User login

UPDATE ON OVARIAN CANCER

- Update on ovarian cancer screening

David G. Mutch, MD; Nora Kizer, MD (July 2010)

A majority of ovarian cancers are diagnosed at an advanced stage, requiring extensive surgical cytoreductive procedures.1 Because the presence of residual macroscopic disease correlates highly with decreased survival,2 these procedures can be lengthy, complicated, and risky for the patient. Many patients who undergo cytoreduction will be left with a suboptimal result despite surgery.

Better identification and improved treatment of patients who are at high risk of a suboptimal result are clearly needed. One treatment option is neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the administration of chemotherapy prior to the main treatment. Although early data suggested that it was associated with worse outcomes, recent studies have yielded new information:

- Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval debulking surgery is not inferior to primary debulking surgery followed by chemotherapy for patients who have bulky stage III or IV ovarian cancer

- In patients who have advanced ovarian cancer, neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgical cytoreduction is associated with improved perioperative outcomes

- Postoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy has not yet proved to be associated with improved survival.

Several questions prompted by these findings include:

- Will neoadjuvant chemotherapy improve surgical outcomes in patients who have advanced ovarian cancer and, thus, improve survival?

- Is neoadjuvant chemotherapy a better strategy for all patients?

- Will neoadjuvant chemotherapy reduce the surgical effort necessary to achieve an optimal result?

- What is the role of intraperitoneal chemotherapy in patients who undergo neoadjuvant chemotherapy?

Further national (or international) data are needed to confirm a survival advantage for patients who receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy, compared with those who undergo primary surgery before the administration of chemotherapy.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is an acceptable alternative to primary surgical cytoreduction

Vergote I, Tropé CG, Amant F, et al; European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Gynaecological Cancer Group; NCIC Clinical Trials Group. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy or primary surgery in stage IIIC or IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(10):943–953.

Historically, the standard of care in ovarian cancer treatment has been surgical cytoreduction followed by chemotherapy.3-6 However, data from prospective randomized trials to support this practice are limited. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is an alternative strategy that has been explored as a way to improve outcomes from interval surgical debulking in patients who have ovarian cancer in whom suboptimal cytoreduction is otherwise expected. Vergote and coworkers attempted to determine which strategy is better through a randomized trial of 632 patients.

Participants had to have biopsy-proven stage IIIc or IV ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer. The two treatment arms were:

- primary debulking surgery followed by at least 6 cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy

- 3 cycles of platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval debulking surgery in responders and those who had stable disease. These patients then received an additional 3 cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy post-operatively.

All surgical procedures were completed by qualified gynecologic oncologists, and all patients were evaluated for eligibility before randomization, with no additional selection criteria.

Postoperative death occurred in 2.5% of patients in the primary-surgery group, compared with 0.7% of patients in the neoadjuvant-chemotherapy group. Grade 3 or 4 hemorrhage occurred in 7.4% of patients after primary debulking, compared with 4.1% of patients after interval debulking. Patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy experienced a lower rate of infection (1.7% versus 8.1%) and venous complications (0% versus 2.6%).

Overall and progression-free survival rates were similar between the two groups. After multivariate analysis, the strongest predictors of survival were absence of residual disease after surgery (P<.001), small tumor size before randomization (P=.001), and endometrioid histology (P=.001)

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is a preferred treatment strategy for patients who are expected to have a suboptimal result after surgery. Because neoadjuvant chemotherapy has a survival outcome similar to that of primary surgery followed by chemotherapy, it may be considered for all patients who have bulky stage IIIc or IV disease.

Although neoadjuvant chemotherapy improves the rate of optimal surgical cytoreduction, data are lacking to demonstrate that this improvement boosts survival.

Administration of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in these patients may improve perioperative morbidity and mortality, although no formal analysis was conducted in this study.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy improves perioperative outcomes

Milam MR, Tao X, Coleman RL, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is associated with prolonged primary treatment intervals in patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21(1):66–71.

Milam and coworkers investigated chemotherapy-associated morbidity and timing in two groups of patients who had advanced epithelial ovarian cancer:

- those undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by maximal cytoreductive surgery

- those undergoing primary surgery followed by chemotherapy.

Their retrospective study involved 263 consecutive patients who were treated at MD Anderson Cancer Center from 1993 to 2005. In this cohort, 47 women (18%) received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. These patients experienced less blood loss (400 mL versus 750 mL) and a shorter hospital stay (6 versus 8 days). Time to the initiation of chemotherapy from the date of diagnosis did not differ between groups, and the amount of residual disease and rate of survival were also similar between arms. However, patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy underwent more cycles of chemotherapy over a longer treatment period.

Although neoadjuvant chemotherapy does not appear to offer a survival advantage, it is equivalent to primary surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy and may be associated with improved perioperative outcomes.

The results of the trial by Vergote and colleagues (page 25), should discourage oncologists from prescribing more than 6 cycles of chemotherapy in the neoadjuvant setting; patients from their study in the neoadjuvant group received a total of 6 cycles and had survival outcomes equivalent to those of women in the primary surgery group.

In the pipeline: Data on intraperitoneal chemotherapy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy

Le T, Latifah H, Jolicoeur L, et al. Does intraperitoneal chemotherapy benefit optimally debulked epithelial ovarian cancer patients after neoadjuvant chemotherapy? Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121(3):451–454.

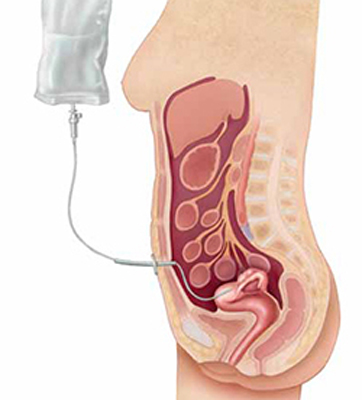

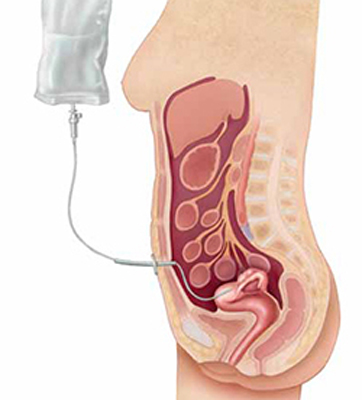

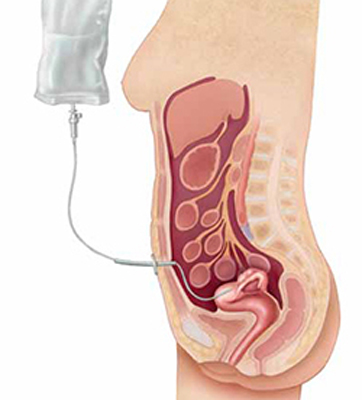

Although several studies have demonstrated that intraperitoneal (IP) chemotherapy provides a survival advantage, compared with intravenous (IV) chemotherapy, after primary surgical debulking, it remains unclear whether IP chemotherapy would provide a similar superior survival outcome following neoadjuvant chemotherapy (FIGURE).

Intraperitoneal chemotherapy: How efficacious?

The jury is still out on whether intraperitoneal chemotherapy improves survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and interval debulking in stages III and IV ovarian cancer.The authors of this paper attempted to answer this question through a retrospective review of 71 patients. All patients were treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval debulking and either IP or IV chemotherapy. Overall, 17 patients (24%) received IP chemotherapy, and 54 patients (76%) received IV chemotherapy. The median number of cycles given prior to and after surgery was the same for both groups (3 for both neoadjuvant chemotherapy and chemotherapy following surgery).

Although patients who received IP chemotherapy had a higher overall response rate (82% versus 67%), there were no differences between groups in terms of progression-free (P=.42) and overall survival (P=.72).

One important limitation of this study was its small sample size and lack of statistical power. In addition, more patients in the IP group had macroscopic residual disease than in the IV group (71% versus 52%; P=.17).

