User login

Shoulder dystocia: Clarifying the care of an old problem

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Brachial plexus injury is a dreaded sequela of shoulder dystocia, one that lies at the root of many medical liability disputes. Although brachial plexus injury cannot be prevented, most of the commonly used maneuvers for freeing a stuck shoulder are designed to maximize fetal safety and minimize injury.

What is the standard of care when dystocia occurs? Several respected sources have offered conflicting recommendations, particularly in regard to maternal pushing once dystocia is diagnosed. My aim in this article is to clarify the issue.

Endogenous force versus exogenous force

The introduction to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ practice bulletin on shoulder dystocia, published in November 2002, provides a useful summary of much of our current knowledge:

Shoulder dystocia is most often an unpredictable and unpreventable obstetric emergency. Failure of the shoulders to deliver spontaneously places both the pregnant woman and fetus at risk for injury. Several maneuvers to release impacted shoulders have been developed, but the urgency of this event makes prospective studies impractical for comparing their effectiveness.1

Because prospective studies are unlikely ever to be performed, some investigators have turned to mathematical modeling to learn more about the forces exerted on the fetal neck overlying the roots of the brachial plexus when a shoulder is impacted against the symphysis pubis.

Gonik and colleagues2 performed elegant modeling of the pressure between the base of the fetal neck and symphysis pubis during dystocia. They utilized data on birth forces gathered by CaldeyroBarcia and Poseiro3 in their classic work on intrauterine pressure. Gonik and colleagues also used data from Allen and associates,4 who measured the force of clinician-applied traction after delivery of the head by having clinicians wear sensory gloves that recorded the force of traction applied.

Gonik and associates2 concluded that the pressure resulting from endogenous forces is four to nine times greater than the pressure generated by a clinician. “Neonatal brachial plexus injury is not a priori explained by iatrogenically induced excessive traction,” they wrote. “Spontaneous endogenous forces may contribute substantially to this type of neonatal trauma.”

How an understanding of endogenous forces alters management

Although fewer than 10% of cases of shoulder dystocia result in permanent brachial plexus injury,1 such injuries are a major source of malpractice litigation in obstetrics, as I noted at the beginning of this article. In most such cases, injury is blamed on excessive traction by the physician (FIGURE). Newer data, such as the study by Gonik and colleagues,2 may implicate expulsive force (ie, maternal pushing) as another, perhaps greater, cause.

As long ago as 1988, Acker and colleagues5 reported on their experience with Erb’s palsy, which was associated with rapid delivery and unusually forceful expulsive effort in one third of cases. Their findings suggest that, when shoulder dystocia occurs and additional maneuvers are necessary to deliver the impacted anterior shoulder, the contribution of potentially harmful endogenous forces should be kept in mind. Counterintuitive strategies, including having the mother stop pushing until the anterior shoulder is freed, may help limit injury.

FIGURE Maternal pushing may contribute to injury

When shoulder dystocia occurs, the progress of labor is interrupted and brachial plexus injury can result, a common cause of litigation. Until now, plaintiff’s attorneys have tended to blame these injuries on the obstetrician and “excess” traction, but it now appears that maternal pushing contributes as well—possibly, to a greater degree than any effort by the physician.

How confusion crept into the literature

The 21st (current) edition of Williams Obstetrics,6 in the section on management of shoulder dystocia, states that “an initial gentle attempt at traction assisted by maternal expulsive efforts is recommended.” There is no reference for this statement. However, a look at the 19th edition of the textbook7 reveals identical wording, and the reference cited is ACOG Technical Bulletin No. 152 (August 1991), entitled Operative Vaginal Delivery. A subsequent version of the same bulletin (no. 196 from August 1994) contains identical wording. By the time that version was replaced by ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 17 (June 2000), however, it no longer contained any information on shoulder dystocia. Instead, ACOG published Practice Pattern No. 7 (October 1997), entitled Shoulder Dystocia. This document did not recommend maternal expulsive force after a diagnosis of shoulder dystocia—in fact, maternal force was not even mentioned. Nor is it mentioned in the current practice bulletin (no. 40 from November 2002), which replaced the previous version of Shoulder Dystocia.

Confusion doesn’t end there

In its section on shoulder dystocia, ACOG’s publication Precis (1998) states:

Management of shoulder dystocia involves both anticipation of and preparation for problems. The key to preventing fetal injury is avoidance of excess traction on the fetal head. When shoulder dystocia is diagnosed, a deliberate and planned sequence of events should be initiated. Pushing should be halted and obstructive causes should be considered. Aggressive fundal pressure or continued pushing will only further impact the anterior shoulder.

We are left with the paradox that the current edition of Williams Obstetrics, in its discussion of shoulder dystocia, carries a statement recommending maternal pushing based on a 1994 ACOG document—a statement that subsequent ACOG documents no longer contain. In fact, one of those documents—Precis—tells us that pushing should be halted, an instruction supported by the mathematical modeling of Gonik and colleagues.2 And a popular online text (UpToDate.com) advises: “The mother should be told not to push during attempts to reposition the fetus.”8 Once the fetus is successfully repositioned, maternal pushing or traction, or both, can be reinstated.

Putting it all into clinical perspective

The current ACOG practice bulletin on shoulder dystocia (no. 40 from November 2002) observes that “retraction of the delivered fetal head against the maternal perineum (turtle sign) may be present and may assist in the diagnosis of shoulder dystocia.” When present, the turtle sign strongly suggests that the anterior shoulder is already impacted against the symphysis pubis. Maternal expulsive forces may have already put enough pressure on the nerve roots of the brachial plexus to cause damage. Any degree of traction or continued maternal pushing is likely to compound an already potentially serious problem.

In such cases, it is prudent to resort to known maneuvers, avoid encouraging continued maternal pushing, and simply support and guide the head without supplying any real traction.

When the turtle sign is absent, shoulder dystocia can be diagnosed only after the head is delivered, when the usual methods (ie, downward traction and continued maternal pushing) fail to advance delivery. Diagnosis in these cases requires recognition on the part of the delivering physician that shoulder dystocia is present. At that point, continued expulsive force and any real degree of traction no longer are appropriate.

1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 40: Shoulder dystocia. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2002.

2. Gonik B, Walker A, Grimm M. Mathematic modeling of forces associated with shoulder dystocia: a comparison of endogenous and exogenous sources. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:689-691.

3. Caldeyro-Barcia R, Poseiro JJ. Physiology of the uterine contraction. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1960;3:386-392.

4. Allen R, Sorab J, Gonik B. Risk factors for shoulder dystocia: an engineering study of clinician-applied forces. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:352-355.

5. Acker DB, Gregory KD, Sachs BP, Friedman EA. Risk factors for Erb-Duchenne palsy. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71:389-392.

6. Dystocia: abnormal presentation position and development of the fetus: shoulder dystocia. In: Cunningham FG, Gant NF, Leveno KJ, Gilstrap LC III, Hauth JC, Wenstrom KD (eds). Williams Obstetrics. 21st ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001:459-464.

7. Dystocia due to abnormalities in presentation position or development of the fetus: shoulder dystocia. In: Cunningham FG, MacDonald PC, Gant NF (eds). Williams Obstetrics. 19th ed. Norwalk, Conn: Appleton & Lange; 1993:509-514.

8. Rodis JF. Management of fetal macrosomia and shoulder dystocia. UpToDate [serial online]. Waltham, MA; November 7, 2007.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Brachial plexus injury is a dreaded sequela of shoulder dystocia, one that lies at the root of many medical liability disputes. Although brachial plexus injury cannot be prevented, most of the commonly used maneuvers for freeing a stuck shoulder are designed to maximize fetal safety and minimize injury.

What is the standard of care when dystocia occurs? Several respected sources have offered conflicting recommendations, particularly in regard to maternal pushing once dystocia is diagnosed. My aim in this article is to clarify the issue.

