User login

Home pregnancy tests—Is ectopic always on your mind?

CASE Unidentified ectopic pregnancy leads to rupture*

A 33-year-old woman (G1 P0010) with 2 positive home pregnancy tests presents to the emergency department (ED) reporting intermittent vaginal bleeding for 3 days. Her last menstrual period was 10 weeks ago, but she reports that her menses are always irregular. She has a history of asymptomatic chlamydia, as well as spontaneous abortion 2 years prior. At present, she denies abdominal pain or vaginal discharge.

Upon examination her vital signs are: temperature, 98.3 °F; pulse, 112 bpm, with a resting rate of 16 bpm; blood pressure (BP), 142/91 mm Hg; pulse O2, 99%; height, 4’ 3”; weight, 115 lb. Her labs are: hemoglobin, 12.1 g/dL; hematocrit, 38%; serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) 236 mIU/mL. Upon pelvic examination, no active bleeding is noted. She agrees to be followed up by her gynecologist and is given a prescription for serum hCG in 2 days. She is instructed to return to the ED should she have pain or increased vaginal bleeding.

Three days later, the patient follows up with her gynecologist reporting mild cramping. She notes having had an episode of heavy vaginal bleeding and a “weakly positive” home pregnancy test. Transvaginal ultrasonography notes endometrial thickness 0.59 mm and unremarkable adnexa. A urine pregnancy test performed in the office is positive; urinalysis is positive for nitrites. With the bleeding slowed, the gynecologist’s overall impression is that the patient has undergone complete spontaneous abortion. She prescribes Macrobid for the urinary tract infection. She does not obtain the ED-prescribed serum HCG levels, as she feels, since complete spontaneous abortion has occurred there is no need to obtain a follow-up serum HCG.

Five days later, the patient returns to the ED reporting abdominal pain after eating. Fever and productive cough of 2 days are noted. The patient states that she had a recent miscarriage. The overall impression of the patient’s condition is bronchitis, and it is noted on the patient’s record, “unlikely ectopic pregnancy and pregnancy test may be false positive,” hence a pregnancy test is not ordered. Examination reveals mild suprapubic tenderness with no rebound; no pelvic exam is performed. The patient is instructed to follow up with a health care clinic within a week, and to return to the ED with severe abdominal pain, higher fever, or any new concerning symptoms. A Zithromax Z-pak is prescribed.

Four days later, the patient is brought by ambulance to the ED of the local major medical center with severe abdominal pain involving the right lower quadrant. She states that she had a miscarriage 3 weeks prior and was recently treated for bronchitis. She has dizziness when standing. Her vital signs are: temperature, 97.8 °F; heart rate, 95 bpm; BP, 72/48 mm Hg; pulse O2, 100%. She reports her abdominal pain to be 6/10.

The patient is given a Lactated Ringer’s bolus of 1,000 mL for a hypotensive episode. Computed tomography is obtained and notes, “low attenuation in the left adnexa with a dilated fallopian tube.” A large heterogeneous collection of fluid in the pelvis is noted with active extravasation, consistent with an “acute bleed.”

The patient is brought to the operating room with a diagnosis of probable ruptured ectopic pregnancy. Intraoperatively she is noted to have a right ruptured ectopic and left tubo-ovarian abscess. The surgeon proceeds with right salpingectomy and left salpingo-oophorectomy. Three liters of hemoperitoneum is found.

She is followed postoperatively with serum hCG until levels are negative. Her postoperative course is uneventful. Her only future option for pregnancy is through assisted reproductive technology (ART) with in vitro fertilization (IVF). The patient sues the gynecologist and second ED physician for presumed inappropriate assessment for ectopic pregnancy.

*The “facts” of this case are a composite, drawn from several cases to illustrate medical and legal issues. The statement of facts should be considered hypothetical.

Continue to: WHAT’S THE VERDICT?...

WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

A defense verdict is returned.

Medical considerations

The incidence of ectopic pregnancy is 2% of all pregnancies, with a higher incidence (about 4%) among infertility patients.1 Up to 10% of ectopic pregnancies have no symptoms.2

Clinical presentations. Classic signs of ectopic pregnancy include:

- abdominal pain

- vaginal bleeding

- late menses (often noted).

A recent case of ectopic pregnancy presenting with chest pain was reported.3 Clinicians must never lose site of the fact that ectopic pregnancy is the most common cause of maternal mortality in the first trimester, with an incidence of 1% to 10% of all first-trimester deaths.4

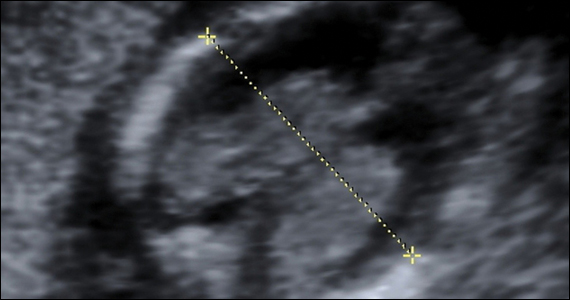

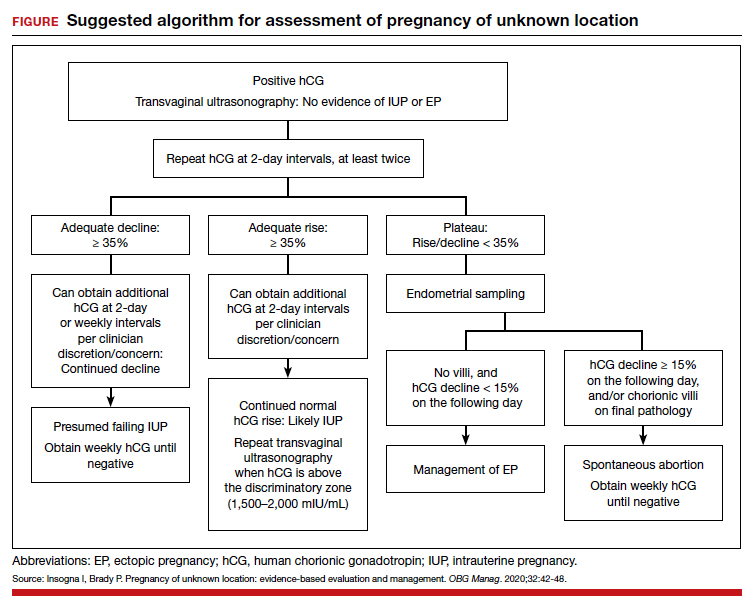

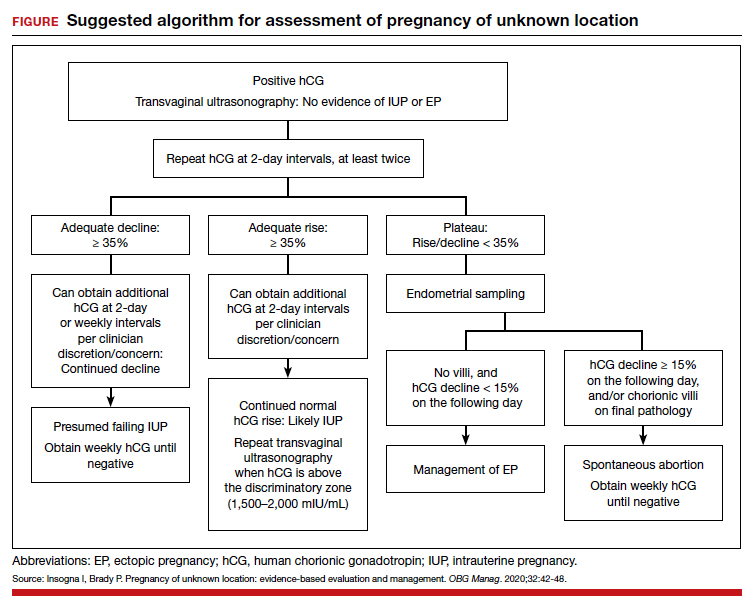

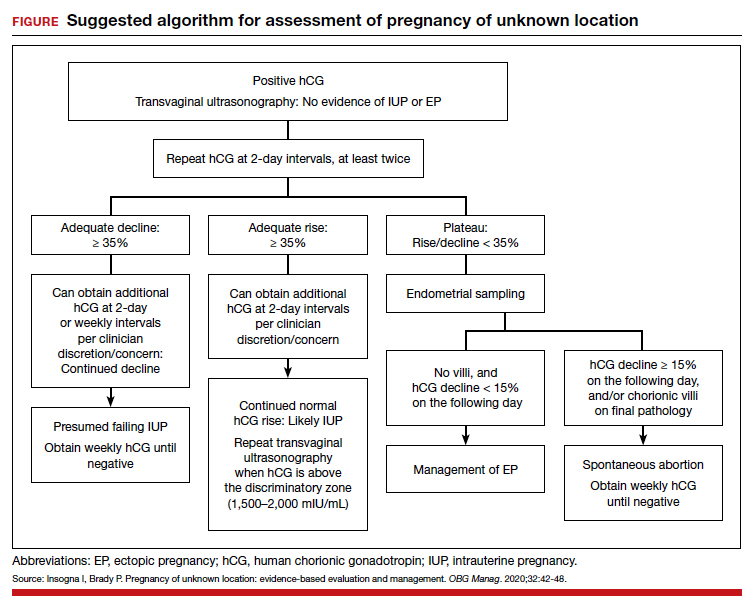

Risk factors include pelvic inflammatory disease, as demonstrated in the opening case. “The silent epidemic of chlamydia” comes to mind, and tobacco smoking can adversely affect tubal cilia, as can pelvic adhesions and/or prior tubal surgery. All of these factors can predispose a patient to ectopic pregnancy; in addition, intrauterine devices, endometriosis, tubal ligation (or ligation reversal), all can set the stage for an ectopic pregnancy.5 Appropriate serum hCG monitoring during early pregnancy can assist in sorting out pregnancies of unknown location (PUL; FIGURE). First trimester ultrasonography, at 5 weeks gestation, usually identifies early intrauterine gestation.

Imaging. With regard to pelvic sonography, the earliest sign of an intrauterine pregnancy (IUP) is a sac eccentrically located in the decidua.6 As the IUP progresses, it becomes equated with a “double decidual sign,” with double rings of tissue around the sac.6 If the pregnancy is located in an adnexal mass, it is frequently inhomogeneous or noncystic in appearance (ie, “the blob” sign); the positive predictive value (PPV) is 96%.2 The PPV of transvaginal ultrasound is 80%, as paratubal, paraovarian, ovarian cyst, and hydrosalpinx can affect the interpretation.7

Heterotopic pregnancy includes an intrauterine gestation and an ectopic pregnancy. This presentation includes the presence of a “pseudosac” in the endometrial cavity plus an extrauterine gestation. Heterotopic pregnancies have become somewhat more common as ART/IVF has unfolded, especially prior to the predominance of single embryo transfer.