A phase II/III study is under way to evaluate the use of IP chemotherapy following neoadjuvant chemotherapy in ovarian cancer patients.7 The two-stage randomized trial will compare IV chemotherapy with platinum-based IP chemotherapy in women who have undergone optimal surgical debulking (>1 cm) after 3 to 4 cycles of platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy. This study is led by the US National Cancer Institute in collaboration with the Society of Gynecologic Oncologists of Canada, the UK National Cancer Research Institute, the Spanish Ovarian Cancer Research Group, and the US Southwest Oncology Group.

Data are limited on the use of intraperitoneal (IP) chemotherapy following neoadjuvant chemotherapy and interval surgical cytoreduction. We await the results of larger prospective studies to definitively determine whether there is a role for IP chemotherapy in this setting. For now, patients who receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy are limited to IV chemotherapy following surgery.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et all. eds. SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1975-2008. National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2008. Published April 15, 2011. Accessed June 10, 2011.

2. du Bois A, Ruess A, Pujade-Lauraine E, Harter P, Ray-Coquard I, Pfisterer J. Role of surgical outcome as prognostic factor in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: a combined exploratory analysis of 3 prospectively randomized phase 3 multicenter trials; by the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie Studiengruppe Ovarialkarzinom (AGO-OVAR) and the Groupe d’Investigateurs Nationaux Pour les Etudes des Cancers de l’Ovaire (GINECO). Cancer. 2009;115(6):1234-1244.

3. Meigs JV. Tumors of the pelvic organs. New York: Macmillan: 1934.

4. Aure JC, Hoeg K, Kolstad P. Clinical and histologic studies of ovarian carcinoma. Long-term follow-up of 990 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1971;37(1):1-9.

5. Griffiths CT, Fuller AF. Intensive surgical and chemotherapeutic management of advanced ovarian cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 1978;58(1):131-142.

6. du Bois A, Quinn M, Thigpen T, et al. 2004 Consensus statements on the management of ovarian cancer: final document of the 3rd International Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup Ovarian Cancer Consensus Conference (GCIG OCCC 2004). Ann Oncol. 2005;16(suppl 8):viii7-viii12.

7. Mackay HJ, Provencheur D, Heywood M, et al. Phase II/III study of intraperitoneal chemotherapy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for ovarian cancer: ncic ctg ov.21. Curr Oncol. 2011;18(2):84-90.

- Update on ovarian cancer screening

David G. Mutch, MD; Nora Kizer, MD (July 2010)

A majority of ovarian cancers are diagnosed at an advanced stage, requiring extensive surgical cytoreductive procedures.1 Because the presence of residual macroscopic disease correlates highly with decreased survival,2 these procedures can be lengthy, complicated, and risky for the patient. Many patients who undergo cytoreduction will be left with a suboptimal result despite surgery.

Better identification and improved treatment of patients who are at high risk of a suboptimal result are clearly needed. One treatment option is neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the administration of chemotherapy prior to the main treatment. Although early data suggested that it was associated with worse outcomes, recent studies have yielded new information:

- Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval debulking surgery is not inferior to primary debulking surgery followed by chemotherapy for patients who have bulky stage III or IV ovarian cancer

- In patients who have advanced ovarian cancer, neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgical cytoreduction is associated with improved perioperative outcomes

- Postoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy has not yet proved to be associated with improved survival.

Several questions prompted by these findings include:

- Will neoadjuvant chemotherapy improve surgical outcomes in patients who have advanced ovarian cancer and, thus, improve survival?

- Is neoadjuvant chemotherapy a better strategy for all patients?

- Will neoadjuvant chemotherapy reduce the surgical effort necessary to achieve an optimal result?

- What is the role of intraperitoneal chemotherapy in patients who undergo neoadjuvant chemotherapy?

Further national (or international) data are needed to confirm a survival advantage for patients who receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy, compared with those who undergo primary surgery before the administration of chemotherapy.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is an acceptable alternative to primary surgical cytoreduction

Vergote I, Tropé CG, Amant F, et al; European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Gynaecological Cancer Group; NCIC Clinical Trials Group. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy or primary surgery in stage IIIC or IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(10):943–953.

Historically, the standard of care in ovarian cancer treatment has been surgical cytoreduction followed by chemotherapy.3-6 However, data from prospective randomized trials to support this practice are limited. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is an alternative strategy that has been explored as a way to improve outcomes from interval surgical debulking in patients who have ovarian cancer in whom suboptimal cytoreduction is otherwise expected. Vergote and coworkers attempted to determine which strategy is better through a randomized trial of 632 patients.

Participants had to have biopsy-proven stage IIIc or IV ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer. The two treatment arms were:

- primary debulking surgery followed by at least 6 cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy

- 3 cycles of platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval debulking surgery in responders and those who had stable disease. These patients then received an additional 3 cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy post-operatively.

All surgical procedures were completed by qualified gynecologic oncologists, and all patients were evaluated for eligibility before randomization, with no additional selection criteria.

Postoperative death occurred in 2.5% of patients in the primary-surgery group, compared with 0.7% of patients in the neoadjuvant-chemotherapy group. Grade 3 or 4 hemorrhage occurred in 7.4% of patients after primary debulking, compared with 4.1% of patients after interval debulking. Patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy experienced a lower rate of infection (1.7% versus 8.1%) and venous complications (0% versus 2.6%).

Overall and progression-free survival rates were similar between the two groups. After multivariate analysis, the strongest predictors of survival were absence of residual disease after surgery (P<.001), small tumor size before randomization (P=.001), and endometrioid histology (P=.001)

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is a preferred treatment strategy for patients who are expected to have a suboptimal result after surgery. Because neoadjuvant chemotherapy has a survival outcome similar to that of primary surgery followed by chemotherapy, it may be considered for all patients who have bulky stage IIIc or IV disease.

Although neoadjuvant chemotherapy improves the rate of optimal surgical cytoreduction, data are lacking to demonstrate that this improvement boosts survival.

Administration of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in these patients may improve perioperative morbidity and mortality, although no formal analysis was conducted in this study.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy improves perioperative outcomes

Milam MR, Tao X, Coleman RL, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is associated with prolonged primary treatment intervals in patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21(1):66–71.

Milam and coworkers investigated chemotherapy-associated morbidity and timing in two groups of patients who had advanced epithelial ovarian cancer:

- those undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by maximal cytoreductive surgery

- those undergoing primary surgery followed by chemotherapy.

Their retrospective study involved 263 consecutive patients who were treated at MD Anderson Cancer Center from 1993 to 2005. In this cohort, 47 women (18%) received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. These patients experienced less blood loss (400 mL versus 750 mL) and a shorter hospital stay (6 versus 8 days). Time to the initiation of chemotherapy from the date of diagnosis did not differ between groups, and the amount of residual disease and rate of survival were also similar between arms. However, patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy underwent more cycles of chemotherapy over a longer treatment period.

Although neoadjuvant chemotherapy does not appear to offer a survival advantage, it is equivalent to primary surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy and may be associated with improved perioperative outcomes.

The results of the trial by Vergote and colleagues (page 25), should discourage oncologists from prescribing more than 6 cycles of chemotherapy in the neoadjuvant setting; patients from their study in the neoadjuvant group received a total of 6 cycles and had survival outcomes equivalent to those of women in the primary surgery group.

In the pipeline: Data on intraperitoneal chemotherapy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy

Le T, Latifah H, Jolicoeur L, et al. Does intraperitoneal chemotherapy benefit optimally debulked epithelial ovarian cancer patients after neoadjuvant chemotherapy? Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121(3):451–454.

Although several studies have demonstrated that intraperitoneal (IP) chemotherapy provides a survival advantage, compared with intravenous (IV) chemotherapy, after primary surgical debulking, it remains unclear whether IP chemotherapy would provide a similar superior survival outcome following neoadjuvant chemotherapy (FIGURE).

Intraperitoneal chemotherapy: How efficacious?

The jury is still out on whether intraperitoneal chemotherapy improves survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and interval debulking in stages III and IV ovarian cancer.The authors of this paper attempted to answer this question through a retrospective review of 71 patients. All patients were treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval debulking and either IP or IV chemotherapy. Overall, 17 patients (24%) received IP chemotherapy, and 54 patients (76%) received IV chemotherapy. The median number of cycles given prior to and after surgery was the same for both groups (3 for both neoadjuvant chemotherapy and chemotherapy following surgery).

