User login

A Case Series of Rare Immune-Mediated Adverse Reactions at the New Mexico Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), often broadly referred to as immunotherapy, are being prescribed at increasing rates due to their effectiveness in treating a growing number of advanced solid tumors and hematologic malignancies.1 It has been well established that T-cell signaling mechanisms designed to combat foreign pathogens have been involved in the mitigation of tumor proliferation.2 This protective process can be supported or restricted by infection, medication, or mutations.

ICIs support T-cell–mediated destruction of tumor cells by inhibiting the mechanisms designed to limit autoimmunity, specifically the programmed cell death protein 1/programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) pathways. The results have been impressive, leading to an expansive number of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals across a diverse set of malignancies. Consequently, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded for such work in 2018.3

BACKGROUND

While altering these pathways has been shown to hinder tumor growth, the lesser restrictions on the immune system can drive unwanted autoimmune inflammation to host tissue. These toxicities are collectively known as immune-mediated adverse reactions (IMARs). Clinically and histologically, IMARs frequently manifest similarly to other autoimmune conditions and may affect any organ, including skin, liver, lungs, heart, intestine (small and large), kidneys, eyes, endocrine glands, and neurologic tissue.4,5 According to recent studies, as many as 20% to 30% of patients receiving a single ICI will experience at least 1 clinically significant IMAR, and about 13% are classified as severe; however, < 10% of patients will have their ICIs discontinued due to these reactions.6

Though infrequent, a thorough understanding of the severity of IMARs to ICIs is critical for the diagnosis and management of these organ-threatening and potentially life-threatening toxicities. With the growing use of these agents and more FDA approvals for dual checkpoint blockage (concurrent use of CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors), the absolute number of IMARs is expected to rise, thereby leading to more exposure of such events to both oncology and nononcology clinicians. Prior literature has clearly described the treatments and outcomes for many common severe toxicities; however, information regarding presentations and outcomes for rare IMARs is lacking.7

A few fascinating cases of rare toxicities have been observed at the New Mexico Veterans Affairs Medical Center (NMVAMC) in Albuquerque despite its relatively small size compared with other US Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers. As such, herein, the diagnostic evaluation, treatments, and outcomes of rare IMARs are reported for each case, and the related literature is reviewed.

Patient Selection

Patients who were required to discontinue or postpone treatment with any ICI blocking the CTLA-4 (ipilimumab), PD-1 (pembrolizumab, nivolumab, cemiplimab), or PD-L1 (atezolizumab, avelumab, durvalumab) pathways between 2015 to 2021 due to toxicity at the NMVAMC were eligible for inclusion. The electronic health record was reviewed for each eligible case, and the patient demographics, disease characteristics, toxicities, and outcomes were documented for each patient. For the 57 patients who received ICIs within the chosen period, 11 required a treatment break or discontinuation. Of these, 3 cases were selected for reporting due to the rare IMARs observed. This study was approved by the NMVAMC Institutional Review Board.

Case 1: Myocarditis

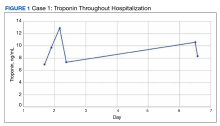

An 84-year-old man receiving a chemoimmunotherapy regimen consisting of carboplatin, pemetrexed, and pembrolizumab for recurrent, stage IV lung adenocarcinoma developed grade 4 cardiomyopathy, as defined by the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v5.0, during his treatment.8 He was treated for 2 cycles before he began experiencing an increase in liver enzymes.

The patient’s presentation was concerning for myocarditis, and he was quickly admitted to NMVAMC. Cardiac catheterization did not reveal any signs of coronary occlusive disease. Prednisone 1 mg/kg was administered immediately; however, given continued chest pain and volume overload, he was quickly transitioned to solumedrol 1000 mg IV daily. After the initiation of his treatment, the patient’s transaminitis began to resolve, and troponin levels began to decrease; however, his symptoms continued to worsen, and his troponin rose again. By the fourth day of hospitalization, the patient was treated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor shown to reverse ICI-induced autoimmune inflammation, with only mild improvement of his symptoms. The patient’s condition continued to deteriorate, his troponin levels remained elevated, and his family decided to withhold additional treatment. The patient died shortly thereafter.

Discussion

Cardiotoxicity resulting from ICI therapy is far less common than the other potential severe toxicities associated with ICIs. Nevertheless, many cases of ICI-induced cardiac inflammation have been reported, and it has been widely established that patients treated with ICIs are generally at higher risk for acute coronary syndrome.9-11 Acute cardiotoxicity secondary to autoimmune destruction of cardiac tissue includes myocarditis, pericarditis, and vasculitis, which may manifest with symptoms of heart failure and/or arrhythmia. Grading of ICI-induced cardiomyopathy has been defined by both CTCAE and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), with grade 4 representing moderate to severe clinical decompensation requiring IV medications in the setting of life-threatening conditions.

Review articles have described the treatment options for severe cases.7,12 As detailed in prior reports, once ICI-induced cardiomyopathy is suspected, urgent admission and immediate evaluation to rule out acute coronary syndrome should be undertaken. Given the potential for deterioration despite the occasional insidious onset, aggressive cardiac monitoring, and close follow-up to measure response to interventions should be undertaken.

Case 2: Uveitis

A 70-year-old man who received pembrolizumab as a bladder-sparing approach for his superficial bladder cancer refractory to intravesical treatments developed uveitis. Approximately 3 months following the initiation of treatment, the patient reported bilateral itchy eyes, erythema, and tearing. He had a known history of allergic conjunctivitis that predated the ICI therapy, and consequently, it was unclear whether his symptoms were reflective of a more concerning issue. The patient’s symptoms continued to wax and wane for a few months, prompting a referral to ophthalmology colleagues at NMVAMC.

Ophthalmology evaluation identified uveitic glaucoma in the setting of his underlying chronic glaucoma. Pembrolizumab was discontinued, and the patient was counseled on choosing either cystectomy or locoregional therapies if further tumors arose. However, within a few weeks of administering topical steroid drops, his symptoms markedly improved, and he wished to be restarted on pembrolizumab. His uveitis remained in remission, and he has been treated with pembrolizumab for more than 1 year since this episode. He has had no clear findings of superficial bladder cancer recurrence while receiving ICI therapy.

Discussion

Uveitis is a known complication of pembrolizumab, and it has been shown to occur in 1% of patients with this treatment.13,14 It should be noted that most of the studies of this IMAR occurred in patients with metastatic melanoma; therefore the rate of this condition in other patients is less understood. Overall, ocular IMARs secondary to anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 therapies are rare.

The most common IMAR is surface ocular disease, consisting of dry eye disease (DED), conjunctivitis, uveitis, and keratitis. Of these, the most common ocular surface disease is DED, which occurred in 1% to 4% of patients treated with ICI therapy; most of these reactions are mild and self-limiting.15 Atezolizumab has the highest association with ocular inflammation and ipilimumab has the highest association with uveitis, with reported odds ratios of 18.89 and 10.54, respectively.16 Treatment of ICI-induced uveitis generally includes topical steroids and treatment discontinuation or break.17 Oral or IV steroids, infliximab, and procedural involvement may be considered in refractory cases or those initially presenting with marked vision loss. Close communication with ophthalmology colleagues to monitor visual acuity and ocular pressure multiple times weekly during the acute phase is required for treatment titration.

