User login

Metastatic angiosarcoma arising in a patient with long-standing treatment-refractory hemangioma

Angiosarcomas are malignant tumors of the vascular endothelium and are typically idiopathic. These tumors comprise 2% of all soft tissue sarcomas and have an estimated incidence of 2 per million.1,2 Known causes of angiosarcoma include genetic syndromes—such as von Hippel- Lindau, Chuvash polycythemia, Bannayan- Riley-Ruvalcaba, Cowden, and hamartomatous polyposis syndromes— chronic lymphedema, and exposure to radiation.3 Vinyl chloride, arsenicals, and thorotrast are known to increase the incidence of liver angiosarcoma.4

Malignant transformation of hemangioma is rare. We describe metastatic angiosarcoma in a patient with a large, longterm treatment-resistant subcutaneous hemangioma, illustrating such a possibility. We review similar cases and discuss the value of determining pathogenesis in such patients.

Case Presentation and Summary

A 55-year-old female with a long-standing childhood hemangioma of the left lower extremity was referred to Ochsner Medical Center for tissue diagnosis of new pulmonary nodules. Her medical history included a 7 pack-year smoking history; she had quit 3 years prior. Her family history included a sister who died from breast cancer. The patient initially had a progressive, intermittently bleeding tumor in the left foot at age 7. She was diagnosed with hemangioma in her twenties. At that point, her tumor began to involve the posterior calf and femur, causing deformity. She had multiple surgical resections but reportedly all pathology demonstrated benign hemangioma. She received radiation for pain, a routine treatment at the time, but developed a focus of progression in the heel. Above-knee amputation was considered but could not be performed when hemangioma was discovered in the hip area. She was lost to follow-up between 2001 and 2015. Lower extremity magnetic resonance imaging in 2015 was stable with imaging prior to 2001. A repeat biopsy in 2016 demonstrated hemangioma. The patient then received radiation to a wider field, including the femur, with minimal response. She completed a course of steroids as well. Bevacizumab was started in 2017 and improved foot deformity. She also briefly trialed pazopanib for 4 weeks in 2018 in an attempt to switch to oral medications. Despite partial response, she discontinued both agents in July 2018 because of toxicity and the burden of recurrent infusions.

Four months later, she presented with 2 months of intermittent hemoptysis and 18 months of metallic odors. Additionally, she lost 25 pounds in 3 months, which she attributed to a diet plan. At this visit, her left lower extremity exhibited multiple subcutaneous tumors and nodules.

Computed tomography (CT) with contrast demonstrated innumerable pulmonary nodules, the largest measuring 2.2 cm in the right lower lobe superior segment. Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT revealed 2 nodules with mild hypermetabolic activity; the largest nodule had a maximum standardized uptake value of 2.7. Bronchoalveolar lavage studies showed intra-alveolar hemorrhage with hemosiderin-laden macrophages. No malignancy, granuloma, or dysplasia was found in transbronchial needle aspirate of the largest nodule. The patient had no lymphadenopathy.

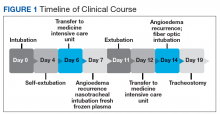

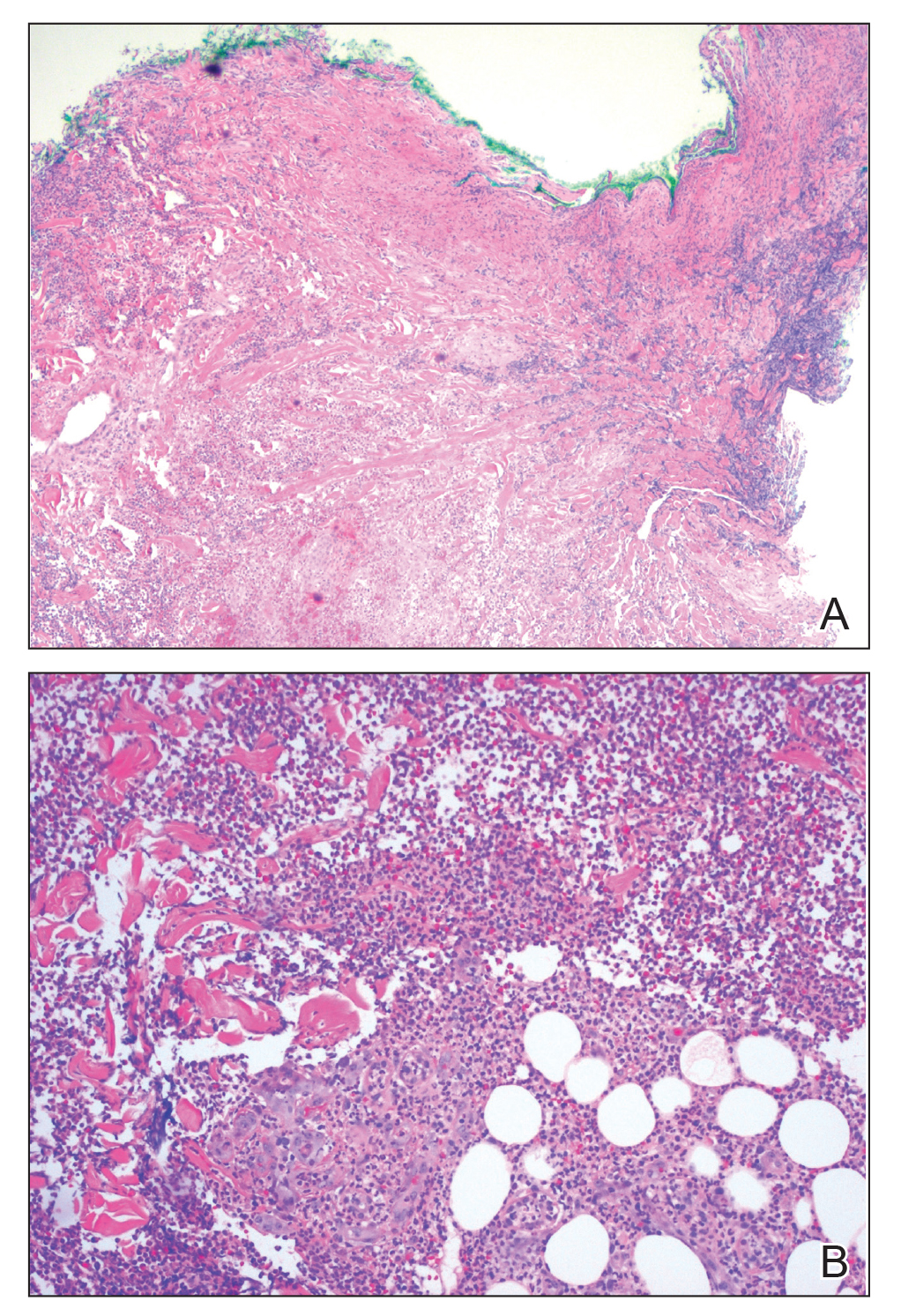

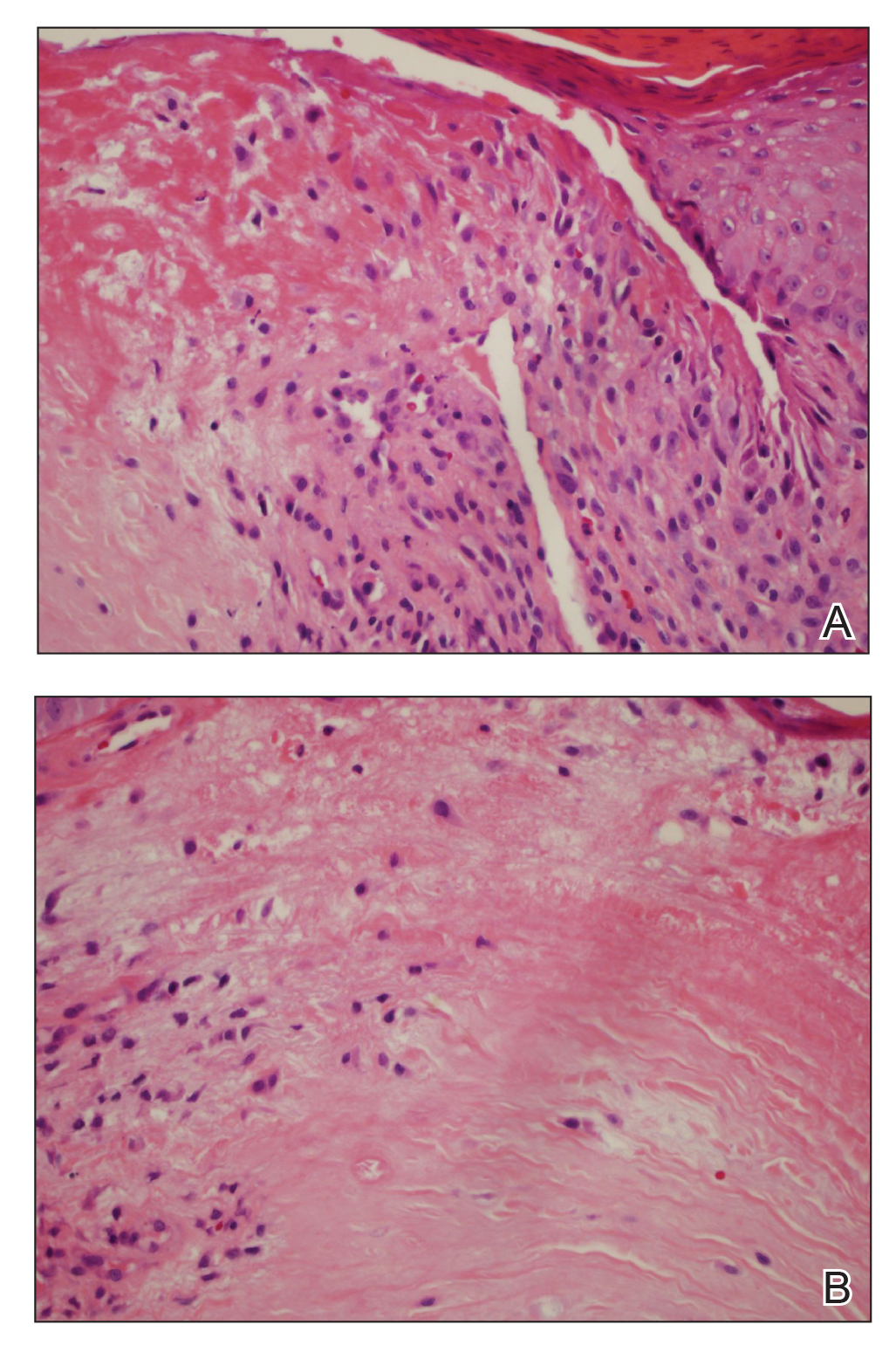

At this hospital, surgical resection by video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery confirmed multifocal malignant epithelioid neoplasm suspicious for angiosarcoma. Multiple areas showed proliferation of atypical epithelioid-to-spindle cells. There were prominent associated hemosiderin-laden macrophages, fresh red blood cells, and dilated blood-filled spaces. Cells demonstrated hyperchromasia with irregular nuclear contours, prominent nucleoli, and mitoses (FIGURE 1). Additionally, there were areas of focal organizing pneumonia. For atypical cells, staining was CD31-positive and CD34-negative. Staining was strongly positive for ERG. There was increased Ki-67 with retained INI expression and patchy weak reactivity for Fli-1.

Next-generation sequencing was performed. Specimen tumor content was 15%. Genomic findings included IDH1 p.R132C mutation, with variant allele frequency <10%. Testing was inconclusive for MSI and TMB mutations. PD-L1 assessment could not be performed. Unfortunately, the patient did not qualify for any clinical trials, as there were no matching alterations. This patient was lost to follow-up.

Discussion

Angiosarcoma accounts for 2% of soft tissue sarcomas.1 Cutaneous angiosarcomas most commonly occur in the face and scalp of the elderly, or in sites of chronic lymphedema. Angiosarcoma also develops following radiation therapy.5 For breast cancers and tumors of the head and neck, irradiation has <1% risk of inducing secondary malignancy, including angiosarcoma.6

This patient had a new diagnosis of angiosarcoma in the setting of long-standing benign hemangioma with history of radiation treatment. Thus, it is unclear whether this angiosarcoma was primary, radiation-induced, or secondary to transformation from the preexisting vascular tumor. Post-irradiation sarcoma carries a less favorable prognosis compared to de novo sarcoma; however, reports conflict on whether this holds for angiosarcoma subtypes.6 Determining etiology may benefit patients for prognostication and possibly inform future selection of treatment modalities.

The mutational signature in radiation- associated sarcomas differs from that of sporadic sarcomas. First, radiation- associated sarcomas demonstrate more frequent small deletions and balanced translocations. TP53 mutations are found in up to 1/3 of radiation-associated sarcomas and are more often due to small deletions than in sporadic sarcomas.7 High-level MYC amplification occurs in 54%-100% of secondary angiosarcomas, compared to 0-7% in sporadic angiosarcomas. Co-amplification of FLT4 occurs in 11%-25% of secondary angiosarcomas.8 Additionally, transcriptome analysis revealed differential expression of a 135-gene signature compared to non-radiation- induced sarcomas.7 Although this patient was not specifically analyzed for such alterations, such tests may differentiate post-irradiation angiosarcoma from sporadic etiologies.

In this patient, the R132C IDH1 mutation was identified and may be the first reported case in angiosarcoma. Typically, this mutation occurs in chondrosarcoma, myeloid neoplasms, gliomas, and cholangiocarcinomas. It is also found in spindle cell hemangiomas but not in other vascular tumors.9 The clinical significance of this mutation is uncertain at this time.

