User login

Five-day treatment of ear infections

In December 2016, the results of a randomized, controlled trial of 5-day vs. 10-day amoxicillin/clavulanate treatment of acute otitis media (AOM) in children aged 6-23 months was reported by Hoberman et al. in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).1 Predefined criteria for clinical failure were used that considered both symptoms and signs of AOM, assessed on days 12-14 after start of treatment with 5 vs. 10 days of treatment with the antibiotic. The conclusion reached was clear: The clinical failure rate for the 5-day regimen was 34% vs. 16% in the 10-day group, supporting a preference for the 10-day treatment.

I was surprised. The clinical failure rate for the 5-day regimen seemed very high for treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanate. If it is 34% with amoxicillin/clavulanate, then what would it have been with amoxicillin, as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics?

So, why did the systematic review conclude that there was a minimal difference between shortened treatments and the standard 10-day when the NEJM study reported such a striking difference?

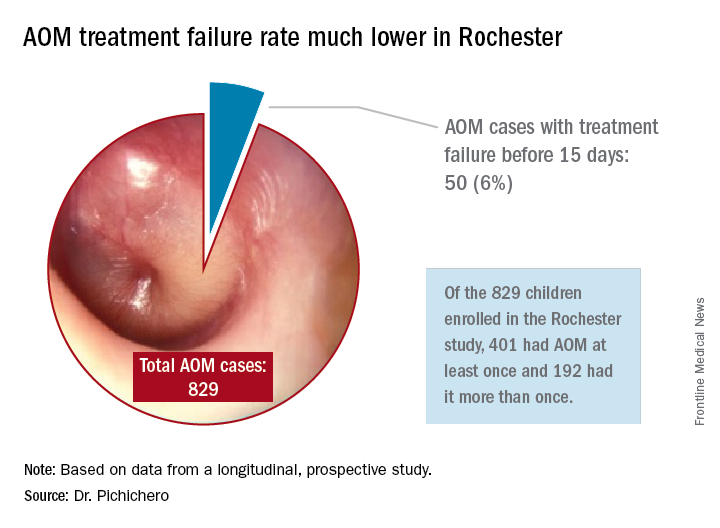

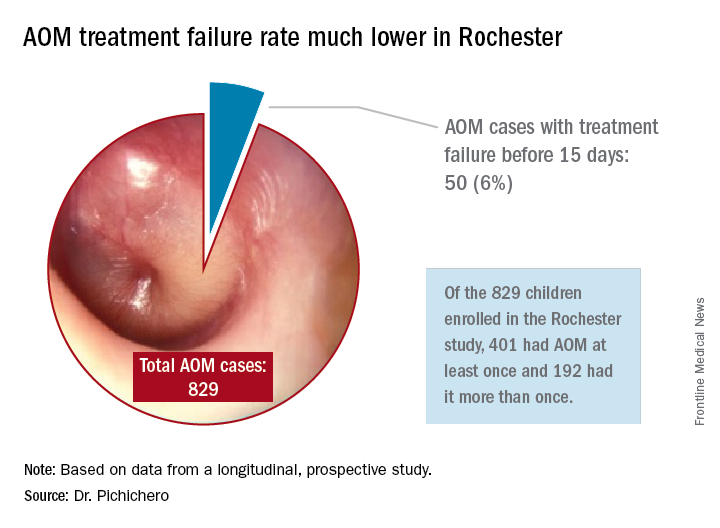

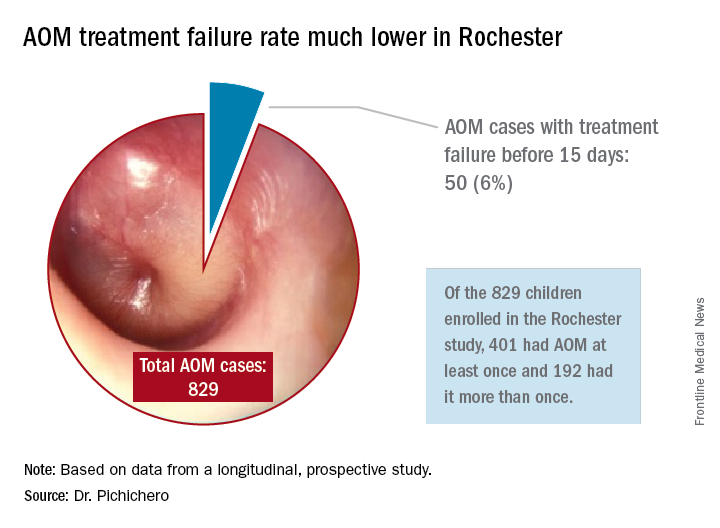

In Rochester, N.Y., we have been conducting a longitudinal, prospective study of AOM that is NIH-sponsored to better understand the immune response to AOM, especially in otitis-prone children.3,4 In that study we are treating all children aged 6-23 months with amoxicillin/clavulanate using the same dose as used in the study by Hoberman et al. We have two exceptions: If the child has a second AOM within 30 days of a prior episode or they have an eardrum rupture, we treat for 10 days.5 Our clinical failure rate is 6%. Why is the failure rate in Rochester so much lower than that in Pittsburgh and Bardstown, Ky., where the Hoberman et al. study was done?

One possibility is an important difference in our study design, compared with that of the NEJM study. All the children in our prospective study have a tympanocentesis to confirm the clinical diagnosis, and our research has shown that tympanocentesis results in immediate relief of ear pain and reduces the frequency of antibiotic treatment failure about twofold, compared with children diagnosed and treated by the same physicians in the same clinic practice.6 So, if the tympanocentesis is factored out of the equation, the Rochester clinical failure comes out to 14% for 5-day treatment. Why would the children in Rochester not getting a tympanocentesis, being treated with the same antibiotic, same dose, and same definition of clinical failure, during the same time frame, and having the same bacteria with the same antibiotic resistance rates have a clinical failure rate of 14%, compared with the 34% in the NEJM study?

Next question: How does a clinical failure rate of 34% fit according to past studies of shortened course antibiotic treatment of AOM? Besides the systematic review and meta-analysis noted above, in many countries outside the United States the 5-day regimen is standard, so, if health care providers were seeing a 34% failure rate, that would have been noticeable for sure.8 So, if health care providers were seeing a 34% failure rate, would that not have been noticeable? And would not a 16% failure rate, nearly 1 of 5 cases, be noticeable for children treated for 10 days?

Was there something different about the children who were in the Hoberman et al. study and the children treated in countries outside the United States and in our practice in Rochester? My group has collaborated and published on studies of AOM with the Pittsburgh and Kentucky groups, and we have not found significant site to site differences in outcomes, demonstrating that a population difference is unlikely.9-11

Next question: How does a clinical failure rate of 16% fit according to past studies of 10 days’ antibiotic treatment of AOM? It is on target with the meta-analysis and two other recent studies in the NEJM.12,13 However, if the failure rate was 16% with amoxicillin/clavulanate (which is effective against beta-lactamase–producing Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis, whereas amoxicillin is not), then the predicted failure rate with amoxicillin for 10 days should be double (34%) or triple (51%) had amoxicillin been used as recommended by the AAP in light of the bacterial resistance of otopathogens. That calculation is based on the prevalence of beta-lactamase–producing H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis in the Pittsburgh and Kentucky populations, the same prevalence seen in the Rochester population.” 14

So, I conclude that this wonderful study does not convince me to change my practice from standard use of 5-day amoxicillin/clavulanate treatment of AOM. Besides, outside of a study setting, most parents don’t give the full 10-day treatment. They stop when their child seems normal (a few days after starting treatment) and save the remainder of the medicine in the refrigerator for the next illness to save a trip to the doctor. Plus, in this column, I did not even get into the issue of disturbing the microbiome with longer courses of antibiotic treatment, a topic for a future discussion.

