User login

Alcohol: An unfortunate teratogen

Medical students learn early in their education that alcohol is a teratogen. Despite this widespread knowledge, many obstetricians counsel patients about the safety of low doses of alcohol in pregnancy.1 Indeed, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists’ position on this is, “while the safest approach may be to avoid any alcohol during pregnancy, it remains the case that there is no evidence of harm from low levels of alcohol consumption, defined as no more than one or two units of alcohol once or twice a week.”2

Like many providers, I was aware of this controversy, but it became truly personal when a beloved family member was diagnosed with fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS). In this paper, I will review some of the controversy regarding alcohol in pregnancy, highlight findings from the literature, provide tools for prevention, and identify new developments regarding this devastating, preventable condition.

Charlie

To know my nephew Charlie is to fall in love with my nephew Charlie. One of the happiest moments of my life was when I learned my brother and sister-in-law had adopted twins from Kazakhstan. When my little niece and nephew started their new life in the United States, certain medical issues seemed to merit additional attention. Although both were very small for their age and required significant nutritional support, Charlie seemed to be a bit more rambunctious and required additional supervision.

The children were fortunate enough to have incredibly loving, dedicated parents, who have access to exceptional medical care as residents of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. After extensive testing, it became clear what was causing Charlie’s developmental delay; his pediatric team made the diagnosis of FAS. My brother and sister-in-law became incredibly well-read about this challenging disorder, and threw themselves into national advocacy work to help prevent this unnecessary tragedy.

Recent data point to teratogenicity, but media confuse the issue

Some recent media coverage3 of celebrities who apparently drank while pregnant was in response to an article in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health.4 The authors of this study concluded that, “at age 5 years, cohort members born to mothers who drank up to one to two drinks per week or per occasion during pregnancy were not at increased risk of clinically relevant behavioral difficulties or cognitive deficits, compared with children of mothers in the not-in-pregnancy group.”

This is certainly not the first occasion the popular press has covered a published study that seems to indicate no ill effects of alcohol use in pregnancy. A 2008 report by Kelly and colleagues,5 and its subsequent media coverage, prompted the Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders Study Group to state that the panel of experts was “alarmed” by recent newspaper reports suggesting that light drinking during pregnancy may be beneficial for an unborn child.6 They noted misleading and irresponsible media reports of the findings, which suggested that 3-year-old children whose mothers drank “lightly” during pregnancy were not at risk for certain behavioral problems.

What the study authors proceeded to note, however (that the media did not mention), was that the light drinkers in their study had socioeconomic advantages, compared with nondrinkers.5 (Advantaged economic status is established to be beneficial for childhood development.) They also noted that the study involved preschool-aged children, stating “Generally the adverse effects of light drinking during pregnancy are subtle and may go undetected in young children. However, other group studies of more moderate or ‘social’ drinking levels during pregnancy have shown an adverse impact on multiple aspects of development through adolescence and young adulthood, even when important environmental factors are taken into account.” A sentence I thought was most compelling in their statement was, “It is an inconvenient fact of life that alcohol is a teratogen.” Now, this fact is well supported in the literature.7

There are animal studies regarding the use of “low-dose” or “moderate” alcohol in pregnancy that demonstrate adverse behavioral outcomes with exposure to even small doses of alcohol.8,9 It is an American tragedy that, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), rates of FAS in this country range from 0.2 to 2.0 cases per 1,000 live births. Indeed, the rates of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) might be at least three times this rate.10 As is the case with other disorders, there are health disparities regarding the prevalence of this condition as well.11

FAS: A long history of preventable disease

1973: Identified. FAS was first described in a 1973 Lancet report, “Pattern of malformation in offspring of chronic alcoholic mothers.”12

1996: Call for prevention. In 1995, the US Surgeon General issued a statement regarding alcohol use in pregnancy, noting, “We do not know what, if any, amount of alcohol is safe.”13 In 1996, the Institute of Medicine released a paper calling FAS and FASD “completely preventable birth defects and neurodevelopmental abnormalities.”14

2000: The troubling effects gathered. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published a monograph on FAS in 2000, defining it as a constellation of physical, behavioral, and cognitive abnormalities.15

These features classically define FAS:

- dysmorphic facial features

- prenatal and postnatal growth abnormalities

- mental retardation.

Approximately 80% of children with this condition have:

- microcephaly

- behavioral abnormalities.

As many as 50% of affected children also exhibit:

- poor coordination

- hypotonia

- attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

- decreased adipose tissue

- identifiable facial anomalies (such as maxillary hypoplasia, cleft palate, and micrognathia).

Also common:

- cardiac defects

- hemangiomas

- eye or ear abnormalities.

The AAP further noted that data current to the time (and still true today) did not support the concept of a safe level of alcohol consumption by pregnant women below which no damage to a fetus will occur.15

Alcohol intake during pregnancy puts the fetus at risk for cognitive and neuropsychological impairment and physical abnormalities, including dysmorphic facial features (such as micrognathia), restricted prenatal growth, cardiac defects, and eye and ear abnormalities. There is no threshold dose of alcohol that is safe during pregnancy, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Despite the knowledge we’ve gained, FAS persists

According to a 2006–2010 CDC analysis involving more than 345,000 women of reproductive age from all 50 states, 7.6% of pregnant women reported alcohol use and 1.4% (or 1 in 71) reported binge drinking (defined, respectively, as at least one alcoholic drink and four or more alcoholic drinks on one occasion in the past 30 days).16 The highest prevalence of obstetric alcohol consumption occurs in women who are:

- aged 35 to 44 years

- white

- college graduates

- employed.

The problem may be bigger than reported. The incidences of alcohol and binge drinking found in the CDC report include women’s self-report—but women drink alcohol without knowing they’re pregnant. Only 40% of women realize they’re pregnant at 4 weeks of gestation, a critical time for organogenesis, and approximately half of all births are unplanned.9

When my brother and sister-in law adopted my beautiful niece and nephew, they were very aware of the risk for conditions like FAS. In an evaluation of 71 children adopted from Eastern Europe at 5 years of age, FAS was diagnosed in 30% of children and “partial FAS” in another 9%.17 Birth defects attributed to alcohol were present in 11% of the children.

Are women’s health providers up to date on FAS education?

In recognition of alcohol’s potentially life-altering consequences for the developing fetus, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) produced an FASD prevention tool kit in 2006 and published a 2011 committee opinion on at-risk drinking and alcohol dependence and their implications for obstetrics and gynecology.18,19 Both guidelines direct clinicians to advise patients to abstain from alcohol during pregnancy.

Results from a 2010 survey of 800 ACOG fellows revealed that only 78% of obstetricians advised abstinence from alcohol during pregnancy. Fifty-eight percent of respondents did not use a validated screening tool for alcohol use in their pregnant patients, and only 72% felt prepared to screen for risky or hazardous drinking.19 (Most were unaware of the ACOG tool kit, which had been published several years earlier.)

In a survey of pediatricians, obstetricians, and family physicians, clinicians said that about 67% of their patients asked about alcohol use in pregnancy, with about 2% of those patients specifically mentioning FAS. About 41% of these same physicians erroneously placed the threshold for FAS at one to three drinks per day,20 when in fact there is no threshold of drinking that has been proven to be safe.

A survey of 1,000 actively practicing ACOG fellows revealed that, while 97% of obstetricians routinely asked their patients about alcohol use, only 20% of providers reported to their patients that abstinence was safest, and 4% of providers didn’t believe that consumption of eight or more drinks weekly posed fetal risk.21

How can we educate our patients about the dangers of alcohol in pregnancy?

Fetal death. A recent Danish study of 79,216 pregnant women revealed that 45% had consumed some alcohol during pregnancy. Two percent reported at least four drinks per week, and 25% admitted to binge drinking during pregnancy. Term infants born to women in the latter two groups had increased neonatal mortality, with hazard ratios of 3.56 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.15–8.43) and 2.69 (95% CI, 1.27–5.69), respectively.22

Decreased cognitive status. A study by Willford and colleagues evaluated the relationship between prenatal alcohol exposure and cognitive status of 1,360 10-year-old children.23 The authors utilized the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Test, including the composite scores and verbal, abstract/visual, quantitative, and short-term memory scores. After controlling for other variables, among African American offspring they found that, for each additional drink, the average composite score decreased by 1.9 points. This difference was more striking for second-trimester use, and was significant even for one drink daily versus abstention from alcohol.

