User login

Long-Term Follow-Up Emphasizes HPV Vaccination Importance

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I want to briefly discuss a critically important topic that cannot be overly emphasized. It is the relevance, the importance, the benefits, and the outcome of HPV vaccination.

The paper I’m referring to was published in Pediatrics in October 2023. It’s titled, “Ten-Year Follow-up of 9-Valent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: Immunogenicity, Effectiveness, and Safety.”

Let me emphasize that we’re talking about a 10-year follow-up. In this particular paper and analysis, 301 boys — I emphasize boys — were included and 971 girls at 40 different sites in 13 countries, who received the 9-valent vaccine, which includes HPV 16, 18, and seven other types.

Most importantly, there was not a single case. Not one. Let me repeat this: There was not a single case of high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia, or worse, or condyloma in either males or females. There was not a single case in over 1000 individuals with a follow-up of more than 10 years.

It is difficult to overstate the magnitude of the benefit associated with HPV vaccination for our children and young adults on their risk of developing highly relevant, life-changing, potentially deadly cancers.

For those of you who are interested in this topic — which should include almost all of you, if not all of you — I encourage you to read this very important follow-up paper, again, demonstrating the simple, overwhelming magnitude of the benefit of HPV vaccination. I thank you for your attention.

Dr. Markman is a professor in the department of medical oncology and therapeutics research, City of Hope, Duarte, California, and president of medicine and science, City of Hope Atlanta, Chicago, and Phoenix. He disclosed ties with GlaxoSmithKline; AstraZeneca.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I want to briefly discuss a critically important topic that cannot be overly emphasized. It is the relevance, the importance, the benefits, and the outcome of HPV vaccination.

The paper I’m referring to was published in Pediatrics in October 2023. It’s titled, “Ten-Year Follow-up of 9-Valent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: Immunogenicity, Effectiveness, and Safety.”

Let me emphasize that we’re talking about a 10-year follow-up. In this particular paper and analysis, 301 boys — I emphasize boys — were included and 971 girls at 40 different sites in 13 countries, who received the 9-valent vaccine, which includes HPV 16, 18, and seven other types.

Most importantly, there was not a single case. Not one. Let me repeat this: There was not a single case of high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia, or worse, or condyloma in either males or females. There was not a single case in over 1000 individuals with a follow-up of more than 10 years.

It is difficult to overstate the magnitude of the benefit associated with HPV vaccination for our children and young adults on their risk of developing highly relevant, life-changing, potentially deadly cancers.

For those of you who are interested in this topic — which should include almost all of you, if not all of you — I encourage you to read this very important follow-up paper, again, demonstrating the simple, overwhelming magnitude of the benefit of HPV vaccination. I thank you for your attention.

Dr. Markman is a professor in the department of medical oncology and therapeutics research, City of Hope, Duarte, California, and president of medicine and science, City of Hope Atlanta, Chicago, and Phoenix. He disclosed ties with GlaxoSmithKline; AstraZeneca.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I want to briefly discuss a critically important topic that cannot be overly emphasized. It is the relevance, the importance, the benefits, and the outcome of HPV vaccination.

The paper I’m referring to was published in Pediatrics in October 2023. It’s titled, “Ten-Year Follow-up of 9-Valent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: Immunogenicity, Effectiveness, and Safety.”

Let me emphasize that we’re talking about a 10-year follow-up. In this particular paper and analysis, 301 boys — I emphasize boys — were included and 971 girls at 40 different sites in 13 countries, who received the 9-valent vaccine, which includes HPV 16, 18, and seven other types.

Most importantly, there was not a single case. Not one. Let me repeat this: There was not a single case of high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia, or worse, or condyloma in either males or females. There was not a single case in over 1000 individuals with a follow-up of more than 10 years.

It is difficult to overstate the magnitude of the benefit associated with HPV vaccination for our children and young adults on their risk of developing highly relevant, life-changing, potentially deadly cancers.

For those of you who are interested in this topic — which should include almost all of you, if not all of you — I encourage you to read this very important follow-up paper, again, demonstrating the simple, overwhelming magnitude of the benefit of HPV vaccination. I thank you for your attention.

Dr. Markman is a professor in the department of medical oncology and therapeutics research, City of Hope, Duarte, California, and president of medicine and science, City of Hope Atlanta, Chicago, and Phoenix. He disclosed ties with GlaxoSmithKline; AstraZeneca.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Healing From Trauma

“You’ll never walk alone.” — Nettie Fowler, Carousel

A few winters ago, a young man and his fiancée were driving on the 91 freeway in southern California during a torrential downpour when their Honda Civic hydroplaned, slamming into the jersey barrier. They were both unhurt. Unsure what to do next, they made the catastrophic decision to exit the vehicle. As the man walked around the back of the car he was nearly hit by a black sedan sliding out of control trying to avoid them. When he came around the car, his fiancé was nowhere to be found. She had been struck at highway speed and lay crushed under the sedan hundreds of feet away.

I know this poor man because he was referred to me. Not as a dermatologist, but as a fellow human healing from trauma. On January 1, 2019, at about 9:30 PM, while we were home together, my beloved wife of 24 years took her own life. Even 5 years on it is difficult to believe that she isn’t proofing this paragraph like she had done for every one of my Derm News columns for years. We had been together since teenagers and had lived a joy-filled life. There isn’t any medical reason to share. But that day I joined the community of those who have carried unbearable heaviness of grief and survived. Sometimes others seek me out for help.

At first, my instinct was to guide them, to give advice, to tell them what to do and where to go. But I’ve learned that people in this dark valley don’t need a guide. They need someone to accompany them. To walk with them for a few minutes on their lonely journey. I recently read David Brooks’s new book, How to Know a Person. I’ve been a fan of his since he joined the New York Times in 2003 and have read almost everything he’s written. I sometimes even imagine how he might approach a column whenever I’m stuck (thank you, David). His The Road to Character book is in my canon of literature for self-growth. This latest book is an interesting digression from that central theme. He argues that our society is in acute need of forming better connections and that an important way we can be moral is to learn, and to practice, how to know each other. He shares an emotional experience of losing a close friend to suicide and writes a poignant explanation of what it means to accompany someone in need. It particularly resonated with me. We are doctors and are wired to find the source of a problem, like quickly rotating through the 4X, 10X, 40X on a microscope. Once identified, we spend most of our time creating and explaining treatments. I see how this makes me a great dermatologist but just an average human.

Brooks tells the story of a woman with a brain tumor who often finds herself on the ground surrounded by well-meaning people trying to help. She explains later that what she really needs in those moments is just for someone to get on the ground and lie with her. To accompany her.

Having crossed the midpoint of life, I see with the benefit of perspective how suffering has afforded me wisdom: I am more sensitive and attuned to others. It also gave me credibility: I know how it feels to walk life’s loneliest journey. I’ve also learned to make myself vulnerable for someone to share their story with me. I won’t be afraid to hear the details. I won’t judge them for weeping too little or for sobbing too much. I don’t answer whys. I won’t say what they should do next. But for a few minutes I can walk beside them as a person who cares.

I do not try to remember the hours and days after Susan’s death, but one moment stands out and makes my eyes well when I think of it. That following day my dear brother flew across the country on the next flight out. I was sitting in a psychiatry waiting room when he came down the hall with his luggage in tow. He hugged me as only a brother could, then looked me in my eyes, which were bloodshot from tears just as his were, and he said, “We’re going to be OK.” And with that he walked with me into the office.

We physicians are blessed to have so many intimate human interactions. This book reminded me that sometimes my most important job is not to be the optimized doctor, but just a good human walking alongside.

I have no conflict of interest and purchased these books.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at [email protected].

“You’ll never walk alone.” — Nettie Fowler, Carousel

A few winters ago, a young man and his fiancée were driving on the 91 freeway in southern California during a torrential downpour when their Honda Civic hydroplaned, slamming into the jersey barrier. They were both unhurt. Unsure what to do next, they made the catastrophic decision to exit the vehicle. As the man walked around the back of the car he was nearly hit by a black sedan sliding out of control trying to avoid them. When he came around the car, his fiancé was nowhere to be found. She had been struck at highway speed and lay crushed under the sedan hundreds of feet away.

