User login

A Boxed Warning for Inadequate Psoriasis Treatment

The US Food and Drug Administration uses the term boxed warning to highlight potentially dangerous situations associated with prescription drugs. A boxed warning is used when “[T]here is an adverse reaction so serious in proportion to the potential benefit from the drug (e.g., a fatal, life-threatening or permanently disabling adverse reaction) that it is essential that it be considered in assessing the risks and benefits of using the drug.”1 However, drugs are not the only potential cause of severe adverse outcomes in patients with psoriasis. Untreated psoriasis also is a well-established cause of serious morbidity and mortality. What are the risks of inadequate psoriasis treatment?

Psoriasis is associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease.2-4 Patients with psoriasis also have a higher prevalence of classic cardiovascular risk factors including smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity, and hyperlipidemia.5,6 Psoriasis is a T-cell mediated disease process driven by IL-23 and TH17 helper cell–derived proinflammatory cytokines, sharing certain genetic aspects with metabolic syndrome.6 Cytokine actions on insulin signaling, lipid metabolism, and adipogenesis may underlie the increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk factors in patients with psoriasis. In addition to treating the cutaneous manifestations of psoriasis, reducing inflammation in these patients reduces C-reactive protein and lipid peroxidation and increases high-density lipoprotein levels.6 Tumor necrosis factor α blockers decrease the risk for cardiovascular disease in patients with psoriasis.7,8 Lower than expected rates of cardiovascular disease also have been reported in a large cohort of psoriasis patients (ie, PSOLAR [Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry] registry) being treated with either ustekinumab or tumor necrosis factor α blockers.9

Psoriatic arthritis is a chronic inflammatory disease in which active inflammation results in progressive joint destruction.10 Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors suppress disease progression, preserve function, and delay destruction of the joints. Ustekinumab also helps control psoriatic arthritis and inhibits radiographic progression of joint disease.11

Importantly, untreated moderate to severe psoriasis is associated with several comorbidities that may lead to early death such as heart attacks and strokes.12 Furthermore, patients not taking biologic medications may have higher death rates than patients taking biologic medications.9 Psoriasis also is associated with tremendous suffering and negative psychosocial effects. The mental and physical impact of the disease is comparable to other major medical conditions (eg, cancer, arthritis, hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, depression).13 Patients also may experience physical discomfort from pain and itching.14 Children with psoriasis may experience bullying, which is associated with an increased number of depressive episodes, thereby increasing their risk for developing psychiatric conditions such as depression and anxiety as adults.15 The stigma associated with psoriasis may affect patients’ ability to build relationships. Patients with psoriasis experience higher divorce rates than patients with other chronic medical conditions, and direct involvement of genital regions may negatively impact patients’ sex lives. Patients have noted that the stigma of psoriasis also is associated with the inability to obtain employment.15 Almost one-third of patients with psoriasis who are either not working or are retired base their work status on their skin condition.16 Furthermore, psoriasis may contribute to economic burden for patients due to indirect costs associated with work absenteeism.17

Adequate treatment of psoriasis improves patients’ physical and psychological health as well as their ability to function in the workplace. However, despite the benefits of treatment, 30% of patients with severe psoriasis and 53% of patients with moderate psoriasis receive no treatment or only topical medications instead of systemic therapies.16 The potential adverse events of inadequate psoriasis treatment far outweigh any potential benefits of withholding treatment. Perhaps a boxed warning should be issued for inadequate treatment of psoriasis patients.

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. Guidance for industry: warning and precautions, contraindications, and boxed warning sections of labeling for human prescription drug and biological products—content and format. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/.../Guidances/ucm075096.pdf. Published October 6, 2011. Accessed August 10, 2016.

- Ogdie A, Yu Y, Haynes K, et al. Risk of major cardiovascular events in patients with psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:326-332.

- Rose S, Sheth NH, Baker JF, et al. A comparison of vascular inflammation in psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and healthy subjects by FDG-PET/CT: a pilot study. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;3:273-278.

- Shlyankevich J, Mehta NN, Krueger JG, et al. Accumulating evidence for the association and shared pathogenic mechanisms between psoriasis and cardiovascular-related comorbidities. Am J Med. 2014;127:1148-1153.

- Lee MK, Kim HS, Cho EB, et al. A study of awareness and screening behavior of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with psoriasis and dermatologists. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:59-65.

- Voiculescu VM, Lupu M, Papagheorghe L, et al. Psoriasis and metabolic syndrome—scientific evidence and therapeutic implications. J Med Life. 2014;7:468-471.

- Wu JJ, Poon KY, Bebchuk JD. Association between the type and length of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy and myocardial infarction risk in patients with psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:899-903.

- Famenini S, Sako EY, Wu JJ. Effect of treating psoriasis on cardiovascular comorbidities: focus on TNF inhibitors. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:45-50.

- Gottlieb AB, Kalb RE, Langley RG, et al. Safety observations in 12095 patients with psoriasis enrolled in an international registry (PSOLAR): experience with infliximab and other systemic and biologic therapies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:1441-1448.

- Chimenti MS, Graceffa D, Perricone R. Anti-TNFα discontinuation in rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis: is it possible after disease remission [published online Apr 21, 2011]? Autoimmun Rev. 2011;10:636-640.

- Kavanaugh A, Ritchlin C, Rahman P, et al. Ustekinumab, an anti-IL-12/23 p40 monoclonal antibody, inhibits radiographic progression in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: results of an integrated analysis of radiographic data from the phase 3, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled PSUMMIT-1 and PSUMMIT-2 trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1000-1006.

- Pietrzak A, Bartosinska J, Blaszczyk R, et al. Increased serum level of N-terminal Pro-B-type natriuretic peptide as a possible biomarker of cardiovascular risk in psoriatic patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1010-1014.

- Rapp SR, Feldman SR, Exum ML, et al. Psoriasis causes as much disability as other major medical diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(3, pt 1):401-407.

- Pettey AA, Balkrishnan R, Rapp SR, et al. Patients with palmoplantar psoriasis have more physical disability and discomfort than patients with other forms of psoriasis: implications for clinical practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:271-275.

- Garshick MK, Kimball AB. Psoriasis and the life cycle of persistent life effects. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:25-39.

- Feldman SR, Malakouti M, Koo JY. Social impact of the burden of psoriasis: effects on patients and practice. Dermatol Online J. August 17, 2014;20. pii:13030/qt48r4w8h2.

- Brezinski EA, Dhillon JS, Armstrong AW. Economic burden of psoriasis in the United States: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:651-658.

The US Food and Drug Administration uses the term boxed warning to highlight potentially dangerous situations associated with prescription drugs. A boxed warning is used when “[T]here is an adverse reaction so serious in proportion to the potential benefit from the drug (e.g., a fatal, life-threatening or permanently disabling adverse reaction) that it is essential that it be considered in assessing the risks and benefits of using the drug.”1 However, drugs are not the only potential cause of severe adverse outcomes in patients with psoriasis. Untreated psoriasis also is a well-established cause of serious morbidity and mortality. What are the risks of inadequate psoriasis treatment?

