User login

Rapid Development of Perifolliculitis Following Mesotherapy

To the Editor:

Mesotherapy, also known as intradermotherapy, is a cosmetic procedure in which multiple intradermal or subcutaneous injections of homeopathic substances, vitamins, chemicals, and plant extracts are administered.1 First conceived in Europe, mesotherapy is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration but is gaining popularity in the United States as an alternative cosmetic procedure for various purposes, including lipolysis, body contouring, stretch marks, acne scars, actinic damage, and skin rejuvenation.1,2 We report a case of a healthy woman who developed perifolliculitis, transaminitis, and neutropenia 2 weeks after mesotherapy administration to the face, neck, and chest. We also review other potential side effects of this procedure.

A 36-year-old woman with no notable medical history presented to the emergency department with a worsening pruritic and painful rash on the face, chest, and neck of 2 weeks’ duration. The rash had developed 3 days after the patient received mesotherapy with an unknown substance for cosmetic rejuvenation; the rash was localized only to the injection sites. She did not note any fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, arthralgia, or upper respiratory tract symptoms. She further denied starting any new medications, herbal products, or topical therapies apart from the procedure she had received 2 weeks prior.

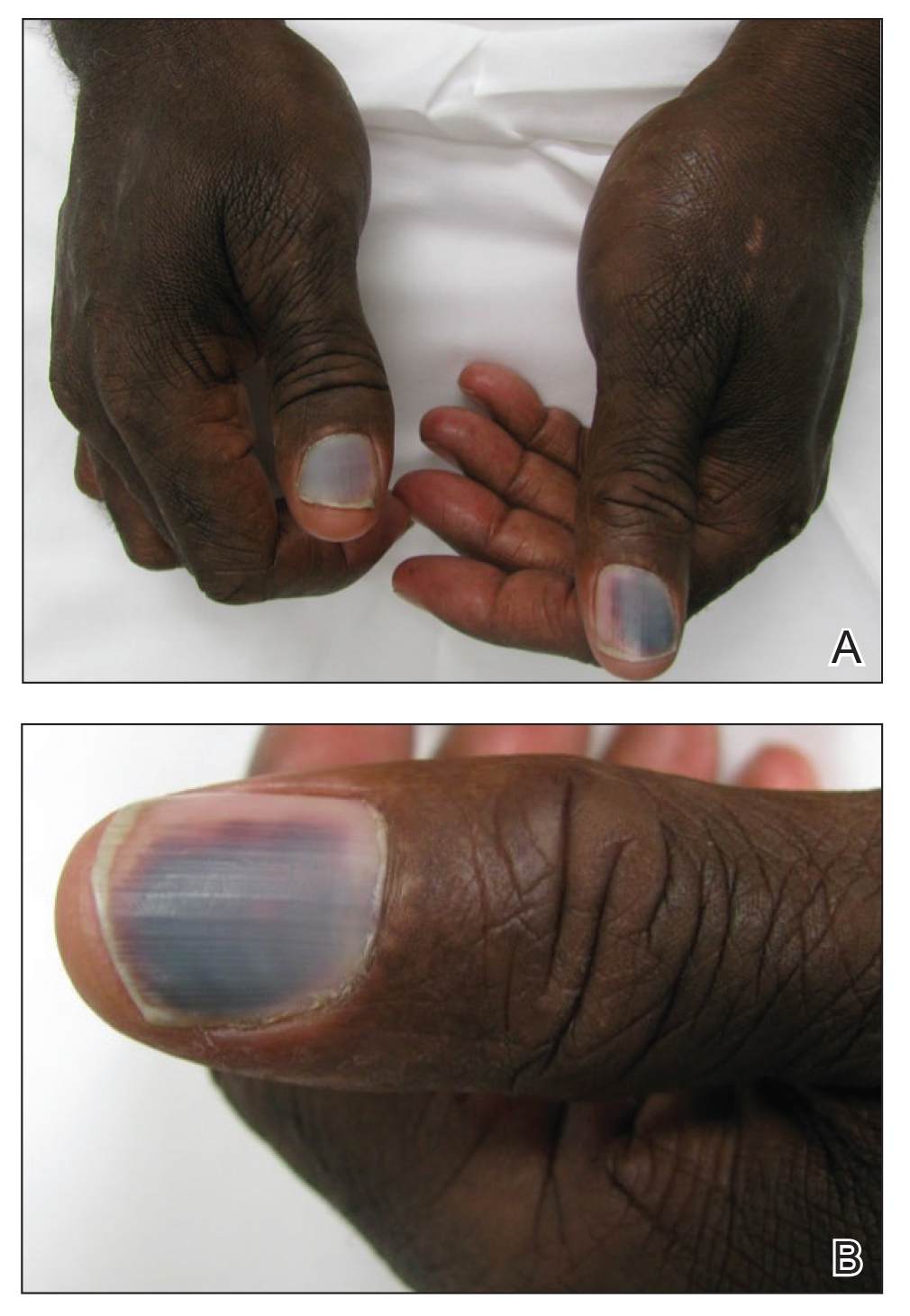

The patient was found to be in no acute distress and vital signs were stable. Laboratory testing was remarkable for elevations in alanine aminotransferase (62 U/L [reference range, 10–40 U/L]) and aspartate aminotransferase (72 U/L [reference range 10–30 U/L]). Moreover, she had an absolute neutrophil count of 0.5×103 cells/µL (reference range 1.8–8.0×103 cells/µL). An electrolyte panel, creatinine level, and urinalysis were normal. Physical examination revealed numerous 4- to 5-mm erythematous papules in a gridlike distribution across the face, neck, and chest (Figure 1). No pustules or nodules were present. There was no discharge, crust, excoriations, or secondary lesions. Additionally, there was no lymphadenopathy and no mucous membrane or ocular involvement.

