User login

The diagnosis and treatment of ureteral injury

A gynecologic surgeon learns very early in his/her career to respect the ureter. Whether from the procedure being performed (endometriosis surgery, hysterectomy, myomectomy for ligamentous fibroids, salpingo-oophorectomy, excision of ovarian remnants, adhesiolysis), blood loss that obscures visualization and must be controlled, or use of energy for cutting, desiccation, and coagulation leading to potential lateral tissue damage, ureteral injury is a well-known complication. Even normal anatomic variations may put some women at greater risk; according to Hurd et al. (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:336-9). In a small subset of women, the distance between the cervix and the ureter may be less than 0.5 cm.

As a practicing minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon for the past 30 years, and an early adapter to laparoscopic hysterectomy, I remember quite well the recommendation to always dissect out ureters at time of the procedure. At present, most will agree that selective dissection is safe and thus, more desirable, as bleeding, damage secondary to desiccation, and ureter devascularization with subsequent necrosis are all increased with ureterolysis.

I agree with Dr. Kenton and Dr. Mueller that ureteral stenting has not been shown to significantly decrease ureteral injury rates. Often times, with loss of peristalsis secondary to stent placement, locating the ureter may be even more difficult. Recent advances using lighted stents or indocyanine green, which fluoresces in response to near-infrared laser and can be injected into the ureter via the ureteral catheter tip, are still in the feasibility phase of evaluation and can be costly.

As most urogenital fistulae are secondary to unrecognized injuries at time of surgery, and due to the fact that intraoperative recognition of the injury allows for primary repair, thus, decreasing the rate of secondary surgery and the associated increased morbidity, I recommend cystoscopy to check for ureteral jets (ureteral efflux) be performed when there is concern regarding ureter compromise.

Currently, I utilize a 70° cystoscope to visualize the ureters. While in the past, I have used intravenous indigo carmine, methylene blue, or fluorescein sodium, I currently use Pyridium (phenazopyridine) 200 mg taken by mouth 1 hour prior to the procedure.

Unfortunately, ureteral jetting still may be noted despite partial ligation, laceration, or desiccation of the ureter.

If ureteral injury is not recognized at time of surgery, it can lead to various postoperative symptoms. If there is a ureteral defect, the patient may note profuse wound leakage, increased abdominal fluid, or a urinoma, ileus, fever, peritonitis, or hematuria. With ureteral obstruction, flank or abdominal pain or anuria can be noted; while, with fistula formation, the patient will likely present with urinary incontinence or watery vaginal discharge.

Dr. Miller is a minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in Naperville, Ill., and a past president of the AAGL.

A gynecologic surgeon learns very early in his/her career to respect the ureter. Whether from the procedure being performed (endometriosis surgery, hysterectomy, myomectomy for ligamentous fibroids, salpingo-oophorectomy, excision of ovarian remnants, adhesiolysis), blood loss that obscures visualization and must be controlled, or use of energy for cutting, desiccation, and coagulation leading to potential lateral tissue damage, ureteral injury is a well-known complication. Even normal anatomic variations may put some women at greater risk; according to Hurd et al. (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:336-9). In a small subset of women, the distance between the cervix and the ureter may be less than 0.5 cm.

As a practicing minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon for the past 30 years, and an early adapter to laparoscopic hysterectomy, I remember quite well the recommendation to always dissect out ureters at time of the procedure. At present, most will agree that selective dissection is safe and thus, more desirable, as bleeding, damage secondary to desiccation, and ureter devascularization with subsequent necrosis are all increased with ureterolysis.

I agree with Dr. Kenton and Dr. Mueller that ureteral stenting has not been shown to significantly decrease ureteral injury rates. Often times, with loss of peristalsis secondary to stent placement, locating the ureter may be even more difficult. Recent advances using lighted stents or indocyanine green, which fluoresces in response to near-infrared laser and can be injected into the ureter via the ureteral catheter tip, are still in the feasibility phase of evaluation and can be costly.

As most urogenital fistulae are secondary to unrecognized injuries at time of surgery, and due to the fact that intraoperative recognition of the injury allows for primary repair, thus, decreasing the rate of secondary surgery and the associated increased morbidity, I recommend cystoscopy to check for ureteral jets (ureteral efflux) be performed when there is concern regarding ureter compromise.

Currently, I utilize a 70° cystoscope to visualize the ureters. While in the past, I have used intravenous indigo carmine, methylene blue, or fluorescein sodium, I currently use Pyridium (phenazopyridine) 200 mg taken by mouth 1 hour prior to the procedure.

Unfortunately, ureteral jetting still may be noted despite partial ligation, laceration, or desiccation of the ureter.

If ureteral injury is not recognized at time of surgery, it can lead to various postoperative symptoms. If there is a ureteral defect, the patient may note profuse wound leakage, increased abdominal fluid, or a urinoma, ileus, fever, peritonitis, or hematuria. With ureteral obstruction, flank or abdominal pain or anuria can be noted; while, with fistula formation, the patient will likely present with urinary incontinence or watery vaginal discharge.

Dr. Miller is a minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in Naperville, Ill., and a past president of the AAGL.

A gynecologic surgeon learns very early in his/her career to respect the ureter. Whether from the procedure being performed (endometriosis surgery, hysterectomy, myomectomy for ligamentous fibroids, salpingo-oophorectomy, excision of ovarian remnants, adhesiolysis), blood loss that obscures visualization and must be controlled, or use of energy for cutting, desiccation, and coagulation leading to potential lateral tissue damage, ureteral injury is a well-known complication. Even normal anatomic variations may put some women at greater risk; according to Hurd et al. (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:336-9). In a small subset of women, the distance between the cervix and the ureter may be less than 0.5 cm.

As a practicing minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon for the past 30 years, and an early adapter to laparoscopic hysterectomy, I remember quite well the recommendation to always dissect out ureters at time of the procedure. At present, most will agree that selective dissection is safe and thus, more desirable, as bleeding, damage secondary to desiccation, and ureter devascularization with subsequent necrosis are all increased with ureterolysis.

I agree with Dr. Kenton and Dr. Mueller that ureteral stenting has not been shown to significantly decrease ureteral injury rates. Often times, with loss of peristalsis secondary to stent placement, locating the ureter may be even more difficult. Recent advances using lighted stents or indocyanine green, which fluoresces in response to near-infrared laser and can be injected into the ureter via the ureteral catheter tip, are still in the feasibility phase of evaluation and can be costly.

As most urogenital fistulae are secondary to unrecognized injuries at time of surgery, and due to the fact that intraoperative recognition of the injury allows for primary repair, thus, decreasing the rate of secondary surgery and the associated increased morbidity, I recommend cystoscopy to check for ureteral jets (ureteral efflux) be performed when there is concern regarding ureter compromise.

Currently, I utilize a 70° cystoscope to visualize the ureters. While in the past, I have used intravenous indigo carmine, methylene blue, or fluorescein sodium, I currently use Pyridium (phenazopyridine) 200 mg taken by mouth 1 hour prior to the procedure.

Unfortunately, ureteral jetting still may be noted despite partial ligation, laceration, or desiccation of the ureter.

If ureteral injury is not recognized at time of surgery, it can lead to various postoperative symptoms. If there is a ureteral defect, the patient may note profuse wound leakage, increased abdominal fluid, or a urinoma, ileus, fever, peritonitis, or hematuria. With ureteral obstruction, flank or abdominal pain or anuria can be noted; while, with fistula formation, the patient will likely present with urinary incontinence or watery vaginal discharge.

Dr. Miller is a minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in Naperville, Ill., and a past president of the AAGL.

The FDA’s novel drugs approved in 2017

Novel drugs are innovative new products that have never before been used in clinical practice. Among the 46 that the Food and Drug Administration approved in 2017, 45 could be used in pregnancy. One, cerliponase alfa (Brineura), is indicated for pediatric patients 3 years of age or older, for treatment of late infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 2. It is doubtful that this drug would be used in pregnancy or during breastfeeding.

With the two exceptions noted below, there are no human pregnancy data for these drugs. It is important to consider that although high molecular weight (MW) drugs (for example, greater than 1,000) probably do not usually cross the placenta in the first half of pregnancy, they may do so in late pregnancy. The cited MWs are shown as the nearest whole number. Animal reproductive data are also cited because, although not definitive, they can provide some measure of the human embryo-fetal risk.

