User login

Standing with our patients

One-half of my practice is taking care of employees and dependents employed by the organization for which I work. Most of these patients sit … a lot … and present to me with musculoskeletal pain and weight concerns. My patients have a high degree of health literacy and are fully aware that 6 hours of sitting might have at least something to do with these problems.

We currently seem to be on the other side of the “walk station” mania. Sanity has been restored through a combination of concerns about medical liability for work-related treadmill injuries, expense, space issues, and reports that walkers were more forgetful and less focused. The last study resulted in some personal email for my own indulgences in walking while researching.

But let us not throw out an upright posture with the treadmill. Sitters have an increased risk for elevated blood sugars, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and death. Standers have been suggested to burn 50 more calories per hour. Some experts recommend that people should stand for at least 2 hours each day, and 4 hours is even better.

Dr. Graves and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the impact of a sit-stand workstation on sitting time, vascular, metabolic, and musculoskeletal outcomes and to investigate workstation acceptability and feasibility. Forty-seven participants without any bodily symptoms were randomized to either a sit-stand workstation or no intervention for 8 weeks. The sit-stand workstation was associated with decreased sit time (80 minutes per 8-hour work day), increased standing time (73 minutes per 8-hour work day), and a decrease in total cholesterol. No increase in musculoskeletal pain was observed with a suggestion of possible benefit in the neck and upper back (BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1145. doi 10.1186/s12889-015-2469-8).

Each of the devices cost about $550 to install for a single monitor ($20 more for a dual monitor). The intervention was only 8 weeks in duration and stronger effects in musculoskeletal and cardiovascular risk markers might be seen with longer durations of study. The qualitative work in this study suggested that several factors may influence use of a sit-stand desk such as social environment (for example, other colleagues not using it may decrease use), work tasks (for example, paperwork made difficult by limited elevated work surface), and design (for example, keyboard surface bounces too much). From personal experience, the sit-stand desk is ideal if the vast majority of work is on the computer. I’d also like to say I was standing when I wrote this. But I wasn’t. And I wasn’t walking either because I can’t remember where that desk is.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician. Dr. Ebbert has no relevant financial disclosures about this article. Follow him on Twitter @jonebbert.

One-half of my practice is taking care of employees and dependents employed by the organization for which I work. Most of these patients sit … a lot … and present to me with musculoskeletal pain and weight concerns. My patients have a high degree of health literacy and are fully aware that 6 hours of sitting might have at least something to do with these problems.

We currently seem to be on the other side of the “walk station” mania. Sanity has been restored through a combination of concerns about medical liability for work-related treadmill injuries, expense, space issues, and reports that walkers were more forgetful and less focused. The last study resulted in some personal email for my own indulgences in walking while researching.

But let us not throw out an upright posture with the treadmill. Sitters have an increased risk for elevated blood sugars, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and death. Standers have been suggested to burn 50 more calories per hour. Some experts recommend that people should stand for at least 2 hours each day, and 4 hours is even better.

Dr. Graves and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the impact of a sit-stand workstation on sitting time, vascular, metabolic, and musculoskeletal outcomes and to investigate workstation acceptability and feasibility. Forty-seven participants without any bodily symptoms were randomized to either a sit-stand workstation or no intervention for 8 weeks. The sit-stand workstation was associated with decreased sit time (80 minutes per 8-hour work day), increased standing time (73 minutes per 8-hour work day), and a decrease in total cholesterol. No increase in musculoskeletal pain was observed with a suggestion of possible benefit in the neck and upper back (BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1145. doi 10.1186/s12889-015-2469-8).

Each of the devices cost about $550 to install for a single monitor ($20 more for a dual monitor). The intervention was only 8 weeks in duration and stronger effects in musculoskeletal and cardiovascular risk markers might be seen with longer durations of study. The qualitative work in this study suggested that several factors may influence use of a sit-stand desk such as social environment (for example, other colleagues not using it may decrease use), work tasks (for example, paperwork made difficult by limited elevated work surface), and design (for example, keyboard surface bounces too much). From personal experience, the sit-stand desk is ideal if the vast majority of work is on the computer. I’d also like to say I was standing when I wrote this. But I wasn’t. And I wasn’t walking either because I can’t remember where that desk is.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician. Dr. Ebbert has no relevant financial disclosures about this article. Follow him on Twitter @jonebbert.

One-half of my practice is taking care of employees and dependents employed by the organization for which I work. Most of these patients sit … a lot … and present to me with musculoskeletal pain and weight concerns. My patients have a high degree of health literacy and are fully aware that 6 hours of sitting might have at least something to do with these problems.

We currently seem to be on the other side of the “walk station” mania. Sanity has been restored through a combination of concerns about medical liability for work-related treadmill injuries, expense, space issues, and reports that walkers were more forgetful and less focused. The last study resulted in some personal email for my own indulgences in walking while researching.

But let us not throw out an upright posture with the treadmill. Sitters have an increased risk for elevated blood sugars, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and death. Standers have been suggested to burn 50 more calories per hour. Some experts recommend that people should stand for at least 2 hours each day, and 4 hours is even better.

Dr. Graves and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the impact of a sit-stand workstation on sitting time, vascular, metabolic, and musculoskeletal outcomes and to investigate workstation acceptability and feasibility. Forty-seven participants without any bodily symptoms were randomized to either a sit-stand workstation or no intervention for 8 weeks. The sit-stand workstation was associated with decreased sit time (80 minutes per 8-hour work day), increased standing time (73 minutes per 8-hour work day), and a decrease in total cholesterol. No increase in musculoskeletal pain was observed with a suggestion of possible benefit in the neck and upper back (BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1145. doi 10.1186/s12889-015-2469-8).

Each of the devices cost about $550 to install for a single monitor ($20 more for a dual monitor). The intervention was only 8 weeks in duration and stronger effects in musculoskeletal and cardiovascular risk markers might be seen with longer durations of study. The qualitative work in this study suggested that several factors may influence use of a sit-stand desk such as social environment (for example, other colleagues not using it may decrease use), work tasks (for example, paperwork made difficult by limited elevated work surface), and design (for example, keyboard surface bounces too much). From personal experience, the sit-stand desk is ideal if the vast majority of work is on the computer. I’d also like to say I was standing when I wrote this. But I wasn’t. And I wasn’t walking either because I can’t remember where that desk is.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician. Dr. Ebbert has no relevant financial disclosures about this article. Follow him on Twitter @jonebbert.

Erratum

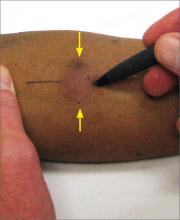

A photo in the article “Tuberculosis testing: Which patients, which test?” (J Fam Pract. 2015;64:553-557,563-565) incorrectly depicted how the induration that arises from a tuberculin skin test should be measured. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (http://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/testing/skintesting.htm), the induration should be measured across the forearm, perpendicular to the long axis (elbow to wrist), as indicated by the yellow arrows below.

A photo in the article “Tuberculosis testing: Which patients, which test?” (J Fam Pract. 2015;64:553-557,563-565) incorrectly depicted how the induration that arises from a tuberculin skin test should be measured. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (http://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/testing/skintesting.htm), the induration should be measured across the forearm, perpendicular to the long axis (elbow to wrist), as indicated by the yellow arrows below.

A photo in the article “Tuberculosis testing: Which patients, which test?” (J Fam Pract. 2015;64:553-557,563-565) incorrectly depicted how the induration that arises from a tuberculin skin test should be measured. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (http://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/testing/skintesting.htm), the induration should be measured across the forearm, perpendicular to the long axis (elbow to wrist), as indicated by the yellow arrows below.

