User login

Sacred cows

Within the academic pediatric community, there is little argument that the concepts “evidence based” and “early intervention” are gold standards against which we must measure our efforts.

It should be obvious to everyone that if we can intervene early in a child’s developmental trajectory, our chances of affecting his/her outcome are improved. And the earlier the better. If we aren’t supremely committed to prevention, then what sets pediatrics apart from the other specialties?

Likewise, if we aren’t willing to systematically measure our efforts at improving the health of our patients, we run the risk of simply spinning our wheels and even worse, squandering our patients’ time and their parents’ energies. However, a recent article in Pediatrics and a companion commentary suggest that we need to be more careful as we interpret the buzz that surrounds the terms “early intervention” and “evidence based.”

In their one-sentence conclusion of a paper reviewing 48 studies of early intervention in early childhood development, the authors observe, “Although several interventions resulted in improved child development outcomes age 0 to 3 years, comparison across studies and interventions is limited by the use of different outcome measures, time of evaluation, and variability of results” (“Primary Care Interventions for Early Childhood Development: A Systematic Review,” Peacock-Chambers et al. Pediatrics. 2017, Nov 14. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1661). Unless you are looking for another reason to slip further into an abyss of despair, I urge that you skip reading the details of the Peacock-Chambers paper and turn instead to Dr. Jack P. Shonkoff’s excellent commentary (“Rethinking the Definition of Evidence-Based Interventions to Promote Early Child Development,” Pediatrics. 2017, Dec. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3136).

Dr. Shonkoff observes that there is ample evidence to support the general concept of early intervention as it relates to childhood development. However, he acknowledges that the improvements observed generally have been small. And there has been little success in scaling these few successes to larger populations. It would seem that the sacred cow of early intervention remains standing, albeit on somewhat shaky legs.

Dr. Shonkoff points out that an obsession with statistical significance often has blinded some of us to the importance of the magnitude of (or the lack of) impact when interpreting studies of early intervention. As a result, we may have failed to realize how far research in early childhood development has fallen behind the other fields of biomedical research such as cancer, HIV, and AIDS. His plea is that we begin to leverage our successes in fields such as molecular biology, epigenetics, and neuroscience when designing future studies of early childhood development. He asserts that this kind of basic science – in concert with “on-the-ground experience” (that’s you and me) and “authentic parental engagement” – is more likely to result in greater scalable impact for our patients threatened by developmental delays.

It is refreshing and encouraging reading a critical consideration of the evidence-based sacred cow. Evidence can be viewed from a variety of perspectives. If we continue to filter all of our observations through a statistical significance filter, we run the risk of missing both the forest and the trees.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Within the academic pediatric community, there is little argument that the concepts “evidence based” and “early intervention” are gold standards against which we must measure our efforts.

It should be obvious to everyone that if we can intervene early in a child’s developmental trajectory, our chances of affecting his/her outcome are improved. And the earlier the better. If we aren’t supremely committed to prevention, then what sets pediatrics apart from the other specialties?

Likewise, if we aren’t willing to systematically measure our efforts at improving the health of our patients, we run the risk of simply spinning our wheels and even worse, squandering our patients’ time and their parents’ energies. However, a recent article in Pediatrics and a companion commentary suggest that we need to be more careful as we interpret the buzz that surrounds the terms “early intervention” and “evidence based.”

In their one-sentence conclusion of a paper reviewing 48 studies of early intervention in early childhood development, the authors observe, “Although several interventions resulted in improved child development outcomes age 0 to 3 years, comparison across studies and interventions is limited by the use of different outcome measures, time of evaluation, and variability of results” (“Primary Care Interventions for Early Childhood Development: A Systematic Review,” Peacock-Chambers et al. Pediatrics. 2017, Nov 14. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1661). Unless you are looking for another reason to slip further into an abyss of despair, I urge that you skip reading the details of the Peacock-Chambers paper and turn instead to Dr. Jack P. Shonkoff’s excellent commentary (“Rethinking the Definition of Evidence-Based Interventions to Promote Early Child Development,” Pediatrics. 2017, Dec. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3136).

Dr. Shonkoff observes that there is ample evidence to support the general concept of early intervention as it relates to childhood development. However, he acknowledges that the improvements observed generally have been small. And there has been little success in scaling these few successes to larger populations. It would seem that the sacred cow of early intervention remains standing, albeit on somewhat shaky legs.

Dr. Shonkoff points out that an obsession with statistical significance often has blinded some of us to the importance of the magnitude of (or the lack of) impact when interpreting studies of early intervention. As a result, we may have failed to realize how far research in early childhood development has fallen behind the other fields of biomedical research such as cancer, HIV, and AIDS. His plea is that we begin to leverage our successes in fields such as molecular biology, epigenetics, and neuroscience when designing future studies of early childhood development. He asserts that this kind of basic science – in concert with “on-the-ground experience” (that’s you and me) and “authentic parental engagement” – is more likely to result in greater scalable impact for our patients threatened by developmental delays.

It is refreshing and encouraging reading a critical consideration of the evidence-based sacred cow. Evidence can be viewed from a variety of perspectives. If we continue to filter all of our observations through a statistical significance filter, we run the risk of missing both the forest and the trees.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Within the academic pediatric community, there is little argument that the concepts “evidence based” and “early intervention” are gold standards against which we must measure our efforts.

It should be obvious to everyone that if we can intervene early in a child’s developmental trajectory, our chances of affecting his/her outcome are improved. And the earlier the better. If we aren’t supremely committed to prevention, then what sets pediatrics apart from the other specialties?

Likewise, if we aren’t willing to systematically measure our efforts at improving the health of our patients, we run the risk of simply spinning our wheels and even worse, squandering our patients’ time and their parents’ energies. However, a recent article in Pediatrics and a companion commentary suggest that we need to be more careful as we interpret the buzz that surrounds the terms “early intervention” and “evidence based.”

In their one-sentence conclusion of a paper reviewing 48 studies of early intervention in early childhood development, the authors observe, “Although several interventions resulted in improved child development outcomes age 0 to 3 years, comparison across studies and interventions is limited by the use of different outcome measures, time of evaluation, and variability of results” (“Primary Care Interventions for Early Childhood Development: A Systematic Review,” Peacock-Chambers et al. Pediatrics. 2017, Nov 14. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1661). Unless you are looking for another reason to slip further into an abyss of despair, I urge that you skip reading the details of the Peacock-Chambers paper and turn instead to Dr. Jack P. Shonkoff’s excellent commentary (“Rethinking the Definition of Evidence-Based Interventions to Promote Early Child Development,” Pediatrics. 2017, Dec. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3136).

Dr. Shonkoff observes that there is ample evidence to support the general concept of early intervention as it relates to childhood development. However, he acknowledges that the improvements observed generally have been small. And there has been little success in scaling these few successes to larger populations. It would seem that the sacred cow of early intervention remains standing, albeit on somewhat shaky legs.

Dr. Shonkoff points out that an obsession with statistical significance often has blinded some of us to the importance of the magnitude of (or the lack of) impact when interpreting studies of early intervention. As a result, we may have failed to realize how far research in early childhood development has fallen behind the other fields of biomedical research such as cancer, HIV, and AIDS. His plea is that we begin to leverage our successes in fields such as molecular biology, epigenetics, and neuroscience when designing future studies of early childhood development. He asserts that this kind of basic science – in concert with “on-the-ground experience” (that’s you and me) and “authentic parental engagement” – is more likely to result in greater scalable impact for our patients threatened by developmental delays.

It is refreshing and encouraging reading a critical consideration of the evidence-based sacred cow. Evidence can be viewed from a variety of perspectives. If we continue to filter all of our observations through a statistical significance filter, we run the risk of missing both the forest and the trees.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Stressed for Success

As I write this column, the holiday season has just begun, and its incumbent demands lie ahead. By the time this article reaches you, we will have outlasted the season and its associated stress. But it’s not just the holiday baking, gift-wrapping, and decorating that overwhelms us—we face enormous professional stress during this time of year, with its emphasis on home, family, good health, and harmony.

