User login

The month of new beginnings is here

This month’s Letter from the Editor is guest authored by Dr. Megan A. Adams, GI & Hepatology News Associate Editor

September is a month of new beginnings, as summer transitions to fall, kids go back to school, and we return to more consistent work routines, refreshed and reinvigorated after some well-deserved time off with family and friends. Among our cover stories this month is a study showing a novel application of deep learning to inform clinical care of patients with pancreatic cysts. We also feature several high-impact studies from AGA’s journals, including a large randomized controlled trial by Dr. Paul Moayyedi and colleagues, demonstrating that PPI therapy may be unnecessary in the majority of patients on oral anticoagulants, despite current guideline recommendations. This study has the potential to substantially change clinical practice, particularly in the context of the current discussion regarding PPI benefits and harms, and our transition to value-based care.

We also highlight a proof-of-concept study demonstrating a potential role for probiotics (specifically Bifidobacteria) in reducing the risk of NSAID-related gastrointestinal bleeding, and another study showing a possible role for clopidogrel in chemoprevention of colorectal cancer. Both articles are accompanied by expert commentaries highlighting their potential effect on clinical practice.

Our September issue also emphasizes the importance of professional advocacy by chronicling the participation of four AGA leaders (Dr. Carr, Dr. Kaufman, Dr. Ketwaroo, and Dr. Mathews) in the 2019 Alliance of Specialty Medicine Fly In, a multisociety effort to lobby legislators on key issues such as reducing prior authorization burdens and minimizing the strict constraints of step-therapy protocols. We also are pleased to acknowledge the future leaders of gastroenterology by recognizing the 17 exceptional fellows who demonstrated their passion for advancing GI clinical care by presenting their institutional quality improvement projects at a special session at DDW® 2019. We hope you find these stories to be thought provoking, inspiring, and directly relevant to your clinical practice – thank you for reading!

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Associate Editor

This month’s Letter from the Editor is guest authored by Dr. Megan A. Adams, GI & Hepatology News Associate Editor

September is a month of new beginnings, as summer transitions to fall, kids go back to school, and we return to more consistent work routines, refreshed and reinvigorated after some well-deserved time off with family and friends. Among our cover stories this month is a study showing a novel application of deep learning to inform clinical care of patients with pancreatic cysts. We also feature several high-impact studies from AGA’s journals, including a large randomized controlled trial by Dr. Paul Moayyedi and colleagues, demonstrating that PPI therapy may be unnecessary in the majority of patients on oral anticoagulants, despite current guideline recommendations. This study has the potential to substantially change clinical practice, particularly in the context of the current discussion regarding PPI benefits and harms, and our transition to value-based care.

We also highlight a proof-of-concept study demonstrating a potential role for probiotics (specifically Bifidobacteria) in reducing the risk of NSAID-related gastrointestinal bleeding, and another study showing a possible role for clopidogrel in chemoprevention of colorectal cancer. Both articles are accompanied by expert commentaries highlighting their potential effect on clinical practice.

Our September issue also emphasizes the importance of professional advocacy by chronicling the participation of four AGA leaders (Dr. Carr, Dr. Kaufman, Dr. Ketwaroo, and Dr. Mathews) in the 2019 Alliance of Specialty Medicine Fly In, a multisociety effort to lobby legislators on key issues such as reducing prior authorization burdens and minimizing the strict constraints of step-therapy protocols. We also are pleased to acknowledge the future leaders of gastroenterology by recognizing the 17 exceptional fellows who demonstrated their passion for advancing GI clinical care by presenting their institutional quality improvement projects at a special session at DDW® 2019. We hope you find these stories to be thought provoking, inspiring, and directly relevant to your clinical practice – thank you for reading!

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Associate Editor

This month’s Letter from the Editor is guest authored by Dr. Megan A. Adams, GI & Hepatology News Associate Editor

September is a month of new beginnings, as summer transitions to fall, kids go back to school, and we return to more consistent work routines, refreshed and reinvigorated after some well-deserved time off with family and friends. Among our cover stories this month is a study showing a novel application of deep learning to inform clinical care of patients with pancreatic cysts. We also feature several high-impact studies from AGA’s journals, including a large randomized controlled trial by Dr. Paul Moayyedi and colleagues, demonstrating that PPI therapy may be unnecessary in the majority of patients on oral anticoagulants, despite current guideline recommendations. This study has the potential to substantially change clinical practice, particularly in the context of the current discussion regarding PPI benefits and harms, and our transition to value-based care.

We also highlight a proof-of-concept study demonstrating a potential role for probiotics (specifically Bifidobacteria) in reducing the risk of NSAID-related gastrointestinal bleeding, and another study showing a possible role for clopidogrel in chemoprevention of colorectal cancer. Both articles are accompanied by expert commentaries highlighting their potential effect on clinical practice.

Our September issue also emphasizes the importance of professional advocacy by chronicling the participation of four AGA leaders (Dr. Carr, Dr. Kaufman, Dr. Ketwaroo, and Dr. Mathews) in the 2019 Alliance of Specialty Medicine Fly In, a multisociety effort to lobby legislators on key issues such as reducing prior authorization burdens and minimizing the strict constraints of step-therapy protocols. We also are pleased to acknowledge the future leaders of gastroenterology by recognizing the 17 exceptional fellows who demonstrated their passion for advancing GI clinical care by presenting their institutional quality improvement projects at a special session at DDW® 2019. We hope you find these stories to be thought provoking, inspiring, and directly relevant to your clinical practice – thank you for reading!

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Associate Editor

‘Miracle cures’ in psychiatry?

For a patient with a major mental illness, the road to wellness is long and uncertain. The medications commonly used to treat mood and thought disorders can take weeks to months to start providing benefits, and they carry significant risks for adverse effects, such as weight gain, sexual dysfunction, and movement disorders. Patients often have to take psychotropic medications for the rest of their lives. In addition to these downsides, there is no guarantee that these medications will provide complete or even partial relief.2,3

Recently, there has been growing excitement about new treatments that might be “miracle cures” for patients with mental illness, particularly for individuals with treatment-resistant depression (TRD). Two of these treatments—ketamine-related compounds, and hallucinogenic drugs—seem to promise therapeutic effects that are vastly different from those of other psychiatric medications: They appear to improve patients’ symptoms very quickly, and their effects may persist long after these drugs have been cleared from the body.

Intravenous ketamine is an older generic drug used in anesthesia; recently, it has been used off-label for TRD and other mental illnesses. On March 5, 2019, the FDA approved an intranasal formulation of esketamine—the S-enantiomer of ketamine—for TRD.4 Hallucinogens have also been tested in small studies and have seemingly significant effects in alleviating depression in patients with terminal illnesses5 and reducing smoking behavior in patients with tobacco use disorder.6,7

These miracle cures are becoming increasingly available to patients and continue to gain credibility among clinicians and researchers. How should we evaluate the usefulness of these new treatments? And how should we talk to our patients about them? To answer these questions, this article:

- explores our duty to our patients, ourselves, and our colleagues

- describes the dilemma

- discusses ways to evaluate claims made about these new miracle cures.

Duty: Protecting and helping our patients

The physician–patient relationship is a fiduciary relationship. According to both common law and medical ethics, a physician who enters into a treatment relationship with a patient creates a bond of special trust and confidence. Such a relationship requires a physician to act in good faith and in the patient’s best interests.8 As physicians, we have a duty to evaluate the safety and efficacy of new treatments that are available for our patients, whether or not they are FDA-approved.

We should also protect our patients from the adverse consequences of relatively untested drugs. For example, ketamine and hallucinogens both produce dissociative effects, and may carry high risks for patients who have a predisposition to psychosis.9 We should protect our patients from any false hopes that might lead them to abandon their current treatment regimens due to adverse effects and imperfect results. At the same time, we also have a duty to acknowledge our patients’ suffering and to recognize that they might be desperate for new treatment options. We should remain open-minded about new treatments, and acknowledge that they might work. Finally, we have a duty to be mindful of any financial benefits that we may derive from the development, marketing, and administration of these medications.

