User login

PA Autonomy Levels the Field

I can’t tell you how refreshing it is to read an editorial that portrays PA autonomy in a positive light (2017;27[2]:12-14). I live in Michigan, and the physician I worked with for years is relieved to finally see laws changing for PAs. Physicians want less accountability, as they are carrying so much already. The phrase “supervising physician” can feel burdensome, particularly because of its implications in a court of law. When I took time off to spend with my kids, the physician I worked with hired two NPs; he said that their increased drive for autonomy made him feel less legally responsible. The new bill passed here has altered his thinking about hiring PAs versus NPs.

I believe eventually, with increased practice authority, a title change is inevitable for the PA profession. According to my 14–year-old niece, “PAs obviously can’t do anything by themselves, or their title wouldn’t be ‘assistant.’” This is truly a misnomer that doesn’t reflect the PA scope of practice.

Diana Burmeister,

Southfield, MI

I can’t tell you how refreshing it is to read an editorial that portrays PA autonomy in a positive light (2017;27[2]:12-14). I live in Michigan, and the physician I worked with for years is relieved to finally see laws changing for PAs. Physicians want less accountability, as they are carrying so much already. The phrase “supervising physician” can feel burdensome, particularly because of its implications in a court of law. When I took time off to spend with my kids, the physician I worked with hired two NPs; he said that their increased drive for autonomy made him feel less legally responsible. The new bill passed here has altered his thinking about hiring PAs versus NPs.

I believe eventually, with increased practice authority, a title change is inevitable for the PA profession. According to my 14–year-old niece, “PAs obviously can’t do anything by themselves, or their title wouldn’t be ‘assistant.’” This is truly a misnomer that doesn’t reflect the PA scope of practice.

Diana Burmeister,

Southfield, MI

I can’t tell you how refreshing it is to read an editorial that portrays PA autonomy in a positive light (2017;27[2]:12-14). I live in Michigan, and the physician I worked with for years is relieved to finally see laws changing for PAs. Physicians want less accountability, as they are carrying so much already. The phrase “supervising physician” can feel burdensome, particularly because of its implications in a court of law. When I took time off to spend with my kids, the physician I worked with hired two NPs; he said that their increased drive for autonomy made him feel less legally responsible. The new bill passed here has altered his thinking about hiring PAs versus NPs.

I believe eventually, with increased practice authority, a title change is inevitable for the PA profession. According to my 14–year-old niece, “PAs obviously can’t do anything by themselves, or their title wouldn’t be ‘assistant.’” This is truly a misnomer that doesn’t reflect the PA scope of practice.

Diana Burmeister,

Southfield, MI

When Did I Start Consulting for Dr. Google?

I have witnessed firsthand the evolution of patient satisfaction (2017;27[1]:13-14). When I became an NP in 1986, I worked in rural areas as the primary provider. My patients trusted that I cared for them and in the best way possible. A lot changed with the internet—Google became the primary care provider, and I became the consultant. Expressions of gratitude and respect from patients have been replaced by entitlement to services mandated by them. I have had patients bring in requests for diagnostic studies and further work-up for which there is no clinical evidence of need. They have their minds made up; if I am noncompliant, there is something wrong with me.

I have been reported to administration for being rude, insensitive, and incompetent. Now, I am not perfect, but most of these complaints were a result of me saying “no.” I was initially shocked by these demands and complaints, but they have become the new normal. Precious care time has been replaced by explanations and discussions about why I can’t do what patients want me to do.

Many providers give in to patients’ desires just to keep them happy and coming back. Unnecessary antibiotics, misuse of controlled pain medication, and pointless diagnostic studies have drained insurance and kept providers from just doing what is right. Big corporations run many medical practices, and unfortunately their main goal is to keep the doors open—even if that means compromising evidence-based medicine.

We have a generation of entitled people who become offended when you disagree with them. Many administrators transfer patient complaints to providers so that they will toe the line but fail to include pertinent information, such as what the complaint was and who filed it. This is a control technique; the provider is now automatically guilty, without a trial or defense.

I am blessed to work for a company that agrees that if concern is expressed, I have the right, as the provider, to know the details. If I am perceived as rude or abrupt, then knowing who feels that way can help me improve. Upon that patient’s next visit, I will adopt a gentler attitude and make an extra effort to pick up on cues that I may have missed.

Sometimes, patients express dissatisfaction because I will not dispense a controlled substance for pain upon request. My administration allows me to respond to situations like this in writing, and they can then verify that the complaint is unwarranted, and it will not be held against me or used as a control tactic. This approach has been so helpful. The company I work for also informs providers when patients express gratitude and thankfulness, which creates a great balance.

Surveys can be useful, but only if they are used as a tool to help the provider excel at his/her job—not create compliance for maintaining the patient head count. Providers should not have to worry about pleasing administration; they need to give quality care without fear.

Sue Beebe, APRN

Wichita, KA

I have witnessed firsthand the evolution of patient satisfaction (2017;27[1]:13-14). When I became an NP in 1986, I worked in rural areas as the primary provider. My patients trusted that I cared for them and in the best way possible. A lot changed with the internet—Google became the primary care provider, and I became the consultant. Expressions of gratitude and respect from patients have been replaced by entitlement to services mandated by them. I have had patients bring in requests for diagnostic studies and further work-up for which there is no clinical evidence of need. They have their minds made up; if I am noncompliant, there is something wrong with me.

I have been reported to administration for being rude, insensitive, and incompetent. Now, I am not perfect, but most of these complaints were a result of me saying “no.” I was initially shocked by these demands and complaints, but they have become the new normal. Precious care time has been replaced by explanations and discussions about why I can’t do what patients want me to do.

Many providers give in to patients’ desires just to keep them happy and coming back. Unnecessary antibiotics, misuse of controlled pain medication, and pointless diagnostic studies have drained insurance and kept providers from just doing what is right. Big corporations run many medical practices, and unfortunately their main goal is to keep the doors open—even if that means compromising evidence-based medicine.

We have a generation of entitled people who become offended when you disagree with them. Many administrators transfer patient complaints to providers so that they will toe the line but fail to include pertinent information, such as what the complaint was and who filed it. This is a control technique; the provider is now automatically guilty, without a trial or defense.

I am blessed to work for a company that agrees that if concern is expressed, I have the right, as the provider, to know the details. If I am perceived as rude or abrupt, then knowing who feels that way can help me improve. Upon that patient’s next visit, I will adopt a gentler attitude and make an extra effort to pick up on cues that I may have missed.

Sometimes, patients express dissatisfaction because I will not dispense a controlled substance for pain upon request. My administration allows me to respond to situations like this in writing, and they can then verify that the complaint is unwarranted, and it will not be held against me or used as a control tactic. This approach has been so helpful. The company I work for also informs providers when patients express gratitude and thankfulness, which creates a great balance.

Surveys can be useful, but only if they are used as a tool to help the provider excel at his/her job—not create compliance for maintaining the patient head count. Providers should not have to worry about pleasing administration; they need to give quality care without fear.

Sue Beebe, APRN

Wichita, KA

I have witnessed firsthand the evolution of patient satisfaction (2017;27[1]:13-14). When I became an NP in 1986, I worked in rural areas as the primary provider. My patients trusted that I cared for them and in the best way possible. A lot changed with the internet—Google became the primary care provider, and I became the consultant. Expressions of gratitude and respect from patients have been replaced by entitlement to services mandated by them. I have had patients bring in requests for diagnostic studies and further work-up for which there is no clinical evidence of need. They have their minds made up; if I am noncompliant, there is something wrong with me.

I have been reported to administration for being rude, insensitive, and incompetent. Now, I am not perfect, but most of these complaints were a result of me saying “no.” I was initially shocked by these demands and complaints, but they have become the new normal. Precious care time has been replaced by explanations and discussions about why I can’t do what patients want me to do.

Many providers give in to patients’ desires just to keep them happy and coming back. Unnecessary antibiotics, misuse of controlled pain medication, and pointless diagnostic studies have drained insurance and kept providers from just doing what is right. Big corporations run many medical practices, and unfortunately their main goal is to keep the doors open—even if that means compromising evidence-based medicine.

We have a generation of entitled people who become offended when you disagree with them. Many administrators transfer patient complaints to providers so that they will toe the line but fail to include pertinent information, such as what the complaint was and who filed it. This is a control technique; the provider is now automatically guilty, without a trial or defense.

I am blessed to work for a company that agrees that if concern is expressed, I have the right, as the provider, to know the details. If I am perceived as rude or abrupt, then knowing who feels that way can help me improve. Upon that patient’s next visit, I will adopt a gentler attitude and make an extra effort to pick up on cues that I may have missed.