Although patients who received IP chemotherapy had a higher overall response rate (82% versus 67%), there were no differences between groups in terms of progression-free (P=.42) and overall survival (P=.72).

One important limitation of this study was its small sample size and lack of statistical power. In addition, more patients in the IP group had macroscopic residual disease than in the IV group (71% versus 52%; P=.17).

A phase II/III study is under way to evaluate the use of IP chemotherapy following neoadjuvant chemotherapy in ovarian cancer patients.7 The two-stage randomized trial will compare IV chemotherapy with platinum-based IP chemotherapy in women who have undergone optimal surgical debulking (>1 cm) after 3 to 4 cycles of platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy. This study is led by the US National Cancer Institute in collaboration with the Society of Gynecologic Oncologists of Canada, the UK National Cancer Research Institute, the Spanish Ovarian Cancer Research Group, and the US Southwest Oncology Group.

Data are limited on the use of intraperitoneal (IP) chemotherapy following neoadjuvant chemotherapy and interval surgical cytoreduction. We await the results of larger prospective studies to definitively determine whether there is a role for IP chemotherapy in this setting. For now, patients who receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy are limited to IV chemotherapy following surgery.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

- Update on ovarian cancer screening

David G. Mutch, MD; Nora Kizer, MD (July 2010)

A majority of ovarian cancers are diagnosed at an advanced stage, requiring extensive surgical cytoreductive procedures.1 Because the presence of residual macroscopic disease correlates highly with decreased survival,2 these procedures can be lengthy, complicated, and risky for the patient. Many patients who undergo cytoreduction will be left with a suboptimal result despite surgery.

Better identification and improved treatment of patients who are at high risk of a suboptimal result are clearly needed. One treatment option is neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the administration of chemotherapy prior to the main treatment. Although early data suggested that it was associated with worse outcomes, recent studies have yielded new information:

- Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval debulking surgery is not inferior to primary debulking surgery followed by chemotherapy for patients who have bulky stage III or IV ovarian cancer

- In patients who have advanced ovarian cancer, neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgical cytoreduction is associated with improved perioperative outcomes

- Postoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy has not yet proved to be associated with improved survival.

Several questions prompted by these findings include:

- Will neoadjuvant chemotherapy improve surgical outcomes in patients who have advanced ovarian cancer and, thus, improve survival?

- Is neoadjuvant chemotherapy a better strategy for all patients?

- Will neoadjuvant chemotherapy reduce the surgical effort necessary to achieve an optimal result?

- What is the role of intraperitoneal chemotherapy in patients who undergo neoadjuvant chemotherapy?

Further national (or international) data are needed to confirm a survival advantage for patients who receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy, compared with those who undergo primary surgery before the administration of chemotherapy.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is an acceptable alternative to primary surgical cytoreduction

Vergote I, Tropé CG, Amant F, et al; European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Gynaecological Cancer Group; NCIC Clinical Trials Group. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy or primary surgery in stage IIIC or IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(10):943–953.

Historically, the standard of care in ovarian cancer treatment has been surgical cytoreduction followed by chemotherapy.3-6 However, data from prospective randomized trials to support this practice are limited. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is an alternative strategy that has been explored as a way to improve outcomes from interval surgical debulking in patients who have ovarian cancer in whom suboptimal cytoreduction is otherwise expected. Vergote and coworkers attempted to determine which strategy is better through a randomized trial of 632 patients.

Participants had to have biopsy-proven stage IIIc or IV ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer. The two treatment arms were:

- primary debulking surgery followed by at least 6 cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy

- 3 cycles of platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval debulking surgery in responders and those who had stable disease. These patients then received an additional 3 cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy post-operatively.

All surgical procedures were completed by qualified gynecologic oncologists, and all patients were evaluated for eligibility before randomization, with no additional selection criteria.

Postoperative death occurred in 2.5% of patients in the primary-surgery group, compared with 0.7% of patients in the neoadjuvant-chemotherapy group. Grade 3 or 4 hemorrhage occurred in 7.4% of patients after primary debulking, compared with 4.1% of patients after interval debulking. Patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy experienced a lower rate of infection (1.7% versus 8.1%) and venous complications (0% versus 2.6%).

Overall and progression-free survival rates were similar between the two groups. After multivariate analysis, the strongest predictors of survival were absence of residual disease after surgery (P<.001), small tumor size before randomization (P=.001), and endometrioid histology (P=.001)

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is a preferred treatment strategy for patients who are expected to have a suboptimal result after surgery. Because neoadjuvant chemotherapy has a survival outcome similar to that of primary surgery followed by chemotherapy, it may be considered for all patients who have bulky stage IIIc or IV disease.

Although neoadjuvant chemotherapy improves the rate of optimal surgical cytoreduction, data are lacking to demonstrate that this improvement boosts survival.

Administration of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in these patients may improve perioperative morbidity and mortality, although no formal analysis was conducted in this study.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy improves perioperative outcomes

Milam MR, Tao X, Coleman RL, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is associated with prolonged primary treatment intervals in patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21(1):66–71.

Milam and coworkers investigated chemotherapy-associated morbidity and timing in two groups of patients who had advanced epithelial ovarian cancer:

- those undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by maximal cytoreductive surgery

- those undergoing primary surgery followed by chemotherapy.

Their retrospective study involved 263 consecutive patients who were treated at MD Anderson Cancer Center from 1993 to 2005. In this cohort, 47 women (18%) received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. These patients experienced less blood loss (400 mL versus 750 mL) and a shorter hospital stay (6 versus 8 days). Time to the initiation of chemotherapy from the date of diagnosis did not differ between groups, and the amount of residual disease and rate of survival were also similar between arms. However, patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy underwent more cycles of chemotherapy over a longer treatment period.

Although neoadjuvant chemotherapy does not appear to offer a survival advantage, it is equivalent to primary surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy and may be associated with improved perioperative outcomes.

The results of the trial by Vergote and colleagues (page 25), should discourage oncologists from prescribing more than 6 cycles of chemotherapy in the neoadjuvant setting; patients from their study in the neoadjuvant group received a total of 6 cycles and had survival outcomes equivalent to those of women in the primary surgery group.

In the pipeline: Data on intraperitoneal chemotherapy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy

Le T, Latifah H, Jolicoeur L, et al. Does intraperitoneal chemotherapy benefit optimally debulked epithelial ovarian cancer patients after neoadjuvant chemotherapy? Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121(3):451–454.

Although several studies have demonstrated that intraperitoneal (IP) chemotherapy provides a survival advantage, compared with intravenous (IV) chemotherapy, after primary surgical debulking, it remains unclear whether IP chemotherapy would provide a similar superior survival outcome following neoadjuvant chemotherapy (FIGURE).

Intraperitoneal chemotherapy: How efficacious?

The jury is still out on whether intraperitoneal chemotherapy improves survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and interval debulking in stages III and IV ovarian cancer.The authors of this paper attempted to answer this question through a retrospective review of 71 patients. All patients were treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval debulking and either IP or IV chemotherapy. Overall, 17 patients (24%) received IP chemotherapy, and 54 patients (76%) received IV chemotherapy. The median number of cycles given prior to and after surgery was the same for both groups (3 for both neoadjuvant chemotherapy and chemotherapy following surgery).

Although patients who received IP chemotherapy had a higher overall response rate (82% versus 67%), there were no differences between groups in terms of progression-free (P=.42) and overall survival (P=.72).

One important limitation of this study was its small sample size and lack of statistical power. In addition, more patients in the IP group had macroscopic residual disease than in the IV group (71% versus 52%; P=.17).

A phase II/III study is under way to evaluate the use of IP chemotherapy following neoadjuvant chemotherapy in ovarian cancer patients.7 The two-stage randomized trial will compare IV chemotherapy with platinum-based IP chemotherapy in women who have undergone optimal surgical debulking (>1 cm) after 3 to 4 cycles of platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy. This study is led by the US National Cancer Institute in collaboration with the Society of Gynecologic Oncologists of Canada, the UK National Cancer Research Institute, the Spanish Ovarian Cancer Research Group, and the US Southwest Oncology Group.

