User login

Case Studies in Toxicology: The Perils of Playing Catch-up

Case

A 16-year-old girl, who recently emigrated from Haiti, was brought to the pediatric ED by her mother for evaluation of a 2-hour history of gastric discomfort. Upon arrival at the ED waiting area, the patient experienced a sudden onset of generalized tonic-clonic movement with altered sensorium, though she did not fall to the ground and was not injured. Vital signs from triage were: blood pressure, 110/76 mm Hg; heart rate, 112 beats/min; respiratory rate, 22 breaths/min; and temperature, 97°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air.

The patient was immediately attached to a cardiac monitor, given oxygen via a face mask, and received airway suctioning. Despite receiving a total of 4 mg of lorazepam, the seizure continued. Physical examination revealed no signs of external injury, but the ongoing generalized status epilepticus made the examination difficult.

What are the causes of refractory seizures in an adolescent patient?

The differential diagnosis for pediatric patients presenting with refractory seizure is the same as that for adult patients and should include treatment noncompliance, infection, vascular event (eg, stroke, hemorrhage), trauma (eg, cerebral contusions), metabolic and electrolyte disturbances, anticonvulsant toxicity, and exposure to a convulsant toxin.

While certain drugs (eg, cocaine) may cause status epilepticus through a secondary effect such as ischemia or a bleed, some drugs can directly cause refractory seizures. A few drugs and toxins are responsible for the majority of such seizures: bupropion; carbon monoxide; diphenhydramine; ethanol (withdrawal); hypoglycemics; lead; theophylline; tramadol; and certain antibiotics, including cephalosporins, penicillins, quinolones, and, in particular, isoniazid (INH).1

Case Continuation

Upon further history-taking, the patient’s mother informed the ED staff that during a recent visit to a local clinic, her daughter tested positive on routine screening for tuberculosis and was given “some medications.” The patient’s mother further noted that her daughter was scheduled for a follow-up appointment at the same clinic later this morning. She believed the patient had taken “a few” of the prescribed pills at once to “catch-up” on missed doses prior to that appointment, and provided the ED staff with an empty bottle of INH that she had found in her daughter’s purse.

What are the signs and symptoms of acute isoniazid toxicity?

Isoniazid toxicity should be suspected in any patient who has access to INH—even if the drug was prescribed for someone other than the patient. Acute toxicity develops rapidly after the ingestion of supratherapeutic doses of INH and includes nausea, abdominal discomfort, vomiting, dizziness, and excessive fatigue or lethargy. Patients can present with tachycardia, stupor, agitation, mydriasis, increased anion gap metabolic acidosis, and encephalopathy.

Seizures occur due to an INH-induced functional pyridoxine deficiency. Isoniazid inhibits pyridoxine phosphokinase, the enzyme that converts pyridoxine (vitamin B6) to its physiologically active form, pyridoxal 5’-phosphate (PLP). Because the conversion of glutamate (an excitatory neurotransmitter) to gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA; the body’s main inhibitory neurotransmitter) is dependent on PLP, an excess of glutamate and a deficiency of GABA occurs following INH overdose. The result is neuroexcitation, which manifests as generalized seizures in affected patients.

The most consequential effect of INH overdose, however, is the development of seizure refractory to conventional therapy, such as benzodiazepines. This occurs because benzodiazepines are indirect-acting GABA agonists, and require the presence of GABA to elicit their effect. Therefore, due to the impairment of GABA synthesis, benzodiazepines are limited or ineffective as anticonvulsants. Although INH doses in excess of 20 mg/kg may result in neuroexcitation, refractory seizures are uncommon with doses <70 mg/kg.

Complications of chronic INH use include hepatotoxicity, and patients will present with jaundice, hepatomegaly, and right upper quadrant pain and tenderness. Isoniazid must be discontinued rapidly in

How is acute isoniazid-induced seizure managed?

Management of patients with refractory seizure should initially include an assessment and management of the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulation. Although seizures induced by INH toxicity are often resistant to benzodiazepines, these agents remain the first-line therapy. For patients who fail to respond to a reasonable trial of benzodiazepines (eg, lorazepam 6 mg intravenously [IV]), pyridoxine should be administered.3 The recommended dose is 1 g pyridoxine per every 1 g of INH ingested—if the initial dose ingested is known—with a maximum dose of 5 g pyridoxine. If the initial dose of INH is not known, 70 mg/kg of pyridoxine, up to 5 g, is recommended. Repeated doses of pyridoxine can be administered if the seizure continues, up to a total dose of 10 g in an adult. At extremely high doses, pyridoxine itself can be neurotoxic, limiting the maximal antidotal dose.

Rapid initiation of pyridoxine is a challenge since typical stocks in most EDs are not in an adequate supply required for treatment. Additionally, a typical vial of pyridoxine contains 100 mg, highlighting the rare need to open dozens of vials for a single patient. Drawing up adequate doses of the IV formulation can be a challenge and time-consuming.

Regardless, the most reliable and rapid route of administration for pyridoxine is IV, at a rate of 0.5 to 1 g/min. Even if the seizure resolves prior to completion of the initial dose, the remaining doses should still be administered over a 4- to 6-hour period. Oral or (more likely) nasogastric administration of pyridoxine can be administered if the IV formulation is not available, but neither are optimal routes of delivery. Every effort should be made to stock pyridoxine in the antidote supply in the ED to avoid time delays involving finding, preparing, and administering the drug in these scenarios. Previous studies have found that most EDs are not prepared to handle pyridoxine replacement.4,5

Since benzodiazepines and barbiturates are GABA agonists with complementary mechanisms of actions to pyridoxine, they should be administered to potentiate the antiseizure effect of pyridoxine. If the seizure does not terminate, the use of propofol or general anesthesia may be required. Once the seizure is terminated, oral activated charcoal can be administered if the ingestion occurred within several hours of presentation. Given the rapid onset of effect of a large dose of INH, most patients will develop seizure shortly after exposure, limiting the benefits of both aggressive gastrointestinal decontamination and delayed activated charcoal. Charcoal also can be used for patients who overdose on INH but do not develop seizures.

Although the utility of a head computed tomography (CT) scan or laboratory studies is limited given the context of the exposure, these are generally obtained for patients with new-onset seizure. Since many patients with INH toxicity do not seize, such a patient may have a lower seizure threshold due to the existence of a subclinical cerebral lesion or metabolic abnormality.

Case Conclusion

The patient’s INH-induced refractory seizure was treated with pyridoxine. Her history suggested that she had ingested an unknown number of INH tablets within an hour. On this initial basis, an IV dose of 5,000 mg of pyridoxine was administered. The patient’s seizures terminated within 2 minutes of the infusion, and no additional doses of pyridoxine were required. Given the lack of concern for self-harm, an acetaminophen concentration was not obtained. A urine toxicology screen was negative for cocaine and amphetamines, and a CT scan of the head was negative for any abnormality. The patient was admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit for status epileptics and was discharged home on hospital day 2 after an uneventful stay.

1. Cock HR. Drug-induced status epilepticus. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;49:76-82. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.04.034.

2. Latent tuberculosis infection: a guide for primary health care providers. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/LTBI/treatment.htm. Updated August 5, 2016. Accessed December 13, 2016.

3. Howland MA. Antidotes in depth: pyridoxine. In: Hoffman RS, Howland MA, Lewin NA, Nelson LS, Goldfrank LR, eds. Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies. 10th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2015:797-799.

4. Shah BR, Santucci K, Sinert R, Steiner P. Acute isoniazid neurotoxicity in an urban hospital. Pediatrics. 1995;95(5):700-704.

5. Santucci KA, Shah BR, Linakis JG. Acute isoniazid exposures and antidote availability. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1999;15(2):99-101.

Case

A 16-year-old girl, who recently emigrated from Haiti, was brought to the pediatric ED by her mother for evaluation of a 2-hour history of gastric discomfort. Upon arrival at the ED waiting area, the patient experienced a sudden onset of generalized tonic-clonic movement with altered sensorium, though she did not fall to the ground and was not injured. Vital signs from triage were: blood pressure, 110/76 mm Hg; heart rate, 112 beats/min; respiratory rate, 22 breaths/min; and temperature, 97°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air.

The patient was immediately attached to a cardiac monitor, given oxygen via a face mask, and received airway suctioning. Despite receiving a total of 4 mg of lorazepam, the seizure continued. Physical examination revealed no signs of external injury, but the ongoing generalized status epilepticus made the examination difficult.

What are the causes of refractory seizures in an adolescent patient?

The differential diagnosis for pediatric patients presenting with refractory seizure is the same as that for adult patients and should include treatment noncompliance, infection, vascular event (eg, stroke, hemorrhage), trauma (eg, cerebral contusions), metabolic and electrolyte disturbances, anticonvulsant toxicity, and exposure to a convulsant toxin.

While certain drugs (eg, cocaine) may cause status epilepticus through a secondary effect such as ischemia or a bleed, some drugs can directly cause refractory seizures. A few drugs and toxins are responsible for the majority of such seizures: bupropion; carbon monoxide; diphenhydramine; ethanol (withdrawal); hypoglycemics; lead; theophylline; tramadol; and certain antibiotics, including cephalosporins, penicillins, quinolones, and, in particular, isoniazid (INH).1

Case Continuation

Upon further history-taking, the patient’s mother informed the ED staff that during a recent visit to a local clinic, her daughter tested positive on routine screening for tuberculosis and was given “some medications.” The patient’s mother further noted that her daughter was scheduled for a follow-up appointment at the same clinic later this morning. She believed the patient had taken “a few” of the prescribed pills at once to “catch-up” on missed doses prior to that appointment, and provided the ED staff with an empty bottle of INH that she had found in her daughter’s purse.

What are the signs and symptoms of acute isoniazid toxicity?

Isoniazid toxicity should be suspected in any patient who has access to INH—even if the drug was prescribed for someone other than the patient. Acute toxicity develops rapidly after the ingestion of supratherapeutic doses of INH and includes nausea, abdominal discomfort, vomiting, dizziness, and excessive fatigue or lethargy. Patients can present with tachycardia, stupor, agitation, mydriasis, increased anion gap metabolic acidosis, and encephalopathy.

Seizures occur due to an INH-induced functional pyridoxine deficiency. Isoniazid inhibits pyridoxine phosphokinase, the enzyme that converts pyridoxine (vitamin B6) to its physiologically active form, pyridoxal 5’-phosphate (PLP). Because the conversion of glutamate (an excitatory neurotransmitter) to gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA; the body’s main inhibitory neurotransmitter) is dependent on PLP, an excess of glutamate and a deficiency of GABA occurs following INH overdose. The result is neuroexcitation, which manifests as generalized seizures in affected patients.

The most consequential effect of INH overdose, however, is the development of seizure refractory to conventional therapy, such as benzodiazepines. This occurs because benzodiazepines are indirect-acting GABA agonists, and require the presence of GABA to elicit their effect. Therefore, due to the impairment of GABA synthesis, benzodiazepines are limited or ineffective as anticonvulsants. Although INH doses in excess of 20 mg/kg may result in neuroexcitation, refractory seizures are uncommon with doses <70 mg/kg.

Complications of chronic INH use include hepatotoxicity, and patients will present with jaundice, hepatomegaly, and right upper quadrant pain and tenderness. Isoniazid must be discontinued rapidly in

How is acute isoniazid-induced seizure managed?

Management of patients with refractory seizure should initially include an assessment and management of the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulation. Although seizures induced by INH toxicity are often resistant to benzodiazepines, these agents remain the first-line therapy. For patients who fail to respond to a reasonable trial of benzodiazepines (eg, lorazepam 6 mg intravenously [IV]), pyridoxine should be administered.3 The recommended dose is 1 g pyridoxine per every 1 g of INH ingested—if the initial dose ingested is known—with a maximum dose of 5 g pyridoxine. If the initial dose of INH is not known, 70 mg/kg of pyridoxine, up to 5 g, is recommended. Repeated doses of pyridoxine can be administered if the seizure continues, up to a total dose of 10 g in an adult. At extremely high doses, pyridoxine itself can be neurotoxic, limiting the maximal antidotal dose.

Rapid initiation of pyridoxine is a challenge since typical stocks in most EDs are not in an adequate supply required for treatment. Additionally, a typical vial of pyridoxine contains 100 mg, highlighting the rare need to open dozens of vials for a single patient. Drawing up adequate doses of the IV formulation can be a challenge and time-consuming.