Managing ectopic pregnancy

For cases of early pregnancy complicated by intermittent bleeding and/or pain, monitoring with serum hCG levels at 48-hour intervals to distinguish a viable IUP from an abnormal IUP or an ectopic is appropriate. The “discriminatory zone” collates serum hCG levels with findings on ultrasonography. Specific lower limits of serum hCG levels are not clear cut, with recommendations of 3,500 mIU/mL to provide sonographic evidence of an intrauterine gestation “to avoid misdiagnosis and possible interruption of intrauterine pregnancy,” as conveyed in the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2018 practice bulletin.8 Serum progesterone levels also have been suggested to complement hCG levels; a progesterone level of <20 nmol/L is consistent with an abnormal pregnancy, whereas levels >25 nmol/L are suggestive of a viable pregnancy.2 Inhibin A levels also have been suggested to be helpful, but they are not an ideal monitoring tool.

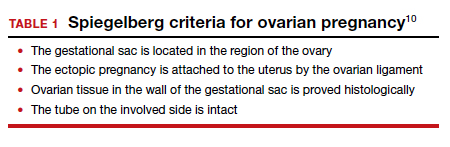

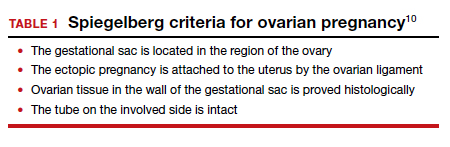

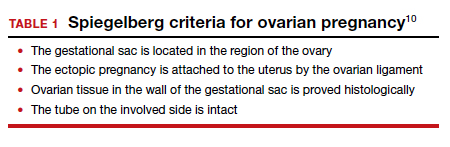

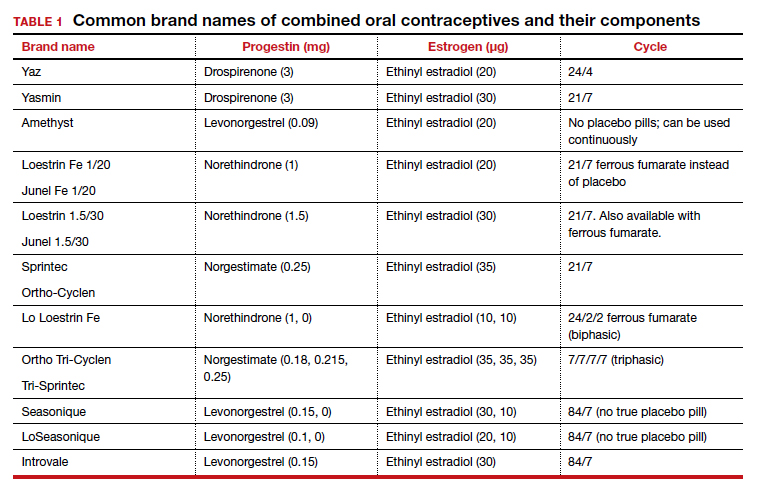

While most ectopic pregnancies are located in the fallopian tube, other locations also can be abdominal or ovarian. In addition, cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy can occur and often is associated with delay in diagnosis and greater morbidity due to such delay.9 With regard to ovarian ectopic, Spiegelberg criteria are established for diagnosis (TABLE 1).10

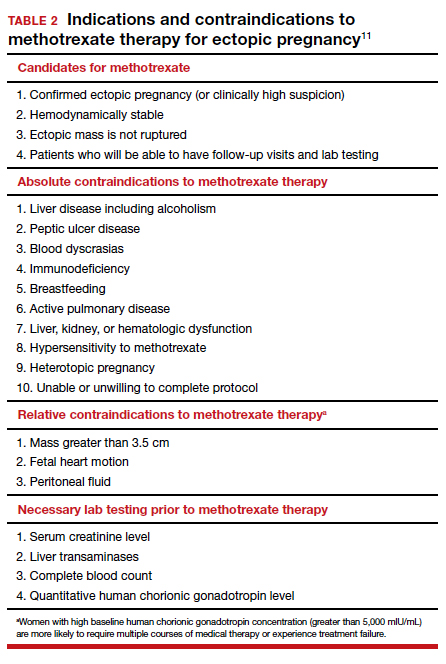

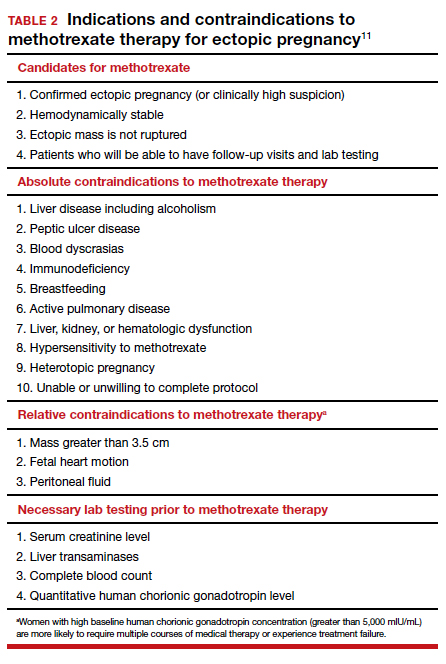

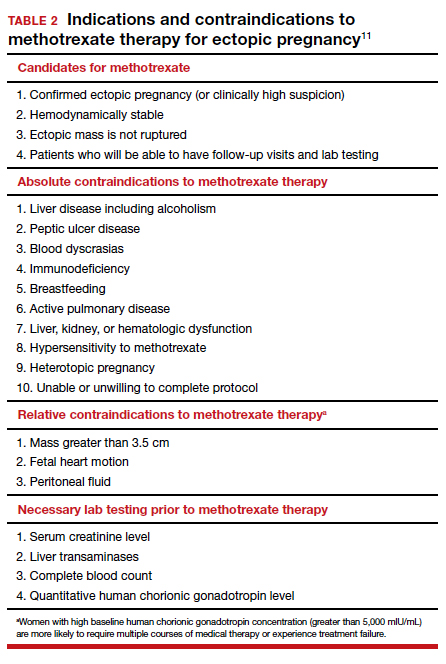

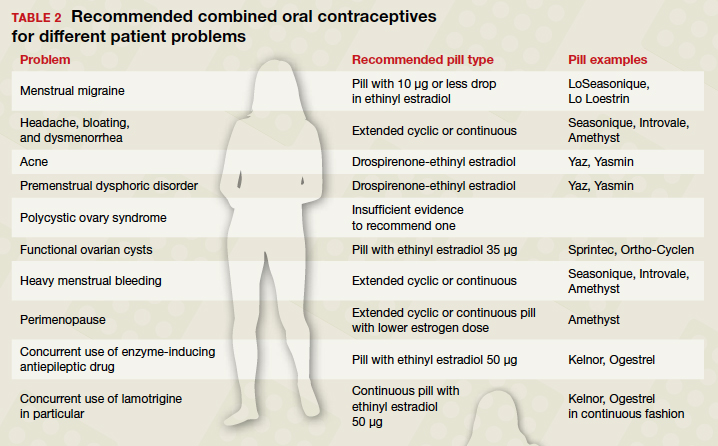

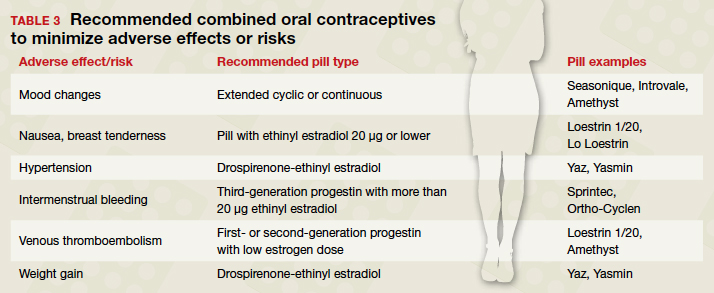

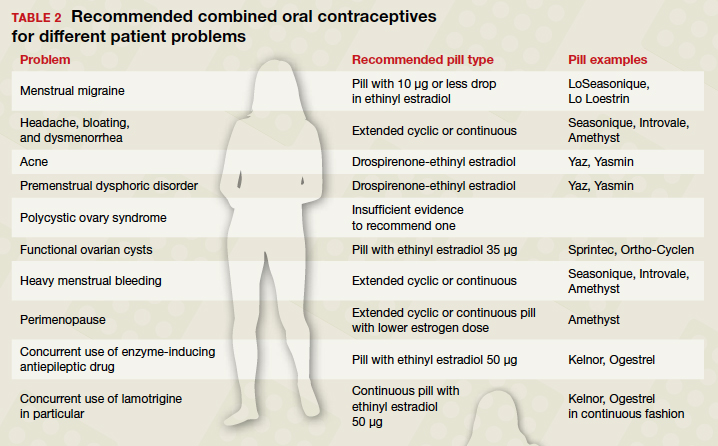

Appropriate management of an ectopic pregnancy is dependent upon the gestational age, serum hCG levels, and imaging findings, as well as the patient’s symptoms and exam findings. Treatment is established in large part on a case-by-case basis and includes, for early pregnancy, expectant management and use of methotrexate (TABLE 2).11 Dilation and curettage may be used to identify the pregnancy’s location when the serum hCG level is below 2,000 mIU/mL and there is no evidence of an IUP on ultrasound. Surgical treatment can include minimally invasive salpingostomy or salpingectomy and, depending on circumstance, laparotomy may be indicated.

Fertility following ectopic pregnancy varies and is affected by location, treatment, predisposing factors, total number of ectopic pregnancies, and other factors. Ectopic pregnancy, although rare, also can occur with use of IVF. Humans are not unique with regard to ectopic pregnancies, as they also occur in sheep.12

Continue to: Legal perspective...

Legal perspective

Lawsuits related to ectopic pregnancy are not a new phenomenon. In fact, in 1897, a physician in Ohio who misdiagnosed an “extrauterine pregnancy” as appendicitis was the center of a malpractice lawsuit.13 Unrecognized or mishandled ectopic pregnancy can result in serious injuries—in the range of 1% to 10% (see above) of maternal deaths are related to ectopic pregnancy.14 Ectopic pregnancy cases, therefore, have been the subject of substantial litigation over the years. An informal, noncomprehensive review of malpractice lawsuits brought from 2000 to 2019, found more than 300 ectopic pregnancy cases. Given the large number of malpractice claims against ObGyns,15 ectopic pregnancy cases are only a small portion of all ObGyn malpractice cases.16

A common claim: negligent diagnosis or treatment

The most common basis for lawsuits in cases of ectopic pregnancy is the clinician’s negligent failure to properly diagnose the ectopic nature of the pregnancy. There are also a number of cases claiming negligent treatment of an identified ectopic pregnancy. Not every missed diagnosis, or unsuccessful treatment, leads to liability, of course. It is only when a diagnosis or treatment fails to meet the standard of care within the profession that there should be liability. That standard of care is generally defined by what a reasonably prudent physician would do under the circumstances. Expert witnesses, who are familiar with the standard of practice within the specialty, are usually necessary to establish what that practice is. Both the plaintiff and the defense obtain experts, the former to prove what the standard of care is and that the standard was not met in the case at hand. The defense experts are usually arguing that the standard of care was met.17 Inadequate diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy or other condition may arise from a failure to take a sufficient history, conduct an appropriately thorough physical examination, recognize any of the symptoms that would suggest it is present, use and conduct ultrasound correctly, or follow-up appropriately with additional testing.18

A malpractice claim of negligent treatment can involve any the following circumstances19:

- failure to establish an appropriate treatment plan

- prescribing inappropriate medications for the patient (eg, methotrexate, when it is contraindicated)

- delivering the wrong medication or the wrong amount of the right medication

- performing a procedure badly

- undertaking a new treatment without adequate instruction and preparation.

