User login

Safety and Usefulness of Free Fat Grafts After Microdiscectomy Using an Access Cannula: A Prospective Pilot Study and Literature Review

Hardware for the Heart: The Increasing Impact of Pacemakers, ICDs, and LVADs

Alicia S. Devine, JD, MD

Dr Devine is an assistant professor, department of emergency medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk.

Disclosure: The author reports no conflict of interest.

Heart disease affects a growing number of patients each year. The causes of heart disease are diverse, but whether the etiology is ischemic or structural, the disease often progresses to the point where patients are at risk for fatal dysrhythmias and heart failure. Treatment modalities for heart disease range from lifestyle modification and medical management to interventional reperfusion, and often involve the surgical implantation of devices designed to improve cardiac function and/or to detect and terminate lethal dysrhythmias.

Over the past two decades, the use of automated implantable cardiac devices (AICDs) such as pacemakers, implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs), and left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) has increased significantly. From 1993 to 2009, nearly 3 million patients received permanent pacemakers in the United States; in 2009 alone, over 188,000 were placed. From 2006 to 2011 (the period for which the most recent data are available), approximately 850,000 patients had an AICD implanted. For the 20-month period running from April 2010 to December 2011, nearly 260,000 patients received the device. Finally, from 2006 through 2013, over 9,000 LVADs were placed. Like the other cardiac devices discussed, the frequency of use continues to increase, with 3,834 LVADs placed in just the first 9 months of 2013.

Emergency physicians are expected to be able to stabilize and manage patients with these devices who present to the ED. Care for these patients requires an understanding of the components and function of the different devices as well as their complications. All of the devices are subject to complications from infection, bleeding, migration, or fracture of the component parts, and, more ominously, complete failure of the device. While the current generation of cardiac devices are much smaller in size than their initial prototypes, they are more technically complex, and consultation with cardiology after initial stabilization is recommended.

Cardiac Hardware

Management of the Patient With an Implanted Pacemaker

Martin Huecker, MD

Thomas Cunningham, MD

Dr Huecker is an assistant professor, department of emergency medicine, University of Louisville, Kentucky.

Dr Cunningham is chief resident, department of emergency medicine, University of Louisville, Kentucky.

Disclosure: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Introduction

Cardiac pacing was conceived in 1899, and the first successful pacemaker was implanted in 1960.1,2 New concepts and evolution of design have made pacemakers increasingly complex. Over the last decade, the rate of implantation has grown by over 50%.3 At the forefront of cardiac care, today’s EP must be proficient in the care of patients with cardiac pacemakers.

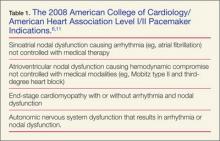

The pacemaker consists of a generator and its leads. The generator produces an electrical impulse that travels down the leads to depolarize myocardial tissue.4 A pacemaker corrects abnormal heart rhythms, using these electrical pulses to induce a novel sinus rhythm.5,6Table 1 summarizes the 2008 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Level I/II indications for pacemaker placement.

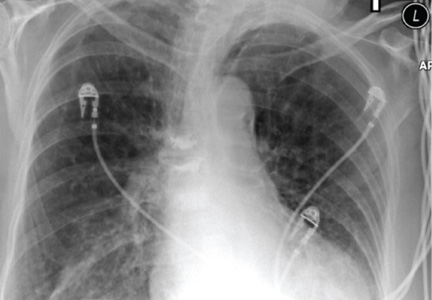

Permanent pacing involves fluoroscopic placement of leads into a chamber(s) of the heart. The generator is implanted most commonly in the left subcutaneous chest.7-9 A single-chamber pacemaker’s leads are located in either the right atrium or ventricle. Dual-chamber pacemakers function with one electrode in the atrium and one in the ventricle. A biventricular pacemaker, also known as cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) paces both ventricles via the septal walls.4,7,10

All pacemaker patients need prompt identification of the device manufacturer.8 Patients should carry identification cards. Chest X-ray may identify the device and will give information as to the location and structural integrity of wires. Interrogation should generally be performed in all patients and will provide valuable information such as battery status, current mode, rate, past rhythms, parameters to detect malignant rhythms, and therapeutic settings.4

Evaluation of the patient with a pacemaker begins with a detailed history and physical examination, including any complications involving the device. Clinicians should ask about pacemaker-related symptoms—ie, palpitations, light-headedness, syncope, or changes in exercise tolerance.3 As with all chest pain complaints in the ED, addressing abnormal vital signs and identification of myocardial infarction (MI) must precede other considerations.

Myocardial Infarction in the Pacemaker Patient

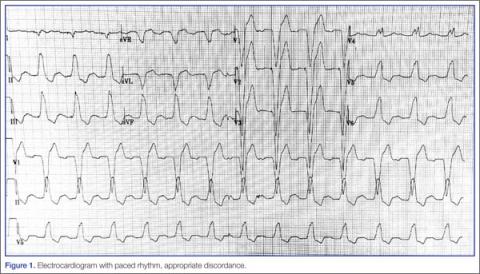

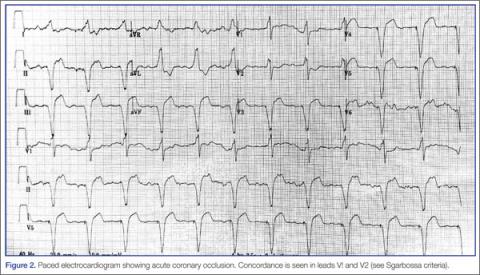

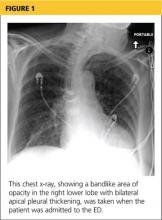

Because of the underlying rhythm induced by the cardiac pacemaker stimulation, acute coronary occlusion can be subtle.12 Since the pacemaker depolarizes the right ventricle, the delay in left ventricular depolarization is seen as left bundle branch block (LBBB) on electrocardiogram (ECG).13,14Figure 1 shows an ECG demonstrating paced rhythm and appropriate discordance, while the ECG in Figure 2 demonstrates acute coronary occlusion. Therefore, identification of coronary occlusion in the paced patient is done using the following Sgarbossa criteria:

- ST elevation ≥1 mm in a lead with upward (concordant) QRS complex; 5 points.

- ST depression ≥1 mm in lead V1, V2, or V3; 3 points.

- ST elevation ≥5 mm in a lead with downward (discordant) QRS complex; 2 points.13,15

An ECG demonstrating three points of Sgarbossa criteria yields a diagnosis of ST segment elevation MI with 98% specificity and 20% sensitivity.16 A modified Sgarbossa criteria replaces the absolute ST-elevation measurement (Sgarbossa criteria 3) with an ST/S ratio greater than -0.25. This yields a sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 90%.17

Pacemaker-Related Complications

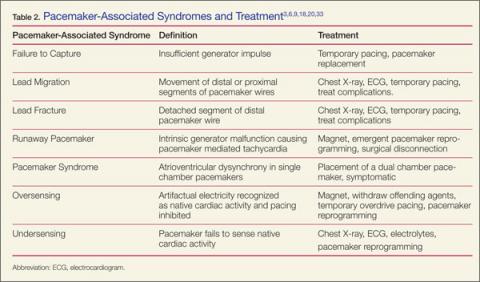

When ischemia is no longer a concern, address the device itself. Workup involves history and physical examination, with complete blood count, chest X-ray, cardiac biomarkers, basic metabolic panel, ultrasound, and device interrogation, as indicated. Table 2 provides a summary of associated pacemaker syndromes and treatment.