References

1. N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 22;375(25):2446-56.

2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Sep 8;(9):CD001095.

3. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Sep;35(9):1027-32.

4. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Sep;35(9):1033-9.

5. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001 Apr;124(4):381-7.

6. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013 May;32(5):473-8.

7. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006 Mar;25(3):211-8.

8. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000 Sep;19(9):929-37.

9. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999 Aug;18(8):741-4.

10. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2008 Nov;47(9):901-6.

11. Drugs. 2012 Oct 22;72(15):1991-7.

12. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jan 13;364(2):105-15.

13. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jan 13;364(2):116-26.

14. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Aug;35(8):901-6.

Dr. Pichichero, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute, Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. He has no disclosures.

In December 2016, the results of a randomized, controlled trial of 5-day vs. 10-day amoxicillin/clavulanate treatment of acute otitis media (AOM) in children aged 6-23 months was reported by Hoberman et al. in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).1 Predefined criteria for clinical failure were used that considered both symptoms and signs of AOM, assessed on days 12-14 after start of treatment with 5 vs. 10 days of treatment with the antibiotic. The conclusion reached was clear: The clinical failure rate for the 5-day regimen was 34% vs. 16% in the 10-day group, supporting a preference for the 10-day treatment.

I was surprised. The clinical failure rate for the 5-day regimen seemed very high for treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanate. If it is 34% with amoxicillin/clavulanate, then what would it have been with amoxicillin, as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics?

So, why did the systematic review conclude that there was a minimal difference between shortened treatments and the standard 10-day when the NEJM study reported such a striking difference?

In Rochester, N.Y., we have been conducting a longitudinal, prospective study of AOM that is NIH-sponsored to better understand the immune response to AOM, especially in otitis-prone children.3,4 In that study we are treating all children aged 6-23 months with amoxicillin/clavulanate using the same dose as used in the study by Hoberman et al. We have two exceptions: If the child has a second AOM within 30 days of a prior episode or they have an eardrum rupture, we treat for 10 days.5 Our clinical failure rate is 6%. Why is the failure rate in Rochester so much lower than that in Pittsburgh and Bardstown, Ky., where the Hoberman et al. study was done?

One possibility is an important difference in our study design, compared with that of the NEJM study. All the children in our prospective study have a tympanocentesis to confirm the clinical diagnosis, and our research has shown that tympanocentesis results in immediate relief of ear pain and reduces the frequency of antibiotic treatment failure about twofold, compared with children diagnosed and treated by the same physicians in the same clinic practice.6 So, if the tympanocentesis is factored out of the equation, the Rochester clinical failure comes out to 14% for 5-day treatment. Why would the children in Rochester not getting a tympanocentesis, being treated with the same antibiotic, same dose, and same definition of clinical failure, during the same time frame, and having the same bacteria with the same antibiotic resistance rates have a clinical failure rate of 14%, compared with the 34% in the NEJM study?

Next question: How does a clinical failure rate of 34% fit according to past studies of shortened course antibiotic treatment of AOM? Besides the systematic review and meta-analysis noted above, in many countries outside the United States the 5-day regimen is standard, so, if health care providers were seeing a 34% failure rate, that would have been noticeable for sure.8 So, if health care providers were seeing a 34% failure rate, would that not have been noticeable? And would not a 16% failure rate, nearly 1 of 5 cases, be noticeable for children treated for 10 days?

Was there something different about the children who were in the Hoberman et al. study and the children treated in countries outside the United States and in our practice in Rochester? My group has collaborated and published on studies of AOM with the Pittsburgh and Kentucky groups, and we have not found significant site to site differences in outcomes, demonstrating that a population difference is unlikely.9-11

Next question: How does a clinical failure rate of 16% fit according to past studies of 10 days’ antibiotic treatment of AOM? It is on target with the meta-analysis and two other recent studies in the NEJM.12,13 However, if the failure rate was 16% with amoxicillin/clavulanate (which is effective against beta-lactamase–producing Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis, whereas amoxicillin is not), then the predicted failure rate with amoxicillin for 10 days should be double (34%) or triple (51%) had amoxicillin been used as recommended by the AAP in light of the bacterial resistance of otopathogens. That calculation is based on the prevalence of beta-lactamase–producing H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis in the Pittsburgh and Kentucky populations, the same prevalence seen in the Rochester population.” 14

So, I conclude that this wonderful study does not convince me to change my practice from standard use of 5-day amoxicillin/clavulanate treatment of AOM. Besides, outside of a study setting, most parents don’t give the full 10-day treatment. They stop when their child seems normal (a few days after starting treatment) and save the remainder of the medicine in the refrigerator for the next illness to save a trip to the doctor. Plus, in this column, I did not even get into the issue of disturbing the microbiome with longer courses of antibiotic treatment, a topic for a future discussion.

References

1. N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 22;375(25):2446-56.

2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Sep 8;(9):CD001095.

3. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Sep;35(9):1027-32.

4. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Sep;35(9):1033-9.

5. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001 Apr;124(4):381-7.

6. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013 May;32(5):473-8.

7. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006 Mar;25(3):211-8.

8. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000 Sep;19(9):929-37.

9. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999 Aug;18(8):741-4.

10. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2008 Nov;47(9):901-6.

11. Drugs. 2012 Oct 22;72(15):1991-7.

12. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jan 13;364(2):105-15.

13. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jan 13;364(2):116-26.

14. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Aug;35(8):901-6.

Dr. Pichichero, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute, Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. He has no disclosures.

In December 2016, the results of a randomized, controlled trial of 5-day vs. 10-day amoxicillin/clavulanate treatment of acute otitis media (AOM) in children aged 6-23 months was reported by Hoberman et al. in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).1 Predefined criteria for clinical failure were used that considered both symptoms and signs of AOM, assessed on days 12-14 after start of treatment with 5 vs. 10 days of treatment with the antibiotic. The conclusion reached was clear: The clinical failure rate for the 5-day regimen was 34% vs. 16% in the 10-day group, supporting a preference for the 10-day treatment.

I was surprised. The clinical failure rate for the 5-day regimen seemed very high for treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanate. If it is 34% with amoxicillin/clavulanate, then what would it have been with amoxicillin, as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics?

So, why did the systematic review conclude that there was a minimal difference between shortened treatments and the standard 10-day when the NEJM study reported such a striking difference?

In Rochester, N.Y., we have been conducting a longitudinal, prospective study of AOM that is NIH-sponsored to better understand the immune response to AOM, especially in otitis-prone children.3,4 In that study we are treating all children aged 6-23 months with amoxicillin/clavulanate using the same dose as used in the study by Hoberman et al. We have two exceptions: If the child has a second AOM within 30 days of a prior episode or they have an eardrum rupture, we treat for 10 days.5 Our clinical failure rate is 6%. Why is the failure rate in Rochester so much lower than that in Pittsburgh and Bardstown, Ky., where the Hoberman et al. study was done?

One possibility is an important difference in our study design, compared with that of the NEJM study. All the children in our prospective study have a tympanocentesis to confirm the clinical diagnosis, and our research has shown that tympanocentesis results in immediate relief of ear pain and reduces the frequency of antibiotic treatment failure about twofold, compared with children diagnosed and treated by the same physicians in the same clinic practice.6 So, if the tympanocentesis is factored out of the equation, the Rochester clinical failure comes out to 14% for 5-day treatment. Why would the children in Rochester not getting a tympanocentesis, being treated with the same antibiotic, same dose, and same definition of clinical failure, during the same time frame, and having the same bacteria with the same antibiotic resistance rates have a clinical failure rate of 14%, compared with the 34% in the NEJM study?

