User login

Antibiotic prophylaxis for artificial joints

A 66-year-old woman 3 years status post hip replacement is seen for dental work. The dentist contacts the clinic for an antibiotic prescription. The patient has a penicillin allergy (rash). What do you recommend?

A. Clindamycin one dose before dental work.

B. Amoxicillin one dose before dental work.

C. Amoxicillin one dose before, one dose 4 hours after dental work.

D. Clindamycin one dose before dental work, one dose 4 hours after dental work.

E. No antibiotics.

Many patients with prosthetic joints will request antibiotics to take prior to dental procedures. Sometimes this request comes from the dental office.

When I ask patients why they feel they need antibiotics, they often reply that they were told by their orthopedic surgeons or their dentist that they would need to take antibiotics before dental procedures.

In an era when Clostridium difficile infection is a common and dangerous complication in the elderly, avoidance of unnecessary antibiotics is critical. In the United States, it is estimated that there are 240,000 patients infected with C. difficile annually, with 24,000 deaths at a cost of $6 billion.1

Is there compelling evidence to justify giving antibiotic prophylaxis for dental procedures to patients with prosthetic joints?

This information has called into question the wisdom of giving antibiotic prophylaxis for dental procedures when the same patients have transient bacteremias as a regular part of day-to-day life, and mouth organisms were infrequent causes of prosthetic joint infections.

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) and the American Dental Association (ADA) released an advisory statement 20 years ago on antibiotic prophylaxis for patients with dental replacements, which concluded: “Antibiotic prophylaxis is not indicated for dental patients with pins, plates, and screws, nor is it routinely indicated for most dental patients with total joint replacements.”4

In 2003, the AAOS and the ADA released updated guidelines that stated: “Presently, no scientific evidence supports the position that antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent hematogenous infections is required prior to dental treatment in patients with total joint prostheses. The risk/benefit and cost/effectiveness ratios fail to justify the administration of routine antibiotics.”5

Great confusion arose in 2009 when the AAOS published a position paper on its website that reversed this position.6 Interestingly, the statement was done by the AAOS alone, and not done in conjunction with the ADA.

In this position paper, the AAOS recommended that health care providers consider antibiotic prophylaxis prior to invasive procedures on all patients who had prosthetic joints, regardless of how long those joints have been in place. This major change in recommendations was not based on any new evidence that had been reviewed since the 2003 guidelines.

There are two studies that address outcome of patients with prosthetic joints who have and have not received prophylactic antibiotics.

Elie Berbari, MD, and colleagues reported on the results of a prospective case-control study comparing patients with prosthetic joints hospitalized with hip or knee infections with patients who had prosthetic joints hospitalized at the same time who did not have hip or knee infections.7

There was no increased risk of prosthetic hip or knee infection for patients undergoing a dental procedure who were not receiving antibiotic prophylaxis (odds ratio, 0.8; 95% confidence interval, 0.4-1.6), compared with the risk for patients not undergoing a dental procedure (OR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.4-1.1). Antibiotic prophylaxis in patients undergoing high and low risk dental procedures did not decrease the risk of prosthetic joint infections.

In 2012, the AAOS and the ADA published updated guidelines with the following summary recommendation: “The practitioner might consider discontinuing the practice of routinely prescribing prophylactic antibiotics for patients with hip and knee prosthetic joint implants undergoing dental procedures.”8 They referenced the Berbari study as the best available evidence.

Feng-Chen Kao, MD, and colleagues published a study this year with a design very similar to the Berbari study, with similar results.9 All Taiwanese residents who had received hip or knee replacements over a 12-year period were screened. Those who had received dental procedures were matched with individuals who had not had dental procedures. The dental procedure group was subdivided into a group that received antibiotics and one that didn’t.

There was no difference in infection rates between the group that had received dental procedures and the group that did not, and no difference in infection rates between those who received prophylactic antibiotics and those who didn’t.

I think this myth can be put to rest. There is no evidence to give patients with joint prostheses prophylactic antibiotics before dental procedures.

References

1. Steckelberg J.M., Osmon D.R. Prosthetic joint infections. In: Bisno A.L., Waldvogel F.A., eds. Infections associated with indwelling medical devices. Third ed., Washington, D.C.: American Society of Microbiology Press, 2000:173-209.

2. J Dent Res. 2004 Feb;83(2):170-4.

3. J Clin Periodontol. 2006 Feb;33(6):401-7.

4. J Am Dent Assoc. 1997 Jul;128(7):1004-8.

5. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003 Jul;134(7):895-9.

6. Spec Care Dentist. 2009 Nov-Dec;29(6):229-31.

7. Clin Infect Dis. 2010 Jan 1;50(1):8-16.

8. J Dent (Shiraz). 2013 Mar;14(1):49-52.

9. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017 Feb;38(2):154-61.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

A 66-year-old woman 3 years status post hip replacement is seen for dental work. The dentist contacts the clinic for an antibiotic prescription. The patient has a penicillin allergy (rash). What do you recommend?

A. Clindamycin one dose before dental work.

B. Amoxicillin one dose before dental work.

C. Amoxicillin one dose before, one dose 4 hours after dental work.

D. Clindamycin one dose before dental work, one dose 4 hours after dental work.

E. No antibiotics.

Many patients with prosthetic joints will request antibiotics to take prior to dental procedures. Sometimes this request comes from the dental office.

When I ask patients why they feel they need antibiotics, they often reply that they were told by their orthopedic surgeons or their dentist that they would need to take antibiotics before dental procedures.

In an era when Clostridium difficile infection is a common and dangerous complication in the elderly, avoidance of unnecessary antibiotics is critical. In the United States, it is estimated that there are 240,000 patients infected with C. difficile annually, with 24,000 deaths at a cost of $6 billion.1

Is there compelling evidence to justify giving antibiotic prophylaxis for dental procedures to patients with prosthetic joints?

This information has called into question the wisdom of giving antibiotic prophylaxis for dental procedures when the same patients have transient bacteremias as a regular part of day-to-day life, and mouth organisms were infrequent causes of prosthetic joint infections.

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) and the American Dental Association (ADA) released an advisory statement 20 years ago on antibiotic prophylaxis for patients with dental replacements, which concluded: “Antibiotic prophylaxis is not indicated for dental patients with pins, plates, and screws, nor is it routinely indicated for most dental patients with total joint replacements.”4

In 2003, the AAOS and the ADA released updated guidelines that stated: “Presently, no scientific evidence supports the position that antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent hematogenous infections is required prior to dental treatment in patients with total joint prostheses. The risk/benefit and cost/effectiveness ratios fail to justify the administration of routine antibiotics.”5

Great confusion arose in 2009 when the AAOS published a position paper on its website that reversed this position.6 Interestingly, the statement was done by the AAOS alone, and not done in conjunction with the ADA.

In this position paper, the AAOS recommended that health care providers consider antibiotic prophylaxis prior to invasive procedures on all patients who had prosthetic joints, regardless of how long those joints have been in place. This major change in recommendations was not based on any new evidence that had been reviewed since the 2003 guidelines.

There are two studies that address outcome of patients with prosthetic joints who have and have not received prophylactic antibiotics.

Elie Berbari, MD, and colleagues reported on the results of a prospective case-control study comparing patients with prosthetic joints hospitalized with hip or knee infections with patients who had prosthetic joints hospitalized at the same time who did not have hip or knee infections.7

There was no increased risk of prosthetic hip or knee infection for patients undergoing a dental procedure who were not receiving antibiotic prophylaxis (odds ratio, 0.8; 95% confidence interval, 0.4-1.6), compared with the risk for patients not undergoing a dental procedure (OR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.4-1.1). Antibiotic prophylaxis in patients undergoing high and low risk dental procedures did not decrease the risk of prosthetic joint infections.