Dilemma: The need for new treatments

This is not the first time that novel treatments in mental health have seemed to hold incredible promise. In the late 1800s, Sigmund Freud began to regularly use a compound that led him to feel “the normal euphoria of a healthy person.” He wrote that this substance produced:

…exhilaration and lasting euphoria, which does not differ in any way from the normal euphoria of a healthy person. The feeling of excitement which accompanies stimulus by alcohol is completely lacking; the characteristic urge for immediate activity which alcohol produces is also absent. One senses an increase of self-control and feels more vigorous and more capable of work; on the other hand, if one works, one misses that heightening of the mental powers which alcohol, tea, or coffee induce. One is simply normal, and soon finds it difficult to believe that one is under the influence of any drug at all.1

Continue to: The compound Freud was describing...

The compound Freud was describing is cocaine, which we now know is an addictive and dangerous drug that can in fact worsen depression.10 Another treatment regarded as a miracle cure in its time involved placing patients with schizophrenia into an insulin-induced coma to treat their symptoms; this therapy was used from 1933 to 1960.11 We now recognize that this practice is unacceptably dangerous.

The past is filled with cautionary tales of the enthusiastic adoption of treatments for mental illness that later turned out to be ineffective, counterproductive, dangerous, or inhumane. Yet, the long, arduous journeys our patients go through continue to weigh heavily on us. We would love to offer our patients newer, more efficacious, and longer-lasting treatments with fewer adverse effects.

Discussion: How to best evaluate miracle cures

To help quickly assess a new treatment, the following 5 categories can help guide and organize our thought process.

1. Evidence

What type of evidence do we have that a new treatment is safe and effective? Psychiatric research may be even more susceptible to a placebo effect than other medical research, particularly for illnesses with subjective symptoms, such as depression.12 Double-blinded, placebo-controlled studies, such as the IV ketamine trial conducted by Singh et al,13 are the gold standard for separating a substance’s actual biologic effect from a placebo effect. Studies that do not include a control group should not be regarded as providing scientific evidence of efficacy.

2. Mechanism

If a new compound appears to have a beneficial effect on mental health, it is important to consider the potential mechanism underlying this effect to determine if it is biologically plausible. A compound that is claimed to be a panacea for every symptom of every mental illness should be heavily scrutinized. For example, based on available research, ketamine’s long-lasting effects seem to come from 2 mechanisms14,15:

- Activation of endogenous opioid receptors, which is also responsible for the euphoria induced by heroin and oxycodone.

- Blockade of N-methyl-

D -aspartate receptors. N-methyl-D -aspartate receptor activation is a key mechanism by which learning and memory function in the brain, and blocking these receptors may increase brain plasticity.

Continue to: Therefore, it seems plausible...

Therefore, it seems plausible that ketamine could produce both short- and long-term improvements in mood. Hallucinogenic drugs are thought to profoundly alter brain function through several mechanisms, including activating serotonin receptors, enhancing brain plasticity, and increasing brain connectivity.16

3. Reinforcement

Psychiatric medications that are acutely reinforcing have significant potential for abuse. Antidepressants and mood stabilizers are not acutely rewarding. They don’t make patients feel good right away. Medications such as stimulants and opioids do, and must be used with extreme care because of their abuse potential. The problem with acutely reinforcing medications is that in the long run, they can worsen depression by decreasing the brain’s ability to produce endogenous opioids.17

4.

A mental disorder is unlikely to have a single solution. Rather than regarding a new treatment as capable of rapidly alleviating every symptom of a patient’s illness, it should be viewed as a tool that can be helpful when used in combination with other treatments and lifestyle practices. In an interview with the web site STAT, Cristina Cusin, MD, co-director of the Intravenous Ketamine Clinic for Depression at Massachusetts General Hospital, said, “You don’t treat an advanced disease with just an infusion and a ‘see you next time.’ If [doctors] replace your knee but [you] don’t do physical therapy, you don’t walk again.”18 To sustain the benefits of a novel medication, patients with serious mental illnesses need to maintain strong social supports, see a mental health care provider regularly, and abstain from illicit drug and alcohol use.

5. Context matters

For a medication to obtain approval to treat a specific indication, the FDA usually require 2 trials that demonstrate efficacy. Off-label use of generic medications such as ketamine may have benefits, but it is unlikely that a generic drug would be put through a costly FDA-approval process.19

When learning about new medications, remember that patients might assume that these agents have undergone a thorough review process for safety and effectiveness. When our patients request such treatments—whether FDA-approved or off-label—it is our responsibility as physicians to educate them about the benefits, risks, effectiveness, and limitations of these treatments, as well as to evaluate the appropriateness of a treatment for a specific patient’s symptoms.

Continue to: Tempering excitement with caution

Tempering excitement with caution

Our patients are not the only ones desperate for a miracle cure. As psychiatrists, many of us are desperate, too. New compounds may ultimately change the way we treat mental illness. However, we have an obligation to temper our excitement with caution by remembering past mistakes, and systematically evaluating new miracle cures to determine if they are safe and effective.

1. Freud S. Cocaine papers. In: Freud S, Byck R. Sigmund Freud collection (Library of Congress). New York, NY: Stonehill; 1975;7.

2. Rush AJ. STAR*D: what have we learned? Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(2):201-204.

3. Demjaha A, Lappin JM, Stahl D, et al. Antipsychotic treatment resistance in first-episode psychosis: prevalence, subtypes and predictors. Psychol Med. 2017;47(11):1981-1989.

4. Carey B. Fast-acting depression drug, newly approved, could help millions. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/05/health/depression-treatment-ketamine-fda.html. Published March 5, 2019. Accessed July 26, 2019.

5. Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Carducci MA, et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1181-1197.

6. Johnson MW, Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths RR. Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43:55-60.

7. Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths RR, Johnson MW. Psilocybin-occasioned mystical experiences in the treatment of tobacco addiction. Curr Drug Abuse Rev 2014;7(3):157-164.

8. Simon RI. Clinical psychiatry and the law. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1992.

9. Lahti AC, Weiler MA, Tamara Michaelidis BA, et al. Effects of ketamine in normal and schizophrenic volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25(4):455-467.

10. Perrine SA, Sheikh IS, Nwaneshiudu CA, et al. Withdrawal from chronic administration of cocaine decreases delta opioid receptor signaling and increases anxiety- and depression-like behaviors in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54(2):355-364.

11. Doroshow DB. Performing a cure for schizophrenia: insulin coma therapy on the wards. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 2007;62(2):213-243.

12. Khan A, Kolts RL, Rapaport MH, et al. Magnitude of placebo response and drug-placebo differences across psychiatric disorders. Psychol Med. 2005;35(5):743-749.

13. Singh JB, Fedgchin M, Daly EJ, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-frequency study of intravenous ketamine in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(8):816-826.

14. Williams NR, Heifets BD, Blasey C, et al. Attenuation of antidepressant effects of ketamine by opioid receptor antagonism. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1205-1215.

15. Duman RS, Aghajanian GK, Sanacora G, et al. Synaptic plasticity and depression: new insights from stress and rapid-acting antidepressants. Nat Med. 2016;22(2):238-249.

16. Carhart-Harris RL. How do psychedelics work? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(1):16-21.

17. Martins SS, Fenton MC, Keyes KM, et al. Mood and anxiety disorders and their association with non-medical prescription opioid use and prescription opioid-use disorder: longitudinal evidence from the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2012;42(6):1261-1272.

18. Thielking M. Ketamine gives hope to patients with severe depression. But some clinics stray from the science and hype its benefits. STAT. https://www.statnews.com/2018/09/24/ketamine-clinics-severe-depression-treatment/. Published September 24, 2018. Accessed July 26, 2019.