There are approximately 36 reported cases of malignant disease arising in patients with less aggressive vascular tumors (TABLE 1). Of these, 25 of 36 involve angiosarcoma arising in patients with hemangioma. Four cases of angiosarcoma were reported in patients with hemangioendothelioma, 1 case of hemangioendothelioma in a patient with hemangioma, 1 case of Dabska tumor in a patient with hemangioma, and 1 case of angiosarcoma in a patient with Dabska tumor. Fifteen cases involved initial disease with adult onset and 21 involved initial disease with pediatric onset, suggesting even distribution. Malignant disease mostly occurred in adulthood, in 26 out of 33 cases. Latency to malignancy ranged from concurrent discovery to 54 years. Mean latency, excluding cases with concurrent discovery, was shorter with adult-onset initial disease, at 4.2 years, compared to 16 years among patients with onset of initial disease in childhood. Longer latency in the pediatric-onset population correlated with longer latent periods for radiation-induced angiosarcoma following benign disease, which is reported to average 23 years.10 Thirteen of 19 cases with pediatric onset disease had a history of radiotherapy, while 2 of 13 cases with adult onset disease did. Sixteen cases involved tumor in the bone and soft tissue, as in this patient. Notably, 4 of these cases involved long-standing hemangioma for 10 years or more, as in this patient, suggesting a possible correlation between long-standing vascular tumors and malignant transformation. Angiosarcoma arising in non-irradiated patients suggests that malignant transformation and de novo transformation may compete with radiation-induced mutation in tumorigenesis. Further, 8 cases involved angiosarcoma growing within another vascular tumor, demonstrating the possibility of malignant transformation. Dehner and Ishak described a histological model for quantifying such a risk; a validated model may be particularly useful in patients with long-standing hemangioma.11

Etiology of tumorigenesis in cases of angiosarcoma arising in patients with a history of benign hemangioma may benefit prognostication and inform treatment selection in the future. Owing to long latent periods, radiation-associated angiosarcoma incidence may rise, as radiation therapy for benign hemangioma was recently routine. Future research may provide insight into disease progression and possibly predict the risk of angiosarcoma in patients with long-standing benign disease. TSJ

1. Tambe SA, Nayak CS. Metastatic angiosarcoma of lower extremity. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9(3)177-181.

2. Cioffi A, Reichert S, Antonescu CR, Maki RG. Angiosarcomas and other sarcomas of endothelial origin. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am.2013;27(5):975-988.

3. Cohen SM, Storer RD, Criswell KA, et al. Hemangiosarcoma in rodents: mode-of-action evaluation and human relevance. Toxicol Sci. 2009;111(1):4-18.

4. Popper H, Thomas LB, Telles NC, Falk H, Selikoff IJ. Development of hepatic angiosarcoma in man induced by vinyl chloride, thorotrast, and arsenic. Comparison with cases of unknown etiology. Am J Pathol. 1978;92(2):349- 376.

5. Mark RJ, Bailet JW, Poen J, et al. Postirradiation sarcoma of the head and neck. Cancer. 1993;72(3):887-893.

6. Torres KE, Ravi V, Kin K, et al. Long-term outcomes in patients with radiation-associated angiosarcomas of the breast following surgery and radiotherapy for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(4):1267-1274.

7. Mito JK, Mitra D, Doyle LA. Radiation-associated sarcomas: an update on clinical, histologic, and molecular features. Surg Pathol Clin. 2019;12(1):139-148.

8. Weidema ME, Versleijen-Jonkers YMH, Flucke UE, Desar IME, van der Graaf WTA. Targeting angiosarcomas of the soft tissues: A challenging effort in a heterogeneous and rare disease. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2019;138:120-131.

9. Kurek KC, Pansuriya TC, van Ruler MAJH, et al. R132C IDH1 mutations are found in spindle cell hemangiomas and not in other vascular tumors or malformations. Am J Pathol. 2013;182(5):1494-1500.

10. Goette DK, Detlefs RL. Postirradiation angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12(5 pt 2):922-926.

11. Dehner LP, Ishak KG. Vascular tumors of the liver in infants and children. A study of 30 cases and review of the literature. Arch Pathol. 1971;92(2):101-111.

Angiosarcomas are malignant tumors of the vascular endothelium and are typically idiopathic. These tumors comprise 2% of all soft tissue sarcomas and have an estimated incidence of 2 per million.1,2 Known causes of angiosarcoma include genetic syndromes—such as von Hippel- Lindau, Chuvash polycythemia, Bannayan- Riley-Ruvalcaba, Cowden, and hamartomatous polyposis syndromes— chronic lymphedema, and exposure to radiation.3 Vinyl chloride, arsenicals, and thorotrast are known to increase the incidence of liver angiosarcoma.4

Malignant transformation of hemangioma is rare. We describe metastatic angiosarcoma in a patient with a large, longterm treatment-resistant subcutaneous hemangioma, illustrating such a possibility. We review similar cases and discuss the value of determining pathogenesis in such patients.

Case Presentation and Summary

A 55-year-old female with a long-standing childhood hemangioma of the left lower extremity was referred to Ochsner Medical Center for tissue diagnosis of new pulmonary nodules. Her medical history included a 7 pack-year smoking history; she had quit 3 years prior. Her family history included a sister who died from breast cancer. The patient initially had a progressive, intermittently bleeding tumor in the left foot at age 7. She was diagnosed with hemangioma in her twenties. At that point, her tumor began to involve the posterior calf and femur, causing deformity. She had multiple surgical resections but reportedly all pathology demonstrated benign hemangioma. She received radiation for pain, a routine treatment at the time, but developed a focus of progression in the heel. Above-knee amputation was considered but could not be performed when hemangioma was discovered in the hip area. She was lost to follow-up between 2001 and 2015. Lower extremity magnetic resonance imaging in 2015 was stable with imaging prior to 2001. A repeat biopsy in 2016 demonstrated hemangioma. The patient then received radiation to a wider field, including the femur, with minimal response. She completed a course of steroids as well. Bevacizumab was started in 2017 and improved foot deformity. She also briefly trialed pazopanib for 4 weeks in 2018 in an attempt to switch to oral medications. Despite partial response, she discontinued both agents in July 2018 because of toxicity and the burden of recurrent infusions.

Four months later, she presented with 2 months of intermittent hemoptysis and 18 months of metallic odors. Additionally, she lost 25 pounds in 3 months, which she attributed to a diet plan. At this visit, her left lower extremity exhibited multiple subcutaneous tumors and nodules.

Computed tomography (CT) with contrast demonstrated innumerable pulmonary nodules, the largest measuring 2.2 cm in the right lower lobe superior segment. Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT revealed 2 nodules with mild hypermetabolic activity; the largest nodule had a maximum standardized uptake value of 2.7. Bronchoalveolar lavage studies showed intra-alveolar hemorrhage with hemosiderin-laden macrophages. No malignancy, granuloma, or dysplasia was found in transbronchial needle aspirate of the largest nodule. The patient had no lymphadenopathy.

At this hospital, surgical resection by video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery confirmed multifocal malignant epithelioid neoplasm suspicious for angiosarcoma. Multiple areas showed proliferation of atypical epithelioid-to-spindle cells. There were prominent associated hemosiderin-laden macrophages, fresh red blood cells, and dilated blood-filled spaces. Cells demonstrated hyperchromasia with irregular nuclear contours, prominent nucleoli, and mitoses (FIGURE 1). Additionally, there were areas of focal organizing pneumonia. For atypical cells, staining was CD31-positive and CD34-negative. Staining was strongly positive for ERG. There was increased Ki-67 with retained INI expression and patchy weak reactivity for Fli-1.

Next-generation sequencing was performed. Specimen tumor content was 15%. Genomic findings included IDH1 p.R132C mutation, with variant allele frequency <10%. Testing was inconclusive for MSI and TMB mutations. PD-L1 assessment could not be performed. Unfortunately, the patient did not qualify for any clinical trials, as there were no matching alterations. This patient was lost to follow-up.

Discussion

Angiosarcoma accounts for 2% of soft tissue sarcomas.1 Cutaneous angiosarcomas most commonly occur in the face and scalp of the elderly, or in sites of chronic lymphedema. Angiosarcoma also develops following radiation therapy.5 For breast cancers and tumors of the head and neck, irradiation has <1% risk of inducing secondary malignancy, including angiosarcoma.6

This patient had a new diagnosis of angiosarcoma in the setting of long-standing benign hemangioma with history of radiation treatment. Thus, it is unclear whether this angiosarcoma was primary, radiation-induced, or secondary to transformation from the preexisting vascular tumor. Post-irradiation sarcoma carries a less favorable prognosis compared to de novo sarcoma; however, reports conflict on whether this holds for angiosarcoma subtypes.6 Determining etiology may benefit patients for prognostication and possibly inform future selection of treatment modalities.

The mutational signature in radiation- associated sarcomas differs from that of sporadic sarcomas. First, radiation- associated sarcomas demonstrate more frequent small deletions and balanced translocations. TP53 mutations are found in up to 1/3 of radiation-associated sarcomas and are more often due to small deletions than in sporadic sarcomas.7 High-level MYC amplification occurs in 54%-100% of secondary angiosarcomas, compared to 0-7% in sporadic angiosarcomas. Co-amplification of FLT4 occurs in 11%-25% of secondary angiosarcomas.8 Additionally, transcriptome analysis revealed differential expression of a 135-gene signature compared to non-radiation- induced sarcomas.7 Although this patient was not specifically analyzed for such alterations, such tests may differentiate post-irradiation angiosarcoma from sporadic etiologies.

In this patient, the R132C IDH1 mutation was identified and may be the first reported case in angiosarcoma. Typically, this mutation occurs in chondrosarcoma, myeloid neoplasms, gliomas, and cholangiocarcinomas. It is also found in spindle cell hemangiomas but not in other vascular tumors.9 The clinical significance of this mutation is uncertain at this time.

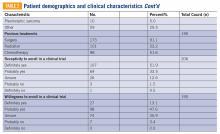

There are approximately 36 reported cases of malignant disease arising in patients with less aggressive vascular tumors (TABLE 1). Of these, 25 of 36 involve angiosarcoma arising in patients with hemangioma. Four cases of angiosarcoma were reported in patients with hemangioendothelioma, 1 case of hemangioendothelioma in a patient with hemangioma, 1 case of Dabska tumor in a patient with hemangioma, and 1 case of angiosarcoma in a patient with Dabska tumor. Fifteen cases involved initial disease with adult onset and 21 involved initial disease with pediatric onset, suggesting even distribution. Malignant disease mostly occurred in adulthood, in 26 out of 33 cases. Latency to malignancy ranged from concurrent discovery to 54 years. Mean latency, excluding cases with concurrent discovery, was shorter with adult-onset initial disease, at 4.2 years, compared to 16 years among patients with onset of initial disease in childhood. Longer latency in the pediatric-onset population correlated with longer latent periods for radiation-induced angiosarcoma following benign disease, which is reported to average 23 years.10 Thirteen of 19 cases with pediatric onset disease had a history of radiotherapy, while 2 of 13 cases with adult onset disease did. Sixteen cases involved tumor in the bone and soft tissue, as in this patient. Notably, 4 of these cases involved long-standing hemangioma for 10 years or more, as in this patient, suggesting a possible correlation between long-standing vascular tumors and malignant transformation. Angiosarcoma arising in non-irradiated patients suggests that malignant transformation and de novo transformation may compete with radiation-induced mutation in tumorigenesis. Further, 8 cases involved angiosarcoma growing within another vascular tumor, demonstrating the possibility of malignant transformation. Dehner and Ishak described a histological model for quantifying such a risk; a validated model may be particularly useful in patients with long-standing hemangioma.11

Etiology of tumorigenesis in cases of angiosarcoma arising in patients with a history of benign hemangioma may benefit prognostication and inform treatment selection in the future. Owing to long latent periods, radiation-associated angiosarcoma incidence may rise, as radiation therapy for benign hemangioma was recently routine. Future research may provide insight into disease progression and possibly predict the risk of angiosarcoma in patients with long-standing benign disease. TSJ

Angiosarcomas are malignant tumors of the vascular endothelium and are typically idiopathic. These tumors comprise 2% of all soft tissue sarcomas and have an estimated incidence of 2 per million.1,2 Known causes of angiosarcoma include genetic syndromes—such as von Hippel- Lindau, Chuvash polycythemia, Bannayan- Riley-Ruvalcaba, Cowden, and hamartomatous polyposis syndromes— chronic lymphedema, and exposure to radiation.3 Vinyl chloride, arsenicals, and thorotrast are known to increase the incidence of liver angiosarcoma.4

Malignant transformation of hemangioma is rare. We describe metastatic angiosarcoma in a patient with a large, longterm treatment-resistant subcutaneous hemangioma, illustrating such a possibility. We review similar cases and discuss the value of determining pathogenesis in such patients.

Case Presentation and Summary

A 55-year-old female with a long-standing childhood hemangioma of the left lower extremity was referred to Ochsner Medical Center for tissue diagnosis of new pulmonary nodules. Her medical history included a 7 pack-year smoking history; she had quit 3 years prior. Her family history included a sister who died from breast cancer. The patient initially had a progressive, intermittently bleeding tumor in the left foot at age 7. She was diagnosed with hemangioma in her twenties. At that point, her tumor began to involve the posterior calf and femur, causing deformity. She had multiple surgical resections but reportedly all pathology demonstrated benign hemangioma. She received radiation for pain, a routine treatment at the time, but developed a focus of progression in the heel. Above-knee amputation was considered but could not be performed when hemangioma was discovered in the hip area. She was lost to follow-up between 2001 and 2015. Lower extremity magnetic resonance imaging in 2015 was stable with imaging prior to 2001. A repeat biopsy in 2016 demonstrated hemangioma. The patient then received radiation to a wider field, including the femur, with minimal response. She completed a course of steroids as well. Bevacizumab was started in 2017 and improved foot deformity. She also briefly trialed pazopanib for 4 weeks in 2018 in an attempt to switch to oral medications. Despite partial response, she discontinued both agents in July 2018 because of toxicity and the burden of recurrent infusions.

