User login

Private Equity in GI

Dear colleagues,

In this issue of Perspectives we will explore the business of medicine. With changes in reimbursement models and health care regulation over the past decades, private practice gastroenterology has evolved. Many gastroenterologists are now employed or are part of larger consolidated organizations. A key part of this evolution has been the influx of private equity in GI. The impact of private equity is still being written, and while many have embraced this business model, others have been critical of its influence.

In this issue, Dr. Paul J. Berggreen discusses his group’s experience with private equity and how it has helped improve the quality of patient care that they provide.

Dr. Michael L. Weinstein provides the counterpoint, discussing potential issues with the private equity model, and also highlighting an alternative path taken by his practice. An important topic for gastroenterologists of all ages. We welcome your experience with this issue. Please share with us on X @AGA_GIHN.

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, MSc, is associate professor of medicine, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and chief of endoscopy at West Haven (Conn.) VA Medical Center. He is an associate editor for GI & Hepatology News.

The Future of Medical Practice

BY DR. PAUL J. BERGGREEN

The future of medicine is being written as we speak. Trends that began in past decades have accelerated. Consolidation among massive hospital systems and health insurance conglomerates has gained momentum.

Physicians have been slow to organize and slower to mobilize. We spend our time caring for patients while national forces shape the future of our profession.

These trends have motivated many physicians to explore vehicles that allow them to remain independent. Creating business relationships with financial entities, including private equity, is one of those methods.

Before exploring those models, some background is instructive.

More than 100,000 doctors have left private practice and become employees of hospitals and other corporate entities since 2019. Today, approximately 75% of physicians are employees of larger health care entities – a record high.

This trend ought to alarm patients and policymakers. Research shows that independent medical practices often deliver better outcomes for patients than hospitals. Physician-owned practices also have lower per-patient costs, fewer preventable hospital admissions, and fewer re-admissions than their larger hospital-owned counterparts.

The business of medicine is very different than it was 40 years ago, when more than three in four doctors cared for patients in their own medical practices. The cost of managing a practice has surged. Labor, rent, and malpractice insurance have grown more expensive. Physicians have had to make significant investments in information technology and electronic health records.

Medicare’s reimbursement rates have not kept pace with these higher operational costs. In fact, Medicare payments to doctors have declined more than 25% in the last two decades after accounting for inflation.

By contrast, reimbursement for inpatient and outpatient hospital services as well as skilled nursing facilities has outpaced inflation since 2001.

Given these economic headwinds – and the mounting administrative and financial burdens that government regulation poses – many independent practitioners have concluded that they have little choice but to sell to larger entities like hospitals, health systems, or insurers.

If they do, they lose autonomy. Patients lose the personal touch an independent practice can offer.

To stay independent, many physicians are partnering with management services organizations (MSOs), which provide nonclinical services such as compliance, contracting, legal and IT support, cybersecurity, marketing, community outreach, recruiting assistance, billing, accounts payable, and guidance on the transition to value-based care.

MSOs are typically backed by investors: perhaps a public company, or a private equity firm. But it’s important to note that the clinical entity – the practice – remains separate from the MSO. Physicians retain control over clinical decision-making after partnering with an MSO.

Private equity is best viewed as a neutral financing mechanism that provides independent practices access to capital so they can build the business, clinical, and technological infrastructure to compete against the vertically integrated health systems that dominate medicine.

Private equity firms don’t “acquire” independent practices. A partnership with a private equity-backed MSO is often what empowers a practice to resist acquisition by a larger hospital or health care system.

The experience of my own practice, Arizona Digestive Health, is instructive. We partnered with GI Alliance – a private equity-backed, gastroenterologist-led MSO – in 2019.

My physician colleagues and I have retained complete clinical autonomy. But we now have the financial and operational support we need to remain independent – and deliver better care for our patients.

For example, we led the development of a GI-focused, population-based clinical dashboard that aggregates real-time data from almost 3 million patients across 16 states who are treated by practices affiliated with GI Alliance.

By drawing on that data, we’ve been able to implement comprehensive care-management programs. In the case of inflammatory bowel disease, for instance, we’ve been able to identify the highest-cost, most at-risk patients and implement more proactive treatment protocols, including dedicated care managers and hotlines. We’ve replicated this model in other disease states as well.

This kind of ongoing, high-touch intervention improves patient outcomes and reduces overall cost by minimizing unplanned episodes of care – like visits to the emergency room.

It’s not possible to provide this level of care in a smaller setting. I should know. I tried to implement a similar approach for the 55 doctors that comprise Arizona Digestive Health in Phoenix. We simply didn’t have the capital or resources to succeed.

Our experience at Arizona Digestive Health is not an outlier. I have seen numerous independent practices in gastroenterology and other specialties throughout the country leverage the resources of private equity-backed MSOs to enhance the level of care they provide – and improve patient outcomes and experiences.

In 2022, the physician leadership of GI Alliance spearheaded a transaction that resulted in the nearly 700 physicians whose independent gastroenterology practices were part of the alliance to grow their collective equity stake in the MSO to more than 85%. Our independent physicians now have voting control of the MSO board of directors.

This evolution of GI Alliance has enabled us to remain true to our mission of putting patients first while enhancing our ability to shape the business support our partnered gastroenterology practices need to expand access to the highest-quality, most affordable care in our communities.

Doctors caring for patients in their own practices used to be the foundation of the U.S. health care system – and for good reason. The model enables patients to receive more personalized care and build deeper, more longitudinal, more trusting relationships with their doctors. That remains the goal of physicians who value autonomy and independence.

Inaction will result in more of the same, with hospitals and insurance companies snapping up independent practices. It’s encouraging to see physicians take back control of their profession. But the climb remains steep.

The easiest way to predict the future is to invent it. Doing so in a patient-centric, physician-led, and physician-owned group is a great start to that journey.

Dr. Paul Berggreen is board chair and president of the American Independent Medical Practice Association. He is founder and president of Arizona Digestive Health, chief strategy officer for the GI Alliance, and chair of data analytics for the Digestive Health Physicians Association. He is also a consultant to Specialty Networks, which is not directly relevant to this article.

Thinking Strategically About Gastroenterology Practice

BY MICHAEL L. WEINSTEIN, MD

Whether you are a young gastroenterologist assessing your career opportunities, or a gastroenterology practice trying to assure your future success, you are likely considering how a private equity transaction might influence your options. In this column, I am going to share what I’ve learned and why my practice chose not to go the route of a private equity investment partner.

In 2018, Capital Digestive Care was an independent practice of 70 physicians centered around Washington, DC. Private equity firms were increasingly investing in health care, seeking to capitalize on the industry’s fragmentation, recession-proof business, and ability to leverage consolidation. Our leadership chose to spend a weekend on a strategic planning retreat to agree on our priorities and long-term goals. I highly recommend that you and/or your practice sit down to list your priorities as your first task.

After defining priorities, a SWOT analysis of your position today and what you project over the next decade will determine a strategy. There is a current shortage of more than 1,400 gastroenterologists in the United States. That gives us a pretty powerful “strength.” However, the consolidation of commercial payers and hospital systems is forcing physicians to accept low reimbursement and navigate a maze of administrative burdens. The mountain of regulatory, administrative, and financial functions can push physicians away from independent practice. Additionally, recruiting, training, and managing an office of medical personnel is not what most gastroenterologists want to do with their time.

The common denominator to achieve success with all of these practice management issues is size. So before providing thoughts about private equity, I recommend consolidation of medical practices as the strategy to achieving long-term goals. Practice size will allow physicians to spread out the administrative work, the cost of the business personnel, the IT systems, and the specialized resources. Purchasing power and negotiation relevance is achieved with size. Our priorities are taking care of our patients, our staff, and our practice colleagues. If we are providing high-value service and have a size relevant to the insurance companies, then we can negotiate value-based contracts, and at the end of the day, we will be financially well-off.

In contrast to the list of priorities a physician would create, the private equity fund manager’s goal is to generate wealth for themselves and their investors. Everything else, like innovation, enhanced service, employee satisfaction, and great quality, takes a back seat to accumulating profit. Their investments are made with a life-cycle of 4-6 years during which money is deployed by acquiring companies, improving the company bottom line profit through cost cutting or bolt-on acquisitions, increasing company profit distributions by adding leveraged debt to the corporate ledger, and then selling the companies often to another private equity fund. Physicians are trained to provide care to patients, and fund managers are trained to create wealth.

The medical practice as a business can grow over a career and provides physicians with top tier incomes. We are proud of the businesses we build and believe they are valuable. Private equity funds acquire medical practices for the future revenue and not the past results. They value a medical practice based on a multiple of the portion of future income the practice wants to sell. They ensure their future revenue through agreements that provide them management fees plus 25%-35% of future physician income for the current and all future physicians. The private equity company will say that the physicians are still independent but in reality all providers become employees of the company with wages defined by a formula. The private equity-owned Management Services Organization (MSO) controls decisions on carrier contracts, practice investments, purchasing, hiring, and the operations of the medical office. To get around corporate practice of medicine regulations, the ownership of the medical practice is placed in the hands of a single friendly physician who has a unique relationship to the MSO.

In my opinion, private equity is not the best strategy to achieve a successful medical practice, including acquiring the needed technology and human resources. It comes at a steep price, including loss of control and a permanent forfeiture of income (“the scrape”). The rhetoric professes that there will be income repair, monetization of practice value, and opportunity for a “second bite of the apple” when the private equity managers sell your practice to the next owner. Private equity’s main contribution for their outsized gains is the capital they bring to the practice. Everything else they bring can be found without selling the income of future partners to create a little more wealth for current partners.

The long-term results of private equity investment in gastroenterology practices has yet to be written. The experience in other specialties is partly documented in literature but the real stories are often hidden behind non-disparagement and non-disclosure clauses. Several investigations show that private equity ownership of health care providers leads to higher costs to patients and payers, employee dissatisfaction, diminished patient access, and worse health outcomes. The Federal Trade Commission and Department of Justice have vowed to scrutinize private equity deals because of mounting evidence that the motive for profit can conflict with maintaining quality.

In 2019, Capital Digestive Care chose Physicians Endoscopy as our strategic partner with the goal of separating and expanding our back-office functions into an MSO capable of providing business services to a larger practice and services to other practices outside of our own. Physicians Endoscopy has since been acquired by Optum/SCA. PE GI Solutions, the MSO, is now a partnership of CDC physician partners and Optum/SCA. Capital Digestive Care remains a practice owned 100% by the physicians. A Business Support Services Agreement defines the services CDC receives and the fees paid to the PE GI Solutions. We maintain MSO Board seats and have input into the operations of the MSO.

