User login

Two more and counting: Suicide in medical trainees

Like everyone in the arc of social media impact, I was shocked and terribly saddened by the recent suicides of two New York women in medicine – a final-year medical student on May 1 and a second-year resident on May 5. As a specialist in physician health, a former training director, a long-standing member of our institution’s medical student admissions committee, and the ombudsman for our medical students, I am finding these tragedies harder and harder to reconcile. Something isn’t working. But before I get to that, what follows is a bulleted list of some events of the past couple of weeks that may give a context for my statements and have informed my two recommendations.

- May 3, 2018: I give an invited GI grand rounds on stress, burnout, depression, and suicide in physicians. The residents are quiet and say nothing. Faculty members seem only concerned about preventing and eradicating burnout – and not that interested in anything more severe.

- May 5: A psychiatry resident from Melbourne arrives to spend 10 days with me to do an elective in physician health. As in the United States, there is a significant suicide death rate in medical students and residents Down Under. In the afternoon, I present a paper at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Psychodynamic Psychiatry and Psychoanalysis on the use of psychotherapy in treatment-resistant suicidal depression in physicians. There is increasing hope that this essential modality of care will return to the contemporary psychiatrist’s toolbox.

- May 6: At the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in New York, I’m the discussant for powerful heartfelt papers of five psychiatrists (mostly early career psychiatrists and one resident) that talked about living with a psychiatric illness. The audience is huge, and we hear narratives about internal stigma, self-disclosure, external stigma, shunning, bullying, acceptance, rejection, alienation, connection, and love by peers and family. The authenticity and valor of the speakers create an atmosphere of safety, which enables psychiatrists in attendance from all over the world to share their personal stories – some at the microphone, some privately.

- May 7: Again at the APA, I chair and facilitate a workshop on physician suicide. We hear from four speakers, all women, who have lost a loved one to suicide – a husband, a father, a brother, a son – all doctors. Two of the speakers are psychiatrists. The stories are gripping, detailed, and tender. Yes, the atmosphere is very sad, but there is not a pall. We learn how these doctors lived, not just how they died. They all loved medicine; they were creative; they cared deeply; they suffered silently; and with shame, they lost hope. Again, a big audience of psychiatrists, many of whom share their own stories, that they, too, had lost a physician son, wife, or mother to suicide. Some of their deceased family members fell through the cracks and did not receive the life-saving care they deserved; some, fearing assaults to their medical license, hospital privileges, or insurance, refused to see anyone. They died untreated.

- May 8: Still at the APA, a psychiatrist colleague and I collaborate on a clinical case conference. Each of us describes losing a physician patient to suicide. We walk the attendees through the clinical details of assessment, treatment, and the aftermath of their deaths. We talk openly and frankly about our feelings, grief, outreach to colleagues and the family, and our own personal journeys of learning, growth, and healing. The clinician audience members give constructive feedback, and some share their own stories of losing patients to suicide. Like the day before, some psychiatrists are grieving the loss of a physician son or sibling to suicide. As mental health professionals, they suffer from an additional layer of failure and guilt that a loved one died “under their watch.”

- May 8: I rush across the Javits Center to catch the discussant for a concurrent symposium on physician burnout and depression. She foregoes any prepared remarks to share her previous 48 hours with the audience. She is the training director of the program that lost the second-year resident on May 5. She did not learn of the death until 24 hours later. We are all on the edge of our seats as we listen to this grieving, courageous woman, a seasoned psychiatrist and educator, who has been blindsided by this tragedy. She has not slept. She called all of her residents and broke the news personally as best she could. Aided by “After A Suicide: A Toolkit for Residency/Fellowship Programs” (American Foundation for Suicide Prevention), she and her colleagues instituted a plan of action and worked with administration and faculty. Her strength and commitment to the well-being of her trainees is palpable and magnanimous. When the session ends, many of us stand in line to give her a hug. It is a stark reminder of how many lives are affected when someone you know or care about takes his/her own life – and how, in the house of medicine, medical students and residents really are part of an institutional family.

- May 10: I facilitate a meeting of our 12 second-year residents, many of whom knew of or had met the resident who died. Almost everyone speaks, shares their feelings, poses questions, and calls for answers and change. There is disbelief, sadness, confusion, some guilt, and lots of anger. Also a feeling of disillusionment or paradox about the field of psychiatry: “Of all branches of medicine, shouldn’t residents who are struggling with psychiatric issues feel safe, protected, cared for in psychiatry?” There is also a feeling of lip service being paid to personal treatment, as in quoted statements: “By all means, get treatment for your issues, but don’t let it encroach on your duty hours” or “It’s good you’re getting help, but do you still have to go weekly?”

In the immediate aftermath of suicide, feelings run high, as they should. But rather than wait it out – and fearing a return to “business as usual” – let me make only two suggestions:

2. In psychiatry, we need to redouble our efforts in fighting the stigma attached to psychiatric illness in trainees. It is unconscionable that medical students and residents are dying of treatable disorders (I’ve never heard of a doctor dying of cancer who didn’t go to an oncologist at least once), yet too many are not availing themselves of services we provide – even when they’re free of charge or covered by insurance. And are we certain that, when they knock on our doors, we are providing them with state-of-the-art care? Is it possible that unrecognized internal stigma and shame deep within us might make us hesitant to help our trainees in their hour of need? Or cut corners? Or not get a second opinion? Very few psychiatrists on faculty of our medical schools divulge their personal experiences of depression, posttraumatic stress disorders, substance use disorders, and more (with the exception of being in therapy during residency, which is normative and isn’t stigmatized). Coming out is leveling, humane, and respectful – and it shrinks the power differential in the teaching dyad. It might even save a life.

Dr. Myers is a professor of clinical psychiatry at State University of New York, Brooklyn, and the author of “Why Physicians Die by Suicide: Lessons Learned From Their Families and Others Who Cared.”

Like everyone in the arc of social media impact, I was shocked and terribly saddened by the recent suicides of two New York women in medicine – a final-year medical student on May 1 and a second-year resident on May 5. As a specialist in physician health, a former training director, a long-standing member of our institution’s medical student admissions committee, and the ombudsman for our medical students, I am finding these tragedies harder and harder to reconcile. Something isn’t working. But before I get to that, what follows is a bulleted list of some events of the past couple of weeks that may give a context for my statements and have informed my two recommendations.

- May 3, 2018: I give an invited GI grand rounds on stress, burnout, depression, and suicide in physicians. The residents are quiet and say nothing. Faculty members seem only concerned about preventing and eradicating burnout – and not that interested in anything more severe.

- May 5: A psychiatry resident from Melbourne arrives to spend 10 days with me to do an elective in physician health. As in the United States, there is a significant suicide death rate in medical students and residents Down Under. In the afternoon, I present a paper at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Psychodynamic Psychiatry and Psychoanalysis on the use of psychotherapy in treatment-resistant suicidal depression in physicians. There is increasing hope that this essential modality of care will return to the contemporary psychiatrist’s toolbox.

- May 6: At the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in New York, I’m the discussant for powerful heartfelt papers of five psychiatrists (mostly early career psychiatrists and one resident) that talked about living with a psychiatric illness. The audience is huge, and we hear narratives about internal stigma, self-disclosure, external stigma, shunning, bullying, acceptance, rejection, alienation, connection, and love by peers and family. The authenticity and valor of the speakers create an atmosphere of safety, which enables psychiatrists in attendance from all over the world to share their personal stories – some at the microphone, some privately.

- May 7: Again at the APA, I chair and facilitate a workshop on physician suicide. We hear from four speakers, all women, who have lost a loved one to suicide – a husband, a father, a brother, a son – all doctors. Two of the speakers are psychiatrists. The stories are gripping, detailed, and tender. Yes, the atmosphere is very sad, but there is not a pall. We learn how these doctors lived, not just how they died. They all loved medicine; they were creative; they cared deeply; they suffered silently; and with shame, they lost hope. Again, a big audience of psychiatrists, many of whom share their own stories, that they, too, had lost a physician son, wife, or mother to suicide. Some of their deceased family members fell through the cracks and did not receive the life-saving care they deserved; some, fearing assaults to their medical license, hospital privileges, or insurance, refused to see anyone. They died untreated.

- May 8: Still at the APA, a psychiatrist colleague and I collaborate on a clinical case conference. Each of us describes losing a physician patient to suicide. We walk the attendees through the clinical details of assessment, treatment, and the aftermath of their deaths. We talk openly and frankly about our feelings, grief, outreach to colleagues and the family, and our own personal journeys of learning, growth, and healing. The clinician audience members give constructive feedback, and some share their own stories of losing patients to suicide. Like the day before, some psychiatrists are grieving the loss of a physician son or sibling to suicide. As mental health professionals, they suffer from an additional layer of failure and guilt that a loved one died “under their watch.”