I know this poor man because he was referred to me. Not as a dermatologist, but as a fellow human healing from trauma. On January 1, 2019, at about 9:30 PM, while we were home together, my beloved wife of 24 years took her own life. Even 5 years on it is difficult to believe that she isn’t proofing this paragraph like she had done for every one of my Derm News columns for years. We had been together since teenagers and had lived a joy-filled life. There isn’t any medical reason to share. But that day I joined the community of those who have carried unbearable heaviness of grief and survived. Sometimes others seek me out for help.

At first, my instinct was to guide them, to give advice, to tell them what to do and where to go. But I’ve learned that people in this dark valley don’t need a guide. They need someone to accompany them. To walk with them for a few minutes on their lonely journey. I recently read David Brooks’s new book, How to Know a Person. I’ve been a fan of his since he joined the New York Times in 2003 and have read almost everything he’s written. I sometimes even imagine how he might approach a column whenever I’m stuck (thank you, David). His The Road to Character book is in my canon of literature for self-growth. This latest book is an interesting digression from that central theme. He argues that our society is in acute need of forming better connections and that an important way we can be moral is to learn, and to practice, how to know each other. He shares an emotional experience of losing a close friend to suicide and writes a poignant explanation of what it means to accompany someone in need. It particularly resonated with me. We are doctors and are wired to find the source of a problem, like quickly rotating through the 4X, 10X, 40X on a microscope. Once identified, we spend most of our time creating and explaining treatments. I see how this makes me a great dermatologist but just an average human.

Brooks tells the story of a woman with a brain tumor who often finds herself on the ground surrounded by well-meaning people trying to help. She explains later that what she really needs in those moments is just for someone to get on the ground and lie with her. To accompany her.

Having crossed the midpoint of life, I see with the benefit of perspective how suffering has afforded me wisdom: I am more sensitive and attuned to others. It also gave me credibility: I know how it feels to walk life’s loneliest journey. I’ve also learned to make myself vulnerable for someone to share their story with me. I won’t be afraid to hear the details. I won’t judge them for weeping too little or for sobbing too much. I don’t answer whys. I won’t say what they should do next. But for a few minutes I can walk beside them as a person who cares.

I do not try to remember the hours and days after Susan’s death, but one moment stands out and makes my eyes well when I think of it. That following day my dear brother flew across the country on the next flight out. I was sitting in a psychiatry waiting room when he came down the hall with his luggage in tow. He hugged me as only a brother could, then looked me in my eyes, which were bloodshot from tears just as his were, and he said, “We’re going to be OK.” And with that he walked with me into the office.

We physicians are blessed to have so many intimate human interactions. This book reminded me that sometimes my most important job is not to be the optimized doctor, but just a good human walking alongside.

I have no conflict of interest and purchased these books.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at [email protected].

“You’ll never walk alone.” — Nettie Fowler, Carousel

A few winters ago, a young man and his fiancée were driving on the 91 freeway in southern California during a torrential downpour when their Honda Civic hydroplaned, slamming into the jersey barrier. They were both unhurt. Unsure what to do next, they made the catastrophic decision to exit the vehicle. As the man walked around the back of the car he was nearly hit by a black sedan sliding out of control trying to avoid them. When he came around the car, his fiancé was nowhere to be found. She had been struck at highway speed and lay crushed under the sedan hundreds of feet away.

I know this poor man because he was referred to me. Not as a dermatologist, but as a fellow human healing from trauma. On January 1, 2019, at about 9:30 PM, while we were home together, my beloved wife of 24 years took her own life. Even 5 years on it is difficult to believe that she isn’t proofing this paragraph like she had done for every one of my Derm News columns for years. We had been together since teenagers and had lived a joy-filled life. There isn’t any medical reason to share. But that day I joined the community of those who have carried unbearable heaviness of grief and survived. Sometimes others seek me out for help.

At first, my instinct was to guide them, to give advice, to tell them what to do and where to go. But I’ve learned that people in this dark valley don’t need a guide. They need someone to accompany them. To walk with them for a few minutes on their lonely journey. I recently read David Brooks’s new book, How to Know a Person. I’ve been a fan of his since he joined the New York Times in 2003 and have read almost everything he’s written. I sometimes even imagine how he might approach a column whenever I’m stuck (thank you, David). His The Road to Character book is in my canon of literature for self-growth. This latest book is an interesting digression from that central theme. He argues that our society is in acute need of forming better connections and that an important way we can be moral is to learn, and to practice, how to know each other. He shares an emotional experience of losing a close friend to suicide and writes a poignant explanation of what it means to accompany someone in need. It particularly resonated with me. We are doctors and are wired to find the source of a problem, like quickly rotating through the 4X, 10X, 40X on a microscope. Once identified, we spend most of our time creating and explaining treatments. I see how this makes me a great dermatologist but just an average human.

Brooks tells the story of a woman with a brain tumor who often finds herself on the ground surrounded by well-meaning people trying to help. She explains later that what she really needs in those moments is just for someone to get on the ground and lie with her. To accompany her.

Having crossed the midpoint of life, I see with the benefit of perspective how suffering has afforded me wisdom: I am more sensitive and attuned to others. It also gave me credibility: I know how it feels to walk life’s loneliest journey. I’ve also learned to make myself vulnerable for someone to share their story with me. I won’t be afraid to hear the details. I won’t judge them for weeping too little or for sobbing too much. I don’t answer whys. I won’t say what they should do next. But for a few minutes I can walk beside them as a person who cares.

I do not try to remember the hours and days after Susan’s death, but one moment stands out and makes my eyes well when I think of it. That following day my dear brother flew across the country on the next flight out. I was sitting in a psychiatry waiting room when he came down the hall with his luggage in tow. He hugged me as only a brother could, then looked me in my eyes, which were bloodshot from tears just as his were, and he said, “We’re going to be OK.” And with that he walked with me into the office.

We physicians are blessed to have so many intimate human interactions. This book reminded me that sometimes my most important job is not to be the optimized doctor, but just a good human walking alongside.

I have no conflict of interest and purchased these books.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at [email protected].

Bivalent Vaccines Protect Even Children Who’ve Had COVID

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It was only 3 years ago when we called the pathogen we now refer to as the coronavirus “nCOV-19.” It was, in many ways, more descriptive than what we have today. The little “n” there stood for “novel” — and it was really that little “n” that caused us all the trouble.

You see, coronaviruses themselves were not really new to us. Understudied, perhaps, but with four strains running around the globe at any time giving rise to the common cold, these were viruses our bodies understood.

But Instead of acting like a cold, it acted like nothing we had seen before, at least in our lifetime. The story of the pandemic is very much a bildungsroman of our immune systems — a story of how our immunity grew up.

The difference between the start of 2020 and now, when infections with the coronavirus remain common but not as deadly, can be measured in terms of immune education. Some of our immune systems were educated by infection, some by vaccination, and many by both.

When the first vaccines emerged in December 2020, the opportunity to educate our immune systems was still huge. Though, at the time, an estimated 20 million had been infected in the US and 350,000 had died, there was a large population that remained immunologically naive. I was one of them.

If 2020 into early 2021 was the era of immune education, the postvaccine period was the era of the variant. From one COVID strain to two, to five, to innumerable, our immune memory — trained on a specific version of the virus or its spike protein — became imperfect again. Not naive; these variants were not “novel” in the way COVID-19 was novel, but they were different. And different enough to cause infection.

Following the playbook of another virus that loves to come dressed up in different outfits, the flu virus, we find ourselves in the booster era — a world where yearly doses of a vaccine, ideally matched to the variants circulating when the vaccine is given, are the recommendation if not the norm.

But questions remain about the vaccination program, particularly around who should get it. And two populations with big question marks over their heads are (1) people who have already been infected and (2) kids, because their risk for bad outcomes is so much lower.

