User login

Distress and Factors Associated with Suicidal Ideation in Veterans Living with Cancer (FULL)

It was estimated that physicians would diagnose a form of invasive cancer > 1.7 million times in 2019. As the second most common cause of death in the US, > 600,000 people were projected to die from cancer in 2019.1 Many individuals with cancer endure distress, which the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) defines as a “multifactorial unpleasant experience of a psychological (ie, cognitive, behavioral, emotional), social, spiritual, and/or physical nature that may interfere with the ability to cope effectively with cancer, its physical symptoms, and its treatment.”2,3 Distress in people living with cancer has been attributed to various psychosocial concerns, such as family problems, whichinclude dealing with partners and children; emotional problems, such as depression and anxiety; and physical symptoms, such as pain and fatigue.4-9 Certain factors associated with distress may increase a patient’s risk for suicide.4

Veterans are at particularly high risk for suicide.10 In 2014, veterans accounted for 18% of completed suicides in the US but only were 8.5% of the total population that same year.10 Yet, little research has been done on the relationship between distress and suicide in veterans living with cancer. Aboumrad and colleagues found that 45% of veterans with cancer who completed suicide reported family issues and 41% endorsed chronic pain.11 This study recommended continued efforts to assess and treat distress to lessen risk of suicide in veterans living with cancer; however, to date, only 1 study has specifically evaluated distress and problems endorsed among veterans living with cancer.7

Suicide prevention is of the highest priority to the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).12 Consistent with the VA mission to end veteran suicide, the current study aimed to better understand the relationship between distress and suicide within a sample of veterans living with cancer. Findings would additionally be used to tailor clinical assessments and interventions for veterans living with cancer.

This study had 3 primary goals. First, we sought to understand demographic and clinical factors associated with low, moderate, and severe levels of distress in veterans living with cancer who were referred for psychology services. Second, the study investigated the most commonly endorsed problems by veterans living with cancer. Finally, we examined which problems were related to suicidal ideation (SI). It was hypothesized that veterans who reported severe distress would be significantly more likely to endorse SI when compared with veterans who reported mild or moderate distress. Based on existing literature, it was further hypothesized that family, emotional, and physical problems would be significantly associated with SI.7,11

Methods

The current study was conducted at James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital (JAHVH) in Tampa, Florida. Inclusion criteria included veterans who were diagnosed with cancer, attended an outpatient psychology-oncology evaluation, and completed mental health screening measures provided during their evaluation. Exclusion criteria included veterans who: were seen in response to an inpatient consult, were seen solely for a stem cell transplant evaluation, or did not complete the screening measures.

Measures

A veteran’s demographic (eg, age, sex, ethnicity) and clinical (eg, cancer type, stage of disease, recurrence, cancer treatments received) information was abstracted from their VA medical records. Marital status was assessed during a clinical interview and documented as part of the standardized suicide risk assessment.

The Distress Thermometer (DT) is a subjective measure developed by the NCCN.2 The DT provides a visual representation of a thermometer and asks patients to rate their level of distress over the past week with 0 indicating no distress and 10 indicating extreme distress.

The measurement additionally lists 39 problems nested within 5 domains: practical, family, emotional, spiritual/religious, and physical. Patients may endorse listed items under each problem domain by indicating yes or no. Endorsement of various items are intended to provide more detailed information about sources of distress. Due to the predominantly male and mostly older population included in this study the ability to have children measure was removed from the family problem domain.

SI was assessed in 2 ways. First, by patients’ self-report through item-9 of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9).14 Item-9 asks “over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way?” Responses range from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day).14 Responses > 0 were considered a positive screen for SI.

Procedure

Participants were a sample of veterans who were referred for psychology-oncology services. The NCCN DT and Problems List were administered prior to the start of clinical interviews, which followed a checklist and included standardized assessments of SI and history of a suicide attempt(s). A licensed clinical psychologist or a postdoctoral resident conducted these assessments under the supervision of a licensed psychologist. Data gathered during the clinical interview and from the DT and problems list were documented in health records, which were retrospectively reviewed for relevant information (eg, cancer diagnosis, SI). Therefore, informed consent was waived. This study was approved by the JAHVH Institutional Review Board.

Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS Version 25. Data analysis proceeded in 3 steps. First, descriptive statistics included the demographic and clinical factors present in the current sample. Difference between those with and without suicidal ideation were compared using F-statistic for continuous variables and χ2 analyses for categorical variables. Second, to examine relationships between each DT problem domain and SI, χ2 analyses were conducted. Third, DT problem domains that had a significant relationship with SI were entered in a logistic regression. This analysis determined which items, if any, from a DT problem domain predicted SI. In the logistic regression model, history of suicide attempts was entered into the first block, as history of suicide attempts is a well-established risk factor for subsequent suicidal ideation. In the second block, other variables that were significantly related to suicidal ideation in the second step of analyses were included. Before interpreting the results of the logistic regression, model fit was tested using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. Significance of each individual predictor variable in the model is reported using the Wald χ2 statistic; each Wald statistic is compared with a χ2 distribution with 1 degree of freedom (df). Results of logistic regression models also provide information about the effect of each predictor variable in the regression equation (beta weight), odds a veteran who endorsed each predictor variable in the model would also endorse SI (as indicated by the odds ratio), and an estimate of the amount of variance accounted for by each predictor variable (using Nagelkerke’s pseudo R2, which ranges in value from 0 to 1 with higher values indicating more variance explained). For all analyses, P value of .05 (2-tailed) was used for statistical significance.

Results

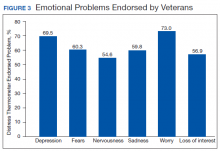

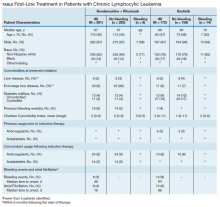

The sample consisted of 174 veterans (Table 1). The majority (77.6%) were male with a mean age of nearly 62 years (range, 29-87). Most identified as white (74.1%) with half reporting they were either married or living with a partner.

Prostate cancer (19.0%) was the most common type of cancer among study participants followed by head and neck (18.4%), lymphoma/leukemia (11.5%), lung (11.5%), and breast (10.9%); 31.6% had metastatic disease and 14.9% had recurrent disease. Chemotherapy (42.5%) was the most common treatment modality, followed by surgery (38.5%) and radiation (31.6%). The sample was distributed among the 3 distress DT categories: mild (18.4%), moderate (42.5%), and severe (39.1%).

Problems Endorsed

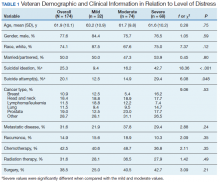

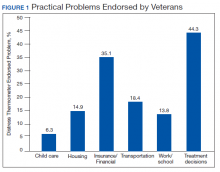

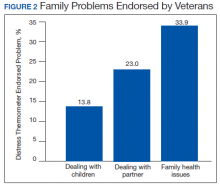

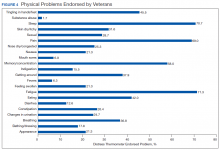

Treatment decisions (44.3%) and insurance/financial concerns (35.1%) were the most frequently endorsed practical problems (Figure 1). Family health issues (33.9%) and dealing with partner (23.0%) were the most frequently endorsed family problems (Figure 2). Worry (73.0%) and depression (69.5%) were the most frequent emotional problems; of note, all emotional problems were endorsed by at least 50% of veterans (Figure 3). Fatigue (71.3%), sleep (70.7%), and pain (69%), were the most frequently endorsed physical problems (Figure 4). Spiritual/religious problems were endorsed by 15% of veterans.