Data are limited on the use of intraperitoneal (IP) chemotherapy following neoadjuvant chemotherapy and interval surgical cytoreduction. We await the results of larger prospective studies to definitively determine whether there is a role for IP chemotherapy in this setting. For now, patients who receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy are limited to IV chemotherapy following surgery.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et all. eds. SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1975-2008. National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2008. Published April 15, 2011. Accessed June 10, 2011.

2. du Bois A, Ruess A, Pujade-Lauraine E, Harter P, Ray-Coquard I, Pfisterer J. Role of surgical outcome as prognostic factor in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: a combined exploratory analysis of 3 prospectively randomized phase 3 multicenter trials; by the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie Studiengruppe Ovarialkarzinom (AGO-OVAR) and the Groupe d’Investigateurs Nationaux Pour les Etudes des Cancers de l’Ovaire (GINECO). Cancer. 2009;115(6):1234-1244.

3. Meigs JV. Tumors of the pelvic organs. New York: Macmillan: 1934.

4. Aure JC, Hoeg K, Kolstad P. Clinical and histologic studies of ovarian carcinoma. Long-term follow-up of 990 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1971;37(1):1-9.

5. Griffiths CT, Fuller AF. Intensive surgical and chemotherapeutic management of advanced ovarian cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 1978;58(1):131-142.

6. du Bois A, Quinn M, Thigpen T, et al. 2004 Consensus statements on the management of ovarian cancer: final document of the 3rd International Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup Ovarian Cancer Consensus Conference (GCIG OCCC 2004). Ann Oncol. 2005;16(suppl 8):viii7-viii12.

7. Mackay HJ, Provencheur D, Heywood M, et al. Phase II/III study of intraperitoneal chemotherapy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for ovarian cancer: ncic ctg ov.21. Curr Oncol. 2011;18(2):84-90.

1. Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et all. eds. SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1975-2008. National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2008. Published April 15, 2011. Accessed June 10, 2011.

2. du Bois A, Ruess A, Pujade-Lauraine E, Harter P, Ray-Coquard I, Pfisterer J. Role of surgical outcome as prognostic factor in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: a combined exploratory analysis of 3 prospectively randomized phase 3 multicenter trials; by the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie Studiengruppe Ovarialkarzinom (AGO-OVAR) and the Groupe d’Investigateurs Nationaux Pour les Etudes des Cancers de l’Ovaire (GINECO). Cancer. 2009;115(6):1234-1244.

3. Meigs JV. Tumors of the pelvic organs. New York: Macmillan: 1934.

4. Aure JC, Hoeg K, Kolstad P. Clinical and histologic studies of ovarian carcinoma. Long-term follow-up of 990 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1971;37(1):1-9.

5. Griffiths CT, Fuller AF. Intensive surgical and chemotherapeutic management of advanced ovarian cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 1978;58(1):131-142.

6. du Bois A, Quinn M, Thigpen T, et al. 2004 Consensus statements on the management of ovarian cancer: final document of the 3rd International Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup Ovarian Cancer Consensus Conference (GCIG OCCC 2004). Ann Oncol. 2005;16(suppl 8):viii7-viii12.

7. Mackay HJ, Provencheur D, Heywood M, et al. Phase II/III study of intraperitoneal chemotherapy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for ovarian cancer: ncic ctg ov.21. Curr Oncol. 2011;18(2):84-90.

How much vitamin D should you recommend to your nonpregnant patients?

No question: Vitamin D plays a vital role in bone health. In recent years, the possibility that it plays a role in other aspects of health has prompted considerable speculation, fueled by both widespread media coverage and dissemination of conflicting information about the potential nonskeletal benefits of high-dose vitamin D supplementation. Controversy has emerged about:

- the appropriate criteria for defining vitamin D deficiency

- the extent to which vitamin D influences nonskeletal health conditions

- the optimal level of vitamin D supplementation.

In 2010, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released a report that provided recommendations for vitamin D intake, which were also summarized in a recent article for clinicians.1,2 The IOM report provided much-needed clinical guidance, but it has also fueled additional questions.

This article describes the IOM recommendations, explains what we know now about the effect of vitamin D on various health outcomes, and offers concrete recommendations on vitamin D measurement, intake, and supplementation.

How the Institute of Medicine formulated its recommendations

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) committee conducted a comprehensive review of the literature to date on the relationship between vitamin D (and calcium) intake and several health outcomes. In terms of skeletal health, the IOM committee concluded that a 25OHD level of at least 20 ng/mL is sufficient to meet the needs of at least 97.5% of the population. The vitamin D intake thought to be necessary to achieve this 25OHD level for at least 97.5% of the population was provided for different age groups (TABLE 2).

The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) of vitamin D is 600 IU daily for all adults up to age 70 years, and 800 IU daily for adults older than 70 years. These values were based on an assumption of minimal sun exposure, due to wide variability in vitamin D synthesis from ultraviolet light, as well as the risk of skin cancer. The IOM concluded that there is no compelling evidence that a 25OHD level above 20 ng/mL or a vitamin D intake greater than 600 IU (800Â IU for adults over 70) affords greater skeletal or nonskeletal benefits.

The IOM recommendations were based on the integration of bone health outcomes. The evidence supporting causal relationships between vitamin D insufficiency and nonskeletal outcomes such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, impaired physical performance, autoimmune disorders, and other chronic diseases was found to be inconsistent and inconclusive.

The IOM report also noted the emergence of a “U”-shaped curve in regard to vitamin D and several health outcomes, which has fueled concern about attainment of a 25OHD level above 50 ng/mL. The IOM committee designated 4,000 IU daily as the tolerable upper intake but emphasized that research into long-term outcomes and safety at intakes above the RDA is limited. Therefore, this upper limit should not be interpreted as a target intake level.

How is vitamin D metabolized?

Vitamin D is produced endogenously in the skin in the form of vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol). It also can be ingested exogenously in the form of vitamin D3 or vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol). Cutaneous synthesis of vitamin D is stimulated by solar ultraviolet radiation.

Vitamin D2 and D3 are hydroxylated in the liver to form 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD). Measurement of the serum 25OHD level is thought to be the most reliable indicator of vitamin D exposure.3 25OHD is hydroxylated again, primarily in the kidneys, to the most active form of vitamin D (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D).

The adverse skeletal effects of severe vitamin D deficiency are well established; those effects include calcium malabsorption, secondary hyperparathyroidism, bone loss, and increased risk of fracture. In this setting, secondary hyperparathyroidism results from both decreased gastrointestinal calcium absorption and decreased suppression of parathyroid hormone (PTH) production by the parathyroid glands from vitamin D metabolites. Secondary hyperparathyroidism leads to increased bone resorption and bone loss. Rickets, osteomalacia, hypocalcemia, hypophosphatemia, muscle weakness, and bone pain are less common effects that can occur with severe vitamin D deficiency.

It is worth noting that women of color are at increased risk of vitamin D deficiency as a result of greater skin pigmentation.3 Obesity is also a risk factor for vitamin D deficiency.3 Additional risk factors for vitamin D insufficiency are listed in TABLE 1.

TABLE 1

Risk factors for vitamin D insufficiency

| Obesity |

| Dark skin pigmentation |

Decreased sun exposure

|

| Low dietary intake of vitamin D |

| Malabsorption of ingested vitamin D |

Increased hepatic degradation of 25-hydroxyvitamin D

|

| Decreased hepatic hydroxylation of vitamin D (occurs only with severe hepatic disease) |

| Impaired renal hydroxylation of vitamin D (renal insufficiency) |

| Osteoporosis or osteopenia |

How should vitamin D insufficiency be defined?

Biochemical criteria for defining vitamin D insufficiency vary. That makes it difficult to estimate the prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency.

Severe vitamin D deficiency is commonly defined as a serum 25OHD level below 10 ng/mL.3 Vitamin D insufficiency has been variably defined as a serum 25OHD level below 20 to 32 ng/mL,3,4 and the lower limit of normal in most clinical laboratories is now typically 30 to 32 ng/mL. Many patients become concerned when their serum 25OHD level is flagged as “low” on a laboratory report, and it’s likely that you are called on from time to time to interpret and make recommendations about the appropriate response to this “abnormal” finding.

