User login

Cognitive Screening Tools

The purpose of cognitive screening tests is to aid the clinician in early detection of cognitive change as a first step toward accurate diagnosis—a process that requires further assessment. Such changes may herald the beginning of a dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease, or may indicate an increased risk for delirium, such as in the postoperative setting,6 or functional decline with accompanying safety concerns.7 Early identification of cognitive changes provides an opportunity for case finding, crisis avoidance, and identification of patients for earlier intervention and management, including a discussion of goals with the patient, and assurance that advance directives are complete and accurate.

There is no clear consensus on who should undergo cognitive screening or how frequently it should be carried out. Screening should be targeted at individuals who are at greatest risk for either progressive dementia or delirium. Advancing age is a known risk factor for dementia, but there is no agreement on a specific age at which to initiate cognitive screening. In patients older than 80, there is a 25% to 50% prevalence of dementia,1,11,12 thus suggesting that cognitive screening should be initiated before this age. Furthermore, clinicians who provide medical care for patients of advanced age must be increasingly attentive to the possible presence of cognitive decline.

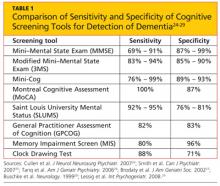

There is no single, ideal cognitive screening tool that can be recommended for use in every clinical setting. However, the ideal tool would have high sensitivity (ie, the proportion of those with impairment correctly classified as impaired), high specificity (the proportion of those who are unimpaired correctly identified as not having cognitive problems; see Table 1,24-29 below), and a high positive predictive value (proportion identified by screening as impaired who really have cognitive impairment). Additionally, such a tool should be easy to administer and score, and should take a minimum amount of time to conduct in our time-pressured clinical environment.

Cognitive screening does involve some risk, and every tool has known limitations. A significant barrier can be the administration time required, possibly ranging from five to 20 minutes. There is a potential for false-positive results, and there can be distress and stigma associated with a diagnosis of dementia, for both patients and families.

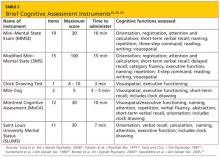

A variety of tools are available for bedside/clinical assessment of cognition (see Table 226,30-34 below). Their administration can be learned without difficulty, and they can be conducted with relative ease to provide insight into a patient’s cognitive abilities and deficits.

The most commonly used cognitive screening tool is the Folstein Mini–Mental State Exam (MMSE).30 With administration taking about 15 minutes, the MMSE includes assessment of attention, orientation, registration, recall/short-term memory, language, and visuospatial construction. Clinicians will find this tool most useful in assessing the individual with suspected early dementia and to follow progression through the early and middle stages of cognitive decline in those with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementing disorders.

The Clock Drawing Test (CDT) is perhaps the simplest test to administer.29,32 The patient is given a blank sheet of paper and asked to draw a large circle, then to write numbers inside the circle so that it resembles a face of a clock. Once this is completed, the patient is instructed to “draw the hands on the clock to read ten past eleven.”

The Mini-Cog Test (with instructions available at http://geriatrics.uthscsa.edu/tools/MINICog.pdf) includes the clock-drawing task and a three-word recall, with a simple scoring algorithm.33 Ability to recall all three words, or to recall one or two words with normal results on the clock test, represents a negative screening result for dementia. Conversely, an inability to recall any of the three words, or ability to recall only one or two words with an abnormal clock test, is considered a positive screen for dementia. The Mini-Cog is a good tool for identification of early dementia, but not useful for following changes in individuals identified with cognitive impairment.

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) was originally designed as a brief screening instrument for mild cognitive impairment.34 It is a single-page, 30-point test, available in multiple languages (with several versions in some languages) at www.mocatest.org. The MoCA includes assessment of short-term memory, visuospatial ability, executive function, attention, concentration, working memory, language, and orientation. A score of 25 or lower is considered subnormal.

The Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) has also been shown to have better sensitivity than the MMSE for early cognitive changes.26 This 11-item tool, with a maximum score of 30 points, includes assessment of seven cognitive domains: orientation, recall, attention, calculation, fluency, language, and visuospatial construction. The five-item delayed recall in the SLUMS has been shown to be an excellent discriminator of those with normal cognition versus mild cognitive change. It is available for general use with no fee; currently, it is widely used by the Veterans Administration system.41

The General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition (GPCOG)27 is a unique two-part tool that includes questions for the patient and for someone who knows the patient well (“informant”). The patient items include memory/recall, orientation, and visuospatial tasks. The six informant questions ask about recall, language, and functional abilities. The GPCOG has been shown to have sensitivity and specificity similar to those of the MMSE27; as its name indicates, it is designed and best suited for screening in a family medicine or general internal medicine practice.

The Memory Impairment Screen (MIS)28 uses a four-item memory recall with simple scoring of 0 to 8, based on the formula: 2x [the number recalled spontaneously) + (the number recalled with cuing)]. It takes less than five minutes to administer, making it a useful tool to screen for suspected memory problems in a busy setting, such as an emergency room. However, the sole reliance on memory, without screening for any other areas of cognition (especially executive function or visuospatial copying), significantly limits the usefulness of the MIS as a general cognitive screening tool.

The cognitive screening instruments described thus far were all designed to be administered in person in a medical setting (office, clinic, or hospital). The 11-item Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS)42 was developed as a brief (taking less than 10 minutes) standardized test of cognitive function, specifically suited for situations in which in-person screening is not possible (eg, for patients who are unable to appear in person for clinical follow-up).42-44 The modified TICS (TICS-M), which includes 13 items, has been shown to have less of a ceiling effect than the MMSE.45 It has also been shown to be a cost-effective screening tool for mild cognitive impairment.46

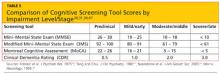

The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale is a useful tool for staging cognitive decline, regardless of the patient’s diagnosis.47 It uses a 0-to-5 rating system in which 0 is considered normal and 5 represents profound impairment/total dependence (see Table 4,47-49 below). The CDR rating system addresses three areas of cognition (memory, orientation, judgment) and three areas of function (community affairs, home and hobbies, personal care). This tool is very helpful to explain to families where an individual with cognitive impairment is in the course of the disease, and what to expect and plan for in the future as the condition progresses. A comparison of CDR level and cognitive screening test scores is presented in Table 5.30,31,34,49

Clinicians in all settings need to become familiar with the use and interpretation of readily available instruments for cognitive screening. None of the tools reviewed is diagnostic in itself, and no one tool is appropriate for all patients in all settings. Familiarity with the components of the most commonly used cognitive screening tools and associated clinical instruments will aid the clinician in the appropriate use and interpretation of these to improve clinical care and outcomes for patients.

1. Alzheimer’s Association. 2012 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. www.alz.org/downloads/facts_figures_2012.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2012.

The purpose of cognitive screening tests is to aid the clinician in early detection of cognitive change as a first step toward accurate diagnosis—a process that requires further assessment. Such changes may herald the beginning of a dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease, or may indicate an increased risk for delirium, such as in the postoperative setting,6 or functional decline with accompanying safety concerns.7 Early identification of cognitive changes provides an opportunity for case finding, crisis avoidance, and identification of patients for earlier intervention and management, including a discussion of goals with the patient, and assurance that advance directives are complete and accurate.

There is no clear consensus on who should undergo cognitive screening or how frequently it should be carried out. Screening should be targeted at individuals who are at greatest risk for either progressive dementia or delirium. Advancing age is a known risk factor for dementia, but there is no agreement on a specific age at which to initiate cognitive screening. In patients older than 80, there is a 25% to 50% prevalence of dementia,1,11,12 thus suggesting that cognitive screening should be initiated before this age. Furthermore, clinicians who provide medical care for patients of advanced age must be increasingly attentive to the possible presence of cognitive decline.

There is no single, ideal cognitive screening tool that can be recommended for use in every clinical setting. However, the ideal tool would have high sensitivity (ie, the proportion of those with impairment correctly classified as impaired), high specificity (the proportion of those who are unimpaired correctly identified as not having cognitive problems; see Table 1,24-29 below), and a high positive predictive value (proportion identified by screening as impaired who really have cognitive impairment). Additionally, such a tool should be easy to administer and score, and should take a minimum amount of time to conduct in our time-pressured clinical environment.

Cognitive screening does involve some risk, and every tool has known limitations. A significant barrier can be the administration time required, possibly ranging from five to 20 minutes. There is a potential for false-positive results, and there can be distress and stigma associated with a diagnosis of dementia, for both patients and families.

A variety of tools are available for bedside/clinical assessment of cognition (see Table 226,30-34 below). Their administration can be learned without difficulty, and they can be conducted with relative ease to provide insight into a patient’s cognitive abilities and deficits.

The most commonly used cognitive screening tool is the Folstein Mini–Mental State Exam (MMSE).30 With administration taking about 15 minutes, the MMSE includes assessment of attention, orientation, registration, recall/short-term memory, language, and visuospatial construction. Clinicians will find this tool most useful in assessing the individual with suspected early dementia and to follow progression through the early and middle stages of cognitive decline in those with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementing disorders.