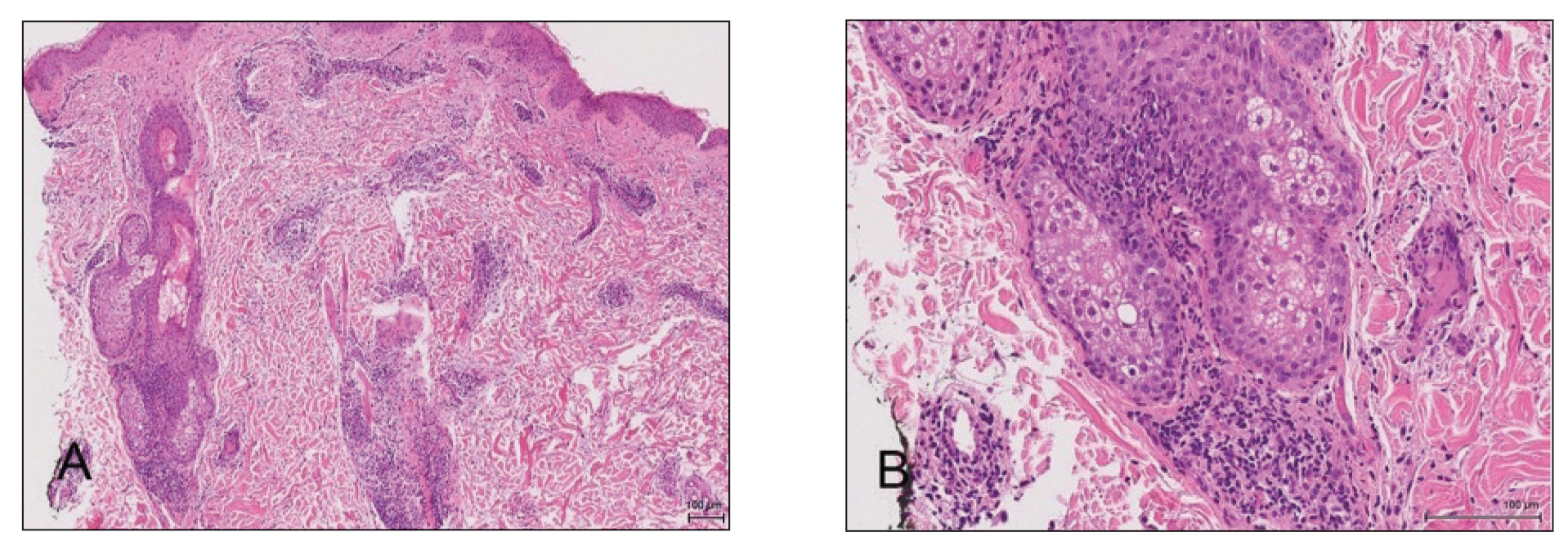

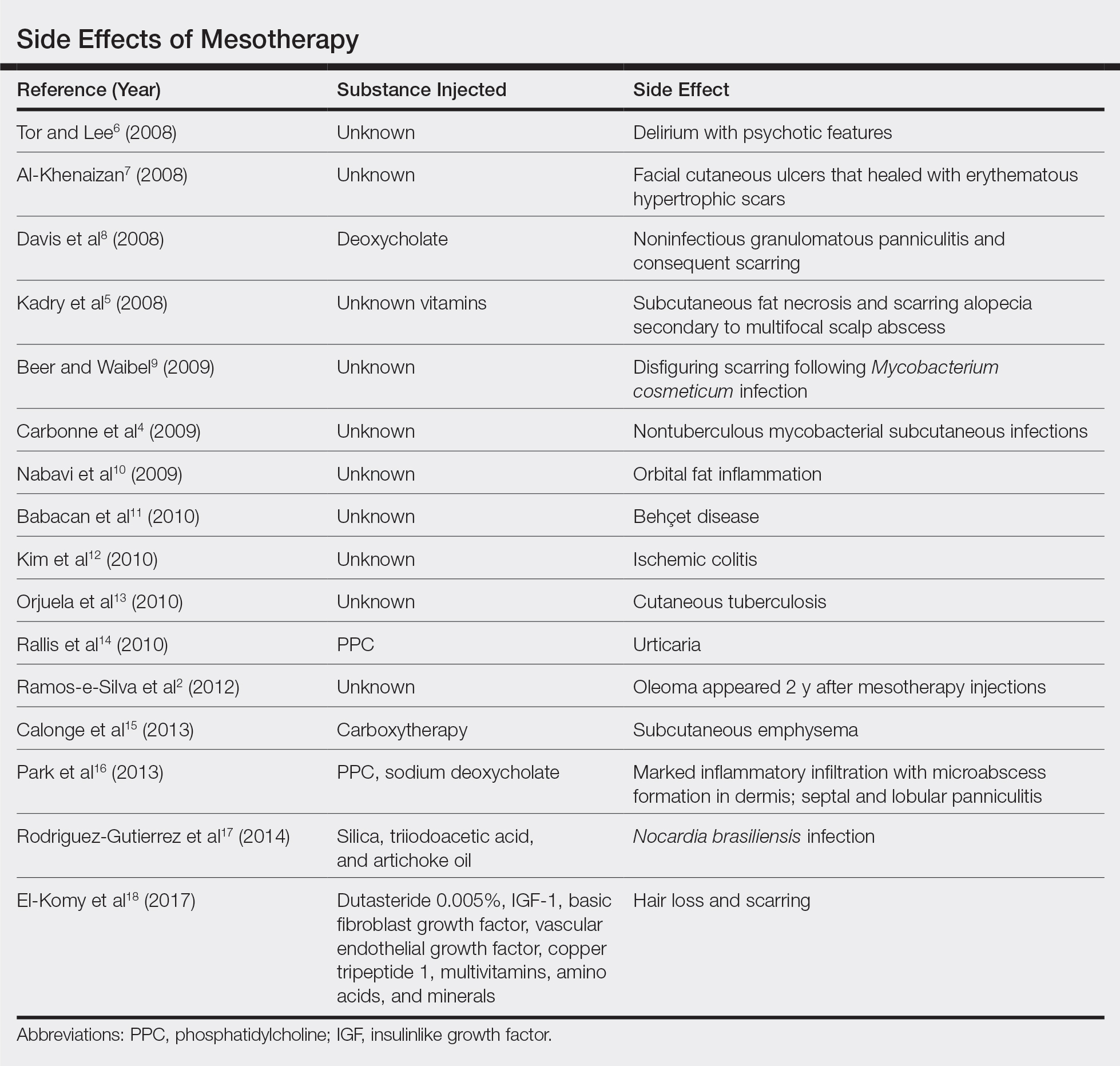

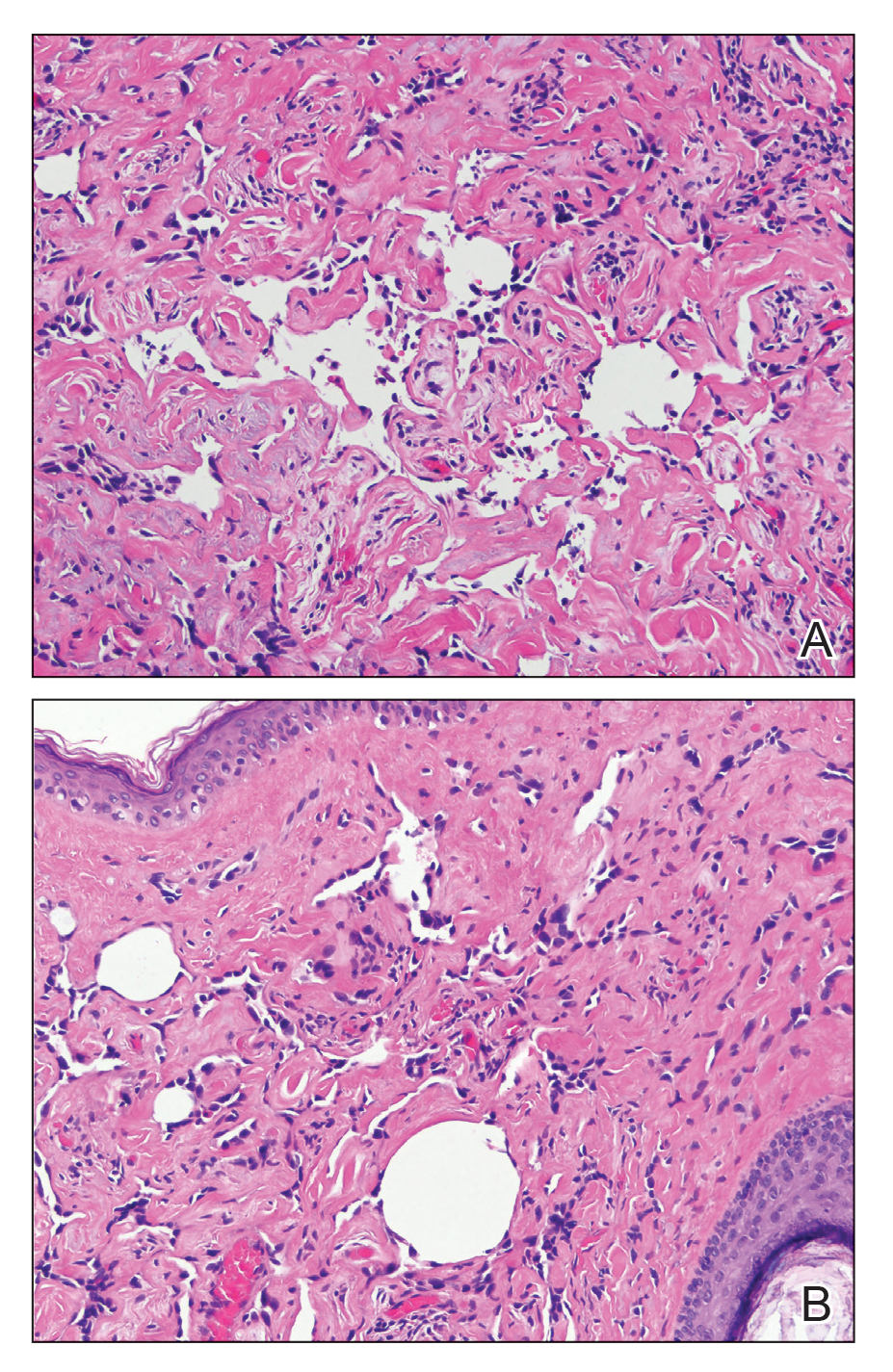

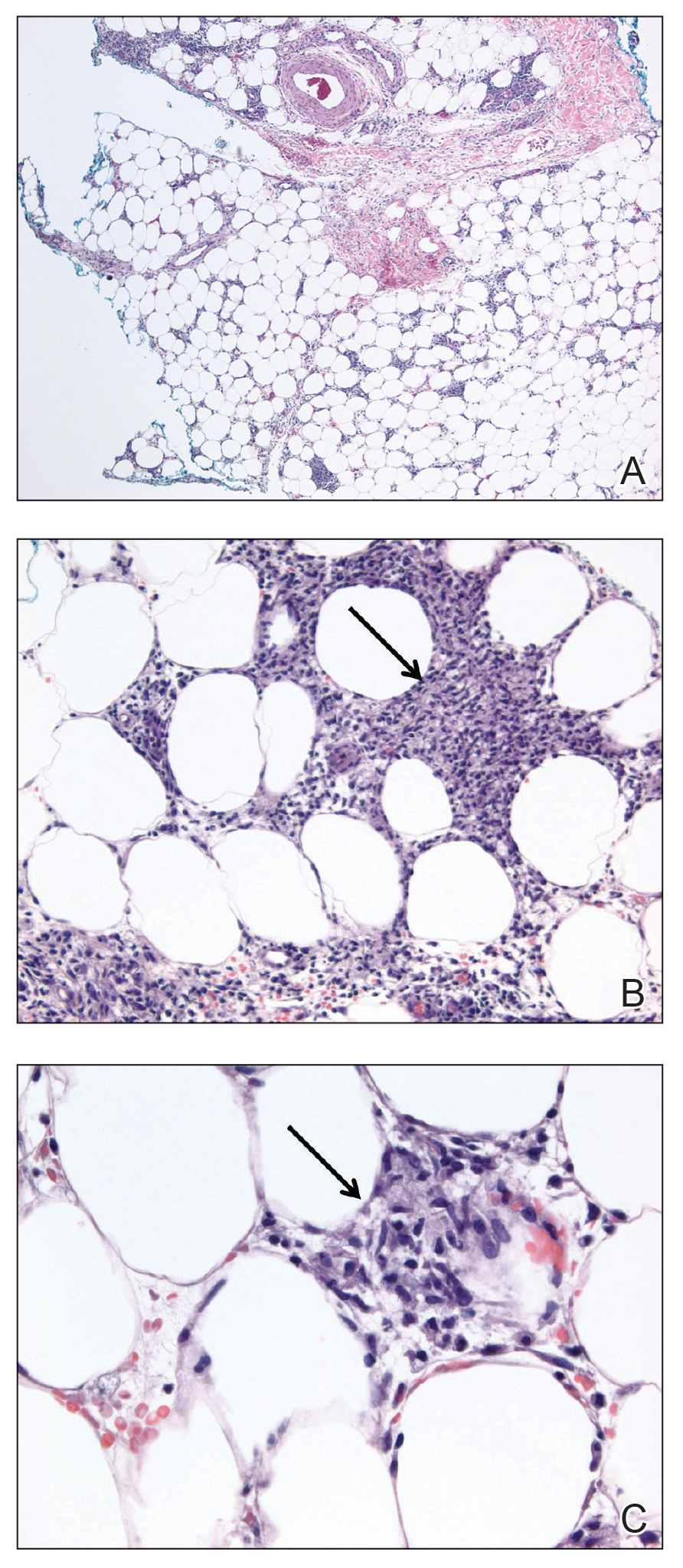

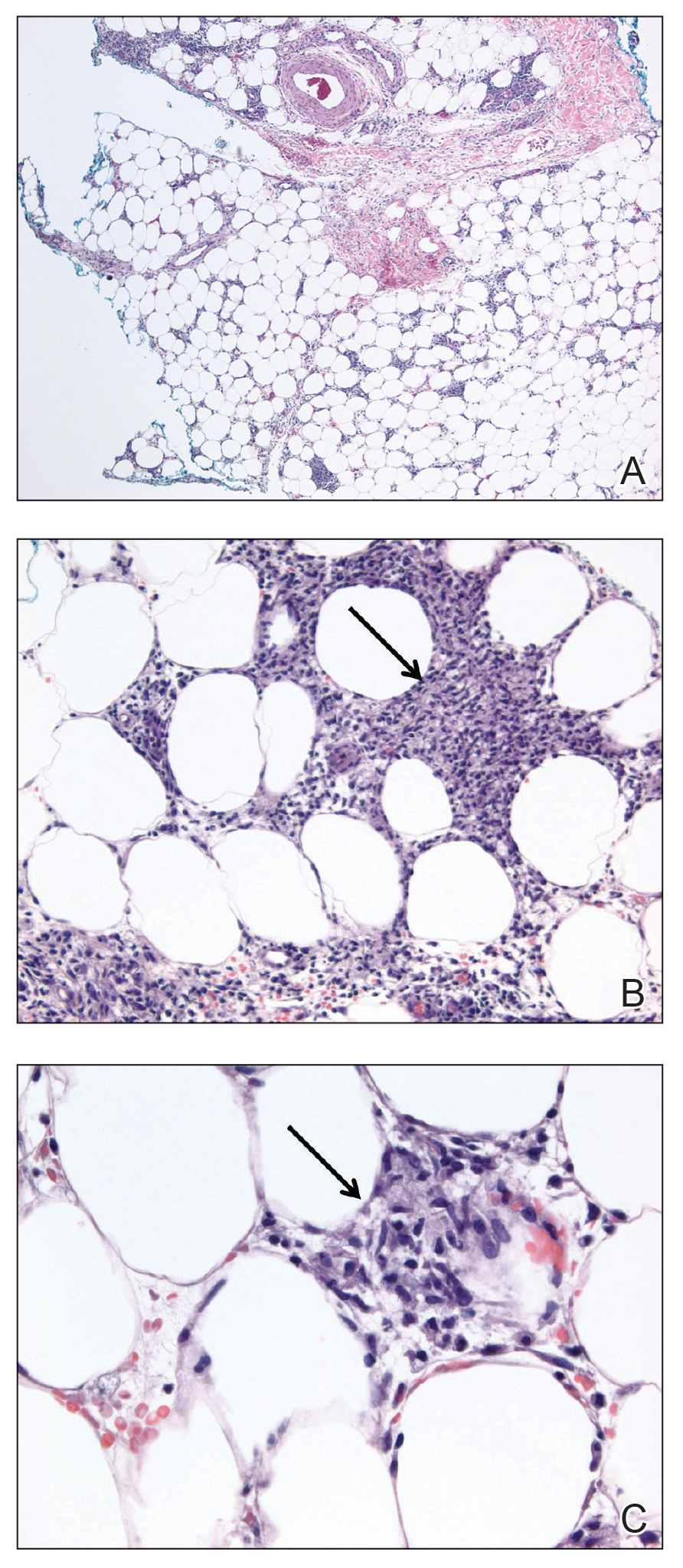

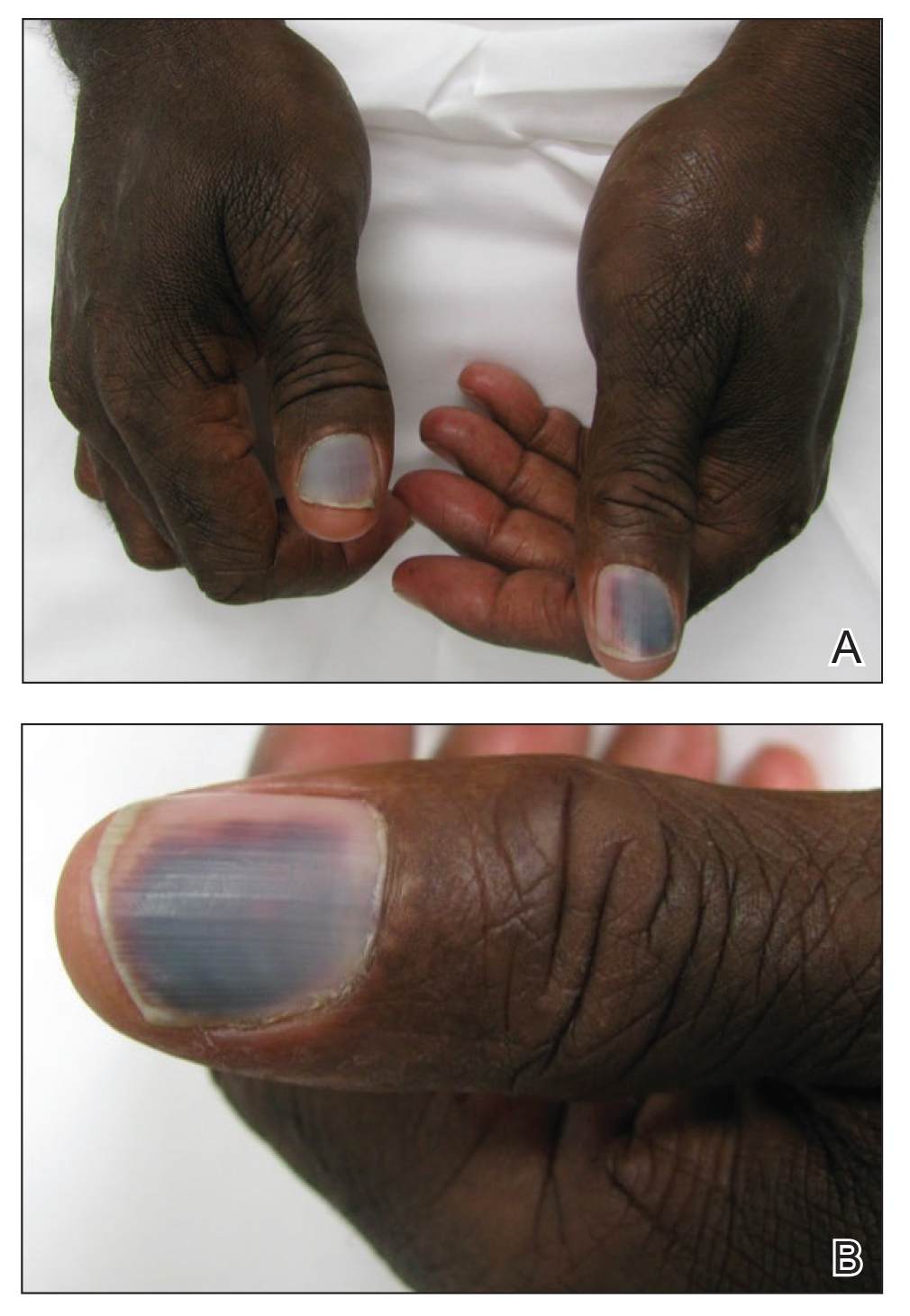

A 4-mm punch biopsy from a representative papule on the right lateral aspect of the neck demonstrated a perifollicular and perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with some focal granulomatous changes. No polarizable foreign body material was found (Figure 2). Bacterial, fungal, mycobacterial, and skin cultures were obtained, and results were all negative after several weeks.

A diagnosis of perifolliculitis from the mesotherapy procedure was on the top of the differential vs a fast-growing mycobacterial or granulomatous reaction. The patient was started on a prednisone taper at 40 mg once daily tapered down completely over 3 weeks in addition to triamcinolone cream 0.1% applied 2 to 4 times daily as needed. Although she did not return to our outpatient clinic for follow-up, she informed us that her rash had improved 1 month after starting the prednisone taper. She was later lost to follow-up. It is unclear if the transaminitis and neutropenia were related to the materials injected during the mesotherapy procedure or from long-standing health issues.

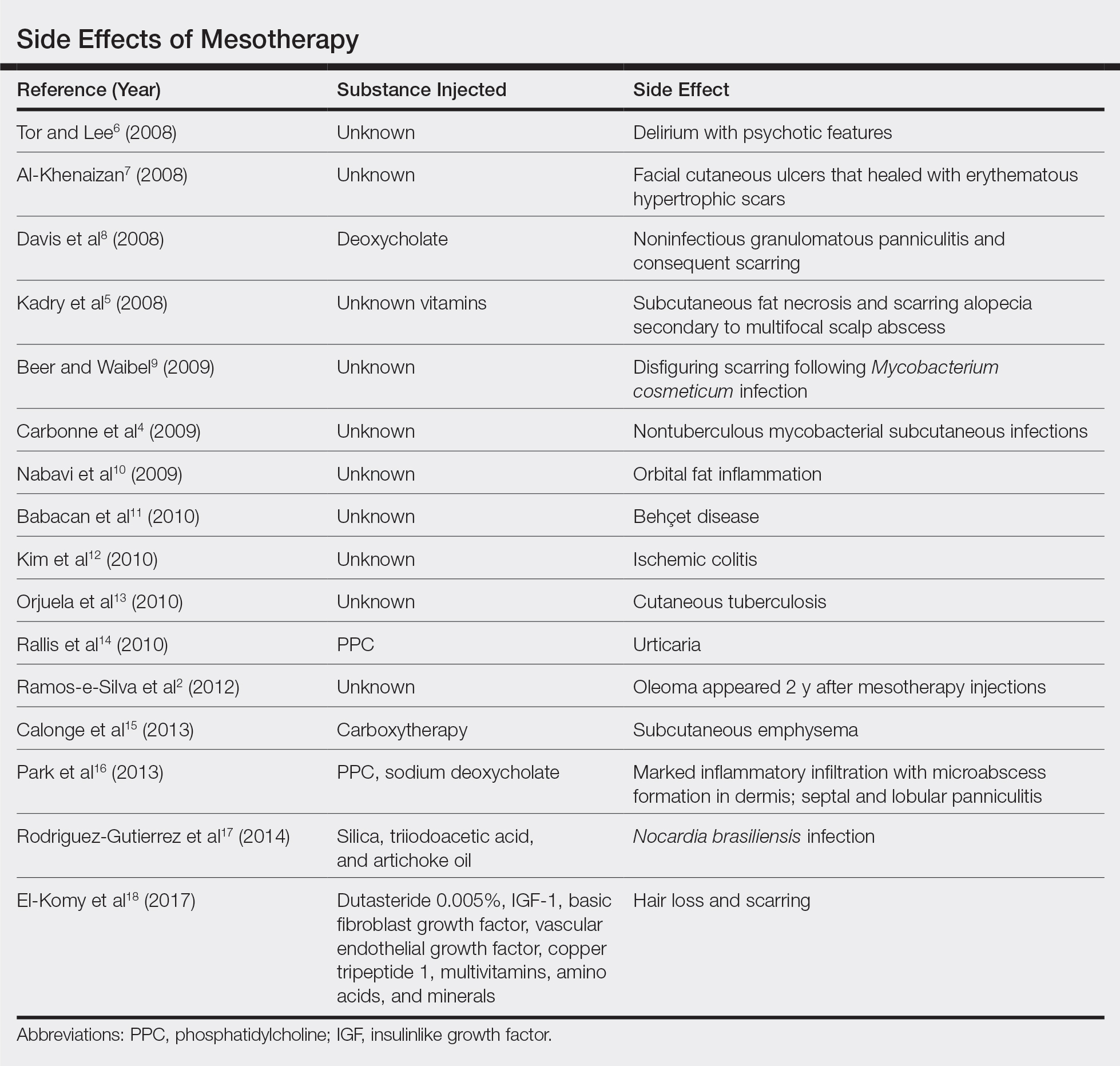

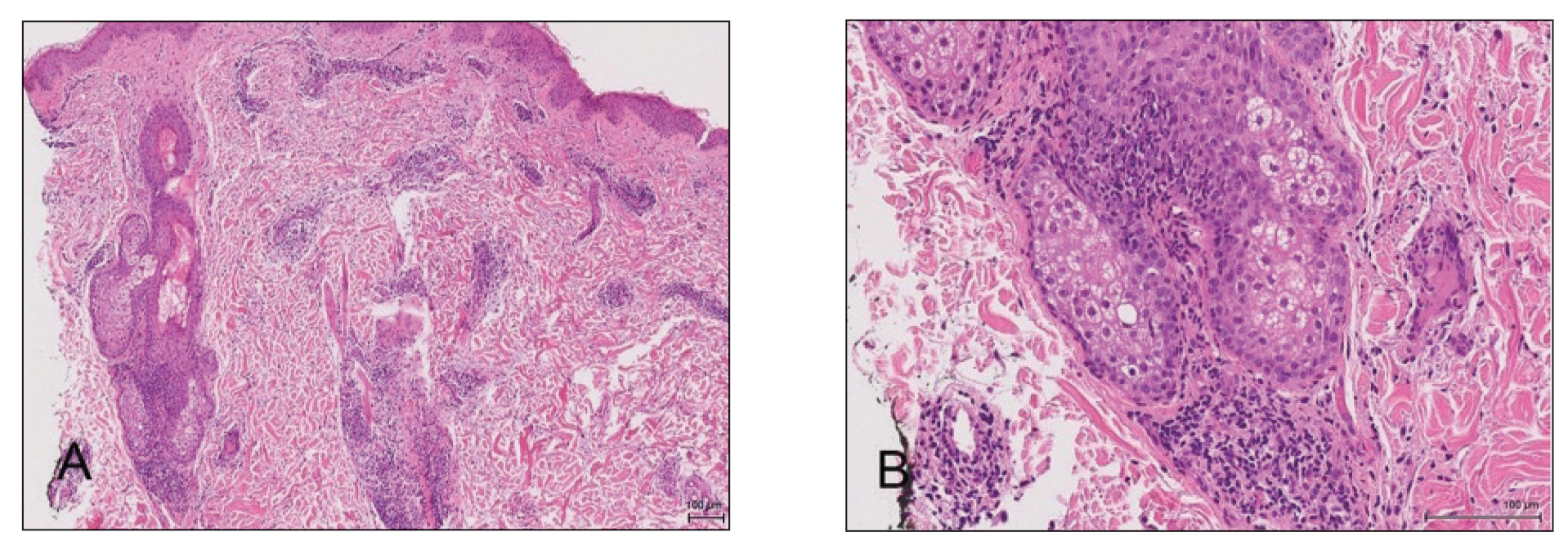

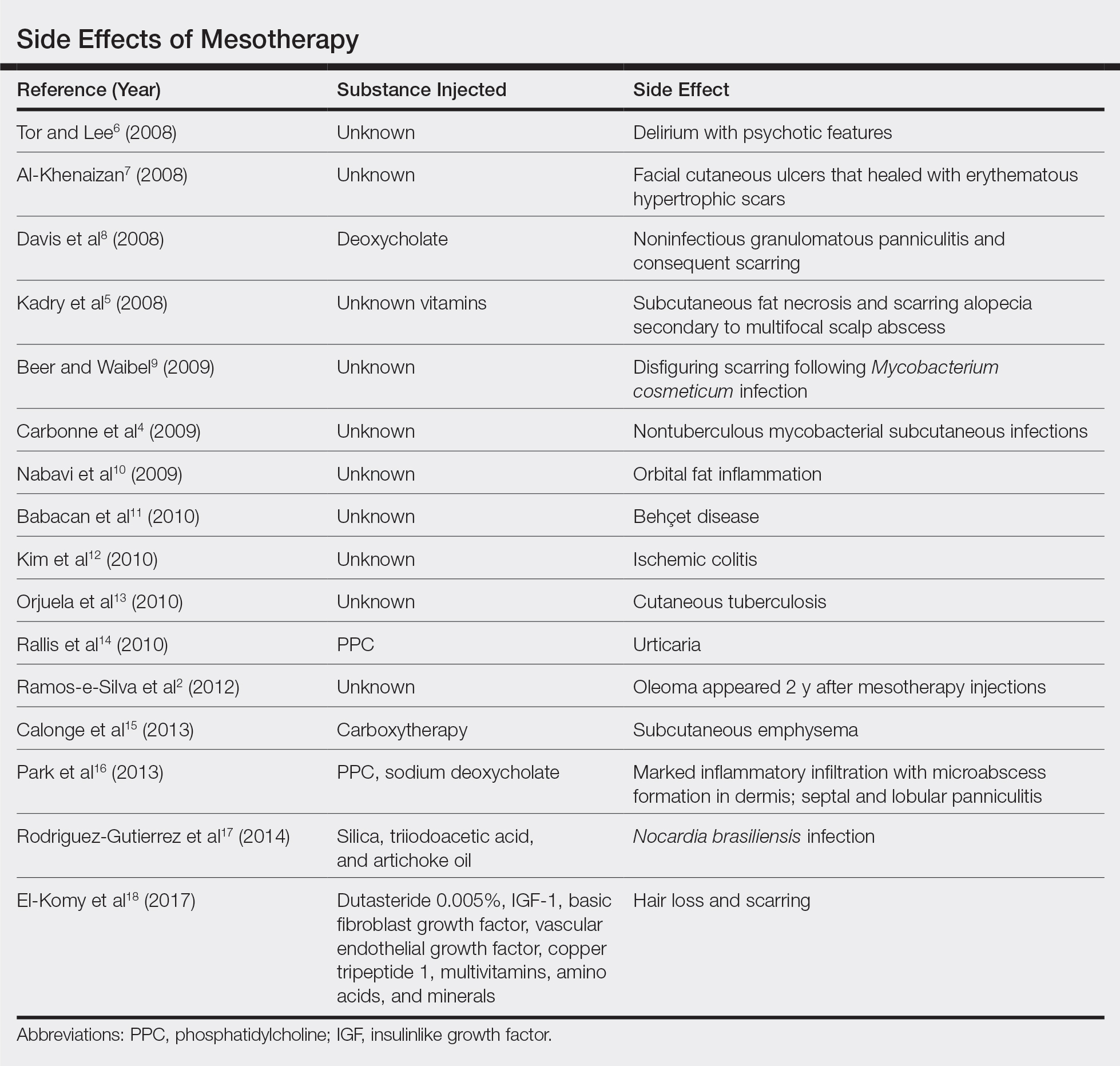

Mesotherapy promises aesthetic benefits through a minimally invasive procedure and therefore is rapidly gaining popularity in aesthetic spas and treatment centers. Due to the lack of regulation in treatment protocols and substances used, there have been numerous reported cases of adverse side effects following mesotherapy, such as pain, allergic reactions, urticaria, panniculitis, ulceration, hair loss, necrosis, paraffinoma, cutaneous tuberculosis, and rapidly growing nontuberculous mycobacterial infections.1-5 More serious side effects also have been reported, such as permanent scarring, deformities, delirium, and massive subcutaneous emphysema (Table).2,4-18

Given the potential complications of mesotherapy documented in the literature, we believe clinical investigations and trials must be performed to appropriately assess the safety and efficacy of this potentially hazardous procedure. Because there currently is insufficient research showing why certain patients are developing these adverse side effects, aesthetic spas and treatment centers should inform patients of all potential side effects associated with mesotherapy for the patient to make an informed decision about the procedure. Mesotherapy should be a point of focus for both the US Food and Drug Administration and researchers to determine its efficacy, safety, and standardization of the procedure.

- Bishara AS, Ibrahim AE, Dibo SA. Cosmetic mesotherapy: between scientific evidence, science fiction, and lucrative business. Aesth Plast Surg. 2008;32:842-849.

- Ramos-e-Silva M, Pereira AL, Ramos-e-Silva S, et al. Oleoma: a rare complication of mesotherapy for cellulite. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:162-167.

- Rotunda AM, Kolodney MS. Mesotherapy and phosphatidylcholine injections: historical clarification and review. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:465-480.

- Carbonne A, Brossier F, Arnaud I, et al. Outbreak of nontuberculous mycobacterial subcutaneous infections related to multiple mesotherapy injections. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1961-1964.