Regardless, the most reliable and rapid route of administration for pyridoxine is IV, at a rate of 0.5 to 1 g/min. Even if the seizure resolves prior to completion of the initial dose, the remaining doses should still be administered over a 4- to 6-hour period. Oral or (more likely) nasogastric administration of pyridoxine can be administered if the IV formulation is not available, but neither are optimal routes of delivery. Every effort should be made to stock pyridoxine in the antidote supply in the ED to avoid time delays involving finding, preparing, and administering the drug in these scenarios. Previous studies have found that most EDs are not prepared to handle pyridoxine replacement.4,5

Since benzodiazepines and barbiturates are GABA agonists with complementary mechanisms of actions to pyridoxine, they should be administered to potentiate the antiseizure effect of pyridoxine. If the seizure does not terminate, the use of propofol or general anesthesia may be required. Once the seizure is terminated, oral activated charcoal can be administered if the ingestion occurred within several hours of presentation. Given the rapid onset of effect of a large dose of INH, most patients will develop seizure shortly after exposure, limiting the benefits of both aggressive gastrointestinal decontamination and delayed activated charcoal. Charcoal also can be used for patients who overdose on INH but do not develop seizures.

Although the utility of a head computed tomography (CT) scan or laboratory studies is limited given the context of the exposure, these are generally obtained for patients with new-onset seizure. Since many patients with INH toxicity do not seize, such a patient may have a lower seizure threshold due to the existence of a subclinical cerebral lesion or metabolic abnormality.

Case Conclusion

The patient’s INH-induced refractory seizure was treated with pyridoxine. Her history suggested that she had ingested an unknown number of INH tablets within an hour. On this initial basis, an IV dose of 5,000 mg of pyridoxine was administered. The patient’s seizures terminated within 2 minutes of the infusion, and no additional doses of pyridoxine were required. Given the lack of concern for self-harm, an acetaminophen concentration was not obtained. A urine toxicology screen was negative for cocaine and amphetamines, and a CT scan of the head was negative for any abnormality. The patient was admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit for status epileptics and was discharged home on hospital day 2 after an uneventful stay.

Case

A 16-year-old girl, who recently emigrated from Haiti, was brought to the pediatric ED by her mother for evaluation of a 2-hour history of gastric discomfort. Upon arrival at the ED waiting area, the patient experienced a sudden onset of generalized tonic-clonic movement with altered sensorium, though she did not fall to the ground and was not injured. Vital signs from triage were: blood pressure, 110/76 mm Hg; heart rate, 112 beats/min; respiratory rate, 22 breaths/min; and temperature, 97°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air.

The patient was immediately attached to a cardiac monitor, given oxygen via a face mask, and received airway suctioning. Despite receiving a total of 4 mg of lorazepam, the seizure continued. Physical examination revealed no signs of external injury, but the ongoing generalized status epilepticus made the examination difficult.

What are the causes of refractory seizures in an adolescent patient?

The differential diagnosis for pediatric patients presenting with refractory seizure is the same as that for adult patients and should include treatment noncompliance, infection, vascular event (eg, stroke, hemorrhage), trauma (eg, cerebral contusions), metabolic and electrolyte disturbances, anticonvulsant toxicity, and exposure to a convulsant toxin.

While certain drugs (eg, cocaine) may cause status epilepticus through a secondary effect such as ischemia or a bleed, some drugs can directly cause refractory seizures. A few drugs and toxins are responsible for the majority of such seizures: bupropion; carbon monoxide; diphenhydramine; ethanol (withdrawal); hypoglycemics; lead; theophylline; tramadol; and certain antibiotics, including cephalosporins, penicillins, quinolones, and, in particular, isoniazid (INH).1

Case Continuation

Upon further history-taking, the patient’s mother informed the ED staff that during a recent visit to a local clinic, her daughter tested positive on routine screening for tuberculosis and was given “some medications.” The patient’s mother further noted that her daughter was scheduled for a follow-up appointment at the same clinic later this morning. She believed the patient had taken “a few” of the prescribed pills at once to “catch-up” on missed doses prior to that appointment, and provided the ED staff with an empty bottle of INH that she had found in her daughter’s purse.

What are the signs and symptoms of acute isoniazid toxicity?

Isoniazid toxicity should be suspected in any patient who has access to INH—even if the drug was prescribed for someone other than the patient. Acute toxicity develops rapidly after the ingestion of supratherapeutic doses of INH and includes nausea, abdominal discomfort, vomiting, dizziness, and excessive fatigue or lethargy. Patients can present with tachycardia, stupor, agitation, mydriasis, increased anion gap metabolic acidosis, and encephalopathy.

Seizures occur due to an INH-induced functional pyridoxine deficiency. Isoniazid inhibits pyridoxine phosphokinase, the enzyme that converts pyridoxine (vitamin B6) to its physiologically active form, pyridoxal 5’-phosphate (PLP). Because the conversion of glutamate (an excitatory neurotransmitter) to gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA; the body’s main inhibitory neurotransmitter) is dependent on PLP, an excess of glutamate and a deficiency of GABA occurs following INH overdose. The result is neuroexcitation, which manifests as generalized seizures in affected patients.

The most consequential effect of INH overdose, however, is the development of seizure refractory to conventional therapy, such as benzodiazepines. This occurs because benzodiazepines are indirect-acting GABA agonists, and require the presence of GABA to elicit their effect. Therefore, due to the impairment of GABA synthesis, benzodiazepines are limited or ineffective as anticonvulsants. Although INH doses in excess of 20 mg/kg may result in neuroexcitation, refractory seizures are uncommon with doses <70 mg/kg.

Complications of chronic INH use include hepatotoxicity, and patients will present with jaundice, hepatomegaly, and right upper quadrant pain and tenderness. Isoniazid must be discontinued rapidly in

How is acute isoniazid-induced seizure managed?

Management of patients with refractory seizure should initially include an assessment and management of the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulation. Although seizures induced by INH toxicity are often resistant to benzodiazepines, these agents remain the first-line therapy. For patients who fail to respond to a reasonable trial of benzodiazepines (eg, lorazepam 6 mg intravenously [IV]), pyridoxine should be administered.3 The recommended dose is 1 g pyridoxine per every 1 g of INH ingested—if the initial dose ingested is known—with a maximum dose of 5 g pyridoxine. If the initial dose of INH is not known, 70 mg/kg of pyridoxine, up to 5 g, is recommended. Repeated doses of pyridoxine can be administered if the seizure continues, up to a total dose of 10 g in an adult. At extremely high doses, pyridoxine itself can be neurotoxic, limiting the maximal antidotal dose.

Rapid initiation of pyridoxine is a challenge since typical stocks in most EDs are not in an adequate supply required for treatment. Additionally, a typical vial of pyridoxine contains 100 mg, highlighting the rare need to open dozens of vials for a single patient. Drawing up adequate doses of the IV formulation can be a challenge and time-consuming.

Regardless, the most reliable and rapid route of administration for pyridoxine is IV, at a rate of 0.5 to 1 g/min. Even if the seizure resolves prior to completion of the initial dose, the remaining doses should still be administered over a 4- to 6-hour period. Oral or (more likely) nasogastric administration of pyridoxine can be administered if the IV formulation is not available, but neither are optimal routes of delivery. Every effort should be made to stock pyridoxine in the antidote supply in the ED to avoid time delays involving finding, preparing, and administering the drug in these scenarios. Previous studies have found that most EDs are not prepared to handle pyridoxine replacement.4,5

Since benzodiazepines and barbiturates are GABA agonists with complementary mechanisms of actions to pyridoxine, they should be administered to potentiate the antiseizure effect of pyridoxine. If the seizure does not terminate, the use of propofol or general anesthesia may be required. Once the seizure is terminated, oral activated charcoal can be administered if the ingestion occurred within several hours of presentation. Given the rapid onset of effect of a large dose of INH, most patients will develop seizure shortly after exposure, limiting the benefits of both aggressive gastrointestinal decontamination and delayed activated charcoal. Charcoal also can be used for patients who overdose on INH but do not develop seizures.

Although the utility of a head computed tomography (CT) scan or laboratory studies is limited given the context of the exposure, these are generally obtained for patients with new-onset seizure. Since many patients with INH toxicity do not seize, such a patient may have a lower seizure threshold due to the existence of a subclinical cerebral lesion or metabolic abnormality.

Case Conclusion

The patient’s INH-induced refractory seizure was treated with pyridoxine. Her history suggested that she had ingested an unknown number of INH tablets within an hour. On this initial basis, an IV dose of 5,000 mg of pyridoxine was administered. The patient’s seizures terminated within 2 minutes of the infusion, and no additional doses of pyridoxine were required. Given the lack of concern for self-harm, an acetaminophen concentration was not obtained. A urine toxicology screen was negative for cocaine and amphetamines, and a CT scan of the head was negative for any abnormality. The patient was admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit for status epileptics and was discharged home on hospital day 2 after an uneventful stay.

1. Cock HR. Drug-induced status epilepticus. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;49:76-82. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.04.034.

2. Latent tuberculosis infection: a guide for primary health care providers. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/LTBI/treatment.htm. Updated August 5, 2016. Accessed December 13, 2016.

3. Howland MA. Antidotes in depth: pyridoxine. In: Hoffman RS, Howland MA, Lewin NA, Nelson LS, Goldfrank LR, eds. Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies. 10th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2015:797-799.

4. Shah BR, Santucci K, Sinert R, Steiner P. Acute isoniazid neurotoxicity in an urban hospital. Pediatrics. 1995;95(5):700-704.

5. Santucci KA, Shah BR, Linakis JG. Acute isoniazid exposures and antidote availability. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1999;15(2):99-101.

1. Cock HR. Drug-induced status epilepticus. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;49:76-82. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.04.034.

2. Latent tuberculosis infection: a guide for primary health care providers. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/LTBI/treatment.htm. Updated August 5, 2016. Accessed December 13, 2016.

3. Howland MA. Antidotes in depth: pyridoxine. In: Hoffman RS, Howland MA, Lewin NA, Nelson LS, Goldfrank LR, eds. Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies. 10th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2015:797-799.

4. Shah BR, Santucci K, Sinert R, Steiner P. Acute isoniazid neurotoxicity in an urban hospital. Pediatrics. 1995;95(5):700-704.

5. Santucci KA, Shah BR, Linakis JG. Acute isoniazid exposures and antidote availability. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1999;15(2):99-101.

Dissection of the Celiac Artery

Case

A 41-year-old man presented to our ED with a 4-day history of epigastric pain radiating to the bilateral flanks and back. His medical history was significant for hypertension, for which he was prescribed isosorbide dinitrite 30 mg four times per day; however, he reported that he did not regularly take this medication.

The patient had visited our ED 3 days earlier with the same complaint. Since his blood pressure (BP) reading at the first ED presentation was 213/141 mm Hg, he had been admitted for hypertensive urgency. The patient’s BP was controlled with antihypertensive agents during his stay, but he continued to experience epigastric pain. A basic work-up for abdominal pain was ordered, the results of which were normal. Based on these findings, the patient’s pain was attributed to gastritis, and he was discharged home with instructions to return to the ED if his pain became worse or persisted.

At both ED presentations, the patient denied experiencing any nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or chest pain. At the second presentation, his triage BP was 158/106 mm Hg. A chest X-ray, complete blood count (CBC), basic metabolic profile (BMP), hepatic panel, and lipase evaluation were all unremarkable, with the exception of a mild increase in creatinine to 1.38 mg/dL. A point-of-care (POC) ultrasound study of the aorta was normal.

Based on the CTA findings, a nicardipine infusion was immediately started, and the patient was admitted to the medical intensive care unit (MICU). Because his heart rate was in the range of 60 beats/min, an esmolol infusion was not required. Prior to transferring the patient to MICU, a second ultrasound study of the aorta was performed by our fellowship-trained director of emergency medicine ultrasound.

In the MICU, the patient’s BP was stabilized on hospital day 2, and he was transitioned to oral antihypertensive medications. He was also started on a heparin infusion at the recommendation of vascular surgery services.

A repeat CTA of the abdomen taken on hospital day 3 showed an unchanged dissection in the celiac axis extending into the hepatic artery. The vascular surgeon recommended strict BP control, anticoagulation therapy, and a vascular surgery follow-up with a repeat CTA of the abdomen in 6 months.