The Clock Drawing Test (CDT) is perhaps the simplest test to administer.29,32 The patient is given a blank sheet of paper and asked to draw a large circle, then to write numbers inside the circle so that it resembles a face of a clock. Once this is completed, the patient is instructed to “draw the hands on the clock to read ten past eleven.”

The Mini-Cog Test (with instructions available at http://geriatrics.uthscsa.edu/tools/MINICog.pdf) includes the clock-drawing task and a three-word recall, with a simple scoring algorithm.33 Ability to recall all three words, or to recall one or two words with normal results on the clock test, represents a negative screening result for dementia. Conversely, an inability to recall any of the three words, or ability to recall only one or two words with an abnormal clock test, is considered a positive screen for dementia. The Mini-Cog is a good tool for identification of early dementia, but not useful for following changes in individuals identified with cognitive impairment.

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) was originally designed as a brief screening instrument for mild cognitive impairment.34 It is a single-page, 30-point test, available in multiple languages (with several versions in some languages) at www.mocatest.org. The MoCA includes assessment of short-term memory, visuospatial ability, executive function, attention, concentration, working memory, language, and orientation. A score of 25 or lower is considered subnormal.

The Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) has also been shown to have better sensitivity than the MMSE for early cognitive changes.26 This 11-item tool, with a maximum score of 30 points, includes assessment of seven cognitive domains: orientation, recall, attention, calculation, fluency, language, and visuospatial construction. The five-item delayed recall in the SLUMS has been shown to be an excellent discriminator of those with normal cognition versus mild cognitive change. It is available for general use with no fee; currently, it is widely used by the Veterans Administration system.41

The General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition (GPCOG)27 is a unique two-part tool that includes questions for the patient and for someone who knows the patient well (“informant”). The patient items include memory/recall, orientation, and visuospatial tasks. The six informant questions ask about recall, language, and functional abilities. The GPCOG has been shown to have sensitivity and specificity similar to those of the MMSE27; as its name indicates, it is designed and best suited for screening in a family medicine or general internal medicine practice.

The Memory Impairment Screen (MIS)28 uses a four-item memory recall with simple scoring of 0 to 8, based on the formula: 2x [the number recalled spontaneously) + (the number recalled with cuing)]. It takes less than five minutes to administer, making it a useful tool to screen for suspected memory problems in a busy setting, such as an emergency room. However, the sole reliance on memory, without screening for any other areas of cognition (especially executive function or visuospatial copying), significantly limits the usefulness of the MIS as a general cognitive screening tool.

The cognitive screening instruments described thus far were all designed to be administered in person in a medical setting (office, clinic, or hospital). The 11-item Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS)42 was developed as a brief (taking less than 10 minutes) standardized test of cognitive function, specifically suited for situations in which in-person screening is not possible (eg, for patients who are unable to appear in person for clinical follow-up).42-44 The modified TICS (TICS-M), which includes 13 items, has been shown to have less of a ceiling effect than the MMSE.45 It has also been shown to be a cost-effective screening tool for mild cognitive impairment.46

The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale is a useful tool for staging cognitive decline, regardless of the patient’s diagnosis.47 It uses a 0-to-5 rating system in which 0 is considered normal and 5 represents profound impairment/total dependence (see Table 4,47-49 below). The CDR rating system addresses three areas of cognition (memory, orientation, judgment) and three areas of function (community affairs, home and hobbies, personal care). This tool is very helpful to explain to families where an individual with cognitive impairment is in the course of the disease, and what to expect and plan for in the future as the condition progresses. A comparison of CDR level and cognitive screening test scores is presented in Table 5.30,31,34,49

Clinicians in all settings need to become familiar with the use and interpretation of readily available instruments for cognitive screening. None of the tools reviewed is diagnostic in itself, and no one tool is appropriate for all patients in all settings. Familiarity with the components of the most commonly used cognitive screening tools and associated clinical instruments will aid the clinician in the appropriate use and interpretation of these to improve clinical care and outcomes for patients.

1. Alzheimer’s Association. 2012 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. www.alz.org/downloads/facts_figures_2012.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2012.

The purpose of cognitive screening tests is to aid the clinician in early detection of cognitive change as a first step toward accurate diagnosis—a process that requires further assessment. Such changes may herald the beginning of a dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease, or may indicate an increased risk for delirium, such as in the postoperative setting,6 or functional decline with accompanying safety concerns.7 Early identification of cognitive changes provides an opportunity for case finding, crisis avoidance, and identification of patients for earlier intervention and management, including a discussion of goals with the patient, and assurance that advance directives are complete and accurate.

There is no clear consensus on who should undergo cognitive screening or how frequently it should be carried out. Screening should be targeted at individuals who are at greatest risk for either progressive dementia or delirium. Advancing age is a known risk factor for dementia, but there is no agreement on a specific age at which to initiate cognitive screening. In patients older than 80, there is a 25% to 50% prevalence of dementia,1,11,12 thus suggesting that cognitive screening should be initiated before this age. Furthermore, clinicians who provide medical care for patients of advanced age must be increasingly attentive to the possible presence of cognitive decline.

There is no single, ideal cognitive screening tool that can be recommended for use in every clinical setting. However, the ideal tool would have high sensitivity (ie, the proportion of those with impairment correctly classified as impaired), high specificity (the proportion of those who are unimpaired correctly identified as not having cognitive problems; see Table 1,24-29 below), and a high positive predictive value (proportion identified by screening as impaired who really have cognitive impairment). Additionally, such a tool should be easy to administer and score, and should take a minimum amount of time to conduct in our time-pressured clinical environment.

Cognitive screening does involve some risk, and every tool has known limitations. A significant barrier can be the administration time required, possibly ranging from five to 20 minutes. There is a potential for false-positive results, and there can be distress and stigma associated with a diagnosis of dementia, for both patients and families.

A variety of tools are available for bedside/clinical assessment of cognition (see Table 226,30-34 below). Their administration can be learned without difficulty, and they can be conducted with relative ease to provide insight into a patient’s cognitive abilities and deficits.

The most commonly used cognitive screening tool is the Folstein Mini–Mental State Exam (MMSE).30 With administration taking about 15 minutes, the MMSE includes assessment of attention, orientation, registration, recall/short-term memory, language, and visuospatial construction. Clinicians will find this tool most useful in assessing the individual with suspected early dementia and to follow progression through the early and middle stages of cognitive decline in those with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementing disorders.

The Clock Drawing Test (CDT) is perhaps the simplest test to administer.29,32 The patient is given a blank sheet of paper and asked to draw a large circle, then to write numbers inside the circle so that it resembles a face of a clock. Once this is completed, the patient is instructed to “draw the hands on the clock to read ten past eleven.”

The Mini-Cog Test (with instructions available at http://geriatrics.uthscsa.edu/tools/MINICog.pdf) includes the clock-drawing task and a three-word recall, with a simple scoring algorithm.33 Ability to recall all three words, or to recall one or two words with normal results on the clock test, represents a negative screening result for dementia. Conversely, an inability to recall any of the three words, or ability to recall only one or two words with an abnormal clock test, is considered a positive screen for dementia. The Mini-Cog is a good tool for identification of early dementia, but not useful for following changes in individuals identified with cognitive impairment.

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) was originally designed as a brief screening instrument for mild cognitive impairment.34 It is a single-page, 30-point test, available in multiple languages (with several versions in some languages) at www.mocatest.org. The MoCA includes assessment of short-term memory, visuospatial ability, executive function, attention, concentration, working memory, language, and orientation. A score of 25 or lower is considered subnormal.

The Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) has also been shown to have better sensitivity than the MMSE for early cognitive changes.26 This 11-item tool, with a maximum score of 30 points, includes assessment of seven cognitive domains: orientation, recall, attention, calculation, fluency, language, and visuospatial construction. The five-item delayed recall in the SLUMS has been shown to be an excellent discriminator of those with normal cognition versus mild cognitive change. It is available for general use with no fee; currently, it is widely used by the Veterans Administration system.41

The General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition (GPCOG)27 is a unique two-part tool that includes questions for the patient and for someone who knows the patient well (“informant”). The patient items include memory/recall, orientation, and visuospatial tasks. The six informant questions ask about recall, language, and functional abilities. The GPCOG has been shown to have sensitivity and specificity similar to those of the MMSE27; as its name indicates, it is designed and best suited for screening in a family medicine or general internal medicine practice.

The Memory Impairment Screen (MIS)28 uses a four-item memory recall with simple scoring of 0 to 8, based on the formula: 2x [the number recalled spontaneously) + (the number recalled with cuing)]. It takes less than five minutes to administer, making it a useful tool to screen for suspected memory problems in a busy setting, such as an emergency room. However, the sole reliance on memory, without screening for any other areas of cognition (especially executive function or visuospatial copying), significantly limits the usefulness of the MIS as a general cognitive screening tool.