Psoriasis is associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease.2-4 Patients with psoriasis also have a higher prevalence of classic cardiovascular risk factors including smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity, and hyperlipidemia.5,6 Psoriasis is a T-cell mediated disease process driven by IL-23 and TH17 helper cell–derived proinflammatory cytokines, sharing certain genetic aspects with metabolic syndrome.6 Cytokine actions on insulin signaling, lipid metabolism, and adipogenesis may underlie the increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk factors in patients with psoriasis. In addition to treating the cutaneous manifestations of psoriasis, reducing inflammation in these patients reduces C-reactive protein and lipid peroxidation and increases high-density lipoprotein levels.6 Tumor necrosis factor α blockers decrease the risk for cardiovascular disease in patients with psoriasis.7,8 Lower than expected rates of cardiovascular disease also have been reported in a large cohort of psoriasis patients (ie, PSOLAR [Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry] registry) being treated with either ustekinumab or tumor necrosis factor α blockers.9

Psoriatic arthritis is a chronic inflammatory disease in which active inflammation results in progressive joint destruction.10 Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors suppress disease progression, preserve function, and delay destruction of the joints. Ustekinumab also helps control psoriatic arthritis and inhibits radiographic progression of joint disease.11

Importantly, untreated moderate to severe psoriasis is associated with several comorbidities that may lead to early death such as heart attacks and strokes.12 Furthermore, patients not taking biologic medications may have higher death rates than patients taking biologic medications.9 Psoriasis also is associated with tremendous suffering and negative psychosocial effects. The mental and physical impact of the disease is comparable to other major medical conditions (eg, cancer, arthritis, hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, depression).13 Patients also may experience physical discomfort from pain and itching.14 Children with psoriasis may experience bullying, which is associated with an increased number of depressive episodes, thereby increasing their risk for developing psychiatric conditions such as depression and anxiety as adults.15 The stigma associated with psoriasis may affect patients’ ability to build relationships. Patients with psoriasis experience higher divorce rates than patients with other chronic medical conditions, and direct involvement of genital regions may negatively impact patients’ sex lives. Patients have noted that the stigma of psoriasis also is associated with the inability to obtain employment.15 Almost one-third of patients with psoriasis who are either not working or are retired base their work status on their skin condition.16 Furthermore, psoriasis may contribute to economic burden for patients due to indirect costs associated with work absenteeism.17

Adequate treatment of psoriasis improves patients’ physical and psychological health as well as their ability to function in the workplace. However, despite the benefits of treatment, 30% of patients with severe psoriasis and 53% of patients with moderate psoriasis receive no treatment or only topical medications instead of systemic therapies.16 The potential adverse events of inadequate psoriasis treatment far outweigh any potential benefits of withholding treatment. Perhaps a boxed warning should be issued for inadequate treatment of psoriasis patients.

The US Food and Drug Administration uses the term boxed warning to highlight potentially dangerous situations associated with prescription drugs. A boxed warning is used when “[T]here is an adverse reaction so serious in proportion to the potential benefit from the drug (e.g., a fatal, life-threatening or permanently disabling adverse reaction) that it is essential that it be considered in assessing the risks and benefits of using the drug.”1 However, drugs are not the only potential cause of severe adverse outcomes in patients with psoriasis. Untreated psoriasis also is a well-established cause of serious morbidity and mortality. What are the risks of inadequate psoriasis treatment?

Psoriasis is associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease.2-4 Patients with psoriasis also have a higher prevalence of classic cardiovascular risk factors including smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity, and hyperlipidemia.5,6 Psoriasis is a T-cell mediated disease process driven by IL-23 and TH17 helper cell–derived proinflammatory cytokines, sharing certain genetic aspects with metabolic syndrome.6 Cytokine actions on insulin signaling, lipid metabolism, and adipogenesis may underlie the increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk factors in patients with psoriasis. In addition to treating the cutaneous manifestations of psoriasis, reducing inflammation in these patients reduces C-reactive protein and lipid peroxidation and increases high-density lipoprotein levels.6 Tumor necrosis factor α blockers decrease the risk for cardiovascular disease in patients with psoriasis.7,8 Lower than expected rates of cardiovascular disease also have been reported in a large cohort of psoriasis patients (ie, PSOLAR [Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry] registry) being treated with either ustekinumab or tumor necrosis factor α blockers.9

Psoriatic arthritis is a chronic inflammatory disease in which active inflammation results in progressive joint destruction.10 Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors suppress disease progression, preserve function, and delay destruction of the joints. Ustekinumab also helps control psoriatic arthritis and inhibits radiographic progression of joint disease.11

Importantly, untreated moderate to severe psoriasis is associated with several comorbidities that may lead to early death such as heart attacks and strokes.12 Furthermore, patients not taking biologic medications may have higher death rates than patients taking biologic medications.9 Psoriasis also is associated with tremendous suffering and negative psychosocial effects. The mental and physical impact of the disease is comparable to other major medical conditions (eg, cancer, arthritis, hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, depression).13 Patients also may experience physical discomfort from pain and itching.14 Children with psoriasis may experience bullying, which is associated with an increased number of depressive episodes, thereby increasing their risk for developing psychiatric conditions such as depression and anxiety as adults.15 The stigma associated with psoriasis may affect patients’ ability to build relationships. Patients with psoriasis experience higher divorce rates than patients with other chronic medical conditions, and direct involvement of genital regions may negatively impact patients’ sex lives. Patients have noted that the stigma of psoriasis also is associated with the inability to obtain employment.15 Almost one-third of patients with psoriasis who are either not working or are retired base their work status on their skin condition.16 Furthermore, psoriasis may contribute to economic burden for patients due to indirect costs associated with work absenteeism.17

Adequate treatment of psoriasis improves patients’ physical and psychological health as well as their ability to function in the workplace. However, despite the benefits of treatment, 30% of patients with severe psoriasis and 53% of patients with moderate psoriasis receive no treatment or only topical medications instead of systemic therapies.16 The potential adverse events of inadequate psoriasis treatment far outweigh any potential benefits of withholding treatment. Perhaps a boxed warning should be issued for inadequate treatment of psoriasis patients.

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. Guidance for industry: warning and precautions, contraindications, and boxed warning sections of labeling for human prescription drug and biological products—content and format. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/.../Guidances/ucm075096.pdf. Published October 6, 2011. Accessed August 10, 2016.

- Ogdie A, Yu Y, Haynes K, et al. Risk of major cardiovascular events in patients with psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:326-332.

- Rose S, Sheth NH, Baker JF, et al. A comparison of vascular inflammation in psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and healthy subjects by FDG-PET/CT: a pilot study. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;3:273-278.

- Shlyankevich J, Mehta NN, Krueger JG, et al. Accumulating evidence for the association and shared pathogenic mechanisms between psoriasis and cardiovascular-related comorbidities. Am J Med. 2014;127:1148-1153.

- Lee MK, Kim HS, Cho EB, et al. A study of awareness and screening behavior of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with psoriasis and dermatologists. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:59-65.

- Voiculescu VM, Lupu M, Papagheorghe L, et al. Psoriasis and metabolic syndrome—scientific evidence and therapeutic implications. J Med Life. 2014;7:468-471.

- Wu JJ, Poon KY, Bebchuk JD. Association between the type and length of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy and myocardial infarction risk in patients with psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:899-903.

- Famenini S, Sako EY, Wu JJ. Effect of treating psoriasis on cardiovascular comorbidities: focus on TNF inhibitors. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:45-50.

- Gottlieb AB, Kalb RE, Langley RG, et al. Safety observations in 12095 patients with psoriasis enrolled in an international registry (PSOLAR): experience with infliximab and other systemic and biologic therapies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:1441-1448.

- Chimenti MS, Graceffa D, Perricone R. Anti-TNFα discontinuation in rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis: is it possible after disease remission [published online Apr 21, 2011]? Autoimmun Rev. 2011;10:636-640.

- Kavanaugh A, Ritchlin C, Rahman P, et al. Ustekinumab, an anti-IL-12/23 p40 monoclonal antibody, inhibits radiographic progression in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: results of an integrated analysis of radiographic data from the phase 3, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled PSUMMIT-1 and PSUMMIT-2 trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1000-1006.

- Pietrzak A, Bartosinska J, Blaszczyk R, et al. Increased serum level of N-terminal Pro-B-type natriuretic peptide as a possible biomarker of cardiovascular risk in psoriatic patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1010-1014.

- Rapp SR, Feldman SR, Exum ML, et al. Psoriasis causes as much disability as other major medical diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(3, pt 1):401-407.