Next question: How does a clinical failure rate of 34% fit according to past studies of shortened course antibiotic treatment of AOM? Besides the systematic review and meta-analysis noted above, in many countries outside the United States the 5-day regimen is standard, so, if health care providers were seeing a 34% failure rate, that would have been noticeable for sure.8 So, if health care providers were seeing a 34% failure rate, would that not have been noticeable? And would not a 16% failure rate, nearly 1 of 5 cases, be noticeable for children treated for 10 days?

Was there something different about the children who were in the Hoberman et al. study and the children treated in countries outside the United States and in our practice in Rochester? My group has collaborated and published on studies of AOM with the Pittsburgh and Kentucky groups, and we have not found significant site to site differences in outcomes, demonstrating that a population difference is unlikely.9-11

Next question: How does a clinical failure rate of 16% fit according to past studies of 10 days’ antibiotic treatment of AOM? It is on target with the meta-analysis and two other recent studies in the NEJM.12,13 However, if the failure rate was 16% with amoxicillin/clavulanate (which is effective against beta-lactamase–producing Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis, whereas amoxicillin is not), then the predicted failure rate with amoxicillin for 10 days should be double (34%) or triple (51%) had amoxicillin been used as recommended by the AAP in light of the bacterial resistance of otopathogens. That calculation is based on the prevalence of beta-lactamase–producing H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis in the Pittsburgh and Kentucky populations, the same prevalence seen in the Rochester population.” 14

So, I conclude that this wonderful study does not convince me to change my practice from standard use of 5-day amoxicillin/clavulanate treatment of AOM. Besides, outside of a study setting, most parents don’t give the full 10-day treatment. They stop when their child seems normal (a few days after starting treatment) and save the remainder of the medicine in the refrigerator for the next illness to save a trip to the doctor. Plus, in this column, I did not even get into the issue of disturbing the microbiome with longer courses of antibiotic treatment, a topic for a future discussion.

References

1. N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 22;375(25):2446-56.

2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Sep 8;(9):CD001095.

3. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Sep;35(9):1027-32.

4. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Sep;35(9):1033-9.

5. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001 Apr;124(4):381-7.

6. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013 May;32(5):473-8.

7. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006 Mar;25(3):211-8.

8. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000 Sep;19(9):929-37.

9. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999 Aug;18(8):741-4.

10. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2008 Nov;47(9):901-6.

11. Drugs. 2012 Oct 22;72(15):1991-7.

12. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jan 13;364(2):105-15.

13. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jan 13;364(2):116-26.

14. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Aug;35(8):901-6.

Dr. Pichichero, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute, Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. He has no disclosures.

Book Review: Psychiatrist rejects ‘physician as cog’ model of care

The title of the book, “Passion for Patients,” by Lee H. Beecher, MD, DLFAPA, FASAM, with writer Dave Racer, MLitt (St. Paul, Minn., Alethos Press, 2017), clearly represents Dr. Beecher’s approach to his professional life: His focal interest has been his patients ever since he went to medical school and started a very long and successful practice.

Dr. Beecher’s years of practice encompass many of the changes that the practice of medicine has seen in the last 50 years.

He attended medical school when an office was the place where a physician and his patients would get together to exchange thoughts, feelings, ideas, and plans so that they would eventually work together directly and unencumbered on the same concepts that they share and that they considered crucial to their relationship.

Shortly after Dr. Beecher graduated, Medicaid and Medicare came into medical practice, together with progressive limitations, threats, and a great many unwelcome interlopers, whose mission drastically changed the doctor-patient relationship. No matter how one examines the actions of the numerous new participants – be they auditors, insurance companies, employers, or money managers – one of their main missions was to modify, qualify, re-identify, and limit the interaction between the doctor and the patient.

“What is amazing – and contrary to truth – about the current evolution of medical care reform is its manifold references to safeguarding the best interests of the patient,” Dr. Beecher wrote. “On the contrary, the medical care reformers in current vogue see the physician as but one cog in the production of a specified medical care outcome – a cog that must be greased by evidence-based medicine and managed by analytical applications derived from data, cured in the crucible of number crunching, and controlled by payment systems.”

We live in an age when forces other than medical thinking and practice are trying to define what psychiatrists do, how we do it, and whether our effort is worth being paid for. This has created lack of satisfaction in the exercise of psychiatry, early retirements, and lack of growth in many quarters. When one considers that practically all psychiatric endeavors can be traced to the efforts of devoted practitioners interested in improving the profession, one can see that the future might look bleak because people other than psychiatrists define, quantify, and evaluate the practice of our specialty.

“I escaped from managed care into the practice model that had served so well for decades prior to HMOs, [preferred provider organizations], and other externally controlled practice models,” he wrote. “My patients paid me directly.”

Dr. Beecher is a witness and protester, as well as a thinking innovator, coming to defend patients and physicians at a time when they are under attack from precisely the same forces that were supposed to help and support them.

Throughout his book, Dr. Beecher tells us the story of his many points of disagreement with the intruders and his many arguments in favor of patients and doctors, going back to the beginning of the forces that are controlling and destroying their relationship at this time and advocating principled resistance and a careful search for independence. The reader easily accompanies the author to the points when independence blends with excellence – accepting that neither one exists without the other.

Dr. Muñoz, a former president of the American Psychiatric Association, has written eight books and more than 200 articles about various aspects of psychiatry. He is a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, and has a private practice. Dr. Muñoz and Dr. Beecher serve on the Editorial Advisory Board of Clinical Psychiatry News.

The title of the book, “Passion for Patients,” by Lee H. Beecher, MD, DLFAPA, FASAM, with writer Dave Racer, MLitt (St. Paul, Minn., Alethos Press, 2017), clearly represents Dr. Beecher’s approach to his professional life: His focal interest has been his patients ever since he went to medical school and started a very long and successful practice.

Dr. Beecher’s years of practice encompass many of the changes that the practice of medicine has seen in the last 50 years.

He attended medical school when an office was the place where a physician and his patients would get together to exchange thoughts, feelings, ideas, and plans so that they would eventually work together directly and unencumbered on the same concepts that they share and that they considered crucial to their relationship.

Shortly after Dr. Beecher graduated, Medicaid and Medicare came into medical practice, together with progressive limitations, threats, and a great many unwelcome interlopers, whose mission drastically changed the doctor-patient relationship. No matter how one examines the actions of the numerous new participants – be they auditors, insurance companies, employers, or money managers – one of their main missions was to modify, qualify, re-identify, and limit the interaction between the doctor and the patient.

“What is amazing – and contrary to truth – about the current evolution of medical care reform is its manifold references to safeguarding the best interests of the patient,” Dr. Beecher wrote. “On the contrary, the medical care reformers in current vogue see the physician as but one cog in the production of a specified medical care outcome – a cog that must be greased by evidence-based medicine and managed by analytical applications derived from data, cured in the crucible of number crunching, and controlled by payment systems.”

We live in an age when forces other than medical thinking and practice are trying to define what psychiatrists do, how we do it, and whether our effort is worth being paid for. This has created lack of satisfaction in the exercise of psychiatry, early retirements, and lack of growth in many quarters. When one considers that practically all psychiatric endeavors can be traced to the efforts of devoted practitioners interested in improving the profession, one can see that the future might look bleak because people other than psychiatrists define, quantify, and evaluate the practice of our specialty.

“I escaped from managed care into the practice model that had served so well for decades prior to HMOs, [preferred provider organizations], and other externally controlled practice models,” he wrote. “My patients paid me directly.”

Dr. Beecher is a witness and protester, as well as a thinking innovator, coming to defend patients and physicians at a time when they are under attack from precisely the same forces that were supposed to help and support them.

Throughout his book, Dr. Beecher tells us the story of his many points of disagreement with the intruders and his many arguments in favor of patients and doctors, going back to the beginning of the forces that are controlling and destroying their relationship at this time and advocating principled resistance and a careful search for independence. The reader easily accompanies the author to the points when independence blends with excellence – accepting that neither one exists without the other.