Sometimes, patients express dissatisfaction because I will not dispense a controlled substance for pain upon request. My administration allows me to respond to situations like this in writing, and they can then verify that the complaint is unwarranted, and it will not be held against me or used as a control tactic. This approach has been so helpful. The company I work for also informs providers when patients express gratitude and thankfulness, which creates a great balance.

Surveys can be useful, but only if they are used as a tool to help the provider excel at his/her job—not create compliance for maintaining the patient head count. Providers should not have to worry about pleasing administration; they need to give quality care without fear.

Sue Beebe, APRN

Wichita, KA

Postoperative pain in women with preexisting chronic pain

Chronic pain disorders have reached epidemic levels in the United States, with the Institute of Medicine reporting more than 100 million Americans affected and health care costs more than $500 billion annually.1 Although many pain disorders are confined to the abdomen or pelvis (chronic pelvic pain, vulvodynia, irritable bowel syndrome, and bladder pain syndrome), others present with global symptoms (fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome). Women are more likely to be diagnosed with a chronic pain condition and more likely to seek treatment for chronic pain, including undergoing a surgical intervention. In fact, chronic pelvic pain alone affects upward of 20% of women in the United States, and, of the 400,000 hysterectomies performed each year (54.2%, abdominal; 16.7%, vaginal; and 16.8%, laparoscopic/robotic assisted), approximately 15% are for chronic pain.2

Neurobiology of pain

Perioperative pain control, specifically in women with preexisting pain disorders, can provide an additional challenge. Unlike acute pain, chronic pain (lasting more than 6 months) is associated with an amplified pain response of the central nervous system. This abnormal pain processing, known as centralization of pain, may result in a decrease of the inhibitory pain pathways and/or an increase of the amplification pathways, often augmenting the pain response of the original peripheral insult, specifically surgery. Because of these physiologic changes, a multimodal approach to perioperative pain should be offered, especially in women with preexisting pain. The approach ideally ought to target the different mechanisms of actions in both the peripheral and central nervous systems to provide an overall reduction in pain perception.

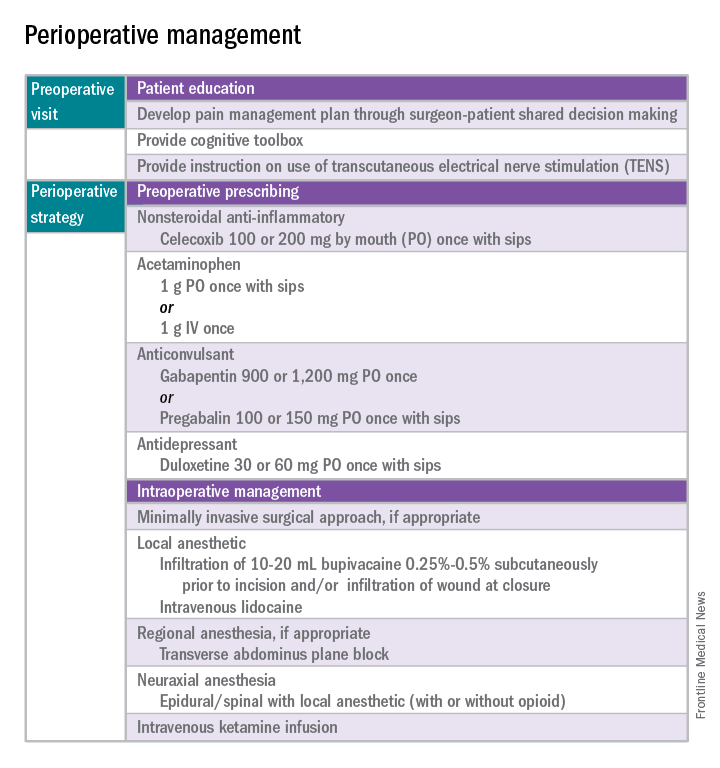

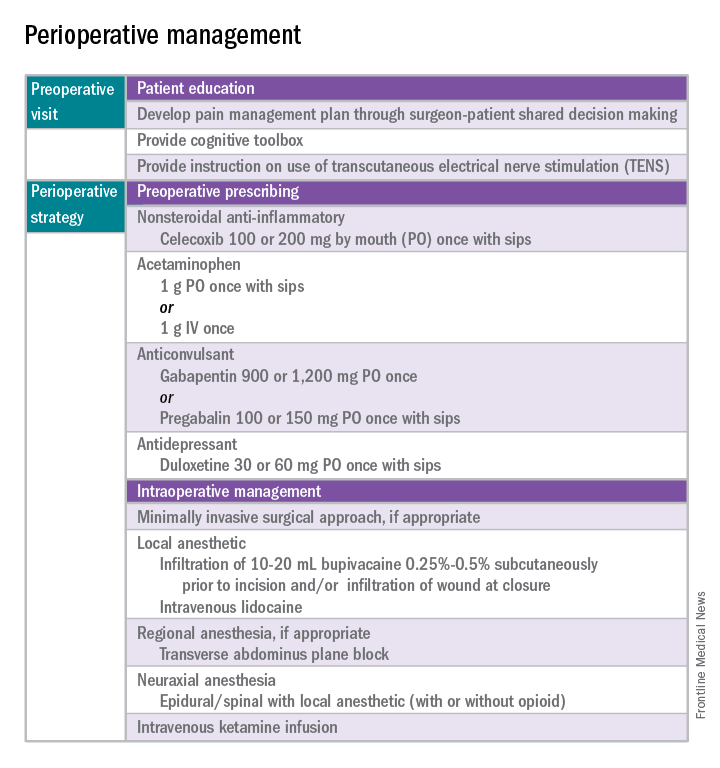

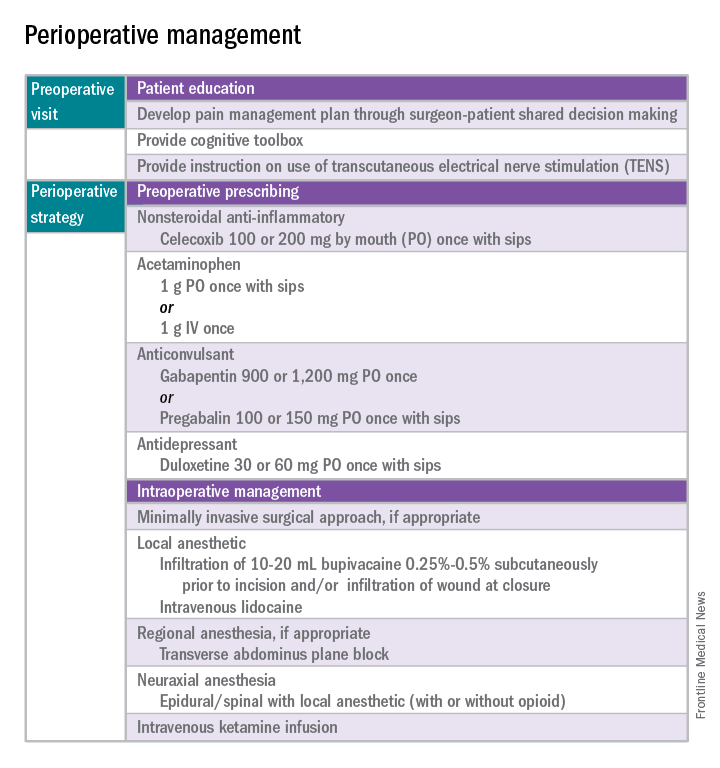

Preoperative visit

Perhaps the most underutilized opportunity to optimize postoperative pain is a proactive, preoperative approach. Preoperative education, including goal setting of postoperative pain expectations, has been associated with a significant reduction in postoperative opioid use, less preoperative anxiety, and a decreased length of surgical stay.3 While it is unknown exactly when this should be provided to the patient in the treatment course, it should occur prior to the day of surgery to allow for appropriate intervention.

The use of a shared decision-making model between the clinician and the chronic pain patient in the development of a pain management plan has been highly successful in improving pain outcomes in the outpatient setting.4 A similar method can be applied to the preoperative course as well. A detailed history (including the use of an opioid risk assessment tool) allows the clinician to identify patients at risk for opioid misuse and abuse. This is also an opportunity to review a plan for an opioid taper with the patient and the prescriber, if the postoperative plan includes opioid reduction/cessation. The preoperative visit may be an opportunity to adjust centrally acting medications (antidepressants, anticonvulsants) before surgery or to reduce the dose or frequency of high-risk medications, such as benzodiazepines.