Infectious Complications

Patients with device-related infection can present with local or systemic signs, depending on time from implantation. Tenderness to palpation over the generator is sensitive for pocket infection. Although rare, pocket infections require urgent evaluation with mortality rates as high as 20%.18

Early (< 30 days) pocket complications are usually attributable to hematomas with or without infection. When infection is present, Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis are the most likely culprits. Up to 50% of isolates can be methicillin resistant S aureus.19 Although needle aspiration has been used in the past for evacuation and microbial identification, current recommendations do not advocate this approach.20 Incision and debridement are the mainstays of therapy. Over 70% of patients with pocket infections will have positive blood cultures and should receive antibiotic therapy with vancomycin.21

Patients with wound separation or pocket infection are at risk for lead infection, lead separation, and lead fracture with related thoracic involvement (ie, pneumonia, empyema, hemothorax, pneumothorax, or diaphragmatic rupture).20

Infectious complications greater than 30 days from implantation are more likely lead-related. Because of the risk for embolic disease to pulmonary or cardiac tissues, emergent line removal and empiric antibiotics are recommended.18 After admission, a transesophageal echocardiogram should be performed to evaluate for valvular involvement and baseline cardiac function.22-24

Physiologic Complications

Patients without ischemia or infection should be evaluated for device-related chest pain. Pain resulting from malfunction of the device usually occurs in the first 48 hours after implantation.9

Patients may present with chest pain related to lead migration or malposition. Perforation of the pleural cavity during the initial procedure can cause hemothorax or pneumothorax. Perforation of the myocardium can lead to hemopericardium and cardiac tamponade. Patients present with respiratory distress and cardiac dysfunction with or without pacing failure.4,9 Bedside cardiac ultrasound assists in assessing these complications and degree of severity.25

Lead migration occurs when a lead detaches from the generator and migrates. Complete separation from the generator may present as failure to capture and should be addressed before lead localization, as temporary pacing may be warranted. Leads coil and regress from patient tampering (ie, Twiddler’s Syndrome) or through spontaneous detachment.3

The ECG may detect functional leads that have migrated to the left heart (coronary sinus, entricular septal defect, perforation). Right bundle branch morphology, rather than the expected left bundle branch morphology, indicates a lead depolarizing the left ventricle.26,27

Lead fracture may occur at any time after implantation. In addition to the complications seen with lead separation and migration, lead fracture is associated with pulmonary vein thrombosis. Because of the volatile nature of fractured leads, patients present more frequently with pacemaker failure, dysrhythmias, and hemodynamic compromise. Temporary pacing may be necessary pending surgical intervention.4,20

Days to weeks postprocedure, patients are at risk for central venous thrombus due to creation of a thrombogenic environment. These thrombi can embolize to the pulmonary circulation and computed tomography pulmonary angiogram should be considered if suspicious.3

Electrical Complications

Failure to pace can be attributed to lead complication (ie, lead malposition, lead fracture), poor lead-tissue interface, or generator complication.28 Electrical complications arise from intrinsic generator malfunction, lack of pacemaker capture, oversensing/undersensing, and poor pacemaker output.29 Poor output results from battery failure, generator failure, or lead misplacement.9

Generator malfunction can produce unwanted tachycardia and exacerbate intrinsic poor cardiac function. Pacemaker-mediated tachycardia (PMT), pacemaker syndrome, and runaway pacemaker should be eliminated from the differential though interrogation and ECG.

Patients presenting with signs of hypotension and cardiac failure may have pacemaker syndrome. With single-chamber conduction, atrioventricular dysynchrony occurs, producing a lack of ventricular preload and poor cardiac output. Treatment includes symptomatic management and pacemaker replacement with a dual-chamber device. In the hemodynamically unstable patient, applications to increase the preload and reduce the afterload should be attempted.20,25

Trauma, battery failure, and intrinsic pacer malfunction can cause PMT such as runaway pacemaker. Application of a magnet has been shown effective only in some cases.3,30 Definitive therapy with emergent pacer reprogramming or surgical disconnection of pacer leads from the generator may be warranted.

Failure to capture occurs when the device electrical impulse is insufficient to depolarize the heart. Battery failure, generator failure, electrode impedance (from fibrosing of the electrodes), lead fracture or malposition, and long QT syndrome are all causes of failure to capture.29 Chest X-ray, ECG, device interrogation, and electrolyte measurement are imperative. The patient with intrinsic generator failure usually requires admission and surgical correction or replacement.3

Oversensing occurs when the device incorrectly interprets artifactual electricity as intrinsic cardiac depolarization. This results in a lack of cardiac stimulation by the pacemaker and can lead to heart block. Shivering, fasciculations from depolarizing neuromuscular blockade, and external interference can cause oversensing. Nonmedical causes include cell phones, security gates, Taser guns, magnets, and iPods.28 Iatrogenic causes include electrosurgery, LVADs, radiation therapy, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), cardioversion, and lithotripsy.31,32 Treatment involves withdrawing the offending agent, then either placing a magnet over the generator to activate its asynchronous mode or temporary overdrive pacing.26,28,31

Undersensing occurs when the pacer fails to sense intrinsic cardiac activity. The result is competitive asynchronous activity between the native cardiac depolarization and the pacemaker impulses. Introduction of new intrinsic rhythms from lead complications (lead fracture, lead migration), ischemia (premature ventricular contraction, premature atrial contraction), or underlying cardiac disease (atrial fibrillation, right BBB [RBBB], LBBB) can precipitate undersensing.4,5,30 These patients are prone to arrhythmias and decompensation of cardiac function. Management requires identifying the cause of the underlying arrhythmia.29 Chest X-ray, ECG, device interrogation, and electrolyte measurement are useful diagnostics for patients with new arrhythmias or ischemia.3,14,27

Conclusion

To assist the EP in evaluating a patient with a suspected pacemaker problem, we propose the algorithm presented in Figure 3.

Recent advancements and the increased prevalence of pacemakers require the EPs to be facile with their operating systems and morbidity. A detailed history and physical examination, along with utilization of simple diagnostics and device interrogation, can prove sufficient to diagnose most pacemaker-related complaints. Acute coronary syndrome and serious infections may be subtle, so a high level of suspicion should be maintained. With a knowledgeable EP and a supportive team, pacemaker complications can be successfully managed.

Managing Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator Shock Complications

Dustin G. Leigh, MD; Cameron R. Wangsgard, MD; Daniel Cabrera, MD

Dr Leigh is a chief resident, department of emergency medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. Dr Wangsgard is a chief resident, department of emergency medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. Dr Cabrera is an assistant professor of emergency medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota.

Disclosure: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Introduction

Despite significant advances in emergency medical care and resuscitation techniques, sudden cardiac death remains a major public health problem, accounting for approximately 450,000 deaths annually in the United States.1 Moreover, the vast majority of people who suffer an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest will not survive. This is often the end result of fatal ventricular arrhythmias, including ventricular fibrillation (VF) and ventricular tachycardia (VT). The most effective therapy is rapid electrical defibrillation.2

During the 1970s, Mirowski and Mower developed the concept of an implantable defibrillator device that could monitor and analyze cardiac rhythms with automatic delivery of defibrillating shocks after detecting VF.3,4 In 1980, the first clinical implantation of a cardiac defibrillation device was performed. Development continued steadily until the 1996 the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial was prematurely aborted when a statistically significant reduction in mortality (54%) was recognized in patients who received ICD therapy instead of antiarrhythmic therapy.5,6 This was followed by large prospective, randomized, multicenter studies establishing that ICD therapy is effective for primary prevention of sudden death.7 Based on these developments, the ICD has rapidly evolved from a therapy of last resort for patients with recurrent malignant arrhythmias to the standard of care in the primary and secondary prevention of sudden cardiac death, and more recently as cardiac resynchronization devices in patients with congestive heart failure (CHF).3

These developments have led to a dramatic increase in the use of the ICD for monitoring and treatment of VT and VF. The dismal survival rate after cardiac arrest provides a strong impetus to identify high risk patients of sudden cardiac death resulting from VF/VT by primary prevention with an ICD.2,5 More than 100,000 ICDs are implanted annually in the United States.1 As a result of increased prevalence, the EP will often encounter patients who have received an ICD shock or complication of the device. Thus, experienced a general knowledge of implantation, components, complications, and acute management is crucial for clinicians who may care for these patients.

Indications

Implantable cardioverter defibrillators are generally indicated for the primary and secondary prevention of sudden cardiac death.8 The commonly accepted indications for ICD use are summarized here:

Primary Prevention

- Patients with previous MI and LV ejection fraction (LVEF) < 30%

- Patients with cardiomyopathy, New York Heart Association functional class III or IV and LVEF < 35%.

Secondary Prevention

- I Patients with an episode of sustained or unstable VT/VF with no reversible cause.

- I Patients with nonprovoked VT/VF with concomitant structural heart disease (valvular, ischemic, hypertrophic, infiltrative, dilated, channelopathies).

ICD Design

Current ICDs are third-generation device, only slightly larger than pacemakers. ICDs are small (25-45 mm), reliable, and contain sophisticated electrophysiologic analysis algorithms. They can store and report a large number of variables, such as ECGs, defibrillation logs, various energies, lead impedance, as well as battery charge.3,9 Stevenson et al1 describe four major functions of the ICD: sensing of electrical activity from the heart, detection of appropriate therapy, provision of therapy to terminate VT/VF, and pacing for bradycardia and/or CRT.