- Kadry R, Hamadah I, Al-Issa A, et al. Multifocal scalp abscess with subcutaneous fat necrosis and scarring alopecia as a complication of scalp mesotherapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:72-73.

- Tor PC, Lee TS. Delirium with psychotic features possibly associated with mesotherapy. Psychosomatics. 2008;49:273-274.

- Al-Khenaizan S. Facial cutaneous ulcers following mesotherapy. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:832-834.

- Davis MD, Wright TI, Shehan JM. A complication of mesotherapy: noninfectious granulomatous panniculitis. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:808-809.

- Beer K, Waibel J. Disfiguring scarring following mesotherapy-associated Mycobacterium cosmeticum infection. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:391-393.

- Nabavi CB, Minckler DS, Tao JP. Histologic features of mesotherapy-induced orbital fat inflammation. Opthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;25:69-70.

- Babacan T, Onat AM, Pehlivan Y, et al. A case of Behçet’s disease diagnosed by the panniculitis after mesotherapy. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:1657-1659.

- Kim JB, Moon W, Park SJ, et al. Ischemic colitis after mesotherapy combined with anti-obesity medications. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1537-1540.

- Orjuela D, Puerto G, Mejia G, et al. Cutaneous tuberculosis after mesotherapy: report of six cases. Biomedica. 2010;30:321-326.

- Rallis E, Kintzoglou S, Moussatou V, et al. Mesotherapy-induced urticaria. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1355-1356.

- Calonge WM, Lesbros-Pantoflickova D, Hodina M, et al. Massive subcutaneous emphysema after carbon dioxide mesotherapy. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2013;37:194-197.

- Park EJ, Kim HS, Kim M, et al. Histological changes after treatment for localized fat deposits with phosphatidylcholine and sodium deoxycholate. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;3:240-243.

- Rodriguez-Gutierrez G, Toussaint S, Hernandez-Castro R, et al. Norcardia brasiliensis infection: an emergent suppurative granuloma after mesotherapy. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:888-890.

- El-Komy M, Hassan A, Tawdy A, et al. Hair loss at injection sites of mesotherapy for alopecia [published online February 3, 2017]. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017;16:E28-E30.

To the Editor:

Mesotherapy, also known as intradermotherapy, is a cosmetic procedure in which multiple intradermal or subcutaneous injections of homeopathic substances, vitamins, chemicals, and plant extracts are administered.1 First conceived in Europe, mesotherapy is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration but is gaining popularity in the United States as an alternative cosmetic procedure for various purposes, including lipolysis, body contouring, stretch marks, acne scars, actinic damage, and skin rejuvenation.1,2 We report a case of a healthy woman who developed perifolliculitis, transaminitis, and neutropenia 2 weeks after mesotherapy administration to the face, neck, and chest. We also review other potential side effects of this procedure.

A 36-year-old woman with no notable medical history presented to the emergency department with a worsening pruritic and painful rash on the face, chest, and neck of 2 weeks’ duration. The rash had developed 3 days after the patient received mesotherapy with an unknown substance for cosmetic rejuvenation; the rash was localized only to the injection sites. She did not note any fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, arthralgia, or upper respiratory tract symptoms. She further denied starting any new medications, herbal products, or topical therapies apart from the procedure she had received 2 weeks prior.

The patient was found to be in no acute distress and vital signs were stable. Laboratory testing was remarkable for elevations in alanine aminotransferase (62 U/L [reference range, 10–40 U/L]) and aspartate aminotransferase (72 U/L [reference range 10–30 U/L]). Moreover, she had an absolute neutrophil count of 0.5×103 cells/µL (reference range 1.8–8.0×103 cells/µL). An electrolyte panel, creatinine level, and urinalysis were normal. Physical examination revealed numerous 4- to 5-mm erythematous papules in a gridlike distribution across the face, neck, and chest (Figure 1). No pustules or nodules were present. There was no discharge, crust, excoriations, or secondary lesions. Additionally, there was no lymphadenopathy and no mucous membrane or ocular involvement.

A 4-mm punch biopsy from a representative papule on the right lateral aspect of the neck demonstrated a perifollicular and perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with some focal granulomatous changes. No polarizable foreign body material was found (Figure 2). Bacterial, fungal, mycobacterial, and skin cultures were obtained, and results were all negative after several weeks.

A diagnosis of perifolliculitis from the mesotherapy procedure was on the top of the differential vs a fast-growing mycobacterial or granulomatous reaction. The patient was started on a prednisone taper at 40 mg once daily tapered down completely over 3 weeks in addition to triamcinolone cream 0.1% applied 2 to 4 times daily as needed. Although she did not return to our outpatient clinic for follow-up, she informed us that her rash had improved 1 month after starting the prednisone taper. She was later lost to follow-up. It is unclear if the transaminitis and neutropenia were related to the materials injected during the mesotherapy procedure or from long-standing health issues.

Mesotherapy promises aesthetic benefits through a minimally invasive procedure and therefore is rapidly gaining popularity in aesthetic spas and treatment centers. Due to the lack of regulation in treatment protocols and substances used, there have been numerous reported cases of adverse side effects following mesotherapy, such as pain, allergic reactions, urticaria, panniculitis, ulceration, hair loss, necrosis, paraffinoma, cutaneous tuberculosis, and rapidly growing nontuberculous mycobacterial infections.1-5 More serious side effects also have been reported, such as permanent scarring, deformities, delirium, and massive subcutaneous emphysema (Table).2,4-18

Given the potential complications of mesotherapy documented in the literature, we believe clinical investigations and trials must be performed to appropriately assess the safety and efficacy of this potentially hazardous procedure. Because there currently is insufficient research showing why certain patients are developing these adverse side effects, aesthetic spas and treatment centers should inform patients of all potential side effects associated with mesotherapy for the patient to make an informed decision about the procedure. Mesotherapy should be a point of focus for both the US Food and Drug Administration and researchers to determine its efficacy, safety, and standardization of the procedure.

To the Editor:

Mesotherapy, also known as intradermotherapy, is a cosmetic procedure in which multiple intradermal or subcutaneous injections of homeopathic substances, vitamins, chemicals, and plant extracts are administered.1 First conceived in Europe, mesotherapy is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration but is gaining popularity in the United States as an alternative cosmetic procedure for various purposes, including lipolysis, body contouring, stretch marks, acne scars, actinic damage, and skin rejuvenation.1,2 We report a case of a healthy woman who developed perifolliculitis, transaminitis, and neutropenia 2 weeks after mesotherapy administration to the face, neck, and chest. We also review other potential side effects of this procedure.

A 36-year-old woman with no notable medical history presented to the emergency department with a worsening pruritic and painful rash on the face, chest, and neck of 2 weeks’ duration. The rash had developed 3 days after the patient received mesotherapy with an unknown substance for cosmetic rejuvenation; the rash was localized only to the injection sites. She did not note any fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, arthralgia, or upper respiratory tract symptoms. She further denied starting any new medications, herbal products, or topical therapies apart from the procedure she had received 2 weeks prior.

The patient was found to be in no acute distress and vital signs were stable. Laboratory testing was remarkable for elevations in alanine aminotransferase (62 U/L [reference range, 10–40 U/L]) and aspartate aminotransferase (72 U/L [reference range 10–30 U/L]). Moreover, she had an absolute neutrophil count of 0.5×103 cells/µL (reference range 1.8–8.0×103 cells/µL). An electrolyte panel, creatinine level, and urinalysis were normal. Physical examination revealed numerous 4- to 5-mm erythematous papules in a gridlike distribution across the face, neck, and chest (Figure 1). No pustules or nodules were present. There was no discharge, crust, excoriations, or secondary lesions. Additionally, there was no lymphadenopathy and no mucous membrane or ocular involvement.

A 4-mm punch biopsy from a representative papule on the right lateral aspect of the neck demonstrated a perifollicular and perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with some focal granulomatous changes. No polarizable foreign body material was found (Figure 2). Bacterial, fungal, mycobacterial, and skin cultures were obtained, and results were all negative after several weeks.

A diagnosis of perifolliculitis from the mesotherapy procedure was on the top of the differential vs a fast-growing mycobacterial or granulomatous reaction. The patient was started on a prednisone taper at 40 mg once daily tapered down completely over 3 weeks in addition to triamcinolone cream 0.1% applied 2 to 4 times daily as needed. Although she did not return to our outpatient clinic for follow-up, she informed us that her rash had improved 1 month after starting the prednisone taper. She was later lost to follow-up. It is unclear if the transaminitis and neutropenia were related to the materials injected during the mesotherapy procedure or from long-standing health issues.

Mesotherapy promises aesthetic benefits through a minimally invasive procedure and therefore is rapidly gaining popularity in aesthetic spas and treatment centers. Due to the lack of regulation in treatment protocols and substances used, there have been numerous reported cases of adverse side effects following mesotherapy, such as pain, allergic reactions, urticaria, panniculitis, ulceration, hair loss, necrosis, paraffinoma, cutaneous tuberculosis, and rapidly growing nontuberculous mycobacterial infections.1-5 More serious side effects also have been reported, such as permanent scarring, deformities, delirium, and massive subcutaneous emphysema (Table).2,4-18

Given the potential complications of mesotherapy documented in the literature, we believe clinical investigations and trials must be performed to appropriately assess the safety and efficacy of this potentially hazardous procedure. Because there currently is insufficient research showing why certain patients are developing these adverse side effects, aesthetic spas and treatment centers should inform patients of all potential side effects associated with mesotherapy for the patient to make an informed decision about the procedure. Mesotherapy should be a point of focus for both the US Food and Drug Administration and researchers to determine its efficacy, safety, and standardization of the procedure.

- Bishara AS, Ibrahim AE, Dibo SA. Cosmetic mesotherapy: between scientific evidence, science fiction, and lucrative business. Aesth Plast Surg. 2008;32:842-849.

- Ramos-e-Silva M, Pereira AL, Ramos-e-Silva S, et al. Oleoma: a rare complication of mesotherapy for cellulite. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:162-167.

- Rotunda AM, Kolodney MS. Mesotherapy and phosphatidylcholine injections: historical clarification and review. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:465-480.

- Carbonne A, Brossier F, Arnaud I, et al. Outbreak of nontuberculous mycobacterial subcutaneous infections related to multiple mesotherapy injections. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1961-1964.

- Kadry R, Hamadah I, Al-Issa A, et al. Multifocal scalp abscess with subcutaneous fat necrosis and scarring alopecia as a complication of scalp mesotherapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:72-73.

- Tor PC, Lee TS. Delirium with psychotic features possibly associated with mesotherapy. Psychosomatics. 2008;49:273-274.

- Al-Khenaizan S. Facial cutaneous ulcers following mesotherapy. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:832-834.

- Davis MD, Wright TI, Shehan JM. A complication of mesotherapy: noninfectious granulomatous panniculitis. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:808-809.

- Beer K, Waibel J. Disfiguring scarring following mesotherapy-associated Mycobacterium cosmeticum infection. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:391-393.

- Nabavi CB, Minckler DS, Tao JP. Histologic features of mesotherapy-induced orbital fat inflammation. Opthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;25:69-70.

- Babacan T, Onat AM, Pehlivan Y, et al. A case of Behçet’s disease diagnosed by the panniculitis after mesotherapy. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:1657-1659.

- Kim JB, Moon W, Park SJ, et al. Ischemic colitis after mesotherapy combined with anti-obesity medications. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1537-1540.

- Orjuela D, Puerto G, Mejia G, et al. Cutaneous tuberculosis after mesotherapy: report of six cases. Biomedica. 2010;30:321-326.

- Rallis E, Kintzoglou S, Moussatou V, et al. Mesotherapy-induced urticaria. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1355-1356.

- Calonge WM, Lesbros-Pantoflickova D, Hodina M, et al. Massive subcutaneous emphysema after carbon dioxide mesotherapy. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2013;37:194-197.

- Park EJ, Kim HS, Kim M, et al. Histological changes after treatment for localized fat deposits with phosphatidylcholine and sodium deoxycholate. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;3:240-243.

- Rodriguez-Gutierrez G, Toussaint S, Hernandez-Castro R, et al. Norcardia brasiliensis infection: an emergent suppurative granuloma after mesotherapy. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:888-890.

- El-Komy M, Hassan A, Tawdy A, et al. Hair loss at injection sites of mesotherapy for alopecia [published online February 3, 2017]. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017;16:E28-E30.

- Bishara AS, Ibrahim AE, Dibo SA. Cosmetic mesotherapy: between scientific evidence, science fiction, and lucrative business. Aesth Plast Surg. 2008;32:842-849.

- Ramos-e-Silva M, Pereira AL, Ramos-e-Silva S, et al. Oleoma: a rare complication of mesotherapy for cellulite. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:162-167.

- Rotunda AM, Kolodney MS. Mesotherapy and phosphatidylcholine injections: historical clarification and review. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:465-480.

- Carbonne A, Brossier F, Arnaud I, et al. Outbreak of nontuberculous mycobacterial subcutaneous infections related to multiple mesotherapy injections. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1961-1964.

- Kadry R, Hamadah I, Al-Issa A, et al. Multifocal scalp abscess with subcutaneous fat necrosis and scarring alopecia as a complication of scalp mesotherapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:72-73.

- Tor PC, Lee TS. Delirium with psychotic features possibly associated with mesotherapy. Psychosomatics. 2008;49:273-274.

- Al-Khenaizan S. Facial cutaneous ulcers following mesotherapy. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:832-834.

- Davis MD, Wright TI, Shehan JM. A complication of mesotherapy: noninfectious granulomatous panniculitis. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:808-809.

- Beer K, Waibel J. Disfiguring scarring following mesotherapy-associated Mycobacterium cosmeticum infection. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:391-393.

- Nabavi CB, Minckler DS, Tao JP. Histologic features of mesotherapy-induced orbital fat inflammation. Opthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;25:69-70.

- Babacan T, Onat AM, Pehlivan Y, et al. A case of Behçet’s disease diagnosed by the panniculitis after mesotherapy. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:1657-1659.

- Kim JB, Moon W, Park SJ, et al. Ischemic colitis after mesotherapy combined with anti-obesity medications. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1537-1540.

- Orjuela D, Puerto G, Mejia G, et al. Cutaneous tuberculosis after mesotherapy: report of six cases. Biomedica. 2010;30:321-326.

- Rallis E, Kintzoglou S, Moussatou V, et al. Mesotherapy-induced urticaria. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1355-1356.

- Calonge WM, Lesbros-Pantoflickova D, Hodina M, et al. Massive subcutaneous emphysema after carbon dioxide mesotherapy. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2013;37:194-197.

- Park EJ, Kim HS, Kim M, et al. Histological changes after treatment for localized fat deposits with phosphatidylcholine and sodium deoxycholate. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;3:240-243.

- Rodriguez-Gutierrez G, Toussaint S, Hernandez-Castro R, et al. Norcardia brasiliensis infection: an emergent suppurative granuloma after mesotherapy. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:888-890.

- El-Komy M, Hassan A, Tawdy A, et al. Hair loss at injection sites of mesotherapy for alopecia [published online February 3, 2017]. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017;16:E28-E30.

Practice Points

- Mesotherapy—the delivery of vitamins, chemicals, and plant extracts directly into the dermis via injections—is a common procedure performed in both medical and nonmedical settings for cosmetic rejuvenation.

- Complications can occur from mesotherapy treatment.

- Patients should be advised to seek medical care with US Food and Drug Administration–approved cosmetic techniques and substances only

Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection in a Hepatitis B Virus–Positive Psoriasis Patient Treated With Ustekinumab

To the Editor:

The incidence of psoriasis in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected patients is similar to the general population, but it usually becomes more severe as immunosuppression increases. Additionally, it tends to be more resistant to conventional therapies, and the incidence and severity of psoriatic arthropathy is increased. Psoriasis often worsens at the time of HIV primary infection.1 We describe a case of a patient with hepatitis B virus (HBV) whose severe plaque psoriasis was controlled on ustekinumab; he was later diagnosed with HIV infection.

A 42-year-old man with HBV treated with entecavir (HBV DNA viral load, <20 copies/mL [inactive carrier, <2000 copies/mL]) presented to our dermatology unit with severe plaque psoriasis (psoriasis area and severity index 23) that caused notable psychologic difficulties such as anxiety and depression. Treatment was attempted with cyclosporine; acitretin; psoralen plus UVA; infliximab; adalimumab; and eventually ustekinumab (45 mg every 3 months), which controlled the condition well (psoriasis area and severity index 0) in an almost completely sustained manner.

Serologic tests requested at one of his analytical control appointments 2 years after initiating treatment with ustekinumab revealed he was HIV positive. The patient reported unprotected sexual intercourse 4 months prior. He was referred to the infectious disease unit and was classified in subtype A1 of HIV infection (CD4 count, 583 cells/µL [reference range, 500-1200 cells/µL]; viral load, 159,268 copies/mL [rapid progression to AIDS, >100,000 copies/mL]). Treatment was initiated with raltegravir, ritonavir, darunavir, and abacavir; tolerance was suitable. Because of the patient’s history of severe psoriasis, treatment with ustekinumab was maintained. Normally, treatment with this drug would be contraindicated in patients with HIV, as it can lead to viral reactivation. Four years after his HIV diagnosis, neither the patient’s cutaneous nor HIV-associated condition had worsened.

For patients with HIV and mild or moderate psoriasis, topical therapies (eg, corticosteroids, vitamin D analogues, tazarotene) are recommended, similar to patients who are HIV negative. Human immunodeficiency virus–positive patients with severe psoriasis who do not respond to topical treatment should receive phototherapy (UVB or psoralen plus UVA) or acitretin along with their antiretroviral drugs.2 In refractory cases, immunosuppressants, including cyclosporine, methotrexate, or tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, might be used, though experience with them is limited.3,4 Maintaining antiretroviral therapy and prophylaxis against opportunist disease is important in patients who receive such immunosuppressants, as is close monitoring of the viral load.

Ustekinumab is an IL-12/IL-23 monoclonal antibody indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, active psoriatic arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease. It is contraindicated in patients with clinically important active infections, such as HBV and hepatitis C virus infections.5 However, it was shown to be safe in a group of 18 patients with HBV who had received antiviral prophylaxis6; a degree of reactivation was observed in similar patients who received no such prophylaxis and in others with hepatitis C virus infection.7 The simultaneous use of methotrexate with ustekinumab in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis does not appear to affect the safety of the latter drug.8 Paparizos et al9 described a patient with HIV controlled with antiretroviral drugs who was treated with ustekinumab for psoriasis; no adverse effects were observed.

We report the case of a patient with HBV and psoriasis who was treated with ustekinumab and later became infected with HIV. His ustekinumab treatment was maintained without subsequent cutaneous or systemic complications.

- Menon K, Van Voorhees V, Bebo B, et al. Psoriasis in patients with HIV infection: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:291-299.

- Chiricozzi A, Saraceno R, Cannizzaro MV. Complete resolution of erythrodermic psoriasis in an HIV and HCV patient unresponsive to antipsoriatic treatments after highly active antiretroviral therapy. Dermatology. 2012;225:333-337.

- Barco D, Puig L, Alomar A. Treatment of moderate-severe psoriasis with etanercept in patients with chronic human immunodeficiency virus infection. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101(suppl 1):77-81.

- Lindsey SF, Weiss J, Lee ES, et al. Treatment of severe psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis with adalimumab in an HIV positive patient. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:869-871.

- Rustin MH. Long-term safety of biologics in the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: review of the current data. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167(suppl 3):3-11.

- Navarro R, Vilarrasa E, Herranz P, et al. Safety and effectiveness of ustekinumab and antitumour necrosis factor therapy in patients with psoriasis and chronic viral hepatitis B or C: a retrospective, multicentre study in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:609-616.