Perioperative strategy

One of the most impactful ways for us, as surgeons, to reduce tissue injury and decrease pain from surgery is by offering a minimally invasive approach. The benefits of minimally invasive surgery are well established, resulting in improved perioperative pain control, decreased blood loss, lower infection rates, decreased length of hospital stay, and a faster recovery, compared with laparotomy. Because patients with chronic pain disorders are at increased risk of greater acute postoperative pain and have an elevated risk for the development of chronic postsurgical pain, a minimally invasive surgical approach should be prioritized, when available.

Perioperative multimodal drug therapy is associated with significant decreases in opioid consumption and reductions in acute postoperative pain.6 Recently, a multidisciplinary expert panel from the American Pain Society devised an evidence-based clinical practice guideline for postoperative pain.7 While there is no consensus as to the best regimen specific to gynecologic surgery, the general principles are similar across disciplines.

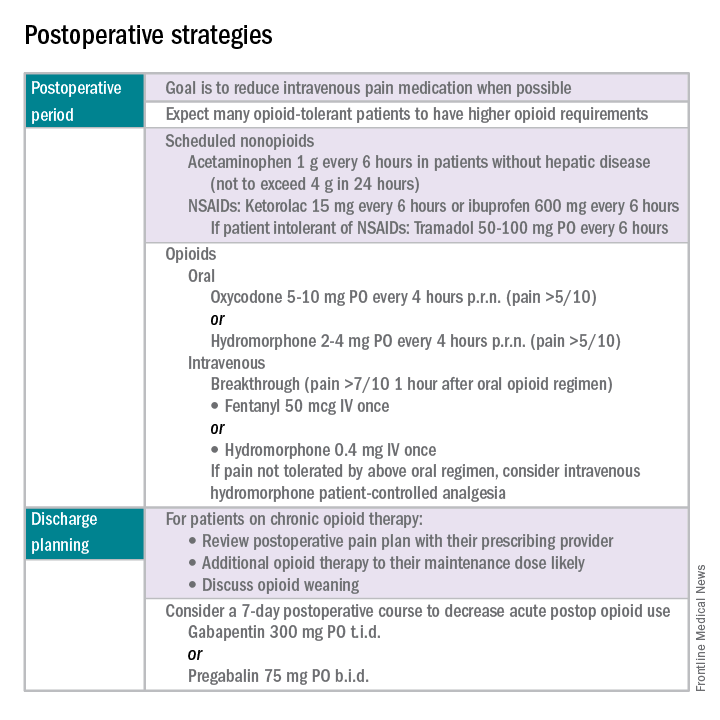

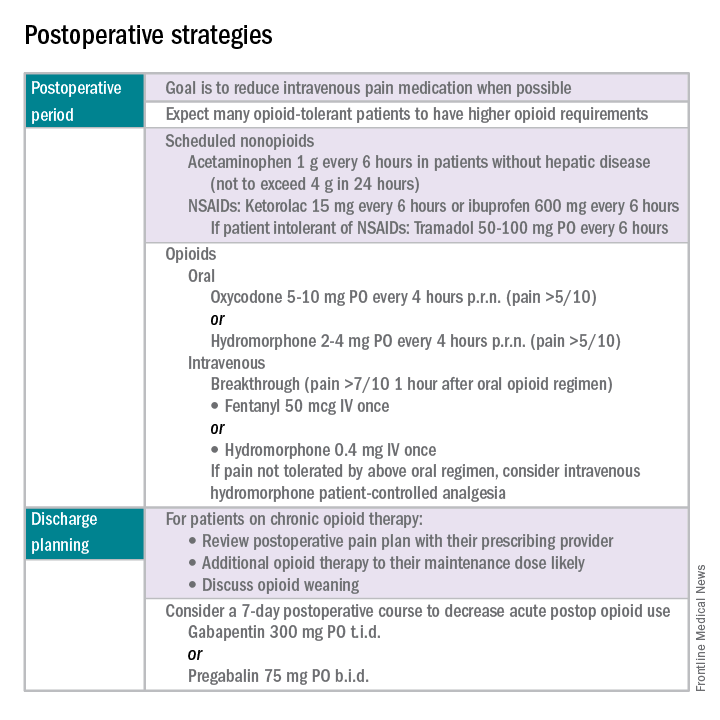

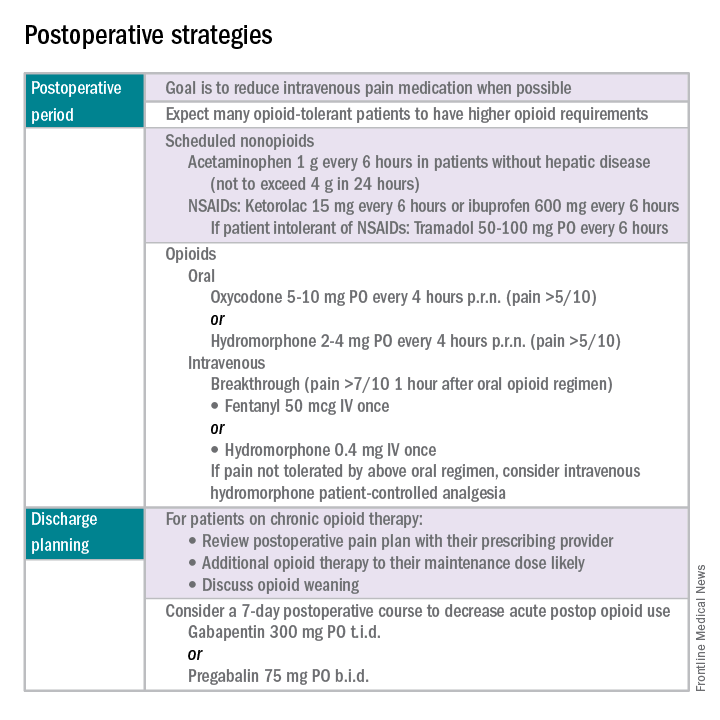

The postoperative period

Opioid-tolerant patients may experience greater pain during the first 24 hours postoperatively and require an increase in opioids, compared with opioid-naive patients.8 In the event that a postoperative patient does not respond as expected to the usual course, that patient should be evaluated for barriers to routine postoperative care, such as a surgical complication, opioid tolerance, or psychological distress. Surgeons should be aggressive with pain management immediately after surgery, even in the opioid-tolerant patient, and make short-term adjustments as needed based on the pain response. These patients will require pain medications beyond their baseline dose. Additionally, if an opioid taper is not planned in a chronic opioid user, work with the patient and the long-term opioid prescriber in restarting baseline opioid therapy outside of the acute surgical window.

References

1. Institute of Medicine. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2011.

2. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Aug;122(2 Pt 1):233-41.

3. N Engl J Med. 1964 Apr 16;270:825-7.

4. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999 Jul;18(1):38-48.

5. Pain. 2010 Dec;151(3):694-702.

6. Anesthesiology. 2005 Dec;103(6):1296-304.

7. J Pain. 2016 Feb;17(2):131-57.

8. Pharmacotherapy. 2008 Dec;28(12):1453-60.

Dr. Carey is the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and specializes in the medical and surgical management of pelvic pain disorders. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC–Chapel Hill. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Chronic pain disorders have reached epidemic levels in the United States, with the Institute of Medicine reporting more than 100 million Americans affected and health care costs more than $500 billion annually.1 Although many pain disorders are confined to the abdomen or pelvis (chronic pelvic pain, vulvodynia, irritable bowel syndrome, and bladder pain syndrome), others present with global symptoms (fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome). Women are more likely to be diagnosed with a chronic pain condition and more likely to seek treatment for chronic pain, including undergoing a surgical intervention. In fact, chronic pelvic pain alone affects upward of 20% of women in the United States, and, of the 400,000 hysterectomies performed each year (54.2%, abdominal; 16.7%, vaginal; and 16.8%, laparoscopic/robotic assisted), approximately 15% are for chronic pain.2

Neurobiology of pain

Perioperative pain control, specifically in women with preexisting pain disorders, can provide an additional challenge. Unlike acute pain, chronic pain (lasting more than 6 months) is associated with an amplified pain response of the central nervous system. This abnormal pain processing, known as centralization of pain, may result in a decrease of the inhibitory pain pathways and/or an increase of the amplification pathways, often augmenting the pain response of the original peripheral insult, specifically surgery. Because of these physiologic changes, a multimodal approach to perioperative pain should be offered, especially in women with preexisting pain. The approach ideally ought to target the different mechanisms of actions in both the peripheral and central nervous systems to provide an overall reduction in pain perception.

