User login

Breaking down blockchain: How this novel technology will unfetter health care

One evening in 2016, my 9-year-old son suggested we use Bitcoin to purchase something on the Microsoft Xbox store. Surprised by his suggestion, I was suddenly struck with two thoughts: 1) Microsoft, by accepting Bitcoin, was validating cryptocurrency as a credible form of payment, and 2) I was getting old. My 9-year-old seemed to have a better understanding of a new technology than I did, hardly the first time – or the last time – that happened. In spite of my initial feelings of defeat, I resolved not to cede victory to my son without a fight. I immediately set out to understand cryptocurrencies and, more importantly, the technology underpinning them known as blockchain.

Even just a few years ago, my ignorance of how blockchains work may have been acceptable, but it hardly seems acceptable now. Much more than just cryptocurrency, blockchain technology is beginning to affect every industry that values information sharing and security, and it is about to usher in a revolution in health care. But what are blockchains, and why are they so important?

Explaining blockchains

Blockchains were first conceptualized almost 3 decades ago, but the invention of the first blockchain as we know it today occurred in 2008 by Satoshi Nakomoto, creator of Bitcoin. Blockchains can be thought of as a way to store and communicate information while ensuring its integrity and security. Admittedly, the technology can be a bit confusing, but we’ll attempt to simplify it by focusing on a few fundamental elements.

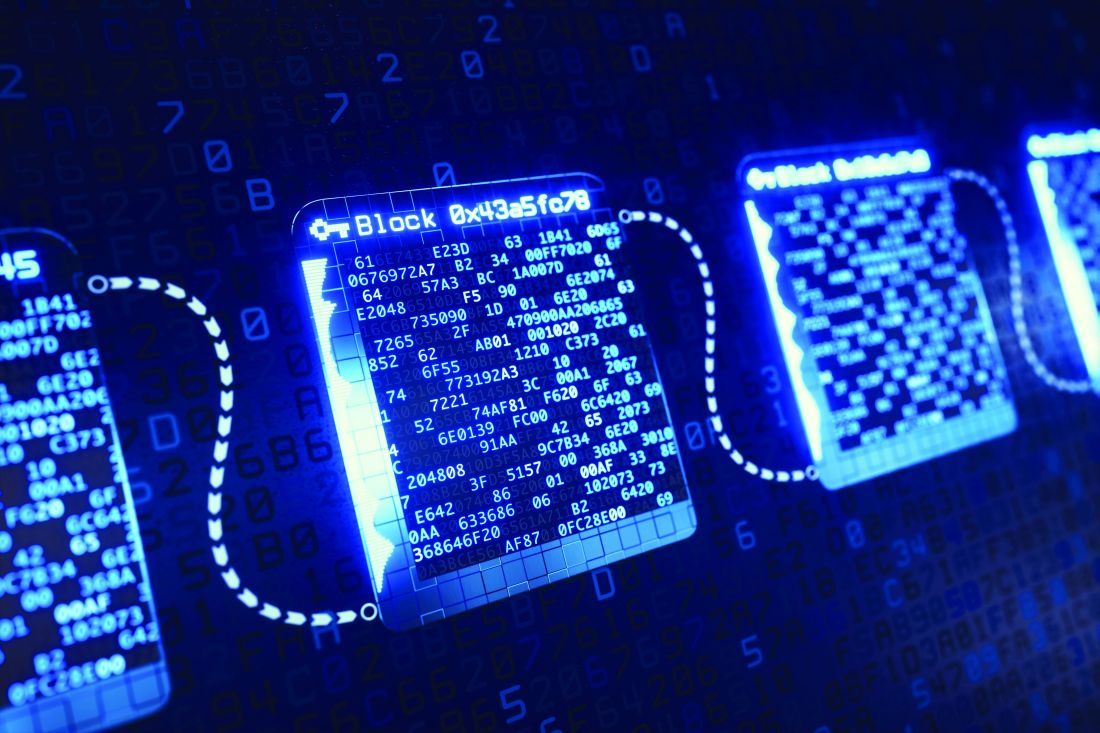

As the name indicates, the blockchain model relies on a chain of connected blocks. Each block contains some data (which can be financial, medical, legal, or anything else) and bears a unique fingerprint known as a “hash.” Each hash is different and depends entirely on the data stored in the block. In other words, if the contents of the block change, the hash changes, creating an entirely new fingerprint. Each block on the chain also keeps a record of the hash of the previous block. This “links” the chain together, and is the first key to its robust security: If any block is tampered with, its fingerprint will change and it will no longer be linked, thus invalidating all following blocks on the chain.

Ensuring the integrity of the blockchain doesn’t stop there. Just as actual fingerprints can be spoofed by enterprising criminals, hash technology isn’t enough to provide complete security. Thus, several other security features are built into blockchains, with the most noteworthy and important being “decentralization.” This means that blockchains are not stored on any single computer. On the contrary, duplicate copies of every blockchain exist on thousands of computers around the world, creating redundancy and minimizing the vulnerability that any single chain could be tampered with. Before any change in the blockchain can be made and accepted, it must be validated by a majority of the computers storing the chain.

If this all seems perplexing, that’s because it is. Blockchains are complex and difficult to visualize. (But if you’d like a deeper understanding, there are many great YouTube videos that do a great job explaining them.) For now, just remember this: Blockchains are very secure yet highly accessible, and will be essential to how data – especially health data – are stored and communicated in the future.

Blockchains in health care

On Jan. 24, 2019, five major companies (Aetna, Anthem, Health Care Services, IBM, and PNC Bank) “announced a new collaboration to design and create a network using blockchain technology to improve transparency and interoperability in the health care industry.”1 This team of industry leaders is hoping to build the engine that will power the future and impact how health records are created, maintained, and communicated. They’ll achieve this by taking advantage of blockchain’s inclusiveness and decentralization, storing records in a manner that is safe and accessible anywhere a patient seeks care. Because of the redundancy built into blockchains, they can also ensure data integrity. Physicians will benefit from information that is easy to obtain and always accurate; patients will benefit by gaining greater access and ownership of their personal medical records.

The collaboration mentioned above is the latest, but certainly not the first, attempt to exploit the benefits of blockchain for health care. Other major players have already entered the game, and the field is growing quickly. While it’s easy to find their efforts admirable, corporate involvement also means there is money to be saved or made in the space. Chris Ward, head of product for PNC Treasury Management, alluded to this as he commented publicly in the press release: “This collaboration will enable health care–related data and business transactions to occur in way that addresses market demands for transparency and security, while making it easier for the patient, payer, and provider to handle payments. Using this technology, we can remove friction, duplication, and administrative costs that continue to plague the industry.”

Industry executives recognize that interoperability is still the greatest challenge facing the future of health care and are particularly sensitive to the costs of not facing the challenge successfully. Clearly, they see an investment in blockchains as an opportunity to be part of a financially beneficial solution.

Why we should care

As we’ve now covered, there are many advantages of blockchain technology. In fact, we see it as the natural evolution of the patient-centered EHR. Instead of siloed and proprietary information spread across disparate EHRs that can’t communicate, the future of data exchange will be more transparent, yet more secure. Blockchain represents a unique opportunity to democratize the availability of health care information while increasing information quality and lowering costs. It is also shaping up to be the way we’ll exchange sensitive data in the future.