19. Stafford RS. Regulating off-label drug use--rethinking the role of the FDA. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(14):1427-1429.

For a patient with a major mental illness, the road to wellness is long and uncertain. The medications commonly used to treat mood and thought disorders can take weeks to months to start providing benefits, and they carry significant risks for adverse effects, such as weight gain, sexual dysfunction, and movement disorders. Patients often have to take psychotropic medications for the rest of their lives. In addition to these downsides, there is no guarantee that these medications will provide complete or even partial relief.2,3

Recently, there has been growing excitement about new treatments that might be “miracle cures” for patients with mental illness, particularly for individuals with treatment-resistant depression (TRD). Two of these treatments—ketamine-related compounds, and hallucinogenic drugs—seem to promise therapeutic effects that are vastly different from those of other psychiatric medications: They appear to improve patients’ symptoms very quickly, and their effects may persist long after these drugs have been cleared from the body.

Intravenous ketamine is an older generic drug used in anesthesia; recently, it has been used off-label for TRD and other mental illnesses. On March 5, 2019, the FDA approved an intranasal formulation of esketamine—the S-enantiomer of ketamine—for TRD.4 Hallucinogens have also been tested in small studies and have seemingly significant effects in alleviating depression in patients with terminal illnesses5 and reducing smoking behavior in patients with tobacco use disorder.6,7

These miracle cures are becoming increasingly available to patients and continue to gain credibility among clinicians and researchers. How should we evaluate the usefulness of these new treatments? And how should we talk to our patients about them? To answer these questions, this article:

- explores our duty to our patients, ourselves, and our colleagues

- describes the dilemma

- discusses ways to evaluate claims made about these new miracle cures.

Duty: Protecting and helping our patients

The physician–patient relationship is a fiduciary relationship. According to both common law and medical ethics, a physician who enters into a treatment relationship with a patient creates a bond of special trust and confidence. Such a relationship requires a physician to act in good faith and in the patient’s best interests.8 As physicians, we have a duty to evaluate the safety and efficacy of new treatments that are available for our patients, whether or not they are FDA-approved.

We should also protect our patients from the adverse consequences of relatively untested drugs. For example, ketamine and hallucinogens both produce dissociative effects, and may carry high risks for patients who have a predisposition to psychosis.9 We should protect our patients from any false hopes that might lead them to abandon their current treatment regimens due to adverse effects and imperfect results. At the same time, we also have a duty to acknowledge our patients’ suffering and to recognize that they might be desperate for new treatment options. We should remain open-minded about new treatments, and acknowledge that they might work. Finally, we have a duty to be mindful of any financial benefits that we may derive from the development, marketing, and administration of these medications.

Dilemma: The need for new treatments

This is not the first time that novel treatments in mental health have seemed to hold incredible promise. In the late 1800s, Sigmund Freud began to regularly use a compound that led him to feel “the normal euphoria of a healthy person.” He wrote that this substance produced:

…exhilaration and lasting euphoria, which does not differ in any way from the normal euphoria of a healthy person. The feeling of excitement which accompanies stimulus by alcohol is completely lacking; the characteristic urge for immediate activity which alcohol produces is also absent. One senses an increase of self-control and feels more vigorous and more capable of work; on the other hand, if one works, one misses that heightening of the mental powers which alcohol, tea, or coffee induce. One is simply normal, and soon finds it difficult to believe that one is under the influence of any drug at all.1

Continue to: The compound Freud was describing...

The compound Freud was describing is cocaine, which we now know is an addictive and dangerous drug that can in fact worsen depression.10 Another treatment regarded as a miracle cure in its time involved placing patients with schizophrenia into an insulin-induced coma to treat their symptoms; this therapy was used from 1933 to 1960.11 We now recognize that this practice is unacceptably dangerous.

The past is filled with cautionary tales of the enthusiastic adoption of treatments for mental illness that later turned out to be ineffective, counterproductive, dangerous, or inhumane. Yet, the long, arduous journeys our patients go through continue to weigh heavily on us. We would love to offer our patients newer, more efficacious, and longer-lasting treatments with fewer adverse effects.

Discussion: How to best evaluate miracle cures

To help quickly assess a new treatment, the following 5 categories can help guide and organize our thought process.

1. Evidence

What type of evidence do we have that a new treatment is safe and effective? Psychiatric research may be even more susceptible to a placebo effect than other medical research, particularly for illnesses with subjective symptoms, such as depression.12 Double-blinded, placebo-controlled studies, such as the IV ketamine trial conducted by Singh et al,13 are the gold standard for separating a substance’s actual biologic effect from a placebo effect. Studies that do not include a control group should not be regarded as providing scientific evidence of efficacy.

2. Mechanism

If a new compound appears to have a beneficial effect on mental health, it is important to consider the potential mechanism underlying this effect to determine if it is biologically plausible. A compound that is claimed to be a panacea for every symptom of every mental illness should be heavily scrutinized. For example, based on available research, ketamine’s long-lasting effects seem to come from 2 mechanisms14,15:

- Activation of endogenous opioid receptors, which is also responsible for the euphoria induced by heroin and oxycodone.

- Blockade of N-methyl-

D -aspartate receptors. N-methyl-D -aspartate receptor activation is a key mechanism by which learning and memory function in the brain, and blocking these receptors may increase brain plasticity.

Continue to: Therefore, it seems plausible...

Therefore, it seems plausible that ketamine could produce both short- and long-term improvements in mood. Hallucinogenic drugs are thought to profoundly alter brain function through several mechanisms, including activating serotonin receptors, enhancing brain plasticity, and increasing brain connectivity.16

3. Reinforcement

Psychiatric medications that are acutely reinforcing have significant potential for abuse. Antidepressants and mood stabilizers are not acutely rewarding. They don’t make patients feel good right away. Medications such as stimulants and opioids do, and must be used with extreme care because of their abuse potential. The problem with acutely reinforcing medications is that in the long run, they can worsen depression by decreasing the brain’s ability to produce endogenous opioids.17

4.

A mental disorder is unlikely to have a single solution. Rather than regarding a new treatment as capable of rapidly alleviating every symptom of a patient’s illness, it should be viewed as a tool that can be helpful when used in combination with other treatments and lifestyle practices. In an interview with the web site STAT, Cristina Cusin, MD, co-director of the Intravenous Ketamine Clinic for Depression at Massachusetts General Hospital, said, “You don’t treat an advanced disease with just an infusion and a ‘see you next time.’ If [doctors] replace your knee but [you] don’t do physical therapy, you don’t walk again.”18 To sustain the benefits of a novel medication, patients with serious mental illnesses need to maintain strong social supports, see a mental health care provider regularly, and abstain from illicit drug and alcohol use.

5. Context matters

For a medication to obtain approval to treat a specific indication, the FDA usually require 2 trials that demonstrate efficacy. Off-label use of generic medications such as ketamine may have benefits, but it is unlikely that a generic drug would be put through a costly FDA-approval process.19

When learning about new medications, remember that patients might assume that these agents have undergone a thorough review process for safety and effectiveness. When our patients request such treatments—whether FDA-approved or off-label—it is our responsibility as physicians to educate them about the benefits, risks, effectiveness, and limitations of these treatments, as well as to evaluate the appropriateness of a treatment for a specific patient’s symptoms.

Continue to: Tempering excitement with caution

Tempering excitement with caution

Our patients are not the only ones desperate for a miracle cure. As psychiatrists, many of us are desperate, too. New compounds may ultimately change the way we treat mental illness. However, we have an obligation to temper our excitement with caution by remembering past mistakes, and systematically evaluating new miracle cures to determine if they are safe and effective.

