User login

Looking beyond the D-dimer

A 44-year-old woman sought care at the emergency department (ED) because she was having difficulty breathing and felt faint. She had been fine until that morning. Three days earlier the patient, who had a history of high blood pressure and elevated cholesterol levels, had driven from Connecticut to New York and back, spending a total of 4 hours in her car. The patient indicated that she’d been taking oral contraceptives (OCPs) for several years, but she did not smoke. There was no history of hemoptysis, recent surgery, or trauma. Neither blood clots nor cancer were part of her or her family’s history.

In the ED, the patient did not have any signs or symptoms of a deep venous thrombosis (DVT). She was obese, with a body mass index of 40.3 kg/m2; other vitals were: blood pressure (BP), 134/88 mm Hg; heart rate (HR), 64 beats per minute (bpm); respiratory rate (RR), 12; and O2 saturation, 99% with ambulation.

The ED physician strongly suspected a pulmonary embolism (PE), but the patient’s score on a clinical probability algorithm (using the Wells criteria) was a 3, indicating only “moderate probability“ of a PE (TABLE 1). (She scored a 3 because an “alternative diagnosis [was] less likely than PE.”) In addition, her D-dimer level was 160 ng/mL using the Triage D-Dimer Test by Biosite, Inc (normal <400 ng/mL), which ruled out a PE. (Many ED physicians at our institution are more cautious when using this D-dimer assay and use a lower cutoff value.)

Given these results, the ED physician did not order imaging studies because the expense and radiation exposure outweighed the probability of the patient having a PE. A subsequent coronary work-up was also negative. The patient was discharged to home and advised to follow up with her primary care physician a few days later.

Two days later we saw the patient at our office. Not only had her dyspnea gotten worse while the presyncope remained, but she now had left-sided pleuritic chest pain. She also reported mild pain in her right calf. On examination, the patient’s BP was 126/86 mm Hg, HR was 82 bpm, RR was 12, and O2 saturation was 96% with ambulation. Her Wells score was now 6, still a moderate probability for PE. (She received another 3 points for the new DVT symptoms—“clinically suspected DVT.”)

Although the patient did not also have signs of a DVT, her additional symptoms along with the original symptoms’ persistence and the existence of other risk factors (OCP use and obesity) led us to reconsider a PE diagnosis. These suspicions prompted us to send the patient back to the ED, where a Doppler ultrasound of the right lower extremity was negative, but the D-dimer was positive at 565 ng/mL.

A pulmonary computed tomography angiogram (CTA) showed 2 small pulmonary emboli within the distal left upper lobe pulmonary arteries.

The patient was treated with heparin and warfarin and discharged without complications.

TABLE 1

Calculating and interpreting the Wells score4,5,7,9,10

| Clinical parameter | Points |

|---|---|

| Clinically suspected DVT | 3.0 |

| Alternative diagnosis less likely than PE | 3.0 |

| Tachycardia | 1.5 |

| Immobilization/surgery (within 4 weeks) | 1.5 |

| History of DVT or PE | 1.5 |

| Hemoptysis | 1.0 |

| Malignancy (treatment within 6 months, palliative) | 1.0 |

| TOTAL | |

| Score | Traditional interpretation |

| <2.0 | Low probability of PE |

| 2.0-6.0 | Moderate probability of PE |

| >6.0 | High probability of PE |

| Score | Alternative classification scheme |

| ≤4.0 | PE unlikely |

| >4.0 | PE likely |

| DVT, deep venous thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism. | |

Discussion

The incidence of PE in the United States varies significantly: Individuals younger than 40 have a risk of 1 in 10,000 compared with 1 in 100 for those older than 80.1 Mortality associated with undiagnosed PE varies widely, from 9.2% to 51%.2 This percentage is significant given that half of all PEs go undiagnosed.3 In addition, when left untreated, PE will recur in 30% to 50% of patients, with a fatality rate of 10% to 45%.1 Further, up to 4% of patients with acute PE develop chronic PE and subsequent pulmonary hypertension.4,5 Given the consequences of failing to diagnose a PE, clinicians must consider this condition in patients who present with unexplained hypotension, dyspnea, or chest pain.6

Not an easy diagnosis

This case report demonstrates the inherent difficulty in diagnosing a PE. Still, certain clinical symptoms/signs can aid in the decision-making process. Fever, crackles, and wheezes decrease the probability of PE, whereas syncope, hemodynamic shock, leg edema, and hemoptysis increase its likelihood.7 Despite the many commonly reported risk factors for PE, only malignancy, recent surgery, or a history of DVT/PE significantly increase the risk of developing a clot.8

The Wells criteria. This scoring system groups patients according to the probability of having a PE: low (score: <2), moderate (score: 2-6), and high (score: >6).6 An alternative classification scheme divides patients into 2 groups: likely to have a PE (score: >4) or unlikely to have a PE (score: ≤4).8

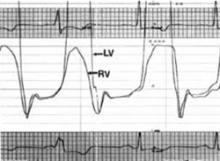

This case report illustrates a key problem with the Wells criteria—the somewhat subjective nature of the scoring. Some physicians find it questionable to award 3 points for “alternative diagnosis less likely than PE,” for example.4 Similarly, with respect to immobilization, some clinicians might have awarded our patient 1.5 points for her recent car trip to New York. We did not think that riding in a car for 2 uninterrupted hours for each leg of the trip was significant enough. However, awarding this patient 1.5 points could have made an important difference in her clinical management if the alternative classification scheme was used. Instead of having a score of 3, the patient would have had a score of 4.5, placing her in the “likely to have a PE” group and prompting us to perform a CTA sooner (FIGURE).

FIGURE

Diagnostic algorithm for pulmonary embolism6,7,10

CTA, computed tomography angiogram; PE, pulmonary embolism.

Inappropriate work-ups are common

Some physicians ignore algorithms when working up a PE and simply order a CTA. In fact, a large multicenter trial showed that 43% of patients suspected of having a PE were inappropriately managed diagnostically.9 Similarly, a meta-analysis of 4 studies including 1660 patients found that only 58% of those with a positive D-dimer had the requisite CTA, as did 7% of patients with a negative D-dimer.2

Physicians should not be concerned about ruling out a PE in the setting of a negative D-dimer, as a meta-analysis found that this diagnostic approach has a negative predictive value (NPV) of 99.7%.2 It is important to note that the NPV is significantly affected by the sensitivity of the D-dimer assay used. If the D-dimer assay is highly sensitive, a negative result in combination with a low, moderate, or unlikely probability Wells score rules out the diagnosis of PE. If the assay is moderately sensitive, however, only a low or unlikely probability Wells score rules out PE.10

The inappropriate work-up of this group of patients is significant and extends beyond the ultimate goal of preventing morbidity and mortality. The unnecessary use of pulmonary CTA is extremely expensive, exposes patients to unnecessary radiation, and results in contrast nephrotoxicity in about 4% of patients.9 Although pulmonary CTA is the standard diagnostic test for PE, other imaging modalities are more appropriate in some cases (TABLE 2).

TABLE 2

Alternative imaging modalities for diagnosing PE1,4,7,11

| Modality | Indication |

|---|---|

| Ventilation-perfusion scanning | Patients with contrast allergies or renal failure; test of choice for diagnosing chronic PE due to limited sensitivity of CT |

| Venous compression ultrasonography | Patients with symptoms of PE and signs/symptoms of DVT |

| Pulmonary angiography | Most invasive test. Should be used only in patients with high probability of PE who may need vascular intervention |

| CT, computed tomography; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism. | |

The bottom line

This case report illustrates the importance of using sound clinical judgment when diagnosing a PE. Although our patient initially had a moderate probability Wells score and a negative D-dimer, her symptoms persisted. Her history of OCP use, persistent dyspnea, and new symptoms of a DVT prompted us to reinitiate the diagnostic algorithm and eventually diagnose a PE.

It is always essential to treat the patient and not simply react to laboratory values. To avoid unnecessary testing, however, adhering to the algorithm is equally important.

CORRESPONDENCE

Michael S. Kelleher, MD, University of Connecticut School of Medicine, 263 Farmington Avenue, Farmington, CT 06030; [email protected]

1. Meyer G, Roy PM, Gilberg S, et al. Pulmonary embolism. BMJ. 2010;340:1421.-

2. Pasha SM, Kiok FA, Snoep JD, et al. Safety of excluding acute pulmonary embolism based on an unlikely clinical probability by the Wells rule and normal D-dimer concentration: a meta-analysis. Thromb Res. 2010;125:e123-e127.

3. Taira T, Taira BR, Carmen M, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with borderline quantitative D-dimer levels. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:450-453.