Don’t believe us? Just ask any 9-year-old.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter, @doctornotte. Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

Reference

1. https://newsroom.ibm.com/2019-01-24-Aetna-Anthem-Health-Care-Service-Corporation-PNC-Bank-and-IBM-announce-collaboration-to-establish-blockchain-based-ecosystem-for-the-healthcare-industry

One evening in 2016, my 9-year-old son suggested we use Bitcoin to purchase something on the Microsoft Xbox store. Surprised by his suggestion, I was suddenly struck with two thoughts: 1) Microsoft, by accepting Bitcoin, was validating cryptocurrency as a credible form of payment, and 2) I was getting old. My 9-year-old seemed to have a better understanding of a new technology than I did, hardly the first time – or the last time – that happened. In spite of my initial feelings of defeat, I resolved not to cede victory to my son without a fight. I immediately set out to understand cryptocurrencies and, more importantly, the technology underpinning them known as blockchain.

Even just a few years ago, my ignorance of how blockchains work may have been acceptable, but it hardly seems acceptable now. Much more than just cryptocurrency, blockchain technology is beginning to affect every industry that values information sharing and security, and it is about to usher in a revolution in health care. But what are blockchains, and why are they so important?

Explaining blockchains

Blockchains were first conceptualized almost 3 decades ago, but the invention of the first blockchain as we know it today occurred in 2008 by Satoshi Nakomoto, creator of Bitcoin. Blockchains can be thought of as a way to store and communicate information while ensuring its integrity and security. Admittedly, the technology can be a bit confusing, but we’ll attempt to simplify it by focusing on a few fundamental elements.

As the name indicates, the blockchain model relies on a chain of connected blocks. Each block contains some data (which can be financial, medical, legal, or anything else) and bears a unique fingerprint known as a “hash.” Each hash is different and depends entirely on the data stored in the block. In other words, if the contents of the block change, the hash changes, creating an entirely new fingerprint. Each block on the chain also keeps a record of the hash of the previous block. This “links” the chain together, and is the first key to its robust security: If any block is tampered with, its fingerprint will change and it will no longer be linked, thus invalidating all following blocks on the chain.

Ensuring the integrity of the blockchain doesn’t stop there. Just as actual fingerprints can be spoofed by enterprising criminals, hash technology isn’t enough to provide complete security. Thus, several other security features are built into blockchains, with the most noteworthy and important being “decentralization.” This means that blockchains are not stored on any single computer. On the contrary, duplicate copies of every blockchain exist on thousands of computers around the world, creating redundancy and minimizing the vulnerability that any single chain could be tampered with. Before any change in the blockchain can be made and accepted, it must be validated by a majority of the computers storing the chain.

If this all seems perplexing, that’s because it is. Blockchains are complex and difficult to visualize. (But if you’d like a deeper understanding, there are many great YouTube videos that do a great job explaining them.) For now, just remember this: Blockchains are very secure yet highly accessible, and will be essential to how data – especially health data – are stored and communicated in the future.

Blockchains in health care

On Jan. 24, 2019, five major companies (Aetna, Anthem, Health Care Services, IBM, and PNC Bank) “announced a new collaboration to design and create a network using blockchain technology to improve transparency and interoperability in the health care industry.”1 This team of industry leaders is hoping to build the engine that will power the future and impact how health records are created, maintained, and communicated. They’ll achieve this by taking advantage of blockchain’s inclusiveness and decentralization, storing records in a manner that is safe and accessible anywhere a patient seeks care. Because of the redundancy built into blockchains, they can also ensure data integrity. Physicians will benefit from information that is easy to obtain and always accurate; patients will benefit by gaining greater access and ownership of their personal medical records.

The collaboration mentioned above is the latest, but certainly not the first, attempt to exploit the benefits of blockchain for health care. Other major players have already entered the game, and the field is growing quickly. While it’s easy to find their efforts admirable, corporate involvement also means there is money to be saved or made in the space. Chris Ward, head of product for PNC Treasury Management, alluded to this as he commented publicly in the press release: “This collaboration will enable health care–related data and business transactions to occur in way that addresses market demands for transparency and security, while making it easier for the patient, payer, and provider to handle payments. Using this technology, we can remove friction, duplication, and administrative costs that continue to plague the industry.”

Industry executives recognize that interoperability is still the greatest challenge facing the future of health care and are particularly sensitive to the costs of not facing the challenge successfully. Clearly, they see an investment in blockchains as an opportunity to be part of a financially beneficial solution.

Why we should care

As we’ve now covered, there are many advantages of blockchain technology. In fact, we see it as the natural evolution of the patient-centered EHR. Instead of siloed and proprietary information spread across disparate EHRs that can’t communicate, the future of data exchange will be more transparent, yet more secure. Blockchain represents a unique opportunity to democratize the availability of health care information while increasing information quality and lowering costs. It is also shaping up to be the way we’ll exchange sensitive data in the future.

Don’t believe us? Just ask any 9-year-old.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter, @doctornotte. Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

Reference

1. https://newsroom.ibm.com/2019-01-24-Aetna-Anthem-Health-Care-Service-Corporation-PNC-Bank-and-IBM-announce-collaboration-to-establish-blockchain-based-ecosystem-for-the-healthcare-industry

One evening in 2016, my 9-year-old son suggested we use Bitcoin to purchase something on the Microsoft Xbox store. Surprised by his suggestion, I was suddenly struck with two thoughts: 1) Microsoft, by accepting Bitcoin, was validating cryptocurrency as a credible form of payment, and 2) I was getting old. My 9-year-old seemed to have a better understanding of a new technology than I did, hardly the first time – or the last time – that happened. In spite of my initial feelings of defeat, I resolved not to cede victory to my son without a fight. I immediately set out to understand cryptocurrencies and, more importantly, the technology underpinning them known as blockchain.

Even just a few years ago, my ignorance of how blockchains work may have been acceptable, but it hardly seems acceptable now. Much more than just cryptocurrency, blockchain technology is beginning to affect every industry that values information sharing and security, and it is about to usher in a revolution in health care. But what are blockchains, and why are they so important?

Explaining blockchains

Blockchains were first conceptualized almost 3 decades ago, but the invention of the first blockchain as we know it today occurred in 2008 by Satoshi Nakomoto, creator of Bitcoin. Blockchains can be thought of as a way to store and communicate information while ensuring its integrity and security. Admittedly, the technology can be a bit confusing, but we’ll attempt to simplify it by focusing on a few fundamental elements.

As the name indicates, the blockchain model relies on a chain of connected blocks. Each block contains some data (which can be financial, medical, legal, or anything else) and bears a unique fingerprint known as a “hash.” Each hash is different and depends entirely on the data stored in the block. In other words, if the contents of the block change, the hash changes, creating an entirely new fingerprint. Each block on the chain also keeps a record of the hash of the previous block. This “links” the chain together, and is the first key to its robust security: If any block is tampered with, its fingerprint will change and it will no longer be linked, thus invalidating all following blocks on the chain.

Ensuring the integrity of the blockchain doesn’t stop there. Just as actual fingerprints can be spoofed by enterprising criminals, hash technology isn’t enough to provide complete security. Thus, several other security features are built into blockchains, with the most noteworthy and important being “decentralization.” This means that blockchains are not stored on any single computer. On the contrary, duplicate copies of every blockchain exist on thousands of computers around the world, creating redundancy and minimizing the vulnerability that any single chain could be tampered with. Before any change in the blockchain can be made and accepted, it must be validated by a majority of the computers storing the chain.

