User login

Low-Dose Radiotherapy for Primary Cutaneous Anaplastic Large-Cell Lymphoma While on Low-Dose Methotrexate

CD30+ primary cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders (pcLPDs) are the second most common cause of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, accounting for approximately 25% to 30% of cases.1 These disorders comprise a spectrum that includes primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (pcALCL); lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP); and borderline lesions, which share clinicopathologic features of both pcALCL and LyP. Lymphomatoid papulosis is characterized as chronic, recurrent, papular or papulonodular skin lesions that typically are multifocal and regress spontaneously within weeks to months, only leaving small scars with atrophy and/or hyperpigmentation.2 Cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma typically presents as solitary or grouped nodules or tumors that may undergo spontaneous partial or complete regression in approximately 25% of cases3 but often persist if not treated. Patients may have an array of lesions comprising the spectrum of CD30 pcLPDs.4

There is no curative therapy for CD30+ pcLPDs. Although active treatment is not necessary for LyP, low-dose methotrexate (MTX)(10–50 mg weekly) or phototherapy are the preferred initial suppressive therapies for symptomatic patients with scarring, facial lesions, or multiple symptomatic lesions.5 Observation with expectant follow-up is an option in pcALCL, though spontaneous regression is less likely than in LyP. For single or grouped pcALCL lesions, local radiation is the first-line therapy.6 Multifocal pcALCL lesions also can be treated with low-dose MTX,2,5 as in LyP, or local radiation to selected areas. Although local radiotherapy is considered a first-line treatment in pcALCL, there is limited evidence on its clinical efficacy as well as the optimal dose and technique. We report the complete response of refractory pcALCL lesions to low-dose radiation while remaining on MTX weekly without any adverse effects.

Case Report

A 51-year-old woman presented with a 3-year history of CD30+ pcLPD manifesting primarily as pcALCL involving the head and neck, as well as LyP involving the head, arms, and trunk (T3N0M0). For 2 years her treatment regimen included clobetasol propionate cream 0.05% as needed for new lesions and 2 courses of standard-dose localized external beam radiation for larger pcALCL tumors on the right cheek and right side of the chin (Figure 1)(total dose for each course of treatment was 20 Gy and 36 Gy, respectively, each administered over 2–3 weeks). Because new unsightly papulonodules continued to develop on the patient’s face, she subsequently required low-dose oral MTX 30 mg once weekly for suppression of new lesions and was stable on this regimen for a year. However, she experienced an increase in LyP/pcALCL activity on the face during a 2-week break from MTX when she developed a herpes zoster infection on the right side of the forehead.

On physical examination 1 month later, 5 tiny pink papules scattered on the left eyebrow, left cheek, and left side of the chin were noted. She was advised to continue applying the clobetasol cream as needed and was restarted on MTX 10 mg once weekly. However, she developed 2 additional 1-cm nodules on the left side of the chin, neck, and shoulder. Methotrexate was increased to 30 mg once weekly over 2 weeks, which was the original dose prior to interruption, but the nodules grew to 1.5-cm in diameter. Due to their clinical appearance, the nodules were believed to be early pcALCL lesions (Figure 2A). Given the cosmetically sensitive location of the nodules, palliative radiotherapy was recommended rather than observe for possible regression. Based on a prior report by Neelis et al7 demonstrating efficacy of low-dose radiotherapy for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and cutaneous B-cell lymphoma, we recommended starting with low radiation doses. Our patient was treated with 400 cGy twice to the left side of the chin and left side of the neck (800 cGy total at each site) while remaining on MTX 30 mg once weekly. This treatment was well tolerated without side effects and no evidence of radiation dermatitis. On follow-up examination 1 week later, the nodules had regressed and no new lesions were present (Figure 2B).

The patient has stayed on oral MTX and occasionally develops small lesions that quickly resolve with clobetasol cream. She has been followed for 3 years after radiotherapy and all 3 previously irradiated sites have remained recurrence free. Furthermore, she has not developed any new larger nodules or tumors and her MTX dose has been decreased to 15 mg once weekly.

Comment

Local radiotherapy is considered a first-line treatment of pcALCL; however, there is limited evidence on its clinical efficacy as well as the optimal dose and technique. Although no standard dose exists for pcALCL, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines8 recommend doses of 12 to 36 Gy in mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome subtypes of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, which are consistent with guidelines published by the European Society for Medical Oncology.9 High complete response rates have been demonstrated in pcALCL at doses of 34 to 44 Gy6; however, lesions tend to recur elsewhere on the skin in 36% to 41% of patients despite treatment.2,10 Lower doses of radiation therapy would provide several advantages over higher-dose therapy if a complete response could be achieved without greatly increasing the local recurrence rate. In cases of local recurrence, low-dose radiation would more easily permit retreatment of lesions compared to higher doses of radiation. Similarly, in patients with multifocal pcALCL, lower doses of radiotherapy may allow for treatment of larger skin areas while limiting potential treatment risks. Furthermore, low-dose therapy would allow for treatments to be delivered more quickly and with less inconvenience to the patient who is likely to need multiple future treatments to other areas. Low-dose radiation has been described with a favorable efficacy profile for mycosis fungoides7,11 but has not been studied in patients with CD30+ pcLPDs.

Our case is notable because the patient remained on MTX during radiation therapy. B

Conclusion

We reported the use of low-dose radiation therapy for the treatment of localized pcALCL in a patient who remained on low-dose oral MTX. Additional studies will be necessary to more fully evaluate the efficacy of using low-dose radiation both as monotherapy and in combination with MTX for pcALCL.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Bekkenk MW, Geelen FA, van Voorst Vader PC, et al. Primary and secondary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders: a report from the Dutch Cutaneous Lymphoma Group on the long-term follow-up data of 219 patients and guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Blood. 2000;95:3653-3661.

- Willemze R, Beljaards RC. Spectrum of primary cutaneous CD30 (Ki-1)-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: a proposal for classification and guidelines for management and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:973-980.

- Kadin ME. The spectrum of Ki-1+ cutaneous lymphomas. Curr Probl Dermatol. 1990;19:132-143.

- Vonderheid EC, Sajjadian A, Kadin ME. Methotrexate is effective therapy for lymphomatoid papulosis and other primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:470-481.

- Yu JB, McNiff JM, Lund MW, et al. Treatment of primary cutaneous CD30+ anaplastic large-cell lymphoma with radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:1542-1545.

- Neelis KJ, Schimmel EC, Vermeer MH, et al. Low-dose palliative radiotherapy B-cell and T-cell lymphomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:154-158.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. CD30 lymphoproliferative disorders section in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (Version 3.2016). http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nhl.pdf. Accessed September 26, 2016.

- Willemze R, Hodak E, Zinzani PL, et al; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Primary cutaneous lymphomas: EMSO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up [published online July 17, 2013]. Ann Onc. 2013;24(suppl 6):vi149-vi154.

- Liu HL, Hoppe RT, Kohler S, et al. CD30+ cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders: the Stanford experience in lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1049-1058.

- Harrison C, Young J, Navi D, et al. Revisiting low dose total skin electron beam radiotherapy in mycosis fungoides. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:651-657.

- Jaffe N, Farber S, Traggis D, et al. Favorable response of metastatic osteogenic sarcoma to pulse high-dose methotrexate with citrovorum rescue and radiation therapy. Cancer. 1973;31:1367-1373.

- Rosen G, Tefft M, Martinez A, et al. Combination chemotherapy and radiation therapy in the treatment of metastatic osteogenic sarcoma. Cancer. 1975;35:622-630.

- Kim YH, Aye MS, Fayos JV. Radiation necrosis of the scalp: a complication of cranial irradiation and methotrexate. Radiology. 1977;124:813-814.

CD30+ primary cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders (pcLPDs) are the second most common cause of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, accounting for approximately 25% to 30% of cases.1 These disorders comprise a spectrum that includes primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (pcALCL); lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP); and borderline lesions, which share clinicopathologic features of both pcALCL and LyP. Lymphomatoid papulosis is characterized as chronic, recurrent, papular or papulonodular skin lesions that typically are multifocal and regress spontaneously within weeks to months, only leaving small scars with atrophy and/or hyperpigmentation.2 Cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma typically presents as solitary or grouped nodules or tumors that may undergo spontaneous partial or complete regression in approximately 25% of cases3 but often persist if not treated. Patients may have an array of lesions comprising the spectrum of CD30 pcLPDs.4

There is no curative therapy for CD30+ pcLPDs. Although active treatment is not necessary for LyP, low-dose methotrexate (MTX)(10–50 mg weekly) or phototherapy are the preferred initial suppressive therapies for symptomatic patients with scarring, facial lesions, or multiple symptomatic lesions.5 Observation with expectant follow-up is an option in pcALCL, though spontaneous regression is less likely than in LyP. For single or grouped pcALCL lesions, local radiation is the first-line therapy.6 Multifocal pcALCL lesions also can be treated with low-dose MTX,2,5 as in LyP, or local radiation to selected areas. Although local radiotherapy is considered a first-line treatment in pcALCL, there is limited evidence on its clinical efficacy as well as the optimal dose and technique. We report the complete response of refractory pcALCL lesions to low-dose radiation while remaining on MTX weekly without any adverse effects.

Case Report

A 51-year-old woman presented with a 3-year history of CD30+ pcLPD manifesting primarily as pcALCL involving the head and neck, as well as LyP involving the head, arms, and trunk (T3N0M0). For 2 years her treatment regimen included clobetasol propionate cream 0.05% as needed for new lesions and 2 courses of standard-dose localized external beam radiation for larger pcALCL tumors on the right cheek and right side of the chin (Figure 1)(total dose for each course of treatment was 20 Gy and 36 Gy, respectively, each administered over 2–3 weeks). Because new unsightly papulonodules continued to develop on the patient’s face, she subsequently required low-dose oral MTX 30 mg once weekly for suppression of new lesions and was stable on this regimen for a year. However, she experienced an increase in LyP/pcALCL activity on the face during a 2-week break from MTX when she developed a herpes zoster infection on the right side of the forehead.

On physical examination 1 month later, 5 tiny pink papules scattered on the left eyebrow, left cheek, and left side of the chin were noted. She was advised to continue applying the clobetasol cream as needed and was restarted on MTX 10 mg once weekly. However, she developed 2 additional 1-cm nodules on the left side of the chin, neck, and shoulder. Methotrexate was increased to 30 mg once weekly over 2 weeks, which was the original dose prior to interruption, but the nodules grew to 1.5-cm in diameter. Due to their clinical appearance, the nodules were believed to be early pcALCL lesions (Figure 2A). Given the cosmetically sensitive location of the nodules, palliative radiotherapy was recommended rather than observe for possible regression. Based on a prior report by Neelis et al7 demonstrating efficacy of low-dose radiotherapy for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and cutaneous B-cell lymphoma, we recommended starting with low radiation doses. Our patient was treated with 400 cGy twice to the left side of the chin and left side of the neck (800 cGy total at each site) while remaining on MTX 30 mg once weekly. This treatment was well tolerated without side effects and no evidence of radiation dermatitis. On follow-up examination 1 week later, the nodules had regressed and no new lesions were present (Figure 2B).

The patient has stayed on oral MTX and occasionally develops small lesions that quickly resolve with clobetasol cream. She has been followed for 3 years after radiotherapy and all 3 previously irradiated sites have remained recurrence free. Furthermore, she has not developed any new larger nodules or tumors and her MTX dose has been decreased to 15 mg once weekly.

