User login

Emergency Imaging: Abdominal Pain 6 Months After Cesarean Delivery

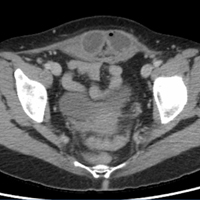

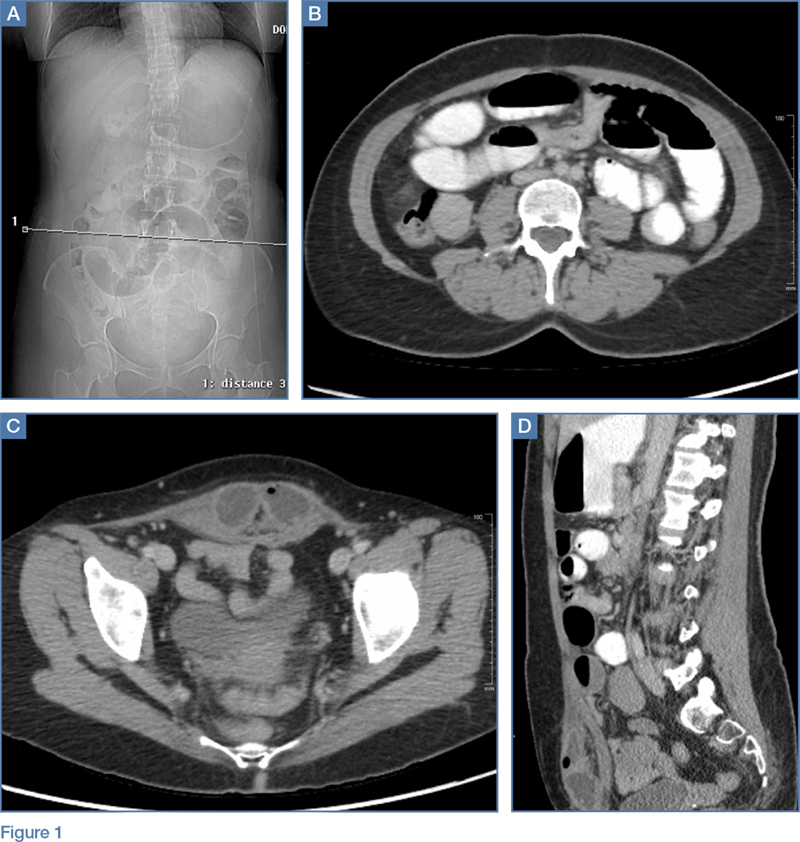

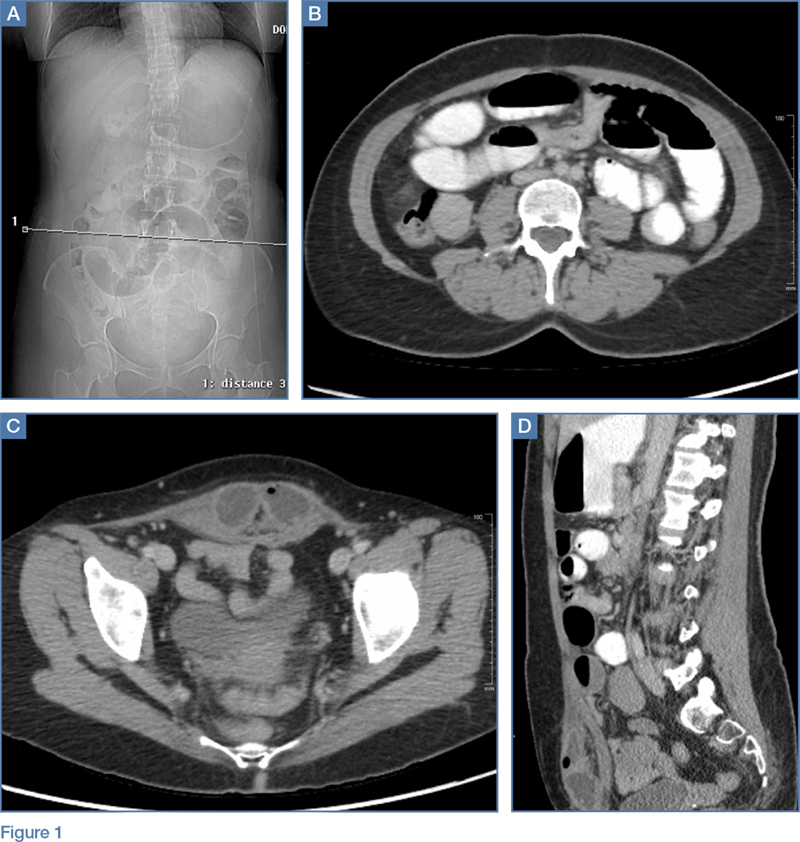

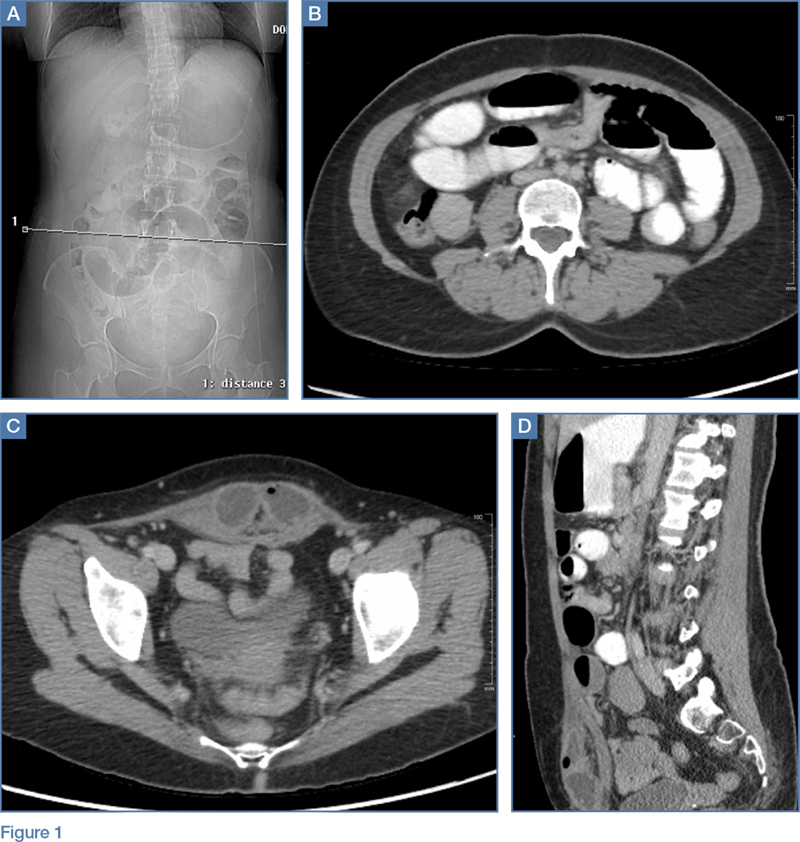

A 45-year-old woman with a history of polycystic ovary syndrome presented to the ED for evaluation of acute abdominal pain. The patient’s surgical history was significant for a cesarean delivery 6 months prior to presentation. Abdominal examination revealed a well-healed suprapubic cesarean incision scar, which was tender upon palpation. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast were ordered; representative images are shown above (Figure 1a-1d).

What is the diagnosis? What are the associated complications and preferred management for this entity?

Answer

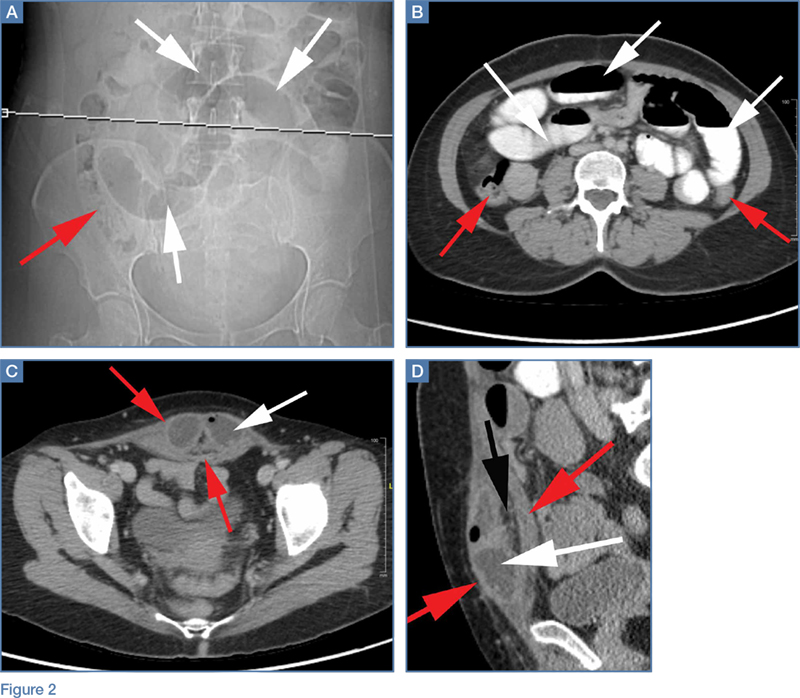

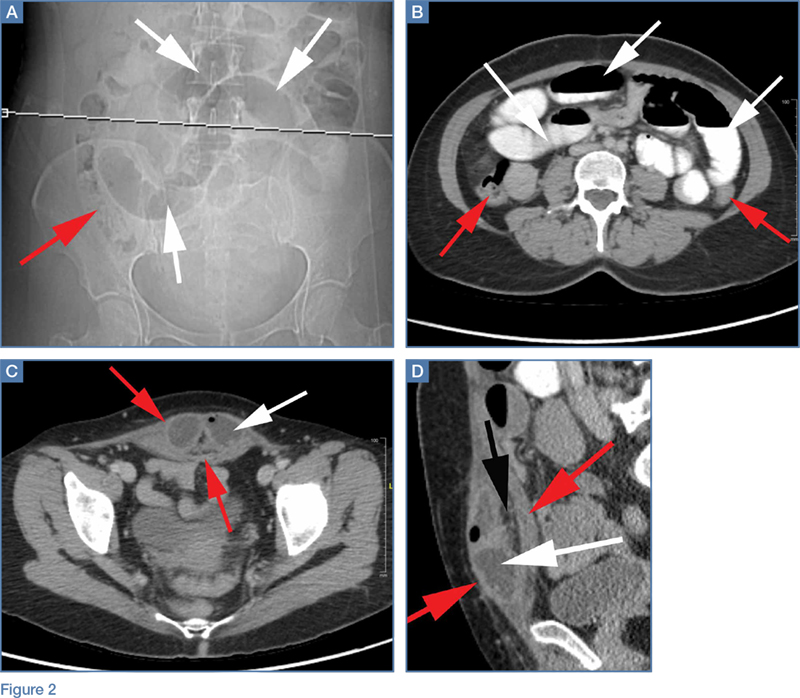

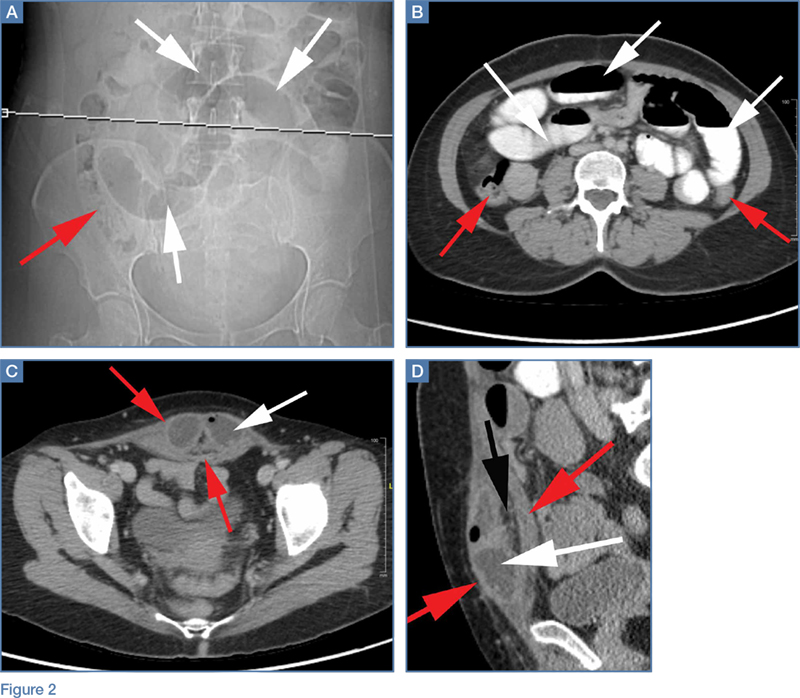

The scout image from the CT scan shows multiple dilated loops of small bowel (white arrows, Figure 2a) and only a small amount of air within a decompressed colon (red arrow, Figure 2a). The multiplanar CT image confirmed multiple dilated small bowel loops (white arrows, Figure 2b) and the decompressed large bowel (red arrows, Figure 2b), indicating the presence of a small bowel obstruction. A distal small bowel loop (white arrows, Figure 2c and 2d) was identified in a hernia sac within the walls of the rectus abdominis muscle (red arrows, Figure 2c and 2d). Mesenteric stranding within the hernia sac was suggestive of incarceration (black arrow, Figure 2d). No signs of intestinal ischemia, such as pneumatosis or wall thickening, were present.