Suicidal Ideation

Overall, 25.3% of veterans endorsed SI. About 20% of veterans reported a history of ≥ 1 suicide attempts in their lifetime. A significant relationship among distress categories and SI was found (χ2 = 18.36, P < .001). Veterans with severe distress were more likely to endorse SI (42.7%) when compared with veterans with mild (9.4%) or moderate (16.2%) distress.

Similarly, a significant relationship among distress categories and a history of a suicide attempt(s) was found (χ2 = 6.08, P = .048). Veterans with severe distress were more likely to have attempted suicide (29.4%) when compared with veterans with mild (12.5%) or moderate (14.9%) distress.

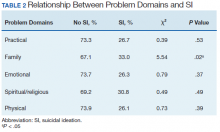

χ2 analyses were conducted to examine the relationships between DT problem domains and SI. A significant relationship was found between family problems and SI (

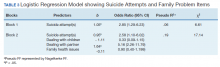

Logistic regression analyses determined whether items representative of the family problems domain were predictive of SI. Suicide attempt(s) were entered in the first step of the model to evaluate risk factors for SI over this already established risk factor. The assumptions of logistic regression were met.

The Hosmer-Lemeshow test (χ2 = 3.66, df = 5, P = .56) demonstrated that the model fit was good. The group of predictors used in the model differentiate between people who were experiencing SI and those who were not experiencing SI at the time of evaluation. A history of a suicide attempt(s) predicted SI, as expected (Wald = 6.821, df = 1, P = .01). The odds that a veteran with a history of a suicide attempt(s) would endorse SI at the time of the evaluation was nearly 3 times greater than that of veterans without a history of a suicide attempt(s). Over and above suicide attempts, problems dealing with partner (Wald = 15.142; df = 1, P < .001) was a second significant predictor of current SI. The odds that a veteran who endorsed problems dealing with partner would also endorse SI was > 5 times higher than that of veterans who did not endorse problems dealing with partner. This finding represents a significant risk factor for SI, over and above a history of a suicide attempt(s). The other items from the family problems domains were not significant (P > .05) (Table 3).

Discussion

This study aimed to understand factors associated with low, moderate, and severe levels of distress in veterans living with cancer who were referred for psychology services. As hypothesized, veterans who endorsed severe distress were significantly more likely to endorse SI. They also were more likely to have a history of a suicide attempt(s) when compared with those with mild or moderate distress.

A second aim of this study was to understand the most commonly endorsed problems. Consistent with prior literature, treatment decisions were the most commonly endorsed practical problem; worry and depression were the most common emotional problems; and fatigue, sleep, and pain were the most common physical problems.7

A finding unique to the current study is that family health issues and dealing with partner were specified as the most common family problems. However, a study by Smith and colleagues did not provide information about the rank of most frequently reported problems within this domain.7

The third aim was to understand which problems were related to SI. It was hypothesized that family, emotional, and physical problems would be related to SI. However, results indicated that only family problems (specifically, problems dealing with a partner) were significantly associated with SI among veterans living with cancer.

Contrary to expectations, emotional and physical problems were not found to have a significant relationship with SI. This is likely because veterans endorsed items nested within these problem domains with similar frequency. The lack of significant findings does not suggest that emotional and physical problems are not significant predictors of SI for veterans living with cancer, but that no specific emotional or physical symptom stood out as a predictor of suicidal ideation above the others.

The finding of a significant relationship between family problems (specifically, problems dealing with a partner) and SI in this study is consistent with findings of Aboumrad and colleagues in a study that examined root-cause analyses of completed suicides by veterans living with cancer.11 They found that nearly half the sample endorsed family problems prior to their death, and a small but notable percentage of veterans who completed suicide reported divorce as a stressor prior to their death.

This finding may be explained by Thomas Joiner's interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior (IPT), which suggests that completed suicide may result from a thwarted sense of belonging, perceived burdensomeness, and acquired capability for suicide.16 Problems dealing with a partner may impact a veteran’s sense of belonging or social connectedness. Problems dealing with a partner also may be attributed to perceived burdens due to limitations imposed by living with cancer and/or undergoing treatment. In both circumstances, the veteran’s social support system may be negatively impacted, and perceived social support is a well-established protective factor against suicide.17

Partner distress is a second consideration. It is likely that veterans’ partners experienced their own distress in response to the veteran’s cancer diagnosis and/or treatment. The partner’s cause, severity, and expression of distress may contribute to problems for the couple.

Finally, the latter point of the IPT refers to acquired capability, or the ability to inflict deadly harm to oneself.18 A military sample was found to have more acquired capability for suicide when compared with a college undergraduate sample.19 A history of a suicide attempt(s) and male gender have been found to significantly predict acquired capability to complete suicide.18 Furthermore, because veterans living with cancer often are in pain, fear of pain associated with suicide may be reduced and, therefore, acquired capability increased. This suggests that male veterans living with cancer who are in pain, have a history of a suicide attempt(s), and current problems with their partner may be an extremely vulnerable population at-risk for suicide. Results from the current study emphasize the importance of veterans having access to mental health and crisis resources for problems dealing with their partner. Partner problems may foreshadow a potentially lethal type of distress.

Strengths

This study’s aims are consistent with the VA’s mission to end veteran suicide and contributes to literature in several important ways.12 First, veterans living with cancer are an understudied population. The current study addresses a gap in existing literature by researching veterans living with cancer and aims to better understand the relationship between cancer-related distress and SI. Second, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first to find that problems dealing with a partner significantly increases a veteran’s risk for SI above a history of a suicide attempt(s). Risk assessments now may be more comprehensive through inclusion of this distress factor.

It is recommended that future research use IPT to further investigate the relationship between problems dealing with a partner and SI.16 Future research may do so by including specific measures to assess for the tenants of the theory, including measurements of burdensomeness and belongingness. An expanded knowledge base about what makes problems dealing with a partner a significant suicide risk factor (eg, increased conflict, lack of support, etc.) would better enable clinicians to intervene effectively. Effective intervention may lessen suicidal behaviors or deaths from suicides within the Veteran population.

Limitations

One limitation is the focus on patients who accepted a mental health referral. This study design may limit the generalizability of results to veterans who would not accept mental health treatment. The homogenous sample of veterans is a second limitation. Most participants were male, white, and had a mean age of 62 years. These demographics are representative of the veterans that most typically utilize VA services; however, more research is needed on veterans living with cancer who are female and of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. There are likely differences in problems endorsed and factors associated with SI based on age, race, sex, and other socioeconomic factors. A third limitation is the cross-sectional, retrospective nature of this study. Future studies are advised to assess for distress at multiple time points. This is consistent with NCCN Standards of Care for Distress Management.2 Longitudinal data would enable more findings about distress and SI throughout the course of cancer diagnosis and treatment, therefore enhancing clinical implications and informing future research.

Conclusion

This is among the first of studies to investigate distress and factors associated with SI in veterans living with cancer who were referred for psychology services. The prevalence of distress caused by psychosocial factors (including treatment decisions, worry, and depression) highlights the importance of including mental health services as part of comprehensive cancer treatment.

Distress due to treatment decisions may be attributed to a litany of factors such as a veteran’s consideration of adverse effects, effectiveness of treatments, changes to quality of life or functioning, and inclusion of alternative or complimentary treatments. These types of decisions often are reported to be difficult conversations to have with family members or loved ones, who are likely experiencing distress of their own. The role of a mental health provider to assist veterans in exploring their treatment decisions and the implications of such decisions appears important to lessening distress.