Anti-infectives

Benznidazole (same trade name) (MW 441), given orally, is indicated for pediatric patients aged 2-12 years for treatment of Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis) caused by Trypanosoma cruzi. However, there are international reports describing its use in pregnancy and breastfeeding. No fetal harm from these exposures were noted. Nevertheless, because of the low MW and the reported animal risk, avoiding the drug during the first half of pregnancy appears to be the best choice. Delafloxacin (Baxdela) (MW 441), a fluoroquinolone antimicrobial given intravenously or orally, is indicated for acute bacterial skin infections. The animal data suggest low risk. However, like other fluoroquinolones, it is contraindicated in pregnancy and should be used only if there are no other alternatives.

Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir /voxilaprevir (Vosevi) (MWs 529, 883, 869), a fixed oral dose combination of three antivirals, is indicated for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. The MWs suggest that all three will cross the human placenta. The animal data suggest low risk. Secnidazole (Solosec) (MW 185), given orally, is indicated for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis. It is closely related to metronidazole. No evidence of embryo-fetal toxicity was observed in rats and rabbits, suggesting that the human risk is low. In a report from Brazil, 134 pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis were treated with secnidazole, metronidazole, or tinidazole in the second and third trimesters. Treatment significantly decreased the incidence of premature rupture of membranes, preterm labor, preterm birth, and low birth weight. No fetal harm was reported.

Antineoplastics

[Note: All of the drugs in this category are best avoided, if possible, in pregnancy and breastfeeding.]

Abemaciclib (Verzenio) (MW 507), an oral inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinases, is indicated for the treatment of breast cancer. The drug is teratogenic in rats. Acalabrutinib (Calquence) (MW 466) is an oral kinase inhibitor indicated for mantle cell lymphoma. The drug had no effect on the rat embryo-fetus but caused decreased fetal body weights and delayed skeletal ossification in rabbits. Avelumab (Bavencio) (MW 147,000) is given intravenously for the treatment of metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma and metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Animal reproduction studies have not been conducted. However, based on its mechanism of action, fetal exposure may increase the risk of developing immune-related disorders or altering the normal immune response.

Brigatinib (Alunbrig) (MW 584) is given orally for the treatment of metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. In rats, doses less than or slightly above the human exposure caused multiple anomalies in the fetuses of pregnant rats. Copanlisib (Aliqopa) (MW 553) is a kinase inhibitor that is given intravenously for relapsed follicular lymphoma. In rats during organogenesis, doses based on body surface area that were a fraction of the human dose caused embryo-fetal death and fetal defects. Durvalumab (Imfinzi) (MW 146,000), given intravenously, is indicated for the treatment of metastatic urothelial carcinoma and non–small-cell lung cancer. Monkeys given the drug from organogenesis through delivery experienced increased premature birth, fetal loss, and premature neonatal death. Women of reproductive potential should use effective contraception during treatment and for at least 3 months after the last dose.

Enasidenib (Idhifa) (MW 569), given orally, is indicated for the treatment of myeloid leukemia. The drug caused maternal toxicity and adverse embryo-fetal effects (postimplantation loss, resorptions, decrease viable fetuses, lower fetal birth weights, and skeletal variations) in rats and spontaneous abortions in rabbits. Inotuzumab ozogamicin (Besponsa) (MW 160,000), given intravenously, is indicated for relapsed or refractory B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. The drug caused fetal harm in rats but not in rabbits. Midostaurin (Rydapt) (MW 571) is an oral kinase inhibitor indicated for myeloid leukemia. In rats, a dose given during the first week of pregnancy that was a small fraction of the human exposure caused pre- and postimplantation loss. When very small doses were given during organogenesis to rats and rabbits there was significant maternal and fetal toxicity.

Neratinib (Nerlynx) (MW 673) is an oral kinase inhibitor for breast cancer. Although the drug did not cause embryo-fetal toxicity in rats, it did cause this toxicity in rabbits. Doses that resulted in exposures that were less than the human exposure caused maternal toxicity, abortions, and embryo-fetal death. Lower doses caused multiple fetal anomalies. Niraparib (Zejula) (MW 511) is indicated for treatment of epithelial ovarian, fallopian, or peritoneal cancer. Because of the potential human embryo-fetal risk based on its mechanism of action, pregnant animal studies were not conducted. Women with reproductive potential should use effective contraception during treatment and for 6 months after the last dose. Ribociclib (Kisqali) (MW 553) is an oral kinase inhibitor indicated for postmenopausal women with breast cancer. In rats, the drug cause reduced fetal weights and skeletal changes. Increased incidences of fetal abnormalities and lower fetal weights were observed in rabbits.

Cardiovascular

Angiotensin II (Giapreza) (MW 1,046) is a naturally occurring peptide hormone given as an intravenous infusion. It is indicated as a vasoconstrictor to increase blood pressure in adults with septic or other distributive shock. Animal reproduction studies have not been conducted. Because septic or other distributive shock is a medical emergency that can be fatal, the use of this agent in pregnancy should not be withheld.

Central nervous system

Deutetrabenazine (Austedo) (MW 324) is an oral drug indicated for the treatment of chorea associated with Huntington’s disease and for tardive dyskinesia. When given to rats during organogenesis there was no clear effect on embryo-fetal development.

Edaravone (Radicava) (MW 174), given as an intravenous infusion, is indicated for the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Doses that were not maternal toxic did not cause embryo-fetal toxicity in rats and rabbits. However, the no-effect dose for developmental toxicity was less than the recommended human dose. Naldemedine (Symproic) (MW 743) is an opioid antagonist indicated for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation. The drug crosses the human placenta and may precipitate opioid withdrawal in the fetus. The drug caused no embryo-fetal adverse effects, even at high doses, in pregnant rats and rabbits.

Ocrelizumab (Ocrevus) (MW 145,000), an intravenous agent, is used to treat patients with multiple sclerosis. The MW is high but immunoglobulins are known to cross the placenta. When given to monkeys at doses similar to or greater than the human dose, there was increased perinatal mortality, depletion of B-cell populations, and renal, bone marrow, and testicular toxicity in the offspring in the absence of maternal toxicity. Safinamide (Xadago) (MW 399) is an oral drug indicated as adjunctive treatment to levodopa/carbidopa in Parkinson’s disease. In rats, the drug was teratogenic (mainly urogenital defects) at all doses. When it was combined with levodopa/carbidopa or used alone, increased rates of fetal visceral and skeletal defects occurred at all doses studied. In rabbits, given the combination throughout organogenesis, there was an increased incidence of embryo-fetal death and cardiac and skeletal defects. Based on these data, avoiding the drug in pregnancy appears to be the best course.

Valbenazine (Ingrezza) (MW 419) is indicated for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia. The drug caused no malformations in rats and rabbits. However, in rats given the drug during organogenesis through lactation, an increase in the number of stillborn pups and postnatal pup mortalities was observed.

Dermatologic

Brodalumab (Siliq) (MW 144,000), given subcutaneously, is indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. It is a human monoclonal IgG antibody and, even though the MW is high, IgG antibodies are known to cross the placenta. In monkeys, no drug-related effects on embryo-fetal toxicity or malformations, or on morphological, functional, or immunological development were observed in infants from mothers given weekly subcutaneous doses of the drug. Dupilumab (Dupixent) (MW 144,000) is given subcutaneously for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. It is a human monoclonal IgG antibody and, even though the MW is high, IgG antibodies are known to cross the placenta. In pregnant monkeys given subcutaneous doses of the drug, no drug-related effects on embryo-fetal toxicity or malformations, or on morphological, functional, or immunological development were observed in infants from birth to 6 months of age.

Guselkumab (Tremfya) (MW 143,600) is given subcutaneously for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. It is a human monoclonal IgG antibody and, even though the MW is high, IgG antibodies are known to cross the placenta. In pregnant monkeys given subcutaneous doses of the drug, no drug-related effects on embryo-fetal toxicity or malformations, or on morphological, functional, or immunological development were observed in infants from birth to 6 months of age. However, neonatal deaths were observed in three monkeys given six times the maximum recommended human dose.

Endocrine/metabolic

Deflazacort (Emflaza) (MW 442) is an oral corticosteroid prodrug indicated for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. The drug is converted in vivo to an active metabolite. The drug readily crosses the placenta. Although animal reproduction studies have not been conducted, such studies with other corticosteroids in various animal species have shown an increased incidence of cleft palate. In some species, there was an increase in embryo-fetal death, intrauterine growth restriction, and constriction of the ductus arteriosus.

