User login

Intralymphatic Histiocytosis Treated With Intralesional Triamcinolone Acetonide and Pressure Bandage

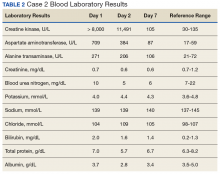

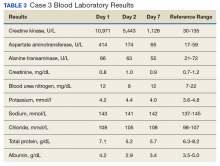

Intralymphatic histiocytosis was first described in 1994.1 To date, at least 70 cases have been reported in the English-language literature, the majority being associated with systemic or local inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), malignancy, and metal prostheses. The remaining cases arose independent of any detectable disease process.2 The clinical lesion localizes to areas around surgical scars or inflamed joints and generally presents with erythematous livedoid papules and plaques. Because of its rarity, pathologists and clinicians may be unfamiliar with this entity, leading to delayed or missed diagnoses.

Although the pathogenesis of intralymphatic histiocytosis remains unclear, it may be related to dysregulated immune signaling. The condition follows a chronic, relapsing-remitting course that has shown variable response to topical and systemic treatments. We present a rare case of intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with joint replacement/metal prosthesis3-14 that was responsive to a novel treatment with intralesional steroid injection and pressure bandage.

Case Report

An 89-year-old woman presented with a relapsing and remitting rash on the right calf and popliteal fossa of 11 months’ duration. It was becoming more painful over time and recently began to hurt when walking. Her medical history was remarkable for deep vein thromboses of the bilateral legs, Factor V Leiden deficiency, osteoarthritis, and a popliteal (Baker) cyst on the right leg that ruptured 22 months prior to presentation. Her surgical history included bilateral knee replacements (10 years and 2 years prior to the current presentation for the right and left knees, respectively). Her international normalized ratio (2.0) was therapeutic on warfarin.

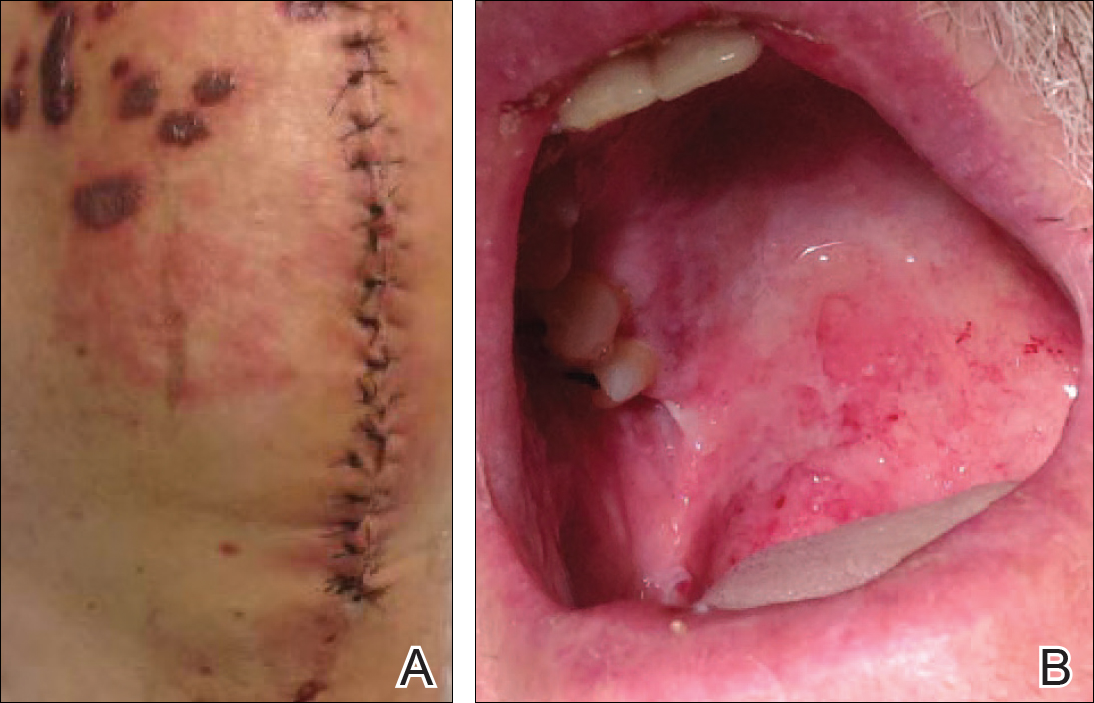

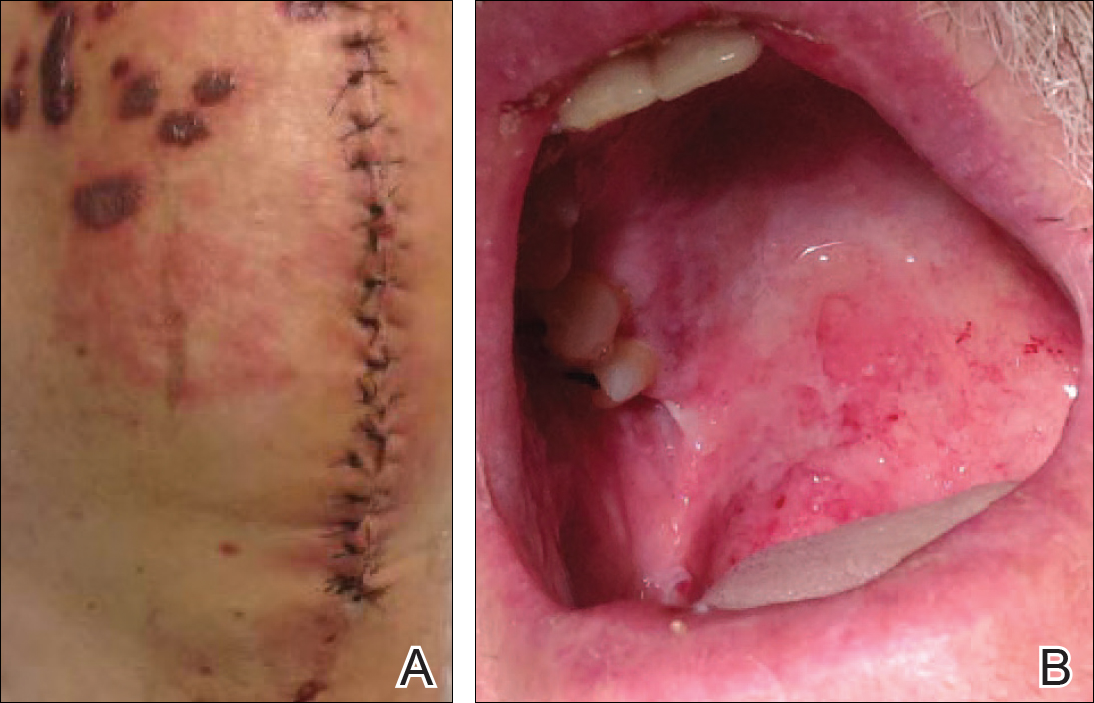

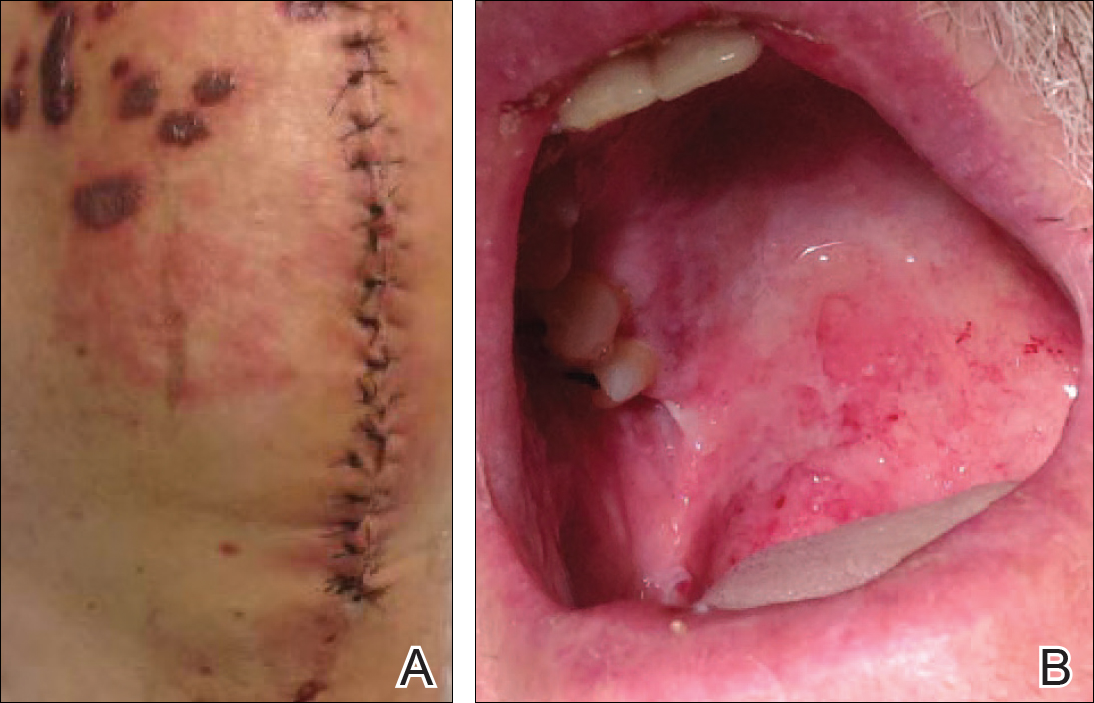

Initially, swelling, pain, and redness developed in the right calf, and recurrent right-leg deep venous thrombosis was ruled out by Doppler ultrasound. The findings were considered to be secondary to inflammation from a popliteal cyst. Symptoms persisted despite application of warm compresses, leg elevation, and compression stockings. Treatment with doxycycline prescribed by the patient’s primary care physician 9 months prior for presumed cellulitis produced little improvement. Physical examination revealed a well-healed vertical scar on the right calf from an incisional biopsy within an 8-cm, tender, erythematous, indurated, sclerotic plaque with erythematous streaks radiating from the center of the plaque (Figure 1). There also was red-brown, indurated discoloration on the right shin.