The cognitive screening instruments described thus far were all designed to be administered in person in a medical setting (office, clinic, or hospital). The 11-item Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS)42 was developed as a brief (taking less than 10 minutes) standardized test of cognitive function, specifically suited for situations in which in-person screening is not possible (eg, for patients who are unable to appear in person for clinical follow-up).42-44 The modified TICS (TICS-M), which includes 13 items, has been shown to have less of a ceiling effect than the MMSE.45 It has also been shown to be a cost-effective screening tool for mild cognitive impairment.46

The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale is a useful tool for staging cognitive decline, regardless of the patient’s diagnosis.47 It uses a 0-to-5 rating system in which 0 is considered normal and 5 represents profound impairment/total dependence (see Table 4,47-49 below). The CDR rating system addresses three areas of cognition (memory, orientation, judgment) and three areas of function (community affairs, home and hobbies, personal care). This tool is very helpful to explain to families where an individual with cognitive impairment is in the course of the disease, and what to expect and plan for in the future as the condition progresses. A comparison of CDR level and cognitive screening test scores is presented in Table 5.30,31,34,49

Clinicians in all settings need to become familiar with the use and interpretation of readily available instruments for cognitive screening. None of the tools reviewed is diagnostic in itself, and no one tool is appropriate for all patients in all settings. Familiarity with the components of the most commonly used cognitive screening tools and associated clinical instruments will aid the clinician in the appropriate use and interpretation of these to improve clinical care and outcomes for patients.

1. Alzheimer’s Association. 2012 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. www.alz.org/downloads/facts_figures_2012.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2012.

Military Women's Health While Deployed: Feminine Hygiene and Health in Austere Environments

Tackling a Delicate Subject With Heart Failure Patients

Bronchial Breathing and Resonant Percussion—An Important Combination of Signs in Pneumothorax

Osteoporosis in Veterans With Chronic Alcohol Use: An Early Recognition and Treatment Program

Man, 56, With Wrist Pain After a Fall

A white man, age 56, presented to his primary care clinician with wrist pain and swelling. Two days earlier, he had fallen from a step stool and landed on his right wrist. He treated the pain by resting, elevating his arm, applying ice, and taking ibuprofen 800 mg tid. He said he had lost strength in his hand and arm and was experiencing numbness and tingling in his right hand and fingers.

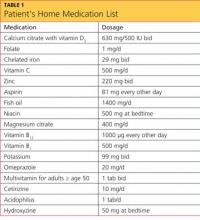

The patient’s medical history included hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, asthma, carpel tunnel syndrome, and peripheral neuropathy. His surgical history was significant for duodenal switch gastric bypass surgery, performed eight years earlier, and his weight at the time of presentation was 200 lb; before his gastric bypass, he weighed 385 lb. Since the surgery, his hypertension, diabetes, asthma, and sleep apnea had all resolved. Table 1 shows a list of medications he was taking at the time of presentation.

The patient, a registered nurse, had been married for 30 years and had one child. He had quit smoking 15 years earlier, with a 43–pack-year smoking history. He reported social drinking but denied any recreational drug use. He was unaware of having any allergies to food or medication.

His vital signs on presentation were blood pressure, 110/75 mm Hg; heart rate, 53 beats/min; respiration, 18 breaths/min; O2 saturation, 97% on room air; and temperature, 97.5°F.

Physical exam revealed that the patient’s right wrist was ecchymotic and swollen with +1 pitting edema. The skin was warm and dry to the touch. Decreased range of motion was noted in the right wrist, compared with the left. Pain with point tenderness was noted at the right lateral wrist. Pulses were +3 with capillary refill of less than 3 seconds. The rest of the exam was unremarkable.

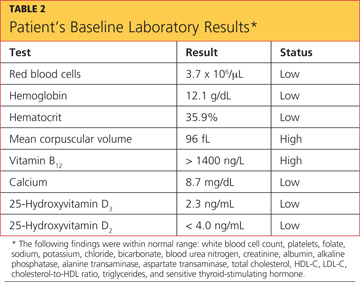

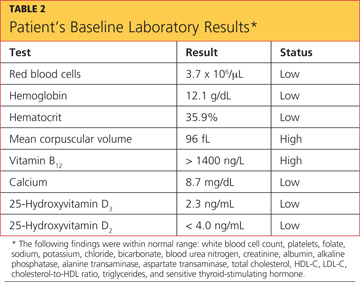

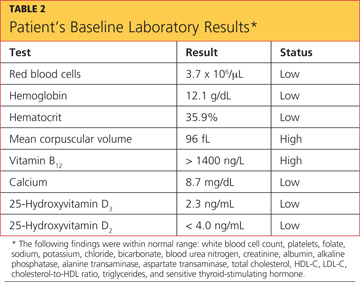

The differential diagnosis included fracture secondary to the fall, osteoporosis, osteopenia, osteomalacia, Paget’s disease, tumor, infection, and sprain or strain of the wrist. A wrist x-ray was ordered, as were the following baseline labs: complete blood count with differential (CBC), vitamin B12 and folate levels, blood chemistry, lipid profile, liver profile, total vitamin D, and sensitive thyroid-stimulating hormone. Test results are shown in Table 2.

X-ray of the wrist showed fracture only, making it possible to rule out Paget’s disease (ie, no patchy white areas noted in the bone) and tumor (no masses seen) as the immediate cause of fracture. Normal body temperature and normal white blood cell count eliminated the possibility of infection.

Because the patient was only 56 and had a history of bariatric surgery, further testing was pursued to investigate a cause for the weakened bone. Bone mineral density (BMD) testing revealed the following results:

• The lumbar spine in frontal projection measured 0.968 g/cm2 with a T-score of –2.2 and a Z-score of –2.2.

• Total BMD of the left hip was 0.863 g/cm2 with a T-score of –1.7 and a Z-score of –1.4.

• Total BMD of the left femoral neck was 0.863 g/cm2 with a T-score of 1.7 and a Z-score of –1.1.

These findings suggested osteopenia1,2 (not osteoporosis) in all sites, with a 12% decrease of BMD in the spine (suggesting increased risk for spinal fracture) and a 16.3% decrease of BMD in the hip since the patient’s most recent bone scan five years earlier (radiologist’s report). Other abnormal findings were elevated parathyroid hormone (PTH) serum, 95.7 pg/mL (reference range, 10 to 65 pg/mL); low total calcium serum, 8.7 mg/dL (reference range, 8.9 to 10.2 mg/dL), and low 25-hydroxyvitamin D total, 12.3 ng/mL (reference range, 25 to 80 ng/mL).

A 2010 clinical practice guideline from the Endocrine Society3 specifies that after malabsorptive surgery, vitamin D and calcium supplementation should be adjusted by a qualified medical professional, based on serum markers and measures of bone density. An endocrinologist who was consulted at the patient’s initial visit prescribed the following medications: vitamin D2, 50,000 U/wk PO; combined calcium citrate (vitamin D3) 500 IU with calcium 630 mg, 1 tab bid; and calcitriol 0.5 μg bid.

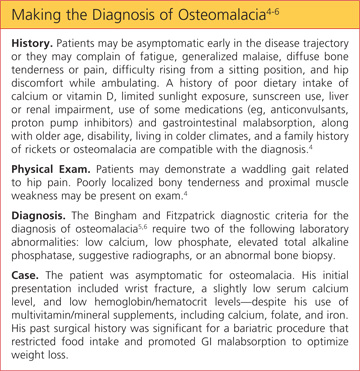

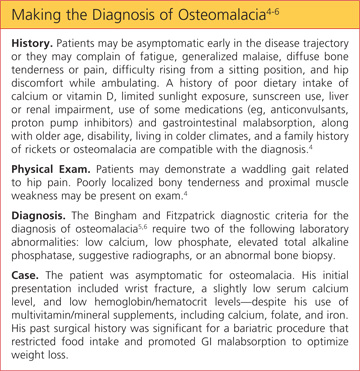

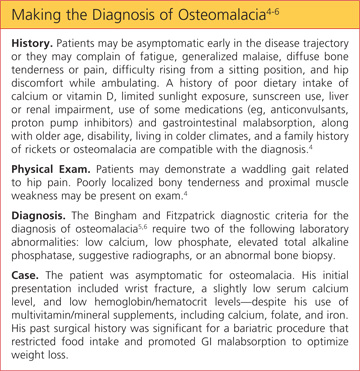

The patient’s final diagnosis was osteomalacia secondary to gastric bypass surgery. (See “Making the Diagnosis of Osteomalacia.”4-6)

DISCUSSION

According to 2008 data from the World Health Organization (WHO),7 1.4 billion persons older than 20 worldwide were overweight, and 200 million men and 300 million women were considered obese—meaning that one in every 10 adults worldwide is overweight or obese. In 2010, the WHO reports, 40 million children younger than 5 worldwide were considered overweight.7 Health care providers need to be prepared to care for the increasing number of patients who will undergo bariatric surgeries to treat obesity and its related comorbidities.8

Postoperative follow-up for the malabsorption deficiencies related to bariatric procedures should be performed every six months, including obtaining levels of alkaline phosphatase and others previously discussed. In addition, the Endocrine Society guideline3 recommends measuring levels of vitamin B12, albumin, pre-albumin, iron, and ferritin, and obtaining a CBC, a liver profile, glucose reading, creatinine measurement, and a metabolic profile at one month and two months after surgery, then every six months until two years after surgery, then annually if findings are stable.