On hospital day 6, repeat serial CBC, BMP, and hepatic panels revealed only slight increases in aspartate transaminase to 88 U/L and alanine aminotransferase to 117 U/L. The patient was transitioned to enoxaparin and discharged home on hospital day 6, and instructed to follow-up with his primary care physician for transition to warfarin. Unfortunately, this patient was lost to follow-up.

Discussion

Isolated DCA is a rare cause of abdominal pain. The first documented case of isolated DCA is often incorrectly attributed to Bauersfeld’s1 1947 case series on dissections,but that report described superior mesenteric artery dissection rather than a celiac artery dissection. Watson’s2 1956 dissection series is also incorrectly cited as the first DCA, but that series described a dissection of the splenic artery, which is a branch of the celiac artery. In a 1959 series, Foord and Lewis3 described what is most likely the first report of DCA as an incidental finding at autopsy. More frequent descriptions in recent years are thought to be due to the routine use of abdominal CTA.4

Dissection of the celiac artery is a rare occurrence, with less than 100 cases reported, and little evidence exists to guide its management.5 These dissections represent 36.8% of all visceral artery dissections,6 which themselves are less common than renal, carotid, and vertebral artery dissections.7 Dissection of visceral arteries occurs predominantly in men and more often in middle-aged patients.8 Risk factors for DCA are thought to mirror risk factors for dissection of other arteries, including atherosclerotic disease, hypertension, connective tissue disorders, trauma, vasculitis, and pregnancy.9-11

Signs and Symptoms

Patients with DCA typically present with sudden onset of epigastric, flank, and/or chest pain, though 50% of patients may be asymptomatic.12 This pain is easily overlooked because the physical examination and laboratory studies are typically unremarkable.13 Fortunately, DCA is rarely accompanied by fatal organ dysfunction due to collateral flow from other vessels.14

Diagnosis and Management

While CTA with contrast is considered the mainstay of diagnosis of DCA,15 optimal treatment for DCA has not been well established. Management options include medical management, operative repair, and endovascular embolization. Medical management is reserved for stable patients without signs of end organ dysfunction. Typical management involves anticoagulation with warfarin for 3 to 6 months and strict BP control accompanied by close surveillance for progression.10,13 Some clinicians have argued that anticoagulation therapy may be unnecessary and that risk factor modification and BP control alone may be sufficient.5,6 Others have advocated that surgical management should be favored in cases of persistent pain, development of aneurysm, or threatened or compromised flow to end organs.7

Point-of-Care Ultrasound

The American College of Emergency Physicians considers ultrasound of the abdominal aorta a core application of emergency ultrasound.16 While sensitivity and specificity of emergency ultrasound for abdominal aortic aneurysm are well established, data supporting its use for screening for dissections are less definitive. With a sensitivity of 67% to 80% and a specificity of 99% to 100% with visualization of an intimal flap, aortic dissection screening using ultrasound is less reliable than most emergency physicians (EPs) would prefer.17,18 There are no published data reporting the sensitivity or specificity of emergency ultrasound for DCA. However, the vascular surgery literature encourages color Doppler ultrasound as part of the initial diagnostic work-up for this rare entity.19 While this may seem like an area ripe for emergency ultrasound, it is important to note—as seen in our case—that the site of the dissection is not often seen. Instead, the use of Doppler allows a screening for an abnormal flow pattern suggestive of dissection.20

Conclusion

In our case, both resident EPs and an expert fellowship-trained emergency ultrasound attending physician were unable to visualize a dissection—even after knowledge of the lesion was established by CTA. This points out a limitation of emergency ultrasound. While a POC ultrasound may be able to effectively rule in dissections of the aorta and its branches, we cannot reliably rule out these lesions. As EPs continue to expand the use of ultrasound, it is important to balance the desire for efficiency and cost-effectiveness with a high index of suspicion, experience, and clinical acumen.

1. Bauersfeld SR. Dissecting aneurysm of the aorta; a presentation of 15 cases and a review of the recent literature. Ann Intern Med. 1947;26(6):873-889.

2. Watson AJ. Dissecting aneurysm of arteries other than the aorta. J Pathol. 1956;72(2):439-449. doi:10.1002/path.1700720209.

3. Foord AG, Lewis RD. Primary dissecting aneurysms of peripheral and pulmonary arteries: dissecting hemorrhage of media. Arch Pathol. 1959;68:553-577.

4. Neychev V, Krol E, Dietzek A. Unusual presentation and treatment of spontaneous celiac artery dissection. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58(2):491-495. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2012.10.136.

5. DiMusto PD, Oberdoerster MM, Criado E. Isolated celiac artery dissection. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61(4):972-976. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.10.108.

6. Takayama T, Miyata T, Shirakawa M, Nagawa H. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48(2):329-333. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2008.03.002.

7. Glehen O, Feugier P, Aleksic Y, Delannoy P, Chevalier JM. Spontaneous dissection of the celiac artery. Ann Vasc Surg. 2001;15(6):687-692.

8. Patel KS, Benshar O, Vrabie R, Patel A, Adler M, Hines G. A major pain in the … back and epigastrium: an unusual case of spontaneous celiac artery dissection. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2014;4(5):23840. doi:10.3402/jchimp.v4.23840.

9. Kang TL, Teich DL, McGillicuddy DC. Isolated, spontaneous superior mesenteric and celiac artery dissection: case report and review of literature. J Emerg Med. 2011;40(2):e21-e25. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.12.038.

10. Galastri FL, Cavalcante RN, Motta-Leal-Filho JM, et al. Evaluation and management of symptomatic isolated spontaneous celiac trunk dissection. Vasc Med. 2015;20(4):358-363. doi:10.1177/1358863X15581447.

11. Wang HC, Chen JH, Hsiao CC, Jeng CM, Chen WL. Spontaneous dissection of the celiac artery: a case report and literature review. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(6):1000.e3-e5. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2013.02.007.

12. Oh S, Cho YP, Kim JH, Shin S, Kwon TW, Ko GY. Symptomatic spontaneous celiac artery dissection treated by conservative management: serial imaging findings. Abdom Imaging. 2011;36(1):79-82. doi:10.1007/s00261-010-9657-x.

13. Wang JL, Hsieh MJ, Lee CH, Chen CC, Hsieh IC. Celiac artery dissection presenting with abdominal and chest pain. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28(1):111.e3-e5. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2009.02.023.

14. Takayama Y, Takao M, Inoue T, Yoshimi F, Koyama K, Nagai H. Isolated spontaneous dissection of the celiac artery: report of two cases. Ann Vasc Dis. 2014;7(1):64-67. doi:10.3400/avd.cr.13-00102.

15. Rehman AU, Almanfi A, Nadella S, Sohail U. Isolated spontaneous celiac artery dissection in a 47-year-old man with von Willebrand disease. Tex Heart Inst J. 2014;41(3):344-345. doi:10.14503/THIJ-13-3404.

16. American College of Emergency Physicians. Policy statement. Ultrasound Guidelines: Emergency, Point-of-Care, and Clinical Ultrasound Guidelines in Medicine, June 2016. https://www.acep.org/Clinical---Practice-Management/Ultrasound/. Accessed November 15, 2016.

17. Williams J, Heiner JD, Perreault MD, McArthur TJ. Aortic dissection diagnosed by ultrasound. West J Emerg Med. 2010;11(1):98-99.

18. Fojtik JP, Costantino TG, Dean AJ. The diagnosis of aortic dissection by emergency medicine ultrasound. J Emerg Med. 2007;32(2):191-196.

19. Woolard JD, Ammar AD. Spontaneous dissection of the celiac artery: a case report. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(6):1256-1258.

20. Fenoglio L, Allione A, Scalabrino E, et al. Spontaneous dissection of the celiac artery: a pitfall in the diagnosis of acute abdominal pain. Presentation of two cases. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49(7-8):1223-1227.

Case

A 41-year-old man presented to our ED with a 4-day history of epigastric pain radiating to the bilateral flanks and back. His medical history was significant for hypertension, for which he was prescribed isosorbide dinitrite 30 mg four times per day; however, he reported that he did not regularly take this medication.

The patient had visited our ED 3 days earlier with the same complaint. Since his blood pressure (BP) reading at the first ED presentation was 213/141 mm Hg, he had been admitted for hypertensive urgency. The patient’s BP was controlled with antihypertensive agents during his stay, but he continued to experience epigastric pain. A basic work-up for abdominal pain was ordered, the results of which were normal. Based on these findings, the patient’s pain was attributed to gastritis, and he was discharged home with instructions to return to the ED if his pain became worse or persisted.

At both ED presentations, the patient denied experiencing any nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or chest pain. At the second presentation, his triage BP was 158/106 mm Hg. A chest X-ray, complete blood count (CBC), basic metabolic profile (BMP), hepatic panel, and lipase evaluation were all unremarkable, with the exception of a mild increase in creatinine to 1.38 mg/dL. A point-of-care (POC) ultrasound study of the aorta was normal.

Based on the CTA findings, a nicardipine infusion was immediately started, and the patient was admitted to the medical intensive care unit (MICU). Because his heart rate was in the range of 60 beats/min, an esmolol infusion was not required. Prior to transferring the patient to MICU, a second ultrasound study of the aorta was performed by our fellowship-trained director of emergency medicine ultrasound.

In the MICU, the patient’s BP was stabilized on hospital day 2, and he was transitioned to oral antihypertensive medications. He was also started on a heparin infusion at the recommendation of vascular surgery services.

A repeat CTA of the abdomen taken on hospital day 3 showed an unchanged dissection in the celiac axis extending into the hepatic artery. The vascular surgeon recommended strict BP control, anticoagulation therapy, and a vascular surgery follow-up with a repeat CTA of the abdomen in 6 months.

On hospital day 6, repeat serial CBC, BMP, and hepatic panels revealed only slight increases in aspartate transaminase to 88 U/L and alanine aminotransferase to 117 U/L. The patient was transitioned to enoxaparin and discharged home on hospital day 6, and instructed to follow-up with his primary care physician for transition to warfarin. Unfortunately, this patient was lost to follow-up.

Discussion

Isolated DCA is a rare cause of abdominal pain. The first documented case of isolated DCA is often incorrectly attributed to Bauersfeld’s1 1947 case series on dissections,but that report described superior mesenteric artery dissection rather than a celiac artery dissection. Watson’s2 1956 dissection series is also incorrectly cited as the first DCA, but that series described a dissection of the splenic artery, which is a branch of the celiac artery. In a 1959 series, Foord and Lewis3 described what is most likely the first report of DCA as an incidental finding at autopsy. More frequent descriptions in recent years are thought to be due to the routine use of abdominal CTA.4

Dissection of the celiac artery is a rare occurrence, with less than 100 cases reported, and little evidence exists to guide its management.5 These dissections represent 36.8% of all visceral artery dissections,6 which themselves are less common than renal, carotid, and vertebral artery dissections.7 Dissection of visceral arteries occurs predominantly in men and more often in middle-aged patients.8 Risk factors for DCA are thought to mirror risk factors for dissection of other arteries, including atherosclerotic disease, hypertension, connective tissue disorders, trauma, vasculitis, and pregnancy.9-11

Signs and Symptoms

Patients with DCA typically present with sudden onset of epigastric, flank, and/or chest pain, though 50% of patients may be asymptomatic.12 This pain is easily overlooked because the physical examination and laboratory studies are typically unremarkable.13 Fortunately, DCA is rarely accompanied by fatal organ dysfunction due to collateral flow from other vessels.14

Diagnosis and Management

While CTA with contrast is considered the mainstay of diagnosis of DCA,15 optimal treatment for DCA has not been well established. Management options include medical management, operative repair, and endovascular embolization. Medical management is reserved for stable patients without signs of end organ dysfunction. Typical management involves anticoagulation with warfarin for 3 to 6 months and strict BP control accompanied by close surveillance for progression.10,13 Some clinicians have argued that anticoagulation therapy may be unnecessary and that risk factor modification and BP control alone may be sufficient.5,6 Others have advocated that surgical management should be favored in cases of persistent pain, development of aneurysm, or threatened or compromised flow to end organs.7

Point-of-Care Ultrasound

The American College of Emergency Physicians considers ultrasound of the abdominal aorta a core application of emergency ultrasound.16 While sensitivity and specificity of emergency ultrasound for abdominal aortic aneurysm are well established, data supporting its use for screening for dissections are less definitive. With a sensitivity of 67% to 80% and a specificity of 99% to 100% with visualization of an intimal flap, aortic dissection screening using ultrasound is less reliable than most emergency physicians (EPs) would prefer.17,18 There are no published data reporting the sensitivity or specificity of emergency ultrasound for DCA. However, the vascular surgery literature encourages color Doppler ultrasound as part of the initial diagnostic work-up for this rare entity.19 While this may seem like an area ripe for emergency ultrasound, it is important to note—as seen in our case—that the site of the dissection is not often seen. Instead, the use of Doppler allows a screening for an abnormal flow pattern suggestive of dissection.20

Conclusion

In our case, both resident EPs and an expert fellowship-trained emergency ultrasound attending physician were unable to visualize a dissection—even after knowledge of the lesion was established by CTA. This points out a limitation of emergency ultrasound. While a POC ultrasound may be able to effectively rule in dissections of the aorta and its branches, we cannot reliably rule out these lesions. As EPs continue to expand the use of ultrasound, it is important to balance the desire for efficiency and cost-effectiveness with a high index of suspicion, experience, and clinical acumen.