An exploratory laparotomy was emergently performed, which confirmed the presence of incarcerated small bowel within the posterior rectus sheath defect without evidence of strangulation. Reduction of small bowel and primary closure of the hernia defect was subsequently performed without complication.

Abdominal Wall Hernias

Abdominal wall hernias are common in the United States, with more than 1 million abdominal wall hernia repairs performed annually.1 A posterior rectus sheath hernia is a rare type of abdominal wall hernia; the majority are postsurgical (as seen in this patient) or posttraumatic, with only a few reported congenital cases.2

Anatomy

The rectus sheath encloses the rectus abdominis muscle and is composed of the aponeuroses of the transversus abdominis, external oblique, and internal oblique muscles. The aponeuroses form an anterior and posterior sheath, which together serve as a strong barrier against the herniation of abdominal contents, accounting for the rarity of a spontaneous rectus sheath hernia. However, inferior to the umbilicus (below the arcuate line), the posterior rectus sheath is composed primarily of transversalis fascia, which may make this region more susceptible to herniation.3 Additional predisposing factors to herniation include increased muscle weakness and elevated intra-abdominal pressure, such as that which occurs during pregnancy or from ascites.4

Clinical Presentation

Like other abdominal wall hernias, the clinical presentation of posterior rectus sheath hernias is nonspecific. Patients may be asymptomatic or may develop abdominal pain, distension, and vomiting as a result of acute complications that necessitate emergent surgery. During history-taking, inquiry into a patient’s surgical history is crucial because it may raise clinical suspicion for an abdominal wall hernia, as was the case in our patient, who recently had a cesarean delivery.

Diagnosis

Because prompt and accurate diagnosis of acute complications of abdominal wall hernias is essential, imaging studies are typically required for diagnosis. Computed tomography is the modality of choice based on its ability to provide superior anatomic detail of the abdominal wall, permitting identification of hernias and differentiating them from other abdominal masses, such as hematomas, abscesses, or tumors. Additionally, CT is able to detect early signs of hernia sac complications, including bowel obstruction, incarceration, and strangulation.5

Treatment

Treatment for a posterior rectus sheath hernia is surgical with primary closure being the preferred method. Prosthetic repair may also be performed, particularly when the hernia defect is large, but it has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of intestinal strangulation.3

1. Rutkow IM. Demographic and socioeconomic aspects of hernia repair in the United States in 2003. Surg Clin North Am. 2003;83(5):1045-1051, v-vi. doi:10.1016/S0039-6109(03)00132-4.

2. Lenobel S, Lenobel R, Yu J. Posterior rectus sheath hernia causing intermittent small bowel obstruction. J Radiol Case Rep J. 2014;8(9):25-29. doi:10.3941/jrcr.v8i9.2081.

3. Losanoff JE, Basson MD, Gruber SA. Spontaneous hernia through the posterior rectus abdominis sheath: case report and review of the published literature 1937-2008. Hernia. 2009;13(5):555-558. doi:10.1007/s10029-009-0481-6.

4. Bentzon N, Adamsen S. Hernia of the posterior rectus sheath: a new entity? Eur J Surg. 1995;161(3):215-216.

5. Aguirre DA, Santosa AC, Casola G, Sirlin CB. Abdominal wall hernias: imaging features, complications, and diagnostic pitfalls at mutli-detector row CT. Radiographics. 2005;25(6):1501-1520. doi:10.1148/rg.256055018.

A 45-year-old woman with a history of polycystic ovary syndrome presented to the ED for evaluation of acute abdominal pain. The patient’s surgical history was significant for a cesarean delivery 6 months prior to presentation. Abdominal examination revealed a well-healed suprapubic cesarean incision scar, which was tender upon palpation. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast were ordered; representative images are shown above (Figure 1a-1d).

What is the diagnosis? What are the associated complications and preferred management for this entity?

Answer

The scout image from the CT scan shows multiple dilated loops of small bowel (white arrows, Figure 2a) and only a small amount of air within a decompressed colon (red arrow, Figure 2a). The multiplanar CT image confirmed multiple dilated small bowel loops (white arrows, Figure 2b) and the decompressed large bowel (red arrows, Figure 2b), indicating the presence of a small bowel obstruction. A distal small bowel loop (white arrows, Figure 2c and 2d) was identified in a hernia sac within the walls of the rectus abdominis muscle (red arrows, Figure 2c and 2d). Mesenteric stranding within the hernia sac was suggestive of incarceration (black arrow, Figure 2d). No signs of intestinal ischemia, such as pneumatosis or wall thickening, were present.

An exploratory laparotomy was emergently performed, which confirmed the presence of incarcerated small bowel within the posterior rectus sheath defect without evidence of strangulation. Reduction of small bowel and primary closure of the hernia defect was subsequently performed without complication.

Abdominal Wall Hernias

Abdominal wall hernias are common in the United States, with more than 1 million abdominal wall hernia repairs performed annually.1 A posterior rectus sheath hernia is a rare type of abdominal wall hernia; the majority are postsurgical (as seen in this patient) or posttraumatic, with only a few reported congenital cases.2

Anatomy

The rectus sheath encloses the rectus abdominis muscle and is composed of the aponeuroses of the transversus abdominis, external oblique, and internal oblique muscles. The aponeuroses form an anterior and posterior sheath, which together serve as a strong barrier against the herniation of abdominal contents, accounting for the rarity of a spontaneous rectus sheath hernia. However, inferior to the umbilicus (below the arcuate line), the posterior rectus sheath is composed primarily of transversalis fascia, which may make this region more susceptible to herniation.3 Additional predisposing factors to herniation include increased muscle weakness and elevated intra-abdominal pressure, such as that which occurs during pregnancy or from ascites.4

Clinical Presentation

Like other abdominal wall hernias, the clinical presentation of posterior rectus sheath hernias is nonspecific. Patients may be asymptomatic or may develop abdominal pain, distension, and vomiting as a result of acute complications that necessitate emergent surgery. During history-taking, inquiry into a patient’s surgical history is crucial because it may raise clinical suspicion for an abdominal wall hernia, as was the case in our patient, who recently had a cesarean delivery.

Diagnosis

Because prompt and accurate diagnosis of acute complications of abdominal wall hernias is essential, imaging studies are typically required for diagnosis. Computed tomography is the modality of choice based on its ability to provide superior anatomic detail of the abdominal wall, permitting identification of hernias and differentiating them from other abdominal masses, such as hematomas, abscesses, or tumors. Additionally, CT is able to detect early signs of hernia sac complications, including bowel obstruction, incarceration, and strangulation.5

Treatment

Treatment for a posterior rectus sheath hernia is surgical with primary closure being the preferred method. Prosthetic repair may also be performed, particularly when the hernia defect is large, but it has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of intestinal strangulation.3

A 45-year-old woman with a history of polycystic ovary syndrome presented to the ED for evaluation of acute abdominal pain. The patient’s surgical history was significant for a cesarean delivery 6 months prior to presentation. Abdominal examination revealed a well-healed suprapubic cesarean incision scar, which was tender upon palpation. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast were ordered; representative images are shown above (Figure 1a-1d).

What is the diagnosis? What are the associated complications and preferred management for this entity?

Answer

The scout image from the CT scan shows multiple dilated loops of small bowel (white arrows, Figure 2a) and only a small amount of air within a decompressed colon (red arrow, Figure 2a). The multiplanar CT image confirmed multiple dilated small bowel loops (white arrows, Figure 2b) and the decompressed large bowel (red arrows, Figure 2b), indicating the presence of a small bowel obstruction. A distal small bowel loop (white arrows, Figure 2c and 2d) was identified in a hernia sac within the walls of the rectus abdominis muscle (red arrows, Figure 2c and 2d). Mesenteric stranding within the hernia sac was suggestive of incarceration (black arrow, Figure 2d). No signs of intestinal ischemia, such as pneumatosis or wall thickening, were present.

An exploratory laparotomy was emergently performed, which confirmed the presence of incarcerated small bowel within the posterior rectus sheath defect without evidence of strangulation. Reduction of small bowel and primary closure of the hernia defect was subsequently performed without complication.

Abdominal Wall Hernias

Abdominal wall hernias are common in the United States, with more than 1 million abdominal wall hernia repairs performed annually.1 A posterior rectus sheath hernia is a rare type of abdominal wall hernia; the majority are postsurgical (as seen in this patient) or posttraumatic, with only a few reported congenital cases.2

Anatomy

The rectus sheath encloses the rectus abdominis muscle and is composed of the aponeuroses of the transversus abdominis, external oblique, and internal oblique muscles. The aponeuroses form an anterior and posterior sheath, which together serve as a strong barrier against the herniation of abdominal contents, accounting for the rarity of a spontaneous rectus sheath hernia. However, inferior to the umbilicus (below the arcuate line), the posterior rectus sheath is composed primarily of transversalis fascia, which may make this region more susceptible to herniation.3 Additional predisposing factors to herniation include increased muscle weakness and elevated intra-abdominal pressure, such as that which occurs during pregnancy or from ascites.4

Clinical Presentation

Like other abdominal wall hernias, the clinical presentation of posterior rectus sheath hernias is nonspecific. Patients may be asymptomatic or may develop abdominal pain, distension, and vomiting as a result of acute complications that necessitate emergent surgery. During history-taking, inquiry into a patient’s surgical history is crucial because it may raise clinical suspicion for an abdominal wall hernia, as was the case in our patient, who recently had a cesarean delivery.

Diagnosis

Because prompt and accurate diagnosis of acute complications of abdominal wall hernias is essential, imaging studies are typically required for diagnosis. Computed tomography is the modality of choice based on its ability to provide superior anatomic detail of the abdominal wall, permitting identification of hernias and differentiating them from other abdominal masses, such as hematomas, abscesses, or tumors. Additionally, CT is able to detect early signs of hernia sac complications, including bowel obstruction, incarceration, and strangulation.5

Treatment

Treatment for a posterior rectus sheath hernia is surgical with primary closure being the preferred method. Prosthetic repair may also be performed, particularly when the hernia defect is large, but it has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of intestinal strangulation.3

1. Rutkow IM. Demographic and socioeconomic aspects of hernia repair in the United States in 2003. Surg Clin North Am. 2003;83(5):1045-1051, v-vi. doi:10.1016/S0039-6109(03)00132-4.

2. Lenobel S, Lenobel R, Yu J. Posterior rectus sheath hernia causing intermittent small bowel obstruction. J Radiol Case Rep J. 2014;8(9):25-29. doi:10.3941/jrcr.v8i9.2081.