Endogenous force versus exogenous force

The introduction to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ practice bulletin on shoulder dystocia, published in November 2002, provides a useful summary of much of our current knowledge:

Shoulder dystocia is most often an unpredictable and unpreventable obstetric emergency. Failure of the shoulders to deliver spontaneously places both the pregnant woman and fetus at risk for injury. Several maneuvers to release impacted shoulders have been developed, but the urgency of this event makes prospective studies impractical for comparing their effectiveness.1

Because prospective studies are unlikely ever to be performed, some investigators have turned to mathematical modeling to learn more about the forces exerted on the fetal neck overlying the roots of the brachial plexus when a shoulder is impacted against the symphysis pubis.

Gonik and colleagues2 performed elegant modeling of the pressure between the base of the fetal neck and symphysis pubis during dystocia. They utilized data on birth forces gathered by CaldeyroBarcia and Poseiro3 in their classic work on intrauterine pressure. Gonik and colleagues also used data from Allen and associates,4 who measured the force of clinician-applied traction after delivery of the head by having clinicians wear sensory gloves that recorded the force of traction applied.

Gonik and associates2 concluded that the pressure resulting from endogenous forces is four to nine times greater than the pressure generated by a clinician. “Neonatal brachial plexus injury is not a priori explained by iatrogenically induced excessive traction,” they wrote. “Spontaneous endogenous forces may contribute substantially to this type of neonatal trauma.”

How an understanding of endogenous forces alters management

Although fewer than 10% of cases of shoulder dystocia result in permanent brachial plexus injury,1 such injuries are a major source of malpractice litigation in obstetrics, as I noted at the beginning of this article. In most such cases, injury is blamed on excessive traction by the physician (FIGURE). Newer data, such as the study by Gonik and colleagues,2 may implicate expulsive force (ie, maternal pushing) as another, perhaps greater, cause.

As long ago as 1988, Acker and colleagues5 reported on their experience with Erb’s palsy, which was associated with rapid delivery and unusually forceful expulsive effort in one third of cases. Their findings suggest that, when shoulder dystocia occurs and additional maneuvers are necessary to deliver the impacted anterior shoulder, the contribution of potentially harmful endogenous forces should be kept in mind. Counterintuitive strategies, including having the mother stop pushing until the anterior shoulder is freed, may help limit injury.

FIGURE Maternal pushing may contribute to injury

When shoulder dystocia occurs, the progress of labor is interrupted and brachial plexus injury can result, a common cause of litigation. Until now, plaintiff’s attorneys have tended to blame these injuries on the obstetrician and “excess” traction, but it now appears that maternal pushing contributes as well—possibly, to a greater degree than any effort by the physician.

How confusion crept into the literature

The 21st (current) edition of Williams Obstetrics,6 in the section on management of shoulder dystocia, states that “an initial gentle attempt at traction assisted by maternal expulsive efforts is recommended.” There is no reference for this statement. However, a look at the 19th edition of the textbook7 reveals identical wording, and the reference cited is ACOG Technical Bulletin No. 152 (August 1991), entitled Operative Vaginal Delivery. A subsequent version of the same bulletin (no. 196 from August 1994) contains identical wording. By the time that version was replaced by ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 17 (June 2000), however, it no longer contained any information on shoulder dystocia. Instead, ACOG published Practice Pattern No. 7 (October 1997), entitled Shoulder Dystocia. This document did not recommend maternal expulsive force after a diagnosis of shoulder dystocia—in fact, maternal force was not even mentioned. Nor is it mentioned in the current practice bulletin (no. 40 from November 2002), which replaced the previous version of Shoulder Dystocia.

Confusion doesn’t end there

In its section on shoulder dystocia, ACOG’s publication Precis (1998) states:

Management of shoulder dystocia involves both anticipation of and preparation for problems. The key to preventing fetal injury is avoidance of excess traction on the fetal head. When shoulder dystocia is diagnosed, a deliberate and planned sequence of events should be initiated. Pushing should be halted and obstructive causes should be considered. Aggressive fundal pressure or continued pushing will only further impact the anterior shoulder.

We are left with the paradox that the current edition of Williams Obstetrics, in its discussion of shoulder dystocia, carries a statement recommending maternal pushing based on a 1994 ACOG document—a statement that subsequent ACOG documents no longer contain. In fact, one of those documents—Precis—tells us that pushing should be halted, an instruction supported by the mathematical modeling of Gonik and colleagues.2 And a popular online text (UpToDate.com) advises: “The mother should be told not to push during attempts to reposition the fetus.”8 Once the fetus is successfully repositioned, maternal pushing or traction, or both, can be reinstated.

Putting it all into clinical perspective

The current ACOG practice bulletin on shoulder dystocia (no. 40 from November 2002) observes that “retraction of the delivered fetal head against the maternal perineum (turtle sign) may be present and may assist in the diagnosis of shoulder dystocia.” When present, the turtle sign strongly suggests that the anterior shoulder is already impacted against the symphysis pubis. Maternal expulsive forces may have already put enough pressure on the nerve roots of the brachial plexus to cause damage. Any degree of traction or continued maternal pushing is likely to compound an already potentially serious problem.

In such cases, it is prudent to resort to known maneuvers, avoid encouraging continued maternal pushing, and simply support and guide the head without supplying any real traction.

When the turtle sign is absent, shoulder dystocia can be diagnosed only after the head is delivered, when the usual methods (ie, downward traction and continued maternal pushing) fail to advance delivery. Diagnosis in these cases requires recognition on the part of the delivering physician that shoulder dystocia is present. At that point, continued expulsive force and any real degree of traction no longer are appropriate.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Brachial plexus injury is a dreaded sequela of shoulder dystocia, one that lies at the root of many medical liability disputes. Although brachial plexus injury cannot be prevented, most of the commonly used maneuvers for freeing a stuck shoulder are designed to maximize fetal safety and minimize injury.

What is the standard of care when dystocia occurs? Several respected sources have offered conflicting recommendations, particularly in regard to maternal pushing once dystocia is diagnosed. My aim in this article is to clarify the issue.

Endogenous force versus exogenous force

The introduction to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ practice bulletin on shoulder dystocia, published in November 2002, provides a useful summary of much of our current knowledge:

Shoulder dystocia is most often an unpredictable and unpreventable obstetric emergency. Failure of the shoulders to deliver spontaneously places both the pregnant woman and fetus at risk for injury. Several maneuvers to release impacted shoulders have been developed, but the urgency of this event makes prospective studies impractical for comparing their effectiveness.1

Because prospective studies are unlikely ever to be performed, some investigators have turned to mathematical modeling to learn more about the forces exerted on the fetal neck overlying the roots of the brachial plexus when a shoulder is impacted against the symphysis pubis.

Gonik and colleagues2 performed elegant modeling of the pressure between the base of the fetal neck and symphysis pubis during dystocia. They utilized data on birth forces gathered by CaldeyroBarcia and Poseiro3 in their classic work on intrauterine pressure. Gonik and colleagues also used data from Allen and associates,4 who measured the force of clinician-applied traction after delivery of the head by having clinicians wear sensory gloves that recorded the force of traction applied.

Gonik and associates2 concluded that the pressure resulting from endogenous forces is four to nine times greater than the pressure generated by a clinician. “Neonatal brachial plexus injury is not a priori explained by iatrogenically induced excessive traction,” they wrote. “Spontaneous endogenous forces may contribute substantially to this type of neonatal trauma.”

How an understanding of endogenous forces alters management

Although fewer than 10% of cases of shoulder dystocia result in permanent brachial plexus injury,1 such injuries are a major source of malpractice litigation in obstetrics, as I noted at the beginning of this article. In most such cases, injury is blamed on excessive traction by the physician (FIGURE). Newer data, such as the study by Gonik and colleagues,2 may implicate expulsive force (ie, maternal pushing) as another, perhaps greater, cause.

As long ago as 1988, Acker and colleagues5 reported on their experience with Erb’s palsy, which was associated with rapid delivery and unusually forceful expulsive effort in one third of cases. Their findings suggest that, when shoulder dystocia occurs and additional maneuvers are necessary to deliver the impacted anterior shoulder, the contribution of potentially harmful endogenous forces should be kept in mind. Counterintuitive strategies, including having the mother stop pushing until the anterior shoulder is freed, may help limit injury.