I will click those boxes, but first, I will care for my patient

I am a member of a large primary care group certified as a level 3 patient-centered medical home; we are in the midst of certifying for Meaningful Use Stage 2. Recently, my first patient of the day was a 65-year-old widowed man who used tobacco, had diabetes, hypertension, and elevated lipid levels, and hadn’t seen me in 2 years. He came in for a Medicare Advantage comprehensive physical examination.

To meet all Meaningful Use Stage 2 expectations during his physical exam, I had to:

• check the box to document discussion of body mass index (his was 26 kg/m2),

• check the box for functional status assessment,

• check the box to indicate that his blood pressure was under 140/90 mm Hg (the threshold for a previously diagnosed hypertensive patient),

• generate annual care guides for the “clinically important conditions” of hypertension with diabetes, tobacco use, and hyperlipidemia,

• review the quality information stoplight for lab tests to be ordered,

• remind the patient to complete his annual eye examination,

• identify hierarchical categorical coding to maximize the accurate morbidity determination of my patient and, therefore, funding for our medical group,

• click on the code for annual prostate examination screening,

• click on the code to bill for tobacco cessation counseling, and

• generate a visit summary.

Naturally, all of this was in addition to giving my patient my full, undivided attention, providing him with the opportunity to express his concerns, and then pursuing a careful examination of his health problems.

Documentation expectations, coding, billing, and the like degrade the clinician-patient relationship, and I’m not going to redirect my attention away from the patient’s concerns and toward these activities. I will continue to listen and respect what my patients have to say and engage with them, and not my keyboard. I will strive to identify and meet their health needs.

Click the boxes? Yes, I will click all the right boxes; my livelihood and my medical group’s future success depend on that. But how much congruence will there be between what I “click” and what I “do”? Well …

We are challenged by good intentions but crushingly poor execution—and it’s taking its toll.

H. Andrew Selinger, MD

Bristol, Conn

I am a member of a large primary care group certified as a level 3 patient-centered medical home; we are in the midst of certifying for Meaningful Use Stage 2. Recently, my first patient of the day was a 65-year-old widowed man who used tobacco, had diabetes, hypertension, and elevated lipid levels, and hadn’t seen me in 2 years. He came in for a Medicare Advantage comprehensive physical examination.

To meet all Meaningful Use Stage 2 expectations during his physical exam, I had to:

• check the box to document discussion of body mass index (his was 26 kg/m2),

• check the box for functional status assessment,

• check the box to indicate that his blood pressure was under 140/90 mm Hg (the threshold for a previously diagnosed hypertensive patient),

• generate annual care guides for the “clinically important conditions” of hypertension with diabetes, tobacco use, and hyperlipidemia,

• review the quality information stoplight for lab tests to be ordered,

• remind the patient to complete his annual eye examination,

• identify hierarchical categorical coding to maximize the accurate morbidity determination of my patient and, therefore, funding for our medical group,

• click on the code for annual prostate examination screening,

• click on the code to bill for tobacco cessation counseling, and

• generate a visit summary.

Naturally, all of this was in addition to giving my patient my full, undivided attention, providing him with the opportunity to express his concerns, and then pursuing a careful examination of his health problems.

Documentation expectations, coding, billing, and the like degrade the clinician-patient relationship, and I’m not going to redirect my attention away from the patient’s concerns and toward these activities. I will continue to listen and respect what my patients have to say and engage with them, and not my keyboard. I will strive to identify and meet their health needs.

Click the boxes? Yes, I will click all the right boxes; my livelihood and my medical group’s future success depend on that. But how much congruence will there be between what I “click” and what I “do”? Well …

We are challenged by good intentions but crushingly poor execution—and it’s taking its toll.

H. Andrew Selinger, MD

Bristol, Conn

I am a member of a large primary care group certified as a level 3 patient-centered medical home; we are in the midst of certifying for Meaningful Use Stage 2. Recently, my first patient of the day was a 65-year-old widowed man who used tobacco, had diabetes, hypertension, and elevated lipid levels, and hadn’t seen me in 2 years. He came in for a Medicare Advantage comprehensive physical examination.

To meet all Meaningful Use Stage 2 expectations during his physical exam, I had to:

• check the box to document discussion of body mass index (his was 26 kg/m2),

• check the box for functional status assessment,

• check the box to indicate that his blood pressure was under 140/90 mm Hg (the threshold for a previously diagnosed hypertensive patient),

• generate annual care guides for the “clinically important conditions” of hypertension with diabetes, tobacco use, and hyperlipidemia,

• review the quality information stoplight for lab tests to be ordered,

• remind the patient to complete his annual eye examination,

• identify hierarchical categorical coding to maximize the accurate morbidity determination of my patient and, therefore, funding for our medical group,

• click on the code for annual prostate examination screening,

• click on the code to bill for tobacco cessation counseling, and

• generate a visit summary.

Naturally, all of this was in addition to giving my patient my full, undivided attention, providing him with the opportunity to express his concerns, and then pursuing a careful examination of his health problems.

Documentation expectations, coding, billing, and the like degrade the clinician-patient relationship, and I’m not going to redirect my attention away from the patient’s concerns and toward these activities. I will continue to listen and respect what my patients have to say and engage with them, and not my keyboard. I will strive to identify and meet their health needs.

Click the boxes? Yes, I will click all the right boxes; my livelihood and my medical group’s future success depend on that. But how much congruence will there be between what I “click” and what I “do”? Well …

We are challenged by good intentions but crushingly poor execution—and it’s taking its toll.

H. Andrew Selinger, MD

Bristol, Conn

Being honest about diagnostic uncertainty

Like everyone else’s grandmother, mine gave me all kinds of advice while I was growing up. Some tips I still remember.

One came when I was home for Thanksgiving during my first year of medical school. She was frustrated over her recent visit to an internist. He kept ordering more tests but wouldn’t answer questions about what might be causing her symptoms.

She told me that, if I didn’t know what was going on, to just say so. As a patient, she felt that an honest answer was better than silence.

Today, as a doctor, I agree with her. So, while I may still be doing tests to crack the case, I have no problem, when asked what I think is going on, with saying “I don’t know.”

This approach isn’t perfect for everyone. Some docs (and patients) may see it as a sign of incompetence or weakness, thinking that admitting fallibility is a breach of the relationship or that with some tests the doctor becomes omniscient. Of course, that’s far from the truth.

In my experience, patients prefer the honesty of my saying “I don’t know.” I’m not saying I’ll never know, I’m just saying that, at present, I’m still looking for the answer.

Nobody likes being in the dark about their health, but at the same time they don’t want to feel their doctor is keeping a secret from them. By making it clear that I’m not, I’m hoping to keep a strong therapeutic relationship. I promise them that when I know, they’ll know, and that I’m honest when stumped. If I need to refer elsewhere for an answer, I have no problem doing that. Medicine, and neurology in particular, is a complex field. If every diagnosis were a slam-dunk, we wouldn’t need specialists and subspecialists (and even subsubspecialists).

Most people know and understand that, recognize the inherent uncertainty of this job, and know that I don’t know. I promise them that “I don’t know” doesn’t mean I’m done looking, it just means I’m going to keep trying. That’s the best anyone can do. Right, Granny?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Like everyone else’s grandmother, mine gave me all kinds of advice while I was growing up. Some tips I still remember.

One came when I was home for Thanksgiving during my first year of medical school. She was frustrated over her recent visit to an internist. He kept ordering more tests but wouldn’t answer questions about what might be causing her symptoms.

She told me that, if I didn’t know what was going on, to just say so. As a patient, she felt that an honest answer was better than silence.