Consider your motivations and the degree of control you need. Do you recognize your gaps of knowledge and are you willing to hire people to advise you? Will your practice achieve a balance between the interests of older and younger physicians? Becoming an employed physician in a large practice is an option to manage the concerns about future career stability. Improved quality, expanded service offerings, clout to negotiate value-based payment deals with payers, and back-office business efficiency does not require selling yourself to a private equity fund.

Dr. Michael L. Weinstein is a founder and now chief executive officer of Capital Digestive Care. He is a founder and past president of the Digestive Health Physicians Association, previous counselor on the Governing Board of the American Gastroenterological Association. He reports no relevant conflicts.

References

The FTC and DOJ have vowed to scrutinize private equity deals. Here’s what it means for health care. FIERCE Healthcare, 2022, Oct. 21.

The Effect of Private Equity Investment in Health Care. Penn LDI. 2023 Mar. 10.

Olson, LK. Ethically challenged: Private equity storms US health care. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. 2022.

Dear colleagues,

In this issue of Perspectives we will explore the business of medicine. With changes in reimbursement models and health care regulation over the past decades, private practice gastroenterology has evolved. Many gastroenterologists are now employed or are part of larger consolidated organizations. A key part of this evolution has been the influx of private equity in GI. The impact of private equity is still being written, and while many have embraced this business model, others have been critical of its influence.

In this issue, Dr. Paul J. Berggreen discusses his group’s experience with private equity and how it has helped improve the quality of patient care that they provide.

Dr. Michael L. Weinstein provides the counterpoint, discussing potential issues with the private equity model, and also highlighting an alternative path taken by his practice. An important topic for gastroenterologists of all ages. We welcome your experience with this issue. Please share with us on X @AGA_GIHN.

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, MSc, is associate professor of medicine, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and chief of endoscopy at West Haven (Conn.) VA Medical Center. He is an associate editor for GI & Hepatology News.

The Future of Medical Practice

BY DR. PAUL J. BERGGREEN

The future of medicine is being written as we speak. Trends that began in past decades have accelerated. Consolidation among massive hospital systems and health insurance conglomerates has gained momentum.

Physicians have been slow to organize and slower to mobilize. We spend our time caring for patients while national forces shape the future of our profession.

These trends have motivated many physicians to explore vehicles that allow them to remain independent. Creating business relationships with financial entities, including private equity, is one of those methods.

Before exploring those models, some background is instructive.

More than 100,000 doctors have left private practice and become employees of hospitals and other corporate entities since 2019. Today, approximately 75% of physicians are employees of larger health care entities – a record high.

This trend ought to alarm patients and policymakers. Research shows that independent medical practices often deliver better outcomes for patients than hospitals. Physician-owned practices also have lower per-patient costs, fewer preventable hospital admissions, and fewer re-admissions than their larger hospital-owned counterparts.

The business of medicine is very different than it was 40 years ago, when more than three in four doctors cared for patients in their own medical practices. The cost of managing a practice has surged. Labor, rent, and malpractice insurance have grown more expensive. Physicians have had to make significant investments in information technology and electronic health records.

Medicare’s reimbursement rates have not kept pace with these higher operational costs. In fact, Medicare payments to doctors have declined more than 25% in the last two decades after accounting for inflation.

By contrast, reimbursement for inpatient and outpatient hospital services as well as skilled nursing facilities has outpaced inflation since 2001.

Given these economic headwinds – and the mounting administrative and financial burdens that government regulation poses – many independent practitioners have concluded that they have little choice but to sell to larger entities like hospitals, health systems, or insurers.

If they do, they lose autonomy. Patients lose the personal touch an independent practice can offer.

To stay independent, many physicians are partnering with management services organizations (MSOs), which provide nonclinical services such as compliance, contracting, legal and IT support, cybersecurity, marketing, community outreach, recruiting assistance, billing, accounts payable, and guidance on the transition to value-based care.

MSOs are typically backed by investors: perhaps a public company, or a private equity firm. But it’s important to note that the clinical entity – the practice – remains separate from the MSO. Physicians retain control over clinical decision-making after partnering with an MSO.

Private equity is best viewed as a neutral financing mechanism that provides independent practices access to capital so they can build the business, clinical, and technological infrastructure to compete against the vertically integrated health systems that dominate medicine.

Private equity firms don’t “acquire” independent practices. A partnership with a private equity-backed MSO is often what empowers a practice to resist acquisition by a larger hospital or health care system.

The experience of my own practice, Arizona Digestive Health, is instructive. We partnered with GI Alliance – a private equity-backed, gastroenterologist-led MSO – in 2019.

My physician colleagues and I have retained complete clinical autonomy. But we now have the financial and operational support we need to remain independent – and deliver better care for our patients.

For example, we led the development of a GI-focused, population-based clinical dashboard that aggregates real-time data from almost 3 million patients across 16 states who are treated by practices affiliated with GI Alliance.

By drawing on that data, we’ve been able to implement comprehensive care-management programs. In the case of inflammatory bowel disease, for instance, we’ve been able to identify the highest-cost, most at-risk patients and implement more proactive treatment protocols, including dedicated care managers and hotlines. We’ve replicated this model in other disease states as well.

This kind of ongoing, high-touch intervention improves patient outcomes and reduces overall cost by minimizing unplanned episodes of care – like visits to the emergency room.

It’s not possible to provide this level of care in a smaller setting. I should know. I tried to implement a similar approach for the 55 doctors that comprise Arizona Digestive Health in Phoenix. We simply didn’t have the capital or resources to succeed.

Our experience at Arizona Digestive Health is not an outlier. I have seen numerous independent practices in gastroenterology and other specialties throughout the country leverage the resources of private equity-backed MSOs to enhance the level of care they provide – and improve patient outcomes and experiences.

In 2022, the physician leadership of GI Alliance spearheaded a transaction that resulted in the nearly 700 physicians whose independent gastroenterology practices were part of the alliance to grow their collective equity stake in the MSO to more than 85%. Our independent physicians now have voting control of the MSO board of directors.

This evolution of GI Alliance has enabled us to remain true to our mission of putting patients first while enhancing our ability to shape the business support our partnered gastroenterology practices need to expand access to the highest-quality, most affordable care in our communities.

Doctors caring for patients in their own practices used to be the foundation of the U.S. health care system – and for good reason. The model enables patients to receive more personalized care and build deeper, more longitudinal, more trusting relationships with their doctors. That remains the goal of physicians who value autonomy and independence.

Inaction will result in more of the same, with hospitals and insurance companies snapping up independent practices. It’s encouraging to see physicians take back control of their profession. But the climb remains steep.

The easiest way to predict the future is to invent it. Doing so in a patient-centric, physician-led, and physician-owned group is a great start to that journey.

Dr. Paul Berggreen is board chair and president of the American Independent Medical Practice Association. He is founder and president of Arizona Digestive Health, chief strategy officer for the GI Alliance, and chair of data analytics for the Digestive Health Physicians Association. He is also a consultant to Specialty Networks, which is not directly relevant to this article.

Thinking Strategically About Gastroenterology Practice

BY MICHAEL L. WEINSTEIN, MD

Whether you are a young gastroenterologist assessing your career opportunities, or a gastroenterology practice trying to assure your future success, you are likely considering how a private equity transaction might influence your options. In this column, I am going to share what I’ve learned and why my practice chose not to go the route of a private equity investment partner.

In 2018, Capital Digestive Care was an independent practice of 70 physicians centered around Washington, DC. Private equity firms were increasingly investing in health care, seeking to capitalize on the industry’s fragmentation, recession-proof business, and ability to leverage consolidation. Our leadership chose to spend a weekend on a strategic planning retreat to agree on our priorities and long-term goals. I highly recommend that you and/or your practice sit down to list your priorities as your first task.

After defining priorities, a SWOT analysis of your position today and what you project over the next decade will determine a strategy. There is a current shortage of more than 1,400 gastroenterologists in the United States. That gives us a pretty powerful “strength.” However, the consolidation of commercial payers and hospital systems is forcing physicians to accept low reimbursement and navigate a maze of administrative burdens. The mountain of regulatory, administrative, and financial functions can push physicians away from independent practice. Additionally, recruiting, training, and managing an office of medical personnel is not what most gastroenterologists want to do with their time.

The common denominator to achieve success with all of these practice management issues is size. So before providing thoughts about private equity, I recommend consolidation of medical practices as the strategy to achieving long-term goals. Practice size will allow physicians to spread out the administrative work, the cost of the business personnel, the IT systems, and the specialized resources. Purchasing power and negotiation relevance is achieved with size. Our priorities are taking care of our patients, our staff, and our practice colleagues. If we are providing high-value service and have a size relevant to the insurance companies, then we can negotiate value-based contracts, and at the end of the day, we will be financially well-off.

In contrast to the list of priorities a physician would create, the private equity fund manager’s goal is to generate wealth for themselves and their investors. Everything else, like innovation, enhanced service, employee satisfaction, and great quality, takes a back seat to accumulating profit. Their investments are made with a life-cycle of 4-6 years during which money is deployed by acquiring companies, improving the company bottom line profit through cost cutting or bolt-on acquisitions, increasing company profit distributions by adding leveraged debt to the corporate ledger, and then selling the companies often to another private equity fund. Physicians are trained to provide care to patients, and fund managers are trained to create wealth.

The medical practice as a business can grow over a career and provides physicians with top tier incomes. We are proud of the businesses we build and believe they are valuable. Private equity funds acquire medical practices for the future revenue and not the past results. They value a medical practice based on a multiple of the portion of future income the practice wants to sell. They ensure their future revenue through agreements that provide them management fees plus 25%-35% of future physician income for the current and all future physicians. The private equity company will say that the physicians are still independent but in reality all providers become employees of the company with wages defined by a formula. The private equity-owned Management Services Organization (MSO) controls decisions on carrier contracts, practice investments, purchasing, hiring, and the operations of the medical office. To get around corporate practice of medicine regulations, the ownership of the medical practice is placed in the hands of a single friendly physician who has a unique relationship to the MSO.

In my opinion, private equity is not the best strategy to achieve a successful medical practice, including acquiring the needed technology and human resources. It comes at a steep price, including loss of control and a permanent forfeiture of income (“the scrape”). The rhetoric professes that there will be income repair, monetization of practice value, and opportunity for a “second bite of the apple” when the private equity managers sell your practice to the next owner. Private equity’s main contribution for their outsized gains is the capital they bring to the practice. Everything else they bring can be found without selling the income of future partners to create a little more wealth for current partners.