Dr. Muñoz, a former president of the American Psychiatric Association, has written eight books and more than 200 articles about various aspects of psychiatry. He is a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, and has a private practice. Dr. Muñoz and Dr. Beecher serve on the Editorial Advisory Board of Clinical Psychiatry News.

The title of the book, “Passion for Patients,” by Lee H. Beecher, MD, DLFAPA, FASAM, with writer Dave Racer, MLitt (St. Paul, Minn., Alethos Press, 2017), clearly represents Dr. Beecher’s approach to his professional life: His focal interest has been his patients ever since he went to medical school and started a very long and successful practice.

Dr. Beecher’s years of practice encompass many of the changes that the practice of medicine has seen in the last 50 years.

He attended medical school when an office was the place where a physician and his patients would get together to exchange thoughts, feelings, ideas, and plans so that they would eventually work together directly and unencumbered on the same concepts that they share and that they considered crucial to their relationship.

Shortly after Dr. Beecher graduated, Medicaid and Medicare came into medical practice, together with progressive limitations, threats, and a great many unwelcome interlopers, whose mission drastically changed the doctor-patient relationship. No matter how one examines the actions of the numerous new participants – be they auditors, insurance companies, employers, or money managers – one of their main missions was to modify, qualify, re-identify, and limit the interaction between the doctor and the patient.

“What is amazing – and contrary to truth – about the current evolution of medical care reform is its manifold references to safeguarding the best interests of the patient,” Dr. Beecher wrote. “On the contrary, the medical care reformers in current vogue see the physician as but one cog in the production of a specified medical care outcome – a cog that must be greased by evidence-based medicine and managed by analytical applications derived from data, cured in the crucible of number crunching, and controlled by payment systems.”

We live in an age when forces other than medical thinking and practice are trying to define what psychiatrists do, how we do it, and whether our effort is worth being paid for. This has created lack of satisfaction in the exercise of psychiatry, early retirements, and lack of growth in many quarters. When one considers that practically all psychiatric endeavors can be traced to the efforts of devoted practitioners interested in improving the profession, one can see that the future might look bleak because people other than psychiatrists define, quantify, and evaluate the practice of our specialty.

“I escaped from managed care into the practice model that had served so well for decades prior to HMOs, [preferred provider organizations], and other externally controlled practice models,” he wrote. “My patients paid me directly.”

Dr. Beecher is a witness and protester, as well as a thinking innovator, coming to defend patients and physicians at a time when they are under attack from precisely the same forces that were supposed to help and support them.

Throughout his book, Dr. Beecher tells us the story of his many points of disagreement with the intruders and his many arguments in favor of patients and doctors, going back to the beginning of the forces that are controlling and destroying their relationship at this time and advocating principled resistance and a careful search for independence. The reader easily accompanies the author to the points when independence blends with excellence – accepting that neither one exists without the other.

Dr. Muñoz, a former president of the American Psychiatric Association, has written eight books and more than 200 articles about various aspects of psychiatry. He is a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, and has a private practice. Dr. Muñoz and Dr. Beecher serve on the Editorial Advisory Board of Clinical Psychiatry News.

Wired to win

In 1929, an industrialist in Philadelphia whose factories had been plagued by vandalism sought to curtail the problem by organizing the boys in the community into athletic teams. Within a few years, his effort became Pop Warner Football. A few years later, a group of parents in Williamsport, Pa., started what was to become Little League Baseball.

Prior to the development of these two programs, kids organized their own games using shared equipment, if any at all. They drew foul lines and cobbled together goals in the bare dirt and the stubbly weeds of vacant lots and backyards. Kids shared equipment with each other. They picked teams in a manner that reflected the sometimes painful reality that some kids were proven winners and others were not. Rules were adjusted to fit the situation. Disagreements were settled without referees, or the game dissolved and a lesson was learned.

From its start in the 1930’s, the model of adult-organized and miniaturized versions of professional sports has spread from baseball and football to almost every team sport, including soccer, hockey, and lacrosse. Children may have been deprived of some self-organizing and negotiating skills, but, when one considers the electronically dominated sedentary alternatives, for the most part, adult-organized team youth sports have been a positive.

Of course, there have been some growing pains because an adult sport that has simply been miniaturized doesn’t necessarily fit well with young minds and bodies that are still developing. In some sports, adult/parent coaches now are required to undergo rigorous training in hopes of making the sport more child appropriate. However, the truth remains that, when teams compete, there are going to be winners and losers.

I recently read a newspaper article that included references to a few recent studies that suggest humans are hard wired to win (Sapolsky, Robert. “The Grim Truth Behind the ‘Winner Effect.’ ”The Wall Street Journal. Feb. 24, 2017). Well, not to win exactly but to be more likely to win again once they have been victorious, a phenomenon known as the “winner effect.”

A mouse that has been allowed to win a fixed fight with another mouse is more likely to win his next fight. Other studies on a variety of species, including humans, have found that winning can elevate testosterone levels and suppress stress-mediating hormones – winning boosts confidence and risk taking. More recent studies on zebra fish have demonstrated that a region of the habenula, a portion of the brain, seems to be critical for controlling these behaviors and chemical mediators.

Of course, the problem is that, when there are winners, there have to be losers. From time to time, the adult organizers have struggled with how to compensate for this unfortunate reality in the structure of their youth sports programs. One response has been to give every participant a trophy. Except when the children are so young that they don’t know which goal is theirs, however, awarding trophies to all is a transparent and foolish charade. The winners know who they are and so do the losers. Skillful and compassionate coaches of both winning and losing teams can cooperate to soften the cutting edge of competition, but it will never disappear. It should be fun to play, but it is always going to be more fun to win.

If there is a solution, it falls on the shoulders of parents, educators, and sometimes pediatricians to help the losers find environments and activities in which their skills and aptitudes will give them the greatest chance of enjoying the benefits of the “winner effect.” Winning isn’t everything, but it feels a lot better than losing. If we can help a child to win once – whether it is on the athletic field or in a classroom – it is more likely he or she will do it again.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

In 1929, an industrialist in Philadelphia whose factories had been plagued by vandalism sought to curtail the problem by organizing the boys in the community into athletic teams. Within a few years, his effort became Pop Warner Football. A few years later, a group of parents in Williamsport, Pa., started what was to become Little League Baseball.

Prior to the development of these two programs, kids organized their own games using shared equipment, if any at all. They drew foul lines and cobbled together goals in the bare dirt and the stubbly weeds of vacant lots and backyards. Kids shared equipment with each other. They picked teams in a manner that reflected the sometimes painful reality that some kids were proven winners and others were not. Rules were adjusted to fit the situation. Disagreements were settled without referees, or the game dissolved and a lesson was learned.

From its start in the 1930’s, the model of adult-organized and miniaturized versions of professional sports has spread from baseball and football to almost every team sport, including soccer, hockey, and lacrosse. Children may have been deprived of some self-organizing and negotiating skills, but, when one considers the electronically dominated sedentary alternatives, for the most part, adult-organized team youth sports have been a positive.

Of course, there have been some growing pains because an adult sport that has simply been miniaturized doesn’t necessarily fit well with young minds and bodies that are still developing. In some sports, adult/parent coaches now are required to undergo rigorous training in hopes of making the sport more child appropriate. However, the truth remains that, when teams compete, there are going to be winners and losers.

I recently read a newspaper article that included references to a few recent studies that suggest humans are hard wired to win (Sapolsky, Robert. “The Grim Truth Behind the ‘Winner Effect.’ ”The Wall Street Journal. Feb. 24, 2017). Well, not to win exactly but to be more likely to win again once they have been victorious, a phenomenon known as the “winner effect.”