This week, we finally have some evidence that can shed light on these questions. The study under the spotlight is this one, appearing in JAMA, which tries to analyze the ability of the bivalent vaccine — that’s the second one to come out, around September 2022 — to protect kids from COVID-19.

Now, right off the bat, this was not a randomized trial. The studies that established the viability of the mRNA vaccine platform were; they happened before the vaccine was authorized. But trials of the bivalent vaccine were mostly limited to proving immune response, not protection from disease.

Nevertheless, with some good observational methods and some statistics, we can try to tease out whether bivalent vaccines in kids worked.

The study combines three prospective cohort studies. The details are in the paper, but what you need to know is that the special sauce of these studies was that the kids were tested for COVID-19 on a weekly basis, whether they had symptoms or not. This is critical because asymptomatic infections can transmit COVID-19.

Let’s do the variables of interest. First and foremost, the bivalent vaccine. Some of these kids got the bivalent vaccine, some didn’t. Other key variables include prior vaccination with the monovalent vaccine. Some had been vaccinated with the monovalent vaccine before, some hadn’t. And, of course, prior infection. Some had been infected before (based on either nasal swabs or blood tests).

Let’s focus first on the primary exposure of interest: getting that bivalent vaccine. Again, this was not randomly assigned; kids who got the bivalent vaccine were different from those who did not. In general, they lived in smaller households, they were more likely to be White, less likely to have had a prior COVID infection, and quite a bit more likely to have at least one chronic condition.

To me, this constellation of factors describes a slightly higher-risk group; it makes sense that they were more likely to get the second vaccine.

Given those factors, what were the rates of COVID infection? After nearly a year of follow-up, around 15% of the kids who hadn’t received the bivalent vaccine got infected compared with 5% of the vaccinated kids. Symptomatic infections represented roughly half of all infections in both groups.

After adjustment for factors that differed between the groups, this difference translated into a vaccine efficacy of about 50% in this population. That’s our first data point. Yes, the bivalent vaccine worked. Not amazingly, of course. But it worked.

What about the kids who had had a prior COVID infection? Somewhat surprisingly, the vaccine was just as effective in this population, despite the fact that their immune systems already had some knowledge of COVID. Ten percent of unvaccinated kids got infected, even though they had been infected before. Just 2.5% of kids who received the bivalent vaccine got infected, suggesting some synergy between prior infection and vaccination.

These data suggest that the bivalent vaccine did reduce the risk for COVID infection in kids. All good. But the piece still missing is how severe these infections were. It doesn’t appear that any of the 426 infections documented in this study resulted in hospitalization or death, fortunately. And no data are presented on the incidence of multisystem inflammatory syndrome of children, though given the rarity, I’d be surprised if any of these kids have this either.

So where are we? Well, it seems that the narrative out there that says “the vaccines don’t work” or “the vaccines don’t work if you’ve already been infected” is probably not true. They do work. This study and others in adults show that. If they work to reduce infections, as this study shows, they will also work to reduce deaths. It’s just that death is fortunately so rare in children that the number needed to vaccinate to prevent one death is very large. In that situation, the decision to vaccinate comes down to the risks associated with vaccination. So far, those risk seem very minimal.

Perhaps falling into a flu-like yearly vaccination schedule is not simply the result of old habits dying hard. Maybe it’s actually not a bad idea.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It was only 3 years ago when we called the pathogen we now refer to as the coronavirus “nCOV-19.” It was, in many ways, more descriptive than what we have today. The little “n” there stood for “novel” — and it was really that little “n” that caused us all the trouble.

You see, coronaviruses themselves were not really new to us. Understudied, perhaps, but with four strains running around the globe at any time giving rise to the common cold, these were viruses our bodies understood.

But Instead of acting like a cold, it acted like nothing we had seen before, at least in our lifetime. The story of the pandemic is very much a bildungsroman of our immune systems — a story of how our immunity grew up.

The difference between the start of 2020 and now, when infections with the coronavirus remain common but not as deadly, can be measured in terms of immune education. Some of our immune systems were educated by infection, some by vaccination, and many by both.

When the first vaccines emerged in December 2020, the opportunity to educate our immune systems was still huge. Though, at the time, an estimated 20 million had been infected in the US and 350,000 had died, there was a large population that remained immunologically naive. I was one of them.

If 2020 into early 2021 was the era of immune education, the postvaccine period was the era of the variant. From one COVID strain to two, to five, to innumerable, our immune memory — trained on a specific version of the virus or its spike protein — became imperfect again. Not naive; these variants were not “novel” in the way COVID-19 was novel, but they were different. And different enough to cause infection.

Following the playbook of another virus that loves to come dressed up in different outfits, the flu virus, we find ourselves in the booster era — a world where yearly doses of a vaccine, ideally matched to the variants circulating when the vaccine is given, are the recommendation if not the norm.

But questions remain about the vaccination program, particularly around who should get it. And two populations with big question marks over their heads are (1) people who have already been infected and (2) kids, because their risk for bad outcomes is so much lower.

This week, we finally have some evidence that can shed light on these questions. The study under the spotlight is this one, appearing in JAMA, which tries to analyze the ability of the bivalent vaccine — that’s the second one to come out, around September 2022 — to protect kids from COVID-19.

Now, right off the bat, this was not a randomized trial. The studies that established the viability of the mRNA vaccine platform were; they happened before the vaccine was authorized. But trials of the bivalent vaccine were mostly limited to proving immune response, not protection from disease.

Nevertheless, with some good observational methods and some statistics, we can try to tease out whether bivalent vaccines in kids worked.

The study combines three prospective cohort studies. The details are in the paper, but what you need to know is that the special sauce of these studies was that the kids were tested for COVID-19 on a weekly basis, whether they had symptoms or not. This is critical because asymptomatic infections can transmit COVID-19.

Let’s do the variables of interest. First and foremost, the bivalent vaccine. Some of these kids got the bivalent vaccine, some didn’t. Other key variables include prior vaccination with the monovalent vaccine. Some had been vaccinated with the monovalent vaccine before, some hadn’t. And, of course, prior infection. Some had been infected before (based on either nasal swabs or blood tests).

Let’s focus first on the primary exposure of interest: getting that bivalent vaccine. Again, this was not randomly assigned; kids who got the bivalent vaccine were different from those who did not. In general, they lived in smaller households, they were more likely to be White, less likely to have had a prior COVID infection, and quite a bit more likely to have at least one chronic condition.

To me, this constellation of factors describes a slightly higher-risk group; it makes sense that they were more likely to get the second vaccine.

Given those factors, what were the rates of COVID infection? After nearly a year of follow-up, around 15% of the kids who hadn’t received the bivalent vaccine got infected compared with 5% of the vaccinated kids. Symptomatic infections represented roughly half of all infections in both groups.

After adjustment for factors that differed between the groups, this difference translated into a vaccine efficacy of about 50% in this population. That’s our first data point. Yes, the bivalent vaccine worked. Not amazingly, of course. But it worked.

What about the kids who had had a prior COVID infection? Somewhat surprisingly, the vaccine was just as effective in this population, despite the fact that their immune systems already had some knowledge of COVID. Ten percent of unvaccinated kids got infected, even though they had been infected before. Just 2.5% of kids who received the bivalent vaccine got infected, suggesting some synergy between prior infection and vaccination.

These data suggest that the bivalent vaccine did reduce the risk for COVID infection in kids. All good. But the piece still missing is how severe these infections were. It doesn’t appear that any of the 426 infections documented in this study resulted in hospitalization or death, fortunately. And no data are presented on the incidence of multisystem inflammatory syndrome of children, though given the rarity, I’d be surprised if any of these kids have this either.

So where are we? Well, it seems that the narrative out there that says “the vaccines don’t work” or “the vaccines don’t work if you’ve already been infected” is probably not true. They do work. This study and others in adults show that. If they work to reduce infections, as this study shows, they will also work to reduce deaths. It’s just that death is fortunately so rare in children that the number needed to vaccinate to prevent one death is very large. In that situation, the decision to vaccinate comes down to the risks associated with vaccination. So far, those risk seem very minimal.