In 2012, the AAOS and the ADA published updated guidelines with the following summary recommendation: “The practitioner might consider discontinuing the practice of routinely prescribing prophylactic antibiotics for patients with hip and knee prosthetic joint implants undergoing dental procedures.”8 They referenced the Berbari study as the best available evidence.

Feng-Chen Kao, MD, and colleagues published a study this year with a design very similar to the Berbari study, with similar results.9 All Taiwanese residents who had received hip or knee replacements over a 12-year period were screened. Those who had received dental procedures were matched with individuals who had not had dental procedures. The dental procedure group was subdivided into a group that received antibiotics and one that didn’t.

There was no difference in infection rates between the group that had received dental procedures and the group that did not, and no difference in infection rates between those who received prophylactic antibiotics and those who didn’t.

I think this myth can be put to rest. There is no evidence to give patients with joint prostheses prophylactic antibiotics before dental procedures.

References

1. Steckelberg J.M., Osmon D.R. Prosthetic joint infections. In: Bisno A.L., Waldvogel F.A., eds. Infections associated with indwelling medical devices. Third ed., Washington, D.C.: American Society of Microbiology Press, 2000:173-209.

2. J Dent Res. 2004 Feb;83(2):170-4.

3. J Clin Periodontol. 2006 Feb;33(6):401-7.

4. J Am Dent Assoc. 1997 Jul;128(7):1004-8.

5. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003 Jul;134(7):895-9.

6. Spec Care Dentist. 2009 Nov-Dec;29(6):229-31.

7. Clin Infect Dis. 2010 Jan 1;50(1):8-16.

8. J Dent (Shiraz). 2013 Mar;14(1):49-52.

9. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017 Feb;38(2):154-61.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

A 66-year-old woman 3 years status post hip replacement is seen for dental work. The dentist contacts the clinic for an antibiotic prescription. The patient has a penicillin allergy (rash). What do you recommend?

A. Clindamycin one dose before dental work.

B. Amoxicillin one dose before dental work.

C. Amoxicillin one dose before, one dose 4 hours after dental work.

D. Clindamycin one dose before dental work, one dose 4 hours after dental work.

E. No antibiotics.

Many patients with prosthetic joints will request antibiotics to take prior to dental procedures. Sometimes this request comes from the dental office.

When I ask patients why they feel they need antibiotics, they often reply that they were told by their orthopedic surgeons or their dentist that they would need to take antibiotics before dental procedures.

In an era when Clostridium difficile infection is a common and dangerous complication in the elderly, avoidance of unnecessary antibiotics is critical. In the United States, it is estimated that there are 240,000 patients infected with C. difficile annually, with 24,000 deaths at a cost of $6 billion.1

Is there compelling evidence to justify giving antibiotic prophylaxis for dental procedures to patients with prosthetic joints?

This information has called into question the wisdom of giving antibiotic prophylaxis for dental procedures when the same patients have transient bacteremias as a regular part of day-to-day life, and mouth organisms were infrequent causes of prosthetic joint infections.

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) and the American Dental Association (ADA) released an advisory statement 20 years ago on antibiotic prophylaxis for patients with dental replacements, which concluded: “Antibiotic prophylaxis is not indicated for dental patients with pins, plates, and screws, nor is it routinely indicated for most dental patients with total joint replacements.”4

In 2003, the AAOS and the ADA released updated guidelines that stated: “Presently, no scientific evidence supports the position that antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent hematogenous infections is required prior to dental treatment in patients with total joint prostheses. The risk/benefit and cost/effectiveness ratios fail to justify the administration of routine antibiotics.”5

Great confusion arose in 2009 when the AAOS published a position paper on its website that reversed this position.6 Interestingly, the statement was done by the AAOS alone, and not done in conjunction with the ADA.

In this position paper, the AAOS recommended that health care providers consider antibiotic prophylaxis prior to invasive procedures on all patients who had prosthetic joints, regardless of how long those joints have been in place. This major change in recommendations was not based on any new evidence that had been reviewed since the 2003 guidelines.

There are two studies that address outcome of patients with prosthetic joints who have and have not received prophylactic antibiotics.

Elie Berbari, MD, and colleagues reported on the results of a prospective case-control study comparing patients with prosthetic joints hospitalized with hip or knee infections with patients who had prosthetic joints hospitalized at the same time who did not have hip or knee infections.7

There was no increased risk of prosthetic hip or knee infection for patients undergoing a dental procedure who were not receiving antibiotic prophylaxis (odds ratio, 0.8; 95% confidence interval, 0.4-1.6), compared with the risk for patients not undergoing a dental procedure (OR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.4-1.1). Antibiotic prophylaxis in patients undergoing high and low risk dental procedures did not decrease the risk of prosthetic joint infections.

In 2012, the AAOS and the ADA published updated guidelines with the following summary recommendation: “The practitioner might consider discontinuing the practice of routinely prescribing prophylactic antibiotics for patients with hip and knee prosthetic joint implants undergoing dental procedures.”8 They referenced the Berbari study as the best available evidence.

Feng-Chen Kao, MD, and colleagues published a study this year with a design very similar to the Berbari study, with similar results.9 All Taiwanese residents who had received hip or knee replacements over a 12-year period were screened. Those who had received dental procedures were matched with individuals who had not had dental procedures. The dental procedure group was subdivided into a group that received antibiotics and one that didn’t.

There was no difference in infection rates between the group that had received dental procedures and the group that did not, and no difference in infection rates between those who received prophylactic antibiotics and those who didn’t.

I think this myth can be put to rest. There is no evidence to give patients with joint prostheses prophylactic antibiotics before dental procedures.

References

1. Steckelberg J.M., Osmon D.R. Prosthetic joint infections. In: Bisno A.L., Waldvogel F.A., eds. Infections associated with indwelling medical devices. Third ed., Washington, D.C.: American Society of Microbiology Press, 2000:173-209.

2. J Dent Res. 2004 Feb;83(2):170-4.

3. J Clin Periodontol. 2006 Feb;33(6):401-7.

4. J Am Dent Assoc. 1997 Jul;128(7):1004-8.

5. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003 Jul;134(7):895-9.

6. Spec Care Dentist. 2009 Nov-Dec;29(6):229-31.

7. Clin Infect Dis. 2010 Jan 1;50(1):8-16.

8. J Dent (Shiraz). 2013 Mar;14(1):49-52.

9. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017 Feb;38(2):154-61.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

Adverse childhood experiences

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are the traumatic experiences in a person’s life occurring before the age of 18 years that the person remembers as an adult and that have consequences on a diverse set of outcomes. ACEs include physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, mental illness of a household member, problematic drinking or alcoholism of a household member, illegal street or prescription drug use by a household member, divorce or separation of a parent, domestic violence toward a parent, and incarceration of a household member. Each of these experiences before the age of 18 years increases the likelihood of not only adulthood depression, suicide, and substance use disorders, but also a range of nonpsychiatric outcomes such as heart disease and chronic lung disease.

Case summary

Ellie is a 16-year-old girl with a past history of ADHD and oppositionality who arrives on her own in a walk-in clinic to be seen for a sports physical. Ellie has been generally healthy and was previously on a stable medical regimen of methylphenidate but has not been taking it for about 1 year. The oppositionality that she previously experienced in her early school-age years has slowly decreased. She generally does well in school and is in several clubs. In the course of the history, Ellie reveals that her mother’s depression has been worse lately to the point where her mother has resumed her drinking and illegal opiate use. You discuss safety with Ellie, and she reveals that, while she has never been threatened or injured, there has been domestic violence in the home that Ellie felt responsible to try to stop by calling the police. This led to the one and only time that Ellie was physically struck. Her father is now incarcerated, and Ellie feels guilty. After a discussion with Ellie, you report this situation to social services, who already has the case on file. Ellie’s mental status exam, including a thorough examination of symptoms of mood disorders, anxiety, substance use, and PTSD, is within normal limits.