Furthermore, the Endocrine Society3 recommends obtaining zinc levels every six months for the first year, then annually. An annual vitamin A level is optional.9 Yearly bone density testing is recommended until the patient’s BMD is deemed stable.3

Additionally, Koch and Finelli10 recommend performing the following labs postoperatively: hemoglobin A1C every three months; copper, magnesium, whole blood thiamine, vitamin B12, and a 24-hour urinary calcium every six months for the first three years, then once a year if findings remain stable.

Use of alcohol should be discouraged among patients who have undergone bariatric surgery, as its use alters micronutrient requirements and metabolism. Alcohol consumption may also contribute to dumping syndrome (ie, rapid gastric emptying).11

Any patient with a history of malabsorptive bypass surgery who complains of neurologic, visual, or skin disorders, anemia, or edema may require a further workup to rule out other absorptive deficiencies. These include vitamins A, E, and B12, zinc, folate, thiamine, niacin, selenium, and ferritin.10

Osteomalacia

Metabolic bone diseases can result from genetics, dietary factors, medication use, surgery, or hormonal irregularities. They alter the normal biochemical reactions in bone structure.

The three most common forms of metabolic bone disease are osteoporosis, osteopenia, and osteomalacia. The WHO diagnostic classifications and associated T-scores for bone mineral density1,2 indicate a T-score above –1.0 as normal. A score between –1.0 and –2.5 is indicative of osteopenia, and a score below –2.5 indicates osteoporosis. A T-score below –2.5 in the patient with a history of fragility fracture indicates severe osteoporosis.1,2

In osteomalacia, bone volume remains unchanged, but mineralization of osteoid in the mature compact and spongy bone is either delayed or inadequate. The remolding cycle continues unchanged in the formation of osteoid, but mineral calcification and deposition do not occur.3-5

Osteomalacia is normally considered a rare disorder, but it may become more common as increasing numbers of patients undergo gastric bypass operations.12,13 Primary care practitioners should monitor for this condition in such patients before serious bone loss or other problems develop.9,13,14

Vitamin D deficiency (see “Vitamin D Metabolism,”4,15-19 below), whether or not the result of gastric bypass surgery, is a major risk factor for osteomalacia. Disorders of the small bowel, the hepatobiliary system, and the pancreas are all common causes of vitamin D deficiency. Liver disease interferes with the metabolism of vitamin D. Diseases of the pancreas may cause a deficiency of bile salts, which are vital for the intestinal absorption of vitamin D.17

Restriction and Malabsorption

The case patient had undergone a gastric bypass (duodenal switch), in which a large portion of the stomach is removed and a large part of the small bowel rerouted—with both parts of the procedure causing malabsorption.11 It is in the small bowel that absorption of vitamin D and calcium takes place.

The duodenal switch gastric bypass surgery causes both restriction and malabsorption. Though similar to a biliopancreatic diversion, the duodenal switch preserves the distal stomach and the pylorus20 by way of a sleeve gastrectomy that is performed to reduce the gastric reservoir; the common channel length after revision is 100 cm, not 50 cm (as in conventional biliopancreatic diversion).13 The sleeve gastrectomy involves removal of parietal cells, reducing production of hydrochloric acid (which is necessary to break down food), and hindering the absorption of certain nutrients, including the fat-soluble vitamins, vitamin B12, and iron.12 Patients who take H2-blockers or proton pump inhibitors experience an additional decrease in the production and availability of HCl and may have an increased risk for fracture.14,20,21

In addition to its biliopancreatic diversion component, the duodenal switch diverts a large portion of the small bowel, with food restricted from moving through it. Vitamin D and protein are normally absorbed at the jejunum and ileum, but only when bile salts are present; after a duodenal switch, bile and pancreatic enzymes are not introduced into the small intestines until 75 to 100 cm before they reach the large intestine. Thus, absorption of vitamin D, protein, calcium, and other nutrients is impaired.20,22

Since phosphorus and magnesium are also absorbed at the sites of the duodenum and jejunum, malabsorption of these nutrients may occur in a patient who has undergone a duodenal switch. Although vitamin B12 is absorbed at the site of the distal ileum, it also requires gastric acid to free it from the food. Zinc absorption, which normally occurs at the site of the jejunum, may be impaired after duodenal switch surgery, and calcium supplementation, though essential, may further reduce zinc absorption.9 Iron absorption requires HCl, facilitated by the presence of vitamin C. Use of H2-blockers and proton pump inhibitors may impair iron metabolism, resulting in anemia.20

In a randomized controlled trial, Aasheim et al23 compared the effects of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with those of duodenal switch gastric bypass on patients’ vitamin metabolism. The researchers concluded that patients who undergo a duodenal switch are at greater risk for vitamin A and D deficiencies in the first year after surgery; and for thiamine deficiency in the months following surgery as a result of malabsorption, compared with patients who undergo Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.20,23

Patient Management

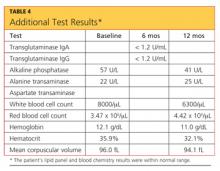

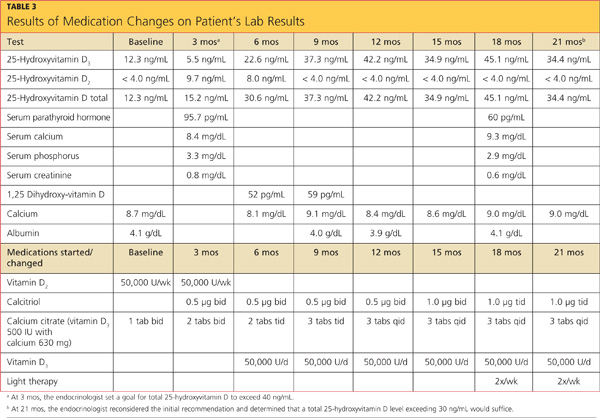

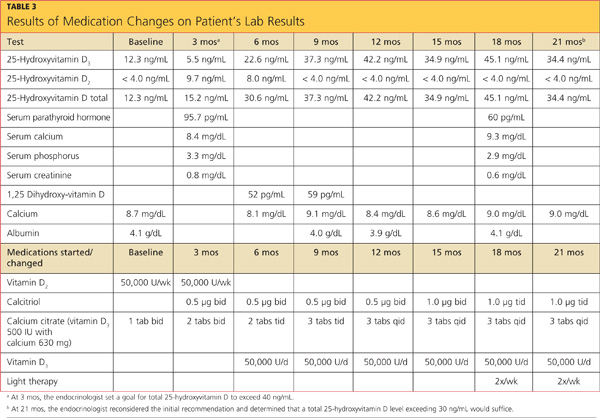

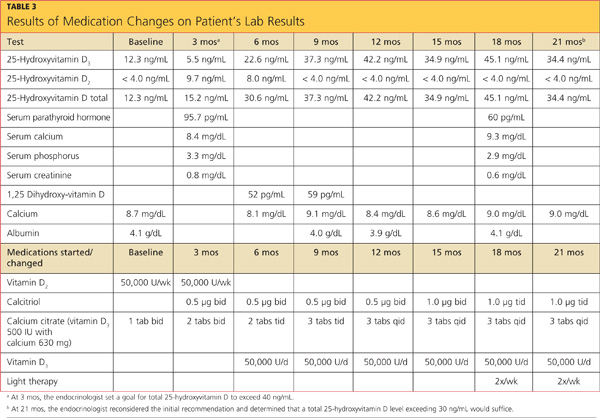

The case patient’s care necessitated consultations with endocrinology, dermatology, and gastroenterology (GI). Table 3 (below) shows the laboratory findings and the medication changes prompted by the patient’s physical exam and lab results. Table 4 lists the findings from other lab studies ordered throughout the patient’s course of treatment.

The endocrinologist was consulted at the first sign of osteopenia, and a workup was soon initiated, followed by treatment. GI was consulted six months after the beginning of treatment, when the patient began to complain of reflux while sleeping and frequent diarrhea throughout the day.

Results of esophagogastroduodenoscopy with biopsy ruled out celiac disease and mucosal ulceration, but a small hiatal hernia that was detected (< 3 cm) was determined to be an aggravating factor for the patient’s reflux. The patient was instructed in lifestyle modifications for hiatal hernia, including the need to remain upright one to two hours after eating before going to sleep to prevent aspiration. The patient was instructed to avoid taking iron and calcium within two hours of each other and to limit his alcohol intake. He was also educated in precautions against falls.

Dermatology was consulted nine months into treatment so that light therapy could be initiated, allowing the patient to take advantage of the body’s natural pathway to manufacture vitamin D3.

CONCLUSION

For post–bariatric surgery patients, primary care practitioners are in a position to coordinate care recommendations from multiple specialists, including those in nutrition, to determine the best course of action.