The broad definition of vitamin D insufficiency stems, in part, from the assessment of a wide range of outcomes. Measures that have been used include fracture risk, calcium absorptive capacity, and the serum concentration of PTH. In regard to calcium absorption, most studies suggest that maximal dietary calcium absorption occurs when the 25OHD level reaches 20 ng/mL, although some studies suggest a higher threshold.1,3

The optimal level of 25OHD for PTH suppression remains unclear. Several studies have suggested that the PTH level increases when the 25OHD concentration falls below 30 ng/mL,4,5 although this threshold has varied substantially across studies.6

How prevalent is vitamin D insufficiency?

Estimates of the prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency vary by the criteria used to define the condition. A recent report using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) estimated that approximately 30% of US adults 20 years of age or older have a 25OHD level below 20Â ng/mL, and more than 70% of this age group has a 25OHD level below 32 ng/mL.7

The IOM committee noted that several reports have most likely overestimated the prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency through the use of 25OHD cut points higher than 20Â ng/mL.

The data on vitamin D insufficiency and skeletal health

Many studies have examined the relationship between vitamin D supplementation or the 25OHD level and fracture risk, and conflicting results have emerged. Many trials have examined the combination of calcium and vitamin D supplementation, the effects of which are tightly interwoven, confounding interpretation.

Interpretation of large observational studies is further confounded by the inability to attribute association to causation. In the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study of calcium with vitamin D, treatment of healthy postmenopausal women with 1,000 mg of calcium and 400 IU of vitamin D daily led to improved bone density at the hip but no statistically significant reduction in hip fracture.8 However, a reduced risk of hip fracture was demonstrated in secondary analyses among women who adhered to treatment and among women 60 years or older. Meta-analyses of clinical trials have reported that treatment with varying doses of vitamin D (more than 400 IU daily) reduces the risk of vertebral,9 nonvertebral,10 and hip fractures.10

Several studies have examined the relationship between the 25OHD level and fracture risk, with inconsistent findings:

- A nested case-control study from the WHI found that the risk of hip fracture was significantly increased among postmenopausal women who had a 25OHD level of 19 ng/mL or lower.11

- A 2009 report from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) concluded that the association between the 25OHD level and the risk of fracture was inconsistent.12

After a comprehensive review of the available research, the IOM committee concluded that a serum 25OHD level of 20 ng/mL would meet the needs for bone health for at least 97.5% of the US and Canadian populations.

TABLE 2

Calcium and vitamin D dietary reference intakes for adults, by life stage

| Life stage (gender) | Calcium | Vitamin D | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RDA (mg/d) | Tolerable upper intake level (mg/d)* | RDA (IU/d) | Serum 25OHD level (ng/mL) (corresponding to the RDA)† | Tolerable upper intake level (IU/d)* | |

| 19–50 yr (male and female) | 1,000 | 2,500 | 600 | 20 | 4,000 |

| 51–70 yr (male) | 1,000 | 2,000 | 600 | 20 | 4,000 |

| 51–70 yr (female) | 1,200 | 2,000 | 600 | 20 | 4,000 |

| 71+ yr (male and female) | 1,200 | 2,000 | 800 | 20 | 4,000 |

| Adapted from: Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(1):53–58. RDA = Recommended Dietary Allowance, 25OHD=25-hydroxyvitamin D * The tolerable upper intake level is the threshold above which is a risk of adverse events. The upper intake level is not intended to be a target intake. There is no consistent evidence of greater benefit at intake levels above the RDA. The serum 25OHD level corresponding to the upper intake level is 50 ng/mL. † Measures of the serum 25OHD level corresponding to the RDA and covering the requirements of at least 97.5% of the population. | |||||

The data on vitamin D insufficiency and nonskeletal outcomes

Many observational studies have reported relationships between vitamin D insufficiency and myriad nonskeletal health outcomes, particularly cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, and autoimmune disorders.3 However, well-designed randomized clinical trials that examine nonskeletal outcomes as primary pre-specified outcomes are lacking.13 Such studies will be essential to elucidate the relationship between vitamin D insufficiency and nonskeletal chronic diseases. The VITamin D and OmegA-3 TriaL (VITAL) is an ongoing large-scale, randomized clinical trial designed to evaluate the role of supplementation with 2,000 IU of vitamin D3 daily in the primary prevention of cancer and cardiovascular disease.14

- Vitamin D plays a vital role in bone health

- The Institute of Medicine released a 2010 report that provided public health recommendations for vitamin D intake based on bone health outcomes

- Many observational studies have reported a relationship between vitamin D insufficiency and adverse nonskeletal health outcomes, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, and autoimmune disorders, but evidence from randomized clinical trials on the potential nonskeletal benefits of vitamin D is sparse

- Excessive vitamin D intake should be avoided because of the potential for harm and the lack of evidence from well-designed clinical trials that vitamin D intake beyond the recommended amount affords greater skeletal or nonskeletal health benefits

- Among women who have an increased risk of vitamin D insufficiency or bone loss, 25OHD concentration should be measured and vitamin D supplementation should be provided as necessary to achieve the target 25OHD level

What we recommend for treatment

The IOM report provided the medical community with evidence-based recommendations for vitamin D intake at the population level, based on a public health perspective.1,2 However, the public health guideline model must be distinguished from the medical model, in which shared clinical decision-making between physician and patient occurs on an individual level and is informed by individual clinical risk factors. The public health recommendations detailed in the IOM report are not intended to replace or interfere with clinical judgment or preclude individualized clinical decision-making.

The debate over optimal levels of vitamin D supplementation for individual patients who have osteoporosis or other health conditions continues.15 Here, we provide general guidelines for treatment, based on the evidence available to date.

Clear benefits of vitamin D in bone health notwithstanding, advise your patients to avoid excessive intake because it can cause harm. See “More is not necessarily better”.

Recommendations for healthy adult nonpregnant women

Vitamin D intake: We recommend a daily vitamin D intake of 600 IU for healthy nonpregnant women up to age 70 years (and 800 Â IU daily for women older than 70 years) who are at average risk of vitamin D insufficiency and bone loss, consistent with the IOM recommendations. The IOM guidelines assume minimal to no sun exposure.

Measurement of 25OHD: It is not necessary to routinely measure the 25OHD level in these women. However, it is prudent to measure 25OHD in women who have risk factors for vitamin D insufficiency (TABLE 1) or a clinical condition associated with severe vitamin D deficiency. In these cases, if the 25OHD level is found to be below 20 ng/mL, vitamin D therapy should be initiated, with the goal of boosting the 25OHD level above the threshold of 20 ng/mL.

Treatment of vitamin D insufficiency: Options include daily vitamin D supplementation and higher-dose weekly preparations.

Many clinicians treat severe vitamin D insufficiency with 50,000 IU of vitamin D2 once weekly for 8 weeks, followed by a maintenance dose (described below) of vitamin D to preserve the target 25OHD level.5 An alternative is daily vitamin D supplementation, with the dosage based on the degree of insufficiency.

A general rule of thumb, for persons who have normal vitamin D absorption, is that every 1,000 IU of vitamin D3 ingested daily increases the 25OHD level by approximately 6 to 10 ng/mL.4,16 However, the incremental increase in the 25OHD concentration varies among individuals, depending on the baseline 25OHD level, with a greater incremental increase occurring at lower baseline 25OHD levels.

Monitoring of the 25OHD level after adjustment of the dosage is necessary to ensure that the target level is achieved.

Maintaining an adequate vitamin D level: Once vitamin D insufficiency has been corrected, a maintenance dosage of vitamin D should be selected—commonly 800 to 1,000 Â IU daily. A higher maintenance dosage may be required for persons who have genetic or ongoing environmental factors that predispose them to vitamin D insufficiency.

Vitamin D3 is reportedly more potent than D2 in increasing the 25OHD level,17 although this finding has not been universal.18 Monthly or twice-monthly administration of 50,000 IU of vitamin D2 is another option for maintenance of vitamin D sufficiency,5,16 although daily doses are more commonly used and are readily available in over-the-counter preparations.