If this all seems perplexing, that’s because it is. Blockchains are complex and difficult to visualize. (But if you’d like a deeper understanding, there are many great YouTube videos that do a great job explaining them.) For now, just remember this: Blockchains are very secure yet highly accessible, and will be essential to how data – especially health data – are stored and communicated in the future.

Blockchains in health care

On Jan. 24, 2019, five major companies (Aetna, Anthem, Health Care Services, IBM, and PNC Bank) “announced a new collaboration to design and create a network using blockchain technology to improve transparency and interoperability in the health care industry.”1 This team of industry leaders is hoping to build the engine that will power the future and impact how health records are created, maintained, and communicated. They’ll achieve this by taking advantage of blockchain’s inclusiveness and decentralization, storing records in a manner that is safe and accessible anywhere a patient seeks care. Because of the redundancy built into blockchains, they can also ensure data integrity. Physicians will benefit from information that is easy to obtain and always accurate; patients will benefit by gaining greater access and ownership of their personal medical records.

The collaboration mentioned above is the latest, but certainly not the first, attempt to exploit the benefits of blockchain for health care. Other major players have already entered the game, and the field is growing quickly. While it’s easy to find their efforts admirable, corporate involvement also means there is money to be saved or made in the space. Chris Ward, head of product for PNC Treasury Management, alluded to this as he commented publicly in the press release: “This collaboration will enable health care–related data and business transactions to occur in way that addresses market demands for transparency and security, while making it easier for the patient, payer, and provider to handle payments. Using this technology, we can remove friction, duplication, and administrative costs that continue to plague the industry.”

Industry executives recognize that interoperability is still the greatest challenge facing the future of health care and are particularly sensitive to the costs of not facing the challenge successfully. Clearly, they see an investment in blockchains as an opportunity to be part of a financially beneficial solution.

Why we should care

As we’ve now covered, there are many advantages of blockchain technology. In fact, we see it as the natural evolution of the patient-centered EHR. Instead of siloed and proprietary information spread across disparate EHRs that can’t communicate, the future of data exchange will be more transparent, yet more secure. Blockchain represents a unique opportunity to democratize the availability of health care information while increasing information quality and lowering costs. It is also shaping up to be the way we’ll exchange sensitive data in the future.

Don’t believe us? Just ask any 9-year-old.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter, @doctornotte. Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

Reference

1. https://newsroom.ibm.com/2019-01-24-Aetna-Anthem-Health-Care-Service-Corporation-PNC-Bank-and-IBM-announce-collaboration-to-establish-blockchain-based-ecosystem-for-the-healthcare-industry

Keeping Your Brain in Shape

Every year, thousands of us vow to “get in shape” by eating right and exercising. (Whether we keep that resolution is another story.) But while we view physical exercise as a way to lose or maintain weight, reduce stress, or even hone athletic skills, we seldom think about exercising one of the most important muscles in our body: the brain.

“What?” you say. “The brain is not like other muscles.” No, it’s not … and yet, it isn’t as different as we used to think. Historically (maybe histologically?), it was believed that if nerve cells in the adult brain were damaged or had died, they, unlike other cells in t

But since the late 1990s, scientists have been debunking the negative myths about our brains as we age. They are not as static and unable to change as we have been led to fear! In fact, in 1998, American and Swedish scientists demonstrated that adult humans can generate new brain cells.1,2 Moreover, the brain does replicate neurons in the hippocampus, the area in our brains that is central to learning and memory. Neurons continue to grow and change beyond the first years of development and well into adulthood.

So learning (and teaching) movements to encourage the rebuilding of our neurons is key to keeping our minds sharp. In his work, Ratey found that “our physical movements can directly influence our ability to learn, think, and remember.”3 He also tells us that exercise enhances circulation to the brain, “priming it for improved function, including mental health as well as cognitive ability.”4

No, you can’t put your brain on a treadmill to get, and help keep, it “in shape.” But you can do something to maintain mental sharpness and delay decline in mental agility. And these exercises don’t require a health club membership or special equipment. They can be done anytime, anywhere … and no one knows you are doing them!

I’m talking about neurobics, a term coined to describe exercises that keep us mentally fit.5 The purpose of these activities is to work our brains in nonroutine or unexpected ways, using all of our senses to experience, or re-experience, a common activity.

Not sure what that means? Here are some examples:

Spend time in a new environment. Go to a different park or a new store. Travel, by the way, seems to slow age-related mental decline.

Continue to: Smell new odors in the morning

Smell new odors in the morning. Have new scents, like a bottle of mint extract, ready to smell first thing in the morning, to “wake up” your brain.

Take a shower with your eyes closed. Other senses become more active when you cannot see, and a shower engages several.

Try brushing your teeth with your nondominant hand. This may be difficult for some of us—and it definitely requires full attention the first time you try it!

Learn to read braille. This is a tough one, but learning to read with your fingers definitely involves one of your senses in a new context. Or, you could try learning American Sign Language, which also uses your fingers to communicate.

Respond to a situation differently. Catch yourself in a normal, unconscious response to a situation, and choose to respond in an alternate (and preferably better) way.

Continue to: Find a new route to work

Find a new route to work. It doesn’t have to be longer, just different. You may even find a faster way to work once you break your routine.

Act confidently. In a situation you are unsure about, choose to act confidently. You’ll notice that your mind gets very active once you adopt the assumption that you will know what to do.

Distinguish coins using only your sense of touch. This brain exercise can be used to kill time while waiting for an appointment. If you really want a challenge, see if you can distinguish paper currency denominations by touch.

Leave the lights off in the house. Get around your home by memory and feel. This certainly fully engages your attention—but be careful, of course!

If you give neurobics a try, let me know what you think! Or if you have other tips for staying mentally “fit,” please share them. I can be reached at [email protected]. And thank you to my friend Gail, who suggested this topic to me!

1. Kempermann G, Gage FH. New nerve cells for the adult brain. Scientific American. 1999;280(5):38-44.

2. Eriksson PS, Perfilieva E, Björk-Eriksson T, et al. Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nature Medicine. 1998;4(11):1313-1317.

3. Ratey J. A User’s Guide to the Brain: Perception, Attention, and the Four Theaters of the Brain. New York, NY: Vintage Books; 2002.

4. Ratey J. SPARK: The Revolutionary New Science of Exercise and the Brain. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company; 2008.

5. Katz LC, Rubin M. Keep Your Brain Alive: 83 Neurobic Exercises. New York, NY: Workman Publishing Company; 1999.

Every year, thousands of us vow to “get in shape” by eating right and exercising. (Whether we keep that resolution is another story.) But while we view physical exercise as a way to lose or maintain weight, reduce stress, or even hone athletic skills, we seldom think about exercising one of the most important muscles in our body: the brain.

“What?” you say. “The brain is not like other muscles.” No, it’s not … and yet, it isn’t as different as we used to think. Historically (maybe histologically?), it was believed that if nerve cells in the adult brain were damaged or had died, they, unlike other cells in t

But since the late 1990s, scientists have been debunking the negative myths about our brains as we age. They are not as static and unable to change as we have been led to fear! In fact, in 1998, American and Swedish scientists demonstrated that adult humans can generate new brain cells.1,2 Moreover, the brain does replicate neurons in the hippocampus, the area in our brains that is central to learning and memory. Neurons continue to grow and change beyond the first years of development and well into adulthood.