This case illustrates complications of bariatric surgery (malabsorption of key vitamins and minerals, wrist fracture, osteopenia, osteomalacia) that require diagnosis and treatment. The specialists and the primary care practitioner, along with the patient, had to weigh the risks and benefits of continued proton pump inhibitor use, as such medications can increase the risk for fracture. They also addressed the patient’s anemia and remained attentive to his preventive health care needs.

REFERENCES

1. Brusin JH. Update on bone densitometry. Radiol Technol. 2009;81(2):153BD-170BD.

2. Wilson CR. Essentials of bone densitometry for the medical physicist. Presented at: The American Association of Physicists in Medicine 2003 Annual Meeting; July 22-26, 2003; San Diego, CA.

3. Heber D, Greenway FL, Kaplan LM. et al. Endocrine and nutritional management of the post-bariatric surgery patient: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(11):4825-4843.

4. Osteomalacia: step-by-step diagnostic approach (2011). http://bestpractice.bmj.com/best-practice/monograph/517/diagnosis/step-by-step.html. Accessed December 18, 2012.

5. Gifre L, Peris P, Monegal A, et al. Osteomalacia revisited : a report on 28 cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30(5):639-645.

6. Bingham CT, Fitzpatrick LA. Noninvasive testing in the diagnosis of osteomalacia. Am J Med. 1993;95(5):519-523.

7. World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight (May 2012). Fact Sheet No 311. www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/index.html. Accessed December 18, 2012.

8. Tanner BD, Allen JW. Complications of bariatric surgery: implications for the covering physician. Am Surg. 2009;75(2):103-112.

9. Soleymani T, Tejavanija S, Morgan S. Obesity, bariatric surgery, and bone. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23(4):396-405.

10. Koch TR, Finelli FC. Postoperative metabolic and nutritional complications of bariatric surgery. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010;39(1):109-124.

11. Manchester S, Roye GD. Bariatric surgery: an overview for dietetics professionals. Nutr Today. 2011;46(6):264-275.

12. Bal BS, Finelli FC, Shope TR, Koch TR. Nutritional deficiencies after bariatric surgery. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8(9):544-546.

13. Iannelli A, Schneck AS, Dahman M, et al. Two-step laparoscopic duodenal switch for superobesity: a feasibility study. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(10):2385-2389.

14. Lalmohamed A, de Vries F, Bazelier MT, et al. Risk of fracture after bariatric surgery in the United Kingdom: population based, retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2012;345:e5085.

15. Holrick MF. Vitamin D: important for prevention of osteoporosis, cardiovascular heart disease, type 1 diabetes, autoimmune diseases, and some cancers. South Med J. 2005;98 (10):1024-1027.

16. Kalro BN. Vitamin D and the skeleton. Alt Ther Womens Health. 2009;2(4):25-32.

17. Crowther-Radulewicz CL, McCance KL. Alterations of musculoskeletal function. In: McCance KL, Huether SE, Brashers VL, Rote NS, eds. Pathophysiology: The Biologic Basis for Disease in Adults and Children. 6th ed. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2010:1568-1617.

18. Huether SE. Structure and function of the renal and urologic systems. In: McCance KL, Huether SE, Brashers VL, Rote NS, eds. Pathophysiology: The Biologic Basis for Disease in Adults and Children. 6th ed. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2010:1344-1364.

19. Bhan A, Rao AD, Rao DS. Osteomalacia as a result of vitamin D deficiency. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2010;39(2):321-331.

20. Decker GA, Swain JM, Crowell MD. Gastrointestinal and nutritional complications after bariatric surgery. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(11):2571-2580.

21. Targownik LE, Lix LM, Metge C, et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors and risk of osteoporosis-related fractures. CMAJ. 2008;179(4):319-326.

22. Ybarra J, Sánchez-Hernández J, Pérez A. Hypovitaminosis D and morbid obesity. Nurs Clin North Am. 2007;42(1):19-27.

23. Aasheim ET, Björkman S, Søvik TT, et al. Vitamin status after bariatric surgery: a randomized study of gastric bypass and duodenal switch. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(1):15-22.

A white man, age 56, presented to his primary care clinician with wrist pain and swelling. Two days earlier, he had fallen from a step stool and landed on his right wrist. He treated the pain by resting, elevating his arm, applying ice, and taking ibuprofen 800 mg tid. He said he had lost strength in his hand and arm and was experiencing numbness and tingling in his right hand and fingers.

The patient’s medical history included hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, asthma, carpel tunnel syndrome, and peripheral neuropathy. His surgical history was significant for duodenal switch gastric bypass surgery, performed eight years earlier, and his weight at the time of presentation was 200 lb; before his gastric bypass, he weighed 385 lb. Since the surgery, his hypertension, diabetes, asthma, and sleep apnea had all resolved. Table 1 shows a list of medications he was taking at the time of presentation.

The patient, a registered nurse, had been married for 30 years and had one child. He had quit smoking 15 years earlier, with a 43–pack-year smoking history. He reported social drinking but denied any recreational drug use. He was unaware of having any allergies to food or medication.

His vital signs on presentation were blood pressure, 110/75 mm Hg; heart rate, 53 beats/min; respiration, 18 breaths/min; O2 saturation, 97% on room air; and temperature, 97.5°F.

Physical exam revealed that the patient’s right wrist was ecchymotic and swollen with +1 pitting edema. The skin was warm and dry to the touch. Decreased range of motion was noted in the right wrist, compared with the left. Pain with point tenderness was noted at the right lateral wrist. Pulses were +3 with capillary refill of less than 3 seconds. The rest of the exam was unremarkable.

The differential diagnosis included fracture secondary to the fall, osteoporosis, osteopenia, osteomalacia, Paget’s disease, tumor, infection, and sprain or strain of the wrist. A wrist x-ray was ordered, as were the following baseline labs: complete blood count with differential (CBC), vitamin B12 and folate levels, blood chemistry, lipid profile, liver profile, total vitamin D, and sensitive thyroid-stimulating hormone. Test results are shown in Table 2.

X-ray of the wrist showed fracture only, making it possible to rule out Paget’s disease (ie, no patchy white areas noted in the bone) and tumor (no masses seen) as the immediate cause of fracture. Normal body temperature and normal white blood cell count eliminated the possibility of infection.

Because the patient was only 56 and had a history of bariatric surgery, further testing was pursued to investigate a cause for the weakened bone. Bone mineral density (BMD) testing revealed the following results:

• The lumbar spine in frontal projection measured 0.968 g/cm2 with a T-score of –2.2 and a Z-score of –2.2.

• Total BMD of the left hip was 0.863 g/cm2 with a T-score of –1.7 and a Z-score of –1.4.

• Total BMD of the left femoral neck was 0.863 g/cm2 with a T-score of 1.7 and a Z-score of –1.1.

These findings suggested osteopenia1,2 (not osteoporosis) in all sites, with a 12% decrease of BMD in the spine (suggesting increased risk for spinal fracture) and a 16.3% decrease of BMD in the hip since the patient’s most recent bone scan five years earlier (radiologist’s report). Other abnormal findings were elevated parathyroid hormone (PTH) serum, 95.7 pg/mL (reference range, 10 to 65 pg/mL); low total calcium serum, 8.7 mg/dL (reference range, 8.9 to 10.2 mg/dL), and low 25-hydroxyvitamin D total, 12.3 ng/mL (reference range, 25 to 80 ng/mL).

A 2010 clinical practice guideline from the Endocrine Society3 specifies that after malabsorptive surgery, vitamin D and calcium supplementation should be adjusted by a qualified medical professional, based on serum markers and measures of bone density. An endocrinologist who was consulted at the patient’s initial visit prescribed the following medications: vitamin D2, 50,000 U/wk PO; combined calcium citrate (vitamin D3) 500 IU with calcium 630 mg, 1 tab bid; and calcitriol 0.5 μg bid.

The patient’s final diagnosis was osteomalacia secondary to gastric bypass surgery. (See “Making the Diagnosis of Osteomalacia.”4-6)

DISCUSSION

According to 2008 data from the World Health Organization (WHO),7 1.4 billion persons older than 20 worldwide were overweight, and 200 million men and 300 million women were considered obese—meaning that one in every 10 adults worldwide is overweight or obese. In 2010, the WHO reports, 40 million children younger than 5 worldwide were considered overweight.7 Health care providers need to be prepared to care for the increasing number of patients who will undergo bariatric surgeries to treat obesity and its related comorbidities.8

Postoperative follow-up for the malabsorption deficiencies related to bariatric procedures should be performed every six months, including obtaining levels of alkaline phosphatase and others previously discussed. In addition, the Endocrine Society guideline3 recommends measuring levels of vitamin B12, albumin, pre-albumin, iron, and ferritin, and obtaining a CBC, a liver profile, glucose reading, creatinine measurement, and a metabolic profile at one month and two months after surgery, then every six months until two years after surgery, then annually if findings are stable.