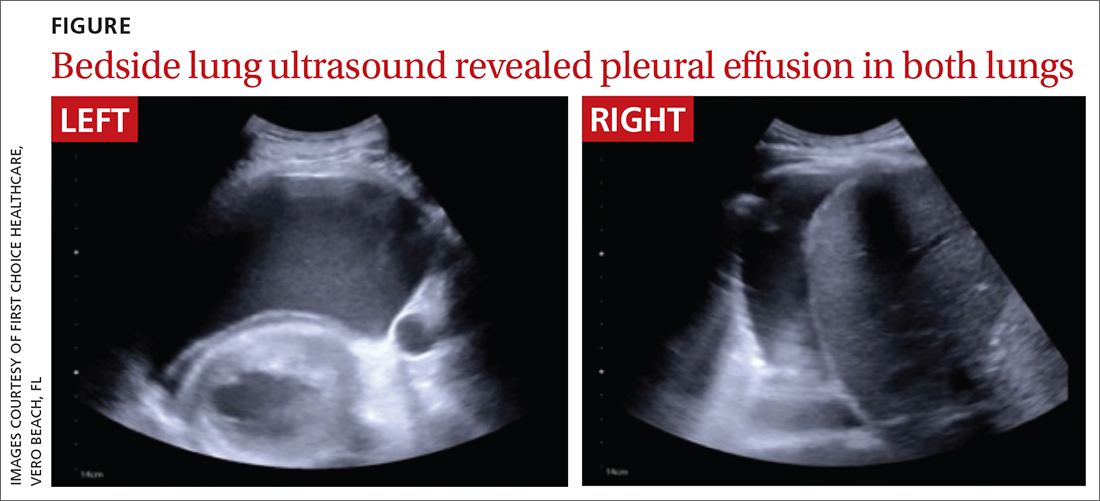

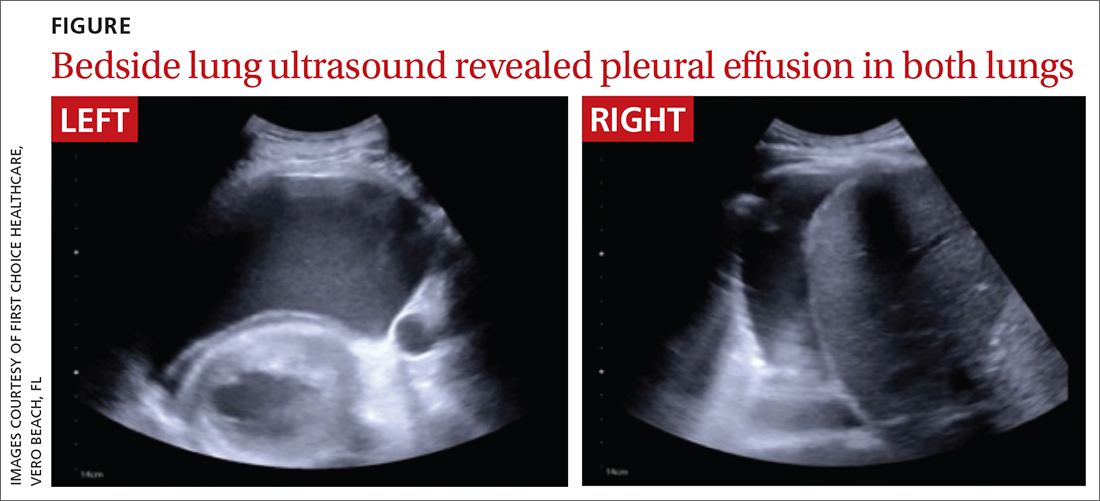

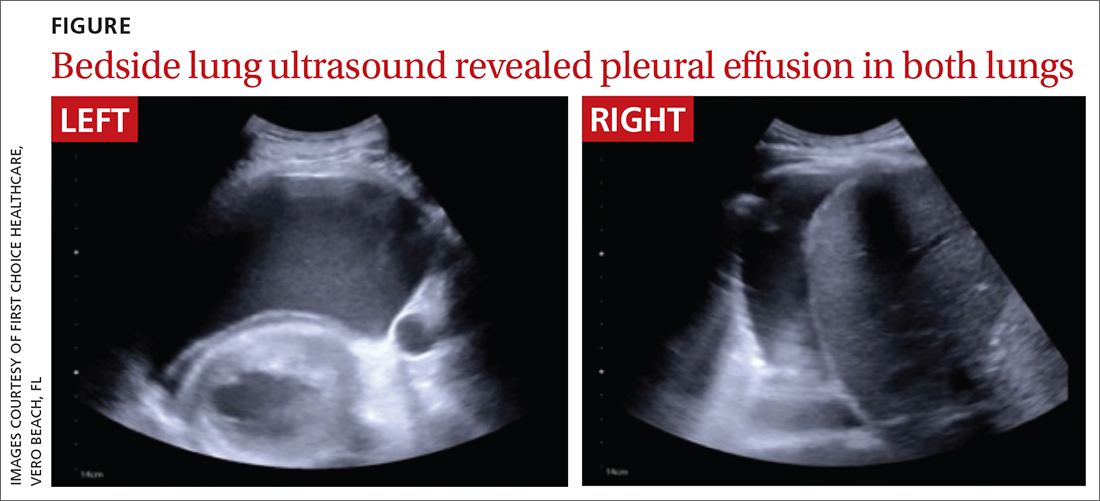

Case 3: Organizing Pneumonia

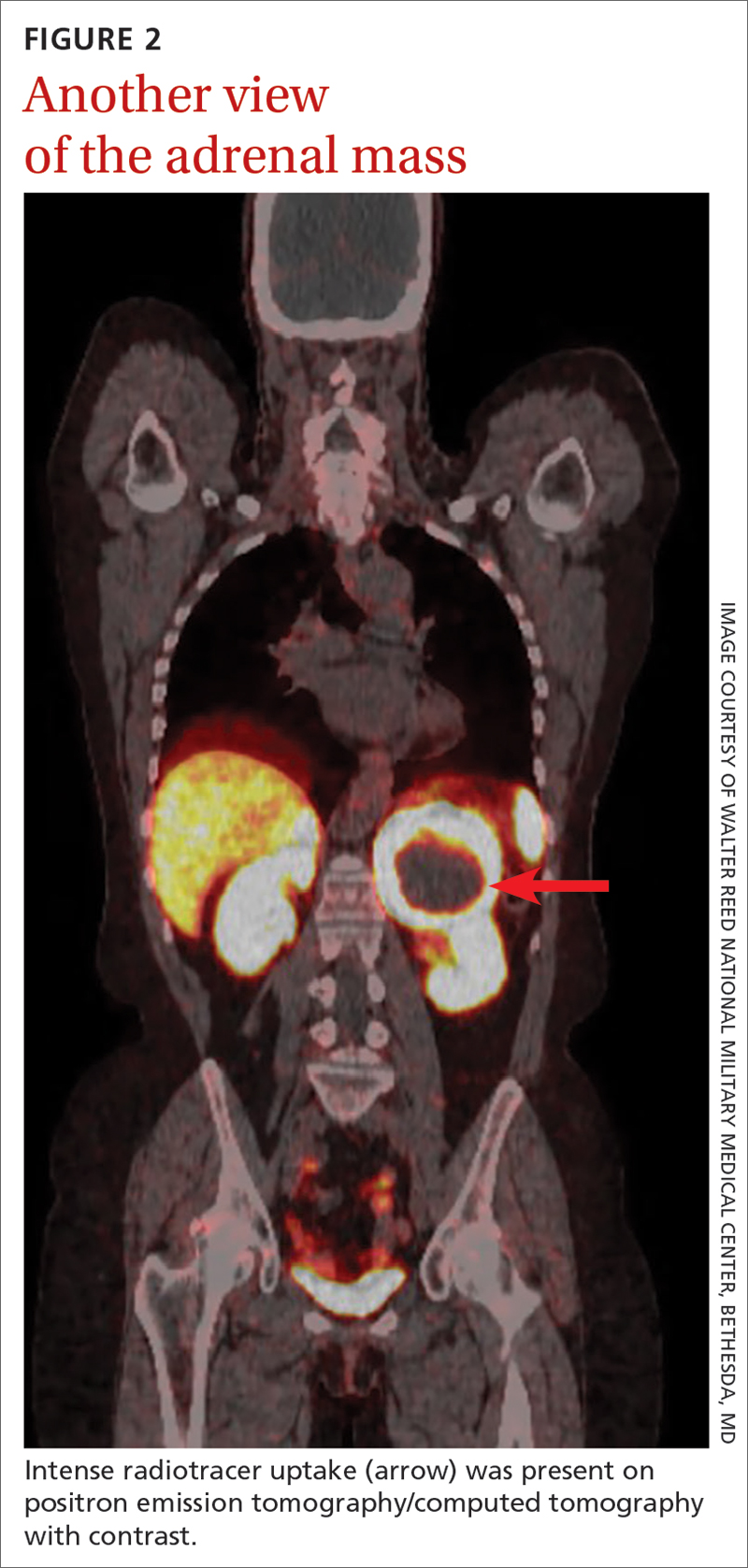

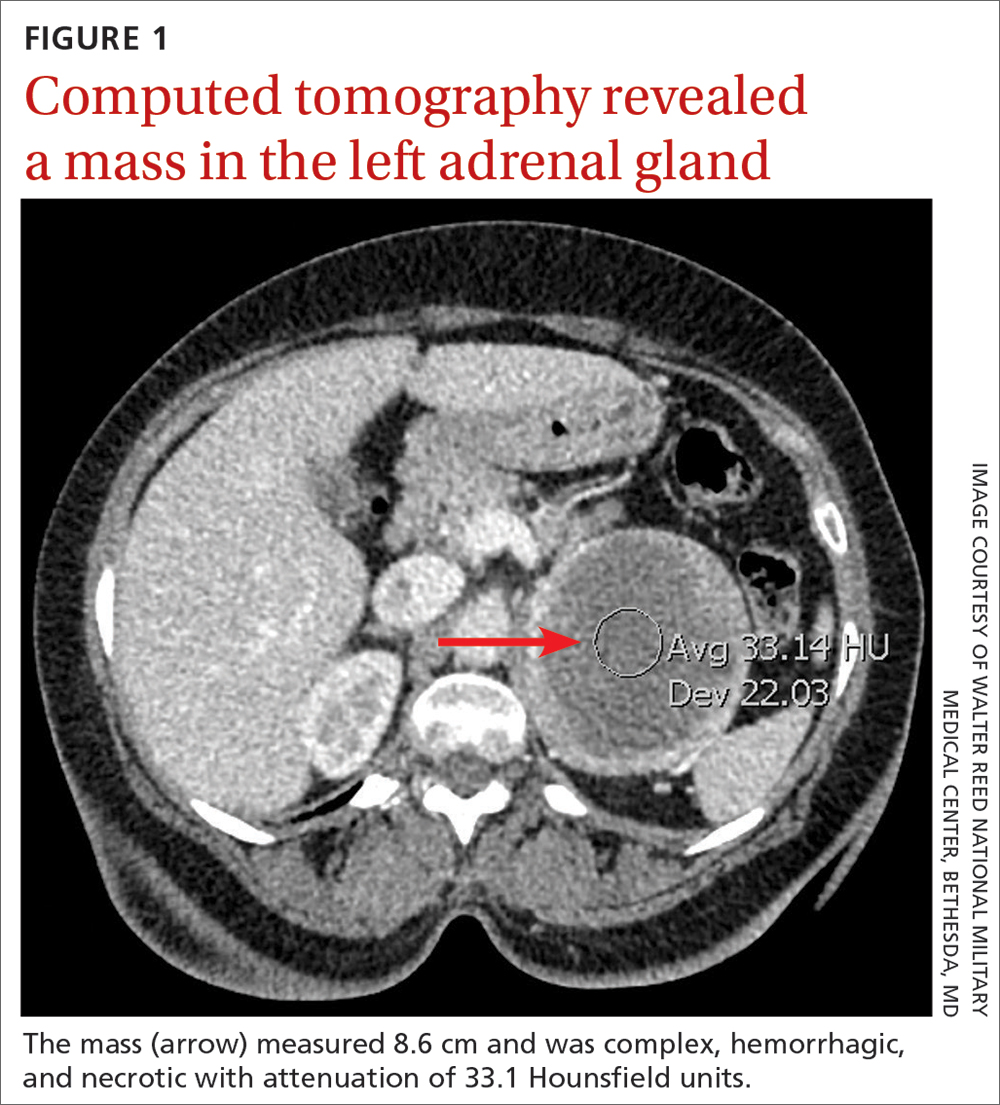

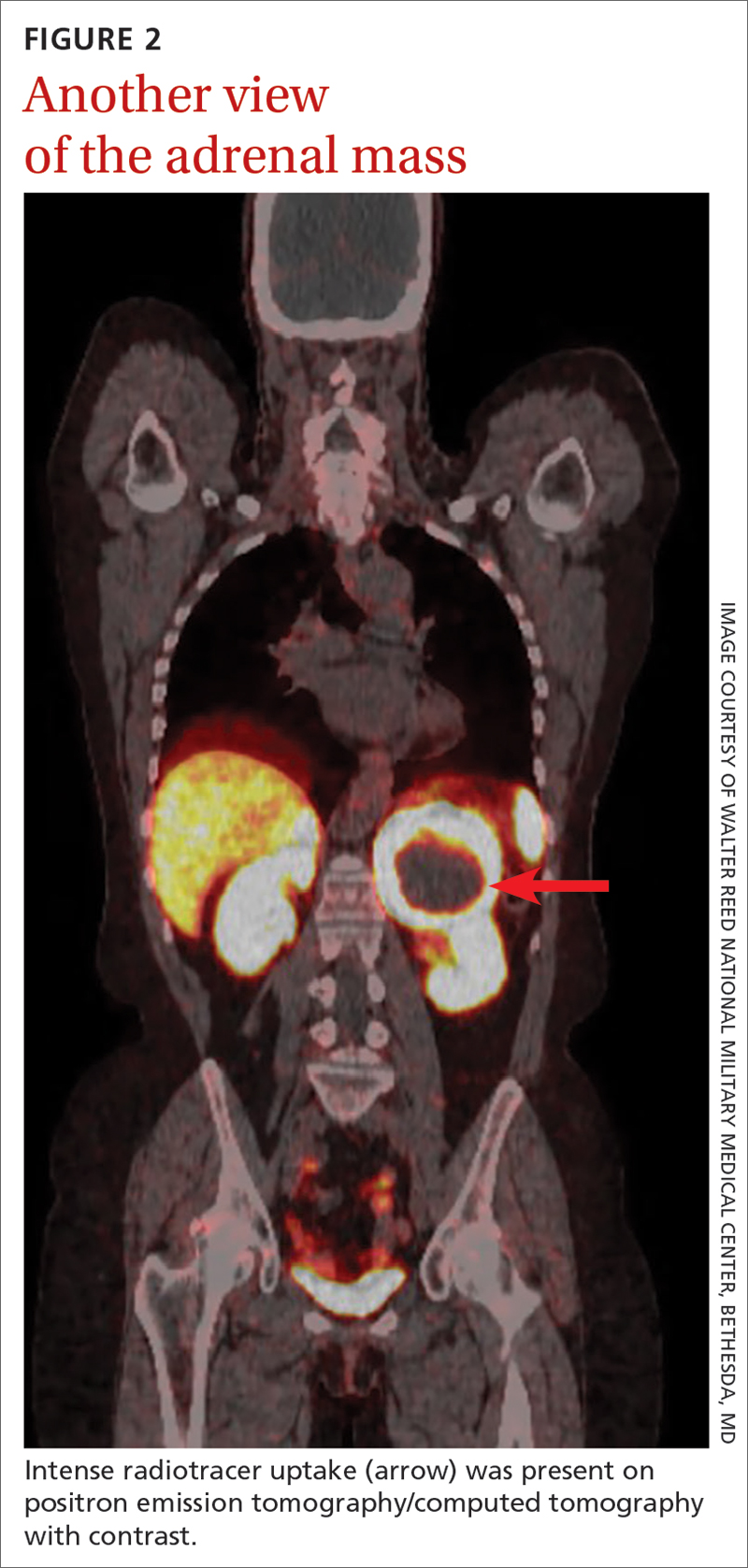

A man aged 63 years was diagnosed with malignant mesothelioma after incidentally noting a pleural effusion and thickening on routine low-dose computed tomography surveillance of pulmonary nodules. A biopsy was performed and was consistent with mesothelioma, and the patient was started on nivolumab (PD-1 inhibitor) and ipilimumab (CTLA-4 inhibitor). The patient was initiated on dual ICIs, and after 6 months of therapy, he had a promising complete response. However, after 9 months of therapy, he developed a new left upper lobe (LUL) pleural-based lesion (Figure 2A).