Given the nature and risks of ectopic pregnancy, ongoing, frequent contact with the patient is essential from the point at which the condition is suspected. The greater the risk of harm (probability or consequence), the more careful any professional ought to be. Because ectopic pregnancy is not an uncommon occurrence, and because it can have devastating effects, including death, a reasonably prudent practitioner would be especially aware of the clinical presentations discussed above.20 In the opening case, the treatment plan was not well documented.

Negligence must lead to patient harm. In addition to negligence (proving that the physician did not act in accordance with the standard of care), to prevail in a malpractice case, the plaintiff-patient must prove that the negligence caused the injury, or worsened it. If the failure to make a diagnosis would not have made any difference in a harm the patient suffered, there are no damages and no liability. Suppose, for example, that a physician negligently failed to diagnose ectopic pregnancy, but performed surgery expecting to find the misdiagnosed condition. In the course of the surgery, however, the surgeon discovered and appropriately treated the ectopic pregnancy. (A version of this happened in the old 19th century case mentioned above.) The negligence of the physician did not cause harm, so there are no damages and no liability.

Continue to: Informed consent is vital...

Informed consent is vital

A part of malpractice is informed consent (or the absence of it)—issues that can arise in any medical care.21 It is wise to pay particular attention in cases where the nature of the illness is unknown, and where there are significant uncertainties and the nature of testing and treatment may change substantially over a period of a few days or few weeks. As always, informed consent should include a discussion of what process or procedure is proposed, its risks and benefits, alternative approaches that might be available, and the risk of doing nothing. Frequently, the uncertainty of ectopic pregnancy complicates the informed consent process.22

Because communication with the patient is an essential function of informed consent, the consent process should productively be used in PUL and similar cases to inform the patient about the uncertainty, and the testing and (nonsurgical) treatment that will occur. This is an opportunity to reinforce the message that the patient must maintain ongoing communication with the physician’s office about changes in her condition, and appear for each appointment scheduled. If more invasive procedures—notably surgery—become required, a separate consent process should be completed, because the risks and considerations are now meaningfully different than when treatment began. As a general matter, any possible treatment that may result in infertility or reduced reproductive capacity should specifically be included in the consent process.

In the hypothetical case, the gynecologist failed to obtain a follow-up serum hCG level. In addition, the record did not reflect ectopic pregnancy in the differential diagnosis. As noted above, the patient had predisposing factors for an ectopic pregnancy. The physician should have acknowledged the history of sexually transmitted disease predisposing her to an ectopic pregnancy. Monitoring of serum hCG levels until they are negative is appropriate with ectopic, or presumed ectopic, pregnancy management. Appropriate monitoring did not occur in this case. Each of these errors (following up on serum hCG levels and the inadequacy of notations about the possibility of ectopic pregnancy) seem inconsistent with the usual standard of care. Furthermore, as a result of the outcome, the only future option for the patient to pursue pregnancy was IVF.

Other legal issues

There are a number of other legal issues that are associated with the topic of ectopic pregnancy. There is evidence, for example, that Catholic and non-Catholic hospitals treat ectopic pregnancies differently,23 which may reflect different views on taking a life or the use of methotrexate and its association with abortion.24 In addition, the possibility of an increase in future ectopic pregnancies is one of the “risks” of abortion that pro-life organizations have pushed to see included in abortion informed consent.25 This has led some commentators to conclude that some Catholic hospitals violate federal law in managing ectopic pregnancy. There is also evidence of “overwhelming rates of medical misinformation on pregnancy center websites, including a link between abortion and ectopic pregnancy.”26

The fact that cesarean deliveries are related to an increased risk for ectopic pregnancy (because of the risk of cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy) also has been cited as information that should play a role in the consent process for cesarean delivery.27 In terms of liability, failed tubal ligation leads to a 33% risk of ectopic pregnancy.28 The risk of ectopic pregnancy is also commonly included in surrogacy contracts.29

Why the outcome was for the defense

The opening hypothetical case illustrates some of the uncertainties of medical malpractice cases. As noted, there appeared a deviation from the usual standard of care, particularly the failure to follow up on the serum hCG level. The weakness in the medical record, failing to note the possibility of ectopic pregnancy, also was probably an error but, apparently, the court felt that this did not result in any harm to the patient.

The question arises of how there would be a defense verdict in light of the failure to track consecutive serum hCG levels. A speculative explanation is that there are many uncertainties in most lawsuits. Procedural problems may result in a case being limited, expert witnesses are essential to both the plaintiff and defense, with the quality of their review and testimony possibly uneven. Judges and juries may rely on one expert witness rather than another, juries vary, and the quality of advocacy differs. Any of these situations can contribute to the unpredictability of the outcome of a case. In the case above, the liability was somewhat uncertain, and the various other factors tipped in favor of a defense verdict. ●

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ectopic pregnancy—United States, 1990‒1992. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;44:46-48.

- Kirk E, Bottomley C, Bourne T. Diagnosing ectopic pregnancy and current concepts in the management of pregnancy of unknown location. Hum Reprod Update. 2012;20:250-261.

- Dichter E, Espinosa J, Baird J, Lucerna A. An unusual emergency department case: ruptured ectopic pregnancy presenting as chest pain. World J Emerg Med. 2017;8:71-73.

- Cecchino GN, Araujo E, Elito J. Methotrexate for ectopic pregnancy: when and how. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;290:417- 423.

- Barnhart KT, Sammel MD, Cracia CR, et al. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy in women with symptomatic firsttrimester pregnancies. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:36-43.

- Carusi D. Pregnancy of unknown location: evaluation and management. Semin Perinatol. 2019;43:95-100.

- Barnhart KT, Fay CA, Suescum M, et al. Clinical factors affecting the accuracy of ultrasonography in symptomatic first-trimester pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:299-306.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulletin No. 193: tubal ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e91-e103.

- Bouyer J, Coste J, Fernandez H, et al. Sites of ectopic pregnancy: a 10-year population-based study of 1800 cases. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:3224-3230.

- Spiegelberg O. Zur casuistic der ovarial schwangerschaft. Arch Gynecol. 1978;13:73.

- OB Hospitalist Group. Methotrexate use for ectopic pregnancies guidelines. https://www.obhg.com/wp-content /uploads/2020/01/Methotrexate-Use-for-EctopicPregnancies_2016-updates.pdf. Accessed December 10, 2020.

- Brozos C, Kargiannis I, Kiossis E, et al. Ectopic pregnancy through a caesarean scar in a ewe. N Z Vet J. 2013;61:373-375.

- Tucker v. Gillette, 12 Ohio Cir. Dec. 401 (Cir. Ct. 1901).

- Creanga AA, Syverson C, Seed K, et al. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2011–2013. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:366-373.

- Matthews LR, Alvi FA, Milad MP. Reproductive surgery malpractice patterns. Fertil Steril. 2016;106:e42-e43.

- Kim B. The impact of malpractice risk on the use of obstetrics procedures. J Legal Studies. 2006;36:S79-S120.

- Abinader R, Warsof S. Complications involving obstetrical ultrasound. In: Warsof S, Shwayder JM, eds. Legal Concepts and Best Practices in Obstetrics: The Nuts and Bolts Guide to Mitigating Risk. 2019;45-48.

- Creanga AA, Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Bish CL, et al. Trends in ectopic pregnancy mortality in the United States: 1980-2007. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:837-843.

- Shwayder JM. IUP diagnosed and treated as ectopic: How bad can it get? Contemporary OB/GYN. 2019;64:49-46.

- Kaplan AI. Should this ectopic pregnancy have been diagnosed earlier? Contemporary OB/GYN. 2017;62:53.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Ethics. Committee opinion 439: informed consent. Reaffirmed 2015. https://www.acog.org/clinical /clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2009/08 /informed-consent. Accessed December 9, 2020.

- Shwayder JM. Liability in ob/gyn ultrasound. Contemporary OB/GYN. 2017;62:32-49.

- Fisher LN. Institutional religious exemptions: a balancing approach. BYU Law Review. 2014;415-444.

- Makdisi J. Aquinas’s prohibition of killing reconsidered. J Catholic Legal Stud. 2019:57:67-128.

- Franzonello A. Remarks of Anna Franzonello. Alb Law J Sci Tech. 2012;23:519-530.

- Malcolm HE. Pregnancy centers and the limits of mandated disclosure. Columbia Law Rev. 2019;119:1133-1168.

- Kukura E. Contested care: the limitations of evidencebased maternity care reform. Berkeley J Gender Law Justice. 2016;31:241-298.

- Donley G. Contraceptive equity: curing the sex discrimination in the ACA’s mandate. Alabama Law Rev. 2019;71:499-560.

- Berk H. Savvy surrogates and rock star parents: compensation provisions, contracting practices, and the value of womb work. Law Social Inquiry. 2020;45:398-431.

CASE Unidentified ectopic pregnancy leads to rupture*

A 33-year-old woman (G1 P0010) with 2 positive home pregnancy tests presents to the emergency department (ED) reporting intermittent vaginal bleeding for 3 days. Her last menstrual period was 10 weeks ago, but she reports that her menses are always irregular. She has a history of asymptomatic chlamydia, as well as spontaneous abortion 2 years prior. At present, she denies abdominal pain or vaginal discharge.

Upon examination her vital signs are: temperature, 98.3 °F; pulse, 112 bpm, with a resting rate of 16 bpm; blood pressure (BP), 142/91 mm Hg; pulse O2, 99%; height, 4’ 3”; weight, 115 lb. Her labs are: hemoglobin, 12.1 g/dL; hematocrit, 38%; serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) 236 mIU/mL. Upon pelvic examination, no active bleeding is noted. She agrees to be followed up by her gynecologist and is given a prescription for serum hCG in 2 days. She is instructed to return to the ED should she have pain or increased vaginal bleeding.

Three days later, the patient follows up with her gynecologist reporting mild cramping. She notes having had an episode of heavy vaginal bleeding and a “weakly positive” home pregnancy test. Transvaginal ultrasonography notes endometrial thickness 0.59 mm and unremarkable adnexa. A urine pregnancy test performed in the office is positive; urinalysis is positive for nitrites. With the bleeding slowed, the gynecologist’s overall impression is that the patient has undergone complete spontaneous abortion. She prescribes Macrobid for the urinary tract infection. She does not obtain the ED-prescribed serum HCG levels, as she feels, since complete spontaneous abortion has occurred there is no need to obtain a follow-up serum HCG.

Five days later, the patient returns to the ED reporting abdominal pain after eating. Fever and productive cough of 2 days are noted. The patient states that she had a recent miscarriage. The overall impression of the patient’s condition is bronchitis, and it is noted on the patient’s record, “unlikely ectopic pregnancy and pregnancy test may be false positive,” hence a pregnancy test is not ordered. Examination reveals mild suprapubic tenderness with no rebound; no pelvic exam is performed. The patient is instructed to follow up with a health care clinic within a week, and to return to the ED with severe abdominal pain, higher fever, or any new concerning symptoms. A Zithromax Z-pak is prescribed.

