.001) (data not shown).

Adverse events were mild to moderate; the most common in the famciclovir and placebo groups, respectively, were headache (13.5% vs 5.4%), nausea (2.5% vs 3.6%), and diarrhea (4.9% vs 1.2%).

TABLE 1

Short-course, patient-initiated OAV therapy is effective for treating episodic genital herpes

| DRUG | TREATMENT DURATION | TREATMENT DOSE | CONTROL | MEDIAN TIME (DAYS) TO LESION HEALING (TREATMENT VS CONTROL) | MEDIAN EP ISODE DURATION (DAYS) (TREATMENT VS CONTROL) | PATIENTS WITH ABORTED EPISODES (%) (TREATMENT VS CONTROL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valacyclovir3 | 3 days | 500 mg 2×daily | valacyclovir 500 mg 2×/day for 5 days | 4.4 vs 4.7 (P=NS) | 4.3 vs 4.4 (P=NS) | 25 vs 27 (P=NS) |

| Acyclovir28 | 2 days | 800 mg 3×daily | Placebo | 4.0 vs 6.0 (P=.001) | 4.0 vs 6.0 (P=.001) | 27 vs 11 (P=.029) |

| Famciclovir29 | 1 day | 1000 mg 2×daily | Placebo | 4.3 vs 6.1 (P<.001) | 3.5 vs 5.0 (P<.001) | 23 vs 13 (P=.003) |

| Lesion healing time measures the duration of a subset of severe or classical herpetic outbreaks, characterized by the formation of vesicles, ulcers, or crusts (also papules in some studies28,29). The endpoint is lesion reepithelialization/loss of crust. Episodes where there were only prodromal symptoms, erythema, and/or papule formation (or only symptoms and/or erythema in some studies28,29) were considered “aborted” or prevented lesions. The occurrence of these favorable episode outcomes is described as a percentage of all episodes. Episode duration, sometimes called healing time of all lesions or time to return to normal skin, is the time to resolution of all episodes, regardless of lesion severity. The definition of normal skin varies among the different studies. | ||||||

| NS=not significant. | ||||||

Short-course, high-dose, patient-initiated episodic OAV therapy for recurrent herpes labialis

Placebo-controlled trial of single-day and 2-day valacyclovir therapy. Spruance and coworkers studied the efficacy of single-day and 2-day valacyclovir treatments in comparison with placebo for an episode of herpes labialis.27 Two identical studies were performed on individuals who were at least 12 years old, had a clinical history of recurrent cold sores, and had experienced ≥3 episodes in the preceding year. Participants in both studies (study 1, N=1524; study 2, N=1627) were required to self-administer 2 g valacyclovir twice daily for 1 day (valacyclovir 1 day), 2 g valacyclovir twice daily for 1 day followed by 1 g twice daily for 1 day (valacyclovir 2 days), or matching placebo at the earliest onset of prodromal symptoms and before the appearance of lesions. Patients were asked to return to the clinic within 24 hours of initiation of therapy.

The primary endpoint in study 1 was clinician-observed duration of all herpes labialis lesions and the secondary endpoint was the percentage of subjects who had herpes labialis lesions that did not progress beyond the papule stage. In study 2, the endpoints were reversed: the primary endpoint was the percentage of patients with lesions that did not progress and the secondary endpoint was the duration of lesions. Other efficacy endpoints were time to healing of vesicular (classical) lesions and duration of pain and discomfort.

Both studies demonstrated that single-day valacyclovir treatment significantly decreased lesion healing time and the duration of herpes labialis episodes by 0.5 to 1.0 days compared with placebo (TABLE 2). A statistically significant decrease in the duration of pain and other symptoms was also seen with single-day valacyclovir compared with placebo (data not shown). In both studies, a higher percentage of patients in the valacyclovir group did not progress to full outbreak compared with placebo, but these differences were not statistically significant. The results with 2 days of valacyclovir treatment were similar. Adverse events were similar between the treatment groups and the placebo group.

Placebo-controlled trial of single-dose and single-day famciclovir therapy. Spruance and coworkers assessed patient-initiated famciclovir 1500 mg (single-dose) and 750 mg twice daily (single-day) in immunocompetent adults with recurrent cold sores.30 Subjects (N=1376) were at least 18 years of age and had experienced ≥3 episodes of cold sores over the previous 12 months. Subjects were instructed to administer 1500 mg (single-dose), 750 mg twice daily (single-day), or matching placebo within 1 hour of the onset of prodromal symptoms and before the onset of lesions, and were asked to return to the clinic within 24 hours of initiating medication.

Topical antiviral drug formulations were the first treatments approved for recurrent HSV-1 and HSV-2 outbreaks, but these were only marginally efficacious.19-21,31 orally-administered antiviral agents appear to be more effective, possibly because of better delivery of the drug to the site of infection. Three oral antiviral agents (OAVs) are currently approved for the treatment of recurrent genital herpes: acyclovir, an acyclic nucleoside analog; valacyclovir, the prodrug of acyclovir; and famciclovir, the prodrug of penciclovir, another acyclic nucleoside analog. one OAV (valacyclovir) is currently approved for the treatment of herpes labialis in immunocompetent patients.27 The prodrugs of acyclovir and penciclovir, valacyclovir and famciclovir, respectively, were synthesized to provide high oral bioavailability and thus permit less frequent administration and potentially greater efficacy compared to the parent compounds.