- Pettey AA, Balkrishnan R, Rapp SR, et al. Patients with palmoplantar psoriasis have more physical disability and discomfort than patients with other forms of psoriasis: implications for clinical practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:271-275.

- Garshick MK, Kimball AB. Psoriasis and the life cycle of persistent life effects. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:25-39.

- Feldman SR, Malakouti M, Koo JY. Social impact of the burden of psoriasis: effects on patients and practice. Dermatol Online J. August 17, 2014;20. pii:13030/qt48r4w8h2.

- Brezinski EA, Dhillon JS, Armstrong AW. Economic burden of psoriasis in the United States: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:651-658.

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. Guidance for industry: warning and precautions, contraindications, and boxed warning sections of labeling for human prescription drug and biological products—content and format. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/.../Guidances/ucm075096.pdf. Published October 6, 2011. Accessed August 10, 2016.

- Ogdie A, Yu Y, Haynes K, et al. Risk of major cardiovascular events in patients with psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:326-332.

- Rose S, Sheth NH, Baker JF, et al. A comparison of vascular inflammation in psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and healthy subjects by FDG-PET/CT: a pilot study. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;3:273-278.

- Shlyankevich J, Mehta NN, Krueger JG, et al. Accumulating evidence for the association and shared pathogenic mechanisms between psoriasis and cardiovascular-related comorbidities. Am J Med. 2014;127:1148-1153.

- Lee MK, Kim HS, Cho EB, et al. A study of awareness and screening behavior of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with psoriasis and dermatologists. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:59-65.

- Voiculescu VM, Lupu M, Papagheorghe L, et al. Psoriasis and metabolic syndrome—scientific evidence and therapeutic implications. J Med Life. 2014;7:468-471.

- Wu JJ, Poon KY, Bebchuk JD. Association between the type and length of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy and myocardial infarction risk in patients with psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:899-903.

- Famenini S, Sako EY, Wu JJ. Effect of treating psoriasis on cardiovascular comorbidities: focus on TNF inhibitors. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:45-50.

- Gottlieb AB, Kalb RE, Langley RG, et al. Safety observations in 12095 patients with psoriasis enrolled in an international registry (PSOLAR): experience with infliximab and other systemic and biologic therapies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:1441-1448.

- Chimenti MS, Graceffa D, Perricone R. Anti-TNFα discontinuation in rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis: is it possible after disease remission [published online Apr 21, 2011]? Autoimmun Rev. 2011;10:636-640.

- Kavanaugh A, Ritchlin C, Rahman P, et al. Ustekinumab, an anti-IL-12/23 p40 monoclonal antibody, inhibits radiographic progression in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: results of an integrated analysis of radiographic data from the phase 3, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled PSUMMIT-1 and PSUMMIT-2 trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1000-1006.

- Pietrzak A, Bartosinska J, Blaszczyk R, et al. Increased serum level of N-terminal Pro-B-type natriuretic peptide as a possible biomarker of cardiovascular risk in psoriatic patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1010-1014.

- Rapp SR, Feldman SR, Exum ML, et al. Psoriasis causes as much disability as other major medical diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(3, pt 1):401-407.

- Pettey AA, Balkrishnan R, Rapp SR, et al. Patients with palmoplantar psoriasis have more physical disability and discomfort than patients with other forms of psoriasis: implications for clinical practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:271-275.

- Garshick MK, Kimball AB. Psoriasis and the life cycle of persistent life effects. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:25-39.

- Feldman SR, Malakouti M, Koo JY. Social impact of the burden of psoriasis: effects on patients and practice. Dermatol Online J. August 17, 2014;20. pii:13030/qt48r4w8h2.

- Brezinski EA, Dhillon JS, Armstrong AW. Economic burden of psoriasis in the United States: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:651-658.

Back to Basics: The Role of the Team Physician

Editor’s Note: AJO Deputy Editor-in-Chief Robin West, MD, is the Head Team Physician for the Washington Redskins and the Washington Nationals. She has previously served as a team physician for 2 Super Bowl-winning Pittsburgh Steelers teams. I am pleased to “hand off” this issue to her.

—Bryan T. Hanypsiak, MD

The summer is over, football season has begun, and team physicians are busy trying to manage and treat the plethora of injuries that come with the game. Football is one of the most popular sports played by young athletes. Youth participation (ages 6-14 years) in tackle football was 2.169 million in 2015, according to a study conducted by the Physical Activity Council and presented by USA Football. There were 1.084 million boys (and 1500 girls) playing high school football in the 2014-2015 season, nearly twice the number of the next most popular sport, track and field, according to the National Federation of State High School Associations.Due to the sheer volume of athletes and high-impact nature of the game, football leads all other sports in the number of sustained injuries.

Team physicians have the leadership role in the organization, management, and provision of care of the athletes on the team. The roles and responsibilities of the team physician are ever-evolving. The team physician has to meet certain medical qualifications and education requirements, and understand the ethical and medicolegal issues.

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and several other medical associations have put together a Team Physician Consensus Statement (available at http://bit.ly/2b8rOzS). All team physicians, coaches, and athletic trainers should read and understand this statement, as it delineates the qualifications, duties, and responsibilities of the team physician.

Our Football Issue focuses on the most common injuries that the team physician will encounter during the season. Our goal is to create a comprehensive guide for the team physician on the acute management of these injuries. As team physicians, we have to make quick return-to-play decisions that are often difficult, as we are dealing with extremely competitive athletes and coaches in the heat of the moment. Since we can’t control the high levels of adrenalin, loud stadium, or rapid speed of the game, we need to be prepared to perform a comprehensive evaluation and diagnosis under these circumstances. This return-to-play decision should be based solely on the severity of the injury and safety of the player. As a team physician, you are responsible for making the “final call” on when the player is safe to return to the game.

This issue includes a section on the most common medical issues (ophthalmology, dental, and dermatology), concussion, exertional heat stroke, knee injuries, and foot and ankle injuries. We also have a special list of the most common items to include in the athletic trainer’s medical bag when covering a high school or collegiate football game (see page 376). Our prominent contributing authors all have extensive experience covering high school, collegiate, and professional teams.

I hope that our Football Issue helps you to keep your athletes safe and injury-free, which is necessary to have a successful season. Remember, as the team physician, your primary focus is the well being of the players. The success of the team only comes when the players are healthy. A cohesive, well-organized medical team, led by the head athletic trainer and team physician, is a key component to the care of the athletes. It truly takes a village to provide top-notch medical care to a football team.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(6):338. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

Editor’s Note: AJO Deputy Editor-in-Chief Robin West, MD, is the Head Team Physician for the Washington Redskins and the Washington Nationals. She has previously served as a team physician for 2 Super Bowl-winning Pittsburgh Steelers teams. I am pleased to “hand off” this issue to her.

—Bryan T. Hanypsiak, MD

The summer is over, football season has begun, and team physicians are busy trying to manage and treat the plethora of injuries that come with the game. Football is one of the most popular sports played by young athletes. Youth participation (ages 6-14 years) in tackle football was 2.169 million in 2015, according to a study conducted by the Physical Activity Council and presented by USA Football. There were 1.084 million boys (and 1500 girls) playing high school football in the 2014-2015 season, nearly twice the number of the next most popular sport, track and field, according to the National Federation of State High School Associations.Due to the sheer volume of athletes and high-impact nature of the game, football leads all other sports in the number of sustained injuries.

Team physicians have the leadership role in the organization, management, and provision of care of the athletes on the team. The roles and responsibilities of the team physician are ever-evolving. The team physician has to meet certain medical qualifications and education requirements, and understand the ethical and medicolegal issues.

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and several other medical associations have put together a Team Physician Consensus Statement (available at http://bit.ly/2b8rOzS). All team physicians, coaches, and athletic trainers should read and understand this statement, as it delineates the qualifications, duties, and responsibilities of the team physician.

