User login

49-year-old woman • headache and neck pain radiating to ears and eyes • severe hypertension • Dx?

THE CASE

A 49-year-old woman was hospitalized with a headache and neck pain that radiated to her ears and eyes in the context of severe hypertension (270/150 mm Hg). Her medical history was significant for heterozygous factor V Leiden mutation, longstanding untreated hypertension, and multiple severe episodes of HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets) syndrome during pregnancy.

After receiving antihypertensive treatment at a community hospital, her blood pressure gradually improved to 160/100 mm Hg with the addition of a third medication. However, on Day 3 of her stay, her systolic blood pressure rose to more than 200 mm Hg and was accompanied by somnolence, emesis, and paleness. She was transferred to a tertiary care center.

THE DIAGNOSIS

On admission, the patient had left-side hemiparesis and facial droop with dysarthria, resulting in a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of 7 (out of 42) and a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 13 (out of 15). Noncontrast computed tomography (CT) and CT angiography of the head and neck were ordered and showed occlusion of both intracranial vertebral arteries. There were also signs of multifocal infarction in her occipital lobes, thus systemic recombinant human-tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) could not be administered.

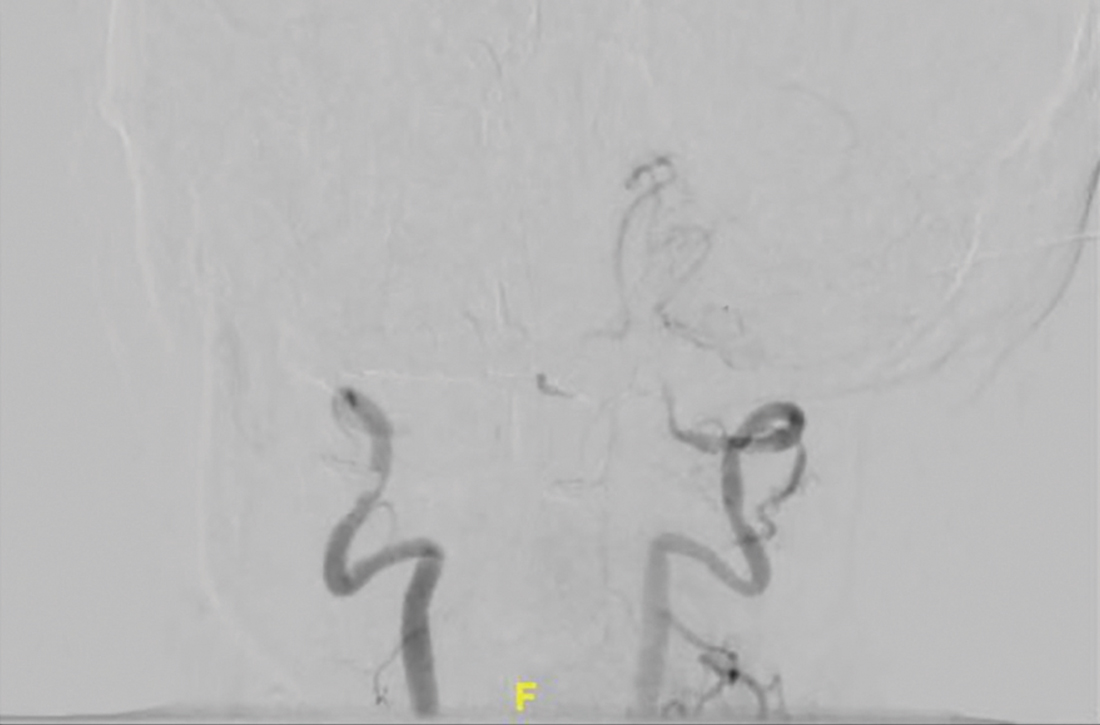

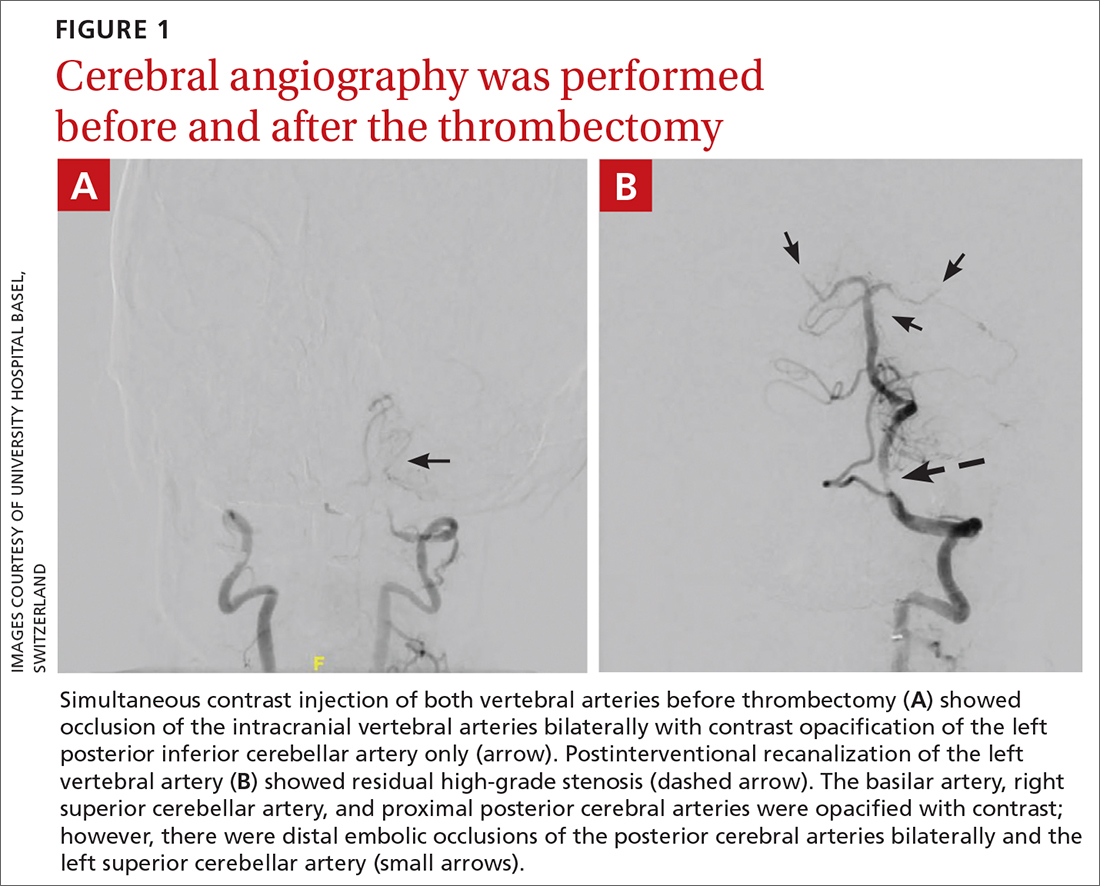

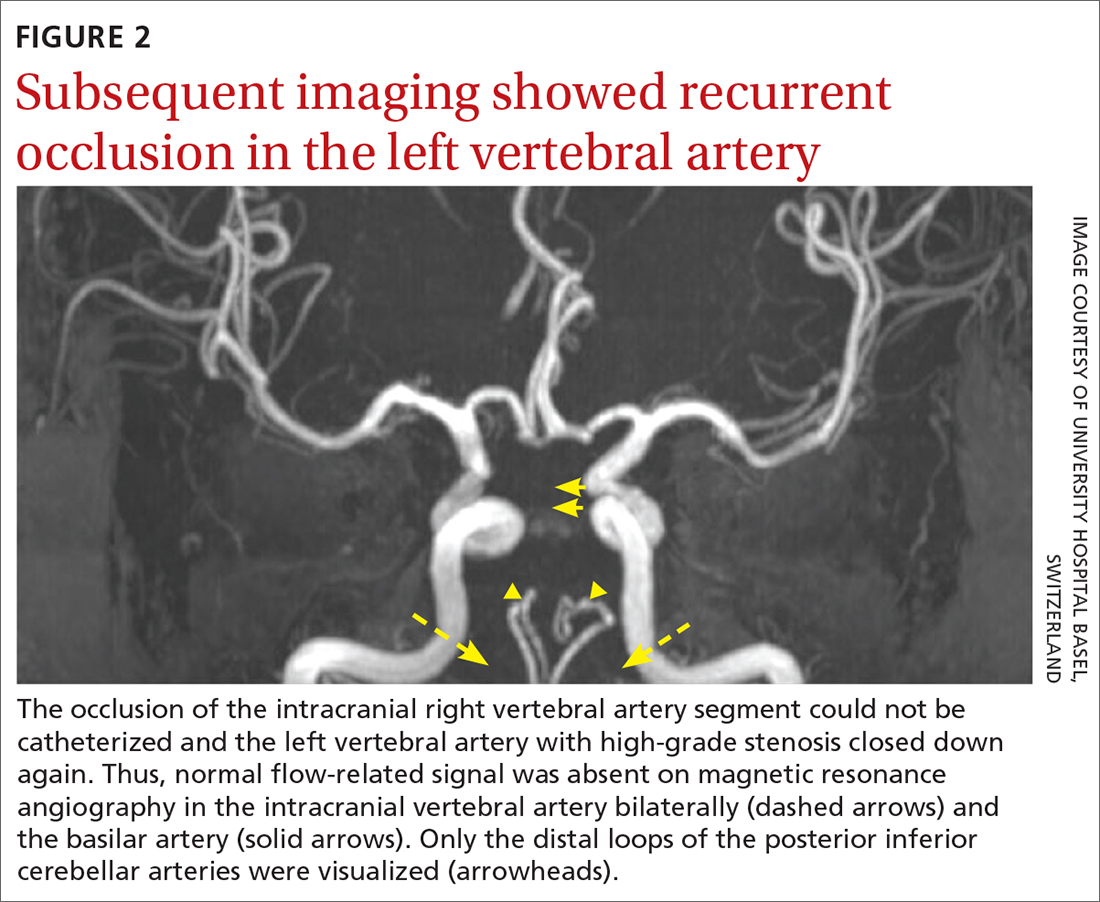

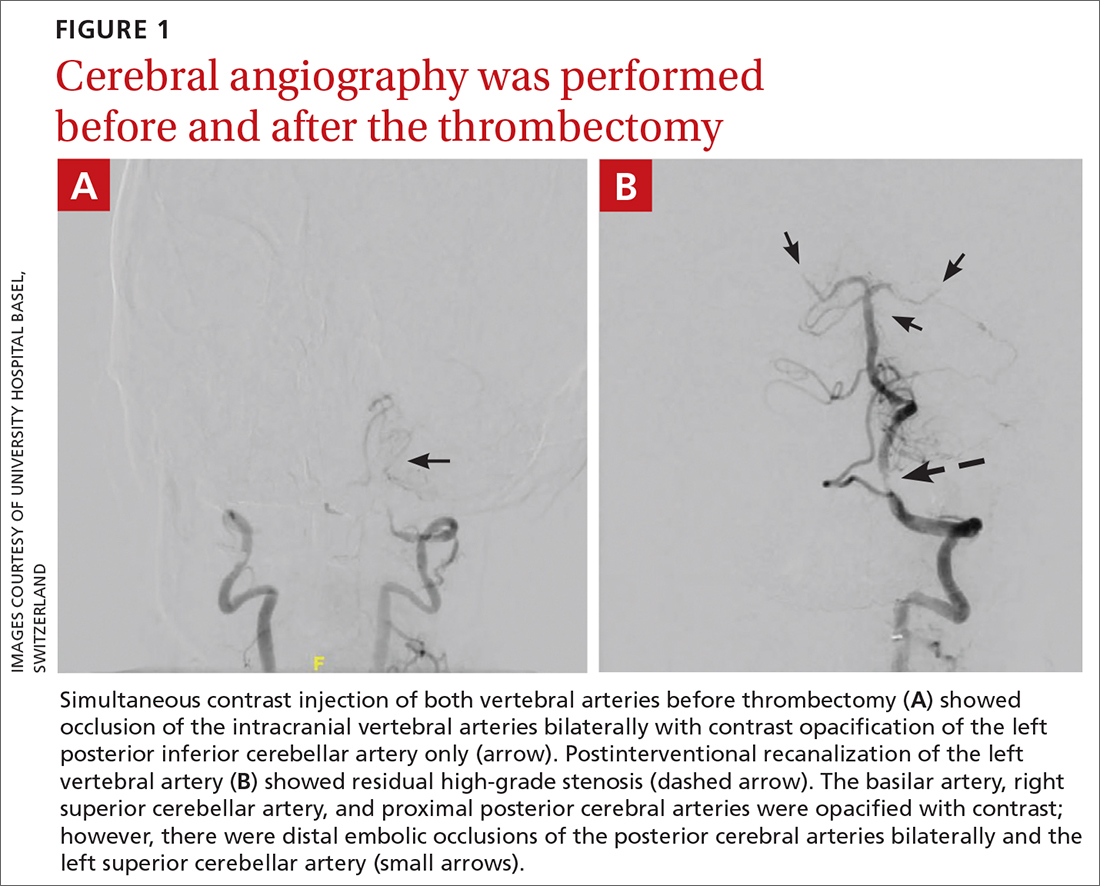

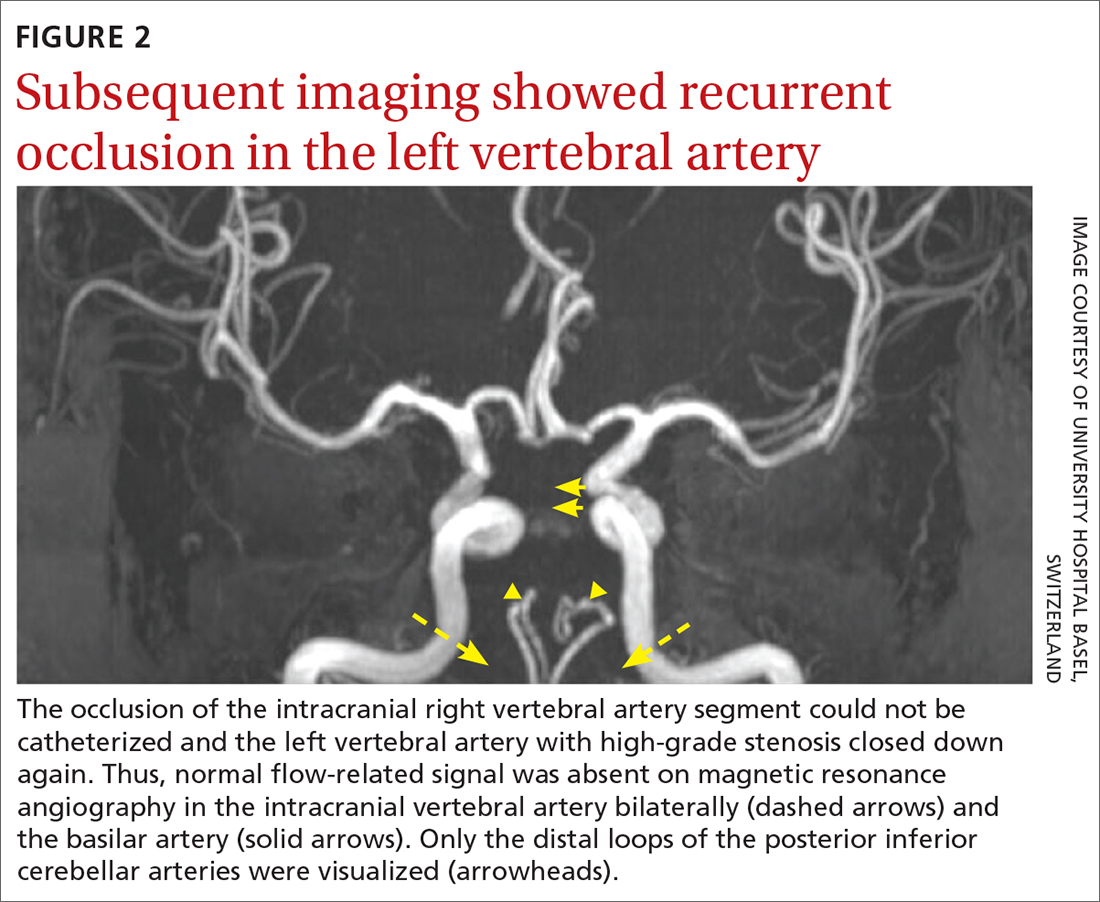

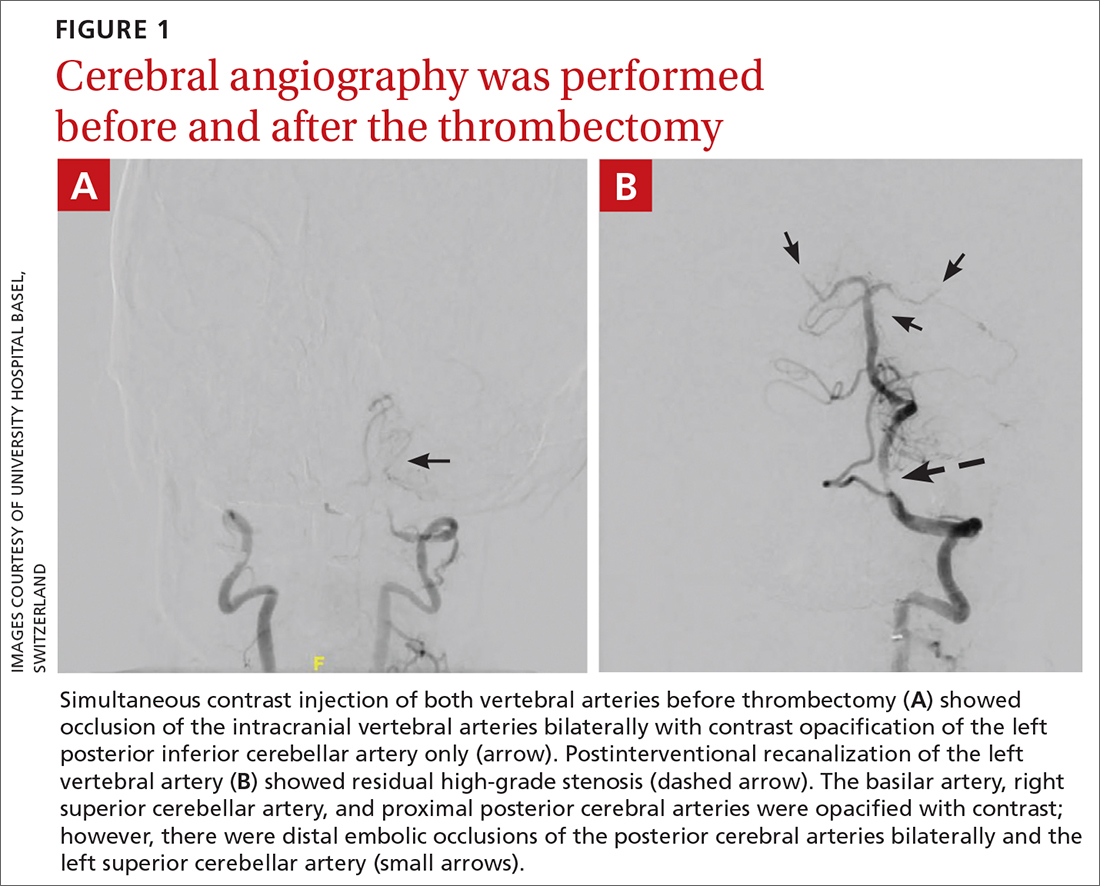

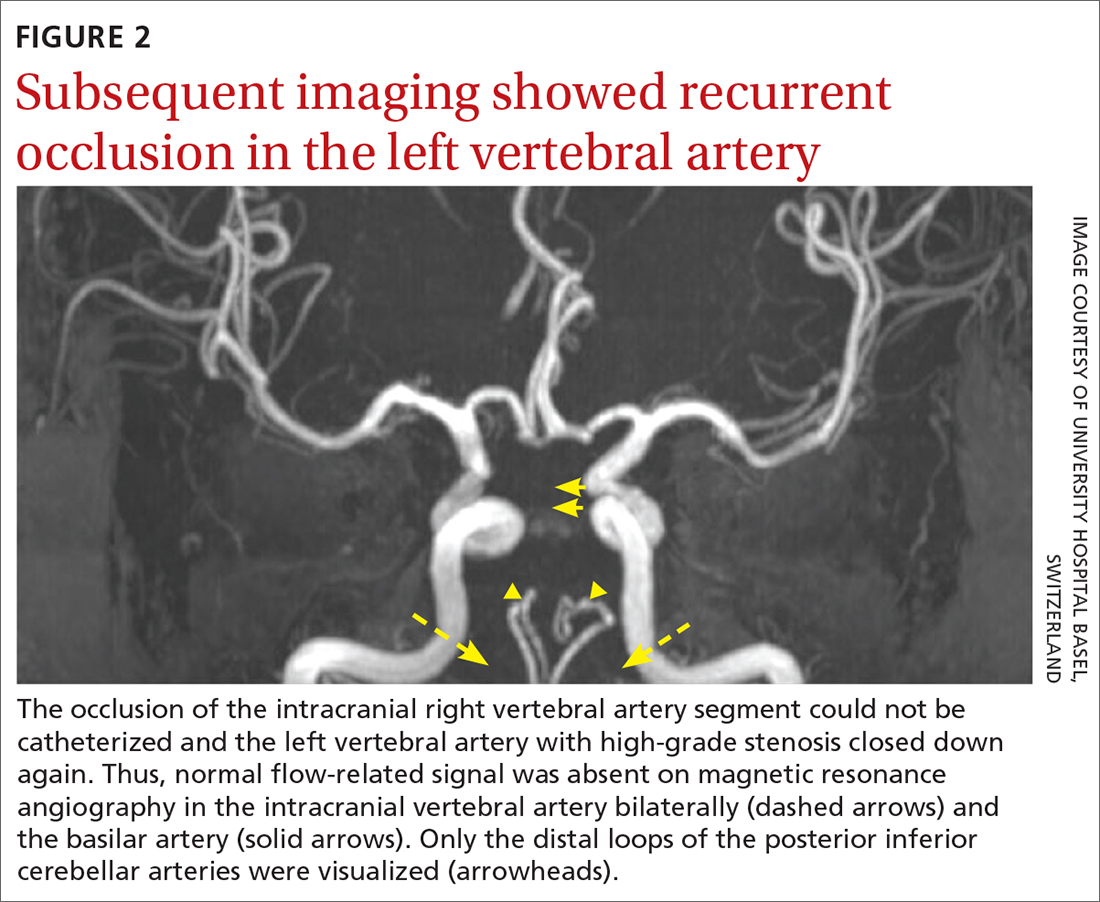

The patient was next taken to the angiography suite, where a digital subtraction angiography confirmed the presence of bilateral vertebral artery occlusions (FIGURE 1A). A thrombectomy was performed to open the left occluded segment, resulting in recanalization; however, a high-grade stenosis remained in the intracranial left vertebral artery (FIGURE 1B). The right vertebral artery had a severe extracranial origin stenosis, and balloon angioplasty was performed in order to reach the intracranial circulation; however, the occlusion of the intracranial right vertebral artery segment could not be catheterized. Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with a time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography showed that the intracranial left vertebral artery with high-grade stenosis had closed down again; thus, there was occlusion of both intracranial vertebral arteries and absent flow signal in the basilar artery (FIGURE 2). There were scattered small acute strokes within the cerebellum, brainstem, and occipital lobes.

Unfortunately, within 48 hours, the patient’s NIHSS score increased from 7 to 29. She developed tetraplegia, was significantly less responsive (GCS score, 3/15), and required intubation and mechanical ventilation. Reopening the stenosis and keeping it open with a stent would be an aggressive procedure with poor odds for success and would require antithrombotic medications with the associated risk for intracranial hemorrhage in the setting of demarcated strokes. Thus, no further intervention was pursued.

Further standard stroke work-up (echocardiography, extracranial ultrasound of the cerebral circulation, and vasculitis screening) was unremarkable. In the intensive care unit, intravenous therapeutic heparin was initiated because of the potential prothrombotic effect of the factor V Leiden mutation but was subsequently switched to dual anti-aggregation therapy (aspirin 100 mg/d and clopidogrel 75 mg/d) as secondary stroke prevention given the final diagnosis of severe atherosclerosis. Nevertheless, the patient remained tetraplegic with a partial locked-in syndrome when she was discharged, after 2 weeks in the tertiary care center, to a rehabilitation center.

DISCUSSION

Posterior circulation strokes account for 20% to 25% of all ischemic strokes1,2 and are associated with infarction within the vertebrobasilar arterial system. Common etiologies of these infarctions include atherosclerosis (as seen in our patient), embolism, small-artery penetrating disease, and arterial dissection.2 Although the estimated overall mortality of these strokes is low (3.6% to 11%),2 basilar occlusion syndrome, in particular, is a life-threatening condition with a high mortality rate of 80% to 90%.3

Continue to: Diagnosis can be particularly challenging...