Components

The components of an ICD can be organized in the following manner:

I Pacing/sensing electrodes. Contemporary units complete these functions through use of two electrodes; one at the distal tip of the lead and one several millimeters back (bipolar leads).1

I Defibrillation electrodes/coils. The defibrillation electrode is a small coil of wire that has a relatively large surface area and extends along the distal aspect of the ventricular lead, positioned at the apex. This lead delivers current directly to the myocardium.11,12 Both the sensing and defibrillation electrodes are often housed in the same, single wire.

I Pulse generator. The pulse generator contains a microprocessor with sensing circuitry as well as high voltage capacitors, a battery, and memory storage component. Modern battery life is typically 5 to 7 years (frequency of shocks will lead to early termination of the battery life).2,11 Some ICDs have automatic self-checks of battery life and will emit a tone when the battery is low or near failure; these patients should be promptly evaluated and referred to the electrophysiologist as indicated.

Functions

The original concept of the ICD was to sense a potentially lethal dysrhythmia and to provide an appropriate therapy. As ICD technology has evolved, the number and variety of available programming and therapies have dramatically increased. Detection of the cardiac rhythm was designed initially to only detect ventricular fibrillation. With current generation models, the ventricular sensing lead filters the incoming signal to eliminate unwanted low frequency components (eg, T-waveand baseline drift) and high frequency components (eg, skeletal muscle electrical activity).3,13 Newer ICDs have the capability for remote monitoring and communication via telephone line or the Internet.

During implantation, the device is programmed with analysis criteria. Criteria for therapy are largely based on the rate, duration, polarity, and waveform of the signal sensed. When the device detects a signal fulfilling the preprogrammed criteria for VT/VF, it selects the appropriate tier of treatment as follows:

I Antitachycardia pacing (ATP). Ventricular tachycardia, particularly reentrant VT associated with scar formation from a prior MI, can sometimes be terminated by pacing the ventricle at a rate slightly faster than the tachycardia. This form of therapy involves the delivery of short bursts (eg, eight beats) of rapid ventricular pacing to terminate VT.14,15 This therapy is low voltage and usually not felt by patients. Antitachycardia pacing successfully terminates VT in over 80% of those with sustained dysrhythmia.16 In the Pain-FREE Rx II trial, data indicate ATP could successfully treat not only standard but rapid VT as well; outcomes revealed a 70% reduction in shocks without adverse effects.5,16

I Synchronized cardioversion. Typically, VT is an organized rhythm. Synchronization of the shock (delivered on R wave peak) and conversion can often be accomplished with low voltage. This helps to minimize discomfort and avoids defibrillation, which potentially could lead to degeneration of VT to VF.

I Defibrillation. This is the delivery of an unsynchronized shock during the cardiac cycle. This can be accomplished through a range of energies. Initial shocks are often programmed for lower energies to reduce capacitor charge time and expedite therapy. Typically, shocks are set to 5 to 10 joules above the defibrillatory threshold (determined at time of implantation).9,16

I Cardiac pacing. All models now have pacing modes similar to single- or dual-chamber pacers.

Implantation

Original ICDs were placed into the intraabdominal cavity through a large thoracotomy. With current-generation ICDs, leads are typically placed transvenously (subclavian, axillary, or cephalic vein), which has led to fewer perioperative complications, including shorter procedure time, shorter hospital stay, and lower costs as compared to abdominal implantation.5,17

The pulse generator remains subcutaneous or submuscular in the pectoral region. An electrode is advanced into the endocardium of the right ventricle apex; dual-chamber ICDs have an additional electrode placed in the right atrial appendage and biventricular ICDs have a third electrode placed transcutaneously in a branch off the coronary sinus.

At the time of the procedure, the electrophysiology team implanting the ICD will configure the diagnostic and therapeutic options; in particular, the defibrillatory threshold will be determined for each specific patient and the device set up with this value.

Complications

Acute complications in the peri-implantation period range from 4% to 5%.18 These are similar to other transvenous procedures and include bleeding, air embolism, infection, lead dislodgment, hemopneumothorax, and rarely death (perioperative mortality 0.2%-0.4%).2,19 Long-term complications may present consistent with other indwelling artificial hardware. Subclavian vein thrombosis with pulmonary thromboembolization, superior vena cava syndrome, as well as lead colonization with infection, are potential complications. superior vena cava thrombosis has been demonstrated in up to 40% of patients. These complications often present insidiously and the clinician should retain a high degree of suspicion.

Infection of the pocket or leads has been observed in up to 7%. Technical causes leading to inappropriate shock include faulty components, oversensing of electrical noise, lead fracture, electromagnetic interference, oversensing of diaphragm myopotentials, oversensing of T-waves, and double counting of QRS complexes.22

Lead complications can include infection, dislodgement (most will occur in the first 3 months after placement), fracture, and insulation defects. Lead failure rates have been reported at up to 1% to 9% at 2 years and as high as 40% at 8 years. Failure occurs secondary to insulation defects (26%), artifact oversensing (24%), fracture (24%), and 26% of the time secondary to infection.3,23

Cardiac perforation is uncommon but potentially devastating. These cases almost always occur with lead manipulation or repair of a screw in the lead; this rarely would lead to clinical significance but possibly the most emergent manifestation would be cardiac tamponade. Chest pain with signs and symptoms of tamponade require prompt diagnosis. Suspect this in the patient with a newly paced RBBB pattern on ECG, diaphragmatic contractions (hiccups), and pericardial effusion. Eighty percent of such perforations with tamponades will occur in first 4 days after implantation, and a chest X-ray or the echocardiogram can help confirm the diagnosis.

Pulse-generator complications include migration, skin erosion, and premature battery depletion.24 Twiddler’s syndrome after pacemaker insertion is a well-described syndrome in which twisting or rotating of the device in the pocket (from constant patient manipulation) results in device malfunction, and Boyle et al describe a similar scenario occurring after ICDs are implanted.25 The authors suggest that an increase in bradycardic pacing threshold or lead impedance may be the initial presentation; however, the possibility that the device failed to sense or treat arrhythmias also should be considered.

Lastly, several studies have documented a statistically significant adverse effect on quality of life in patients living with ICDs. Patients often describe a shock as “being struck by a truck”.22 This may result in depression and anxiety; both are especially prevalent in those who receive frequent shocks. It may be important to consider anxiolytics, support groups, or outpatient referral.2,22,26,27

Management of the Patient With an ICD in the Emergency Department

Patients with ICDs will present to the ED with a variety of complaints, ranging from general/non-specific (eg, dizziness) to life threatening (eg, cardiac arrest). The following section systematizes the approach to these patients.

Frequently, patients with ICDs will present with the complaint of having been shocked. In those patients, the most important initial step is to determine if the shock was appropriate. Initial management should include placement of a cardiac monitor and a rapid 12-lead ECG. A general assessment for the etiology of the shock may reveal a patient’s clinical deterioration, a change in medical therapy, or electrolyte imbalance.2 An accurate history of the surrounding events is key in determining the reason for patients presenting after receiving a shock. A history of chest pain or strenuous physical activity that preceded the shock may indicate, respectively, an appropriate shock from cardiac ischemia or an inappropriate shock caused by skeletal muscle activity. Also, presentations such as a fall following an episode of syncope may represent an ICD-related event and this possibility needs to be considered during the management of these patients.

Clinically Stable Patients After Isolated Shocks

For the patient who received an isolated shock and afterwards is asymptomatic, perform a general assessment as above. Often these patients have experienced an episode of sustained VT that was appropriately recognized and treated.1 For those who feel ill following a shock, emergent assessment is required for the possibility of a resultant arrhythmia following inappropriate shock (eg, device malfunction or battery depletion) or underlying active acute medical illness such as acute coronary syndrome. Always consider interrogation of the device, which will confirm appropriate shock delivery and successful termination of VT/VF. Interrogation also may reveal signs of altered impedance, which may be treated by ICD reprogramming or lead revision in the case of lead malfunction.2 Look for alternative explanations for inappropriate shocks. For example, obtain a chest X-ray to assess proper position of pulse generator or look for presence of lead fracture or migration. Lead fractures tend to occur at three sites: (1) the origin of the lead at the pulse generator, (2) the venous entry site, and (3) within the heart. A basic metabolic panel may reveal hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia leading to lower threshold for dysrhythmia. It is also important to inquire about new medication regimens. Patients with ICDs also are often on multiple cardiac medications, which could lead to alteration in the QT interval or to electrolyte imbalance.