Our Football Issue focuses on the most common injuries that the team physician will encounter during the season. Our goal is to create a comprehensive guide for the team physician on the acute management of these injuries. As team physicians, we have to make quick return-to-play decisions that are often difficult, as we are dealing with extremely competitive athletes and coaches in the heat of the moment. Since we can’t control the high levels of adrenalin, loud stadium, or rapid speed of the game, we need to be prepared to perform a comprehensive evaluation and diagnosis under these circumstances. This return-to-play decision should be based solely on the severity of the injury and safety of the player. As a team physician, you are responsible for making the “final call” on when the player is safe to return to the game.

This issue includes a section on the most common medical issues (ophthalmology, dental, and dermatology), concussion, exertional heat stroke, knee injuries, and foot and ankle injuries. We also have a special list of the most common items to include in the athletic trainer’s medical bag when covering a high school or collegiate football game (see page 376). Our prominent contributing authors all have extensive experience covering high school, collegiate, and professional teams.

I hope that our Football Issue helps you to keep your athletes safe and injury-free, which is necessary to have a successful season. Remember, as the team physician, your primary focus is the well being of the players. The success of the team only comes when the players are healthy. A cohesive, well-organized medical team, led by the head athletic trainer and team physician, is a key component to the care of the athletes. It truly takes a village to provide top-notch medical care to a football team.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(6):338. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

Editor’s Note: AJO Deputy Editor-in-Chief Robin West, MD, is the Head Team Physician for the Washington Redskins and the Washington Nationals. She has previously served as a team physician for 2 Super Bowl-winning Pittsburgh Steelers teams. I am pleased to “hand off” this issue to her.

—Bryan T. Hanypsiak, MD

The summer is over, football season has begun, and team physicians are busy trying to manage and treat the plethora of injuries that come with the game. Football is one of the most popular sports played by young athletes. Youth participation (ages 6-14 years) in tackle football was 2.169 million in 2015, according to a study conducted by the Physical Activity Council and presented by USA Football. There were 1.084 million boys (and 1500 girls) playing high school football in the 2014-2015 season, nearly twice the number of the next most popular sport, track and field, according to the National Federation of State High School Associations.Due to the sheer volume of athletes and high-impact nature of the game, football leads all other sports in the number of sustained injuries.

Team physicians have the leadership role in the organization, management, and provision of care of the athletes on the team. The roles and responsibilities of the team physician are ever-evolving. The team physician has to meet certain medical qualifications and education requirements, and understand the ethical and medicolegal issues.

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and several other medical associations have put together a Team Physician Consensus Statement (available at http://bit.ly/2b8rOzS). All team physicians, coaches, and athletic trainers should read and understand this statement, as it delineates the qualifications, duties, and responsibilities of the team physician.

Our Football Issue focuses on the most common injuries that the team physician will encounter during the season. Our goal is to create a comprehensive guide for the team physician on the acute management of these injuries. As team physicians, we have to make quick return-to-play decisions that are often difficult, as we are dealing with extremely competitive athletes and coaches in the heat of the moment. Since we can’t control the high levels of adrenalin, loud stadium, or rapid speed of the game, we need to be prepared to perform a comprehensive evaluation and diagnosis under these circumstances. This return-to-play decision should be based solely on the severity of the injury and safety of the player. As a team physician, you are responsible for making the “final call” on when the player is safe to return to the game.

This issue includes a section on the most common medical issues (ophthalmology, dental, and dermatology), concussion, exertional heat stroke, knee injuries, and foot and ankle injuries. We also have a special list of the most common items to include in the athletic trainer’s medical bag when covering a high school or collegiate football game (see page 376). Our prominent contributing authors all have extensive experience covering high school, collegiate, and professional teams.

I hope that our Football Issue helps you to keep your athletes safe and injury-free, which is necessary to have a successful season. Remember, as the team physician, your primary focus is the well being of the players. The success of the team only comes when the players are healthy. A cohesive, well-organized medical team, led by the head athletic trainer and team physician, is a key component to the care of the athletes. It truly takes a village to provide top-notch medical care to a football team.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(6):338. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

Taking hysteroscopy to the office

Along with global endometrial ablation, diagnostic and minor operative hysteroscopy are excellent procedures to bring into your office environment. These operations are generally of short duration and provide little risk to the patient. Moreover, reimbursement exceeds that for the hospital setting. A constant revenue stream can be created after an initial moderate expenditure.

The key to a successful office procedure is patient comfort; this begins with minimizing pain and trauma. In our practice, we note decreased pain when performing vaginoscopy and hysteroscopy without the use of a speculum or tenaculum. This is well substantiated in literature by Professor Stefano Bettocchi, who immediately preceded me as president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE).

In this issue of Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have asked my partner, Aarathi Cholkeri-Singh, MD, to discuss vaginoscopy. Dr. Cholkeri-Singh is clinical assistant professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, lecturer at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, and associate director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.

She also serves as codirector of the AAGL/Society of Reproductive Surgeons fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and director of gynecologic surgical education at Advocate Lutheran, and is chair for a postgraduate course on hysteroscopy at the upcoming AAGL 45th Annual Global Congress. Among her publications is a recent review in the Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology on hysteroscopy for infertile women (doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2014.12.163).

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and past president of the AAGL and the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville and Schaumburg, Ill.; director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/SRS fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. He reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email him at [email protected].

Along with global endometrial ablation, diagnostic and minor operative hysteroscopy are excellent procedures to bring into your office environment. These operations are generally of short duration and provide little risk to the patient. Moreover, reimbursement exceeds that for the hospital setting. A constant revenue stream can be created after an initial moderate expenditure.

The key to a successful office procedure is patient comfort; this begins with minimizing pain and trauma. In our practice, we note decreased pain when performing vaginoscopy and hysteroscopy without the use of a speculum or tenaculum. This is well substantiated in literature by Professor Stefano Bettocchi, who immediately preceded me as president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE).

In this issue of Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have asked my partner, Aarathi Cholkeri-Singh, MD, to discuss vaginoscopy. Dr. Cholkeri-Singh is clinical assistant professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, lecturer at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, and associate director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.

She also serves as codirector of the AAGL/Society of Reproductive Surgeons fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and director of gynecologic surgical education at Advocate Lutheran, and is chair for a postgraduate course on hysteroscopy at the upcoming AAGL 45th Annual Global Congress. Among her publications is a recent review in the Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology on hysteroscopy for infertile women (doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2014.12.163).

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and past president of the AAGL and the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville and Schaumburg, Ill.; director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/SRS fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. He reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email him at [email protected].

Along with global endometrial ablation, diagnostic and minor operative hysteroscopy are excellent procedures to bring into your office environment. These operations are generally of short duration and provide little risk to the patient. Moreover, reimbursement exceeds that for the hospital setting. A constant revenue stream can be created after an initial moderate expenditure.

The key to a successful office procedure is patient comfort; this begins with minimizing pain and trauma. In our practice, we note decreased pain when performing vaginoscopy and hysteroscopy without the use of a speculum or tenaculum. This is well substantiated in literature by Professor Stefano Bettocchi, who immediately preceded me as president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE).

In this issue of Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have asked my partner, Aarathi Cholkeri-Singh, MD, to discuss vaginoscopy. Dr. Cholkeri-Singh is clinical assistant professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, lecturer at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, and associate director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.

She also serves as codirector of the AAGL/Society of Reproductive Surgeons fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and director of gynecologic surgical education at Advocate Lutheran, and is chair for a postgraduate course on hysteroscopy at the upcoming AAGL 45th Annual Global Congress. Among her publications is a recent review in the Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology on hysteroscopy for infertile women (doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2014.12.163).

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and past president of the AAGL and the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville and Schaumburg, Ill.; director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/SRS fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. He reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email him at [email protected].