- May 8: I rush across the Javits Center to catch the discussant for a concurrent symposium on physician burnout and depression. She foregoes any prepared remarks to share her previous 48 hours with the audience. She is the training director of the program that lost the second-year resident on May 5. She did not learn of the death until 24 hours later. We are all on the edge of our seats as we listen to this grieving, courageous woman, a seasoned psychiatrist and educator, who has been blindsided by this tragedy. She has not slept. She called all of her residents and broke the news personally as best she could. Aided by “After A Suicide: A Toolkit for Residency/Fellowship Programs” (American Foundation for Suicide Prevention), she and her colleagues instituted a plan of action and worked with administration and faculty. Her strength and commitment to the well-being of her trainees is palpable and magnanimous. When the session ends, many of us stand in line to give her a hug. It is a stark reminder of how many lives are affected when someone you know or care about takes his/her own life – and how, in the house of medicine, medical students and residents really are part of an institutional family.

- May 10: I facilitate a meeting of our 12 second-year residents, many of whom knew of or had met the resident who died. Almost everyone speaks, shares their feelings, poses questions, and calls for answers and change. There is disbelief, sadness, confusion, some guilt, and lots of anger. Also a feeling of disillusionment or paradox about the field of psychiatry: “Of all branches of medicine, shouldn’t residents who are struggling with psychiatric issues feel safe, protected, cared for in psychiatry?” There is also a feeling of lip service being paid to personal treatment, as in quoted statements: “By all means, get treatment for your issues, but don’t let it encroach on your duty hours” or “It’s good you’re getting help, but do you still have to go weekly?”

In the immediate aftermath of suicide, feelings run high, as they should. But rather than wait it out – and fearing a return to “business as usual” – let me make only two suggestions:

2. In psychiatry, we need to redouble our efforts in fighting the stigma attached to psychiatric illness in trainees. It is unconscionable that medical students and residents are dying of treatable disorders (I’ve never heard of a doctor dying of cancer who didn’t go to an oncologist at least once), yet too many are not availing themselves of services we provide – even when they’re free of charge or covered by insurance. And are we certain that, when they knock on our doors, we are providing them with state-of-the-art care? Is it possible that unrecognized internal stigma and shame deep within us might make us hesitant to help our trainees in their hour of need? Or cut corners? Or not get a second opinion? Very few psychiatrists on faculty of our medical schools divulge their personal experiences of depression, posttraumatic stress disorders, substance use disorders, and more (with the exception of being in therapy during residency, which is normative and isn’t stigmatized). Coming out is leveling, humane, and respectful – and it shrinks the power differential in the teaching dyad. It might even save a life.

Dr. Myers is a professor of clinical psychiatry at State University of New York, Brooklyn, and the author of “Why Physicians Die by Suicide: Lessons Learned From Their Families and Others Who Cared.”

Like everyone in the arc of social media impact, I was shocked and terribly saddened by the recent suicides of two New York women in medicine – a final-year medical student on May 1 and a second-year resident on May 5. As a specialist in physician health, a former training director, a long-standing member of our institution’s medical student admissions committee, and the ombudsman for our medical students, I am finding these tragedies harder and harder to reconcile. Something isn’t working. But before I get to that, what follows is a bulleted list of some events of the past couple of weeks that may give a context for my statements and have informed my two recommendations.

- May 3, 2018: I give an invited GI grand rounds on stress, burnout, depression, and suicide in physicians. The residents are quiet and say nothing. Faculty members seem only concerned about preventing and eradicating burnout – and not that interested in anything more severe.

- May 5: A psychiatry resident from Melbourne arrives to spend 10 days with me to do an elective in physician health. As in the United States, there is a significant suicide death rate in medical students and residents Down Under. In the afternoon, I present a paper at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Psychodynamic Psychiatry and Psychoanalysis on the use of psychotherapy in treatment-resistant suicidal depression in physicians. There is increasing hope that this essential modality of care will return to the contemporary psychiatrist’s toolbox.

- May 6: At the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in New York, I’m the discussant for powerful heartfelt papers of five psychiatrists (mostly early career psychiatrists and one resident) that talked about living with a psychiatric illness. The audience is huge, and we hear narratives about internal stigma, self-disclosure, external stigma, shunning, bullying, acceptance, rejection, alienation, connection, and love by peers and family. The authenticity and valor of the speakers create an atmosphere of safety, which enables psychiatrists in attendance from all over the world to share their personal stories – some at the microphone, some privately.

- May 7: Again at the APA, I chair and facilitate a workshop on physician suicide. We hear from four speakers, all women, who have lost a loved one to suicide – a husband, a father, a brother, a son – all doctors. Two of the speakers are psychiatrists. The stories are gripping, detailed, and tender. Yes, the atmosphere is very sad, but there is not a pall. We learn how these doctors lived, not just how they died. They all loved medicine; they were creative; they cared deeply; they suffered silently; and with shame, they lost hope. Again, a big audience of psychiatrists, many of whom share their own stories, that they, too, had lost a physician son, wife, or mother to suicide. Some of their deceased family members fell through the cracks and did not receive the life-saving care they deserved; some, fearing assaults to their medical license, hospital privileges, or insurance, refused to see anyone. They died untreated.

- May 8: Still at the APA, a psychiatrist colleague and I collaborate on a clinical case conference. Each of us describes losing a physician patient to suicide. We walk the attendees through the clinical details of assessment, treatment, and the aftermath of their deaths. We talk openly and frankly about our feelings, grief, outreach to colleagues and the family, and our own personal journeys of learning, growth, and healing. The clinician audience members give constructive feedback, and some share their own stories of losing patients to suicide. Like the day before, some psychiatrists are grieving the loss of a physician son or sibling to suicide. As mental health professionals, they suffer from an additional layer of failure and guilt that a loved one died “under their watch.”

- May 8: I rush across the Javits Center to catch the discussant for a concurrent symposium on physician burnout and depression. She foregoes any prepared remarks to share her previous 48 hours with the audience. She is the training director of the program that lost the second-year resident on May 5. She did not learn of the death until 24 hours later. We are all on the edge of our seats as we listen to this grieving, courageous woman, a seasoned psychiatrist and educator, who has been blindsided by this tragedy. She has not slept. She called all of her residents and broke the news personally as best she could. Aided by “After A Suicide: A Toolkit for Residency/Fellowship Programs” (American Foundation for Suicide Prevention), she and her colleagues instituted a plan of action and worked with administration and faculty. Her strength and commitment to the well-being of her trainees is palpable and magnanimous. When the session ends, many of us stand in line to give her a hug. It is a stark reminder of how many lives are affected when someone you know or care about takes his/her own life – and how, in the house of medicine, medical students and residents really are part of an institutional family.

- May 10: I facilitate a meeting of our 12 second-year residents, many of whom knew of or had met the resident who died. Almost everyone speaks, shares their feelings, poses questions, and calls for answers and change. There is disbelief, sadness, confusion, some guilt, and lots of anger. Also a feeling of disillusionment or paradox about the field of psychiatry: “Of all branches of medicine, shouldn’t residents who are struggling with psychiatric issues feel safe, protected, cared for in psychiatry?” There is also a feeling of lip service being paid to personal treatment, as in quoted statements: “By all means, get treatment for your issues, but don’t let it encroach on your duty hours” or “It’s good you’re getting help, but do you still have to go weekly?”

In the immediate aftermath of suicide, feelings run high, as they should. But rather than wait it out – and fearing a return to “business as usual” – let me make only two suggestions:

2. In psychiatry, we need to redouble our efforts in fighting the stigma attached to psychiatric illness in trainees. It is unconscionable that medical students and residents are dying of treatable disorders (I’ve never heard of a doctor dying of cancer who didn’t go to an oncologist at least once), yet too many are not availing themselves of services we provide – even when they’re free of charge or covered by insurance. And are we certain that, when they knock on our doors, we are providing them with state-of-the-art care? Is it possible that unrecognized internal stigma and shame deep within us might make us hesitant to help our trainees in their hour of need? Or cut corners? Or not get a second opinion? Very few psychiatrists on faculty of our medical schools divulge their personal experiences of depression, posttraumatic stress disorders, substance use disorders, and more (with the exception of being in therapy during residency, which is normative and isn’t stigmatized). Coming out is leveling, humane, and respectful – and it shrinks the power differential in the teaching dyad. It might even save a life.

Dr. Myers is a professor of clinical psychiatry at State University of New York, Brooklyn, and the author of “Why Physicians Die by Suicide: Lessons Learned From Their Families and Others Who Cared.”