Following oral administration, valacyclovir and famciclovir undergo first-pass metabolism to acyclovir and penciclovir, respectively.4,32 acyclovir and penciclovir are selectively phosphorylated by the viral thymidine kinase of infected cells and then converted to the active triphosphate by cellular enzymes. The triphosphate forms (which have different half-lives depending upon the compound)33 inhibit viral DNA polymerase and interfere with DNA chain extension,34 thereby halting viral DNA synthesis. The drugs cannot prevent the death of a cell once it is infected, but they can reduce, in a dose-dependent manner, the quantity of virions produced by an infected cell. The mechanism of action of HSV-selective antiviral drugs suggests that the most logical strategy for episodic treatment is to maximally inhibit HSV replication using high doses.18,35

The primary endpoint was time to healing of primary vesicular lesions. Secondary endpoints included time to healing of all vesicular lesions (primary and secondary [secondary lesions are defined as lesions that developed in addition to and on 1 or more days after primary lesions and that were located at least 1 cm from primary lesions]), time to return to normal skin for all lesions (defined as loss of crust, swelling, and dry flaking), duration of lesion tenderness and pain, and proportion of patients with aborted lesions.

There was a statistically significant decrease in time to healing of primary vesicular lesions by approximately 2 days with both single-dose and single-day famciclovir compared with placebo, with no significant difference between the 2 famciclovir regimens in time to healing of primary vesicular lesions (TABLE 2). There was also a statistically significant decrease in the time to healing of all lesions (primary and secondary) by approximately 2 days with both famciclovir treatments compared with placebo, with no significant differences seen in healing between the famciclovir arms (data not shown).

However, only single-dose famciclovir had a statistically significant decrease in the duration of lesion tenderness and pain and the time to return to normal skin compared with placebo (data not shown). No difference was noted between the famciclovir arms in the percentage of patients with aborted lesions compared with placebo. Adverse events in both famciclovir groups were similar to those in the placebo group.

TABLE 2

Short-course, patient-initiated OAV therapy is effective against recurrent herpes labialis

| DRUG | TREATMENT DURATION | TREATMENT DOSE | COMPARATOR REGIMEN | CONTROL | MEDIAN TIME (DAYS) TO LESION HEALING (TREATMENT VS COMPARATOR VS CONTROL)* | MEDIAN EP ISODE DURATION (DAYS) (TREATMENT VS COMPARATOR VS CONTROL)* | PATIENTS WITH ABORTED LESIONS (%)(TREATMENT VS COMPARATOR VS CONTROL)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valacyclovir27 | 1 day | 2000 mg 2×daily | valacyclovir 2000 mg 2×daily×1 day 1000 mg 2×daily for a 2nd day | Placebo | study 1 4.3 vs 4.3 vs 5.1 study 2 4.8 vs 4.6 vs 5.4 | study 1 4.0 vs 4.5 vs 5.0 study 2 2 5.0 vs 5.0 vs 5.5 | study 1 44 vs 46 vs 38 study 2 43 vs 43 vs 35 |

| Famciclovir30 1 dose | 1 Does | 1500 mg | famciclovir 750 mg 2x daily for 1 day | Placebo | 4.4 vs 4.0 vs 6.2 | 4.5 vs 5.7 vs 7.0 | 33 vs 29 vs 34 |

| Lesion healing time measures the duration of a subset of severe or classical herpetic outbreaks, characterized by the formation of vesicles, ulcers, or crusts (also papules in some studies28,29). The endpoint is lesion reepithelialization/loss of crust. Episodes where there were only prodromal symptoms, erythema, and/or papule formation (or only symptoms and/or erythema in some studies28,29) were considered “aborted” or prevented lesions. The occurrence of these favorable episode outcomes is described as a percentage of all episodes. Episode duration, sometimes called healing time of all lesions or time to return to normal skin, is the time to resolution of all episodes, regardless of lesion severity. The definition of normal skin varies among the different studies. | |||||||

| *All of the healing time and episode duration values for the active treatment arms in both studies differed statistically significantly from placebo, except for famciclovir 750 mg twice daily for 1 day. | |||||||

| †None of the frequencies of aborted lesions in the active treatment arms in either study differed statistically significantly from placebo. | |||||||

CORRESPONDENCE

Spotswood Spruance MD Professor of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Utah School of Medicine, Room 4B319, 30 North 1900 East, Salt Lake City, UT 84132-2405. E-mail:[email protected]

- Consider giving patients an oral antiviral (OAV) medication to self-administer when HSV prodromal symptoms occur.

- Patient-initiated, short-course, high-dose OAV treatment of recurrent HSV outbreaks may be as effective as the traditional, longer-course regimens.

Hit early, hit hard. That expression arose during the evolution of treatment for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).1 While this approach has not lived up to expectations for HIV treatment, it may have found its place in the treatment of recurrent herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections.

