User login

Keep Patients Informed, Involved

Total Knee Arthroplasty With Concurrent Femoral and Tibial Osteotomies in Osteogenesis Imperfecta

Symptomatic Hip Impingement Due to Exostosis Associated With Supra-Acetabular Pelvic External Fixator Pin

Subacute Superior Patellar Pole Sleeve Fracture

Man, 45, With Greasy Rash and Deformed Nails

A 45-year-old man presented to the dermatology office complaining of a pruritic rash on his neck, chest, abdomen, and upper back. The rash had been present since the patient was 20, intermittently flaring and causing severe pruritus. For the past two weeks, it had become increasingly bothersome.

The patient described the rash as “greasy” brown plaques diffusely scattered on his body. The rash on his neck was the most bothersome, and the patient felt an uncontrollable need to scratch that area.

Since it first developed 25 years ago, he had used OTC hydrocortisone cream as needed to treat the rash. Although effective for past flares, the cream provided only minimal relief during the current episode.

The patient’s medical history included brittle nails with a worsening of nail quality in recent years. The family history revealed that the patient’s father and sister were affected by the same type of rash, which developed in adolescence for each of them, as well as brittle nails.

On physical examination, the skin was warm and moist to the touch. Flat, slightly elevated, greasy brown papules were scattered on the chest, abdomen, and upper back, with mild surrounding erythema (see Figure 1). Excoriated lesions were noted on the anterior surface of the neck, with pinpoint bleeding resulting from constant irritation. The patient’s fingernails were deformed, with longitudinal ridges and v-shaped notching of the free margin. The remainder of the physical exam was unremarkable, and review of systems was negative.

This patient’s symptoms could result from a variety of causes. Seborrheic dermatitis is a common skin condition that presents with brown plaques similar to those on the patient’s trunk. Another possible diagnosis is Grover’s disease, a rare disorder also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis, in which keratotic plaques appear on the torso and are thought to occur from trauma to sun-damaged skin. An additional consideration is Hailey-Hailey disease, a rare genetic disorder also known as benign familial pemphigus, which is characterized by red-brown plaques located predominantly on flexure surfaces.1 Skin biopsy should be performed for a definitive diagnosis.

Given the family history of a similar rash occurring in first-degree relatives and the distinct physical exam findings, the most likely diagnosis for this patient is keratosis follicularis, also known as Darier disease (DD) or Darier-White disease.

DISCUSSION

Named after Ferdinand-Jean Darier, who discovered this rare genodermatosis, DD is a rare genetic skin disorder caused by mutations of the ATP2A2 gene, located on the long arm of chromosome 12 at position 24,11.1,2 The mutation disrupts the encoding of the enzyme sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium-ATPase 2 (SERCA2). This enzyme is important in the transport of calcium ions across the cell membrane, and insufficient amounts lead to a defect in intracellular calcium signaling.2,3

This genetic mutation is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait with complete penetrance. DD affects men and women equally, with progressive skin signs of interfamilial and intrafamilial variability.4 Skin manifestations occur from late childhood to early adulthood and are typical during adolescence.4 Acute flare-ups can be triggered by heat, perspiration, sunlight, ultraviolet B exposure, stress, or certain medications (in particular, lithium).2 DD is not contagious.2

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The characteristics of DD include yellow or brown, rough, firm papules that are frequently crusted. The papules often appear in seborrheic areas of the body, such as the chest, back, ears, nasolabial fold, forehead, scalp, and groin.4 The severity of expression varies from mild, with few lesions, to severe, in which the entire body is covered with disfiguring, macerated plaques emitting a strong odor. On biopsy, the histopathologic findings are typical of dyskeratosis and acantholysis.4

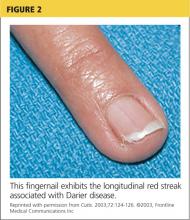

Fingernails (and occasionally toenails) display broad, white or red, somewhat translucent, longitudinal bands accompanied by v-shaped notching1,4,5 (see Figure 2). Such nail changes are diagnostic and occur in 92% to 95% of patients with DD.6 They may, in fact, occur in the absence of cutaneous disease. All nails may be affected, but usually only two to three are involved.6

Although uncommon in DD, white, umbilicated, or cobblestone plaques may be found on intraoral mucous membranes (ie, tongue, buccal mucosa, palate, epiglottis, pharyngeal wall, and esophagus); due to confluence, papules may mimic leukoplakia.7 Lesions may also appear on the vulva or rectum.1,5 In severe cases, the salivary glands can become blocked, and the gums can hypertrophy.5

Since epidermal and brain tissue both derive from ectoderm, pathologic processes that affect one organ system may also affect the other.8 Indeed, among patients with DD, neuropsychiatric problems—including epilepsy, learning difficulties, and schizoaffective disorder—are commonly reported.1 To confirm an association between DD and ATP2A2 mutations, Jacobsen and colleagues performed an analysis of 19 unrelated DD patients with neuropsychiatric phenotypes. They discovered evidence to support the gene’s pleiotropic effects in the brain and hypothesized that mutations in the enzyme SERCA2 correlate with these phenotypes, most specifically for mood disorders.9

TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT

Although no cure is currently available for DD, both short- and long-term treatment options are available; the choice should be based on the severity of an individual patient’s signs and symptoms. For mild cases, topical therapy, such as general emollients, corticosteroid ointments, and high sun protection factor sunscreen, is sufficient.1

For moderate cases, topical retinoids, including tretinoin cream, adapalene gel or cream, and tazarotene gel, may be necessary.4 Keratolytics, including salicylic acid in propylene glycol gel, may be used to regulate hyperkeratosis.4 Celecoxib, a COX-2 inhibitor, is another option that may restore the down regulation of SERCA2. This can prevent progression of the disease.10

Long-term management includes use of oral retinoid therapy (eg, acitretin), which might reduce the frequency of inflammatory flares.1 Systemic adverse effects from long-term use of oral retinoids are cause for concern, however. Close monitoring along with patient education can limit the occurrence of complications.11

If DD is uncontrolled with medication, dermabrasion and erbium:YAG laser ablation have been used to successfully treat chronic cases.12 Although these treatment options may remove existing lesions, it is important to inform patients that the disease has not been cured, that remission is difficult to attain, and that lesions may recur.

Because viral, bacterial, and fungal superinfections are common and may exacerbate the disease, be sure to check for signs of infection while examining the patient.4 Patients should be advised to avoid hot environments, and if that is not possible, to dress in cool cotton clothing to allow for proper ventilation and avoid the build-up of perspiration. Excessive perspiration along with poor hygiene can contribute to the formation of infections as well as trigger a flare-up. If an infection develops, patients should consult a health care provider.

Keeping the skin well moisturized can alleviate the constant pruritus that many patients experience. Daily sunscreen use is essential to avoid skin irritation caused by the sun, which can trigger an acute flare-up. Patients should be advised to avoid the long-term use of corticosteroid ointment. They should also contact their health care provider before using OTC treatments such as Burow’s solution.

CONCLUSION

A thorough history and physical exam are crucial in the diagnosis of DD. In this particular case, inquiry into family history was the key to proper diagnosis. That information, paired with a thorough physical exam, led to the correct diagnosis of this rare genetic skin disorder. A skin biopsy provided definitive confirmation.

This patient had a mild-to-moderate manifestation of DD. He was prescribed retinoid therapy, and routine follow-up visits were recommended to monitor the efficacy of medical therapy and to screen for secondary infections or neuropsychiatric disorders.

This case illustrates the importance of taking a full history and performing an in-depth physical exam when a patient presents with an unfamiliar complaint. Being thorough reduces the risk of missing a crucial element that can guide the diagnostic process.

REFERENCES

1. Creamer D, Barker J, Kerdel FA. Papular and papulosquamous dermatoses. In: Acute Adult Dermatology: Diagnosis and Management (A Colour Handbook). London, UK: Manson Publishing Ltd; 2011:48.

2. Kelly EB. Darier disease (DAR). In: Encyclopedia of Human Genetics and Disease. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO; 2013:186-187.

3. Klausegger A, Laimer M, Bauer JW. Darier disease. [In German.] Hautarzt. 2013;64:22-25.

4. Ringpfeil F. Dermatologic disorders. In: NORD Guide to Rare Disorders. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003:101.