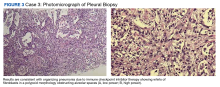

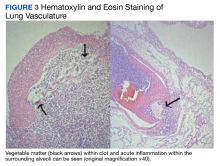

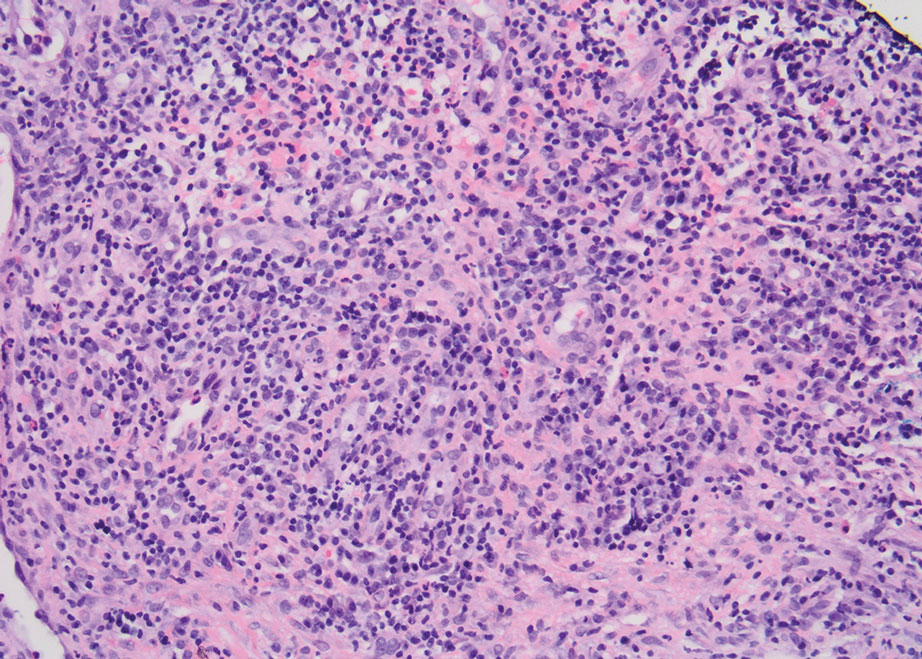

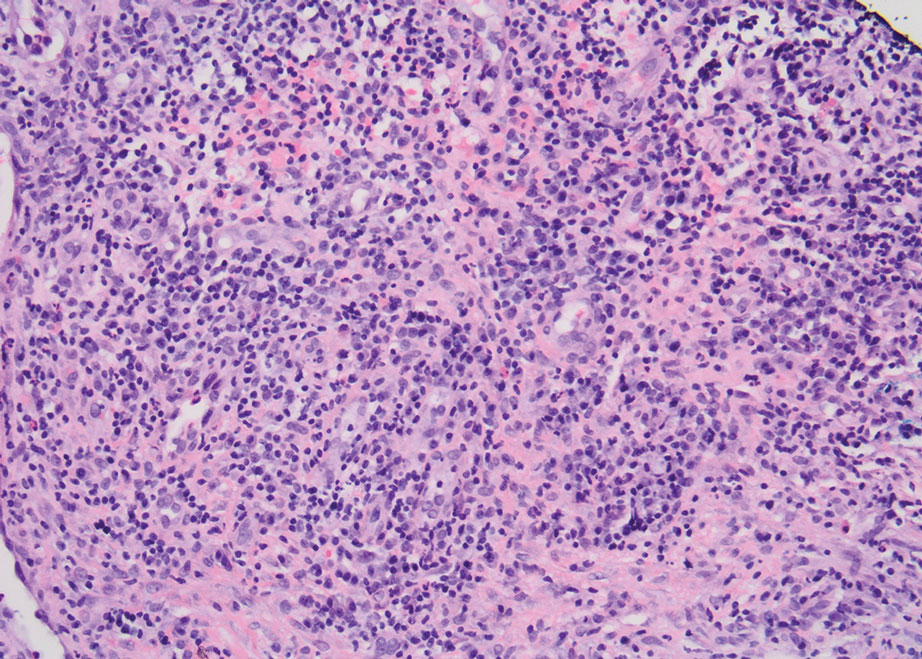

A biopsy was performed, and the histopathologic appearance was consistent with organizing pneumonia (OP) (Figure 3).

Discussion

ICIs can uncommonly drive pneumonitis, with the frequency adjusted based on the number of ICIs prescribed and the primary cancer involved. Across all cancers, up to 5% of patients treated with single-agent ICI therapy may experience pneumonitis, though often the findings may simply be radiographic without symptoms. Moreover, up to 10% of patients undergoing treatment for pulmonary cancer or those with dual ICI treatment regimens experience radiographic and/or clinical pneumonitis.18 The clinical manifestations include a broad spectrum of respiratory symptoms. Given the convoluting concerns of cancer progression and infection, a biopsy is often obtained. Histopathologic findings of pneumonitis may include diffuse alveolar damage and/or interstitial lung disease, with OP being a rare variant of ILD.

Among pulmonologists, OP is felt to have polymorphous imaging findings, and biopsy is required to confirm histology; however, histopathology cannot define etiology, and consequently, OP is somewhat of an umbrella diagnosis. The condition can be cryptogenic (idiopathic) or secondary to a multitude of conditions (infection, drug toxicity, or systemic disease). It is classically described as polypoid aggregations of fibroblasts that obstruct the alveolar spaces.19 This histopathologic pattern was demonstrated in our patient’s lung biopsy. Given a prior case description of ICIs, mesothelioma, OP development, and the unremarkable infectious workup, we felt that the patient’s OP was driven by his dual ICI therapy, thereby leading to the ultimate discontinuation of his ICIs and initiation of steroids.20 Thankfully, the patient had already obtained a complete response to his ICIs, and hopefully, he can attain a durable remission with the addition of maintenance chemotherapy.

CONCLUSIONS

ICIs have revolutionized the treatment of a myriad of solid tumors and hematologic malignancies, and their use internationally is expected to increase. With the alteration in immunology pathways, clinicians in all fields will need to be familiarized with IMARs secondary to these agents, including rare subtypes. In addition, the variability in presentations relative to the patients’ treatment course was significant (between 2-9 months), and this highlights that these IMARs can occur at any time point and clinicians should be ever vigilant to spot symptoms in their patients.

It was unexpected for the 3 aforementioned rare toxicities to arise at NMVAMC among only 57 treated patients, and we speculate that these findings may have been observed for 1 of 3 reasons. First, caring for 3 patients with this collection of rare toxicities may have been due to chance. Second, though there is sparse literature studying the topic, the regional environment, including sunlight exposure and air quality, may play a role in the development of one or all of these rare toxicities. Third, rates of these toxicities may be underreported in the literature or attributed to other conditions rather than due to ICIs at other sites, and the uncommon nature of these IMARs may be overstated. Investigations evaluating rates of toxicities, including those traditionally uncommonly seen, based on regional location should be conducted before any further conclusions are drawn.

1. Bagchi S, Yuan R, Engleman EG. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of cancer: clinical impact and mechanisms of response and resistance. Published online 2020. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathol-042020

2. Chen DS, Mellman I. Oncology meets immunology: The cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity. 2013;39(1):1-10. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.012

3. Smyth MJ, Teng MWL. 2018 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine. Clin Transl Immunology. 2018;7(10). doi:10.1002/cti2.1041

4. Baxi S, Yang A, Gennarelli RL, et al. Immune-related adverse events for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 drugs: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Online). 2018;360. doi:10.1136/bmj.k793

5. Ellithi M, Elnair R, Chang GV, Abdallah MA. Toxicities of immune checkpoint inhibitors: itis-ending adverse reactions and more. Cureus. Published online February 10, 2020. doi:10.7759/cureus.6935

6. Berti A, Bortolotti R, Dipasquale M, et al. Meta-analysis of immune-related adverse events in phase 3 clinical trials assessing immune checkpoint inhibitors for lung cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;162. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103351

7. Davies M, Duffield EA. Safety of checkpoint inhibitors for cancer treatment: strategies for patient monitoring and management of immune-mediated adverse events. Immunotargets Ther. 2017;Volume 6:51-71. doi:10.2147/itt.s141577

8. US Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events V5.0. Accessed July 17, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5584920/

9. Johnson DB, Balko JM, Compton ML, et al. Fulminant myocarditis with combination immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(18):1749-1755. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1609214

10. Mahmood SS, Fradley MG, Cohen J V., et al. Myocarditis in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(16):1755-1764. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.037

11. Wang DY, Salem JE, Cohen JV, et al. Fatal toxic effects associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(12):1721-1728. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.3923

12. Brahmer JR, Lacchetti C, Schneider BJ, et al; National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Onc. 2018;36(17):1714-1768. doi:10.1200/JCO

13. Ribas A, Hamid O, Daud A, et al. Association of pembrolizumab with tumor response and survival among patients with advanced melanoma. JAMA. 2016;315:1600-1609. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.4059

14. Dalvin LA, Shields CL, Orloff M, Sato T, Shields JA. Checkpoint inhibitor immune therapy: systemic indications and ophthalmic side effects. Retina. 2018;38(6):1063-1078. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000002181

15. Park RB, Jain S, Han H, Park J. Ocular surface disease associated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Ocular Surface. 2021;20:115-129. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2021.02.004

16. Fang T, Maberley DA, Etminan M. Ocular adverse events with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Curr Ophthalmol. 2019;31(3):319-322. doi:10.1016/j.joco.2019.05.002

17. Whist E, Symes RJ, Chang JH, et al. Uveitis caused by treatment for malignant melanoma: a case series. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2021;15(6):718-723. doi:10.1097/ICB.0000000000000876

18. Naidoo J, Wang X, Woo KM, et al. Pneumonitis in patients treated with anti-programmed death-1/programmed death ligand 1 therapy. J Clin Onc. 2017;35(7):709-717. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.68.2005

19. Yoshikawa A, Bychkov A, Sathirareuangchai S. Other nonneoplastic conditions, acute lung injury, organizing pneumonia. Accessed July 17, 2023. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/lungnontumorboop.html

20. Kuint R, Lotem M, Neuman T, et al. Organizing pneumonia following treatment with pembrolizumab for metastatic malignant melanoma–a case report. Respir Med Case Rep. 2017;20:95-97. doi:10.1016/j.rmcr.2017.01.003

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), often broadly referred to as immunotherapy, are being prescribed at increasing rates due to their effectiveness in treating a growing number of advanced solid tumors and hematologic malignancies.1 It has been well established that T-cell signaling mechanisms designed to combat foreign pathogens have been involved in the mitigation of tumor proliferation.2 This protective process can be supported or restricted by infection, medication, or mutations.

ICIs support T-cell–mediated destruction of tumor cells by inhibiting the mechanisms designed to limit autoimmunity, specifically the programmed cell death protein 1/programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) pathways. The results have been impressive, leading to an expansive number of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals across a diverse set of malignancies. Consequently, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded for such work in 2018.3

BACKGROUND

While altering these pathways has been shown to hinder tumor growth, the lesser restrictions on the immune system can drive unwanted autoimmune inflammation to host tissue. These toxicities are collectively known as immune-mediated adverse reactions (IMARs). Clinically and histologically, IMARs frequently manifest similarly to other autoimmune conditions and may affect any organ, including skin, liver, lungs, heart, intestine (small and large), kidneys, eyes, endocrine glands, and neurologic tissue.4,5 According to recent studies, as many as 20% to 30% of patients receiving a single ICI will experience at least 1 clinically significant IMAR, and about 13% are classified as severe; however, < 10% of patients will have their ICIs discontinued due to these reactions.6

Though infrequent, a thorough understanding of the severity of IMARs to ICIs is critical for the diagnosis and management of these organ-threatening and potentially life-threatening toxicities. With the growing use of these agents and more FDA approvals for dual checkpoint blockage (concurrent use of CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors), the absolute number of IMARs is expected to rise, thereby leading to more exposure of such events to both oncology and nononcology clinicians. Prior literature has clearly described the treatments and outcomes for many common severe toxicities; however, information regarding presentations and outcomes for rare IMARs is lacking.7

A few fascinating cases of rare toxicities have been observed at the New Mexico Veterans Affairs Medical Center (NMVAMC) in Albuquerque despite its relatively small size compared with other US Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers. As such, herein, the diagnostic evaluation, treatments, and outcomes of rare IMARs are reported for each case, and the related literature is reviewed.

Patient Selection

Patients who were required to discontinue or postpone treatment with any ICI blocking the CTLA-4 (ipilimumab), PD-1 (pembrolizumab, nivolumab, cemiplimab), or PD-L1 (atezolizumab, avelumab, durvalumab) pathways between 2015 to 2021 due to toxicity at the NMVAMC were eligible for inclusion. The electronic health record was reviewed for each eligible case, and the patient demographics, disease characteristics, toxicities, and outcomes were documented for each patient. For the 57 patients who received ICIs within the chosen period, 11 required a treatment break or discontinuation. Of these, 3 cases were selected for reporting due to the rare IMARs observed. This study was approved by the NMVAMC Institutional Review Board.

Case 1: Myocarditis

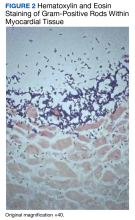

An 84-year-old man receiving a chemoimmunotherapy regimen consisting of carboplatin, pemetrexed, and pembrolizumab for recurrent, stage IV lung adenocarcinoma developed grade 4 cardiomyopathy, as defined by the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v5.0, during his treatment.8 He was treated for 2 cycles before he began experiencing an increase in liver enzymes.