3. Losanoff JE, Basson MD, Gruber SA. Spontaneous hernia through the posterior rectus abdominis sheath: case report and review of the published literature 1937-2008. Hernia. 2009;13(5):555-558. doi:10.1007/s10029-009-0481-6.

4. Bentzon N, Adamsen S. Hernia of the posterior rectus sheath: a new entity? Eur J Surg. 1995;161(3):215-216.

5. Aguirre DA, Santosa AC, Casola G, Sirlin CB. Abdominal wall hernias: imaging features, complications, and diagnostic pitfalls at mutli-detector row CT. Radiographics. 2005;25(6):1501-1520. doi:10.1148/rg.256055018.

1. Rutkow IM. Demographic and socioeconomic aspects of hernia repair in the United States in 2003. Surg Clin North Am. 2003;83(5):1045-1051, v-vi. doi:10.1016/S0039-6109(03)00132-4.

2. Lenobel S, Lenobel R, Yu J. Posterior rectus sheath hernia causing intermittent small bowel obstruction. J Radiol Case Rep J. 2014;8(9):25-29. doi:10.3941/jrcr.v8i9.2081.

3. Losanoff JE, Basson MD, Gruber SA. Spontaneous hernia through the posterior rectus abdominis sheath: case report and review of the published literature 1937-2008. Hernia. 2009;13(5):555-558. doi:10.1007/s10029-009-0481-6.

4. Bentzon N, Adamsen S. Hernia of the posterior rectus sheath: a new entity? Eur J Surg. 1995;161(3):215-216.

5. Aguirre DA, Santosa AC, Casola G, Sirlin CB. Abdominal wall hernias: imaging features, complications, and diagnostic pitfalls at mutli-detector row CT. Radiographics. 2005;25(6):1501-1520. doi:10.1148/rg.256055018.

Nausea/vomiting • tachycardia • unintentional weight loss • Dx?

THE CASE

A 22-year-old woman presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 24-hour history of nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, generalized abdominal pain, and mild headache. She denied shortness of breath, chest pain, or anxiety, and didn’t have a history of cardiac problems. The physical examination revealed tachycardia (heart rate, 135 beats/min) and a respiratory rate of 24 breaths per minute. The patient was diagnosed with dehydration and was given 3 liters of intravenous (IV) fluids. After fluid administration, her heart rate decreased to 94 beats/min and she was discharged home.

The patient returned to the ED later that same day with recurrent nausea, vomiting, and a mild fever. This time she reported a several week history of palpitations, heat intolerance, agitation, mild cognitive impairment, and difficulty sleeping. Her mother accompanied her to this visit and added that the patient had unintentionally lost 13 pounds over the past 2 weeks. The patient denied pain or enlargement in her neck, obstructive symptoms, hives, pruritus, or changes in vision. Reexamination revealed tachycardia (132 beats/min) with no murmurs, rubs, or gallops; increased respiratory rate (26 breaths/min); and diffuse thyromegaly without distinct nodules. The thyroid was nontender to palpation. The patient was also found to have a fine resting tremor, hyperactive deep tendon reflexes, and clonus in her lower extremities. Bibasilar crackles were noted on lung exam.

THE DIAGNOSIS

An electrocardiogram (EKG) revealed sinus tachycardia with some sinus arrhythmia. A chest radiograph revealed prominent pulmonary vasculature and the presence of Kerley B lines consistent with marked pulmonary edema. Laboratory testing revealed an elevated N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide level of 2420 pg/mL (normal range: <100 pg/mL). Evaluation of thyroid function revealed overt hyperthyroidism with an elevated free thyroxine of 4.6 ng/dL (normal range: 0.8-1.8 ng/dL), a total triiodothyronine of 199 ng/dL (normal range: 60-181 ng/dL), and a suppressed thyroid-stimulating hormone level of <0.02 mcU/mL (normal range: 0.35-5 mcU/mL). A subsequent thyroid ultrasound showed a diffusely enlarged thyroid gland with a thickened isthmus, but no nodules.

The patient’s results were discussed with the on-call endocrinology provider at the time of her revisit to the ED. The patient was started on antithyroid medications (methimazole 20 mg/d) and a beta-blocker (atenolol 25 mg/d). Arrangements were made for an outpatient endocrine consultation within 3 days of her visit to the ED.

Upon evaluation in the outpatient endocrinology clinic, a thyrotropin receptor antibody test was positive, confirming Graves’ disease. The patient was given a diagnosis of thyrotoxicosis secondary to hyperthyroidism due to Graves’ disease. Her marked pulmonary edema was secondary to thyrotoxicosis and aggressive hydration with IV fluids.

DISCUSSION

Hyperthyroidism is a common metabolic disorder with prominent cardiovascular manifestations.1 Classically, patients with hyperthyroidism develop irritability, heat intolerance, emotional lability, muscle weakness, menstrual abnormalities, and weight loss (despite an increased appetite). Cardiovascular manifestations include palpitations in up to 85% of patients, and dyspnea on exertion and fatigue in approximately 50% of patients.2 Hyperthyroidism has also been shown to produce changes in cardiac contractility, myocardial oxygen consumption, cardiac output, blood pressure, and systemic vascular resistance.3,4 Hyperthyroidism may complicate preexisting cardiac disease or may cause cardiac complications in individuals without structural abnormalities. (Our patient had no known structural abnormalities.)

In a small subset of patients with severe hyperthyroidism and exaggerated sinus tachycardia or atrial fibrillation, rate-related left ventricular dysfunction may cause heart failure.5 The assessment of thyrotoxic manifestations, especially potential cardiovascular complications, is essential to formulating an appropriate treatment plan.6 Cardiac evaluation may require an echocardiogram, EKG, Holter monitor, or myocardial perfusion studies.

Beta-blockers, diuretics among treatment options

Treatment with beta-blockers to reduce heart rate should be first-line therapy.7 In patients with overt heart failure involving pulmonary congestion, the use of diuretics may be appropriate.8

Our patient continued to take the medications prescribed during her ED visit: methimazole 20 mg/d and atenolol 25 mg/d for her Graves’ disease. A

THE TAKEAWAY

The cardiovascular manifestations of hyperthyroidism remain some of the most common signs and symptoms of thyroid disease. Pulmonary edema and congestive heart failure, however, are uncommon. Physicians need to be aware of this rare—but important—clinical presentation of a common condition.

1. Klein I, Ojamaa K. Thyroid hormone and the cardiovascular system. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:501-509.

2. Fadel BM, Ellahham S, Ringel MD, et al. Hyperthyroid heart disease. Clin Cardiol. 2000;23:402-408.

3. Biondi B, Palmieri EA, Lombardi G, et al. Effects of thyroid hormone on cardiac function: the relative importance of heart rate, loading conditions, and myocardial contractility in the regulation of cardiac performance in human hyperthyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:968-974.

4. Kahaly GJ, Dillmann WH. Thyroid hormone action in the heart. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:704-728.

5. Klein I, Danzi S. Thyroid disease and the heart. Circulation. 2007;116:1725-1735.

6. Bahn Chair RS, Burch HB, Cooper DS, et al; American Thyroid Association; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis: management guidelines of the American Thyroid Association and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Thyroid. 2011;21:593-646.

7. Klein I, Becker DV, Levey GS. Treatment of hyperthyroid disease. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:281-288.

8. Danzi S, Klein I. Thyroid hormone and blood pressure regulation. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2003;5:513-520.

THE CASE

A 22-year-old woman presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 24-hour history of nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, generalized abdominal pain, and mild headache. She denied shortness of breath, chest pain, or anxiety, and didn’t have a history of cardiac problems. The physical examination revealed tachycardia (heart rate, 135 beats/min) and a respiratory rate of 24 breaths per minute. The patient was diagnosed with dehydration and was given 3 liters of intravenous (IV) fluids. After fluid administration, her heart rate decreased to 94 beats/min and she was discharged home.

The patient returned to the ED later that same day with recurrent nausea, vomiting, and a mild fever. This time she reported a several week history of palpitations, heat intolerance, agitation, mild cognitive impairment, and difficulty sleeping. Her mother accompanied her to this visit and added that the patient had unintentionally lost 13 pounds over the past 2 weeks. The patient denied pain or enlargement in her neck, obstructive symptoms, hives, pruritus, or changes in vision. Reexamination revealed tachycardia (132 beats/min) with no murmurs, rubs, or gallops; increased respiratory rate (26 breaths/min); and diffuse thyromegaly without distinct nodules. The thyroid was nontender to palpation. The patient was also found to have a fine resting tremor, hyperactive deep tendon reflexes, and clonus in her lower extremities. Bibasilar crackles were noted on lung exam.

THE DIAGNOSIS

An electrocardiogram (EKG) revealed sinus tachycardia with some sinus arrhythmia. A chest radiograph revealed prominent pulmonary vasculature and the presence of Kerley B lines consistent with marked pulmonary edema. Laboratory testing revealed an elevated N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide level of 2420 pg/mL (normal range: <100 pg/mL). Evaluation of thyroid function revealed overt hyperthyroidism with an elevated free thyroxine of 4.6 ng/dL (normal range: 0.8-1.8 ng/dL), a total triiodothyronine of 199 ng/dL (normal range: 60-181 ng/dL), and a suppressed thyroid-stimulating hormone level of <0.02 mcU/mL (normal range: 0.35-5 mcU/mL). A subsequent thyroid ultrasound showed a diffusely enlarged thyroid gland with a thickened isthmus, but no nodules.

The patient’s results were discussed with the on-call endocrinology provider at the time of her revisit to the ED. The patient was started on antithyroid medications (methimazole 20 mg/d) and a beta-blocker (atenolol 25 mg/d). Arrangements were made for an outpatient endocrine consultation within 3 days of her visit to the ED.

Upon evaluation in the outpatient endocrinology clinic, a thyrotropin receptor antibody test was positive, confirming Graves’ disease. The patient was given a diagnosis of thyrotoxicosis secondary to hyperthyroidism due to Graves’ disease. Her marked pulmonary edema was secondary to thyrotoxicosis and aggressive hydration with IV fluids.

DISCUSSION

Hyperthyroidism is a common metabolic disorder with prominent cardiovascular manifestations.1 Classically, patients with hyperthyroidism develop irritability, heat intolerance, emotional lability, muscle weakness, menstrual abnormalities, and weight loss (despite an increased appetite). Cardiovascular manifestations include palpitations in up to 85% of patients, and dyspnea on exertion and fatigue in approximately 50% of patients.2 Hyperthyroidism has also been shown to produce changes in cardiac contractility, myocardial oxygen consumption, cardiac output, blood pressure, and systemic vascular resistance.3,4 Hyperthyroidism may complicate preexisting cardiac disease or may cause cardiac complications in individuals without structural abnormalities. (Our patient had no known structural abnormalities.)

In a small subset of patients with severe hyperthyroidism and exaggerated sinus tachycardia or atrial fibrillation, rate-related left ventricular dysfunction may cause heart failure.5 The assessment of thyrotoxic manifestations, especially potential cardiovascular complications, is essential to formulating an appropriate treatment plan.6 Cardiac evaluation may require an echocardiogram, EKG, Holter monitor, or myocardial perfusion studies.

Beta-blockers, diuretics among treatment options

Treatment with beta-blockers to reduce heart rate should be first-line therapy.7 In patients with overt heart failure involving pulmonary congestion, the use of diuretics may be appropriate.8

Our patient continued to take the medications prescribed during her ED visit: methimazole 20 mg/d and atenolol 25 mg/d for her Graves’ disease. A

THE TAKEAWAY

The cardiovascular manifestations of hyperthyroidism remain some of the most common signs and symptoms of thyroid disease. Pulmonary edema and congestive heart failure, however, are uncommon. Physicians need to be aware of this rare—but important—clinical presentation of a common condition.

THE CASE

A 22-year-old woman presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 24-hour history of nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, generalized abdominal pain, and mild headache. She denied shortness of breath, chest pain, or anxiety, and didn’t have a history of cardiac problems. The physical examination revealed tachycardia (heart rate, 135 beats/min) and a respiratory rate of 24 breaths per minute. The patient was diagnosed with dehydration and was given 3 liters of intravenous (IV) fluids. After fluid administration, her heart rate decreased to 94 beats/min and she was discharged home.