Case discussion

Ellie has suffered a set of ACEs. Specifically, her mother has a mental illness, has a drinking problem, and uses illegal drugs; Ellie has witnessed domestic violence toward her mother, has a family member who is incarcerated, and has suffered from physical abuse. This ACEs score of 6 puts her at markedly increased risk for multiple psychiatric and nonpsychiatric medical outcomes. Individuals with scores of 4 or above on the simple ACEs questionnaire have demonstrated a 4- to 12-fold increased health risks for alcoholism, drug abuse, depression, and suicide attempts. Further, studies have shown a twofold to fourfold increase in smoking, poor self-rated health, increased numbers of sexual partners and sexually transmitted disease, and 1.4- to 1.6-fold increase in physical inactivity and severe obesity (Am J Prev Med. 1998 May;14[4]:245-58). In Ellie’s case, her history of ADHD and family history of substance use puts her at even further increased risk for later substance use disorders.

While there is no pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy specific to the treatment of having suffered adversity, it is critical for the clinician to note her increased risk. Ellie would be an individual for whom health promotion and prevention would be critical. It is excellent that she is exercising and participating in sports, which appear to be protective. Careful counseling and follow-up with regard to her increased risk for psychiatric and nonpsychiatric disorders is paramount.

Dr. Althoff is associate professor of psychiatry, psychology, and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington. He is director of the division of behavioral genetics and conducts research on the development of self-regulation in children. Email him at [email protected].

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are the traumatic experiences in a person’s life occurring before the age of 18 years that the person remembers as an adult and that have consequences on a diverse set of outcomes. ACEs include physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, mental illness of a household member, problematic drinking or alcoholism of a household member, illegal street or prescription drug use by a household member, divorce or separation of a parent, domestic violence toward a parent, and incarceration of a household member. Each of these experiences before the age of 18 years increases the likelihood of not only adulthood depression, suicide, and substance use disorders, but also a range of nonpsychiatric outcomes such as heart disease and chronic lung disease.

Case summary

Ellie is a 16-year-old girl with a past history of ADHD and oppositionality who arrives on her own in a walk-in clinic to be seen for a sports physical. Ellie has been generally healthy and was previously on a stable medical regimen of methylphenidate but has not been taking it for about 1 year. The oppositionality that she previously experienced in her early school-age years has slowly decreased. She generally does well in school and is in several clubs. In the course of the history, Ellie reveals that her mother’s depression has been worse lately to the point where her mother has resumed her drinking and illegal opiate use. You discuss safety with Ellie, and she reveals that, while she has never been threatened or injured, there has been domestic violence in the home that Ellie felt responsible to try to stop by calling the police. This led to the one and only time that Ellie was physically struck. Her father is now incarcerated, and Ellie feels guilty. After a discussion with Ellie, you report this situation to social services, who already has the case on file. Ellie’s mental status exam, including a thorough examination of symptoms of mood disorders, anxiety, substance use, and PTSD, is within normal limits.

Case discussion

Ellie has suffered a set of ACEs. Specifically, her mother has a mental illness, has a drinking problem, and uses illegal drugs; Ellie has witnessed domestic violence toward her mother, has a family member who is incarcerated, and has suffered from physical abuse. This ACEs score of 6 puts her at markedly increased risk for multiple psychiatric and nonpsychiatric medical outcomes. Individuals with scores of 4 or above on the simple ACEs questionnaire have demonstrated a 4- to 12-fold increased health risks for alcoholism, drug abuse, depression, and suicide attempts. Further, studies have shown a twofold to fourfold increase in smoking, poor self-rated health, increased numbers of sexual partners and sexually transmitted disease, and 1.4- to 1.6-fold increase in physical inactivity and severe obesity (Am J Prev Med. 1998 May;14[4]:245-58). In Ellie’s case, her history of ADHD and family history of substance use puts her at even further increased risk for later substance use disorders.

While there is no pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy specific to the treatment of having suffered adversity, it is critical for the clinician to note her increased risk. Ellie would be an individual for whom health promotion and prevention would be critical. It is excellent that she is exercising and participating in sports, which appear to be protective. Careful counseling and follow-up with regard to her increased risk for psychiatric and nonpsychiatric disorders is paramount.

Dr. Althoff is associate professor of psychiatry, psychology, and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington. He is director of the division of behavioral genetics and conducts research on the development of self-regulation in children. Email him at [email protected].

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are the traumatic experiences in a person’s life occurring before the age of 18 years that the person remembers as an adult and that have consequences on a diverse set of outcomes. ACEs include physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, mental illness of a household member, problematic drinking or alcoholism of a household member, illegal street or prescription drug use by a household member, divorce or separation of a parent, domestic violence toward a parent, and incarceration of a household member. Each of these experiences before the age of 18 years increases the likelihood of not only adulthood depression, suicide, and substance use disorders, but also a range of nonpsychiatric outcomes such as heart disease and chronic lung disease.

Case summary

Ellie is a 16-year-old girl with a past history of ADHD and oppositionality who arrives on her own in a walk-in clinic to be seen for a sports physical. Ellie has been generally healthy and was previously on a stable medical regimen of methylphenidate but has not been taking it for about 1 year. The oppositionality that she previously experienced in her early school-age years has slowly decreased. She generally does well in school and is in several clubs. In the course of the history, Ellie reveals that her mother’s depression has been worse lately to the point where her mother has resumed her drinking and illegal opiate use. You discuss safety with Ellie, and she reveals that, while she has never been threatened or injured, there has been domestic violence in the home that Ellie felt responsible to try to stop by calling the police. This led to the one and only time that Ellie was physically struck. Her father is now incarcerated, and Ellie feels guilty. After a discussion with Ellie, you report this situation to social services, who already has the case on file. Ellie’s mental status exam, including a thorough examination of symptoms of mood disorders, anxiety, substance use, and PTSD, is within normal limits.

Case discussion

Ellie has suffered a set of ACEs. Specifically, her mother has a mental illness, has a drinking problem, and uses illegal drugs; Ellie has witnessed domestic violence toward her mother, has a family member who is incarcerated, and has suffered from physical abuse. This ACEs score of 6 puts her at markedly increased risk for multiple psychiatric and nonpsychiatric medical outcomes. Individuals with scores of 4 or above on the simple ACEs questionnaire have demonstrated a 4- to 12-fold increased health risks for alcoholism, drug abuse, depression, and suicide attempts. Further, studies have shown a twofold to fourfold increase in smoking, poor self-rated health, increased numbers of sexual partners and sexually transmitted disease, and 1.4- to 1.6-fold increase in physical inactivity and severe obesity (Am J Prev Med. 1998 May;14[4]:245-58). In Ellie’s case, her history of ADHD and family history of substance use puts her at even further increased risk for later substance use disorders.

While there is no pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy specific to the treatment of having suffered adversity, it is critical for the clinician to note her increased risk. Ellie would be an individual for whom health promotion and prevention would be critical. It is excellent that she is exercising and participating in sports, which appear to be protective. Careful counseling and follow-up with regard to her increased risk for psychiatric and nonpsychiatric disorders is paramount.

Dr. Althoff is associate professor of psychiatry, psychology, and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington. He is director of the division of behavioral genetics and conducts research on the development of self-regulation in children. Email him at [email protected].

Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Overcoming one obstacle on the road to elimination

March 24 is World TB Day. It was on this date in 1882 that physician Robert Koch announced the discovery of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative agent of tuberculosis. Worldwide, activities are planned to raise awareness of TB and to support initiatives for prevention, better control, and ultimately the elimination of this disease.

Globally in 2015, the World Health Organization estimated there were 10.4 million new cases of TB, including 1 million in children. Data from the United States reveal that after 20 years of annual decline, the incidence of TB has plateaued. In 2015, 9,563 cases of TB disease were reported, including 440 cases in children less than 15 years of age. While the overall incidence was 3 cases per 100,000, the incidence among foreign-born persons was 15.1 cases per 100,000. There were 3,201 cases (33.5%) among U.S.-born individuals. Foreign-born persons accounted for 66.2% of cases; however, the majority of those cases were diagnosed several years after their arrival in the United States. The top five countries of origin of these individuals were China, India, Mexico, the Philippines, and Vietnam. In contrast, only one-quarter of all pediatric cases occurred in foreign-born children. Four states (California, Florida, New York, and Texas) reported more than 500 cases each in 2015, as they have for the last 7 consecutive years. In 2015, these states accounted for slightly more than half (4,839) of all cases (MMWR 2016 Mar 25;65[11]:273-8).

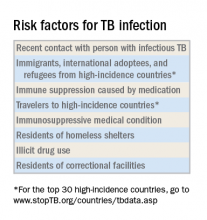

Why as pediatricians should we be concerned? TB in a child is a sentinel event and represents recent or ongoing transmission. Young children who are infected are more likely to progress to TB disease and develop severe manifestations such as miliary TB or meningitis. Children less than 4 years old and those with certain underlying disorders, including those with an immunodeficiency or who are receiving immunosuppressive agents, also are at greater risk for progression from infection to disease. Other predictors of disease progression include diagnosis of the infection within the past 2 years, use of chemotherapy and high-dose corticosteroids, as well as certain cancers, diabetes, and chronic renal failure.

Once infected, most children and adolescents remain asymptomatic. If disease occurs, symptoms develop 1-6 months after infection and include fever, cough, weight loss or failure to thrive, night sweats, and chills. Chest radiographic findings are nonspecific. Infiltrates and intrathoracic lymph node enlargement may or may not be present. However, our goal is to diagnose at-risk children with infection, treat them, and avoid their progression to TB disease.

Screening tests

The interferon-gamma release assay is a blood test that has a greater specificity than TST and requires only one visit. A positive test is seen in both latent TB infection and TB disease. There is no cross-reaction with BCG. This is the ideal test for prior BCG recipients and others who are unlikely to return for TST readings and are at least 5 years of age.

A chest radiograph is required to differentiate latent TB infection from TB disease. Latent TB infection is diagnosed when there is an absence of parenchymal disease, opacification, or intrathoracic adenopathy.

Treatment of latent TB infection versus TB disease is beyond the scope of this article. Consultation with an infectious disease expert is recommended.

For additional information and resources, go to www.cdc.gov/tb, and for a sample TB risk assessment tool, go to www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/ltbi/appendixa.htm.

As we mark the passing of another World TB Day, we have one goal – to identify, screen, and treat children and adolescents at risk for latent TB infection and help eliminate future cases of TB disease.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

March 24 is World TB Day. It was on this date in 1882 that physician Robert Koch announced the discovery of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative agent of tuberculosis. Worldwide, activities are planned to raise awareness of TB and to support initiatives for prevention, better control, and ultimately the elimination of this disease.

Globally in 2015, the World Health Organization estimated there were 10.4 million new cases of TB, including 1 million in children. Data from the United States reveal that after 20 years of annual decline, the incidence of TB has plateaued. In 2015, 9,563 cases of TB disease were reported, including 440 cases in children less than 15 years of age. While the overall incidence was 3 cases per 100,000, the incidence among foreign-born persons was 15.1 cases per 100,000. There were 3,201 cases (33.5%) among U.S.-born individuals. Foreign-born persons accounted for 66.2% of cases; however, the majority of those cases were diagnosed several years after their arrival in the United States. The top five countries of origin of these individuals were China, India, Mexico, the Philippines, and Vietnam. In contrast, only one-quarter of all pediatric cases occurred in foreign-born children. Four states (California, Florida, New York, and Texas) reported more than 500 cases each in 2015, as they have for the last 7 consecutive years. In 2015, these states accounted for slightly more than half (4,839) of all cases (MMWR 2016 Mar 25;65[11]:273-8).

Why as pediatricians should we be concerned? TB in a child is a sentinel event and represents recent or ongoing transmission. Young children who are infected are more likely to progress to TB disease and develop severe manifestations such as miliary TB or meningitis. Children less than 4 years old and those with certain underlying disorders, including those with an immunodeficiency or who are receiving immunosuppressive agents, also are at greater risk for progression from infection to disease. Other predictors of disease progression include diagnosis of the infection within the past 2 years, use of chemotherapy and high-dose corticosteroids, as well as certain cancers, diabetes, and chronic renal failure.

Once infected, most children and adolescents remain asymptomatic. If disease occurs, symptoms develop 1-6 months after infection and include fever, cough, weight loss or failure to thrive, night sweats, and chills. Chest radiographic findings are nonspecific. Infiltrates and intrathoracic lymph node enlargement may or may not be present. However, our goal is to diagnose at-risk children with infection, treat them, and avoid their progression to TB disease.

Screening tests

The interferon-gamma release assay is a blood test that has a greater specificity than TST and requires only one visit. A positive test is seen in both latent TB infection and TB disease. There is no cross-reaction with BCG. This is the ideal test for prior BCG recipients and others who are unlikely to return for TST readings and are at least 5 years of age.

A chest radiograph is required to differentiate latent TB infection from TB disease. Latent TB infection is diagnosed when there is an absence of parenchymal disease, opacification, or intrathoracic adenopathy.

Treatment of latent TB infection versus TB disease is beyond the scope of this article. Consultation with an infectious disease expert is recommended.

For additional information and resources, go to www.cdc.gov/tb, and for a sample TB risk assessment tool, go to www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/ltbi/appendixa.htm.

As we mark the passing of another World TB Day, we have one goal – to identify, screen, and treat children and adolescents at risk for latent TB infection and help eliminate future cases of TB disease.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

March 24 is World TB Day. It was on this date in 1882 that physician Robert Koch announced the discovery of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative agent of tuberculosis. Worldwide, activities are planned to raise awareness of TB and to support initiatives for prevention, better control, and ultimately the elimination of this disease.

Globally in 2015, the World Health Organization estimated there were 10.4 million new cases of TB, including 1 million in children. Data from the United States reveal that after 20 years of annual decline, the incidence of TB has plateaued. In 2015, 9,563 cases of TB disease were reported, including 440 cases in children less than 15 years of age. While the overall incidence was 3 cases per 100,000, the incidence among foreign-born persons was 15.1 cases per 100,000. There were 3,201 cases (33.5%) among U.S.-born individuals. Foreign-born persons accounted for 66.2% of cases; however, the majority of those cases were diagnosed several years after their arrival in the United States. The top five countries of origin of these individuals were China, India, Mexico, the Philippines, and Vietnam. In contrast, only one-quarter of all pediatric cases occurred in foreign-born children. Four states (California, Florida, New York, and Texas) reported more than 500 cases each in 2015, as they have for the last 7 consecutive years. In 2015, these states accounted for slightly more than half (4,839) of all cases (MMWR 2016 Mar 25;65[11]:273-8).