For a patient with a major mental illness, the road to wellness is long and uncertain. The medications commonly used to treat mood and thought disorders can take weeks to months to start providing benefits, and they carry significant risks for adverse effects, such as weight gain, sexual dysfunction, and movement disorders. Patients often have to take psychotropic medications for the rest of their lives. In addition to these downsides, there is no guarantee that these medications will provide complete or even partial relief.2,3

Recently, there has been growing excitement about new treatments that might be “miracle cures” for patients with mental illness, particularly for individuals with treatment-resistant depression (TRD). Two of these treatments—ketamine-related compounds, and hallucinogenic drugs—seem to promise therapeutic effects that are vastly different from those of other psychiatric medications: They appear to improve patients’ symptoms very quickly, and their effects may persist long after these drugs have been cleared from the body.

Intravenous ketamine is an older generic drug used in anesthesia; recently, it has been used off-label for TRD and other mental illnesses. On March 5, 2019, the FDA approved an intranasal formulation of esketamine—the S-enantiomer of ketamine—for TRD.4 Hallucinogens have also been tested in small studies and have seemingly significant effects in alleviating depression in patients with terminal illnesses5 and reducing smoking behavior in patients with tobacco use disorder.6,7

These miracle cures are becoming increasingly available to patients and continue to gain credibility among clinicians and researchers. How should we evaluate the usefulness of these new treatments? And how should we talk to our patients about them? To answer these questions, this article:

- explores our duty to our patients, ourselves, and our colleagues

- describes the dilemma

- discusses ways to evaluate claims made about these new miracle cures.

Duty: Protecting and helping our patients

The physician–patient relationship is a fiduciary relationship. According to both common law and medical ethics, a physician who enters into a treatment relationship with a patient creates a bond of special trust and confidence. Such a relationship requires a physician to act in good faith and in the patient’s best interests.8 As physicians, we have a duty to evaluate the safety and efficacy of new treatments that are available for our patients, whether or not they are FDA-approved.

We should also protect our patients from the adverse consequences of relatively untested drugs. For example, ketamine and hallucinogens both produce dissociative effects, and may carry high risks for patients who have a predisposition to psychosis.9 We should protect our patients from any false hopes that might lead them to abandon their current treatment regimens due to adverse effects and imperfect results. At the same time, we also have a duty to acknowledge our patients’ suffering and to recognize that they might be desperate for new treatment options. We should remain open-minded about new treatments, and acknowledge that they might work. Finally, we have a duty to be mindful of any financial benefits that we may derive from the development, marketing, and administration of these medications.

Dilemma: The need for new treatments

This is not the first time that novel treatments in mental health have seemed to hold incredible promise. In the late 1800s, Sigmund Freud began to regularly use a compound that led him to feel “the normal euphoria of a healthy person.” He wrote that this substance produced:

…exhilaration and lasting euphoria, which does not differ in any way from the normal euphoria of a healthy person. The feeling of excitement which accompanies stimulus by alcohol is completely lacking; the characteristic urge for immediate activity which alcohol produces is also absent. One senses an increase of self-control and feels more vigorous and more capable of work; on the other hand, if one works, one misses that heightening of the mental powers which alcohol, tea, or coffee induce. One is simply normal, and soon finds it difficult to believe that one is under the influence of any drug at all.1

Continue to: The compound Freud was describing...

The compound Freud was describing is cocaine, which we now know is an addictive and dangerous drug that can in fact worsen depression.10 Another treatment regarded as a miracle cure in its time involved placing patients with schizophrenia into an insulin-induced coma to treat their symptoms; this therapy was used from 1933 to 1960.11 We now recognize that this practice is unacceptably dangerous.

The past is filled with cautionary tales of the enthusiastic adoption of treatments for mental illness that later turned out to be ineffective, counterproductive, dangerous, or inhumane. Yet, the long, arduous journeys our patients go through continue to weigh heavily on us. We would love to offer our patients newer, more efficacious, and longer-lasting treatments with fewer adverse effects.

Discussion: How to best evaluate miracle cures

To help quickly assess a new treatment, the following 5 categories can help guide and organize our thought process.

1. Evidence

What type of evidence do we have that a new treatment is safe and effective? Psychiatric research may be even more susceptible to a placebo effect than other medical research, particularly for illnesses with subjective symptoms, such as depression.12 Double-blinded, placebo-controlled studies, such as the IV ketamine trial conducted by Singh et al,13 are the gold standard for separating a substance’s actual biologic effect from a placebo effect. Studies that do not include a control group should not be regarded as providing scientific evidence of efficacy.

2. Mechanism

If a new compound appears to have a beneficial effect on mental health, it is important to consider the potential mechanism underlying this effect to determine if it is biologically plausible. A compound that is claimed to be a panacea for every symptom of every mental illness should be heavily scrutinized. For example, based on available research, ketamine’s long-lasting effects seem to come from 2 mechanisms14,15:

- Activation of endogenous opioid receptors, which is also responsible for the euphoria induced by heroin and oxycodone.

- Blockade of N-methyl-

D -aspartate receptors. N-methyl-D -aspartate receptor activation is a key mechanism by which learning and memory function in the brain, and blocking these receptors may increase brain plasticity.

Continue to: Therefore, it seems plausible...

Therefore, it seems plausible that ketamine could produce both short- and long-term improvements in mood. Hallucinogenic drugs are thought to profoundly alter brain function through several mechanisms, including activating serotonin receptors, enhancing brain plasticity, and increasing brain connectivity.16

3. Reinforcement

Psychiatric medications that are acutely reinforcing have significant potential for abuse. Antidepressants and mood stabilizers are not acutely rewarding. They don’t make patients feel good right away. Medications such as stimulants and opioids do, and must be used with extreme care because of their abuse potential. The problem with acutely reinforcing medications is that in the long run, they can worsen depression by decreasing the brain’s ability to produce endogenous opioids.17

4.

A mental disorder is unlikely to have a single solution. Rather than regarding a new treatment as capable of rapidly alleviating every symptom of a patient’s illness, it should be viewed as a tool that can be helpful when used in combination with other treatments and lifestyle practices. In an interview with the web site STAT, Cristina Cusin, MD, co-director of the Intravenous Ketamine Clinic for Depression at Massachusetts General Hospital, said, “You don’t treat an advanced disease with just an infusion and a ‘see you next time.’ If [doctors] replace your knee but [you] don’t do physical therapy, you don’t walk again.”18 To sustain the benefits of a novel medication, patients with serious mental illnesses need to maintain strong social supports, see a mental health care provider regularly, and abstain from illicit drug and alcohol use.

5. Context matters

For a medication to obtain approval to treat a specific indication, the FDA usually require 2 trials that demonstrate efficacy. Off-label use of generic medications such as ketamine may have benefits, but it is unlikely that a generic drug would be put through a costly FDA-approval process.19

When learning about new medications, remember that patients might assume that these agents have undergone a thorough review process for safety and effectiveness. When our patients request such treatments—whether FDA-approved or off-label—it is our responsibility as physicians to educate them about the benefits, risks, effectiveness, and limitations of these treatments, as well as to evaluate the appropriateness of a treatment for a specific patient’s symptoms.

Continue to: Tempering excitement with caution

Tempering excitement with caution

Our patients are not the only ones desperate for a miracle cure. As psychiatrists, many of us are desperate, too. New compounds may ultimately change the way we treat mental illness. However, we have an obligation to temper our excitement with caution by remembering past mistakes, and systematically evaluating new miracle cures to determine if they are safe and effective.

1. Freud S. Cocaine papers. In: Freud S, Byck R. Sigmund Freud collection (Library of Congress). New York, NY: Stonehill; 1975;7.

2. Rush AJ. STAR*D: what have we learned? Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(2):201-204.

3. Demjaha A, Lappin JM, Stahl D, et al. Antipsychotic treatment resistance in first-episode psychosis: prevalence, subtypes and predictors. Psychol Med. 2017;47(11):1981-1989.