Impaired neuropsychological development. Another study evaluating light to moderate amounts of prenatal alcohol exposure in 10- and 11-year-old children found significantly worse scores regarding a number of neuropsychological developmental assessments.24

No threshold dose of causation. Results of a 2012 prospective study in California, with data collected on 992 subjects from 1978 until 2005, revealed that many physical FAS features, including microcephaly, smooth philtrum, and thin vermillion border; reduced birth length; and reduced birth weight, were associated with alcohol exposure at specific gestational ages, and were dose-related.25 This paper didn’t reveal any evidence of a threshold dose of causation.

Neurobehavioral outcomes of FAS are not always considered

Another recent study that the media recently highlighted as finding “no association between low or moderate prenatal alcohol exposure and birth defects” was by O’Leary and colleagues.26 Like other similarly limited studies, this one involved only children younger than 6 years and didn’t assess any of the important neurobehavioral outcomes of FAS.

FAS encompasses much more than visible birth defects. As the aforementioned ACOG tool kit stated, “For every child born with FAS, many more children are born with neurobehavioral deficits caused by alcohol exposure but without the physical characteristics of FAS.”

The costs of FAS are felt with dollars, too

The financial cost to our nation is extraordinary. In 1991, Abel and Sokol estimated the incremental annual cost of treating FAS at nearly $75 million, with about three-quarters of that cost associated with FAS cases involving mental retardation.27

A 2002 assessment estimated the lifetime cost for each individual with FAS (adjusting for the change in the cost of medical care services, lost productivity, and inflation) at $2 million. This figure consists of $1.6 million for medical treatment, special education, and residential care for persons with mental retardation, and $0.4 million for productivity losses.28

Where human studies fall short, animal studies can help elucidate causation

Unquestionably, there are flaws in the existing literature on the causation of FAS. Many studies rely on self-reporting by pregnant women, and underreporting in these cases is a real concern. There often are other confounders potentially negatively affecting fetal development, making it difficult to differentiate causation. The animal studies that don’t share these limitations do suggest a causal relationship between antenatal alcohol exposure and poor obstetric outcomes, however.29 These studies suggest mechanisms such as altered gene expression, oxidative stress, and apoptosis (programmed cell death).30

Warren, Hewitt, and Thomas describe how intrauterine alcohol exposure interferes with the function of L1CAM, the L1 cell-adhesion molecule.31 They noted that just one drink could interfere with the ability of L1CAM to mediate cell adhesion and axonal growth. Prenatal alcohol exposure is also thought to contribute to interference in neurotransmitter and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor coupling, which may have potential therapeutic implications.32

Considerations in FAS identification and treatment

There is a potential to identify alcohol exposure in the womb. The majority of ingested alcohol is eventually converted to carbon dioxide and water in both maternal and fetal circulations, which has hampered the identification of biomarkers for clinical use in FAS. Fatty acid ethyl esters (FAEEs), nonoxidative metabolites of ethanol, may prove to be such markers.33 FAEEs have been measured in a variety of tissues, including blood and meconium. FAEEs can be measured in both neonatal and maternal hair samples.

A study evaluating the utility of such testing in 324 at-risk pregnancies revealed 90% sensitivity and 90% specificity for identifying “excessive drinking” using a cutoff of 0.5 ng/mg.34

Research shows potential therapeutic approaches during pregnancy. While the use of biomarkers has the potential to assist with the identification of at-risk newborns, it merely identifies past alcohol use; it doesn’t necessarily permit identification and prevention of the known negative pediatric sequelae. Preliminary animal studies reveal the potential benefit of neuroprotective peptides to prevent brain damage in alcohol-exposed mice.35 Further research is ongoing.

Treatment: The earlier the better

Early diagnosis and a positive environment improve outcomes. It is well established that early intervention improves outcomes. One comprehensive review of 415 patients with FAS noted troubling outcomes in general for adolescents and adults.36 Over their life spans, the prevalence of such outcomes was:

- 61% for disrupted school experiences

- 60% for trouble with the law

- 50% for confinement (in detention, jail, prison, or a psychiatric or alcohol/drug inpatient setting)

- 49% for inappropriate sexual behaviors on repeated occasions

- 35% for alcohol/drug problems.

The odds of escaping these adverse life outcomes are increased up to fourfold when the individual receives a FAS or FASD diagnosis at an earlier age and is reared in a stable environment.36

Barrier to treatment: A mother’s guilt. One of the challenges I’ve learned from my sister-in-law is the stigma mothers face when they bring their child in for services once the diagnosis of FAS is suspected. While adoptive mothers obviously can’t be held accountable for the intrauterine environment to which a fetus is exposed, the same can’t be said of biologic mothers. Therefore, there is a real risk that a mother who is unwilling or unable to face the potentially devastating news that her baby’s issues might be related to choices she made during pregnancy, might not bring her child in for necessary assessment and treatment. Therefore, prevention is a key proponent of treatment.

Prevent FAS: Provide contraception, screen for alcohol use, intervene

While ObGyns aren’t likely to diagnose many children with FAS, we are in an excellent position to try to prevent this tragedy through our counseling of reproductive-aged women. I suspect that most obstetricians spend a considerable amount of time discussing much less frequent obstetric sequelae, such as listeriosis, in the prenatal care setting. Validated alcohol screening tools take moments to administer, and once patients who might have alcohol problems are identified, either a serious discussion about contraception or an honest discussion of FAS may be appropriate. There have been a number of screening tools developed.

The CAGE screen is frequently taught in medical schools, but it isn’t as sensitive for women or minorities.19

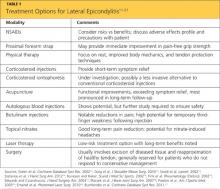

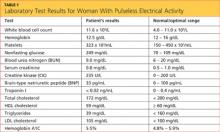

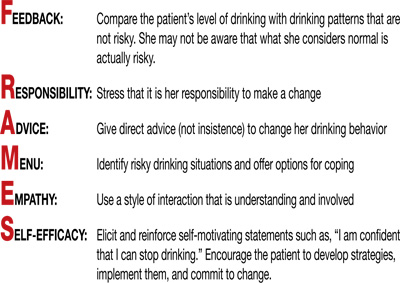

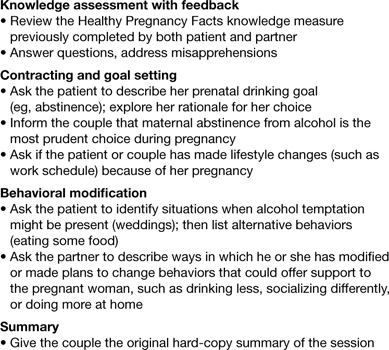

The T-ACE (Tolerance, Annoyed, Cut Down, Eye-opener) tool involves four questions that take less than 1 minute to administer (FIGURE 1).39

TWEAK is another potential tool identified by Russell and colleagues (Tolerance, Worry, Eye opener, Amnesia, and Cut down in drinking).39 Other methods utilized include an AUDIT screen and a CRAFFT screen.40 Regardless of which tool is utilized, screening is not time-consuming and is better than merely inquiring about alcohol consumption in general.

FIGURE 1 T-ACE validated alcohol screening tool

Source: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. At risk drinking and illicit drug use: Ethical issues in obstetric and gynecologic practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(6):1449–1460.

When alcohol use is found, intervene

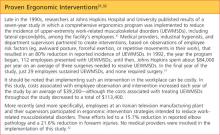

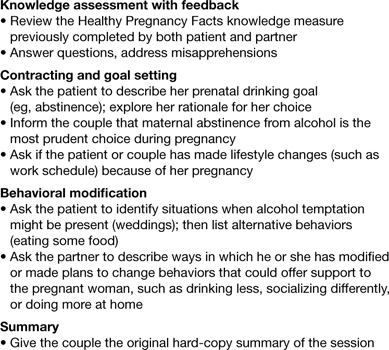

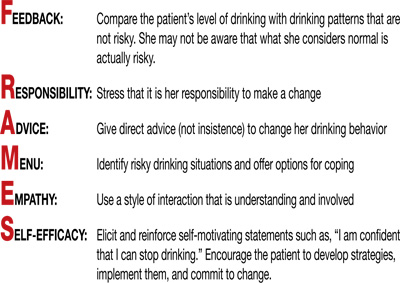

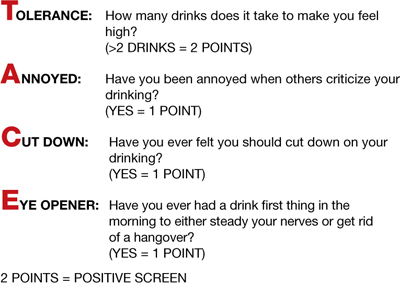

Once patients with at-risk behavior are identified, obstetric staff should offer brief interventions to influence problem drinking. Miller and Sanchez summarized the key elements that were most successful in these programs with the acronym FRAMES: Feedback, Responsibility, Advice, Menu, Empathy, Self-efficacy (FIGURE 2).41 This approach has been formally evaluated in the CDC’s multisite pilot study entitled Project CHOICES.42

In this motivational intervention, sexually active, fertile women of reproductive age underwent up to four motivational counseling sessions and one visit to a provider. At 6 months, 69% of women reduced their risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy—although the women who drank the least amount had the greatest benefit, primarily by choosing effective contraception, but also by reducing alcohol intake.