A mouse that has been allowed to win a fixed fight with another mouse is more likely to win his next fight. Other studies on a variety of species, including humans, have found that winning can elevate testosterone levels and suppress stress-mediating hormones – winning boosts confidence and risk taking. More recent studies on zebra fish have demonstrated that a region of the habenula, a portion of the brain, seems to be critical for controlling these behaviors and chemical mediators.

Of course, the problem is that, when there are winners, there have to be losers. From time to time, the adult organizers have struggled with how to compensate for this unfortunate reality in the structure of their youth sports programs. One response has been to give every participant a trophy. Except when the children are so young that they don’t know which goal is theirs, however, awarding trophies to all is a transparent and foolish charade. The winners know who they are and so do the losers. Skillful and compassionate coaches of both winning and losing teams can cooperate to soften the cutting edge of competition, but it will never disappear. It should be fun to play, but it is always going to be more fun to win.

If there is a solution, it falls on the shoulders of parents, educators, and sometimes pediatricians to help the losers find environments and activities in which their skills and aptitudes will give them the greatest chance of enjoying the benefits of the “winner effect.” Winning isn’t everything, but it feels a lot better than losing. If we can help a child to win once – whether it is on the athletic field or in a classroom – it is more likely he or she will do it again.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

In 1929, an industrialist in Philadelphia whose factories had been plagued by vandalism sought to curtail the problem by organizing the boys in the community into athletic teams. Within a few years, his effort became Pop Warner Football. A few years later, a group of parents in Williamsport, Pa., started what was to become Little League Baseball.

Prior to the development of these two programs, kids organized their own games using shared equipment, if any at all. They drew foul lines and cobbled together goals in the bare dirt and the stubbly weeds of vacant lots and backyards. Kids shared equipment with each other. They picked teams in a manner that reflected the sometimes painful reality that some kids were proven winners and others were not. Rules were adjusted to fit the situation. Disagreements were settled without referees, or the game dissolved and a lesson was learned.

From its start in the 1930’s, the model of adult-organized and miniaturized versions of professional sports has spread from baseball and football to almost every team sport, including soccer, hockey, and lacrosse. Children may have been deprived of some self-organizing and negotiating skills, but, when one considers the electronically dominated sedentary alternatives, for the most part, adult-organized team youth sports have been a positive.

Of course, there have been some growing pains because an adult sport that has simply been miniaturized doesn’t necessarily fit well with young minds and bodies that are still developing. In some sports, adult/parent coaches now are required to undergo rigorous training in hopes of making the sport more child appropriate. However, the truth remains that, when teams compete, there are going to be winners and losers.

I recently read a newspaper article that included references to a few recent studies that suggest humans are hard wired to win (Sapolsky, Robert. “The Grim Truth Behind the ‘Winner Effect.’ ”The Wall Street Journal. Feb. 24, 2017). Well, not to win exactly but to be more likely to win again once they have been victorious, a phenomenon known as the “winner effect.”

A mouse that has been allowed to win a fixed fight with another mouse is more likely to win his next fight. Other studies on a variety of species, including humans, have found that winning can elevate testosterone levels and suppress stress-mediating hormones – winning boosts confidence and risk taking. More recent studies on zebra fish have demonstrated that a region of the habenula, a portion of the brain, seems to be critical for controlling these behaviors and chemical mediators.

Of course, the problem is that, when there are winners, there have to be losers. From time to time, the adult organizers have struggled with how to compensate for this unfortunate reality in the structure of their youth sports programs. One response has been to give every participant a trophy. Except when the children are so young that they don’t know which goal is theirs, however, awarding trophies to all is a transparent and foolish charade. The winners know who they are and so do the losers. Skillful and compassionate coaches of both winning and losing teams can cooperate to soften the cutting edge of competition, but it will never disappear. It should be fun to play, but it is always going to be more fun to win.

If there is a solution, it falls on the shoulders of parents, educators, and sometimes pediatricians to help the losers find environments and activities in which their skills and aptitudes will give them the greatest chance of enjoying the benefits of the “winner effect.” Winning isn’t everything, but it feels a lot better than losing. If we can help a child to win once – whether it is on the athletic field or in a classroom – it is more likely he or she will do it again.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Two boys, a dog, and our electronic health records

“Speak clearly, if you speak at all; carve every word before you let it fall.” – Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.

One of our favorite stories is that of two boys talking to one another with a dog sitting nearby. One boy says to the other, “I taught my dog how to whistle.” Skeptically, the other boy responds, “Really? I don’t hear him whistling.” The first boys then replies, “I said I taught him. I didn’t say he learned!”

We spend a lot of time as physicians going over information with our patients, yet, according to the best data available, they retain only a small portion of what we tell them. Medication adherence rates for chronic disease range from 30% to 70%, showing that many doses of important medications are missed. Patients often don’t even remember the last instructions we give them as they are walking out of the office. This raises questions about both the way we explain information and how we can use the tools at our disposal to enhance the communication so vital to patient outcomes.

Obviously, we need to consider our words carefully and focus on teaching, not just speaking. What sets teaching apart from speaking is consideration of the learner. The better we understand our patients’ perspectives, the better the knowledge transfer will be. A simple way to address this may be better eye contact.

We have all heard the expression “the eyes are a window to the soul.” Yet, we now have computers that acts as a virtual shades, covering that window and drawing our gaze away from our patients. These shades can blind us to important clues, impeding communication and leading to misunderstanding, missed opportunity, and even patient harm. This is why some practices have chosen to use scribes to handle documentation, freeing up physicians’ eyes and addressing another obstacle to communication: time.

One of the most cited complaints from physicians is lack of time. There is an ever-growing demand on us to see more patients, manage more data, and “check off more boxes” to meet bureaucratic requirements. It should come as no surprise that these impede good patient care. We are thankful that attempts to modernize payment models are recognizing this problem. For example, the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) helps to blaze the trail by focusing on care quality, practice improvement, and patient satisfaction for incentive payments. While these are early steps, they certainly point to a future more concerned with value than with volume.

As we move toward that future, we need to acknowledge that information technology can be both the problem and the answer. The current state of health IT is far from perfect. The tools we use have been designed, seemingly, around financial performance or developed to meet government requirements. It appears that neither physicians nor patients were consulted to ensure their usability or utility. Step No. 1 was getting EHRs out there. Steps 2-10 will be making them useful to clinicians, patients, and health care systems. Part of that utility will come in their ability to enhance communication.

Take patient portals, for example. The “meaningful use program” set as a requirement the ability for patients to “view, download, or transmit” their health information through electronic means. EHR vendors complied with this request but seem to have missed the intent of the measure. Patients accessing the information often are confronted with a morass of technical jargon and unfamiliar medical terms, which may even be offensive. For example, we recently spoke to a parent of a teenager with moderate intellectual disabilities. A hold-out ICD-9 code on the teen’s chart translated to her portal as “318.0 – Imbecile.” Her mother was appropriately upset, and she decided to leave the practice.

As we begin to understand technology’s advantages – and learn its pitfalls – we believe EHR vendors must enhance their offerings while engaging both providers and patients in the process of improvement. We also believe physicians need to leverage the entire care team to realize the software’s full potential. This approach may present new challenges in communication, but it also presents new opportunities. We hope that this collaborative approach will allow physicians to have more time to spend connecting with patients, leading to enhanced understanding and satisfaction.

Our knowledge of human health and disease is growing more sophisticated and so is the challenge of imparting that knowledge to patients. It is critical to find ways to do so that are relevant and understandable and give patients the tools they need to reinforce and remember what we say. This is one of the promises that we are just beginning to see fulfilled by modern EHR technology. Unlike the boy who was trying to teach his dog to whistle, our words have deep impact, and our roles as educators have never been more important.

This article was updated 3/24/17.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

“Speak clearly, if you speak at all; carve every word before you let it fall.” – Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.

