User login

Zulresso: Hope and lingering questions

The last decade has brought increasing awareness of the need to effectively screen for postpartum depression, with a majority of states across the country now having some sort of formal program by which women are screened for mood disorder during the postnatal period, typically with scales such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS).

In addition to effective screening is a pressing need for effective referral networks of clinicians who have both the expertise and time to manage the 10%-15% of women who have been identified and who suffer from postpartum psychiatric disorders – both postpartum mood and anxiety disorders. Several studies have suggested that only a small percentage of postpartum women who score with clinically significant level of depressive symptoms actually get to a clinician or, if they do get to a clinician, receive adequate treatment restoring their emotional well-being (J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;77[9]:1189-200).

Zulresso (brexanolone), a novel new antidepressant medication which recently received Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of postpartum depression, is a first-in-class molecule to get such approval. Zulresso is a neurosteroid, an analogue of allopregnanolone and a GABAA receptor–positive allosteric modulator, a primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain.

There is every reason to believe that, as a class, this group of neurosteroid molecules are effective in treating depression in other populations aside from women with postpartum depression and hence may not be specific to the postpartum period. For example, recent presentations of preliminary data suggest other neurosteroids such as zuranolone (an oral medication also developed by Sage Therapeutics) is effective for both men and women who have major depression in addition to women suffering from postpartum depression.

Zulresso is approved through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy–restricted program and, per that protocol, needs to be administered by a health care provider in a recognized health care setting intravenously over 2.5 days (60 hours). Because of concerns regarding increased sedation, continuous pulse oximetry is required, and this is outlined in a boxed warning in the prescribing information. Zulresso has been classified by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) as a Schedule IV injection and is subject to the prescribing regulations for a controlled substance.

Since Zulresso’s approval, my colleagues and I at the Center for Women’s Mental Health have received numerous queries from patients and colleagues about our clinical impression of this new molecule with a different mechanism of action – a welcome addition to the antidepressant pharmacopeia. The question posed to us essentially is: Where does brexanolone fit into our algorithm for treating women who suffer from postpartum depression? And frequently, the follow-up query is: Because subjects in the clinical trials for this medication included women who had onset of depression either late in pregnancy or during the postpartum period, how specific is brexanolone with respect to being a targeted therapy for postpartum depression, compared with depression encountered in other clinical settings.

What clearly can be stated is that Zulresso has a rapid onset of action and was demonstrated across clinical trials to have sustained benefit up to 30 days after IV administration. The question is whether patients have sustained benefit after 30 days or if this is a medicine to be considered as a “bridge” to other treatment. Data answering that critical clinical question are unavailable at this time. From a clinical standpoint, do patients receive this treatment and get sent home on antidepressants, as we would for patients who receive ECT, often discharging them with prophylactic antidepressants to sustain the benefit of the treatment? Or do patients receive this new medicine with the clinician providing close follow-up, assuming a wait-and-see approach? Because data informing the answer to that question are not available, this decision will be made empirically, frequently factoring in the patient’s past clinical history where presumably more liberal use of antidepressant immediately after the administration of Zulresso will be pursued in those with histories of highly recurrent major depression.

So where might this new medicine fit into the treatment of postpartum depression of moderate severity, or modest to moderate severity? It should be kept in mind that for patients with mild to moderate postpartum depression, there are data supporting the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). CBT frequently is pursued with concurrent mobilization of substantial social support with good outcomes. In patients with more severe postpartum depression, there are data supporting the use of antidepressants, and in these patients as well, use of established support from the ever-growing network of community-based support groups and services can be particularly helpful. It is unlikely that Zulresso will be a first-line medication for the treatment of postpartum depression, but it may be particularly appropriate for patients with severe illness who have not responded to other interventions.

Other practical considerations regarding use of Zulresso include the requirement that the medicine be administered in hospitals that have established clinical infrastructure to accommodate this particular population of patients and where pharmacists and other relevant parties in hospitals have accepted the medicine into its drug formulary. While coverage by various insurance policies may vary, the cost of this new medication is substantial, between $24,000 and $34,000 per treatment, according to reports.

Where Zulresso fits into the pharmacopeia for treating postpartum depression may fall well beyond the issues of efficacy. Given all of the attention to this first-in-class medicine, Zulresso has reinforced the growing interest in the substantial prevalence and the morbidity associated with postpartum depression. It is hard to imagine Zulresso being used in cases of more mild to moderate depression, in which there is nonemergent opportunity to pursue options that do not require a new mom to absent herself from homelife with a newborn. However, in picking cases of severe new onset or recurrence of depression in postpartum women, the rapid onset of benefit that was noted within days could be an extraordinary relief and be the beginning of a road to wellness for some women.

Ultimately, the collaboration of patients with their doctors, the realities of cost, and the acceptability of use in various clinical settings will determine how Zulresso is incorporated into seeking treatment to mitigate the suffering associated with postpartum depression. We at the Center for Women’s Mental Health are interested in user experience with respect to this medicine and welcome comments from both patients and their doctors at [email protected].

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. This center was an investigator site for one of the studies supported by Sage Therapeutics, the manufacturer of Zulresso. Dr. Cohen is also the Edmund and Carroll Carpenter professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

The last decade has brought increasing awareness of the need to effectively screen for postpartum depression, with a majority of states across the country now having some sort of formal program by which women are screened for mood disorder during the postnatal period, typically with scales such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS).

In addition to effective screening is a pressing need for effective referral networks of clinicians who have both the expertise and time to manage the 10%-15% of women who have been identified and who suffer from postpartum psychiatric disorders – both postpartum mood and anxiety disorders. Several studies have suggested that only a small percentage of postpartum women who score with clinically significant level of depressive symptoms actually get to a clinician or, if they do get to a clinician, receive adequate treatment restoring their emotional well-being (J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;77[9]:1189-200).

Zulresso (brexanolone), a novel new antidepressant medication which recently received Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of postpartum depression, is a first-in-class molecule to get such approval. Zulresso is a neurosteroid, an analogue of allopregnanolone and a GABAA receptor–positive allosteric modulator, a primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain.

There is every reason to believe that, as a class, this group of neurosteroid molecules are effective in treating depression in other populations aside from women with postpartum depression and hence may not be specific to the postpartum period. For example, recent presentations of preliminary data suggest other neurosteroids such as zuranolone (an oral medication also developed by Sage Therapeutics) is effective for both men and women who have major depression in addition to women suffering from postpartum depression.

Zulresso is approved through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy–restricted program and, per that protocol, needs to be administered by a health care provider in a recognized health care setting intravenously over 2.5 days (60 hours). Because of concerns regarding increased sedation, continuous pulse oximetry is required, and this is outlined in a boxed warning in the prescribing information. Zulresso has been classified by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) as a Schedule IV injection and is subject to the prescribing regulations for a controlled substance.

Since Zulresso’s approval, my colleagues and I at the Center for Women’s Mental Health have received numerous queries from patients and colleagues about our clinical impression of this new molecule with a different mechanism of action – a welcome addition to the antidepressant pharmacopeia. The question posed to us essentially is: Where does brexanolone fit into our algorithm for treating women who suffer from postpartum depression? And frequently, the follow-up query is: Because subjects in the clinical trials for this medication included women who had onset of depression either late in pregnancy or during the postpartum period, how specific is brexanolone with respect to being a targeted therapy for postpartum depression, compared with depression encountered in other clinical settings.

What clearly can be stated is that Zulresso has a rapid onset of action and was demonstrated across clinical trials to have sustained benefit up to 30 days after IV administration. The question is whether patients have sustained benefit after 30 days or if this is a medicine to be considered as a “bridge” to other treatment. Data answering that critical clinical question are unavailable at this time. From a clinical standpoint, do patients receive this treatment and get sent home on antidepressants, as we would for patients who receive ECT, often discharging them with prophylactic antidepressants to sustain the benefit of the treatment? Or do patients receive this new medicine with the clinician providing close follow-up, assuming a wait-and-see approach? Because data informing the answer to that question are not available, this decision will be made empirically, frequently factoring in the patient’s past clinical history where presumably more liberal use of antidepressant immediately after the administration of Zulresso will be pursued in those with histories of highly recurrent major depression.