Today, as a doctor, I agree with her. So, while I may still be doing tests to crack the case, I have no problem, when asked what I think is going on, with saying “I don’t know.”

This approach isn’t perfect for everyone. Some docs (and patients) may see it as a sign of incompetence or weakness, thinking that admitting fallibility is a breach of the relationship or that with some tests the doctor becomes omniscient. Of course, that’s far from the truth.

In my experience, patients prefer the honesty of my saying “I don’t know.” I’m not saying I’ll never know, I’m just saying that, at present, I’m still looking for the answer.

Nobody likes being in the dark about their health, but at the same time they don’t want to feel their doctor is keeping a secret from them. By making it clear that I’m not, I’m hoping to keep a strong therapeutic relationship. I promise them that when I know, they’ll know, and that I’m honest when stumped. If I need to refer elsewhere for an answer, I have no problem doing that. Medicine, and neurology in particular, is a complex field. If every diagnosis were a slam-dunk, we wouldn’t need specialists and subspecialists (and even subsubspecialists).

Most people know and understand that, recognize the inherent uncertainty of this job, and know that I don’t know. I promise them that “I don’t know” doesn’t mean I’m done looking, it just means I’m going to keep trying. That’s the best anyone can do. Right, Granny?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Like everyone else’s grandmother, mine gave me all kinds of advice while I was growing up. Some tips I still remember.

One came when I was home for Thanksgiving during my first year of medical school. She was frustrated over her recent visit to an internist. He kept ordering more tests but wouldn’t answer questions about what might be causing her symptoms.

She told me that, if I didn’t know what was going on, to just say so. As a patient, she felt that an honest answer was better than silence.

Today, as a doctor, I agree with her. So, while I may still be doing tests to crack the case, I have no problem, when asked what I think is going on, with saying “I don’t know.”

This approach isn’t perfect for everyone. Some docs (and patients) may see it as a sign of incompetence or weakness, thinking that admitting fallibility is a breach of the relationship or that with some tests the doctor becomes omniscient. Of course, that’s far from the truth.

In my experience, patients prefer the honesty of my saying “I don’t know.” I’m not saying I’ll never know, I’m just saying that, at present, I’m still looking for the answer.

Nobody likes being in the dark about their health, but at the same time they don’t want to feel their doctor is keeping a secret from them. By making it clear that I’m not, I’m hoping to keep a strong therapeutic relationship. I promise them that when I know, they’ll know, and that I’m honest when stumped. If I need to refer elsewhere for an answer, I have no problem doing that. Medicine, and neurology in particular, is a complex field. If every diagnosis were a slam-dunk, we wouldn’t need specialists and subspecialists (and even subsubspecialists).

Most people know and understand that, recognize the inherent uncertainty of this job, and know that I don’t know. I promise them that “I don’t know” doesn’t mean I’m done looking, it just means I’m going to keep trying. That’s the best anyone can do. Right, Granny?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Use of isolation in juvenile detention centers

Isolation in juvenile detention centers persists despite ample data demonstrating the traumatizing consequences to youth who often already have been traumatized. I recently visited a detention center as part of my pediatric residency’s advocacy rotation. There, I learned that youth are kept in isolation for several days, with a vague definition by staff on the limit of “several days.” Multiple words were used for confinement, the most stunning and horrific of which was “segregation” – “He got into a fight and was placed in segregation.” While in isolation or segregation – whatever it is called – mental illness and posttraumatic stress disorder are exacerbated. Youth do not participate in school classes, and they are barred from the daily hour of physical activity. In extreme cases, they go from complete isolation one day to complete freedom the next.

The vibe word in the facility I visited was “evidence-based strategies,” stressed by the new administration. But evidence-based strategies do not include isolation. They include educating staff about the pervasive effects of trauma in children. They include communication interventions, conflict resolution, and the implementation of rewards such as extra visitation, computer time, or the use of an adolescent’s own personal hygiene items or clothing. They include knowledge of the adolescent brain, and how the use of isolation in juvenile centers has led to increased suicide rates in those children.

Lindsay M. Hayes, author of the National Center on Institutions and Alternatives’ 2004 report “Juvenile Suicide in Confinement: A National Study,” wrote: ”Although room confinement remains a staple in most juvenile facilities, it is a sanction that can have deadly consequences. … More than 50% of all youths’ suicides in juvenile facilities occurred while young people were isolated alone in their rooms, and … more than 60% of young people who committed suicide in custody had a history of being held in isolation.”

The United Nations has called on all countries to absolutely prohibit solitary confinement for juveniles, as has the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Thus, extreme isolation should not be another tool for juvenile detention centers.

Currently, 20 states have banned solitary confinement in juvenile detention facilities. The major barriers are from staff, who state it would remove a tool, put staff in danger, and allow youth to run the facilities. None of these has been shown to be true. Some juvenile detention centers have changed the traditional meaning of isolation – youth will have a minimum of 8 hours away from isolation when confined for a day or longer. “During that 8 hours, they have the opportunity to talk to and be in the company of staff,” said Adam Schwartz, a lawyer for the American Civil Liberties Union of Illinois, whose lawsuit drastically limited solitary confinement practices in Illinois’s juvenile detention centers. The policy also requires that inmates in isolation continue to receive education and mental health services.

There is a human dignity that not even detainees deserve to lose. President Obama has discussed this, as has the 2012 Report of the Attorney General’s National Task Force on Children Exposed to Violence, which concluded: “Nowhere is the damaging impact of incarceration on vulnerable children more obvious than when it involves solitary confinement.” I am writing this article to raise awareness about this underreported problem in hopes that new legislation will lead to change that is in the best interest of our children.

Dr. Raffa is in postgraduate year 2 in her pediatric residency at Vanderbilt Children’s Hospital in Nashville, Tenn.

Isolation in juvenile detention centers persists despite ample data demonstrating the traumatizing consequences to youth who often already have been traumatized. I recently visited a detention center as part of my pediatric residency’s advocacy rotation. There, I learned that youth are kept in isolation for several days, with a vague definition by staff on the limit of “several days.” Multiple words were used for confinement, the most stunning and horrific of which was “segregation” – “He got into a fight and was placed in segregation.” While in isolation or segregation – whatever it is called – mental illness and posttraumatic stress disorder are exacerbated. Youth do not participate in school classes, and they are barred from the daily hour of physical activity. In extreme cases, they go from complete isolation one day to complete freedom the next.

The vibe word in the facility I visited was “evidence-based strategies,” stressed by the new administration. But evidence-based strategies do not include isolation. They include educating staff about the pervasive effects of trauma in children. They include communication interventions, conflict resolution, and the implementation of rewards such as extra visitation, computer time, or the use of an adolescent’s own personal hygiene items or clothing. They include knowledge of the adolescent brain, and how the use of isolation in juvenile centers has led to increased suicide rates in those children.

Lindsay M. Hayes, author of the National Center on Institutions and Alternatives’ 2004 report “Juvenile Suicide in Confinement: A National Study,” wrote: ”Although room confinement remains a staple in most juvenile facilities, it is a sanction that can have deadly consequences. … More than 50% of all youths’ suicides in juvenile facilities occurred while young people were isolated alone in their rooms, and … more than 60% of young people who committed suicide in custody had a history of being held in isolation.”

The United Nations has called on all countries to absolutely prohibit solitary confinement for juveniles, as has the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Thus, extreme isolation should not be another tool for juvenile detention centers.