Comment

Local radiotherapy is considered a first-line treatment of pcALCL; however, there is limited evidence on its clinical efficacy as well as the optimal dose and technique. Although no standard dose exists for pcALCL, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines8 recommend doses of 12 to 36 Gy in mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome subtypes of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, which are consistent with guidelines published by the European Society for Medical Oncology.9 High complete response rates have been demonstrated in pcALCL at doses of 34 to 44 Gy6; however, lesions tend to recur elsewhere on the skin in 36% to 41% of patients despite treatment.2,10 Lower doses of radiation therapy would provide several advantages over higher-dose therapy if a complete response could be achieved without greatly increasing the local recurrence rate. In cases of local recurrence, low-dose radiation would more easily permit retreatment of lesions compared to higher doses of radiation. Similarly, in patients with multifocal pcALCL, lower doses of radiotherapy may allow for treatment of larger skin areas while limiting potential treatment risks. Furthermore, low-dose therapy would allow for treatments to be delivered more quickly and with less inconvenience to the patient who is likely to need multiple future treatments to other areas. Low-dose radiation has been described with a favorable efficacy profile for mycosis fungoides7,11 but has not been studied in patients with CD30+ pcLPDs.

Our case is notable because the patient remained on MTX during radiation therapy. B

Conclusion

We reported the use of low-dose radiation therapy for the treatment of localized pcALCL in a patient who remained on low-dose oral MTX. Additional studies will be necessary to more fully evaluate the efficacy of using low-dose radiation both as monotherapy and in combination with MTX for pcALCL.

CD30+ primary cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders (pcLPDs) are the second most common cause of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, accounting for approximately 25% to 30% of cases.1 These disorders comprise a spectrum that includes primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (pcALCL); lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP); and borderline lesions, which share clinicopathologic features of both pcALCL and LyP. Lymphomatoid papulosis is characterized as chronic, recurrent, papular or papulonodular skin lesions that typically are multifocal and regress spontaneously within weeks to months, only leaving small scars with atrophy and/or hyperpigmentation.2 Cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma typically presents as solitary or grouped nodules or tumors that may undergo spontaneous partial or complete regression in approximately 25% of cases3 but often persist if not treated. Patients may have an array of lesions comprising the spectrum of CD30 pcLPDs.4

There is no curative therapy for CD30+ pcLPDs. Although active treatment is not necessary for LyP, low-dose methotrexate (MTX)(10–50 mg weekly) or phototherapy are the preferred initial suppressive therapies for symptomatic patients with scarring, facial lesions, or multiple symptomatic lesions.5 Observation with expectant follow-up is an option in pcALCL, though spontaneous regression is less likely than in LyP. For single or grouped pcALCL lesions, local radiation is the first-line therapy.6 Multifocal pcALCL lesions also can be treated with low-dose MTX,2,5 as in LyP, or local radiation to selected areas. Although local radiotherapy is considered a first-line treatment in pcALCL, there is limited evidence on its clinical efficacy as well as the optimal dose and technique. We report the complete response of refractory pcALCL lesions to low-dose radiation while remaining on MTX weekly without any adverse effects.

Case Report

A 51-year-old woman presented with a 3-year history of CD30+ pcLPD manifesting primarily as pcALCL involving the head and neck, as well as LyP involving the head, arms, and trunk (T3N0M0). For 2 years her treatment regimen included clobetasol propionate cream 0.05% as needed for new lesions and 2 courses of standard-dose localized external beam radiation for larger pcALCL tumors on the right cheek and right side of the chin (Figure 1)(total dose for each course of treatment was 20 Gy and 36 Gy, respectively, each administered over 2–3 weeks). Because new unsightly papulonodules continued to develop on the patient’s face, she subsequently required low-dose oral MTX 30 mg once weekly for suppression of new lesions and was stable on this regimen for a year. However, she experienced an increase in LyP/pcALCL activity on the face during a 2-week break from MTX when she developed a herpes zoster infection on the right side of the forehead.

On physical examination 1 month later, 5 tiny pink papules scattered on the left eyebrow, left cheek, and left side of the chin were noted. She was advised to continue applying the clobetasol cream as needed and was restarted on MTX 10 mg once weekly. However, she developed 2 additional 1-cm nodules on the left side of the chin, neck, and shoulder. Methotrexate was increased to 30 mg once weekly over 2 weeks, which was the original dose prior to interruption, but the nodules grew to 1.5-cm in diameter. Due to their clinical appearance, the nodules were believed to be early pcALCL lesions (Figure 2A). Given the cosmetically sensitive location of the nodules, palliative radiotherapy was recommended rather than observe for possible regression. Based on a prior report by Neelis et al7 demonstrating efficacy of low-dose radiotherapy for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and cutaneous B-cell lymphoma, we recommended starting with low radiation doses. Our patient was treated with 400 cGy twice to the left side of the chin and left side of the neck (800 cGy total at each site) while remaining on MTX 30 mg once weekly. This treatment was well tolerated without side effects and no evidence of radiation dermatitis. On follow-up examination 1 week later, the nodules had regressed and no new lesions were present (Figure 2B).

The patient has stayed on oral MTX and occasionally develops small lesions that quickly resolve with clobetasol cream. She has been followed for 3 years after radiotherapy and all 3 previously irradiated sites have remained recurrence free. Furthermore, she has not developed any new larger nodules or tumors and her MTX dose has been decreased to 15 mg once weekly.

Comment

Local radiotherapy is considered a first-line treatment of pcALCL; however, there is limited evidence on its clinical efficacy as well as the optimal dose and technique. Although no standard dose exists for pcALCL, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines8 recommend doses of 12 to 36 Gy in mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome subtypes of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, which are consistent with guidelines published by the European Society for Medical Oncology.9 High complete response rates have been demonstrated in pcALCL at doses of 34 to 44 Gy6; however, lesions tend to recur elsewhere on the skin in 36% to 41% of patients despite treatment.2,10 Lower doses of radiation therapy would provide several advantages over higher-dose therapy if a complete response could be achieved without greatly increasing the local recurrence rate. In cases of local recurrence, low-dose radiation would more easily permit retreatment of lesions compared to higher doses of radiation. Similarly, in patients with multifocal pcALCL, lower doses of radiotherapy may allow for treatment of larger skin areas while limiting potential treatment risks. Furthermore, low-dose therapy would allow for treatments to be delivered more quickly and with less inconvenience to the patient who is likely to need multiple future treatments to other areas. Low-dose radiation has been described with a favorable efficacy profile for mycosis fungoides7,11 but has not been studied in patients with CD30+ pcLPDs.

Our case is notable because the patient remained on MTX during radiation therapy. B

Conclusion

We reported the use of low-dose radiation therapy for the treatment of localized pcALCL in a patient who remained on low-dose oral MTX. Additional studies will be necessary to more fully evaluate the efficacy of using low-dose radiation both as monotherapy and in combination with MTX for pcALCL.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Bekkenk MW, Geelen FA, van Voorst Vader PC, et al. Primary and secondary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders: a report from the Dutch Cutaneous Lymphoma Group on the long-term follow-up data of 219 patients and guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Blood. 2000;95:3653-3661.

- Willemze R, Beljaards RC. Spectrum of primary cutaneous CD30 (Ki-1)-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: a proposal for classification and guidelines for management and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:973-980.

- Kadin ME. The spectrum of Ki-1+ cutaneous lymphomas. Curr Probl Dermatol. 1990;19:132-143.

- Vonderheid EC, Sajjadian A, Kadin ME. Methotrexate is effective therapy for lymphomatoid papulosis and other primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:470-481.

- Yu JB, McNiff JM, Lund MW, et al. Treatment of primary cutaneous CD30+ anaplastic large-cell lymphoma with radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:1542-1545.

- Neelis KJ, Schimmel EC, Vermeer MH, et al. Low-dose palliative radiotherapy B-cell and T-cell lymphomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:154-158.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. CD30 lymphoproliferative disorders section in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (Version 3.2016). http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nhl.pdf. Accessed September 26, 2016.

- Willemze R, Hodak E, Zinzani PL, et al; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Primary cutaneous lymphomas: EMSO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up [published online July 17, 2013]. Ann Onc. 2013;24(suppl 6):vi149-vi154.

- Liu HL, Hoppe RT, Kohler S, et al. CD30+ cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders: the Stanford experience in lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1049-1058.

- Harrison C, Young J, Navi D, et al. Revisiting low dose total skin electron beam radiotherapy in mycosis fungoides. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:651-657.

- Jaffe N, Farber S, Traggis D, et al. Favorable response of metastatic osteogenic sarcoma to pulse high-dose methotrexate with citrovorum rescue and radiation therapy. Cancer. 1973;31:1367-1373.

- Rosen G, Tefft M, Martinez A, et al. Combination chemotherapy and radiation therapy in the treatment of metastatic osteogenic sarcoma. Cancer. 1975;35:622-630.

- Kim YH, Aye MS, Fayos JV. Radiation necrosis of the scalp: a complication of cranial irradiation and methotrexate. Radiology. 1977;124:813-814.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Bekkenk MW, Geelen FA, van Voorst Vader PC, et al. Primary and secondary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders: a report from the Dutch Cutaneous Lymphoma Group on the long-term follow-up data of 219 patients and guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Blood. 2000;95:3653-3661.

- Willemze R, Beljaards RC. Spectrum of primary cutaneous CD30 (Ki-1)-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: a proposal for classification and guidelines for management and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:973-980.

- Kadin ME. The spectrum of Ki-1+ cutaneous lymphomas. Curr Probl Dermatol. 1990;19:132-143.

- Vonderheid EC, Sajjadian A, Kadin ME. Methotrexate is effective therapy for lymphomatoid papulosis and other primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:470-481.

- Yu JB, McNiff JM, Lund MW, et al. Treatment of primary cutaneous CD30+ anaplastic large-cell lymphoma with radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:1542-1545.

- Neelis KJ, Schimmel EC, Vermeer MH, et al. Low-dose palliative radiotherapy B-cell and T-cell lymphomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:154-158.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. CD30 lymphoproliferative disorders section in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (Version 3.2016). http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nhl.pdf. Accessed September 26, 2016.

- Willemze R, Hodak E, Zinzani PL, et al; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Primary cutaneous lymphomas: EMSO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up [published online July 17, 2013]. Ann Onc. 2013;24(suppl 6):vi149-vi154.

- Liu HL, Hoppe RT, Kohler S, et al. CD30+ cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders: the Stanford experience in lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1049-1058.

- Harrison C, Young J, Navi D, et al. Revisiting low dose total skin electron beam radiotherapy in mycosis fungoides. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:651-657.

- Jaffe N, Farber S, Traggis D, et al. Favorable response of metastatic osteogenic sarcoma to pulse high-dose methotrexate with citrovorum rescue and radiation therapy. Cancer. 1973;31:1367-1373.

- Rosen G, Tefft M, Martinez A, et al. Combination chemotherapy and radiation therapy in the treatment of metastatic osteogenic sarcoma. Cancer. 1975;35:622-630.

- Kim YH, Aye MS, Fayos JV. Radiation necrosis of the scalp: a complication of cranial irradiation and methotrexate. Radiology. 1977;124:813-814.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma tumors such as primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma can respond to low-dose radiation therapy, which enables future retreatment of sensitive sites.

- Low-dose radiation therapy requires a shorter course of therapy than traditional dosing, which is more convenient and less costly.

Bullous Pemphigoid Associated With a Lymphoepithelial Cyst of the Pancreas

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is an acquired, autoimmune, subepidermal blistering disease that is more common in elderly patients.1 An association with internal neoplasms and BP has been established; however, there is debate regarding the precise nature of the relationship.2 Several gastrointestinal tract tumors have been associated with BP, including adenocarcinoma of the colon, adenosquamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the stomach, adenocarcinoma of the rectum, and liver and bile duct malignancies.3-5 Association with pancreatic neoplasms (eg, carcinoma of the pancreas) rarely has been reported.5-7 We present an unusual case of a lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas in a patient with BP.