Perhaps falling into a flu-like yearly vaccination schedule is not simply the result of old habits dying hard. Maybe it’s actually not a bad idea.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It was only 3 years ago when we called the pathogen we now refer to as the coronavirus “nCOV-19.” It was, in many ways, more descriptive than what we have today. The little “n” there stood for “novel” — and it was really that little “n” that caused us all the trouble.

You see, coronaviruses themselves were not really new to us. Understudied, perhaps, but with four strains running around the globe at any time giving rise to the common cold, these were viruses our bodies understood.

But Instead of acting like a cold, it acted like nothing we had seen before, at least in our lifetime. The story of the pandemic is very much a bildungsroman of our immune systems — a story of how our immunity grew up.

The difference between the start of 2020 and now, when infections with the coronavirus remain common but not as deadly, can be measured in terms of immune education. Some of our immune systems were educated by infection, some by vaccination, and many by both.

When the first vaccines emerged in December 2020, the opportunity to educate our immune systems was still huge. Though, at the time, an estimated 20 million had been infected in the US and 350,000 had died, there was a large population that remained immunologically naive. I was one of them.

If 2020 into early 2021 was the era of immune education, the postvaccine period was the era of the variant. From one COVID strain to two, to five, to innumerable, our immune memory — trained on a specific version of the virus or its spike protein — became imperfect again. Not naive; these variants were not “novel” in the way COVID-19 was novel, but they were different. And different enough to cause infection.

Following the playbook of another virus that loves to come dressed up in different outfits, the flu virus, we find ourselves in the booster era — a world where yearly doses of a vaccine, ideally matched to the variants circulating when the vaccine is given, are the recommendation if not the norm.

But questions remain about the vaccination program, particularly around who should get it. And two populations with big question marks over their heads are (1) people who have already been infected and (2) kids, because their risk for bad outcomes is so much lower.

This week, we finally have some evidence that can shed light on these questions. The study under the spotlight is this one, appearing in JAMA, which tries to analyze the ability of the bivalent vaccine — that’s the second one to come out, around September 2022 — to protect kids from COVID-19.

Now, right off the bat, this was not a randomized trial. The studies that established the viability of the mRNA vaccine platform were; they happened before the vaccine was authorized. But trials of the bivalent vaccine were mostly limited to proving immune response, not protection from disease.

Nevertheless, with some good observational methods and some statistics, we can try to tease out whether bivalent vaccines in kids worked.

The study combines three prospective cohort studies. The details are in the paper, but what you need to know is that the special sauce of these studies was that the kids were tested for COVID-19 on a weekly basis, whether they had symptoms or not. This is critical because asymptomatic infections can transmit COVID-19.

Let’s do the variables of interest. First and foremost, the bivalent vaccine. Some of these kids got the bivalent vaccine, some didn’t. Other key variables include prior vaccination with the monovalent vaccine. Some had been vaccinated with the monovalent vaccine before, some hadn’t. And, of course, prior infection. Some had been infected before (based on either nasal swabs or blood tests).

Let’s focus first on the primary exposure of interest: getting that bivalent vaccine. Again, this was not randomly assigned; kids who got the bivalent vaccine were different from those who did not. In general, they lived in smaller households, they were more likely to be White, less likely to have had a prior COVID infection, and quite a bit more likely to have at least one chronic condition.

To me, this constellation of factors describes a slightly higher-risk group; it makes sense that they were more likely to get the second vaccine.

Given those factors, what were the rates of COVID infection? After nearly a year of follow-up, around 15% of the kids who hadn’t received the bivalent vaccine got infected compared with 5% of the vaccinated kids. Symptomatic infections represented roughly half of all infections in both groups.

After adjustment for factors that differed between the groups, this difference translated into a vaccine efficacy of about 50% in this population. That’s our first data point. Yes, the bivalent vaccine worked. Not amazingly, of course. But it worked.

What about the kids who had had a prior COVID infection? Somewhat surprisingly, the vaccine was just as effective in this population, despite the fact that their immune systems already had some knowledge of COVID. Ten percent of unvaccinated kids got infected, even though they had been infected before. Just 2.5% of kids who received the bivalent vaccine got infected, suggesting some synergy between prior infection and vaccination.

These data suggest that the bivalent vaccine did reduce the risk for COVID infection in kids. All good. But the piece still missing is how severe these infections were. It doesn’t appear that any of the 426 infections documented in this study resulted in hospitalization or death, fortunately. And no data are presented on the incidence of multisystem inflammatory syndrome of children, though given the rarity, I’d be surprised if any of these kids have this either.

So where are we? Well, it seems that the narrative out there that says “the vaccines don’t work” or “the vaccines don’t work if you’ve already been infected” is probably not true. They do work. This study and others in adults show that. If they work to reduce infections, as this study shows, they will also work to reduce deaths. It’s just that death is fortunately so rare in children that the number needed to vaccinate to prevent one death is very large. In that situation, the decision to vaccinate comes down to the risks associated with vaccination. So far, those risk seem very minimal.

Perhaps falling into a flu-like yearly vaccination schedule is not simply the result of old habits dying hard. Maybe it’s actually not a bad idea.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Hospital Marriage Proposals: The Good, the Bad, the Helipad

Picture your marriage proposal fantasy. Do you see a beautiful beach at sunset? The place where you first met your partner? Maybe a dream vacation — Paris, anyone? And perhaps most popular of all ... the ER?

Why not? For some couples who share medical careers, the hospital is home, and they turn the moment into something just as romantic as any Eiffel Tower backdrop. (And admittedly, sometimes they don’t.)

We spoke with three couples whose medical-themed proposals ended in the word “yes!”

Heaven on the Helipad

When emergency medicine physician Anna Darby, MD, heard a trauma patient was arriving and urgently needed to be intubated, she raced up to the rooftop helipad. As soon as the elevator doors opened, she was met with quite a different scene than expected. There were rose petals ... lots and lots of rose petals.

With her best friends and colleagues lining a red carpet, the roof had been turned into a scene from The Bachelor. Each person gave her a rose. A friend even touched up her makeup and handed over her favorite hoop earrings, transforming her from busy doctor to soon-to-be fiancée. Her boyfriend, cardiologist Merije Chukumerije, MD, stood waiting. You can guess what happened next.

Dr. Chukumerije later wrote in an Instagram post, “We met at this hospital. So, it was only right that I bring her to its highest place as we’ve reached the peak of our union.” The couple actually met in the hospital cafeteria “like all the clichés,” Dr. Darby jokes. For them, the helipad experience was just as Insta-worthy as any braggable, grandiose proposal at a fancy restaurant or on a mountaintop.

“Seeing that scene was totally not what I expected,” Dr. Darby says. “I can’t even describe it. It’s like the second biggest hormonal shift, [second only to] having a baby.” She and Dr. Chukumerije now have two babies of their own, aged 2 months and 2 years old.

Good Morning, Doctor

It was February 2021, the height of the pandemic, and Raaga Vemula, MD, now in her palliative care/hospice care fellowship, was “selected” for a local news interview on COVID-19. Except the interview was really with Good Morning America. And the topic was really a proposal.

Dr. Vemula met Steven Bean, MD, now doing a sleep medicine fellowship, in 2015. “I first saw her, and thought she was one of the prettiest women I’d ever seen. ... We ended up being in the same study group,” he says. “Let’s be honest, I applied to every med school she applied to.”

Six years later, Dr. Bean connected with GMA through The Knot, a wedding planning website and registry. The made-up interview request for Dr. Vemula came from the residency program director, who was in on the surprise. Dr. Vemula’s family also knew what was up when she called with the “news.”

The live broadcast took place at the hospital. Dr. Bean had an earpiece for the producers to give him directions. But “I was so nervous, I walked out immediately,” he says. He ended up standing behind Dr. Vemula. The mistake worked well for viewers though, building anticipation while she answered a COVID-19 question. “We got everybody excited,” says Dr. Bean. “So, when they said ’Raaga, turn around’ it worked out perfectly. She was confused as hell.”

