User login

FDA advisors vote to recommend Moderna boosters

A panel of experts that advises the Food and Drug Administration on vaccine decisions voted unanimously Oct. 14 to approve booster doses of Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine.

The 19 members of the FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee voted to authorize a 50-milligram dose -- half the dose used in the primary series of shots -- to boost immunity against COVID-19 at least 6 months after the second dose. Those who might need a booster are the same groups who’ve gotten a green light for third Pfizer doses. They include people:

- Over age 65

- Ages 18 to 64 who are at higher risk for severe COVID

- Who are at higher risk of catching COVID because they live in group settings like nursing homes or prisons, or because they are frequently exposed at work, as health care workers are

The agency is not bound by the committee’s vote but usually follows its recommendations.

Some members of the committee said they weren’t satisfied with the data Moderna submitted to support its application but, for practical reasons, said it wouldn’t be fair to take booster doses off the table for Moderna recipients when Pfizer’s boosters were already available.

“The data are not perfect, but these are extraordinary times and we have to work with data that are not perfect,” said Eric Rubin, MD, editor-in-chief of TheNew England Journal of Medicine and a temporary voting member on the committee.

Patrick Moore, MD, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute who is also a temporary voting member, said he voted to approve the Moderna boosters based “more on a gut feeling than on truly serious data.”

“I’ve got some real issues with this vote,” he said.

“We need to see good solid data, and it needs to be explained well,” Dr. Moore said, challenging companies making future applications to do better.

Next, the FDA will have to formally sign off on the emergency use authorization, which it is expected to do. Then, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices will meet to make formal recommendations on use of the Moderna boosters. That group is scheduled to meet Oct. 21 to take up questions of exactly how these boosters should be used.

Peter Marks, MD, head of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, cautioned that the CDC is more constrained in making recommendations under an emergency use authorization than it would be if the boosters had gotten full approval. So it will likely align its vote with the conditions of the emergency use authorization from the FDA.

After the advisory committee votes, the director of the CDC has to approve its recommendation.

Overall, data show that two doses of the Moderna vaccine remains highly effective at preventing hospitalization and death. But over time, levels of the body’s first line of defense against a virus -- its neutralizing antibodies -- fall somewhat. This drop seems to correspond with an increased risk for breakthrough cases of COVID-19.

Data presented by Moderna Oct. 14 showed the risk of breakthrough infections increased by 36% in study participants who received the vaccine in their clinical trials, compared to people in the same study who received a placebo first, and got the vaccine later, when the trial was unblended. Their protection was more recent, and they had fewer breakthrough infections.

In considering booster doses, the FDA has asked drugmakers to do studies that look at the immune responses of small groups of study participants and compare them to the immune responses seen in study participants after their first two vaccine doses.

To be considered effective, boosters have to clear two bars. The first looks at the concentration of antibodies generated in the blood of boosted study volunteers. The second looks at how many boosted study participants saw a four-fold increase in their blood antibody levels a month after the booster minus the number of people who saw the same increase after their original two doses.

Moderna presented data that its boosters met the first criteria, but failed to meet the second, perhaps because so many people in the study had good responses after their first two doses of the vaccines.

The FDA’s advisory committee will reconvene Oct. 15 to hear evidence supporting the emergency use authorization of a booster dose of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

This article was updated Oct. 15 and first appeared on WebMD.com.

A panel of experts that advises the Food and Drug Administration on vaccine decisions voted unanimously Oct. 14 to approve booster doses of Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine.

The 19 members of the FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee voted to authorize a 50-milligram dose -- half the dose used in the primary series of shots -- to boost immunity against COVID-19 at least 6 months after the second dose. Those who might need a booster are the same groups who’ve gotten a green light for third Pfizer doses. They include people:

- Over age 65

- Ages 18 to 64 who are at higher risk for severe COVID

- Who are at higher risk of catching COVID because they live in group settings like nursing homes or prisons, or because they are frequently exposed at work, as health care workers are

The agency is not bound by the committee’s vote but usually follows its recommendations.

Some members of the committee said they weren’t satisfied with the data Moderna submitted to support its application but, for practical reasons, said it wouldn’t be fair to take booster doses off the table for Moderna recipients when Pfizer’s boosters were already available.

“The data are not perfect, but these are extraordinary times and we have to work with data that are not perfect,” said Eric Rubin, MD, editor-in-chief of TheNew England Journal of Medicine and a temporary voting member on the committee.

Patrick Moore, MD, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute who is also a temporary voting member, said he voted to approve the Moderna boosters based “more on a gut feeling than on truly serious data.”

“I’ve got some real issues with this vote,” he said.

“We need to see good solid data, and it needs to be explained well,” Dr. Moore said, challenging companies making future applications to do better.

Next, the FDA will have to formally sign off on the emergency use authorization, which it is expected to do. Then, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices will meet to make formal recommendations on use of the Moderna boosters. That group is scheduled to meet Oct. 21 to take up questions of exactly how these boosters should be used.

Peter Marks, MD, head of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, cautioned that the CDC is more constrained in making recommendations under an emergency use authorization than it would be if the boosters had gotten full approval. So it will likely align its vote with the conditions of the emergency use authorization from the FDA.

After the advisory committee votes, the director of the CDC has to approve its recommendation.

Overall, data show that two doses of the Moderna vaccine remains highly effective at preventing hospitalization and death. But over time, levels of the body’s first line of defense against a virus -- its neutralizing antibodies -- fall somewhat. This drop seems to correspond with an increased risk for breakthrough cases of COVID-19.

Data presented by Moderna Oct. 14 showed the risk of breakthrough infections increased by 36% in study participants who received the vaccine in their clinical trials, compared to people in the same study who received a placebo first, and got the vaccine later, when the trial was unblended. Their protection was more recent, and they had fewer breakthrough infections.

In considering booster doses, the FDA has asked drugmakers to do studies that look at the immune responses of small groups of study participants and compare them to the immune responses seen in study participants after their first two vaccine doses.

To be considered effective, boosters have to clear two bars. The first looks at the concentration of antibodies generated in the blood of boosted study volunteers. The second looks at how many boosted study participants saw a four-fold increase in their blood antibody levels a month after the booster minus the number of people who saw the same increase after their original two doses.

Moderna presented data that its boosters met the first criteria, but failed to meet the second, perhaps because so many people in the study had good responses after their first two doses of the vaccines.

The FDA’s advisory committee will reconvene Oct. 15 to hear evidence supporting the emergency use authorization of a booster dose of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

This article was updated Oct. 15 and first appeared on WebMD.com.

A panel of experts that advises the Food and Drug Administration on vaccine decisions voted unanimously Oct. 14 to approve booster doses of Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine.

The 19 members of the FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee voted to authorize a 50-milligram dose -- half the dose used in the primary series of shots -- to boost immunity against COVID-19 at least 6 months after the second dose. Those who might need a booster are the same groups who’ve gotten a green light for third Pfizer doses. They include people:

- Over age 65

- Ages 18 to 64 who are at higher risk for severe COVID

- Who are at higher risk of catching COVID because they live in group settings like nursing homes or prisons, or because they are frequently exposed at work, as health care workers are

The agency is not bound by the committee’s vote but usually follows its recommendations.

Some members of the committee said they weren’t satisfied with the data Moderna submitted to support its application but, for practical reasons, said it wouldn’t be fair to take booster doses off the table for Moderna recipients when Pfizer’s boosters were already available.

“The data are not perfect, but these are extraordinary times and we have to work with data that are not perfect,” said Eric Rubin, MD, editor-in-chief of TheNew England Journal of Medicine and a temporary voting member on the committee.

Patrick Moore, MD, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute who is also a temporary voting member, said he voted to approve the Moderna boosters based “more on a gut feeling than on truly serious data.”

“I’ve got some real issues with this vote,” he said.

“We need to see good solid data, and it needs to be explained well,” Dr. Moore said, challenging companies making future applications to do better.

Next, the FDA will have to formally sign off on the emergency use authorization, which it is expected to do. Then, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices will meet to make formal recommendations on use of the Moderna boosters. That group is scheduled to meet Oct. 21 to take up questions of exactly how these boosters should be used.