So where might this new medicine fit into the treatment of postpartum depression of moderate severity, or modest to moderate severity? It should be kept in mind that for patients with mild to moderate postpartum depression, there are data supporting the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). CBT frequently is pursued with concurrent mobilization of substantial social support with good outcomes. In patients with more severe postpartum depression, there are data supporting the use of antidepressants, and in these patients as well, use of established support from the ever-growing network of community-based support groups and services can be particularly helpful. It is unlikely that Zulresso will be a first-line medication for the treatment of postpartum depression, but it may be particularly appropriate for patients with severe illness who have not responded to other interventions.

Other practical considerations regarding use of Zulresso include the requirement that the medicine be administered in hospitals that have established clinical infrastructure to accommodate this particular population of patients and where pharmacists and other relevant parties in hospitals have accepted the medicine into its drug formulary. While coverage by various insurance policies may vary, the cost of this new medication is substantial, between $24,000 and $34,000 per treatment, according to reports.

Where Zulresso fits into the pharmacopeia for treating postpartum depression may fall well beyond the issues of efficacy. Given all of the attention to this first-in-class medicine, Zulresso has reinforced the growing interest in the substantial prevalence and the morbidity associated with postpartum depression. It is hard to imagine Zulresso being used in cases of more mild to moderate depression, in which there is nonemergent opportunity to pursue options that do not require a new mom to absent herself from homelife with a newborn. However, in picking cases of severe new onset or recurrence of depression in postpartum women, the rapid onset of benefit that was noted within days could be an extraordinary relief and be the beginning of a road to wellness for some women.

Ultimately, the collaboration of patients with their doctors, the realities of cost, and the acceptability of use in various clinical settings will determine how Zulresso is incorporated into seeking treatment to mitigate the suffering associated with postpartum depression. We at the Center for Women’s Mental Health are interested in user experience with respect to this medicine and welcome comments from both patients and their doctors at [email protected].

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. This center was an investigator site for one of the studies supported by Sage Therapeutics, the manufacturer of Zulresso. Dr. Cohen is also the Edmund and Carroll Carpenter professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

The last decade has brought increasing awareness of the need to effectively screen for postpartum depression, with a majority of states across the country now having some sort of formal program by which women are screened for mood disorder during the postnatal period, typically with scales such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS).

In addition to effective screening is a pressing need for effective referral networks of clinicians who have both the expertise and time to manage the 10%-15% of women who have been identified and who suffer from postpartum psychiatric disorders – both postpartum mood and anxiety disorders. Several studies have suggested that only a small percentage of postpartum women who score with clinically significant level of depressive symptoms actually get to a clinician or, if they do get to a clinician, receive adequate treatment restoring their emotional well-being (J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;77[9]:1189-200).

Zulresso (brexanolone), a novel new antidepressant medication which recently received Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of postpartum depression, is a first-in-class molecule to get such approval. Zulresso is a neurosteroid, an analogue of allopregnanolone and a GABAA receptor–positive allosteric modulator, a primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain.

There is every reason to believe that, as a class, this group of neurosteroid molecules are effective in treating depression in other populations aside from women with postpartum depression and hence may not be specific to the postpartum period. For example, recent presentations of preliminary data suggest other neurosteroids such as zuranolone (an oral medication also developed by Sage Therapeutics) is effective for both men and women who have major depression in addition to women suffering from postpartum depression.

Zulresso is approved through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy–restricted program and, per that protocol, needs to be administered by a health care provider in a recognized health care setting intravenously over 2.5 days (60 hours). Because of concerns regarding increased sedation, continuous pulse oximetry is required, and this is outlined in a boxed warning in the prescribing information. Zulresso has been classified by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) as a Schedule IV injection and is subject to the prescribing regulations for a controlled substance.

Since Zulresso’s approval, my colleagues and I at the Center for Women’s Mental Health have received numerous queries from patients and colleagues about our clinical impression of this new molecule with a different mechanism of action – a welcome addition to the antidepressant pharmacopeia. The question posed to us essentially is: Where does brexanolone fit into our algorithm for treating women who suffer from postpartum depression? And frequently, the follow-up query is: Because subjects in the clinical trials for this medication included women who had onset of depression either late in pregnancy or during the postpartum period, how specific is brexanolone with respect to being a targeted therapy for postpartum depression, compared with depression encountered in other clinical settings.

What clearly can be stated is that Zulresso has a rapid onset of action and was demonstrated across clinical trials to have sustained benefit up to 30 days after IV administration. The question is whether patients have sustained benefit after 30 days or if this is a medicine to be considered as a “bridge” to other treatment. Data answering that critical clinical question are unavailable at this time. From a clinical standpoint, do patients receive this treatment and get sent home on antidepressants, as we would for patients who receive ECT, often discharging them with prophylactic antidepressants to sustain the benefit of the treatment? Or do patients receive this new medicine with the clinician providing close follow-up, assuming a wait-and-see approach? Because data informing the answer to that question are not available, this decision will be made empirically, frequently factoring in the patient’s past clinical history where presumably more liberal use of antidepressant immediately after the administration of Zulresso will be pursued in those with histories of highly recurrent major depression.

So where might this new medicine fit into the treatment of postpartum depression of moderate severity, or modest to moderate severity? It should be kept in mind that for patients with mild to moderate postpartum depression, there are data supporting the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). CBT frequently is pursued with concurrent mobilization of substantial social support with good outcomes. In patients with more severe postpartum depression, there are data supporting the use of antidepressants, and in these patients as well, use of established support from the ever-growing network of community-based support groups and services can be particularly helpful. It is unlikely that Zulresso will be a first-line medication for the treatment of postpartum depression, but it may be particularly appropriate for patients with severe illness who have not responded to other interventions.

Other practical considerations regarding use of Zulresso include the requirement that the medicine be administered in hospitals that have established clinical infrastructure to accommodate this particular population of patients and where pharmacists and other relevant parties in hospitals have accepted the medicine into its drug formulary. While coverage by various insurance policies may vary, the cost of this new medication is substantial, between $24,000 and $34,000 per treatment, according to reports.

Where Zulresso fits into the pharmacopeia for treating postpartum depression may fall well beyond the issues of efficacy. Given all of the attention to this first-in-class medicine, Zulresso has reinforced the growing interest in the substantial prevalence and the morbidity associated with postpartum depression. It is hard to imagine Zulresso being used in cases of more mild to moderate depression, in which there is nonemergent opportunity to pursue options that do not require a new mom to absent herself from homelife with a newborn. However, in picking cases of severe new onset or recurrence of depression in postpartum women, the rapid onset of benefit that was noted within days could be an extraordinary relief and be the beginning of a road to wellness for some women.

Ultimately, the collaboration of patients with their doctors, the realities of cost, and the acceptability of use in various clinical settings will determine how Zulresso is incorporated into seeking treatment to mitigate the suffering associated with postpartum depression. We at the Center for Women’s Mental Health are interested in user experience with respect to this medicine and welcome comments from both patients and their doctors at [email protected].

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. This center was an investigator site for one of the studies supported by Sage Therapeutics, the manufacturer of Zulresso. Dr. Cohen is also the Edmund and Carroll Carpenter professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

Supporting our gender-diverse patients

CASE Patient has adverse effects from halted estrogen pills

JR twists her hands nervously as you step into the room. “They stopped my hormones,” she sighs as you pull up her lab results.

JR recently had been admitted to an inpatient cardiology unit for several days for a heart failure exacerbation. Her ankles are still swollen beneath her floral print skirt, but she is breathing much easier now. She is back at your primary care office, hoping to get clearance to restart her estrogen pills.

JR reports having mood swings and terrible nightmares while not taking her hormones, which she has been taking for more than 3 years. She hesitates before sharing, “One of the doctors kept asking me questions about my sex life that had nothing to do with my heart condition. I don’t want to go back there.”