We recommend contacting and discussing the care of patients who present after ICD shocks with the treating electrophysiologist or cardiologist whether or not the shock is considered appropriate.

Patients who have an ongoing arrhythmia when evaluated emergently should be managed according to advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) guidelines, regardless of the presence of an ICD,1 particularly in cases of cardiac arrest from a non-shockable rhythm.

Initially, the shocks should be presumed to be appropriate. Presence of VT/VF in setting of shock would be consistent with appropriate shock delivery. Next, the clinician needs to consider if shock delivery was effective and if it achieved termination of malignant ventricular arrhythmia. Patients with persistent VT/VF despite delivery of a shock may have ICDs with inadequate voltage in the batteries to terminate; external shocks and intravenous (IV) antiarrhythmic medications may be required and should be administered per ACLS guidelines.

When patients present with multiple shocks, the shocks are typically appropriate and often triggered by episodes of VT/VF. Treatment of the underlying causes is the priority; the patient may have sustained or recurrent VT/VF as a result of an acute event, such as cardiac ischemia, hypokalemia, or severe acute heart failure exacerbation. Aggressive reperfusion, management of potassium imbalance, and circulatory support are paramount.

Inappropriate shocks most commonly are delivered for supraventricular tachycardias such as atrial fibrillation that is incorrectly interpreted by the ICD as VT/VF. In these cases, the treatment is the same as for a patient without an ICD (eg, IV diltiazem to slow atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response).

In patients experiencing multiple inappropriate ICD shocks, the device can be immediately disarmed by placing a magnet over the ICD pocket until the electrophysiologist can reprogram it. This will not inhibit baseline/backup pacing. However, while a magnet is in place, neither supraventricular tachycardias nor VT/VF will be detected.1 If appropriate shock delivery has been performed for ventricular dysrhythmia, these patients must remain on a cardiac monitor under close medical observation. It is good practice to assume device failure after application of a magnet, and appropriate management strategies include placing external defibrillators pads on the patient’s chest. Fortunately, most ICDs will resume normal function following magnet removal.

In the Canadian Journal of Cardiology (1996), Kowey defined electrical storm as a state of cardiac electrical instability characterized by multiple episodes of ventricular tachycardia (VT storm) or ventricular fibrillation (VF storm) within a relatively short period of time.28,30,31,32

In the patient with an ICD, the generally accepted definition is occurrence of two or more appropriate therapies (antitachycardia pacing or shocks) in a 24-hour period. Triggers may include drug toxicity, electrolyte disturbances (hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia being the most common culprits), new or worsened heart failure, or myocardial ischemia, which account for more than a quarter of all episodes. Electrical storm usually heralds a life-threatening acute pathology placing these patients at immediate high risk of death.28 Immediate communication and consultation with the electrophysiology team is recommended.

Left Ventricular Assist Devices: From Mystery to Mastery

Alicia S. Devine, JD, MD

Dr Devine is an assistant professor, department of emergency medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk.

Disclosure: The author reports no conflict of interest.

Approximately 5.7 million people in the United States have heart failure, and complications from heart failure represent 668,000 ED visits annually. Heart failure is the primary cause of death in 55,000 people each year. Half of patients die within 5 years of being diagnosed with heart failure.1

Heart failure is initially managed medically; however, some patients become refractory to medical treatment and require heart transplant. Unfortunately, the demand for donor hearts far exceeds the supply, and patients can spend a long time waiting for a donor heart. In addition, not all patients are candidates for transplantation. Left ventricular assist devices are mechanical devices implanted in patients with advanced heart failure in order to provide circulatory support when medications alone are not efficacious. LVADs have been associated with improved survival for heart failure patients.

There are generally two indications for LVAD support: as a bridge to transplant for patients waiting for a donor heart, or as destination therapy for patients who are not candidates for heart transplant. Some patients have had improvement in their cardiac function after LVAD implantation and are able to have the LVAD explanted, leading to a third use for LVADs: bridge to recovery.

LVADs have been in use for over 30 years, and they have evolved during that time to become smaller in size with much fewer complications. Initial models operated with a pulsatile-flow pump that, while adequate in terms of blood flow, contained several parts susceptible to breaking down. Early models were large and cumbersome, especially for smaller patients. New-generation LVADs use a continuous-flow design with either a centrifugal or an axial flow pump with a single moving part, the impeller. The continuous-flow LVADs are quieter, smaller, and significantly more durable than the earlier, pulsatile-flow LVADs. These improvements have expanded the pool of eligible patients to include children and smaller adults.2 Moreover, continuous-flow LVADs provide greater rates of survival and quality of life than the earlier pulsatile-flow models.3

There are fewer adverse events overall with the continuous-flow LVADs compared with the pulsatile-flow LVADs. The number of LVADs implanted each year continues to increase, and more than 95% of these are continuous-flow. As more and more advanced heart failure patients are receiving these devices, emergency physicians should have a basic familiarity with their function and their common complications.4

There are several manufacturers and types of continuous-flow LVADs, but they generally consist of a pump that is surgically implanted into the abdominal or chest cavity of the patient with an inflow cannula positioned in the left ventricle and an outflow cannula inserted into the ascending aorta. The device draws blood from the ventricle and directs it to the aorta. There is a driveline connected to the internal pump that exits the body through the abdominal or chest wall and connects to a system controller. The controller is usually housed in a garment worn by patients that also includes the external battery that powers the LVAD. The controller can also be powered by a base unit that can be plugged into an electrical outlet.5 Patients with continuous-flow LVADs are anticoagulated with warfarin with a target international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.5 to 2.5 and will usually be on an antiplatelet agent as well.2

LVAD patients are typically managed by a team of providers that includes a VAD coordinator; a cardiologist and/or a cardiothoracic surgeon; and a perfusionist, who should be notified as soon as the patient arrives in the ED. Patients understand that it is vital that their LVAD be powered at all times and will usually arrive in the ED with their charged backup batteries. If a power base is available in the hospital, the LVAD can be connected to it to save battery life. If power is interrupted to the LVAD, the pump will stop working. This can be fatal to patients with severe aortic insufficiency who have had their outflow tract surgically occluded and are therefore completely dependent on the LVAD.2

With continuous-flow LVADs, blood is pumped continuously, and a constant, machine-like murmur will be heard on auscultation rather than the typical heart sounds. LVAD patients may not have palpable arterial pulses, and in that case a doppler of the brachial artery and a manual blood pressure cuff are used to listen for the start of Korotkoff sounds as the cuff is released. The pressure at which the first sound is heard is used as an estimate of the mean arterial pressure (MAP). Left ventricular assist device patients should have a MAP between 70 and 90 mm Hg. An accurate pulse oximetry reading may not be attainable, and some centers use cerebral oximetry to obtain oxygenation status.2

The EP should examine all of the connections from the percutaneous lead to the controller and from the controller to the batteries to ensure that they are intact. The exit site for the percutaneous lead should also be examined for evidence of trauma and signs of infection. The exit site is a potential nidus for infection, and even minor trauma from a pull or tug on the lead can damage the tissue and seed an infection. Emergency physicians should ask LVAD patients about any recent trauma to the driveline.6,7

The ED evaluation for an LVAD patient should be focused toward the patient’s chief complaint, recognizing that often patients with LVADs presenting to the ED will have vague complaints of malaise or weakness that may represent a serious pathologic process. Infection, bleeding, thrombosis, and problems with volume status are common reasons for ED visits by LVAD patients.3,5

Infection

In addition to infections in the lung, skin, and urinary tract, patients with LVADs are at risk for infectious complications relating to their device. Implantation of an LVAD involves a sternal incision, the creation of an internal pocket for the LVAD, and a driveline connecting the internal LVAD with an external power source. An infection in any one of these locations can lead to endocarditis, bacteremia, and sepsis.6

Driveline and/or pocket infections are very common, affecting up to 36% of patients with continuous-flow LVADs.8 The exit site for the driveline is an access point for the entry of pathogens, and can be the source of infections in the driveline or in the pump pocket. Pump pocket infections can also occur from exposure to pathogens during surgery or in the immediate postoperative period. In addition, the pump itself can become infected from similar sources, as well as from bacteremia or fungemia from infections in the urine, lung, or central catheters.6

Infections in the driveline will often present with obvious signs such as purulent drainage, erythema, and tenderness at the exit site, but providers should have a high index of suspicion if there is dehiscence at the exit site or even persistent serous drainage from the site, as these can suggest a driveline infection. Pump pocket infections and device-related endocarditis can present with vague symptoms such as weight loss, malaise, and a low-grade fever.