Peter Marks, MD, head of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, cautioned that the CDC is more constrained in making recommendations under an emergency use authorization than it would be if the boosters had gotten full approval. So it will likely align its vote with the conditions of the emergency use authorization from the FDA.

After the advisory committee votes, the director of the CDC has to approve its recommendation.

Overall, data show that two doses of the Moderna vaccine remains highly effective at preventing hospitalization and death. But over time, levels of the body’s first line of defense against a virus -- its neutralizing antibodies -- fall somewhat. This drop seems to correspond with an increased risk for breakthrough cases of COVID-19.

Data presented by Moderna Oct. 14 showed the risk of breakthrough infections increased by 36% in study participants who received the vaccine in their clinical trials, compared to people in the same study who received a placebo first, and got the vaccine later, when the trial was unblended. Their protection was more recent, and they had fewer breakthrough infections.

In considering booster doses, the FDA has asked drugmakers to do studies that look at the immune responses of small groups of study participants and compare them to the immune responses seen in study participants after their first two vaccine doses.

To be considered effective, boosters have to clear two bars. The first looks at the concentration of antibodies generated in the blood of boosted study volunteers. The second looks at how many boosted study participants saw a four-fold increase in their blood antibody levels a month after the booster minus the number of people who saw the same increase after their original two doses.

Moderna presented data that its boosters met the first criteria, but failed to meet the second, perhaps because so many people in the study had good responses after their first two doses of the vaccines.

The FDA’s advisory committee will reconvene Oct. 15 to hear evidence supporting the emergency use authorization of a booster dose of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

This article was updated Oct. 15 and first appeared on WebMD.com.

D-dimer unreliable for ruling out pulmonary embolism in COVID-19

The plasma D-dimer assay has been used, along with clinical prediction scores, to rule out pulmonary embolism (PE) in critically ill patients for decades, but a new study suggests it may not be the right test to use in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

The results showed that all hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and radiographic evidence of PE had plasma D-dimer levels of 0.05 mcg/mL or greater, the cutoff point for the diagnosis.

“If using D-dimer to exclude patients with PE, the increased values we found among 92.3% of patients suggest that this assay would be less useful than in the populations in which it was originally validated, among which a minority of patients had increased D-dimer values,” the authors write. “Setting higher D-dimer thresholds was associated with improved specificity at the cost of an increased false-negative rate that could be associated with an unacceptable patient safety risk.”

The inclusion of patients with D-dimer and computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) was necessary to estimate diagnostic performance, they note, but “this may have introduced selection bias by excluding patients unable to undergo CTPA.”

“Nonetheless, given the high pretest probability of PE and low specificity observed in this and other studies, these results suggest that use of D-dimer levels to exclude PE among patients hospitalized with COVID-19 may be inappropriate and have limited clinical utility,” they conclude.

Led by Constantine N. Logothetis, MD, from Morsani College of Medicine, University of South Florida, Tampa, the study was published online Oct. 8 as a Research Letter in JAMA Network Open.

Uncertain utility

The authors note that the availability of D-dimer samples routinely collected from hospitalized COVID-19 patients – as well as the heterogeneity of early, smaller studies – generated uncertainty about the utility of this assay.

This uncertainty prompted them to test the diagnostic accuracy of the D-dimer assay among a sample of 1,541 patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19 at their institution between January 2020 and February 2021 for a possible PE.

They compared plasma D-dimer concentrations with CTPA, the criterion standard for diagnosing PE, in 287 of those patients.

Overall, 118 patients (41.1%) required care in the ICU, and 27 patients (9.4%) died during hospitalization.

The investigators looked at the ability of plasma D-dimer levels collected on the same day as CTPA to diagnose PE.

Thirty-seven patients (12.9%) had radiographic evidence of PE, and 250 patients (87.1%) did not.

Overall, the vast majority of patients (92.3%; n = 265 patients) had plasma D-dimer levels of 0.05 mcg/mL or more, including all patients with PE and 225 of 250 patients without PE (91.2%).

The median D-dimer values were 1.0 mcg/mL for 250 patients without PE and 6.1 mcg/mL for 37 patients with PE.

D-dimer values ranged from 0.2 mcg/mL to 128 mcg/mL among patients without PE, and from 0.5 mcg/mL to more than 10,000 mcg/mL among patients with PE. Patients without PE had statistically significantly decreased mean D-dimer values (8.7 mcg/mL vs. 1.2 mcg/mL; P < .001).

A D-dimer concentration of 0.05 mcg/mL was associated with a sensitivity of 100%, specificity of 8.8%, negative predictive value (NPV) of 100%, positive predictive value (PPV) of 13.9%, and a negative likelihood ratio (NLR) of less than 0.1.

The age-adjusted threshold was associated with a sensitivity of 94.6%, specificity of 22.8%, NPV of 96.6%, PPV of 13.9%, and NLR of 0.24.

The authors note that all hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and radiographic evidence of PE had plasma D-dimer levels of 0.05 mcg/mL or greater.

D-dimer in VTE may not extrapolate to COVID-19

“The D-dimer test, which is a measure of circulating byproducts of blood clot dissolution, has long been incorporated into diagnostic algorithms for venous thromboembolic [VTE] disease, including deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. It is uncertain whether this diagnostic use of D-dimer testing can be extrapolated to the context of COVID-19 – an illness we now understand to be associated itself with intravascular thrombosis and fibrinolysis,” Matthew Tomey, MD, a cardiologist at Mount Sinai Morningside, New York, said in an interview.

“The authors of this study sought to evaluate the test characteristics of the D-dimer assay for diagnosis of pulmonary embolism in a consecutive series of 287 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 who underwent computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA). This was a selected group of patients representing less than 20% of the 1,541 patients screened. Exclusion of data on the more than 80% of screened patients who did not undergo CTPA is a significant limitation of the study,” Dr. Tomey said.

“In the highly selected, small cohort studied, representing a group of patients at high pretest probability of pulmonary embolism, there was no patient with pulmonary embolism who had a D-dimer value less than 0.5 mcg/mL. Yet broad ranges of D-dimer values were observed in COVID-19 patients with (0.5 to >10,000 mcg/mL) and without (0.2 to 128 mcg/mL) pulmonary embolism,” he added.

Based on the presented data, it is likely true that very low levels of D-dimer decrease the likelihood of finding a pulmonary embolus on a CTPA, if it is performed, Dr. Tomey noted.

“Yet the data confirm that a wide range of D-dimer values can be observed in COVID-19 patients with or without pulmonary embolism. It is not clear at this time that D-dimer levels should be used as gatekeepers to diagnostic imaging studies such as CTPA when pretest suspicion of pulmonary embolism is high,” he said.

“This issue becomes relevant as we consider evolving data on use of anticoagulation in treatment of hospitalized patients with COVID-19. We learned this year that in critically ill patients hospitalized with COVID-19, routine therapeutic anticoagulation (with heparin) was not beneficial and potentially harmful when compared with usual thromboprophylaxis,” he concluded.

“As we strive to balance competing risks of bleeding and thrombosis, accurate diagnosis of pulmonary embolism is important to guide decision-making about therapeutic anticoagulation, including in COVID-19.”

Dr. Logothetis and Dr. Tomey have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The plasma D-dimer assay has been used, along with clinical prediction scores, to rule out pulmonary embolism (PE) in critically ill patients for decades, but a new study suggests it may not be the right test to use in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

The results showed that all hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and radiographic evidence of PE had plasma D-dimer levels of 0.05 mcg/mL or greater, the cutoff point for the diagnosis.

“If using D-dimer to exclude patients with PE, the increased values we found among 92.3% of patients suggest that this assay would be less useful than in the populations in which it was originally validated, among which a minority of patients had increased D-dimer values,” the authors write. “Setting higher D-dimer thresholds was associated with improved specificity at the cost of an increased false-negative rate that could be associated with an unacceptable patient safety risk.”

The inclusion of patients with D-dimer and computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) was necessary to estimate diagnostic performance, they note, but “this may have introduced selection bias by excluding patients unable to undergo CTPA.”

“Nonetheless, given the high pretest probability of PE and low specificity observed in this and other studies, these results suggest that use of D-dimer levels to exclude PE among patients hospitalized with COVID-19 may be inappropriate and have limited clinical utility,” they conclude.