4. Bounameaux H, Perrier A, Righini M. Diagnosis of venous thromboembolism: an update. Vasc Med. 2010;15:399-406.

5. Pengo V, Lensing AW, Prins MH, et al. Incidence of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2257-2264.

6. Agnelli G, Becattini C. Acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:266-274.

7. Gandara E, Wells PS. Diagnosis: use of clinical probability algorithms. Clin Chest Med. 2010;31:629-639.

8. Drescher FS, Chandrika S, Weir ID, et al. Effectiveness and acceptability of a computerized decision support system using modified wells criteria for evaluation of suspected pulmonary embolism. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57:613-621.

9. Gimber LH, Travis RI, Takahashi JM, et al. Computed tomography angiography in patients evaluated for acute pulmonary embolism with low serum D-dimer levels: a prospective study. Perm J. 2009;13:4-10.

10. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Available at: http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=13410#Section420. Accessed February 12, 2011.

11. Kim NH. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: diagnosis. Medscape. Available at: http://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/556058_3. Accessed May 9, 2011.

A 44-year-old woman sought care at the emergency department (ED) because she was having difficulty breathing and felt faint. She had been fine until that morning. Three days earlier the patient, who had a history of high blood pressure and elevated cholesterol levels, had driven from Connecticut to New York and back, spending a total of 4 hours in her car. The patient indicated that she’d been taking oral contraceptives (OCPs) for several years, but she did not smoke. There was no history of hemoptysis, recent surgery, or trauma. Neither blood clots nor cancer were part of her or her family’s history.

In the ED, the patient did not have any signs or symptoms of a deep venous thrombosis (DVT). She was obese, with a body mass index of 40.3 kg/m2; other vitals were: blood pressure (BP), 134/88 mm Hg; heart rate (HR), 64 beats per minute (bpm); respiratory rate (RR), 12; and O2 saturation, 99% with ambulation.

The ED physician strongly suspected a pulmonary embolism (PE), but the patient’s score on a clinical probability algorithm (using the Wells criteria) was a 3, indicating only “moderate probability“ of a PE (TABLE 1). (She scored a 3 because an “alternative diagnosis [was] less likely than PE.”) In addition, her D-dimer level was 160 ng/mL using the Triage D-Dimer Test by Biosite, Inc (normal <400 ng/mL), which ruled out a PE. (Many ED physicians at our institution are more cautious when using this D-dimer assay and use a lower cutoff value.)

Given these results, the ED physician did not order imaging studies because the expense and radiation exposure outweighed the probability of the patient having a PE. A subsequent coronary work-up was also negative. The patient was discharged to home and advised to follow up with her primary care physician a few days later.

Two days later we saw the patient at our office. Not only had her dyspnea gotten worse while the presyncope remained, but she now had left-sided pleuritic chest pain. She also reported mild pain in her right calf. On examination, the patient’s BP was 126/86 mm Hg, HR was 82 bpm, RR was 12, and O2 saturation was 96% with ambulation. Her Wells score was now 6, still a moderate probability for PE. (She received another 3 points for the new DVT symptoms—“clinically suspected DVT.”)

Although the patient did not also have signs of a DVT, her additional symptoms along with the original symptoms’ persistence and the existence of other risk factors (OCP use and obesity) led us to reconsider a PE diagnosis. These suspicions prompted us to send the patient back to the ED, where a Doppler ultrasound of the right lower extremity was negative, but the D-dimer was positive at 565 ng/mL.

A pulmonary computed tomography angiogram (CTA) showed 2 small pulmonary emboli within the distal left upper lobe pulmonary arteries.

The patient was treated with heparin and warfarin and discharged without complications.

TABLE 1

Calculating and interpreting the Wells score4,5,7,9,10

| Clinical parameter | Points |

|---|---|

| Clinically suspected DVT | 3.0 |

| Alternative diagnosis less likely than PE | 3.0 |

| Tachycardia | 1.5 |

| Immobilization/surgery (within 4 weeks) | 1.5 |

| History of DVT or PE | 1.5 |

| Hemoptysis | 1.0 |

| Malignancy (treatment within 6 months, palliative) | 1.0 |

| TOTAL | |

| Score | Traditional interpretation |

| <2.0 | Low probability of PE |

| 2.0-6.0 | Moderate probability of PE |

| >6.0 | High probability of PE |

| Score | Alternative classification scheme |

| ≤4.0 | PE unlikely |

| >4.0 | PE likely |

| DVT, deep venous thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism. | |

Discussion

The incidence of PE in the United States varies significantly: Individuals younger than 40 have a risk of 1 in 10,000 compared with 1 in 100 for those older than 80.1 Mortality associated with undiagnosed PE varies widely, from 9.2% to 51%.2 This percentage is significant given that half of all PEs go undiagnosed.3 In addition, when left untreated, PE will recur in 30% to 50% of patients, with a fatality rate of 10% to 45%.1 Further, up to 4% of patients with acute PE develop chronic PE and subsequent pulmonary hypertension.4,5 Given the consequences of failing to diagnose a PE, clinicians must consider this condition in patients who present with unexplained hypotension, dyspnea, or chest pain.6

Not an easy diagnosis

This case report demonstrates the inherent difficulty in diagnosing a PE. Still, certain clinical symptoms/signs can aid in the decision-making process. Fever, crackles, and wheezes decrease the probability of PE, whereas syncope, hemodynamic shock, leg edema, and hemoptysis increase its likelihood.7 Despite the many commonly reported risk factors for PE, only malignancy, recent surgery, or a history of DVT/PE significantly increase the risk of developing a clot.8

The Wells criteria. This scoring system groups patients according to the probability of having a PE: low (score: <2), moderate (score: 2-6), and high (score: >6).6 An alternative classification scheme divides patients into 2 groups: likely to have a PE (score: >4) or unlikely to have a PE (score: ≤4).8

This case report illustrates a key problem with the Wells criteria—the somewhat subjective nature of the scoring. Some physicians find it questionable to award 3 points for “alternative diagnosis less likely than PE,” for example.4 Similarly, with respect to immobilization, some clinicians might have awarded our patient 1.5 points for her recent car trip to New York. We did not think that riding in a car for 2 uninterrupted hours for each leg of the trip was significant enough. However, awarding this patient 1.5 points could have made an important difference in her clinical management if the alternative classification scheme was used. Instead of having a score of 3, the patient would have had a score of 4.5, placing her in the “likely to have a PE” group and prompting us to perform a CTA sooner (FIGURE).

FIGURE

Diagnostic algorithm for pulmonary embolism6,7,10

CTA, computed tomography angiogram; PE, pulmonary embolism.

Inappropriate work-ups are common

Some physicians ignore algorithms when working up a PE and simply order a CTA. In fact, a large multicenter trial showed that 43% of patients suspected of having a PE were inappropriately managed diagnostically.9 Similarly, a meta-analysis of 4 studies including 1660 patients found that only 58% of those with a positive D-dimer had the requisite CTA, as did 7% of patients with a negative D-dimer.2

Physicians should not be concerned about ruling out a PE in the setting of a negative D-dimer, as a meta-analysis found that this diagnostic approach has a negative predictive value (NPV) of 99.7%.2 It is important to note that the NPV is significantly affected by the sensitivity of the D-dimer assay used. If the D-dimer assay is highly sensitive, a negative result in combination with a low, moderate, or unlikely probability Wells score rules out the diagnosis of PE. If the assay is moderately sensitive, however, only a low or unlikely probability Wells score rules out PE.10

The inappropriate work-up of this group of patients is significant and extends beyond the ultimate goal of preventing morbidity and mortality. The unnecessary use of pulmonary CTA is extremely expensive, exposes patients to unnecessary radiation, and results in contrast nephrotoxicity in about 4% of patients.9 Although pulmonary CTA is the standard diagnostic test for PE, other imaging modalities are more appropriate in some cases (TABLE 2).

TABLE 2

Alternative imaging modalities for diagnosing PE1,4,7,11

| Modality | Indication |

|---|---|

| Ventilation-perfusion scanning | Patients with contrast allergies or renal failure; test of choice for diagnosing chronic PE due to limited sensitivity of CT |

| Venous compression ultrasonography | Patients with symptoms of PE and signs/symptoms of DVT |

| Pulmonary angiography | Most invasive test. Should be used only in patients with high probability of PE who may need vascular intervention |

| CT, computed tomography; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism. | |

The bottom line

This case report illustrates the importance of using sound clinical judgment when diagnosing a PE. Although our patient initially had a moderate probability Wells score and a negative D-dimer, her symptoms persisted. Her history of OCP use, persistent dyspnea, and new symptoms of a DVT prompted us to reinitiate the diagnostic algorithm and eventually diagnose a PE.

It is always essential to treat the patient and not simply react to laboratory values. To avoid unnecessary testing, however, adhering to the algorithm is equally important.