The benefits of integrating in-office hysteroscopy

The benefits of integrating hysteroscopy into office practice are compelling. Most importantly, patients appreciate the comfort and convenience of having hysteroscopic procedures done in a familiar setting. Patients can generally be in and out of the office in less than 30 minutes for a diagnostic procedure, and in less than 1-2 hours for an operative procedure.

Not only is an in-office approach patient centered and clinically valuable, but it is more efficient and economically favorable for the gynecologic surgeon. Physicians earn higher reimbursement for diagnostic hysteroscopies, as well as many therapeutic and operative hysteroscopies, when these procedures are done in the office rather than when they’re performed in a hospital or an outpatient center.

Transitioning to in-office hysteroscopy need not be daunting: The setup is relatively simple and does not require an operating suite, just a dedicated exam room. And the need for premedication and local anesthesia can be low, particularly when a vaginoscopic approach to hysteroscopy is employed. For most gynecologic surgeons, the necessary skills and comfort levels fall into place after only a few vaginoscopic procedures.

A vaginoscopic approach avoids the use of a vaginal speculum or cervical tenaculum, significantly decreasing discomfort or pain. Not using these instruments is the only difference between this and traditional hysteroscopy. It is a less invasive approach that is much more tolerable for patients. And for the surgeon, it can be easier and quicker and provides equally good visualization without any impairment in cervical passage.

Described in the literature as far back as the 1950s, vaginoscopy has its roots in the pediatric/adolescent population, where it was used for the removal of foreign bodies and evaluation of the vagina and external cervical os.

More recently, Stefano Bettocchi, MD, and Luigi Selvaggi, MD, in Italy were the first to describe a vaginoscopic approach to hysteroscopy for evaluating the endocervical canal and uterine cavity.

In a series of papers from 1997 to 2004, Dr. Bettocchi and Dr. Selvaggi documented their efforts to improve patient tolerance during diagnostic hysteroscopies. When they used both the speculum and tenaculum in 163 patients, with local anesthesia, 8% reported severe pain, 11% reported moderate pain, and 69% reported mild pain. Only 12% reported no discomfort. With speculum use only, and no anesthesia, in 308 patients, none reported severe pain, 2% reported moderate pain, 32% reported mild pain, and 66% reported no discomfort. When neither instrument was used (again, no anesthesia), patient discomfort was nearly eliminated: In 680 procedures, patients had a 96% no-discomfort rate (J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1997 Feb;4[2]:255-8; Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Aug;15[4]:303-8; Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2004 Sep;31[3]:641-54, xi).

Since then, research has affirmed the differences in patient tolerance and has shown that there is no significant difference between traditional and vaginoscopic hysteroscopy in the rate of procedure failure (0%-10%).

In my practice, in addition to vaginal or cervical examination and evaluation of the uterine cavity, I utilize a vaginoscopic approach to perform minor therapeutic and operative procedures such as biopsies, polypectomies, tubal occlusion using the Essure system, and removal of lost intrauterine devices. I can assess infertility, trauma, abnormal uterine bleeding, and mesh erosion, and provide pre- and postsurgical evaluations. In all of these cases, I use minimal premedication and only rarely need any local anesthetic and/or sedation.

Instrumentation and technique

There are a variety of hysteroscopes available on the market, from single-channel flexible diagnostic hysteroscopes that are 3 mm to 4 mm in diameter, to “see-and-treat” operative hysteroscopes that are rigid and have various diameters and camera lens angles.

A hysteroscope with a 5.5-mm outer diameter works well for a vaginoscopic approach that avoids cervical dilation. Accessory instrumentation includes semirigid 5 Fr 35-cm–long biopsy forceps, scissors, and alligator forceps.

In timing the procedure, our main goal is a thin uterine lining. This can be achieved by scheduling the procedure during the early proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle or by using a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist or a transdermal or transvaginal contraceptive medication.

By far the most important element of pain control and analgesia is the time spent with each patient to thoroughly discuss the experience of hysteroscopy and to set expectations about what she will hear, see, and feel. An unexpected experience can worsen anxiety, which in turn can worsen pain. If everything is as familiar and relaxed as possible, there will be little need for analgesia.

I tell patients in preprocedure counseling that the distention of the uterine walls usually causes some cramping, and that NSAIDs can minimize this cramping. In rare cases, when a patient is very worried about her pain tolerance, I will prescribe diazepam. However, many of my patients opt to do nothing other than take ibuprofen. On a case-by-case basis, you can determine with your patient what type and level of analgesia and preprocedure medication will be best.

Paracervical blocks are an option for some surgical patients, but I advise my patients to move forward without the block and assure them that it can be administered later if needed. Thus far, I’ve never proceeded with a paracervical block. There are other methods and sites for introducing local anesthesia, including intracervical, by injection or topical, or topical intracavitary techniques. Nevertheless, it is unclear from randomized controlled trials whether local anesthesia is effective. Trials of paracervical blocks similarly have had inconsistent outcomes.

I do commonly premedicate patients – mainly nulliparous patients and postmenopausal patients – with misoprostol, which softens the cervix and facilitates an easier entry of the hysteroscope into the cervix.

Published studies on misoprostol administration before hysteroscopy have had mixed results. A Cochrane review from 2015 concluded there is moderate-quality evidence in support of preoperative ripening with the agent, while another meta-analysis also published in 2015 concluded that data are poor and do not support its use. Recently, however, there appear to be more supportive studies demonstrating or suggesting that misoprostol is effective in reducing discomfort.

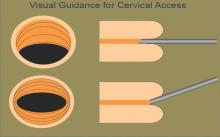

Patient discomfort is also minimized when there is little manipulation of the hysteroscope. Scopes that are angled (12, 25, or 30 degrees) allow optimal visualization with minimal movement; the scope can be brought to the midline of the uterine cavity and the light cord rotated to the 3:00 and 9:00 o’clock positions to enable visualization of the cornu. A 0-degree scope, on the other hand, must be manipulated quite a bit for the same degree of visualization, potentially increasing patient discomfort.

Prior to hysteroscopy, the cervix and vagina are cleaned with a small-diameter swab dipped in povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine gluconate in the case of allergies. One or two 1,000-cc bags of saline inserted into pressure bags are attached to Y-type tubing. (A diagnostic procedure rarely will require two bags.) I spread the labia initially while guiding the scope into the posterior fornix of the vagina. If the leakage of fluid causes inadequate distension of the vaginal walls, I will gently pinch the labia together with gauze.

I then gently pull back the scope and manipulate it posteriorly to visualize the external cervical os anteriorly. The hysteroscope may then be introduced through the cervical os, endocervical canal, and uterine cavity, with care taken so that the instrument does not rub against the cervix or the uterine tissue and cause trauma, pain, and bleeding. The uterus will progressively align with the cervix and vagina, thereby eliminating the need for a tenaculum to straighten the uterine axis.

Fluid monitoring is important, especially during operative hysteroscopy. In my practice, a nurse watches inflow and outflow amounts while I explain what I am doing and visualizing. Some patients like to be able to view the surgery, so I am always ready to tilt the screen accordingly.

The economics

How do you know if office hysteroscopy is right for you? Your own surgical skill and the skills of your staff, who must be trained to handle and sterilize equipment and to consistently assist you, are major factors, as is ensurance of a return on your investment.

One manufacturer contacted for this Master Class lists the price of a complete office tower (light source, camera, and monitor) at approximately $9,700 and the price of a rigid hysteroscope, sheath, and hand instruments at about $6,300. A complete setup for office hysteroscopy, including a standard operative (rigid) hysteroscope, should therefore cost between $15,000 and $17,000. Companies also offer leasing options for about $300-400/month.

Flexible hysteroscopes cost about $6,000 more, which prompts many gynecologic surgeons to focus their investment on a rigid scope that can be used for both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Disposables cost $10 or less, and $40-50 or less, for each diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy, respectively.