Four months later, she presented with 2 months of intermittent hemoptysis and 18 months of metallic odors. Additionally, she lost 25 pounds in 3 months, which she attributed to a diet plan. At this visit, her left lower extremity exhibited multiple subcutaneous tumors and nodules.

Computed tomography (CT) with contrast demonstrated innumerable pulmonary nodules, the largest measuring 2.2 cm in the right lower lobe superior segment. Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT revealed 2 nodules with mild hypermetabolic activity; the largest nodule had a maximum standardized uptake value of 2.7. Bronchoalveolar lavage studies showed intra-alveolar hemorrhage with hemosiderin-laden macrophages. No malignancy, granuloma, or dysplasia was found in transbronchial needle aspirate of the largest nodule. The patient had no lymphadenopathy.

At this hospital, surgical resection by video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery confirmed multifocal malignant epithelioid neoplasm suspicious for angiosarcoma. Multiple areas showed proliferation of atypical epithelioid-to-spindle cells. There were prominent associated hemosiderin-laden macrophages, fresh red blood cells, and dilated blood-filled spaces. Cells demonstrated hyperchromasia with irregular nuclear contours, prominent nucleoli, and mitoses (FIGURE 1). Additionally, there were areas of focal organizing pneumonia. For atypical cells, staining was CD31-positive and CD34-negative. Staining was strongly positive for ERG. There was increased Ki-67 with retained INI expression and patchy weak reactivity for Fli-1.

Next-generation sequencing was performed. Specimen tumor content was 15%. Genomic findings included IDH1 p.R132C mutation, with variant allele frequency <10%. Testing was inconclusive for MSI and TMB mutations. PD-L1 assessment could not be performed. Unfortunately, the patient did not qualify for any clinical trials, as there were no matching alterations. This patient was lost to follow-up.

Discussion

Angiosarcoma accounts for 2% of soft tissue sarcomas.1 Cutaneous angiosarcomas most commonly occur in the face and scalp of the elderly, or in sites of chronic lymphedema. Angiosarcoma also develops following radiation therapy.5 For breast cancers and tumors of the head and neck, irradiation has <1% risk of inducing secondary malignancy, including angiosarcoma.6

This patient had a new diagnosis of angiosarcoma in the setting of long-standing benign hemangioma with history of radiation treatment. Thus, it is unclear whether this angiosarcoma was primary, radiation-induced, or secondary to transformation from the preexisting vascular tumor. Post-irradiation sarcoma carries a less favorable prognosis compared to de novo sarcoma; however, reports conflict on whether this holds for angiosarcoma subtypes.6 Determining etiology may benefit patients for prognostication and possibly inform future selection of treatment modalities.

The mutational signature in radiation- associated sarcomas differs from that of sporadic sarcomas. First, radiation- associated sarcomas demonstrate more frequent small deletions and balanced translocations. TP53 mutations are found in up to 1/3 of radiation-associated sarcomas and are more often due to small deletions than in sporadic sarcomas.7 High-level MYC amplification occurs in 54%-100% of secondary angiosarcomas, compared to 0-7% in sporadic angiosarcomas. Co-amplification of FLT4 occurs in 11%-25% of secondary angiosarcomas.8 Additionally, transcriptome analysis revealed differential expression of a 135-gene signature compared to non-radiation- induced sarcomas.7 Although this patient was not specifically analyzed for such alterations, such tests may differentiate post-irradiation angiosarcoma from sporadic etiologies.

In this patient, the R132C IDH1 mutation was identified and may be the first reported case in angiosarcoma. Typically, this mutation occurs in chondrosarcoma, myeloid neoplasms, gliomas, and cholangiocarcinomas. It is also found in spindle cell hemangiomas but not in other vascular tumors.9 The clinical significance of this mutation is uncertain at this time.

There are approximately 36 reported cases of malignant disease arising in patients with less aggressive vascular tumors (TABLE 1). Of these, 25 of 36 involve angiosarcoma arising in patients with hemangioma. Four cases of angiosarcoma were reported in patients with hemangioendothelioma, 1 case of hemangioendothelioma in a patient with hemangioma, 1 case of Dabska tumor in a patient with hemangioma, and 1 case of angiosarcoma in a patient with Dabska tumor. Fifteen cases involved initial disease with adult onset and 21 involved initial disease with pediatric onset, suggesting even distribution. Malignant disease mostly occurred in adulthood, in 26 out of 33 cases. Latency to malignancy ranged from concurrent discovery to 54 years. Mean latency, excluding cases with concurrent discovery, was shorter with adult-onset initial disease, at 4.2 years, compared to 16 years among patients with onset of initial disease in childhood. Longer latency in the pediatric-onset population correlated with longer latent periods for radiation-induced angiosarcoma following benign disease, which is reported to average 23 years.10 Thirteen of 19 cases with pediatric onset disease had a history of radiotherapy, while 2 of 13 cases with adult onset disease did. Sixteen cases involved tumor in the bone and soft tissue, as in this patient. Notably, 4 of these cases involved long-standing hemangioma for 10 years or more, as in this patient, suggesting a possible correlation between long-standing vascular tumors and malignant transformation. Angiosarcoma arising in non-irradiated patients suggests that malignant transformation and de novo transformation may compete with radiation-induced mutation in tumorigenesis. Further, 8 cases involved angiosarcoma growing within another vascular tumor, demonstrating the possibility of malignant transformation. Dehner and Ishak described a histological model for quantifying such a risk; a validated model may be particularly useful in patients with long-standing hemangioma.11

Etiology of tumorigenesis in cases of angiosarcoma arising in patients with a history of benign hemangioma may benefit prognostication and inform treatment selection in the future. Owing to long latent periods, radiation-associated angiosarcoma incidence may rise, as radiation therapy for benign hemangioma was recently routine. Future research may provide insight into disease progression and possibly predict the risk of angiosarcoma in patients with long-standing benign disease. TSJ

1. Tambe SA, Nayak CS. Metastatic angiosarcoma of lower extremity. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9(3)177-181.

2. Cioffi A, Reichert S, Antonescu CR, Maki RG. Angiosarcomas and other sarcomas of endothelial origin. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am.2013;27(5):975-988.

3. Cohen SM, Storer RD, Criswell KA, et al. Hemangiosarcoma in rodents: mode-of-action evaluation and human relevance. Toxicol Sci. 2009;111(1):4-18.

4. Popper H, Thomas LB, Telles NC, Falk H, Selikoff IJ. Development of hepatic angiosarcoma in man induced by vinyl chloride, thorotrast, and arsenic. Comparison with cases of unknown etiology. Am J Pathol. 1978;92(2):349- 376.

5. Mark RJ, Bailet JW, Poen J, et al. Postirradiation sarcoma of the head and neck. Cancer. 1993;72(3):887-893.

6. Torres KE, Ravi V, Kin K, et al. Long-term outcomes in patients with radiation-associated angiosarcomas of the breast following surgery and radiotherapy for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(4):1267-1274.

7. Mito JK, Mitra D, Doyle LA. Radiation-associated sarcomas: an update on clinical, histologic, and molecular features. Surg Pathol Clin. 2019;12(1):139-148.

8. Weidema ME, Versleijen-Jonkers YMH, Flucke UE, Desar IME, van der Graaf WTA. Targeting angiosarcomas of the soft tissues: A challenging effort in a heterogeneous and rare disease. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2019;138:120-131.

9. Kurek KC, Pansuriya TC, van Ruler MAJH, et al. R132C IDH1 mutations are found in spindle cell hemangiomas and not in other vascular tumors or malformations. Am J Pathol. 2013;182(5):1494-1500.

10. Goette DK, Detlefs RL. Postirradiation angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12(5 pt 2):922-926.

11. Dehner LP, Ishak KG. Vascular tumors of the liver in infants and children. A study of 30 cases and review of the literature. Arch Pathol. 1971;92(2):101-111.

1. Tambe SA, Nayak CS. Metastatic angiosarcoma of lower extremity. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9(3)177-181.

2. Cioffi A, Reichert S, Antonescu CR, Maki RG. Angiosarcomas and other sarcomas of endothelial origin. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am.2013;27(5):975-988.

3. Cohen SM, Storer RD, Criswell KA, et al. Hemangiosarcoma in rodents: mode-of-action evaluation and human relevance. Toxicol Sci. 2009;111(1):4-18.

4. Popper H, Thomas LB, Telles NC, Falk H, Selikoff IJ. Development of hepatic angiosarcoma in man induced by vinyl chloride, thorotrast, and arsenic. Comparison with cases of unknown etiology. Am J Pathol. 1978;92(2):349- 376.

5. Mark RJ, Bailet JW, Poen J, et al. Postirradiation sarcoma of the head and neck. Cancer. 1993;72(3):887-893.

6. Torres KE, Ravi V, Kin K, et al. Long-term outcomes in patients with radiation-associated angiosarcomas of the breast following surgery and radiotherapy for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(4):1267-1274.

7. Mito JK, Mitra D, Doyle LA. Radiation-associated sarcomas: an update on clinical, histologic, and molecular features. Surg Pathol Clin. 2019;12(1):139-148.

8. Weidema ME, Versleijen-Jonkers YMH, Flucke UE, Desar IME, van der Graaf WTA. Targeting angiosarcomas of the soft tissues: A challenging effort in a heterogeneous and rare disease. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2019;138:120-131.

9. Kurek KC, Pansuriya TC, van Ruler MAJH, et al. R132C IDH1 mutations are found in spindle cell hemangiomas and not in other vascular tumors or malformations. Am J Pathol. 2013;182(5):1494-1500.

10. Goette DK, Detlefs RL. Postirradiation angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12(5 pt 2):922-926.

11. Dehner LP, Ishak KG. Vascular tumors of the liver in infants and children. A study of 30 cases and review of the literature. Arch Pathol. 1971;92(2):101-111.

Was this patient's transdermal Tx making her dog sick?

THE CASE

A 56-year-old postmenopausal woman with a history of anxiety, depression, alcohol abuse, fatigue, insomnia, and mental fogginess presented to the family medicine clinic with concerns about her companion animal because of symptoms possibly associated with the patient’s medication. Of note, the patient’s physical exam was unremarkable.

The patient noticed that her 5-year-old, 4.5-lb spayed female Chihuahua dog was exhibiting peculiar behaviors, including excessive licking of the abdomen, nipples, and vulvar areas and straining with urination. The dog’s symptoms had started 1 week after the patient began using estradiol transdermal spray (Evamist) for her menopause symptoms. The patient’s menopause symptoms included hot flushes, insomnia, and mental fogginess.

The patient had been applying the estradiol transdermal spray on her inner forearm twice daily, in the morning and at bedtime. She would let the applied medication dry for approximately 2 hours before allowing her arm to come in contact with other items. She worried that some of the hormone may have wiped off onto her couch, pillows, blankets, and other surfaces. In addition, she often cradled the dog in her arms, which allowed the canine’s back to come in contact with her inner forearms. To her knowledge, the dog did not lick or ingest the medication.

The patient had taken the dog to her veterinarian. On physical exam, the veterinarian noted that the dog had nipple and vulvar enlargement but no vaginal discharge, vaginal bleeding, skin changes, or urine abnormalities.

THE (PET’S) DIAGNOSIS, THE PATIENT’S Rx

The veterinarian diagnosed the Chihuahua with vaginal hyperplasia and vulvar enlargement secondary to hyperestrogenism. The animal’s symptoms were likely caused by exposure to the owner’s hormone replacement therapy (HRT) medication—the estradiol spray. The veterinarian advised the woman to return to her family physician to discuss her use of the topical estrogen.

The patient asked her physician (SS) to change her HRT formulation. She was given a prescription for an estradiol 0.05 mg/24-hour transdermal patch to be placed on her abdomen twice weekly. After 2 weeks of using the patch therapy, the patient’s menopausal symptoms were reported to be well controlled. In addition, the companion animal’s breast and vulvar changes resolved, as did the dog’s licking behavior.

DISCUSSION

Estrogen therapy, with or without progesterone, is the most effective treatment for postmenopausal vasomotor symptoms.1 Given the concerns raised in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) and other clinical trials regarding hormone therapy and cardiovascular and breast cancer findings, many clinicians look to alternative, nonoral dosage forms to improve the safety profile.