Providing compassionate and comprehensive care to gender-nonconforming individuals is challenging for a multitude of reasons, from clinician ignorance to systemic discrimination. About 33% of transgender patients reported being harassed, denied care, or even being assaulted when seeking health care, while 23% reported avoiding going to the doctor altogether when sick or injured out of fear of discrimination.1

Unfortunately, now, further increases to barriers to care may be put in place. In late May of this year, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) proposed new regulations that would reverse previous regulations granted through section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA)—the Health Care Rights Law—which affirmed the rights of gender nonbinary persons to medical care. Among the proposed changes is the elimination of protections against discrimination in health care based on gender identity.2 The proposed regulation changes come on the heels of a federal court case, which seeks to declare that hospital systems may turn away patients based on gender identity.3

Unraveling rights afforded under the ACA

The Health Care Rights Law was passed under the ACA; it prohibits discrimination based on race, color, national origin, sex, age, and disability in health programs and activities receiving federal financial assistance. Multiple lower courts have supported that the rights of transgender individuals is included within these protections against discrimination on the basis of sex.4 These court rulings not only have ensured the ability of gender-diverse individuals to access care but also have enforced insurance coverage of therapies for gender dysphoria. It was only in 2014 that Medicaid began providing coverage for gender-affirming surgeries and eliminating language that such procedures were “experimental” or “cosmetic.” The 2016 passage of the ACA mandated that private insurance companies follow suit. Unfortunately, the recent proposed regulation changes to the Health Care Rights Law may spark a reversal from insurance companies as well. Such a setback would affect gender-diverse individuals’ hormone treatments as well as their ability to access a full spectrum of care within the health care system.

Continue to: ACOG urges nondiscriminatory practices...

ACOG urges nondiscriminatory practices

The proposed regulation changes to the Health Care Rights Law are from the Conscience and Religious Freedom Division of the HHS Office for Civil Rights, which was established in 2018 and has been advocating for the rights of health care providers to refuse to treat patients based on their own religious beliefs.5 We argue, however, that providing care to persons of varying backgrounds is not an assault on our individual liberties but rather a privilege as providers. As obstetrician-gynecologists, it may be easy to only consider cis-gendered women our responsibility. But our field also emphasizes individual empowerment above all else—we fight every day for our patients’ rights to contraception, fertility, pregnancy, parenthood, and sexual freedoms. Let us continue speaking up for the rights of all those who need gynecologic care, regardless of the pronouns they use.

“The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists urges health care providers to foster nondiscriminatory practices and policies to increase identification and to facilitate quality health care for transgender individuals, both in assisting with the transition if desired as well as providing long-term preventive health care.”6

We urge you to take action

- Reach out to your local representatives about protecting transgender health access

- Educate yourself on the unique needs of transgender individuals

- Read personal accounts

- Share your personal story

- Find referring providers near your practice

- 2015 US Transgender Survey. December 2016. https://www.transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/USTS-Full-Report-FINAL.PDF. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- Musumeci M, Kates J, Dawson J, et al. HHS’ proposed changes to non-discrimination regulations under ACA section 1557. July 1, 2019. https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/hhss-proposed-changes-to-non-discrimination-regulations-under-aca-section-1557/. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- Franciscan Alliance v. Burwell. ACLU website. https://www.aclu.org/cases/franciscan-alliance-v-burwell. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- Pear R. Trump plan would cut back health care protections for transgender people. April 21, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/21/us/politics/trump-transgender-health-care.html. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. HHS announces new conscience and religious freedom division. January 18, 2018. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2018/01/18/hhs-ocr-announces-new-conscience-and-religious-freedom-division.html. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Committee Opinion no. 512: health care for transgender individuals. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1454–1458.

CASE Patient has adverse effects from halted estrogen pills

JR twists her hands nervously as you step into the room. “They stopped my hormones,” she sighs as you pull up her lab results.

JR recently had been admitted to an inpatient cardiology unit for several days for a heart failure exacerbation. Her ankles are still swollen beneath her floral print skirt, but she is breathing much easier now. She is back at your primary care office, hoping to get clearance to restart her estrogen pills.

JR reports having mood swings and terrible nightmares while not taking her hormones, which she has been taking for more than 3 years. She hesitates before sharing, “One of the doctors kept asking me questions about my sex life that had nothing to do with my heart condition. I don’t want to go back there.”

Providing compassionate and comprehensive care to gender-nonconforming individuals is challenging for a multitude of reasons, from clinician ignorance to systemic discrimination. About 33% of transgender patients reported being harassed, denied care, or even being assaulted when seeking health care, while 23% reported avoiding going to the doctor altogether when sick or injured out of fear of discrimination.1

Unfortunately, now, further increases to barriers to care may be put in place. In late May of this year, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) proposed new regulations that would reverse previous regulations granted through section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA)—the Health Care Rights Law—which affirmed the rights of gender nonbinary persons to medical care. Among the proposed changes is the elimination of protections against discrimination in health care based on gender identity.2 The proposed regulation changes come on the heels of a federal court case, which seeks to declare that hospital systems may turn away patients based on gender identity.3

Unraveling rights afforded under the ACA

The Health Care Rights Law was passed under the ACA; it prohibits discrimination based on race, color, national origin, sex, age, and disability in health programs and activities receiving federal financial assistance. Multiple lower courts have supported that the rights of transgender individuals is included within these protections against discrimination on the basis of sex.4 These court rulings not only have ensured the ability of gender-diverse individuals to access care but also have enforced insurance coverage of therapies for gender dysphoria. It was only in 2014 that Medicaid began providing coverage for gender-affirming surgeries and eliminating language that such procedures were “experimental” or “cosmetic.” The 2016 passage of the ACA mandated that private insurance companies follow suit. Unfortunately, the recent proposed regulation changes to the Health Care Rights Law may spark a reversal from insurance companies as well. Such a setback would affect gender-diverse individuals’ hormone treatments as well as their ability to access a full spectrum of care within the health care system.

Continue to: ACOG urges nondiscriminatory practices...

ACOG urges nondiscriminatory practices

The proposed regulation changes to the Health Care Rights Law are from the Conscience and Religious Freedom Division of the HHS Office for Civil Rights, which was established in 2018 and has been advocating for the rights of health care providers to refuse to treat patients based on their own religious beliefs.5 We argue, however, that providing care to persons of varying backgrounds is not an assault on our individual liberties but rather a privilege as providers. As obstetrician-gynecologists, it may be easy to only consider cis-gendered women our responsibility. But our field also emphasizes individual empowerment above all else—we fight every day for our patients’ rights to contraception, fertility, pregnancy, parenthood, and sexual freedoms. Let us continue speaking up for the rights of all those who need gynecologic care, regardless of the pronouns they use.

“The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists urges health care providers to foster nondiscriminatory practices and policies to increase identification and to facilitate quality health care for transgender individuals, both in assisting with the transition if desired as well as providing long-term preventive health care.”6

We urge you to take action

- Reach out to your local representatives about protecting transgender health access

- Educate yourself on the unique needs of transgender individuals

- Read personal accounts

- Share your personal story

- Find referring providers near your practice

CASE Patient has adverse effects from halted estrogen pills

JR twists her hands nervously as you step into the room. “They stopped my hormones,” she sighs as you pull up her lab results.

JR recently had been admitted to an inpatient cardiology unit for several days for a heart failure exacerbation. Her ankles are still swollen beneath her floral print skirt, but she is breathing much easier now. She is back at your primary care office, hoping to get clearance to restart her estrogen pills.

JR reports having mood swings and terrible nightmares while not taking her hormones, which she has been taking for more than 3 years. She hesitates before sharing, “One of the doctors kept asking me questions about my sex life that had nothing to do with my heart condition. I don’t want to go back there.”

Providing compassionate and comprehensive care to gender-nonconforming individuals is challenging for a multitude of reasons, from clinician ignorance to systemic discrimination. About 33% of transgender patients reported being harassed, denied care, or even being assaulted when seeking health care, while 23% reported avoiding going to the doctor altogether when sick or injured out of fear of discrimination.1

Unfortunately, now, further increases to barriers to care may be put in place. In late May of this year, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) proposed new regulations that would reverse previous regulations granted through section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA)—the Health Care Rights Law—which affirmed the rights of gender nonbinary persons to medical care. Among the proposed changes is the elimination of protections against discrimination in health care based on gender identity.2 The proposed regulation changes come on the heels of a federal court case, which seeks to declare that hospital systems may turn away patients based on gender identity.3

Unraveling rights afforded under the ACA

The Health Care Rights Law was passed under the ACA; it prohibits discrimination based on race, color, national origin, sex, age, and disability in health programs and activities receiving federal financial assistance. Multiple lower courts have supported that the rights of transgender individuals is included within these protections against discrimination on the basis of sex.4 These court rulings not only have ensured the ability of gender-diverse individuals to access care but also have enforced insurance coverage of therapies for gender dysphoria. It was only in 2014 that Medicaid began providing coverage for gender-affirming surgeries and eliminating language that such procedures were “experimental” or “cosmetic.” The 2016 passage of the ACA mandated that private insurance companies follow suit. Unfortunately, the recent proposed regulation changes to the Health Care Rights Law may spark a reversal from insurance companies as well. Such a setback would affect gender-diverse individuals’ hormone treatments as well as their ability to access a full spectrum of care within the health care system.