Why as pediatricians should we be concerned? TB in a child is a sentinel event and represents recent or ongoing transmission. Young children who are infected are more likely to progress to TB disease and develop severe manifestations such as miliary TB or meningitis. Children less than 4 years old and those with certain underlying disorders, including those with an immunodeficiency or who are receiving immunosuppressive agents, also are at greater risk for progression from infection to disease. Other predictors of disease progression include diagnosis of the infection within the past 2 years, use of chemotherapy and high-dose corticosteroids, as well as certain cancers, diabetes, and chronic renal failure.

Once infected, most children and adolescents remain asymptomatic. If disease occurs, symptoms develop 1-6 months after infection and include fever, cough, weight loss or failure to thrive, night sweats, and chills. Chest radiographic findings are nonspecific. Infiltrates and intrathoracic lymph node enlargement may or may not be present. However, our goal is to diagnose at-risk children with infection, treat them, and avoid their progression to TB disease.

Screening tests

The interferon-gamma release assay is a blood test that has a greater specificity than TST and requires only one visit. A positive test is seen in both latent TB infection and TB disease. There is no cross-reaction with BCG. This is the ideal test for prior BCG recipients and others who are unlikely to return for TST readings and are at least 5 years of age.

A chest radiograph is required to differentiate latent TB infection from TB disease. Latent TB infection is diagnosed when there is an absence of parenchymal disease, opacification, or intrathoracic adenopathy.

Treatment of latent TB infection versus TB disease is beyond the scope of this article. Consultation with an infectious disease expert is recommended.

For additional information and resources, go to www.cdc.gov/tb, and for a sample TB risk assessment tool, go to www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/ltbi/appendixa.htm.

As we mark the passing of another World TB Day, we have one goal – to identify, screen, and treat children and adolescents at risk for latent TB infection and help eliminate future cases of TB disease.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Hot Threads in ACS Communities

Your colleagues already have a lot to say in 2017. Here are the top discussion threads in ACS Communities just prior to press time (communities in which the threads appear are listed in parentheses):

1. Music in the OR. (General Surgery)

2. Nephrologist to surgeon in 3 months! (General Surgery)

3. MACRA. (Advocacy)

4. Mini-fellowship – or how to “brush up” on trauma? (General Surgery)

5. Trauma/PEG for intubated polytrauma patient. (Trauma Surgery)

6. Students observing in OR. (General Surgery)

7. Pediatric appendectomy. (General Surgery)

8. Call-bladders. (General Surgery)

9. Physician rehabilitation. (General Surgery)

10. Letters to ACS Fellows, Members and Members of Congress. (Vascular Surgery)

To join communities, log in to ACS Communities at http://acscommunities.facs.org/home, go to “Browse All Communities” near the top of any page, and click the blue “Join” button next to the community you’d like to join. If you have any questions, please send them to [email protected].

Your colleagues already have a lot to say in 2017. Here are the top discussion threads in ACS Communities just prior to press time (communities in which the threads appear are listed in parentheses):

1. Music in the OR. (General Surgery)

2. Nephrologist to surgeon in 3 months! (General Surgery)

3. MACRA. (Advocacy)

4. Mini-fellowship – or how to “brush up” on trauma? (General Surgery)

5. Trauma/PEG for intubated polytrauma patient. (Trauma Surgery)

6. Students observing in OR. (General Surgery)

7. Pediatric appendectomy. (General Surgery)

8. Call-bladders. (General Surgery)

9. Physician rehabilitation. (General Surgery)

10. Letters to ACS Fellows, Members and Members of Congress. (Vascular Surgery)

To join communities, log in to ACS Communities at http://acscommunities.facs.org/home, go to “Browse All Communities” near the top of any page, and click the blue “Join” button next to the community you’d like to join. If you have any questions, please send them to [email protected].

Your colleagues already have a lot to say in 2017. Here are the top discussion threads in ACS Communities just prior to press time (communities in which the threads appear are listed in parentheses):

1. Music in the OR. (General Surgery)

2. Nephrologist to surgeon in 3 months! (General Surgery)

3. MACRA. (Advocacy)

4. Mini-fellowship – or how to “brush up” on trauma? (General Surgery)

5. Trauma/PEG for intubated polytrauma patient. (Trauma Surgery)

6. Students observing in OR. (General Surgery)

7. Pediatric appendectomy. (General Surgery)

8. Call-bladders. (General Surgery)

9. Physician rehabilitation. (General Surgery)

10. Letters to ACS Fellows, Members and Members of Congress. (Vascular Surgery)

To join communities, log in to ACS Communities at http://acscommunities.facs.org/home, go to “Browse All Communities” near the top of any page, and click the blue “Join” button next to the community you’d like to join. If you have any questions, please send them to [email protected].

Your colleagues already have a lot to say in 2017. Here are the top discussion threads in ACS Communities just prior to press time

Cooperation must overcome polarization

Each profession has its own core set of knowledge, skills, and values. For physicians, the core set of knowledge is anatomy, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Skills include taking a history, the physical exam, and surgical procedures. The core values traditionally have been compassion and altruism. For modern medical practice, I urge adding cooperation as a core value. Medical school and the apprenticeship of residency are designed to teach, role model, foster, develop, and groom these core competencies.

Getting into medical school is highly competitive. Medical training uses methods that are very different than those used to train elite Olympic and professional athletes. Some competitiveness persists in medical school, but in general the faculty emphasizes cooperation rather than competition. The metric is not whether one student or resident is better than another. Gold and silver medals are not awarded. It is about whether each physician-to-be has passed the milestones needed to practice medicine.

But American health care is threatened by the continued polarization of our government and our society. For years both Cleveland Clinic and Dana Farber have held annual fundraising events at Mar-a-Lago. In February 2017, because of that location’s association with President Trump, some people associated with the organizations advocated boycotting those important fund-raisers. These past few months, it seems every action and every purchase has become a political statement. One restaurant mentioned immigrants on its receipt. The action went viral and caused other people to advocate boycotting the restaurant or not tipping the wait staff (“The new political battleground: Your restaurant receipt,” The Washington Post, by Maura Judkis, Feb. 14, 2017).

Secondary boycotts are an ethical quandary. In labor disputes, organized unions can go on strike. In the 1970s, Japanese cars were not welcome in the employee parking lot of a Ford assembly plant. People do vote with their pocketbook. But in labor disputes, there are legal restrictions on secondary boycotts against other companies. People do need to get along with their neighbors and so do businesses. Politics is the art of encouraging cooperation on one project amongst people who disagree about the goals of many other proposed projects. The Preamble to the United States Constitution enumerates the benefits of cooperation.

In any large-scale human endeavor, conflicts arise that may limit cooperation. Accommodating conscientious objection is the safety valve that permits cooperation when dealing with contested government endeavors such as war, abortion, and physician-assisted suicide. It is meant as a last ditch effort to maintain cohesion of both societal and individual moral integrity. But if every proposed action is met with votes divided along party lines, conscientious objection loses its moral high ground.

Judge Neil Gorsuch, the nominee for the U.S. Supreme Court, has a record of supporting religious freedom in Yellowbear v. Lambert (10th Cir. 2014). He would likely support conscientious objection in relation to assisted dying by physicians, contrary to the arguments made recently by bioethicists Julian Savulescu and Udo Schuklenk. In related news, the liberty of physicians to address gun safety was affirmed when a Florida appeals court upheld the overturning of the state’s Privacy of Firearm Owners Act.

Summing up a tumultuous month of medical ethics, I leave you with the words of Voltaire: “Cherish those who seek the truth but beware of those who find it.”

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

Each profession has its own core set of knowledge, skills, and values. For physicians, the core set of knowledge is anatomy, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Skills include taking a history, the physical exam, and surgical procedures. The core values traditionally have been compassion and altruism. For modern medical practice, I urge adding cooperation as a core value. Medical school and the apprenticeship of residency are designed to teach, role model, foster, develop, and groom these core competencies.