Luckily, Dr. Vemula loves a good surprise. “He knows me very well,” she says.

For her, the proposal was even more meaningful given their background together. “Medicine means so much to both of us and was such a big part of our lives,” she says. “That’s what shaped us to do this. ... I think in our hearts it was meant to be this way.”

Who Says Masks Don’t Work?

Masks conjure up feelings for anyone living through the pandemic, especially medical personnel. But for Rhett Franklin and wife Lauren Gray, they will always symbolize of one of the biggest days of their lives.

Mr. Franklin worked in registration, often following Ms. Gray, an emergency room nurse, around with a wheeled computer station to gather patient information (what’s known as a “creeper,” which isn’t as creepy as it sounds). Eventually, she offered to grab a coffee with him, and when he suggested another coffee, she said it was time for him to buy her a drink.

Mr. Franklin, now a manager of business operations for nursing administration, originally planned to propose to Ms. Gray on a trip to England. But the pandemic prevented their vacation with its potential castle backdrop.

Mr. Franklin often picked up shifts making masks for frontline workers, and an alternate proposal idea started brewing. He schemed to have two very special masks made. “Mine was a black tuxedo that said, ‘Will you marry me?’ and hers resembled a white dress that said, ‘I said yes!’ ” Mr. Franklin says.

But a text almost ruined the surprise. When Mr. Franklin messaged family members about his proposal plan the day before, one relative responded in a group chat that included Ms. Gray. This was when the busy ER came to the rescue — no time to read texts. Family members also started calling Ms. Gray on the hospital’s phoneline as a distraction. Unfazed, Mr. Franklin simply moved up the proposal to that night.

At their favorite dog beach, as the sunset gleamed on the water, Mr. Franklin pulled his mask out and took a knee. He can’t recall what he said behind that mask. “It was kind of one of those blackout moments.” But Ms. Gray remembers for him — “You said ‘Let’s do this.’ ”

Warning Label

Everyone has different tastes. Some healthcare professionals have taken the medical theme further than these couples — maybe too far. A few have even faked life-threatening emergencies, showing up in the ER on a gurney with a made-up peanut allergy reaction or a severe injury and then pulling out a ring.

But who’s to judge? For some, thinking your partner is “dying” and then learning you’ve been tricked might not conjure up the warmest feelings. For others, apparently, it’s a virtual bouquet of roses.

A Few Proposal Pointers

If you’re planning to pop the question, this group says, “go for the medical setting!” But according to them, there are other must-haves to get that “yes” and the lifetime of wedded bliss, of course:

- Make it a hospital-wide morale-booster. “Everyone loves surprises,” Dr. Bean maintains. So, why not bring your colleagues in on the conspiracy? “Involving coworkers will strengthen relationships with their work family by leaving lasting memories for everyone,” he says. “In a busy medical setting, it’s usually unexpected, so it makes it extra special.”

- Have a backup plan. As healthcare professionals, you know that schedules get in the way of everything. So, practice that flexibility you will need as a marriage skill. When Mr. Franklin’s first two engagement locations fell though, he says, it was important to adapt and not panic when things went awry.

- Seize the moment. Think you can’t get engaged during residency? “Planning a proposal during intern year of residency is totally manageable,” Dr. Vemula says. “That way as residency progresses and you have more time, there is more time to focus on the wedding planning.” But she cautions that, “wedding planning during the intern year would be quite difficult.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Picture your marriage proposal fantasy. Do you see a beautiful beach at sunset? The place where you first met your partner? Maybe a dream vacation — Paris, anyone? And perhaps most popular of all ... the ER?

Why not? For some couples who share medical careers, the hospital is home, and they turn the moment into something just as romantic as any Eiffel Tower backdrop. (And admittedly, sometimes they don’t.)

We spoke with three couples whose medical-themed proposals ended in the word “yes!”

Heaven on the Helipad

When emergency medicine physician Anna Darby, MD, heard a trauma patient was arriving and urgently needed to be intubated, she raced up to the rooftop helipad. As soon as the elevator doors opened, she was met with quite a different scene than expected. There were rose petals ... lots and lots of rose petals.

With her best friends and colleagues lining a red carpet, the roof had been turned into a scene from The Bachelor. Each person gave her a rose. A friend even touched up her makeup and handed over her favorite hoop earrings, transforming her from busy doctor to soon-to-be fiancée. Her boyfriend, cardiologist Merije Chukumerije, MD, stood waiting. You can guess what happened next.

Dr. Chukumerije later wrote in an Instagram post, “We met at this hospital. So, it was only right that I bring her to its highest place as we’ve reached the peak of our union.” The couple actually met in the hospital cafeteria “like all the clichés,” Dr. Darby jokes. For them, the helipad experience was just as Insta-worthy as any braggable, grandiose proposal at a fancy restaurant or on a mountaintop.

“Seeing that scene was totally not what I expected,” Dr. Darby says. “I can’t even describe it. It’s like the second biggest hormonal shift, [second only to] having a baby.” She and Dr. Chukumerije now have two babies of their own, aged 2 months and 2 years old.

Good Morning, Doctor

It was February 2021, the height of the pandemic, and Raaga Vemula, MD, now in her palliative care/hospice care fellowship, was “selected” for a local news interview on COVID-19. Except the interview was really with Good Morning America. And the topic was really a proposal.

Dr. Vemula met Steven Bean, MD, now doing a sleep medicine fellowship, in 2015. “I first saw her, and thought she was one of the prettiest women I’d ever seen. ... We ended up being in the same study group,” he says. “Let’s be honest, I applied to every med school she applied to.”

Six years later, Dr. Bean connected with GMA through The Knot, a wedding planning website and registry. The made-up interview request for Dr. Vemula came from the residency program director, who was in on the surprise. Dr. Vemula’s family also knew what was up when she called with the “news.”

The live broadcast took place at the hospital. Dr. Bean had an earpiece for the producers to give him directions. But “I was so nervous, I walked out immediately,” he says. He ended up standing behind Dr. Vemula. The mistake worked well for viewers though, building anticipation while she answered a COVID-19 question. “We got everybody excited,” says Dr. Bean. “So, when they said ’Raaga, turn around’ it worked out perfectly. She was confused as hell.”

Luckily, Dr. Vemula loves a good surprise. “He knows me very well,” she says.

For her, the proposal was even more meaningful given their background together. “Medicine means so much to both of us and was such a big part of our lives,” she says. “That’s what shaped us to do this. ... I think in our hearts it was meant to be this way.”

Who Says Masks Don’t Work?

Masks conjure up feelings for anyone living through the pandemic, especially medical personnel. But for Rhett Franklin and wife Lauren Gray, they will always symbolize of one of the biggest days of their lives.

Mr. Franklin worked in registration, often following Ms. Gray, an emergency room nurse, around with a wheeled computer station to gather patient information (what’s known as a “creeper,” which isn’t as creepy as it sounds). Eventually, she offered to grab a coffee with him, and when he suggested another coffee, she said it was time for him to buy her a drink.

Mr. Franklin, now a manager of business operations for nursing administration, originally planned to propose to Ms. Gray on a trip to England. But the pandemic prevented their vacation with its potential castle backdrop.

Mr. Franklin often picked up shifts making masks for frontline workers, and an alternate proposal idea started brewing. He schemed to have two very special masks made. “Mine was a black tuxedo that said, ‘Will you marry me?’ and hers resembled a white dress that said, ‘I said yes!’ ” Mr. Franklin says.

But a text almost ruined the surprise. When Mr. Franklin messaged family members about his proposal plan the day before, one relative responded in a group chat that included Ms. Gray. This was when the busy ER came to the rescue — no time to read texts. Family members also started calling Ms. Gray on the hospital’s phoneline as a distraction. Unfazed, Mr. Franklin simply moved up the proposal to that night.