Case

A 41-year-old man presented to our ED with a 4-day history of epigastric pain radiating to the bilateral flanks and back. His medical history was significant for hypertension, for which he was prescribed isosorbide dinitrite 30 mg four times per day; however, he reported that he did not regularly take this medication.

The patient had visited our ED 3 days earlier with the same complaint. Since his blood pressure (BP) reading at the first ED presentation was 213/141 mm Hg, he had been admitted for hypertensive urgency. The patient’s BP was controlled with antihypertensive agents during his stay, but he continued to experience epigastric pain. A basic work-up for abdominal pain was ordered, the results of which were normal. Based on these findings, the patient’s pain was attributed to gastritis, and he was discharged home with instructions to return to the ED if his pain became worse or persisted.

At both ED presentations, the patient denied experiencing any nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or chest pain. At the second presentation, his triage BP was 158/106 mm Hg. A chest X-ray, complete blood count (CBC), basic metabolic profile (BMP), hepatic panel, and lipase evaluation were all unremarkable, with the exception of a mild increase in creatinine to 1.38 mg/dL. A point-of-care (POC) ultrasound study of the aorta was normal.

Based on the CTA findings, a nicardipine infusion was immediately started, and the patient was admitted to the medical intensive care unit (MICU). Because his heart rate was in the range of 60 beats/min, an esmolol infusion was not required. Prior to transferring the patient to MICU, a second ultrasound study of the aorta was performed by our fellowship-trained director of emergency medicine ultrasound.

In the MICU, the patient’s BP was stabilized on hospital day 2, and he was transitioned to oral antihypertensive medications. He was also started on a heparin infusion at the recommendation of vascular surgery services.

A repeat CTA of the abdomen taken on hospital day 3 showed an unchanged dissection in the celiac axis extending into the hepatic artery. The vascular surgeon recommended strict BP control, anticoagulation therapy, and a vascular surgery follow-up with a repeat CTA of the abdomen in 6 months.

On hospital day 6, repeat serial CBC, BMP, and hepatic panels revealed only slight increases in aspartate transaminase to 88 U/L and alanine aminotransferase to 117 U/L. The patient was transitioned to enoxaparin and discharged home on hospital day 6, and instructed to follow-up with his primary care physician for transition to warfarin. Unfortunately, this patient was lost to follow-up.

Discussion

Isolated DCA is a rare cause of abdominal pain. The first documented case of isolated DCA is often incorrectly attributed to Bauersfeld’s1 1947 case series on dissections,but that report described superior mesenteric artery dissection rather than a celiac artery dissection. Watson’s2 1956 dissection series is also incorrectly cited as the first DCA, but that series described a dissection of the splenic artery, which is a branch of the celiac artery. In a 1959 series, Foord and Lewis3 described what is most likely the first report of DCA as an incidental finding at autopsy. More frequent descriptions in recent years are thought to be due to the routine use of abdominal CTA.4

Dissection of the celiac artery is a rare occurrence, with less than 100 cases reported, and little evidence exists to guide its management.5 These dissections represent 36.8% of all visceral artery dissections,6 which themselves are less common than renal, carotid, and vertebral artery dissections.7 Dissection of visceral arteries occurs predominantly in men and more often in middle-aged patients.8 Risk factors for DCA are thought to mirror risk factors for dissection of other arteries, including atherosclerotic disease, hypertension, connective tissue disorders, trauma, vasculitis, and pregnancy.9-11

Signs and Symptoms

Patients with DCA typically present with sudden onset of epigastric, flank, and/or chest pain, though 50% of patients may be asymptomatic.12 This pain is easily overlooked because the physical examination and laboratory studies are typically unremarkable.13 Fortunately, DCA is rarely accompanied by fatal organ dysfunction due to collateral flow from other vessels.14

Diagnosis and Management

While CTA with contrast is considered the mainstay of diagnosis of DCA,15 optimal treatment for DCA has not been well established. Management options include medical management, operative repair, and endovascular embolization. Medical management is reserved for stable patients without signs of end organ dysfunction. Typical management involves anticoagulation with warfarin for 3 to 6 months and strict BP control accompanied by close surveillance for progression.10,13 Some clinicians have argued that anticoagulation therapy may be unnecessary and that risk factor modification and BP control alone may be sufficient.5,6 Others have advocated that surgical management should be favored in cases of persistent pain, development of aneurysm, or threatened or compromised flow to end organs.7

Point-of-Care Ultrasound

The American College of Emergency Physicians considers ultrasound of the abdominal aorta a core application of emergency ultrasound.16 While sensitivity and specificity of emergency ultrasound for abdominal aortic aneurysm are well established, data supporting its use for screening for dissections are less definitive. With a sensitivity of 67% to 80% and a specificity of 99% to 100% with visualization of an intimal flap, aortic dissection screening using ultrasound is less reliable than most emergency physicians (EPs) would prefer.17,18 There are no published data reporting the sensitivity or specificity of emergency ultrasound for DCA. However, the vascular surgery literature encourages color Doppler ultrasound as part of the initial diagnostic work-up for this rare entity.19 While this may seem like an area ripe for emergency ultrasound, it is important to note—as seen in our case—that the site of the dissection is not often seen. Instead, the use of Doppler allows a screening for an abnormal flow pattern suggestive of dissection.20

Conclusion

In our case, both resident EPs and an expert fellowship-trained emergency ultrasound attending physician were unable to visualize a dissection—even after knowledge of the lesion was established by CTA. This points out a limitation of emergency ultrasound. While a POC ultrasound may be able to effectively rule in dissections of the aorta and its branches, we cannot reliably rule out these lesions. As EPs continue to expand the use of ultrasound, it is important to balance the desire for efficiency and cost-effectiveness with a high index of suspicion, experience, and clinical acumen.

1. Bauersfeld SR. Dissecting aneurysm of the aorta; a presentation of 15 cases and a review of the recent literature. Ann Intern Med. 1947;26(6):873-889.

2. Watson AJ. Dissecting aneurysm of arteries other than the aorta. J Pathol. 1956;72(2):439-449. doi:10.1002/path.1700720209.

3. Foord AG, Lewis RD. Primary dissecting aneurysms of peripheral and pulmonary arteries: dissecting hemorrhage of media. Arch Pathol. 1959;68:553-577.

4. Neychev V, Krol E, Dietzek A. Unusual presentation and treatment of spontaneous celiac artery dissection. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58(2):491-495. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2012.10.136.

5. DiMusto PD, Oberdoerster MM, Criado E. Isolated celiac artery dissection. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61(4):972-976. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.10.108.

6. Takayama T, Miyata T, Shirakawa M, Nagawa H. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48(2):329-333. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2008.03.002.

7. Glehen O, Feugier P, Aleksic Y, Delannoy P, Chevalier JM. Spontaneous dissection of the celiac artery. Ann Vasc Surg. 2001;15(6):687-692.

8. Patel KS, Benshar O, Vrabie R, Patel A, Adler M, Hines G. A major pain in the … back and epigastrium: an unusual case of spontaneous celiac artery dissection. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2014;4(5):23840. doi:10.3402/jchimp.v4.23840.

9. Kang TL, Teich DL, McGillicuddy DC. Isolated, spontaneous superior mesenteric and celiac artery dissection: case report and review of literature. J Emerg Med. 2011;40(2):e21-e25. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.12.038.

10. Galastri FL, Cavalcante RN, Motta-Leal-Filho JM, et al. Evaluation and management of symptomatic isolated spontaneous celiac trunk dissection. Vasc Med. 2015;20(4):358-363. doi:10.1177/1358863X15581447.

11. Wang HC, Chen JH, Hsiao CC, Jeng CM, Chen WL. Spontaneous dissection of the celiac artery: a case report and literature review. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(6):1000.e3-e5. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2013.02.007.

12. Oh S, Cho YP, Kim JH, Shin S, Kwon TW, Ko GY. Symptomatic spontaneous celiac artery dissection treated by conservative management: serial imaging findings. Abdom Imaging. 2011;36(1):79-82. doi:10.1007/s00261-010-9657-x.

13. Wang JL, Hsieh MJ, Lee CH, Chen CC, Hsieh IC. Celiac artery dissection presenting with abdominal and chest pain. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28(1):111.e3-e5. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2009.02.023.

14. Takayama Y, Takao M, Inoue T, Yoshimi F, Koyama K, Nagai H. Isolated spontaneous dissection of the celiac artery: report of two cases. Ann Vasc Dis. 2014;7(1):64-67. doi:10.3400/avd.cr.13-00102.

15. Rehman AU, Almanfi A, Nadella S, Sohail U. Isolated spontaneous celiac artery dissection in a 47-year-old man with von Willebrand disease. Tex Heart Inst J. 2014;41(3):344-345. doi:10.14503/THIJ-13-3404.

16. American College of Emergency Physicians. Policy statement. Ultrasound Guidelines: Emergency, Point-of-Care, and Clinical Ultrasound Guidelines in Medicine, June 2016. https://www.acep.org/Clinical---Practice-Management/Ultrasound/. Accessed November 15, 2016.

17. Williams J, Heiner JD, Perreault MD, McArthur TJ. Aortic dissection diagnosed by ultrasound. West J Emerg Med. 2010;11(1):98-99.

18. Fojtik JP, Costantino TG, Dean AJ. The diagnosis of aortic dissection by emergency medicine ultrasound. J Emerg Med. 2007;32(2):191-196.

19. Woolard JD, Ammar AD. Spontaneous dissection of the celiac artery: a case report. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(6):1256-1258.

20. Fenoglio L, Allione A, Scalabrino E, et al. Spontaneous dissection of the celiac artery: a pitfall in the diagnosis of acute abdominal pain. Presentation of two cases. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49(7-8):1223-1227.

1. Bauersfeld SR. Dissecting aneurysm of the aorta; a presentation of 15 cases and a review of the recent literature. Ann Intern Med. 1947;26(6):873-889.

2. Watson AJ. Dissecting aneurysm of arteries other than the aorta. J Pathol. 1956;72(2):439-449. doi:10.1002/path.1700720209.

3. Foord AG, Lewis RD. Primary dissecting aneurysms of peripheral and pulmonary arteries: dissecting hemorrhage of media. Arch Pathol. 1959;68:553-577.

4. Neychev V, Krol E, Dietzek A. Unusual presentation and treatment of spontaneous celiac artery dissection. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58(2):491-495. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2012.10.136.

5. DiMusto PD, Oberdoerster MM, Criado E. Isolated celiac artery dissection. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61(4):972-976. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.10.108.

6. Takayama T, Miyata T, Shirakawa M, Nagawa H. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48(2):329-333. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2008.03.002.

7. Glehen O, Feugier P, Aleksic Y, Delannoy P, Chevalier JM. Spontaneous dissection of the celiac artery. Ann Vasc Surg. 2001;15(6):687-692.

8. Patel KS, Benshar O, Vrabie R, Patel A, Adler M, Hines G. A major pain in the … back and epigastrium: an unusual case of spontaneous celiac artery dissection. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2014;4(5):23840. doi:10.3402/jchimp.v4.23840.

9. Kang TL, Teich DL, McGillicuddy DC. Isolated, spontaneous superior mesenteric and celiac artery dissection: case report and review of literature. J Emerg Med. 2011;40(2):e21-e25. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.12.038.