The long-term results of private equity investment in gastroenterology practices has yet to be written. The experience in other specialties is partly documented in literature but the real stories are often hidden behind non-disparagement and non-disclosure clauses. Several investigations show that private equity ownership of health care providers leads to higher costs to patients and payers, employee dissatisfaction, diminished patient access, and worse health outcomes. The Federal Trade Commission and Department of Justice have vowed to scrutinize private equity deals because of mounting evidence that the motive for profit can conflict with maintaining quality.

In 2019, Capital Digestive Care chose Physicians Endoscopy as our strategic partner with the goal of separating and expanding our back-office functions into an MSO capable of providing business services to a larger practice and services to other practices outside of our own. Physicians Endoscopy has since been acquired by Optum/SCA. PE GI Solutions, the MSO, is now a partnership of CDC physician partners and Optum/SCA. Capital Digestive Care remains a practice owned 100% by the physicians. A Business Support Services Agreement defines the services CDC receives and the fees paid to the PE GI Solutions. We maintain MSO Board seats and have input into the operations of the MSO.

Consider your motivations and the degree of control you need. Do you recognize your gaps of knowledge and are you willing to hire people to advise you? Will your practice achieve a balance between the interests of older and younger physicians? Becoming an employed physician in a large practice is an option to manage the concerns about future career stability. Improved quality, expanded service offerings, clout to negotiate value-based payment deals with payers, and back-office business efficiency does not require selling yourself to a private equity fund.

Dr. Michael L. Weinstein is a founder and now chief executive officer of Capital Digestive Care. He is a founder and past president of the Digestive Health Physicians Association, previous counselor on the Governing Board of the American Gastroenterological Association. He reports no relevant conflicts.

References

The FTC and DOJ have vowed to scrutinize private equity deals. Here’s what it means for health care. FIERCE Healthcare, 2022, Oct. 21.

The Effect of Private Equity Investment in Health Care. Penn LDI. 2023 Mar. 10.

Olson, LK. Ethically challenged: Private equity storms US health care. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. 2022.

Dear colleagues,

In this issue of Perspectives we will explore the business of medicine. With changes in reimbursement models and health care regulation over the past decades, private practice gastroenterology has evolved. Many gastroenterologists are now employed or are part of larger consolidated organizations. A key part of this evolution has been the influx of private equity in GI. The impact of private equity is still being written, and while many have embraced this business model, others have been critical of its influence.

In this issue, Dr. Paul J. Berggreen discusses his group’s experience with private equity and how it has helped improve the quality of patient care that they provide.

Dr. Michael L. Weinstein provides the counterpoint, discussing potential issues with the private equity model, and also highlighting an alternative path taken by his practice. An important topic for gastroenterologists of all ages. We welcome your experience with this issue. Please share with us on X @AGA_GIHN.

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, MSc, is associate professor of medicine, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and chief of endoscopy at West Haven (Conn.) VA Medical Center. He is an associate editor for GI & Hepatology News.

The Future of Medical Practice

BY DR. PAUL J. BERGGREEN

The future of medicine is being written as we speak. Trends that began in past decades have accelerated. Consolidation among massive hospital systems and health insurance conglomerates has gained momentum.

Physicians have been slow to organize and slower to mobilize. We spend our time caring for patients while national forces shape the future of our profession.

These trends have motivated many physicians to explore vehicles that allow them to remain independent. Creating business relationships with financial entities, including private equity, is one of those methods.

Before exploring those models, some background is instructive.

More than 100,000 doctors have left private practice and become employees of hospitals and other corporate entities since 2019. Today, approximately 75% of physicians are employees of larger health care entities – a record high.

This trend ought to alarm patients and policymakers. Research shows that independent medical practices often deliver better outcomes for patients than hospitals. Physician-owned practices also have lower per-patient costs, fewer preventable hospital admissions, and fewer re-admissions than their larger hospital-owned counterparts.

The business of medicine is very different than it was 40 years ago, when more than three in four doctors cared for patients in their own medical practices. The cost of managing a practice has surged. Labor, rent, and malpractice insurance have grown more expensive. Physicians have had to make significant investments in information technology and electronic health records.

Medicare’s reimbursement rates have not kept pace with these higher operational costs. In fact, Medicare payments to doctors have declined more than 25% in the last two decades after accounting for inflation.

By contrast, reimbursement for inpatient and outpatient hospital services as well as skilled nursing facilities has outpaced inflation since 2001.

Given these economic headwinds – and the mounting administrative and financial burdens that government regulation poses – many independent practitioners have concluded that they have little choice but to sell to larger entities like hospitals, health systems, or insurers.

If they do, they lose autonomy. Patients lose the personal touch an independent practice can offer.

To stay independent, many physicians are partnering with management services organizations (MSOs), which provide nonclinical services such as compliance, contracting, legal and IT support, cybersecurity, marketing, community outreach, recruiting assistance, billing, accounts payable, and guidance on the transition to value-based care.

MSOs are typically backed by investors: perhaps a public company, or a private equity firm. But it’s important to note that the clinical entity – the practice – remains separate from the MSO. Physicians retain control over clinical decision-making after partnering with an MSO.

Private equity is best viewed as a neutral financing mechanism that provides independent practices access to capital so they can build the business, clinical, and technological infrastructure to compete against the vertically integrated health systems that dominate medicine.

Private equity firms don’t “acquire” independent practices. A partnership with a private equity-backed MSO is often what empowers a practice to resist acquisition by a larger hospital or health care system.

The experience of my own practice, Arizona Digestive Health, is instructive. We partnered with GI Alliance – a private equity-backed, gastroenterologist-led MSO – in 2019.

My physician colleagues and I have retained complete clinical autonomy. But we now have the financial and operational support we need to remain independent – and deliver better care for our patients.

For example, we led the development of a GI-focused, population-based clinical dashboard that aggregates real-time data from almost 3 million patients across 16 states who are treated by practices affiliated with GI Alliance.

By drawing on that data, we’ve been able to implement comprehensive care-management programs. In the case of inflammatory bowel disease, for instance, we’ve been able to identify the highest-cost, most at-risk patients and implement more proactive treatment protocols, including dedicated care managers and hotlines. We’ve replicated this model in other disease states as well.

This kind of ongoing, high-touch intervention improves patient outcomes and reduces overall cost by minimizing unplanned episodes of care – like visits to the emergency room.

It’s not possible to provide this level of care in a smaller setting. I should know. I tried to implement a similar approach for the 55 doctors that comprise Arizona Digestive Health in Phoenix. We simply didn’t have the capital or resources to succeed.

Our experience at Arizona Digestive Health is not an outlier. I have seen numerous independent practices in gastroenterology and other specialties throughout the country leverage the resources of private equity-backed MSOs to enhance the level of care they provide – and improve patient outcomes and experiences.

In 2022, the physician leadership of GI Alliance spearheaded a transaction that resulted in the nearly 700 physicians whose independent gastroenterology practices were part of the alliance to grow their collective equity stake in the MSO to more than 85%. Our independent physicians now have voting control of the MSO board of directors.

This evolution of GI Alliance has enabled us to remain true to our mission of putting patients first while enhancing our ability to shape the business support our partnered gastroenterology practices need to expand access to the highest-quality, most affordable care in our communities.

Doctors caring for patients in their own practices used to be the foundation of the U.S. health care system – and for good reason. The model enables patients to receive more personalized care and build deeper, more longitudinal, more trusting relationships with their doctors. That remains the goal of physicians who value autonomy and independence.

Inaction will result in more of the same, with hospitals and insurance companies snapping up independent practices. It’s encouraging to see physicians take back control of their profession. But the climb remains steep.

The easiest way to predict the future is to invent it. Doing so in a patient-centric, physician-led, and physician-owned group is a great start to that journey.

Dr. Paul Berggreen is board chair and president of the American Independent Medical Practice Association. He is founder and president of Arizona Digestive Health, chief strategy officer for the GI Alliance, and chair of data analytics for the Digestive Health Physicians Association. He is also a consultant to Specialty Networks, which is not directly relevant to this article.

Thinking Strategically About Gastroenterology Practice

BY MICHAEL L. WEINSTEIN, MD

Whether you are a young gastroenterologist assessing your career opportunities, or a gastroenterology practice trying to assure your future success, you are likely considering how a private equity transaction might influence your options. In this column, I am going to share what I’ve learned and why my practice chose not to go the route of a private equity investment partner.

In 2018, Capital Digestive Care was an independent practice of 70 physicians centered around Washington, DC. Private equity firms were increasingly investing in health care, seeking to capitalize on the industry’s fragmentation, recession-proof business, and ability to leverage consolidation. Our leadership chose to spend a weekend on a strategic planning retreat to agree on our priorities and long-term goals. I highly recommend that you and/or your practice sit down to list your priorities as your first task.

After defining priorities, a SWOT analysis of your position today and what you project over the next decade will determine a strategy. There is a current shortage of more than 1,400 gastroenterologists in the United States. That gives us a pretty powerful “strength.” However, the consolidation of commercial payers and hospital systems is forcing physicians to accept low reimbursement and navigate a maze of administrative burdens. The mountain of regulatory, administrative, and financial functions can push physicians away from independent practice. Additionally, recruiting, training, and managing an office of medical personnel is not what most gastroenterologists want to do with their time.

The common denominator to achieve success with all of these practice management issues is size. So before providing thoughts about private equity, I recommend consolidation of medical practices as the strategy to achieving long-term goals. Practice size will allow physicians to spread out the administrative work, the cost of the business personnel, the IT systems, and the specialized resources. Purchasing power and negotiation relevance is achieved with size. Our priorities are taking care of our patients, our staff, and our practice colleagues. If we are providing high-value service and have a size relevant to the insurance companies, then we can negotiate value-based contracts, and at the end of the day, we will be financially well-off.

In contrast to the list of priorities a physician would create, the private equity fund manager’s goal is to generate wealth for themselves and their investors. Everything else, like innovation, enhanced service, employee satisfaction, and great quality, takes a back seat to accumulating profit. Their investments are made with a life-cycle of 4-6 years during which money is deployed by acquiring companies, improving the company bottom line profit through cost cutting or bolt-on acquisitions, increasing company profit distributions by adding leveraged debt to the corporate ledger, and then selling the companies often to another private equity fund. Physicians are trained to provide care to patients, and fund managers are trained to create wealth.