Led by Constantine N. Logothetis, MD, from Morsani College of Medicine, University of South Florida, Tampa, the study was published online Oct. 8 as a Research Letter in JAMA Network Open.

Uncertain utility

The authors note that the availability of D-dimer samples routinely collected from hospitalized COVID-19 patients – as well as the heterogeneity of early, smaller studies – generated uncertainty about the utility of this assay.

This uncertainty prompted them to test the diagnostic accuracy of the D-dimer assay among a sample of 1,541 patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19 at their institution between January 2020 and February 2021 for a possible PE.

They compared plasma D-dimer concentrations with CTPA, the criterion standard for diagnosing PE, in 287 of those patients.

Overall, 118 patients (41.1%) required care in the ICU, and 27 patients (9.4%) died during hospitalization.

The investigators looked at the ability of plasma D-dimer levels collected on the same day as CTPA to diagnose PE.

Thirty-seven patients (12.9%) had radiographic evidence of PE, and 250 patients (87.1%) did not.

Overall, the vast majority of patients (92.3%; n = 265 patients) had plasma D-dimer levels of 0.05 mcg/mL or more, including all patients with PE and 225 of 250 patients without PE (91.2%).

The median D-dimer values were 1.0 mcg/mL for 250 patients without PE and 6.1 mcg/mL for 37 patients with PE.

D-dimer values ranged from 0.2 mcg/mL to 128 mcg/mL among patients without PE, and from 0.5 mcg/mL to more than 10,000 mcg/mL among patients with PE. Patients without PE had statistically significantly decreased mean D-dimer values (8.7 mcg/mL vs. 1.2 mcg/mL; P < .001).

A D-dimer concentration of 0.05 mcg/mL was associated with a sensitivity of 100%, specificity of 8.8%, negative predictive value (NPV) of 100%, positive predictive value (PPV) of 13.9%, and a negative likelihood ratio (NLR) of less than 0.1.

The age-adjusted threshold was associated with a sensitivity of 94.6%, specificity of 22.8%, NPV of 96.6%, PPV of 13.9%, and NLR of 0.24.

The authors note that all hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and radiographic evidence of PE had plasma D-dimer levels of 0.05 mcg/mL or greater.

D-dimer in VTE may not extrapolate to COVID-19

“The D-dimer test, which is a measure of circulating byproducts of blood clot dissolution, has long been incorporated into diagnostic algorithms for venous thromboembolic [VTE] disease, including deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. It is uncertain whether this diagnostic use of D-dimer testing can be extrapolated to the context of COVID-19 – an illness we now understand to be associated itself with intravascular thrombosis and fibrinolysis,” Matthew Tomey, MD, a cardiologist at Mount Sinai Morningside, New York, said in an interview.

“The authors of this study sought to evaluate the test characteristics of the D-dimer assay for diagnosis of pulmonary embolism in a consecutive series of 287 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 who underwent computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA). This was a selected group of patients representing less than 20% of the 1,541 patients screened. Exclusion of data on the more than 80% of screened patients who did not undergo CTPA is a significant limitation of the study,” Dr. Tomey said.

“In the highly selected, small cohort studied, representing a group of patients at high pretest probability of pulmonary embolism, there was no patient with pulmonary embolism who had a D-dimer value less than 0.5 mcg/mL. Yet broad ranges of D-dimer values were observed in COVID-19 patients with (0.5 to >10,000 mcg/mL) and without (0.2 to 128 mcg/mL) pulmonary embolism,” he added.

Based on the presented data, it is likely true that very low levels of D-dimer decrease the likelihood of finding a pulmonary embolus on a CTPA, if it is performed, Dr. Tomey noted.

“Yet the data confirm that a wide range of D-dimer values can be observed in COVID-19 patients with or without pulmonary embolism. It is not clear at this time that D-dimer levels should be used as gatekeepers to diagnostic imaging studies such as CTPA when pretest suspicion of pulmonary embolism is high,” he said.

“This issue becomes relevant as we consider evolving data on use of anticoagulation in treatment of hospitalized patients with COVID-19. We learned this year that in critically ill patients hospitalized with COVID-19, routine therapeutic anticoagulation (with heparin) was not beneficial and potentially harmful when compared with usual thromboprophylaxis,” he concluded.

“As we strive to balance competing risks of bleeding and thrombosis, accurate diagnosis of pulmonary embolism is important to guide decision-making about therapeutic anticoagulation, including in COVID-19.”

Dr. Logothetis and Dr. Tomey have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The plasma D-dimer assay has been used, along with clinical prediction scores, to rule out pulmonary embolism (PE) in critically ill patients for decades, but a new study suggests it may not be the right test to use in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

The results showed that all hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and radiographic evidence of PE had plasma D-dimer levels of 0.05 mcg/mL or greater, the cutoff point for the diagnosis.

“If using D-dimer to exclude patients with PE, the increased values we found among 92.3% of patients suggest that this assay would be less useful than in the populations in which it was originally validated, among which a minority of patients had increased D-dimer values,” the authors write. “Setting higher D-dimer thresholds was associated with improved specificity at the cost of an increased false-negative rate that could be associated with an unacceptable patient safety risk.”

The inclusion of patients with D-dimer and computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) was necessary to estimate diagnostic performance, they note, but “this may have introduced selection bias by excluding patients unable to undergo CTPA.”

“Nonetheless, given the high pretest probability of PE and low specificity observed in this and other studies, these results suggest that use of D-dimer levels to exclude PE among patients hospitalized with COVID-19 may be inappropriate and have limited clinical utility,” they conclude.

Led by Constantine N. Logothetis, MD, from Morsani College of Medicine, University of South Florida, Tampa, the study was published online Oct. 8 as a Research Letter in JAMA Network Open.

Uncertain utility

The authors note that the availability of D-dimer samples routinely collected from hospitalized COVID-19 patients – as well as the heterogeneity of early, smaller studies – generated uncertainty about the utility of this assay.

This uncertainty prompted them to test the diagnostic accuracy of the D-dimer assay among a sample of 1,541 patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19 at their institution between January 2020 and February 2021 for a possible PE.

They compared plasma D-dimer concentrations with CTPA, the criterion standard for diagnosing PE, in 287 of those patients.

Overall, 118 patients (41.1%) required care in the ICU, and 27 patients (9.4%) died during hospitalization.

The investigators looked at the ability of plasma D-dimer levels collected on the same day as CTPA to diagnose PE.

Thirty-seven patients (12.9%) had radiographic evidence of PE, and 250 patients (87.1%) did not.

Overall, the vast majority of patients (92.3%; n = 265 patients) had plasma D-dimer levels of 0.05 mcg/mL or more, including all patients with PE and 225 of 250 patients without PE (91.2%).

The median D-dimer values were 1.0 mcg/mL for 250 patients without PE and 6.1 mcg/mL for 37 patients with PE.

D-dimer values ranged from 0.2 mcg/mL to 128 mcg/mL among patients without PE, and from 0.5 mcg/mL to more than 10,000 mcg/mL among patients with PE. Patients without PE had statistically significantly decreased mean D-dimer values (8.7 mcg/mL vs. 1.2 mcg/mL; P < .001).

A D-dimer concentration of 0.05 mcg/mL was associated with a sensitivity of 100%, specificity of 8.8%, negative predictive value (NPV) of 100%, positive predictive value (PPV) of 13.9%, and a negative likelihood ratio (NLR) of less than 0.1.

The age-adjusted threshold was associated with a sensitivity of 94.6%, specificity of 22.8%, NPV of 96.6%, PPV of 13.9%, and NLR of 0.24.

The authors note that all hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and radiographic evidence of PE had plasma D-dimer levels of 0.05 mcg/mL or greater.

D-dimer in VTE may not extrapolate to COVID-19

“The D-dimer test, which is a measure of circulating byproducts of blood clot dissolution, has long been incorporated into diagnostic algorithms for venous thromboembolic [VTE] disease, including deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. It is uncertain whether this diagnostic use of D-dimer testing can be extrapolated to the context of COVID-19 – an illness we now understand to be associated itself with intravascular thrombosis and fibrinolysis,” Matthew Tomey, MD, a cardiologist at Mount Sinai Morningside, New York, said in an interview.