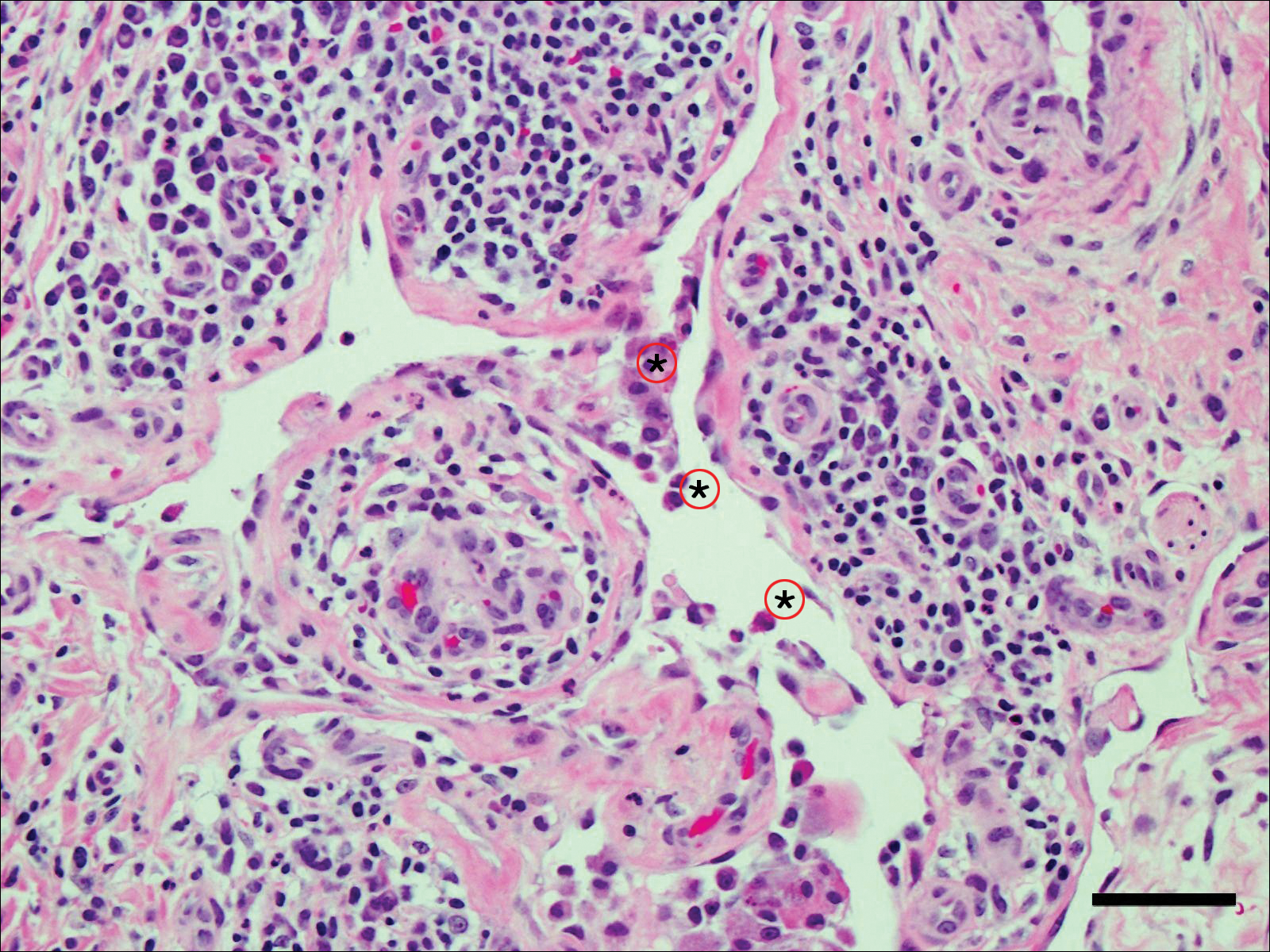

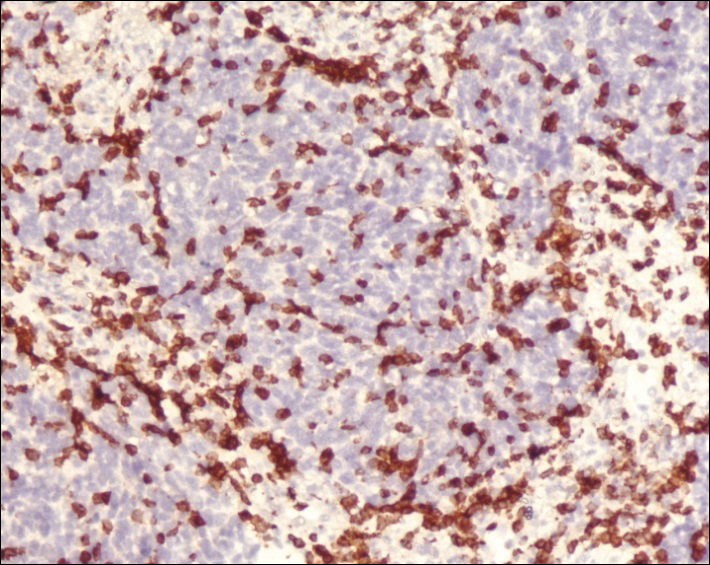

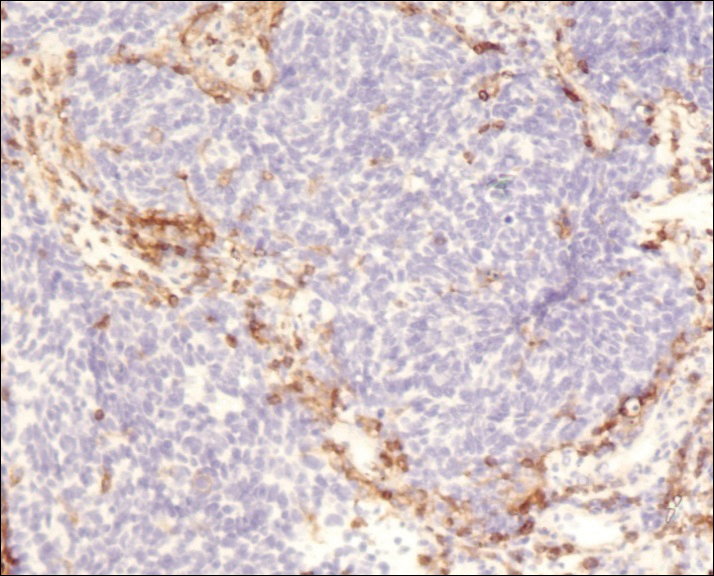

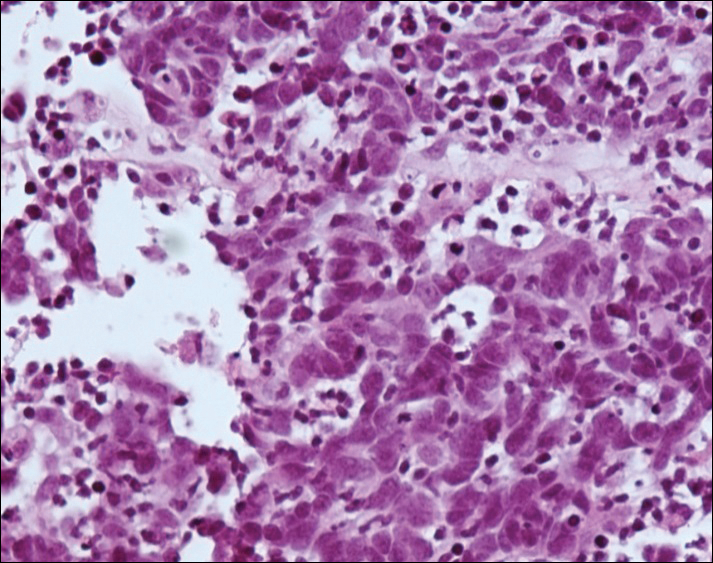

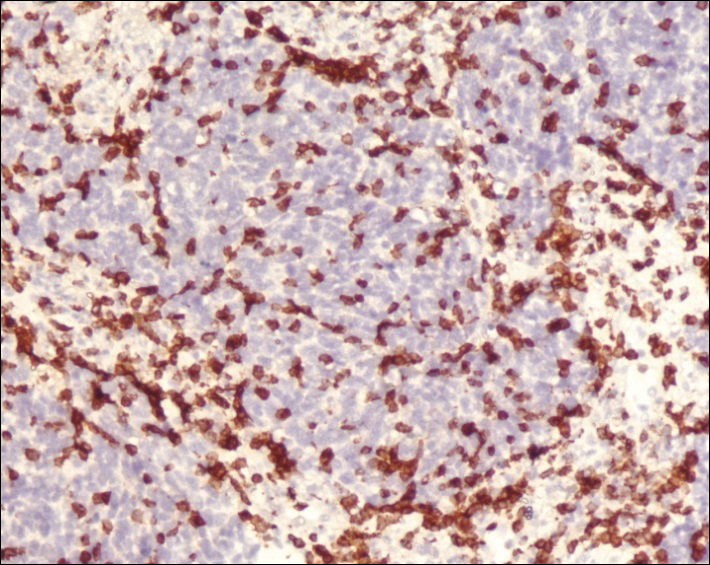

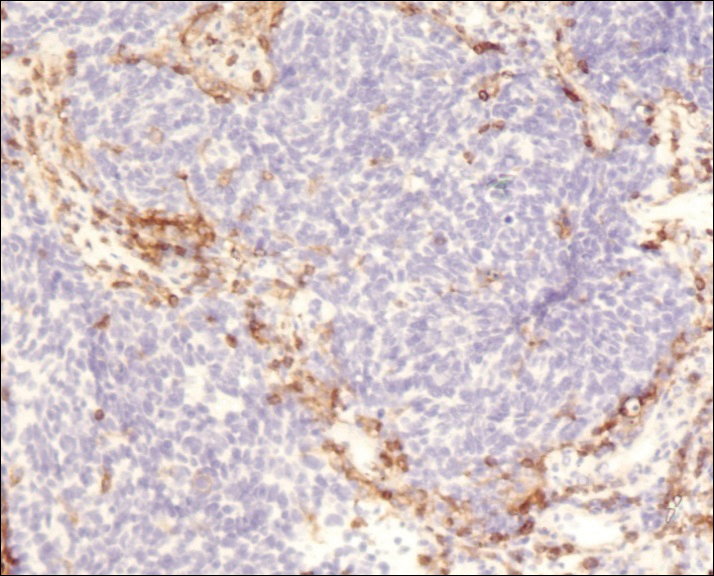

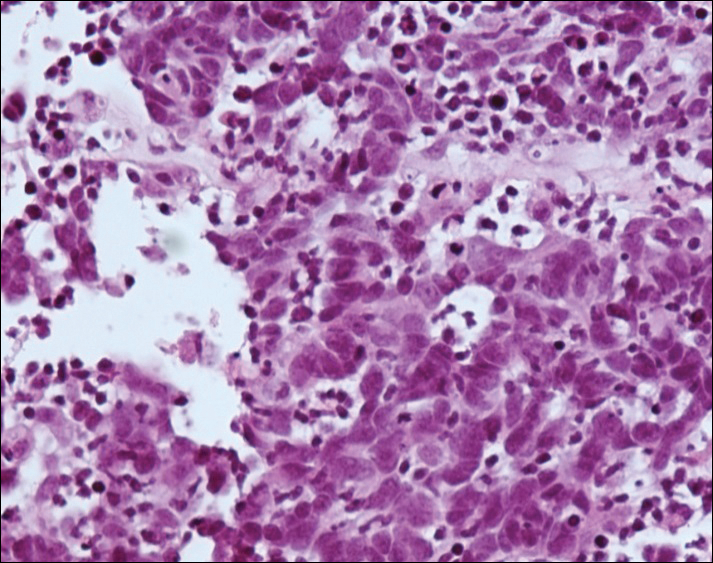

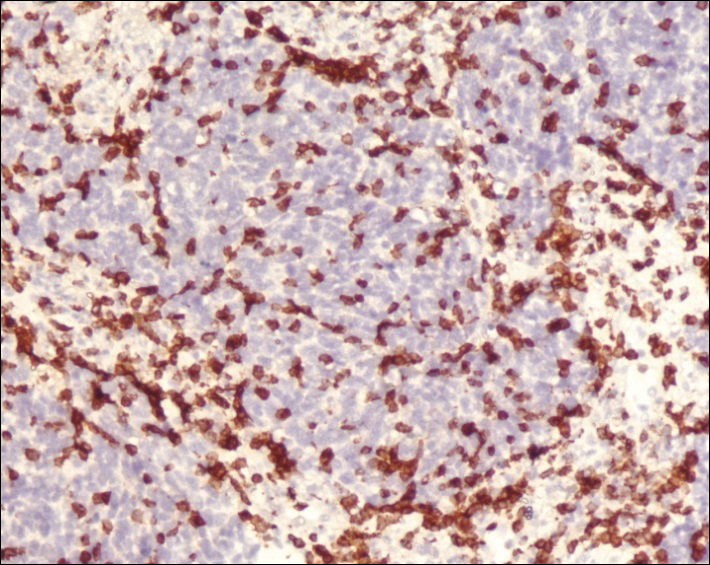

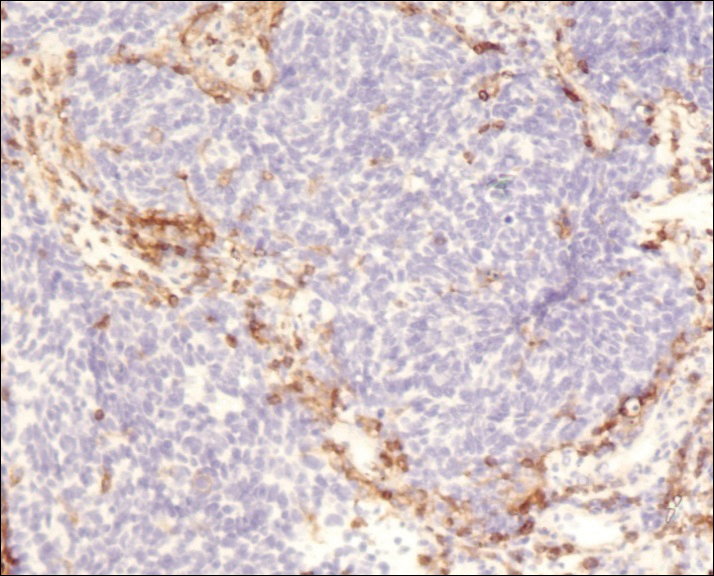

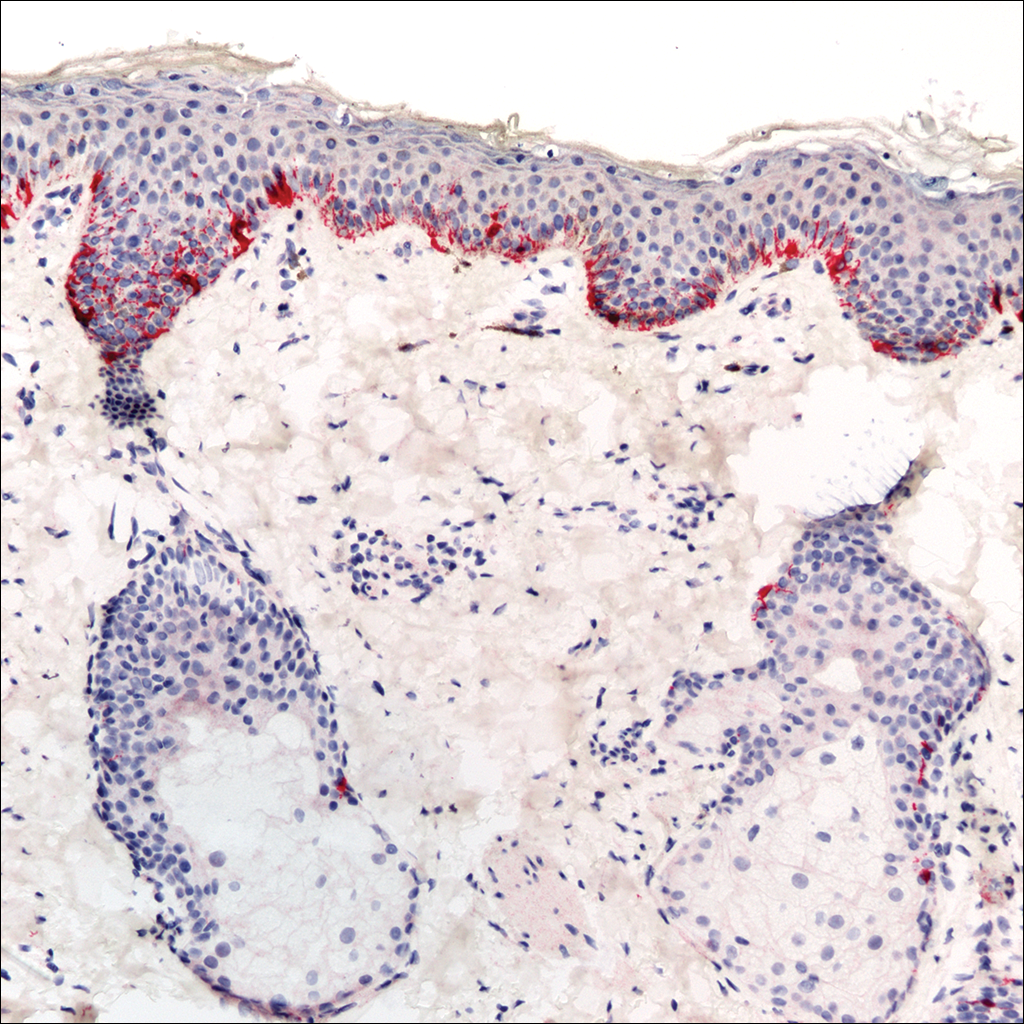

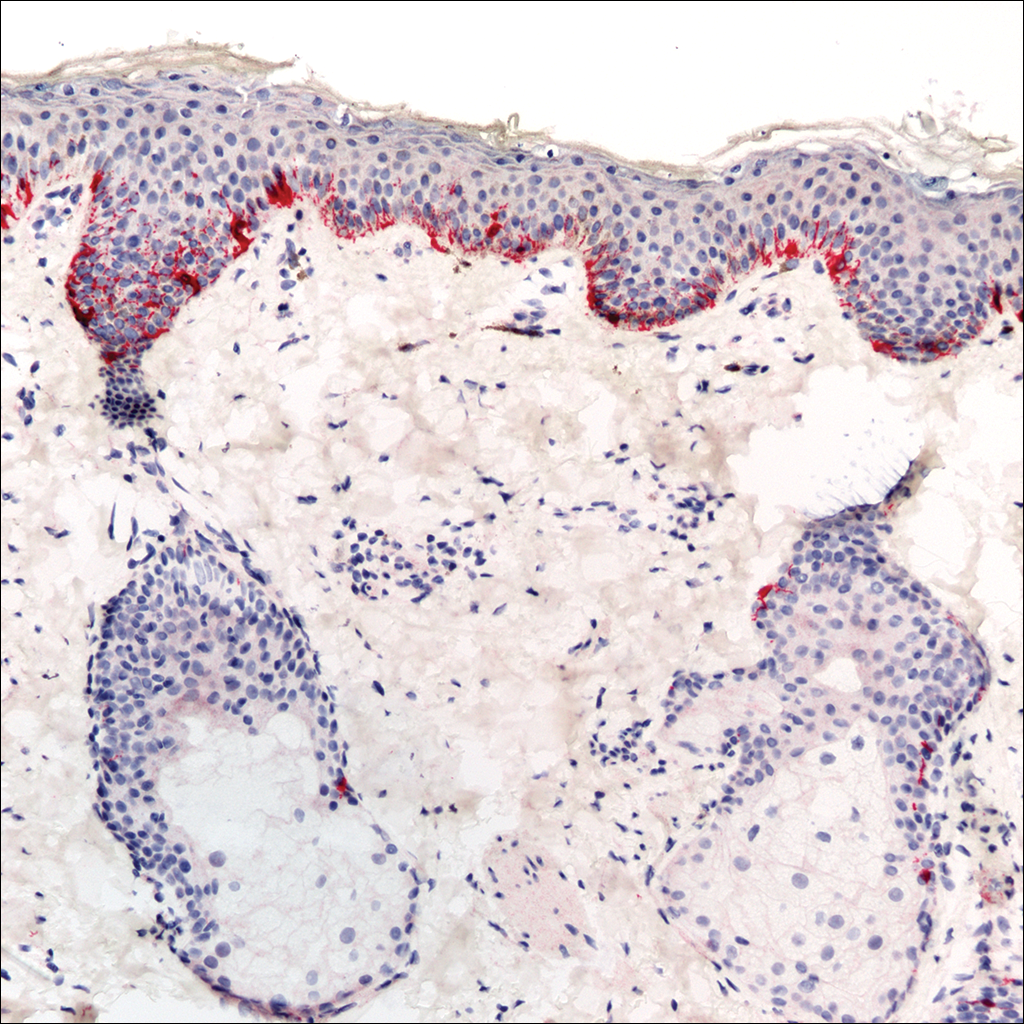

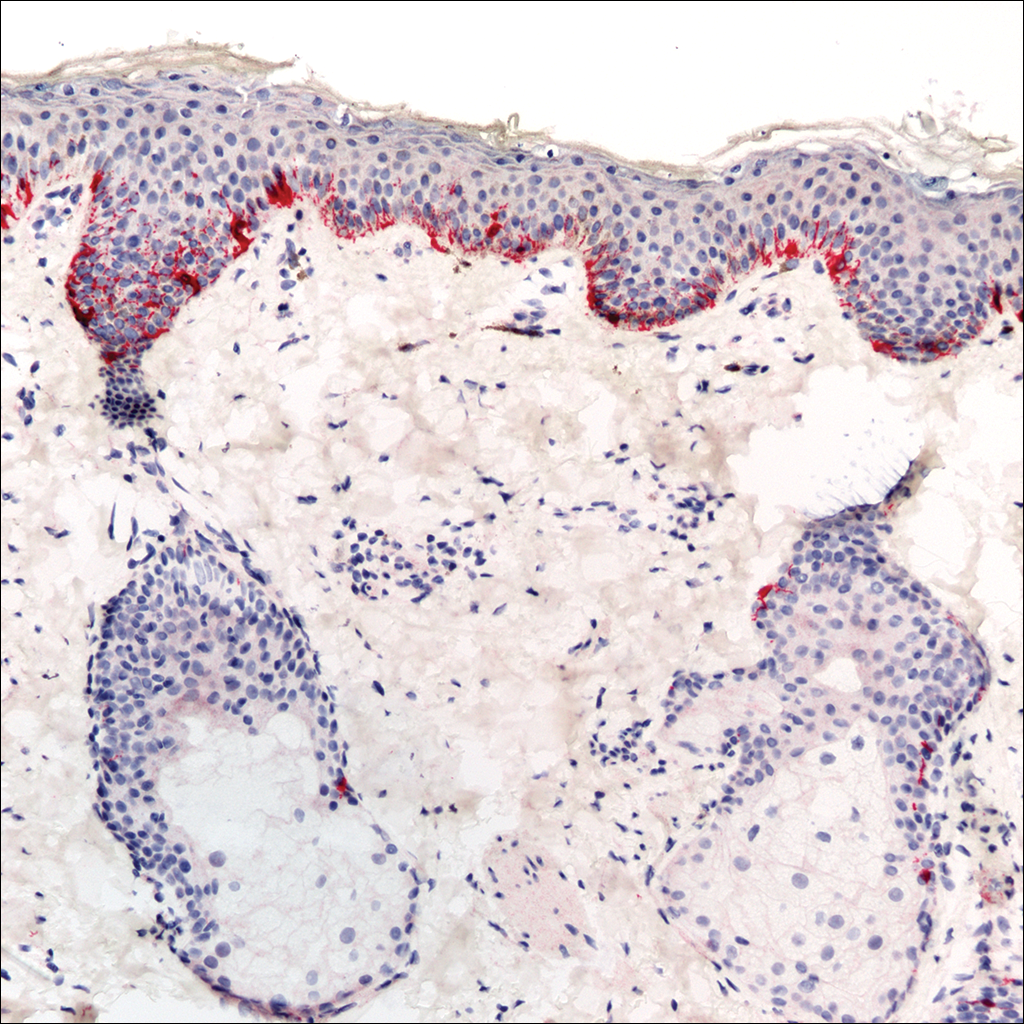

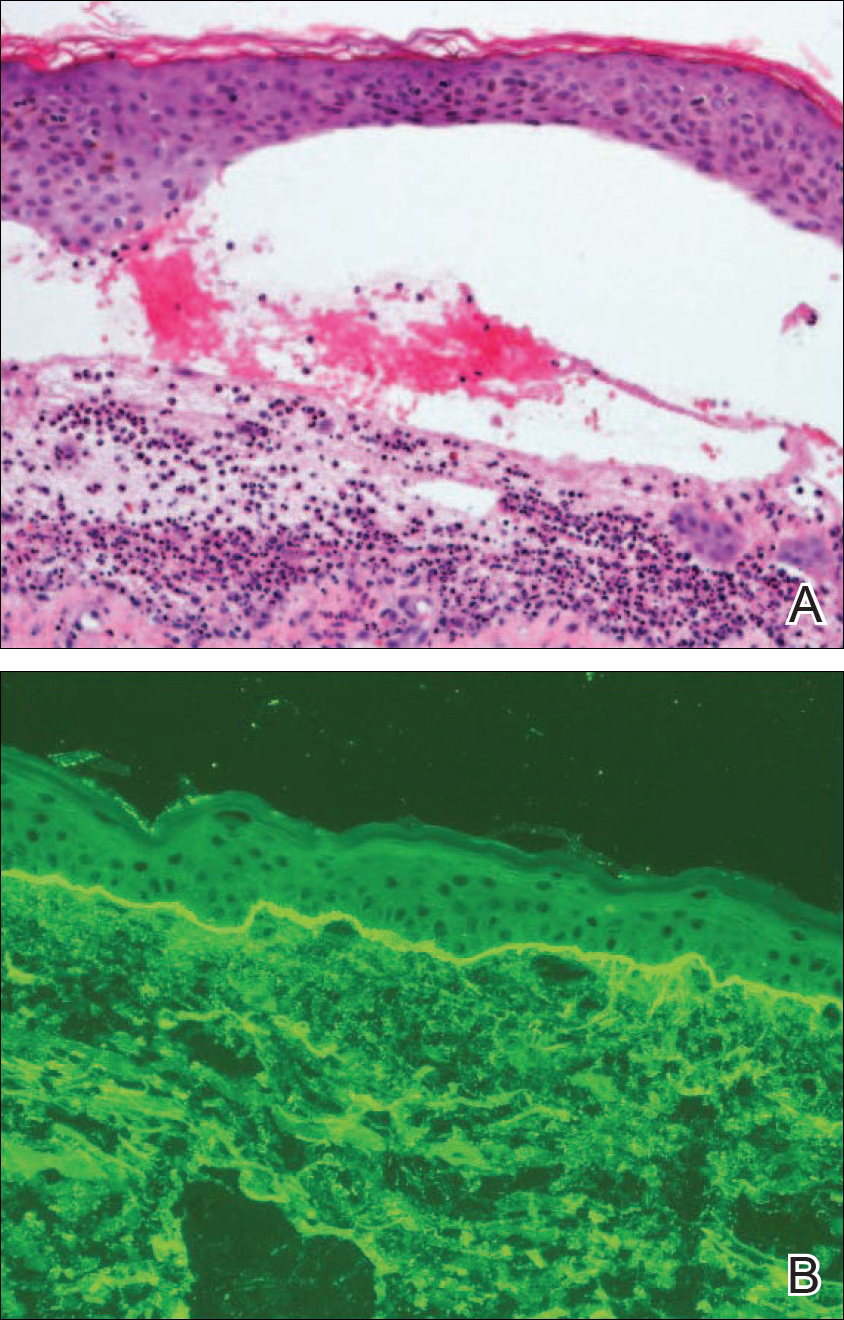

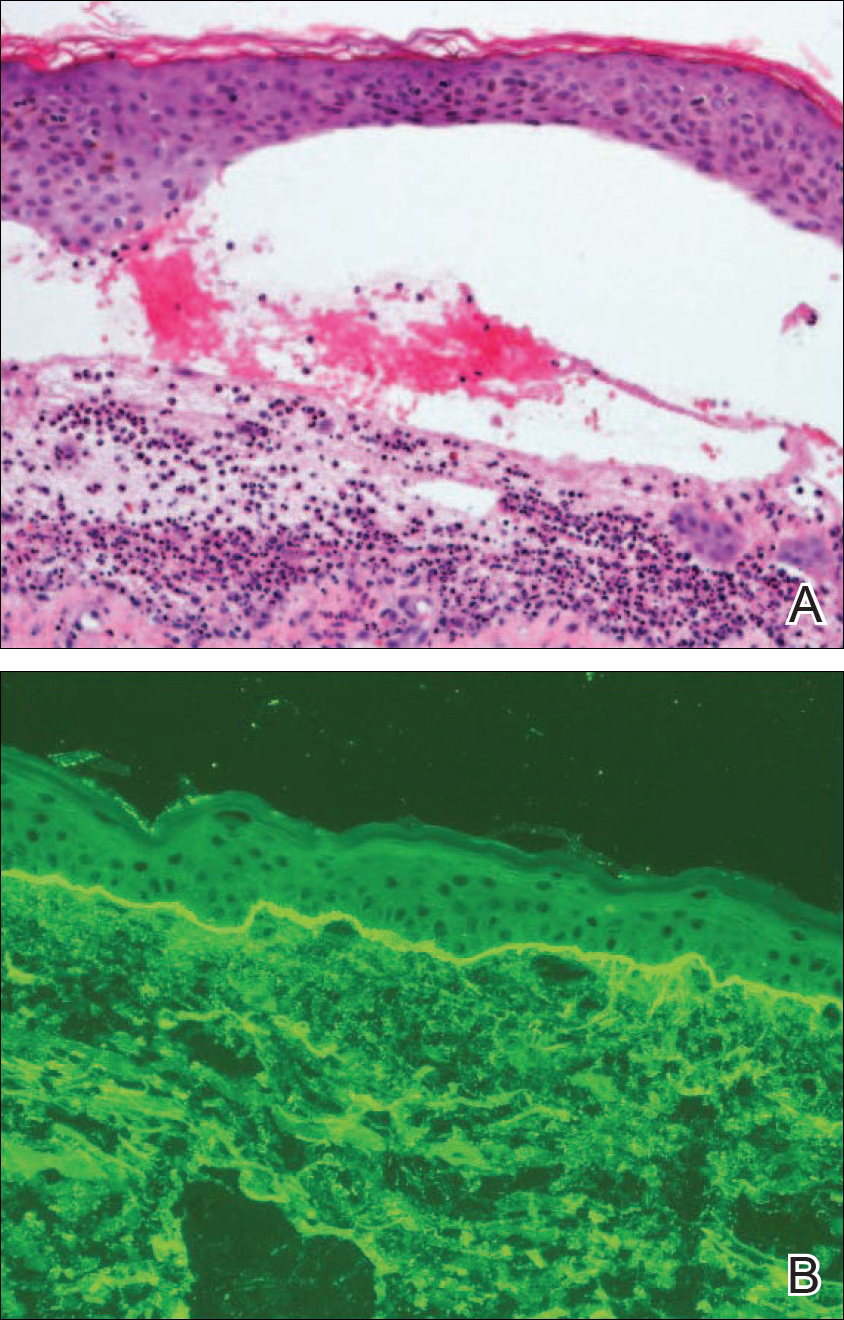

Fine-needle aspiration of the lesion revealed red blood cells and histiocytes. Laboratory studies showed an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 74 mm/h (reference range, 0–30 mm/h) and a C-reactive protein level of 39 mg/L (reference range, 0–10 mg/L). An incisional biopsy including the muscular fascia showed dense dermal fibrosis with chronic inflammation and scarring. A dermatopathologist (G. A. S.) reviewed the case and confirmed variable fibrosis and chronic inflammation associated with edema in the dermis and epidermal acanthosis. Inspection of vessels in the mid to upper dermis in one area revealed stellate, thin-walled, vascular structures that contained bland epithelioid cells lining the lumen as well as packed within the vessels. The epithelioid cells did not show atypia or mitotic figures, and they did not show intracytoplasmic vacuoles (Figure 2). Immunocytochemical staining for D2-40 was strongly positive in cells lining the vessels, consistent with lymphatics (Figure 3). CD68 immunohistochemistry for histiocytes stained the cells within the lymphatics (Figure 4). A diagnosis of intralymphatic histiocytosis was made.

Intralesional triamcinolone acetonide 10 mg/cc×1.6 cc was injected into the plaque once monthly for 2 consecutive months, and daily compression with a pressure bandage of the right lower leg was initiated. Four months after the first treatment with this regimen, the plaque was smaller and no longer sclerotic or painful, and the erythema was markedly reduced (Figure 5). Clinical and symptomatic improvement continued at 1-year follow-up.

Comment

Intralymphatic histiocytosis is a rare cutaneous disorder defined histologically by histiocytes within the lumina of lymphatics. In addition to the current case, our review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term intralymphatic histiocytosis yielded more than 70 total cases. The condition has a slight female predominance and typically is seen in individuals over the age of 60 years (age range, 16–89 years).12 Many cases are associated with RA/elevated rheumatoid factor.2,4,8,15-30 At least 9 cases of intralymphatic histiocytosis were associated with premalignant or malignant conditions (ie, adenocarcinoma of the breasts, lungs, and colon; Merkel cell carcinoma; melanoma; melanoma in situ; Mullerian carcinoma, gammopathy).4,15,31-34 Primary disease, defined as occurring in patients who are otherwise healthy, was noted in at least 10 cases.1,2,4,12,35,36 Finally, intralymphatic histiocytosis was identified in areas adjacent to metal implants and joint replacements or exploration in approximately 15 cases (including the current case).3-14,29,37

The condition presents with papules, plaques, and nodules in the setting of characteristic livedoid discoloration; however, some patients present with nonspecific nodules or plaques. Lesions may be symptomatic (eg, pruritic, tender) or asymptomatic. The histologic features of intralymphatic histiocytosis are distinctive but may be focal, as in our case, and the diagnosis is easily missed. The histologic differential diagnosis includes diseases in which intravascular accumulations of cells may be seen, including intravascular B-cell lymphoma, which can be excluded with stains that detect B cells (CD20/CD79a), and reactive angioendotheliomatosis, a benign proliferation of endothelial cells, which may be excluded with stains against endothelial markers (CD31/CD34). The course typically is chronic, and treatment with topical steroids,3,9,15,22,26 cyclophosphamide,15 local radiation,1 thalidomide,35 pentoxifylline,7 and RA medications (eg, prednisolone, methotrexate, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, hydroxychloroquine) generally are ineffective.2,16,20,25 Symptoms may improve with joint replacement,4 excision of the involved lesion, treatment of an associated malignancy/infection,33,36,38,39 nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, intra-articular steroid injection,18 amoxicillin and aspirin,19 infliximab,25 pressure bandage application,26 steroid-containing adhesive application,18 arthrocentesis,3,27 oral pentoxifylline,21 tacrolimus,29 CO2 laser,40 prednisolone,41 and tocilizumab.28 Treatment of associated RA is beneficial in rare cases.2,15,20,25,26

The pathogenesis of intralymphatic histiocytosis has not been elucidated with certainty but may represent an abnormal proliferative response of histiocytes and vessels in response to chronic systemic or local inflammation. Lymphangiectasis caused by lymphatic obstruction secondary to trauma, surgical manipulation, or chronic inflammation can promote lymphostasis and slowed clearance of antigens producing an accumulation of histiocytes and subsequent local immunologic reactions, thus an “immunocompromised district” is formed.42 It also is thought that rheumatic or prosthetic joints produce inflammatory mediator–rich (namely tumor necrosis factor α) synovial fluid that drains and collects within the dilated lymphatics, creating a nidus for histiocytes.1,5 In one case, treatment with an anti–tumor necrosis factor antibody (infliximab) improved the skin presentation and rheumatoid joint pain.25 Bakr et al2 noted an association with increased intralymphatic macrophage HLA-DR expression. This T-cell surface receptor typically is upregulated in cases of chronic antigen stimulation and autoimmune conditions.