FIGURE 2 FRAMES model to deliver brief interventions

Source: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Drinking and reproductive health: A fetal alcohol spectrum disorders prevention tool kit. Washington, DC: ACOG; 2006.

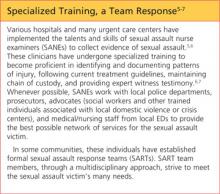

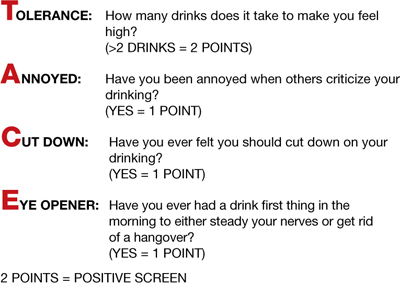

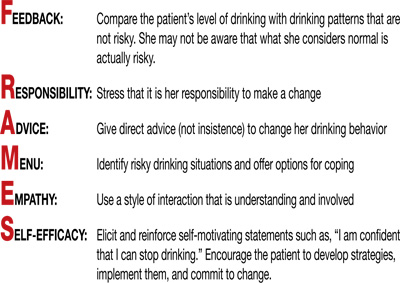

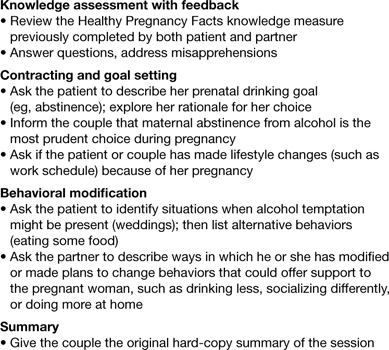

A single, brief intervention is effective in already-pregnant women. Chang and colleagues conducted a randomized trial of a single-session brief intervention given to pregnant women with positive T-ACE screens and their partners (FIGURE 3).43 Either the study nurse or physician participated in the intervention, and each single session took 25 minutes on average. The pregnant women with the highest level of alcohol use reduced their drinking the most, and this effect was even larger when their partners participated. Other studies of brief interventions showed similar benefits.44,45

Another study evaluating a brief intervention involving training of health-care providers to improve screening rates revealed improved detection and therapy among at-risk patients.46

FIGURE 3 Single session, 25-minute intervention for patients and their partners

Source: Chang G, McNamara T, Orav J, et al. Brief intervention for prenatal alcohol use: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(5 Pt 1):991–998.

FAS prevention begins with routine counseling and contraception

Although FAS is often thought of in relation to obstetric populations, appointments for preconception counseling or routine health maintenance among women of reproductive age are an essential tool in FAS prevention. As previously mentioned, since approximately half of all pregnancies in this country are unplanned, long-acting reversible contraception is widely available to facilitate improved family planning.

Other contraceptive options also should be discussed. ACOG has teamed up with the CDC to develop a phone app for providers to use at the patient’s bedside to assist with identification and treatment of women at risk for alcohol use during pregnancy.47

The stakes are high, it’s time to step up

As obstetricians, we are powerless to prevent many conditions—such as vasa previa, acute fatty liver of pregnancy, and amniotic band syndrome. FAS is 100% preventable.

There aren’t that many proven teratogens in our profession, and there are none that involve behavior that is more socially acceptable than alcohol consumption. It is time for our profession to encourage women to appreciate how small a percentage of one’s life is spent pregnant, how many more years there are to enjoy an occasional cocktail, and how very high the stakes are during this important period of their lives. Oh, how I wish someone had been able to communicate all of this to sweet Charlie’s biologic mother. I am so grateful he’s getting the exceptional care he’s getting and very optimistic regarding his future. I only hope others in his situation are given the same opportunities.

Prenatal counseling

Louise Wilkins-Haug, MD, PhD (January 2008)

Prevention of fetal alcohol syndrome requires routine screening of all women of reproductive age

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Baram M. Moms-to-be get mixed messages on drinking. ABC News. http://abcnews.go.com/Health/story?id=2654849&page=1#.UM9l-RyeARY. Published November 15 2006. Accessed December 14, 2012.

2. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Alcohol consumption and the outcomes of pregnancy (RCOG Statement No. 5). London UK: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. January 3, 2006.

3. Pearson C. Alcohol during pregnancy: How dangerous is it really? The Huffington Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/04/06/alcohol-during-pregnancy_n_845103.html. Published April 6 2011. Updated September 16, 2011. Accessed December 14, 2012.

4. Kelly YJ, Sacker A, Gray R, et al. Light drinking during pregnancy: still no increased risk for socioemotional difficulties or cognitive deficits at 5 years of age? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(1):41-48.Epub Oct 5, 2010.

5. Kelly Y, Sacker A, Gray R, Kelly J, Wolke D, Quigley MA. Light drinking in pregnancy a risk for behavioural problems and cognitive deficits at 3 years of age? Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(1):129-140.Epub Oct 30, 2008.

6. Zhou F. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders Study Group (FASDSG). Research Society on Alcoholism. http://rsoa.org/fas.html. Updated September 9 2010. Accessed December 14, 2012.

7. Kelly S, Day N, Streissguth AP. Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on social behavior in humans and other species. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2000;22(2):143-149.

8. Vaglenova J, Petkov V. Fetal alcohol effects in rats exposed pre-and postnatally to a low dose of ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22(3):697-703.

9. Schneider M, Moore C, Kraemer G. Moderate alcohol during pregnancy: learning and behavior in adolescent rhesus monkeys. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25(9):1383-1392.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Data and statistics in the United States. http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/fasd/data.html. Updated August 16 2012. Accessed December 14, 2012.

11. Egeland G, Perham-Hestere KA, Gessner BD, Ingle D, Berner JE, Middaugh J. Fetal alcohol syndrome in Alaska 1977 through 1992: an administrative prevalence derived from multiple data sources. Am J Pub Health. 1998;88(5):781-786.

12. Jones K, Smith D, Ulleland C, Streissguth A. Pattern of malformation in offspring of chronic alcoholic mothers. Lancet. 1973;1(7815):1267-1271.

13. Institute of Medicine. Fetal alcohol syndrome: diagnosis epidemiology, prevention, and treatment (1996). http://www.come-over.to/FAS/IOMsummary.htm. Accessed December 14, 2012.

14. Committee of Substance Abuse and Committee on Children with Disabilities. American Academy of Pediatrics. Fetal alcohol syndrome and alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorders. Pediatrics. 2000;106(2):358-361.

15. US Department of Health & Human Services. US Surgeon General releases advisory on alcohol use in pregnancy. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/news/2005/02/sg02222005.html. Published February 21 2005. Accessed December 13, 2012.

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol use and binge drinking among women of childbearing age–United States 2006–2010. MMWR. 2012;61(28):534-538.http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6128a4.htm?s_cid=mm6128a4_w. Accessed December 17, 2012.

17. Landgren M, Svensson L, Stromland K, Gronlund M. Prenatal alcohol exposure and neurodvelopmental disorders in children adopted from Eastern Europe. Pediatrics. 2010;125(5):e1178-1185.doi:10.1542/peds.2009-0712.

18. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Drinking and reproductive health: A fetal alcohol spectrum disorders prevention tool kit. http://www.acog.org/~/media/Departments/Tobacco%20Alcohol%20and%20Substance%20Abuse/FASDToolKit.pdf?dmc=1&ts=20121217T1504384811. Published 2006. Accessed December 14 2012.

19. Anderson B, Dang E, Floyd R, Sokol R, Mahoney J, Schulkin J. Knowledge opinions, and practice patterns of obstetrician-gynecologist regarding their patients’ use of alcohol. J Addiction Med. 2010;4(2):114-121.

20. Abel EL, Kruger M. What do physicians know and say about fetal alcohol syndrome: a survey of obstetricians pediatricians, and family medicine physicians. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22(9):1951-1954.