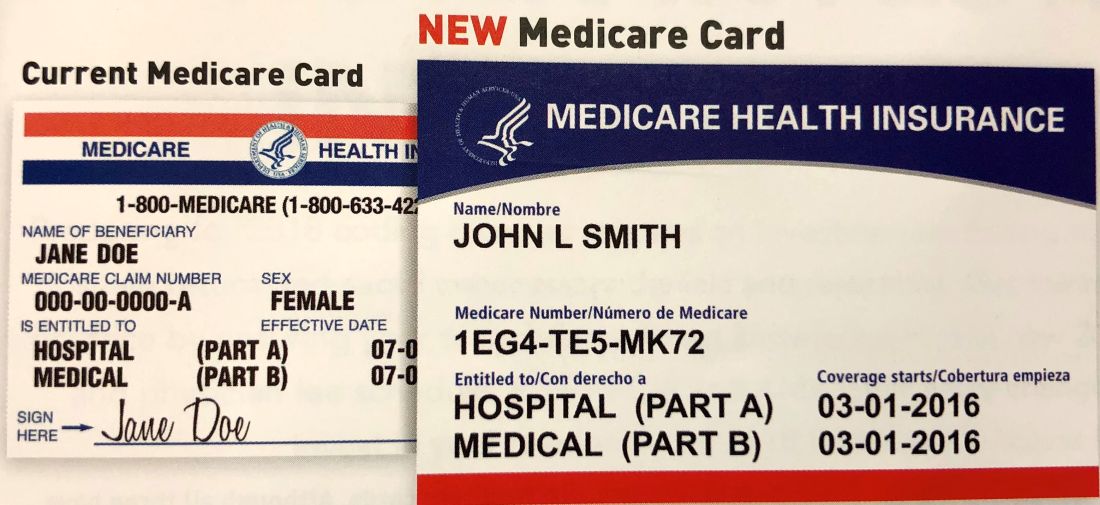

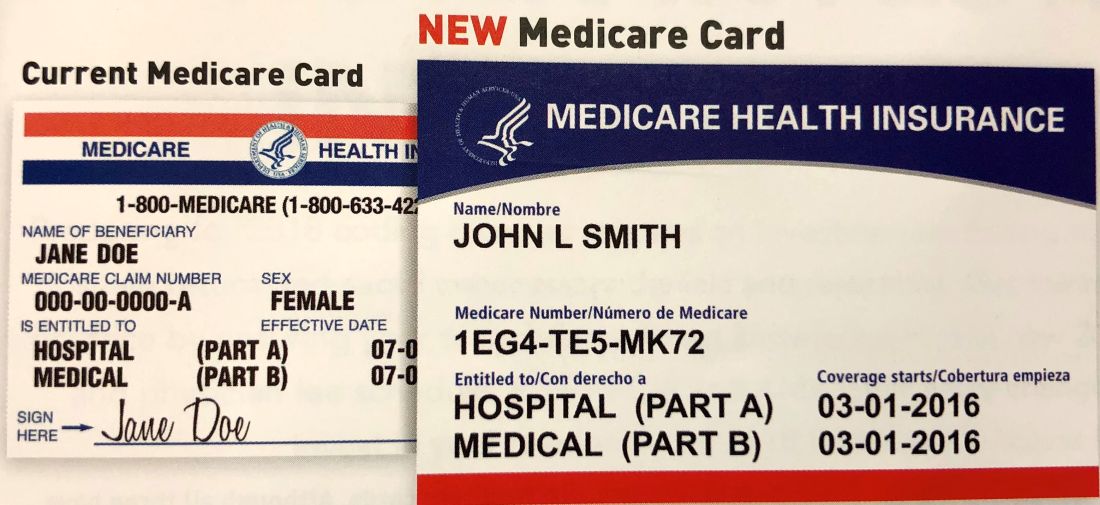

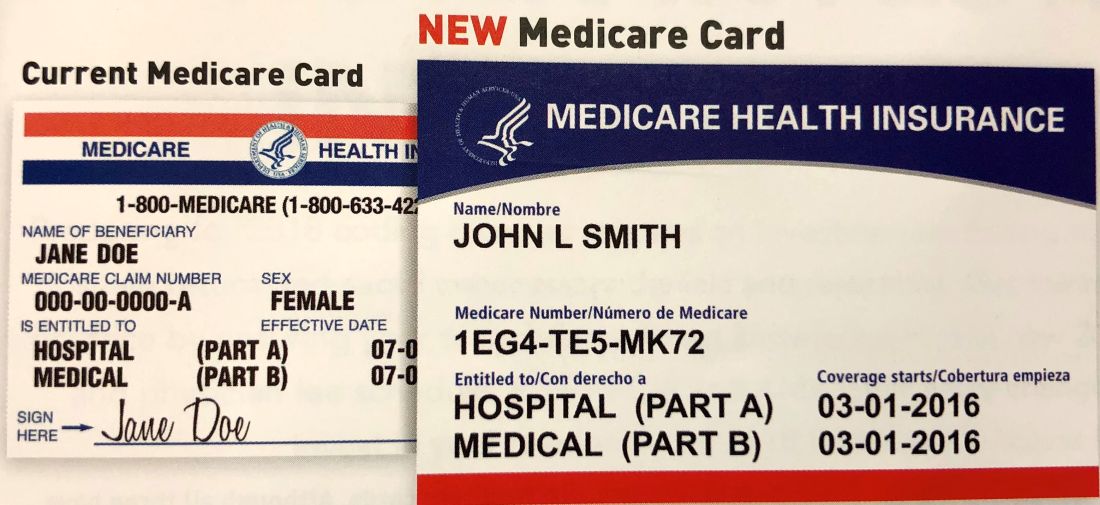

How to harness value-based care codes

Many of you reading this column joined Medicare accountable care organizations (ACOs) sometime between 2011 and 2016. As the power of prevention, wellness, and the medical home model are starting to be realized and appreciated, those benefits may be swamped by two new Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services value-based revenue streams that did not exist when many of you first joined your ACO.

The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) was passed in 2015 and is just now being implemented. Value-based, fee-for-service payments started out rather modestly a few years ago as chronic care management codes, but they have exploded to include more than 20 codes, counting the new ones coming online in 2018. Let’s call them collectively value-based care codes, or VCCs.

Many practices are trying to understand and perform the basic requirements to avoid penalties under MACRA’s Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) program. Some primary care practices, however, see the upside potential and bonuses stacking up to 30% or more.

Did you know that even if you are in, let’s say, a basic Medicare Shared Savings Program ACO – the MSSP Track 1, with no exposure to risk – you get special treatment on reporting under MACRA as a MIPS Advanced Practice Model (APM)?

But more importantly, MACRA is a team game. Getting into an MSSP Track 1 is justified just to get practice for the care coordination you’ll need. Few physicians know that they are judged under MACRA MIPS for the total costs of their patients, not just their own costs. A primary care physician receives only up to 8% of the $10 million your patients consume on average. The best way to counter that is through an ACO.

Further, we are aware of ACOs that have chosen risk-taking Medicare models such as NextGen, even though they predict small losses. Those losses are because of the automatic 5% fee-for-service payment bump to its physicians for risk taking if they are in a MACRA Advanced Alternative Payment Model (AAPM).

There’s a wide range of primary care physicians who are seizing opportunities offered by VCCs.

A family physician friend of mine who practices in a rural area generated more than 50% of his revenue from value-based care coding last year. And he has personally generated more than $350,000 in additional annual revenue, not counting the revenue from additional medically necessary procedures revealed by this more proactive wellness assessment activity and early diagnoses.

On the other hand, because busy physicians have a hard time wading through all these regulations and implementing the required staff and technology changes, it is reported that only about 8% of physicians are employing even the chronic care management codes. And when they do, they only achieve an 18% eligible patient penetration. My friend has broken the code, so to speak; he has protocolized and templated the process, has happy patients, has an ongoing 93% penetration rate, and actually has more free time.

While you are busy saving lives, I have had the luxury of looking from a high level at these tectonic, value-based payment shifts. To me, it’s a no-brainer for a primary care physician to leverage their ACO to maximize all three revenue streams. Look at MACRA MIPS, MIPS-APM, and AAPM measures anew, and see how well they play into integrated care.

As quarterback of health care through the patient-centered medical home, you are in great position to drive substantial bonuses. Similarly, when one looks at VCCs, the ACO can: help you navigate through the paperwork, perform much of the required reporting, and select the highest value-adding initiatives to monitor and drive higher quality and shared savings for the ACO.

As readers know, we firmly believe that, to have sustained incentivization, every ACO needs to have a merit-based, shared savings distribution formula. Accordingly, your compensation should rise under MACRA, VCCs, and the ACO.

This shift to value care is hard. But your colleagues who have made these changes are enjoying practice as never before. Their professional and financial rewards have climbed. But, most important, their patients love it.