Case Report

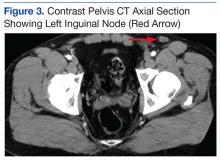

A 67-year-old man presented with erythematous crusted plaques and pink scars over the chest, back, arms, and legs (Figure 1). A 1.5-cm tense bullous lesion was observed on the right knee. The patient’s medical history was notable for biopsy-proven BP of 8 months’ duration as well as diabetes mellitus and hypothyroidism. The patient was being followed by his surgeon for a 1.9-cm soft-tissue lesion in the pancreatic tail and was awaiting surgical excision at the time of the current presentation. The pancreatic lesion was discovered incidentally on magnetic resonance imaging performed following urologic concerns. At the current presentation, the patient’s medications included nifedipine, hydralazine, metoprolol, torsemide, aspirin, levothyroxine, atorvastatin, insulin lispro, and insulin glargine. He had previously been treated for BP with prednisone at a maximum dosage of 60 mg daily, clobetasol propionate cream 0.05%, and mupirocin ointment 2% without improvement. Because of substantial weight gain and poorly controlled diabetes, prednisone was discontinued.

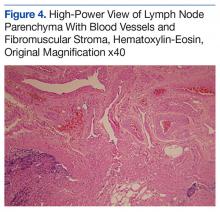

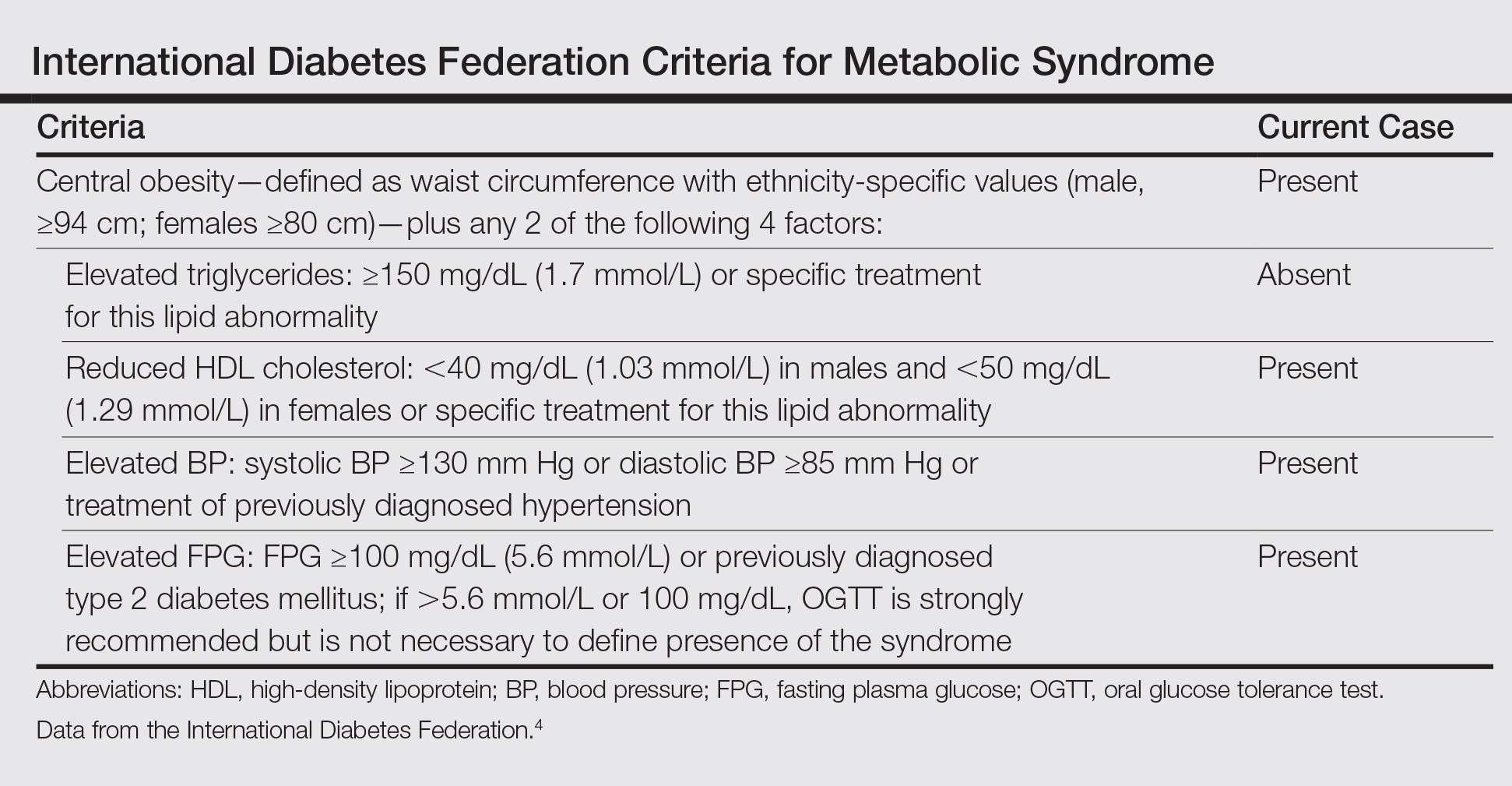

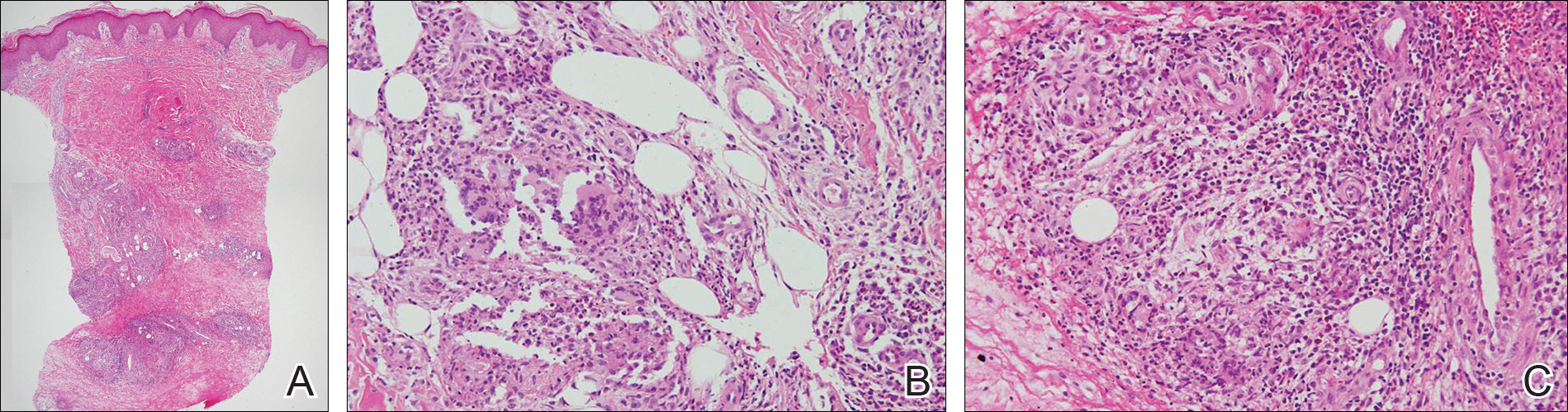

Bullous pemphigoid had been diagnosed histopathologically by a prior dermatologist. Hematoxylin and eosin staining demonstrated a subepidermal separation with eosinophils within the perivascular infiltrate (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence was noted in a linear pattern at the dermoepidermal junction with IgG and C3. Bullous pemphigoid antigen antibodies 1 and 2 were obtained via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with a positive BP-1 antigen antibody of 19 U/mL (positive, >15 U/mL) and a normal BP-2 antigen antibody of less than 9 U/mL (reference range, <9 U/mL). The glucagon level was elevated at 245 pg/mL (reference range, ≤134 pg/mL).

The patient was prescribed minocycline 100 mg twice daily and niacinamide 500 mg 3 times daily. Topical treatment with clobetasol and mupirocin was continued. One month later, the patient returned with an increase in disease activity. Changes to his therapeutic regimen were deferred until after excision of the pancreatic lesion based on the decision not to start immunosuppressive therapy until the precise nature of the pancreatic lesion was determined.