10. Galastri FL, Cavalcante RN, Motta-Leal-Filho JM, et al. Evaluation and management of symptomatic isolated spontaneous celiac trunk dissection. Vasc Med. 2015;20(4):358-363. doi:10.1177/1358863X15581447.

11. Wang HC, Chen JH, Hsiao CC, Jeng CM, Chen WL. Spontaneous dissection of the celiac artery: a case report and literature review. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(6):1000.e3-e5. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2013.02.007.

12. Oh S, Cho YP, Kim JH, Shin S, Kwon TW, Ko GY. Symptomatic spontaneous celiac artery dissection treated by conservative management: serial imaging findings. Abdom Imaging. 2011;36(1):79-82. doi:10.1007/s00261-010-9657-x.

13. Wang JL, Hsieh MJ, Lee CH, Chen CC, Hsieh IC. Celiac artery dissection presenting with abdominal and chest pain. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28(1):111.e3-e5. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2009.02.023.

14. Takayama Y, Takao M, Inoue T, Yoshimi F, Koyama K, Nagai H. Isolated spontaneous dissection of the celiac artery: report of two cases. Ann Vasc Dis. 2014;7(1):64-67. doi:10.3400/avd.cr.13-00102.

15. Rehman AU, Almanfi A, Nadella S, Sohail U. Isolated spontaneous celiac artery dissection in a 47-year-old man with von Willebrand disease. Tex Heart Inst J. 2014;41(3):344-345. doi:10.14503/THIJ-13-3404.

16. American College of Emergency Physicians. Policy statement. Ultrasound Guidelines: Emergency, Point-of-Care, and Clinical Ultrasound Guidelines in Medicine, June 2016. https://www.acep.org/Clinical---Practice-Management/Ultrasound/. Accessed November 15, 2016.

17. Williams J, Heiner JD, Perreault MD, McArthur TJ. Aortic dissection diagnosed by ultrasound. West J Emerg Med. 2010;11(1):98-99.

18. Fojtik JP, Costantino TG, Dean AJ. The diagnosis of aortic dissection by emergency medicine ultrasound. J Emerg Med. 2007;32(2):191-196.

19. Woolard JD, Ammar AD. Spontaneous dissection of the celiac artery: a case report. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(6):1256-1258.

20. Fenoglio L, Allione A, Scalabrino E, et al. Spontaneous dissection of the celiac artery: a pitfall in the diagnosis of acute abdominal pain. Presentation of two cases. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49(7-8):1223-1227.

Relapsing Polychondritis With Meningoencephalitis

Relapsing polychondritis (RP) is an autoimmune disease affecting cartilaginous structures such as the ears, respiratory passages, joints, and cardiovascular system.1,2 In rare cases, the systemic effects of this autoimmune process can cause central nervous system (CNS) involvement such as meningoencephalitis (ME).3 In 2011, Wang et al4 described 4 cases of RP with ME and reviewed 24 cases from the literature. We present a case of a man with RP-associated ME that was responsive to steroid treatment. We also provide an updated review of the literature.

Case Report

A 44-year-old man developed gradually worsening bilateral ear pain, headaches, and seizures. He was briefly hospitalized and discharged with levetiracetam and quetiapine. However, his mental status continued to deteriorate and he was subsequently hospitalized 3 months later with confusion, hallucinations, and seizures.