Ertugliflozin (Steglatro) (MW 566) is an oral drug indicated to improve glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. In juvenile rats, doses that were about 13 times the human dose caused increased kidney weight, renal tubule and renal pelvis dilatation, and renal mineralization. These effects occurred during periods of rat renal development that correspond to the late second and third trimester of human renal development, and did not fully reverse within a 1-month recovery period. Etelcalcetide (Parsabiv) (MW 1,048), an intravenous calcium-sensing receptor agonist, is indicated for patients on hemodialysis who have secondary hyperparathyroidism. In rats and rabbits given the drug during organogenesis, there was reduced fetal growth. In rats given the drug during organogenesis through birth and weaning, there was a slight increase in pup mortality, delay in parturition, and transient effects on pup growth, but there were no effects on sexual maturation, neurobehavioral, or reproductive function. Macimorelin (Macrilen) (MW 535) is an oral growth hormone secretagogue receptor agonist. It is indicated for adult growth hormone deficiency. Animal reproduction studies have not been conducted.

Semaglutide (Ozempic) (MW 4,114), given subcutaneously, is a glucagon-like peptide indicated to improve glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. In rats given the drug during organogenesis, embryo-fetal death, structural defects, and alterations in growth were observed. In rabbits and monkeys given the drug during organogenesis, there were early pregnancy losses and structural abnormalities. In addition, there was marked maternal body weight loss in both animal species. Vestronidase alfa-vjbk (Mepsevii) is given intravenously. It is indicated for the treatment of Mucopolysaccharidosis VII (Sly syndrome). The calculated average MW of each nonglycosylated peptide chain is 72,562. In rats and rabbits given the drug during organogenesis, there was no maternal toxicity or adverse developmental outcomes.

Gastrointestinal

Plecanatide (Trulance) (MW 1,682) is an oral drug indicated for the treatment of constipation. The drug and its active metabolite are negligibly absorbed systemically and fetal exposure to the drug is not expected. In mice and rabbits given the oral drug during organogenesis, no effects on embryo-fetal development were observed. Telotristat ethyl (Xermelo) (MW 754) is an oral drug indicated for the treatment of carcinoid syndrome diarrhea in combination with somatostatin analog (MW not specified) therapy in adults not controlled by somatostatin analog. When given during organogenesis in rats, there was no effect on embryo-fetal development at doses that were about nine times the recommended human dose. However, an increased incidence of mortality in rat offspring was observed when the drug was given from organogenesis through lactation. During organogenesis in rabbits, the drug had no embryo-fetal effects at doses that were 10 or more times the human dose.

Hematologics

Betrixaban (Bevyxxa) (MW 568) is an oral factor Xa inhibitor indicated for the prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism. The drug was not associated with adverse developmental fetal outcomes in rats and rabbits. However, maternal hemorrhage did occur. In humans, there is an increased risk of hemorrhage during pregnancy and delivery. Emicizumab (Hemlibra) (MW 145,600), given subcutaneously, is indicated for routine prophylaxis to prevent or reduce the frequency of bleeding in patients with hemophilia A with factor VIII inhibitors. Animal reproduction studies have not been conducted. It is a human monoclonal IgG antibody and, though the MW is high, IgG antibodies are known to cross the placenta.

Immunologic

Sarilumab (Kevzara) (MW 150,000) is given subcutaneously. It is indicated for patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis. Reproduction studies were conducted in pregnant monkeys. There was no evidence of embryo toxicity or fetal malformations. Based on this data, the human pregnancy risk is low.

Ophthalmic

Latanoprostene bunod (Vyzulta) (MW 508) is a prostaglandin analog that is indicated to reduce intraocular pressure. No quantifiable plasma concentrations of latanoprostene bunod were detected in nonpregnant patients. However, very low levels of latanoprost acid (51-59 pg/mL), the active metabolite, were detected with the maximal plasma concentration occurring 5 minutes after administration. When given intravenously to pregnant rabbits, the drug was shown to be abortifacient and teratogenic, but these effects were not observed in pregnant rats. Netarsudil (Rhopressa) (MW 454) is a kinase inhibitor indicated to reduce intraocular pressure in patients with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension. No quantifiable plasma concentrations of netarsudil were detected in 18 subjects. For the active metabolite, a plasma level of 0.11 ng/mL was found in one subject. Intravenous doses to pregnant rats and rabbits during organogenesis did not cause embryo-fetal adverse effects at clinically relevant systemic exposures.

Parathyroid hormone

Abaloparatide (Tymlos) (MW 3,961), given subcutaneously, is a human parathyroid hormone related peptide analog that is indicated for postmenopausal women with osteoporosis at high risk for fracture. Reproduction studies in animals have not been conducted. Because of the indication, it is doubtful if the agent will be used in pregnancy or during breastfeeding.

Respiratory

Benralizumab (Fasenra) (MW 150,000), given subcutaneously, is indicated for the add-on maintenance treatment of severe eosinophilic asthma. It is a human monoclonal IgG antibody and, though the MW is high, IgG antibodies are known to cross the placenta. Studies in monkeys found no evidence of fetal harm with intravenous doses throughout pregnancy that produced exposures up to about 310 times the exposure at the maximum recommended human dose.

The potential adverse effects in an infant when the mother is taking one of the above drugs while breastfeeding will be covered in my next column.

Mr. Briggs is clinical professor of pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco, and adjunct professor of pharmacy at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, as well as at Washington State University, Spokane. He coauthored “Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation” and coedited “Diseases, Complications, and Drug Therapy in Obstetrics.” He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Novel drugs are innovative new products that have never before been used in clinical practice. Among the 46 that the Food and Drug Administration approved in 2017, 45 could be used in pregnancy. One, cerliponase alfa (Brineura), is indicated for pediatric patients 3 years of age or older, for treatment of late infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 2. It is doubtful that this drug would be used in pregnancy or during breastfeeding.

With the two exceptions noted below, there are no human pregnancy data for these drugs. It is important to consider that although high molecular weight (MW) drugs (for example, greater than 1,000) probably do not usually cross the placenta in the first half of pregnancy, they may do so in late pregnancy. The cited MWs are shown as the nearest whole number. Animal reproductive data are also cited because, although not definitive, they can provide some measure of the human embryo-fetal risk.

Anti-infectives

Benznidazole (same trade name) (MW 441), given orally, is indicated for pediatric patients aged 2-12 years for treatment of Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis) caused by Trypanosoma cruzi. However, there are international reports describing its use in pregnancy and breastfeeding. No fetal harm from these exposures were noted. Nevertheless, because of the low MW and the reported animal risk, avoiding the drug during the first half of pregnancy appears to be the best choice. Delafloxacin (Baxdela) (MW 441), a fluoroquinolone antimicrobial given intravenously or orally, is indicated for acute bacterial skin infections. The animal data suggest low risk. However, like other fluoroquinolones, it is contraindicated in pregnancy and should be used only if there are no other alternatives.

Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir /voxilaprevir (Vosevi) (MWs 529, 883, 869), a fixed oral dose combination of three antivirals, is indicated for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. The MWs suggest that all three will cross the human placenta. The animal data suggest low risk. Secnidazole (Solosec) (MW 185), given orally, is indicated for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis. It is closely related to metronidazole. No evidence of embryo-fetal toxicity was observed in rats and rabbits, suggesting that the human risk is low. In a report from Brazil, 134 pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis were treated with secnidazole, metronidazole, or tinidazole in the second and third trimesters. Treatment significantly decreased the incidence of premature rupture of membranes, preterm labor, preterm birth, and low birth weight. No fetal harm was reported.

Antineoplastics

[Note: All of the drugs in this category are best avoided, if possible, in pregnancy and breastfeeding.]

Abemaciclib (Verzenio) (MW 507), an oral inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinases, is indicated for the treatment of breast cancer. The drug is teratogenic in rats. Acalabrutinib (Calquence) (MW 466) is an oral kinase inhibitor indicated for mantle cell lymphoma. The drug had no effect on the rat embryo-fetus but caused decreased fetal body weights and delayed skeletal ossification in rabbits. Avelumab (Bavencio) (MW 147,000) is given intravenously for the treatment of metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma and metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Animal reproduction studies have not been conducted. However, based on its mechanism of action, fetal exposure may increase the risk of developing immune-related disorders or altering the normal immune response.

Brigatinib (Alunbrig) (MW 584) is given orally for the treatment of metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. In rats, doses less than or slightly above the human exposure caused multiple anomalies in the fetuses of pregnant rats. Copanlisib (Aliqopa) (MW 553) is a kinase inhibitor that is given intravenously for relapsed follicular lymphoma. In rats during organogenesis, doses based on body surface area that were a fraction of the human dose caused embryo-fetal death and fetal defects. Durvalumab (Imfinzi) (MW 146,000), given intravenously, is indicated for the treatment of metastatic urothelial carcinoma and non–small-cell lung cancer. Monkeys given the drug from organogenesis through delivery experienced increased premature birth, fetal loss, and premature neonatal death. Women of reproductive potential should use effective contraception during treatment and for at least 3 months after the last dose.