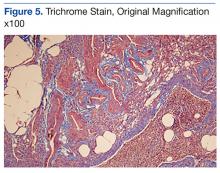

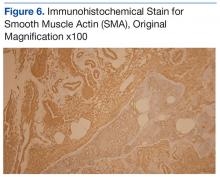

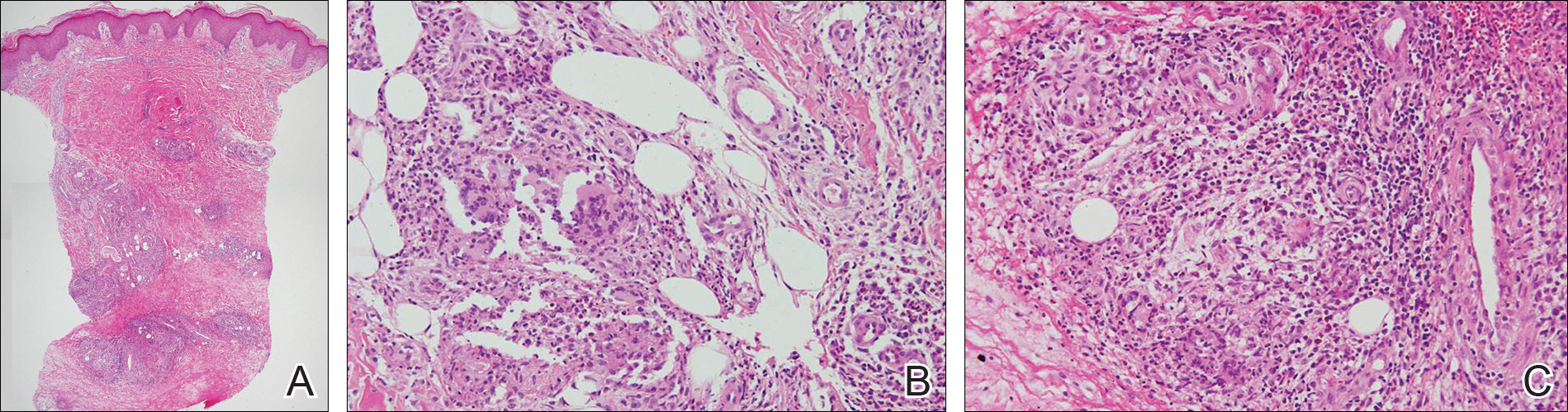

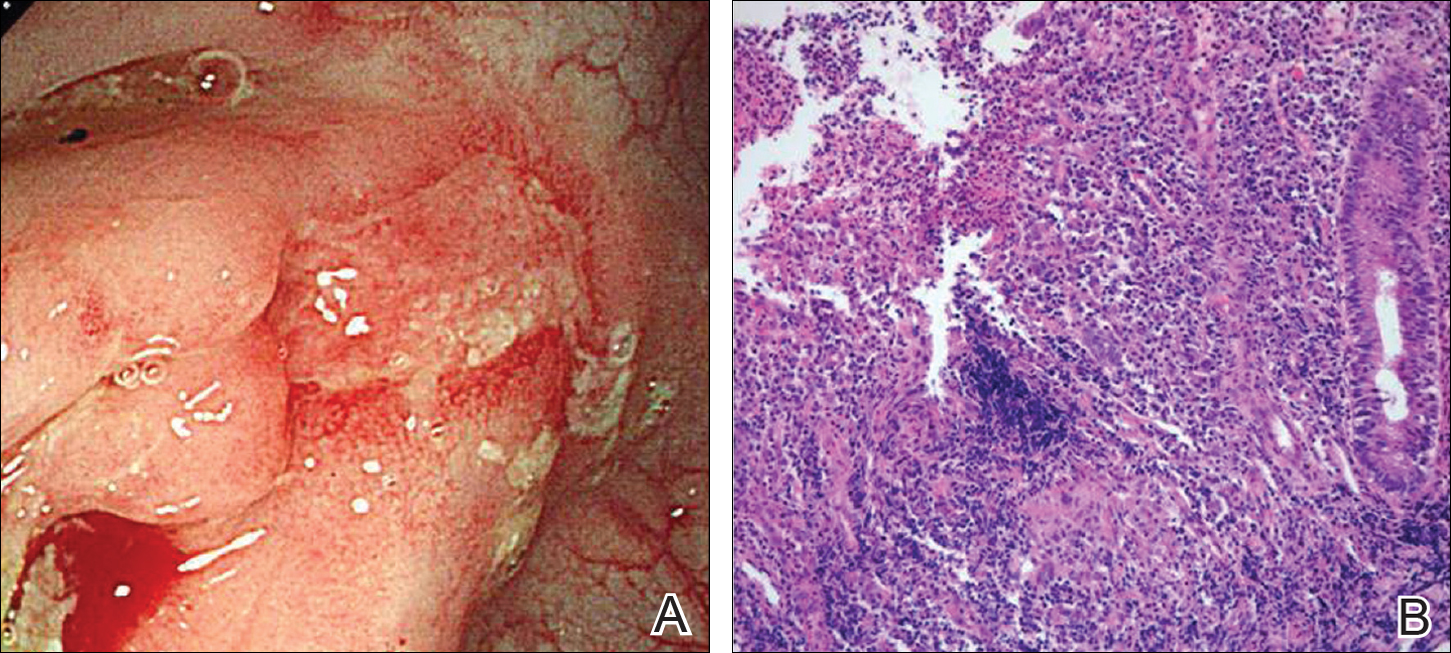

The patient underwent excision of the pancreatic lesion approximately 3 months later, which proved to be a benign lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas. Histology of the cyst consisted of dense fibrous tissue with a squamous epithelial lining focally infiltrated by lymphocytes (Figure 3A). Immunoperoxidase staining of the cyst revealed focal linear areas of C3d staining along the basement membrane of the stratified squamous epithelium (Figure 3B).

The patient stated that his skin started to improve virtually immediately following the excision without systemic treatment for BP. On follow-up examination 3 weeks postoperatively, no bullae were observed and there was a notable decrease in erythematous crusted plaques (Figure 4).

Comment

Paraneoplastic BP has been documented; however, lymphoepithelial cysts of the pancreas in association with BP are rare. We propose that the lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas provided the immunologic stimulus for the development of cutaneous BP based on the observation that our patient’s condition remarkably improved with resection of the tumor.

There are fewer than 100 cases of lymphoepithelial cysts of the pancreas reported in the literature.8 The histologic appearance is consistent with a true cyst exhibiting a well-differentiated stratified squamous epithelium, often with keratinization, surrounded by lymphoid tissue. These tumors are most commonly seen in middle-aged men and are frequently found incidentally,8-10 as was the case with our patient. Although histologically similar, lymphoepithelial cysts of the pancreas are considered distinct from lymphoepithelial cysts of the parotid gland or head and neck region.10 Lymphoepithelial cysts of the pancreas are unrelated to elevated glucagon levels; it is likely that our patient’s glucagon levels were associated with his history of diabetes.11

The diagnosis of BP is characteristically confirmed by direct immunofluorescence. Although it was performed for our patient’s cutaneous lesions, it was not obtained for the lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas. Once the diagnosis of the lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas was established, as direct immunofluorescence could not be performed in formalin-fixed tissue, immunoperoxidase staining with C3d was obtained. C3 has a well-established role in activation of complement and as a marker in BP. Deposition of C3d is a result of deactivation of C3b, a cleavage product of C3. In a study of 6 autoimmune blistering disorders that included 32 patients with BP, Pfaltz et al12 found positive immunoperoxidase staining for C3d in 31 of 32 patients, which translated to a sensitivity of 97%, a positive predictive value of 100%, and a negative predictive value of 98% among the blistering diseases being studied. Similarly, Magro and Dyrsen13 had positive staining of C3d in 17 of 17 (100%) patients with BP.

In theory, any process that involves deposition of C3 should be positive for C3d on immunoperoxidase staining. Other dermatologic inflammatory conditions stain positively with C3d, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, discoid lupus erythematosus, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and dermatomysositis.13 The staining for these diseases correlates with the site of the associated inflammatory component seen on hematoxylin and eosin staining. The staining of C3d along the basement membrane of stratified squamous epithelium in the lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas seen in our patient closely resembles the staining seen in cutaneous BP.

A proposed mechanism for BP in our patient would be exposure of BP-1 antigen in the pancreatic cyst leading to antibody recognition and C3 deposition along the basement membrane in the cyst, as evidenced by C3d immunoperoxidase staining. The IgG and C3 deposition along the cutaneous basement membrane would then represent a systemic response to the antigen exposure in the cyst. Thus, the lymphoepithelial cyst provided the immunologic stimulus for the development of the cutaneous BP. This theory is based on the observation of our patient’s rapid improvement without a change in his treatment regimen immediately after surgical excision of the cyst.

Despite the plausibility of our hypothesis, several questions remain regarding the validity of our assumptions. Although sensitive for C3 deposition, C3d immunoperoxidase staining is not specific for BP. If the proposed mechanism for causation is true, one might have expected that a subepithelial cleft along the basement membrane of the pancreatic cyst would be observed, which was not seen. A repeat BP antigen antibody was not obtained, which would have been helpful in determining if there was clearance of the antibody that would have correlated with the clinical resolution of the BP lesions.

Conclusion

Our case suggests that paraneoplastic BP is a genuine entity. Indeed, the primary tumor itself may be the immunologic stimulus in the development of BP. Recalcitrant BP should raise the question of a neoplastic process that is exposing the BP antigen. If a thorough review of systems accompanied by corroborating laboratory studies suggests a neoplastic process, the suspect lesion should be further evaluated and surgically excised if clinically indicated. Further evaluation of neoplasms with advanced staining methods may aid in establishing the causative nature of tumors in the development of BP.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to John Stanley, MD, and Aimee Payne, MD (both from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), for theirinsights into this case.

- Charneux J, Lorin J, Vitry F, et al. Usefulness of BP230 and BP180-NC16a enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays in the initial diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:286-291.

- Patel M, Sniha AA, Gilbert E. Bullous pemphigoid associated with renal cell carcinoma and invasive squamous cell carcinoma. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:234-238.

- Song HJ, Han SH, Hong WK, et al. Paraneoplastic bullous pemphigoid: clinical disease activity correlated with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay index for NC16A domain of BP180. J Dermatol. 2009;36:66-68.

- Muramatsu T, Iida T, Tada H, et al. Bullous pemphigoid associated with internal malignancies: identification of 180-kDa antigen by Western immunoblotting. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:782-784.

- Ogawa H, Sakuma M, Morioka S, et al. The incidence of internal malignancies in pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid in Japan. J Dermatol Sci. 1995;9:136-141.

- Boyd RV. Pemphigoid and carcinoma of the pancreas. Br Med J. 1964;1:1092.

- Eustace S, Morrow G, O’Loughlin S, et al. The role of computed tomography and sonography in acute bullous pemphigoid. Ir J Med Sci. 1993;162:401-404.

- Clemente G, Sarno G, De Rose AM, et al. Lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas: case report and review of the literature. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2011;74:343-346.

- Frezza E, Wachtel MS. Lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas tail. case report and review of the literature. JOP. 2008;9:46-49.

- Basturk O, Coban I, Adsay NV. Pancreatic cysts: pathologic classification, differential diagnosis and clinical implications. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:423-438.

- Unger RH, Cherrington AD. Glucagonocentric restructuring of diabetes: a pathophysiologic and therapeutic makeover. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4-12.

- Pfaltz K, Mertz K, Rose C, et al. C3d immunohistochemistry on formalin-fixed tissue is a valuable tool in the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:654-658.

- Magro CM, Dyrsen ME. The use of C3d and C4d immunohistochemistry on formalin-fixed tissue as a diagnostic adjunct in the assessment of inflammatory skin disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:822-833.

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is an acquired, autoimmune, subepidermal blistering disease that is more common in elderly patients.1 An association with internal neoplasms and BP has been established; however, there is debate regarding the precise nature of the relationship.2 Several gastrointestinal tract tumors have been associated with BP, including adenocarcinoma of the colon, adenosquamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the stomach, adenocarcinoma of the rectum, and liver and bile duct malignancies.3-5 Association with pancreatic neoplasms (eg, carcinoma of the pancreas) rarely has been reported.5-7 We present an unusual case of a lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas in a patient with BP.

Case Report

A 67-year-old man presented with erythematous crusted plaques and pink scars over the chest, back, arms, and legs (Figure 1). A 1.5-cm tense bullous lesion was observed on the right knee. The patient’s medical history was notable for biopsy-proven BP of 8 months’ duration as well as diabetes mellitus and hypothyroidism. The patient was being followed by his surgeon for a 1.9-cm soft-tissue lesion in the pancreatic tail and was awaiting surgical excision at the time of the current presentation. The pancreatic lesion was discovered incidentally on magnetic resonance imaging performed following urologic concerns. At the current presentation, the patient’s medications included nifedipine, hydralazine, metoprolol, torsemide, aspirin, levothyroxine, atorvastatin, insulin lispro, and insulin glargine. He had previously been treated for BP with prednisone at a maximum dosage of 60 mg daily, clobetasol propionate cream 0.05%, and mupirocin ointment 2% without improvement. Because of substantial weight gain and poorly controlled diabetes, prednisone was discontinued.

Bullous pemphigoid had been diagnosed histopathologically by a prior dermatologist. Hematoxylin and eosin staining demonstrated a subepidermal separation with eosinophils within the perivascular infiltrate (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence was noted in a linear pattern at the dermoepidermal junction with IgG and C3. Bullous pemphigoid antigen antibodies 1 and 2 were obtained via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with a positive BP-1 antigen antibody of 19 U/mL (positive, >15 U/mL) and a normal BP-2 antigen antibody of less than 9 U/mL (reference range, <9 U/mL). The glucagon level was elevated at 245 pg/mL (reference range, ≤134 pg/mL).

The patient was prescribed minocycline 100 mg twice daily and niacinamide 500 mg 3 times daily. Topical treatment with clobetasol and mupirocin was continued. One month later, the patient returned with an increase in disease activity. Changes to his therapeutic regimen were deferred until after excision of the pancreatic lesion based on the decision not to start immunosuppressive therapy until the precise nature of the pancreatic lesion was determined.

The patient underwent excision of the pancreatic lesion approximately 3 months later, which proved to be a benign lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas. Histology of the cyst consisted of dense fibrous tissue with a squamous epithelial lining focally infiltrated by lymphocytes (Figure 3A). Immunoperoxidase staining of the cyst revealed focal linear areas of C3d staining along the basement membrane of the stratified squamous epithelium (Figure 3B).

The patient stated that his skin started to improve virtually immediately following the excision without systemic treatment for BP. On follow-up examination 3 weeks postoperatively, no bullae were observed and there was a notable decrease in erythematous crusted plaques (Figure 4).