Stress is simply a part of human nature. And despite its bad rap, not all stress is problematic; it’s what motivates people to prepare or perform. Routine, “normal” stress that is temporary or short-lived can actually be beneficial. When placed in danger, the body prepares to either face the threat or flee to safety. During these times, your pulse quickens, you breathe faster, your muscles tense, your brain uses more oxygen and increases activity—all functions that aid in survival.1

But not every situation we encounter necessitates an increase in endorphin levels and blood pressure. Tell that to our stress levels, which are often persistently elevated! Chronic stress can cause the self-protective responses your body activates when threatened to suppress immune, digestive, sleep, and reproductive systems, leading them to cease normal functioning over time.1 This “bad” stress—or distress—can contribute to health problems such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and diabetes.

Stress can elicit a variety of responses: behavioral, psychologic/emotional, physical, cognitive, and social.2 For many, consumption (of tobacco, alcohol, drugs, sugar, fat, or caffeine) is a coping mechanism. While many people look to food for comfort and stress relief, research suggests it may have undesired effects. Eating a high-fat meal when under stress can slow your metabolism and result in significant weight gain.3 Stress can also influence whether people undereat or overeat and affect neurohormonal activity—which leads to increased production of cortisol, which leads to weight gain (particularly in women).4 Let’s be honest: Gaining weight seldom lowers someone’s stress level.

Everyone has different triggers that cause their stress levels to spike, but the workplace has been found to top the list. Within the “work” category, commonly reported stressors include

- Heavy workload or too much responsibility

- Long hours

- Poor management, unclear expectations, or having no say in decision-making.5

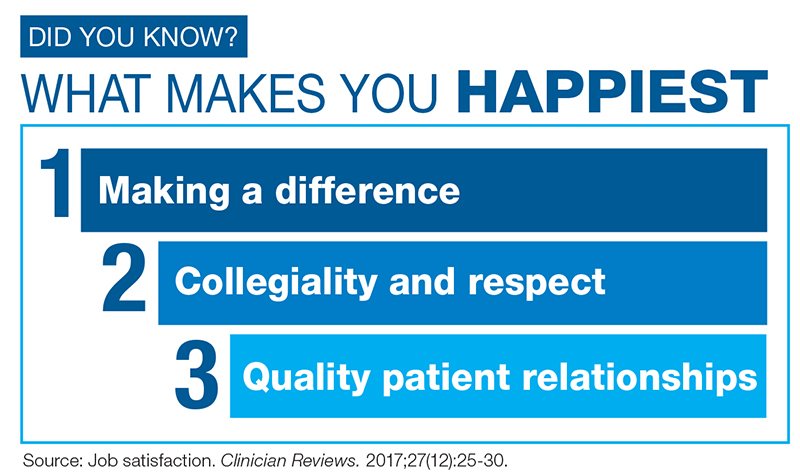

For health care providers, day-to-day stress is a chronic problem; responses to the Clinician Reviews annual job satisfaction survey have demonstrated that.6,7 Many of our readers report ongoing issues related to scheduling, work/life balance, compensation, and working conditions. That tension has a direct negative effect, not only on us, but on our families and our patients as well. A missed soccer game or a holiday on call are obvious stressors—but our inability to help patients achieve optimal health is a source of distress that we may not recognize the ramifications of. How often has a clinician felt caught in what feels like an unattainable quest?

Mitigating this workplace stress is the challenge. Changing jobs is another high-stress event, so up and quitting is probably not the answer. Identifying the problem is the first essential step.

If workload is the issue, focus on setting realistic goals for your day. Goal-setting provides purposeful direction and helps you feel in control. There will undeniably be days in which your plan must be completely abandoned. When this happens, don’t fret—reassess! Decide what must get done and what can wait. If possible, avoid scheduling patient appointments that will put you into overload. Learn to say “no” without feeling as though you are not a team player. And when you feel swamped, put a positive spin on the day by noting what you have accomplished, rather than what you have been unable to achieve.

If you find that your voice is but a whisper in the decision-making process, look for ways to become more involved. How can you provide direction on issues relating to organizational structure and clinical efficiency? Don’t suppress your feelings or concerns about the work environment. Pulling up a chair at the management table is crucial to improving the workplace and reducing stress for everyone (including the management!). Discuss key frustration points. Clear documentation of the issues that impede patient satisfaction (eg, long wait times) will aid in your dialogue.

Literature has identified common professional frustrations related to base pay rates, on-call pay, overtime pay, individual productivity compensation, and general incentive payments, which are further supported by our job satisfaction surveys.6-8 Knowing what’s included in the typical compensation packages in your region can reduce not only your own stress, but your employer’s as well. While this may seem a futile exercise, the investment in evaluating your own value, and the value your employer places on you, is well worth the return.

Previous experience dictates our ability to handle stress. If you have confidence in yourself, your contribution to your patients, and your ability to influence events and persevere through challenges, you are better equipped to handle the stress. If you can put the stressors in perspective by knowing the time frame of the stress, how long it will last, and what to expect, it will be easier to cope with the situation.

While trying to write this column, I was initially so stressed that I could barely compose a sentence! I knew that the stress of meeting my editorial deadline was “good” stress, though, so I kept taking short walks, and (as you can read) I got through it. Whether you turn to exercise or music or (as one friend does!) closet purging—managing your stress is key to maintaining good health.

[polldaddy:9906029]

1. National Institute of Mental Health. 5 things you should know about stress. www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/stress/index.shtml. Accessed December 4, 2017.

2. New York State Office of Mental Health. Common stress reactions: a self-assessment. www.omh.ny.gov/omhweb/disaster_resources/pandemic_influenza/doctors_nurses/Common_Stress_Reactions.html. Accessed December 7, 2017.

3. Smith M. Stress, high fat, and your metabolism [video]. WebMD. www.webmd.com/balance/stress-management/video/stress-high-fat-and-your-metabolism. Accessed December 7, 2017.

4. Slachta A. Stressed women more likely to develop obesity. Cardiovascular Business. November 15, 2017. www.cardiovascularbusiness.com/topics/lipid-metabolic/stressed-women-more-likely-develop-obesity-study-finds. Accessed December 7, 2017.

5. WebMD. Causes of stress. www.webmd.com/balance/guide/causes-of-stress#1. Accessed December 7, 2017.

6. Job satisfaction. Clinician Reviews. 2017;27(12):25-30.

7. Beyond salary: are you happy with your work? Clinician Reviews. 2016;26(12):23-26.

8. O’Hare S, Young AF. The advancing role of advanced practice clinicians: compensation, development, & leadership trends (2016). HealthLeaders Media. www.healthleadersmedia.com/whitepaper/advancing-role-advanced-practice-clinicians-compensation-development-leadership-trends. Accessed December 7, 2017.

As I write this column, the holiday season has just begun, and its incumbent demands lie ahead. By the time this article reaches you, we will have outlasted the season and its associated stress. But it’s not just the holiday baking, gift-wrapping, and decorating that overwhelms us—we face enormous professional stress during this time of year, with its emphasis on home, family, good health, and harmony.

Stress is simply a part of human nature. And despite its bad rap, not all stress is problematic; it’s what motivates people to prepare or perform. Routine, “normal” stress that is temporary or short-lived can actually be beneficial. When placed in danger, the body prepares to either face the threat or flee to safety. During these times, your pulse quickens, you breathe faster, your muscles tense, your brain uses more oxygen and increases activity—all functions that aid in survival.1

But not every situation we encounter necessitates an increase in endorphin levels and blood pressure. Tell that to our stress levels, which are often persistently elevated! Chronic stress can cause the self-protective responses your body activates when threatened to suppress immune, digestive, sleep, and reproductive systems, leading them to cease normal functioning over time.1 This “bad” stress—or distress—can contribute to health problems such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and diabetes.