A thorough evaluation should be undertaken in all LVAD patients with a suspected infection to detect a source, and cultures of blood, urine, and the driveline exit site should be obtained. Imaging techniques frequently used when considering device-related infections include ultrasound of the pump pocket and echocardiography to evaluate for endocarditis. Computed tomography is also used to evaluate for device-related infections.6,7,9,10 LVADs are not compatible with MRI.11

The majority of device-related infections are caused by bacteria, although fungal and viral species can be the source as well. Common pathogens implicated include S aureus, S epidermidis, enterococci, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella species and Enterobacter species. Empiric antibiotics with both gram-positive and gram-negative coverage should be initiated for suspected infection related to the device. If the infection has spread to the pump pocket or the device, patients may need surgery for drainage and possible removal of the device.6,7,9,10

Bleeding and Thrombosis

Bleeding complications occur with pulsatile-flow and continuous-flow LVADs at the same rate, and represent one of the most common adverse events seen in LVAD patients. Sites of bleeding include intracranial, nasal cavity, genitourinary tract, and gastrointestinal (GI).11

Interestingly, GI bleeding occurs at a much higher rate in patients with continuous-flow LVADs than in patients with pulsatile-flow devices.2,5,11,12 Patients with continuous-flow LVADs are anticoagulated with warfarin (to a target INR of between 1.5 and 2.5) and an antiplatelet agent to prevent pump thrombosis as well as other thromboembolic events.11 In addition to the effects of warfarin and aspirin, several other factors contribute to the increased incidence of GI bleeding, including an acquired von Willebrand disease and the development of small bowel angiodysplasias from the alteration in vascular hemodynamics from the continuous flow.13,14,15

Emergency physicians should have a high index of suspicion for a bleeding event in patients with an LVAD presenting to the ED. The evaluation of GI bleeding in LVAD patients is the same as in patients without LVADs, and management includes resuscitation with fluids, blood transfusion, and careful correction of coagulopathy. Gastrointestinal bleeding in an LVAD patient necessitates a consultation with a gastroenterologist and admission to the hospital.11

Pump thrombosis, though rare, can result in death and must be considered in cases of MAP < 60 mm Hg and/or an increased power requirement accompanied by a decrease in pulsatility index and flow. Markers of hemolysis such as elevated lactate dehydrogenase or hemoglobinuria also suggest pump thrombosis. Interrogation of the LVAD by the perfusionist is imperative when LVAD patients present to the ED. Echocardiography is the modality of choice in evaluating suspected pump thrombosis. Treatment may require replacement of the pump, or in some cases, anticoagulation or thrombolysis.2,11

Volume Status

Patients with LVADs can present with complaints of weakness and/or dizziness that can be due to dehydration and/or electrolyte deficiencies. Often, these patients will continue to restrict their salt and fluid intake after device implantation. They are frequently on diuretics, which can contribute to these problems. Checking and repleting electrolytes as well as administering a gentle bolus of IV fluids in patients with a MAP < 60 mm Hg will often correct the hypovolemia and electrolyte abnormalities. Evaluation for sepsis, pump thrombosis, and cannula malposition as causes of hypotension should be undertaken in the appropriate circumstances.2,11 Severe hypovolemia can interfere with effective LVAD function if it leads to the collapse of the left ventricle over the inflow cannula. Bedside ultrasound can be a useful adjunct in the evaluation of cannula position and volume status.2 An emergent consult with a cardiovascular surgeon is indicated in the event of pump thrombosis or cannula malposition.

Conclusion

The number of LVADs implanted each year continues to grow, and EPs need to have a basic familiarity with these devices and how to manage typical complaints seen in the ED. Patients and their caregivers have been given extensive education and training on the care and management of their LVAD components and can be a valuable source of information. They should bring the devices with them to the ED, along with the names and phone numbers of all of the members of their VAD treatment team, who should be called shortly after the patient’s arrival, as well as backup charged batteries to power their LVAD.

A priority is ensuring that all of the LVAD connections are intact and that there is adequate power to the device. A perfusionist will need to interrogate the controller if there is any concern about its function, including alarms sounding or lights flashing. The manufacturer’s website can be accessed if necessary for further information.

Cardiac Hardware Management of the Patient With an Implanted Pacemaker

- Chardack WM, Gage AA, Greatbatch W. A transistorized, self-contained, implantable pacemaker for the long-term correction of complete heart block. Surgery. 1960;48:643-654.

- Beck H, Boden WE, Patibandla S, Kireyev D, Gupta V, Campagna F, et al. 50th anniversary of the first successful permanent pacemaker implantation in the United States: historical review and future directions. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106(6):810-818.

- McMullan J, Valento M, Attari M, Venkat A. Care of the pacemaker/implantable cardioverter defibrillator patient in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25(7):812-822.

- Kaszala K, Huizar JF, Ellenbogen KA. Contemporary pacemakers: what the primary care physician needs to know. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(10):1170-1186.

- Park DS, Fishman GI. The cardiac conduction system. Circulation. 2011;123(8):904-915.

- Gregoratos G. Indications and Recommendations for Pacemaker Therapy. Am Fam Phys. 2005;71(8):1563-1570.

- Vardas PE, Simantirakis EN, Kanoupakis EM. New developments in cardiac pacemakers. Circulation. 2013;127(23):2343-2350.

- Cheng A, Tereshchenko LG. Evolutionary innovations in cardiac pacing. J Electrocardiol. 2011;44(6):611-615.

- Stone KR, McPherson CA. Assessment and management of patients with pacemakers and implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(4 Suppl):S155-S165.

- Bernstein AD, Daubert JC, Fletcher RD, Hayes DL, Luderitz B, Reynolds DW, et al. The revised NASPE/BPEG generic code for antibradycardia, adaptive-rate, and multisite pacing. North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology/British Pacing and Electrophysiology Group. Pacing and clinical electrophysiology : Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2002;25(2):260-264.

- Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, Estes NA, 3rd, Freedman RA, Gettes LS, et al. ACC/AHA/HRS 2008 Guidelines for Device-Based Therapy of Cardiac Rhythm Abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the ACC/AHA/NASPE 2002 Guideline Update for Implantation of Cardiac Pacemakers and Antiarrhythmia Devices) developed in collaboration with the American Association for Thoracic Surgery and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Am J Cardiol. 2008;51(21):e1-e62.

- Chang AM, Shofer FS, Tabas JA, Magid DJ, McCusker CM, Hollander JE. Lack of association between left bundle-branch block and acute myocardial infarction in symptomatic ED patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27(8):916-921.

- Sgarbossa EB, Pinski SL, Barbagelata A, Underwood DA, Gates KB, Topol EJ, et al. Electrocardiographic diagnosis of evolving acute myocardial infarction in the presence of left bundle-branch block. GUSTO-1 (Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries) Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(8):481-487.

- Venkatachalam KL. Common pitfalls in interpreting pacemaker electrocardiograms in the emergency department. J Electrocardiol. 2011;44(6):616-621.

- Sgarbossa EB, Pinski SL, Topol EJ, Califf RM, Barbagelata A, Goodman SG, et al. Acute myocardial infarction and complete bundle branch block at hospital admission: clinical characteristics and outcome in the thrombolytic era. GUSTO-I Investigators. Global Utilization of Streptokinase and t-PA [tissue-type plasminogen activator] for Occluded Coronary Arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31(1):105-110.

- Tabas JA, Rodriguez RM, Seligman HK, Goldschlager NF. Electrocardiographic criteria for detecting acute myocardial infarction in patients with left bundle branch block: a meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52(4):329-336 e1.

- Smith SW, Dodd KW, Henry TD, Dvorak DM, Pearce LA. Diagnosis of ST-elevation myocardial infarction in the presence of left bundle branch block with the ST-elevation to S-wave ratio in a modified Sgarbossa rule. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(6):766-776.

- Nof E, Epstein LM. Complications of cardiac implants: handling device infections. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(3):229-236.