So learning (and teaching) movements to encourage the rebuilding of our neurons is key to keeping our minds sharp. In his work, Ratey found that “our physical movements can directly influence our ability to learn, think, and remember.”3 He also tells us that exercise enhances circulation to the brain, “priming it for improved function, including mental health as well as cognitive ability.”4

No, you can’t put your brain on a treadmill to get, and help keep, it “in shape.” But you can do something to maintain mental sharpness and delay decline in mental agility. And these exercises don’t require a health club membership or special equipment. They can be done anytime, anywhere … and no one knows you are doing them!

I’m talking about neurobics, a term coined to describe exercises that keep us mentally fit.5 The purpose of these activities is to work our brains in nonroutine or unexpected ways, using all of our senses to experience, or re-experience, a common activity.

Not sure what that means? Here are some examples:

Spend time in a new environment. Go to a different park or a new store. Travel, by the way, seems to slow age-related mental decline.

Continue to: Smell new odors in the morning

Smell new odors in the morning. Have new scents, like a bottle of mint extract, ready to smell first thing in the morning, to “wake up” your brain.

Take a shower with your eyes closed. Other senses become more active when you cannot see, and a shower engages several.

Try brushing your teeth with your nondominant hand. This may be difficult for some of us—and it definitely requires full attention the first time you try it!

Learn to read braille. This is a tough one, but learning to read with your fingers definitely involves one of your senses in a new context. Or, you could try learning American Sign Language, which also uses your fingers to communicate.

Respond to a situation differently. Catch yourself in a normal, unconscious response to a situation, and choose to respond in an alternate (and preferably better) way.

Continue to: Find a new route to work

Find a new route to work. It doesn’t have to be longer, just different. You may even find a faster way to work once you break your routine.

Act confidently. In a situation you are unsure about, choose to act confidently. You’ll notice that your mind gets very active once you adopt the assumption that you will know what to do.

Distinguish coins using only your sense of touch. This brain exercise can be used to kill time while waiting for an appointment. If you really want a challenge, see if you can distinguish paper currency denominations by touch.

Leave the lights off in the house. Get around your home by memory and feel. This certainly fully engages your attention—but be careful, of course!

If you give neurobics a try, let me know what you think! Or if you have other tips for staying mentally “fit,” please share them. I can be reached at [email protected]. And thank you to my friend Gail, who suggested this topic to me!

Every year, thousands of us vow to “get in shape” by eating right and exercising. (Whether we keep that resolution is another story.) But while we view physical exercise as a way to lose or maintain weight, reduce stress, or even hone athletic skills, we seldom think about exercising one of the most important muscles in our body: the brain.

“What?” you say. “The brain is not like other muscles.” No, it’s not … and yet, it isn’t as different as we used to think. Historically (maybe histologically?), it was believed that if nerve cells in the adult brain were damaged or had died, they, unlike other cells in t

But since the late 1990s, scientists have been debunking the negative myths about our brains as we age. They are not as static and unable to change as we have been led to fear! In fact, in 1998, American and Swedish scientists demonstrated that adult humans can generate new brain cells.1,2 Moreover, the brain does replicate neurons in the hippocampus, the area in our brains that is central to learning and memory. Neurons continue to grow and change beyond the first years of development and well into adulthood.

So learning (and teaching) movements to encourage the rebuilding of our neurons is key to keeping our minds sharp. In his work, Ratey found that “our physical movements can directly influence our ability to learn, think, and remember.”3 He also tells us that exercise enhances circulation to the brain, “priming it for improved function, including mental health as well as cognitive ability.”4

No, you can’t put your brain on a treadmill to get, and help keep, it “in shape.” But you can do something to maintain mental sharpness and delay decline in mental agility. And these exercises don’t require a health club membership or special equipment. They can be done anytime, anywhere … and no one knows you are doing them!

I’m talking about neurobics, a term coined to describe exercises that keep us mentally fit.5 The purpose of these activities is to work our brains in nonroutine or unexpected ways, using all of our senses to experience, or re-experience, a common activity.

Not sure what that means? Here are some examples:

Spend time in a new environment. Go to a different park or a new store. Travel, by the way, seems to slow age-related mental decline.

Continue to: Smell new odors in the morning

Smell new odors in the morning. Have new scents, like a bottle of mint extract, ready to smell first thing in the morning, to “wake up” your brain.

Take a shower with your eyes closed. Other senses become more active when you cannot see, and a shower engages several.

Try brushing your teeth with your nondominant hand. This may be difficult for some of us—and it definitely requires full attention the first time you try it!

Learn to read braille. This is a tough one, but learning to read with your fingers definitely involves one of your senses in a new context. Or, you could try learning American Sign Language, which also uses your fingers to communicate.

Respond to a situation differently. Catch yourself in a normal, unconscious response to a situation, and choose to respond in an alternate (and preferably better) way.

Continue to: Find a new route to work

Find a new route to work. It doesn’t have to be longer, just different. You may even find a faster way to work once you break your routine.

Act confidently. In a situation you are unsure about, choose to act confidently. You’ll notice that your mind gets very active once you adopt the assumption that you will know what to do.

Distinguish coins using only your sense of touch. This brain exercise can be used to kill time while waiting for an appointment. If you really want a challenge, see if you can distinguish paper currency denominations by touch.

Leave the lights off in the house. Get around your home by memory and feel. This certainly fully engages your attention—but be careful, of course!

If you give neurobics a try, let me know what you think! Or if you have other tips for staying mentally “fit,” please share them. I can be reached at [email protected]. And thank you to my friend Gail, who suggested this topic to me!

1. Kempermann G, Gage FH. New nerve cells for the adult brain. Scientific American. 1999;280(5):38-44.

2. Eriksson PS, Perfilieva E, Björk-Eriksson T, et al. Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nature Medicine. 1998;4(11):1313-1317.

3. Ratey J. A User’s Guide to the Brain: Perception, Attention, and the Four Theaters of the Brain. New York, NY: Vintage Books; 2002.

4. Ratey J. SPARK: The Revolutionary New Science of Exercise and the Brain. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company; 2008.

5. Katz LC, Rubin M. Keep Your Brain Alive: 83 Neurobic Exercises. New York, NY: Workman Publishing Company; 1999.

1. Kempermann G, Gage FH. New nerve cells for the adult brain. Scientific American. 1999;280(5):38-44.

2. Eriksson PS, Perfilieva E, Björk-Eriksson T, et al. Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nature Medicine. 1998;4(11):1313-1317.

3. Ratey J. A User’s Guide to the Brain: Perception, Attention, and the Four Theaters of the Brain. New York, NY: Vintage Books; 2002.

4. Ratey J. SPARK: The Revolutionary New Science of Exercise and the Brain. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company; 2008.

5. Katz LC, Rubin M. Keep Your Brain Alive: 83 Neurobic Exercises. New York, NY: Workman Publishing Company; 1999.

Preventing postpartum depression: Start with women at greatest risk

The last decade has brought appropriate attention to the high prevalence of postpartum mood and anxiety disorders, with postpartum depression (PPD) constituting the most common complication in modern obstetrics.