Comment

Paraneoplastic BP has been documented; however, lymphoepithelial cysts of the pancreas in association with BP are rare. We propose that the lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas provided the immunologic stimulus for the development of cutaneous BP based on the observation that our patient’s condition remarkably improved with resection of the tumor.

There are fewer than 100 cases of lymphoepithelial cysts of the pancreas reported in the literature.8 The histologic appearance is consistent with a true cyst exhibiting a well-differentiated stratified squamous epithelium, often with keratinization, surrounded by lymphoid tissue. These tumors are most commonly seen in middle-aged men and are frequently found incidentally,8-10 as was the case with our patient. Although histologically similar, lymphoepithelial cysts of the pancreas are considered distinct from lymphoepithelial cysts of the parotid gland or head and neck region.10 Lymphoepithelial cysts of the pancreas are unrelated to elevated glucagon levels; it is likely that our patient’s glucagon levels were associated with his history of diabetes.11

The diagnosis of BP is characteristically confirmed by direct immunofluorescence. Although it was performed for our patient’s cutaneous lesions, it was not obtained for the lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas. Once the diagnosis of the lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas was established, as direct immunofluorescence could not be performed in formalin-fixed tissue, immunoperoxidase staining with C3d was obtained. C3 has a well-established role in activation of complement and as a marker in BP. Deposition of C3d is a result of deactivation of C3b, a cleavage product of C3. In a study of 6 autoimmune blistering disorders that included 32 patients with BP, Pfaltz et al12 found positive immunoperoxidase staining for C3d in 31 of 32 patients, which translated to a sensitivity of 97%, a positive predictive value of 100%, and a negative predictive value of 98% among the blistering diseases being studied. Similarly, Magro and Dyrsen13 had positive staining of C3d in 17 of 17 (100%) patients with BP.

In theory, any process that involves deposition of C3 should be positive for C3d on immunoperoxidase staining. Other dermatologic inflammatory conditions stain positively with C3d, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, discoid lupus erythematosus, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and dermatomysositis.13 The staining for these diseases correlates with the site of the associated inflammatory component seen on hematoxylin and eosin staining. The staining of C3d along the basement membrane of stratified squamous epithelium in the lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas seen in our patient closely resembles the staining seen in cutaneous BP.

A proposed mechanism for BP in our patient would be exposure of BP-1 antigen in the pancreatic cyst leading to antibody recognition and C3 deposition along the basement membrane in the cyst, as evidenced by C3d immunoperoxidase staining. The IgG and C3 deposition along the cutaneous basement membrane would then represent a systemic response to the antigen exposure in the cyst. Thus, the lymphoepithelial cyst provided the immunologic stimulus for the development of the cutaneous BP. This theory is based on the observation of our patient’s rapid improvement without a change in his treatment regimen immediately after surgical excision of the cyst.

Despite the plausibility of our hypothesis, several questions remain regarding the validity of our assumptions. Although sensitive for C3 deposition, C3d immunoperoxidase staining is not specific for BP. If the proposed mechanism for causation is true, one might have expected that a subepithelial cleft along the basement membrane of the pancreatic cyst would be observed, which was not seen. A repeat BP antigen antibody was not obtained, which would have been helpful in determining if there was clearance of the antibody that would have correlated with the clinical resolution of the BP lesions.

Conclusion

Our case suggests that paraneoplastic BP is a genuine entity. Indeed, the primary tumor itself may be the immunologic stimulus in the development of BP. Recalcitrant BP should raise the question of a neoplastic process that is exposing the BP antigen. If a thorough review of systems accompanied by corroborating laboratory studies suggests a neoplastic process, the suspect lesion should be further evaluated and surgically excised if clinically indicated. Further evaluation of neoplasms with advanced staining methods may aid in establishing the causative nature of tumors in the development of BP.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to John Stanley, MD, and Aimee Payne, MD (both from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), for theirinsights into this case.

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is an acquired, autoimmune, subepidermal blistering disease that is more common in elderly patients.1 An association with internal neoplasms and BP has been established; however, there is debate regarding the precise nature of the relationship.2 Several gastrointestinal tract tumors have been associated with BP, including adenocarcinoma of the colon, adenosquamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the stomach, adenocarcinoma of the rectum, and liver and bile duct malignancies.3-5 Association with pancreatic neoplasms (eg, carcinoma of the pancreas) rarely has been reported.5-7 We present an unusual case of a lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas in a patient with BP.

Case Report

A 67-year-old man presented with erythematous crusted plaques and pink scars over the chest, back, arms, and legs (Figure 1). A 1.5-cm tense bullous lesion was observed on the right knee. The patient’s medical history was notable for biopsy-proven BP of 8 months’ duration as well as diabetes mellitus and hypothyroidism. The patient was being followed by his surgeon for a 1.9-cm soft-tissue lesion in the pancreatic tail and was awaiting surgical excision at the time of the current presentation. The pancreatic lesion was discovered incidentally on magnetic resonance imaging performed following urologic concerns. At the current presentation, the patient’s medications included nifedipine, hydralazine, metoprolol, torsemide, aspirin, levothyroxine, atorvastatin, insulin lispro, and insulin glargine. He had previously been treated for BP with prednisone at a maximum dosage of 60 mg daily, clobetasol propionate cream 0.05%, and mupirocin ointment 2% without improvement. Because of substantial weight gain and poorly controlled diabetes, prednisone was discontinued.

Bullous pemphigoid had been diagnosed histopathologically by a prior dermatologist. Hematoxylin and eosin staining demonstrated a subepidermal separation with eosinophils within the perivascular infiltrate (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence was noted in a linear pattern at the dermoepidermal junction with IgG and C3. Bullous pemphigoid antigen antibodies 1 and 2 were obtained via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with a positive BP-1 antigen antibody of 19 U/mL (positive, >15 U/mL) and a normal BP-2 antigen antibody of less than 9 U/mL (reference range, <9 U/mL). The glucagon level was elevated at 245 pg/mL (reference range, ≤134 pg/mL).

The patient was prescribed minocycline 100 mg twice daily and niacinamide 500 mg 3 times daily. Topical treatment with clobetasol and mupirocin was continued. One month later, the patient returned with an increase in disease activity. Changes to his therapeutic regimen were deferred until after excision of the pancreatic lesion based on the decision not to start immunosuppressive therapy until the precise nature of the pancreatic lesion was determined.

The patient underwent excision of the pancreatic lesion approximately 3 months later, which proved to be a benign lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas. Histology of the cyst consisted of dense fibrous tissue with a squamous epithelial lining focally infiltrated by lymphocytes (Figure 3A). Immunoperoxidase staining of the cyst revealed focal linear areas of C3d staining along the basement membrane of the stratified squamous epithelium (Figure 3B).

The patient stated that his skin started to improve virtually immediately following the excision without systemic treatment for BP. On follow-up examination 3 weeks postoperatively, no bullae were observed and there was a notable decrease in erythematous crusted plaques (Figure 4).

Comment

Paraneoplastic BP has been documented; however, lymphoepithelial cysts of the pancreas in association with BP are rare. We propose that the lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas provided the immunologic stimulus for the development of cutaneous BP based on the observation that our patient’s condition remarkably improved with resection of the tumor.

There are fewer than 100 cases of lymphoepithelial cysts of the pancreas reported in the literature.8 The histologic appearance is consistent with a true cyst exhibiting a well-differentiated stratified squamous epithelium, often with keratinization, surrounded by lymphoid tissue. These tumors are most commonly seen in middle-aged men and are frequently found incidentally,8-10 as was the case with our patient. Although histologically similar, lymphoepithelial cysts of the pancreas are considered distinct from lymphoepithelial cysts of the parotid gland or head and neck region.10 Lymphoepithelial cysts of the pancreas are unrelated to elevated glucagon levels; it is likely that our patient’s glucagon levels were associated with his history of diabetes.11

The diagnosis of BP is characteristically confirmed by direct immunofluorescence. Although it was performed for our patient’s cutaneous lesions, it was not obtained for the lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas. Once the diagnosis of the lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas was established, as direct immunofluorescence could not be performed in formalin-fixed tissue, immunoperoxidase staining with C3d was obtained. C3 has a well-established role in activation of complement and as a marker in BP. Deposition of C3d is a result of deactivation of C3b, a cleavage product of C3. In a study of 6 autoimmune blistering disorders that included 32 patients with BP, Pfaltz et al12 found positive immunoperoxidase staining for C3d in 31 of 32 patients, which translated to a sensitivity of 97%, a positive predictive value of 100%, and a negative predictive value of 98% among the blistering diseases being studied. Similarly, Magro and Dyrsen13 had positive staining of C3d in 17 of 17 (100%) patients with BP.

In theory, any process that involves deposition of C3 should be positive for C3d on immunoperoxidase staining. Other dermatologic inflammatory conditions stain positively with C3d, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, discoid lupus erythematosus, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and dermatomysositis.13 The staining for these diseases correlates with the site of the associated inflammatory component seen on hematoxylin and eosin staining. The staining of C3d along the basement membrane of stratified squamous epithelium in the lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas seen in our patient closely resembles the staining seen in cutaneous BP.

A proposed mechanism for BP in our patient would be exposure of BP-1 antigen in the pancreatic cyst leading to antibody recognition and C3 deposition along the basement membrane in the cyst, as evidenced by C3d immunoperoxidase staining. The IgG and C3 deposition along the cutaneous basement membrane would then represent a systemic response to the antigen exposure in the cyst. Thus, the lymphoepithelial cyst provided the immunologic stimulus for the development of the cutaneous BP. This theory is based on the observation of our patient’s rapid improvement without a change in his treatment regimen immediately after surgical excision of the cyst.

Despite the plausibility of our hypothesis, several questions remain regarding the validity of our assumptions. Although sensitive for C3 deposition, C3d immunoperoxidase staining is not specific for BP. If the proposed mechanism for causation is true, one might have expected that a subepithelial cleft along the basement membrane of the pancreatic cyst would be observed, which was not seen. A repeat BP antigen antibody was not obtained, which would have been helpful in determining if there was clearance of the antibody that would have correlated with the clinical resolution of the BP lesions.

Conclusion

Our case suggests that paraneoplastic BP is a genuine entity. Indeed, the primary tumor itself may be the immunologic stimulus in the development of BP. Recalcitrant BP should raise the question of a neoplastic process that is exposing the BP antigen. If a thorough review of systems accompanied by corroborating laboratory studies suggests a neoplastic process, the suspect lesion should be further evaluated and surgically excised if clinically indicated. Further evaluation of neoplasms with advanced staining methods may aid in establishing the causative nature of tumors in the development of BP.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to John Stanley, MD, and Aimee Payne, MD (both from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), for theirinsights into this case.

- Charneux J, Lorin J, Vitry F, et al. Usefulness of BP230 and BP180-NC16a enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays in the initial diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:286-291.

- Patel M, Sniha AA, Gilbert E. Bullous pemphigoid associated with renal cell carcinoma and invasive squamous cell carcinoma. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:234-238.

- Song HJ, Han SH, Hong WK, et al. Paraneoplastic bullous pemphigoid: clinical disease activity correlated with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay index for NC16A domain of BP180. J Dermatol. 2009;36:66-68.

- Muramatsu T, Iida T, Tada H, et al. Bullous pemphigoid associated with internal malignancies: identification of 180-kDa antigen by Western immunoblotting. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:782-784.

- Ogawa H, Sakuma M, Morioka S, et al. The incidence of internal malignancies in pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid in Japan. J Dermatol Sci. 1995;9:136-141.

- Boyd RV. Pemphigoid and carcinoma of the pancreas. Br Med J. 1964;1:1092.