CORRESPONDENCE

Michael S. Kelleher, MD, University of Connecticut School of Medicine, 263 Farmington Avenue, Farmington, CT 06030; [email protected]

A 44-year-old woman sought care at the emergency department (ED) because she was having difficulty breathing and felt faint. She had been fine until that morning. Three days earlier the patient, who had a history of high blood pressure and elevated cholesterol levels, had driven from Connecticut to New York and back, spending a total of 4 hours in her car. The patient indicated that she’d been taking oral contraceptives (OCPs) for several years, but she did not smoke. There was no history of hemoptysis, recent surgery, or trauma. Neither blood clots nor cancer were part of her or her family’s history.

In the ED, the patient did not have any signs or symptoms of a deep venous thrombosis (DVT). She was obese, with a body mass index of 40.3 kg/m2; other vitals were: blood pressure (BP), 134/88 mm Hg; heart rate (HR), 64 beats per minute (bpm); respiratory rate (RR), 12; and O2 saturation, 99% with ambulation.

The ED physician strongly suspected a pulmonary embolism (PE), but the patient’s score on a clinical probability algorithm (using the Wells criteria) was a 3, indicating only “moderate probability“ of a PE (TABLE 1). (She scored a 3 because an “alternative diagnosis [was] less likely than PE.”) In addition, her D-dimer level was 160 ng/mL using the Triage D-Dimer Test by Biosite, Inc (normal <400 ng/mL), which ruled out a PE. (Many ED physicians at our institution are more cautious when using this D-dimer assay and use a lower cutoff value.)

Given these results, the ED physician did not order imaging studies because the expense and radiation exposure outweighed the probability of the patient having a PE. A subsequent coronary work-up was also negative. The patient was discharged to home and advised to follow up with her primary care physician a few days later.

Two days later we saw the patient at our office. Not only had her dyspnea gotten worse while the presyncope remained, but she now had left-sided pleuritic chest pain. She also reported mild pain in her right calf. On examination, the patient’s BP was 126/86 mm Hg, HR was 82 bpm, RR was 12, and O2 saturation was 96% with ambulation. Her Wells score was now 6, still a moderate probability for PE. (She received another 3 points for the new DVT symptoms—“clinically suspected DVT.”)

Although the patient did not also have signs of a DVT, her additional symptoms along with the original symptoms’ persistence and the existence of other risk factors (OCP use and obesity) led us to reconsider a PE diagnosis. These suspicions prompted us to send the patient back to the ED, where a Doppler ultrasound of the right lower extremity was negative, but the D-dimer was positive at 565 ng/mL.

A pulmonary computed tomography angiogram (CTA) showed 2 small pulmonary emboli within the distal left upper lobe pulmonary arteries.

The patient was treated with heparin and warfarin and discharged without complications.

TABLE 1

Calculating and interpreting the Wells score4,5,7,9,10

| Clinical parameter | Points |

|---|---|

| Clinically suspected DVT | 3.0 |

| Alternative diagnosis less likely than PE | 3.0 |

| Tachycardia | 1.5 |

| Immobilization/surgery (within 4 weeks) | 1.5 |

| History of DVT or PE | 1.5 |

| Hemoptysis | 1.0 |

| Malignancy (treatment within 6 months, palliative) | 1.0 |

| TOTAL | |

| Score | Traditional interpretation |

| <2.0 | Low probability of PE |

| 2.0-6.0 | Moderate probability of PE |

| >6.0 | High probability of PE |

| Score | Alternative classification scheme |

| ≤4.0 | PE unlikely |

| >4.0 | PE likely |

| DVT, deep venous thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism. | |

Discussion

The incidence of PE in the United States varies significantly: Individuals younger than 40 have a risk of 1 in 10,000 compared with 1 in 100 for those older than 80.1 Mortality associated with undiagnosed PE varies widely, from 9.2% to 51%.2 This percentage is significant given that half of all PEs go undiagnosed.3 In addition, when left untreated, PE will recur in 30% to 50% of patients, with a fatality rate of 10% to 45%.1 Further, up to 4% of patients with acute PE develop chronic PE and subsequent pulmonary hypertension.4,5 Given the consequences of failing to diagnose a PE, clinicians must consider this condition in patients who present with unexplained hypotension, dyspnea, or chest pain.6

Not an easy diagnosis

This case report demonstrates the inherent difficulty in diagnosing a PE. Still, certain clinical symptoms/signs can aid in the decision-making process. Fever, crackles, and wheezes decrease the probability of PE, whereas syncope, hemodynamic shock, leg edema, and hemoptysis increase its likelihood.7 Despite the many commonly reported risk factors for PE, only malignancy, recent surgery, or a history of DVT/PE significantly increase the risk of developing a clot.8

The Wells criteria. This scoring system groups patients according to the probability of having a PE: low (score: <2), moderate (score: 2-6), and high (score: >6).6 An alternative classification scheme divides patients into 2 groups: likely to have a PE (score: >4) or unlikely to have a PE (score: ≤4).8

This case report illustrates a key problem with the Wells criteria—the somewhat subjective nature of the scoring. Some physicians find it questionable to award 3 points for “alternative diagnosis less likely than PE,” for example.4 Similarly, with respect to immobilization, some clinicians might have awarded our patient 1.5 points for her recent car trip to New York. We did not think that riding in a car for 2 uninterrupted hours for each leg of the trip was significant enough. However, awarding this patient 1.5 points could have made an important difference in her clinical management if the alternative classification scheme was used. Instead of having a score of 3, the patient would have had a score of 4.5, placing her in the “likely to have a PE” group and prompting us to perform a CTA sooner (FIGURE).

FIGURE

Diagnostic algorithm for pulmonary embolism6,7,10

CTA, computed tomography angiogram; PE, pulmonary embolism.

Inappropriate work-ups are common

Some physicians ignore algorithms when working up a PE and simply order a CTA. In fact, a large multicenter trial showed that 43% of patients suspected of having a PE were inappropriately managed diagnostically.9 Similarly, a meta-analysis of 4 studies including 1660 patients found that only 58% of those with a positive D-dimer had the requisite CTA, as did 7% of patients with a negative D-dimer.2

Physicians should not be concerned about ruling out a PE in the setting of a negative D-dimer, as a meta-analysis found that this diagnostic approach has a negative predictive value (NPV) of 99.7%.2 It is important to note that the NPV is significantly affected by the sensitivity of the D-dimer assay used. If the D-dimer assay is highly sensitive, a negative result in combination with a low, moderate, or unlikely probability Wells score rules out the diagnosis of PE. If the assay is moderately sensitive, however, only a low or unlikely probability Wells score rules out PE.10

The inappropriate work-up of this group of patients is significant and extends beyond the ultimate goal of preventing morbidity and mortality. The unnecessary use of pulmonary CTA is extremely expensive, exposes patients to unnecessary radiation, and results in contrast nephrotoxicity in about 4% of patients.9 Although pulmonary CTA is the standard diagnostic test for PE, other imaging modalities are more appropriate in some cases (TABLE 2).

TABLE 2

Alternative imaging modalities for diagnosing PE1,4,7,11

| Modality | Indication |

|---|---|

| Ventilation-perfusion scanning | Patients with contrast allergies or renal failure; test of choice for diagnosing chronic PE due to limited sensitivity of CT |

| Venous compression ultrasonography | Patients with symptoms of PE and signs/symptoms of DVT |

| Pulmonary angiography | Most invasive test. Should be used only in patients with high probability of PE who may need vascular intervention |

| CT, computed tomography; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism. | |

The bottom line

This case report illustrates the importance of using sound clinical judgment when diagnosing a PE. Although our patient initially had a moderate probability Wells score and a negative D-dimer, her symptoms persisted. Her history of OCP use, persistent dyspnea, and new symptoms of a DVT prompted us to reinitiate the diagnostic algorithm and eventually diagnose a PE.

It is always essential to treat the patient and not simply react to laboratory values. To avoid unnecessary testing, however, adhering to the algorithm is equally important.

CORRESPONDENCE

Michael S. Kelleher, MD, University of Connecticut School of Medicine, 263 Farmington Avenue, Farmington, CT 06030; [email protected]

1. Meyer G, Roy PM, Gilberg S, et al. Pulmonary embolism. BMJ. 2010;340:1421.-

2. Pasha SM, Kiok FA, Snoep JD, et al. Safety of excluding acute pulmonary embolism based on an unlikely clinical probability by the Wells rule and normal D-dimer concentration: a meta-analysis. Thromb Res. 2010;125:e123-e127.

3. Taira T, Taira BR, Carmen M, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with borderline quantitative D-dimer levels. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:450-453.

4. Bounameaux H, Perrier A, Righini M. Diagnosis of venous thromboembolism: an update. Vasc Med. 2010;15:399-406.

5. Pengo V, Lensing AW, Prins MH, et al. Incidence of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2257-2264.

6. Agnelli G, Becattini C. Acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:266-274.

7. Gandara E, Wells PS. Diagnosis: use of clinical probability algorithms. Clin Chest Med. 2010;31:629-639.

8. Drescher FS, Chandrika S, Weir ID, et al. Effectiveness and acceptability of a computerized decision support system using modified wells criteria for evaluation of suspected pulmonary embolism. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57:613-621.