5. Disorders of keratinization. In: Ostler HB, Maibach HI, Hoke AW, Schwab IR, eds. Diseases of the Eye and Skin: A Color Atlas. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:23-34.

6. Baran R, de Berker D, Holzberg M, Thomas L, eds. Baran & Dawber’s Diseases of the Nails and their Management. 4th ed. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2012:295-296.

7. Thiagarajan MK, Narasimhan M, Sankarasubramanian A. Darier disease with oral and esophageal involvement: a case report. Indian J Dent Res. 2011;22:843-846.

8. Medansky RS, Woloshin AA. Darier’s disease: an evaluation of its neuropsychiatric component. Arch Dermatol. 1961;84:482-484.

9. Jacobsen NJ, Lyons I, Hoogendoorn B, et al. ATP2A2 mutations in Darier’s disease and their relationship to neuropsychiatric phenotypes. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1631-1636.

10. Kamijo M, Nishiyama C, Takagi A, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition restores ultraviolet B-induced downregulation of ATP2A2/SERCA2 in keratinocytes: possible therapeutic approach of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition for treatment of Darier disease. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166: 1017-1022.

11. Brecher AR, Orlow SJ. Oral retinoid therapy for dermatologic conditions in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:171-182.

12. Beier C, Kaufmann R. Efficacy of erbium:YAG laser ablation in Darier disease and Hailey-Hailey disease. Arch Dermatol. 1999;35:423-427.

A 45-year-old man presented to the dermatology office complaining of a pruritic rash on his neck, chest, abdomen, and upper back. The rash had been present since the patient was 20, intermittently flaring and causing severe pruritus. For the past two weeks, it had become increasingly bothersome.

The patient described the rash as “greasy” brown plaques diffusely scattered on his body. The rash on his neck was the most bothersome, and the patient felt an uncontrollable need to scratch that area.

Since it first developed 25 years ago, he had used OTC hydrocortisone cream as needed to treat the rash. Although effective for past flares, the cream provided only minimal relief during the current episode.

The patient’s medical history included brittle nails with a worsening of nail quality in recent years. The family history revealed that the patient’s father and sister were affected by the same type of rash, which developed in adolescence for each of them, as well as brittle nails.

On physical examination, the skin was warm and moist to the touch. Flat, slightly elevated, greasy brown papules were scattered on the chest, abdomen, and upper back, with mild surrounding erythema (see Figure 1). Excoriated lesions were noted on the anterior surface of the neck, with pinpoint bleeding resulting from constant irritation. The patient’s fingernails were deformed, with longitudinal ridges and v-shaped notching of the free margin. The remainder of the physical exam was unremarkable, and review of systems was negative.

This patient’s symptoms could result from a variety of causes. Seborrheic dermatitis is a common skin condition that presents with brown plaques similar to those on the patient’s trunk. Another possible diagnosis is Grover’s disease, a rare disorder also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis, in which keratotic plaques appear on the torso and are thought to occur from trauma to sun-damaged skin. An additional consideration is Hailey-Hailey disease, a rare genetic disorder also known as benign familial pemphigus, which is characterized by red-brown plaques located predominantly on flexure surfaces.1 Skin biopsy should be performed for a definitive diagnosis.

Given the family history of a similar rash occurring in first-degree relatives and the distinct physical exam findings, the most likely diagnosis for this patient is keratosis follicularis, also known as Darier disease (DD) or Darier-White disease.

DISCUSSION

Named after Ferdinand-Jean Darier, who discovered this rare genodermatosis, DD is a rare genetic skin disorder caused by mutations of the ATP2A2 gene, located on the long arm of chromosome 12 at position 24,11.1,2 The mutation disrupts the encoding of the enzyme sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium-ATPase 2 (SERCA2). This enzyme is important in the transport of calcium ions across the cell membrane, and insufficient amounts lead to a defect in intracellular calcium signaling.2,3

This genetic mutation is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait with complete penetrance. DD affects men and women equally, with progressive skin signs of interfamilial and intrafamilial variability.4 Skin manifestations occur from late childhood to early adulthood and are typical during adolescence.4 Acute flare-ups can be triggered by heat, perspiration, sunlight, ultraviolet B exposure, stress, or certain medications (in particular, lithium).2 DD is not contagious.2

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The characteristics of DD include yellow or brown, rough, firm papules that are frequently crusted. The papules often appear in seborrheic areas of the body, such as the chest, back, ears, nasolabial fold, forehead, scalp, and groin.4 The severity of expression varies from mild, with few lesions, to severe, in which the entire body is covered with disfiguring, macerated plaques emitting a strong odor. On biopsy, the histopathologic findings are typical of dyskeratosis and acantholysis.4

Fingernails (and occasionally toenails) display broad, white or red, somewhat translucent, longitudinal bands accompanied by v-shaped notching1,4,5 (see Figure 2). Such nail changes are diagnostic and occur in 92% to 95% of patients with DD.6 They may, in fact, occur in the absence of cutaneous disease. All nails may be affected, but usually only two to three are involved.6

Although uncommon in DD, white, umbilicated, or cobblestone plaques may be found on intraoral mucous membranes (ie, tongue, buccal mucosa, palate, epiglottis, pharyngeal wall, and esophagus); due to confluence, papules may mimic leukoplakia.7 Lesions may also appear on the vulva or rectum.1,5 In severe cases, the salivary glands can become blocked, and the gums can hypertrophy.5

Since epidermal and brain tissue both derive from ectoderm, pathologic processes that affect one organ system may also affect the other.8 Indeed, among patients with DD, neuropsychiatric problems—including epilepsy, learning difficulties, and schizoaffective disorder—are commonly reported.1 To confirm an association between DD and ATP2A2 mutations, Jacobsen and colleagues performed an analysis of 19 unrelated DD patients with neuropsychiatric phenotypes. They discovered evidence to support the gene’s pleiotropic effects in the brain and hypothesized that mutations in the enzyme SERCA2 correlate with these phenotypes, most specifically for mood disorders.9

TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT

Although no cure is currently available for DD, both short- and long-term treatment options are available; the choice should be based on the severity of an individual patient’s signs and symptoms. For mild cases, topical therapy, such as general emollients, corticosteroid ointments, and high sun protection factor sunscreen, is sufficient.1

For moderate cases, topical retinoids, including tretinoin cream, adapalene gel or cream, and tazarotene gel, may be necessary.4 Keratolytics, including salicylic acid in propylene glycol gel, may be used to regulate hyperkeratosis.4 Celecoxib, a COX-2 inhibitor, is another option that may restore the down regulation of SERCA2. This can prevent progression of the disease.10

Long-term management includes use of oral retinoid therapy (eg, acitretin), which might reduce the frequency of inflammatory flares.1 Systemic adverse effects from long-term use of oral retinoids are cause for concern, however. Close monitoring along with patient education can limit the occurrence of complications.11

If DD is uncontrolled with medication, dermabrasion and erbium:YAG laser ablation have been used to successfully treat chronic cases.12 Although these treatment options may remove existing lesions, it is important to inform patients that the disease has not been cured, that remission is difficult to attain, and that lesions may recur.

Because viral, bacterial, and fungal superinfections are common and may exacerbate the disease, be sure to check for signs of infection while examining the patient.4 Patients should be advised to avoid hot environments, and if that is not possible, to dress in cool cotton clothing to allow for proper ventilation and avoid the build-up of perspiration. Excessive perspiration along with poor hygiene can contribute to the formation of infections as well as trigger a flare-up. If an infection develops, patients should consult a health care provider.

Keeping the skin well moisturized can alleviate the constant pruritus that many patients experience. Daily sunscreen use is essential to avoid skin irritation caused by the sun, which can trigger an acute flare-up. Patients should be advised to avoid the long-term use of corticosteroid ointment. They should also contact their health care provider before using OTC treatments such as Burow’s solution.

CONCLUSION

A thorough history and physical exam are crucial in the diagnosis of DD. In this particular case, inquiry into family history was the key to proper diagnosis. That information, paired with a thorough physical exam, led to the correct diagnosis of this rare genetic skin disorder. A skin biopsy provided definitive confirmation.