Preoperative visit

Perhaps the most underutilized opportunity to optimize postoperative pain is a proactive, preoperative approach. Preoperative education, including goal setting of postoperative pain expectations, has been associated with a significant reduction in postoperative opioid use, less preoperative anxiety, and a decreased length of surgical stay.3 While it is unknown exactly when this should be provided to the patient in the treatment course, it should occur prior to the day of surgery to allow for appropriate intervention.

The use of a shared decision-making model between the clinician and the chronic pain patient in the development of a pain management plan has been highly successful in improving pain outcomes in the outpatient setting.4 A similar method can be applied to the preoperative course as well. A detailed history (including the use of an opioid risk assessment tool) allows the clinician to identify patients at risk for opioid misuse and abuse. This is also an opportunity to review a plan for an opioid taper with the patient and the prescriber, if the postoperative plan includes opioid reduction/cessation. The preoperative visit may be an opportunity to adjust centrally acting medications (antidepressants, anticonvulsants) before surgery or to reduce the dose or frequency of high-risk medications, such as benzodiazepines.

Perioperative strategy

One of the most impactful ways for us, as surgeons, to reduce tissue injury and decrease pain from surgery is by offering a minimally invasive approach. The benefits of minimally invasive surgery are well established, resulting in improved perioperative pain control, decreased blood loss, lower infection rates, decreased length of hospital stay, and a faster recovery, compared with laparotomy. Because patients with chronic pain disorders are at increased risk of greater acute postoperative pain and have an elevated risk for the development of chronic postsurgical pain, a minimally invasive surgical approach should be prioritized, when available.

Perioperative multimodal drug therapy is associated with significant decreases in opioid consumption and reductions in acute postoperative pain.6 Recently, a multidisciplinary expert panel from the American Pain Society devised an evidence-based clinical practice guideline for postoperative pain.7 While there is no consensus as to the best regimen specific to gynecologic surgery, the general principles are similar across disciplines.

The postoperative period

Opioid-tolerant patients may experience greater pain during the first 24 hours postoperatively and require an increase in opioids, compared with opioid-naive patients.8 In the event that a postoperative patient does not respond as expected to the usual course, that patient should be evaluated for barriers to routine postoperative care, such as a surgical complication, opioid tolerance, or psychological distress. Surgeons should be aggressive with pain management immediately after surgery, even in the opioid-tolerant patient, and make short-term adjustments as needed based on the pain response. These patients will require pain medications beyond their baseline dose. Additionally, if an opioid taper is not planned in a chronic opioid user, work with the patient and the long-term opioid prescriber in restarting baseline opioid therapy outside of the acute surgical window.

References

1. Institute of Medicine. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2011.

2. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Aug;122(2 Pt 1):233-41.

3. N Engl J Med. 1964 Apr 16;270:825-7.

4. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999 Jul;18(1):38-48.

5. Pain. 2010 Dec;151(3):694-702.

6. Anesthesiology. 2005 Dec;103(6):1296-304.

7. J Pain. 2016 Feb;17(2):131-57.

8. Pharmacotherapy. 2008 Dec;28(12):1453-60.

Dr. Carey is the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and specializes in the medical and surgical management of pelvic pain disorders. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC–Chapel Hill. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Chronic pain disorders have reached epidemic levels in the United States, with the Institute of Medicine reporting more than 100 million Americans affected and health care costs more than $500 billion annually.1 Although many pain disorders are confined to the abdomen or pelvis (chronic pelvic pain, vulvodynia, irritable bowel syndrome, and bladder pain syndrome), others present with global symptoms (fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome). Women are more likely to be diagnosed with a chronic pain condition and more likely to seek treatment for chronic pain, including undergoing a surgical intervention. In fact, chronic pelvic pain alone affects upward of 20% of women in the United States, and, of the 400,000 hysterectomies performed each year (54.2%, abdominal; 16.7%, vaginal; and 16.8%, laparoscopic/robotic assisted), approximately 15% are for chronic pain.2

Neurobiology of pain

Perioperative pain control, specifically in women with preexisting pain disorders, can provide an additional challenge. Unlike acute pain, chronic pain (lasting more than 6 months) is associated with an amplified pain response of the central nervous system. This abnormal pain processing, known as centralization of pain, may result in a decrease of the inhibitory pain pathways and/or an increase of the amplification pathways, often augmenting the pain response of the original peripheral insult, specifically surgery. Because of these physiologic changes, a multimodal approach to perioperative pain should be offered, especially in women with preexisting pain. The approach ideally ought to target the different mechanisms of actions in both the peripheral and central nervous systems to provide an overall reduction in pain perception.

Preoperative visit

Perhaps the most underutilized opportunity to optimize postoperative pain is a proactive, preoperative approach. Preoperative education, including goal setting of postoperative pain expectations, has been associated with a significant reduction in postoperative opioid use, less preoperative anxiety, and a decreased length of surgical stay.3 While it is unknown exactly when this should be provided to the patient in the treatment course, it should occur prior to the day of surgery to allow for appropriate intervention.

The use of a shared decision-making model between the clinician and the chronic pain patient in the development of a pain management plan has been highly successful in improving pain outcomes in the outpatient setting.4 A similar method can be applied to the preoperative course as well. A detailed history (including the use of an opioid risk assessment tool) allows the clinician to identify patients at risk for opioid misuse and abuse. This is also an opportunity to review a plan for an opioid taper with the patient and the prescriber, if the postoperative plan includes opioid reduction/cessation. The preoperative visit may be an opportunity to adjust centrally acting medications (antidepressants, anticonvulsants) before surgery or to reduce the dose or frequency of high-risk medications, such as benzodiazepines.

Perioperative strategy

One of the most impactful ways for us, as surgeons, to reduce tissue injury and decrease pain from surgery is by offering a minimally invasive approach. The benefits of minimally invasive surgery are well established, resulting in improved perioperative pain control, decreased blood loss, lower infection rates, decreased length of hospital stay, and a faster recovery, compared with laparotomy. Because patients with chronic pain disorders are at increased risk of greater acute postoperative pain and have an elevated risk for the development of chronic postsurgical pain, a minimally invasive surgical approach should be prioritized, when available.

Perioperative multimodal drug therapy is associated with significant decreases in opioid consumption and reductions in acute postoperative pain.6 Recently, a multidisciplinary expert panel from the American Pain Society devised an evidence-based clinical practice guideline for postoperative pain.7 While there is no consensus as to the best regimen specific to gynecologic surgery, the general principles are similar across disciplines.

The postoperative period

Opioid-tolerant patients may experience greater pain during the first 24 hours postoperatively and require an increase in opioids, compared with opioid-naive patients.8 In the event that a postoperative patient does not respond as expected to the usual course, that patient should be evaluated for barriers to routine postoperative care, such as a surgical complication, opioid tolerance, or psychological distress. Surgeons should be aggressive with pain management immediately after surgery, even in the opioid-tolerant patient, and make short-term adjustments as needed based on the pain response. These patients will require pain medications beyond their baseline dose. Additionally, if an opioid taper is not planned in a chronic opioid user, work with the patient and the long-term opioid prescriber in restarting baseline opioid therapy outside of the acute surgical window.

References

1. Institute of Medicine. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2011.

2. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Aug;122(2 Pt 1):233-41.

3. N Engl J Med. 1964 Apr 16;270:825-7.

4. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999 Jul;18(1):38-48.

5. Pain. 2010 Dec;151(3):694-702.

6. Anesthesiology. 2005 Dec;103(6):1296-304.

7. J Pain. 2016 Feb;17(2):131-57.

8. Pharmacotherapy. 2008 Dec;28(12):1453-60.

Dr. Carey is the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and specializes in the medical and surgical management of pelvic pain disorders. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC–Chapel Hill. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Perinatal depression screening is just the start

Over the last decade, appreciation of the prevalence of perinatal depression – depression during pregnancy and/or the postpartum period – along with interest and willingness to diagnose and to treat these disorders across primary care, obstetric, and psychiatric clinical settings – has grown.

The passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010 included the Melanie Blocker Stokes MOTHERS Act, which provides federal funding for programs to enhance awareness of postpartum depression and conduct research into its causes and treatment. At the same time, there has been increasing destigmatization associated with perinatal mood and anxiety disorders across many communities, and enhanced knowledge among clinicians and the public regarding evidence-based treatments, which mitigate suffering from untreated perinatal psychiatric illness.

The importance of identification of perinatal depression cannot be overestimated given the impact of untreated perinatal mood and anxiety disorders on women and families. Unfortunately, data describing the outcomes of these screening initiatives have been profoundly lacking.