One of our favorite stories is that of two boys talking to one another with a dog sitting nearby. One boy says to the other, “I taught my dog how to whistle.” Skeptically, the other boy responds, “Really? I don’t hear him whistling.” The first boys then replies, “I said I taught him. I didn’t say he learned!”

We spend a lot of time as physicians going over information with our patients, yet, according to the best data available, they retain only a small portion of what we tell them. Medication adherence rates for chronic disease range from 30% to 70%, showing that many doses of important medications are missed. Patients often don’t even remember the last instructions we give them as they are walking out of the office. This raises questions about both the way we explain information and how we can use the tools at our disposal to enhance the communication so vital to patient outcomes.

Obviously, we need to consider our words carefully and focus on teaching, not just speaking. What sets teaching apart from speaking is consideration of the learner. The better we understand our patients’ perspectives, the better the knowledge transfer will be. A simple way to address this may be better eye contact.

We have all heard the expression “the eyes are a window to the soul.” Yet, we now have computers that acts as a virtual shades, covering that window and drawing our gaze away from our patients. These shades can blind us to important clues, impeding communication and leading to misunderstanding, missed opportunity, and even patient harm. This is why some practices have chosen to use scribes to handle documentation, freeing up physicians’ eyes and addressing another obstacle to communication: time.

One of the most cited complaints from physicians is lack of time. There is an ever-growing demand on us to see more patients, manage more data, and “check off more boxes” to meet bureaucratic requirements. It should come as no surprise that these impede good patient care. We are thankful that attempts to modernize payment models are recognizing this problem. For example, the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) helps to blaze the trail by focusing on care quality, practice improvement, and patient satisfaction for incentive payments. While these are early steps, they certainly point to a future more concerned with value than with volume.

As we move toward that future, we need to acknowledge that information technology can be both the problem and the answer. The current state of health IT is far from perfect. The tools we use have been designed, seemingly, around financial performance or developed to meet government requirements. It appears that neither physicians nor patients were consulted to ensure their usability or utility. Step No. 1 was getting EHRs out there. Steps 2-10 will be making them useful to clinicians, patients, and health care systems. Part of that utility will come in their ability to enhance communication.

Take patient portals, for example. The “meaningful use program” set as a requirement the ability for patients to “view, download, or transmit” their health information through electronic means. EHR vendors complied with this request but seem to have missed the intent of the measure. Patients accessing the information often are confronted with a morass of technical jargon and unfamiliar medical terms, which may even be offensive. For example, we recently spoke to a parent of a teenager with moderate intellectual disabilities. A hold-out ICD-9 code on the teen’s chart translated to her portal as “318.0 – Imbecile.” Her mother was appropriately upset, and she decided to leave the practice.

As we begin to understand technology’s advantages – and learn its pitfalls – we believe EHR vendors must enhance their offerings while engaging both providers and patients in the process of improvement. We also believe physicians need to leverage the entire care team to realize the software’s full potential. This approach may present new challenges in communication, but it also presents new opportunities. We hope that this collaborative approach will allow physicians to have more time to spend connecting with patients, leading to enhanced understanding and satisfaction.

Our knowledge of human health and disease is growing more sophisticated and so is the challenge of imparting that knowledge to patients. It is critical to find ways to do so that are relevant and understandable and give patients the tools they need to reinforce and remember what we say. This is one of the promises that we are just beginning to see fulfilled by modern EHR technology. Unlike the boy who was trying to teach his dog to whistle, our words have deep impact, and our roles as educators have never been more important.

This article was updated 3/24/17.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

“Speak clearly, if you speak at all; carve every word before you let it fall.” – Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.

One of our favorite stories is that of two boys talking to one another with a dog sitting nearby. One boy says to the other, “I taught my dog how to whistle.” Skeptically, the other boy responds, “Really? I don’t hear him whistling.” The first boys then replies, “I said I taught him. I didn’t say he learned!”

We spend a lot of time as physicians going over information with our patients, yet, according to the best data available, they retain only a small portion of what we tell them. Medication adherence rates for chronic disease range from 30% to 70%, showing that many doses of important medications are missed. Patients often don’t even remember the last instructions we give them as they are walking out of the office. This raises questions about both the way we explain information and how we can use the tools at our disposal to enhance the communication so vital to patient outcomes.

Obviously, we need to consider our words carefully and focus on teaching, not just speaking. What sets teaching apart from speaking is consideration of the learner. The better we understand our patients’ perspectives, the better the knowledge transfer will be. A simple way to address this may be better eye contact.

We have all heard the expression “the eyes are a window to the soul.” Yet, we now have computers that acts as a virtual shades, covering that window and drawing our gaze away from our patients. These shades can blind us to important clues, impeding communication and leading to misunderstanding, missed opportunity, and even patient harm. This is why some practices have chosen to use scribes to handle documentation, freeing up physicians’ eyes and addressing another obstacle to communication: time.

One of the most cited complaints from physicians is lack of time. There is an ever-growing demand on us to see more patients, manage more data, and “check off more boxes” to meet bureaucratic requirements. It should come as no surprise that these impede good patient care. We are thankful that attempts to modernize payment models are recognizing this problem. For example, the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) helps to blaze the trail by focusing on care quality, practice improvement, and patient satisfaction for incentive payments. While these are early steps, they certainly point to a future more concerned with value than with volume.

As we move toward that future, we need to acknowledge that information technology can be both the problem and the answer. The current state of health IT is far from perfect. The tools we use have been designed, seemingly, around financial performance or developed to meet government requirements. It appears that neither physicians nor patients were consulted to ensure their usability or utility. Step No. 1 was getting EHRs out there. Steps 2-10 will be making them useful to clinicians, patients, and health care systems. Part of that utility will come in their ability to enhance communication.

Take patient portals, for example. The “meaningful use program” set as a requirement the ability for patients to “view, download, or transmit” their health information through electronic means. EHR vendors complied with this request but seem to have missed the intent of the measure. Patients accessing the information often are confronted with a morass of technical jargon and unfamiliar medical terms, which may even be offensive. For example, we recently spoke to a parent of a teenager with moderate intellectual disabilities. A hold-out ICD-9 code on the teen’s chart translated to her portal as “318.0 – Imbecile.” Her mother was appropriately upset, and she decided to leave the practice.

As we begin to understand technology’s advantages – and learn its pitfalls – we believe EHR vendors must enhance their offerings while engaging both providers and patients in the process of improvement. We also believe physicians need to leverage the entire care team to realize the software’s full potential. This approach may present new challenges in communication, but it also presents new opportunities. We hope that this collaborative approach will allow physicians to have more time to spend connecting with patients, leading to enhanced understanding and satisfaction.

Our knowledge of human health and disease is growing more sophisticated and so is the challenge of imparting that knowledge to patients. It is critical to find ways to do so that are relevant and understandable and give patients the tools they need to reinforce and remember what we say. This is one of the promises that we are just beginning to see fulfilled by modern EHR technology. Unlike the boy who was trying to teach his dog to whistle, our words have deep impact, and our roles as educators have never been more important.

This article was updated 3/24/17.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

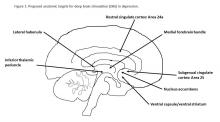

Depression and deep brain stimulation: ‘Furor therapeuticus redux’

Looking back after a long and distinguished career, Leon Eisenberg, MD, invoked the term “furor therapeuticus” to describe overzealous treatment by doctors who became frustrated with therapeutic limitations or motivated by professional enthusiasm.1

With this in mind, Dr. Eisenberg criticized expansive marketing and prescribing of psychotropic drugs in an editorial published exactly 10 years ago. He might also have questioned the current interest in deep brain stimulation (DBS) as a treatment for depression and a growing list of behavioral disorders. Initial studies of DBS in depression were promising, but recent setbacks have brought research to a scientific and ethical crossroads that compels broader discussion.