Continue to: Safety of nonroal estrogen therapy

Safety of nonoral estrogen therapy. Administration of nonoral estrogen is associated with avoidance of hepatic first-pass metabolism and a resulting lower impact on hepatic proteins. Thus, data indicate a potentially lower risk for venous thromboembolic events with transdermal estrogen compared to oral estrogen.1 Since the publication of the results of the WHI trials, prescribing patterns in the United States indicate a general decline in the proportion of oral hormones, while transdermal prescription volume has remained steady, and the use of vaginal formulations has increased.2

Topical estrogen formulations. Transdermal or topical delivery of estrogen can be achieved through various formulations, including patches, gels, and a spray. While patches are simple to use, some women display hypersensitivity to the adhesive. Use of gel and spray formulations avoids exposure to adhesives, but these pose a risk of transfer of hormonal ingredients that are not covered by a patch. This risk is amplified by the relative accessibility of the product-specific application sites, which include the arms or thighs. Each manufacturer recommends careful handwashing after handling the product, a specific drying time before the user covers the site with clothing, and avoidance of contact with the application site for a prescribed period of time, usually at least 1 to 2 hours.3-6

Our patient. This case illustrates the importance of discussing the risk of medication transfer to both humans and animals when prescribing individualized hormone therapy. While the Evamist prescribing information specifically addresses the risk of unintentional medication transfer to children, it does not discuss other contact risks.6 In the literature, there have been a limited number of reports on the adverse effects from transdermal or topical human medication transfer to pets. Notably, the American Pet Products Association estimates that in the United States, approximately 90 million dogs and 94 million cats are owned as a pet in 67% of households.7

THE TAKEAWAY

Use of HRT, including transdermal or topical estrogen formulations, is common. Given the large number of companion animals in the United States, physicians should consider that all members of a patient’s household—including pets—may be subject to unintentional secondary exposure to topical estrogen formulations and that they may experience adverse effects. This presents an opportunity for patient education, which can have a larger impact on all occupants of the home.

CORRESPONDENCE

Shannon Scott, DO, FACOFP, Clinical Associate Professor, Arizona College of Osteopathic Medicine, 19389 North 59th Avenue, Glendale, AZ 85308; [email protected].

1. The NAMS 2017 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017;24:728-753.

2. Steinkellner AR, Denison SE, Eldridge SL, et al. A decade of postmenopausal hormone therapy prescribing in the United States: long-term effects of the Women’s Health Initiative. Menopause. 2012;19:616-621.

3. Divigel [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Vertical Pharmaceuticals, LLC; 2014.

4. Elestrin [package insert]. Somerset, NJ: Meda Pharmaceuticals; 2014.

5. Estrogel [package insert]. Herndon, VA: Ascend Therapeutics; 2018.

6. Evamist [package insert]. Minneapolis, MN: Perrigo; 2017.

7. American Pet Products Association. Pet Industry Market Size & Ownership Statistics. www.americanpetproducts.org/press_industrytrends.asp. Accessed November 1, 2019.

THE CASE

A 56-year-old postmenopausal woman with a history of anxiety, depression, alcohol abuse, fatigue, insomnia, and mental fogginess presented to the family medicine clinic with concerns about her companion animal because of symptoms possibly associated with the patient’s medication. Of note, the patient’s physical exam was unremarkable.

The patient noticed that her 5-year-old, 4.5-lb spayed female Chihuahua dog was exhibiting peculiar behaviors, including excessive licking of the abdomen, nipples, and vulvar areas and straining with urination. The dog’s symptoms had started 1 week after the patient began using estradiol transdermal spray (Evamist) for her menopause symptoms. The patient’s menopause symptoms included hot flushes, insomnia, and mental fogginess.

The patient had been applying the estradiol transdermal spray on her inner forearm twice daily, in the morning and at bedtime. She would let the applied medication dry for approximately 2 hours before allowing her arm to come in contact with other items. She worried that some of the hormone may have wiped off onto her couch, pillows, blankets, and other surfaces. In addition, she often cradled the dog in her arms, which allowed the canine’s back to come in contact with her inner forearms. To her knowledge, the dog did not lick or ingest the medication.

The patient had taken the dog to her veterinarian. On physical exam, the veterinarian noted that the dog had nipple and vulvar enlargement but no vaginal discharge, vaginal bleeding, skin changes, or urine abnormalities.

THE (PET’S) DIAGNOSIS, THE PATIENT’S Rx

The veterinarian diagnosed the Chihuahua with vaginal hyperplasia and vulvar enlargement secondary to hyperestrogenism. The animal’s symptoms were likely caused by exposure to the owner’s hormone replacement therapy (HRT) medication—the estradiol spray. The veterinarian advised the woman to return to her family physician to discuss her use of the topical estrogen.

The patient asked her physician (SS) to change her HRT formulation. She was given a prescription for an estradiol 0.05 mg/24-hour transdermal patch to be placed on her abdomen twice weekly. After 2 weeks of using the patch therapy, the patient’s menopausal symptoms were reported to be well controlled. In addition, the companion animal’s breast and vulvar changes resolved, as did the dog’s licking behavior.

DISCUSSION

Estrogen therapy, with or without progesterone, is the most effective treatment for postmenopausal vasomotor symptoms.1 Given the concerns raised in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) and other clinical trials regarding hormone therapy and cardiovascular and breast cancer findings, many clinicians look to alternative, nonoral dosage forms to improve the safety profile.

Continue to: Safety of nonroal estrogen therapy

Safety of nonoral estrogen therapy. Administration of nonoral estrogen is associated with avoidance of hepatic first-pass metabolism and a resulting lower impact on hepatic proteins. Thus, data indicate a potentially lower risk for venous thromboembolic events with transdermal estrogen compared to oral estrogen.1 Since the publication of the results of the WHI trials, prescribing patterns in the United States indicate a general decline in the proportion of oral hormones, while transdermal prescription volume has remained steady, and the use of vaginal formulations has increased.2

Topical estrogen formulations. Transdermal or topical delivery of estrogen can be achieved through various formulations, including patches, gels, and a spray. While patches are simple to use, some women display hypersensitivity to the adhesive. Use of gel and spray formulations avoids exposure to adhesives, but these pose a risk of transfer of hormonal ingredients that are not covered by a patch. This risk is amplified by the relative accessibility of the product-specific application sites, which include the arms or thighs. Each manufacturer recommends careful handwashing after handling the product, a specific drying time before the user covers the site with clothing, and avoidance of contact with the application site for a prescribed period of time, usually at least 1 to 2 hours.3-6

Our patient. This case illustrates the importance of discussing the risk of medication transfer to both humans and animals when prescribing individualized hormone therapy. While the Evamist prescribing information specifically addresses the risk of unintentional medication transfer to children, it does not discuss other contact risks.6 In the literature, there have been a limited number of reports on the adverse effects from transdermal or topical human medication transfer to pets. Notably, the American Pet Products Association estimates that in the United States, approximately 90 million dogs and 94 million cats are owned as a pet in 67% of households.7

THE TAKEAWAY

Use of HRT, including transdermal or topical estrogen formulations, is common. Given the large number of companion animals in the United States, physicians should consider that all members of a patient’s household—including pets—may be subject to unintentional secondary exposure to topical estrogen formulations and that they may experience adverse effects. This presents an opportunity for patient education, which can have a larger impact on all occupants of the home.

CORRESPONDENCE

Shannon Scott, DO, FACOFP, Clinical Associate Professor, Arizona College of Osteopathic Medicine, 19389 North 59th Avenue, Glendale, AZ 85308; [email protected].

THE CASE

A 56-year-old postmenopausal woman with a history of anxiety, depression, alcohol abuse, fatigue, insomnia, and mental fogginess presented to the family medicine clinic with concerns about her companion animal because of symptoms possibly associated with the patient’s medication. Of note, the patient’s physical exam was unremarkable.

The patient noticed that her 5-year-old, 4.5-lb spayed female Chihuahua dog was exhibiting peculiar behaviors, including excessive licking of the abdomen, nipples, and vulvar areas and straining with urination. The dog’s symptoms had started 1 week after the patient began using estradiol transdermal spray (Evamist) for her menopause symptoms. The patient’s menopause symptoms included hot flushes, insomnia, and mental fogginess.

The patient had been applying the estradiol transdermal spray on her inner forearm twice daily, in the morning and at bedtime. She would let the applied medication dry for approximately 2 hours before allowing her arm to come in contact with other items. She worried that some of the hormone may have wiped off onto her couch, pillows, blankets, and other surfaces. In addition, she often cradled the dog in her arms, which allowed the canine’s back to come in contact with her inner forearms. To her knowledge, the dog did not lick or ingest the medication.

The patient had taken the dog to her veterinarian. On physical exam, the veterinarian noted that the dog had nipple and vulvar enlargement but no vaginal discharge, vaginal bleeding, skin changes, or urine abnormalities.

THE (PET’S) DIAGNOSIS, THE PATIENT’S Rx

The veterinarian diagnosed the Chihuahua with vaginal hyperplasia and vulvar enlargement secondary to hyperestrogenism. The animal’s symptoms were likely caused by exposure to the owner’s hormone replacement therapy (HRT) medication—the estradiol spray. The veterinarian advised the woman to return to her family physician to discuss her use of the topical estrogen.

The patient asked her physician (SS) to change her HRT formulation. She was given a prescription for an estradiol 0.05 mg/24-hour transdermal patch to be placed on her abdomen twice weekly. After 2 weeks of using the patch therapy, the patient’s menopausal symptoms were reported to be well controlled. In addition, the companion animal’s breast and vulvar changes resolved, as did the dog’s licking behavior.

DISCUSSION

Estrogen therapy, with or without progesterone, is the most effective treatment for postmenopausal vasomotor symptoms.1 Given the concerns raised in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) and other clinical trials regarding hormone therapy and cardiovascular and breast cancer findings, many clinicians look to alternative, nonoral dosage forms to improve the safety profile.

Continue to: Safety of nonroal estrogen therapy

Safety of nonoral estrogen therapy. Administration of nonoral estrogen is associated with avoidance of hepatic first-pass metabolism and a resulting lower impact on hepatic proteins. Thus, data indicate a potentially lower risk for venous thromboembolic events with transdermal estrogen compared to oral estrogen.1 Since the publication of the results of the WHI trials, prescribing patterns in the United States indicate a general decline in the proportion of oral hormones, while transdermal prescription volume has remained steady, and the use of vaginal formulations has increased.2

Topical estrogen formulations. Transdermal or topical delivery of estrogen can be achieved through various formulations, including patches, gels, and a spray. While patches are simple to use, some women display hypersensitivity to the adhesive. Use of gel and spray formulations avoids exposure to adhesives, but these pose a risk of transfer of hormonal ingredients that are not covered by a patch. This risk is amplified by the relative accessibility of the product-specific application sites, which include the arms or thighs. Each manufacturer recommends careful handwashing after handling the product, a specific drying time before the user covers the site with clothing, and avoidance of contact with the application site for a prescribed period of time, usually at least 1 to 2 hours.3-6

Our patient. This case illustrates the importance of discussing the risk of medication transfer to both humans and animals when prescribing individualized hormone therapy. While the Evamist prescribing information specifically addresses the risk of unintentional medication transfer to children, it does not discuss other contact risks.6 In the literature, there have been a limited number of reports on the adverse effects from transdermal or topical human medication transfer to pets. Notably, the American Pet Products Association estimates that in the United States, approximately 90 million dogs and 94 million cats are owned as a pet in 67% of households.7

THE TAKEAWAY

Use of HRT, including transdermal or topical estrogen formulations, is common. Given the large number of companion animals in the United States, physicians should consider that all members of a patient’s household—including pets—may be subject to unintentional secondary exposure to topical estrogen formulations and that they may experience adverse effects. This presents an opportunity for patient education, which can have a larger impact on all occupants of the home.

CORRESPONDENCE

Shannon Scott, DO, FACOFP, Clinical Associate Professor, Arizona College of Osteopathic Medicine, 19389 North 59th Avenue, Glendale, AZ 85308; [email protected].

1. The NAMS 2017 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017;24:728-753.

2. Steinkellner AR, Denison SE, Eldridge SL, et al. A decade of postmenopausal hormone therapy prescribing in the United States: long-term effects of the Women’s Health Initiative. Menopause. 2012;19:616-621.

3. Divigel [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Vertical Pharmaceuticals, LLC; 2014.

4. Elestrin [package insert]. Somerset, NJ: Meda Pharmaceuticals; 2014.

5. Estrogel [package insert]. Herndon, VA: Ascend Therapeutics; 2018.

6. Evamist [package insert]. Minneapolis, MN: Perrigo; 2017.

7. American Pet Products Association. Pet Industry Market Size & Ownership Statistics. www.americanpetproducts.org/press_industrytrends.asp. Accessed November 1, 2019.

1. The NAMS 2017 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017;24:728-753.

2. Steinkellner AR, Denison SE, Eldridge SL, et al. A decade of postmenopausal hormone therapy prescribing in the United States: long-term effects of the Women’s Health Initiative. Menopause. 2012;19:616-621.

3. Divigel [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Vertical Pharmaceuticals, LLC; 2014.

4. Elestrin [package insert]. Somerset, NJ: Meda Pharmaceuticals; 2014.

5. Estrogel [package insert]. Herndon, VA: Ascend Therapeutics; 2018.

6. Evamist [package insert]. Minneapolis, MN: Perrigo; 2017.

7. American Pet Products Association. Pet Industry Market Size & Ownership Statistics. www.americanpetproducts.org/press_industrytrends.asp. Accessed November 1, 2019.

Pyoderma Gangrenosum Developing After Chest Tube Placement in a Patient With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

Diagnosis of a neutrophilic dermatosis, such as pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), often is challenging at onset because it can be impossible to distinguish clinically and histopathologically from acute infection in an immunosuppressed patient, necessitating a detailed history as well as correlation pathology with microbial tissue cultures. The dermatologist’s ability to distinguish a neutrophilic dermatosis from active infection is of paramount importance because the decision to treat with surgical debridement, in addition to an antibiotic regimen, can have grave consequences in the misdiagnosed patient.