Continue to: ACOG urges nondiscriminatory practices...

ACOG urges nondiscriminatory practices

The proposed regulation changes to the Health Care Rights Law are from the Conscience and Religious Freedom Division of the HHS Office for Civil Rights, which was established in 2018 and has been advocating for the rights of health care providers to refuse to treat patients based on their own religious beliefs.5 We argue, however, that providing care to persons of varying backgrounds is not an assault on our individual liberties but rather a privilege as providers. As obstetrician-gynecologists, it may be easy to only consider cis-gendered women our responsibility. But our field also emphasizes individual empowerment above all else—we fight every day for our patients’ rights to contraception, fertility, pregnancy, parenthood, and sexual freedoms. Let us continue speaking up for the rights of all those who need gynecologic care, regardless of the pronouns they use.

“The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists urges health care providers to foster nondiscriminatory practices and policies to increase identification and to facilitate quality health care for transgender individuals, both in assisting with the transition if desired as well as providing long-term preventive health care.”6

We urge you to take action

- Reach out to your local representatives about protecting transgender health access

- Educate yourself on the unique needs of transgender individuals

- Read personal accounts

- Share your personal story

- Find referring providers near your practice

- 2015 US Transgender Survey. December 2016. https://www.transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/USTS-Full-Report-FINAL.PDF. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- Musumeci M, Kates J, Dawson J, et al. HHS’ proposed changes to non-discrimination regulations under ACA section 1557. July 1, 2019. https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/hhss-proposed-changes-to-non-discrimination-regulations-under-aca-section-1557/. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- Franciscan Alliance v. Burwell. ACLU website. https://www.aclu.org/cases/franciscan-alliance-v-burwell. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- Pear R. Trump plan would cut back health care protections for transgender people. April 21, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/21/us/politics/trump-transgender-health-care.html. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. HHS announces new conscience and religious freedom division. January 18, 2018. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2018/01/18/hhs-ocr-announces-new-conscience-and-religious-freedom-division.html. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Committee Opinion no. 512: health care for transgender individuals. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1454–1458.

- 2015 US Transgender Survey. December 2016. https://www.transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/USTS-Full-Report-FINAL.PDF. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- Musumeci M, Kates J, Dawson J, et al. HHS’ proposed changes to non-discrimination regulations under ACA section 1557. July 1, 2019. https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/hhss-proposed-changes-to-non-discrimination-regulations-under-aca-section-1557/. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- Franciscan Alliance v. Burwell. ACLU website. https://www.aclu.org/cases/franciscan-alliance-v-burwell. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- Pear R. Trump plan would cut back health care protections for transgender people. April 21, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/21/us/politics/trump-transgender-health-care.html. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. HHS announces new conscience and religious freedom division. January 18, 2018. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2018/01/18/hhs-ocr-announces-new-conscience-and-religious-freedom-division.html. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Committee Opinion no. 512: health care for transgender individuals. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1454–1458.

Medical Cannabis: Not just a passing fad

In this issue of JFP, Weinstein and Worster provide a wealth of information about prescribing marijuana. Medical marijuana (Cannabis) is now legal in the majority of states, so it’s likely that some of your patients are using marijuana for symptom relief. For those physicians who elect to prescribe marijuana, reading this review will help you avoid harming patients while maximizing potential benefits.

I say “potential benefits” because the research evidence to support benefit for most conditions and symptoms is weak at best. In addition to the JAMA meta-analysis cited by Weinstein and Worster,1 several meta-analyses and systematic reviews published since January 2018 reach similar conclusions.2-4

Marijuana can provide significant relief from chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, and it is effective in reducing intractable seizures in 2 rare pediatric seizure disorders. There may be some benefit for treatment of spasticity, and there may be some therapeutic value for relief of neuropathic pain, although the evidence is not strong. Interestingly, there is some preliminary evidence that cannabis can improve gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis.5,6

Why do people use marijuana as medicine? A meta-analysis found that pain (64%), anxiety (50%), and depression/mood (34%) were common reasons.7 People use marijuana for a plethora of other conditions and symptoms, which is reflected in the long list of “approved” conditions in most state medical marijuana laws. The problem I have with prescribing cannabis for non-neuropathic pain, anxiety, and depression is that there is no good randomized trial evidence of its effectiveness beyond a placebo effect (which is probably quite strong considering the psychotropic effects of marijuana). And, as Weinstein and Worster point out, there is evidence of increased mental health symptoms in chronic marijuana users.

Regardless of the scientific evidence, use of cannabis for symptom relief is unlikely to be a passing fad. Surveys show that about 70% of users believe they receive benefit from it.8 Therefore, it behooves us to be prepared to discuss the pros and cons of cannabis use with our patients—even if we decide not to prescribe it. Warn patients with anxiety and depression that it is unlikely to be effective and may make matters worse.

There is intense interest in medical marijuana and better research will likely change the way we use cannabis for medical purposes in the future. So, for now, our best approach is to stay informed as the research unfolds.

1. Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313:2456-2473.

2. Allan GM, Finley CR, Ton J, et al. Systematic review of systematic reviews for medical cannabinoids: pain, nausea and vomiting, spasticity, and harms. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64:E78-E94.

3. Abrams DI. The therapeutic effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: an update from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine report. Eur J Intern Med. 2018;49:7-11.

4. Mücke M, Phillips T, Radbruch L, et al. Cannabis-based medicines for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;3:CD012182.

5. Kafil TS, Nguyen TM, MacDonald JK, et al. Cannabis for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;11:CD012853.

6. Kafil TS, Nguyen TM, MacDonald JK, et al. Cannabis for the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;11:CD012954.

7. Kosiba JD, Maisto SA, Ditre JW. Patient-reported use of medical cannabis for pain, anxiety, and depression symptoms: systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2019;233:181-192.

8. Park JY, Wu LT. Prevalence, reasons, perceived effects, and correlates of medical marijuana use: a review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;177:1–13. Epub 2017 May 16.

In this issue of JFP, Weinstein and Worster provide a wealth of information about prescribing marijuana. Medical marijuana (Cannabis) is now legal in the majority of states, so it’s likely that some of your patients are using marijuana for symptom relief. For those physicians who elect to prescribe marijuana, reading this review will help you avoid harming patients while maximizing potential benefits.

I say “potential benefits” because the research evidence to support benefit for most conditions and symptoms is weak at best. In addition to the JAMA meta-analysis cited by Weinstein and Worster,1 several meta-analyses and systematic reviews published since January 2018 reach similar conclusions.2-4

Marijuana can provide significant relief from chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, and it is effective in reducing intractable seizures in 2 rare pediatric seizure disorders. There may be some benefit for treatment of spasticity, and there may be some therapeutic value for relief of neuropathic pain, although the evidence is not strong. Interestingly, there is some preliminary evidence that cannabis can improve gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis.5,6

Why do people use marijuana as medicine? A meta-analysis found that pain (64%), anxiety (50%), and depression/mood (34%) were common reasons.7 People use marijuana for a plethora of other conditions and symptoms, which is reflected in the long list of “approved” conditions in most state medical marijuana laws. The problem I have with prescribing cannabis for non-neuropathic pain, anxiety, and depression is that there is no good randomized trial evidence of its effectiveness beyond a placebo effect (which is probably quite strong considering the psychotropic effects of marijuana). And, as Weinstein and Worster point out, there is evidence of increased mental health symptoms in chronic marijuana users.

Regardless of the scientific evidence, use of cannabis for symptom relief is unlikely to be a passing fad. Surveys show that about 70% of users believe they receive benefit from it.8 Therefore, it behooves us to be prepared to discuss the pros and cons of cannabis use with our patients—even if we decide not to prescribe it. Warn patients with anxiety and depression that it is unlikely to be effective and may make matters worse.