Furthermore, the Endocrine Society3 recommends obtaining zinc levels every six months for the first year, then annually. An annual vitamin A level is optional.9 Yearly bone density testing is recommended until the patient’s BMD is deemed stable.3

Additionally, Koch and Finelli10 recommend performing the following labs postoperatively: hemoglobin A1C every three months; copper, magnesium, whole blood thiamine, vitamin B12, and a 24-hour urinary calcium every six months for the first three years, then once a year if findings remain stable.

Use of alcohol should be discouraged among patients who have undergone bariatric surgery, as its use alters micronutrient requirements and metabolism. Alcohol consumption may also contribute to dumping syndrome (ie, rapid gastric emptying).11

Any patient with a history of malabsorptive bypass surgery who complains of neurologic, visual, or skin disorders, anemia, or edema may require a further workup to rule out other absorptive deficiencies. These include vitamins A, E, and B12, zinc, folate, thiamine, niacin, selenium, and ferritin.10

Osteomalacia

Metabolic bone diseases can result from genetics, dietary factors, medication use, surgery, or hormonal irregularities. They alter the normal biochemical reactions in bone structure.

The three most common forms of metabolic bone disease are osteoporosis, osteopenia, and osteomalacia. The WHO diagnostic classifications and associated T-scores for bone mineral density1,2 indicate a T-score above –1.0 as normal. A score between –1.0 and –2.5 is indicative of osteopenia, and a score below –2.5 indicates osteoporosis. A T-score below –2.5 in the patient with a history of fragility fracture indicates severe osteoporosis.1,2

In osteomalacia, bone volume remains unchanged, but mineralization of osteoid in the mature compact and spongy bone is either delayed or inadequate. The remolding cycle continues unchanged in the formation of osteoid, but mineral calcification and deposition do not occur.3-5

Osteomalacia is normally considered a rare disorder, but it may become more common as increasing numbers of patients undergo gastric bypass operations.12,13 Primary care practitioners should monitor for this condition in such patients before serious bone loss or other problems develop.9,13,14

Vitamin D deficiency (see “Vitamin D Metabolism,”4,15-19 below), whether or not the result of gastric bypass surgery, is a major risk factor for osteomalacia. Disorders of the small bowel, the hepatobiliary system, and the pancreas are all common causes of vitamin D deficiency. Liver disease interferes with the metabolism of vitamin D. Diseases of the pancreas may cause a deficiency of bile salts, which are vital for the intestinal absorption of vitamin D.17

Restriction and Malabsorption

The case patient had undergone a gastric bypass (duodenal switch), in which a large portion of the stomach is removed and a large part of the small bowel rerouted—with both parts of the procedure causing malabsorption.11 It is in the small bowel that absorption of vitamin D and calcium takes place.

The duodenal switch gastric bypass surgery causes both restriction and malabsorption. Though similar to a biliopancreatic diversion, the duodenal switch preserves the distal stomach and the pylorus20 by way of a sleeve gastrectomy that is performed to reduce the gastric reservoir; the common channel length after revision is 100 cm, not 50 cm (as in conventional biliopancreatic diversion).13 The sleeve gastrectomy involves removal of parietal cells, reducing production of hydrochloric acid (which is necessary to break down food), and hindering the absorption of certain nutrients, including the fat-soluble vitamins, vitamin B12, and iron.12 Patients who take H2-blockers or proton pump inhibitors experience an additional decrease in the production and availability of HCl and may have an increased risk for fracture.14,20,21

In addition to its biliopancreatic diversion component, the duodenal switch diverts a large portion of the small bowel, with food restricted from moving through it. Vitamin D and protein are normally absorbed at the jejunum and ileum, but only when bile salts are present; after a duodenal switch, bile and pancreatic enzymes are not introduced into the small intestines until 75 to 100 cm before they reach the large intestine. Thus, absorption of vitamin D, protein, calcium, and other nutrients is impaired.20,22

Since phosphorus and magnesium are also absorbed at the sites of the duodenum and jejunum, malabsorption of these nutrients may occur in a patient who has undergone a duodenal switch. Although vitamin B12 is absorbed at the site of the distal ileum, it also requires gastric acid to free it from the food. Zinc absorption, which normally occurs at the site of the jejunum, may be impaired after duodenal switch surgery, and calcium supplementation, though essential, may further reduce zinc absorption.9 Iron absorption requires HCl, facilitated by the presence of vitamin C. Use of H2-blockers and proton pump inhibitors may impair iron metabolism, resulting in anemia.20

In a randomized controlled trial, Aasheim et al23 compared the effects of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with those of duodenal switch gastric bypass on patients’ vitamin metabolism. The researchers concluded that patients who undergo a duodenal switch are at greater risk for vitamin A and D deficiencies in the first year after surgery; and for thiamine deficiency in the months following surgery as a result of malabsorption, compared with patients who undergo Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.20,23

Patient Management

The case patient’s care necessitated consultations with endocrinology, dermatology, and gastroenterology (GI). Table 3 (below) shows the laboratory findings and the medication changes prompted by the patient’s physical exam and lab results. Table 4 lists the findings from other lab studies ordered throughout the patient’s course of treatment.

The endocrinologist was consulted at the first sign of osteopenia, and a workup was soon initiated, followed by treatment. GI was consulted six months after the beginning of treatment, when the patient began to complain of reflux while sleeping and frequent diarrhea throughout the day.

Results of esophagogastroduodenoscopy with biopsy ruled out celiac disease and mucosal ulceration, but a small hiatal hernia that was detected (< 3 cm) was determined to be an aggravating factor for the patient’s reflux. The patient was instructed in lifestyle modifications for hiatal hernia, including the need to remain upright one to two hours after eating before going to sleep to prevent aspiration. The patient was instructed to avoid taking iron and calcium within two hours of each other and to limit his alcohol intake. He was also educated in precautions against falls.

Dermatology was consulted nine months into treatment so that light therapy could be initiated, allowing the patient to take advantage of the body’s natural pathway to manufacture vitamin D3.

CONCLUSION

For post–bariatric surgery patients, primary care practitioners are in a position to coordinate care recommendations from multiple specialists, including those in nutrition, to determine the best course of action.

This case illustrates complications of bariatric surgery (malabsorption of key vitamins and minerals, wrist fracture, osteopenia, osteomalacia) that require diagnosis and treatment. The specialists and the primary care practitioner, along with the patient, had to weigh the risks and benefits of continued proton pump inhibitor use, as such medications can increase the risk for fracture. They also addressed the patient’s anemia and remained attentive to his preventive health care needs.

REFERENCES

1. Brusin JH. Update on bone densitometry. Radiol Technol. 2009;81(2):153BD-170BD.

2. Wilson CR. Essentials of bone densitometry for the medical physicist. Presented at: The American Association of Physicists in Medicine 2003 Annual Meeting; July 22-26, 2003; San Diego, CA.

3. Heber D, Greenway FL, Kaplan LM. et al. Endocrine and nutritional management of the post-bariatric surgery patient: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(11):4825-4843.

4. Osteomalacia: step-by-step diagnostic approach (2011). http://bestpractice.bmj.com/best-practice/monograph/517/diagnosis/step-by-step.html. Accessed December 18, 2012.

5. Gifre L, Peris P, Monegal A, et al. Osteomalacia revisited : a report on 28 cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30(5):639-645.

6. Bingham CT, Fitzpatrick LA. Noninvasive testing in the diagnosis of osteomalacia. Am J Med. 1993;95(5):519-523.

7. World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight (May 2012). Fact Sheet No 311. www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/index.html. Accessed December 18, 2012.

8. Tanner BD, Allen JW. Complications of bariatric surgery: implications for the covering physician. Am Surg. 2009;75(2):103-112.

9. Soleymani T, Tejavanija S, Morgan S. Obesity, bariatric surgery, and bone. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23(4):396-405.

10. Koch TR, Finelli FC. Postoperative metabolic and nutritional complications of bariatric surgery. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010;39(1):109-124.

11. Manchester S, Roye GD. Bariatric surgery: an overview for dietetics professionals. Nutr Today. 2011;46(6):264-275.

12. Bal BS, Finelli FC, Shope TR, Koch TR. Nutritional deficiencies after bariatric surgery. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8(9):544-546.

13. Iannelli A, Schneck AS, Dahman M, et al. Two-step laparoscopic duodenal switch for superobesity: a feasibility study. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(10):2385-2389.

14. Lalmohamed A, de Vries F, Bazelier MT, et al. Risk of fracture after bariatric surgery in the United Kingdom: population based, retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2012;345:e5085.

15. Holrick MF. Vitamin D: important for prevention of osteoporosis, cardiovascular heart disease, type 1 diabetes, autoimmune diseases, and some cancers. South Med J. 2005;98 (10):1024-1027.

16. Kalro BN. Vitamin D and the skeleton. Alt Ther Womens Health. 2009;2(4):25-32.

17. Crowther-Radulewicz CL, McCance KL. Alterations of musculoskeletal function. In: McCance KL, Huether SE, Brashers VL, Rote NS, eds. Pathophysiology: The Biologic Basis for Disease in Adults and Children. 6th ed. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2010:1568-1617.