The medical practice as a business can grow over a career and provides physicians with top tier incomes. We are proud of the businesses we build and believe they are valuable. Private equity funds acquire medical practices for the future revenue and not the past results. They value a medical practice based on a multiple of the portion of future income the practice wants to sell. They ensure their future revenue through agreements that provide them management fees plus 25%-35% of future physician income for the current and all future physicians. The private equity company will say that the physicians are still independent but in reality all providers become employees of the company with wages defined by a formula. The private equity-owned Management Services Organization (MSO) controls decisions on carrier contracts, practice investments, purchasing, hiring, and the operations of the medical office. To get around corporate practice of medicine regulations, the ownership of the medical practice is placed in the hands of a single friendly physician who has a unique relationship to the MSO.

In my opinion, private equity is not the best strategy to achieve a successful medical practice, including acquiring the needed technology and human resources. It comes at a steep price, including loss of control and a permanent forfeiture of income (“the scrape”). The rhetoric professes that there will be income repair, monetization of practice value, and opportunity for a “second bite of the apple” when the private equity managers sell your practice to the next owner. Private equity’s main contribution for their outsized gains is the capital they bring to the practice. Everything else they bring can be found without selling the income of future partners to create a little more wealth for current partners.

The long-term results of private equity investment in gastroenterology practices has yet to be written. The experience in other specialties is partly documented in literature but the real stories are often hidden behind non-disparagement and non-disclosure clauses. Several investigations show that private equity ownership of health care providers leads to higher costs to patients and payers, employee dissatisfaction, diminished patient access, and worse health outcomes. The Federal Trade Commission and Department of Justice have vowed to scrutinize private equity deals because of mounting evidence that the motive for profit can conflict with maintaining quality.

In 2019, Capital Digestive Care chose Physicians Endoscopy as our strategic partner with the goal of separating and expanding our back-office functions into an MSO capable of providing business services to a larger practice and services to other practices outside of our own. Physicians Endoscopy has since been acquired by Optum/SCA. PE GI Solutions, the MSO, is now a partnership of CDC physician partners and Optum/SCA. Capital Digestive Care remains a practice owned 100% by the physicians. A Business Support Services Agreement defines the services CDC receives and the fees paid to the PE GI Solutions. We maintain MSO Board seats and have input into the operations of the MSO.

Consider your motivations and the degree of control you need. Do you recognize your gaps of knowledge and are you willing to hire people to advise you? Will your practice achieve a balance between the interests of older and younger physicians? Becoming an employed physician in a large practice is an option to manage the concerns about future career stability. Improved quality, expanded service offerings, clout to negotiate value-based payment deals with payers, and back-office business efficiency does not require selling yourself to a private equity fund.

Dr. Michael L. Weinstein is a founder and now chief executive officer of Capital Digestive Care. He is a founder and past president of the Digestive Health Physicians Association, previous counselor on the Governing Board of the American Gastroenterological Association. He reports no relevant conflicts.

References

The FTC and DOJ have vowed to scrutinize private equity deals. Here’s what it means for health care. FIERCE Healthcare, 2022, Oct. 21.

The Effect of Private Equity Investment in Health Care. Penn LDI. 2023 Mar. 10.

Olson, LK. Ethically challenged: Private equity storms US health care. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. 2022.

‘Less is More’ in Myeloma

Among those that intrigue me most are the pioneering “less is more” trials that challenged conventional practices and remain relevant today. One such trial was inspired by a patient’s dissatisfaction with high doses of dexamethasone and its side effects.

Unlike the prevailing norm of frequent high doses, this trial compared a steroid dose administered weekly (as opposed to doses given several days a week). Lo and behold, the lower steroid dosage was associated with significantly better survival rates. At 1-year follow-up, 96% of patients in the lower-dose group were alive, compared with 87% in the higher-dose group.

Another noteworthy “less-is more” trial that I love, spearheaded by an Italian team, also focused on steroid dosage. This trial investigated discontinuing dexamethasone after nine cycles, along with reducing the dose of lenalidomide, versus maintaining long-term treatment without reductions. The findings revealed comparable progression-free survival with reduced toxicity, highlighting the potential benefits of this less-is-more approach.

While these trials are inspirational, a closer examination of myeloma trial history, especially those that led to regulatory approvals, reveals a preponderance of “add-on” trials. You add a potentially effective drug to an existing backbone, and you get an improvement in an outcome such as response rate (shrinking cancer) or duration of remission or progression free survival (amount of time alive and in remission).

Such trials have led to an abundance of effective options. But these same trials have almost always been a comparison of three drugs versus two drugs, and almost never three drugs versus three. And the drugs are often given continuously, especially the “newer” added drug, without a break. As a result, we are left completely unsure of how to sequence our drugs, and whether a finite course of the new drug would be equivalent to administering that new drug forever.

This problem is not unique to myeloma. Yet it is very apparent in myeloma, because we have been lucky to have so many good drugs (or at least “potentially” good drugs) that make it to phase 3 trials.

Unfortunately, the landscape of clinical trials is heavily influenced by the pharmaceutical industry, with limited funding available from alternative sources. As a result, there is a scarcity of trials exploring “less is more” approaches, despite their potential to optimize treatment outcomes and quality of life.

Even government-funded trials run by cooperative groups require industry buy-in or are run by people who have very close contacts and conflicts of interest with industry. We need so many more of these less-is-more trials, but we have limited means to fund them.

These are the kinds of discussions I have with my patients daily. We grapple with questions about the necessity of lifelong (or any) maintenance therapy or the feasibility of treatment breaks for patients with stable disease. While we strive to provide the best care possible, the lack of definitive data often leaves us making tough decisions in the clinic.

I am grateful to those who are working tirelessly to facilitate trials that prioritize quality of life and “less is more” approaches. Your efforts are invaluable. Looking forward, I aspire to contribute to this important work.

Dr. Mohyuddin is assistant professor in the multiple myeloma program at the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

Among those that intrigue me most are the pioneering “less is more” trials that challenged conventional practices and remain relevant today. One such trial was inspired by a patient’s dissatisfaction with high doses of dexamethasone and its side effects.

Unlike the prevailing norm of frequent high doses, this trial compared a steroid dose administered weekly (as opposed to doses given several days a week). Lo and behold, the lower steroid dosage was associated with significantly better survival rates. At 1-year follow-up, 96% of patients in the lower-dose group were alive, compared with 87% in the higher-dose group.

Another noteworthy “less-is more” trial that I love, spearheaded by an Italian team, also focused on steroid dosage. This trial investigated discontinuing dexamethasone after nine cycles, along with reducing the dose of lenalidomide, versus maintaining long-term treatment without reductions. The findings revealed comparable progression-free survival with reduced toxicity, highlighting the potential benefits of this less-is-more approach.

While these trials are inspirational, a closer examination of myeloma trial history, especially those that led to regulatory approvals, reveals a preponderance of “add-on” trials. You add a potentially effective drug to an existing backbone, and you get an improvement in an outcome such as response rate (shrinking cancer) or duration of remission or progression free survival (amount of time alive and in remission).

Such trials have led to an abundance of effective options. But these same trials have almost always been a comparison of three drugs versus two drugs, and almost never three drugs versus three. And the drugs are often given continuously, especially the “newer” added drug, without a break. As a result, we are left completely unsure of how to sequence our drugs, and whether a finite course of the new drug would be equivalent to administering that new drug forever.

This problem is not unique to myeloma. Yet it is very apparent in myeloma, because we have been lucky to have so many good drugs (or at least “potentially” good drugs) that make it to phase 3 trials.

Unfortunately, the landscape of clinical trials is heavily influenced by the pharmaceutical industry, with limited funding available from alternative sources. As a result, there is a scarcity of trials exploring “less is more” approaches, despite their potential to optimize treatment outcomes and quality of life.

Even government-funded trials run by cooperative groups require industry buy-in or are run by people who have very close contacts and conflicts of interest with industry. We need so many more of these less-is-more trials, but we have limited means to fund them.

These are the kinds of discussions I have with my patients daily. We grapple with questions about the necessity of lifelong (or any) maintenance therapy or the feasibility of treatment breaks for patients with stable disease. While we strive to provide the best care possible, the lack of definitive data often leaves us making tough decisions in the clinic.

I am grateful to those who are working tirelessly to facilitate trials that prioritize quality of life and “less is more” approaches. Your efforts are invaluable. Looking forward, I aspire to contribute to this important work.

Dr. Mohyuddin is assistant professor in the multiple myeloma program at the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

Among those that intrigue me most are the pioneering “less is more” trials that challenged conventional practices and remain relevant today. One such trial was inspired by a patient’s dissatisfaction with high doses of dexamethasone and its side effects.

Unlike the prevailing norm of frequent high doses, this trial compared a steroid dose administered weekly (as opposed to doses given several days a week). Lo and behold, the lower steroid dosage was associated with significantly better survival rates. At 1-year follow-up, 96% of patients in the lower-dose group were alive, compared with 87% in the higher-dose group.

Another noteworthy “less-is more” trial that I love, spearheaded by an Italian team, also focused on steroid dosage. This trial investigated discontinuing dexamethasone after nine cycles, along with reducing the dose of lenalidomide, versus maintaining long-term treatment without reductions. The findings revealed comparable progression-free survival with reduced toxicity, highlighting the potential benefits of this less-is-more approach.

While these trials are inspirational, a closer examination of myeloma trial history, especially those that led to regulatory approvals, reveals a preponderance of “add-on” trials. You add a potentially effective drug to an existing backbone, and you get an improvement in an outcome such as response rate (shrinking cancer) or duration of remission or progression free survival (amount of time alive and in remission).

Such trials have led to an abundance of effective options. But these same trials have almost always been a comparison of three drugs versus two drugs, and almost never three drugs versus three. And the drugs are often given continuously, especially the “newer” added drug, without a break. As a result, we are left completely unsure of how to sequence our drugs, and whether a finite course of the new drug would be equivalent to administering that new drug forever.

This problem is not unique to myeloma. Yet it is very apparent in myeloma, because we have been lucky to have so many good drugs (or at least “potentially” good drugs) that make it to phase 3 trials.

Unfortunately, the landscape of clinical trials is heavily influenced by the pharmaceutical industry, with limited funding available from alternative sources. As a result, there is a scarcity of trials exploring “less is more” approaches, despite their potential to optimize treatment outcomes and quality of life.

Even government-funded trials run by cooperative groups require industry buy-in or are run by people who have very close contacts and conflicts of interest with industry. We need so many more of these less-is-more trials, but we have limited means to fund them.

These are the kinds of discussions I have with my patients daily. We grapple with questions about the necessity of lifelong (or any) maintenance therapy or the feasibility of treatment breaks for patients with stable disease. While we strive to provide the best care possible, the lack of definitive data often leaves us making tough decisions in the clinic.