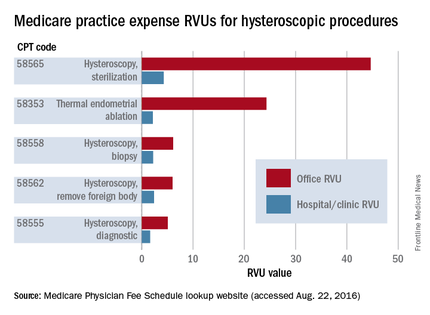

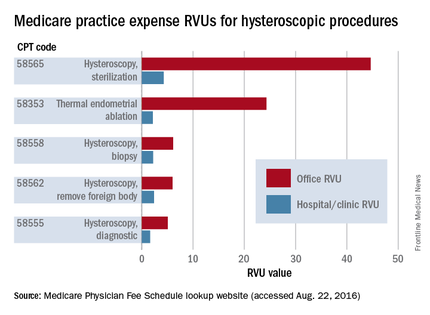

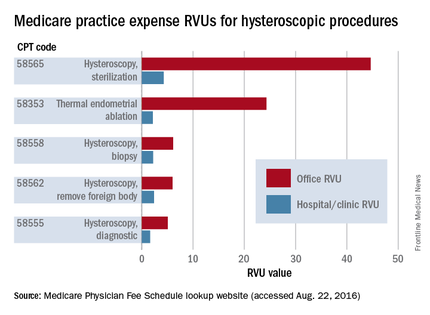

A look at the Medicare Relative Value Units (RVUs) – a key component of the Medicare reimbursement system and a standard for many payers in determining compensation – shows higher reimbursement for quite a few hysteroscopic codes when these procedures are performed in the office.

Total RVUs have three components:

1. Physician work, including time and the technical skill and intensity of effort it takes to perform a service or procedure.

2. Practice expenses, such as rent, equipment and supplies, and nonphysician salaries.

3. Malpractice insurance premiums.

Each component is multiplied by a factor that accounts for geographic cost variations, and each total RVU is multiplied by a dollar amount known as the conversion factor.

Practice expense (PE) RVUs for services provided in a “facility” (e.g., hospital or outpatient clinic) are often lower than office-based PE RVUs for the same services. Hysteroscopy is no exception. The PE RVU value for diagnostic hysteroscopy performed in the office, for instance, is approximately 5 units, compared with 1.64 units for diagnostic hysteroscopy performed in a facility.

Information on hysteroscopic procedures, and their associated RVUs, on geographic practice cost indices and on pricing, can be accessed using Medicare’s Physician Fee Schedule lookup tool (www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule/overview.aspx).

This tool is useful for calculating returns on investment. According to national payment amounts listed in August, a diagnostic hysteroscopy performed in the office will earn an average of $315.08 vs. $192.27 for each case performed in the hospital. If you perform 12 such procedures a year, that’s about $3,781 in the office, compared with $2,307 in the hospital.

This difference alone might not be worth an investment of $15,000 or more, but if you anticipate performing additional procedures with higher margins and higher reimbursement, such as 12 thermal endometrial ablations a year in combination with diagnostic hysteroscopy (which, according to the Medicare national fee schedule averages would earn $15,962 in the office vs. $4,971 in the hospital), or 12 Essure tubal occlusions ($22,595 vs. $5,263), the investment will look more favorable.

And if your patients are largely privately insured, your return on investment will occur much more quickly. In metropolitan Chicago, Blue Cross Blue Shield is reimbursing in-office diagnostic hysteroscopy at approximately $568, hysteroscopic ablations at $3,844, and Essure tubal occlusions at $3,885.

In addition to reimbursement levels, it’s important to consider the efficiencies of in-office hysteroscopy. You can perform an annual exam while the assistant sets up the room and greets each patient, for instance, or see another established patient while the assistant discharges your patient and turns the room over. Our patients, in turn, benefit from increased accessibility, with less time spent away from work or family, as well as more familiarity and comfort and reduced out-of-pocket expenses.

Dr. Cholkeri-Singh is clinical assistant professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago and is director of gynecologic surgical education and associate director of minimally invasive gynecology at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital. She is in private practice with Dr. Charles Miller and Dr. Kristen Sasaki at the Advanced Gynecologic Surgical Institute in Chicago. She is a consultant for DySIS Medical, Hologic, and Bayer HealthCare.

The benefits of integrating hysteroscopy into office practice are compelling. Most importantly, patients appreciate the comfort and convenience of having hysteroscopic procedures done in a familiar setting. Patients can generally be in and out of the office in less than 30 minutes for a diagnostic procedure, and in less than 1-2 hours for an operative procedure.

Not only is an in-office approach patient centered and clinically valuable, but it is more efficient and economically favorable for the gynecologic surgeon. Physicians earn higher reimbursement for diagnostic hysteroscopies, as well as many therapeutic and operative hysteroscopies, when these procedures are done in the office rather than when they’re performed in a hospital or an outpatient center.

Transitioning to in-office hysteroscopy need not be daunting: The setup is relatively simple and does not require an operating suite, just a dedicated exam room. And the need for premedication and local anesthesia can be low, particularly when a vaginoscopic approach to hysteroscopy is employed. For most gynecologic surgeons, the necessary skills and comfort levels fall into place after only a few vaginoscopic procedures.

A vaginoscopic approach avoids the use of a vaginal speculum or cervical tenaculum, significantly decreasing discomfort or pain. Not using these instruments is the only difference between this and traditional hysteroscopy. It is a less invasive approach that is much more tolerable for patients. And for the surgeon, it can be easier and quicker and provides equally good visualization without any impairment in cervical passage.

Described in the literature as far back as the 1950s, vaginoscopy has its roots in the pediatric/adolescent population, where it was used for the removal of foreign bodies and evaluation of the vagina and external cervical os.

More recently, Stefano Bettocchi, MD, and Luigi Selvaggi, MD, in Italy were the first to describe a vaginoscopic approach to hysteroscopy for evaluating the endocervical canal and uterine cavity.

In a series of papers from 1997 to 2004, Dr. Bettocchi and Dr. Selvaggi documented their efforts to improve patient tolerance during diagnostic hysteroscopies. When they used both the speculum and tenaculum in 163 patients, with local anesthesia, 8% reported severe pain, 11% reported moderate pain, and 69% reported mild pain. Only 12% reported no discomfort. With speculum use only, and no anesthesia, in 308 patients, none reported severe pain, 2% reported moderate pain, 32% reported mild pain, and 66% reported no discomfort. When neither instrument was used (again, no anesthesia), patient discomfort was nearly eliminated: In 680 procedures, patients had a 96% no-discomfort rate (J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1997 Feb;4[2]:255-8; Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Aug;15[4]:303-8; Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2004 Sep;31[3]:641-54, xi).

Since then, research has affirmed the differences in patient tolerance and has shown that there is no significant difference between traditional and vaginoscopic hysteroscopy in the rate of procedure failure (0%-10%).

In my practice, in addition to vaginal or cervical examination and evaluation of the uterine cavity, I utilize a vaginoscopic approach to perform minor therapeutic and operative procedures such as biopsies, polypectomies, tubal occlusion using the Essure system, and removal of lost intrauterine devices. I can assess infertility, trauma, abnormal uterine bleeding, and mesh erosion, and provide pre- and postsurgical evaluations. In all of these cases, I use minimal premedication and only rarely need any local anesthetic and/or sedation.

Instrumentation and technique

There are a variety of hysteroscopes available on the market, from single-channel flexible diagnostic hysteroscopes that are 3 mm to 4 mm in diameter, to “see-and-treat” operative hysteroscopes that are rigid and have various diameters and camera lens angles.

A hysteroscope with a 5.5-mm outer diameter works well for a vaginoscopic approach that avoids cervical dilation. Accessory instrumentation includes semirigid 5 Fr 35-cm–long biopsy forceps, scissors, and alligator forceps.