“The authors of this study sought to evaluate the test characteristics of the D-dimer assay for diagnosis of pulmonary embolism in a consecutive series of 287 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 who underwent computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA). This was a selected group of patients representing less than 20% of the 1,541 patients screened. Exclusion of data on the more than 80% of screened patients who did not undergo CTPA is a significant limitation of the study,” Dr. Tomey said.

“In the highly selected, small cohort studied, representing a group of patients at high pretest probability of pulmonary embolism, there was no patient with pulmonary embolism who had a D-dimer value less than 0.5 mcg/mL. Yet broad ranges of D-dimer values were observed in COVID-19 patients with (0.5 to >10,000 mcg/mL) and without (0.2 to 128 mcg/mL) pulmonary embolism,” he added.

Based on the presented data, it is likely true that very low levels of D-dimer decrease the likelihood of finding a pulmonary embolus on a CTPA, if it is performed, Dr. Tomey noted.

“Yet the data confirm that a wide range of D-dimer values can be observed in COVID-19 patients with or without pulmonary embolism. It is not clear at this time that D-dimer levels should be used as gatekeepers to diagnostic imaging studies such as CTPA when pretest suspicion of pulmonary embolism is high,” he said.

“This issue becomes relevant as we consider evolving data on use of anticoagulation in treatment of hospitalized patients with COVID-19. We learned this year that in critically ill patients hospitalized with COVID-19, routine therapeutic anticoagulation (with heparin) was not beneficial and potentially harmful when compared with usual thromboprophylaxis,” he concluded.

“As we strive to balance competing risks of bleeding and thrombosis, accurate diagnosis of pulmonary embolism is important to guide decision-making about therapeutic anticoagulation, including in COVID-19.”

Dr. Logothetis and Dr. Tomey have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Medical comanagement did not improve hip fracture outcomes

Background: Medical comanagement of hip fracture patients is common. Prior evidence comes from mostly single-center studies, with most improvements being in process indicators such as length of stay and staff satisfaction.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database.

Synopsis: With the NSQIP database targeted user file for hip fracture of 19,896 patients from 2016 to 2017, unadjusted analysis showed patients in the medical comanagement cohort were older with higher burden of comorbidities, higher morbidity (19.5% vs. 9.6%, odds ratio, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.98-2.63; P < .0001), and higher mortality rate (6.9% vs. 4.0%; OR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.44-2.22; P < .0001). Both cohorts had similar proportion of patients participating in a standardized hip fracture program. After propensity score matching, patients in the comanagement cohort continued to show inferior morbidity (OR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.52-2.20; P < .0001) and mortality (OR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.02-1.81; P = .033).

This study failed to show superior outcomes in comanagement patients. The retrospective nature and propensity matching will lead to the question of unmeasured confounding in this large multinational database.

Bottom line: Medical comanagement of hip fractures was not associated with improved outcomes in the NSQIP database.

Citation: Maxwell BG, Mirza A. Medical comanagement of hip fracture patients is not associated with superior perioperative outcomes: A propensity score–matched retrospective cohort analysis of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Project. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:468-74.

Dr. Lockwood is a hospitalist and chief of quality, performance, and patient safety at the Lexington (Ky.) VA Health Care System.

Background: Medical comanagement of hip fracture patients is common. Prior evidence comes from mostly single-center studies, with most improvements being in process indicators such as length of stay and staff satisfaction.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database.

Synopsis: With the NSQIP database targeted user file for hip fracture of 19,896 patients from 2016 to 2017, unadjusted analysis showed patients in the medical comanagement cohort were older with higher burden of comorbidities, higher morbidity (19.5% vs. 9.6%, odds ratio, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.98-2.63; P < .0001), and higher mortality rate (6.9% vs. 4.0%; OR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.44-2.22; P < .0001). Both cohorts had similar proportion of patients participating in a standardized hip fracture program. After propensity score matching, patients in the comanagement cohort continued to show inferior morbidity (OR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.52-2.20; P < .0001) and mortality (OR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.02-1.81; P = .033).

This study failed to show superior outcomes in comanagement patients. The retrospective nature and propensity matching will lead to the question of unmeasured confounding in this large multinational database.

Bottom line: Medical comanagement of hip fractures was not associated with improved outcomes in the NSQIP database.

Citation: Maxwell BG, Mirza A. Medical comanagement of hip fracture patients is not associated with superior perioperative outcomes: A propensity score–matched retrospective cohort analysis of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Project. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:468-74.

Dr. Lockwood is a hospitalist and chief of quality, performance, and patient safety at the Lexington (Ky.) VA Health Care System.

Background: Medical comanagement of hip fracture patients is common. Prior evidence comes from mostly single-center studies, with most improvements being in process indicators such as length of stay and staff satisfaction.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database.

Synopsis: With the NSQIP database targeted user file for hip fracture of 19,896 patients from 2016 to 2017, unadjusted analysis showed patients in the medical comanagement cohort were older with higher burden of comorbidities, higher morbidity (19.5% vs. 9.6%, odds ratio, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.98-2.63; P < .0001), and higher mortality rate (6.9% vs. 4.0%; OR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.44-2.22; P < .0001). Both cohorts had similar proportion of patients participating in a standardized hip fracture program. After propensity score matching, patients in the comanagement cohort continued to show inferior morbidity (OR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.52-2.20; P < .0001) and mortality (OR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.02-1.81; P = .033).

This study failed to show superior outcomes in comanagement patients. The retrospective nature and propensity matching will lead to the question of unmeasured confounding in this large multinational database.

Bottom line: Medical comanagement of hip fractures was not associated with improved outcomes in the NSQIP database.

Citation: Maxwell BG, Mirza A. Medical comanagement of hip fracture patients is not associated with superior perioperative outcomes: A propensity score–matched retrospective cohort analysis of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Project. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:468-74.

Dr. Lockwood is a hospitalist and chief of quality, performance, and patient safety at the Lexington (Ky.) VA Health Care System.

New safety data regarding COVID vaccines

from the French National Agency for the Safety of Medicines and Health Products (ANSM).

The rare condition — more common in men than in women — is characterized by the sudden onset of severe pain in the shoulder, followed by arm paralysis. Its etiopathogenesis is not well understood, but vaccines, in particular the flu vaccine, have been implicated in some cases, the report states.

Six serious cases of the syndrome related to the Comirnaty (Pfizer) vaccine were reported by healthcare professionals and vaccinated individuals or their family and friends since the start of the monitoring program. Four of these cases occurred from September 3 to 16.

All six cases involved patients 19 to 69 years of age — two women and four men — who developed symptoms in the 50 days after vaccination. Half were reported after the first dose and half after the second dose. Four of the patients are currently recovering; the outcomes of the other two are unknown.

In the case of the Spikevax vaccine (Moderna), two cases of Parsonage-Turner syndrome were reported after vaccination (plus one that occurred after 50 days, which is currently being managed). The onset of symptoms in these two men — one in his early 30s and one in his early 60s — occurred less than 18 days after vaccination. One occurred after the first dose and one after the second dose. This timing indicates a possible link between the syndrome and the vaccine. Both men are currently in recovery.

This signal of mRNA vaccines is now “officially recognized,” according to the Pfizer and Moderna reports.

It is also considered a “potential signal” in the Vaxzevria (AstraZeneca) pharmacovigilance report, released October 8, which describes eight cases of Parsonage-Turner syndrome after vaccination.

Safety profile of mRNA COVID vaccines in youth

Between June 15, when children 12 years and older became eligible for vaccination, and August 26, there were 591 reports of potential adverse events — out of 6 million Pfizer doses administered — in 12- to 18-year-old children.

Of the 591 cases, 35.2% were deemed serious. The majority of these were cases of reactogenicity, malaise, or postvaccine discomfort (25%), followed by instances of myocarditis and pericarditis (15.9% and 7.2%, respectively). In eight of 10 cases, one of the first symptom reported was chest pain.

Myocarditis occurred in 39.4% of people after the first injection (mean time to onset, 13 days) and 54.5% after the second (mean time to onset, 4 days). Recorded progress was favorable in nearly nine of 10 cases.

Pericarditis occurred in 53.3% of people after the first injection (mean time to onset, 13 days), and 40.0% after the second (mean time to onset, 4 days).