21. Diekman S, Floyd R, Decoufle P, Schulkin J, Ebrahim S, Sokol R. A survey of obstetrician-gynecologists on their patients’ alcohol use during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(5):756-763.

22. Strandberg-Larsen K, Gronboek M, Andersen A, Andersen P, Olsen J. Alcohol drinking pattern during pregnancy and risk of infant mortality. Epidemiology. 2009;20(6):884-891.

23. Willford J, Leech S, Day N. Moderate prenatal alcohol exposure and cognitive status of children at age 10. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30(6):1051-1059.

24. Richardson G, Ryan C, Willford J, Day N, Goldschmidt. Prenatal alcohol and marijuana exposure: Effects on neuropsychological outcomes at 10 years. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2002;24(3):309-320.

25. Feldman H, Jones K, Lindsay S, et al. Prenatal alcohol exposure patterns and alcohol-related birth defects and growth deficiencies: a prospective study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36(4):670-676.

26. O’Leary C, Nassar N, Kurinczuk J, et al. Prenatal alcohol exposure and risk of birth defects. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):e843-850.doi:10.1542/peds.2010-0256.

27. Abel E, Sokol R. A revised conservative estimate of the incidence of FAS and its economic its impact. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1991;15(3):514-524.

28. Lupton C. The financial impact of fetal alcohol syndrome. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders Center for Excellence. www.fasdcenter.samhsa.gov/publications/cost.cfm. Accessed December 14 2012.

29. Bailey B, Sokol R. Prenatal alcohol exposure and miscarriage stillbirth, preterm delivery, and sudden infant death syndrome. Alcohol Res Health. 2011;34(1):86-91.

30. Yelin R, Kot H, Yelin D, Fainsod A. Early molecular effects of ethanol during vertebrate embryogenesis. Differentiation. 2007;75(5):393-403.

31. Warren K, Hewitt B, Thomas J. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: research challenges and opportunities. Alcohol Res Health. 2011;34(1):4-15.

32. Ramanathan R, Wilkemeyer M, Mittal B, Perides G, Chamess ME. Alcohol inhibits cell-cell adhesion mediated by human L1. J Cell Biol. 1996;133(2):381-390.

33. Burd L, Hofer R. Biomarkers for detection of prenatal alcohol exposure: a critical review of fatty acid ethyl estsers in meconium. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2008;82(7):487-493.

34. Kulaga V, Pragst F, Fulga N, Koren G. Hair análisis of fatty acid esters in the detection of excessive drinking in the context of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Ther Drug Monit. 2009;31(2):261-266.

35. Sari Y, Gozes I. Brain deficits associated with fetal alcohol exposure may be protected in part, by peptides derived from activity-dependent neurotrophic factor and activity-dependent neuroprotective protein. Brain Res Rev. 2006;52(1):107-118.

36. Streissguth A, Bookstein F, Barr H, Sampson P, O’malley K, Young J. Risk factors for adverse life outcomes in fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol effects. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2004;25(4):228-238.

37. 19. Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 496: At-risk drinking and alcohol dependence: Obstetric and gynecologic implications. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 Pt 1):383-388.

38. Sokol R, Martier S, Ager J. The T-ACE questions: practical prenatal detection of risk-drinking. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160(4):863-868.

39. Chan A, Pristach E, Weite J, Russell M. Use of the TWEAK test in screening for alcoholism/ heavy drinking in three populations. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1993;17(6):1188-1192.

40. Floyd R, O’Connor M, Bertrand J, Sokol R. Reducing adverse outcomes from prenatal alcohol exposure: a clinical plan of action. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30(8):1271-1275.

41. Miller W, Sanchez V. Motivating young adults for treatment and lifestyle change. In: Howard GS Nathan PE, eds. Alcohol use and misuse by young adults. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press; 1994:55–81.

42. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Motivational intervention to reduce alcohol-exposed pregnancies—Florida Texas, and Virginia, 1997–2001. MMWR. 2003;52(19):441-444.

43. Chang G, McNamara T, Orav J, et al. Brief intervention for prenatal alcohol use: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(5 Pt 1):991-998.

44. Manwell L, Fleming M, Mundt M, Stauffacher E, Barry K. Treatment of problem alcohol use in women of childbearing age: results of a brief intervention trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24(10):1517-1524.

45. O’Connor M, Whaley S. Brief intervention for alcohol use by pregnant women. Am J Pub Health. 2007;97(2):252-258.

46. Mwansa-Kambafwile J, Rendall-Mkosi K, Jacobs R, Nel E, London L. Evaluation of a service provider short course for prevention of fetal alcohol syndrome. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2011;72(4):530-535.

47. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. At-risk alcohol use screening and intervention. http://198.87.1.43/womenalcohol/index.html. Published 2011. Accessed December 16 2012.

Medical students learn early in their education that alcohol is a teratogen. Despite this widespread knowledge, many obstetricians counsel patients about the safety of low doses of alcohol in pregnancy.1 Indeed, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists’ position on this is, “while the safest approach may be to avoid any alcohol during pregnancy, it remains the case that there is no evidence of harm from low levels of alcohol consumption, defined as no more than one or two units of alcohol once or twice a week.”2

Like many providers, I was aware of this controversy, but it became truly personal when a beloved family member was diagnosed with fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS). In this paper, I will review some of the controversy regarding alcohol in pregnancy, highlight findings from the literature, provide tools for prevention, and identify new developments regarding this devastating, preventable condition.

Charlie

To know my nephew Charlie is to fall in love with my nephew Charlie. One of the happiest moments of my life was when I learned my brother and sister-in-law had adopted twins from Kazakhstan. When my little niece and nephew started their new life in the United States, certain medical issues seemed to merit additional attention. Although both were very small for their age and required significant nutritional support, Charlie seemed to be a bit more rambunctious and required additional supervision.

The children were fortunate enough to have incredibly loving, dedicated parents, who have access to exceptional medical care as residents of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. After extensive testing, it became clear what was causing Charlie’s developmental delay; his pediatric team made the diagnosis of FAS. My brother and sister-in-law became incredibly well-read about this challenging disorder, and threw themselves into national advocacy work to help prevent this unnecessary tragedy.

Recent data point to teratogenicity, but media confuse the issue

Some recent media coverage3 of celebrities who apparently drank while pregnant was in response to an article in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health.4 The authors of this study concluded that, “at age 5 years, cohort members born to mothers who drank up to one to two drinks per week or per occasion during pregnancy were not at increased risk of clinically relevant behavioral difficulties or cognitive deficits, compared with children of mothers in the not-in-pregnancy group.”

This is certainly not the first occasion the popular press has covered a published study that seems to indicate no ill effects of alcohol use in pregnancy. A 2008 report by Kelly and colleagues,5 and its subsequent media coverage, prompted the Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders Study Group to state that the panel of experts was “alarmed” by recent newspaper reports suggesting that light drinking during pregnancy may be beneficial for an unborn child.6 They noted misleading and irresponsible media reports of the findings, which suggested that 3-year-old children whose mothers drank “lightly” during pregnancy were not at risk for certain behavioral problems.

What the study authors proceeded to note, however (that the media did not mention), was that the light drinkers in their study had socioeconomic advantages, compared with nondrinkers.5 (Advantaged economic status is established to be beneficial for childhood development.) They also noted that the study involved preschool-aged children, stating “Generally the adverse effects of light drinking during pregnancy are subtle and may go undetected in young children. However, other group studies of more moderate or ‘social’ drinking levels during pregnancy have shown an adverse impact on multiple aspects of development through adolescence and young adulthood, even when important environmental factors are taken into account.” A sentence I thought was most compelling in their statement was, “It is an inconvenient fact of life that alcohol is a teratogen.” Now, this fact is well supported in the literature.7

There are animal studies regarding the use of “low-dose” or “moderate” alcohol in pregnancy that demonstrate adverse behavioral outcomes with exposure to even small doses of alcohol.8,9 It is an American tragedy that, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), rates of FAS in this country range from 0.2 to 2.0 cases per 1,000 live births. Indeed, the rates of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) might be at least three times this rate.10 As is the case with other disorders, there are health disparities regarding the prevalence of this condition as well.11

FAS: A long history of preventable disease

1973: Identified. FAS was first described in a 1973 Lancet report, “Pattern of malformation in offspring of chronic alcoholic mothers.”12

1996: Call for prevention. In 1995, the US Surgeon General issued a statement regarding alcohol use in pregnancy, noting, “We do not know what, if any, amount of alcohol is safe.”13 In 1996, the Institute of Medicine released a paper calling FAS and FASD “completely preventable birth defects and neurodevelopmental abnormalities.”14

2000: The troubling effects gathered. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published a monograph on FAS in 2000, defining it as a constellation of physical, behavioral, and cognitive abnormalities.15

These features classically define FAS:

- dysmorphic facial features

- prenatal and postnatal growth abnormalities

- mental retardation.