Early intervention for emotional symptoms would likely benefit veterans’ management of distress and may lessen suicide risk as depression is known to place veterans at-risk for SI.20 This underscores the importance of timely distress assessment to prevent mild emotional distress from progressing to potentially severe or life-threatening emotional distress. For veterans with a psychiatric history, timely assessment and intervention is essential because psychiatric history is an established suicide risk factor that may be exacerbated by cancer-related distress.12

Furthermore, management of intolerable physical symptoms may lessen risk for suicide.4 Under medical guidance, fatigue may be improved using exercise.21 Behavioral intervention is commonly used as first-line treatment for sleep problems.22 While pain may be lessened through medication or nonpharmacological interventions.23

Considering the numerous ways that distress may present itself (eg, practical, emotional, or physical) and increase risk for SI, it is essential that all veterans living with cancer are assessed for distress and SI, regardless of their presentation. Although veterans may not outwardly express distress, this does not indicate the absence of either distress or risk for suicide. For example, a veteran may be distressed due to financial concerns, transportation issues, and the health of his/her partner or spouse. This veteran may not exhibit visible symptoms of distress, as would be expected when the source of distress is emotional (eg, depression, anxiety). However, this veteran is equally vulnerable to impairing distress and SI as someone who exhibits emotional distress. Distress assessments should be further developed to capture both the visible and less apparent sources of distress, while also serving the imperative function of screening for suicide. Other researchers also have noted the necessity of this development.24 Currently, the NCCN DT and Problems List does not include any assessment of SI or behavior.

Finally, this study identified a potentially critical factor to include in distress assessment: problems dealing with a partner. Problems dealing with a partner have been noted as a source of distress in existing literature, but this is the first study to find problems dealing with a partner to be a predictor of SI in veterans living with cancer.4-6

Because partners often attend appointments with veterans, it is not surprising that problems dealing with their partner are not disclosed more readily. It is recommended that clinicians ask veterans about potential problems with their partner when they are alone. Directly gathering information about such problems while assessing for distress may assist health care workers in providing the most effective, accurate type of intervention in a timely manner, and potentially mitigate risk for suicide.

As recommended by the NCCN and numerous researchers, findings from the current study underscore the importance of accurate, timely assessment of distress.2,4,8 This study makes several important recommendations about how distress assessment may be strengthened and further developed, specifically for the veteran population. This study also expands the current knowledge base of what is known about veterans living with cancer, and has begun to fill a gap in the existing literature. Consistent with the VA mission to end veteran suicide, results suggest that veterans living with cancer should be regularly screened for distress, asked about distress related to their partner, and assessed for SI. Continued efforts to enhance assessment of and response to distress may lessen suicide risk in veterans with cancer.11

Acknowledgements

This study is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital.

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7-34.

2. Riba MB, Donovan, KA, Andersen, B. National Comprehensive Cancer Network clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Distress management (Version 3.2019). J Natl Compr Can Net, 2019;17(10):1229-1249.

3. Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Pianta dosi S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology. 2001;10(1):19–28.

4. Holland JC, Alici Y. Management of distress in cancer patients. J Support Oncol. 2010;8(1):4-12.

5. Bulli F, Miccinesi G, Maruelli A, Katz M, Paci E. The measure of psychological distress in cancer patients: the use of distress thermometer in the oncological rehabilitation center of Florence. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17(7):771–779.

6. Jacobsen PB, Donovan KA, Trask PC, et al. Screening for psychologic distress in ambulatory cancer patients. Cancer. 2005;103(7):1494-1502.

7. Smith J, Berman S, Dimick J, et al. Distress Screening and Management in an Outpatient VA Cancer Clinic: A Pilot Project Involving Ambulatory Patients Across the Disease Trajectory. Fed Pract. 2017;34(Suppl 1):43S–50S.

8. Carlson LE, Waller A, Groff SL, Bultz BD. Screening for distress, the sixth vital sign, in lung cancer patients: effects on pain, fatigue, and common problems--secondary outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2013;22(8):1880-1888.

9. Cooley ME, Short TH, Moriarty HJ. Symptom prevalence, distress, and change over time in adults receiving treatment for lung cancer. Psychooncology. 2003;12(7):694-708.

10. US Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Suicide Prevention. Suicide among veterans and other Americans 2001-2014. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/2016suicidedatareport.pdf. Published August 3, 2016. Accessed April 13, 2020.

11. Aboumrad M, Shiner B, Riblet N, Mills, PD, Watts BV. Factors contributing to cancer-related suicide: a study of root-cause-analysis reports. Psychooncology. 2018;27(9):2237-2244.

12. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide 2018–2028. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/docs/Office-of-Mental-Health-and-Suicide-Prevention-National-Strategy-for-Preventing-Veterans-Suicide.pdf Published 2018. Accessed April 13, 2020.

13. Carlson LE, Waller A, Mitchell AJ. Screening for distress and unmet needs in patients with cancer: review and recommendations. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(11):1160-1177.

14. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613.

15. Martin A, Rief W, Klaiberg A, Braehler E. Validity of the brief patient health questionnaire mood scale (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(1):71-77.

16. Joiner TE. Why People Die by Suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005.

17. Kleiman EM, Riskind JH, Schaefer KE. Social support and positive events as suicide resiliency factors: examination of synergistic buffering effects. Arch Suicide Res. 2014;18(2):144-155.

18. Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Gordon KH, Bender TW, Joiner TE Jr. Suicidal desire and the capability for suicide: tests of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior among adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(1):72–83.

19. Bryan CJ, Morrow CE, Anestis MD, Joiner TE. A preliminary test of the interpersonal -psychological theory of suicidal behavior in a military sample. Personal Individual Differ. 2010;48(3):347-350.

20. Miller SN, Monahan CJ, Phillips KM, Agliata D, Gironda RJ. Mental health utilization among veterans at risk for suicide: Data from a post-deployment clinic [published online ahead of print, 2018 Oct 8]. Psychol Serv. 2018;10.1037/ser0000311.

21. Galvão DA, Newton RU. Review of exercise intervention studies in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(4):899-909.

22. Qaseem A, Kansagara D, Forciea MA, Cooke M, Denberg TD; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Management of chronic insomnia disorder in adults: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(2):125-133.

23. Ngamkham S, Holden JE, Smith EL. A systematic review: Mindfulness intervention for cancer-related pain. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2019;6(2):161-169.

24. Granek L, Nakash O, Ben-David M, Shapira S, Ariad S. Oncologists’, nurses’, and social workers’ strategies and barriers to identifying suicide risk in cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2018;27(1):148-154.

It was estimated that physicians would diagnose a form of invasive cancer > 1.7 million times in 2019. As the second most common cause of death in the US, > 600,000 people were projected to die from cancer in 2019.1 Many individuals with cancer endure distress, which the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) defines as a “multifactorial unpleasant experience of a psychological (ie, cognitive, behavioral, emotional), social, spiritual, and/or physical nature that may interfere with the ability to cope effectively with cancer, its physical symptoms, and its treatment.”2,3 Distress in people living with cancer has been attributed to various psychosocial concerns, such as family problems, whichinclude dealing with partners and children; emotional problems, such as depression and anxiety; and physical symptoms, such as pain and fatigue.4-9 Certain factors associated with distress may increase a patient’s risk for suicide.4

Veterans are at particularly high risk for suicide.10 In 2014, veterans accounted for 18% of completed suicides in the US but only were 8.5% of the total population that same year.10 Yet, little research has been done on the relationship between distress and suicide in veterans living with cancer. Aboumrad and colleagues found that 45% of veterans with cancer who completed suicide reported family issues and 41% endorsed chronic pain.11 This study recommended continued efforts to assess and treat distress to lessen risk of suicide in veterans living with cancer; however, to date, only 1 study has specifically evaluated distress and problems endorsed among veterans living with cancer.7

Suicide prevention is of the highest priority to the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).12 Consistent with the VA mission to end veteran suicide, the current study aimed to better understand the relationship between distress and suicide within a sample of veterans living with cancer. Findings would additionally be used to tailor clinical assessments and interventions for veterans living with cancer.