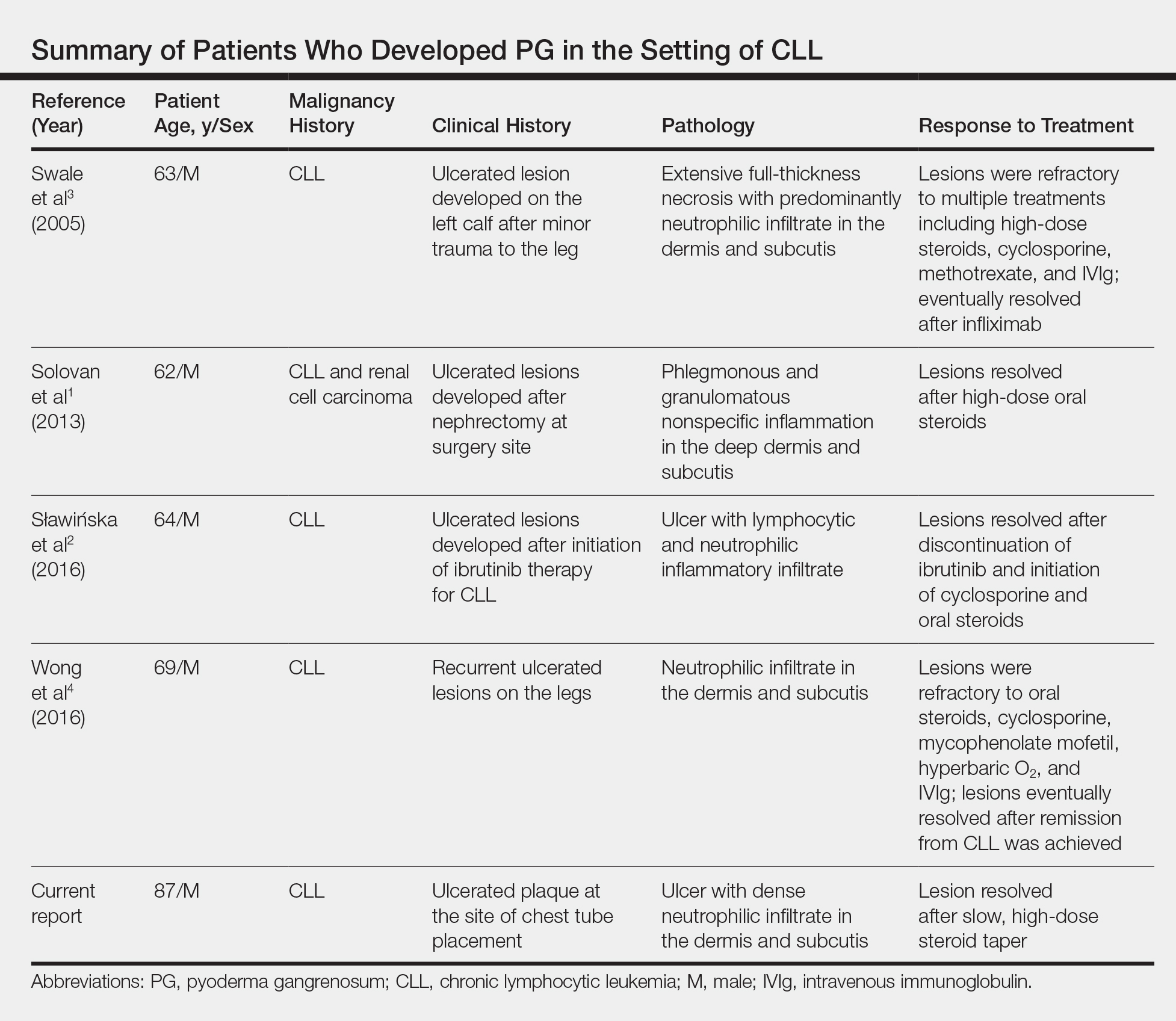

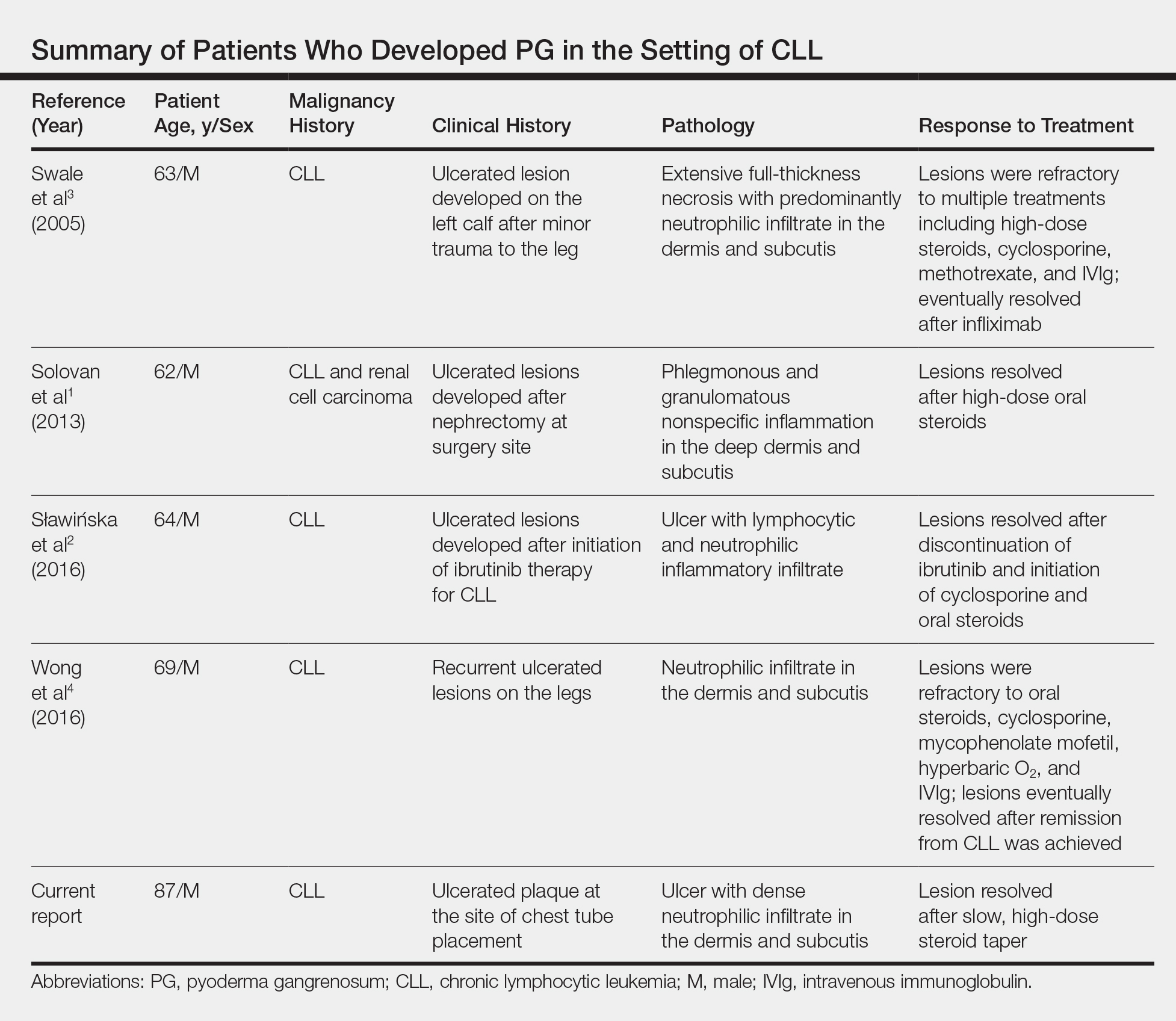

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis histologically characterized by a pandermal neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of an infectious cause or true vasculitis. It is classically associated with inflammatory bowel disease or an underlying hematologic malignancy. Pyoderma gangrenosum in the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is rare, with as few as 4 cases having been described in the literature and only 1 case of PG developing after a surgical procedure.1-4 We present a case of PG occurring at a chest tube site in a patient with CLL. We highlight the challenges and therapeutic importance of arriving at the correct diagnosis.