Stress can elicit a variety of responses: behavioral, psychologic/emotional, physical, cognitive, and social.2 For many, consumption (of tobacco, alcohol, drugs, sugar, fat, or caffeine) is a coping mechanism. While many people look to food for comfort and stress relief, research suggests it may have undesired effects. Eating a high-fat meal when under stress can slow your metabolism and result in significant weight gain.3 Stress can also influence whether people undereat or overeat and affect neurohormonal activity—which leads to increased production of cortisol, which leads to weight gain (particularly in women).4 Let’s be honest: Gaining weight seldom lowers someone’s stress level.

Everyone has different triggers that cause their stress levels to spike, but the workplace has been found to top the list. Within the “work” category, commonly reported stressors include

- Heavy workload or too much responsibility

- Long hours

- Poor management, unclear expectations, or having no say in decision-making.5

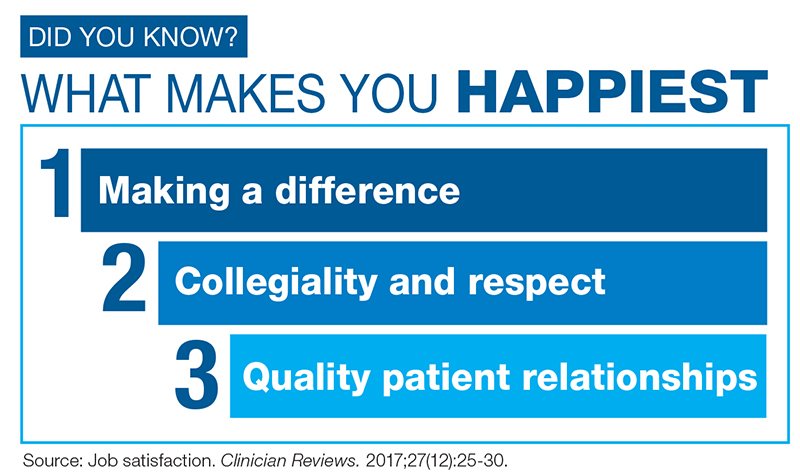

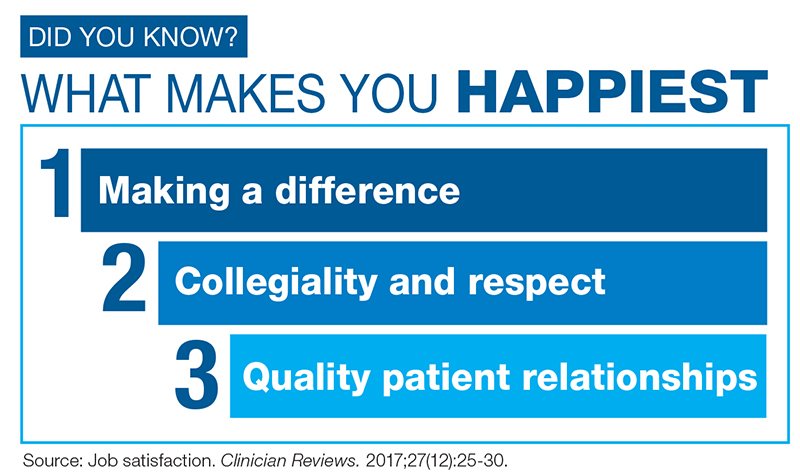

For health care providers, day-to-day stress is a chronic problem; responses to the Clinician Reviews annual job satisfaction survey have demonstrated that.6,7 Many of our readers report ongoing issues related to scheduling, work/life balance, compensation, and working conditions. That tension has a direct negative effect, not only on us, but on our families and our patients as well. A missed soccer game or a holiday on call are obvious stressors—but our inability to help patients achieve optimal health is a source of distress that we may not recognize the ramifications of. How often has a clinician felt caught in what feels like an unattainable quest?

Mitigating this workplace stress is the challenge. Changing jobs is another high-stress event, so up and quitting is probably not the answer. Identifying the problem is the first essential step.

If workload is the issue, focus on setting realistic goals for your day. Goal-setting provides purposeful direction and helps you feel in control. There will undeniably be days in which your plan must be completely abandoned. When this happens, don’t fret—reassess! Decide what must get done and what can wait. If possible, avoid scheduling patient appointments that will put you into overload. Learn to say “no” without feeling as though you are not a team player. And when you feel swamped, put a positive spin on the day by noting what you have accomplished, rather than what you have been unable to achieve.

If you find that your voice is but a whisper in the decision-making process, look for ways to become more involved. How can you provide direction on issues relating to organizational structure and clinical efficiency? Don’t suppress your feelings or concerns about the work environment. Pulling up a chair at the management table is crucial to improving the workplace and reducing stress for everyone (including the management!). Discuss key frustration points. Clear documentation of the issues that impede patient satisfaction (eg, long wait times) will aid in your dialogue.

Literature has identified common professional frustrations related to base pay rates, on-call pay, overtime pay, individual productivity compensation, and general incentive payments, which are further supported by our job satisfaction surveys.6-8 Knowing what’s included in the typical compensation packages in your region can reduce not only your own stress, but your employer’s as well. While this may seem a futile exercise, the investment in evaluating your own value, and the value your employer places on you, is well worth the return.

Previous experience dictates our ability to handle stress. If you have confidence in yourself, your contribution to your patients, and your ability to influence events and persevere through challenges, you are better equipped to handle the stress. If you can put the stressors in perspective by knowing the time frame of the stress, how long it will last, and what to expect, it will be easier to cope with the situation.

While trying to write this column, I was initially so stressed that I could barely compose a sentence! I knew that the stress of meeting my editorial deadline was “good” stress, though, so I kept taking short walks, and (as you can read) I got through it. Whether you turn to exercise or music or (as one friend does!) closet purging—managing your stress is key to maintaining good health.

[polldaddy:9906029]

As I write this column, the holiday season has just begun, and its incumbent demands lie ahead. By the time this article reaches you, we will have outlasted the season and its associated stress. But it’s not just the holiday baking, gift-wrapping, and decorating that overwhelms us—we face enormous professional stress during this time of year, with its emphasis on home, family, good health, and harmony.

Stress is simply a part of human nature. And despite its bad rap, not all stress is problematic; it’s what motivates people to prepare or perform. Routine, “normal” stress that is temporary or short-lived can actually be beneficial. When placed in danger, the body prepares to either face the threat or flee to safety. During these times, your pulse quickens, you breathe faster, your muscles tense, your brain uses more oxygen and increases activity—all functions that aid in survival.1

But not every situation we encounter necessitates an increase in endorphin levels and blood pressure. Tell that to our stress levels, which are often persistently elevated! Chronic stress can cause the self-protective responses your body activates when threatened to suppress immune, digestive, sleep, and reproductive systems, leading them to cease normal functioning over time.1 This “bad” stress—or distress—can contribute to health problems such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and diabetes.

Stress can elicit a variety of responses: behavioral, psychologic/emotional, physical, cognitive, and social.2 For many, consumption (of tobacco, alcohol, drugs, sugar, fat, or caffeine) is a coping mechanism. While many people look to food for comfort and stress relief, research suggests it may have undesired effects. Eating a high-fat meal when under stress can slow your metabolism and result in significant weight gain.3 Stress can also influence whether people undereat or overeat and affect neurohormonal activity—which leads to increased production of cortisol, which leads to weight gain (particularly in women).4 Let’s be honest: Gaining weight seldom lowers someone’s stress level.