There is intense interest in medical marijuana and better research will likely change the way we use cannabis for medical purposes in the future. So, for now, our best approach is to stay informed as the research unfolds.

In this issue of JFP, Weinstein and Worster provide a wealth of information about prescribing marijuana. Medical marijuana (Cannabis) is now legal in the majority of states, so it’s likely that some of your patients are using marijuana for symptom relief. For those physicians who elect to prescribe marijuana, reading this review will help you avoid harming patients while maximizing potential benefits.

I say “potential benefits” because the research evidence to support benefit for most conditions and symptoms is weak at best. In addition to the JAMA meta-analysis cited by Weinstein and Worster,1 several meta-analyses and systematic reviews published since January 2018 reach similar conclusions.2-4

Marijuana can provide significant relief from chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, and it is effective in reducing intractable seizures in 2 rare pediatric seizure disorders. There may be some benefit for treatment of spasticity, and there may be some therapeutic value for relief of neuropathic pain, although the evidence is not strong. Interestingly, there is some preliminary evidence that cannabis can improve gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis.5,6

Why do people use marijuana as medicine? A meta-analysis found that pain (64%), anxiety (50%), and depression/mood (34%) were common reasons.7 People use marijuana for a plethora of other conditions and symptoms, which is reflected in the long list of “approved” conditions in most state medical marijuana laws. The problem I have with prescribing cannabis for non-neuropathic pain, anxiety, and depression is that there is no good randomized trial evidence of its effectiveness beyond a placebo effect (which is probably quite strong considering the psychotropic effects of marijuana). And, as Weinstein and Worster point out, there is evidence of increased mental health symptoms in chronic marijuana users.

Regardless of the scientific evidence, use of cannabis for symptom relief is unlikely to be a passing fad. Surveys show that about 70% of users believe they receive benefit from it.8 Therefore, it behooves us to be prepared to discuss the pros and cons of cannabis use with our patients—even if we decide not to prescribe it. Warn patients with anxiety and depression that it is unlikely to be effective and may make matters worse.

There is intense interest in medical marijuana and better research will likely change the way we use cannabis for medical purposes in the future. So, for now, our best approach is to stay informed as the research unfolds.

1. Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313:2456-2473.

2. Allan GM, Finley CR, Ton J, et al. Systematic review of systematic reviews for medical cannabinoids: pain, nausea and vomiting, spasticity, and harms. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64:E78-E94.

3. Abrams DI. The therapeutic effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: an update from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine report. Eur J Intern Med. 2018;49:7-11.

4. Mücke M, Phillips T, Radbruch L, et al. Cannabis-based medicines for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;3:CD012182.

5. Kafil TS, Nguyen TM, MacDonald JK, et al. Cannabis for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;11:CD012853.

6. Kafil TS, Nguyen TM, MacDonald JK, et al. Cannabis for the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;11:CD012954.

7. Kosiba JD, Maisto SA, Ditre JW. Patient-reported use of medical cannabis for pain, anxiety, and depression symptoms: systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2019;233:181-192.

8. Park JY, Wu LT. Prevalence, reasons, perceived effects, and correlates of medical marijuana use: a review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;177:1–13. Epub 2017 May 16.

1. Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313:2456-2473.

2. Allan GM, Finley CR, Ton J, et al. Systematic review of systematic reviews for medical cannabinoids: pain, nausea and vomiting, spasticity, and harms. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64:E78-E94.

3. Abrams DI. The therapeutic effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: an update from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine report. Eur J Intern Med. 2018;49:7-11.

4. Mücke M, Phillips T, Radbruch L, et al. Cannabis-based medicines for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;3:CD012182.

5. Kafil TS, Nguyen TM, MacDonald JK, et al. Cannabis for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;11:CD012853.

6. Kafil TS, Nguyen TM, MacDonald JK, et al. Cannabis for the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;11:CD012954.

7. Kosiba JD, Maisto SA, Ditre JW. Patient-reported use of medical cannabis for pain, anxiety, and depression symptoms: systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2019;233:181-192.

8. Park JY, Wu LT. Prevalence, reasons, perceived effects, and correlates of medical marijuana use: a review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;177:1–13. Epub 2017 May 16.

Women with epilepsy: 5 clinical pearls for contraception and preconception counseling

In 2015, 1.2% of the US population was estimated to have active epilepsy.1 For neurologists, key goals in the treatment of epilepsy include: controlling seizures, minimizing adverse effects of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) and optimizing quality of life. For obstetrician-gynecologists, women with epilepsy (WWE) have unique contraceptive, preconception, and obstetric needs that require highly specialized approaches to care. Here, I highlight 5 care points that are important to keep in mind when counseling WWE.