Our review focuses on episodic treatment of acute recurrent HSV outbreaks for immunocompetent persons. We do not discuss suppressive therapy, which may be indicated for frequent or severe recurrences (6 or more per year) in immunocompetent persons, for immunocompromised patients, or as an adjunctive measure to reduce genital herpes transmission.2

As we will describe in detail, the efficacy of the new short-course therapy is, at minimum, comparable to that seen with the older, longer-course trials of topical and oral antiviral therapy. In one head-to-head comparison, Leone et al compared a short-course regimen (3 days) of valacyclovir with 5 days of treatment; they found no difference in results.3 If the efficacy of short-course treatment is the same as that of longer courses, the increased convenience and expected improvement in patient adherence with these new regimens argue strongly in their favor. (See Scope of the problem.)

The strategy: Take advantage of a brief therapeutic window

The innate and acquired immune responses of chronically infected, immunocompetent persons rapidly limit cutaneous viral replication, thereby truncating the duration of recurrent HSV outbreaks.13,14 In both recurrent herpes labialis and genital herpes, HSV viral titers peak in the first 24 hours following lesion onset (FIGURE 1A).13-15

Herpes labialis lesion size and pain are also greatest in the first 24 hours.13,16 Most herpes labialis lesions progress from the vesicle stage to the ulcer/soft crust stage within 48 hours, with a hard crust forming by day 2 or 3 (FIGURE 1B).17

With genital lesions, crust formation depends on whether the skin area is dry (3–4 days) or moist (8–9 days).14

The likely events are a burst of virus replication in the first 24 hours of outbreak that lyses basal keratinocytes in a discreet area of epidermis innervated by the infected neuron(s), followed by a vigorous immune response that curtails the infection and creates, in part, the clinical disease (erythema, swelling, vesiculation, and ulceration). The subsequent elements of the illness, which are the majority of the lesion course, are related to wound healing

Recognizing the window. Given the brief period of viral replication and the rapid evolution of lesions, the therapeutic window for treating HSV outbreaks with antiviral drugs is both early and short, making it problematic to effectively treat HSV recurrences. Patients often have mature lesions by the time they consult a physician, rendering subsequent anti-viral treatment less effective.18 However, before lesions appear, many patients experience prodromal symptoms such as pain, burning, or itching.13,18 These symptoms can be a prompt to start treatment early, thereby taking advantage of the transient therapeutic window.

If a patient is able to self-administer therapy when prodromal symptoms occur, there may be a greater benefit to treatment. Giving patients drugs for self-administration is therefore an important strategy in managing HSV recurrences.

Traditionally, patient-initiated episodic therapy for recurrent genital herpes and herpes labialis has involved multiple daily doses of topical or oral antiviral agents for 4 to 5 days.19-26 Studies of the pathogenesis of HSV recurrences, however, indicate—as said earlier—that the period of virus replication is early and brief, such that a shorter duration of treatment might be more appropriate and equally effective. Other recent clinical studies have indicated that patient-initiated, short-course, high-dose OAV treatment of recurrent HSV infections may be as effective as the traditional therapies.3,27-30 In the section that follows, we examine and compare the results of these trials. (See The agents and how they work.)

FIGURE 1A

Lesion HSV-1 titer peaks within 24 hours of onset of herpes labialis lesions

Source: Krueger et al, J Clin Epidemiol Derm 1978.15 Reproduced with permission from GG Krueger.

FIGURE 1B

Hard crust formation occurs by 48 to 72 hours of onset of herpes labialis lesions

Source: Spruance, Sem Dermatol 1992.17 With permission from Elsevier.

Clinical trials: Short-course, high-dose, patient-initiated episodic OAV therapy for recurrent genital herpes

Three-day vs 5-day valacyclovir therapy. The efficacy of 3-day treatment with oral valacyclovir was compared with that of 5-day treatment in immunocompetent adults with a history of ≥4 episodes of recurrent genital herpes and confirmed HSV infection.3 Eight hundred participants were randomized to receive 500 mg twice daily valacyclovir for 3 days (and placebo for the remaining 2 days) or 500 mg twice daily for 5 days, and were required to self-administer therapy no later than 24 hours after the onset of symptoms.

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 (HSV-1) or type 2 (HSV-2) results in periodic, recurrent outbreaks of skin lesions after first infection. Herpes labialis (fever blisters or cold sores) is usually caused by HSV-1, while genital herpes is usually caused by HSV-2.4 HSV-2 lesions of the lips have been reported, and the incidence of genital herpes caused by HSV-1 is on the rise in the developed world, likely because of increased oral-genital sexual behavior.5,6 Patients with HSV-1 genital herpes typically have fewer recurrences than those with HSV-2 genital infection.7

The prevalence of HSV-1 and HSV-2 infection varies according to age, geography, gender, and population subgroup, such as people who exhibit high-risk sexual behavior.8 approximately 45% of americans are infected with HSV-1 by adolescence,8 and approximately 22% of all american adults are infected with HSV-2.9 The global prevalence of HSV is even greater: as many as 60% to 90% of older adults worldwide are seropositive for HSV-1, and as many as 30% are seropositive for HSV-2. HSV-2 seropositivity is more prevalent among women than men.8 overall, the burden of recurrent genital herpes outbreaks can have a profound, negative impact on patient quality of life.10,11 The psychological impact of recurrent herpes labialis has not been thoroughly investigated, but an undefined burden is thought to exist, particularly in young patients with frequent or severe recurrences.12

The primary endpoint was time to lesion healing (defined as the number of days from initiation of therapy to lesion reepithelialization). Secondary endpoints were pain duration, episode duration (defined as time from initiation of therapy to resolution of all symptoms) and percentage of patients with aborted lesions.