The patient’s presentation was concerning for myocarditis, and he was quickly admitted to NMVAMC. Cardiac catheterization did not reveal any signs of coronary occlusive disease. Prednisone 1 mg/kg was administered immediately; however, given continued chest pain and volume overload, he was quickly transitioned to solumedrol 1000 mg IV daily. After the initiation of his treatment, the patient’s transaminitis began to resolve, and troponin levels began to decrease; however, his symptoms continued to worsen, and his troponin rose again. By the fourth day of hospitalization, the patient was treated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor shown to reverse ICI-induced autoimmune inflammation, with only mild improvement of his symptoms. The patient’s condition continued to deteriorate, his troponin levels remained elevated, and his family decided to withhold additional treatment. The patient died shortly thereafter.

Discussion

Cardiotoxicity resulting from ICI therapy is far less common than the other potential severe toxicities associated with ICIs. Nevertheless, many cases of ICI-induced cardiac inflammation have been reported, and it has been widely established that patients treated with ICIs are generally at higher risk for acute coronary syndrome.9-11 Acute cardiotoxicity secondary to autoimmune destruction of cardiac tissue includes myocarditis, pericarditis, and vasculitis, which may manifest with symptoms of heart failure and/or arrhythmia. Grading of ICI-induced cardiomyopathy has been defined by both CTCAE and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), with grade 4 representing moderate to severe clinical decompensation requiring IV medications in the setting of life-threatening conditions.

Review articles have described the treatment options for severe cases.7,12 As detailed in prior reports, once ICI-induced cardiomyopathy is suspected, urgent admission and immediate evaluation to rule out acute coronary syndrome should be undertaken. Given the potential for deterioration despite the occasional insidious onset, aggressive cardiac monitoring, and close follow-up to measure response to interventions should be undertaken.

Case 2: Uveitis

A 70-year-old man who received pembrolizumab as a bladder-sparing approach for his superficial bladder cancer refractory to intravesical treatments developed uveitis. Approximately 3 months following the initiation of treatment, the patient reported bilateral itchy eyes, erythema, and tearing. He had a known history of allergic conjunctivitis that predated the ICI therapy, and consequently, it was unclear whether his symptoms were reflective of a more concerning issue. The patient’s symptoms continued to wax and wane for a few months, prompting a referral to ophthalmology colleagues at NMVAMC.

Ophthalmology evaluation identified uveitic glaucoma in the setting of his underlying chronic glaucoma. Pembrolizumab was discontinued, and the patient was counseled on choosing either cystectomy or locoregional therapies if further tumors arose. However, within a few weeks of administering topical steroid drops, his symptoms markedly improved, and he wished to be restarted on pembrolizumab. His uveitis remained in remission, and he has been treated with pembrolizumab for more than 1 year since this episode. He has had no clear findings of superficial bladder cancer recurrence while receiving ICI therapy.

Discussion

Uveitis is a known complication of pembrolizumab, and it has been shown to occur in 1% of patients with this treatment.13,14 It should be noted that most of the studies of this IMAR occurred in patients with metastatic melanoma; therefore the rate of this condition in other patients is less understood. Overall, ocular IMARs secondary to anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 therapies are rare.

The most common IMAR is surface ocular disease, consisting of dry eye disease (DED), conjunctivitis, uveitis, and keratitis. Of these, the most common ocular surface disease is DED, which occurred in 1% to 4% of patients treated with ICI therapy; most of these reactions are mild and self-limiting.15 Atezolizumab has the highest association with ocular inflammation and ipilimumab has the highest association with uveitis, with reported odds ratios of 18.89 and 10.54, respectively.16 Treatment of ICI-induced uveitis generally includes topical steroids and treatment discontinuation or break.17 Oral or IV steroids, infliximab, and procedural involvement may be considered in refractory cases or those initially presenting with marked vision loss. Close communication with ophthalmology colleagues to monitor visual acuity and ocular pressure multiple times weekly during the acute phase is required for treatment titration.

Case 3: Organizing Pneumonia

A man aged 63 years was diagnosed with malignant mesothelioma after incidentally noting a pleural effusion and thickening on routine low-dose computed tomography surveillance of pulmonary nodules. A biopsy was performed and was consistent with mesothelioma, and the patient was started on nivolumab (PD-1 inhibitor) and ipilimumab (CTLA-4 inhibitor). The patient was initiated on dual ICIs, and after 6 months of therapy, he had a promising complete response. However, after 9 months of therapy, he developed a new left upper lobe (LUL) pleural-based lesion (Figure 2A).

A biopsy was performed, and the histopathologic appearance was consistent with organizing pneumonia (OP) (Figure 3).

Discussion

ICIs can uncommonly drive pneumonitis, with the frequency adjusted based on the number of ICIs prescribed and the primary cancer involved. Across all cancers, up to 5% of patients treated with single-agent ICI therapy may experience pneumonitis, though often the findings may simply be radiographic without symptoms. Moreover, up to 10% of patients undergoing treatment for pulmonary cancer or those with dual ICI treatment regimens experience radiographic and/or clinical pneumonitis.18 The clinical manifestations include a broad spectrum of respiratory symptoms. Given the convoluting concerns of cancer progression and infection, a biopsy is often obtained. Histopathologic findings of pneumonitis may include diffuse alveolar damage and/or interstitial lung disease, with OP being a rare variant of ILD.

Among pulmonologists, OP is felt to have polymorphous imaging findings, and biopsy is required to confirm histology; however, histopathology cannot define etiology, and consequently, OP is somewhat of an umbrella diagnosis. The condition can be cryptogenic (idiopathic) or secondary to a multitude of conditions (infection, drug toxicity, or systemic disease). It is classically described as polypoid aggregations of fibroblasts that obstruct the alveolar spaces.19 This histopathologic pattern was demonstrated in our patient’s lung biopsy. Given a prior case description of ICIs, mesothelioma, OP development, and the unremarkable infectious workup, we felt that the patient’s OP was driven by his dual ICI therapy, thereby leading to the ultimate discontinuation of his ICIs and initiation of steroids.20 Thankfully, the patient had already obtained a complete response to his ICIs, and hopefully, he can attain a durable remission with the addition of maintenance chemotherapy.

CONCLUSIONS

ICIs have revolutionized the treatment of a myriad of solid tumors and hematologic malignancies, and their use internationally is expected to increase. With the alteration in immunology pathways, clinicians in all fields will need to be familiarized with IMARs secondary to these agents, including rare subtypes. In addition, the variability in presentations relative to the patients’ treatment course was significant (between 2-9 months), and this highlights that these IMARs can occur at any time point and clinicians should be ever vigilant to spot symptoms in their patients.

It was unexpected for the 3 aforementioned rare toxicities to arise at NMVAMC among only 57 treated patients, and we speculate that these findings may have been observed for 1 of 3 reasons. First, caring for 3 patients with this collection of rare toxicities may have been due to chance. Second, though there is sparse literature studying the topic, the regional environment, including sunlight exposure and air quality, may play a role in the development of one or all of these rare toxicities. Third, rates of these toxicities may be underreported in the literature or attributed to other conditions rather than due to ICIs at other sites, and the uncommon nature of these IMARs may be overstated. Investigations evaluating rates of toxicities, including those traditionally uncommonly seen, based on regional location should be conducted before any further conclusions are drawn.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), often broadly referred to as immunotherapy, are being prescribed at increasing rates due to their effectiveness in treating a growing number of advanced solid tumors and hematologic malignancies.1 It has been well established that T-cell signaling mechanisms designed to combat foreign pathogens have been involved in the mitigation of tumor proliferation.2 This protective process can be supported or restricted by infection, medication, or mutations.

ICIs support T-cell–mediated destruction of tumor cells by inhibiting the mechanisms designed to limit autoimmunity, specifically the programmed cell death protein 1/programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) pathways. The results have been impressive, leading to an expansive number of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals across a diverse set of malignancies. Consequently, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded for such work in 2018.3

BACKGROUND

While altering these pathways has been shown to hinder tumor growth, the lesser restrictions on the immune system can drive unwanted autoimmune inflammation to host tissue. These toxicities are collectively known as immune-mediated adverse reactions (IMARs). Clinically and histologically, IMARs frequently manifest similarly to other autoimmune conditions and may affect any organ, including skin, liver, lungs, heart, intestine (small and large), kidneys, eyes, endocrine glands, and neurologic tissue.4,5 According to recent studies, as many as 20% to 30% of patients receiving a single ICI will experience at least 1 clinically significant IMAR, and about 13% are classified as severe; however, < 10% of patients will have their ICIs discontinued due to these reactions.6

Though infrequent, a thorough understanding of the severity of IMARs to ICIs is critical for the diagnosis and management of these organ-threatening and potentially life-threatening toxicities. With the growing use of these agents and more FDA approvals for dual checkpoint blockage (concurrent use of CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors), the absolute number of IMARs is expected to rise, thereby leading to more exposure of such events to both oncology and nononcology clinicians. Prior literature has clearly described the treatments and outcomes for many common severe toxicities; however, information regarding presentations and outcomes for rare IMARs is lacking.7

A few fascinating cases of rare toxicities have been observed at the New Mexico Veterans Affairs Medical Center (NMVAMC) in Albuquerque despite its relatively small size compared with other US Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers. As such, herein, the diagnostic evaluation, treatments, and outcomes of rare IMARs are reported for each case, and the related literature is reviewed.

Patient Selection

Patients who were required to discontinue or postpone treatment with any ICI blocking the CTLA-4 (ipilimumab), PD-1 (pembrolizumab, nivolumab, cemiplimab), or PD-L1 (atezolizumab, avelumab, durvalumab) pathways between 2015 to 2021 due to toxicity at the NMVAMC were eligible for inclusion. The electronic health record was reviewed for each eligible case, and the patient demographics, disease characteristics, toxicities, and outcomes were documented for each patient. For the 57 patients who received ICIs within the chosen period, 11 required a treatment break or discontinuation. Of these, 3 cases were selected for reporting due to the rare IMARs observed. This study was approved by the NMVAMC Institutional Review Board.

Case 1: Myocarditis

An 84-year-old man receiving a chemoimmunotherapy regimen consisting of carboplatin, pemetrexed, and pembrolizumab for recurrent, stage IV lung adenocarcinoma developed grade 4 cardiomyopathy, as defined by the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v5.0, during his treatment.8 He was treated for 2 cycles before he began experiencing an increase in liver enzymes.

The patient’s presentation was concerning for myocarditis, and he was quickly admitted to NMVAMC. Cardiac catheterization did not reveal any signs of coronary occlusive disease. Prednisone 1 mg/kg was administered immediately; however, given continued chest pain and volume overload, he was quickly transitioned to solumedrol 1000 mg IV daily. After the initiation of his treatment, the patient’s transaminitis began to resolve, and troponin levels began to decrease; however, his symptoms continued to worsen, and his troponin rose again. By the fourth day of hospitalization, the patient was treated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor shown to reverse ICI-induced autoimmune inflammation, with only mild improvement of his symptoms. The patient’s condition continued to deteriorate, his troponin levels remained elevated, and his family decided to withhold additional treatment. The patient died shortly thereafter.

Discussion

Cardiotoxicity resulting from ICI therapy is far less common than the other potential severe toxicities associated with ICIs. Nevertheless, many cases of ICI-induced cardiac inflammation have been reported, and it has been widely established that patients treated with ICIs are generally at higher risk for acute coronary syndrome.9-11 Acute cardiotoxicity secondary to autoimmune destruction of cardiac tissue includes myocarditis, pericarditis, and vasculitis, which may manifest with symptoms of heart failure and/or arrhythmia. Grading of ICI-induced cardiomyopathy has been defined by both CTCAE and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), with grade 4 representing moderate to severe clinical decompensation requiring IV medications in the setting of life-threatening conditions.

Review articles have described the treatment options for severe cases.7,12 As detailed in prior reports, once ICI-induced cardiomyopathy is suspected, urgent admission and immediate evaluation to rule out acute coronary syndrome should be undertaken. Given the potential for deterioration despite the occasional insidious onset, aggressive cardiac monitoring, and close follow-up to measure response to interventions should be undertaken.

Case 2: Uveitis

A 70-year-old man who received pembrolizumab as a bladder-sparing approach for his superficial bladder cancer refractory to intravesical treatments developed uveitis. Approximately 3 months following the initiation of treatment, the patient reported bilateral itchy eyes, erythema, and tearing. He had a known history of allergic conjunctivitis that predated the ICI therapy, and consequently, it was unclear whether his symptoms were reflective of a more concerning issue. The patient’s symptoms continued to wax and wane for a few months, prompting a referral to ophthalmology colleagues at NMVAMC.

Ophthalmology evaluation identified uveitic glaucoma in the setting of his underlying chronic glaucoma. Pembrolizumab was discontinued, and the patient was counseled on choosing either cystectomy or locoregional therapies if further tumors arose. However, within a few weeks of administering topical steroid drops, his symptoms markedly improved, and he wished to be restarted on pembrolizumab. His uveitis remained in remission, and he has been treated with pembrolizumab for more than 1 year since this episode. He has had no clear findings of superficial bladder cancer recurrence while receiving ICI therapy.