- Chiu HY, Chen CH, Wu MS, et al. The safety profile of ustekinumab in the treatment of patients with psoriasis and concurrent hepatitis B or C. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1295-1303.

- Weitz JE, Ritchlin CT. Ustekinumab: targeting the IL-17 pathway to improve outcomes in psoriatic arthritis. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2014;14:515-526.

- Paparizos V, Rallis E, Kirsten L, et al. Ustekinumab for the treatment of HIV psoriasis. J Dermatol Treat. 2012;23:398-399.

To the Editor:

The incidence of psoriasis in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected patients is similar to the general population, but it usually becomes more severe as immunosuppression increases. Additionally, it tends to be more resistant to conventional therapies, and the incidence and severity of psoriatic arthropathy is increased. Psoriasis often worsens at the time of HIV primary infection.1 We describe a case of a patient with hepatitis B virus (HBV) whose severe plaque psoriasis was controlled on ustekinumab; he was later diagnosed with HIV infection.

A 42-year-old man with HBV treated with entecavir (HBV DNA viral load, <20 copies/mL [inactive carrier, <2000 copies/mL]) presented to our dermatology unit with severe plaque psoriasis (psoriasis area and severity index 23) that caused notable psychologic difficulties such as anxiety and depression. Treatment was attempted with cyclosporine; acitretin; psoralen plus UVA; infliximab; adalimumab; and eventually ustekinumab (45 mg every 3 months), which controlled the condition well (psoriasis area and severity index 0) in an almost completely sustained manner.

Serologic tests requested at one of his analytical control appointments 2 years after initiating treatment with ustekinumab revealed he was HIV positive. The patient reported unprotected sexual intercourse 4 months prior. He was referred to the infectious disease unit and was classified in subtype A1 of HIV infection (CD4 count, 583 cells/µL [reference range, 500-1200 cells/µL]; viral load, 159,268 copies/mL [rapid progression to AIDS, >100,000 copies/mL]). Treatment was initiated with raltegravir, ritonavir, darunavir, and abacavir; tolerance was suitable. Because of the patient’s history of severe psoriasis, treatment with ustekinumab was maintained. Normally, treatment with this drug would be contraindicated in patients with HIV, as it can lead to viral reactivation. Four years after his HIV diagnosis, neither the patient’s cutaneous nor HIV-associated condition had worsened.

For patients with HIV and mild or moderate psoriasis, topical therapies (eg, corticosteroids, vitamin D analogues, tazarotene) are recommended, similar to patients who are HIV negative. Human immunodeficiency virus–positive patients with severe psoriasis who do not respond to topical treatment should receive phototherapy (UVB or psoralen plus UVA) or acitretin along with their antiretroviral drugs.2 In refractory cases, immunosuppressants, including cyclosporine, methotrexate, or tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, might be used, though experience with them is limited.3,4 Maintaining antiretroviral therapy and prophylaxis against opportunist disease is important in patients who receive such immunosuppressants, as is close monitoring of the viral load.

Ustekinumab is an IL-12/IL-23 monoclonal antibody indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, active psoriatic arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease. It is contraindicated in patients with clinically important active infections, such as HBV and hepatitis C virus infections.5 However, it was shown to be safe in a group of 18 patients with HBV who had received antiviral prophylaxis6; a degree of reactivation was observed in similar patients who received no such prophylaxis and in others with hepatitis C virus infection.7 The simultaneous use of methotrexate with ustekinumab in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis does not appear to affect the safety of the latter drug.8 Paparizos et al9 described a patient with HIV controlled with antiretroviral drugs who was treated with ustekinumab for psoriasis; no adverse effects were observed.

We report the case of a patient with HBV and psoriasis who was treated with ustekinumab and later became infected with HIV. His ustekinumab treatment was maintained without subsequent cutaneous or systemic complications.

To the Editor:

The incidence of psoriasis in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected patients is similar to the general population, but it usually becomes more severe as immunosuppression increases. Additionally, it tends to be more resistant to conventional therapies, and the incidence and severity of psoriatic arthropathy is increased. Psoriasis often worsens at the time of HIV primary infection.1 We describe a case of a patient with hepatitis B virus (HBV) whose severe plaque psoriasis was controlled on ustekinumab; he was later diagnosed with HIV infection.

A 42-year-old man with HBV treated with entecavir (HBV DNA viral load, <20 copies/mL [inactive carrier, <2000 copies/mL]) presented to our dermatology unit with severe plaque psoriasis (psoriasis area and severity index 23) that caused notable psychologic difficulties such as anxiety and depression. Treatment was attempted with cyclosporine; acitretin; psoralen plus UVA; infliximab; adalimumab; and eventually ustekinumab (45 mg every 3 months), which controlled the condition well (psoriasis area and severity index 0) in an almost completely sustained manner.

Serologic tests requested at one of his analytical control appointments 2 years after initiating treatment with ustekinumab revealed he was HIV positive. The patient reported unprotected sexual intercourse 4 months prior. He was referred to the infectious disease unit and was classified in subtype A1 of HIV infection (CD4 count, 583 cells/µL [reference range, 500-1200 cells/µL]; viral load, 159,268 copies/mL [rapid progression to AIDS, >100,000 copies/mL]). Treatment was initiated with raltegravir, ritonavir, darunavir, and abacavir; tolerance was suitable. Because of the patient’s history of severe psoriasis, treatment with ustekinumab was maintained. Normally, treatment with this drug would be contraindicated in patients with HIV, as it can lead to viral reactivation. Four years after his HIV diagnosis, neither the patient’s cutaneous nor HIV-associated condition had worsened.

For patients with HIV and mild or moderate psoriasis, topical therapies (eg, corticosteroids, vitamin D analogues, tazarotene) are recommended, similar to patients who are HIV negative. Human immunodeficiency virus–positive patients with severe psoriasis who do not respond to topical treatment should receive phototherapy (UVB or psoralen plus UVA) or acitretin along with their antiretroviral drugs.2 In refractory cases, immunosuppressants, including cyclosporine, methotrexate, or tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, might be used, though experience with them is limited.3,4 Maintaining antiretroviral therapy and prophylaxis against opportunist disease is important in patients who receive such immunosuppressants, as is close monitoring of the viral load.

Ustekinumab is an IL-12/IL-23 monoclonal antibody indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, active psoriatic arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease. It is contraindicated in patients with clinically important active infections, such as HBV and hepatitis C virus infections.5 However, it was shown to be safe in a group of 18 patients with HBV who had received antiviral prophylaxis6; a degree of reactivation was observed in similar patients who received no such prophylaxis and in others with hepatitis C virus infection.7 The simultaneous use of methotrexate with ustekinumab in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis does not appear to affect the safety of the latter drug.8 Paparizos et al9 described a patient with HIV controlled with antiretroviral drugs who was treated with ustekinumab for psoriasis; no adverse effects were observed.

We report the case of a patient with HBV and psoriasis who was treated with ustekinumab and later became infected with HIV. His ustekinumab treatment was maintained without subsequent cutaneous or systemic complications.

- Menon K, Van Voorhees V, Bebo B, et al. Psoriasis in patients with HIV infection: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:291-299.

- Chiricozzi A, Saraceno R, Cannizzaro MV. Complete resolution of erythrodermic psoriasis in an HIV and HCV patient unresponsive to antipsoriatic treatments after highly active antiretroviral therapy. Dermatology. 2012;225:333-337.

- Barco D, Puig L, Alomar A. Treatment of moderate-severe psoriasis with etanercept in patients with chronic human immunodeficiency virus infection. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101(suppl 1):77-81.

- Lindsey SF, Weiss J, Lee ES, et al. Treatment of severe psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis with adalimumab in an HIV positive patient. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:869-871.

- Rustin MH. Long-term safety of biologics in the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: review of the current data. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167(suppl 3):3-11.

- Navarro R, Vilarrasa E, Herranz P, et al. Safety and effectiveness of ustekinumab and antitumour necrosis factor therapy in patients with psoriasis and chronic viral hepatitis B or C: a retrospective, multicentre study in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:609-616.

- Chiu HY, Chen CH, Wu MS, et al. The safety profile of ustekinumab in the treatment of patients with psoriasis and concurrent hepatitis B or C. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1295-1303.

- Weitz JE, Ritchlin CT. Ustekinumab: targeting the IL-17 pathway to improve outcomes in psoriatic arthritis. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2014;14:515-526.

- Paparizos V, Rallis E, Kirsten L, et al. Ustekinumab for the treatment of HIV psoriasis. J Dermatol Treat. 2012;23:398-399.

- Menon K, Van Voorhees V, Bebo B, et al. Psoriasis in patients with HIV infection: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:291-299.

- Chiricozzi A, Saraceno R, Cannizzaro MV. Complete resolution of erythrodermic psoriasis in an HIV and HCV patient unresponsive to antipsoriatic treatments after highly active antiretroviral therapy. Dermatology. 2012;225:333-337.

- Barco D, Puig L, Alomar A. Treatment of moderate-severe psoriasis with etanercept in patients with chronic human immunodeficiency virus infection. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101(suppl 1):77-81.

- Lindsey SF, Weiss J, Lee ES, et al. Treatment of severe psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis with adalimumab in an HIV positive patient. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:869-871.

- Rustin MH. Long-term safety of biologics in the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: review of the current data. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167(suppl 3):3-11.

- Navarro R, Vilarrasa E, Herranz P, et al. Safety and effectiveness of ustekinumab and antitumour necrosis factor therapy in patients with psoriasis and chronic viral hepatitis B or C: a retrospective, multicentre study in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:609-616.

- Chiu HY, Chen CH, Wu MS, et al. The safety profile of ustekinumab in the treatment of patients with psoriasis and concurrent hepatitis B or C. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1295-1303.

- Weitz JE, Ritchlin CT. Ustekinumab: targeting the IL-17 pathway to improve outcomes in psoriatic arthritis. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2014;14:515-526.

- Paparizos V, Rallis E, Kirsten L, et al. Ustekinumab for the treatment of HIV psoriasis. J Dermatol Treat. 2012;23:398-399.

Practice Points

- Psoriasis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) tends to be more resistant to conventional therapies.

- Experience is limited in the use of immunosuppressants and biologics to treat psoriasis in HIV patients.

- Maintaining antiretroviral therapy and prophylaxis against opportunist disease is important in HIV patients who receive biologics, as is close monitoring of the viral load.

Angiosarcoma Imitating a Morpheaform Basal Cell Carcinoma

To the Editor:

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common of the nonmelanoma skin cancers and is a highly curable skin growth.1,2 Conversely, angiosarcomas are aggressive vascular tumors of endothelial origin that classically appear as reddish purple patches or plaques that exhibit rapid growth and invasion.3 Sporadic cutaneous angiosarcomas are the most common type of this soft tissue tumor, occurring most often in the head and neck regions in men older than 70 years.4,5 Other types of angiosarcomas include those associated with radiation therapy and chronic lymphedema. Postradiation angiosarcomas have been most frequently reported after treatment of breast cancer and appear as infiltrative plaques over the irradiated area.4,5 Patients with chronic lymphedema, which most commonly is related to axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer (90% of cases), may develop angiosarcoma presenting as a violaceous indurated plaque.5 Although angiosarcomas most often are seen with these distinct clinical characteristics, especially their violaceous color, they have been shown to mimic a few other skin disorders such as eczema and keratoacanthoma, but a limited number of cases of angiosarcoma mimicking BCC have been reported.1,6,7 We present a case of an elderly man with a unique presentation of a lesion that clinically appeared as a morpheaform BCC but was confirmed to be an angiosarcoma on histopathology.

A 75-year-old man was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a flesh-colored plaque on the face that initially had developed 2 years prior on the right central malar cheek. Computed tomography of the head and neck 1 year prior, which the patient reported was for workup of the lesion, was found to be negative; however, these medical records were not obtained for confirmation. The lesion had been stable in size and remained flesh colored until 6 months prior to the current presentation when it exhibited a rapid increase in size. An initial biopsy was performed 1 month prior to presentation by an outside dermatology office and had been read as an angiosarcoma.

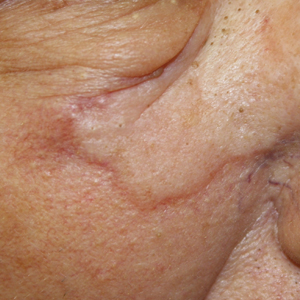

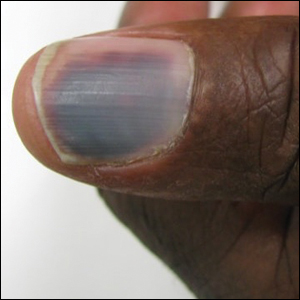

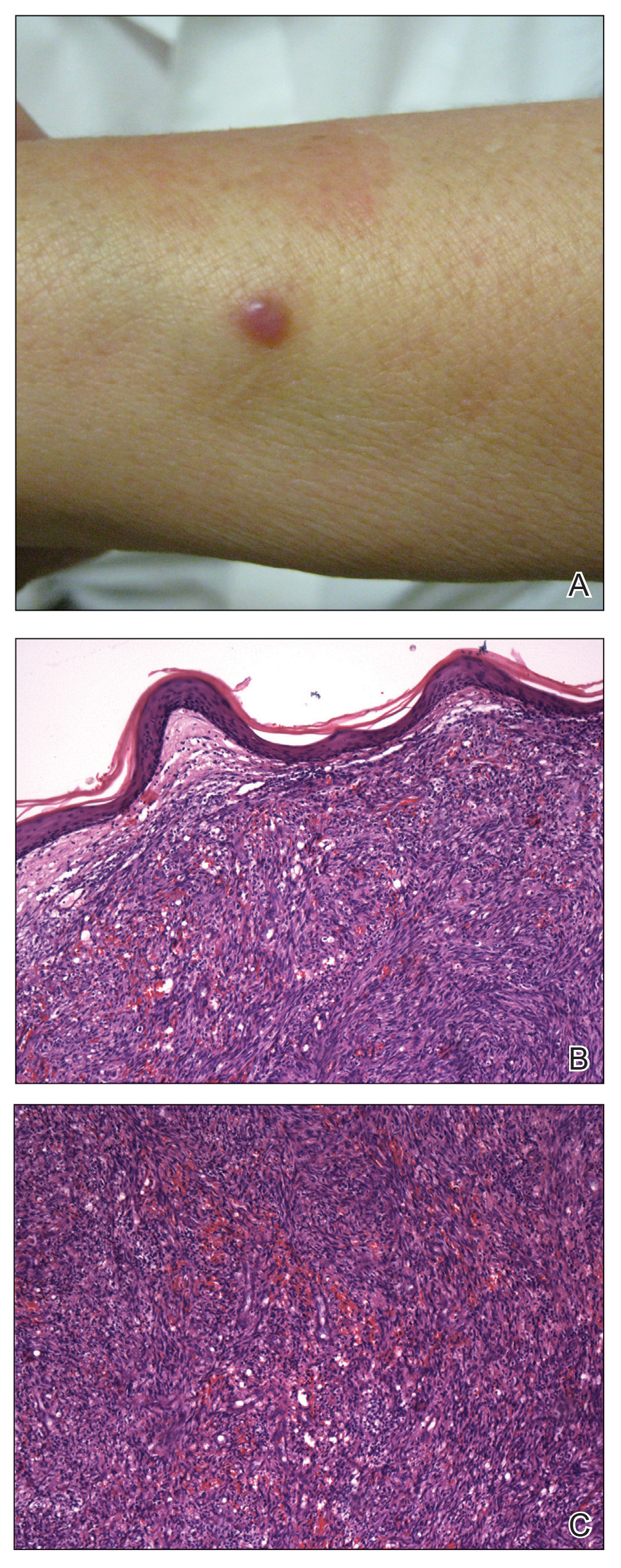

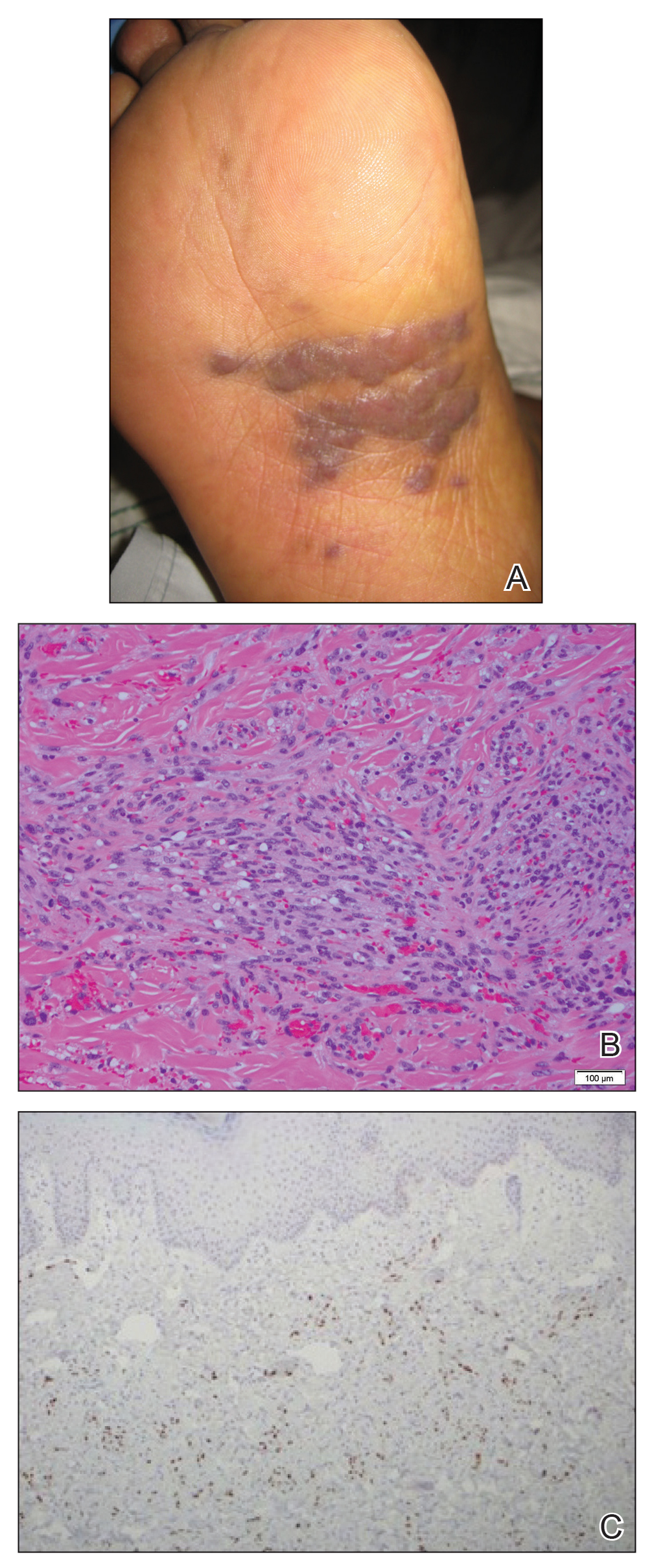

Physical examination revealed a 6-cm, flesh-colored, indurated, ill-defined plaque distributed on the right malar cheek below the eye and extending to the nasal bridge (Figure 1). There was no cervical or facial lymphadenopathy. The clinical features resembled a morpheaform BCC, and the lesion did not exhibit any reddish or purple color indicating it was of vascular origin. However, due to the prior histopathology report and recent rapid enlargement, a repeat sampling with a larger punch biopsy was performed, which confirmed the diagnosis of angiosarcoma. Histopathology demonstrated multiple atypical vascular channels lined by hyperchromatic cells extending from the upper dermis to the base of the biopsy site (Figure 2). Large, oval, atypical nuclei were present in multiple endothelial cells in the vascular channels, with some forming irregularly contoured and slitlike formations (Figure 3). Immunochemical staining was intensely and uniformly positive for CD31 and CD34, both endothelial markers. Diffuse positive staining with CD31 is considered to have high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of angiosarcoma.4 Other pertinent staining demonstrated 2+ positivity for factor VIII and 1+ positivity for D2-40; CD45, AE1/AE3, S-100, and human herpesvirus 8 were negative, consistent with angiosarcoma. The patient was referred to radiation oncology and otolaryngology at our Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Oncology Center for further investigation of the extent of the disease and discussion of treatment. Computed tomography of the head and neck region at this time showed extensive disease extending into the medial canthal area without metastasis. Due to the extent of disease and facial location, he was not deemed a candidate for surgery. He was treated with 6 weeks of targeted radiation therapy with concurrent chemotherapy. He tolerated this treatment with minimal side effects and was found to be free from clinical disease 1 year after diagnosis. He was followed for 20 months by our Multidisciplinary Oncology Clinic without recurrence of his disease but was then lost to follow-up.