Conclusion

Our patient had a history of a joint prosthesis and a popliteal cyst, which could have altered lymphatic drainage promoting abnormal immune cell trafficking contributing to the development of intralymphatic histiocytosis. The response to intralesional steroids supports this pathogenic hypothesis. Specifically, direct injection of the area suppressed the immune dysregulation, while compression lessened the degree of lymphostasis. In light of previously reported cases of intralymphatic histiocytosis in association with metal implants,3-9 we suggest that the condition should be considered in patients with chronic painful livedoid nodules or plaques around an affected joint, even in the absence of RA. The dermatopathologist should be warned to search carefully for the subtle but distinctive histologic features of the disease that confirm the diagnosis. Treatment with intralesional triamcinolone acetonide with an overlying pressure wrap has minimal side effects and can work quickly with sustained benefits.

- O’Grady JT, Shahidullah H, Doherty VR, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis. Histopathology. 1994;24:265-268.

- Bakr F, Webber N, Fassihi H, et al. Primary and secondary intralymphatic histiocytosis [published online January 17, 2014]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:927-933.

- Watanabe T, Yamada N, Yoshida Y, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis with granuloma formation associated with orthopaedic metal implants [published online November 10, 2007]. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:402-404.

- Requena L, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, Walsh SN, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis. a clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:140-151.

- Grekin S, Mesfin M, Kang S, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis following placement of a metal implant. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:351-353.

- Rossari S, Scatena C, Gori A, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis: cutaneous nodules and metal implants [published online March 6, 2011]. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:534-535.

- de Unamuno Bustos B, García Rabasco A, Ballester Sánchez R, et al. Erythematous indurated plaque on the right upper limb. intralymphatic histiocytosis (IH) associated with orthopedic metal implant. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:547-549.

- Chiu YE, Maloney JE, Bengana C. Erythematous patch overlying a swollen knee—quiz case. intralymphatic histiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1037-1042.

- Saggar S, Lee B, Krivo J, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with orthopedic implants. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:1208-1209.

- Bidier M, Hamsch C, Kutzner H, et al. Two cases of intralymphatic histiocytosis following hip replacement [published online June 9, 2015]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:700-702.

- Darling MD, Akin R, Tarbox MB, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis overlying hip implantation treated with pentoxifilline. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2015;29(1 suppl):117-121.

- Demirkesen C, Kran T, Leblebici C, et al. Intravascular/intralymphatic histiocytosis: a report of 3 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:783-789.

- Gómez-Sánchez ME, Azaña-Defez JM, Martínez-Martínez ML, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis: a report of 2 cases. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109:E1-E5.

- Haitz KA, Chapman MS, Seidel GD. Intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with an orthopedic metal implant. Cutis. 2016;97:E12-E14.

- Rieger E, Soyer HP, Leboit PE, et al. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis or intravascular histiocytosis? an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study in two cases of intravascular histiocytic cell proliferation. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:497-504.

- Pruim B, Strutton G, Congdon S, et al. Cutaneous histiocytic lymphangitis: an unusual manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:101-105.

- Magro CM, Crowson AN. The spectrum of cutaneous lesions in rheumatoid arthritis: a clinical and pathological study of 43 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:1-10.

- Takiwaki H, Adachi A, Kohno H, et al. Intravascular or intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: a report of 4 cases.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:585-590.

- Mensing CH, Krengel S, Tronnier M, et al. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis: is it “intravascular histiocytosis”? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:216-219.

- Okazaki A, Asada H, Niizeki H, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: report of a case with lymphatic endothelial proliferation. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1385-1387.

- Catalina-Fernández I, Alvárez AC, Martin FC, et al. Cutaneous intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:165-168.