The 3-day valacyclovir treatment exhibited similar time to lesion healing, length of episode, and percentage of patients with aborted lesions as the 5-day treatment (TABLE 1), suggesting equal efficacy. Duration of pain was also similar (data not shown). Adverse events were similar for both treatment groups, with the most common being headache (10%), nausea (4%), and diarrhea (4%, 5-day treatment vs 2%, 3-day treatment).

Placebo-controlled trial of 2-day acyclovir therapy. Wald and coworkers examined the effect of a shorter treatment regimen of acyclovir (2 days) on recurrent genital herpes.28 Eighty-four immunocompetent HSV-2–infected patients with a history of ≥3 recurrences in the previous 12 months were randomized to receive either 2 days of 800 mg 3 times daily acyclovir or matching placebo. Patients were asked to take their medication no later than 12 hours after the first sign or symptom of an episode.

Efficacy endpoints were time to lesion healing, episode duration, and percentage of patients with aborted lesions. Short-course acyclovir therapy was shown to decrease time to healing (P=.001) and episode duration (P<.001) by 2 days compared with placebo (TABLE 1). Short-course acyclovir therapy also increased the percentage of patients with aborted lesions compared with placebo (27% vs 11%; P=.029 (TABLE 1). Adverse events were not recorded in this analysis.

Placebo-controlled trial of single-day famciclovir therapy. Aoki and colleagues29 performed a randomized, double-blind, patient-initiated, placebo-controlled trial to assess the efficacy and safety of patient-initiated, single-day famciclovir 1000 mg twice daily in immunocompetent adults with recurrent genital herpes. The 329 patients in the study were instructed to self-initiate therapy within 6 hours of the onset of prodromal symptoms or genital herpes lesions, and were asked to return to the clinic no later than 24 hours after initiation of therapy. Patients were followed until their lesions healed or for up to 14 days.

The primary endpoint was time to lesion healing of nonaborted lesions. Secondary endpoints were time to healing of all lesions (aborted and nonaborted), time to resolution of pain and other symptoms, and the percentage of patients who did not progress to a full outbreak.

Single-day treatment with famciclovir shortened the time to healing of nonaborted genital herpes lesions by approximately 2 days (P<.001), and the time to healing of all lesions by 1.5 days (P<.001) compared with placebo, and increased the percentage of patients who did not progress to a full outbreak (23% vs 13%;P=.003) (TABLE 1). Famciclovir also reduced the time to resolution of all symptoms by approximately 2 days (P<.001) (data not shown).

Adverse events were mild to moderate; the most common in the famciclovir and placebo groups, respectively, were headache (13.5% vs 5.4%), nausea (2.5% vs 3.6%), and diarrhea (4.9% vs 1.2%).

TABLE 1

Short-course, patient-initiated OAV therapy is effective for treating episodic genital herpes

| DRUG | TREATMENT DURATION | TREATMENT DOSE | CONTROL | MEDIAN TIME (DAYS) TO LESION HEALING (TREATMENT VS CONTROL) | MEDIAN EP ISODE DURATION (DAYS) (TREATMENT VS CONTROL) | PATIENTS WITH ABORTED EPISODES (%) (TREATMENT VS CONTROL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valacyclovir3 | 3 days | 500 mg 2×daily | valacyclovir 500 mg 2×/day for 5 days | 4.4 vs 4.7 (P=NS) | 4.3 vs 4.4 (P=NS) | 25 vs 27 (P=NS) |

| Acyclovir28 | 2 days | 800 mg 3×daily | Placebo | 4.0 vs 6.0 (P=.001) | 4.0 vs 6.0 (P=.001) | 27 vs 11 (P=.029) |

| Famciclovir29 | 1 day | 1000 mg 2×daily | Placebo | 4.3 vs 6.1 (P<.001) | 3.5 vs 5.0 (P<.001) | 23 vs 13 (P=.003) |

| Lesion healing time measures the duration of a subset of severe or classical herpetic outbreaks, characterized by the formation of vesicles, ulcers, or crusts (also papules in some studies28,29). The endpoint is lesion reepithelialization/loss of crust. Episodes where there were only prodromal symptoms, erythema, and/or papule formation (or only symptoms and/or erythema in some studies28,29) were considered “aborted” or prevented lesions. The occurrence of these favorable episode outcomes is described as a percentage of all episodes. Episode duration, sometimes called healing time of all lesions or time to return to normal skin, is the time to resolution of all episodes, regardless of lesion severity. The definition of normal skin varies among the different studies. | ||||||

| NS=not significant. | ||||||

Short-course, high-dose, patient-initiated episodic OAV therapy for recurrent herpes labialis

Placebo-controlled trial of single-day and 2-day valacyclovir therapy. Spruance and coworkers studied the efficacy of single-day and 2-day valacyclovir treatments in comparison with placebo for an episode of herpes labialis.27 Two identical studies were performed on individuals who were at least 12 years old, had a clinical history of recurrent cold sores, and had experienced ≥3 episodes in the preceding year. Participants in both studies (study 1, N=1524; study 2, N=1627) were required to self-administer 2 g valacyclovir twice daily for 1 day (valacyclovir 1 day), 2 g valacyclovir twice daily for 1 day followed by 1 g twice daily for 1 day (valacyclovir 2 days), or matching placebo at the earliest onset of prodromal symptoms and before the appearance of lesions. Patients were asked to return to the clinic within 24 hours of initiation of therapy.