Enasidenib (Idhifa) (MW 569), given orally, is indicated for the treatment of myeloid leukemia. The drug caused maternal toxicity and adverse embryo-fetal effects (postimplantation loss, resorptions, decrease viable fetuses, lower fetal birth weights, and skeletal variations) in rats and spontaneous abortions in rabbits. Inotuzumab ozogamicin (Besponsa) (MW 160,000), given intravenously, is indicated for relapsed or refractory B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. The drug caused fetal harm in rats but not in rabbits. Midostaurin (Rydapt) (MW 571) is an oral kinase inhibitor indicated for myeloid leukemia. In rats, a dose given during the first week of pregnancy that was a small fraction of the human exposure caused pre- and postimplantation loss. When very small doses were given during organogenesis to rats and rabbits there was significant maternal and fetal toxicity.

Neratinib (Nerlynx) (MW 673) is an oral kinase inhibitor for breast cancer. Although the drug did not cause embryo-fetal toxicity in rats, it did cause this toxicity in rabbits. Doses that resulted in exposures that were less than the human exposure caused maternal toxicity, abortions, and embryo-fetal death. Lower doses caused multiple fetal anomalies. Niraparib (Zejula) (MW 511) is indicated for treatment of epithelial ovarian, fallopian, or peritoneal cancer. Because of the potential human embryo-fetal risk based on its mechanism of action, pregnant animal studies were not conducted. Women with reproductive potential should use effective contraception during treatment and for 6 months after the last dose. Ribociclib (Kisqali) (MW 553) is an oral kinase inhibitor indicated for postmenopausal women with breast cancer. In rats, the drug cause reduced fetal weights and skeletal changes. Increased incidences of fetal abnormalities and lower fetal weights were observed in rabbits.

Cardiovascular

Angiotensin II (Giapreza) (MW 1,046) is a naturally occurring peptide hormone given as an intravenous infusion. It is indicated as a vasoconstrictor to increase blood pressure in adults with septic or other distributive shock. Animal reproduction studies have not been conducted. Because septic or other distributive shock is a medical emergency that can be fatal, the use of this agent in pregnancy should not be withheld.

Central nervous system

Deutetrabenazine (Austedo) (MW 324) is an oral drug indicated for the treatment of chorea associated with Huntington’s disease and for tardive dyskinesia. When given to rats during organogenesis there was no clear effect on embryo-fetal development.

Edaravone (Radicava) (MW 174), given as an intravenous infusion, is indicated for the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Doses that were not maternal toxic did not cause embryo-fetal toxicity in rats and rabbits. However, the no-effect dose for developmental toxicity was less than the recommended human dose. Naldemedine (Symproic) (MW 743) is an opioid antagonist indicated for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation. The drug crosses the human placenta and may precipitate opioid withdrawal in the fetus. The drug caused no embryo-fetal adverse effects, even at high doses, in pregnant rats and rabbits.

Ocrelizumab (Ocrevus) (MW 145,000), an intravenous agent, is used to treat patients with multiple sclerosis. The MW is high but immunoglobulins are known to cross the placenta. When given to monkeys at doses similar to or greater than the human dose, there was increased perinatal mortality, depletion of B-cell populations, and renal, bone marrow, and testicular toxicity in the offspring in the absence of maternal toxicity. Safinamide (Xadago) (MW 399) is an oral drug indicated as adjunctive treatment to levodopa/carbidopa in Parkinson’s disease. In rats, the drug was teratogenic (mainly urogenital defects) at all doses. When it was combined with levodopa/carbidopa or used alone, increased rates of fetal visceral and skeletal defects occurred at all doses studied. In rabbits, given the combination throughout organogenesis, there was an increased incidence of embryo-fetal death and cardiac and skeletal defects. Based on these data, avoiding the drug in pregnancy appears to be the best course.

Valbenazine (Ingrezza) (MW 419) is indicated for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia. The drug caused no malformations in rats and rabbits. However, in rats given the drug during organogenesis through lactation, an increase in the number of stillborn pups and postnatal pup mortalities was observed.

Dermatologic

Brodalumab (Siliq) (MW 144,000), given subcutaneously, is indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. It is a human monoclonal IgG antibody and, even though the MW is high, IgG antibodies are known to cross the placenta. In monkeys, no drug-related effects on embryo-fetal toxicity or malformations, or on morphological, functional, or immunological development were observed in infants from mothers given weekly subcutaneous doses of the drug. Dupilumab (Dupixent) (MW 144,000) is given subcutaneously for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. It is a human monoclonal IgG antibody and, even though the MW is high, IgG antibodies are known to cross the placenta. In pregnant monkeys given subcutaneous doses of the drug, no drug-related effects on embryo-fetal toxicity or malformations, or on morphological, functional, or immunological development were observed in infants from birth to 6 months of age.

Guselkumab (Tremfya) (MW 143,600) is given subcutaneously for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. It is a human monoclonal IgG antibody and, even though the MW is high, IgG antibodies are known to cross the placenta. In pregnant monkeys given subcutaneous doses of the drug, no drug-related effects on embryo-fetal toxicity or malformations, or on morphological, functional, or immunological development were observed in infants from birth to 6 months of age. However, neonatal deaths were observed in three monkeys given six times the maximum recommended human dose.

Endocrine/metabolic

Deflazacort (Emflaza) (MW 442) is an oral corticosteroid prodrug indicated for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. The drug is converted in vivo to an active metabolite. The drug readily crosses the placenta. Although animal reproduction studies have not been conducted, such studies with other corticosteroids in various animal species have shown an increased incidence of cleft palate. In some species, there was an increase in embryo-fetal death, intrauterine growth restriction, and constriction of the ductus arteriosus.

Ertugliflozin (Steglatro) (MW 566) is an oral drug indicated to improve glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. In juvenile rats, doses that were about 13 times the human dose caused increased kidney weight, renal tubule and renal pelvis dilatation, and renal mineralization. These effects occurred during periods of rat renal development that correspond to the late second and third trimester of human renal development, and did not fully reverse within a 1-month recovery period. Etelcalcetide (Parsabiv) (MW 1,048), an intravenous calcium-sensing receptor agonist, is indicated for patients on hemodialysis who have secondary hyperparathyroidism. In rats and rabbits given the drug during organogenesis, there was reduced fetal growth. In rats given the drug during organogenesis through birth and weaning, there was a slight increase in pup mortality, delay in parturition, and transient effects on pup growth, but there were no effects on sexual maturation, neurobehavioral, or reproductive function. Macimorelin (Macrilen) (MW 535) is an oral growth hormone secretagogue receptor agonist. It is indicated for adult growth hormone deficiency. Animal reproduction studies have not been conducted.

Semaglutide (Ozempic) (MW 4,114), given subcutaneously, is a glucagon-like peptide indicated to improve glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. In rats given the drug during organogenesis, embryo-fetal death, structural defects, and alterations in growth were observed. In rabbits and monkeys given the drug during organogenesis, there were early pregnancy losses and structural abnormalities. In addition, there was marked maternal body weight loss in both animal species. Vestronidase alfa-vjbk (Mepsevii) is given intravenously. It is indicated for the treatment of Mucopolysaccharidosis VII (Sly syndrome). The calculated average MW of each nonglycosylated peptide chain is 72,562. In rats and rabbits given the drug during organogenesis, there was no maternal toxicity or adverse developmental outcomes.

Gastrointestinal

Plecanatide (Trulance) (MW 1,682) is an oral drug indicated for the treatment of constipation. The drug and its active metabolite are negligibly absorbed systemically and fetal exposure to the drug is not expected. In mice and rabbits given the oral drug during organogenesis, no effects on embryo-fetal development were observed. Telotristat ethyl (Xermelo) (MW 754) is an oral drug indicated for the treatment of carcinoid syndrome diarrhea in combination with somatostatin analog (MW not specified) therapy in adults not controlled by somatostatin analog. When given during organogenesis in rats, there was no effect on embryo-fetal development at doses that were about nine times the recommended human dose. However, an increased incidence of mortality in rat offspring was observed when the drug was given from organogenesis through lactation. During organogenesis in rabbits, the drug had no embryo-fetal effects at doses that were 10 or more times the human dose.

Hematologics

Betrixaban (Bevyxxa) (MW 568) is an oral factor Xa inhibitor indicated for the prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism. The drug was not associated with adverse developmental fetal outcomes in rats and rabbits. However, maternal hemorrhage did occur. In humans, there is an increased risk of hemorrhage during pregnancy and delivery. Emicizumab (Hemlibra) (MW 145,600), given subcutaneously, is indicated for routine prophylaxis to prevent or reduce the frequency of bleeding in patients with hemophilia A with factor VIII inhibitors. Animal reproduction studies have not been conducted. It is a human monoclonal IgG antibody and, though the MW is high, IgG antibodies are known to cross the placenta.