Case Report

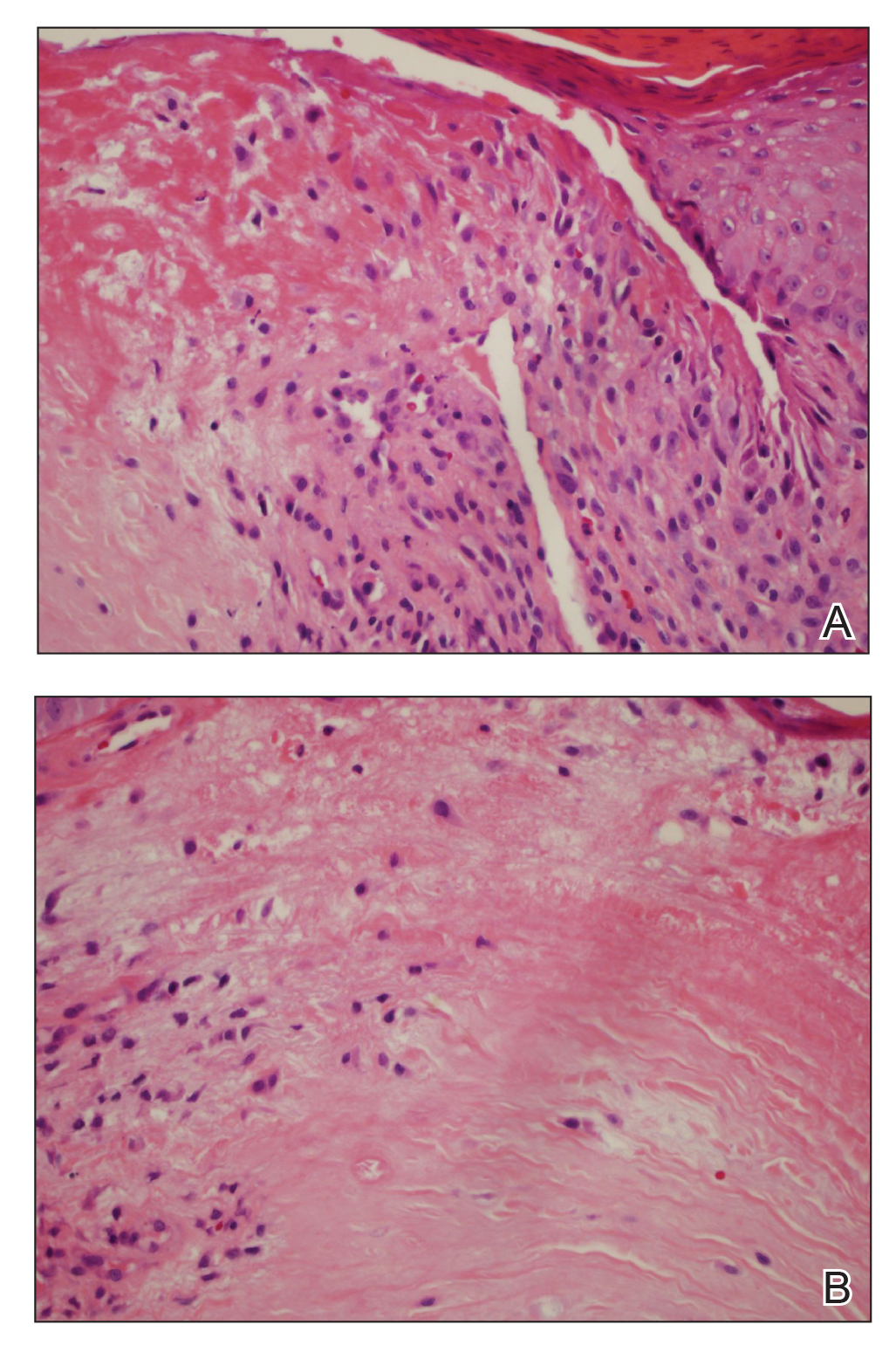

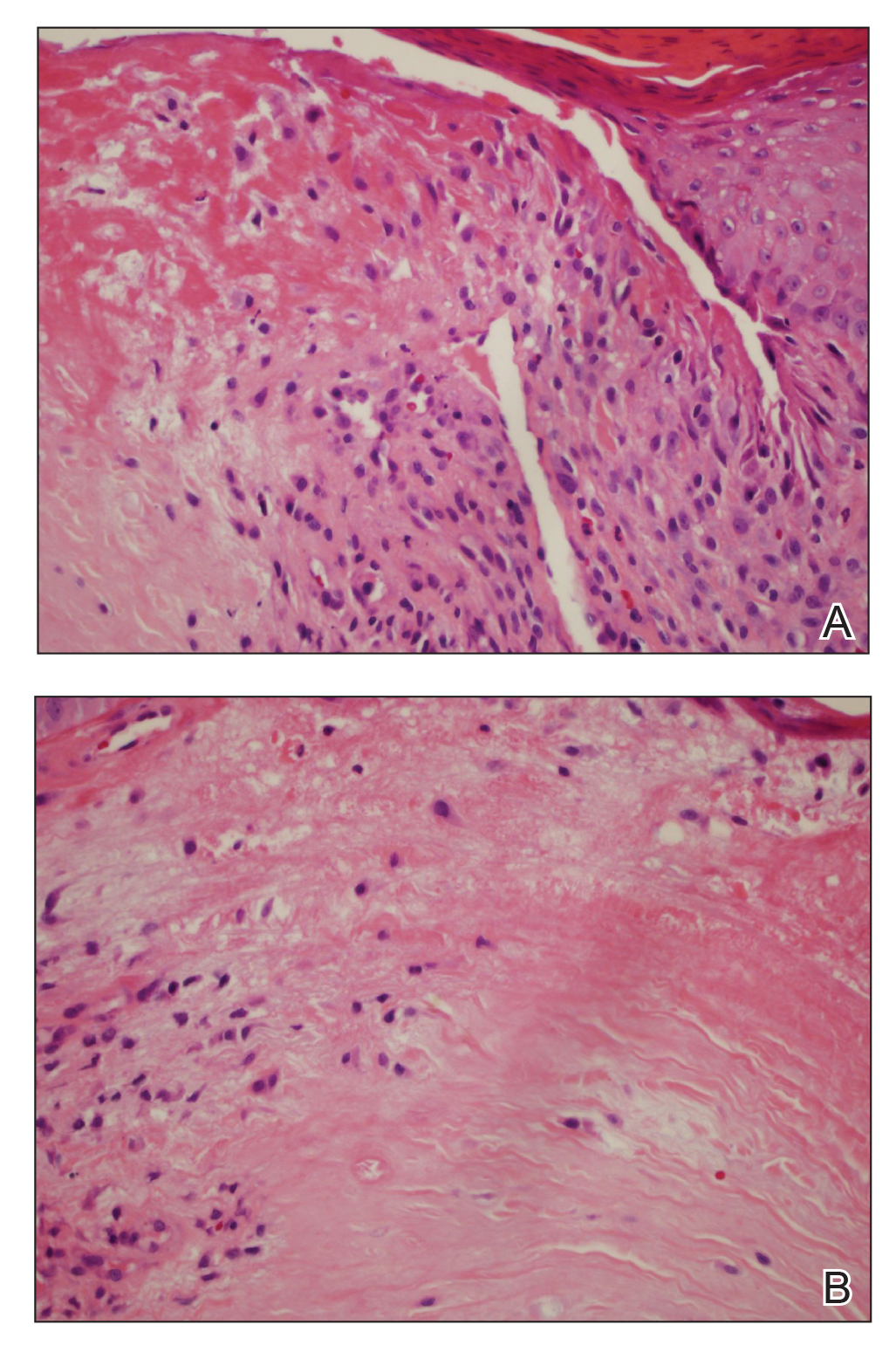

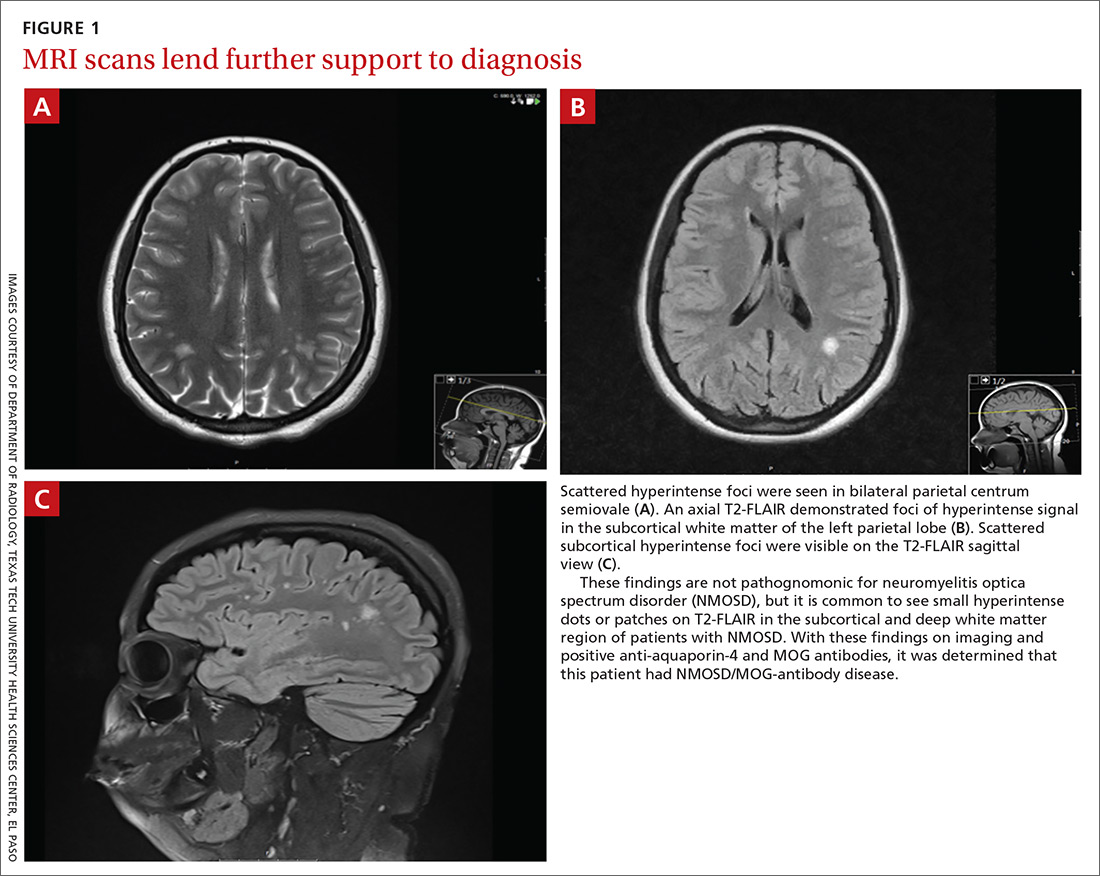

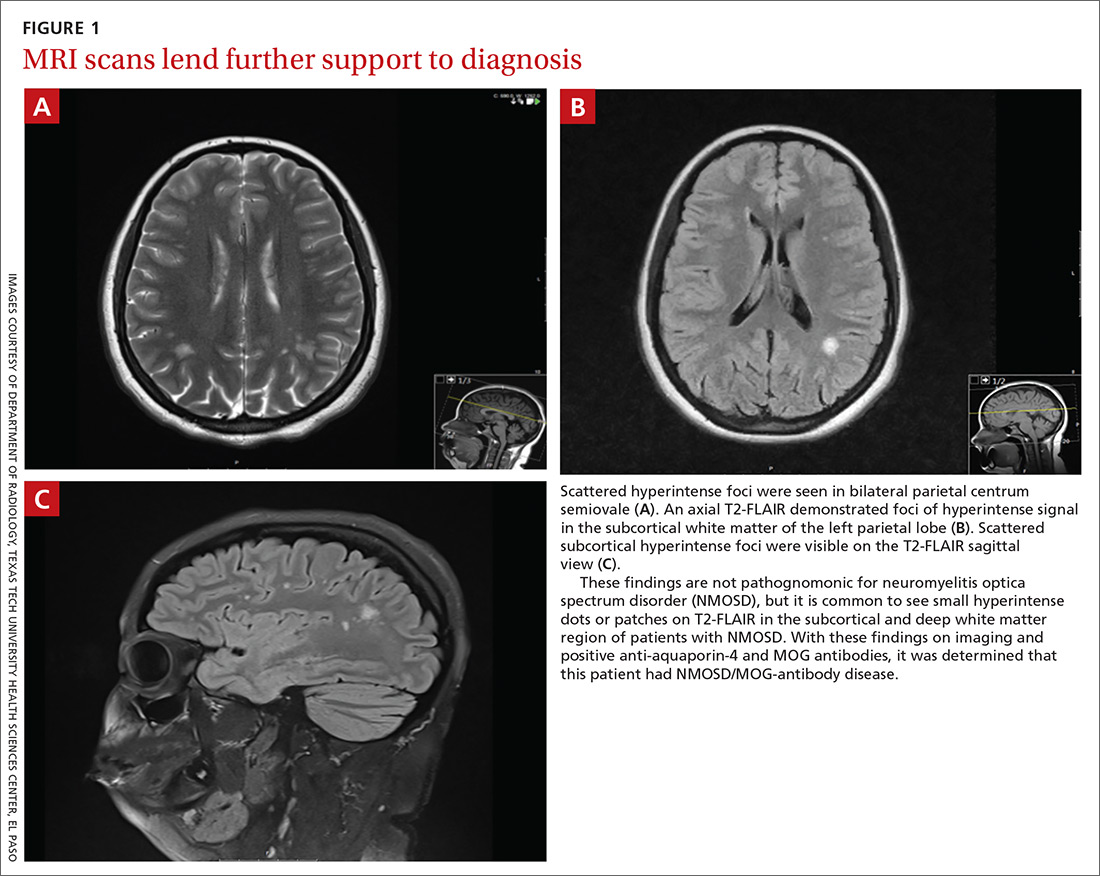

An 87-year-old man with a history of refractory CLL was admitted to the hospital with pneumonia and pleural effusion requiring chest tube placement (left). His most recent therapeutic regimen for CLL was rituximab and bendamustine, which was administered 9 days prior to admission. After removal of the chest tube, an erythematous plaque with central necrosis surrounding the chest tube site developed (Figure 1A). During this time period, the patient had documented intermittent fevers, leukopenia, and neutropenia. Serial blood cultures yielded no growth. Because the patient was on broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage, dermatology was consulted for possible angioinvasive fungal infection.

Physical examination revealed an indurated, erythematous-violaceous, targetoid, well-defined, ulcerated plaque with central necrosis on the left side of the chest. Notably, we observed an isolated bulla with an erythematous base within the right antecubital fossa at the site of intravenous placement, suggesting pathergy.