The primary endpoint in study 1 was clinician-observed duration of all herpes labialis lesions and the secondary endpoint was the percentage of subjects who had herpes labialis lesions that did not progress beyond the papule stage. In study 2, the endpoints were reversed: the primary endpoint was the percentage of patients with lesions that did not progress and the secondary endpoint was the duration of lesions. Other efficacy endpoints were time to healing of vesicular (classical) lesions and duration of pain and discomfort.

Both studies demonstrated that single-day valacyclovir treatment significantly decreased lesion healing time and the duration of herpes labialis episodes by 0.5 to 1.0 days compared with placebo (TABLE 2). A statistically significant decrease in the duration of pain and other symptoms was also seen with single-day valacyclovir compared with placebo (data not shown). In both studies, a higher percentage of patients in the valacyclovir group did not progress to full outbreak compared with placebo, but these differences were not statistically significant. The results with 2 days of valacyclovir treatment were similar. Adverse events were similar between the treatment groups and the placebo group.

Placebo-controlled trial of single-dose and single-day famciclovir therapy. Spruance and coworkers assessed patient-initiated famciclovir 1500 mg (single-dose) and 750 mg twice daily (single-day) in immunocompetent adults with recurrent cold sores.30 Subjects (N=1376) were at least 18 years of age and had experienced ≥3 episodes of cold sores over the previous 12 months. Subjects were instructed to administer 1500 mg (single-dose), 750 mg twice daily (single-day), or matching placebo within 1 hour of the onset of prodromal symptoms and before the onset of lesions, and were asked to return to the clinic within 24 hours of initiating medication.

Topical antiviral drug formulations were the first treatments approved for recurrent HSV-1 and HSV-2 outbreaks, but these were only marginally efficacious.19-21,31 orally-administered antiviral agents appear to be more effective, possibly because of better delivery of the drug to the site of infection. Three oral antiviral agents (OAVs) are currently approved for the treatment of recurrent genital herpes: acyclovir, an acyclic nucleoside analog; valacyclovir, the prodrug of acyclovir; and famciclovir, the prodrug of penciclovir, another acyclic nucleoside analog. one OAV (valacyclovir) is currently approved for the treatment of herpes labialis in immunocompetent patients.27 The prodrugs of acyclovir and penciclovir, valacyclovir and famciclovir, respectively, were synthesized to provide high oral bioavailability and thus permit less frequent administration and potentially greater efficacy compared to the parent compounds.

Following oral administration, valacyclovir and famciclovir undergo first-pass metabolism to acyclovir and penciclovir, respectively.4,32 acyclovir and penciclovir are selectively phosphorylated by the viral thymidine kinase of infected cells and then converted to the active triphosphate by cellular enzymes. The triphosphate forms (which have different half-lives depending upon the compound)33 inhibit viral DNA polymerase and interfere with DNA chain extension,34 thereby halting viral DNA synthesis. The drugs cannot prevent the death of a cell once it is infected, but they can reduce, in a dose-dependent manner, the quantity of virions produced by an infected cell. The mechanism of action of HSV-selective antiviral drugs suggests that the most logical strategy for episodic treatment is to maximally inhibit HSV replication using high doses.18,35

The primary endpoint was time to healing of primary vesicular lesions. Secondary endpoints included time to healing of all vesicular lesions (primary and secondary [secondary lesions are defined as lesions that developed in addition to and on 1 or more days after primary lesions and that were located at least 1 cm from primary lesions]), time to return to normal skin for all lesions (defined as loss of crust, swelling, and dry flaking), duration of lesion tenderness and pain, and proportion of patients with aborted lesions.

There was a statistically significant decrease in time to healing of primary vesicular lesions by approximately 2 days with both single-dose and single-day famciclovir compared with placebo, with no significant difference between the 2 famciclovir regimens in time to healing of primary vesicular lesions (TABLE 2). There was also a statistically significant decrease in the time to healing of all lesions (primary and secondary) by approximately 2 days with both famciclovir treatments compared with placebo, with no significant differences seen in healing between the famciclovir arms (data not shown).

However, only single-dose famciclovir had a statistically significant decrease in the duration of lesion tenderness and pain and the time to return to normal skin compared with placebo (data not shown). No difference was noted between the famciclovir arms in the percentage of patients with aborted lesions compared with placebo. Adverse events in both famciclovir groups were similar to those in the placebo group.