4. Carey B. Fast-acting depression drug, newly approved, could help millions. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/05/health/depression-treatment-ketamine-fda.html. Published March 5, 2019. Accessed July 26, 2019.

5. Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Carducci MA, et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1181-1197.

6. Johnson MW, Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths RR. Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43:55-60.

7. Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths RR, Johnson MW. Psilocybin-occasioned mystical experiences in the treatment of tobacco addiction. Curr Drug Abuse Rev 2014;7(3):157-164.

8. Simon RI. Clinical psychiatry and the law. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1992.

9. Lahti AC, Weiler MA, Tamara Michaelidis BA, et al. Effects of ketamine in normal and schizophrenic volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25(4):455-467.

10. Perrine SA, Sheikh IS, Nwaneshiudu CA, et al. Withdrawal from chronic administration of cocaine decreases delta opioid receptor signaling and increases anxiety- and depression-like behaviors in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54(2):355-364.

11. Doroshow DB. Performing a cure for schizophrenia: insulin coma therapy on the wards. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 2007;62(2):213-243.

12. Khan A, Kolts RL, Rapaport MH, et al. Magnitude of placebo response and drug-placebo differences across psychiatric disorders. Psychol Med. 2005;35(5):743-749.

13. Singh JB, Fedgchin M, Daly EJ, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-frequency study of intravenous ketamine in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(8):816-826.

14. Williams NR, Heifets BD, Blasey C, et al. Attenuation of antidepressant effects of ketamine by opioid receptor antagonism. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1205-1215.

15. Duman RS, Aghajanian GK, Sanacora G, et al. Synaptic plasticity and depression: new insights from stress and rapid-acting antidepressants. Nat Med. 2016;22(2):238-249.

16. Carhart-Harris RL. How do psychedelics work? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(1):16-21.

17. Martins SS, Fenton MC, Keyes KM, et al. Mood and anxiety disorders and their association with non-medical prescription opioid use and prescription opioid-use disorder: longitudinal evidence from the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2012;42(6):1261-1272.

18. Thielking M. Ketamine gives hope to patients with severe depression. But some clinics stray from the science and hype its benefits. STAT. https://www.statnews.com/2018/09/24/ketamine-clinics-severe-depression-treatment/. Published September 24, 2018. Accessed July 26, 2019.

19. Stafford RS. Regulating off-label drug use--rethinking the role of the FDA. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(14):1427-1429.

1. Freud S. Cocaine papers. In: Freud S, Byck R. Sigmund Freud collection (Library of Congress). New York, NY: Stonehill; 1975;7.

2. Rush AJ. STAR*D: what have we learned? Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(2):201-204.

3. Demjaha A, Lappin JM, Stahl D, et al. Antipsychotic treatment resistance in first-episode psychosis: prevalence, subtypes and predictors. Psychol Med. 2017;47(11):1981-1989.

4. Carey B. Fast-acting depression drug, newly approved, could help millions. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/05/health/depression-treatment-ketamine-fda.html. Published March 5, 2019. Accessed July 26, 2019.

5. Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Carducci MA, et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1181-1197.

6. Johnson MW, Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths RR. Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43:55-60.

7. Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths RR, Johnson MW. Psilocybin-occasioned mystical experiences in the treatment of tobacco addiction. Curr Drug Abuse Rev 2014;7(3):157-164.

8. Simon RI. Clinical psychiatry and the law. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1992.

9. Lahti AC, Weiler MA, Tamara Michaelidis BA, et al. Effects of ketamine in normal and schizophrenic volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25(4):455-467.

10. Perrine SA, Sheikh IS, Nwaneshiudu CA, et al. Withdrawal from chronic administration of cocaine decreases delta opioid receptor signaling and increases anxiety- and depression-like behaviors in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54(2):355-364.

11. Doroshow DB. Performing a cure for schizophrenia: insulin coma therapy on the wards. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 2007;62(2):213-243.

12. Khan A, Kolts RL, Rapaport MH, et al. Magnitude of placebo response and drug-placebo differences across psychiatric disorders. Psychol Med. 2005;35(5):743-749.

13. Singh JB, Fedgchin M, Daly EJ, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-frequency study of intravenous ketamine in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(8):816-826.

14. Williams NR, Heifets BD, Blasey C, et al. Attenuation of antidepressant effects of ketamine by opioid receptor antagonism. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1205-1215.

15. Duman RS, Aghajanian GK, Sanacora G, et al. Synaptic plasticity and depression: new insights from stress and rapid-acting antidepressants. Nat Med. 2016;22(2):238-249.

16. Carhart-Harris RL. How do psychedelics work? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(1):16-21.

17. Martins SS, Fenton MC, Keyes KM, et al. Mood and anxiety disorders and their association with non-medical prescription opioid use and prescription opioid-use disorder: longitudinal evidence from the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2012;42(6):1261-1272.

18. Thielking M. Ketamine gives hope to patients with severe depression. But some clinics stray from the science and hype its benefits. STAT. https://www.statnews.com/2018/09/24/ketamine-clinics-severe-depression-treatment/. Published September 24, 2018. Accessed July 26, 2019.

19. Stafford RS. Regulating off-label drug use--rethinking the role of the FDA. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(14):1427-1429.

Transformative advances are unfolding in psychiatry

The future of psychiatry is bright, even scintillating. Disruptive changes are gradually unfolding and will proceed at a brisk pace. Psychiatric practice will be transformed into a clinical neuroscience that will heal the mind by repairing the brain. The ingredients of change are already in place, and the trend will accelerate.

Consider the following scientific, technical, and therapeutic advances that will continue to transform the psychiatric practice landscape.

Scientific advances

- Pluripotent cells. By dedifferentiating fibroblasts or skin cells and re-differentiating them into neurons and glia, the study of the structure and function of psychiatric patients’ brains can be conducted in a test tube. That will exponentially expand the knowledge of the neural circuitry that underpin psychiatric disorders and will lead to novel strategies for brain repair.1

- CRISPR. This revolutionary advance in excising and inserting genes will eventually lead to the prevention of a psychiatric disease by replacing risk genes or mutations.1

- Molecular genetics. The flurry of identifying risk genes, copy number variants (CNV), and de novo mutations using gene-wide association studies (GWAS) will facilitate gene therapy in psychiatric disorders.

- Neuroimmunology. The discovery of the role of neuroinflammation and oxidative stress (free radicals exceeding glutathione and other antioxidants) in neuropsychiatric disorders will ultimately lead to new insights into preventing the neurodegeneration associated with acute psychotic or mood disorders. Inhibiting the activation of microglia (the immune cells of the brain) is one example of innovative therapeutic targets in the future.2

- Recognizing the role of mitochondrial dysfunction as a pathogenic pathway to neuropsychiatric disorders such as depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and even the comorbid diabetes that is common among those psychiatric disorders will chart an entirely new approach to diagnosis and treatment.2

- The role of the microbiota and microbiome in psychiatric disorders has emerged as a fertile new frontier in psychiatry, both for etiology and as therapeutic targets.3

- The enteric brain in the gut, in close proximity with the microbiome, is now known to be a major source of neurotransmitters that modulate brain functions (dopamine, serotonin, and others). Consequently, it is implicated in psychopathology, rendering this “second brain” a target for therapeutic interventions in the future, in addition to the “cephalic brain.”4

- Biomarkers and endophenotypes. The rapid discoveries of biomarkers are setting the stage for the recognition of hundreds of biologic subtypes of complex neuropsychiatric syndromes such as schizophrenia, autism, depression, anxiety, and dementia. Biomarkers will steadily pave the road to precision psychiatry.5,6

Technical advances

- Artificial intelligence is beginning to revolutionize psychiatric practice by identifying psychopathology via voice patterns, facial features, motor activity, sleep patterns, and analysis of writing and language. It will significantly enhance the early detection and diagnosis of neuropsychiatric disorders.7