Three cases of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MISC) were reported after monitoring ended.

For this age group, “all reported events will continue to be monitored, especially serious events and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children,” report authors conclude.

Data for adverse events after the Moderna vaccine remain limited, but the report stipulates that “the adverse events reported in 12- to 18-year-olds who received an injection do not display any particular pattern, compared with those reported in older subjects, with the exception of a roughly 100-fold lower incidence of reported adverse effects in the 12- to 17-year age group.”

No safety warnings for pregnant women

The pharmacovigilance report — which covered the period from December 27, 2020 to September 9, 2021 — “raises no safety warnings for pregnant or nursing women with any of the COVID-19 vaccines.” In addition, two recent studies — one published in JAMA and one in the New England Journal of Medicine — have shown no link between spontaneous miscarriage and mRNA vaccines.

“Moreover, it should be stressed that current data from the international literature consistently show that maternal SARS COV-2 infection increases the risk for fetal, maternal, and neonatal complications, and that this risk may increase with the arrival of the Alpha and Delta variants,” they write. “It is therefore important to reiterate the current recommendations to vaccinate all pregnant women, regardless of the stage of pregnancy.”

Some adverse effects, such as thromboembolic effects, in utero death, HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets) syndrome, and uterine contractions, will continue to be monitored.

Questions regarding menstrual disorders

As for gynecological disorders reported after vaccination, questions still remain. “In most of the reported cases, it is difficult to accurately determine whether the vaccine played a role in the occurrence of menstrual/genital bleeding,” the authors of the pharmacovigilance monitoring report state.

“Nonetheless, these cases warrant attention,” they add, and further discussions with the French National Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the French Society of Endocrinology are needed in regard to these potential safety signals.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

from the French National Agency for the Safety of Medicines and Health Products (ANSM).

The rare condition — more common in men than in women — is characterized by the sudden onset of severe pain in the shoulder, followed by arm paralysis. Its etiopathogenesis is not well understood, but vaccines, in particular the flu vaccine, have been implicated in some cases, the report states.

Six serious cases of the syndrome related to the Comirnaty (Pfizer) vaccine were reported by healthcare professionals and vaccinated individuals or their family and friends since the start of the monitoring program. Four of these cases occurred from September 3 to 16.

All six cases involved patients 19 to 69 years of age — two women and four men — who developed symptoms in the 50 days after vaccination. Half were reported after the first dose and half after the second dose. Four of the patients are currently recovering; the outcomes of the other two are unknown.

In the case of the Spikevax vaccine (Moderna), two cases of Parsonage-Turner syndrome were reported after vaccination (plus one that occurred after 50 days, which is currently being managed). The onset of symptoms in these two men — one in his early 30s and one in his early 60s — occurred less than 18 days after vaccination. One occurred after the first dose and one after the second dose. This timing indicates a possible link between the syndrome and the vaccine. Both men are currently in recovery.

This signal of mRNA vaccines is now “officially recognized,” according to the Pfizer and Moderna reports.

It is also considered a “potential signal” in the Vaxzevria (AstraZeneca) pharmacovigilance report, released October 8, which describes eight cases of Parsonage-Turner syndrome after vaccination.

Safety profile of mRNA COVID vaccines in youth

Between June 15, when children 12 years and older became eligible for vaccination, and August 26, there were 591 reports of potential adverse events — out of 6 million Pfizer doses administered — in 12- to 18-year-old children.

Of the 591 cases, 35.2% were deemed serious. The majority of these were cases of reactogenicity, malaise, or postvaccine discomfort (25%), followed by instances of myocarditis and pericarditis (15.9% and 7.2%, respectively). In eight of 10 cases, one of the first symptom reported was chest pain.

Myocarditis occurred in 39.4% of people after the first injection (mean time to onset, 13 days) and 54.5% after the second (mean time to onset, 4 days). Recorded progress was favorable in nearly nine of 10 cases.

Pericarditis occurred in 53.3% of people after the first injection (mean time to onset, 13 days), and 40.0% after the second (mean time to onset, 4 days).

Three cases of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MISC) were reported after monitoring ended.

For this age group, “all reported events will continue to be monitored, especially serious events and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children,” report authors conclude.

Data for adverse events after the Moderna vaccine remain limited, but the report stipulates that “the adverse events reported in 12- to 18-year-olds who received an injection do not display any particular pattern, compared with those reported in older subjects, with the exception of a roughly 100-fold lower incidence of reported adverse effects in the 12- to 17-year age group.”

No safety warnings for pregnant women

The pharmacovigilance report — which covered the period from December 27, 2020 to September 9, 2021 — “raises no safety warnings for pregnant or nursing women with any of the COVID-19 vaccines.” In addition, two recent studies — one published in JAMA and one in the New England Journal of Medicine — have shown no link between spontaneous miscarriage and mRNA vaccines.

“Moreover, it should be stressed that current data from the international literature consistently show that maternal SARS COV-2 infection increases the risk for fetal, maternal, and neonatal complications, and that this risk may increase with the arrival of the Alpha and Delta variants,” they write. “It is therefore important to reiterate the current recommendations to vaccinate all pregnant women, regardless of the stage of pregnancy.”

Some adverse effects, such as thromboembolic effects, in utero death, HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets) syndrome, and uterine contractions, will continue to be monitored.

Questions regarding menstrual disorders

As for gynecological disorders reported after vaccination, questions still remain. “In most of the reported cases, it is difficult to accurately determine whether the vaccine played a role in the occurrence of menstrual/genital bleeding,” the authors of the pharmacovigilance monitoring report state.

“Nonetheless, these cases warrant attention,” they add, and further discussions with the French National Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the French Society of Endocrinology are needed in regard to these potential safety signals.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

from the French National Agency for the Safety of Medicines and Health Products (ANSM).

The rare condition — more common in men than in women — is characterized by the sudden onset of severe pain in the shoulder, followed by arm paralysis. Its etiopathogenesis is not well understood, but vaccines, in particular the flu vaccine, have been implicated in some cases, the report states.

Six serious cases of the syndrome related to the Comirnaty (Pfizer) vaccine were reported by healthcare professionals and vaccinated individuals or their family and friends since the start of the monitoring program. Four of these cases occurred from September 3 to 16.

All six cases involved patients 19 to 69 years of age — two women and four men — who developed symptoms in the 50 days after vaccination. Half were reported after the first dose and half after the second dose. Four of the patients are currently recovering; the outcomes of the other two are unknown.

In the case of the Spikevax vaccine (Moderna), two cases of Parsonage-Turner syndrome were reported after vaccination (plus one that occurred after 50 days, which is currently being managed). The onset of symptoms in these two men — one in his early 30s and one in his early 60s — occurred less than 18 days after vaccination. One occurred after the first dose and one after the second dose. This timing indicates a possible link between the syndrome and the vaccine. Both men are currently in recovery.

This signal of mRNA vaccines is now “officially recognized,” according to the Pfizer and Moderna reports.

It is also considered a “potential signal” in the Vaxzevria (AstraZeneca) pharmacovigilance report, released October 8, which describes eight cases of Parsonage-Turner syndrome after vaccination.

Safety profile of mRNA COVID vaccines in youth

Between June 15, when children 12 years and older became eligible for vaccination, and August 26, there were 591 reports of potential adverse events — out of 6 million Pfizer doses administered — in 12- to 18-year-old children.

Of the 591 cases, 35.2% were deemed serious. The majority of these were cases of reactogenicity, malaise, or postvaccine discomfort (25%), followed by instances of myocarditis and pericarditis (15.9% and 7.2%, respectively). In eight of 10 cases, one of the first symptom reported was chest pain.

Myocarditis occurred in 39.4% of people after the first injection (mean time to onset, 13 days) and 54.5% after the second (mean time to onset, 4 days). Recorded progress was favorable in nearly nine of 10 cases.

Pericarditis occurred in 53.3% of people after the first injection (mean time to onset, 13 days), and 40.0% after the second (mean time to onset, 4 days).

Three cases of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MISC) were reported after monitoring ended.

For this age group, “all reported events will continue to be monitored, especially serious events and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children,” report authors conclude.