- Tarakji KG, Wilkoff BL. Management of cardiac implantable electronic device infections: the challenges of understanding the scope of the problem and its associated mortality. Expert Rev ardiovasc Ther. 2013;11(5):607-616.

- Balachander J, Rajagopal S. Pacemaker trouble shooting and follow up. Indian Heart J. 2011;63(4):356-370.

- Klug D, Wallet F, Lacroix D, Marquie C, Kouakam C, Kacet S, et al. Local symptoms at the site of pacemaker implantation indicate latent systemic infection. Heart. 2004;90(8):882-886.

- Kwak YL, Shim JK. Assessment of endocarditis and intracardiac masses by TEE. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2008;46(2):105-120.

- Ryan EW, Bolger AF. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) in the evaluation of infective endocarditis. Cardiol Clin. 2000;18(4):773-787.

- Baddour LM. Cardiac device infection--or not. Circulation. 2010;121(15):1686-1687.

- Ghani SN, Kirkpatrick JN, Spencer KT, Smith GL, Burke MC, Kim SS, et al. Rapid assessment of left ventricular systolic function in a pacemaker clinic using a hand-carried ultrasound device. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2006;16(1):39-43.

- Scheibly K. Pacemaker timing and electrocardiogram interpretation. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2010;21(4):386-396.

- Zimetbaum PJ, Josephson ME. Use of the electrocardiogram in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(10):933-940.

- Misiri J, Kusumoto F, Goldschlager N. Electromagnetic interference and implanted cardiac devices: the nonmedical environment (part I). Clin Cardiol. 2012;35(5):276-280.

- Trohman RG, Kim MH, Pinski SL. Cardiac pacing: the state of the art. Lancet. 2004;364(9446):1701-1719.

- Kramer DB, Mitchell SL, Brock DW. Deactivation of pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;55(3):290-299.

- Misiri J, Kusumoto F, Goldschlager N. Electromagnetic interference and implanted cardiac devices: the medical environment (part II). Clin Cardiol. 2012;35(6):321-328.

- Zikria JF, Machnicki S, Rhim E, Bhatti T, Graham RE. MRI of patients with cardiac pacemakers: a review of the medical literature. Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196(2):390-401.

- Cai Q, Mehta N, Sgarbossa EB, Pinski SL, Wagner GS, Califf RM, et al. The left bundle-branch block puzzle in the 2013 ST-elevation myocardial infarction guideline: from falsely declaring emergency to denying reperfusion in a high-risk population. Are the Sgarbossa Criteria ready for prime time? Am Heart J. 2013;166(3):409-413.

Managing Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator Shock Complications

- Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2-e220.

- Slaughter MS, Pagani FD, Rogers JG, et al. Clinical management of continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices in advanced heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29(4 Suppl):S1-S39.

- Slaughter MS, Rogers JG, Milano GC, et al. Advanced heart failure treated with continuous-flow left ventricular assist device. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361(23):2241-2251.

- Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Kormos RL, et al. Fifth INTERMACS annual report: risk factor analysis from more than 6,000 mechanical circulatory support patients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32(2):141-156.

- Miller LW, Pagani FD, Russell SD, et al. Use of a continuous-flow device in patients awaiting heart transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(9):885-896.

- Califano S, Pagani FD, Malani PN. Left ventricular assist device-associated infections. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2012;26(1):77-87.

- Peredo D, Conte JV. Left ventricular assist device driveline infections. Cardiol Clin. 2011;29(4):515-527.

- Schaffer JM, Allen JG, Weiss ES, et al. Infectious complications after pulsatile-flow and continuous-flow left ventricular assist device implantation.

J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30(2):164-174. - Gordon RJ, Quagliarello B, Lowy FD. Ventricular assist device-related infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6(7):426-437.

- Maniar S, Kondareddy S, Topkara VK. Left ventricular assist-device-related infections: past, present and future. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2011;8(5):627-634.

- Klein T, Jacob M. Management of implantable assisted circulation devices. Cardiol Clin. 2012;30:673-682

- John RJ, Kamdar F, Liao K, et al. Improved survival and decreasing incidence of adverse events with the HeartMate II left ventricular assist device as bridge-to-transplant therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:1227-1235.

- Klovaite J, Gustafsson F, Mortensen SA, Sander K, Nielson LB. Severely impaired von Willebrand factor-dependent platelet aggregation in patients with a continuous-flow left ventricular assist device (HeartMate II). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(23):2162-2167.

- Stern DR, Kazam J, Edwards P, et al. Increased incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding following implantation of the HeartMate II LVAD. J Card Surg. 2010:25(3):352-356.

- Kushnir VM, Sharma S, Ewald GA, et al. Evaluation of GI bleeding after implantation of left ventricular assist device. Gastrointest Endoscopy. 2012;75(5):973-979.

Left Ventricular Assist Devices: From Mystery to Mastery

- Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2-e220.

- Slaughter MS, Pagani FD, Rogers JG, et al. Clinical management of continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices in advanced heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29(4 Suppl):S1-S39.

- Slaughter MS, Rogers JG, Milano GC, et al. Advanced heart failure treated with continuous-flow left ventricular assist device. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361(23):2241-2251.

- Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Kormos RL, et al. Fifth INTERMACS annual report: risk factor analysis from more than 6,000 mechanical circulatory support patients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32(2):141-156.

- Miller LW, Pagani FD, Russell SD, et al. Use of a continuous-flow device in patients awaiting heart transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(9):885-896.

- Califano S, Pagani FD, Malani PN. Left ventricular assist device-associated infections. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2012;26(1):77-87.

- Peredo D, Conte JV. Left ventricular assist device driveline infections. Cardiol Clin. 2011;29(4):515-527.

- Schaffer JM, Allen JG, Weiss ES, et al. Infectious complications after pulsatile-flow and continuous-flow left ventricular assist device implantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30(2):164-174.

- Gordon RJ, Quagliarello B, Lowy FD. Ventricular assist device-related infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6(7):426-437.

- Maniar S, Kondareddy S, Topkara VK. Left ventricular assist-device-related infections: past, present and future. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2011;8(5):627-634.

- Klein T, Jacob M. Management of implantable assisted circulation devices. Cardiol Clin. 2012;30:673-682

- John RJ, Kamdar F, Liao K, et al. Improved survival and decreasing incidence of adverse events with the HeartMate II left ventricular assist device as bridge-to-transplant therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:1227-1235.

- Klovaite J, Gustafsson F, Mortensen SA, Sander K, Nielson LB. Severely impaired von Willebrand factor-dependent platelet aggregation in patients with a continuous-flow left ventricular assist device (HeartMate II). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(23):2162-2167.

- Stern DR, Kazam J, Edwards P, et al. Increased incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding following implantation of the HeartMate II LVAD. J Card Surg. 2010:25(3):352-356.

- Kushnir VM, Sharma S, Ewald GA, et al. Evaluation of GI bleeding after implantation of left ventricular assist device. Gastrointest Endoscopy. 2012;75(5):973-979.

Alicia S. Devine, JD, MD

Dr Devine is an assistant professor, department of emergency medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk.

Disclosure: The author reports no conflict of interest.

Heart disease affects a growing number of patients each year. The causes of heart disease are diverse, but whether the etiology is ischemic or structural, the disease often progresses to the point where patients are at risk for fatal dysrhythmias and heart failure. Treatment modalities for heart disease range from lifestyle modification and medical management to interventional reperfusion, and often involve the surgical implantation of devices designed to improve cardiac function and/or to detect and terminate lethal dysrhythmias.

Over the past two decades, the use of automated implantable cardiac devices (AICDs) such as pacemakers, implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs), and left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) has increased significantly. From 1993 to 2009, nearly 3 million patients received permanent pacemakers in the United States; in 2009 alone, over 188,000 were placed. From 2006 to 2011 (the period for which the most recent data are available), approximately 850,000 patients had an AICD implanted. For the 20-month period running from April 2010 to December 2011, nearly 260,000 patients received the device. Finally, from 2006 through 2013, over 9,000 LVADs were placed. Like the other cardiac devices discussed, the frequency of use continues to increase, with 3,834 LVADs placed in just the first 9 months of 2013.

Emergency physicians are expected to be able to stabilize and manage patients with these devices who present to the ED. Care for these patients requires an understanding of the components and function of the different devices as well as their complications. All of the devices are subject to complications from infection, bleeding, migration, or fracture of the component parts, and, more ominously, complete failure of the device. While the current generation of cardiac devices are much smaller in size than their initial prototypes, they are more technically complex, and consultation with cardiology after initial stabilization is recommended.