There have been very substantial efforts in more than 40 states in the United States to enhance screening for PPD and to increase support groups for women with postpartum depressive or anxiety symptoms. However, less focus has been paid to the outcomes of these screening initiatives.

A question that comes to mind is whether patients who are screened actually get referred for treatment, and if they do receive treatment, whether they recover and become well. One study referenced previously in this column noted that even in settings where women are screened for PPD, the vast majority of women are not referred, and of those who are referred, even fewer of those are treated or become well.1

It is noteworthy, then, that the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has recommended screening for perinatal depression (just before and after birth) and issued draft recommendations regarding prevention of perinatal depression where it is suggested that patients at risk for perinatal depression be referred for appropriate “counseling interventions” – specifically, either cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) or interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT).2

The recommendation is a striking one because of the volume of patients who would be included. For example, the USPSTF recommends patients with histories of depression, depression during pregnancy, a history of child abuse, or even a family history of depression should receive preventive interventions with CBT or IPT. The recommendation is puzzling because of the data on risk for perinatal depression in those populations and the lack of available resources for patients who would be deemed “at risk.” Women with histories of depression are at a threefold increased risk for PPD (25%-30%). Depression during pregnancy is the strongest predictor of PPD and risk for PPD among these patients is as high as 75%.

So, there are a vast number of women who may be “at risk” for perinatal depression. But even with some data suggesting that IPT and CBT may be able to prevent perinatal depression, the suggestion that resources be made available to patients who are at risk is naive, because counseling interventions such as IPT or CBT, or even simply referrals to psychiatrists are not available even to patients who screen in for perinatal depression in real time during pregnancy and the postpartum period. I have previously written that the follow-up of women post partum who suffer from PPD is still far from meeting the needs who suffer from the disorder, and early detection and referrals to appropriate clinicians who are facile with both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions seem the most effective way to manage these patients and to see that they receive treatment.

The question then becomes: If the numbers or scale of the prevention initiative suggested in this draft recommendation from the USPSTF is an overreach, is there a group of patients for whom a preventive intervention could be pursued? The patients at highest risk for PPD include those with a history of PPD (50%), bipolar disorder (50%-60%), or postpartum psychosis (80%). And while there is not substantial literature for specifically using IPT, CBT, or other counseling interventions to mitigate risk for recurrence in women with histories of PPD, bipolar disorder, or postpartum psychosis, there are ways of identifying this population at risk and following them closely to mitigate the risk for recurrence.

To make this recommendation feasible, an infrastructure needs to be in place in both low resource settings and in all communities so that these patients can be referred and effectively treated. If we move to prevention, we ought to start with the populations that we already know are at greatest risk and that we can inquire about, and there are very easy-to-use screens that screen for bipolar disorder or that screen for past history of depression with which these women can be identified.

In committee opinion 757, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends women be screened at least once during the perinatal period for depression and anxiety symptoms and highlighted several validated tools, such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale.3 We also need a better system of early detection and early intervention so that women at less-considerable risk for perinatal depression would have the opportunity for early identification, treatment, and referral, which we do not have at the current time.

An update of the ACOG committee opinion also states, “It is recommended that all obstetrician-gynecologists and other obstetric care providers complete a full assessment of mood and emotional well-being (including screening for PPD and anxiety with a validated instrument) during the comprehensive postpartum visit for each patient.” This is recommended in addition to any screening for depression and anxiety during the pregnancy.

It is exciting that after decades of failing to attend to such a common complication of modern obstetrics, particularly now that we understand the adverse effects of PPD as it affects child development, family functioning, and risk for later childhood psychopathology. But in addition to recognizing the problem, we must come up with methods to carefully identify a navigable route for the women suffering from PPD to get their needs met. The route includes publicly identifying the illness, understanding which treatments are most effective and can be scaled for delivery to large numbers of women, and then, most critically, configuring social systems to absorb, effectively manage, and monitor the women we identify as needing treatment.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;77[9]:1189-200.

2. Draft Recommendation Statement: Perinatal Depression: Preventive Interventions. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Aug 2018.

The last decade has brought appropriate attention to the high prevalence of postpartum mood and anxiety disorders, with postpartum depression (PPD) constituting the most common complication in modern obstetrics.

There have been very substantial efforts in more than 40 states in the United States to enhance screening for PPD and to increase support groups for women with postpartum depressive or anxiety symptoms. However, less focus has been paid to the outcomes of these screening initiatives.

A question that comes to mind is whether patients who are screened actually get referred for treatment, and if they do receive treatment, whether they recover and become well. One study referenced previously in this column noted that even in settings where women are screened for PPD, the vast majority of women are not referred, and of those who are referred, even fewer of those are treated or become well.1

It is noteworthy, then, that the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has recommended screening for perinatal depression (just before and after birth) and issued draft recommendations regarding prevention of perinatal depression where it is suggested that patients at risk for perinatal depression be referred for appropriate “counseling interventions” – specifically, either cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) or interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT).2

The recommendation is a striking one because of the volume of patients who would be included. For example, the USPSTF recommends patients with histories of depression, depression during pregnancy, a history of child abuse, or even a family history of depression should receive preventive interventions with CBT or IPT. The recommendation is puzzling because of the data on risk for perinatal depression in those populations and the lack of available resources for patients who would be deemed “at risk.” Women with histories of depression are at a threefold increased risk for PPD (25%-30%). Depression during pregnancy is the strongest predictor of PPD and risk for PPD among these patients is as high as 75%.

So, there are a vast number of women who may be “at risk” for perinatal depression. But even with some data suggesting that IPT and CBT may be able to prevent perinatal depression, the suggestion that resources be made available to patients who are at risk is naive, because counseling interventions such as IPT or CBT, or even simply referrals to psychiatrists are not available even to patients who screen in for perinatal depression in real time during pregnancy and the postpartum period. I have previously written that the follow-up of women post partum who suffer from PPD is still far from meeting the needs who suffer from the disorder, and early detection and referrals to appropriate clinicians who are facile with both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions seem the most effective way to manage these patients and to see that they receive treatment.

The question then becomes: If the numbers or scale of the prevention initiative suggested in this draft recommendation from the USPSTF is an overreach, is there a group of patients for whom a preventive intervention could be pursued? The patients at highest risk for PPD include those with a history of PPD (50%), bipolar disorder (50%-60%), or postpartum psychosis (80%). And while there is not substantial literature for specifically using IPT, CBT, or other counseling interventions to mitigate risk for recurrence in women with histories of PPD, bipolar disorder, or postpartum psychosis, there are ways of identifying this population at risk and following them closely to mitigate the risk for recurrence.

To make this recommendation feasible, an infrastructure needs to be in place in both low resource settings and in all communities so that these patients can be referred and effectively treated. If we move to prevention, we ought to start with the populations that we already know are at greatest risk and that we can inquire about, and there are very easy-to-use screens that screen for bipolar disorder or that screen for past history of depression with which these women can be identified.

In committee opinion 757, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends women be screened at least once during the perinatal period for depression and anxiety symptoms and highlighted several validated tools, such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale.3 We also need a better system of early detection and early intervention so that women at less-considerable risk for perinatal depression would have the opportunity for early identification, treatment, and referral, which we do not have at the current time.