FIGURE Maternal pushing may contribute to injury

When shoulder dystocia occurs, the progress of labor is interrupted and brachial plexus injury can result, a common cause of litigation. Until now, plaintiff’s attorneys have tended to blame these injuries on the obstetrician and “excess” traction, but it now appears that maternal pushing contributes as well—possibly, to a greater degree than any effort by the physician.

How confusion crept into the literature

The 21st (current) edition of Williams Obstetrics,6 in the section on management of shoulder dystocia, states that “an initial gentle attempt at traction assisted by maternal expulsive efforts is recommended.” There is no reference for this statement. However, a look at the 19th edition of the textbook7 reveals identical wording, and the reference cited is ACOG Technical Bulletin No. 152 (August 1991), entitled Operative Vaginal Delivery. A subsequent version of the same bulletin (no. 196 from August 1994) contains identical wording. By the time that version was replaced by ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 17 (June 2000), however, it no longer contained any information on shoulder dystocia. Instead, ACOG published Practice Pattern No. 7 (October 1997), entitled Shoulder Dystocia. This document did not recommend maternal expulsive force after a diagnosis of shoulder dystocia—in fact, maternal force was not even mentioned. Nor is it mentioned in the current practice bulletin (no. 40 from November 2002), which replaced the previous version of Shoulder Dystocia.

Confusion doesn’t end there

In its section on shoulder dystocia, ACOG’s publication Precis (1998) states:

Management of shoulder dystocia involves both anticipation of and preparation for problems. The key to preventing fetal injury is avoidance of excess traction on the fetal head. When shoulder dystocia is diagnosed, a deliberate and planned sequence of events should be initiated. Pushing should be halted and obstructive causes should be considered. Aggressive fundal pressure or continued pushing will only further impact the anterior shoulder.

We are left with the paradox that the current edition of Williams Obstetrics, in its discussion of shoulder dystocia, carries a statement recommending maternal pushing based on a 1994 ACOG document—a statement that subsequent ACOG documents no longer contain. In fact, one of those documents—Precis—tells us that pushing should be halted, an instruction supported by the mathematical modeling of Gonik and colleagues.2 And a popular online text (UpToDate.com) advises: “The mother should be told not to push during attempts to reposition the fetus.”8 Once the fetus is successfully repositioned, maternal pushing or traction, or both, can be reinstated.

Putting it all into clinical perspective

The current ACOG practice bulletin on shoulder dystocia (no. 40 from November 2002) observes that “retraction of the delivered fetal head against the maternal perineum (turtle sign) may be present and may assist in the diagnosis of shoulder dystocia.” When present, the turtle sign strongly suggests that the anterior shoulder is already impacted against the symphysis pubis. Maternal expulsive forces may have already put enough pressure on the nerve roots of the brachial plexus to cause damage. Any degree of traction or continued maternal pushing is likely to compound an already potentially serious problem.

In such cases, it is prudent to resort to known maneuvers, avoid encouraging continued maternal pushing, and simply support and guide the head without supplying any real traction.

When the turtle sign is absent, shoulder dystocia can be diagnosed only after the head is delivered, when the usual methods (ie, downward traction and continued maternal pushing) fail to advance delivery. Diagnosis in these cases requires recognition on the part of the delivering physician that shoulder dystocia is present. At that point, continued expulsive force and any real degree of traction no longer are appropriate.

1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 40: Shoulder dystocia. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2002.

2. Gonik B, Walker A, Grimm M. Mathematic modeling of forces associated with shoulder dystocia: a comparison of endogenous and exogenous sources. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:689-691.

3. Caldeyro-Barcia R, Poseiro JJ. Physiology of the uterine contraction. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1960;3:386-392.

4. Allen R, Sorab J, Gonik B. Risk factors for shoulder dystocia: an engineering study of clinician-applied forces. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:352-355.

5. Acker DB, Gregory KD, Sachs BP, Friedman EA. Risk factors for Erb-Duchenne palsy. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71:389-392.

6. Dystocia: abnormal presentation position and development of the fetus: shoulder dystocia. In: Cunningham FG, Gant NF, Leveno KJ, Gilstrap LC III, Hauth JC, Wenstrom KD (eds). Williams Obstetrics. 21st ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001:459-464.

7. Dystocia due to abnormalities in presentation position or development of the fetus: shoulder dystocia. In: Cunningham FG, MacDonald PC, Gant NF (eds). Williams Obstetrics. 19th ed. Norwalk, Conn: Appleton & Lange; 1993:509-514.

8. Rodis JF. Management of fetal macrosomia and shoulder dystocia. UpToDate [serial online]. Waltham, MA; November 7, 2007.

1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 40: Shoulder dystocia. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2002.

2. Gonik B, Walker A, Grimm M. Mathematic modeling of forces associated with shoulder dystocia: a comparison of endogenous and exogenous sources. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:689-691.

3. Caldeyro-Barcia R, Poseiro JJ. Physiology of the uterine contraction. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1960;3:386-392.

4. Allen R, Sorab J, Gonik B. Risk factors for shoulder dystocia: an engineering study of clinician-applied forces. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:352-355.

5. Acker DB, Gregory KD, Sachs BP, Friedman EA. Risk factors for Erb-Duchenne palsy. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71:389-392.

6. Dystocia: abnormal presentation position and development of the fetus: shoulder dystocia. In: Cunningham FG, Gant NF, Leveno KJ, Gilstrap LC III, Hauth JC, Wenstrom KD (eds). Williams Obstetrics. 21st ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001:459-464.

7. Dystocia due to abnormalities in presentation position or development of the fetus: shoulder dystocia. In: Cunningham FG, MacDonald PC, Gant NF (eds). Williams Obstetrics. 19th ed. Norwalk, Conn: Appleton & Lange; 1993:509-514.

8. Rodis JF. Management of fetal macrosomia and shoulder dystocia. UpToDate [serial online]. Waltham, MA; November 7, 2007.

PELVIC SURGERY

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

The use of transvaginal mesh—with or without trocar placement—is surrounded by controversy. A number of minimally invasive vaginal mesh kits are commercially available for the repair of pelvic organ prolapse, and new kits are entering the market rapidly. The challenge is determining whether these new techniques are as effective and safe as traditional prolapse repairs.

Although the use of permanent mesh to repair prolapse has been explored in retrospective and prospective studies, no rigorous controlled trials have compared these new procedures with abdominal sacrocolpopexy or uterosacral ligament suspension, for example. The current body of literature does suggest a high rate of recurrent prolapse after traditional anterior or posterior colporrhaphy, and the use of allograft material has not been shown to improve outcomes. Surgeons are now turning their attention to permanent polypropylene mesh as a possible alternative. In addition, repair of the vaginal apex at the time of anterior and posterior vaginal wall repair is being explored as a way to increase durability of the repair. The new trocar-delivered mesh kits address this issue by suspending the vaginal vault while providing support to the vaginal walls.

This article highlights three recent studies that focus on a new trocar-delivered, protected, low-weight polypropylene mesh (Ugytex, distributed by Bard as Pelvitex) and three trocar-delivered mesh kits (Prolift, Apogee, and Perigee).

One-year outcomes encouraging for low-weight polypropylene mesh

De Tayrac R, Devoldere G, Renaudie J, Villard P, Guilbaud O, Eglin G. Prolapse repair by vaginal route using a new protected low-weight polypropylene mesh: 1-year functional and anatomical outcome in a prospective multicentre study. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:251–256.

This study evaluated functional and anatomic outcomes after placement for prolapse repair of low-weight polypropylene mesh protected by absorbable hydrophilic film. The film, a combination of atelocollagen, polyethylene glycol, and glycerol, is designed to protect pelvic organs from acute inflammation during healing. In a separate investigation of unprotected, heavyweight polypropylene mesh in prolapse repair, the anatomic success rate ranged from 75% to 100%, but the rate of mesh erosion (13%) and dyspareunia (69%) seemed unacceptably high.1

Rigorous preoperative assessment

In this trial, 230 women with symptomatic vaginal wall prolapse were recruited at 13 centers in a consecutive fashion. At enrollment, all patients were measured using the pelvic organ prolapse quantitative staging system (POP-Q). They also completed the validated Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire. The presence and severity of dyspareunia were also recorded, as well as the Urinary Dysfunction Measurement Scale. All participants had prolapse equal to or exceeding stage II.