- Machine learning. As with other medical specialties, this radical and important new technology is likely to generate currently unrecognized information and decision options for psychiatric practitioners in the future.8

- Neuromodulation. The future is already here when it comes to employing neuromodulation as a therapeutic technique in psychiatry. The past was prologue with the discovery of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) 30 years ago, evolving into vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) over the past 2 decades. Their application will go beyond depression into several other psychiatric conditions. A flurry of other neuromodulation techniques are being developed, including cranial electrical stimulation (CES), deep brain stimulation (DBS), epidural cortical stimulation (ECS), focused ultrasound (FUS), low-field magnetic stimulation (LFMS), magnetic seizure therapy (MST), near infrared light therapy (NIR), and transcranial direct current stimulation (TDCS).9

Continue to: Therapeutic advances

Therapeutic advances

- Rapid-acting parenteral antidepressants are one of the most exciting paradigm shifts for the treatment of severe depression and suicidal urges. In controlled clinical trials, ketamine, scopolamine, and nitrous oxide were shown to reverse chronic depression that had failed to respond to multiple oral antidepressants in a matter of hours instead of weeks or months.10 This remarkable new frontier of psychiatric therapeutics has revolutionized our concept of the neurobiology of depression and its reversibility into rapid remission. The use of IV, intranasal, and inhalable delivery of pharmacotherapies is bound to become an integral component of the future of psychiatry.

- Telepsychiatry is an example of how the future has already arrived for psychiatric practice. Clinicians’ virtual access to patients living in remote areas for evaluation and treatment is certainly a totally new model of health care delivery when compared with traditional face-to-face psychiatry, where patients must travel to see a psychiatrist.

- New terminology for psychotropic agents is also an impending part of the future. The neuroscience-based nomenclature (NbN) will rename more than 100 psychotropic medications by their mechanisms of action rather than by their clinical indication.11 Not only will this new lexicon be more scientifically accurate, but it also will avoid pigeon-holing drugs such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants, which also are used to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), anxiety, bulimia nervosa, and pain, or second-generation “atypical” antipsychotics, which are indicated not only for schizophrenia but also for bipolar mania and bipolar depression, and have been reported to improve treatment-resistant major depression, treatment-resistant OCD, borderline personality disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and delirium.12

- Early intervention during the prodromal phase of serious psychiatric disorders is already here and will advance rapidly in the future. This will spare patients the anguish and suffering of acute psychosis or mania, hospitalization, or disability. It will likely reduce the huge direct and indirect costs to society of serious psychiatric disorders.13

- Repurposing hallucinogens into therapeutic agents is one of the most interesting discoveries in psychiatry. As with ketamine, a dissociative hallucinogen that has been rebranded as a rapid antidepressant, other hallucinogens such as psilocybin, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), and 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA) are being investigated as therapeutic agents for depression, anxiety, and PTSD. They will become part of our expanding future pharmacotherapeutic armamentarium.14

It is obvious that parts of the future of psychiatry are already in place today, but other trends will emerge and thrill us clinicians. These advances will gradually but certainly alter psychiatric practice for the better, as the neuroscience of the mind expands and guides psychiatrists to more objective diagnoses and precise treatment options. The pace of advances in psychiatry is one of the most rapid in medicine.

So hold on: This will be a fascinating journey of creative destruction of traditional psychiatry.15 But as Emily Dickinson wrote: “Truth must dazzle gradually, or every man be blind.”

1. Moslem M, Olive J, Falk A. Stem cell models of schizophrenia, what have we learned and what is the potential. Schizophrenia Res. 2019;210:3-12.

2. Nasrallah HA. Psychopharmacology 3.0. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(11):4-7.

3. Nasrallah HA. It takes guts to be mentally ill: microbiota and psychopathology. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(9):4-6.

4. Nasrallah HA. Psychoneurogastroenterology: the abdominal brain, the microbiome, and psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(5):19-20.

5. Nasrallah HA. The dawn of precision psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2012;16(12):7-8,11.

6. Nasrallah HA. From bedlam to biomarkers: the transformation of psychiatry’s terminology reflects its 4 conceptual earthquakes. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(1):5-7.

7. Kalanderian H, Nasrallah HA. Artificial intelligence in psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(8):33-38.

8. Tandon N, Tandon R. Will machine learning enable us to finally cut the Gordian knot of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(5):939-941.

9. Rosa MA, Lisanby SH. Somatic treatments for mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(1):102-116.

10. Nasrallah HA. A brave new era of IV psychopharmacotherapy. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):10-12.

11. Stahl SM. Neuroscience-based nomenclature: classifying psychotropics by mechanism of action rather than indication. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(5):15-16.

12. Alexander GC, Gallagher SA, Mascola A, et al. Increasing off-label use of antipsychotic medications in the United States, 1995-2008. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(2):177-184.

13. Nasrallah HA. Psychiatry’s social impact: pervasive and multifaceted. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):4,6-7.

14. Nasrallah HA. Maddening therapies: how hallucinogens morphed into novel treatments. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):19-21.

15. Nasrallah HA. Is psychiatry ripe for creative destruction? Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(4):20-21.

The future of psychiatry is bright, even scintillating. Disruptive changes are gradually unfolding and will proceed at a brisk pace. Psychiatric practice will be transformed into a clinical neuroscience that will heal the mind by repairing the brain. The ingredients of change are already in place, and the trend will accelerate.

Consider the following scientific, technical, and therapeutic advances that will continue to transform the psychiatric practice landscape.

Scientific advances

- Pluripotent cells. By dedifferentiating fibroblasts or skin cells and re-differentiating them into neurons and glia, the study of the structure and function of psychiatric patients’ brains can be conducted in a test tube. That will exponentially expand the knowledge of the neural circuitry that underpin psychiatric disorders and will lead to novel strategies for brain repair.1

- CRISPR. This revolutionary advance in excising and inserting genes will eventually lead to the prevention of a psychiatric disease by replacing risk genes or mutations.1

- Molecular genetics. The flurry of identifying risk genes, copy number variants (CNV), and de novo mutations using gene-wide association studies (GWAS) will facilitate gene therapy in psychiatric disorders.

- Neuroimmunology. The discovery of the role of neuroinflammation and oxidative stress (free radicals exceeding glutathione and other antioxidants) in neuropsychiatric disorders will ultimately lead to new insights into preventing the neurodegeneration associated with acute psychotic or mood disorders. Inhibiting the activation of microglia (the immune cells of the brain) is one example of innovative therapeutic targets in the future.2

- Recognizing the role of mitochondrial dysfunction as a pathogenic pathway to neuropsychiatric disorders such as depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and even the comorbid diabetes that is common among those psychiatric disorders will chart an entirely new approach to diagnosis and treatment.2

- The role of the microbiota and microbiome in psychiatric disorders has emerged as a fertile new frontier in psychiatry, both for etiology and as therapeutic targets.3

- The enteric brain in the gut, in close proximity with the microbiome, is now known to be a major source of neurotransmitters that modulate brain functions (dopamine, serotonin, and others). Consequently, it is implicated in psychopathology, rendering this “second brain” a target for therapeutic interventions in the future, in addition to the “cephalic brain.”4

- Biomarkers and endophenotypes. The rapid discoveries of biomarkers are setting the stage for the recognition of hundreds of biologic subtypes of complex neuropsychiatric syndromes such as schizophrenia, autism, depression, anxiety, and dementia. Biomarkers will steadily pave the road to precision psychiatry.5,6

Technical advances

- Artificial intelligence is beginning to revolutionize psychiatric practice by identifying psychopathology via voice patterns, facial features, motor activity, sleep patterns, and analysis of writing and language. It will significantly enhance the early detection and diagnosis of neuropsychiatric disorders.7