9. Gimber LH, Travis RI, Takahashi JM, et al. Computed tomography angiography in patients evaluated for acute pulmonary embolism with low serum D-dimer levels: a prospective study. Perm J. 2009;13:4-10.

10. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Available at: http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=13410#Section420. Accessed February 12, 2011.

11. Kim NH. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: diagnosis. Medscape. Available at: http://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/556058_3. Accessed May 9, 2011.

1. Meyer G, Roy PM, Gilberg S, et al. Pulmonary embolism. BMJ. 2010;340:1421.-

2. Pasha SM, Kiok FA, Snoep JD, et al. Safety of excluding acute pulmonary embolism based on an unlikely clinical probability by the Wells rule and normal D-dimer concentration: a meta-analysis. Thromb Res. 2010;125:e123-e127.

3. Taira T, Taira BR, Carmen M, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with borderline quantitative D-dimer levels. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:450-453.

4. Bounameaux H, Perrier A, Righini M. Diagnosis of venous thromboembolism: an update. Vasc Med. 2010;15:399-406.

5. Pengo V, Lensing AW, Prins MH, et al. Incidence of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2257-2264.

6. Agnelli G, Becattini C. Acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:266-274.

7. Gandara E, Wells PS. Diagnosis: use of clinical probability algorithms. Clin Chest Med. 2010;31:629-639.

8. Drescher FS, Chandrika S, Weir ID, et al. Effectiveness and acceptability of a computerized decision support system using modified wells criteria for evaluation of suspected pulmonary embolism. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57:613-621.

9. Gimber LH, Travis RI, Takahashi JM, et al. Computed tomography angiography in patients evaluated for acute pulmonary embolism with low serum D-dimer levels: a prospective study. Perm J. 2009;13:4-10.

10. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Available at: http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=13410#Section420. Accessed February 12, 2011.

11. Kim NH. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: diagnosis. Medscape. Available at: http://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/556058_3. Accessed May 9, 2011.

Failure to monitor INR leads to severe bleeding, disability ... Rash and hives not taken seriously enough ... More

Failure to monitor INR leads to severe bleeding, disability

A MAN WITH A HISTORY OF DEEP VEIN THROMBOSIS was taking warfarin 10 mg every even day and 7.5 mg every odd day. His physician changed the warfarin dosage while the patient was taking ciprofloxacin, then resumed the original regimen once the patient finished taking the antibiotic.

No new prescriptions were written to confirm the change nor, the patient claimed, was a proper explanation of the new regimen provided. His international normalized ratio (INR) wasn’t checked after the dosage change.

After 2 weeks on the new warfarin dosage, the patient went to the emergency department (ED) complaining of groin pain and a change in urine color. Urinalysis found red blood cells too numerous to count. Although the patient told the ED staff he was taking warfarin, they didn’t check his INR. He was given a diagnosis of urinary tract infection (UTI) and discharged.

Three days later, the patient returned to the ED because of increased bleeding from his Foley catheter. Once again his INR wasn’t checked and he was discharged with a UTI diagnosis and a prescription for antibiotics. Two days afterwards, he was taken back to the hospital bleeding from all orifices. His INR was 75.

The patient spent a month in the hospital, most of it in the intensive care unit, followed by 3 months in a rehabilitation facility before returning home. He remained confined to a hospital bed.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The physician and hospital were negligent for failing to instruct the patient regarding the change in warfarin dosage and neglecting to check his INR.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $700,000 Maryland settlement.

COMMENT The management of anticoagulation has numerous pitfalls for the unwary. Careful monitoring can save lives—and lawsuits.

Rash and hives not taken seriously enough

A HISTORY OF 3 SEIZURES in a 7-year-old boy prompted a neurologist to prescribe valproic acid. The neurologist later added lamotrigine because of the child’s behavior problems. After taking both medications for 2 weeks, the child developed a rash, at which point the neurologist discontinued the lamotrigine and started diphenhydramine.

The following day, the child was brought to the ED with an itchy rash and hives on his torso and extremities. An allergic reaction was diagnosed and the child was discharged with instructions to take diphenhydramine along with acetaminophen and ibuprofen as needed. When informed of the ED visit, the neurologist requested a follow-up appointment in 4 weeks.

Two days later, the child was back in the ED because the rash had progressed to include redness and swelling of the face. Once again, he was discharged with a diagnosis of allergic reaction and instructions to take diphenhydramine and acetaminophen.

Two days afterward, the child was taken to a different ED, from which he was airlifted to a tertiary care center and admitted to the intensive care unit for treatment of Stevens-Johnson syndrome. The condition advanced to toxic epidermal necrolysis with sloughing of skin and the lining of the gastrointestinal tract. Several weeks later, the child died.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The neurologist was negligent in prescribing lamotrigine for the behavior problem instead of referring the boy to a child psychologist. The lamotrigine dosage was excessive; the neurologist didn’t respond properly to the report of a rash.

The pharmacist was negligent in failing to contact the neurologist to discuss the excessive dosage. Discharging the child from the ED with a life-threatening drug reaction was unreasonable.

THE DEFENSE The defendants denied that they were negligent or caused the child’s death. They were prepared to present the histories of the parents, whose backgrounds included drug abuse, and state investigations regarding the care of the child.

VERDICT $1.55 million Washington settlement.

COMMENT When prescribing a drug with a potentially serious adverse effect, it’s always prudent to document patient education and follow-up thoroughly. Even though hindsight is 20/20, an “allergic reaction” in a patient on lamotrigine should raise red flags.

Delay in spotting compartment syndrome has permanent consequences

SEVERE NUMBNESS, TINGLING, AND PAIN IN HER LEFT CALF brought a 20-year-old woman to the ED. She couldn’t lift her left foot or bear weight on her left foot or leg. She reported awakening with the symptoms after a New Year’s Eve party the previous evening. After an examination, but no tests, she was discharged with a diagnosis of “floppy foot syndrome” and a prescription for a non-narcotic pain medication.

The young woman went to another ED the next day, complaining of continued pain and swelling in her left calf. She was admitted to the hospital for an orthopedic consultation, which resulted in a diagnosis of compartment syndrome. By that time, the patient had gone into renal failure from rhabdomyolysis caused by tissue breakdown. She underwent a fasciotomy, after which she required hemodialysis (until her kidney function returned) and rehabilitation. Damage to the nerves of her left calf and leg left her with permanent foot drop.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The hospital was negligent in failing to diagnose compartment syndrome when the woman went to the ED. Proper diagnosis and treatment at that time would have prevented the nerve damage and foot drop.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $750,000 Maryland settlement.

COMMENT Compartment syndrome can be challenging to recognize. Recently I have come across several allegations of malpractice for untimely diagnosis. Remember this important problem when faced with a patient with leg pain.

Multiple errors end in death from pneumonia

A 24-YEAR-OLD MAN WITH CHEST PAIN AND A COUGH went to his physician, who diagnosed chest wall pain and prescribed a narcotic pain reliever. The young man returned the next day complaining of increased chest pain. He said he’d been spitting up blood-stained sputum. He was perspiring and vomited in the doctor’s waiting room. The doctor diagnosed an upper respiratory infection and prescribed a cough syrup containing more narcotics.

Later that day the patient had a radiograph at a hospital. It revealed pneumonia. Shortly afterward, the hospital confirmed by fax with the doctor’s office that the doctor had received the results. The doctor didn’t read the radiograph results for 2 days.

After the doctor read the radiograph report, his office tried to contact the patient but misdialed his phone number, then made no further attempts at contact. The patient’s former wife found him at home unresponsive. He was admitted to the ED, where he died of pneumonia shortly thereafter.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM No information about the plaintiff’s claim is available.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $1.85 million net verdict in Virginia.

COMMENT A cascade of mistakes (sometimes referred to as the Swiss cheese effect) occurs, and a preventable death results. Are you at risk for such an event? What fail-safe measures do you have in place in your practice?

Failure to monitor INR leads to severe bleeding, disability

A MAN WITH A HISTORY OF DEEP VEIN THROMBOSIS was taking warfarin 10 mg every even day and 7.5 mg every odd day. His physician changed the warfarin dosage while the patient was taking ciprofloxacin, then resumed the original regimen once the patient finished taking the antibiotic.

No new prescriptions were written to confirm the change nor, the patient claimed, was a proper explanation of the new regimen provided. His international normalized ratio (INR) wasn’t checked after the dosage change.

After 2 weeks on the new warfarin dosage, the patient went to the emergency department (ED) complaining of groin pain and a change in urine color. Urinalysis found red blood cells too numerous to count. Although the patient told the ED staff he was taking warfarin, they didn’t check his INR. He was given a diagnosis of urinary tract infection (UTI) and discharged.