Everyone has different triggers that cause their stress levels to spike, but the workplace has been found to top the list. Within the “work” category, commonly reported stressors include

- Heavy workload or too much responsibility

- Long hours

- Poor management, unclear expectations, or having no say in decision-making.5

For health care providers, day-to-day stress is a chronic problem; responses to the Clinician Reviews annual job satisfaction survey have demonstrated that.6,7 Many of our readers report ongoing issues related to scheduling, work/life balance, compensation, and working conditions. That tension has a direct negative effect, not only on us, but on our families and our patients as well. A missed soccer game or a holiday on call are obvious stressors—but our inability to help patients achieve optimal health is a source of distress that we may not recognize the ramifications of. How often has a clinician felt caught in what feels like an unattainable quest?

Mitigating this workplace stress is the challenge. Changing jobs is another high-stress event, so up and quitting is probably not the answer. Identifying the problem is the first essential step.

If workload is the issue, focus on setting realistic goals for your day. Goal-setting provides purposeful direction and helps you feel in control. There will undeniably be days in which your plan must be completely abandoned. When this happens, don’t fret—reassess! Decide what must get done and what can wait. If possible, avoid scheduling patient appointments that will put you into overload. Learn to say “no” without feeling as though you are not a team player. And when you feel swamped, put a positive spin on the day by noting what you have accomplished, rather than what you have been unable to achieve.

If you find that your voice is but a whisper in the decision-making process, look for ways to become more involved. How can you provide direction on issues relating to organizational structure and clinical efficiency? Don’t suppress your feelings or concerns about the work environment. Pulling up a chair at the management table is crucial to improving the workplace and reducing stress for everyone (including the management!). Discuss key frustration points. Clear documentation of the issues that impede patient satisfaction (eg, long wait times) will aid in your dialogue.

Literature has identified common professional frustrations related to base pay rates, on-call pay, overtime pay, individual productivity compensation, and general incentive payments, which are further supported by our job satisfaction surveys.6-8 Knowing what’s included in the typical compensation packages in your region can reduce not only your own stress, but your employer’s as well. While this may seem a futile exercise, the investment in evaluating your own value, and the value your employer places on you, is well worth the return.

Previous experience dictates our ability to handle stress. If you have confidence in yourself, your contribution to your patients, and your ability to influence events and persevere through challenges, you are better equipped to handle the stress. If you can put the stressors in perspective by knowing the time frame of the stress, how long it will last, and what to expect, it will be easier to cope with the situation.

While trying to write this column, I was initially so stressed that I could barely compose a sentence! I knew that the stress of meeting my editorial deadline was “good” stress, though, so I kept taking short walks, and (as you can read) I got through it. Whether you turn to exercise or music or (as one friend does!) closet purging—managing your stress is key to maintaining good health.

[polldaddy:9906029]

1. National Institute of Mental Health. 5 things you should know about stress. www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/stress/index.shtml. Accessed December 4, 2017.

2. New York State Office of Mental Health. Common stress reactions: a self-assessment. www.omh.ny.gov/omhweb/disaster_resources/pandemic_influenza/doctors_nurses/Common_Stress_Reactions.html. Accessed December 7, 2017.

3. Smith M. Stress, high fat, and your metabolism [video]. WebMD. www.webmd.com/balance/stress-management/video/stress-high-fat-and-your-metabolism. Accessed December 7, 2017.

4. Slachta A. Stressed women more likely to develop obesity. Cardiovascular Business. November 15, 2017. www.cardiovascularbusiness.com/topics/lipid-metabolic/stressed-women-more-likely-develop-obesity-study-finds. Accessed December 7, 2017.

5. WebMD. Causes of stress. www.webmd.com/balance/guide/causes-of-stress#1. Accessed December 7, 2017.

6. Job satisfaction. Clinician Reviews. 2017;27(12):25-30.

7. Beyond salary: are you happy with your work? Clinician Reviews. 2016;26(12):23-26.

8. O’Hare S, Young AF. The advancing role of advanced practice clinicians: compensation, development, & leadership trends (2016). HealthLeaders Media. www.healthleadersmedia.com/whitepaper/advancing-role-advanced-practice-clinicians-compensation-development-leadership-trends. Accessed December 7, 2017.

1. National Institute of Mental Health. 5 things you should know about stress. www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/stress/index.shtml. Accessed December 4, 2017.

2. New York State Office of Mental Health. Common stress reactions: a self-assessment. www.omh.ny.gov/omhweb/disaster_resources/pandemic_influenza/doctors_nurses/Common_Stress_Reactions.html. Accessed December 7, 2017.

3. Smith M. Stress, high fat, and your metabolism [video]. WebMD. www.webmd.com/balance/stress-management/video/stress-high-fat-and-your-metabolism. Accessed December 7, 2017.

4. Slachta A. Stressed women more likely to develop obesity. Cardiovascular Business. November 15, 2017. www.cardiovascularbusiness.com/topics/lipid-metabolic/stressed-women-more-likely-develop-obesity-study-finds. Accessed December 7, 2017.

5. WebMD. Causes of stress. www.webmd.com/balance/guide/causes-of-stress#1. Accessed December 7, 2017.

6. Job satisfaction. Clinician Reviews. 2017;27(12):25-30.

7. Beyond salary: are you happy with your work? Clinician Reviews. 2016;26(12):23-26.

8. O’Hare S, Young AF. The advancing role of advanced practice clinicians: compensation, development, & leadership trends (2016). HealthLeaders Media. www.healthleadersmedia.com/whitepaper/advancing-role-advanced-practice-clinicians-compensation-development-leadership-trends. Accessed December 7, 2017.

See for yourself

About 800 million radiology exams were performed in this country in the past year, and they generated approximately 60 billion images, according to an article published in 2017 in the Wall Street Journal (“No need for radiologists to be negative on AI,” by Greg Ip, Nov. 24, 2017). How many of those millions of radiology studies did you order? And how many of the scores of images you requested did you see with your own two eyes? In fact, how many of the radiologists’ reports that were sent to you did you read in their entirety? How often did you just skip over the radiologist’s CYA disclaimers and simply read the final summary, “exam negative”?

I enjoy the challenge of interpreting x-ray images. In fact, I toyed with becoming a pediatric radiologist, but that career path would have meant settling in or near a large city, a compromise my wife and I were unwilling to make. I hoped to continue my habit of looking at all my patients’ x-rays, but because my practice was not in or near the hospital, I reluctantly had to bend my rules and admit I didn’t see every image I had ordered. But, I did read every report in its entirety. In one case, an offhand comment buried in the middle of the radiologist’s report referring to the “residual barium from a previous study” caught my eye, because I knew the patient hadn’t had a previous contrast study. Unfortunately, the neuroblastoma that the radiologist had missed initially, and I had seen the next day, never responded to treatment.

Toward the end of my career, digital imagery allowed me to view my patients’ x-rays without having to leave my desk, which got me closer to my goal of seeing all my patients’ studies. However, the advent of computerized axial tomography and magnetic resonance imaging meant that an increasing number of studies pushed my anatomic knowledge beyond its limits.

I suspect that many of you benefited from the if-you-order-it-look-at-it mantra during your training. How many of you have continued to follow the dictum? With the advent of digitized imagery, there is really little excuse for not taking a minute or 2 to pull up your patients’ images on your desktop. One could argue that looking inside your patient is part of a complete exam. Forcing yourself to take that extra step and look at the study may nudge you into thinking twice about whether you really needed the information the imaging study might add to the diagnostic process. Was your click to order the study just a reflex subliminally related to the fear of a lawsuit? Was it important enough to deserve a firsthand look?

At the very least, being able to say, “I’ve looked at your x-rays myself, and they look fine” may be more comforting to your patient than a third-hand relay of a “negative reading” performed by someone whom they have likely never met.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

About 800 million radiology exams were performed in this country in the past year, and they generated approximately 60 billion images, according to an article published in 2017 in the Wall Street Journal (“No need for radiologists to be negative on AI,” by Greg Ip, Nov. 24, 2017). How many of those millions of radiology studies did you order? And how many of the scores of images you requested did you see with your own two eyes? In fact, how many of the radiologists’ reports that were sent to you did you read in their entirety? How often did you just skip over the radiologist’s CYA disclaimers and simply read the final summary, “exam negative”?