Currently, 20 states have banned solitary confinement in juvenile detention facilities. The major barriers are from staff, who state it would remove a tool, put staff in danger, and allow youth to run the facilities. None of these has been shown to be true. Some juvenile detention centers have changed the traditional meaning of isolation – youth will have a minimum of 8 hours away from isolation when confined for a day or longer. “During that 8 hours, they have the opportunity to talk to and be in the company of staff,” said Adam Schwartz, a lawyer for the American Civil Liberties Union of Illinois, whose lawsuit drastically limited solitary confinement practices in Illinois’s juvenile detention centers. The policy also requires that inmates in isolation continue to receive education and mental health services.

There is a human dignity that not even detainees deserve to lose. President Obama has discussed this, as has the 2012 Report of the Attorney General’s National Task Force on Children Exposed to Violence, which concluded: “Nowhere is the damaging impact of incarceration on vulnerable children more obvious than when it involves solitary confinement.” I am writing this article to raise awareness about this underreported problem in hopes that new legislation will lead to change that is in the best interest of our children.

Dr. Raffa is in postgraduate year 2 in her pediatric residency at Vanderbilt Children’s Hospital in Nashville, Tenn.

Isolation in juvenile detention centers persists despite ample data demonstrating the traumatizing consequences to youth who often already have been traumatized. I recently visited a detention center as part of my pediatric residency’s advocacy rotation. There, I learned that youth are kept in isolation for several days, with a vague definition by staff on the limit of “several days.” Multiple words were used for confinement, the most stunning and horrific of which was “segregation” – “He got into a fight and was placed in segregation.” While in isolation or segregation – whatever it is called – mental illness and posttraumatic stress disorder are exacerbated. Youth do not participate in school classes, and they are barred from the daily hour of physical activity. In extreme cases, they go from complete isolation one day to complete freedom the next.

The vibe word in the facility I visited was “evidence-based strategies,” stressed by the new administration. But evidence-based strategies do not include isolation. They include educating staff about the pervasive effects of trauma in children. They include communication interventions, conflict resolution, and the implementation of rewards such as extra visitation, computer time, or the use of an adolescent’s own personal hygiene items or clothing. They include knowledge of the adolescent brain, and how the use of isolation in juvenile centers has led to increased suicide rates in those children.

Lindsay M. Hayes, author of the National Center on Institutions and Alternatives’ 2004 report “Juvenile Suicide in Confinement: A National Study,” wrote: ”Although room confinement remains a staple in most juvenile facilities, it is a sanction that can have deadly consequences. … More than 50% of all youths’ suicides in juvenile facilities occurred while young people were isolated alone in their rooms, and … more than 60% of young people who committed suicide in custody had a history of being held in isolation.”

The United Nations has called on all countries to absolutely prohibit solitary confinement for juveniles, as has the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Thus, extreme isolation should not be another tool for juvenile detention centers.

Currently, 20 states have banned solitary confinement in juvenile detention facilities. The major barriers are from staff, who state it would remove a tool, put staff in danger, and allow youth to run the facilities. None of these has been shown to be true. Some juvenile detention centers have changed the traditional meaning of isolation – youth will have a minimum of 8 hours away from isolation when confined for a day or longer. “During that 8 hours, they have the opportunity to talk to and be in the company of staff,” said Adam Schwartz, a lawyer for the American Civil Liberties Union of Illinois, whose lawsuit drastically limited solitary confinement practices in Illinois’s juvenile detention centers. The policy also requires that inmates in isolation continue to receive education and mental health services.

There is a human dignity that not even detainees deserve to lose. President Obama has discussed this, as has the 2012 Report of the Attorney General’s National Task Force on Children Exposed to Violence, which concluded: “Nowhere is the damaging impact of incarceration on vulnerable children more obvious than when it involves solitary confinement.” I am writing this article to raise awareness about this underreported problem in hopes that new legislation will lead to change that is in the best interest of our children.

Dr. Raffa is in postgraduate year 2 in her pediatric residency at Vanderbilt Children’s Hospital in Nashville, Tenn.

“Where is it safe to practice obstetrics?” is a broader question

“SHOULD THE 30-MINUTE RULE FOR EMERGENT CESAREAN DELIVERY BE APPLIED UNIVERSALLY?”

“Where is it safe to practice obstetrics?” is a broader question Drs. Chauhan and Mendez-Figueroa presented a thoughtful series of case studies. Unfortunately, the cases were intended for the considerate ObGyn—the one who can appreciate that every case has a differing set of variables—and did not account for the context and legal environment in which we practice. In the theater that is our malpractice reality, these cases would carry little weight with a jury that is empathizing with a child with cerebral palsy, often years after the event.

“Where is it safe to practice obstetrics?” is a broader, and perhaps more interesting, question. And a more relevant case would involve a smaller hospital, perhaps in a rural area, that does not have in-house anesthesia available for 30-minute starts.

Daniel R. Szekely, MD, PhD

Tacoma, Washington

We are hoisted on a petard of our own makingThere is absolutely no justification for ObGyns being held to this so-called “standard of care.” The evidence is scant or lacking that delivery in a 30-minute timeframe has any significant bearing on the neonatal outcome. Despite this, the lay public and medical-legal community see this as an absolute rule to be followed. If there is a less-than-perfect outcome, we are hoisted on this petard of our own making.

We as a group (that is, the American College of Obstetricians and

Gynecologists) need to work to right this unfortunate wrong!

William H. Deschner, MD

Seattle, Washington

Practicing is downright scary The “30-minute rule” is no help to ObGyns in the field. At a community hospital, where surgical teams are called in from home (we cannot afford to do otherwise), it is often impossible to meet this standard. University-level care even cannot meet the measure at times. We never should have been painted into this corner. Now, any attempts to loosen the rule will be seen as trying to practice defensive medicine.

People who do not do what we do for a living have no concept of the anxiety and sleep loss we incur while seeking the best outcomes for our patients. I long for the soon-to-come day when I retire. Due to the litigious environment, I am saddened that I cannot heartily recommend the field to young doctors.

James Nunn, MD

Chicago, Illinois

“UPDATE ON VAGINAL HYSTERECTOMY”

BARBARA S. LEVY, MD (SEPTEMBER 2015)

Why has TAH remained the dominant hysterectomy route for generations?I read with great interest Dr. Levy’s recent comments on the benefits of new technology to improve the vaginal hysterectomy (VH) rate. Thank you and Dr. Levy for all the work you have done to advance the care of our patients. I have some other fundamental concerns about the future of hysterectomy.

Why has total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH) remained the dominant route of hysterectomy for generations? Why have past efforts to minimize TAH met with limited results?

Dr. Levy maintains in her article that, “the biggest barrier to widespread use [of VH] may simply be the lack of industry support.” What industry has supported TAH in a manner not also applicable to VH?

What do the techniques in Dr. Levy’s article and the efforts by ACOG and other authorities1 offer that will materially increase the adoption of VH? What evidence is there that the use of such devices as VITOM system will overcome the low rate of VH? How much training is required before a surgeon can realize patient-centered benefit from using the VITOM or other new devices during VH?

The lack of evidence-based training and implementation of robotic surgery has resulted in well-deserved criticism of robotics, centered, in part, around complications. Will the complication rate rise as those who do not perform VH transition to its adoption using VITOM and other devices?

I hope that the generations-long failure of all efforts to raise the VH rate is overcome with evidence-based educational protocols.

Antonio R. Pizarro, MD

Shreveport, Louisiana

Reference

1. Bosworth T. ACOG taking steps to increase vaginal hysterectomy rates. Ob.Gyn. News. http://www.obgynnews.com/?id=11146&tx_ttnews[tt_news]=392609&cHash=d78b8bea4aa3483c10dc5d843207d211. Posted April 6, 2015. Accessed October 2, 2015.