Mr. Bobbitt is head of the health law group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, N.C. He is president of Value Health Partners, a health care strategic consulting company. He has years of experience assisting physicians form integrated delivery systems. He has spoken and written nationally to primary care physicians on the strategies and practicalities of forming or joining ACOs. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected] or 919-821-6612.

Many of you reading this column joined Medicare accountable care organizations (ACOs) sometime between 2011 and 2016. As the power of prevention, wellness, and the medical home model are starting to be realized and appreciated, those benefits may be swamped by two new Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services value-based revenue streams that did not exist when many of you first joined your ACO.

The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) was passed in 2015 and is just now being implemented. Value-based, fee-for-service payments started out rather modestly a few years ago as chronic care management codes, but they have exploded to include more than 20 codes, counting the new ones coming online in 2018. Let’s call them collectively value-based care codes, or VCCs.

Many practices are trying to understand and perform the basic requirements to avoid penalties under MACRA’s Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) program. Some primary care practices, however, see the upside potential and bonuses stacking up to 30% or more.

Did you know that even if you are in, let’s say, a basic Medicare Shared Savings Program ACO – the MSSP Track 1, with no exposure to risk – you get special treatment on reporting under MACRA as a MIPS Advanced Practice Model (APM)?

But more importantly, MACRA is a team game. Getting into an MSSP Track 1 is justified just to get practice for the care coordination you’ll need. Few physicians know that they are judged under MACRA MIPS for the total costs of their patients, not just their own costs. A primary care physician receives only up to 8% of the $10 million your patients consume on average. The best way to counter that is through an ACO.

Further, we are aware of ACOs that have chosen risk-taking Medicare models such as NextGen, even though they predict small losses. Those losses are because of the automatic 5% fee-for-service payment bump to its physicians for risk taking if they are in a MACRA Advanced Alternative Payment Model (AAPM).

There’s a wide range of primary care physicians who are seizing opportunities offered by VCCs.

A family physician friend of mine who practices in a rural area generated more than 50% of his revenue from value-based care coding last year. And he has personally generated more than $350,000 in additional annual revenue, not counting the revenue from additional medically necessary procedures revealed by this more proactive wellness assessment activity and early diagnoses.

On the other hand, because busy physicians have a hard time wading through all these regulations and implementing the required staff and technology changes, it is reported that only about 8% of physicians are employing even the chronic care management codes. And when they do, they only achieve an 18% eligible patient penetration. My friend has broken the code, so to speak; he has protocolized and templated the process, has happy patients, has an ongoing 93% penetration rate, and actually has more free time.

While you are busy saving lives, I have had the luxury of looking from a high level at these tectonic, value-based payment shifts. To me, it’s a no-brainer for a primary care physician to leverage their ACO to maximize all three revenue streams. Look at MACRA MIPS, MIPS-APM, and AAPM measures anew, and see how well they play into integrated care.

As quarterback of health care through the patient-centered medical home, you are in great position to drive substantial bonuses. Similarly, when one looks at VCCs, the ACO can: help you navigate through the paperwork, perform much of the required reporting, and select the highest value-adding initiatives to monitor and drive higher quality and shared savings for the ACO.

As readers know, we firmly believe that, to have sustained incentivization, every ACO needs to have a merit-based, shared savings distribution formula. Accordingly, your compensation should rise under MACRA, VCCs, and the ACO.

This shift to value care is hard. But your colleagues who have made these changes are enjoying practice as never before. Their professional and financial rewards have climbed. But, most important, their patients love it.

Mr. Bobbitt is head of the health law group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, N.C. He is president of Value Health Partners, a health care strategic consulting company. He has years of experience assisting physicians form integrated delivery systems. He has spoken and written nationally to primary care physicians on the strategies and practicalities of forming or joining ACOs. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected] or 919-821-6612.

Many of you reading this column joined Medicare accountable care organizations (ACOs) sometime between 2011 and 2016. As the power of prevention, wellness, and the medical home model are starting to be realized and appreciated, those benefits may be swamped by two new Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services value-based revenue streams that did not exist when many of you first joined your ACO.

The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) was passed in 2015 and is just now being implemented. Value-based, fee-for-service payments started out rather modestly a few years ago as chronic care management codes, but they have exploded to include more than 20 codes, counting the new ones coming online in 2018. Let’s call them collectively value-based care codes, or VCCs.

Many practices are trying to understand and perform the basic requirements to avoid penalties under MACRA’s Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) program. Some primary care practices, however, see the upside potential and bonuses stacking up to 30% or more.

Did you know that even if you are in, let’s say, a basic Medicare Shared Savings Program ACO – the MSSP Track 1, with no exposure to risk – you get special treatment on reporting under MACRA as a MIPS Advanced Practice Model (APM)?

But more importantly, MACRA is a team game. Getting into an MSSP Track 1 is justified just to get practice for the care coordination you’ll need. Few physicians know that they are judged under MACRA MIPS for the total costs of their patients, not just their own costs. A primary care physician receives only up to 8% of the $10 million your patients consume on average. The best way to counter that is through an ACO.

Further, we are aware of ACOs that have chosen risk-taking Medicare models such as NextGen, even though they predict small losses. Those losses are because of the automatic 5% fee-for-service payment bump to its physicians for risk taking if they are in a MACRA Advanced Alternative Payment Model (AAPM).

There’s a wide range of primary care physicians who are seizing opportunities offered by VCCs.

A family physician friend of mine who practices in a rural area generated more than 50% of his revenue from value-based care coding last year. And he has personally generated more than $350,000 in additional annual revenue, not counting the revenue from additional medically necessary procedures revealed by this more proactive wellness assessment activity and early diagnoses.

On the other hand, because busy physicians have a hard time wading through all these regulations and implementing the required staff and technology changes, it is reported that only about 8% of physicians are employing even the chronic care management codes. And when they do, they only achieve an 18% eligible patient penetration. My friend has broken the code, so to speak; he has protocolized and templated the process, has happy patients, has an ongoing 93% penetration rate, and actually has more free time.

While you are busy saving lives, I have had the luxury of looking from a high level at these tectonic, value-based payment shifts. To me, it’s a no-brainer for a primary care physician to leverage their ACO to maximize all three revenue streams. Look at MACRA MIPS, MIPS-APM, and AAPM measures anew, and see how well they play into integrated care.

As quarterback of health care through the patient-centered medical home, you are in great position to drive substantial bonuses. Similarly, when one looks at VCCs, the ACO can: help you navigate through the paperwork, perform much of the required reporting, and select the highest value-adding initiatives to monitor and drive higher quality and shared savings for the ACO.

As readers know, we firmly believe that, to have sustained incentivization, every ACO needs to have a merit-based, shared savings distribution formula. Accordingly, your compensation should rise under MACRA, VCCs, and the ACO.

This shift to value care is hard. But your colleagues who have made these changes are enjoying practice as never before. Their professional and financial rewards have climbed. But, most important, their patients love it.

Mr. Bobbitt is head of the health law group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, N.C. He is president of Value Health Partners, a health care strategic consulting company. He has years of experience assisting physicians form integrated delivery systems. He has spoken and written nationally to primary care physicians on the strategies and practicalities of forming or joining ACOs. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected] or 919-821-6612.

Diet

I’m about to embark on a controversial topic. Perhaps it’s safer to avoid, but I can’t put it off any longer. We need to talk about diet.

Discussing diet, like politics, religion, or salary, is best done just with oneself. Yet, I’m compelled to share what I’ve learned. First, I’m agnostic. I don’t believe you need to be vegan or paleo to be saved. I eat plant-based foods. I also eat things that eat plants. I’m sure you’d find a fine film of gluten in my kitchen. What I’ve learned is that for me, it doesn’t matter.

Specifically, I have little or nothing to eat from when I wake until dinner. As a busy dermatologist, that may seem draconian, but in fact it is easier than you might think. Patients are a constant all day, while hunger is fleeting. Got a craving at 10:15 a.m.? Easy. Walk in to see the next patient. Then repeat. Most days, this continues until 6:30 p.m. or so, when it’s time to head home. It’s not that hard, particularly when you don’t have anything in your office to eat except Dentyne Ice gum and green tea.

Now, this doesn’t always work. Why? Meetings. How do I manage fasting on those days? I don’t. If I know I have a lunch meeting scheduled, then I eat a healthy breakfast before I leave home, such as a protein smoothie or a bowl of hot oats with a dollop of Greek yogurt, sunflower seeds, walnuts, and berries. By eating a wholesome, well-balanced meal of fiber, carbs, lean protein, and good fats, I’m not starving before the meeting and am less likely to overeat. (That’s because I have also learned I’m not one of those enviable people who can simply say “no” to a crispy fish taco and guacamole if I’m hungry. I’m gonna eat it.) So, I avoid fasting and the inevitable frustration of breaking a fast on those days.