I enjoy the challenge of interpreting x-ray images. In fact, I toyed with becoming a pediatric radiologist, but that career path would have meant settling in or near a large city, a compromise my wife and I were unwilling to make. I hoped to continue my habit of looking at all my patients’ x-rays, but because my practice was not in or near the hospital, I reluctantly had to bend my rules and admit I didn’t see every image I had ordered. But, I did read every report in its entirety. In one case, an offhand comment buried in the middle of the radiologist’s report referring to the “residual barium from a previous study” caught my eye, because I knew the patient hadn’t had a previous contrast study. Unfortunately, the neuroblastoma that the radiologist had missed initially, and I had seen the next day, never responded to treatment.

Toward the end of my career, digital imagery allowed me to view my patients’ x-rays without having to leave my desk, which got me closer to my goal of seeing all my patients’ studies. However, the advent of computerized axial tomography and magnetic resonance imaging meant that an increasing number of studies pushed my anatomic knowledge beyond its limits.

I suspect that many of you benefited from the if-you-order-it-look-at-it mantra during your training. How many of you have continued to follow the dictum? With the advent of digitized imagery, there is really little excuse for not taking a minute or 2 to pull up your patients’ images on your desktop. One could argue that looking inside your patient is part of a complete exam. Forcing yourself to take that extra step and look at the study may nudge you into thinking twice about whether you really needed the information the imaging study might add to the diagnostic process. Was your click to order the study just a reflex subliminally related to the fear of a lawsuit? Was it important enough to deserve a firsthand look?

At the very least, being able to say, “I’ve looked at your x-rays myself, and they look fine” may be more comforting to your patient than a third-hand relay of a “negative reading” performed by someone whom they have likely never met.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

About 800 million radiology exams were performed in this country in the past year, and they generated approximately 60 billion images, according to an article published in 2017 in the Wall Street Journal (“No need for radiologists to be negative on AI,” by Greg Ip, Nov. 24, 2017). How many of those millions of radiology studies did you order? And how many of the scores of images you requested did you see with your own two eyes? In fact, how many of the radiologists’ reports that were sent to you did you read in their entirety? How often did you just skip over the radiologist’s CYA disclaimers and simply read the final summary, “exam negative”?

I enjoy the challenge of interpreting x-ray images. In fact, I toyed with becoming a pediatric radiologist, but that career path would have meant settling in or near a large city, a compromise my wife and I were unwilling to make. I hoped to continue my habit of looking at all my patients’ x-rays, but because my practice was not in or near the hospital, I reluctantly had to bend my rules and admit I didn’t see every image I had ordered. But, I did read every report in its entirety. In one case, an offhand comment buried in the middle of the radiologist’s report referring to the “residual barium from a previous study” caught my eye, because I knew the patient hadn’t had a previous contrast study. Unfortunately, the neuroblastoma that the radiologist had missed initially, and I had seen the next day, never responded to treatment.

Toward the end of my career, digital imagery allowed me to view my patients’ x-rays without having to leave my desk, which got me closer to my goal of seeing all my patients’ studies. However, the advent of computerized axial tomography and magnetic resonance imaging meant that an increasing number of studies pushed my anatomic knowledge beyond its limits.

I suspect that many of you benefited from the if-you-order-it-look-at-it mantra during your training. How many of you have continued to follow the dictum? With the advent of digitized imagery, there is really little excuse for not taking a minute or 2 to pull up your patients’ images on your desktop. One could argue that looking inside your patient is part of a complete exam. Forcing yourself to take that extra step and look at the study may nudge you into thinking twice about whether you really needed the information the imaging study might add to the diagnostic process. Was your click to order the study just a reflex subliminally related to the fear of a lawsuit? Was it important enough to deserve a firsthand look?

At the very least, being able to say, “I’ve looked at your x-rays myself, and they look fine” may be more comforting to your patient than a third-hand relay of a “negative reading” performed by someone whom they have likely never met.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

ISSOP’s Budapest Declaration: A call to action for children on the move

In late October 2017, pediatricians from over 25 countries gathered at the annual meeting of the International Society of Social Pediatrics and Child Health in Budapest to develop strategies to address the health and well-being of children on the move. With the staggering global increase in the displacement of children – due to conflict, climate change, natural disasters, and economic deprivation – there is a critical need for action.

An international slate of experts, including pediatricians who are responding to the needs of these children, provided an evidence base for intervention and action. These discussions informed the development of a consensus statement, the Budapest Declaration, that establishes a framework for a global response to the exigencies confronting these children and families.

The Budapest Declaration is grounded in children’s rights as guaranteed in the United Nation’s Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). All countries in the world have signed onto the CRC, with a notable exception being the United States. But leading American pediatric groups, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, have endorsed the CRC, making it a basis of organizational advocacy. The CRC entitles all children to optimal survival and development (Article 6) and optimal health and health care (Article 24).

As prescribed by these accepted legal rights for children, children and youth on the move are entitled to the same services, including health care, as resident populations of children, regardless of their legal status. Countries can be held accountable to ensure they receive the full rights due them as articulated in the CRC. Furthermore, efforts to do so should be assessed in national periodic reports to the Committee on the Rights of the Child to ensure accountability.

The relevance of the Budapest Declaration to the United States cannot be overstated. National and regional public policy throughout our country, and in particular along our Southern border, is having a devastating effect on the physical and mental health of children and youth on the move – and will continue to do so throughout their life course.

The involvement of pediatricians and other child health providers is essential to the planning and implementation of clinical and public health programs for children on the move. Child health professionals, in conjunction with their professional organizations, must be engaged in all aspects of local, national, and global responses. Leadership and contributions by pediatricians and pediatric societies and academic institutions are integral to the success of key partners, such as UNICEF, the World Health Organization, the International Organization for Migration, and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees.

Systems of care should be provided that address the physical, mental, and social health care needs of these children without bias and prejudice. Pregnant mothers on the move also should receive services to ensure the delivery of healthy newborns. Every nation should develop approaches and commitments to advance equity in the health and well-being for these children and families.

For much of the world, working within the realm of children’s rights provides a strategy and moral and legal basis for our efforts. Pediatricians need to work with colleagues in a transdisciplinary approach to ensure all children live in nurturing, rights-respecting environments. Our ongoing efforts should include encouraging academic institutions to assist with professional education, research, and evaluation in this regard. We need evaluations that contribute to continuous quality improvement in our efforts and integrate the metrics of child rights, social justice, and health equity into our care of children on the move.

We call on other national and international public, private, and academic sector organizations to advance the health and well-being of children and youth on the move. These children and families are depending on us to do so.

For the complete text of the Budapest Declaration, see www.issop.org/2017/11/10/budapest-declaration-rights-health-well-children-youth-move/.

Dr. Rushton is medical director of the South Carolina Quality Through Innovation in Pediatrics (SCQTIP) network. Dr. Goldhagen is president-elect, International Society for Social Pediatrics and Child Health, and professor of pediatrics, University of Florida, Jacksonville. Email them at [email protected].

In late October 2017, pediatricians from over 25 countries gathered at the annual meeting of the International Society of Social Pediatrics and Child Health in Budapest to develop strategies to address the health and well-being of children on the move. With the staggering global increase in the displacement of children – due to conflict, climate change, natural disasters, and economic deprivation – there is a critical need for action.

An international slate of experts, including pediatricians who are responding to the needs of these children, provided an evidence base for intervention and action. These discussions informed the development of a consensus statement, the Budapest Declaration, that establishes a framework for a global response to the exigencies confronting these children and families.

The Budapest Declaration is grounded in children’s rights as guaranteed in the United Nation’s Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). All countries in the world have signed onto the CRC, with a notable exception being the United States. But leading American pediatric groups, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, have endorsed the CRC, making it a basis of organizational advocacy. The CRC entitles all children to optimal survival and development (Article 6) and optimal health and health care (Article 24).