The patient returned to the ED later that same day with recurrent nausea, vomiting, and a mild fever. This time she reported a several week history of palpitations, heat intolerance, agitation, mild cognitive impairment, and difficulty sleeping. Her mother accompanied her to this visit and added that the patient had unintentionally lost 13 pounds over the past 2 weeks. The patient denied pain or enlargement in her neck, obstructive symptoms, hives, pruritus, or changes in vision. Reexamination revealed tachycardia (132 beats/min) with no murmurs, rubs, or gallops; increased respiratory rate (26 breaths/min); and diffuse thyromegaly without distinct nodules. The thyroid was nontender to palpation. The patient was also found to have a fine resting tremor, hyperactive deep tendon reflexes, and clonus in her lower extremities. Bibasilar crackles were noted on lung exam.

THE DIAGNOSIS

An electrocardiogram (EKG) revealed sinus tachycardia with some sinus arrhythmia. A chest radiograph revealed prominent pulmonary vasculature and the presence of Kerley B lines consistent with marked pulmonary edema. Laboratory testing revealed an elevated N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide level of 2420 pg/mL (normal range: <100 pg/mL). Evaluation of thyroid function revealed overt hyperthyroidism with an elevated free thyroxine of 4.6 ng/dL (normal range: 0.8-1.8 ng/dL), a total triiodothyronine of 199 ng/dL (normal range: 60-181 ng/dL), and a suppressed thyroid-stimulating hormone level of <0.02 mcU/mL (normal range: 0.35-5 mcU/mL). A subsequent thyroid ultrasound showed a diffusely enlarged thyroid gland with a thickened isthmus, but no nodules.

The patient’s results were discussed with the on-call endocrinology provider at the time of her revisit to the ED. The patient was started on antithyroid medications (methimazole 20 mg/d) and a beta-blocker (atenolol 25 mg/d). Arrangements were made for an outpatient endocrine consultation within 3 days of her visit to the ED.

Upon evaluation in the outpatient endocrinology clinic, a thyrotropin receptor antibody test was positive, confirming Graves’ disease. The patient was given a diagnosis of thyrotoxicosis secondary to hyperthyroidism due to Graves’ disease. Her marked pulmonary edema was secondary to thyrotoxicosis and aggressive hydration with IV fluids.

DISCUSSION

Hyperthyroidism is a common metabolic disorder with prominent cardiovascular manifestations.1 Classically, patients with hyperthyroidism develop irritability, heat intolerance, emotional lability, muscle weakness, menstrual abnormalities, and weight loss (despite an increased appetite). Cardiovascular manifestations include palpitations in up to 85% of patients, and dyspnea on exertion and fatigue in approximately 50% of patients.2 Hyperthyroidism has also been shown to produce changes in cardiac contractility, myocardial oxygen consumption, cardiac output, blood pressure, and systemic vascular resistance.3,4 Hyperthyroidism may complicate preexisting cardiac disease or may cause cardiac complications in individuals without structural abnormalities. (Our patient had no known structural abnormalities.)

In a small subset of patients with severe hyperthyroidism and exaggerated sinus tachycardia or atrial fibrillation, rate-related left ventricular dysfunction may cause heart failure.5 The assessment of thyrotoxic manifestations, especially potential cardiovascular complications, is essential to formulating an appropriate treatment plan.6 Cardiac evaluation may require an echocardiogram, EKG, Holter monitor, or myocardial perfusion studies.

Beta-blockers, diuretics among treatment options

Treatment with beta-blockers to reduce heart rate should be first-line therapy.7 In patients with overt heart failure involving pulmonary congestion, the use of diuretics may be appropriate.8

Our patient continued to take the medications prescribed during her ED visit: methimazole 20 mg/d and atenolol 25 mg/d for her Graves’ disease. A

THE TAKEAWAY

The cardiovascular manifestations of hyperthyroidism remain some of the most common signs and symptoms of thyroid disease. Pulmonary edema and congestive heart failure, however, are uncommon. Physicians need to be aware of this rare—but important—clinical presentation of a common condition.

1. Klein I, Ojamaa K. Thyroid hormone and the cardiovascular system. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:501-509.

2. Fadel BM, Ellahham S, Ringel MD, et al. Hyperthyroid heart disease. Clin Cardiol. 2000;23:402-408.

3. Biondi B, Palmieri EA, Lombardi G, et al. Effects of thyroid hormone on cardiac function: the relative importance of heart rate, loading conditions, and myocardial contractility in the regulation of cardiac performance in human hyperthyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:968-974.

4. Kahaly GJ, Dillmann WH. Thyroid hormone action in the heart. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:704-728.

5. Klein I, Danzi S. Thyroid disease and the heart. Circulation. 2007;116:1725-1735.

6. Bahn Chair RS, Burch HB, Cooper DS, et al; American Thyroid Association; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis: management guidelines of the American Thyroid Association and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Thyroid. 2011;21:593-646.

7. Klein I, Becker DV, Levey GS. Treatment of hyperthyroid disease. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:281-288.

8. Danzi S, Klein I. Thyroid hormone and blood pressure regulation. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2003;5:513-520.

1. Klein I, Ojamaa K. Thyroid hormone and the cardiovascular system. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:501-509.

2. Fadel BM, Ellahham S, Ringel MD, et al. Hyperthyroid heart disease. Clin Cardiol. 2000;23:402-408.

3. Biondi B, Palmieri EA, Lombardi G, et al. Effects of thyroid hormone on cardiac function: the relative importance of heart rate, loading conditions, and myocardial contractility in the regulation of cardiac performance in human hyperthyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:968-974.

4. Kahaly GJ, Dillmann WH. Thyroid hormone action in the heart. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:704-728.

5. Klein I, Danzi S. Thyroid disease and the heart. Circulation. 2007;116:1725-1735.

6. Bahn Chair RS, Burch HB, Cooper DS, et al; American Thyroid Association; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis: management guidelines of the American Thyroid Association and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Thyroid. 2011;21:593-646.

7. Klein I, Becker DV, Levey GS. Treatment of hyperthyroid disease. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:281-288.

8. Danzi S, Klein I. Thyroid hormone and blood pressure regulation. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2003;5:513-520.

Muscle cramps/pain • weakness • muscle twitching • Dx?

THE CASE

A 39-year-old man who worked in construction presented to our clinic with complaints of muscle cramps and muscle pain that had been bothering him for several months. The cramps and pain started in both of his arms and subsequently became diffuse and generalized. He also reported an unintentional 15-pound weight loss.

His exam at that time was unremarkable. He was diagnosed with dehydration and cramping due to overexertion at work. A basic metabolic panel, hemogram, lipid panel, and thyroid stimulating hormone level were ordered. The patient’s triglyceride level, which was 227 mg/dL, was the only significant result (normal level: <150 mg/dL).

The patient’s symptoms continued to worsen until he returned to the clinic 6 months later, again complaining of muscle cramps and pain throughout his body. At that second visit, he also reported profound overall weakness and the development of diffuse muscle twitching, which his wife had observed while he was sleeping. As a result of these worrisome symptoms, he had become anxious and depressed.

A review of his medical record revealed a weight loss of about 20 pounds over the previous year. On exam, he had diffuse fasciculations in all the major muscle groups, including his tongue. The patient’s strength was 4/5 in all muscle groups. His deep tendon reflexes were 3+. He had a negative Babinski reflex (ie, he had downward facing toes with plantar stimulation), and cranial nerves II to XII were all intact. His rapid alternating movements and gait were slow.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on the exam, the primary diagnostic consideration for the patient was amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Lab tests were ordered and revealed normal calcium and electrolyte levels, a normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate, a normal C-reactive protein level, and a negative test for acetylcholine receptor antibodies. However, the patient had an elevated creatine kinase level of 664 U/L (normal: 30-200 U/L). The patient was sent to a neuromuscular specialist, who identified signs of upper and lower motor neuron disease in all 4 of the patient’s extremities (he had foot drop that had not been present previously) and a very brisk jaw jerk. Along with the tongue fasciculations, the results of the specialist’s physical exam suggested ALS. Four-limb electromyography (EMG) showed widespread fasciculations and some large motor unit potentials and recruitment abnormalities, which were also consistent with ALS. It appeared that the patient’s weight loss was due to both muscle atrophy and the amount of calories burned from his constant twitching.

Extensive testing was done to rule out other potential causes of the patient’s symptoms, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine and brain (which was normal). In addition, the patient’s aldolase level and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were normal. The patient tested negative for human immunodeficiency virus and antibodies to double-stranded DNA. After serial neurologic exams, the final diagnosis of ALS was made.

DISCUSSION

ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a degenerative motor neuron disease.1-3 The incidence in North America is 1.5 to 2.7 per 100,000 per year, and the prevalence is 2.7 to 7.4 per 100,000.4 The incidence of ALS increases with each decade of life, especially after age 40, and peaks at 74 years of age.4 The male to female ratio is 1:1.5-2.4 ALS affects upper and lower motor neurons and is progressive; however, the rate of progression and phenotype vary greatly between individuals.2 Most patients with ALS die within 2 to 5 years of onset.5

There is no specific test for ALS; the diagnosis is made clinically based on the revised El Escorial World Federation of Neurology criteria, also known as the Airlie House criteria.2,6,7 These criteria include evidence of lower motor neuron degeneration by clinical, electrophysiologic, or neuropathologic exam; evidence of upper motor neuron disease by clinical exam; progressive spread of symptoms or signs within a region or to other regions (by history or exam); and the absence of electrophysiologic, neuroimaging, or pathologic evidence of other disease processes that could explain the symptoms. If patients have evidence of upper and lower motor neuron disease, they should be reevaluated in 4 weeks to see if symptoms are improving or progressing.

Like our patient, many patients will have an elevated creatine kinase level (some with levels as high as 1000 U/L), and calcium may also be elevated because, rarely, ALS is associated with primary hyperparathyroidism.8 Electrophysiologic studies can be helpful in identifying active denervation of lower motor neurons.4,6,7