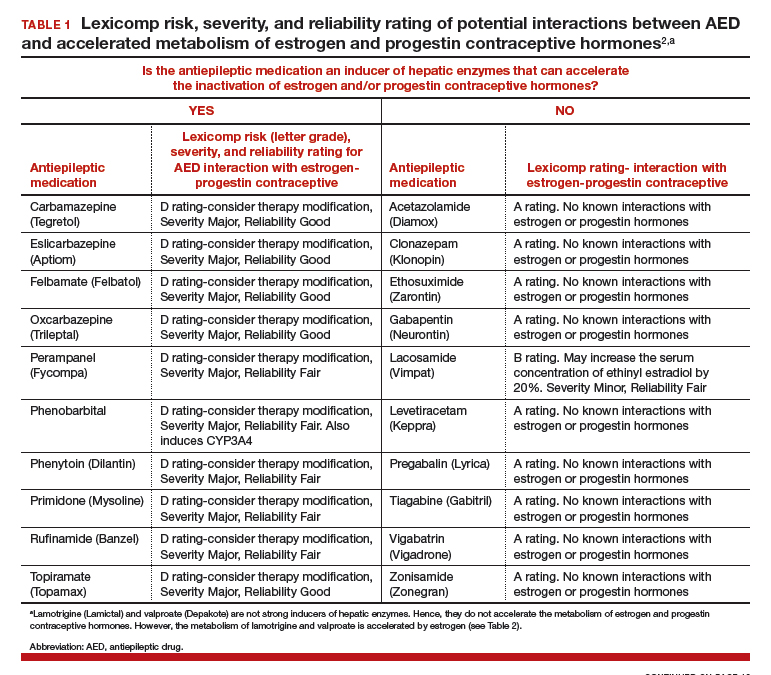

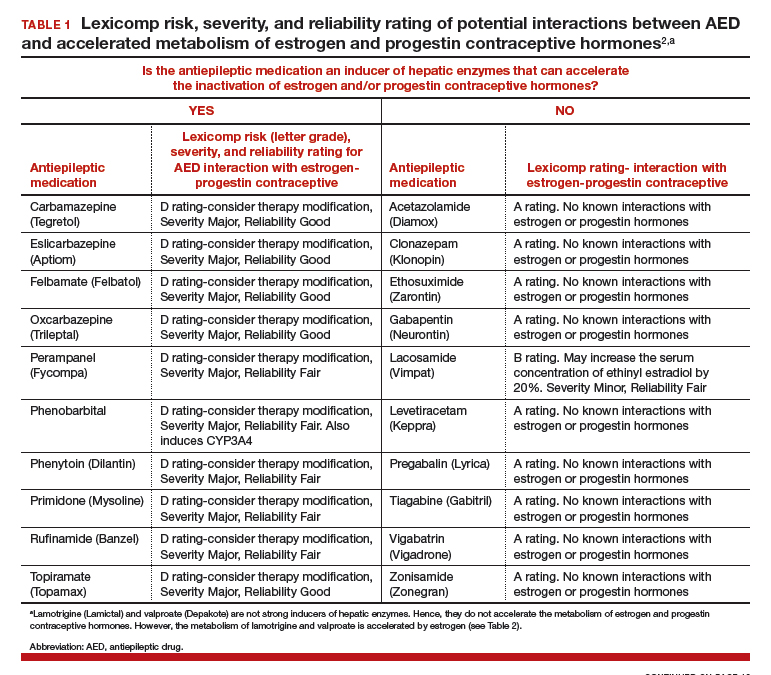

1. Enzyme-inducing AEDs reduce the effectiveness of estrogen-progestin and some progestin contraceptives.

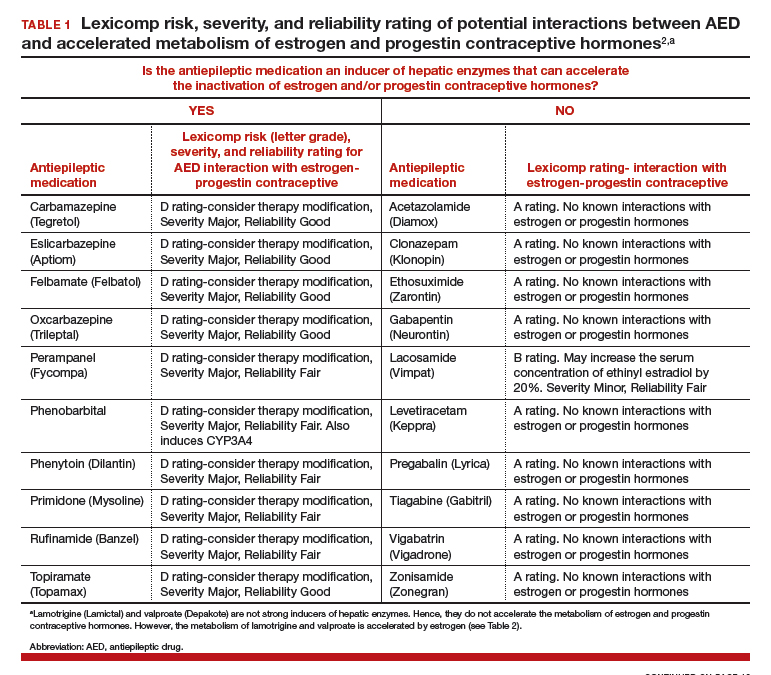

AEDs can induce hepatic enzymes that accelerate steroid hormone metabolism, producing clinically important reductions in bioavailable steroid hormone concentration (TABLE 1). According to Lexicomp, AEDs that are inducers of hepatic enzymes that metabolize steroid hormones include: carbamazepine (Tegretol), eslicarbazepine (Aptiom), felbamate (Felbatol), oxcarbazepine (Trileptal), perampanel (Fycompa), phenobarbital, phenytoin (Dilantin), primidone (Mysoline), rufinamide (Banzel), and topiramate (Topamax) (at dosages >200 mg daily). According to Lexicomp, the following AEDs do not cause clinically significant changes in hepatic enzymes that metabolize steroid hormones: acetazolamide (Diamox), clonazepam (Klonopin), ethosuximide (Zarontin), gabapentin (Neurontin), lacosamide (Vimpat), levetiracetam (Keppra), pregabalin (Lyrica), tiagabine (Gabitril), vigabatrin (Vigadrone), and zonisamide (Zonegran).2,3 In addition, lamotrigine (Lamictal) and valproate (Depakote) do not significantly influence the metabolism of contraceptive steroids,4,5 but contraceptive steroids significantly influence their metabolism (TABLE 2).

For WWE taking an AED that accelerates steroid hormone metabolism, estrogen-progestin contraceptive failure is common. In a survey of 111 WWE taking both an oral contraceptive and an AED, 27 reported becoming pregnant while taking the oral contraceptive.6 Carbamazepine, a strong inducer of hepatic enzymes, was the most frequently used AED in this sample.

Many studies report that carbamazepine accelerates the metabolisms of estrogen and progestins and reduces contraceptive efficacy. For example, in one study 20 healthy women were administered an ethinyl estradiol (20 µg)-levonorgestrel (100 µg) contraceptive, and randomly assigned to either receive carbamazepine 600 mg daily or a placebo pill.7 In this study, based on serum progesterone measurements, 5 of 10 women in the carbamazepine group ovulated, compared with 1 of 10 women in the placebo group. Women taking carbamazepine had integrated serum ethinyl estradiol and levonorgestrel concentrations approximately 45% lower than women taking placebo.7 Other studies also report that carbamazepine accelerates steroid hormone metabolism and reduces the circulating concentration of ethinyl estradiol, norethindrone, and levonorgestrel by about 50%.5,8

WWE taking an AED that induces hepatic enzymes should be counseled to use a copper or levonorgestrel (LNG) intrauterine device (IUD) or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) for contraception.9 WWE taking AEDs that do not induce hepatic enzymes can be offered the full array of contraceptive options, as outlined in Table 1. Occasionally, a WWE taking an AED that is an inducer of hepatic enzymes may strongly prefer to use an estrogen-progestin contraceptive and decline the preferred option of using an IUD or DMPA. If an estrogen-progestin contraceptive is to be prescribed, safeguards to reduce the risk of pregnancy include:

- prescribe a contraceptive with ≥35 µg of ethinyl estradiol

- prescribe a contraceptive with the highest dose of progestin with a long half-life (drospirenone, desogestrel, levonorgestrel)

- consider continuous hormonal contraception rather than 4 or 7 days off hormones and

- recommend use of a barrier contraceptive in addition to the hormonal contraceptive.

The effectiveness of levonorgestrel emergency contraception may also be reduced in WWE taking an enzyme-inducing AED. In these cases, some experts recommend a regimen of two doses of levonorgestrel 1.5 mg, separated by 12 hours.10 The effectiveness of progestin subdermal contraceptives may be reduced in women taking phenytoin. In one study of 9 WWE using a progestin subdermal implant, phenytoin reduced the circulating levonorgestrel level by approximately 40%.11

Continue to: 2. Do not use lamotrigine with cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptives...

2. Do not use lamotrigine with cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptives.

Estrogens, but not progestins, are known to reduce the serum concentration of lamotrigine by about 50%.12,13 This is a clinically significant pharmacologic interaction. Consequently, when a cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptive is prescribed to a woman taking lamotrigine, oscillation in lamotrigine serum concentration can occur. When the woman is taking estrogen-containing pills, lamotrigine levels decrease, which increases the risk of seizure. When the woman is not taking the estrogen-containing pills, lamotrigine levels increase, possibly causing such adverse effects as nausea and vomiting. If a woman taking lamotrigine insists on using an estrogen-progestin contraceptive, the medication should be prescribed in a continuous regimen and the neurologist alerted so that they can increase the dose of lamotrigine and intensify their monitoring of lamotrigine levels. Lamotrigine does not change the metabolism of ethinyl estradiol and has minimal impact on the metabolism of levonorgestrel.4

3. Estrogen-progestin contraceptives require valproate dosage adjustment.

A few studies report that estrogen-progestin contraceptives accelerate the metabolism of valproate and reduce circulating valproate concentration,14,15 as noted in Table 2.In one study, estrogen-progestin contraceptive was associated with 18% and 29% decreases in total and unbound valproate concentrations, respectively.14 Valproate may induce polycystic ovary syndrome in women.16 Therefore, it is common that valproate and an estrogen-progestin contraceptive are co-prescribed. In these situations, the neurologist should be alerted prior to prescribing an estrogen-progestin contraceptive to WWE taking valproate so that dosage adjustment may occur, if indicated. Valproate does not appear to change the metabolism of ethinyl estradiol or levonorgestrel.5

4. Preconception counseling: Before conception consider using an AED with low teratogenicity.

Valproate is a potent teratogen, and consideration should be given to discontinuing valproate prior to conception. In a study of 1,788 pregnancies exposed to valproate, the risk of a major congenital malformation was 10% for valproate monotherapy, 11.3% for valproate combined with lamotrigine, and 11.7% for valproate combined with another AED, but not lamotrigine.17 At a valproate dose of ≥1,500 mg daily, the risk of major malformation was 24% for valproate monotherapy, 31% for valproate plus lamotrigine, and 19% for valproate plus another AED, but not lamotrigine.17 Valproate is reported to be associated with the following major congenital malformations: spina bifida, ventricular and atrial septal defects, pulmonary valve atresia, hypoplastic left heart syndrome, cleft palate, anorectal atresia, and hypospadias.18

In a study of 7,555 pregnancies in women using a single AED, the risk of major congenital anomalies varied greatly among the AEDs, including: valproate (10.3%), phenobarbital (6.5%), phenytoin (6.4%), carbamazepine (5.5%), topiramate (3.9%), oxcarbazepine (3.0%), lamotrigine (2.9%), and levetiracetam (2.8%).19 For WWE considering pregnancy, many experts recommend use of lamotrigine, levetiracetam, or oxcarbazepine to minimize the risk of fetal anomalies.