Diagnosis can be particularly challenging due to the anatomic variations of posterior arterial circulation, as well as the fluctuating nonfocal or multifocal symptoms.2 Specific symptoms include vertigo, ataxia, unilateral motor weakness, dysarthria, and oculomotor dysfunction. However, nonspecific symptoms such as headache, nausea, dizziness, hoarseness, falls, and Horner syndrome may be the only presenting signs of a posterior circulation stroke—as was the case with our patient.2 Her radiating neck pain could have been interpreted as a pointer to vertebral artery dissection within the context of severe hypertension.4 Unfortunately, the diagnosis was delayed and head imaging was obtained only after her mental status deteriorated.

Immediate neuroimaging is necessary to guide treatment in patients with suspected acute posterior circulation stroke,1,5,6 although it is not always definitive. While CT is pivotal in stroke work-up and may reliably exclude intracranial hemorrhage, its ability to detect acute posterior circulation ischemic strokes is limited given its poor visualization of the posterior fossa (as low as 16% sensitivity).5 Fortunately, CT angiography has a high sensitivity (nearing 100%) for large-vessel occlusion and high predictive values for dissection (65%-100% positive predictive value and 70%-98% negative predictive value).5,7 Diffusion-weighted MRI (when available in the emergency setting) has the highest sensitivity for detecting acute infarcts, although posterior circulation infarcts still can be missed (19% false-negative rate).5,8 Thus, correlative vessel imaging with magnetic resonance or CT angiography is very important, along with a high index of suspicion. In some instances, repeat MRI may be necessary to detect small strokes.

A patient-specific approach to management is key for individuals with suspected posterior circulation stroke.5 Because specific data for the appropriate management of posterior circulation ischemic stroke are lacking, current American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) guidelines apply to anterior and posterior circulation strokes.6 For eligible patients without multifocal disease, intravenous tPA is the first-line therapy and should be initiated according to guidelines within 4.5 hours of stroke onset9; it is important to note that these guidelines are based on studies that focused more on anterior circulation strokes than posterior circulation strokes.6,9-13 This can be done in combination with endovascular therapy, which consists of mechanical thrombectomy, intra-arterial thrombolysis, or a combination of revascularization techniques.3,5,6

Mechanical thrombectomy specifically has high proven recanalization rates for all target vessels.3-6 The latest AHA/ASA guidelines recommend mechanical thrombectomy be performed within 6 hours of stroke onset.6 However, there is emerging evidence that suggests this timeframe should be extended—even beyond 24 hours—given the poor prognosis of posterior circulation strokes.5,6,14 More data on the management of posterior circulation strokes are urgently needed to better understand which therapeutic approach is most efficient.

In patients such as ours, who have evidence of multifocal disease, treatment may be limited to endovascular therapy. Intracranial stenting of symptomatic lesions in particular has been controversial since the publication of the Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent Stroke in Intracranial Stenosis trial, which found that aggressive medical management was superior to stenting in patients who recently had a transient ischemic attack or stroke attributed to stenosis.15 Although additional studies have been performed, there are no definitive data on the topic—and certainly no data in the emergency setting.16 Further challenges are raised in patients with bilateral disease, as was the case with this patient.

When our patient was admitted to the rehabilitation clinic, she had a GCS score of 10 to 11/15. After 9 months of rehabilitation, she was discharged home with a GCS score of 15/15 and persistent left-side hemiparesis.

THE TAKEAWAY

Posterior circulation stroke is a life-threatening disease that may manifest with a variety of symptoms and be difficult to identify on emergent imaging. Thus, a high degree of clinical suspicion and additional follow-up are paramount to ensure prompt diagnosis and a patient-tailored treatment strategy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kristine A. Blackham, MD, Associate Professor, University Hospital Basel, Petersgraben 4, 4031 Basel, Switzerland; [email protected] Orcid no: 0000-0002-1620-1144 (Dr. Blackham); 0000-0002- 5225-5414 (Dr. Saleh)