There are many unanswered questions. What proportion of women get screened from state to state? What are the obstacles to screening across different sociodemographic populations? If screened, what proportion of women are referred for treatment and receive appropriate treatment? Of those who receive treatment, how many recover emotional well-being? These are all critically relevant questions and one has to wonder if they would be the same from other nonpsychiatric disease states. For example, would one screen for HIV or cervical cancer and not know the number of women who screened positive but failed to go on to receive referral or frank treatment?

This knowledge gap with respect to outcome of screening for perinatal depression was highlighted in one of the few studies that addresses this specific question. Published in 2016, the systematic review describes the so-called “perinatal depression treatment cascade” – the cumulative shortfalls in clinical recognition, initiation of treatment, adequacy of treatment, and treatment response among women with either depression during pregnancy or postpartum depression (J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;77[9]:1189-1200).

The investigators included 32 studies where they were able to look specifically at this question of what happens to women who are identified as having either antenatal depression or postpartum depression. In total, six studies examined the rate of treatment of women who had been diagnosed with antenatal depression, resulting in a weighted mean treatment rate of 13.6%. For women identified as having postpartum depression, four studies examined showed a weighted mean treatment rate of 15.8%. What that means is that even if we have a sensitive and specific screening tool and we look only at women who have screened positive, we still have just 14% and 16% of women receiving treatment of any kind.

Drilling down to the issue of treatment adequacy – defined in the review as at least 6 weeks of daily use of antidepressants or at least 6 weeks of psychotherapy – the picture is unfortunately worse. Among the entire population of women with diagnosed antenatal depression, 8.6% received an adequate trial of treatment. Similarly, 6.3% of women with diagnosed postpartum depression received an adequate trial of treatment.

Continuing down the treatment cascade, remission rates also were extremely low. The overall weighted mean remission rate – reflecting the percentage of women who actually ended up getting well – was just 4.8% for women with antenatal depression and 3.2% for women with postpartum depression. These are striking, although perhaps not surprising, data. It suggests, at least in part, the fundamental absence of adequate referral networks and systems for follow-up for those women who suffer from perinatal depression.

It is well established that postpartum depression is the most common complication in modern obstetrics. The data presented in this paper suggest that most women identified with perinatal depressive illness are not getting well. Assuming a prevalence of 10% for antenatal depression and 13% for postpartum depression, there are about 657,000 women with antenatal depression and about 550,000 women with postpartum depression in the United States. If this review is correct, more than 31,000 women with antenatal depression and almost 18,000 women with postpartum depression achieved remission. That leaves more than 600,000 women with undermanaged depression in pregnancy and more than 500,000 women with incompletely treated postpartum depression.

This is a wake-up call to consider a refocusing of effort. The importance of identification of women suffering from postpartum depression is clear and intuitive. We should certainly not abandon screening, but perhaps there has been an overemphasis on identification and incomplete attention to ensuring that referral networks and opportunities for clinical follow-up are in place following positive screening. There also has been inadequate focus on the obstacles to getting women in to see clinicians and getting those clinicians up to speed on the evidence base that supports treatment, both pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic.

Right now, we don’t even know for sure what obstacles exist to referral and treatment. Surveys of community clinicians suggest that collaborative care in managing reproductive-age women or pregnant and postpartum women has not evolved to the point where we have a clear, user-friendly system for getting patients referred and treated. In Massachusetts, where I practice, we have a state-funded effort (MCPAP [Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Program] for Moms) to train colleagues in obstetrics about how to identify and treat perinatal depression; perinatal psychiatrists also are available to consult with community-based clinicians. However, we do not have data to tell us if these efforts and the resources used to support them have yielded improvement in the overall symptom burden associated with perinatal mood disorders.

The bottom line is that even after identification of perinatal depression through screening programs, we still have women suffering in silence. It is so easy to get on the bandwagon regarding screening, but it seems even more challenging to design the systems that will accommodate the volume of women who are being identified. The fact that we do not have parallel efforts focusing on getting these women referred and treated, and a system to monitor improvement, conjures the image of setting off to sail without checking whether the boat is equipped with life preservers.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications.

Over the last decade, appreciation of the prevalence of perinatal depression – depression during pregnancy and/or the postpartum period – along with interest and willingness to diagnose and to treat these disorders across primary care, obstetric, and psychiatric clinical settings – has grown.

The passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010 included the Melanie Blocker Stokes MOTHERS Act, which provides federal funding for programs to enhance awareness of postpartum depression and conduct research into its causes and treatment. At the same time, there has been increasing destigmatization associated with perinatal mood and anxiety disorders across many communities, and enhanced knowledge among clinicians and the public regarding evidence-based treatments, which mitigate suffering from untreated perinatal psychiatric illness.

The importance of identification of perinatal depression cannot be overestimated given the impact of untreated perinatal mood and anxiety disorders on women and families. Unfortunately, data describing the outcomes of these screening initiatives have been profoundly lacking.

There are many unanswered questions. What proportion of women get screened from state to state? What are the obstacles to screening across different sociodemographic populations? If screened, what proportion of women are referred for treatment and receive appropriate treatment? Of those who receive treatment, how many recover emotional well-being? These are all critically relevant questions and one has to wonder if they would be the same from other nonpsychiatric disease states. For example, would one screen for HIV or cervical cancer and not know the number of women who screened positive but failed to go on to receive referral or frank treatment?

This knowledge gap with respect to outcome of screening for perinatal depression was highlighted in one of the few studies that addresses this specific question. Published in 2016, the systematic review describes the so-called “perinatal depression treatment cascade” – the cumulative shortfalls in clinical recognition, initiation of treatment, adequacy of treatment, and treatment response among women with either depression during pregnancy or postpartum depression (J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;77[9]:1189-1200).

The investigators included 32 studies where they were able to look specifically at this question of what happens to women who are identified as having either antenatal depression or postpartum depression. In total, six studies examined the rate of treatment of women who had been diagnosed with antenatal depression, resulting in a weighted mean treatment rate of 13.6%. For women identified as having postpartum depression, four studies examined showed a weighted mean treatment rate of 15.8%. What that means is that even if we have a sensitive and specific screening tool and we look only at women who have screened positive, we still have just 14% and 16% of women receiving treatment of any kind.

Drilling down to the issue of treatment adequacy – defined in the review as at least 6 weeks of daily use of antidepressants or at least 6 weeks of psychotherapy – the picture is unfortunately worse. Among the entire population of women with diagnosed antenatal depression, 8.6% received an adequate trial of treatment. Similarly, 6.3% of women with diagnosed postpartum depression received an adequate trial of treatment.

Continuing down the treatment cascade, remission rates also were extremely low. The overall weighted mean remission rate – reflecting the percentage of women who actually ended up getting well – was just 4.8% for women with antenatal depression and 3.2% for women with postpartum depression. These are striking, although perhaps not surprising, data. It suggests, at least in part, the fundamental absence of adequate referral networks and systems for follow-up for those women who suffer from perinatal depression.

It is well established that postpartum depression is the most common complication in modern obstetrics. The data presented in this paper suggest that most women identified with perinatal depressive illness are not getting well. Assuming a prevalence of 10% for antenatal depression and 13% for postpartum depression, there are about 657,000 women with antenatal depression and about 550,000 women with postpartum depression in the United States. If this review is correct, more than 31,000 women with antenatal depression and almost 18,000 women with postpartum depression achieved remission. That leaves more than 600,000 women with undermanaged depression in pregnancy and more than 500,000 women with incompletely treated postpartum depression.

This is a wake-up call to consider a refocusing of effort. The importance of identification of women suffering from postpartum depression is clear and intuitive. We should certainly not abandon screening, but perhaps there has been an overemphasis on identification and incomplete attention to ensuring that referral networks and opportunities for clinical follow-up are in place following positive screening. There also has been inadequate focus on the obstacles to getting women in to see clinicians and getting those clinicians up to speed on the evidence base that supports treatment, both pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic.

Right now, we don’t even know for sure what obstacles exist to referral and treatment. Surveys of community clinicians suggest that collaborative care in managing reproductive-age women or pregnant and postpartum women has not evolved to the point where we have a clear, user-friendly system for getting patients referred and treated. In Massachusetts, where I practice, we have a state-funded effort (MCPAP [Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Program] for Moms) to train colleagues in obstetrics about how to identify and treat perinatal depression; perinatal psychiatrists also are available to consult with community-based clinicians. However, we do not have data to tell us if these efforts and the resources used to support them have yielded improvement in the overall symptom burden associated with perinatal mood disorders.