Cardiac Hardware

Management of the Patient With an Implanted Pacemaker

Martin Huecker, MD

Thomas Cunningham, MD

Dr Huecker is an assistant professor, department of emergency medicine, University of Louisville, Kentucky.

Dr Cunningham is chief resident, department of emergency medicine, University of Louisville, Kentucky.

Disclosure: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Introduction

Cardiac pacing was conceived in 1899, and the first successful pacemaker was implanted in 1960.1,2 New concepts and evolution of design have made pacemakers increasingly complex. Over the last decade, the rate of implantation has grown by over 50%.3 At the forefront of cardiac care, today’s EP must be proficient in the care of patients with cardiac pacemakers.

The pacemaker consists of a generator and its leads. The generator produces an electrical impulse that travels down the leads to depolarize myocardial tissue.4 A pacemaker corrects abnormal heart rhythms, using these electrical pulses to induce a novel sinus rhythm.5,6Table 1 summarizes the 2008 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Level I/II indications for pacemaker placement.

Permanent pacing involves fluoroscopic placement of leads into a chamber(s) of the heart. The generator is implanted most commonly in the left subcutaneous chest.7-9 A single-chamber pacemaker’s leads are located in either the right atrium or ventricle. Dual-chamber pacemakers function with one electrode in the atrium and one in the ventricle. A biventricular pacemaker, also known as cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) paces both ventricles via the septal walls.4,7,10

All pacemaker patients need prompt identification of the device manufacturer.8 Patients should carry identification cards. Chest X-ray may identify the device and will give information as to the location and structural integrity of wires. Interrogation should generally be performed in all patients and will provide valuable information such as battery status, current mode, rate, past rhythms, parameters to detect malignant rhythms, and therapeutic settings.4

Evaluation of the patient with a pacemaker begins with a detailed history and physical examination, including any complications involving the device. Clinicians should ask about pacemaker-related symptoms—ie, palpitations, light-headedness, syncope, or changes in exercise tolerance.3 As with all chest pain complaints in the ED, addressing abnormal vital signs and identification of myocardial infarction (MI) must precede other considerations.

Myocardial Infarction in the Pacemaker Patient

Because of the underlying rhythm induced by the cardiac pacemaker stimulation, acute coronary occlusion can be subtle.12 Since the pacemaker depolarizes the right ventricle, the delay in left ventricular depolarization is seen as left bundle branch block (LBBB) on electrocardiogram (ECG).13,14Figure 1 shows an ECG demonstrating paced rhythm and appropriate discordance, while the ECG in Figure 2 demonstrates acute coronary occlusion. Therefore, identification of coronary occlusion in the paced patient is done using the following Sgarbossa criteria:

- ST elevation ≥1 mm in a lead with upward (concordant) QRS complex; 5 points.

- ST depression ≥1 mm in lead V1, V2, or V3; 3 points.

- ST elevation ≥5 mm in a lead with downward (discordant) QRS complex; 2 points.13,15

An ECG demonstrating three points of Sgarbossa criteria yields a diagnosis of ST segment elevation MI with 98% specificity and 20% sensitivity.16 A modified Sgarbossa criteria replaces the absolute ST-elevation measurement (Sgarbossa criteria 3) with an ST/S ratio greater than -0.25. This yields a sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 90%.17

Pacemaker-Related Complications

When ischemia is no longer a concern, address the device itself. Workup involves history and physical examination, with complete blood count, chest X-ray, cardiac biomarkers, basic metabolic panel, ultrasound, and device interrogation, as indicated. Table 2 provides a summary of associated pacemaker syndromes and treatment.

Infectious Complications

Patients with device-related infection can present with local or systemic signs, depending on time from implantation. Tenderness to palpation over the generator is sensitive for pocket infection. Although rare, pocket infections require urgent evaluation with mortality rates as high as 20%.18

Early (< 30 days) pocket complications are usually attributable to hematomas with or without infection. When infection is present, Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis are the most likely culprits. Up to 50% of isolates can be methicillin resistant S aureus.19 Although needle aspiration has been used in the past for evacuation and microbial identification, current recommendations do not advocate this approach.20 Incision and debridement are the mainstays of therapy. Over 70% of patients with pocket infections will have positive blood cultures and should receive antibiotic therapy with vancomycin.21

Patients with wound separation or pocket infection are at risk for lead infection, lead separation, and lead fracture with related thoracic involvement (ie, pneumonia, empyema, hemothorax, pneumothorax, or diaphragmatic rupture).20

Infectious complications greater than 30 days from implantation are more likely lead-related. Because of the risk for embolic disease to pulmonary or cardiac tissues, emergent line removal and empiric antibiotics are recommended.18 After admission, a transesophageal echocardiogram should be performed to evaluate for valvular involvement and baseline cardiac function.22-24

Physiologic Complications

Patients without ischemia or infection should be evaluated for device-related chest pain. Pain resulting from malfunction of the device usually occurs in the first 48 hours after implantation.9

Patients may present with chest pain related to lead migration or malposition. Perforation of the pleural cavity during the initial procedure can cause hemothorax or pneumothorax. Perforation of the myocardium can lead to hemopericardium and cardiac tamponade. Patients present with respiratory distress and cardiac dysfunction with or without pacing failure.4,9 Bedside cardiac ultrasound assists in assessing these complications and degree of severity.25

Lead migration occurs when a lead detaches from the generator and migrates. Complete separation from the generator may present as failure to capture and should be addressed before lead localization, as temporary pacing may be warranted. Leads coil and regress from patient tampering (ie, Twiddler’s Syndrome) or through spontaneous detachment.3

The ECG may detect functional leads that have migrated to the left heart (coronary sinus, entricular septal defect, perforation). Right bundle branch morphology, rather than the expected left bundle branch morphology, indicates a lead depolarizing the left ventricle.26,27

Lead fracture may occur at any time after implantation. In addition to the complications seen with lead separation and migration, lead fracture is associated with pulmonary vein thrombosis. Because of the volatile nature of fractured leads, patients present more frequently with pacemaker failure, dysrhythmias, and hemodynamic compromise. Temporary pacing may be necessary pending surgical intervention.4,20

Days to weeks postprocedure, patients are at risk for central venous thrombus due to creation of a thrombogenic environment. These thrombi can embolize to the pulmonary circulation and computed tomography pulmonary angiogram should be considered if suspicious.3

Electrical Complications

Failure to pace can be attributed to lead complication (ie, lead malposition, lead fracture), poor lead-tissue interface, or generator complication.28 Electrical complications arise from intrinsic generator malfunction, lack of pacemaker capture, oversensing/undersensing, and poor pacemaker output.29 Poor output results from battery failure, generator failure, or lead misplacement.9

Generator malfunction can produce unwanted tachycardia and exacerbate intrinsic poor cardiac function. Pacemaker-mediated tachycardia (PMT), pacemaker syndrome, and runaway pacemaker should be eliminated from the differential though interrogation and ECG.

Patients presenting with signs of hypotension and cardiac failure may have pacemaker syndrome. With single-chamber conduction, atrioventricular dysynchrony occurs, producing a lack of ventricular preload and poor cardiac output. Treatment includes symptomatic management and pacemaker replacement with a dual-chamber device. In the hemodynamically unstable patient, applications to increase the preload and reduce the afterload should be attempted.20,25

Trauma, battery failure, and intrinsic pacer malfunction can cause PMT such as runaway pacemaker. Application of a magnet has been shown effective only in some cases.3,30 Definitive therapy with emergent pacer reprogramming or surgical disconnection of pacer leads from the generator may be warranted.