I am grateful to those who are working tirelessly to facilitate trials that prioritize quality of life and “less is more” approaches. Your efforts are invaluable. Looking forward, I aspire to contribute to this important work.

Dr. Mohyuddin is assistant professor in the multiple myeloma program at the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

It Sure Looks Like Cannabis Is Bad for the Heart, Doesn’t It?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

If you’re an epidemiologist trying to explore whether some exposure is a risk factor for a disease, you can run into a tough problem when your exposure of interest is highly correlated with another risk factor for the disease. For decades, this stymied investigations into the link, if any, between marijuana use and cardiovascular disease because, for decades, most people who used marijuana in some way also smoked cigarettes — which is a very clear risk factor for heart disease.

But the times they are a-changing.

Thanks to the legalization of marijuana for recreational use in many states, and even broader social trends, there is now a large population of people who use marijuana but do not use cigarettes. That means we can start to determine whether marijuana use is an independent risk factor for heart disease.

And this week, we have the largest study yet to attempt to answer that question, though, as I’ll explain momentarily, the smoke hasn’t entirely cleared yet.

The centerpiece of the study we are discussing this week, “Association of Cannabis Use With Cardiovascular Outcomes Among US Adults,” which appeared in the Journal of the American Heart Association, is the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, an annual telephone survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention since 1984 that gathers data on all sorts of stuff that we do to ourselves: our drinking habits, our smoking habits, and, more recently, our marijuana habits.

The paper combines annual data from 2016 to 2020 representing 27 states and two US territories for a total sample size of more than 430,000 individuals. The key exposure? Marijuana use, which was coded as the number of days of marijuana use in the past 30 days. The key outcome? Coronary heart disease, collected through questions such as “Has a doctor, nurse, or other health professional ever told you that you had a heart attack?”

Right away you might detect a couple of problems here. But let me show you the results before we worry about what they mean.

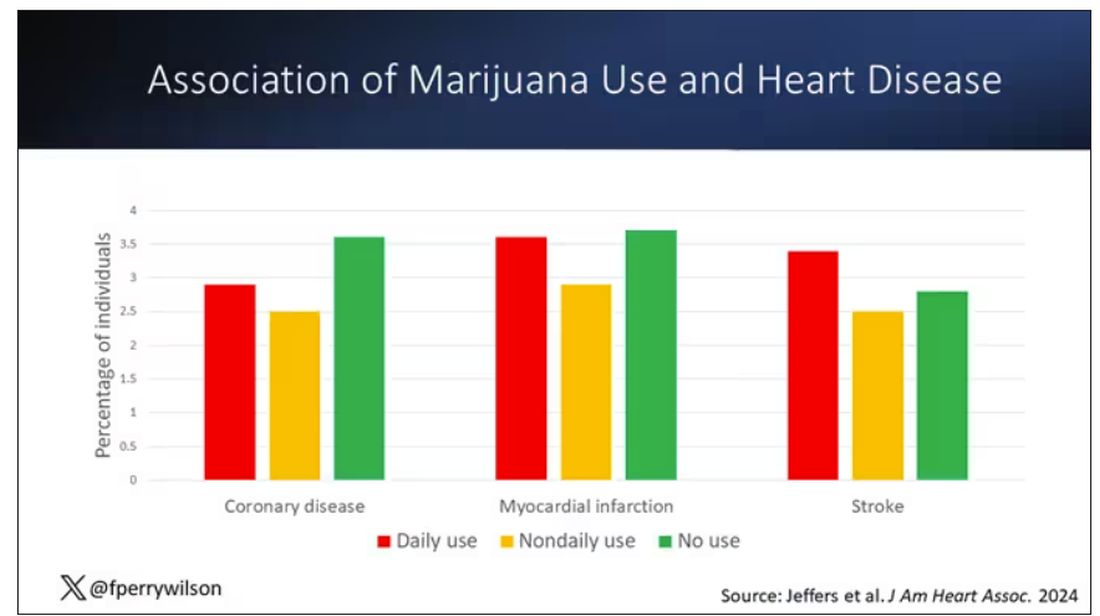

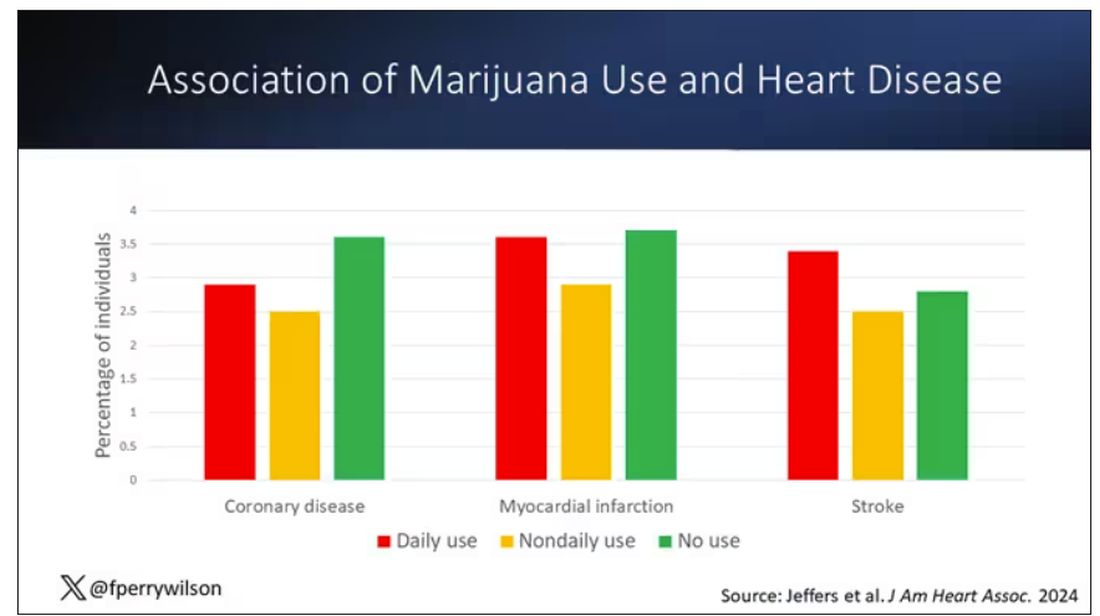

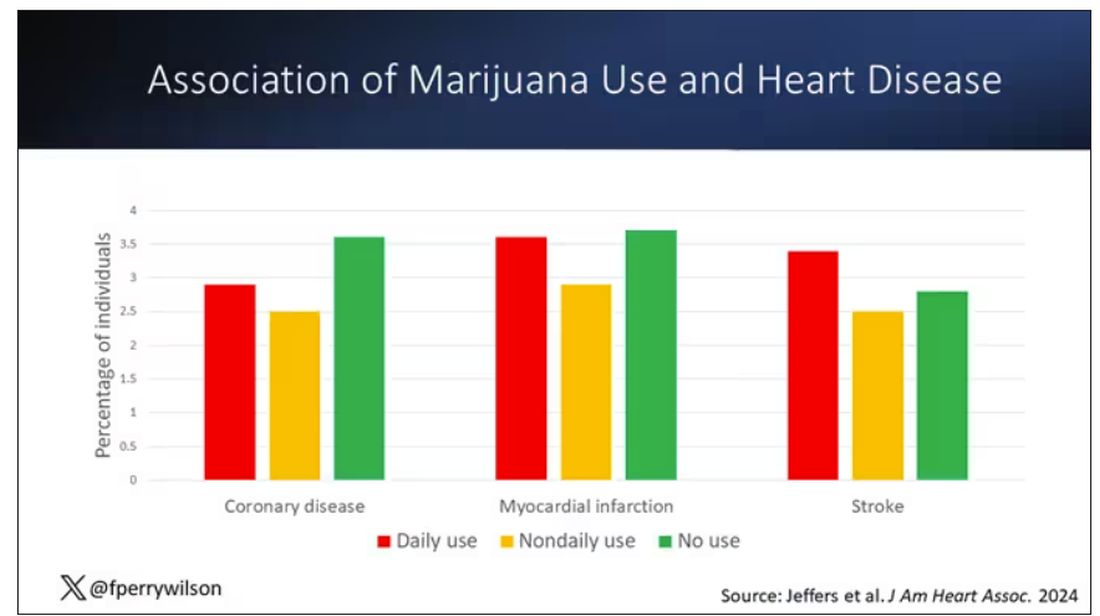

You can see the rates of the major cardiovascular outcomes here, stratified by daily use of marijuana, nondaily use, and no use. Broadly speaking, the risk was highest for daily users, lowest for occasional users, and in the middle for non-users.