On days when I fast, I monitor how I feel. Fortunately, I have rarely felt hypoglycemic; except for that one Tuesday a couple of months ago. I had completed a long, hard early morning workout, and by mid-morning my hands were shaking and I felt nauseous. I quickly downed two RX bars and felt fine within minutes. Better for me, better for my patients.

Right now, intermittent fasting is working for me. Here’s my weekly plan:

I don’t fast on Fridays or weekends or when I travel. I eat out rarely. On weekends, my wife and I shop at the local farmers’ and fish markets to prepare ourselves for a week of healthy eating. And on Sundays, we continue our treasured family tradition of Sunday supper, which is basted with nostalgia and drizzled liberally with comfort. Often it requires long preparation, which is part of the appeal, and short attention is paid to its nutritional value. That’s not the point of Sunday dinner. A delicious dunk of fresh Italian bread in grassy-green olive oil or fresh pasta doused with homemade tomato basil sauce is the best possible meal I can have to prepare for a long, hard week ahead.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

I’m about to embark on a controversial topic. Perhaps it’s safer to avoid, but I can’t put it off any longer. We need to talk about diet.

Discussing diet, like politics, religion, or salary, is best done just with oneself. Yet, I’m compelled to share what I’ve learned. First, I’m agnostic. I don’t believe you need to be vegan or paleo to be saved. I eat plant-based foods. I also eat things that eat plants. I’m sure you’d find a fine film of gluten in my kitchen. What I’ve learned is that for me, it doesn’t matter.

Specifically, I have little or nothing to eat from when I wake until dinner. As a busy dermatologist, that may seem draconian, but in fact it is easier than you might think. Patients are a constant all day, while hunger is fleeting. Got a craving at 10:15 a.m.? Easy. Walk in to see the next patient. Then repeat. Most days, this continues until 6:30 p.m. or so, when it’s time to head home. It’s not that hard, particularly when you don’t have anything in your office to eat except Dentyne Ice gum and green tea.

Now, this doesn’t always work. Why? Meetings. How do I manage fasting on those days? I don’t. If I know I have a lunch meeting scheduled, then I eat a healthy breakfast before I leave home, such as a protein smoothie or a bowl of hot oats with a dollop of Greek yogurt, sunflower seeds, walnuts, and berries. By eating a wholesome, well-balanced meal of fiber, carbs, lean protein, and good fats, I’m not starving before the meeting and am less likely to overeat. (That’s because I have also learned I’m not one of those enviable people who can simply say “no” to a crispy fish taco and guacamole if I’m hungry. I’m gonna eat it.) So, I avoid fasting and the inevitable frustration of breaking a fast on those days.

On days when I fast, I monitor how I feel. Fortunately, I have rarely felt hypoglycemic; except for that one Tuesday a couple of months ago. I had completed a long, hard early morning workout, and by mid-morning my hands were shaking and I felt nauseous. I quickly downed two RX bars and felt fine within minutes. Better for me, better for my patients.

Right now, intermittent fasting is working for me. Here’s my weekly plan:

I don’t fast on Fridays or weekends or when I travel. I eat out rarely. On weekends, my wife and I shop at the local farmers’ and fish markets to prepare ourselves for a week of healthy eating. And on Sundays, we continue our treasured family tradition of Sunday supper, which is basted with nostalgia and drizzled liberally with comfort. Often it requires long preparation, which is part of the appeal, and short attention is paid to its nutritional value. That’s not the point of Sunday dinner. A delicious dunk of fresh Italian bread in grassy-green olive oil or fresh pasta doused with homemade tomato basil sauce is the best possible meal I can have to prepare for a long, hard week ahead.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

I’m about to embark on a controversial topic. Perhaps it’s safer to avoid, but I can’t put it off any longer. We need to talk about diet.

Discussing diet, like politics, religion, or salary, is best done just with oneself. Yet, I’m compelled to share what I’ve learned. First, I’m agnostic. I don’t believe you need to be vegan or paleo to be saved. I eat plant-based foods. I also eat things that eat plants. I’m sure you’d find a fine film of gluten in my kitchen. What I’ve learned is that for me, it doesn’t matter.

Specifically, I have little or nothing to eat from when I wake until dinner. As a busy dermatologist, that may seem draconian, but in fact it is easier than you might think. Patients are a constant all day, while hunger is fleeting. Got a craving at 10:15 a.m.? Easy. Walk in to see the next patient. Then repeat. Most days, this continues until 6:30 p.m. or so, when it’s time to head home. It’s not that hard, particularly when you don’t have anything in your office to eat except Dentyne Ice gum and green tea.

Now, this doesn’t always work. Why? Meetings. How do I manage fasting on those days? I don’t. If I know I have a lunch meeting scheduled, then I eat a healthy breakfast before I leave home, such as a protein smoothie or a bowl of hot oats with a dollop of Greek yogurt, sunflower seeds, walnuts, and berries. By eating a wholesome, well-balanced meal of fiber, carbs, lean protein, and good fats, I’m not starving before the meeting and am less likely to overeat. (That’s because I have also learned I’m not one of those enviable people who can simply say “no” to a crispy fish taco and guacamole if I’m hungry. I’m gonna eat it.) So, I avoid fasting and the inevitable frustration of breaking a fast on those days.

On days when I fast, I monitor how I feel. Fortunately, I have rarely felt hypoglycemic; except for that one Tuesday a couple of months ago. I had completed a long, hard early morning workout, and by mid-morning my hands were shaking and I felt nauseous. I quickly downed two RX bars and felt fine within minutes. Better for me, better for my patients.

Right now, intermittent fasting is working for me. Here’s my weekly plan:

I don’t fast on Fridays or weekends or when I travel. I eat out rarely. On weekends, my wife and I shop at the local farmers’ and fish markets to prepare ourselves for a week of healthy eating. And on Sundays, we continue our treasured family tradition of Sunday supper, which is basted with nostalgia and drizzled liberally with comfort. Often it requires long preparation, which is part of the appeal, and short attention is paid to its nutritional value. That’s not the point of Sunday dinner. A delicious dunk of fresh Italian bread in grassy-green olive oil or fresh pasta doused with homemade tomato basil sauce is the best possible meal I can have to prepare for a long, hard week ahead.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

Patients who record office visits

Question: During an office visit, the patient used a smartphone to record his conversation with the doctor. Which of the following statements is best?

A. This is an intrusion into a private and confidential physician-patient encounter and violates laws against eavesdropping and wiretapping.

B. Recordings are rarely made in the doctor’s office.

C. Both parties must consent before the patient or doctor can legally make such a recording.

D. Surreptitious recording by one party is always illegal.

E. All are incorrect.

Answer: E.

Scholars from Dartmouth recently published their viewpoint on this topic in the Aug. 7, 2017, issue of JAMA.1 Many individuals believe that taping or recording a private conversation is per se illegal.

This is a misconception. Although it is a serious felony to violate wiretapping laws, in fact every jurisdiction permits the taping or recording of doctor-patient conversations where there is all-party consent. A majority of states actually allow the recording even if one party has not given his/her consent. This one-party consent rule is the law in 39 states, including Hawaii and New York. On the other hand, 11 states, such as California, Florida, Massachusetts, and Washington, deem such recordings illegal. A listing of the law in the various states can be found in the JAMA article, in which the authors call for “clear policies that facilitate the positive use of digital recordings.”

In a 2011 case against the Cleveland Clinic, a patient died of a cardiac arrest from hyperkalemia 3 days after elective knee surgery.2 The patient’s children had made a covert recording of a meeting with the chief medical officer when discussing the incident. The hospital attempted to bar the use of the recording, claiming that the information was nondiscoverable under the “peer review” privilege.

Both the trial court and the court of appeals disagreed, being unconvinced that such discussions fell within peer review protection. That the recording was made surreptitiously was not raised as an issue, as Ohio is a one-party consent state, i.e., the law permits a patient to legally tape his/her conversations without obtaining prior approval from the doctor.3

There are clear advantages to having a permanent record of a doctor’s professional opinion. The patient can review the information after the visit for a better understanding or for recall purposes, even sharing the information with family members, caregivers, or others, especially where there is a lack of clarity on instructions.4 In the area of informed consent, this is particularly useful for a reminder of medication side effects and potential complications of proposed surgery.

However, many doctors believe that recordings may be disruptive or prove inhibitory to free and open discussions, and they are concerned about their potential use should litigation arises.

Risk managers and malpractice carriers are divided in their views. For example, it has been stated that, “at the Barrow Neurological Institute, in Phoenix, Arizona, where patients are routinely offered video recordings of their visits, clinicians who participate in these recordings receive a 10% reduction in the cost of their medical defense and $1 million extra liability coverage” (P.J. Barr, unpublished data, 2017, as cited in reference 1). Other carriers are not as supportive, discouraging their insureds from allowing recordings to be made.