As prescribed by these accepted legal rights for children, children and youth on the move are entitled to the same services, including health care, as resident populations of children, regardless of their legal status. Countries can be held accountable to ensure they receive the full rights due them as articulated in the CRC. Furthermore, efforts to do so should be assessed in national periodic reports to the Committee on the Rights of the Child to ensure accountability.

The relevance of the Budapest Declaration to the United States cannot be overstated. National and regional public policy throughout our country, and in particular along our Southern border, is having a devastating effect on the physical and mental health of children and youth on the move – and will continue to do so throughout their life course.

The involvement of pediatricians and other child health providers is essential to the planning and implementation of clinical and public health programs for children on the move. Child health professionals, in conjunction with their professional organizations, must be engaged in all aspects of local, national, and global responses. Leadership and contributions by pediatricians and pediatric societies and academic institutions are integral to the success of key partners, such as UNICEF, the World Health Organization, the International Organization for Migration, and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees.

Systems of care should be provided that address the physical, mental, and social health care needs of these children without bias and prejudice. Pregnant mothers on the move also should receive services to ensure the delivery of healthy newborns. Every nation should develop approaches and commitments to advance equity in the health and well-being for these children and families.

For much of the world, working within the realm of children’s rights provides a strategy and moral and legal basis for our efforts. Pediatricians need to work with colleagues in a transdisciplinary approach to ensure all children live in nurturing, rights-respecting environments. Our ongoing efforts should include encouraging academic institutions to assist with professional education, research, and evaluation in this regard. We need evaluations that contribute to continuous quality improvement in our efforts and integrate the metrics of child rights, social justice, and health equity into our care of children on the move.

We call on other national and international public, private, and academic sector organizations to advance the health and well-being of children and youth on the move. These children and families are depending on us to do so.

For the complete text of the Budapest Declaration, see www.issop.org/2017/11/10/budapest-declaration-rights-health-well-children-youth-move/.

Dr. Rushton is medical director of the South Carolina Quality Through Innovation in Pediatrics (SCQTIP) network. Dr. Goldhagen is president-elect, International Society for Social Pediatrics and Child Health, and professor of pediatrics, University of Florida, Jacksonville. Email them at [email protected].

In late October 2017, pediatricians from over 25 countries gathered at the annual meeting of the International Society of Social Pediatrics and Child Health in Budapest to develop strategies to address the health and well-being of children on the move. With the staggering global increase in the displacement of children – due to conflict, climate change, natural disasters, and economic deprivation – there is a critical need for action.

An international slate of experts, including pediatricians who are responding to the needs of these children, provided an evidence base for intervention and action. These discussions informed the development of a consensus statement, the Budapest Declaration, that establishes a framework for a global response to the exigencies confronting these children and families.

The Budapest Declaration is grounded in children’s rights as guaranteed in the United Nation’s Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). All countries in the world have signed onto the CRC, with a notable exception being the United States. But leading American pediatric groups, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, have endorsed the CRC, making it a basis of organizational advocacy. The CRC entitles all children to optimal survival and development (Article 6) and optimal health and health care (Article 24).

As prescribed by these accepted legal rights for children, children and youth on the move are entitled to the same services, including health care, as resident populations of children, regardless of their legal status. Countries can be held accountable to ensure they receive the full rights due them as articulated in the CRC. Furthermore, efforts to do so should be assessed in national periodic reports to the Committee on the Rights of the Child to ensure accountability.

The relevance of the Budapest Declaration to the United States cannot be overstated. National and regional public policy throughout our country, and in particular along our Southern border, is having a devastating effect on the physical and mental health of children and youth on the move – and will continue to do so throughout their life course.

The involvement of pediatricians and other child health providers is essential to the planning and implementation of clinical and public health programs for children on the move. Child health professionals, in conjunction with their professional organizations, must be engaged in all aspects of local, national, and global responses. Leadership and contributions by pediatricians and pediatric societies and academic institutions are integral to the success of key partners, such as UNICEF, the World Health Organization, the International Organization for Migration, and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees.

Systems of care should be provided that address the physical, mental, and social health care needs of these children without bias and prejudice. Pregnant mothers on the move also should receive services to ensure the delivery of healthy newborns. Every nation should develop approaches and commitments to advance equity in the health and well-being for these children and families.

For much of the world, working within the realm of children’s rights provides a strategy and moral and legal basis for our efforts. Pediatricians need to work with colleagues in a transdisciplinary approach to ensure all children live in nurturing, rights-respecting environments. Our ongoing efforts should include encouraging academic institutions to assist with professional education, research, and evaluation in this regard. We need evaluations that contribute to continuous quality improvement in our efforts and integrate the metrics of child rights, social justice, and health equity into our care of children on the move.

We call on other national and international public, private, and academic sector organizations to advance the health and well-being of children and youth on the move. These children and families are depending on us to do so.

For the complete text of the Budapest Declaration, see www.issop.org/2017/11/10/budapest-declaration-rights-health-well-children-youth-move/.

Dr. Rushton is medical director of the South Carolina Quality Through Innovation in Pediatrics (SCQTIP) network. Dr. Goldhagen is president-elect, International Society for Social Pediatrics and Child Health, and professor of pediatrics, University of Florida, Jacksonville. Email them at [email protected].

Don’t give up on influenza vaccine

I suspect most health care providers have heard the complaint, “The vaccine doesn’t work. One year I got the vaccine, and I still came down with the flu.”

Over the years, I’ve polished my responses to vaccine naysayers.

Influenza vaccine doesn’t protect you against every virus that can cause cold and flu symptoms. It only prevents influenza. It’s possible you had a different virus, such as adenovirus, coronavirus, parainfluenza virus, or respiratory syncytial virus.

Some years, the vaccine works better than others because there is a mismatch between the viruses chosen for the vaccine, and the viruses that end up circulating. Even when it doesn’t prevent flu, the vaccine can potentially reduce the severity of illness.

The discussion became a little more complicated in 2016 when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices withdrew its support for the live attenuated influenza virus vaccine (LAIV4) because of concerns about effectiveness. During the 2015-2016 influenza season, LAIV4 demonstrated no statistically significant effectiveness in children 2-17 years of age against H1N1pdm09, the predominant influenza strain. Fortunately, inactivated injectable vaccine did offer protection. An estimated 41.8 million children aged 6 months to 17 years ultimately received this vaccine during the 2016-2017 influenza season.

Now with the 2017-2018 influenza season in full swing, some media reports are proclaiming the influenza vaccine is only 10% effective this year. This claim is based on an interim analysis of data from the most recent flu season in Australia and the effectiveness of the vaccine against the circulating H3N2 virus strain. News from the U.S. CDC is more encouraging. The H3N2 virus contained in this year’s vaccine is the same as that used last year, and so far, circulating H3N2 viruses in the United States are similar to the vaccine virus. Public health officials suggest that we can hope that the vaccine works as well as it did last year, when overall vaccine effectiveness against all circulating flu viruses was 39%, and effectiveness against the H3N2 virus specifically was 32%.

I’m upping my game when talking to parents about flu vaccine. I mention one study conducted between 2010 and 2012 in which influenza immunization reduced a child’s risk of being admitted to an intensive care unit with flu by 74% (J Infect Dis. 2014 Sep 1;210[5]:674-83). I emphasize that flu vaccine reduces the chance that a child will die from flu. According to a study published in 2017, influenza vaccine reduced the risk of death from flu by 65% in healthy children and 51% in children with high-risk medical conditions (Pediatrics. 2017 May. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-4244).