Immunologic

Sarilumab (Kevzara) (MW 150,000) is given subcutaneously. It is indicated for patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis. Reproduction studies were conducted in pregnant monkeys. There was no evidence of embryo toxicity or fetal malformations. Based on this data, the human pregnancy risk is low.

Ophthalmic

Latanoprostene bunod (Vyzulta) (MW 508) is a prostaglandin analog that is indicated to reduce intraocular pressure. No quantifiable plasma concentrations of latanoprostene bunod were detected in nonpregnant patients. However, very low levels of latanoprost acid (51-59 pg/mL), the active metabolite, were detected with the maximal plasma concentration occurring 5 minutes after administration. When given intravenously to pregnant rabbits, the drug was shown to be abortifacient and teratogenic, but these effects were not observed in pregnant rats. Netarsudil (Rhopressa) (MW 454) is a kinase inhibitor indicated to reduce intraocular pressure in patients with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension. No quantifiable plasma concentrations of netarsudil were detected in 18 subjects. For the active metabolite, a plasma level of 0.11 ng/mL was found in one subject. Intravenous doses to pregnant rats and rabbits during organogenesis did not cause embryo-fetal adverse effects at clinically relevant systemic exposures.

Parathyroid hormone

Abaloparatide (Tymlos) (MW 3,961), given subcutaneously, is a human parathyroid hormone related peptide analog that is indicated for postmenopausal women with osteoporosis at high risk for fracture. Reproduction studies in animals have not been conducted. Because of the indication, it is doubtful if the agent will be used in pregnancy or during breastfeeding.

Respiratory

Benralizumab (Fasenra) (MW 150,000), given subcutaneously, is indicated for the add-on maintenance treatment of severe eosinophilic asthma. It is a human monoclonal IgG antibody and, though the MW is high, IgG antibodies are known to cross the placenta. Studies in monkeys found no evidence of fetal harm with intravenous doses throughout pregnancy that produced exposures up to about 310 times the exposure at the maximum recommended human dose.

The potential adverse effects in an infant when the mother is taking one of the above drugs while breastfeeding will be covered in my next column.

Mr. Briggs is clinical professor of pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco, and adjunct professor of pharmacy at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, as well as at Washington State University, Spokane. He coauthored “Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation” and coedited “Diseases, Complications, and Drug Therapy in Obstetrics.” He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Novel drugs are innovative new products that have never before been used in clinical practice. Among the 46 that the Food and Drug Administration approved in 2017, 45 could be used in pregnancy. One, cerliponase alfa (Brineura), is indicated for pediatric patients 3 years of age or older, for treatment of late infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 2. It is doubtful that this drug would be used in pregnancy or during breastfeeding.

With the two exceptions noted below, there are no human pregnancy data for these drugs. It is important to consider that although high molecular weight (MW) drugs (for example, greater than 1,000) probably do not usually cross the placenta in the first half of pregnancy, they may do so in late pregnancy. The cited MWs are shown as the nearest whole number. Animal reproductive data are also cited because, although not definitive, they can provide some measure of the human embryo-fetal risk.

Anti-infectives

Benznidazole (same trade name) (MW 441), given orally, is indicated for pediatric patients aged 2-12 years for treatment of Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis) caused by Trypanosoma cruzi. However, there are international reports describing its use in pregnancy and breastfeeding. No fetal harm from these exposures were noted. Nevertheless, because of the low MW and the reported animal risk, avoiding the drug during the first half of pregnancy appears to be the best choice. Delafloxacin (Baxdela) (MW 441), a fluoroquinolone antimicrobial given intravenously or orally, is indicated for acute bacterial skin infections. The animal data suggest low risk. However, like other fluoroquinolones, it is contraindicated in pregnancy and should be used only if there are no other alternatives.

Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir /voxilaprevir (Vosevi) (MWs 529, 883, 869), a fixed oral dose combination of three antivirals, is indicated for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. The MWs suggest that all three will cross the human placenta. The animal data suggest low risk. Secnidazole (Solosec) (MW 185), given orally, is indicated for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis. It is closely related to metronidazole. No evidence of embryo-fetal toxicity was observed in rats and rabbits, suggesting that the human risk is low. In a report from Brazil, 134 pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis were treated with secnidazole, metronidazole, or tinidazole in the second and third trimesters. Treatment significantly decreased the incidence of premature rupture of membranes, preterm labor, preterm birth, and low birth weight. No fetal harm was reported.

Antineoplastics

[Note: All of the drugs in this category are best avoided, if possible, in pregnancy and breastfeeding.]

Abemaciclib (Verzenio) (MW 507), an oral inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinases, is indicated for the treatment of breast cancer. The drug is teratogenic in rats. Acalabrutinib (Calquence) (MW 466) is an oral kinase inhibitor indicated for mantle cell lymphoma. The drug had no effect on the rat embryo-fetus but caused decreased fetal body weights and delayed skeletal ossification in rabbits. Avelumab (Bavencio) (MW 147,000) is given intravenously for the treatment of metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma and metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Animal reproduction studies have not been conducted. However, based on its mechanism of action, fetal exposure may increase the risk of developing immune-related disorders or altering the normal immune response.

Brigatinib (Alunbrig) (MW 584) is given orally for the treatment of metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. In rats, doses less than or slightly above the human exposure caused multiple anomalies in the fetuses of pregnant rats. Copanlisib (Aliqopa) (MW 553) is a kinase inhibitor that is given intravenously for relapsed follicular lymphoma. In rats during organogenesis, doses based on body surface area that were a fraction of the human dose caused embryo-fetal death and fetal defects. Durvalumab (Imfinzi) (MW 146,000), given intravenously, is indicated for the treatment of metastatic urothelial carcinoma and non–small-cell lung cancer. Monkeys given the drug from organogenesis through delivery experienced increased premature birth, fetal loss, and premature neonatal death. Women of reproductive potential should use effective contraception during treatment and for at least 3 months after the last dose.

Enasidenib (Idhifa) (MW 569), given orally, is indicated for the treatment of myeloid leukemia. The drug caused maternal toxicity and adverse embryo-fetal effects (postimplantation loss, resorptions, decrease viable fetuses, lower fetal birth weights, and skeletal variations) in rats and spontaneous abortions in rabbits. Inotuzumab ozogamicin (Besponsa) (MW 160,000), given intravenously, is indicated for relapsed or refractory B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. The drug caused fetal harm in rats but not in rabbits. Midostaurin (Rydapt) (MW 571) is an oral kinase inhibitor indicated for myeloid leukemia. In rats, a dose given during the first week of pregnancy that was a small fraction of the human exposure caused pre- and postimplantation loss. When very small doses were given during organogenesis to rats and rabbits there was significant maternal and fetal toxicity.

Neratinib (Nerlynx) (MW 673) is an oral kinase inhibitor for breast cancer. Although the drug did not cause embryo-fetal toxicity in rats, it did cause this toxicity in rabbits. Doses that resulted in exposures that were less than the human exposure caused maternal toxicity, abortions, and embryo-fetal death. Lower doses caused multiple fetal anomalies. Niraparib (Zejula) (MW 511) is indicated for treatment of epithelial ovarian, fallopian, or peritoneal cancer. Because of the potential human embryo-fetal risk based on its mechanism of action, pregnant animal studies were not conducted. Women with reproductive potential should use effective contraception during treatment and for 6 months after the last dose. Ribociclib (Kisqali) (MW 553) is an oral kinase inhibitor indicated for postmenopausal women with breast cancer. In rats, the drug cause reduced fetal weights and skeletal changes. Increased incidences of fetal abnormalities and lower fetal weights were observed in rabbits.

Cardiovascular

Angiotensin II (Giapreza) (MW 1,046) is a naturally occurring peptide hormone given as an intravenous infusion. It is indicated as a vasoconstrictor to increase blood pressure in adults with septic or other distributive shock. Animal reproduction studies have not been conducted. Because septic or other distributive shock is a medical emergency that can be fatal, the use of this agent in pregnancy should not be withheld.

Central nervous system

Deutetrabenazine (Austedo) (MW 324) is an oral drug indicated for the treatment of chorea associated with Huntington’s disease and for tardive dyskinesia. When given to rats during organogenesis there was no clear effect on embryo-fetal development.

Edaravone (Radicava) (MW 174), given as an intravenous infusion, is indicated for the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Doses that were not maternal toxic did not cause embryo-fetal toxicity in rats and rabbits. However, the no-effect dose for developmental toxicity was less than the recommended human dose. Naldemedine (Symproic) (MW 743) is an opioid antagonist indicated for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation. The drug crosses the human placenta and may precipitate opioid withdrawal in the fetus. The drug caused no embryo-fetal adverse effects, even at high doses, in pregnant rats and rabbits.