This case illustrates a rare presentation of an angiosarcoma clinically mimicking a BCC, which has been described in a small number of case reports and retrospective reviews. One study of 656 patients diagnosed with BCC based on clinical features revealed that 48 of these lesions were proven to be a BCC-mimicking lesion and only 1 was an angiosarcoma.1 Cutaneous lesions that appear on physical examination to be a highly curable BCC may not induce the same urgency for treatment as an angiosarcoma. Although the clinical presentation may mimic a morpheaform BCC, our case demonstrates that it is imperative to include angiosarcoma in the differential diagnosis and underscores the utility of tissue sampling. Angiosarcoma has a poor overall 5-year survival rate, and patients often are found to have multiple metastatic lesions at diagnosis. However, diagnosis prior to metastasis may improve prognosis.8

Our patient’s angiosarcoma did not exhibit metastasis at the time of diagnosis, and he was able to achieve a favorable outcome. However, the 5-year survival rate is only 40%, and close clinical monitoring after diagnosis is required.8 Including angiosarcoma in the differential diagnosis for our patient, particularly upon lesion appearance 2 years prior, may have resulted in diagnosis antecedent to local invasion, possibly providing more treatment options. Employing a higher index of clinical suspicion for angiosarcoma may lead to decreased mortality in other patients due to increased detection.

- Kim HS, Kim TW, Mun JH, et al. Basal cell carcinoma–mimicking lesions in Korean clinical settings. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:431-436.

- Christenson LJ, Borrowman TA, Vachon CM, et al. Incidence of basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas in a population younger than 40 years. JAMA. 2005;294:681-690.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz S, Gilchrest BA. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2012.

- Dosset LA, Harrington M, Cruse CW, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma. Curr Probl Cancer. 2015;39:258-263.

- North PE, Kincannon J. Vascular neoplasms and neoplastic-like proliferations. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1915-1942.

- Kong YL, Chandran NS, Goh SG, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp mimicking a keratoacanthoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18566.

- Trinh NQ, Rashed I, Hutchens KA, et al. Unusual clinical presentation of cutaneous angiosarcoma masquerading as eczema: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2013;2013:906426.

- Buehler D, Rice SR, Moody JS, et al. Angiosarcoma outcomes and prognostic factors. a 25-year single institution experience. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014;37:473-479.

To the Editor:

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common of the nonmelanoma skin cancers and is a highly curable skin growth.1,2 Conversely, angiosarcomas are aggressive vascular tumors of endothelial origin that classically appear as reddish purple patches or plaques that exhibit rapid growth and invasion.3 Sporadic cutaneous angiosarcomas are the most common type of this soft tissue tumor, occurring most often in the head and neck regions in men older than 70 years.4,5 Other types of angiosarcomas include those associated with radiation therapy and chronic lymphedema. Postradiation angiosarcomas have been most frequently reported after treatment of breast cancer and appear as infiltrative plaques over the irradiated area.4,5 Patients with chronic lymphedema, which most commonly is related to axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer (90% of cases), may develop angiosarcoma presenting as a violaceous indurated plaque.5 Although angiosarcomas most often are seen with these distinct clinical characteristics, especially their violaceous color, they have been shown to mimic a few other skin disorders such as eczema and keratoacanthoma, but a limited number of cases of angiosarcoma mimicking BCC have been reported.1,6,7 We present a case of an elderly man with a unique presentation of a lesion that clinically appeared as a morpheaform BCC but was confirmed to be an angiosarcoma on histopathology.

A 75-year-old man was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a flesh-colored plaque on the face that initially had developed 2 years prior on the right central malar cheek. Computed tomography of the head and neck 1 year prior, which the patient reported was for workup of the lesion, was found to be negative; however, these medical records were not obtained for confirmation. The lesion had been stable in size and remained flesh colored until 6 months prior to the current presentation when it exhibited a rapid increase in size. An initial biopsy was performed 1 month prior to presentation by an outside dermatology office and had been read as an angiosarcoma.

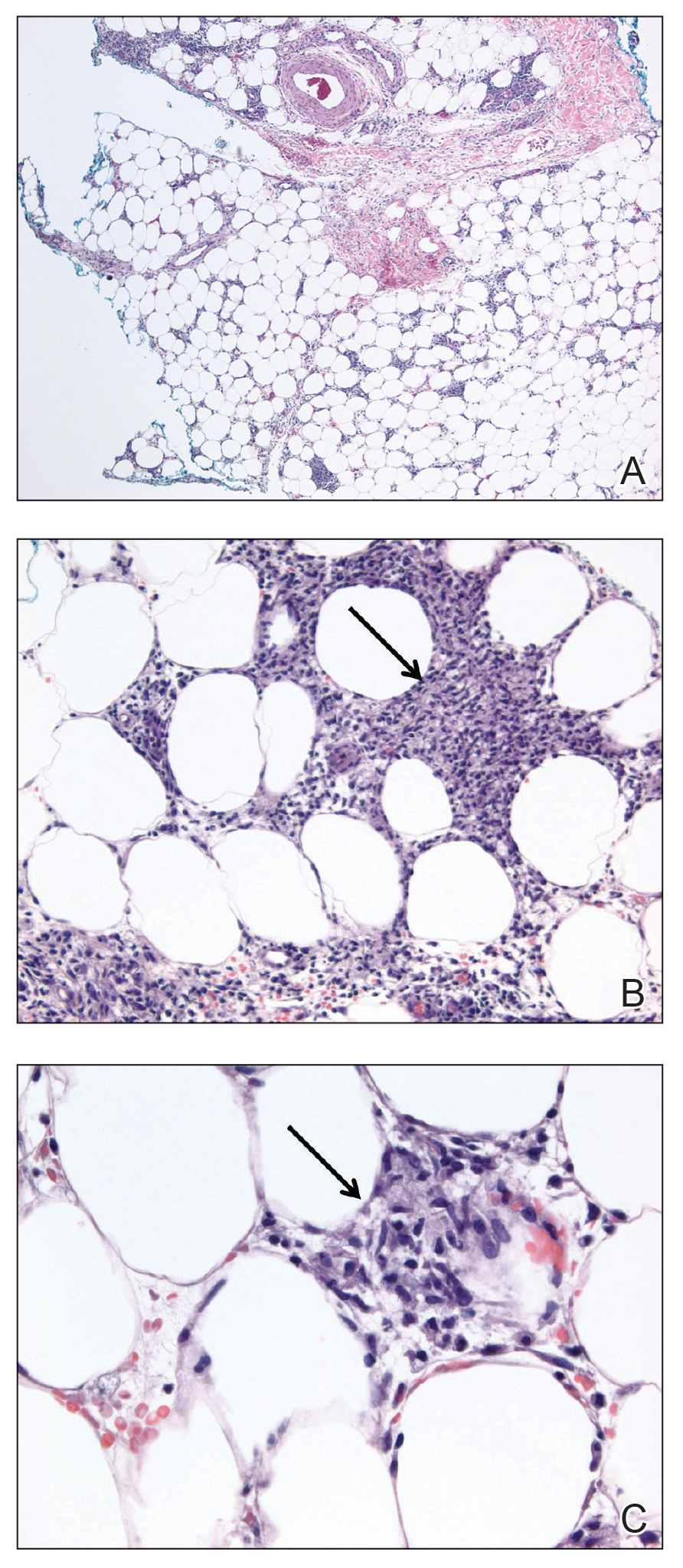

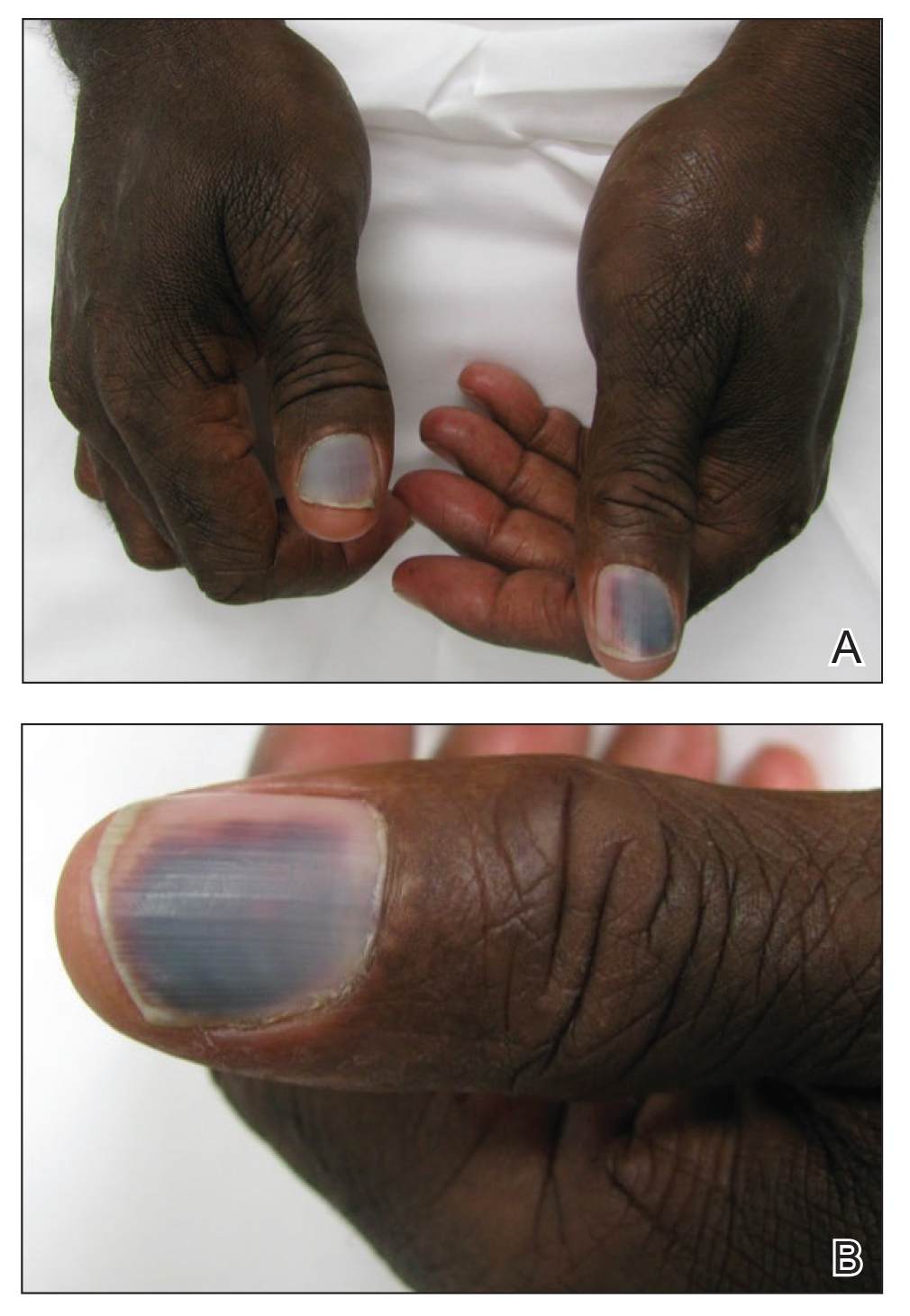

Physical examination revealed a 6-cm, flesh-colored, indurated, ill-defined plaque distributed on the right malar cheek below the eye and extending to the nasal bridge (Figure 1). There was no cervical or facial lymphadenopathy. The clinical features resembled a morpheaform BCC, and the lesion did not exhibit any reddish or purple color indicating it was of vascular origin. However, due to the prior histopathology report and recent rapid enlargement, a repeat sampling with a larger punch biopsy was performed, which confirmed the diagnosis of angiosarcoma. Histopathology demonstrated multiple atypical vascular channels lined by hyperchromatic cells extending from the upper dermis to the base of the biopsy site (Figure 2). Large, oval, atypical nuclei were present in multiple endothelial cells in the vascular channels, with some forming irregularly contoured and slitlike formations (Figure 3). Immunochemical staining was intensely and uniformly positive for CD31 and CD34, both endothelial markers. Diffuse positive staining with CD31 is considered to have high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of angiosarcoma.4 Other pertinent staining demonstrated 2+ positivity for factor VIII and 1+ positivity for D2-40; CD45, AE1/AE3, S-100, and human herpesvirus 8 were negative, consistent with angiosarcoma. The patient was referred to radiation oncology and otolaryngology at our Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Oncology Center for further investigation of the extent of the disease and discussion of treatment. Computed tomography of the head and neck region at this time showed extensive disease extending into the medial canthal area without metastasis. Due to the extent of disease and facial location, he was not deemed a candidate for surgery. He was treated with 6 weeks of targeted radiation therapy with concurrent chemotherapy. He tolerated this treatment with minimal side effects and was found to be free from clinical disease 1 year after diagnosis. He was followed for 20 months by our Multidisciplinary Oncology Clinic without recurrence of his disease but was then lost to follow-up.

This case illustrates a rare presentation of an angiosarcoma clinically mimicking a BCC, which has been described in a small number of case reports and retrospective reviews. One study of 656 patients diagnosed with BCC based on clinical features revealed that 48 of these lesions were proven to be a BCC-mimicking lesion and only 1 was an angiosarcoma.1 Cutaneous lesions that appear on physical examination to be a highly curable BCC may not induce the same urgency for treatment as an angiosarcoma. Although the clinical presentation may mimic a morpheaform BCC, our case demonstrates that it is imperative to include angiosarcoma in the differential diagnosis and underscores the utility of tissue sampling. Angiosarcoma has a poor overall 5-year survival rate, and patients often are found to have multiple metastatic lesions at diagnosis. However, diagnosis prior to metastasis may improve prognosis.8

Our patient’s angiosarcoma did not exhibit metastasis at the time of diagnosis, and he was able to achieve a favorable outcome. However, the 5-year survival rate is only 40%, and close clinical monitoring after diagnosis is required.8 Including angiosarcoma in the differential diagnosis for our patient, particularly upon lesion appearance 2 years prior, may have resulted in diagnosis antecedent to local invasion, possibly providing more treatment options. Employing a higher index of clinical suspicion for angiosarcoma may lead to decreased mortality in other patients due to increased detection.

To the Editor:

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common of the nonmelanoma skin cancers and is a highly curable skin growth.1,2 Conversely, angiosarcomas are aggressive vascular tumors of endothelial origin that classically appear as reddish purple patches or plaques that exhibit rapid growth and invasion.3 Sporadic cutaneous angiosarcomas are the most common type of this soft tissue tumor, occurring most often in the head and neck regions in men older than 70 years.4,5 Other types of angiosarcomas include those associated with radiation therapy and chronic lymphedema. Postradiation angiosarcomas have been most frequently reported after treatment of breast cancer and appear as infiltrative plaques over the irradiated area.4,5 Patients with chronic lymphedema, which most commonly is related to axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer (90% of cases), may develop angiosarcoma presenting as a violaceous indurated plaque.5 Although angiosarcomas most often are seen with these distinct clinical characteristics, especially their violaceous color, they have been shown to mimic a few other skin disorders such as eczema and keratoacanthoma, but a limited number of cases of angiosarcoma mimicking BCC have been reported.1,6,7 We present a case of an elderly man with a unique presentation of a lesion that clinically appeared as a morpheaform BCC but was confirmed to be an angiosarcoma on histopathology.

A 75-year-old man was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a flesh-colored plaque on the face that initially had developed 2 years prior on the right central malar cheek. Computed tomography of the head and neck 1 year prior, which the patient reported was for workup of the lesion, was found to be negative; however, these medical records were not obtained for confirmation. The lesion had been stable in size and remained flesh colored until 6 months prior to the current presentation when it exhibited a rapid increase in size. An initial biopsy was performed 1 month prior to presentation by an outside dermatology office and had been read as an angiosarcoma.

Physical examination revealed a 6-cm, flesh-colored, indurated, ill-defined plaque distributed on the right malar cheek below the eye and extending to the nasal bridge (Figure 1). There was no cervical or facial lymphadenopathy. The clinical features resembled a morpheaform BCC, and the lesion did not exhibit any reddish or purple color indicating it was of vascular origin. However, due to the prior histopathology report and recent rapid enlargement, a repeat sampling with a larger punch biopsy was performed, which confirmed the diagnosis of angiosarcoma. Histopathology demonstrated multiple atypical vascular channels lined by hyperchromatic cells extending from the upper dermis to the base of the biopsy site (Figure 2). Large, oval, atypical nuclei were present in multiple endothelial cells in the vascular channels, with some forming irregularly contoured and slitlike formations (Figure 3). Immunochemical staining was intensely and uniformly positive for CD31 and CD34, both endothelial markers. Diffuse positive staining with CD31 is considered to have high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of angiosarcoma.4 Other pertinent staining demonstrated 2+ positivity for factor VIII and 1+ positivity for D2-40; CD45, AE1/AE3, S-100, and human herpesvirus 8 were negative, consistent with angiosarcoma. The patient was referred to radiation oncology and otolaryngology at our Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Oncology Center for further investigation of the extent of the disease and discussion of treatment. Computed tomography of the head and neck region at this time showed extensive disease extending into the medial canthal area without metastasis. Due to the extent of disease and facial location, he was not deemed a candidate for surgery. He was treated with 6 weeks of targeted radiation therapy with concurrent chemotherapy. He tolerated this treatment with minimal side effects and was found to be free from clinical disease 1 year after diagnosis. He was followed for 20 months by our Multidisciplinary Oncology Clinic without recurrence of his disease but was then lost to follow-up.

This case illustrates a rare presentation of an angiosarcoma clinically mimicking a BCC, which has been described in a small number of case reports and retrospective reviews. One study of 656 patients diagnosed with BCC based on clinical features revealed that 48 of these lesions were proven to be a BCC-mimicking lesion and only 1 was an angiosarcoma.1 Cutaneous lesions that appear on physical examination to be a highly curable BCC may not induce the same urgency for treatment as an angiosarcoma. Although the clinical presentation may mimic a morpheaform BCC, our case demonstrates that it is imperative to include angiosarcoma in the differential diagnosis and underscores the utility of tissue sampling. Angiosarcoma has a poor overall 5-year survival rate, and patients often are found to have multiple metastatic lesions at diagnosis. However, diagnosis prior to metastasis may improve prognosis.8

Our patient’s angiosarcoma did not exhibit metastasis at the time of diagnosis, and he was able to achieve a favorable outcome. However, the 5-year survival rate is only 40%, and close clinical monitoring after diagnosis is required.8 Including angiosarcoma in the differential diagnosis for our patient, particularly upon lesion appearance 2 years prior, may have resulted in diagnosis antecedent to local invasion, possibly providing more treatment options. Employing a higher index of clinical suspicion for angiosarcoma may lead to decreased mortality in other patients due to increased detection.

- Kim HS, Kim TW, Mun JH, et al. Basal cell carcinoma–mimicking lesions in Korean clinical settings. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:431-436.