1. Cloud GC, Markus HS. Diagnosis and management of vertebral artery stenosis. QJM. 2003;96:27-54. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcg003

2. Sparaco M, Ciolli L, Zini A. Posterior circulation ischaemic stroke–a review part I: anatomy, aetiology and clinical presentations. Neurol Sci. 2019;40:1995-2006. doi: 10.1007/s10072-019-03977-2

3. Lin DDM, Gailloud P, Beauchamp NJ, et al. Combined stent placement and thrombolysis in acute vertebrobasilar ischemic stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:1827-1833.

4. Pezzini A, Caso V, Zanferrari C, et al. Arterial hypertension as risk factor for spontaneous cervical artery dissection. A case-control study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:95-97. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2005.063107

5. Merwick Á, Werring D. Posterior circulation ischaemic stroke. BMJ. 2014;348:g3175. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3175

6. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018;49:e46-e110. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158

7. Provenzale JM, Sarikaya B. Comparison of test performance characteristics of MRI, MR angiography, and CT angiography in the diagnosis of carotid and vertebral artery dissection: a review of the medical literature. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:1167-1174. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1688

8. Husnoo Q. A case of missed diagnosis of posterior circulation stroke. Clin Med (Lond). 2019;19(suppl 2):63. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.19-2-s63

9. Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1317-1329. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804656

10. Schneider AM, Neuhaus AA, Hadley G, et al. Posterior circulation ischaemic stroke diagnosis and management. Clin Med (Lond). 2023;23:219-227. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2022-0499

11. Dorňák T, Král M, Šaňák D, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis in posterior circulation stroke. Front Neurol. 2019;10:417. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00417

12. van der Hoeven EJ, Schonewille WJ, Vos JA, et al. The Basilar Artery International Cooperation Study (BASICS): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:200. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-200

13. Nouh A, Remke J, Ruland S. Ischemic posterior circulation stroke: a review of anatomy, clinical presentations, diagnosis, and current management. Front Neurol. 2014;5:30. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2014.00030

14. Purrucker JC, Ringleb PA, Seker F, et al. Leaving the day behind: endovascular therapy beyond 24 h in acute stroke of the anterior and posterior circulation. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2022;15:17562864221101083. doi: 10.1177/17562864221101083

15. Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Derdeyn CP, et al. Stenting versus aggressive medical therapy for intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:993-1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105335

16. Markus HS, Michel P. Treatment of posterior circulation stroke: acute management and secondary prevention. Int J Stroke. 2022;17:723-732. doi: 10.1177/17474930221107500

THE CASE

A 49-year-old woman was hospitalized with a headache and neck pain that radiated to her ears and eyes in the context of severe hypertension (270/150 mm Hg). Her medical history was significant for heterozygous factor V Leiden mutation, longstanding untreated hypertension, and multiple severe episodes of HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets) syndrome during pregnancy.

After receiving antihypertensive treatment at a community hospital, her blood pressure gradually improved to 160/100 mm Hg with the addition of a third medication. However, on Day 3 of her stay, her systolic blood pressure rose to more than 200 mm Hg and was accompanied by somnolence, emesis, and paleness. She was transferred to a tertiary care center.

THE DIAGNOSIS

On admission, the patient had left-side hemiparesis and facial droop with dysarthria, resulting in a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of 7 (out of 42) and a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 13 (out of 15). Noncontrast computed tomography (CT) and CT angiography of the head and neck were ordered and showed occlusion of both intracranial vertebral arteries. There were also signs of multifocal infarction in her occipital lobes, thus systemic recombinant human-tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) could not be administered.