Getting into medical school is highly competitive. Medical training uses methods that are very different than those used to train elite Olympic and professional athletes. Some competitiveness persists in medical school, but in general the faculty emphasizes cooperation rather than competition. The metric is not whether one student or resident is better than another. Gold and silver medals are not awarded. It is about whether each physician-to-be has passed the milestones needed to practice medicine.

But American health care is threatened by the continued polarization of our government and our society. For years both Cleveland Clinic and Dana Farber have held annual fundraising events at Mar-a-Lago. In February 2017, because of that location’s association with President Trump, some people associated with the organizations advocated boycotting those important fund-raisers. These past few months, it seems every action and every purchase has become a political statement. One restaurant mentioned immigrants on its receipt. The action went viral and caused other people to advocate boycotting the restaurant or not tipping the wait staff (“The new political battleground: Your restaurant receipt,” The Washington Post, by Maura Judkis, Feb. 14, 2017).

Secondary boycotts are an ethical quandary. In labor disputes, organized unions can go on strike. In the 1970s, Japanese cars were not welcome in the employee parking lot of a Ford assembly plant. People do vote with their pocketbook. But in labor disputes, there are legal restrictions on secondary boycotts against other companies. People do need to get along with their neighbors and so do businesses. Politics is the art of encouraging cooperation on one project amongst people who disagree about the goals of many other proposed projects. The Preamble to the United States Constitution enumerates the benefits of cooperation.

In any large-scale human endeavor, conflicts arise that may limit cooperation. Accommodating conscientious objection is the safety valve that permits cooperation when dealing with contested government endeavors such as war, abortion, and physician-assisted suicide. It is meant as a last ditch effort to maintain cohesion of both societal and individual moral integrity. But if every proposed action is met with votes divided along party lines, conscientious objection loses its moral high ground.

Judge Neil Gorsuch, the nominee for the U.S. Supreme Court, has a record of supporting religious freedom in Yellowbear v. Lambert (10th Cir. 2014). He would likely support conscientious objection in relation to assisted dying by physicians, contrary to the arguments made recently by bioethicists Julian Savulescu and Udo Schuklenk. In related news, the liberty of physicians to address gun safety was affirmed when a Florida appeals court upheld the overturning of the state’s Privacy of Firearm Owners Act.

Summing up a tumultuous month of medical ethics, I leave you with the words of Voltaire: “Cherish those who seek the truth but beware of those who find it.”

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

Each profession has its own core set of knowledge, skills, and values. For physicians, the core set of knowledge is anatomy, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Skills include taking a history, the physical exam, and surgical procedures. The core values traditionally have been compassion and altruism. For modern medical practice, I urge adding cooperation as a core value. Medical school and the apprenticeship of residency are designed to teach, role model, foster, develop, and groom these core competencies.

Getting into medical school is highly competitive. Medical training uses methods that are very different than those used to train elite Olympic and professional athletes. Some competitiveness persists in medical school, but in general the faculty emphasizes cooperation rather than competition. The metric is not whether one student or resident is better than another. Gold and silver medals are not awarded. It is about whether each physician-to-be has passed the milestones needed to practice medicine.

But American health care is threatened by the continued polarization of our government and our society. For years both Cleveland Clinic and Dana Farber have held annual fundraising events at Mar-a-Lago. In February 2017, because of that location’s association with President Trump, some people associated with the organizations advocated boycotting those important fund-raisers. These past few months, it seems every action and every purchase has become a political statement. One restaurant mentioned immigrants on its receipt. The action went viral and caused other people to advocate boycotting the restaurant or not tipping the wait staff (“The new political battleground: Your restaurant receipt,” The Washington Post, by Maura Judkis, Feb. 14, 2017).

Secondary boycotts are an ethical quandary. In labor disputes, organized unions can go on strike. In the 1970s, Japanese cars were not welcome in the employee parking lot of a Ford assembly plant. People do vote with their pocketbook. But in labor disputes, there are legal restrictions on secondary boycotts against other companies. People do need to get along with their neighbors and so do businesses. Politics is the art of encouraging cooperation on one project amongst people who disagree about the goals of many other proposed projects. The Preamble to the United States Constitution enumerates the benefits of cooperation.

In any large-scale human endeavor, conflicts arise that may limit cooperation. Accommodating conscientious objection is the safety valve that permits cooperation when dealing with contested government endeavors such as war, abortion, and physician-assisted suicide. It is meant as a last ditch effort to maintain cohesion of both societal and individual moral integrity. But if every proposed action is met with votes divided along party lines, conscientious objection loses its moral high ground.

Judge Neil Gorsuch, the nominee for the U.S. Supreme Court, has a record of supporting religious freedom in Yellowbear v. Lambert (10th Cir. 2014). He would likely support conscientious objection in relation to assisted dying by physicians, contrary to the arguments made recently by bioethicists Julian Savulescu and Udo Schuklenk. In related news, the liberty of physicians to address gun safety was affirmed when a Florida appeals court upheld the overturning of the state’s Privacy of Firearm Owners Act.

Summing up a tumultuous month of medical ethics, I leave you with the words of Voltaire: “Cherish those who seek the truth but beware of those who find it.”

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

Medication for life

Some areas of psychiatry would benefit from more controversy. One of them is the prescription of antidepressants to young people dealing with romantic disappointments.

I have seen many young men and women given an antidepressant for the very painful, but ordinary, romantic break-ups characteristic of this phase of life, who then become habituated to the drug. They take the medication indefinitely, their brains accommodate neurophysiologically to the presence of the chemical, and they become unable to discontinue it without intolerable withdrawal symptoms that look like an underlying illness. A parallel phenomenon occurs not infrequently with the use of amphetamines (and other stimulants) for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder that is at times mistakenly diagnosed in this age group.

Antidepressants for early romantic disappointments

Mr. A, now in his 30s, became sullen and withdrawn at age 16 after a girl refused his romantic approaches. His well-intentioned parents took him to a psychiatrist, who, after a brief evaluation, prescribed fluoxetine. Mr. A is now well adjusted and happily married but unable to get off fluoxetine. Even when it is carefully tapered, 2 or 3 months after it is discontinued, he becomes anxious and depressed. This is an iatrogenic problem. It is not related to goings-on in his mind or his life; rather it is the result of his brain’s accommodation to a medication, producing a serious withdrawal syndrome.

His original psychiatrist made only a descriptive diagnosis. He did not inquire about what was going on in Mr. A’s mind and thus could not make a dynamic diagnosis (that is, a diagnosis of a patient’s central emotional conflicts, ability to function in relation to other people, strengths, and weaknesses). Mr. A, like many adolescents, had a lot of anxiety and guilt about sexual and romantic involvement, and potential success. He defended against his anxiety and guilt by assuring himself life would never work out for him. When the girl he admired rebuffed him, he immediately concluded this would perpetually be his fate, so the girl’s refusal was particularly painful. Mr. A feels that had this dynamic been discussed with him at the time, he may well not have needed medication at all.

Ms. B, like Mr. A, was prescribed antidepressants for depressive reactions to early romantic disappointments. Likewise, she self-punitively convinced herself, despite easily attracting men’s attentions, that these disappointments meant a lifetime alone. Ms. B has a family history of depression (although neither of her brothers struggles with it), and she felt that she needed the medications to help negotiate difficult periods. But should she have been on them for extended periods of time? Therapeutic attention to her emotional conflicts helped her to form lasting relationships, marry, and have children. Unable to get off the medications, she had to deal with the risks of their use during pregnancy, which she then subjected to the same sort of guilty self-accusations as she previously had used to limit her romantic prospects.