In timing the procedure, our main goal is a thin uterine lining. This can be achieved by scheduling the procedure during the early proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle or by using a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist or a transdermal or transvaginal contraceptive medication.

By far the most important element of pain control and analgesia is the time spent with each patient to thoroughly discuss the experience of hysteroscopy and to set expectations about what she will hear, see, and feel. An unexpected experience can worsen anxiety, which in turn can worsen pain. If everything is as familiar and relaxed as possible, there will be little need for analgesia.

I tell patients in preprocedure counseling that the distention of the uterine walls usually causes some cramping, and that NSAIDs can minimize this cramping. In rare cases, when a patient is very worried about her pain tolerance, I will prescribe diazepam. However, many of my patients opt to do nothing other than take ibuprofen. On a case-by-case basis, you can determine with your patient what type and level of analgesia and preprocedure medication will be best.

Paracervical blocks are an option for some surgical patients, but I advise my patients to move forward without the block and assure them that it can be administered later if needed. Thus far, I’ve never proceeded with a paracervical block. There are other methods and sites for introducing local anesthesia, including intracervical, by injection or topical, or topical intracavitary techniques. Nevertheless, it is unclear from randomized controlled trials whether local anesthesia is effective. Trials of paracervical blocks similarly have had inconsistent outcomes.

I do commonly premedicate patients – mainly nulliparous patients and postmenopausal patients – with misoprostol, which softens the cervix and facilitates an easier entry of the hysteroscope into the cervix.

Published studies on misoprostol administration before hysteroscopy have had mixed results. A Cochrane review from 2015 concluded there is moderate-quality evidence in support of preoperative ripening with the agent, while another meta-analysis also published in 2015 concluded that data are poor and do not support its use. Recently, however, there appear to be more supportive studies demonstrating or suggesting that misoprostol is effective in reducing discomfort.

Patient discomfort is also minimized when there is little manipulation of the hysteroscope. Scopes that are angled (12, 25, or 30 degrees) allow optimal visualization with minimal movement; the scope can be brought to the midline of the uterine cavity and the light cord rotated to the 3:00 and 9:00 o’clock positions to enable visualization of the cornu. A 0-degree scope, on the other hand, must be manipulated quite a bit for the same degree of visualization, potentially increasing patient discomfort.

Prior to hysteroscopy, the cervix and vagina are cleaned with a small-diameter swab dipped in povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine gluconate in the case of allergies. One or two 1,000-cc bags of saline inserted into pressure bags are attached to Y-type tubing. (A diagnostic procedure rarely will require two bags.) I spread the labia initially while guiding the scope into the posterior fornix of the vagina. If the leakage of fluid causes inadequate distension of the vaginal walls, I will gently pinch the labia together with gauze.

I then gently pull back the scope and manipulate it posteriorly to visualize the external cervical os anteriorly. The hysteroscope may then be introduced through the cervical os, endocervical canal, and uterine cavity, with care taken so that the instrument does not rub against the cervix or the uterine tissue and cause trauma, pain, and bleeding. The uterus will progressively align with the cervix and vagina, thereby eliminating the need for a tenaculum to straighten the uterine axis.

Fluid monitoring is important, especially during operative hysteroscopy. In my practice, a nurse watches inflow and outflow amounts while I explain what I am doing and visualizing. Some patients like to be able to view the surgery, so I am always ready to tilt the screen accordingly.

The economics

How do you know if office hysteroscopy is right for you? Your own surgical skill and the skills of your staff, who must be trained to handle and sterilize equipment and to consistently assist you, are major factors, as is ensurance of a return on your investment.

One manufacturer contacted for this Master Class lists the price of a complete office tower (light source, camera, and monitor) at approximately $9,700 and the price of a rigid hysteroscope, sheath, and hand instruments at about $6,300. A complete setup for office hysteroscopy, including a standard operative (rigid) hysteroscope, should therefore cost between $15,000 and $17,000. Companies also offer leasing options for about $300-400/month.

Flexible hysteroscopes cost about $6,000 more, which prompts many gynecologic surgeons to focus their investment on a rigid scope that can be used for both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Disposables cost $10 or less, and $40-50 or less, for each diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy, respectively.

A look at the Medicare Relative Value Units (RVUs) – a key component of the Medicare reimbursement system and a standard for many payers in determining compensation – shows higher reimbursement for quite a few hysteroscopic codes when these procedures are performed in the office.

Total RVUs have three components:

1. Physician work, including time and the technical skill and intensity of effort it takes to perform a service or procedure.

2. Practice expenses, such as rent, equipment and supplies, and nonphysician salaries.

3. Malpractice insurance premiums.

Each component is multiplied by a factor that accounts for geographic cost variations, and each total RVU is multiplied by a dollar amount known as the conversion factor.

Practice expense (PE) RVUs for services provided in a “facility” (e.g., hospital or outpatient clinic) are often lower than office-based PE RVUs for the same services. Hysteroscopy is no exception. The PE RVU value for diagnostic hysteroscopy performed in the office, for instance, is approximately 5 units, compared with 1.64 units for diagnostic hysteroscopy performed in a facility.

Information on hysteroscopic procedures, and their associated RVUs, on geographic practice cost indices and on pricing, can be accessed using Medicare’s Physician Fee Schedule lookup tool (www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule/overview.aspx).

This tool is useful for calculating returns on investment. According to national payment amounts listed in August, a diagnostic hysteroscopy performed in the office will earn an average of $315.08 vs. $192.27 for each case performed in the hospital. If you perform 12 such procedures a year, that’s about $3,781 in the office, compared with $2,307 in the hospital.

This difference alone might not be worth an investment of $15,000 or more, but if you anticipate performing additional procedures with higher margins and higher reimbursement, such as 12 thermal endometrial ablations a year in combination with diagnostic hysteroscopy (which, according to the Medicare national fee schedule averages would earn $15,962 in the office vs. $4,971 in the hospital), or 12 Essure tubal occlusions ($22,595 vs. $5,263), the investment will look more favorable.

And if your patients are largely privately insured, your return on investment will occur much more quickly. In metropolitan Chicago, Blue Cross Blue Shield is reimbursing in-office diagnostic hysteroscopy at approximately $568, hysteroscopic ablations at $3,844, and Essure tubal occlusions at $3,885.

In addition to reimbursement levels, it’s important to consider the efficiencies of in-office hysteroscopy. You can perform an annual exam while the assistant sets up the room and greets each patient, for instance, or see another established patient while the assistant discharges your patient and turns the room over. Our patients, in turn, benefit from increased accessibility, with less time spent away from work or family, as well as more familiarity and comfort and reduced out-of-pocket expenses.

Dr. Cholkeri-Singh is clinical assistant professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago and is director of gynecologic surgical education and associate director of minimally invasive gynecology at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital. She is in private practice with Dr. Charles Miller and Dr. Kristen Sasaki at the Advanced Gynecologic Surgical Institute in Chicago. She is a consultant for DySIS Medical, Hologic, and Bayer HealthCare.

The benefits of integrating hysteroscopy into office practice are compelling. Most importantly, patients appreciate the comfort and convenience of having hysteroscopic procedures done in a familiar setting. Patients can generally be in and out of the office in less than 30 minutes for a diagnostic procedure, and in less than 1-2 hours for an operative procedure.

Not only is an in-office approach patient centered and clinically valuable, but it is more efficient and economically favorable for the gynecologic surgeon. Physicians earn higher reimbursement for diagnostic hysteroscopies, as well as many therapeutic and operative hysteroscopies, when these procedures are done in the office rather than when they’re performed in a hospital or an outpatient center.

Transitioning to in-office hysteroscopy need not be daunting: The setup is relatively simple and does not require an operating suite, just a dedicated exam room. And the need for premedication and local anesthesia can be low, particularly when a vaginoscopic approach to hysteroscopy is employed. For most gynecologic surgeons, the necessary skills and comfort levels fall into place after only a few vaginoscopic procedures.