Data for adverse events after the Moderna vaccine remain limited, but the report stipulates that “the adverse events reported in 12- to 18-year-olds who received an injection do not display any particular pattern, compared with those reported in older subjects, with the exception of a roughly 100-fold lower incidence of reported adverse effects in the 12- to 17-year age group.”

No safety warnings for pregnant women

The pharmacovigilance report — which covered the period from December 27, 2020 to September 9, 2021 — “raises no safety warnings for pregnant or nursing women with any of the COVID-19 vaccines.” In addition, two recent studies — one published in JAMA and one in the New England Journal of Medicine — have shown no link between spontaneous miscarriage and mRNA vaccines.

“Moreover, it should be stressed that current data from the international literature consistently show that maternal SARS COV-2 infection increases the risk for fetal, maternal, and neonatal complications, and that this risk may increase with the arrival of the Alpha and Delta variants,” they write. “It is therefore important to reiterate the current recommendations to vaccinate all pregnant women, regardless of the stage of pregnancy.”

Some adverse effects, such as thromboembolic effects, in utero death, HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets) syndrome, and uterine contractions, will continue to be monitored.

Questions regarding menstrual disorders

As for gynecological disorders reported after vaccination, questions still remain. “In most of the reported cases, it is difficult to accurately determine whether the vaccine played a role in the occurrence of menstrual/genital bleeding,” the authors of the pharmacovigilance monitoring report state.

“Nonetheless, these cases warrant attention,” they add, and further discussions with the French National Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the French Society of Endocrinology are needed in regard to these potential safety signals.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Even one vaccinated member can cut family’s COVID risk

The chances are reduced even further with each additional vaccinated or otherwise immune family member, according to new data.

Lead author Peter Nordström, MD, PhD, with the unit of geriatric medicine, Umeå (Sweden) University, said in an interview the message is important for public health: “When you vaccinate, you do not just protect yourself but also your relatives.”

The findings were published online on Oct. 11, 2021, in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Researchers analyzed data from 1,789,728 individuals from 814,806 families from nationwide registries in Sweden. All individuals had acquired immunity either from previously being infected with SARS-CoV-2 or by being fully vaccinated (that is, having received two doses of the Moderna, Pfizer, or Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccines). Persons were considered for inclusion until May 26, 2021.

Each person with immunity was matched in a 1:1 ratio to a person without immunity from a cohort of individuals with families that had from two to five members. Families with more than five members were excluded because of small sample sizes.

Primarily nonimmune families in which there was one immune family member had a 45%-61% lower risk of contracting COVID-19 (hazard ratio, 0.39-0.55; 95% confidence interval, 0.37-0.61; P < .001).

The risk reduction increased to 75%-86% when two family members were immune (HR, 0.14-0.25; 95% CI, 0.11-0.27; P < .001).

It increased to 91%-94% when three family members were immune (HR, 0.06-0.09; 95% CI, 0.04-0.10; P < .001) and to 97% with four immune family members (HR, 0.03; 95% CI, 0.02-0.05; P < .001).

“The results were similar for the outcome of COVID-19 infection that was severe enough to warrant a hospital stay,” the authors wrote. They listed as an example that, in three-member families in which two members were immune, the remaining nonimmune family member had an 80% lower risk for hospitalization (HR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.10-0.43; P < .001).

Global implications

Dr. Nordström said the team used the family setting because it was more easily identifiable as a cohort with the national registries and because COVID-19 is spread among people in close contact with each other. The findings have implications for other groups that spend large amounts of time together and for herd immunity, he added.

The findings may be particularly welcome in regions of the world where vaccination rates are very low. The authors noted that most of the global population has not yet been vaccinated and that “it is anticipated that most of the population in low-income countries will be unable to receive a vaccine in 2021, with current vaccination rates suggesting that completely inoculating 70%-85% of the global population may take up to 5 years.”

Jill Foster, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, said in an interview she agrees that the news could encourage countries that have very low vaccination rates.

This study may help motivate areas with few resources to start small, she said: “Even one is better than zero.”

She added that this news could also help ease the minds of families that have immunocompromised members or in which there are children who are too young to be vaccinated.

With these data, she said, people can see there’s something they can do to help protect a family member.

Dr. Foster said that although it’s intuitive to think that the more vaccinated people there are in a family, the safer people are, “it’s really nice to see the data coming out of such a large dataset.”

The authors acknowledged that a limitation of the study is that, at the time the study was conducted, the Delta variant was uncommon in Sweden. It is therefore unclear whether the findings regarding immunity are still relevant in Sweden and elsewhere now that the Delta strain is dominant.

The authors reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Foster has received grant support from Moderna.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The chances are reduced even further with each additional vaccinated or otherwise immune family member, according to new data.

Lead author Peter Nordström, MD, PhD, with the unit of geriatric medicine, Umeå (Sweden) University, said in an interview the message is important for public health: “When you vaccinate, you do not just protect yourself but also your relatives.”

The findings were published online on Oct. 11, 2021, in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Researchers analyzed data from 1,789,728 individuals from 814,806 families from nationwide registries in Sweden. All individuals had acquired immunity either from previously being infected with SARS-CoV-2 or by being fully vaccinated (that is, having received two doses of the Moderna, Pfizer, or Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccines). Persons were considered for inclusion until May 26, 2021.

Each person with immunity was matched in a 1:1 ratio to a person without immunity from a cohort of individuals with families that had from two to five members. Families with more than five members were excluded because of small sample sizes.

Primarily nonimmune families in which there was one immune family member had a 45%-61% lower risk of contracting COVID-19 (hazard ratio, 0.39-0.55; 95% confidence interval, 0.37-0.61; P < .001).

The risk reduction increased to 75%-86% when two family members were immune (HR, 0.14-0.25; 95% CI, 0.11-0.27; P < .001).

It increased to 91%-94% when three family members were immune (HR, 0.06-0.09; 95% CI, 0.04-0.10; P < .001) and to 97% with four immune family members (HR, 0.03; 95% CI, 0.02-0.05; P < .001).

“The results were similar for the outcome of COVID-19 infection that was severe enough to warrant a hospital stay,” the authors wrote. They listed as an example that, in three-member families in which two members were immune, the remaining nonimmune family member had an 80% lower risk for hospitalization (HR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.10-0.43; P < .001).

Global implications

Dr. Nordström said the team used the family setting because it was more easily identifiable as a cohort with the national registries and because COVID-19 is spread among people in close contact with each other. The findings have implications for other groups that spend large amounts of time together and for herd immunity, he added.

The findings may be particularly welcome in regions of the world where vaccination rates are very low. The authors noted that most of the global population has not yet been vaccinated and that “it is anticipated that most of the population in low-income countries will be unable to receive a vaccine in 2021, with current vaccination rates suggesting that completely inoculating 70%-85% of the global population may take up to 5 years.”

Jill Foster, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, said in an interview she agrees that the news could encourage countries that have very low vaccination rates.

This study may help motivate areas with few resources to start small, she said: “Even one is better than zero.”

She added that this news could also help ease the minds of families that have immunocompromised members or in which there are children who are too young to be vaccinated.

With these data, she said, people can see there’s something they can do to help protect a family member.

Dr. Foster said that although it’s intuitive to think that the more vaccinated people there are in a family, the safer people are, “it’s really nice to see the data coming out of such a large dataset.”

The authors acknowledged that a limitation of the study is that, at the time the study was conducted, the Delta variant was uncommon in Sweden. It is therefore unclear whether the findings regarding immunity are still relevant in Sweden and elsewhere now that the Delta strain is dominant.

The authors reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Foster has received grant support from Moderna.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The chances are reduced even further with each additional vaccinated or otherwise immune family member, according to new data.

Lead author Peter Nordström, MD, PhD, with the unit of geriatric medicine, Umeå (Sweden) University, said in an interview the message is important for public health: “When you vaccinate, you do not just protect yourself but also your relatives.”

The findings were published online on Oct. 11, 2021, in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Researchers analyzed data from 1,789,728 individuals from 814,806 families from nationwide registries in Sweden. All individuals had acquired immunity either from previously being infected with SARS-CoV-2 or by being fully vaccinated (that is, having received two doses of the Moderna, Pfizer, or Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccines). Persons were considered for inclusion until May 26, 2021.

Each person with immunity was matched in a 1:1 ratio to a person without immunity from a cohort of individuals with families that had from two to five members. Families with more than five members were excluded because of small sample sizes.