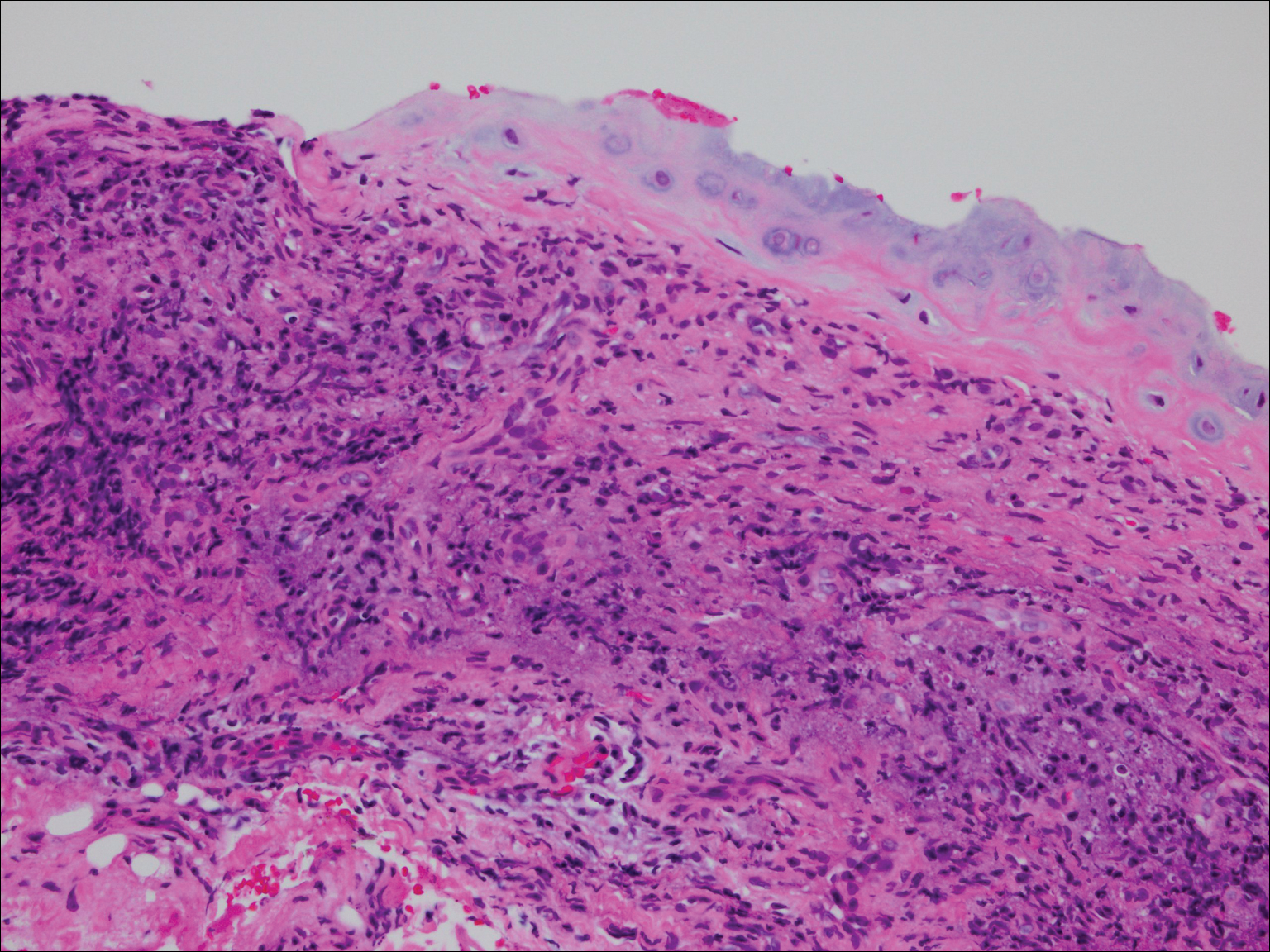

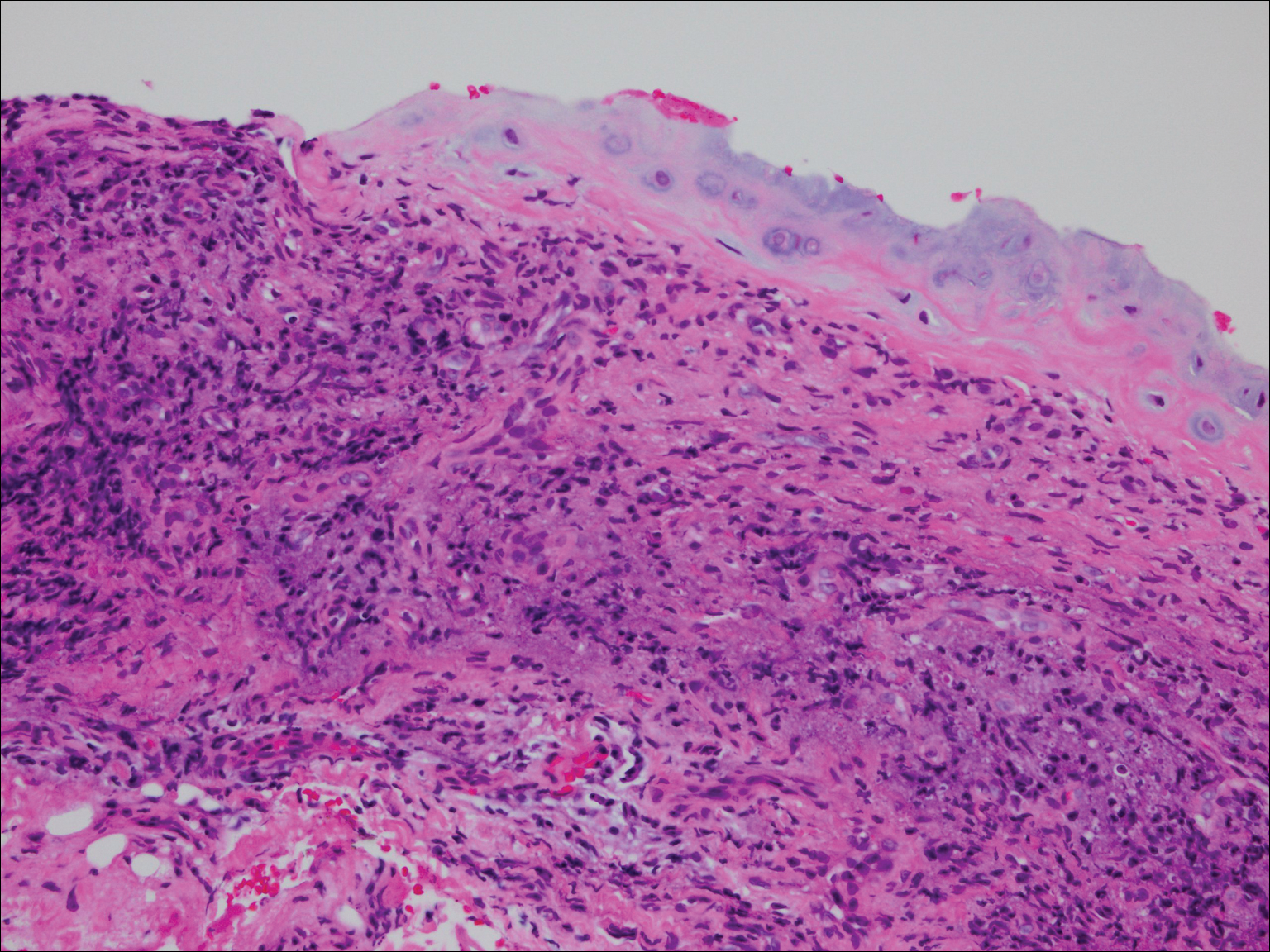

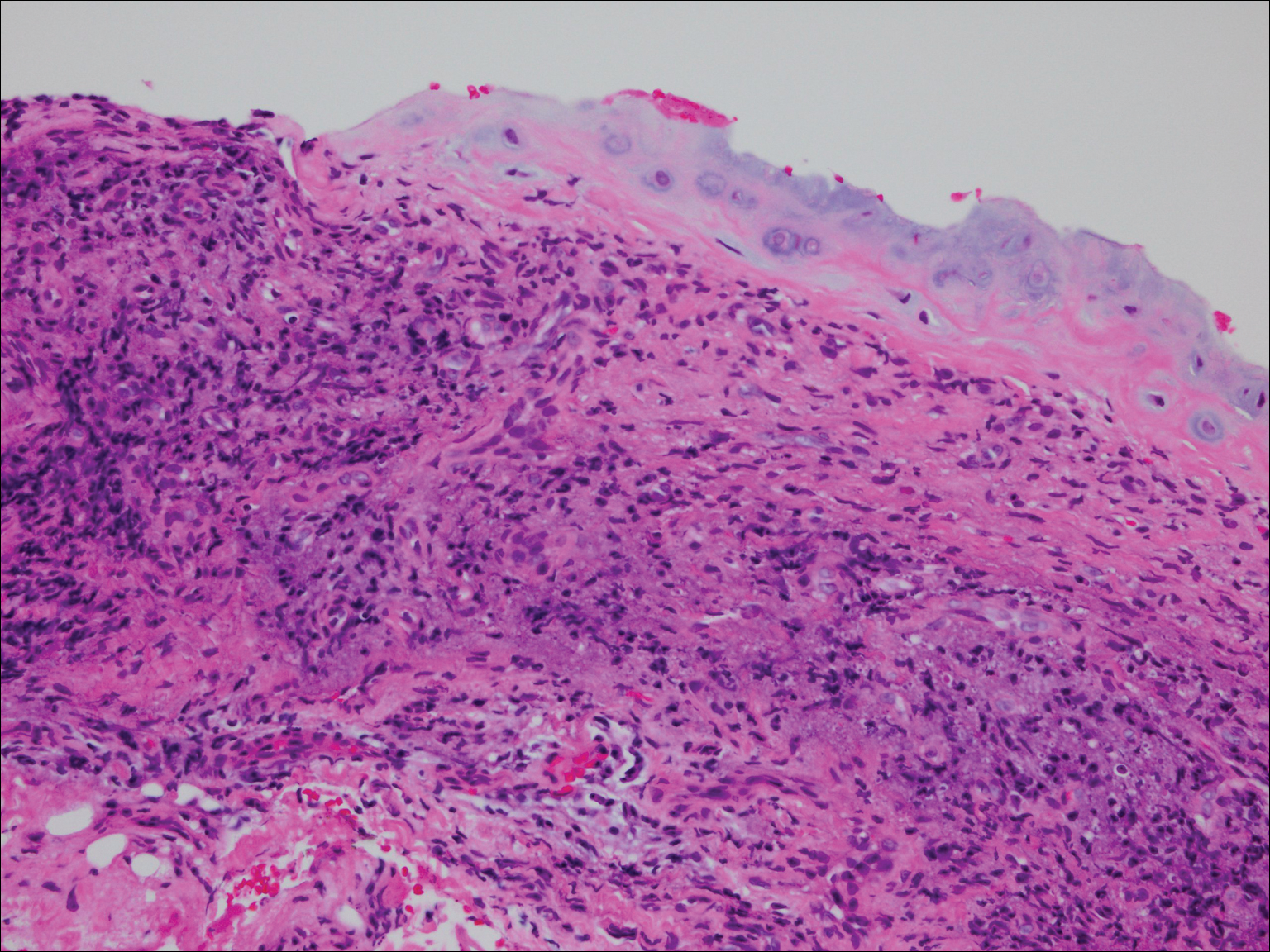

On physical examination the patient was disoriented and unable to form cohesive sentences. He had bilateral tenderness, erythema, and edema of the auricles, which notably spared the lobules (Figure 1). The conjunctivae were injected bilaterally, and joint involvement included bilateral knee tenderness and swelling. Neurologic examination revealed questionable meningeal signs but no motor or sensory deficits. An extensive laboratory workup for the etiology of his altered mental status was unremarkable, except for a mildly elevated white blood cell count in the cerebrospinal fluid with predominantly lymphocytes. No infectious etiologies were identified on laboratory testing, and rheumatologic markers were negative including antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, and anti–Sjögren syndrome antigen A/Sjögren syndrome antigen B. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed nonspecific findings of bilateral T2 hyperdensities in the subcortical white matter; however, cerebral angiography revealed no evidence of vasculitis. A biopsy of the right antihelix revealed prominent perichondritis and a neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate with several lymphocytes and histiocytes (Figure 2). There was degeneration of the cartilaginous tissue with evidence of pyknotic nuclei, eosinophilia, and vacuolization of the chondrocytes. He was diagnosed with RP on the basis of clinical and histologic inflammation of the auricular cartilage, polyarthritis, and ocular inflammation.

The patient was treated with high-dose immunosuppression with methylprednisolone (1000 mg intravenous once daily for 5 days) and cyclophosphamide (one dose at 500 mg/m2), which resulted in remarkable improvement in his mental status, auricular inflammation, and knee pain. After 31 days of hospitalization the patient was discharged with a course of oral prednisone (starting at 60 mg/d, then tapered over the following 2 months) and monthly cyclophosphamide infusions (5 months total; starting at 500 mg/m2, then uptitrated to goal of 1000 mg/m2). Maintenance suppression was achieved with azathioprine (starting at 50 mg daily, then uptitrated to 100 mg daily), which was continued without any evidence of relapsed disease through his last outpatient visit 1 year after the diagnosis.

Comment

Auricular inflammation is a hallmark of RP and is present in 83% to 95% of patients.1,3 The affected ears can appear erythematous to violaceous with tender edema of the auricle that spares the lobules where no cartilage is present. The inflammation can extend into the ear canal and cause hearing loss, tinnitus, and vertigo. Histologically, RP can present with a nonspecific leukocytoclastic vasculitis and inflammatory destruction of the cartilage. Therefore, diagnosis of RP is reliant mainly on clinical characteristics rather than pathologic findings. In 1976, McAdam et al5 established diagnostic criteria for RP based on the presence of common clinical manifestations (eg, auricular chondritis, seronegative inflammatory polyarthritis, nasal chondritis, ocular inflammation). Michet et al6 later proposed major and minor criteria to classify and diagnose RP based on clinical manifestations. Diagnosis of our patient was confirmed by the presence of auricular chondritis, polyarthritis, and ocular inflammation. Diagnosing RP can be difficult because it has many systemic manifestations that can evoke a broad differential diagnosis. The time to diagnosis in our patient was 3 months, but the mean delay in diagnosis for patients with RP and ME is 2.9 years.4

The etiology of RP remains unclear, but current evidence supports an immune-mediated process directed toward proteins found in cartilage. Animal studies have suggested that RP may be driven by antibodies to matrillin 1 and type II collagen. There also may be a familial association with HLA-DR4 and genetic predisposition to autoimmune diseases in individuals affected by RP.1,3 The pathogenesis of CNS involvement in RP is thought to be due to a localized small vessel vasculitis.7,8 In our patient, however, cerebral angiography was negative for vasculitis, and thus our case may represent another mechanism for CNS involvement. There have been cases of encephalitis in RP caused by pathways other than CNS vasculitis. Kashihara et al9 reported a case of RP with encephalitis associated with antiglutamate receptor antibodies found in the cerebrospinal fluid and blood.

Treatment of RP has been based on pathophysiological considerations rather than empiric data due to its rarity. Relapsing polychondritis has been responsive to steroid treatment in reported cases as well as in our patient; however, in cases in which RP did not respond to steroids, infliximab may be effective for RP with ME.10 Further research regarding the treatment outcomes of RP with ME may be warranted.