This patient had a mild-to-moderate manifestation of DD. He was prescribed retinoid therapy, and routine follow-up visits were recommended to monitor the efficacy of medical therapy and to screen for secondary infections or neuropsychiatric disorders.

This case illustrates the importance of taking a full history and performing an in-depth physical exam when a patient presents with an unfamiliar complaint. Being thorough reduces the risk of missing a crucial element that can guide the diagnostic process.

REFERENCES

1. Creamer D, Barker J, Kerdel FA. Papular and papulosquamous dermatoses. In: Acute Adult Dermatology: Diagnosis and Management (A Colour Handbook). London, UK: Manson Publishing Ltd; 2011:48.

2. Kelly EB. Darier disease (DAR). In: Encyclopedia of Human Genetics and Disease. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO; 2013:186-187.

3. Klausegger A, Laimer M, Bauer JW. Darier disease. [In German.] Hautarzt. 2013;64:22-25.

4. Ringpfeil F. Dermatologic disorders. In: NORD Guide to Rare Disorders. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003:101.

5. Disorders of keratinization. In: Ostler HB, Maibach HI, Hoke AW, Schwab IR, eds. Diseases of the Eye and Skin: A Color Atlas. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:23-34.

6. Baran R, de Berker D, Holzberg M, Thomas L, eds. Baran & Dawber’s Diseases of the Nails and their Management. 4th ed. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2012:295-296.

7. Thiagarajan MK, Narasimhan M, Sankarasubramanian A. Darier disease with oral and esophageal involvement: a case report. Indian J Dent Res. 2011;22:843-846.

8. Medansky RS, Woloshin AA. Darier’s disease: an evaluation of its neuropsychiatric component. Arch Dermatol. 1961;84:482-484.

9. Jacobsen NJ, Lyons I, Hoogendoorn B, et al. ATP2A2 mutations in Darier’s disease and their relationship to neuropsychiatric phenotypes. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1631-1636.

10. Kamijo M, Nishiyama C, Takagi A, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition restores ultraviolet B-induced downregulation of ATP2A2/SERCA2 in keratinocytes: possible therapeutic approach of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition for treatment of Darier disease. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166: 1017-1022.

11. Brecher AR, Orlow SJ. Oral retinoid therapy for dermatologic conditions in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:171-182.

12. Beier C, Kaufmann R. Efficacy of erbium:YAG laser ablation in Darier disease and Hailey-Hailey disease. Arch Dermatol. 1999;35:423-427.

A 45-year-old man presented to the dermatology office complaining of a pruritic rash on his neck, chest, abdomen, and upper back. The rash had been present since the patient was 20, intermittently flaring and causing severe pruritus. For the past two weeks, it had become increasingly bothersome.

The patient described the rash as “greasy” brown plaques diffusely scattered on his body. The rash on his neck was the most bothersome, and the patient felt an uncontrollable need to scratch that area.

Since it first developed 25 years ago, he had used OTC hydrocortisone cream as needed to treat the rash. Although effective for past flares, the cream provided only minimal relief during the current episode.

The patient’s medical history included brittle nails with a worsening of nail quality in recent years. The family history revealed that the patient’s father and sister were affected by the same type of rash, which developed in adolescence for each of them, as well as brittle nails.

On physical examination, the skin was warm and moist to the touch. Flat, slightly elevated, greasy brown papules were scattered on the chest, abdomen, and upper back, with mild surrounding erythema (see Figure 1). Excoriated lesions were noted on the anterior surface of the neck, with pinpoint bleeding resulting from constant irritation. The patient’s fingernails were deformed, with longitudinal ridges and v-shaped notching of the free margin. The remainder of the physical exam was unremarkable, and review of systems was negative.

This patient’s symptoms could result from a variety of causes. Seborrheic dermatitis is a common skin condition that presents with brown plaques similar to those on the patient’s trunk. Another possible diagnosis is Grover’s disease, a rare disorder also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis, in which keratotic plaques appear on the torso and are thought to occur from trauma to sun-damaged skin. An additional consideration is Hailey-Hailey disease, a rare genetic disorder also known as benign familial pemphigus, which is characterized by red-brown plaques located predominantly on flexure surfaces.1 Skin biopsy should be performed for a definitive diagnosis.

Given the family history of a similar rash occurring in first-degree relatives and the distinct physical exam findings, the most likely diagnosis for this patient is keratosis follicularis, also known as Darier disease (DD) or Darier-White disease.

DISCUSSION

Named after Ferdinand-Jean Darier, who discovered this rare genodermatosis, DD is a rare genetic skin disorder caused by mutations of the ATP2A2 gene, located on the long arm of chromosome 12 at position 24,11.1,2 The mutation disrupts the encoding of the enzyme sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium-ATPase 2 (SERCA2). This enzyme is important in the transport of calcium ions across the cell membrane, and insufficient amounts lead to a defect in intracellular calcium signaling.2,3

This genetic mutation is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait with complete penetrance. DD affects men and women equally, with progressive skin signs of interfamilial and intrafamilial variability.4 Skin manifestations occur from late childhood to early adulthood and are typical during adolescence.4 Acute flare-ups can be triggered by heat, perspiration, sunlight, ultraviolet B exposure, stress, or certain medications (in particular, lithium).2 DD is not contagious.2

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The characteristics of DD include yellow or brown, rough, firm papules that are frequently crusted. The papules often appear in seborrheic areas of the body, such as the chest, back, ears, nasolabial fold, forehead, scalp, and groin.4 The severity of expression varies from mild, with few lesions, to severe, in which the entire body is covered with disfiguring, macerated plaques emitting a strong odor. On biopsy, the histopathologic findings are typical of dyskeratosis and acantholysis.4

Fingernails (and occasionally toenails) display broad, white or red, somewhat translucent, longitudinal bands accompanied by v-shaped notching1,4,5 (see Figure 2). Such nail changes are diagnostic and occur in 92% to 95% of patients with DD.6 They may, in fact, occur in the absence of cutaneous disease. All nails may be affected, but usually only two to three are involved.6

Although uncommon in DD, white, umbilicated, or cobblestone plaques may be found on intraoral mucous membranes (ie, tongue, buccal mucosa, palate, epiglottis, pharyngeal wall, and esophagus); due to confluence, papules may mimic leukoplakia.7 Lesions may also appear on the vulva or rectum.1,5 In severe cases, the salivary glands can become blocked, and the gums can hypertrophy.5

Since epidermal and brain tissue both derive from ectoderm, pathologic processes that affect one organ system may also affect the other.8 Indeed, among patients with DD, neuropsychiatric problems—including epilepsy, learning difficulties, and schizoaffective disorder—are commonly reported.1 To confirm an association between DD and ATP2A2 mutations, Jacobsen and colleagues performed an analysis of 19 unrelated DD patients with neuropsychiatric phenotypes. They discovered evidence to support the gene’s pleiotropic effects in the brain and hypothesized that mutations in the enzyme SERCA2 correlate with these phenotypes, most specifically for mood disorders.9

TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT

Although no cure is currently available for DD, both short- and long-term treatment options are available; the choice should be based on the severity of an individual patient’s signs and symptoms. For mild cases, topical therapy, such as general emollients, corticosteroid ointments, and high sun protection factor sunscreen, is sufficient.1

For moderate cases, topical retinoids, including tretinoin cream, adapalene gel or cream, and tazarotene gel, may be necessary.4 Keratolytics, including salicylic acid in propylene glycol gel, may be used to regulate hyperkeratosis.4 Celecoxib, a COX-2 inhibitor, is another option that may restore the down regulation of SERCA2. This can prevent progression of the disease.10

Long-term management includes use of oral retinoid therapy (eg, acitretin), which might reduce the frequency of inflammatory flares.1 Systemic adverse effects from long-term use of oral retinoids are cause for concern, however. Close monitoring along with patient education can limit the occurrence of complications.11

If DD is uncontrolled with medication, dermabrasion and erbium:YAG laser ablation have been used to successfully treat chronic cases.12 Although these treatment options may remove existing lesions, it is important to inform patients that the disease has not been cured, that remission is difficult to attain, and that lesions may recur.