Regardless of the regimen selected, the 25OHD level should be measured again approximately 3 months after a change in dosage to ensure that the target level has been achieved, with further dosage adjustments as indicated.

Recommendations for adult women at increased risk of skeletal disease

Measurement of 25OHD: The 25OHD level should be measured among women at increased risk of vitamin D insufficiency, bone loss, or fracture and among women who have established skeletal disease.

Vitamin D intake: We recommend that women at increased risk of osteoporosis and women older than 70 years receive at least 800 IU daily and, potentially, more if necessary to achieve the target 25OHD level.

Although the evidence to date does not support routine achievement of a 25OHD level substantially above 20 ng/mL in most women, many clinicians recommend that women in this higher-risk group maintain a 25OHD level above 30 ng/mL because of the possibly greater (although unproven) skeletal and nonskeletal benefits. As more data become available regarding the benefits and safety of vitamin D doses higher than those recommended by the IOM, these recommendations may be revised.

In 2010, the National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) recommended a vitamin D intake of 800 to 1,000 IU daily for all adults 50 years and older. Among persons at risk of deficiency, the NOF also recommended measurement of the serum 25OHD level, with vitamin D supplementation, as necessary, to achieve a 25OHD level of 30 ng/mL or higher.19 Also in 2010, the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) recommended a target 25OHD level above 30 ng/mL for all older adults. The IOF also estimated that the average dosage required to achieve this level in older adults is 800 to 1,000 IU daily, noting that upward adjustment may be required in some people.4 It is unclear whether these guidelines will be revised in the future, based on the IOM report.

We recommend against achieving a 25OHD level above 50 ng/mL, based on evidence suggesting potential adverse health effects above this level.

Excessive vitamin D intake should be avoided because of the potential for harm and the lack of evidence from well-designed clinical trials that vitamin D intake beyond the currently recommended amount affords greater skeletal or nonskeletal health benefits. Although moderate vitamin D supplementation has proven skeletal benefits, a “U-shaped” curve for some outcomes has emerged, suggesting that excessive vitamin D supplementation may pose health risks. Notably, a recent clinical trial reported a higher risk of fracture (and falls) among elderly women treated annually with high-dose (500,000 IU) oral vitamin D3 versus placebo.20

A suggestion of adverse effects associated with 25OHD levels above 50 ng/mL has also emerged, from observational studies, for several nonskeletal health outcomes, including pancreatic cancer,21 cardiovascular disease,1 and all-cause mortality.22

Limited evidence is available regarding the safety and overall risk-benefit profile of long-term maintenance of 25OHD levels above the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) range. Therefore, you should remind your patients that, despite the importance of both prevention and treatment of vitamin D insufficiency, more is not necessarily better.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Institute of Medicine. 2011 Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2011.

2. Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, et al. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(1):53-58.

3. Rosen CJ. Clinical practice. Vitamin D insufficiency. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(3):248-254.

4. Dawson-Hughes B, Mithal A, Bonjour JP, et al. IOF position statement: vitamin D recommendations for older adults. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21(7):1151-1154.

5. Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(3):266-281.

6. Sai AJ, Walters RW, Fang X, Gallagher JC. Relationship between vitamin D parathyroid hormone, and bone health. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(3):E436-446.

7. Yetley EA. Assessing the vitamin D status of the US population. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(2):558S-564S.

8. Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, Gass M, et al. Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of fractures. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(7):669-683.

9. Papadimitropoulos E, Wells G, Shea B, et al. Osteoporosis Methodology Group and The Osteoporosis Research Advisory Group. Meta-analyses of therapies for postmenopausal osteoporosis. VIII: Meta-analysis of the efficacy of vitamin D treatment in preventing osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Endocr Rev. 2002;23(4):560-569.

10. Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Willett WC, Wong JB, et al. Prevention of nonvertebral fractures with oral vitamin D and dose dependency: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(6):551-561.

11. Cauley JA, Lacroix AZ, Wu L, et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations and risk for hip fractures. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(4):242-250.

12. Chung M, Balk EM, Brendel M, et al. Vitamin D and calcium: a systematic review of health outcomes. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2009;(183):1-420.

13. Manson JE, Mayne ST, Clinton SK. Vitamin D and prevention of cancer—ready for prime time? N Engl J Med. 2011;364(15):1385-1387.

14. Manson JE. Vitamin D and the heart: why we need large-scale clinical trials. Cleve Clin J Med. 2010;77(12):903-910.

15. The Forum at Harvard School of Public Health. Boosting Vitamin D: Not enough or too much? The Andelot Series on Current Science Controversies. http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/forum/boosting-vitamin-d-not-enough-or-too-much.cfm. Published March 29 2011. Accessed April 22, 2011.

16. Binkley N, Gemar D, Engelke J, et al. Evaluation of ergocalciferol or cholecalciferol dosing, 1,600 IU daily or 50,000 IU monthly in older adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(4):981-988.

17. Heaney RP, Recker RR, Grote J, Horst RL, Armas LA. Vitamin D(3) is more potent than vitamin D(2) in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(3):E447-452.

18. Holick MF, Biancuzzo RM, Chen TC, et al. Vitamin D2 is as effective as vitamin D3 in maintaining circulating concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(3):677-681.

19. National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Washington DC: National Osteoporosis Foundation; 2010. http://www.nof.org/professionals/clinical-guidelines. Accessed June 7, 2011.

20. Sanders KM, Stuart AL, Williamson EJ, et al. Annual high-dose oral vitamin D and falls and fractures in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;303(18):1815-1822.

21. Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ, Jacobs EJ, Arslan AA, et al. Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D and risk of pancreatic cancer: Cohort Consortium Vitamin D Pooling Project of Rarer Cancers. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(1):81-93.

22. Melamed ML, Michos ED, Post W, Astor B. 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and the risk of mortality in the general population. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(15):1629-1637.

No question: Vitamin D plays a vital role in bone health. In recent years, the possibility that it plays a role in other aspects of health has prompted considerable speculation, fueled by both widespread media coverage and dissemination of conflicting information about the potential nonskeletal benefits of high-dose vitamin D supplementation. Controversy has emerged about:

- the appropriate criteria for defining vitamin D deficiency

- the extent to which vitamin D influences nonskeletal health conditions

- the optimal level of vitamin D supplementation.

In 2010, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released a report that provided recommendations for vitamin D intake, which were also summarized in a recent article for clinicians.1,2 The IOM report provided much-needed clinical guidance, but it has also fueled additional questions.

This article describes the IOM recommendations, explains what we know now about the effect of vitamin D on various health outcomes, and offers concrete recommendations on vitamin D measurement, intake, and supplementation.

How the Institute of Medicine formulated its recommendations

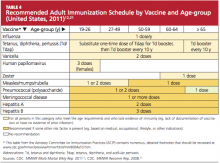

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) committee conducted a comprehensive review of the literature to date on the relationship between vitamin D (and calcium) intake and several health outcomes. In terms of skeletal health, the IOM committee concluded that a 25OHD level of at least 20 ng/mL is sufficient to meet the needs of at least 97.5% of the population. The vitamin D intake thought to be necessary to achieve this 25OHD level for at least 97.5% of the population was provided for different age groups (TABLE 2).

The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) of vitamin D is 600 IU daily for all adults up to age 70 years, and 800 IU daily for adults older than 70 years. These values were based on an assumption of minimal sun exposure, due to wide variability in vitamin D synthesis from ultraviolet light, as well as the risk of skin cancer. The IOM concluded that there is no compelling evidence that a 25OHD level above 20 ng/mL or a vitamin D intake greater than 600 IU (800Â IU for adults over 70) affords greater skeletal or nonskeletal benefits.

The IOM recommendations were based on the integration of bone health outcomes. The evidence supporting causal relationships between vitamin D insufficiency and nonskeletal outcomes such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, impaired physical performance, autoimmune disorders, and other chronic diseases was found to be inconsistent and inconclusive.