Four days later, the patient is brought by ambulance to the ED of the local major medical center with severe abdominal pain involving the right lower quadrant. She states that she had a miscarriage 3 weeks prior and was recently treated for bronchitis. She has dizziness when standing. Her vital signs are: temperature, 97.8 °F; heart rate, 95 bpm; BP, 72/48 mm Hg; pulse O2, 100%. She reports her abdominal pain to be 6/10.

The patient is given a Lactated Ringer’s bolus of 1,000 mL for a hypotensive episode. Computed tomography is obtained and notes, “low attenuation in the left adnexa with a dilated fallopian tube.” A large heterogeneous collection of fluid in the pelvis is noted with active extravasation, consistent with an “acute bleed.”

The patient is brought to the operating room with a diagnosis of probable ruptured ectopic pregnancy. Intraoperatively she is noted to have a right ruptured ectopic and left tubo-ovarian abscess. The surgeon proceeds with right salpingectomy and left salpingo-oophorectomy. Three liters of hemoperitoneum is found.

She is followed postoperatively with serum hCG until levels are negative. Her postoperative course is uneventful. Her only future option for pregnancy is through assisted reproductive technology (ART) with in vitro fertilization (IVF). The patient sues the gynecologist and second ED physician for presumed inappropriate assessment for ectopic pregnancy.

*The “facts” of this case are a composite, drawn from several cases to illustrate medical and legal issues. The statement of facts should be considered hypothetical.

Continue to: WHAT’S THE VERDICT?...

WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

A defense verdict is returned.

Medical considerations

The incidence of ectopic pregnancy is 2% of all pregnancies, with a higher incidence (about 4%) among infertility patients.1 Up to 10% of ectopic pregnancies have no symptoms.2

Clinical presentations. Classic signs of ectopic pregnancy include:

- abdominal pain

- vaginal bleeding

- late menses (often noted).

A recent case of ectopic pregnancy presenting with chest pain was reported.3 Clinicians must never lose site of the fact that ectopic pregnancy is the most common cause of maternal mortality in the first trimester, with an incidence of 1% to 10% of all first-trimester deaths.4

Risk factors include pelvic inflammatory disease, as demonstrated in the opening case. “The silent epidemic of chlamydia” comes to mind, and tobacco smoking can adversely affect tubal cilia, as can pelvic adhesions and/or prior tubal surgery. All of these factors can predispose a patient to ectopic pregnancy; in addition, intrauterine devices, endometriosis, tubal ligation (or ligation reversal), all can set the stage for an ectopic pregnancy.5 Appropriate serum hCG monitoring during early pregnancy can assist in sorting out pregnancies of unknown location (PUL; FIGURE). First trimester ultrasonography, at 5 weeks gestation, usually identifies early intrauterine gestation.

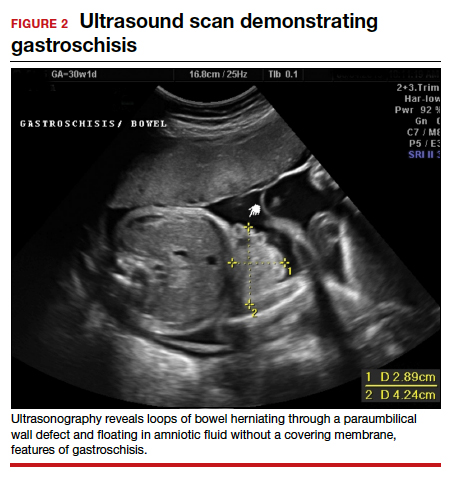

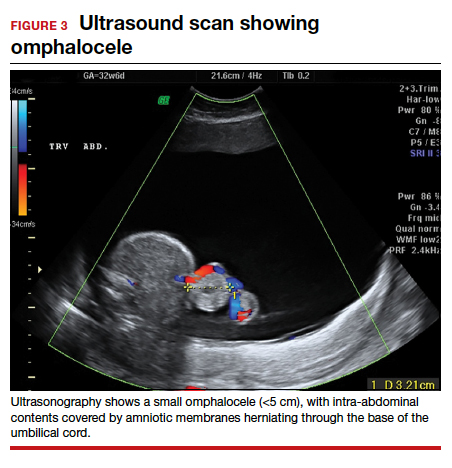

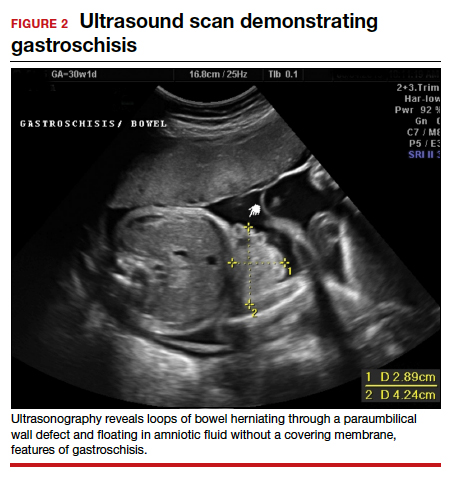

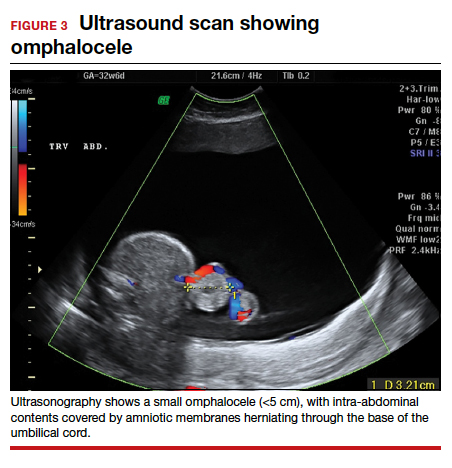

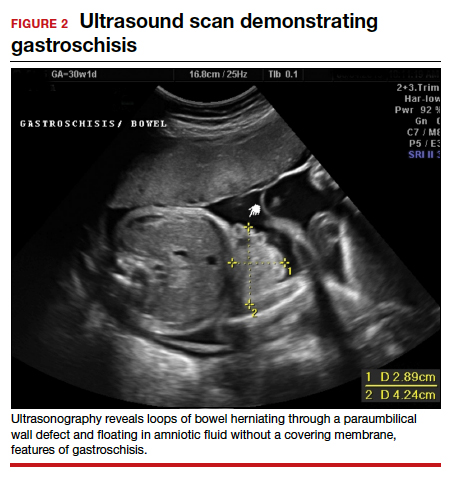

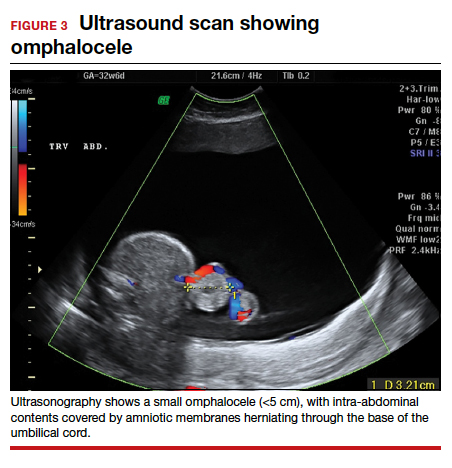

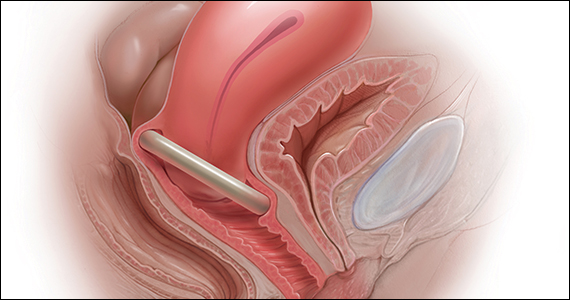

Imaging. With regard to pelvic sonography, the earliest sign of an intrauterine pregnancy (IUP) is a sac eccentrically located in the decidua.6 As the IUP progresses, it becomes equated with a “double decidual sign,” with double rings of tissue around the sac.6 If the pregnancy is located in an adnexal mass, it is frequently inhomogeneous or noncystic in appearance (ie, “the blob” sign); the positive predictive value (PPV) is 96%.2 The PPV of transvaginal ultrasound is 80%, as paratubal, paraovarian, ovarian cyst, and hydrosalpinx can affect the interpretation.7

Heterotopic pregnancy includes an intrauterine gestation and an ectopic pregnancy. This presentation includes the presence of a “pseudosac” in the endometrial cavity plus an extrauterine gestation. Heterotopic pregnancies have become somewhat more common as ART/IVF has unfolded, especially prior to the predominance of single embryo transfer.

Managing ectopic pregnancy

For cases of early pregnancy complicated by intermittent bleeding and/or pain, monitoring with serum hCG levels at 48-hour intervals to distinguish a viable IUP from an abnormal IUP or an ectopic is appropriate. The “discriminatory zone” collates serum hCG levels with findings on ultrasonography. Specific lower limits of serum hCG levels are not clear cut, with recommendations of 3,500 mIU/mL to provide sonographic evidence of an intrauterine gestation “to avoid misdiagnosis and possible interruption of intrauterine pregnancy,” as conveyed in the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2018 practice bulletin.8 Serum progesterone levels also have been suggested to complement hCG levels; a progesterone level of <20 nmol/L is consistent with an abnormal pregnancy, whereas levels >25 nmol/L are suggestive of a viable pregnancy.2 Inhibin A levels also have been suggested to be helpful, but they are not an ideal monitoring tool.

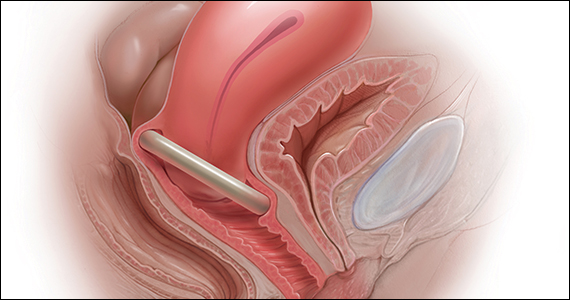

While most ectopic pregnancies are located in the fallopian tube, other locations also can be abdominal or ovarian. In addition, cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy can occur and often is associated with delay in diagnosis and greater morbidity due to such delay.9 With regard to ovarian ectopic, Spiegelberg criteria are established for diagnosis (TABLE 1).10

Appropriate management of an ectopic pregnancy is dependent upon the gestational age, serum hCG levels, and imaging findings, as well as the patient’s symptoms and exam findings. Treatment is established in large part on a case-by-case basis and includes, for early pregnancy, expectant management and use of methotrexate (TABLE 2).11 Dilation and curettage may be used to identify the pregnancy’s location when the serum hCG level is below 2,000 mIU/mL and there is no evidence of an IUP on ultrasound. Surgical treatment can include minimally invasive salpingostomy or salpingectomy and, depending on circumstance, laparotomy may be indicated.

Fertility following ectopic pregnancy varies and is affected by location, treatment, predisposing factors, total number of ectopic pregnancies, and other factors. Ectopic pregnancy, although rare, also can occur with use of IVF. Humans are not unique with regard to ectopic pregnancies, as they also occur in sheep.12

Continue to: Legal perspective...