The bottom line is that even after identification of perinatal depression through screening programs, we still have women suffering in silence. It is so easy to get on the bandwagon regarding screening, but it seems even more challenging to design the systems that will accommodate the volume of women who are being identified. The fact that we do not have parallel efforts focusing on getting these women referred and treated, and a system to monitor improvement, conjures the image of setting off to sail without checking whether the boat is equipped with life preservers.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications.

Over the last decade, appreciation of the prevalence of perinatal depression – depression during pregnancy and/or the postpartum period – along with interest and willingness to diagnose and to treat these disorders across primary care, obstetric, and psychiatric clinical settings – has grown.

The passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010 included the Melanie Blocker Stokes MOTHERS Act, which provides federal funding for programs to enhance awareness of postpartum depression and conduct research into its causes and treatment. At the same time, there has been increasing destigmatization associated with perinatal mood and anxiety disorders across many communities, and enhanced knowledge among clinicians and the public regarding evidence-based treatments, which mitigate suffering from untreated perinatal psychiatric illness.

The importance of identification of perinatal depression cannot be overestimated given the impact of untreated perinatal mood and anxiety disorders on women and families. Unfortunately, data describing the outcomes of these screening initiatives have been profoundly lacking.

There are many unanswered questions. What proportion of women get screened from state to state? What are the obstacles to screening across different sociodemographic populations? If screened, what proportion of women are referred for treatment and receive appropriate treatment? Of those who receive treatment, how many recover emotional well-being? These are all critically relevant questions and one has to wonder if they would be the same from other nonpsychiatric disease states. For example, would one screen for HIV or cervical cancer and not know the number of women who screened positive but failed to go on to receive referral or frank treatment?

This knowledge gap with respect to outcome of screening for perinatal depression was highlighted in one of the few studies that addresses this specific question. Published in 2016, the systematic review describes the so-called “perinatal depression treatment cascade” – the cumulative shortfalls in clinical recognition, initiation of treatment, adequacy of treatment, and treatment response among women with either depression during pregnancy or postpartum depression (J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;77[9]:1189-1200).

The investigators included 32 studies where they were able to look specifically at this question of what happens to women who are identified as having either antenatal depression or postpartum depression. In total, six studies examined the rate of treatment of women who had been diagnosed with antenatal depression, resulting in a weighted mean treatment rate of 13.6%. For women identified as having postpartum depression, four studies examined showed a weighted mean treatment rate of 15.8%. What that means is that even if we have a sensitive and specific screening tool and we look only at women who have screened positive, we still have just 14% and 16% of women receiving treatment of any kind.

Drilling down to the issue of treatment adequacy – defined in the review as at least 6 weeks of daily use of antidepressants or at least 6 weeks of psychotherapy – the picture is unfortunately worse. Among the entire population of women with diagnosed antenatal depression, 8.6% received an adequate trial of treatment. Similarly, 6.3% of women with diagnosed postpartum depression received an adequate trial of treatment.

Continuing down the treatment cascade, remission rates also were extremely low. The overall weighted mean remission rate – reflecting the percentage of women who actually ended up getting well – was just 4.8% for women with antenatal depression and 3.2% for women with postpartum depression. These are striking, although perhaps not surprising, data. It suggests, at least in part, the fundamental absence of adequate referral networks and systems for follow-up for those women who suffer from perinatal depression.

It is well established that postpartum depression is the most common complication in modern obstetrics. The data presented in this paper suggest that most women identified with perinatal depressive illness are not getting well. Assuming a prevalence of 10% for antenatal depression and 13% for postpartum depression, there are about 657,000 women with antenatal depression and about 550,000 women with postpartum depression in the United States. If this review is correct, more than 31,000 women with antenatal depression and almost 18,000 women with postpartum depression achieved remission. That leaves more than 600,000 women with undermanaged depression in pregnancy and more than 500,000 women with incompletely treated postpartum depression.

This is a wake-up call to consider a refocusing of effort. The importance of identification of women suffering from postpartum depression is clear and intuitive. We should certainly not abandon screening, but perhaps there has been an overemphasis on identification and incomplete attention to ensuring that referral networks and opportunities for clinical follow-up are in place following positive screening. There also has been inadequate focus on the obstacles to getting women in to see clinicians and getting those clinicians up to speed on the evidence base that supports treatment, both pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic.

Right now, we don’t even know for sure what obstacles exist to referral and treatment. Surveys of community clinicians suggest that collaborative care in managing reproductive-age women or pregnant and postpartum women has not evolved to the point where we have a clear, user-friendly system for getting patients referred and treated. In Massachusetts, where I practice, we have a state-funded effort (MCPAP [Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Program] for Moms) to train colleagues in obstetrics about how to identify and treat perinatal depression; perinatal psychiatrists also are available to consult with community-based clinicians. However, we do not have data to tell us if these efforts and the resources used to support them have yielded improvement in the overall symptom burden associated with perinatal mood disorders.

The bottom line is that even after identification of perinatal depression through screening programs, we still have women suffering in silence. It is so easy to get on the bandwagon regarding screening, but it seems even more challenging to design the systems that will accommodate the volume of women who are being identified. The fact that we do not have parallel efforts focusing on getting these women referred and treated, and a system to monitor improvement, conjures the image of setting off to sail without checking whether the boat is equipped with life preservers.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications.

Celebrating Federal Social Work!

March is National Professional Social Work Month, so it is an apt time to celebrate social workers’ contributions to our respective health care organizations. Military social workers are members of all 3 major federal practice organizations—DoD, VA, and the PHS—and fill a plethora of roles and positions, including active duty in all military branches

We all intuitively grasp that military service places immense stress and strain not only on soldiers, airmen, sailors, and marines, but also on their spouses and children. This is especially true during times of conflict and in theaters of combat. Social workers in the DoD provide consolation and consultation to the family unit of those who have been wounded in body or mind in Iraq, Afghanistan, and other war-torn areas.

In an article describing military social work, Nikki R. Wooten, PhD, offers this description of the profession: “Military social work is a specialized practice area that differs from generalized practice with civilians in that military personnel, veterans, and their families live, work, and receive health care and social benefits in a hierarchical, sociopolitical environment within a structured military organization.”1

Unfortunately, as with other mental health specialties in federal practice, a shortage of social workers exists. In order to publicize the need and promote the education and training of social workers who specialize in the care of military members, their families, and veterans, Former First Lady Michelle Obama and former Second Lady Jill Biden, PhD, created Joining Forces. The program is a national effort to galvanize public support for all aspects of social and economic life for military service members and veterans. The National Association of Social Workers has been part of Joining Forces since 2011.

The VA employs more than 12,000 social workers, making the agency the largest employer of social workers in the U.S. Last year, the VA commemorated 90 years of social work excellence. Social workers are the front line for many of the most innovative social programs in the VA, such as the outreach to homeless veterans to locate and support housing; the medical foster home program for veterans who need assistance with activities of daily living that enables them to live with families in their home; the caregiver support program that assists friends and family to provide care for veterans who might otherwise not be able to live outside a facility; and the mental health intensive case management program that empowers veterans with serious mental illness to function as independently as possible and reduce the need for hospitalization.

Social workers also are part of the USPHS Commissioned Corps as allied health professionals. As crucial participants in multidisciplinary teams, social workers in the PHS respond to fill basic needs of people who are displaced by national disasters. They also provide mental health and clinical social work care in the clinics and hospitals of the IHS and other facilities that offer medical treatment and psychosocial intervention to disadvantaged populations and underserved regions. Social workers also offer public health education, social services, and administrative leadership.Another vital function that social workers perform in federal health care is facilitating the difficult transition of men and women from uniform to civilian life. A young person leaving the services needs the help of military social workers to negotiate the complexities of the VA health and education benefits application processes. Like runners in a relay, military and attached civilian social workers coordinate with VA social workers toward a smooth transition from one organization and way of life to another.

Social workers inhabit almost every corner of the federal health care world. Here are just a few examples from my own experience:

- The social worker is the first professional encounter for a service member returning from deployment and having difficulty adjusting, resulting in family dysfunction. Whether it is substance use treatment, marital counseling, or intimate partner violence, the social worker will be integral in coordinating the care of the service member and family.• The social worker is the professional who will arrange the discharge plan for an elderly veteran who has been hospitalized for cardiac surgery in a VAMC and requires a brief stay in a rehabilitation facility and then aid and assistance to return home to his wife of 40 years.

- The social worker is the professional at a vet center who provides confidential counseling to a veteran with posttraumatic stress disorder who does not feel safe or comfortable at a VAMC but who needs a therapist who has knowledge of the military and specialized trauma skills to help and heal. I suspect that if most readers of this column reflect on their federal career, they will remember an action of a social worker who smoothed their life path at a rough spot. Take a moment in this month to thank a social worker for giving help and hope to service members, veterans, and their families.