Besides uncertainties over the right targets to stimulate, identification of the right candidates for DBS treatment can be difficult. Trials of DBS recruited highly selected depressed subjects with no consensus on symptoms or biomarkers that could be used to predict who might respond. Doctors still rely on clinical symptoms to distinguish patients with melancholic depression, who respond to medications or electroconvulsive therapy and might also respond to DBS, from patients with depressed mood because of psychosocial problems, who respond to psychotherapy or social interventions.

Evidence on the efficacy and safety of DBS in depression is mixed. Initial open trials were promising, with dramatic and sustained recovery in some patients, but they were limited by small numbers of subjects and a lack of randomized controls and standardized methods.4,5

DBS is not without serious side effects, and substantial maintenance costs are not always covered by insurance. So, two recent industry trials were eagerly anticipated but showed no significant differences between active and sham stimulations in depression.6,7 These disappointing results prompted soul-searching among investigators, who presented ingenious ideas for correcting shortcomings that could be tested in future trials but also raised doubts as to the prospects of DBS in depression.4,5

Given that DBS devices already are marketed for neurological disorders, regulation of practice is crucial to prevent off-label misuse in behavioral disorders.8 Federal agencies enforce rules governing DBS devices but rely on investigators and local review boards in research and on voluntary postmarketing reports by individual practitioners to monitor compliance and safety. Unscrupulous commercial interests could expand the market for these devices, as demonstrated by the proliferation of psychotropic drug prescribing decried by Dr. Eisenberg. DBS also must be restricted to specialized teams and medical centers to prevent inappropriate implantation by poorly trained providers.

Because behavioral disorders exact an enormous toll on patients, families, and society, better access to effective care and the search for better treatments must remain public health priorities.

Transformative, breakthrough discoveries in brain research will undoubtedly lead to improvements in treatment, including surgical devices in some cases, but, DBS is at risk of being exaggerated and oversold. Adverse consequences of misuse could provoke a public backlash that would have a chilling effect on vital brain research.

One possible way to prevent this is the risk evaluation and mitigation strategy established by the Food and Drug Administration to manage high-risk pharmaceuticals. The FDA mandates that certain high-risk drugs can be prescribed only if doctors are certified and only if patients are enrolled in a national registry where eligibility, course, and outcome are monitored. A similar mechanism should apply to high-risk surgical devices when used for behavioral disorders.9,10

People with behavioral disorders deserve the right to volunteer for experimental programs that offer hope of recovery for themselves and future generations, but they also deserve to be treated with the utmost scientific rigor and protection that society can provide.

Dr. Caroff is emeritus professor of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He has received research grant funding from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals and serves as a consultant to Neurocrine Biosciences and TEVA.

References

1. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(4):552-5

2. Curr Behav Neurosci Rep. 2014;1(2):55-63

3. J Affect Disord. 2014;156:1-7

4. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;739(5):439-40

5. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):e9-10

6. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2015;93:366-9

7. Neurotherapeutics. 2014;11(3):475-84

8. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(9):1003-8

9. Brain Stimul. 2012;5(4):653-5

10. Fed Reg. 1977 May 23;42(99):26318-32

Looking back after a long and distinguished career, Leon Eisenberg, MD, invoked the term “furor therapeuticus” to describe overzealous treatment by doctors who became frustrated with therapeutic limitations or motivated by professional enthusiasm.1

With this in mind, Dr. Eisenberg criticized expansive marketing and prescribing of psychotropic drugs in an editorial published exactly 10 years ago. He might also have questioned the current interest in deep brain stimulation (DBS) as a treatment for depression and a growing list of behavioral disorders. Initial studies of DBS in depression were promising, but recent setbacks have brought research to a scientific and ethical crossroads that compels broader discussion.

Besides uncertainties over the right targets to stimulate, identification of the right candidates for DBS treatment can be difficult. Trials of DBS recruited highly selected depressed subjects with no consensus on symptoms or biomarkers that could be used to predict who might respond. Doctors still rely on clinical symptoms to distinguish patients with melancholic depression, who respond to medications or electroconvulsive therapy and might also respond to DBS, from patients with depressed mood because of psychosocial problems, who respond to psychotherapy or social interventions.

Evidence on the efficacy and safety of DBS in depression is mixed. Initial open trials were promising, with dramatic and sustained recovery in some patients, but they were limited by small numbers of subjects and a lack of randomized controls and standardized methods.4,5

DBS is not without serious side effects, and substantial maintenance costs are not always covered by insurance. So, two recent industry trials were eagerly anticipated but showed no significant differences between active and sham stimulations in depression.6,7 These disappointing results prompted soul-searching among investigators, who presented ingenious ideas for correcting shortcomings that could be tested in future trials but also raised doubts as to the prospects of DBS in depression.4,5

Given that DBS devices already are marketed for neurological disorders, regulation of practice is crucial to prevent off-label misuse in behavioral disorders.8 Federal agencies enforce rules governing DBS devices but rely on investigators and local review boards in research and on voluntary postmarketing reports by individual practitioners to monitor compliance and safety. Unscrupulous commercial interests could expand the market for these devices, as demonstrated by the proliferation of psychotropic drug prescribing decried by Dr. Eisenberg. DBS also must be restricted to specialized teams and medical centers to prevent inappropriate implantation by poorly trained providers.

Because behavioral disorders exact an enormous toll on patients, families, and society, better access to effective care and the search for better treatments must remain public health priorities.

Transformative, breakthrough discoveries in brain research will undoubtedly lead to improvements in treatment, including surgical devices in some cases, but, DBS is at risk of being exaggerated and oversold. Adverse consequences of misuse could provoke a public backlash that would have a chilling effect on vital brain research.

One possible way to prevent this is the risk evaluation and mitigation strategy established by the Food and Drug Administration to manage high-risk pharmaceuticals. The FDA mandates that certain high-risk drugs can be prescribed only if doctors are certified and only if patients are enrolled in a national registry where eligibility, course, and outcome are monitored. A similar mechanism should apply to high-risk surgical devices when used for behavioral disorders.9,10

People with behavioral disorders deserve the right to volunteer for experimental programs that offer hope of recovery for themselves and future generations, but they also deserve to be treated with the utmost scientific rigor and protection that society can provide.

Dr. Caroff is emeritus professor of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He has received research grant funding from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals and serves as a consultant to Neurocrine Biosciences and TEVA.

References

1. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(4):552-5

2. Curr Behav Neurosci Rep. 2014;1(2):55-63

3. J Affect Disord. 2014;156:1-7

4. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;739(5):439-40

5. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):e9-10

6. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2015;93:366-9

7. Neurotherapeutics. 2014;11(3):475-84

8. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(9):1003-8

9. Brain Stimul. 2012;5(4):653-5

10. Fed Reg. 1977 May 23;42(99):26318-32

Looking back after a long and distinguished career, Leon Eisenberg, MD, invoked the term “furor therapeuticus” to describe overzealous treatment by doctors who became frustrated with therapeutic limitations or motivated by professional enthusiasm.1

With this in mind, Dr. Eisenberg criticized expansive marketing and prescribing of psychotropic drugs in an editorial published exactly 10 years ago. He might also have questioned the current interest in deep brain stimulation (DBS) as a treatment for depression and a growing list of behavioral disorders. Initial studies of DBS in depression were promising, but recent setbacks have brought research to a scientific and ethical crossroads that compels broader discussion.

Besides uncertainties over the right targets to stimulate, identification of the right candidates for DBS treatment can be difficult. Trials of DBS recruited highly selected depressed subjects with no consensus on symptoms or biomarkers that could be used to predict who might respond. Doctors still rely on clinical symptoms to distinguish patients with melancholic depression, who respond to medications or electroconvulsive therapy and might also respond to DBS, from patients with depressed mood because of psychosocial problems, who respond to psychotherapy or social interventions.