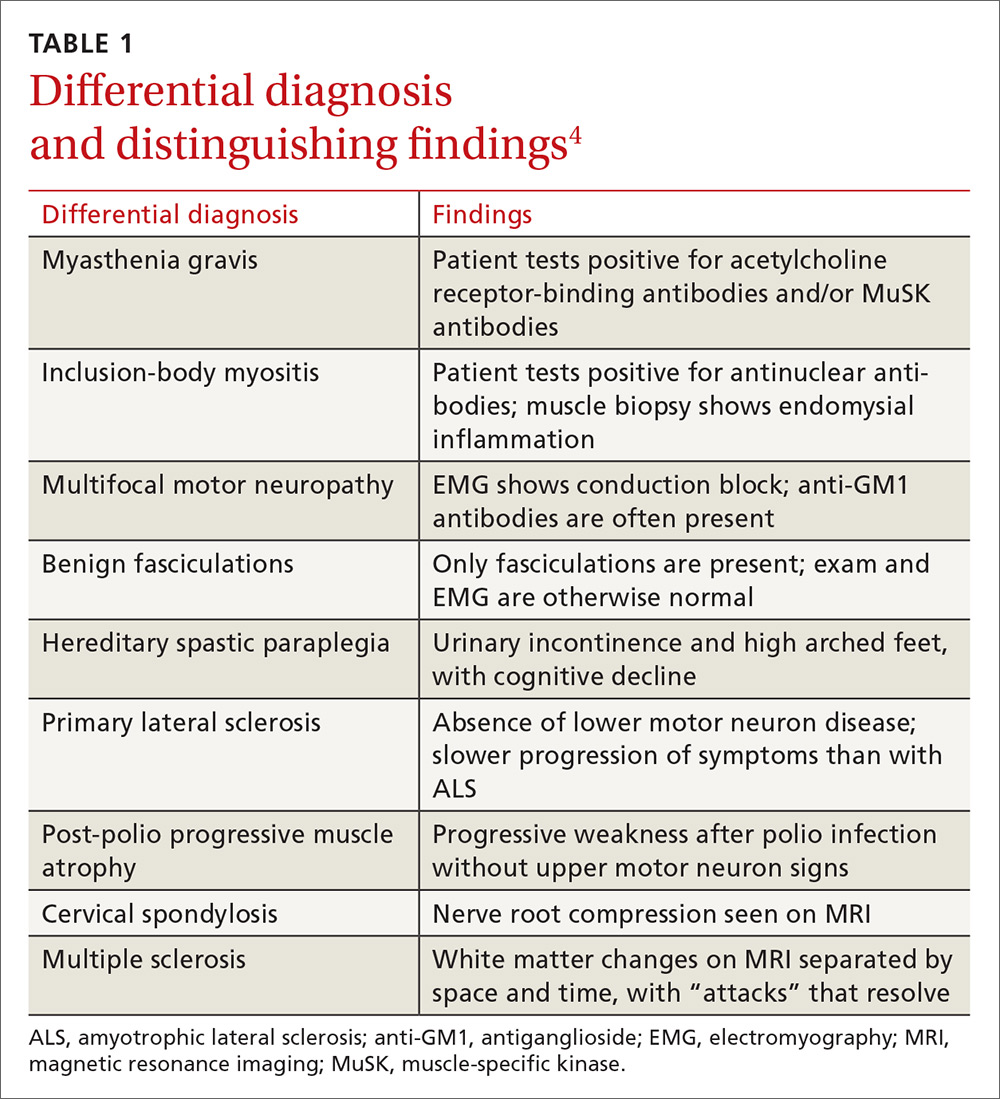

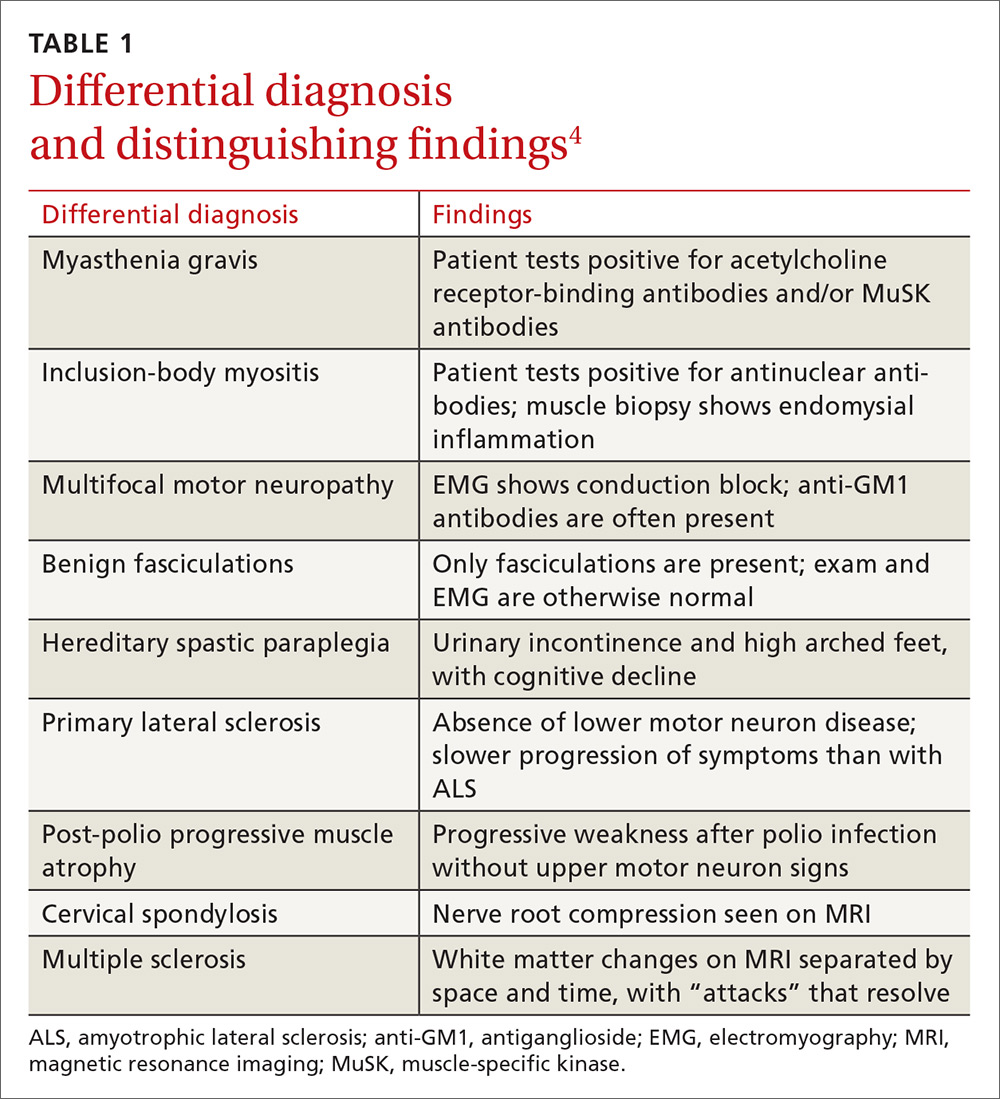

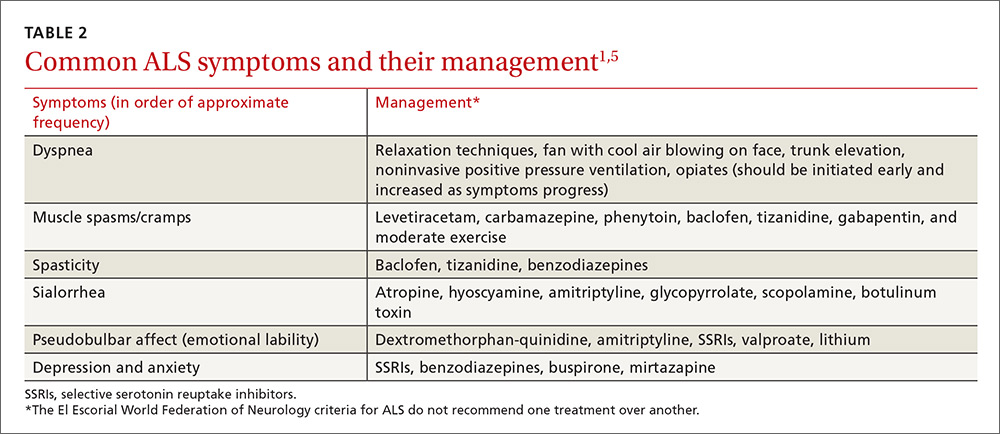

The differential diagnosis for ALS includes myasthenia gravis, inclusion-body myositis, multifocal motor neuropathy, benign fasciculations, hereditary spastic paraplegia, primary lateral sclerosis, post-polio progressive muscle atrophy, cervical spondylosis, and multiple sclerosis. A negative acetylcholine receptor antibody test will rule out myasthenia gravis, imaging of the spine can rule out cervical spondylosis, and electrophysiologic testing helps eliminate the other conditions (TABLE 14).

Treatment in specialty clinics can prolong survival

The mainstays of treatment are symptom management, multidisciplinary care (by physicians, physical/occupational/speech therapists, nutritionists, psychologists, psychotherapists, and genetic counselors), palliative care, and counseling about end-of-life issues for patients and family.1,5 Utilization of an ALS specialty clinic can provide access to all of these services and should be considered, as there is evidence that treatment in such clinics can prolong survival.5 The location of ALS specialty clinics can be found on the ALS Association’s Web site at http://www.alsa.org/community/.

Despite treatment, however, ALS is a progressive disease. The prognosis is poor, with a median survival of 2 to 5 years after diagnosis.9