Ocrelizumab (Ocrevus) (MW 145,000), an intravenous agent, is used to treat patients with multiple sclerosis. The MW is high but immunoglobulins are known to cross the placenta. When given to monkeys at doses similar to or greater than the human dose, there was increased perinatal mortality, depletion of B-cell populations, and renal, bone marrow, and testicular toxicity in the offspring in the absence of maternal toxicity. Safinamide (Xadago) (MW 399) is an oral drug indicated as adjunctive treatment to levodopa/carbidopa in Parkinson’s disease. In rats, the drug was teratogenic (mainly urogenital defects) at all doses. When it was combined with levodopa/carbidopa or used alone, increased rates of fetal visceral and skeletal defects occurred at all doses studied. In rabbits, given the combination throughout organogenesis, there was an increased incidence of embryo-fetal death and cardiac and skeletal defects. Based on these data, avoiding the drug in pregnancy appears to be the best course.

Valbenazine (Ingrezza) (MW 419) is indicated for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia. The drug caused no malformations in rats and rabbits. However, in rats given the drug during organogenesis through lactation, an increase in the number of stillborn pups and postnatal pup mortalities was observed.

Dermatologic

Brodalumab (Siliq) (MW 144,000), given subcutaneously, is indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. It is a human monoclonal IgG antibody and, even though the MW is high, IgG antibodies are known to cross the placenta. In monkeys, no drug-related effects on embryo-fetal toxicity or malformations, or on morphological, functional, or immunological development were observed in infants from mothers given weekly subcutaneous doses of the drug. Dupilumab (Dupixent) (MW 144,000) is given subcutaneously for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. It is a human monoclonal IgG antibody and, even though the MW is high, IgG antibodies are known to cross the placenta. In pregnant monkeys given subcutaneous doses of the drug, no drug-related effects on embryo-fetal toxicity or malformations, or on morphological, functional, or immunological development were observed in infants from birth to 6 months of age.

Guselkumab (Tremfya) (MW 143,600) is given subcutaneously for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. It is a human monoclonal IgG antibody and, even though the MW is high, IgG antibodies are known to cross the placenta. In pregnant monkeys given subcutaneous doses of the drug, no drug-related effects on embryo-fetal toxicity or malformations, or on morphological, functional, or immunological development were observed in infants from birth to 6 months of age. However, neonatal deaths were observed in three monkeys given six times the maximum recommended human dose.

Endocrine/metabolic

Deflazacort (Emflaza) (MW 442) is an oral corticosteroid prodrug indicated for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. The drug is converted in vivo to an active metabolite. The drug readily crosses the placenta. Although animal reproduction studies have not been conducted, such studies with other corticosteroids in various animal species have shown an increased incidence of cleft palate. In some species, there was an increase in embryo-fetal death, intrauterine growth restriction, and constriction of the ductus arteriosus.

Ertugliflozin (Steglatro) (MW 566) is an oral drug indicated to improve glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. In juvenile rats, doses that were about 13 times the human dose caused increased kidney weight, renal tubule and renal pelvis dilatation, and renal mineralization. These effects occurred during periods of rat renal development that correspond to the late second and third trimester of human renal development, and did not fully reverse within a 1-month recovery period. Etelcalcetide (Parsabiv) (MW 1,048), an intravenous calcium-sensing receptor agonist, is indicated for patients on hemodialysis who have secondary hyperparathyroidism. In rats and rabbits given the drug during organogenesis, there was reduced fetal growth. In rats given the drug during organogenesis through birth and weaning, there was a slight increase in pup mortality, delay in parturition, and transient effects on pup growth, but there were no effects on sexual maturation, neurobehavioral, or reproductive function. Macimorelin (Macrilen) (MW 535) is an oral growth hormone secretagogue receptor agonist. It is indicated for adult growth hormone deficiency. Animal reproduction studies have not been conducted.

Semaglutide (Ozempic) (MW 4,114), given subcutaneously, is a glucagon-like peptide indicated to improve glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. In rats given the drug during organogenesis, embryo-fetal death, structural defects, and alterations in growth were observed. In rabbits and monkeys given the drug during organogenesis, there were early pregnancy losses and structural abnormalities. In addition, there was marked maternal body weight loss in both animal species. Vestronidase alfa-vjbk (Mepsevii) is given intravenously. It is indicated for the treatment of Mucopolysaccharidosis VII (Sly syndrome). The calculated average MW of each nonglycosylated peptide chain is 72,562. In rats and rabbits given the drug during organogenesis, there was no maternal toxicity or adverse developmental outcomes.

Gastrointestinal

Plecanatide (Trulance) (MW 1,682) is an oral drug indicated for the treatment of constipation. The drug and its active metabolite are negligibly absorbed systemically and fetal exposure to the drug is not expected. In mice and rabbits given the oral drug during organogenesis, no effects on embryo-fetal development were observed. Telotristat ethyl (Xermelo) (MW 754) is an oral drug indicated for the treatment of carcinoid syndrome diarrhea in combination with somatostatin analog (MW not specified) therapy in adults not controlled by somatostatin analog. When given during organogenesis in rats, there was no effect on embryo-fetal development at doses that were about nine times the recommended human dose. However, an increased incidence of mortality in rat offspring was observed when the drug was given from organogenesis through lactation. During organogenesis in rabbits, the drug had no embryo-fetal effects at doses that were 10 or more times the human dose.

Hematologics

Betrixaban (Bevyxxa) (MW 568) is an oral factor Xa inhibitor indicated for the prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism. The drug was not associated with adverse developmental fetal outcomes in rats and rabbits. However, maternal hemorrhage did occur. In humans, there is an increased risk of hemorrhage during pregnancy and delivery. Emicizumab (Hemlibra) (MW 145,600), given subcutaneously, is indicated for routine prophylaxis to prevent or reduce the frequency of bleeding in patients with hemophilia A with factor VIII inhibitors. Animal reproduction studies have not been conducted. It is a human monoclonal IgG antibody and, though the MW is high, IgG antibodies are known to cross the placenta.

Immunologic

Sarilumab (Kevzara) (MW 150,000) is given subcutaneously. It is indicated for patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis. Reproduction studies were conducted in pregnant monkeys. There was no evidence of embryo toxicity or fetal malformations. Based on this data, the human pregnancy risk is low.

Ophthalmic

Latanoprostene bunod (Vyzulta) (MW 508) is a prostaglandin analog that is indicated to reduce intraocular pressure. No quantifiable plasma concentrations of latanoprostene bunod were detected in nonpregnant patients. However, very low levels of latanoprost acid (51-59 pg/mL), the active metabolite, were detected with the maximal plasma concentration occurring 5 minutes after administration. When given intravenously to pregnant rabbits, the drug was shown to be abortifacient and teratogenic, but these effects were not observed in pregnant rats. Netarsudil (Rhopressa) (MW 454) is a kinase inhibitor indicated to reduce intraocular pressure in patients with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension. No quantifiable plasma concentrations of netarsudil were detected in 18 subjects. For the active metabolite, a plasma level of 0.11 ng/mL was found in one subject. Intravenous doses to pregnant rats and rabbits during organogenesis did not cause embryo-fetal adverse effects at clinically relevant systemic exposures.

Parathyroid hormone

Abaloparatide (Tymlos) (MW 3,961), given subcutaneously, is a human parathyroid hormone related peptide analog that is indicated for postmenopausal women with osteoporosis at high risk for fracture. Reproduction studies in animals have not been conducted. Because of the indication, it is doubtful if the agent will be used in pregnancy or during breastfeeding.

Respiratory

Benralizumab (Fasenra) (MW 150,000), given subcutaneously, is indicated for the add-on maintenance treatment of severe eosinophilic asthma. It is a human monoclonal IgG antibody and, though the MW is high, IgG antibodies are known to cross the placenta. Studies in monkeys found no evidence of fetal harm with intravenous doses throughout pregnancy that produced exposures up to about 310 times the exposure at the maximum recommended human dose.

The potential adverse effects in an infant when the mother is taking one of the above drugs while breastfeeding will be covered in my next column.

Mr. Briggs is clinical professor of pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco, and adjunct professor of pharmacy at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, as well as at Washington State University, Spokane. He coauthored “Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation” and coedited “Diseases, Complications, and Drug Therapy in Obstetrics.” He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Melanoma in situ: It’s hard to know what you don’t know

The emergency department locum tenens staff recruiter was persuasive. “It’s a quiet little ER where you can study and sleep.” I was board certified in internal medicine and had trained in a busy urban emergency department. This was just the spot to make a little folding money and study for my mock dermatology boards, I thought.