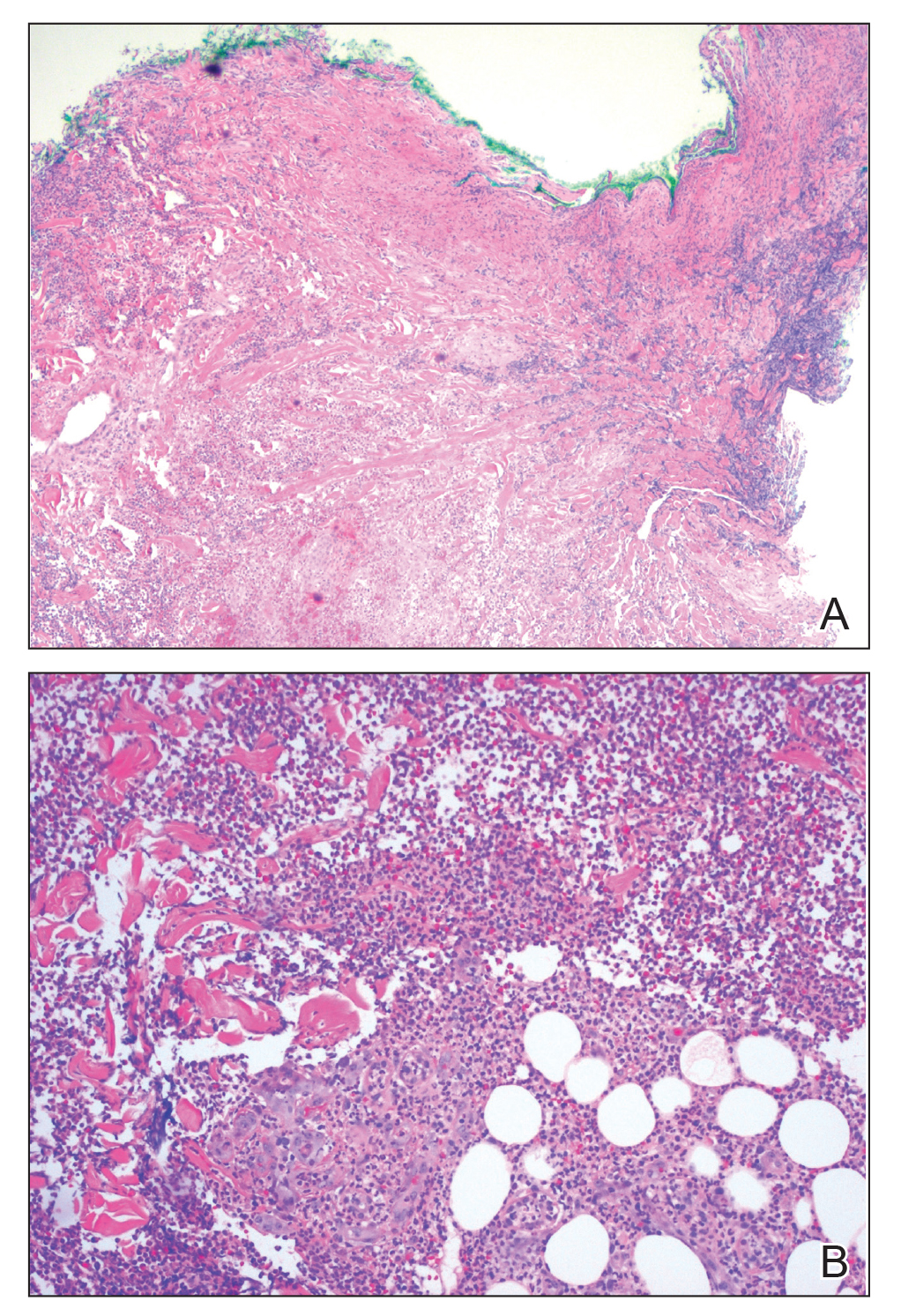

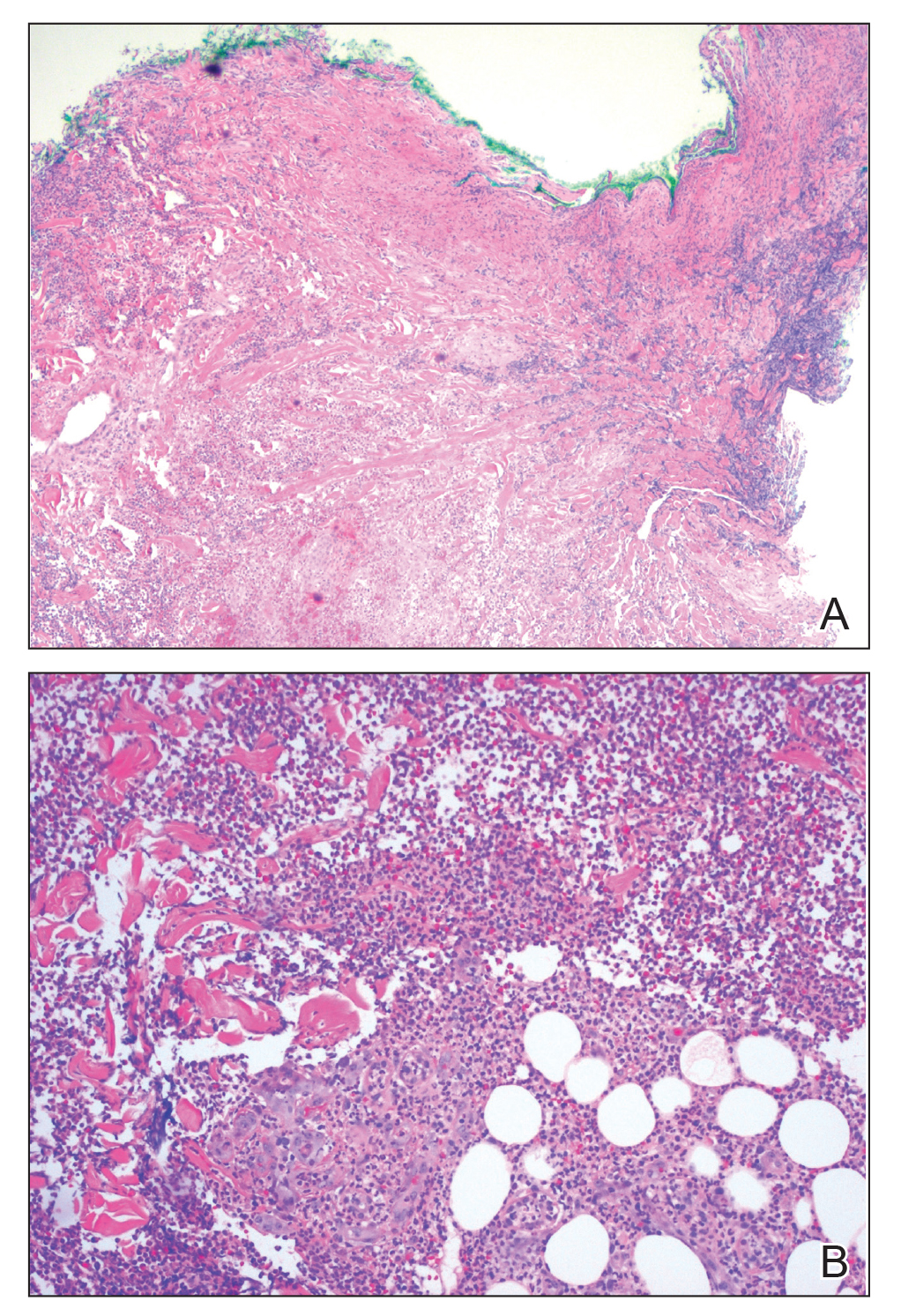

Multiple punch biopsies revealed an ulcer with an underlying dense neutrophilic infiltrate within the dermis and subcutaneous tissues (Figure 2). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, periodic acid–Schiff, and acid-fast bacillus stains were all negative for organisms. Tissue cultures for bacterial, fungal, and acid-fast bacilli revealed no growth. Due to the rapidly expanding nature of the plaque and the possibility of infection despite negative microbial stains and cultures, the patient was scheduled for surgical debridement by the surgical team.

Opportunely, after thoughtful consideration of the clinical history, histopathology, and negative tissue cultures, we made a diagnosis of PG, a condition that would have been further exacerbated by debridement and unimproved with antibiotics. Based on our recommendation, the patient received immunosuppressive treatment with prednisone 60 mg/d and triamcinolone ointment 0.1%. He experienced immediate clinical improvement, allowing him to be discharged to the care of dermatology as an outpatient. He continued to receive a monthly rituximab infusion. We intentionally tapered the patient’s prednisone dosage slowly over 4 months and photodocumented steady improvement with eventual resolution of the PG (Figure 1B).

Comment

Pathogenesis of PG

Pyoderma gangrenosum lies in the spectrum of neutrophilic dermatoses, which are characterized histologically by a pandermal neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of an infectious cause or true vasculitis. Clinically, PG typically presents as a steadily expanding ulceration with an undermined or slightly raised border, and often is associated with the pathergy phenomenon. Historically, PG is classically linked to inflammatory bowel disease; however, association with underlying malignancy, including acute myelogenous leukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia, myeloma, and myeloid metaplasia, also has been described.5

Pathogenesis of CLL

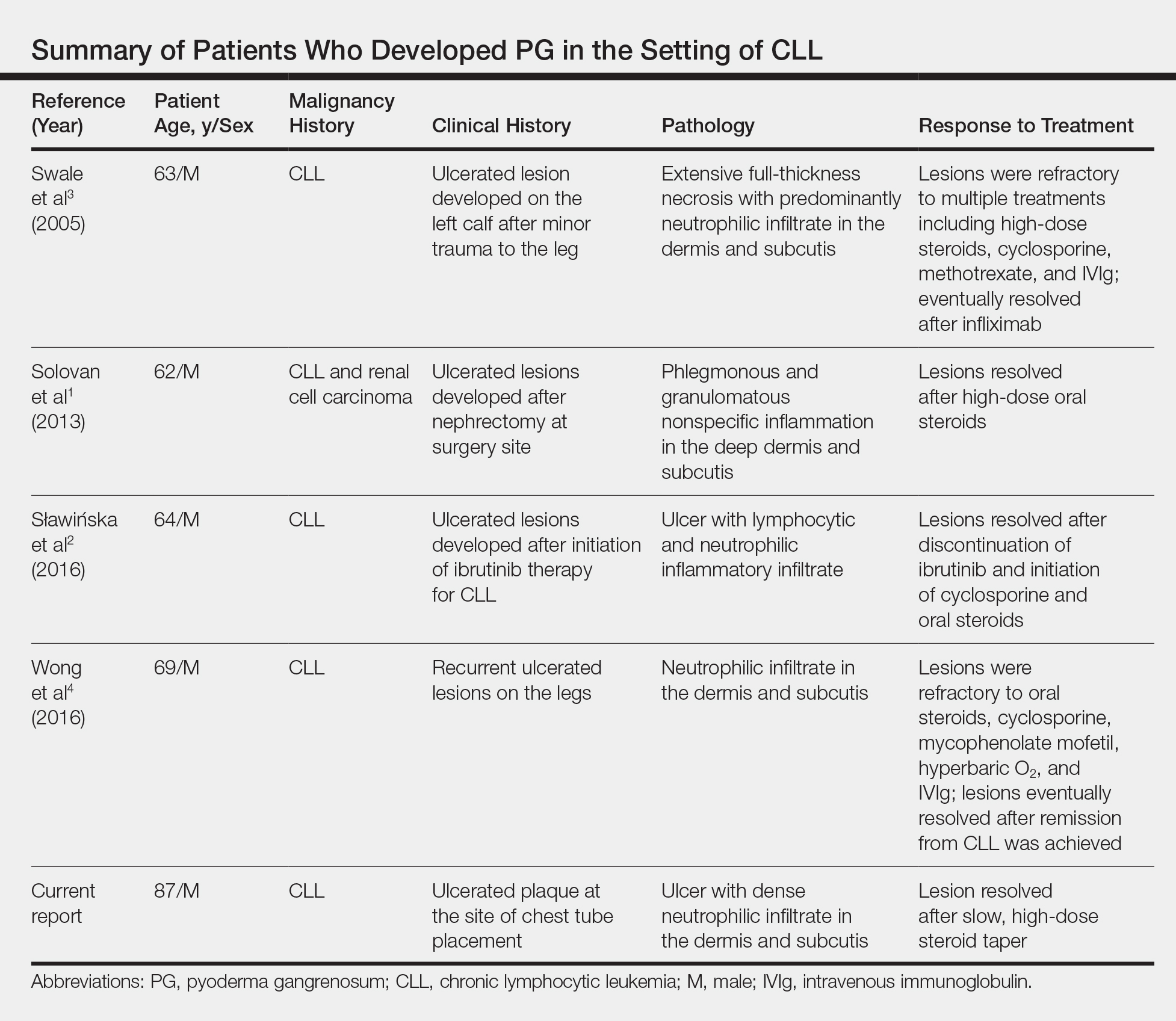

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia represents the most prevalent form of leukemia in US adults, with the second highest annual incidence.6 Cutaneous findings are seen in 25% of patients with CLL, varying from leukemia cutis to secondary findings such as vasculitis, purpura, generalized pruritus, exfoliative erythroderma, paraneoplastic pemphigus, infections, and rarely neutrophilic dermatoses.7 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term pyoderma gangrenosum in CLL, only 4 cases of PG occurring in the setting of CLL exist in the literature, with 1 case demonstrating development after a surgical procedure, making ours the second such case (Table).1-4

Diagnosis

Making the diagnosis of a neutrophilic dermatosis such as PG or Sweet syndrome (SS) in the hospital setting is not only difficult but also imperative, considering that the counterdiagnosis more often is an infectious process. The distinction between individual neutrophilic dermatoses is less crucial at the onset because the initial treatment is the same.

Sweet syndrome is classically the most challenging entity within the spectrum to differentiate from PG. However, our case outlines several key distinguishing features:

• The lesion in classic PG is a rapidly expanding ulceration with undermined borders, whereas SS is less commonly associated with ulceration and instead classically presents with multiple edematous papules that progress to juicy plaques.8

• The pathergy phenomenon has been reported in SS, though it is more commonly associated with PG.9

• In reported cases of SS that were related to cutaneous trauma, lesions developed outside the area of trauma and there was documented leukocytosis and neutrophilia.10-14

• Although leukocytosis is part of the minor diagnostic criteria for SS, it is not required for the diagnosis of PG. Considering that our patient had ulcerated lesions, lesions only at the site of trauma, and leukopenia with intermittent neutropenia, the diagnosis was consistent with PG.

The primary value of early recognition and diagnosis of PG lies in the physician’s ability to distinguish PG from an infectious process, which can be challenging in an immunosuppressed patient with an underlying hematologic malignancy.

Conclusion

This case report represents our experience in arriving at the correct diagnosis of PG in a febrile neutrophilic patient with CLL. In the case of PG in a complicated patient, it is critical to initiate appropriate treatment and avoid inappropriate therapies. Aggressive surgical debridement could have resulted in a fatal outcome for our patient, highlighting the need for dermatologists to raise physician awareness of this challenging disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Sarah Shalin, MD, PhD; Nikhil Meena, MD; and Aditya Chada, MD (all from Little Rock, Arkansas), for excellent patient care.

- Solovan C, Smiszek R, Wickenhauser C, et al. Postoperative pyoderma gangrenosum in association with renal cell carcinoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Infect Dis Ther. 2013;2:75-80.

- Sławińska M, Barańska-Rybak W, Sobjanek M, et al. Ibrutinib-induced pyoderma gangrenosum. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2016;126:710-711.

- Swale VJ, Saha M, Kapur N, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum outside the context of inflammatory bowel disease treated successfully with infliximab. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:134-136.

- Wong SM, McComish J, Douglass J, et al. Rare skin manifestations successfully treated with primary B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia treatment. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:552-555.

- Jockenhöfer F, Herberger K, Schaller J, et al. Tricenter analysis of cofactors and comorbidity in patients with pyoderma gangrenosum. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:1023-1030.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7-30. 7.

- Robak E, Robak T. Skin lesions in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:855-865.

- Beasley JM, Sluzevich JC. A recurrent vesiculobullous eruption on the head, trunk, and extremities. Bullous Sweet’s syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:149-150.

- Awan F, Hamadani M, Devine S. Paraneoplastic Sweet’s syndrome and the pathergy phenomenon. Ann Hematol. 2007;86:613-614.

- de Moya MA, Wong JT, Kroshinsky D, et al. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 28-2012. A 30-year-old woman with shock and abdominal-wall necrosis after cesarean section. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1046-1057.

- Minocha R, Sebaratnam DF, Choi JY. Sweet’s syndrome following surgery: cutaneous trauma as a possible aetiological co-factor in neutrophilic dermatoses. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:

e74-e76. - Phua YS, Al-Ani SA, She RB, et al. Sweet’s syndrome triggered by scalding: a case study and review of the literature. Burns. 2010;36:e49-e52.

- Schwarz RE, Quinn MA, Molina A. Acute postoperative dermatosis at the site of the electrocautery pad: sweet diagnosis of a burning issue. Surg Today. 2000;30:207-209.

- Tan AW, Tan HH, Lim PL. Bullous Sweet’s syndrome following influenza vaccination in a HIV-infected patient. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1254-1255.

Diagnosis of a neutrophilic dermatosis, such as pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), often is challenging at onset because it can be impossible to distinguish clinically and histopathologically from acute infection in an immunosuppressed patient, necessitating a detailed history as well as correlation pathology with microbial tissue cultures. The dermatologist’s ability to distinguish a neutrophilic dermatosis from active infection is of paramount importance because the decision to treat with surgical debridement, in addition to an antibiotic regimen, can have grave consequences in the misdiagnosed patient.