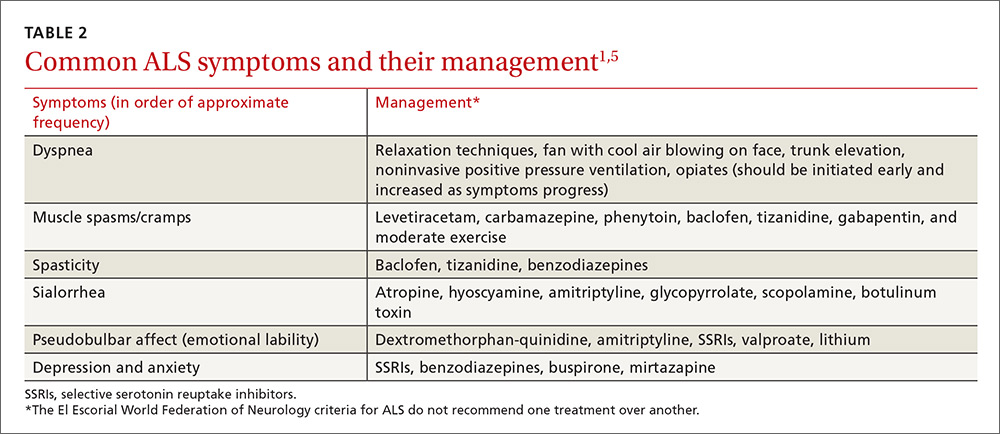

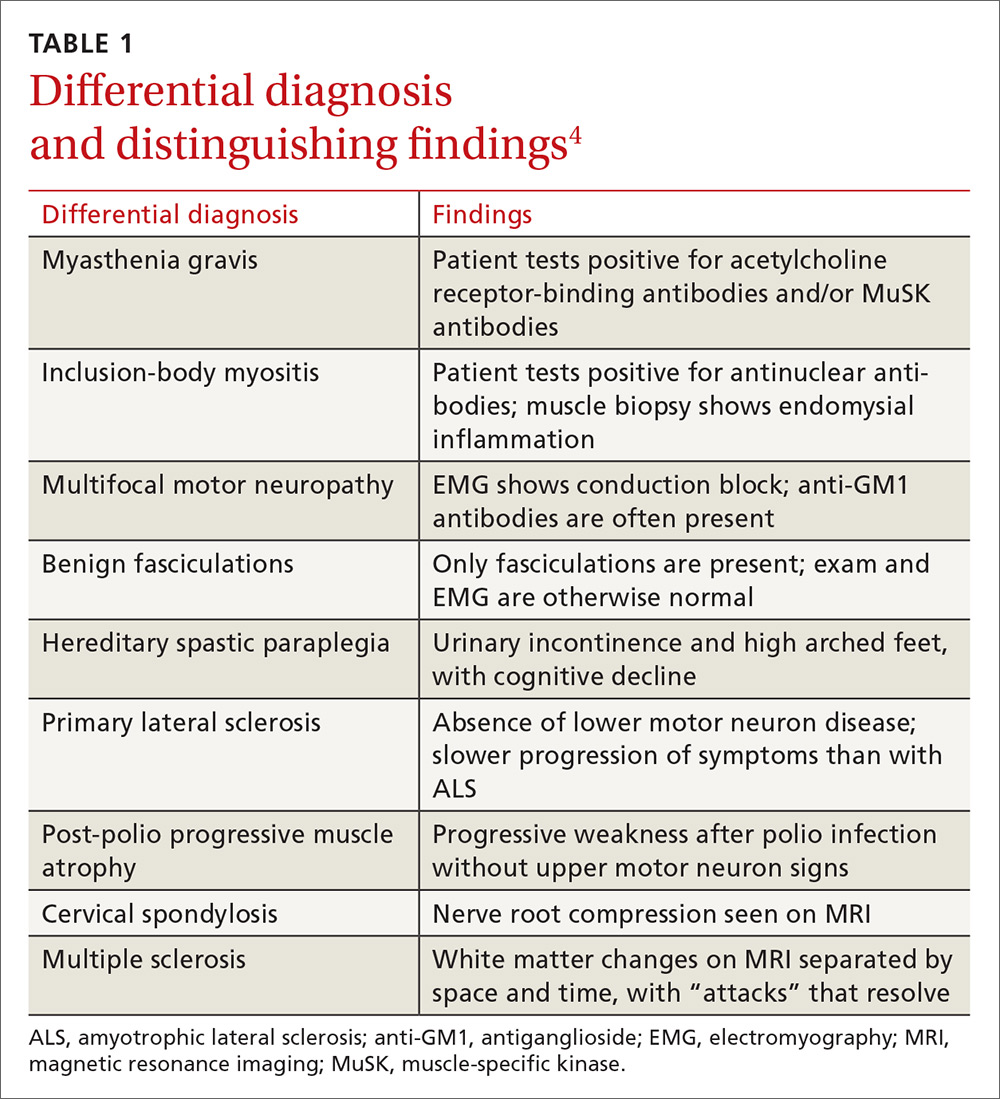

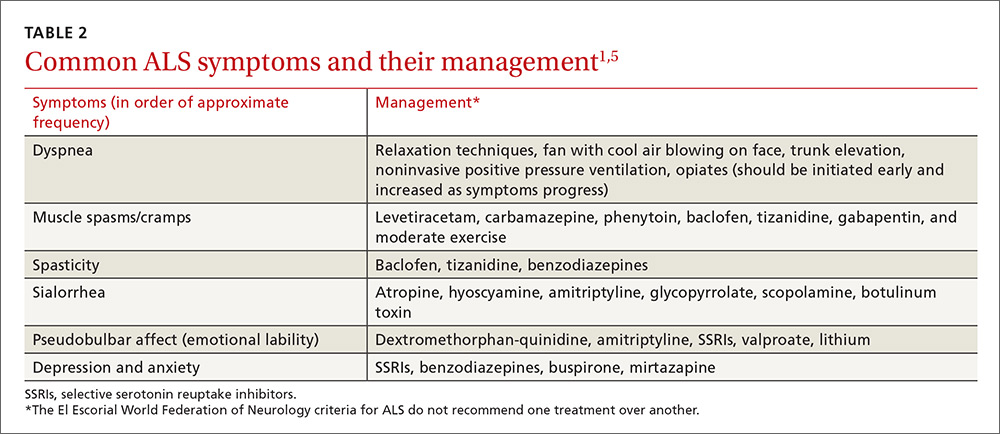

The El Escorial World Federation of Neurology criteria for the diagnosis of ALS address how to treat the most common symptoms of ALS that occur as the disease progresses. These symptoms include dyspnea, muscle spasms, spasticity, sialorrhea, and pseudobulbar affect (TABLE 21,5).

Our patient was started on baclofen 10 mg 3 times per day (titrated up as needed) for muscle spasms and cramps, which resulted in some improvement of his cramps, but no improvement in the spasms. He was also started on sertraline 50 mg for anxiety and depression. His overall weakness continued to progress, and we recommended that the patient get ankle-foot orthosis braces to help with the mobility impairment caused by foot drop.

We then referred him to an ALS specialty clinic recommended by the neuromuscular specialist. The patient is now enrolled in a clinical trial designed to test a cerebrospinal fluid marker for diagnosis and for a new drug aimed at symptom management.

THE TAKEAWAY

Muscle cramps and pain are early signs of ALS. Although ALS is uncommon, patients who present with muscle cramps and muscle pain should have a creatine kinase test ordered (which, if elevated, should prompt further investigation into ALS as the possible cause). Patients should also undergo a neurologic examination to seek evidence of upper and lower motor neuron disease. They should then be reevaluated in 4 weeks to see if symptoms are improving or progressing. If no improvement is seen and symptoms are progressive, a work-up for ALS should be considered.

The mainstay of treatment for patients with ALS is multidisciplinary symptom management and palliative care. Utilization of an ALS specialty clinic should also be recommended, as it can improve survival.5

1. Miller RG, Gelinas D, O’Connor P. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: American Academy of Neurology Press Quality of Life Guide Series. Demos Medical Publishing; 2004.

2. Simon NG, Turner MR, Vucic S, et al. Quantifying disease progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2014;76:643-657.

3. Worms PM. The epidemiology of motor neuron diseases: a review of recent studies. J Neurol Sci. 2001;191:3-9.

4. Shaw PJ. ALS and other motor neuron diseases. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Goldman’s Cecil Medicine. 24th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2015:chap 418.

5. Miller RG, Jackson CE, Kasarskis EJ, et al. Practice Parameter update: The Care of the Patient with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Multidisciplinary care, symptom management, and cognitive/behavioral impairment (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2009;73:1227-1233.

6. Brooks BR. El Escorial World Federation of Neurology criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Subcommittee on Motor Neuron Diseases/Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis of the World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Neuromuscular Diseases and the El Escorial “Clinical limits of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis” workshop contributors. J Neurol Sci. 1994;124:96-107.

7. Brooks BR, Miller RG, Swash M, et al; World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Motor Neuron Diseases. El Escorial revisited: revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2000;1:293-299.

8. Jackson CE, Amato AA, Bryan WW, et al. Primary hyperparathyroidism and ALS: is there a relation? Neurology. 1998;50:1795-1799.

9. Jablecki CK, Berry C, Leach J. Survival prediction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve. 1989;12:833-841.

THE CASE

A 39-year-old man who worked in construction presented to our clinic with complaints of muscle cramps and muscle pain that had been bothering him for several months. The cramps and pain started in both of his arms and subsequently became diffuse and generalized. He also reported an unintentional 15-pound weight loss.

His exam at that time was unremarkable. He was diagnosed with dehydration and cramping due to overexertion at work. A basic metabolic panel, hemogram, lipid panel, and thyroid stimulating hormone level were ordered. The patient’s triglyceride level, which was 227 mg/dL, was the only significant result (normal level: <150 mg/dL).

The patient’s symptoms continued to worsen until he returned to the clinic 6 months later, again complaining of muscle cramps and pain throughout his body. At that second visit, he also reported profound overall weakness and the development of diffuse muscle twitching, which his wife had observed while he was sleeping. As a result of these worrisome symptoms, he had become anxious and depressed.

A review of his medical record revealed a weight loss of about 20 pounds over the previous year. On exam, he had diffuse fasciculations in all the major muscle groups, including his tongue. The patient’s strength was 4/5 in all muscle groups. His deep tendon reflexes were 3+. He had a negative Babinski reflex (ie, he had downward facing toes with plantar stimulation), and cranial nerves II to XII were all intact. His rapid alternating movements and gait were slow.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on the exam, the primary diagnostic consideration for the patient was amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Lab tests were ordered and revealed normal calcium and electrolyte levels, a normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate, a normal C-reactive protein level, and a negative test for acetylcholine receptor antibodies. However, the patient had an elevated creatine kinase level of 664 U/L (normal: 30-200 U/L). The patient was sent to a neuromuscular specialist, who identified signs of upper and lower motor neuron disease in all 4 of the patient’s extremities (he had foot drop that had not been present previously) and a very brisk jaw jerk. Along with the tongue fasciculations, the results of the specialist’s physical exam suggested ALS. Four-limb electromyography (EMG) showed widespread fasciculations and some large motor unit potentials and recruitment abnormalities, which were also consistent with ALS. It appeared that the patient’s weight loss was due to both muscle atrophy and the amount of calories burned from his constant twitching.

Extensive testing was done to rule out other potential causes of the patient’s symptoms, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine and brain (which was normal). In addition, the patient’s aldolase level and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were normal. The patient tested negative for human immunodeficiency virus and antibodies to double-stranded DNA. After serial neurologic exams, the final diagnosis of ALS was made.

DISCUSSION

ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a degenerative motor neuron disease.1-3 The incidence in North America is 1.5 to 2.7 per 100,000 per year, and the prevalence is 2.7 to 7.4 per 100,000.4 The incidence of ALS increases with each decade of life, especially after age 40, and peaks at 74 years of age.4 The male to female ratio is 1:1.5-2.4 ALS affects upper and lower motor neurons and is progressive; however, the rate of progression and phenotype vary greatly between individuals.2 Most patients with ALS die within 2 to 5 years of onset.5

There is no specific test for ALS; the diagnosis is made clinically based on the revised El Escorial World Federation of Neurology criteria, also known as the Airlie House criteria.2,6,7 These criteria include evidence of lower motor neuron degeneration by clinical, electrophysiologic, or neuropathologic exam; evidence of upper motor neuron disease by clinical exam; progressive spread of symptoms or signs within a region or to other regions (by history or exam); and the absence of electrophysiologic, neuroimaging, or pathologic evidence of other disease processes that could explain the symptoms. If patients have evidence of upper and lower motor neuron disease, they should be reevaluated in 4 weeks to see if symptoms are improving or progressing.

Like our patient, many patients will have an elevated creatine kinase level (some with levels as high as 1000 U/L), and calcium may also be elevated because, rarely, ALS is associated with primary hyperparathyroidism.8 Electrophysiologic studies can be helpful in identifying active denervation of lower motor neurons.4,6,7

The differential diagnosis for ALS includes myasthenia gravis, inclusion-body myositis, multifocal motor neuropathy, benign fasciculations, hereditary spastic paraplegia, primary lateral sclerosis, post-polio progressive muscle atrophy, cervical spondylosis, and multiple sclerosis. A negative acetylcholine receptor antibody test will rule out myasthenia gravis, imaging of the spine can rule out cervical spondylosis, and electrophysiologic testing helps eliminate the other conditions (TABLE 14).

Treatment in specialty clinics can prolong survival

The mainstays of treatment are symptom management, multidisciplinary care (by physicians, physical/occupational/speech therapists, nutritionists, psychologists, psychotherapists, and genetic counselors), palliative care, and counseling about end-of-life issues for patients and family.1,5 Utilization of an ALS specialty clinic can provide access to all of these services and should be considered, as there is evidence that treatment in such clinics can prolong survival.5 The location of ALS specialty clinics can be found on the ALS Association’s Web site at http://www.alsa.org/community/.

Despite treatment, however, ALS is a progressive disease. The prognosis is poor, with a median survival of 2 to 5 years after diagnosis.9

The El Escorial World Federation of Neurology criteria for the diagnosis of ALS address how to treat the most common symptoms of ALS that occur as the disease progresses. These symptoms include dyspnea, muscle spasms, spasticity, sialorrhea, and pseudobulbar affect (TABLE 21,5).

Our patient was started on baclofen 10 mg 3 times per day (titrated up as needed) for muscle spasms and cramps, which resulted in some improvement of his cramps, but no improvement in the spasms. He was also started on sertraline 50 mg for anxiety and depression. His overall weakness continued to progress, and we recommended that the patient get ankle-foot orthosis braces to help with the mobility impairment caused by foot drop.

We then referred him to an ALS specialty clinic recommended by the neuromuscular specialist. The patient is now enrolled in a clinical trial designed to test a cerebrospinal fluid marker for diagnosis and for a new drug aimed at symptom management.

THE TAKEAWAY

Muscle cramps and pain are early signs of ALS. Although ALS is uncommon, patients who present with muscle cramps and muscle pain should have a creatine kinase test ordered (which, if elevated, should prompt further investigation into ALS as the possible cause). Patients should also undergo a neurologic examination to seek evidence of upper and lower motor neuron disease. They should then be reevaluated in 4 weeks to see if symptoms are improving or progressing. If no improvement is seen and symptoms are progressive, a work-up for ALS should be considered.

The mainstay of treatment for patients with ALS is multidisciplinary symptom management and palliative care. Utilization of an ALS specialty clinic should also be recommended, as it can improve survival.5

THE CASE

A 39-year-old man who worked in construction presented to our clinic with complaints of muscle cramps and muscle pain that had been bothering him for several months. The cramps and pain started in both of his arms and subsequently became diffuse and generalized. He also reported an unintentional 15-pound weight loss.

His exam at that time was unremarkable. He was diagnosed with dehydration and cramping due to overexertion at work. A basic metabolic panel, hemogram, lipid panel, and thyroid stimulating hormone level were ordered. The patient’s triglyceride level, which was 227 mg/dL, was the only significant result (normal level: <150 mg/dL).