And so, on a Saturday night in rural Texas, after grinding rust out of a pipe fitter’s eye and stitching up two brawlers from the local biker bar, I was faced with treating a comatose kid brought in after a car crash. He had not been wearing a seat belt, and his car had rolled over on his head.

I was way over my skill level, but I was lucky. I was able to stabilize him and, after several long hours, I got him on an emergency helicopter into Dallas.

But the experience changed me. I realized I did not know enough to deal with this case on my own. After making it through that night in the ED, I never put myself in that position again.

I now knew what I did not know.

The finding that jumped out to me, though, was that patients screened by a PA were significantly less likely to be diagnosed with melanoma in situ, the stage when melanoma is 100% curable. Yet, those patients screened by PAs underwent a lot more skin biopsies – 36% more skin biopsies per melanoma in situ diagnosed, compared with patients of dermatologists. Interestingly, in the health care system studied, any PA with a question about a patient can ask an attending dermatologist to see the patient. Did that factor account for the diagnostic comparability for nonmelanoma skin cancer and invasive melanoma? Did the PAs not ask for help on the missed melanomas in situ? If so, I believe this may be a situation of PAs not knowing what they didn’t know.

Now a knowledgeable friend of mine thinks this study is biased because 17% more patients with prior melanomas were seen by a dermatologist rather than by a PA. While it’s true that patients with prior melanomas are more likely to develop new melanomas, the counterargument is that the bar for a biopsy in a patient with a prior melanoma is much lower. Patients with a history of melanoma should have more skin biopsies, but the dermatologists in this study still took many fewer biopsies to diagnose melanomas in situ.

Why do these findings matter for patients and for the health care system?

PAs billed independently for 12% of skin biopsies (including lip, ear, ear canal, vulva, penis, and eyelid) in Medicare Fee for Service in 2016. Skin biopsies paid for by Medicare have been increasing at a very rapid rate, about twice as fast as the rate reflected in the current skin cancer epidemic.

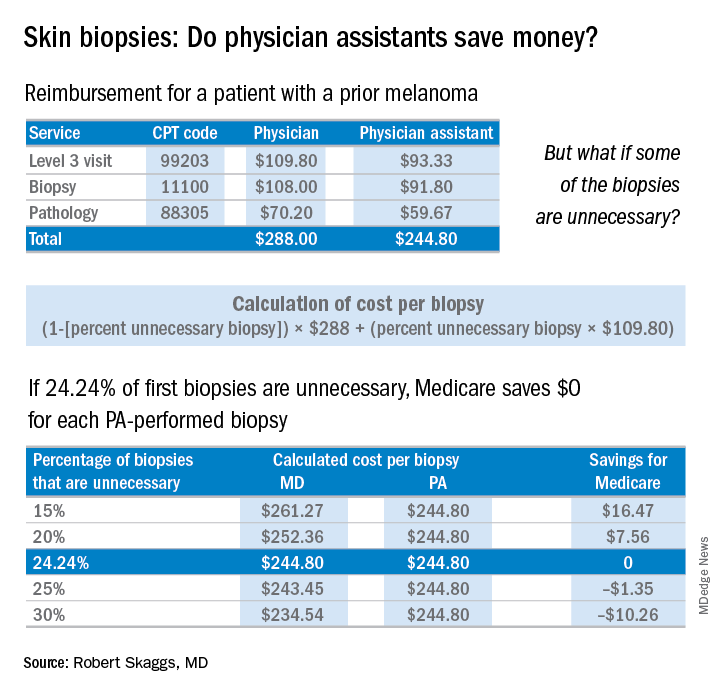

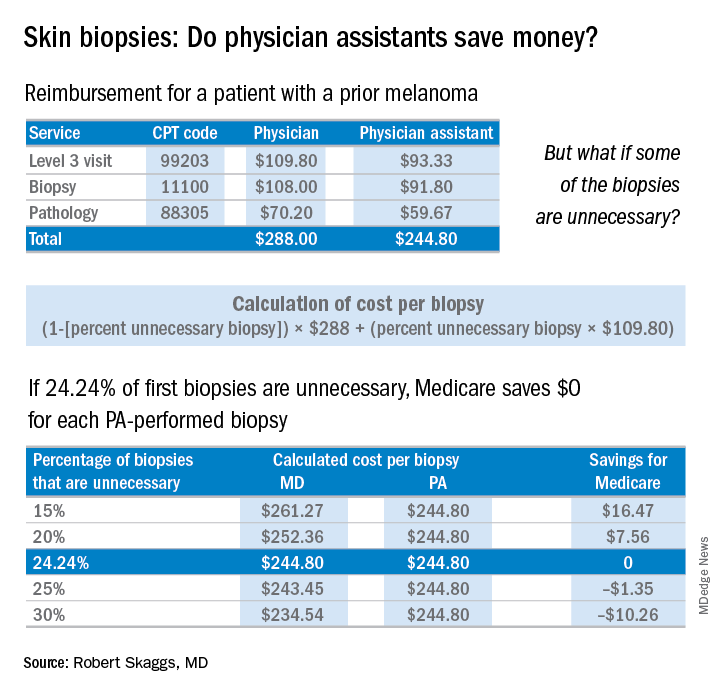

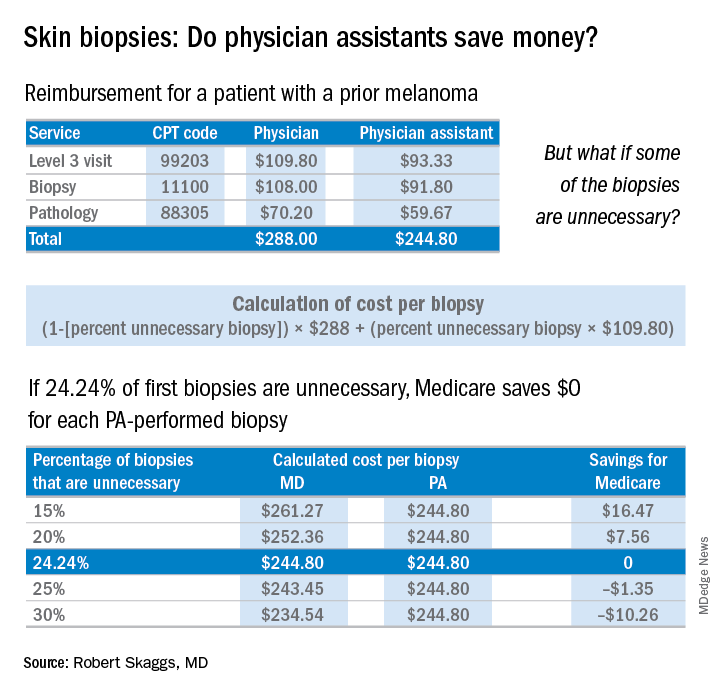

Every skin biopsy results in a pathology charge, for which Medicare pays about $70. A level 3 new patient visit pays $110. If PAs bill independently, they are paid at 85% of the fee schedule, which often is touted as a great savings. Therefore, if only 24.2% of skin biopsies by PAs were unnecessary, even at a reduced 85% reimbursement, it costs Medicare more than having these visits and biopsies provided by a dermatologist. The cost savings decrease even more with additional skin biopsies, because they pay so little ($33 for a doctor, $28 for a PA), yet the pathology charge is unchanged.

There are other costs beyond monetary ones from unnecessary skin biopsies: scarring, follow-up procedures for uncertain diagnoses such as mild dysplastic nevi, ambiguous results, and emotional angst to patients.

If the results of this large study are to be believed, many melanomas in situ are going to be missed if PAs perform unsupervised skin cancer screenings. This is not a tenable proposition, ethically or legally. Dermatologists and PAs need to work together to ensure this does not happen.

An estimated 2,520 dermatology PAs were practicing in the United States in 2016, based on membership data from the Society of Dermatology PAs (SDPA), according to a research letter published last year (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Jun;76[6]:1200-2). The SDPA, as stated in an SDPA position statement published in the winter 2017 newsletter, hopes to gain access to direct billing to public and private insurers, which would include the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and for PAs to no longer report to other health care professionals.

Many dermatologists, as well as teaching programs, use PAs to perform skin cancer screenings, sometimes unsupervised, which makes diagnostic accuracy critical. The issues at hand are the safety of patients and the accuracy of diagnosis as well as the costs to the health care system. A team effort, which includes direct supervision, is needed to ensure those issues are addressed.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

The emergency department locum tenens staff recruiter was persuasive. “It’s a quiet little ER where you can study and sleep.” I was board certified in internal medicine and had trained in a busy urban emergency department. This was just the spot to make a little folding money and study for my mock dermatology boards, I thought.