When I’m talking to trainees, I no longer just focus on the match between circulating strains of flu and vaccine strains. I mention that viruses used to produce most seasonal flu vaccines are grown in eggs, a process that can result in minor antigenic changes in the hemagglutinin protein, especially in H3N2 viruses. These “egg-adapted changes” may result in a vaccine that stimulates a less effective immune response, even with a good match between circulating strains and vaccine strains. For example, Zost et al. found that the H3N2 virus that emerged during the 2014-2015 season possessed a new hemagglutinin-associated glycosylation site (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 Nov 21;114[47]:12578-83). Although this virus was represented in the 2016-2017 influenza vaccine, the egg-adapted version lost the glycosylation site, resulting in decreased vaccine immunogenicity and less protection against H3N2 viruses circulating in the community.

The real take-home message here is that we need better flu vaccines. In the short term, cell-based flu vaccines that use virus grown in animal cells are a potential alternative to egg-based vaccines. In the long term, we need a universal flu vaccine. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases is prioritizing work on a vaccine that could provide long-lasting protection against multiple subtypes of the virus. According to a report on the National Institutes of Health website, such a vaccine could “eliminate the need to update and administer the seasonal flu vaccine each year and could provide protection against newly emerging flu strains,” including those with the potential to cause a pandemic. The NIH researchers acknowledge, however, that achieving this goal will require “a broad range of expertise and substantial resources.”

Until new vaccines are available, we need to do a better job of using available, albeit imperfect, flu vaccines. During the 2016-2017 season, only 59% of children 6 months to 17 years were immunized, and there were 110 influenza-associated deaths in children, according to the CDC. It’s likely that some of these were preventable.

The total magnitude of suffering associated with flu is more difficult to quantify, but anecdotes can be illuminating. A friend recently diagnosed with influenza shared her experience via Facebook. “Rough night. I’m seconds away from a meltdown. My body aches so bad that I can’t get comfortable on the couch or my bed. Can’t breathe, and I cough until I vomit. My head is about to burst along with my ears. Just took a hot bath hoping that would help. I don’t know what else to do. The flu really sucks.”

Indeed. Even a 1 in 10 chance of preventing the flu is better than no chance at all.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

I suspect most health care providers have heard the complaint, “The vaccine doesn’t work. One year I got the vaccine, and I still came down with the flu.”

Over the years, I’ve polished my responses to vaccine naysayers.

Influenza vaccine doesn’t protect you against every virus that can cause cold and flu symptoms. It only prevents influenza. It’s possible you had a different virus, such as adenovirus, coronavirus, parainfluenza virus, or respiratory syncytial virus.

Some years, the vaccine works better than others because there is a mismatch between the viruses chosen for the vaccine, and the viruses that end up circulating. Even when it doesn’t prevent flu, the vaccine can potentially reduce the severity of illness.

The discussion became a little more complicated in 2016 when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices withdrew its support for the live attenuated influenza virus vaccine (LAIV4) because of concerns about effectiveness. During the 2015-2016 influenza season, LAIV4 demonstrated no statistically significant effectiveness in children 2-17 years of age against H1N1pdm09, the predominant influenza strain. Fortunately, inactivated injectable vaccine did offer protection. An estimated 41.8 million children aged 6 months to 17 years ultimately received this vaccine during the 2016-2017 influenza season.

Now with the 2017-2018 influenza season in full swing, some media reports are proclaiming the influenza vaccine is only 10% effective this year. This claim is based on an interim analysis of data from the most recent flu season in Australia and the effectiveness of the vaccine against the circulating H3N2 virus strain. News from the U.S. CDC is more encouraging. The H3N2 virus contained in this year’s vaccine is the same as that used last year, and so far, circulating H3N2 viruses in the United States are similar to the vaccine virus. Public health officials suggest that we can hope that the vaccine works as well as it did last year, when overall vaccine effectiveness against all circulating flu viruses was 39%, and effectiveness against the H3N2 virus specifically was 32%.

I’m upping my game when talking to parents about flu vaccine. I mention one study conducted between 2010 and 2012 in which influenza immunization reduced a child’s risk of being admitted to an intensive care unit with flu by 74% (J Infect Dis. 2014 Sep 1;210[5]:674-83). I emphasize that flu vaccine reduces the chance that a child will die from flu. According to a study published in 2017, influenza vaccine reduced the risk of death from flu by 65% in healthy children and 51% in children with high-risk medical conditions (Pediatrics. 2017 May. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-4244).

When I’m talking to trainees, I no longer just focus on the match between circulating strains of flu and vaccine strains. I mention that viruses used to produce most seasonal flu vaccines are grown in eggs, a process that can result in minor antigenic changes in the hemagglutinin protein, especially in H3N2 viruses. These “egg-adapted changes” may result in a vaccine that stimulates a less effective immune response, even with a good match between circulating strains and vaccine strains. For example, Zost et al. found that the H3N2 virus that emerged during the 2014-2015 season possessed a new hemagglutinin-associated glycosylation site (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 Nov 21;114[47]:12578-83). Although this virus was represented in the 2016-2017 influenza vaccine, the egg-adapted version lost the glycosylation site, resulting in decreased vaccine immunogenicity and less protection against H3N2 viruses circulating in the community.

The real take-home message here is that we need better flu vaccines. In the short term, cell-based flu vaccines that use virus grown in animal cells are a potential alternative to egg-based vaccines. In the long term, we need a universal flu vaccine. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases is prioritizing work on a vaccine that could provide long-lasting protection against multiple subtypes of the virus. According to a report on the National Institutes of Health website, such a vaccine could “eliminate the need to update and administer the seasonal flu vaccine each year and could provide protection against newly emerging flu strains,” including those with the potential to cause a pandemic. The NIH researchers acknowledge, however, that achieving this goal will require “a broad range of expertise and substantial resources.”

Until new vaccines are available, we need to do a better job of using available, albeit imperfect, flu vaccines. During the 2016-2017 season, only 59% of children 6 months to 17 years were immunized, and there were 110 influenza-associated deaths in children, according to the CDC. It’s likely that some of these were preventable.

The total magnitude of suffering associated with flu is more difficult to quantify, but anecdotes can be illuminating. A friend recently diagnosed with influenza shared her experience via Facebook. “Rough night. I’m seconds away from a meltdown. My body aches so bad that I can’t get comfortable on the couch or my bed. Can’t breathe, and I cough until I vomit. My head is about to burst along with my ears. Just took a hot bath hoping that would help. I don’t know what else to do. The flu really sucks.”

Indeed. Even a 1 in 10 chance of preventing the flu is better than no chance at all.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

I suspect most health care providers have heard the complaint, “The vaccine doesn’t work. One year I got the vaccine, and I still came down with the flu.”

Over the years, I’ve polished my responses to vaccine naysayers.

Influenza vaccine doesn’t protect you against every virus that can cause cold and flu symptoms. It only prevents influenza. It’s possible you had a different virus, such as adenovirus, coronavirus, parainfluenza virus, or respiratory syncytial virus.

Some years, the vaccine works better than others because there is a mismatch between the viruses chosen for the vaccine, and the viruses that end up circulating. Even when it doesn’t prevent flu, the vaccine can potentially reduce the severity of illness.

The discussion became a little more complicated in 2016 when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices withdrew its support for the live attenuated influenza virus vaccine (LAIV4) because of concerns about effectiveness. During the 2015-2016 influenza season, LAIV4 demonstrated no statistically significant effectiveness in children 2-17 years of age against H1N1pdm09, the predominant influenza strain. Fortunately, inactivated injectable vaccine did offer protection. An estimated 41.8 million children aged 6 months to 17 years ultimately received this vaccine during the 2016-2017 influenza season.

Now with the 2017-2018 influenza season in full swing, some media reports are proclaiming the influenza vaccine is only 10% effective this year. This claim is based on an interim analysis of data from the most recent flu season in Australia and the effectiveness of the vaccine against the circulating H3N2 virus strain. News from the U.S. CDC is more encouraging. The H3N2 virus contained in this year’s vaccine is the same as that used last year, and so far, circulating H3N2 viruses in the United States are similar to the vaccine virus. Public health officials suggest that we can hope that the vaccine works as well as it did last year, when overall vaccine effectiveness against all circulating flu viruses was 39%, and effectiveness against the H3N2 virus specifically was 32%.