Approximately 80% of children with this condition have:

- microcephaly

- behavioral abnormalities.

As many as 50% of affected children also exhibit:

- poor coordination

- hypotonia

- attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

- decreased adipose tissue

- identifiable facial anomalies (such as maxillary hypoplasia, cleft palate, and micrognathia).

Also common:

- cardiac defects

- hemangiomas

- eye or ear abnormalities.

The AAP further noted that data current to the time (and still true today) did not support the concept of a safe level of alcohol consumption by pregnant women below which no damage to a fetus will occur.15

Alcohol intake during pregnancy puts the fetus at risk for cognitive and neuropsychological impairment and physical abnormalities, including dysmorphic facial features (such as micrognathia), restricted prenatal growth, cardiac defects, and eye and ear abnormalities. There is no threshold dose of alcohol that is safe during pregnancy, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Despite the knowledge we’ve gained, FAS persists

According to a 2006–2010 CDC analysis involving more than 345,000 women of reproductive age from all 50 states, 7.6% of pregnant women reported alcohol use and 1.4% (or 1 in 71) reported binge drinking (defined, respectively, as at least one alcoholic drink and four or more alcoholic drinks on one occasion in the past 30 days).16 The highest prevalence of obstetric alcohol consumption occurs in women who are:

- aged 35 to 44 years

- white

- college graduates

- employed.

The problem may be bigger than reported. The incidences of alcohol and binge drinking found in the CDC report include women’s self-report—but women drink alcohol without knowing they’re pregnant. Only 40% of women realize they’re pregnant at 4 weeks of gestation, a critical time for organogenesis, and approximately half of all births are unplanned.9

When my brother and sister-in law adopted my beautiful niece and nephew, they were very aware of the risk for conditions like FAS. In an evaluation of 71 children adopted from Eastern Europe at 5 years of age, FAS was diagnosed in 30% of children and “partial FAS” in another 9%.17 Birth defects attributed to alcohol were present in 11% of the children.

Are women’s health providers up to date on FAS education?

In recognition of alcohol’s potentially life-altering consequences for the developing fetus, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) produced an FASD prevention tool kit in 2006 and published a 2011 committee opinion on at-risk drinking and alcohol dependence and their implications for obstetrics and gynecology.18,19 Both guidelines direct clinicians to advise patients to abstain from alcohol during pregnancy.

Results from a 2010 survey of 800 ACOG fellows revealed that only 78% of obstetricians advised abstinence from alcohol during pregnancy. Fifty-eight percent of respondents did not use a validated screening tool for alcohol use in their pregnant patients, and only 72% felt prepared to screen for risky or hazardous drinking.19 (Most were unaware of the ACOG tool kit, which had been published several years earlier.)

In a survey of pediatricians, obstetricians, and family physicians, clinicians said that about 67% of their patients asked about alcohol use in pregnancy, with about 2% of those patients specifically mentioning FAS. About 41% of these same physicians erroneously placed the threshold for FAS at one to three drinks per day,20 when in fact there is no threshold of drinking that has been proven to be safe.

A survey of 1,000 actively practicing ACOG fellows revealed that, while 97% of obstetricians routinely asked their patients about alcohol use, only 20% of providers reported to their patients that abstinence was safest, and 4% of providers didn’t believe that consumption of eight or more drinks weekly posed fetal risk.21

How can we educate our patients about the dangers of alcohol in pregnancy?

Fetal death. A recent Danish study of 79,216 pregnant women revealed that 45% had consumed some alcohol during pregnancy. Two percent reported at least four drinks per week, and 25% admitted to binge drinking during pregnancy. Term infants born to women in the latter two groups had increased neonatal mortality, with hazard ratios of 3.56 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.15–8.43) and 2.69 (95% CI, 1.27–5.69), respectively.22

Decreased cognitive status. A study by Willford and colleagues evaluated the relationship between prenatal alcohol exposure and cognitive status of 1,360 10-year-old children.23 The authors utilized the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Test, including the composite scores and verbal, abstract/visual, quantitative, and short-term memory scores. After controlling for other variables, among African American offspring they found that, for each additional drink, the average composite score decreased by 1.9 points. This difference was more striking for second-trimester use, and was significant even for one drink daily versus abstention from alcohol.

Impaired neuropsychological development. Another study evaluating light to moderate amounts of prenatal alcohol exposure in 10- and 11-year-old children found significantly worse scores regarding a number of neuropsychological developmental assessments.24

No threshold dose of causation. Results of a 2012 prospective study in California, with data collected on 992 subjects from 1978 until 2005, revealed that many physical FAS features, including microcephaly, smooth philtrum, and thin vermillion border; reduced birth length; and reduced birth weight, were associated with alcohol exposure at specific gestational ages, and were dose-related.25 This paper didn’t reveal any evidence of a threshold dose of causation.

Neurobehavioral outcomes of FAS are not always considered

Another recent study that the media recently highlighted as finding “no association between low or moderate prenatal alcohol exposure and birth defects” was by O’Leary and colleagues.26 Like other similarly limited studies, this one involved only children younger than 6 years and didn’t assess any of the important neurobehavioral outcomes of FAS.

FAS encompasses much more than visible birth defects. As the aforementioned ACOG tool kit stated, “For every child born with FAS, many more children are born with neurobehavioral deficits caused by alcohol exposure but without the physical characteristics of FAS.”

The costs of FAS are felt with dollars, too

The financial cost to our nation is extraordinary. In 1991, Abel and Sokol estimated the incremental annual cost of treating FAS at nearly $75 million, with about three-quarters of that cost associated with FAS cases involving mental retardation.27

A 2002 assessment estimated the lifetime cost for each individual with FAS (adjusting for the change in the cost of medical care services, lost productivity, and inflation) at $2 million. This figure consists of $1.6 million for medical treatment, special education, and residential care for persons with mental retardation, and $0.4 million for productivity losses.28

Where human studies fall short, animal studies can help elucidate causation

Unquestionably, there are flaws in the existing literature on the causation of FAS. Many studies rely on self-reporting by pregnant women, and underreporting in these cases is a real concern. There often are other confounders potentially negatively affecting fetal development, making it difficult to differentiate causation. The animal studies that don’t share these limitations do suggest a causal relationship between antenatal alcohol exposure and poor obstetric outcomes, however.29 These studies suggest mechanisms such as altered gene expression, oxidative stress, and apoptosis (programmed cell death).30

Warren, Hewitt, and Thomas describe how intrauterine alcohol exposure interferes with the function of L1CAM, the L1 cell-adhesion molecule.31 They noted that just one drink could interfere with the ability of L1CAM to mediate cell adhesion and axonal growth. Prenatal alcohol exposure is also thought to contribute to interference in neurotransmitter and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor coupling, which may have potential therapeutic implications.32

Considerations in FAS identification and treatment

There is a potential to identify alcohol exposure in the womb. The majority of ingested alcohol is eventually converted to carbon dioxide and water in both maternal and fetal circulations, which has hampered the identification of biomarkers for clinical use in FAS. Fatty acid ethyl esters (FAEEs), nonoxidative metabolites of ethanol, may prove to be such markers.33 FAEEs have been measured in a variety of tissues, including blood and meconium. FAEEs can be measured in both neonatal and maternal hair samples.

A study evaluating the utility of such testing in 324 at-risk pregnancies revealed 90% sensitivity and 90% specificity for identifying “excessive drinking” using a cutoff of 0.5 ng/mg.34

Research shows potential therapeutic approaches during pregnancy. While the use of biomarkers has the potential to assist with the identification of at-risk newborns, it merely identifies past alcohol use; it doesn’t necessarily permit identification and prevention of the known negative pediatric sequelae. Preliminary animal studies reveal the potential benefit of neuroprotective peptides to prevent brain damage in alcohol-exposed mice.35 Further research is ongoing.

Treatment: The earlier the better

Early diagnosis and a positive environment improve outcomes. It is well established that early intervention improves outcomes. One comprehensive review of 415 patients with FAS noted troubling outcomes in general for adolescents and adults.36 Over their life spans, the prevalence of such outcomes was:

- 61% for disrupted school experiences

- 60% for trouble with the law

- 50% for confinement (in detention, jail, prison, or a psychiatric or alcohol/drug inpatient setting)

- 49% for inappropriate sexual behaviors on repeated occasions

- 35% for alcohol/drug problems.