Discussion

Uveitis is a known complication of pembrolizumab, and it has been shown to occur in 1% of patients with this treatment.13,14 It should be noted that most of the studies of this IMAR occurred in patients with metastatic melanoma; therefore the rate of this condition in other patients is less understood. Overall, ocular IMARs secondary to anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 therapies are rare.

The most common IMAR is surface ocular disease, consisting of dry eye disease (DED), conjunctivitis, uveitis, and keratitis. Of these, the most common ocular surface disease is DED, which occurred in 1% to 4% of patients treated with ICI therapy; most of these reactions are mild and self-limiting.15 Atezolizumab has the highest association with ocular inflammation and ipilimumab has the highest association with uveitis, with reported odds ratios of 18.89 and 10.54, respectively.16 Treatment of ICI-induced uveitis generally includes topical steroids and treatment discontinuation or break.17 Oral or IV steroids, infliximab, and procedural involvement may be considered in refractory cases or those initially presenting with marked vision loss. Close communication with ophthalmology colleagues to monitor visual acuity and ocular pressure multiple times weekly during the acute phase is required for treatment titration.

Case 3: Organizing Pneumonia

A man aged 63 years was diagnosed with malignant mesothelioma after incidentally noting a pleural effusion and thickening on routine low-dose computed tomography surveillance of pulmonary nodules. A biopsy was performed and was consistent with mesothelioma, and the patient was started on nivolumab (PD-1 inhibitor) and ipilimumab (CTLA-4 inhibitor). The patient was initiated on dual ICIs, and after 6 months of therapy, he had a promising complete response. However, after 9 months of therapy, he developed a new left upper lobe (LUL) pleural-based lesion (Figure 2A).

A biopsy was performed, and the histopathologic appearance was consistent with organizing pneumonia (OP) (Figure 3).

Discussion

ICIs can uncommonly drive pneumonitis, with the frequency adjusted based on the number of ICIs prescribed and the primary cancer involved. Across all cancers, up to 5% of patients treated with single-agent ICI therapy may experience pneumonitis, though often the findings may simply be radiographic without symptoms. Moreover, up to 10% of patients undergoing treatment for pulmonary cancer or those with dual ICI treatment regimens experience radiographic and/or clinical pneumonitis.18 The clinical manifestations include a broad spectrum of respiratory symptoms. Given the convoluting concerns of cancer progression and infection, a biopsy is often obtained. Histopathologic findings of pneumonitis may include diffuse alveolar damage and/or interstitial lung disease, with OP being a rare variant of ILD.

Among pulmonologists, OP is felt to have polymorphous imaging findings, and biopsy is required to confirm histology; however, histopathology cannot define etiology, and consequently, OP is somewhat of an umbrella diagnosis. The condition can be cryptogenic (idiopathic) or secondary to a multitude of conditions (infection, drug toxicity, or systemic disease). It is classically described as polypoid aggregations of fibroblasts that obstruct the alveolar spaces.19 This histopathologic pattern was demonstrated in our patient’s lung biopsy. Given a prior case description of ICIs, mesothelioma, OP development, and the unremarkable infectious workup, we felt that the patient’s OP was driven by his dual ICI therapy, thereby leading to the ultimate discontinuation of his ICIs and initiation of steroids.20 Thankfully, the patient had already obtained a complete response to his ICIs, and hopefully, he can attain a durable remission with the addition of maintenance chemotherapy.

CONCLUSIONS

ICIs have revolutionized the treatment of a myriad of solid tumors and hematologic malignancies, and their use internationally is expected to increase. With the alteration in immunology pathways, clinicians in all fields will need to be familiarized with IMARs secondary to these agents, including rare subtypes. In addition, the variability in presentations relative to the patients’ treatment course was significant (between 2-9 months), and this highlights that these IMARs can occur at any time point and clinicians should be ever vigilant to spot symptoms in their patients.

It was unexpected for the 3 aforementioned rare toxicities to arise at NMVAMC among only 57 treated patients, and we speculate that these findings may have been observed for 1 of 3 reasons. First, caring for 3 patients with this collection of rare toxicities may have been due to chance. Second, though there is sparse literature studying the topic, the regional environment, including sunlight exposure and air quality, may play a role in the development of one or all of these rare toxicities. Third, rates of these toxicities may be underreported in the literature or attributed to other conditions rather than due to ICIs at other sites, and the uncommon nature of these IMARs may be overstated. Investigations evaluating rates of toxicities, including those traditionally uncommonly seen, based on regional location should be conducted before any further conclusions are drawn.

1. Bagchi S, Yuan R, Engleman EG. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of cancer: clinical impact and mechanisms of response and resistance. Published online 2020. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathol-042020

2. Chen DS, Mellman I. Oncology meets immunology: The cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity. 2013;39(1):1-10. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.012

3. Smyth MJ, Teng MWL. 2018 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine. Clin Transl Immunology. 2018;7(10). doi:10.1002/cti2.1041

4. Baxi S, Yang A, Gennarelli RL, et al. Immune-related adverse events for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 drugs: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Online). 2018;360. doi:10.1136/bmj.k793

5. Ellithi M, Elnair R, Chang GV, Abdallah MA. Toxicities of immune checkpoint inhibitors: itis-ending adverse reactions and more. Cureus. Published online February 10, 2020. doi:10.7759/cureus.6935

6. Berti A, Bortolotti R, Dipasquale M, et al. Meta-analysis of immune-related adverse events in phase 3 clinical trials assessing immune checkpoint inhibitors for lung cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;162. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103351

7. Davies M, Duffield EA. Safety of checkpoint inhibitors for cancer treatment: strategies for patient monitoring and management of immune-mediated adverse events. Immunotargets Ther. 2017;Volume 6:51-71. doi:10.2147/itt.s141577

8. US Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events V5.0. Accessed July 17, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5584920/

9. Johnson DB, Balko JM, Compton ML, et al. Fulminant myocarditis with combination immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(18):1749-1755. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1609214

10. Mahmood SS, Fradley MG, Cohen J V., et al. Myocarditis in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(16):1755-1764. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.037

11. Wang DY, Salem JE, Cohen JV, et al. Fatal toxic effects associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(12):1721-1728. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.3923

12. Brahmer JR, Lacchetti C, Schneider BJ, et al; National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Onc. 2018;36(17):1714-1768. doi:10.1200/JCO

13. Ribas A, Hamid O, Daud A, et al. Association of pembrolizumab with tumor response and survival among patients with advanced melanoma. JAMA. 2016;315:1600-1609. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.4059

14. Dalvin LA, Shields CL, Orloff M, Sato T, Shields JA. Checkpoint inhibitor immune therapy: systemic indications and ophthalmic side effects. Retina. 2018;38(6):1063-1078. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000002181

15. Park RB, Jain S, Han H, Park J. Ocular surface disease associated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Ocular Surface. 2021;20:115-129. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2021.02.004

16. Fang T, Maberley DA, Etminan M. Ocular adverse events with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Curr Ophthalmol. 2019;31(3):319-322. doi:10.1016/j.joco.2019.05.002

17. Whist E, Symes RJ, Chang JH, et al. Uveitis caused by treatment for malignant melanoma: a case series. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2021;15(6):718-723. doi:10.1097/ICB.0000000000000876

18. Naidoo J, Wang X, Woo KM, et al. Pneumonitis in patients treated with anti-programmed death-1/programmed death ligand 1 therapy. J Clin Onc. 2017;35(7):709-717. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.68.2005

19. Yoshikawa A, Bychkov A, Sathirareuangchai S. Other nonneoplastic conditions, acute lung injury, organizing pneumonia. Accessed July 17, 2023. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/lungnontumorboop.html

20. Kuint R, Lotem M, Neuman T, et al. Organizing pneumonia following treatment with pembrolizumab for metastatic malignant melanoma–a case report. Respir Med Case Rep. 2017;20:95-97. doi:10.1016/j.rmcr.2017.01.003

1. Bagchi S, Yuan R, Engleman EG. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of cancer: clinical impact and mechanisms of response and resistance. Published online 2020. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathol-042020

2. Chen DS, Mellman I. Oncology meets immunology: The cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity. 2013;39(1):1-10. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.012

3. Smyth MJ, Teng MWL. 2018 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine. Clin Transl Immunology. 2018;7(10). doi:10.1002/cti2.1041

4. Baxi S, Yang A, Gennarelli RL, et al. Immune-related adverse events for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 drugs: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Online). 2018;360. doi:10.1136/bmj.k793

5. Ellithi M, Elnair R, Chang GV, Abdallah MA. Toxicities of immune checkpoint inhibitors: itis-ending adverse reactions and more. Cureus. Published online February 10, 2020. doi:10.7759/cureus.6935

6. Berti A, Bortolotti R, Dipasquale M, et al. Meta-analysis of immune-related adverse events in phase 3 clinical trials assessing immune checkpoint inhibitors for lung cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;162. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103351

7. Davies M, Duffield EA. Safety of checkpoint inhibitors for cancer treatment: strategies for patient monitoring and management of immune-mediated adverse events. Immunotargets Ther. 2017;Volume 6:51-71. doi:10.2147/itt.s141577

8. US Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events V5.0. Accessed July 17, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5584920/

9. Johnson DB, Balko JM, Compton ML, et al. Fulminant myocarditis with combination immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(18):1749-1755. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1609214

10. Mahmood SS, Fradley MG, Cohen J V., et al. Myocarditis in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(16):1755-1764. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.037

11. Wang DY, Salem JE, Cohen JV, et al. Fatal toxic effects associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(12):1721-1728. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.3923

12. Brahmer JR, Lacchetti C, Schneider BJ, et al; National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Onc. 2018;36(17):1714-1768. doi:10.1200/JCO

13. Ribas A, Hamid O, Daud A, et al. Association of pembrolizumab with tumor response and survival among patients with advanced melanoma. JAMA. 2016;315:1600-1609. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.4059

14. Dalvin LA, Shields CL, Orloff M, Sato T, Shields JA. Checkpoint inhibitor immune therapy: systemic indications and ophthalmic side effects. Retina. 2018;38(6):1063-1078. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000002181

15. Park RB, Jain S, Han H, Park J. Ocular surface disease associated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Ocular Surface. 2021;20:115-129. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2021.02.004

16. Fang T, Maberley DA, Etminan M. Ocular adverse events with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Curr Ophthalmol. 2019;31(3):319-322. doi:10.1016/j.joco.2019.05.002

17. Whist E, Symes RJ, Chang JH, et al. Uveitis caused by treatment for malignant melanoma: a case series. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2021;15(6):718-723. doi:10.1097/ICB.0000000000000876

18. Naidoo J, Wang X, Woo KM, et al. Pneumonitis in patients treated with anti-programmed death-1/programmed death ligand 1 therapy. J Clin Onc. 2017;35(7):709-717. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.68.2005

19. Yoshikawa A, Bychkov A, Sathirareuangchai S. Other nonneoplastic conditions, acute lung injury, organizing pneumonia. Accessed July 17, 2023. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/lungnontumorboop.html

20. Kuint R, Lotem M, Neuman T, et al. Organizing pneumonia following treatment with pembrolizumab for metastatic malignant melanoma–a case report. Respir Med Case Rep. 2017;20:95-97. doi:10.1016/j.rmcr.2017.01.003

Gastrointestinal Bleeding Caused by Large Intestine Amyloidosis

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a common cause of hospital admissions. The yearly incidence of upper GI bleeding is 80 to 150/100,000 people and lower GI bleeding is 87/100,000 people.1,2 The differential tends to initially be broad but narrows with good history followed by endoscopic findings. Getting an appropriate history can be difficult at times, which leads health care practitioners to rely more on interventional results.

Amyloidosis is a rare disorder of abnormal protein folding, leading to the deposition of insoluble fibrils that disrupt normal tissues and cause disease.3 There are 2 main types of amyloidosis, systemic and transthyretin, and 4 subtypes. Systemic amyloidosis includes amyloid light-chain (AL) deposition, caused by plasma cell dyscrasia, and amyloid A (AA) protein deposition, caused by systemic autoimmune illness or infections. Transthyretin amyloidosis is caused by changes and deposition of the transthyretin protein consisting of either unstable, mutant protein or wild type protein. Biopsy-proven amyloidosis of the GI tract is rare.4 About 60% of patients with AA amyloidosis and 8% with AL amyloidosis have GI involvement.5

We present a case of nonspecific symptoms that ultimately lined up perfectly with the official histologic confirmation of intestinal amyloidosis.