Continue to: 5. Folic acid...

5. Folic acid: Although the optimal dose for WWE taking an AED and planning to become pregnant is unknown, a high dose is reasonable.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that women planning pregnancy take 0.4 mg of folic acid daily, starting at least 1 month before pregnancy and continuing through at least the 12th week of gestation.20 ACOG also recommends that women at high risk of a neural tube defect should take 4 mg of folic acid daily. WWE taking a teratogenic AED are known to be at increased risk for fetal malformations, including neural tube defects. Should these women take 4 mg of folic acid daily? ACOG notes that, for women taking valproate, the benefit of high-dose folic acid (4 mg daily) has not been definitively proven,21 and guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology do not recommend high-dose folic acid for women receiving AEDs.22 Hence, ACOG does not recommend that WWE taking an AED take high-dose folic acid.

By contrast, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RCOG) recommends that all WWE planning a pregnancy take folic acid 5 mg daily, initiated 3 months before conception and continued through the first trimester of pregnancy.23 The RCOG notes that among WWE taking an AED, intelligence quotient is greater in children whose mothers took folic acid during pregnancy.24 Given the potential benefit of folic acid on long-term outcomes and the known safety of folic acid, it is reasonable to recommend high-dose folic acid for WWE.

Final takeaways

Surveys consistently report that WWE have a low-level of awareness about the interaction between AEDs and hormonal contraceptives and the teratogenicity of AEDs. For example, in a survey of 2,000 WWE, 45% who were taking an enzyme-inducing AED and an estrogen-progestin oral contraceptive reported that they had not been warned about the potential interaction between the medications.25 Surprisingly, surveys of neurologists and obstetrician-gynecologists also report that there is a low level of awareness about the interaction between AEDs and hormonal contraceptives.26 When providing contraceptive counseling for WWE, prioritize the use of a copper or levonorgestrel IUD. When providing preconception counseling for WWE, educate the patient about the high teratogenicity of valproate and the lower risk of malformations associated with the use of lamotrigine, levetiracetam, and oxcarbazepine.

For most women with epilepsy, maintaining a valid driver's license is important for completion of daily life tasks. Most states require that a patient with seizures be seizure-free for 6 to 12 months to operate a motor vehicle. Estrogen-containing hormonal contraceptives can reduce the concentration of some AEDs, such as lamotrigine. Hence, it is important that the patient be aware of this interaction and that the primary neurologist be alerted if an estrogen-containing contraceptive is prescribed to a woman taking lamotrigine or valproate. Specific state laws related to epilepsy and driving are available at the Epilepsy Foundation website (https://www.epilepsy.com/driving-laws).

- Zack MM, Kobau R. National and state estimates of the numbers of adults and children with active epilepsy - United States 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:821-825.

- Lexicomp. https://www.wolterskluwercdi.com/lexicomp-online/. Accessed August 16, 2019.

- Reimers A, Brodtkorb E, Sabers A. Interactions between hormonal contraception and antiepileptic drugs: clinical and mechanistic considerations. Seizure. 2015;28:66-70.

- Sidhu J, Job S, Singh S, et al. The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic consequences of the co-administration of lamotrigine and a combined oral contraceptive in healthy female subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61:191-199.

- Crawford P, Chadwick D, Cleland P, et al. The lack of effect of sodium valproate on the pharmacokinetics of oral contraceptive steroids. Contraception. 1986;33:23-29.

- Fairgrieve SD, Jackson M, Jonas P, et al. Population-based, prospective study of the care of women with epilepsy in pregnancy. BMJ. 2000;321:674-675.

- Davis AR, Westhoff CL, Stanczyk FZ. Carbamazepine coadministration with an oral contraceptive: effects on steroid pharmacokinetics, ovulation, and bleeding. Epilepsia. 2011;52:243-247.

- Doose DR, Wang SS, Padmanabhan M, et al. Effect of topiramate or carbamazepine on the pharmacokinetics of an oral contraceptive containing norethindrone and ethinyl estradiol in healthy obese and nonobese female subjects. Epilepsia. 2003;44:540-549.

- Vieira CS, Pack A, Roberts K, et al. A pilot study of levonorgestrel concentrations and bleeding patterns in women with epilepsy using a levonorgestrel IUD and treated with antiepileptic drugs. Contraception. 2019;99:251-255.

- O'Brien MD, Guillebaud J. Contraception for women with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2006;47:1419-1422.

- Haukkamaa M. Contraception by Norplant subdermal capsules is not reliable in epileptic patients on anticonvulsant treatment. Contraception. 1986;33:559-565.

- Sabers A, Buchholt JM, Uldall P, et al. Lamotrigine plasma levels reduced by oral contraceptives. Epilepsy Res. 2001;47:151-154.

- Reimers A, Helde G, Brodtkorb E. Ethinyl estradiol, not progestogens, reduces lamotrigine serum concentrations. Epilepsia. 2005;46:1414-1417.

- Galimberti CA, Mazzucchelli I, Arbasino C, et al. Increased apparent oral clearance of valproic acid during intake of combined contraceptive steroids in women with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2006;47:1569-1572.

- Herzog AG, Farina EL, Blum AS. Serum valproate levels with oral contraceptive use. Epilepsia. 2005;46:970-971.

- Morrell MJ, Hayes FJ, Sluss PM, et al. Hyperandrogenism, ovulatory dysfunction, and polycystic ovary syndrome with valproate versus lamotrigine. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:200-211.

- Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E, et al; EURAP Study Group. Dose-dependent teratogenicity of valproate in mono- and polytherapy: an observational study. Neurology. 2015;85:866-872.

- Blotière PO, Raguideau F, Weill A, et al. Risks of 23 specific malformations associated with prenatal exposure to 10 antiepileptic drugs. Neurology. 2019;93:e167-e180.

- Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E, et al; EURAP Study Group. Comparative risk of major congenital malformations with eight different antiepileptic drugs: a prospective cohort study of the EURAP registry. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:530-538.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 187: neural tube defects. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e279-e290.

- Ban L, Fleming KM, Doyle P, et al. Congenital anomalies in children of mothers taking antiepileptic drugs with and without periconceptional high dose folic acid use: a population-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131130.

- Harden CL, Pennell PB, Koppel BS, et al; American Academy of Neurology and American Epilepsy Society. Practice parameter update: management issues for women with epilepsy--focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): vitamin K, folic acid, blood levels, and breastfeeding: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee and Therapeutics and technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2009;73:142-149.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Epilepsy in pregnancy. Green-top Guideline No. 68; June 2016. https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/green-top-guidelines/gtg68_epilepsy.pdf. Accessed August 16, 2019.

- Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N, et al; NEAD Study Group. Fetal antiepileptic drug exposure and cognitive outcomes at age 6 years (NEAD study): a prospective observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:244-252.

- Crawford P, Hudson S. Understanding the information needs of women with epilepsy at different life stages: results of the 'Ideal World' survey. Seizure. 2003;12:502-507.

- Krauss GL, Brandt J, Campbell M, et al. Antiepileptic medication and oral contraceptive interactions: a national survey of neurologists and obstetricians. Neurology. 1996;46:1534-1539.

In 2015, 1.2% of the US population was estimated to have active epilepsy.1 For neurologists, key goals in the treatment of epilepsy include: controlling seizures, minimizing adverse effects of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) and optimizing quality of life. For obstetrician-gynecologists, women with epilepsy (WWE) have unique contraceptive, preconception, and obstetric needs that require highly specialized approaches to care. Here, I highlight 5 care points that are important to keep in mind when counseling WWE.