Surgeons used trocars to percutaneously place a low-weight (38 g/m2) and highly porous polypropylene monofilament mesh (Ugytex/Pelvitex) for vaginal repair and performed any concomitant procedures. Perioperative and postoperative complications were recorded. Patients were evaluated at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 1 year. The first 143 patients with at least 10 months of follow-up were analyzed, with a mean follow-up of 13±2 months (range: 10–19). Anatomic cure was defined as no prolapse greater than or equal to stage II.

Patient satisfaction was high

The anatomic cure rate was 92.3%, with a 6.8% recurrence of anterior vaginal wall prolapse and 2.6% recurrence of posterior vaginal wall prolapse. Only one patient with recurrence was symptomatic.

Six of 143 patients (4.2%) sustained an intraoperative complication: three bladder injuries, one rectal injury, one uterine artery hemorrhage (during hysterectomy), and one vaginal sulcus perforation (during transobturator tape placement). The most significant postoperative complication related to the vaginal mesh kit was vaginal hematoma; one of the two cases required reoperation and partial removal of the mesh.

Nine patients developed mesh erosion in the first 3 months, for an erosion rate of 6.3%. Six required partial excision of the mesh. Overall, symptoms and quality of life improved significantly, with an overall satisfaction rate at follow-up of 96.5%. No significant difference was noted between pre- and postoperative rates of dyspareunia.

Further evaluation is warranted

The authors are already conducting a randomized trial to compare anterior vaginal wall repair using this low-weight polypropylene mesh with traditional anterior colporrhaphy to confirm and explore these results.

Note: Bard now offers a kit called Avaulta Plus that uses the same mesh material with a trocar delivery system, previously lacking (although investigators used trocars in this study).

Perioperative complications were uncommon with Prolift system

Altman D, Falconer C. Perioperative morbidity using transvaginal mesh in pelvic organ prolapse repair. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:303–308.

This study explored the frequency and characteristics of perioperative complications associated with the use of Prolift, a transvaginal mesh system for the repair of pelvic organ prolapse (FIGURE). Twenty-five centers participated by registering a standardized safety protocol form for 248 women who underwent surgery using the system over a 6-month period. The form included information about perioperative complications, adverse intraoperative events, and the associated hospital stay, as well as obstetric and gynecologic medical history and previous pelvic surgery.

Pelvic organ perforation (lower urinary tract or anorectal injury) and blood loss greater than 1,000 mL were recorded as major complications, and any other adverse events related to the hospital stay were documented as minor complications. Most of the cohort had already undergone prolapse repair, and prolapse had recurred in the same vaginal compartment.

One author was an educational adviser for Gynecare Sweden AB, and the other an adviser for Johnson & Johnson. Although the study was funded entirely by university-administered research funds, pretrial scientific meetings were paid for by Gynecare Sweden AB.

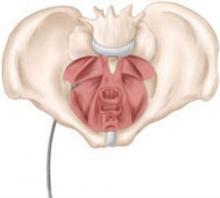

FIGURE: Mesh support of pelvic organs

Prolift mesh in final position, with extension arms passed through the sacrospinous ligaments and the obturator foramen bilaterally.

4.4% rate of serious complications

Serious complications occurred in 4.4% (11 of 248) of cases (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.5–7.8). The predominant complication was visceral injury, which included bladder, urethral, and rectal perforation. One patient had blood loss exceeding 1,000 mL.

Minor complications occurred in 44 patients (18%). The most common minor complication was urinary tract infection. Adverse events included urinary retention requiring catheterization, anemia, transfusion, fever, groin and buttock pain, and vaginal hematoma, among others.

Concurrent pelvic floor surgery increased the risk for minor complications (odds ratio, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.1–6.9). Concurrent procedures included vaginal hysterectomy, sling procedure with tension-free vaginal tape or transobturator tension-free tape, sacrospinal fixation, repair of vaginal enterocele, and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. This risk analysis identified no other predictors of outcome.

Posterior/apical repair

- Adequately infiltrate the vaginal epithelium with diluted epinephrine solution, especially toward the lateral apices, to facilitate hemostasis and dissection

- Be thorough in lateral dissection toward the ischial spine and stay in the proper surgical plane to create a thick vaginal epithelial flap

- Palpate the ischial spine, with the preoperatively packed rectum retracted medially

- During passage of the trocar, place an index finger along the vaginal dissection to palpate the trocar in the ischiorectal fossa and deep to the levator ani muscles until the tip is palpated at the level of the ischial spine

- Pass the trocar through the arcus tendineus/levator fascia at the level of the ischial spine, as shown below:

- Do not apply excess tension to the straps of the graft material

- Do not trim the vaginal epithelium

Anterior wall (obturator foramen trocar passage)

- Same key points as posterior wall technique, but in anterior repair, there are two passes through the obturator foramen

- The first trocar is inserted into the inferior obturator foramen, rotated, and guided with the surgeon’s finger inserted into and held in the vaginal dissection, as shown below:

- The superior passage exits close to the bladder neck, and the inferior passage approximates the ischial spine. Penetrate along the arcus tendineus approximately 1 cm from the ischial spine

Caution! Keep summary points in context

These key points are not intended as formal medical training, but as general information only. Continued research into these techniques is needed to assess long-term outcomes.

Short-term outcomes data only

Because this study focused on immediate complications, no long-term data on such complications as persistent pain, mesh erosion, or infection were collected.

All surgeons underwent hands-on training with the transvaginal repair system before patients were enrolled in the study. Nevertheless, the authors observe that many repair procedures were performed at the beginning of the physicians’ learning curve, with a higher number of complications than would be expected from more experienced surgeons.

The data may also have been affected by selection bias (ie, toward more complicated cases), given that most patients had already undergone prolapse repair.

Two systems yield excellent short-term results in women with recurrent prolapse

Gauruder-Burmester A, Koutouzidou P, Rohne J, Gronewold M, Tunn R. Follow-up after polypropylene mesh repair of anterior and posterior compartments in patients with recurrent prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:1059–1064.

This retrospective study involved women who had already undergone one or more prolapse repairs. These patients then underwent reoperation with mesh-reinforced repair. The authors hypothesized that recurrent prolapse represents poor tissue quality, necessitating the use of mesh in subsequent repairs. Both pre- and postoperative symptoms and functional changes were analyzed, with a special focus on mesh erosion and sexual function.

Details of the study

Of 145 women who underwent repair with the Apogee (apical posterior) or Perigee (anterior wall) system during a 1-year period, 120 were included in the analysis. The other 25 patients were excluded because they did not return for follow-up, were missing urodynamic data, or had inaccurate POP-Q staging. All patients had recurrent stage III posterior or anterior vaginal wall prolapse. Forty percent of patients had an apical posterior repair, and 60% had anterior wall repair. None had both procedures performed simultaneously.

All patients had undergone hysterectomy and received vaginal estrogen before and after surgery. Urinary incontinence was treated in a two-step fashion; that is, it was not addressed until 3 months after repair of the prolapse. Routine follow-up occurred at 1 month and 1 year after surgery.

One-year cure rate was 93%

No perioperative or intraoperative complications occurred, and mean operative time was 35±4.5 minutes. Mesh erosion occurred in four patients (3%) and involved anterior mesh placement only. No mesh infections were noted.

At 1 year, 93% of women were anatomically cured of prolapse (ie, they had less than stage II prolapse). Prolapse recurred in eight women; all cases involved the anterior compartment.

No dyspareunia was associated with the repair. In fact, prolapse-associated dyspareunia resolved in all 15 women who reported this symptom before surgery. In addition, questionnaires about quality of life and satisfaction revealed significant improvement after mesh placement (P=.023).

The authors attribute the positive results to the fact that both surgeons involved in the study used the technique on 15 patients before operating on study participants, minimizing the effect of the learning curve. The authors were also careful about patient selection.