The IOM report also noted the emergence of a “U”-shaped curve in regard to vitamin D and several health outcomes, which has fueled concern about attainment of a 25OHD level above 50 ng/mL. The IOM committee designated 4,000 IU daily as the tolerable upper intake but emphasized that research into long-term outcomes and safety at intakes above the RDA is limited. Therefore, this upper limit should not be interpreted as a target intake level.

How is vitamin D metabolized?

Vitamin D is produced endogenously in the skin in the form of vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol). It also can be ingested exogenously in the form of vitamin D3 or vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol). Cutaneous synthesis of vitamin D is stimulated by solar ultraviolet radiation.

Vitamin D2 and D3 are hydroxylated in the liver to form 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD). Measurement of the serum 25OHD level is thought to be the most reliable indicator of vitamin D exposure.3 25OHD is hydroxylated again, primarily in the kidneys, to the most active form of vitamin D (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D).

The adverse skeletal effects of severe vitamin D deficiency are well established; those effects include calcium malabsorption, secondary hyperparathyroidism, bone loss, and increased risk of fracture. In this setting, secondary hyperparathyroidism results from both decreased gastrointestinal calcium absorption and decreased suppression of parathyroid hormone (PTH) production by the parathyroid glands from vitamin D metabolites. Secondary hyperparathyroidism leads to increased bone resorption and bone loss. Rickets, osteomalacia, hypocalcemia, hypophosphatemia, muscle weakness, and bone pain are less common effects that can occur with severe vitamin D deficiency.

It is worth noting that women of color are at increased risk of vitamin D deficiency as a result of greater skin pigmentation.3 Obesity is also a risk factor for vitamin D deficiency.3 Additional risk factors for vitamin D insufficiency are listed in TABLE 1.

TABLE 1

Risk factors for vitamin D insufficiency

| Obesity |

| Dark skin pigmentation |

Decreased sun exposure

|

| Low dietary intake of vitamin D |

| Malabsorption of ingested vitamin D |

Increased hepatic degradation of 25-hydroxyvitamin D

|

| Decreased hepatic hydroxylation of vitamin D (occurs only with severe hepatic disease) |

| Impaired renal hydroxylation of vitamin D (renal insufficiency) |

| Osteoporosis or osteopenia |

How should vitamin D insufficiency be defined?

Biochemical criteria for defining vitamin D insufficiency vary. That makes it difficult to estimate the prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency.

Severe vitamin D deficiency is commonly defined as a serum 25OHD level below 10 ng/mL.3 Vitamin D insufficiency has been variably defined as a serum 25OHD level below 20 to 32 ng/mL,3,4 and the lower limit of normal in most clinical laboratories is now typically 30 to 32 ng/mL. Many patients become concerned when their serum 25OHD level is flagged as “low” on a laboratory report, and it’s likely that you are called on from time to time to interpret and make recommendations about the appropriate response to this “abnormal” finding.

The broad definition of vitamin D insufficiency stems, in part, from the assessment of a wide range of outcomes. Measures that have been used include fracture risk, calcium absorptive capacity, and the serum concentration of PTH. In regard to calcium absorption, most studies suggest that maximal dietary calcium absorption occurs when the 25OHD level reaches 20 ng/mL, although some studies suggest a higher threshold.1,3

The optimal level of 25OHD for PTH suppression remains unclear. Several studies have suggested that the PTH level increases when the 25OHD concentration falls below 30 ng/mL,4,5 although this threshold has varied substantially across studies.6

How prevalent is vitamin D insufficiency?

Estimates of the prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency vary by the criteria used to define the condition. A recent report using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) estimated that approximately 30% of US adults 20 years of age or older have a 25OHD level below 20Â ng/mL, and more than 70% of this age group has a 25OHD level below 32 ng/mL.7

The IOM committee noted that several reports have most likely overestimated the prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency through the use of 25OHD cut points higher than 20Â ng/mL.

The data on vitamin D insufficiency and skeletal health

Many studies have examined the relationship between vitamin D supplementation or the 25OHD level and fracture risk, and conflicting results have emerged. Many trials have examined the combination of calcium and vitamin D supplementation, the effects of which are tightly interwoven, confounding interpretation.

Interpretation of large observational studies is further confounded by the inability to attribute association to causation. In the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study of calcium with vitamin D, treatment of healthy postmenopausal women with 1,000 mg of calcium and 400 IU of vitamin D daily led to improved bone density at the hip but no statistically significant reduction in hip fracture.8 However, a reduced risk of hip fracture was demonstrated in secondary analyses among women who adhered to treatment and among women 60 years or older. Meta-analyses of clinical trials have reported that treatment with varying doses of vitamin D (more than 400 IU daily) reduces the risk of vertebral,9 nonvertebral,10 and hip fractures.10

Several studies have examined the relationship between the 25OHD level and fracture risk, with inconsistent findings:

- A nested case-control study from the WHI found that the risk of hip fracture was significantly increased among postmenopausal women who had a 25OHD level of 19 ng/mL or lower.11

- A 2009 report from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) concluded that the association between the 25OHD level and the risk of fracture was inconsistent.12

After a comprehensive review of the available research, the IOM committee concluded that a serum 25OHD level of 20 ng/mL would meet the needs for bone health for at least 97.5% of the US and Canadian populations.

TABLE 2

Calcium and vitamin D dietary reference intakes for adults, by life stage

| Life stage (gender) | Calcium | Vitamin D | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RDA (mg/d) | Tolerable upper intake level (mg/d)* | RDA (IU/d) | Serum 25OHD level (ng/mL) (corresponding to the RDA)† | Tolerable upper intake level (IU/d)* | |

| 19–50 yr (male and female) | 1,000 | 2,500 | 600 | 20 | 4,000 |

| 51–70 yr (male) | 1,000 | 2,000 | 600 | 20 | 4,000 |

| 51–70 yr (female) | 1,200 | 2,000 | 600 | 20 | 4,000 |

| 71+ yr (male and female) | 1,200 | 2,000 | 800 | 20 | 4,000 |

| Adapted from: Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(1):53–58. RDA = Recommended Dietary Allowance, 25OHD=25-hydroxyvitamin D * The tolerable upper intake level is the threshold above which is a risk of adverse events. The upper intake level is not intended to be a target intake. There is no consistent evidence of greater benefit at intake levels above the RDA. The serum 25OHD level corresponding to the upper intake level is 50 ng/mL. † Measures of the serum 25OHD level corresponding to the RDA and covering the requirements of at least 97.5% of the population. | |||||

The data on vitamin D insufficiency and nonskeletal outcomes

Many observational studies have reported relationships between vitamin D insufficiency and myriad nonskeletal health outcomes, particularly cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, and autoimmune disorders.3 However, well-designed randomized clinical trials that examine nonskeletal outcomes as primary pre-specified outcomes are lacking.13 Such studies will be essential to elucidate the relationship between vitamin D insufficiency and nonskeletal chronic diseases. The VITamin D and OmegA-3 TriaL (VITAL) is an ongoing large-scale, randomized clinical trial designed to evaluate the role of supplementation with 2,000 IU of vitamin D3 daily in the primary prevention of cancer and cardiovascular disease.14

- Vitamin D plays a vital role in bone health

- The Institute of Medicine released a 2010 report that provided public health recommendations for vitamin D intake based on bone health outcomes

- Many observational studies have reported a relationship between vitamin D insufficiency and adverse nonskeletal health outcomes, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, and autoimmune disorders, but evidence from randomized clinical trials on the potential nonskeletal benefits of vitamin D is sparse

- Excessive vitamin D intake should be avoided because of the potential for harm and the lack of evidence from well-designed clinical trials that vitamin D intake beyond the recommended amount affords greater skeletal or nonskeletal health benefits

- Among women who have an increased risk of vitamin D insufficiency or bone loss, 25OHD concentration should be measured and vitamin D supplementation should be provided as necessary to achieve the target 25OHD level

What we recommend for treatment

The IOM report provided the medical community with evidence-based recommendations for vitamin D intake at the population level, based on a public health perspective.1,2 However, the public health guideline model must be distinguished from the medical model, in which shared clinical decision-making between physician and patient occurs on an individual level and is informed by individual clinical risk factors. The public health recommendations detailed in the IOM report are not intended to replace or interfere with clinical judgment or preclude individualized clinical decision-making.