Legal perspective

Lawsuits related to ectopic pregnancy are not a new phenomenon. In fact, in 1897, a physician in Ohio who misdiagnosed an “extrauterine pregnancy” as appendicitis was the center of a malpractice lawsuit.13 Unrecognized or mishandled ectopic pregnancy can result in serious injuries—in the range of 1% to 10% (see above) of maternal deaths are related to ectopic pregnancy.14 Ectopic pregnancy cases, therefore, have been the subject of substantial litigation over the years. An informal, noncomprehensive review of malpractice lawsuits brought from 2000 to 2019, found more than 300 ectopic pregnancy cases. Given the large number of malpractice claims against ObGyns,15 ectopic pregnancy cases are only a small portion of all ObGyn malpractice cases.16

A common claim: negligent diagnosis or treatment

The most common basis for lawsuits in cases of ectopic pregnancy is the clinician’s negligent failure to properly diagnose the ectopic nature of the pregnancy. There are also a number of cases claiming negligent treatment of an identified ectopic pregnancy. Not every missed diagnosis, or unsuccessful treatment, leads to liability, of course. It is only when a diagnosis or treatment fails to meet the standard of care within the profession that there should be liability. That standard of care is generally defined by what a reasonably prudent physician would do under the circumstances. Expert witnesses, who are familiar with the standard of practice within the specialty, are usually necessary to establish what that practice is. Both the plaintiff and the defense obtain experts, the former to prove what the standard of care is and that the standard was not met in the case at hand. The defense experts are usually arguing that the standard of care was met.17 Inadequate diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy or other condition may arise from a failure to take a sufficient history, conduct an appropriately thorough physical examination, recognize any of the symptoms that would suggest it is present, use and conduct ultrasound correctly, or follow-up appropriately with additional testing.18

A malpractice claim of negligent treatment can involve any the following circumstances19:

- failure to establish an appropriate treatment plan

- prescribing inappropriate medications for the patient (eg, methotrexate, when it is contraindicated)

- delivering the wrong medication or the wrong amount of the right medication

- performing a procedure badly

- undertaking a new treatment without adequate instruction and preparation.

Given the nature and risks of ectopic pregnancy, ongoing, frequent contact with the patient is essential from the point at which the condition is suspected. The greater the risk of harm (probability or consequence), the more careful any professional ought to be. Because ectopic pregnancy is not an uncommon occurrence, and because it can have devastating effects, including death, a reasonably prudent practitioner would be especially aware of the clinical presentations discussed above.20 In the opening case, the treatment plan was not well documented.

Negligence must lead to patient harm. In addition to negligence (proving that the physician did not act in accordance with the standard of care), to prevail in a malpractice case, the plaintiff-patient must prove that the negligence caused the injury, or worsened it. If the failure to make a diagnosis would not have made any difference in a harm the patient suffered, there are no damages and no liability. Suppose, for example, that a physician negligently failed to diagnose ectopic pregnancy, but performed surgery expecting to find the misdiagnosed condition. In the course of the surgery, however, the surgeon discovered and appropriately treated the ectopic pregnancy. (A version of this happened in the old 19th century case mentioned above.) The negligence of the physician did not cause harm, so there are no damages and no liability.

Continue to: Informed consent is vital...

Informed consent is vital

A part of malpractice is informed consent (or the absence of it)—issues that can arise in any medical care.21 It is wise to pay particular attention in cases where the nature of the illness is unknown, and where there are significant uncertainties and the nature of testing and treatment may change substantially over a period of a few days or few weeks. As always, informed consent should include a discussion of what process or procedure is proposed, its risks and benefits, alternative approaches that might be available, and the risk of doing nothing. Frequently, the uncertainty of ectopic pregnancy complicates the informed consent process.22

Because communication with the patient is an essential function of informed consent, the consent process should productively be used in PUL and similar cases to inform the patient about the uncertainty, and the testing and (nonsurgical) treatment that will occur. This is an opportunity to reinforce the message that the patient must maintain ongoing communication with the physician’s office about changes in her condition, and appear for each appointment scheduled. If more invasive procedures—notably surgery—become required, a separate consent process should be completed, because the risks and considerations are now meaningfully different than when treatment began. As a general matter, any possible treatment that may result in infertility or reduced reproductive capacity should specifically be included in the consent process.

In the hypothetical case, the gynecologist failed to obtain a follow-up serum hCG level. In addition, the record did not reflect ectopic pregnancy in the differential diagnosis. As noted above, the patient had predisposing factors for an ectopic pregnancy. The physician should have acknowledged the history of sexually transmitted disease predisposing her to an ectopic pregnancy. Monitoring of serum hCG levels until they are negative is appropriate with ectopic, or presumed ectopic, pregnancy management. Appropriate monitoring did not occur in this case. Each of these errors (following up on serum hCG levels and the inadequacy of notations about the possibility of ectopic pregnancy) seem inconsistent with the usual standard of care. Furthermore, as a result of the outcome, the only future option for the patient to pursue pregnancy was IVF.

Other legal issues

There are a number of other legal issues that are associated with the topic of ectopic pregnancy. There is evidence, for example, that Catholic and non-Catholic hospitals treat ectopic pregnancies differently,23 which may reflect different views on taking a life or the use of methotrexate and its association with abortion.24 In addition, the possibility of an increase in future ectopic pregnancies is one of the “risks” of abortion that pro-life organizations have pushed to see included in abortion informed consent.25 This has led some commentators to conclude that some Catholic hospitals violate federal law in managing ectopic pregnancy. There is also evidence of “overwhelming rates of medical misinformation on pregnancy center websites, including a link between abortion and ectopic pregnancy.”26

The fact that cesarean deliveries are related to an increased risk for ectopic pregnancy (because of the risk of cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy) also has been cited as information that should play a role in the consent process for cesarean delivery.27 In terms of liability, failed tubal ligation leads to a 33% risk of ectopic pregnancy.28 The risk of ectopic pregnancy is also commonly included in surrogacy contracts.29

Why the outcome was for the defense

The opening hypothetical case illustrates some of the uncertainties of medical malpractice cases. As noted, there appeared a deviation from the usual standard of care, particularly the failure to follow up on the serum hCG level. The weakness in the medical record, failing to note the possibility of ectopic pregnancy, also was probably an error but, apparently, the court felt that this did not result in any harm to the patient.

The question arises of how there would be a defense verdict in light of the failure to track consecutive serum hCG levels. A speculative explanation is that there are many uncertainties in most lawsuits. Procedural problems may result in a case being limited, expert witnesses are essential to both the plaintiff and defense, with the quality of their review and testimony possibly uneven. Judges and juries may rely on one expert witness rather than another, juries vary, and the quality of advocacy differs. Any of these situations can contribute to the unpredictability of the outcome of a case. In the case above, the liability was somewhat uncertain, and the various other factors tipped in favor of a defense verdict. ●

CASE Unidentified ectopic pregnancy leads to rupture*

A 33-year-old woman (G1 P0010) with 2 positive home pregnancy tests presents to the emergency department (ED) reporting intermittent vaginal bleeding for 3 days. Her last menstrual period was 10 weeks ago, but she reports that her menses are always irregular. She has a history of asymptomatic chlamydia, as well as spontaneous abortion 2 years prior. At present, she denies abdominal pain or vaginal discharge.

Upon examination her vital signs are: temperature, 98.3 °F; pulse, 112 bpm, with a resting rate of 16 bpm; blood pressure (BP), 142/91 mm Hg; pulse O2, 99%; height, 4’ 3”; weight, 115 lb. Her labs are: hemoglobin, 12.1 g/dL; hematocrit, 38%; serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) 236 mIU/mL. Upon pelvic examination, no active bleeding is noted. She agrees to be followed up by her gynecologist and is given a prescription for serum hCG in 2 days. She is instructed to return to the ED should she have pain or increased vaginal bleeding.

Three days later, the patient follows up with her gynecologist reporting mild cramping. She notes having had an episode of heavy vaginal bleeding and a “weakly positive” home pregnancy test. Transvaginal ultrasonography notes endometrial thickness 0.59 mm and unremarkable adnexa. A urine pregnancy test performed in the office is positive; urinalysis is positive for nitrites. With the bleeding slowed, the gynecologist’s overall impression is that the patient has undergone complete spontaneous abortion. She prescribes Macrobid for the urinary tract infection. She does not obtain the ED-prescribed serum HCG levels, as she feels, since complete spontaneous abortion has occurred there is no need to obtain a follow-up serum HCG.

Five days later, the patient returns to the ED reporting abdominal pain after eating. Fever and productive cough of 2 days are noted. The patient states that she had a recent miscarriage. The overall impression of the patient’s condition is bronchitis, and it is noted on the patient’s record, “unlikely ectopic pregnancy and pregnancy test may be false positive,” hence a pregnancy test is not ordered. Examination reveals mild suprapubic tenderness with no rebound; no pelvic exam is performed. The patient is instructed to follow up with a health care clinic within a week, and to return to the ED with severe abdominal pain, higher fever, or any new concerning symptoms. A Zithromax Z-pak is prescribed.

Four days later, the patient is brought by ambulance to the ED of the local major medical center with severe abdominal pain involving the right lower quadrant. She states that she had a miscarriage 3 weeks prior and was recently treated for bronchitis. She has dizziness when standing. Her vital signs are: temperature, 97.8 °F; heart rate, 95 bpm; BP, 72/48 mm Hg; pulse O2, 100%. She reports her abdominal pain to be 6/10.

The patient is given a Lactated Ringer’s bolus of 1,000 mL for a hypotensive episode. Computed tomography is obtained and notes, “low attenuation in the left adnexa with a dilated fallopian tube.” A large heterogeneous collection of fluid in the pelvis is noted with active extravasation, consistent with an “acute bleed.”

The patient is brought to the operating room with a diagnosis of probable ruptured ectopic pregnancy. Intraoperatively she is noted to have a right ruptured ectopic and left tubo-ovarian abscess. The surgeon proceeds with right salpingectomy and left salpingo-oophorectomy. Three liters of hemoperitoneum is found.

She is followed postoperatively with serum hCG until levels are negative. Her postoperative course is uneventful. Her only future option for pregnancy is through assisted reproductive technology (ART) with in vitro fertilization (IVF). The patient sues the gynecologist and second ED physician for presumed inappropriate assessment for ectopic pregnancy.

*The “facts” of this case are a composite, drawn from several cases to illustrate medical and legal issues. The statement of facts should be considered hypothetical.

Continue to: WHAT’S THE VERDICT?...

WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

A defense verdict is returned.

Medical considerations

The incidence of ectopic pregnancy is 2% of all pregnancies, with a higher incidence (about 4%) among infertility patients.1 Up to 10% of ectopic pregnancies have no symptoms.2

Clinical presentations. Classic signs of ectopic pregnancy include:

- abdominal pain

- vaginal bleeding

- late menses (often noted).