This study had 3 primary goals. First, we sought to understand demographic and clinical factors associated with low, moderate, and severe levels of distress in veterans living with cancer who were referred for psychology services. Second, the study investigated the most commonly endorsed problems by veterans living with cancer. Finally, we examined which problems were related to suicidal ideation (SI). It was hypothesized that veterans who reported severe distress would be significantly more likely to endorse SI when compared with veterans who reported mild or moderate distress. Based on existing literature, it was further hypothesized that family, emotional, and physical problems would be significantly associated with SI.7,11

Methods

The current study was conducted at James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital (JAHVH) in Tampa, Florida. Inclusion criteria included veterans who were diagnosed with cancer, attended an outpatient psychology-oncology evaluation, and completed mental health screening measures provided during their evaluation. Exclusion criteria included veterans who: were seen in response to an inpatient consult, were seen solely for a stem cell transplant evaluation, or did not complete the screening measures.

Measures

A veteran’s demographic (eg, age, sex, ethnicity) and clinical (eg, cancer type, stage of disease, recurrence, cancer treatments received) information was abstracted from their VA medical records. Marital status was assessed during a clinical interview and documented as part of the standardized suicide risk assessment.

The Distress Thermometer (DT) is a subjective measure developed by the NCCN.2 The DT provides a visual representation of a thermometer and asks patients to rate their level of distress over the past week with 0 indicating no distress and 10 indicating extreme distress.

The measurement additionally lists 39 problems nested within 5 domains: practical, family, emotional, spiritual/religious, and physical. Patients may endorse listed items under each problem domain by indicating yes or no. Endorsement of various items are intended to provide more detailed information about sources of distress. Due to the predominantly male and mostly older population included in this study the ability to have children measure was removed from the family problem domain.

SI was assessed in 2 ways. First, by patients’ self-report through item-9 of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9).14 Item-9 asks “over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way?” Responses range from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day).14 Responses > 0 were considered a positive screen for SI.

Procedure

Participants were a sample of veterans who were referred for psychology-oncology services. The NCCN DT and Problems List were administered prior to the start of clinical interviews, which followed a checklist and included standardized assessments of SI and history of a suicide attempt(s). A licensed clinical psychologist or a postdoctoral resident conducted these assessments under the supervision of a licensed psychologist. Data gathered during the clinical interview and from the DT and problems list were documented in health records, which were retrospectively reviewed for relevant information (eg, cancer diagnosis, SI). Therefore, informed consent was waived. This study was approved by the JAHVH Institutional Review Board.

Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS Version 25. Data analysis proceeded in 3 steps. First, descriptive statistics included the demographic and clinical factors present in the current sample. Difference between those with and without suicidal ideation were compared using F-statistic for continuous variables and χ2 analyses for categorical variables. Second, to examine relationships between each DT problem domain and SI, χ2 analyses were conducted. Third, DT problem domains that had a significant relationship with SI were entered in a logistic regression. This analysis determined which items, if any, from a DT problem domain predicted SI. In the logistic regression model, history of suicide attempts was entered into the first block, as history of suicide attempts is a well-established risk factor for subsequent suicidal ideation. In the second block, other variables that were significantly related to suicidal ideation in the second step of analyses were included. Before interpreting the results of the logistic regression, model fit was tested using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. Significance of each individual predictor variable in the model is reported using the Wald χ2 statistic; each Wald statistic is compared with a χ2 distribution with 1 degree of freedom (df). Results of logistic regression models also provide information about the effect of each predictor variable in the regression equation (beta weight), odds a veteran who endorsed each predictor variable in the model would also endorse SI (as indicated by the odds ratio), and an estimate of the amount of variance accounted for by each predictor variable (using Nagelkerke’s pseudo R2, which ranges in value from 0 to 1 with higher values indicating more variance explained). For all analyses, P value of .05 (2-tailed) was used for statistical significance.

Results

The sample consisted of 174 veterans (Table 1). The majority (77.6%) were male with a mean age of nearly 62 years (range, 29-87). Most identified as white (74.1%) with half reporting they were either married or living with a partner.

Prostate cancer (19.0%) was the most common type of cancer among study participants followed by head and neck (18.4%), lymphoma/leukemia (11.5%), lung (11.5%), and breast (10.9%); 31.6% had metastatic disease and 14.9% had recurrent disease. Chemotherapy (42.5%) was the most common treatment modality, followed by surgery (38.5%) and radiation (31.6%). The sample was distributed among the 3 distress DT categories: mild (18.4%), moderate (42.5%), and severe (39.1%).

Problems Endorsed

Treatment decisions (44.3%) and insurance/financial concerns (35.1%) were the most frequently endorsed practical problems (Figure 1). Family health issues (33.9%) and dealing with partner (23.0%) were the most frequently endorsed family problems (Figure 2). Worry (73.0%) and depression (69.5%) were the most frequent emotional problems; of note, all emotional problems were endorsed by at least 50% of veterans (Figure 3). Fatigue (71.3%), sleep (70.7%), and pain (69%), were the most frequently endorsed physical problems (Figure 4). Spiritual/religious problems were endorsed by 15% of veterans.

Suicidal Ideation

Overall, 25.3% of veterans endorsed SI. About 20% of veterans reported a history of ≥ 1 suicide attempts in their lifetime. A significant relationship among distress categories and SI was found (χ2 = 18.36, P < .001). Veterans with severe distress were more likely to endorse SI (42.7%) when compared with veterans with mild (9.4%) or moderate (16.2%) distress.

Similarly, a significant relationship among distress categories and a history of a suicide attempt(s) was found (χ2 = 6.08, P = .048). Veterans with severe distress were more likely to have attempted suicide (29.4%) when compared with veterans with mild (12.5%) or moderate (14.9%) distress.

χ2 analyses were conducted to examine the relationships between DT problem domains and SI. A significant relationship was found between family problems and SI (

Logistic regression analyses determined whether items representative of the family problems domain were predictive of SI. Suicide attempt(s) were entered in the first step of the model to evaluate risk factors for SI over this already established risk factor. The assumptions of logistic regression were met.

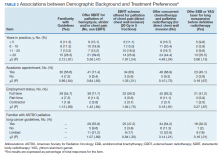

The Hosmer-Lemeshow test (χ2 = 3.66, df = 5, P = .56) demonstrated that the model fit was good. The group of predictors used in the model differentiate between people who were experiencing SI and those who were not experiencing SI at the time of evaluation. A history of a suicide attempt(s) predicted SI, as expected (Wald = 6.821, df = 1, P = .01). The odds that a veteran with a history of a suicide attempt(s) would endorse SI at the time of the evaluation was nearly 3 times greater than that of veterans without a history of a suicide attempt(s). Over and above suicide attempts, problems dealing with partner (Wald = 15.142; df = 1, P < .001) was a second significant predictor of current SI. The odds that a veteran who endorsed problems dealing with partner would also endorse SI was > 5 times higher than that of veterans who did not endorse problems dealing with partner. This finding represents a significant risk factor for SI, over and above a history of a suicide attempt(s). The other items from the family problems domains were not significant (P > .05) (Table 3).