Because viral, bacterial, and fungal superinfections are common and may exacerbate the disease, be sure to check for signs of infection while examining the patient.4 Patients should be advised to avoid hot environments, and if that is not possible, to dress in cool cotton clothing to allow for proper ventilation and avoid the build-up of perspiration. Excessive perspiration along with poor hygiene can contribute to the formation of infections as well as trigger a flare-up. If an infection develops, patients should consult a health care provider.

Keeping the skin well moisturized can alleviate the constant pruritus that many patients experience. Daily sunscreen use is essential to avoid skin irritation caused by the sun, which can trigger an acute flare-up. Patients should be advised to avoid the long-term use of corticosteroid ointment. They should also contact their health care provider before using OTC treatments such as Burow’s solution.

CONCLUSION

A thorough history and physical exam are crucial in the diagnosis of DD. In this particular case, inquiry into family history was the key to proper diagnosis. That information, paired with a thorough physical exam, led to the correct diagnosis of this rare genetic skin disorder. A skin biopsy provided definitive confirmation.

This patient had a mild-to-moderate manifestation of DD. He was prescribed retinoid therapy, and routine follow-up visits were recommended to monitor the efficacy of medical therapy and to screen for secondary infections or neuropsychiatric disorders.

This case illustrates the importance of taking a full history and performing an in-depth physical exam when a patient presents with an unfamiliar complaint. Being thorough reduces the risk of missing a crucial element that can guide the diagnostic process.

REFERENCES

1. Creamer D, Barker J, Kerdel FA. Papular and papulosquamous dermatoses. In: Acute Adult Dermatology: Diagnosis and Management (A Colour Handbook). London, UK: Manson Publishing Ltd; 2011:48.

2. Kelly EB. Darier disease (DAR). In: Encyclopedia of Human Genetics and Disease. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO; 2013:186-187.

3. Klausegger A, Laimer M, Bauer JW. Darier disease. [In German.] Hautarzt. 2013;64:22-25.

4. Ringpfeil F. Dermatologic disorders. In: NORD Guide to Rare Disorders. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003:101.

5. Disorders of keratinization. In: Ostler HB, Maibach HI, Hoke AW, Schwab IR, eds. Diseases of the Eye and Skin: A Color Atlas. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:23-34.

6. Baran R, de Berker D, Holzberg M, Thomas L, eds. Baran & Dawber’s Diseases of the Nails and their Management. 4th ed. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2012:295-296.

7. Thiagarajan MK, Narasimhan M, Sankarasubramanian A. Darier disease with oral and esophageal involvement: a case report. Indian J Dent Res. 2011;22:843-846.

8. Medansky RS, Woloshin AA. Darier’s disease: an evaluation of its neuropsychiatric component. Arch Dermatol. 1961;84:482-484.

9. Jacobsen NJ, Lyons I, Hoogendoorn B, et al. ATP2A2 mutations in Darier’s disease and their relationship to neuropsychiatric phenotypes. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1631-1636.

10. Kamijo M, Nishiyama C, Takagi A, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition restores ultraviolet B-induced downregulation of ATP2A2/SERCA2 in keratinocytes: possible therapeutic approach of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition for treatment of Darier disease. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166: 1017-1022.

11. Brecher AR, Orlow SJ. Oral retinoid therapy for dermatologic conditions in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:171-182.

12. Beier C, Kaufmann R. Efficacy of erbium:YAG laser ablation in Darier disease and Hailey-Hailey disease. Arch Dermatol. 1999;35:423-427.

Managing Difficult Patient Encounters

It’s a scenario all office-based clinicians are familiar with: Your day has been going well, and all your appointments have been (relatively) on time. But when you scan your afternoon schedule your mood shifts from buoyant to crestfallen. The reason: Three patients whom you find particularly frustrating are slotted for the last appointments of the day.

Case 1: Mr. E, a 44-year-old high-powered attorney, has chronic headache that he has complained off and on about for several years. He has no other past medical history. Physical examination strongly suggests that Mr. E experiences tension-type headaches, but he continues to demand MRI of the brain. “I think there’s something wrong in there,” he has stated repeatedly. “If my last doctor, who is one of the best in the country, ordered an MRI for me, why can’t you?”

Case 2: Mr. A is a 37-year-old man who lost his home in a hurricane three years ago. Although he sustained only minor physical injuries, Mr. A appears to have lost his sense of well-being. He has developed chronic—and debilitating—musculoskeletal pain in his neck and low back in the aftermath of the storm and has been unable to work since then.

At his last two visits, Mr. A requested increasing doses of oxycodone, insisting that nothing else alleviates the pain. When you suggested a nonopioid analgesic, he broke down in tears. “Nobody takes my injuries seriously! My insurance doesn’t want to compensate me for my losses. Now you don’t even believe I’m in pain.”

Case 3: Ms. S is a 65-year-old socially isolated widow who lost her husband several years ago. She has a history of multiple somatic complaints, including fatigue, abdominal pain, back pain, joint pain, and dizziness. As a result, she has undergone numerous diagnostic procedures, including esophagastroduodenoscopy, colonoscopy, and various blood tests, all of which have been negative. Ms. S consistently requires longer than the usual 20-minute visit. When you try to end an appointment, she typically brings up new issues. “Two days ago, I had this pain by my belly button and left shoulder blade. I think that there must be something wrong with me. Can you examine me?” she asked toward the end of her last visit, six weeks ago.

THE BURDEN OF DIFFICULT PATIENT ENCOUNTERS

Cases such as these are frustrating, not so much for their clinical complexity but rather because of the elusiveness of satisfying doctor-patient interactions. Besides a litany of physical complaints, such patients typically present with anxiety, depression, and other psychiatric symptoms; express dissatisfaction with the care they are receiving; and repeatedly request tests and interventions that are not medically indicated.1

From a primary care perspective, such cases can be frustrating and time-consuming, significantly contribute to exhaustion and burnout, and result in unnecessary health care expenditures.1 Studies suggest that family physicians see such patients on a daily basis, and rate about one patient in six as a “difficult” case.2,3

Attitudes, training play a role

Research has established other critical spheres of influence that conspire to create difficult or frustrating patient encounters, including “system” factors (ie, reduced duration of visits and interrupted visits)4 and clinician factors. In fact, negative attitudes toward psychosocial aspects of patient care may be a more potent factor in shaping difficult encounters than any patient characteristic.3,5

Consider the following statements:

• “Talking about psychosocial issues causes more trouble than it is worth.”

• “I do not focus on psychosocial problems until I have ruled out organic disease.”

• “I am too pressed for time to routinely investigate psychosocial issues.”

Such sentiments, which have been associated with difficult encounters, are part of the 32-item Physician Belief Scale, developed 30 years ago and still used to assess beliefs about psychosocial aspects of patient care held by primary care physicians.6

Lack of training is a potential problem, as well. In one survey, more than half of directors of family medicine programs agreed that training in mental health is inadequate.7 Thus, family practice providers often respond to patients like Mr. E, Mr. A, and Ms. S by becoming irritated or avoiding further interaction. A more appropriate response is for the clinician to self-acknowledge his or her emotions, then to engage in an empathic interaction in keeping with patient expectations.4

As mental health treatment becomes more integrated within family medicine,8 pointers for handling difficult patient encounters can be gleaned from the traditional psychiatric approach to difficult or frustrating cases. Indeed, we believe that what is now known as a “patient-centered approach” is rooted in traditions and techniques that psychiatrists and psychologists have used for decades.9

CORE PRINCIPLES FOR HANDLING FRUSTRATING CASES

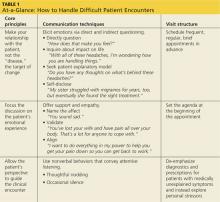

A useful approach to the difficult patient encounter, detailed in Table 1, is based on three key principles:

• The clinician-patient relationship should be the target for change.

• The patient’s emotional experience should be an explicit focus of the clinical interaction.

• The patient’s perspective should guide the clinical encounter.

In our experience, when the interaction between patient and clinician shifts from searching for specific pathologies to building a collaborative relationship, previously recalcitrant symptoms often improve.

Use these communication techniques

There are two main ways to elicit a conversation about personal issues, including emotions, with patients. One is to directly ask patients to describe the distress they are experiencing and elicit the emotions connected to this distress. The other is to invite a discussion about emotional issues indirectly, by asking patients how the symptoms affect their lives and what they think is causing the problem or by selectively sharing an emotional experience of your own.