The patient was next taken to the angiography suite, where a digital subtraction angiography confirmed the presence of bilateral vertebral artery occlusions (FIGURE 1A). A thrombectomy was performed to open the left occluded segment, resulting in recanalization; however, a high-grade stenosis remained in the intracranial left vertebral artery (FIGURE 1B). The right vertebral artery had a severe extracranial origin stenosis, and balloon angioplasty was performed in order to reach the intracranial circulation; however, the occlusion of the intracranial right vertebral artery segment could not be catheterized. Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with a time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography showed that the intracranial left vertebral artery with high-grade stenosis had closed down again; thus, there was occlusion of both intracranial vertebral arteries and absent flow signal in the basilar artery (FIGURE 2). There were scattered small acute strokes within the cerebellum, brainstem, and occipital lobes.

Unfortunately, within 48 hours, the patient’s NIHSS score increased from 7 to 29. She developed tetraplegia, was significantly less responsive (GCS score, 3/15), and required intubation and mechanical ventilation. Reopening the stenosis and keeping it open with a stent would be an aggressive procedure with poor odds for success and would require antithrombotic medications with the associated risk for intracranial hemorrhage in the setting of demarcated strokes. Thus, no further intervention was pursued.

Further standard stroke work-up (echocardiography, extracranial ultrasound of the cerebral circulation, and vasculitis screening) was unremarkable. In the intensive care unit, intravenous therapeutic heparin was initiated because of the potential prothrombotic effect of the factor V Leiden mutation but was subsequently switched to dual anti-aggregation therapy (aspirin 100 mg/d and clopidogrel 75 mg/d) as secondary stroke prevention given the final diagnosis of severe atherosclerosis. Nevertheless, the patient remained tetraplegic with a partial locked-in syndrome when she was discharged, after 2 weeks in the tertiary care center, to a rehabilitation center.

DISCUSSION

Posterior circulation strokes account for 20% to 25% of all ischemic strokes1,2 and are associated with infarction within the vertebrobasilar arterial system. Common etiologies of these infarctions include atherosclerosis (as seen in our patient), embolism, small-artery penetrating disease, and arterial dissection.2 Although the estimated overall mortality of these strokes is low (3.6% to 11%),2 basilar occlusion syndrome, in particular, is a life-threatening condition with a high mortality rate of 80% to 90%.3

Continue to: Diagnosis can be particularly challenging...

Diagnosis can be particularly challenging due to the anatomic variations of posterior arterial circulation, as well as the fluctuating nonfocal or multifocal symptoms.2 Specific symptoms include vertigo, ataxia, unilateral motor weakness, dysarthria, and oculomotor dysfunction. However, nonspecific symptoms such as headache, nausea, dizziness, hoarseness, falls, and Horner syndrome may be the only presenting signs of a posterior circulation stroke—as was the case with our patient.2 Her radiating neck pain could have been interpreted as a pointer to vertebral artery dissection within the context of severe hypertension.4 Unfortunately, the diagnosis was delayed and head imaging was obtained only after her mental status deteriorated.

Immediate neuroimaging is necessary to guide treatment in patients with suspected acute posterior circulation stroke,1,5,6 although it is not always definitive. While CT is pivotal in stroke work-up and may reliably exclude intracranial hemorrhage, its ability to detect acute posterior circulation ischemic strokes is limited given its poor visualization of the posterior fossa (as low as 16% sensitivity).5 Fortunately, CT angiography has a high sensitivity (nearing 100%) for large-vessel occlusion and high predictive values for dissection (65%-100% positive predictive value and 70%-98% negative predictive value).5,7 Diffusion-weighted MRI (when available in the emergency setting) has the highest sensitivity for detecting acute infarcts, although posterior circulation infarcts still can be missed (19% false-negative rate).5,8 Thus, correlative vessel imaging with magnetic resonance or CT angiography is very important, along with a high index of suspicion. In some instances, repeat MRI may be necessary to detect small strokes.

A patient-specific approach to management is key for individuals with suspected posterior circulation stroke.5 Because specific data for the appropriate management of posterior circulation ischemic stroke are lacking, current American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) guidelines apply to anterior and posterior circulation strokes.6 For eligible patients without multifocal disease, intravenous tPA is the first-line therapy and should be initiated according to guidelines within 4.5 hours of stroke onset9; it is important to note that these guidelines are based on studies that focused more on anterior circulation strokes than posterior circulation strokes.6,9-13 This can be done in combination with endovascular therapy, which consists of mechanical thrombectomy, intra-arterial thrombolysis, or a combination of revascularization techniques.3,5,6

Mechanical thrombectomy specifically has high proven recanalization rates for all target vessels.3-6 The latest AHA/ASA guidelines recommend mechanical thrombectomy be performed within 6 hours of stroke onset.6 However, there is emerging evidence that suggests this timeframe should be extended—even beyond 24 hours—given the poor prognosis of posterior circulation strokes.5,6,14 More data on the management of posterior circulation strokes are urgently needed to better understand which therapeutic approach is most efficient.

In patients such as ours, who have evidence of multifocal disease, treatment may be limited to endovascular therapy. Intracranial stenting of symptomatic lesions in particular has been controversial since the publication of the Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent Stroke in Intracranial Stenosis trial, which found that aggressive medical management was superior to stenting in patients who recently had a transient ischemic attack or stroke attributed to stenosis.15 Although additional studies have been performed, there are no definitive data on the topic—and certainly no data in the emergency setting.16 Further challenges are raised in patients with bilateral disease, as was the case with this patient.

When our patient was admitted to the rehabilitation clinic, she had a GCS score of 10 to 11/15. After 9 months of rehabilitation, she was discharged home with a GCS score of 15/15 and persistent left-side hemiparesis.

THE TAKEAWAY

Posterior circulation stroke is a life-threatening disease that may manifest with a variety of symptoms and be difficult to identify on emergent imaging. Thus, a high degree of clinical suspicion and additional follow-up are paramount to ensure prompt diagnosis and a patient-tailored treatment strategy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kristine A. Blackham, MD, Associate Professor, University Hospital Basel, Petersgraben 4, 4031 Basel, Switzerland; [email protected] Orcid no: 0000-0002-1620-1144 (Dr. Blackham); 0000-0002- 5225-5414 (Dr. Saleh)

THE CASE

A 49-year-old woman was hospitalized with a headache and neck pain that radiated to her ears and eyes in the context of severe hypertension (270/150 mm Hg). Her medical history was significant for heterozygous factor V Leiden mutation, longstanding untreated hypertension, and multiple severe episodes of HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets) syndrome during pregnancy.

After receiving antihypertensive treatment at a community hospital, her blood pressure gradually improved to 160/100 mm Hg with the addition of a third medication. However, on Day 3 of her stay, her systolic blood pressure rose to more than 200 mm Hg and was accompanied by somnolence, emesis, and paleness. She was transferred to a tertiary care center.

THE DIAGNOSIS

On admission, the patient had left-side hemiparesis and facial droop with dysarthria, resulting in a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of 7 (out of 42) and a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 13 (out of 15). Noncontrast computed tomography (CT) and CT angiography of the head and neck were ordered and showed occlusion of both intracranial vertebral arteries. There were also signs of multifocal infarction in her occipital lobes, thus systemic recombinant human-tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) could not be administered.

The patient was next taken to the angiography suite, where a digital subtraction angiography confirmed the presence of bilateral vertebral artery occlusions (FIGURE 1A). A thrombectomy was performed to open the left occluded segment, resulting in recanalization; however, a high-grade stenosis remained in the intracranial left vertebral artery (FIGURE 1B). The right vertebral artery had a severe extracranial origin stenosis, and balloon angioplasty was performed in order to reach the intracranial circulation; however, the occlusion of the intracranial right vertebral artery segment could not be catheterized. Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with a time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography showed that the intracranial left vertebral artery with high-grade stenosis had closed down again; thus, there was occlusion of both intracranial vertebral arteries and absent flow signal in the basilar artery (FIGURE 2). There were scattered small acute strokes within the cerebellum, brainstem, and occipital lobes.

Unfortunately, within 48 hours, the patient’s NIHSS score increased from 7 to 29. She developed tetraplegia, was significantly less responsive (GCS score, 3/15), and required intubation and mechanical ventilation. Reopening the stenosis and keeping it open with a stent would be an aggressive procedure with poor odds for success and would require antithrombotic medications with the associated risk for intracranial hemorrhage in the setting of demarcated strokes. Thus, no further intervention was pursued.

Further standard stroke work-up (echocardiography, extracranial ultrasound of the cerebral circulation, and vasculitis screening) was unremarkable. In the intensive care unit, intravenous therapeutic heparin was initiated because of the potential prothrombotic effect of the factor V Leiden mutation but was subsequently switched to dual anti-aggregation therapy (aspirin 100 mg/d and clopidogrel 75 mg/d) as secondary stroke prevention given the final diagnosis of severe atherosclerosis. Nevertheless, the patient remained tetraplegic with a partial locked-in syndrome when she was discharged, after 2 weeks in the tertiary care center, to a rehabilitation center.

DISCUSSION

Posterior circulation strokes account for 20% to 25% of all ischemic strokes1,2 and are associated with infarction within the vertebrobasilar arterial system. Common etiologies of these infarctions include atherosclerosis (as seen in our patient), embolism, small-artery penetrating disease, and arterial dissection.2 Although the estimated overall mortality of these strokes is low (3.6% to 11%),2 basilar occlusion syndrome, in particular, is a life-threatening condition with a high mortality rate of 80% to 90%.3

Continue to: Diagnosis can be particularly challenging...

Diagnosis can be particularly challenging due to the anatomic variations of posterior arterial circulation, as well as the fluctuating nonfocal or multifocal symptoms.2 Specific symptoms include vertigo, ataxia, unilateral motor weakness, dysarthria, and oculomotor dysfunction. However, nonspecific symptoms such as headache, nausea, dizziness, hoarseness, falls, and Horner syndrome may be the only presenting signs of a posterior circulation stroke—as was the case with our patient.2 Her radiating neck pain could have been interpreted as a pointer to vertebral artery dissection within the context of severe hypertension.4 Unfortunately, the diagnosis was delayed and head imaging was obtained only after her mental status deteriorated.

Immediate neuroimaging is necessary to guide treatment in patients with suspected acute posterior circulation stroke,1,5,6 although it is not always definitive. While CT is pivotal in stroke work-up and may reliably exclude intracranial hemorrhage, its ability to detect acute posterior circulation ischemic strokes is limited given its poor visualization of the posterior fossa (as low as 16% sensitivity).5 Fortunately, CT angiography has a high sensitivity (nearing 100%) for large-vessel occlusion and high predictive values for dissection (65%-100% positive predictive value and 70%-98% negative predictive value).5,7 Diffusion-weighted MRI (when available in the emergency setting) has the highest sensitivity for detecting acute infarcts, although posterior circulation infarcts still can be missed (19% false-negative rate).5,8 Thus, correlative vessel imaging with magnetic resonance or CT angiography is very important, along with a high index of suspicion. In some instances, repeat MRI may be necessary to detect small strokes.