Discussion

This study aimed to understand factors associated with low, moderate, and severe levels of distress in veterans living with cancer who were referred for psychology services. As hypothesized, veterans who endorsed severe distress were significantly more likely to endorse SI. They also were more likely to have a history of a suicide attempt(s) when compared with those with mild or moderate distress.

A second aim of this study was to understand the most commonly endorsed problems. Consistent with prior literature, treatment decisions were the most commonly endorsed practical problem; worry and depression were the most common emotional problems; and fatigue, sleep, and pain were the most common physical problems.7

A finding unique to the current study is that family health issues and dealing with partner were specified as the most common family problems. However, a study by Smith and colleagues did not provide information about the rank of most frequently reported problems within this domain.7

The third aim was to understand which problems were related to SI. It was hypothesized that family, emotional, and physical problems would be related to SI. However, results indicated that only family problems (specifically, problems dealing with a partner) were significantly associated with SI among veterans living with cancer.

Contrary to expectations, emotional and physical problems were not found to have a significant relationship with SI. This is likely because veterans endorsed items nested within these problem domains with similar frequency. The lack of significant findings does not suggest that emotional and physical problems are not significant predictors of SI for veterans living with cancer, but that no specific emotional or physical symptom stood out as a predictor of suicidal ideation above the others.

The finding of a significant relationship between family problems (specifically, problems dealing with a partner) and SI in this study is consistent with findings of Aboumrad and colleagues in a study that examined root-cause analyses of completed suicides by veterans living with cancer.11 They found that nearly half the sample endorsed family problems prior to their death, and a small but notable percentage of veterans who completed suicide reported divorce as a stressor prior to their death.

This finding may be explained by Thomas Joiner's interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior (IPT), which suggests that completed suicide may result from a thwarted sense of belonging, perceived burdensomeness, and acquired capability for suicide.16 Problems dealing with a partner may impact a veteran’s sense of belonging or social connectedness. Problems dealing with a partner also may be attributed to perceived burdens due to limitations imposed by living with cancer and/or undergoing treatment. In both circumstances, the veteran’s social support system may be negatively impacted, and perceived social support is a well-established protective factor against suicide.17

Partner distress is a second consideration. It is likely that veterans’ partners experienced their own distress in response to the veteran’s cancer diagnosis and/or treatment. The partner’s cause, severity, and expression of distress may contribute to problems for the couple.

Finally, the latter point of the IPT refers to acquired capability, or the ability to inflict deadly harm to oneself.18 A military sample was found to have more acquired capability for suicide when compared with a college undergraduate sample.19 A history of a suicide attempt(s) and male gender have been found to significantly predict acquired capability to complete suicide.18 Furthermore, because veterans living with cancer often are in pain, fear of pain associated with suicide may be reduced and, therefore, acquired capability increased. This suggests that male veterans living with cancer who are in pain, have a history of a suicide attempt(s), and current problems with their partner may be an extremely vulnerable population at-risk for suicide. Results from the current study emphasize the importance of veterans having access to mental health and crisis resources for problems dealing with their partner. Partner problems may foreshadow a potentially lethal type of distress.

Strengths

This study’s aims are consistent with the VA’s mission to end veteran suicide and contributes to literature in several important ways.12 First, veterans living with cancer are an understudied population. The current study addresses a gap in existing literature by researching veterans living with cancer and aims to better understand the relationship between cancer-related distress and SI. Second, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first to find that problems dealing with a partner significantly increases a veteran’s risk for SI above a history of a suicide attempt(s). Risk assessments now may be more comprehensive through inclusion of this distress factor.

It is recommended that future research use IPT to further investigate the relationship between problems dealing with a partner and SI.16 Future research may do so by including specific measures to assess for the tenants of the theory, including measurements of burdensomeness and belongingness. An expanded knowledge base about what makes problems dealing with a partner a significant suicide risk factor (eg, increased conflict, lack of support, etc.) would better enable clinicians to intervene effectively. Effective intervention may lessen suicidal behaviors or deaths from suicides within the Veteran population.

Limitations

One limitation is the focus on patients who accepted a mental health referral. This study design may limit the generalizability of results to veterans who would not accept mental health treatment. The homogenous sample of veterans is a second limitation. Most participants were male, white, and had a mean age of 62 years. These demographics are representative of the veterans that most typically utilize VA services; however, more research is needed on veterans living with cancer who are female and of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. There are likely differences in problems endorsed and factors associated with SI based on age, race, sex, and other socioeconomic factors. A third limitation is the cross-sectional, retrospective nature of this study. Future studies are advised to assess for distress at multiple time points. This is consistent with NCCN Standards of Care for Distress Management.2 Longitudinal data would enable more findings about distress and SI throughout the course of cancer diagnosis and treatment, therefore enhancing clinical implications and informing future research.

Conclusion

This is among the first of studies to investigate distress and factors associated with SI in veterans living with cancer who were referred for psychology services. The prevalence of distress caused by psychosocial factors (including treatment decisions, worry, and depression) highlights the importance of including mental health services as part of comprehensive cancer treatment.

Distress due to treatment decisions may be attributed to a litany of factors such as a veteran’s consideration of adverse effects, effectiveness of treatments, changes to quality of life or functioning, and inclusion of alternative or complimentary treatments. These types of decisions often are reported to be difficult conversations to have with family members or loved ones, who are likely experiencing distress of their own. The role of a mental health provider to assist veterans in exploring their treatment decisions and the implications of such decisions appears important to lessening distress.

Early intervention for emotional symptoms would likely benefit veterans’ management of distress and may lessen suicide risk as depression is known to place veterans at-risk for SI.20 This underscores the importance of timely distress assessment to prevent mild emotional distress from progressing to potentially severe or life-threatening emotional distress. For veterans with a psychiatric history, timely assessment and intervention is essential because psychiatric history is an established suicide risk factor that may be exacerbated by cancer-related distress.12

Furthermore, management of intolerable physical symptoms may lessen risk for suicide.4 Under medical guidance, fatigue may be improved using exercise.21 Behavioral intervention is commonly used as first-line treatment for sleep problems.22 While pain may be lessened through medication or nonpharmacological interventions.23

Considering the numerous ways that distress may present itself (eg, practical, emotional, or physical) and increase risk for SI, it is essential that all veterans living with cancer are assessed for distress and SI, regardless of their presentation. Although veterans may not outwardly express distress, this does not indicate the absence of either distress or risk for suicide. For example, a veteran may be distressed due to financial concerns, transportation issues, and the health of his/her partner or spouse. This veteran may not exhibit visible symptoms of distress, as would be expected when the source of distress is emotional (eg, depression, anxiety). However, this veteran is equally vulnerable to impairing distress and SI as someone who exhibits emotional distress. Distress assessments should be further developed to capture both the visible and less apparent sources of distress, while also serving the imperative function of screening for suicide. Other researchers also have noted the necessity of this development.24 Currently, the NCCN DT and Problems List does not include any assessment of SI or behavior.

Finally, this study identified a potentially critical factor to include in distress assessment: problems dealing with a partner. Problems dealing with a partner have been noted as a source of distress in existing literature, but this is the first study to find problems dealing with a partner to be a predictor of SI in veterans living with cancer.4-6

Because partners often attend appointments with veterans, it is not surprising that problems dealing with their partner are not disclosed more readily. It is recommended that clinicians ask veterans about potential problems with their partner when they are alone. Directly gathering information about such problems while assessing for distress may assist health care workers in providing the most effective, accurate type of intervention in a timely manner, and potentially mitigate risk for suicide.