I’m upping my game when talking to parents about flu vaccine. I mention one study conducted between 2010 and 2012 in which influenza immunization reduced a child’s risk of being admitted to an intensive care unit with flu by 74% (J Infect Dis. 2014 Sep 1;210[5]:674-83). I emphasize that flu vaccine reduces the chance that a child will die from flu. According to a study published in 2017, influenza vaccine reduced the risk of death from flu by 65% in healthy children and 51% in children with high-risk medical conditions (Pediatrics. 2017 May. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-4244).

When I’m talking to trainees, I no longer just focus on the match between circulating strains of flu and vaccine strains. I mention that viruses used to produce most seasonal flu vaccines are grown in eggs, a process that can result in minor antigenic changes in the hemagglutinin protein, especially in H3N2 viruses. These “egg-adapted changes” may result in a vaccine that stimulates a less effective immune response, even with a good match between circulating strains and vaccine strains. For example, Zost et al. found that the H3N2 virus that emerged during the 2014-2015 season possessed a new hemagglutinin-associated glycosylation site (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 Nov 21;114[47]:12578-83). Although this virus was represented in the 2016-2017 influenza vaccine, the egg-adapted version lost the glycosylation site, resulting in decreased vaccine immunogenicity and less protection against H3N2 viruses circulating in the community.

The real take-home message here is that we need better flu vaccines. In the short term, cell-based flu vaccines that use virus grown in animal cells are a potential alternative to egg-based vaccines. In the long term, we need a universal flu vaccine. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases is prioritizing work on a vaccine that could provide long-lasting protection against multiple subtypes of the virus. According to a report on the National Institutes of Health website, such a vaccine could “eliminate the need to update and administer the seasonal flu vaccine each year and could provide protection against newly emerging flu strains,” including those with the potential to cause a pandemic. The NIH researchers acknowledge, however, that achieving this goal will require “a broad range of expertise and substantial resources.”

Until new vaccines are available, we need to do a better job of using available, albeit imperfect, flu vaccines. During the 2016-2017 season, only 59% of children 6 months to 17 years were immunized, and there were 110 influenza-associated deaths in children, according to the CDC. It’s likely that some of these were preventable.

The total magnitude of suffering associated with flu is more difficult to quantify, but anecdotes can be illuminating. A friend recently diagnosed with influenza shared her experience via Facebook. “Rough night. I’m seconds away from a meltdown. My body aches so bad that I can’t get comfortable on the couch or my bed. Can’t breathe, and I cough until I vomit. My head is about to burst along with my ears. Just took a hot bath hoping that would help. I don’t know what else to do. The flu really sucks.”

Indeed. Even a 1 in 10 chance of preventing the flu is better than no chance at all.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Commentary—Study Heightens Awareness, But at What Cost?

The study conducted by Brookmeyer and colleagues is a logical and thoughtful attempt to size the potential impact of Alzheimer's disease now and in the future, updating old-technology estimates based on actual diagnoses with new technologically derived diagnoses of preclinical neurodegenerative states. They acknowledge that the uncertainty in the actual disease burden we will face is centered on the question of conversion rates, which vary between studies and are far less certain in the preclinical stages than the symptomatic ones.

Scientific interest aside, the main purpose of an article like this is to heighten awareness and concern by demonstrating that symptomatic Alzheimer's disease is the tip of a much larger iceberg and warrants more funding for research and clinical care. The worry that articles like this—or that the media attention they receive—create for me, however, is that they potentially contribute to a growing public panic at a time when we still lack truly meaningful therapy. As a doctor, I want to give my patients with MCI and dementia reason to believe they still have a meaningful life and that there is hope, rather than having them feel that I have just pronounced a death sentence.

The attention paid by the Alzheimer's Association is understandable, given its mission of increasing awareness and supporting more funding, but it omits to mention another important article showing that dementia rates are actually declining when data are adjusted for our aging population (observed vs expected).

We need to maintain public awareness without creating panic. There is no question that Alzheimer's disease is a major public health issue that warrants all the funding we can provide to researchers seeking a cure. How to balance that need with the need to give our population hope that all is not lost when they misplace their keys is the challenge this article raises.

—Richard J. Caselli, MD

Professor of Neurology

Mayo Clinic

Scottsdale, Arizona

The study conducted by Brookmeyer and colleagues is a logical and thoughtful attempt to size the potential impact of Alzheimer's disease now and in the future, updating old-technology estimates based on actual diagnoses with new technologically derived diagnoses of preclinical neurodegenerative states. They acknowledge that the uncertainty in the actual disease burden we will face is centered on the question of conversion rates, which vary between studies and are far less certain in the preclinical stages than the symptomatic ones.

Scientific interest aside, the main purpose of an article like this is to heighten awareness and concern by demonstrating that symptomatic Alzheimer's disease is the tip of a much larger iceberg and warrants more funding for research and clinical care. The worry that articles like this—or that the media attention they receive—create for me, however, is that they potentially contribute to a growing public panic at a time when we still lack truly meaningful therapy. As a doctor, I want to give my patients with MCI and dementia reason to believe they still have a meaningful life and that there is hope, rather than having them feel that I have just pronounced a death sentence.

The attention paid by the Alzheimer's Association is understandable, given its mission of increasing awareness and supporting more funding, but it omits to mention another important article showing that dementia rates are actually declining when data are adjusted for our aging population (observed vs expected).

We need to maintain public awareness without creating panic. There is no question that Alzheimer's disease is a major public health issue that warrants all the funding we can provide to researchers seeking a cure. How to balance that need with the need to give our population hope that all is not lost when they misplace their keys is the challenge this article raises.

—Richard J. Caselli, MD

Professor of Neurology

Mayo Clinic

Scottsdale, Arizona

The study conducted by Brookmeyer and colleagues is a logical and thoughtful attempt to size the potential impact of Alzheimer's disease now and in the future, updating old-technology estimates based on actual diagnoses with new technologically derived diagnoses of preclinical neurodegenerative states. They acknowledge that the uncertainty in the actual disease burden we will face is centered on the question of conversion rates, which vary between studies and are far less certain in the preclinical stages than the symptomatic ones.

Scientific interest aside, the main purpose of an article like this is to heighten awareness and concern by demonstrating that symptomatic Alzheimer's disease is the tip of a much larger iceberg and warrants more funding for research and clinical care. The worry that articles like this—or that the media attention they receive—create for me, however, is that they potentially contribute to a growing public panic at a time when we still lack truly meaningful therapy. As a doctor, I want to give my patients with MCI and dementia reason to believe they still have a meaningful life and that there is hope, rather than having them feel that I have just pronounced a death sentence.

The attention paid by the Alzheimer's Association is understandable, given its mission of increasing awareness and supporting more funding, but it omits to mention another important article showing that dementia rates are actually declining when data are adjusted for our aging population (observed vs expected).

We need to maintain public awareness without creating panic. There is no question that Alzheimer's disease is a major public health issue that warrants all the funding we can provide to researchers seeking a cure. How to balance that need with the need to give our population hope that all is not lost when they misplace their keys is the challenge this article raises.

—Richard J. Caselli, MD

Professor of Neurology

Mayo Clinic

Scottsdale, Arizona

Dementia: Past, Present, and Future

Jeffrey Cummings, MD, ScD

Director, Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health, Las Vegas

Disclosure: Jeffrey Cummings has provided consultation to Axovant, biOasis Technologies, Biogen, Boehinger-Ingelheim, Bracket, Dart, Eisai, Genentech, Grifols, Intracellular Therapies, Kyowa, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Medavante, Merck, Neurotrope, Novartis, Nutricia, Orion, Otsuka, Pfizer, Probiodrug, QR, Resverlogix, Servier, Suven, Takeda, Toyoma, and United Neuroscience companies.