Case Presentation

A 79-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, hyperlipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, hypothyroidism, hypertension, coronary artery disease status postcoronary artery bypass grafting, and stent placements presented for 3 episodes of large, bright red bowel movements. He reported past bleeding and straining with stools, but bleeding of this amount had not been noted prior. He also reported dry heaves, lower abdominal pain, constipation with straining, early satiety with dysphagia, weakness, and decreased appetite. Lastly, he mentioned intentionally losing about 35 to 40 pounds in the past 3 to 4 months and over the past several months increased abdominal distention. However, he stated he had no history of alcohol misuse, liver or intestinal disease, cirrhosis, or other autoimmune diseases. His most recent colonoscopy was more than a decade prior and showed no acute process. The patient never had an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD).

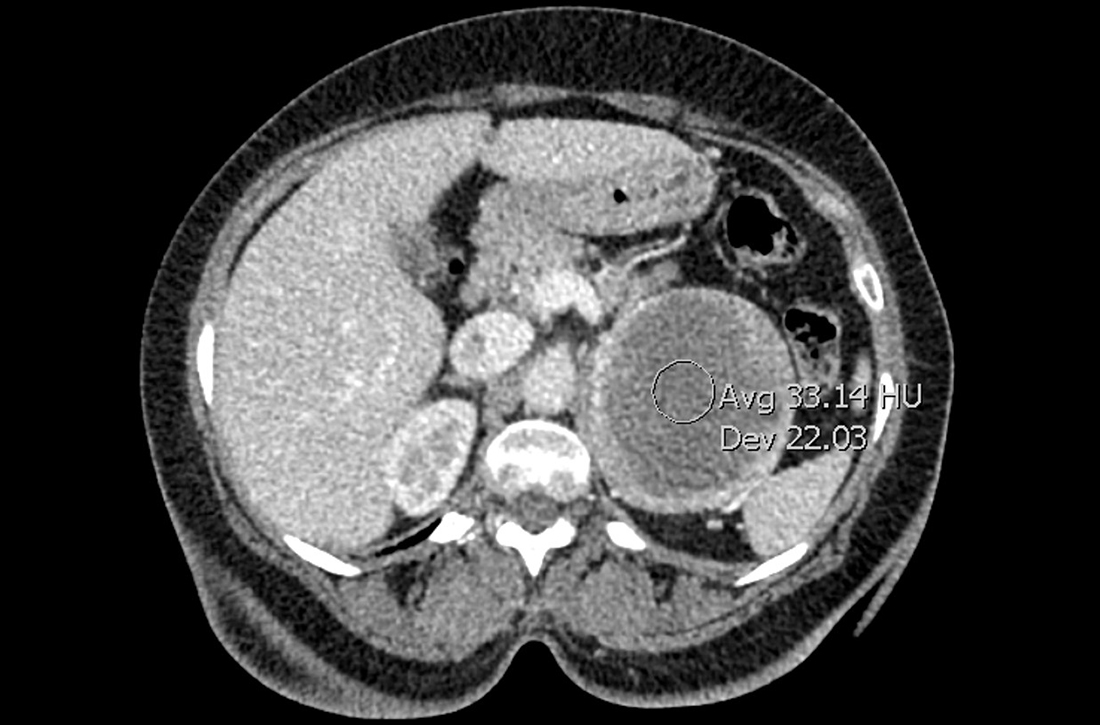

On initial presentation, the patient’s vital signs showed no acute findings. His physical examination noted a chronically ill–appearing male with decreased breath sounds to the bases bilaterally and noted abdominal distention with mild generalized tenderness. Laboratory findings were significant for a hemoglobin level, 9.4 g/dL (reference range, 11.6-15.3); iron, 23 ug/dL (reference range, 45-160); transferrin saturation, 8% (reference range, 15-50); ferritin level, 80 ng/mL (reference range, 30-300); and carcinoembryonic antigen level, 1.5 ng/mL (reference range, 0-2.9). Aspartate aminotransferase level was 54 IU/L (reference range, 0-40); alanine transaminase, 24 IU/L (reference range, 7-52); albumin, 2.7 g/dL (reference range, 3.4-5.7); international normalized ratio, 1.3 (reference range, 0-1.1); creatinine, 1.74 mg/dL (reference range, 0.44-1.27); alkaline phosphatase, 369 IU/L (reference range, 39-117). White blood cell count was 15.5 × 109/L (reference range, 3.5-10.3), and lactic acid was 2.5 mmol/L (reference range, 0.5-2.2). He was started on piperacillin/tazobactam in the emergency department and transitioned to ciprofloxacin and metronidazole for presumed intra-abdominal infection. Paracentesis showed a serum ascites albumin gradient of > 1.1 g/dL with no signs of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast was suspicious for colitis involving the proximal colon, and colonic mass could not be excluded. Also noted was hepatosplenomegaly with abdominopelvic ascites.

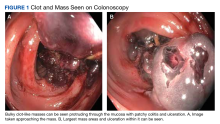

Based on these findings, an EGD and colonoscopy were done. The EGD showed mild portal hypertensive gastropathy.