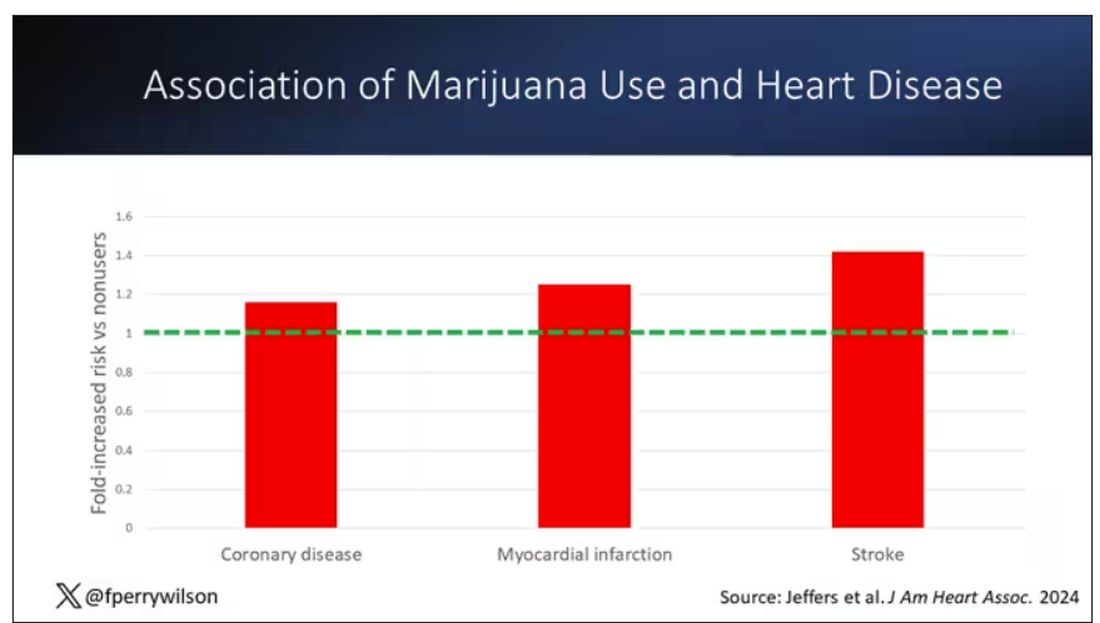

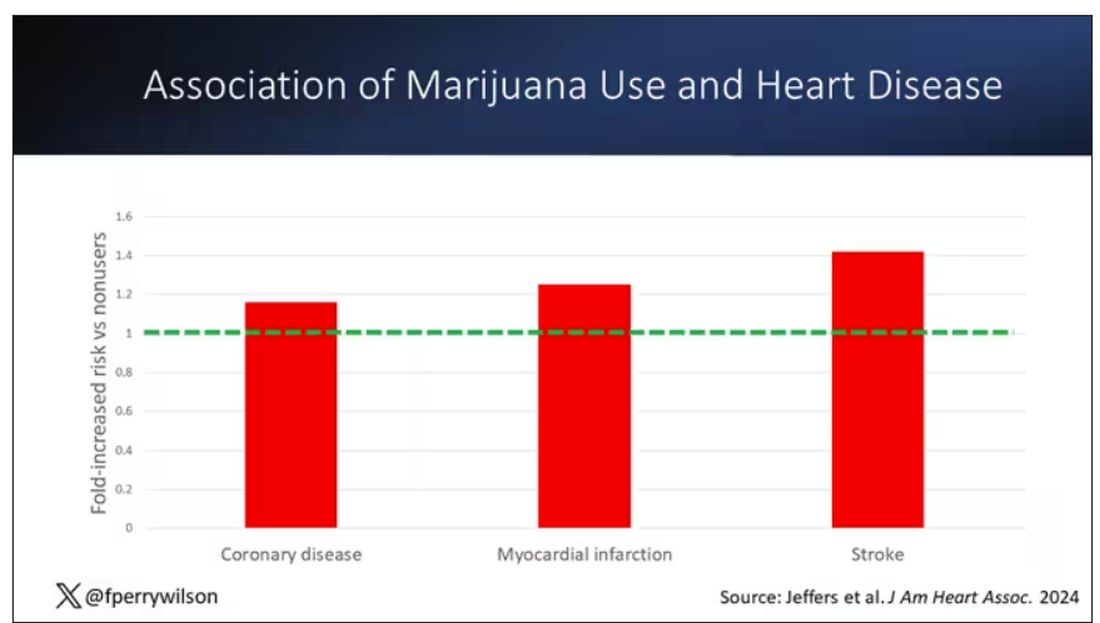

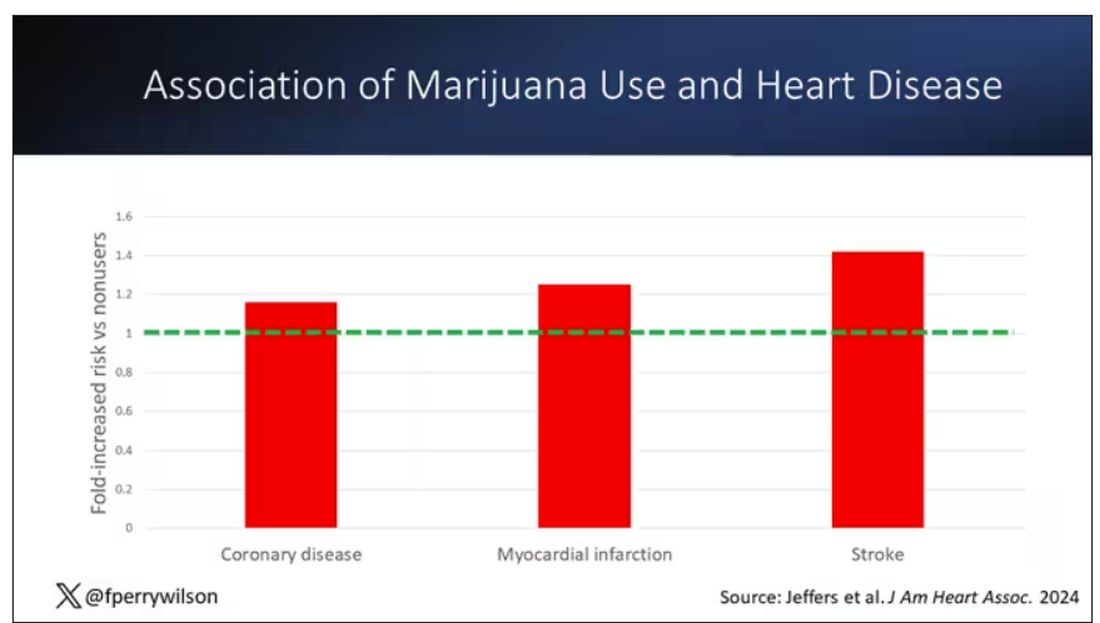

Of course, non-users and users are different in lots of other ways; non-users were quite a bit older, for example. Adjusting for all those factors showed that, independent of age, smoking status, the presence of diabetes, and so on, there was an independently increased risk for cardiovascular outcomes in people who used marijuana.