And so, on a Saturday night in rural Texas, after grinding rust out of a pipe fitter’s eye and stitching up two brawlers from the local biker bar, I was faced with treating a comatose kid brought in after a car crash. He had not been wearing a seat belt, and his car had rolled over on his head.

I was way over my skill level, but I was lucky. I was able to stabilize him and, after several long hours, I got him on an emergency helicopter into Dallas.

But the experience changed me. I realized I did not know enough to deal with this case on my own. After making it through that night in the ED, I never put myself in that position again.

I now knew what I did not know.

The finding that jumped out to me, though, was that patients screened by a PA were significantly less likely to be diagnosed with melanoma in situ, the stage when melanoma is 100% curable. Yet, those patients screened by PAs underwent a lot more skin biopsies – 36% more skin biopsies per melanoma in situ diagnosed, compared with patients of dermatologists. Interestingly, in the health care system studied, any PA with a question about a patient can ask an attending dermatologist to see the patient. Did that factor account for the diagnostic comparability for nonmelanoma skin cancer and invasive melanoma? Did the PAs not ask for help on the missed melanomas in situ? If so, I believe this may be a situation of PAs not knowing what they didn’t know.

Now a knowledgeable friend of mine thinks this study is biased because 17% more patients with prior melanomas were seen by a dermatologist rather than by a PA. While it’s true that patients with prior melanomas are more likely to develop new melanomas, the counterargument is that the bar for a biopsy in a patient with a prior melanoma is much lower. Patients with a history of melanoma should have more skin biopsies, but the dermatologists in this study still took many fewer biopsies to diagnose melanomas in situ.

Why do these findings matter for patients and for the health care system?

PAs billed independently for 12% of skin biopsies (including lip, ear, ear canal, vulva, penis, and eyelid) in Medicare Fee for Service in 2016. Skin biopsies paid for by Medicare have been increasing at a very rapid rate, about twice as fast as the rate reflected in the current skin cancer epidemic.

Every skin biopsy results in a pathology charge, for which Medicare pays about $70. A level 3 new patient visit pays $110. If PAs bill independently, they are paid at 85% of the fee schedule, which often is touted as a great savings. Therefore, if only 24.2% of skin biopsies by PAs were unnecessary, even at a reduced 85% reimbursement, it costs Medicare more than having these visits and biopsies provided by a dermatologist. The cost savings decrease even more with additional skin biopsies, because they pay so little ($33 for a doctor, $28 for a PA), yet the pathology charge is unchanged.

There are other costs beyond monetary ones from unnecessary skin biopsies: scarring, follow-up procedures for uncertain diagnoses such as mild dysplastic nevi, ambiguous results, and emotional angst to patients.

If the results of this large study are to be believed, many melanomas in situ are going to be missed if PAs perform unsupervised skin cancer screenings. This is not a tenable proposition, ethically or legally. Dermatologists and PAs need to work together to ensure this does not happen.

An estimated 2,520 dermatology PAs were practicing in the United States in 2016, based on membership data from the Society of Dermatology PAs (SDPA), according to a research letter published last year (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Jun;76[6]:1200-2). The SDPA, as stated in an SDPA position statement published in the winter 2017 newsletter, hopes to gain access to direct billing to public and private insurers, which would include the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and for PAs to no longer report to other health care professionals.

Many dermatologists, as well as teaching programs, use PAs to perform skin cancer screenings, sometimes unsupervised, which makes diagnostic accuracy critical. The issues at hand are the safety of patients and the accuracy of diagnosis as well as the costs to the health care system. A team effort, which includes direct supervision, is needed to ensure those issues are addressed.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

The emergency department locum tenens staff recruiter was persuasive. “It’s a quiet little ER where you can study and sleep.” I was board certified in internal medicine and had trained in a busy urban emergency department. This was just the spot to make a little folding money and study for my mock dermatology boards, I thought.

And so, on a Saturday night in rural Texas, after grinding rust out of a pipe fitter’s eye and stitching up two brawlers from the local biker bar, I was faced with treating a comatose kid brought in after a car crash. He had not been wearing a seat belt, and his car had rolled over on his head.

I was way over my skill level, but I was lucky. I was able to stabilize him and, after several long hours, I got him on an emergency helicopter into Dallas.

But the experience changed me. I realized I did not know enough to deal with this case on my own. After making it through that night in the ED, I never put myself in that position again.

I now knew what I did not know.

The finding that jumped out to me, though, was that patients screened by a PA were significantly less likely to be diagnosed with melanoma in situ, the stage when melanoma is 100% curable. Yet, those patients screened by PAs underwent a lot more skin biopsies – 36% more skin biopsies per melanoma in situ diagnosed, compared with patients of dermatologists. Interestingly, in the health care system studied, any PA with a question about a patient can ask an attending dermatologist to see the patient. Did that factor account for the diagnostic comparability for nonmelanoma skin cancer and invasive melanoma? Did the PAs not ask for help on the missed melanomas in situ? If so, I believe this may be a situation of PAs not knowing what they didn’t know.

Now a knowledgeable friend of mine thinks this study is biased because 17% more patients with prior melanomas were seen by a dermatologist rather than by a PA. While it’s true that patients with prior melanomas are more likely to develop new melanomas, the counterargument is that the bar for a biopsy in a patient with a prior melanoma is much lower. Patients with a history of melanoma should have more skin biopsies, but the dermatologists in this study still took many fewer biopsies to diagnose melanomas in situ.

Why do these findings matter for patients and for the health care system?

PAs billed independently for 12% of skin biopsies (including lip, ear, ear canal, vulva, penis, and eyelid) in Medicare Fee for Service in 2016. Skin biopsies paid for by Medicare have been increasing at a very rapid rate, about twice as fast as the rate reflected in the current skin cancer epidemic.

Every skin biopsy results in a pathology charge, for which Medicare pays about $70. A level 3 new patient visit pays $110. If PAs bill independently, they are paid at 85% of the fee schedule, which often is touted as a great savings. Therefore, if only 24.2% of skin biopsies by PAs were unnecessary, even at a reduced 85% reimbursement, it costs Medicare more than having these visits and biopsies provided by a dermatologist. The cost savings decrease even more with additional skin biopsies, because they pay so little ($33 for a doctor, $28 for a PA), yet the pathology charge is unchanged.

There are other costs beyond monetary ones from unnecessary skin biopsies: scarring, follow-up procedures for uncertain diagnoses such as mild dysplastic nevi, ambiguous results, and emotional angst to patients.

If the results of this large study are to be believed, many melanomas in situ are going to be missed if PAs perform unsupervised skin cancer screenings. This is not a tenable proposition, ethically or legally. Dermatologists and PAs need to work together to ensure this does not happen.

An estimated 2,520 dermatology PAs were practicing in the United States in 2016, based on membership data from the Society of Dermatology PAs (SDPA), according to a research letter published last year (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Jun;76[6]:1200-2). The SDPA, as stated in an SDPA position statement published in the winter 2017 newsletter, hopes to gain access to direct billing to public and private insurers, which would include the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and for PAs to no longer report to other health care professionals.

Many dermatologists, as well as teaching programs, use PAs to perform skin cancer screenings, sometimes unsupervised, which makes diagnostic accuracy critical. The issues at hand are the safety of patients and the accuracy of diagnosis as well as the costs to the health care system. A team effort, which includes direct supervision, is needed to ensure those issues are addressed.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

Oophorectomy for premenopausal breast cancer

One-quarter of patients with breast cancer are diagnosed at a premenopausal age and these young women may be directed to discuss oophorectomy with their ob.gyn. This may be because of the discovery of a deleterious BRCA gene mutation, which places them at increased risk for ovarian cancer, but oophorectomy may also be a therapeutic option for their breast cancer: 60% of premenopausal breast cancers are hormone receptor–positive. Ovarian ablation has been associated with improved overall survival and disease-free survival among these patients.1

Estrogen is an important promoter of breast cancer and is predominantly derived from ovarian tissue in premenopausal women. However, in postmenopausal women, the majority of estrogen is produced peripherally through the conversion of androgens to estrogen via the enzyme aromatase. Aromatase inhibitors, such as exemestane, anastrazole, and letrazole, are drugs which block this conversion in peripheral tissues. They are contraindicated in premenopausal women with intact ovarian function, because there is a reflex pituitary stimulation of ovarian estrogen release in response to suppression of peripheral conversion of androgens. For such patients, ovarian function must be ablated either with surgery or with gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues such as leuprorelin and goserelin if aromatase inhibitors are desired.