As recommended by the NCCN and numerous researchers, findings from the current study underscore the importance of accurate, timely assessment of distress.2,4,8 This study makes several important recommendations about how distress assessment may be strengthened and further developed, specifically for the veteran population. This study also expands the current knowledge base of what is known about veterans living with cancer, and has begun to fill a gap in the existing literature. Consistent with the VA mission to end veteran suicide, results suggest that veterans living with cancer should be regularly screened for distress, asked about distress related to their partner, and assessed for SI. Continued efforts to enhance assessment of and response to distress may lessen suicide risk in veterans with cancer.11

Acknowledgements

This study is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital.

It was estimated that physicians would diagnose a form of invasive cancer > 1.7 million times in 2019. As the second most common cause of death in the US, > 600,000 people were projected to die from cancer in 2019.1 Many individuals with cancer endure distress, which the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) defines as a “multifactorial unpleasant experience of a psychological (ie, cognitive, behavioral, emotional), social, spiritual, and/or physical nature that may interfere with the ability to cope effectively with cancer, its physical symptoms, and its treatment.”2,3 Distress in people living with cancer has been attributed to various psychosocial concerns, such as family problems, whichinclude dealing with partners and children; emotional problems, such as depression and anxiety; and physical symptoms, such as pain and fatigue.4-9 Certain factors associated with distress may increase a patient’s risk for suicide.4

Veterans are at particularly high risk for suicide.10 In 2014, veterans accounted for 18% of completed suicides in the US but only were 8.5% of the total population that same year.10 Yet, little research has been done on the relationship between distress and suicide in veterans living with cancer. Aboumrad and colleagues found that 45% of veterans with cancer who completed suicide reported family issues and 41% endorsed chronic pain.11 This study recommended continued efforts to assess and treat distress to lessen risk of suicide in veterans living with cancer; however, to date, only 1 study has specifically evaluated distress and problems endorsed among veterans living with cancer.7

Suicide prevention is of the highest priority to the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).12 Consistent with the VA mission to end veteran suicide, the current study aimed to better understand the relationship between distress and suicide within a sample of veterans living with cancer. Findings would additionally be used to tailor clinical assessments and interventions for veterans living with cancer.

This study had 3 primary goals. First, we sought to understand demographic and clinical factors associated with low, moderate, and severe levels of distress in veterans living with cancer who were referred for psychology services. Second, the study investigated the most commonly endorsed problems by veterans living with cancer. Finally, we examined which problems were related to suicidal ideation (SI). It was hypothesized that veterans who reported severe distress would be significantly more likely to endorse SI when compared with veterans who reported mild or moderate distress. Based on existing literature, it was further hypothesized that family, emotional, and physical problems would be significantly associated with SI.7,11

Methods

The current study was conducted at James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital (JAHVH) in Tampa, Florida. Inclusion criteria included veterans who were diagnosed with cancer, attended an outpatient psychology-oncology evaluation, and completed mental health screening measures provided during their evaluation. Exclusion criteria included veterans who: were seen in response to an inpatient consult, were seen solely for a stem cell transplant evaluation, or did not complete the screening measures.

Measures

A veteran’s demographic (eg, age, sex, ethnicity) and clinical (eg, cancer type, stage of disease, recurrence, cancer treatments received) information was abstracted from their VA medical records. Marital status was assessed during a clinical interview and documented as part of the standardized suicide risk assessment.

The Distress Thermometer (DT) is a subjective measure developed by the NCCN.2 The DT provides a visual representation of a thermometer and asks patients to rate their level of distress over the past week with 0 indicating no distress and 10 indicating extreme distress.

The measurement additionally lists 39 problems nested within 5 domains: practical, family, emotional, spiritual/religious, and physical. Patients may endorse listed items under each problem domain by indicating yes or no. Endorsement of various items are intended to provide more detailed information about sources of distress. Due to the predominantly male and mostly older population included in this study the ability to have children measure was removed from the family problem domain.

SI was assessed in 2 ways. First, by patients’ self-report through item-9 of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9).14 Item-9 asks “over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way?” Responses range from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day).14 Responses > 0 were considered a positive screen for SI.

Procedure

Participants were a sample of veterans who were referred for psychology-oncology services. The NCCN DT and Problems List were administered prior to the start of clinical interviews, which followed a checklist and included standardized assessments of SI and history of a suicide attempt(s). A licensed clinical psychologist or a postdoctoral resident conducted these assessments under the supervision of a licensed psychologist. Data gathered during the clinical interview and from the DT and problems list were documented in health records, which were retrospectively reviewed for relevant information (eg, cancer diagnosis, SI). Therefore, informed consent was waived. This study was approved by the JAHVH Institutional Review Board.

Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS Version 25. Data analysis proceeded in 3 steps. First, descriptive statistics included the demographic and clinical factors present in the current sample. Difference between those with and without suicidal ideation were compared using F-statistic for continuous variables and χ2 analyses for categorical variables. Second, to examine relationships between each DT problem domain and SI, χ2 analyses were conducted. Third, DT problem domains that had a significant relationship with SI were entered in a logistic regression. This analysis determined which items, if any, from a DT problem domain predicted SI. In the logistic regression model, history of suicide attempts was entered into the first block, as history of suicide attempts is a well-established risk factor for subsequent suicidal ideation. In the second block, other variables that were significantly related to suicidal ideation in the second step of analyses were included. Before interpreting the results of the logistic regression, model fit was tested using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. Significance of each individual predictor variable in the model is reported using the Wald χ2 statistic; each Wald statistic is compared with a χ2 distribution with 1 degree of freedom (df). Results of logistic regression models also provide information about the effect of each predictor variable in the regression equation (beta weight), odds a veteran who endorsed each predictor variable in the model would also endorse SI (as indicated by the odds ratio), and an estimate of the amount of variance accounted for by each predictor variable (using Nagelkerke’s pseudo R2, which ranges in value from 0 to 1 with higher values indicating more variance explained). For all analyses, P value of .05 (2-tailed) was used for statistical significance.

Results

The sample consisted of 174 veterans (Table 1). The majority (77.6%) were male with a mean age of nearly 62 years (range, 29-87). Most identified as white (74.1%) with half reporting they were either married or living with a partner.

Prostate cancer (19.0%) was the most common type of cancer among study participants followed by head and neck (18.4%), lymphoma/leukemia (11.5%), lung (11.5%), and breast (10.9%); 31.6% had metastatic disease and 14.9% had recurrent disease. Chemotherapy (42.5%) was the most common treatment modality, followed by surgery (38.5%) and radiation (31.6%). The sample was distributed among the 3 distress DT categories: mild (18.4%), moderate (42.5%), and severe (39.1%).

Problems Endorsed

Treatment decisions (44.3%) and insurance/financial concerns (35.1%) were the most frequently endorsed practical problems (Figure 1). Family health issues (33.9%) and dealing with partner (23.0%) were the most frequently endorsed family problems (Figure 2). Worry (73.0%) and depression (69.5%) were the most frequent emotional problems; of note, all emotional problems were endorsed by at least 50% of veterans (Figure 3). Fatigue (71.3%), sleep (70.7%), and pain (69%), were the most frequently endorsed physical problems (Figure 4). Spiritual/religious problems were endorsed by 15% of veterans.

Suicidal Ideation

Overall, 25.3% of veterans endorsed SI. About 20% of veterans reported a history of ≥ 1 suicide attempts in their lifetime. A significant relationship among distress categories and SI was found (χ2 = 18.36, P < .001). Veterans with severe distress were more likely to endorse SI (42.7%) when compared with veterans with mild (9.4%) or moderate (16.2%) distress.

Similarly, a significant relationship among distress categories and a history of a suicide attempt(s) was found (χ2 = 6.08, P = .048). Veterans with severe distress were more likely to have attempted suicide (29.4%) when compared with veterans with mild (12.5%) or moderate (14.9%) distress.