- Christenson LJ, Borrowman TA, Vachon CM, et al. Incidence of basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas in a population younger than 40 years. JAMA. 2005;294:681-690.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz S, Gilchrest BA. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2012.

- Dosset LA, Harrington M, Cruse CW, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma. Curr Probl Cancer. 2015;39:258-263.

- North PE, Kincannon J. Vascular neoplasms and neoplastic-like proliferations. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1915-1942.

- Kong YL, Chandran NS, Goh SG, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp mimicking a keratoacanthoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18566.

- Trinh NQ, Rashed I, Hutchens KA, et al. Unusual clinical presentation of cutaneous angiosarcoma masquerading as eczema: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2013;2013:906426.

- Buehler D, Rice SR, Moody JS, et al. Angiosarcoma outcomes and prognostic factors. a 25-year single institution experience. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014;37:473-479.

- Kim HS, Kim TW, Mun JH, et al. Basal cell carcinoma–mimicking lesions in Korean clinical settings. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:431-436.

- Christenson LJ, Borrowman TA, Vachon CM, et al. Incidence of basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas in a population younger than 40 years. JAMA. 2005;294:681-690.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz S, Gilchrest BA. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2012.

- Dosset LA, Harrington M, Cruse CW, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma. Curr Probl Cancer. 2015;39:258-263.

- North PE, Kincannon J. Vascular neoplasms and neoplastic-like proliferations. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1915-1942.

- Kong YL, Chandran NS, Goh SG, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp mimicking a keratoacanthoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18566.

- Trinh NQ, Rashed I, Hutchens KA, et al. Unusual clinical presentation of cutaneous angiosarcoma masquerading as eczema: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2013;2013:906426.

- Buehler D, Rice SR, Moody JS, et al. Angiosarcoma outcomes and prognostic factors. a 25-year single institution experience. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014;37:473-479.

Practice Points

- Angiosarcoma is an aggressive vascular tumor with a poor prognosis.

- Angiosarcomas can arise in the setting of chronic lymphedema or prior radiation therapy or can arise spontaneously.

- Classically, angiosarcoma presents as a violaceous patch or plaque but occasionally can exhibit atypical clinical features. Angiosarcomas should be considered on the differential for any changing plaque on the head or neck.

Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy

To the Editor:

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is a rare idiopathic microangiopathy characterized by diffuse blanchable telangiectases that usually develop in late adulthood. It appears morphologically identical to generalized essential telangiectasia (GET), but skin biopsy characteristically shows dilated superficial blood vessels in the papillary dermis that are surrounded by a thickened layer of type IV collagen.1 We report a case of CCV occurring in an elderly white man.

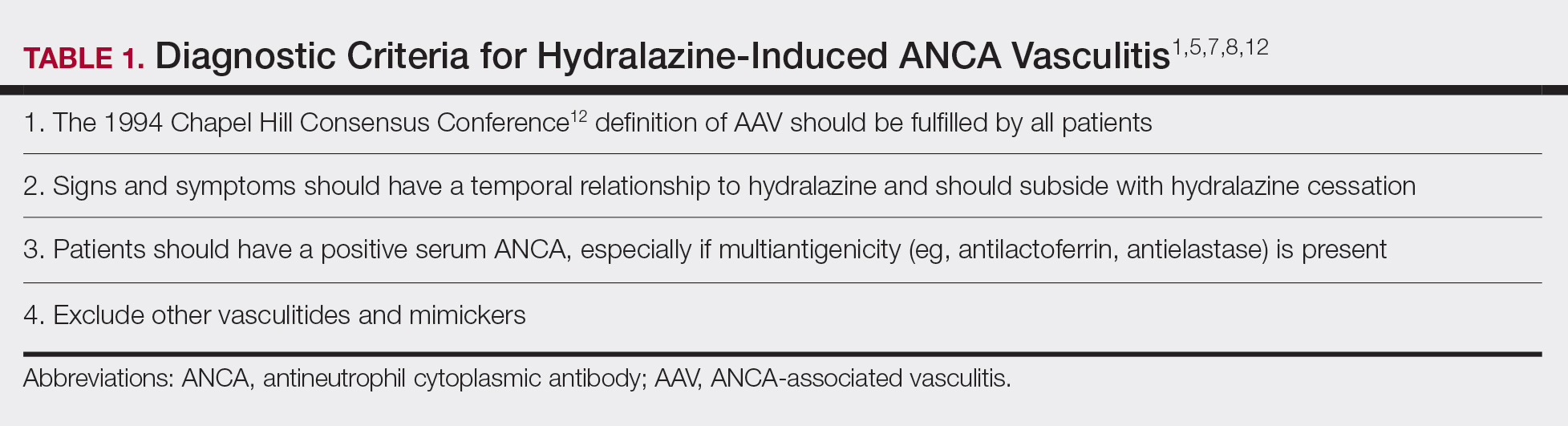

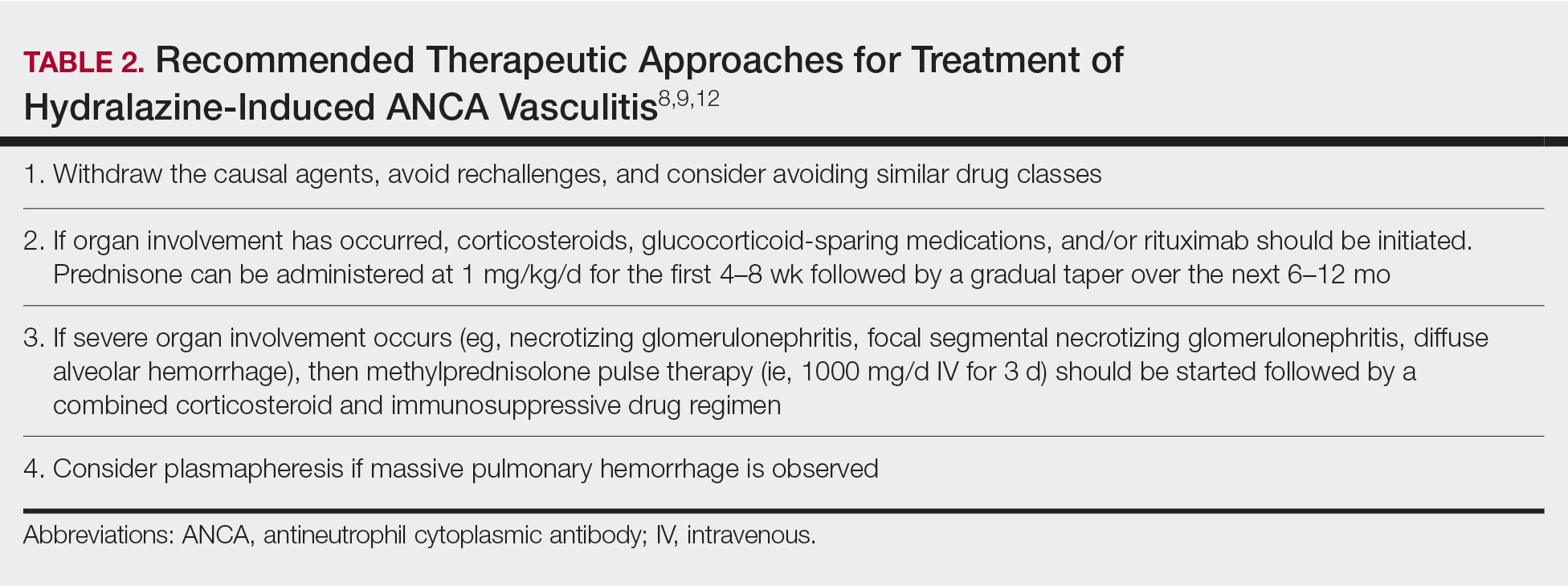

A 72-year-old man presented with an asymptomatic rash on the arms, legs, and abdomen of 3 years’ duration. His medical history was remarkable for hypothyroidism, hypertension, reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome, coronary artery disease, and nonmelanoma skin cancer. He denied any changes in medications or illnesses prior to onset of the rash. Physical examination revealed diffuse, erythematous, blanchable telangiectases on the arms, legs, and trunk (Figure 1). No petechiae, atrophy, or epidermal changes were appreciated. Darier sign was negative.

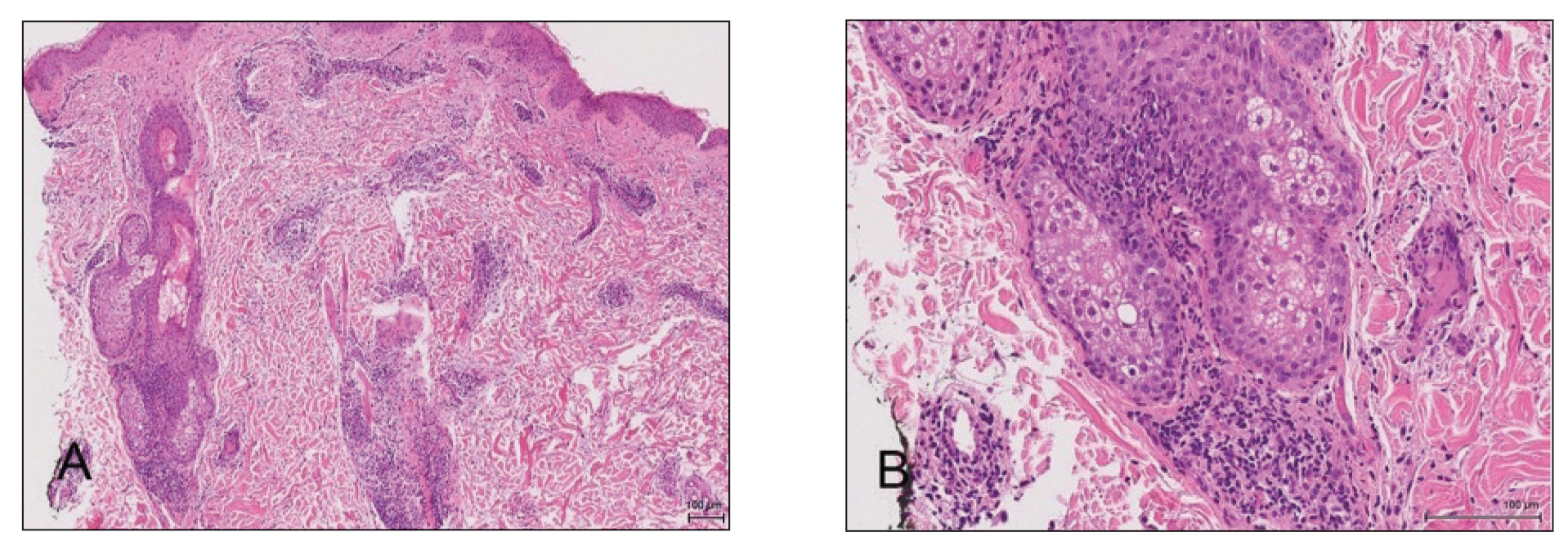

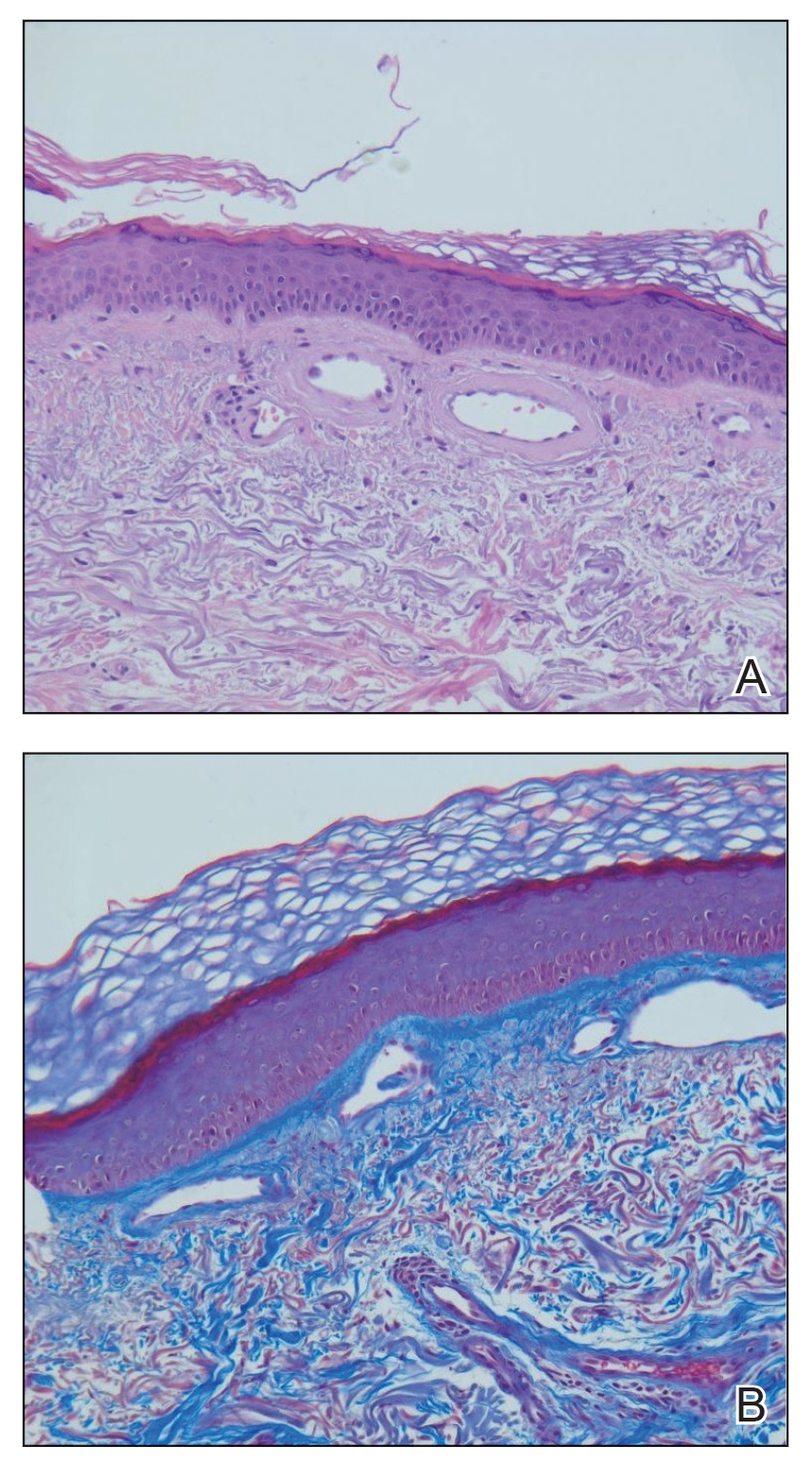

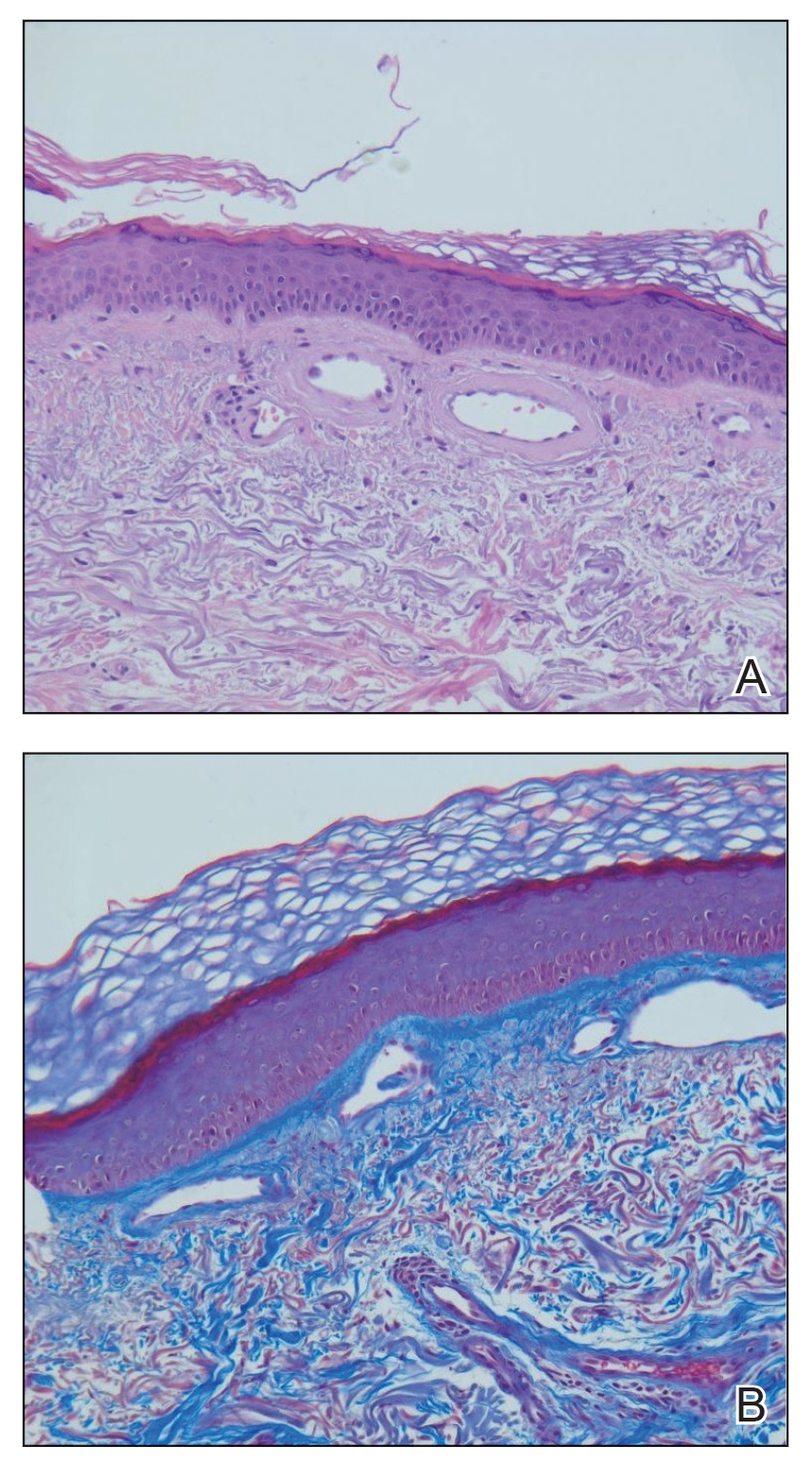

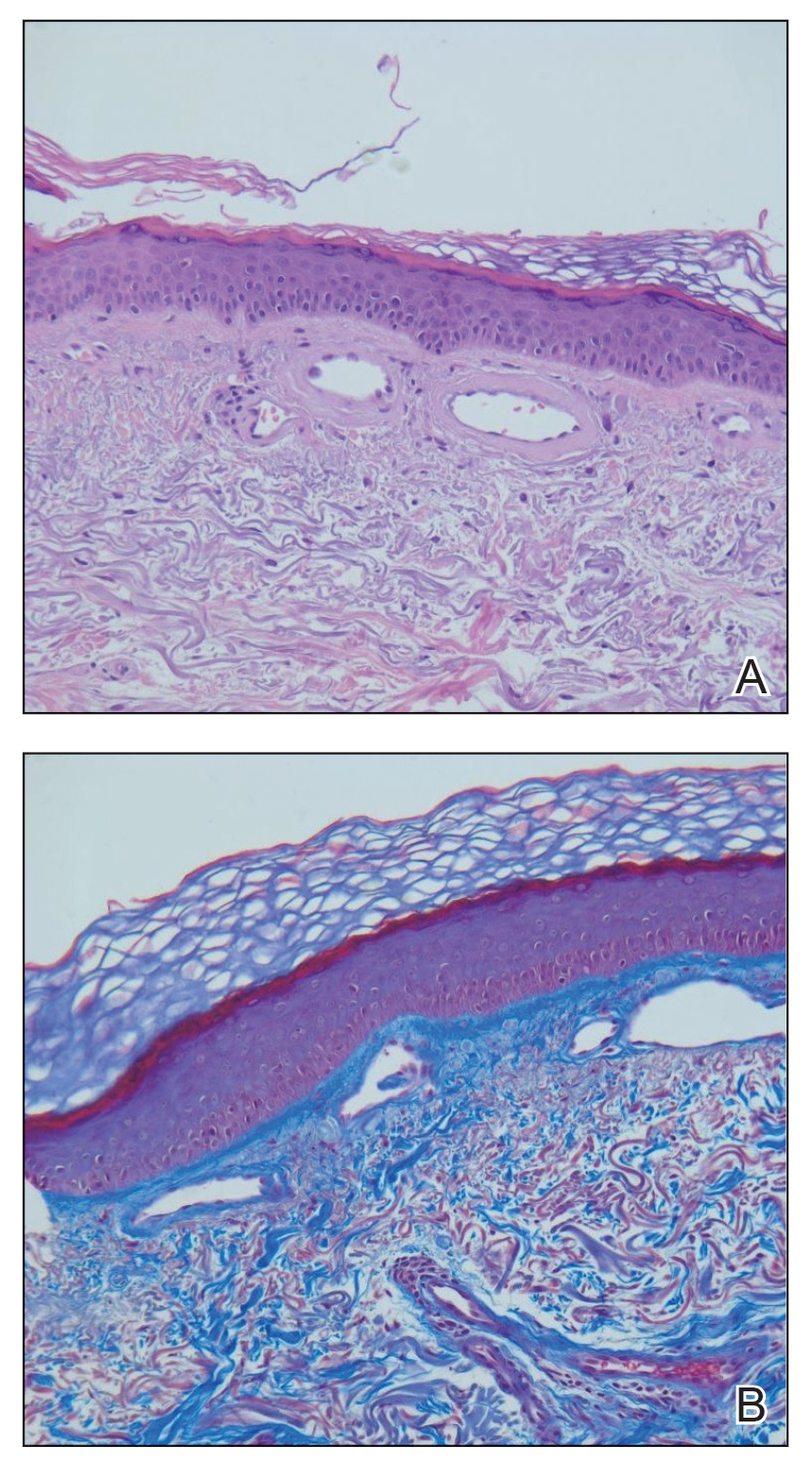

Hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections of skin from the abdomen showed an unremarkable epidermis overlying a superficial dermis with dilated blood vessels with thickened walls that contained eosinophilic amorphous hyaline material (Figure 2A). This material stained positive with Masson trichrome (Figure 2B), a finding that was consistent with increased collagen fiber deposition within the vessel walls. Phosphotungstic acid–hematoxylin and Congo red stains were negative. No histologic features of a vaso-occlusive disorder or vasculitis were identified. These histologic findings were consistent with the rare diagnosis of CCV.