- Nishie W, Sawamura D, Iitoyo M, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Dermatology. 2008;217:144-145.

- Okamoto N, Tanioka M, Yamamoto T, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:516-518.

- Huang H-Y, Liang C-W, Hu S-L, et al. Cutaneous intravascular histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E302-E303.

- Sakaguchi M, Nagai H, Tsuji G, et al. Effectiveness of infliximab for intralymphatic histiocytosis with rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:131-133.

- Washio K, Nakata K, Nakamura A, et al. Pressure bandage as an effective treatment for intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Dermatology. 2011;223:20-24.

- Kaneko T, Takeuchi S, Nakano H, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis with rheumatoid arthritis: possible association with the joint involvement. Case Reports Clin Med. 2014;3:149-152.

- Nakajima T, Kawabata D, Nakabo S, et al. Successful treatment with tocilizumab in a case of intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Intern Med. 2014;53:2255-2258.

- Tsujiwaki M, Hata H, Miyauchi T, et al. Warty intralymphatic histiocytosis successfully treated with topical tacrolimus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2267-2269.

- Tanaka M, Funasaka Y, Tsuruta K, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis with massive interstitial granulomatous foci in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:237-238.

- Cornejo KM, Cosar EF, O’Donnell P. Cutaneous intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with lung adenocarcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38:568-570.

- Tran TAN, Tran Q, Carlson JA. Intralymphatic histiocytosis of the appendix and fallopian tube associated with primary peritoneal high-grade, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of Müllerian origin. Int J Surg Pathol. 2017;25:357-364.

- Echeverría-García B, Botella-Estrada R, Requena C, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis and cancer of the colon [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:257-262.

- Ergen EN, Zwerner JP. Cover image: intralymphatic histiocytosis with giant blanching violaceous plaques. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:325-326.

- Wang Y, Yang H, Tu P. Upper facial swelling: an uncommon manifestation of intralymphatic histiocytosis. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:814-815.

- Rhee D-Y, Lee D-W, Chang S-E, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis without rheumatoid arthritis. J Dermatol. 2008;35:691-693.

- Gilchrest BA, Eller MS, Geller AC, et al. The pathogenesis of melanoma induced by ultraviolet radiation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1341-1348.

- Asagoe K, Torigoe R, Ofuji R, et al. Reactive intravascular histiocytosis associated with tonsillitis. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:560-563.

- Pouryazdanparast P, Yu L, Dalton VK, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis presenting with extensive vulvar necrosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;(36 suppl 1):1-7.

- Reznitsky M, Daugaard S, Charabi BW. Two rare cases of laryngeal intralymphatic histiocytosis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:783-788.

- Fujimoto N, Nakanishi G, Manabe T, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis comprises M2 macrophages in superficial dermal lymphatics with or without smooth muscles. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:898-902.

- Piccolo V, Ruocco E, Russo T, et al. A possible relationship between metal implant-induced intralymphatic histiocytosis and the concept of the immunocompromised district. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E365.

Intralymphatic histiocytosis was first described in 1994.1 To date, at least 70 cases have been reported in the English-language literature, the majority being associated with systemic or local inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), malignancy, and metal prostheses. The remaining cases arose independent of any detectable disease process.2 The clinical lesion localizes to areas around surgical scars or inflamed joints and generally presents with erythematous livedoid papules and plaques. Because of its rarity, pathologists and clinicians may be unfamiliar with this entity, leading to delayed or missed diagnoses.

Although the pathogenesis of intralymphatic histiocytosis remains unclear, it may be related to dysregulated immune signaling. The condition follows a chronic, relapsing-remitting course that has shown variable response to topical and systemic treatments. We present a rare case of intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with joint replacement/metal prosthesis3-14 that was responsive to a novel treatment with intralesional steroid injection and pressure bandage.

Case Report

An 89-year-old woman presented with a relapsing and remitting rash on the right calf and popliteal fossa of 11 months’ duration. It was becoming more painful over time and recently began to hurt when walking. Her medical history was remarkable for deep vein thromboses of the bilateral legs, Factor V Leiden deficiency, osteoarthritis, and a popliteal (Baker) cyst on the right leg that ruptured 22 months prior to presentation. Her surgical history included bilateral knee replacements (10 years and 2 years prior to the current presentation for the right and left knees, respectively). Her international normalized ratio (2.0) was therapeutic on warfarin.