In the majority of jurisdictions, recordings are legal if consented to by one of the parties. This means that recordings by the patient with/without consent from or with/without knowledge of the doctor are fully legitimate. It also means that the recordings will be admissible into evidence in a courtroom, unless the information is privileged (protected from discovery) or is otherwise irrelevant or unreliable.

On the other hand, in states requiring all-party consent, such recordings are illegal absent across-the-board consent, and they will be inadmissible into evidence. This cardinal difference in state law raises vital implications for both plaintiff and defendant in litigation, because the recordings may contain incriminating or exculpatory information.

Recordings of conversations in the doctor’s office are by no means rare. A survey in the United Kingdom revealed that 15% of the public had secretly recorded a clinic visit, and 11% were aware of someone else doing the same.5 The concerned physician could proactively prohibit all office recordings by posting a “no recording” sign in the waiting room in the name of confidentiality and privacy. And should a physician discover that a patient is covertly recording, risk managers have suggested terminating the visit with a warning that a repeat attempt will result in discharge.

Like it or not, recordings are here to stay, and the omnipresence of modern communications devices such as smartphones, tablets, etc., is likely to increase the prevalence of recordings. A practical approach for practicing physicians is to familiarize themselves with the law in the individual state in which they practice and to improve their communication skills irrespective of whether or not there is a recording.

They may wish to consider the view attributed to Richard Boothman, JD, chief risk officer at the University of Michigan Health System: “Recording should cause any caregiver to mind their professionalism and be disciplined in their remarks to their patients. … I believe it can be a very powerful tool to cement the patient/physician relationship and the patient’s understanding of the clinical messages and information. Physicians are significantly benefited by an informed patient.”6

References

1. JAMA. 2017 Aug 8;318(6):513-4.

2. Smith v. Cleveland Clinic, 197 Ohio App.3d 524, 2011.

3. Ohio Revised Code 2933.52.

4. JAMA. 2015 Apr 28;313(16):1615-6.

5. BMJ Open. 2015 Aug 11;5(8):e008566.

6. “Your office is being recorded.” Medscape, April 3, 2018.

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and a former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

Question: During an office visit, the patient used a smartphone to record his conversation with the doctor. Which of the following statements is best?

A. This is an intrusion into a private and confidential physician-patient encounter and violates laws against eavesdropping and wiretapping.

B. Recordings are rarely made in the doctor’s office.

C. Both parties must consent before the patient or doctor can legally make such a recording.

D. Surreptitious recording by one party is always illegal.

E. All are incorrect.

Answer: E.

Scholars from Dartmouth recently published their viewpoint on this topic in the Aug. 7, 2017, issue of JAMA.1 Many individuals believe that taping or recording a private conversation is per se illegal.

This is a misconception. Although it is a serious felony to violate wiretapping laws, in fact every jurisdiction permits the taping or recording of doctor-patient conversations where there is all-party consent. A majority of states actually allow the recording even if one party has not given his/her consent. This one-party consent rule is the law in 39 states, including Hawaii and New York. On the other hand, 11 states, such as California, Florida, Massachusetts, and Washington, deem such recordings illegal. A listing of the law in the various states can be found in the JAMA article, in which the authors call for “clear policies that facilitate the positive use of digital recordings.”

In a 2011 case against the Cleveland Clinic, a patient died of a cardiac arrest from hyperkalemia 3 days after elective knee surgery.2 The patient’s children had made a covert recording of a meeting with the chief medical officer when discussing the incident. The hospital attempted to bar the use of the recording, claiming that the information was nondiscoverable under the “peer review” privilege.

Both the trial court and the court of appeals disagreed, being unconvinced that such discussions fell within peer review protection. That the recording was made surreptitiously was not raised as an issue, as Ohio is a one-party consent state, i.e., the law permits a patient to legally tape his/her conversations without obtaining prior approval from the doctor.3

There are clear advantages to having a permanent record of a doctor’s professional opinion. The patient can review the information after the visit for a better understanding or for recall purposes, even sharing the information with family members, caregivers, or others, especially where there is a lack of clarity on instructions.4 In the area of informed consent, this is particularly useful for a reminder of medication side effects and potential complications of proposed surgery.

However, many doctors believe that recordings may be disruptive or prove inhibitory to free and open discussions, and they are concerned about their potential use should litigation arises.

Risk managers and malpractice carriers are divided in their views. For example, it has been stated that, “at the Barrow Neurological Institute, in Phoenix, Arizona, where patients are routinely offered video recordings of their visits, clinicians who participate in these recordings receive a 10% reduction in the cost of their medical defense and $1 million extra liability coverage” (P.J. Barr, unpublished data, 2017, as cited in reference 1). Other carriers are not as supportive, discouraging their insureds from allowing recordings to be made.

In the majority of jurisdictions, recordings are legal if consented to by one of the parties. This means that recordings by the patient with/without consent from or with/without knowledge of the doctor are fully legitimate. It also means that the recordings will be admissible into evidence in a courtroom, unless the information is privileged (protected from discovery) or is otherwise irrelevant or unreliable.

On the other hand, in states requiring all-party consent, such recordings are illegal absent across-the-board consent, and they will be inadmissible into evidence. This cardinal difference in state law raises vital implications for both plaintiff and defendant in litigation, because the recordings may contain incriminating or exculpatory information.

Recordings of conversations in the doctor’s office are by no means rare. A survey in the United Kingdom revealed that 15% of the public had secretly recorded a clinic visit, and 11% were aware of someone else doing the same.5 The concerned physician could proactively prohibit all office recordings by posting a “no recording” sign in the waiting room in the name of confidentiality and privacy. And should a physician discover that a patient is covertly recording, risk managers have suggested terminating the visit with a warning that a repeat attempt will result in discharge.

Like it or not, recordings are here to stay, and the omnipresence of modern communications devices such as smartphones, tablets, etc., is likely to increase the prevalence of recordings. A practical approach for practicing physicians is to familiarize themselves with the law in the individual state in which they practice and to improve their communication skills irrespective of whether or not there is a recording.

They may wish to consider the view attributed to Richard Boothman, JD, chief risk officer at the University of Michigan Health System: “Recording should cause any caregiver to mind their professionalism and be disciplined in their remarks to their patients. … I believe it can be a very powerful tool to cement the patient/physician relationship and the patient’s understanding of the clinical messages and information. Physicians are significantly benefited by an informed patient.”6

References

1. JAMA. 2017 Aug 8;318(6):513-4.

2. Smith v. Cleveland Clinic, 197 Ohio App.3d 524, 2011.

3. Ohio Revised Code 2933.52.

4. JAMA. 2015 Apr 28;313(16):1615-6.

5. BMJ Open. 2015 Aug 11;5(8):e008566.

6. “Your office is being recorded.” Medscape, April 3, 2018.

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and a former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

Question: During an office visit, the patient used a smartphone to record his conversation with the doctor. Which of the following statements is best?

A. This is an intrusion into a private and confidential physician-patient encounter and violates laws against eavesdropping and wiretapping.

B. Recordings are rarely made in the doctor’s office.

C. Both parties must consent before the patient or doctor can legally make such a recording.

D. Surreptitious recording by one party is always illegal.

E. All are incorrect.

Answer: E.

Scholars from Dartmouth recently published their viewpoint on this topic in the Aug. 7, 2017, issue of JAMA.1 Many individuals believe that taping or recording a private conversation is per se illegal.

This is a misconception. Although it is a serious felony to violate wiretapping laws, in fact every jurisdiction permits the taping or recording of doctor-patient conversations where there is all-party consent. A majority of states actually allow the recording even if one party has not given his/her consent. This one-party consent rule is the law in 39 states, including Hawaii and New York. On the other hand, 11 states, such as California, Florida, Massachusetts, and Washington, deem such recordings illegal. A listing of the law in the various states can be found in the JAMA article, in which the authors call for “clear policies that facilitate the positive use of digital recordings.”

In a 2011 case against the Cleveland Clinic, a patient died of a cardiac arrest from hyperkalemia 3 days after elective knee surgery.2 The patient’s children had made a covert recording of a meeting with the chief medical officer when discussing the incident. The hospital attempted to bar the use of the recording, claiming that the information was nondiscoverable under the “peer review” privilege.

Both the trial court and the court of appeals disagreed, being unconvinced that such discussions fell within peer review protection. That the recording was made surreptitiously was not raised as an issue, as Ohio is a one-party consent state, i.e., the law permits a patient to legally tape his/her conversations without obtaining prior approval from the doctor.3

There are clear advantages to having a permanent record of a doctor’s professional opinion. The patient can review the information after the visit for a better understanding or for recall purposes, even sharing the information with family members, caregivers, or others, especially where there is a lack of clarity on instructions.4 In the area of informed consent, this is particularly useful for a reminder of medication side effects and potential complications of proposed surgery.