A vaginoscopic approach avoids the use of a vaginal speculum or cervical tenaculum, significantly decreasing discomfort or pain. Not using these instruments is the only difference between this and traditional hysteroscopy. It is a less invasive approach that is much more tolerable for patients. And for the surgeon, it can be easier and quicker and provides equally good visualization without any impairment in cervical passage.

Described in the literature as far back as the 1950s, vaginoscopy has its roots in the pediatric/adolescent population, where it was used for the removal of foreign bodies and evaluation of the vagina and external cervical os.

More recently, Stefano Bettocchi, MD, and Luigi Selvaggi, MD, in Italy were the first to describe a vaginoscopic approach to hysteroscopy for evaluating the endocervical canal and uterine cavity.

In a series of papers from 1997 to 2004, Dr. Bettocchi and Dr. Selvaggi documented their efforts to improve patient tolerance during diagnostic hysteroscopies. When they used both the speculum and tenaculum in 163 patients, with local anesthesia, 8% reported severe pain, 11% reported moderate pain, and 69% reported mild pain. Only 12% reported no discomfort. With speculum use only, and no anesthesia, in 308 patients, none reported severe pain, 2% reported moderate pain, 32% reported mild pain, and 66% reported no discomfort. When neither instrument was used (again, no anesthesia), patient discomfort was nearly eliminated: In 680 procedures, patients had a 96% no-discomfort rate (J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1997 Feb;4[2]:255-8; Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Aug;15[4]:303-8; Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2004 Sep;31[3]:641-54, xi).

Since then, research has affirmed the differences in patient tolerance and has shown that there is no significant difference between traditional and vaginoscopic hysteroscopy in the rate of procedure failure (0%-10%).

In my practice, in addition to vaginal or cervical examination and evaluation of the uterine cavity, I utilize a vaginoscopic approach to perform minor therapeutic and operative procedures such as biopsies, polypectomies, tubal occlusion using the Essure system, and removal of lost intrauterine devices. I can assess infertility, trauma, abnormal uterine bleeding, and mesh erosion, and provide pre- and postsurgical evaluations. In all of these cases, I use minimal premedication and only rarely need any local anesthetic and/or sedation.

Instrumentation and technique

There are a variety of hysteroscopes available on the market, from single-channel flexible diagnostic hysteroscopes that are 3 mm to 4 mm in diameter, to “see-and-treat” operative hysteroscopes that are rigid and have various diameters and camera lens angles.

A hysteroscope with a 5.5-mm outer diameter works well for a vaginoscopic approach that avoids cervical dilation. Accessory instrumentation includes semirigid 5 Fr 35-cm–long biopsy forceps, scissors, and alligator forceps.

In timing the procedure, our main goal is a thin uterine lining. This can be achieved by scheduling the procedure during the early proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle or by using a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist or a transdermal or transvaginal contraceptive medication.

By far the most important element of pain control and analgesia is the time spent with each patient to thoroughly discuss the experience of hysteroscopy and to set expectations about what she will hear, see, and feel. An unexpected experience can worsen anxiety, which in turn can worsen pain. If everything is as familiar and relaxed as possible, there will be little need for analgesia.

I tell patients in preprocedure counseling that the distention of the uterine walls usually causes some cramping, and that NSAIDs can minimize this cramping. In rare cases, when a patient is very worried about her pain tolerance, I will prescribe diazepam. However, many of my patients opt to do nothing other than take ibuprofen. On a case-by-case basis, you can determine with your patient what type and level of analgesia and preprocedure medication will be best.

Paracervical blocks are an option for some surgical patients, but I advise my patients to move forward without the block and assure them that it can be administered later if needed. Thus far, I’ve never proceeded with a paracervical block. There are other methods and sites for introducing local anesthesia, including intracervical, by injection or topical, or topical intracavitary techniques. Nevertheless, it is unclear from randomized controlled trials whether local anesthesia is effective. Trials of paracervical blocks similarly have had inconsistent outcomes.

I do commonly premedicate patients – mainly nulliparous patients and postmenopausal patients – with misoprostol, which softens the cervix and facilitates an easier entry of the hysteroscope into the cervix.

Published studies on misoprostol administration before hysteroscopy have had mixed results. A Cochrane review from 2015 concluded there is moderate-quality evidence in support of preoperative ripening with the agent, while another meta-analysis also published in 2015 concluded that data are poor and do not support its use. Recently, however, there appear to be more supportive studies demonstrating or suggesting that misoprostol is effective in reducing discomfort.

Patient discomfort is also minimized when there is little manipulation of the hysteroscope. Scopes that are angled (12, 25, or 30 degrees) allow optimal visualization with minimal movement; the scope can be brought to the midline of the uterine cavity and the light cord rotated to the 3:00 and 9:00 o’clock positions to enable visualization of the cornu. A 0-degree scope, on the other hand, must be manipulated quite a bit for the same degree of visualization, potentially increasing patient discomfort.

Prior to hysteroscopy, the cervix and vagina are cleaned with a small-diameter swab dipped in povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine gluconate in the case of allergies. One or two 1,000-cc bags of saline inserted into pressure bags are attached to Y-type tubing. (A diagnostic procedure rarely will require two bags.) I spread the labia initially while guiding the scope into the posterior fornix of the vagina. If the leakage of fluid causes inadequate distension of the vaginal walls, I will gently pinch the labia together with gauze.

I then gently pull back the scope and manipulate it posteriorly to visualize the external cervical os anteriorly. The hysteroscope may then be introduced through the cervical os, endocervical canal, and uterine cavity, with care taken so that the instrument does not rub against the cervix or the uterine tissue and cause trauma, pain, and bleeding. The uterus will progressively align with the cervix and vagina, thereby eliminating the need for a tenaculum to straighten the uterine axis.

Fluid monitoring is important, especially during operative hysteroscopy. In my practice, a nurse watches inflow and outflow amounts while I explain what I am doing and visualizing. Some patients like to be able to view the surgery, so I am always ready to tilt the screen accordingly.

The economics

How do you know if office hysteroscopy is right for you? Your own surgical skill and the skills of your staff, who must be trained to handle and sterilize equipment and to consistently assist you, are major factors, as is ensurance of a return on your investment.

One manufacturer contacted for this Master Class lists the price of a complete office tower (light source, camera, and monitor) at approximately $9,700 and the price of a rigid hysteroscope, sheath, and hand instruments at about $6,300. A complete setup for office hysteroscopy, including a standard operative (rigid) hysteroscope, should therefore cost between $15,000 and $17,000. Companies also offer leasing options for about $300-400/month.

Flexible hysteroscopes cost about $6,000 more, which prompts many gynecologic surgeons to focus their investment on a rigid scope that can be used for both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Disposables cost $10 or less, and $40-50 or less, for each diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy, respectively.

A look at the Medicare Relative Value Units (RVUs) – a key component of the Medicare reimbursement system and a standard for many payers in determining compensation – shows higher reimbursement for quite a few hysteroscopic codes when these procedures are performed in the office.

Total RVUs have three components:

1. Physician work, including time and the technical skill and intensity of effort it takes to perform a service or procedure.

2. Practice expenses, such as rent, equipment and supplies, and nonphysician salaries.

3. Malpractice insurance premiums.

Each component is multiplied by a factor that accounts for geographic cost variations, and each total RVU is multiplied by a dollar amount known as the conversion factor.

Practice expense (PE) RVUs for services provided in a “facility” (e.g., hospital or outpatient clinic) are often lower than office-based PE RVUs for the same services. Hysteroscopy is no exception. The PE RVU value for diagnostic hysteroscopy performed in the office, for instance, is approximately 5 units, compared with 1.64 units for diagnostic hysteroscopy performed in a facility.