The problem: lack of trainingSadly, lack of training is the problem in this best approach to removing the benign uterus. These tools are helpful and should be in the surgeon’s armamentarium. We need experienced vaginal surgeons to teach this procedure. In some ways, just as much skill and dexterity are needed as with laparoscopic or robotic methods.

William H. Deschner, MD

Seattle, Washington

Dr. Levy respondsI appreciate the insightful comments of Drs. Pizarro and Deschner. Clearly, as the volume of hysterectomies has decreased and the number of techniques we must teach our residents has expanded, we are challenged to provide robust training in all hysterectomy routes. TAH, as the status quo, has not required the development of new equipment and technology, whereas assisting gynecologic surgeons to convert open procedures to minimally invasive approaches has been advanced and driven by our industry partners.

I totally agree with the concern that we cannot rely on historic data to determine the safest and most cost-effective route for hysterectomy. I encourage all of us to track and publically report our outcomes and monitor the complication rates of gynecologic surgical procedures. Our ongoing commitment to delivering the best care for our patients requires nothing less.

Structured business methods will improve outcomesDr. Barbieri’s call for getting organized and breaking down health care silos while establishing multidisciplinary teams is of great importance. Most providers have not witnessed a maternal mortality in their careers and many are not aware of the near misses. Incorporating foundations of established business methods has been advocated to reduce waste, improve collaboration, decrease variance, and improve patient safety.

If we view the adverse outcomes through this lens, then the increase in maternal mortality and morbidity are lagging indicators in the structured analysis methods (such as Six Sigma and Lean Six Sigma). These methods lead us to focus and measure the leading indicators of input and process (prenatal care and pregnancy management). Our reliance on lagging indicators often comes too late to make any change effective.

Around 1973, several important processes were introduced into obstetric practice: fetal heart-rate monitoring; ultrasonography; and a reduction of the use of forceps with an increase in the use of vacuum extraction. Safety rates improved, but we witnessed the 8% cesarean delivery rate in 1973 rise to 32% in 2013.1,2 The maternal mortality rate reported in 2013 is now the same as it was in 1973. A corresponding increase in the cesarean delivery rate over this time frame could be inferred.

By focusing on analysis and management of variables in pregnancy and implementing standardization of care based on good evidence from all disciplines involved in patient safety, we can improve maternal mortality. Simulations and debriefings are critical instruments to enhance management of all aspects of prenatal management, particularly emergent care.

As leaders in improving maternal quality, ObGyns must implement structured business methods (input and process analysis) to improve outcomes. A culture also can be positively altered if the mission and vision are clearly elucidated. Transparent, dynamic, granular, accurate, and reliable data will facilitate “buy-in” of the caregivers and provide more successful solutions. Decreased variance is critical. Expect resistance due to provider autonomy. The alteration in culture of the multidisciplinary team takes time, but a reduction in cesarean delivery rates should be number one on the list to reduce maternal mortality. The unintended consequences of all interventions and monitoring methods also should be pursued.

Robert A. Knuppel, MD, MPH, MBA

Naples, Florida

Judith Withers, RN, MN, MBA

San Diego, California

References

1. Blanchette E. The rising cesarean delivery rate in America. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(3):687–690.

2. Knuppel RA. Personal review of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Vital Statistics Reports, 1973–2015.

Dr. Barbieri respondsI wholeheartedly agree with Dr. Knuppel and Ms. Withers: increasing the use of high reliability clinical processes is critically important in our quest to reduce maternal mortality. In addition to decreasing the cesarean delivery rate, I would prioritize ensuring the use of highly effective contraceptives by women with serious medical comorbidities that increase their risk of maternal mortality.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

“SHOULD THE 30-MINUTE RULE FOR EMERGENT CESAREAN DELIVERY BE APPLIED UNIVERSALLY?”

“Where is it safe to practice obstetrics?” is a broader question Drs. Chauhan and Mendez-Figueroa presented a thoughtful series of case studies. Unfortunately, the cases were intended for the considerate ObGyn—the one who can appreciate that every case has a differing set of variables—and did not account for the context and legal environment in which we practice. In the theater that is our malpractice reality, these cases would carry little weight with a jury that is empathizing with a child with cerebral palsy, often years after the event.

“Where is it safe to practice obstetrics?” is a broader, and perhaps more interesting, question. And a more relevant case would involve a smaller hospital, perhaps in a rural area, that does not have in-house anesthesia available for 30-minute starts.

Daniel R. Szekely, MD, PhD

Tacoma, Washington

We are hoisted on a petard of our own makingThere is absolutely no justification for ObGyns being held to this so-called “standard of care.” The evidence is scant or lacking that delivery in a 30-minute timeframe has any significant bearing on the neonatal outcome. Despite this, the lay public and medical-legal community see this as an absolute rule to be followed. If there is a less-than-perfect outcome, we are hoisted on this petard of our own making.

We as a group (that is, the American College of Obstetricians and

Gynecologists) need to work to right this unfortunate wrong!

William H. Deschner, MD

Seattle, Washington

Practicing is downright scary The “30-minute rule” is no help to ObGyns in the field. At a community hospital, where surgical teams are called in from home (we cannot afford to do otherwise), it is often impossible to meet this standard. University-level care even cannot meet the measure at times. We never should have been painted into this corner. Now, any attempts to loosen the rule will be seen as trying to practice defensive medicine.

People who do not do what we do for a living have no concept of the anxiety and sleep loss we incur while seeking the best outcomes for our patients. I long for the soon-to-come day when I retire. Due to the litigious environment, I am saddened that I cannot heartily recommend the field to young doctors.

James Nunn, MD

Chicago, Illinois

“UPDATE ON VAGINAL HYSTERECTOMY”

BARBARA S. LEVY, MD (SEPTEMBER 2015)

Why has TAH remained the dominant hysterectomy route for generations?I read with great interest Dr. Levy’s recent comments on the benefits of new technology to improve the vaginal hysterectomy (VH) rate. Thank you and Dr. Levy for all the work you have done to advance the care of our patients. I have some other fundamental concerns about the future of hysterectomy.

Why has total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH) remained the dominant route of hysterectomy for generations? Why have past efforts to minimize TAH met with limited results?

Dr. Levy maintains in her article that, “the biggest barrier to widespread use [of VH] may simply be the lack of industry support.” What industry has supported TAH in a manner not also applicable to VH?

What do the techniques in Dr. Levy’s article and the efforts by ACOG and other authorities1 offer that will materially increase the adoption of VH? What evidence is there that the use of such devices as VITOM system will overcome the low rate of VH? How much training is required before a surgeon can realize patient-centered benefit from using the VITOM or other new devices during VH?

The lack of evidence-based training and implementation of robotic surgery has resulted in well-deserved criticism of robotics, centered, in part, around complications. Will the complication rate rise as those who do not perform VH transition to its adoption using VITOM and other devices?

I hope that the generations-long failure of all efforts to raise the VH rate is overcome with evidence-based educational protocols.

Antonio R. Pizarro, MD

Shreveport, Louisiana

Reference

1. Bosworth T. ACOG taking steps to increase vaginal hysterectomy rates. Ob.Gyn. News. http://www.obgynnews.com/?id=11146&tx_ttnews[tt_news]=392609&cHash=d78b8bea4aa3483c10dc5d843207d211. Posted April 6, 2015. Accessed October 2, 2015.

The problem: lack of trainingSadly, lack of training is the problem in this best approach to removing the benign uterus. These tools are helpful and should be in the surgeon’s armamentarium. We need experienced vaginal surgeons to teach this procedure. In some ways, just as much skill and dexterity are needed as with laparoscopic or robotic methods.