χ2 analyses were conducted to examine the relationships between DT problem domains and SI. A significant relationship was found between family problems and SI (

Logistic regression analyses determined whether items representative of the family problems domain were predictive of SI. Suicide attempt(s) were entered in the first step of the model to evaluate risk factors for SI over this already established risk factor. The assumptions of logistic regression were met.

The Hosmer-Lemeshow test (χ2 = 3.66, df = 5, P = .56) demonstrated that the model fit was good. The group of predictors used in the model differentiate between people who were experiencing SI and those who were not experiencing SI at the time of evaluation. A history of a suicide attempt(s) predicted SI, as expected (Wald = 6.821, df = 1, P = .01). The odds that a veteran with a history of a suicide attempt(s) would endorse SI at the time of the evaluation was nearly 3 times greater than that of veterans without a history of a suicide attempt(s). Over and above suicide attempts, problems dealing with partner (Wald = 15.142; df = 1, P < .001) was a second significant predictor of current SI. The odds that a veteran who endorsed problems dealing with partner would also endorse SI was > 5 times higher than that of veterans who did not endorse problems dealing with partner. This finding represents a significant risk factor for SI, over and above a history of a suicide attempt(s). The other items from the family problems domains were not significant (P > .05) (Table 3).

Discussion

This study aimed to understand factors associated with low, moderate, and severe levels of distress in veterans living with cancer who were referred for psychology services. As hypothesized, veterans who endorsed severe distress were significantly more likely to endorse SI. They also were more likely to have a history of a suicide attempt(s) when compared with those with mild or moderate distress.

A second aim of this study was to understand the most commonly endorsed problems. Consistent with prior literature, treatment decisions were the most commonly endorsed practical problem; worry and depression were the most common emotional problems; and fatigue, sleep, and pain were the most common physical problems.7

A finding unique to the current study is that family health issues and dealing with partner were specified as the most common family problems. However, a study by Smith and colleagues did not provide information about the rank of most frequently reported problems within this domain.7

The third aim was to understand which problems were related to SI. It was hypothesized that family, emotional, and physical problems would be related to SI. However, results indicated that only family problems (specifically, problems dealing with a partner) were significantly associated with SI among veterans living with cancer.

Contrary to expectations, emotional and physical problems were not found to have a significant relationship with SI. This is likely because veterans endorsed items nested within these problem domains with similar frequency. The lack of significant findings does not suggest that emotional and physical problems are not significant predictors of SI for veterans living with cancer, but that no specific emotional or physical symptom stood out as a predictor of suicidal ideation above the others.

The finding of a significant relationship between family problems (specifically, problems dealing with a partner) and SI in this study is consistent with findings of Aboumrad and colleagues in a study that examined root-cause analyses of completed suicides by veterans living with cancer.11 They found that nearly half the sample endorsed family problems prior to their death, and a small but notable percentage of veterans who completed suicide reported divorce as a stressor prior to their death.

This finding may be explained by Thomas Joiner's interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior (IPT), which suggests that completed suicide may result from a thwarted sense of belonging, perceived burdensomeness, and acquired capability for suicide.16 Problems dealing with a partner may impact a veteran’s sense of belonging or social connectedness. Problems dealing with a partner also may be attributed to perceived burdens due to limitations imposed by living with cancer and/or undergoing treatment. In both circumstances, the veteran’s social support system may be negatively impacted, and perceived social support is a well-established protective factor against suicide.17

Partner distress is a second consideration. It is likely that veterans’ partners experienced their own distress in response to the veteran’s cancer diagnosis and/or treatment. The partner’s cause, severity, and expression of distress may contribute to problems for the couple.

Finally, the latter point of the IPT refers to acquired capability, or the ability to inflict deadly harm to oneself.18 A military sample was found to have more acquired capability for suicide when compared with a college undergraduate sample.19 A history of a suicide attempt(s) and male gender have been found to significantly predict acquired capability to complete suicide.18 Furthermore, because veterans living with cancer often are in pain, fear of pain associated with suicide may be reduced and, therefore, acquired capability increased. This suggests that male veterans living with cancer who are in pain, have a history of a suicide attempt(s), and current problems with their partner may be an extremely vulnerable population at-risk for suicide. Results from the current study emphasize the importance of veterans having access to mental health and crisis resources for problems dealing with their partner. Partner problems may foreshadow a potentially lethal type of distress.

Strengths

This study’s aims are consistent with the VA’s mission to end veteran suicide and contributes to literature in several important ways.12 First, veterans living with cancer are an understudied population. The current study addresses a gap in existing literature by researching veterans living with cancer and aims to better understand the relationship between cancer-related distress and SI. Second, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first to find that problems dealing with a partner significantly increases a veteran’s risk for SI above a history of a suicide attempt(s). Risk assessments now may be more comprehensive through inclusion of this distress factor.

It is recommended that future research use IPT to further investigate the relationship between problems dealing with a partner and SI.16 Future research may do so by including specific measures to assess for the tenants of the theory, including measurements of burdensomeness and belongingness. An expanded knowledge base about what makes problems dealing with a partner a significant suicide risk factor (eg, increased conflict, lack of support, etc.) would better enable clinicians to intervene effectively. Effective intervention may lessen suicidal behaviors or deaths from suicides within the Veteran population.

Limitations

One limitation is the focus on patients who accepted a mental health referral. This study design may limit the generalizability of results to veterans who would not accept mental health treatment. The homogenous sample of veterans is a second limitation. Most participants were male, white, and had a mean age of 62 years. These demographics are representative of the veterans that most typically utilize VA services; however, more research is needed on veterans living with cancer who are female and of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. There are likely differences in problems endorsed and factors associated with SI based on age, race, sex, and other socioeconomic factors. A third limitation is the cross-sectional, retrospective nature of this study. Future studies are advised to assess for distress at multiple time points. This is consistent with NCCN Standards of Care for Distress Management.2 Longitudinal data would enable more findings about distress and SI throughout the course of cancer diagnosis and treatment, therefore enhancing clinical implications and informing future research.

Conclusion

This is among the first of studies to investigate distress and factors associated with SI in veterans living with cancer who were referred for psychology services. The prevalence of distress caused by psychosocial factors (including treatment decisions, worry, and depression) highlights the importance of including mental health services as part of comprehensive cancer treatment.

Distress due to treatment decisions may be attributed to a litany of factors such as a veteran’s consideration of adverse effects, effectiveness of treatments, changes to quality of life or functioning, and inclusion of alternative or complimentary treatments. These types of decisions often are reported to be difficult conversations to have with family members or loved ones, who are likely experiencing distress of their own. The role of a mental health provider to assist veterans in exploring their treatment decisions and the implications of such decisions appears important to lessening distress.

Early intervention for emotional symptoms would likely benefit veterans’ management of distress and may lessen suicide risk as depression is known to place veterans at-risk for SI.20 This underscores the importance of timely distress assessment to prevent mild emotional distress from progressing to potentially severe or life-threatening emotional distress. For veterans with a psychiatric history, timely assessment and intervention is essential because psychiatric history is an established suicide risk factor that may be exacerbated by cancer-related distress.12

Furthermore, management of intolerable physical symptoms may lessen risk for suicide.4 Under medical guidance, fatigue may be improved using exercise.21 Behavioral intervention is commonly used as first-line treatment for sleep problems.22 While pain may be lessened through medication or nonpharmacological interventions.23

Considering the numerous ways that distress may present itself (eg, practical, emotional, or physical) and increase risk for SI, it is essential that all veterans living with cancer are assessed for distress and SI, regardless of their presentation. Although veterans may not outwardly express distress, this does not indicate the absence of either distress or risk for suicide. For example, a veteran may be distressed due to financial concerns, transportation issues, and the health of his/her partner or spouse. This veteran may not exhibit visible symptoms of distress, as would be expected when the source of distress is emotional (eg, depression, anxiety). However, this veteran is equally vulnerable to impairing distress and SI as someone who exhibits emotional distress. Distress assessments should be further developed to capture both the visible and less apparent sources of distress, while also serving the imperative function of screening for suicide. Other researchers also have noted the necessity of this development.24 Currently, the NCCN DT and Problems List does not include any assessment of SI or behavior.