- Eustace S, Morrow G, O’Loughlin S, et al. The role of computed tomography and sonography in acute bullous pemphigoid. Ir J Med Sci. 1993;162:401-404.

- Clemente G, Sarno G, De Rose AM, et al. Lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas: case report and review of the literature. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2011;74:343-346.

- Frezza E, Wachtel MS. Lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas tail. case report and review of the literature. JOP. 2008;9:46-49.

- Basturk O, Coban I, Adsay NV. Pancreatic cysts: pathologic classification, differential diagnosis and clinical implications. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:423-438.

- Unger RH, Cherrington AD. Glucagonocentric restructuring of diabetes: a pathophysiologic and therapeutic makeover. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4-12.

- Pfaltz K, Mertz K, Rose C, et al. C3d immunohistochemistry on formalin-fixed tissue is a valuable tool in the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:654-658.

- Magro CM, Dyrsen ME. The use of C3d and C4d immunohistochemistry on formalin-fixed tissue as a diagnostic adjunct in the assessment of inflammatory skin disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:822-833.

- Charneux J, Lorin J, Vitry F, et al. Usefulness of BP230 and BP180-NC16a enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays in the initial diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:286-291.

- Patel M, Sniha AA, Gilbert E. Bullous pemphigoid associated with renal cell carcinoma and invasive squamous cell carcinoma. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:234-238.

- Song HJ, Han SH, Hong WK, et al. Paraneoplastic bullous pemphigoid: clinical disease activity correlated with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay index for NC16A domain of BP180. J Dermatol. 2009;36:66-68.

- Muramatsu T, Iida T, Tada H, et al. Bullous pemphigoid associated with internal malignancies: identification of 180-kDa antigen by Western immunoblotting. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:782-784.

- Ogawa H, Sakuma M, Morioka S, et al. The incidence of internal malignancies in pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid in Japan. J Dermatol Sci. 1995;9:136-141.

- Boyd RV. Pemphigoid and carcinoma of the pancreas. Br Med J. 1964;1:1092.

- Eustace S, Morrow G, O’Loughlin S, et al. The role of computed tomography and sonography in acute bullous pemphigoid. Ir J Med Sci. 1993;162:401-404.

- Clemente G, Sarno G, De Rose AM, et al. Lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas: case report and review of the literature. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2011;74:343-346.

- Frezza E, Wachtel MS. Lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas tail. case report and review of the literature. JOP. 2008;9:46-49.

- Basturk O, Coban I, Adsay NV. Pancreatic cysts: pathologic classification, differential diagnosis and clinical implications. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:423-438.

- Unger RH, Cherrington AD. Glucagonocentric restructuring of diabetes: a pathophysiologic and therapeutic makeover. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4-12.

- Pfaltz K, Mertz K, Rose C, et al. C3d immunohistochemistry on formalin-fixed tissue is a valuable tool in the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:654-658.

- Magro CM, Dyrsen ME. The use of C3d and C4d immunohistochemistry on formalin-fixed tissue as a diagnostic adjunct in the assessment of inflammatory skin disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:822-833.

Epistaxis, mass in right nostril • Dx?

THE CASE

A 49-year-old woman visited our family medicine clinic because she’d had 3 episodes of epistaxis during the previous month. She’d already visited the emergency department, and the doctor there had treated her symptomatically and referred her to our clinic.

On physical examination, we noted a whitish mass in the patient’s right nostril that was attached to the nasal septum. The patient’s vital signs were within normal limits. She had a history of hypertension, depression, anxiety, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Her medications included amlodipine-benazepril, atenolol-chlorthalidone, citalopram, clonazepam, prazosin, and omeprazole. The patient lived alone and denied using tobacco or illicit drugs, but she drank one to 2 glasses of brandy every day. She denied any past medical or family history of similar complaints, autoimmune disorders, or skin rashes.

A complete blood count, international normalized ratio, sedimentation rate, anti-nuclear antibody test, and an anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody panel were normal.

THE DIAGNOSIS

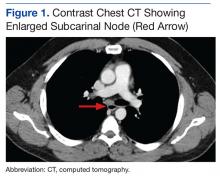

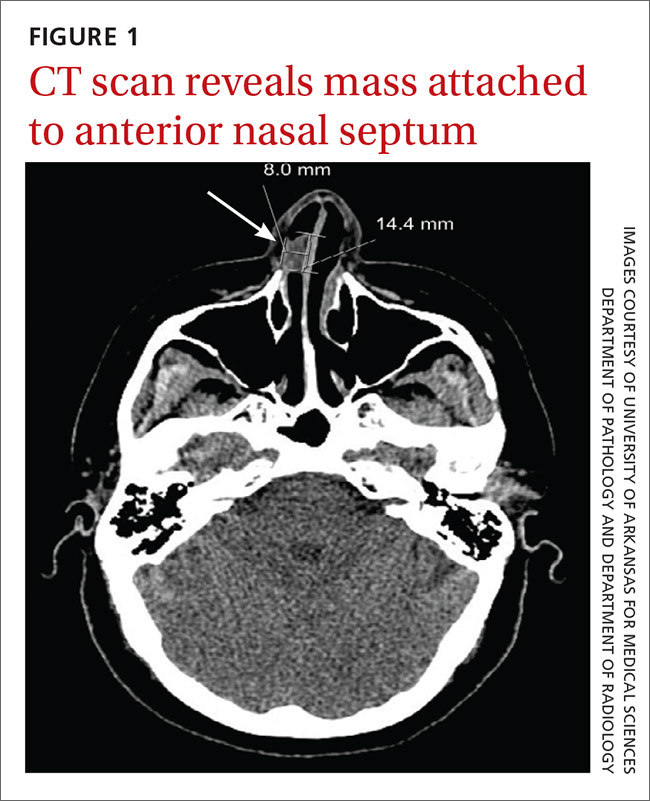

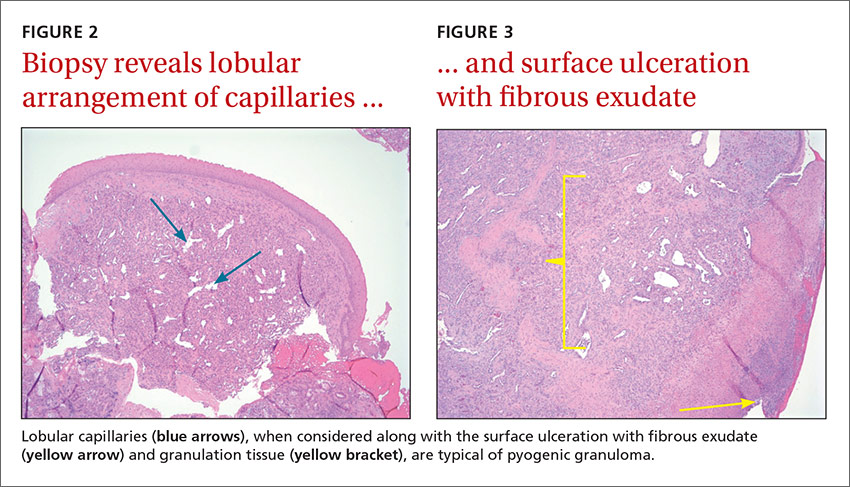

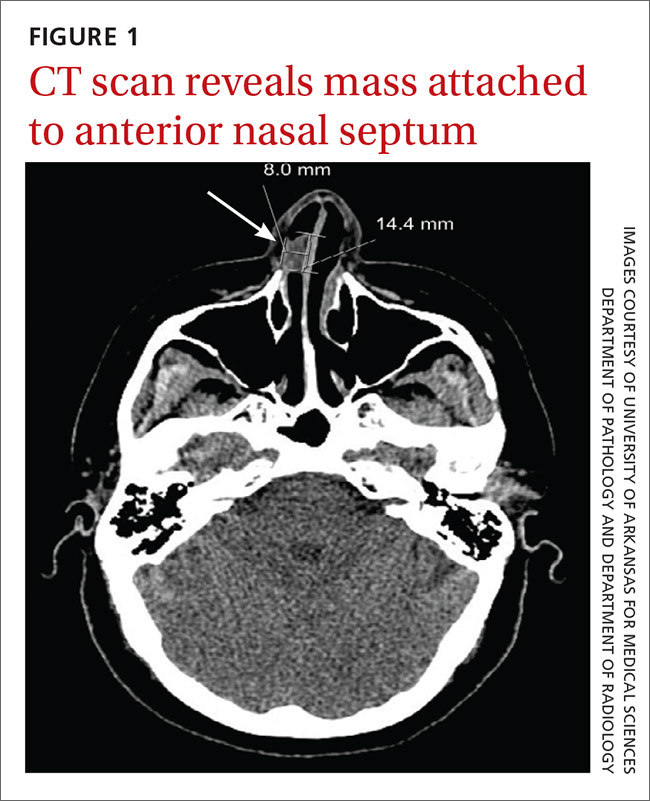

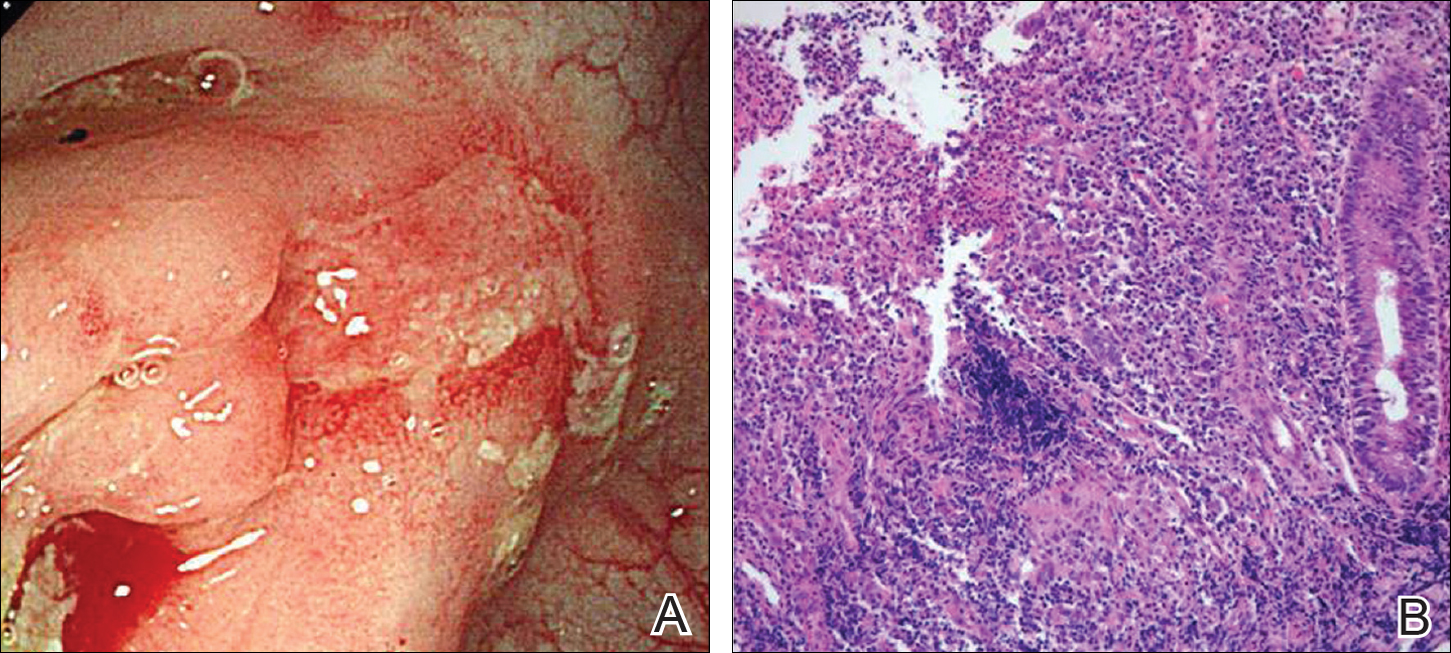

We referred the patient to an ear, nose, and throat doctor for a nasal endoscopy and a biopsy, which showed granulation tissue. A maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 1.44 cm x 0.8 cm polypoid soft tissue mass in the right nasal cavity adherent to the nasal septum with no posterior extension (FIGURE 1).