Results merit cautious optimism

The authors propose that the low erosion rate and lack of new-onset dyspareunia after surgery may be misleading because long-term results have not yet been obtained. We also speculate that precise dissection in the proper surgical plane likely minimized early erosions.

Reference

1. Milani R, Salvatore S, Soligo M, Pifarotti P, Meschia M, Cortese M. Functional and anatomical outcome of anterior and posterior vaginal prolapse repair with prolene mesh. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;111:1-5.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

The use of transvaginal mesh—with or without trocar placement—is surrounded by controversy. A number of minimally invasive vaginal mesh kits are commercially available for the repair of pelvic organ prolapse, and new kits are entering the market rapidly. The challenge is determining whether these new techniques are as effective and safe as traditional prolapse repairs.

Although the use of permanent mesh to repair prolapse has been explored in retrospective and prospective studies, no rigorous controlled trials have compared these new procedures with abdominal sacrocolpopexy or uterosacral ligament suspension, for example. The current body of literature does suggest a high rate of recurrent prolapse after traditional anterior or posterior colporrhaphy, and the use of allograft material has not been shown to improve outcomes. Surgeons are now turning their attention to permanent polypropylene mesh as a possible alternative. In addition, repair of the vaginal apex at the time of anterior and posterior vaginal wall repair is being explored as a way to increase durability of the repair. The new trocar-delivered mesh kits address this issue by suspending the vaginal vault while providing support to the vaginal walls.

This article highlights three recent studies that focus on a new trocar-delivered, protected, low-weight polypropylene mesh (Ugytex, distributed by Bard as Pelvitex) and three trocar-delivered mesh kits (Prolift, Apogee, and Perigee).

One-year outcomes encouraging for low-weight polypropylene mesh

De Tayrac R, Devoldere G, Renaudie J, Villard P, Guilbaud O, Eglin G. Prolapse repair by vaginal route using a new protected low-weight polypropylene mesh: 1-year functional and anatomical outcome in a prospective multicentre study. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:251–256.

This study evaluated functional and anatomic outcomes after placement for prolapse repair of low-weight polypropylene mesh protected by absorbable hydrophilic film. The film, a combination of atelocollagen, polyethylene glycol, and glycerol, is designed to protect pelvic organs from acute inflammation during healing. In a separate investigation of unprotected, heavyweight polypropylene mesh in prolapse repair, the anatomic success rate ranged from 75% to 100%, but the rate of mesh erosion (13%) and dyspareunia (69%) seemed unacceptably high.1

Rigorous preoperative assessment

In this trial, 230 women with symptomatic vaginal wall prolapse were recruited at 13 centers in a consecutive fashion. At enrollment, all patients were measured using the pelvic organ prolapse quantitative staging system (POP-Q). They also completed the validated Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire. The presence and severity of dyspareunia were also recorded, as well as the Urinary Dysfunction Measurement Scale. All participants had prolapse equal to or exceeding stage II.

Surgeons used trocars to percutaneously place a low-weight (38 g/m2) and highly porous polypropylene monofilament mesh (Ugytex/Pelvitex) for vaginal repair and performed any concomitant procedures. Perioperative and postoperative complications were recorded. Patients were evaluated at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 1 year. The first 143 patients with at least 10 months of follow-up were analyzed, with a mean follow-up of 13±2 months (range: 10–19). Anatomic cure was defined as no prolapse greater than or equal to stage II.

Patient satisfaction was high

The anatomic cure rate was 92.3%, with a 6.8% recurrence of anterior vaginal wall prolapse and 2.6% recurrence of posterior vaginal wall prolapse. Only one patient with recurrence was symptomatic.

Six of 143 patients (4.2%) sustained an intraoperative complication: three bladder injuries, one rectal injury, one uterine artery hemorrhage (during hysterectomy), and one vaginal sulcus perforation (during transobturator tape placement). The most significant postoperative complication related to the vaginal mesh kit was vaginal hematoma; one of the two cases required reoperation and partial removal of the mesh.

Nine patients developed mesh erosion in the first 3 months, for an erosion rate of 6.3%. Six required partial excision of the mesh. Overall, symptoms and quality of life improved significantly, with an overall satisfaction rate at follow-up of 96.5%. No significant difference was noted between pre- and postoperative rates of dyspareunia.

Further evaluation is warranted

The authors are already conducting a randomized trial to compare anterior vaginal wall repair using this low-weight polypropylene mesh with traditional anterior colporrhaphy to confirm and explore these results.

Note: Bard now offers a kit called Avaulta Plus that uses the same mesh material with a trocar delivery system, previously lacking (although investigators used trocars in this study).

Perioperative complications were uncommon with Prolift system

Altman D, Falconer C. Perioperative morbidity using transvaginal mesh in pelvic organ prolapse repair. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:303–308.

This study explored the frequency and characteristics of perioperative complications associated with the use of Prolift, a transvaginal mesh system for the repair of pelvic organ prolapse (FIGURE). Twenty-five centers participated by registering a standardized safety protocol form for 248 women who underwent surgery using the system over a 6-month period. The form included information about perioperative complications, adverse intraoperative events, and the associated hospital stay, as well as obstetric and gynecologic medical history and previous pelvic surgery.

Pelvic organ perforation (lower urinary tract or anorectal injury) and blood loss greater than 1,000 mL were recorded as major complications, and any other adverse events related to the hospital stay were documented as minor complications. Most of the cohort had already undergone prolapse repair, and prolapse had recurred in the same vaginal compartment.

One author was an educational adviser for Gynecare Sweden AB, and the other an adviser for Johnson & Johnson. Although the study was funded entirely by university-administered research funds, pretrial scientific meetings were paid for by Gynecare Sweden AB.

FIGURE: Mesh support of pelvic organs

Prolift mesh in final position, with extension arms passed through the sacrospinous ligaments and the obturator foramen bilaterally.

4.4% rate of serious complications

Serious complications occurred in 4.4% (11 of 248) of cases (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.5–7.8). The predominant complication was visceral injury, which included bladder, urethral, and rectal perforation. One patient had blood loss exceeding 1,000 mL.

Minor complications occurred in 44 patients (18%). The most common minor complication was urinary tract infection. Adverse events included urinary retention requiring catheterization, anemia, transfusion, fever, groin and buttock pain, and vaginal hematoma, among others.

Concurrent pelvic floor surgery increased the risk for minor complications (odds ratio, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.1–6.9). Concurrent procedures included vaginal hysterectomy, sling procedure with tension-free vaginal tape or transobturator tension-free tape, sacrospinal fixation, repair of vaginal enterocele, and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. This risk analysis identified no other predictors of outcome.

Posterior/apical repair

- Adequately infiltrate the vaginal epithelium with diluted epinephrine solution, especially toward the lateral apices, to facilitate hemostasis and dissection

- Be thorough in lateral dissection toward the ischial spine and stay in the proper surgical plane to create a thick vaginal epithelial flap

- Palpate the ischial spine, with the preoperatively packed rectum retracted medially

- During passage of the trocar, place an index finger along the vaginal dissection to palpate the trocar in the ischiorectal fossa and deep to the levator ani muscles until the tip is palpated at the level of the ischial spine

- Pass the trocar through the arcus tendineus/levator fascia at the level of the ischial spine, as shown below:

- Do not apply excess tension to the straps of the graft material

- Do not trim the vaginal epithelium

Anterior wall (obturator foramen trocar passage)

- Same key points as posterior wall technique, but in anterior repair, there are two passes through the obturator foramen

- The first trocar is inserted into the inferior obturator foramen, rotated, and guided with the surgeon’s finger inserted into and held in the vaginal dissection, as shown below:

- The superior passage exits close to the bladder neck, and the inferior passage approximates the ischial spine. Penetrate along the arcus tendineus approximately 1 cm from the ischial spine

Caution! Keep summary points in context

These key points are not intended as formal medical training, but as general information only. Continued research into these techniques is needed to assess long-term outcomes.

Short-term outcomes data only

Because this study focused on immediate complications, no long-term data on such complications as persistent pain, mesh erosion, or infection were collected.