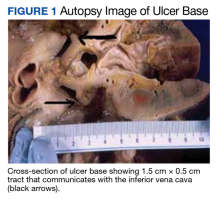

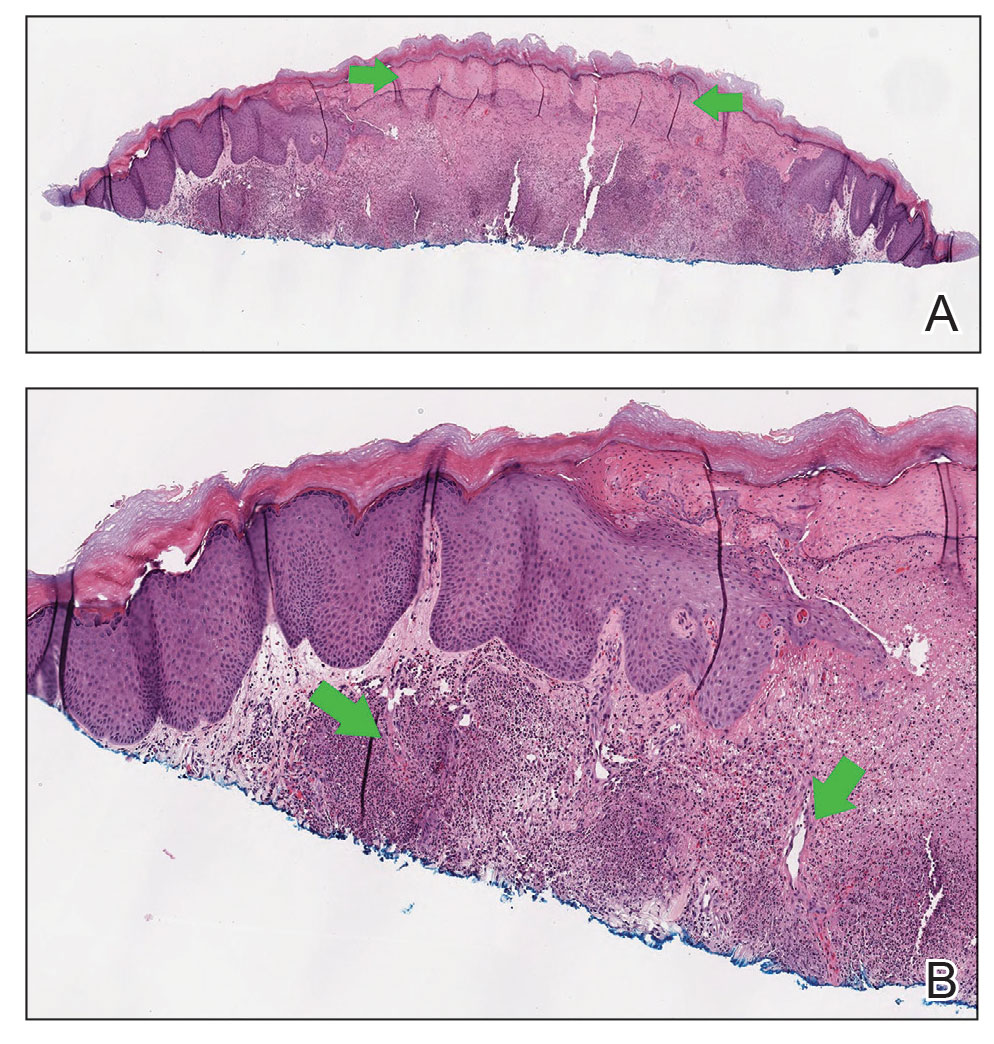

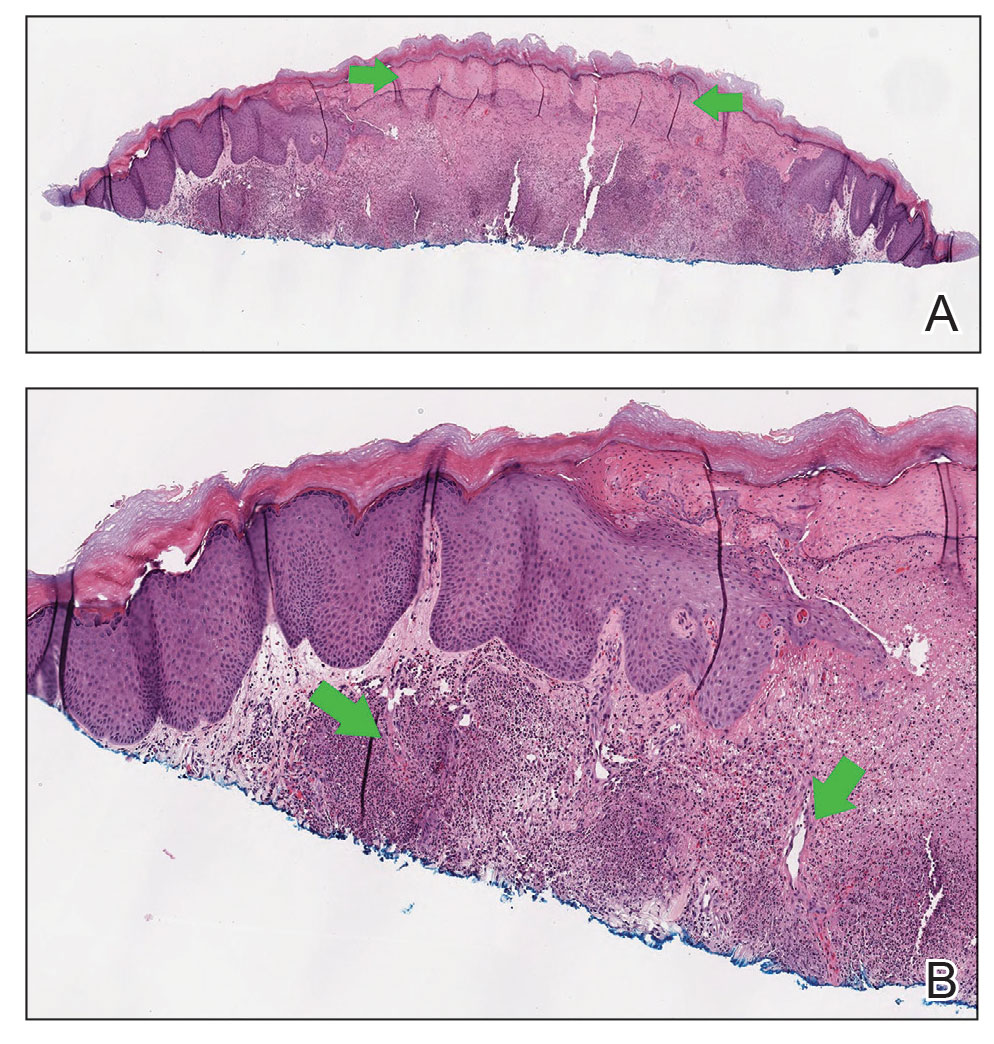

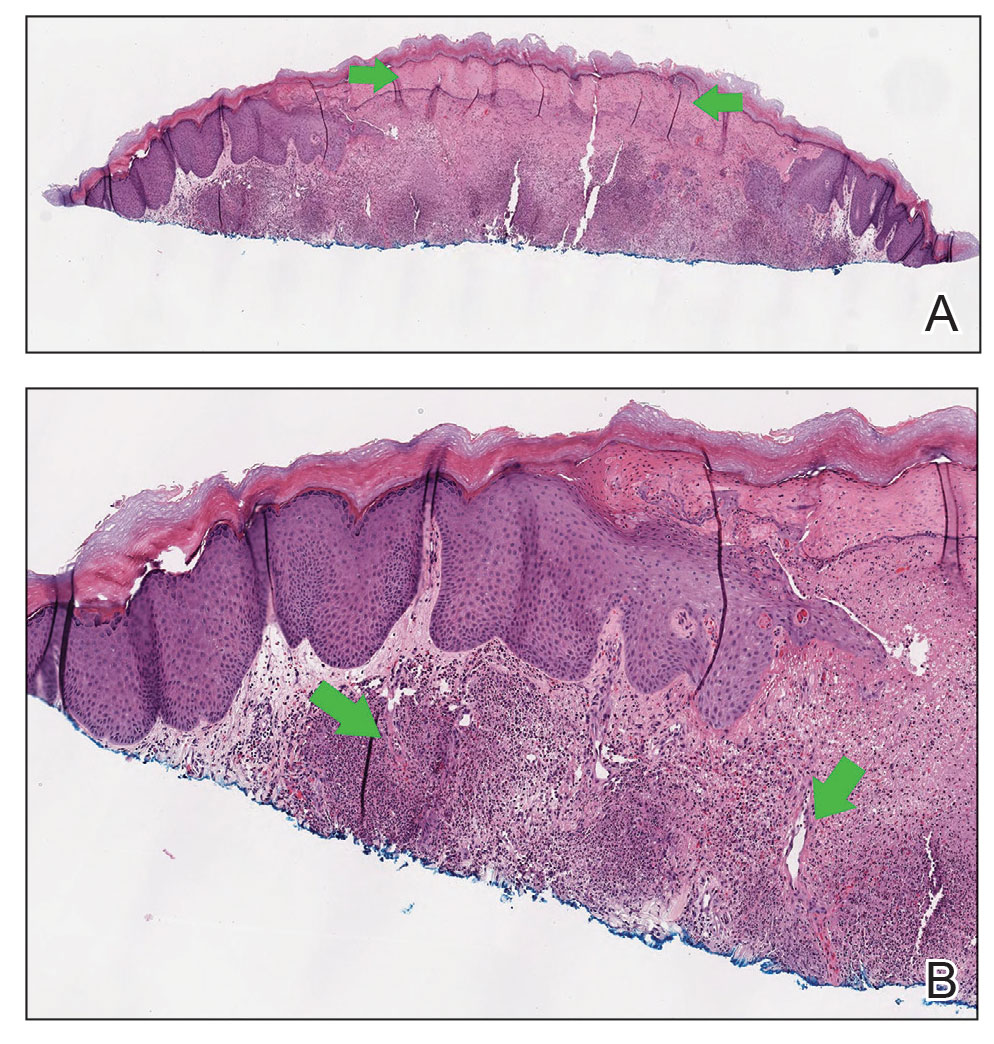

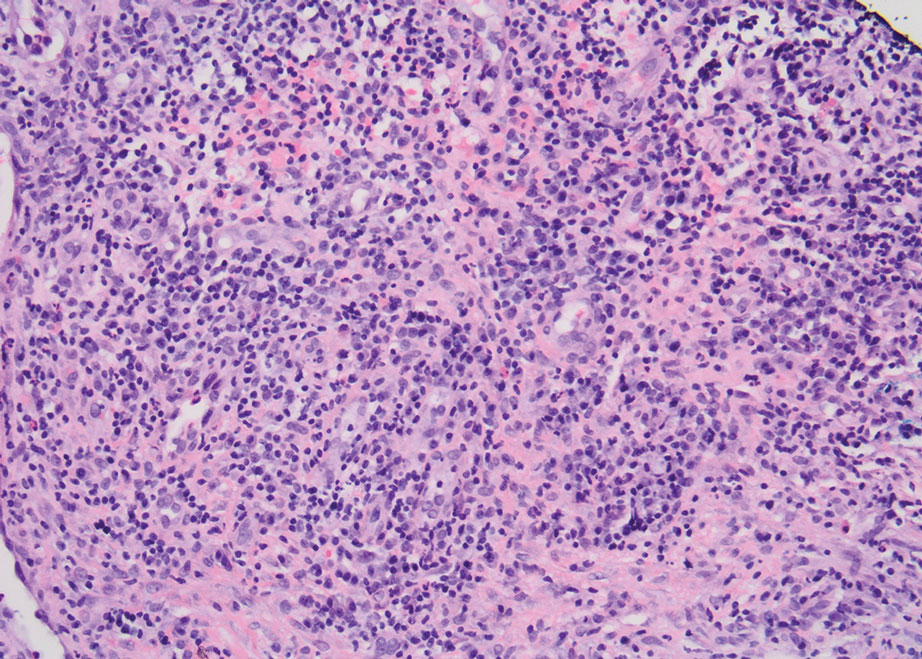

After the biopsy results, the patient was officially diagnosed with intestinal amyloidosis (Figure 2).

He returned to the gastroenterology clinic 2 months later. At that point, he had worsening symptoms, liver function test results, and international normalized ratio. He was admitted for further investigation. A bone biopsy was done to confirm the histology and define the underlying disorder. The biopsy returned showing Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia, and he was started on bortezomib. Unfortunately, his clinical status rapidly worsened, leading to acute renal and hepatic failure and the development of encephalopathy. He eventually died under palliative care services.

Discussion

Amyloidosis is a rare disorder of abnormal protein folding, leading to the deposition of insoluble fibrils that disrupt normal tissues and cause disease.3 There are several variations of amyloid, but the most common type is AL amyloidosis, which affects several organs, including the heart, kidney, liver, nervous system, and GI tract. When AL amyloidosis involves the liver, the median survival time is about 8.5 months.6 There are different ways to diagnose the disease, but a tissue biopsy and Congo Red staining can confirm specific organ involvement as seen in our case.

This case adds another layer to our constantly expanding differential as health care practitioners and proves that atypical patient presentations may not be atypical after all. GI amyloidosis tends to present similarly to our patient with bleeding, malabsorption, dysmotility, and protein-losing gastroenteropathy as ascites, edema, pericardial effusions, and laboratory evidence of hypoalbuminemia.7 Because amyloidosis is a systemic illness, early recognition is important as intestinal complications tend to present as symptoms, but mortality is more often caused by renal failure, cardiomyopathy, or ischemic heart disease, making early multispecialty involvement very important.8

Conclusions

Health care practitioners in all specialties should be aware of and include intestinal amyloidosis in their differential diagnosis when working up GI bleeds with the hope of identifying the disease early. With early recognition, rapid biopsy identification, and early specialist involvement, patients will get the opportunity for expedited multidisciplinary treatment and potentially delay rapid decompensation as shown by the evidence in this case.

1. Antunes C, Copelin II EL. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding. StatPearls [internet]. Updated July 18, 2022. Accessed May 25, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470300

2. Almaghrabi M, Gandhi M, Guizzetti L, et al. Comparison of risk scores for lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(5):e2214253. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.14253

3. Pepys MB. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of systemic amyloidosis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356(1406):203-211. doi:10.1098/rstb.2000.0766

4. Cowan AJ, Skinner M, Seldin DC, et al. Amyloidosis of the gastrointestinal tract: a 13-year, single-center, referral experience. Haematologica. 2013;98(1):141-146. doi:10.3324/haematol.2012.068155

5. Lee BS, Chudasama Y, Chen AI, Lim BS, Taira MT. Colonoscopy leading to the diagnosis of AL amyloidosis in the gastrointestinal tract mimicking an acute ulcerative colitis flare. ACG Case Rep J. 2019;6(11):e00289. doi:10.14309/crj.0000000000000289

6. Zhao L, Ren G, Guo J, Chen W, Xu W, Huang X. The clinical features and outcomes of systemic light chain amyloidosis with hepatic involvement. Ann Med. 2022;54(1):1226-1232. doi:10.1080/07853890.2022.2069281

7. Rowe K, Pankow J, Nehme F, Salyers W. Gastrointestinal amyloidosis: review of the literature. Cureus. 2017;9(5):e1228. doi:10.7759/cureus.1228

8. Kyle RA, Greipp PR, O’Fallon WM. Primary systemic amyloidosis: multivariate analysis for prognostic factors in 168 cases. Blood. 1986;68(1):220-224.

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a common cause of hospital admissions. The yearly incidence of upper GI bleeding is 80 to 150/100,000 people and lower GI bleeding is 87/100,000 people.1,2 The differential tends to initially be broad but narrows with good history followed by endoscopic findings. Getting an appropriate history can be difficult at times, which leads health care practitioners to rely more on interventional results.

Amyloidosis is a rare disorder of abnormal protein folding, leading to the deposition of insoluble fibrils that disrupt normal tissues and cause disease.3 There are 2 main types of amyloidosis, systemic and transthyretin, and 4 subtypes. Systemic amyloidosis includes amyloid light-chain (AL) deposition, caused by plasma cell dyscrasia, and amyloid A (AA) protein deposition, caused by systemic autoimmune illness or infections. Transthyretin amyloidosis is caused by changes and deposition of the transthyretin protein consisting of either unstable, mutant protein or wild type protein. Biopsy-proven amyloidosis of the GI tract is rare.4 About 60% of patients with AA amyloidosis and 8% with AL amyloidosis have GI involvement.5

We present a case of nonspecific symptoms that ultimately lined up perfectly with the official histologic confirmation of intestinal amyloidosis.

Case Presentation

A 79-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, hyperlipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, hypothyroidism, hypertension, coronary artery disease status postcoronary artery bypass grafting, and stent placements presented for 3 episodes of large, bright red bowel movements. He reported past bleeding and straining with stools, but bleeding of this amount had not been noted prior. He also reported dry heaves, lower abdominal pain, constipation with straining, early satiety with dysphagia, weakness, and decreased appetite. Lastly, he mentioned intentionally losing about 35 to 40 pounds in the past 3 to 4 months and over the past several months increased abdominal distention. However, he stated he had no history of alcohol misuse, liver or intestinal disease, cirrhosis, or other autoimmune diseases. His most recent colonoscopy was more than a decade prior and showed no acute process. The patient never had an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD).

On initial presentation, the patient’s vital signs showed no acute findings. His physical examination noted a chronically ill–appearing male with decreased breath sounds to the bases bilaterally and noted abdominal distention with mild generalized tenderness. Laboratory findings were significant for a hemoglobin level, 9.4 g/dL (reference range, 11.6-15.3); iron, 23 ug/dL (reference range, 45-160); transferrin saturation, 8% (reference range, 15-50); ferritin level, 80 ng/mL (reference range, 30-300); and carcinoembryonic antigen level, 1.5 ng/mL (reference range, 0-2.9). Aspartate aminotransferase level was 54 IU/L (reference range, 0-40); alanine transaminase, 24 IU/L (reference range, 7-52); albumin, 2.7 g/dL (reference range, 3.4-5.7); international normalized ratio, 1.3 (reference range, 0-1.1); creatinine, 1.74 mg/dL (reference range, 0.44-1.27); alkaline phosphatase, 369 IU/L (reference range, 39-117). White blood cell count was 15.5 × 109/L (reference range, 3.5-10.3), and lactic acid was 2.5 mmol/L (reference range, 0.5-2.2). He was started on piperacillin/tazobactam in the emergency department and transitioned to ciprofloxacin and metronidazole for presumed intra-abdominal infection. Paracentesis showed a serum ascites albumin gradient of > 1.1 g/dL with no signs of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast was suspicious for colitis involving the proximal colon, and colonic mass could not be excluded. Also noted was hepatosplenomegaly with abdominopelvic ascites.

Based on these findings, an EGD and colonoscopy were done. The EGD showed mild portal hypertensive gastropathy.

After the biopsy results, the patient was officially diagnosed with intestinal amyloidosis (Figure 2).

He returned to the gastroenterology clinic 2 months later. At that point, he had worsening symptoms, liver function test results, and international normalized ratio. He was admitted for further investigation. A bone biopsy was done to confirm the histology and define the underlying disorder. The biopsy returned showing Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia, and he was started on bortezomib. Unfortunately, his clinical status rapidly worsened, leading to acute renal and hepatic failure and the development of encephalopathy. He eventually died under palliative care services.

Discussion

Amyloidosis is a rare disorder of abnormal protein folding, leading to the deposition of insoluble fibrils that disrupt normal tissues and cause disease.3 There are several variations of amyloid, but the most common type is AL amyloidosis, which affects several organs, including the heart, kidney, liver, nervous system, and GI tract. When AL amyloidosis involves the liver, the median survival time is about 8.5 months.6 There are different ways to diagnose the disease, but a tissue biopsy and Congo Red staining can confirm specific organ involvement as seen in our case.