A patient-specific approach to management is key for individuals with suspected posterior circulation stroke.5 Because specific data for the appropriate management of posterior circulation ischemic stroke are lacking, current American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) guidelines apply to anterior and posterior circulation strokes.6 For eligible patients without multifocal disease, intravenous tPA is the first-line therapy and should be initiated according to guidelines within 4.5 hours of stroke onset9; it is important to note that these guidelines are based on studies that focused more on anterior circulation strokes than posterior circulation strokes.6,9-13 This can be done in combination with endovascular therapy, which consists of mechanical thrombectomy, intra-arterial thrombolysis, or a combination of revascularization techniques.3,5,6

Mechanical thrombectomy specifically has high proven recanalization rates for all target vessels.3-6 The latest AHA/ASA guidelines recommend mechanical thrombectomy be performed within 6 hours of stroke onset.6 However, there is emerging evidence that suggests this timeframe should be extended—even beyond 24 hours—given the poor prognosis of posterior circulation strokes.5,6,14 More data on the management of posterior circulation strokes are urgently needed to better understand which therapeutic approach is most efficient.

In patients such as ours, who have evidence of multifocal disease, treatment may be limited to endovascular therapy. Intracranial stenting of symptomatic lesions in particular has been controversial since the publication of the Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent Stroke in Intracranial Stenosis trial, which found that aggressive medical management was superior to stenting in patients who recently had a transient ischemic attack or stroke attributed to stenosis.15 Although additional studies have been performed, there are no definitive data on the topic—and certainly no data in the emergency setting.16 Further challenges are raised in patients with bilateral disease, as was the case with this patient.

When our patient was admitted to the rehabilitation clinic, she had a GCS score of 10 to 11/15. After 9 months of rehabilitation, she was discharged home with a GCS score of 15/15 and persistent left-side hemiparesis.

THE TAKEAWAY

Posterior circulation stroke is a life-threatening disease that may manifest with a variety of symptoms and be difficult to identify on emergent imaging. Thus, a high degree of clinical suspicion and additional follow-up are paramount to ensure prompt diagnosis and a patient-tailored treatment strategy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kristine A. Blackham, MD, Associate Professor, University Hospital Basel, Petersgraben 4, 4031 Basel, Switzerland; [email protected] Orcid no: 0000-0002-1620-1144 (Dr. Blackham); 0000-0002- 5225-5414 (Dr. Saleh)

1. Cloud GC, Markus HS. Diagnosis and management of vertebral artery stenosis. QJM. 2003;96:27-54. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcg003

2. Sparaco M, Ciolli L, Zini A. Posterior circulation ischaemic stroke–a review part I: anatomy, aetiology and clinical presentations. Neurol Sci. 2019;40:1995-2006. doi: 10.1007/s10072-019-03977-2

3. Lin DDM, Gailloud P, Beauchamp NJ, et al. Combined stent placement and thrombolysis in acute vertebrobasilar ischemic stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:1827-1833.

4. Pezzini A, Caso V, Zanferrari C, et al. Arterial hypertension as risk factor for spontaneous cervical artery dissection. A case-control study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:95-97. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2005.063107

5. Merwick Á, Werring D. Posterior circulation ischaemic stroke. BMJ. 2014;348:g3175. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3175

6. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018;49:e46-e110. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158

7. Provenzale JM, Sarikaya B. Comparison of test performance characteristics of MRI, MR angiography, and CT angiography in the diagnosis of carotid and vertebral artery dissection: a review of the medical literature. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:1167-1174. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1688

8. Husnoo Q. A case of missed diagnosis of posterior circulation stroke. Clin Med (Lond). 2019;19(suppl 2):63. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.19-2-s63

9. Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1317-1329. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804656

10. Schneider AM, Neuhaus AA, Hadley G, et al. Posterior circulation ischaemic stroke diagnosis and management. Clin Med (Lond). 2023;23:219-227. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2022-0499

11. Dorňák T, Král M, Šaňák D, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis in posterior circulation stroke. Front Neurol. 2019;10:417. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00417

12. van der Hoeven EJ, Schonewille WJ, Vos JA, et al. The Basilar Artery International Cooperation Study (BASICS): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:200. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-200

13. Nouh A, Remke J, Ruland S. Ischemic posterior circulation stroke: a review of anatomy, clinical presentations, diagnosis, and current management. Front Neurol. 2014;5:30. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2014.00030

14. Purrucker JC, Ringleb PA, Seker F, et al. Leaving the day behind: endovascular therapy beyond 24 h in acute stroke of the anterior and posterior circulation. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2022;15:17562864221101083. doi: 10.1177/17562864221101083

15. Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Derdeyn CP, et al. Stenting versus aggressive medical therapy for intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:993-1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105335

16. Markus HS, Michel P. Treatment of posterior circulation stroke: acute management and secondary prevention. Int J Stroke. 2022;17:723-732. doi: 10.1177/17474930221107500

1. Cloud GC, Markus HS. Diagnosis and management of vertebral artery stenosis. QJM. 2003;96:27-54. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcg003

2. Sparaco M, Ciolli L, Zini A. Posterior circulation ischaemic stroke–a review part I: anatomy, aetiology and clinical presentations. Neurol Sci. 2019;40:1995-2006. doi: 10.1007/s10072-019-03977-2

3. Lin DDM, Gailloud P, Beauchamp NJ, et al. Combined stent placement and thrombolysis in acute vertebrobasilar ischemic stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:1827-1833.

4. Pezzini A, Caso V, Zanferrari C, et al. Arterial hypertension as risk factor for spontaneous cervical artery dissection. A case-control study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:95-97. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2005.063107

5. Merwick Á, Werring D. Posterior circulation ischaemic stroke. BMJ. 2014;348:g3175. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3175

6. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018;49:e46-e110. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158

7. Provenzale JM, Sarikaya B. Comparison of test performance characteristics of MRI, MR angiography, and CT angiography in the diagnosis of carotid and vertebral artery dissection: a review of the medical literature. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:1167-1174. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1688

8. Husnoo Q. A case of missed diagnosis of posterior circulation stroke. Clin Med (Lond). 2019;19(suppl 2):63. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.19-2-s63

9. Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1317-1329. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804656

10. Schneider AM, Neuhaus AA, Hadley G, et al. Posterior circulation ischaemic stroke diagnosis and management. Clin Med (Lond). 2023;23:219-227. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2022-0499

11. Dorňák T, Král M, Šaňák D, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis in posterior circulation stroke. Front Neurol. 2019;10:417. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00417

12. van der Hoeven EJ, Schonewille WJ, Vos JA, et al. The Basilar Artery International Cooperation Study (BASICS): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:200. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-200

13. Nouh A, Remke J, Ruland S. Ischemic posterior circulation stroke: a review of anatomy, clinical presentations, diagnosis, and current management. Front Neurol. 2014;5:30. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2014.00030

14. Purrucker JC, Ringleb PA, Seker F, et al. Leaving the day behind: endovascular therapy beyond 24 h in acute stroke of the anterior and posterior circulation. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2022;15:17562864221101083. doi: 10.1177/17562864221101083

15. Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Derdeyn CP, et al. Stenting versus aggressive medical therapy for intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:993-1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105335

16. Markus HS, Michel P. Treatment of posterior circulation stroke: acute management and secondary prevention. Int J Stroke. 2022;17:723-732. doi: 10.1177/17474930221107500

► Headache and neck pain radiating to ears and eyes

► Severe hypertension

A Case of Compound Heterozygous Factor V Leiden and Prothrombin G20210A Mutations With Recurrent Arterial Thromboembolism

BACKGROUND

There are 5 germline mutations that lead to hypercoagulability in the general population including: Factor V Leiden (FVL), Prothrombin G20210A (F2A), Protein C Deficiency (PCD), Protein S Deficiency (PSD), and Antithrombin Deficiency (ATD). Typical guidance is to defer testing, as it is thought not to change management.

CASE REPORT

We present a case of a patient who was found to be compound heterozygous mutations for FVL and F2A, who presented with two episodes of arterial thromboembolism resulting in cerebrovascular accident (CVA). A 63-year-old male with past medical history of hypertension, a CVA four years prior, and medication non-compliance presents with new onset left sided hemiparesis after an episode of convulsions. MRI and CT imaging of the head revealed ischemic CVA secondary to thromboembolism in the right posterior cerebral artery’s (PCA), P1 branch. Following administration of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) he had rapid symptom improvement. This second ischemic CVA prompted a workup which was notable for: negative echocardiogram, negative 30-day cardiac monitor, CT chest negative for malignancy, no significant vascular findings, negative for antiphospholipid syndrome, but genetic testing revealed the patient to be heterozygous for FVL and F2A mutations. He was started on apixaban 5 mg twice daily for ongoing secondary prevention. Though medication compliance continues to be difficult, after being placed on direct anticoagulant (DOAC), he has not had recurrent venous or arterial thrombotic events. A small case series found double heterozygosity for FVL and F2A further increases the risk of venous thromboembolism up to 17% or more in a lifetime.

CONCLUSIONS

Although current recommendations advocate against testing for specific mutations in most cases as it is likely not to change management1, this case suggests that it may be of some benefit in patients that have a workup that does not yield a clear etiology, especially in cryptogenic stroke which is typically managed with aspirin rather than direct oral anticoagulant.

BACKGROUND

There are 5 germline mutations that lead to hypercoagulability in the general population including: Factor V Leiden (FVL), Prothrombin G20210A (F2A), Protein C Deficiency (PCD), Protein S Deficiency (PSD), and Antithrombin Deficiency (ATD). Typical guidance is to defer testing, as it is thought not to change management.

CASE REPORT

We present a case of a patient who was found to be compound heterozygous mutations for FVL and F2A, who presented with two episodes of arterial thromboembolism resulting in cerebrovascular accident (CVA). A 63-year-old male with past medical history of hypertension, a CVA four years prior, and medication non-compliance presents with new onset left sided hemiparesis after an episode of convulsions. MRI and CT imaging of the head revealed ischemic CVA secondary to thromboembolism in the right posterior cerebral artery’s (PCA), P1 branch. Following administration of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) he had rapid symptom improvement. This second ischemic CVA prompted a workup which was notable for: negative echocardiogram, negative 30-day cardiac monitor, CT chest negative for malignancy, no significant vascular findings, negative for antiphospholipid syndrome, but genetic testing revealed the patient to be heterozygous for FVL and F2A mutations. He was started on apixaban 5 mg twice daily for ongoing secondary prevention. Though medication compliance continues to be difficult, after being placed on direct anticoagulant (DOAC), he has not had recurrent venous or arterial thrombotic events. A small case series found double heterozygosity for FVL and F2A further increases the risk of venous thromboembolism up to 17% or more in a lifetime.

CONCLUSIONS

Although current recommendations advocate against testing for specific mutations in most cases as it is likely not to change management1, this case suggests that it may be of some benefit in patients that have a workup that does not yield a clear etiology, especially in cryptogenic stroke which is typically managed with aspirin rather than direct oral anticoagulant.