However, many doctors believe that recordings may be disruptive or prove inhibitory to free and open discussions, and they are concerned about their potential use should litigation arises.

Risk managers and malpractice carriers are divided in their views. For example, it has been stated that, “at the Barrow Neurological Institute, in Phoenix, Arizona, where patients are routinely offered video recordings of their visits, clinicians who participate in these recordings receive a 10% reduction in the cost of their medical defense and $1 million extra liability coverage” (P.J. Barr, unpublished data, 2017, as cited in reference 1). Other carriers are not as supportive, discouraging their insureds from allowing recordings to be made.

In the majority of jurisdictions, recordings are legal if consented to by one of the parties. This means that recordings by the patient with/without consent from or with/without knowledge of the doctor are fully legitimate. It also means that the recordings will be admissible into evidence in a courtroom, unless the information is privileged (protected from discovery) or is otherwise irrelevant or unreliable.

On the other hand, in states requiring all-party consent, such recordings are illegal absent across-the-board consent, and they will be inadmissible into evidence. This cardinal difference in state law raises vital implications for both plaintiff and defendant in litigation, because the recordings may contain incriminating or exculpatory information.

Recordings of conversations in the doctor’s office are by no means rare. A survey in the United Kingdom revealed that 15% of the public had secretly recorded a clinic visit, and 11% were aware of someone else doing the same.5 The concerned physician could proactively prohibit all office recordings by posting a “no recording” sign in the waiting room in the name of confidentiality and privacy. And should a physician discover that a patient is covertly recording, risk managers have suggested terminating the visit with a warning that a repeat attempt will result in discharge.

Like it or not, recordings are here to stay, and the omnipresence of modern communications devices such as smartphones, tablets, etc., is likely to increase the prevalence of recordings. A practical approach for practicing physicians is to familiarize themselves with the law in the individual state in which they practice and to improve their communication skills irrespective of whether or not there is a recording.

They may wish to consider the view attributed to Richard Boothman, JD, chief risk officer at the University of Michigan Health System: “Recording should cause any caregiver to mind their professionalism and be disciplined in their remarks to their patients. … I believe it can be a very powerful tool to cement the patient/physician relationship and the patient’s understanding of the clinical messages and information. Physicians are significantly benefited by an informed patient.”6

References

1. JAMA. 2017 Aug 8;318(6):513-4.

2. Smith v. Cleveland Clinic, 197 Ohio App.3d 524, 2011.

3. Ohio Revised Code 2933.52.

4. JAMA. 2015 Apr 28;313(16):1615-6.

5. BMJ Open. 2015 Aug 11;5(8):e008566.

6. “Your office is being recorded.” Medscape, April 3, 2018.

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and a former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

Words do matter – especially in psychiatry

As psychiatrists, we must be more precise with our language. When we speak, we must not use psychiatric diagnoses to describe common, everyday problems in life.

For example, at the recent American Psychiatric Association meeting in New York City, I frequently heard my colleagues talking about being “traumatized” over a microinsult or a microaggression. Although these individuals suggested that they were so fragile and vulnerable that stressful events caused them to develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), I seriously doubted it. Moreover, with further dialogue, it became clear that they were stressed or distressed over the stressful event – not traumatized in the purest sense of the term.

Traumatic stress, on the other hand, is an event that is so painful and disruptive that it runs the risk of breaking the mind’s ability to process or make peace with the event because it is so overwhelming that it disrupts or destroys normal psychic life. Such an event has the potential of causing PTSD, which is a chronic anxiety disorder that needs to be addressed clinically. This precision may seem nitpicky; however, the research on traumatic stress is clear. If you expose 100 people to a genuine traumatic experience, about 10% of the males and 20% of the females will develop PTSD, thus, something must be protecting people from developing PTSD from exposure to trauma. The research also is lucid that catastrophizing increases the risk of developing PTSD from exposure to a trauma by about 33%, and not having a sense of self-efficacy increases the risk by an additional 33%. Accordingly, , as this is catastrophizing and minimizes the belief in self-efficacy.

Similarly, we must be careful how we use the word “depression.” My understanding is depression is a clinical phenomenon that can be disabling. Unfortunately, I often hear patients and others talking about how they are depressed over various events in life that to me are a part of living, for example, being out of a job and not being able to make a way in life. Of course, if you are out actively looking for a job, that is probably not a clinical depression that would respond to antidepressant medication, but which would respond to finding a job. If a person were depressed from not having a job and unable to summon the energy to look for a job for 2 weeks or longer, I possibly would consider them clinically depressed. It seems laypeople are always using the word “depression” interchangeably for “unhappy,” “sad,” “grief,” or even “demoralization,” and although they all have common threads and are interlinked to one another, they are also very different.

Finally, the use of the word “bipolar” seems to be creeping into common usage, as I frequently hear patients who have poor affect regulation, for example, bad tempers, referring to themselves as being “bipolar.” However, after more dialogue, it becomes clear that they are describing a loss of self-control that lasts for maybe for 30 minutes or an hour. What is more distressing are the number of psychiatrists who are willing to take the patients’ word for it that they are “bipolar” and willing to prescribe mood stabilizers for such patients.

We must do better. We must not mislead the public into thinking that the ordinary problems of living are psychiatric disorders.

Dr. Bell is staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital Surgical-Medical/Psychiatric Inpatient Unit; clinical professor emeritus, department of psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago; and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (the birthplace of child psychiatry), all in Chicago. He also serves as chair of psychiatry at Windsor University, St. Kitts.

As psychiatrists, we must be more precise with our language. When we speak, we must not use psychiatric diagnoses to describe common, everyday problems in life.

For example, at the recent American Psychiatric Association meeting in New York City, I frequently heard my colleagues talking about being “traumatized” over a microinsult or a microaggression. Although these individuals suggested that they were so fragile and vulnerable that stressful events caused them to develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), I seriously doubted it. Moreover, with further dialogue, it became clear that they were stressed or distressed over the stressful event – not traumatized in the purest sense of the term.

Traumatic stress, on the other hand, is an event that is so painful and disruptive that it runs the risk of breaking the mind’s ability to process or make peace with the event because it is so overwhelming that it disrupts or destroys normal psychic life. Such an event has the potential of causing PTSD, which is a chronic anxiety disorder that needs to be addressed clinically. This precision may seem nitpicky; however, the research on traumatic stress is clear. If you expose 100 people to a genuine traumatic experience, about 10% of the males and 20% of the females will develop PTSD, thus, something must be protecting people from developing PTSD from exposure to trauma. The research also is lucid that catastrophizing increases the risk of developing PTSD from exposure to a trauma by about 33%, and not having a sense of self-efficacy increases the risk by an additional 33%. Accordingly, , as this is catastrophizing and minimizes the belief in self-efficacy.

Similarly, we must be careful how we use the word “depression.” My understanding is depression is a clinical phenomenon that can be disabling. Unfortunately, I often hear patients and others talking about how they are depressed over various events in life that to me are a part of living, for example, being out of a job and not being able to make a way in life. Of course, if you are out actively looking for a job, that is probably not a clinical depression that would respond to antidepressant medication, but which would respond to finding a job. If a person were depressed from not having a job and unable to summon the energy to look for a job for 2 weeks or longer, I possibly would consider them clinically depressed. It seems laypeople are always using the word “depression” interchangeably for “unhappy,” “sad,” “grief,” or even “demoralization,” and although they all have common threads and are interlinked to one another, they are also very different.

Finally, the use of the word “bipolar” seems to be creeping into common usage, as I frequently hear patients who have poor affect regulation, for example, bad tempers, referring to themselves as being “bipolar.” However, after more dialogue, it becomes clear that they are describing a loss of self-control that lasts for maybe for 30 minutes or an hour. What is more distressing are the number of psychiatrists who are willing to take the patients’ word for it that they are “bipolar” and willing to prescribe mood stabilizers for such patients.

We must do better. We must not mislead the public into thinking that the ordinary problems of living are psychiatric disorders.

Dr. Bell is staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital Surgical-Medical/Psychiatric Inpatient Unit; clinical professor emeritus, department of psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago; and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (the birthplace of child psychiatry), all in Chicago. He also serves as chair of psychiatry at Windsor University, St. Kitts.

As psychiatrists, we must be more precise with our language. When we speak, we must not use psychiatric diagnoses to describe common, everyday problems in life.