Initially, swelling, pain, and redness developed in the right calf, and recurrent right-leg deep venous thrombosis was ruled out by Doppler ultrasound. The findings were considered to be secondary to inflammation from a popliteal cyst. Symptoms persisted despite application of warm compresses, leg elevation, and compression stockings. Treatment with doxycycline prescribed by the patient’s primary care physician 9 months prior for presumed cellulitis produced little improvement. Physical examination revealed a well-healed vertical scar on the right calf from an incisional biopsy within an 8-cm, tender, erythematous, indurated, sclerotic plaque with erythematous streaks radiating from the center of the plaque (Figure 1). There also was red-brown, indurated discoloration on the right shin.

Fine-needle aspiration of the lesion revealed red blood cells and histiocytes. Laboratory studies showed an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 74 mm/h (reference range, 0–30 mm/h) and a C-reactive protein level of 39 mg/L (reference range, 0–10 mg/L). An incisional biopsy including the muscular fascia showed dense dermal fibrosis with chronic inflammation and scarring. A dermatopathologist (G. A. S.) reviewed the case and confirmed variable fibrosis and chronic inflammation associated with edema in the dermis and epidermal acanthosis. Inspection of vessels in the mid to upper dermis in one area revealed stellate, thin-walled, vascular structures that contained bland epithelioid cells lining the lumen as well as packed within the vessels. The epithelioid cells did not show atypia or mitotic figures, and they did not show intracytoplasmic vacuoles (Figure 2). Immunocytochemical staining for D2-40 was strongly positive in cells lining the vessels, consistent with lymphatics (Figure 3). CD68 immunohistochemistry for histiocytes stained the cells within the lymphatics (Figure 4). A diagnosis of intralymphatic histiocytosis was made.

Intralesional triamcinolone acetonide 10 mg/cc×1.6 cc was injected into the plaque once monthly for 2 consecutive months, and daily compression with a pressure bandage of the right lower leg was initiated. Four months after the first treatment with this regimen, the plaque was smaller and no longer sclerotic or painful, and the erythema was markedly reduced (Figure 5). Clinical and symptomatic improvement continued at 1-year follow-up.

Comment

Intralymphatic histiocytosis is a rare cutaneous disorder defined histologically by histiocytes within the lumina of lymphatics. In addition to the current case, our review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term intralymphatic histiocytosis yielded more than 70 total cases. The condition has a slight female predominance and typically is seen in individuals over the age of 60 years (age range, 16–89 years).12 Many cases are associated with RA/elevated rheumatoid factor.2,4,8,15-30 At least 9 cases of intralymphatic histiocytosis were associated with premalignant or malignant conditions (ie, adenocarcinoma of the breasts, lungs, and colon; Merkel cell carcinoma; melanoma; melanoma in situ; Mullerian carcinoma, gammopathy).4,15,31-34 Primary disease, defined as occurring in patients who are otherwise healthy, was noted in at least 10 cases.1,2,4,12,35,36 Finally, intralymphatic histiocytosis was identified in areas adjacent to metal implants and joint replacements or exploration in approximately 15 cases (including the current case).3-14,29,37

The condition presents with papules, plaques, and nodules in the setting of characteristic livedoid discoloration; however, some patients present with nonspecific nodules or plaques. Lesions may be symptomatic (eg, pruritic, tender) or asymptomatic. The histologic features of intralymphatic histiocytosis are distinctive but may be focal, as in our case, and the diagnosis is easily missed. The histologic differential diagnosis includes diseases in which intravascular accumulations of cells may be seen, including intravascular B-cell lymphoma, which can be excluded with stains that detect B cells (CD20/CD79a), and reactive angioendotheliomatosis, a benign proliferation of endothelial cells, which may be excluded with stains against endothelial markers (CD31/CD34). The course typically is chronic, and treatment with topical steroids,3,9,15,22,26 cyclophosphamide,15 local radiation,1 thalidomide,35 pentoxifylline,7 and RA medications (eg, prednisolone, methotrexate, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, hydroxychloroquine) generally are ineffective.2,16,20,25 Symptoms may improve with joint replacement,4 excision of the involved lesion, treatment of an associated malignancy/infection,33,36,38,39 nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, intra-articular steroid injection,18 amoxicillin and aspirin,19 infliximab,25 pressure bandage application,26 steroid-containing adhesive application,18 arthrocentesis,3,27 oral pentoxifylline,21 tacrolimus,29 CO2 laser,40 prednisolone,41 and tocilizumab.28 Treatment of associated RA is beneficial in rare cases.2,15,20,25,26

The pathogenesis of intralymphatic histiocytosis has not been elucidated with certainty but may represent an abnormal proliferative response of histiocytes and vessels in response to chronic systemic or local inflammation. Lymphangiectasis caused by lymphatic obstruction secondary to trauma, surgical manipulation, or chronic inflammation can promote lymphostasis and slowed clearance of antigens producing an accumulation of histiocytes and subsequent local immunologic reactions, thus an “immunocompromised district” is formed.42 It also is thought that rheumatic or prosthetic joints produce inflammatory mediator–rich (namely tumor necrosis factor α) synovial fluid that drains and collects within the dilated lymphatics, creating a nidus for histiocytes.1,5 In one case, treatment with an anti–tumor necrosis factor antibody (infliximab) improved the skin presentation and rheumatoid joint pain.25 Bakr et al2 noted an association with increased intralymphatic macrophage HLA-DR expression. This T-cell surface receptor typically is upregulated in cases of chronic antigen stimulation and autoimmune conditions.

Conclusion

Our patient had a history of a joint prosthesis and a popliteal cyst, which could have altered lymphatic drainage promoting abnormal immune cell trafficking contributing to the development of intralymphatic histiocytosis. The response to intralesional steroids supports this pathogenic hypothesis. Specifically, direct injection of the area suppressed the immune dysregulation, while compression lessened the degree of lymphostasis. In light of previously reported cases of intralymphatic histiocytosis in association with metal implants,3-9 we suggest that the condition should be considered in patients with chronic painful livedoid nodules or plaques around an affected joint, even in the absence of RA. The dermatopathologist should be warned to search carefully for the subtle but distinctive histologic features of the disease that confirm the diagnosis. Treatment with intralesional triamcinolone acetonide with an overlying pressure wrap has minimal side effects and can work quickly with sustained benefits.

Intralymphatic histiocytosis was first described in 1994.1 To date, at least 70 cases have been reported in the English-language literature, the majority being associated with systemic or local inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), malignancy, and metal prostheses. The remaining cases arose independent of any detectable disease process.2 The clinical lesion localizes to areas around surgical scars or inflamed joints and generally presents with erythematous livedoid papules and plaques. Because of its rarity, pathologists and clinicians may be unfamiliar with this entity, leading to delayed or missed diagnoses.

Although the pathogenesis of intralymphatic histiocytosis remains unclear, it may be related to dysregulated immune signaling. The condition follows a chronic, relapsing-remitting course that has shown variable response to topical and systemic treatments. We present a rare case of intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with joint replacement/metal prosthesis3-14 that was responsive to a novel treatment with intralesional steroid injection and pressure bandage.

Case Report

An 89-year-old woman presented with a relapsing and remitting rash on the right calf and popliteal fossa of 11 months’ duration. It was becoming more painful over time and recently began to hurt when walking. Her medical history was remarkable for deep vein thromboses of the bilateral legs, Factor V Leiden deficiency, osteoarthritis, and a popliteal (Baker) cyst on the right leg that ruptured 22 months prior to presentation. Her surgical history included bilateral knee replacements (10 years and 2 years prior to the current presentation for the right and left knees, respectively). Her international normalized ratio (2.0) was therapeutic on warfarin.

Initially, swelling, pain, and redness developed in the right calf, and recurrent right-leg deep venous thrombosis was ruled out by Doppler ultrasound. The findings were considered to be secondary to inflammation from a popliteal cyst. Symptoms persisted despite application of warm compresses, leg elevation, and compression stockings. Treatment with doxycycline prescribed by the patient’s primary care physician 9 months prior for presumed cellulitis produced little improvement. Physical examination revealed a well-healed vertical scar on the right calf from an incisional biopsy within an 8-cm, tender, erythematous, indurated, sclerotic plaque with erythematous streaks radiating from the center of the plaque (Figure 1). There also was red-brown, indurated discoloration on the right shin.

Fine-needle aspiration of the lesion revealed red blood cells and histiocytes. Laboratory studies showed an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 74 mm/h (reference range, 0–30 mm/h) and a C-reactive protein level of 39 mg/L (reference range, 0–10 mg/L). An incisional biopsy including the muscular fascia showed dense dermal fibrosis with chronic inflammation and scarring. A dermatopathologist (G. A. S.) reviewed the case and confirmed variable fibrosis and chronic inflammation associated with edema in the dermis and epidermal acanthosis. Inspection of vessels in the mid to upper dermis in one area revealed stellate, thin-walled, vascular structures that contained bland epithelioid cells lining the lumen as well as packed within the vessels. The epithelioid cells did not show atypia or mitotic figures, and they did not show intracytoplasmic vacuoles (Figure 2). Immunocytochemical staining for D2-40 was strongly positive in cells lining the vessels, consistent with lymphatics (Figure 3). CD68 immunohistochemistry for histiocytes stained the cells within the lymphatics (Figure 4). A diagnosis of intralymphatic histiocytosis was made.

Intralesional triamcinolone acetonide 10 mg/cc×1.6 cc was injected into the plaque once monthly for 2 consecutive months, and daily compression with a pressure bandage of the right lower leg was initiated. Four months after the first treatment with this regimen, the plaque was smaller and no longer sclerotic or painful, and the erythema was markedly reduced (Figure 5). Clinical and symptomatic improvement continued at 1-year follow-up.

Comment

Intralymphatic histiocytosis is a rare cutaneous disorder defined histologically by histiocytes within the lumina of lymphatics. In addition to the current case, our review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term intralymphatic histiocytosis yielded more than 70 total cases. The condition has a slight female predominance and typically is seen in individuals over the age of 60 years (age range, 16–89 years).12 Many cases are associated with RA/elevated rheumatoid factor.2,4,8,15-30 At least 9 cases of intralymphatic histiocytosis were associated with premalignant or malignant conditions (ie, adenocarcinoma of the breasts, lungs, and colon; Merkel cell carcinoma; melanoma; melanoma in situ; Mullerian carcinoma, gammopathy).4,15,31-34 Primary disease, defined as occurring in patients who are otherwise healthy, was noted in at least 10 cases.1,2,4,12,35,36 Finally, intralymphatic histiocytosis was identified in areas adjacent to metal implants and joint replacements or exploration in approximately 15 cases (including the current case).3-14,29,37

The condition presents with papules, plaques, and nodules in the setting of characteristic livedoid discoloration; however, some patients present with nonspecific nodules or plaques. Lesions may be symptomatic (eg, pruritic, tender) or asymptomatic. The histologic features of intralymphatic histiocytosis are distinctive but may be focal, as in our case, and the diagnosis is easily missed. The histologic differential diagnosis includes diseases in which intravascular accumulations of cells may be seen, including intravascular B-cell lymphoma, which can be excluded with stains that detect B cells (CD20/CD79a), and reactive angioendotheliomatosis, a benign proliferation of endothelial cells, which may be excluded with stains against endothelial markers (CD31/CD34). The course typically is chronic, and treatment with topical steroids,3,9,15,22,26 cyclophosphamide,15 local radiation,1 thalidomide,35 pentoxifylline,7 and RA medications (eg, prednisolone, methotrexate, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, hydroxychloroquine) generally are ineffective.2,16,20,25 Symptoms may improve with joint replacement,4 excision of the involved lesion, treatment of an associated malignancy/infection,33,36,38,39 nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, intra-articular steroid injection,18 amoxicillin and aspirin,19 infliximab,25 pressure bandage application,26 steroid-containing adhesive application,18 arthrocentesis,3,27 oral pentoxifylline,21 tacrolimus,29 CO2 laser,40 prednisolone,41 and tocilizumab.28 Treatment of associated RA is beneficial in rare cases.2,15,20,25,26

The pathogenesis of intralymphatic histiocytosis has not been elucidated with certainty but may represent an abnormal proliferative response of histiocytes and vessels in response to chronic systemic or local inflammation. Lymphangiectasis caused by lymphatic obstruction secondary to trauma, surgical manipulation, or chronic inflammation can promote lymphostasis and slowed clearance of antigens producing an accumulation of histiocytes and subsequent local immunologic reactions, thus an “immunocompromised district” is formed.42 It also is thought that rheumatic or prosthetic joints produce inflammatory mediator–rich (namely tumor necrosis factor α) synovial fluid that drains and collects within the dilated lymphatics, creating a nidus for histiocytes.1,5 In one case, treatment with an anti–tumor necrosis factor antibody (infliximab) improved the skin presentation and rheumatoid joint pain.25 Bakr et al2 noted an association with increased intralymphatic macrophage HLA-DR expression. This T-cell surface receptor typically is upregulated in cases of chronic antigen stimulation and autoimmune conditions.