BACKGROUND

There are 5 germline mutations that lead to hypercoagulability in the general population including: Factor V Leiden (FVL), Prothrombin G20210A (F2A), Protein C Deficiency (PCD), Protein S Deficiency (PSD), and Antithrombin Deficiency (ATD). Typical guidance is to defer testing, as it is thought not to change management.

CASE REPORT

We present a case of a patient who was found to be compound heterozygous mutations for FVL and F2A, who presented with two episodes of arterial thromboembolism resulting in cerebrovascular accident (CVA). A 63-year-old male with past medical history of hypertension, a CVA four years prior, and medication non-compliance presents with new onset left sided hemiparesis after an episode of convulsions. MRI and CT imaging of the head revealed ischemic CVA secondary to thromboembolism in the right posterior cerebral artery’s (PCA), P1 branch. Following administration of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) he had rapid symptom improvement. This second ischemic CVA prompted a workup which was notable for: negative echocardiogram, negative 30-day cardiac monitor, CT chest negative for malignancy, no significant vascular findings, negative for antiphospholipid syndrome, but genetic testing revealed the patient to be heterozygous for FVL and F2A mutations. He was started on apixaban 5 mg twice daily for ongoing secondary prevention. Though medication compliance continues to be difficult, after being placed on direct anticoagulant (DOAC), he has not had recurrent venous or arterial thrombotic events. A small case series found double heterozygosity for FVL and F2A further increases the risk of venous thromboembolism up to 17% or more in a lifetime.

CONCLUSIONS

Although current recommendations advocate against testing for specific mutations in most cases as it is likely not to change management1, this case suggests that it may be of some benefit in patients that have a workup that does not yield a clear etiology, especially in cryptogenic stroke which is typically managed with aspirin rather than direct oral anticoagulant.

Successful Treatment With Oral Steroids of Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia Associated With Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

INTRODUCTION

We present an unusual case of autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) associated with Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease (KFD) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) that resolved with steroid therapy.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 25-year-old female with no medical history presented with 6 weeks of high fevers, syncope, and 10-lb weight loss. Exam revealed generalized lymphadenopathy (LAD) and tiny malar papules. Labs showed IgG and IgM Coombs-positivity, hemoglobin of 5 g/dL, hyperbilirubinemia, low haptoglobin, LDH >2000 IU/L, thrombocytopenia, and leukopenia. Cryoglobulins were absent. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) markers showed ferritin of 18,000 ng/mL, moderately elevated soluble IL-2 receptor, negative CD107, minimally elevated CXCL9, borderline transaminitis, and high-normal triglycerides. ANA was 1:1280, speckled, with high anti-RNP, high anti-Smith, and negative anti-dsDNA antibodies. CT confirmed LAD without organomegaly. A 4cm excised node reviewed at 2 institutions showed necrotizing lymphadenitis without granulomas, consistent with KFD. Flow cytometry and gene rearrangement assay showed no monoclonality. Bone marrow biopsy demonstrated erythroid hyperplasia, normal flow cytometry, and no hemophagocytosis. Infectious workup was unremarkable. Treatment was initiated with 50mg prednisone daily, weaned off over 5 months. 2 months post-initiation, the fevers resolved, hemoglobin increased, and LDH normalized. 3 months later, rheumatology service diagnosed SLE based on 2019 ACR/EULAR Criteria and initiated hydroxychloroquine. 9 months later, patient remains without recurrence.

DISCUSSION

KFD presents subacutely with LAD, fever, weight loss, and varying skin findings, often self-resolving. Diagnosis requires lymph node biopsy. Etiology is unclear, with infectious, neoplastic, and autoimmune mechanisms implicated. Studies suggest up to 15% of patients have SLE.

CONCLUSIONS

This case is a rare combination of AIHA, KFD, and SLE successfully treated with steroids and, later, hydroxychloroquine. It calls for vigilance for KFD in patients with LAD and AIHA. A successful treatment strategy could include highdose steroids. The presentation may mimic lymphoma and HLH, which must be ruled out with careful pathologic and lab evaluation. To our knowledge, this is the 3rd reported case of KFD with AIHA, and 2nd case of concomitant SLE, KFD, and AIHA. The only similar patient was treated with methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide and did not have longer-term follow-up.

INTRODUCTION

We present an unusual case of autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) associated with Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease (KFD) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) that resolved with steroid therapy.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 25-year-old female with no medical history presented with 6 weeks of high fevers, syncope, and 10-lb weight loss. Exam revealed generalized lymphadenopathy (LAD) and tiny malar papules. Labs showed IgG and IgM Coombs-positivity, hemoglobin of 5 g/dL, hyperbilirubinemia, low haptoglobin, LDH >2000 IU/L, thrombocytopenia, and leukopenia. Cryoglobulins were absent. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) markers showed ferritin of 18,000 ng/mL, moderately elevated soluble IL-2 receptor, negative CD107, minimally elevated CXCL9, borderline transaminitis, and high-normal triglycerides. ANA was 1:1280, speckled, with high anti-RNP, high anti-Smith, and negative anti-dsDNA antibodies. CT confirmed LAD without organomegaly. A 4cm excised node reviewed at 2 institutions showed necrotizing lymphadenitis without granulomas, consistent with KFD. Flow cytometry and gene rearrangement assay showed no monoclonality. Bone marrow biopsy demonstrated erythroid hyperplasia, normal flow cytometry, and no hemophagocytosis. Infectious workup was unremarkable. Treatment was initiated with 50mg prednisone daily, weaned off over 5 months. 2 months post-initiation, the fevers resolved, hemoglobin increased, and LDH normalized. 3 months later, rheumatology service diagnosed SLE based on 2019 ACR/EULAR Criteria and initiated hydroxychloroquine. 9 months later, patient remains without recurrence.

DISCUSSION

KFD presents subacutely with LAD, fever, weight loss, and varying skin findings, often self-resolving. Diagnosis requires lymph node biopsy. Etiology is unclear, with infectious, neoplastic, and autoimmune mechanisms implicated. Studies suggest up to 15% of patients have SLE.

CONCLUSIONS

This case is a rare combination of AIHA, KFD, and SLE successfully treated with steroids and, later, hydroxychloroquine. It calls for vigilance for KFD in patients with LAD and AIHA. A successful treatment strategy could include highdose steroids. The presentation may mimic lymphoma and HLH, which must be ruled out with careful pathologic and lab evaluation. To our knowledge, this is the 3rd reported case of KFD with AIHA, and 2nd case of concomitant SLE, KFD, and AIHA. The only similar patient was treated with methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide and did not have longer-term follow-up.

INTRODUCTION

We present an unusual case of autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) associated with Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease (KFD) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) that resolved with steroid therapy.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 25-year-old female with no medical history presented with 6 weeks of high fevers, syncope, and 10-lb weight loss. Exam revealed generalized lymphadenopathy (LAD) and tiny malar papules. Labs showed IgG and IgM Coombs-positivity, hemoglobin of 5 g/dL, hyperbilirubinemia, low haptoglobin, LDH >2000 IU/L, thrombocytopenia, and leukopenia. Cryoglobulins were absent. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) markers showed ferritin of 18,000 ng/mL, moderately elevated soluble IL-2 receptor, negative CD107, minimally elevated CXCL9, borderline transaminitis, and high-normal triglycerides. ANA was 1:1280, speckled, with high anti-RNP, high anti-Smith, and negative anti-dsDNA antibodies. CT confirmed LAD without organomegaly. A 4cm excised node reviewed at 2 institutions showed necrotizing lymphadenitis without granulomas, consistent with KFD. Flow cytometry and gene rearrangement assay showed no monoclonality. Bone marrow biopsy demonstrated erythroid hyperplasia, normal flow cytometry, and no hemophagocytosis. Infectious workup was unremarkable. Treatment was initiated with 50mg prednisone daily, weaned off over 5 months. 2 months post-initiation, the fevers resolved, hemoglobin increased, and LDH normalized. 3 months later, rheumatology service diagnosed SLE based on 2019 ACR/EULAR Criteria and initiated hydroxychloroquine. 9 months later, patient remains without recurrence.

DISCUSSION

KFD presents subacutely with LAD, fever, weight loss, and varying skin findings, often self-resolving. Diagnosis requires lymph node biopsy. Etiology is unclear, with infectious, neoplastic, and autoimmune mechanisms implicated. Studies suggest up to 15% of patients have SLE.

CONCLUSIONS

This case is a rare combination of AIHA, KFD, and SLE successfully treated with steroids and, later, hydroxychloroquine. It calls for vigilance for KFD in patients with LAD and AIHA. A successful treatment strategy could include highdose steroids. The presentation may mimic lymphoma and HLH, which must be ruled out with careful pathologic and lab evaluation. To our knowledge, this is the 3rd reported case of KFD with AIHA, and 2nd case of concomitant SLE, KFD, and AIHA. The only similar patient was treated with methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide and did not have longer-term follow-up.

Does Gemcitabine Have a Curative Role in Treatment of Relapsed/Refractory Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia?

INTRODUCTION

Gemcitabine is a part of National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines as salvage therapy for relapsed/refractory B-cell lymphomas, but its role in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) remains unclear. We describe a case of relapsed CLL showing complete response while on gemcitabine for another primary malignancy, suggesting a potential curative role of gemcitabine for CLL.

CASE REPORT

A 78-year-old male with relapsed CD38+ CLL with del11q on ibrutinib with partial response, presented with gross hematuria for one week. Of note, he was diagnosed with BRCA-negative Stage Ib pancreatic adenocarcinoma within the previous year, treated with surgery and adjuvant capecitabine-gemcitabine. Physical examination was unremarkable and bloodwork showed a white cell count of 32,000 cells/ mm3 with 1.5% lymphocytes, hemoglobin 9.5 g/dL, and platelets 866,000 cells/mm3. Hematuria remained persistent despite frequent bladder irrigations but resolved within a week of stopping ibrutinib. Eight months later, his white cell count is 6,600 cells/mm3, with 16% lymphocytes, hemoglobin 10.2 g/dL, platelets 519,000/m3, and CT scans show no pathological lymphadenopathy. A recent flow cytometry done for academic purposes showed no clonal B cells.

DISCUSSION

Relapsed CLL has a poor prognosis with no curative treatment. Gemcitabine is a part of NCCN guidelines for relapse/refractory B-cell lymphomas but is not included in guidelines for CLL. A study by Jamie et al in 2001 suggested the pre-clinical effectiveness of gemcitabine for relapsed/refractory CLL and phase II trials conducted in 2005 and 2012 on combination chemotherapy including gemcitabine have shown overall CLL response rates of 50-65%. The resolution of B-cell clonality and improvement in biochemical markers after treatment with gemcitabine for an alternate primary malignancy suggested that gemcitabine played a potential curative role in our patient. Further prospective studies are needed to explore this avenue for the role of gemcitabine as a salvage as well as potentially curative therapy for relapsed CLL with variable cytogenetics and treatment histories.

CONCLUSIONS

Gemcitabine is not part of NCCN guidelines for CLL currently but it is a reasonable treatment option for relapsed/refractory CLL. Further studies are needed to explore its potential curative role for relapsed CLL, and update existing guidelines.