Once a patient has shared emotions, you will need to show support and empathy in order to build an alliance. There is more than one way to do this, and methods can be used alone or in combination, depending on the particular situation. (You’ll find examples in Table 1.)

Name the affect. The simple act of naming the patient’s affect or emotional expression (eg, “You sound sad”) is surprisingly helpful, as it lets patients know they have been “heard.”

Validate. You can also validate patients like Mr. E, Mr. A, and Ms. S by stating that their emotional reactions are legitimate, praising them for how well they have coped with difficult symptoms, and acknowledging the seriousness and complexity of their situations.

Align. Once a patient expresses his or her interests and goals, aligning yourself with them (eg, “I want to do everything in my power to help you reduce your pain …”) will elicit hope and improve patient satisfaction.

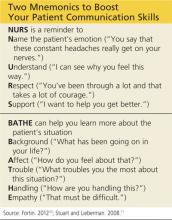

And two mnemonic devices—detailed in the box above—can help you improve the way you communicate with patients.10,11

Communication can also be nonverbal, such as thoughtful nodding or a timely therapeutic silence. The former is characterized by slow, steady, and purposeful movement accompanied by eye contact; in the latter case, you simply resist the urge to immediately respond after a patient has revealed something emotionally laden, and wait a few seconds to take in what has been said.

HOW TO PROVIDE THERAPEUTIC STRUCTURE

Family practice clinicians can further manage patient behaviors that they find bothersome by implementing changes in the way they organize and conduct patient visits. Studies of patients with complex somatic symptoms offer additional hints for the management of frustrating cases. The following strategies can lead to positive outcomes, including a decrease in disability and health care

costs.12

Schedule regular brief visits. Mr. E, Mr. A, and Ms. S should have frequent and regular, but brief, appointments (eg, 15 minutes every two weeks for two months). Proactively schedule return visits, rather than waiting for the patient to call for an appointment prn.11 Sharing this kind of plan gives such patients a concrete time line and clear evidence of support. Avoid the temptation to schedule difficult cases for the last time slot of the day, as going over the allotted time can insidiously give some patients the expectation of progressively longer visits.

Set the agenda. To prevent “doorknob questions” like Ms. S’s new symptoms, reported just as you’re about to leave the exam room, the agenda must be set at the outset of the visit. This can be done by asking, “What did you want to discuss today?”, “Is there anything else you want to address today?”, or “What else did you need taken care of?”13

Explicitly inquiring about patient expectations at the start of the visit lets patients like Ms. S know that they are being taken seriously. If the agenda still balloons, you can simply state, “You deserve more than 15 minutes for all these issues. Let’s pick the top two for today and tackle others at our next visit in two weeks.” To further save time, you can ask the patient to bring a symptom diary or written agenda to the appointment. We’ve found that many anxious patients benefit from this exercise.

Avoid the urge to act. When a patient has unexplained symptoms, effective interventions require clinicians to avoid certain “reflex” behaviors—repeatedly performing diagnostic tests, prescribing medications for symptoms of unknown etiology, insinuating that the problem is “in your head,” formulating ambiguous diagnoses, and repeating physical exams.12 Such behaviors tend to reinforce the pathology in patients with unexplained symptoms. The time saved avoiding these pitfalls is better invested in exploring personal issues and stressors.

The point is that such patients should be reassured via discussion, rather than with dubious diagnostic labels and potentially dangerous drugs. This approach has been shown to improve patients’ physical functioning while reducing medical expenditures.12

INTO ACTION WITH OUR THREE CASES

Case 1: Given these principles, how would you handle Mr. E, the patient who is demanding an MRI for a simple tension headache? Although placating him by ordering the test, providing a referral to a specialist, or defending your recommendation through medical reasoning may seem to be more intuitive (or a “quick fix”), these strategies often lead to excessive medical spending, transfer of the burden to a specialist colleague, and ongoing frustration and dissatisfaction on the part of the patient. In this case, validation may be a more useful approach.

“I can totally understand why you’re frustrated that we disagree,” you might say to Mr. E. “But you’re right! You definitely deserve the best care. That’s why I’m recommending against the MRI, as I feel that would be a suboptimal approach.”

Often patients like Mr. E will require repeated validation of their suffering and frustration. The key is to be persistent in validating their feelings without compromising your own principles in providing optimal medical care.

Case 2: Let’s turn now to Mr. A, who is requesting escalating doses of opioids. Some clinicians might write the prescription for the dose he’s insisting on, while others draw a hard boundary by refusing to prescribe above a certain dose or beyond a specific time frame. Both strategies may compromise optimal care or endanger the clinician-patient alliance. Another quick solution would be to provide a referral to a psychiatrist, without further discussion.

In cases like that of Mr. A, however, the patient’s demands are often a sign of more complicated emotions and dynamics below the surface. So you might respond by stating, “I’m sorry to hear that things haven’t been going well. How are you feeling about these things? How does the oxycodone help you? In what way doesn’t it help?”

It is important here to understand how the medication serves the patient—in addition to the ways it hurts him—in order for him to feel understood. Inviting Mr. A to have an open-ended discussion may allow him to reveal what is the real source of his distress—losing his job and his home.

Case 3: Now let’s turn to Ms. S, who is convinced that she has a physical malady despite negative exams and tests. In truth, she may be depressed or anxious over her husband’s death. One way to address this is to confront the patient directly by suggesting that she has depression triggered by her husband’s death. But this strategy—if used too early—may feel like an accusation, make her angry, and jeopardize your relationship with her.

An alternative approach would be to say, “I think your problems are long-standing and could require a while to treat. Let’s see each other every two weeks for the next two months so we get adequate time to work on them.” This would be an example of structuring more frequent visits, while also validating the distressing nature of her symptoms.

These strategies are evidence-based

These techniques, while easily adaptable to primary care, are grounded in psychotherapy theory and are evidence-based. A seminal randomized controlled trial conducted more than 30 years ago showed that a patient-centered interview incorporating a number of these techniques bolstered clinicians’ knowledge, interviewing skills, attitudes, and ability to manage patients with unexplained complaints.14

A multicenter study analyzed audio recordings of strategies used by primary care physicians to deny patient requests for a particular medication. It revealed that explanations based on patient perspectives were significantly more likely to result in excellent patient satisfaction than biomedical explanations or other explanatory approaches.15 Research has also shown that agenda-setting improves both patient and provider satisfaction.16

Some cases will still be frustrating, and some “difficult” patients will still need a psychiatric referral at some point—ideally, to a psychiatric or psychological consultant who collaborates closely with the primary care clinic.17,18

Clinicians sometimes worry that the communication techniques outlined here cannot be incorporated into an already harried primary care visit. Many may think it’s better not to ask at all than risk opening a Pandora’s box. We urge you to reconsider. Although the techniques we’ve outlined certainly require practice, they need not be time-consuming.19 By embracing this management approach, you can improve patient satisfaction while enhancing your own repertoire of doctoring skills.

The authors thank Drs. Michael Fetters and Rod Hayward for their help in the development of this manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

REFERENCES

1.Hahn SR, Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, et al. The difficult patient: prevalence, psychopathology, and functional impairment. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:1-8.

2. An PG, Rabatin JS, Manwell LB, et al. Burden of difficult encounters in primary care: data from the minimizing error, maximizing outcomes study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:410-414.

3. Hinchey SA, Jackson JL. A cohort study assessing difficult patient encounters in a walk-in primary care clinic, predictors and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:588-594.

4. Haas LJ, Leiser JP, Magill MK, et al. Management of the difficult patient. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:2063-2068.

5. Jackson JL, Kroenke K. Difficult patient encounters in the ambulatory clinic: clinical predictors and outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1069-1075.

6. Ashworth CD, Williamson P, Montano D. A scale to measure physician beliefs about psychosocial aspects of patient care. Soc Sci Med. 1984;19:1235-1238.

7. Leigh H, Stewart D, Mallios R. Mental health and psychiatry training in primary care residency programs. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:189-194.

8. Katon W, Unützer J. Collaborative care models for depression: time to move from evidence to practice. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2304-2306.