Three days later, the patient returned to the ED because of increased bleeding from his Foley catheter. Once again his INR wasn’t checked and he was discharged with a UTI diagnosis and a prescription for antibiotics. Two days afterwards, he was taken back to the hospital bleeding from all orifices. His INR was 75.

The patient spent a month in the hospital, most of it in the intensive care unit, followed by 3 months in a rehabilitation facility before returning home. He remained confined to a hospital bed.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The physician and hospital were negligent for failing to instruct the patient regarding the change in warfarin dosage and neglecting to check his INR.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $700,000 Maryland settlement.

COMMENT The management of anticoagulation has numerous pitfalls for the unwary. Careful monitoring can save lives—and lawsuits.

Rash and hives not taken seriously enough

A HISTORY OF 3 SEIZURES in a 7-year-old boy prompted a neurologist to prescribe valproic acid. The neurologist later added lamotrigine because of the child’s behavior problems. After taking both medications for 2 weeks, the child developed a rash, at which point the neurologist discontinued the lamotrigine and started diphenhydramine.

The following day, the child was brought to the ED with an itchy rash and hives on his torso and extremities. An allergic reaction was diagnosed and the child was discharged with instructions to take diphenhydramine along with acetaminophen and ibuprofen as needed. When informed of the ED visit, the neurologist requested a follow-up appointment in 4 weeks.

Two days later, the child was back in the ED because the rash had progressed to include redness and swelling of the face. Once again, he was discharged with a diagnosis of allergic reaction and instructions to take diphenhydramine and acetaminophen.

Two days afterward, the child was taken to a different ED, from which he was airlifted to a tertiary care center and admitted to the intensive care unit for treatment of Stevens-Johnson syndrome. The condition advanced to toxic epidermal necrolysis with sloughing of skin and the lining of the gastrointestinal tract. Several weeks later, the child died.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The neurologist was negligent in prescribing lamotrigine for the behavior problem instead of referring the boy to a child psychologist. The lamotrigine dosage was excessive; the neurologist didn’t respond properly to the report of a rash.

The pharmacist was negligent in failing to contact the neurologist to discuss the excessive dosage. Discharging the child from the ED with a life-threatening drug reaction was unreasonable.

THE DEFENSE The defendants denied that they were negligent or caused the child’s death. They were prepared to present the histories of the parents, whose backgrounds included drug abuse, and state investigations regarding the care of the child.

VERDICT $1.55 million Washington settlement.

COMMENT When prescribing a drug with a potentially serious adverse effect, it’s always prudent to document patient education and follow-up thoroughly. Even though hindsight is 20/20, an “allergic reaction” in a patient on lamotrigine should raise red flags.

Delay in spotting compartment syndrome has permanent consequences

SEVERE NUMBNESS, TINGLING, AND PAIN IN HER LEFT CALF brought a 20-year-old woman to the ED. She couldn’t lift her left foot or bear weight on her left foot or leg. She reported awakening with the symptoms after a New Year’s Eve party the previous evening. After an examination, but no tests, she was discharged with a diagnosis of “floppy foot syndrome” and a prescription for a non-narcotic pain medication.

The young woman went to another ED the next day, complaining of continued pain and swelling in her left calf. She was admitted to the hospital for an orthopedic consultation, which resulted in a diagnosis of compartment syndrome. By that time, the patient had gone into renal failure from rhabdomyolysis caused by tissue breakdown. She underwent a fasciotomy, after which she required hemodialysis (until her kidney function returned) and rehabilitation. Damage to the nerves of her left calf and leg left her with permanent foot drop.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The hospital was negligent in failing to diagnose compartment syndrome when the woman went to the ED. Proper diagnosis and treatment at that time would have prevented the nerve damage and foot drop.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $750,000 Maryland settlement.

COMMENT Compartment syndrome can be challenging to recognize. Recently I have come across several allegations of malpractice for untimely diagnosis. Remember this important problem when faced with a patient with leg pain.

Multiple errors end in death from pneumonia

A 24-YEAR-OLD MAN WITH CHEST PAIN AND A COUGH went to his physician, who diagnosed chest wall pain and prescribed a narcotic pain reliever. The young man returned the next day complaining of increased chest pain. He said he’d been spitting up blood-stained sputum. He was perspiring and vomited in the doctor’s waiting room. The doctor diagnosed an upper respiratory infection and prescribed a cough syrup containing more narcotics.

Later that day the patient had a radiograph at a hospital. It revealed pneumonia. Shortly afterward, the hospital confirmed by fax with the doctor’s office that the doctor had received the results. The doctor didn’t read the radiograph results for 2 days.

After the doctor read the radiograph report, his office tried to contact the patient but misdialed his phone number, then made no further attempts at contact. The patient’s former wife found him at home unresponsive. He was admitted to the ED, where he died of pneumonia shortly thereafter.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM No information about the plaintiff’s claim is available.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $1.85 million net verdict in Virginia.

COMMENT A cascade of mistakes (sometimes referred to as the Swiss cheese effect) occurs, and a preventable death results. Are you at risk for such an event? What fail-safe measures do you have in place in your practice?

Failure to monitor INR leads to severe bleeding, disability

A MAN WITH A HISTORY OF DEEP VEIN THROMBOSIS was taking warfarin 10 mg every even day and 7.5 mg every odd day. His physician changed the warfarin dosage while the patient was taking ciprofloxacin, then resumed the original regimen once the patient finished taking the antibiotic.

No new prescriptions were written to confirm the change nor, the patient claimed, was a proper explanation of the new regimen provided. His international normalized ratio (INR) wasn’t checked after the dosage change.

After 2 weeks on the new warfarin dosage, the patient went to the emergency department (ED) complaining of groin pain and a change in urine color. Urinalysis found red blood cells too numerous to count. Although the patient told the ED staff he was taking warfarin, they didn’t check his INR. He was given a diagnosis of urinary tract infection (UTI) and discharged.

Three days later, the patient returned to the ED because of increased bleeding from his Foley catheter. Once again his INR wasn’t checked and he was discharged with a UTI diagnosis and a prescription for antibiotics. Two days afterwards, he was taken back to the hospital bleeding from all orifices. His INR was 75.

The patient spent a month in the hospital, most of it in the intensive care unit, followed by 3 months in a rehabilitation facility before returning home. He remained confined to a hospital bed.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The physician and hospital were negligent for failing to instruct the patient regarding the change in warfarin dosage and neglecting to check his INR.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $700,000 Maryland settlement.

COMMENT The management of anticoagulation has numerous pitfalls for the unwary. Careful monitoring can save lives—and lawsuits.

Rash and hives not taken seriously enough

A HISTORY OF 3 SEIZURES in a 7-year-old boy prompted a neurologist to prescribe valproic acid. The neurologist later added lamotrigine because of the child’s behavior problems. After taking both medications for 2 weeks, the child developed a rash, at which point the neurologist discontinued the lamotrigine and started diphenhydramine.

The following day, the child was brought to the ED with an itchy rash and hives on his torso and extremities. An allergic reaction was diagnosed and the child was discharged with instructions to take diphenhydramine along with acetaminophen and ibuprofen as needed. When informed of the ED visit, the neurologist requested a follow-up appointment in 4 weeks.

Two days later, the child was back in the ED because the rash had progressed to include redness and swelling of the face. Once again, he was discharged with a diagnosis of allergic reaction and instructions to take diphenhydramine and acetaminophen.

Two days afterward, the child was taken to a different ED, from which he was airlifted to a tertiary care center and admitted to the intensive care unit for treatment of Stevens-Johnson syndrome. The condition advanced to toxic epidermal necrolysis with sloughing of skin and the lining of the gastrointestinal tract. Several weeks later, the child died.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The neurologist was negligent in prescribing lamotrigine for the behavior problem instead of referring the boy to a child psychologist. The lamotrigine dosage was excessive; the neurologist didn’t respond properly to the report of a rash.

The pharmacist was negligent in failing to contact the neurologist to discuss the excessive dosage. Discharging the child from the ED with a life-threatening drug reaction was unreasonable.

THE DEFENSE The defendants denied that they were negligent or caused the child’s death. They were prepared to present the histories of the parents, whose backgrounds included drug abuse, and state investigations regarding the care of the child.

VERDICT $1.55 million Washington settlement.

COMMENT When prescribing a drug with a potentially serious adverse effect, it’s always prudent to document patient education and follow-up thoroughly. Even though hindsight is 20/20, an “allergic reaction” in a patient on lamotrigine should raise red flags.

Delay in spotting compartment syndrome has permanent consequences

SEVERE NUMBNESS, TINGLING, AND PAIN IN HER LEFT CALF brought a 20-year-old woman to the ED. She couldn’t lift her left foot or bear weight on her left foot or leg. She reported awakening with the symptoms after a New Year’s Eve party the previous evening. After an examination, but no tests, she was discharged with a diagnosis of “floppy foot syndrome” and a prescription for a non-narcotic pain medication.