A recent case of ectopic pregnancy presenting with chest pain was reported.3 Clinicians must never lose site of the fact that ectopic pregnancy is the most common cause of maternal mortality in the first trimester, with an incidence of 1% to 10% of all first-trimester deaths.4

Risk factors include pelvic inflammatory disease, as demonstrated in the opening case. “The silent epidemic of chlamydia” comes to mind, and tobacco smoking can adversely affect tubal cilia, as can pelvic adhesions and/or prior tubal surgery. All of these factors can predispose a patient to ectopic pregnancy; in addition, intrauterine devices, endometriosis, tubal ligation (or ligation reversal), all can set the stage for an ectopic pregnancy.5 Appropriate serum hCG monitoring during early pregnancy can assist in sorting out pregnancies of unknown location (PUL; FIGURE). First trimester ultrasonography, at 5 weeks gestation, usually identifies early intrauterine gestation.

Imaging. With regard to pelvic sonography, the earliest sign of an intrauterine pregnancy (IUP) is a sac eccentrically located in the decidua.6 As the IUP progresses, it becomes equated with a “double decidual sign,” with double rings of tissue around the sac.6 If the pregnancy is located in an adnexal mass, it is frequently inhomogeneous or noncystic in appearance (ie, “the blob” sign); the positive predictive value (PPV) is 96%.2 The PPV of transvaginal ultrasound is 80%, as paratubal, paraovarian, ovarian cyst, and hydrosalpinx can affect the interpretation.7

Heterotopic pregnancy includes an intrauterine gestation and an ectopic pregnancy. This presentation includes the presence of a “pseudosac” in the endometrial cavity plus an extrauterine gestation. Heterotopic pregnancies have become somewhat more common as ART/IVF has unfolded, especially prior to the predominance of single embryo transfer.

Managing ectopic pregnancy

For cases of early pregnancy complicated by intermittent bleeding and/or pain, monitoring with serum hCG levels at 48-hour intervals to distinguish a viable IUP from an abnormal IUP or an ectopic is appropriate. The “discriminatory zone” collates serum hCG levels with findings on ultrasonography. Specific lower limits of serum hCG levels are not clear cut, with recommendations of 3,500 mIU/mL to provide sonographic evidence of an intrauterine gestation “to avoid misdiagnosis and possible interruption of intrauterine pregnancy,” as conveyed in the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2018 practice bulletin.8 Serum progesterone levels also have been suggested to complement hCG levels; a progesterone level of <20 nmol/L is consistent with an abnormal pregnancy, whereas levels >25 nmol/L are suggestive of a viable pregnancy.2 Inhibin A levels also have been suggested to be helpful, but they are not an ideal monitoring tool.

While most ectopic pregnancies are located in the fallopian tube, other locations also can be abdominal or ovarian. In addition, cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy can occur and often is associated with delay in diagnosis and greater morbidity due to such delay.9 With regard to ovarian ectopic, Spiegelberg criteria are established for diagnosis (TABLE 1).10

Appropriate management of an ectopic pregnancy is dependent upon the gestational age, serum hCG levels, and imaging findings, as well as the patient’s symptoms and exam findings. Treatment is established in large part on a case-by-case basis and includes, for early pregnancy, expectant management and use of methotrexate (TABLE 2).11 Dilation and curettage may be used to identify the pregnancy’s location when the serum hCG level is below 2,000 mIU/mL and there is no evidence of an IUP on ultrasound. Surgical treatment can include minimally invasive salpingostomy or salpingectomy and, depending on circumstance, laparotomy may be indicated.

Fertility following ectopic pregnancy varies and is affected by location, treatment, predisposing factors, total number of ectopic pregnancies, and other factors. Ectopic pregnancy, although rare, also can occur with use of IVF. Humans are not unique with regard to ectopic pregnancies, as they also occur in sheep.12

Continue to: Legal perspective...

Legal perspective

Lawsuits related to ectopic pregnancy are not a new phenomenon. In fact, in 1897, a physician in Ohio who misdiagnosed an “extrauterine pregnancy” as appendicitis was the center of a malpractice lawsuit.13 Unrecognized or mishandled ectopic pregnancy can result in serious injuries—in the range of 1% to 10% (see above) of maternal deaths are related to ectopic pregnancy.14 Ectopic pregnancy cases, therefore, have been the subject of substantial litigation over the years. An informal, noncomprehensive review of malpractice lawsuits brought from 2000 to 2019, found more than 300 ectopic pregnancy cases. Given the large number of malpractice claims against ObGyns,15 ectopic pregnancy cases are only a small portion of all ObGyn malpractice cases.16

A common claim: negligent diagnosis or treatment

The most common basis for lawsuits in cases of ectopic pregnancy is the clinician’s negligent failure to properly diagnose the ectopic nature of the pregnancy. There are also a number of cases claiming negligent treatment of an identified ectopic pregnancy. Not every missed diagnosis, or unsuccessful treatment, leads to liability, of course. It is only when a diagnosis or treatment fails to meet the standard of care within the profession that there should be liability. That standard of care is generally defined by what a reasonably prudent physician would do under the circumstances. Expert witnesses, who are familiar with the standard of practice within the specialty, are usually necessary to establish what that practice is. Both the plaintiff and the defense obtain experts, the former to prove what the standard of care is and that the standard was not met in the case at hand. The defense experts are usually arguing that the standard of care was met.17 Inadequate diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy or other condition may arise from a failure to take a sufficient history, conduct an appropriately thorough physical examination, recognize any of the symptoms that would suggest it is present, use and conduct ultrasound correctly, or follow-up appropriately with additional testing.18

A malpractice claim of negligent treatment can involve any the following circumstances19:

- failure to establish an appropriate treatment plan

- prescribing inappropriate medications for the patient (eg, methotrexate, when it is contraindicated)

- delivering the wrong medication or the wrong amount of the right medication

- performing a procedure badly

- undertaking a new treatment without adequate instruction and preparation.

Given the nature and risks of ectopic pregnancy, ongoing, frequent contact with the patient is essential from the point at which the condition is suspected. The greater the risk of harm (probability or consequence), the more careful any professional ought to be. Because ectopic pregnancy is not an uncommon occurrence, and because it can have devastating effects, including death, a reasonably prudent practitioner would be especially aware of the clinical presentations discussed above.20 In the opening case, the treatment plan was not well documented.

Negligence must lead to patient harm. In addition to negligence (proving that the physician did not act in accordance with the standard of care), to prevail in a malpractice case, the plaintiff-patient must prove that the negligence caused the injury, or worsened it. If the failure to make a diagnosis would not have made any difference in a harm the patient suffered, there are no damages and no liability. Suppose, for example, that a physician negligently failed to diagnose ectopic pregnancy, but performed surgery expecting to find the misdiagnosed condition. In the course of the surgery, however, the surgeon discovered and appropriately treated the ectopic pregnancy. (A version of this happened in the old 19th century case mentioned above.) The negligence of the physician did not cause harm, so there are no damages and no liability.

Continue to: Informed consent is vital...

Informed consent is vital

A part of malpractice is informed consent (or the absence of it)—issues that can arise in any medical care.21 It is wise to pay particular attention in cases where the nature of the illness is unknown, and where there are significant uncertainties and the nature of testing and treatment may change substantially over a period of a few days or few weeks. As always, informed consent should include a discussion of what process or procedure is proposed, its risks and benefits, alternative approaches that might be available, and the risk of doing nothing. Frequently, the uncertainty of ectopic pregnancy complicates the informed consent process.22

Because communication with the patient is an essential function of informed consent, the consent process should productively be used in PUL and similar cases to inform the patient about the uncertainty, and the testing and (nonsurgical) treatment that will occur. This is an opportunity to reinforce the message that the patient must maintain ongoing communication with the physician’s office about changes in her condition, and appear for each appointment scheduled. If more invasive procedures—notably surgery—become required, a separate consent process should be completed, because the risks and considerations are now meaningfully different than when treatment began. As a general matter, any possible treatment that may result in infertility or reduced reproductive capacity should specifically be included in the consent process.

In the hypothetical case, the gynecologist failed to obtain a follow-up serum hCG level. In addition, the record did not reflect ectopic pregnancy in the differential diagnosis. As noted above, the patient had predisposing factors for an ectopic pregnancy. The physician should have acknowledged the history of sexually transmitted disease predisposing her to an ectopic pregnancy. Monitoring of serum hCG levels until they are negative is appropriate with ectopic, or presumed ectopic, pregnancy management. Appropriate monitoring did not occur in this case. Each of these errors (following up on serum hCG levels and the inadequacy of notations about the possibility of ectopic pregnancy) seem inconsistent with the usual standard of care. Furthermore, as a result of the outcome, the only future option for the patient to pursue pregnancy was IVF.

Other legal issues

There are a number of other legal issues that are associated with the topic of ectopic pregnancy. There is evidence, for example, that Catholic and non-Catholic hospitals treat ectopic pregnancies differently,23 which may reflect different views on taking a life or the use of methotrexate and its association with abortion.24 In addition, the possibility of an increase in future ectopic pregnancies is one of the “risks” of abortion that pro-life organizations have pushed to see included in abortion informed consent.25 This has led some commentators to conclude that some Catholic hospitals violate federal law in managing ectopic pregnancy. There is also evidence of “overwhelming rates of medical misinformation on pregnancy center websites, including a link between abortion and ectopic pregnancy.”26

The fact that cesarean deliveries are related to an increased risk for ectopic pregnancy (because of the risk of cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy) also has been cited as information that should play a role in the consent process for cesarean delivery.27 In terms of liability, failed tubal ligation leads to a 33% risk of ectopic pregnancy.28 The risk of ectopic pregnancy is also commonly included in surrogacy contracts.29

Why the outcome was for the defense

The opening hypothetical case illustrates some of the uncertainties of medical malpractice cases. As noted, there appeared a deviation from the usual standard of care, particularly the failure to follow up on the serum hCG level. The weakness in the medical record, failing to note the possibility of ectopic pregnancy, also was probably an error but, apparently, the court felt that this did not result in any harm to the patient.

The question arises of how there would be a defense verdict in light of the failure to track consecutive serum hCG levels. A speculative explanation is that there are many uncertainties in most lawsuits. Procedural problems may result in a case being limited, expert witnesses are essential to both the plaintiff and defense, with the quality of their review and testimony possibly uneven. Judges and juries may rely on one expert witness rather than another, juries vary, and the quality of advocacy differs. Any of these situations can contribute to the unpredictability of the outcome of a case. In the case above, the liability was somewhat uncertain, and the various other factors tipped in favor of a defense verdict. ●

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ectopic pregnancy—United States, 1990‒1992. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;44:46-48.

- Kirk E, Bottomley C, Bourne T. Diagnosing ectopic pregnancy and current concepts in the management of pregnancy of unknown location. Hum Reprod Update. 2012;20:250-261.

- Dichter E, Espinosa J, Baird J, Lucerna A. An unusual emergency department case: ruptured ectopic pregnancy presenting as chest pain. World J Emerg Med. 2017;8:71-73.

- Cecchino GN, Araujo E, Elito J. Methotrexate for ectopic pregnancy: when and how. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;290:417- 423.

- Barnhart KT, Sammel MD, Cracia CR, et al. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy in women with symptomatic firsttrimester pregnancies. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:36-43.

- Carusi D. Pregnancy of unknown location: evaluation and management. Semin Perinatol. 2019;43:95-100.