TABLE 2

Short-course, patient-initiated OAV therapy is effective against recurrent herpes labialis

| DRUG | TREATMENT DURATION | TREATMENT DOSE | COMPARATOR REGIMEN | CONTROL | MEDIAN TIME (DAYS) TO LESION HEALING (TREATMENT VS COMPARATOR VS CONTROL)* | MEDIAN EP ISODE DURATION (DAYS) (TREATMENT VS COMPARATOR VS CONTROL)* | PATIENTS WITH ABORTED LESIONS (%)(TREATMENT VS COMPARATOR VS CONTROL)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valacyclovir27 | 1 day | 2000 mg 2×daily | valacyclovir 2000 mg 2×daily×1 day 1000 mg 2×daily for a 2nd day | Placebo | study 1 4.3 vs 4.3 vs 5.1 study 2 4.8 vs 4.6 vs 5.4 | study 1 4.0 vs 4.5 vs 5.0 study 2 2 5.0 vs 5.0 vs 5.5 | study 1 44 vs 46 vs 38 study 2 43 vs 43 vs 35 |

| Famciclovir30 1 dose | 1 Does | 1500 mg | famciclovir 750 mg 2x daily for 1 day | Placebo | 4.4 vs 4.0 vs 6.2 | 4.5 vs 5.7 vs 7.0 | 33 vs 29 vs 34 |

| Lesion healing time measures the duration of a subset of severe or classical herpetic outbreaks, characterized by the formation of vesicles, ulcers, or crusts (also papules in some studies28,29). The endpoint is lesion reepithelialization/loss of crust. Episodes where there were only prodromal symptoms, erythema, and/or papule formation (or only symptoms and/or erythema in some studies28,29) were considered “aborted” or prevented lesions. The occurrence of these favorable episode outcomes is described as a percentage of all episodes. Episode duration, sometimes called healing time of all lesions or time to return to normal skin, is the time to resolution of all episodes, regardless of lesion severity. The definition of normal skin varies among the different studies. | |||||||

| *All of the healing time and episode duration values for the active treatment arms in both studies differed statistically significantly from placebo, except for famciclovir 750 mg twice daily for 1 day. | |||||||

| †None of the frequencies of aborted lesions in the active treatment arms in either study differed statistically significantly from placebo. | |||||||

CORRESPONDENCE

Spotswood Spruance MD Professor of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Utah School of Medicine, Room 4B319, 30 North 1900 East, Salt Lake City, UT 84132-2405. E-mail:[email protected]

1. Ho D. Time to hit HIV, early and hard. N Engl J Med 1995;333:450-451.

2. Corey L, Wald A, Patel R, et al. Once-daily valacyclovir to reduce the risk of transmission of genital herpes. N Engl J Med 2004;350:11-20.

3. Leone PA, Trottier S, Miller JM. Valacyclovir for episodic treatment of genital herpes: a shorter 3-day treatment course compared with 5-day treatment. Clin Infect Dis 2002;34:958-962.

4. Whitley RJ, Kimberlin DW, Roizman B. Herpes simplex viruses. Clin Infect Dis 1998;26:541-555.

5. Wald A, Ericsson M, Krantz E, Selkes S, Corey L. Oral shedding of herpes simplex virus type 2. Sex Transm Infect 2004;80:272-276.

6. Mertz GJ, Rosenthal Sl, Stanberry LR. Editorial response: Is herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) now more common than HSV-2 in first episodes of genital herpes? Sex Transm Dis 2003;30:801-802.

7. Lafferty WE, Coombs RW, Benedetti J, Critchlow C, Corey L. Recurrences after oral and genital herpes simplex virus infection. N Engl J Med 1987;316:1444-1449.

8. Smith JS, Robinson RJ. Age-specific prevalence of infection with herpes simplex virus types 2 and 1: a global review. J Infect Dis 2002;186(suppl 1):S3-S28.

9. Fleming DT, McQuillan GM, Johnson RE, et al. Herpes simplex virus type 2 in the united States, 1976 to 1994. N Engl J Med 1997;337:1105-1111.

10. Bierman SM. A retrospective study of 375 patients with genital herpes simplex infections seen between 1973 and 1980. Cutis 1983;31:548-565.

11. Drob S, Loemer M, Lifshutz H. Genital herpes: the psychological consequences. Br J Med Psychol 1985;58:307-315.

12. Spruance SL, Kriesel JD. Treatment of herpes simplex labialis. Herpes 2002;9:64-69.

13. Spruance SL, overall JC, Jr, Kern ER, Krueger GG, Pliam V, Miller W. The natural history of recurrent herpes simplex labialis. N Engl J Med 1977;297:69-75.

14. Brown ZA, Kern ER, Spruance SL, Overall JC, Jr. Clinical and virologic course of herpes simplex genitalis. West J Med 1979;130:414-421.

15. Krueger GG, Spruance SL, Overall JC, Jr. Herpes simplex labialis: a review of pathogenesis and therapy. J Clin Epidemiol Derm 1978;1:19-37.

16. Spruance SL, Wenerstrom G. Pathogenesis of herpes simplex labialis: IV. Maturation of lesions during within 8 hours after onset and implications for antiviral treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Path 1984;58:667-671.

17. Spruance SL. The natural history of recurrent oral-facial herpes simplex virus infection. Sem Dermatol 1992;11:200-206.

18. Spruance SL. Herpes simplex labialis. In: Clinical Management of Herpes Viruses. Sacks SL, Straus SE, Whitley RJ, Griffiths PD, eds. amsterdam, Netherlands: IOS Press; 1995.