For more information

You can learn more about federal social workers by visiting the following organizations: National Association of Social Workers (https://www.socialworkers.org/military.asp), VA Social Work (http://www.socialwork.va.gov), Joining Forces (https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/joiningforces), and Social Work Today (http://www.socialworktoday.com/archive/031513p12.shtml).

1. Wooten NR. Military social work: opportunities and challenges for social work education. J Soc Work Educ. 2015;51(suppl 1):S6-S25.

March is National Professional Social Work Month, so it is an apt time to celebrate social workers’ contributions to our respective health care organizations. Military social workers are members of all 3 major federal practice organizations—DoD, VA, and the PHS—and fill a plethora of roles and positions, including active duty in all military branches

We all intuitively grasp that military service places immense stress and strain not only on soldiers, airmen, sailors, and marines, but also on their spouses and children. This is especially true during times of conflict and in theaters of combat. Social workers in the DoD provide consolation and consultation to the family unit of those who have been wounded in body or mind in Iraq, Afghanistan, and other war-torn areas.

In an article describing military social work, Nikki R. Wooten, PhD, offers this description of the profession: “Military social work is a specialized practice area that differs from generalized practice with civilians in that military personnel, veterans, and their families live, work, and receive health care and social benefits in a hierarchical, sociopolitical environment within a structured military organization.”1

Unfortunately, as with other mental health specialties in federal practice, a shortage of social workers exists. In order to publicize the need and promote the education and training of social workers who specialize in the care of military members, their families, and veterans, Former First Lady Michelle Obama and former Second Lady Jill Biden, PhD, created Joining Forces. The program is a national effort to galvanize public support for all aspects of social and economic life for military service members and veterans. The National Association of Social Workers has been part of Joining Forces since 2011.

The VA employs more than 12,000 social workers, making the agency the largest employer of social workers in the U.S. Last year, the VA commemorated 90 years of social work excellence. Social workers are the front line for many of the most innovative social programs in the VA, such as the outreach to homeless veterans to locate and support housing; the medical foster home program for veterans who need assistance with activities of daily living that enables them to live with families in their home; the caregiver support program that assists friends and family to provide care for veterans who might otherwise not be able to live outside a facility; and the mental health intensive case management program that empowers veterans with serious mental illness to function as independently as possible and reduce the need for hospitalization.

Social workers also are part of the USPHS Commissioned Corps as allied health professionals. As crucial participants in multidisciplinary teams, social workers in the PHS respond to fill basic needs of people who are displaced by national disasters. They also provide mental health and clinical social work care in the clinics and hospitals of the IHS and other facilities that offer medical treatment and psychosocial intervention to disadvantaged populations and underserved regions. Social workers also offer public health education, social services, and administrative leadership.Another vital function that social workers perform in federal health care is facilitating the difficult transition of men and women from uniform to civilian life. A young person leaving the services needs the help of military social workers to negotiate the complexities of the VA health and education benefits application processes. Like runners in a relay, military and attached civilian social workers coordinate with VA social workers toward a smooth transition from one organization and way of life to another.

Social workers inhabit almost every corner of the federal health care world. Here are just a few examples from my own experience:

- The social worker is the first professional encounter for a service member returning from deployment and having difficulty adjusting, resulting in family dysfunction. Whether it is substance use treatment, marital counseling, or intimate partner violence, the social worker will be integral in coordinating the care of the service member and family.• The social worker is the professional who will arrange the discharge plan for an elderly veteran who has been hospitalized for cardiac surgery in a VAMC and requires a brief stay in a rehabilitation facility and then aid and assistance to return home to his wife of 40 years.

- The social worker is the professional at a vet center who provides confidential counseling to a veteran with posttraumatic stress disorder who does not feel safe or comfortable at a VAMC but who needs a therapist who has knowledge of the military and specialized trauma skills to help and heal. I suspect that if most readers of this column reflect on their federal career, they will remember an action of a social worker who smoothed their life path at a rough spot. Take a moment in this month to thank a social worker for giving help and hope to service members, veterans, and their families.

For more information

You can learn more about federal social workers by visiting the following organizations: National Association of Social Workers (https://www.socialworkers.org/military.asp), VA Social Work (http://www.socialwork.va.gov), Joining Forces (https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/joiningforces), and Social Work Today (http://www.socialworktoday.com/archive/031513p12.shtml).

March is National Professional Social Work Month, so it is an apt time to celebrate social workers’ contributions to our respective health care organizations. Military social workers are members of all 3 major federal practice organizations—DoD, VA, and the PHS—and fill a plethora of roles and positions, including active duty in all military branches

We all intuitively grasp that military service places immense stress and strain not only on soldiers, airmen, sailors, and marines, but also on their spouses and children. This is especially true during times of conflict and in theaters of combat. Social workers in the DoD provide consolation and consultation to the family unit of those who have been wounded in body or mind in Iraq, Afghanistan, and other war-torn areas.

In an article describing military social work, Nikki R. Wooten, PhD, offers this description of the profession: “Military social work is a specialized practice area that differs from generalized practice with civilians in that military personnel, veterans, and their families live, work, and receive health care and social benefits in a hierarchical, sociopolitical environment within a structured military organization.”1

Unfortunately, as with other mental health specialties in federal practice, a shortage of social workers exists. In order to publicize the need and promote the education and training of social workers who specialize in the care of military members, their families, and veterans, Former First Lady Michelle Obama and former Second Lady Jill Biden, PhD, created Joining Forces. The program is a national effort to galvanize public support for all aspects of social and economic life for military service members and veterans. The National Association of Social Workers has been part of Joining Forces since 2011.

The VA employs more than 12,000 social workers, making the agency the largest employer of social workers in the U.S. Last year, the VA commemorated 90 years of social work excellence. Social workers are the front line for many of the most innovative social programs in the VA, such as the outreach to homeless veterans to locate and support housing; the medical foster home program for veterans who need assistance with activities of daily living that enables them to live with families in their home; the caregiver support program that assists friends and family to provide care for veterans who might otherwise not be able to live outside a facility; and the mental health intensive case management program that empowers veterans with serious mental illness to function as independently as possible and reduce the need for hospitalization.

Social workers also are part of the USPHS Commissioned Corps as allied health professionals. As crucial participants in multidisciplinary teams, social workers in the PHS respond to fill basic needs of people who are displaced by national disasters. They also provide mental health and clinical social work care in the clinics and hospitals of the IHS and other facilities that offer medical treatment and psychosocial intervention to disadvantaged populations and underserved regions. Social workers also offer public health education, social services, and administrative leadership.Another vital function that social workers perform in federal health care is facilitating the difficult transition of men and women from uniform to civilian life. A young person leaving the services needs the help of military social workers to negotiate the complexities of the VA health and education benefits application processes. Like runners in a relay, military and attached civilian social workers coordinate with VA social workers toward a smooth transition from one organization and way of life to another.

Social workers inhabit almost every corner of the federal health care world. Here are just a few examples from my own experience:

- The social worker is the first professional encounter for a service member returning from deployment and having difficulty adjusting, resulting in family dysfunction. Whether it is substance use treatment, marital counseling, or intimate partner violence, the social worker will be integral in coordinating the care of the service member and family.• The social worker is the professional who will arrange the discharge plan for an elderly veteran who has been hospitalized for cardiac surgery in a VAMC and requires a brief stay in a rehabilitation facility and then aid and assistance to return home to his wife of 40 years.

- The social worker is the professional at a vet center who provides confidential counseling to a veteran with posttraumatic stress disorder who does not feel safe or comfortable at a VAMC but who needs a therapist who has knowledge of the military and specialized trauma skills to help and heal. I suspect that if most readers of this column reflect on their federal career, they will remember an action of a social worker who smoothed their life path at a rough spot. Take a moment in this month to thank a social worker for giving help and hope to service members, veterans, and their families.

For more information

You can learn more about federal social workers by visiting the following organizations: National Association of Social Workers (https://www.socialworkers.org/military.asp), VA Social Work (http://www.socialwork.va.gov), Joining Forces (https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/joiningforces), and Social Work Today (http://www.socialworktoday.com/archive/031513p12.shtml).

1. Wooten NR. Military social work: opportunities and challenges for social work education. J Soc Work Educ. 2015;51(suppl 1):S6-S25.

1. Wooten NR. Military social work: opportunities and challenges for social work education. J Soc Work Educ. 2015;51(suppl 1):S6-S25.