- Machine learning. As with other medical specialties, this radical and important new technology is likely to generate currently unrecognized information and decision options for psychiatric practitioners in the future.8

- Neuromodulation. The future is already here when it comes to employing neuromodulation as a therapeutic technique in psychiatry. The past was prologue with the discovery of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) 30 years ago, evolving into vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) over the past 2 decades. Their application will go beyond depression into several other psychiatric conditions. A flurry of other neuromodulation techniques are being developed, including cranial electrical stimulation (CES), deep brain stimulation (DBS), epidural cortical stimulation (ECS), focused ultrasound (FUS), low-field magnetic stimulation (LFMS), magnetic seizure therapy (MST), near infrared light therapy (NIR), and transcranial direct current stimulation (TDCS).9

Continue to: Therapeutic advances

Therapeutic advances

- Rapid-acting parenteral antidepressants are one of the most exciting paradigm shifts for the treatment of severe depression and suicidal urges. In controlled clinical trials, ketamine, scopolamine, and nitrous oxide were shown to reverse chronic depression that had failed to respond to multiple oral antidepressants in a matter of hours instead of weeks or months.10 This remarkable new frontier of psychiatric therapeutics has revolutionized our concept of the neurobiology of depression and its reversibility into rapid remission. The use of IV, intranasal, and inhalable delivery of pharmacotherapies is bound to become an integral component of the future of psychiatry.

- Telepsychiatry is an example of how the future has already arrived for psychiatric practice. Clinicians’ virtual access to patients living in remote areas for evaluation and treatment is certainly a totally new model of health care delivery when compared with traditional face-to-face psychiatry, where patients must travel to see a psychiatrist.

- New terminology for psychotropic agents is also an impending part of the future. The neuroscience-based nomenclature (NbN) will rename more than 100 psychotropic medications by their mechanisms of action rather than by their clinical indication.11 Not only will this new lexicon be more scientifically accurate, but it also will avoid pigeon-holing drugs such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants, which also are used to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), anxiety, bulimia nervosa, and pain, or second-generation “atypical” antipsychotics, which are indicated not only for schizophrenia but also for bipolar mania and bipolar depression, and have been reported to improve treatment-resistant major depression, treatment-resistant OCD, borderline personality disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and delirium.12

- Early intervention during the prodromal phase of serious psychiatric disorders is already here and will advance rapidly in the future. This will spare patients the anguish and suffering of acute psychosis or mania, hospitalization, or disability. It will likely reduce the huge direct and indirect costs to society of serious psychiatric disorders.13

- Repurposing hallucinogens into therapeutic agents is one of the most interesting discoveries in psychiatry. As with ketamine, a dissociative hallucinogen that has been rebranded as a rapid antidepressant, other hallucinogens such as psilocybin, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), and 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA) are being investigated as therapeutic agents for depression, anxiety, and PTSD. They will become part of our expanding future pharmacotherapeutic armamentarium.14

It is obvious that parts of the future of psychiatry are already in place today, but other trends will emerge and thrill us clinicians. These advances will gradually but certainly alter psychiatric practice for the better, as the neuroscience of the mind expands and guides psychiatrists to more objective diagnoses and precise treatment options. The pace of advances in psychiatry is one of the most rapid in medicine.

So hold on: This will be a fascinating journey of creative destruction of traditional psychiatry.15 But as Emily Dickinson wrote: “Truth must dazzle gradually, or every man be blind.”

The future of psychiatry is bright, even scintillating. Disruptive changes are gradually unfolding and will proceed at a brisk pace. Psychiatric practice will be transformed into a clinical neuroscience that will heal the mind by repairing the brain. The ingredients of change are already in place, and the trend will accelerate.

Consider the following scientific, technical, and therapeutic advances that will continue to transform the psychiatric practice landscape.

Scientific advances

- Pluripotent cells. By dedifferentiating fibroblasts or skin cells and re-differentiating them into neurons and glia, the study of the structure and function of psychiatric patients’ brains can be conducted in a test tube. That will exponentially expand the knowledge of the neural circuitry that underpin psychiatric disorders and will lead to novel strategies for brain repair.1

- CRISPR. This revolutionary advance in excising and inserting genes will eventually lead to the prevention of a psychiatric disease by replacing risk genes or mutations.1

- Molecular genetics. The flurry of identifying risk genes, copy number variants (CNV), and de novo mutations using gene-wide association studies (GWAS) will facilitate gene therapy in psychiatric disorders.

- Neuroimmunology. The discovery of the role of neuroinflammation and oxidative stress (free radicals exceeding glutathione and other antioxidants) in neuropsychiatric disorders will ultimately lead to new insights into preventing the neurodegeneration associated with acute psychotic or mood disorders. Inhibiting the activation of microglia (the immune cells of the brain) is one example of innovative therapeutic targets in the future.2

- Recognizing the role of mitochondrial dysfunction as a pathogenic pathway to neuropsychiatric disorders such as depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and even the comorbid diabetes that is common among those psychiatric disorders will chart an entirely new approach to diagnosis and treatment.2

- The role of the microbiota and microbiome in psychiatric disorders has emerged as a fertile new frontier in psychiatry, both for etiology and as therapeutic targets.3

- The enteric brain in the gut, in close proximity with the microbiome, is now known to be a major source of neurotransmitters that modulate brain functions (dopamine, serotonin, and others). Consequently, it is implicated in psychopathology, rendering this “second brain” a target for therapeutic interventions in the future, in addition to the “cephalic brain.”4

- Biomarkers and endophenotypes. The rapid discoveries of biomarkers are setting the stage for the recognition of hundreds of biologic subtypes of complex neuropsychiatric syndromes such as schizophrenia, autism, depression, anxiety, and dementia. Biomarkers will steadily pave the road to precision psychiatry.5,6

Technical advances

- Artificial intelligence is beginning to revolutionize psychiatric practice by identifying psychopathology via voice patterns, facial features, motor activity, sleep patterns, and analysis of writing and language. It will significantly enhance the early detection and diagnosis of neuropsychiatric disorders.7

- Machine learning. As with other medical specialties, this radical and important new technology is likely to generate currently unrecognized information and decision options for psychiatric practitioners in the future.8

- Neuromodulation. The future is already here when it comes to employing neuromodulation as a therapeutic technique in psychiatry. The past was prologue with the discovery of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) 30 years ago, evolving into vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) over the past 2 decades. Their application will go beyond depression into several other psychiatric conditions. A flurry of other neuromodulation techniques are being developed, including cranial electrical stimulation (CES), deep brain stimulation (DBS), epidural cortical stimulation (ECS), focused ultrasound (FUS), low-field magnetic stimulation (LFMS), magnetic seizure therapy (MST), near infrared light therapy (NIR), and transcranial direct current stimulation (TDCS).9

Continue to: Therapeutic advances

Therapeutic advances

- Rapid-acting parenteral antidepressants are one of the most exciting paradigm shifts for the treatment of severe depression and suicidal urges. In controlled clinical trials, ketamine, scopolamine, and nitrous oxide were shown to reverse chronic depression that had failed to respond to multiple oral antidepressants in a matter of hours instead of weeks or months.10 This remarkable new frontier of psychiatric therapeutics has revolutionized our concept of the neurobiology of depression and its reversibility into rapid remission. The use of IV, intranasal, and inhalable delivery of pharmacotherapies is bound to become an integral component of the future of psychiatry.

- Telepsychiatry is an example of how the future has already arrived for psychiatric practice. Clinicians’ virtual access to patients living in remote areas for evaluation and treatment is certainly a totally new model of health care delivery when compared with traditional face-to-face psychiatry, where patients must travel to see a psychiatrist.