An update of the ACOG committee opinion also states, “It is recommended that all obstetrician-gynecologists and other obstetric care providers complete a full assessment of mood and emotional well-being (including screening for PPD and anxiety with a validated instrument) during the comprehensive postpartum visit for each patient.” This is recommended in addition to any screening for depression and anxiety during the pregnancy.

It is exciting that after decades of failing to attend to such a common complication of modern obstetrics, particularly now that we understand the adverse effects of PPD as it affects child development, family functioning, and risk for later childhood psychopathology. But in addition to recognizing the problem, we must come up with methods to carefully identify a navigable route for the women suffering from PPD to get their needs met. The route includes publicly identifying the illness, understanding which treatments are most effective and can be scaled for delivery to large numbers of women, and then, most critically, configuring social systems to absorb, effectively manage, and monitor the women we identify as needing treatment.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;77[9]:1189-200.

2. Draft Recommendation Statement: Perinatal Depression: Preventive Interventions. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Aug 2018.

The last decade has brought appropriate attention to the high prevalence of postpartum mood and anxiety disorders, with postpartum depression (PPD) constituting the most common complication in modern obstetrics.

There have been very substantial efforts in more than 40 states in the United States to enhance screening for PPD and to increase support groups for women with postpartum depressive or anxiety symptoms. However, less focus has been paid to the outcomes of these screening initiatives.

A question that comes to mind is whether patients who are screened actually get referred for treatment, and if they do receive treatment, whether they recover and become well. One study referenced previously in this column noted that even in settings where women are screened for PPD, the vast majority of women are not referred, and of those who are referred, even fewer of those are treated or become well.1

It is noteworthy, then, that the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has recommended screening for perinatal depression (just before and after birth) and issued draft recommendations regarding prevention of perinatal depression where it is suggested that patients at risk for perinatal depression be referred for appropriate “counseling interventions” – specifically, either cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) or interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT).2

The recommendation is a striking one because of the volume of patients who would be included. For example, the USPSTF recommends patients with histories of depression, depression during pregnancy, a history of child abuse, or even a family history of depression should receive preventive interventions with CBT or IPT. The recommendation is puzzling because of the data on risk for perinatal depression in those populations and the lack of available resources for patients who would be deemed “at risk.” Women with histories of depression are at a threefold increased risk for PPD (25%-30%). Depression during pregnancy is the strongest predictor of PPD and risk for PPD among these patients is as high as 75%.

So, there are a vast number of women who may be “at risk” for perinatal depression. But even with some data suggesting that IPT and CBT may be able to prevent perinatal depression, the suggestion that resources be made available to patients who are at risk is naive, because counseling interventions such as IPT or CBT, or even simply referrals to psychiatrists are not available even to patients who screen in for perinatal depression in real time during pregnancy and the postpartum period. I have previously written that the follow-up of women post partum who suffer from PPD is still far from meeting the needs who suffer from the disorder, and early detection and referrals to appropriate clinicians who are facile with both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions seem the most effective way to manage these patients and to see that they receive treatment.

The question then becomes: If the numbers or scale of the prevention initiative suggested in this draft recommendation from the USPSTF is an overreach, is there a group of patients for whom a preventive intervention could be pursued? The patients at highest risk for PPD include those with a history of PPD (50%), bipolar disorder (50%-60%), or postpartum psychosis (80%). And while there is not substantial literature for specifically using IPT, CBT, or other counseling interventions to mitigate risk for recurrence in women with histories of PPD, bipolar disorder, or postpartum psychosis, there are ways of identifying this population at risk and following them closely to mitigate the risk for recurrence.

To make this recommendation feasible, an infrastructure needs to be in place in both low resource settings and in all communities so that these patients can be referred and effectively treated. If we move to prevention, we ought to start with the populations that we already know are at greatest risk and that we can inquire about, and there are very easy-to-use screens that screen for bipolar disorder or that screen for past history of depression with which these women can be identified.

In committee opinion 757, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends women be screened at least once during the perinatal period for depression and anxiety symptoms and highlighted several validated tools, such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale.3 We also need a better system of early detection and early intervention so that women at less-considerable risk for perinatal depression would have the opportunity for early identification, treatment, and referral, which we do not have at the current time.

An update of the ACOG committee opinion also states, “It is recommended that all obstetrician-gynecologists and other obstetric care providers complete a full assessment of mood and emotional well-being (including screening for PPD and anxiety with a validated instrument) during the comprehensive postpartum visit for each patient.” This is recommended in addition to any screening for depression and anxiety during the pregnancy.

It is exciting that after decades of failing to attend to such a common complication of modern obstetrics, particularly now that we understand the adverse effects of PPD as it affects child development, family functioning, and risk for later childhood psychopathology. But in addition to recognizing the problem, we must come up with methods to carefully identify a navigable route for the women suffering from PPD to get their needs met. The route includes publicly identifying the illness, understanding which treatments are most effective and can be scaled for delivery to large numbers of women, and then, most critically, configuring social systems to absorb, effectively manage, and monitor the women we identify as needing treatment.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;77[9]:1189-200.

2. Draft Recommendation Statement: Perinatal Depression: Preventive Interventions. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Aug 2018.

Medical ethics and economics

The balance between medical research and the pharmaceutical world has always been unsettling. The recent spate of articles in the press reporting the large payments by industry to a number of highly paid medical staff of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Institute in New York has raised again the continuing issue around that relationship.

When large sums of money are paid to medical leaders for serving on advisory boards, it is reasonable to question whom are they representing: industry or medical science. These relationships are not limited to cancer hospitals and can be presumed to pertain to cardiology and other specialties. One need only look at the disclosure statements of contemporary published articles to become aware of the entanglement of science and industry.

There is little question that both industry and science need to interact to focus direct resources to appropriate targets. No one is better able to do that than well informed scientists working in their disease fields. Industry needs scientific input and scientists need the financial resources of industry. I have been able to see that relationship play out to achieve major impacts on heart disease. But corporate decisions also can be driven by market forces and not altruism. Drug and device research has been redirected or stopped as a result of decisions made by sales forces. At other times, drugs that have great potential in the laboratory have been shelved because of a lack of scientific leadership.

So where is the moral and ethical balance? Published disclosures by authors is not much more than a catharsis in the process where action is required. Medical advisory boards are critical for successful drug and device development. That exchange is crucial to move medical science forward, but the large sums of money raise appropriate questions of what is driving the discussion.

At a more grass roots level, the financial role of investigators and hospitals in clinical trials has raised some concern. Traditionally, the institution and investigators have been reimbursed for their time and expense for recruiting and following patients. Patients, of course, are not reimbursed in clinical trials but are placed at considerable risk of an uncertain result. The reimbursements for marginal expenses seem to be appropriate. More recently, payments to physicians and hospitals have been made at current fee schedules for the implantation of a variety of new devices such as pacemakers and valves. In addition, both physicians and hospitals have invested in the financial success of these clinical trials clouding over their altruistic goals. It has been an incentive for recruiting patients for trials and has been a source of considerable revenue both for the physicians and the institution, without informing the patients of their financial relationship to industry. .

There is a lot of money sloshing around in the health care world that has the potential to lead to ethical uncertainty. It is the physician’s responsibility to build up ethical barriers to prevent us from slipping into that morass.