This case adds another layer to our constantly expanding differential as health care practitioners and proves that atypical patient presentations may not be atypical after all. GI amyloidosis tends to present similarly to our patient with bleeding, malabsorption, dysmotility, and protein-losing gastroenteropathy as ascites, edema, pericardial effusions, and laboratory evidence of hypoalbuminemia.7 Because amyloidosis is a systemic illness, early recognition is important as intestinal complications tend to present as symptoms, but mortality is more often caused by renal failure, cardiomyopathy, or ischemic heart disease, making early multispecialty involvement very important.8

Conclusions

Health care practitioners in all specialties should be aware of and include intestinal amyloidosis in their differential diagnosis when working up GI bleeds with the hope of identifying the disease early. With early recognition, rapid biopsy identification, and early specialist involvement, patients will get the opportunity for expedited multidisciplinary treatment and potentially delay rapid decompensation as shown by the evidence in this case.

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a common cause of hospital admissions. The yearly incidence of upper GI bleeding is 80 to 150/100,000 people and lower GI bleeding is 87/100,000 people.1,2 The differential tends to initially be broad but narrows with good history followed by endoscopic findings. Getting an appropriate history can be difficult at times, which leads health care practitioners to rely more on interventional results.

Amyloidosis is a rare disorder of abnormal protein folding, leading to the deposition of insoluble fibrils that disrupt normal tissues and cause disease.3 There are 2 main types of amyloidosis, systemic and transthyretin, and 4 subtypes. Systemic amyloidosis includes amyloid light-chain (AL) deposition, caused by plasma cell dyscrasia, and amyloid A (AA) protein deposition, caused by systemic autoimmune illness or infections. Transthyretin amyloidosis is caused by changes and deposition of the transthyretin protein consisting of either unstable, mutant protein or wild type protein. Biopsy-proven amyloidosis of the GI tract is rare.4 About 60% of patients with AA amyloidosis and 8% with AL amyloidosis have GI involvement.5

We present a case of nonspecific symptoms that ultimately lined up perfectly with the official histologic confirmation of intestinal amyloidosis.

Case Presentation

A 79-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, hyperlipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, hypothyroidism, hypertension, coronary artery disease status postcoronary artery bypass grafting, and stent placements presented for 3 episodes of large, bright red bowel movements. He reported past bleeding and straining with stools, but bleeding of this amount had not been noted prior. He also reported dry heaves, lower abdominal pain, constipation with straining, early satiety with dysphagia, weakness, and decreased appetite. Lastly, he mentioned intentionally losing about 35 to 40 pounds in the past 3 to 4 months and over the past several months increased abdominal distention. However, he stated he had no history of alcohol misuse, liver or intestinal disease, cirrhosis, or other autoimmune diseases. His most recent colonoscopy was more than a decade prior and showed no acute process. The patient never had an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD).

On initial presentation, the patient’s vital signs showed no acute findings. His physical examination noted a chronically ill–appearing male with decreased breath sounds to the bases bilaterally and noted abdominal distention with mild generalized tenderness. Laboratory findings were significant for a hemoglobin level, 9.4 g/dL (reference range, 11.6-15.3); iron, 23 ug/dL (reference range, 45-160); transferrin saturation, 8% (reference range, 15-50); ferritin level, 80 ng/mL (reference range, 30-300); and carcinoembryonic antigen level, 1.5 ng/mL (reference range, 0-2.9). Aspartate aminotransferase level was 54 IU/L (reference range, 0-40); alanine transaminase, 24 IU/L (reference range, 7-52); albumin, 2.7 g/dL (reference range, 3.4-5.7); international normalized ratio, 1.3 (reference range, 0-1.1); creatinine, 1.74 mg/dL (reference range, 0.44-1.27); alkaline phosphatase, 369 IU/L (reference range, 39-117). White blood cell count was 15.5 × 109/L (reference range, 3.5-10.3), and lactic acid was 2.5 mmol/L (reference range, 0.5-2.2). He was started on piperacillin/tazobactam in the emergency department and transitioned to ciprofloxacin and metronidazole for presumed intra-abdominal infection. Paracentesis showed a serum ascites albumin gradient of > 1.1 g/dL with no signs of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast was suspicious for colitis involving the proximal colon, and colonic mass could not be excluded. Also noted was hepatosplenomegaly with abdominopelvic ascites.

Based on these findings, an EGD and colonoscopy were done. The EGD showed mild portal hypertensive gastropathy.

After the biopsy results, the patient was officially diagnosed with intestinal amyloidosis (Figure 2).

He returned to the gastroenterology clinic 2 months later. At that point, he had worsening symptoms, liver function test results, and international normalized ratio. He was admitted for further investigation. A bone biopsy was done to confirm the histology and define the underlying disorder. The biopsy returned showing Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia, and he was started on bortezomib. Unfortunately, his clinical status rapidly worsened, leading to acute renal and hepatic failure and the development of encephalopathy. He eventually died under palliative care services.

Discussion

Amyloidosis is a rare disorder of abnormal protein folding, leading to the deposition of insoluble fibrils that disrupt normal tissues and cause disease.3 There are several variations of amyloid, but the most common type is AL amyloidosis, which affects several organs, including the heart, kidney, liver, nervous system, and GI tract. When AL amyloidosis involves the liver, the median survival time is about 8.5 months.6 There are different ways to diagnose the disease, but a tissue biopsy and Congo Red staining can confirm specific organ involvement as seen in our case.

This case adds another layer to our constantly expanding differential as health care practitioners and proves that atypical patient presentations may not be atypical after all. GI amyloidosis tends to present similarly to our patient with bleeding, malabsorption, dysmotility, and protein-losing gastroenteropathy as ascites, edema, pericardial effusions, and laboratory evidence of hypoalbuminemia.7 Because amyloidosis is a systemic illness, early recognition is important as intestinal complications tend to present as symptoms, but mortality is more often caused by renal failure, cardiomyopathy, or ischemic heart disease, making early multispecialty involvement very important.8

Conclusions

Health care practitioners in all specialties should be aware of and include intestinal amyloidosis in their differential diagnosis when working up GI bleeds with the hope of identifying the disease early. With early recognition, rapid biopsy identification, and early specialist involvement, patients will get the opportunity for expedited multidisciplinary treatment and potentially delay rapid decompensation as shown by the evidence in this case.

1. Antunes C, Copelin II EL. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding. StatPearls [internet]. Updated July 18, 2022. Accessed May 25, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470300

2. Almaghrabi M, Gandhi M, Guizzetti L, et al. Comparison of risk scores for lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(5):e2214253. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.14253

3. Pepys MB. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of systemic amyloidosis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356(1406):203-211. doi:10.1098/rstb.2000.0766

4. Cowan AJ, Skinner M, Seldin DC, et al. Amyloidosis of the gastrointestinal tract: a 13-year, single-center, referral experience. Haematologica. 2013;98(1):141-146. doi:10.3324/haematol.2012.068155

5. Lee BS, Chudasama Y, Chen AI, Lim BS, Taira MT. Colonoscopy leading to the diagnosis of AL amyloidosis in the gastrointestinal tract mimicking an acute ulcerative colitis flare. ACG Case Rep J. 2019;6(11):e00289. doi:10.14309/crj.0000000000000289

6. Zhao L, Ren G, Guo J, Chen W, Xu W, Huang X. The clinical features and outcomes of systemic light chain amyloidosis with hepatic involvement. Ann Med. 2022;54(1):1226-1232. doi:10.1080/07853890.2022.2069281

7. Rowe K, Pankow J, Nehme F, Salyers W. Gastrointestinal amyloidosis: review of the literature. Cureus. 2017;9(5):e1228. doi:10.7759/cureus.1228

8. Kyle RA, Greipp PR, O’Fallon WM. Primary systemic amyloidosis: multivariate analysis for prognostic factors in 168 cases. Blood. 1986;68(1):220-224.

1. Antunes C, Copelin II EL. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding. StatPearls [internet]. Updated July 18, 2022. Accessed May 25, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470300

2. Almaghrabi M, Gandhi M, Guizzetti L, et al. Comparison of risk scores for lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(5):e2214253. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.14253

3. Pepys MB. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of systemic amyloidosis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356(1406):203-211. doi:10.1098/rstb.2000.0766

4. Cowan AJ, Skinner M, Seldin DC, et al. Amyloidosis of the gastrointestinal tract: a 13-year, single-center, referral experience. Haematologica. 2013;98(1):141-146. doi:10.3324/haematol.2012.068155

5. Lee BS, Chudasama Y, Chen AI, Lim BS, Taira MT. Colonoscopy leading to the diagnosis of AL amyloidosis in the gastrointestinal tract mimicking an acute ulcerative colitis flare. ACG Case Rep J. 2019;6(11):e00289. doi:10.14309/crj.0000000000000289

6. Zhao L, Ren G, Guo J, Chen W, Xu W, Huang X. The clinical features and outcomes of systemic light chain amyloidosis with hepatic involvement. Ann Med. 2022;54(1):1226-1232. doi:10.1080/07853890.2022.2069281

7. Rowe K, Pankow J, Nehme F, Salyers W. Gastrointestinal amyloidosis: review of the literature. Cureus. 2017;9(5):e1228. doi:10.7759/cureus.1228

8. Kyle RA, Greipp PR, O’Fallon WM. Primary systemic amyloidosis: multivariate analysis for prognostic factors in 168 cases. Blood. 1986;68(1):220-224.

Spider Bite Wound Care and Review of Traditional and Advanced Treatment Options

The costs for wound care play a significant role in total health care costs and are expected to rise dramatically. A 2018 Medicare analysis estimated chronic wound care cost $28.1 to $96.8 billion in supplies, hospitalization, and nursing care: Most costs were accrued in outpatient wound care.1 The global market for advanced wound care supplies is projected to reach $13.7 billion by 2027, and negative wound pressure therapy alone is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 5% over the analysis period 2020 to 2027.2 Chronic wound care also impacts the patient physiologically, socially, and psychologically. One study compared the 5-year mortality of a patient with a diabetic foot ulcer (30.5%) as similar to those patients with cancer (31%).3 Yet the investment in cancer research far outstrips wound care research.

There is no perfect wound dressing for all chronic wounds, but there is expert consensus on interventions that facilitate wound healing. In 2021, Nuutila and Eriksson stated that wound dressings should fulfill the following criteria: protection against trauma, esthetically acceptable, painless to remove, easy to apply, protection for the wound from contamination and further trauma, a moist environment, and an optimal water vapor transmission rate.4 Balanced moisture control is considered essential for healing chronic wounds. Indeed, moisture control within the wound bed may be the most important factor in chronic wound management and healing. The body communicates through a liquid medium, and if that medium is compromised, communication and marshaling of the immune and healing responses may become inefficient.4 Too much moisture, exudate, or fluid in the wound, and the healing is slowed; too little moisture in the wound results in a compromised responses from the body’s immune system, thus delaying healing. In 1988, Dyson and colleagues demonstrated that moist wound care was superior for the inflammatory and proliferative phases of dermal repair compared with dry wound care. The results showed that 5 days after injury, 66% of the cells in the moist wound were fibroblasts and endothelial cells vs 48% of those in the dry wounds.5

The question of dry vs moist wound care has resulted in various wound dressings that produce favorable moisture balance. Moisture balance in a wound creates the ideal environment for wound healing. Sound wound care practices promote the following physiologic responses: increased probability of autolytic debridement; increased collagen synthesis; keratinocyte migration and reepithelization; decreased pain, inflammation, scarring, and necrosis;enhancement of cell-to-cell signaling; and increase in growth factors.5,6 All these processes are mediated through proper wound moisture control. In addition to proper moisture control, antibiotics added to the wound care milieu (either directly to the wound or systemically) may have a place in chronic wound care. In 2013, Junker and colleagues reported that low-dose antibiotics combined with appropriate moisture balance in wounds demonstrated less scar tissue compared with dry wound care.6

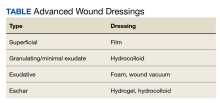

Approaches to chronic wound care are worlds apart: In developing nations the care of chronic wounds often involves traditional management with local products (eg, honey, boiled potato peels, aloe vera gel, banana leaves), whereas in developed nations, more expensive and technologically advanced products are available (eg, wound vacuum, saline wound chamber, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, antibacterial foam). Developing countries often do not have access to technologically advanced wound care products. Local products are often used by local healers, priests, and shamans. The use of these wound interventions in developing countries has produced satisfactory results. In contrast, developed countries have multiple chronic wound care products available (Table).

CASE Presentation

An athletic, healthy 60-year-old Utah National Guard member presented to the George E. Wahlen Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Salt Lake City, Utah, 6 days after experiencing a spider bite. For the first 6 days, the patient applied bacitracin at home. On day 7, the patient noticed that the wound was enlarging and appeared to be fluctuant. The patient was prescribed clindamycin 300 mg 4 times daily on an outpatient basis, which was taken on days 7 to 14.