All surgeons underwent hands-on training with the transvaginal repair system before patients were enrolled in the study. Nevertheless, the authors observe that many repair procedures were performed at the beginning of the physicians’ learning curve, with a higher number of complications than would be expected from more experienced surgeons.

The data may also have been affected by selection bias (ie, toward more complicated cases), given that most patients had already undergone prolapse repair.

Two systems yield excellent short-term results in women with recurrent prolapse

Gauruder-Burmester A, Koutouzidou P, Rohne J, Gronewold M, Tunn R. Follow-up after polypropylene mesh repair of anterior and posterior compartments in patients with recurrent prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:1059–1064.

This retrospective study involved women who had already undergone one or more prolapse repairs. These patients then underwent reoperation with mesh-reinforced repair. The authors hypothesized that recurrent prolapse represents poor tissue quality, necessitating the use of mesh in subsequent repairs. Both pre- and postoperative symptoms and functional changes were analyzed, with a special focus on mesh erosion and sexual function.

Details of the study

Of 145 women who underwent repair with the Apogee (apical posterior) or Perigee (anterior wall) system during a 1-year period, 120 were included in the analysis. The other 25 patients were excluded because they did not return for follow-up, were missing urodynamic data, or had inaccurate POP-Q staging. All patients had recurrent stage III posterior or anterior vaginal wall prolapse. Forty percent of patients had an apical posterior repair, and 60% had anterior wall repair. None had both procedures performed simultaneously.

All patients had undergone hysterectomy and received vaginal estrogen before and after surgery. Urinary incontinence was treated in a two-step fashion; that is, it was not addressed until 3 months after repair of the prolapse. Routine follow-up occurred at 1 month and 1 year after surgery.

One-year cure rate was 93%

No perioperative or intraoperative complications occurred, and mean operative time was 35±4.5 minutes. Mesh erosion occurred in four patients (3%) and involved anterior mesh placement only. No mesh infections were noted.

At 1 year, 93% of women were anatomically cured of prolapse (ie, they had less than stage II prolapse). Prolapse recurred in eight women; all cases involved the anterior compartment.

No dyspareunia was associated with the repair. In fact, prolapse-associated dyspareunia resolved in all 15 women who reported this symptom before surgery. In addition, questionnaires about quality of life and satisfaction revealed significant improvement after mesh placement (P=.023).

The authors attribute the positive results to the fact that both surgeons involved in the study used the technique on 15 patients before operating on study participants, minimizing the effect of the learning curve. The authors were also careful about patient selection.

Results merit cautious optimism

The authors propose that the low erosion rate and lack of new-onset dyspareunia after surgery may be misleading because long-term results have not yet been obtained. We also speculate that precise dissection in the proper surgical plane likely minimized early erosions.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

The use of transvaginal mesh—with or without trocar placement—is surrounded by controversy. A number of minimally invasive vaginal mesh kits are commercially available for the repair of pelvic organ prolapse, and new kits are entering the market rapidly. The challenge is determining whether these new techniques are as effective and safe as traditional prolapse repairs.

Although the use of permanent mesh to repair prolapse has been explored in retrospective and prospective studies, no rigorous controlled trials have compared these new procedures with abdominal sacrocolpopexy or uterosacral ligament suspension, for example. The current body of literature does suggest a high rate of recurrent prolapse after traditional anterior or posterior colporrhaphy, and the use of allograft material has not been shown to improve outcomes. Surgeons are now turning their attention to permanent polypropylene mesh as a possible alternative. In addition, repair of the vaginal apex at the time of anterior and posterior vaginal wall repair is being explored as a way to increase durability of the repair. The new trocar-delivered mesh kits address this issue by suspending the vaginal vault while providing support to the vaginal walls.

This article highlights three recent studies that focus on a new trocar-delivered, protected, low-weight polypropylene mesh (Ugytex, distributed by Bard as Pelvitex) and three trocar-delivered mesh kits (Prolift, Apogee, and Perigee).

One-year outcomes encouraging for low-weight polypropylene mesh

De Tayrac R, Devoldere G, Renaudie J, Villard P, Guilbaud O, Eglin G. Prolapse repair by vaginal route using a new protected low-weight polypropylene mesh: 1-year functional and anatomical outcome in a prospective multicentre study. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:251–256.

This study evaluated functional and anatomic outcomes after placement for prolapse repair of low-weight polypropylene mesh protected by absorbable hydrophilic film. The film, a combination of atelocollagen, polyethylene glycol, and glycerol, is designed to protect pelvic organs from acute inflammation during healing. In a separate investigation of unprotected, heavyweight polypropylene mesh in prolapse repair, the anatomic success rate ranged from 75% to 100%, but the rate of mesh erosion (13%) and dyspareunia (69%) seemed unacceptably high.1

Rigorous preoperative assessment

In this trial, 230 women with symptomatic vaginal wall prolapse were recruited at 13 centers in a consecutive fashion. At enrollment, all patients were measured using the pelvic organ prolapse quantitative staging system (POP-Q). They also completed the validated Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire. The presence and severity of dyspareunia were also recorded, as well as the Urinary Dysfunction Measurement Scale. All participants had prolapse equal to or exceeding stage II.

Surgeons used trocars to percutaneously place a low-weight (38 g/m2) and highly porous polypropylene monofilament mesh (Ugytex/Pelvitex) for vaginal repair and performed any concomitant procedures. Perioperative and postoperative complications were recorded. Patients were evaluated at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 1 year. The first 143 patients with at least 10 months of follow-up were analyzed, with a mean follow-up of 13±2 months (range: 10–19). Anatomic cure was defined as no prolapse greater than or equal to stage II.

Patient satisfaction was high

The anatomic cure rate was 92.3%, with a 6.8% recurrence of anterior vaginal wall prolapse and 2.6% recurrence of posterior vaginal wall prolapse. Only one patient with recurrence was symptomatic.

Six of 143 patients (4.2%) sustained an intraoperative complication: three bladder injuries, one rectal injury, one uterine artery hemorrhage (during hysterectomy), and one vaginal sulcus perforation (during transobturator tape placement). The most significant postoperative complication related to the vaginal mesh kit was vaginal hematoma; one of the two cases required reoperation and partial removal of the mesh.

Nine patients developed mesh erosion in the first 3 months, for an erosion rate of 6.3%. Six required partial excision of the mesh. Overall, symptoms and quality of life improved significantly, with an overall satisfaction rate at follow-up of 96.5%. No significant difference was noted between pre- and postoperative rates of dyspareunia.

Further evaluation is warranted

The authors are already conducting a randomized trial to compare anterior vaginal wall repair using this low-weight polypropylene mesh with traditional anterior colporrhaphy to confirm and explore these results.

Note: Bard now offers a kit called Avaulta Plus that uses the same mesh material with a trocar delivery system, previously lacking (although investigators used trocars in this study).

Perioperative complications were uncommon with Prolift system

Altman D, Falconer C. Perioperative morbidity using transvaginal mesh in pelvic organ prolapse repair. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:303–308.

This study explored the frequency and characteristics of perioperative complications associated with the use of Prolift, a transvaginal mesh system for the repair of pelvic organ prolapse (FIGURE). Twenty-five centers participated by registering a standardized safety protocol form for 248 women who underwent surgery using the system over a 6-month period. The form included information about perioperative complications, adverse intraoperative events, and the associated hospital stay, as well as obstetric and gynecologic medical history and previous pelvic surgery.

Pelvic organ perforation (lower urinary tract or anorectal injury) and blood loss greater than 1,000 mL were recorded as major complications, and any other adverse events related to the hospital stay were documented as minor complications. Most of the cohort had already undergone prolapse repair, and prolapse had recurred in the same vaginal compartment.

One author was an educational adviser for Gynecare Sweden AB, and the other an adviser for Johnson & Johnson. Although the study was funded entirely by university-administered research funds, pretrial scientific meetings were paid for by Gynecare Sweden AB.

FIGURE: Mesh support of pelvic organs

Prolift mesh in final position, with extension arms passed through the sacrospinous ligaments and the obturator foramen bilaterally.

4.4% rate of serious complications

Serious complications occurred in 4.4% (11 of 248) of cases (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.5–7.8). The predominant complication was visceral injury, which included bladder, urethral, and rectal perforation. One patient had blood loss exceeding 1,000 mL.