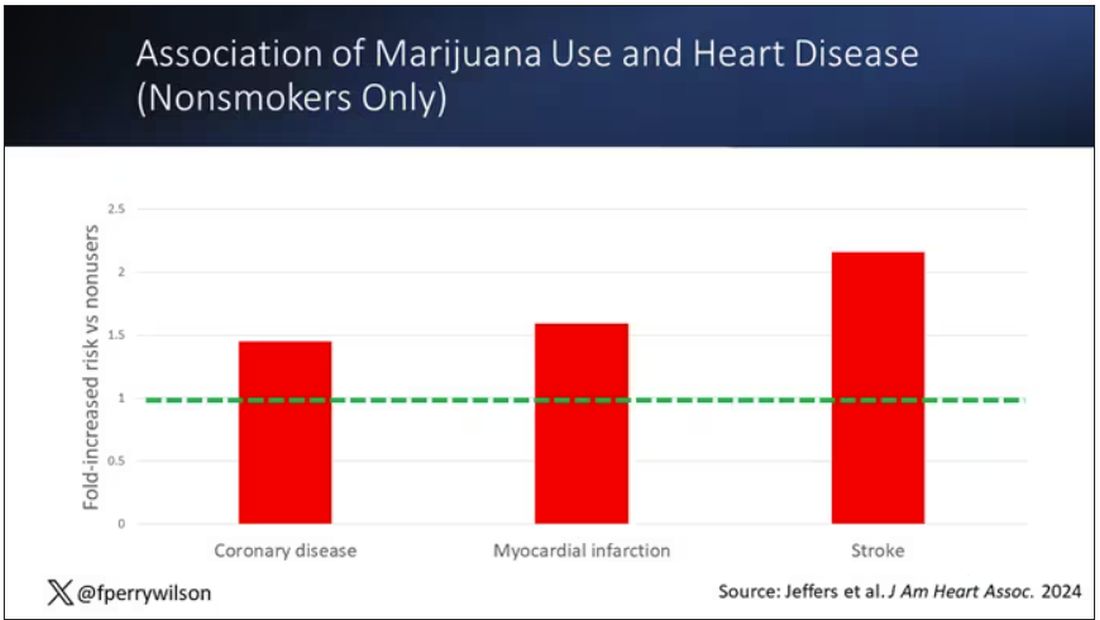

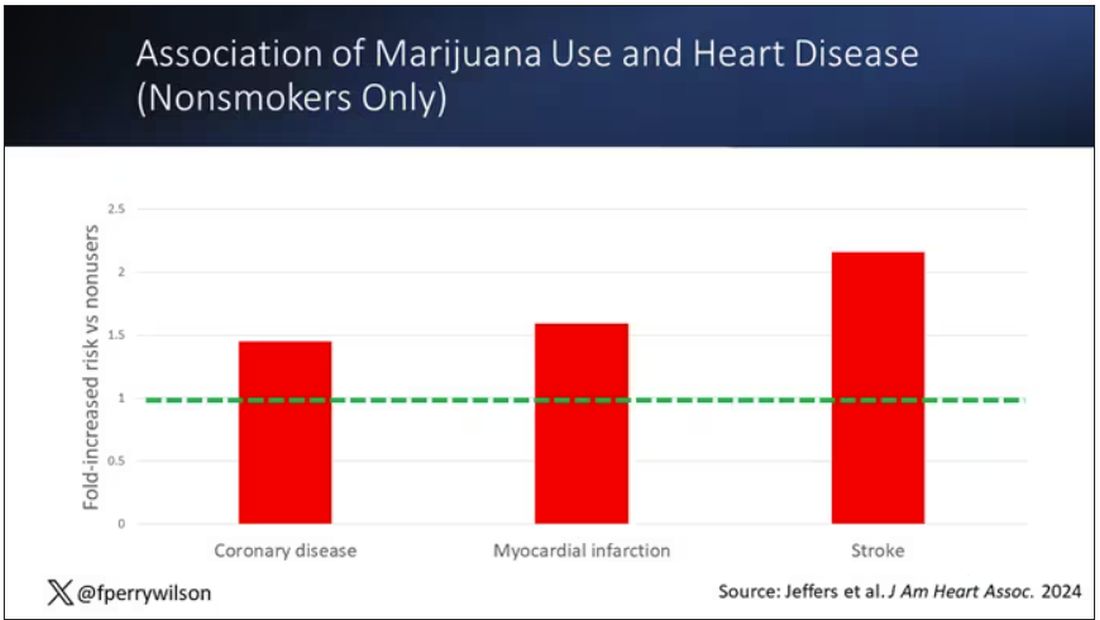

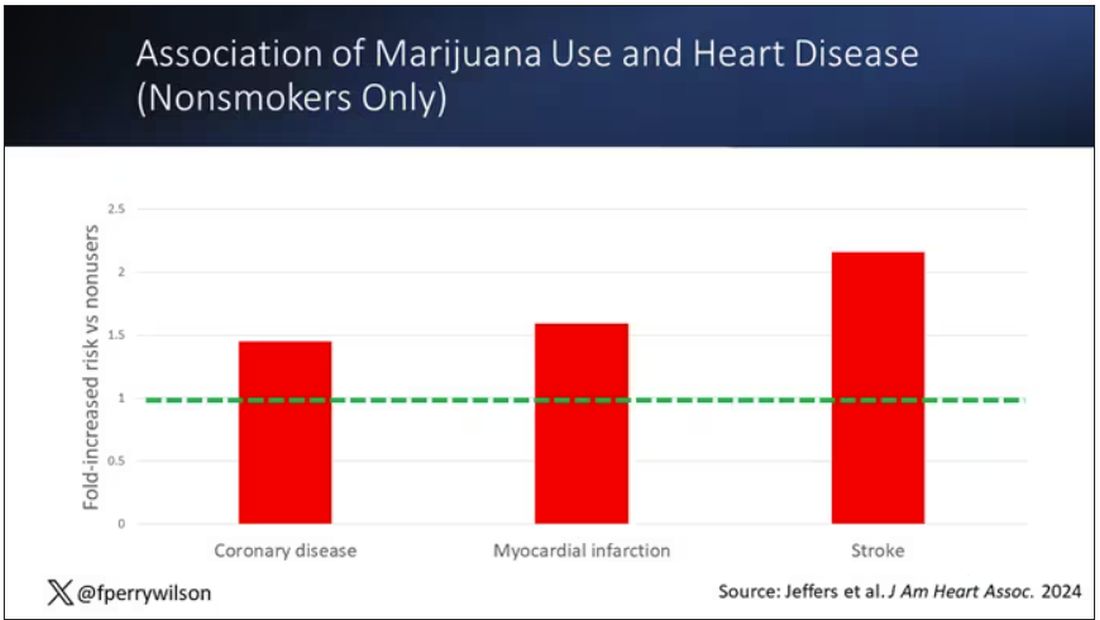

Importantly, 60% of people in this study were never smokers, and the results in that group looked pretty similar to the results overall.

But I said there were a couple of problems, so let’s dig into those a bit.

First, like most survey studies, this one requires honest and accurate reporting from its subjects. There was no verification of heart disease using electronic health records or of marijuana usage based on biosamples. Broadly, miscategorization of exposure and outcomes in surveys tends to bias the results toward the null hypothesis, toward concluding that there is no link between exposure and outcome, so perhaps this is okay.

The bigger problem is the fact that this is a cross-sectional design. If you really wanted to know whether marijuana led to heart disease, you’d do a longitudinal study following users and non-users for some number of decades and see who developed heart disease and who didn’t. (For the pedants out there, I suppose you’d actually want to randomize people to use marijuana or not and then see who had a heart attack, but the IRB keeps rejecting my protocol when I submit it.)

Here, though, we literally can’t tell whether people who use marijuana have more heart attacks or whether people who have heart attacks use more marijuana. The authors argue that there are no data that show that people are more likely to use marijuana after a heart attack or stroke, but at the time the survey was conducted, they had already had their heart attack or stroke.

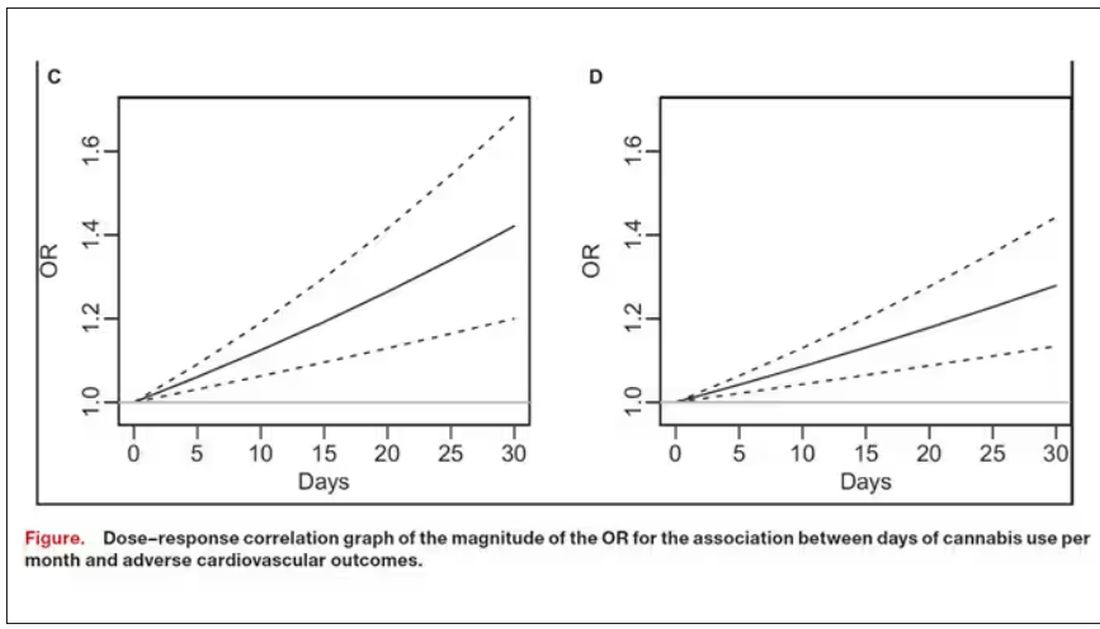

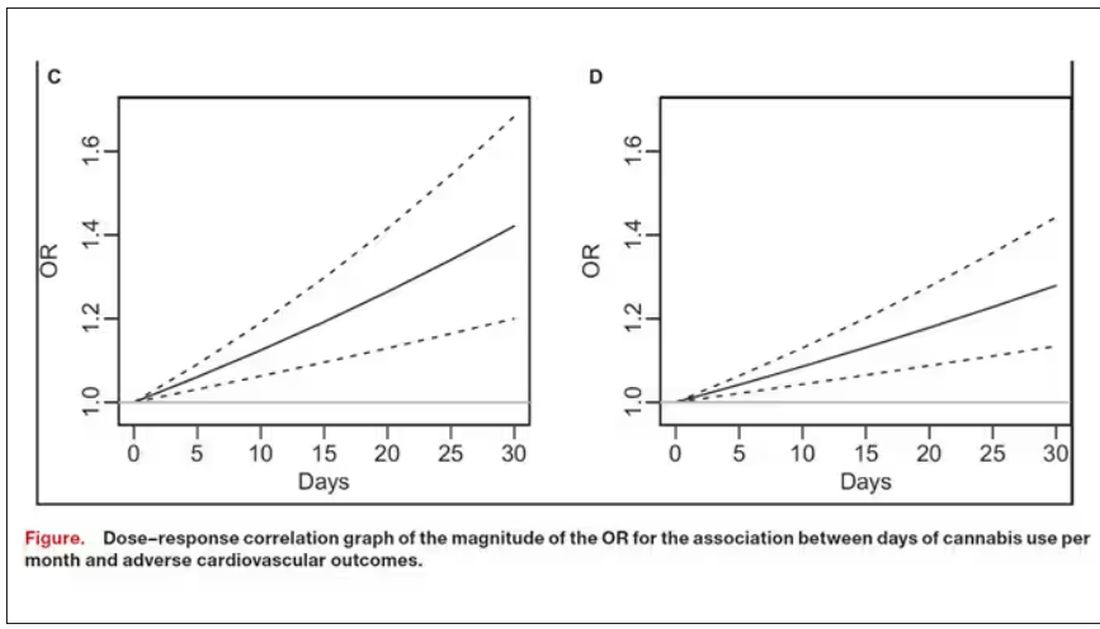

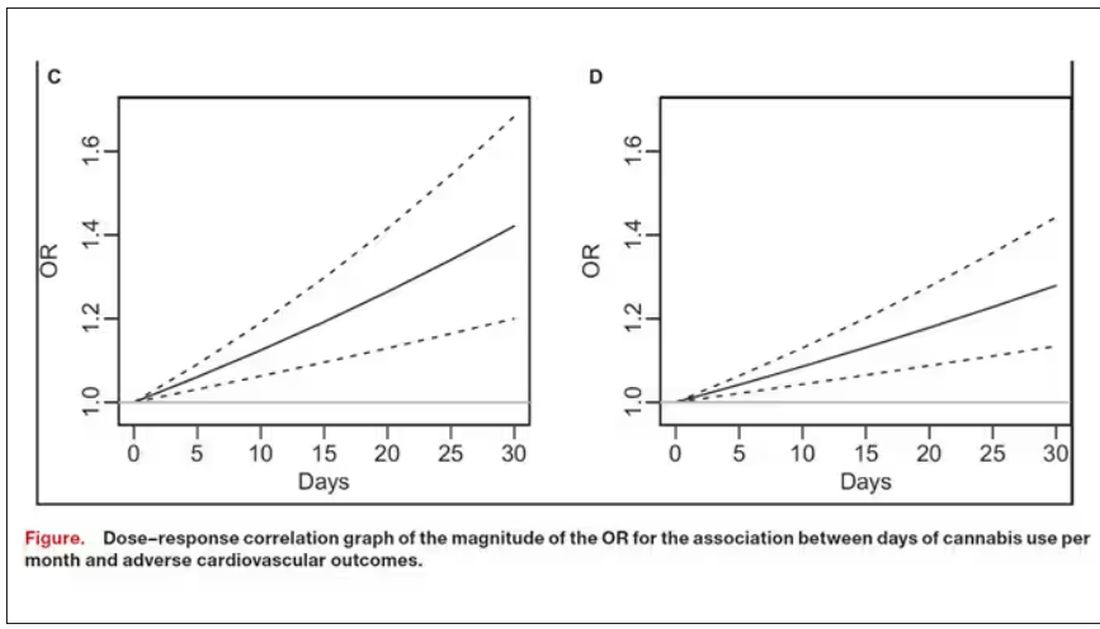

The authors also imply that they found a dose-response relationship between marijuana use and these cardiovascular outcomes. This is an important statement because dose response is one factor that we use to determine whether a risk factor may actually be causative as opposed to just correlative.

But I take issue with the dose-response language here. The model used to make these graphs classifies marijuana use as a single continuous variable ranging from 0 (no days of use in the past 30 days) to 1 (30 days of use in the past 30 days). The model is thus constrained to monotonically increase or decrease with respect to the outcome. To prove a dose response, you have to give the model the option to find something that isn’t a dose response — for example, by classifying marijuana use into discrete, independent categories rather than a single continuous number.

Am I arguing here that marijuana use is good for you? Of course not. Nor am I even arguing that it has no effect on the cardiovascular system. There are endocannabinoid receptors all over your vasculature. But a cross-sectional survey study, while a good start, is not quite the right way to answer the question. So, while the jury is still out, it’s high time for more research.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

If you’re an epidemiologist trying to explore whether some exposure is a risk factor for a disease, you can run into a tough problem when your exposure of interest is highly correlated with another risk factor for the disease. For decades, this stymied investigations into the link, if any, between marijuana use and cardiovascular disease because, for decades, most people who used marijuana in some way also smoked cigarettes — which is a very clear risk factor for heart disease.