9. Groves JE. Taking care of the hateful patient. N Engl J Med. 1978;298:883-887.

10. Fortin AH, Dwamena FC, Frankel RM, et al. Smith’s Patient-Centered Interviewing: An Evidence-Based Method. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

11. Stuart MR, Lieberman JA. The Fifteen Minute Hour: Therapeutic Talk in Primary Care. 4th ed. Milton Keynes, UK: Radcliffe Publishing; 2008.

12. Smith GR Jr, Rost K, Kashner TM. A trial of the effect of a standardized psychiatric consultation on health outcomes and costs in somatizing patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:238-243.

13. Baker LH, O’Connell D, Platt FW. “What else?” Setting the agenda for the clinical interview. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:766 -770.

14. Smith RC, Lyles JS, Mettler J, et al. The effectiveness of intensive training for residents in interviewing: a randomized, controlled study. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:118-126.

15. Paterniti DA, Fancher TL, Cipri CS, et al. Getting to “no”: strategies primary care physicians use to deny patient requests. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170: 381-388.

16. Kroenke K. Unburdening the difficult clinical encounter. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:333-334.

17. Katon W, Unützer J, Wells K, et al. Collaborative depression care: history, evolution and ways to enhance dissemination and sustainability. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:456-464.

18. Williams M, Angstman K, Johnson I, et al. Implementation of a care management model for depression at two primary care clinics. J Ambul Care Manage. 2011;34:163-173.

19. Lieberman JA III, Stuart MR. The BATHE method: incorporating counseling and psychotherapy into the everyday management of patients. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;1:35-38.

It’s a scenario all office-based clinicians are familiar with: Your day has been going well, and all your appointments have been (relatively) on time. But when you scan your afternoon schedule your mood shifts from buoyant to crestfallen. The reason: Three patients whom you find particularly frustrating are slotted for the last appointments of the day.

Case 1: Mr. E, a 44-year-old high-powered attorney, has chronic headache that he has complained off and on about for several years. He has no other past medical history. Physical examination strongly suggests that Mr. E experiences tension-type headaches, but he continues to demand MRI of the brain. “I think there’s something wrong in there,” he has stated repeatedly. “If my last doctor, who is one of the best in the country, ordered an MRI for me, why can’t you?”

Case 2: Mr. A is a 37-year-old man who lost his home in a hurricane three years ago. Although he sustained only minor physical injuries, Mr. A appears to have lost his sense of well-being. He has developed chronic—and debilitating—musculoskeletal pain in his neck and low back in the aftermath of the storm and has been unable to work since then.

At his last two visits, Mr. A requested increasing doses of oxycodone, insisting that nothing else alleviates the pain. When you suggested a nonopioid analgesic, he broke down in tears. “Nobody takes my injuries seriously! My insurance doesn’t want to compensate me for my losses. Now you don’t even believe I’m in pain.”

Case 3: Ms. S is a 65-year-old socially isolated widow who lost her husband several years ago. She has a history of multiple somatic complaints, including fatigue, abdominal pain, back pain, joint pain, and dizziness. As a result, she has undergone numerous diagnostic procedures, including esophagastroduodenoscopy, colonoscopy, and various blood tests, all of which have been negative. Ms. S consistently requires longer than the usual 20-minute visit. When you try to end an appointment, she typically brings up new issues. “Two days ago, I had this pain by my belly button and left shoulder blade. I think that there must be something wrong with me. Can you examine me?” she asked toward the end of her last visit, six weeks ago.

THE BURDEN OF DIFFICULT PATIENT ENCOUNTERS

Cases such as these are frustrating, not so much for their clinical complexity but rather because of the elusiveness of satisfying doctor-patient interactions. Besides a litany of physical complaints, such patients typically present with anxiety, depression, and other psychiatric symptoms; express dissatisfaction with the care they are receiving; and repeatedly request tests and interventions that are not medically indicated.1

From a primary care perspective, such cases can be frustrating and time-consuming, significantly contribute to exhaustion and burnout, and result in unnecessary health care expenditures.1 Studies suggest that family physicians see such patients on a daily basis, and rate about one patient in six as a “difficult” case.2,3

Attitudes, training play a role

Research has established other critical spheres of influence that conspire to create difficult or frustrating patient encounters, including “system” factors (ie, reduced duration of visits and interrupted visits)4 and clinician factors. In fact, negative attitudes toward psychosocial aspects of patient care may be a more potent factor in shaping difficult encounters than any patient characteristic.3,5

Consider the following statements:

• “Talking about psychosocial issues causes more trouble than it is worth.”

• “I do not focus on psychosocial problems until I have ruled out organic disease.”

• “I am too pressed for time to routinely investigate psychosocial issues.”

Such sentiments, which have been associated with difficult encounters, are part of the 32-item Physician Belief Scale, developed 30 years ago and still used to assess beliefs about psychosocial aspects of patient care held by primary care physicians.6

Lack of training is a potential problem, as well. In one survey, more than half of directors of family medicine programs agreed that training in mental health is inadequate.7 Thus, family practice providers often respond to patients like Mr. E, Mr. A, and Ms. S by becoming irritated or avoiding further interaction. A more appropriate response is for the clinician to self-acknowledge his or her emotions, then to engage in an empathic interaction in keeping with patient expectations.4

As mental health treatment becomes more integrated within family medicine,8 pointers for handling difficult patient encounters can be gleaned from the traditional psychiatric approach to difficult or frustrating cases. Indeed, we believe that what is now known as a “patient-centered approach” is rooted in traditions and techniques that psychiatrists and psychologists have used for decades.9

CORE PRINCIPLES FOR HANDLING FRUSTRATING CASES

A useful approach to the difficult patient encounter, detailed in Table 1, is based on three key principles:

• The clinician-patient relationship should be the target for change.

• The patient’s emotional experience should be an explicit focus of the clinical interaction.

• The patient’s perspective should guide the clinical encounter.

In our experience, when the interaction between patient and clinician shifts from searching for specific pathologies to building a collaborative relationship, previously recalcitrant symptoms often improve.

Use these communication techniques

There are two main ways to elicit a conversation about personal issues, including emotions, with patients. One is to directly ask patients to describe the distress they are experiencing and elicit the emotions connected to this distress. The other is to invite a discussion about emotional issues indirectly, by asking patients how the symptoms affect their lives and what they think is causing the problem or by selectively sharing an emotional experience of your own.

Once a patient has shared emotions, you will need to show support and empathy in order to build an alliance. There is more than one way to do this, and methods can be used alone or in combination, depending on the particular situation. (You’ll find examples in Table 1.)

Name the affect. The simple act of naming the patient’s affect or emotional expression (eg, “You sound sad”) is surprisingly helpful, as it lets patients know they have been “heard.”

Validate. You can also validate patients like Mr. E, Mr. A, and Ms. S by stating that their emotional reactions are legitimate, praising them for how well they have coped with difficult symptoms, and acknowledging the seriousness and complexity of their situations.

Align. Once a patient expresses his or her interests and goals, aligning yourself with them (eg, “I want to do everything in my power to help you reduce your pain …”) will elicit hope and improve patient satisfaction.

And two mnemonic devices—detailed in the box above—can help you improve the way you communicate with patients.10,11

Communication can also be nonverbal, such as thoughtful nodding or a timely therapeutic silence. The former is characterized by slow, steady, and purposeful movement accompanied by eye contact; in the latter case, you simply resist the urge to immediately respond after a patient has revealed something emotionally laden, and wait a few seconds to take in what has been said.

HOW TO PROVIDE THERAPEUTIC STRUCTURE

Family practice clinicians can further manage patient behaviors that they find bothersome by implementing changes in the way they organize and conduct patient visits. Studies of patients with complex somatic symptoms offer additional hints for the management of frustrating cases. The following strategies can lead to positive outcomes, including a decrease in disability and health care

costs.12

Schedule regular brief visits. Mr. E, Mr. A, and Ms. S should have frequent and regular, but brief, appointments (eg, 15 minutes every two weeks for two months). Proactively schedule return visits, rather than waiting for the patient to call for an appointment prn.11 Sharing this kind of plan gives such patients a concrete time line and clear evidence of support. Avoid the temptation to schedule difficult cases for the last time slot of the day, as going over the allotted time can insidiously give some patients the expectation of progressively longer visits.