19. Spruance SL, Nett R, Marbury T, Wolff R, Johnson J, Spaulding T. Acyclovir cream for treatment of herpes simplex labialis: results of two randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, multicenter clinical trials. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002;46:2238-2243.

20. Spruance SL, Rea TL, Thoming C, Tucker R, Saltzman R, Boon R. Penciclovir cream for the treatment of herpes simplex labialis. JAMA 1997;277:1374-1379.

21. Raborn GW, Martel AY, lassonde M, et al. Worldwide Topical Penciclovir Collaborative Study Group. Effective treatment of herpes simplex labialis with penciclovir cream: combined results of two trials. J Am Dent Assoc 2002;133:303-309.

22. Reichman RC, Badger GJ, Mertz GJ, et al. Treatment of recurrent genital herpes simplex infections with oral acyclovir: a controlled trial. JAMA 1984;251:2103-2107.

23. Sacks SL, Aoki FY, Diaz-Mitoma F, Sellors J, Shafran SD. Canadian Famciclovir Study Group. Patient-initiated, twice-daily oral famciclovir for early recurrent genital herpes: a randomized, double-blind multicenter trial. JAMA 1996;276:44-49.

24. Tyring SK, Douglas JM, Jr, Corey L, Spruance SL, Esmann J. The valaciclovir International Study Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled comparison of oral valcyclovir and acyclovir in immunocompetent patients with recurrent genital herpes infections. Arch Dermatol 1998;134:185-191.

25. Spruance S, Stewart JCB, Rowe NH, McKeough MB, Wenerstrom G, Freeman DJ. Treatment of herpes simplex labialis with oral acyclovir. J Infect Dis 1990;161:185-190.

26. Spruance SL, Tyring SK, DeGregorio B, Miller C, Beutner K; valaciclovir HSV Study Group. A large-scale, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trial of peroral valaciclovir for episodic treatment of recurrent herpes genitalis. Arch Intern Med 1996;156:1729-1735.

27. Spruance SL, Jones TM, Blatter MM, et al. High-dose, short-duration, early valacyclovir therapy for episodic treatment of cold sores: results of two randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter studies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2003;47:1072-1080.

28. Wald A, Carrell D, Remington M, Kexel E, Zeh J, Corey L. Two-day regimen of acyclovir for treatment of recurrent genital herpes simplex virus type 2 infection. Clin Infect Dis 2002;34:944-948.

29. Aoki FY, Tyring S, Dias-Mitoma F, Gross G, Gao J, Hamed K. Single-day patient initiated famciclovir therapy for recurrent genital herpes: a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 2006;42:8-13.

30. Spruance S, Bodsworth N, Resnick H, et al. Single-dose, patient-initiated famciclovir: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial for episodic treatment of herpes labialis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;55:47-53.

31. Reichman RC, Badger GJ, Guinan ME, et al. Topically administered acyclovir in the treatment of recurrent herpes simplex genitalis: a controlled trial. J Infect Dis 1983;147:336-340.

32. Gill KS, Wood MJ. The clinical pharmacokinetics of famciclovir. Clin Pharmacokinet 1996;31:1-8.

33. Earnshaw DL, Bacon TH, Darlison SJ, Edmonds K, Perkins RM, Vere Hodge RA. Mode of antiviral action of penciclovir in MRC-5 cells infected with herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), HSV-2, and varicella-zoster virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1992;36:2747-2757.

34. Vere Hodge RA, Perkins RM. Mode of action of 9-(4-hydroxy-3-hydroxymethylbut-1-yl)guanine (Brl 39123) against herpes simplex virus in MrC-5 cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1989;33:223-229.

35. Spruance SL, Freeman DJ. Topical treatment of cutaneous herpes simplex virus infections. Antivir Res 1990;14:305-321.

1. Ho D. Time to hit HIV, early and hard. N Engl J Med 1995;333:450-451.

2. Corey L, Wald A, Patel R, et al. Once-daily valacyclovir to reduce the risk of transmission of genital herpes. N Engl J Med 2004;350:11-20.

3. Leone PA, Trottier S, Miller JM. Valacyclovir for episodic treatment of genital herpes: a shorter 3-day treatment course compared with 5-day treatment. Clin Infect Dis 2002;34:958-962.

4. Whitley RJ, Kimberlin DW, Roizman B. Herpes simplex viruses. Clin Infect Dis 1998;26:541-555.

5. Wald A, Ericsson M, Krantz E, Selkes S, Corey L. Oral shedding of herpes simplex virus type 2. Sex Transm Infect 2004;80:272-276.

6. Mertz GJ, Rosenthal Sl, Stanberry LR. Editorial response: Is herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) now more common than HSV-2 in first episodes of genital herpes? Sex Transm Dis 2003;30:801-802.

7. Lafferty WE, Coombs RW, Benedetti J, Critchlow C, Corey L. Recurrences after oral and genital herpes simplex virus infection. N Engl J Med 1987;316:1444-1449.

8. Smith JS, Robinson RJ. Age-specific prevalence of infection with herpes simplex virus types 2 and 1: a global review. J Infect Dis 2002;186(suppl 1):S3-S28.

9. Fleming DT, McQuillan GM, Johnson RE, et al. Herpes simplex virus type 2 in the united States, 1976 to 1994. N Engl J Med 1997;337:1105-1111.