But the times they are a-changing.

Thanks to the legalization of marijuana for recreational use in many states, and even broader social trends, there is now a large population of people who use marijuana but do not use cigarettes. That means we can start to determine whether marijuana use is an independent risk factor for heart disease.

And this week, we have the largest study yet to attempt to answer that question, though, as I’ll explain momentarily, the smoke hasn’t entirely cleared yet.

The centerpiece of the study we are discussing this week, “Association of Cannabis Use With Cardiovascular Outcomes Among US Adults,” which appeared in the Journal of the American Heart Association, is the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, an annual telephone survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention since 1984 that gathers data on all sorts of stuff that we do to ourselves: our drinking habits, our smoking habits, and, more recently, our marijuana habits.

The paper combines annual data from 2016 to 2020 representing 27 states and two US territories for a total sample size of more than 430,000 individuals. The key exposure? Marijuana use, which was coded as the number of days of marijuana use in the past 30 days. The key outcome? Coronary heart disease, collected through questions such as “Has a doctor, nurse, or other health professional ever told you that you had a heart attack?”

Right away you might detect a couple of problems here. But let me show you the results before we worry about what they mean.

You can see the rates of the major cardiovascular outcomes here, stratified by daily use of marijuana, nondaily use, and no use. Broadly speaking, the risk was highest for daily users, lowest for occasional users, and in the middle for non-users.

Of course, non-users and users are different in lots of other ways; non-users were quite a bit older, for example. Adjusting for all those factors showed that, independent of age, smoking status, the presence of diabetes, and so on, there was an independently increased risk for cardiovascular outcomes in people who used marijuana.

Importantly, 60% of people in this study were never smokers, and the results in that group looked pretty similar to the results overall.

But I said there were a couple of problems, so let’s dig into those a bit.

First, like most survey studies, this one requires honest and accurate reporting from its subjects. There was no verification of heart disease using electronic health records or of marijuana usage based on biosamples. Broadly, miscategorization of exposure and outcomes in surveys tends to bias the results toward the null hypothesis, toward concluding that there is no link between exposure and outcome, so perhaps this is okay.

The bigger problem is the fact that this is a cross-sectional design. If you really wanted to know whether marijuana led to heart disease, you’d do a longitudinal study following users and non-users for some number of decades and see who developed heart disease and who didn’t. (For the pedants out there, I suppose you’d actually want to randomize people to use marijuana or not and then see who had a heart attack, but the IRB keeps rejecting my protocol when I submit it.)

Here, though, we literally can’t tell whether people who use marijuana have more heart attacks or whether people who have heart attacks use more marijuana. The authors argue that there are no data that show that people are more likely to use marijuana after a heart attack or stroke, but at the time the survey was conducted, they had already had their heart attack or stroke.

The authors also imply that they found a dose-response relationship between marijuana use and these cardiovascular outcomes. This is an important statement because dose response is one factor that we use to determine whether a risk factor may actually be causative as opposed to just correlative.

But I take issue with the dose-response language here. The model used to make these graphs classifies marijuana use as a single continuous variable ranging from 0 (no days of use in the past 30 days) to 1 (30 days of use in the past 30 days). The model is thus constrained to monotonically increase or decrease with respect to the outcome. To prove a dose response, you have to give the model the option to find something that isn’t a dose response — for example, by classifying marijuana use into discrete, independent categories rather than a single continuous number.

Am I arguing here that marijuana use is good for you? Of course not. Nor am I even arguing that it has no effect on the cardiovascular system. There are endocannabinoid receptors all over your vasculature. But a cross-sectional survey study, while a good start, is not quite the right way to answer the question. So, while the jury is still out, it’s high time for more research.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

If you’re an epidemiologist trying to explore whether some exposure is a risk factor for a disease, you can run into a tough problem when your exposure of interest is highly correlated with another risk factor for the disease. For decades, this stymied investigations into the link, if any, between marijuana use and cardiovascular disease because, for decades, most people who used marijuana in some way also smoked cigarettes — which is a very clear risk factor for heart disease.

But the times they are a-changing.

Thanks to the legalization of marijuana for recreational use in many states, and even broader social trends, there is now a large population of people who use marijuana but do not use cigarettes. That means we can start to determine whether marijuana use is an independent risk factor for heart disease.

And this week, we have the largest study yet to attempt to answer that question, though, as I’ll explain momentarily, the smoke hasn’t entirely cleared yet.

The centerpiece of the study we are discussing this week, “Association of Cannabis Use With Cardiovascular Outcomes Among US Adults,” which appeared in the Journal of the American Heart Association, is the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, an annual telephone survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention since 1984 that gathers data on all sorts of stuff that we do to ourselves: our drinking habits, our smoking habits, and, more recently, our marijuana habits.

The paper combines annual data from 2016 to 2020 representing 27 states and two US territories for a total sample size of more than 430,000 individuals. The key exposure? Marijuana use, which was coded as the number of days of marijuana use in the past 30 days. The key outcome? Coronary heart disease, collected through questions such as “Has a doctor, nurse, or other health professional ever told you that you had a heart attack?”

Right away you might detect a couple of problems here. But let me show you the results before we worry about what they mean.

You can see the rates of the major cardiovascular outcomes here, stratified by daily use of marijuana, nondaily use, and no use. Broadly speaking, the risk was highest for daily users, lowest for occasional users, and in the middle for non-users.

Of course, non-users and users are different in lots of other ways; non-users were quite a bit older, for example. Adjusting for all those factors showed that, independent of age, smoking status, the presence of diabetes, and so on, there was an independently increased risk for cardiovascular outcomes in people who used marijuana.

Importantly, 60% of people in this study were never smokers, and the results in that group looked pretty similar to the results overall.

But I said there were a couple of problems, so let’s dig into those a bit.

First, like most survey studies, this one requires honest and accurate reporting from its subjects. There was no verification of heart disease using electronic health records or of marijuana usage based on biosamples. Broadly, miscategorization of exposure and outcomes in surveys tends to bias the results toward the null hypothesis, toward concluding that there is no link between exposure and outcome, so perhaps this is okay.

The bigger problem is the fact that this is a cross-sectional design. If you really wanted to know whether marijuana led to heart disease, you’d do a longitudinal study following users and non-users for some number of decades and see who developed heart disease and who didn’t. (For the pedants out there, I suppose you’d actually want to randomize people to use marijuana or not and then see who had a heart attack, but the IRB keeps rejecting my protocol when I submit it.)

Here, though, we literally can’t tell whether people who use marijuana have more heart attacks or whether people who have heart attacks use more marijuana. The authors argue that there are no data that show that people are more likely to use marijuana after a heart attack or stroke, but at the time the survey was conducted, they had already had their heart attack or stroke.

The authors also imply that they found a dose-response relationship between marijuana use and these cardiovascular outcomes. This is an important statement because dose response is one factor that we use to determine whether a risk factor may actually be causative as opposed to just correlative.

But I take issue with the dose-response language here. The model used to make these graphs classifies marijuana use as a single continuous variable ranging from 0 (no days of use in the past 30 days) to 1 (30 days of use in the past 30 days). The model is thus constrained to monotonically increase or decrease with respect to the outcome. To prove a dose response, you have to give the model the option to find something that isn’t a dose response — for example, by classifying marijuana use into discrete, independent categories rather than a single continuous number.

Am I arguing here that marijuana use is good for you? Of course not. Nor am I even arguing that it has no effect on the cardiovascular system. There are endocannabinoid receptors all over your vasculature. But a cross-sectional survey study, while a good start, is not quite the right way to answer the question. So, while the jury is still out, it’s high time for more research.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Oxaliplatin in Older Adults With Resected Colorectal Cancer: Is There a Benefit?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Our group, the QUASAR Group, made a very significant contribution in terms of trials and knowledge in this field. One of the things that we still need to discuss and think about in our wider community is the impact of adjuvant chemotherapy in older patients.

Colorectal cancer is a disease of the elderly, with the median age of presentation around 72. We know that, at presentation, more than 50% of patients are aged 65 or over and one third of patients are 75 or over. It’s a disease predominantly of the elderly. Are we justified in giving combination chemotherapy with oxaliplatin to high-risk resected colorectal cancer patients?

There’s a very nice report of a meta-analysis by Dottorini and colleagues that came out recently in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. It’s an excellent group. They did their meta-analytical work according to a strict, rational protocol. Their statistical analyses were on point, and they collected data from all the relevant trials.

According to the results of their study, it could be concluded that the addition of oxaliplatin to adjuvant therapy for resected high-risk colorectal cancer in older patients — patients older than 70 — doesn’t result in any statistically significant gain in terms of preventing recurrences or saving lives.

When we did our QUASAR trials, initially we were looking at control vs fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy. Although there was an overall impact on survival of the whole trial group (the 5000 patients in our study), when we looked by decile, there was a significant diminution of benefit even to fluoropyrimidine therapy in our trial in patients aged 70 or above. I think this careful meta-analysis must make us question the use of oxaliplatin in elderly patients.

What could the explanation be? Why could the well-known and described benefits of oxaliplatin, particularly for stage III disease, attenuate in older people? It may be to do with reduction in dose intensity. Older people have more side effects; therefore, the chemotherapy isn’t completed as planned. Although, increasingly these days, we tend only to be giving 3 months of treatment.

Is there something biologically in terms of the biology or the somatic mutational landscape of the tumor in older people? I don’t think so. Certainly, in terms of their capacity, in terms of stem cell reserve to be as resistant to the side effects of chemotherapy as younger people, we know that does attenuate with age.

Food for thought: The majority of patients I see in the clinic for the adjuvant treatment are elderly. The majority are coming these days with high-risk stage II or stage III disease. There is a real question mark about whether we should be using oxaliplatin at all.

Clearly, one would say that we need more trials of chemotherapy in older folk to see if the addition of drugs like oxaliplatin to a fluoropyrimidine backbone really does make a difference. I’ve said many times before that we, the medical community recommending adjuvant treatment, need to have better risk stratifiers. We need to have better prognostic markers. We need to have better indices that would allow us to perhaps consider these combination treatments in a more focused group of patients who may have a higher risk for recurrence.

Have a look at the paper and see what you think. I think it’s well done. It’s certainly given me pause for thought about the treatment that we will offer our elderly patients.

Have a think about it. Let me know if there are any comments that you’d like to make. For the time being, over and out.