Evidence on the efficacy and safety of DBS in depression is mixed. Initial open trials were promising, with dramatic and sustained recovery in some patients, but they were limited by small numbers of subjects and a lack of randomized controls and standardized methods.4,5

DBS is not without serious side effects, and substantial maintenance costs are not always covered by insurance. So, two recent industry trials were eagerly anticipated but showed no significant differences between active and sham stimulations in depression.6,7 These disappointing results prompted soul-searching among investigators, who presented ingenious ideas for correcting shortcomings that could be tested in future trials but also raised doubts as to the prospects of DBS in depression.4,5

Given that DBS devices already are marketed for neurological disorders, regulation of practice is crucial to prevent off-label misuse in behavioral disorders.8 Federal agencies enforce rules governing DBS devices but rely on investigators and local review boards in research and on voluntary postmarketing reports by individual practitioners to monitor compliance and safety. Unscrupulous commercial interests could expand the market for these devices, as demonstrated by the proliferation of psychotropic drug prescribing decried by Dr. Eisenberg. DBS also must be restricted to specialized teams and medical centers to prevent inappropriate implantation by poorly trained providers.

Because behavioral disorders exact an enormous toll on patients, families, and society, better access to effective care and the search for better treatments must remain public health priorities.

Transformative, breakthrough discoveries in brain research will undoubtedly lead to improvements in treatment, including surgical devices in some cases, but, DBS is at risk of being exaggerated and oversold. Adverse consequences of misuse could provoke a public backlash that would have a chilling effect on vital brain research.

One possible way to prevent this is the risk evaluation and mitigation strategy established by the Food and Drug Administration to manage high-risk pharmaceuticals. The FDA mandates that certain high-risk drugs can be prescribed only if doctors are certified and only if patients are enrolled in a national registry where eligibility, course, and outcome are monitored. A similar mechanism should apply to high-risk surgical devices when used for behavioral disorders.9,10

People with behavioral disorders deserve the right to volunteer for experimental programs that offer hope of recovery for themselves and future generations, but they also deserve to be treated with the utmost scientific rigor and protection that society can provide.

Dr. Caroff is emeritus professor of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He has received research grant funding from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals and serves as a consultant to Neurocrine Biosciences and TEVA.

References

1. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(4):552-5

2. Curr Behav Neurosci Rep. 2014;1(2):55-63

3. J Affect Disord. 2014;156:1-7

4. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;739(5):439-40

5. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):e9-10

6. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2015;93:366-9

7. Neurotherapeutics. 2014;11(3):475-84

8. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(9):1003-8

9. Brain Stimul. 2012;5(4):653-5

10. Fed Reg. 1977 May 23;42(99):26318-32

Acute Department Syndrome

In this issue of Emergency Medicine, Greg Weingart, MD, and Shravan Kumar, MD, guide readers through the diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of acute compartment syndrome, a relatively uncommon but devastating injury that may affect an extremity following a long bone fracture, deep vein thrombosis, or rhabdomyolysis from crush injuries or high-intensity exercising. Compartment syndrome occurs when increased pressure within a limited anatomic space compresses the circulation and tissue within that space until function becomes impossible. Even with heightened awareness of the disastrous sequelae, and with very early pressure monitoring of the injured compartment, physicians are at a loss to effectively intervene to prevent the continuing rise in pressure until a fasciotomy is required.

The disastrous consequences of rising pressure in a closed space suggests what can occur in the severely overcrowded EDs that now are common in every city in this country—EDs with too many patients waiting for treatment and inpatient beds.

Pressure on the nation’s ED capacity has been steadily increasing for the past three decades. Hospital/ED closings, demand for preadmission testing by managed care and primary care physicians, increasing numbers of documented and undocumented people seeking care, a rapidly aging population with more comorbidities, and increased numbers of patients seeking care under the Affordable Care Act have not been met with a commensurate increase in ED capacity. Between 1990 and 2010, the country’s urban and suburban areas lost one quarter of their hospital EDs (Hsia RY et al. JAMA. 2011;305[19]:1978-1985). In that same period, New York City lost 20 hospitals and about 5,000 inpatient beds; after 2010, when the state stopped bailing out financially failing hospitals, four more hospitals closed and were replaced by three freestanding EDs (FSEDs). Though FSEDs may partially fulfill the need for 24/7 emergency care at their former hospital sites, when patients in FSEDs require admission, they must compete with patients in hospital-based EDs for inpatient beds.

Despite the many and varied sources of increasing numbers of patients arriving in EDs, by all accounts this influx in and of itself is not the major driver of ED overcrowding. Trained, competent EPs, supported by skilled and highly motivated RNs, NPs, and PAs, are capable of efficiently managing even frequent surges in patient volume—as long as the “outflow” is not blocked. In many cases, this means having adequate, timely outpatient follow-up available to allow for safe discharge. But overwhelmingly, it means having adequate numbers of inpatient beds.

The discomfort and loss of privacy that patients experience from spending many hours or days on hallway stretchers are bad enough, but eventually patient safety also becomes a concern. With some creative approaches varying by location and circumstances, EPs have generally been able to successfully address the safety issues—so far. For example, many years ago, we began holding in reserve a small portion of our fee-for-service EM revenue available to supplement the hospital-provided base salaries. By frequently monitoring conditions throughout the day, taking into account rate of registration in the ED, day of the week, OR schedules, etc, we were able to decide before noon whether there was a need to offer 4, 6, or 8 evening/night hours at double the hourly sessional rate to the first EPs, PAs, and NPs in our group who responded to the e-mails. The hours worked did not earn these “first responders” any additional “RVU” credits as, for the most part, they were working closely with the inpatient services to moni

In this issue of Emergency Medicine, Greg Weingart, MD, and Shravan Kumar, MD, guide readers through the diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of acute compartment syndrome, a relatively uncommon but devastating injury that may affect an extremity following a long bone fracture, deep vein thrombosis, or rhabdomyolysis from crush injuries or high-intensity exercising. Compartment syndrome occurs when increased pressure within a limited anatomic space compresses the circulation and tissue within that space until function becomes impossible. Even with heightened awareness of the disastrous sequelae, and with very early pressure monitoring of the injured compartment, physicians are at a loss to effectively intervene to prevent the continuing rise in pressure until a fasciotomy is required.

The disastrous consequences of rising pressure in a closed space suggests what can occur in the severely overcrowded EDs that now are common in every city in this country—EDs with too many patients waiting for treatment and inpatient beds.

Pressure on the nation’s ED capacity has been steadily increasing for the past three decades. Hospital/ED closings, demand for preadmission testing by managed care and primary care physicians, increasing numbers of documented and undocumented people seeking care, a rapidly aging population with more comorbidities, and increased numbers of patients seeking care under the Affordable Care Act have not been met with a commensurate increase in ED capacity. Between 1990 and 2010, the country’s urban and suburban areas lost one quarter of their hospital EDs (Hsia RY et al. JAMA. 2011;305[19]:1978-1985). In that same period, New York City lost 20 hospitals and about 5,000 inpatient beds; after 2010, when the state stopped bailing out financially failing hospitals, four more hospitals closed and were replaced by three freestanding EDs (FSEDs). Though FSEDs may partially fulfill the need for 24/7 emergency care at their former hospital sites, when patients in FSEDs require admission, they must compete with patients in hospital-based EDs for inpatient beds.

Despite the many and varied sources of increasing numbers of patients arriving in EDs, by all accounts this influx in and of itself is not the major driver of ED overcrowding. Trained, competent EPs, supported by skilled and highly motivated RNs, NPs, and PAs, are capable of efficiently managing even frequent surges in patient volume—as long as the “outflow” is not blocked. In many cases, this means having adequate, timely outpatient follow-up available to allow for safe discharge. But overwhelmingly, it means having adequate numbers of inpatient beds.