Primarily nonimmune families in which there was one immune family member had a 45%-61% lower risk of contracting COVID-19 (hazard ratio, 0.39-0.55; 95% confidence interval, 0.37-0.61; P < .001).

The risk reduction increased to 75%-86% when two family members were immune (HR, 0.14-0.25; 95% CI, 0.11-0.27; P < .001).

It increased to 91%-94% when three family members were immune (HR, 0.06-0.09; 95% CI, 0.04-0.10; P < .001) and to 97% with four immune family members (HR, 0.03; 95% CI, 0.02-0.05; P < .001).

“The results were similar for the outcome of COVID-19 infection that was severe enough to warrant a hospital stay,” the authors wrote. They listed as an example that, in three-member families in which two members were immune, the remaining nonimmune family member had an 80% lower risk for hospitalization (HR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.10-0.43; P < .001).

Global implications

Dr. Nordström said the team used the family setting because it was more easily identifiable as a cohort with the national registries and because COVID-19 is spread among people in close contact with each other. The findings have implications for other groups that spend large amounts of time together and for herd immunity, he added.

The findings may be particularly welcome in regions of the world where vaccination rates are very low. The authors noted that most of the global population has not yet been vaccinated and that “it is anticipated that most of the population in low-income countries will be unable to receive a vaccine in 2021, with current vaccination rates suggesting that completely inoculating 70%-85% of the global population may take up to 5 years.”

Jill Foster, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, said in an interview she agrees that the news could encourage countries that have very low vaccination rates.

This study may help motivate areas with few resources to start small, she said: “Even one is better than zero.”

She added that this news could also help ease the minds of families that have immunocompromised members or in which there are children who are too young to be vaccinated.

With these data, she said, people can see there’s something they can do to help protect a family member.

Dr. Foster said that although it’s intuitive to think that the more vaccinated people there are in a family, the safer people are, “it’s really nice to see the data coming out of such a large dataset.”

The authors acknowledged that a limitation of the study is that, at the time the study was conducted, the Delta variant was uncommon in Sweden. It is therefore unclear whether the findings regarding immunity are still relevant in Sweden and elsewhere now that the Delta strain is dominant.

The authors reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Foster has received grant support from Moderna.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

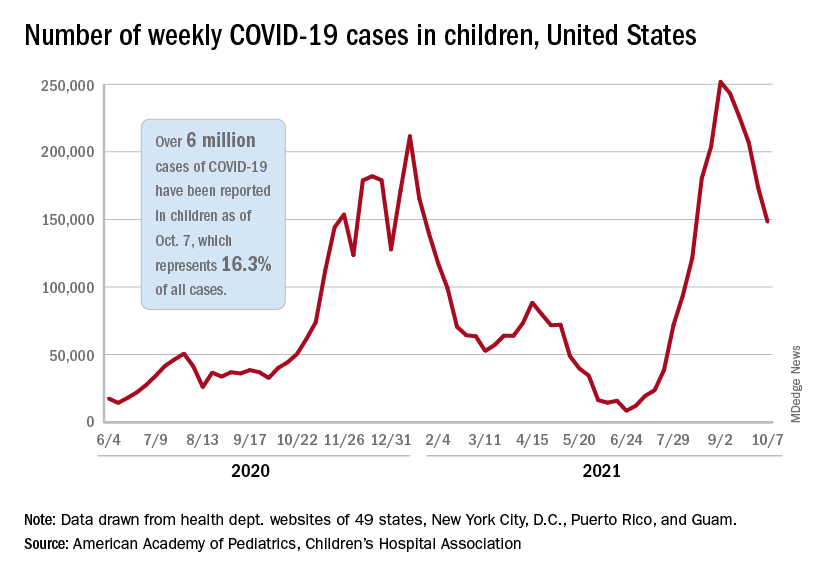

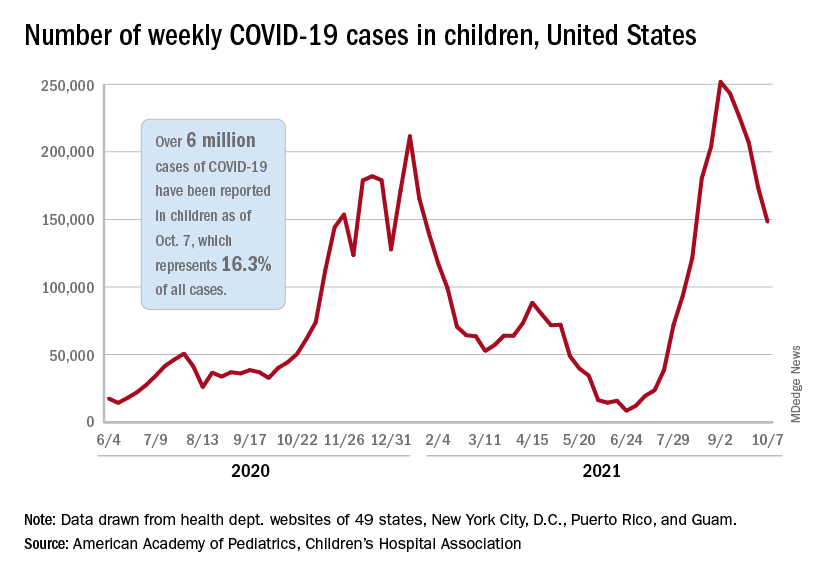

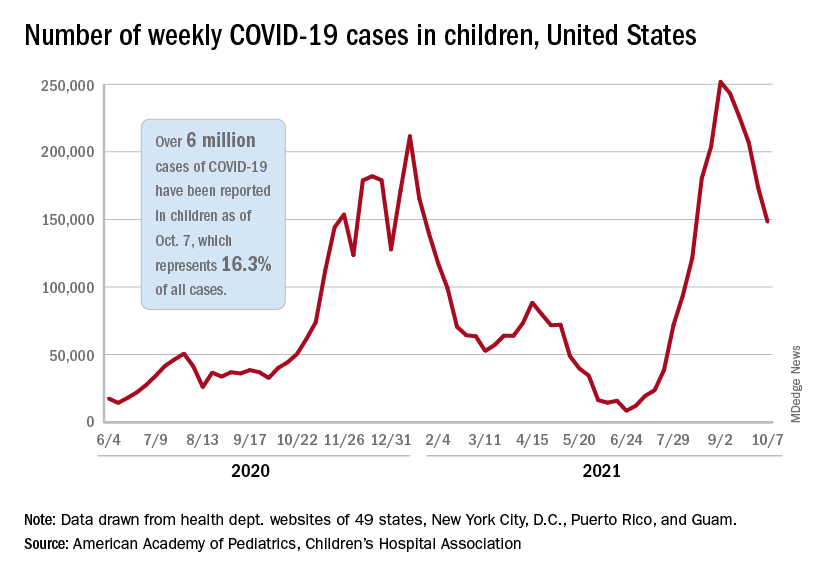

CDC: Children just as vulnerable to COVID as adults

The study, which focused on 1,000 schools in Arizona’s Maricopa and Pima counties, found that there were 113 COVID-19 outbreaks in schools without mask requirements in the first month of in-person learning. There were 16 outbreaks in schools with mask requirements.

“Masks in schools work to protect our children, to keep them and their school communities safe, and to keep them in school for in-person learning,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said at an Oct. 13 White House briefing.

But, she said, more than 95% of schools across the country had remained open through the end of September, despite 1,800 school closures affecting nearly 1 million students.

Protection for children in school is just one piece of the puzzle, Dr. Walensky said – there must also be COVID-safe practices at home to limit transmission. A CDC study published in October found that children had similar infection rates, compared with adults, confirming there is risk to people of all ages.

“For those children not yet eligible for vaccination, the best protection we can provide them is to make sure everyone around them in the household is vaccinated and to make sure they’re wearing a mask in school and during indoor extracurricular activities,” Dr. Walensky said.

Meanwhile, Pfizer’s vaccine for children ages 5-11 may be approved by early November. The Food and Drug Administration’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee will meet Oct. 26 to discuss available data, and the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices will meet Nov. 2. A decision is expected soon after.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The study, which focused on 1,000 schools in Arizona’s Maricopa and Pima counties, found that there were 113 COVID-19 outbreaks in schools without mask requirements in the first month of in-person learning. There were 16 outbreaks in schools with mask requirements.