Set the agenda. To prevent “doorknob questions” like Ms. S’s new symptoms, reported just as you’re about to leave the exam room, the agenda must be set at the outset of the visit. This can be done by asking, “What did you want to discuss today?”, “Is there anything else you want to address today?”, or “What else did you need taken care of?”13

Explicitly inquiring about patient expectations at the start of the visit lets patients like Ms. S know that they are being taken seriously. If the agenda still balloons, you can simply state, “You deserve more than 15 minutes for all these issues. Let’s pick the top two for today and tackle others at our next visit in two weeks.” To further save time, you can ask the patient to bring a symptom diary or written agenda to the appointment. We’ve found that many anxious patients benefit from this exercise.

Avoid the urge to act. When a patient has unexplained symptoms, effective interventions require clinicians to avoid certain “reflex” behaviors—repeatedly performing diagnostic tests, prescribing medications for symptoms of unknown etiology, insinuating that the problem is “in your head,” formulating ambiguous diagnoses, and repeating physical exams.12 Such behaviors tend to reinforce the pathology in patients with unexplained symptoms. The time saved avoiding these pitfalls is better invested in exploring personal issues and stressors.

The point is that such patients should be reassured via discussion, rather than with dubious diagnostic labels and potentially dangerous drugs. This approach has been shown to improve patients’ physical functioning while reducing medical expenditures.12

INTO ACTION WITH OUR THREE CASES

Case 1: Given these principles, how would you handle Mr. E, the patient who is demanding an MRI for a simple tension headache? Although placating him by ordering the test, providing a referral to a specialist, or defending your recommendation through medical reasoning may seem to be more intuitive (or a “quick fix”), these strategies often lead to excessive medical spending, transfer of the burden to a specialist colleague, and ongoing frustration and dissatisfaction on the part of the patient. In this case, validation may be a more useful approach.

“I can totally understand why you’re frustrated that we disagree,” you might say to Mr. E. “But you’re right! You definitely deserve the best care. That’s why I’m recommending against the MRI, as I feel that would be a suboptimal approach.”

Often patients like Mr. E will require repeated validation of their suffering and frustration. The key is to be persistent in validating their feelings without compromising your own principles in providing optimal medical care.

Case 2: Let’s turn now to Mr. A, who is requesting escalating doses of opioids. Some clinicians might write the prescription for the dose he’s insisting on, while others draw a hard boundary by refusing to prescribe above a certain dose or beyond a specific time frame. Both strategies may compromise optimal care or endanger the clinician-patient alliance. Another quick solution would be to provide a referral to a psychiatrist, without further discussion.

In cases like that of Mr. A, however, the patient’s demands are often a sign of more complicated emotions and dynamics below the surface. So you might respond by stating, “I’m sorry to hear that things haven’t been going well. How are you feeling about these things? How does the oxycodone help you? In what way doesn’t it help?”

It is important here to understand how the medication serves the patient—in addition to the ways it hurts him—in order for him to feel understood. Inviting Mr. A to have an open-ended discussion may allow him to reveal what is the real source of his distress—losing his job and his home.

Case 3: Now let’s turn to Ms. S, who is convinced that she has a physical malady despite negative exams and tests. In truth, she may be depressed or anxious over her husband’s death. One way to address this is to confront the patient directly by suggesting that she has depression triggered by her husband’s death. But this strategy—if used too early—may feel like an accusation, make her angry, and jeopardize your relationship with her.

An alternative approach would be to say, “I think your problems are long-standing and could require a while to treat. Let’s see each other every two weeks for the next two months so we get adequate time to work on them.” This would be an example of structuring more frequent visits, while also validating the distressing nature of her symptoms.

These strategies are evidence-based

These techniques, while easily adaptable to primary care, are grounded in psychotherapy theory and are evidence-based. A seminal randomized controlled trial conducted more than 30 years ago showed that a patient-centered interview incorporating a number of these techniques bolstered clinicians’ knowledge, interviewing skills, attitudes, and ability to manage patients with unexplained complaints.14

A multicenter study analyzed audio recordings of strategies used by primary care physicians to deny patient requests for a particular medication. It revealed that explanations based on patient perspectives were significantly more likely to result in excellent patient satisfaction than biomedical explanations or other explanatory approaches.15 Research has also shown that agenda-setting improves both patient and provider satisfaction.16

Some cases will still be frustrating, and some “difficult” patients will still need a psychiatric referral at some point—ideally, to a psychiatric or psychological consultant who collaborates closely with the primary care clinic.17,18

Clinicians sometimes worry that the communication techniques outlined here cannot be incorporated into an already harried primary care visit. Many may think it’s better not to ask at all than risk opening a Pandora’s box. We urge you to reconsider. Although the techniques we’ve outlined certainly require practice, they need not be time-consuming.19 By embracing this management approach, you can improve patient satisfaction while enhancing your own repertoire of doctoring skills.

The authors thank Drs. Michael Fetters and Rod Hayward for their help in the development of this manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

REFERENCES

1.Hahn SR, Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, et al. The difficult patient: prevalence, psychopathology, and functional impairment. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:1-8.

2. An PG, Rabatin JS, Manwell LB, et al. Burden of difficult encounters in primary care: data from the minimizing error, maximizing outcomes study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:410-414.

3. Hinchey SA, Jackson JL. A cohort study assessing difficult patient encounters in a walk-in primary care clinic, predictors and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:588-594.

4. Haas LJ, Leiser JP, Magill MK, et al. Management of the difficult patient. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:2063-2068.

5. Jackson JL, Kroenke K. Difficult patient encounters in the ambulatory clinic: clinical predictors and outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1069-1075.

6. Ashworth CD, Williamson P, Montano D. A scale to measure physician beliefs about psychosocial aspects of patient care. Soc Sci Med. 1984;19:1235-1238.

7. Leigh H, Stewart D, Mallios R. Mental health and psychiatry training in primary care residency programs. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:189-194.

8. Katon W, Unützer J. Collaborative care models for depression: time to move from evidence to practice. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2304-2306.

9. Groves JE. Taking care of the hateful patient. N Engl J Med. 1978;298:883-887.

10. Fortin AH, Dwamena FC, Frankel RM, et al. Smith’s Patient-Centered Interviewing: An Evidence-Based Method. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

11. Stuart MR, Lieberman JA. The Fifteen Minute Hour: Therapeutic Talk in Primary Care. 4th ed. Milton Keynes, UK: Radcliffe Publishing; 2008.

12. Smith GR Jr, Rost K, Kashner TM. A trial of the effect of a standardized psychiatric consultation on health outcomes and costs in somatizing patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:238-243.

13. Baker LH, O’Connell D, Platt FW. “What else?” Setting the agenda for the clinical interview. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:766 -770.

14. Smith RC, Lyles JS, Mettler J, et al. The effectiveness of intensive training for residents in interviewing: a randomized, controlled study. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:118-126.

15. Paterniti DA, Fancher TL, Cipri CS, et al. Getting to “no”: strategies primary care physicians use to deny patient requests. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170: 381-388.

16. Kroenke K. Unburdening the difficult clinical encounter. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:333-334.

17. Katon W, Unützer J, Wells K, et al. Collaborative depression care: history, evolution and ways to enhance dissemination and sustainability. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:456-464.

18. Williams M, Angstman K, Johnson I, et al. Implementation of a care management model for depression at two primary care clinics. J Ambul Care Manage. 2011;34:163-173.

19. Lieberman JA III, Stuart MR. The BATHE method: incorporating counseling and psychotherapy into the everyday management of patients. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;1:35-38.

It’s a scenario all office-based clinicians are familiar with: Your day has been going well, and all your appointments have been (relatively) on time. But when you scan your afternoon schedule your mood shifts from buoyant to crestfallen. The reason: Three patients whom you find particularly frustrating are slotted for the last appointments of the day.

Case 1: Mr. E, a 44-year-old high-powered attorney, has chronic headache that he has complained off and on about for several years. He has no other past medical history. Physical examination strongly suggests that Mr. E experiences tension-type headaches, but he continues to demand MRI of the brain. “I think there’s something wrong in there,” he has stated repeatedly. “If my last doctor, who is one of the best in the country, ordered an MRI for me, why can’t you?”