Conclusion

Our patient had a history of a joint prosthesis and a popliteal cyst, which could have altered lymphatic drainage promoting abnormal immune cell trafficking contributing to the development of intralymphatic histiocytosis. The response to intralesional steroids supports this pathogenic hypothesis. Specifically, direct injection of the area suppressed the immune dysregulation, while compression lessened the degree of lymphostasis. In light of previously reported cases of intralymphatic histiocytosis in association with metal implants,3-9 we suggest that the condition should be considered in patients with chronic painful livedoid nodules or plaques around an affected joint, even in the absence of RA. The dermatopathologist should be warned to search carefully for the subtle but distinctive histologic features of the disease that confirm the diagnosis. Treatment with intralesional triamcinolone acetonide with an overlying pressure wrap has minimal side effects and can work quickly with sustained benefits.

- O’Grady JT, Shahidullah H, Doherty VR, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis. Histopathology. 1994;24:265-268.

- Bakr F, Webber N, Fassihi H, et al. Primary and secondary intralymphatic histiocytosis [published online January 17, 2014]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:927-933.

- Watanabe T, Yamada N, Yoshida Y, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis with granuloma formation associated with orthopaedic metal implants [published online November 10, 2007]. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:402-404.

- Requena L, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, Walsh SN, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis. a clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:140-151.

- Grekin S, Mesfin M, Kang S, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis following placement of a metal implant. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:351-353.

- Rossari S, Scatena C, Gori A, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis: cutaneous nodules and metal implants [published online March 6, 2011]. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:534-535.

- de Unamuno Bustos B, García Rabasco A, Ballester Sánchez R, et al. Erythematous indurated plaque on the right upper limb. intralymphatic histiocytosis (IH) associated with orthopedic metal implant. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:547-549.

- Chiu YE, Maloney JE, Bengana C. Erythematous patch overlying a swollen knee—quiz case. intralymphatic histiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1037-1042.

- Saggar S, Lee B, Krivo J, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with orthopedic implants. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:1208-1209.

- Bidier M, Hamsch C, Kutzner H, et al. Two cases of intralymphatic histiocytosis following hip replacement [published online June 9, 2015]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:700-702.

- Darling MD, Akin R, Tarbox MB, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis overlying hip implantation treated with pentoxifilline. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2015;29(1 suppl):117-121.

- Demirkesen C, Kran T, Leblebici C, et al. Intravascular/intralymphatic histiocytosis: a report of 3 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:783-789.

- Gómez-Sánchez ME, Azaña-Defez JM, Martínez-Martínez ML, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis: a report of 2 cases. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109:E1-E5.

- Haitz KA, Chapman MS, Seidel GD. Intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with an orthopedic metal implant. Cutis. 2016;97:E12-E14.

- Rieger E, Soyer HP, Leboit PE, et al. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis or intravascular histiocytosis? an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study in two cases of intravascular histiocytic cell proliferation. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:497-504.

- Pruim B, Strutton G, Congdon S, et al. Cutaneous histiocytic lymphangitis: an unusual manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:101-105.

- Magro CM, Crowson AN. The spectrum of cutaneous lesions in rheumatoid arthritis: a clinical and pathological study of 43 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:1-10.

- Takiwaki H, Adachi A, Kohno H, et al. Intravascular or intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: a report of 4 cases.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:585-590.

- Mensing CH, Krengel S, Tronnier M, et al. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis: is it “intravascular histiocytosis”? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:216-219.

- Okazaki A, Asada H, Niizeki H, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: report of a case with lymphatic endothelial proliferation. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1385-1387.

- Catalina-Fernández I, Alvárez AC, Martin FC, et al. Cutaneous intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:165-168.

- Nishie W, Sawamura D, Iitoyo M, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Dermatology. 2008;217:144-145.

- Okamoto N, Tanioka M, Yamamoto T, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:516-518.

- Huang H-Y, Liang C-W, Hu S-L, et al. Cutaneous intravascular histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E302-E303.

- Sakaguchi M, Nagai H, Tsuji G, et al. Effectiveness of infliximab for intralymphatic histiocytosis with rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:131-133.

- Washio K, Nakata K, Nakamura A, et al. Pressure bandage as an effective treatment for intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Dermatology. 2011;223:20-24.

- Kaneko T, Takeuchi S, Nakano H, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis with rheumatoid arthritis: possible association with the joint involvement. Case Reports Clin Med. 2014;3:149-152.

- Nakajima T, Kawabata D, Nakabo S, et al. Successful treatment with tocilizumab in a case of intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Intern Med. 2014;53:2255-2258.

- Tsujiwaki M, Hata H, Miyauchi T, et al. Warty intralymphatic histiocytosis successfully treated with topical tacrolimus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2267-2269.

- Tanaka M, Funasaka Y, Tsuruta K, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis with massive interstitial granulomatous foci in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:237-238.

- Cornejo KM, Cosar EF, O’Donnell P. Cutaneous intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with lung adenocarcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38:568-570.

- Tran TAN, Tran Q, Carlson JA. Intralymphatic histiocytosis of the appendix and fallopian tube associated with primary peritoneal high-grade, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of Müllerian origin. Int J Surg Pathol. 2017;25:357-364.

- Echeverría-García B, Botella-Estrada R, Requena C, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis and cancer of the colon [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:257-262.

- Ergen EN, Zwerner JP. Cover image: intralymphatic histiocytosis with giant blanching violaceous plaques. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:325-326.

- Wang Y, Yang H, Tu P. Upper facial swelling: an uncommon manifestation of intralymphatic histiocytosis. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:814-815.

- Rhee D-Y, Lee D-W, Chang S-E, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis without rheumatoid arthritis. J Dermatol. 2008;35:691-693.

- Gilchrest BA, Eller MS, Geller AC, et al. The pathogenesis of melanoma induced by ultraviolet radiation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1341-1348.

- Asagoe K, Torigoe R, Ofuji R, et al. Reactive intravascular histiocytosis associated with tonsillitis. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:560-563.

- Pouryazdanparast P, Yu L, Dalton VK, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis presenting with extensive vulvar necrosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;(36 suppl 1):1-7.

- Reznitsky M, Daugaard S, Charabi BW. Two rare cases of laryngeal intralymphatic histiocytosis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:783-788.

- Fujimoto N, Nakanishi G, Manabe T, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis comprises M2 macrophages in superficial dermal lymphatics with or without smooth muscles. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:898-902.

- Piccolo V, Ruocco E, Russo T, et al. A possible relationship between metal implant-induced intralymphatic histiocytosis and the concept of the immunocompromised district. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E365.

- O’Grady JT, Shahidullah H, Doherty VR, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis. Histopathology. 1994;24:265-268.

- Bakr F, Webber N, Fassihi H, et al. Primary and secondary intralymphatic histiocytosis [published online January 17, 2014]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:927-933.

- Watanabe T, Yamada N, Yoshida Y, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis with granuloma formation associated with orthopaedic metal implants [published online November 10, 2007]. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:402-404.

- Requena L, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, Walsh SN, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis. a clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:140-151.

- Grekin S, Mesfin M, Kang S, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis following placement of a metal implant. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:351-353.

- Rossari S, Scatena C, Gori A, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis: cutaneous nodules and metal implants [published online March 6, 2011]. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:534-535.

- de Unamuno Bustos B, García Rabasco A, Ballester Sánchez R, et al. Erythematous indurated plaque on the right upper limb. intralymphatic histiocytosis (IH) associated with orthopedic metal implant. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:547-549.

- Chiu YE, Maloney JE, Bengana C. Erythematous patch overlying a swollen knee—quiz case. intralymphatic histiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1037-1042.

- Saggar S, Lee B, Krivo J, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with orthopedic implants. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:1208-1209.

- Bidier M, Hamsch C, Kutzner H, et al. Two cases of intralymphatic histiocytosis following hip replacement [published online June 9, 2015]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:700-702.

- Darling MD, Akin R, Tarbox MB, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis overlying hip implantation treated with pentoxifilline. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2015;29(1 suppl):117-121.

- Demirkesen C, Kran T, Leblebici C, et al. Intravascular/intralymphatic histiocytosis: a report of 3 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:783-789.

- Gómez-Sánchez ME, Azaña-Defez JM, Martínez-Martínez ML, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis: a report of 2 cases. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109:E1-E5.

- Haitz KA, Chapman MS, Seidel GD. Intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with an orthopedic metal implant. Cutis. 2016;97:E12-E14.

- Rieger E, Soyer HP, Leboit PE, et al. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis or intravascular histiocytosis? an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study in two cases of intravascular histiocytic cell proliferation. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:497-504.

- Pruim B, Strutton G, Congdon S, et al. Cutaneous histiocytic lymphangitis: an unusual manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:101-105.

- Magro CM, Crowson AN. The spectrum of cutaneous lesions in rheumatoid arthritis: a clinical and pathological study of 43 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:1-10.

- Takiwaki H, Adachi A, Kohno H, et al. Intravascular or intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: a report of 4 cases.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:585-590.

- Mensing CH, Krengel S, Tronnier M, et al. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis: is it “intravascular histiocytosis”? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:216-219.

- Okazaki A, Asada H, Niizeki H, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: report of a case with lymphatic endothelial proliferation. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1385-1387.

- Catalina-Fernández I, Alvárez AC, Martin FC, et al. Cutaneous intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:165-168.

- Nishie W, Sawamura D, Iitoyo M, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Dermatology. 2008;217:144-145.

- Okamoto N, Tanioka M, Yamamoto T, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:516-518.

- Huang H-Y, Liang C-W, Hu S-L, et al. Cutaneous intravascular histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E302-E303.

- Sakaguchi M, Nagai H, Tsuji G, et al. Effectiveness of infliximab for intralymphatic histiocytosis with rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:131-133.

- Washio K, Nakata K, Nakamura A, et al. Pressure bandage as an effective treatment for intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Dermatology. 2011;223:20-24.

- Kaneko T, Takeuchi S, Nakano H, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis with rheumatoid arthritis: possible association with the joint involvement. Case Reports Clin Med. 2014;3:149-152.

- Nakajima T, Kawabata D, Nakabo S, et al. Successful treatment with tocilizumab in a case of intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Intern Med. 2014;53:2255-2258.

- Tsujiwaki M, Hata H, Miyauchi T, et al. Warty intralymphatic histiocytosis successfully treated with topical tacrolimus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2267-2269.

- Tanaka M, Funasaka Y, Tsuruta K, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis with massive interstitial granulomatous foci in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:237-238.

- Cornejo KM, Cosar EF, O’Donnell P. Cutaneous intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with lung adenocarcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38:568-570.

- Tran TAN, Tran Q, Carlson JA. Intralymphatic histiocytosis of the appendix and fallopian tube associated with primary peritoneal high-grade, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of Müllerian origin. Int J Surg Pathol. 2017;25:357-364.

- Echeverría-García B, Botella-Estrada R, Requena C, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis and cancer of the colon [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:257-262.

- Ergen EN, Zwerner JP. Cover image: intralymphatic histiocytosis with giant blanching violaceous plaques. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:325-326.

- Wang Y, Yang H, Tu P. Upper facial swelling: an uncommon manifestation of intralymphatic histiocytosis. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:814-815.

- Rhee D-Y, Lee D-W, Chang S-E, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis without rheumatoid arthritis. J Dermatol. 2008;35:691-693.

- Gilchrest BA, Eller MS, Geller AC, et al. The pathogenesis of melanoma induced by ultraviolet radiation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1341-1348.

- Asagoe K, Torigoe R, Ofuji R, et al. Reactive intravascular histiocytosis associated with tonsillitis. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:560-563.

- Pouryazdanparast P, Yu L, Dalton VK, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis presenting with extensive vulvar necrosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;(36 suppl 1):1-7.

- Reznitsky M, Daugaard S, Charabi BW. Two rare cases of laryngeal intralymphatic histiocytosis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:783-788.

- Fujimoto N, Nakanishi G, Manabe T, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis comprises M2 macrophages in superficial dermal lymphatics with or without smooth muscles. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:898-902.

- Piccolo V, Ruocco E, Russo T, et al. A possible relationship between metal implant-induced intralymphatic histiocytosis and the concept of the immunocompromised district. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E365.

Practice Points

- Intralymphatic histiocytosis is a rare disorder often associated with rheumatic arthritis and joint prostheses.

- The diagnosis is made by histopathology as well as D2-40 and CD68 immunostaining.

- While there is no gold standard of treatment for intralymphatic histiocytosis, intralesional triamcinolone proved efficacious in this case with prolonged results.

Synovial Chondromatosis: An Unusual Case of Knee Pain and Swelling

Joint mice or loose/rice bodies are infrequently encountered within joints. Usually, they are either fibrin or cartilaginous. The fibrin type, typically results from bleeding within a joint from synovitis, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), or tuberculosis, and the cartilaginous/osteocartilaginous type develop from trauma or osteoarthritis.1 A rare cause of osteocartilaginous joint mice is synovial chondromatosis(SC), which can produce multiple loose bodies that originate from the synovial membranes of joints, bursae, and tendon sheaths of large joints; the knee being the most common (50%-65 % of cases).1,2

A case of a male who had multiple years of left knee pain and swelling without a documented traumatic cause is presented

Case Presentation

A 34-year-old male veteran was evaluated and treated in a VA orthopedic outpatient clinic by a physician assistant for anterior left knee pain and swelling of insidious onset that had persisted for 1.5 years. The patient reported experiencing no trauma. His primary care provider already was treating the patient with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), icing, and bracing. He had full motion in his knee with extension/flexion 0° to 130°. Collateral and cruciate ligaments were stable. He had a positive McMurray test. The X-rays showed no pathology. Due to the positive meniscal tear signs, a magnetic resonance image (MRI) was ordered.