- Barnhart KT, Fay CA, Suescum M, et al. Clinical factors affecting the accuracy of ultrasonography in symptomatic first-trimester pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:299-306.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulletin No. 193: tubal ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e91-e103.

- Bouyer J, Coste J, Fernandez H, et al. Sites of ectopic pregnancy: a 10-year population-based study of 1800 cases. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:3224-3230.

- Spiegelberg O. Zur casuistic der ovarial schwangerschaft. Arch Gynecol. 1978;13:73.

- OB Hospitalist Group. Methotrexate use for ectopic pregnancies guidelines. https://www.obhg.com/wp-content /uploads/2020/01/Methotrexate-Use-for-EctopicPregnancies_2016-updates.pdf. Accessed December 10, 2020.

- Brozos C, Kargiannis I, Kiossis E, et al. Ectopic pregnancy through a caesarean scar in a ewe. N Z Vet J. 2013;61:373-375.

- Tucker v. Gillette, 12 Ohio Cir. Dec. 401 (Cir. Ct. 1901).

- Creanga AA, Syverson C, Seed K, et al. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2011–2013. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:366-373.

- Matthews LR, Alvi FA, Milad MP. Reproductive surgery malpractice patterns. Fertil Steril. 2016;106:e42-e43.

- Kim B. The impact of malpractice risk on the use of obstetrics procedures. J Legal Studies. 2006;36:S79-S120.

- Abinader R, Warsof S. Complications involving obstetrical ultrasound. In: Warsof S, Shwayder JM, eds. Legal Concepts and Best Practices in Obstetrics: The Nuts and Bolts Guide to Mitigating Risk. 2019;45-48.

- Creanga AA, Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Bish CL, et al. Trends in ectopic pregnancy mortality in the United States: 1980-2007. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:837-843.

- Shwayder JM. IUP diagnosed and treated as ectopic: How bad can it get? Contemporary OB/GYN. 2019;64:49-46.

- Kaplan AI. Should this ectopic pregnancy have been diagnosed earlier? Contemporary OB/GYN. 2017;62:53.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Ethics. Committee opinion 439: informed consent. Reaffirmed 2015. https://www.acog.org/clinical /clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2009/08 /informed-consent. Accessed December 9, 2020.

- Shwayder JM. Liability in ob/gyn ultrasound. Contemporary OB/GYN. 2017;62:32-49.

- Fisher LN. Institutional religious exemptions: a balancing approach. BYU Law Review. 2014;415-444.

- Makdisi J. Aquinas’s prohibition of killing reconsidered. J Catholic Legal Stud. 2019:57:67-128.

- Franzonello A. Remarks of Anna Franzonello. Alb Law J Sci Tech. 2012;23:519-530.

- Malcolm HE. Pregnancy centers and the limits of mandated disclosure. Columbia Law Rev. 2019;119:1133-1168.

- Kukura E. Contested care: the limitations of evidencebased maternity care reform. Berkeley J Gender Law Justice. 2016;31:241-298.

- Donley G. Contraceptive equity: curing the sex discrimination in the ACA’s mandate. Alabama Law Rev. 2019;71:499-560.

- Berk H. Savvy surrogates and rock star parents: compensation provisions, contracting practices, and the value of womb work. Law Social Inquiry. 2020;45:398-431.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ectopic pregnancy—United States, 1990‒1992. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;44:46-48.

- Kirk E, Bottomley C, Bourne T. Diagnosing ectopic pregnancy and current concepts in the management of pregnancy of unknown location. Hum Reprod Update. 2012;20:250-261.

- Dichter E, Espinosa J, Baird J, Lucerna A. An unusual emergency department case: ruptured ectopic pregnancy presenting as chest pain. World J Emerg Med. 2017;8:71-73.

- Cecchino GN, Araujo E, Elito J. Methotrexate for ectopic pregnancy: when and how. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;290:417- 423.

- Barnhart KT, Sammel MD, Cracia CR, et al. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy in women with symptomatic firsttrimester pregnancies. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:36-43.

- Carusi D. Pregnancy of unknown location: evaluation and management. Semin Perinatol. 2019;43:95-100.

- Barnhart KT, Fay CA, Suescum M, et al. Clinical factors affecting the accuracy of ultrasonography in symptomatic first-trimester pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:299-306.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulletin No. 193: tubal ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e91-e103.

- Bouyer J, Coste J, Fernandez H, et al. Sites of ectopic pregnancy: a 10-year population-based study of 1800 cases. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:3224-3230.

- Spiegelberg O. Zur casuistic der ovarial schwangerschaft. Arch Gynecol. 1978;13:73.

- OB Hospitalist Group. Methotrexate use for ectopic pregnancies guidelines. https://www.obhg.com/wp-content /uploads/2020/01/Methotrexate-Use-for-EctopicPregnancies_2016-updates.pdf. Accessed December 10, 2020.

- Brozos C, Kargiannis I, Kiossis E, et al. Ectopic pregnancy through a caesarean scar in a ewe. N Z Vet J. 2013;61:373-375.

- Tucker v. Gillette, 12 Ohio Cir. Dec. 401 (Cir. Ct. 1901).

- Creanga AA, Syverson C, Seed K, et al. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2011–2013. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:366-373.

- Matthews LR, Alvi FA, Milad MP. Reproductive surgery malpractice patterns. Fertil Steril. 2016;106:e42-e43.

- Kim B. The impact of malpractice risk on the use of obstetrics procedures. J Legal Studies. 2006;36:S79-S120.

- Abinader R, Warsof S. Complications involving obstetrical ultrasound. In: Warsof S, Shwayder JM, eds. Legal Concepts and Best Practices in Obstetrics: The Nuts and Bolts Guide to Mitigating Risk. 2019;45-48.

- Creanga AA, Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Bish CL, et al. Trends in ectopic pregnancy mortality in the United States: 1980-2007. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:837-843.

- Shwayder JM. IUP diagnosed and treated as ectopic: How bad can it get? Contemporary OB/GYN. 2019;64:49-46.

- Kaplan AI. Should this ectopic pregnancy have been diagnosed earlier? Contemporary OB/GYN. 2017;62:53.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Ethics. Committee opinion 439: informed consent. Reaffirmed 2015. https://www.acog.org/clinical /clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2009/08 /informed-consent. Accessed December 9, 2020.

- Shwayder JM. Liability in ob/gyn ultrasound. Contemporary OB/GYN. 2017;62:32-49.

- Fisher LN. Institutional religious exemptions: a balancing approach. BYU Law Review. 2014;415-444.

- Makdisi J. Aquinas’s prohibition of killing reconsidered. J Catholic Legal Stud. 2019:57:67-128.

- Franzonello A. Remarks of Anna Franzonello. Alb Law J Sci Tech. 2012;23:519-530.

- Malcolm HE. Pregnancy centers and the limits of mandated disclosure. Columbia Law Rev. 2019;119:1133-1168.

- Kukura E. Contested care: the limitations of evidencebased maternity care reform. Berkeley J Gender Law Justice. 2016;31:241-298.

- Donley G. Contraceptive equity: curing the sex discrimination in the ACA’s mandate. Alabama Law Rev. 2019;71:499-560.

- Berk H. Savvy surrogates and rock star parents: compensation provisions, contracting practices, and the value of womb work. Law Social Inquiry. 2020;45:398-431.

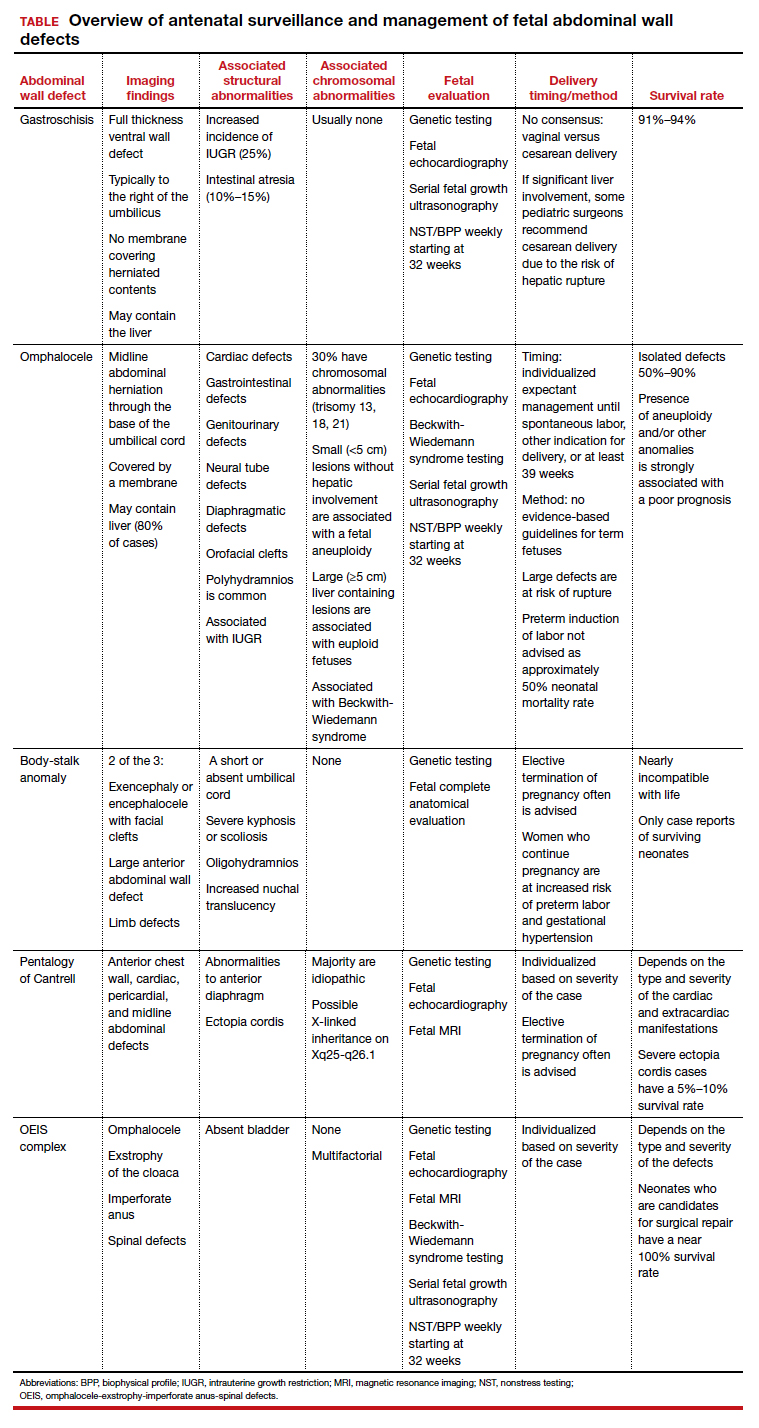

2021 Update on obstetrics

While 2020 was a challenge to say the least, obstetrician-gynecologists remained on the frontline caring for women through it all. Life continued despite the COVID-19 pandemic: prenatal care was delivered, albeit at times in different ways; babies were born; and our role in improving outcomes for women and their children became even more important. This year’s Update focuses on clinical guidelines centered on safety and optimal outcomes for women and children.