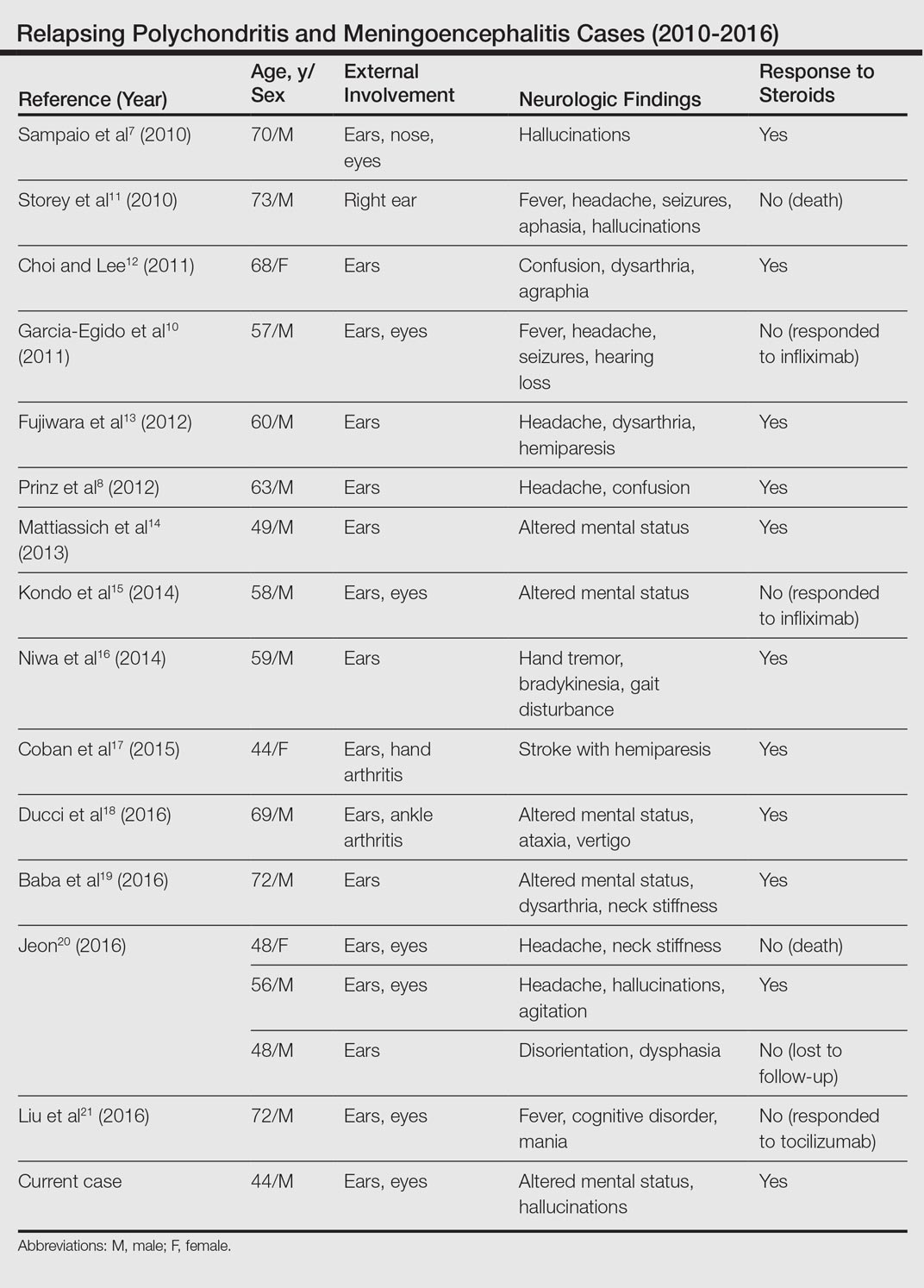

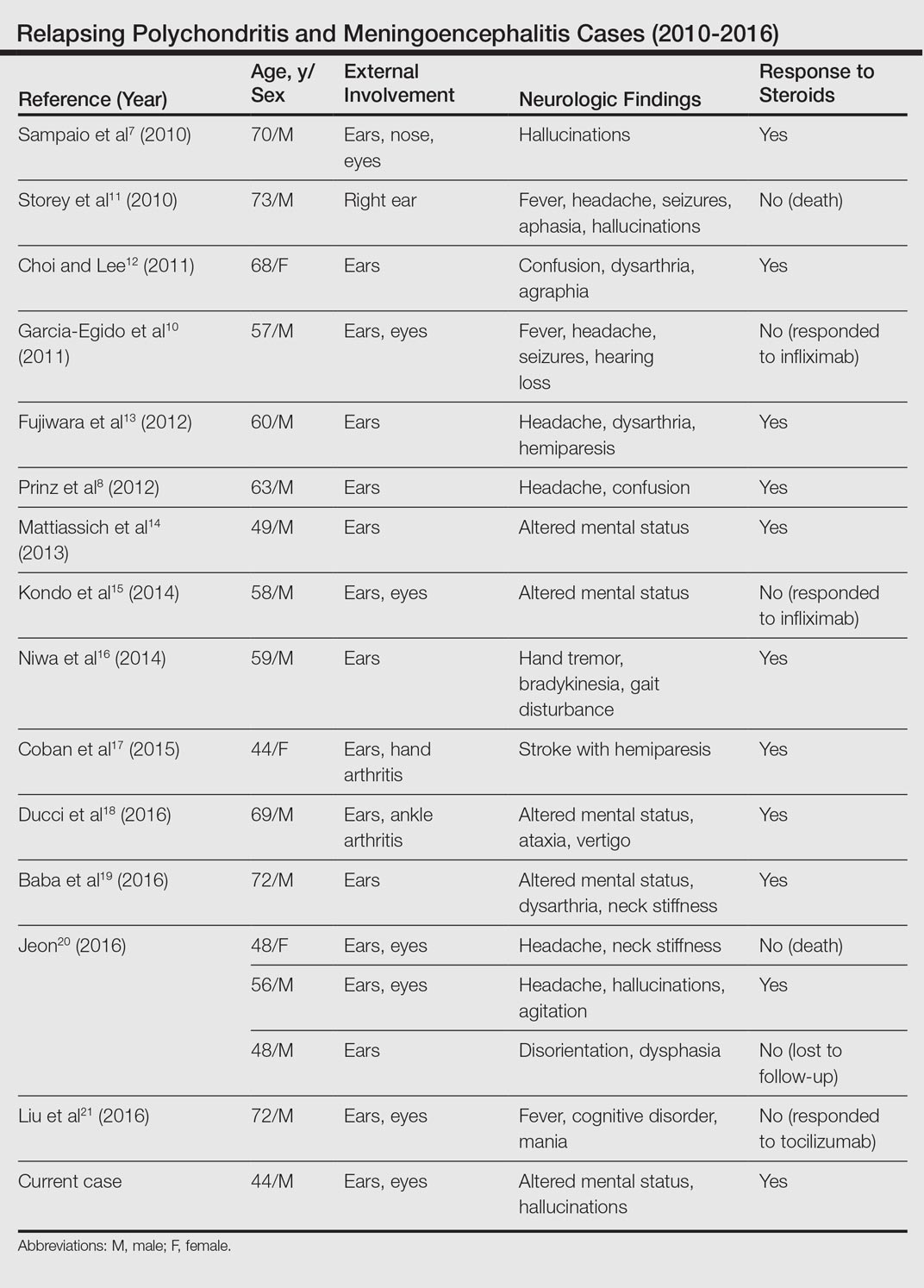

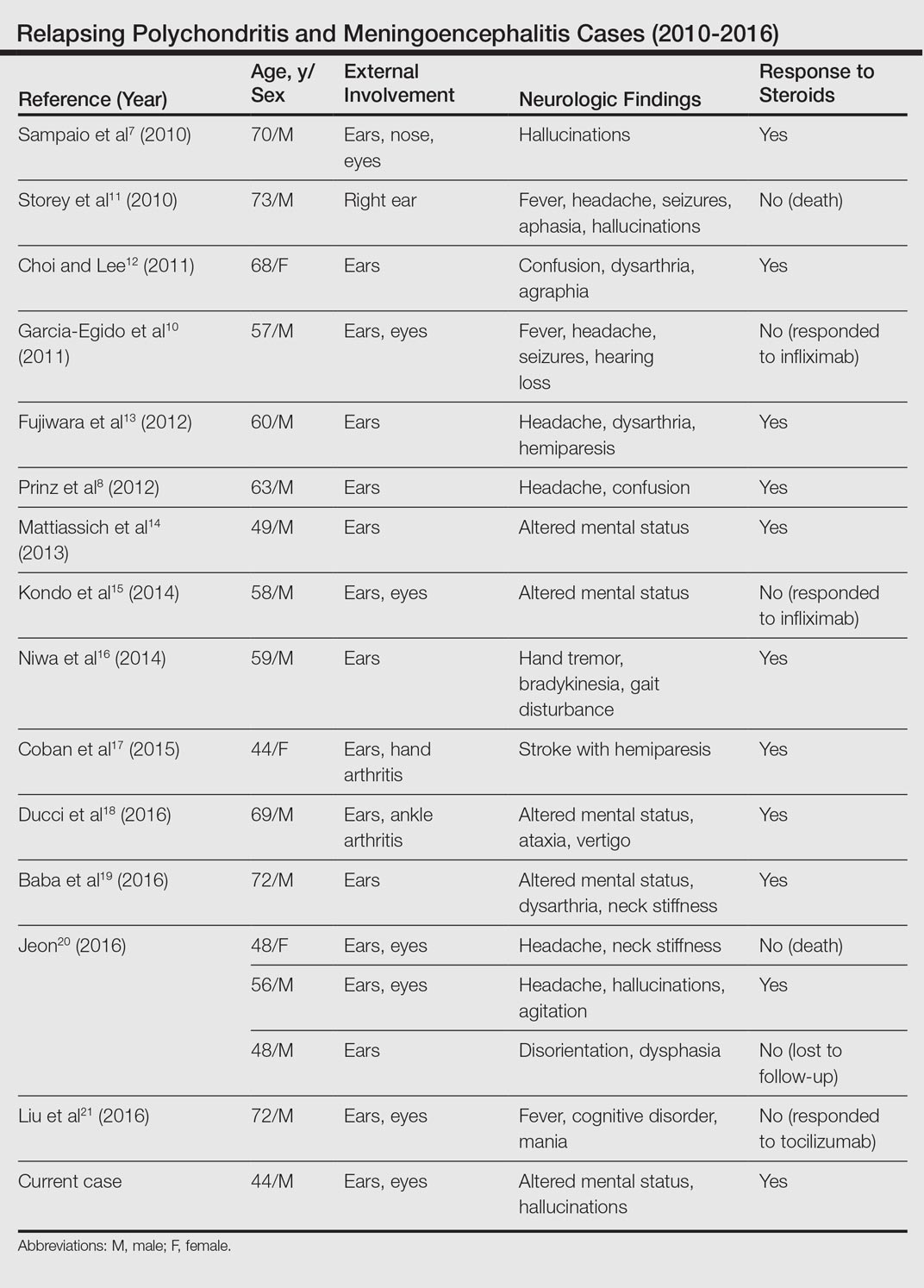

Although rare, additional cases of RP with ME have been reported (Table). Wang et al4 described a series of 28 patients with RP and ME from 1960 to 2010. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE that were published in the English-language literature from 2010 to 2016 was performed using the search terms relapsing polychondritis and nervous system. Including our patient, RP with ME was reported in 17 additional cases since Wang et al4 published their findings. These cases involved adults ranging in age from 44 to 73 years who were mainly men (14/17 [82%]). All of the patients presented with bilateral auricular chondritis, except for a case of unilateral ear involvement reported by Storey et al.11 Common neurologic manifestations included fever, headache, and altered mental status. Motor symptoms ranged from dysarthria and agraphia12 to hemiparesis.13 The mechanism of CNS involvement in RP was not identified in most cases; however, Mattiassich et al14 documented cerebral vasculitis in their patient, and Niwa et al16 found diffuse cerebral vasculitis on autopsy. Eleven of 17 (65%) cases responded to steroid treatment. Of the 6 cases in which RP did not respond to steroids, 2 patients died despite high-dose steroid treatment,11,20 2 responded to infliximab,10,15 1 responded to tocilizumab,21 and 1 was lost to follow-up after initial treatment failure.20

Conclusion

Although rare, RP should not be overlooked in the inpatient setting due to its potential for life-threatening systemic effects. Early diagnosis of this condition may be of benefit to this select population of patients, and further research regarding the prognosis, mechanisms, and treatment of RP may be necessary in the future.

- Arnaud L, Mathian A, Haroche J, et al. Pathogenesis of relapsing polychondritis: a 2013 update. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:90-95.

- Ostrowski RA, Takagishi T, Robinson J. Rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthropathies, and relapsing polychondritis. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;119:449-461.

- Lahmer T, Treiber M, von Werder A, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: an autoimmune disease with many faces. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:540-546.

- Wang ZJ, Pu CQ, Wang ZJ, et al. Meningoencephalitis or meningitis in relapsing polychondritis: four case reports and a literature review. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18:1608-1615.

- McAdam LP, O’Hanlan MA, Bluestone R, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: prospective study of 23 patients and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1976;55:193-215.

- Michet C, McKenna C, Luthra H, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: survival and predictive role of early disease manifestations. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:74-78.

- Sampaio L, Silva L, Mariz E, et al. CNS involvement in relapsing polychondritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2010;77:619-620.

- Prinz S, Dafotakis M, Schneider RK, et al. The red puffy ear sign—a clinical sign to diagnose a rare cause of meningoencephalitis. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2012;80:463-467.

- Kashihara K, Kawada S, Takahashi Y. Autoantibodies to glutamate receptor GluR2 in a patient with limic encephalitis associated with relapsing polychondritis. J Neurol Sci. 2009;287:275-277.

- Garcia-Egido A, Gutierrez C, de la Fuente C, et al. Relapsing polychondritis-associated meningitis and encephalitis: response to infliximab. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50:1721-1723.

- Storey K, Matej R, Rusina R. Unusual association of seronegative, nonparaneoplastic limbic encephalitis and relapsing polychondritis in a patient with history of thymectomy for myasthemia: a case study. J Neurol. 2010;258:159-161.

- Choi HJ, Lee HJ. Relapsing polychondritis with encephalitis. J Clin Rheum. 2011;6:329-331.

- Fujiwara S, Zenke K, Iwata S, et al. Relapsing polychondritis presenting as encephalitis. No Shinkei Geka. 2012;40:247-253.

- Mattiassich G, Egger M, Semlitsch G, et al. Occurrence of relapsing polychondritis with a rising cANCA titre in a cANCA-positive systemic and cerebral vasculitis patient [published online February 5, 2013]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-008717.

- Kondo T, Fukuta M, Takemoto A, et al. Limbic encephalitis associated with relapsing polychondritis responded to infliximab and maintained its condition without recurrence after discontinuation: a case report and review of the literature. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2014;76:361-368.

- Niwa A, Okamoto Y, Kondo T, et al. Perivasculitic pancencephalitis with relapsing polychondritis: an autopsy case report and review of previous cases. Intern Med. 2014;53:1191-1195.

- Coban EK, Xanmemmedoy E, Colak M, et al. A rare complication of a rare disease; stroke due to relapsing polychondritis. Ideggyogy Sz. 2015;68:429-432.

- Ducci R, Germiniani F, Czecko L, et al. Relapsing polychondritis and lymphocytic meningitis with varied neurological symptoms [published online February 5, 2016]. Rev Bras Reumatol. doi:10.1016/j.rbr.2015.09.005.

- Baba T, Kanno S, Shijo T, et al. Callosal disconnection syndrome associated with relapsing polychondritis. Intern Med. 2016;55:1191-1193.

- Jeon C. Relapsing polychondritis with central nervous system involvement: experience of three different cases in a single center. J Korean Med. 2016;31:1846-1850.

- Liu L, Liu S, Guan W, et al. Efficacy of tocilizumab for psychiatric symptoms associated with relapsing polychondritis: the first case report and review of the literature. Rheumatol Int. 2016;36:1185-1189.

Relapsing polychondritis (RP) is an autoimmune disease affecting cartilaginous structures such as the ears, respiratory passages, joints, and cardiovascular system.1,2 In rare cases, the systemic effects of this autoimmune process can cause central nervous system (CNS) involvement such as meningoencephalitis (ME).3 In 2011, Wang et al4 described 4 cases of RP with ME and reviewed 24 cases from the literature. We present a case of a man with RP-associated ME that was responsive to steroid treatment. We also provide an updated review of the literature.

Case Report

A 44-year-old man developed gradually worsening bilateral ear pain, headaches, and seizures. He was briefly hospitalized and discharged with levetiracetam and quetiapine. However, his mental status continued to deteriorate and he was subsequently hospitalized 3 months later with confusion, hallucinations, and seizures.