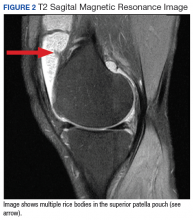

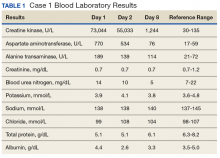

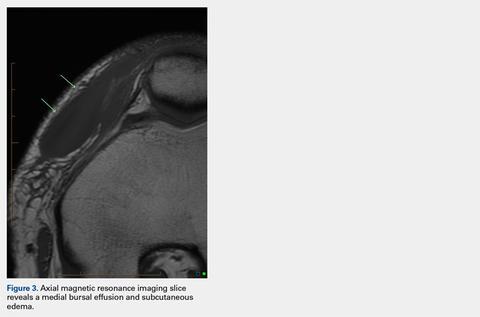

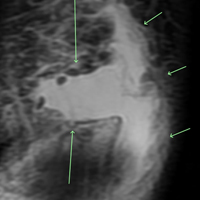

The patient was intermittently nonadherent with follow-up care. The MRI results were available at a subsequent appointment 3 months after the index evaluation, which revealed a large joint effusion with rice bodies, small erosion of the posterior tibialplateau, and synovial proliferation of the anterior knee joint. A steroid injection to his affected knee was given. Concerns for possible RA led to a workup. The laboratory results included rheumatoid factor (weakly positive), antinuclear-antibodies (negative), human immunodeficiency virus (positivewith western blot negative), C-reactive protein (< 0.02 mg/L), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (5 mm/h), white blood cell count (4.6 µL), hepatitis B surface antigen (reactive), hepatitis A antibody (IgG reactive), synovial fluid cultures, and Gram stain (negative).

The patient saw a rheumatologist 7 months after a RA referral was processed. The consulting rheumatologist was unconcerned by a weakly positive rheumatoid factor, which was later repeated and was negative. The rheumatologist excluded the possibility of RA, and the patient was diagnosed with oligoarthritis. The treatment rendered was to continue NSAIDs and to return to the orthopedic clinic for continued care.

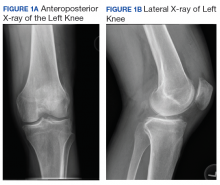

The patient had irregular follow-up visits where he received multiple methylprednisolone acetate intra-articular injections. His motion regressed until extension/flexion had decreased to 5°/85°. At this point the patient was forwarded to an operative orthopedic surgeon for evaluation for surgical intervention. Recent anteroposterior and lateral left knee X-rays showed faint intra-articular calcification, joint effusion, with mild arthritic changes of the patellofemoral joint (Figures 1A and 1B).

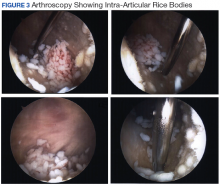

At surgery, on placing the infralateral portal, clear straw-colored fluid exited the cannula followed by copious small white rice bodies, which were sent to pathology for evaluation. The knee was surgically evaluated, and extensive rice bodies were encountered (Figure 3). These were extracted with a full radius shaver. The chondral surfaces were inspected. There were no arthritic changes, but the synovial lining of the joint was hypertrophied and reactive (Milgram phase 2). After all loose bodies were extracted, the patient’s incisions were closed with nylon suture, and he was placed in sterile dressings with a postoperative range of motion brace.

The patient presented for his routine postoperative visit 14 days after surgery. Pathology results showed synociocytes, and inflammatory cells were negative for malignancy. The patient was forwarded to a local hospital for further evaluation and treatment by an orthopedic oncologist due to a reported 5% chance of malignant transformation.1-3

Discussion

Synovial chondromatosis or osteochondromatosis is a rare, benign, metaplastic, typically monoarticular disorder of the synovial lining of joints, bursae, and synovial sheaths, usually affecting large joints.1-5 Although any joint can be involved, such as metacarpalphalangeal joints, temporomandibular joints, distal radio-ulnar joints, and the hips, the knee is the most common with an occurrence rate 50% to 65%.3-5 Extra-articular proliferation can be seen in cases of osteochondromatosis.2 It is characterized by the formation of intra-articular nodules of the synovium that can detach and become loose bodies, which can secondarily become calcified/ossified.4,6 The differential diagnosis associated with SC should include synovial hemangioma, pigmented villonodular synovitis, synovial cyst, lipoma arborescence, and malignancies, such as synovial chondrosarcoma or synovial sarcoma.3

Men are affected twice as much as are women, usually in the fourth through sixth decades of life, and a mean age of 47.7 years.1,3-5,7,8 The SC occurrence rate in adults is 1:100,000.2 Patients typically present with insidious gradual mechanical symptoms, such as pain (> 85% of cases), swelling (42%-58%), and decreased motion (38%-55%) in the affected joint.2,3,6 Often there is crepitus with motion, diffuse tenderness, effusion, and occasionally nodules can be palpated.2,3 Histologically, the synovium exhibits condrocytic metaplasia of fibroblasts with influence from transforming growth factor-β and bone morphogenic proteins.1,4

Synovial chondromatosis can mimic osteoarthritis or meniscal pathology.3 Because of a chance of malignant transformation, any patient with rapid late deterioration of clinical features should be evaluated for chondrosarcoma or synovial sarcoma.1-4 Plain radiographs may help differentiate the cause showing calcific joint mice and peri-articular erosions. However, the intra-articular loose bodies are frequently radiolucent, and a MRI may be warranted to definitively differentiate the diagnosis.2,7,8

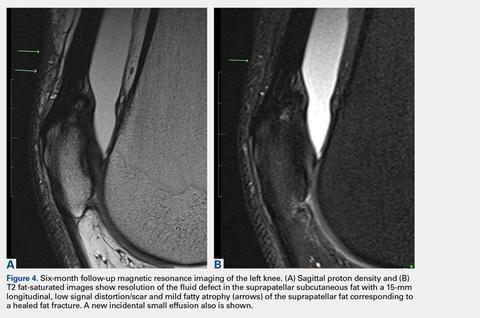

Loose bodies tend to exhibit a low signal on T1-weighted images and a high signal on T2-weighted images, although there may a be low signal on all images where there is extensive calcification of the loose bodies.2 Ultrasound also is a useful diagnostic tool that can show numerous echogenic bodies, effusion, and synovial hypertrophy.2

A classic article by Milgram discussed the phases of the proliferative changes associated with SC, where phase 1 shows active intrasynovial disease with no loose bodies.9 Phase 2 has transitional lesions with osteochondral nodules within the synovial membrane and free bodies within the joint cavity. Last, in phase 3, there are multiple osteochondral free bodies but quiescent intrasynovial disease. The patient in this case study exhibited intra-articular activity mimicking phase 2 with extensive intra-articular loose bodies and reactive synovial lining.3,9

In the early phase of the disease, conservative management may be trialed with NSAIDs, bracing, and injections, but typically surgical intervention is warranted after free bodies are found present, because they limit motion and cause recalcitrant swelling.2,8 There is a controversy whether arthroscopic removal of loose bodies or excision with synovectomy is the treatment of choice.6 Ogilvie-Harris and colleagues reviewed the results of both procedures and found that although removal of loose bodies alone may be sufficient, there is the potential for recurrence.9,10 In order to reduce potential recurrence, removal of loose bodies with anterior and posterior synovectomy is the treatment of choice.9

If arthroscopic removal of loose bodies without synovectomy is performed, then the patient should be followed closely for recurrence, which Jesalpura and colleagues reported to occur for 11.5% of patients.9,11 If there is a reappearance, then a synovectomy should be performed.10 A recommended treatment option for recalcitrant SC is radiation, but this carries the added risk of perpetuating malignant transformation.1,7

Unfortunately, osteoarthritis can be a significant long-term postoperative adverse effect.3,6-8 This typically is related to the amount of articular damage that is present at surgery. Many times, the arthritis becomes significant enough to require total joint arthroplasty.4 Close long-term follow-up is recommended, because although rare, there is a chance of malignant change.1-4

Conclusion

Synovial chondromatosis is an uncommon cause of knee pain and swelling and should be included in the differential diagnosis when evaluating any adult aged 30 years to 50 years with knee pain of insidious onset. Appropriate workup, intervention, and treatment will allow final diagnosis and correlating care to be administered to the patient.

1. Libbey NP, Mirrer F. Synovial chondromatosis. Med Health R I. 2011;94(9):274-275.

2. Giancane G, Tanturri de Horatio L, Buonuomo PS, Barbuti D, Lais G, Cortis E. Swollen knee due to primary synovial chondromatosis in pediatrics: a rare and possibly misdiagnosed condition. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33(8):2183-2185.

3. Serbest S, Tiftikçi U, Karaaslan F, Tosun HB, Sevinç HF, Balci M. A neglected case of giant synovial chondromatosis in knee joint. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;22:5.

4. Hallam P, Ashwood N, Cobb J, Fazal A, Heatley W. Malignant transformation in synovial chondromatosis of the knee? Knee. 2001;8(3):239-242.

5. Pimentel Cde Q, Hoff LS, de Sousa LF, Cordeiro RA, Pereira RM. Primary synovial osteochondromatosis of the knee. Rheumatol (Oxford). 2015;54(10):1815.

6. Damron TA, Sim FH. Soft-tissue tumors about the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1997;5(3):141-152.

7. Krych A, Odland A, Rose P, et al. Onconlogic conditions that simulate common sports injuries. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(4):223-234.

8. Adelani MA, Wupperman RM, Holt GE. Benign synovial disorders. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(5):268-275.

9. Migram JW. Synovial osteochondromatosis: a histopathological study of thirty cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(6):792-801.

10. Ogilvie-Harris DJ, Saleh K. Generalized synovial chondromatosis of the knee: a comparison of removal of the loose bodies alone with arthroscopic synovectomy. Arthroscopy.1994;10(2):166-170.

11. Jesalpura JP, Chung HW, Patnaik S, Choi HW, Kim JI, Nha KW. Athroscopic treatment of localized synovial chondromatosis of the posterior knee joint. Orthopedics. 2010;33(1):49

Joint mice or loose/rice bodies are infrequently encountered within joints. Usually, they are either fibrin or cartilaginous. The fibrin type, typically results from bleeding within a joint from synovitis, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), or tuberculosis, and the cartilaginous/osteocartilaginous type develop from trauma or osteoarthritis.1 A rare cause of osteocartilaginous joint mice is synovial chondromatosis(SC), which can produce multiple loose bodies that originate from the synovial membranes of joints, bursae, and tendon sheaths of large joints; the knee being the most common (50%-65 % of cases).1,2

A case of a male who had multiple years of left knee pain and swelling without a documented traumatic cause is presented

Case Presentation

A 34-year-old male veteran was evaluated and treated in a VA orthopedic outpatient clinic by a physician assistant for anterior left knee pain and swelling of insidious onset that had persisted for 1.5 years. The patient reported experiencing no trauma. His primary care provider already was treating the patient with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), icing, and bracing. He had full motion in his knee with extension/flexion 0° to 130°. Collateral and cruciate ligaments were stable. He had a positive McMurray test. The X-rays showed no pathology. Due to the positive meniscal tear signs, a magnetic resonance image (MRI) was ordered.

The patient was intermittently nonadherent with follow-up care. The MRI results were available at a subsequent appointment 3 months after the index evaluation, which revealed a large joint effusion with rice bodies, small erosion of the posterior tibialplateau, and synovial proliferation of the anterior knee joint. A steroid injection to his affected knee was given. Concerns for possible RA led to a workup. The laboratory results included rheumatoid factor (weakly positive), antinuclear-antibodies (negative), human immunodeficiency virus (positivewith western blot negative), C-reactive protein (< 0.02 mg/L), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (5 mm/h), white blood cell count (4.6 µL), hepatitis B surface antigen (reactive), hepatitis A antibody (IgG reactive), synovial fluid cultures, and Gram stain (negative).

The patient saw a rheumatologist 7 months after a RA referral was processed. The consulting rheumatologist was unconcerned by a weakly positive rheumatoid factor, which was later repeated and was negative. The rheumatologist excluded the possibility of RA, and the patient was diagnosed with oligoarthritis. The treatment rendered was to continue NSAIDs and to return to the orthopedic clinic for continued care.

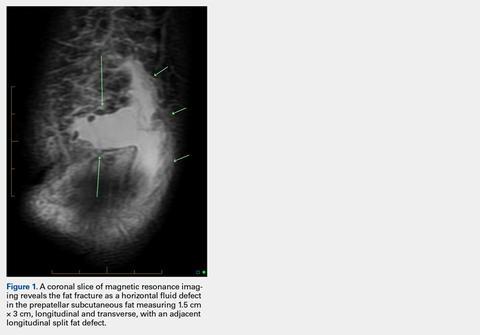

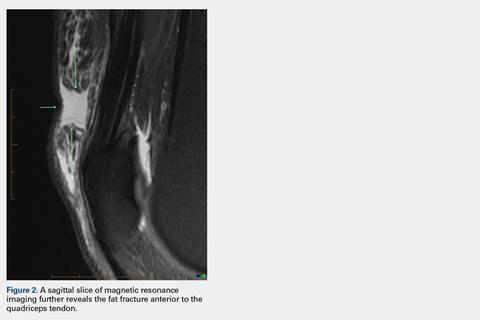

The patient had irregular follow-up visits where he received multiple methylprednisolone acetate intra-articular injections. His motion regressed until extension/flexion had decreased to 5°/85°. At this point the patient was forwarded to an operative orthopedic surgeon for evaluation for surgical intervention. Recent anteroposterior and lateral left knee X-rays showed faint intra-articular calcification, joint effusion, with mild arthritic changes of the patellofemoral joint (Figures 1A and 1B).