ACOG and SMFM update guidance on FGR management

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice advisory: Updated guidance regarding fetal growth restriction. September 2020. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory/articles/2020/09/updated-guidance-regarding-fetal-growth-restriction. Accessed December 18, 2020.

Fetal growth restriction (FGR) affects up to 10% of pregnancies and is a leading cause of infant morbidity and mortality. Suboptimal fetal growth can have lasting negative effects on development into early childhood and, some hypothesize, even into adulthood.1,2 Antenatal detection of fetuses with FGR is critical so that antenatal testing can be implemented in an attempt to deliver improved clinical outcomes. FGR is defined by several different diagnostic criteria, and many studies have been conducted to determine how best to diagnose this condition.

In September 2020, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) released a Practice Advisory regarding guidance on FGR in an effort to align the ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 204, ACOG Committee Opinion No. 764, and SMFM (Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine) Consult Series No. 52.3-5 This guidance updates and replaces prior guidelines, with an emphasis on 3 notable changes.

FGR definition, workup have changed

While the original definition of FGR was an estimated fetal weight (EFW) of less than the 10th percentile for gestational age, a similar level of accuracy in prediction of subsequent small for gestational age (SGA) at birth has been shown when this or an abdominal circumference (AC) of less than the 10th percentile is used. Based on these findings, SMFM now recommends that FGR be defined as an EFW or AC of less than the 10th percentile for gestational age.

Recent studies have done head-to-head comparisons of different methods of estimating fetal weight to determine the best detection and pregnancy outcome improvement in FGR. In all instances, the Hadlock formula has continued to more accurately estimate fetal weight, prediction of SGA, and composite neonatal morbidity. As such, new guidelines recommend that population-based fetal growth references (that is, the Hadlock formula) should be used to determine ultrasonography-derived fetal weight percentiles.

The new guidance also suggests classification of FGR based on gestational age at onset, with early FGR at less than 32 weeks and late FGR at 32 or more weeks. The definition of severe FGR is reserved for fetuses with an EFW of less than the 3rd percentile. A diagnosis of FGR should prompt the recommendation for a detailed obstetric ultrasonography. Diagnostic genetic testing should be offered in cases of early-onset FGR, concomitant sonographic abnormalities, and/or polyhydramnios. Routine serum screening for toxoplasmosis, rubella, herpes, or cytomegalovirus (CMV) should not be done unless there are risk factors for infection. If amniocentesis is performed for genetic diagnostic testing, consideration can be made for polymerase chain reaction for CMV in the amniotic fluid.

Continue to: Timing of delivery in isolated FGR...

Timing of delivery in isolated FGR

A complicating factor in diagnosing FGR is distinguishing between the pathologically growth-restricted fetus and the constitutionally small fetus. Antenatal testing and serial umbilical artery Doppler assessment should be done following diagnosis of FGR to monitor for evidence of fetal compromise until delivery is planned.

The current ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 204 and Committee Opinion No. 764 recommend delivery between 38 0/7 and 39 6/7 weeks in the setting of isolated FGR with reassuring fetal testing and umbilical artery Doppler assessment.To further refine this, the new recommendations use the growth percentiles. In cases of isolated FGR with EFW between the 3rd and 10th percentile in the setting of normal umbilical artery Doppler, delivery is recommended between 38 and 39 weeks’ gestation. In cases of isolated FGR with EFW of less than the 3rd percentile (severe FGR) in the setting of normal umbilical artery Doppler, delivery is recommended at 37 weeks.

Timing of delivery in complicated FGR

A normal umbilical artery Doppler reflects the low impedance that is necessary for continuous forward flow of blood to the fetus. Abnormal umbilical artery Doppler signifies aberrations of this low-pressure system that affect the amount of continuous forward flow during diastole of the cardiac cycle. With continued compromise, there is progression to absent end-diastolic velocity (AEDV) and, most concerning, reversed end-diastolic velocity (REDV).

Serial umbilical artery Doppler assessment should be done following diagnosis of FGR to monitor for progression that is associated with perinatal mortality, since intervention can be initiated in the form of delivery. Delivery at 37 weeks is recommended for FGR with elevated umbilical artery Doppler of greater than the 95th percentile for gestational age. For FGR with AEDV, delivery is recommended between 33 and 34 weeks of gestation and for FGR with REDV between 30 and 32 weeks, as the neonatal morbidity and mortality associated with continuing the pregnancy outweighs the risks of prematurity in this setting. Because of the abnormal placental-fetal circulation in FGR complicated by AEDV/REDV, there may be a higher likelihood of fetal intolerance of labor and cesarean delivery (CD) may be considered.

- Fetal growth restriction is now defined as EFW of less than the 10th percentile or AC of less than the 10th percentile.

- Evaluation of FGR includes detailed anatomic survey and consideration of genetic evaluation, but infection screening should be done only if the patient is at risk for infection.

- With reassuring antenatal testing and normal umbilical artery Doppler studies, delivery is recommended at 38 to 39 weeks for isolated FGR with EFW in the 3rd to 10th percentile and at 37 weeks for FGR with EFW of less than the 3rd percentile.

- Umbilical artery Doppler studies are used to decrease the risk of perinatal mortality and further guide timing of delivery

Continue to: New recommendations for PROM management...

New recommendations for PROM management

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics. ACOG practice bulletin no. 217: Prelabor rupture of membranes. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:e80-e97.

Rupture of membranes prior to the onset of labor occurs at term in 8% of pregnancies and in the preterm period in 2% to 3% of pregnancies.6 Accurate diagnosis, gestational age, evidence of infection, and discussion of the risks and benefits to the mother and fetus/neonate are necessary to optimize outcomes. In the absence of other indications for delivery, a gestational age of 34 or more weeks traditionally has been the cutoff to proceed with delivery, although this has not been globally agreed on and/or practiced.

ACOG has published a comprehensive update that incorporates the results of the PPROMT trial and other recommendations for the diagnosis and management of both term and preterm prelabor rupture of membranes (PROM).6,7

Making the diagnosis

Diagnosis of PROM usually can be made clinically via history and the classic triad of physical exam findings—pooling of fluid, basic pH, and ferning; some institutions also use commercially available tests that detect placental-derived proteins. Both ACOG and the US Food and Drug Administration caution against using these tests alone without clinical evaluation due to concern for false-positives and false-negatives that lead to adverse maternal and fetal/neonatal outcomes. For equivocal cases, ultrasonography for amniotic fluid evaluation and ultrasonography-guided dye tests can be used to assist in accurate diagnosis, especially in the preterm period in which there are significant implications for pregnancy management.

PROM management depends on gestational age

All management recommendations require reassuring fetal testing, evaluation for infection, and no other contraindications to expectant management. Once these are established, the most important determinant of PROM management then becomes gestational age.

Previable PROM

Previable PROM (usually defined as less than 23–24 weeks) has high risks of both maternal and fetal/neonatal morbidity and mortality from infection, hemorrhage, pulmonary hypoplasia, and extreme prematurity. These very difficult cases benefit from a multidisciplinary approach to patient counseling regarding expectant management versus immediate delivery.

If expectant management is chosen, outpatient management with close monitoring for signs of maternal infection may be done until an agreed on gestational age of viability. Then inpatient management with fetal monitoring, corticosteroids, tocolysis, magnesium for neuroprotection, and group B streptococcus (GBS) prophylaxis may be considered as appropriate.

Preterm PROM at less than 34 weeks

If the mother and fetus are otherwise stable, PROM at less than 34 weeks warrants inpatient expectant management with close maternal and fetal monitoring for signs of infection and labor. Management includes latency antibiotics, antenatal corticosteroids, magnesium for neuroprotection if less than 32 weeks’ gestation and at risk for imminent delivery, and GBS prophylaxis. While tocolysis may increase latency and help with steroid course completion, it should be used cautiously and avoided in cases of abruption or chorioamnionitis. Although there is no definitive recommendation published, a rescue course of steroids may be considered as appropriate but should not delay an indicated delivery.

Continue to: Late preterm PROM...

Late preterm PROM

The biggest change to clinical management in this ACOG Practice Bulletin is for late preterm (34–36 6/7 weeks) PROM, with the recommendation for either immediate delivery or expectant management up to 37 weeks stemming from the PPROMPT study by Morris and colleagues.7

From the neonatal perspective, no difference has been demonstrated between immediate delivery and expectant management for neonatal sepsis or a composite neonatal morbidity and mortality. Expectant management may be preferred from the neonatal point of view as immediate delivery was associated with an increased rate of neonatal respiratory distress, mechanical ventilation, and length of stay in the neonatal intensive care unit. The potential for long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes of delivery at 34 versus 37 weeks also should be considered.

From the maternal perspective, expectant management has an increased risk of antepartum and postpartum hemorrhage, fever, antibiotic use, and maternal length of stay, but a decreased risk of CD.

A late preterm steroid course can be considered if delivery is planned in no less than 24 hours and likely to occur in the next 7 days and if the patient has not already received a course of steroids. A rescue course of steroids is not indicated if the patient received a steroid course prior in the pregnancy. While appropriate GBS prophylaxis is recommended, latency antibiotics and tocolysis are not, and delivery should not be delayed if chorioamnionitis is diagnosed.

Ultimately, preterm PROM management with a stable mother and fetus at or beyond 34 weeks requires comprehensive counseling of the risks and benefits for both mother and fetus/neonate. A multidisciplinary team that together counsels the patient also may help with this shared decision making.

Term PROM

For patients with term PROM, delivery is recommended. Although a short period of expectant management for 12 to 24 hours is reported as “reasonable,” the risk of infection increases with the length of rupture of membranes. Therefore, induction of labor or CD soon after rupture of membranes is recommended for patients who are GBS positive and is preferred for all others.

- Accurate diagnosis is necessary for appropriate counseling and management of PROM.

- Delivery is recommended for term PROM, chorioamnionitis, and for patients with previable PROM who do not desire expectant management.

- If the mother and fetus are otherwise stable, expectant management of preterm PROM until 34 to 37 weeks is recommended.

- The decision of when to deliver between 34 and 37 weeks is best made with multidisciplinary counseling and shared decision making with the patient.

VTE prophylaxis in pregnancy: Regimen adjustments, CD strategies, and COVID-19 considerations

Birsner ML, Turrentine M, Pettker CM, et al. ACOG practice advisory: Options for peripartum anticoagulation in areas affected by shortage of unfractionated heparin. March 2020. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory/articles/2020/03/options-for-peripartum-anticoagulation-in-areas-affected-by-shortage-of-unfractionated-heparin. Accessed December 8, 2020.

Pacheco LD, Saade G, Metz TD. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Consult Series No. 51: Thromboembolism prophylaxis for cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:B11-B17

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis is a timely topic for a number of reasons. First, a shortage of unfractionated heparin prompted an ACOG Practice Advisory, endorsed by SMFM and the Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology, regarding use of low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) in the peripartum period.8 In addition, SMFM released updated recommendations for VTE prophylaxis for CD as part of the SMFM Consult Series.9 Finally, there is evidence that COVID-19 infection may increase the risk of coagulopathy, leading to consideration of additional VTE prophylaxis for pregnant and postpartum women with COVID-19.

Candidates for prophylaxis