William H. Deschner, MD

Seattle, Washington

Dr. Levy respondsI appreciate the insightful comments of Drs. Pizarro and Deschner. Clearly, as the volume of hysterectomies has decreased and the number of techniques we must teach our residents has expanded, we are challenged to provide robust training in all hysterectomy routes. TAH, as the status quo, has not required the development of new equipment and technology, whereas assisting gynecologic surgeons to convert open procedures to minimally invasive approaches has been advanced and driven by our industry partners.

I totally agree with the concern that we cannot rely on historic data to determine the safest and most cost-effective route for hysterectomy. I encourage all of us to track and publically report our outcomes and monitor the complication rates of gynecologic surgical procedures. Our ongoing commitment to delivering the best care for our patients requires nothing less.

Structured business methods will improve outcomesDr. Barbieri’s call for getting organized and breaking down health care silos while establishing multidisciplinary teams is of great importance. Most providers have not witnessed a maternal mortality in their careers and many are not aware of the near misses. Incorporating foundations of established business methods has been advocated to reduce waste, improve collaboration, decrease variance, and improve patient safety.

If we view the adverse outcomes through this lens, then the increase in maternal mortality and morbidity are lagging indicators in the structured analysis methods (such as Six Sigma and Lean Six Sigma). These methods lead us to focus and measure the leading indicators of input and process (prenatal care and pregnancy management). Our reliance on lagging indicators often comes too late to make any change effective.

Around 1973, several important processes were introduced into obstetric practice: fetal heart-rate monitoring; ultrasonography; and a reduction of the use of forceps with an increase in the use of vacuum extraction. Safety rates improved, but we witnessed the 8% cesarean delivery rate in 1973 rise to 32% in 2013.1,2 The maternal mortality rate reported in 2013 is now the same as it was in 1973. A corresponding increase in the cesarean delivery rate over this time frame could be inferred.

By focusing on analysis and management of variables in pregnancy and implementing standardization of care based on good evidence from all disciplines involved in patient safety, we can improve maternal mortality. Simulations and debriefings are critical instruments to enhance management of all aspects of prenatal management, particularly emergent care.

As leaders in improving maternal quality, ObGyns must implement structured business methods (input and process analysis) to improve outcomes. A culture also can be positively altered if the mission and vision are clearly elucidated. Transparent, dynamic, granular, accurate, and reliable data will facilitate “buy-in” of the caregivers and provide more successful solutions. Decreased variance is critical. Expect resistance due to provider autonomy. The alteration in culture of the multidisciplinary team takes time, but a reduction in cesarean delivery rates should be number one on the list to reduce maternal mortality. The unintended consequences of all interventions and monitoring methods also should be pursued.

Robert A. Knuppel, MD, MPH, MBA

Naples, Florida

Judith Withers, RN, MN, MBA

San Diego, California

References

1. Blanchette E. The rising cesarean delivery rate in America. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(3):687–690.

2. Knuppel RA. Personal review of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Vital Statistics Reports, 1973–2015.

Dr. Barbieri respondsI wholeheartedly agree with Dr. Knuppel and Ms. Withers: increasing the use of high reliability clinical processes is critically important in our quest to reduce maternal mortality. In addition to decreasing the cesarean delivery rate, I would prioritize ensuring the use of highly effective contraceptives by women with serious medical comorbidities that increase their risk of maternal mortality.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

“SHOULD THE 30-MINUTE RULE FOR EMERGENT CESAREAN DELIVERY BE APPLIED UNIVERSALLY?”

“Where is it safe to practice obstetrics?” is a broader question Drs. Chauhan and Mendez-Figueroa presented a thoughtful series of case studies. Unfortunately, the cases were intended for the considerate ObGyn—the one who can appreciate that every case has a differing set of variables—and did not account for the context and legal environment in which we practice. In the theater that is our malpractice reality, these cases would carry little weight with a jury that is empathizing with a child with cerebral palsy, often years after the event.

“Where is it safe to practice obstetrics?” is a broader, and perhaps more interesting, question. And a more relevant case would involve a smaller hospital, perhaps in a rural area, that does not have in-house anesthesia available for 30-minute starts.

Daniel R. Szekely, MD, PhD

Tacoma, Washington

We are hoisted on a petard of our own makingThere is absolutely no justification for ObGyns being held to this so-called “standard of care.” The evidence is scant or lacking that delivery in a 30-minute timeframe has any significant bearing on the neonatal outcome. Despite this, the lay public and medical-legal community see this as an absolute rule to be followed. If there is a less-than-perfect outcome, we are hoisted on this petard of our own making.

We as a group (that is, the American College of Obstetricians and

Gynecologists) need to work to right this unfortunate wrong!

William H. Deschner, MD

Seattle, Washington

Practicing is downright scary The “30-minute rule” is no help to ObGyns in the field. At a community hospital, where surgical teams are called in from home (we cannot afford to do otherwise), it is often impossible to meet this standard. University-level care even cannot meet the measure at times. We never should have been painted into this corner. Now, any attempts to loosen the rule will be seen as trying to practice defensive medicine.

People who do not do what we do for a living have no concept of the anxiety and sleep loss we incur while seeking the best outcomes for our patients. I long for the soon-to-come day when I retire. Due to the litigious environment, I am saddened that I cannot heartily recommend the field to young doctors.

James Nunn, MD

Chicago, Illinois

“UPDATE ON VAGINAL HYSTERECTOMY”

BARBARA S. LEVY, MD (SEPTEMBER 2015)

Why has TAH remained the dominant hysterectomy route for generations?I read with great interest Dr. Levy’s recent comments on the benefits of new technology to improve the vaginal hysterectomy (VH) rate. Thank you and Dr. Levy for all the work you have done to advance the care of our patients. I have some other fundamental concerns about the future of hysterectomy.

Why has total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH) remained the dominant route of hysterectomy for generations? Why have past efforts to minimize TAH met with limited results?

Dr. Levy maintains in her article that, “the biggest barrier to widespread use [of VH] may simply be the lack of industry support.” What industry has supported TAH in a manner not also applicable to VH?

What do the techniques in Dr. Levy’s article and the efforts by ACOG and other authorities1 offer that will materially increase the adoption of VH? What evidence is there that the use of such devices as VITOM system will overcome the low rate of VH? How much training is required before a surgeon can realize patient-centered benefit from using the VITOM or other new devices during VH?

The lack of evidence-based training and implementation of robotic surgery has resulted in well-deserved criticism of robotics, centered, in part, around complications. Will the complication rate rise as those who do not perform VH transition to its adoption using VITOM and other devices?

I hope that the generations-long failure of all efforts to raise the VH rate is overcome with evidence-based educational protocols.

Antonio R. Pizarro, MD

Shreveport, Louisiana

Reference

1. Bosworth T. ACOG taking steps to increase vaginal hysterectomy rates. Ob.Gyn. News. http://www.obgynnews.com/?id=11146&tx_ttnews[tt_news]=392609&cHash=d78b8bea4aa3483c10dc5d843207d211. Posted April 6, 2015. Accessed October 2, 2015.

The problem: lack of trainingSadly, lack of training is the problem in this best approach to removing the benign uterus. These tools are helpful and should be in the surgeon’s armamentarium. We need experienced vaginal surgeons to teach this procedure. In some ways, just as much skill and dexterity are needed as with laparoscopic or robotic methods.

William H. Deschner, MD

Seattle, Washington

Dr. Levy respondsI appreciate the insightful comments of Drs. Pizarro and Deschner. Clearly, as the volume of hysterectomies has decreased and the number of techniques we must teach our residents has expanded, we are challenged to provide robust training in all hysterectomy routes. TAH, as the status quo, has not required the development of new equipment and technology, whereas assisting gynecologic surgeons to convert open procedures to minimally invasive approaches has been advanced and driven by our industry partners.