Finally, this study identified a potentially critical factor to include in distress assessment: problems dealing with a partner. Problems dealing with a partner have been noted as a source of distress in existing literature, but this is the first study to find problems dealing with a partner to be a predictor of SI in veterans living with cancer.4-6

Because partners often attend appointments with veterans, it is not surprising that problems dealing with their partner are not disclosed more readily. It is recommended that clinicians ask veterans about potential problems with their partner when they are alone. Directly gathering information about such problems while assessing for distress may assist health care workers in providing the most effective, accurate type of intervention in a timely manner, and potentially mitigate risk for suicide.

As recommended by the NCCN and numerous researchers, findings from the current study underscore the importance of accurate, timely assessment of distress.2,4,8 This study makes several important recommendations about how distress assessment may be strengthened and further developed, specifically for the veteran population. This study also expands the current knowledge base of what is known about veterans living with cancer, and has begun to fill a gap in the existing literature. Consistent with the VA mission to end veteran suicide, results suggest that veterans living with cancer should be regularly screened for distress, asked about distress related to their partner, and assessed for SI. Continued efforts to enhance assessment of and response to distress may lessen suicide risk in veterans with cancer.11

Acknowledgements

This study is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital.

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7-34.

2. Riba MB, Donovan, KA, Andersen, B. National Comprehensive Cancer Network clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Distress management (Version 3.2019). J Natl Compr Can Net, 2019;17(10):1229-1249.

3. Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Pianta dosi S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology. 2001;10(1):19–28.

4. Holland JC, Alici Y. Management of distress in cancer patients. J Support Oncol. 2010;8(1):4-12.

5. Bulli F, Miccinesi G, Maruelli A, Katz M, Paci E. The measure of psychological distress in cancer patients: the use of distress thermometer in the oncological rehabilitation center of Florence. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17(7):771–779.

6. Jacobsen PB, Donovan KA, Trask PC, et al. Screening for psychologic distress in ambulatory cancer patients. Cancer. 2005;103(7):1494-1502.

7. Smith J, Berman S, Dimick J, et al. Distress Screening and Management in an Outpatient VA Cancer Clinic: A Pilot Project Involving Ambulatory Patients Across the Disease Trajectory. Fed Pract. 2017;34(Suppl 1):43S–50S.

8. Carlson LE, Waller A, Groff SL, Bultz BD. Screening for distress, the sixth vital sign, in lung cancer patients: effects on pain, fatigue, and common problems--secondary outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2013;22(8):1880-1888.

9. Cooley ME, Short TH, Moriarty HJ. Symptom prevalence, distress, and change over time in adults receiving treatment for lung cancer. Psychooncology. 2003;12(7):694-708.

10. US Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Suicide Prevention. Suicide among veterans and other Americans 2001-2014. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/2016suicidedatareport.pdf. Published August 3, 2016. Accessed April 13, 2020.

11. Aboumrad M, Shiner B, Riblet N, Mills, PD, Watts BV. Factors contributing to cancer-related suicide: a study of root-cause-analysis reports. Psychooncology. 2018;27(9):2237-2244.

12. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide 2018–2028. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/docs/Office-of-Mental-Health-and-Suicide-Prevention-National-Strategy-for-Preventing-Veterans-Suicide.pdf Published 2018. Accessed April 13, 2020.

13. Carlson LE, Waller A, Mitchell AJ. Screening for distress and unmet needs in patients with cancer: review and recommendations. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(11):1160-1177.

14. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613.

15. Martin A, Rief W, Klaiberg A, Braehler E. Validity of the brief patient health questionnaire mood scale (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(1):71-77.

16. Joiner TE. Why People Die by Suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005.

17. Kleiman EM, Riskind JH, Schaefer KE. Social support and positive events as suicide resiliency factors: examination of synergistic buffering effects. Arch Suicide Res. 2014;18(2):144-155.

18. Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Gordon KH, Bender TW, Joiner TE Jr. Suicidal desire and the capability for suicide: tests of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior among adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(1):72–83.

19. Bryan CJ, Morrow CE, Anestis MD, Joiner TE. A preliminary test of the interpersonal -psychological theory of suicidal behavior in a military sample. Personal Individual Differ. 2010;48(3):347-350.

20. Miller SN, Monahan CJ, Phillips KM, Agliata D, Gironda RJ. Mental health utilization among veterans at risk for suicide: Data from a post-deployment clinic [published online ahead of print, 2018 Oct 8]. Psychol Serv. 2018;10.1037/ser0000311.

21. Galvão DA, Newton RU. Review of exercise intervention studies in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(4):899-909.

22. Qaseem A, Kansagara D, Forciea MA, Cooke M, Denberg TD; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Management of chronic insomnia disorder in adults: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(2):125-133.

23. Ngamkham S, Holden JE, Smith EL. A systematic review: Mindfulness intervention for cancer-related pain. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2019;6(2):161-169.

24. Granek L, Nakash O, Ben-David M, Shapira S, Ariad S. Oncologists’, nurses’, and social workers’ strategies and barriers to identifying suicide risk in cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2018;27(1):148-154.

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7-34.

2. Riba MB, Donovan, KA, Andersen, B. National Comprehensive Cancer Network clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Distress management (Version 3.2019). J Natl Compr Can Net, 2019;17(10):1229-1249.

3. Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Pianta dosi S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology. 2001;10(1):19–28.

4. Holland JC, Alici Y. Management of distress in cancer patients. J Support Oncol. 2010;8(1):4-12.

5. Bulli F, Miccinesi G, Maruelli A, Katz M, Paci E. The measure of psychological distress in cancer patients: the use of distress thermometer in the oncological rehabilitation center of Florence. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17(7):771–779.

6. Jacobsen PB, Donovan KA, Trask PC, et al. Screening for psychologic distress in ambulatory cancer patients. Cancer. 2005;103(7):1494-1502.

7. Smith J, Berman S, Dimick J, et al. Distress Screening and Management in an Outpatient VA Cancer Clinic: A Pilot Project Involving Ambulatory Patients Across the Disease Trajectory. Fed Pract. 2017;34(Suppl 1):43S–50S.

8. Carlson LE, Waller A, Groff SL, Bultz BD. Screening for distress, the sixth vital sign, in lung cancer patients: effects on pain, fatigue, and common problems--secondary outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2013;22(8):1880-1888.

9. Cooley ME, Short TH, Moriarty HJ. Symptom prevalence, distress, and change over time in adults receiving treatment for lung cancer. Psychooncology. 2003;12(7):694-708.

10. US Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Suicide Prevention. Suicide among veterans and other Americans 2001-2014. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/2016suicidedatareport.pdf. Published August 3, 2016. Accessed April 13, 2020.

11. Aboumrad M, Shiner B, Riblet N, Mills, PD, Watts BV. Factors contributing to cancer-related suicide: a study of root-cause-analysis reports. Psychooncology. 2018;27(9):2237-2244.