Ms. C came to me on three medications – one for each of her significant romantic break-ups. She, too, was depressively self-diminishing, beginning therapy by letting me know all the things she could think of that might make me think less of her. Understanding some of the reasons for her self-deprecation helped her toward better romantic relationships but did not give her the courage to get off her medications. Pregnancy, however, led her to promptly and successfully discontinue an antidepressant and a mood stabilizer (she has never had any symptoms suggestive of manic depression). She remained on a low dose of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, had an uneventful pregnancy, and then fell in love with a charming baby.

Principles for consideration

• Psychiatrists (and other mental health professionals and primary care physicians treating mental illness) should always make a dynamic, and not merely a descriptive, diagnosis. Even with a more clearly biologically driven problem, such as bipolar disorder, the patient’s personality and conflicts matter.

• Psychiatrists should be very judicious about prescribing medications in adolescence and young adulthood, especially for difficulties adapting to the typical events of those phases of life. Expert psychotherapy should be the first choice in these instances.

• Medication, when necessary, should be prescribed for as limited a time as possible. It is important for young people to advance their own development, not feel needlessly beholden to medications, not get iatrogenically dependent on them, and not feel that they have “diseases” they don’t have.

Amphetamines for misdiagnosed ADHD

When Ms. D’s family moved to a new house, she, her brother, and her sister, each attended a new school. Unlike her siblings, Ms. D, who was in high school, had a difficult adjustment. Her grades fell. She was taken to a psychiatrist who diagnosed ADHD and prescribed amphetamines. The psychiatrist paid little attention to her prior lack of difficulty in school or her struggles making new friends. Nor did the psychiatrist learn that Ms. D had to ward off the seductive advances of an older teacher (although Ms. D would likely not have been immediately forthcoming about this at the time).

When Ms. D came to me as a college student, for troubles with anger, anxiety, and some depression, she was religiously taking 70 mg of amphetamines daily. After I learned a bit about her and raised the question of whether she actually had ADHD, and whether it might make sense to consider tapering the amphetamines, she was appalled and looked like a toddler who was afraid I was about to steal her candy. Helping her to get off the unneeded medication was a multiyear process.

First, she had to recognize that it was prescribed to treat a problem she probably didn’t have, and second, that it was failing to help her with the problems she did have. As we attended to some of her actual emotional conflicts, she became willing to experiment with lower doses. She was able to see that her work was little changed as the dose was lowered, and that her difficulties with school had more to do with feelings toward classmates and teachers than with the presence or absence of amphetamines. After a protracted struggle, finally off the medication, she felt in charge of her life and no longer believed there was something inherently wrong with her mind or her brain.

Mr. E was the only son in a high-powered academic family. His older sisters were all intellectual standouts. Early in high school, he received his first B as a grade in a course. He was taken to a pediatrician, diagnosed with ADHD, and put on stimulants. Like Ms. D, he came to believe that he needed them. In college, he began to develop some magical aspects to his thinking, a potential side effect of the stimulants. It was very difficult to help him see either that he had a problem with his thinking or that it might be attributable to the medication.

Principles to consider

• If the ADHD wasn’t there in elementary school or before, it is unlikely that an adolescent or young adult has new-onset ADHD. A new or newly amplified conflict is occurring in the person’s mind and life A dynamic diagnosis, as always, is essential.

• When medication is prescribed for actual ADHD, as with anything else, the question of how long it will be taken must be asked. For life? Until other means of adaptation are accomplished? Until adequate outcome studies of long-term use of the medication are performed?

Helping patients to get off unneeded, or no longer needed, medications can be a difficult task. Their emotional attachments to the medications can be intense and varied. For some, the prescription is a sign of being loved and cared for. For others, it represents a certification of a deficit, appeases guilt about success, and/or attests to the need for special consideration. Insofar as the medication has been helpful, it may have come to be regarded as a dearly loved friend, or even a part of the self.

When medication has been helpful, there is also, of course, concern about the potential return of the difficulties for which it was prescribed. Few patients are told at the time of first prescription that there is potential risk of habituation and return of, or potential exaggeration of, symptoms with discontinuation. This type of discussion is more difficult to have in situations in which a prescription is urgently needed and the patient is reluctant, but is still not often done in those instances in which a prescription is more optional than essential. The picture is seldom simple.

These few comments only scratch the surface of the difficulties doctors and patients face in helping patients to discontinue their medications. Residency programs pay a lot of attention to helping trainees learn to prescribe medications; rarely do they sufficiently educate residents how to help patients discontinue them. The fact that so many residencies currently pay limited attention to interventions apart from medication contributes further to the difficulty.

Medications have saved the life of many a psychiatric patient. Some patients need medication for life. But some end up on medication for life, even in some instances when the medication may not have been needed in the first place. Although it is often a difficult task, we need to do a better job of distinguishing which patients are which.

Dr. Blum is a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst in private practice in Philadelphia. He teaches in the departments of anthropology and psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania and at the Psychoanalytic Center of Philadelphia.

Some areas of psychiatry would benefit from more controversy. One of them is the prescription of antidepressants to young people dealing with romantic disappointments.

I have seen many young men and women given an antidepressant for the very painful, but ordinary, romantic break-ups characteristic of this phase of life, who then become habituated to the drug. They take the medication indefinitely, their brains accommodate neurophysiologically to the presence of the chemical, and they become unable to discontinue it without intolerable withdrawal symptoms that look like an underlying illness. A parallel phenomenon occurs not infrequently with the use of amphetamines (and other stimulants) for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder that is at times mistakenly diagnosed in this age group.

Antidepressants for early romantic disappointments

Mr. A, now in his 30s, became sullen and withdrawn at age 16 after a girl refused his romantic approaches. His well-intentioned parents took him to a psychiatrist, who, after a brief evaluation, prescribed fluoxetine. Mr. A is now well adjusted and happily married but unable to get off fluoxetine. Even when it is carefully tapered, 2 or 3 months after it is discontinued, he becomes anxious and depressed. This is an iatrogenic problem. It is not related to goings-on in his mind or his life; rather it is the result of his brain’s accommodation to a medication, producing a serious withdrawal syndrome.

His original psychiatrist made only a descriptive diagnosis. He did not inquire about what was going on in Mr. A’s mind and thus could not make a dynamic diagnosis (that is, a diagnosis of a patient’s central emotional conflicts, ability to function in relation to other people, strengths, and weaknesses). Mr. A, like many adolescents, had a lot of anxiety and guilt about sexual and romantic involvement, and potential success. He defended against his anxiety and guilt by assuring himself life would never work out for him. When the girl he admired rebuffed him, he immediately concluded this would perpetually be his fate, so the girl’s refusal was particularly painful. Mr. A feels that had this dynamic been discussed with him at the time, he may well not have needed medication at all.

Ms. B, like Mr. A, was prescribed antidepressants for depressive reactions to early romantic disappointments. Likewise, she self-punitively convinced herself, despite easily attracting men’s attentions, that these disappointments meant a lifetime alone. Ms. B has a family history of depression (although neither of her brothers struggles with it), and she felt that she needed the medications to help negotiate difficult periods. But should she have been on them for extended periods of time? Therapeutic attention to her emotional conflicts helped her to form lasting relationships, marry, and have children. Unable to get off the medications, she had to deal with the risks of their use during pregnancy, which she then subjected to the same sort of guilty self-accusations as she previously had used to limit her romantic prospects.

Ms. C came to me on three medications – one for each of her significant romantic break-ups. She, too, was depressively self-diminishing, beginning therapy by letting me know all the things she could think of that might make me think less of her. Understanding some of the reasons for her self-deprecation helped her toward better romantic relationships but did not give her the courage to get off her medications. Pregnancy, however, led her to promptly and successfully discontinue an antidepressant and a mood stabilizer (she has never had any symptoms suggestive of manic depression). She remained on a low dose of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, had an uneventful pregnancy, and then fell in love with a charming baby.