Minor complications occurred in 44 patients (18%). The most common minor complication was urinary tract infection. Adverse events included urinary retention requiring catheterization, anemia, transfusion, fever, groin and buttock pain, and vaginal hematoma, among others.

Concurrent pelvic floor surgery increased the risk for minor complications (odds ratio, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.1–6.9). Concurrent procedures included vaginal hysterectomy, sling procedure with tension-free vaginal tape or transobturator tension-free tape, sacrospinal fixation, repair of vaginal enterocele, and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. This risk analysis identified no other predictors of outcome.

Posterior/apical repair

- Adequately infiltrate the vaginal epithelium with diluted epinephrine solution, especially toward the lateral apices, to facilitate hemostasis and dissection

- Be thorough in lateral dissection toward the ischial spine and stay in the proper surgical plane to create a thick vaginal epithelial flap

- Palpate the ischial spine, with the preoperatively packed rectum retracted medially

- During passage of the trocar, place an index finger along the vaginal dissection to palpate the trocar in the ischiorectal fossa and deep to the levator ani muscles until the tip is palpated at the level of the ischial spine

- Pass the trocar through the arcus tendineus/levator fascia at the level of the ischial spine, as shown below:

- Do not apply excess tension to the straps of the graft material

- Do not trim the vaginal epithelium

Anterior wall (obturator foramen trocar passage)

- Same key points as posterior wall technique, but in anterior repair, there are two passes through the obturator foramen

- The first trocar is inserted into the inferior obturator foramen, rotated, and guided with the surgeon’s finger inserted into and held in the vaginal dissection, as shown below:

- The superior passage exits close to the bladder neck, and the inferior passage approximates the ischial spine. Penetrate along the arcus tendineus approximately 1 cm from the ischial spine

Caution! Keep summary points in context

These key points are not intended as formal medical training, but as general information only. Continued research into these techniques is needed to assess long-term outcomes.

Short-term outcomes data only

Because this study focused on immediate complications, no long-term data on such complications as persistent pain, mesh erosion, or infection were collected.

All surgeons underwent hands-on training with the transvaginal repair system before patients were enrolled in the study. Nevertheless, the authors observe that many repair procedures were performed at the beginning of the physicians’ learning curve, with a higher number of complications than would be expected from more experienced surgeons.

The data may also have been affected by selection bias (ie, toward more complicated cases), given that most patients had already undergone prolapse repair.

Two systems yield excellent short-term results in women with recurrent prolapse

Gauruder-Burmester A, Koutouzidou P, Rohne J, Gronewold M, Tunn R. Follow-up after polypropylene mesh repair of anterior and posterior compartments in patients with recurrent prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:1059–1064.

This retrospective study involved women who had already undergone one or more prolapse repairs. These patients then underwent reoperation with mesh-reinforced repair. The authors hypothesized that recurrent prolapse represents poor tissue quality, necessitating the use of mesh in subsequent repairs. Both pre- and postoperative symptoms and functional changes were analyzed, with a special focus on mesh erosion and sexual function.

Details of the study

Of 145 women who underwent repair with the Apogee (apical posterior) or Perigee (anterior wall) system during a 1-year period, 120 were included in the analysis. The other 25 patients were excluded because they did not return for follow-up, were missing urodynamic data, or had inaccurate POP-Q staging. All patients had recurrent stage III posterior or anterior vaginal wall prolapse. Forty percent of patients had an apical posterior repair, and 60% had anterior wall repair. None had both procedures performed simultaneously.

All patients had undergone hysterectomy and received vaginal estrogen before and after surgery. Urinary incontinence was treated in a two-step fashion; that is, it was not addressed until 3 months after repair of the prolapse. Routine follow-up occurred at 1 month and 1 year after surgery.

One-year cure rate was 93%

No perioperative or intraoperative complications occurred, and mean operative time was 35±4.5 minutes. Mesh erosion occurred in four patients (3%) and involved anterior mesh placement only. No mesh infections were noted.

At 1 year, 93% of women were anatomically cured of prolapse (ie, they had less than stage II prolapse). Prolapse recurred in eight women; all cases involved the anterior compartment.

No dyspareunia was associated with the repair. In fact, prolapse-associated dyspareunia resolved in all 15 women who reported this symptom before surgery. In addition, questionnaires about quality of life and satisfaction revealed significant improvement after mesh placement (P=.023).

The authors attribute the positive results to the fact that both surgeons involved in the study used the technique on 15 patients before operating on study participants, minimizing the effect of the learning curve. The authors were also careful about patient selection.

Results merit cautious optimism

The authors propose that the low erosion rate and lack of new-onset dyspareunia after surgery may be misleading because long-term results have not yet been obtained. We also speculate that precise dissection in the proper surgical plane likely minimized early erosions.

Reference

1. Milani R, Salvatore S, Soligo M, Pifarotti P, Meschia M, Cortese M. Functional and anatomical outcome of anterior and posterior vaginal prolapse repair with prolene mesh. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;111:1-5.

Reference

1. Milani R, Salvatore S, Soligo M, Pifarotti P, Meschia M, Cortese M. Functional and anatomical outcome of anterior and posterior vaginal prolapse repair with prolene mesh. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;111:1-5.

A Hepatitis C Support Group

Gram-negative Toe Web Infection Complicated by Myiasis

5 Points on Ankle Fractures: It Is Not Just a "Simple" Ankle Fracture

TECHNOLOGY

Over its history, surgery has been defined by the tools available to practitioners. In our era, opportunities to offer patients minimally invasive surgery have expanded dramatically as methods of establishing visualization, achieving hemostasis, and performing tissue dissection have improved. (I remember trying to treat ectopic pregnancy laparoscopically in the early 1980s without benefit of a camera or suction irrigator!)

For surgeons of my generation, the ability to access the abdominal cavity minimally invasively and to clearly visualize the contents was a significant step forward. Hysteroscopic myomectomy was another tremendous incremental improvement for patients with submucous myomas. But there is much more in store for the coming years.

Where are we headed in the next wave of gynecologic surgery? Will patients require an incision at all? Is there room to advance beyond laparoscopy and hysteroscopy? What innovations will industry offer us in the 21st century?

In this article, I describe something that is fairly familiar to most of us by now, but which is not yet practical for routine gynecologic procedures—robotically assisted endoscopic surgery. I then move on to a phenomenon that, in many respects, is still being imagined—natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery, or NOTES.

Robotic systems are best suited for complex surgery

Laparoscopic surgery is limited by the two-dimensional view and need for hand control of long, rigid instruments through ancillary trocar sites. Although these impediments can be overcome with practice and experience, the inability to see in three dimensions and the compromised range of motion hamper optimal management of some surgical procedures.

A number of technological advances may significantly improve our ability to perform suture-intensive or anatomically challenging operations. Several companies are developing camera systems that will permit a three-dimensional view without the need for multiple visual ports. The technology is borrowed from the world of insects, which “see” through multiple lenses within the same eye. The application of such visual processing to optical systems for endoscopic surgery will be a huge advance for laparoscopy—one that is still being perfected by industry. In 2007, the da Vinci robot system (Intuitive Surgical) offers the best opportunity to achieve both three-dimensional visualization and an ability to “feel” tissue and manipulate instruments with markedly increased range of motion.

Cost is the limiting factor

Although the da Vinci system has revolutionized the practice of urology, enabling radical nerve-sparing prostatectomy, its utility in gynecology is still being investigated. Several centers use the robot for a significant percentage of their laparoscopic gynecologic surgery, but the setup time, learning curve, and intraoperative time required make the da Vinci system an impractical tool for many routine procedures. Its true advantage lies in suture-intensive procedures and in surgeries that require meticulous dissection close to major structures. In gynecology, the laparoscopic procedures most likely to benefit from the three-dimensional view and articulating instruments are sacral colpopexy, myomectomy (FIGURE), radical hysterectomy, and lymph node dissection.