The odds of escaping these adverse life outcomes are increased up to fourfold when the individual receives a FAS or FASD diagnosis at an earlier age and is reared in a stable environment.36

Barrier to treatment: A mother’s guilt. One of the challenges I’ve learned from my sister-in-law is the stigma mothers face when they bring their child in for services once the diagnosis of FAS is suspected. While adoptive mothers obviously can’t be held accountable for the intrauterine environment to which a fetus is exposed, the same can’t be said of biologic mothers. Therefore, there is a real risk that a mother who is unwilling or unable to face the potentially devastating news that her baby’s issues might be related to choices she made during pregnancy, might not bring her child in for necessary assessment and treatment. Therefore, prevention is a key proponent of treatment.

Prevent FAS: Provide contraception, screen for alcohol use, intervene

While ObGyns aren’t likely to diagnose many children with FAS, we are in an excellent position to try to prevent this tragedy through our counseling of reproductive-aged women. I suspect that most obstetricians spend a considerable amount of time discussing much less frequent obstetric sequelae, such as listeriosis, in the prenatal care setting. Validated alcohol screening tools take moments to administer, and once patients who might have alcohol problems are identified, either a serious discussion about contraception or an honest discussion of FAS may be appropriate. There have been a number of screening tools developed.

The CAGE screen is frequently taught in medical schools, but it isn’t as sensitive for women or minorities.19

The T-ACE (Tolerance, Annoyed, Cut Down, Eye-opener) tool involves four questions that take less than 1 minute to administer (FIGURE 1).39

TWEAK is another potential tool identified by Russell and colleagues (Tolerance, Worry, Eye opener, Amnesia, and Cut down in drinking).39 Other methods utilized include an AUDIT screen and a CRAFFT screen.40 Regardless of which tool is utilized, screening is not time-consuming and is better than merely inquiring about alcohol consumption in general.

FIGURE 1 T-ACE validated alcohol screening tool

Source: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. At risk drinking and illicit drug use: Ethical issues in obstetric and gynecologic practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(6):1449–1460.

When alcohol use is found, intervene

Once patients with at-risk behavior are identified, obstetric staff should offer brief interventions to influence problem drinking. Miller and Sanchez summarized the key elements that were most successful in these programs with the acronym FRAMES: Feedback, Responsibility, Advice, Menu, Empathy, Self-efficacy (FIGURE 2).41 This approach has been formally evaluated in the CDC’s multisite pilot study entitled Project CHOICES.42

In this motivational intervention, sexually active, fertile women of reproductive age underwent up to four motivational counseling sessions and one visit to a provider. At 6 months, 69% of women reduced their risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy—although the women who drank the least amount had the greatest benefit, primarily by choosing effective contraception, but also by reducing alcohol intake.

FIGURE 2 FRAMES model to deliver brief interventions

Source: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Drinking and reproductive health: A fetal alcohol spectrum disorders prevention tool kit. Washington, DC: ACOG; 2006.

A single, brief intervention is effective in already-pregnant women. Chang and colleagues conducted a randomized trial of a single-session brief intervention given to pregnant women with positive T-ACE screens and their partners (FIGURE 3).43 Either the study nurse or physician participated in the intervention, and each single session took 25 minutes on average. The pregnant women with the highest level of alcohol use reduced their drinking the most, and this effect was even larger when their partners participated. Other studies of brief interventions showed similar benefits.44,45

Another study evaluating a brief intervention involving training of health-care providers to improve screening rates revealed improved detection and therapy among at-risk patients.46

FIGURE 3 Single session, 25-minute intervention for patients and their partners

Source: Chang G, McNamara T, Orav J, et al. Brief intervention for prenatal alcohol use: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(5 Pt 1):991–998.

FAS prevention begins with routine counseling and contraception

Although FAS is often thought of in relation to obstetric populations, appointments for preconception counseling or routine health maintenance among women of reproductive age are an essential tool in FAS prevention. As previously mentioned, since approximately half of all pregnancies in this country are unplanned, long-acting reversible contraception is widely available to facilitate improved family planning.

Other contraceptive options also should be discussed. ACOG has teamed up with the CDC to develop a phone app for providers to use at the patient’s bedside to assist with identification and treatment of women at risk for alcohol use during pregnancy.47

The stakes are high, it’s time to step up

As obstetricians, we are powerless to prevent many conditions—such as vasa previa, acute fatty liver of pregnancy, and amniotic band syndrome. FAS is 100% preventable.

There aren’t that many proven teratogens in our profession, and there are none that involve behavior that is more socially acceptable than alcohol consumption. It is time for our profession to encourage women to appreciate how small a percentage of one’s life is spent pregnant, how many more years there are to enjoy an occasional cocktail, and how very high the stakes are during this important period of their lives. Oh, how I wish someone had been able to communicate all of this to sweet Charlie’s biologic mother. I am so grateful he’s getting the exceptional care he’s getting and very optimistic regarding his future. I only hope others in his situation are given the same opportunities.

Prenatal counseling

Louise Wilkins-Haug, MD, PhD (January 2008)

Prevention of fetal alcohol syndrome requires routine screening of all women of reproductive age

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Medical students learn early in their education that alcohol is a teratogen. Despite this widespread knowledge, many obstetricians counsel patients about the safety of low doses of alcohol in pregnancy.1 Indeed, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists’ position on this is, “while the safest approach may be to avoid any alcohol during pregnancy, it remains the case that there is no evidence of harm from low levels of alcohol consumption, defined as no more than one or two units of alcohol once or twice a week.”2

Like many providers, I was aware of this controversy, but it became truly personal when a beloved family member was diagnosed with fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS). In this paper, I will review some of the controversy regarding alcohol in pregnancy, highlight findings from the literature, provide tools for prevention, and identify new developments regarding this devastating, preventable condition.

Charlie

To know my nephew Charlie is to fall in love with my nephew Charlie. One of the happiest moments of my life was when I learned my brother and sister-in-law had adopted twins from Kazakhstan. When my little niece and nephew started their new life in the United States, certain medical issues seemed to merit additional attention. Although both were very small for their age and required significant nutritional support, Charlie seemed to be a bit more rambunctious and required additional supervision.

The children were fortunate enough to have incredibly loving, dedicated parents, who have access to exceptional medical care as residents of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. After extensive testing, it became clear what was causing Charlie’s developmental delay; his pediatric team made the diagnosis of FAS. My brother and sister-in-law became incredibly well-read about this challenging disorder, and threw themselves into national advocacy work to help prevent this unnecessary tragedy.

Recent data point to teratogenicity, but media confuse the issue

Some recent media coverage3 of celebrities who apparently drank while pregnant was in response to an article in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health.4 The authors of this study concluded that, “at age 5 years, cohort members born to mothers who drank up to one to two drinks per week or per occasion during pregnancy were not at increased risk of clinically relevant behavioral difficulties or cognitive deficits, compared with children of mothers in the not-in-pregnancy group.”

This is certainly not the first occasion the popular press has covered a published study that seems to indicate no ill effects of alcohol use in pregnancy. A 2008 report by Kelly and colleagues,5 and its subsequent media coverage, prompted the Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders Study Group to state that the panel of experts was “alarmed” by recent newspaper reports suggesting that light drinking during pregnancy may be beneficial for an unborn child.6 They noted misleading and irresponsible media reports of the findings, which suggested that 3-year-old children whose mothers drank “lightly” during pregnancy were not at risk for certain behavioral problems.

What the study authors proceeded to note, however (that the media did not mention), was that the light drinkers in their study had socioeconomic advantages, compared with nondrinkers.5 (Advantaged economic status is established to be beneficial for childhood development.) They also noted that the study involved preschool-aged children, stating “Generally the adverse effects of light drinking during pregnancy are subtle and may go undetected in young children. However, other group studies of more moderate or ‘social’ drinking levels during pregnancy have shown an adverse impact on multiple aspects of development through adolescence and young adulthood, even when important environmental factors are taken into account.” A sentence I thought was most compelling in their statement was, “It is an inconvenient fact of life that alcohol is a teratogen.” Now, this fact is well supported in the literature.7

There are animal studies regarding the use of “low-dose” or “moderate” alcohol in pregnancy that demonstrate adverse behavioral outcomes with exposure to even small doses of alcohol.8,9 It is an American tragedy that, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), rates of FAS in this country range from 0.2 to 2.0 cases per 1,000 live births. Indeed, the rates of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) might be at least three times this rate.10 As is the case with other disorders, there are health disparities regarding the prevalence of this condition as well.11

FAS: A long history of preventable disease

1973: Identified. FAS was first described in a 1973 Lancet report, “Pattern of malformation in offspring of chronic alcoholic mothers.”12

1996: Call for prevention. In 1995, the US Surgeon General issued a statement regarding alcohol use in pregnancy, noting, “We do not know what, if any, amount of alcohol is safe.”13 In 1996, the Institute of Medicine released a paper calling FAS and FASD “completely preventable birth defects and neurodevelopmental abnormalities.”14

2000: The troubling effects gathered. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published a monograph on FAS in 2000, defining it as a constellation of physical, behavioral, and cognitive abnormalities.15

These features classically define FAS:

- dysmorphic facial features

- prenatal and postnatal growth abnormalities

- mental retardation.