The young woman went to another ED the next day, complaining of continued pain and swelling in her left calf. She was admitted to the hospital for an orthopedic consultation, which resulted in a diagnosis of compartment syndrome. By that time, the patient had gone into renal failure from rhabdomyolysis caused by tissue breakdown. She underwent a fasciotomy, after which she required hemodialysis (until her kidney function returned) and rehabilitation. Damage to the nerves of her left calf and leg left her with permanent foot drop.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The hospital was negligent in failing to diagnose compartment syndrome when the woman went to the ED. Proper diagnosis and treatment at that time would have prevented the nerve damage and foot drop.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $750,000 Maryland settlement.

COMMENT Compartment syndrome can be challenging to recognize. Recently I have come across several allegations of malpractice for untimely diagnosis. Remember this important problem when faced with a patient with leg pain.

Multiple errors end in death from pneumonia

A 24-YEAR-OLD MAN WITH CHEST PAIN AND A COUGH went to his physician, who diagnosed chest wall pain and prescribed a narcotic pain reliever. The young man returned the next day complaining of increased chest pain. He said he’d been spitting up blood-stained sputum. He was perspiring and vomited in the doctor’s waiting room. The doctor diagnosed an upper respiratory infection and prescribed a cough syrup containing more narcotics.

Later that day the patient had a radiograph at a hospital. It revealed pneumonia. Shortly afterward, the hospital confirmed by fax with the doctor’s office that the doctor had received the results. The doctor didn’t read the radiograph results for 2 days.

After the doctor read the radiograph report, his office tried to contact the patient but misdialed his phone number, then made no further attempts at contact. The patient’s former wife found him at home unresponsive. He was admitted to the ED, where he died of pneumonia shortly thereafter.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM No information about the plaintiff’s claim is available.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $1.85 million net verdict in Virginia.

COMMENT A cascade of mistakes (sometimes referred to as the Swiss cheese effect) occurs, and a preventable death results. Are you at risk for such an event? What fail-safe measures do you have in place in your practice?

How best to diagnose asthma in infants and toddlers?

NO RELIABLE WAY EXISTS TO DIAGNOSE ASTHMA IN INFANTS AND TODDLERS. Recurrent wheezing, especially apart from colds, combined with physician-diagnosed eczema or atopic dermatitis, eosinophilia, and a parental history of asthma, increase the probability of a subsequent asthma diagnosis in the absence of other causes (strength of recommendation: B, 2 good-quality cohort studies).

Evidence summary

Wheezing in children is common and the differential diagnosis is broad. The many potential causes include upper respiratory infection, asthma, cystic fibrosis, foreign body aspiration, vascular ring, tracheomalacia, primary immunodeficiency, and congenital heart disease.1

Outpatient primary care cohort studies estimate that about half of children wheeze before they reach school age. Only one-third of children who wheeze during the first 3 years of life, however, continue to wheeze into later childhood and young adulthood.2-4

These findings have led some experts to suggest that not all wheezing in children is asthma and that asthma exists in variant forms.5-7 Variant wheezing patterns include transient early wheezing, which seems to be most prevalent in the first 3 years of life; wheezing without atopy, which occurs most often at 3 to 6 years of age; and wheezing with immunoglobulin E-associated atopy, which gradually increases in prevalence from birth and dominates in the over-6 age group. It is children in this last group whom we generally consider to have asthma.

Objective measures of lung function are challenging to perform in young children. Clinical signs and symptoms thus suggest the diagnosis of asthma.

Atopy, rhinitis, and eczema most often accompany persistent wheezing

Primary care cohort studies provide the best available evidence on which findings in infants and toddlers most likely predict persistent airway disease in childhood. A whole-population cohort study followed nearly all children born on the Isle of Wight from January 1989 through February 1990 to evaluate the natural history of childhood wheezing and to study associated risk factors.8 Children were seen at birth and at 1, 2, 4, and 10 years of age.

Findings most associated with current wheezing (within the last year) in 10-year-olds were atopy (odds ratio [OR]=4.38; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.07-6.25), rhinitis (OR=3.72; 95% CI, 2.21-6.27), and eczema (OR=3.04; 95% CI, 2.05-4.51).8

An index to predict asthma

Since 1980, the Tucson Children’s Respiratory Study has followed 1246 healthy newborns seen by pediatricians affiliated with a large HMO in Tucson, Arizona. Questionnaires about parental asthma history and prenatal smoking history were obtained at enrollment. Childhood wheezing and its frequency, as well as physician-diagnosed allergies or asthma, were assessed at ages 2 and 3. If the child had wheezed in the past year, then the child was considered to be an “early wheezer.” If the frequency was 3 or more on a 5-point scale, then the child was considered to be an “early frequent wheezer.” Questionnaires were re-administered at ages 6, 8, 11, and 13. Three episodes of wheezing within the past year or a physician diagnosis of asthma with symptoms in the past year was considered “active asthma.” Blood specimens for eosinophils were obtained at age 10.

Using these data, the researchers developed stringent and loose criteria (TABLE 1) and odds ratios (TABLES 2 and 3) for childhood factors most predictive of an asthma diagnosis at an older age. The findings of the study may help clinicians care for wheezing infants and toddlers.9

TABLE 1

A clinical index of asthma risk9*

| Major criteria | Minor criteria |

|---|---|

| Parental asthma (history of physician diagnosis of asthma in a parent) | Allergic rhinitis (physician diagnosis of allergic rhinitis as reported in questionnaires at ages 2 or 3 y) |

| Eczema (physician diagnosis of atopic dermatitis as reported in questionnaires at ages 2 or 3 y) | Wheezing apart from colds |

| Eosinophilia (≥4%) | |

| *Stringent index for predicting asthma: Child has early, frequent wheezing plus at least 1 of the 2 major criteria or 2 of the 3 minor criteria. Loose index for predicting asthma: Child has early wheezing plus at least 1 of the 2 major criteria or 2 of the 3 minor criteria. | |

TABLE 2

Likelihood of active asthma predicted by stringent index9

| Active asthma | OR (95% CI) | Sensitivity, % (95% CI) | Specificity, % (95% CI) | PPV, % (95% CI) | NPV, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At 6 y | 9.8 (5.6-17.2) | 27.5 (24.6-30.4) | 96.3 (95.1-97.5) | 47.5 (44.3-50.7) | 91.6 (89.8-93.4) |

| At 8 y | 5.8 (2.9-11.2) | 16.3 (13.7-18.9) | 96.7 (95.4-98.0) | 43.6 (40.1-47.1) | 88.2 (85.9-90.5) |

| At 11 y | 4.3 (2.4-7.8) | 15 (12.6-17.4) | 96.1 (94.8-97.4) | 42.0 (38.7-45.3) | 85.6 (83.3-87.9) |

| At 13 y | 5.7 (2.8-11.6) | 14.8 (12.1-17.5) | 97.0 (95.7-98.3) | 51.5 (47.7-55.3) | 84.2 (81.4-87.0) |

| CI, confidence interval; NPV, negative predictive value; OR, odds ratio; PPV, positive predictive value. | |||||

TABLE 3

Likelihood of active asthma predicted by loose index9

| Active asthma | OR (95% CI) | Sensitivity, % (95% CI) | Specificity, % (95% CI) | PPV, % (95% CI) | NPV, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At 6 y | 5.5 (3.5-8.4) | 56.6 (53.3-59.9) | 80.8 (78.3-83.3) | 26.2 (23.4-29.0) | 93.9 (92.4-95.4) |

| At 8 y | 4.4 (2.8-6.8) | 50.5 (47.0-54.0) | 81.1 (78.3-83.9) | 29.4 (26.2-32.6) | 91.3 (89.3-93.3) |

| At 11 y | 2.6 (1.8-3.8) | 40.1 (36.8-43.4) | 79.6 (76.9-82.3) | 27.1 (24.1-30.1) | 87.5 (85.3-89.7) |

| At 13 y | 3.0 (1.9-4.6) | 39.3 (35.5-43.1) | 82.1 (79.1-85.1) | 31.7 (28.1-35.3) | 86.5 (83.9-89.1) |

| CI, confidence interval; NPV, negative predictive value; OR, odds ratio; PPV, positive predictive value. | |||||

Recommendations

A European and United States expert panel guide to the diagnosis and treatment of asthma in childhood, PRACTALL, states that “asthma should be suspected in any infant with recurrent wheezing and cough episodes. Frequently, diagnosis is possible only through long-term follow-up, consideration of the extensive differential diagnoses, and by observing the child’s response to bronchodilator and/or anti-inflammatory treatment.”10

The National Asthma Education and Prevention Program’s Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3) notes that diagnostic evaluation for asthma in children 0 to 4 years of age should include history, symptoms, physical examination, and assessment of quality of life.1

1. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert panel report 3 (EPR-3): guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. NIH publication 07-4051. Bethesda, Md: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 2007. Available at: www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.htm. Accessed June 20, 2008.