Although it is interesting and enjoyable to use robotic technology for routine laparoscopic procedures, I believe the cost is prohibitive—several million dollars for each robot. If the financial barriers are removed, however, this system will be a welcome addition to the toolset for gynecologic laparoscopic surgery. Until then, we need to make intelligent use of this powerful tool.

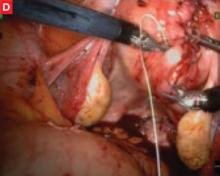

FIGURE Robotic myomectomy

A: Using the da Vinci robot, the surgeon incises the myometrium down to the fibroid.

B: After grasping the fibroid, the surgeon dissects it away from the surrounding myometrium.

C: As the fibroid is freed, another small tumor becomes apparent at the bottom right, and is also removed.

D: The myometrium is sutured in layers after removal of the fibroids. Photos courtesy of Paul Indman, MD.Just as many of us were able to perform laparoscopic surgery without a three-chip camera and high-tech energy system for hemostasis until the cost of those technologies could be recouped in reduced operating room time and fewer conversions to laparotomy, so will today’s surgeons have to continue performing laparoscopic adnexal surgery, routine hysterectomy, and treatment of ectopic pregnancy the “old-fashioned” way. For complex procedures, however, the da Vinci system is proving to be a major advance in endoscopic surgery.

Look for other, perhaps less expensive, technologies coming down the road that will, at the very least, permit three-dimensional visualization without the need for robotics. In addition, as I discuss in the next section, miniaturization of robotics is on the horizon. Only our imagination limits our thinking about how robotic technology may be used in the not-too-distant future.

ROBOTICS IN GYNECOLOGY

Selected studies

- Bocca S, Stadtmauer L, Oehninger S. Uncomplicated fullterm pregnancy after da Vinci-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy. Reprod Biomed Online. 2007;14:246–249.

- Elliott DS, Chow GK, Gettman M. Current status of robotics in female urology and gynecology. World J Urol. 2006;24:188–192.

- Fiorentino RP, Zepeda MA, Goldstein BH, John CR, Rettenmaier MA. Pilot study assessing robotic laparoscopic hysterectomy and patient outcomes. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13:60–63.

- Magrina JF. Robotic surgery in gynecology. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2007;28:77–82.

NOTES takes “minimally invasive” to a new level

Imagine performing surgery for ectopic pregnancy or endometriosis in your office, without anesthesia. Think this is impossible? Think again!

A newer, perhaps better, and definitely less invasive version of endoscopic surgery is on the horizon—natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery, or NOTES. In May, a surgeon in Portland, Oregon, performed a cholecystectomy by dropping an endoscope through the patient’s mouth into the stomach, drilling an opening in the gastric wall, and placing small instruments through that opening to perform the surgery. The specimen was then pulled through the small opening in the stomach and retrieved through the patient’s mouth! The stomach was closed with an endoscopic stapling device.

NOTES appears to be the next true advance in minimally invasive surgery. This should come as no surprise to gynecologists. We are the champions of transcervical and transvaginal surgery. General surgeons and gastroenterologists are recognizing what we have long known—that operating through these natural orifices is less uncomfortable for the patient and provides faster, less complicated recovery. They are also recognizing the challenges involved in such an approach.

A new generation of instruments is in the works

Clearly, operating through the vagina, cervix, or stomach necessitates excellent visualization and instruments flexible enough to navigate through tiny openings but strong enough to transect and retrieve tissue. Many of our industry partners are working diligently to create and perfect new instrumentation for NOTES procedures, and research is under way at many centers in this country and overseas into transgastric and transrectal procedures.

Consider what we might be able to achieve with this technology! By eliminating the need for transabdominal access, we can vastly reduce the risk of intestinal and major vessel injury and eliminate the risk of hernia. We can also markedly reduce the discomfort associated with abdominal incisions.

How might this technology be applied in gynecology? I anticipate that ovarian pathology, endometriosis, and ectopic pregnancy will be managed transvaginally or via a small opening in the uterus. Transvaginal hydrolaparoscopy—in which warm saline is used as the distention medium instead of carbon dioxide, and access to the pelvis is achieved through a small culpotomy—has been around for many years but is limited by the rigid instrumentation and restricted visualization now available. With flexible instruments that can “see” around corners yet provide a wide visual field, microrobots that can be placed through a tiny opening and then deployed to accomplish the surgical task, and systems to achieve hemostasis, NOTES may be the next revolution in gynecologic surgery.

Still in a very early stage of development, natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) has generated considerable enthusiasm among physicians leading research and development efforts. Hoping to steer these efforts in a responsible direction—and avoid the problems encountered during the early days of laparoscopic surgery, when many inexperienced practitioners began adopting the technique prematurely—a working group from the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons was formed in 2005, calling itself the Natural Orifice Surgery Consortium for Assessment and Research (NOSCAR). So far, this group has convened two international conferences and penned two white papers, noting that “the overwhelming sense [at the first international conference]…was that NOTES will develop into a mainstream clinical capability in the near future.”1

Some of the needs NOSCAR has identified are:

- determining the optimal technique and site to achieve access to the peritoneal cavity

- developing a gastric closure method that is 100% reliable

- reducing the risk of intraperitoneal contamination and infection, given the transgastric route that has dominated NOTES so far

- developing the ability to suture

- maintaining spatial orientation during surgery, as well as a multitasking platform that would allow manipulation of tissue, clear visualization, and safe access

- preventing intraperitoneal complications such as bleeding and bowel perforation

- exploring the physiology of pneumoperitoneum in the setting of NOTES

- establishing guidelines for training physicians and reporting both positive and negative outcomes.

In the meantime, NOSCAR recommends that all NOTES procedures in humans be approved by the Institutional Review Board and reported to a registry.

So far, the technology has been used to perform appendectomy and cholecystectomy in humans. Research grants totaling $1.5 million have been pledged by industry.

Reference

1. NOSCAR Working Group. NOTES: gathering momentum. White Paper. May 2006. Available at: http://www.noscar.org/documents/NOTES_White_Paper_May06.pdf. Accessed July 3, 2007.

NATURAL ORIFICE TRANSLUMINAL ENDOSCOPIC SURGERY (NOTES)

Selected studies

To date, 19 abstracts on PubMed discuss the impressive opportunities NOTES will provide. Here is a sample:

- de la Fuente SG, Demaria EJ, Reynolds JD, Portenier DD, Pryor AD. New developments in surgery: natural orifi ce transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES). Arch Surg. 2007;142:295–297.

- Fong DG, Pai RD, Thompson CC. Transcolonic endoscopic abdominal exploration: a NOTES survival study in a porcine model. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:312–318.

- Malik A, Mellinger JD, Hazey JW, Dunkin BJ, MacFadyen BV. Endoluminal and transluminal surgery: current status and future possibilities. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1179–1192.

- McGee MF, Rosen MJ, Marks J, et al. A primer on natural orifi ce transluminal endoscopic surgery: building a new paradigm. Surg Innov. 2006;13:86–93.

- Wilhelm D, Meining A, von Delius S, et al. An innovative, safe and sterile sigmoid access (ISSA) for NOTES. Endoscopy. 2007;39:401–406.

Over its history, surgery has been defined by the tools available to practitioners. In our era, opportunities to offer patients minimally invasive surgery have expanded dramatically as methods of establishing visualization, achieving hemostasis, and performing tissue dissection have improved. (I remember trying to treat ectopic pregnancy laparoscopically in the early 1980s without benefit of a camera or suction irrigator!)

For surgeons of my generation, the ability to access the abdominal cavity minimally invasively and to clearly visualize the contents was a significant step forward. Hysteroscopic myomectomy was another tremendous incremental improvement for patients with submucous myomas. But there is much more in store for the coming years.

Where are we headed in the next wave of gynecologic surgery? Will patients require an incision at all? Is there room to advance beyond laparoscopy and hysteroscopy? What innovations will industry offer us in the 21st century?

In this article, I describe something that is fairly familiar to most of us by now, but which is not yet practical for routine gynecologic procedures—robotically assisted endoscopic surgery. I then move on to a phenomenon that, in many respects, is still being imagined—natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery, or NOTES.

Robotic systems are best suited for complex surgery