The patient’s symptoms continued to worsen until he returned to the clinic 6 months later, again complaining of muscle cramps and pain throughout his body. At that second visit, he also reported profound overall weakness and the development of diffuse muscle twitching, which his wife had observed while he was sleeping. As a result of these worrisome symptoms, he had become anxious and depressed.

A review of his medical record revealed a weight loss of about 20 pounds over the previous year. On exam, he had diffuse fasciculations in all the major muscle groups, including his tongue. The patient’s strength was 4/5 in all muscle groups. His deep tendon reflexes were 3+. He had a negative Babinski reflex (ie, he had downward facing toes with plantar stimulation), and cranial nerves II to XII were all intact. His rapid alternating movements and gait were slow.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on the exam, the primary diagnostic consideration for the patient was amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Lab tests were ordered and revealed normal calcium and electrolyte levels, a normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate, a normal C-reactive protein level, and a negative test for acetylcholine receptor antibodies. However, the patient had an elevated creatine kinase level of 664 U/L (normal: 30-200 U/L). The patient was sent to a neuromuscular specialist, who identified signs of upper and lower motor neuron disease in all 4 of the patient’s extremities (he had foot drop that had not been present previously) and a very brisk jaw jerk. Along with the tongue fasciculations, the results of the specialist’s physical exam suggested ALS. Four-limb electromyography (EMG) showed widespread fasciculations and some large motor unit potentials and recruitment abnormalities, which were also consistent with ALS. It appeared that the patient’s weight loss was due to both muscle atrophy and the amount of calories burned from his constant twitching.

Extensive testing was done to rule out other potential causes of the patient’s symptoms, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine and brain (which was normal). In addition, the patient’s aldolase level and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were normal. The patient tested negative for human immunodeficiency virus and antibodies to double-stranded DNA. After serial neurologic exams, the final diagnosis of ALS was made.

DISCUSSION

ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a degenerative motor neuron disease.1-3 The incidence in North America is 1.5 to 2.7 per 100,000 per year, and the prevalence is 2.7 to 7.4 per 100,000.4 The incidence of ALS increases with each decade of life, especially after age 40, and peaks at 74 years of age.4 The male to female ratio is 1:1.5-2.4 ALS affects upper and lower motor neurons and is progressive; however, the rate of progression and phenotype vary greatly between individuals.2 Most patients with ALS die within 2 to 5 years of onset.5

There is no specific test for ALS; the diagnosis is made clinically based on the revised El Escorial World Federation of Neurology criteria, also known as the Airlie House criteria.2,6,7 These criteria include evidence of lower motor neuron degeneration by clinical, electrophysiologic, or neuropathologic exam; evidence of upper motor neuron disease by clinical exam; progressive spread of symptoms or signs within a region or to other regions (by history or exam); and the absence of electrophysiologic, neuroimaging, or pathologic evidence of other disease processes that could explain the symptoms. If patients have evidence of upper and lower motor neuron disease, they should be reevaluated in 4 weeks to see if symptoms are improving or progressing.

Like our patient, many patients will have an elevated creatine kinase level (some with levels as high as 1000 U/L), and calcium may also be elevated because, rarely, ALS is associated with primary hyperparathyroidism.8 Electrophysiologic studies can be helpful in identifying active denervation of lower motor neurons.4,6,7

The differential diagnosis for ALS includes myasthenia gravis, inclusion-body myositis, multifocal motor neuropathy, benign fasciculations, hereditary spastic paraplegia, primary lateral sclerosis, post-polio progressive muscle atrophy, cervical spondylosis, and multiple sclerosis. A negative acetylcholine receptor antibody test will rule out myasthenia gravis, imaging of the spine can rule out cervical spondylosis, and electrophysiologic testing helps eliminate the other conditions (TABLE 14).

Treatment in specialty clinics can prolong survival

The mainstays of treatment are symptom management, multidisciplinary care (by physicians, physical/occupational/speech therapists, nutritionists, psychologists, psychotherapists, and genetic counselors), palliative care, and counseling about end-of-life issues for patients and family.1,5 Utilization of an ALS specialty clinic can provide access to all of these services and should be considered, as there is evidence that treatment in such clinics can prolong survival.5 The location of ALS specialty clinics can be found on the ALS Association’s Web site at http://www.alsa.org/community/.

Despite treatment, however, ALS is a progressive disease. The prognosis is poor, with a median survival of 2 to 5 years after diagnosis.9

The El Escorial World Federation of Neurology criteria for the diagnosis of ALS address how to treat the most common symptoms of ALS that occur as the disease progresses. These symptoms include dyspnea, muscle spasms, spasticity, sialorrhea, and pseudobulbar affect (TABLE 21,5).

Our patient was started on baclofen 10 mg 3 times per day (titrated up as needed) for muscle spasms and cramps, which resulted in some improvement of his cramps, but no improvement in the spasms. He was also started on sertraline 50 mg for anxiety and depression. His overall weakness continued to progress, and we recommended that the patient get ankle-foot orthosis braces to help with the mobility impairment caused by foot drop.

We then referred him to an ALS specialty clinic recommended by the neuromuscular specialist. The patient is now enrolled in a clinical trial designed to test a cerebrospinal fluid marker for diagnosis and for a new drug aimed at symptom management.

THE TAKEAWAY

Muscle cramps and pain are early signs of ALS. Although ALS is uncommon, patients who present with muscle cramps and muscle pain should have a creatine kinase test ordered (which, if elevated, should prompt further investigation into ALS as the possible cause). Patients should also undergo a neurologic examination to seek evidence of upper and lower motor neuron disease. They should then be reevaluated in 4 weeks to see if symptoms are improving or progressing. If no improvement is seen and symptoms are progressive, a work-up for ALS should be considered.

The mainstay of treatment for patients with ALS is multidisciplinary symptom management and palliative care. Utilization of an ALS specialty clinic should also be recommended, as it can improve survival.5

1. Miller RG, Gelinas D, O’Connor P. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: American Academy of Neurology Press Quality of Life Guide Series. Demos Medical Publishing; 2004.

2. Simon NG, Turner MR, Vucic S, et al. Quantifying disease progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2014;76:643-657.

3. Worms PM. The epidemiology of motor neuron diseases: a review of recent studies. J Neurol Sci. 2001;191:3-9.

4. Shaw PJ. ALS and other motor neuron diseases. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Goldman’s Cecil Medicine. 24th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2015:chap 418.

5. Miller RG, Jackson CE, Kasarskis EJ, et al. Practice Parameter update: The Care of the Patient with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Multidisciplinary care, symptom management, and cognitive/behavioral impairment (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2009;73:1227-1233.

6. Brooks BR. El Escorial World Federation of Neurology criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Subcommittee on Motor Neuron Diseases/Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis of the World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Neuromuscular Diseases and the El Escorial “Clinical limits of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis” workshop contributors. J Neurol Sci. 1994;124:96-107.

7. Brooks BR, Miller RG, Swash M, et al; World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Motor Neuron Diseases. El Escorial revisited: revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2000;1:293-299.

8. Jackson CE, Amato AA, Bryan WW, et al. Primary hyperparathyroidism and ALS: is there a relation? Neurology. 1998;50:1795-1799.

9. Jablecki CK, Berry C, Leach J. Survival prediction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve. 1989;12:833-841.

1. Miller RG, Gelinas D, O’Connor P. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: American Academy of Neurology Press Quality of Life Guide Series. Demos Medical Publishing; 2004.

2. Simon NG, Turner MR, Vucic S, et al. Quantifying disease progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2014;76:643-657.

3. Worms PM. The epidemiology of motor neuron diseases: a review of recent studies. J Neurol Sci. 2001;191:3-9.

4. Shaw PJ. ALS and other motor neuron diseases. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Goldman’s Cecil Medicine. 24th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2015:chap 418.

5. Miller RG, Jackson CE, Kasarskis EJ, et al. Practice Parameter update: The Care of the Patient with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Multidisciplinary care, symptom management, and cognitive/behavioral impairment (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2009;73:1227-1233.

6. Brooks BR. El Escorial World Federation of Neurology criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Subcommittee on Motor Neuron Diseases/Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis of the World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Neuromuscular Diseases and the El Escorial “Clinical limits of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis” workshop contributors. J Neurol Sci. 1994;124:96-107.

7. Brooks BR, Miller RG, Swash M, et al; World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Motor Neuron Diseases. El Escorial revisited: revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2000;1:293-299.

8. Jackson CE, Amato AA, Bryan WW, et al. Primary hyperparathyroidism and ALS: is there a relation? Neurology. 1998;50:1795-1799.

9. Jablecki CK, Berry C, Leach J. Survival prediction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve. 1989;12:833-841.

Torsades de Pointes in Severe Alcohol Withdrawal and Cirrhosis: Implications for Risk Stratification and Management

Torsades de pointes (TdP) is a life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia that is associated with both congenital and acquired QT interval prolongation. QT interval prolongation is commonly observed in acute alcohol withdrawal and cirrhotic cardiomyopathy.1-3 In both conditions, there is a positive correlation between the degree of QT interval prolongation and disease severity.4,5 The precise mechanisms of QT interval prolongation in these conditions are not well understood. One hypothesis is that autonomic hyperexcitability results in altered ventricular repolarization and QT interval prolongation. This mechanism of QT prolongation has been found in acute alcohol withdrawal independent of electrolyte abnormalities, use of QT-prolonging medications, and cirrhosis.1,2,6

The authors report the case of a veteran who was hospitalized for acute alcohol withdrawal and decompensated cirrhosis and was found to have a newly prolonged QT interval. On hospital day 3, the patient developed TdP, which required external defibrillation. Despite correction of electrolyte abnormalities, abstinence from alcohol, avoidance of QT-prolonging medications, and exclusion of cardiac ischemia, there was significant and persistent prolongation of the QT interval—ultimately attributed to cirrhotic cardiomyopathy. Acquired QT interval prolongation is common in both acute alcohol withdrawal and cirrhosis.This case highlights the importance of close monitoring of the QT interval and TdP susceptibility in patients being treated for acute alcohol withdrawal, particularly those with cirrhosis.

Case Report

A 66-year-old male veteran with a 35-year history of alcohol dependence presented for alcohol detoxification. He reported having drunk at least 32 ounces of vodka every day of the preceding 5 years and reported having unsuccessfully attempted self-detoxification several times. Prior detoxification efforts were unsuccessful because of intractable nausea and tremulousness. Additional presenting symptoms included lethargy, anorexia, and a fall with transient right-side hemiparesis (findings on magnetic resonance imaging of the head had been normal).

His medical history included type 2 diabetes, tobacco dependence, and macular degeneration. The only medication being taken was glargine 25 units daily. On admission, the patient was afebrile (98.1°F), normotensive (103/77 mm Hg), and oriented to person, place, and time. Examination also revealed a protuberant abdomen with caput medusae, and no shifting dullness or lower extremity edema. The neurologic examination was nonfocal.

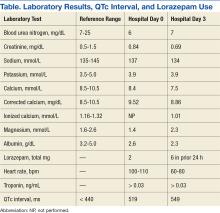

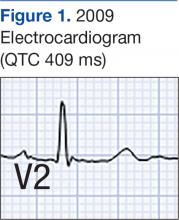

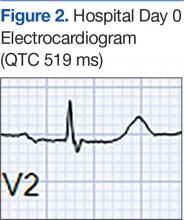

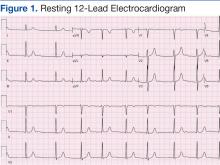

Laboratory test results on admission were significant for elevated serum alcohol level (243.8 mg/dL); elevated levels of aspartate aminotransferase (144 units/L) alanine aminotransferase (25 units/L), and total bilirubin (4.2 mg/L); hypoalbuminemia; normocalemia; hypomagnesemia; normal corrected calcium level; and normal renal function (0.84 mg/dL)(Table). The patient’s admission Child-Pugh score of 10 indicated class C liver disease. Admission electrocardiogram (EKG) revealed normal sinus rhythm, first-degree atrioventricular block, and prolongation of the QTc interval (519 ms). Six years earlier, the patient’s QTc interval had been 409 ms (Figures 1 and 2). As QT interval depends on heart rate, it is most commonly expressed as corrected QT, or QTc, where QTc = QT/(√RR).