DISCUSSION

Pyogenic granuloma (PG) is a benign vascular tumor of the skin and mucous membranes that is not associated with an infection. Rather, it is a hyperplastic, neovascular, inflammatory response to an angiogenic stimulus. Several enhancers and inhibitors of angiogenesis have been shown to play a role in PG, including hormones, medications, and local injury. In fact, a local injury or hormonal factor is identified as a stimulus in more than half of PG patients.1

The hormone connection. Estrogen promotes production of nerve growth factor, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, and transforming growth factor beta 1. Progesterone enhances inflammatory mediators as well. Although there are no direct receptors for estrogen and progesterone in the oral and nasal mucosa, some of these pro-inflammatory effects create an environment conducive to the development of PG. This is supported by several studies documenting an increased incidence of PGs with oral contraceptive use and regression of PGs after childbirth.2-4

Medication may play a role. Drug-induced PG has also been described in several studies.5,6 Offending medications include systemic and topical retinoids, capecitabine, etoposide, 5-fluorouracil, cyclosporine, docetaxel, and human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors.

Local injury may also be a culprit. Nasal PGs are commonly attached to the anterior septum and typically result from nasal packing, habitual picking, or nose boring.7 In this particular case, however, we were unable to identify the irritant.

The classic presentation

PG classically presents as a painless mass that spontaneously develops over days to weeks. The mass can be sessile or pedunculated, and is frequently hemorrhagic. Intranasal PG usually presents with epiphora.7 While the prevalence of intraoral PG was found to be one in 25,000 individuals3, data for nasal lesions is scarce. Most cases of PG are seen in the second and third decades of life.1,3 In children, PG is slightly more predominant in males.1,3 Mucosal lesions, however, have a higher incidence in females.1,3 Granuloma gravidarum, the term used to describe mucosal PG in pregnant females, was found in 0.2% to 5% of pregnancies.2,3,8

Differential Dx includes warts, squamous cell carcinoma

The differential diagnosis of PG includes Spitz nevus, glomus tumors, common warts, amelanotic melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma, bacillary angiomatosis, infantile hemangioma, and angiolymphoid hyperplasia, among others.3,5 Foreign bodies, nasal polyps, angiofibroma, meningocele, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and sarcoidosis should also be considered.

Radiologic evaluation may be beneficial—especially with nasal lesions—when looking for findings suggestive of malignancy. Both CT and magnetic resonance imaging with contrast identify PG as a soft tissue mass with lobulated contours,9,10 but histopathologic analysis is required to confirm the diagnosis. The histopathologic appearance of PG is characterized by a polypoid lesion with circumscribed anastomosing networks of capillaries arranged in one or more lobules at the base in an edematous and fibroblastic stroma.

Treatment is determined by the location and size of the lesion

The most suitable treatment is determined by considering the location of the lesion, the characteristics of the lesion (morphology/size), its amenability to surgery, risk of scar formation, and the presence or absence of a causative irritant. Excision is often preferred because it yields a specimen for pathologic analysis. Alternative treatments include electrocautery, cryotherapy, laser therapy, and intralesional and topical agents,3,6,7 but the recurrence rate is higher (up to 15%) with some of these modalities, when compared with excision (3.6%).3

Our patient underwent excision of the mass and was seen for an annual follow-up appointment. All of her symptoms resolved and no recurrence was noted.

THE TAKEAWAY

Although PG is a common and benign condition, it is rarely seen in the nasal cavity without an obvious history of a possible irritant. PG should be considered as a diagnosis for rapidly growing cutaneous or mucosal hemorrhagic lesions. Appropriate tissue pathology is essential to rule out malignancy and other serious conditions, such as bacillary angiomatosis and Wegener’s granulomatosis.

Treatment is usually required to avoid the frequent complications of ulceration and bleeding. Surgical treatments are preferred. The location of the lesion largely determines whether referral to a specialist is necessary.

1. Harris MN, Desai R, Chuang TY, et al. Lobular capillary hemangiomas: An epidemiologic report, with emphasis on cutaneous lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:1012-1016.

2. Yuan K, Jin YT, Lin MT. The detection and comparison of angiogenesis-associated factors in pyogenic granuloma by immunohistochemistry. J Periodontol. 2000;71:701-709.

3. Giblin AV, Clover AJ, Athanassopoulos A, et al. Pyogenic granuloma–the quest for optimum treatment: audit of treatment of 408 cases. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:1030-1035.

4. Steelman R, Holmes D. Pregnancy tumor in a 16-year-old: case report and treatment considerations. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 1992;16:217-218.

5. Jafarzadeh H, Sanatkhani M, Mohtasham N. Oral pyogenic granuloma: a review. J Oral Sci. 2006;48:167-175.

6. Piraccini BM, Bellavista S, Misciali C, et al. Periungual and subungual pyogenic granuloma. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:941-953.

7. Ozcan C, Apa DD, Görür K. Pediatric lobular capillary hemangioma of the nasal cavity. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;261:449-451.

8. Henry F, Quatresooz P, Valverde-Lopez JC, et al. Blood vessel changes during pregnancy: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:65-69.

9. Puxeddu R, Berlucchi M, Ledda GP, et al. Lobular capillary hemangioma of the nasal cavity: A retrospective study on 40 patients. Am J Rhinol. 2006;20:480-484.

10. Maroldi R, Berlucchi M, Farina D, et al. Benign neoplasms and tumor-like lesions. In: Maroldi R, Nicolai P, eds. Imaging in Treatment Planning for Sinonasal Diseases. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag; 2005:107-158.

THE CASE

A 49-year-old woman visited our family medicine clinic because she’d had 3 episodes of epistaxis during the previous month. She’d already visited the emergency department, and the doctor there had treated her symptomatically and referred her to our clinic.

On physical examination, we noted a whitish mass in the patient’s right nostril that was attached to the nasal septum. The patient’s vital signs were within normal limits. She had a history of hypertension, depression, anxiety, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Her medications included amlodipine-benazepril, atenolol-chlorthalidone, citalopram, clonazepam, prazosin, and omeprazole. The patient lived alone and denied using tobacco or illicit drugs, but she drank one to 2 glasses of brandy every day. She denied any past medical or family history of similar complaints, autoimmune disorders, or skin rashes.

A complete blood count, international normalized ratio, sedimentation rate, anti-nuclear antibody test, and an anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody panel were normal.

THE DIAGNOSIS

We referred the patient to an ear, nose, and throat doctor for a nasal endoscopy and a biopsy, which showed granulation tissue. A maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 1.44 cm x 0.8 cm polypoid soft tissue mass in the right nasal cavity adherent to the nasal septum with no posterior extension (FIGURE 1).

DISCUSSION

Pyogenic granuloma (PG) is a benign vascular tumor of the skin and mucous membranes that is not associated with an infection. Rather, it is a hyperplastic, neovascular, inflammatory response to an angiogenic stimulus. Several enhancers and inhibitors of angiogenesis have been shown to play a role in PG, including hormones, medications, and local injury. In fact, a local injury or hormonal factor is identified as a stimulus in more than half of PG patients.1

The hormone connection. Estrogen promotes production of nerve growth factor, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, and transforming growth factor beta 1. Progesterone enhances inflammatory mediators as well. Although there are no direct receptors for estrogen and progesterone in the oral and nasal mucosa, some of these pro-inflammatory effects create an environment conducive to the development of PG. This is supported by several studies documenting an increased incidence of PGs with oral contraceptive use and regression of PGs after childbirth.2-4

Medication may play a role. Drug-induced PG has also been described in several studies.5,6 Offending medications include systemic and topical retinoids, capecitabine, etoposide, 5-fluorouracil, cyclosporine, docetaxel, and human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors.

Local injury may also be a culprit. Nasal PGs are commonly attached to the anterior septum and typically result from nasal packing, habitual picking, or nose boring.7 In this particular case, however, we were unable to identify the irritant.

The classic presentation

PG classically presents as a painless mass that spontaneously develops over days to weeks. The mass can be sessile or pedunculated, and is frequently hemorrhagic. Intranasal PG usually presents with epiphora.7 While the prevalence of intraoral PG was found to be one in 25,000 individuals3, data for nasal lesions is scarce. Most cases of PG are seen in the second and third decades of life.1,3 In children, PG is slightly more predominant in males.1,3 Mucosal lesions, however, have a higher incidence in females.1,3 Granuloma gravidarum, the term used to describe mucosal PG in pregnant females, was found in 0.2% to 5% of pregnancies.2,3,8

Differential Dx includes warts, squamous cell carcinoma

The differential diagnosis of PG includes Spitz nevus, glomus tumors, common warts, amelanotic melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma, bacillary angiomatosis, infantile hemangioma, and angiolymphoid hyperplasia, among others.3,5 Foreign bodies, nasal polyps, angiofibroma, meningocele, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and sarcoidosis should also be considered.