More Than “Teen Angst”: What to Watch For

The incidence of high-risk behavior among teenagers has attracted increased media attention lately. It feels like a new report surfaces every day detailing the death of one or more teens as a result of alcohol, illicit drug use, or speeding. These risky behaviors grab our attention; they are overt and somewhat public. But behaviors that correlate with anxiety and depression, which can in turn lead to suicide or suicidal ideation, are more subtle—and that is what concerns me.

The data on suicide is staggering. On a daily basis, almost 3,000 people worldwide complete suicide, and approximately 20 times as many survive a suicide attempt.1 Annually, deaths resulting from suicide exceed deaths from homicide and war combined.2 In 2013, there were 41,149 suicides in the US—that translates to a rate of 113 suicides each day, or one every 13 minutes.3 Suicide has surpassed homicide to become the second leading cause of death among 10- to 29-year-olds; in 2012, suicide claimed the lives of more than 5,000 people within this age bracket.4,5 In the 2013 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), 17.7% of high school students reported seriously considering suicide during the prior 12 months, and nearly 9% of those students had attempted suicide during that same period.6 I wonder how many of those students exhibited telling behaviors that went unnoticed.

What are these subtle signs that are so easily overlooked? Behaviors most might consider “within the norm” of today’s youth—hours playing video games, sending hundreds of texts every day, lack of exercise, and lack of sleep. Research has demonstrated that moderate-to-vigorous physical activity reduces the incidence of depression in adolescents.7 A 2014 study of European teens published in World Psychiatry found that the adolescents most at risk for symptoms of depression and anxiety are those who are fixated on media, don’t get enough sleep, and have a sedentary lifestyle.8 Hmm... sounds like many US teenagers today. While that doesn’t mean that every teen who lacks sleep, plays video games, or isn’t active is at risk, we do need to pay closer attention to them, because this combination exacerbates risk.

There’s another unhealthy habit that contributes to the risk for teen suicidality: smoking and use of electronic vapor products (EVPs). The 2015 YRBS, which surveyed more than 15,000 high school students, noted that 3.2% smoked cigarettes only, 15.8% used EVPs only, and 7.5% were dual users. Analysis of that data identified associations between health-risk behaviors and both cigarette smoking and EVP use.9 Teens who smoked or used EVPs were more likely to engage in violence, substance abuse, and other high-risk behaviors, compared with nonusers. Moreover, compared with nonusers, cigarette-only, EVP-only, and dual smokers were significantly more likely to attempt suicide; cigarette-only smokers were more likely than EVP-only users to attempt suicide.9

Smoking, inactivity, sleep deprivation, and social isolation (because texting or face-timing with your friends is not being social) are a recipe for depression and anxiety in an adolescent. Sleep deprivation alone has been linked to depression and may be associated with a decreased ability to control, inhibit, or change emotional responses.10 Far too often, teens view suicide as the only relief from these feelings.

Awareness of this problem has grown in the past 30 years. The YRBS was developed in 1990 to monitor priority health risk behaviors that contribute to the leading causes of death, disability, and social problems among youth in the US—one of which is suicide.11 In 2001, the Department of Health and Human Services introduced the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention, the first national program of its kind, and released an evidence-based practice guide for school-based suicide prevention plans.12 The 2002 Institute of Medicine report Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative recognized the need for early recognition and prevention of suicidality.13 And yet, we still have the staggering statistics I cited earlier.

Because of their proximity to children and adolescents, schools are frequently viewed as an integral setting for youth suicide prevention efforts. It is encouraging that suicide prevention programs exist in more than 77% of US public schools—but disheartening that it is not 100%.

And what about the rest of us? What can we, as health care providers, do to stem this tide of teen suicide? The importance of early prevention strategies to reduce onset of suicidal thoughts and help identify persons who are at risk for or are currently contemplating suicide cannot be overemphasized. We need more health care practitioners who are trained to assess suicide plans and to intervene with young persons. This involves education in recognizing risk factors and making appropriate referrals, expanding access to social services, reducing stigma and other barriers to seeking help, and providing awareness that suicide prevention is paramount.

It is incumbent on us as health care providers to screen for and ask our teenaged patients about those subtle behaviors. As adults, it is our responsibility to support and watch over our youth. In the words of former Surgeon General David Satcher, “We must act now. We cannot change the past, but together we can shape a different future.”14

1. World Health Organization. World Suicide Prevention Day. www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2007/s16/en/. Accessed February 2, 2017

2. World Health Organization. Suicide huge but preventable public health problem, says WHO. www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2004/pr61/en. Accessed February 2, 2017.

3. CDC. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html. Accessed February 2, 2017.

4. World Health Organization. Suicide. www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs398/en. Accessed February 2, 2017.

5. CDC. Suicide trends among persons aged 10-24 years—United States, 1994-2012. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/wk/mm6408.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2017.

6. CDC. Trends in the prevalence of suicide-related behavior. National Youth Risk Behavior Survey: 1991-2013. www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/trends/us_suicide_trend_yrbs.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2017.

7. Zahl T, Steinsbekk S, Wichstrøm L. Physical activity, sedentary behavior, and symptoms of major depression in middle childhood. Pediatrics. 2017;139(2):e20161711.

8. Carli V, Hoven CW, Wasserman C, et al. A newly identified group of adolescents at “invisible” risk for psychopathology and suicidal behavior: findings from the SEYLE study. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(1):78-86.

9. Demissie Z, Everett Jones S, Clayton HB, King BA. Adolescent risk behaviors and use of electronic vapor products and cigarettes. Pediatrics. 2017;139(2):e20162921.

10. National Sleep Foundation. Adolescent sleep needs and patterns. https://sleepfoundation.org/sites/default/files/sleep_and_teens_report1.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2017.

11. CDC. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) overview. www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/overview.htm. Accessed February 2, 2017.

12. Cooper GD, Clements PT, Holt K. A review and application of suicide prevention programs in high school settings. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2011;32(11):696-702.

13. Goldsmith SK, Pellmar TC, Kleinman AM, Bunney WE. Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative. Washington, DC: National Academics Press; 2002.

14. US Public Health Service. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Suicide. Washington, DC: 1999.

The incidence of high-risk behavior among teenagers has attracted increased media attention lately. It feels like a new report surfaces every day detailing the death of one or more teens as a result of alcohol, illicit drug use, or speeding. These risky behaviors grab our attention; they are overt and somewhat public. But behaviors that correlate with anxiety and depression, which can in turn lead to suicide or suicidal ideation, are more subtle—and that is what concerns me.

The data on suicide is staggering. On a daily basis, almost 3,000 people worldwide complete suicide, and approximately 20 times as many survive a suicide attempt.1 Annually, deaths resulting from suicide exceed deaths from homicide and war combined.2 In 2013, there were 41,149 suicides in the US—that translates to a rate of 113 suicides each day, or one every 13 minutes.3 Suicide has surpassed homicide to become the second leading cause of death among 10- to 29-year-olds; in 2012, suicide claimed the lives of more than 5,000 people within this age bracket.4,5 In the 2013 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), 17.7% of high school students reported seriously considering suicide during the prior 12 months, and nearly 9% of those students had attempted suicide during that same period.6 I wonder how many of those students exhibited telling behaviors that went unnoticed.

What are these subtle signs that are so easily overlooked? Behaviors most might consider “within the norm” of today’s youth—hours playing video games, sending hundreds of texts every day, lack of exercise, and lack of sleep. Research has demonstrated that moderate-to-vigorous physical activity reduces the incidence of depression in adolescents.7 A 2014 study of European teens published in World Psychiatry found that the adolescents most at risk for symptoms of depression and anxiety are those who are fixated on media, don’t get enough sleep, and have a sedentary lifestyle.8 Hmm... sounds like many US teenagers today. While that doesn’t mean that every teen who lacks sleep, plays video games, or isn’t active is at risk, we do need to pay closer attention to them, because this combination exacerbates risk.

There’s another unhealthy habit that contributes to the risk for teen suicidality: smoking and use of electronic vapor products (EVPs). The 2015 YRBS, which surveyed more than 15,000 high school students, noted that 3.2% smoked cigarettes only, 15.8% used EVPs only, and 7.5% were dual users. Analysis of that data identified associations between health-risk behaviors and both cigarette smoking and EVP use.9 Teens who smoked or used EVPs were more likely to engage in violence, substance abuse, and other high-risk behaviors, compared with nonusers. Moreover, compared with nonusers, cigarette-only, EVP-only, and dual smokers were significantly more likely to attempt suicide; cigarette-only smokers were more likely than EVP-only users to attempt suicide.9