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy is a rare idiopathic microangiopathy that was first reported by Salama and Rosenthal1 in 2000. They reported the case of a 54-year-old man with spreading, asymptomatic, generalized cutaneous telangiectases of 5 years’ duration. Similar to our patient, skin biopsy showed dilated superficial dermal vasculature with deposition of eosinophilic hyaline material, which stained positive with periodic acid–Schiff with diastase and exhibited immunoreactivity to type IV collagen.1

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy yielded 19 additional patients with biopsy-proven CCV.2-6 The condition has shown no gender prevalence but generally is seen in middle-aged or elderly white individuals, with the exception of a white pediatric patient.4 Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy usually presents as telangiectases on the legs that progress to involve the trunk and arms while sparing the head and neck, nail beds, and mucous membranes.5 However, it also has been described as first presenting on the bilateral breasts2 as well as a nonprogressive localization on the thigh.6

Skin biopsy is essential to differentiate CCV from GET, which appears morphologically identical. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy may be underreported as a result of clinician choice not to biopsy due to a presumptive diagnosis of GET.3 Successful treatment with a pulsed dye laser has been reported,7 though the extent of disease may make complete destruction of the lesions difficult to accomplish. Although it is theorized that CCV may be a marker for underlying systemic disease or even a genetic defect causing abnormal collagen deposition, its cause has yet to be ascertained.5 Previously reported patients have had a variety of comorbidities, including several cases of type 2 diabetes mellitus.6 Another patient was reported to have recently started treatment with an angiotensin receptor blocker prior to onset of CCV.5

Our case contributes to the small series of reported patients with this rare diagnosis and further suggests that it may be underreported at this time. Similar to previously reported cases, our patient was an elderly white individual. Although our patient had long-standing iatrogenic hypothyroidism, no recent medication changes or underlying comorbidities could be tied to the development of CCV. Further studies are needed to determine if this disease process is associated with any underlying systemic illnesses, medications, or family history.

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Borroni RG, Derlino F, Agozzino M, et al. Hypothermic cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with centrifugal spreading [published online March 31, 2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1444-1446.

- Moulonguet I, Hershkovitch D, Fraitag S. Widespread cutaneous telangiectasias: challenge. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:661-662, 688-669.

- Lloyd BM, Pruden SJ 2nd, Lind AC, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of the first pediatric case. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:598-599.

- Kanitakis J, Faisant M, Wagschal D, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study of a new case. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:63-66.

- Davis TL, Mandal RV, Bevona C, et al. Collagenous vasculopathy: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:967-970.

- Echeverría B, Sanmartín O, Botella-Estrada R, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy successfully treated with pulsed dye laser. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1359-1362.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is a rare idiopathic microangiopathy characterized by diffuse blanchable telangiectases that usually develop in late adulthood. It appears morphologically identical to generalized essential telangiectasia (GET), but skin biopsy characteristically shows dilated superficial blood vessels in the papillary dermis that are surrounded by a thickened layer of type IV collagen.1 We report a case of CCV occurring in an elderly white man.

A 72-year-old man presented with an asymptomatic rash on the arms, legs, and abdomen of 3 years’ duration. His medical history was remarkable for hypothyroidism, hypertension, reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome, coronary artery disease, and nonmelanoma skin cancer. He denied any changes in medications or illnesses prior to onset of the rash. Physical examination revealed diffuse, erythematous, blanchable telangiectases on the arms, legs, and trunk (Figure 1). No petechiae, atrophy, or epidermal changes were appreciated. Darier sign was negative.

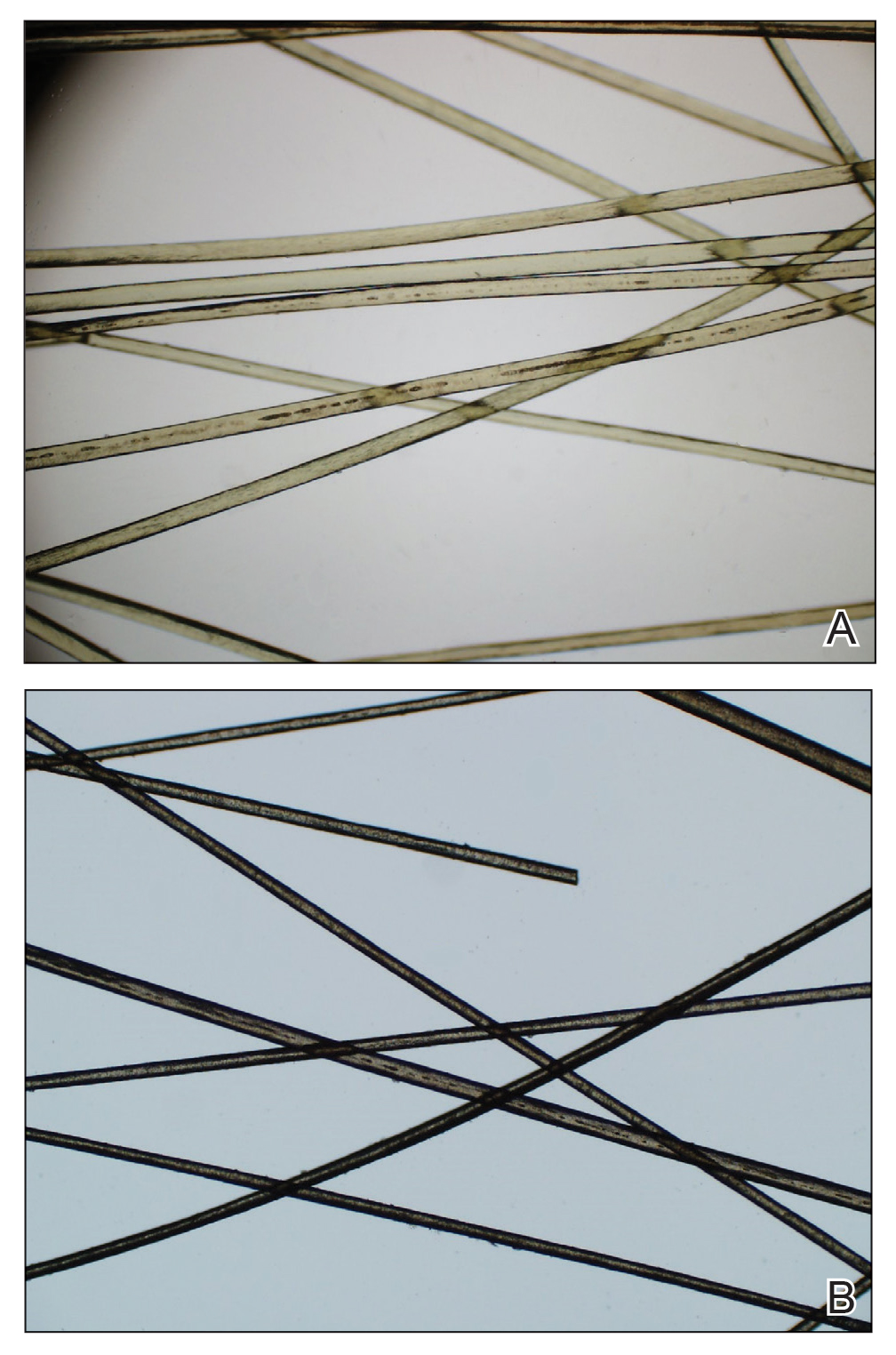

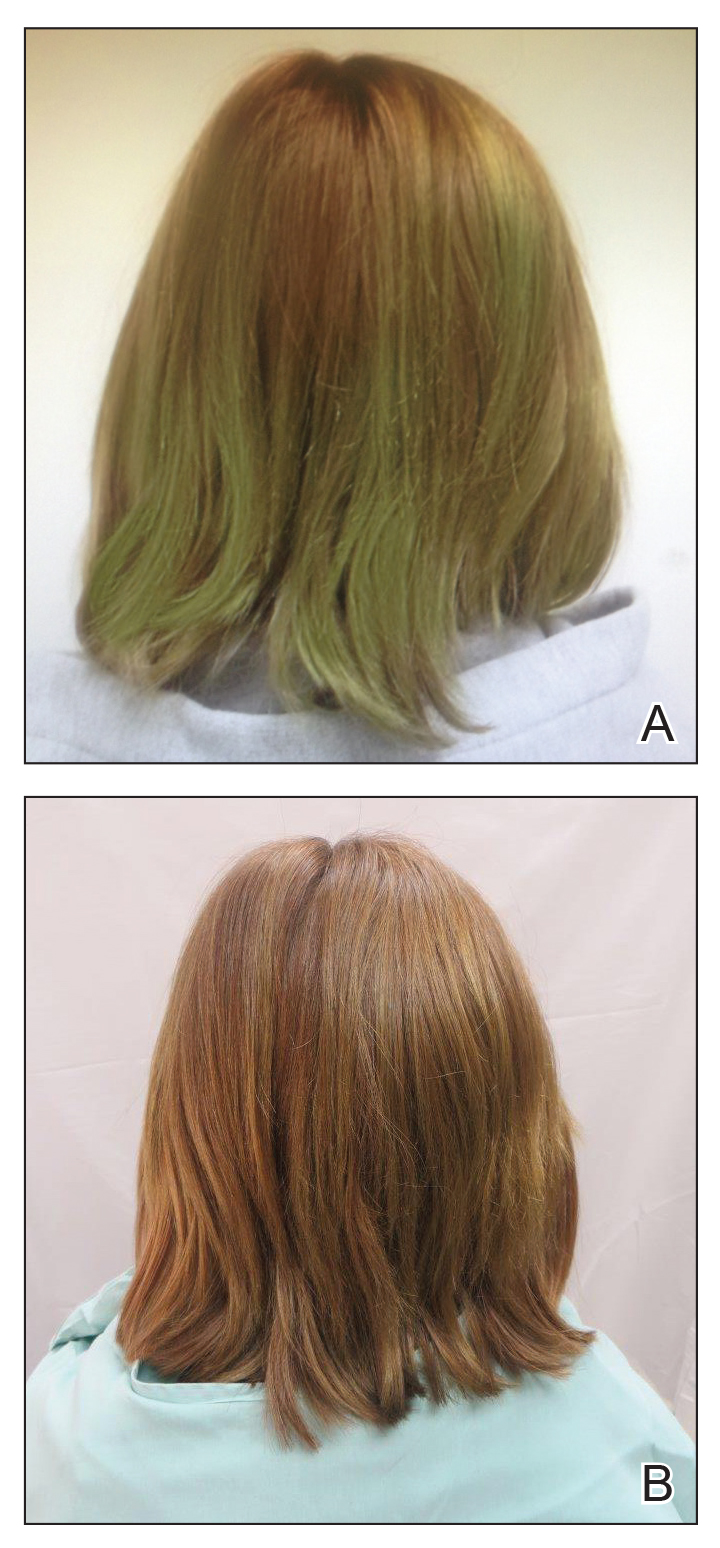

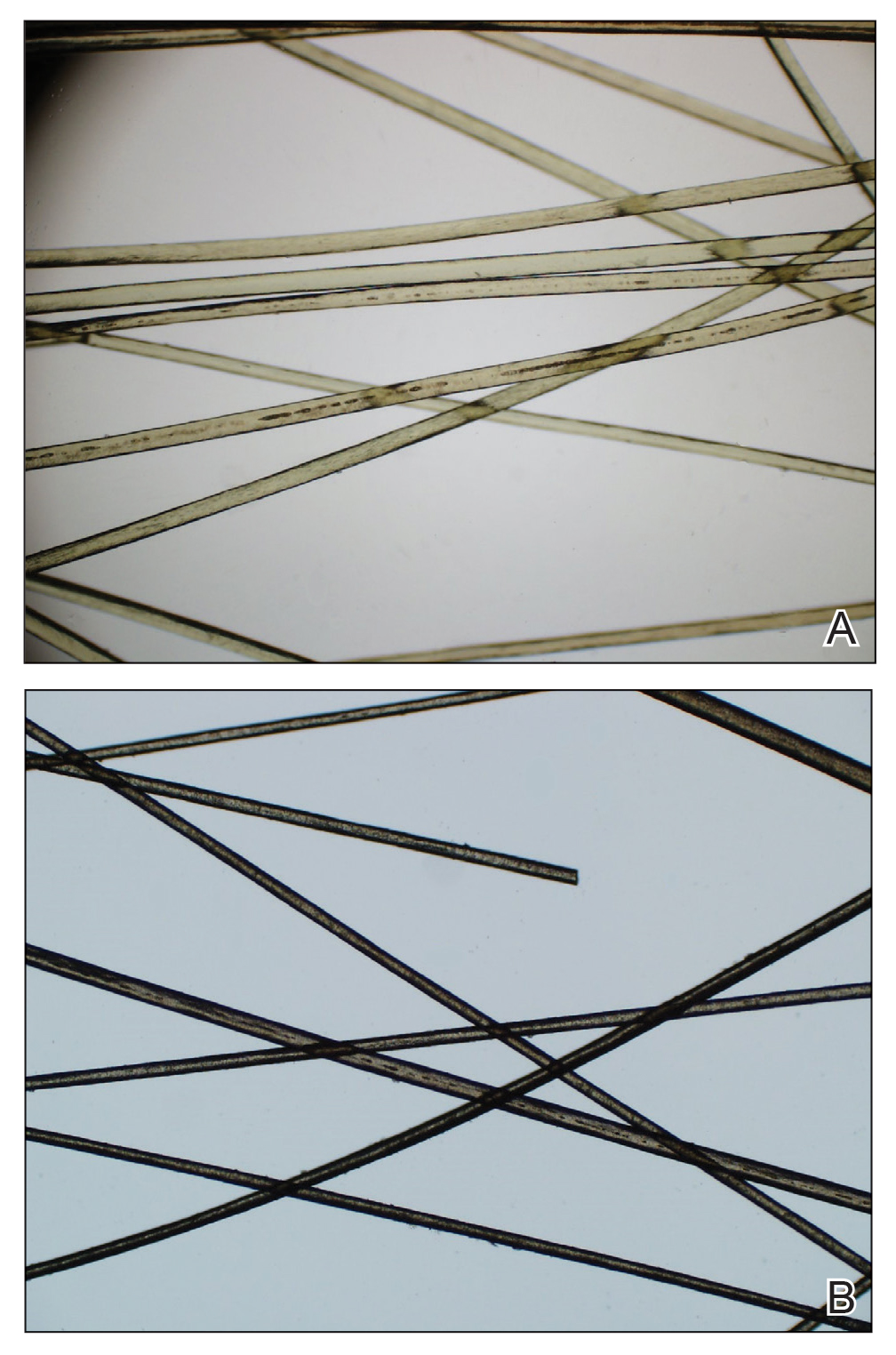

Hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections of skin from the abdomen showed an unremarkable epidermis overlying a superficial dermis with dilated blood vessels with thickened walls that contained eosinophilic amorphous hyaline material (Figure 2A). This material stained positive with Masson trichrome (Figure 2B), a finding that was consistent with increased collagen fiber deposition within the vessel walls. Phosphotungstic acid–hematoxylin and Congo red stains were negative. No histologic features of a vaso-occlusive disorder or vasculitis were identified. These histologic findings were consistent with the rare diagnosis of CCV.

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy is a rare idiopathic microangiopathy that was first reported by Salama and Rosenthal1 in 2000. They reported the case of a 54-year-old man with spreading, asymptomatic, generalized cutaneous telangiectases of 5 years’ duration. Similar to our patient, skin biopsy showed dilated superficial dermal vasculature with deposition of eosinophilic hyaline material, which stained positive with periodic acid–Schiff with diastase and exhibited immunoreactivity to type IV collagen.1

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy yielded 19 additional patients with biopsy-proven CCV.2-6 The condition has shown no gender prevalence but generally is seen in middle-aged or elderly white individuals, with the exception of a white pediatric patient.4 Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy usually presents as telangiectases on the legs that progress to involve the trunk and arms while sparing the head and neck, nail beds, and mucous membranes.5 However, it also has been described as first presenting on the bilateral breasts2 as well as a nonprogressive localization on the thigh.6

Skin biopsy is essential to differentiate CCV from GET, which appears morphologically identical. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy may be underreported as a result of clinician choice not to biopsy due to a presumptive diagnosis of GET.3 Successful treatment with a pulsed dye laser has been reported,7 though the extent of disease may make complete destruction of the lesions difficult to accomplish. Although it is theorized that CCV may be a marker for underlying systemic disease or even a genetic defect causing abnormal collagen deposition, its cause has yet to be ascertained.5 Previously reported patients have had a variety of comorbidities, including several cases of type 2 diabetes mellitus.6 Another patient was reported to have recently started treatment with an angiotensin receptor blocker prior to onset of CCV.5

Our case contributes to the small series of reported patients with this rare diagnosis and further suggests that it may be underreported at this time. Similar to previously reported cases, our patient was an elderly white individual. Although our patient had long-standing iatrogenic hypothyroidism, no recent medication changes or underlying comorbidities could be tied to the development of CCV. Further studies are needed to determine if this disease process is associated with any underlying systemic illnesses, medications, or family history.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is a rare idiopathic microangiopathy characterized by diffuse blanchable telangiectases that usually develop in late adulthood. It appears morphologically identical to generalized essential telangiectasia (GET), but skin biopsy characteristically shows dilated superficial blood vessels in the papillary dermis that are surrounded by a thickened layer of type IV collagen.1 We report a case of CCV occurring in an elderly white man.