1. Enzyme-inducing AEDs reduce the effectiveness of estrogen-progestin and some progestin contraceptives.

AEDs can induce hepatic enzymes that accelerate steroid hormone metabolism, producing clinically important reductions in bioavailable steroid hormone concentration (TABLE 1). According to Lexicomp, AEDs that are inducers of hepatic enzymes that metabolize steroid hormones include: carbamazepine (Tegretol), eslicarbazepine (Aptiom), felbamate (Felbatol), oxcarbazepine (Trileptal), perampanel (Fycompa), phenobarbital, phenytoin (Dilantin), primidone (Mysoline), rufinamide (Banzel), and topiramate (Topamax) (at dosages >200 mg daily). According to Lexicomp, the following AEDs do not cause clinically significant changes in hepatic enzymes that metabolize steroid hormones: acetazolamide (Diamox), clonazepam (Klonopin), ethosuximide (Zarontin), gabapentin (Neurontin), lacosamide (Vimpat), levetiracetam (Keppra), pregabalin (Lyrica), tiagabine (Gabitril), vigabatrin (Vigadrone), and zonisamide (Zonegran).2,3 In addition, lamotrigine (Lamictal) and valproate (Depakote) do not significantly influence the metabolism of contraceptive steroids,4,5 but contraceptive steroids significantly influence their metabolism (TABLE 2).

For WWE taking an AED that accelerates steroid hormone metabolism, estrogen-progestin contraceptive failure is common. In a survey of 111 WWE taking both an oral contraceptive and an AED, 27 reported becoming pregnant while taking the oral contraceptive.6 Carbamazepine, a strong inducer of hepatic enzymes, was the most frequently used AED in this sample.

Many studies report that carbamazepine accelerates the metabolisms of estrogen and progestins and reduces contraceptive efficacy. For example, in one study 20 healthy women were administered an ethinyl estradiol (20 µg)-levonorgestrel (100 µg) contraceptive, and randomly assigned to either receive carbamazepine 600 mg daily or a placebo pill.7 In this study, based on serum progesterone measurements, 5 of 10 women in the carbamazepine group ovulated, compared with 1 of 10 women in the placebo group. Women taking carbamazepine had integrated serum ethinyl estradiol and levonorgestrel concentrations approximately 45% lower than women taking placebo.7 Other studies also report that carbamazepine accelerates steroid hormone metabolism and reduces the circulating concentration of ethinyl estradiol, norethindrone, and levonorgestrel by about 50%.5,8

WWE taking an AED that induces hepatic enzymes should be counseled to use a copper or levonorgestrel (LNG) intrauterine device (IUD) or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) for contraception.9 WWE taking AEDs that do not induce hepatic enzymes can be offered the full array of contraceptive options, as outlined in Table 1. Occasionally, a WWE taking an AED that is an inducer of hepatic enzymes may strongly prefer to use an estrogen-progestin contraceptive and decline the preferred option of using an IUD or DMPA. If an estrogen-progestin contraceptive is to be prescribed, safeguards to reduce the risk of pregnancy include:

- prescribe a contraceptive with ≥35 µg of ethinyl estradiol

- prescribe a contraceptive with the highest dose of progestin with a long half-life (drospirenone, desogestrel, levonorgestrel)

- consider continuous hormonal contraception rather than 4 or 7 days off hormones and

- recommend use of a barrier contraceptive in addition to the hormonal contraceptive.

The effectiveness of levonorgestrel emergency contraception may also be reduced in WWE taking an enzyme-inducing AED. In these cases, some experts recommend a regimen of two doses of levonorgestrel 1.5 mg, separated by 12 hours.10 The effectiveness of progestin subdermal contraceptives may be reduced in women taking phenytoin. In one study of 9 WWE using a progestin subdermal implant, phenytoin reduced the circulating levonorgestrel level by approximately 40%.11

Continue to: 2. Do not use lamotrigine with cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptives...

2. Do not use lamotrigine with cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptives.

Estrogens, but not progestins, are known to reduce the serum concentration of lamotrigine by about 50%.12,13 This is a clinically significant pharmacologic interaction. Consequently, when a cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptive is prescribed to a woman taking lamotrigine, oscillation in lamotrigine serum concentration can occur. When the woman is taking estrogen-containing pills, lamotrigine levels decrease, which increases the risk of seizure. When the woman is not taking the estrogen-containing pills, lamotrigine levels increase, possibly causing such adverse effects as nausea and vomiting. If a woman taking lamotrigine insists on using an estrogen-progestin contraceptive, the medication should be prescribed in a continuous regimen and the neurologist alerted so that they can increase the dose of lamotrigine and intensify their monitoring of lamotrigine levels. Lamotrigine does not change the metabolism of ethinyl estradiol and has minimal impact on the metabolism of levonorgestrel.4

3. Estrogen-progestin contraceptives require valproate dosage adjustment.

A few studies report that estrogen-progestin contraceptives accelerate the metabolism of valproate and reduce circulating valproate concentration,14,15 as noted in Table 2.In one study, estrogen-progestin contraceptive was associated with 18% and 29% decreases in total and unbound valproate concentrations, respectively.14 Valproate may induce polycystic ovary syndrome in women.16 Therefore, it is common that valproate and an estrogen-progestin contraceptive are co-prescribed. In these situations, the neurologist should be alerted prior to prescribing an estrogen-progestin contraceptive to WWE taking valproate so that dosage adjustment may occur, if indicated. Valproate does not appear to change the metabolism of ethinyl estradiol or levonorgestrel.5

4. Preconception counseling: Before conception consider using an AED with low teratogenicity.

Valproate is a potent teratogen, and consideration should be given to discontinuing valproate prior to conception. In a study of 1,788 pregnancies exposed to valproate, the risk of a major congenital malformation was 10% for valproate monotherapy, 11.3% for valproate combined with lamotrigine, and 11.7% for valproate combined with another AED, but not lamotrigine.17 At a valproate dose of ≥1,500 mg daily, the risk of major malformation was 24% for valproate monotherapy, 31% for valproate plus lamotrigine, and 19% for valproate plus another AED, but not lamotrigine.17 Valproate is reported to be associated with the following major congenital malformations: spina bifida, ventricular and atrial septal defects, pulmonary valve atresia, hypoplastic left heart syndrome, cleft palate, anorectal atresia, and hypospadias.18

In a study of 7,555 pregnancies in women using a single AED, the risk of major congenital anomalies varied greatly among the AEDs, including: valproate (10.3%), phenobarbital (6.5%), phenytoin (6.4%), carbamazepine (5.5%), topiramate (3.9%), oxcarbazepine (3.0%), lamotrigine (2.9%), and levetiracetam (2.8%).19 For WWE considering pregnancy, many experts recommend use of lamotrigine, levetiracetam, or oxcarbazepine to minimize the risk of fetal anomalies.

Continue to: 5. Folic acid...

5. Folic acid: Although the optimal dose for WWE taking an AED and planning to become pregnant is unknown, a high dose is reasonable.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that women planning pregnancy take 0.4 mg of folic acid daily, starting at least 1 month before pregnancy and continuing through at least the 12th week of gestation.20 ACOG also recommends that women at high risk of a neural tube defect should take 4 mg of folic acid daily. WWE taking a teratogenic AED are known to be at increased risk for fetal malformations, including neural tube defects. Should these women take 4 mg of folic acid daily? ACOG notes that, for women taking valproate, the benefit of high-dose folic acid (4 mg daily) has not been definitively proven,21 and guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology do not recommend high-dose folic acid for women receiving AEDs.22 Hence, ACOG does not recommend that WWE taking an AED take high-dose folic acid.

By contrast, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RCOG) recommends that all WWE planning a pregnancy take folic acid 5 mg daily, initiated 3 months before conception and continued through the first trimester of pregnancy.23 The RCOG notes that among WWE taking an AED, intelligence quotient is greater in children whose mothers took folic acid during pregnancy.24 Given the potential benefit of folic acid on long-term outcomes and the known safety of folic acid, it is reasonable to recommend high-dose folic acid for WWE.

Final takeaways

Surveys consistently report that WWE have a low-level of awareness about the interaction between AEDs and hormonal contraceptives and the teratogenicity of AEDs. For example, in a survey of 2,000 WWE, 45% who were taking an enzyme-inducing AED and an estrogen-progestin oral contraceptive reported that they had not been warned about the potential interaction between the medications.25 Surprisingly, surveys of neurologists and obstetrician-gynecologists also report that there is a low level of awareness about the interaction between AEDs and hormonal contraceptives.26 When providing contraceptive counseling for WWE, prioritize the use of a copper or levonorgestrel IUD. When providing preconception counseling for WWE, educate the patient about the high teratogenicity of valproate and the lower risk of malformations associated with the use of lamotrigine, levetiracetam, and oxcarbazepine.