Dr. Goldstein is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and the division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit.

The balance between medical research and the pharmaceutical world has always been unsettling. The recent spate of articles in the press reporting the large payments by industry to a number of highly paid medical staff of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Institute in New York has raised again the continuing issue around that relationship.

When large sums of money are paid to medical leaders for serving on advisory boards, it is reasonable to question whom are they representing: industry or medical science. These relationships are not limited to cancer hospitals and can be presumed to pertain to cardiology and other specialties. One need only look at the disclosure statements of contemporary published articles to become aware of the entanglement of science and industry.

There is little question that both industry and science need to interact to focus direct resources to appropriate targets. No one is better able to do that than well informed scientists working in their disease fields. Industry needs scientific input and scientists need the financial resources of industry. I have been able to see that relationship play out to achieve major impacts on heart disease. But corporate decisions also can be driven by market forces and not altruism. Drug and device research has been redirected or stopped as a result of decisions made by sales forces. At other times, drugs that have great potential in the laboratory have been shelved because of a lack of scientific leadership.

So where is the moral and ethical balance? Published disclosures by authors is not much more than a catharsis in the process where action is required. Medical advisory boards are critical for successful drug and device development. That exchange is crucial to move medical science forward, but the large sums of money raise appropriate questions of what is driving the discussion.

At a more grass roots level, the financial role of investigators and hospitals in clinical trials has raised some concern. Traditionally, the institution and investigators have been reimbursed for their time and expense for recruiting and following patients. Patients, of course, are not reimbursed in clinical trials but are placed at considerable risk of an uncertain result. The reimbursements for marginal expenses seem to be appropriate. More recently, payments to physicians and hospitals have been made at current fee schedules for the implantation of a variety of new devices such as pacemakers and valves. In addition, both physicians and hospitals have invested in the financial success of these clinical trials clouding over their altruistic goals. It has been an incentive for recruiting patients for trials and has been a source of considerable revenue both for the physicians and the institution, without informing the patients of their financial relationship to industry. .

There is a lot of money sloshing around in the health care world that has the potential to lead to ethical uncertainty. It is the physician’s responsibility to build up ethical barriers to prevent us from slipping into that morass.

Dr. Goldstein is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and the division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit.

The balance between medical research and the pharmaceutical world has always been unsettling. The recent spate of articles in the press reporting the large payments by industry to a number of highly paid medical staff of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Institute in New York has raised again the continuing issue around that relationship.

When large sums of money are paid to medical leaders for serving on advisory boards, it is reasonable to question whom are they representing: industry or medical science. These relationships are not limited to cancer hospitals and can be presumed to pertain to cardiology and other specialties. One need only look at the disclosure statements of contemporary published articles to become aware of the entanglement of science and industry.

There is little question that both industry and science need to interact to focus direct resources to appropriate targets. No one is better able to do that than well informed scientists working in their disease fields. Industry needs scientific input and scientists need the financial resources of industry. I have been able to see that relationship play out to achieve major impacts on heart disease. But corporate decisions also can be driven by market forces and not altruism. Drug and device research has been redirected or stopped as a result of decisions made by sales forces. At other times, drugs that have great potential in the laboratory have been shelved because of a lack of scientific leadership.

So where is the moral and ethical balance? Published disclosures by authors is not much more than a catharsis in the process where action is required. Medical advisory boards are critical for successful drug and device development. That exchange is crucial to move medical science forward, but the large sums of money raise appropriate questions of what is driving the discussion.

At a more grass roots level, the financial role of investigators and hospitals in clinical trials has raised some concern. Traditionally, the institution and investigators have been reimbursed for their time and expense for recruiting and following patients. Patients, of course, are not reimbursed in clinical trials but are placed at considerable risk of an uncertain result. The reimbursements for marginal expenses seem to be appropriate. More recently, payments to physicians and hospitals have been made at current fee schedules for the implantation of a variety of new devices such as pacemakers and valves. In addition, both physicians and hospitals have invested in the financial success of these clinical trials clouding over their altruistic goals. It has been an incentive for recruiting patients for trials and has been a source of considerable revenue both for the physicians and the institution, without informing the patients of their financial relationship to industry. .

There is a lot of money sloshing around in the health care world that has the potential to lead to ethical uncertainty. It is the physician’s responsibility to build up ethical barriers to prevent us from slipping into that morass.

Dr. Goldstein is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and the division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit.

The fog may be lifting

One of the common symptoms described by postconcussion patients is that their heads feel a bit foggy. It may not be simply by chance that “foggy” is the best word to describe the atmosphere surrounding the entire field of concussion diagnosis and management.

Back in the Dark Ages, when the diagnosis of concussion was a simpler binary call, the issue of management seldom created much discussion. If the patient lost consciousness or was amnesic, he (it was less frequently she) could return to activity when his headache was gone and he could remember what he was supposed to do when the quarterback called for a “Red 34, Drive Right Smash” play. That may have even been during the second half of the game in which he was injured.

As it became more widely understood that the diagnosis of concussion didn’t require loss of consciousness and that repeated concussions could have serious sequelae, management became a bit fuzzier. No one had thought much about the recuperative process. Into this vacuum came a wide variety of researchers and providers. Not surprisingly, much of their advice was based on unproven assumptions, including the concept of “brain rest.”

It has taken time, but fortunately, folks with patience and wisdom have questioned these assumptions and begun collecting data. The result of these investigations and others has prompted the American Academy of Pediatrics to publish an updated set of guidelines on concussion management that includes the observation that extended school absence may slow the rehabilitation process (Pediatrics. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3074).

It is becoming clear that management of concussion can be rather complex and must be individualized to each patient. In my experience, the postconcussion period can unmask behavioral, cognitive, and emotional problems that were preexisting but had received little or no attention. For example, the trauma of the event may trigger anxiety about further injury or exacerbate depression that had been building for years. The student who “couldn’t do algebra” following a head injury may have had a lifelong learning disability that had gone unnoticed. The student athlete with prolonged postconcussion symptoms may indeed have another more serious problem. Hopefully, the new guidelines from the AAP will be a first step toward a more thoughtful and scientifically driven approach to concussion management.

It would be nice if that approach could filter down to the management of the more common but less dramatic pediatric injuries. There is hope. Choosing Wisely – a patient/parent–targeted initiative by the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation in cooperation with the AAP – points out that, although half of the pediatric head injury patients seen in emergency departments received CT scan, only a third of those studies were indicated. Parents are encouraged to learn more about the risks of CT scans and question the physician when one is recommended.

But, doctors’ habits and old wives’ tales die slowly. I hope that you no longer recommend that parents keep their children awake after a head injury, or wake them every hour to check their pupils. Those counterproductive recommendations make about as much sense as staying out of the swimming pool for an hour after eating a chocolate chip cookie.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

One of the common symptoms described by postconcussion patients is that their heads feel a bit foggy. It may not be simply by chance that “foggy” is the best word to describe the atmosphere surrounding the entire field of concussion diagnosis and management.

Back in the Dark Ages, when the diagnosis of concussion was a simpler binary call, the issue of management seldom created much discussion. If the patient lost consciousness or was amnesic, he (it was less frequently she) could return to activity when his headache was gone and he could remember what he was supposed to do when the quarterback called for a “Red 34, Drive Right Smash” play. That may have even been during the second half of the game in which he was injured.