At their favorite dog beach, as the sunset gleamed on the water, Mr. Franklin pulled his mask out and took a knee. He can’t recall what he said behind that mask. “It was kind of one of those blackout moments.” But Ms. Gray remembers for him — “You said ‘Let’s do this.’ ”

Warning Label

Everyone has different tastes. Some healthcare professionals have taken the medical theme further than these couples — maybe too far. A few have even faked life-threatening emergencies, showing up in the ER on a gurney with a made-up peanut allergy reaction or a severe injury and then pulling out a ring.

But who’s to judge? For some, thinking your partner is “dying” and then learning you’ve been tricked might not conjure up the warmest feelings. For others, apparently, it’s a virtual bouquet of roses.

A Few Proposal Pointers

If you’re planning to pop the question, this group says, “go for the medical setting!” But according to them, there are other must-haves to get that “yes” and the lifetime of wedded bliss, of course:

- Make it a hospital-wide morale-booster. “Everyone loves surprises,” Dr. Bean maintains. So, why not bring your colleagues in on the conspiracy? “Involving coworkers will strengthen relationships with their work family by leaving lasting memories for everyone,” he says. “In a busy medical setting, it’s usually unexpected, so it makes it extra special.”

- Have a backup plan. As healthcare professionals, you know that schedules get in the way of everything. So, practice that flexibility you will need as a marriage skill. When Mr. Franklin’s first two engagement locations fell though, he says, it was important to adapt and not panic when things went awry.

- Seize the moment. Think you can’t get engaged during residency? “Planning a proposal during intern year of residency is totally manageable,” Dr. Vemula says. “That way as residency progresses and you have more time, there is more time to focus on the wedding planning.” But she cautions that, “wedding planning during the intern year would be quite difficult.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Picture your marriage proposal fantasy. Do you see a beautiful beach at sunset? The place where you first met your partner? Maybe a dream vacation — Paris, anyone? And perhaps most popular of all ... the ER?

Why not? For some couples who share medical careers, the hospital is home, and they turn the moment into something just as romantic as any Eiffel Tower backdrop. (And admittedly, sometimes they don’t.)

We spoke with three couples whose medical-themed proposals ended in the word “yes!”

Heaven on the Helipad

When emergency medicine physician Anna Darby, MD, heard a trauma patient was arriving and urgently needed to be intubated, she raced up to the rooftop helipad. As soon as the elevator doors opened, she was met with quite a different scene than expected. There were rose petals ... lots and lots of rose petals.

With her best friends and colleagues lining a red carpet, the roof had been turned into a scene from The Bachelor. Each person gave her a rose. A friend even touched up her makeup and handed over her favorite hoop earrings, transforming her from busy doctor to soon-to-be fiancée. Her boyfriend, cardiologist Merije Chukumerije, MD, stood waiting. You can guess what happened next.

Dr. Chukumerije later wrote in an Instagram post, “We met at this hospital. So, it was only right that I bring her to its highest place as we’ve reached the peak of our union.” The couple actually met in the hospital cafeteria “like all the clichés,” Dr. Darby jokes. For them, the helipad experience was just as Insta-worthy as any braggable, grandiose proposal at a fancy restaurant or on a mountaintop.

“Seeing that scene was totally not what I expected,” Dr. Darby says. “I can’t even describe it. It’s like the second biggest hormonal shift, [second only to] having a baby.” She and Dr. Chukumerije now have two babies of their own, aged 2 months and 2 years old.

Good Morning, Doctor

It was February 2021, the height of the pandemic, and Raaga Vemula, MD, now in her palliative care/hospice care fellowship, was “selected” for a local news interview on COVID-19. Except the interview was really with Good Morning America. And the topic was really a proposal.

Dr. Vemula met Steven Bean, MD, now doing a sleep medicine fellowship, in 2015. “I first saw her, and thought she was one of the prettiest women I’d ever seen. ... We ended up being in the same study group,” he says. “Let’s be honest, I applied to every med school she applied to.”

Six years later, Dr. Bean connected with GMA through The Knot, a wedding planning website and registry. The made-up interview request for Dr. Vemula came from the residency program director, who was in on the surprise. Dr. Vemula’s family also knew what was up when she called with the “news.”

The live broadcast took place at the hospital. Dr. Bean had an earpiece for the producers to give him directions. But “I was so nervous, I walked out immediately,” he says. He ended up standing behind Dr. Vemula. The mistake worked well for viewers though, building anticipation while she answered a COVID-19 question. “We got everybody excited,” says Dr. Bean. “So, when they said ’Raaga, turn around’ it worked out perfectly. She was confused as hell.”

Luckily, Dr. Vemula loves a good surprise. “He knows me very well,” she says.

For her, the proposal was even more meaningful given their background together. “Medicine means so much to both of us and was such a big part of our lives,” she says. “That’s what shaped us to do this. ... I think in our hearts it was meant to be this way.”

Who Says Masks Don’t Work?

Masks conjure up feelings for anyone living through the pandemic, especially medical personnel. But for Rhett Franklin and wife Lauren Gray, they will always symbolize of one of the biggest days of their lives.

Mr. Franklin worked in registration, often following Ms. Gray, an emergency room nurse, around with a wheeled computer station to gather patient information (what’s known as a “creeper,” which isn’t as creepy as it sounds). Eventually, she offered to grab a coffee with him, and when he suggested another coffee, she said it was time for him to buy her a drink.

Mr. Franklin, now a manager of business operations for nursing administration, originally planned to propose to Ms. Gray on a trip to England. But the pandemic prevented their vacation with its potential castle backdrop.

Mr. Franklin often picked up shifts making masks for frontline workers, and an alternate proposal idea started brewing. He schemed to have two very special masks made. “Mine was a black tuxedo that said, ‘Will you marry me?’ and hers resembled a white dress that said, ‘I said yes!’ ” Mr. Franklin says.

But a text almost ruined the surprise. When Mr. Franklin messaged family members about his proposal plan the day before, one relative responded in a group chat that included Ms. Gray. This was when the busy ER came to the rescue — no time to read texts. Family members also started calling Ms. Gray on the hospital’s phoneline as a distraction. Unfazed, Mr. Franklin simply moved up the proposal to that night.

At their favorite dog beach, as the sunset gleamed on the water, Mr. Franklin pulled his mask out and took a knee. He can’t recall what he said behind that mask. “It was kind of one of those blackout moments.” But Ms. Gray remembers for him — “You said ‘Let’s do this.’ ”

Warning Label

Everyone has different tastes. Some healthcare professionals have taken the medical theme further than these couples — maybe too far. A few have even faked life-threatening emergencies, showing up in the ER on a gurney with a made-up peanut allergy reaction or a severe injury and then pulling out a ring.

But who’s to judge? For some, thinking your partner is “dying” and then learning you’ve been tricked might not conjure up the warmest feelings. For others, apparently, it’s a virtual bouquet of roses.

A Few Proposal Pointers

If you’re planning to pop the question, this group says, “go for the medical setting!” But according to them, there are other must-haves to get that “yes” and the lifetime of wedded bliss, of course:

- Make it a hospital-wide morale-booster. “Everyone loves surprises,” Dr. Bean maintains. So, why not bring your colleagues in on the conspiracy? “Involving coworkers will strengthen relationships with their work family by leaving lasting memories for everyone,” he says. “In a busy medical setting, it’s usually unexpected, so it makes it extra special.”

- Have a backup plan. As healthcare professionals, you know that schedules get in the way of everything. So, practice that flexibility you will need as a marriage skill. When Mr. Franklin’s first two engagement locations fell though, he says, it was important to adapt and not panic when things went awry.

- Seize the moment. Think you can’t get engaged during residency? “Planning a proposal during intern year of residency is totally manageable,” Dr. Vemula says. “That way as residency progresses and you have more time, there is more time to focus on the wedding planning.” But she cautions that, “wedding planning during the intern year would be quite difficult.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

An Ethical Analysis of Treatment of an Active-Duty Service Member With Limited Follow-up

For active-duty service members, dermatologic conditions are among the most common presenting concerns, comprising 15% to 75% of wartime outpatient visits.1 In general, there are unique considerations when caring for active-duty service members, including meeting designated active-duty retention and hierarchical standards.2 We present a hypothetical case: An active-duty military patient presents to a new dermatologist for cosmetic enhancement of facial skin dyspigmentation. The patient will be leaving soon for deployment and will not be able to follow up for 9 months. How should the dermatologist treat a patient who cannot follow up for so long?