A 72-year-old man presented with an asymptomatic rash on the arms, legs, and abdomen of 3 years’ duration. His medical history was remarkable for hypothyroidism, hypertension, reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome, coronary artery disease, and nonmelanoma skin cancer. He denied any changes in medications or illnesses prior to onset of the rash. Physical examination revealed diffuse, erythematous, blanchable telangiectases on the arms, legs, and trunk (Figure 1). No petechiae, atrophy, or epidermal changes were appreciated. Darier sign was negative.

Hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections of skin from the abdomen showed an unremarkable epidermis overlying a superficial dermis with dilated blood vessels with thickened walls that contained eosinophilic amorphous hyaline material (Figure 2A). This material stained positive with Masson trichrome (Figure 2B), a finding that was consistent with increased collagen fiber deposition within the vessel walls. Phosphotungstic acid–hematoxylin and Congo red stains were negative. No histologic features of a vaso-occlusive disorder or vasculitis were identified. These histologic findings were consistent with the rare diagnosis of CCV.

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy is a rare idiopathic microangiopathy that was first reported by Salama and Rosenthal1 in 2000. They reported the case of a 54-year-old man with spreading, asymptomatic, generalized cutaneous telangiectases of 5 years’ duration. Similar to our patient, skin biopsy showed dilated superficial dermal vasculature with deposition of eosinophilic hyaline material, which stained positive with periodic acid–Schiff with diastase and exhibited immunoreactivity to type IV collagen.1

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy yielded 19 additional patients with biopsy-proven CCV.2-6 The condition has shown no gender prevalence but generally is seen in middle-aged or elderly white individuals, with the exception of a white pediatric patient.4 Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy usually presents as telangiectases on the legs that progress to involve the trunk and arms while sparing the head and neck, nail beds, and mucous membranes.5 However, it also has been described as first presenting on the bilateral breasts2 as well as a nonprogressive localization on the thigh.6

Skin biopsy is essential to differentiate CCV from GET, which appears morphologically identical. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy may be underreported as a result of clinician choice not to biopsy due to a presumptive diagnosis of GET.3 Successful treatment with a pulsed dye laser has been reported,7 though the extent of disease may make complete destruction of the lesions difficult to accomplish. Although it is theorized that CCV may be a marker for underlying systemic disease or even a genetic defect causing abnormal collagen deposition, its cause has yet to be ascertained.5 Previously reported patients have had a variety of comorbidities, including several cases of type 2 diabetes mellitus.6 Another patient was reported to have recently started treatment with an angiotensin receptor blocker prior to onset of CCV.5

Our case contributes to the small series of reported patients with this rare diagnosis and further suggests that it may be underreported at this time. Similar to previously reported cases, our patient was an elderly white individual. Although our patient had long-standing iatrogenic hypothyroidism, no recent medication changes or underlying comorbidities could be tied to the development of CCV. Further studies are needed to determine if this disease process is associated with any underlying systemic illnesses, medications, or family history.

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Borroni RG, Derlino F, Agozzino M, et al. Hypothermic cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with centrifugal spreading [published online March 31, 2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1444-1446.

- Moulonguet I, Hershkovitch D, Fraitag S. Widespread cutaneous telangiectasias: challenge. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:661-662, 688-669.

- Lloyd BM, Pruden SJ 2nd, Lind AC, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of the first pediatric case. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:598-599.

- Kanitakis J, Faisant M, Wagschal D, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study of a new case. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:63-66.

- Davis TL, Mandal RV, Bevona C, et al. Collagenous vasculopathy: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:967-970.

- Echeverría B, Sanmartín O, Botella-Estrada R, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy successfully treated with pulsed dye laser. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1359-1362.

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Borroni RG, Derlino F, Agozzino M, et al. Hypothermic cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with centrifugal spreading [published online March 31, 2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1444-1446.

- Moulonguet I, Hershkovitch D, Fraitag S. Widespread cutaneous telangiectasias: challenge. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:661-662, 688-669.

- Lloyd BM, Pruden SJ 2nd, Lind AC, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of the first pediatric case. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:598-599.

- Kanitakis J, Faisant M, Wagschal D, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study of a new case. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:63-66.

- Davis TL, Mandal RV, Bevona C, et al. Collagenous vasculopathy: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:967-970.

- Echeverría B, Sanmartín O, Botella-Estrada R, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy successfully treated with pulsed dye laser. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1359-1362.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) should be in the differential diagnosis of widespread telangiectases.

- Biopsy is needed to differentiate between CCV and generalized essential telangiectasia because of their similar clinical features.

- There may be underlying comorbidities associated with CCV, but the exact cause of the condition has yet to be found.

Persistent Chlorotrichosis With Chronic Sun Exposure

To the Editor:

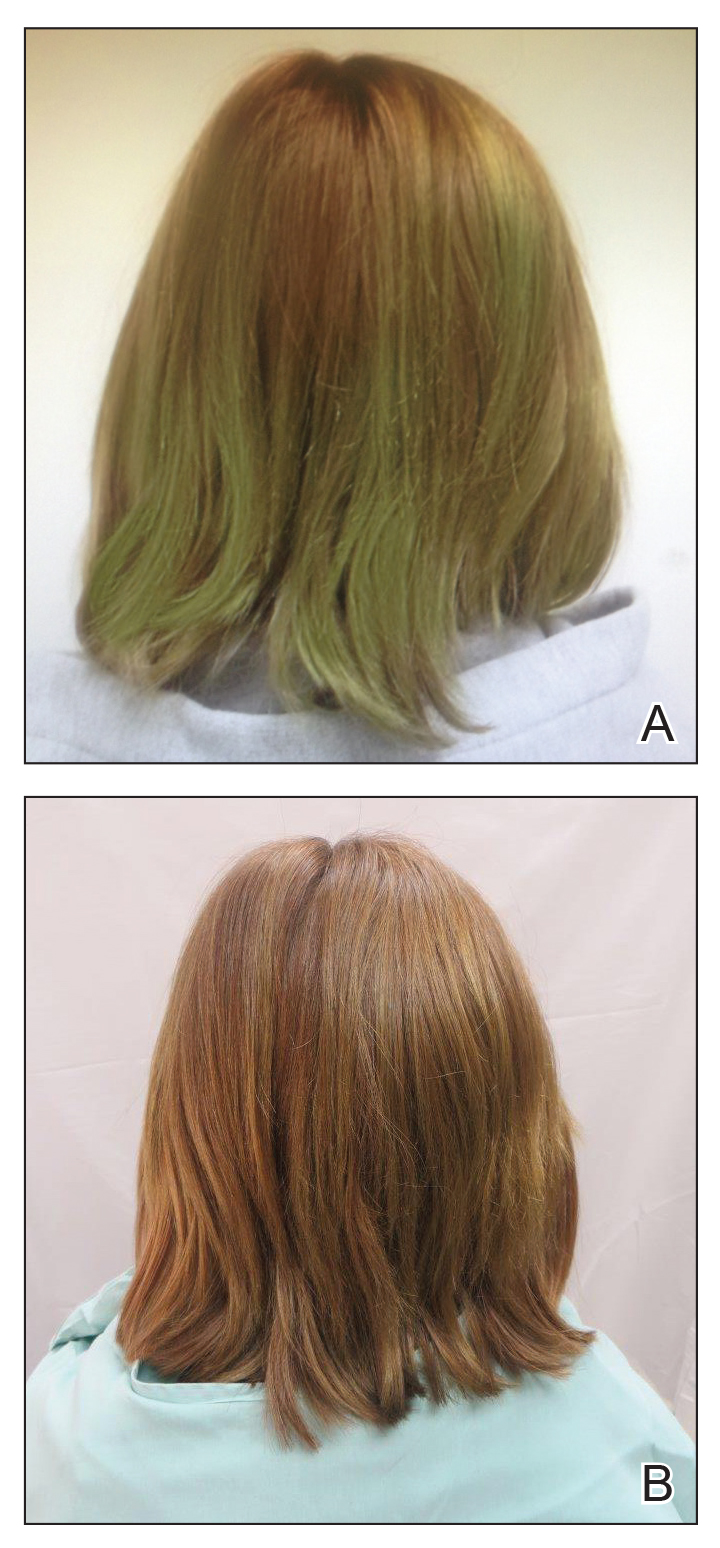

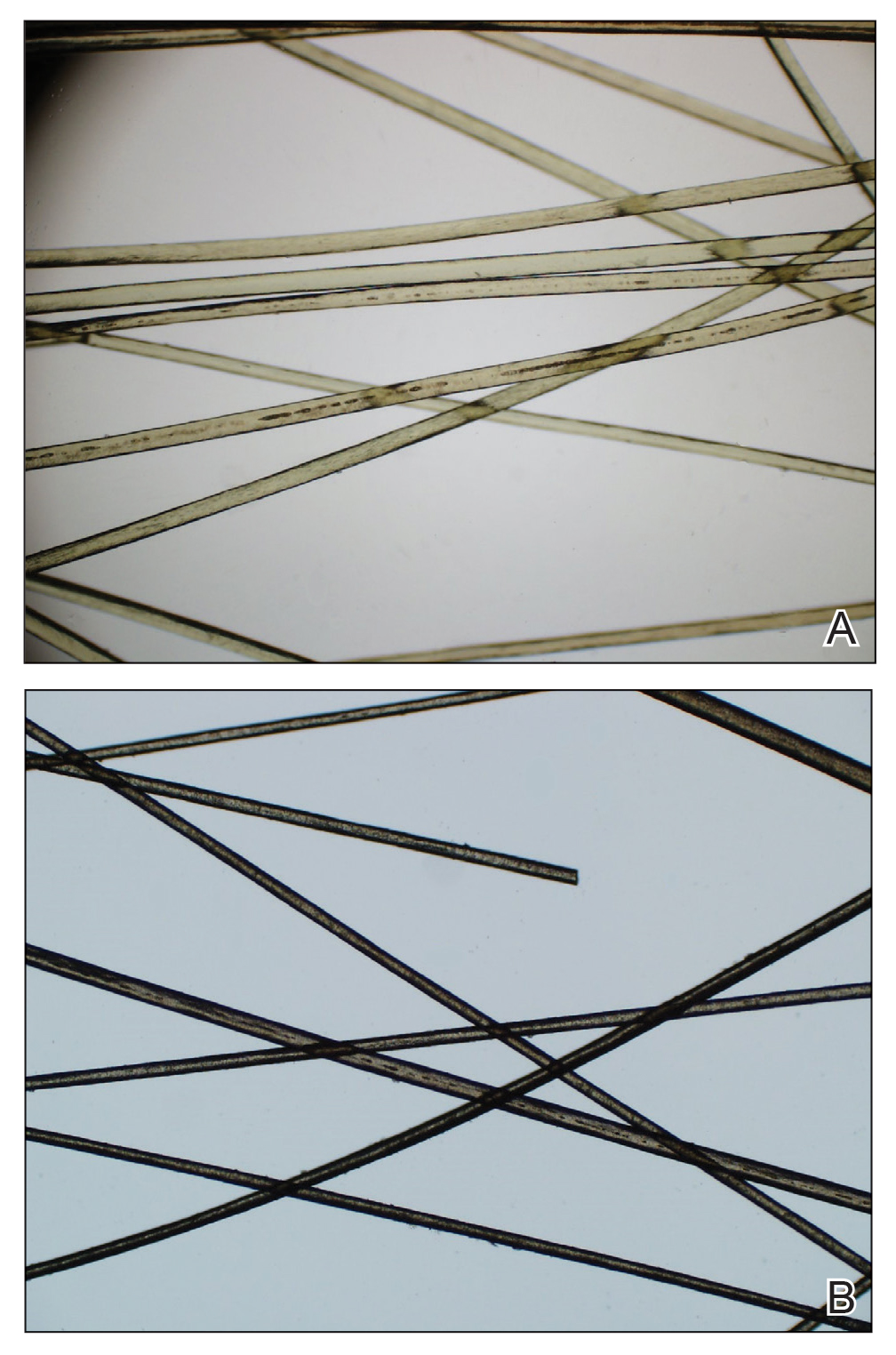

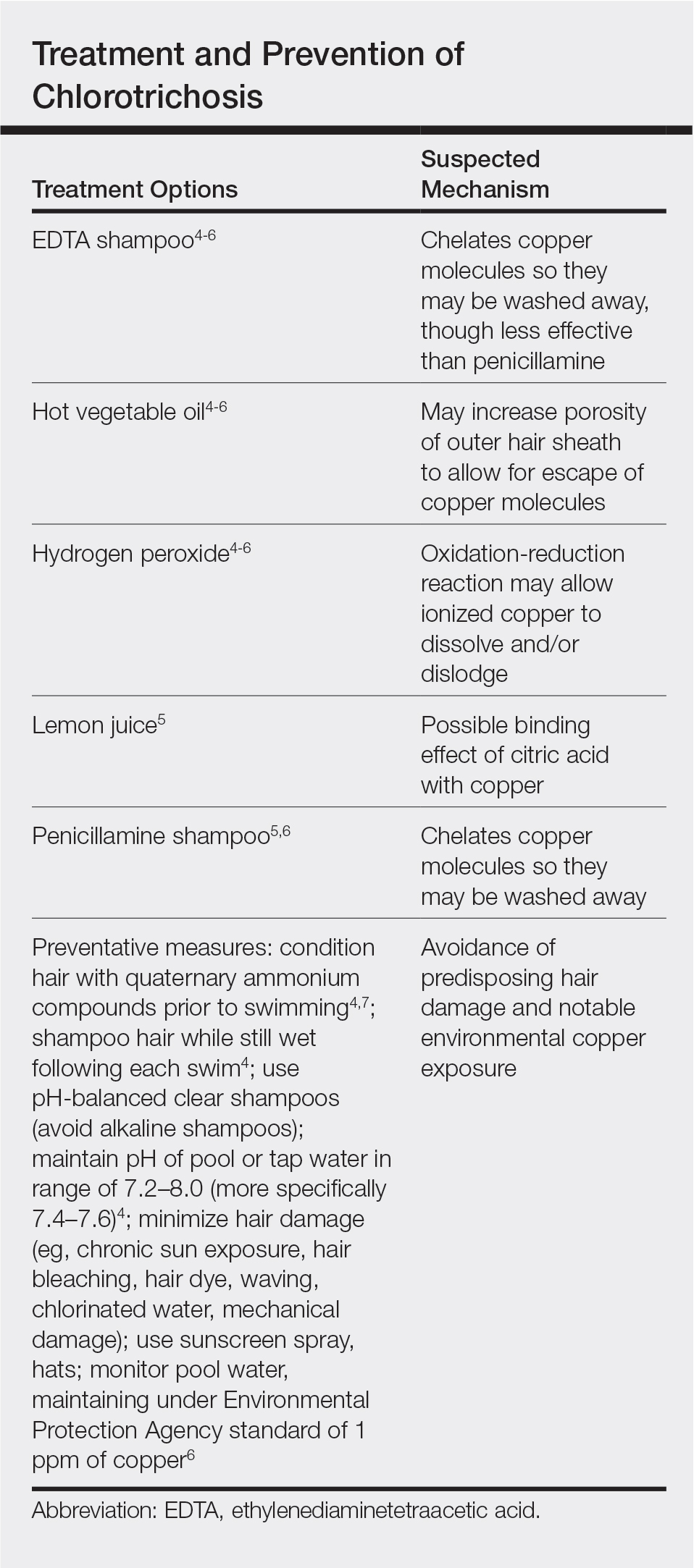

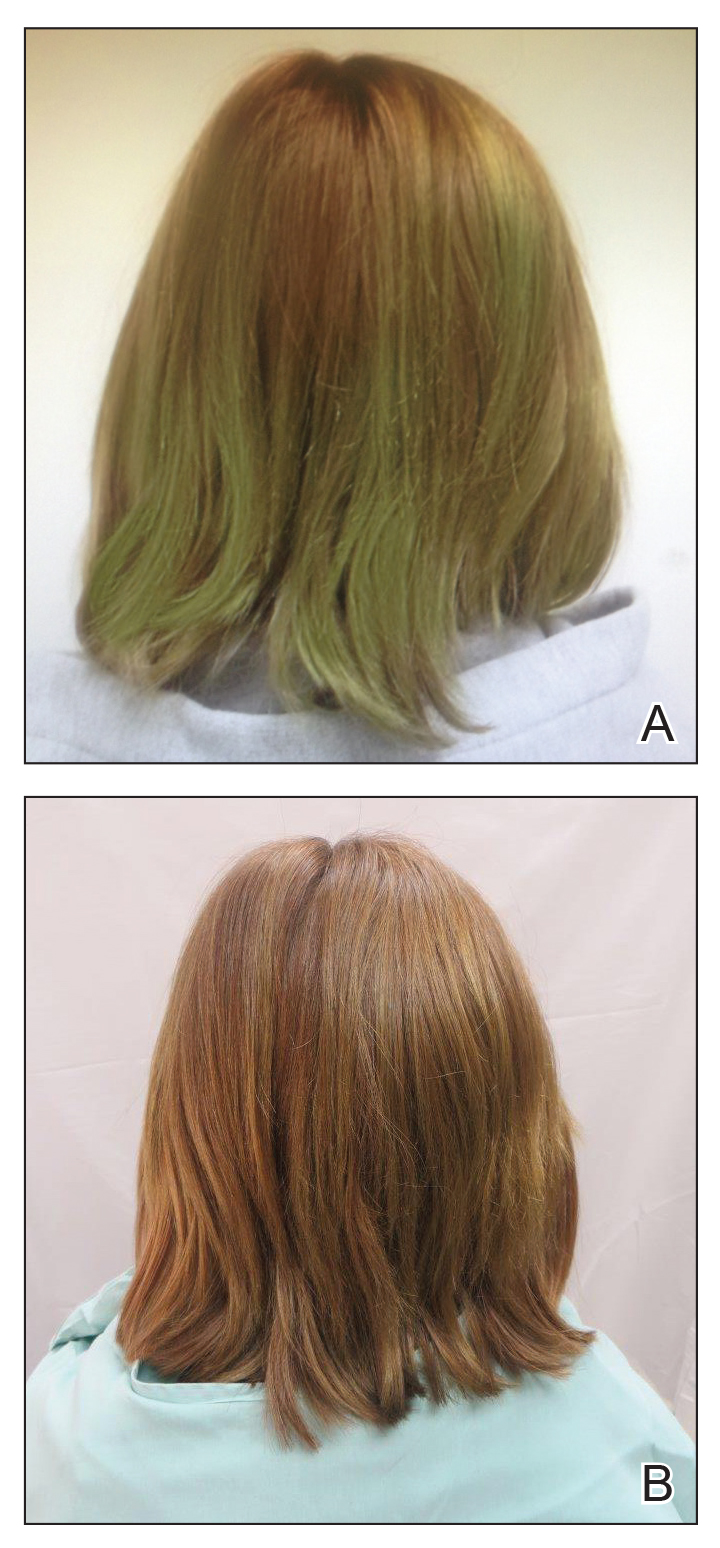

Chlorotrichosis, or green hair discoloration, is a dermatologic condition secondary to copper deposition on the hair. It most often is seen among swimmers who have prolonged exposure to chlorinated pools. The classic patient has predisposing chemical, heat, or mechanical damage to the hair shaft and usually lighter-colored hair.1-3 We present a case of chlorotrichosis in a young brunette patient who did not have predisposing factors except for chronic sun exposure.