10. Bierman SM. A retrospective study of 375 patients with genital herpes simplex infections seen between 1973 and 1980. Cutis 1983;31:548-565.

11. Drob S, Loemer M, Lifshutz H. Genital herpes: the psychological consequences. Br J Med Psychol 1985;58:307-315.

12. Spruance SL, Kriesel JD. Treatment of herpes simplex labialis. Herpes 2002;9:64-69.

13. Spruance SL, overall JC, Jr, Kern ER, Krueger GG, Pliam V, Miller W. The natural history of recurrent herpes simplex labialis. N Engl J Med 1977;297:69-75.

14. Brown ZA, Kern ER, Spruance SL, Overall JC, Jr. Clinical and virologic course of herpes simplex genitalis. West J Med 1979;130:414-421.

15. Krueger GG, Spruance SL, Overall JC, Jr. Herpes simplex labialis: a review of pathogenesis and therapy. J Clin Epidemiol Derm 1978;1:19-37.

16. Spruance SL, Wenerstrom G. Pathogenesis of herpes simplex labialis: IV. Maturation of lesions during within 8 hours after onset and implications for antiviral treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Path 1984;58:667-671.

17. Spruance SL. The natural history of recurrent oral-facial herpes simplex virus infection. Sem Dermatol 1992;11:200-206.

18. Spruance SL. Herpes simplex labialis. In: Clinical Management of Herpes Viruses. Sacks SL, Straus SE, Whitley RJ, Griffiths PD, eds. amsterdam, Netherlands: IOS Press; 1995.

19. Spruance SL, Nett R, Marbury T, Wolff R, Johnson J, Spaulding T. Acyclovir cream for treatment of herpes simplex labialis: results of two randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, multicenter clinical trials. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002;46:2238-2243.

20. Spruance SL, Rea TL, Thoming C, Tucker R, Saltzman R, Boon R. Penciclovir cream for the treatment of herpes simplex labialis. JAMA 1997;277:1374-1379.

21. Raborn GW, Martel AY, lassonde M, et al. Worldwide Topical Penciclovir Collaborative Study Group. Effective treatment of herpes simplex labialis with penciclovir cream: combined results of two trials. J Am Dent Assoc 2002;133:303-309.

22. Reichman RC, Badger GJ, Mertz GJ, et al. Treatment of recurrent genital herpes simplex infections with oral acyclovir: a controlled trial. JAMA 1984;251:2103-2107.

23. Sacks SL, Aoki FY, Diaz-Mitoma F, Sellors J, Shafran SD. Canadian Famciclovir Study Group. Patient-initiated, twice-daily oral famciclovir for early recurrent genital herpes: a randomized, double-blind multicenter trial. JAMA 1996;276:44-49.

24. Tyring SK, Douglas JM, Jr, Corey L, Spruance SL, Esmann J. The valaciclovir International Study Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled comparison of oral valcyclovir and acyclovir in immunocompetent patients with recurrent genital herpes infections. Arch Dermatol 1998;134:185-191.

25. Spruance S, Stewart JCB, Rowe NH, McKeough MB, Wenerstrom G, Freeman DJ. Treatment of herpes simplex labialis with oral acyclovir. J Infect Dis 1990;161:185-190.

26. Spruance SL, Tyring SK, DeGregorio B, Miller C, Beutner K; valaciclovir HSV Study Group. A large-scale, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trial of peroral valaciclovir for episodic treatment of recurrent herpes genitalis. Arch Intern Med 1996;156:1729-1735.

27. Spruance SL, Jones TM, Blatter MM, et al. High-dose, short-duration, early valacyclovir therapy for episodic treatment of cold sores: results of two randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter studies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2003;47:1072-1080.

28. Wald A, Carrell D, Remington M, Kexel E, Zeh J, Corey L. Two-day regimen of acyclovir for treatment of recurrent genital herpes simplex virus type 2 infection. Clin Infect Dis 2002;34:944-948.

29. Aoki FY, Tyring S, Dias-Mitoma F, Gross G, Gao J, Hamed K. Single-day patient initiated famciclovir therapy for recurrent genital herpes: a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 2006;42:8-13.

30. Spruance S, Bodsworth N, Resnick H, et al. Single-dose, patient-initiated famciclovir: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial for episodic treatment of herpes labialis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;55:47-53.

31. Reichman RC, Badger GJ, Guinan ME, et al. Topically administered acyclovir in the treatment of recurrent herpes simplex genitalis: a controlled trial. J Infect Dis 1983;147:336-340.

32. Gill KS, Wood MJ. The clinical pharmacokinetics of famciclovir. Clin Pharmacokinet 1996;31:1-8.

33. Earnshaw DL, Bacon TH, Darlison SJ, Edmonds K, Perkins RM, Vere Hodge RA. Mode of antiviral action of penciclovir in MRC-5 cells infected with herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), HSV-2, and varicella-zoster virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1992;36:2747-2757.

34. Vere Hodge RA, Perkins RM. Mode of action of 9-(4-hydroxy-3-hydroxymethylbut-1-yl)guanine (Brl 39123) against herpes simplex virus in MrC-5 cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1989;33:223-229.