18. Huether SE. Structure and function of the renal and urologic systems. In: McCance KL, Huether SE, Brashers VL, Rote NS, eds. Pathophysiology: The Biologic Basis for Disease in Adults and Children. 6th ed. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2010:1344-1364.

19. Bhan A, Rao AD, Rao DS. Osteomalacia as a result of vitamin D deficiency. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2010;39(2):321-331.

20. Decker GA, Swain JM, Crowell MD. Gastrointestinal and nutritional complications after bariatric surgery. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(11):2571-2580.

21. Targownik LE, Lix LM, Metge C, et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors and risk of osteoporosis-related fractures. CMAJ. 2008;179(4):319-326.

22. Ybarra J, Sánchez-Hernández J, Pérez A. Hypovitaminosis D and morbid obesity. Nurs Clin North Am. 2007;42(1):19-27.

23. Aasheim ET, Björkman S, Søvik TT, et al. Vitamin status after bariatric surgery: a randomized study of gastric bypass and duodenal switch. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(1):15-22.

A white man, age 56, presented to his primary care clinician with wrist pain and swelling. Two days earlier, he had fallen from a step stool and landed on his right wrist. He treated the pain by resting, elevating his arm, applying ice, and taking ibuprofen 800 mg tid. He said he had lost strength in his hand and arm and was experiencing numbness and tingling in his right hand and fingers.

The patient’s medical history included hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, asthma, carpel tunnel syndrome, and peripheral neuropathy. His surgical history was significant for duodenal switch gastric bypass surgery, performed eight years earlier, and his weight at the time of presentation was 200 lb; before his gastric bypass, he weighed 385 lb. Since the surgery, his hypertension, diabetes, asthma, and sleep apnea had all resolved. Table 1 shows a list of medications he was taking at the time of presentation.

The patient, a registered nurse, had been married for 30 years and had one child. He had quit smoking 15 years earlier, with a 43–pack-year smoking history. He reported social drinking but denied any recreational drug use. He was unaware of having any allergies to food or medication.

His vital signs on presentation were blood pressure, 110/75 mm Hg; heart rate, 53 beats/min; respiration, 18 breaths/min; O2 saturation, 97% on room air; and temperature, 97.5°F.

Physical exam revealed that the patient’s right wrist was ecchymotic and swollen with +1 pitting edema. The skin was warm and dry to the touch. Decreased range of motion was noted in the right wrist, compared with the left. Pain with point tenderness was noted at the right lateral wrist. Pulses were +3 with capillary refill of less than 3 seconds. The rest of the exam was unremarkable.

The differential diagnosis included fracture secondary to the fall, osteoporosis, osteopenia, osteomalacia, Paget’s disease, tumor, infection, and sprain or strain of the wrist. A wrist x-ray was ordered, as were the following baseline labs: complete blood count with differential (CBC), vitamin B12 and folate levels, blood chemistry, lipid profile, liver profile, total vitamin D, and sensitive thyroid-stimulating hormone. Test results are shown in Table 2.

X-ray of the wrist showed fracture only, making it possible to rule out Paget’s disease (ie, no patchy white areas noted in the bone) and tumor (no masses seen) as the immediate cause of fracture. Normal body temperature and normal white blood cell count eliminated the possibility of infection.

Because the patient was only 56 and had a history of bariatric surgery, further testing was pursued to investigate a cause for the weakened bone. Bone mineral density (BMD) testing revealed the following results:

• The lumbar spine in frontal projection measured 0.968 g/cm2 with a T-score of –2.2 and a Z-score of –2.2.

• Total BMD of the left hip was 0.863 g/cm2 with a T-score of –1.7 and a Z-score of –1.4.

• Total BMD of the left femoral neck was 0.863 g/cm2 with a T-score of 1.7 and a Z-score of –1.1.

These findings suggested osteopenia1,2 (not osteoporosis) in all sites, with a 12% decrease of BMD in the spine (suggesting increased risk for spinal fracture) and a 16.3% decrease of BMD in the hip since the patient’s most recent bone scan five years earlier (radiologist’s report). Other abnormal findings were elevated parathyroid hormone (PTH) serum, 95.7 pg/mL (reference range, 10 to 65 pg/mL); low total calcium serum, 8.7 mg/dL (reference range, 8.9 to 10.2 mg/dL), and low 25-hydroxyvitamin D total, 12.3 ng/mL (reference range, 25 to 80 ng/mL).

A 2010 clinical practice guideline from the Endocrine Society3 specifies that after malabsorptive surgery, vitamin D and calcium supplementation should be adjusted by a qualified medical professional, based on serum markers and measures of bone density. An endocrinologist who was consulted at the patient’s initial visit prescribed the following medications: vitamin D2, 50,000 U/wk PO; combined calcium citrate (vitamin D3) 500 IU with calcium 630 mg, 1 tab bid; and calcitriol 0.5 μg bid.

The patient’s final diagnosis was osteomalacia secondary to gastric bypass surgery. (See “Making the Diagnosis of Osteomalacia.”4-6)

DISCUSSION

According to 2008 data from the World Health Organization (WHO),7 1.4 billion persons older than 20 worldwide were overweight, and 200 million men and 300 million women were considered obese—meaning that one in every 10 adults worldwide is overweight or obese. In 2010, the WHO reports, 40 million children younger than 5 worldwide were considered overweight.7 Health care providers need to be prepared to care for the increasing number of patients who will undergo bariatric surgeries to treat obesity and its related comorbidities.8

Postoperative follow-up for the malabsorption deficiencies related to bariatric procedures should be performed every six months, including obtaining levels of alkaline phosphatase and others previously discussed. In addition, the Endocrine Society guideline3 recommends measuring levels of vitamin B12, albumin, pre-albumin, iron, and ferritin, and obtaining a CBC, a liver profile, glucose reading, creatinine measurement, and a metabolic profile at one month and two months after surgery, then every six months until two years after surgery, then annually if findings are stable.

Furthermore, the Endocrine Society3 recommends obtaining zinc levels every six months for the first year, then annually. An annual vitamin A level is optional.9 Yearly bone density testing is recommended until the patient’s BMD is deemed stable.3

Additionally, Koch and Finelli10 recommend performing the following labs postoperatively: hemoglobin A1C every three months; copper, magnesium, whole blood thiamine, vitamin B12, and a 24-hour urinary calcium every six months for the first three years, then once a year if findings remain stable.

Use of alcohol should be discouraged among patients who have undergone bariatric surgery, as its use alters micronutrient requirements and metabolism. Alcohol consumption may also contribute to dumping syndrome (ie, rapid gastric emptying).11

Any patient with a history of malabsorptive bypass surgery who complains of neurologic, visual, or skin disorders, anemia, or edema may require a further workup to rule out other absorptive deficiencies. These include vitamins A, E, and B12, zinc, folate, thiamine, niacin, selenium, and ferritin.10

Osteomalacia

Metabolic bone diseases can result from genetics, dietary factors, medication use, surgery, or hormonal irregularities. They alter the normal biochemical reactions in bone structure.

The three most common forms of metabolic bone disease are osteoporosis, osteopenia, and osteomalacia. The WHO diagnostic classifications and associated T-scores for bone mineral density1,2 indicate a T-score above –1.0 as normal. A score between –1.0 and –2.5 is indicative of osteopenia, and a score below –2.5 indicates osteoporosis. A T-score below –2.5 in the patient with a history of fragility fracture indicates severe osteoporosis.1,2

In osteomalacia, bone volume remains unchanged, but mineralization of osteoid in the mature compact and spongy bone is either delayed or inadequate. The remolding cycle continues unchanged in the formation of osteoid, but mineral calcification and deposition do not occur.3-5

Osteomalacia is normally considered a rare disorder, but it may become more common as increasing numbers of patients undergo gastric bypass operations.12,13 Primary care practitioners should monitor for this condition in such patients before serious bone loss or other problems develop.9,13,14

Vitamin D deficiency (see “Vitamin D Metabolism,”4,15-19 below), whether or not the result of gastric bypass surgery, is a major risk factor for osteomalacia. Disorders of the small bowel, the hepatobiliary system, and the pancreas are all common causes of vitamin D deficiency. Liver disease interferes with the metabolism of vitamin D. Diseases of the pancreas may cause a deficiency of bile salts, which are vital for the intestinal absorption of vitamin D.17

Restriction and Malabsorption

The case patient had undergone a gastric bypass (duodenal switch), in which a large portion of the stomach is removed and a large part of the small bowel rerouted—with both parts of the procedure causing malabsorption.11 It is in the small bowel that absorption of vitamin D and calcium takes place.