The therapeutic modalities offered can be impacted by forthcoming deployments3 that may result in delayed time to administer repeat treatments or follow-up. The patient may have high expectations for a single appointment for a condition that requires prolonged treatment courses. Because there often is no reliable mechanism for patients to obtain refills during deployment, any medications prescribed would need to be provided in advance for the entire deployment duration, which often is 6 to 9 months. Additionally, treatment monitoring or modifications are severely limited, especially in the context of treatment nonresponse or adverse reactions. Considering the unique limitations of this patient population, both military and civilian physicians are faced with a need to maximize beneficence and autonomy while balancing nonmaleficence and justice.

One possible option is to decline to treat until the patient can follow up after returning from deployment. However, denying a request for an active treatable indication for which the patient desires treatment compromises patient autonomy and beneficence. Further, treatment should be provided to patients equitably to maintain justice. Although there may be a role for discussing active monitoring with nonintervention with the patient, denying treatment can negatively impact their physical and mental health and may be harmful. However, the patient should know and fully understand the risks and benefits of nonintervention with limited follow-up, including suboptimal outcomes or adverse events.

Another possibility for the management of this case may be conducting a one-time laser or light-based therapy or a one-time superficial- to medium-depth chemical peel before the patient leaves on deployment. Often, a series of laser- or light-based treatments is required to maximize outcomes for dyspigmentation. Without follow-up and with possible deployment to an environment with high UV exposure, the patient may experience disease exacerbation or other adverse effects. Treatment of those adverse effects may be delayed, as further intervention is not possible during deployment. Lower initial laser settings may be safer but may not be highly effective initially. More rigorous treatment upon return from deployment may be considered. Similar to laser therapies, chemical peels usually require several treatments for optimal outcomes. Without follow-up and with potential deployment to remote environments, there is a risk for adverse events that outweighs the minimal benefit of a single treatment. Therefore, either intervention may violate the principle of nonmaleficence.

A more reasonable approach may be initiating topical therapy and following up via telemedicine evaluation. Topical therapy often is the least-invasive approach and carries a reduced risk for adverse effects. Triple-combination therapy with topical retinoids, hydroquinone, and topical steroids is a common first-line approach.4 Because this approach is patient dependent, therapy can be more easily modulated or halted in the context of undesired results. Additionally, if internet connectivity is available, an asynchronous telemedicine approach could be utilized during deployment to monitor and advise changes as necessary, provided the regulatory framework allows for it.5

Although there is no uniformly correct approach in a scenario of limited patient follow-up, the last solution may be most ethically favorable: to begin therapy with milder and safer therapies (topical) and defer higher-intensity regimens until the patient returns from deployment. This allows some treatment initiation to preserve justice, beneficence, and patient autonomy. Associated virtual follow-up via telemedicine also allows avoidance of nonmaleficence in this context.

- Hwang J, Kakimoto C. Teledermatology in the US military: a historic foundation for current and future applications. Cutis. 2018;101:335;337;345.

- Dodd JG, Grant-Kels JM. Ethical concerns in caring for active duty service members who may be seeking dermatologic care outside the military soon. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:445-447. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.07.001

- Burke KR, Larrymore DC, Cho S. Treatment consideration for US military members with skin disease. Cutis. 2019;103:329-332.

- Desai SR. Hyperpigmentation therapy: a review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:13-17.

- Hwang JS, Lappan CM, Sperling LC, et al. Utilization of telemedicine in the U.S. military in a deployed setting. Mil Med. 2014;179:1347-1353. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00115

For active-duty service members, dermatologic conditions are among the most common presenting concerns, comprising 15% to 75% of wartime outpatient visits.1 In general, there are unique considerations when caring for active-duty service members, including meeting designated active-duty retention and hierarchical standards.2 We present a hypothetical case: An active-duty military patient presents to a new dermatologist for cosmetic enhancement of facial skin dyspigmentation. The patient will be leaving soon for deployment and will not be able to follow up for 9 months. How should the dermatologist treat a patient who cannot follow up for so long?

The therapeutic modalities offered can be impacted by forthcoming deployments3 that may result in delayed time to administer repeat treatments or follow-up. The patient may have high expectations for a single appointment for a condition that requires prolonged treatment courses. Because there often is no reliable mechanism for patients to obtain refills during deployment, any medications prescribed would need to be provided in advance for the entire deployment duration, which often is 6 to 9 months. Additionally, treatment monitoring or modifications are severely limited, especially in the context of treatment nonresponse or adverse reactions. Considering the unique limitations of this patient population, both military and civilian physicians are faced with a need to maximize beneficence and autonomy while balancing nonmaleficence and justice.

One possible option is to decline to treat until the patient can follow up after returning from deployment. However, denying a request for an active treatable indication for which the patient desires treatment compromises patient autonomy and beneficence. Further, treatment should be provided to patients equitably to maintain justice. Although there may be a role for discussing active monitoring with nonintervention with the patient, denying treatment can negatively impact their physical and mental health and may be harmful. However, the patient should know and fully understand the risks and benefits of nonintervention with limited follow-up, including suboptimal outcomes or adverse events.

Another possibility for the management of this case may be conducting a one-time laser or light-based therapy or a one-time superficial- to medium-depth chemical peel before the patient leaves on deployment. Often, a series of laser- or light-based treatments is required to maximize outcomes for dyspigmentation. Without follow-up and with possible deployment to an environment with high UV exposure, the patient may experience disease exacerbation or other adverse effects. Treatment of those adverse effects may be delayed, as further intervention is not possible during deployment. Lower initial laser settings may be safer but may not be highly effective initially. More rigorous treatment upon return from deployment may be considered. Similar to laser therapies, chemical peels usually require several treatments for optimal outcomes. Without follow-up and with potential deployment to remote environments, there is a risk for adverse events that outweighs the minimal benefit of a single treatment. Therefore, either intervention may violate the principle of nonmaleficence.

A more reasonable approach may be initiating topical therapy and following up via telemedicine evaluation. Topical therapy often is the least-invasive approach and carries a reduced risk for adverse effects. Triple-combination therapy with topical retinoids, hydroquinone, and topical steroids is a common first-line approach.4 Because this approach is patient dependent, therapy can be more easily modulated or halted in the context of undesired results. Additionally, if internet connectivity is available, an asynchronous telemedicine approach could be utilized during deployment to monitor and advise changes as necessary, provided the regulatory framework allows for it.5

Although there is no uniformly correct approach in a scenario of limited patient follow-up, the last solution may be most ethically favorable: to begin therapy with milder and safer therapies (topical) and defer higher-intensity regimens until the patient returns from deployment. This allows some treatment initiation to preserve justice, beneficence, and patient autonomy. Associated virtual follow-up via telemedicine also allows avoidance of nonmaleficence in this context.

For active-duty service members, dermatologic conditions are among the most common presenting concerns, comprising 15% to 75% of wartime outpatient visits.1 In general, there are unique considerations when caring for active-duty service members, including meeting designated active-duty retention and hierarchical standards.2 We present a hypothetical case: An active-duty military patient presents to a new dermatologist for cosmetic enhancement of facial skin dyspigmentation. The patient will be leaving soon for deployment and will not be able to follow up for 9 months. How should the dermatologist treat a patient who cannot follow up for so long?

The therapeutic modalities offered can be impacted by forthcoming deployments3 that may result in delayed time to administer repeat treatments or follow-up. The patient may have high expectations for a single appointment for a condition that requires prolonged treatment courses. Because there often is no reliable mechanism for patients to obtain refills during deployment, any medications prescribed would need to be provided in advance for the entire deployment duration, which often is 6 to 9 months. Additionally, treatment monitoring or modifications are severely limited, especially in the context of treatment nonresponse or adverse reactions. Considering the unique limitations of this patient population, both military and civilian physicians are faced with a need to maximize beneficence and autonomy while balancing nonmaleficence and justice.

One possible option is to decline to treat until the patient can follow up after returning from deployment. However, denying a request for an active treatable indication for which the patient desires treatment compromises patient autonomy and beneficence. Further, treatment should be provided to patients equitably to maintain justice. Although there may be a role for discussing active monitoring with nonintervention with the patient, denying treatment can negatively impact their physical and mental health and may be harmful. However, the patient should know and fully understand the risks and benefits of nonintervention with limited follow-up, including suboptimal outcomes or adverse events.

Another possibility for the management of this case may be conducting a one-time laser or light-based therapy or a one-time superficial- to medium-depth chemical peel before the patient leaves on deployment. Often, a series of laser- or light-based treatments is required to maximize outcomes for dyspigmentation. Without follow-up and with possible deployment to an environment with high UV exposure, the patient may experience disease exacerbation or other adverse effects. Treatment of those adverse effects may be delayed, as further intervention is not possible during deployment. Lower initial laser settings may be safer but may not be highly effective initially. More rigorous treatment upon return from deployment may be considered. Similar to laser therapies, chemical peels usually require several treatments for optimal outcomes. Without follow-up and with potential deployment to remote environments, there is a risk for adverse events that outweighs the minimal benefit of a single treatment. Therefore, either intervention may violate the principle of nonmaleficence.

A more reasonable approach may be initiating topical therapy and following up via telemedicine evaluation. Topical therapy often is the least-invasive approach and carries a reduced risk for adverse effects. Triple-combination therapy with topical retinoids, hydroquinone, and topical steroids is a common first-line approach.4 Because this approach is patient dependent, therapy can be more easily modulated or halted in the context of undesired results. Additionally, if internet connectivity is available, an asynchronous telemedicine approach could be utilized during deployment to monitor and advise changes as necessary, provided the regulatory framework allows for it.5

Although there is no uniformly correct approach in a scenario of limited patient follow-up, the last solution may be most ethically favorable: to begin therapy with milder and safer therapies (topical) and defer higher-intensity regimens until the patient returns from deployment. This allows some treatment initiation to preserve justice, beneficence, and patient autonomy. Associated virtual follow-up via telemedicine also allows avoidance of nonmaleficence in this context.

- Hwang J, Kakimoto C. Teledermatology in the US military: a historic foundation for current and future applications. Cutis. 2018;101:335;337;345.

- Dodd JG, Grant-Kels JM. Ethical concerns in caring for active duty service members who may be seeking dermatologic care outside the military soon. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:445-447. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.07.001

- Burke KR, Larrymore DC, Cho S. Treatment consideration for US military members with skin disease. Cutis. 2019;103:329-332.

- Desai SR. Hyperpigmentation therapy: a review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:13-17.

- Hwang JS, Lappan CM, Sperling LC, et al. Utilization of telemedicine in the U.S. military in a deployed setting. Mil Med. 2014;179:1347-1353. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00115

- Hwang J, Kakimoto C. Teledermatology in the US military: a historic foundation for current and future applications. Cutis. 2018;101:335;337;345.

- Dodd JG, Grant-Kels JM. Ethical concerns in caring for active duty service members who may be seeking dermatologic care outside the military soon. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:445-447. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.07.001

- Burke KR, Larrymore DC, Cho S. Treatment consideration for US military members with skin disease. Cutis. 2019;103:329-332.

- Desai SR. Hyperpigmentation therapy: a review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:13-17.

- Hwang JS, Lappan CM, Sperling LC, et al. Utilization of telemedicine in the U.S. military in a deployed setting. Mil Med. 2014;179:1347-1353. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00115

PRACTICE POINTS

- Dermatologic conditions are among the most common concerns reported by active-duty service members.

- The unique considerations of deployments are important for dermatologists to consider in the treatment of skin disease.

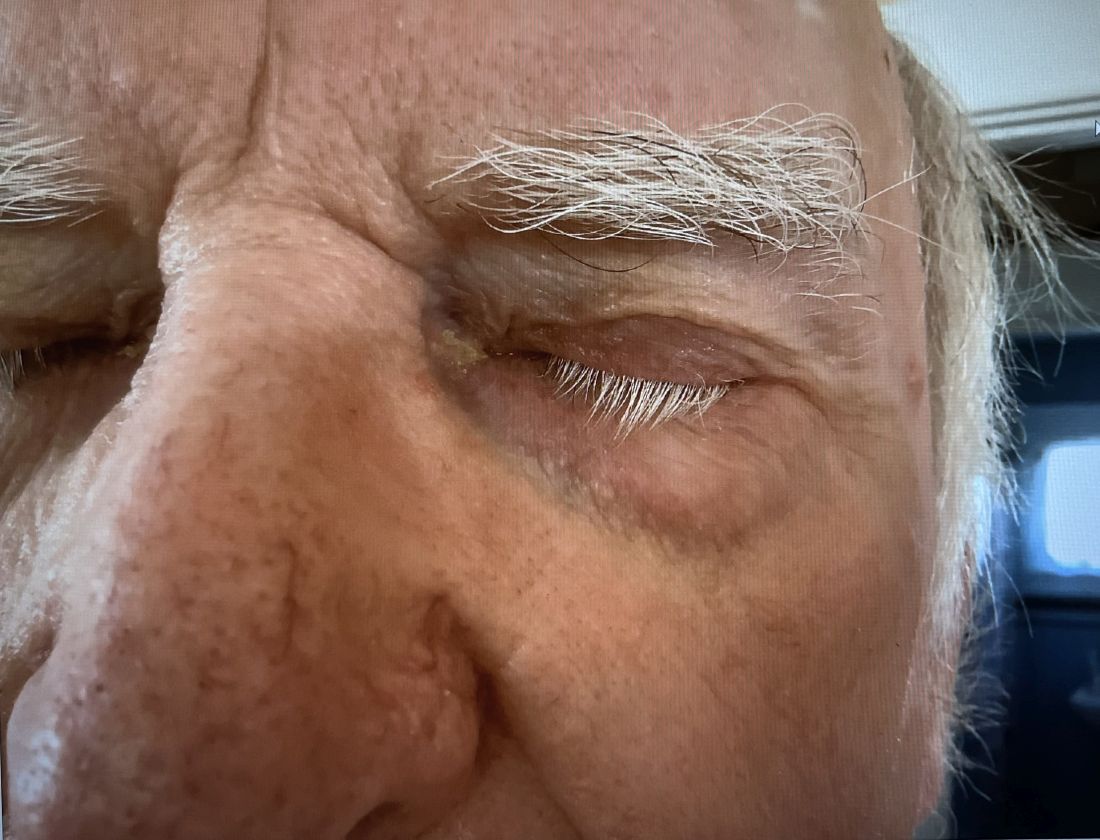

A 74-year-old White male presented with a 1-year history of depigmented patches on the hands, arms, and face, as well as white eyelashes and eyebrows

This patient showed no evidence of recurrence in the scar where the melanoma was excised, and had no enlarged lymph nodes on palpation. His complete blood count and liver function tests were normal. A positron emission tomography (PET) scan was ordered by Dr. Nasser that revealed hypermetabolic right paratracheal, right hilar, and subcarinal lymph nodes, highly suspicious for malignant lymph nodes. The patient was referred to oncology for metastatic melanoma treatment and has been doing well on ipilimumab and nivolumab.

Vitiligo is an autoimmune condition characterized by the progressive destruction of melanocytes resulting in hypopigmentation or depigmentation of the skin. Vitiligo has been associated with cutaneous melanoma. Melanoma-associated leukoderma occurs in a portion of patients with melanoma and is correlated with a favorable prognosis. Additionally, leukoderma has been described as a side effect of melanoma treatment itself. However, cases such as this one have also been reported of vitiligo-like depigmentation presenting prior to the diagnosis of metastatic melanoma.