Principles for consideration

• Psychiatrists (and other mental health professionals and primary care physicians treating mental illness) should always make a dynamic, and not merely a descriptive, diagnosis. Even with a more clearly biologically driven problem, such as bipolar disorder, the patient’s personality and conflicts matter.

• Psychiatrists should be very judicious about prescribing medications in adolescence and young adulthood, especially for difficulties adapting to the typical events of those phases of life. Expert psychotherapy should be the first choice in these instances.

• Medication, when necessary, should be prescribed for as limited a time as possible. It is important for young people to advance their own development, not feel needlessly beholden to medications, not get iatrogenically dependent on them, and not feel that they have “diseases” they don’t have.

Amphetamines for misdiagnosed ADHD

When Ms. D’s family moved to a new house, she, her brother, and her sister, each attended a new school. Unlike her siblings, Ms. D, who was in high school, had a difficult adjustment. Her grades fell. She was taken to a psychiatrist who diagnosed ADHD and prescribed amphetamines. The psychiatrist paid little attention to her prior lack of difficulty in school or her struggles making new friends. Nor did the psychiatrist learn that Ms. D had to ward off the seductive advances of an older teacher (although Ms. D would likely not have been immediately forthcoming about this at the time).

When Ms. D came to me as a college student, for troubles with anger, anxiety, and some depression, she was religiously taking 70 mg of amphetamines daily. After I learned a bit about her and raised the question of whether she actually had ADHD, and whether it might make sense to consider tapering the amphetamines, she was appalled and looked like a toddler who was afraid I was about to steal her candy. Helping her to get off the unneeded medication was a multiyear process.

First, she had to recognize that it was prescribed to treat a problem she probably didn’t have, and second, that it was failing to help her with the problems she did have. As we attended to some of her actual emotional conflicts, she became willing to experiment with lower doses. She was able to see that her work was little changed as the dose was lowered, and that her difficulties with school had more to do with feelings toward classmates and teachers than with the presence or absence of amphetamines. After a protracted struggle, finally off the medication, she felt in charge of her life and no longer believed there was something inherently wrong with her mind or her brain.

Mr. E was the only son in a high-powered academic family. His older sisters were all intellectual standouts. Early in high school, he received his first B as a grade in a course. He was taken to a pediatrician, diagnosed with ADHD, and put on stimulants. Like Ms. D, he came to believe that he needed them. In college, he began to develop some magical aspects to his thinking, a potential side effect of the stimulants. It was very difficult to help him see either that he had a problem with his thinking or that it might be attributable to the medication.

Principles to consider

• If the ADHD wasn’t there in elementary school or before, it is unlikely that an adolescent or young adult has new-onset ADHD. A new or newly amplified conflict is occurring in the person’s mind and life A dynamic diagnosis, as always, is essential.

• When medication is prescribed for actual ADHD, as with anything else, the question of how long it will be taken must be asked. For life? Until other means of adaptation are accomplished? Until adequate outcome studies of long-term use of the medication are performed?

Helping patients to get off unneeded, or no longer needed, medications can be a difficult task. Their emotional attachments to the medications can be intense and varied. For some, the prescription is a sign of being loved and cared for. For others, it represents a certification of a deficit, appeases guilt about success, and/or attests to the need for special consideration. Insofar as the medication has been helpful, it may have come to be regarded as a dearly loved friend, or even a part of the self.

When medication has been helpful, there is also, of course, concern about the potential return of the difficulties for which it was prescribed. Few patients are told at the time of first prescription that there is potential risk of habituation and return of, or potential exaggeration of, symptoms with discontinuation. This type of discussion is more difficult to have in situations in which a prescription is urgently needed and the patient is reluctant, but is still not often done in those instances in which a prescription is more optional than essential. The picture is seldom simple.

These few comments only scratch the surface of the difficulties doctors and patients face in helping patients to discontinue their medications. Residency programs pay a lot of attention to helping trainees learn to prescribe medications; rarely do they sufficiently educate residents how to help patients discontinue them. The fact that so many residencies currently pay limited attention to interventions apart from medication contributes further to the difficulty.

Medications have saved the life of many a psychiatric patient. Some patients need medication for life. But some end up on medication for life, even in some instances when the medication may not have been needed in the first place. Although it is often a difficult task, we need to do a better job of distinguishing which patients are which.

Dr. Blum is a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst in private practice in Philadelphia. He teaches in the departments of anthropology and psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania and at the Psychoanalytic Center of Philadelphia.

Some areas of psychiatry would benefit from more controversy. One of them is the prescription of antidepressants to young people dealing with romantic disappointments.

I have seen many young men and women given an antidepressant for the very painful, but ordinary, romantic break-ups characteristic of this phase of life, who then become habituated to the drug. They take the medication indefinitely, their brains accommodate neurophysiologically to the presence of the chemical, and they become unable to discontinue it without intolerable withdrawal symptoms that look like an underlying illness. A parallel phenomenon occurs not infrequently with the use of amphetamines (and other stimulants) for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder that is at times mistakenly diagnosed in this age group.

Antidepressants for early romantic disappointments

Mr. A, now in his 30s, became sullen and withdrawn at age 16 after a girl refused his romantic approaches. His well-intentioned parents took him to a psychiatrist, who, after a brief evaluation, prescribed fluoxetine. Mr. A is now well adjusted and happily married but unable to get off fluoxetine. Even when it is carefully tapered, 2 or 3 months after it is discontinued, he becomes anxious and depressed. This is an iatrogenic problem. It is not related to goings-on in his mind or his life; rather it is the result of his brain’s accommodation to a medication, producing a serious withdrawal syndrome.

His original psychiatrist made only a descriptive diagnosis. He did not inquire about what was going on in Mr. A’s mind and thus could not make a dynamic diagnosis (that is, a diagnosis of a patient’s central emotional conflicts, ability to function in relation to other people, strengths, and weaknesses). Mr. A, like many adolescents, had a lot of anxiety and guilt about sexual and romantic involvement, and potential success. He defended against his anxiety and guilt by assuring himself life would never work out for him. When the girl he admired rebuffed him, he immediately concluded this would perpetually be his fate, so the girl’s refusal was particularly painful. Mr. A feels that had this dynamic been discussed with him at the time, he may well not have needed medication at all.

Ms. B, like Mr. A, was prescribed antidepressants for depressive reactions to early romantic disappointments. Likewise, she self-punitively convinced herself, despite easily attracting men’s attentions, that these disappointments meant a lifetime alone. Ms. B has a family history of depression (although neither of her brothers struggles with it), and she felt that she needed the medications to help negotiate difficult periods. But should she have been on them for extended periods of time? Therapeutic attention to her emotional conflicts helped her to form lasting relationships, marry, and have children. Unable to get off the medications, she had to deal with the risks of their use during pregnancy, which she then subjected to the same sort of guilty self-accusations as she previously had used to limit her romantic prospects.

Ms. C came to me on three medications – one for each of her significant romantic break-ups. She, too, was depressively self-diminishing, beginning therapy by letting me know all the things she could think of that might make me think less of her. Understanding some of the reasons for her self-deprecation helped her toward better romantic relationships but did not give her the courage to get off her medications. Pregnancy, however, led her to promptly and successfully discontinue an antidepressant and a mood stabilizer (she has never had any symptoms suggestive of manic depression). She remained on a low dose of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, had an uneventful pregnancy, and then fell in love with a charming baby.

Principles for consideration