Symptom-triggered therapy for alcohol withdrawal was instituted, and the patient’s electrolyte abnormalities were corrected. Telemetry monitoring demonstrated polymorphic ventricular ectopy, including a 6.8-s run of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and several shorter runs (4-10 beats) of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, prompting initiation of a low-dose beta blocker. Based on elevated scores on the symptom-triggered scale for alcohol withdrawal, the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessement for Alcohol Withdrawal (CIWA), several doses of oral lorazepam were given for withdrawal symptoms.

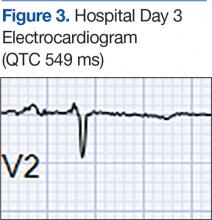

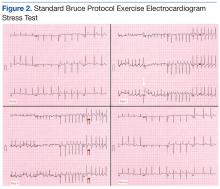

The patient became increasingly confused, and new-onset nystagmus was noted. These findings raised concern for Wernicke encephalopathy, so the patient was empirically started on IV high-dose thiamine supplementation. The CIWA scores remained high, and there were frequent episodes of ventricular ectopy during the first 2 hospital days. Interval EKG revealed further prolongation of the QTc interval (549 ms) without evidence of cardiac ischemia (Figure 3). Cardiac enzymes were negative, and electrolyte levels were within normal limits.

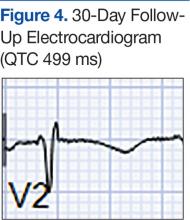

The month-long hospitalization was notable for development of significant ascites, continual electrolyte repletion in the setting of diuresis, formal diagnosis of alcoholic cirrhoisis, cognitive and physical rehabilitation. During the hospitalization, QTc interval remained prolonged (range, 460-500 ms), despite electrolyte repletion, and he was discharged with a wearable cardioverter defibrillator. A month

Discussion

Alcohol dependence is a common chronic and relapsing disease that often requires controlled detoxification. Investigators have found a high incidence of QT interval prolongation in alcohol withdrawal and hepatic disease.3,6 Common causes of QT interval prolongation in this setting are poor nutrition, electrolyte abnormalities (particularly hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia), and use of certain medications.1-3,7,8 In addition, alcohol is directly toxic to the renal tubules, resulting in renal wasting of divalent cations, which may persist up to 30 days after the most recent alcohol exposure.9,10

The patient in this case report was initially thought to have hypomagnesemia-induced long QT syndrome (leading to TdP cardiac arrest), but the authors’ review of laboratory test results revealed the QT interval remained markedly prolonged, despite adequate correction of hypomagnesemia implicating the hyperadrenergic state of acute alcohol withdrawal in QT interval prolongation and TdP cardiac arrest. Interestingly, the QT interval remained prolonged 2 months after TdP arrest, despite sustained normalization of electrolyte levels and the absence of active ischemia or use of QT-prolonging medications.

Given the exclusion of other causes of QT interval prolongation, the authors hypothesized that autonomic hyperactivity of acute alcohol withdrawal and resultant QT interval prolongation were potentiated by underlying cirrhotic cardiomyopathy, a well described cause of QT interval prolongation. Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy is thought to cause QT interval prolongation by delayed repolarization of cardiomyocytes and promotion of sympatho-adrenergic hyperactivity.6 In other case series, TdP development has been associated with severe withdrawal symptoms, particularly delirium tremens.2 In cirrhosis, QT interval prolongation often is described as an early manifestation of cirrhotic cardiomyopathy, irrespective of the underlying etiology, and precedes systolic and diastolic dysfunction.6

The magnitude of QT prolongation has been associated with severity of liver disease as expressed by Child-Pugh score, with reports of QT normalization after liver transplantation.4,5 Patients with higher Child-Pugh scores should be considered to be at elevated risk for malignant ventricular arrhythmias. The authors recommend checking an EKG on admission of any patient who has liver disease or has presented for alcohol withdrawal. Patients with a prolonged QTc interval should be monitored on telemetry. The authors also recommend aggressive repletion of electrolytes, particularly potassium and magnesium, in patients who present with cirrhosis and alcohol withdrawal.

Avoidance of QT-prolonging medications is advisable for all patients with a long QT interval. Beta blockers shorten the QT interval in cirrhotic patients, but the role of beta blockers in preventing malignant arrhythmias in this group of patients is not yet clear.11 The present patient’s QT interval had been normal before he developed cirrhotic liver disease. His presentation was suggestive of acquired long QT syndrome, likely caused by cirrhotic cardiomyopathy given the exhaustive exclusion of other causes of QT interval prolongation.

Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of close monitoring of the QT interval in patients being treated for acute alcohol withdrawal, particularly those with cirrhosis, and suggests that timely and aggressive management of withdrawal, repletion of electrolytes, and telemetry monitoring may prevent life-threatening arrhythmia.

1. Otero-Antón E, González-Quintela A, Saborido J, Torre JA, Virgós A, Barrio E. Prolongation of the QTc interval during alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Acta Cardiol. 1997;52(3):285-294.

2. Cuculi F, Kobza R, Ehmann T, Erne P. ECG changes amongst patients with alcohol withdrawal seizures and delirium tremens. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006;136(13-14):223-227.

3. Mimidis K, Thomopoulos K, Tziakas D, et al. Prolongation of the QTc interval in patients with cirrhosis. Ann Gastroenterol. 2003;16(2):155-158.

4. Bernardi M, Calandra S, Colantoni A, et al. Q-T interval prolongation in cirrhosis: prevalence, relationship with severity, and etiology of the disease and possible pathogenetic factors. Hepatology. 1998;27(1):28-34.

5. Bal JS, Thuluvath PJ. Prolongation of QTc interval: relationship with etiology and severity of liver disease, mortality and liver transplantation. Liver Int. 2003;23(4):243-248.

6. Zardi EM, Abbate A, Zardi DM, et al. Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(7):539-549.

7. Faigel DO, Metz DC, Kochman ML. Torsade de pointes complicating the treatment of bleeding esophageal varices: association with neuroleptics, vasopressin, and electrolyte imbalance. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90(5):822-824.

8. Kotsia AP, Dimitriadis G, Baltogiannis GG, Kolettis TM. Torsade de pointes and persistent QTc prolongation after intravenous amiodarone. Case Rep Med. 2012;2012:673019.

9. Denison H, Jern S, Jagenburg R, Wendestam C, Wallerstedt S. Influence of increased adrenergic activity and magnesium depletion on cardiac rhythm in alcohol withdrawal. Br Heart J. 1994;72(6):554-560.

10. Plaza de los Reyes M, Orozco R, Rosemblitt M, Rendic Y, Espinace M. Renal secretion of magnesium and other electrolytes under the influence of acute ingestion of alcohol, in normal subjects [in Spanish]. Rev Med Chil. 1968;96(3):138-141.

11. Bernardi M, Maggioli C, Dibra V, Zaccherini G. QT interval prolongation in liver cirrhosis: innocent bystander or serious threat? Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;6(1):57-66.

Torsades de pointes (TdP) is a life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia that is associated with both congenital and acquired QT interval prolongation. QT interval prolongation is commonly observed in acute alcohol withdrawal and cirrhotic cardiomyopathy.1-3 In both conditions, there is a positive correlation between the degree of QT interval prolongation and disease severity.4,5 The precise mechanisms of QT interval prolongation in these conditions are not well understood. One hypothesis is that autonomic hyperexcitability results in altered ventricular repolarization and QT interval prolongation. This mechanism of QT prolongation has been found in acute alcohol withdrawal independent of electrolyte abnormalities, use of QT-prolonging medications, and cirrhosis.1,2,6

The authors report the case of a veteran who was hospitalized for acute alcohol withdrawal and decompensated cirrhosis and was found to have a newly prolonged QT interval. On hospital day 3, the patient developed TdP, which required external defibrillation. Despite correction of electrolyte abnormalities, abstinence from alcohol, avoidance of QT-prolonging medications, and exclusion of cardiac ischemia, there was significant and persistent prolongation of the QT interval—ultimately attributed to cirrhotic cardiomyopathy. Acquired QT interval prolongation is common in both acute alcohol withdrawal and cirrhosis.This case highlights the importance of close monitoring of the QT interval and TdP susceptibility in patients being treated for acute alcohol withdrawal, particularly those with cirrhosis.

Case Report

A 66-year-old male veteran with a 35-year history of alcohol dependence presented for alcohol detoxification. He reported having drunk at least 32 ounces of vodka every day of the preceding 5 years and reported having unsuccessfully attempted self-detoxification several times. Prior detoxification efforts were unsuccessful because of intractable nausea and tremulousness. Additional presenting symptoms included lethargy, anorexia, and a fall with transient right-side hemiparesis (findings on magnetic resonance imaging of the head had been normal).

His medical history included type 2 diabetes, tobacco dependence, and macular degeneration. The only medication being taken was glargine 25 units daily. On admission, the patient was afebrile (98.1°F), normotensive (103/77 mm Hg), and oriented to person, place, and time. Examination also revealed a protuberant abdomen with caput medusae, and no shifting dullness or lower extremity edema. The neurologic examination was nonfocal.

Laboratory test results on admission were significant for elevated serum alcohol level (243.8 mg/dL); elevated levels of aspartate aminotransferase (144 units/L) alanine aminotransferase (25 units/L), and total bilirubin (4.2 mg/L); hypoalbuminemia; normocalemia; hypomagnesemia; normal corrected calcium level; and normal renal function (0.84 mg/dL)(Table). The patient’s admission Child-Pugh score of 10 indicated class C liver disease. Admission electrocardiogram (EKG) revealed normal sinus rhythm, first-degree atrioventricular block, and prolongation of the QTc interval (519 ms). Six years earlier, the patient’s QTc interval had been 409 ms (Figures 1 and 2). As QT interval depends on heart rate, it is most commonly expressed as corrected QT, or QTc, where QTc = QT/(√RR).

Symptom-triggered therapy for alcohol withdrawal was instituted, and the patient’s electrolyte abnormalities were corrected. Telemetry monitoring demonstrated polymorphic ventricular ectopy, including a 6.8-s run of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and several shorter runs (4-10 beats) of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, prompting initiation of a low-dose beta blocker. Based on elevated scores on the symptom-triggered scale for alcohol withdrawal, the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessement for Alcohol Withdrawal (CIWA), several doses of oral lorazepam were given for withdrawal symptoms.

The patient became increasingly confused, and new-onset nystagmus was noted. These findings raised concern for Wernicke encephalopathy, so the patient was empirically started on IV high-dose thiamine supplementation. The CIWA scores remained high, and there were frequent episodes of ventricular ectopy during the first 2 hospital days. Interval EKG revealed further prolongation of the QTc interval (549 ms) without evidence of cardiac ischemia (Figure 3). Cardiac enzymes were negative, and electrolyte levels were within normal limits.

The month-long hospitalization was notable for development of significant ascites, continual electrolyte repletion in the setting of diuresis, formal diagnosis of alcoholic cirrhoisis, cognitive and physical rehabilitation. During the hospitalization, QTc interval remained prolonged (range, 460-500 ms), despite electrolyte repletion, and he was discharged with a wearable cardioverter defibrillator. A month

Discussion

Alcohol dependence is a common chronic and relapsing disease that often requires controlled detoxification. Investigators have found a high incidence of QT interval prolongation in alcohol withdrawal and hepatic disease.3,6 Common causes of QT interval prolongation in this setting are poor nutrition, electrolyte abnormalities (particularly hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia), and use of certain medications.1-3,7,8 In addition, alcohol is directly toxic to the renal tubules, resulting in renal wasting of divalent cations, which may persist up to 30 days after the most recent alcohol exposure.9,10