I totally agree with the concern that we cannot rely on historic data to determine the safest and most cost-effective route for hysterectomy. I encourage all of us to track and publically report our outcomes and monitor the complication rates of gynecologic surgical procedures. Our ongoing commitment to delivering the best care for our patients requires nothing less.

Structured business methods will improve outcomesDr. Barbieri’s call for getting organized and breaking down health care silos while establishing multidisciplinary teams is of great importance. Most providers have not witnessed a maternal mortality in their careers and many are not aware of the near misses. Incorporating foundations of established business methods has been advocated to reduce waste, improve collaboration, decrease variance, and improve patient safety.

If we view the adverse outcomes through this lens, then the increase in maternal mortality and morbidity are lagging indicators in the structured analysis methods (such as Six Sigma and Lean Six Sigma). These methods lead us to focus and measure the leading indicators of input and process (prenatal care and pregnancy management). Our reliance on lagging indicators often comes too late to make any change effective.

Around 1973, several important processes were introduced into obstetric practice: fetal heart-rate monitoring; ultrasonography; and a reduction of the use of forceps with an increase in the use of vacuum extraction. Safety rates improved, but we witnessed the 8% cesarean delivery rate in 1973 rise to 32% in 2013.1,2 The maternal mortality rate reported in 2013 is now the same as it was in 1973. A corresponding increase in the cesarean delivery rate over this time frame could be inferred.

By focusing on analysis and management of variables in pregnancy and implementing standardization of care based on good evidence from all disciplines involved in patient safety, we can improve maternal mortality. Simulations and debriefings are critical instruments to enhance management of all aspects of prenatal management, particularly emergent care.

As leaders in improving maternal quality, ObGyns must implement structured business methods (input and process analysis) to improve outcomes. A culture also can be positively altered if the mission and vision are clearly elucidated. Transparent, dynamic, granular, accurate, and reliable data will facilitate “buy-in” of the caregivers and provide more successful solutions. Decreased variance is critical. Expect resistance due to provider autonomy. The alteration in culture of the multidisciplinary team takes time, but a reduction in cesarean delivery rates should be number one on the list to reduce maternal mortality. The unintended consequences of all interventions and monitoring methods also should be pursued.

Robert A. Knuppel, MD, MPH, MBA

Naples, Florida

Judith Withers, RN, MN, MBA

San Diego, California

References

1. Blanchette E. The rising cesarean delivery rate in America. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(3):687–690.

2. Knuppel RA. Personal review of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Vital Statistics Reports, 1973–2015.

Dr. Barbieri respondsI wholeheartedly agree with Dr. Knuppel and Ms. Withers: increasing the use of high reliability clinical processes is critically important in our quest to reduce maternal mortality. In addition to decreasing the cesarean delivery rate, I would prioritize ensuring the use of highly effective contraceptives by women with serious medical comorbidities that increase their risk of maternal mortality.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Radiofrequency volumetric thermal ablation for symptomatic uterine fibroids

In 2002, Dr. Bruce B. Lee first described a laparoscopic technique to ablate symptomatic uterine fibroids utilizing radiofrequency under ultrasound guidance. Since this time, several papers have documented the procedure’s feasibility and efficacy, including reduction in menstrual blood loss, fibroid volume decrease, and improvement in quality of life.

In a randomized, prospective, single-center, longitudinal study that compared laparoscopic radiofrequency volumetric thermal ablation (RFVTA) of fibroids with laparoscopic myomectomy, Dr. Sara Y. Brucker and her colleagues concluded that RFVTA resulted in the treatment of more fibroids, a significantly shorter hospital stay, and less intraoperative blood loss than did laparoscopic myomectomy (Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014 Jun;125[3]:261-5).

More recently, in the literature and at the 2015 American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL) Global Congress in November, viable, full-term pregnancies have been reported in patients previously treated for symptomatic fibroids via RFVTA (J Reprod Med. 2015 May-Jun;60[5-6]:194-8).

The system for performing RFVTA of symptomatic fibroids – the Acessa System (Halt Medical) – has continued to improve. Earlier this year, Dr. Donald I. Galen described the use of electromagnetic image guidance, which has been cleared by the Food and Drug Administration and incorporated into the Acessa Guidance System. Dr. Galen’s feasibility study showed that the guidance system enhances the ultrasonic image of Acessa’s handpiece to facilitate accurate tip placement during the targeting and ablation of uterine fibroids (Biomed Eng Online. 2015 Oct 15;14:90).

In this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, Dr. Jay M. Berman discusses the use of RFVTA for the treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids. Dr. Berman is interim chairman of Wayne State University’s department of obstetrics and gynecology and interim specialist in chief for obstetrics and gynecology at the Detroit Medical Center. He served as a principal investigator of the pivotal trial of Acessa and has reported on reproductive outcomes. Dr. Berman has long been interested in alternatives to hysterectomy for fibroid management and has incorporated RFVTA into his armamentarium of therapies.

Dr. Miller is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and a past president of the AAGL and the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE). He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville and Schaumburg, Ill.; director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/Society of Reproductive Surgery fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller reported that he is a consultant for Halt Medical Inc., which developed the Acessa System.

In 2002, Dr. Bruce B. Lee first described a laparoscopic technique to ablate symptomatic uterine fibroids utilizing radiofrequency under ultrasound guidance. Since this time, several papers have documented the procedure’s feasibility and efficacy, including reduction in menstrual blood loss, fibroid volume decrease, and improvement in quality of life.

In a randomized, prospective, single-center, longitudinal study that compared laparoscopic radiofrequency volumetric thermal ablation (RFVTA) of fibroids with laparoscopic myomectomy, Dr. Sara Y. Brucker and her colleagues concluded that RFVTA resulted in the treatment of more fibroids, a significantly shorter hospital stay, and less intraoperative blood loss than did laparoscopic myomectomy (Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014 Jun;125[3]:261-5).

More recently, in the literature and at the 2015 American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL) Global Congress in November, viable, full-term pregnancies have been reported in patients previously treated for symptomatic fibroids via RFVTA (J Reprod Med. 2015 May-Jun;60[5-6]:194-8).

The system for performing RFVTA of symptomatic fibroids – the Acessa System (Halt Medical) – has continued to improve. Earlier this year, Dr. Donald I. Galen described the use of electromagnetic image guidance, which has been cleared by the Food and Drug Administration and incorporated into the Acessa Guidance System. Dr. Galen’s feasibility study showed that the guidance system enhances the ultrasonic image of Acessa’s handpiece to facilitate accurate tip placement during the targeting and ablation of uterine fibroids (Biomed Eng Online. 2015 Oct 15;14:90).

In this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, Dr. Jay M. Berman discusses the use of RFVTA for the treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids. Dr. Berman is interim chairman of Wayne State University’s department of obstetrics and gynecology and interim specialist in chief for obstetrics and gynecology at the Detroit Medical Center. He served as a principal investigator of the pivotal trial of Acessa and has reported on reproductive outcomes. Dr. Berman has long been interested in alternatives to hysterectomy for fibroid management and has incorporated RFVTA into his armamentarium of therapies.

Dr. Miller is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and a past president of the AAGL and the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE). He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville and Schaumburg, Ill.; director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/Society of Reproductive Surgery fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller reported that he is a consultant for Halt Medical Inc., which developed the Acessa System.

In 2002, Dr. Bruce B. Lee first described a laparoscopic technique to ablate symptomatic uterine fibroids utilizing radiofrequency under ultrasound guidance. Since this time, several papers have documented the procedure’s feasibility and efficacy, including reduction in menstrual blood loss, fibroid volume decrease, and improvement in quality of life.