Approximately 80% of children with this condition have:

- microcephaly

- behavioral abnormalities.

As many as 50% of affected children also exhibit:

- poor coordination

- hypotonia

- attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

- decreased adipose tissue

- identifiable facial anomalies (such as maxillary hypoplasia, cleft palate, and micrognathia).

Also common:

- cardiac defects

- hemangiomas

- eye or ear abnormalities.

The AAP further noted that data current to the time (and still true today) did not support the concept of a safe level of alcohol consumption by pregnant women below which no damage to a fetus will occur.15

Alcohol intake during pregnancy puts the fetus at risk for cognitive and neuropsychological impairment and physical abnormalities, including dysmorphic facial features (such as micrognathia), restricted prenatal growth, cardiac defects, and eye and ear abnormalities. There is no threshold dose of alcohol that is safe during pregnancy, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Despite the knowledge we’ve gained, FAS persists

According to a 2006–2010 CDC analysis involving more than 345,000 women of reproductive age from all 50 states, 7.6% of pregnant women reported alcohol use and 1.4% (or 1 in 71) reported binge drinking (defined, respectively, as at least one alcoholic drink and four or more alcoholic drinks on one occasion in the past 30 days).16 The highest prevalence of obstetric alcohol consumption occurs in women who are:

- aged 35 to 44 years

- white

- college graduates

- employed.

The problem may be bigger than reported. The incidences of alcohol and binge drinking found in the CDC report include women’s self-report—but women drink alcohol without knowing they’re pregnant. Only 40% of women realize they’re pregnant at 4 weeks of gestation, a critical time for organogenesis, and approximately half of all births are unplanned.9

When my brother and sister-in law adopted my beautiful niece and nephew, they were very aware of the risk for conditions like FAS. In an evaluation of 71 children adopted from Eastern Europe at 5 years of age, FAS was diagnosed in 30% of children and “partial FAS” in another 9%.17 Birth defects attributed to alcohol were present in 11% of the children.

Are women’s health providers up to date on FAS education?

In recognition of alcohol’s potentially life-altering consequences for the developing fetus, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) produced an FASD prevention tool kit in 2006 and published a 2011 committee opinion on at-risk drinking and alcohol dependence and their implications for obstetrics and gynecology.18,19 Both guidelines direct clinicians to advise patients to abstain from alcohol during pregnancy.

Results from a 2010 survey of 800 ACOG fellows revealed that only 78% of obstetricians advised abstinence from alcohol during pregnancy. Fifty-eight percent of respondents did not use a validated screening tool for alcohol use in their pregnant patients, and only 72% felt prepared to screen for risky or hazardous drinking.19 (Most were unaware of the ACOG tool kit, which had been published several years earlier.)

In a survey of pediatricians, obstetricians, and family physicians, clinicians said that about 67% of their patients asked about alcohol use in pregnancy, with about 2% of those patients specifically mentioning FAS. About 41% of these same physicians erroneously placed the threshold for FAS at one to three drinks per day,20 when in fact there is no threshold of drinking that has been proven to be safe.

A survey of 1,000 actively practicing ACOG fellows revealed that, while 97% of obstetricians routinely asked their patients about alcohol use, only 20% of providers reported to their patients that abstinence was safest, and 4% of providers didn’t believe that consumption of eight or more drinks weekly posed fetal risk.21

How can we educate our patients about the dangers of alcohol in pregnancy?

Fetal death. A recent Danish study of 79,216 pregnant women revealed that 45% had consumed some alcohol during pregnancy. Two percent reported at least four drinks per week, and 25% admitted to binge drinking during pregnancy. Term infants born to women in the latter two groups had increased neonatal mortality, with hazard ratios of 3.56 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.15–8.43) and 2.69 (95% CI, 1.27–5.69), respectively.22

Decreased cognitive status. A study by Willford and colleagues evaluated the relationship between prenatal alcohol exposure and cognitive status of 1,360 10-year-old children.23 The authors utilized the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Test, including the composite scores and verbal, abstract/visual, quantitative, and short-term memory scores. After controlling for other variables, among African American offspring they found that, for each additional drink, the average composite score decreased by 1.9 points. This difference was more striking for second-trimester use, and was significant even for one drink daily versus abstention from alcohol.

Impaired neuropsychological development. Another study evaluating light to moderate amounts of prenatal alcohol exposure in 10- and 11-year-old children found significantly worse scores regarding a number of neuropsychological developmental assessments.24

No threshold dose of causation. Results of a 2012 prospective study in California, with data collected on 992 subjects from 1978 until 2005, revealed that many physical FAS features, including microcephaly, smooth philtrum, and thin vermillion border; reduced birth length; and reduced birth weight, were associated with alcohol exposure at specific gestational ages, and were dose-related.25 This paper didn’t reveal any evidence of a threshold dose of causation.

Neurobehavioral outcomes of FAS are not always considered

Another recent study that the media recently highlighted as finding “no association between low or moderate prenatal alcohol exposure and birth defects” was by O’Leary and colleagues.26 Like other similarly limited studies, this one involved only children younger than 6 years and didn’t assess any of the important neurobehavioral outcomes of FAS.

FAS encompasses much more than visible birth defects. As the aforementioned ACOG tool kit stated, “For every child born with FAS, many more children are born with neurobehavioral deficits caused by alcohol exposure but without the physical characteristics of FAS.”

The costs of FAS are felt with dollars, too

The financial cost to our nation is extraordinary. In 1991, Abel and Sokol estimated the incremental annual cost of treating FAS at nearly $75 million, with about three-quarters of that cost associated with FAS cases involving mental retardation.27

A 2002 assessment estimated the lifetime cost for each individual with FAS (adjusting for the change in the cost of medical care services, lost productivity, and inflation) at $2 million. This figure consists of $1.6 million for medical treatment, special education, and residential care for persons with mental retardation, and $0.4 million for productivity losses.28

Where human studies fall short, animal studies can help elucidate causation

Unquestionably, there are flaws in the existing literature on the causation of FAS. Many studies rely on self-reporting by pregnant women, and underreporting in these cases is a real concern. There often are other confounders potentially negatively affecting fetal development, making it difficult to differentiate causation. The animal studies that don’t share these limitations do suggest a causal relationship between antenatal alcohol exposure and poor obstetric outcomes, however.29 These studies suggest mechanisms such as altered gene expression, oxidative stress, and apoptosis (programmed cell death).30

Warren, Hewitt, and Thomas describe how intrauterine alcohol exposure interferes with the function of L1CAM, the L1 cell-adhesion molecule.31 They noted that just one drink could interfere with the ability of L1CAM to mediate cell adhesion and axonal growth. Prenatal alcohol exposure is also thought to contribute to interference in neurotransmitter and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor coupling, which may have potential therapeutic implications.32

Considerations in FAS identification and treatment

There is a potential to identify alcohol exposure in the womb. The majority of ingested alcohol is eventually converted to carbon dioxide and water in both maternal and fetal circulations, which has hampered the identification of biomarkers for clinical use in FAS. Fatty acid ethyl esters (FAEEs), nonoxidative metabolites of ethanol, may prove to be such markers.33 FAEEs have been measured in a variety of tissues, including blood and meconium. FAEEs can be measured in both neonatal and maternal hair samples.

A study evaluating the utility of such testing in 324 at-risk pregnancies revealed 90% sensitivity and 90% specificity for identifying “excessive drinking” using a cutoff of 0.5 ng/mg.34

Research shows potential therapeutic approaches during pregnancy. While the use of biomarkers has the potential to assist with the identification of at-risk newborns, it merely identifies past alcohol use; it doesn’t necessarily permit identification and prevention of the known negative pediatric sequelae. Preliminary animal studies reveal the potential benefit of neuroprotective peptides to prevent brain damage in alcohol-exposed mice.35 Further research is ongoing.