For example, at the recent American Psychiatric Association meeting in New York City, I frequently heard my colleagues talking about being “traumatized” over a microinsult or a microaggression. Although these individuals suggested that they were so fragile and vulnerable that stressful events caused them to develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), I seriously doubted it. Moreover, with further dialogue, it became clear that they were stressed or distressed over the stressful event – not traumatized in the purest sense of the term.

Traumatic stress, on the other hand, is an event that is so painful and disruptive that it runs the risk of breaking the mind’s ability to process or make peace with the event because it is so overwhelming that it disrupts or destroys normal psychic life. Such an event has the potential of causing PTSD, which is a chronic anxiety disorder that needs to be addressed clinically. This precision may seem nitpicky; however, the research on traumatic stress is clear. If you expose 100 people to a genuine traumatic experience, about 10% of the males and 20% of the females will develop PTSD, thus, something must be protecting people from developing PTSD from exposure to trauma. The research also is lucid that catastrophizing increases the risk of developing PTSD from exposure to a trauma by about 33%, and not having a sense of self-efficacy increases the risk by an additional 33%. Accordingly, , as this is catastrophizing and minimizes the belief in self-efficacy.

Similarly, we must be careful how we use the word “depression.” My understanding is depression is a clinical phenomenon that can be disabling. Unfortunately, I often hear patients and others talking about how they are depressed over various events in life that to me are a part of living, for example, being out of a job and not being able to make a way in life. Of course, if you are out actively looking for a job, that is probably not a clinical depression that would respond to antidepressant medication, but which would respond to finding a job. If a person were depressed from not having a job and unable to summon the energy to look for a job for 2 weeks or longer, I possibly would consider them clinically depressed. It seems laypeople are always using the word “depression” interchangeably for “unhappy,” “sad,” “grief,” or even “demoralization,” and although they all have common threads and are interlinked to one another, they are also very different.

Finally, the use of the word “bipolar” seems to be creeping into common usage, as I frequently hear patients who have poor affect regulation, for example, bad tempers, referring to themselves as being “bipolar.” However, after more dialogue, it becomes clear that they are describing a loss of self-control that lasts for maybe for 30 minutes or an hour. What is more distressing are the number of psychiatrists who are willing to take the patients’ word for it that they are “bipolar” and willing to prescribe mood stabilizers for such patients.

We must do better. We must not mislead the public into thinking that the ordinary problems of living are psychiatric disorders.

Dr. Bell is staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital Surgical-Medical/Psychiatric Inpatient Unit; clinical professor emeritus, department of psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago; and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (the birthplace of child psychiatry), all in Chicago. He also serves as chair of psychiatry at Windsor University, St. Kitts.

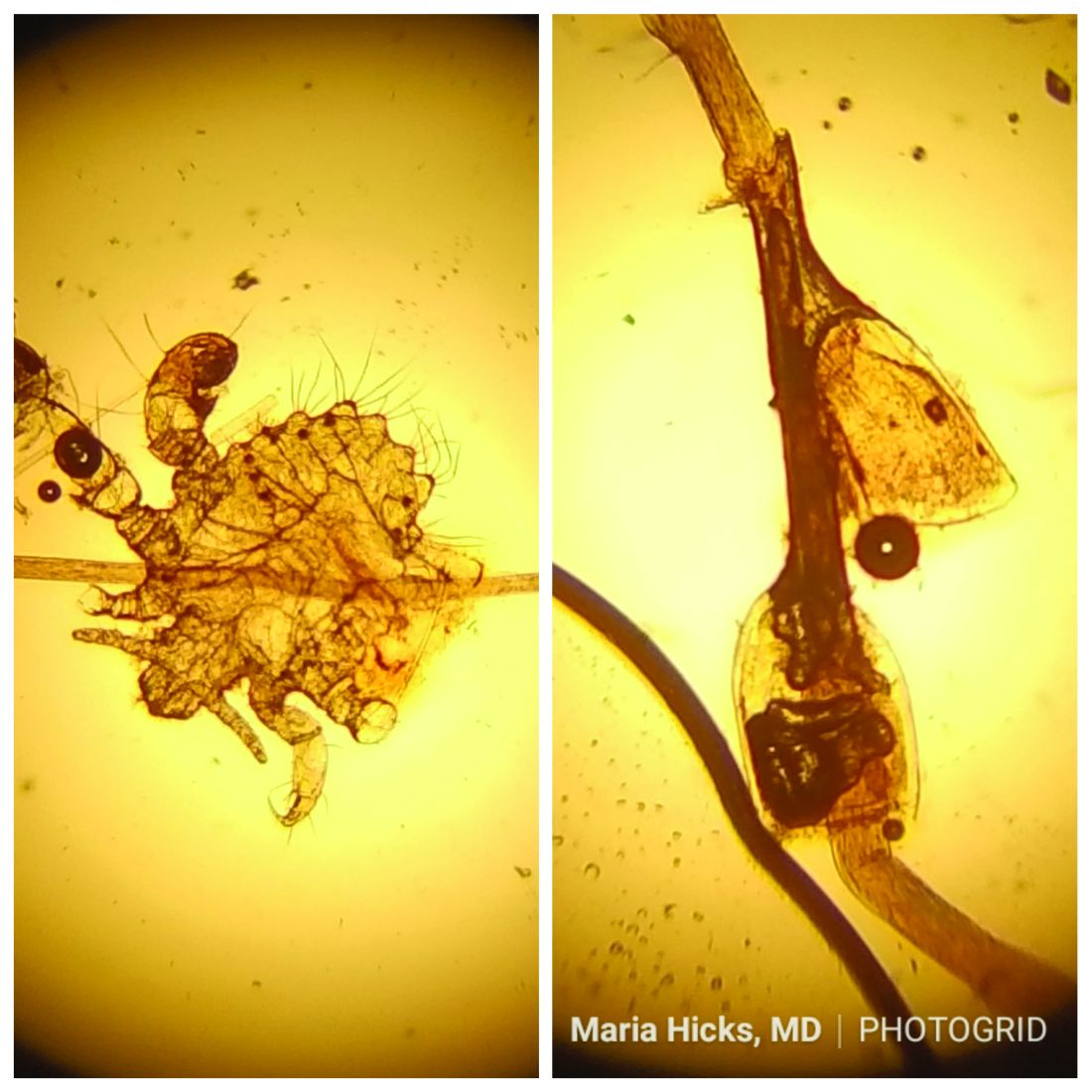

Make the Diagnosis - May 2018

and through close skin contact, as well as contaminated clothes and bedding. Adult lice can live up to 36 hours away from its host. Pubic areas most commonly are affected, although other hair-bearing parts of the body often are affected, including eyelashes.

Pruritus can be severe. Secondary bacterial infections may occur as maculae ceruleae, or blue-colored macules, on the skin. The lice are visible to the naked eye and are approximately 1 mm in length. They have a crablike appearance, six legs, and a wide body. Nits may be present on the hair shaft. Unlike hair casts, which can be moved up and down along the hair shaft, nits firmly adhere to the hair. Diagnosis should prompt a workup for other sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV.

Treatment for patients and their sexual partners include permethrin topically; and laundering of clothing and bedding. Lice on the eyelashes can be treated with 8 days of twice-daily applications of petrolatum. Ivermectin can be used when topical therapy fails, although this is an off-label treatment (not approved by the Food and Drug Administration).

Pediculosis corporis – body lice or clothing lice – is also known as “vagabond’s disease” and is caused by Pediculus humanus var corporis. Body lice lay their eggs in clothing seams and can live in clothing for up to 1 month without feeding on human blood. Often homeless individuals and those living in overcrowded areas can be affected. The louse and nits also are visible to the naked eye. They have a longer, narrower body than Phthirus pubis and are more similar in appearance to head lice. They rarely are found on the skin.

Body lice may carry disease such as epidemic typhus, relapsing fever, and trench fever or endocarditis. Permethrin is the most widely used treatment to kill both lice and ova. Other treatments include Malathion, Lindane, and Crotamiton. Clothing and bedding should be laundered.

Scabies is a mite infestation caused by Sarcoptes scabiei. Unlike lice, scabies often affects the hands and feet. Characteristic linear burrows may be seen in the finger web spaces. The circle of Hebra describes the areas commonly infected by mites: axillae, antecubital fossa, wrists, hands, and the groin. Pruritus may be severe and worse at night. Patients may be afflicted with both lice and scabies at the same time. Mites are not visible to the naked eye but can be seen microscopically. Topical permethrin cream is used most often for treatment. All household contacts should be treated at the same time. As in louse infestations, clothing and bedding should be laundered. Ivermectin can be used for crusted scabies, although this is an off-label treatment.

This case and photo were submitted by Maria Hicks, MD, Advanced Dermatology and Cosmetic Surgery, Tampa, and Dr. Martin.