In a randomized, prospective, single-center, longitudinal study that compared laparoscopic radiofrequency volumetric thermal ablation (RFVTA) of fibroids with laparoscopic myomectomy, Dr. Sara Y. Brucker and her colleagues concluded that RFVTA resulted in the treatment of more fibroids, a significantly shorter hospital stay, and less intraoperative blood loss than did laparoscopic myomectomy (Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014 Jun;125[3]:261-5).

More recently, in the literature and at the 2015 American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL) Global Congress in November, viable, full-term pregnancies have been reported in patients previously treated for symptomatic fibroids via RFVTA (J Reprod Med. 2015 May-Jun;60[5-6]:194-8).

The system for performing RFVTA of symptomatic fibroids – the Acessa System (Halt Medical) – has continued to improve. Earlier this year, Dr. Donald I. Galen described the use of electromagnetic image guidance, which has been cleared by the Food and Drug Administration and incorporated into the Acessa Guidance System. Dr. Galen’s feasibility study showed that the guidance system enhances the ultrasonic image of Acessa’s handpiece to facilitate accurate tip placement during the targeting and ablation of uterine fibroids (Biomed Eng Online. 2015 Oct 15;14:90).

In this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, Dr. Jay M. Berman discusses the use of RFVTA for the treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids. Dr. Berman is interim chairman of Wayne State University’s department of obstetrics and gynecology and interim specialist in chief for obstetrics and gynecology at the Detroit Medical Center. He served as a principal investigator of the pivotal trial of Acessa and has reported on reproductive outcomes. Dr. Berman has long been interested in alternatives to hysterectomy for fibroid management and has incorporated RFVTA into his armamentarium of therapies.

Dr. Miller is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and a past president of the AAGL and the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE). He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville and Schaumburg, Ill.; director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/Society of Reproductive Surgery fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller reported that he is a consultant for Halt Medical Inc., which developed the Acessa System.

RFVTA system offers alternative to myomectomy

Uterine myomas cause heavy menstrual bleeding and other clinically significant symptoms in 35%-50% of affected women and have been shown to be the leading indication for hysterectomy in the United States among women aged 35-54 years.

Research has shown that a significant number of women who undergo hysterectomy for treatment of fibroids later regret the loss of their uterus and have other concerns and complications. Other options for therapy include various pharmacologic treatments, a progestin-releasing intrauterine device, uterine artery embolization, endometrial ablation, MRI-guided focused ultrasound surgery, and myomectomy performed laparoscopically, robotically, or hysteroscopically.

Myomectomy seems largely to preserve fertility, but rates of recurrence and additional procedures for bleeding and myoma symptoms are still high – upward of 30% in some studies. Overall, we need other more efficacious and minimally invasive options.

Radiofrequency volumetric thermal ablation (RFVTA) achieved through the Acessa System (Halt Medical) has been the newest addition to our armamentarium for treatment of symptomatic fibroids. It is suitable for every type of fibroid except for type 0 pedunculated intracavitary fibroids and type 7 pedunculated subserosal fibroids, which is significant because deep intramural fibroids have been difficult to target and treat by other methods.

Three-year outcome data show sustained improvements in fibroid symptoms and quality of life, with an incidence of recurrences and additional procedures – approximately 11% – that appears to be substantially lower than for other uterine-sparing fibroid treatments. In addition, while the technology is not indicated for women seeking future childbearing, successful pregnancies are being reported, suggesting that full-term pregnancies – and vaginal delivery in some cases – may be possible after RFVTA.

The principles

Radiofrequency ablation has been used for years in the treatment of liver and kidney tumors. The basic concept is that volumetric thermal ablation results in coagulative necrosis.

The Acessa System, approved by the Food and Drug Administration in late 2012, was designed to treat fibroids, which have much firmer tissue than the tissues being targeted in other radiofrequency ablation procedures. It uses a specially designed intrauterine ultrasound probe and radiofrequency probe, and it combines three fundamental gynecologic skills: Laparoscopy using two trocars and requiring no special suturing skills; ultrasound using a laparoscopic ultrasound probe to scan and manipulate; and probe placement under laparoscopic ultrasound guidance.

Specifically, the system allows for percutaneous, laparoscopic ultrasound–guided radiofrequency ablation of fibroids with a disposable 3.4-mm handpiece coupled to a dual-function radiofrequency generator. The handpiece contains a retractable array of electrodes, so that the fibroid may be ablated with one electrode or with the deployed electrode array.

The generator controls and monitors the ablation with real-time feedback from thermocouples. It monitors and displays the temperature at each needle tip, the average temperature of the array, and the return temperatures on two dispersive electrode pads that are placed on the anterior thighs. The electrode pads are designed to reduce the incidence of pad burns, which are a complication with other radiofrequency ablation devices. The system will automatically stop treatment if either of the pad thermocouples registers a skin temperature greater than 40° C (JSLS. 2014 Apr-Jun;18[2]:182-90).

The outcomes

Laparoscopic ultrasound–guided RFVTA has been studied in five prospective trials, including one multicenter international trial of 135 premenopausal women – the pivotal trial for FDA clearance – in which 104 women were followed for 3 years and found to have prolonged symptom relief and improved quality of life.

At baseline, the women had symptomatic uterine myomas and moderate to severe heavy menstrual bleeding measured by alkaline hematin analysis of returned sanitary products. Their mean symptom severity scores on the Uterine Fibroid Symptom and Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (UFS-QOL) decreased significantly from baseline to 3 months and changed little after that, for a total change of –32.6 over the study period.

The cumulative repeat intervention rate at 3 years was 11%, with 14 of the 135 participants having repeat interventions to treat bleeding and myoma symptoms. Seven of these women were found to have adenomyosis (J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014 Sep-Oct;21[5]:767-74).

The surprisingly low reintervention rates may stem from the benefits of direct contact imaging of the uterus. A comparison of images from the pivotal trial has shown that intraoperative ultrasound detected more than twice as many fibroids as did preoperative transvaginal ultrasound, and about one-third more than preoperative MRIs (J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013 Nov-Dec;20[6]:770-4).

Interestingly, four women became pregnant over the study’s 3-year follow-up, despite the inclusion requirement that women desire uterine conservation but not future childbearing.

We have followed reproductive outcomes in women after RFVTA of symptomatic fibroids in other studies as well. In our most recent analysis, presented in November at the 2015 American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists Global Congress, we identified 10 pregnancies among participants of the five prospective trials.

Of 232 women enrolled in premarket RFVTA studies – trials in which completing childbearing and continuing contraception were requirements – six conceived at 3.5-15 months post ablation. The number of myomas treated ranged from one to seven and included multiple types and dimensions. Five of these six women delivered full-term healthy babies – one by vaginal delivery and four by cesarean section. The sixth patient had a spontaneous abortion in the first trimester.

Of 43 women who participated in two randomized clinical trials undertaken after FDA clearance, four conceived at 4-23.5 months post ablation. Three of these women had uneventful, full-term pregnancies with vaginal births. The fourth had a cesarean section at 38 weeks.

Considering the theoretical advantages of the Acessa procedure – that it is less damaging to healthy myometrium – and the outcomes reported thus far, it appears likely that Acessa will be preferable to myomectomy. Early results from an ongoing 5-year German study that randomized 50 women to RFVTA or laparoscopic myomectomy show that RFVTA resulted in the treatment of more fibroids and involved a significantly shorter hospital stay and post-operative recovery (Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014 Jun;125[3]:261-5).

The technique