The debate over optimal levels of vitamin D supplementation for individual patients who have osteoporosis or other health conditions continues.15 Here, we provide general guidelines for treatment, based on the evidence available to date.

Clear benefits of vitamin D in bone health notwithstanding, advise your patients to avoid excessive intake because it can cause harm. See “More is not necessarily better”.

Recommendations for healthy adult nonpregnant women

Vitamin D intake: We recommend a daily vitamin D intake of 600 IU for healthy nonpregnant women up to age 70 years (and 800 Â IU daily for women older than 70 years) who are at average risk of vitamin D insufficiency and bone loss, consistent with the IOM recommendations. The IOM guidelines assume minimal to no sun exposure.

Measurement of 25OHD: It is not necessary to routinely measure the 25OHD level in these women. However, it is prudent to measure 25OHD in women who have risk factors for vitamin D insufficiency (TABLE 1) or a clinical condition associated with severe vitamin D deficiency. In these cases, if the 25OHD level is found to be below 20 ng/mL, vitamin D therapy should be initiated, with the goal of boosting the 25OHD level above the threshold of 20 ng/mL.

Treatment of vitamin D insufficiency: Options include daily vitamin D supplementation and higher-dose weekly preparations.

Many clinicians treat severe vitamin D insufficiency with 50,000 IU of vitamin D2 once weekly for 8 weeks, followed by a maintenance dose (described below) of vitamin D to preserve the target 25OHD level.5 An alternative is daily vitamin D supplementation, with the dosage based on the degree of insufficiency.

A general rule of thumb, for persons who have normal vitamin D absorption, is that every 1,000 IU of vitamin D3 ingested daily increases the 25OHD level by approximately 6 to 10 ng/mL.4,16 However, the incremental increase in the 25OHD concentration varies among individuals, depending on the baseline 25OHD level, with a greater incremental increase occurring at lower baseline 25OHD levels.

Monitoring of the 25OHD level after adjustment of the dosage is necessary to ensure that the target level is achieved.

Maintaining an adequate vitamin D level: Once vitamin D insufficiency has been corrected, a maintenance dosage of vitamin D should be selected—commonly 800 to 1,000 Â IU daily. A higher maintenance dosage may be required for persons who have genetic or ongoing environmental factors that predispose them to vitamin D insufficiency.

Vitamin D3 is reportedly more potent than D2 in increasing the 25OHD level,17 although this finding has not been universal.18 Monthly or twice-monthly administration of 50,000 IU of vitamin D2 is another option for maintenance of vitamin D sufficiency,5,16 although daily doses are more commonly used and are readily available in over-the-counter preparations.

Regardless of the regimen selected, the 25OHD level should be measured again approximately 3 months after a change in dosage to ensure that the target level has been achieved, with further dosage adjustments as indicated.

Recommendations for adult women at increased risk of skeletal disease

Measurement of 25OHD: The 25OHD level should be measured among women at increased risk of vitamin D insufficiency, bone loss, or fracture and among women who have established skeletal disease.

Vitamin D intake: We recommend that women at increased risk of osteoporosis and women older than 70 years receive at least 800 IU daily and, potentially, more if necessary to achieve the target 25OHD level.

Although the evidence to date does not support routine achievement of a 25OHD level substantially above 20 ng/mL in most women, many clinicians recommend that women in this higher-risk group maintain a 25OHD level above 30 ng/mL because of the possibly greater (although unproven) skeletal and nonskeletal benefits. As more data become available regarding the benefits and safety of vitamin D doses higher than those recommended by the IOM, these recommendations may be revised.

In 2010, the National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) recommended a vitamin D intake of 800 to 1,000 IU daily for all adults 50 years and older. Among persons at risk of deficiency, the NOF also recommended measurement of the serum 25OHD level, with vitamin D supplementation, as necessary, to achieve a 25OHD level of 30 ng/mL or higher.19 Also in 2010, the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) recommended a target 25OHD level above 30 ng/mL for all older adults. The IOF also estimated that the average dosage required to achieve this level in older adults is 800 to 1,000 IU daily, noting that upward adjustment may be required in some people.4 It is unclear whether these guidelines will be revised in the future, based on the IOM report.

We recommend against achieving a 25OHD level above 50 ng/mL, based on evidence suggesting potential adverse health effects above this level.

Excessive vitamin D intake should be avoided because of the potential for harm and the lack of evidence from well-designed clinical trials that vitamin D intake beyond the currently recommended amount affords greater skeletal or nonskeletal health benefits. Although moderate vitamin D supplementation has proven skeletal benefits, a “U-shaped” curve for some outcomes has emerged, suggesting that excessive vitamin D supplementation may pose health risks. Notably, a recent clinical trial reported a higher risk of fracture (and falls) among elderly women treated annually with high-dose (500,000 IU) oral vitamin D3 versus placebo.20

A suggestion of adverse effects associated with 25OHD levels above 50 ng/mL has also emerged, from observational studies, for several nonskeletal health outcomes, including pancreatic cancer,21 cardiovascular disease,1 and all-cause mortality.22

Limited evidence is available regarding the safety and overall risk-benefit profile of long-term maintenance of 25OHD levels above the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) range. Therefore, you should remind your patients that, despite the importance of both prevention and treatment of vitamin D insufficiency, more is not necessarily better.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

No question: Vitamin D plays a vital role in bone health. In recent years, the possibility that it plays a role in other aspects of health has prompted considerable speculation, fueled by both widespread media coverage and dissemination of conflicting information about the potential nonskeletal benefits of high-dose vitamin D supplementation. Controversy has emerged about:

- the appropriate criteria for defining vitamin D deficiency

- the extent to which vitamin D influences nonskeletal health conditions

- the optimal level of vitamin D supplementation.

In 2010, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released a report that provided recommendations for vitamin D intake, which were also summarized in a recent article for clinicians.1,2 The IOM report provided much-needed clinical guidance, but it has also fueled additional questions.

This article describes the IOM recommendations, explains what we know now about the effect of vitamin D on various health outcomes, and offers concrete recommendations on vitamin D measurement, intake, and supplementation.

How the Institute of Medicine formulated its recommendations

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) committee conducted a comprehensive review of the literature to date on the relationship between vitamin D (and calcium) intake and several health outcomes. In terms of skeletal health, the IOM committee concluded that a 25OHD level of at least 20 ng/mL is sufficient to meet the needs of at least 97.5% of the population. The vitamin D intake thought to be necessary to achieve this 25OHD level for at least 97.5% of the population was provided for different age groups (TABLE 2).

The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) of vitamin D is 600 IU daily for all adults up to age 70 years, and 800 IU daily for adults older than 70 years. These values were based on an assumption of minimal sun exposure, due to wide variability in vitamin D synthesis from ultraviolet light, as well as the risk of skin cancer. The IOM concluded that there is no compelling evidence that a 25OHD level above 20 ng/mL or a vitamin D intake greater than 600 IU (800Â IU for adults over 70) affords greater skeletal or nonskeletal benefits.

The IOM recommendations were based on the integration of bone health outcomes. The evidence supporting causal relationships between vitamin D insufficiency and nonskeletal outcomes such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, impaired physical performance, autoimmune disorders, and other chronic diseases was found to be inconsistent and inconclusive.

The IOM report also noted the emergence of a “U”-shaped curve in regard to vitamin D and several health outcomes, which has fueled concern about attainment of a 25OHD level above 50 ng/mL. The IOM committee designated 4,000 IU daily as the tolerable upper intake but emphasized that research into long-term outcomes and safety at intakes above the RDA is limited. Therefore, this upper limit should not be interpreted as a target intake level.

How is vitamin D metabolized?

Vitamin D is produced endogenously in the skin in the form of vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol). It also can be ingested exogenously in the form of vitamin D3 or vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol). Cutaneous synthesis of vitamin D is stimulated by solar ultraviolet radiation.

Vitamin D2 and D3 are hydroxylated in the liver to form 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD). Measurement of the serum 25OHD level is thought to be the most reliable indicator of vitamin D exposure.3 25OHD is hydroxylated again, primarily in the kidneys, to the most active form of vitamin D (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D).