Treatment: The earlier the better

Early diagnosis and a positive environment improve outcomes. It is well established that early intervention improves outcomes. One comprehensive review of 415 patients with FAS noted troubling outcomes in general for adolescents and adults.36 Over their life spans, the prevalence of such outcomes was:

- 61% for disrupted school experiences

- 60% for trouble with the law

- 50% for confinement (in detention, jail, prison, or a psychiatric or alcohol/drug inpatient setting)

- 49% for inappropriate sexual behaviors on repeated occasions

- 35% for alcohol/drug problems.

The odds of escaping these adverse life outcomes are increased up to fourfold when the individual receives a FAS or FASD diagnosis at an earlier age and is reared in a stable environment.36

Barrier to treatment: A mother’s guilt. One of the challenges I’ve learned from my sister-in-law is the stigma mothers face when they bring their child in for services once the diagnosis of FAS is suspected. While adoptive mothers obviously can’t be held accountable for the intrauterine environment to which a fetus is exposed, the same can’t be said of biologic mothers. Therefore, there is a real risk that a mother who is unwilling or unable to face the potentially devastating news that her baby’s issues might be related to choices she made during pregnancy, might not bring her child in for necessary assessment and treatment. Therefore, prevention is a key proponent of treatment.

Prevent FAS: Provide contraception, screen for alcohol use, intervene

While ObGyns aren’t likely to diagnose many children with FAS, we are in an excellent position to try to prevent this tragedy through our counseling of reproductive-aged women. I suspect that most obstetricians spend a considerable amount of time discussing much less frequent obstetric sequelae, such as listeriosis, in the prenatal care setting. Validated alcohol screening tools take moments to administer, and once patients who might have alcohol problems are identified, either a serious discussion about contraception or an honest discussion of FAS may be appropriate. There have been a number of screening tools developed.

The CAGE screen is frequently taught in medical schools, but it isn’t as sensitive for women or minorities.19

The T-ACE (Tolerance, Annoyed, Cut Down, Eye-opener) tool involves four questions that take less than 1 minute to administer (FIGURE 1).39

TWEAK is another potential tool identified by Russell and colleagues (Tolerance, Worry, Eye opener, Amnesia, and Cut down in drinking).39 Other methods utilized include an AUDIT screen and a CRAFFT screen.40 Regardless of which tool is utilized, screening is not time-consuming and is better than merely inquiring about alcohol consumption in general.

FIGURE 1 T-ACE validated alcohol screening tool

Source: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. At risk drinking and illicit drug use: Ethical issues in obstetric and gynecologic practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(6):1449–1460.

When alcohol use is found, intervene

Once patients with at-risk behavior are identified, obstetric staff should offer brief interventions to influence problem drinking. Miller and Sanchez summarized the key elements that were most successful in these programs with the acronym FRAMES: Feedback, Responsibility, Advice, Menu, Empathy, Self-efficacy (FIGURE 2).41 This approach has been formally evaluated in the CDC’s multisite pilot study entitled Project CHOICES.42

In this motivational intervention, sexually active, fertile women of reproductive age underwent up to four motivational counseling sessions and one visit to a provider. At 6 months, 69% of women reduced their risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy—although the women who drank the least amount had the greatest benefit, primarily by choosing effective contraception, but also by reducing alcohol intake.

FIGURE 2 FRAMES model to deliver brief interventions

Source: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Drinking and reproductive health: A fetal alcohol spectrum disorders prevention tool kit. Washington, DC: ACOG; 2006.

A single, brief intervention is effective in already-pregnant women. Chang and colleagues conducted a randomized trial of a single-session brief intervention given to pregnant women with positive T-ACE screens and their partners (FIGURE 3).43 Either the study nurse or physician participated in the intervention, and each single session took 25 minutes on average. The pregnant women with the highest level of alcohol use reduced their drinking the most, and this effect was even larger when their partners participated. Other studies of brief interventions showed similar benefits.44,45

Another study evaluating a brief intervention involving training of health-care providers to improve screening rates revealed improved detection and therapy among at-risk patients.46

FIGURE 3 Single session, 25-minute intervention for patients and their partners

Source: Chang G, McNamara T, Orav J, et al. Brief intervention for prenatal alcohol use: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(5 Pt 1):991–998.

FAS prevention begins with routine counseling and contraception

Although FAS is often thought of in relation to obstetric populations, appointments for preconception counseling or routine health maintenance among women of reproductive age are an essential tool in FAS prevention. As previously mentioned, since approximately half of all pregnancies in this country are unplanned, long-acting reversible contraception is widely available to facilitate improved family planning.

Other contraceptive options also should be discussed. ACOG has teamed up with the CDC to develop a phone app for providers to use at the patient’s bedside to assist with identification and treatment of women at risk for alcohol use during pregnancy.47

The stakes are high, it’s time to step up

As obstetricians, we are powerless to prevent many conditions—such as vasa previa, acute fatty liver of pregnancy, and amniotic band syndrome. FAS is 100% preventable.

There aren’t that many proven teratogens in our profession, and there are none that involve behavior that is more socially acceptable than alcohol consumption. It is time for our profession to encourage women to appreciate how small a percentage of one’s life is spent pregnant, how many more years there are to enjoy an occasional cocktail, and how very high the stakes are during this important period of their lives. Oh, how I wish someone had been able to communicate all of this to sweet Charlie’s biologic mother. I am so grateful he’s getting the exceptional care he’s getting and very optimistic regarding his future. I only hope others in his situation are given the same opportunities.

Prenatal counseling

Louise Wilkins-Haug, MD, PhD (January 2008)

Prevention of fetal alcohol syndrome requires routine screening of all women of reproductive age

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Baram M. Moms-to-be get mixed messages on drinking. ABC News. http://abcnews.go.com/Health/story?id=2654849&page=1#.UM9l-RyeARY. Published November 15 2006. Accessed December 14, 2012.

2. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Alcohol consumption and the outcomes of pregnancy (RCOG Statement No. 5). London UK: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. January 3, 2006.

3. Pearson C. Alcohol during pregnancy: How dangerous is it really? The Huffington Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/04/06/alcohol-during-pregnancy_n_845103.html. Published April 6 2011. Updated September 16, 2011. Accessed December 14, 2012.

4. Kelly YJ, Sacker A, Gray R, et al. Light drinking during pregnancy: still no increased risk for socioemotional difficulties or cognitive deficits at 5 years of age? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(1):41-48.Epub Oct 5, 2010.

5. Kelly Y, Sacker A, Gray R, Kelly J, Wolke D, Quigley MA. Light drinking in pregnancy a risk for behavioural problems and cognitive deficits at 3 years of age? Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(1):129-140.Epub Oct 30, 2008.

6. Zhou F. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders Study Group (FASDSG). Research Society on Alcoholism. http://rsoa.org/fas.html. Updated September 9 2010. Accessed December 14, 2012.

7. Kelly S, Day N, Streissguth AP. Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on social behavior in humans and other species. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2000;22(2):143-149.

8. Vaglenova J, Petkov V. Fetal alcohol effects in rats exposed pre-and postnatally to a low dose of ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22(3):697-703.

9. Schneider M, Moore C, Kraemer G. Moderate alcohol during pregnancy: learning and behavior in adolescent rhesus monkeys. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25(9):1383-1392.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Data and statistics in the United States. http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/fasd/data.html. Updated August 16 2012. Accessed December 14, 2012.

11. Egeland G, Perham-Hestere KA, Gessner BD, Ingle D, Berner JE, Middaugh J. Fetal alcohol syndrome in Alaska 1977 through 1992: an administrative prevalence derived from multiple data sources. Am J Pub Health. 1998;88(5):781-786.

12. Jones K, Smith D, Ulleland C, Streissguth A. Pattern of malformation in offspring of chronic alcoholic mothers. Lancet. 1973;1(7815):1267-1271.

13. Institute of Medicine. Fetal alcohol syndrome: diagnosis epidemiology, prevention, and treatment (1996). http://www.come-over.to/FAS/IOMsummary.htm. Accessed December 14, 2012.

14. Committee of Substance Abuse and Committee on Children with Disabilities. American Academy of Pediatrics. Fetal alcohol syndrome and alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorders. Pediatrics. 2000;106(2):358-361.

15. US Department of Health & Human Services. US Surgeon General releases advisory on alcohol use in pregnancy. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/news/2005/02/sg02222005.html. Published February 21 2005. Accessed December 13, 2012.