“Masks in schools work to protect our children, to keep them and their school communities safe, and to keep them in school for in-person learning,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said at an Oct. 13 White House briefing.

But, she said, more than 95% of schools across the country had remained open through the end of September, despite 1,800 school closures affecting nearly 1 million students.

Protection for children in school is just one piece of the puzzle, Dr. Walensky said – there must also be COVID-safe practices at home to limit transmission. A CDC study published in October found that children had similar infection rates, compared with adults, confirming there is risk to people of all ages.

“For those children not yet eligible for vaccination, the best protection we can provide them is to make sure everyone around them in the household is vaccinated and to make sure they’re wearing a mask in school and during indoor extracurricular activities,” Dr. Walensky said.

Meanwhile, Pfizer’s vaccine for children ages 5-11 may be approved by early November. The Food and Drug Administration’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee will meet Oct. 26 to discuss available data, and the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices will meet Nov. 2. A decision is expected soon after.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The study, which focused on 1,000 schools in Arizona’s Maricopa and Pima counties, found that there were 113 COVID-19 outbreaks in schools without mask requirements in the first month of in-person learning. There were 16 outbreaks in schools with mask requirements.

“Masks in schools work to protect our children, to keep them and their school communities safe, and to keep them in school for in-person learning,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said at an Oct. 13 White House briefing.

But, she said, more than 95% of schools across the country had remained open through the end of September, despite 1,800 school closures affecting nearly 1 million students.

Protection for children in school is just one piece of the puzzle, Dr. Walensky said – there must also be COVID-safe practices at home to limit transmission. A CDC study published in October found that children had similar infection rates, compared with adults, confirming there is risk to people of all ages.

“For those children not yet eligible for vaccination, the best protection we can provide them is to make sure everyone around them in the household is vaccinated and to make sure they’re wearing a mask in school and during indoor extracurricular activities,” Dr. Walensky said.

Meanwhile, Pfizer’s vaccine for children ages 5-11 may be approved by early November. The Food and Drug Administration’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee will meet Oct. 26 to discuss available data, and the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices will meet Nov. 2. A decision is expected soon after.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

No short-term death risk in elderly after COVID-19 vaccines

and launched an investigation into the safety of the BNT162b2 vaccine (Comirnaty; Pfizer-BioNTech).

Now, the results of that investigation and of a subsequent larger study of nursing home residents in Norway have shown no increased risk for short-term mortality following COVID-19 vaccination in the overall population of elderly patients. The new research also showed clear evidence of a survival benefit compared with the unvaccinated population, Anette Hylen Ranhoff, MD, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the European Geriatric Medicine Society, held in a hybrid format in Athens, Greece, and online.

“We found no evidence of increased short-term mortality among vaccinated older individuals, and particularly not among the nursing home patients,” said Dr. Ranhoff, a senior researcher at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health and professor at University of Bergen, Norway. “But we think that this [lower] mortality risk was most likely a sort of ‘healthy-vaccinee’ effect, which means that people who were a bit more healthy were vaccinated, and not those who were the very, very most frail.”

“We have more or less the same data in France about events, with very high rates of vaccination,” said session moderator Athanase Benetos MD, PhD, professor and chairman of geriatric medicine at the University Hospital of Nancy in France, who was not involved in the study.

“In my department, a month after the end of the vaccination and at the same time while the pandemic in the city was going up, we had a 90% decrease in mortality from COVID in the nursing homes,” he told Dr. Ranhoff.

Potential risks

Frail elderly patients were not included in clinical trials of COVID-19 vaccines, and although previous studies have shown a low incidence of local or systemic reactions to vaccination among older people, “we think that quite mild adverse events following vaccination could trigger and destabilize a frail person,” Dr. Ranhoff said.

As reported Jan. 15, 2021, in BMJ, investigation by the Norwegian Medicines Agency (NOMA) into 13 of the 23 reported cases concluded that common adverse reactions associated with mRNA vaccines could have contributed to the deaths of some of the frail elderly patients

Steinar Madsen, MD, NOMA medical director, told BMJ “we are not alarmed or worried about this, because these are very rare occurrences and they occurred in very frail patients with very serious disease.”

Health authorities investigate

In response to the report and at the request of the Norwegian Public Health Institute and NOMA, Dr. Ranhoff and colleagues investigated the first 100 deaths among nursing-home residents who received the vaccine. The team consisted of three geriatricians and an infectious disease specialist who sees patients in nursing homes.

They looked at each patient’s clinical course before and after vaccination, their health trajectory and life expectancy at the time of vaccination, new symptoms following vaccination, and the time from vaccination to new symptoms and to death.

In addition, the investigators evaluated Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) scores for each patient. CFS scores range from 1 (very fit) to 9 (terminally ill, with a life expectancy of less than 6 months who are otherwise evidently frail).

The initial investigation found that among 95 evaluable patients, the association between vaccination and death was “probable” in 10, “possible” in 26, and “unlikely” in 59.

The mean time from vaccination to symptoms was 1.4 days in the probable cases, 2.5 days in the possible cases, and 4.7 days in the unlikely cases.

The mean time from vaccination to death was 3.1, 8.3, and 8.2 days, respectively.

In all three categories, the patients had mean CFS scores ranging from 7.6 to 7.9, putting them in the “severely frail” category, defined as people who are completely dependent for personal care but seem stable and not at high risk for dying.

“We have quite many nursing home residents in Norway, 35,000; more than 80% have dementia, and the mean age is 85 years. We know that approximately 45 people die every day in these nursing homes, and their mean age of death is 87.5 years,” Dr. Ranhoff said.

Population-wide study

Dr. Ranhoff and colleagues also looked more broadly into the question of potential vaccine-related mortality in the total population of older people in Norway from the day of vaccination to follow-up at 3 weeks.

They conducted a matched cohort study to investigate the relationship between the mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccine and overall death among persons aged 65 and older in the general population, and across four groups: patients receiving home-based care, long-term nursing home patients, short-term nursing home patients, and those not receiving health services.

The researchers identified a total of 967,786 residents of Norway aged 65 and over at the start of the country’s vaccination campaign at the end of December, 2020, and they matched vaccinated individuals with unvaccinated persons based on demographic, geographic, and clinical risk group factors.

Dr. Ranhoff showed Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the total population and for each of the health-service states. In all cases there was a clear survival benefit for vaccinated vs. unvaccinated patients. She did not, however, provide specific numbers or hazard ratios for the differences between vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals in each of the comparisons.

The study was supported by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. Dr. Ranhoff and Dr. Benetos reported no conflicts of interest.

and launched an investigation into the safety of the BNT162b2 vaccine (Comirnaty; Pfizer-BioNTech).

Now, the results of that investigation and of a subsequent larger study of nursing home residents in Norway have shown no increased risk for short-term mortality following COVID-19 vaccination in the overall population of elderly patients. The new research also showed clear evidence of a survival benefit compared with the unvaccinated population, Anette Hylen Ranhoff, MD, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the European Geriatric Medicine Society, held in a hybrid format in Athens, Greece, and online.

“We found no evidence of increased short-term mortality among vaccinated older individuals, and particularly not among the nursing home patients,” said Dr. Ranhoff, a senior researcher at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health and professor at University of Bergen, Norway. “But we think that this [lower] mortality risk was most likely a sort of ‘healthy-vaccinee’ effect, which means that people who were a bit more healthy were vaccinated, and not those who were the very, very most frail.”

“We have more or less the same data in France about events, with very high rates of vaccination,” said session moderator Athanase Benetos MD, PhD, professor and chairman of geriatric medicine at the University Hospital of Nancy in France, who was not involved in the study.

“In my department, a month after the end of the vaccination and at the same time while the pandemic in the city was going up, we had a 90% decrease in mortality from COVID in the nursing homes,” he told Dr. Ranhoff.

Potential risks

Frail elderly patients were not included in clinical trials of COVID-19 vaccines, and although previous studies have shown a low incidence of local or systemic reactions to vaccination among older people, “we think that quite mild adverse events following vaccination could trigger and destabilize a frail person,” Dr. Ranhoff said.