Failure to capture occurs when the device electrical impulse is insufficient to depolarize the heart. Battery failure, generator failure, electrode impedance (from fibrosing of the electrodes), lead fracture or malposition, and long QT syndrome are all causes of failure to capture.29 Chest X-ray, ECG, device interrogation, and electrolyte measurement are imperative. The patient with intrinsic generator failure usually requires admission and surgical correction or replacement.3

Oversensing occurs when the device incorrectly interprets artifactual electricity as intrinsic cardiac depolarization. This results in a lack of cardiac stimulation by the pacemaker and can lead to heart block. Shivering, fasciculations from depolarizing neuromuscular blockade, and external interference can cause oversensing. Nonmedical causes include cell phones, security gates, Taser guns, magnets, and iPods.28 Iatrogenic causes include electrosurgery, LVADs, radiation therapy, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), cardioversion, and lithotripsy.31,32 Treatment involves withdrawing the offending agent, then either placing a magnet over the generator to activate its asynchronous mode or temporary overdrive pacing.26,28,31

Undersensing occurs when the pacer fails to sense intrinsic cardiac activity. The result is competitive asynchronous activity between the native cardiac depolarization and the pacemaker impulses. Introduction of new intrinsic rhythms from lead complications (lead fracture, lead migration), ischemia (premature ventricular contraction, premature atrial contraction), or underlying cardiac disease (atrial fibrillation, right BBB [RBBB], LBBB) can precipitate undersensing.4,5,30 These patients are prone to arrhythmias and decompensation of cardiac function. Management requires identifying the cause of the underlying arrhythmia.29 Chest X-ray, ECG, device interrogation, and electrolyte measurement are useful diagnostics for patients with new arrhythmias or ischemia.3,14,27

Conclusion

To assist the EP in evaluating a patient with a suspected pacemaker problem, we propose the algorithm presented in Figure 3.

Recent advancements and the increased prevalence of pacemakers require the EPs to be facile with their operating systems and morbidity. A detailed history and physical examination, along with utilization of simple diagnostics and device interrogation, can prove sufficient to diagnose most pacemaker-related complaints. Acute coronary syndrome and serious infections may be subtle, so a high level of suspicion should be maintained. With a knowledgeable EP and a supportive team, pacemaker complications can be successfully managed.

Managing Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator Shock Complications

Dustin G. Leigh, MD; Cameron R. Wangsgard, MD; Daniel Cabrera, MD

Dr Leigh is a chief resident, department of emergency medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. Dr Wangsgard is a chief resident, department of emergency medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. Dr Cabrera is an assistant professor of emergency medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota.

Disclosure: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Introduction

Despite significant advances in emergency medical care and resuscitation techniques, sudden cardiac death remains a major public health problem, accounting for approximately 450,000 deaths annually in the United States.1 Moreover, the vast majority of people who suffer an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest will not survive. This is often the end result of fatal ventricular arrhythmias, including ventricular fibrillation (VF) and ventricular tachycardia (VT). The most effective therapy is rapid electrical defibrillation.2

During the 1970s, Mirowski and Mower developed the concept of an implantable defibrillator device that could monitor and analyze cardiac rhythms with automatic delivery of defibrillating shocks after detecting VF.3,4 In 1980, the first clinical implantation of a cardiac defibrillation device was performed. Development continued steadily until the 1996 the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial was prematurely aborted when a statistically significant reduction in mortality (54%) was recognized in patients who received ICD therapy instead of antiarrhythmic therapy.5,6 This was followed by large prospective, randomized, multicenter studies establishing that ICD therapy is effective for primary prevention of sudden death.7 Based on these developments, the ICD has rapidly evolved from a therapy of last resort for patients with recurrent malignant arrhythmias to the standard of care in the primary and secondary prevention of sudden cardiac death, and more recently as cardiac resynchronization devices in patients with congestive heart failure (CHF).3

These developments have led to a dramatic increase in the use of the ICD for monitoring and treatment of VT and VF. The dismal survival rate after cardiac arrest provides a strong impetus to identify high risk patients of sudden cardiac death resulting from VF/VT by primary prevention with an ICD.2,5 More than 100,000 ICDs are implanted annually in the United States.1 As a result of increased prevalence, the EP will often encounter patients who have received an ICD shock or complication of the device. Thus, experienced a general knowledge of implantation, components, complications, and acute management is crucial for clinicians who may care for these patients.

Indications

Implantable cardioverter defibrillators are generally indicated for the primary and secondary prevention of sudden cardiac death.8 The commonly accepted indications for ICD use are summarized here:

Primary Prevention

- Patients with previous MI and LV ejection fraction (LVEF) < 30%

- Patients with cardiomyopathy, New York Heart Association functional class III or IV and LVEF < 35%.

Secondary Prevention

- I Patients with an episode of sustained or unstable VT/VF with no reversible cause.

- I Patients with nonprovoked VT/VF with concomitant structural heart disease (valvular, ischemic, hypertrophic, infiltrative, dilated, channelopathies).

ICD Design

Current ICDs are third-generation device, only slightly larger than pacemakers. ICDs are small (25-45 mm), reliable, and contain sophisticated electrophysiologic analysis algorithms. They can store and report a large number of variables, such as ECGs, defibrillation logs, various energies, lead impedance, as well as battery charge.3,9 Stevenson et al1 describe four major functions of the ICD: sensing of electrical activity from the heart, detection of appropriate therapy, provision of therapy to terminate VT/VF, and pacing for bradycardia and/or CRT.

Components

The components of an ICD can be organized in the following manner:

I Pacing/sensing electrodes. Contemporary units complete these functions through use of two electrodes; one at the distal tip of the lead and one several millimeters back (bipolar leads).1

I Defibrillation electrodes/coils. The defibrillation electrode is a small coil of wire that has a relatively large surface area and extends along the distal aspect of the ventricular lead, positioned at the apex. This lead delivers current directly to the myocardium.11,12 Both the sensing and defibrillation electrodes are often housed in the same, single wire.

I Pulse generator. The pulse generator contains a microprocessor with sensing circuitry as well as high voltage capacitors, a battery, and memory storage component. Modern battery life is typically 5 to 7 years (frequency of shocks will lead to early termination of the battery life).2,11 Some ICDs have automatic self-checks of battery life and will emit a tone when the battery is low or near failure; these patients should be promptly evaluated and referred to the electrophysiologist as indicated.

Functions

The original concept of the ICD was to sense a potentially lethal dysrhythmia and to provide an appropriate therapy. As ICD technology has evolved, the number and variety of available programming and therapies have dramatically increased. Detection of the cardiac rhythm was designed initially to only detect ventricular fibrillation. With current generation models, the ventricular sensing lead filters the incoming signal to eliminate unwanted low frequency components (eg, T-waveand baseline drift) and high frequency components (eg, skeletal muscle electrical activity).3,13 Newer ICDs have the capability for remote monitoring and communication via telephone line or the Internet.

During implantation, the device is programmed with analysis criteria. Criteria for therapy are largely based on the rate, duration, polarity, and waveform of the signal sensed. When the device detects a signal fulfilling the preprogrammed criteria for VT/VF, it selects the appropriate tier of treatment as follows:

I Antitachycardia pacing (ATP). Ventricular tachycardia, particularly reentrant VT associated with scar formation from a prior MI, can sometimes be terminated by pacing the ventricle at a rate slightly faster than the tachycardia. This form of therapy involves the delivery of short bursts (eg, eight beats) of rapid ventricular pacing to terminate VT.14,15 This therapy is low voltage and usually not felt by patients. Antitachycardia pacing successfully terminates VT in over 80% of those with sustained dysrhythmia.16 In the Pain-FREE Rx II trial, data indicate ATP could successfully treat not only standard but rapid VT as well; outcomes revealed a 70% reduction in shocks without adverse effects.5,16

I Synchronized cardioversion. Typically, VT is an organized rhythm. Synchronization of the shock (delivered on R wave peak) and conversion can often be accomplished with low voltage. This helps to minimize discomfort and avoids defibrillation, which potentially could lead to degeneration of VT to VF.

I Defibrillation. This is the delivery of an unsynchronized shock during the cardiac cycle. This can be accomplished through a range of energies. Initial shocks are often programmed for lower energies to reduce capacitor charge time and expedite therapy. Typically, shocks are set to 5 to 10 joules above the defibrillatory threshold (determined at time of implantation).9,16

I Cardiac pacing. All models now have pacing modes similar to single- or dual-chamber pacers.

Implantation

Original ICDs were placed into the intraabdominal cavity through a large thoracotomy. With current-generation ICDs, leads are typically placed transvenously (subclavian, axillary, or cephalic vein), which has led to fewer perioperative complications, including shorter procedure time, shorter hospital stay, and lower costs as compared to abdominal implantation.5,17

The pulse generator remains subcutaneous or submuscular in the pectoral region. An electrode is advanced into the endocardium of the right ventricle apex; dual-chamber ICDs have an additional electrode placed in the right atrial appendage and biventricular ICDs have a third electrode placed transcutaneously in a branch off the coronary sinus.