INTRODUCTION

Gemcitabine is a part of National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines as salvage therapy for relapsed/refractory B-cell lymphomas, but its role in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) remains unclear. We describe a case of relapsed CLL showing complete response while on gemcitabine for another primary malignancy, suggesting a potential curative role of gemcitabine for CLL.

CASE REPORT

A 78-year-old male with relapsed CD38+ CLL with del11q on ibrutinib with partial response, presented with gross hematuria for one week. Of note, he was diagnosed with BRCA-negative Stage Ib pancreatic adenocarcinoma within the previous year, treated with surgery and adjuvant capecitabine-gemcitabine. Physical examination was unremarkable and bloodwork showed a white cell count of 32,000 cells/ mm3 with 1.5% lymphocytes, hemoglobin 9.5 g/dL, and platelets 866,000 cells/mm3. Hematuria remained persistent despite frequent bladder irrigations but resolved within a week of stopping ibrutinib. Eight months later, his white cell count is 6,600 cells/mm3, with 16% lymphocytes, hemoglobin 10.2 g/dL, platelets 519,000/m3, and CT scans show no pathological lymphadenopathy. A recent flow cytometry done for academic purposes showed no clonal B cells.

DISCUSSION

Relapsed CLL has a poor prognosis with no curative treatment. Gemcitabine is a part of NCCN guidelines for relapse/refractory B-cell lymphomas but is not included in guidelines for CLL. A study by Jamie et al in 2001 suggested the pre-clinical effectiveness of gemcitabine for relapsed/refractory CLL and phase II trials conducted in 2005 and 2012 on combination chemotherapy including gemcitabine have shown overall CLL response rates of 50-65%. The resolution of B-cell clonality and improvement in biochemical markers after treatment with gemcitabine for an alternate primary malignancy suggested that gemcitabine played a potential curative role in our patient. Further prospective studies are needed to explore this avenue for the role of gemcitabine as a salvage as well as potentially curative therapy for relapsed CLL with variable cytogenetics and treatment histories.

CONCLUSIONS

Gemcitabine is not part of NCCN guidelines for CLL currently but it is a reasonable treatment option for relapsed/refractory CLL. Further studies are needed to explore its potential curative role for relapsed CLL, and update existing guidelines.

INTRODUCTION

Gemcitabine is a part of National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines as salvage therapy for relapsed/refractory B-cell lymphomas, but its role in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) remains unclear. We describe a case of relapsed CLL showing complete response while on gemcitabine for another primary malignancy, suggesting a potential curative role of gemcitabine for CLL.

CASE REPORT

A 78-year-old male with relapsed CD38+ CLL with del11q on ibrutinib with partial response, presented with gross hematuria for one week. Of note, he was diagnosed with BRCA-negative Stage Ib pancreatic adenocarcinoma within the previous year, treated with surgery and adjuvant capecitabine-gemcitabine. Physical examination was unremarkable and bloodwork showed a white cell count of 32,000 cells/ mm3 with 1.5% lymphocytes, hemoglobin 9.5 g/dL, and platelets 866,000 cells/mm3. Hematuria remained persistent despite frequent bladder irrigations but resolved within a week of stopping ibrutinib. Eight months later, his white cell count is 6,600 cells/mm3, with 16% lymphocytes, hemoglobin 10.2 g/dL, platelets 519,000/m3, and CT scans show no pathological lymphadenopathy. A recent flow cytometry done for academic purposes showed no clonal B cells.

DISCUSSION

Relapsed CLL has a poor prognosis with no curative treatment. Gemcitabine is a part of NCCN guidelines for relapse/refractory B-cell lymphomas but is not included in guidelines for CLL. A study by Jamie et al in 2001 suggested the pre-clinical effectiveness of gemcitabine for relapsed/refractory CLL and phase II trials conducted in 2005 and 2012 on combination chemotherapy including gemcitabine have shown overall CLL response rates of 50-65%. The resolution of B-cell clonality and improvement in biochemical markers after treatment with gemcitabine for an alternate primary malignancy suggested that gemcitabine played a potential curative role in our patient. Further prospective studies are needed to explore this avenue for the role of gemcitabine as a salvage as well as potentially curative therapy for relapsed CLL with variable cytogenetics and treatment histories.

CONCLUSIONS

Gemcitabine is not part of NCCN guidelines for CLL currently but it is a reasonable treatment option for relapsed/refractory CLL. Further studies are needed to explore its potential curative role for relapsed CLL, and update existing guidelines.

Delivering Complex Oncologic Care to the Veteran’s “Front Door”: A Case Report of Leveraging Nationwide VA Expertise

INTRODUCTION

Fragmentation of medical services is a significant barrier in modern patient care with contributing factors including patient and system level details. The Veterans Affairs (VA) department is the largest integrated health care organization in the US. Given the complex challenges of such a system, the VA has developed resources to lessen the impact of care fragmentation, potentially widening services and diminishing traditional barriers to care. We present a patient case as an example of how VA programs are impacting current veteran oncologic care.

CASE PRESENTATION

An 86-year-old veteran with shortness of breath and fatigue was found to have macrocytic anemia. Located nearly 200 miles from the closest VA with hematology services he was referred through the National TeleOncology (NTO) service to see hematology using clinical video telehealth (CVT) technology stationed at a VA approximately 100 miles from his home. Consultation led to lab work revealing no viral, nutritional, or rheumatologic explanation. A bone marrow biopsy was completed without clear diagnosis though molecular alterations demonstrated ASXL1, TET2 and CBL mutations. Hematopathology services were sought, and the patient’s case was presented at the NTO virtual hematologic tumor board where expert VA hematopathology, radiology and medical hematology opinions were available. A diagnosis of myelodysplastic syndrome was rendered with care recommendations including the novel agent luspatercept. Given patient age and comorbidities, transportation remained a barrier. The patient was set up to receive services through home based primary care (HBPC) with weekly lab draws and medication administration. Ultimately, the patient was able to receive the first dose of luspatercept through the NTO affiliated VA with subsequent administrations to be given by HBPC. Additional visits planned using at home VA video Connect (VVC) service and CVT visits with NTO hematology at his local community based outpatient center (CBOC) located 30 miles from his home.

DISCUSSION

Located over 3 hours from the closest in-person VA hematologist, this patient was able to receive complex care thanks to a marriage of in-person and virtual services involving specialty nurses, pharmacists, and physicians from across VA. Services such as the NTO hub-spoke model, virtual tumor boards and HBPC, reveal a care framework unique to the VA.

INTRODUCTION

Fragmentation of medical services is a significant barrier in modern patient care with contributing factors including patient and system level details. The Veterans Affairs (VA) department is the largest integrated health care organization in the US. Given the complex challenges of such a system, the VA has developed resources to lessen the impact of care fragmentation, potentially widening services and diminishing traditional barriers to care. We present a patient case as an example of how VA programs are impacting current veteran oncologic care.

CASE PRESENTATION

An 86-year-old veteran with shortness of breath and fatigue was found to have macrocytic anemia. Located nearly 200 miles from the closest VA with hematology services he was referred through the National TeleOncology (NTO) service to see hematology using clinical video telehealth (CVT) technology stationed at a VA approximately 100 miles from his home. Consultation led to lab work revealing no viral, nutritional, or rheumatologic explanation. A bone marrow biopsy was completed without clear diagnosis though molecular alterations demonstrated ASXL1, TET2 and CBL mutations. Hematopathology services were sought, and the patient’s case was presented at the NTO virtual hematologic tumor board where expert VA hematopathology, radiology and medical hematology opinions were available. A diagnosis of myelodysplastic syndrome was rendered with care recommendations including the novel agent luspatercept. Given patient age and comorbidities, transportation remained a barrier. The patient was set up to receive services through home based primary care (HBPC) with weekly lab draws and medication administration. Ultimately, the patient was able to receive the first dose of luspatercept through the NTO affiliated VA with subsequent administrations to be given by HBPC. Additional visits planned using at home VA video Connect (VVC) service and CVT visits with NTO hematology at his local community based outpatient center (CBOC) located 30 miles from his home.

DISCUSSION

Located over 3 hours from the closest in-person VA hematologist, this patient was able to receive complex care thanks to a marriage of in-person and virtual services involving specialty nurses, pharmacists, and physicians from across VA. Services such as the NTO hub-spoke model, virtual tumor boards and HBPC, reveal a care framework unique to the VA.

INTRODUCTION

Fragmentation of medical services is a significant barrier in modern patient care with contributing factors including patient and system level details. The Veterans Affairs (VA) department is the largest integrated health care organization in the US. Given the complex challenges of such a system, the VA has developed resources to lessen the impact of care fragmentation, potentially widening services and diminishing traditional barriers to care. We present a patient case as an example of how VA programs are impacting current veteran oncologic care.

CASE PRESENTATION

An 86-year-old veteran with shortness of breath and fatigue was found to have macrocytic anemia. Located nearly 200 miles from the closest VA with hematology services he was referred through the National TeleOncology (NTO) service to see hematology using clinical video telehealth (CVT) technology stationed at a VA approximately 100 miles from his home. Consultation led to lab work revealing no viral, nutritional, or rheumatologic explanation. A bone marrow biopsy was completed without clear diagnosis though molecular alterations demonstrated ASXL1, TET2 and CBL mutations. Hematopathology services were sought, and the patient’s case was presented at the NTO virtual hematologic tumor board where expert VA hematopathology, radiology and medical hematology opinions were available. A diagnosis of myelodysplastic syndrome was rendered with care recommendations including the novel agent luspatercept. Given patient age and comorbidities, transportation remained a barrier. The patient was set up to receive services through home based primary care (HBPC) with weekly lab draws and medication administration. Ultimately, the patient was able to receive the first dose of luspatercept through the NTO affiliated VA with subsequent administrations to be given by HBPC. Additional visits planned using at home VA video Connect (VVC) service and CVT visits with NTO hematology at his local community based outpatient center (CBOC) located 30 miles from his home.

DISCUSSION

Located over 3 hours from the closest in-person VA hematologist, this patient was able to receive complex care thanks to a marriage of in-person and virtual services involving specialty nurses, pharmacists, and physicians from across VA. Services such as the NTO hub-spoke model, virtual tumor boards and HBPC, reveal a care framework unique to the VA.

Asciminib Chronic Phase Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: A Real-World Single Institution Case Series

INTRODUCTION

The development of imatinib and now newer tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) has revolutionized the overall survival of patients with CML. However, toxicity and treatment-resistance can result in premature discontinuation of therapy. Asciminib, a novel TKI, may have fewer off-target effects. It also bypasses the mechanism of resistance to first-line TKIs by binding to a different site on the BCR-ABL fusion protein. In our institution, three patients have been initiated on asciminib thus far. We present their cases, with a focus on quality of life.