As it became more widely understood that the diagnosis of concussion didn’t require loss of consciousness and that repeated concussions could have serious sequelae, management became a bit fuzzier. No one had thought much about the recuperative process. Into this vacuum came a wide variety of researchers and providers. Not surprisingly, much of their advice was based on unproven assumptions, including the concept of “brain rest.”

It has taken time, but fortunately, folks with patience and wisdom have questioned these assumptions and begun collecting data. The result of these investigations and others has prompted the American Academy of Pediatrics to publish an updated set of guidelines on concussion management that includes the observation that extended school absence may slow the rehabilitation process (Pediatrics. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3074).

It is becoming clear that management of concussion can be rather complex and must be individualized to each patient. In my experience, the postconcussion period can unmask behavioral, cognitive, and emotional problems that were preexisting but had received little or no attention. For example, the trauma of the event may trigger anxiety about further injury or exacerbate depression that had been building for years. The student who “couldn’t do algebra” following a head injury may have had a lifelong learning disability that had gone unnoticed. The student athlete with prolonged postconcussion symptoms may indeed have another more serious problem. Hopefully, the new guidelines from the AAP will be a first step toward a more thoughtful and scientifically driven approach to concussion management.

It would be nice if that approach could filter down to the management of the more common but less dramatic pediatric injuries. There is hope. Choosing Wisely – a patient/parent–targeted initiative by the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation in cooperation with the AAP – points out that, although half of the pediatric head injury patients seen in emergency departments received CT scan, only a third of those studies were indicated. Parents are encouraged to learn more about the risks of CT scans and question the physician when one is recommended.

But, doctors’ habits and old wives’ tales die slowly. I hope that you no longer recommend that parents keep their children awake after a head injury, or wake them every hour to check their pupils. Those counterproductive recommendations make about as much sense as staying out of the swimming pool for an hour after eating a chocolate chip cookie.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

One of the common symptoms described by postconcussion patients is that their heads feel a bit foggy. It may not be simply by chance that “foggy” is the best word to describe the atmosphere surrounding the entire field of concussion diagnosis and management.

Back in the Dark Ages, when the diagnosis of concussion was a simpler binary call, the issue of management seldom created much discussion. If the patient lost consciousness or was amnesic, he (it was less frequently she) could return to activity when his headache was gone and he could remember what he was supposed to do when the quarterback called for a “Red 34, Drive Right Smash” play. That may have even been during the second half of the game in which he was injured.

As it became more widely understood that the diagnosis of concussion didn’t require loss of consciousness and that repeated concussions could have serious sequelae, management became a bit fuzzier. No one had thought much about the recuperative process. Into this vacuum came a wide variety of researchers and providers. Not surprisingly, much of their advice was based on unproven assumptions, including the concept of “brain rest.”

It has taken time, but fortunately, folks with patience and wisdom have questioned these assumptions and begun collecting data. The result of these investigations and others has prompted the American Academy of Pediatrics to publish an updated set of guidelines on concussion management that includes the observation that extended school absence may slow the rehabilitation process (Pediatrics. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3074).

It is becoming clear that management of concussion can be rather complex and must be individualized to each patient. In my experience, the postconcussion period can unmask behavioral, cognitive, and emotional problems that were preexisting but had received little or no attention. For example, the trauma of the event may trigger anxiety about further injury or exacerbate depression that had been building for years. The student who “couldn’t do algebra” following a head injury may have had a lifelong learning disability that had gone unnoticed. The student athlete with prolonged postconcussion symptoms may indeed have another more serious problem. Hopefully, the new guidelines from the AAP will be a first step toward a more thoughtful and scientifically driven approach to concussion management.

It would be nice if that approach could filter down to the management of the more common but less dramatic pediatric injuries. There is hope. Choosing Wisely – a patient/parent–targeted initiative by the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation in cooperation with the AAP – points out that, although half of the pediatric head injury patients seen in emergency departments received CT scan, only a third of those studies were indicated. Parents are encouraged to learn more about the risks of CT scans and question the physician when one is recommended.

But, doctors’ habits and old wives’ tales die slowly. I hope that you no longer recommend that parents keep their children awake after a head injury, or wake them every hour to check their pupils. Those counterproductive recommendations make about as much sense as staying out of the swimming pool for an hour after eating a chocolate chip cookie.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

The other side of activity

While the increasing prevalence of obesity has been obvious for nearly half a century, it is only in the last decade or two that the focus has broadened to include the associated decline in physical activity.

A recent paper attempts to sharpen that focus by examining the timeline of that decline (Pediatrics 2019 Jan. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-0994.). Using a device incorporating five sensors, one of which was an accelerometer, the investigators collected data from 600 children from five European countries accumulating more than 1,200 observations. What they discovered was that their subjects’ physical activity declined by 75 minutes per day from ages 6 to 11 years of age while sedentary behavior increased more than 100 minutes over that same interval. This observation is concerning because previous attention has focused intervention on adolescents assuming that the erosion of physical activity was occurring primarily during the teen years.

Not surprisingly the authors suggest that more studies should be performed to aid in the design of more sharply targeted interventions. While more information may be helpful, their current findings and an abundance of anecdotal observations suggest that to be effective that intervention must begin well before children reach school age.

What should this intervention look like? Currently, the emphasis seems to have been on programs that encourage activity. The National Football League is promoting its NFL Play 60 initiative. The Afterschool Alliance has its Kids on the Move programs. Former First Lady Michelle Obama has been the spokesperson and driving force behind Let’s Move. And, the American Academy of Pediatrics has recently been encouraging both parents and pediatricians to appreciate The Power of Play to encourage children to get into more physical activity. All of these initiatives are well meaning, but I suspect their effectiveness is usually limited to the public awareness they generate.

We seem to have forgotten that there are two sides to the equation. The accelerometer study from Europe should remind us that our initiatives should also be addressing the problem of epidemic inactivity with equal vigor. Creating programs that focus on increasing activity can be expensive. There may be costs for equipment, spaces to be maintained, and staff to be paid. On the other hand, curbing sedentary behavior requires only an adult with the courage to say, “No.” “No, we will have the television for only an hour today.” “No, you can’t play your video game until after dinner.”

While addressing the disciplinary side of the activity-inactivity dichotomy may be relatively inexpensive, it does seem to have a cost on parents. It requires them to buy into the idea that, given even the most-limited supply of objects and infrastructure, most children can keep themselves entertained and active. There does seem to be a small subset of children who enter the world with a sedentary mindset, possibly inherited from their parents. This unfortunate minority will require some creative intervention to achieve a healthy level of activity.

However, most young children who have become accustomed to being amused by sedentary “activities” such as television and video games still retain their innate creativity and natural inclination to be physically active. Unfortunately, unmasking these health-sustaining attributes may require a long and unpleasant weaning period that many parents don’t seem to have the patience to endure. The longer the child has been allowed to engage in sedentary behaviors, the longer this adjustment period will be, yet another argument for early intervention.

Encouraging physical activity is something we should be doing every day in our offices, but it must go hand in hand with an equivalent emphasis on helping parents create a discipline framework that discourages sedentary behavior.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

While the increasing prevalence of obesity has been obvious for nearly half a century, it is only in the last decade or two that the focus has broadened to include the associated decline in physical activity.