2. Martinez FD, Wright AL, Taussig LM, et al. Asthma and wheezing in the first six years of life. The Group Health Medical Associates. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:133-138.

3. Sears MR, Greene JM, Willan AR, et al. A longitudinal, population-based cohort study of childhood asthma followed to adulthood. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1414-1422.

4. Jenkins MA, Hopper JL, Bowes G, et al. Factors in childhood as predictors of asthma in adult life. BMJ. 1994;309:90-93.

5. Rusconi F, Galassi C, Corbo GM, et al. Risk factors for early, persistent, and late-onset wheezing in young children. SIDRIA Collaborative Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;167:1617-1622.

6. Stein RT, Martinez FD. Asthma phenotypes in childhood: lessons from an epidemiologic approach. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2004;5:155-161.

7. Stein RT, Holberg CJ, Morgan WJ, et al. Peak flow variability, methacholine responsiveness and atopy as markers for detecting different wheezing phenotypes in childhood. Thorax. 1997;52:946-952.

8. Arshad SH, Kurukulaaratchy RJ, Fenn M, et al. Early life risk factors for current wheeze, asthma, and bronchial hyper-responsiveness at 10 years of age. Chest. 2005;127:502-508.

9. Castro-Rodriguez JA, Holberg CJ, Wright AL, et al. A clinical index to define risk of asthma in young children with recurrent wheezing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:1403-1406.

10. Bacharier LB, Boner A, Carlsen KH, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of asthma in childhood: a PRACTALL consensus report. Allergy. 2008;63:5-34.

NO RELIABLE WAY EXISTS TO DIAGNOSE ASTHMA IN INFANTS AND TODDLERS. Recurrent wheezing, especially apart from colds, combined with physician-diagnosed eczema or atopic dermatitis, eosinophilia, and a parental history of asthma, increase the probability of a subsequent asthma diagnosis in the absence of other causes (strength of recommendation: B, 2 good-quality cohort studies).

Evidence summary

Wheezing in children is common and the differential diagnosis is broad. The many potential causes include upper respiratory infection, asthma, cystic fibrosis, foreign body aspiration, vascular ring, tracheomalacia, primary immunodeficiency, and congenital heart disease.1

Outpatient primary care cohort studies estimate that about half of children wheeze before they reach school age. Only one-third of children who wheeze during the first 3 years of life, however, continue to wheeze into later childhood and young adulthood.2-4

These findings have led some experts to suggest that not all wheezing in children is asthma and that asthma exists in variant forms.5-7 Variant wheezing patterns include transient early wheezing, which seems to be most prevalent in the first 3 years of life; wheezing without atopy, which occurs most often at 3 to 6 years of age; and wheezing with immunoglobulin E-associated atopy, which gradually increases in prevalence from birth and dominates in the over-6 age group. It is children in this last group whom we generally consider to have asthma.

Objective measures of lung function are challenging to perform in young children. Clinical signs and symptoms thus suggest the diagnosis of asthma.

Atopy, rhinitis, and eczema most often accompany persistent wheezing

Primary care cohort studies provide the best available evidence on which findings in infants and toddlers most likely predict persistent airway disease in childhood. A whole-population cohort study followed nearly all children born on the Isle of Wight from January 1989 through February 1990 to evaluate the natural history of childhood wheezing and to study associated risk factors.8 Children were seen at birth and at 1, 2, 4, and 10 years of age.

Findings most associated with current wheezing (within the last year) in 10-year-olds were atopy (odds ratio [OR]=4.38; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.07-6.25), rhinitis (OR=3.72; 95% CI, 2.21-6.27), and eczema (OR=3.04; 95% CI, 2.05-4.51).8

An index to predict asthma

Since 1980, the Tucson Children’s Respiratory Study has followed 1246 healthy newborns seen by pediatricians affiliated with a large HMO in Tucson, Arizona. Questionnaires about parental asthma history and prenatal smoking history were obtained at enrollment. Childhood wheezing and its frequency, as well as physician-diagnosed allergies or asthma, were assessed at ages 2 and 3. If the child had wheezed in the past year, then the child was considered to be an “early wheezer.” If the frequency was 3 or more on a 5-point scale, then the child was considered to be an “early frequent wheezer.” Questionnaires were re-administered at ages 6, 8, 11, and 13. Three episodes of wheezing within the past year or a physician diagnosis of asthma with symptoms in the past year was considered “active asthma.” Blood specimens for eosinophils were obtained at age 10.

Using these data, the researchers developed stringent and loose criteria (TABLE 1) and odds ratios (TABLES 2 and 3) for childhood factors most predictive of an asthma diagnosis at an older age. The findings of the study may help clinicians care for wheezing infants and toddlers.9

TABLE 1

A clinical index of asthma risk9*

| Major criteria | Minor criteria |

|---|---|

| Parental asthma (history of physician diagnosis of asthma in a parent) | Allergic rhinitis (physician diagnosis of allergic rhinitis as reported in questionnaires at ages 2 or 3 y) |

| Eczema (physician diagnosis of atopic dermatitis as reported in questionnaires at ages 2 or 3 y) | Wheezing apart from colds |

| Eosinophilia (≥4%) | |

| *Stringent index for predicting asthma: Child has early, frequent wheezing plus at least 1 of the 2 major criteria or 2 of the 3 minor criteria. Loose index for predicting asthma: Child has early wheezing plus at least 1 of the 2 major criteria or 2 of the 3 minor criteria. | |

TABLE 2

Likelihood of active asthma predicted by stringent index9

| Active asthma | OR (95% CI) | Sensitivity, % (95% CI) | Specificity, % (95% CI) | PPV, % (95% CI) | NPV, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At 6 y | 9.8 (5.6-17.2) | 27.5 (24.6-30.4) | 96.3 (95.1-97.5) | 47.5 (44.3-50.7) | 91.6 (89.8-93.4) |

| At 8 y | 5.8 (2.9-11.2) | 16.3 (13.7-18.9) | 96.7 (95.4-98.0) | 43.6 (40.1-47.1) | 88.2 (85.9-90.5) |

| At 11 y | 4.3 (2.4-7.8) | 15 (12.6-17.4) | 96.1 (94.8-97.4) | 42.0 (38.7-45.3) | 85.6 (83.3-87.9) |

| At 13 y | 5.7 (2.8-11.6) | 14.8 (12.1-17.5) | 97.0 (95.7-98.3) | 51.5 (47.7-55.3) | 84.2 (81.4-87.0) |

| CI, confidence interval; NPV, negative predictive value; OR, odds ratio; PPV, positive predictive value. | |||||

TABLE 3

Likelihood of active asthma predicted by loose index9

| Active asthma | OR (95% CI) | Sensitivity, % (95% CI) | Specificity, % (95% CI) | PPV, % (95% CI) | NPV, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At 6 y | 5.5 (3.5-8.4) | 56.6 (53.3-59.9) | 80.8 (78.3-83.3) | 26.2 (23.4-29.0) | 93.9 (92.4-95.4) |

| At 8 y | 4.4 (2.8-6.8) | 50.5 (47.0-54.0) | 81.1 (78.3-83.9) | 29.4 (26.2-32.6) | 91.3 (89.3-93.3) |

| At 11 y | 2.6 (1.8-3.8) | 40.1 (36.8-43.4) | 79.6 (76.9-82.3) | 27.1 (24.1-30.1) | 87.5 (85.3-89.7) |

| At 13 y | 3.0 (1.9-4.6) | 39.3 (35.5-43.1) | 82.1 (79.1-85.1) | 31.7 (28.1-35.3) | 86.5 (83.9-89.1) |

| CI, confidence interval; NPV, negative predictive value; OR, odds ratio; PPV, positive predictive value. | |||||

Recommendations

A European and United States expert panel guide to the diagnosis and treatment of asthma in childhood, PRACTALL, states that “asthma should be suspected in any infant with recurrent wheezing and cough episodes. Frequently, diagnosis is possible only through long-term follow-up, consideration of the extensive differential diagnoses, and by observing the child’s response to bronchodilator and/or anti-inflammatory treatment.”10

The National Asthma Education and Prevention Program’s Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3) notes that diagnostic evaluation for asthma in children 0 to 4 years of age should include history, symptoms, physical examination, and assessment of quality of life.1

NO RELIABLE WAY EXISTS TO DIAGNOSE ASTHMA IN INFANTS AND TODDLERS. Recurrent wheezing, especially apart from colds, combined with physician-diagnosed eczema or atopic dermatitis, eosinophilia, and a parental history of asthma, increase the probability of a subsequent asthma diagnosis in the absence of other causes (strength of recommendation: B, 2 good-quality cohort studies).