CASE PRESENTATIONS

(1) A 76-year-old male with a history of diffuse vascular disease experienced off-target effects on multiple TKIs (i.e. intolerable nausea on imatinib, pleural effusion on dasatinib, complete heart block on nilotinib), so he was switched to asciminib. He has been tolerating asciminib well over five months and continues to see significant log reduction in BCR-ABL transcripts. (2) A 71-year-old male with a history of multiple complicated gastrointestinal infections never achieved major molecular remission on imatinib and was unable to tolerate dasatinib or bosutinib due to severe nausea and vomiting. He was switched to asciminib, which he has been tolerating well for one year, and has achieved complete hematologic response. (3) A 73-year-old male with a history of chronic kidney disease experienced kidney injury thought to be due to imatinib and was switched to bosutinib. His BCRABL transcripts rose on bosutinib, so patient was started on asciminib, which he has been tolerating well.

DISCUSSION

In this series of patients in their 70s with multiple underlying comorbidities, the unifying theme is that of intolerance to first-line TKIs due to toxicity (cardiac, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and renal). Existing data suggests that asciminib results in less toxicity than other first-line TKIs, and this is evident in our patients. More importantly, the combination of efficacy and tolerability gives these patients the opportunity to proceed with life-prolonging therapy, even for those who face treatment resistance with other agents.

CONCLUSIONS

For CML patients who have failed at least two lines of treatment, whether it is due to disease progression or intolerable toxicity, asciminib is an effective alternative. Further study may result in its promotion to first-line therapy for this disease.

INTRODUCTION

The development of imatinib and now newer tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) has revolutionized the overall survival of patients with CML. However, toxicity and treatment-resistance can result in premature discontinuation of therapy. Asciminib, a novel TKI, may have fewer off-target effects. It also bypasses the mechanism of resistance to first-line TKIs by binding to a different site on the BCR-ABL fusion protein. In our institution, three patients have been initiated on asciminib thus far. We present their cases, with a focus on quality of life.

CASE PRESENTATIONS

(1) A 76-year-old male with a history of diffuse vascular disease experienced off-target effects on multiple TKIs (i.e. intolerable nausea on imatinib, pleural effusion on dasatinib, complete heart block on nilotinib), so he was switched to asciminib. He has been tolerating asciminib well over five months and continues to see significant log reduction in BCR-ABL transcripts. (2) A 71-year-old male with a history of multiple complicated gastrointestinal infections never achieved major molecular remission on imatinib and was unable to tolerate dasatinib or bosutinib due to severe nausea and vomiting. He was switched to asciminib, which he has been tolerating well for one year, and has achieved complete hematologic response. (3) A 73-year-old male with a history of chronic kidney disease experienced kidney injury thought to be due to imatinib and was switched to bosutinib. His BCRABL transcripts rose on bosutinib, so patient was started on asciminib, which he has been tolerating well.

DISCUSSION

In this series of patients in their 70s with multiple underlying comorbidities, the unifying theme is that of intolerance to first-line TKIs due to toxicity (cardiac, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and renal). Existing data suggests that asciminib results in less toxicity than other first-line TKIs, and this is evident in our patients. More importantly, the combination of efficacy and tolerability gives these patients the opportunity to proceed with life-prolonging therapy, even for those who face treatment resistance with other agents.

CONCLUSIONS

For CML patients who have failed at least two lines of treatment, whether it is due to disease progression or intolerable toxicity, asciminib is an effective alternative. Further study may result in its promotion to first-line therapy for this disease.

INTRODUCTION

The development of imatinib and now newer tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) has revolutionized the overall survival of patients with CML. However, toxicity and treatment-resistance can result in premature discontinuation of therapy. Asciminib, a novel TKI, may have fewer off-target effects. It also bypasses the mechanism of resistance to first-line TKIs by binding to a different site on the BCR-ABL fusion protein. In our institution, three patients have been initiated on asciminib thus far. We present their cases, with a focus on quality of life.

CASE PRESENTATIONS

(1) A 76-year-old male with a history of diffuse vascular disease experienced off-target effects on multiple TKIs (i.e. intolerable nausea on imatinib, pleural effusion on dasatinib, complete heart block on nilotinib), so he was switched to asciminib. He has been tolerating asciminib well over five months and continues to see significant log reduction in BCR-ABL transcripts. (2) A 71-year-old male with a history of multiple complicated gastrointestinal infections never achieved major molecular remission on imatinib and was unable to tolerate dasatinib or bosutinib due to severe nausea and vomiting. He was switched to asciminib, which he has been tolerating well for one year, and has achieved complete hematologic response. (3) A 73-year-old male with a history of chronic kidney disease experienced kidney injury thought to be due to imatinib and was switched to bosutinib. His BCRABL transcripts rose on bosutinib, so patient was started on asciminib, which he has been tolerating well.

DISCUSSION

In this series of patients in their 70s with multiple underlying comorbidities, the unifying theme is that of intolerance to first-line TKIs due to toxicity (cardiac, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and renal). Existing data suggests that asciminib results in less toxicity than other first-line TKIs, and this is evident in our patients. More importantly, the combination of efficacy and tolerability gives these patients the opportunity to proceed with life-prolonging therapy, even for those who face treatment resistance with other agents.

CONCLUSIONS

For CML patients who have failed at least two lines of treatment, whether it is due to disease progression or intolerable toxicity, asciminib is an effective alternative. Further study may result in its promotion to first-line therapy for this disease.

Recurrence of Adult Cerebellar Medulloblastoma With Bone Marrow Metastasis: A Case Report and Review of the Literature

INTRODUCTION

Medulloblastoma (MB) is rarely seen in adulthood. Treatment guidelines are derived from studies of the pediatric population, results favoring the Packer regimen (cisplatin plus cyclophosphamide or lomustine plus vincristine). MB rarely has extraneural metastases, especially the bone marrow.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 32-year-old female with a past medical history of cerebellar MB confirmed on surgical pathology status post resection, weekly radiation and vincristine treatment presented to us in clinic to re-establish care. She was lost to follow-up 9 months after initial diagnosis and wished to continue treatment. She was started on Lomustine, Cisplatin and Vincristine after discussion with our colleagues at MSKCC, where she had received her initial treatment. After cycle three, she developed intractable bone pain and pancytopenia. Bone marrow biopsy revealed metastasis of Sonic Hedgehog Desmoplastic/nodular variant MB. PET and CT imaging confirmed metastatic disease in the bone marrow and repeat MRI brain showed abnormal nodular enhancement. CSF analysis to assess for spinal metastasis was negative. The patient was started on Temozolomide, Irinotecan and Bevacizumab with significant improvement in bone pain and radiological improvement noted on PET and CT scans. After cycle six, the patient had increased bone pain and repeat FDG-PET showed increased uptake, however, she continued to receive treatment and her pain has improved off narcotics.

DISCUSSION

We highlight a case of adult MB in the bone marrow responsive to temozolomide, irinotecan and bevacizumab. We conducted a literature search using PubMed, Medline and Web of Science between 1990 to 2022. In 2021, COG Phase 2 screening trial showed bevacizumab, temozolamide/irinotecan therapy significantly reduced the risk of death with recurrent MBs, two studies included patients up to 21 and 23 years of age. Other modalities showing some response include Vincristine plus cyclophosphamide as well as high dose carboplatin, thiotepa and etoposide alongside autologous SCT. Vismodegib has also shown varied response of 15 months in two adults with extraneural MB metastasis. Given the unique entity of adult MB and extraneural metastasis, limitations include small sample and lack of generalizability.

CONCLUSIONS

Extraneural metastasis of MB yields a poor prognosis. Future considerations include randomized trials to establish efficacy of Temozolomide, Irinotecan plus Bevacizumab in this population.

INTRODUCTION

Medulloblastoma (MB) is rarely seen in adulthood. Treatment guidelines are derived from studies of the pediatric population, results favoring the Packer regimen (cisplatin plus cyclophosphamide or lomustine plus vincristine). MB rarely has extraneural metastases, especially the bone marrow.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 32-year-old female with a past medical history of cerebellar MB confirmed on surgical pathology status post resection, weekly radiation and vincristine treatment presented to us in clinic to re-establish care. She was lost to follow-up 9 months after initial diagnosis and wished to continue treatment. She was started on Lomustine, Cisplatin and Vincristine after discussion with our colleagues at MSKCC, where she had received her initial treatment. After cycle three, she developed intractable bone pain and pancytopenia. Bone marrow biopsy revealed metastasis of Sonic Hedgehog Desmoplastic/nodular variant MB. PET and CT imaging confirmed metastatic disease in the bone marrow and repeat MRI brain showed abnormal nodular enhancement. CSF analysis to assess for spinal metastasis was negative. The patient was started on Temozolomide, Irinotecan and Bevacizumab with significant improvement in bone pain and radiological improvement noted on PET and CT scans. After cycle six, the patient had increased bone pain and repeat FDG-PET showed increased uptake, however, she continued to receive treatment and her pain has improved off narcotics.

DISCUSSION

We highlight a case of adult MB in the bone marrow responsive to temozolomide, irinotecan and bevacizumab. We conducted a literature search using PubMed, Medline and Web of Science between 1990 to 2022. In 2021, COG Phase 2 screening trial showed bevacizumab, temozolamide/irinotecan therapy significantly reduced the risk of death with recurrent MBs, two studies included patients up to 21 and 23 years of age. Other modalities showing some response include Vincristine plus cyclophosphamide as well as high dose carboplatin, thiotepa and etoposide alongside autologous SCT. Vismodegib has also shown varied response of 15 months in two adults with extraneural MB metastasis. Given the unique entity of adult MB and extraneural metastasis, limitations include small sample and lack of generalizability.

CONCLUSIONS

Extraneural metastasis of MB yields a poor prognosis. Future considerations include randomized trials to establish efficacy of Temozolomide, Irinotecan plus Bevacizumab in this population.

INTRODUCTION

Medulloblastoma (MB) is rarely seen in adulthood. Treatment guidelines are derived from studies of the pediatric population, results favoring the Packer regimen (cisplatin plus cyclophosphamide or lomustine plus vincristine). MB rarely has extraneural metastases, especially the bone marrow.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 32-year-old female with a past medical history of cerebellar MB confirmed on surgical pathology status post resection, weekly radiation and vincristine treatment presented to us in clinic to re-establish care. She was lost to follow-up 9 months after initial diagnosis and wished to continue treatment. She was started on Lomustine, Cisplatin and Vincristine after discussion with our colleagues at MSKCC, where she had received her initial treatment. After cycle three, she developed intractable bone pain and pancytopenia. Bone marrow biopsy revealed metastasis of Sonic Hedgehog Desmoplastic/nodular variant MB. PET and CT imaging confirmed metastatic disease in the bone marrow and repeat MRI brain showed abnormal nodular enhancement. CSF analysis to assess for spinal metastasis was negative. The patient was started on Temozolomide, Irinotecan and Bevacizumab with significant improvement in bone pain and radiological improvement noted on PET and CT scans. After cycle six, the patient had increased bone pain and repeat FDG-PET showed increased uptake, however, she continued to receive treatment and her pain has improved off narcotics.

DISCUSSION