- New terminology for psychotropic agents is also an impending part of the future. The neuroscience-based nomenclature (NbN) will rename more than 100 psychotropic medications by their mechanisms of action rather than by their clinical indication.11 Not only will this new lexicon be more scientifically accurate, but it also will avoid pigeon-holing drugs such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants, which also are used to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), anxiety, bulimia nervosa, and pain, or second-generation “atypical” antipsychotics, which are indicated not only for schizophrenia but also for bipolar mania and bipolar depression, and have been reported to improve treatment-resistant major depression, treatment-resistant OCD, borderline personality disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and delirium.12

- Early intervention during the prodromal phase of serious psychiatric disorders is already here and will advance rapidly in the future. This will spare patients the anguish and suffering of acute psychosis or mania, hospitalization, or disability. It will likely reduce the huge direct and indirect costs to society of serious psychiatric disorders.13

- Repurposing hallucinogens into therapeutic agents is one of the most interesting discoveries in psychiatry. As with ketamine, a dissociative hallucinogen that has been rebranded as a rapid antidepressant, other hallucinogens such as psilocybin, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), and 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA) are being investigated as therapeutic agents for depression, anxiety, and PTSD. They will become part of our expanding future pharmacotherapeutic armamentarium.14

It is obvious that parts of the future of psychiatry are already in place today, but other trends will emerge and thrill us clinicians. These advances will gradually but certainly alter psychiatric practice for the better, as the neuroscience of the mind expands and guides psychiatrists to more objective diagnoses and precise treatment options. The pace of advances in psychiatry is one of the most rapid in medicine.

So hold on: This will be a fascinating journey of creative destruction of traditional psychiatry.15 But as Emily Dickinson wrote: “Truth must dazzle gradually, or every man be blind.”

1. Moslem M, Olive J, Falk A. Stem cell models of schizophrenia, what have we learned and what is the potential. Schizophrenia Res. 2019;210:3-12.

2. Nasrallah HA. Psychopharmacology 3.0. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(11):4-7.

3. Nasrallah HA. It takes guts to be mentally ill: microbiota and psychopathology. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(9):4-6.

4. Nasrallah HA. Psychoneurogastroenterology: the abdominal brain, the microbiome, and psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(5):19-20.

5. Nasrallah HA. The dawn of precision psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2012;16(12):7-8,11.

6. Nasrallah HA. From bedlam to biomarkers: the transformation of psychiatry’s terminology reflects its 4 conceptual earthquakes. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(1):5-7.

7. Kalanderian H, Nasrallah HA. Artificial intelligence in psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(8):33-38.

8. Tandon N, Tandon R. Will machine learning enable us to finally cut the Gordian knot of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(5):939-941.

9. Rosa MA, Lisanby SH. Somatic treatments for mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(1):102-116.

10. Nasrallah HA. A brave new era of IV psychopharmacotherapy. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):10-12.

11. Stahl SM. Neuroscience-based nomenclature: classifying psychotropics by mechanism of action rather than indication. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(5):15-16.

12. Alexander GC, Gallagher SA, Mascola A, et al. Increasing off-label use of antipsychotic medications in the United States, 1995-2008. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(2):177-184.

13. Nasrallah HA. Psychiatry’s social impact: pervasive and multifaceted. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):4,6-7.

14. Nasrallah HA. Maddening therapies: how hallucinogens morphed into novel treatments. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):19-21.

15. Nasrallah HA. Is psychiatry ripe for creative destruction? Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(4):20-21.

1. Moslem M, Olive J, Falk A. Stem cell models of schizophrenia, what have we learned and what is the potential. Schizophrenia Res. 2019;210:3-12.

2. Nasrallah HA. Psychopharmacology 3.0. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(11):4-7.

3. Nasrallah HA. It takes guts to be mentally ill: microbiota and psychopathology. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(9):4-6.

4. Nasrallah HA. Psychoneurogastroenterology: the abdominal brain, the microbiome, and psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(5):19-20.

5. Nasrallah HA. The dawn of precision psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2012;16(12):7-8,11.

6. Nasrallah HA. From bedlam to biomarkers: the transformation of psychiatry’s terminology reflects its 4 conceptual earthquakes. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(1):5-7.

7. Kalanderian H, Nasrallah HA. Artificial intelligence in psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(8):33-38.

8. Tandon N, Tandon R. Will machine learning enable us to finally cut the Gordian knot of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(5):939-941.

9. Rosa MA, Lisanby SH. Somatic treatments for mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(1):102-116.

10. Nasrallah HA. A brave new era of IV psychopharmacotherapy. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):10-12.

11. Stahl SM. Neuroscience-based nomenclature: classifying psychotropics by mechanism of action rather than indication. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(5):15-16.

12. Alexander GC, Gallagher SA, Mascola A, et al. Increasing off-label use of antipsychotic medications in the United States, 1995-2008. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(2):177-184.

13. Nasrallah HA. Psychiatry’s social impact: pervasive and multifaceted. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):4,6-7.

14. Nasrallah HA. Maddening therapies: how hallucinogens morphed into novel treatments. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):19-21.

15. Nasrallah HA. Is psychiatry ripe for creative destruction? Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(4):20-21.

Physician assistants in psychiatry: Helping to meet America’s mental health needs

“Canst thou not minister to a mind diseased, pluck from the memory a rooted sorrow, raze out the written troubles of the brain, and with some sweet oblivious antidote cleanse the stuffed bosom of that perilous stuff which weighs upon the heart?”

– William Shakespeare, Macbeth

For many years, the United States has been experiencing a shortage of psychiatrists. Currently, there are only 28,000 to 33,000 psychiatrists in active patient care practice in the United States.1,2 The lack of psychiatrists is pronounced in many areas of the country, including rural regions, some urban neighborhoods, and community health centers. In approximately half of US counties, there are no psychiatrists at all.3

While patients with mental illnesses often are treated in primary care settings, the need for qualified mental health clinicians remains acute. Two-thirds of primary care physicians report difficulty in referring patients for mental health care, due to the shortage of clinicians and long wait times for patients to be seen.4 In the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the shortage of qualified psychiatrists is even more acute, due to ongoing combat operations and an increased number of missions and manpower requirements to complete them, which also has increased veterans’ mental health needs during life after their service.5

The outlook for providing adequate numbers of psychiatrists in the future is even more concerning. Based on a population analysis, Satiani et al6 predicts an extreme shortage of psychiatrists for the next 30 years, with the availability of psychiatrists per population expected to reach an all-time low by 2024. Based on ratios from the Department of Health and Human Services, this would mean a shortage of 14,000 to 31,000 psychiatrists over the next 5 to 6 years alone. This is due primarily to the expected retirement of more than 25,000 psychiatrists age >55 during the next 5 years. With mental illness becoming the costliest medical condition in the United States, at $201 billion annually, the potential impact of this shortage is alarming.6

Addressing the shortage

Efforts aimed at increasing the number of psychiatrists, improving access to care, and improving efficiency of care have focused on expanding recruitment and training capacity in psychiatry residency programs, utilizing new models such as telepsychiatry and Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) teams, increasing the number of Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics, and embedding psychiatrists in large primary care practices.7 Another avenue for addressing the psychiatrist shortage has been the training and hiring of more advanced practice clinicians, including physician assistants (PAs) and

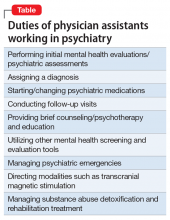

Physician assistants and NPs make up the largest group of non-physician mental health professionals who can prescribe medications. Physician assistant training is most closely aligned with the allopathic training model of physicians.9 Some typical duties of PAs working in a psychiatric setting are outlined in the Table.

How many PAs elect to specialize in psychiatry, compared with the percentage of physicians who choose psychiatry as a career? Data from the National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants (NCCPA) revealed that in 2018 there were 1,470 PAs working in psychiatry, or approximately 1.5% of all PAs in practice.10 In comparison, approximately 5% of physicians complete residency training in psychiatry.2

Continue to: Although the need for more...