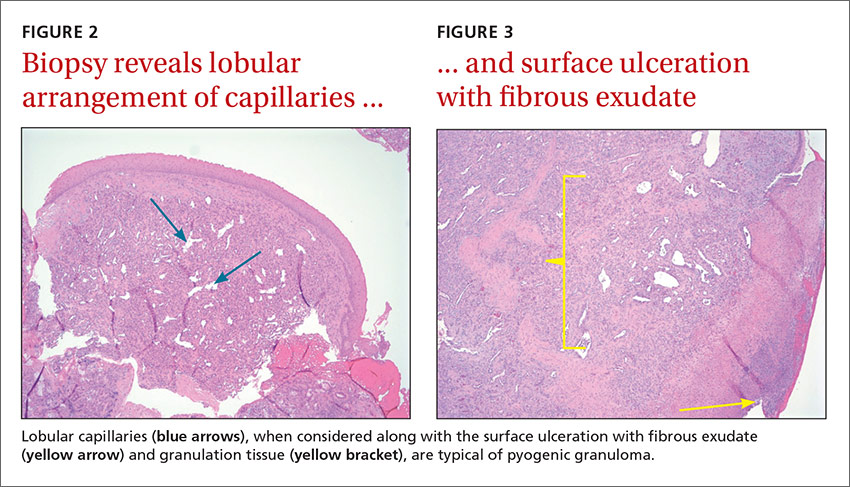

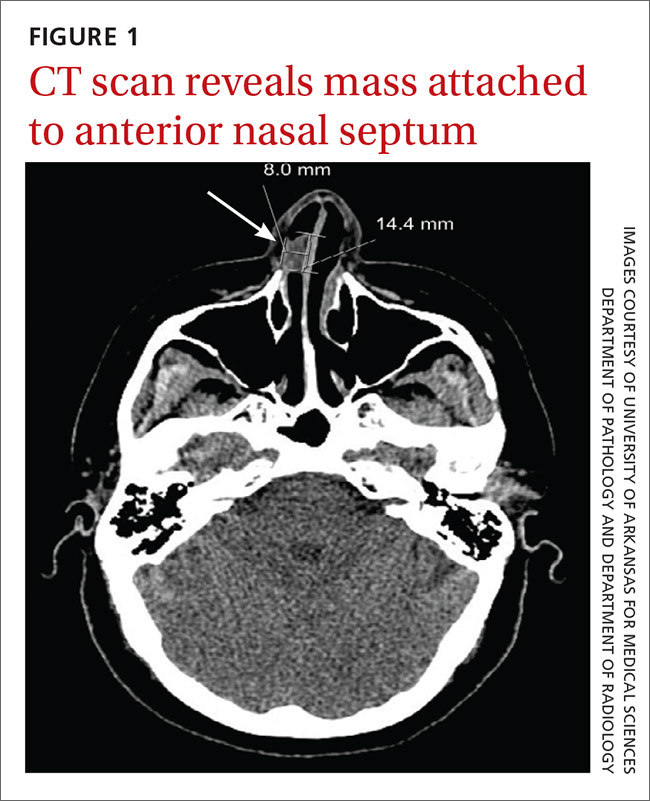

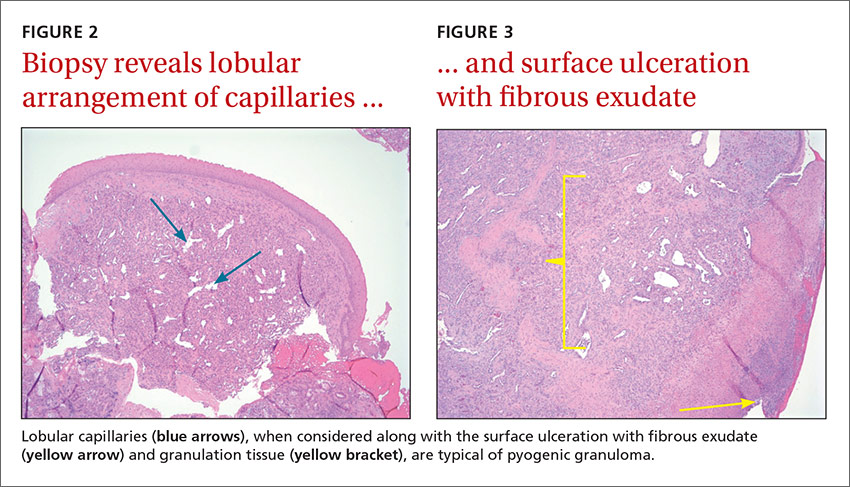

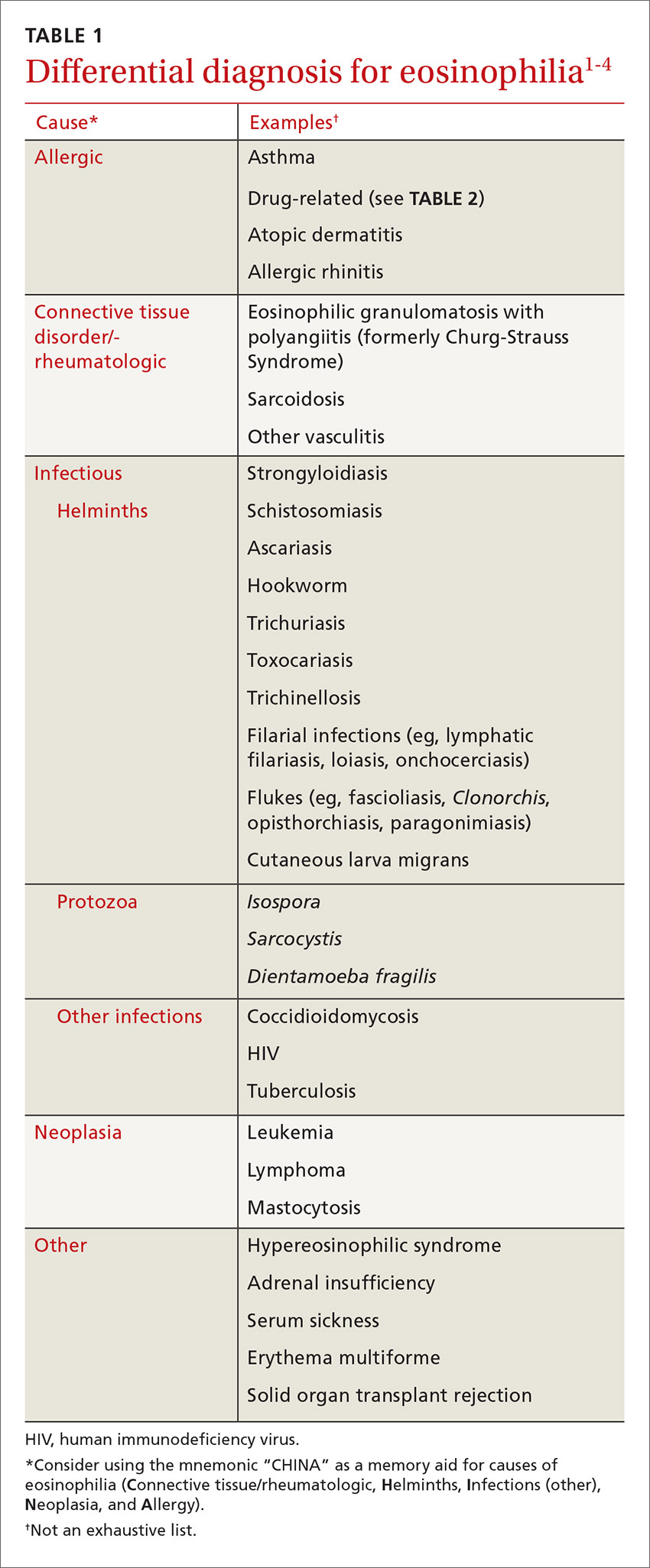

Radiologic evaluation may be beneficial—especially with nasal lesions—when looking for findings suggestive of malignancy. Both CT and magnetic resonance imaging with contrast identify PG as a soft tissue mass with lobulated contours,9,10 but histopathologic analysis is required to confirm the diagnosis. The histopathologic appearance of PG is characterized by a polypoid lesion with circumscribed anastomosing networks of capillaries arranged in one or more lobules at the base in an edematous and fibroblastic stroma.

Treatment is determined by the location and size of the lesion

The most suitable treatment is determined by considering the location of the lesion, the characteristics of the lesion (morphology/size), its amenability to surgery, risk of scar formation, and the presence or absence of a causative irritant. Excision is often preferred because it yields a specimen for pathologic analysis. Alternative treatments include electrocautery, cryotherapy, laser therapy, and intralesional and topical agents,3,6,7 but the recurrence rate is higher (up to 15%) with some of these modalities, when compared with excision (3.6%).3

Our patient underwent excision of the mass and was seen for an annual follow-up appointment. All of her symptoms resolved and no recurrence was noted.

THE TAKEAWAY

Although PG is a common and benign condition, it is rarely seen in the nasal cavity without an obvious history of a possible irritant. PG should be considered as a diagnosis for rapidly growing cutaneous or mucosal hemorrhagic lesions. Appropriate tissue pathology is essential to rule out malignancy and other serious conditions, such as bacillary angiomatosis and Wegener’s granulomatosis.

Treatment is usually required to avoid the frequent complications of ulceration and bleeding. Surgical treatments are preferred. The location of the lesion largely determines whether referral to a specialist is necessary.

THE CASE

A 49-year-old woman visited our family medicine clinic because she’d had 3 episodes of epistaxis during the previous month. She’d already visited the emergency department, and the doctor there had treated her symptomatically and referred her to our clinic.

On physical examination, we noted a whitish mass in the patient’s right nostril that was attached to the nasal septum. The patient’s vital signs were within normal limits. She had a history of hypertension, depression, anxiety, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Her medications included amlodipine-benazepril, atenolol-chlorthalidone, citalopram, clonazepam, prazosin, and omeprazole. The patient lived alone and denied using tobacco or illicit drugs, but she drank one to 2 glasses of brandy every day. She denied any past medical or family history of similar complaints, autoimmune disorders, or skin rashes.

A complete blood count, international normalized ratio, sedimentation rate, anti-nuclear antibody test, and an anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody panel were normal.

THE DIAGNOSIS

We referred the patient to an ear, nose, and throat doctor for a nasal endoscopy and a biopsy, which showed granulation tissue. A maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 1.44 cm x 0.8 cm polypoid soft tissue mass in the right nasal cavity adherent to the nasal septum with no posterior extension (FIGURE 1).

DISCUSSION

Pyogenic granuloma (PG) is a benign vascular tumor of the skin and mucous membranes that is not associated with an infection. Rather, it is a hyperplastic, neovascular, inflammatory response to an angiogenic stimulus. Several enhancers and inhibitors of angiogenesis have been shown to play a role in PG, including hormones, medications, and local injury. In fact, a local injury or hormonal factor is identified as a stimulus in more than half of PG patients.1

The hormone connection. Estrogen promotes production of nerve growth factor, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, and transforming growth factor beta 1. Progesterone enhances inflammatory mediators as well. Although there are no direct receptors for estrogen and progesterone in the oral and nasal mucosa, some of these pro-inflammatory effects create an environment conducive to the development of PG. This is supported by several studies documenting an increased incidence of PGs with oral contraceptive use and regression of PGs after childbirth.2-4

Medication may play a role. Drug-induced PG has also been described in several studies.5,6 Offending medications include systemic and topical retinoids, capecitabine, etoposide, 5-fluorouracil, cyclosporine, docetaxel, and human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors.

Local injury may also be a culprit. Nasal PGs are commonly attached to the anterior septum and typically result from nasal packing, habitual picking, or nose boring.7 In this particular case, however, we were unable to identify the irritant.

The classic presentation

PG classically presents as a painless mass that spontaneously develops over days to weeks. The mass can be sessile or pedunculated, and is frequently hemorrhagic. Intranasal PG usually presents with epiphora.7 While the prevalence of intraoral PG was found to be one in 25,000 individuals3, data for nasal lesions is scarce. Most cases of PG are seen in the second and third decades of life.1,3 In children, PG is slightly more predominant in males.1,3 Mucosal lesions, however, have a higher incidence in females.1,3 Granuloma gravidarum, the term used to describe mucosal PG in pregnant females, was found in 0.2% to 5% of pregnancies.2,3,8

Differential Dx includes warts, squamous cell carcinoma

The differential diagnosis of PG includes Spitz nevus, glomus tumors, common warts, amelanotic melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma, bacillary angiomatosis, infantile hemangioma, and angiolymphoid hyperplasia, among others.3,5 Foreign bodies, nasal polyps, angiofibroma, meningocele, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and sarcoidosis should also be considered.

Radiologic evaluation may be beneficial—especially with nasal lesions—when looking for findings suggestive of malignancy. Both CT and magnetic resonance imaging with contrast identify PG as a soft tissue mass with lobulated contours,9,10 but histopathologic analysis is required to confirm the diagnosis. The histopathologic appearance of PG is characterized by a polypoid lesion with circumscribed anastomosing networks of capillaries arranged in one or more lobules at the base in an edematous and fibroblastic stroma.

Treatment is determined by the location and size of the lesion

The most suitable treatment is determined by considering the location of the lesion, the characteristics of the lesion (morphology/size), its amenability to surgery, risk of scar formation, and the presence or absence of a causative irritant. Excision is often preferred because it yields a specimen for pathologic analysis. Alternative treatments include electrocautery, cryotherapy, laser therapy, and intralesional and topical agents,3,6,7 but the recurrence rate is higher (up to 15%) with some of these modalities, when compared with excision (3.6%).3

Our patient underwent excision of the mass and was seen for an annual follow-up appointment. All of her symptoms resolved and no recurrence was noted.

THE TAKEAWAY