At surgery, on placing the infralateral portal, clear straw-colored fluid exited the cannula followed by copious small white rice bodies, which were sent to pathology for evaluation. The knee was surgically evaluated, and extensive rice bodies were encountered (Figure 3). These were extracted with a full radius shaver. The chondral surfaces were inspected. There were no arthritic changes, but the synovial lining of the joint was hypertrophied and reactive (Milgram phase 2). After all loose bodies were extracted, the patient’s incisions were closed with nylon suture, and he was placed in sterile dressings with a postoperative range of motion brace.

The patient presented for his routine postoperative visit 14 days after surgery. Pathology results showed synociocytes, and inflammatory cells were negative for malignancy. The patient was forwarded to a local hospital for further evaluation and treatment by an orthopedic oncologist due to a reported 5% chance of malignant transformation.1-3

Discussion

Synovial chondromatosis or osteochondromatosis is a rare, benign, metaplastic, typically monoarticular disorder of the synovial lining of joints, bursae, and synovial sheaths, usually affecting large joints.1-5 Although any joint can be involved, such as metacarpalphalangeal joints, temporomandibular joints, distal radio-ulnar joints, and the hips, the knee is the most common with an occurrence rate 50% to 65%.3-5 Extra-articular proliferation can be seen in cases of osteochondromatosis.2 It is characterized by the formation of intra-articular nodules of the synovium that can detach and become loose bodies, which can secondarily become calcified/ossified.4,6 The differential diagnosis associated with SC should include synovial hemangioma, pigmented villonodular synovitis, synovial cyst, lipoma arborescence, and malignancies, such as synovial chondrosarcoma or synovial sarcoma.3

Men are affected twice as much as are women, usually in the fourth through sixth decades of life, and a mean age of 47.7 years.1,3-5,7,8 The SC occurrence rate in adults is 1:100,000.2 Patients typically present with insidious gradual mechanical symptoms, such as pain (> 85% of cases), swelling (42%-58%), and decreased motion (38%-55%) in the affected joint.2,3,6 Often there is crepitus with motion, diffuse tenderness, effusion, and occasionally nodules can be palpated.2,3 Histologically, the synovium exhibits condrocytic metaplasia of fibroblasts with influence from transforming growth factor-β and bone morphogenic proteins.1,4

Synovial chondromatosis can mimic osteoarthritis or meniscal pathology.3 Because of a chance of malignant transformation, any patient with rapid late deterioration of clinical features should be evaluated for chondrosarcoma or synovial sarcoma.1-4 Plain radiographs may help differentiate the cause showing calcific joint mice and peri-articular erosions. However, the intra-articular loose bodies are frequently radiolucent, and a MRI may be warranted to definitively differentiate the diagnosis.2,7,8

Loose bodies tend to exhibit a low signal on T1-weighted images and a high signal on T2-weighted images, although there may a be low signal on all images where there is extensive calcification of the loose bodies.2 Ultrasound also is a useful diagnostic tool that can show numerous echogenic bodies, effusion, and synovial hypertrophy.2

A classic article by Milgram discussed the phases of the proliferative changes associated with SC, where phase 1 shows active intrasynovial disease with no loose bodies.9 Phase 2 has transitional lesions with osteochondral nodules within the synovial membrane and free bodies within the joint cavity. Last, in phase 3, there are multiple osteochondral free bodies but quiescent intrasynovial disease. The patient in this case study exhibited intra-articular activity mimicking phase 2 with extensive intra-articular loose bodies and reactive synovial lining.3,9

In the early phase of the disease, conservative management may be trialed with NSAIDs, bracing, and injections, but typically surgical intervention is warranted after free bodies are found present, because they limit motion and cause recalcitrant swelling.2,8 There is a controversy whether arthroscopic removal of loose bodies or excision with synovectomy is the treatment of choice.6 Ogilvie-Harris and colleagues reviewed the results of both procedures and found that although removal of loose bodies alone may be sufficient, there is the potential for recurrence.9,10 In order to reduce potential recurrence, removal of loose bodies with anterior and posterior synovectomy is the treatment of choice.9

If arthroscopic removal of loose bodies without synovectomy is performed, then the patient should be followed closely for recurrence, which Jesalpura and colleagues reported to occur for 11.5% of patients.9,11 If there is a reappearance, then a synovectomy should be performed.10 A recommended treatment option for recalcitrant SC is radiation, but this carries the added risk of perpetuating malignant transformation.1,7

Unfortunately, osteoarthritis can be a significant long-term postoperative adverse effect.3,6-8 This typically is related to the amount of articular damage that is present at surgery. Many times, the arthritis becomes significant enough to require total joint arthroplasty.4 Close long-term follow-up is recommended, because although rare, there is a chance of malignant change.1-4

Conclusion

Synovial chondromatosis is an uncommon cause of knee pain and swelling and should be included in the differential diagnosis when evaluating any adult aged 30 years to 50 years with knee pain of insidious onset. Appropriate workup, intervention, and treatment will allow final diagnosis and correlating care to be administered to the patient.

Joint mice or loose/rice bodies are infrequently encountered within joints. Usually, they are either fibrin or cartilaginous. The fibrin type, typically results from bleeding within a joint from synovitis, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), or tuberculosis, and the cartilaginous/osteocartilaginous type develop from trauma or osteoarthritis.1 A rare cause of osteocartilaginous joint mice is synovial chondromatosis(SC), which can produce multiple loose bodies that originate from the synovial membranes of joints, bursae, and tendon sheaths of large joints; the knee being the most common (50%-65 % of cases).1,2

A case of a male who had multiple years of left knee pain and swelling without a documented traumatic cause is presented

Case Presentation

A 34-year-old male veteran was evaluated and treated in a VA orthopedic outpatient clinic by a physician assistant for anterior left knee pain and swelling of insidious onset that had persisted for 1.5 years. The patient reported experiencing no trauma. His primary care provider already was treating the patient with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), icing, and bracing. He had full motion in his knee with extension/flexion 0° to 130°. Collateral and cruciate ligaments were stable. He had a positive McMurray test. The X-rays showed no pathology. Due to the positive meniscal tear signs, a magnetic resonance image (MRI) was ordered.

The patient was intermittently nonadherent with follow-up care. The MRI results were available at a subsequent appointment 3 months after the index evaluation, which revealed a large joint effusion with rice bodies, small erosion of the posterior tibialplateau, and synovial proliferation of the anterior knee joint. A steroid injection to his affected knee was given. Concerns for possible RA led to a workup. The laboratory results included rheumatoid factor (weakly positive), antinuclear-antibodies (negative), human immunodeficiency virus (positivewith western blot negative), C-reactive protein (< 0.02 mg/L), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (5 mm/h), white blood cell count (4.6 µL), hepatitis B surface antigen (reactive), hepatitis A antibody (IgG reactive), synovial fluid cultures, and Gram stain (negative).

The patient saw a rheumatologist 7 months after a RA referral was processed. The consulting rheumatologist was unconcerned by a weakly positive rheumatoid factor, which was later repeated and was negative. The rheumatologist excluded the possibility of RA, and the patient was diagnosed with oligoarthritis. The treatment rendered was to continue NSAIDs and to return to the orthopedic clinic for continued care.

The patient had irregular follow-up visits where he received multiple methylprednisolone acetate intra-articular injections. His motion regressed until extension/flexion had decreased to 5°/85°. At this point the patient was forwarded to an operative orthopedic surgeon for evaluation for surgical intervention. Recent anteroposterior and lateral left knee X-rays showed faint intra-articular calcification, joint effusion, with mild arthritic changes of the patellofemoral joint (Figures 1A and 1B).

At surgery, on placing the infralateral portal, clear straw-colored fluid exited the cannula followed by copious small white rice bodies, which were sent to pathology for evaluation. The knee was surgically evaluated, and extensive rice bodies were encountered (Figure 3). These were extracted with a full radius shaver. The chondral surfaces were inspected. There were no arthritic changes, but the synovial lining of the joint was hypertrophied and reactive (Milgram phase 2). After all loose bodies were extracted, the patient’s incisions were closed with nylon suture, and he was placed in sterile dressings with a postoperative range of motion brace.

The patient presented for his routine postoperative visit 14 days after surgery. Pathology results showed synociocytes, and inflammatory cells were negative for malignancy. The patient was forwarded to a local hospital for further evaluation and treatment by an orthopedic oncologist due to a reported 5% chance of malignant transformation.1-3

Discussion

Synovial chondromatosis or osteochondromatosis is a rare, benign, metaplastic, typically monoarticular disorder of the synovial lining of joints, bursae, and synovial sheaths, usually affecting large joints.1-5 Although any joint can be involved, such as metacarpalphalangeal joints, temporomandibular joints, distal radio-ulnar joints, and the hips, the knee is the most common with an occurrence rate 50% to 65%.3-5 Extra-articular proliferation can be seen in cases of osteochondromatosis.2 It is characterized by the formation of intra-articular nodules of the synovium that can detach and become loose bodies, which can secondarily become calcified/ossified.4,6 The differential diagnosis associated with SC should include synovial hemangioma, pigmented villonodular synovitis, synovial cyst, lipoma arborescence, and malignancies, such as synovial chondrosarcoma or synovial sarcoma.3

Men are affected twice as much as are women, usually in the fourth through sixth decades of life, and a mean age of 47.7 years.1,3-5,7,8 The SC occurrence rate in adults is 1:100,000.2 Patients typically present with insidious gradual mechanical symptoms, such as pain (> 85% of cases), swelling (42%-58%), and decreased motion (38%-55%) in the affected joint.2,3,6 Often there is crepitus with motion, diffuse tenderness, effusion, and occasionally nodules can be palpated.2,3 Histologically, the synovium exhibits condrocytic metaplasia of fibroblasts with influence from transforming growth factor-β and bone morphogenic proteins.1,4

Synovial chondromatosis can mimic osteoarthritis or meniscal pathology.3 Because of a chance of malignant transformation, any patient with rapid late deterioration of clinical features should be evaluated for chondrosarcoma or synovial sarcoma.1-4 Plain radiographs may help differentiate the cause showing calcific joint mice and peri-articular erosions. However, the intra-articular loose bodies are frequently radiolucent, and a MRI may be warranted to definitively differentiate the diagnosis.2,7,8

Loose bodies tend to exhibit a low signal on T1-weighted images and a high signal on T2-weighted images, although there may a be low signal on all images where there is extensive calcification of the loose bodies.2 Ultrasound also is a useful diagnostic tool that can show numerous echogenic bodies, effusion, and synovial hypertrophy.2

A classic article by Milgram discussed the phases of the proliferative changes associated with SC, where phase 1 shows active intrasynovial disease with no loose bodies.9 Phase 2 has transitional lesions with osteochondral nodules within the synovial membrane and free bodies within the joint cavity. Last, in phase 3, there are multiple osteochondral free bodies but quiescent intrasynovial disease. The patient in this case study exhibited intra-articular activity mimicking phase 2 with extensive intra-articular loose bodies and reactive synovial lining.3,9

In the early phase of the disease, conservative management may be trialed with NSAIDs, bracing, and injections, but typically surgical intervention is warranted after free bodies are found present, because they limit motion and cause recalcitrant swelling.2,8 There is a controversy whether arthroscopic removal of loose bodies or excision with synovectomy is the treatment of choice.6 Ogilvie-Harris and colleagues reviewed the results of both procedures and found that although removal of loose bodies alone may be sufficient, there is the potential for recurrence.9,10 In order to reduce potential recurrence, removal of loose bodies with anterior and posterior synovectomy is the treatment of choice.9

If arthroscopic removal of loose bodies without synovectomy is performed, then the patient should be followed closely for recurrence, which Jesalpura and colleagues reported to occur for 11.5% of patients.9,11 If there is a reappearance, then a synovectomy should be performed.10 A recommended treatment option for recalcitrant SC is radiation, but this carries the added risk of perpetuating malignant transformation.1,7

Unfortunately, osteoarthritis can be a significant long-term postoperative adverse effect.3,6-8 This typically is related to the amount of articular damage that is present at surgery. Many times, the arthritis becomes significant enough to require total joint arthroplasty.4 Close long-term follow-up is recommended, because although rare, there is a chance of malignant change.1-4

Conclusion

Synovial chondromatosis is an uncommon cause of knee pain and swelling and should be included in the differential diagnosis when evaluating any adult aged 30 years to 50 years with knee pain of insidious onset. Appropriate workup, intervention, and treatment will allow final diagnosis and correlating care to be administered to the patient.

1. Libbey NP, Mirrer F. Synovial chondromatosis. Med Health R I. 2011;94(9):274-275.

2. Giancane G, Tanturri de Horatio L, Buonuomo PS, Barbuti D, Lais G, Cortis E. Swollen knee due to primary synovial chondromatosis in pediatrics: a rare and possibly misdiagnosed condition. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33(8):2183-2185.

3. Serbest S, Tiftikçi U, Karaaslan F, Tosun HB, Sevinç HF, Balci M. A neglected case of giant synovial chondromatosis in knee joint. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;22:5.

4. Hallam P, Ashwood N, Cobb J, Fazal A, Heatley W. Malignant transformation in synovial chondromatosis of the knee? Knee. 2001;8(3):239-242.

5. Pimentel Cde Q, Hoff LS, de Sousa LF, Cordeiro RA, Pereira RM. Primary synovial osteochondromatosis of the knee. Rheumatol (Oxford). 2015;54(10):1815.

6. Damron TA, Sim FH. Soft-tissue tumors about the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1997;5(3):141-152.

7. Krych A, Odland A, Rose P, et al. Onconlogic conditions that simulate common sports injuries. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(4):223-234.

8. Adelani MA, Wupperman RM, Holt GE. Benign synovial disorders. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(5):268-275.

9. Migram JW. Synovial osteochondromatosis: a histopathological study of thirty cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(6):792-801.