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis histologically characterized by a pandermal neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of an infectious cause or true vasculitis. It is classically associated with inflammatory bowel disease or an underlying hematologic malignancy. Pyoderma gangrenosum in the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is rare, with as few as 4 cases having been described in the literature and only 1 case of PG developing after a surgical procedure.1-4 We present a case of PG occurring at a chest tube site in a patient with CLL. We highlight the challenges and therapeutic importance of arriving at the correct diagnosis.

Case Report

An 87-year-old man with a history of refractory CLL was admitted to the hospital with pneumonia and pleural effusion requiring chest tube placement (left). His most recent therapeutic regimen for CLL was rituximab and bendamustine, which was administered 9 days prior to admission. After removal of the chest tube, an erythematous plaque with central necrosis surrounding the chest tube site developed (Figure 1A). During this time period, the patient had documented intermittent fevers, leukopenia, and neutropenia. Serial blood cultures yielded no growth. Because the patient was on broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage, dermatology was consulted for possible angioinvasive fungal infection.

Physical examination revealed an indurated, erythematous-violaceous, targetoid, well-defined, ulcerated plaque with central necrosis on the left side of the chest. Notably, we observed an isolated bulla with an erythematous base within the right antecubital fossa at the site of intravenous placement, suggesting pathergy.

Multiple punch biopsies revealed an ulcer with an underlying dense neutrophilic infiltrate within the dermis and subcutaneous tissues (Figure 2). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, periodic acid–Schiff, and acid-fast bacillus stains were all negative for organisms. Tissue cultures for bacterial, fungal, and acid-fast bacilli revealed no growth. Due to the rapidly expanding nature of the plaque and the possibility of infection despite negative microbial stains and cultures, the patient was scheduled for surgical debridement by the surgical team.

Opportunely, after thoughtful consideration of the clinical history, histopathology, and negative tissue cultures, we made a diagnosis of PG, a condition that would have been further exacerbated by debridement and unimproved with antibiotics. Based on our recommendation, the patient received immunosuppressive treatment with prednisone 60 mg/d and triamcinolone ointment 0.1%. He experienced immediate clinical improvement, allowing him to be discharged to the care of dermatology as an outpatient. He continued to receive a monthly rituximab infusion. We intentionally tapered the patient’s prednisone dosage slowly over 4 months and photodocumented steady improvement with eventual resolution of the PG (Figure 1B).

Comment

Pathogenesis of PG

Pyoderma gangrenosum lies in the spectrum of neutrophilic dermatoses, which are characterized histologically by a pandermal neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of an infectious cause or true vasculitis. Clinically, PG typically presents as a steadily expanding ulceration with an undermined or slightly raised border, and often is associated with the pathergy phenomenon. Historically, PG is classically linked to inflammatory bowel disease; however, association with underlying malignancy, including acute myelogenous leukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia, myeloma, and myeloid metaplasia, also has been described.5

Pathogenesis of CLL

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia represents the most prevalent form of leukemia in US adults, with the second highest annual incidence.6 Cutaneous findings are seen in 25% of patients with CLL, varying from leukemia cutis to secondary findings such as vasculitis, purpura, generalized pruritus, exfoliative erythroderma, paraneoplastic pemphigus, infections, and rarely neutrophilic dermatoses.7 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term pyoderma gangrenosum in CLL, only 4 cases of PG occurring in the setting of CLL exist in the literature, with 1 case demonstrating development after a surgical procedure, making ours the second such case (Table).1-4

Diagnosis

Making the diagnosis of a neutrophilic dermatosis such as PG or Sweet syndrome (SS) in the hospital setting is not only difficult but also imperative, considering that the counterdiagnosis more often is an infectious process. The distinction between individual neutrophilic dermatoses is less crucial at the onset because the initial treatment is the same.

Sweet syndrome is classically the most challenging entity within the spectrum to differentiate from PG. However, our case outlines several key distinguishing features:

• The lesion in classic PG is a rapidly expanding ulceration with undermined borders, whereas SS is less commonly associated with ulceration and instead classically presents with multiple edematous papules that progress to juicy plaques.8

• The pathergy phenomenon has been reported in SS, though it is more commonly associated with PG.9

• In reported cases of SS that were related to cutaneous trauma, lesions developed outside the area of trauma and there was documented leukocytosis and neutrophilia.10-14

• Although leukocytosis is part of the minor diagnostic criteria for SS, it is not required for the diagnosis of PG. Considering that our patient had ulcerated lesions, lesions only at the site of trauma, and leukopenia with intermittent neutropenia, the diagnosis was consistent with PG.

The primary value of early recognition and diagnosis of PG lies in the physician’s ability to distinguish PG from an infectious process, which can be challenging in an immunosuppressed patient with an underlying hematologic malignancy.

Conclusion

This case report represents our experience in arriving at the correct diagnosis of PG in a febrile neutrophilic patient with CLL. In the case of PG in a complicated patient, it is critical to initiate appropriate treatment and avoid inappropriate therapies. Aggressive surgical debridement could have resulted in a fatal outcome for our patient, highlighting the need for dermatologists to raise physician awareness of this challenging disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Sarah Shalin, MD, PhD; Nikhil Meena, MD; and Aditya Chada, MD (all from Little Rock, Arkansas), for excellent patient care.

Diagnosis of a neutrophilic dermatosis, such as pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), often is challenging at onset because it can be impossible to distinguish clinically and histopathologically from acute infection in an immunosuppressed patient, necessitating a detailed history as well as correlation pathology with microbial tissue cultures. The dermatologist’s ability to distinguish a neutrophilic dermatosis from active infection is of paramount importance because the decision to treat with surgical debridement, in addition to an antibiotic regimen, can have grave consequences in the misdiagnosed patient.

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis histologically characterized by a pandermal neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of an infectious cause or true vasculitis. It is classically associated with inflammatory bowel disease or an underlying hematologic malignancy. Pyoderma gangrenosum in the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is rare, with as few as 4 cases having been described in the literature and only 1 case of PG developing after a surgical procedure.1-4 We present a case of PG occurring at a chest tube site in a patient with CLL. We highlight the challenges and therapeutic importance of arriving at the correct diagnosis.

Case Report

An 87-year-old man with a history of refractory CLL was admitted to the hospital with pneumonia and pleural effusion requiring chest tube placement (left). His most recent therapeutic regimen for CLL was rituximab and bendamustine, which was administered 9 days prior to admission. After removal of the chest tube, an erythematous plaque with central necrosis surrounding the chest tube site developed (Figure 1A). During this time period, the patient had documented intermittent fevers, leukopenia, and neutropenia. Serial blood cultures yielded no growth. Because the patient was on broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage, dermatology was consulted for possible angioinvasive fungal infection.

Physical examination revealed an indurated, erythematous-violaceous, targetoid, well-defined, ulcerated plaque with central necrosis on the left side of the chest. Notably, we observed an isolated bulla with an erythematous base within the right antecubital fossa at the site of intravenous placement, suggesting pathergy.

Multiple punch biopsies revealed an ulcer with an underlying dense neutrophilic infiltrate within the dermis and subcutaneous tissues (Figure 2). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, periodic acid–Schiff, and acid-fast bacillus stains were all negative for organisms. Tissue cultures for bacterial, fungal, and acid-fast bacilli revealed no growth. Due to the rapidly expanding nature of the plaque and the possibility of infection despite negative microbial stains and cultures, the patient was scheduled for surgical debridement by the surgical team.

Opportunely, after thoughtful consideration of the clinical history, histopathology, and negative tissue cultures, we made a diagnosis of PG, a condition that would have been further exacerbated by debridement and unimproved with antibiotics. Based on our recommendation, the patient received immunosuppressive treatment with prednisone 60 mg/d and triamcinolone ointment 0.1%. He experienced immediate clinical improvement, allowing him to be discharged to the care of dermatology as an outpatient. He continued to receive a monthly rituximab infusion. We intentionally tapered the patient’s prednisone dosage slowly over 4 months and photodocumented steady improvement with eventual resolution of the PG (Figure 1B).

Comment

Pathogenesis of PG

Pyoderma gangrenosum lies in the spectrum of neutrophilic dermatoses, which are characterized histologically by a pandermal neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of an infectious cause or true vasculitis. Clinically, PG typically presents as a steadily expanding ulceration with an undermined or slightly raised border, and often is associated with the pathergy phenomenon. Historically, PG is classically linked to inflammatory bowel disease; however, association with underlying malignancy, including acute myelogenous leukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia, myeloma, and myeloid metaplasia, also has been described.5

Pathogenesis of CLL

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia represents the most prevalent form of leukemia in US adults, with the second highest annual incidence.6 Cutaneous findings are seen in 25% of patients with CLL, varying from leukemia cutis to secondary findings such as vasculitis, purpura, generalized pruritus, exfoliative erythroderma, paraneoplastic pemphigus, infections, and rarely neutrophilic dermatoses.7 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term pyoderma gangrenosum in CLL, only 4 cases of PG occurring in the setting of CLL exist in the literature, with 1 case demonstrating development after a surgical procedure, making ours the second such case (Table).1-4

Diagnosis

Making the diagnosis of a neutrophilic dermatosis such as PG or Sweet syndrome (SS) in the hospital setting is not only difficult but also imperative, considering that the counterdiagnosis more often is an infectious process. The distinction between individual neutrophilic dermatoses is less crucial at the onset because the initial treatment is the same.

Sweet syndrome is classically the most challenging entity within the spectrum to differentiate from PG. However, our case outlines several key distinguishing features:

• The lesion in classic PG is a rapidly expanding ulceration with undermined borders, whereas SS is less commonly associated with ulceration and instead classically presents with multiple edematous papules that progress to juicy plaques.8

• The pathergy phenomenon has been reported in SS, though it is more commonly associated with PG.9

• In reported cases of SS that were related to cutaneous trauma, lesions developed outside the area of trauma and there was documented leukocytosis and neutrophilia.10-14

• Although leukocytosis is part of the minor diagnostic criteria for SS, it is not required for the diagnosis of PG. Considering that our patient had ulcerated lesions, lesions only at the site of trauma, and leukopenia with intermittent neutropenia, the diagnosis was consistent with PG.

The primary value of early recognition and diagnosis of PG lies in the physician’s ability to distinguish PG from an infectious process, which can be challenging in an immunosuppressed patient with an underlying hematologic malignancy.

Conclusion

This case report represents our experience in arriving at the correct diagnosis of PG in a febrile neutrophilic patient with CLL. In the case of PG in a complicated patient, it is critical to initiate appropriate treatment and avoid inappropriate therapies. Aggressive surgical debridement could have resulted in a fatal outcome for our patient, highlighting the need for dermatologists to raise physician awareness of this challenging disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Sarah Shalin, MD, PhD; Nikhil Meena, MD; and Aditya Chada, MD (all from Little Rock, Arkansas), for excellent patient care.

- Solovan C, Smiszek R, Wickenhauser C, et al. Postoperative pyoderma gangrenosum in association with renal cell carcinoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Infect Dis Ther. 2013;2:75-80.

- Sławińska M, Barańska-Rybak W, Sobjanek M, et al. Ibrutinib-induced pyoderma gangrenosum. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2016;126:710-711.

- Swale VJ, Saha M, Kapur N, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum outside the context of inflammatory bowel disease treated successfully with infliximab. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:134-136.

- Wong SM, McComish J, Douglass J, et al. Rare skin manifestations successfully treated with primary B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia treatment. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:552-555.

- Jockenhöfer F, Herberger K, Schaller J, et al. Tricenter analysis of cofactors and comorbidity in patients with pyoderma gangrenosum. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:1023-1030.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7-30. 7.

- Robak E, Robak T. Skin lesions in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:855-865.

- Beasley JM, Sluzevich JC. A recurrent vesiculobullous eruption on the head, trunk, and extremities. Bullous Sweet’s syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:149-150.

- Awan F, Hamadani M, Devine S. Paraneoplastic Sweet’s syndrome and the pathergy phenomenon. Ann Hematol. 2007;86:613-614.

- de Moya MA, Wong JT, Kroshinsky D, et al. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 28-2012. A 30-year-old woman with shock and abdominal-wall necrosis after cesarean section. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1046-1057.

- Minocha R, Sebaratnam DF, Choi JY. Sweet’s syndrome following surgery: cutaneous trauma as a possible aetiological co-factor in neutrophilic dermatoses. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:

e74-e76. - Phua YS, Al-Ani SA, She RB, et al. Sweet’s syndrome triggered by scalding: a case study and review of the literature. Burns. 2010;36:e49-e52.

- Schwarz RE, Quinn MA, Molina A. Acute postoperative dermatosis at the site of the electrocautery pad: sweet diagnosis of a burning issue. Surg Today. 2000;30:207-209.

- Tan AW, Tan HH, Lim PL. Bullous Sweet’s syndrome following influenza vaccination in a HIV-infected patient. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1254-1255.

- Solovan C, Smiszek R, Wickenhauser C, et al. Postoperative pyoderma gangrenosum in association with renal cell carcinoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Infect Dis Ther. 2013;2:75-80.

- Sławińska M, Barańska-Rybak W, Sobjanek M, et al. Ibrutinib-induced pyoderma gangrenosum. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2016;126:710-711.

- Swale VJ, Saha M, Kapur N, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum outside the context of inflammatory bowel disease treated successfully with infliximab. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:134-136.

- Wong SM, McComish J, Douglass J, et al. Rare skin manifestations successfully treated with primary B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia treatment. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:552-555.

- Jockenhöfer F, Herberger K, Schaller J, et al. Tricenter analysis of cofactors and comorbidity in patients with pyoderma gangrenosum. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:1023-1030.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7-30. 7.