Case 2: Mr. A is a 37-year-old man who lost his home in a hurricane three years ago. Although he sustained only minor physical injuries, Mr. A appears to have lost his sense of well-being. He has developed chronic—and debilitating—musculoskeletal pain in his neck and low back in the aftermath of the storm and has been unable to work since then.

At his last two visits, Mr. A requested increasing doses of oxycodone, insisting that nothing else alleviates the pain. When you suggested a nonopioid analgesic, he broke down in tears. “Nobody takes my injuries seriously! My insurance doesn’t want to compensate me for my losses. Now you don’t even believe I’m in pain.”

Case 3: Ms. S is a 65-year-old socially isolated widow who lost her husband several years ago. She has a history of multiple somatic complaints, including fatigue, abdominal pain, back pain, joint pain, and dizziness. As a result, she has undergone numerous diagnostic procedures, including esophagastroduodenoscopy, colonoscopy, and various blood tests, all of which have been negative. Ms. S consistently requires longer than the usual 20-minute visit. When you try to end an appointment, she typically brings up new issues. “Two days ago, I had this pain by my belly button and left shoulder blade. I think that there must be something wrong with me. Can you examine me?” she asked toward the end of her last visit, six weeks ago.

THE BURDEN OF DIFFICULT PATIENT ENCOUNTERS

Cases such as these are frustrating, not so much for their clinical complexity but rather because of the elusiveness of satisfying doctor-patient interactions. Besides a litany of physical complaints, such patients typically present with anxiety, depression, and other psychiatric symptoms; express dissatisfaction with the care they are receiving; and repeatedly request tests and interventions that are not medically indicated.1

From a primary care perspective, such cases can be frustrating and time-consuming, significantly contribute to exhaustion and burnout, and result in unnecessary health care expenditures.1 Studies suggest that family physicians see such patients on a daily basis, and rate about one patient in six as a “difficult” case.2,3

Attitudes, training play a role

Research has established other critical spheres of influence that conspire to create difficult or frustrating patient encounters, including “system” factors (ie, reduced duration of visits and interrupted visits)4 and clinician factors. In fact, negative attitudes toward psychosocial aspects of patient care may be a more potent factor in shaping difficult encounters than any patient characteristic.3,5

Consider the following statements:

• “Talking about psychosocial issues causes more trouble than it is worth.”

• “I do not focus on psychosocial problems until I have ruled out organic disease.”

• “I am too pressed for time to routinely investigate psychosocial issues.”

Such sentiments, which have been associated with difficult encounters, are part of the 32-item Physician Belief Scale, developed 30 years ago and still used to assess beliefs about psychosocial aspects of patient care held by primary care physicians.6

Lack of training is a potential problem, as well. In one survey, more than half of directors of family medicine programs agreed that training in mental health is inadequate.7 Thus, family practice providers often respond to patients like Mr. E, Mr. A, and Ms. S by becoming irritated or avoiding further interaction. A more appropriate response is for the clinician to self-acknowledge his or her emotions, then to engage in an empathic interaction in keeping with patient expectations.4

As mental health treatment becomes more integrated within family medicine,8 pointers for handling difficult patient encounters can be gleaned from the traditional psychiatric approach to difficult or frustrating cases. Indeed, we believe that what is now known as a “patient-centered approach” is rooted in traditions and techniques that psychiatrists and psychologists have used for decades.9

CORE PRINCIPLES FOR HANDLING FRUSTRATING CASES

A useful approach to the difficult patient encounter, detailed in Table 1, is based on three key principles:

• The clinician-patient relationship should be the target for change.

• The patient’s emotional experience should be an explicit focus of the clinical interaction.

• The patient’s perspective should guide the clinical encounter.

In our experience, when the interaction between patient and clinician shifts from searching for specific pathologies to building a collaborative relationship, previously recalcitrant symptoms often improve.

Use these communication techniques

There are two main ways to elicit a conversation about personal issues, including emotions, with patients. One is to directly ask patients to describe the distress they are experiencing and elicit the emotions connected to this distress. The other is to invite a discussion about emotional issues indirectly, by asking patients how the symptoms affect their lives and what they think is causing the problem or by selectively sharing an emotional experience of your own.

Once a patient has shared emotions, you will need to show support and empathy in order to build an alliance. There is more than one way to do this, and methods can be used alone or in combination, depending on the particular situation. (You’ll find examples in Table 1.)

Name the affect. The simple act of naming the patient’s affect or emotional expression (eg, “You sound sad”) is surprisingly helpful, as it lets patients know they have been “heard.”

Validate. You can also validate patients like Mr. E, Mr. A, and Ms. S by stating that their emotional reactions are legitimate, praising them for how well they have coped with difficult symptoms, and acknowledging the seriousness and complexity of their situations.

Align. Once a patient expresses his or her interests and goals, aligning yourself with them (eg, “I want to do everything in my power to help you reduce your pain …”) will elicit hope and improve patient satisfaction.

And two mnemonic devices—detailed in the box above—can help you improve the way you communicate with patients.10,11

Communication can also be nonverbal, such as thoughtful nodding or a timely therapeutic silence. The former is characterized by slow, steady, and purposeful movement accompanied by eye contact; in the latter case, you simply resist the urge to immediately respond after a patient has revealed something emotionally laden, and wait a few seconds to take in what has been said.

HOW TO PROVIDE THERAPEUTIC STRUCTURE

Family practice clinicians can further manage patient behaviors that they find bothersome by implementing changes in the way they organize and conduct patient visits. Studies of patients with complex somatic symptoms offer additional hints for the management of frustrating cases. The following strategies can lead to positive outcomes, including a decrease in disability and health care

costs.12

Schedule regular brief visits. Mr. E, Mr. A, and Ms. S should have frequent and regular, but brief, appointments (eg, 15 minutes every two weeks for two months). Proactively schedule return visits, rather than waiting for the patient to call for an appointment prn.11 Sharing this kind of plan gives such patients a concrete time line and clear evidence of support. Avoid the temptation to schedule difficult cases for the last time slot of the day, as going over the allotted time can insidiously give some patients the expectation of progressively longer visits.

Set the agenda. To prevent “doorknob questions” like Ms. S’s new symptoms, reported just as you’re about to leave the exam room, the agenda must be set at the outset of the visit. This can be done by asking, “What did you want to discuss today?”, “Is there anything else you want to address today?”, or “What else did you need taken care of?”13

Explicitly inquiring about patient expectations at the start of the visit lets patients like Ms. S know that they are being taken seriously. If the agenda still balloons, you can simply state, “You deserve more than 15 minutes for all these issues. Let’s pick the top two for today and tackle others at our next visit in two weeks.” To further save time, you can ask the patient to bring a symptom diary or written agenda to the appointment. We’ve found that many anxious patients benefit from this exercise.

Avoid the urge to act. When a patient has unexplained symptoms, effective interventions require clinicians to avoid certain “reflex” behaviors—repeatedly performing diagnostic tests, prescribing medications for symptoms of unknown etiology, insinuating that the problem is “in your head,” formulating ambiguous diagnoses, and repeating physical exams.12 Such behaviors tend to reinforce the pathology in patients with unexplained symptoms. The time saved avoiding these pitfalls is better invested in exploring personal issues and stressors.

The point is that such patients should be reassured via discussion, rather than with dubious diagnostic labels and potentially dangerous drugs. This approach has been shown to improve patients’ physical functioning while reducing medical expenditures.12

INTO ACTION WITH OUR THREE CASES

Case 1: Given these principles, how would you handle Mr. E, the patient who is demanding an MRI for a simple tension headache? Although placating him by ordering the test, providing a referral to a specialist, or defending your recommendation through medical reasoning may seem to be more intuitive (or a “quick fix”), these strategies often lead to excessive medical spending, transfer of the burden to a specialist colleague, and ongoing frustration and dissatisfaction on the part of the patient. In this case, validation may be a more useful approach.

“I can totally understand why you’re frustrated that we disagree,” you might say to Mr. E. “But you’re right! You definitely deserve the best care. That’s why I’m recommending against the MRI, as I feel that would be a suboptimal approach.”