Evidence summary

Wheezing in children is common and the differential diagnosis is broad. The many potential causes include upper respiratory infection, asthma, cystic fibrosis, foreign body aspiration, vascular ring, tracheomalacia, primary immunodeficiency, and congenital heart disease.1

Outpatient primary care cohort studies estimate that about half of children wheeze before they reach school age. Only one-third of children who wheeze during the first 3 years of life, however, continue to wheeze into later childhood and young adulthood.2-4

These findings have led some experts to suggest that not all wheezing in children is asthma and that asthma exists in variant forms.5-7 Variant wheezing patterns include transient early wheezing, which seems to be most prevalent in the first 3 years of life; wheezing without atopy, which occurs most often at 3 to 6 years of age; and wheezing with immunoglobulin E-associated atopy, which gradually increases in prevalence from birth and dominates in the over-6 age group. It is children in this last group whom we generally consider to have asthma.

Objective measures of lung function are challenging to perform in young children. Clinical signs and symptoms thus suggest the diagnosis of asthma.

Atopy, rhinitis, and eczema most often accompany persistent wheezing

Primary care cohort studies provide the best available evidence on which findings in infants and toddlers most likely predict persistent airway disease in childhood. A whole-population cohort study followed nearly all children born on the Isle of Wight from January 1989 through February 1990 to evaluate the natural history of childhood wheezing and to study associated risk factors.8 Children were seen at birth and at 1, 2, 4, and 10 years of age.

Findings most associated with current wheezing (within the last year) in 10-year-olds were atopy (odds ratio [OR]=4.38; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.07-6.25), rhinitis (OR=3.72; 95% CI, 2.21-6.27), and eczema (OR=3.04; 95% CI, 2.05-4.51).8

An index to predict asthma

Since 1980, the Tucson Children’s Respiratory Study has followed 1246 healthy newborns seen by pediatricians affiliated with a large HMO in Tucson, Arizona. Questionnaires about parental asthma history and prenatal smoking history were obtained at enrollment. Childhood wheezing and its frequency, as well as physician-diagnosed allergies or asthma, were assessed at ages 2 and 3. If the child had wheezed in the past year, then the child was considered to be an “early wheezer.” If the frequency was 3 or more on a 5-point scale, then the child was considered to be an “early frequent wheezer.” Questionnaires were re-administered at ages 6, 8, 11, and 13. Three episodes of wheezing within the past year or a physician diagnosis of asthma with symptoms in the past year was considered “active asthma.” Blood specimens for eosinophils were obtained at age 10.

Using these data, the researchers developed stringent and loose criteria (TABLE 1) and odds ratios (TABLES 2 and 3) for childhood factors most predictive of an asthma diagnosis at an older age. The findings of the study may help clinicians care for wheezing infants and toddlers.9

TABLE 1

A clinical index of asthma risk9*

| Major criteria | Minor criteria |

|---|---|

| Parental asthma (history of physician diagnosis of asthma in a parent) | Allergic rhinitis (physician diagnosis of allergic rhinitis as reported in questionnaires at ages 2 or 3 y) |

| Eczema (physician diagnosis of atopic dermatitis as reported in questionnaires at ages 2 or 3 y) | Wheezing apart from colds |

| Eosinophilia (≥4%) | |

| *Stringent index for predicting asthma: Child has early, frequent wheezing plus at least 1 of the 2 major criteria or 2 of the 3 minor criteria. Loose index for predicting asthma: Child has early wheezing plus at least 1 of the 2 major criteria or 2 of the 3 minor criteria. | |

TABLE 2

Likelihood of active asthma predicted by stringent index9

| Active asthma | OR (95% CI) | Sensitivity, % (95% CI) | Specificity, % (95% CI) | PPV, % (95% CI) | NPV, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At 6 y | 9.8 (5.6-17.2) | 27.5 (24.6-30.4) | 96.3 (95.1-97.5) | 47.5 (44.3-50.7) | 91.6 (89.8-93.4) |

| At 8 y | 5.8 (2.9-11.2) | 16.3 (13.7-18.9) | 96.7 (95.4-98.0) | 43.6 (40.1-47.1) | 88.2 (85.9-90.5) |

| At 11 y | 4.3 (2.4-7.8) | 15 (12.6-17.4) | 96.1 (94.8-97.4) | 42.0 (38.7-45.3) | 85.6 (83.3-87.9) |

| At 13 y | 5.7 (2.8-11.6) | 14.8 (12.1-17.5) | 97.0 (95.7-98.3) | 51.5 (47.7-55.3) | 84.2 (81.4-87.0) |

| CI, confidence interval; NPV, negative predictive value; OR, odds ratio; PPV, positive predictive value. | |||||

TABLE 3

Likelihood of active asthma predicted by loose index9

| Active asthma | OR (95% CI) | Sensitivity, % (95% CI) | Specificity, % (95% CI) | PPV, % (95% CI) | NPV, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At 6 y | 5.5 (3.5-8.4) | 56.6 (53.3-59.9) | 80.8 (78.3-83.3) | 26.2 (23.4-29.0) | 93.9 (92.4-95.4) |

| At 8 y | 4.4 (2.8-6.8) | 50.5 (47.0-54.0) | 81.1 (78.3-83.9) | 29.4 (26.2-32.6) | 91.3 (89.3-93.3) |

| At 11 y | 2.6 (1.8-3.8) | 40.1 (36.8-43.4) | 79.6 (76.9-82.3) | 27.1 (24.1-30.1) | 87.5 (85.3-89.7) |

| At 13 y | 3.0 (1.9-4.6) | 39.3 (35.5-43.1) | 82.1 (79.1-85.1) | 31.7 (28.1-35.3) | 86.5 (83.9-89.1) |

| CI, confidence interval; NPV, negative predictive value; OR, odds ratio; PPV, positive predictive value. | |||||

Recommendations

A European and United States expert panel guide to the diagnosis and treatment of asthma in childhood, PRACTALL, states that “asthma should be suspected in any infant with recurrent wheezing and cough episodes. Frequently, diagnosis is possible only through long-term follow-up, consideration of the extensive differential diagnoses, and by observing the child’s response to bronchodilator and/or anti-inflammatory treatment.”10

The National Asthma Education and Prevention Program’s Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3) notes that diagnostic evaluation for asthma in children 0 to 4 years of age should include history, symptoms, physical examination, and assessment of quality of life.1

1. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert panel report 3 (EPR-3): guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. NIH publication 07-4051. Bethesda, Md: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 2007. Available at: www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.htm. Accessed June 20, 2008.

2. Martinez FD, Wright AL, Taussig LM, et al. Asthma and wheezing in the first six years of life. The Group Health Medical Associates. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:133-138.

3. Sears MR, Greene JM, Willan AR, et al. A longitudinal, population-based cohort study of childhood asthma followed to adulthood. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1414-1422.

4. Jenkins MA, Hopper JL, Bowes G, et al. Factors in childhood as predictors of asthma in adult life. BMJ. 1994;309:90-93.

5. Rusconi F, Galassi C, Corbo GM, et al. Risk factors for early, persistent, and late-onset wheezing in young children. SIDRIA Collaborative Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;167:1617-1622.

6. Stein RT, Martinez FD. Asthma phenotypes in childhood: lessons from an epidemiologic approach. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2004;5:155-161.

7. Stein RT, Holberg CJ, Morgan WJ, et al. Peak flow variability, methacholine responsiveness and atopy as markers for detecting different wheezing phenotypes in childhood. Thorax. 1997;52:946-952.

8. Arshad SH, Kurukulaaratchy RJ, Fenn M, et al. Early life risk factors for current wheeze, asthma, and bronchial hyper-responsiveness at 10 years of age. Chest. 2005;127:502-508.

9. Castro-Rodriguez JA, Holberg CJ, Wright AL, et al. A clinical index to define risk of asthma in young children with recurrent wheezing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:1403-1406.

10. Bacharier LB, Boner A, Carlsen KH, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of asthma in childhood: a PRACTALL consensus report. Allergy. 2008;63:5-34.

1. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert panel report 3 (EPR-3): guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. NIH publication 07-4051. Bethesda, Md: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 2007. Available at: www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.htm. Accessed June 20, 2008.

2. Martinez FD, Wright AL, Taussig LM, et al. Asthma and wheezing in the first six years of life. The Group Health Medical Associates. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:133-138.

3. Sears MR, Greene JM, Willan AR, et al. A longitudinal, population-based cohort study of childhood asthma followed to adulthood. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1414-1422.

4. Jenkins MA, Hopper JL, Bowes G, et al. Factors in childhood as predictors of asthma in adult life. BMJ. 1994;309:90-93.

5. Rusconi F, Galassi C, Corbo GM, et al. Risk factors for early, persistent, and late-onset wheezing in young children. SIDRIA Collaborative Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;167:1617-1622.