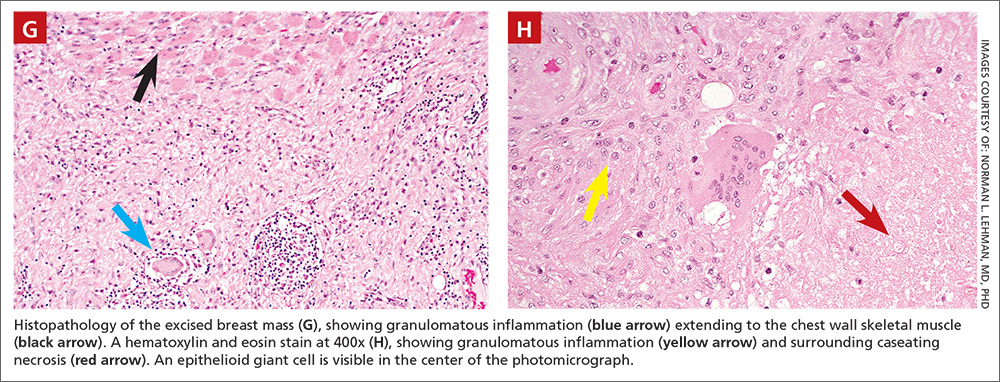

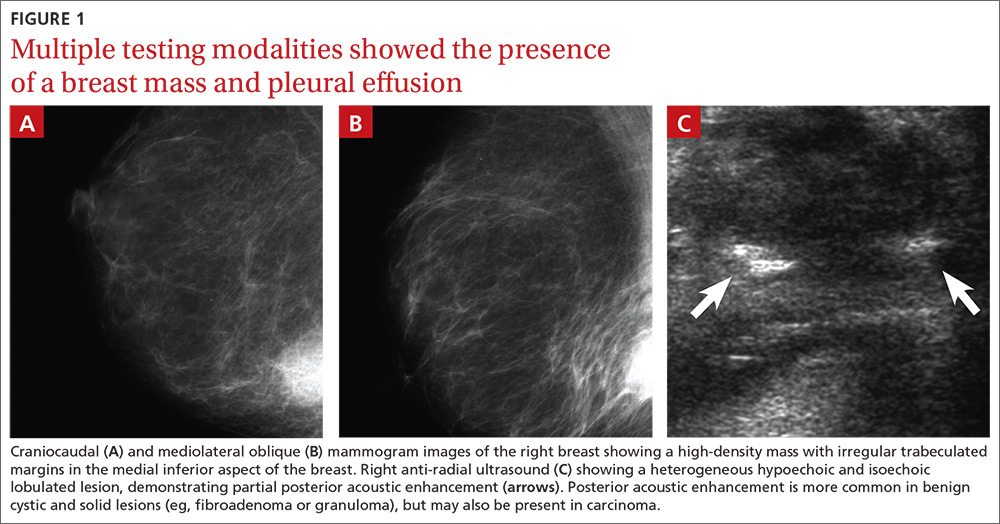

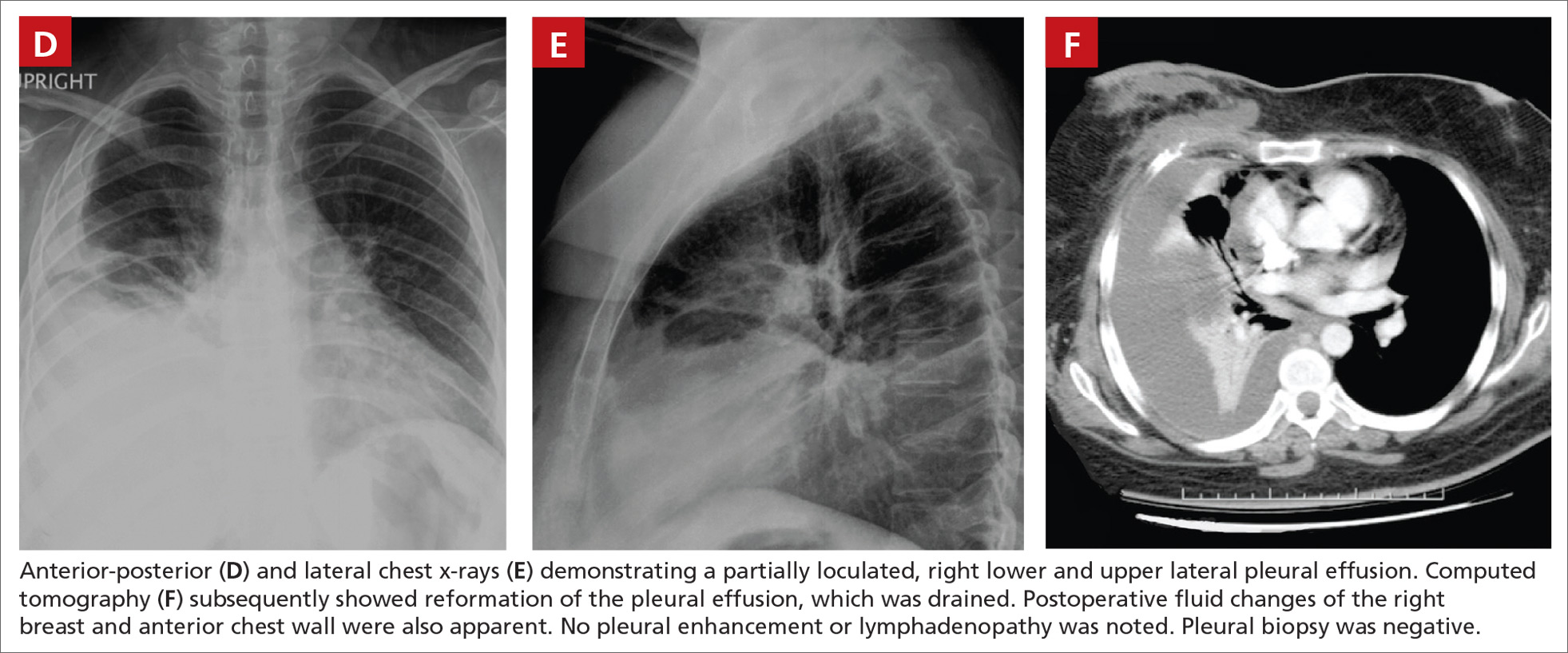

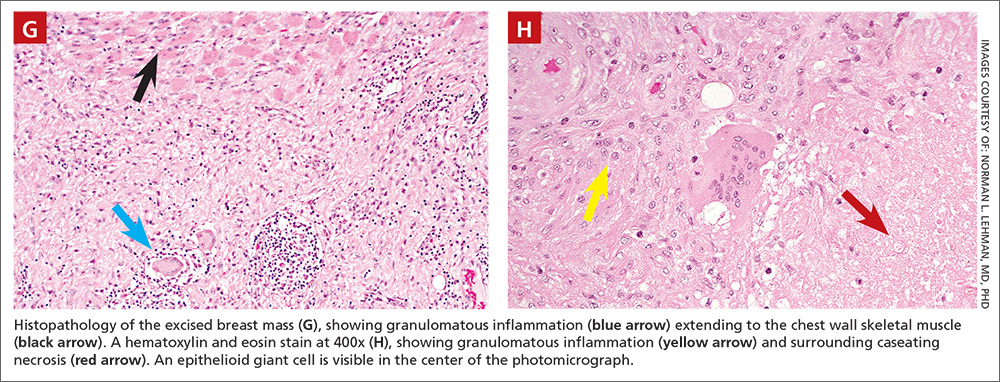

On physical examination the patient was disoriented and unable to form cohesive sentences. He had bilateral tenderness, erythema, and edema of the auricles, which notably spared the lobules (Figure 1). The conjunctivae were injected bilaterally, and joint involvement included bilateral knee tenderness and swelling. Neurologic examination revealed questionable meningeal signs but no motor or sensory deficits. An extensive laboratory workup for the etiology of his altered mental status was unremarkable, except for a mildly elevated white blood cell count in the cerebrospinal fluid with predominantly lymphocytes. No infectious etiologies were identified on laboratory testing, and rheumatologic markers were negative including antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, and anti–Sjögren syndrome antigen A/Sjögren syndrome antigen B. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed nonspecific findings of bilateral T2 hyperdensities in the subcortical white matter; however, cerebral angiography revealed no evidence of vasculitis. A biopsy of the right antihelix revealed prominent perichondritis and a neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate with several lymphocytes and histiocytes (Figure 2). There was degeneration of the cartilaginous tissue with evidence of pyknotic nuclei, eosinophilia, and vacuolization of the chondrocytes. He was diagnosed with RP on the basis of clinical and histologic inflammation of the auricular cartilage, polyarthritis, and ocular inflammation.

The patient was treated with high-dose immunosuppression with methylprednisolone (1000 mg intravenous once daily for 5 days) and cyclophosphamide (one dose at 500 mg/m2), which resulted in remarkable improvement in his mental status, auricular inflammation, and knee pain. After 31 days of hospitalization the patient was discharged with a course of oral prednisone (starting at 60 mg/d, then tapered over the following 2 months) and monthly cyclophosphamide infusions (5 months total; starting at 500 mg/m2, then uptitrated to goal of 1000 mg/m2). Maintenance suppression was achieved with azathioprine (starting at 50 mg daily, then uptitrated to 100 mg daily), which was continued without any evidence of relapsed disease through his last outpatient visit 1 year after the diagnosis.

Comment

Auricular inflammation is a hallmark of RP and is present in 83% to 95% of patients.1,3 The affected ears can appear erythematous to violaceous with tender edema of the auricle that spares the lobules where no cartilage is present. The inflammation can extend into the ear canal and cause hearing loss, tinnitus, and vertigo. Histologically, RP can present with a nonspecific leukocytoclastic vasculitis and inflammatory destruction of the cartilage. Therefore, diagnosis of RP is reliant mainly on clinical characteristics rather than pathologic findings. In 1976, McAdam et al5 established diagnostic criteria for RP based on the presence of common clinical manifestations (eg, auricular chondritis, seronegative inflammatory polyarthritis, nasal chondritis, ocular inflammation). Michet et al6 later proposed major and minor criteria to classify and diagnose RP based on clinical manifestations. Diagnosis of our patient was confirmed by the presence of auricular chondritis, polyarthritis, and ocular inflammation. Diagnosing RP can be difficult because it has many systemic manifestations that can evoke a broad differential diagnosis. The time to diagnosis in our patient was 3 months, but the mean delay in diagnosis for patients with RP and ME is 2.9 years.4

The etiology of RP remains unclear, but current evidence supports an immune-mediated process directed toward proteins found in cartilage. Animal studies have suggested that RP may be driven by antibodies to matrillin 1 and type II collagen. There also may be a familial association with HLA-DR4 and genetic predisposition to autoimmune diseases in individuals affected by RP.1,3 The pathogenesis of CNS involvement in RP is thought to be due to a localized small vessel vasculitis.7,8 In our patient, however, cerebral angiography was negative for vasculitis, and thus our case may represent another mechanism for CNS involvement. There have been cases of encephalitis in RP caused by pathways other than CNS vasculitis. Kashihara et al9 reported a case of RP with encephalitis associated with antiglutamate receptor antibodies found in the cerebrospinal fluid and blood.

Treatment of RP has been based on pathophysiological considerations rather than empiric data due to its rarity. Relapsing polychondritis has been responsive to steroid treatment in reported cases as well as in our patient; however, in cases in which RP did not respond to steroids, infliximab may be effective for RP with ME.10 Further research regarding the treatment outcomes of RP with ME may be warranted.

Although rare, additional cases of RP with ME have been reported (Table). Wang et al4 described a series of 28 patients with RP and ME from 1960 to 2010. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE that were published in the English-language literature from 2010 to 2016 was performed using the search terms relapsing polychondritis and nervous system. Including our patient, RP with ME was reported in 17 additional cases since Wang et al4 published their findings. These cases involved adults ranging in age from 44 to 73 years who were mainly men (14/17 [82%]). All of the patients presented with bilateral auricular chondritis, except for a case of unilateral ear involvement reported by Storey et al.11 Common neurologic manifestations included fever, headache, and altered mental status. Motor symptoms ranged from dysarthria and agraphia12 to hemiparesis.13 The mechanism of CNS involvement in RP was not identified in most cases; however, Mattiassich et al14 documented cerebral vasculitis in their patient, and Niwa et al16 found diffuse cerebral vasculitis on autopsy. Eleven of 17 (65%) cases responded to steroid treatment. Of the 6 cases in which RP did not respond to steroids, 2 patients died despite high-dose steroid treatment,11,20 2 responded to infliximab,10,15 1 responded to tocilizumab,21 and 1 was lost to follow-up after initial treatment failure.20

Conclusion

Although rare, RP should not be overlooked in the inpatient setting due to its potential for life-threatening systemic effects. Early diagnosis of this condition may be of benefit to this select population of patients, and further research regarding the prognosis, mechanisms, and treatment of RP may be necessary in the future.

Relapsing polychondritis (RP) is an autoimmune disease affecting cartilaginous structures such as the ears, respiratory passages, joints, and cardiovascular system.1,2 In rare cases, the systemic effects of this autoimmune process can cause central nervous system (CNS) involvement such as meningoencephalitis (ME).3 In 2011, Wang et al4 described 4 cases of RP with ME and reviewed 24 cases from the literature. We present a case of a man with RP-associated ME that was responsive to steroid treatment. We also provide an updated review of the literature.

Case Report

A 44-year-old man developed gradually worsening bilateral ear pain, headaches, and seizures. He was briefly hospitalized and discharged with levetiracetam and quetiapine. However, his mental status continued to deteriorate and he was subsequently hospitalized 3 months later with confusion, hallucinations, and seizures.