The duodenal switch gastric bypass surgery causes both restriction and malabsorption. Though similar to a biliopancreatic diversion, the duodenal switch preserves the distal stomach and the pylorus20 by way of a sleeve gastrectomy that is performed to reduce the gastric reservoir; the common channel length after revision is 100 cm, not 50 cm (as in conventional biliopancreatic diversion).13 The sleeve gastrectomy involves removal of parietal cells, reducing production of hydrochloric acid (which is necessary to break down food), and hindering the absorption of certain nutrients, including the fat-soluble vitamins, vitamin B12, and iron.12 Patients who take H2-blockers or proton pump inhibitors experience an additional decrease in the production and availability of HCl and may have an increased risk for fracture.14,20,21

In addition to its biliopancreatic diversion component, the duodenal switch diverts a large portion of the small bowel, with food restricted from moving through it. Vitamin D and protein are normally absorbed at the jejunum and ileum, but only when bile salts are present; after a duodenal switch, bile and pancreatic enzymes are not introduced into the small intestines until 75 to 100 cm before they reach the large intestine. Thus, absorption of vitamin D, protein, calcium, and other nutrients is impaired.20,22

Since phosphorus and magnesium are also absorbed at the sites of the duodenum and jejunum, malabsorption of these nutrients may occur in a patient who has undergone a duodenal switch. Although vitamin B12 is absorbed at the site of the distal ileum, it also requires gastric acid to free it from the food. Zinc absorption, which normally occurs at the site of the jejunum, may be impaired after duodenal switch surgery, and calcium supplementation, though essential, may further reduce zinc absorption.9 Iron absorption requires HCl, facilitated by the presence of vitamin C. Use of H2-blockers and proton pump inhibitors may impair iron metabolism, resulting in anemia.20

In a randomized controlled trial, Aasheim et al23 compared the effects of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with those of duodenal switch gastric bypass on patients’ vitamin metabolism. The researchers concluded that patients who undergo a duodenal switch are at greater risk for vitamin A and D deficiencies in the first year after surgery; and for thiamine deficiency in the months following surgery as a result of malabsorption, compared with patients who undergo Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.20,23

Patient Management

The case patient’s care necessitated consultations with endocrinology, dermatology, and gastroenterology (GI). Table 3 (below) shows the laboratory findings and the medication changes prompted by the patient’s physical exam and lab results. Table 4 lists the findings from other lab studies ordered throughout the patient’s course of treatment.

The endocrinologist was consulted at the first sign of osteopenia, and a workup was soon initiated, followed by treatment. GI was consulted six months after the beginning of treatment, when the patient began to complain of reflux while sleeping and frequent diarrhea throughout the day.

Results of esophagogastroduodenoscopy with biopsy ruled out celiac disease and mucosal ulceration, but a small hiatal hernia that was detected (< 3 cm) was determined to be an aggravating factor for the patient’s reflux. The patient was instructed in lifestyle modifications for hiatal hernia, including the need to remain upright one to two hours after eating before going to sleep to prevent aspiration. The patient was instructed to avoid taking iron and calcium within two hours of each other and to limit his alcohol intake. He was also educated in precautions against falls.

Dermatology was consulted nine months into treatment so that light therapy could be initiated, allowing the patient to take advantage of the body’s natural pathway to manufacture vitamin D3.

CONCLUSION

For post–bariatric surgery patients, primary care practitioners are in a position to coordinate care recommendations from multiple specialists, including those in nutrition, to determine the best course of action.

This case illustrates complications of bariatric surgery (malabsorption of key vitamins and minerals, wrist fracture, osteopenia, osteomalacia) that require diagnosis and treatment. The specialists and the primary care practitioner, along with the patient, had to weigh the risks and benefits of continued proton pump inhibitor use, as such medications can increase the risk for fracture. They also addressed the patient’s anemia and remained attentive to his preventive health care needs.

REFERENCES

1. Brusin JH. Update on bone densitometry. Radiol Technol. 2009;81(2):153BD-170BD.

2. Wilson CR. Essentials of bone densitometry for the medical physicist. Presented at: The American Association of Physicists in Medicine 2003 Annual Meeting; July 22-26, 2003; San Diego, CA.

3. Heber D, Greenway FL, Kaplan LM. et al. Endocrine and nutritional management of the post-bariatric surgery patient: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(11):4825-4843.

4. Osteomalacia: step-by-step diagnostic approach (2011). http://bestpractice.bmj.com/best-practice/monograph/517/diagnosis/step-by-step.html. Accessed December 18, 2012.

5. Gifre L, Peris P, Monegal A, et al. Osteomalacia revisited : a report on 28 cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30(5):639-645.

6. Bingham CT, Fitzpatrick LA. Noninvasive testing in the diagnosis of osteomalacia. Am J Med. 1993;95(5):519-523.

7. World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight (May 2012). Fact Sheet No 311. www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/index.html. Accessed December 18, 2012.

8. Tanner BD, Allen JW. Complications of bariatric surgery: implications for the covering physician. Am Surg. 2009;75(2):103-112.

9. Soleymani T, Tejavanija S, Morgan S. Obesity, bariatric surgery, and bone. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23(4):396-405.

10. Koch TR, Finelli FC. Postoperative metabolic and nutritional complications of bariatric surgery. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010;39(1):109-124.

11. Manchester S, Roye GD. Bariatric surgery: an overview for dietetics professionals. Nutr Today. 2011;46(6):264-275.

12. Bal BS, Finelli FC, Shope TR, Koch TR. Nutritional deficiencies after bariatric surgery. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8(9):544-546.

13. Iannelli A, Schneck AS, Dahman M, et al. Two-step laparoscopic duodenal switch for superobesity: a feasibility study. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(10):2385-2389.

14. Lalmohamed A, de Vries F, Bazelier MT, et al. Risk of fracture after bariatric surgery in the United Kingdom: population based, retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2012;345:e5085.

15. Holrick MF. Vitamin D: important for prevention of osteoporosis, cardiovascular heart disease, type 1 diabetes, autoimmune diseases, and some cancers. South Med J. 2005;98 (10):1024-1027.

16. Kalro BN. Vitamin D and the skeleton. Alt Ther Womens Health. 2009;2(4):25-32.

17. Crowther-Radulewicz CL, McCance KL. Alterations of musculoskeletal function. In: McCance KL, Huether SE, Brashers VL, Rote NS, eds. Pathophysiology: The Biologic Basis for Disease in Adults and Children. 6th ed. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2010:1568-1617.

18. Huether SE. Structure and function of the renal and urologic systems. In: McCance KL, Huether SE, Brashers VL, Rote NS, eds. Pathophysiology: The Biologic Basis for Disease in Adults and Children. 6th ed. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2010:1344-1364.

19. Bhan A, Rao AD, Rao DS. Osteomalacia as a result of vitamin D deficiency. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2010;39(2):321-331.

20. Decker GA, Swain JM, Crowell MD. Gastrointestinal and nutritional complications after bariatric surgery. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(11):2571-2580.

21. Targownik LE, Lix LM, Metge C, et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors and risk of osteoporosis-related fractures. CMAJ. 2008;179(4):319-326.

22. Ybarra J, Sánchez-Hernández J, Pérez A. Hypovitaminosis D and morbid obesity. Nurs Clin North Am. 2007;42(1):19-27.

23. Aasheim ET, Björkman S, Søvik TT, et al. Vitamin status after bariatric surgery: a randomized study of gastric bypass and duodenal switch. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(1):15-22.

Cover

Smoking Cessation Can Be Toxic to Your Health

5 Points on Value in Orthopedic Surgery

UPDATE ON OBSTETRICS

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

If there have been overriding themes in obstetrics over the past year, they have been “more,” “sooner,” “faster,” “safer.” Advances in our field have thrilled our scientific curiosity and increased our ability to alleviate suffering—but at what cost? And who will pay that cost?

In this Update, we focus on recent advances in prenatal diagnosis and fetal therapy, as well as the ever-encroaching economic barriers that may limit our ability to get what we want. In particular, we will discuss:

- two technologies in prenatal genetics: noninvasive aneuploidy testing using cell-free DNA and prenatal microarray analysis

- open fetal surgery to reduce mortality and improve the function and quality of life for fetuses with open neural tube defects

- the value and probable impact of bundled payments—that is, one payment for multiple services grouped into one “episode.”

Two noninvasive approaches to prenatal diagnosis offer promise—but practicality and cost are uncertain

Ashoor G, Syngelaki RM, Wagner M, Birdir C, Nicolaides KH. Chromosome-selective sequencing of maternal plasma cell-free DNA for first-trimester detection of trisomy 21 and trisomy 18. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(4):322.e1–e5.

Reddy UM, Page GP, Saade GR, et al. Karyotype versus microarray testing for genetic abnormalities after stillbirth. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(23):2185–2193.

Talkowski ME, Ordulu Z, Pillalamarri V, et al. Clinical diagnosis by whole-genome sequencing of a prenatal sample. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(23):2226–2232.

Wapner RJ, Martin CL, Levy B, et al. Chromosomal microarray versus karyotyping for prenatal diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(23):2175–2184.

Genetic screening and testing are a standard part of prenatal care in most developed countries. We have come a long way since a maternal age of 35 years was the only variable separating patients into low- and high-risk categories. This year, two technologies have emerged that may change forever the way we approach prenatal genetics: